The first batch of French(ish) comics I wrote a bit about a year and a half ago were mostly all comics that I had read many, many times as a teenager. This time out, I remember even less about these comics than I did the last time.

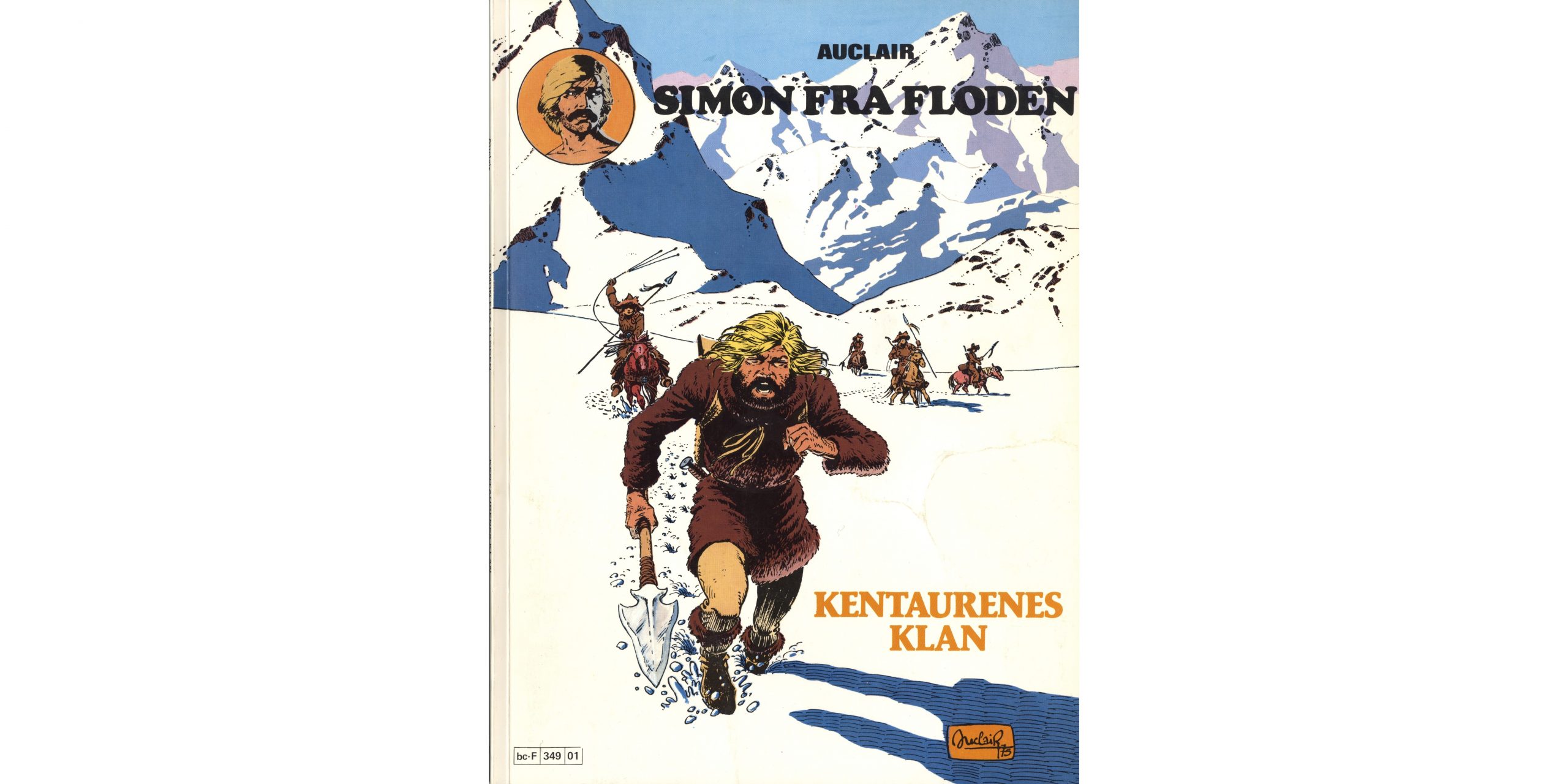

First we have Simon du Fleuve (which means something like Simon of the River) by Auclair. I remember that it’s a post-apocalyptic adventure story, and heavy on the politics. It’s anti Fascism and pro ecology. I think. A woke Mad Max. Kinda. Or is it?

Let’s find out.

Le clan des Centaures by Auclair (1976)

Claude Auclair was born in 1943, and started doing comics in the early 70s. Simon du Fleuve was serialised in the French weekly Tintin magazine starting in 1974.

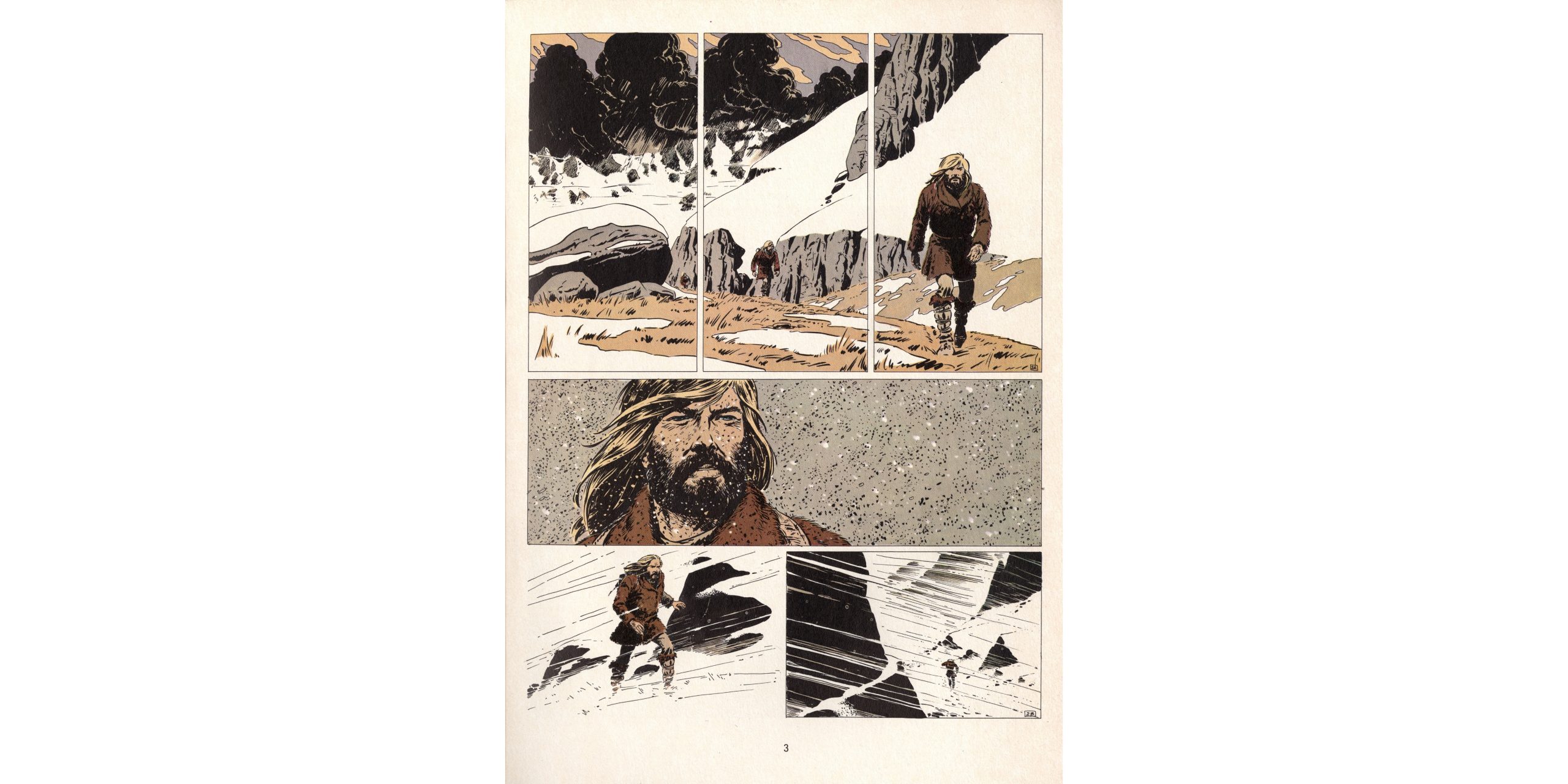

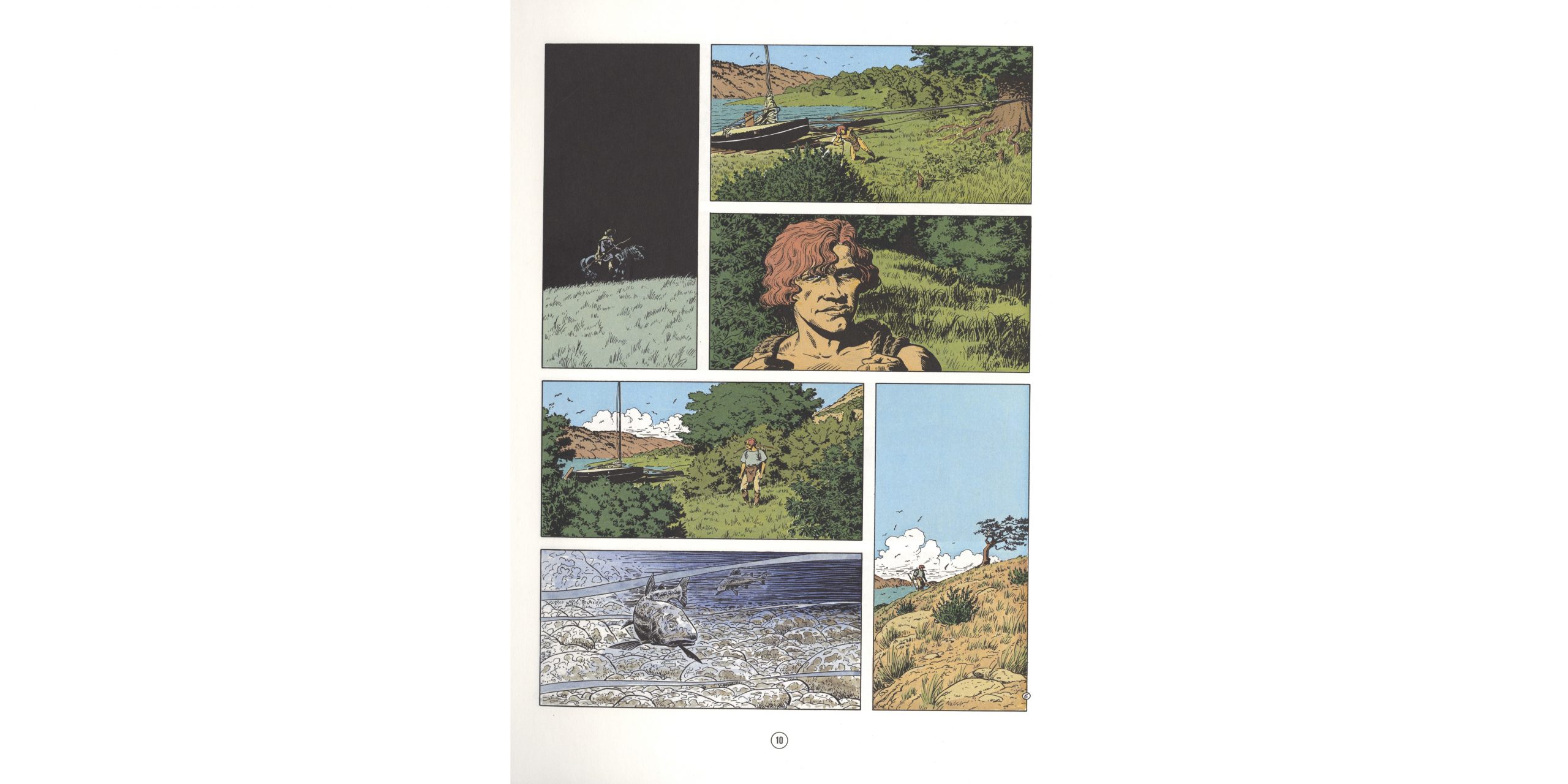

His artwork is, perhaps, a bit generic and rugged. You can see some Giraud influence, but it’s a slightly vague style: Not a real departure from other adventure artists like William Vance or Hermann.

