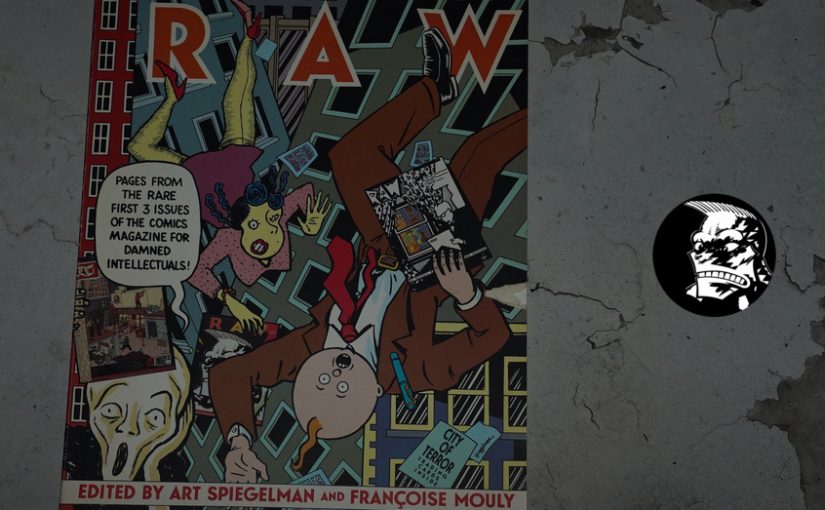

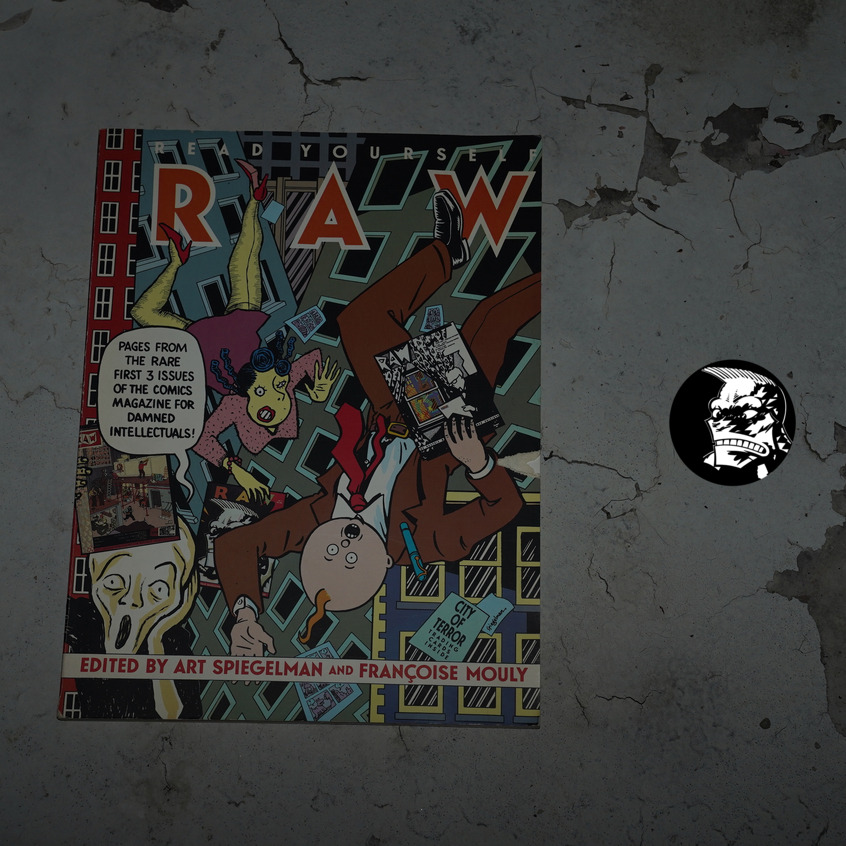

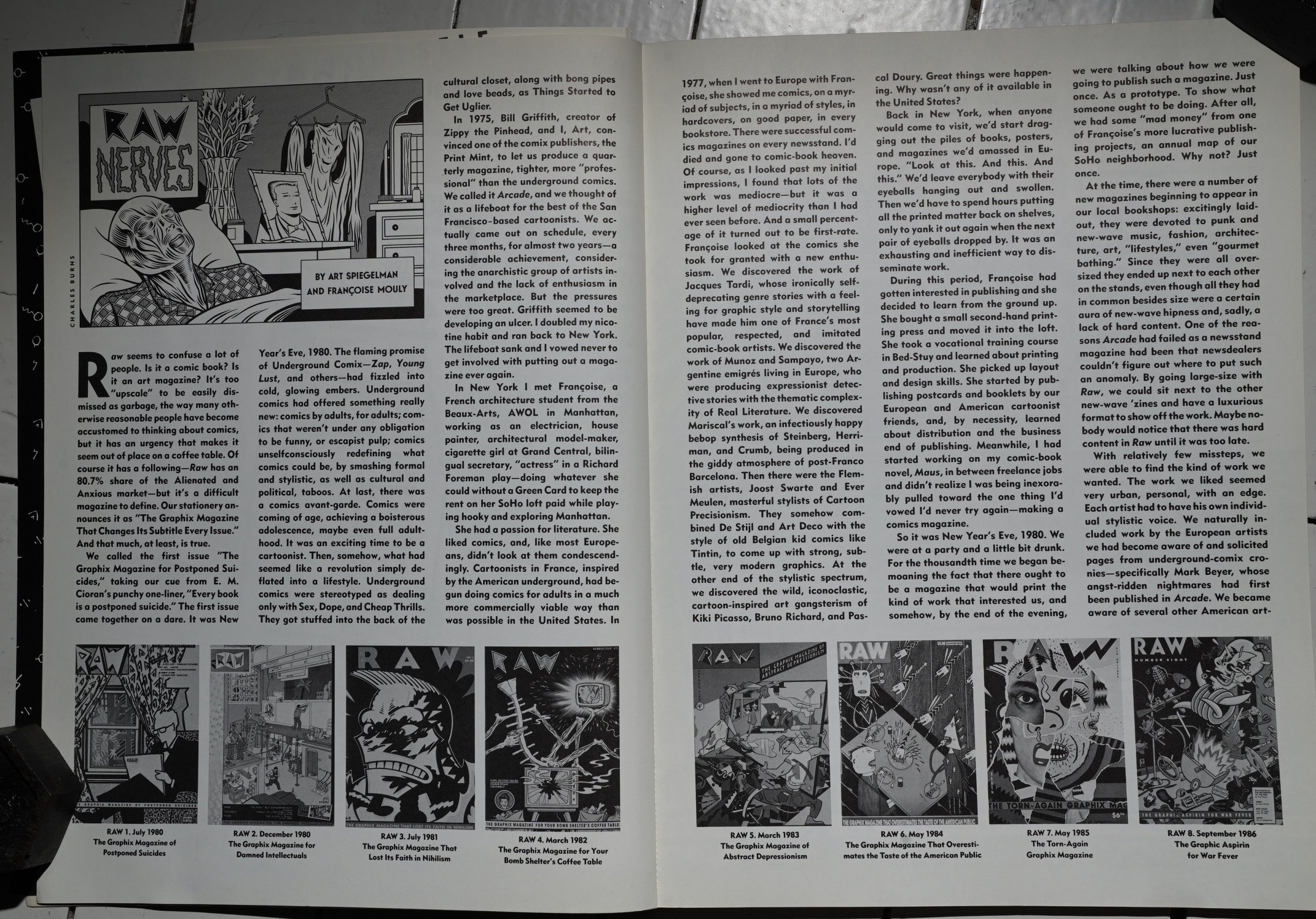

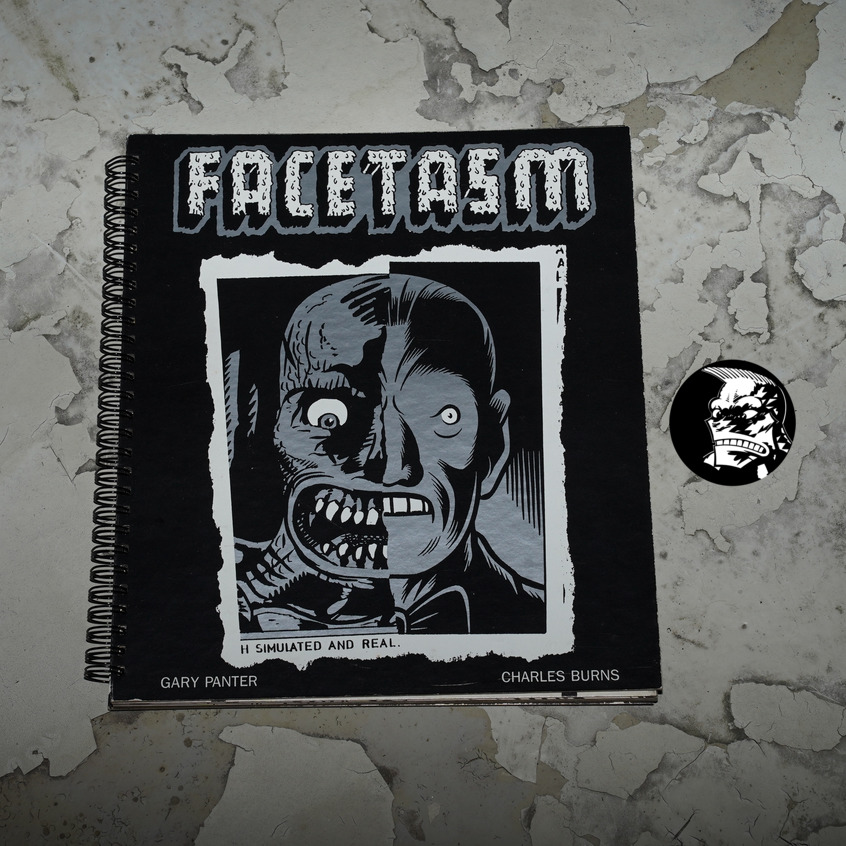

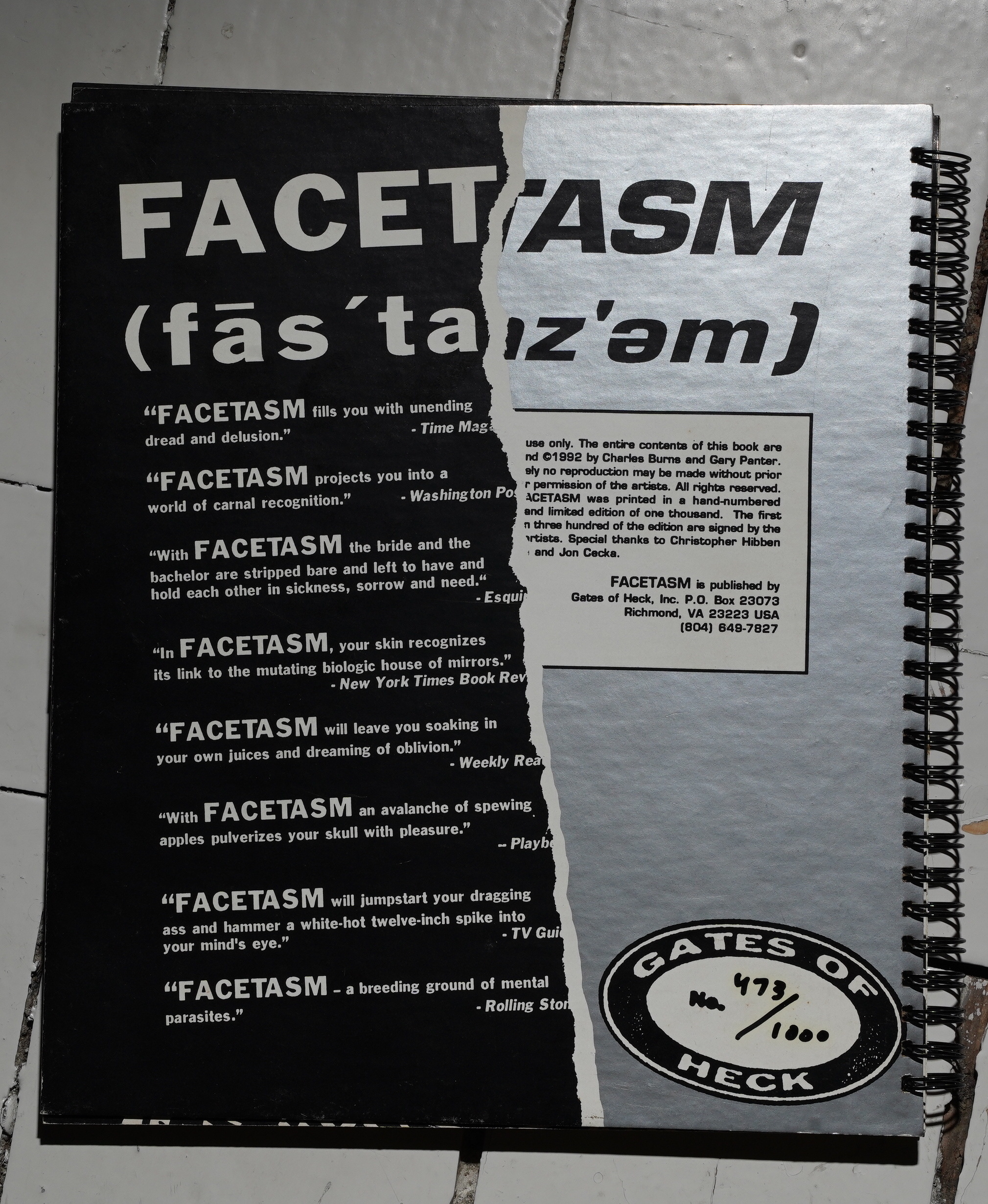

Read Yourself Raw edited by Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman (267x357mm)

This book reprints Raw #1-3 — but not in full. I’ve already covered those three Raw issues in this blog series, so I’m not going to re-read this book once again… instead, I’ll just see if there’s anything interesting about what they’ve kept and what they’ve left out? OK? Ok.

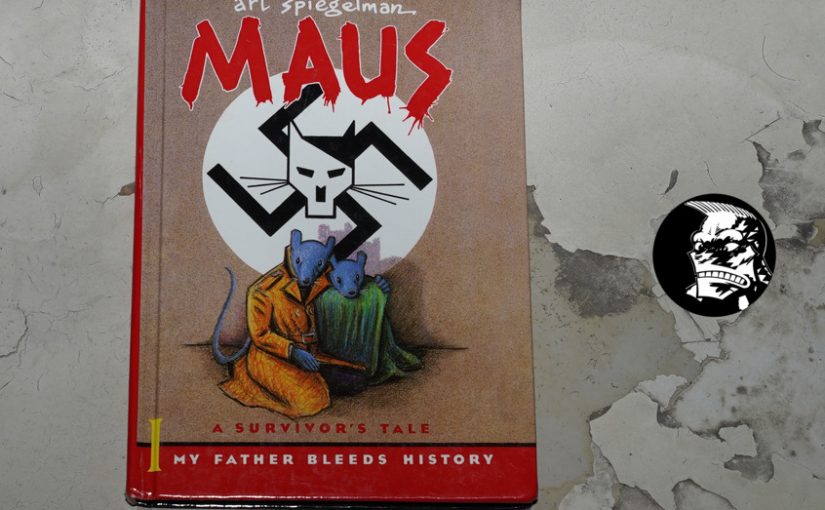

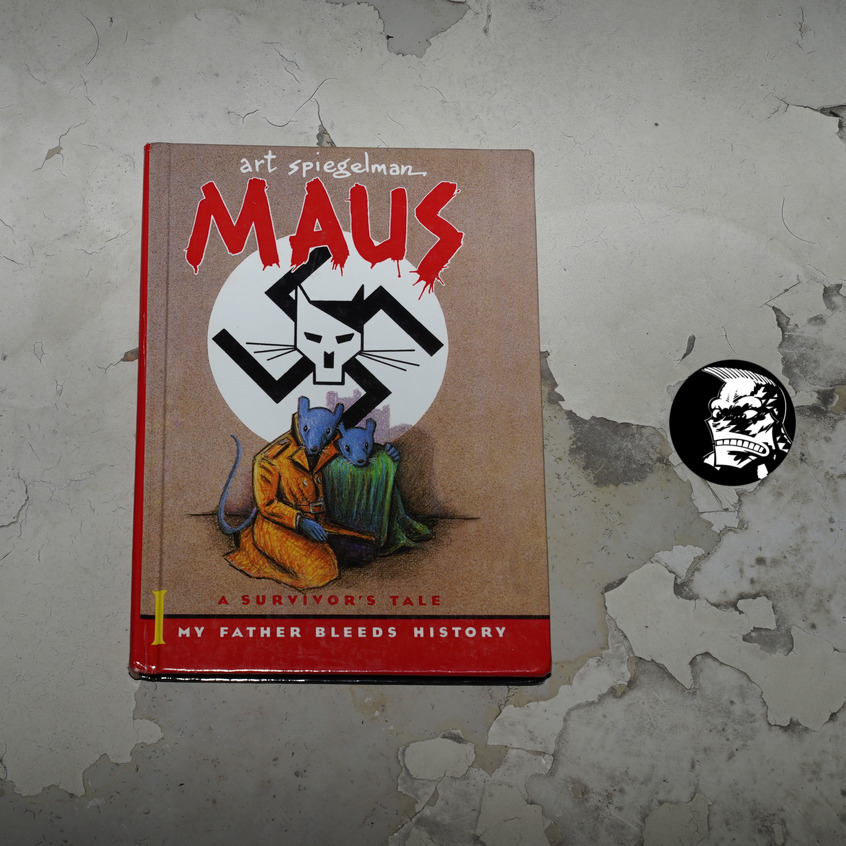

This collection is printed by Pantheon, which is natural (since they’d just had a monumental success with the first Maus book)… But Raw vol 2 would go on to be published by Penguin instead. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

