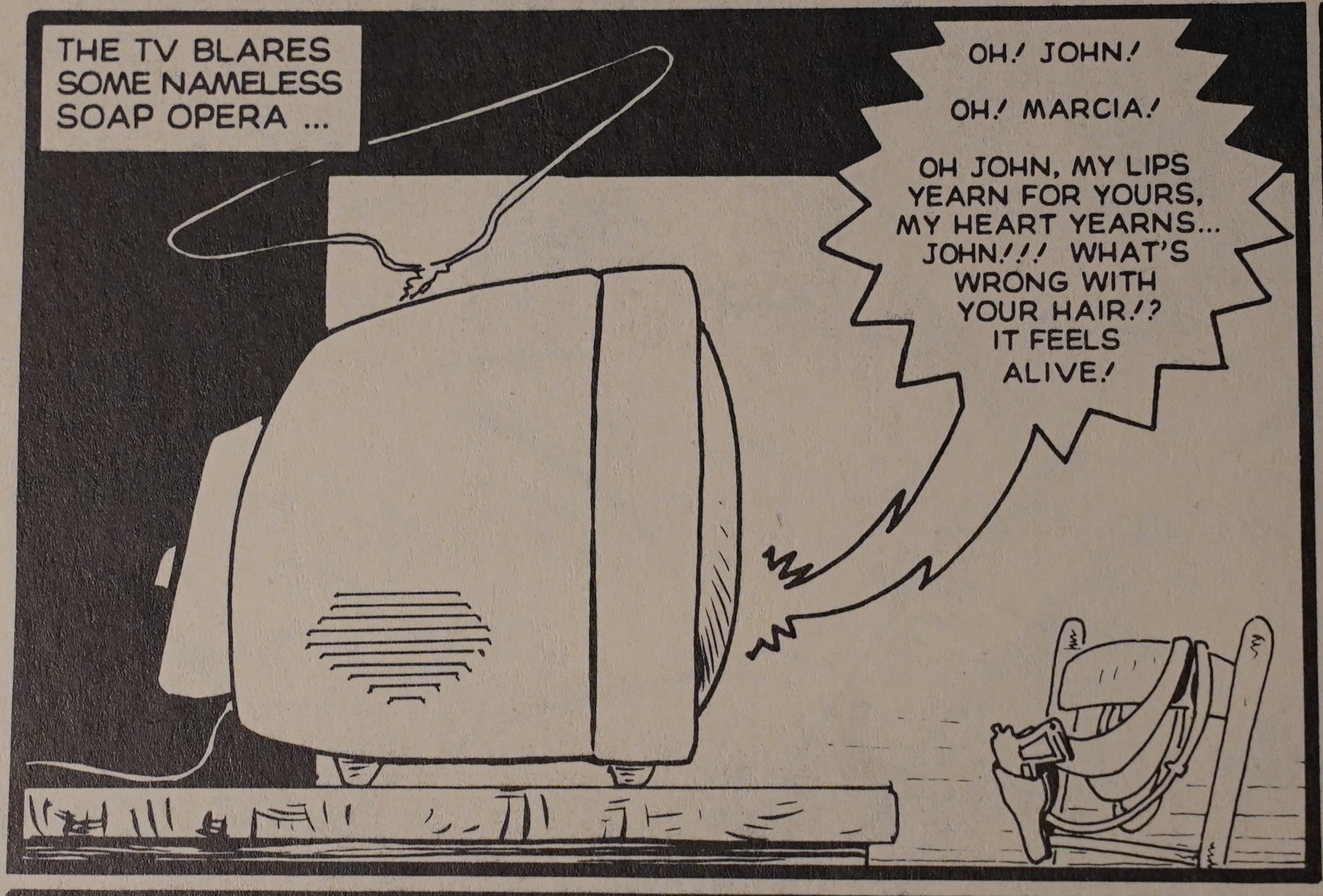

PX07: Will and Abe’s Guide to the Universe

Will and Abe’s Guide to the Universe by Matt Groening (230x229mm)

This is the final collection of Life in Hell strips, and I think I’ve covered them all? The Big Book of Hell and The Huge Book of Hell are collections of the other, er, collections, aren’t they? It’s impossible to google these things, because the publishers never mention tiny details like that…

In any case, this was published a decade after the previous collection, which… is pretty puzzling? According to wikipedia, the strip was published weekly until 2012, but nobody wanted to publish a collection of the stuff? It’s so weird to me: Matt Groening is still a huge name, so you’d think the collections would sell anyway… but… I guess the publishers know what they’re doing?

This collection is a return to the normal format — Binky’s Guide to Love was a bigger hardcover, but this is more modest. It’s just 80 pages, and it’s apparently just strips that are about Will and Abe (Simpsons two sons)?

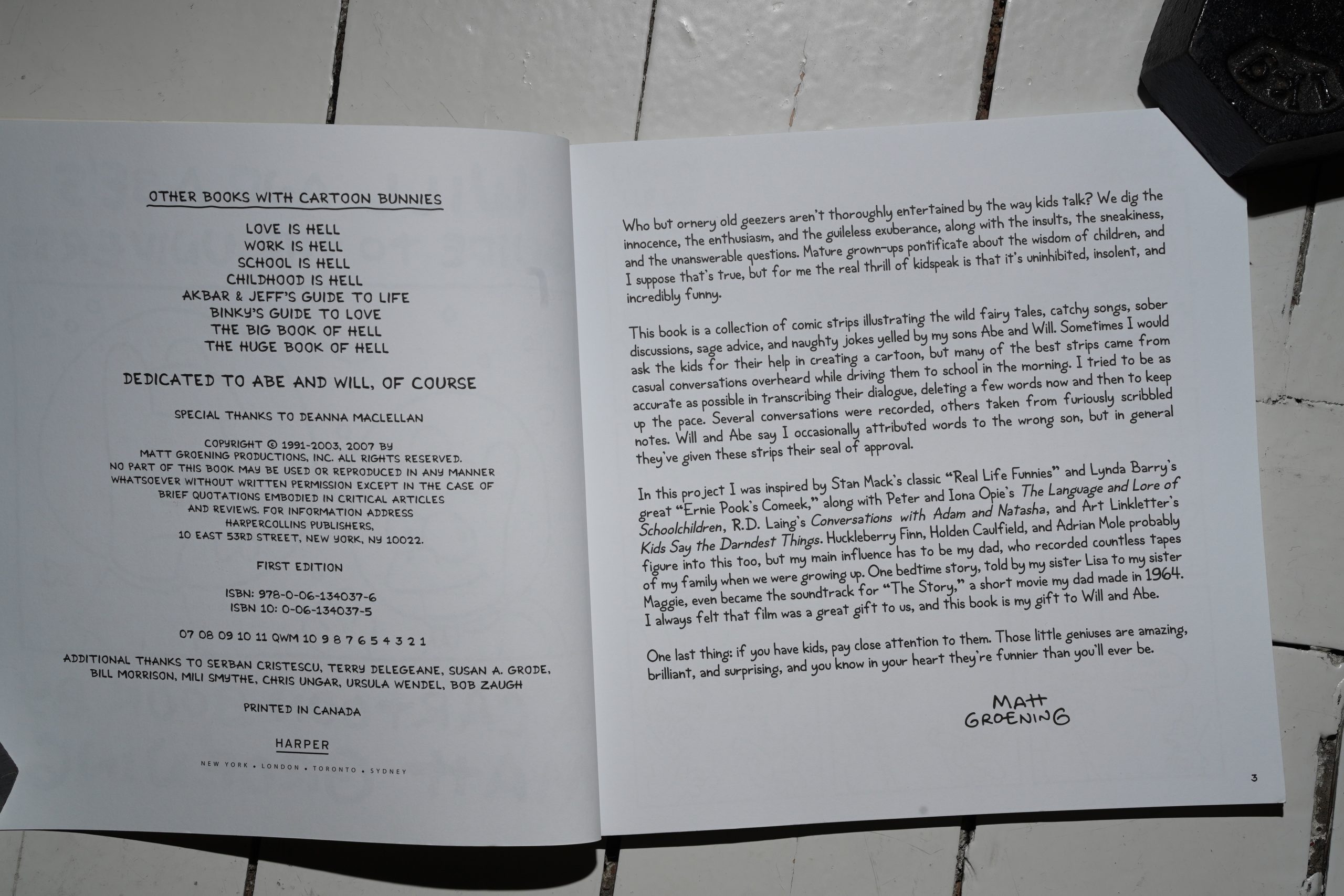

This time around, we get a written introduction by Groening that explains what we’re about to read, which is pretty unusual for one of these collections.

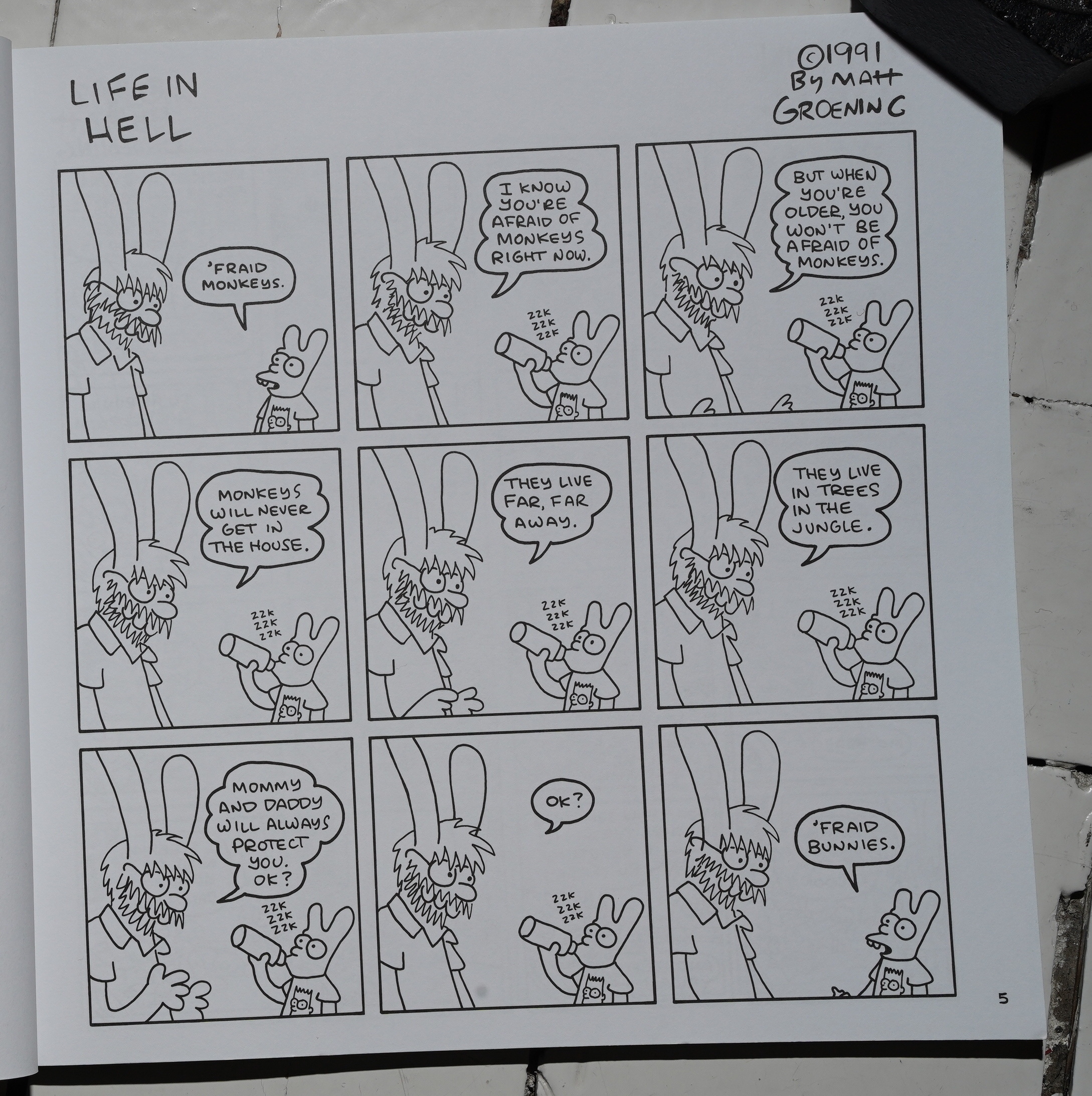

The book starts off with a bunch of strips that were already reprinted in previous collections.

But then the rest is new… to me, at least. Hm. Perhaps I should buy those two Big/Huge collections… I won’t be able to get any sleep until I know whether there’s any strips in those books I haven’t read before.

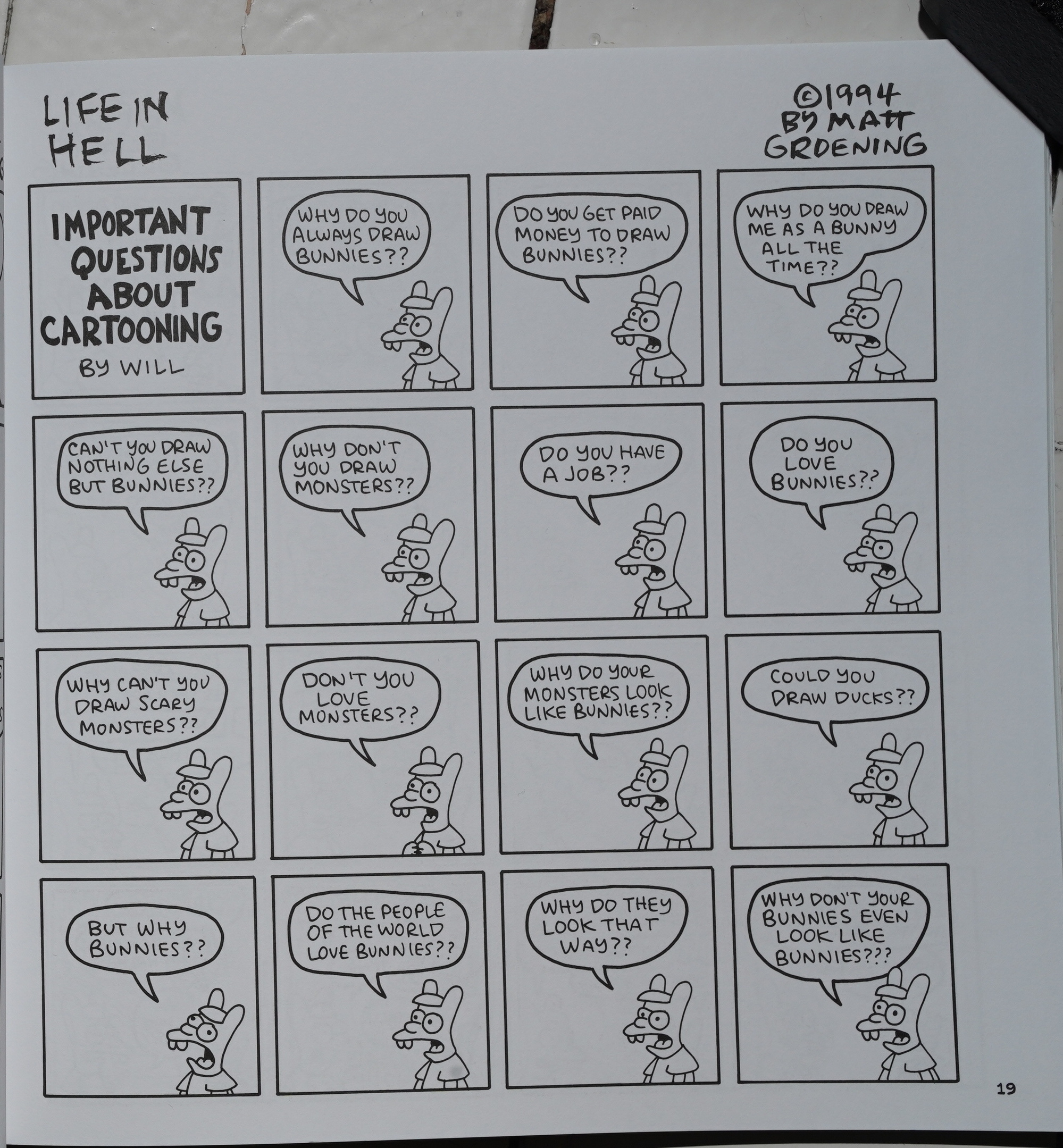

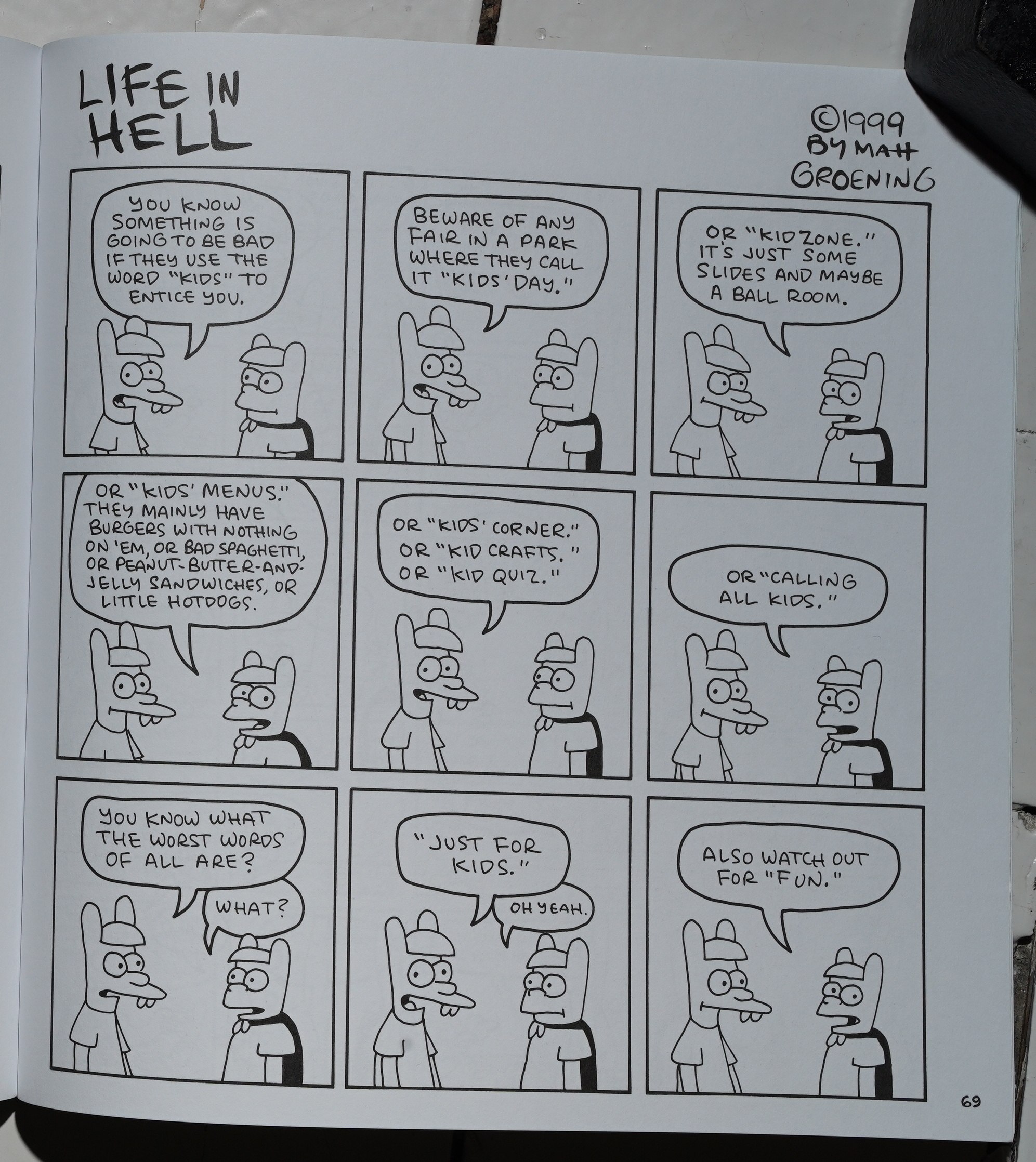

Will asks the real questions.

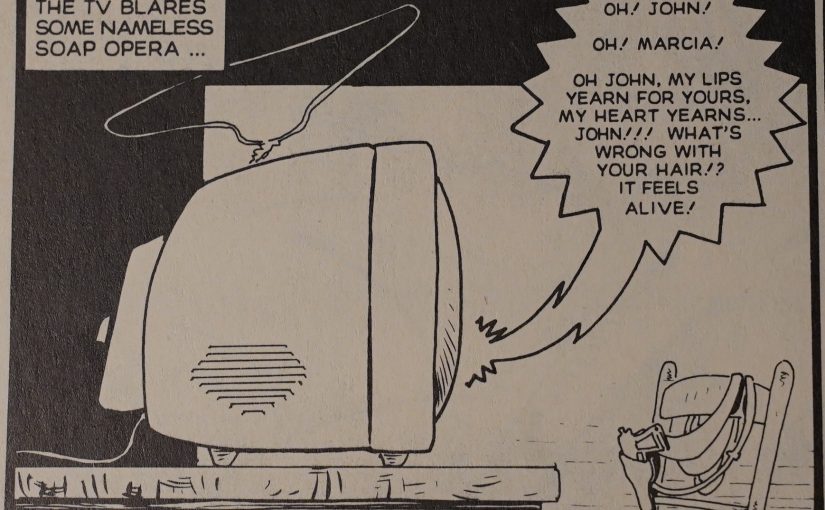

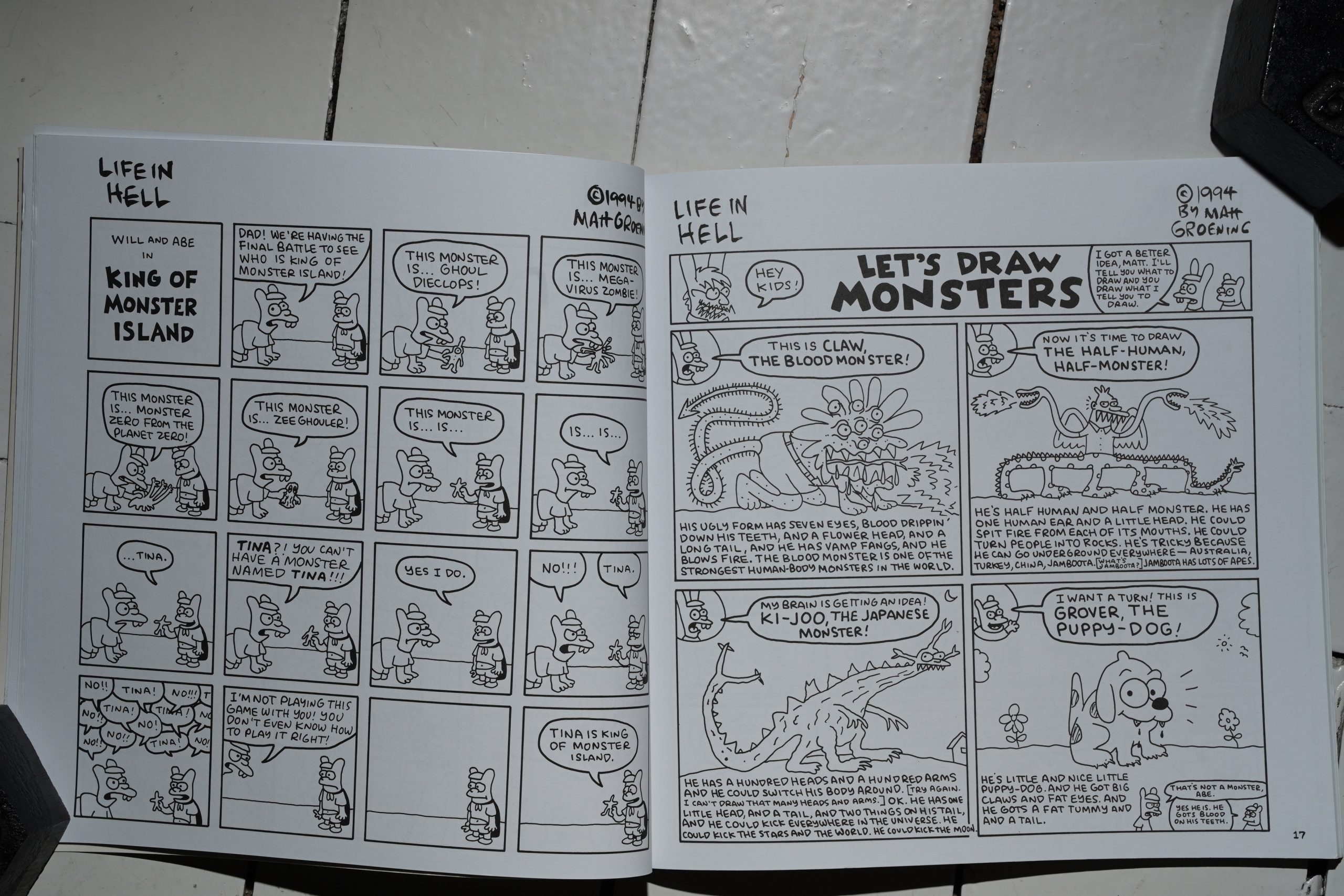

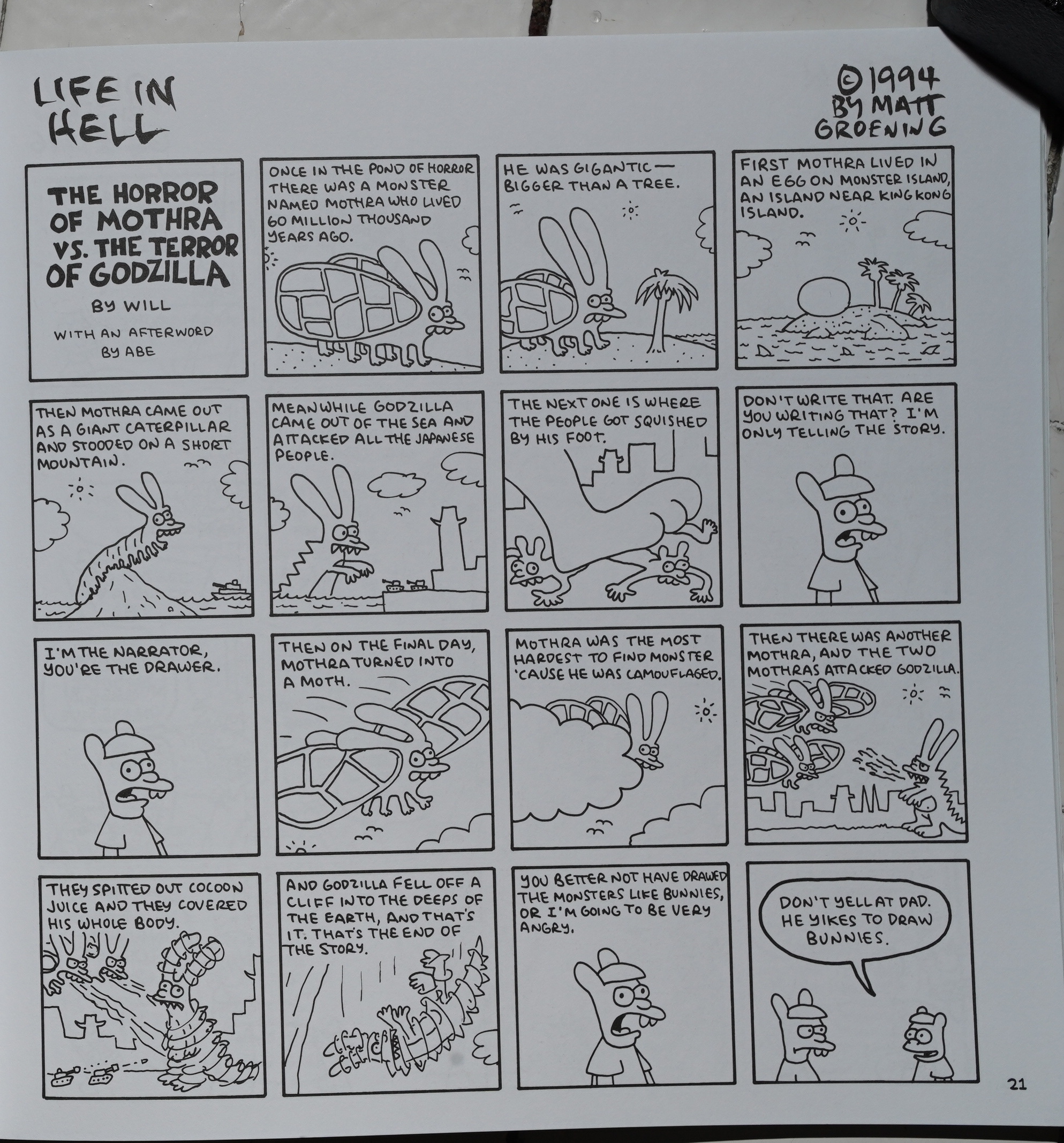

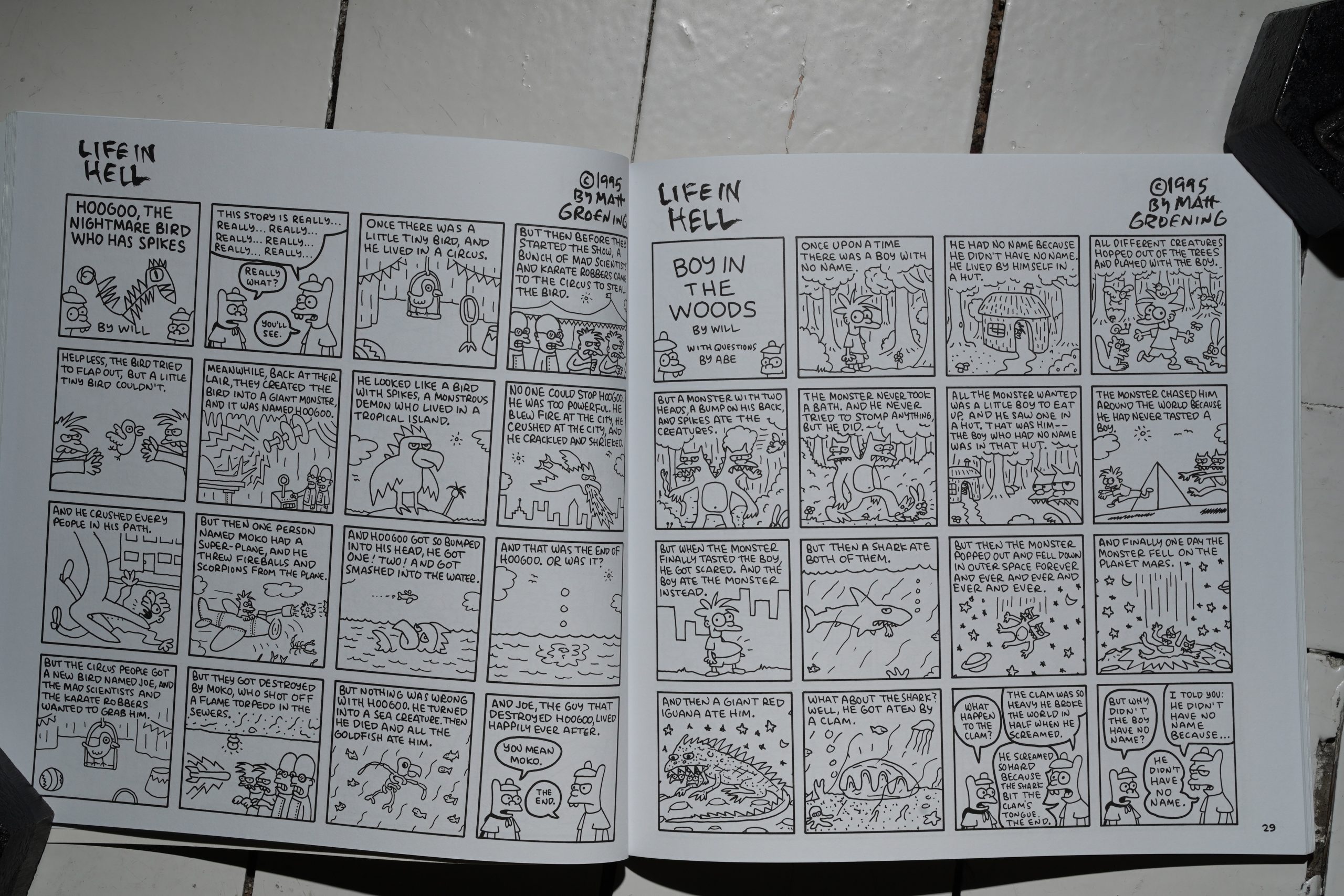

We get a series of stories told by Will (helped by Abe), illustrated by Groening, and it starts off pretty well…

However, there’s too many pages that just go on and on like this. I mean, I appreciate the verisimilitude — reading these pages is just like listening to an eight-year-old tell a story. I think they’d read a whole lot better in the original context — one of these pages in the middle of some Akbar & Jeff hi-jinx is very different from reading page after page of this stuff.

Fun is the worst!

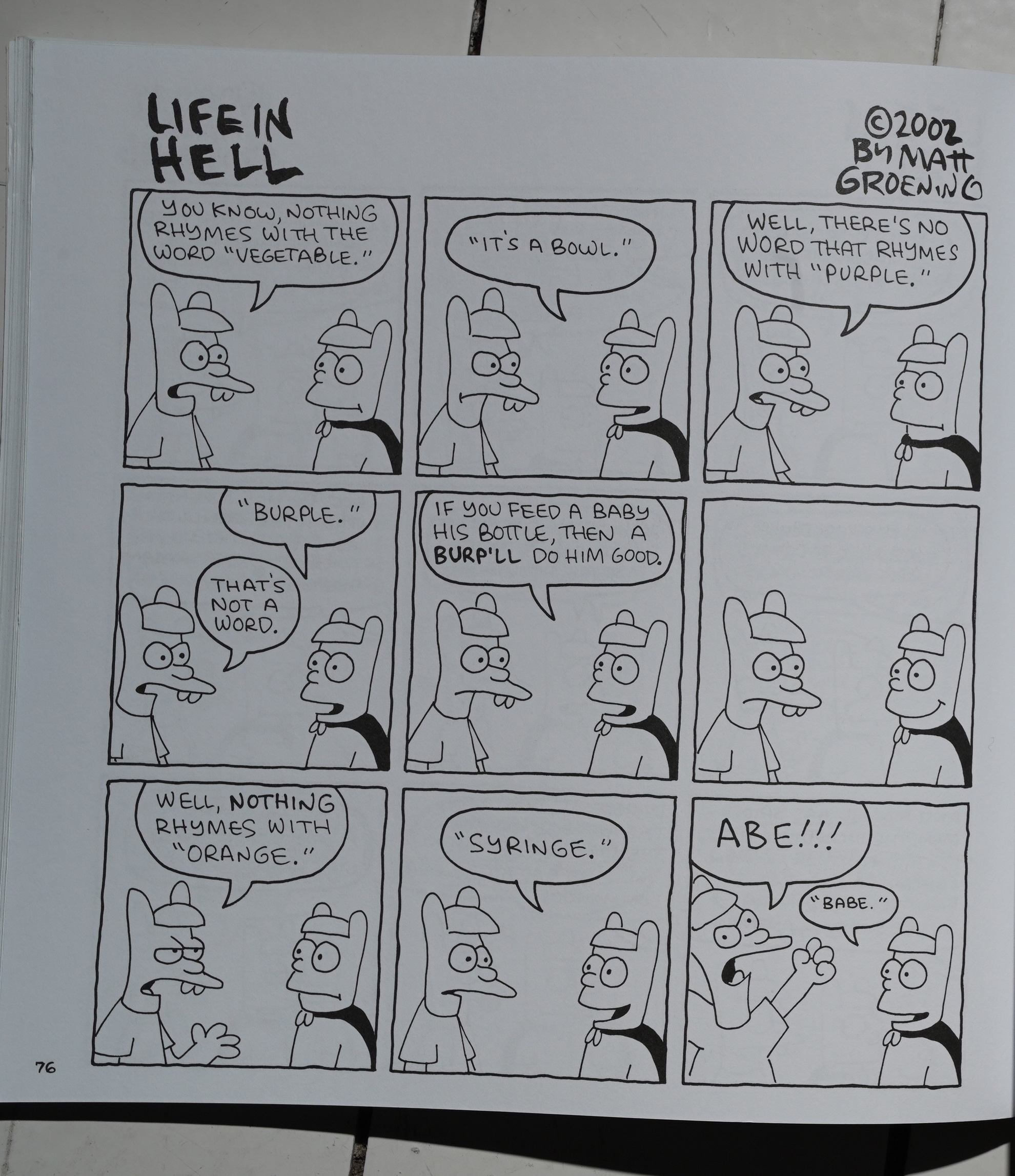

Heh heh.