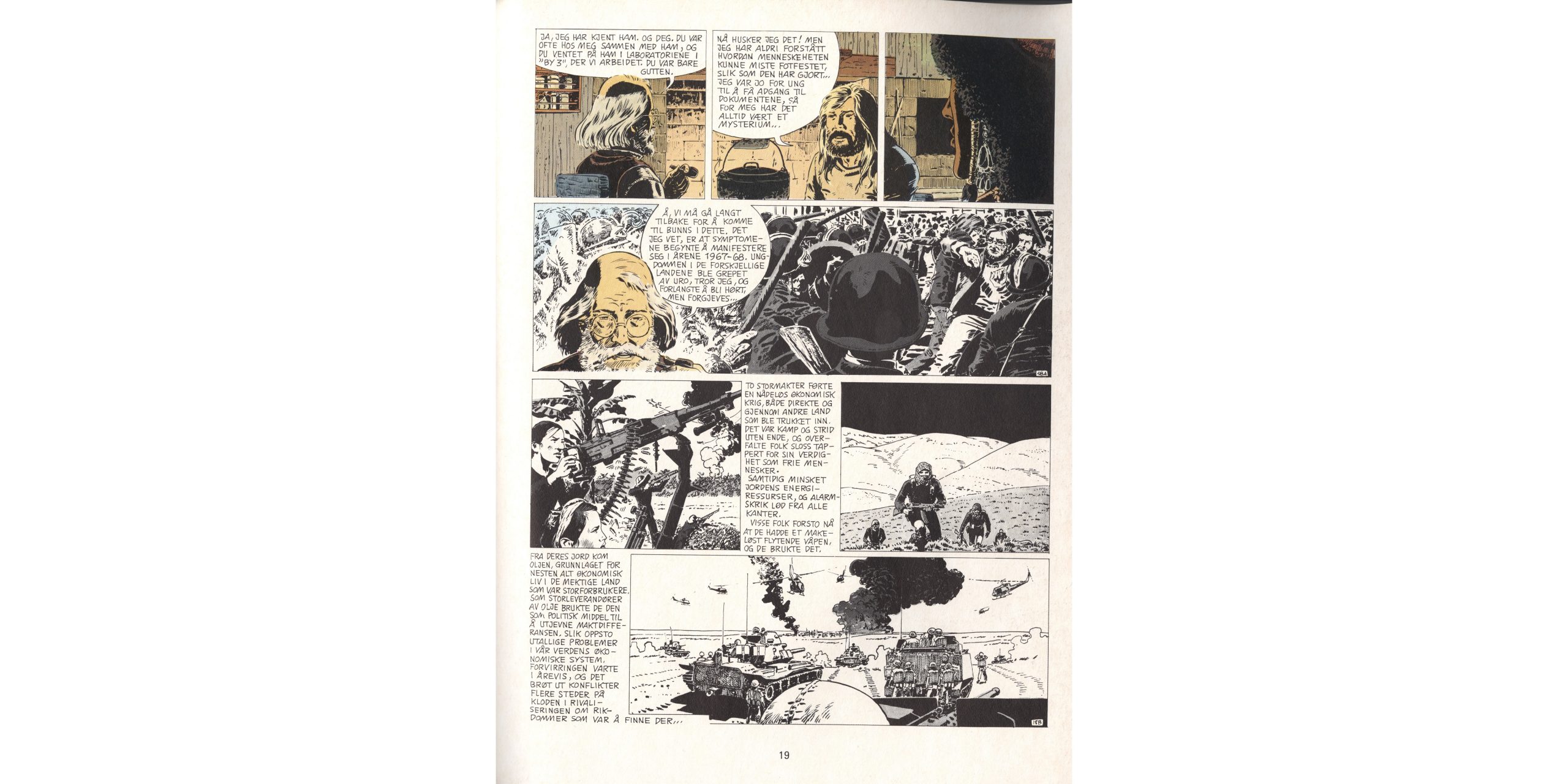

Anyway, the first five albums are, pretty much, one single story. We’re in a post-apocalyptic Europe that went off the rails in the early 70s. Most people now live in agrarian communes, except the evil overlords who still occupy the semi-dead major cities.

The old guy explains how this all happened, but he’s … a bit vague. There were wars? And… something? And then everybody lives in the countryside.

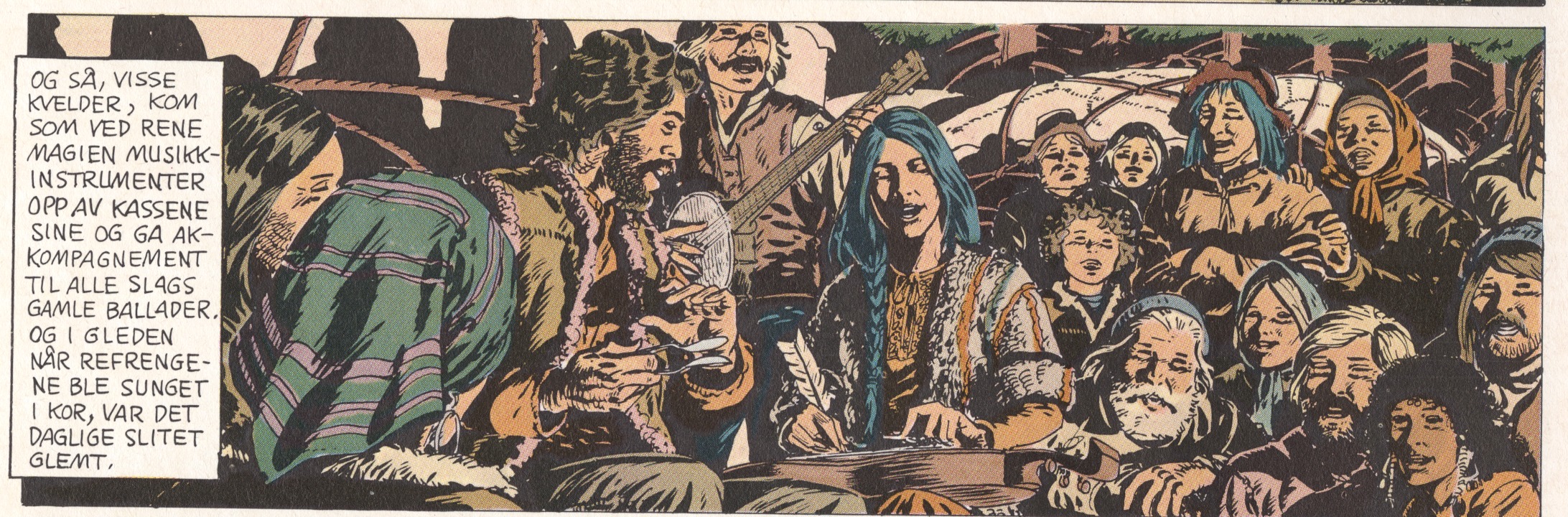

And they are very happy here. Except when bandits raid them or the Evil Overlords pay a visit.

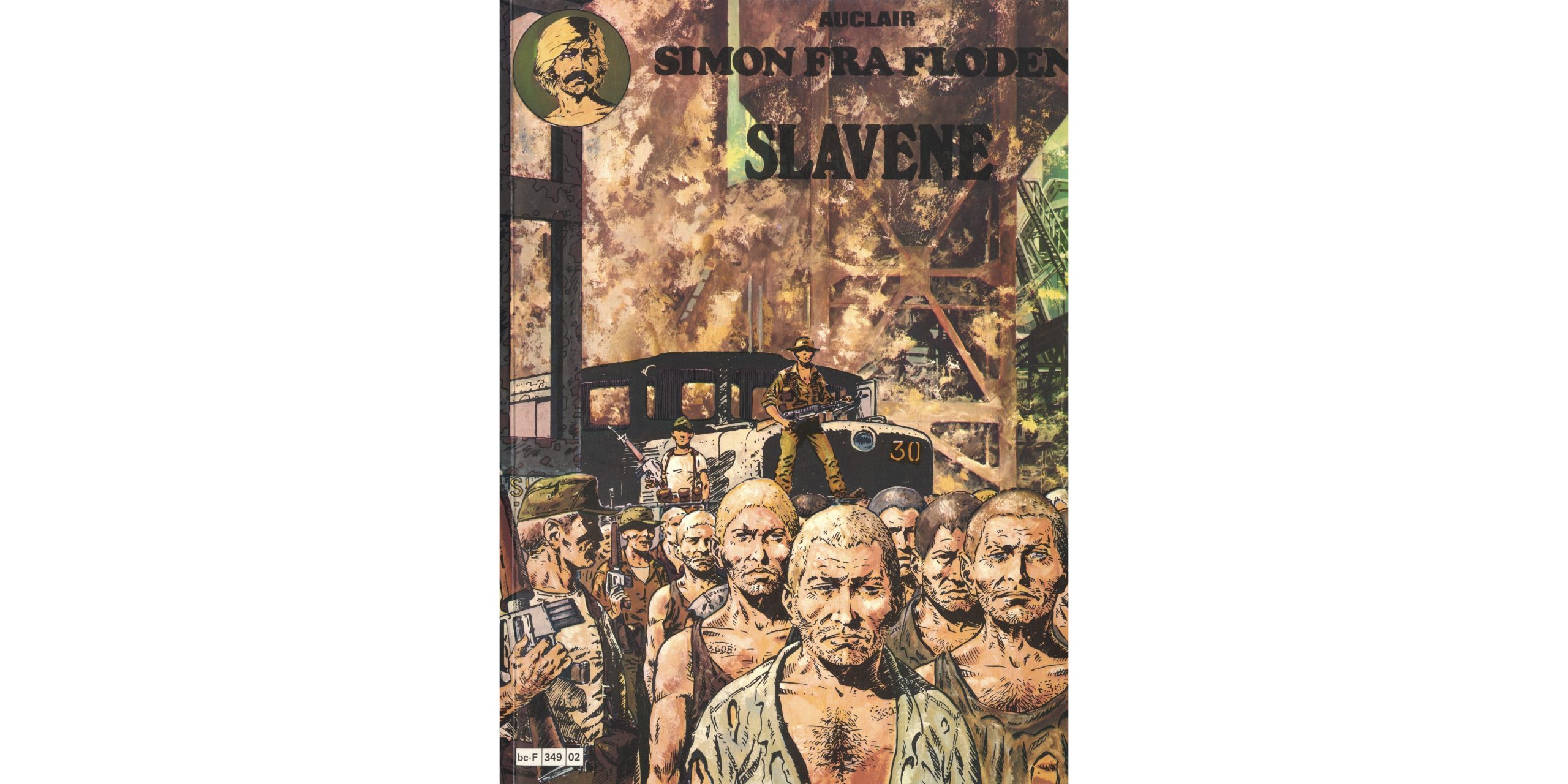

Les esclaves by Auclair (1977)

Which they do from time to time, because they need workers for their evil ironworks.

