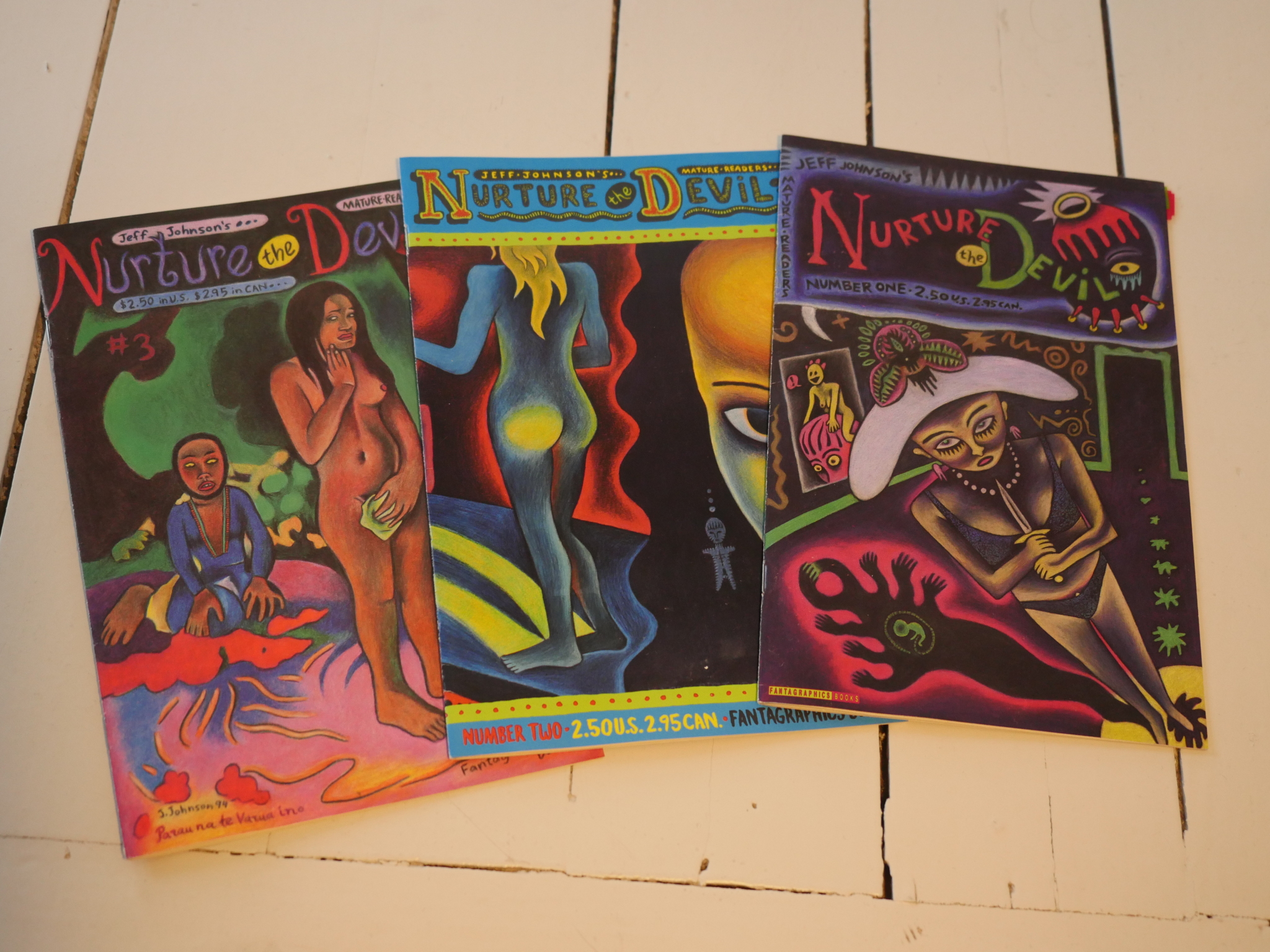

Nurture the Devil #1-3 by Jeff Johnson.

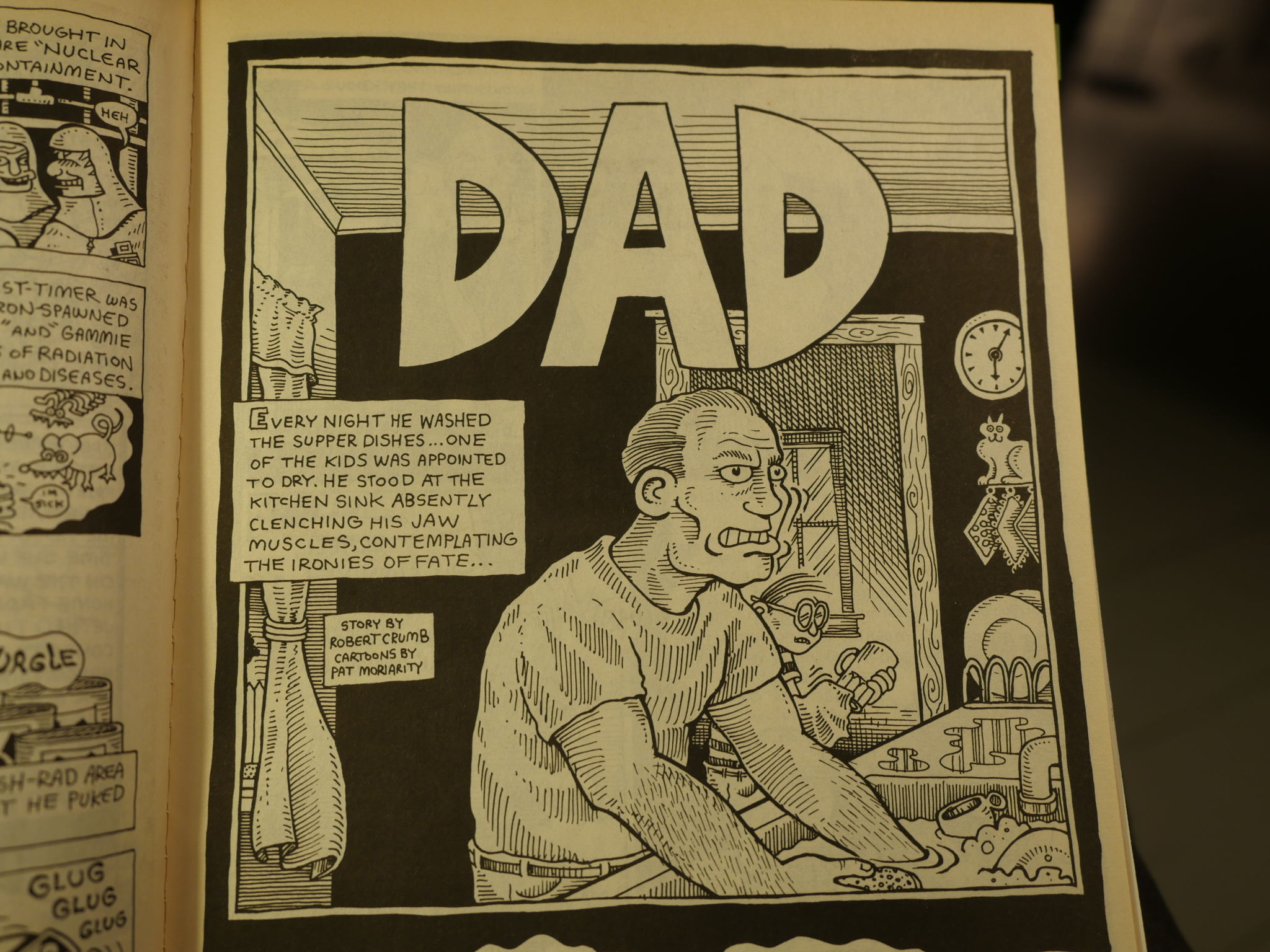

There seemed to be a micro-movement towards body horror going on at Fantagraphics in the mid-90s. Renée French, Dave Cooper and Jeff Johnson all did violent, visceral, sexually charged comics around this time, with squishy, ink-soaked artwork.

