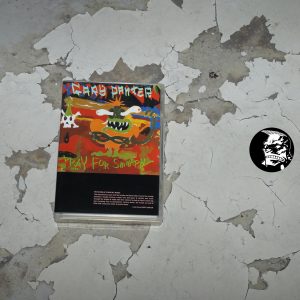

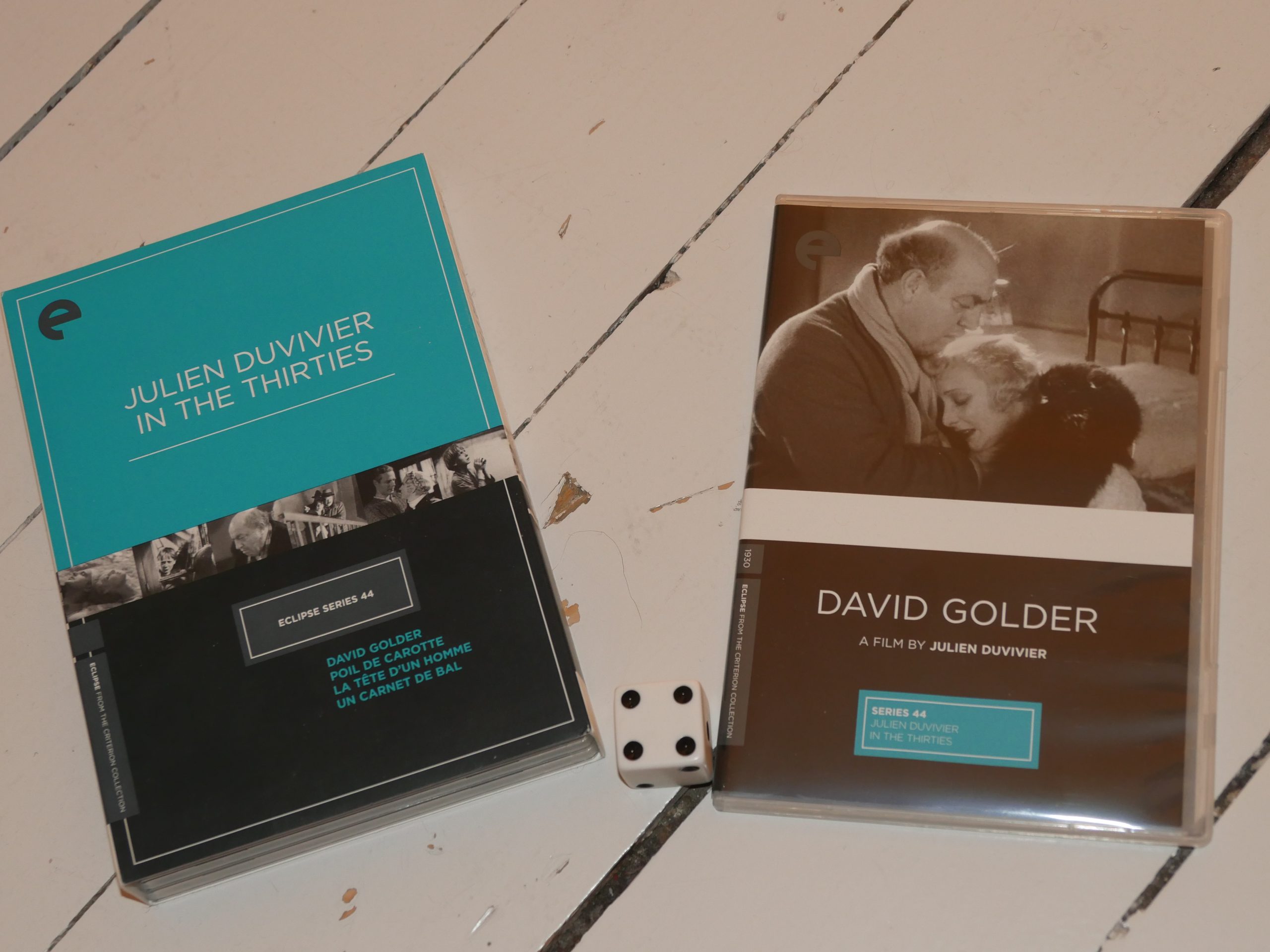

I was gonna watch a whole bunch of these Eclipse movies from Criterion, but I got caught up in a bunch of Emacs stuff.

Back on track: Movies! Movies!

Wow, that’s some close-up camera work. They camera has to be like five centimetres from his nose.

Duvivier is some kind of genius. I mean, on a shot to shot basis. Every shot is just fascinating. And I can’t recall ever seeing that name before starting to watch this box set.

I’m guessing the Cahiers crowd hates these movies so much? Hm… :

We have all read many times of how the young critics at Cahiers du Cinema have savaged Julien Duvivier.

I guessed right? But that’s all about his 50s movies.

There’s a bit of disconnect between how fabulous each shot it and … how choppy the storytelling is. I mean, it’s very stylised and not meant to be naturalistic or anything, but it’s still hard to pay much attention, because it doesn’t seem like the movie isn’t that interested either?