Just so that you won’t miss the allusion to other popular Fascists from history, all the slaves get short-short hairdos and numbered tattoos.

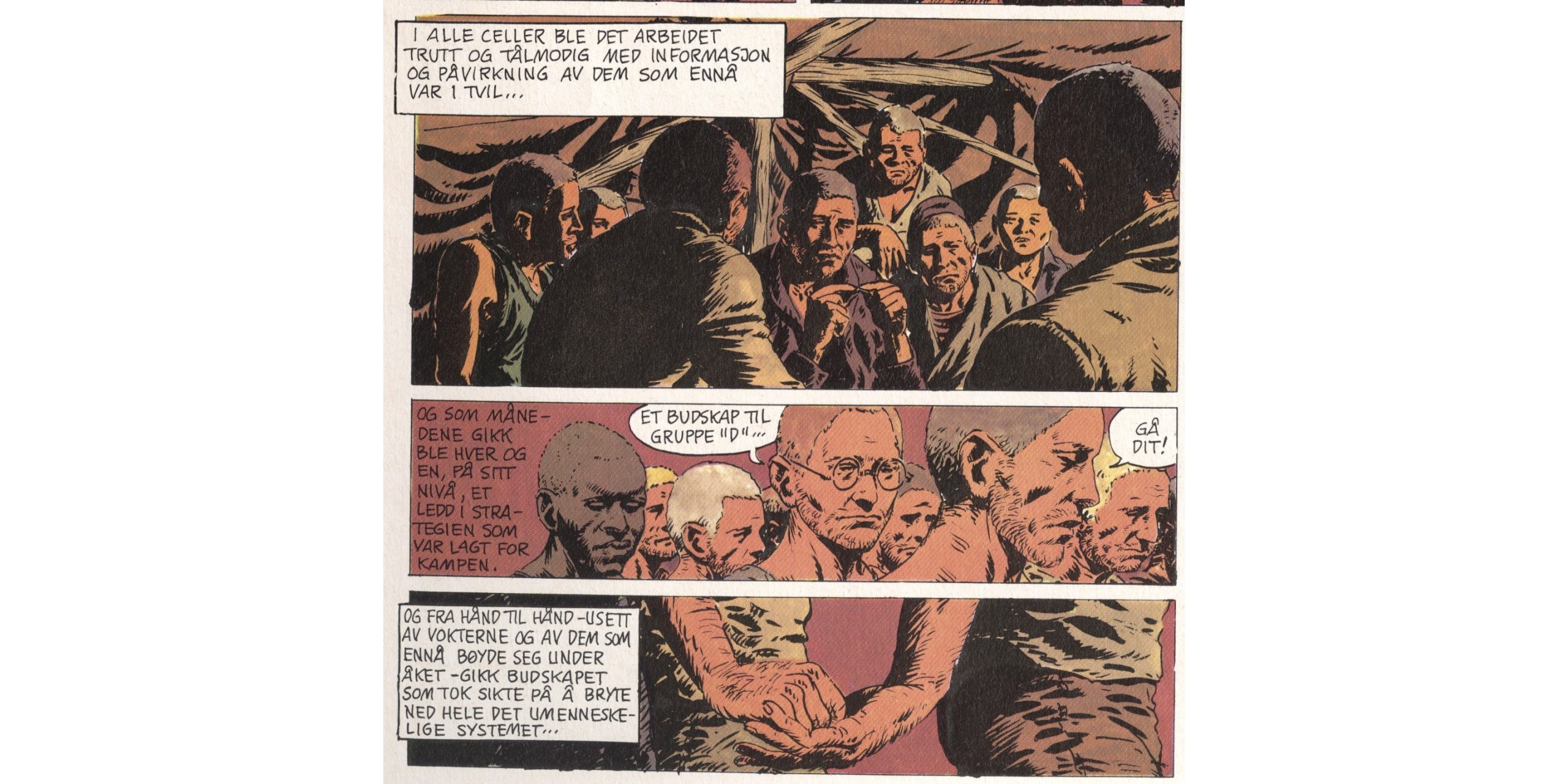

Sorry, writing this, I notice that I’m slipping into a default sarcastic tone, and I didn’t want to do that. Yes, Auclair is didactic and sometimes overbearing, but the comics aren’t failures: They are often moving and heartfelt. And they’re created by someone who I feel wanted to offer something positive: Everything isn’t hopeless, because people can make a difference.

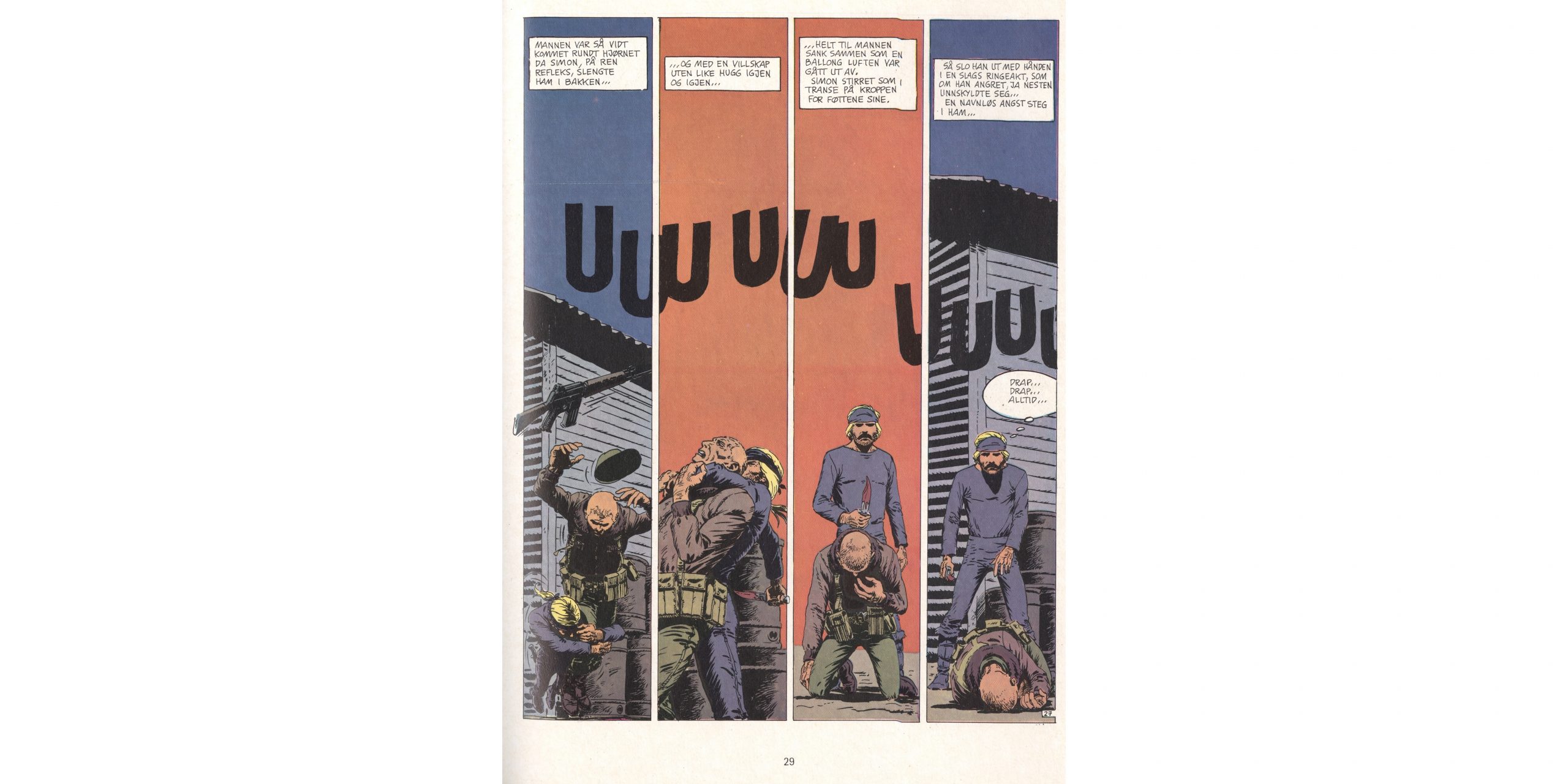

Simon helps organise a slave breakout, of course, because this is an adventure comic book. But he does this by recruiting three others who then come up with a plan to mobilise the slaves themselves, and who then enter the encampment and set up a revolt. This isn’t the kind of comic where the hero goes blazing in and fixes everything by waving his hand, but by creating a situation where resistance can happen.

And then he comes blazing in and kills a bunch of guards. And feels really shitty about doing so.

