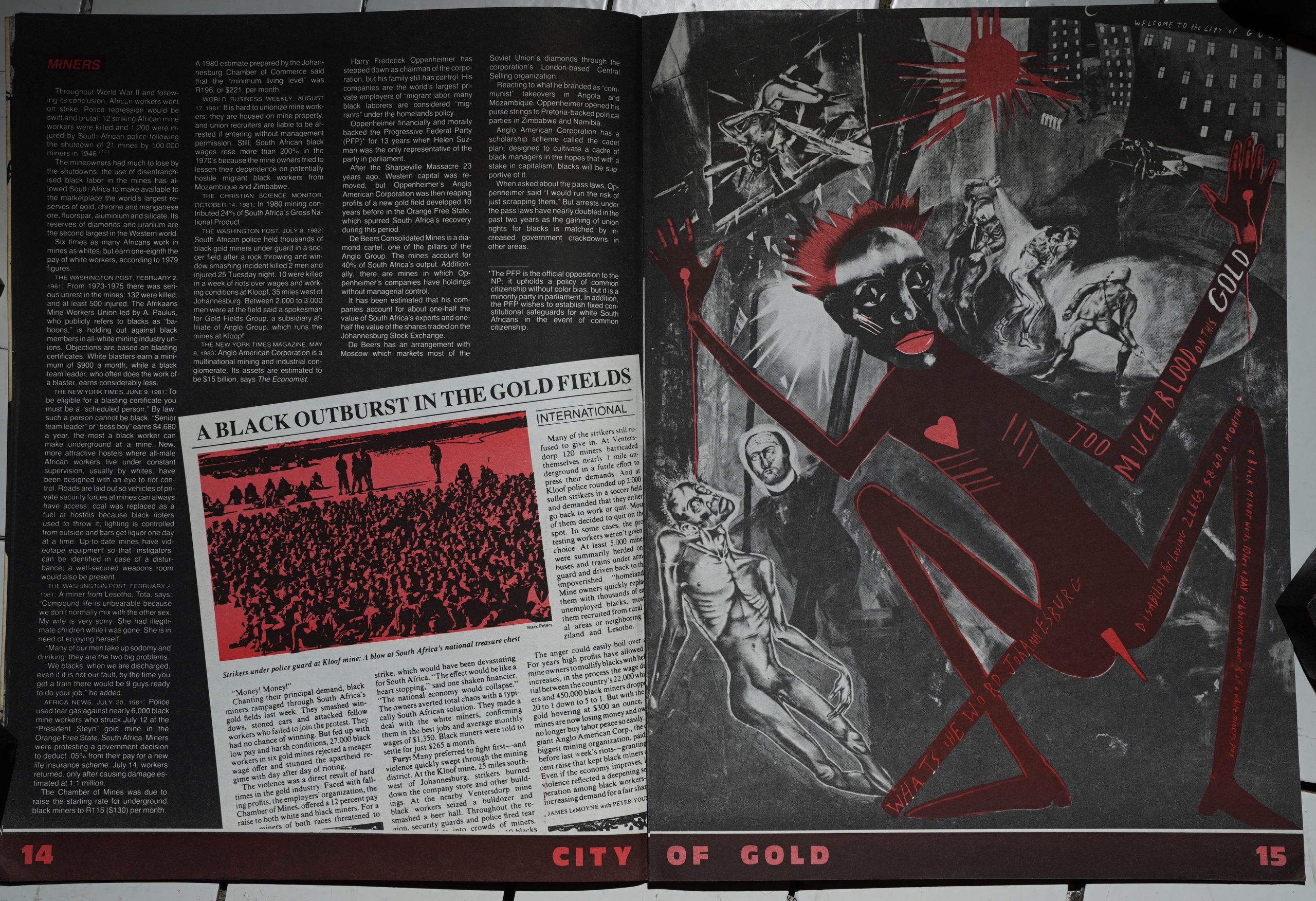

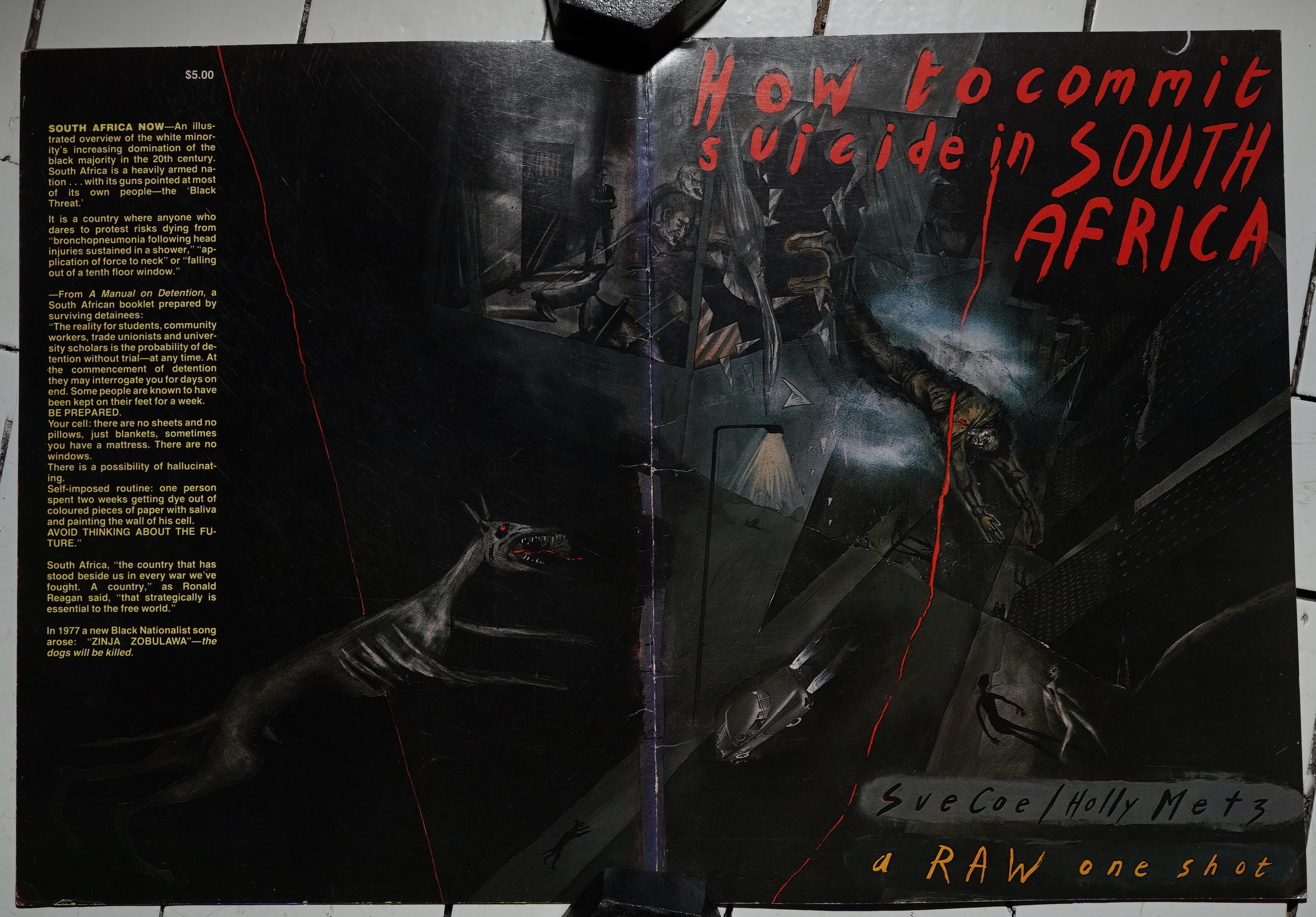

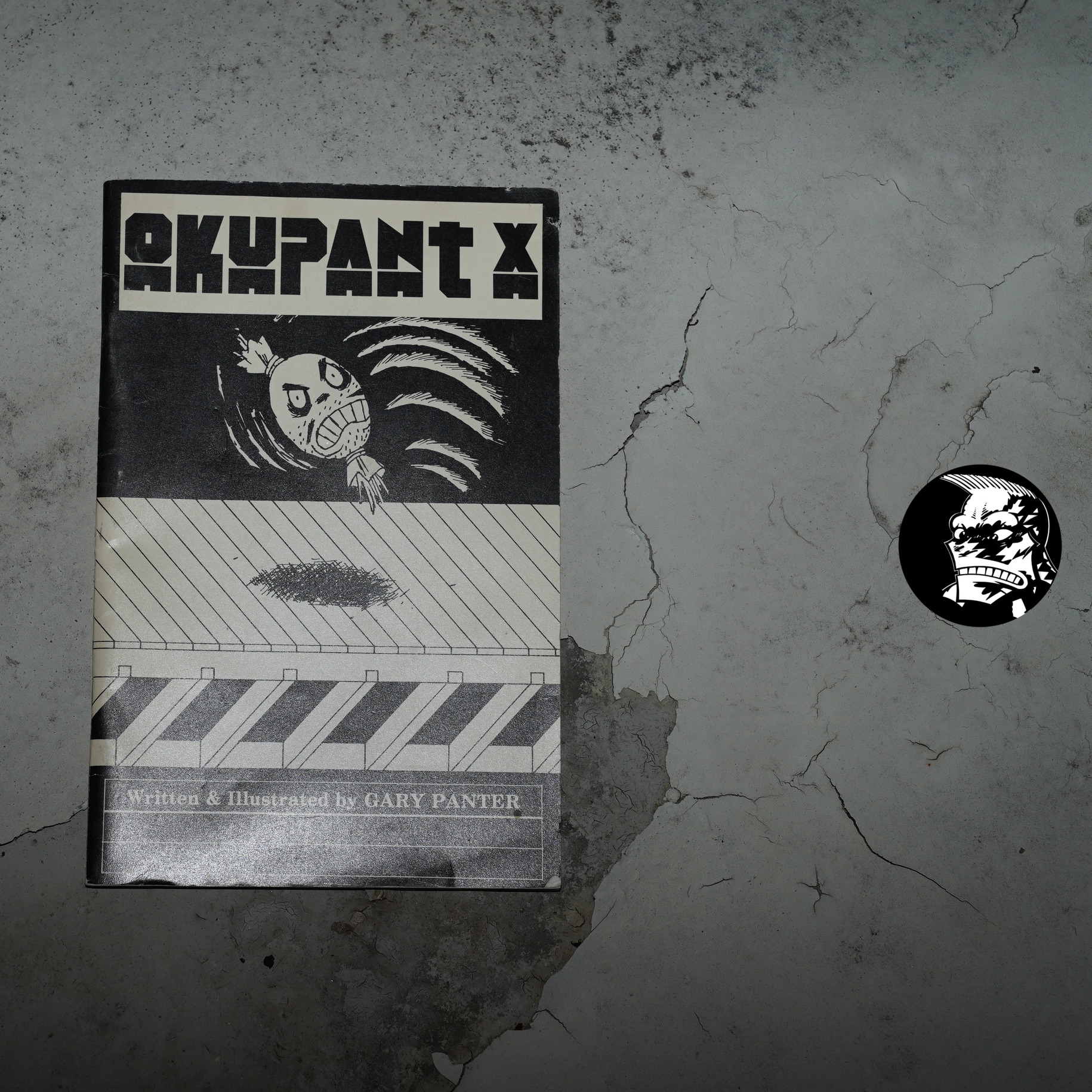

Okupant X by Gary Panter (140x216mm)