It’s in that uncanny valley between avant garde and … not quite getting it right?

Huh:

Julien Duvivier adapted it for movies twice: in 1925 as a silent film and again in 1932 with sound.

That’s some weird bokeh! What kinda lens could result in something like that…

I can totally understand this:

I saw this film at the unlikely venue of the Walter Reade Theatre in New York. The film was introduced by David Grossman, a retired exhibitor who dedicated the showing to film historian and enthusiast William K. Everson. Grossman was so full of love for the film that he could hardly express himself.

That is, I can understand people really loving this movie and being obsessed with it. But I think it’s a bit on the corny side.

It looks gorgeous though. So:

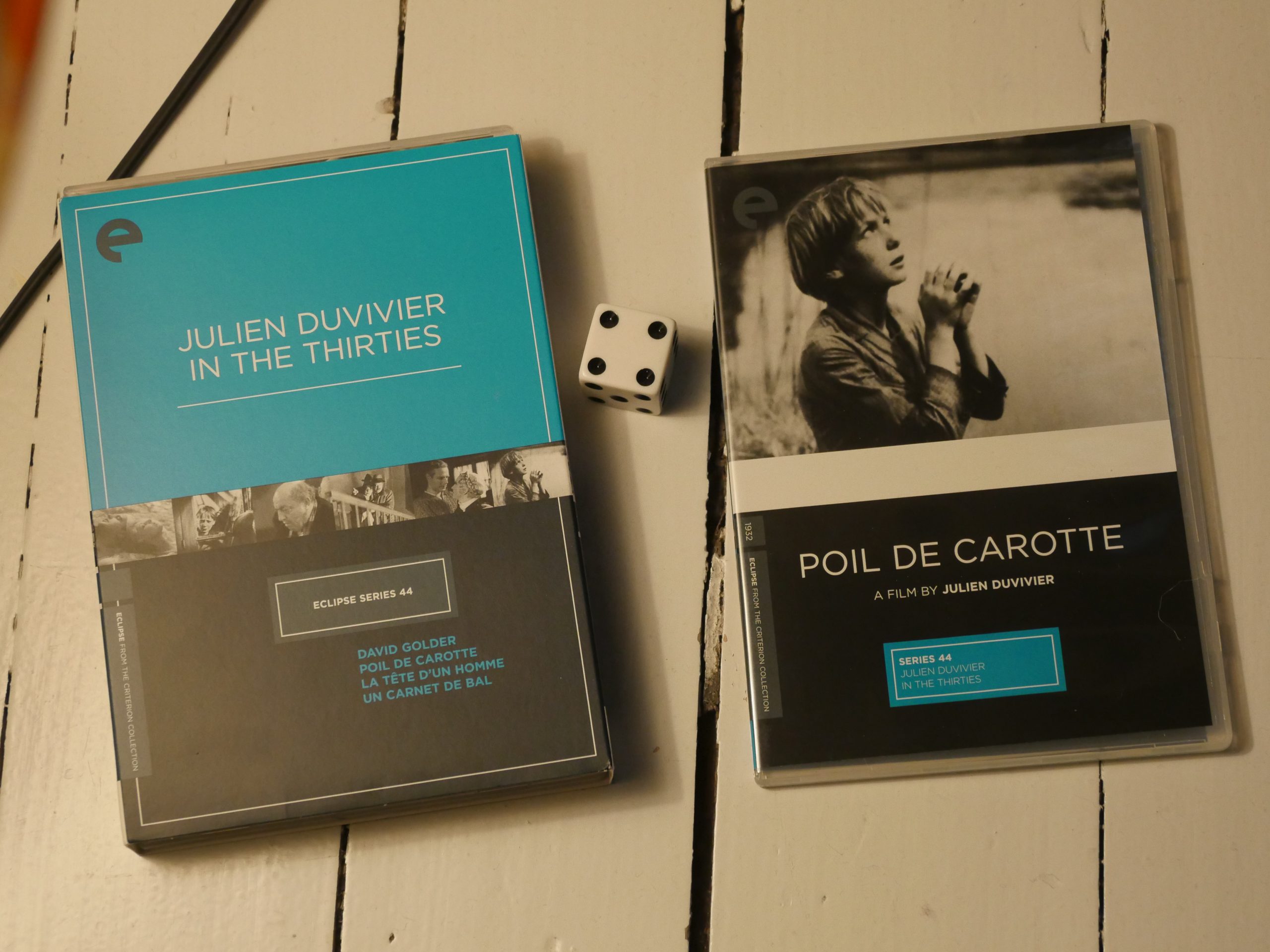

Poil de Carotte. Julien Duvivier. 1932.

This blog post is part of the Eclipse series.

)

)

%3A+Look+At+The+Moon!+(live+Phoenix+Festival+97)+(1))

)

)

%3A+In+the+Court+Of+The+Crimson+King+(Alternate+Album))

+(3))