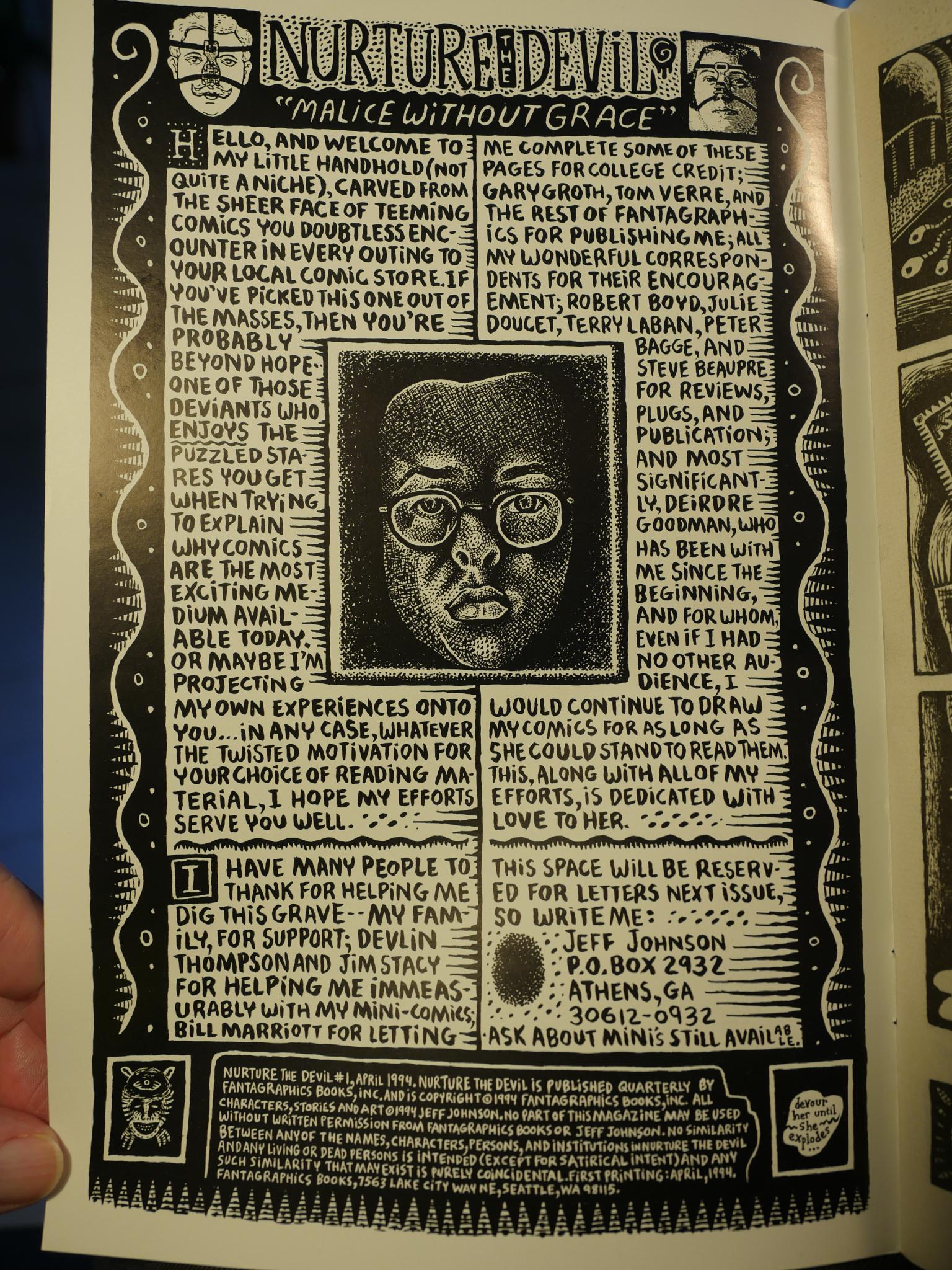

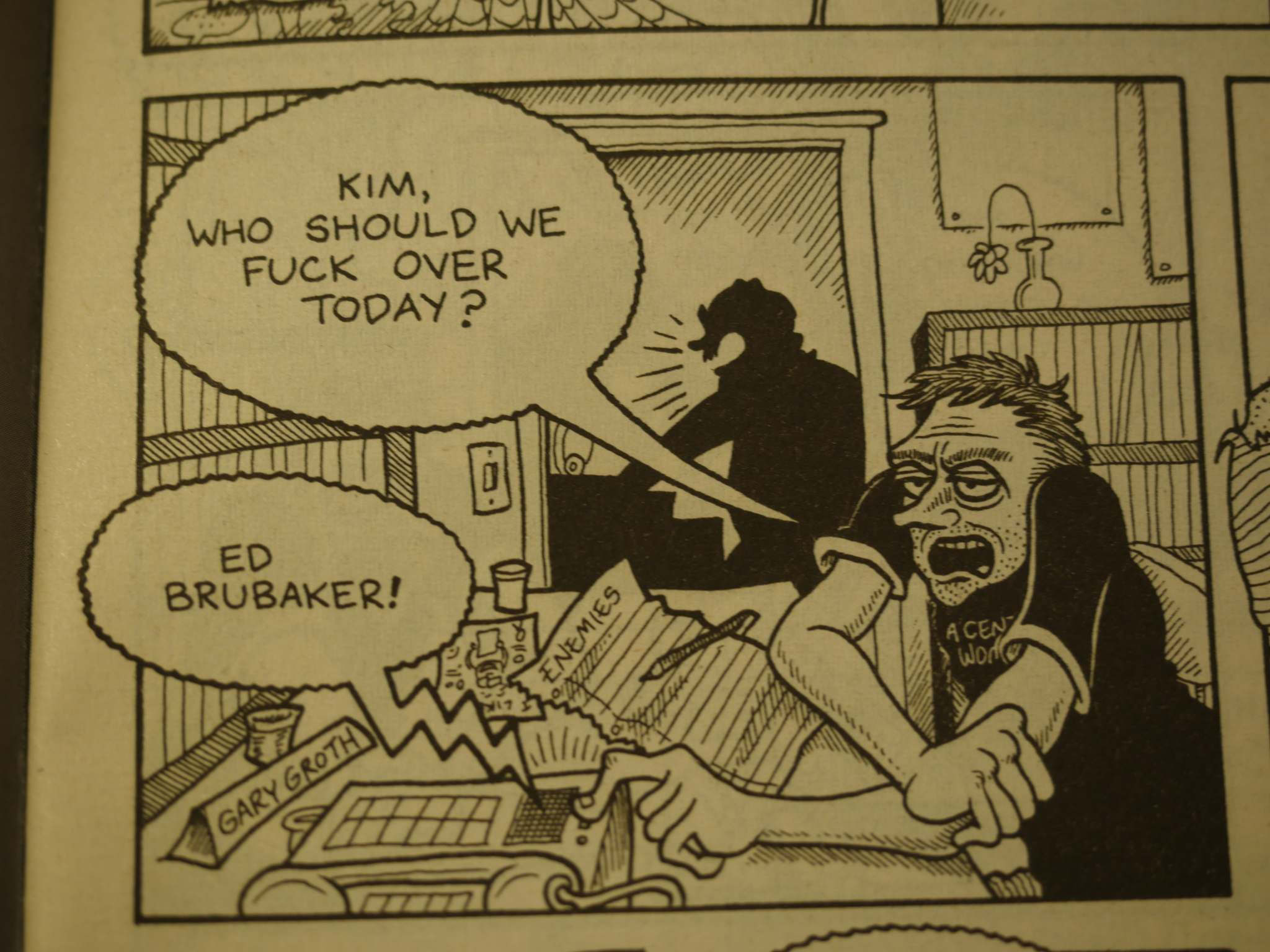

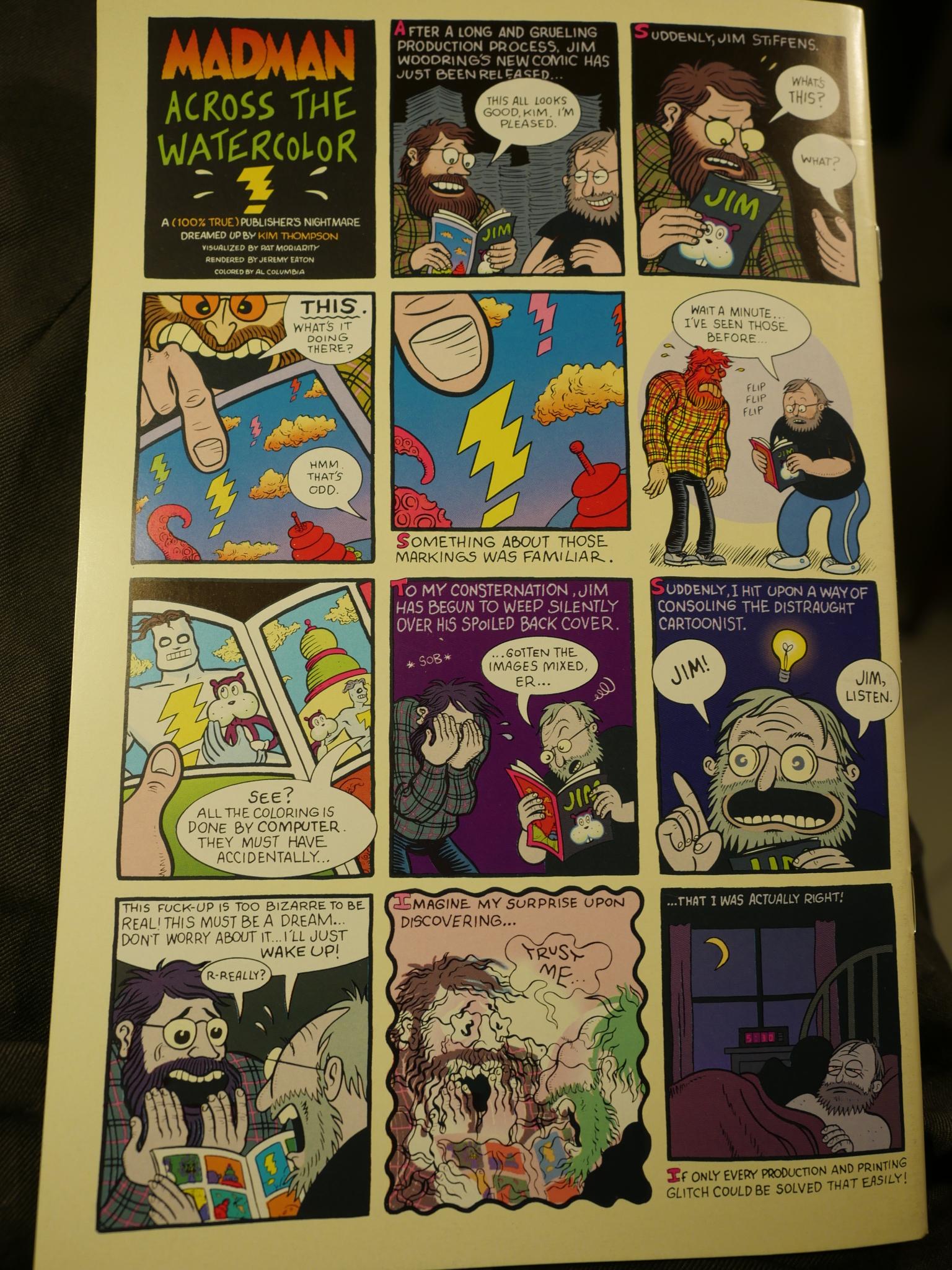

Nice introduction, but I really wanted to highlight a typical Fantagraphics indicia page. Sure, there’s a lot of them that are less personalised than this, but a sizeable portion of them don’t mention anything beyond whatever the artist themselves want to have on the page. Not even an editor is mentioned.

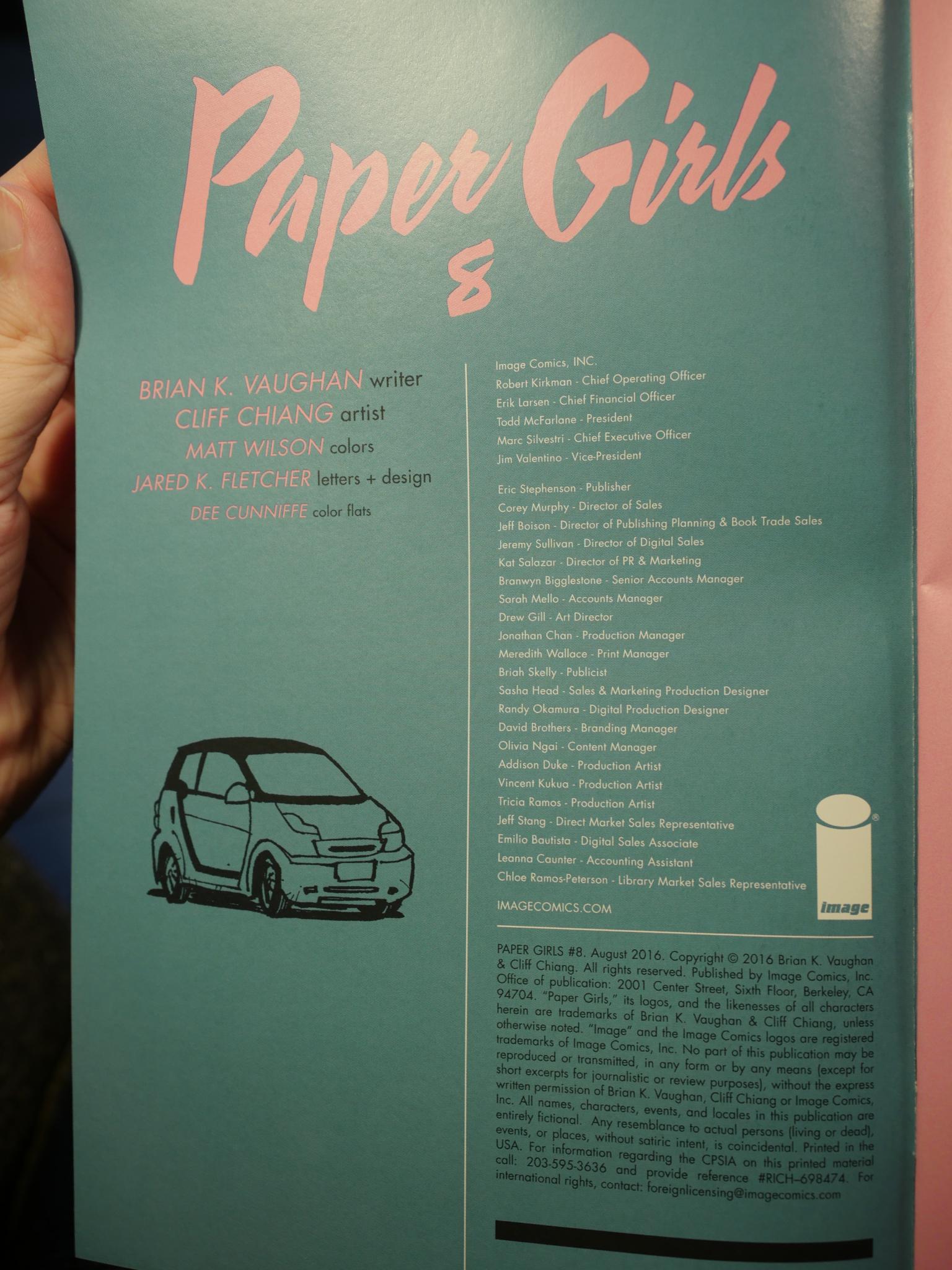

Contrast with a indicia page taken at random from Image:

Knowing that Jeff Boison is the director of publishing planning sure enhanced my reading experience. I only buy comics now that have had their publishing planned by Jeff Boison! I will accept no other publishing planning inside these walls! Jeff Boison! Jeff Boison! Jeff Boison!

ANYWAY! Back to Nurture the Devil.

