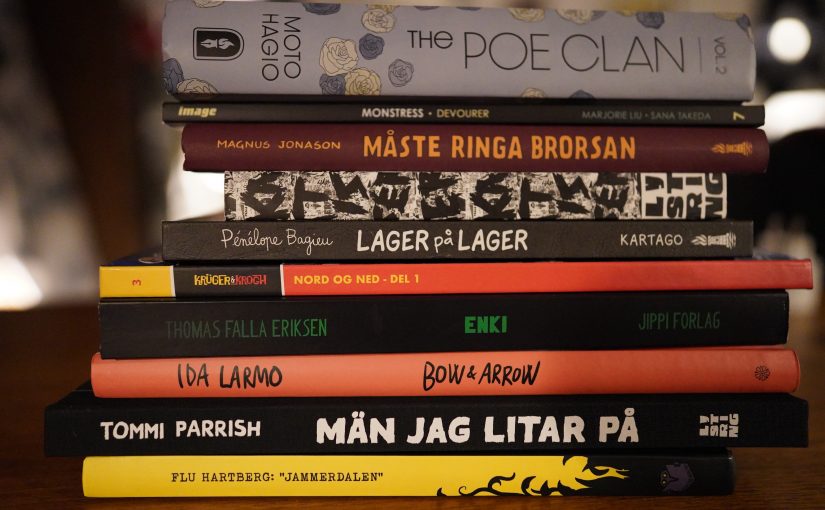

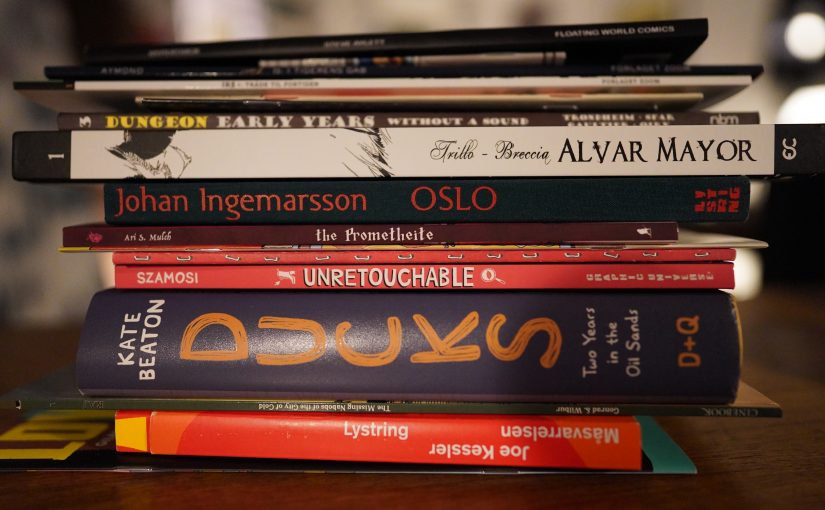

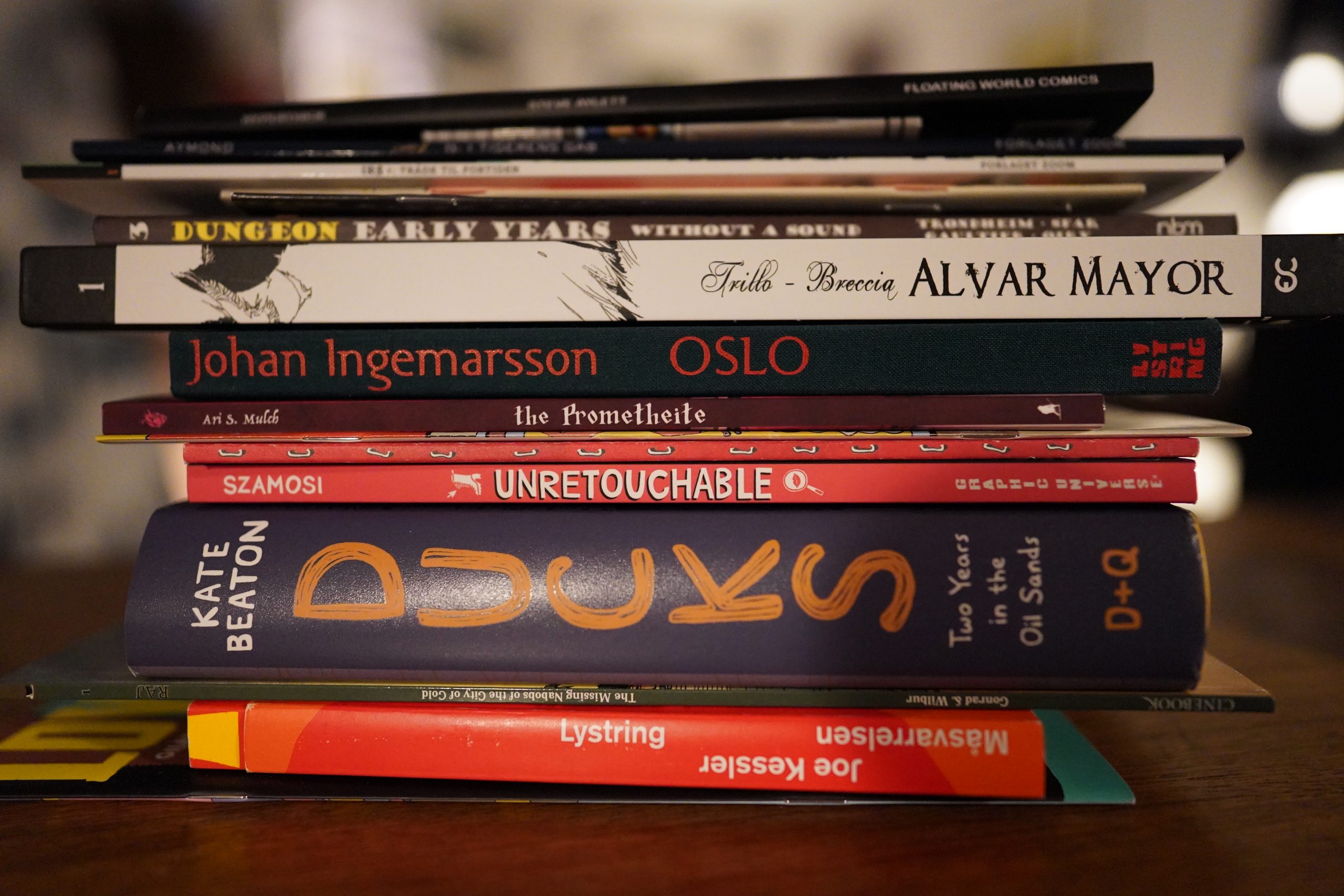

It’s a grey day, so I think comics are required. And this time around, I think I’ve mostly got Norwegian and Swedish comics?