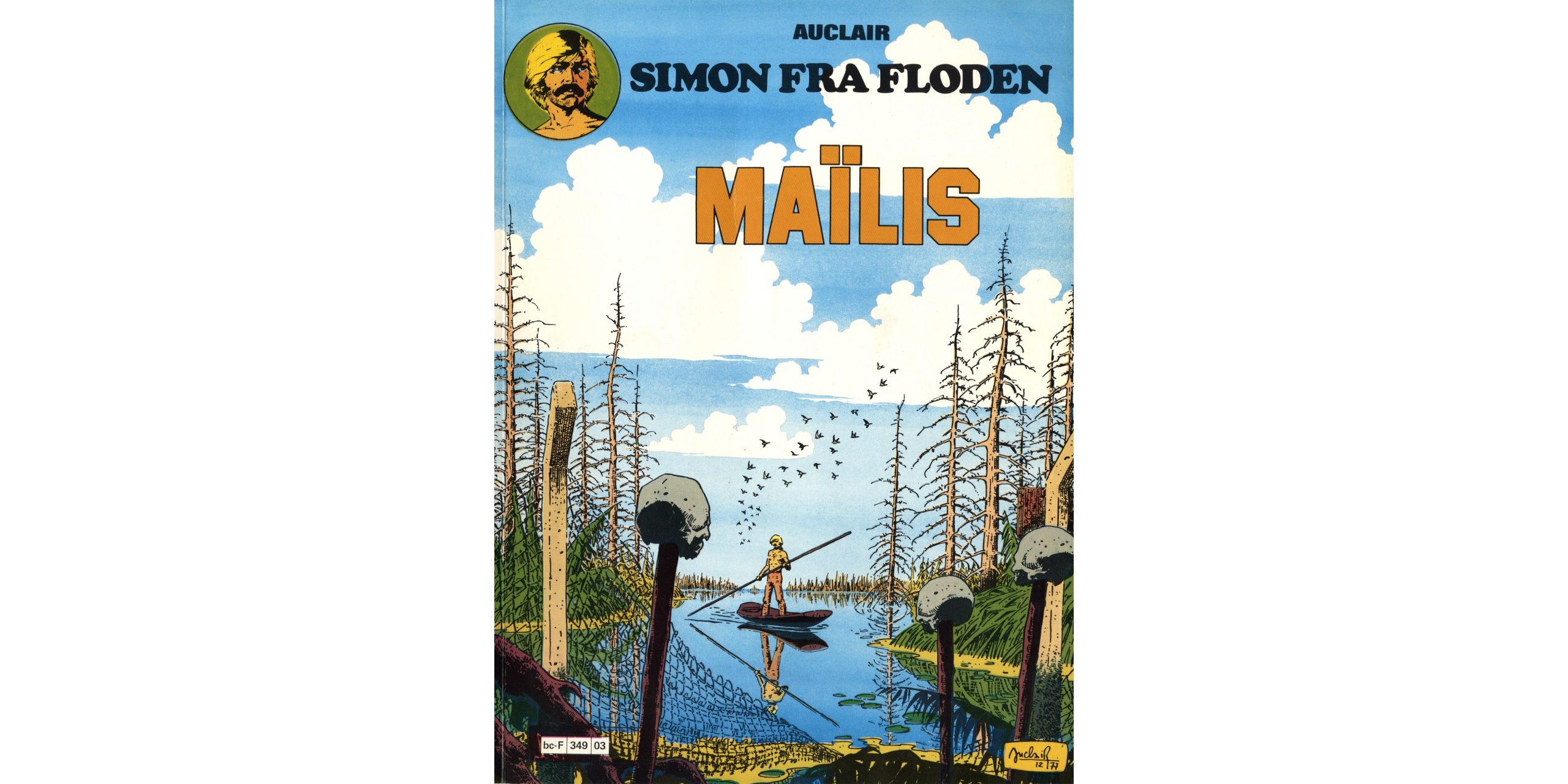

Maïlis by Auclair (1978)

After all that action (for some values of), Simon retreats to a swamp where (basically) a Gothic mystery happens without furthering the central plot (which is a MacGuffin (oops, spoilers)).

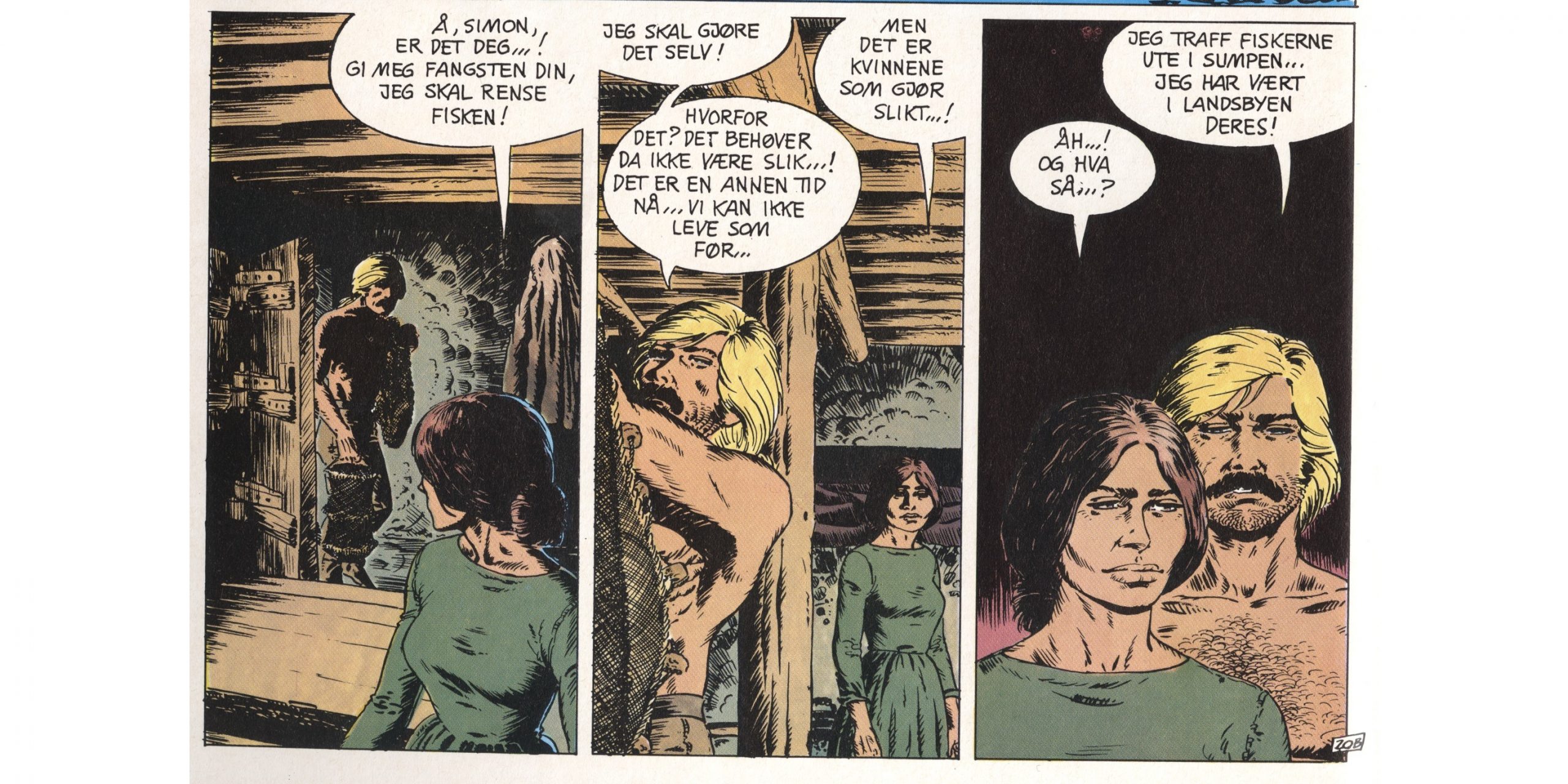

There’s romance in the air. Let me translate the dialogue from the first two panels.

“Oh, Simon, it’s you… Give me your catch, and I’ll clean the fish.”

“I can do it myself.”

“But that’s a woman’s job.”

“Why? It doesn’t have to be. It’s a different age now… We can’t live as we did before…”

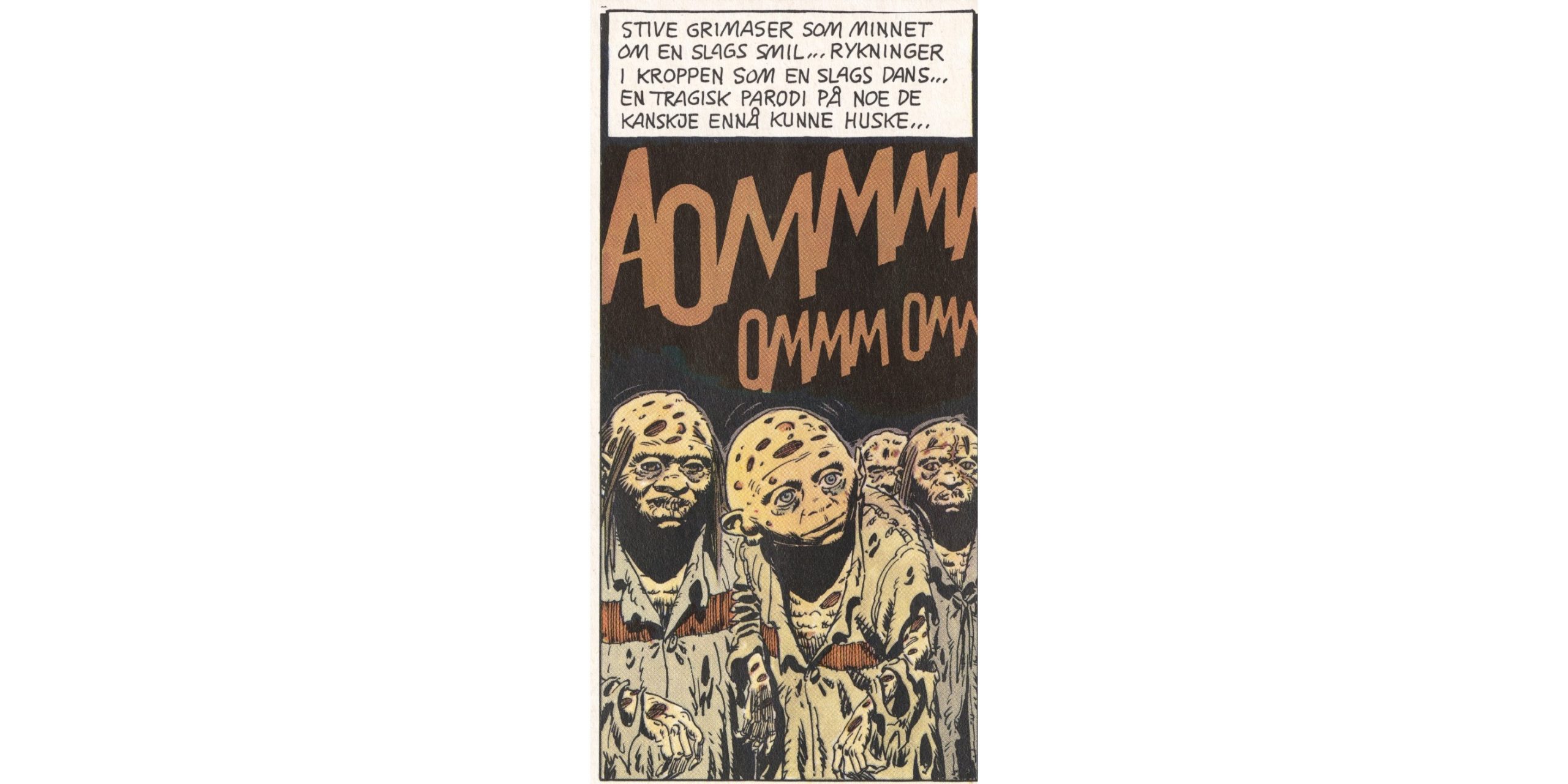

And then Simon runs into a broken down nuclear plant where he meets hundreds of these mutants. Looks a bit like Mad Magazine, doesn’t it? I think they’re meant to be horrifying, though, and we all learn a lesson about how nuclear energy is bad. Really bad.

And no heroics from Simon.