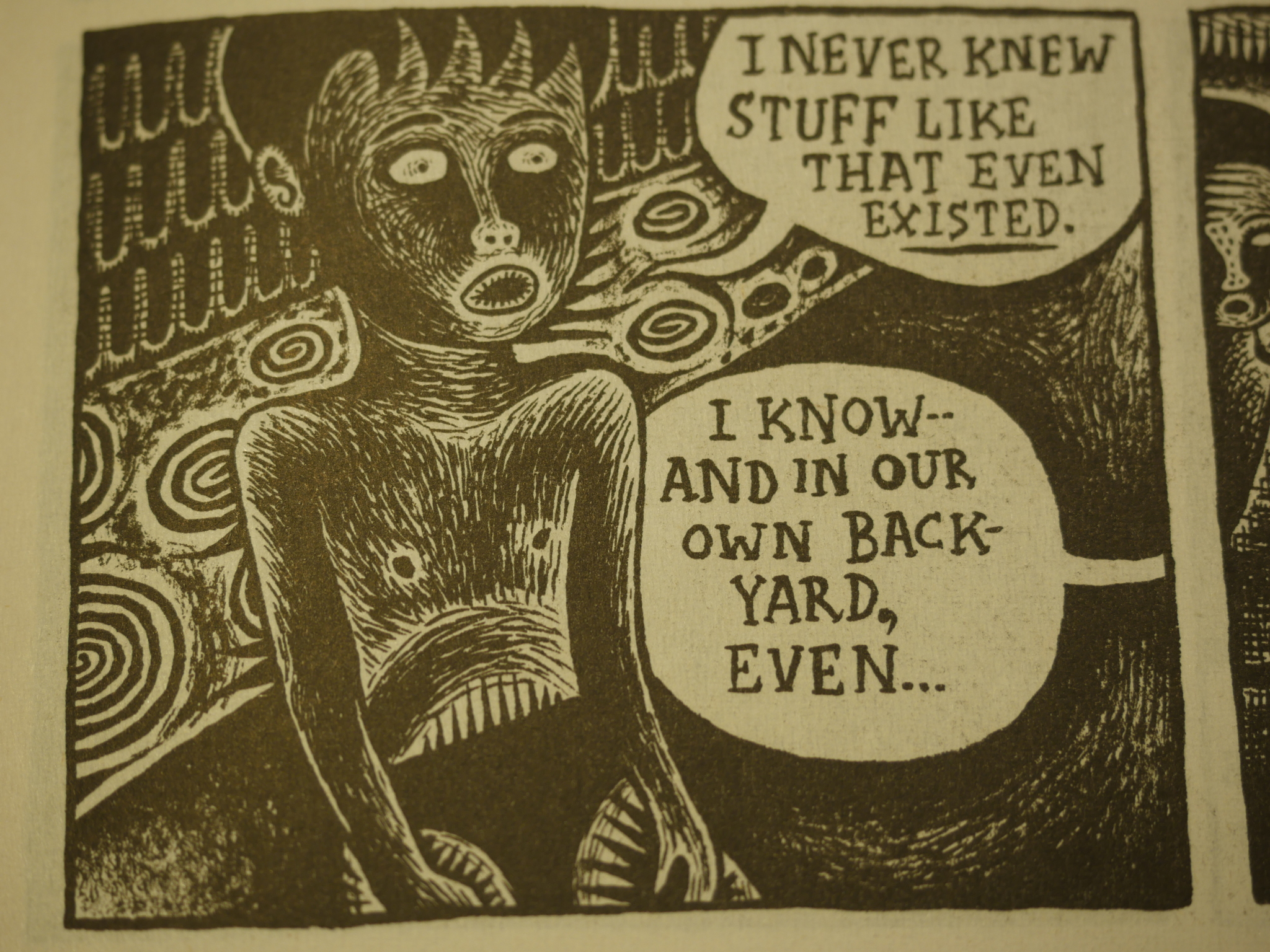

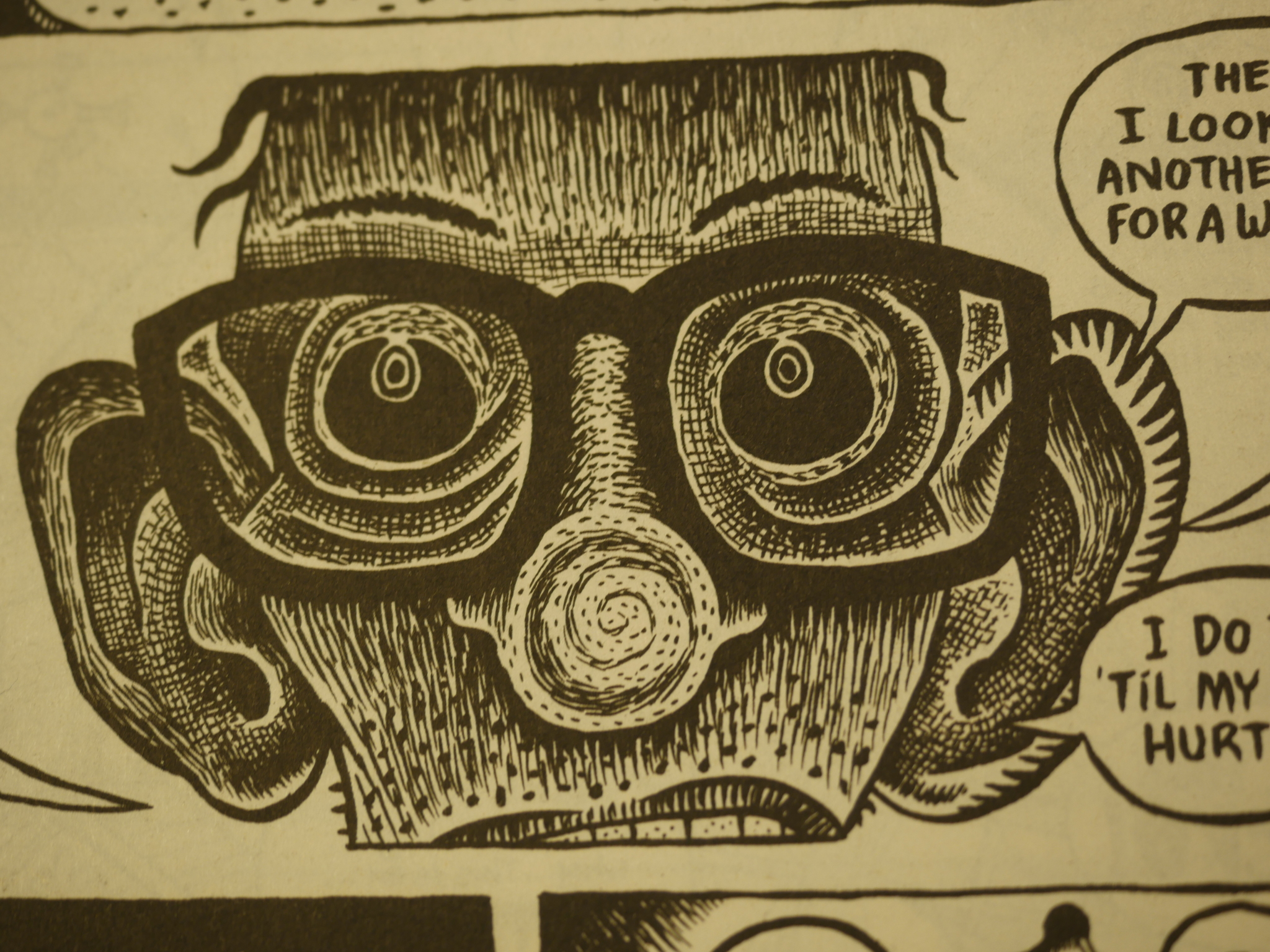

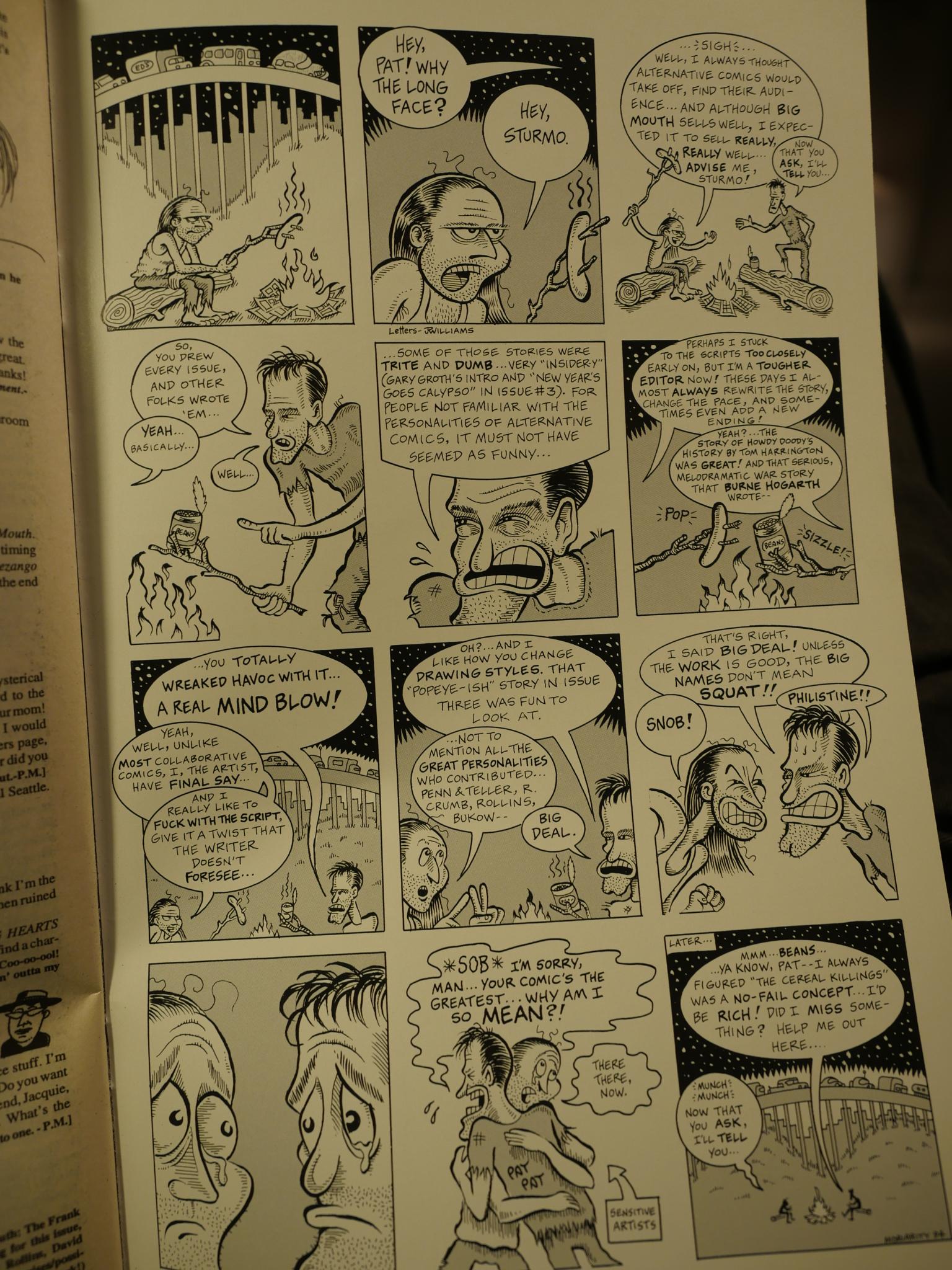

One thing I wonder about the artwork is what size it’s been drawn at. There’s a lot of lines, but they seem to taper off before they get really fine. The lines are kinda blunt, really. Are these pages perhaps drawn just a bit up from published size, instead of more normal, larger sizes?

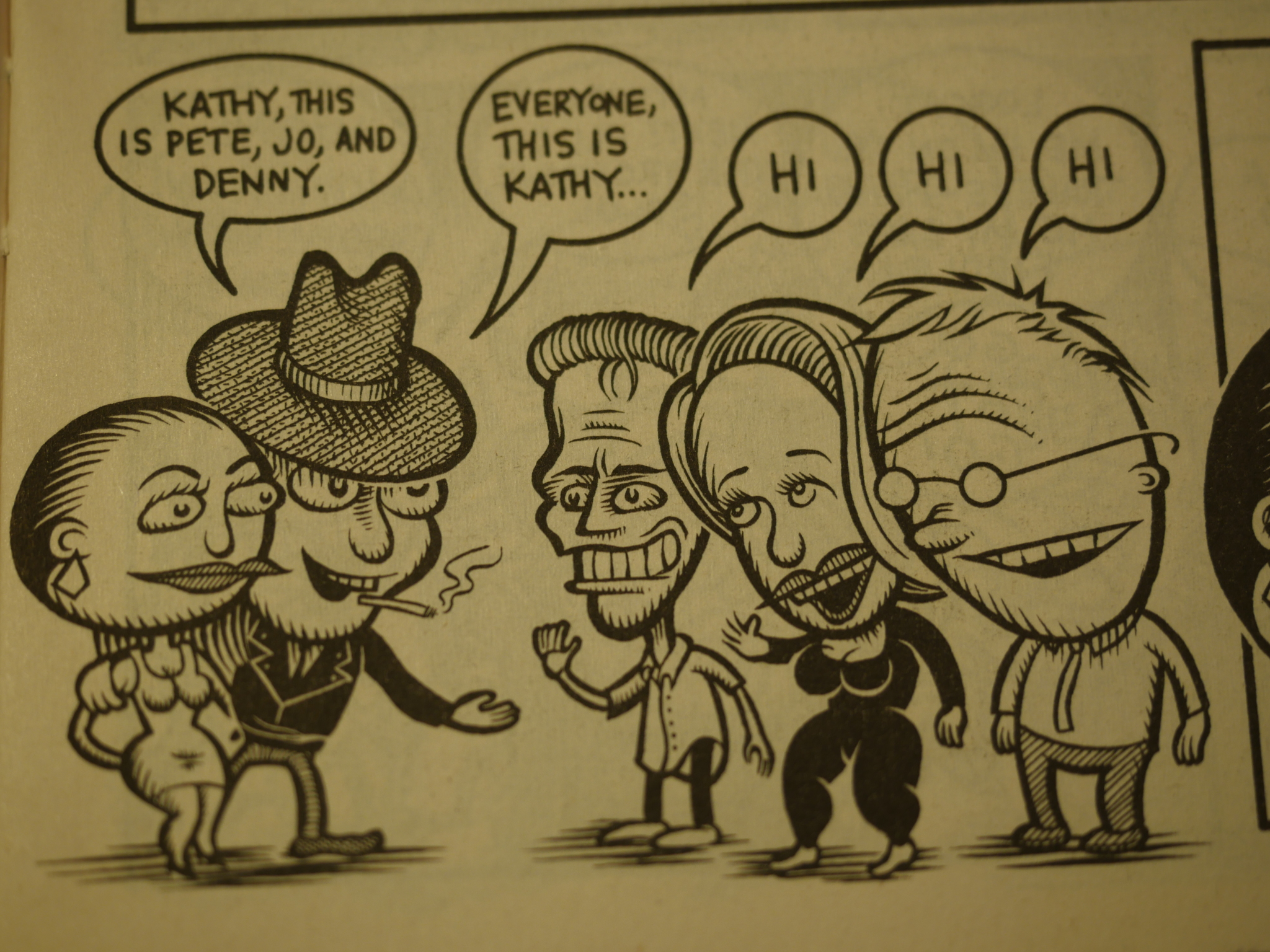

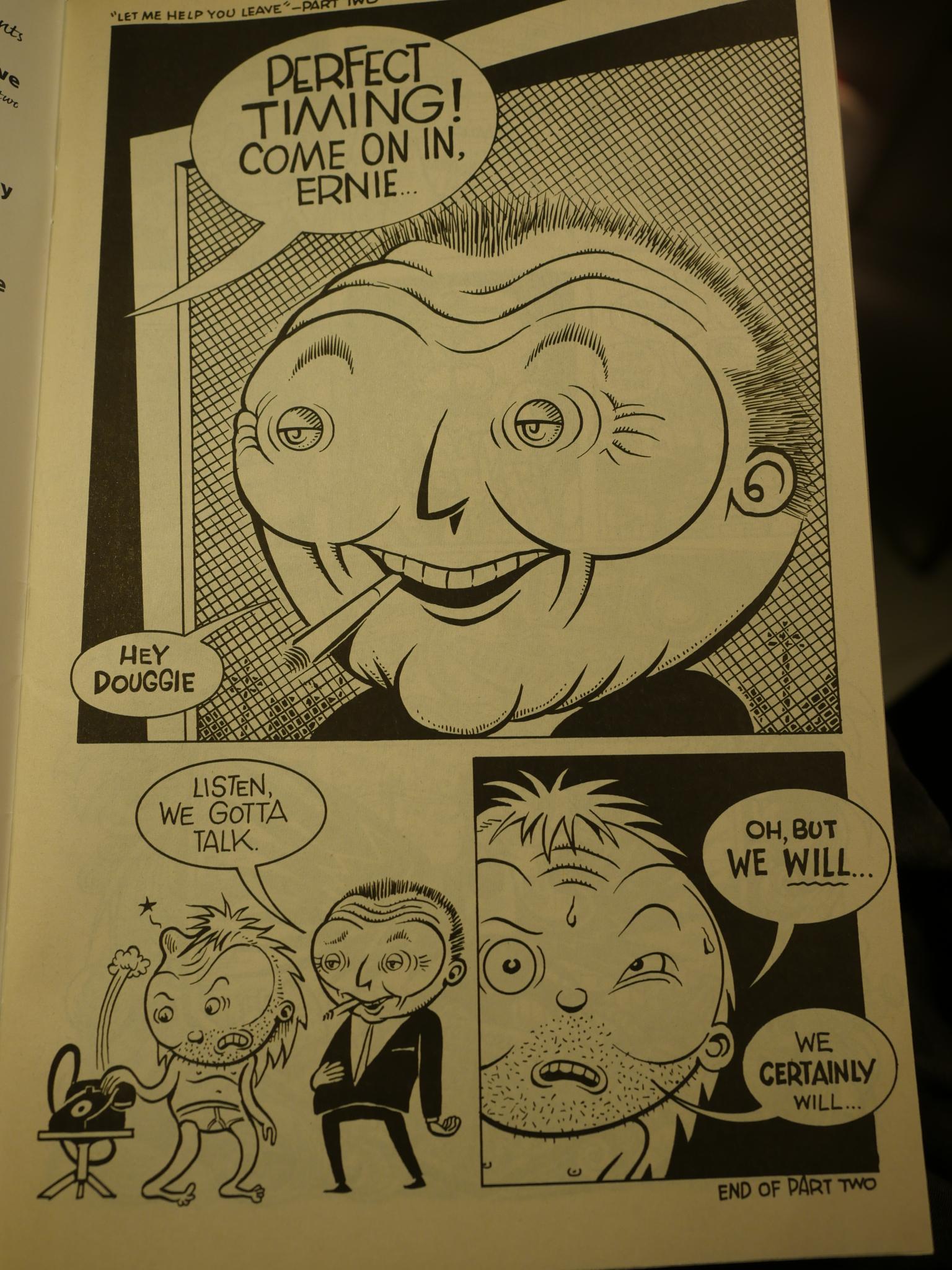

And I think I can perhaps see a bit of a Richard Sala influence going on here?