| Lady Lykez: Woza |  |

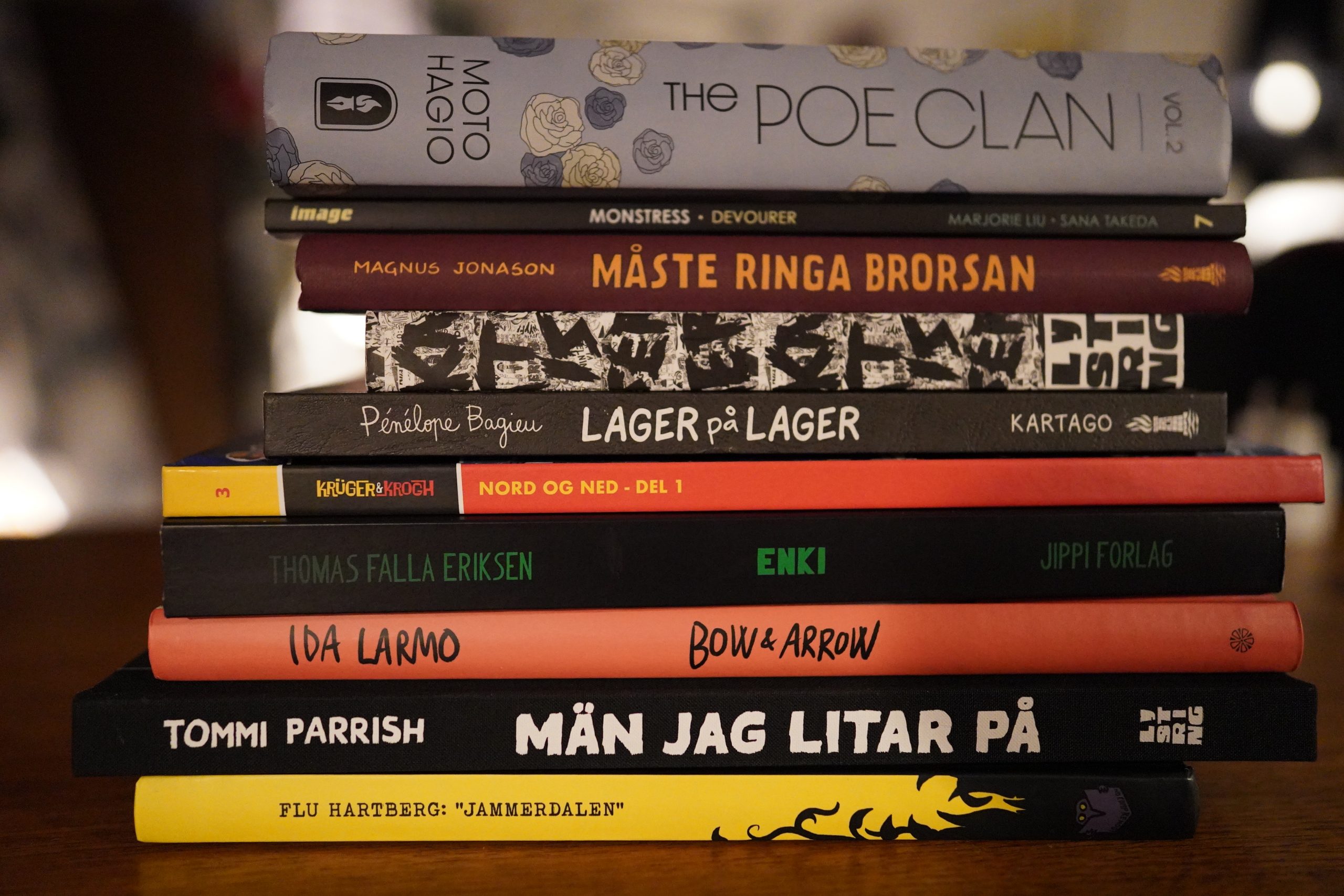

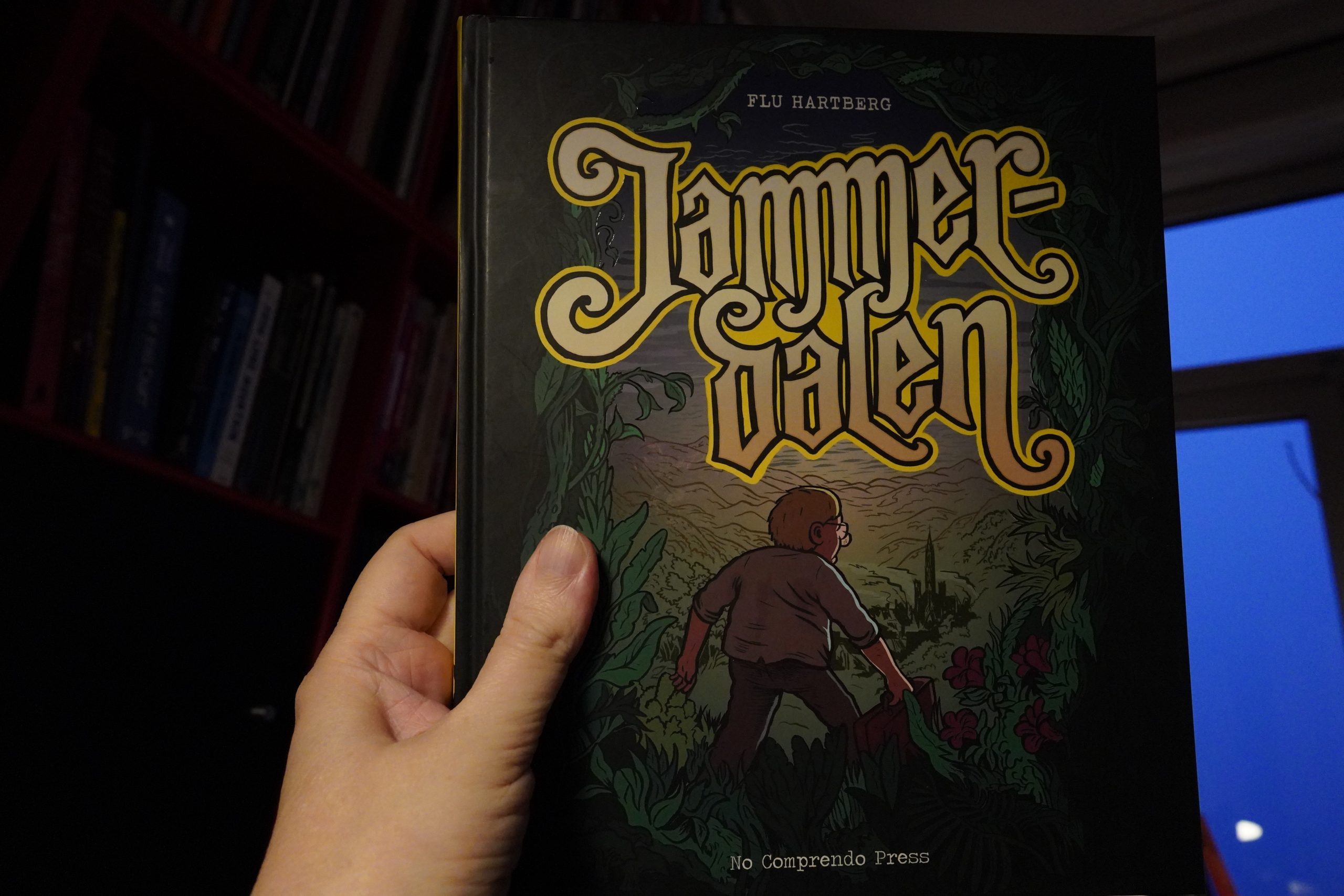

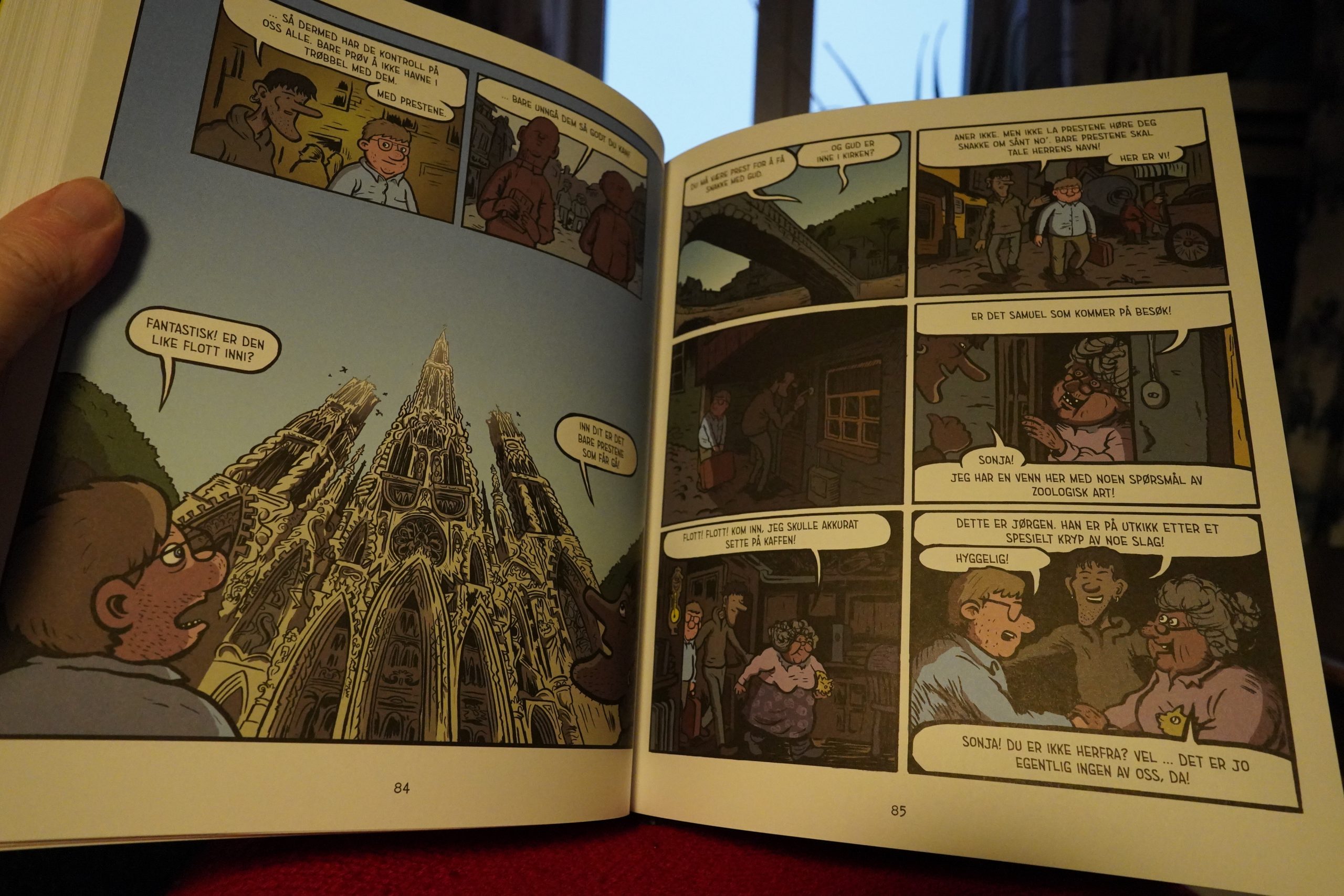

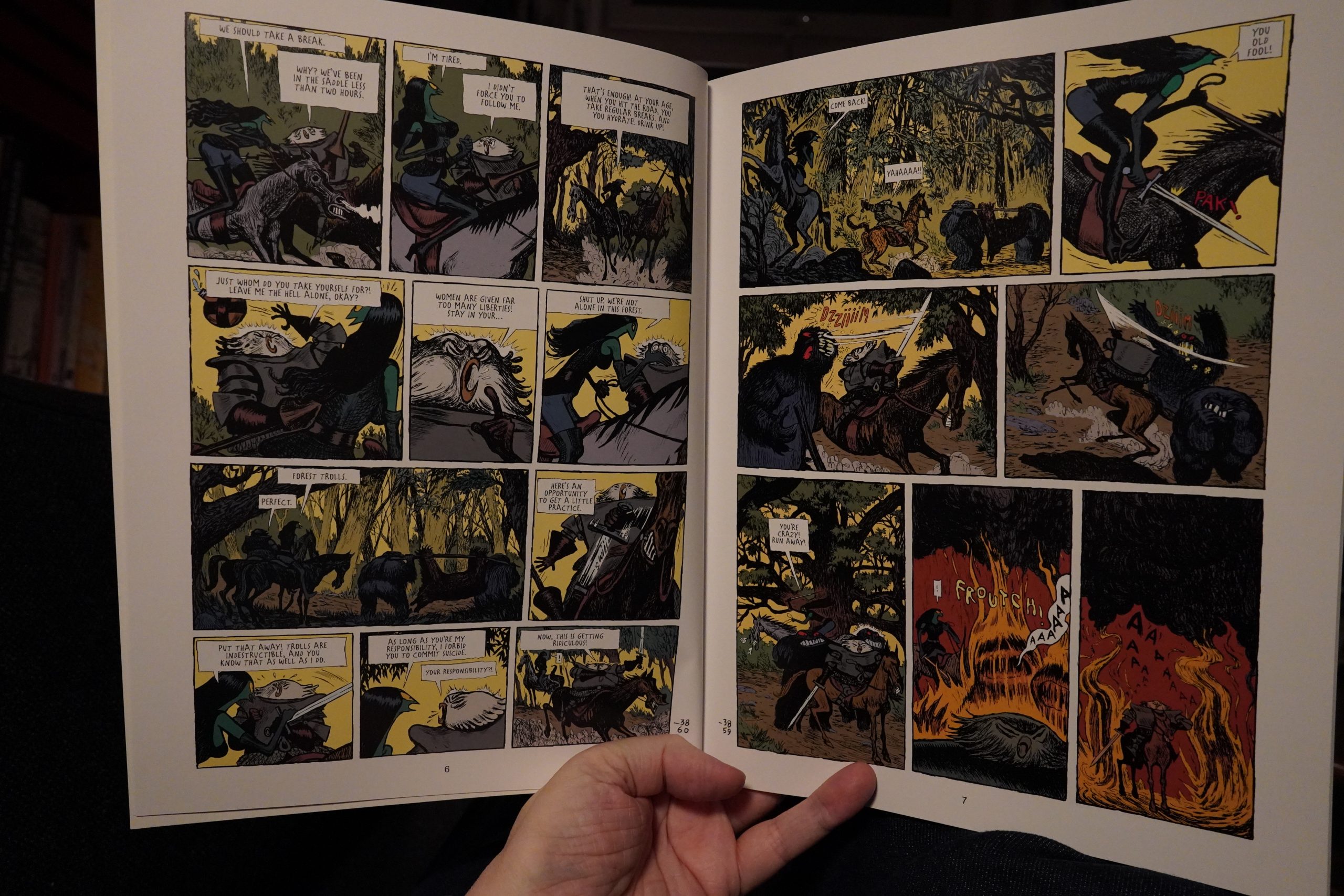

08:32: Jammerdalen by Flu Hartberg (No Comprendo Press)

Hm… I think I’ve read some of his books before, but I think it was mostly absurd humour stuff? This starts off as a kinda-sorta serious story about religion and stuff, and the disparity between the art style and the subject matter makes for odd reading.

Then things take a fantasy turn, and for a couple of pages I was going “this is almost dream-like”, but then I remembered that in the pages preceding this, there was one panel of the protagonist falling asleep. Doh! So I was reading this all annoyed, going “is this going to be revealed a dream now? Now then? Now?”

But it’s… there are interesting bits in here. Some sections work well.