I guess this book was designed by Mouly? It doesn’t totally look like it…

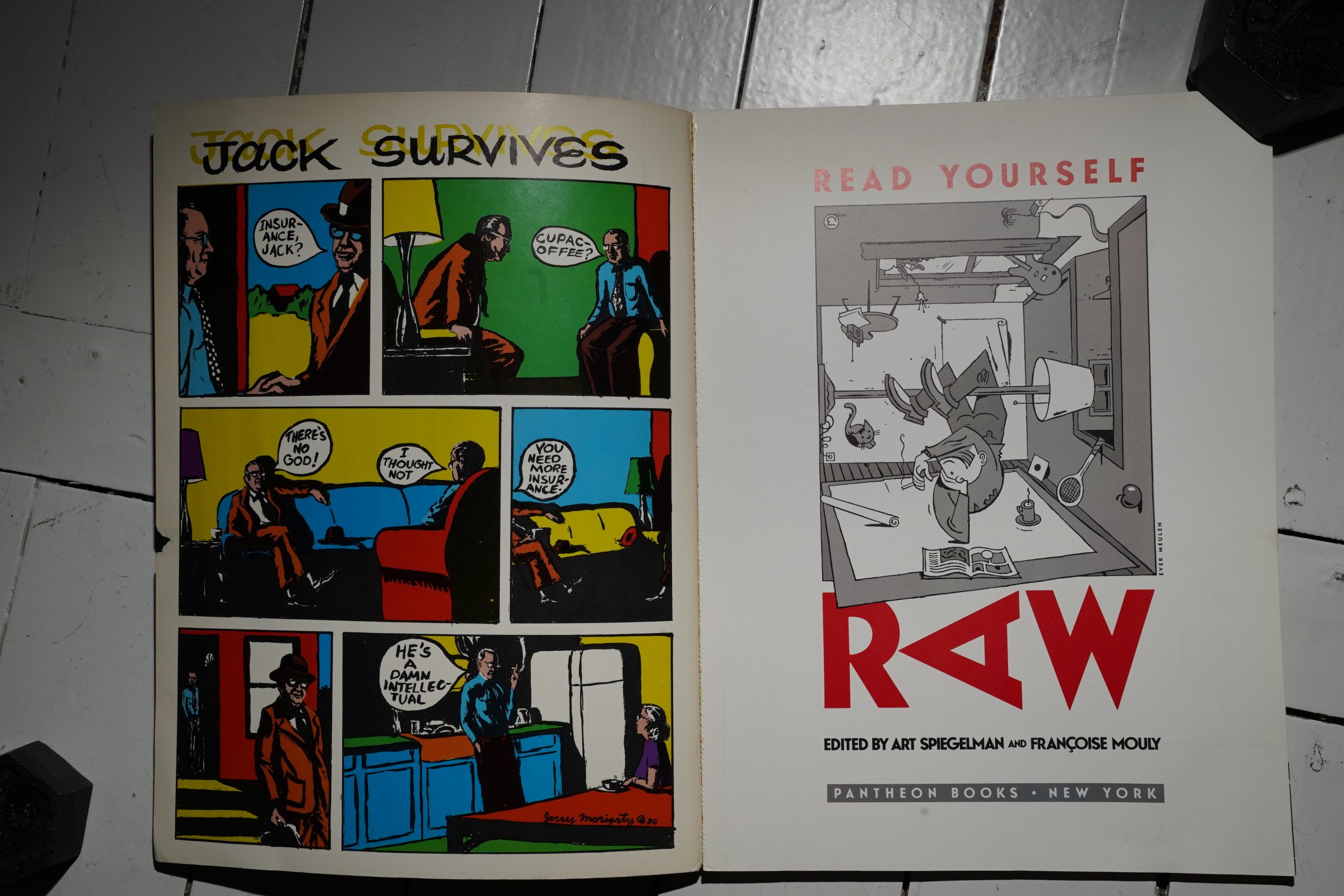

But this looks more like it. It says that the “contents” are designed by Mouly and L. Fili… perhaps that’s everything but the covers?

*gasp* It’s not set in Futura! MOULY! WHAT WERE YOU THINKING!!!

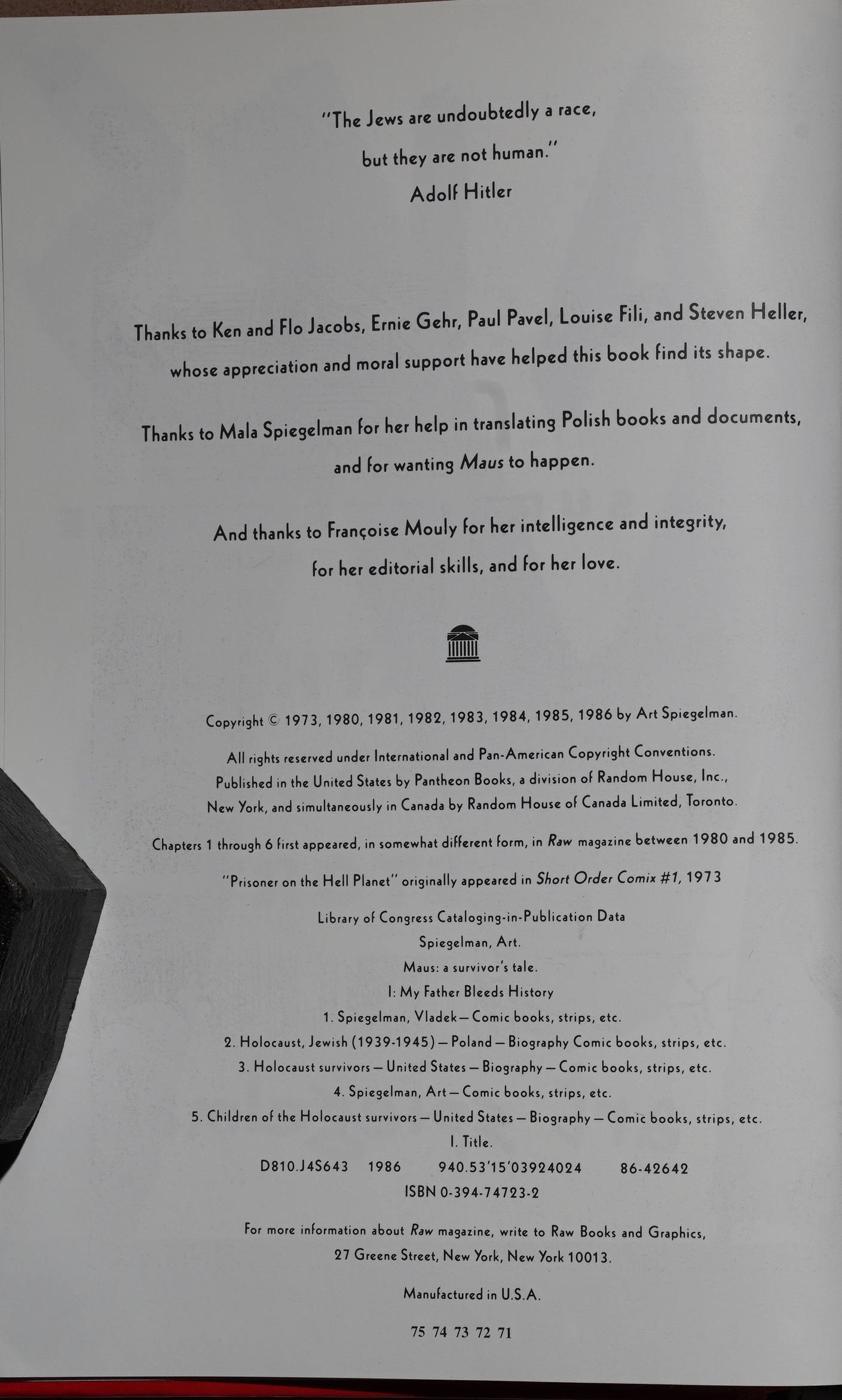

Spiegelman does a very chatty (and amusing introduction). Raw itself mostly eschewed this sort of stuff — the introductions were often more … conceptual, but I guess it’s time to shift to Elder Statesman and look back upon Raw as a youthful folly.

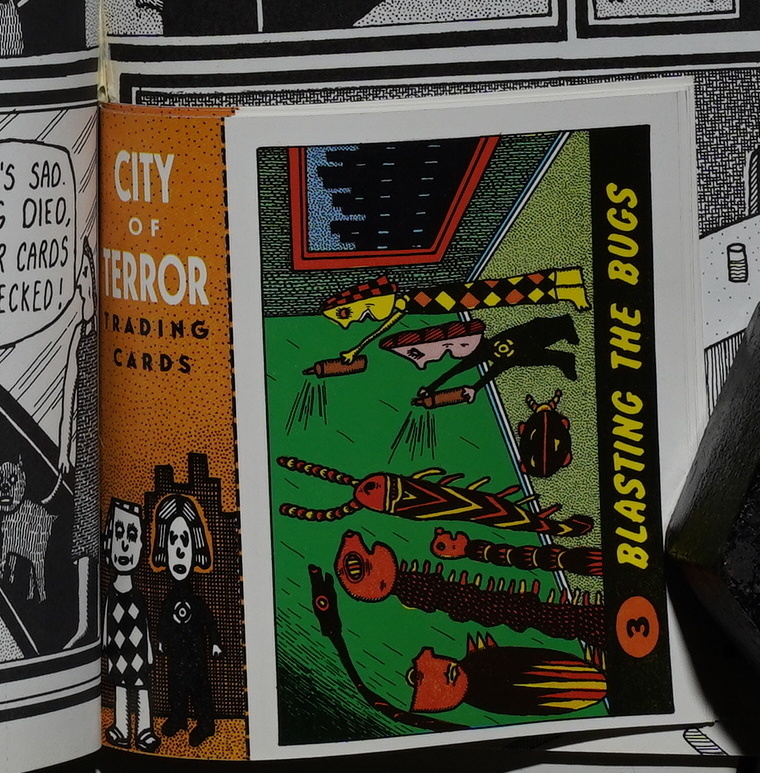

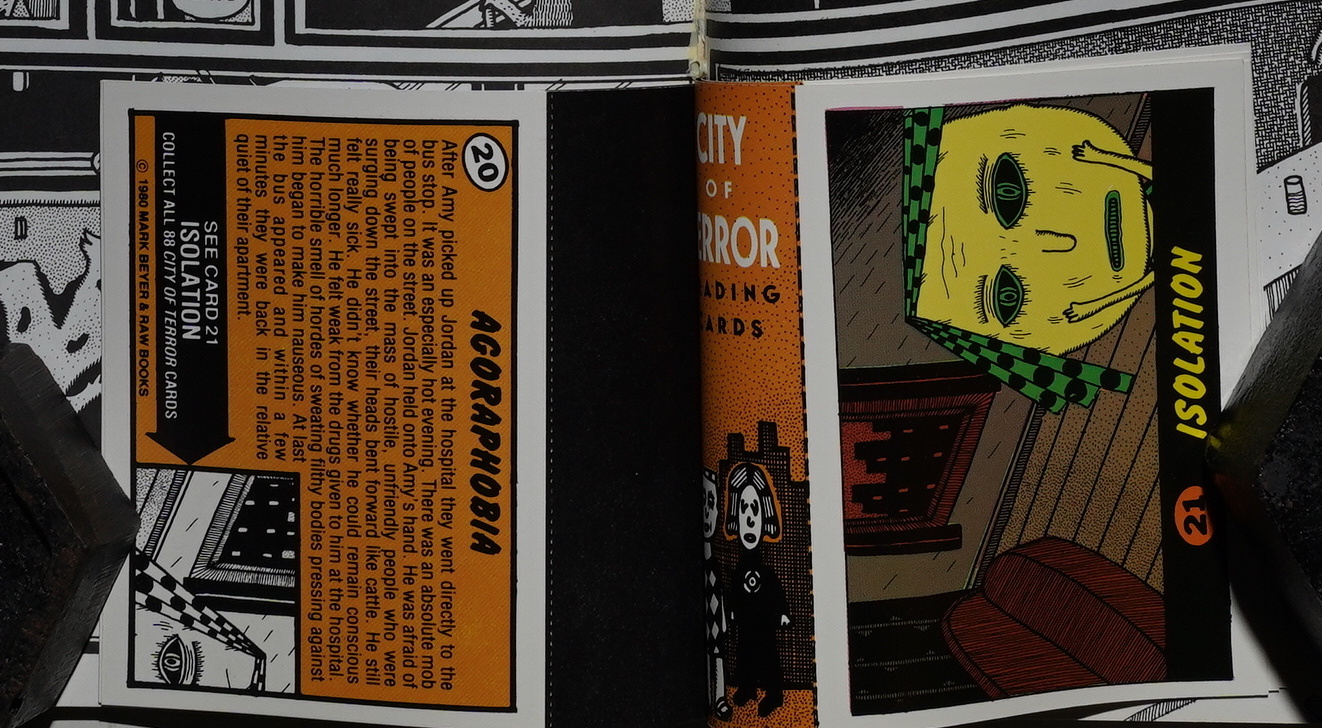

He does go into details about some issues, like the Mark Beyer trading card situation…

And he explains about the “Raw Deal”: Copies of Raw, and then profit sharing, which comes out to about $100 a page. And explains the ineffable thing about Raw: “Although many of the artists didn’t seem to have much in common with each other, either geographically or stylistically, they all seemed to recognize something in each other’s work. It was elusive — maybe it was just the seriousness of their commitment to the form — but they were enthusiastic, and gave us a mandate to do Raw again.”