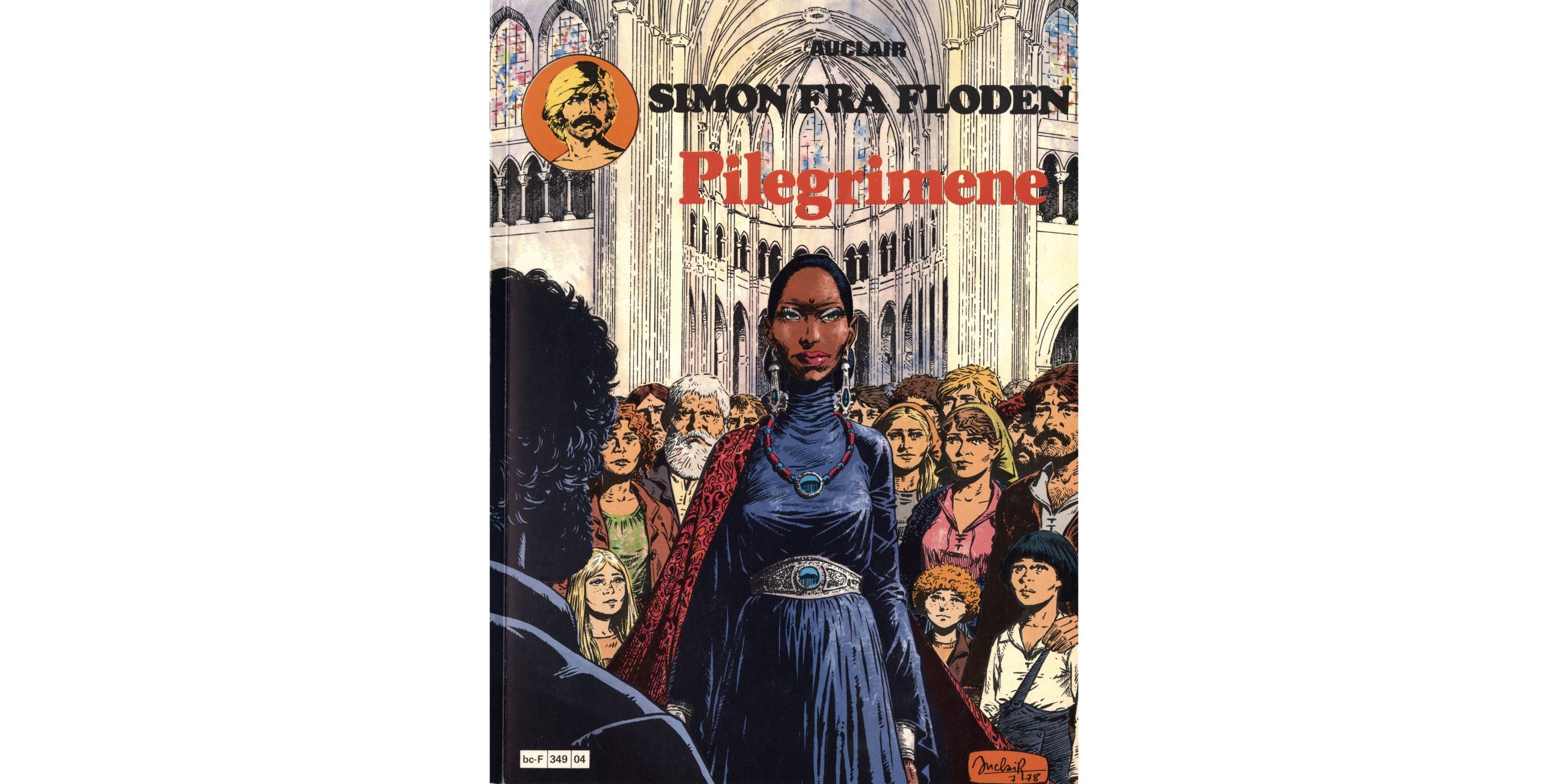

Les pélerins by Auclair (1978)

Geeze, I’m, like recapping these comics, and I didn’t mean to do that, either… Hm… Well, Simon meets up with another happy, happy agrarian community (and some very nice pagans).

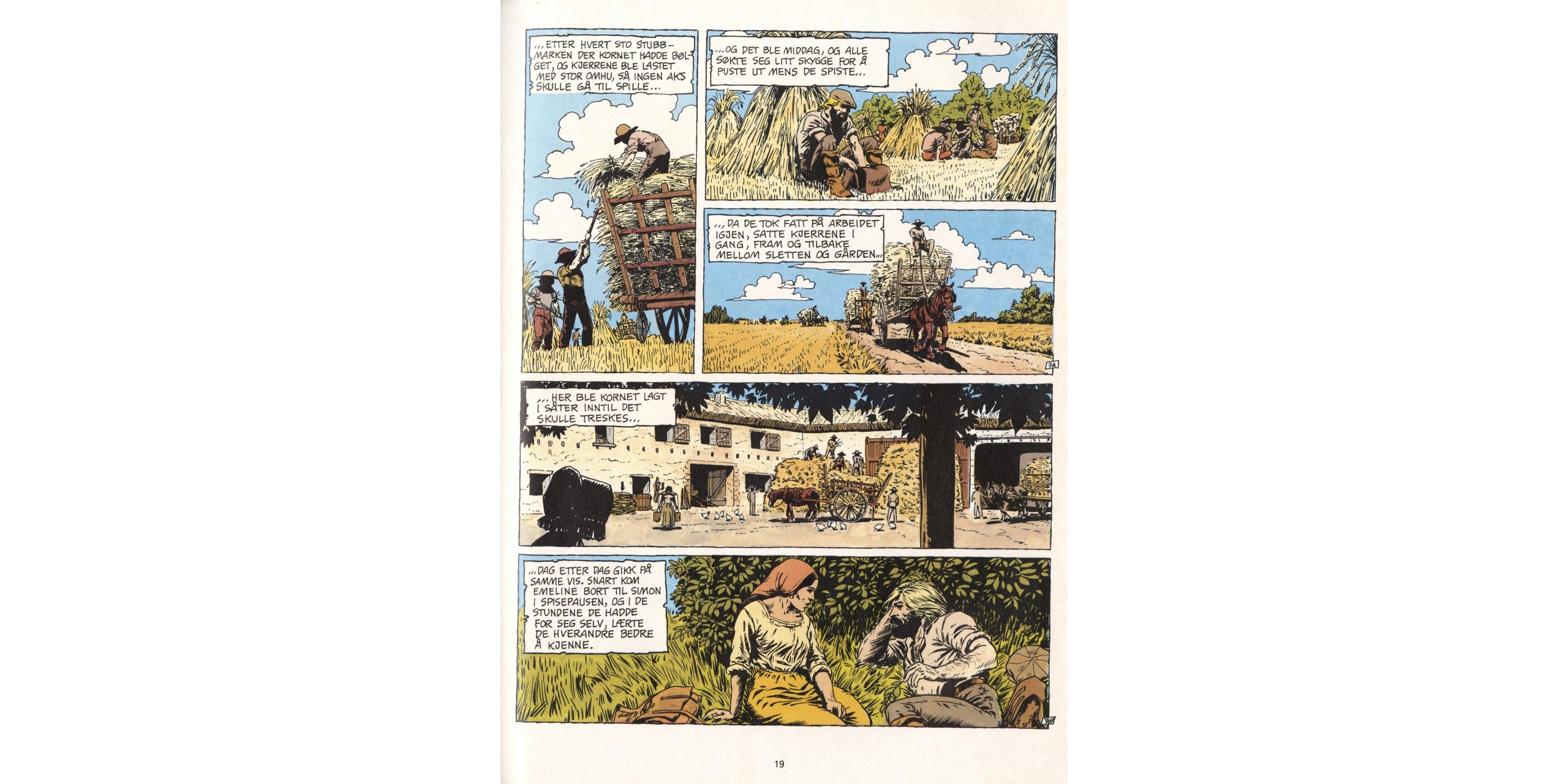

The storytelling in Simon du Fleuve is very old-fashioned. There’s a lot of captioning that partly restates what we’re seeing in the artwork, and always explaining how Simon is feeling. It’s a style that virtually nobody has used for the last couple of decades (except Brandon Graham, who has tried to revive it (I like it)). But it’s not too overpowering. And Auclair does draw very pleasant pastoral scenes.

And then we learn that Christianity is bad and is a tool used by the evil rulers to oppress the people.

And again, it’s hard not to sound sarcastic when recapping here. It’s not that Auclair is wrong (he’s obviously right about almost all the issues he’s touching upon), but you can play 70s Lefty Issues Bingo with Simon du Fleuve. It’s a bit much.

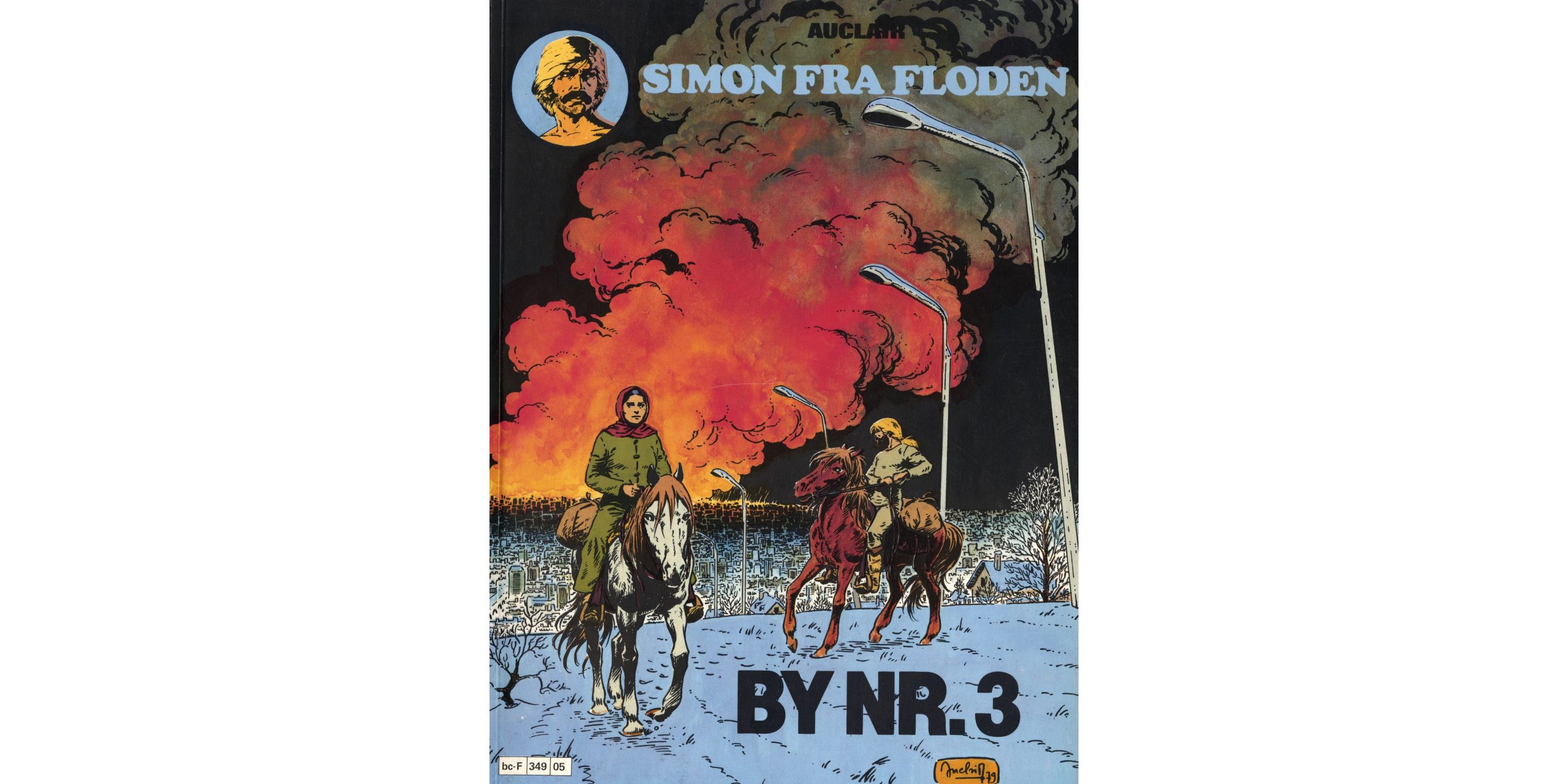

Cité N.W.N°3 by Auclair (1979)

The fifth album brings the story to a close. Simon reaches the bad city and tries to MacGuffin the Red Herring.