| The Soft Pink Truth: Is It Going To Get Any Deeper Than This? |  |

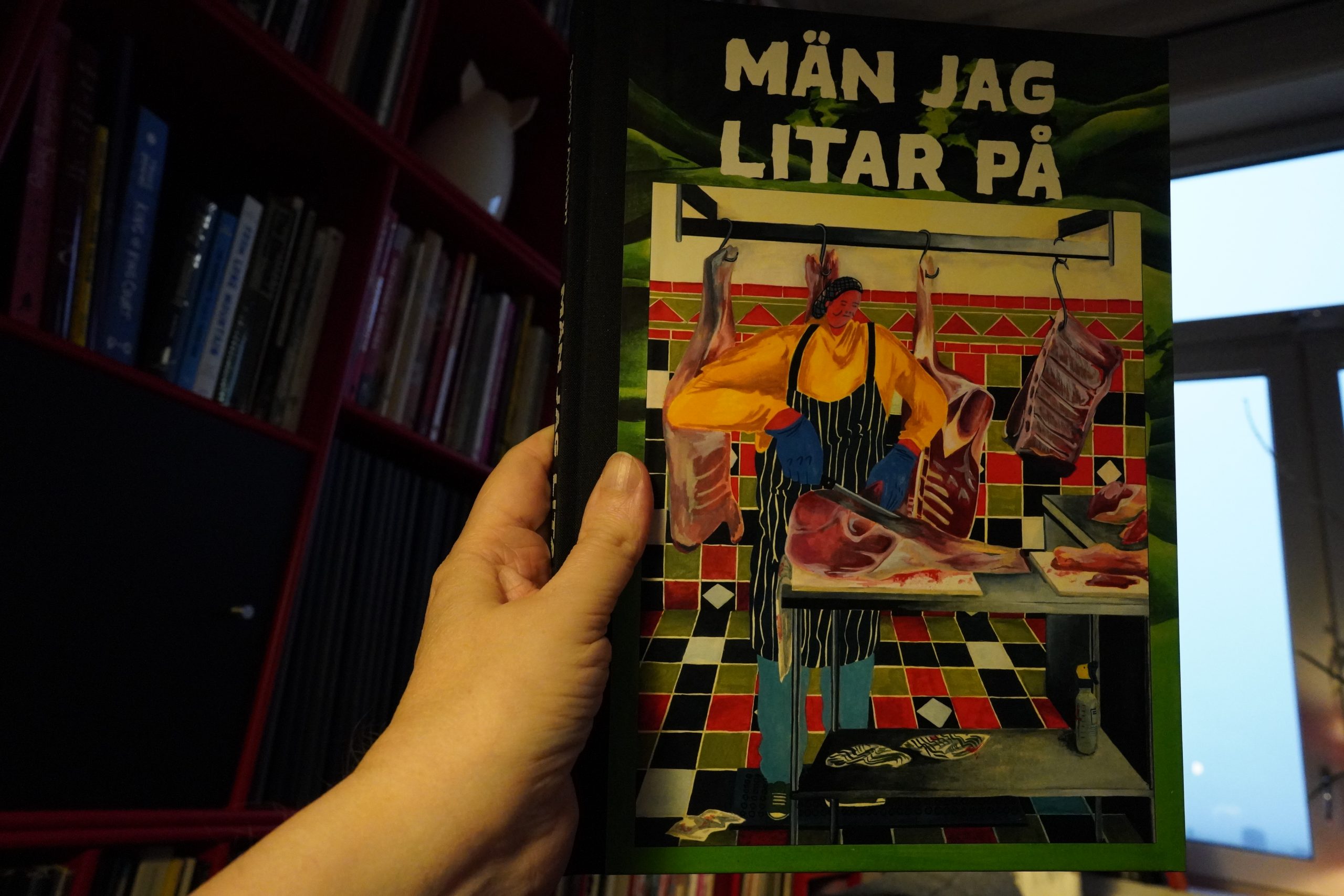

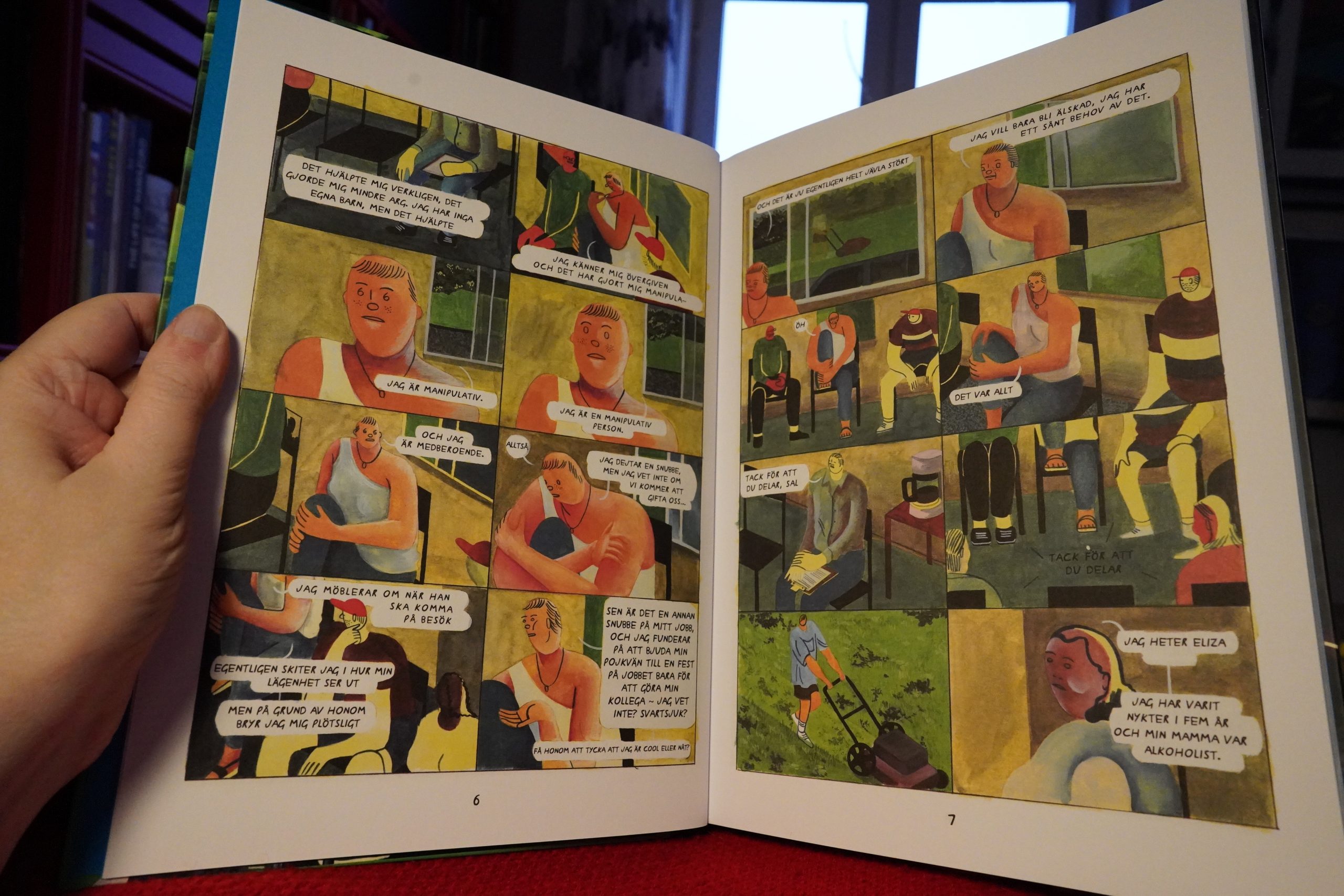

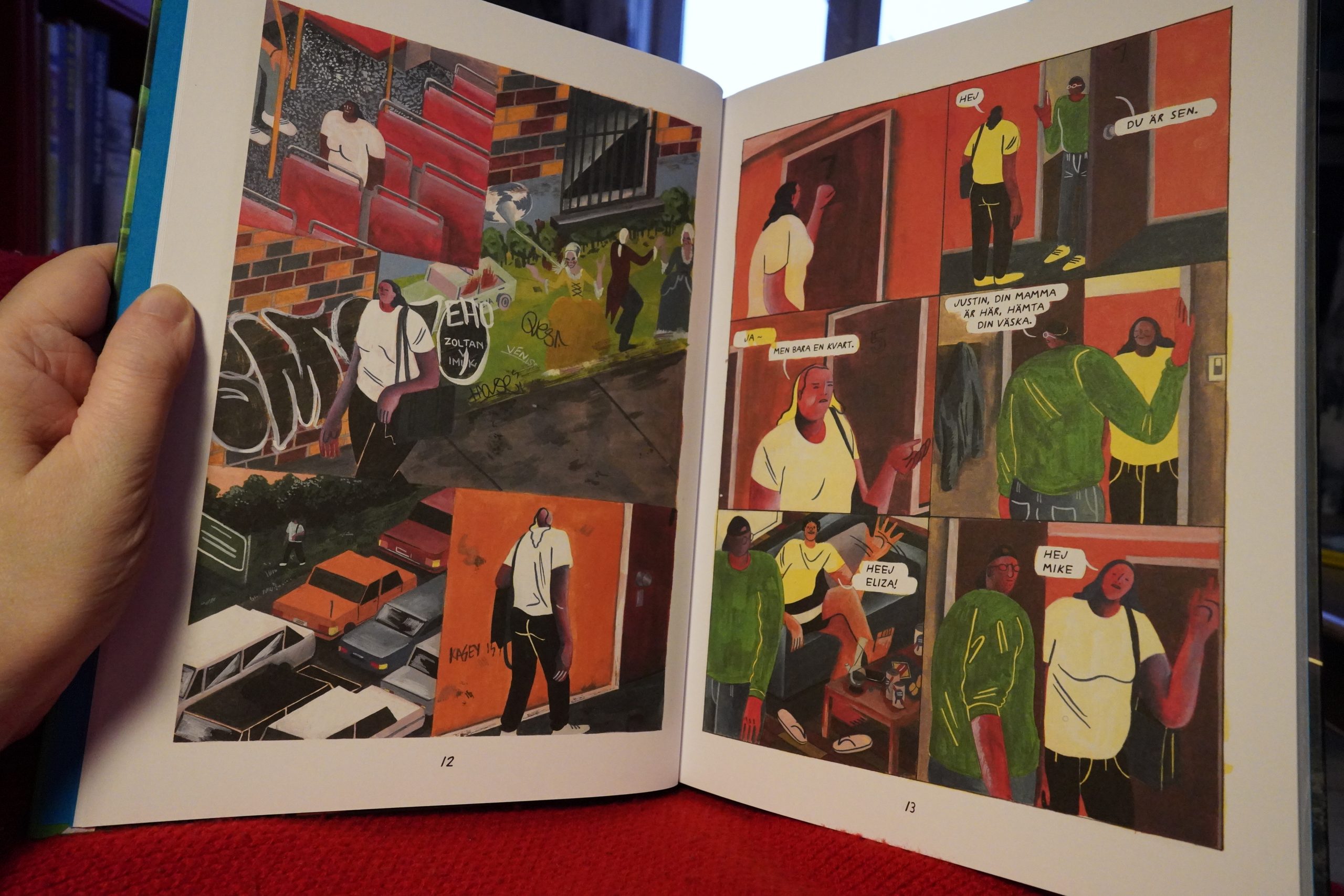

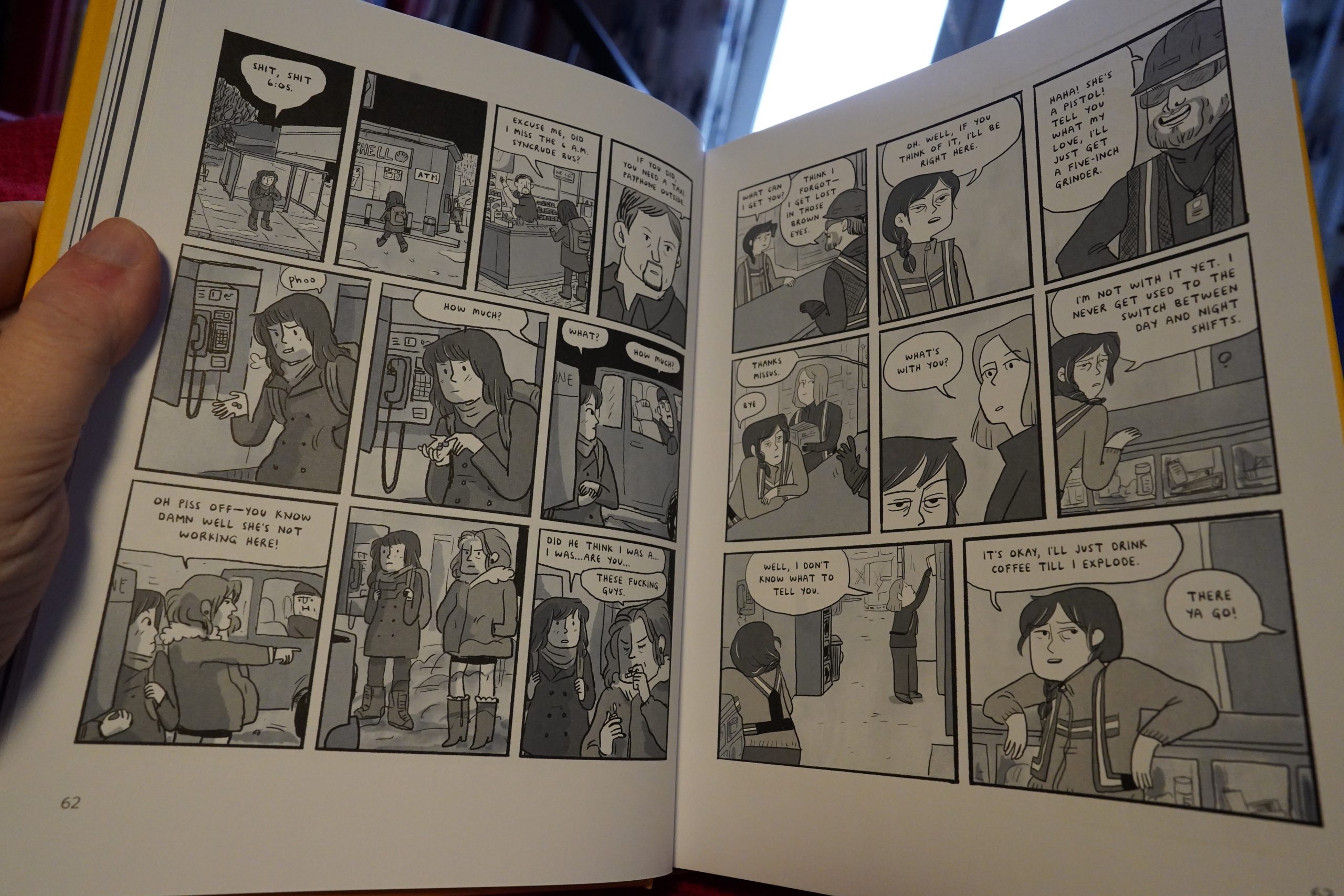

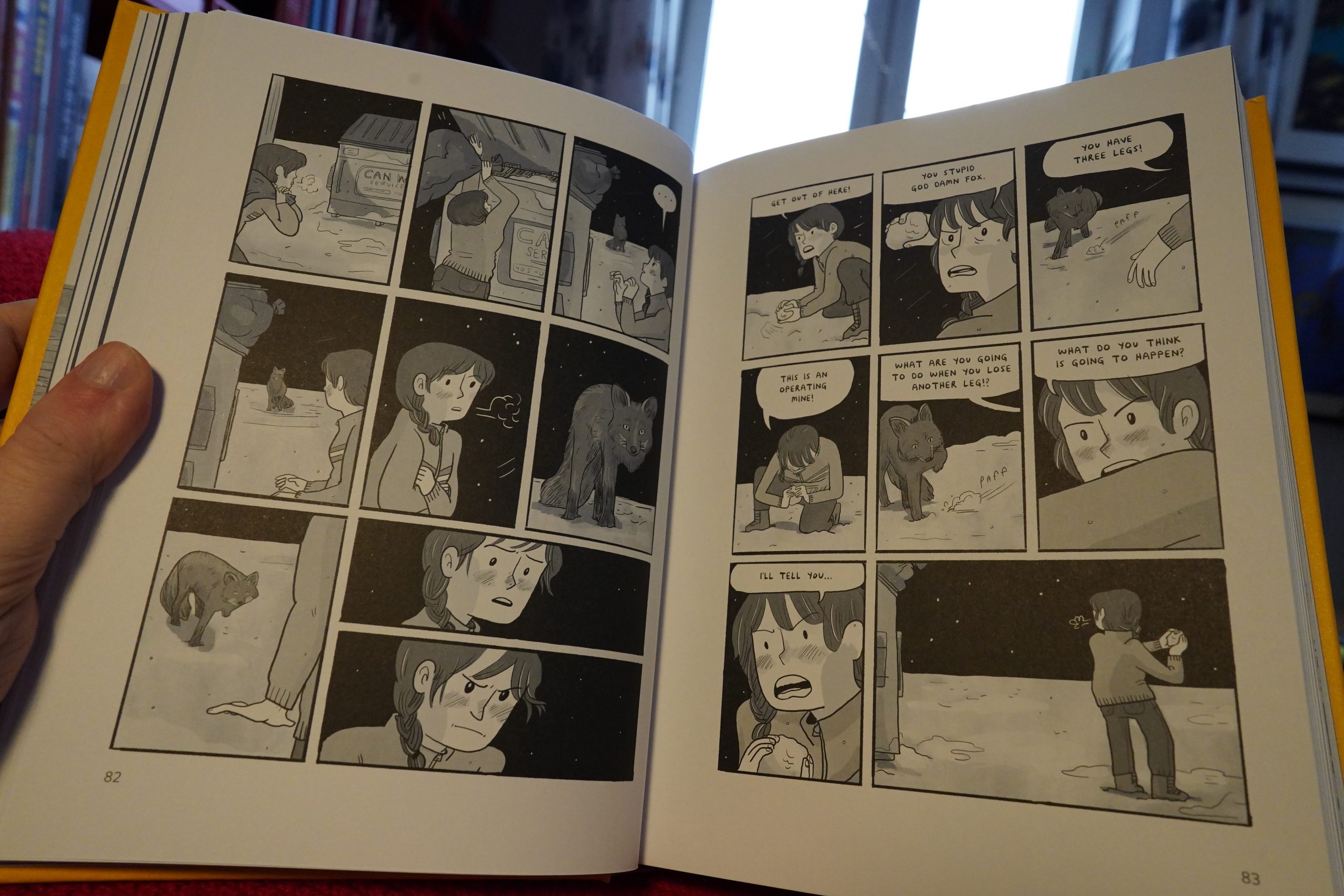

09:14: Men I Trust by Tommi Parrish (Lystring)

Oh — this is the Swedish edition of the book that’s released by Fantagraphics next month. Oops. And I already ordered that book, so now I’ll end up with two copies…

I love the artwork… However, the book seems very informed by AA meeting talk — it’s all swirling down that drain? Pages and pages of this just isn’t very inspiring.

But I mean… the artwork’s so good that I want to love the book anyway.

It’s possible that something was lost in the Swedish translation. I guess I’ll find out when the English version arrives.

| King Crimson: The Complete 1969 Recordings (11): In the Court Of The Crimson King (2019 Stereo Mix) |  |