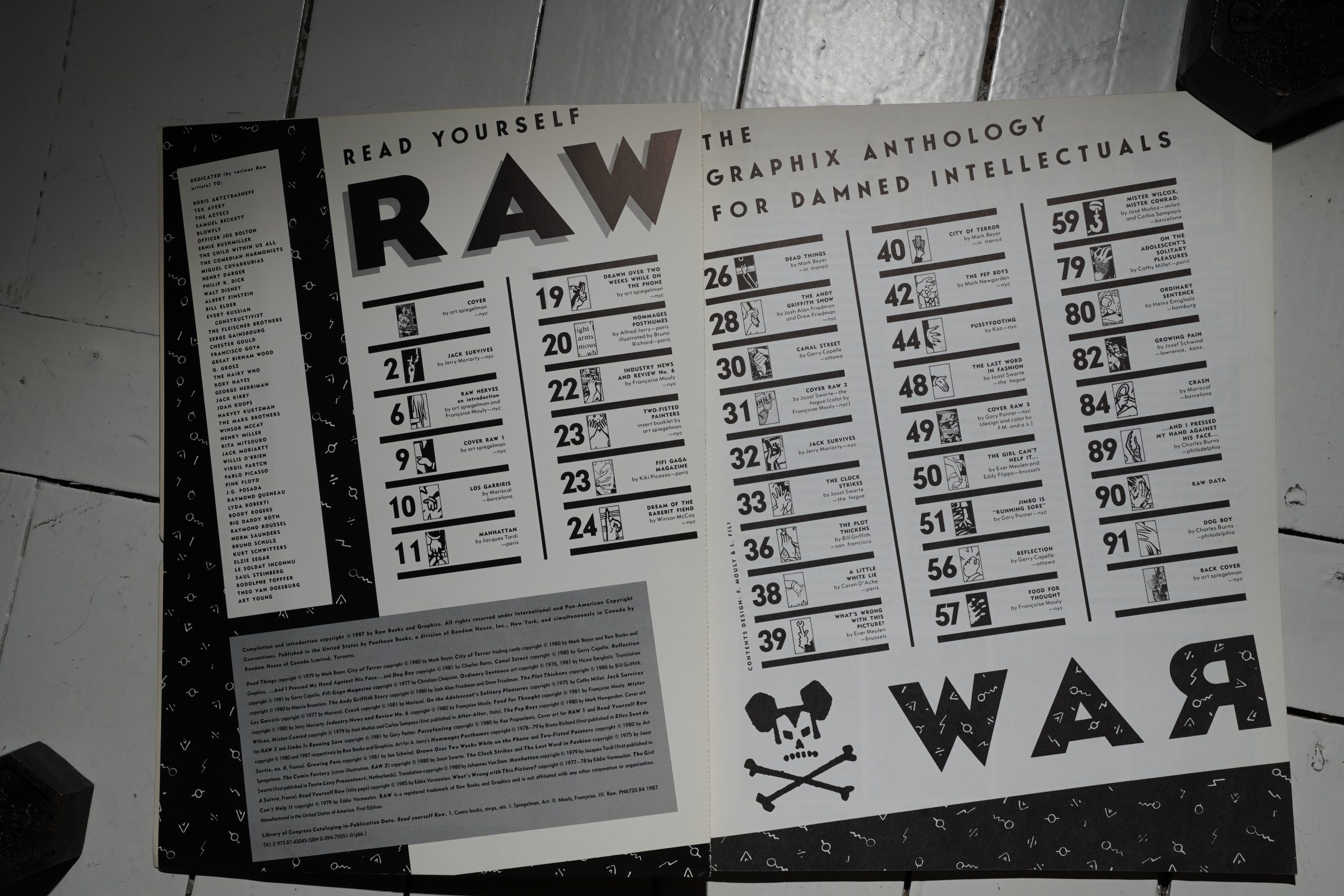

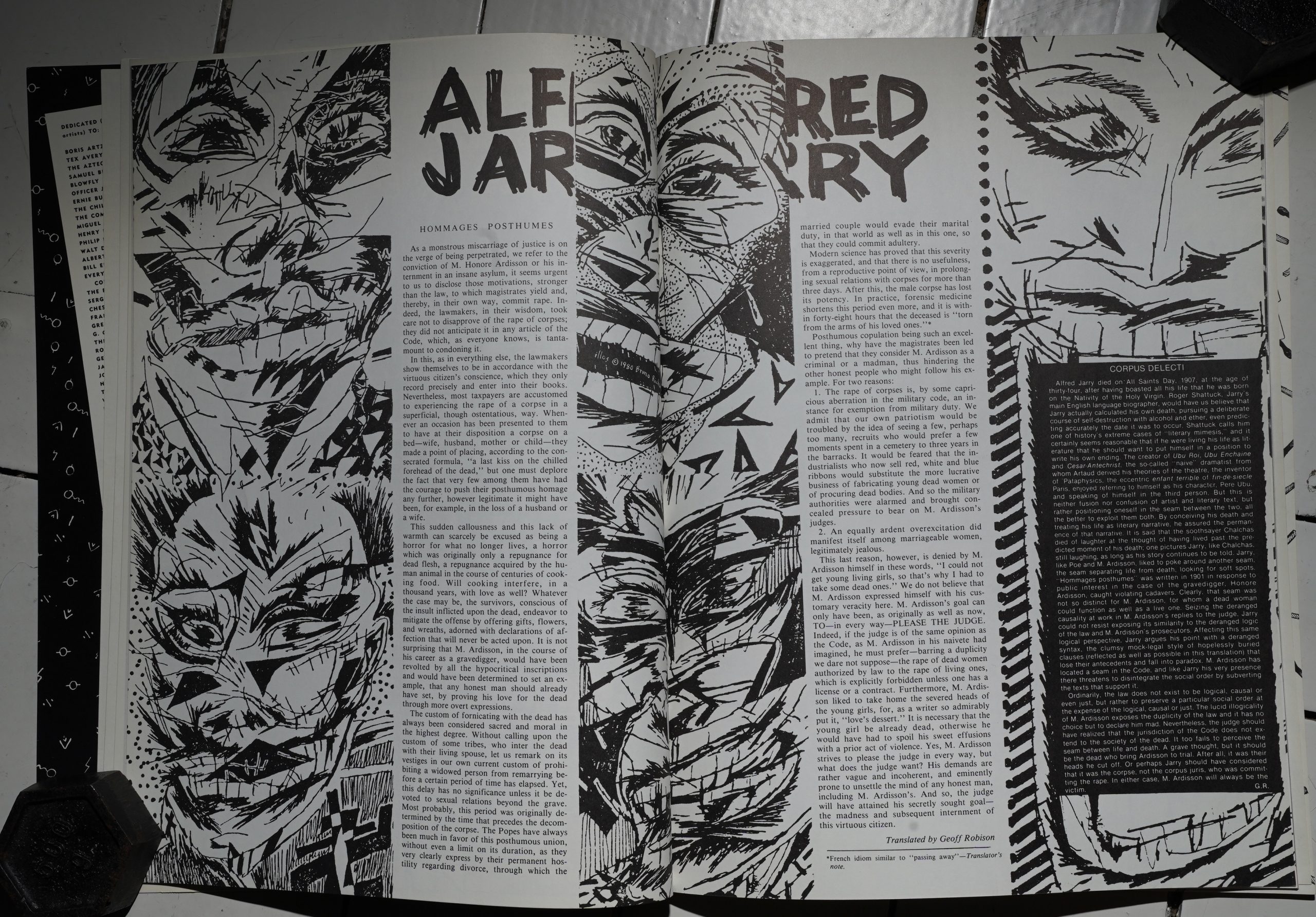

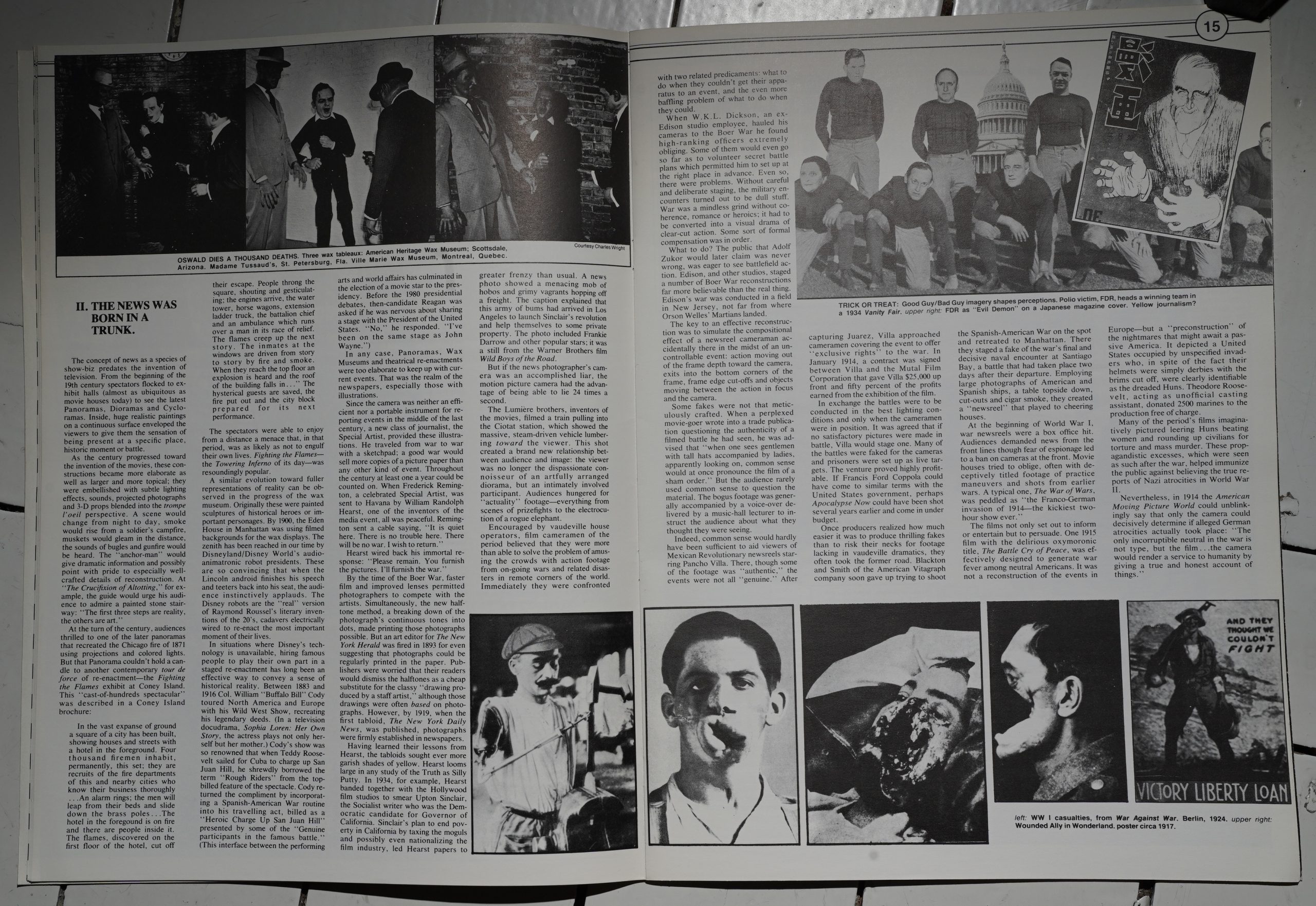

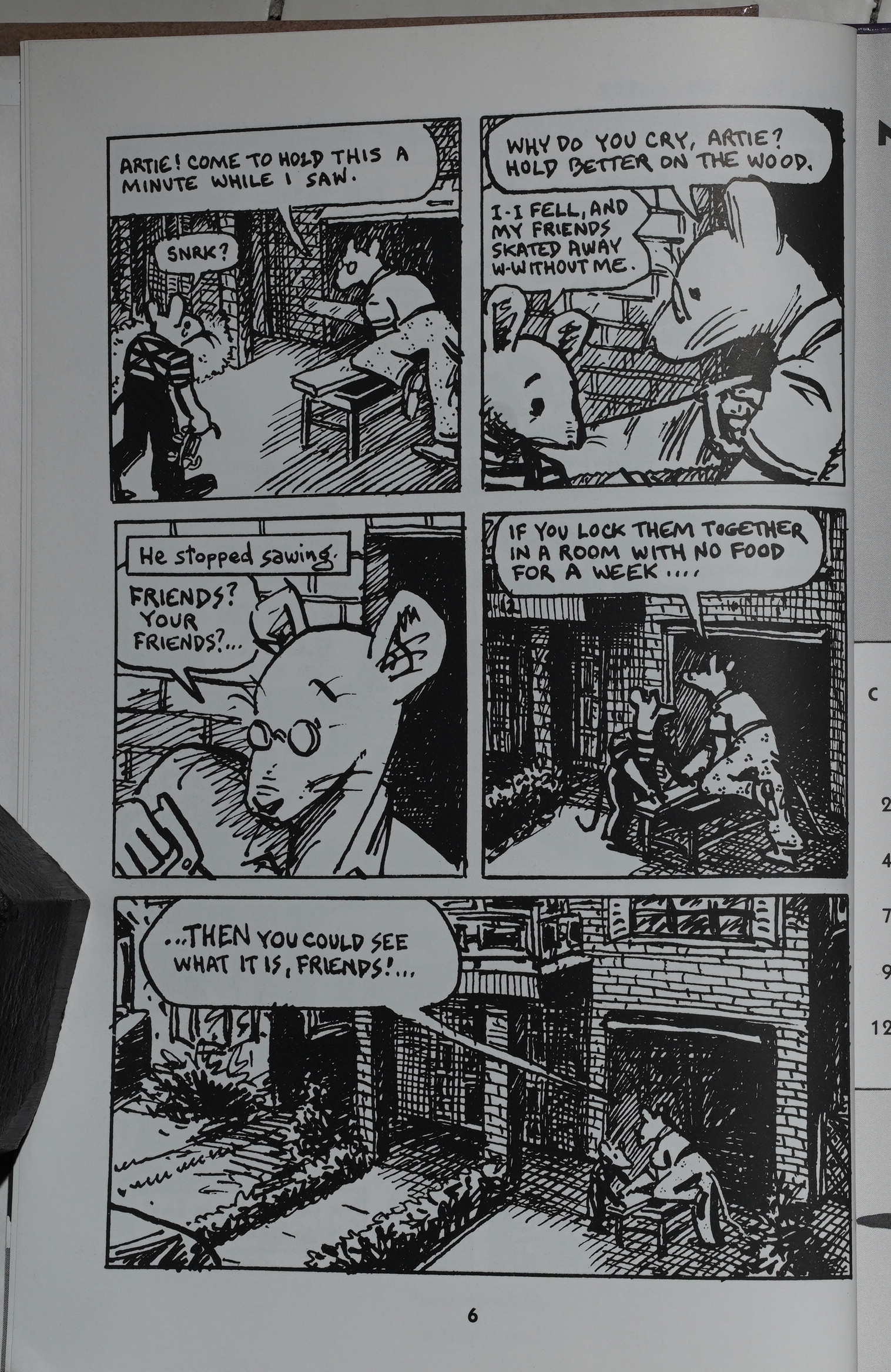

The section reprinting Raw #1 is 22 pages long, and Raw #1 was 36 pages (including covers). I had imagined that they’d dump the text pages, but they included this Alfred Jarry-related text…

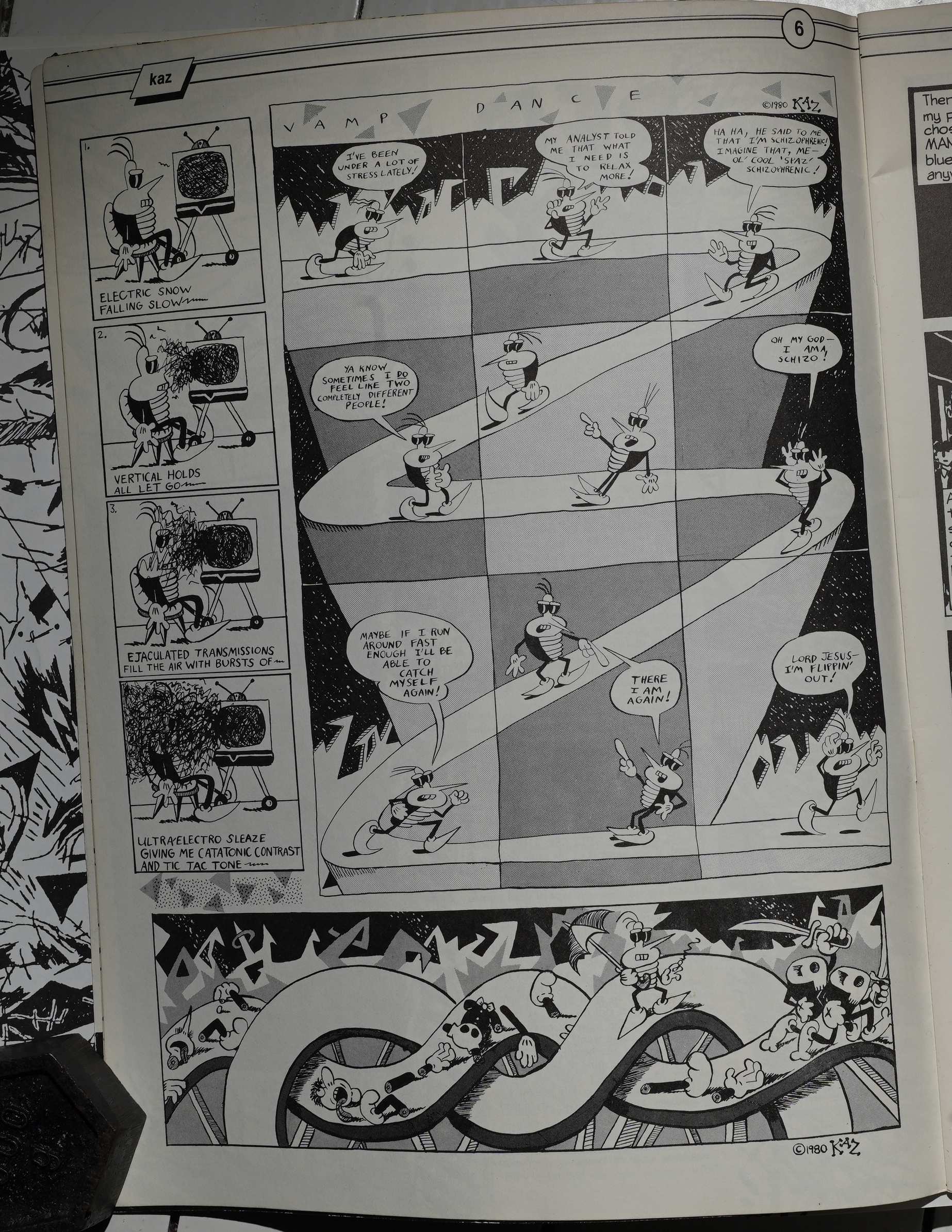

… but dumped this Kaz page…

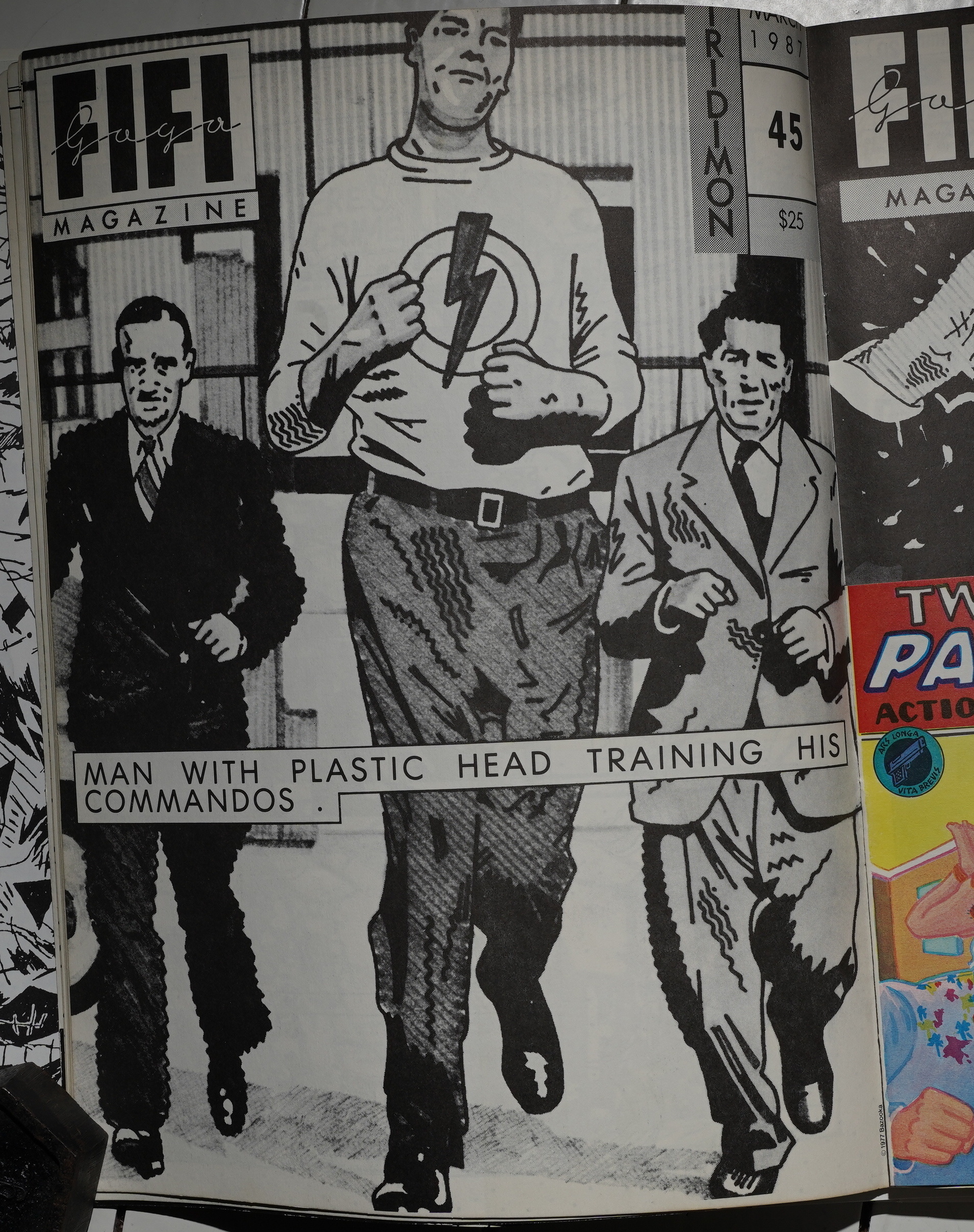

… and this Fifi page that surrounded the Two-Fisted Painters booklet (but the booklet itself is included).

