Music I’ve bought in January.

It’s not a lot, and most of what I’ve bought are box sets of old albums and stuff. TSK TSK

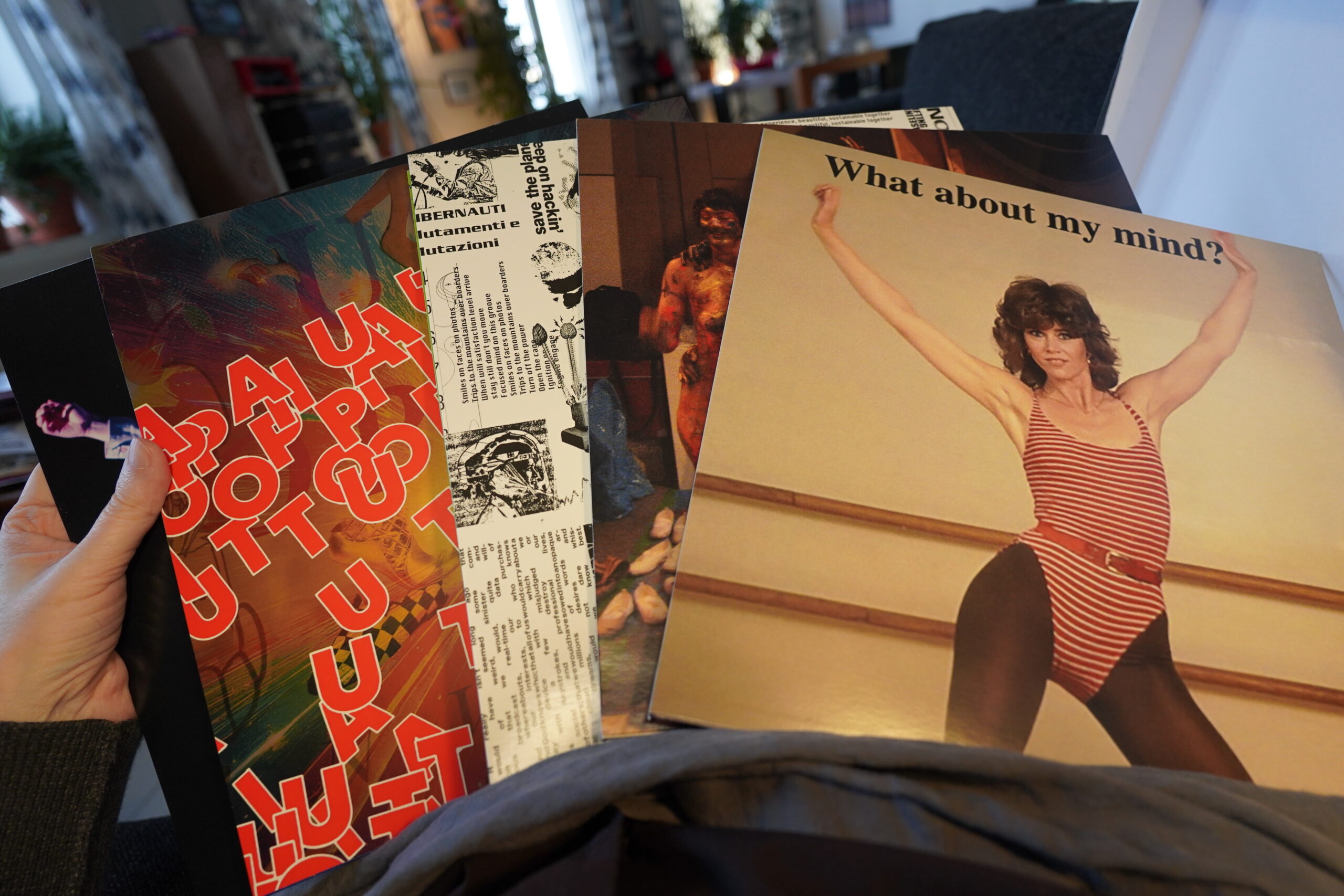

The Chicks on Speed box is a pretty odd one. It’s not really a “best of” box, and it’s not really a retrospective, either. Instead it’s half newish songs, half old ones, and half new versions/remixes of old ones. That’s a lot of halves, but it’s a big box.

I’m not altogether sure that it totally works… interweaving old and new songs like this mostly reminds you that the older songs were better?

But it’s a pretty fun box — there’s a very colourful booklet…

Tasteful cover designs.

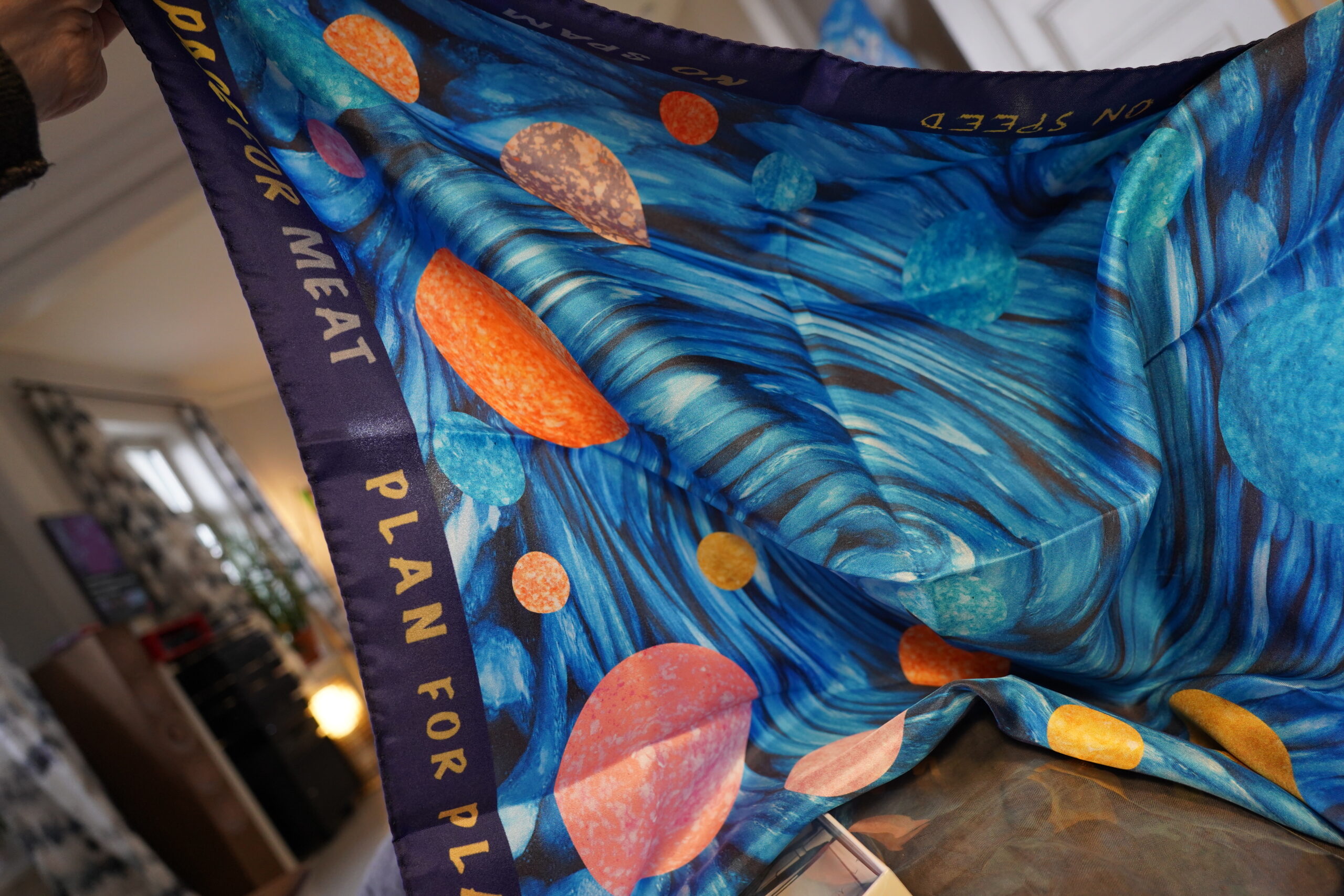

And an Italian silk scarf! That’s not something you get in every box set, eh? Eh?