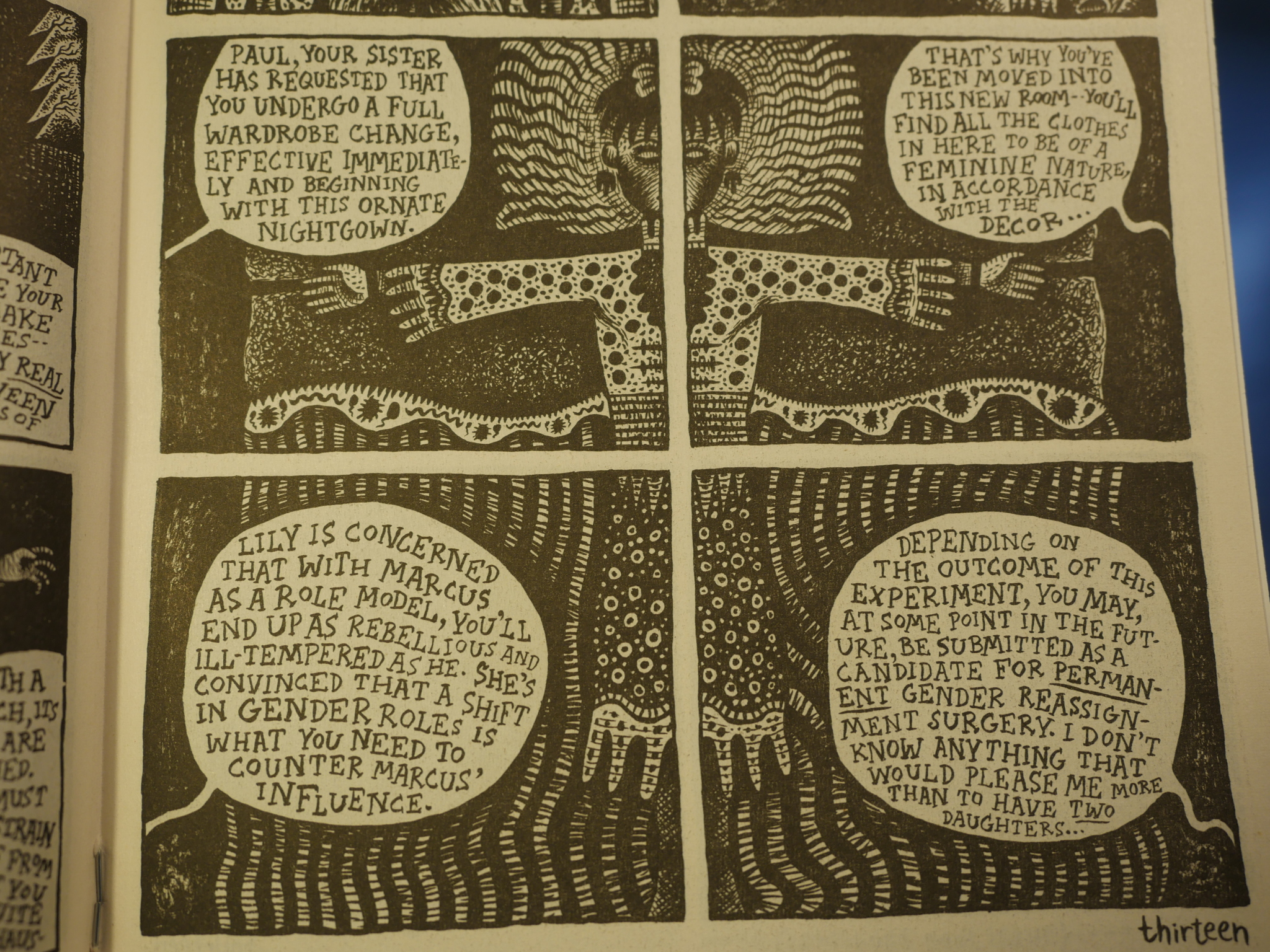

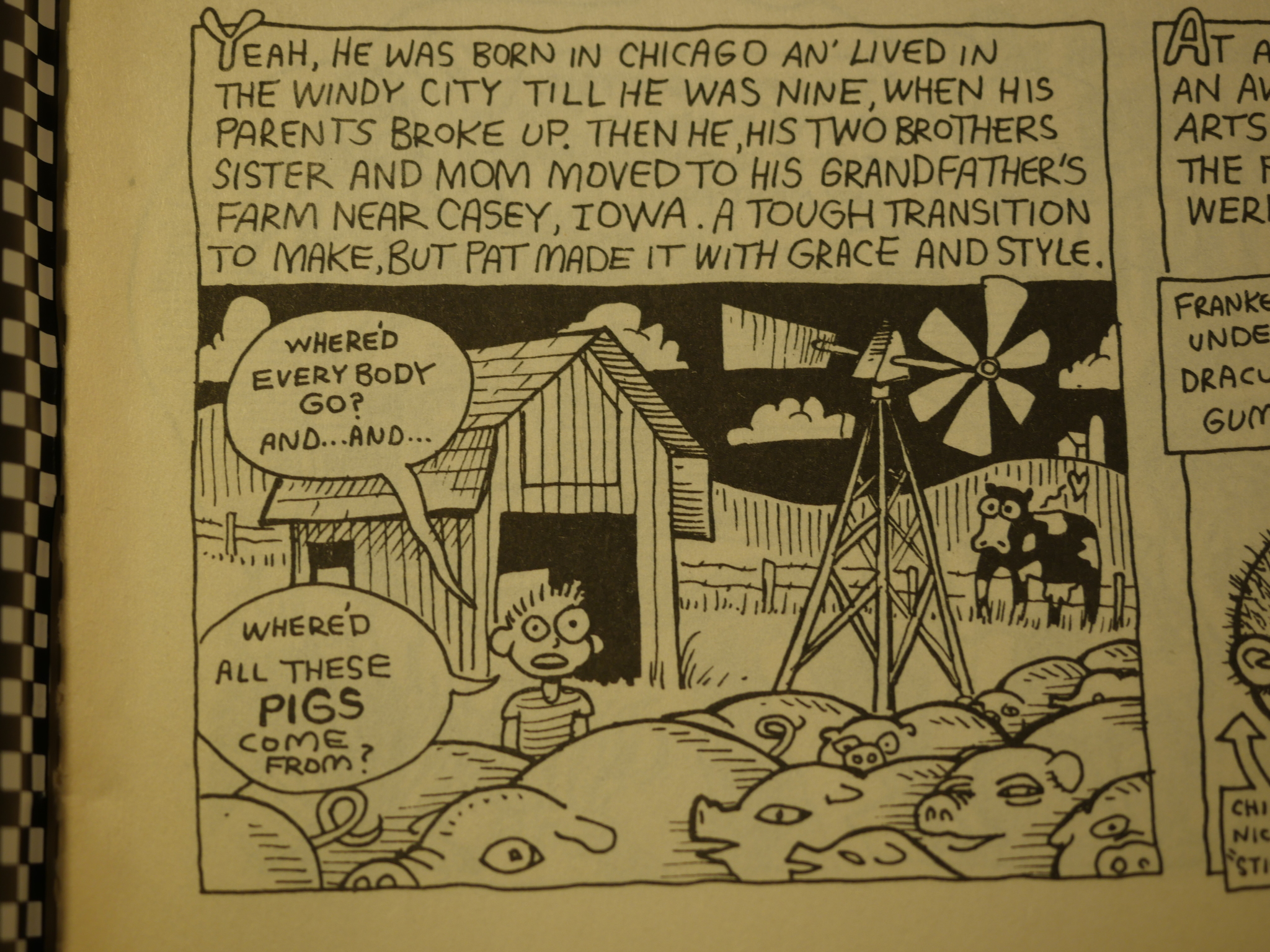

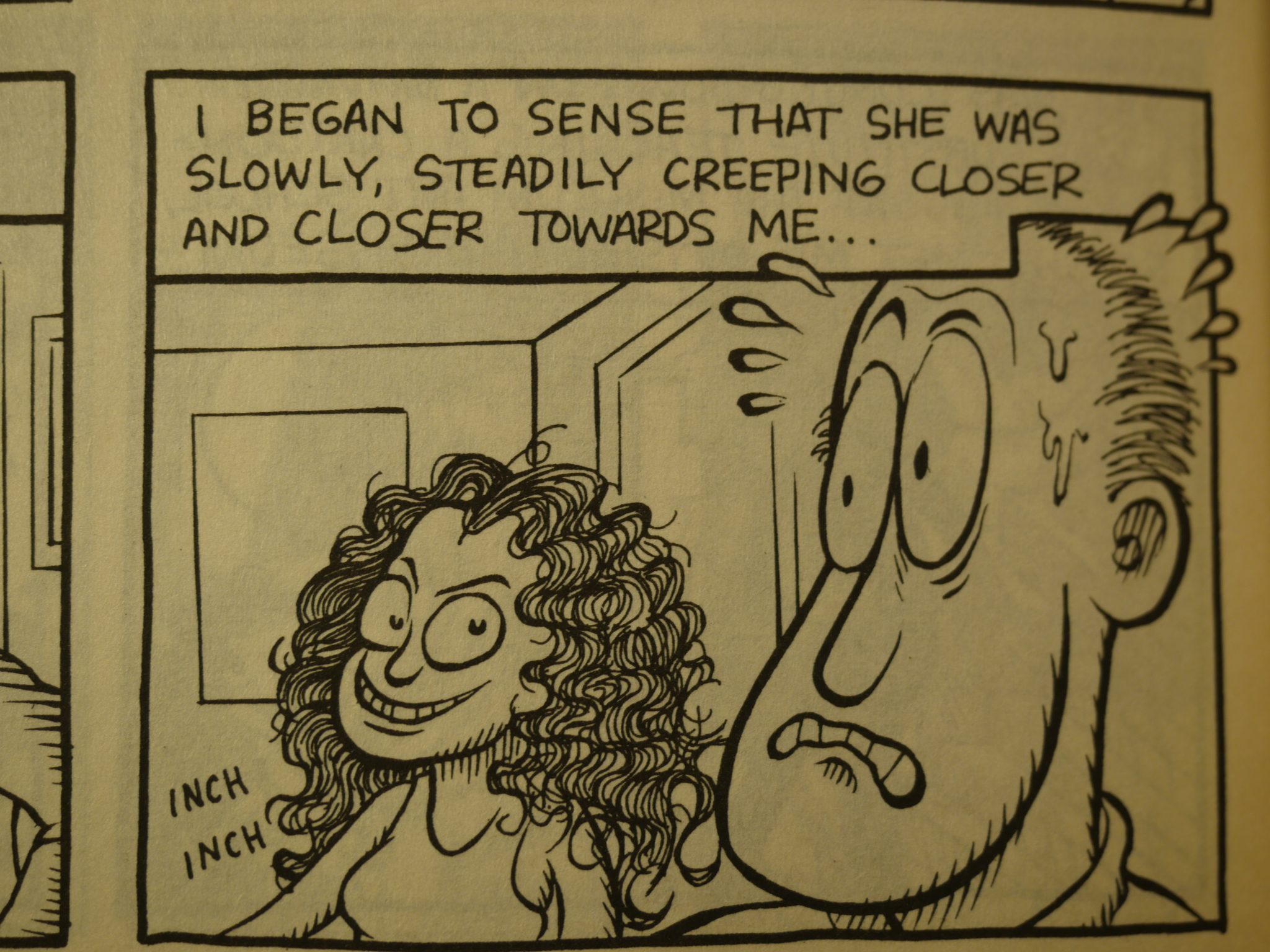

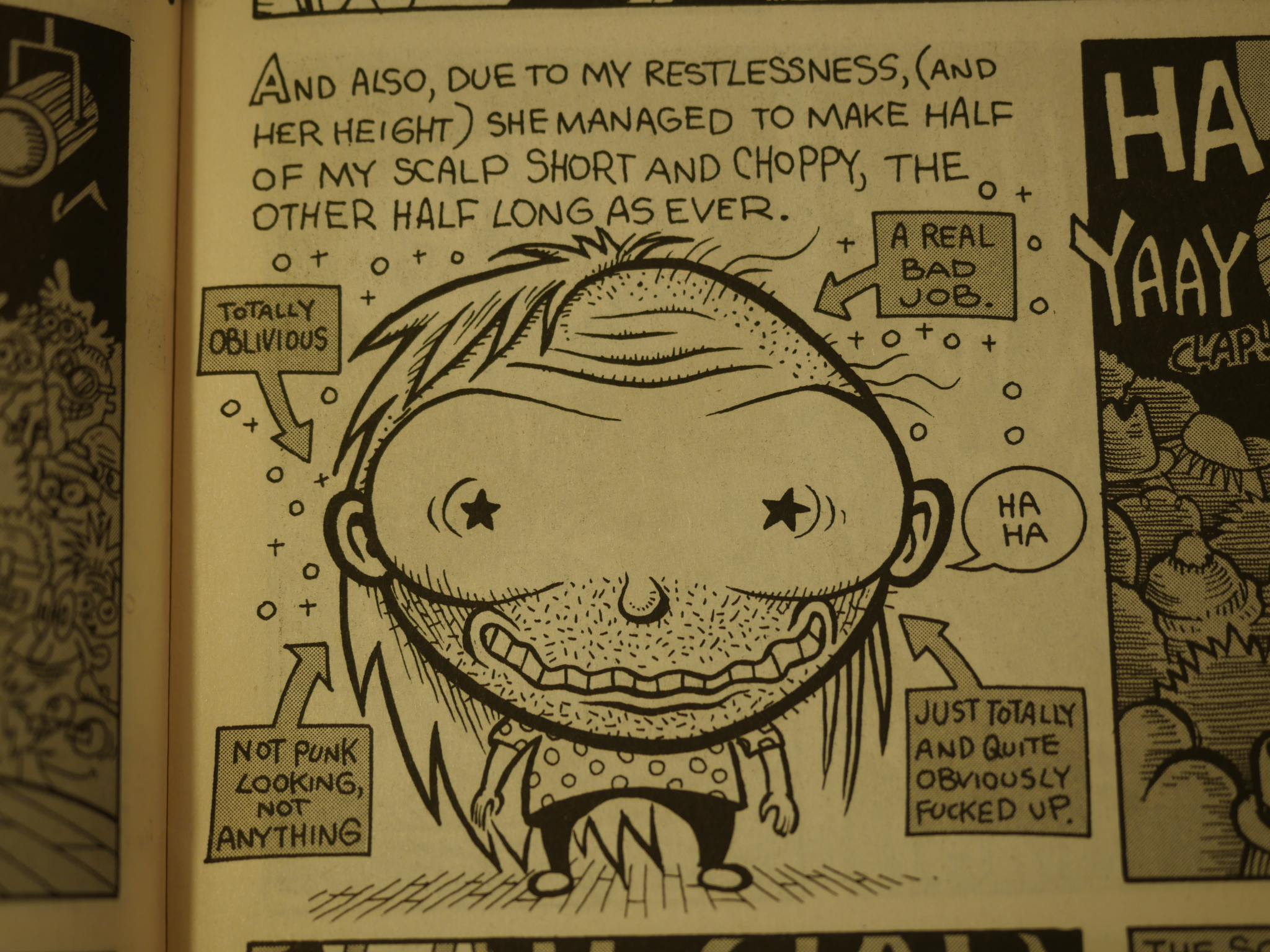

There’s a lot of patterns and meanings to be decoded on just about every page. This boy (turning into a girl) is in a crucifix position, and he’s divided by the panels. Johnson later said that the comic was “mostly driven by unresolved transgender issues”.