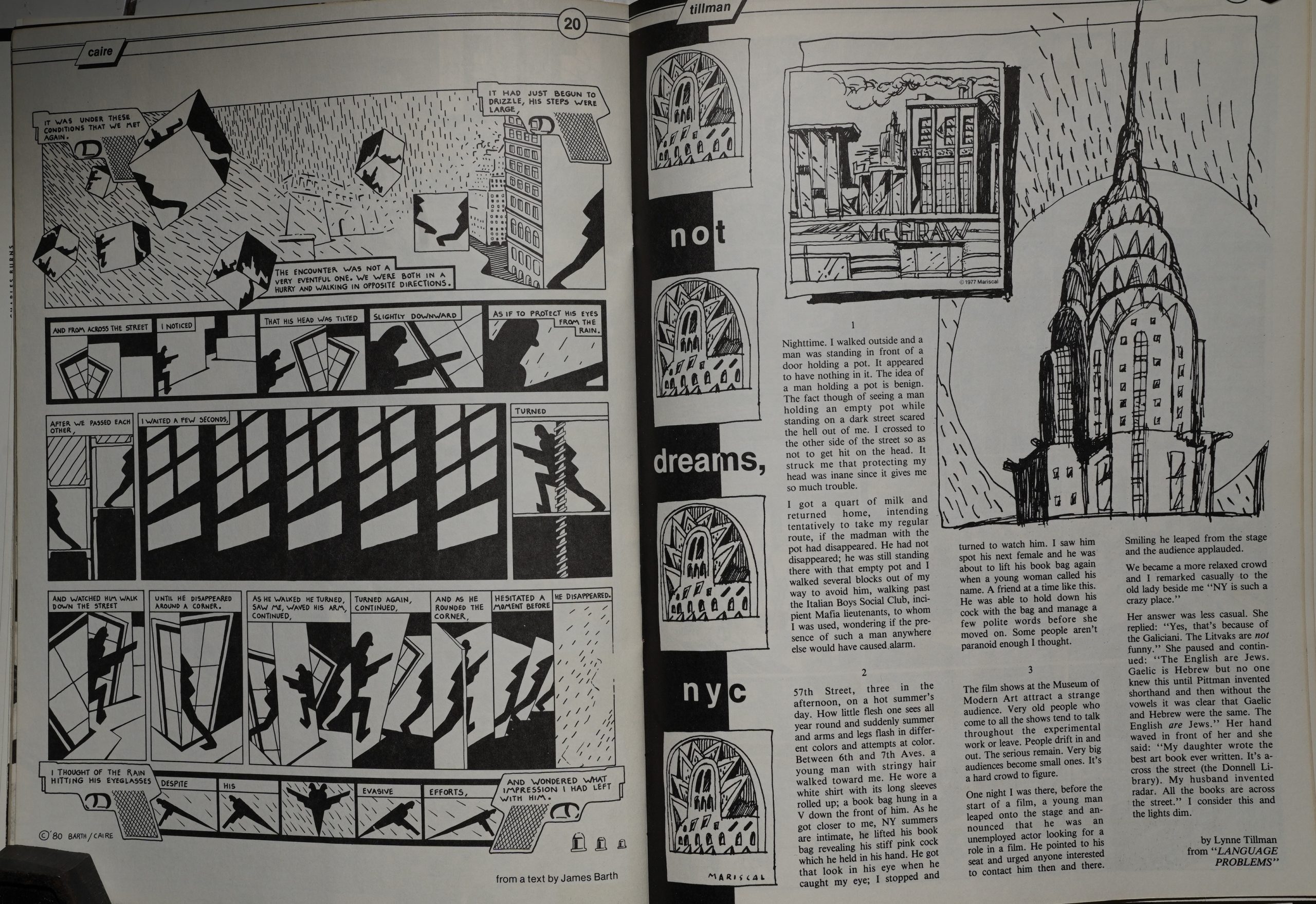

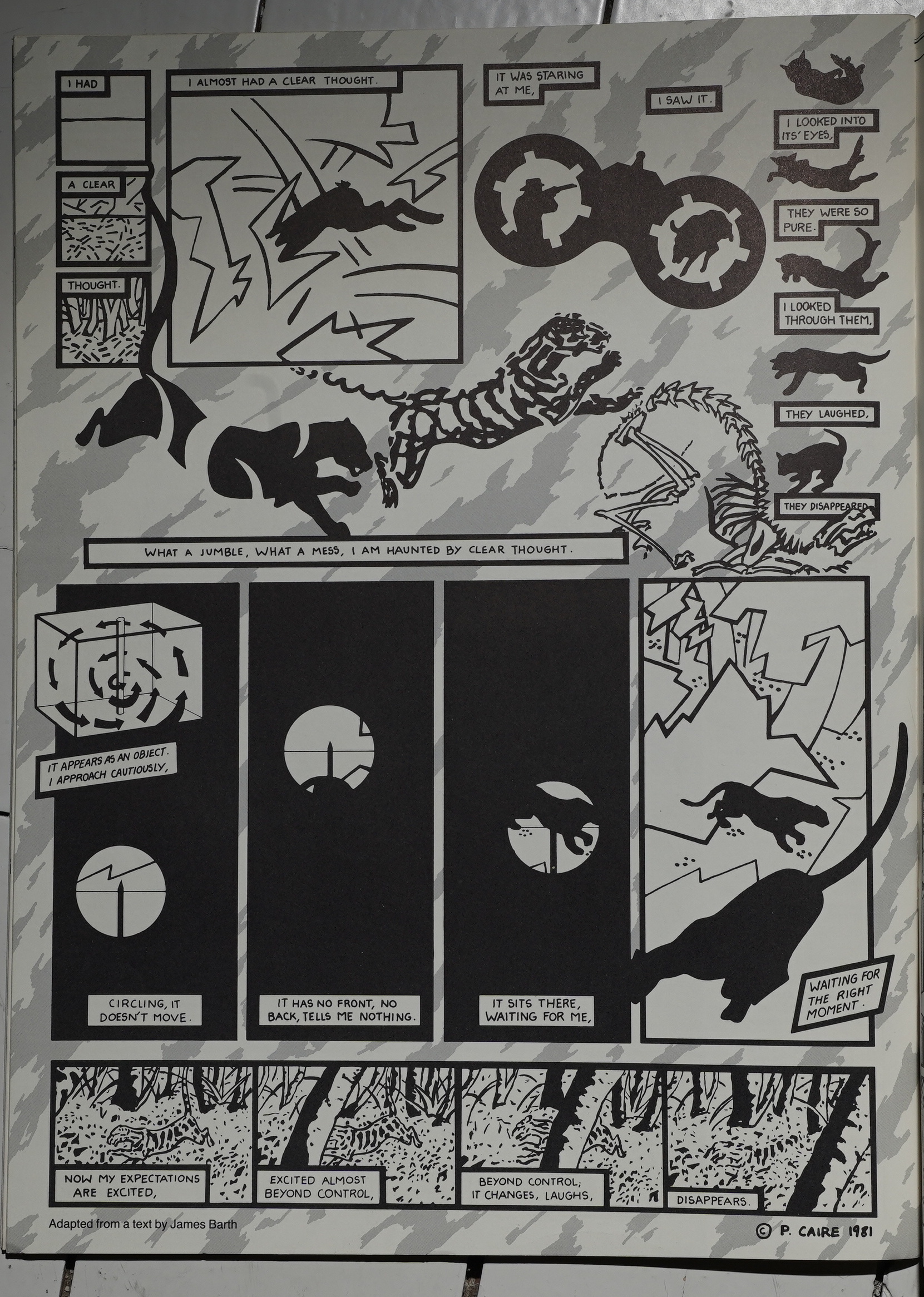

Also gone are Patricia Caire and Lynne Tillman. Did any women (except Mouly) make it into this book? (These two may well have been dropped for rights issues, of course — the Caire is based on a Barth text, and Pantheon may have wanted to be more careful…)

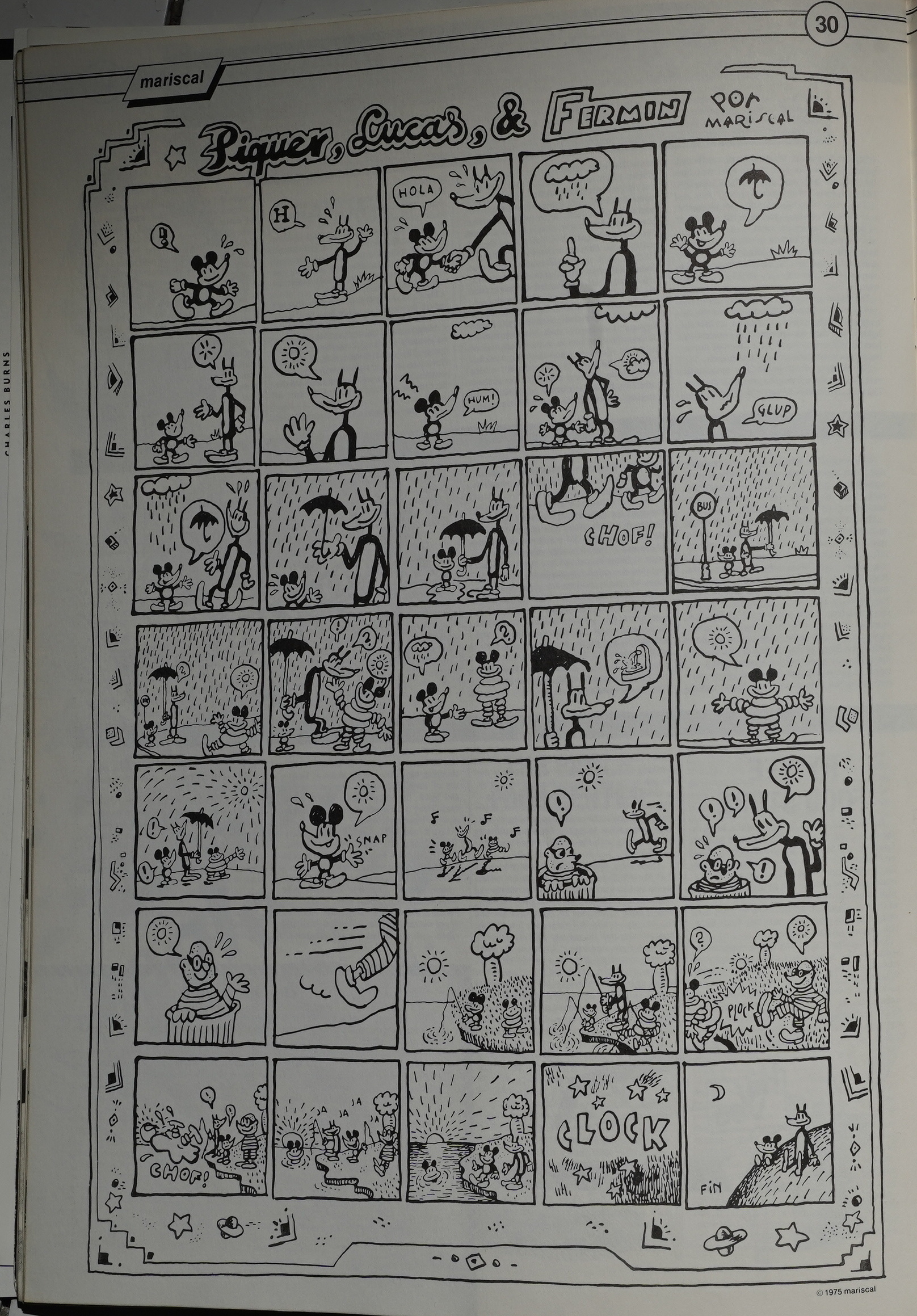

Gone is also this Mariscal, but another Mariscal piece from the same issue survived.

So… did Pantheon just have a target page length in mind, or did the editors just dislike the stuff they left out? Raw #1 is a very strong unit; it’s a great reading experience. With almost half cut, it’s less compelling. (Although the pieces that did make it are great, of course.)

Onto Raw #2 — only 18 of the original 36 pages (including covers) make it. Raw #2 is the weakest issue (until #8), so that’s understandable, but it’s still… a lot.

One thing that did make it was Mark Beyer’s City of Terror trading cards! Which is great, because I’ve never seen a copy of #2 that still had them.

They’re very difficult to enjoy here, though, because of the way they’re glued into the book… still fun.