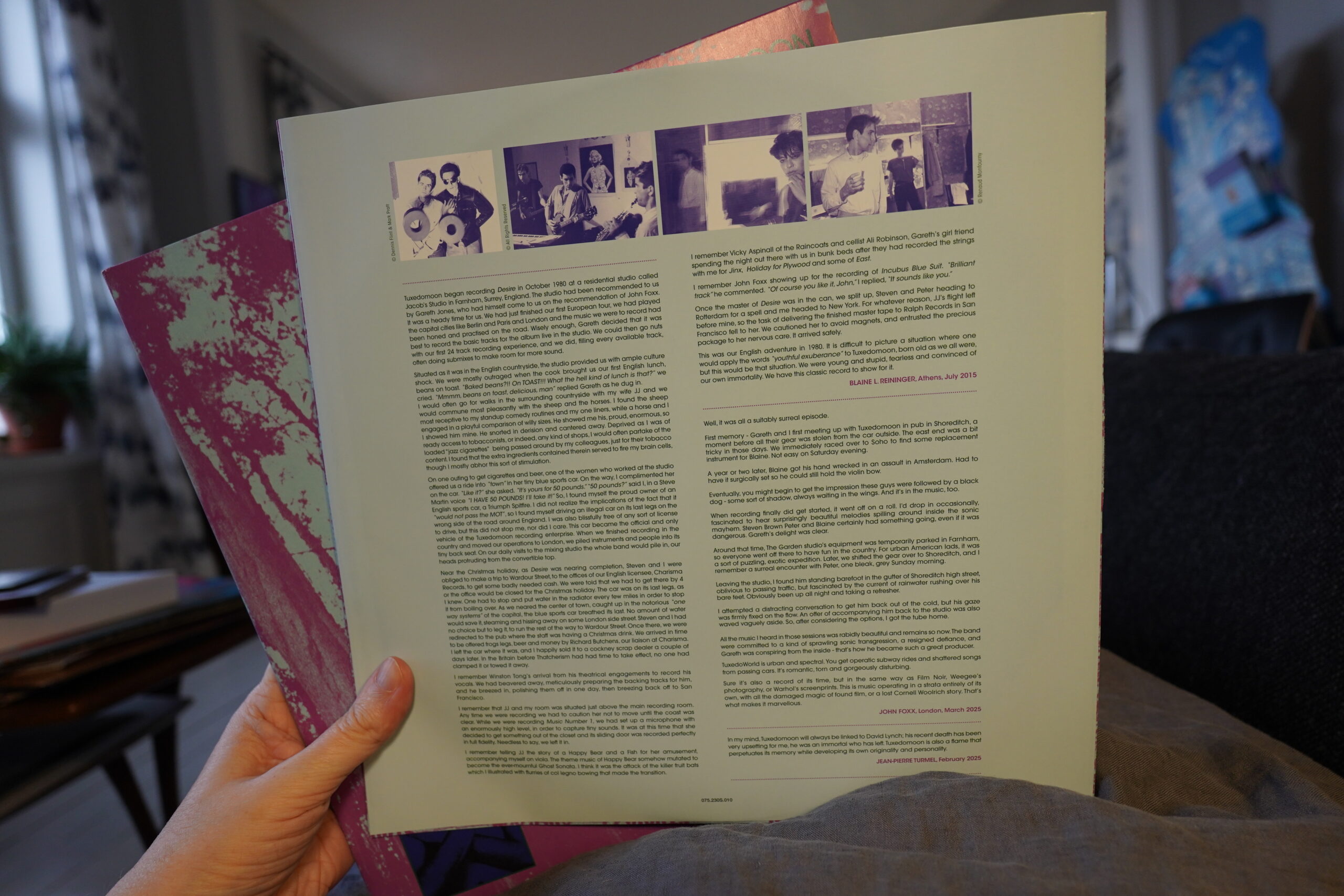

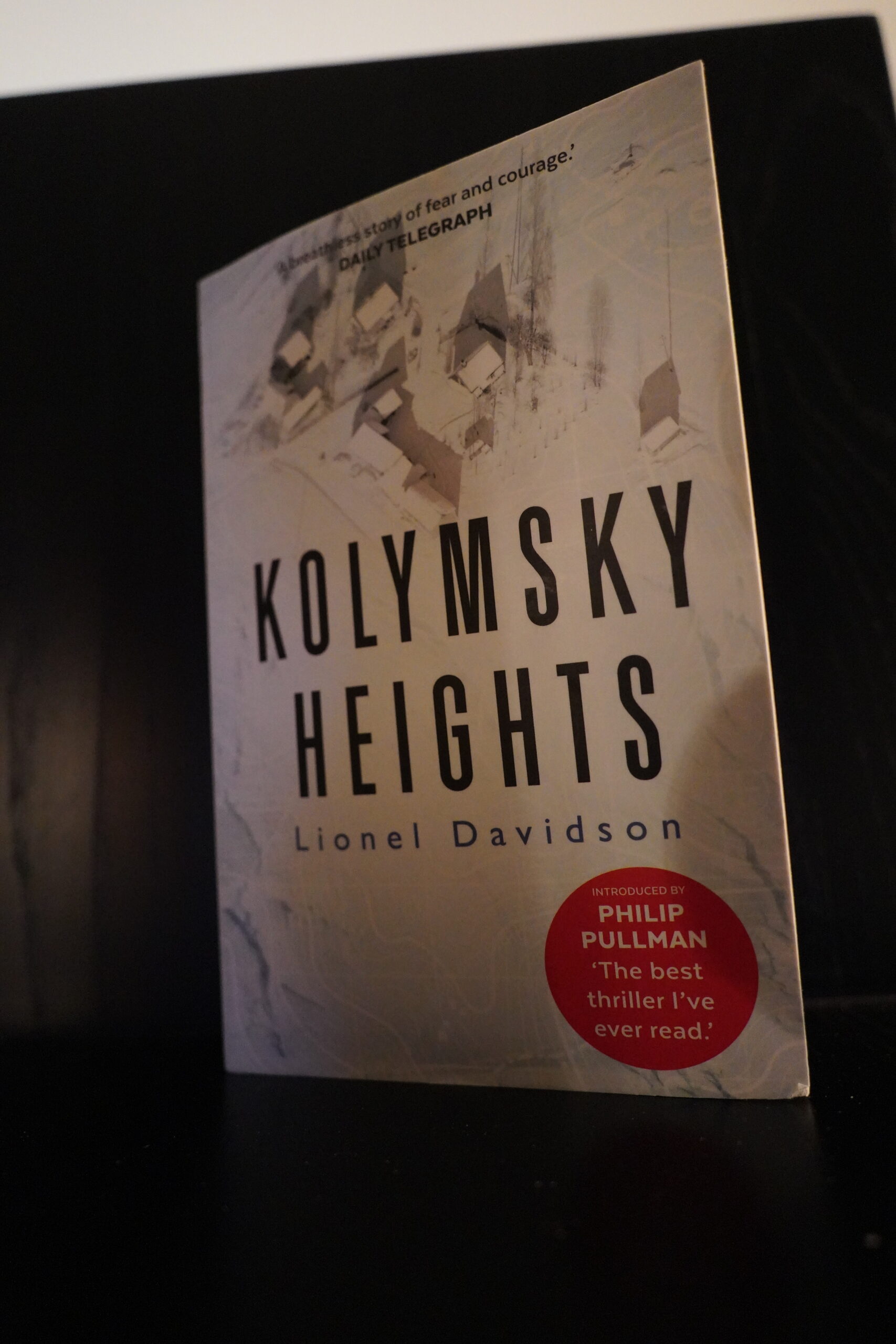

The 2xLP version of Desire by Tuxedomoon has The Worst Design Ever. But why — the original one was pretty spiffy.