And there’s an extensive index, of course.

And… that’s it. This includes strips drawn in 2003, and the book was published in 2007. Groening continued the strip until 2012, but there’s been no collections published.

So weird.

This blog post is part of the Punk Comix series.

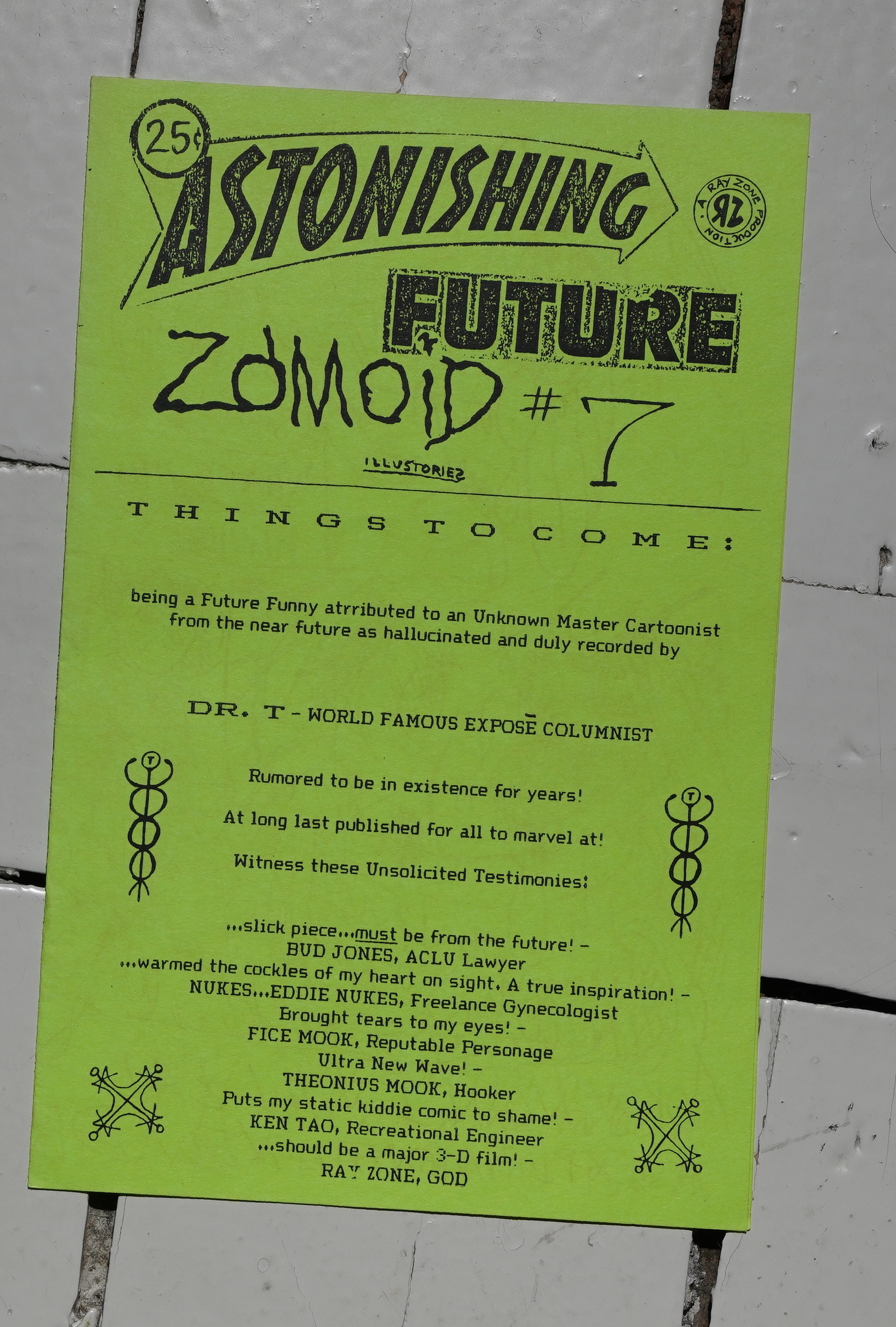

PX83: Zomoid Illustories

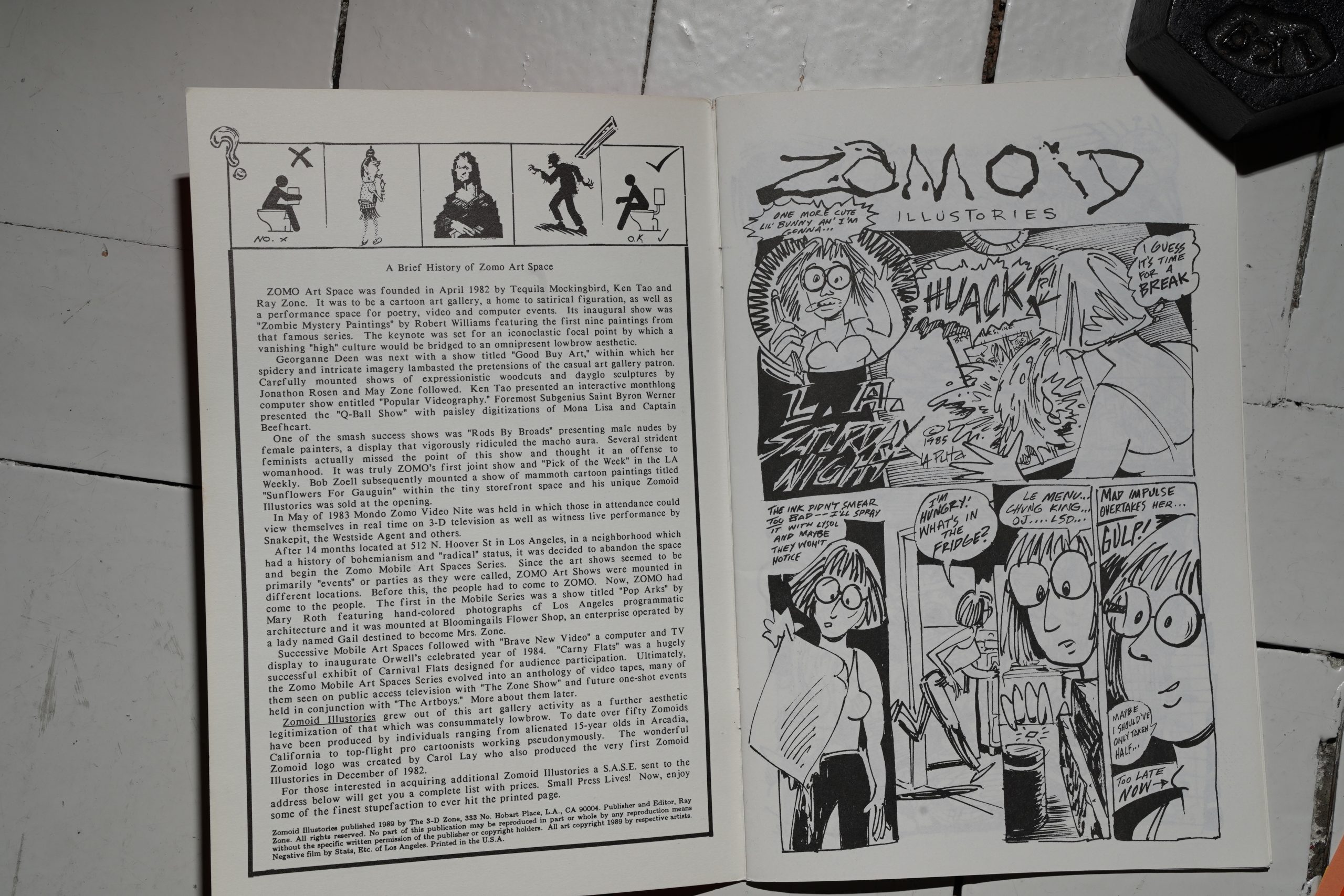

Zomoid Illustories edited by Ray Zone (110x140mm – 140x216mm – 172x260mm)

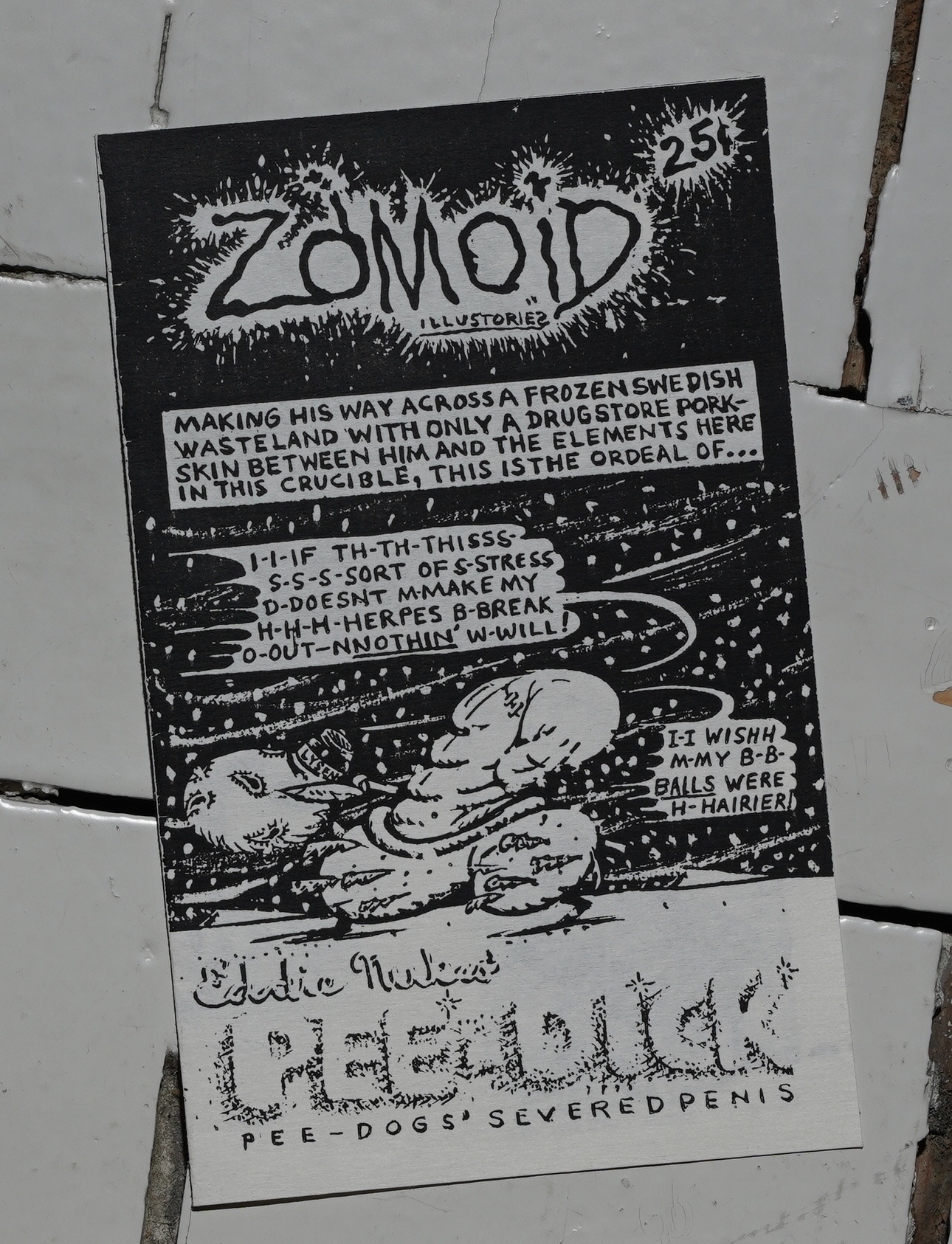

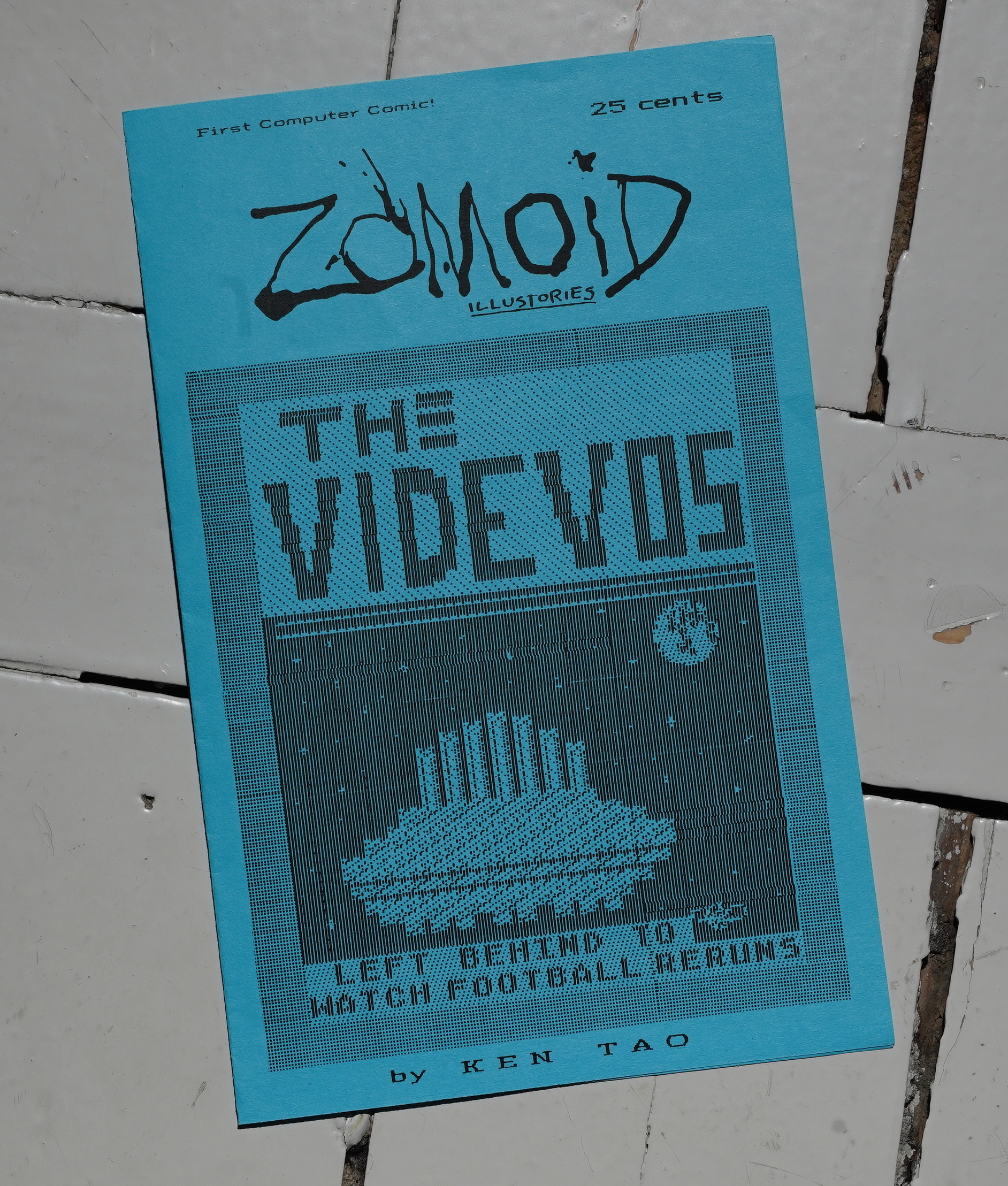

I was ebaying for “punk comics”, as one does, and a collection of Zomoid Illustories appeared. I had the standard US comics-sized one already (it’s the one with the red cover up there), but I was wondering what the minis were like.

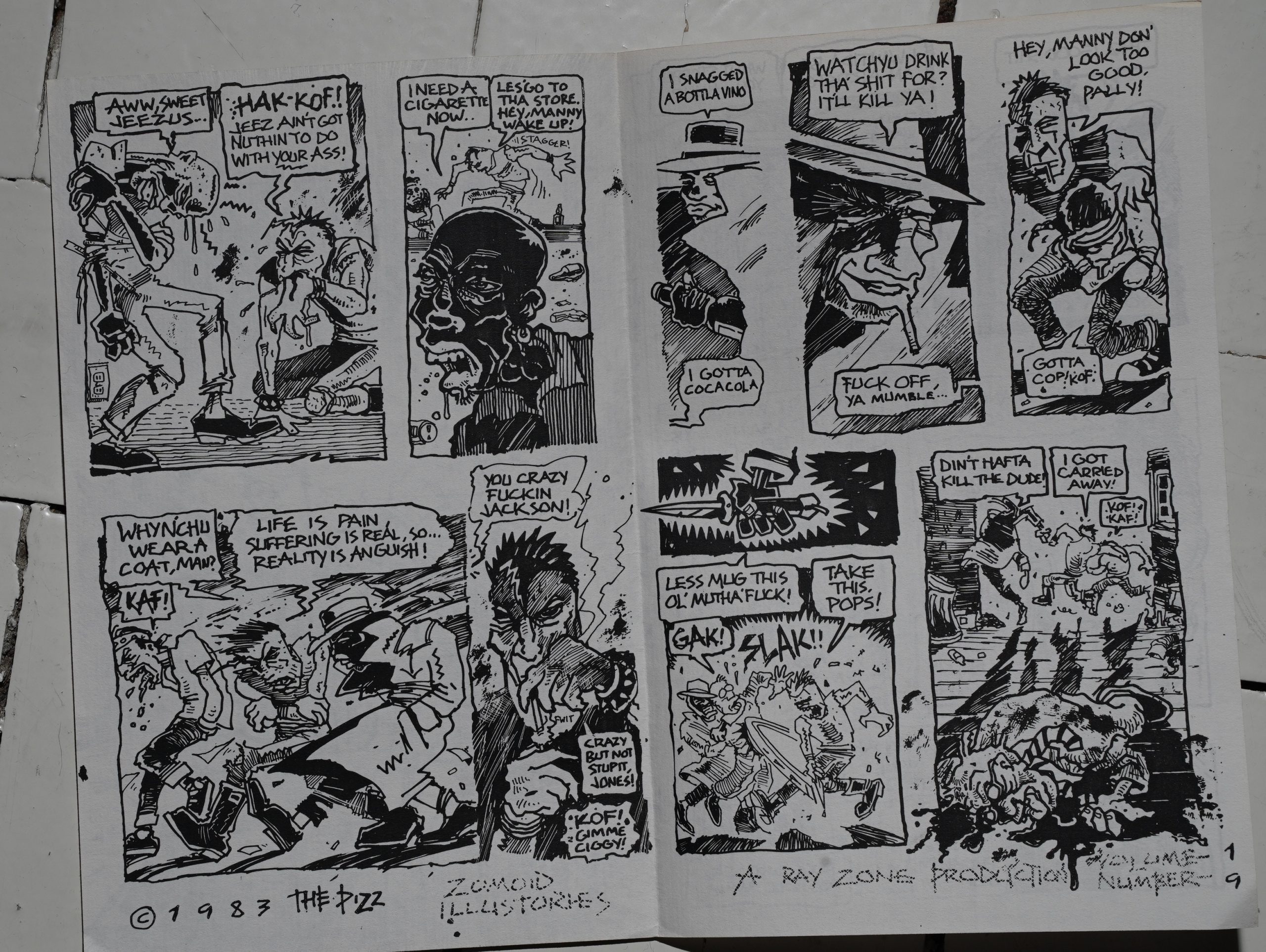

Very varied. Here’s The Pizz, for instance, who’d done a lot of newave/mini comics at the time.

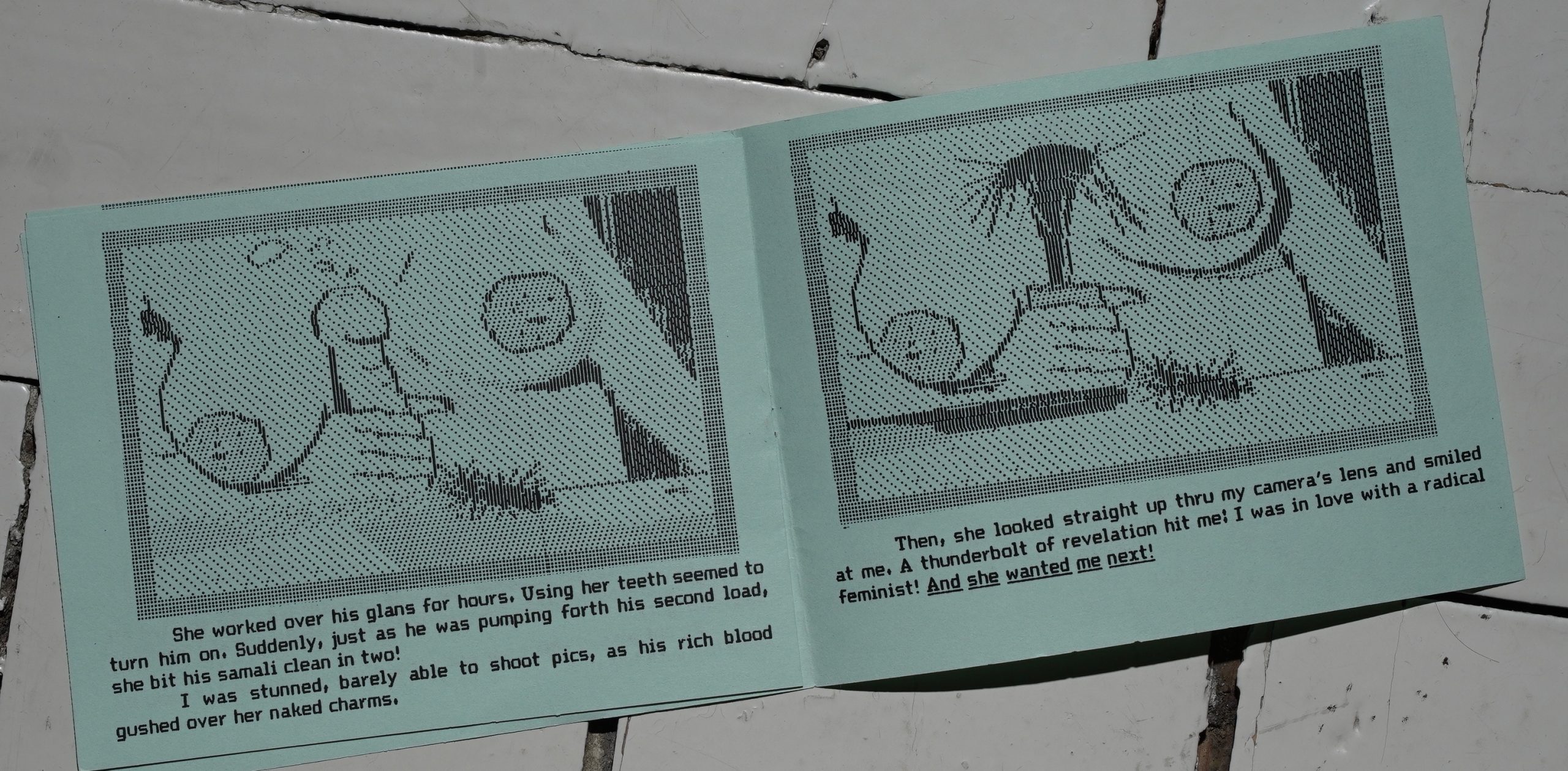

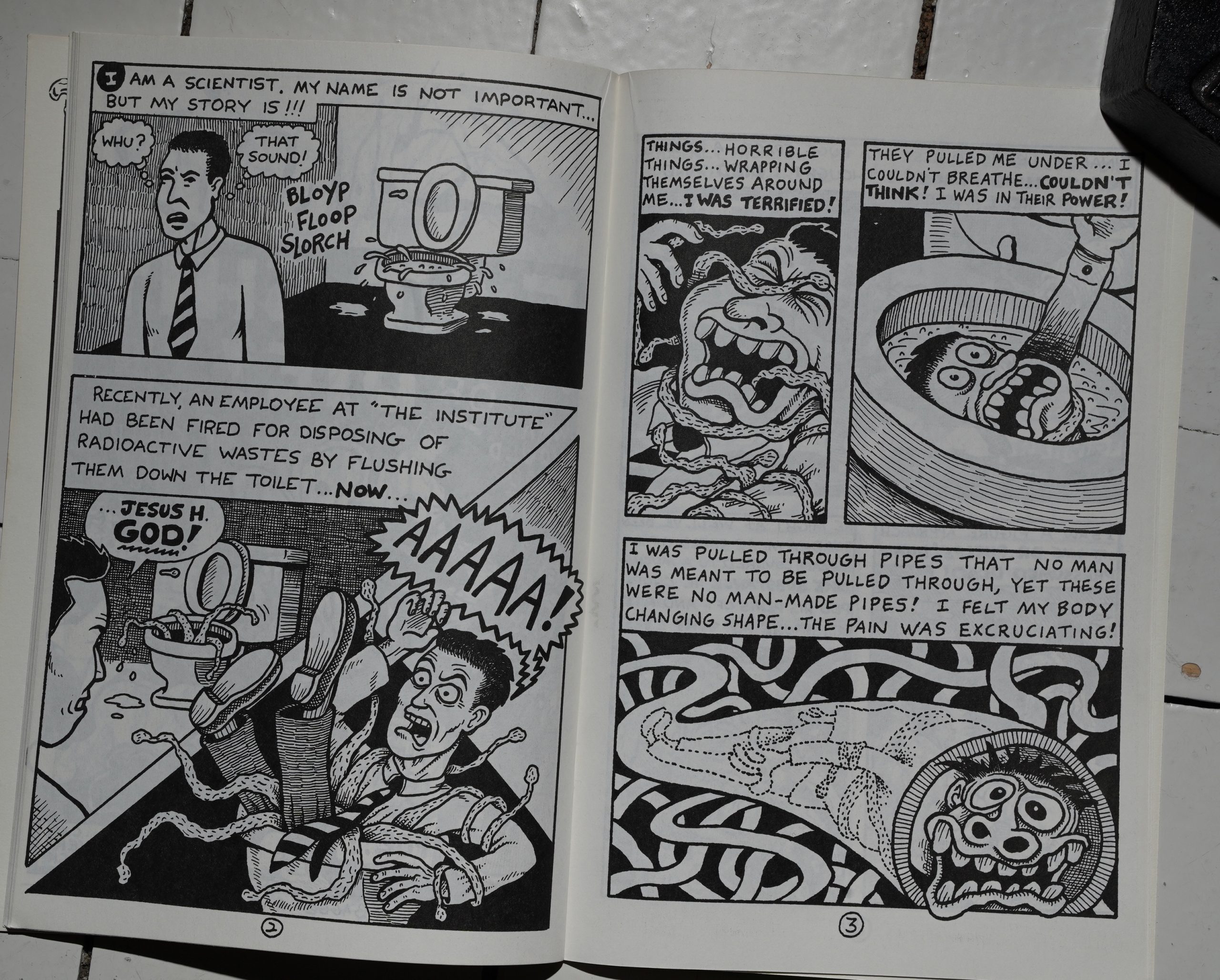

There’s a computer-generated porn comic by “Dr. T”. Must be one of the earliest computer-generated porn comics?

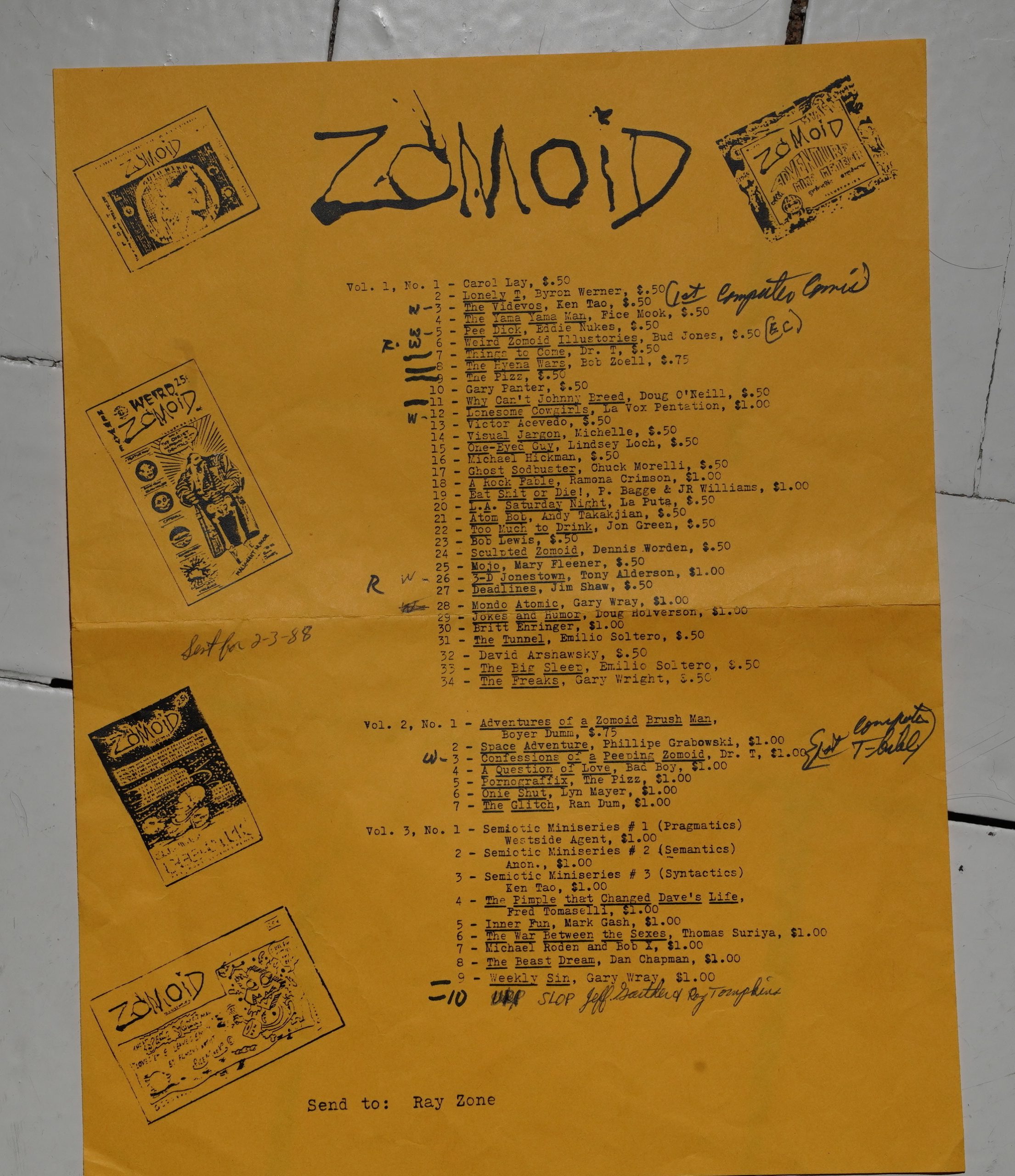

An… inventory sheet? Oh, yeah, some of these may come from Ray Zone’s collection — I saw a bunch of comics from that collection being sold off on ebay.

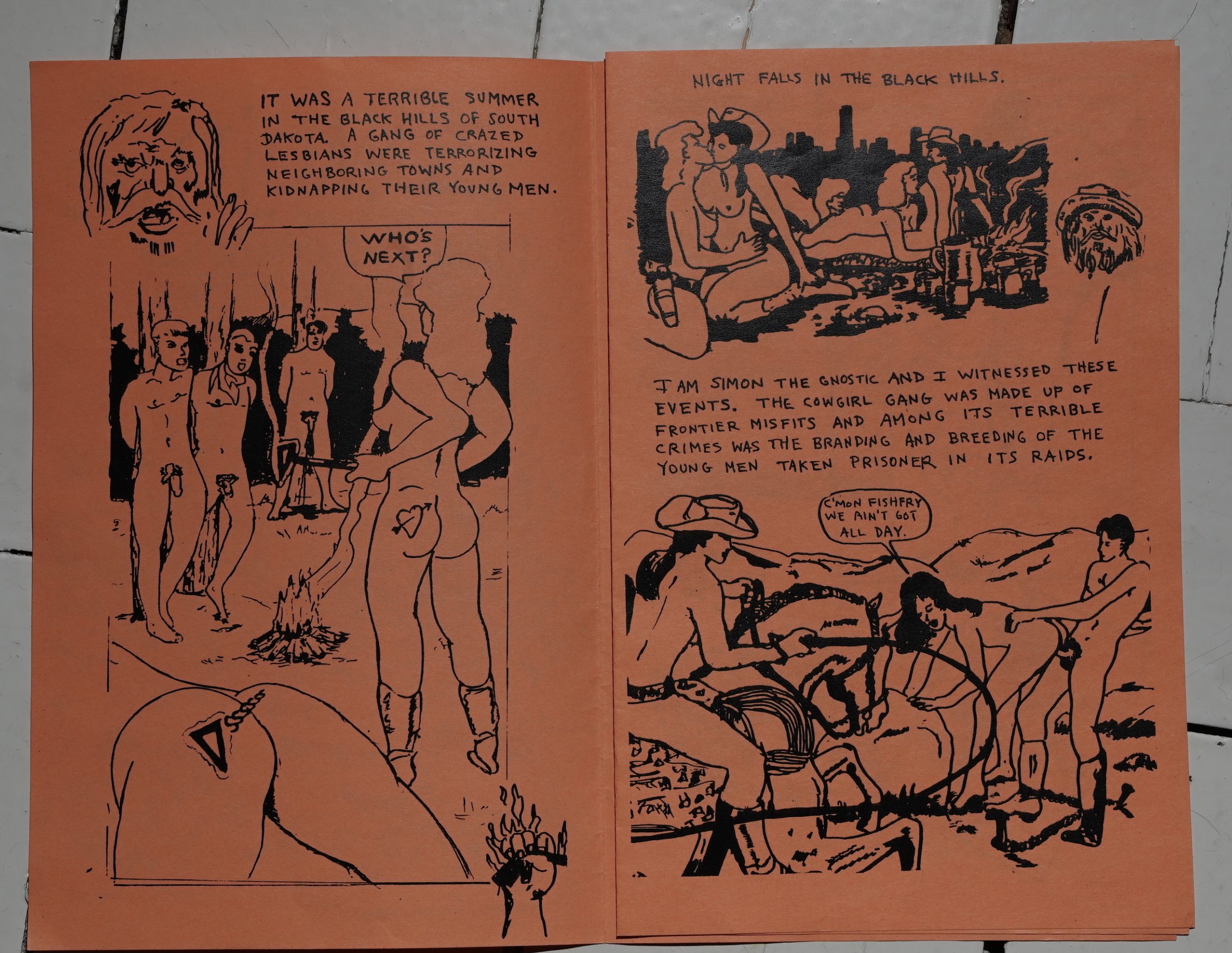

Weird porn from Lavox Fentation (which may be a pseudonym; I know).