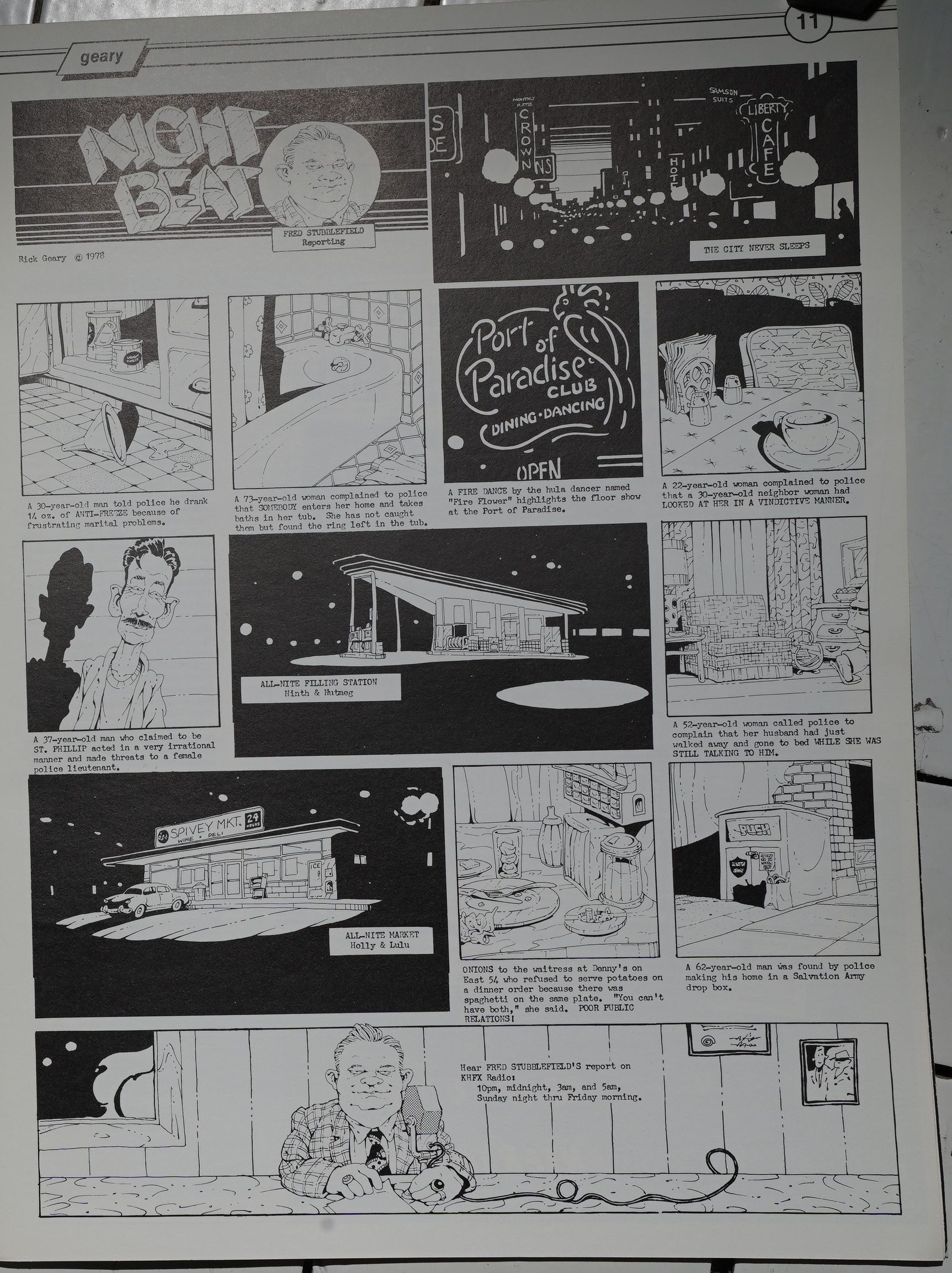

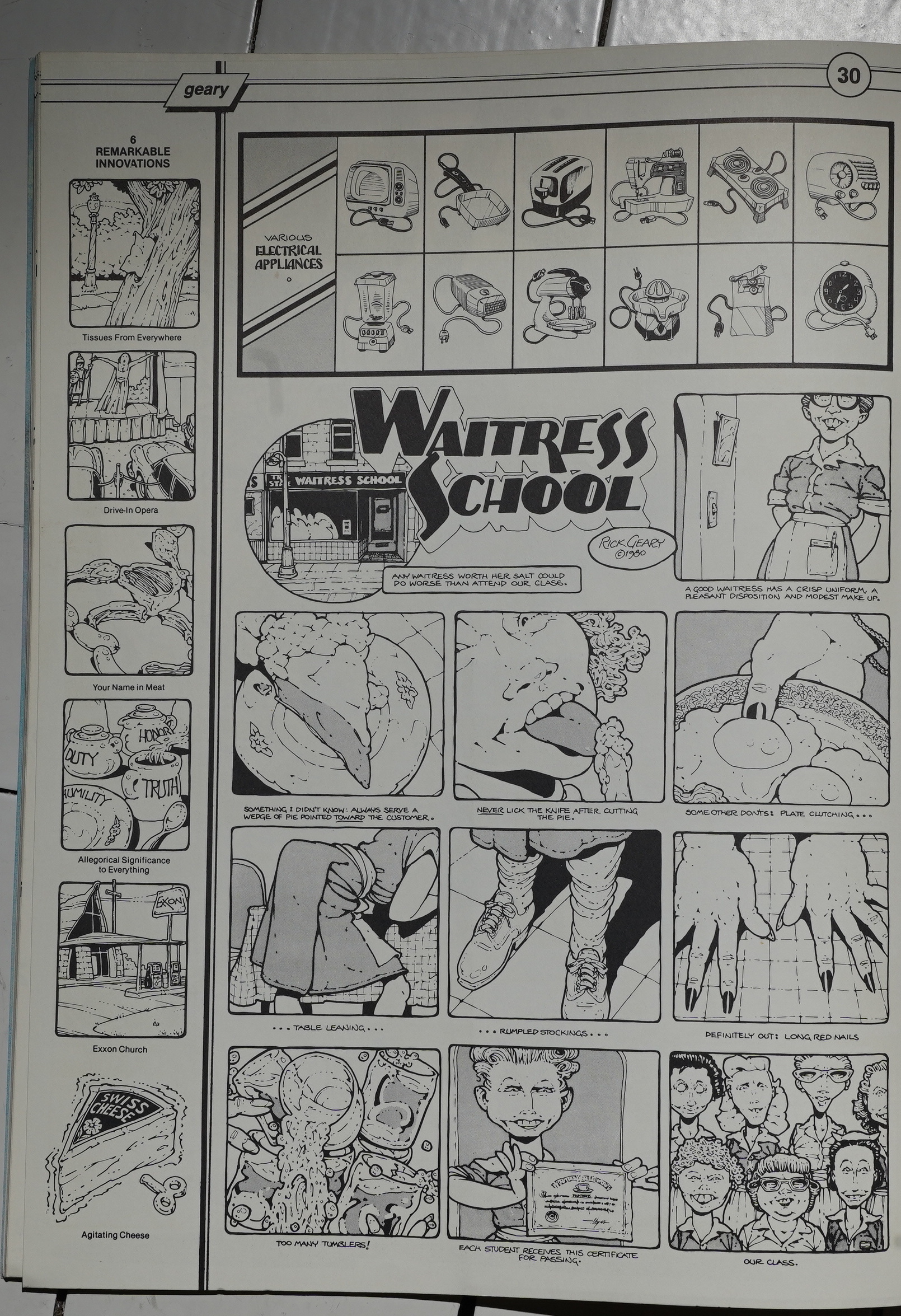

So what was cut? Well, I’m not going to list all the cut pieces, but Rick Geary is gone…

David Levy’s long text piece is gone…

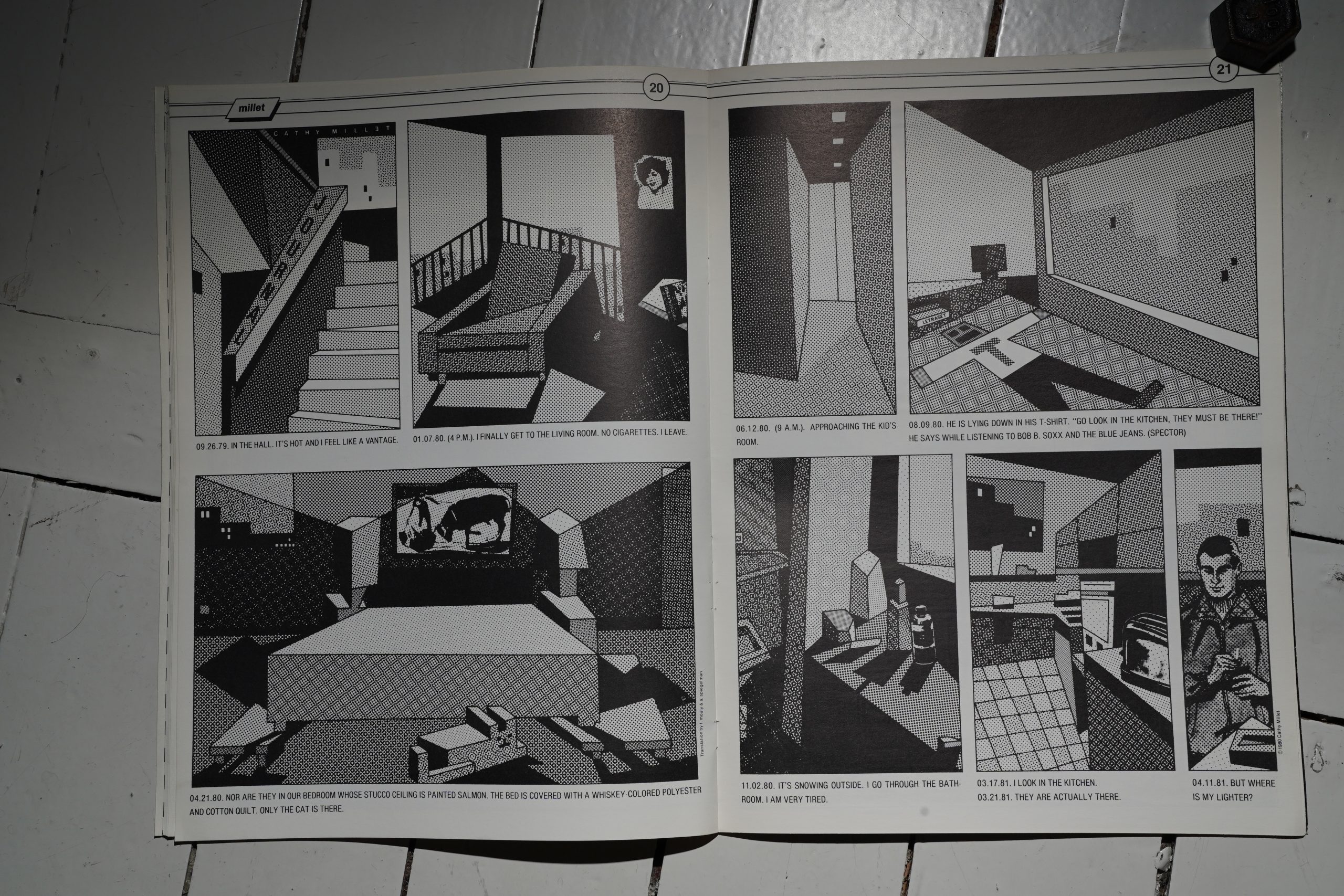

Cathy Millet’s thing is gone…

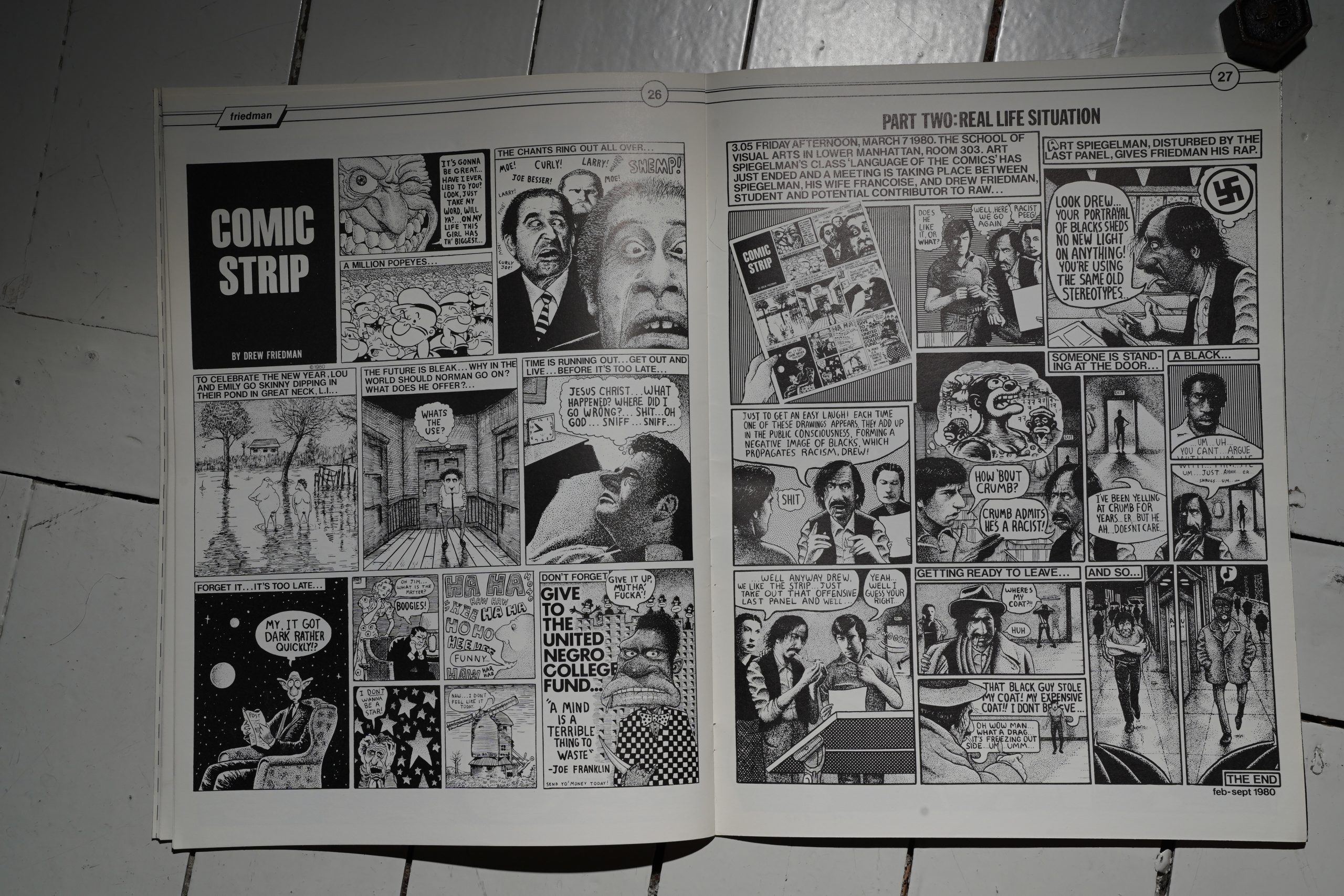

And fortunately Drew Friedman’s racist goof is gone. Which made fun of Spiegelman, so … perhaps that was a contributing factor? Or just because it wasn’t very good?

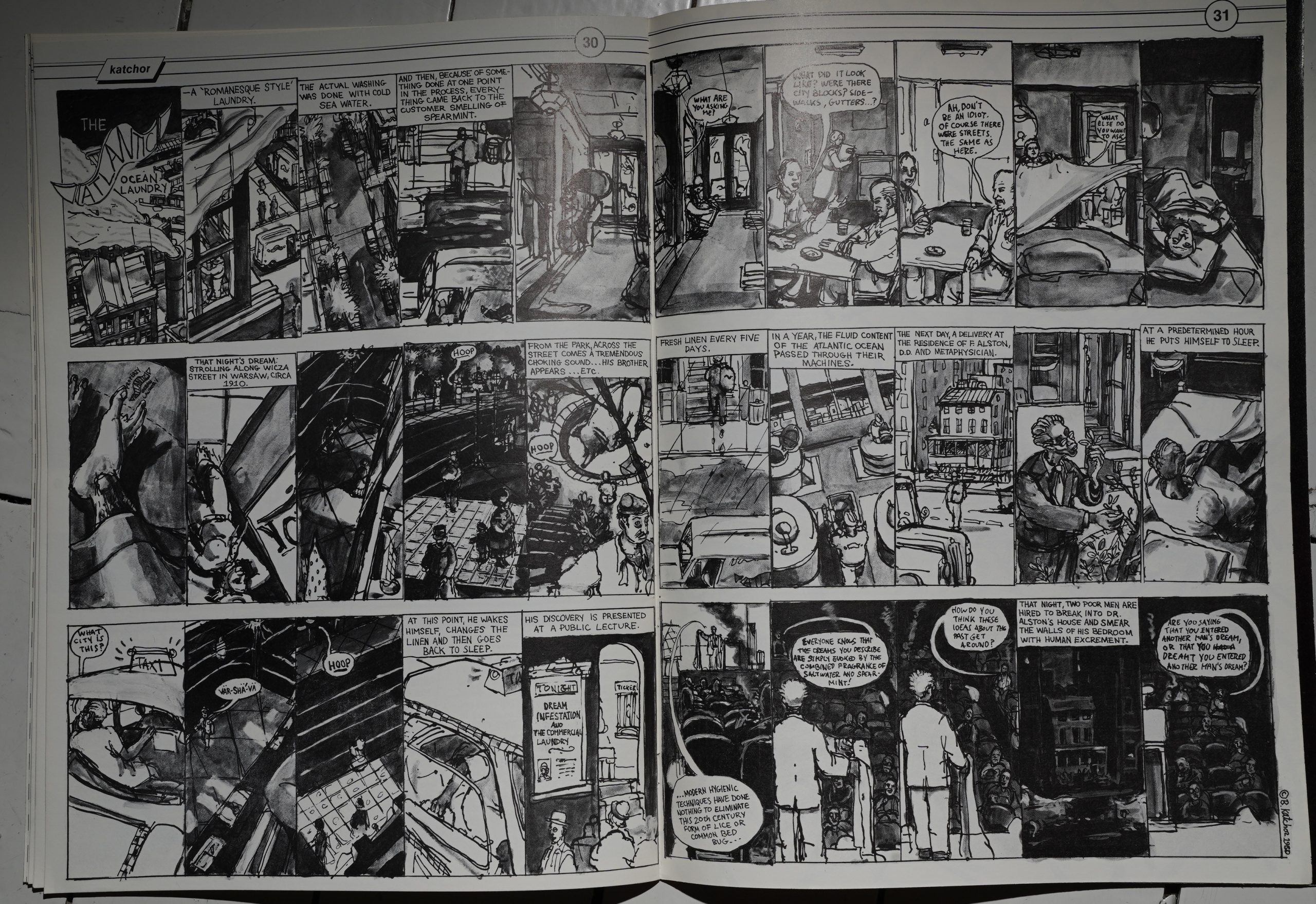

*gasp* The Ben Katchor thing is gone! The outrage!

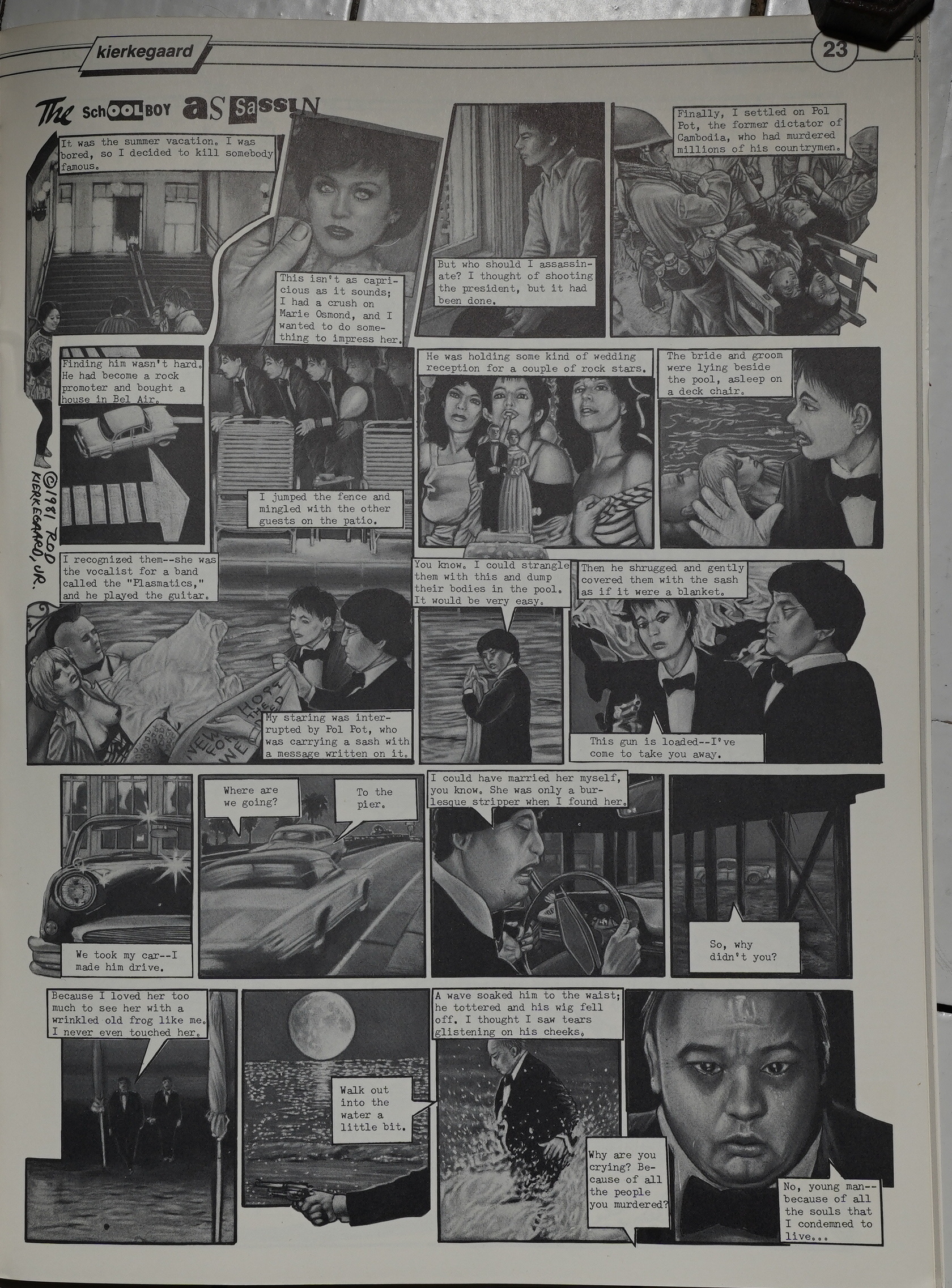

Almost everything is included from the third issue — 42 of 48 pages (including covers). Gone is Kierkegaard…

Rick Geary again…

And the apparent Jihad against women continues — Patricia Caire did one of the few pieces to be removed from #3.