But it does come with some pretty amusing texts about the recording of the album, and it has three previously unpublished outtakes. (And some alternative versions.)

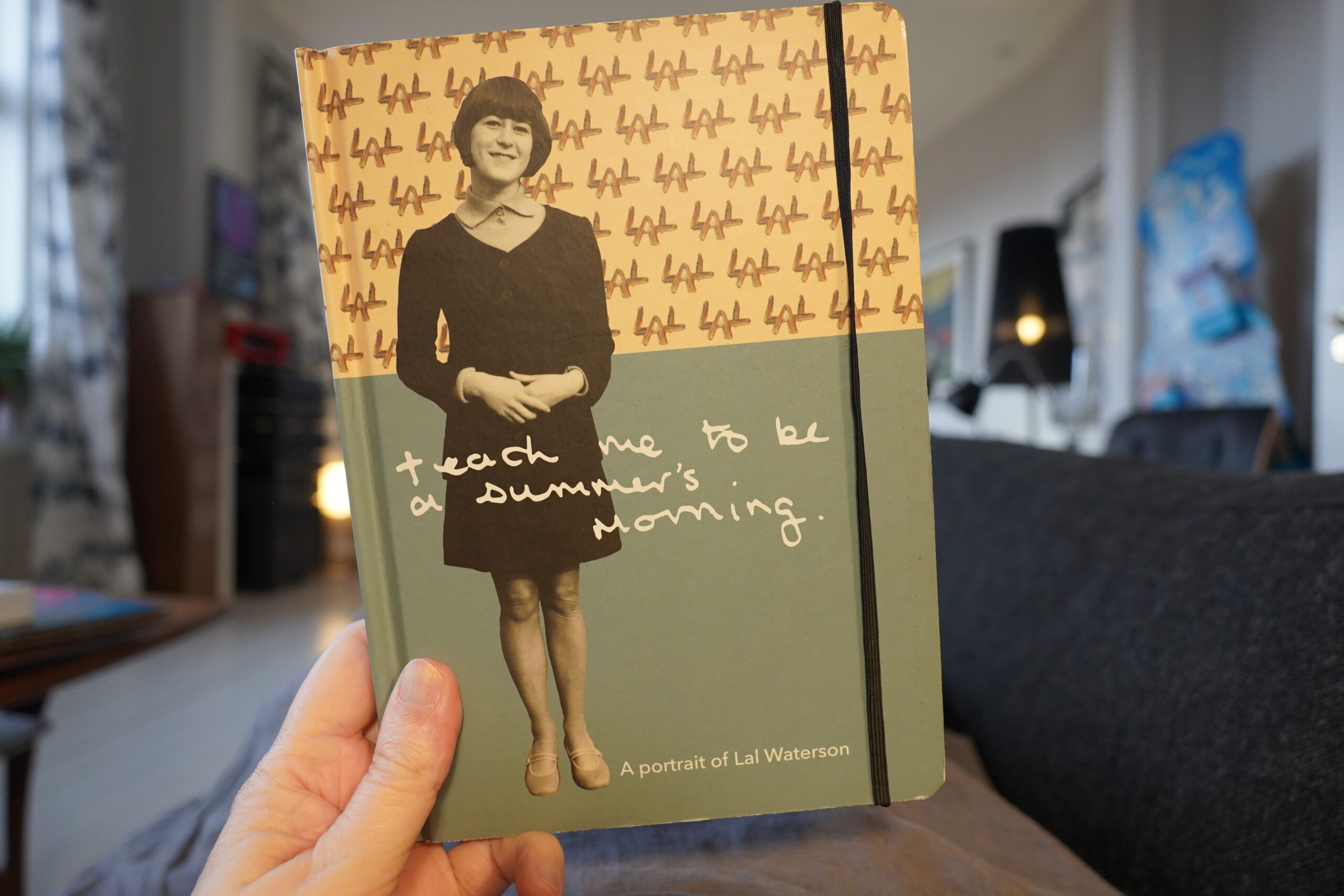

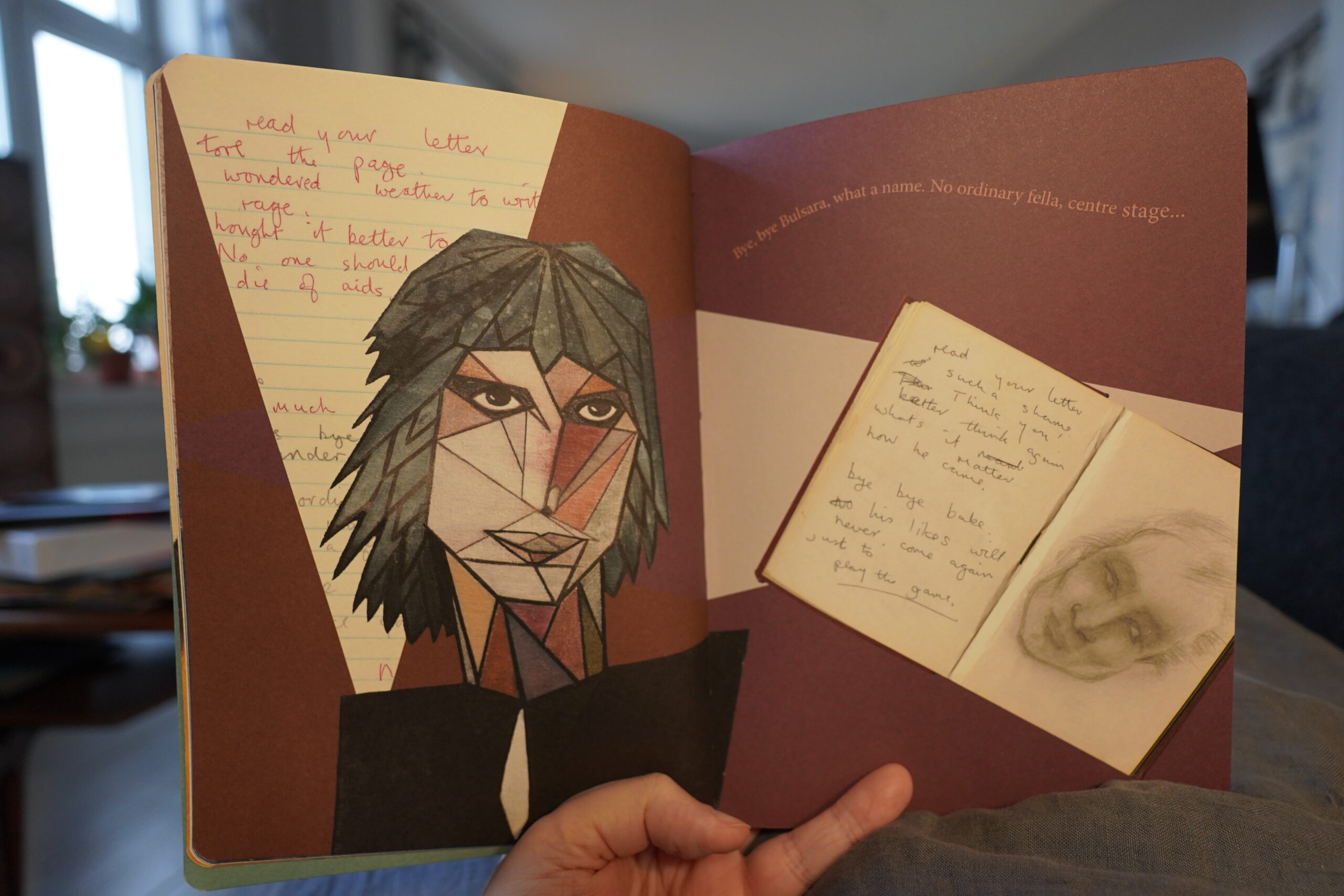

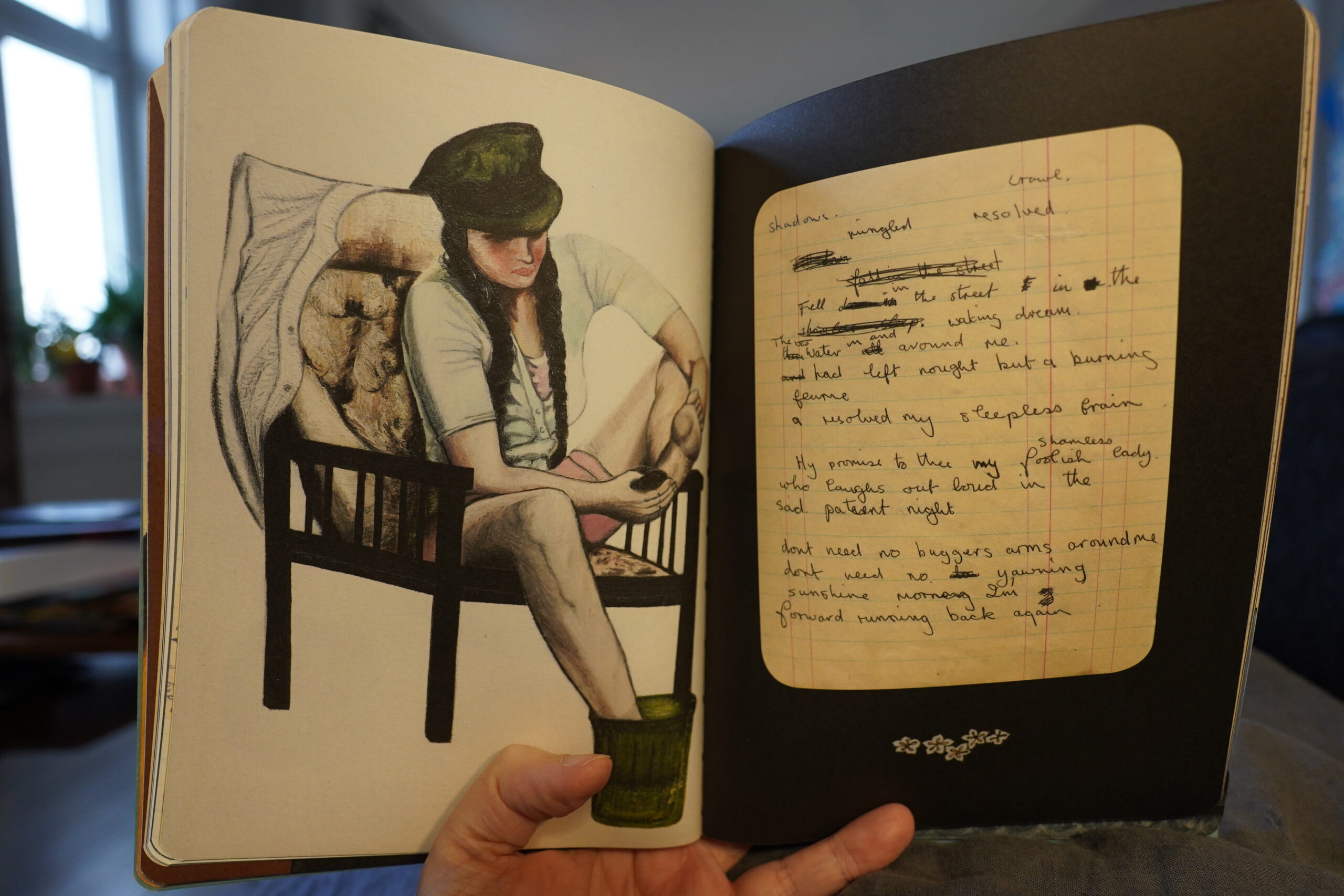

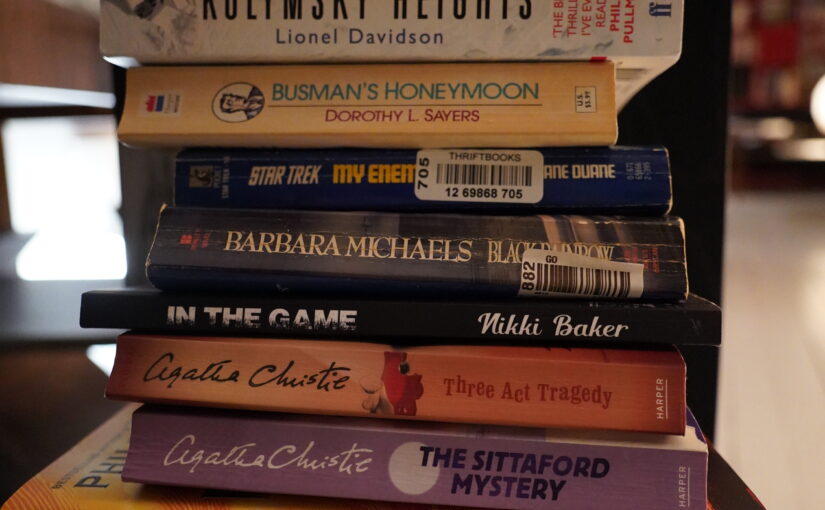

This was released a decade ago, but I’d totally missed it — I just happened onto it on Discogs one day. I really love Lal & Mike Waterson’s album, and she never released anything after it got a pretty tepid (veering towards hostile) reception…

… and this release shows what a tragedy that was. The CD consists of home recordings she did over the years, and there’s some real gems in there.

The accompanying book has excerpts from her notebooks, so we get a lot of her lyrics, and also her artwork, and the artwork’s great, too.

She was just incredibly talented.