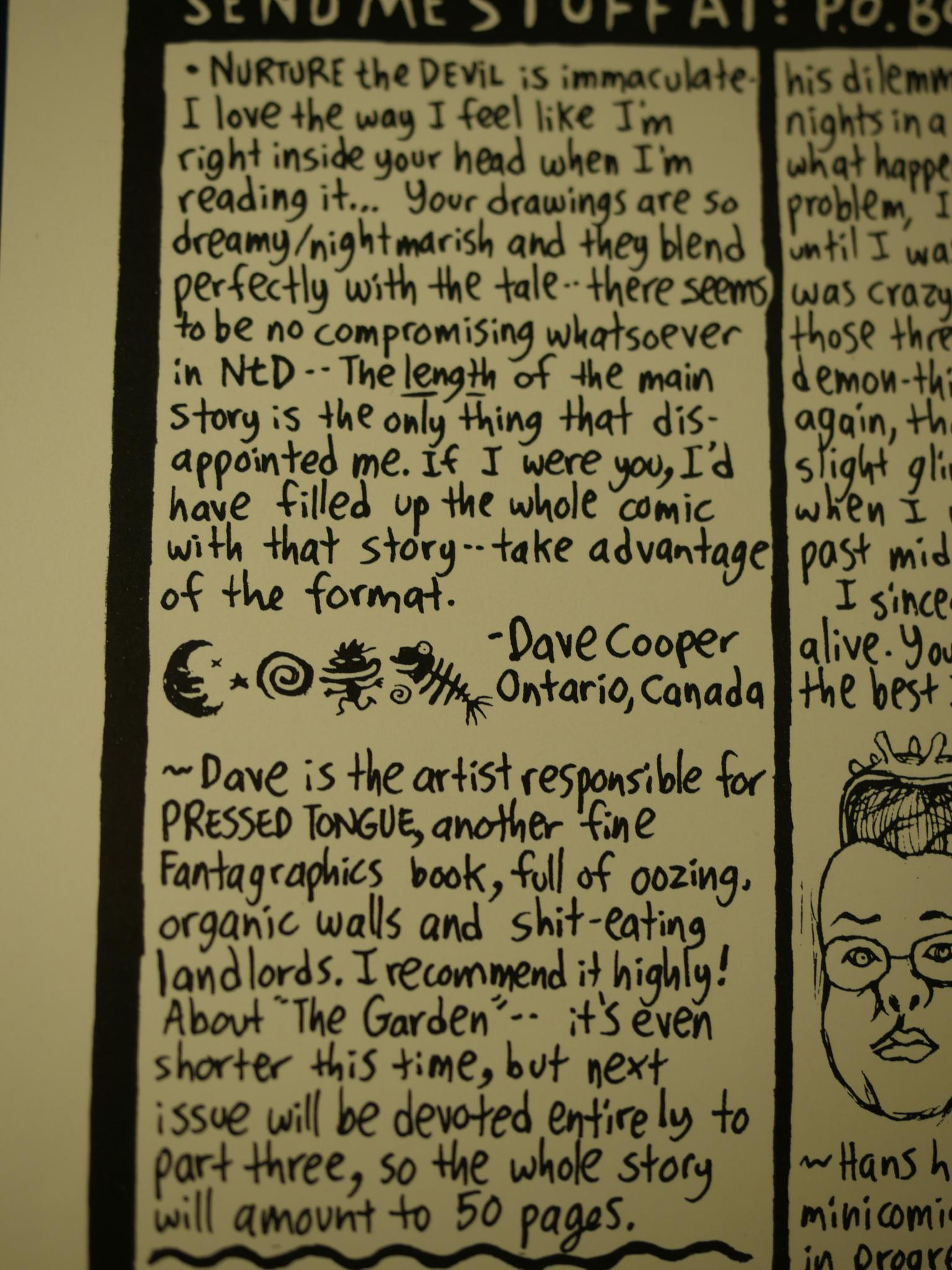

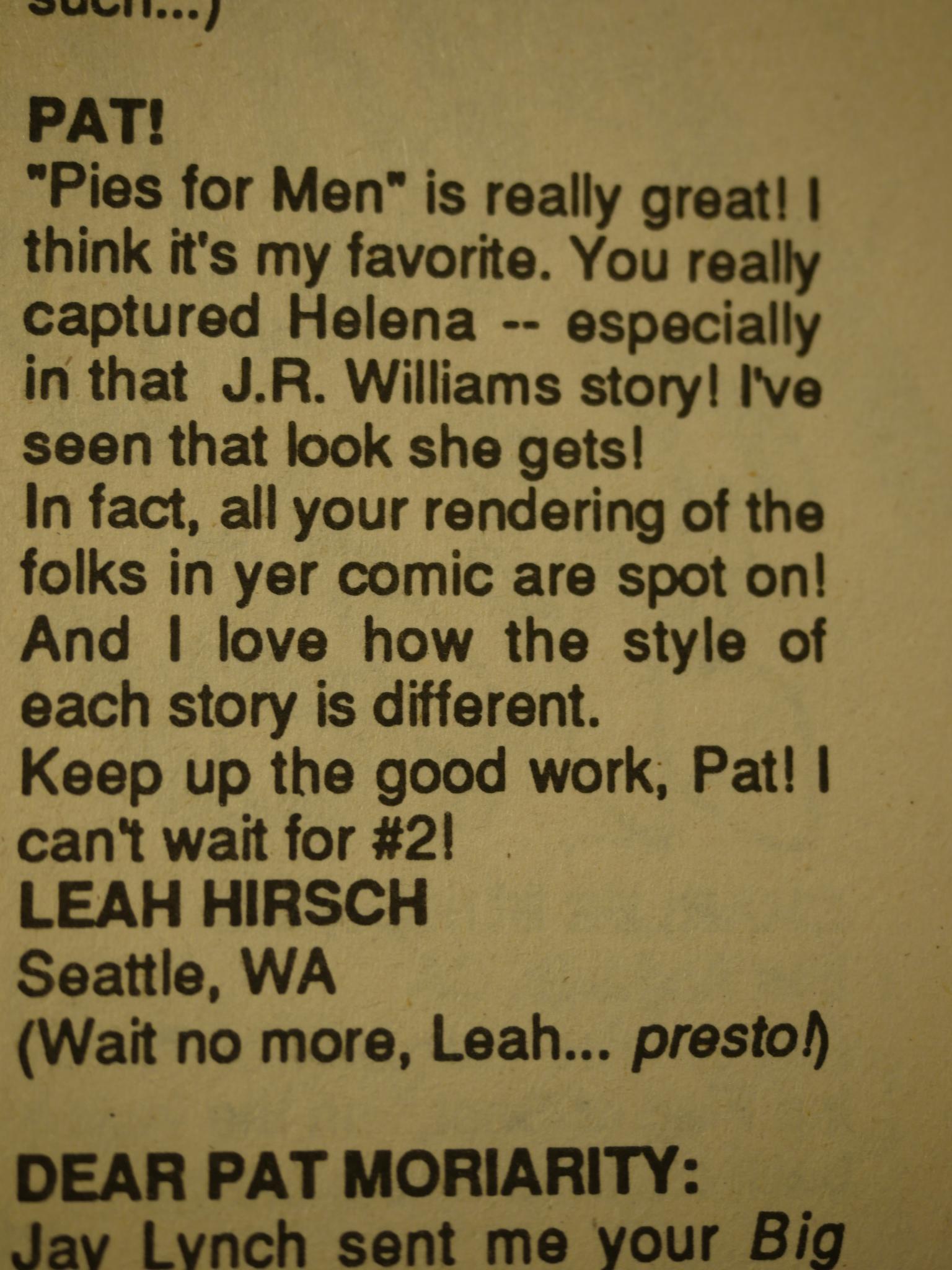

Fellow purveyor of squishy comics, Dave Cooper, shows up on the letters page.