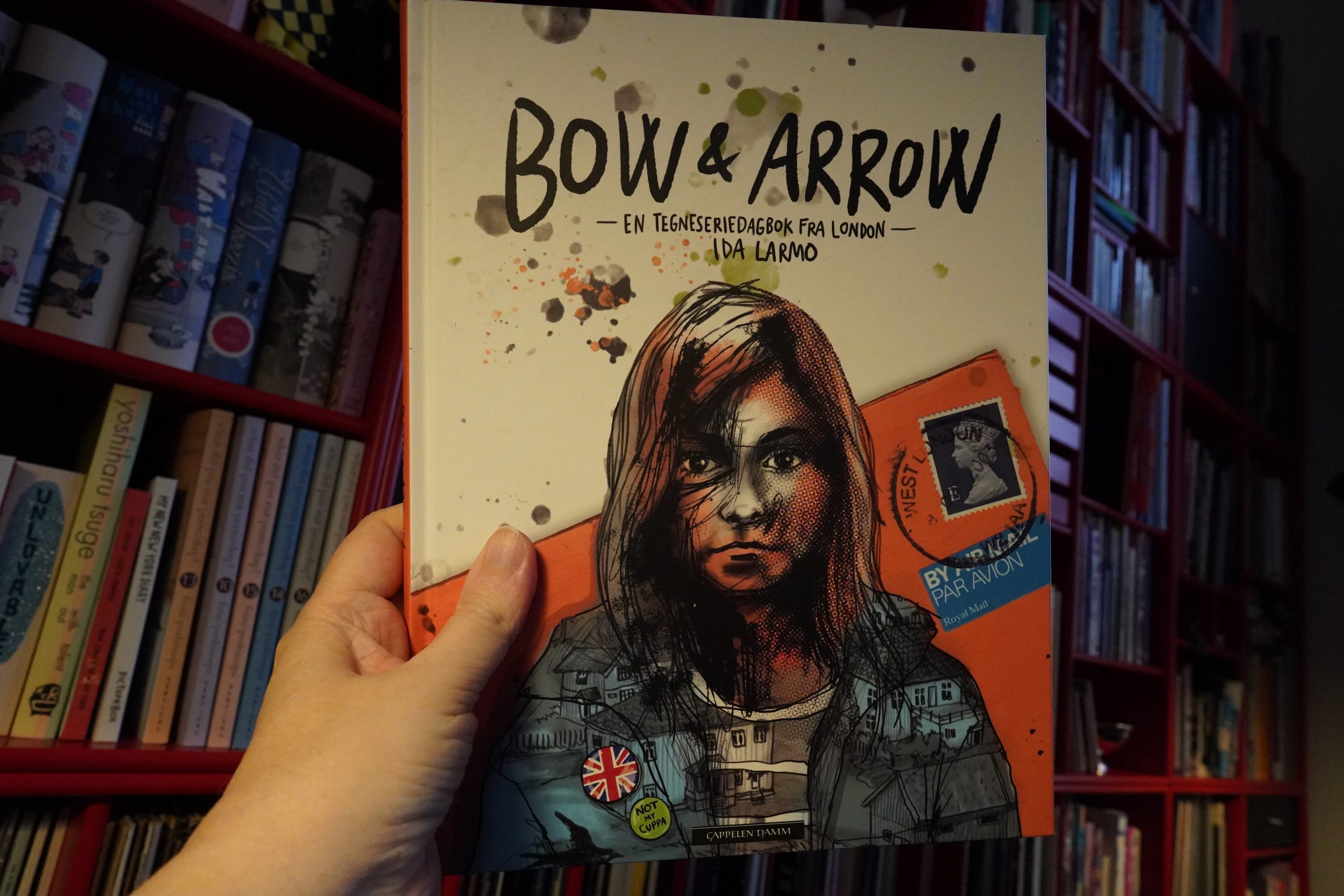

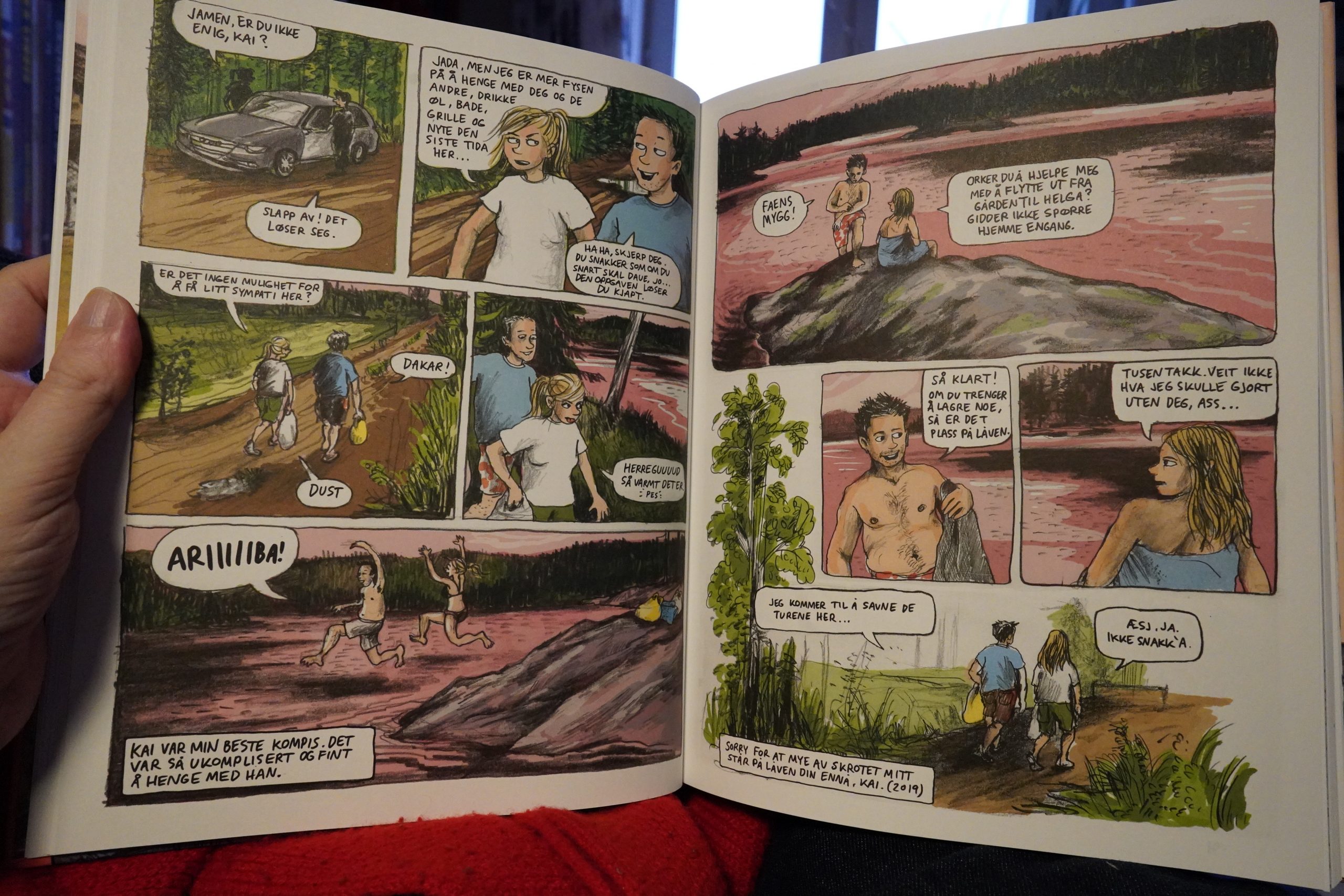

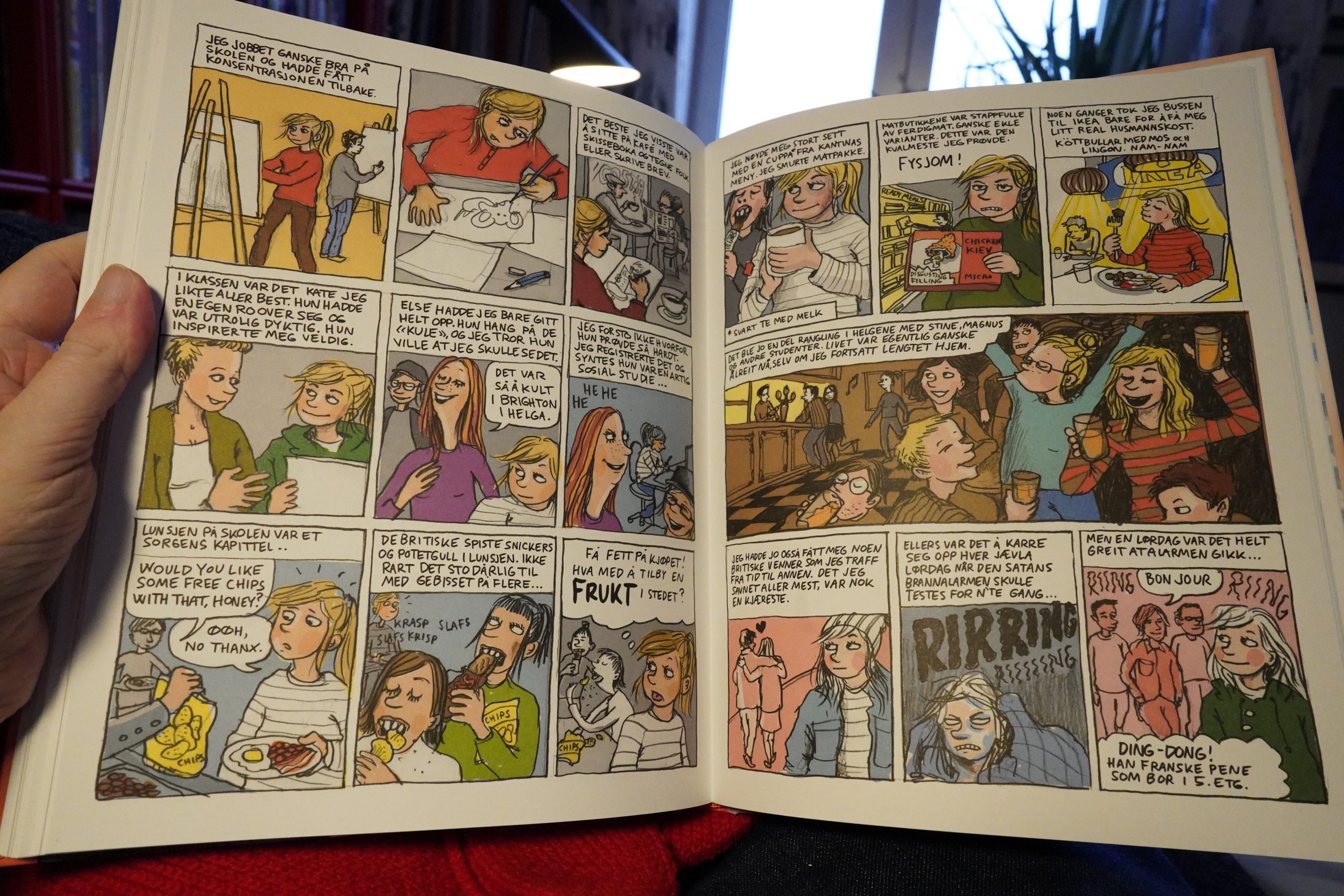

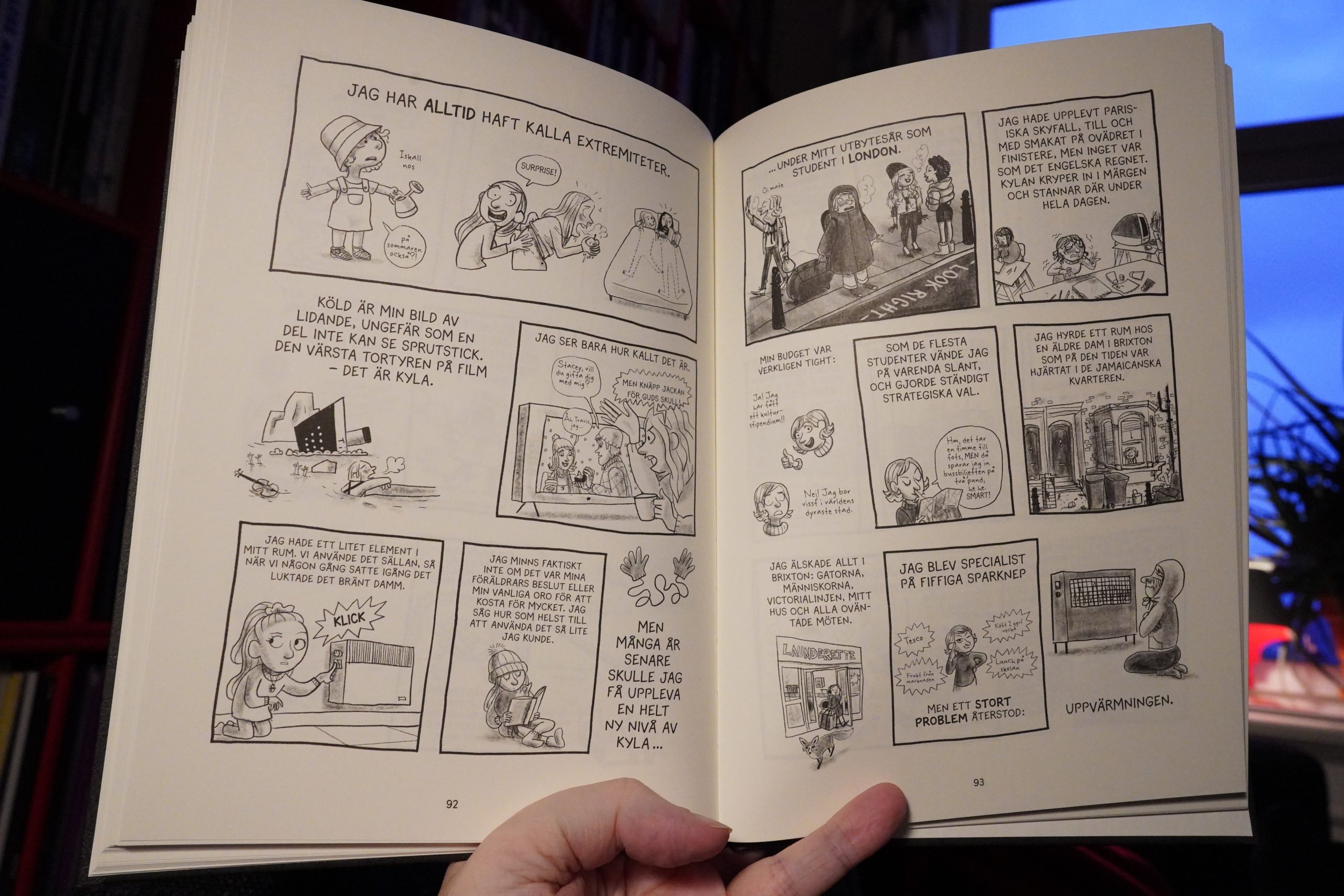

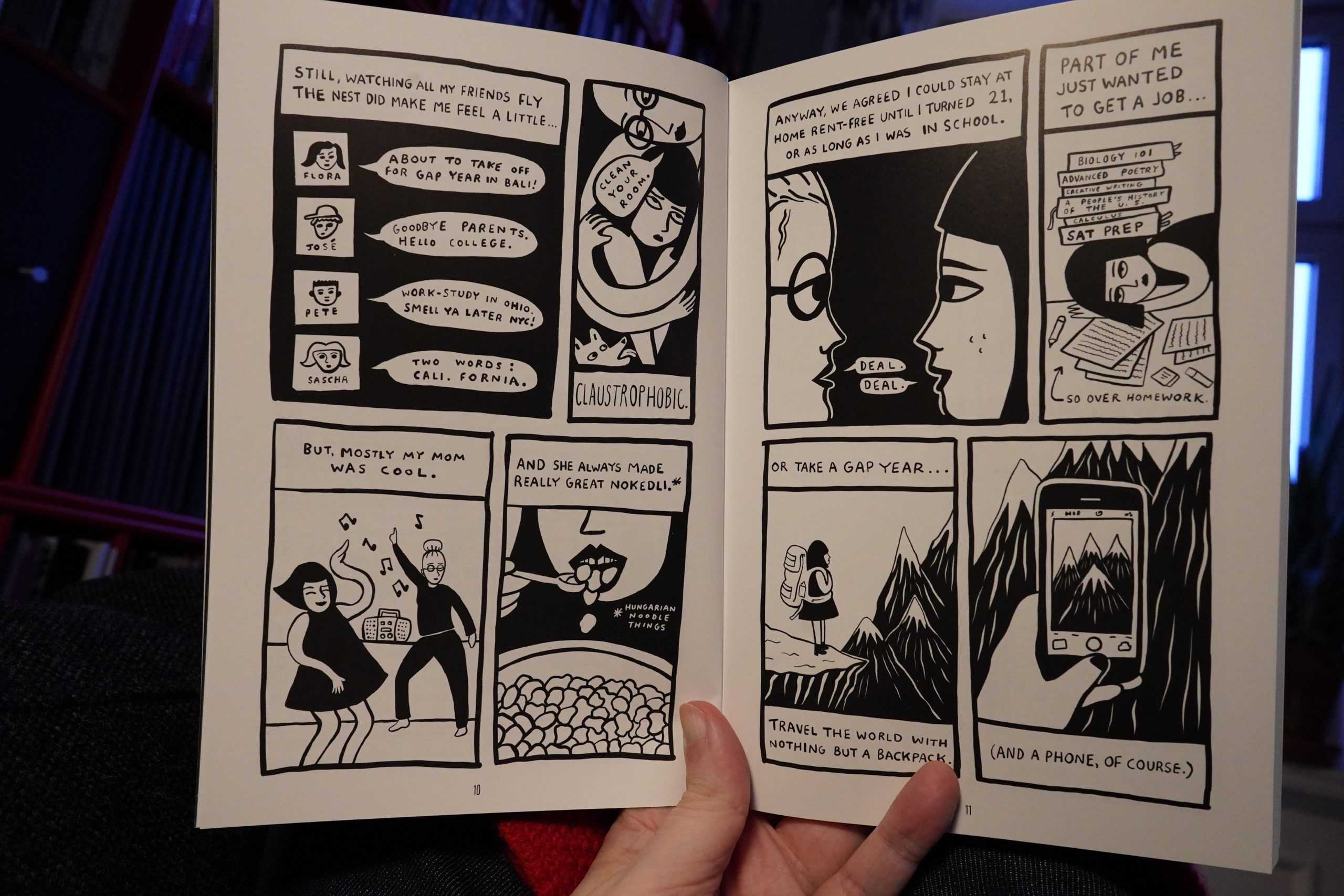

10:12: Bow & Arrow by Ida Larmo (Cappelen Damm)

This is a classic autobio book — it’s about her year as an art school student in London in 2002 (when she was 22). And it’s like… my god, is it possible to be that young? It’s from a different era (pre-smartphone), so it’s also got that nostalgic sheen, but she depicts herself being so incredibly naive that it gets a bit cringe-worthy. And I’m not sure whether she means to come off that way, either, because:

When she’s not self-righteously explaining how reasonable it is for her to not know even the most basic things, she spends the rest of the time detailing what morons British people are, and how disgusting their habits are. That uncomfortable mix of self-righteous prejudice and ignorance?

It makes for entertaining reading, but I had to hide behind a pillow at points, because it’s just so embarrassing. *cringe*