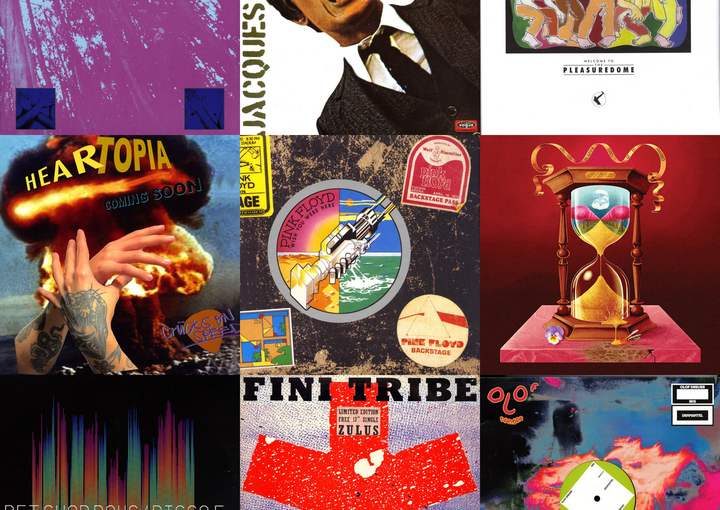

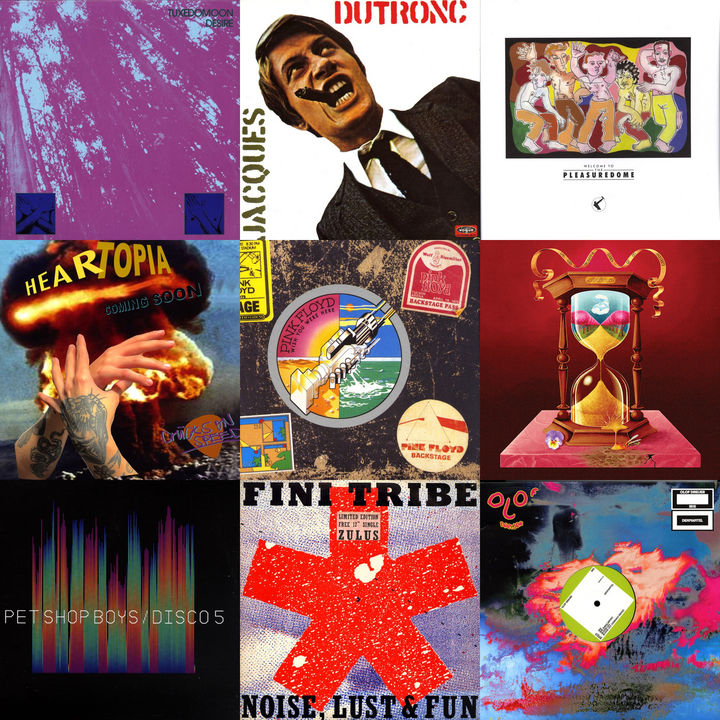

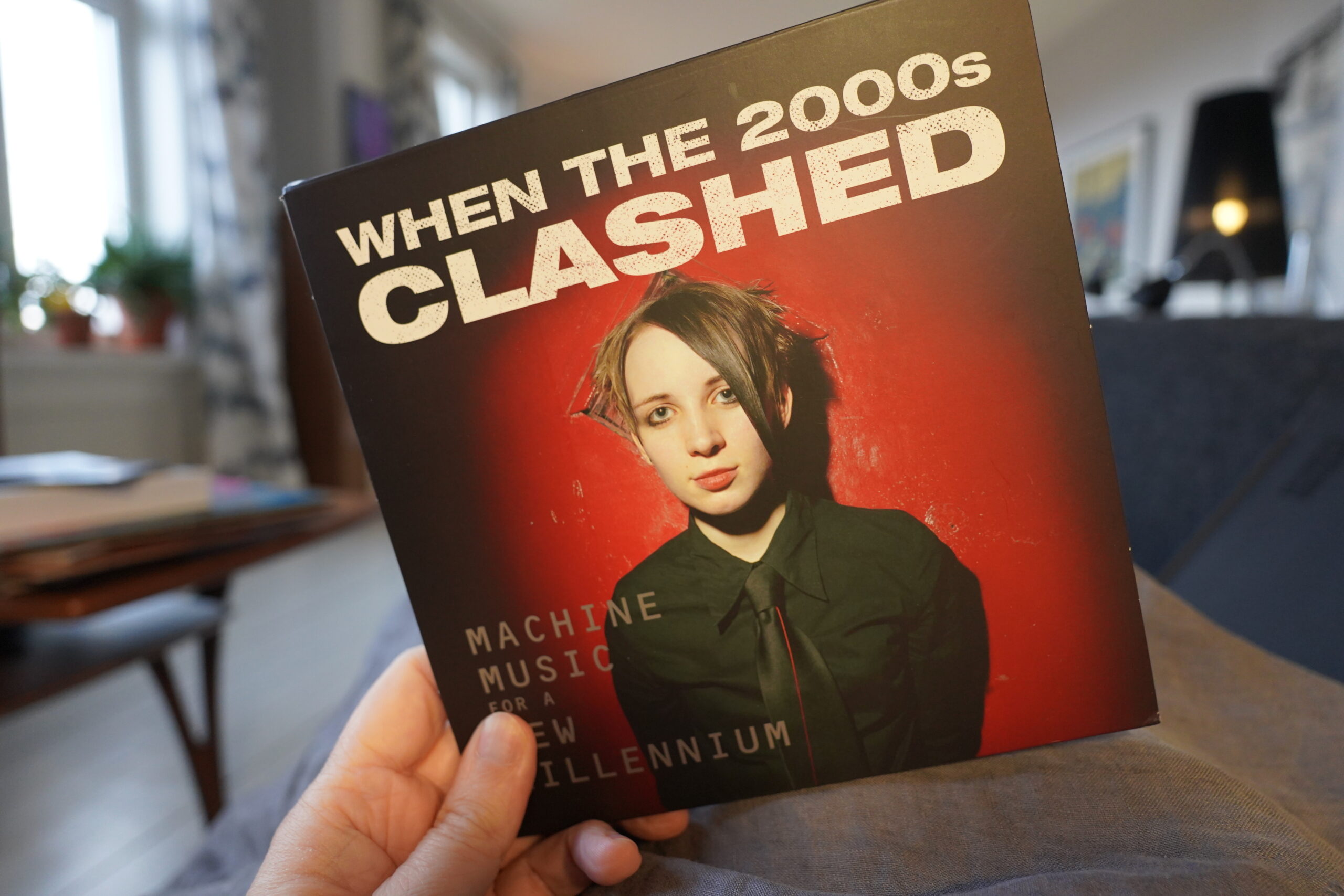

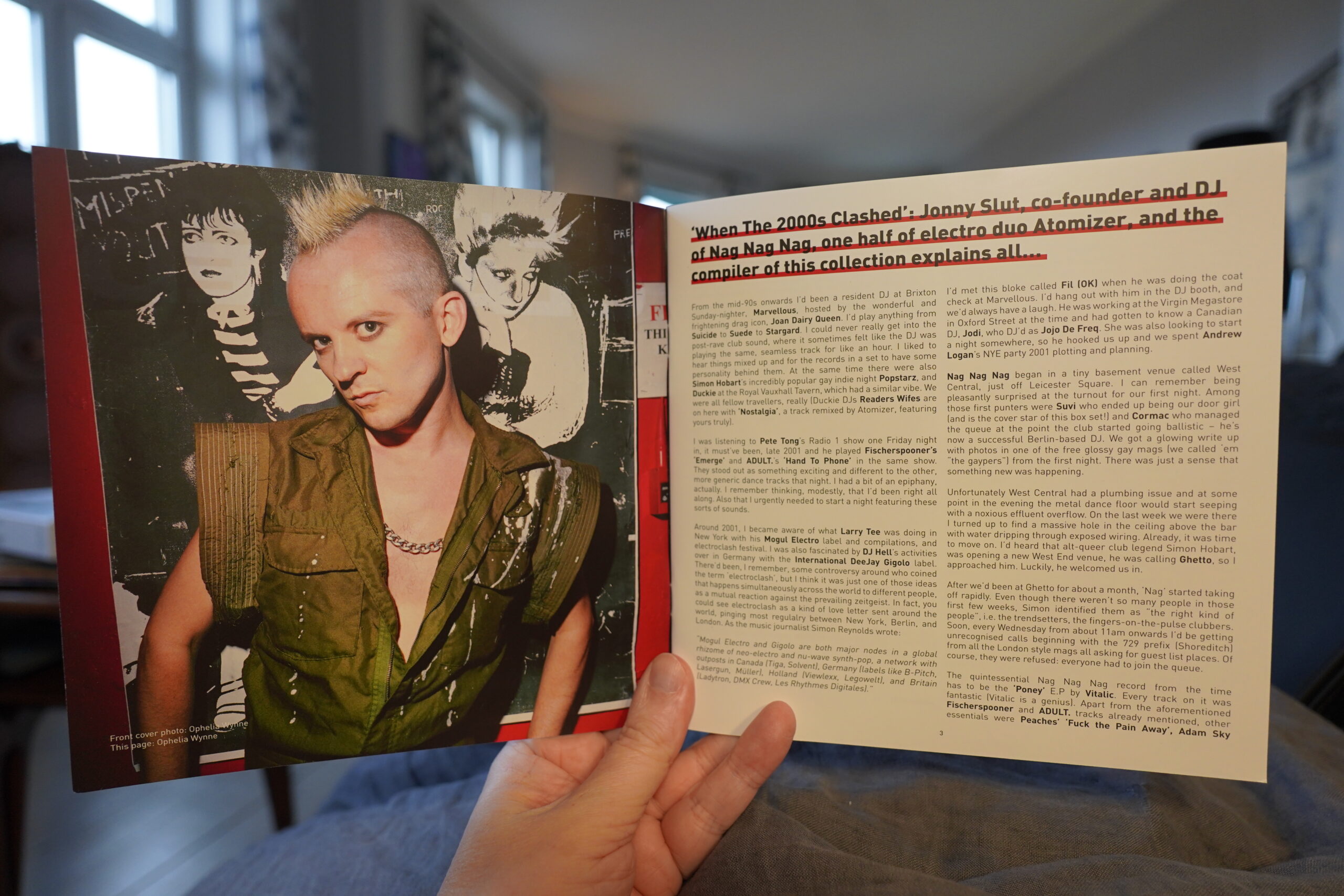

Yes! One can now be nostalgic for Electroclash!

I like buying compilations like this — I mean, I’ve got at least a third of the songs on it already, but the recontextualisation is sometimes fun, and I discover new old bands that I’d missed the first time around, so they often lead to shopping sprees. This one seems like a corker — I’ve only listened to the first CD (I like to “swap in” box sets slowly), but it’s all fun stuff.