Now I have to look at the credits to Read Yourself Raw again — did any women make the cut?

A Kiki Picasso page made it… a Cathy Millet page… a couple of Mouly pages… and that’s it.

Dale Luciano writes in The Comics Journal #119, page 42:

Pantheon Books’s recent publication

of Read Yourself RAW—a splendid

compendium of material from the first

three issues of RAW, the avant-garde

graphic showcase edited by art spieg-

elman and Francoise Mouly—is a

happy occasion on several counts. Its

appearance is yet another indication

of the enhanced marketability of so-

phisticated comics in America. (Pan-

theon, a division of Random House,

published spiegelman•s Maus, whose

success surpassed expectations, and is

planning several future ventures into

comics.) Read Yourself RAW’ also

make possible a further dissemination

of some superb comics that would

otherwise remain unavailable to many

readers. Finally, on some level it

vindicates the faith and persistence

Spiegelman and Mouly demonstrated

in publishing RAW against what must

have seemed insurmountable ob-

stacles.

The first issue of RAW made its ap-

pearance during an especially dreary

period in recent comics history. (To

be exact, the date was July 1980.) As

published and edited by spiegelman

and Mouly. RAW’s boldness and vital-

ity—its blissful and complete disre-

gard for the constricted American no-

lion of what “comics” are supposed

to be—set off some immediate shock

waves. As I noted in a review of the

first two issues of RAW in Journal

#64, spiegelman and Mouly’s intent

was “to shake things up, to move

beyond accepted conventions into new

areas of expressiveness and idiosyn-

crasy… RAW is a Jarryesque toying

with the arrangement of the car-

toonist•s mode of imagining.” More

than anything else. RAWS appearance

offered a corrective. In the face of so

much that is contemptible in our

popular culture. RAW was and remains

a forthright declaration that comics are

a sophisticated, adult medium. cap-

able of producing joy and pathos and

worthy of thought and contemplation.

The comics themselves attested to the

enormous, untapped potential of the

medium.

That RAW came into being at all is

a tribute to the tenacity of spiegelman

and Mouly. They set out to create a

“prototype” (their term) that would

serve “to show what someone ought

to be doing.” Given the track record

of the undergrounds in the preceding

decade, spiegelman and Mouiy had

little reason to anticipate that RAW

sales would be good In fact, they

were surprised when demand con-

tinued to exceed supply over the

course of increasing print runs for the

first four issues—the last published in

1986—RAWs audience and influence,

to everyone’s surprise, continued to

My sense is that RAW: which dev-

eloped out of spiegelman and Mou-

ly’s simple desire to see a magazine

that “would print the kind of uork that

interested us,” fulfilled long-disap-

pointed hopes among many for a

renaissance of understanding that

comics were something more than the

juvenile stuff dominating the mass

market in 1980 Having suffered the

pangs of a slow, prolonged death, the

undergrounds lost most of their econ-

moic base by the early 1970s and

ceased to be a major fixture on the

American comics scene.[…]

Four years later. RAW #1 appeared.

If you weren’t among a select few who

had glimpsed the work of various

European comics artists, the spectacle

of these large, impressively repro-

duced pages—featuring the stark,

naturalistic cityscape of Jacques Tar-

di’s “Manhattan”; the exuberant com-

ic vigor of Joost Swarte, who has been

aptly described as the “warped step-

child of Herge (fintin) and McManus

(Bringing Up Father)”; the startling

expressionism of Munoz and Sam-

payo’s images of despair and human

isolation. “Mister Wilcox. Mister

Conrad” (in RAW 3); and the goofy

mayhem in Mariscal’s epic cartoons—

came as a revelation. There were

samples of other work, short pieces

by the Parisian Cathy Millet, the

Canadian Gerry Capelle, and the

Belgian Ever Meulen. that were in-

triguing suggestions of new

possibilities for the comics medium.

RAW also featured two lovely hom-

mages to the tradition of early com-

ics when it ran pages from Caran

d’Ache and Winsor McCay. These

served as a reminder of the honorable

and distinguished heritage of the past.

And there were the Americans.

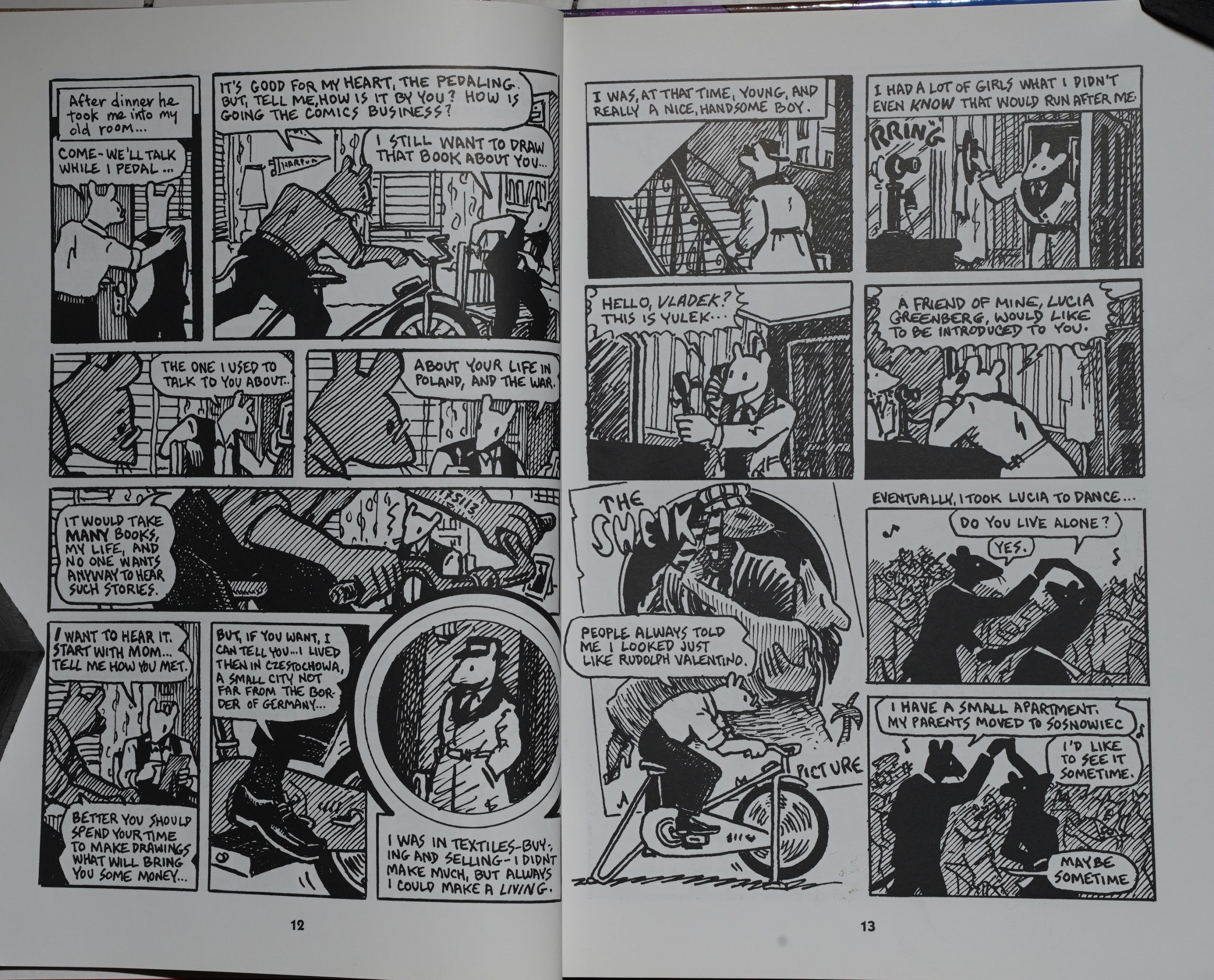

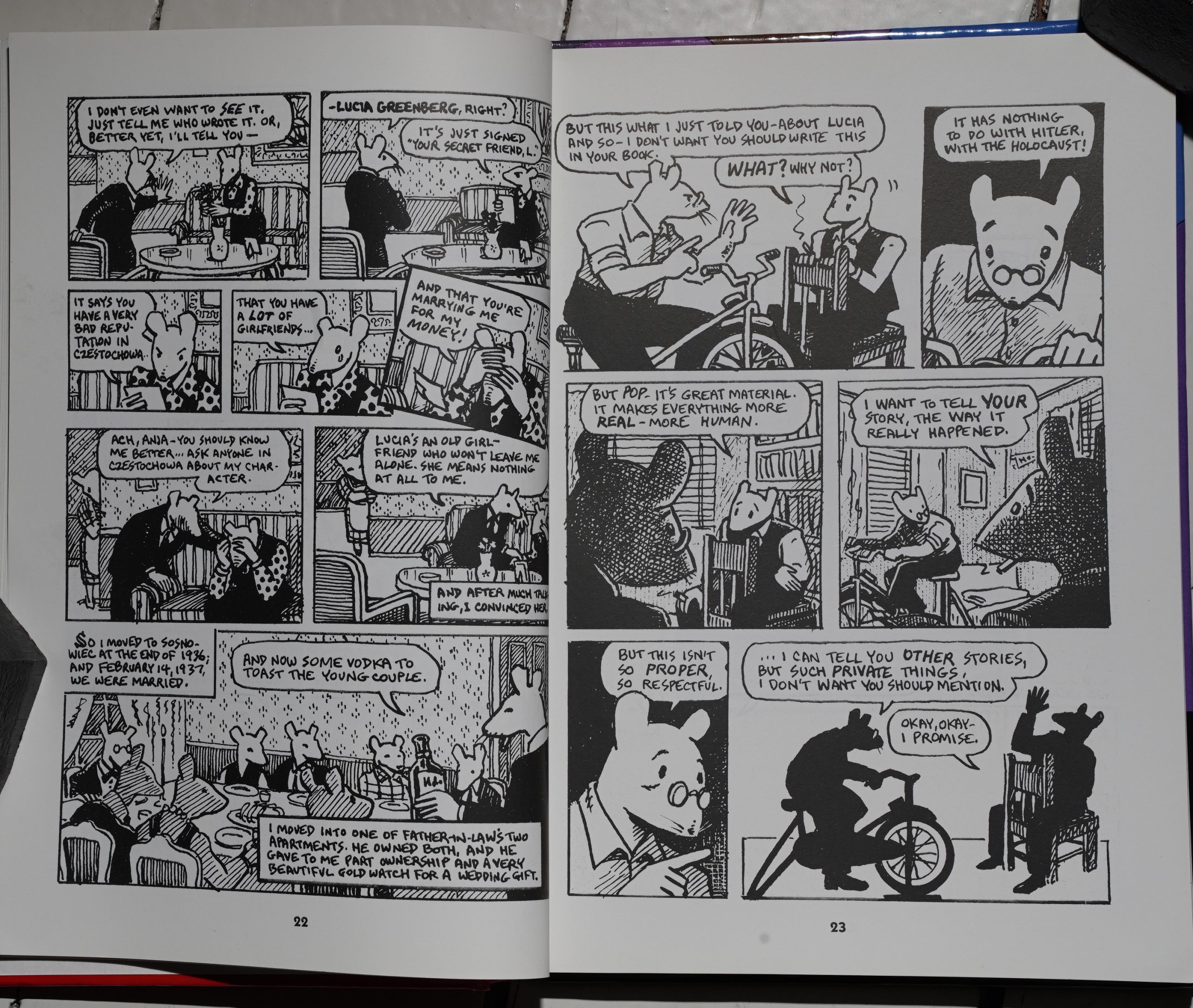

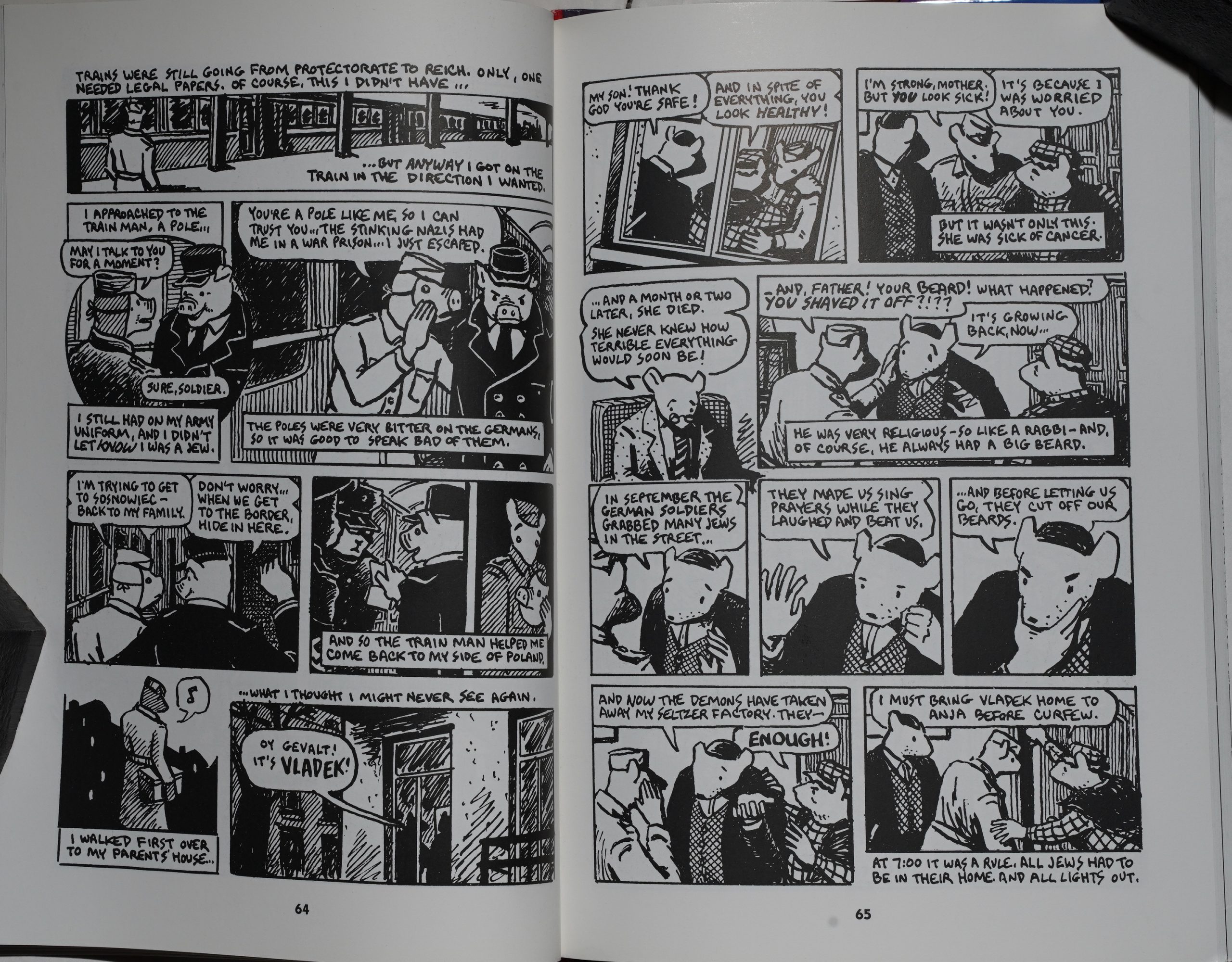

Of special note, of course. were the

installments of spiegelman’s Maus that

began in the second issue Of RAW

These are not, of course, included in

Read Yourself RAW: which does repro-

duce spiegelman’s “Two-Fisted

Painters.” This is a playful tinkering

around with color registrations, abet-

ted by some amusingly melodramatic

contrivances, including an alien with

a color syphon, that justify the tinker-

ing. It’s wonderful stuff, and entirely

a propos of the magazine’s hip, arty

From Mark Beyer, there were his

disturbing strips featuring the child in-

nocents, Amy and Jordan, wandering

through a world of nightmarish land-

scapes and ominous, unpredictable

threats from all directions. (The

notorious Amy and Jordan bubblegum

cards have been included in Read

Yourself RAW.)[…]