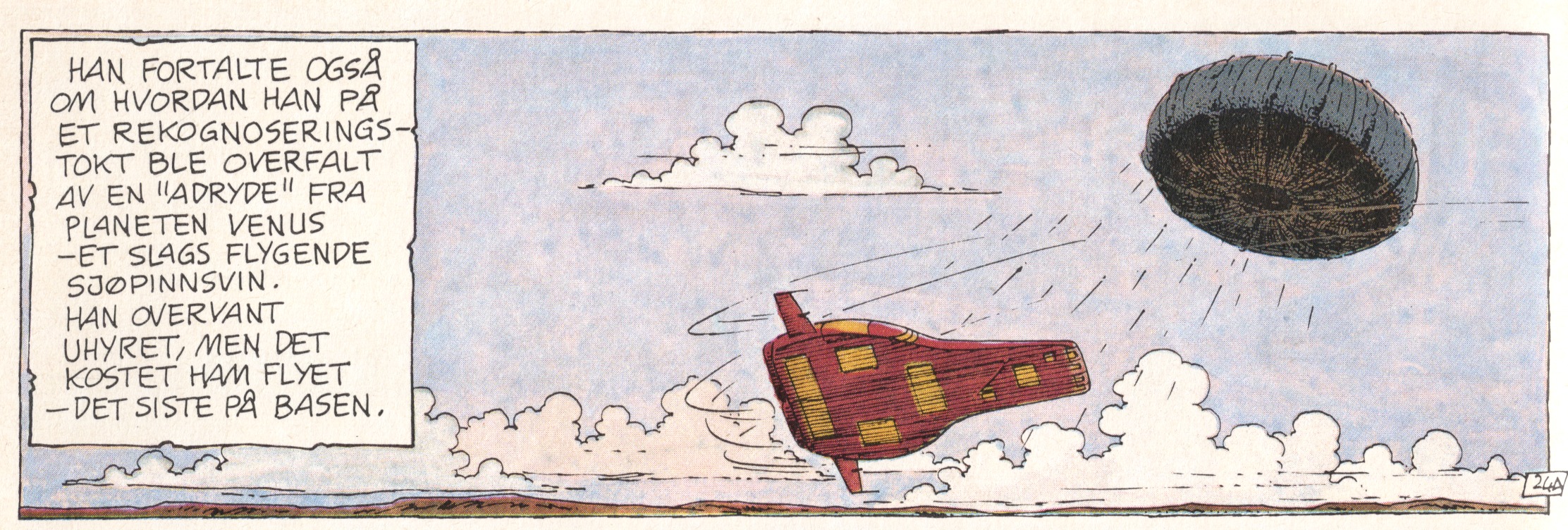

We’re also told some tales by an oldtimer where he explains that the Earth was also attacked by these giant sea urchins from Venus. (Yes. That’s what it says.) I’m pretty sure nothing of the kind had been mentioned up ’till this point, so that’s… a thing.

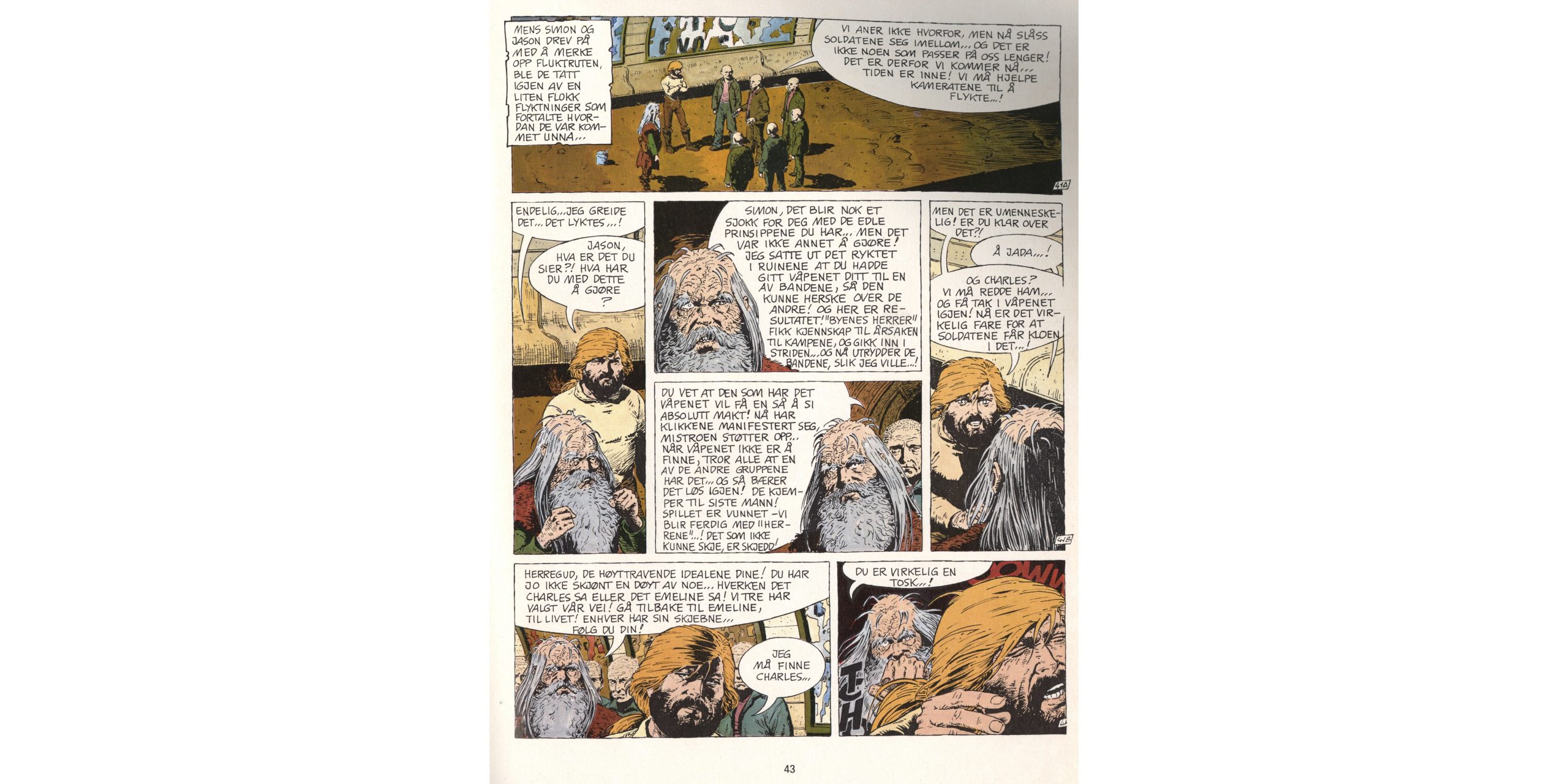

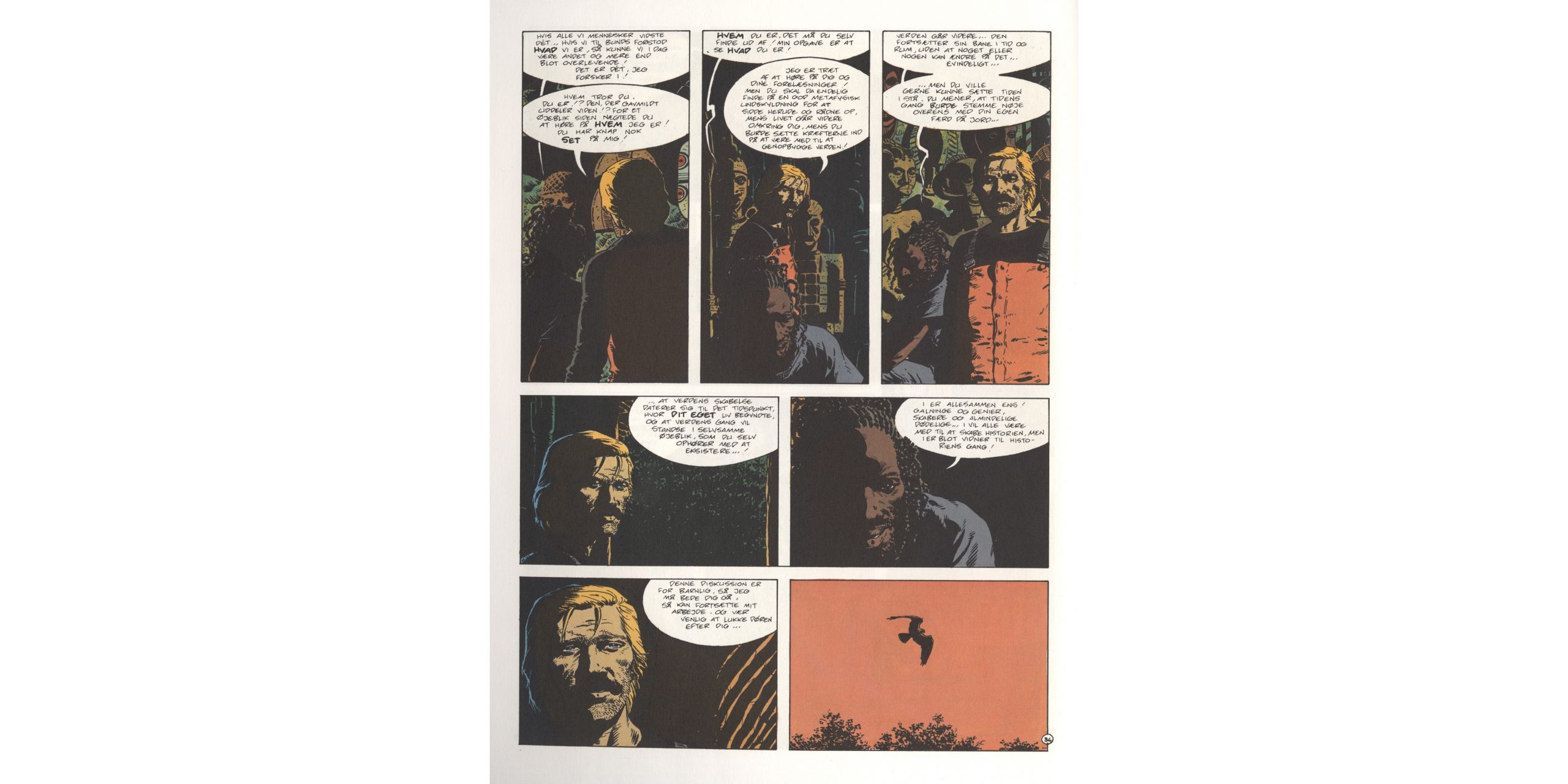

The album is the weakest of them all, with endless monologues about this and that. Simon is, at this point, against using any kind of violence against anybody, so it’s up to the other people (like the older guy up there) to provide the action.