Weird weirdness by Douglas O’Neill.

Er… more by “Dr. T”?

Pee-Dog’s dick Pee-Dick…

More computer-generated stuff by Ken Tao, so perhaps he’s “Dr. T”?

A pretty nice thing by Bob Zoell…

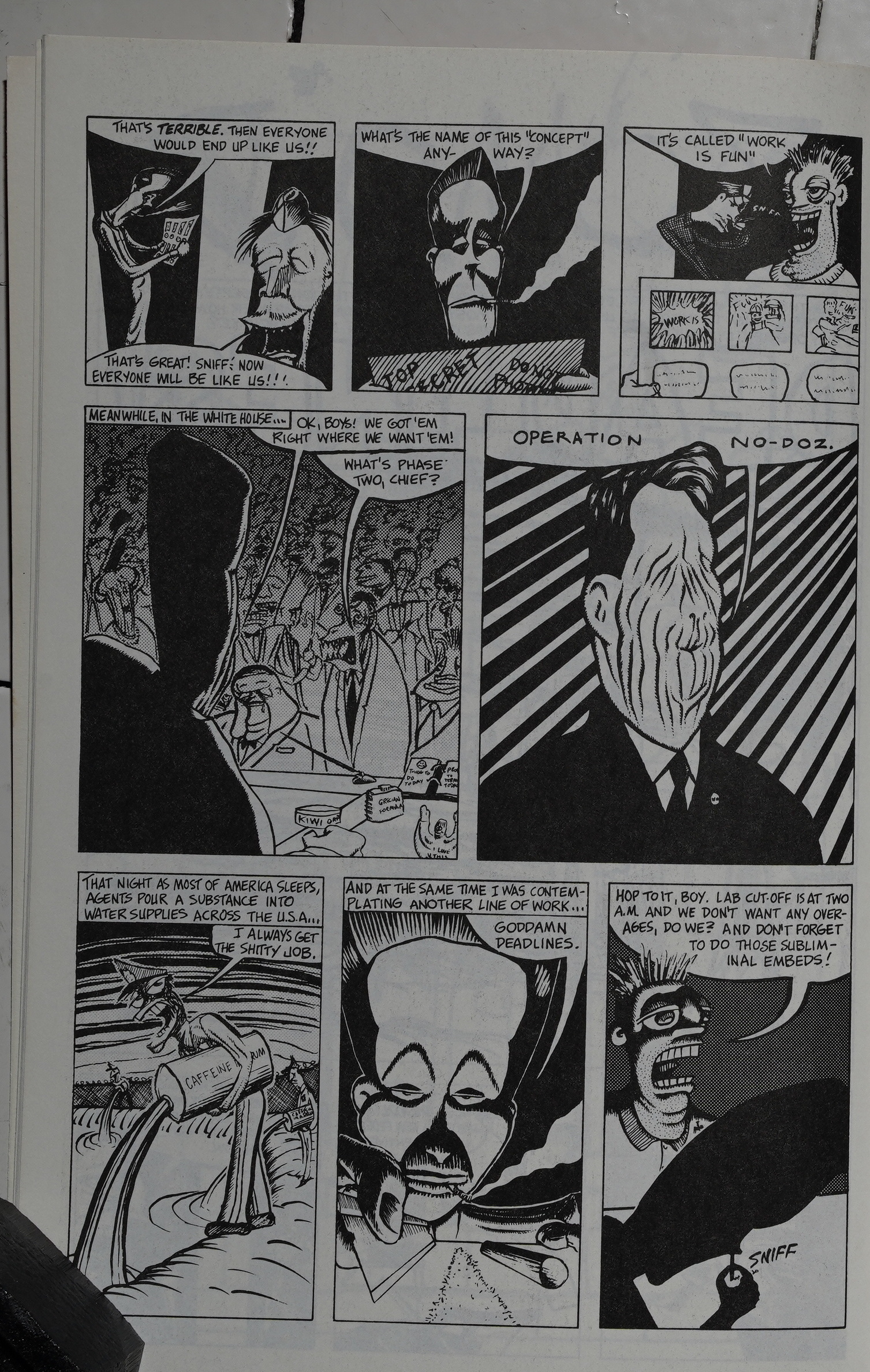

And then finally the book I had, which turns out to be a reprint of various minis (I think? it doesn’t say so explicitly).

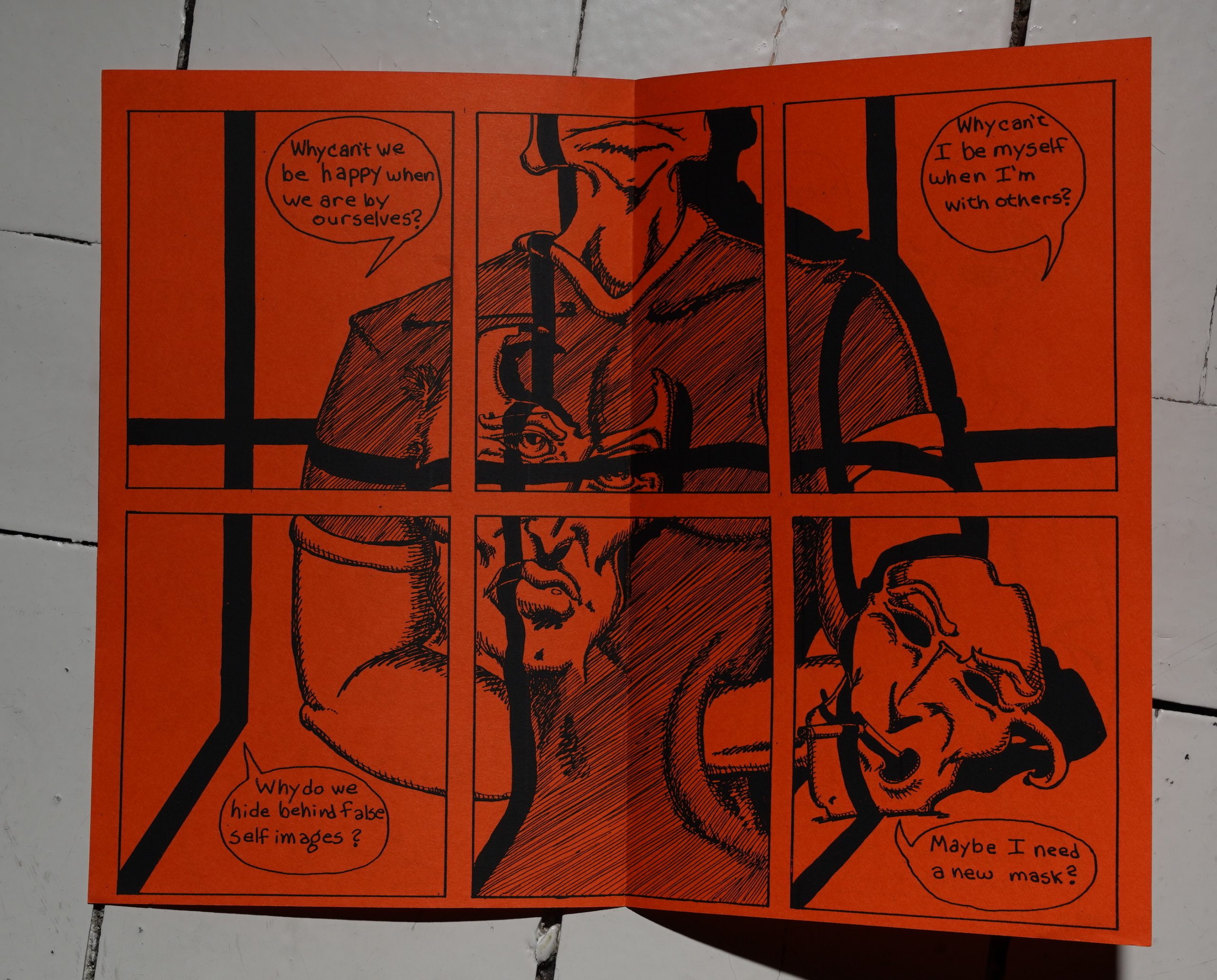

It’s less porny. (Jim Shaw.)

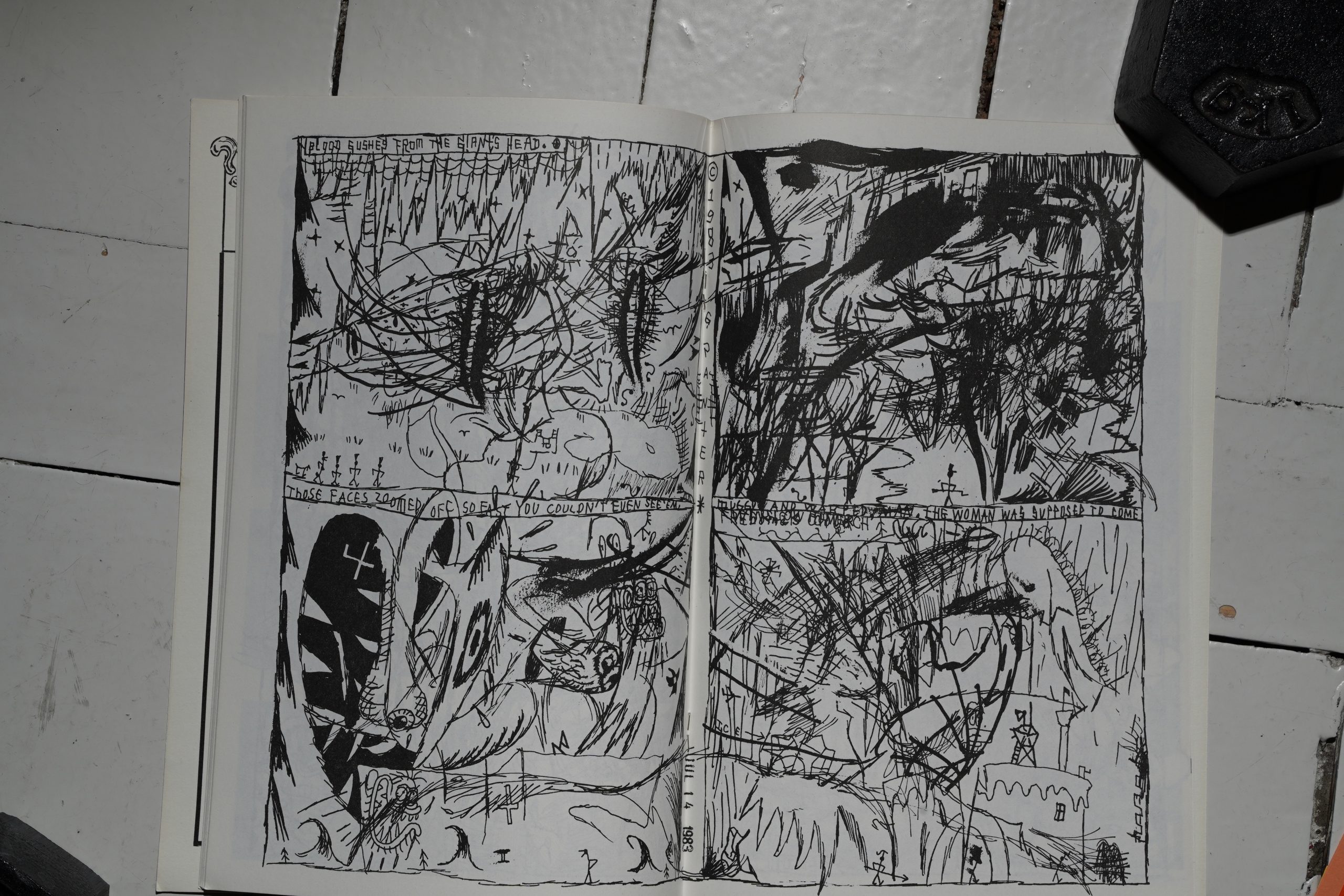

Then! Suddenly! Four pages of prime Gary Panter! I knew there had to be a reason I had bought this at the time…

Peter Bagge and J R Williams? It’s a pretty weird story.

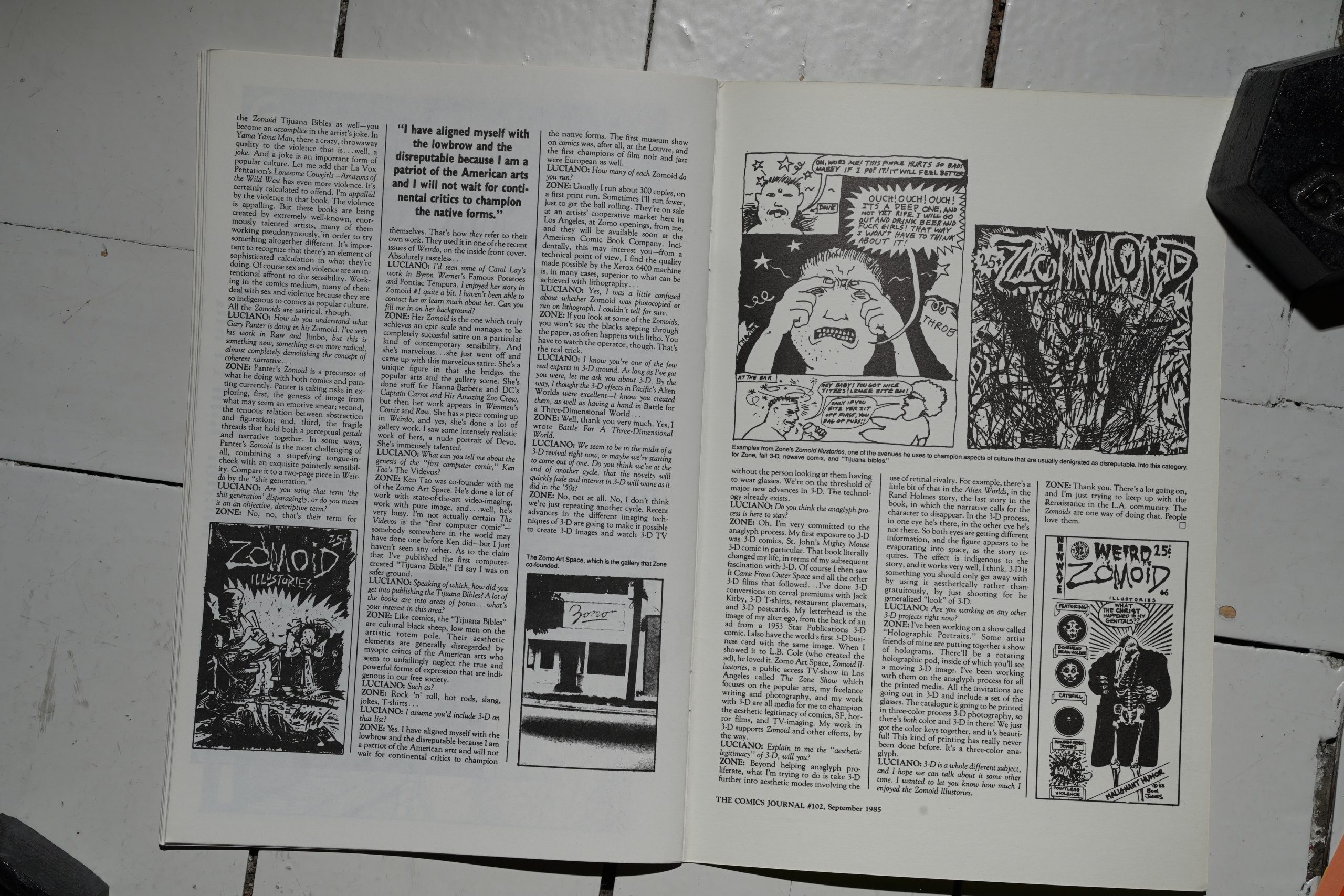

And then a reprint of an interview with Ray Zone from The Comics Journal.

So there you go. I’m not really much of a fan of stuff from the newave/mini comics sphere — it’s usually really unambitious work. Which I guess is what many people like about it: The freedom it represents?

This blog post is part of the Punk Comix series.

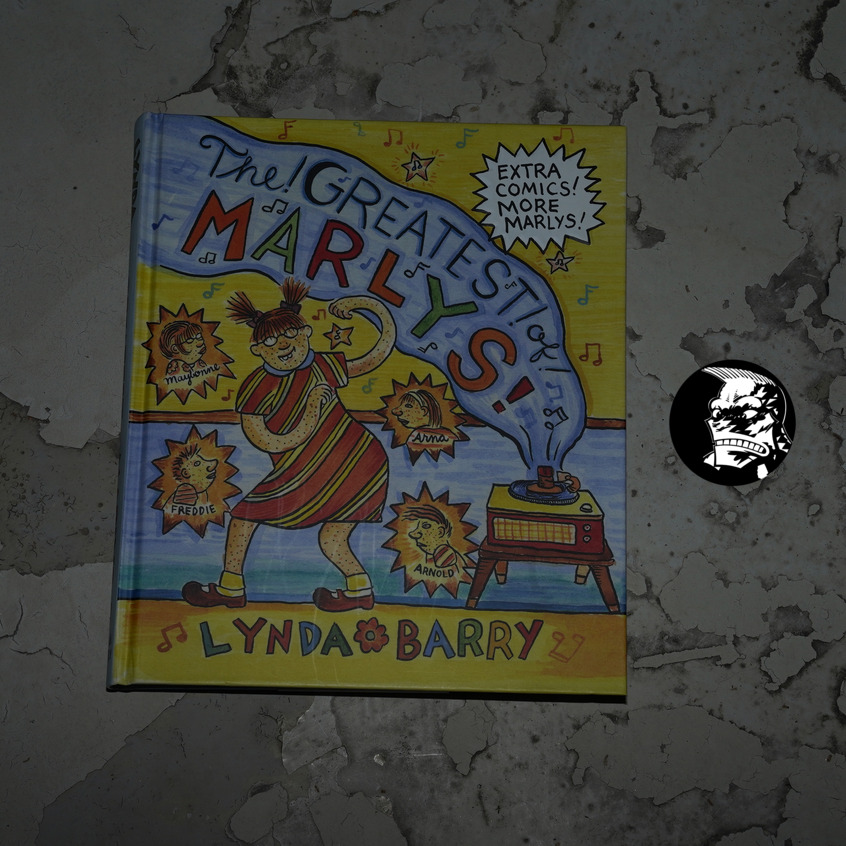

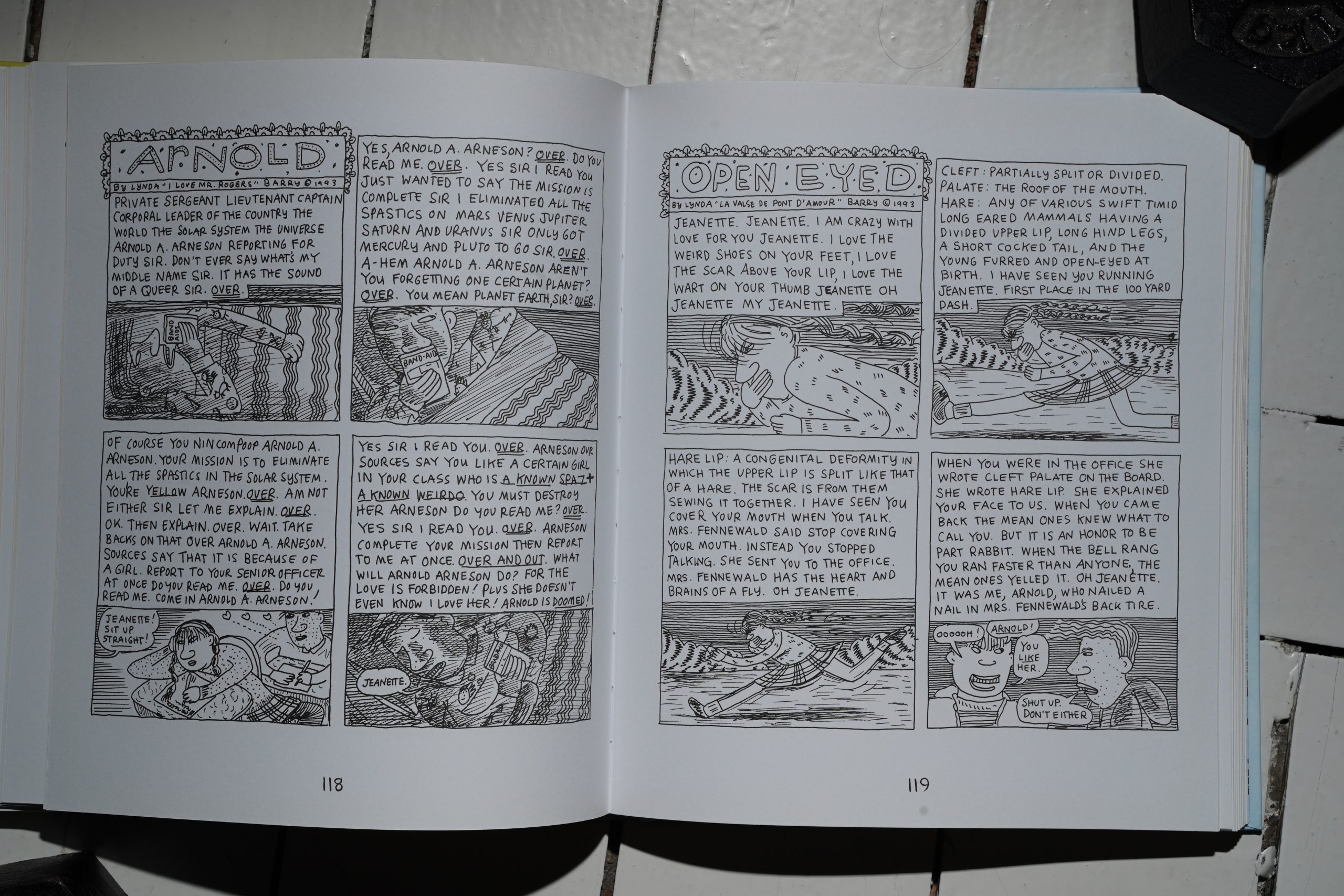

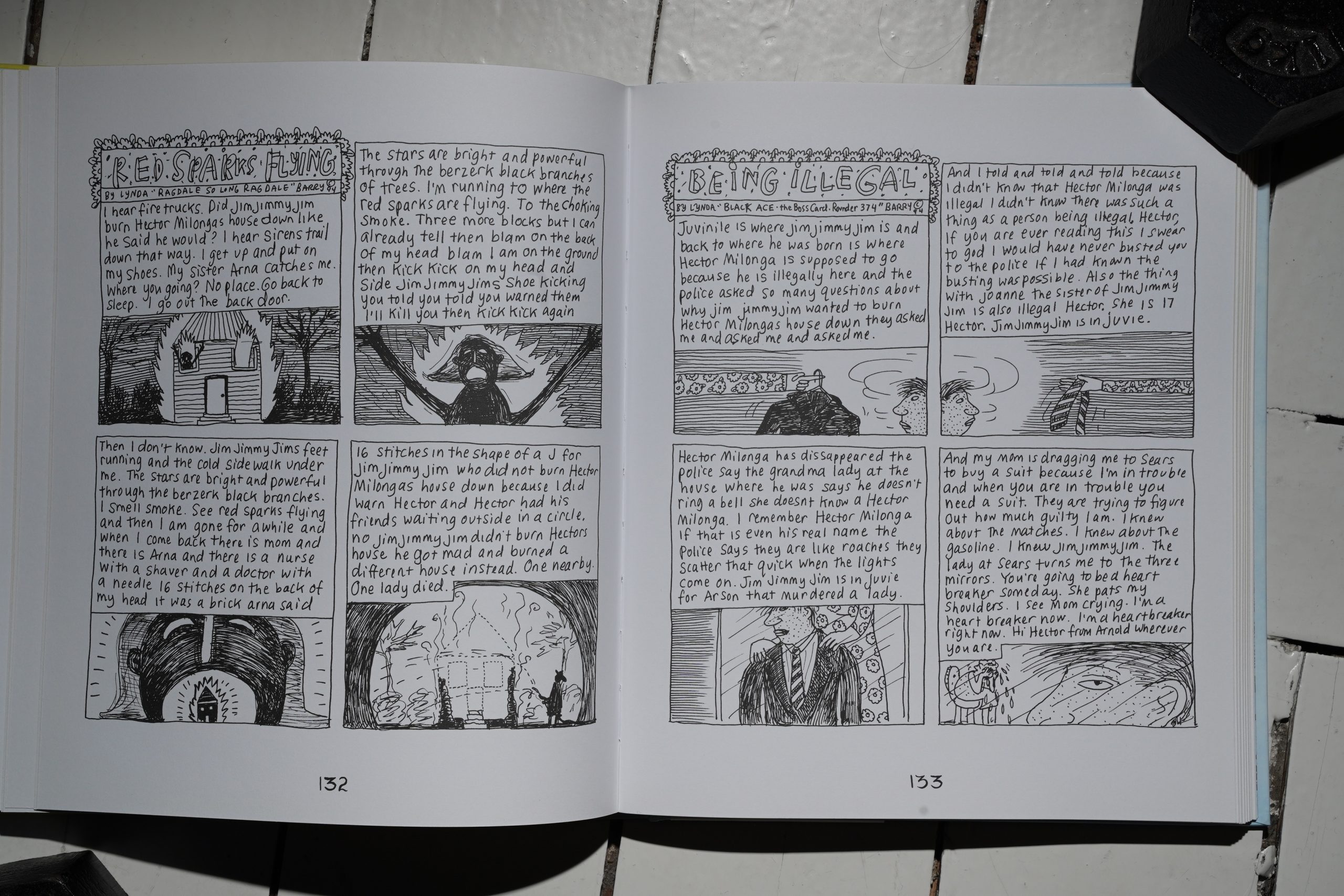

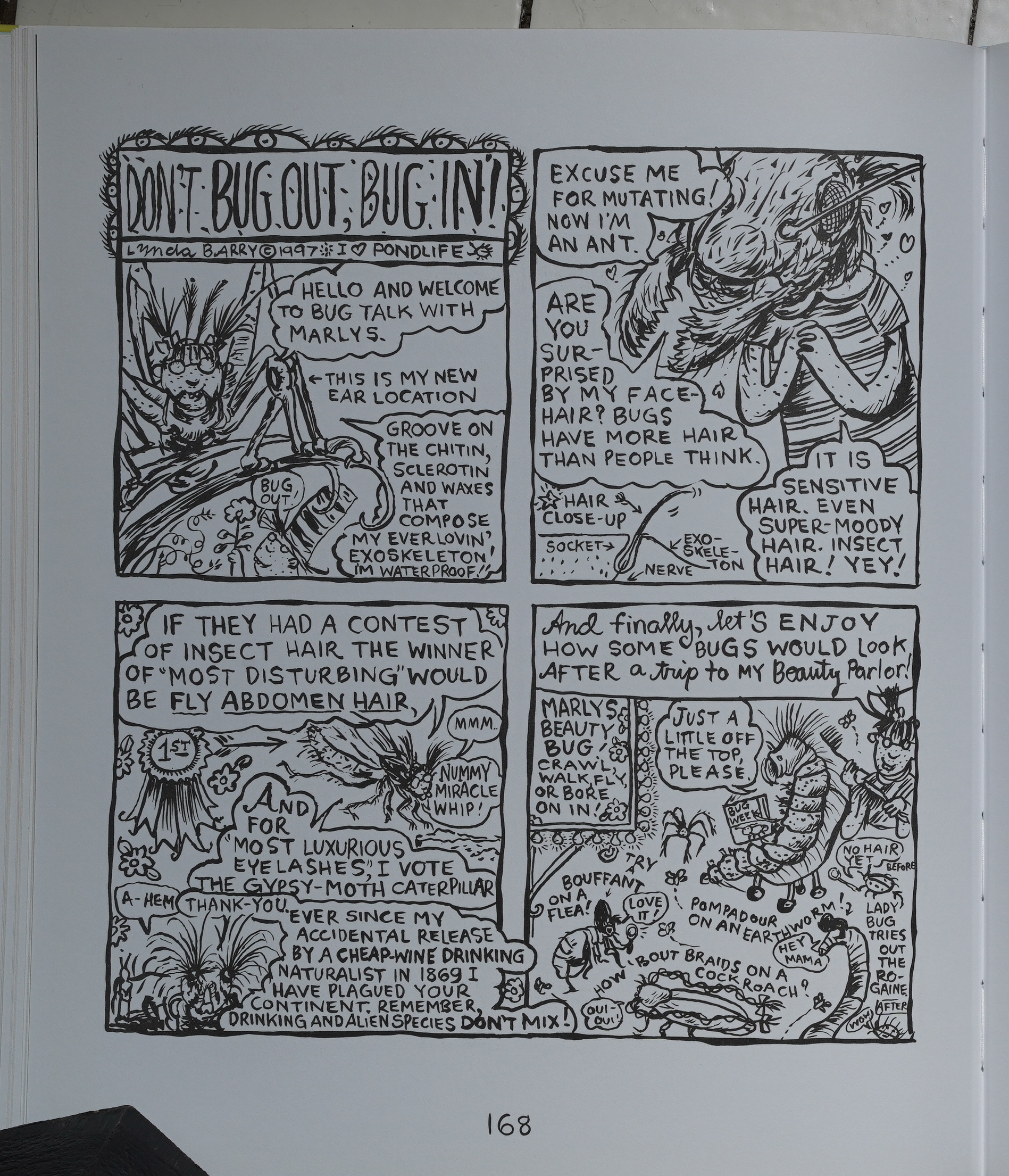

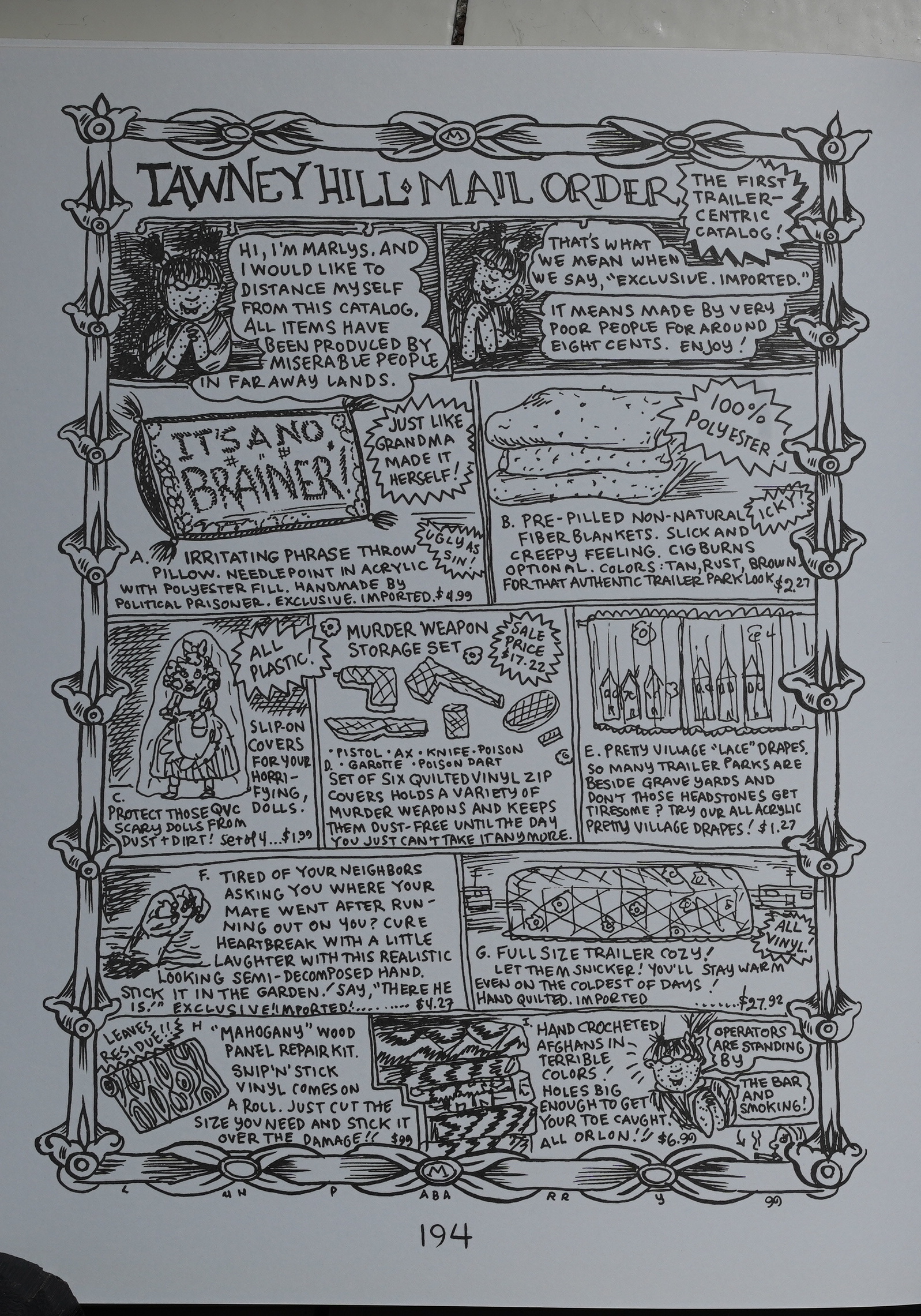

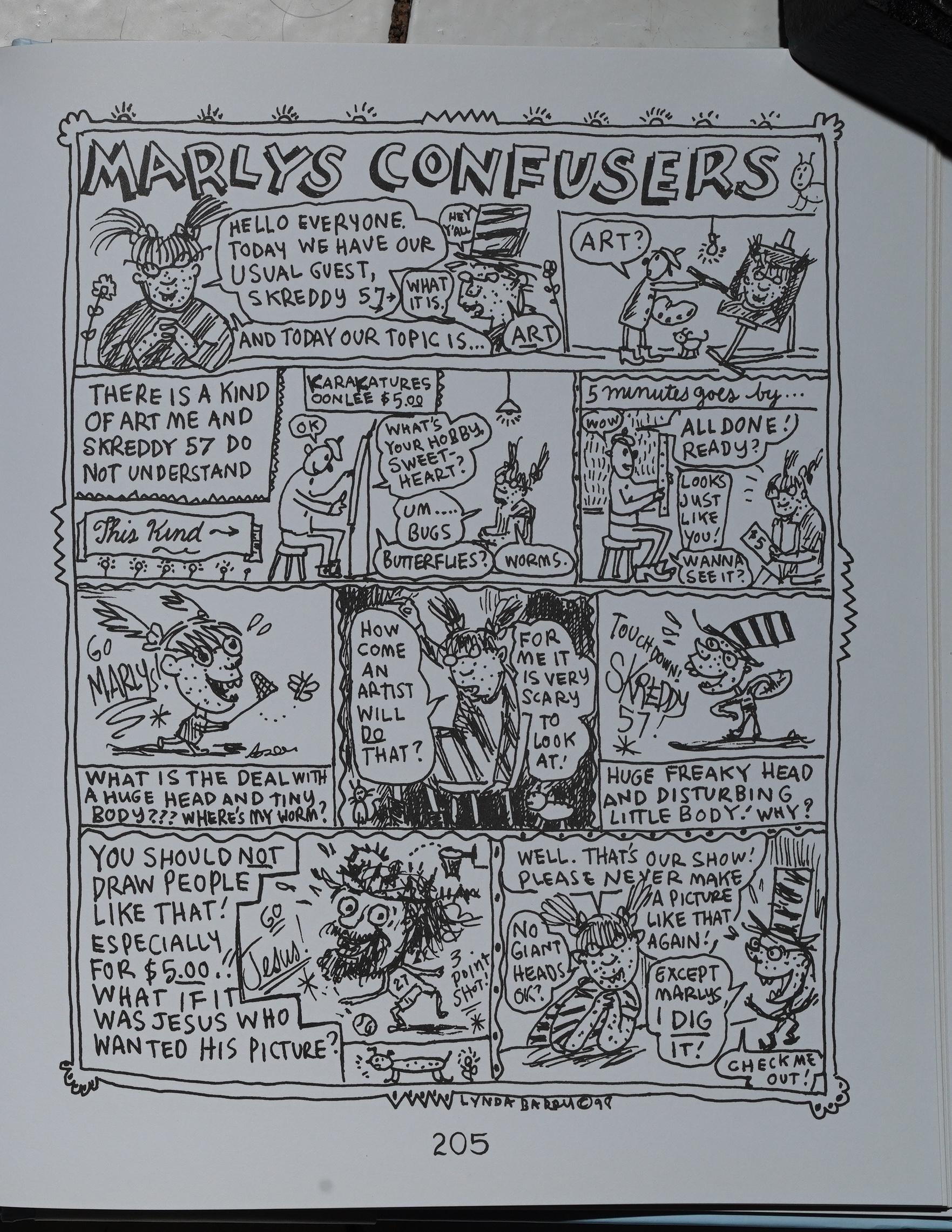

PX16: The! Greatest! Of! Marlys!