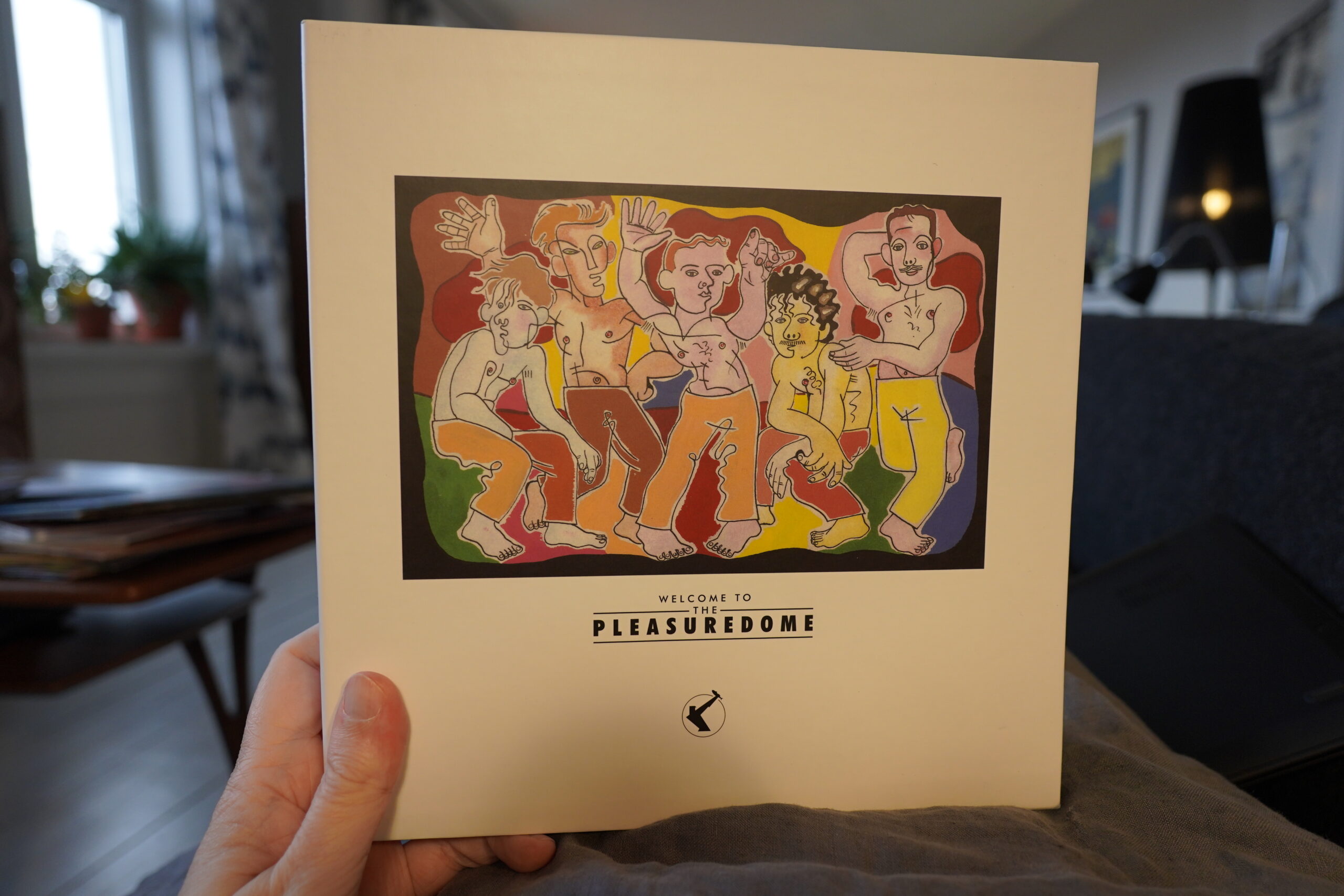

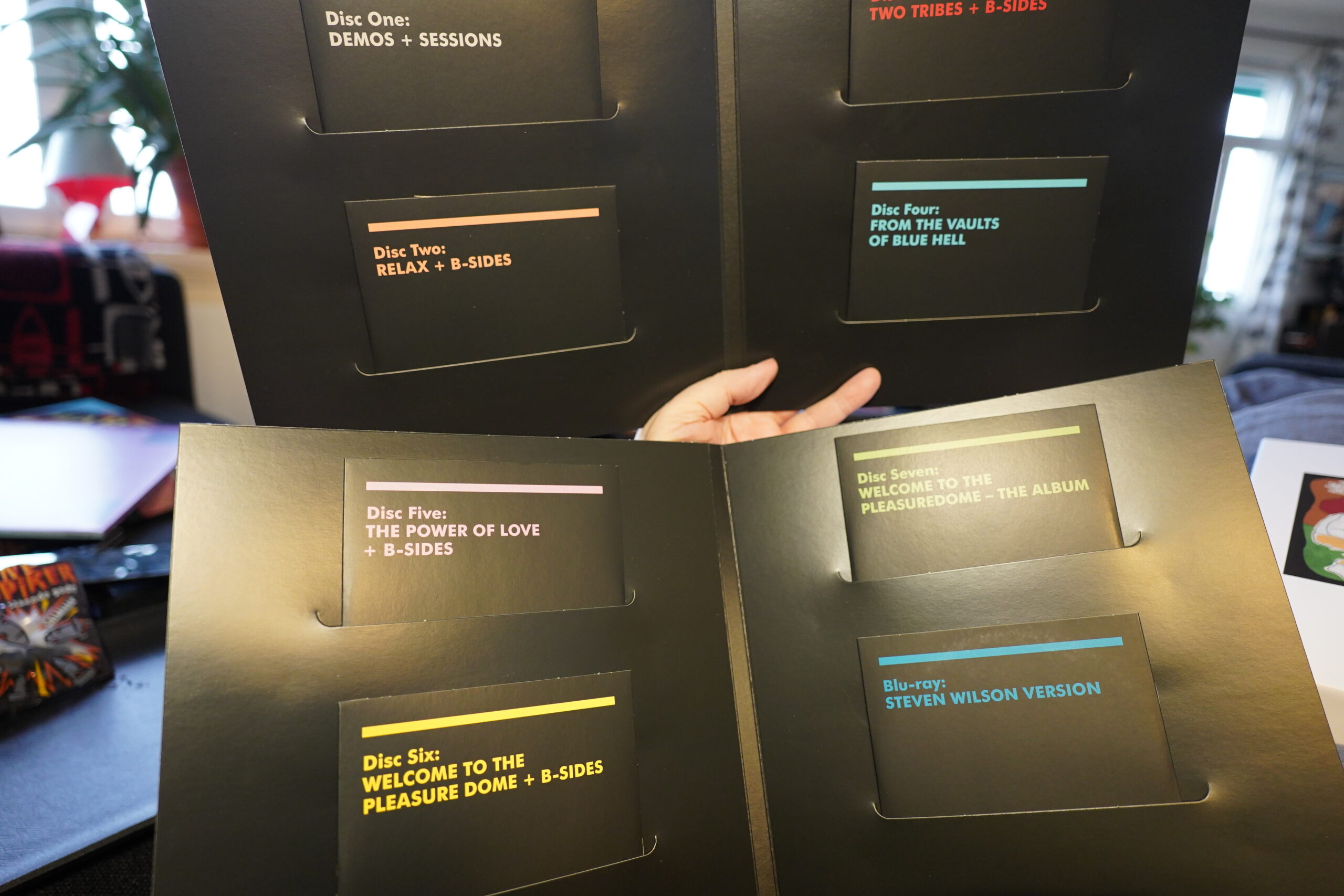

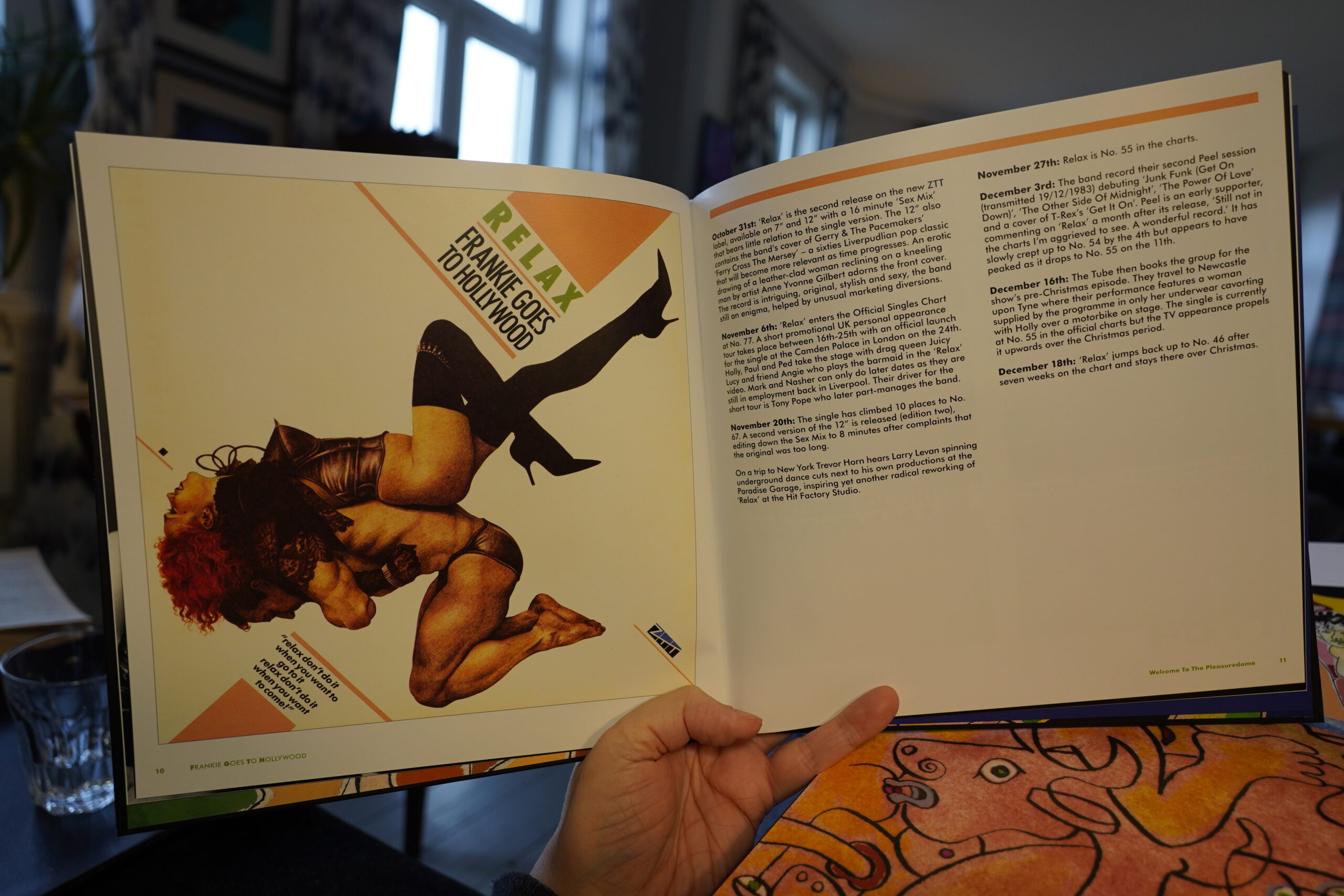

Yes, a Welcome to the Pleasuredome box set. What on Earth could it contain?

Just seven CDs (and a bluray)? As a friend said when I told him about the set “so it only has about half the remixes?”

I dunno, but I’ve only listened to the first CD, and this might be one of those “listen once and then forget” box sets… I mean, it’s fun to listen to the Relax demo the first time… but that’s perhaps sufficient, really.

The booklet is also pretty disappointing. It has no new info, no interviews, no nothing — instead we get a summary of how the album and the singles did chart-wise, so it’s like they only consulted public sources. Snores-ville.