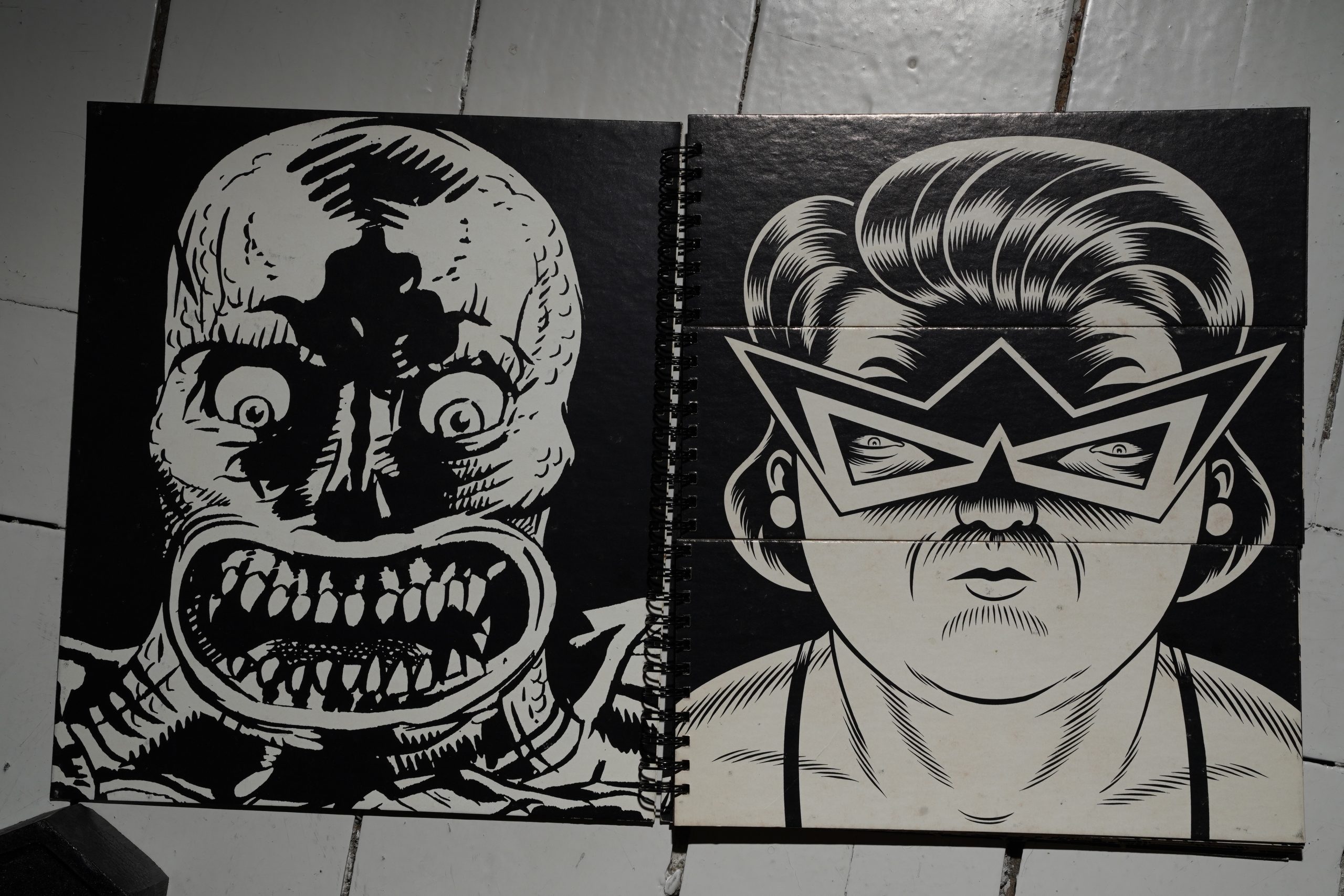

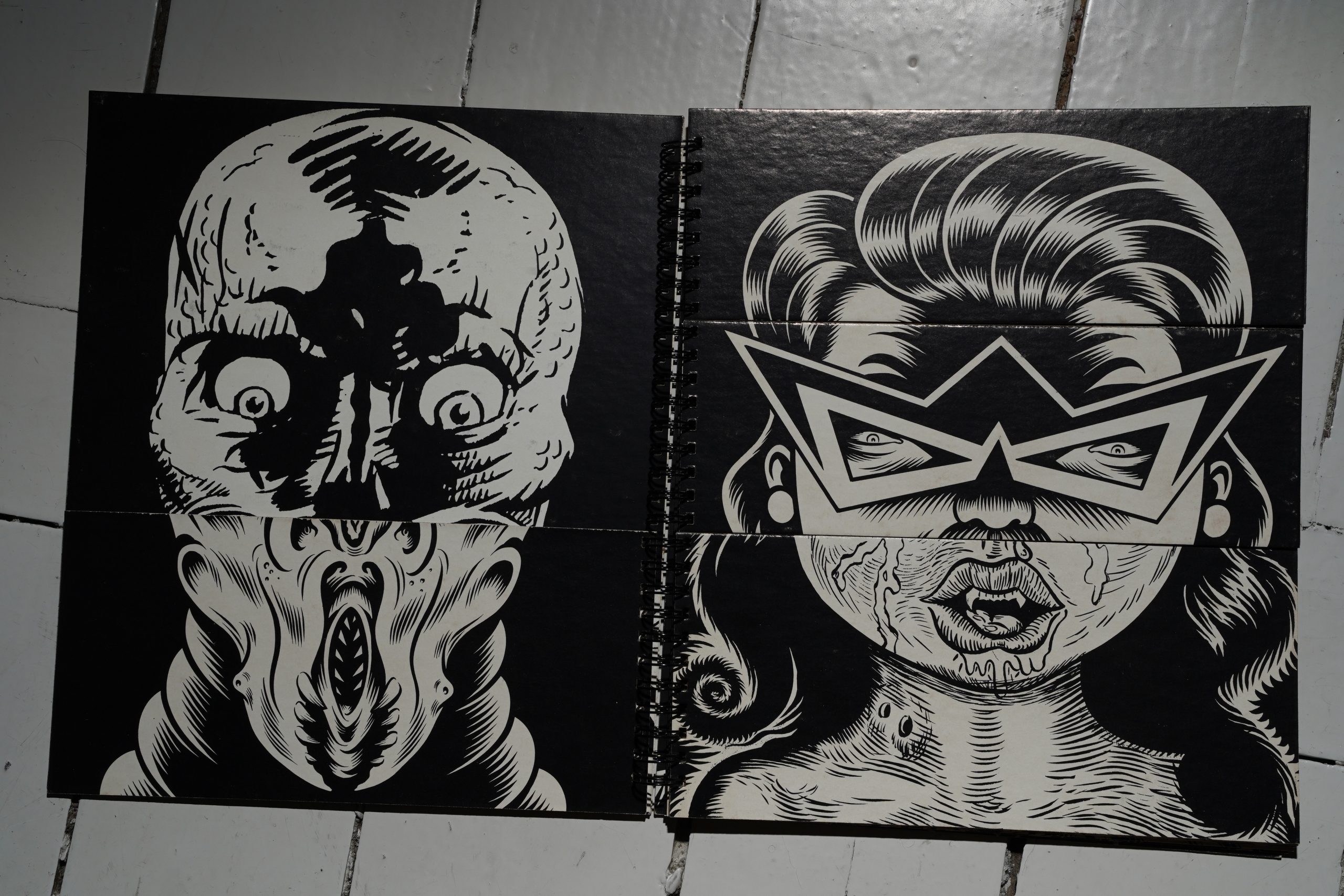

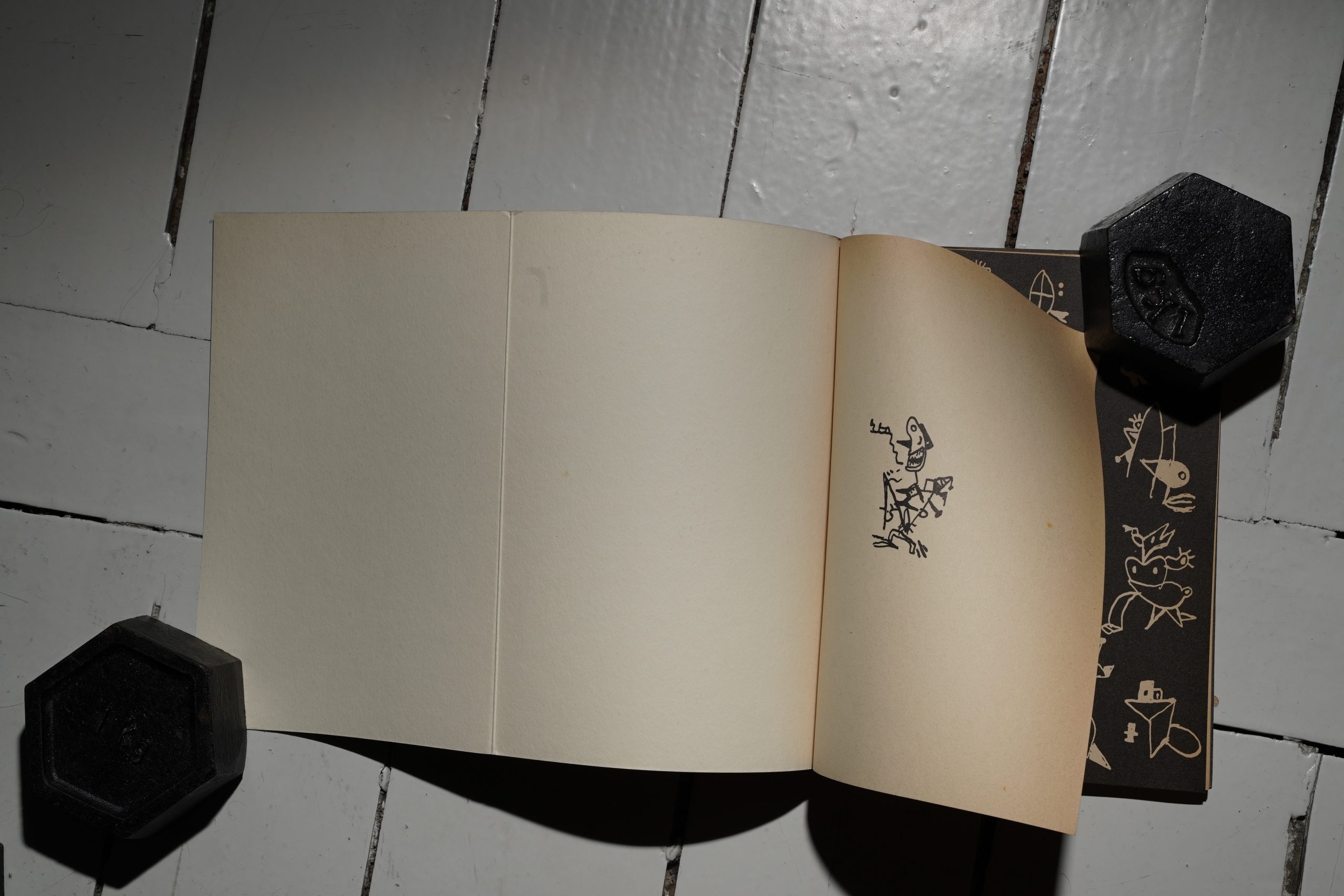

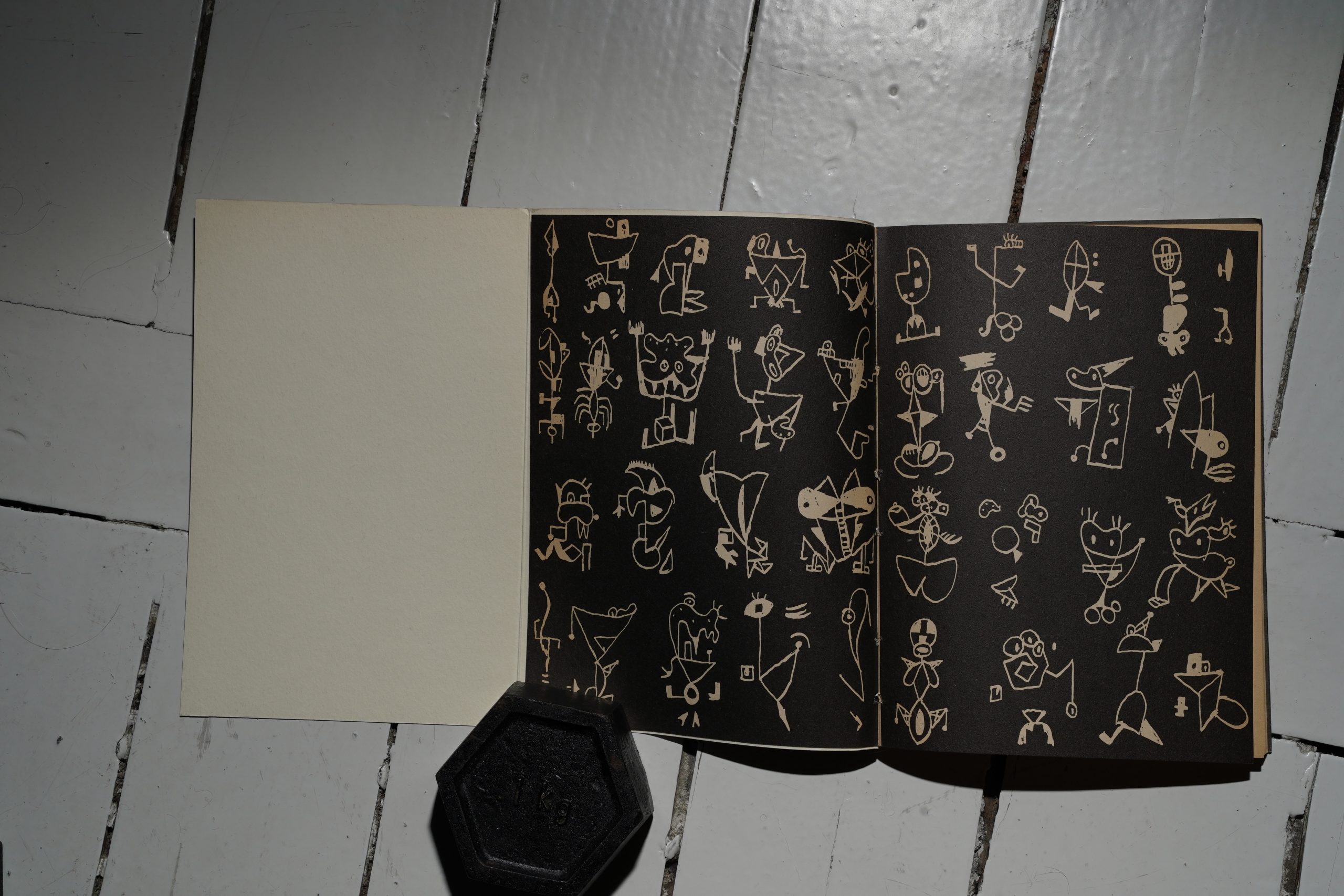

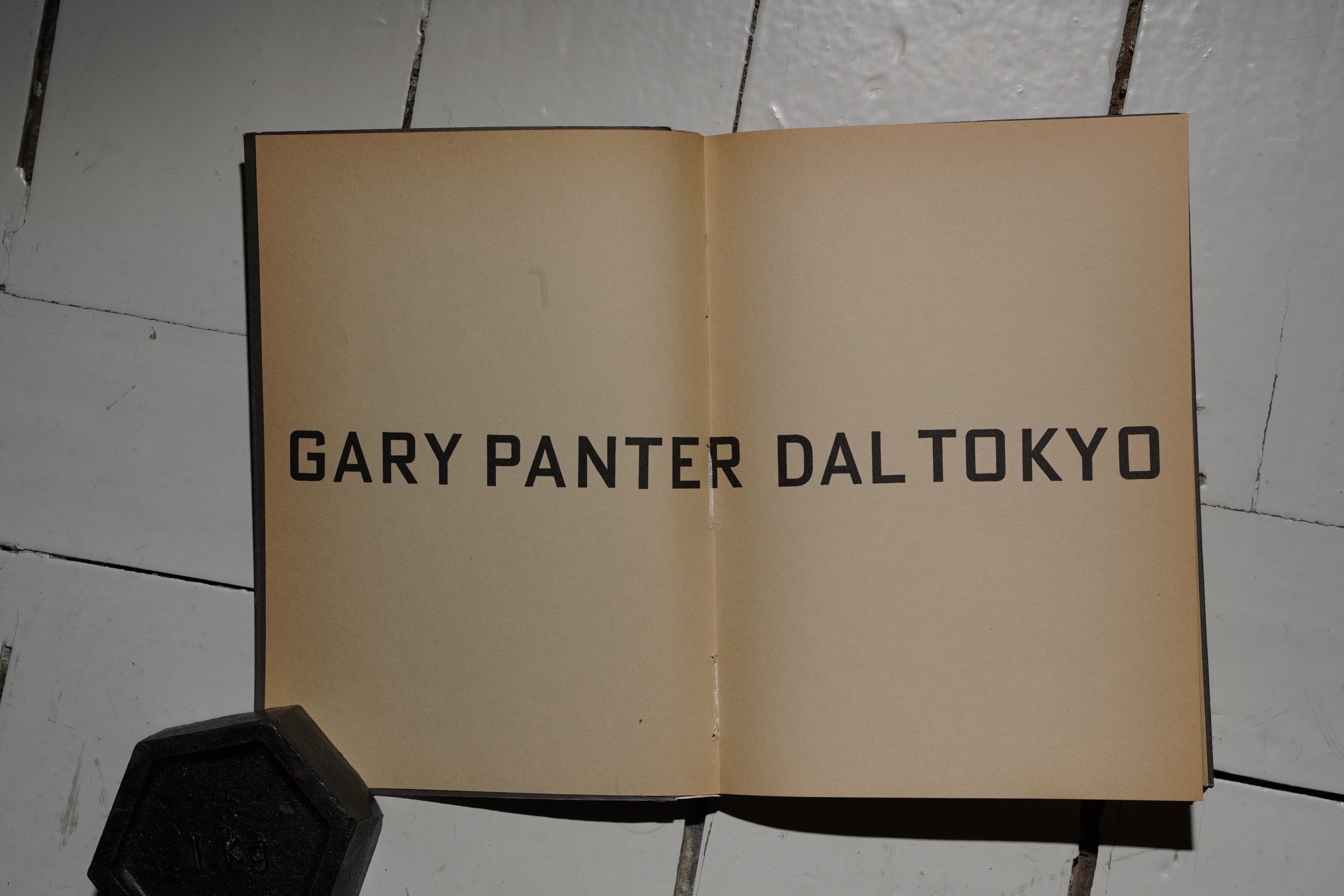

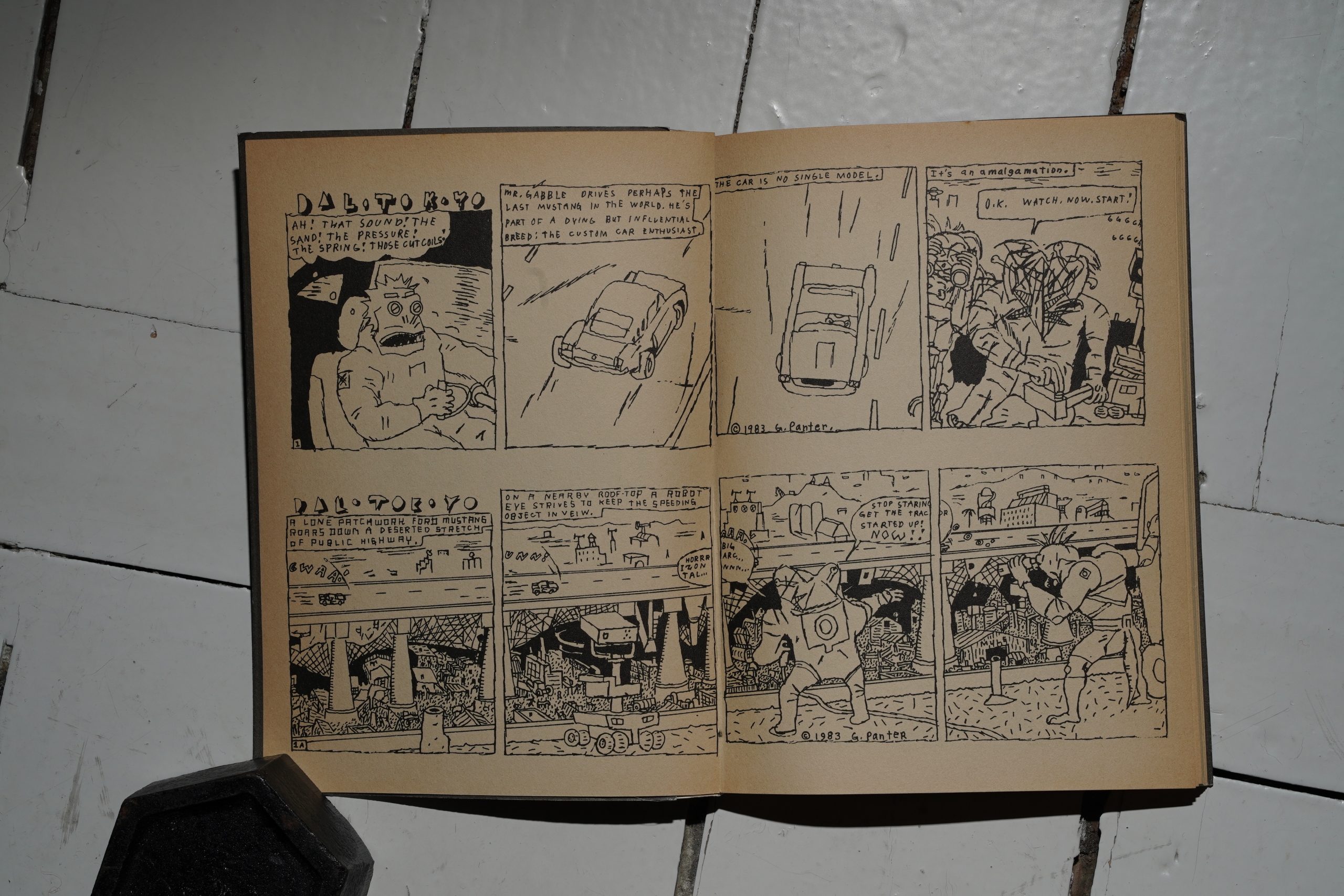

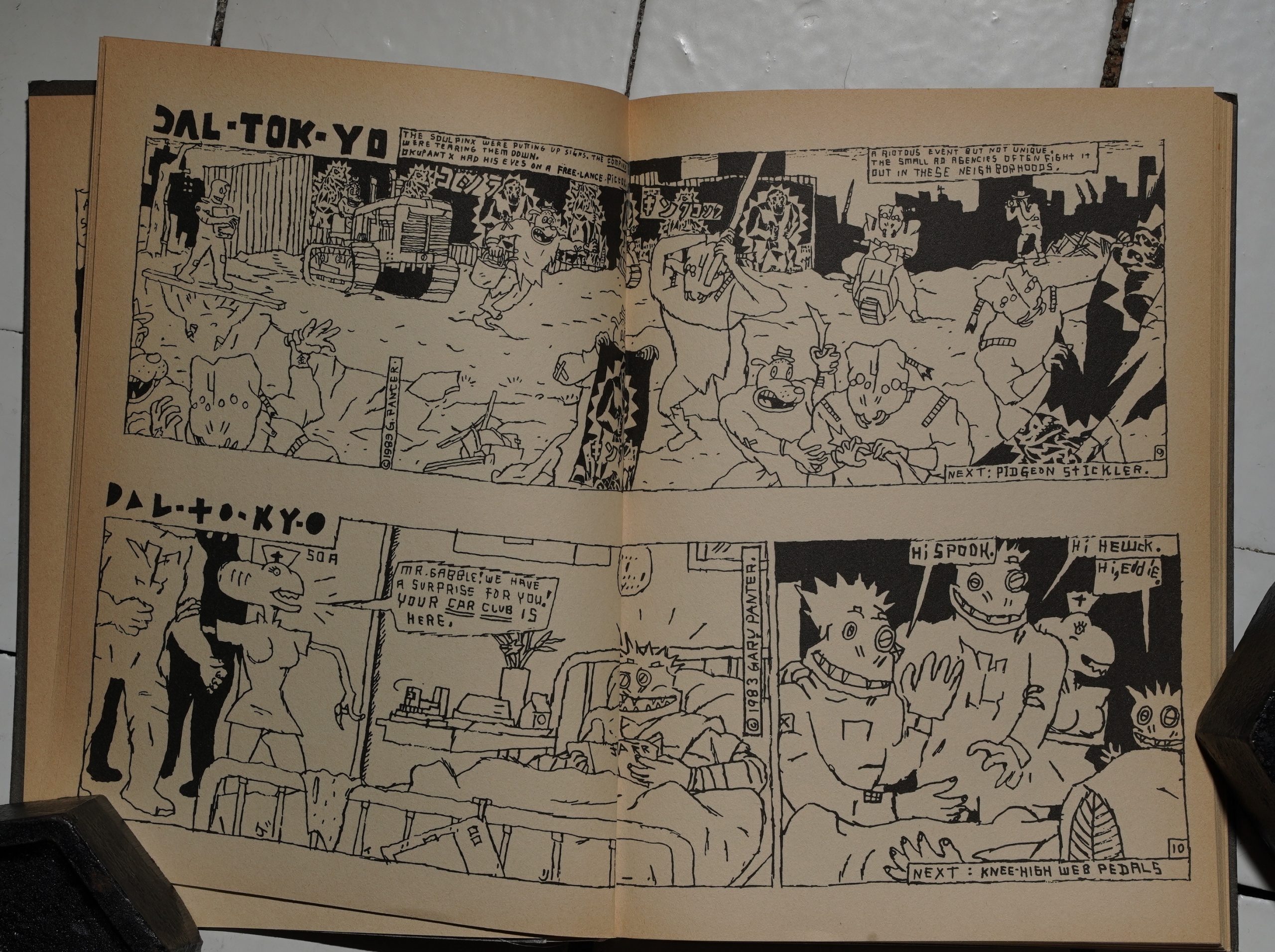

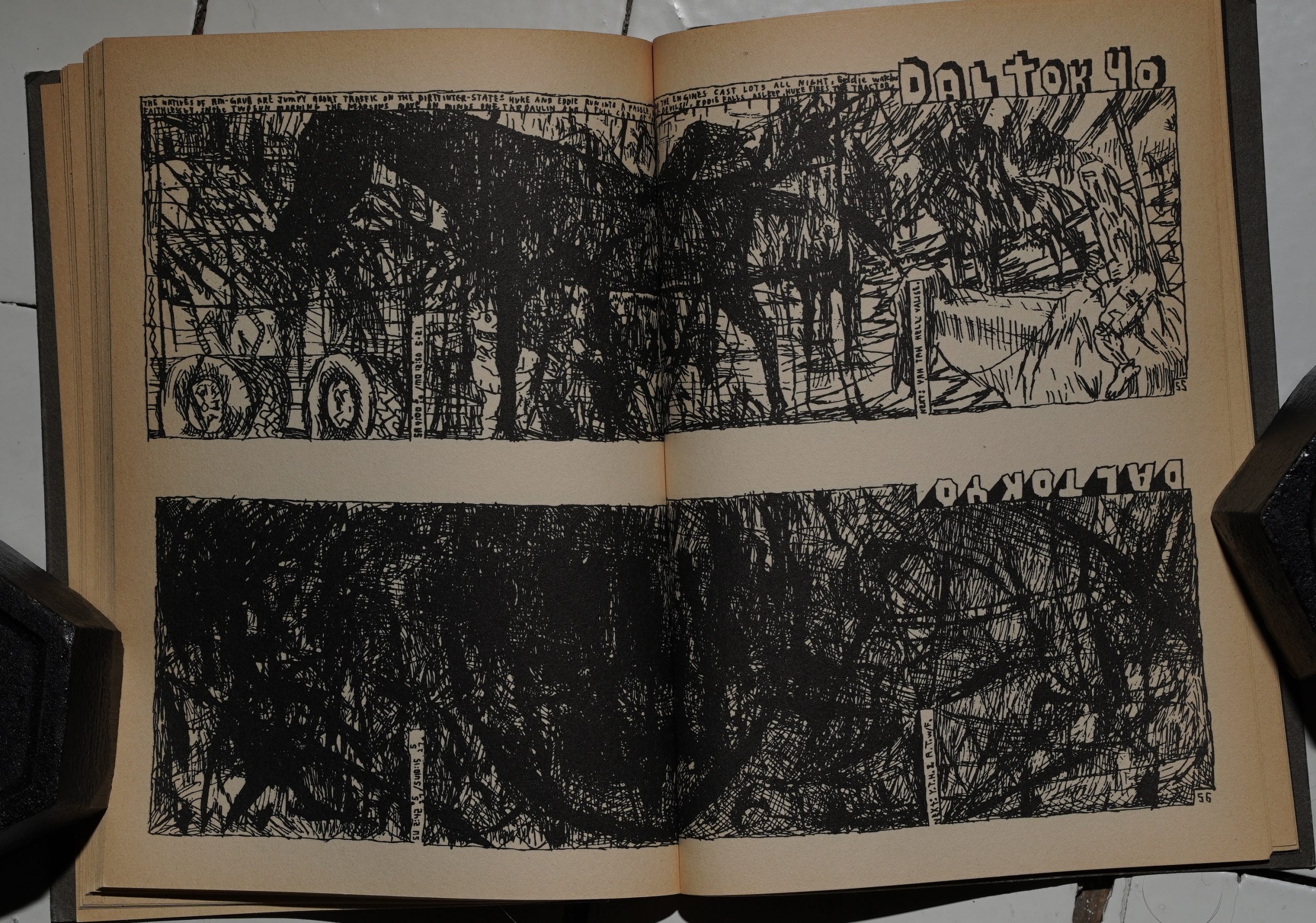

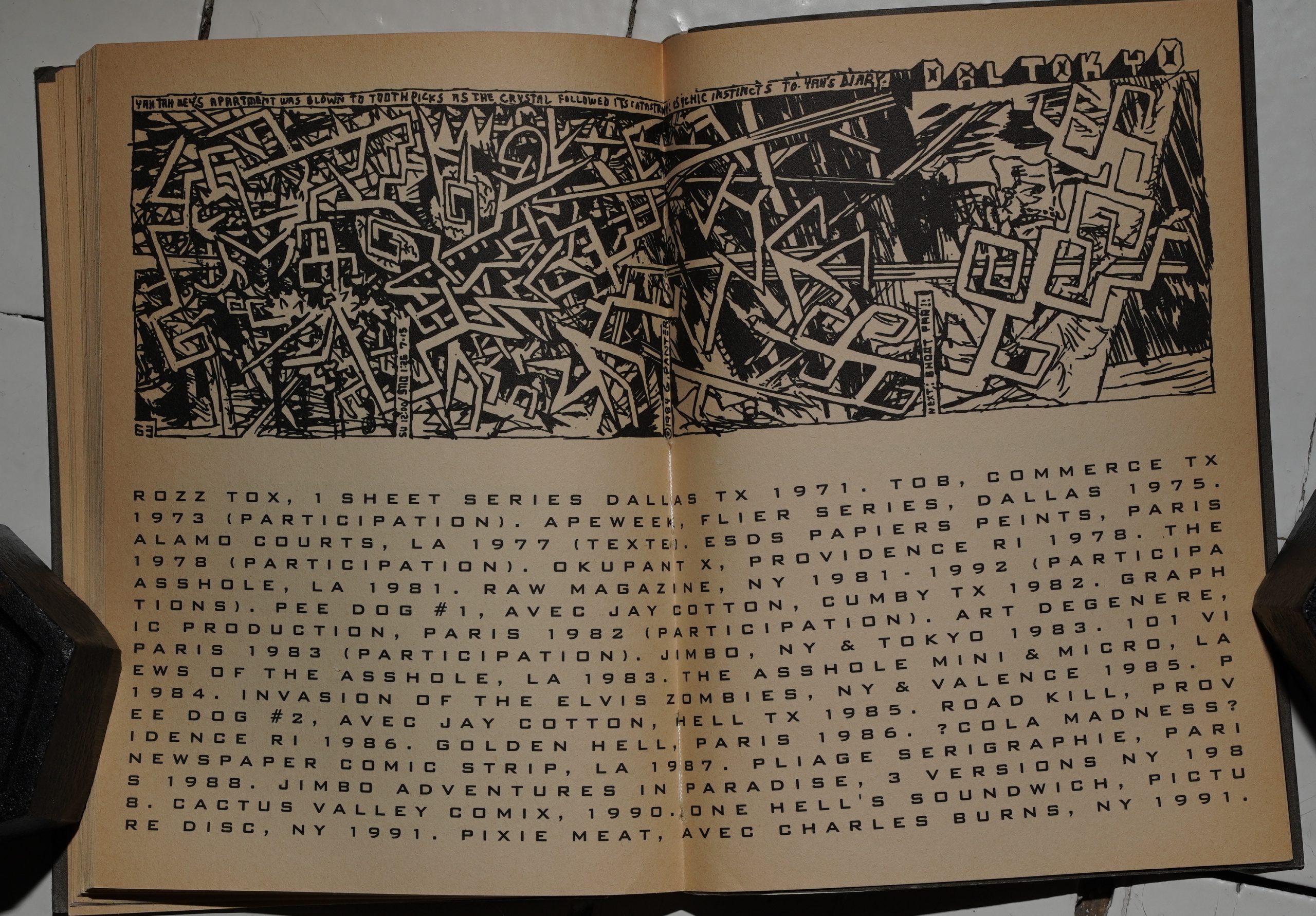

Finally, there was Gary Panter’s

memorable image of Jimbo staring out

from the cover of RAW #3. Panter’s

cartooning has generated its share Of

controversy in the intervening years.

His influence has been considerable

and undeniable. and when many

readers ran across the Jimbo “Run-

ning Sore” strip in RAW 3, they were

encountering an unusual of self-

expression or sensibility. Panter has

termed his “ratty” or punk approach

a calculated reaction against “seam-

less illusion,” and many have attacked

his work for a variety of reasons. My

own estimation is that Panter’s work

is painterly and, in terms of its aspira-

lions, often inspired. In RAW’: Panter

found the perfect outlet for a brilliant-

ly radical, uncompromised, “new”

approach to comics. (See the inter-

view with Panter in Journal #100.)

Read Yourself RAW reproduces a

majority of this material, including the

wonderful covers, exactly as it ap-

peared in the original issues. As a

special treat. there is also a wonder-