The! Greatest! Of! Marlys! by Lynda Barry (225x260mm)

This was originally released in a smaller edition by Sasquatch Books in 00, but I’ve got the 16 edition from Drawn & Quarterly here. (I got rid of the earlier edition while weeding out duplicates the other year, and now I regret it. Sooo much.)

That edition was, according to Amazon, 224 pages, and this one is 248 pages. So it’s not that much extra.

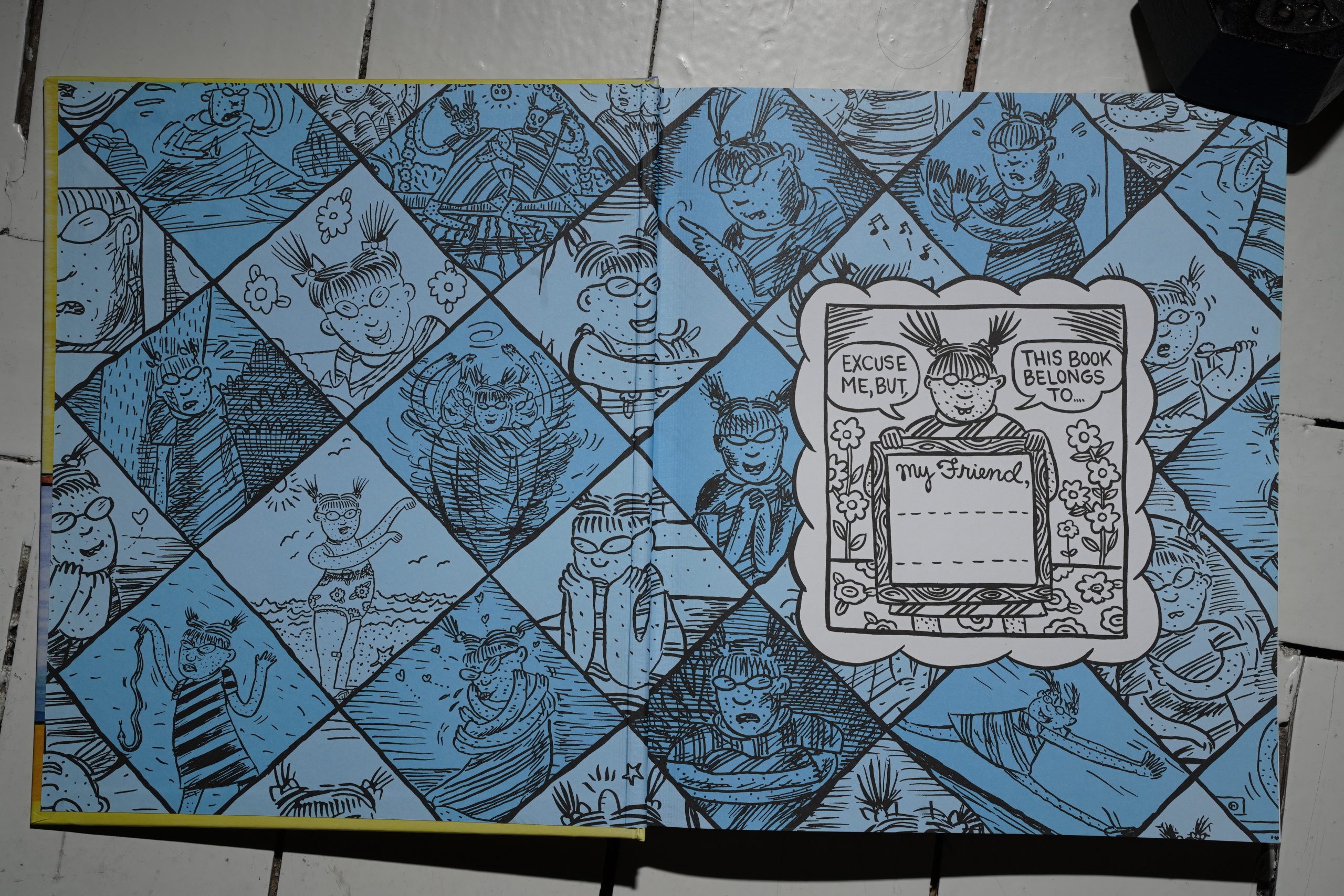

This is a quite handsome book — it’s pretty understated; no introductions by famous authors or anything…

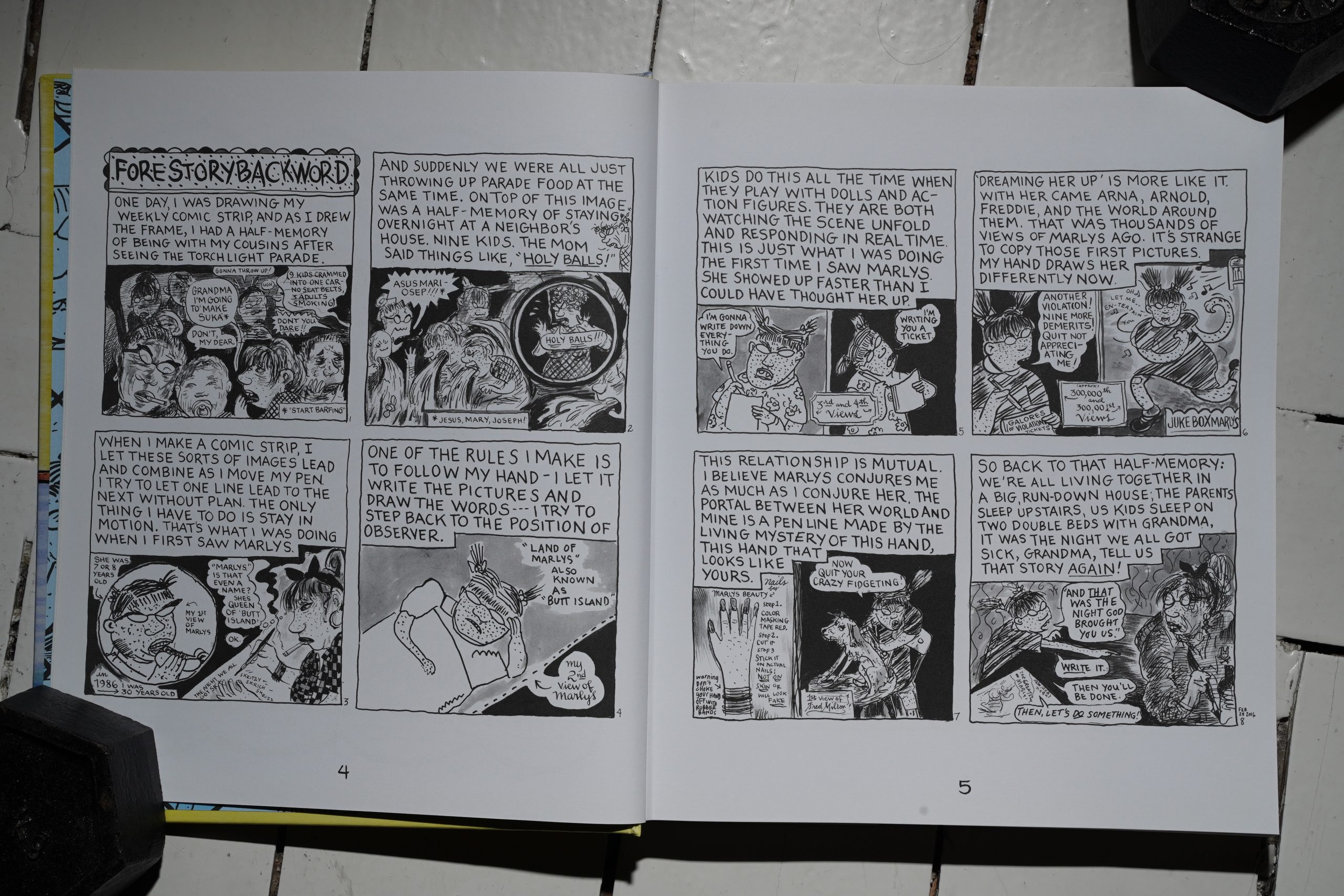

… just a two-page introduction by Barry herself, explaining how Marlys came to be.

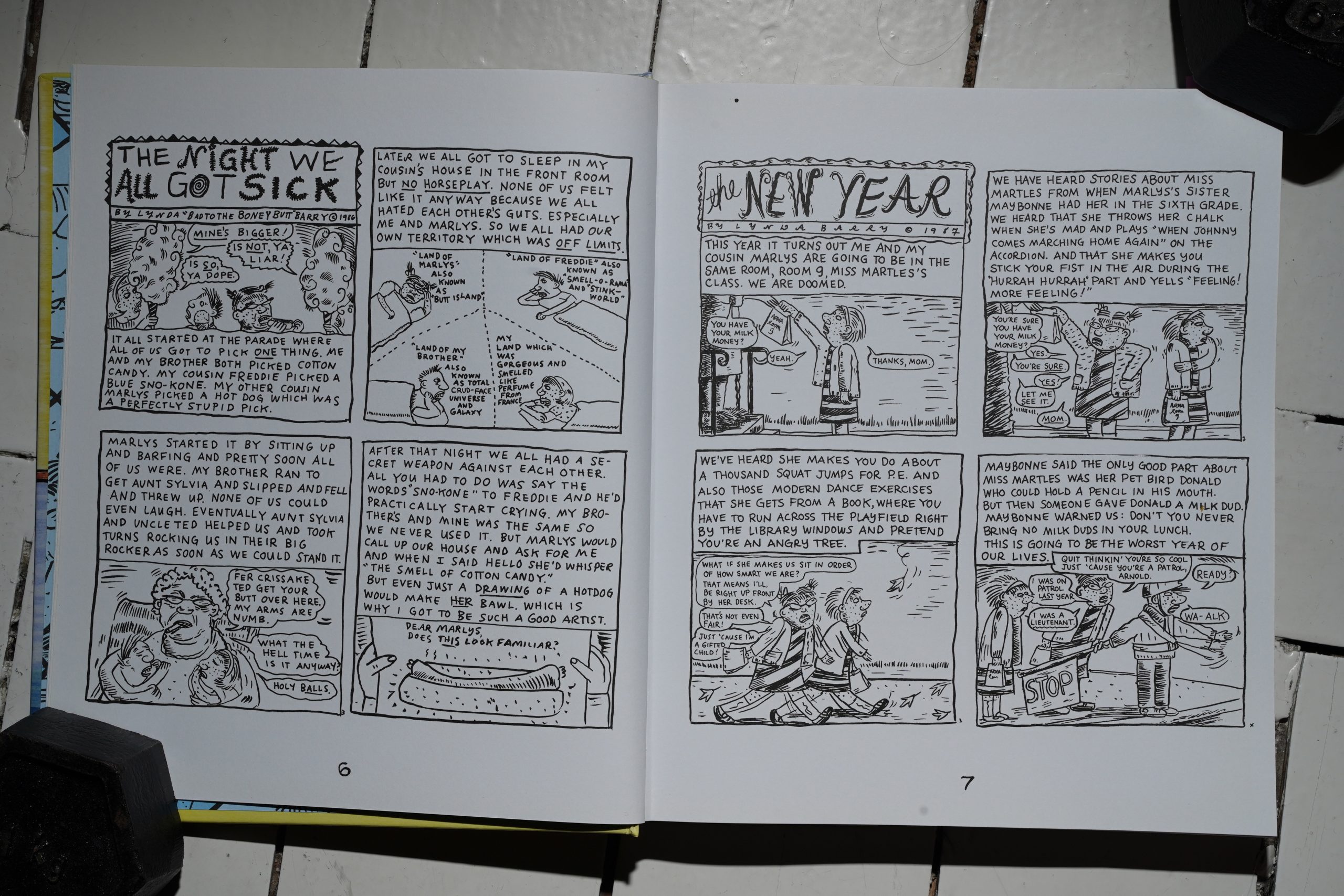

And then we get more than a hundred strips selected from the collections from the late 80s. There was one strip that I wondered whether was new (i.e., not reprinted before), but anyway — we’re getting most (all?) of the old strips that involve Marlys, but none that focus on the rest of her family from those books (in particular, none of the Maybonne strips).

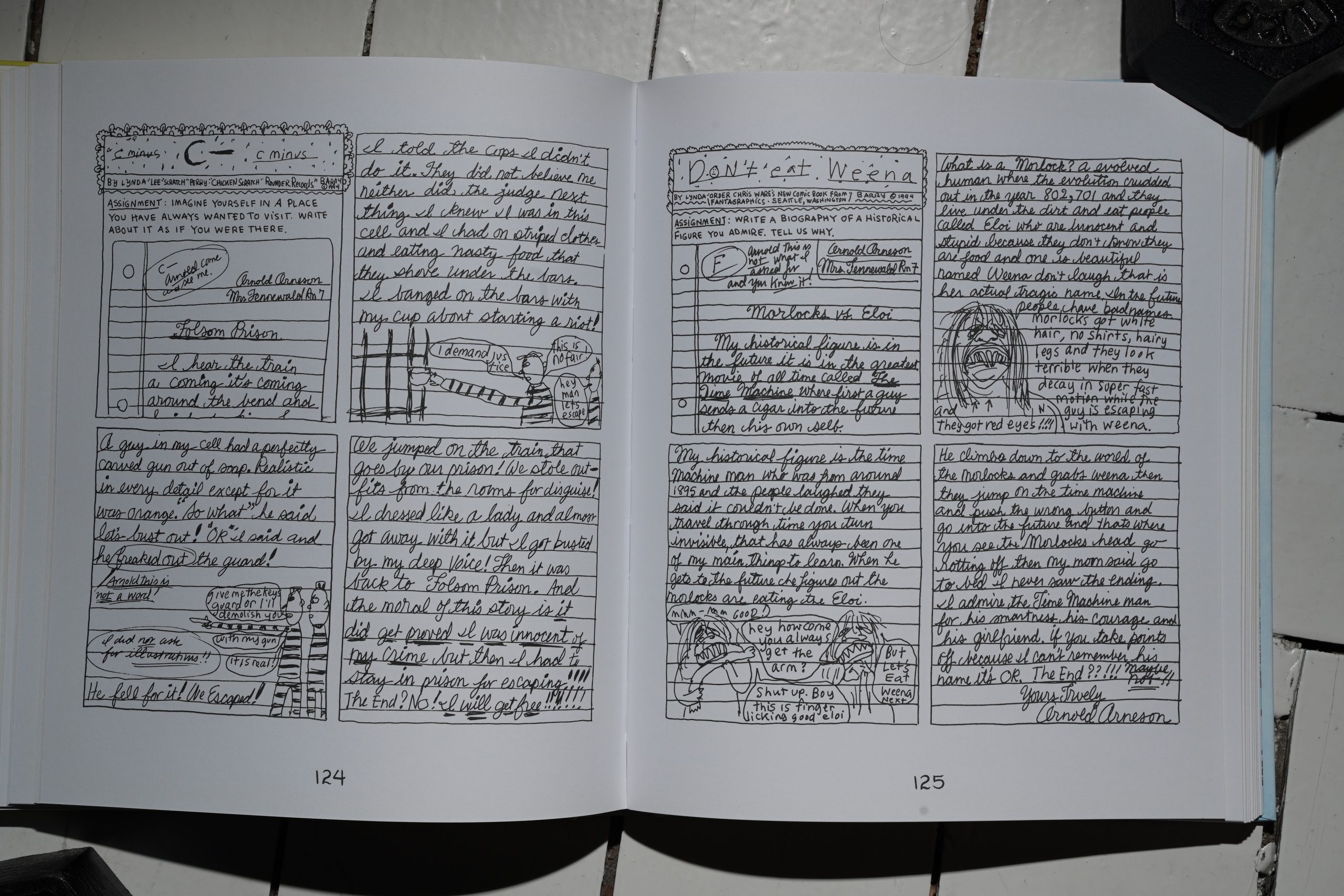

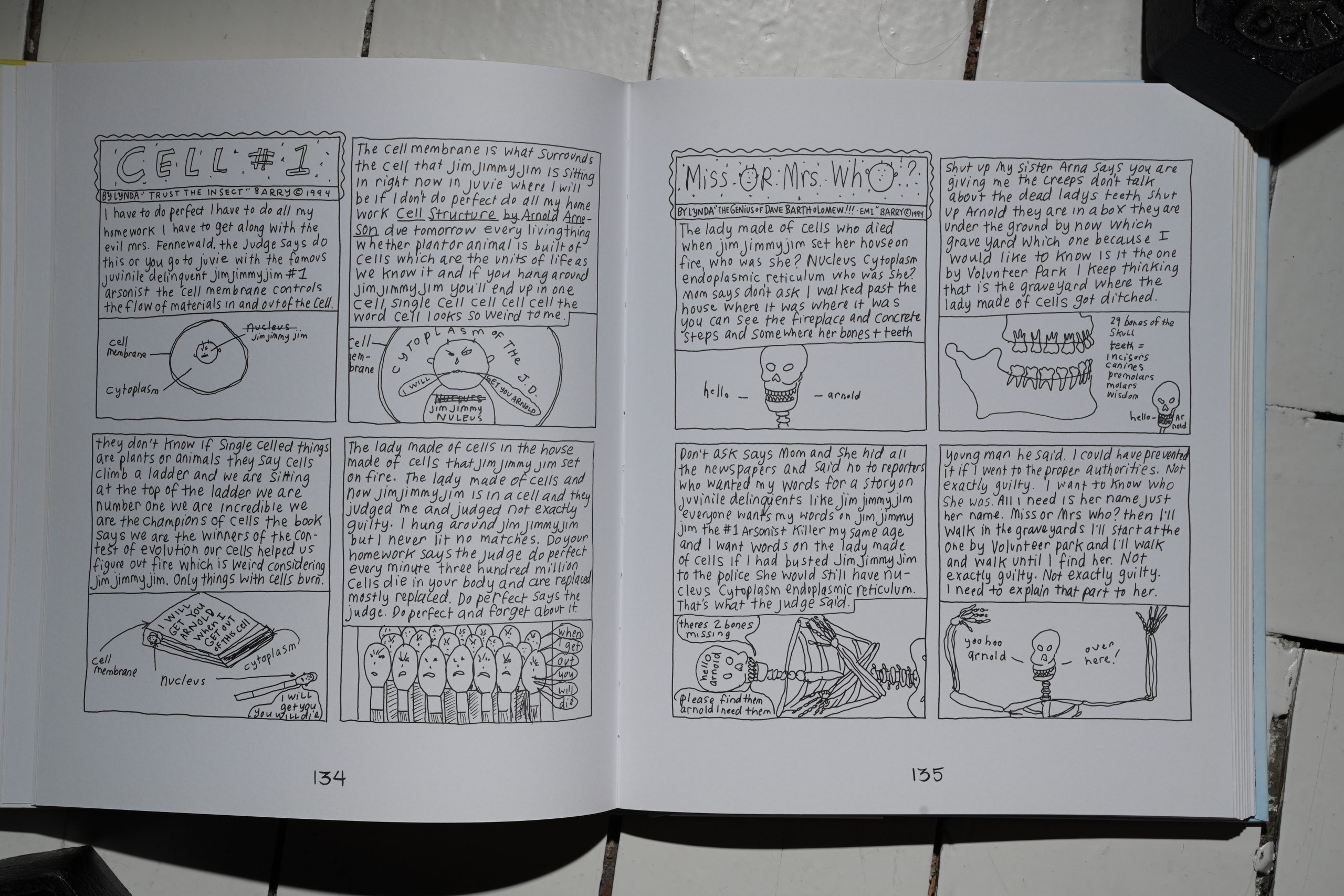

The final Harper Collins (published in 94) had strips (mostly) from 91 and 92… but this collection seems to pick up the reprints right where that book let up. So we get a bunch of strips from 93 and 94, but (confusingly enough) very few of these involve Marlys. Instead most of these are about Arnold (Marlys’ cousin).

I mean, I love finally getting to read these, but… why… stash them in the middle of a book collecting the Marlys strips?

And then it becomes pretty clear — I think it would just be pretty difficult to get a publisher to do a stand-alone book collecting these strips. Barry like experimenting with different approaches, but many of these strips feel pretty dashed off. They’re not graphically attractive (which is very unusual for Barry) and they’re not that gripping (which is even more unusual for Barry).

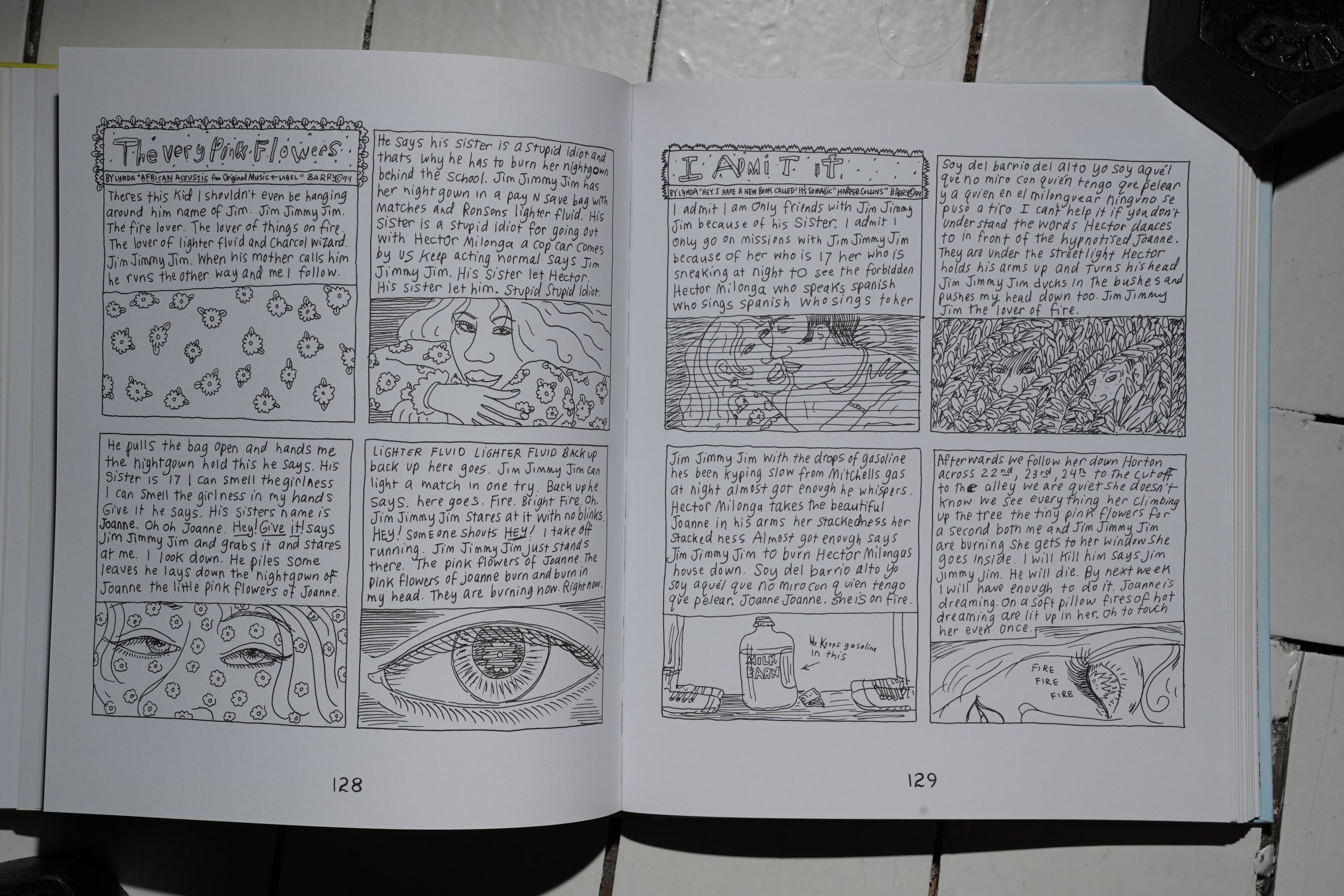

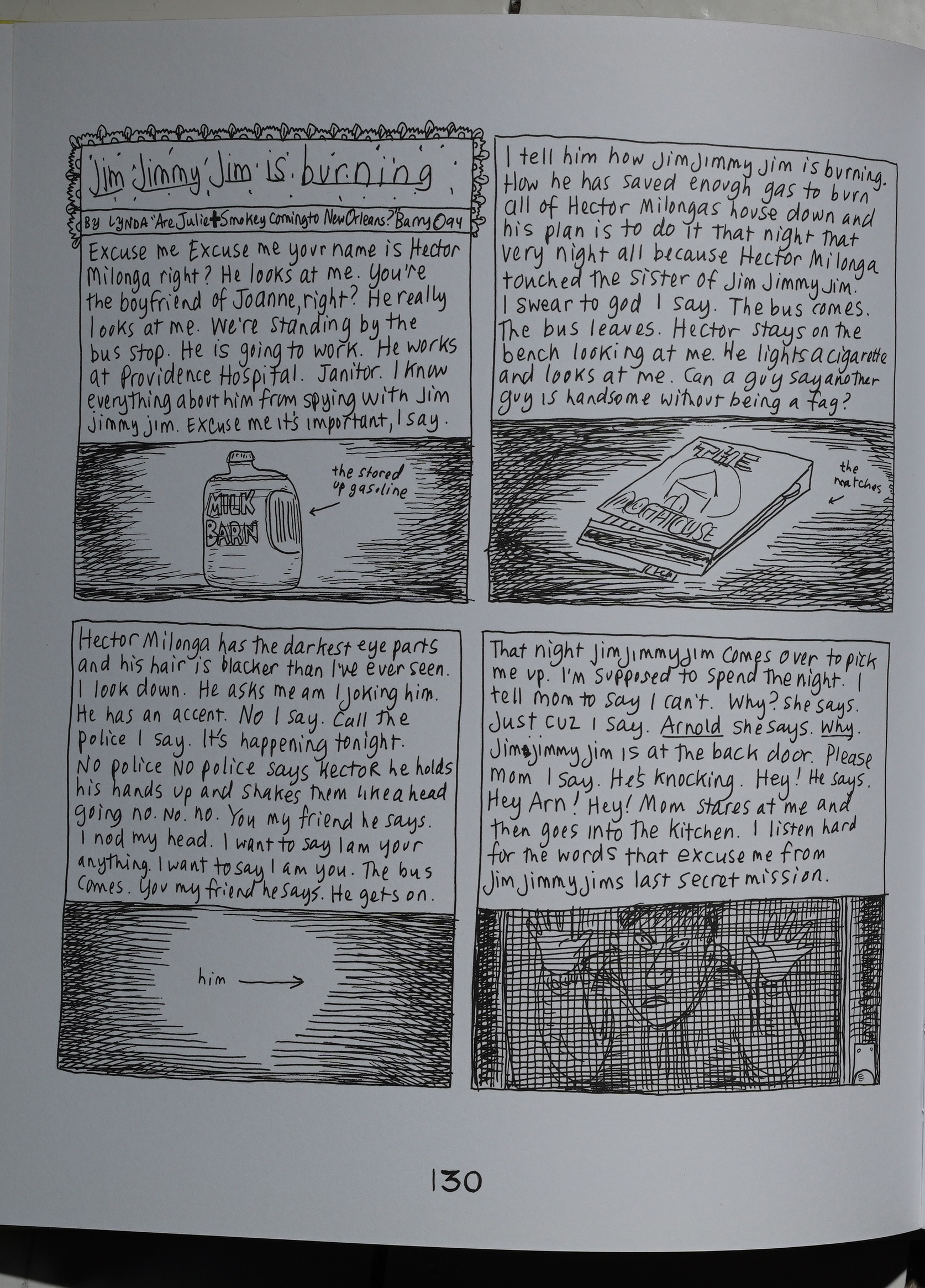

And then the strangest thing of all — the storyline (with Jim Jimmy Jim, the fire bug/killer) is the same as the one that was later printed as The Freddie Stories! But this first time around, it’s Arnold that’s involved with Jim Jimmy Jim and all that drama.

Was Barry just unsatisfied with the results? The storyline is sometimes repeated word for word, and it’s certainly more interestingly drawn in The Freddie Stories (here she seems do have ditched her brush and is just doing everything with a pen).

The version in The Freddie Stories is a lot harsher, though. Perhaps because Freddie is such a vulnerable character, and Arnold is sturdier, the storyline felt more exploitative in The Freddie Stories. And Arnold isn’t sent into a spiral of atrocities like Freddie is, but bounces back pretty quickly.

The artwork gets very basic indeed in parts.

Then it bounces back a bit, but it seems like Barry avoided using a brush for more than a year.

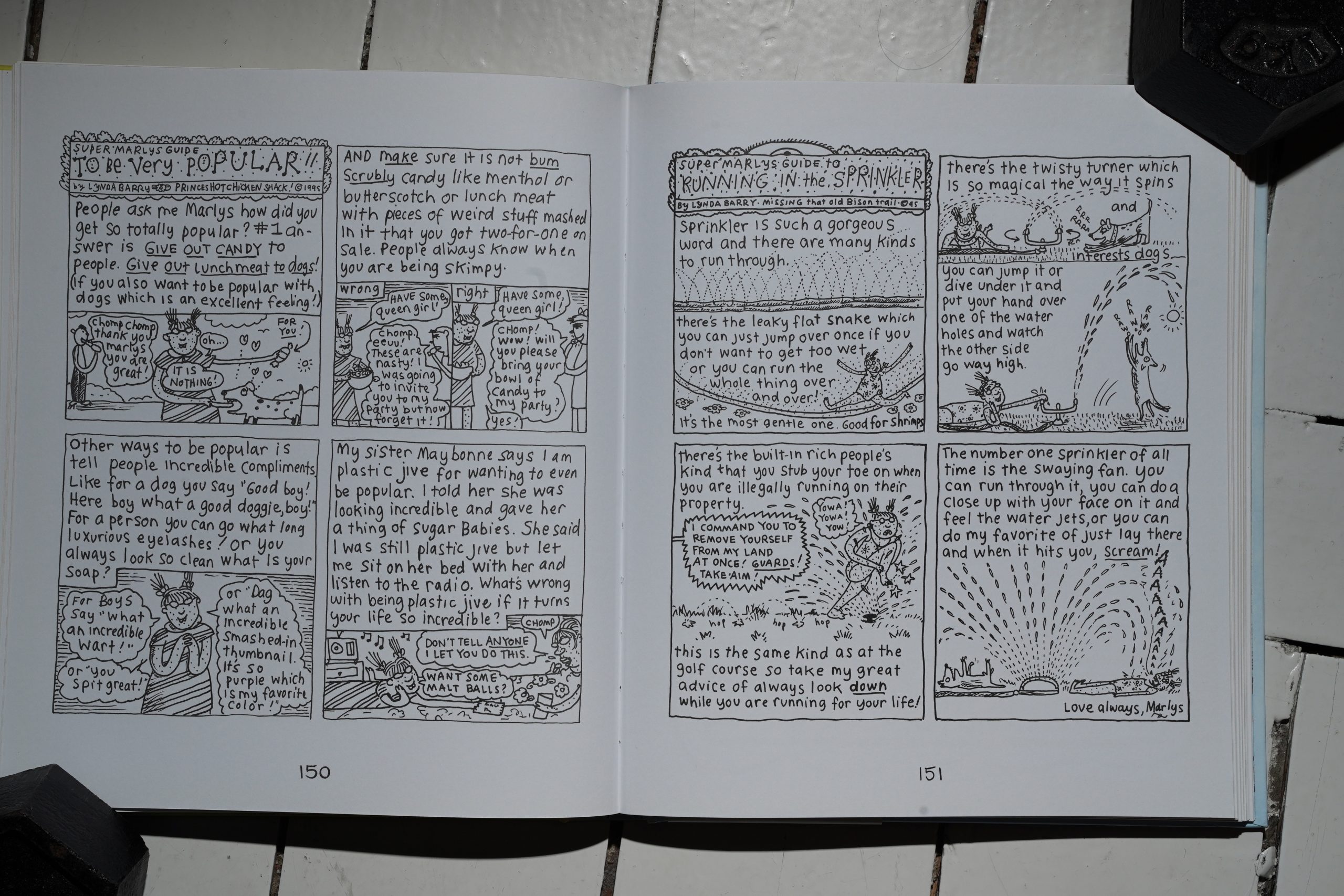

Then when it returns, it’s such a relief. But the storyline kinda evaporates and the characters start doing odd things.