| Mahmoud Fadl: Drummers Of The Nile Go South |  |

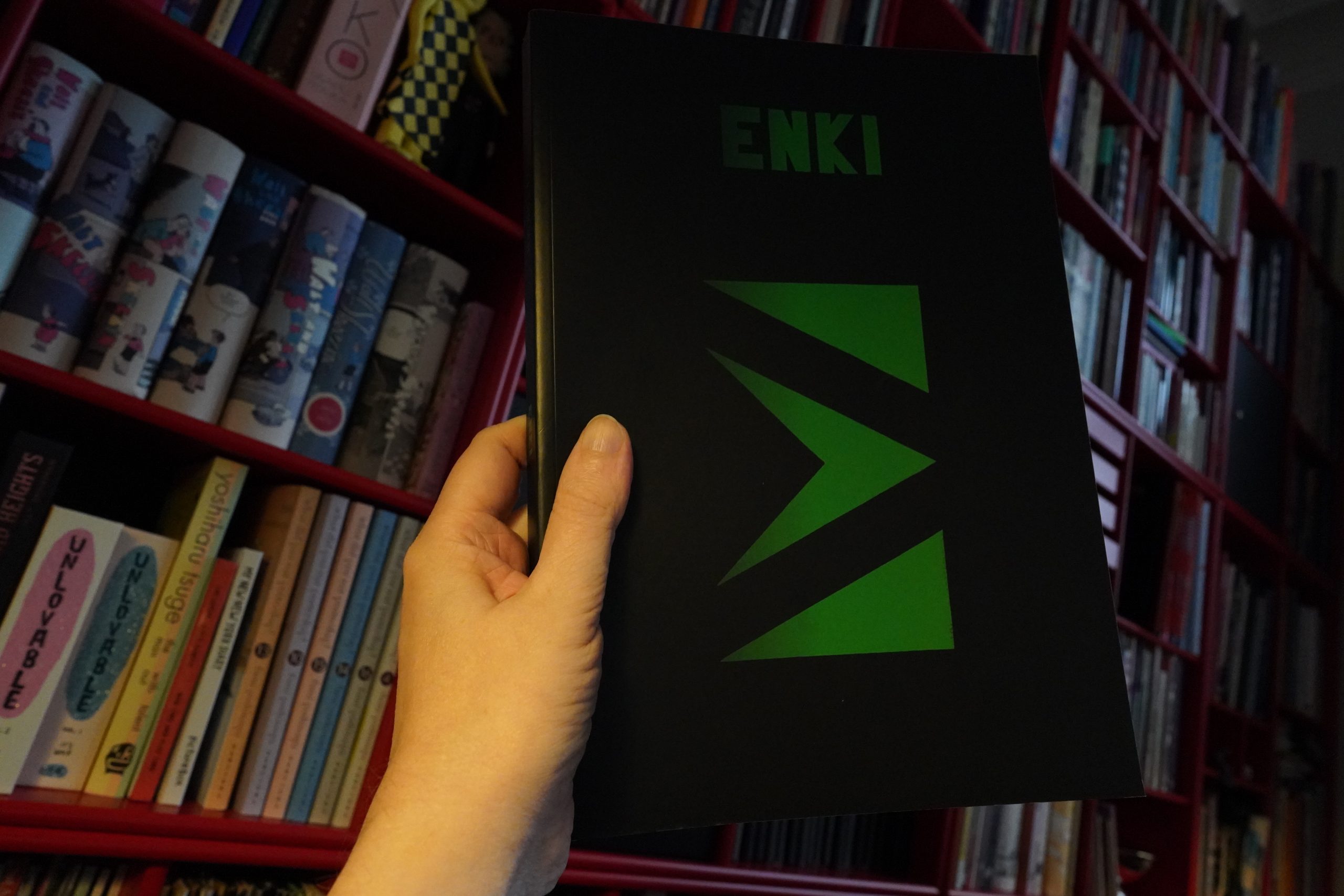

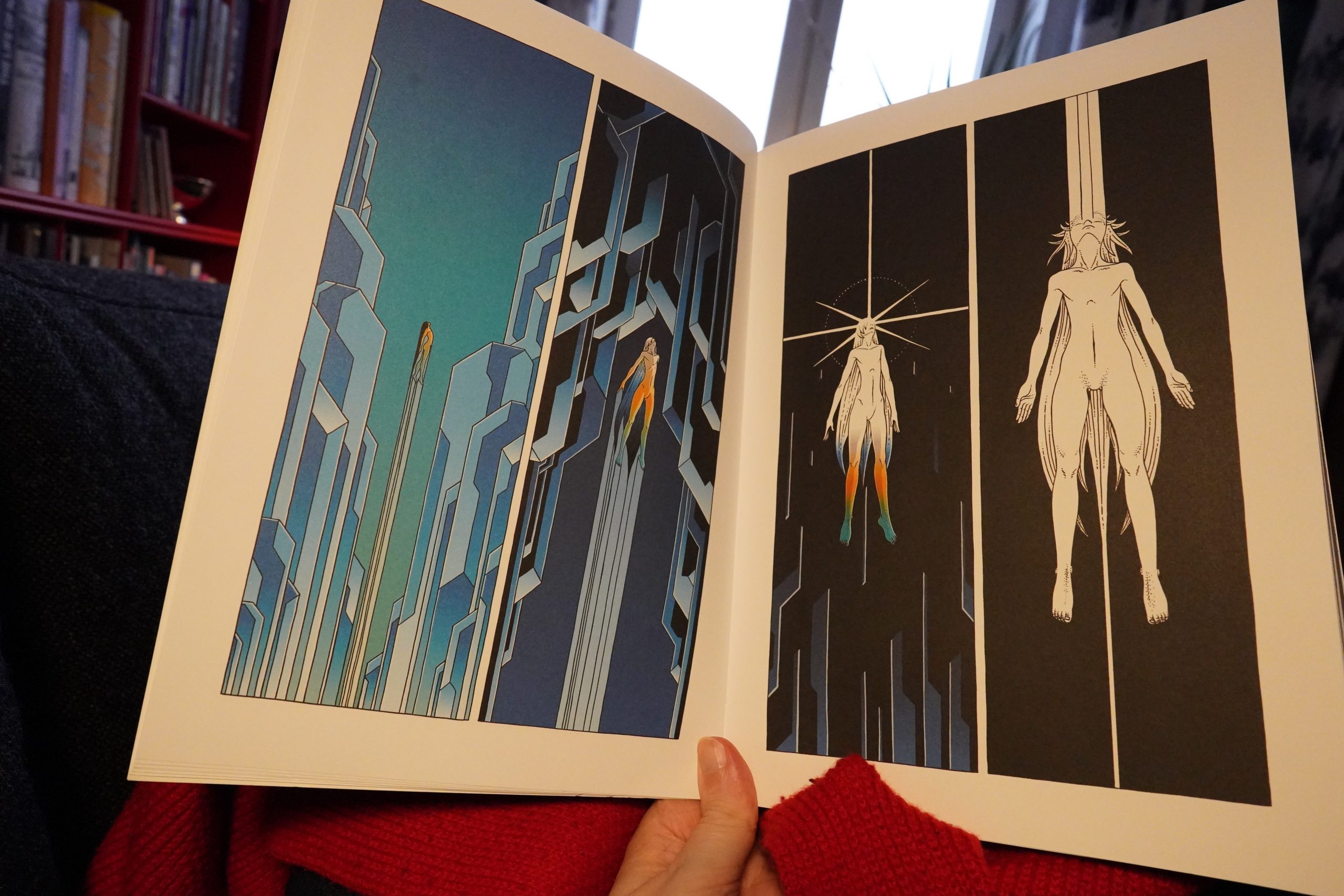

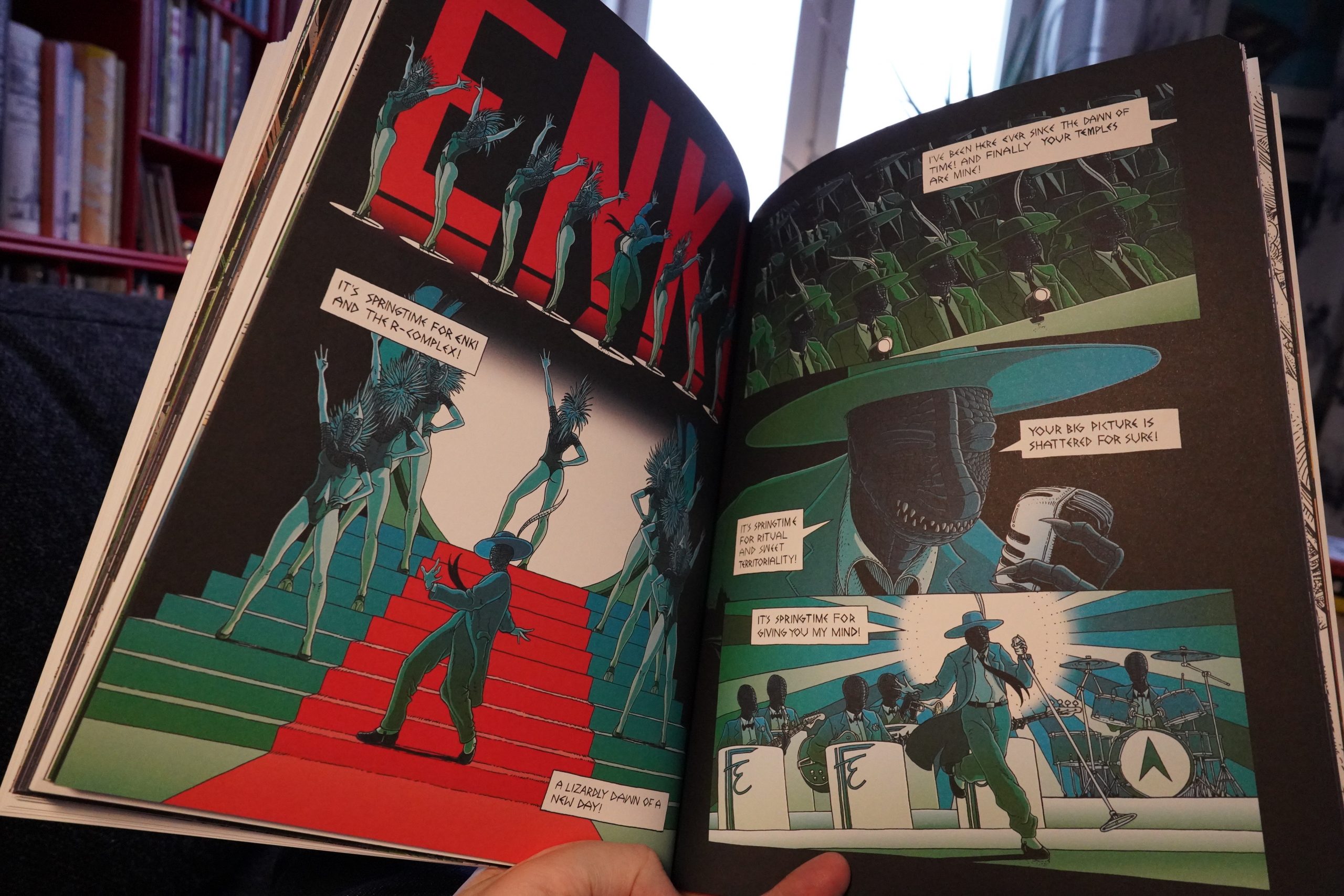

11:07: Enki by Thomas Falla Eriksen (Jippi forlag)

Oh, wow. I think there’s a vague possibility that he’s seen some Moebius artwork once? Briefly? Perhaps?

It’s very nice.

The story is super-duper 70s, too, with crystals, yin & yang, spirituality and good and evil forces and stuff. It’s pretty good? And looks great.

I think it does what it sets out to do very aptly. And perhaps the 70s are back again?