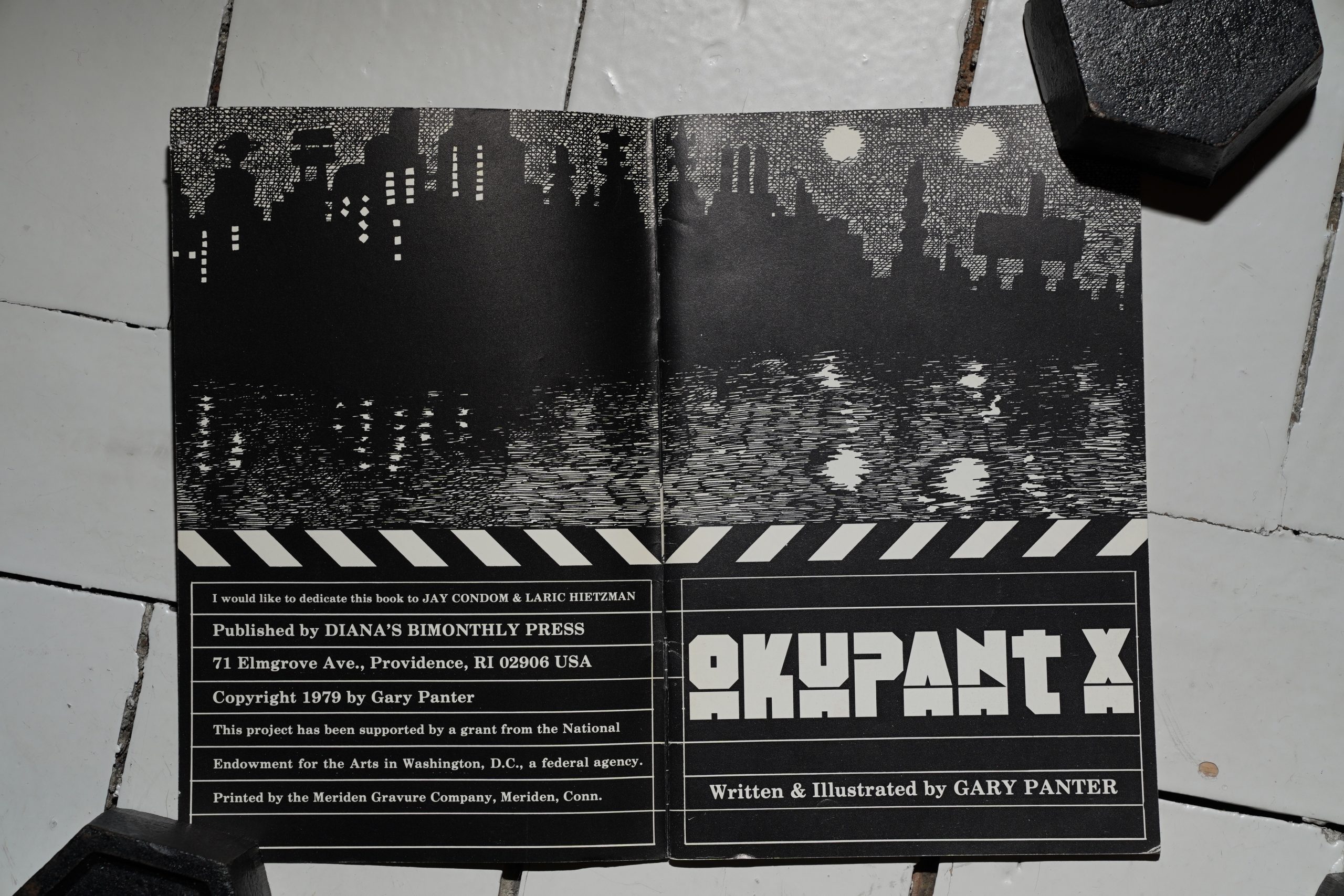

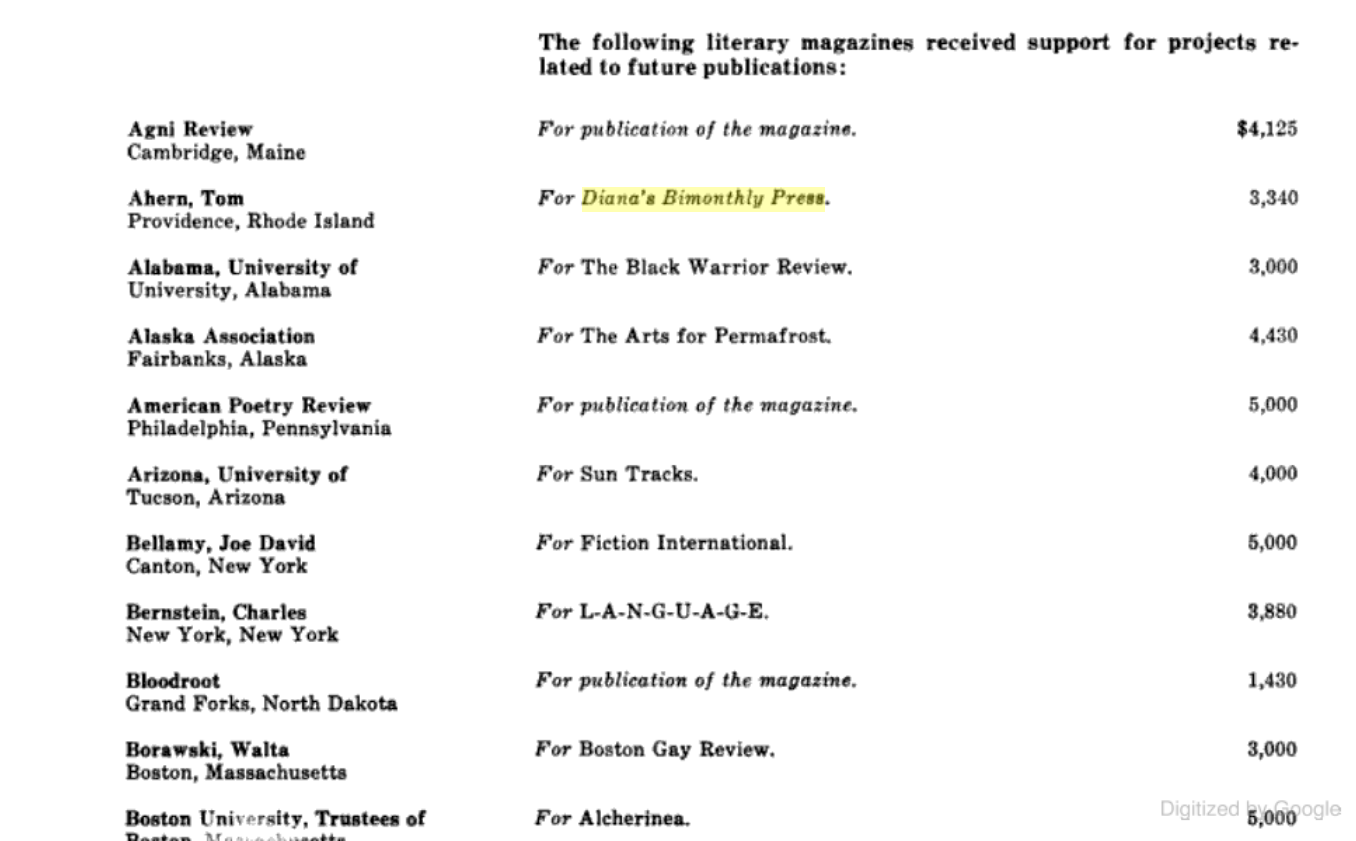

This is a most curious book. It was published in 1979 by Diana’s Bimonthly Press, with a grant from the National Endowment of the Arts. It’s offset-printed (I think; very shiny ink) and stapled. I tried googling the publisher, and I’m finding things like:

And:

But nothing that says what the press actually was…

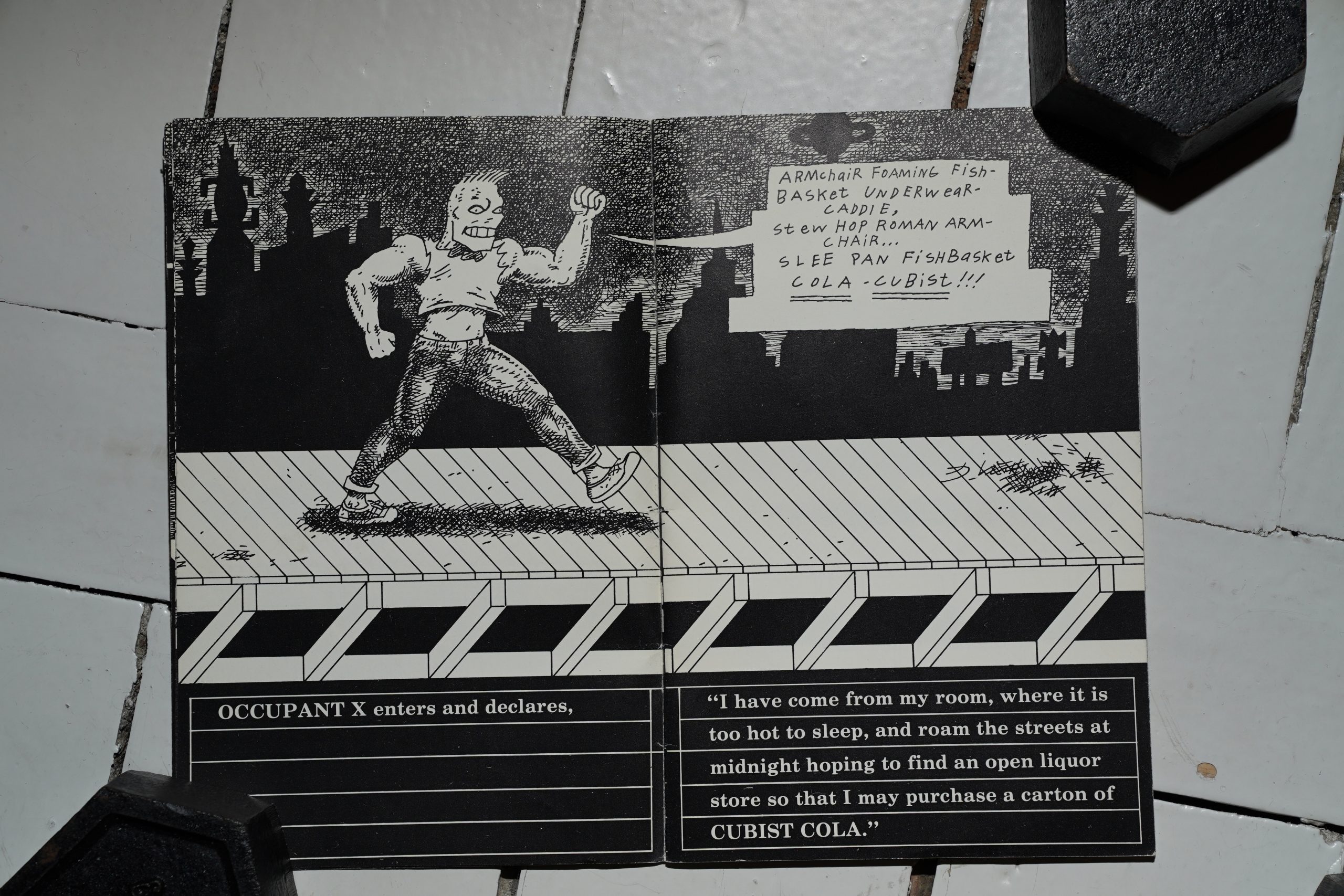

Anyway, the book is about Jimbo playing Occupant X in a play in Dal-Tokyo, and that’s the first of many references here to other works by Panter elsewhere. Dal-Tokyo was a strip Panter published in the LA Reader starting in 1983, so this is before that.