I’m guessing that Barry did other Ernie Pook strips in between the Marlysverse strips, but perhaps the two types of strips started blending together…

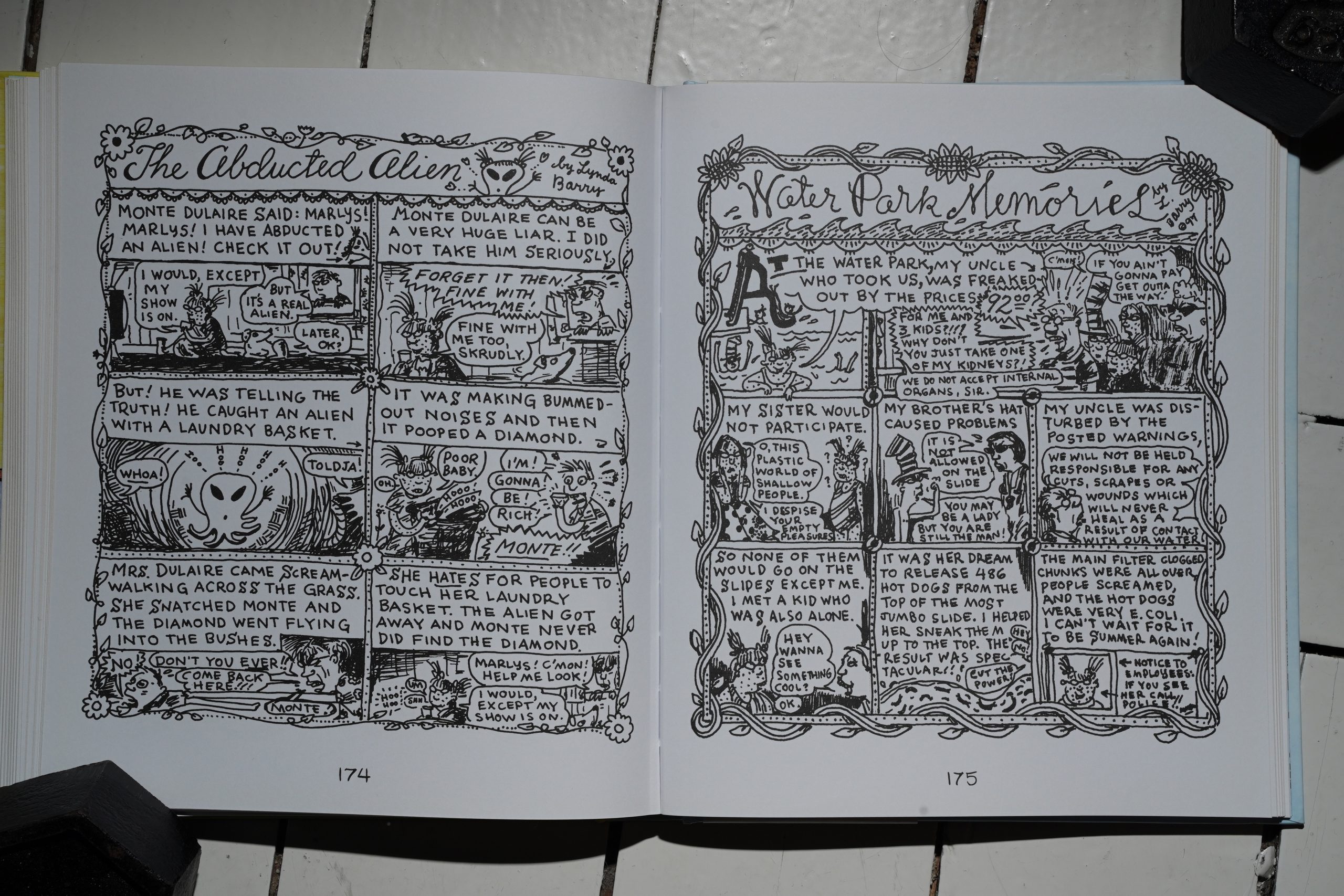

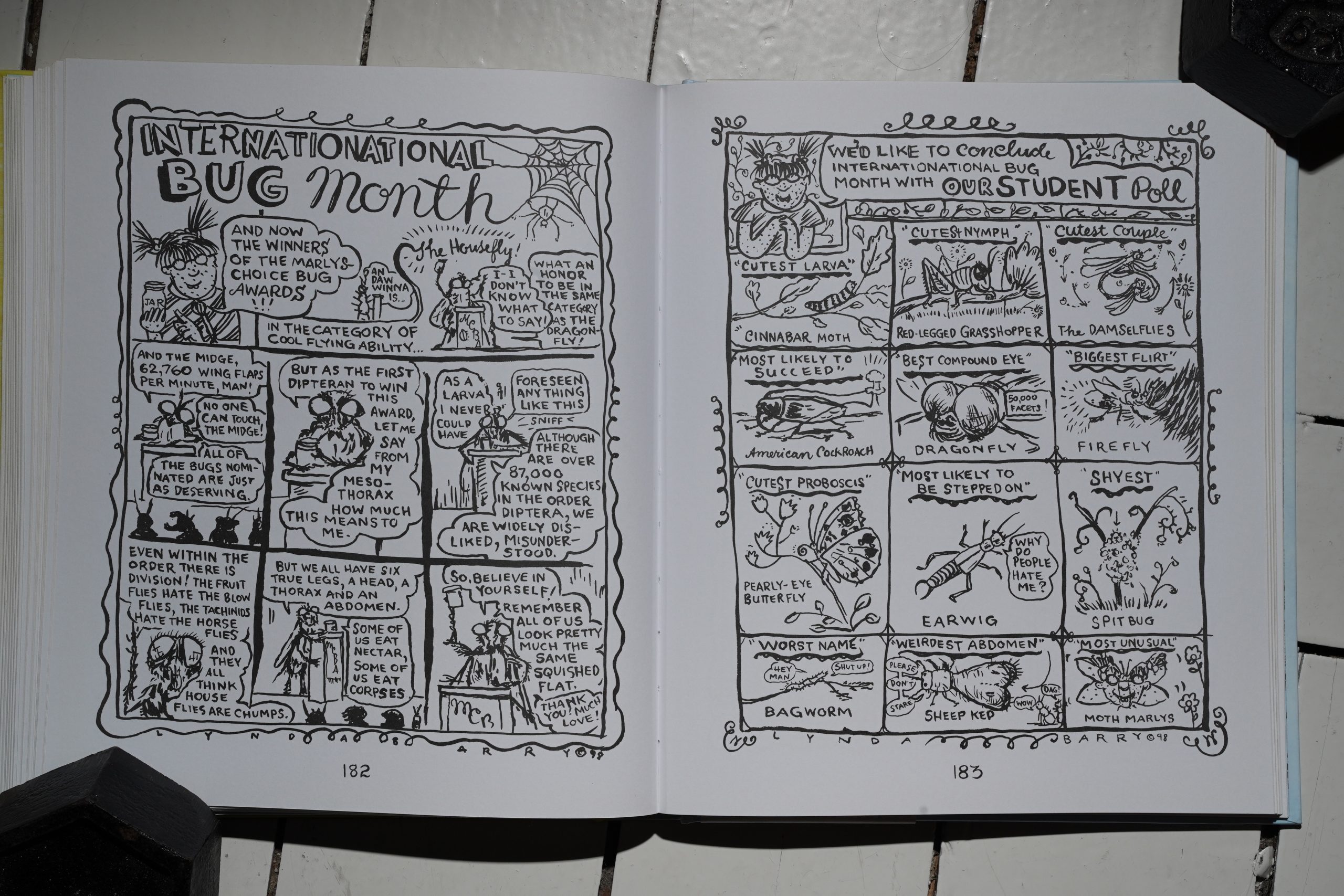

And then we get a bunch of pages done in a different layout — were these made for a different venue than the Pook comics? They seem to have been drawn very small and then blown up… or at least not reduced. The lines are very chunky.

Lots and lots of pages about bugs.

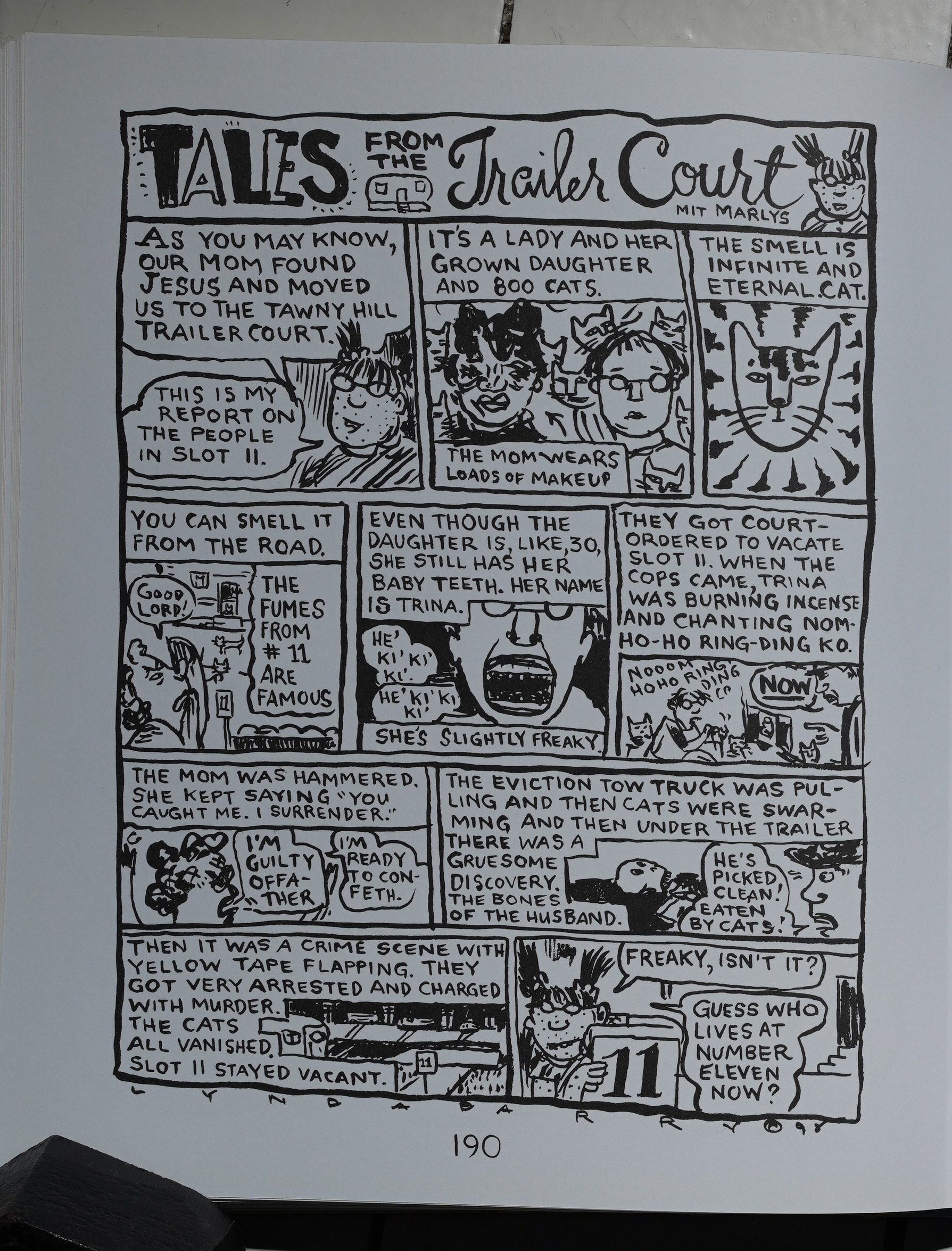

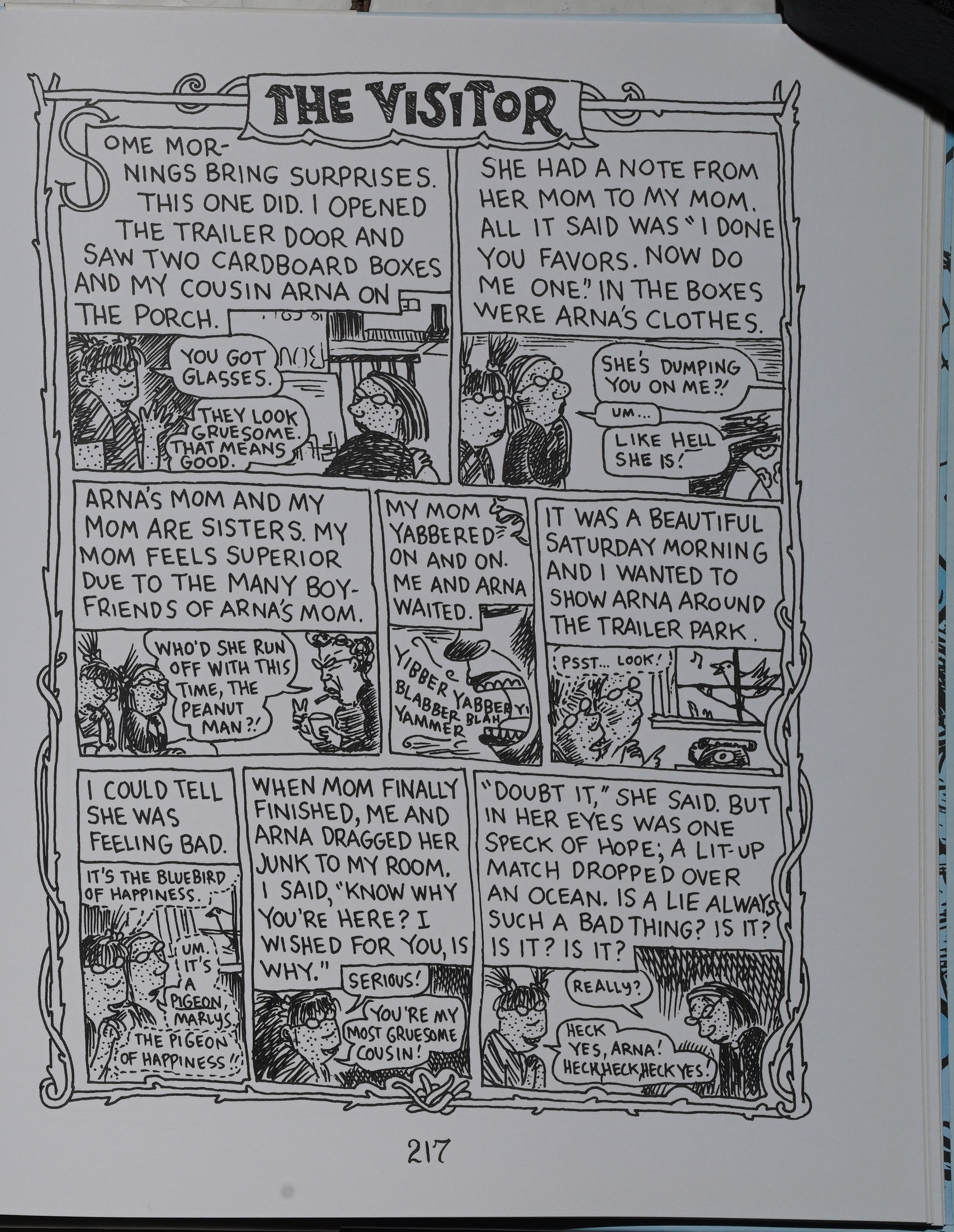

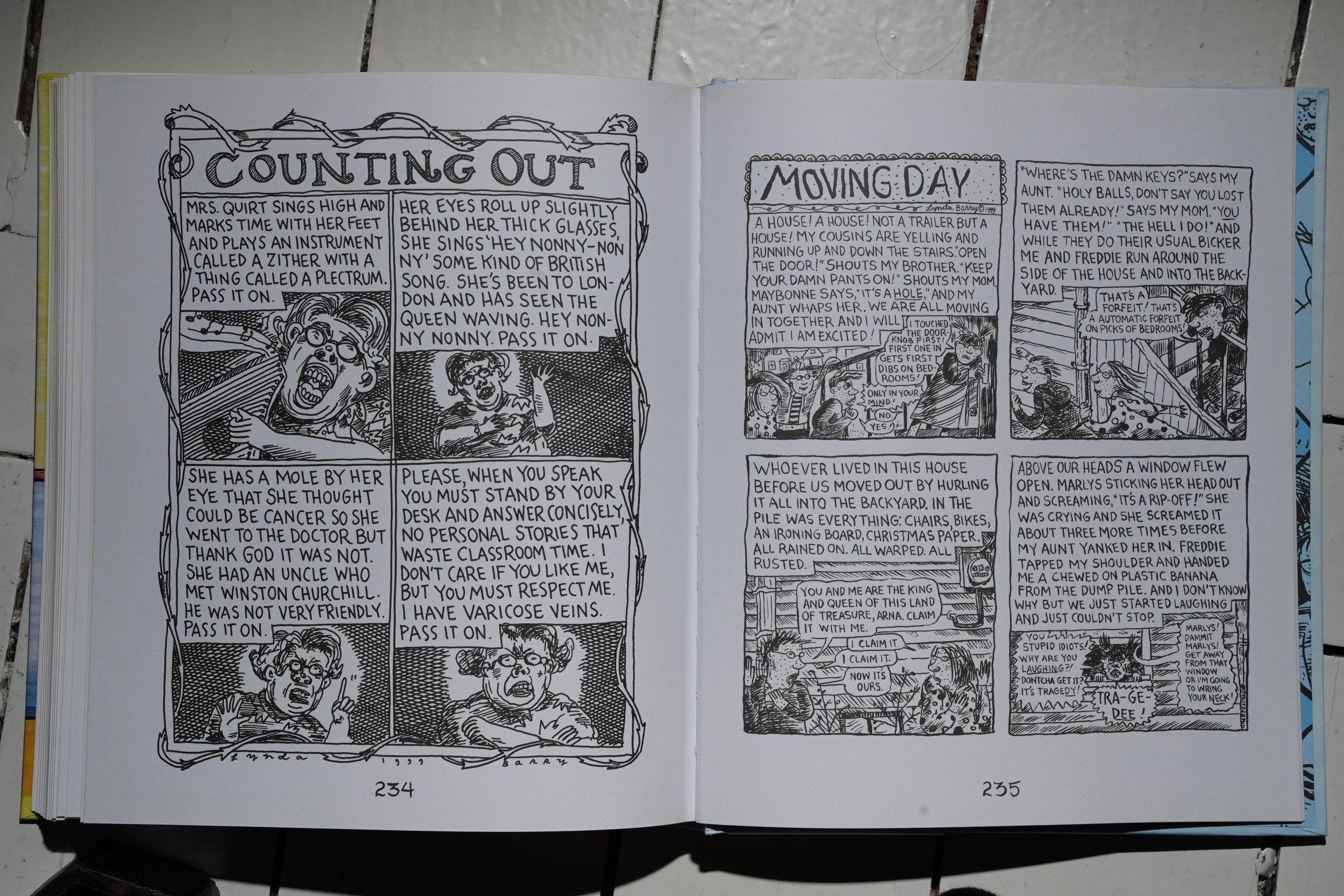

And then! Some plot! They’ve now moved to a trailer park.

And the strips get funnier again.

Yeah, what’s up with people drawing bobble heads? Those caricatures are repulsive! And don’t get me started about Funko Pops. Nauseating things.

Arna returns! We get this slow drip of “real” Marlys strips in between all the pages about bugs…

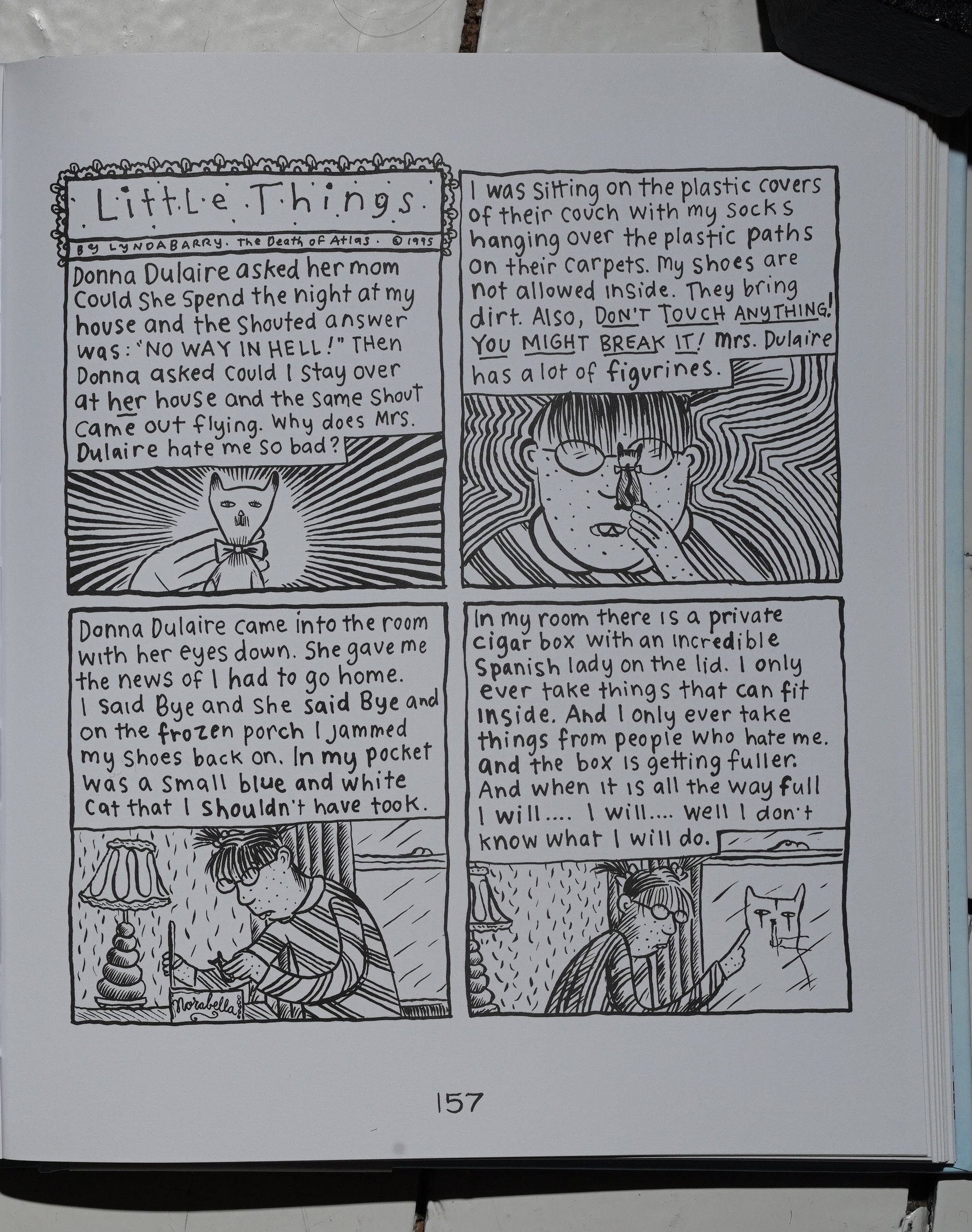

And then! Starting with strips dated 00, Barry snaps back to the style from the late 80s — fine, detailed brushwork, and a more day-to-day plot thing. It’s such a relief, because these strips are really, really good again.

So I wonder what happened in the 94-00 period…

Anne Elizabeth Moore writes in The Comics Journal #231, page 26:

THE! TOTAL! LIST!

lar, and/or otherwise most notable comic works that came out in the

year 2000. We list them here alphabetically, because at heart we are socialists,

and do not like to promote hierarchy when we can avoid it. Sort of unfortunately,[…]

Lynda Barr’s flawed and chunky language, and corresponding unsmooth

drawing style have, in the opinions of many reviewers, lifted her right out

of the realm of comics and dropped her square into the lap of literature. Is

it right to grant someone so much approbation that they no longer fit into

a category of peers? Probably not, but her writing is so exquisite, it is dif-

ficult to limit her praise to that characterized by any sin-

field Of art. Barry is a genius, therek no getting

around it, and her dear darling sweetheart character

Marlys is the perfect vehicle for the underlying

The-world-is-so-dang-groovrsometimes-it-

breaks-your-heart message.

Take this example from “The Total Book,”

a four-paneled single page from 1988 describing

cousin Arnol& written masterpiece: “The most

exciting feature of the book, though, is called The

Earth’s Most ompletely Longest List in the

Galaxy and Universe, Of All Time. It turns out

just to be a list of anything, only numbered, so

by the end you can tell how many.” The final

panel has Arnold asking his sister to name things

while he checks if they arc already on the list: “Um,

ping pong balls?”

“Got it already. Something else.”

“Alfred on Batman.”

“Already got it. Something else.”

“A water wiggle.”

“Oh, yeah.”

For her ingenuity alone — forgetting for a

second about the clunky presentation distracting

you from the fact you’re looking at utter beauty —

Barry earns a place on my personal list of right ons.

Right on.

True:

She makes use of a powerful technique throughout the stories: often the visuals focus on a character reacting to a situation that has either already occurred or is now happening, while the characters’ narration tells the rest of the story. This implicates the reader, inviting her to fill in with her imagination, creating a rare level of interaction and play between cartoonist and reader.

Heh:

But lots of artists are poignant, and lots of them “make you pause, cry and think.” Barry’s unique genius lies in her capacity to wiggle under your skin and, once there, to wiggle some more until you’re gasping and twitching, not sure if it’s with laughter or something else. She provokes existential squirminess.

It’s hard to find anybody being even the slightest bit critical:

The! Greatest! of! Marlys! is one of the best books ever written from a child’s perspective; laugh-out-loud funny, wise, silly, touching, awful, tragic yet ultimately so celebratory of how children survive, even in the worst possible circumstances, that Marlys Mullen is a hero as great as any to be found in fiction.

Marlys is a best-of collection from Barry’s long running comic strip Ernie Pook’s Comeek. The strip follows the adventures of eccentric eight-year-old Marlys Mullen along with her family and friends as they maneuver through the ups and downs of childhood. Each character is spot-on in the bizarre, delightful weirdness of being a kid. Marlys’ enthusiasm for life is endearing, and it’s rare to see such an accurate and nuanced depiction of an eight-year-old.

This blog post is part of the Punk Comix series.

Comics Semidaze

I read comics all day yesterday, so I had to get some work done today, but now I just wanna read comics again until I plotz… So a shorter daze. Microdaze.

| My Life With The Thrill Kill Kult: Confessions Of A Knife (Remastered) |  |

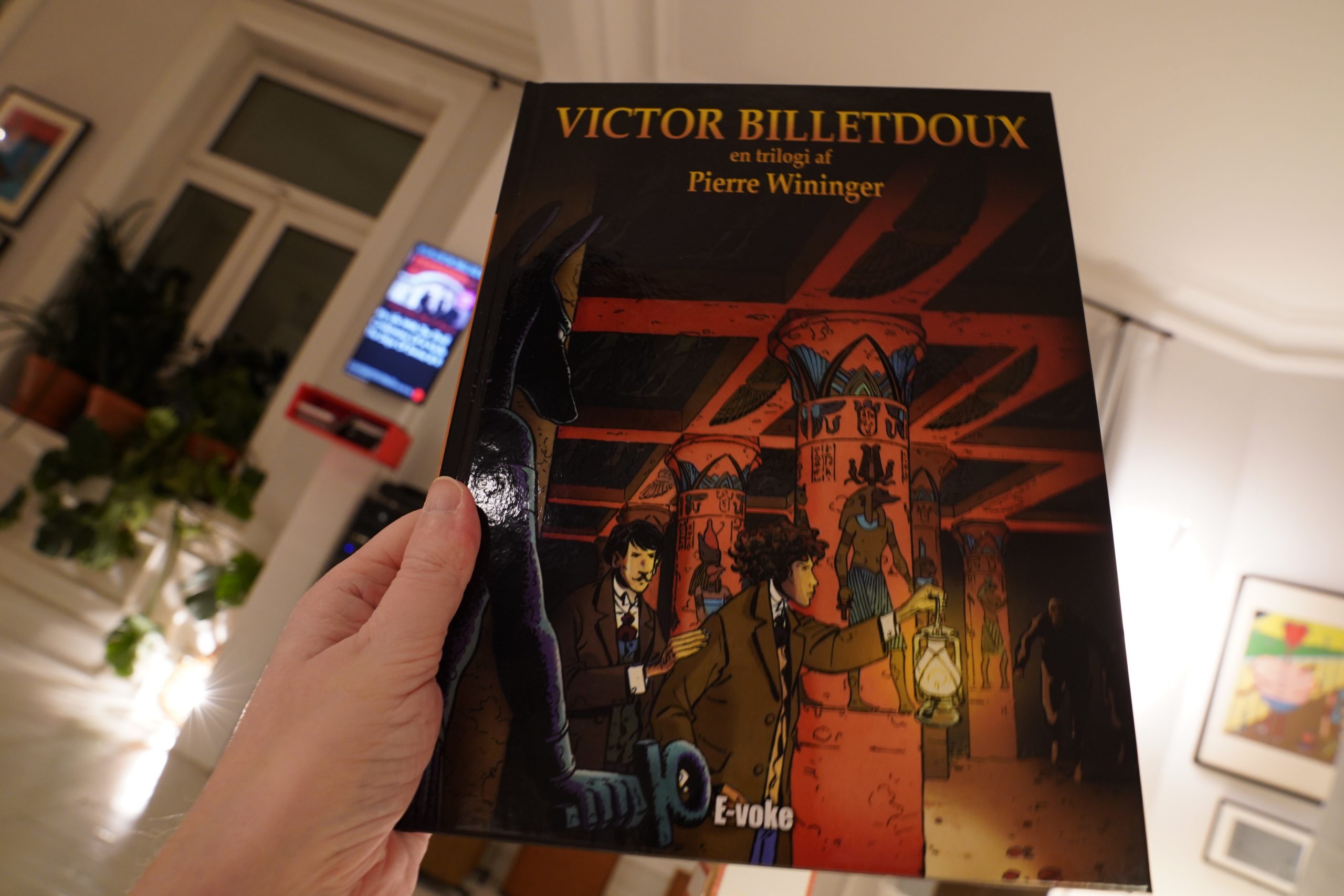

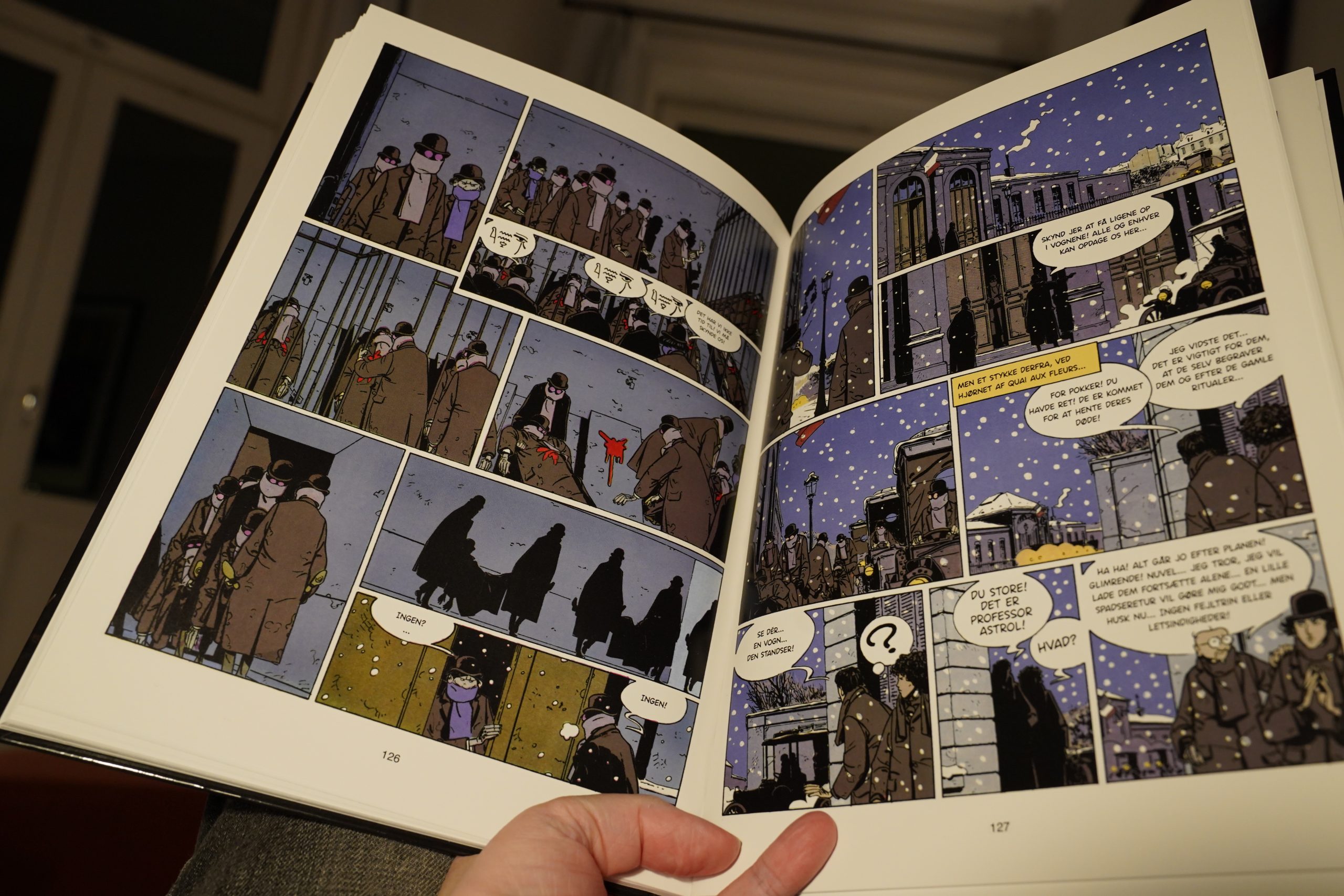

19:10: Victor Billetdoux – en trilogi by Pierre Wininger (E-voke)

This curiously titled book collects three Wininger albums… but I’ve already read five albums by Wininger, and weren’t they also about Billetdoux? Er… or not? But they were also set in the same time period and with very similar-looking characters, so I almost didn’t buy this.

And… it’s two of the albums I’ve already read, but it includes one new one. I mean, an old one — the very first album. So… yay?

The artwork’s pretty rough-looking… and it’s been newly recoloured, and … not in a very exciting way? I mean, I like that they’ve gone for the general look that Wininger used in the original albums, but it’s just too dull.