12:06: Nap Time

And now it’s nap time. I have no idea why I got up at five this morning…

| Dry Cleaning: Stumpwork |  |

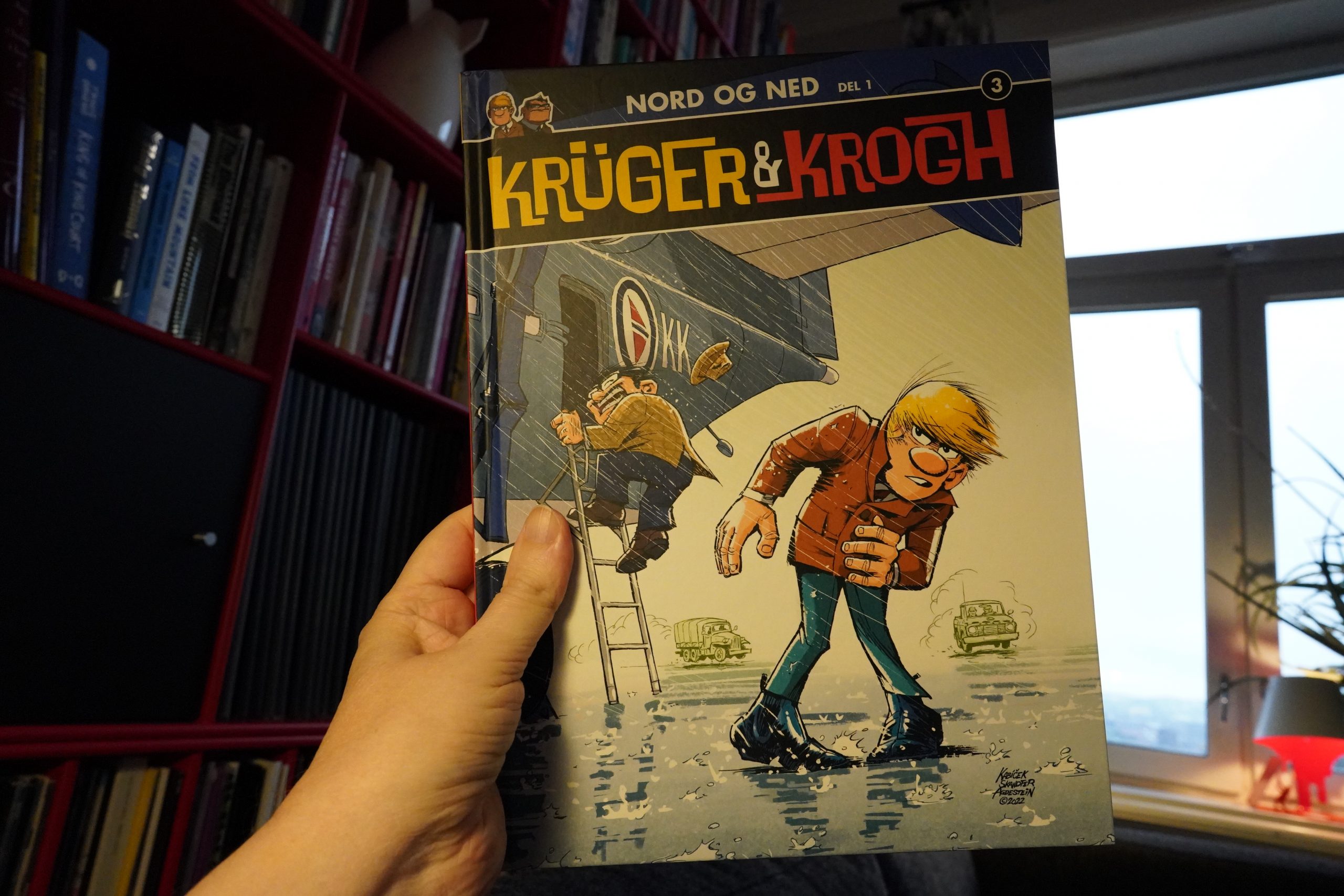

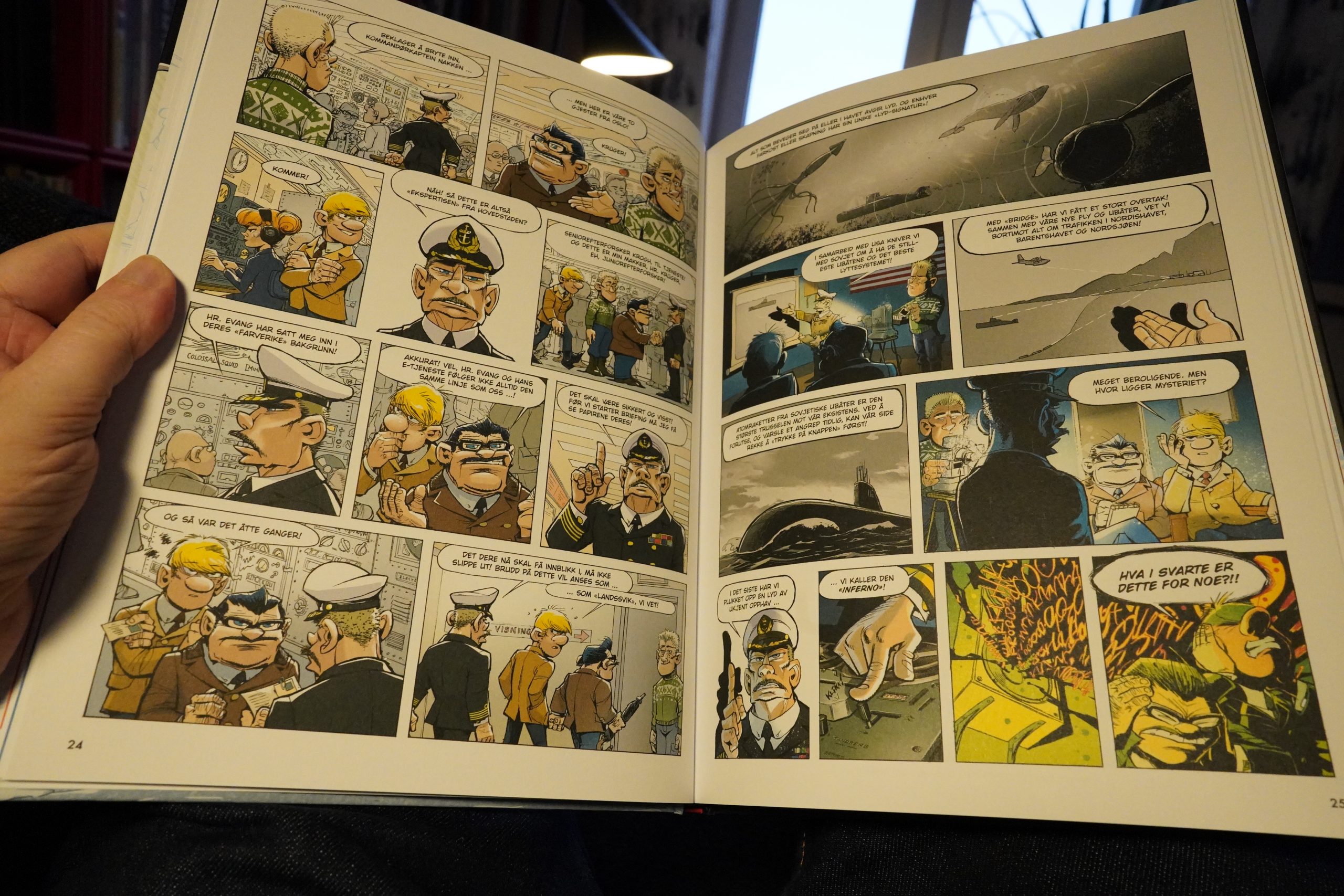

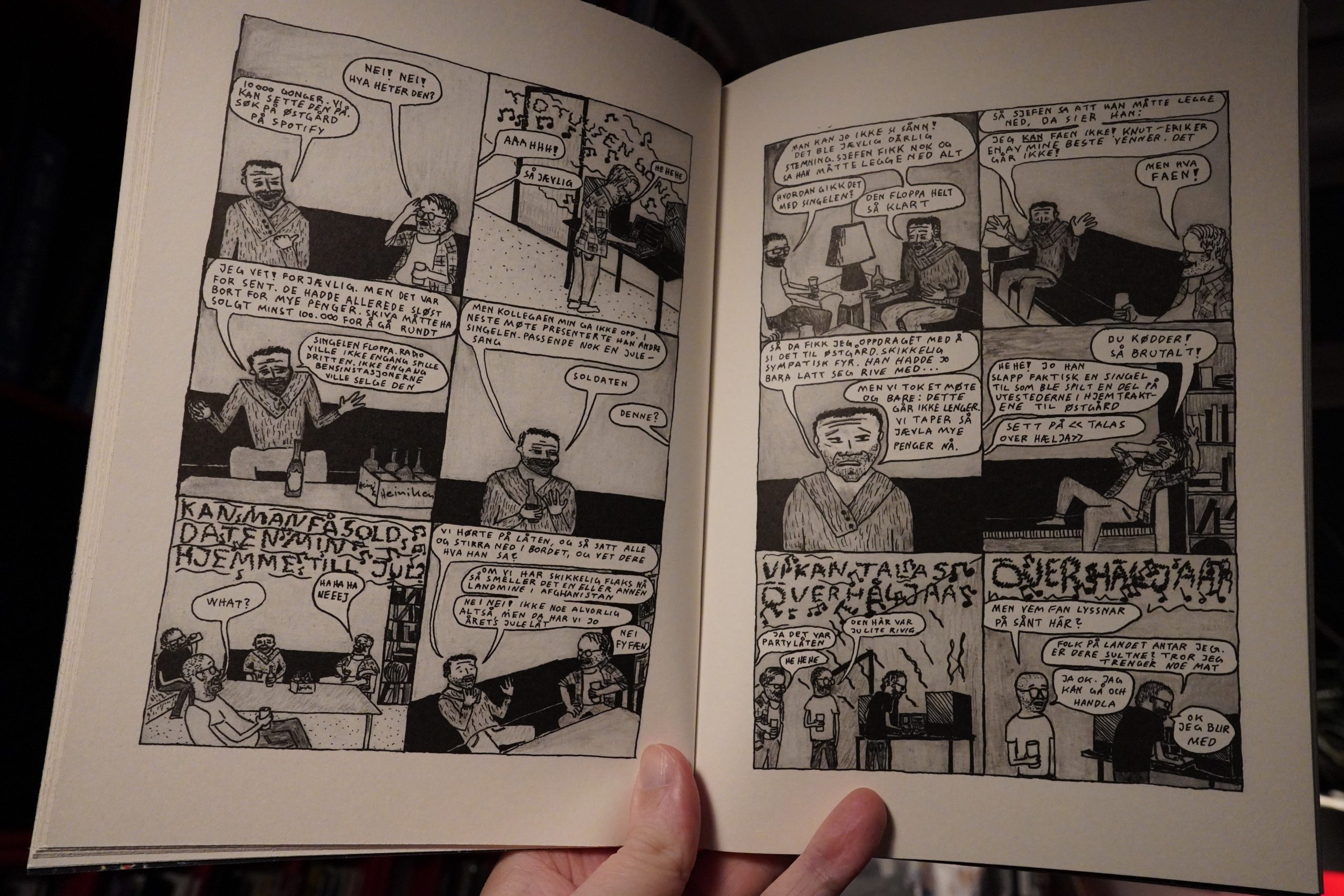

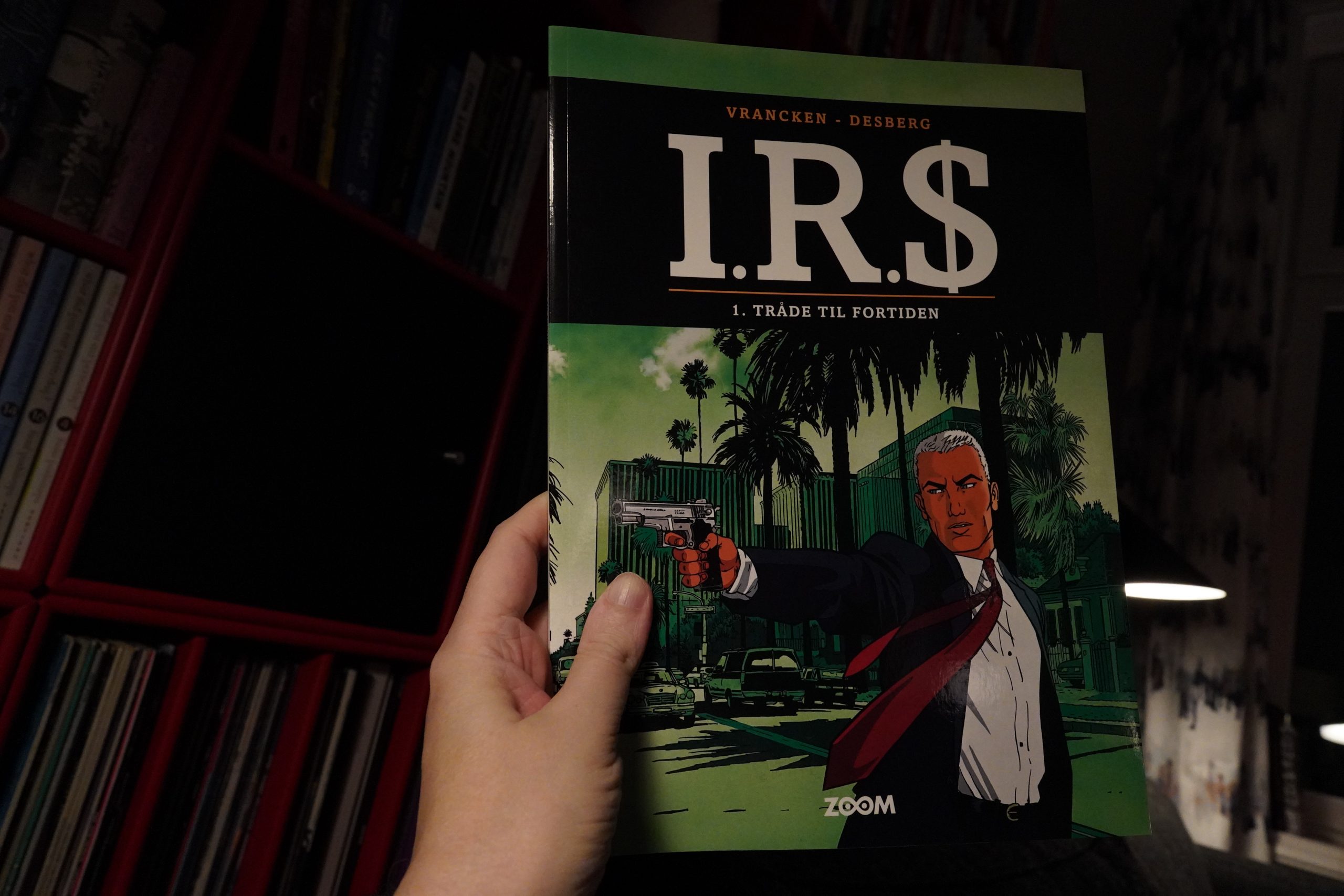

16:08: Krüger & Krogh 3: Nord og ned – del 1 by Kabíček, Skandfer, Agdestein (Strand forlag)

I’m awake! I’m awake!

That’s a weird posture… has he been shot or something? Hunchback?

Oh, it’s supposed to be very windy. Check.

This is supposed to be the most successful Norwegian series in modern times, and the publisher seems to have sent the same talking points to all reviewers (“classic French(ey) comics, set in the past, but new!”, or something). The story is fun, even though if it’s one third fan service, with lots of “oh, there’s that building I recognise from the 60s” and “oh, there’s that reference”.

The artwork isn’t very attractive, though. Everybody’s bobble-headed and relentlessly ugly. At least that leaves a lot of leeway for the artist to draw very distinctive faces that are easy to tell apart.

The book is OK.

| Bobbie Gentry: The Girl From Chickasaw County (7): Patchwork |  |

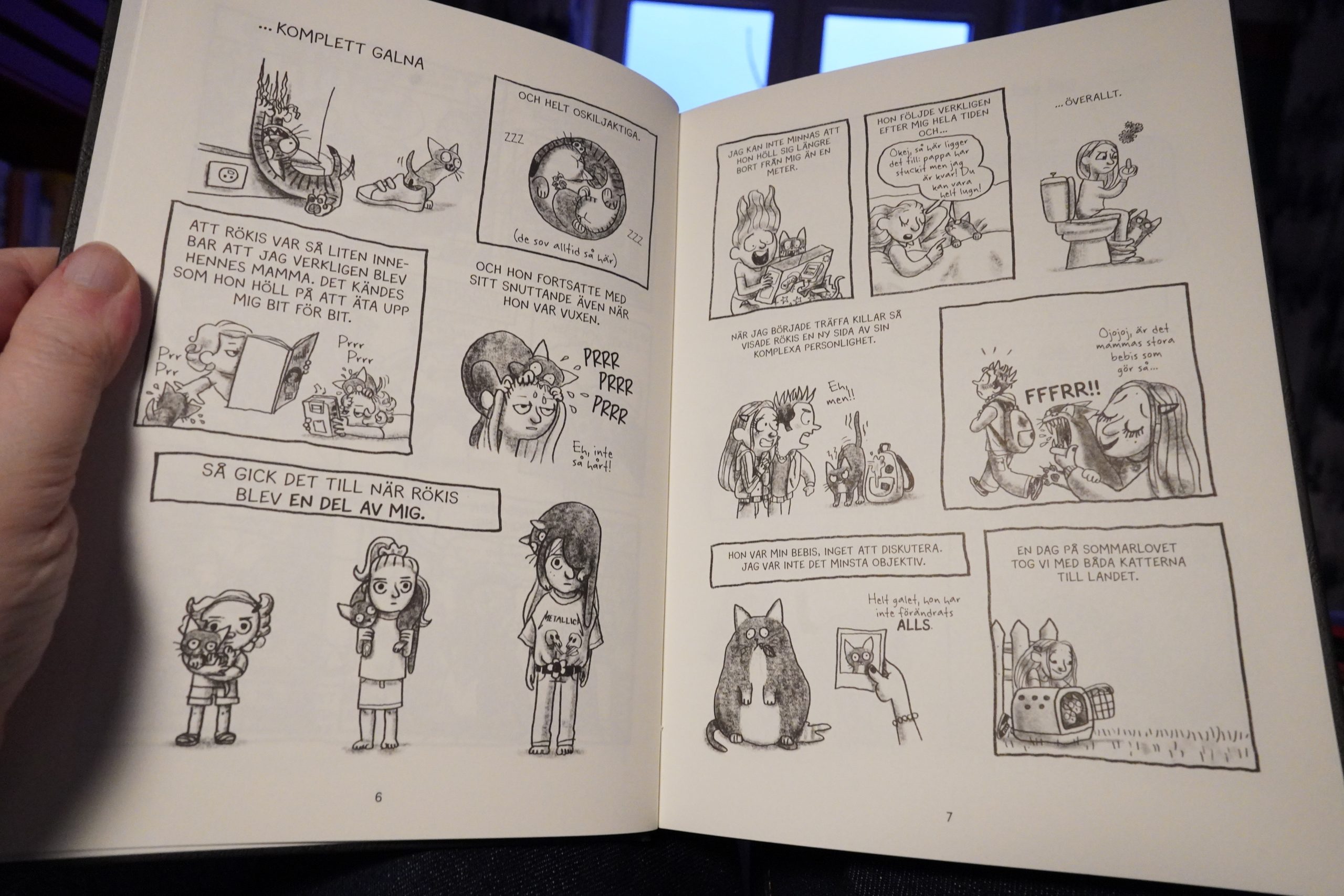

16:58: Les strates by Pénélope Baglieu (Kartago)

This is a collection of anecdotes from Baglieu’s life, mostly from her childhood and teenage years. And it’s so charming — it’s irresistible.

It’s like the polar opposite of Larmo’s book, even if it covers some of the same ground. Baglieu even goes to London as a student! But while the Larmo book was totally seen from the her point-of-view at the time (and it’s unclear whether she’s processed what happened at all), Baglieu tells these anecdotes from her current point-of-view, and reflects upon her choices and pokes gentle fun at herself.

It’s a lot of fun, and sometimes heartbreaking.