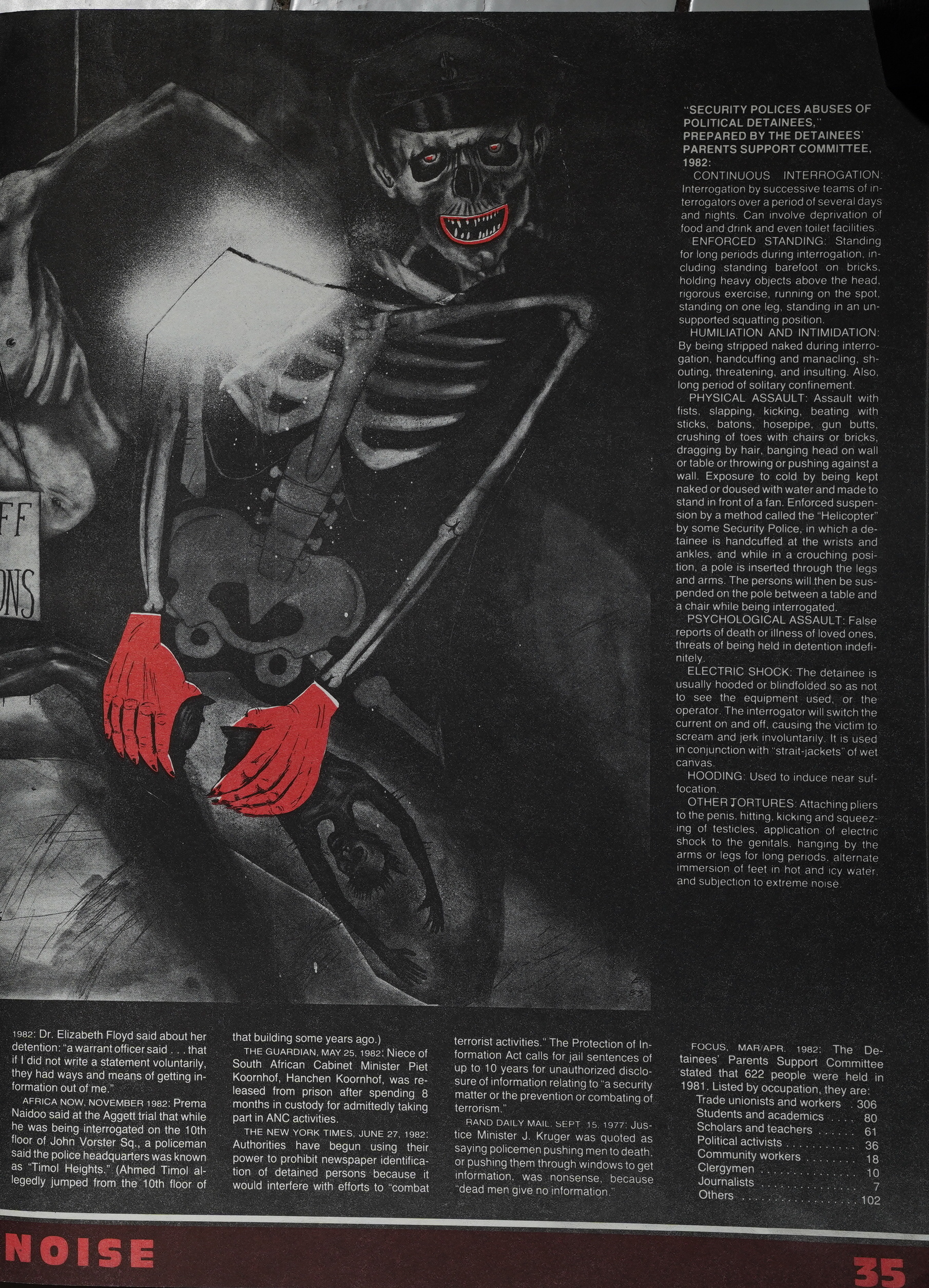

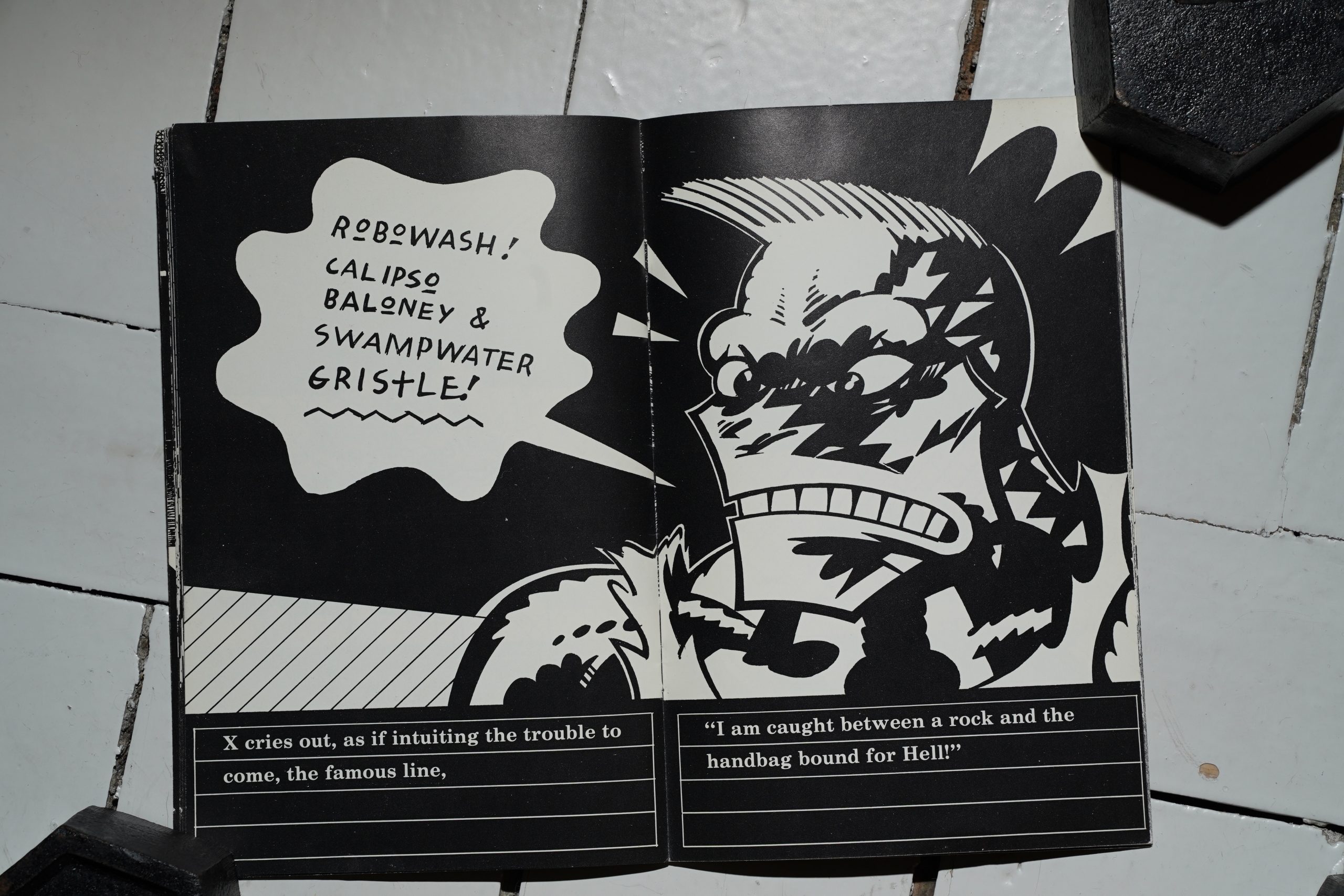

The Jimbo-on-stage/text-below thing gives this a children’s book vibe, sort of.

Panter experiments with different rendering techniques, and on this spread, he’s doing an almost super-hero inking job with Jimbo’s hair.