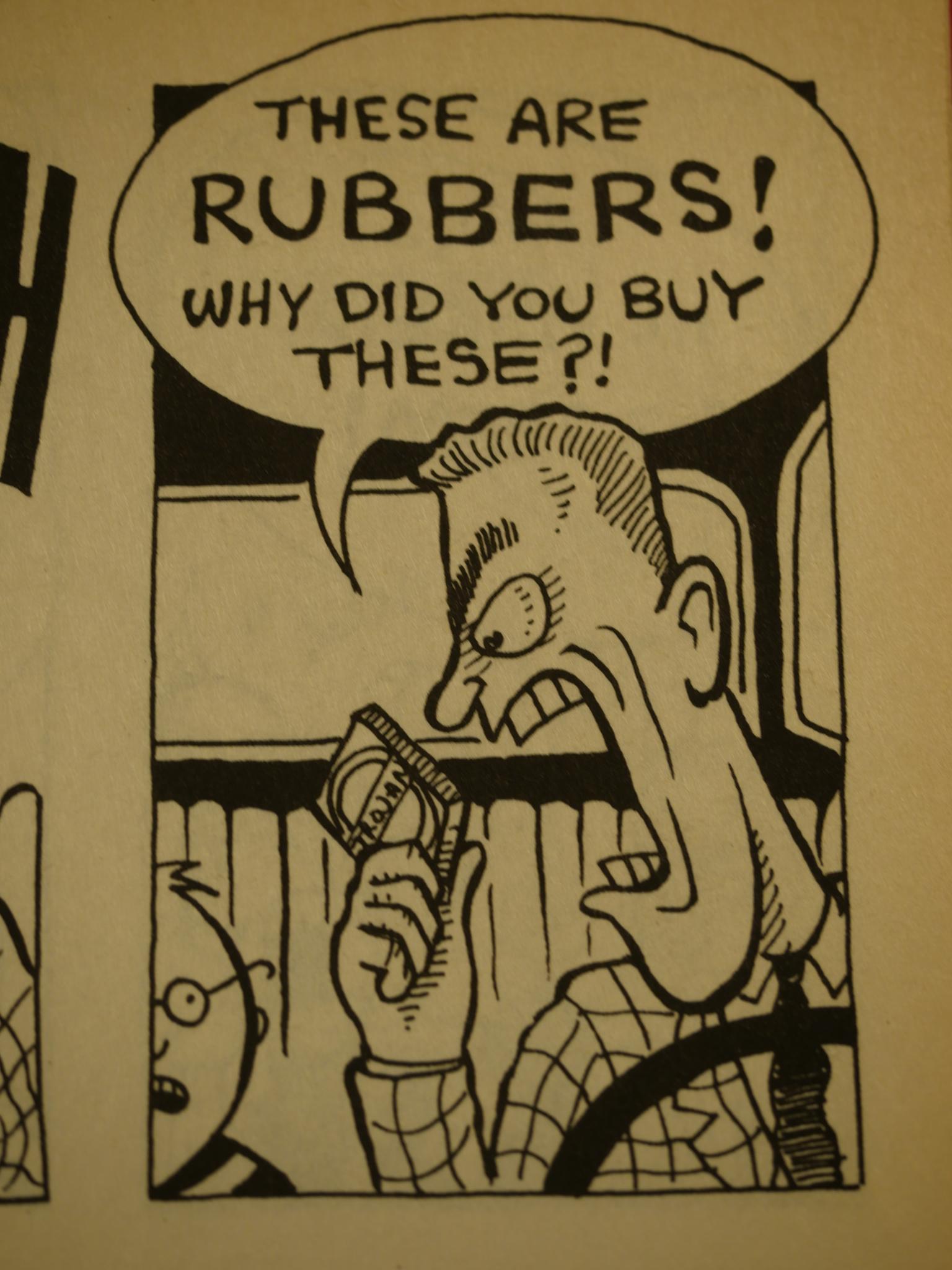

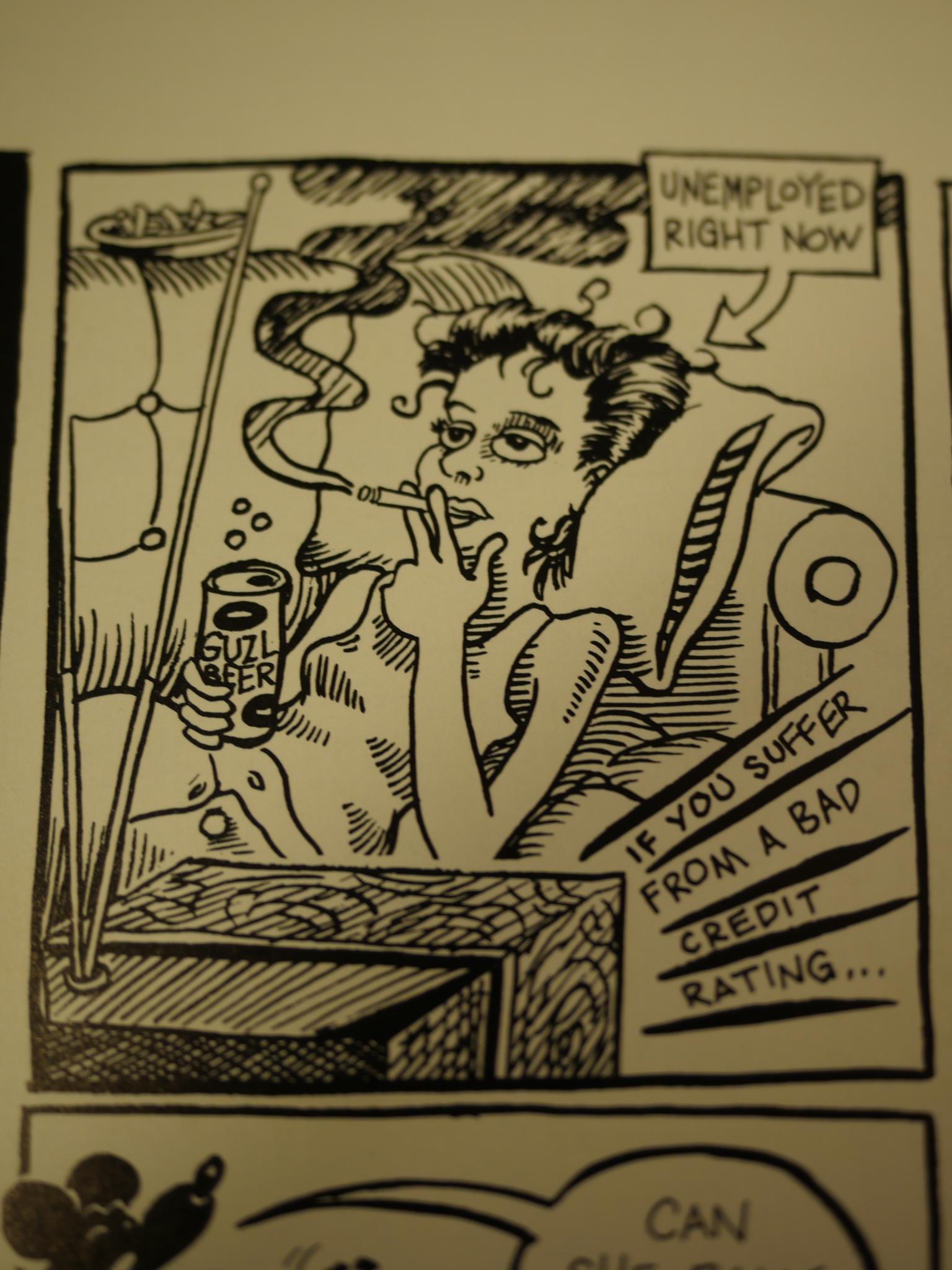

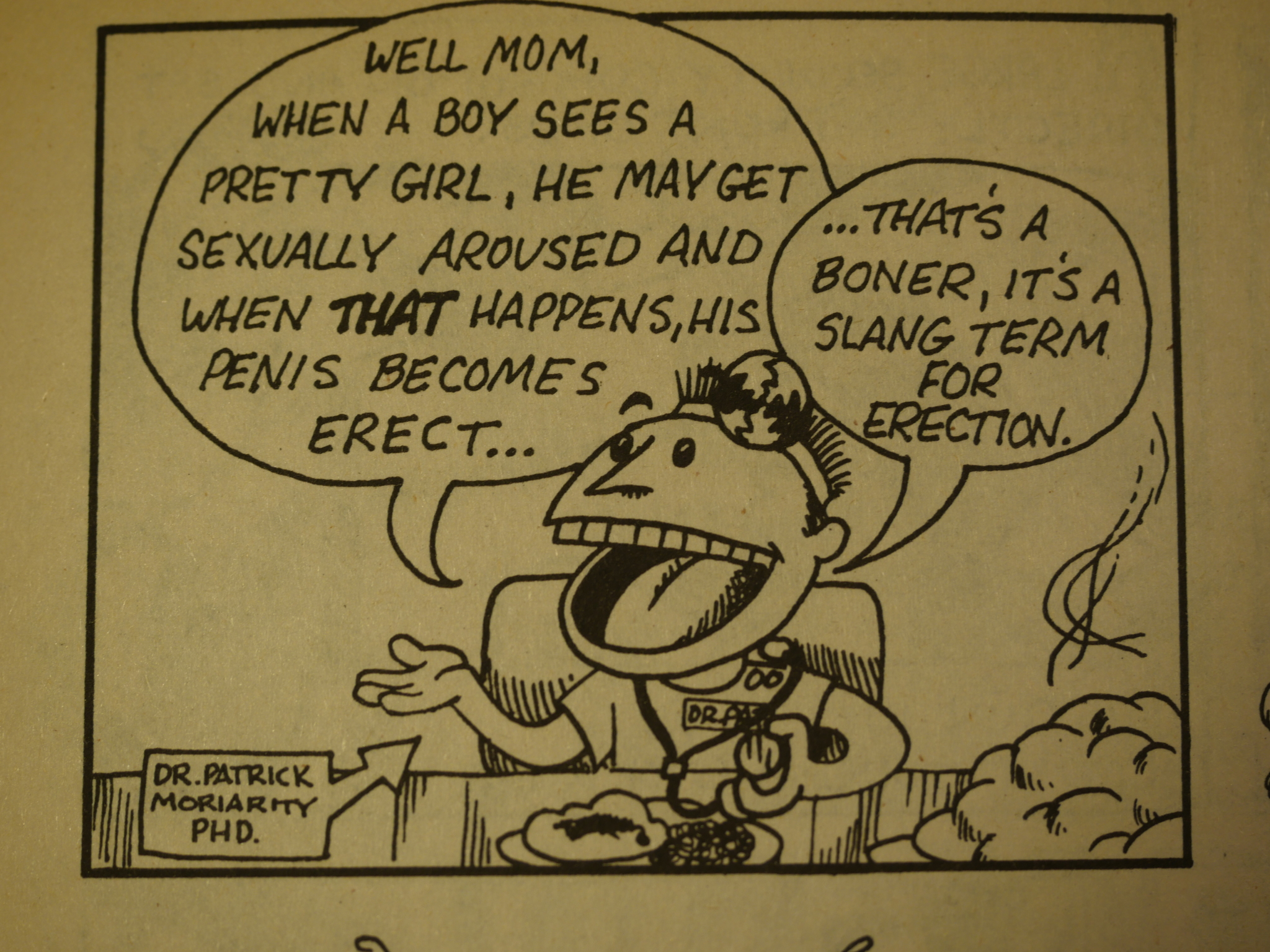

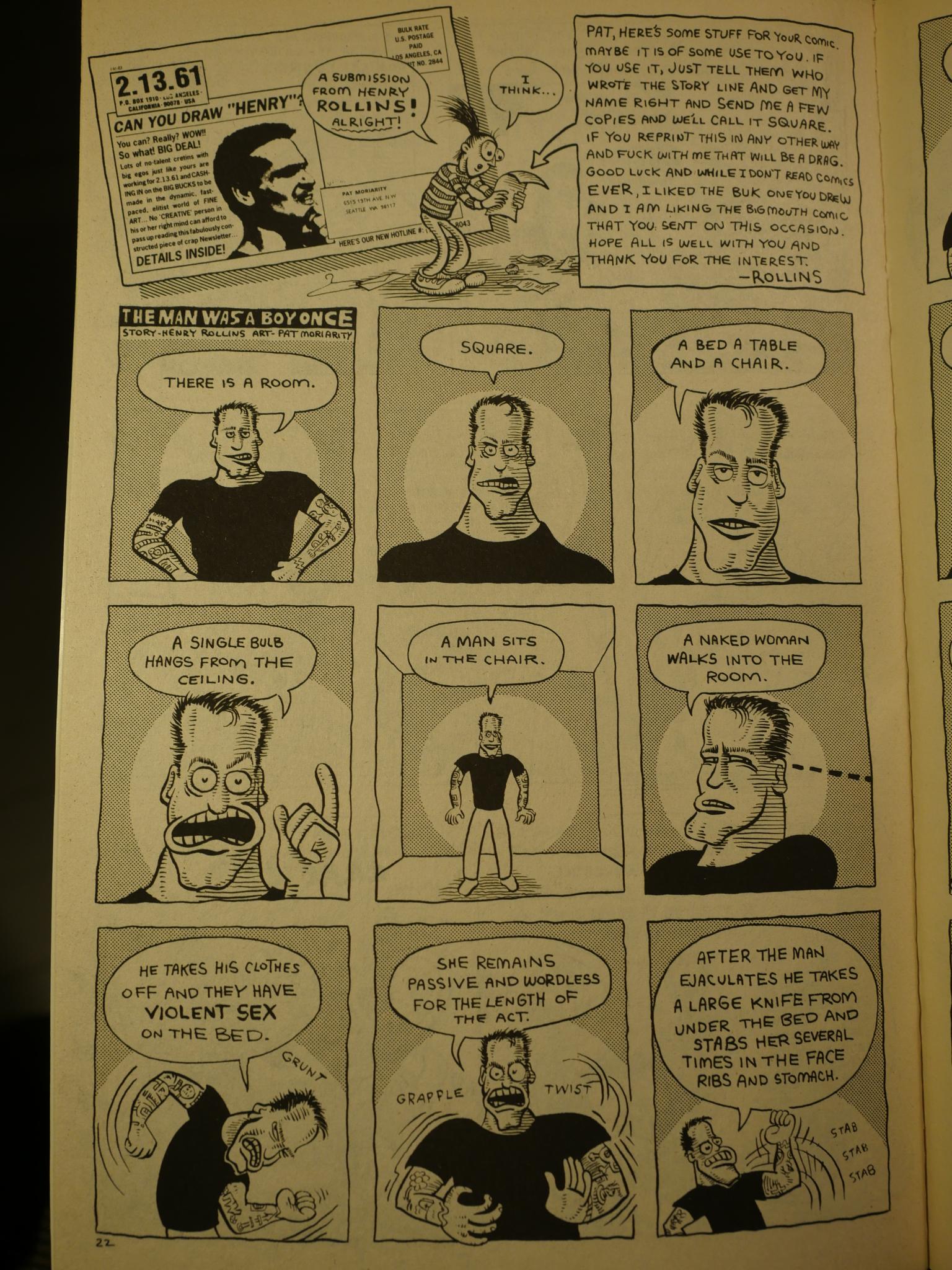

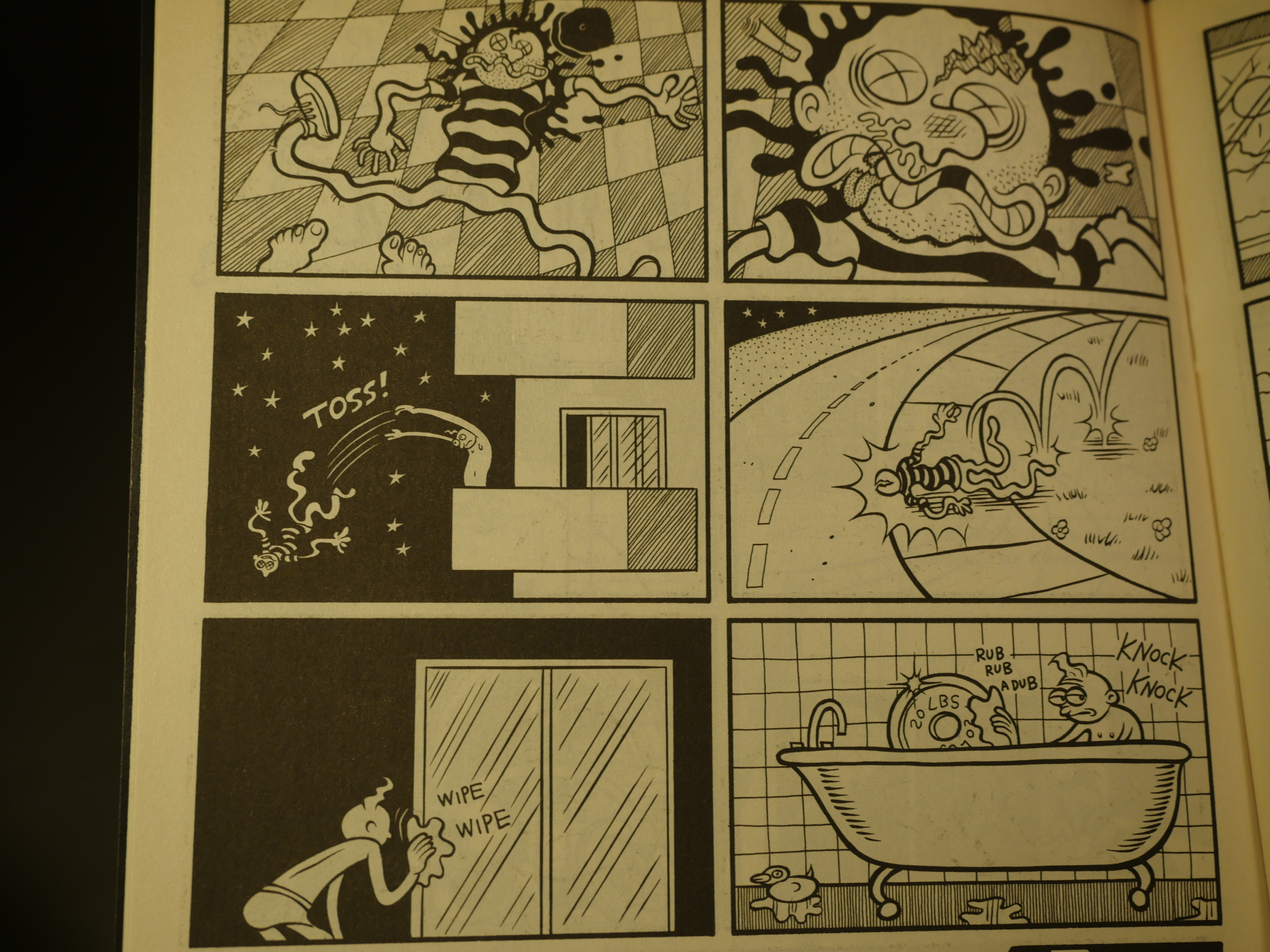

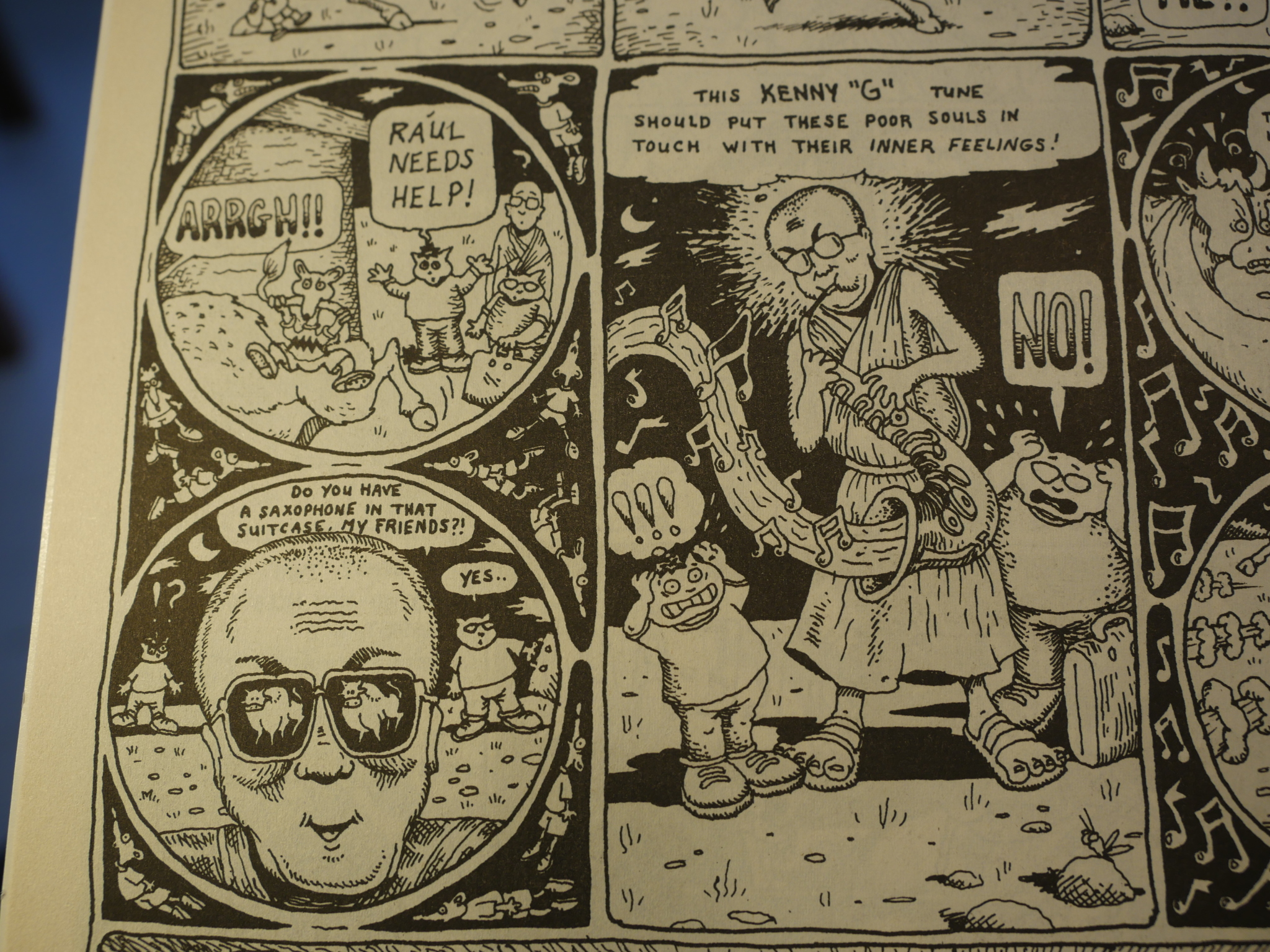

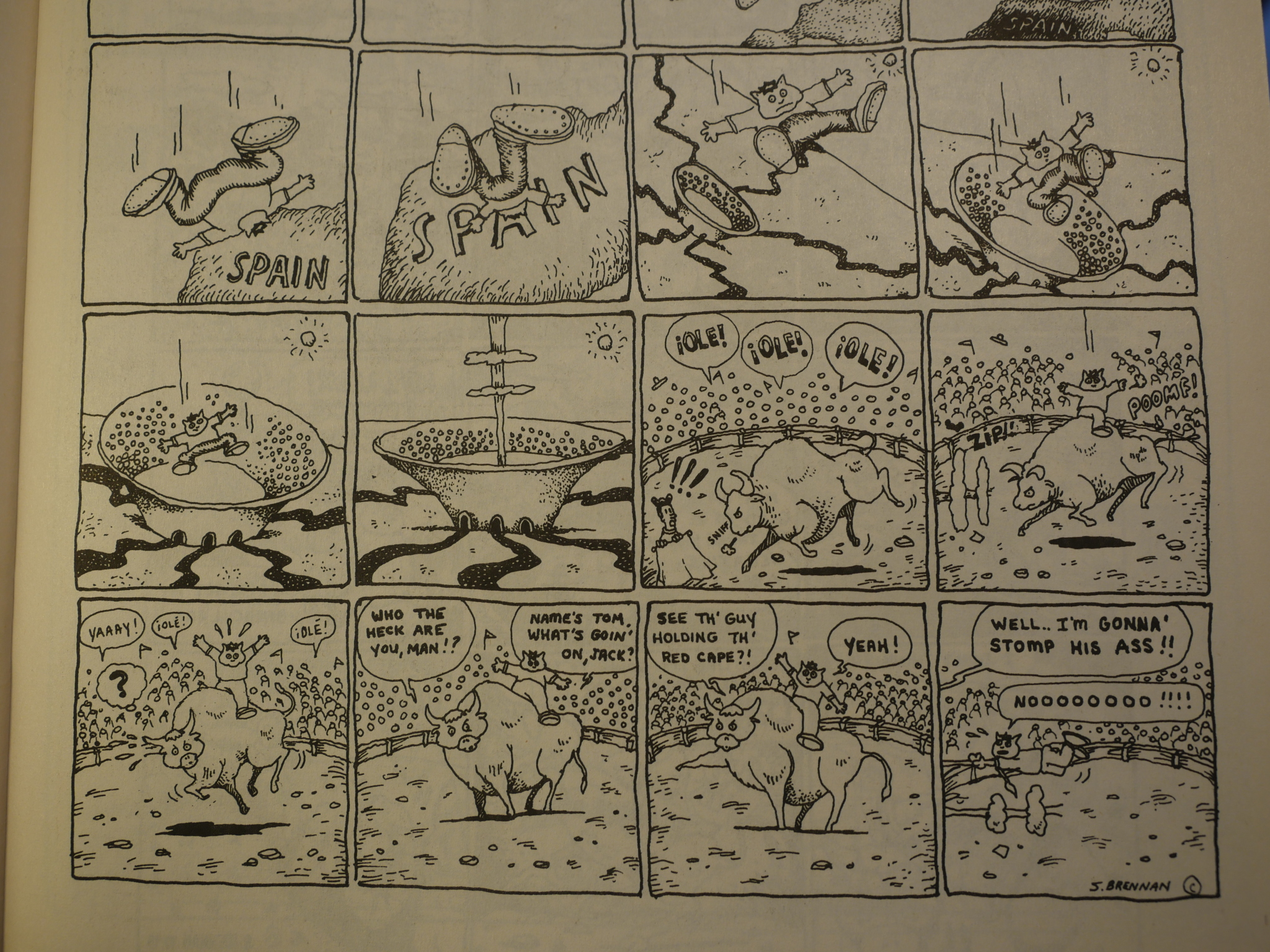

About half the pages of the Nurture the Devil series are taken