| Espen Reinertsen: Forgaflingspop |  |

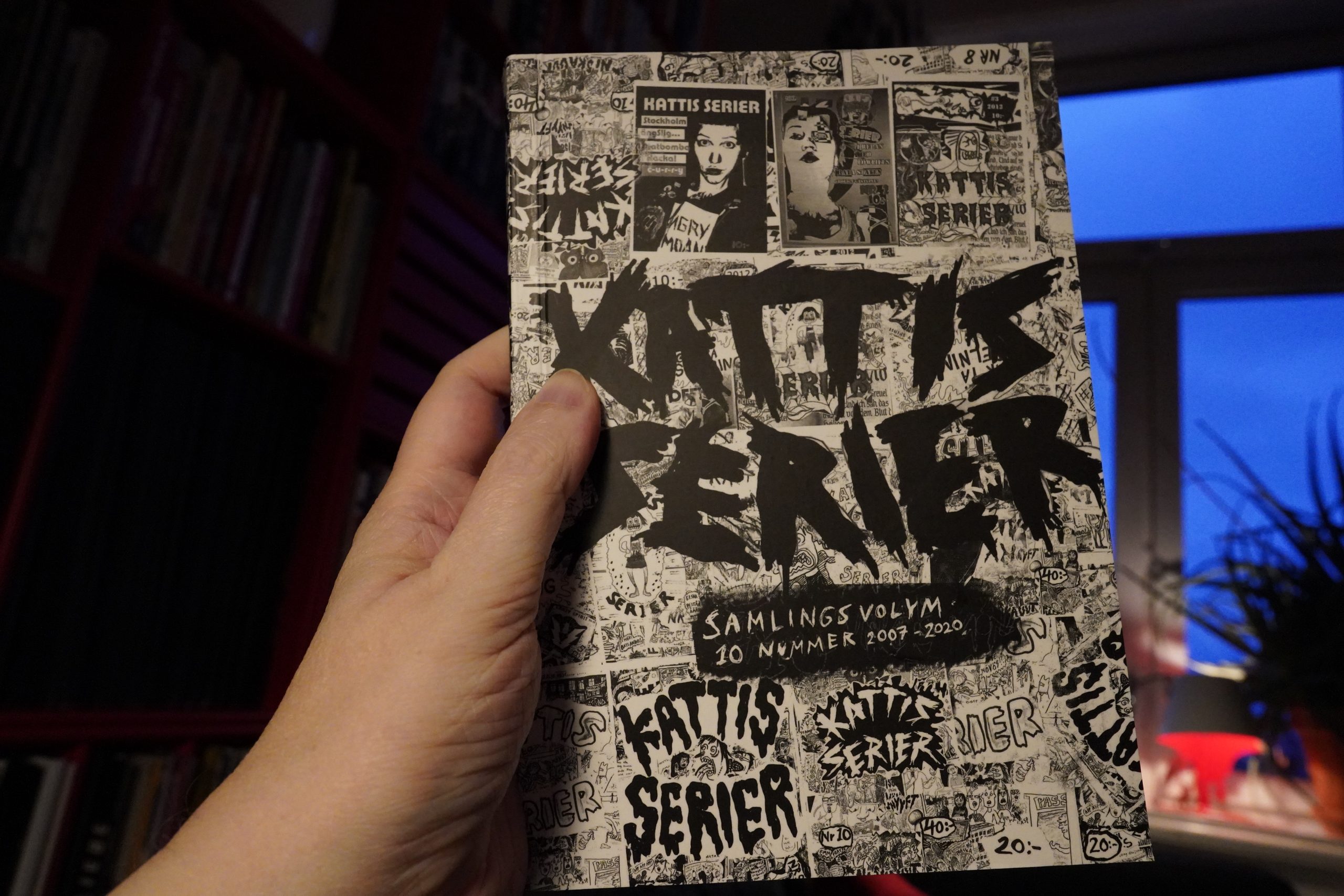

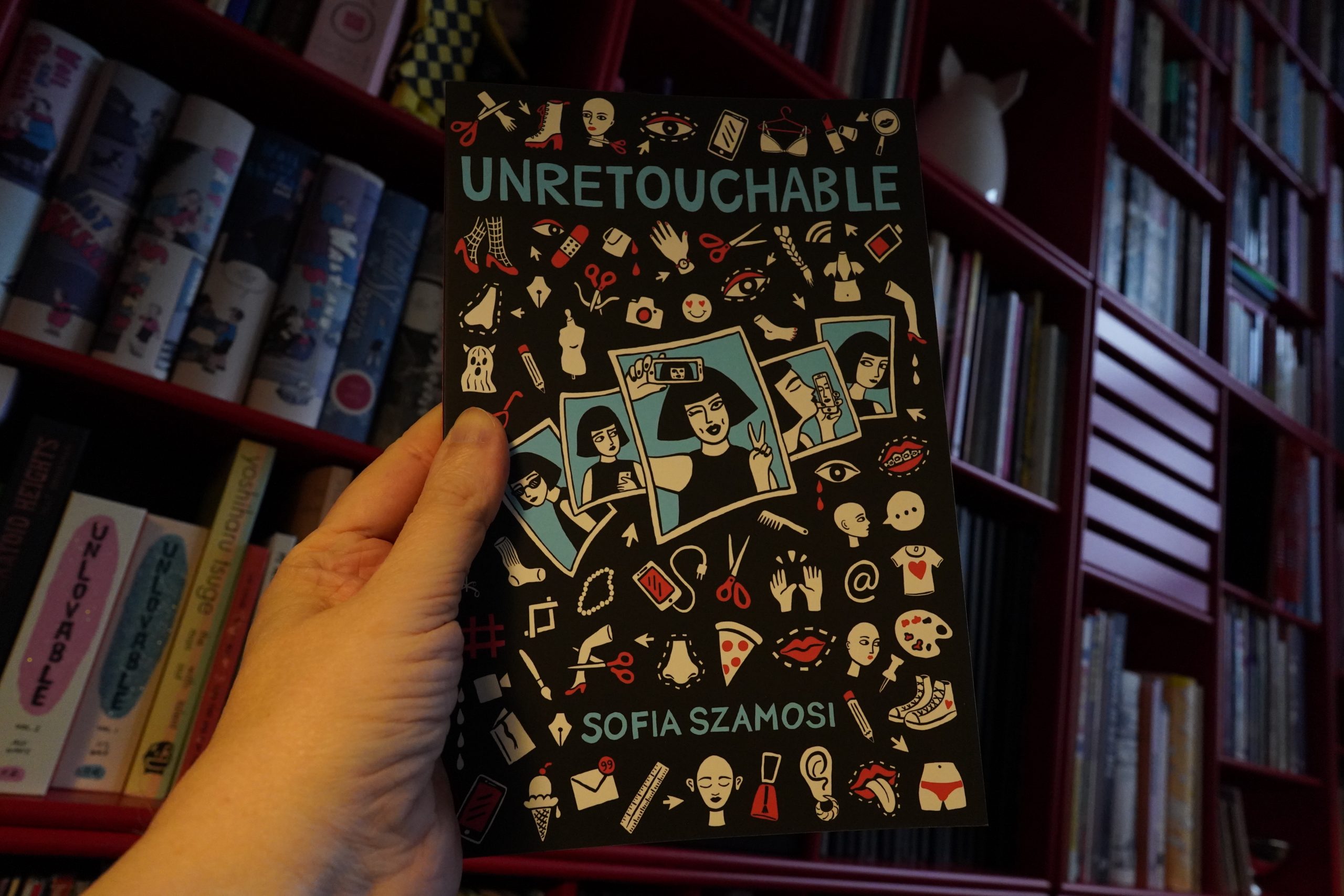

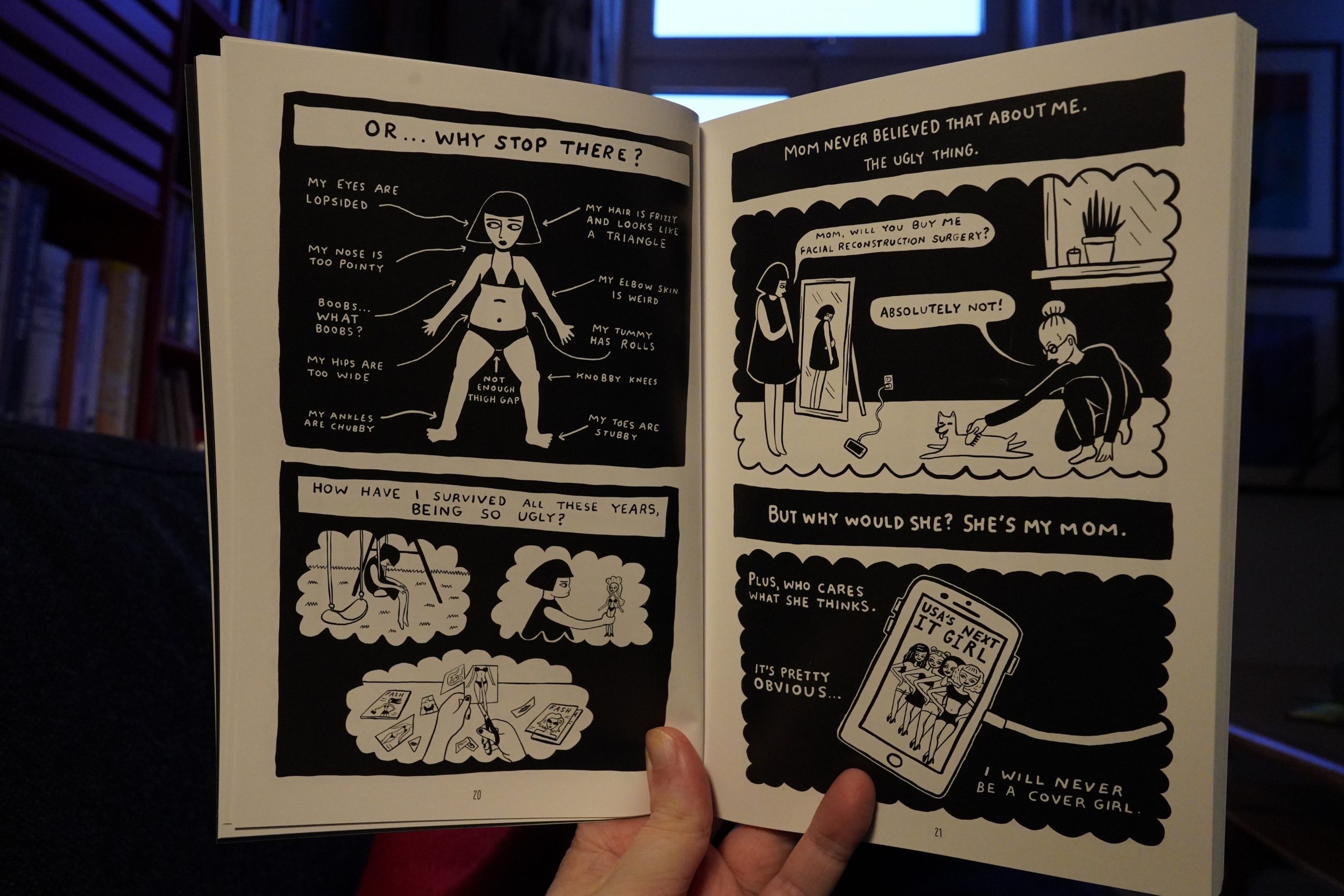

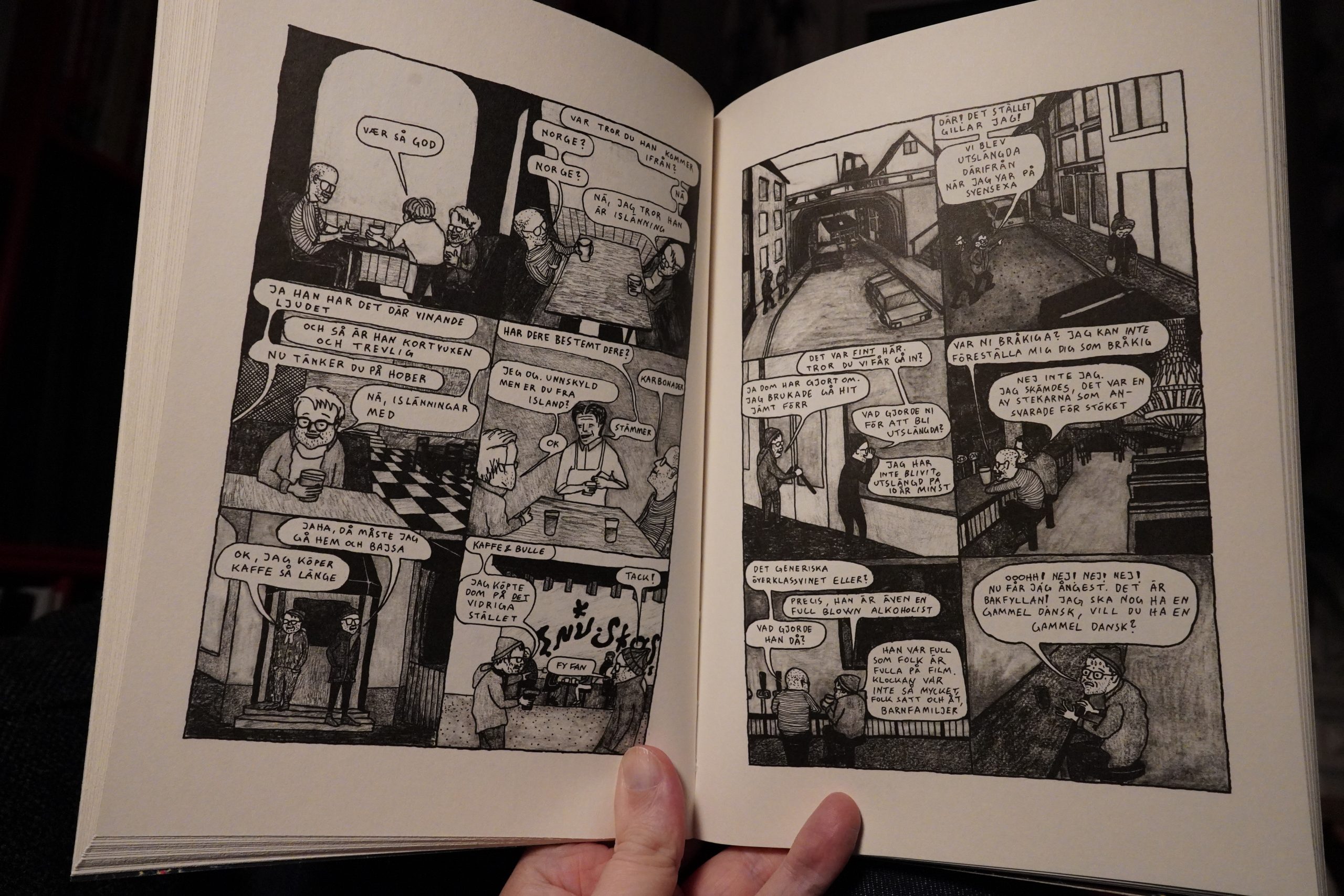

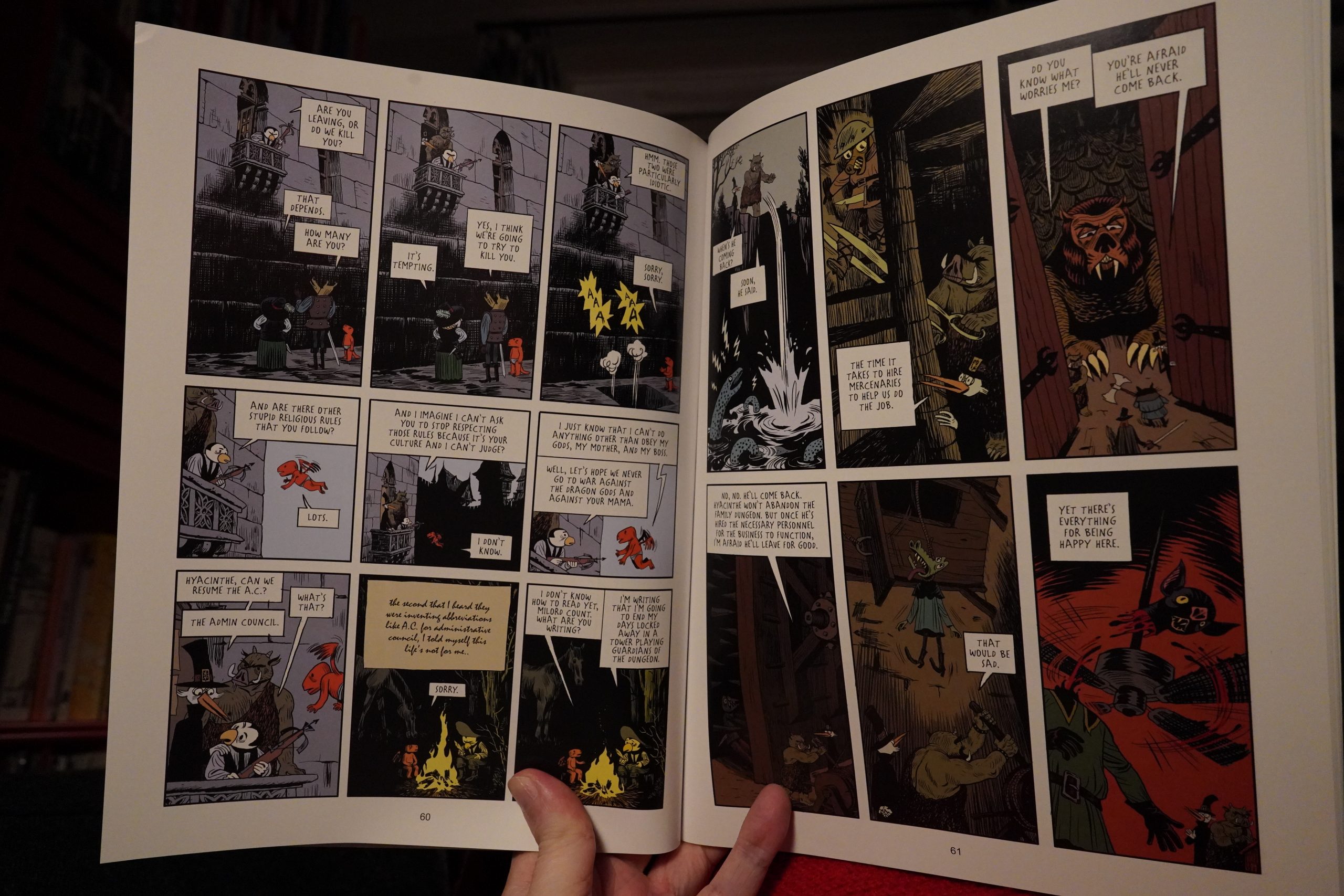

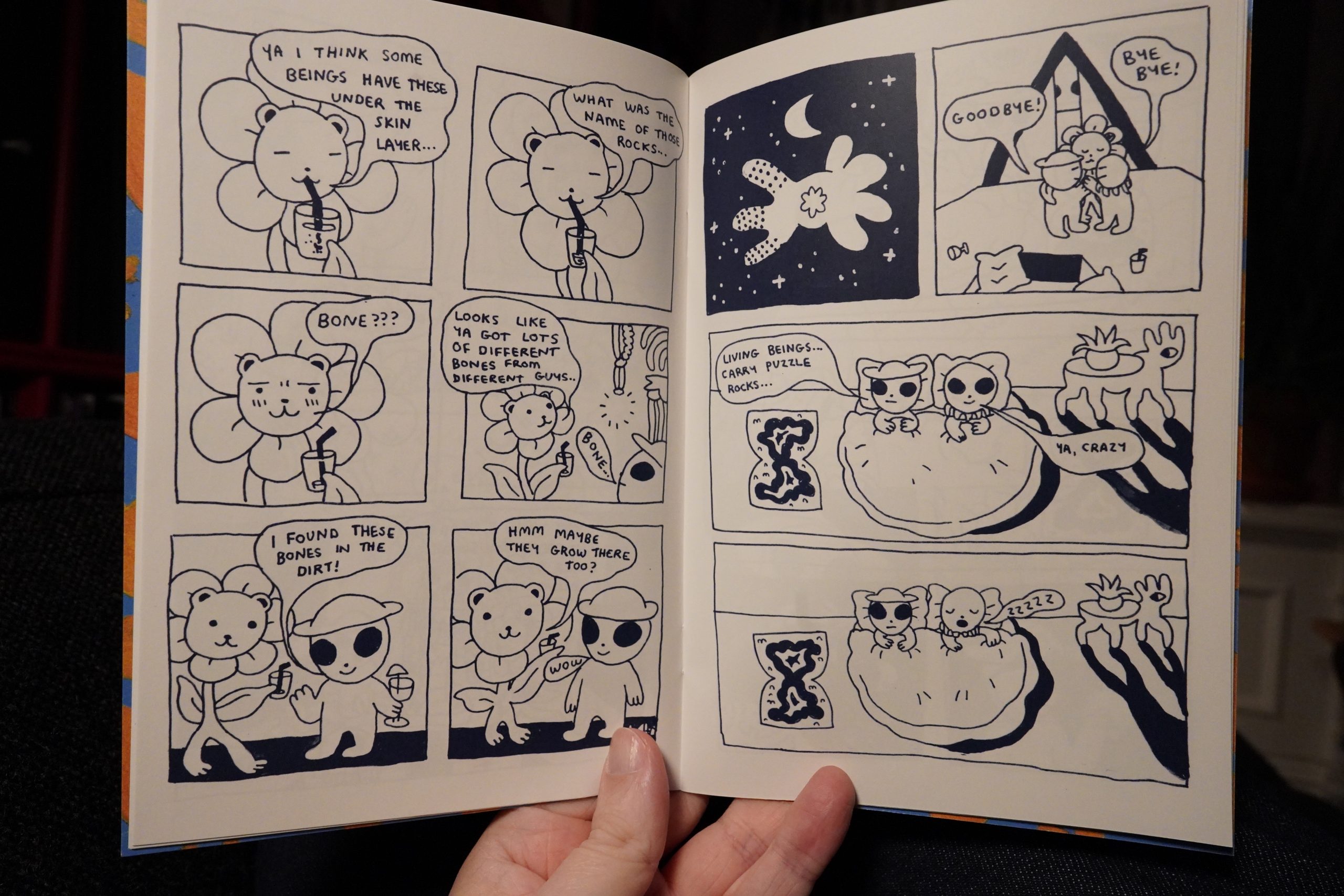

17:39: Kattis serier by Katarina Mörk (Lystring)

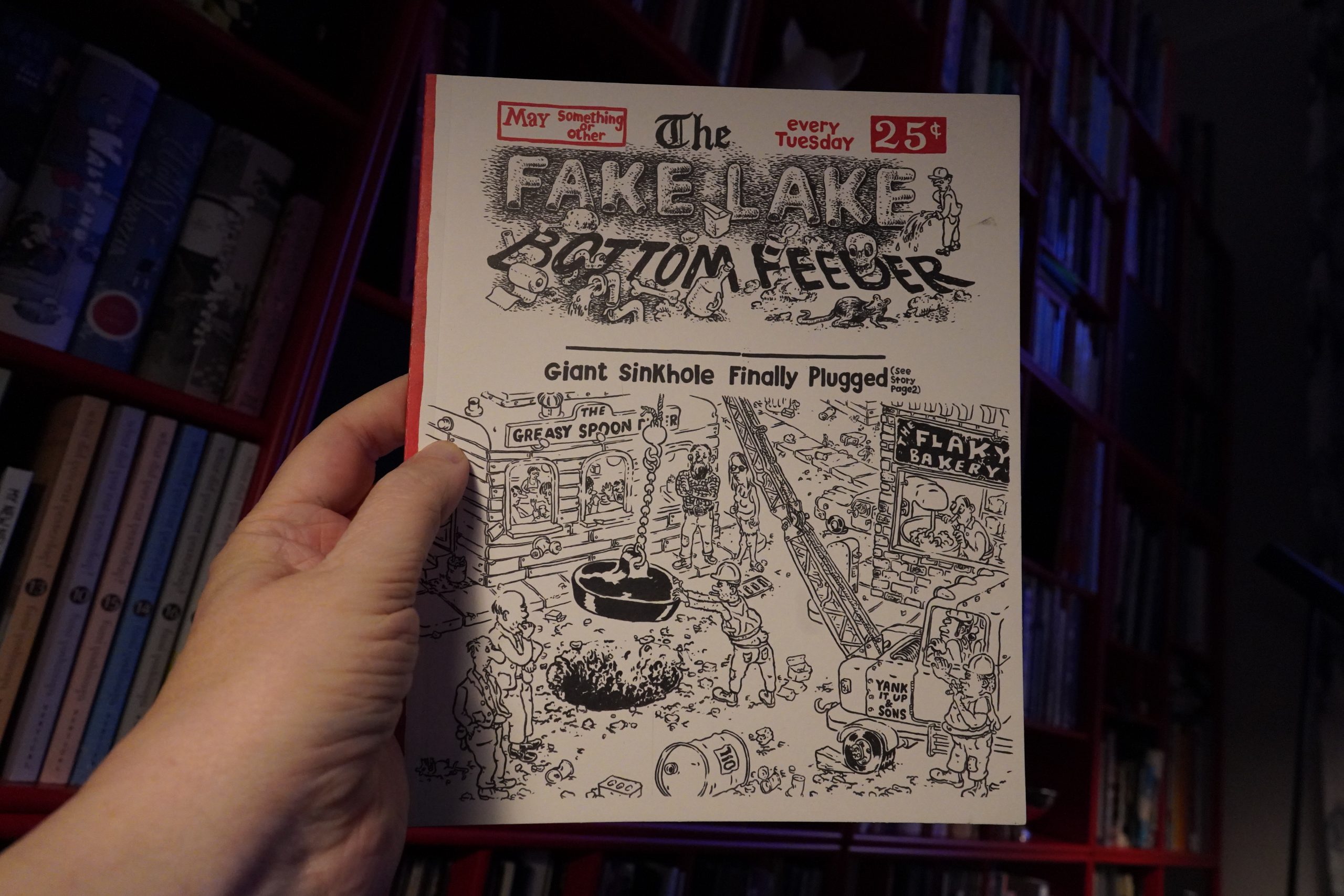

I picked up all these books from Lystring at a book shop in town. I’d never heard of the publisher before, and it seems like the shop owner discovered them recently too or something? Because none of them were in the store the previous time I visited them… Doesn’t look like the web site has been updated since 2009?