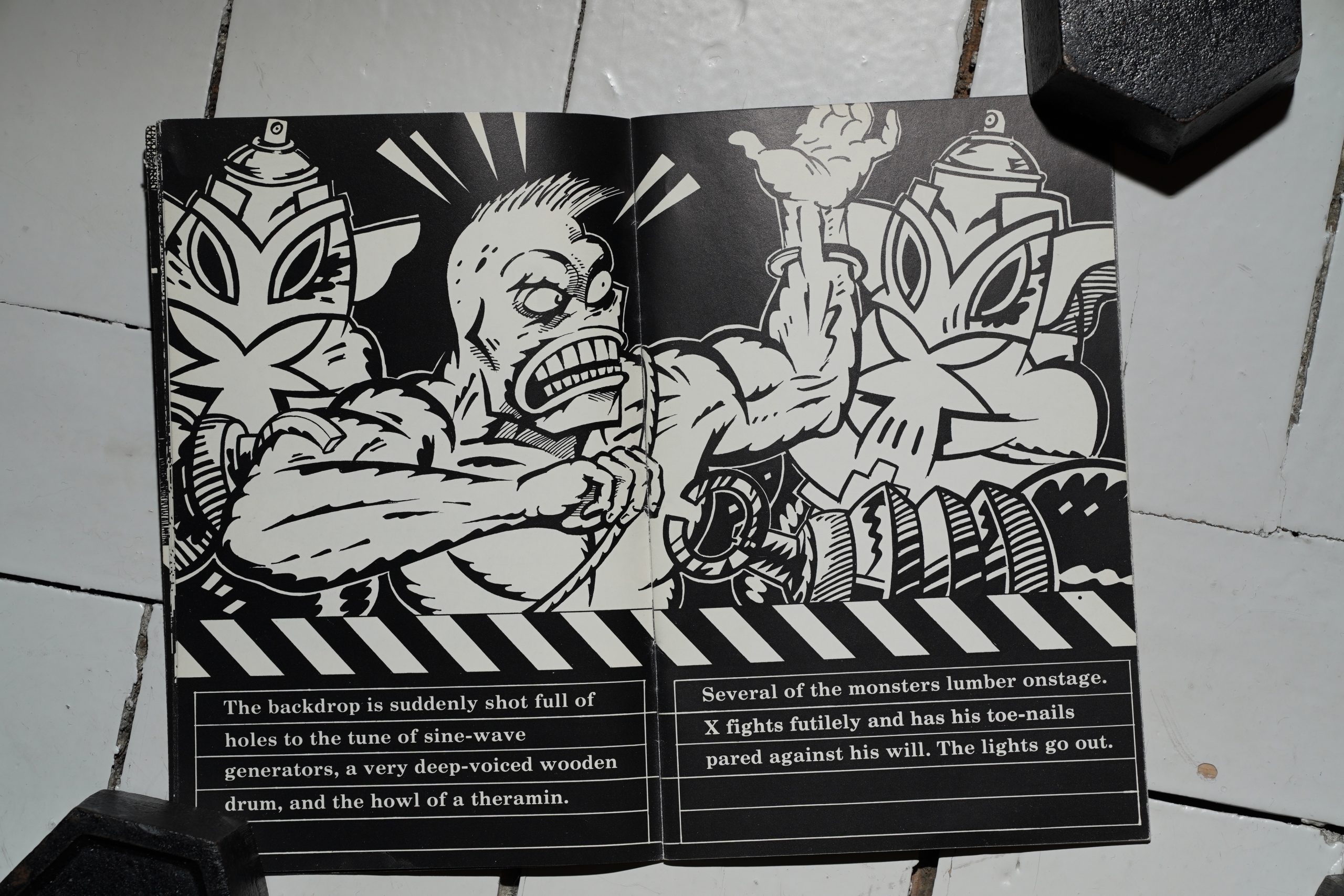

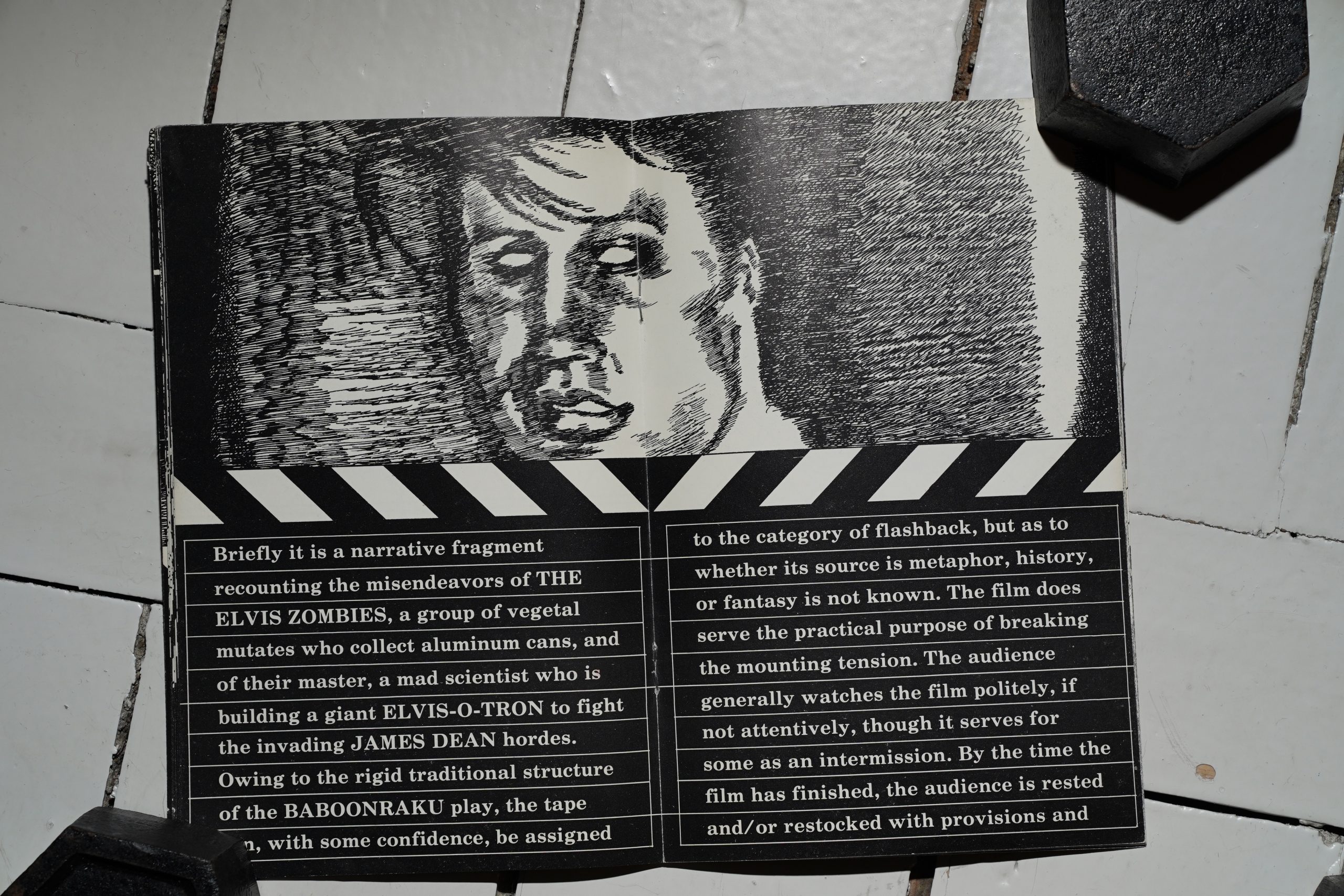

We touch upon Invasion of the Elvis Zombies, published in 1984.