ful new Read Yourself RAW cover by

spiegelman. All of this is good news

for those who missed out on RAW’s

early issues and have found collector

prices for those early issues beyond

their means.

Missing are a few pieces that have

not been included in the collection.

Mark Newgarden’s “Mutton Geoff’

from RAW I was a good use of

familiar icons (Mutt and Jeff) for pur-

poses that brilliantly transcended

parody, and I was sorry to see it ab-

sent here. Drew Friedman’s ‘ ‘Comic

Strip” from RAW 2 is missing as well.

A happy choice might have seen

Friedman’s friendly satirical jabs at

spiegelman and Mouly exchanged for

the tiresome Andy Griffith satire,

which is included. (The Griffith satire

also appears in Any Similarity To Per-

sons Living Or Dead, but, to my

knowledge, “Comic Strip” has not

reprinted from its initial appearance

in RAW.) Some Rick Geary material

that has been reproduced elsewhere

has been dropped, along with some

pages from Kaz that will soon appear

in Buzzbomb. Several text-oriented

features, a handful Of more purely

conceptual pieces. and a few less ac-

cessible strips (like Ben Katchor’s

“The Atlantic Ocean Laundry”) have

also not made it into the collection.

These are not quibbles, just notations

for those who observe such editorial

matters closely.

This blog post is part of the Punk Comix series.