If I were to hazard a guess, I think Auclair had written himself into a corner with his central character, or perhaps he had just planned on this five album arch all along. In any case, he abandoned Simon du Fleuve in 1978.

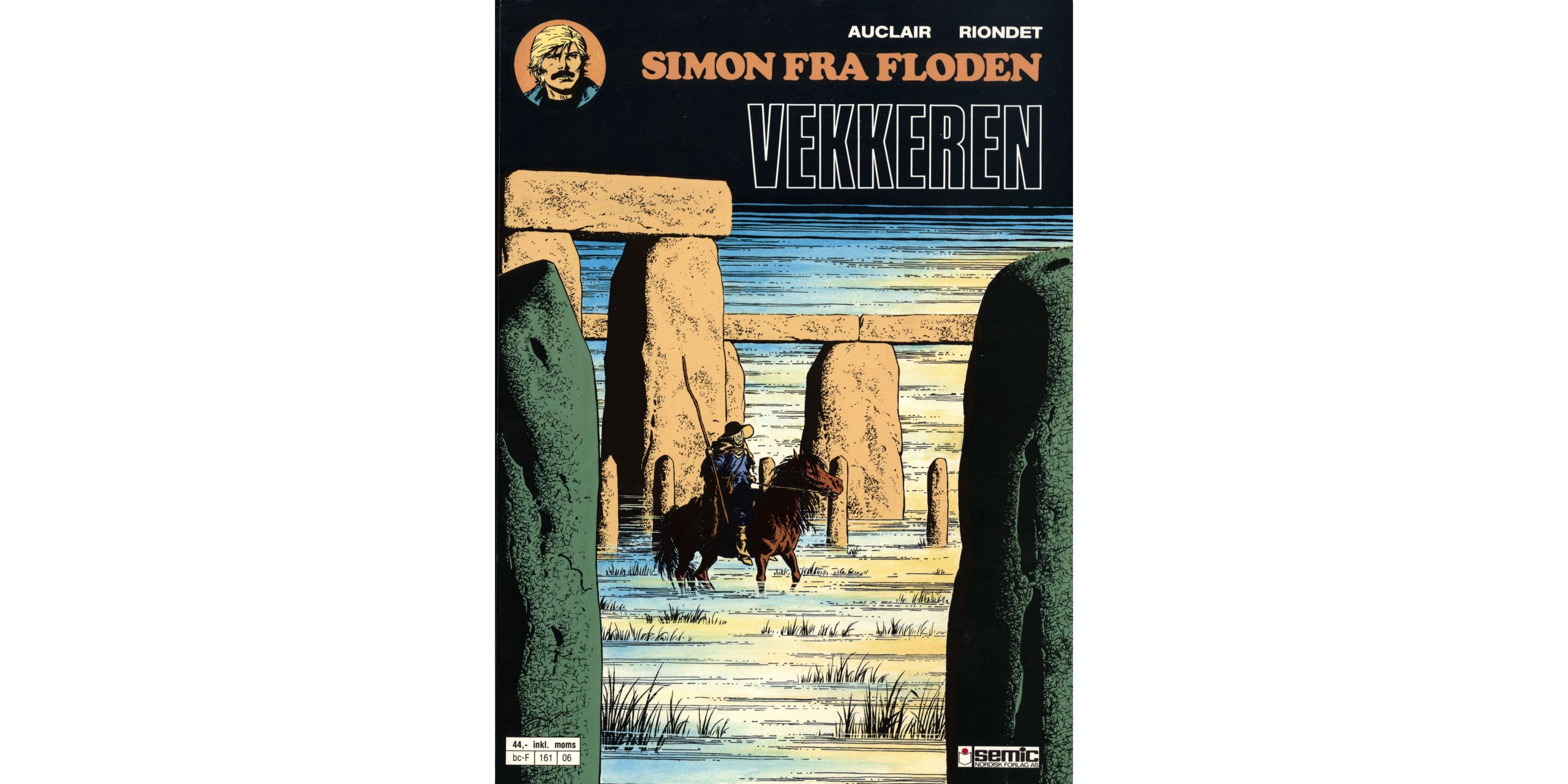

L’eveilleur by Riondet & Auclair (1988)

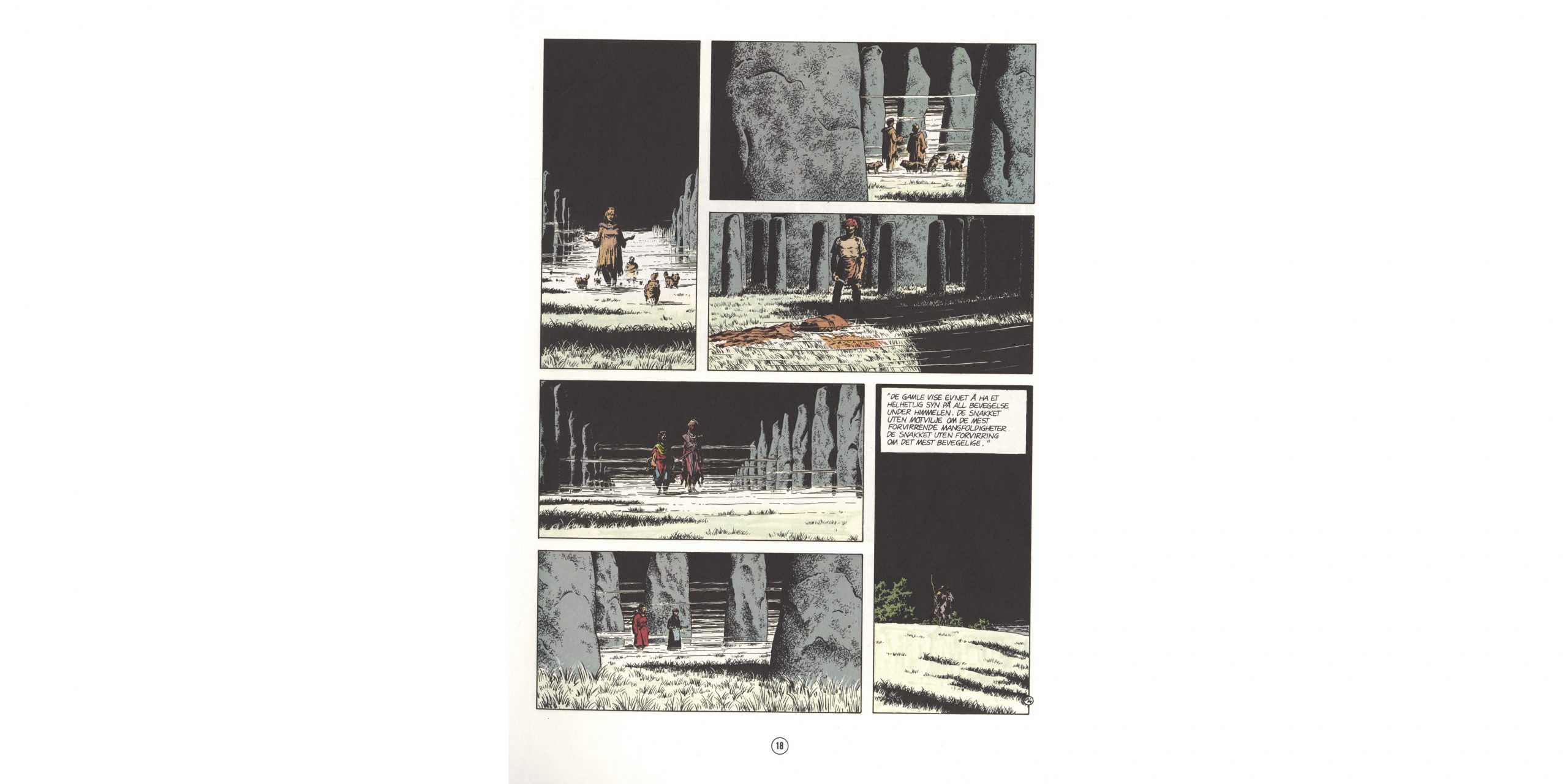

Ten years later, Auclair resurrected the Simon de Fleuve series. Sort of. He brought in Alain Riondet as writer, and the feel of the series changes rather dramatically. Instead of being didactically political, the first of these new albums is all about spirituality and re-awakening the dying Earth through… er… magic, or something.

The storytelling shifts between silent vistas and people who talk and talk and talk. Didactically about spirituality and stuff.

That’s what these meetings amongst the raised stones are all about. There are also “infertile” mutants running around harshing the buzz of these spiritual people, but not a lot of tension is generated.

Let’s translate a typical speech bubble: “West! Your name has thunder and the spring in it, and your name is the source of the riddle! So think about your name and don’t forget who you are!!… More than that I cannot say.”

I don’t think I can say more, either.

Le chemins de l’Ogam by Riondet & Auclair (1988)