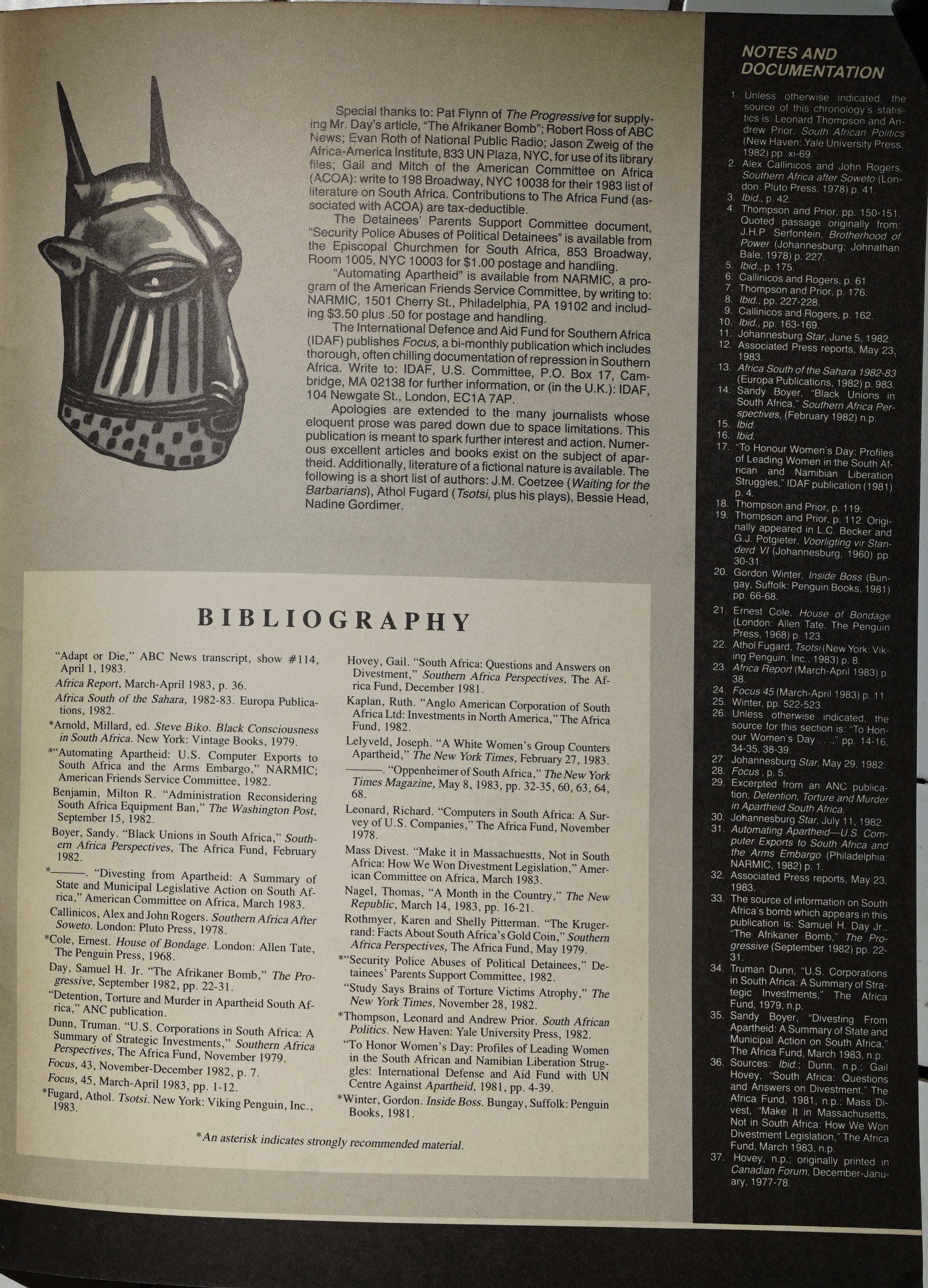

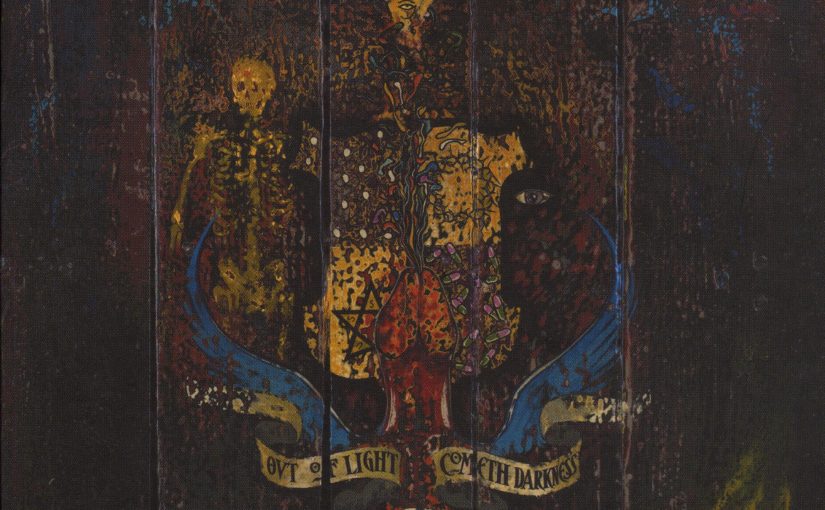

And this was used as the cover of Raw #3, published in 1981:

If Okupant X had been published later, then you’d think of it being very referential, but instead it seems like Panter would cannibalise ideas from it over the next few years? Or perhaps Dal Tokoy/Elvis were things that he had already started working on, and just included here, too?

Dale Luciano interviews Panter in The Comics Journal #100, page 217:

LUCIANO: Tell me about Okupant X. 1

haven’t been able to locate a copy, but people

tell me it’s an important book.

PANTER: Yeah .

LUCIANO: Uhh, what is

PANTER: Okupant X is a book did in

. .uhhhhh… [Gets up, starts rummaging

around in search of a copy] Lemme see if I can

find a copy here.. .Oh yeah, I told you I

had a Xerox of that, and I do. [Thumbing

through the book) I can’t remember what

year. . ’79, ‘SO, something like that .

published on really good paper by an art

publisher in Rhode Island, from Diana’s Bi-

monthly Press.

LUCIANO: Gary, what it??