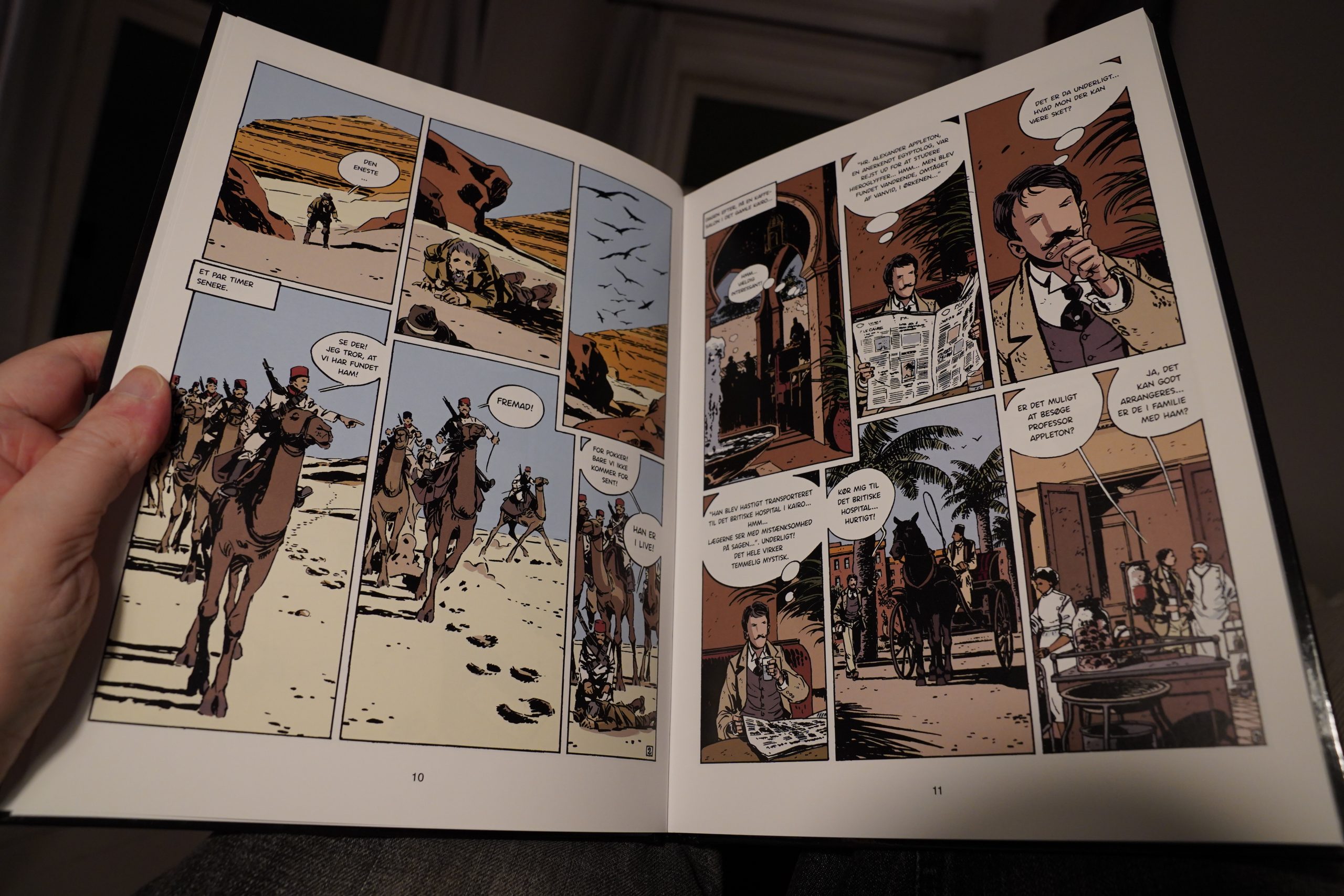

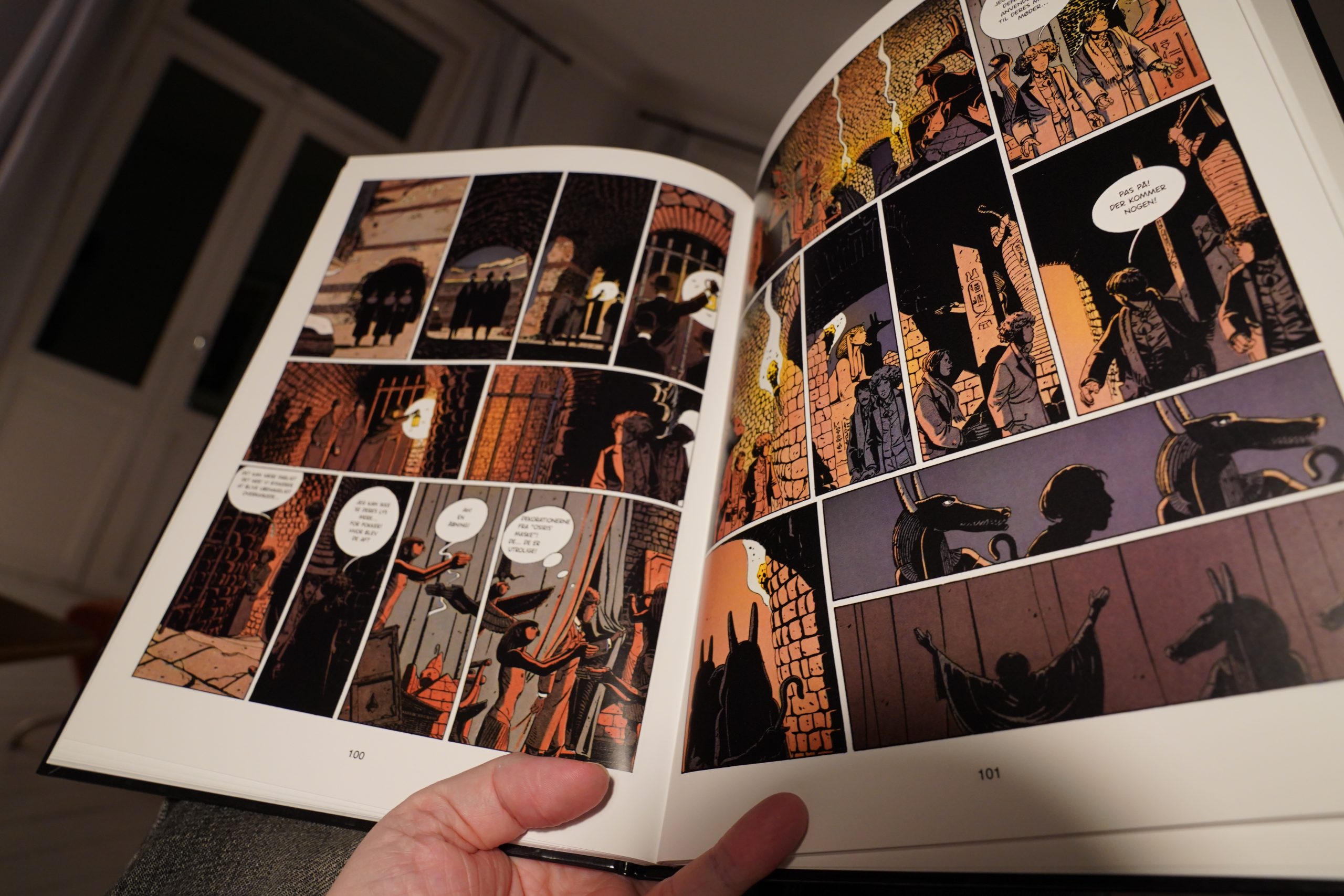

The story doesn’t make much sense, but it’s pretty fun anyway. I like the house in the huge cave. I can see why they skipped this story when translating Wininger in the 80s, though: Parts of it read like the work of a very inexperienced cartoonist, which is what it is.

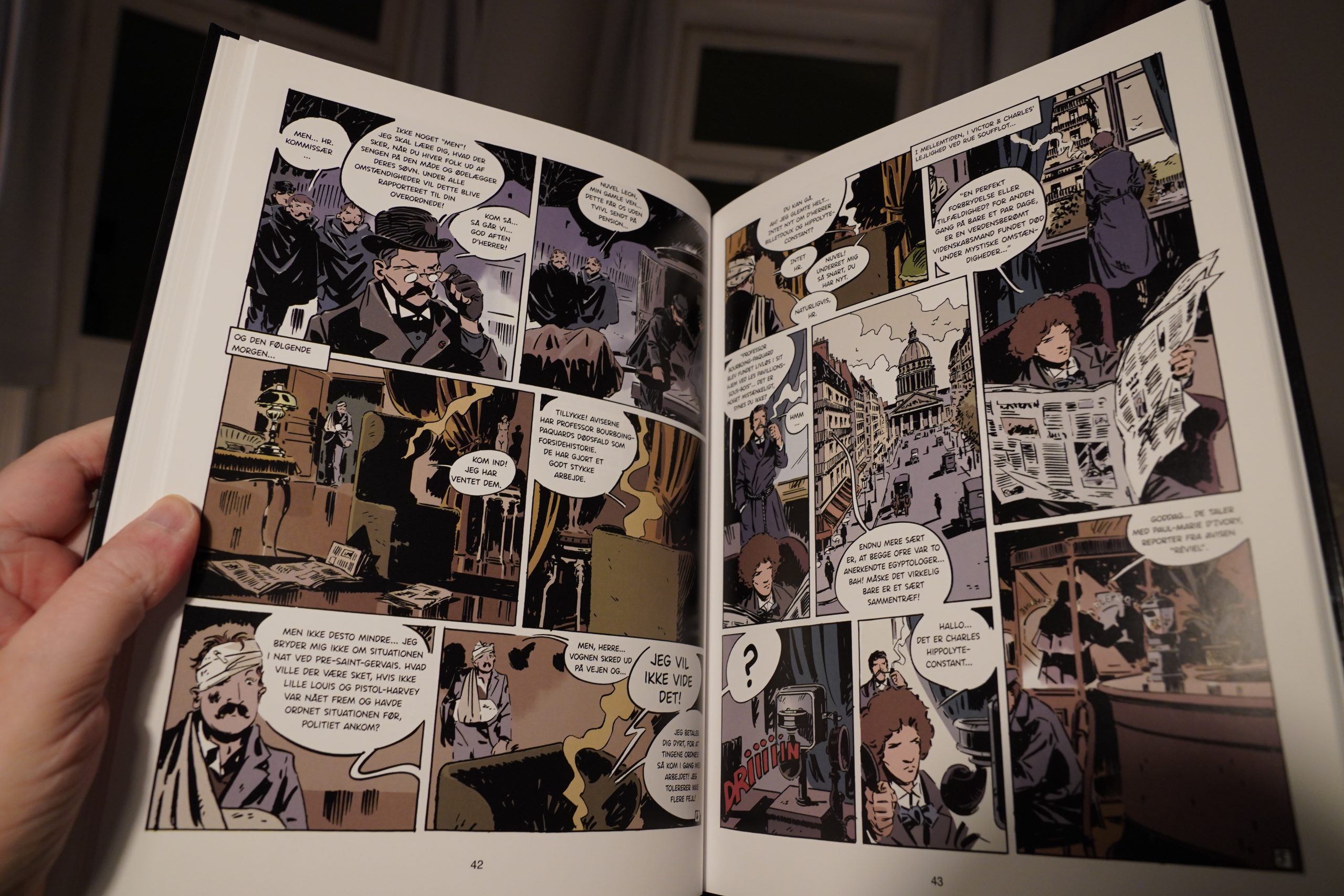

The second album is much more accomplished, and Wininger’s artwork is looking a whole lot more like Tardi. The publishers (in the introduction) say that they think the comparison is unfair, since Wininger’s stories have more in common with Blake & Mortimer… which I guess is pretty accurate. It’s like reading a Black & Mortimer story illustrated by Tardi.

By which I mean that it’s mostly just nonsense, but sure looks pretty.

There’s some scenes here that are pretty riveting, though.

The third album is the strongest one — Wininger’s really got his Tardi mojo going, and it’s got a satisfyingly confusing plot line.

The ending feels a bit… Well, in one way, it’s perfect, but it’s also a let-down.

| Coil: …and the Ambulance Died In His Arms |  |

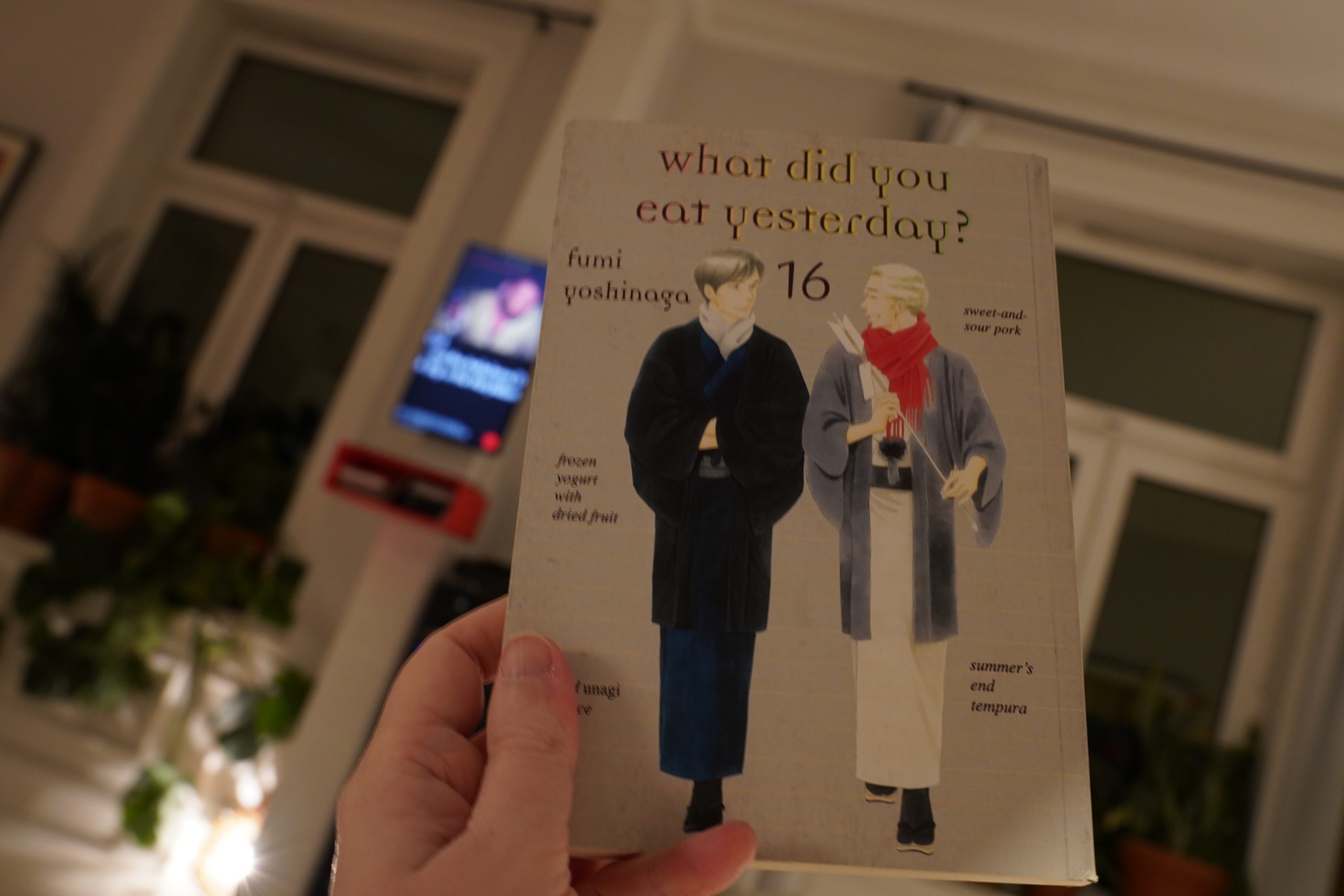

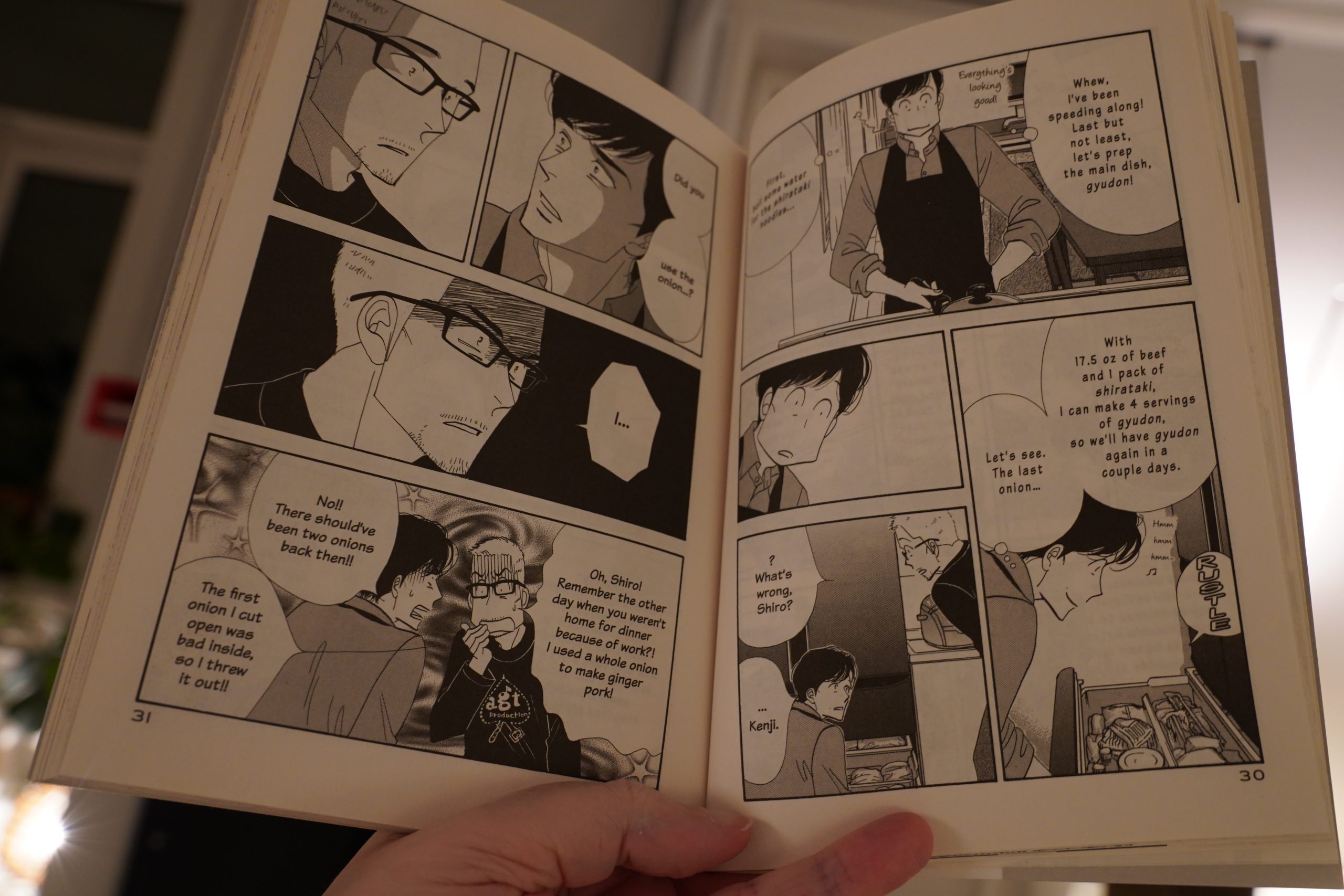

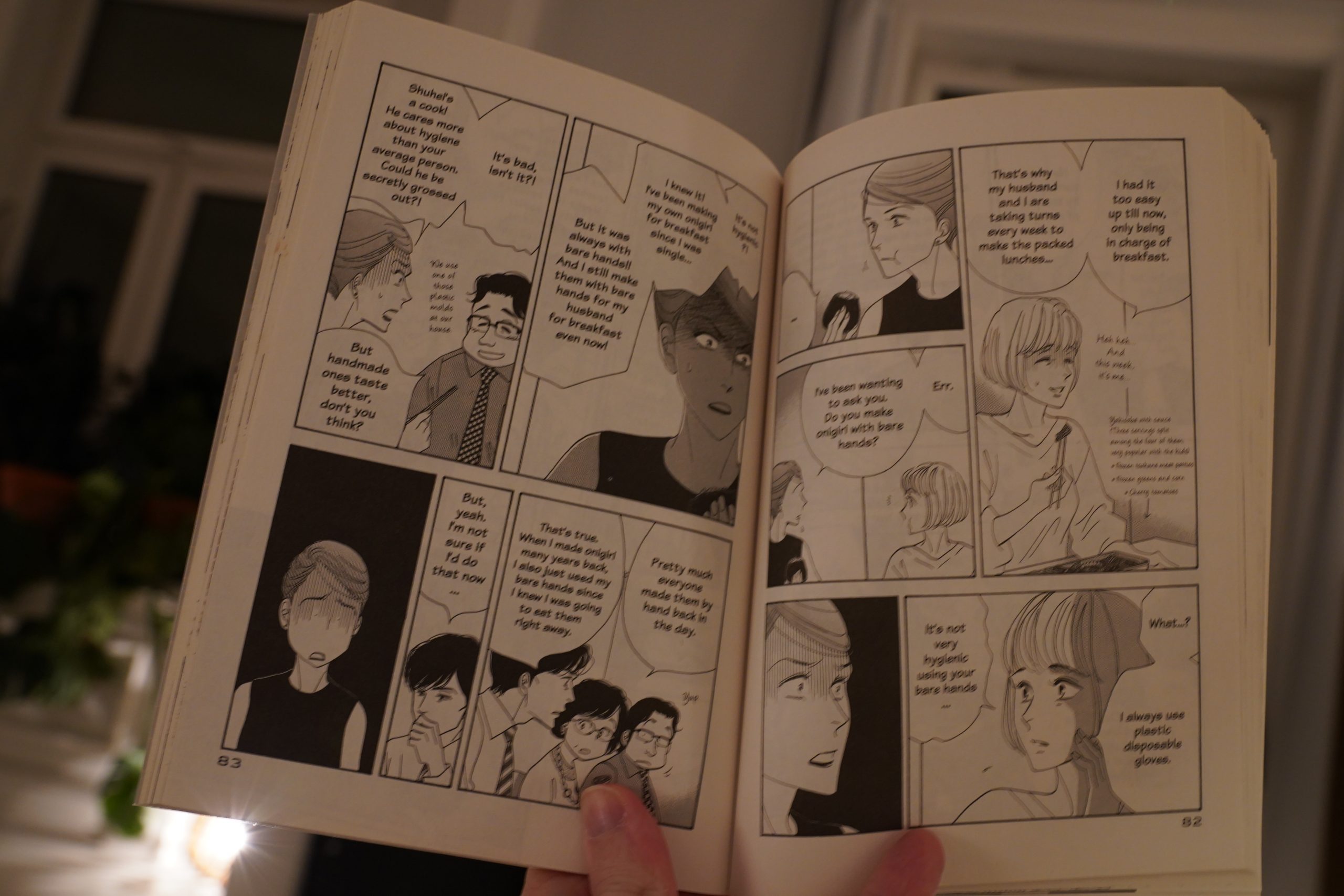

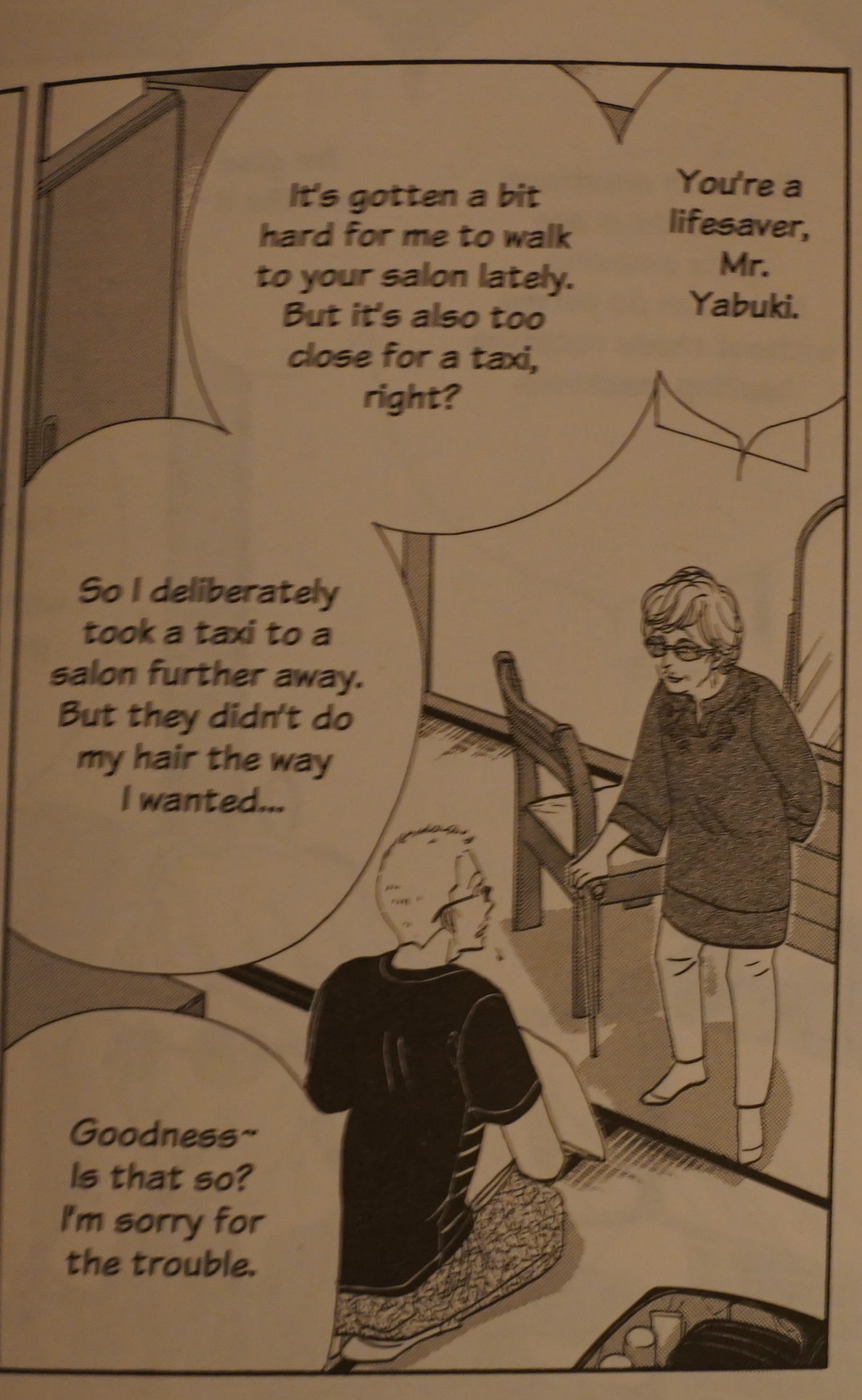

20:40: What Did You Eat Yesterday? 16 by Fumi Yoshinaga (Vertical)

Oh no! They don’t have onions!

Oh no! She made the lunch for herself without using plastic gloves!

I adore how low stakes this series is. And it’s so much fun.

I did have a suspicion that I was an old Japanese woman, though. I’ve booked hotels in cities deliberately far from the train station so that I could take a cab to the hotel without the cabbie getting mad at me.

I hate carrying luggage.

| JPEGMAFIA: LP! |  |

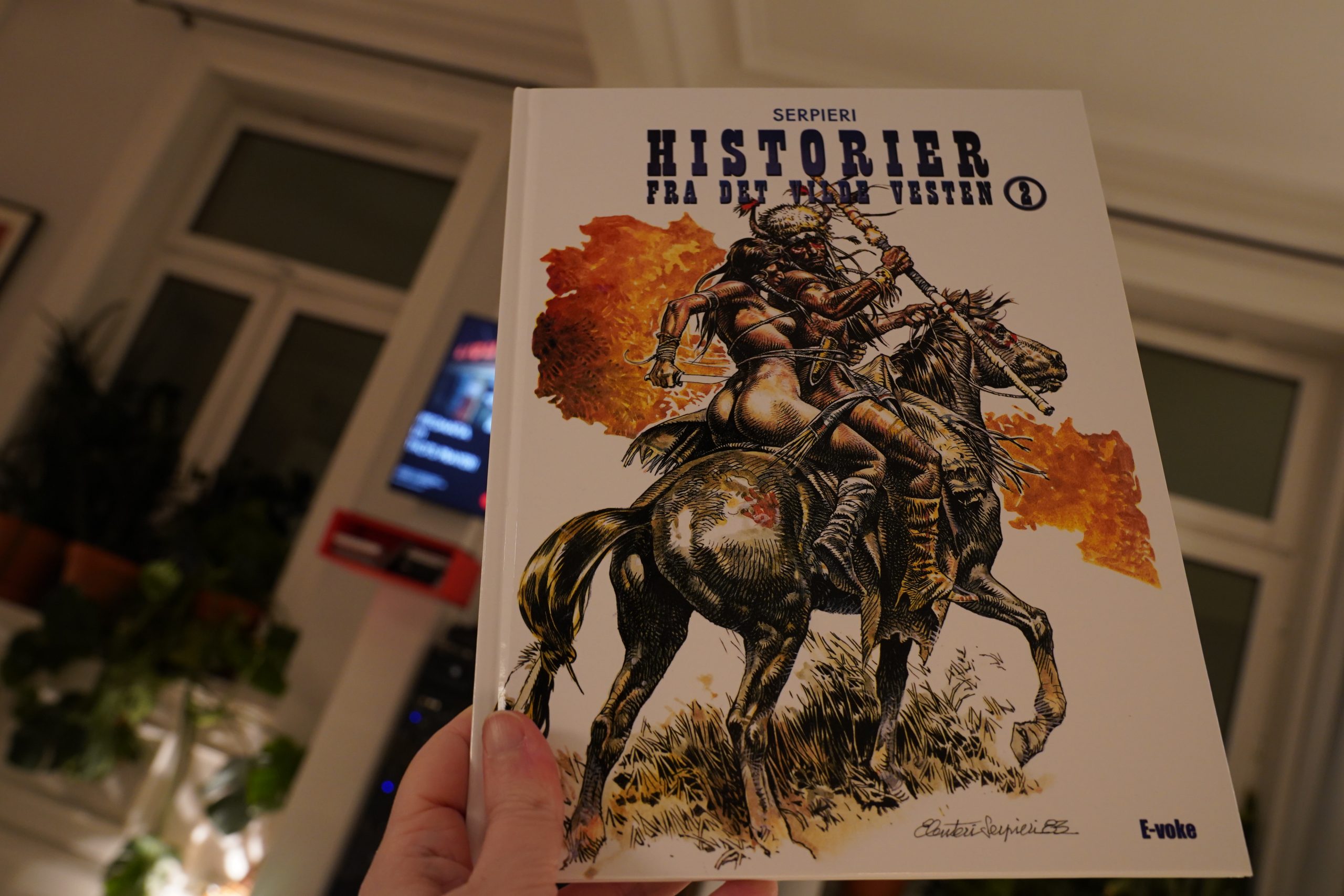

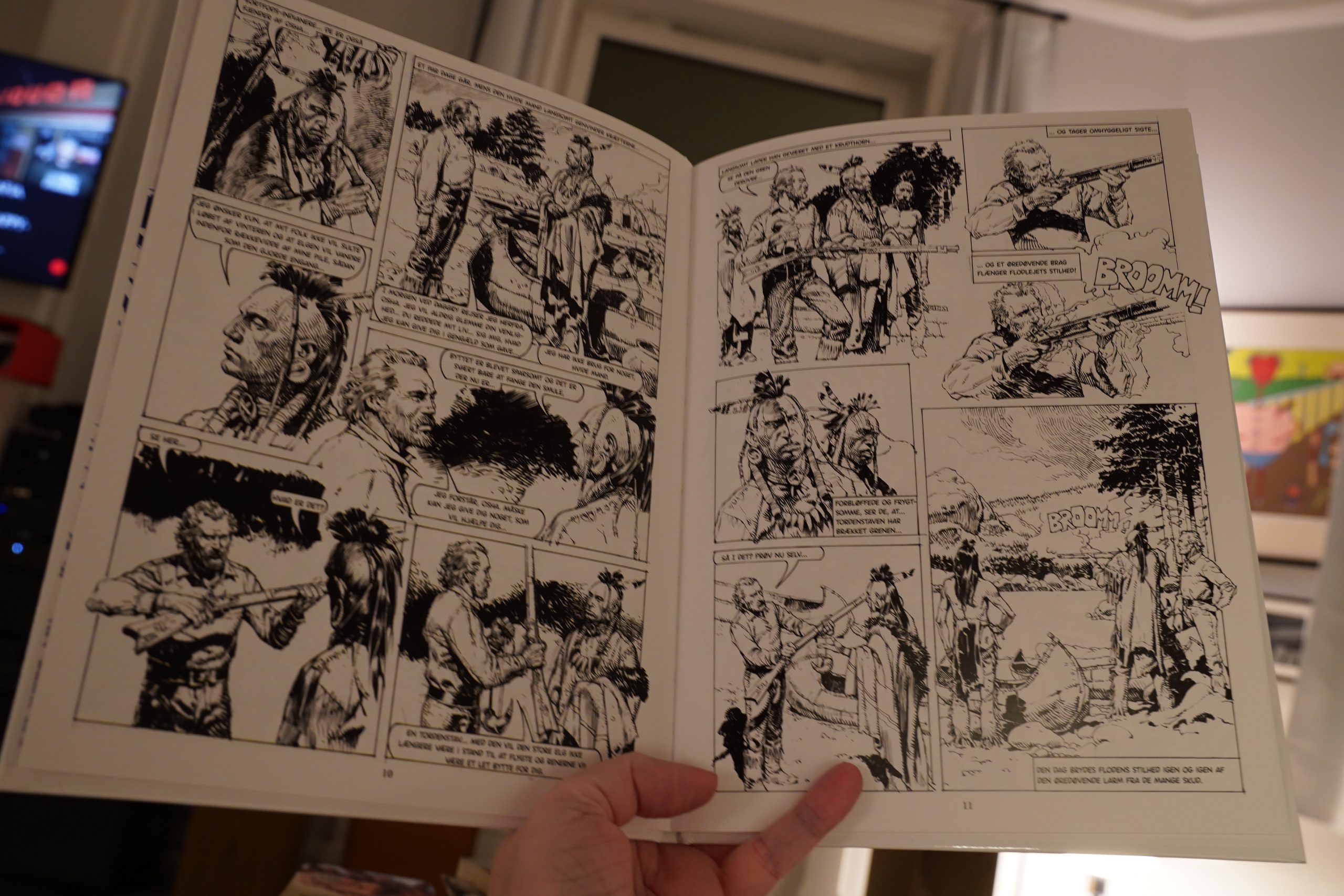

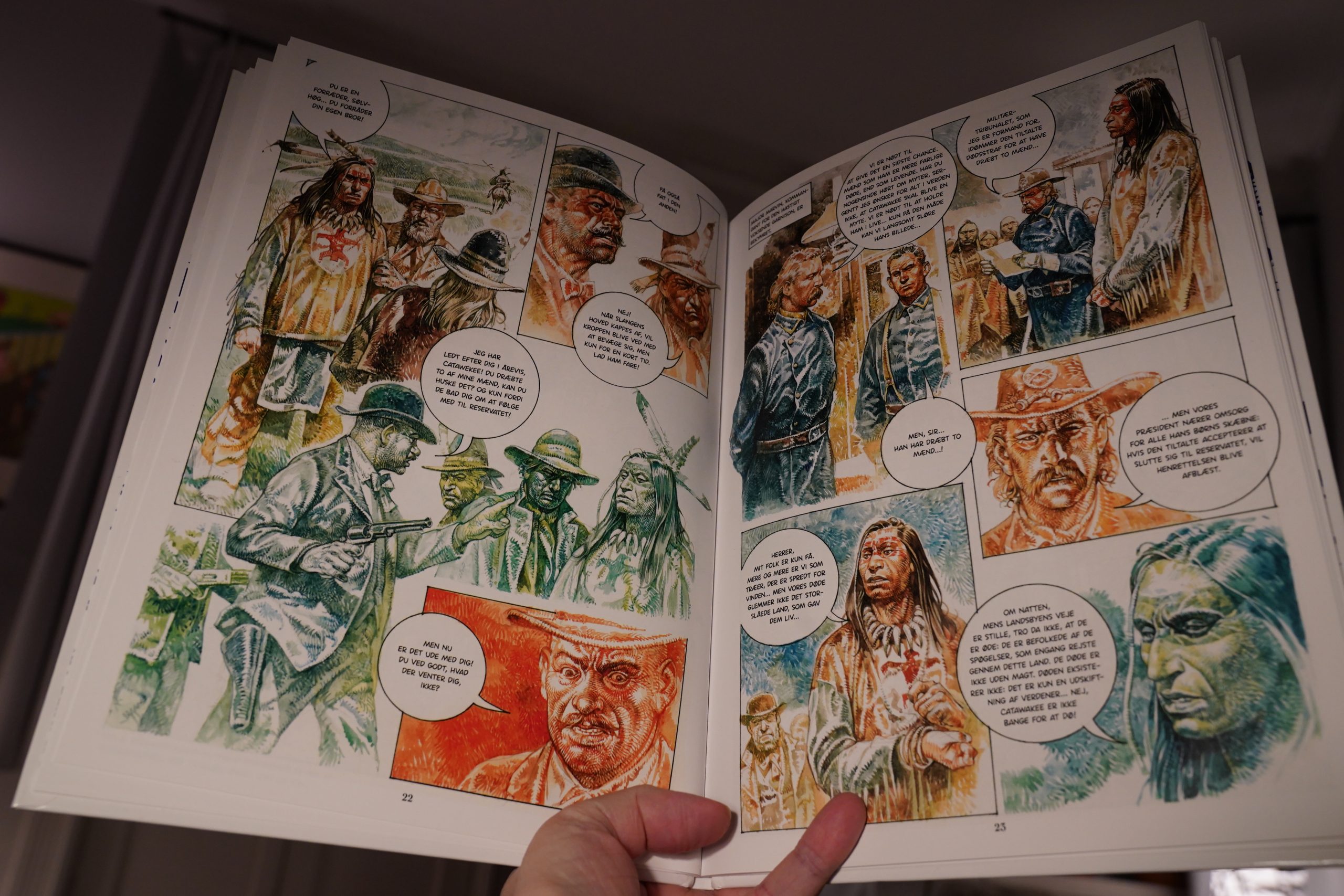

21:38: Historier fra det Vilde Vesten 2 by Serpieri (E-voke)