by a serialisation of a narrative called The Garden, which is about… uhm… stuff… The rest are pretty random, like this one, which is about… uhm… stuff…

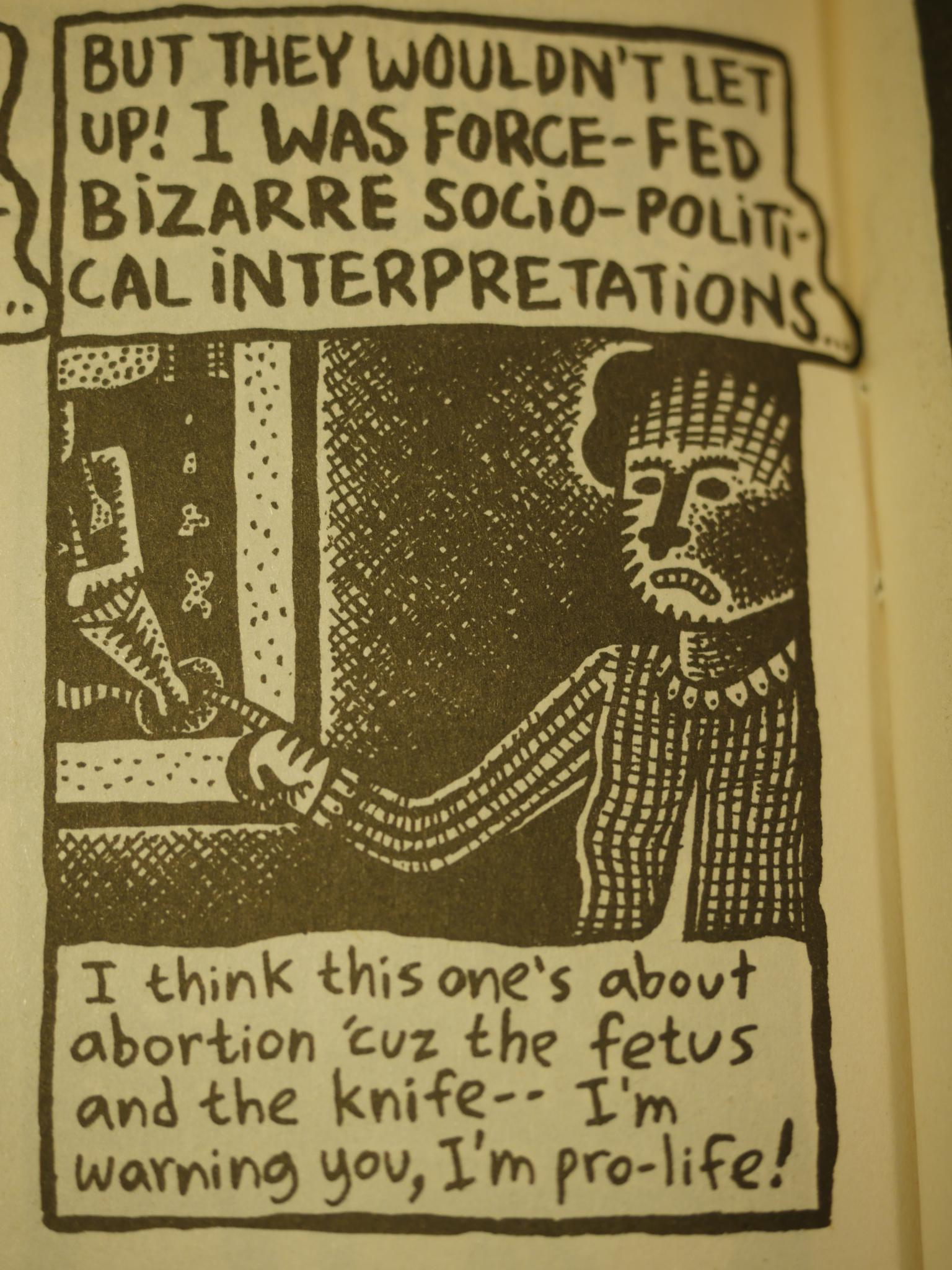

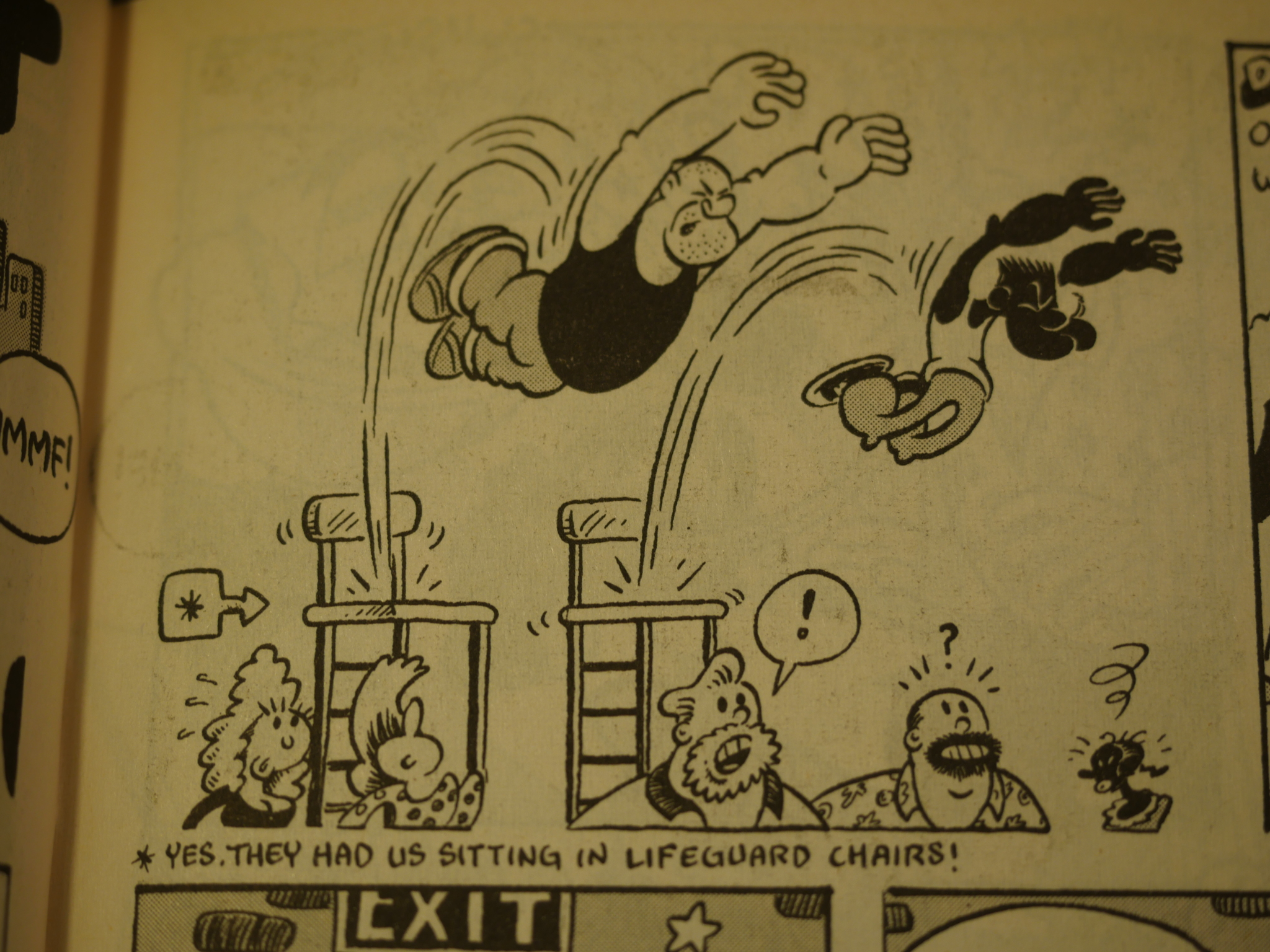

There’s one autobio piece about Johnson graduating from university, and people trying to interpret his paintings.