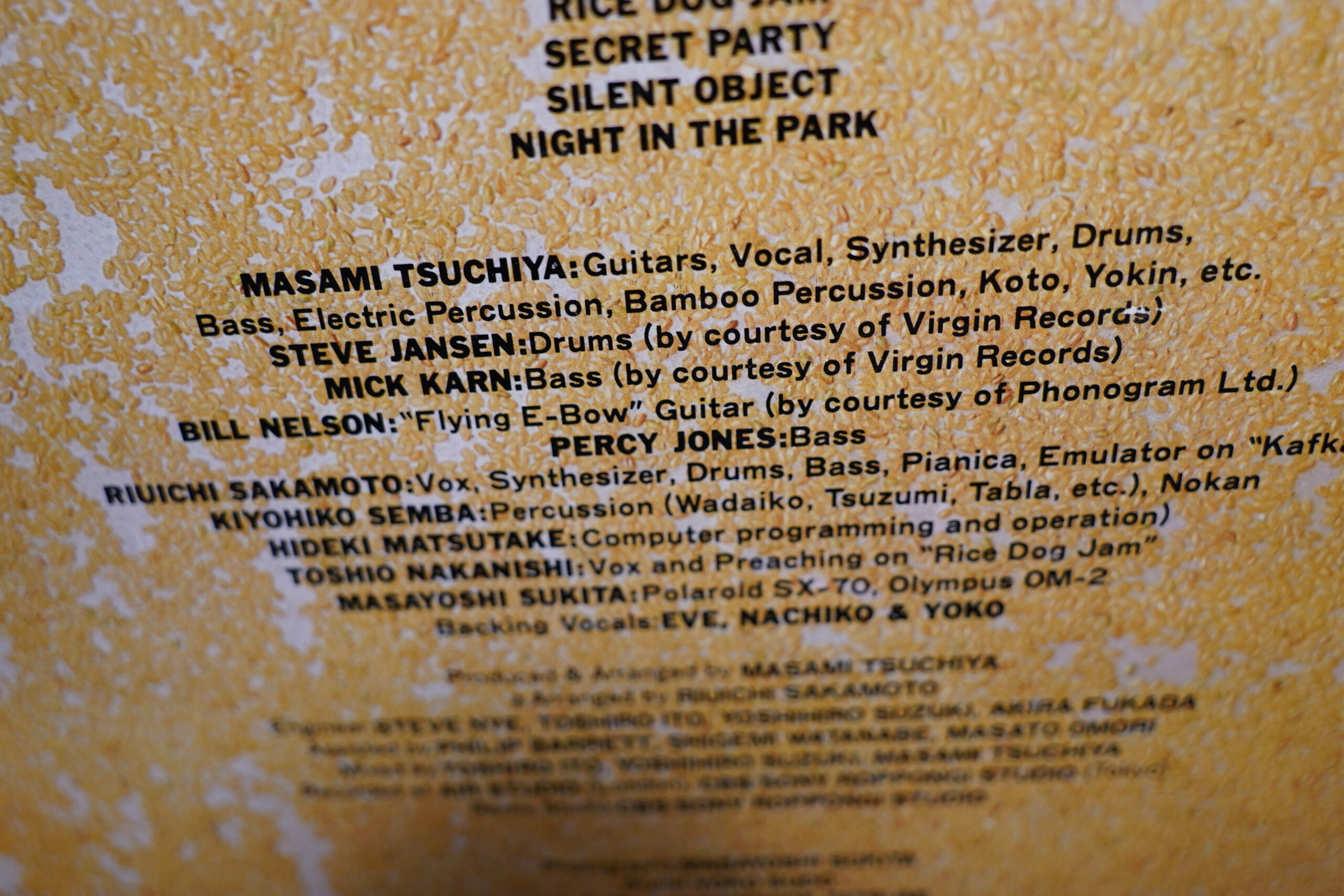

And this isn’t a box set! It’s an early 80s album from an artist I’ve never heard about before, but I bought it because I went on a Bill Nelson Discogs shopping spree.

Look at all these people on this album! Steve Jansen, Mick Karn… that’s half of Japan. And produced by Steve Nye, who produced Japan. And you won’t believe this, but it kinda sounds like Japan! Yes! Whodathunk! (Masami Tsuchiya played with Japan as a touring guitarist.)

And also Ryuichi Sakamoto.

Is the album any good? I’ve only listened to it once so far, and I think… it’s kinda good? Not sure yet.

OK, that’s all I have to say.

Except that the new Dry Cleaning album isn’t as good as the last one.

And that The Soft Pink Truth have a new album out. It’s very different, but they usually are…

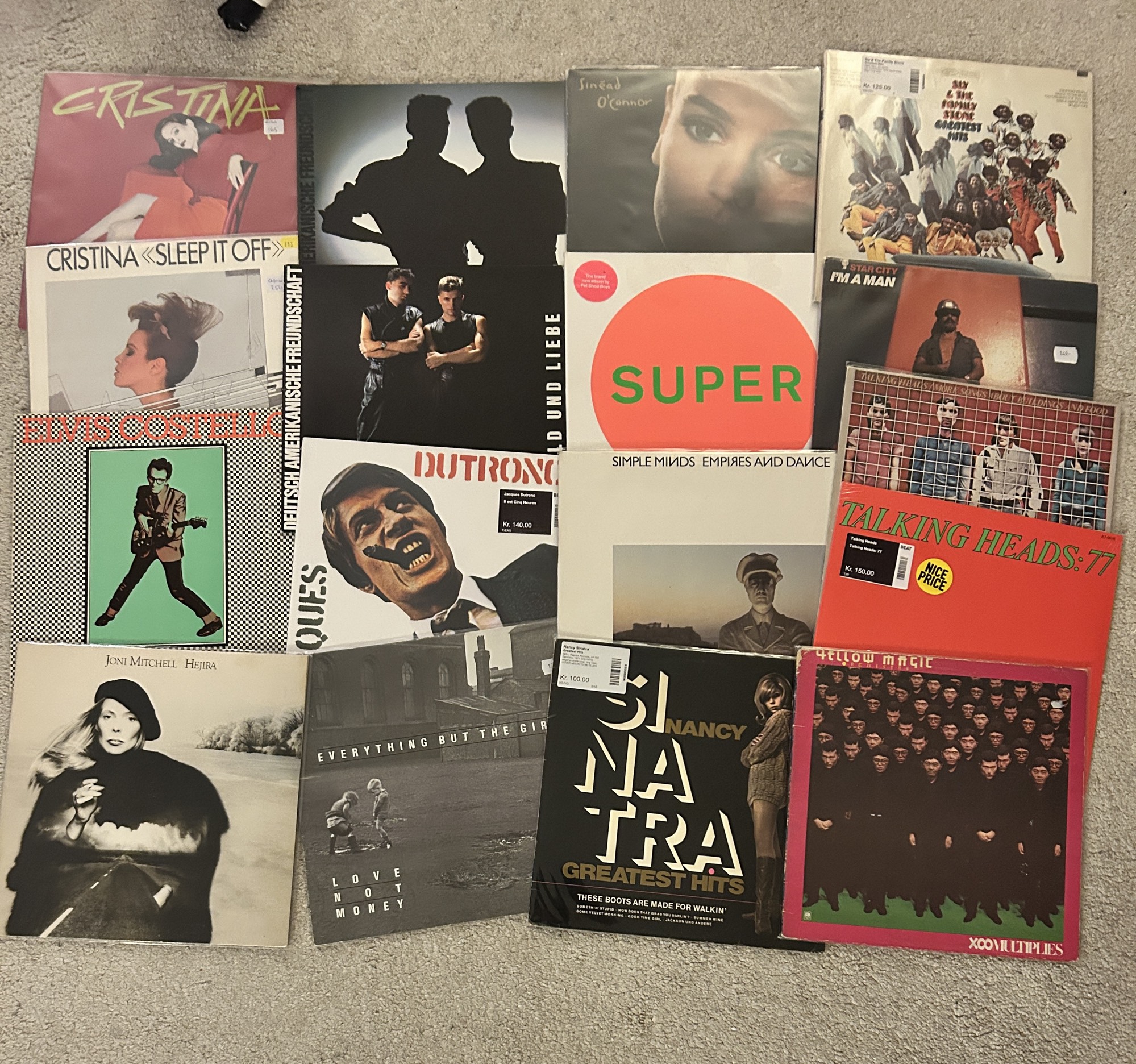

And I bought the Jacques Dutronc album because somebody with good taste posted the grid above, but unfortunately, it’s not very good.

| ) |  | ) |  |

|  |  |  |  |

) | %3A+Demos+%2B+Sessions) | ) | ) | ) |