I don’t understand the economics of printing these days, but this was printed in 200 copies? Perhaps it’s some kind of print-on-demand-like thing? But I mean, you have to translate and (computer) letter it…

Anyway, Serpieri’s chops are impeccable: The artwork’s perfect for a western thing. The stories are all written by different people, but are all kind of … elegiac … and definitely on side of the Native Americans. They’re OK.

| JPEGMAFIA: LP! |  |

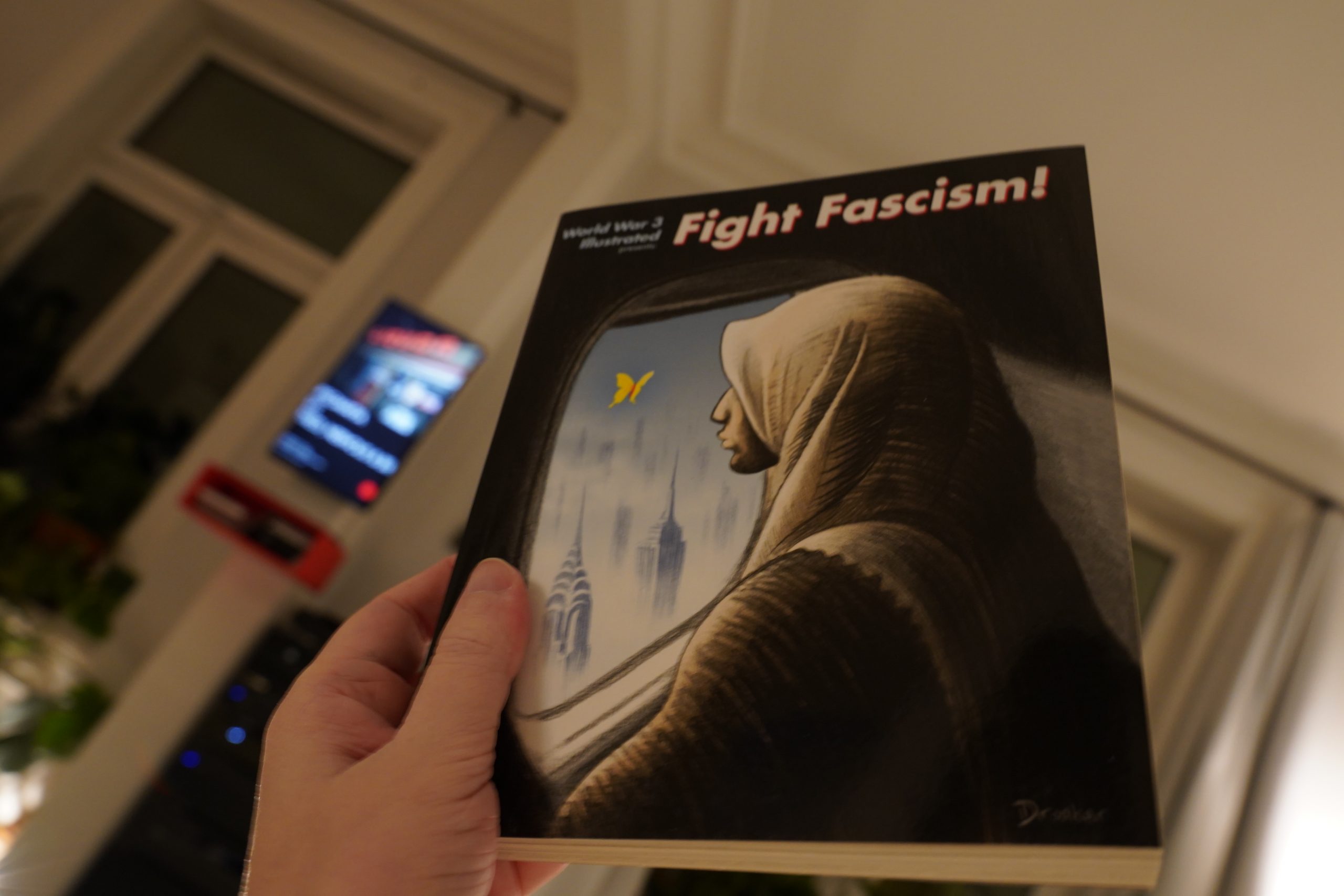

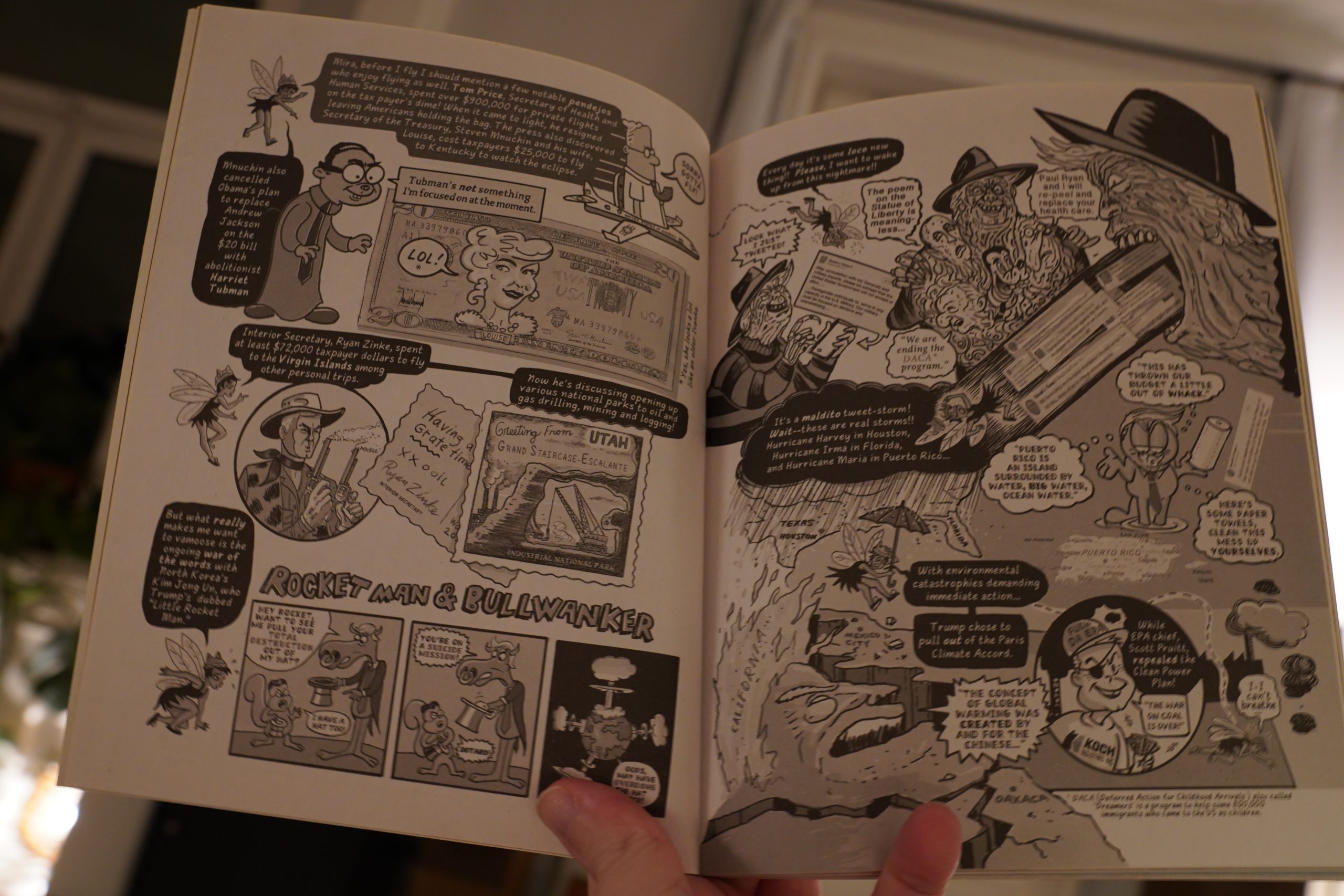

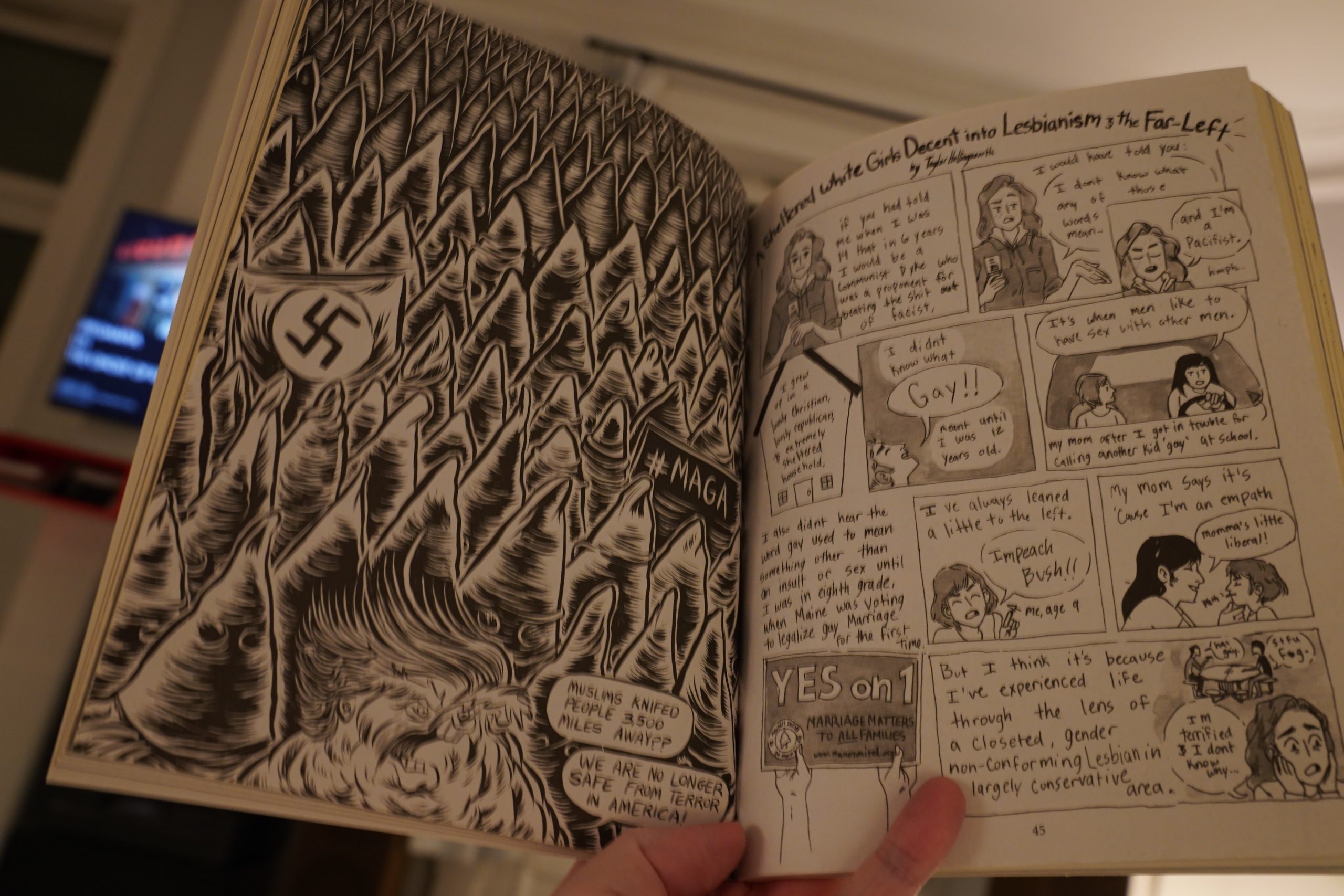

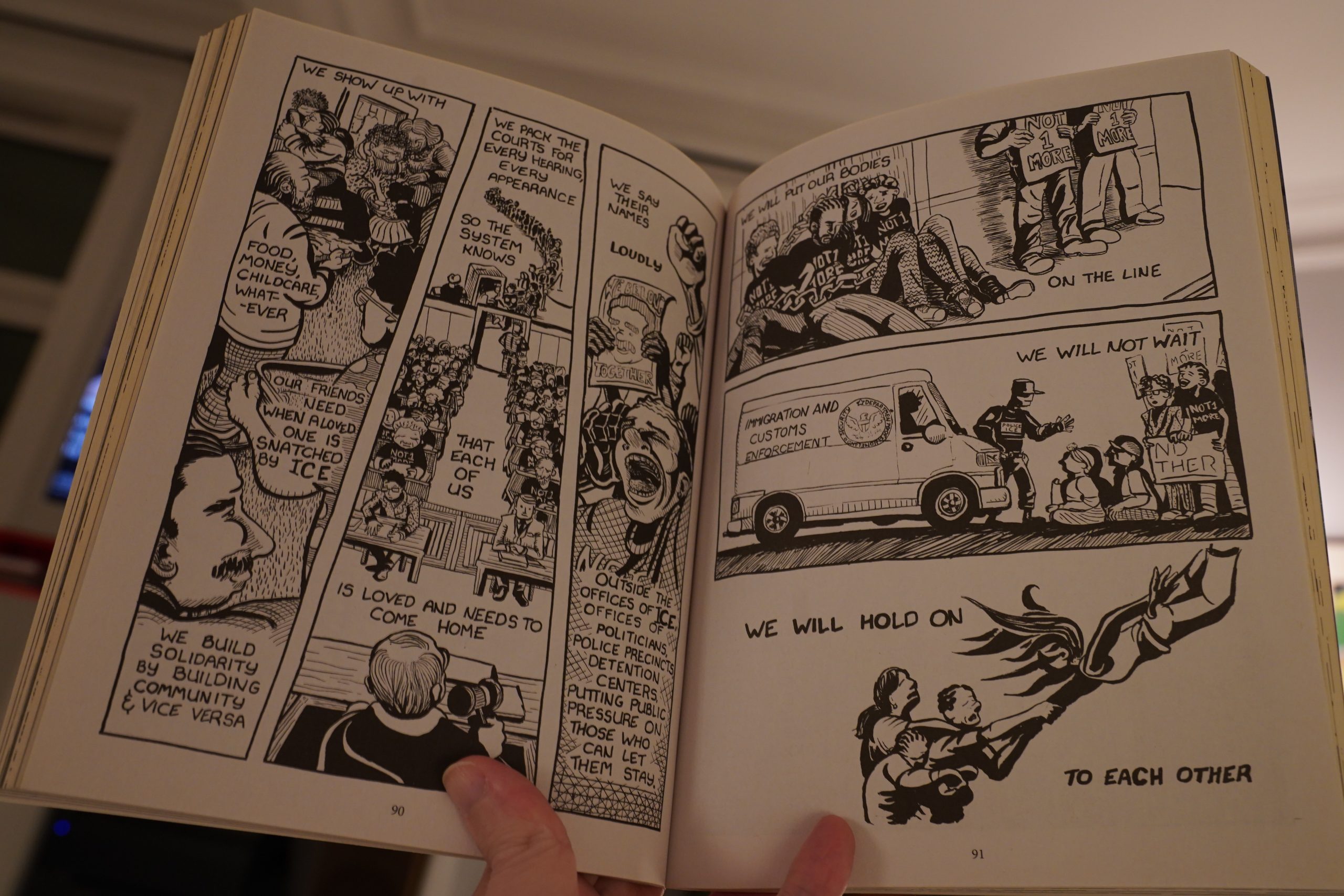

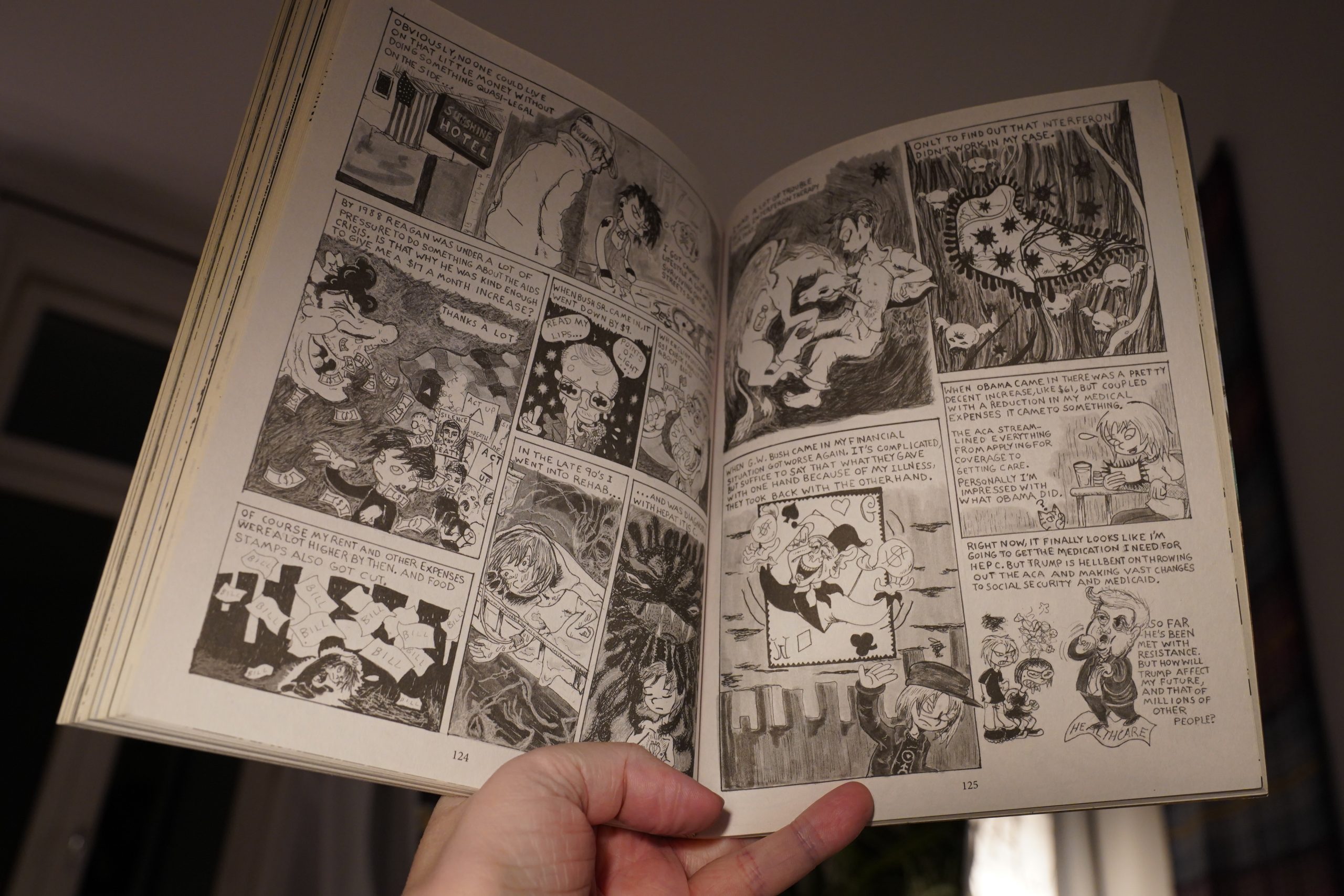

21:58: World War 3 Illustrated #48: Fight Fascism! (AK Press)

This was the first issue after the Trump inauguration, so… I was kinda expecting it to be even better than a normal WW3 issue? (Peter Kuper.)

And there’s indeed good stuff in here, but many of the pieces (not snapped here) just quote Trump a lot, and nobody wants to read that.

So about two thirds of the material made me skim past it, but the rest is good.

So it’s more of a mixed bag than usual.

I know, I know, quibbling about whether people’s anger makes for good reading or not is a bit besides the point.

| Missy “Misdemeanor” Elliott: Supa Dupa Fly |  |

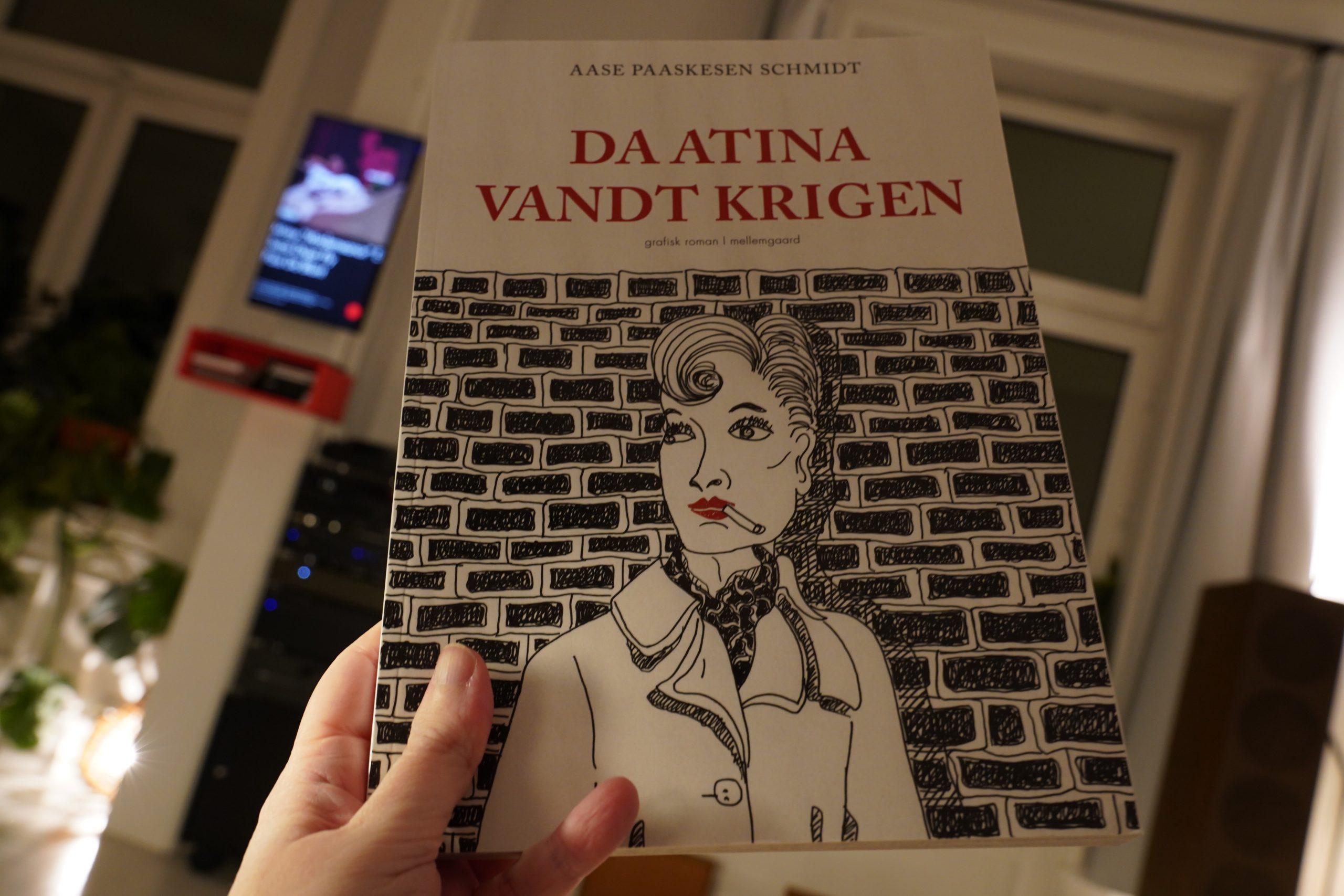

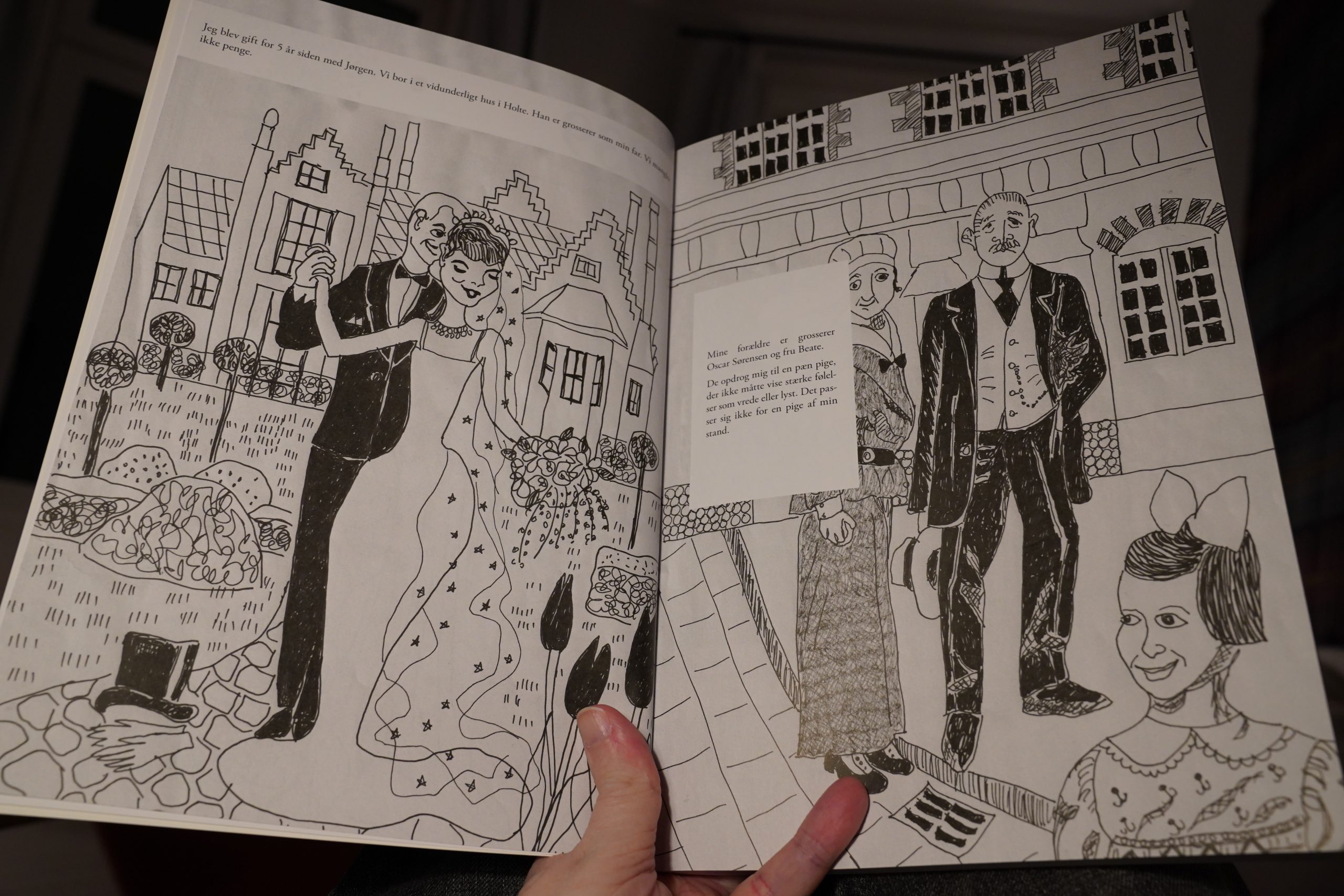

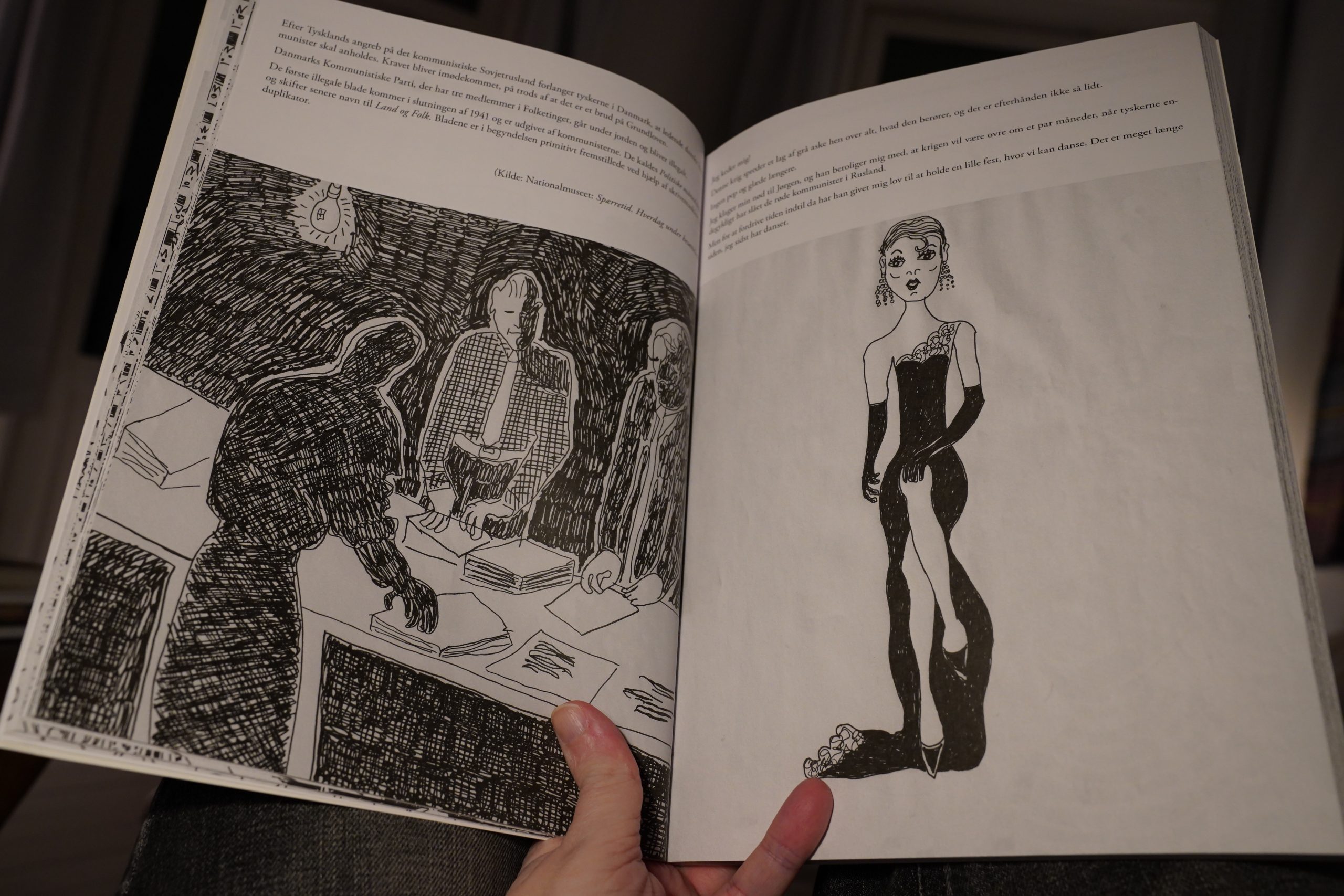

22:42: Da Atina vandt krigen by Aase Paaskesen Schmidt (Mellemgaard)

This is an odd one. It’s basically the story of WWII in Denmark, with a special focus on the resistance, told through the eyes of a society woman who joins up and participates in the actions.

But half the pages (approx.) are basically factoids about what went on during WWII in Denmark — and these factoids are taken from other history books, most of them illustrated — and the author here has basically drawn those illustrations in this style.

Very odd.

It’s not like I have an interest in WWII — I don’t have a particular dis-interest either, but it’s just not… er… my passion in life, as with many other old geezers. But I found myself oddly fascinated here. I knew very little about what transpired in Denmark in WWII (compared to, say, the UK), and the author has picked interesting stuff to reproduce. And the interwoven story was also interesting. So… I really liked this!? I was ready to hate it, but I don’t?