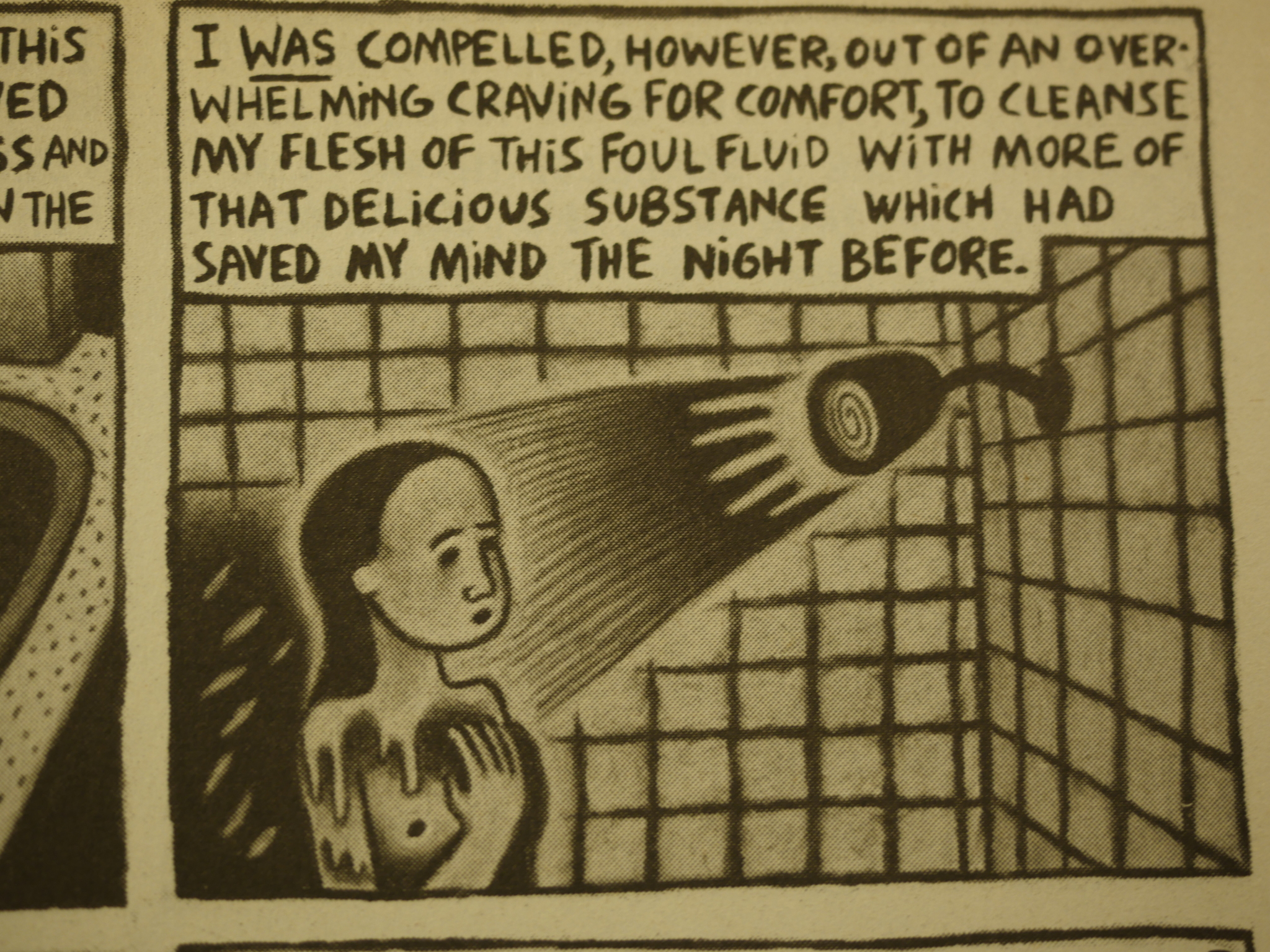

What Johnson’s trying to say here is that he peed himself while drunk and he’s now taking a shower. I think he’s quite funny when he tries to be, but he doesn’t try all that often.

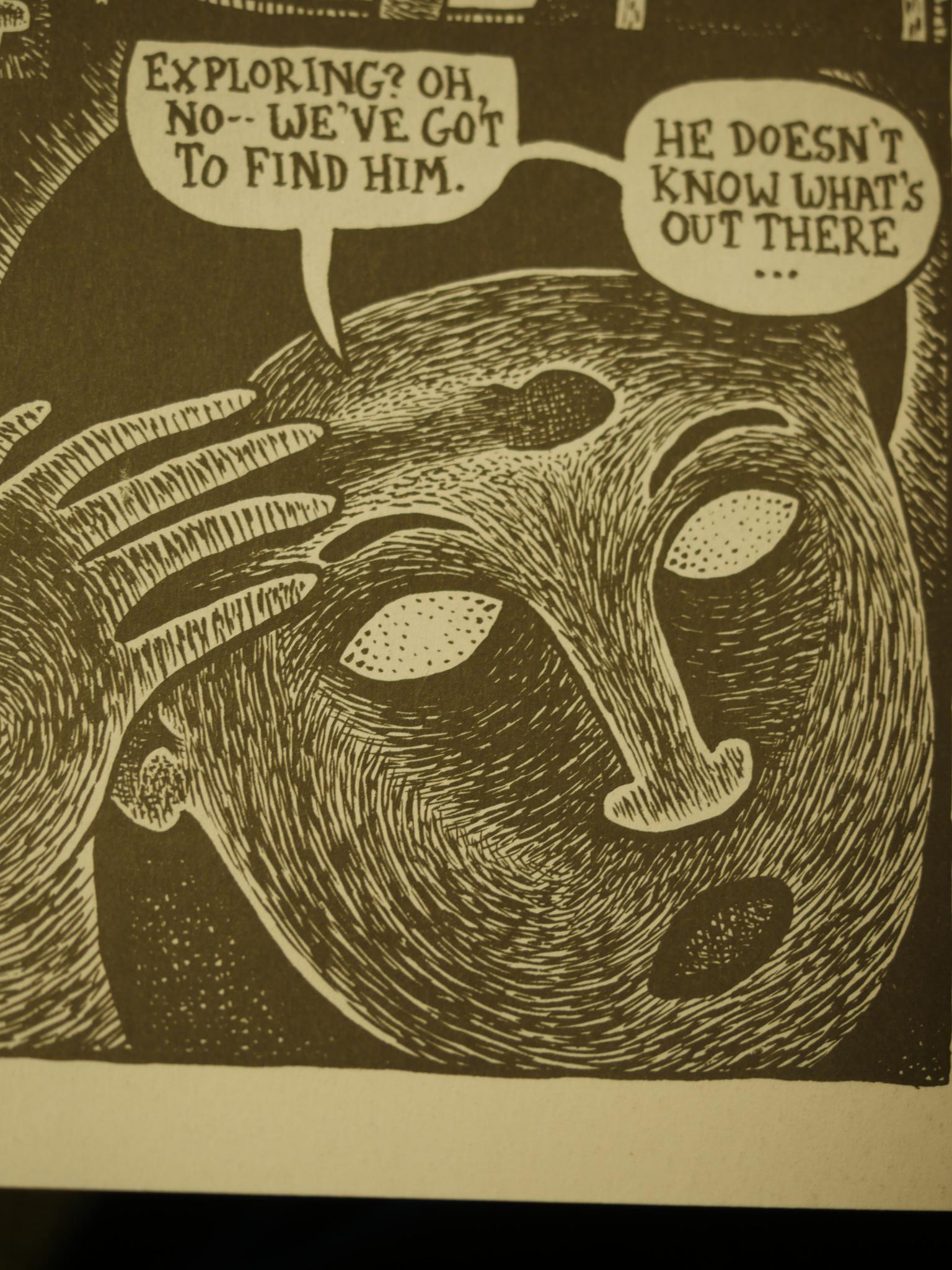

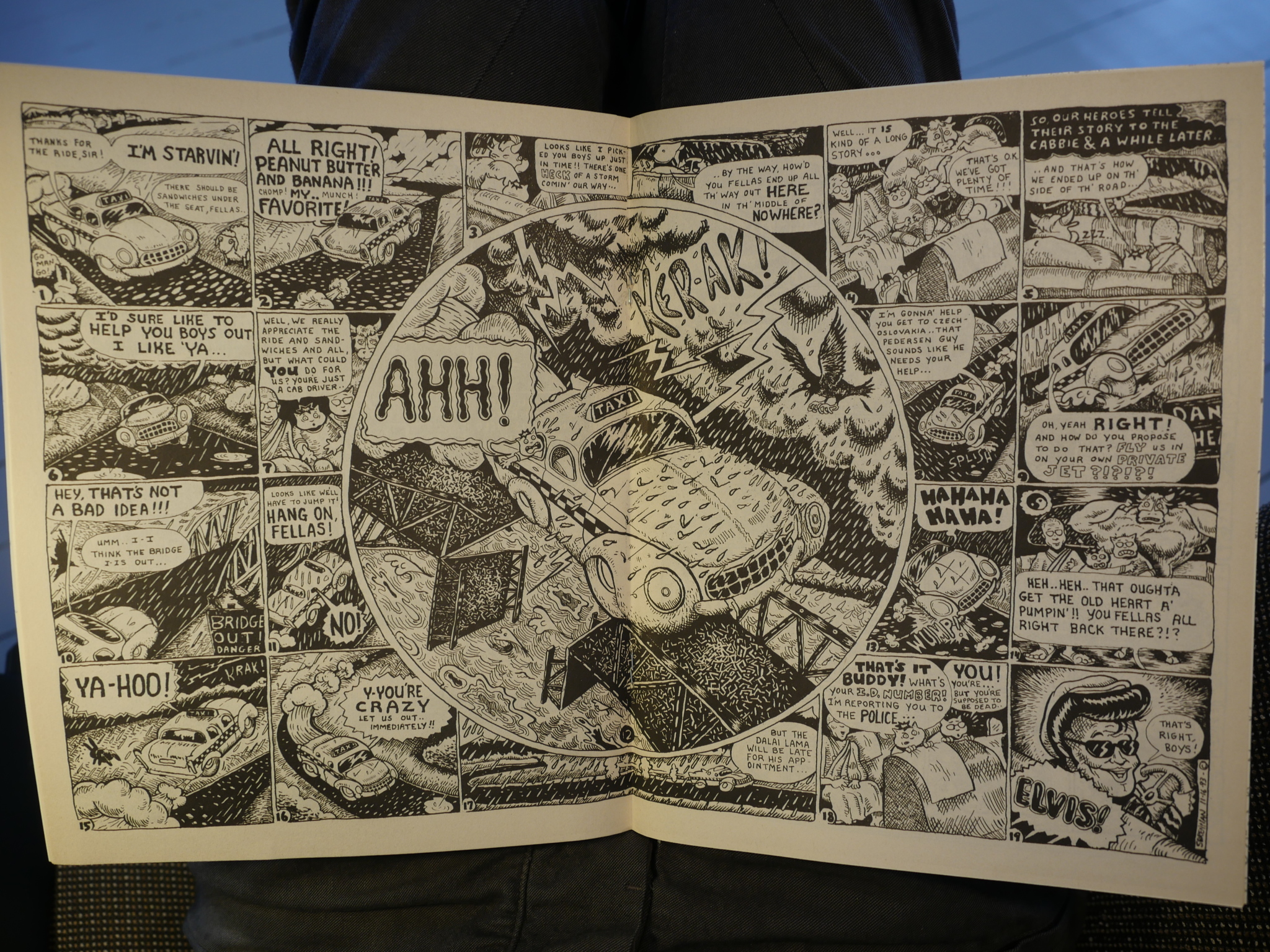

The third and final issue shifts the art style a bit. You get this obsessive swarm of tiny lines swirling though every panel. It’s rather beautiful. I wonder whether that might mean that he was working at a larger scale for this issue?

After Nurture the Devil finished (or was cancelled), Johnson went on to contribute to a large number of anthologies, and self-published quite a bit. He underwent gender assignment therapy in the late 90s, and she died earlier this year.

I think a retrospective collection of her work would be a nice thing to have.

This post is part of the Fantagraphics Floppies series.