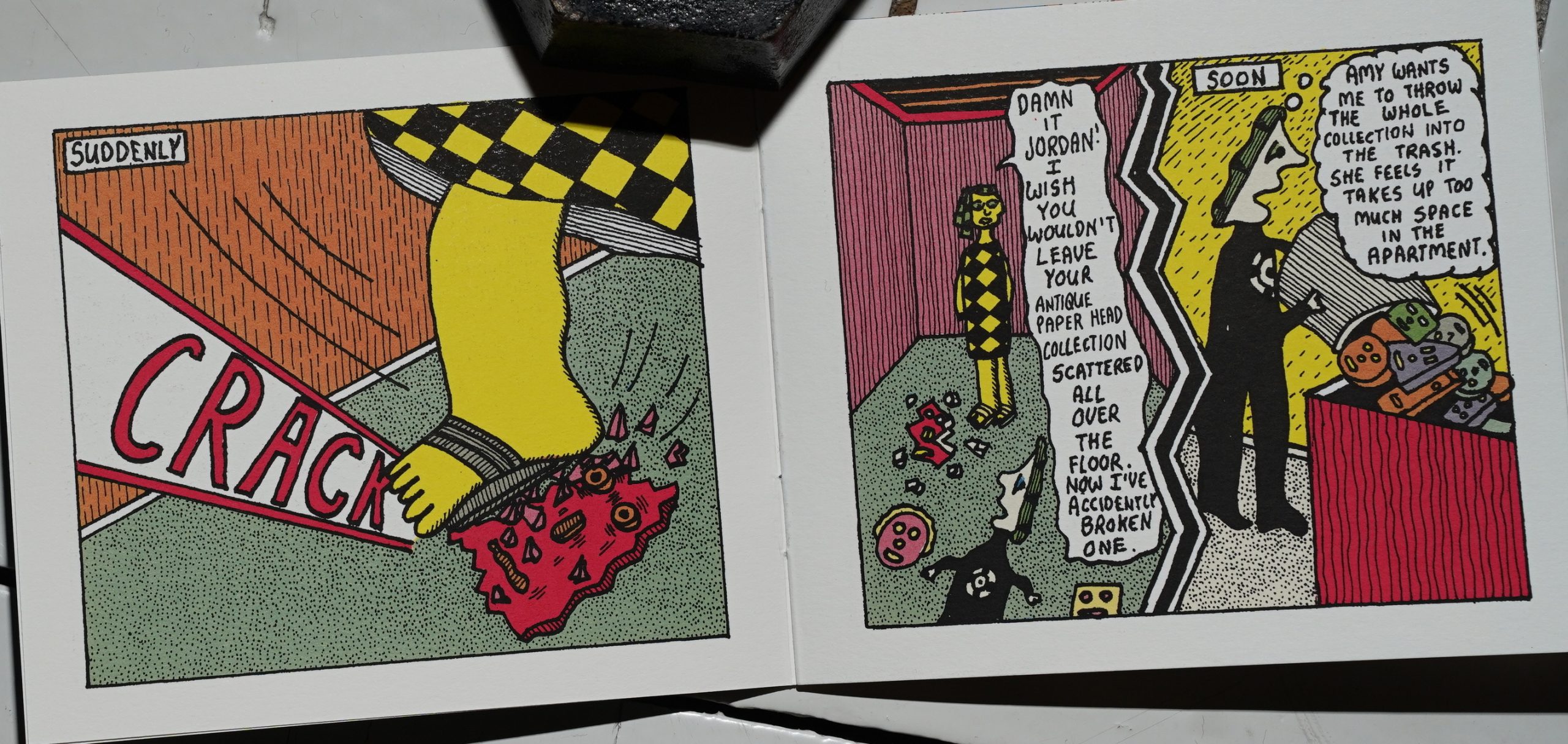

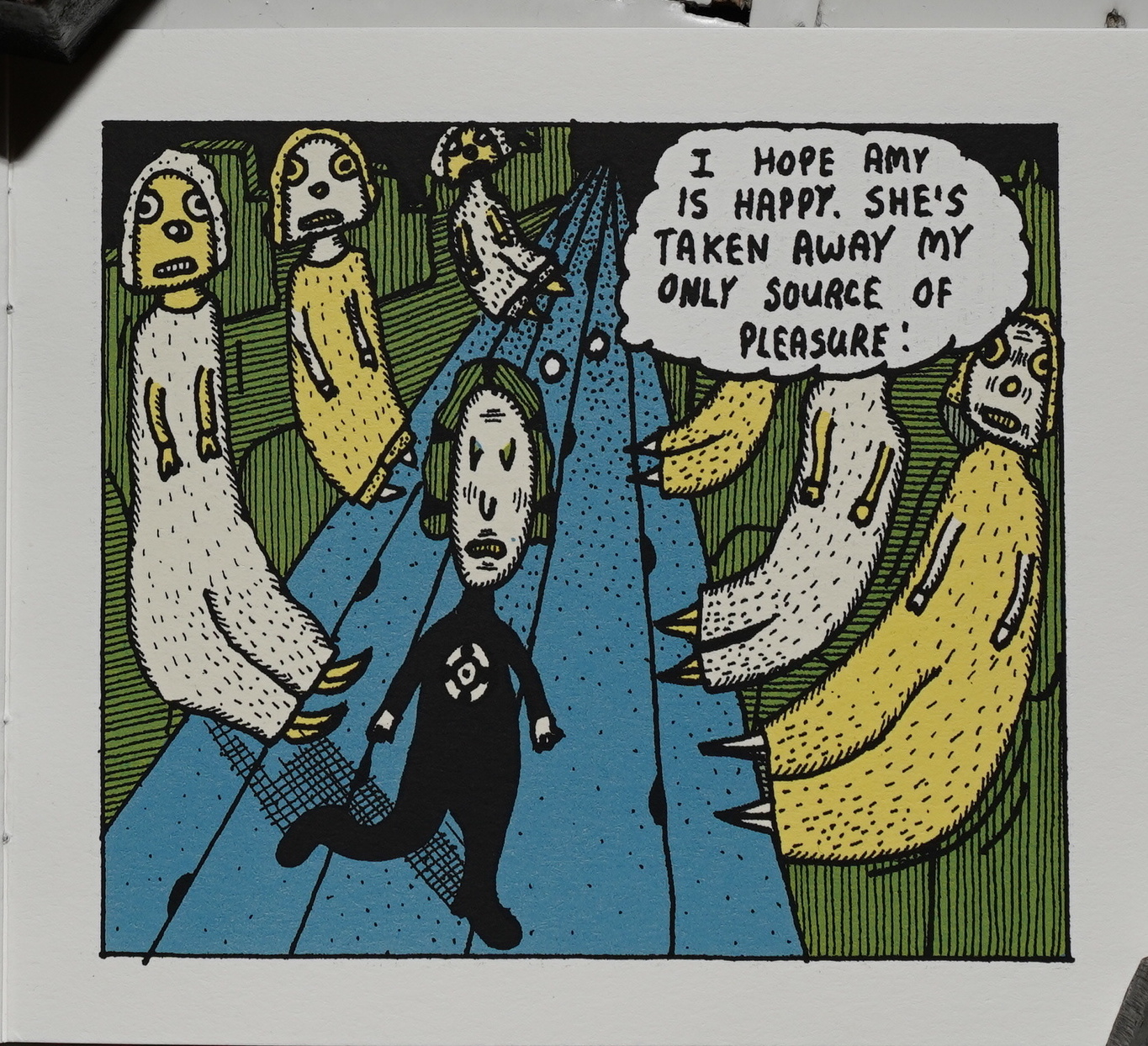

PANTER; It’s a 28-page book about this

guy, OkupantX. It’s kind ofa puppet play.

It’s just about this guy who goes for a walk

and happens onto this corporate property

where this giant monster attacks him.

LUCIANO: A giant monster, did you say?

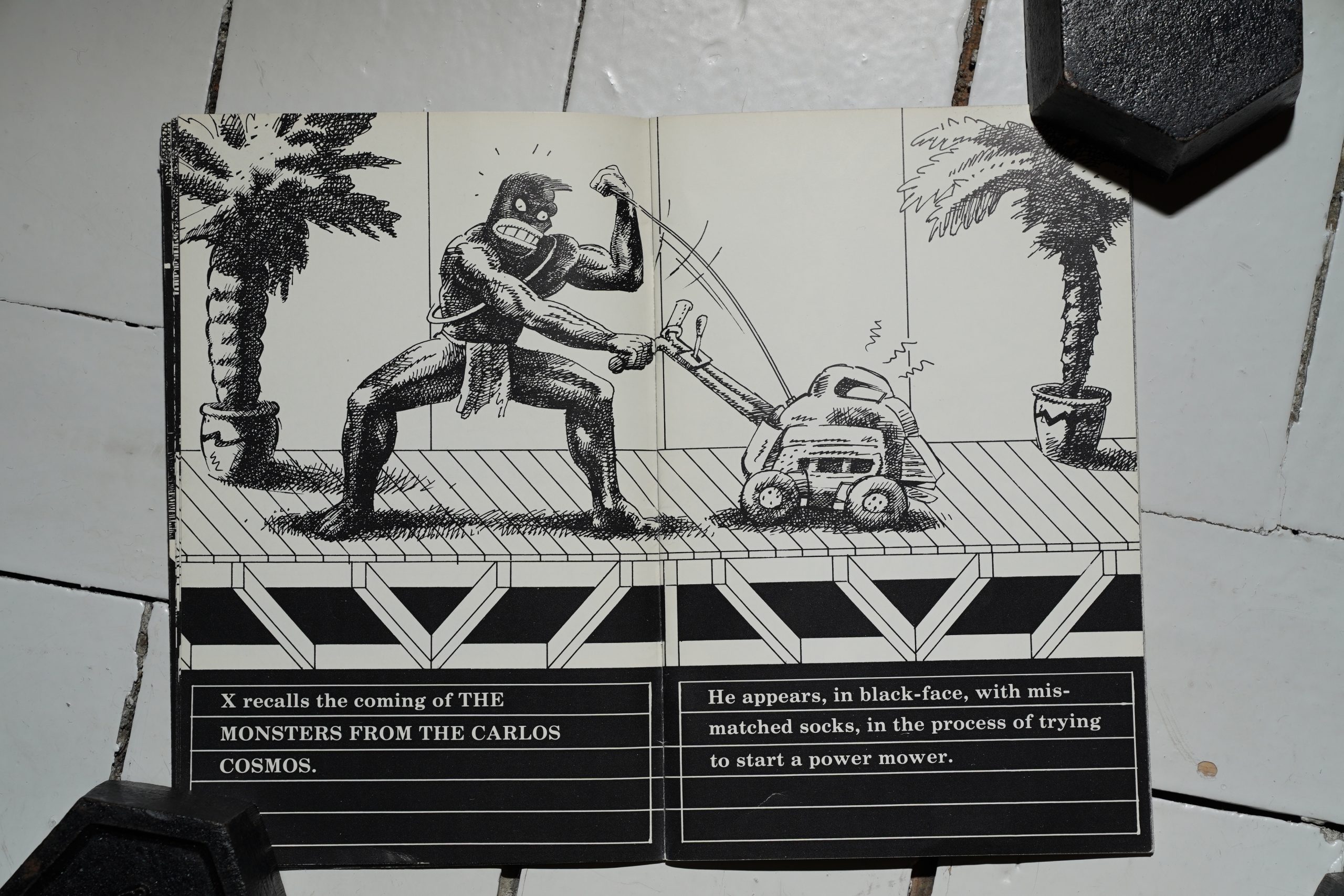

PANTER: Yeah, a large germ. It was an

excuse to draw a ’50s monster with lots of

eyes and arms and stuff, and write some-

thing sort of Kabuki-like.

LUCIANO: That occurred to me, at least on

a subliminal level. At one point, looking at

“Jimbo,” I thought, “This is like Kabuki

Drama.’ .

PANTER: Yeah, it is Kabuki-influenced

in a way. I’ve really studied and looked at

Japan to see what their view of the West

was, to see another view of things.

LUCIANO: Tell me more about. working in

this child-like style.

PANTER: Well, it’s just following tradi-

tions. I don’t think of my stuff as looking

like children’s drawing, really. In some

ways, I’m just working to”fill in a gap. If I see

everyone doing slick, air-brush, beautiful,

really • ‘finessed” drawings, then try to do

something that’s not being done as much.

That’s where my work comes from. But

now, lotsof people are drawing ratty.

LUCIANO: (Laughs) Drawing ratty? That’s •

What call it?

PANTER: Yeah, ratty. That’s pretty

much what I call it. Ratty drawing.

LUCIANO: But you like ratty drawing, cor-

rect ?