But is it comics? Perhaps not.

| Depeche Mode: Black Celebration |  |

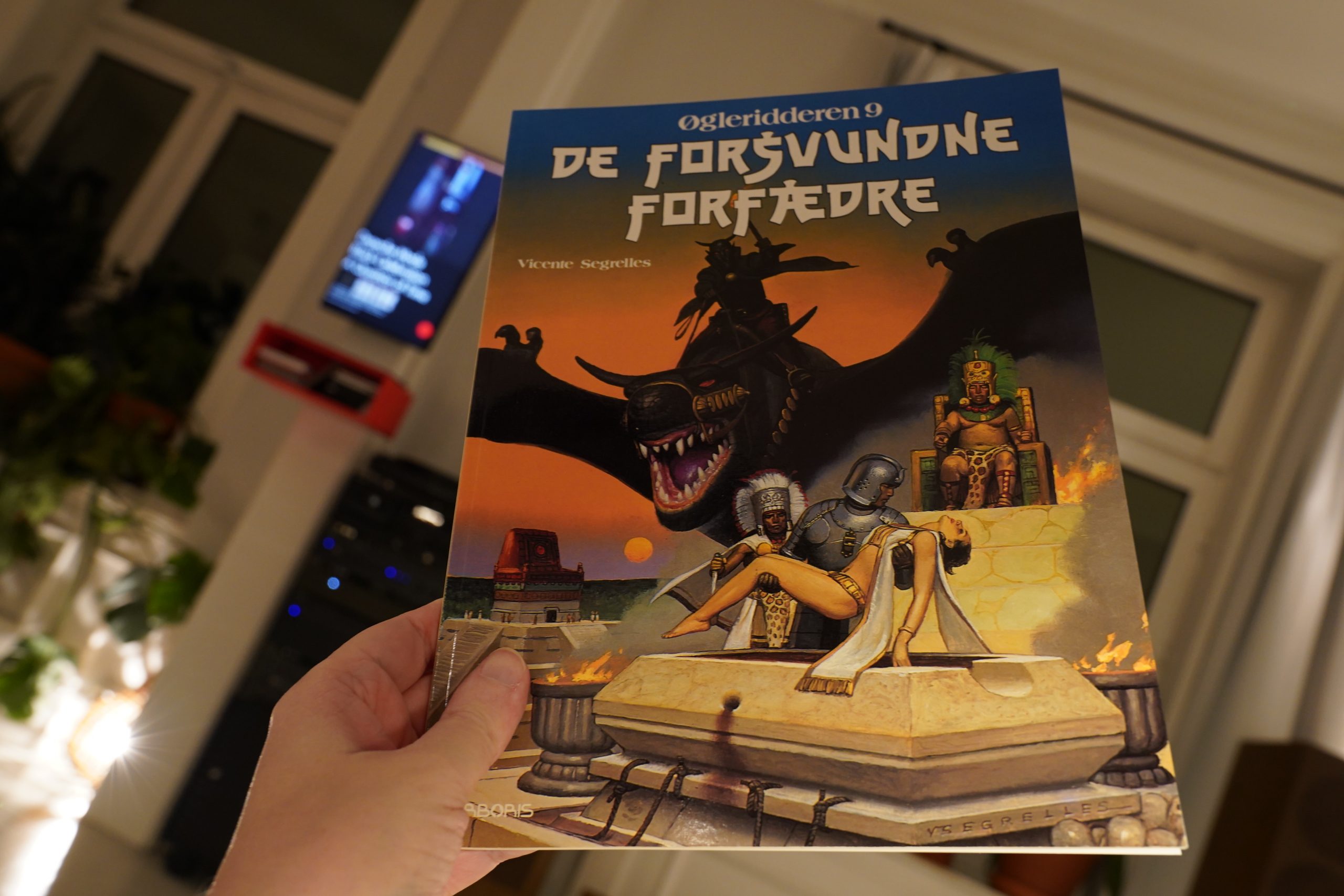

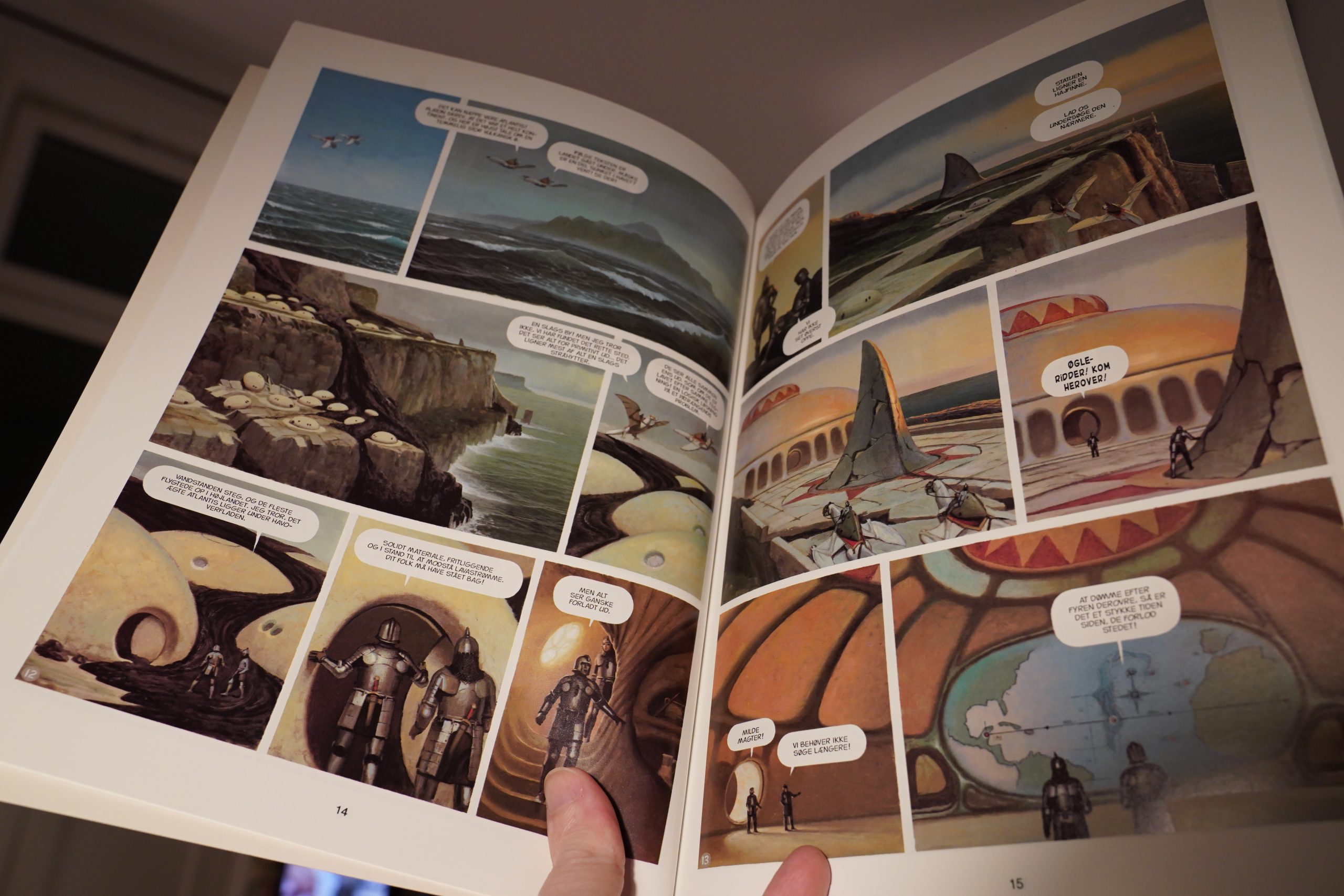

23:40: El Mercenario 9: Los Ascendientes Perdidos by Vincente Segrelles (Arboris)

They were selling (almost) all of The Mercenary series cheaply some months back, so I bought them all and have been slowly making my way through them. They’re kinda fun? But it never feels pressing to read the next one, if you know what I mean.

The series started in 1981, apparently, and this is from 1997. Segrelles is still doing his meticulous painted style — lusher than ever, really.

The figures are less stiff than in the older albums, too. But this album basically has the same problem as most of these: The story is basically that Our Protagonists escape from some mad king/priest or something, so there’s a distinct feeling that nothing has really happened after the album’s over. It’s less the feeling of having read an epic (which I think is what he’s going for) than having seen an episode of some 90s sci-fi TV show.

That’s fine.

| Juana Molina: Tres Cosas |  |

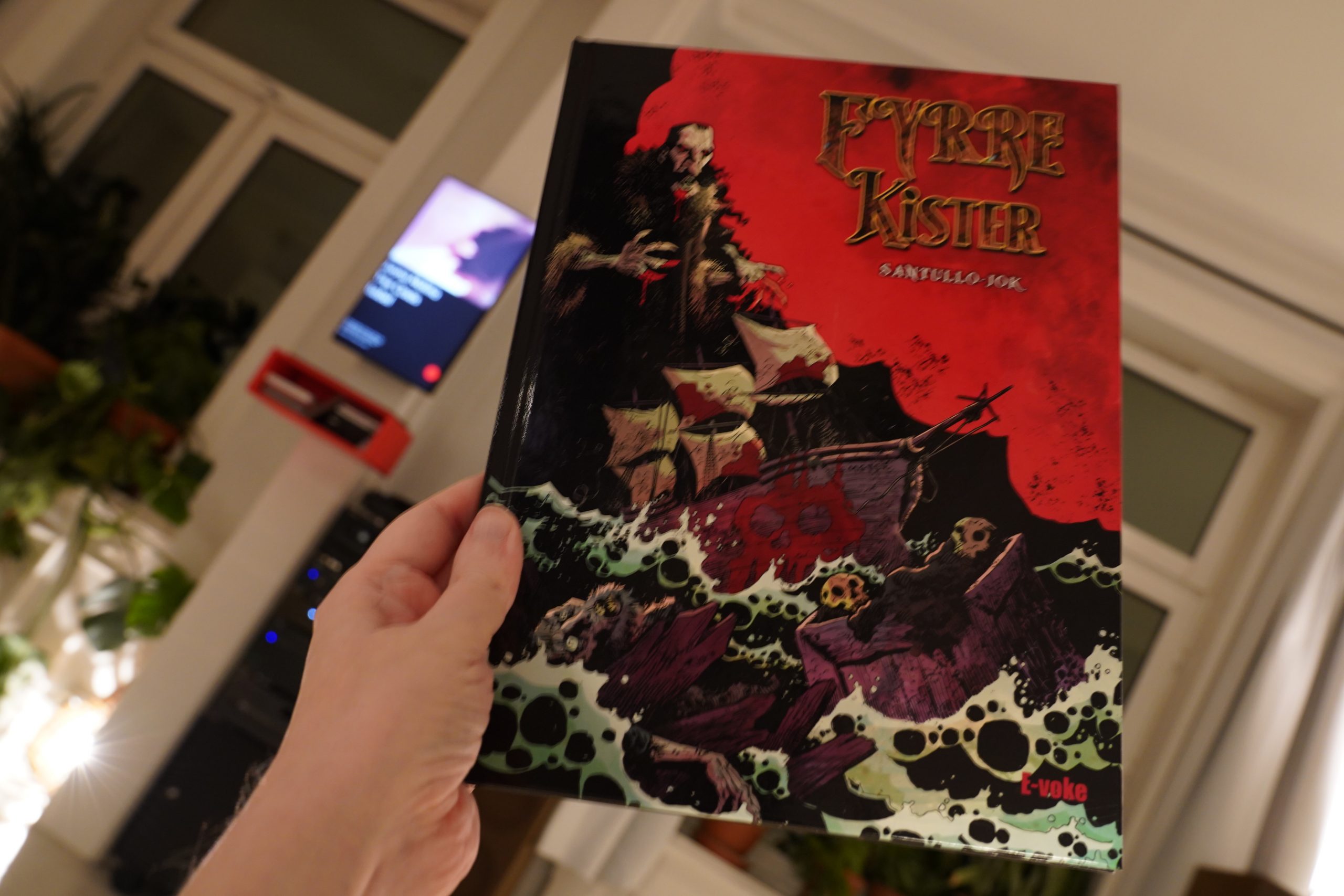

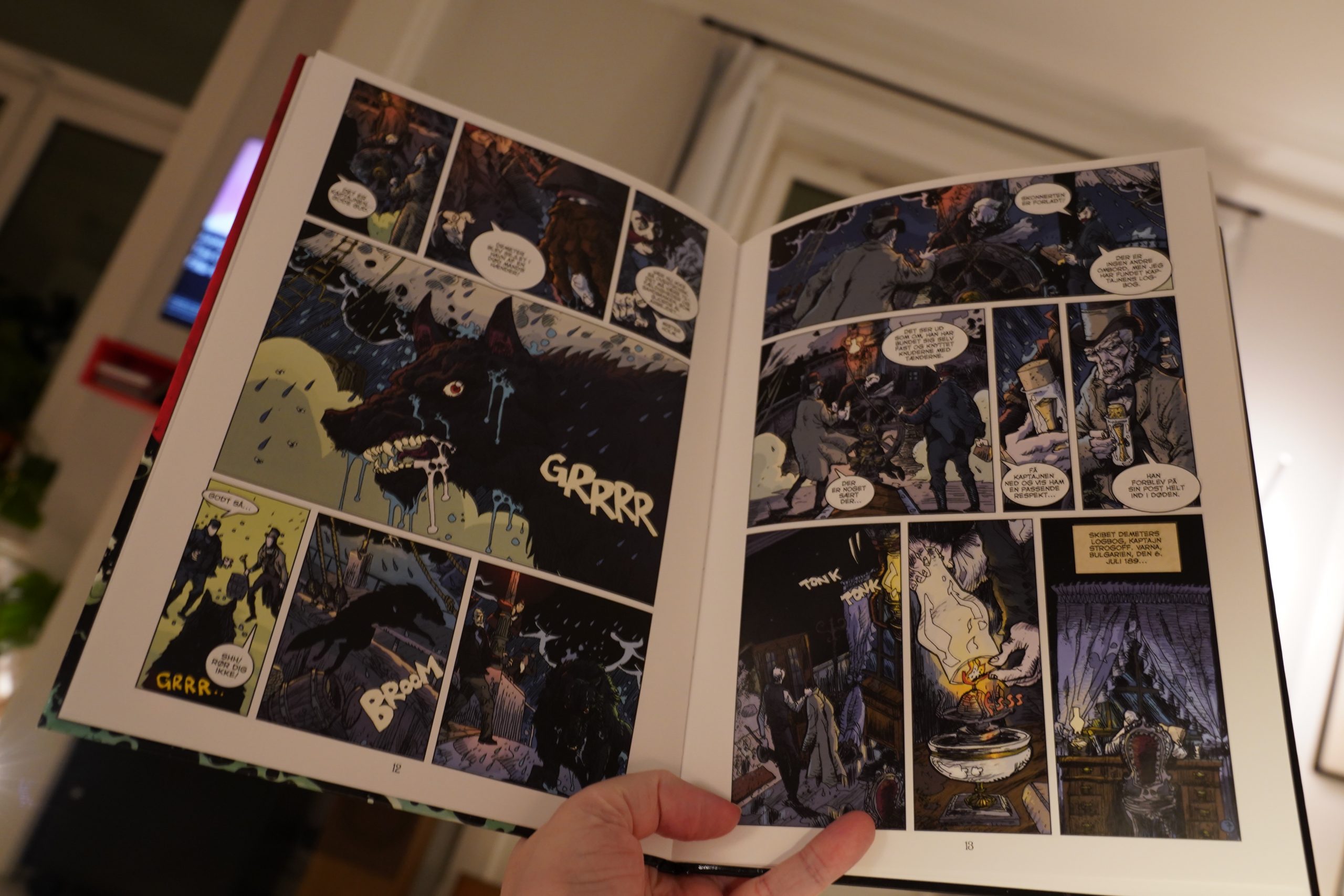

00:27: 40 cajones by Santullo/Jok (E-voke)

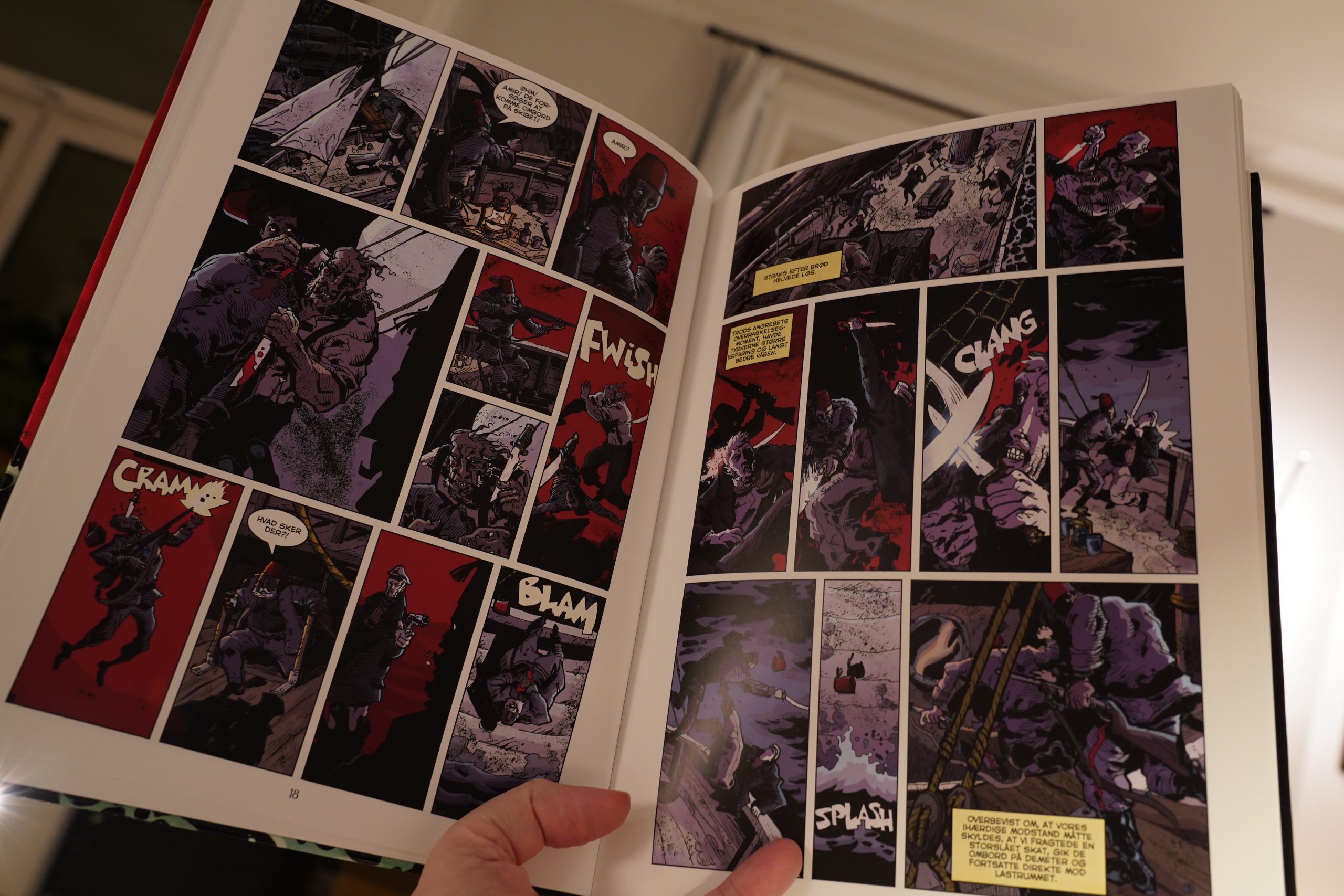

Well, this isn’t what I had expected… It looks very American? That is, it looks like something from the Mike Mignolaverse? But it’s not, I guess.

It basically retells, once again, that story of Dracula sailing to the UK. You know the one — a ship with coffins in the cargo, where the sailors disappear, one by one? Yeah, that one. Which makes me wonder: Why? Oh lord, why!!!!!

Because this isn’t even a fun variation on the theme: It’s just that story, and nothing more.

Really boring.

| Rocket To The Sky: Medea |  |

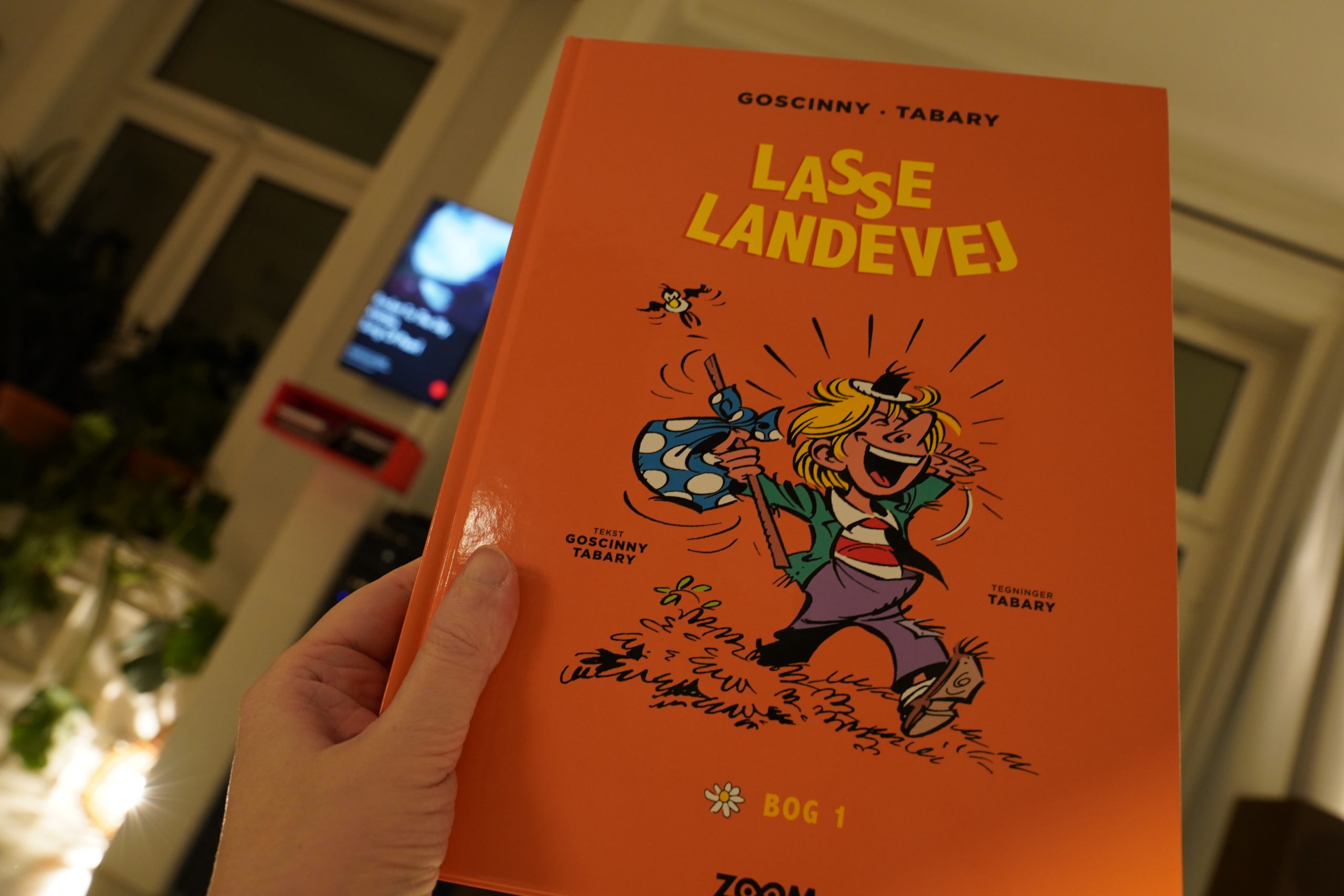

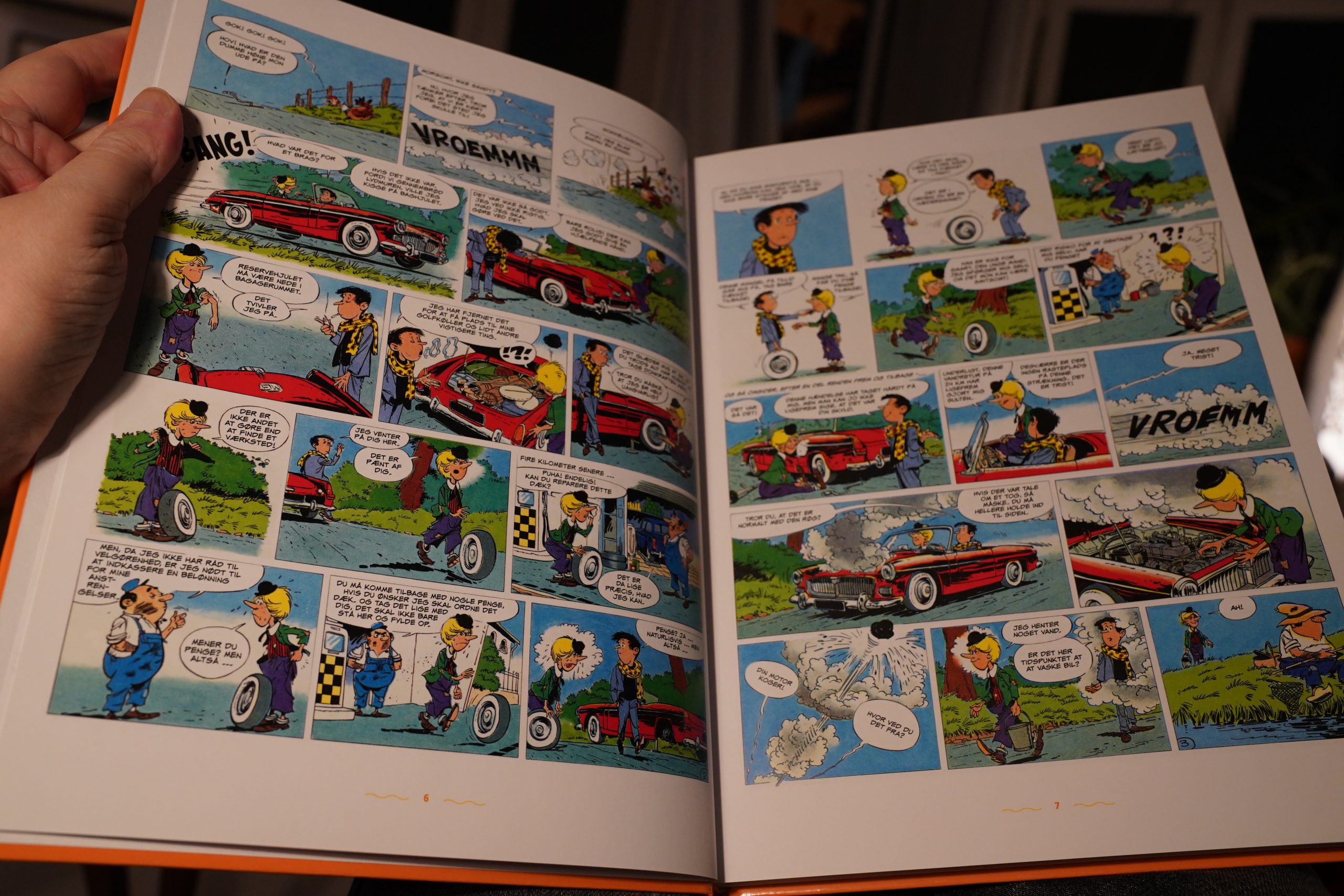

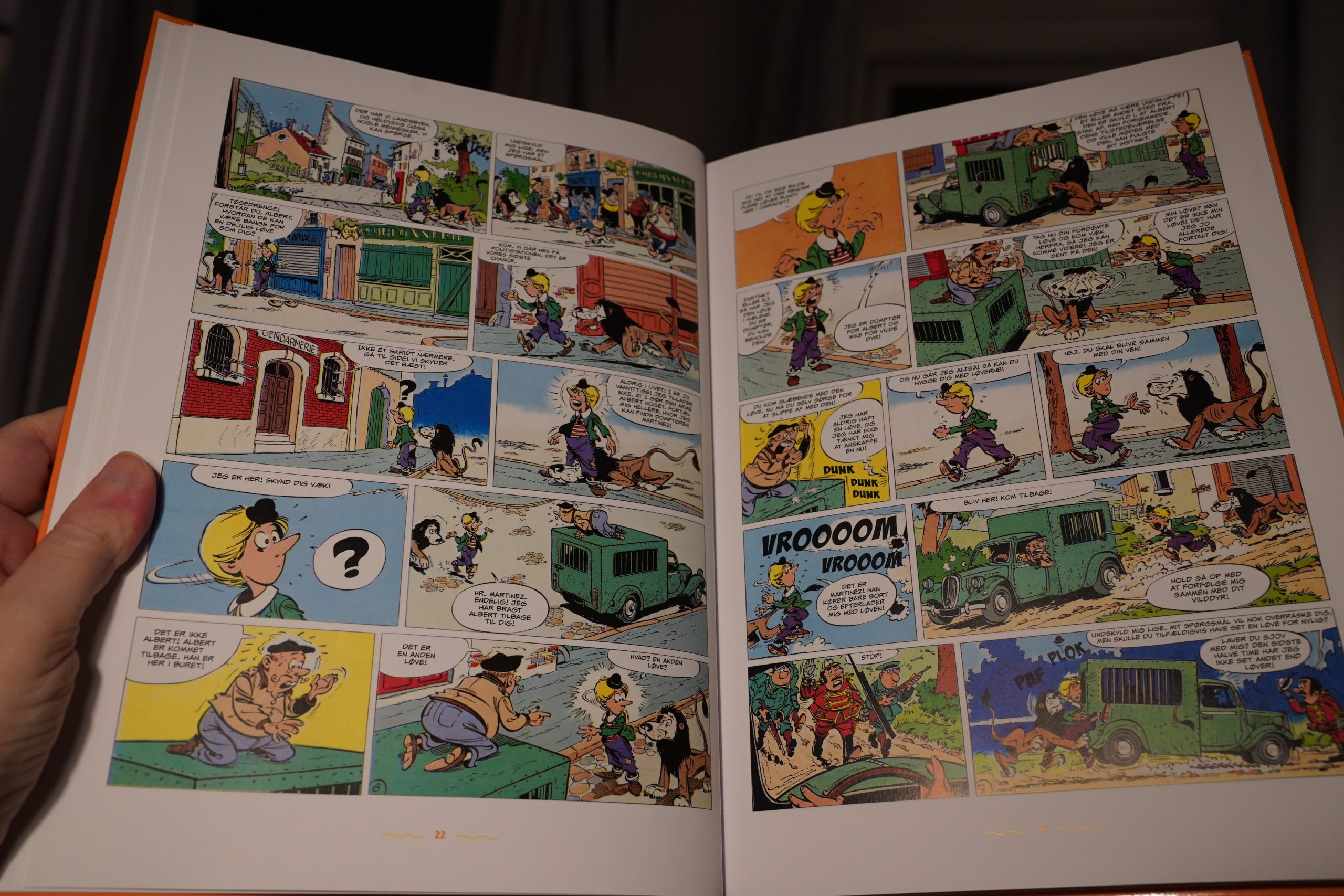

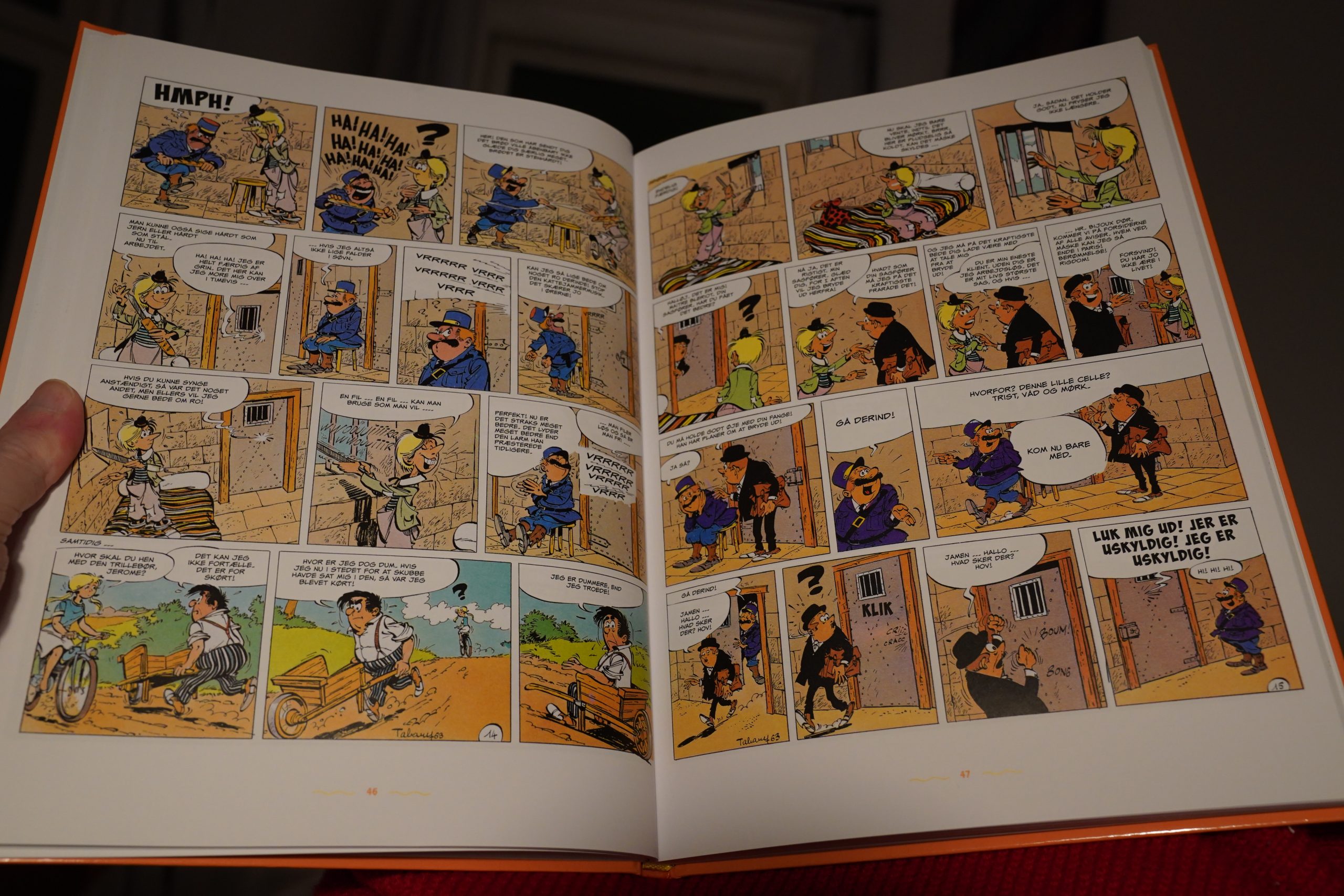

00:56: Valentin le vagabond – Intégrale tome 1 by Goscinny & Tabary (Zoom)

What’s this then? I’ve never heard of this — and it’s by Goscinny & Tabary!? It cannot be! And it’s the first book of a collected edition series, so there were a lot of these? Perhaps it’s really early work?

Yeah, this looks really early. It has that same look the very first Iznogoud albums had. Hm… so was this before both Iznogoud and Asterix? Oh, both Iznogoud and Valentin were started the same year, 1962. I would have guessed earlier. (Asterix started in 1959.)

Huh. It was published until 1974, but didn’t start getting collected in albums until 1973? Very odd indeed; Iznogoud (by the same creators) had been a major hit in album form since the mid-60s. So… is this going to suck?

No! This is most amusing. The plots are surprising (and satisfying), the gags are funny, and Tabary is a much better cartoonist than I remembered.

This is prime Goscinny. The jokes keep on coming, and the gags are never-ending. But it’s not just that — the characterisation is fantastic, and over the 46 pages of the first long storyline, we really get to know these people, even if the fun never stops for a second.

Amazing.

I’m saving the last two stories for another day, though, because now it’s:

| PJ Harvey: Stories From The City, Stories From The Sea |  |

02:24: Sleepytime