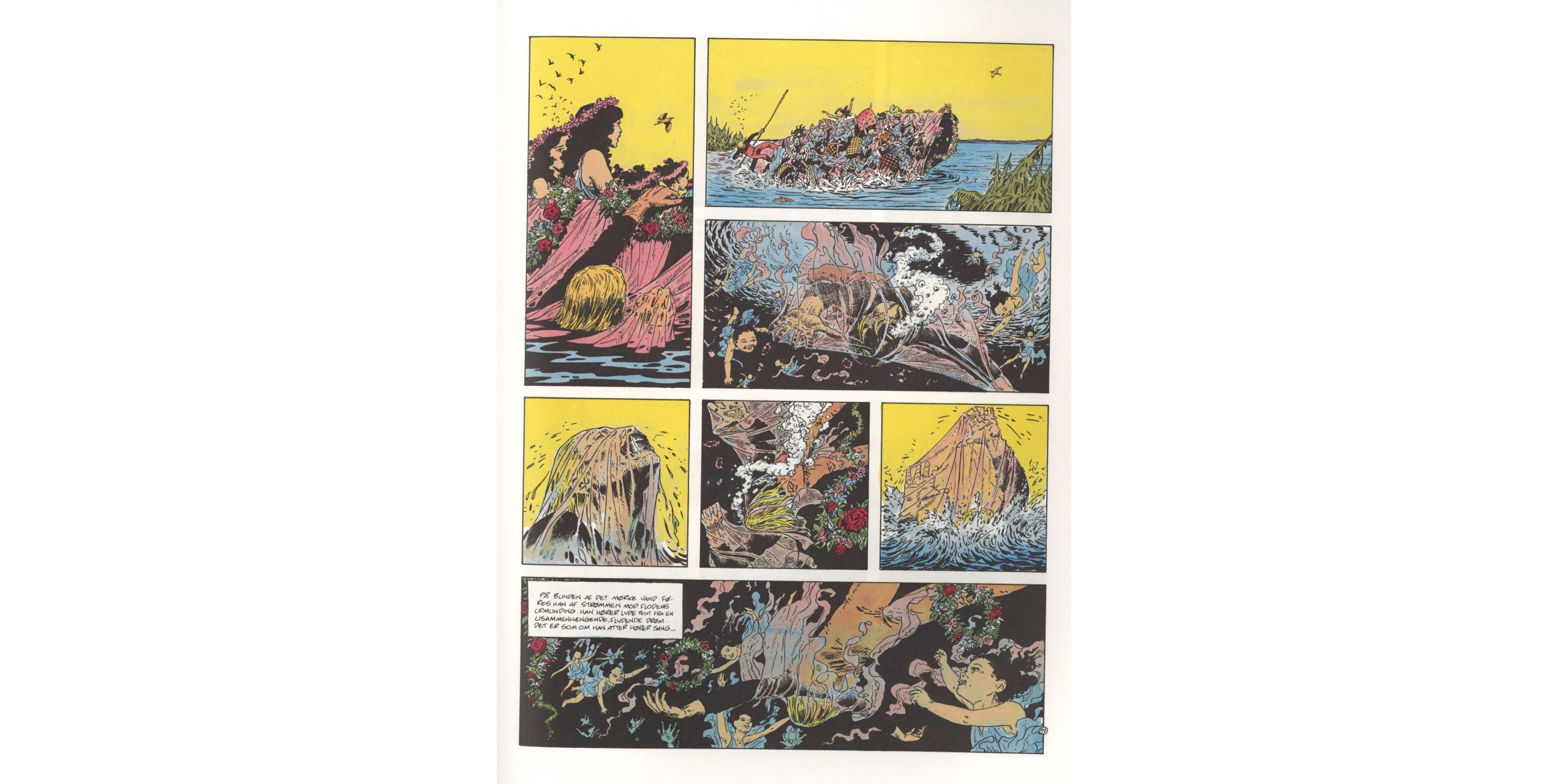

The next book is a further withdrawal into psychology. The change from politics to mysticism and the personal isn’t unique for Auclair in French comics: Quite a lot of people who had made politically explicit works in the 70s turned to either some wishy-washy vaguely “eastern” philosophy, or wrote about mythologies and the subconscious.

Most of the book is Simon having various mythological fantasies (or are they?) before returning to his family as a reborn, stable man again.

Auclair sometimes cheats a bit too much in his artwork. Faces are rather inconsistent and vague, and he retreats into dark corners of rooms given any opportunity.

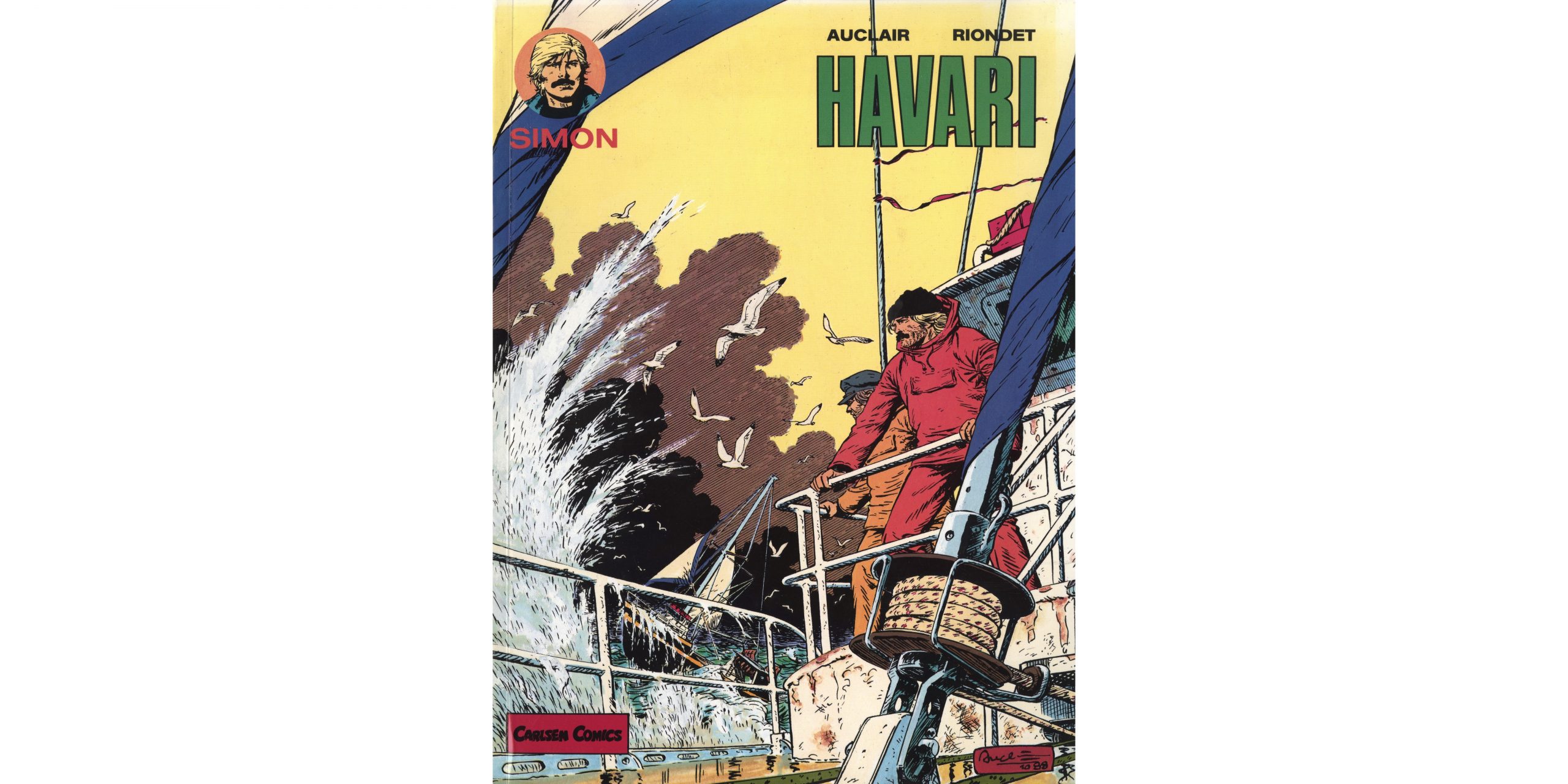

Naufrage by Riondet & Auclair (1989)

The two last books in the series, Naufrage tome 1 & 2, were published in this single Danish volume, and it’s easy to see why. The previous two volumes may have tried the patience of any remaining Simon du Flauve fans, but this one is beyond.

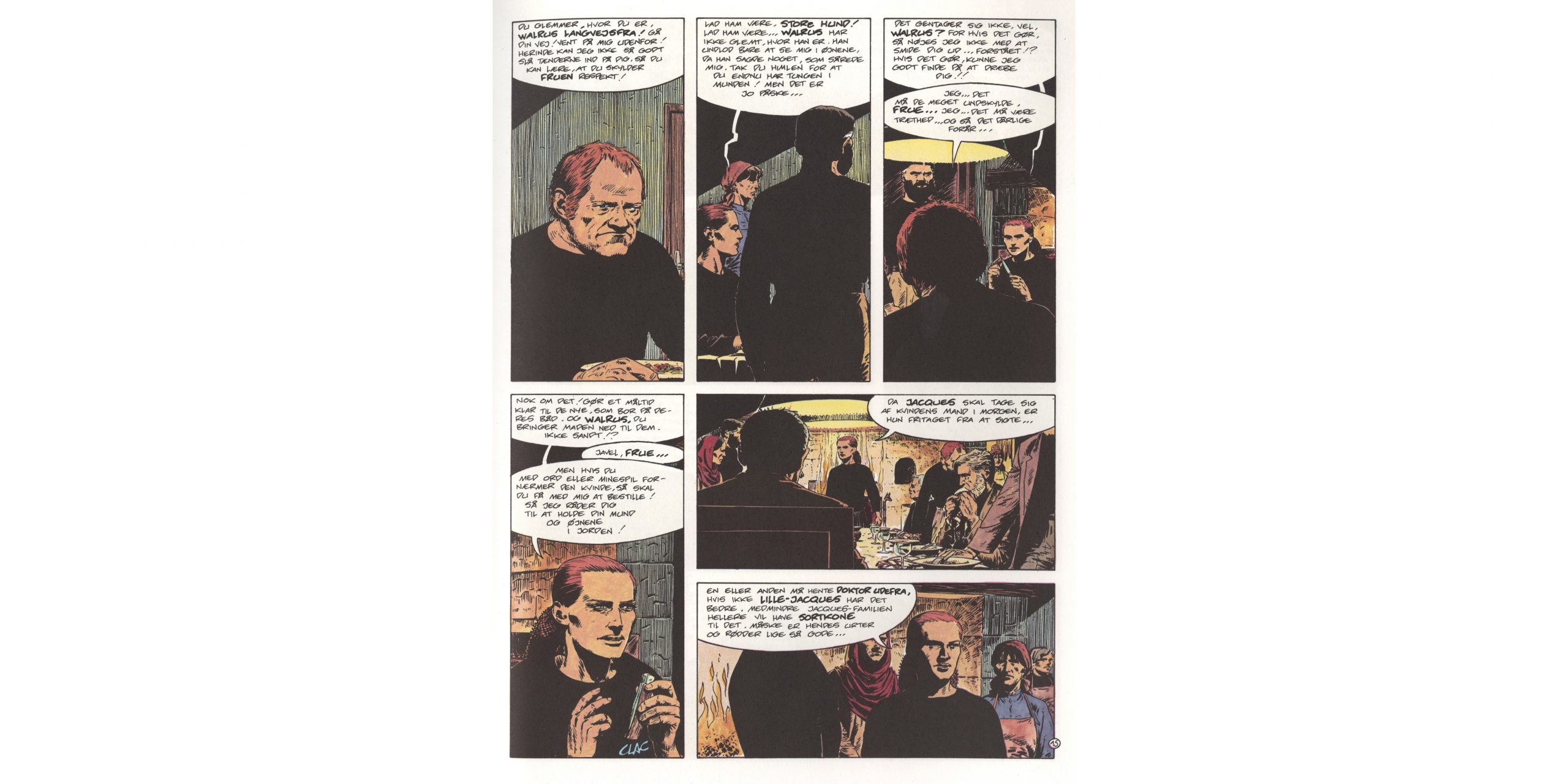

It’s about an insane matriarch ruling a fishing village with an iron hand, and Simon and his family somehow get involved. Most of the post-apocalyptic trappings have disappeared, although sometimes in the dialogue we’re reminded that “they” are still out there. But, basically, everything that happens here could as well have happened in a small, say, Scottish fishing village now. I mean. But not. Not have happened. You know what I mean.

And that includes the tools they have. Getting a trawling net is apparently little problem, and doing the upkeep on their rather big ships is totally under control. (Not to mention that they all seem to have rather modern clothes. (Oops! I mentioned it!))

While the story is tedious, the artwork is rather nice, especially in the (very dramatic) silent scenes. It seems like whenever there’s dialogue, Auclair loses interest and just gets it done. Well. A bit.

The book ends with Simon and family sailing off into the sunset, which is appropriate.

Riondet and Auclair continued the collaboration with two non-Simon albums called Celui-là. I haven’t read them. Auclair died while completing the second album, and Tardi and Jean-Claude Mézières stepped in to finish the final pages.

Riondet went on to collaborate with artist Stéphane Dubois. Riondet then disappeared in 1998.

This post is part of the BD80 series.

One thought on “BD80: Simon du Fleuve”