PANTER: Oh yeah, it comes right out of

the human being. Ratty drawing is natural,

like the marks people make on crates when

they write the numbers on them to ship

them off, or like bathroom graffiti when it’s

just scrawled onto the walls. The line has

some kind of content. It’s got the emotion

of the person doing it. It’s a testament that

the person exists and that they made the

marks.[…]

LUCIANO: You use the word “marks, i’

where hear most cartoonists or artists talk

about “lines. What’s the difference?

PANTER: (Long pause during which he con-

siders the question) I think lines are the kinds

of things an artist uses to construct an illu-

sion. A line is a tool for making or defining

an illusion. A mark is more ofa thing that

exists for and by itself. It’s more abstract as

a building block. I think the idea of

“marks” is •somehow closer to the natural.

Marks get away from the sophisticated

reality of an illusion of depth toward the

reality of something that’s closer to the

natural order of things. Yeah, marks have

the look of nature.

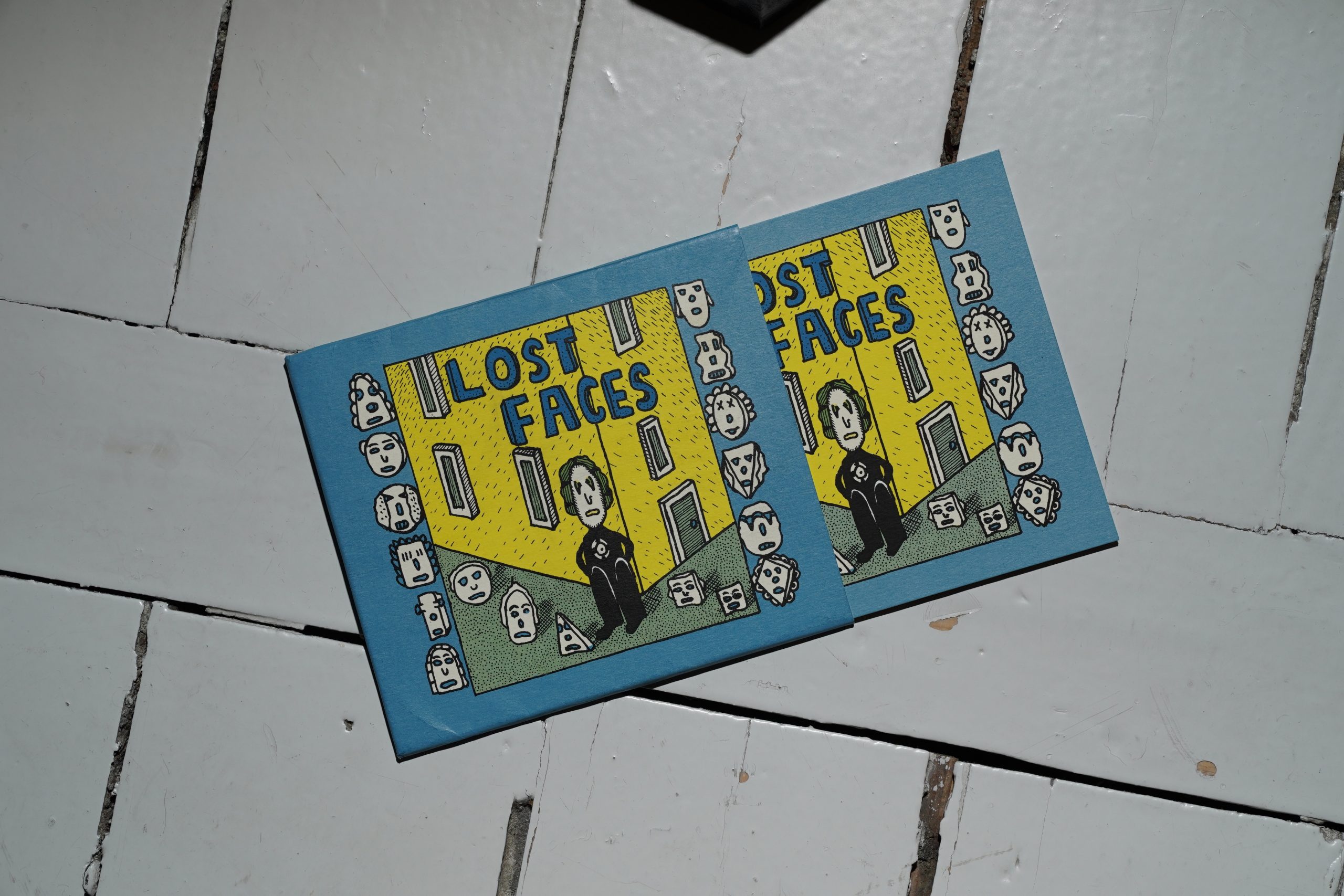

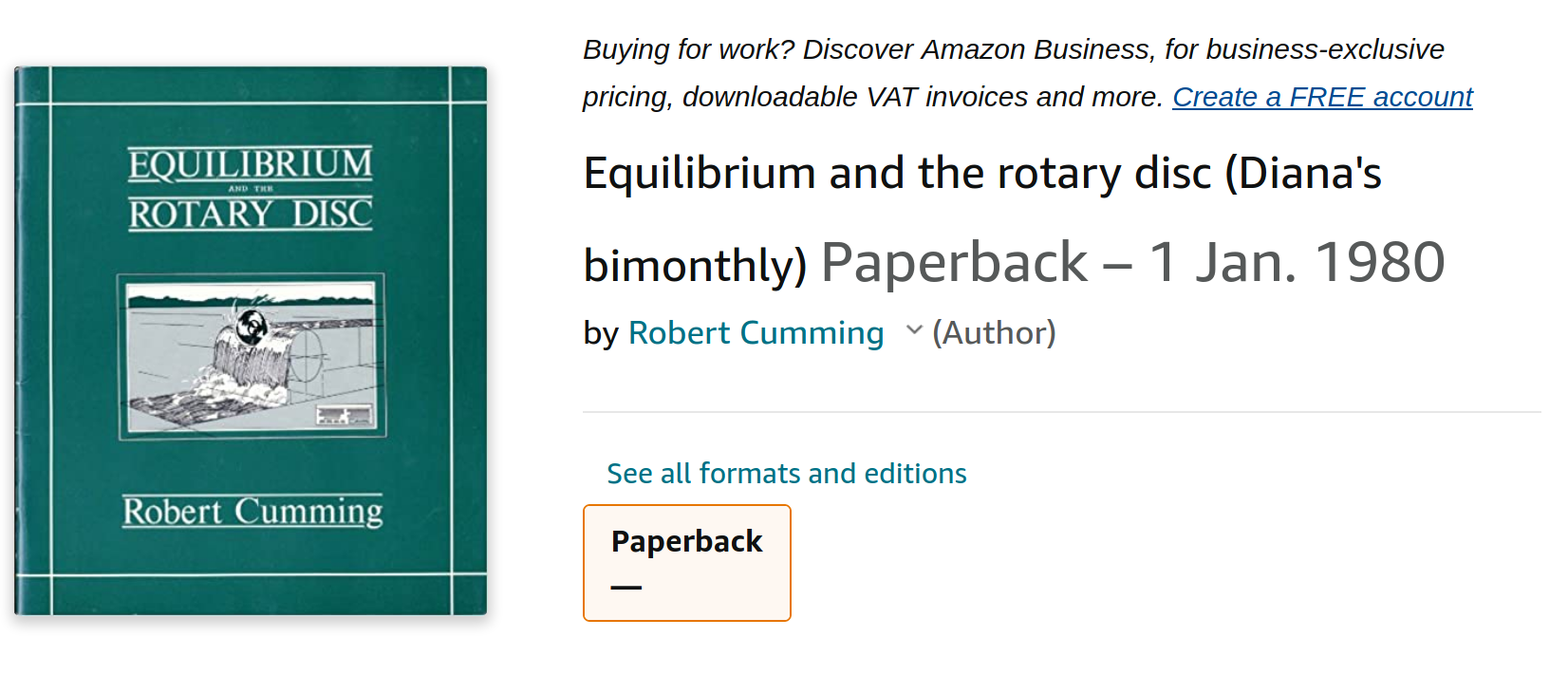

It was apparently also published in a different format:

This blog post is part of the Punk Comix series.

+Redux)

)

)

)

)

)

)

%3A+Sessions+4)