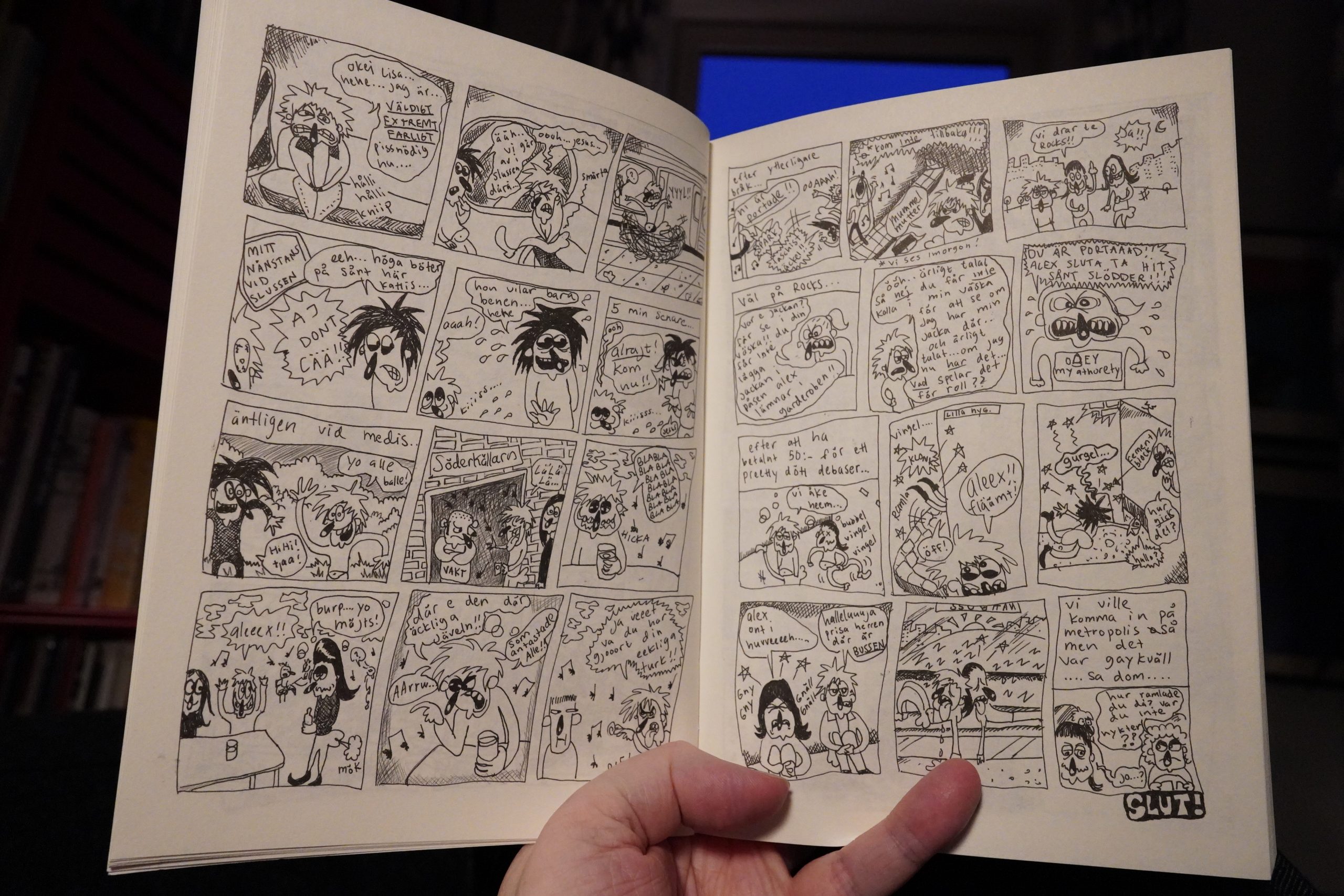

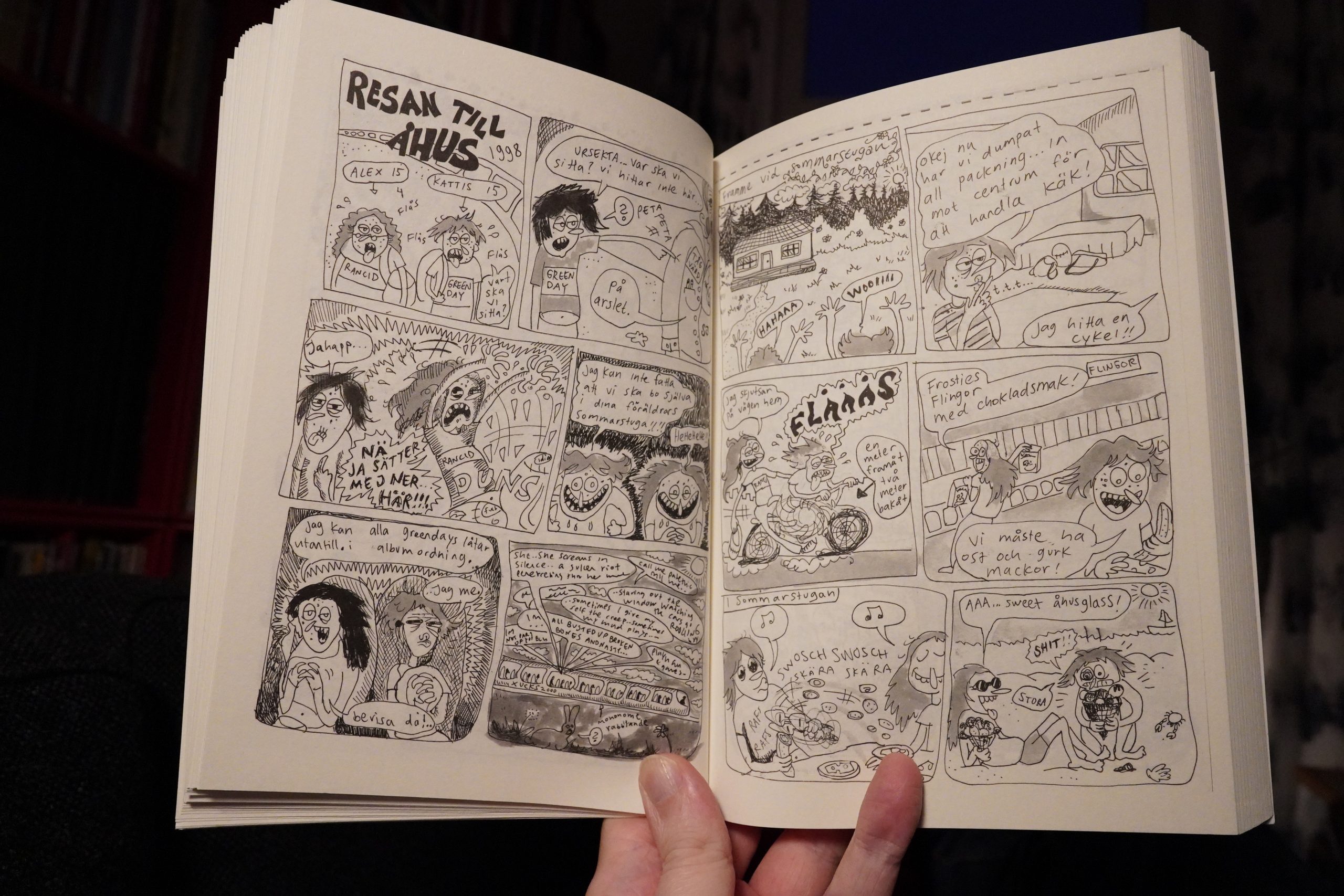

This is a collection of zines from 2007-2022, and it starts off kinda rough (but punk)…

But then rapidly becomes very enjoyable.

| The Lounge Lizards: Voice of Chunk |  |

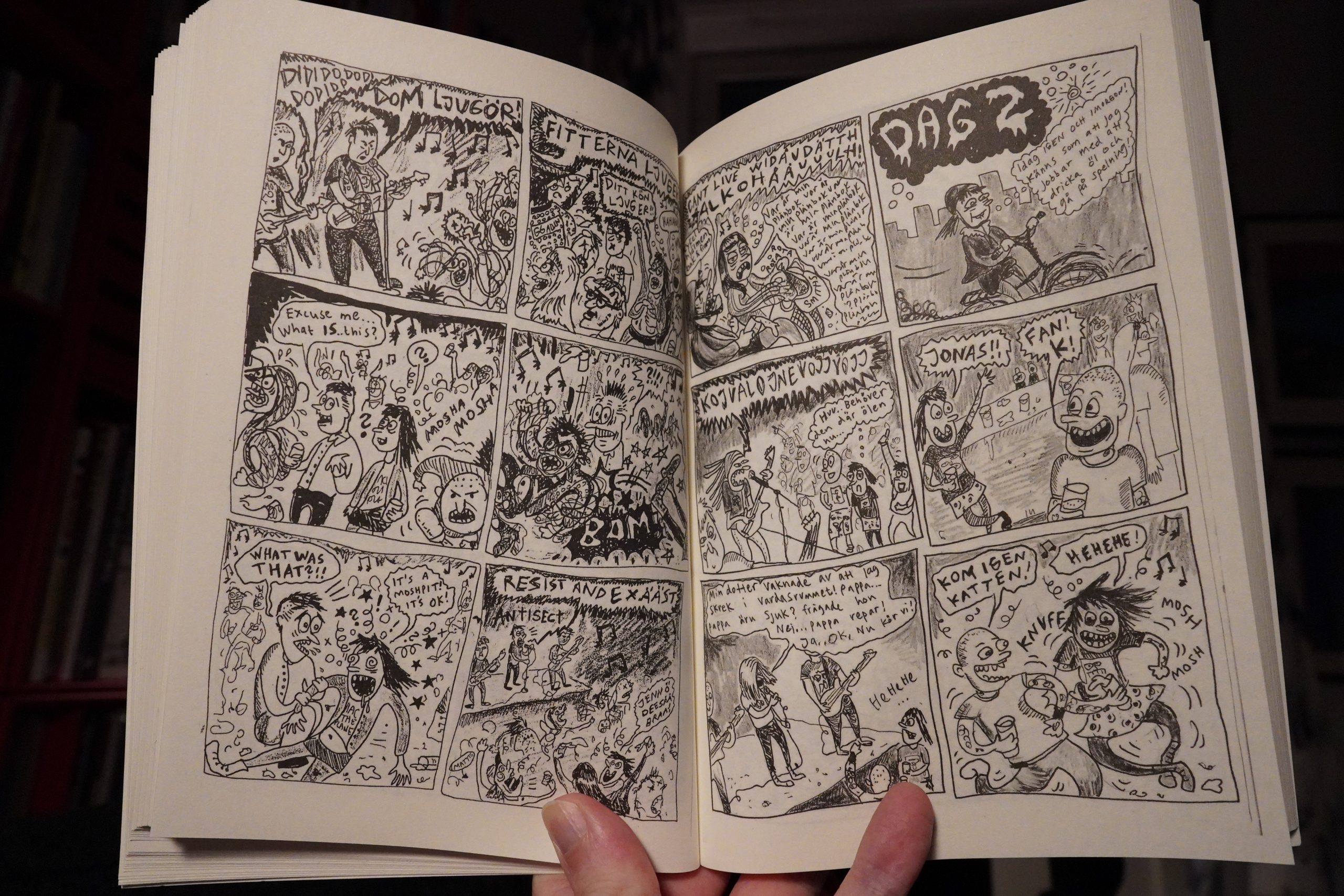

A large number of the strips are about attending punk shows, and they’re a lot of fun. It’s unapologetic and straightforward, and it’s a really entertaining read.

| Alice Coltrane: Kirtan Turiya Sings |  |

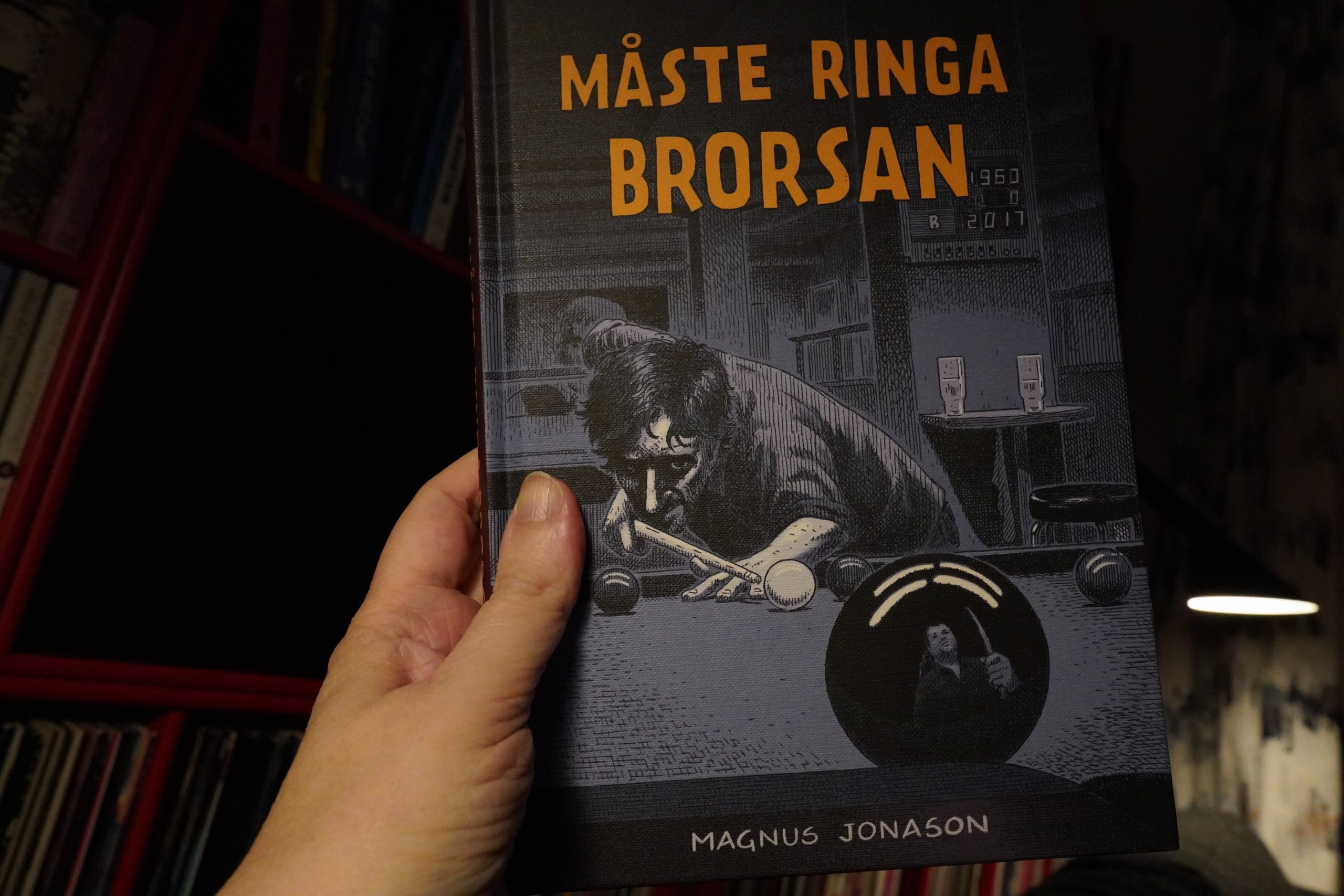

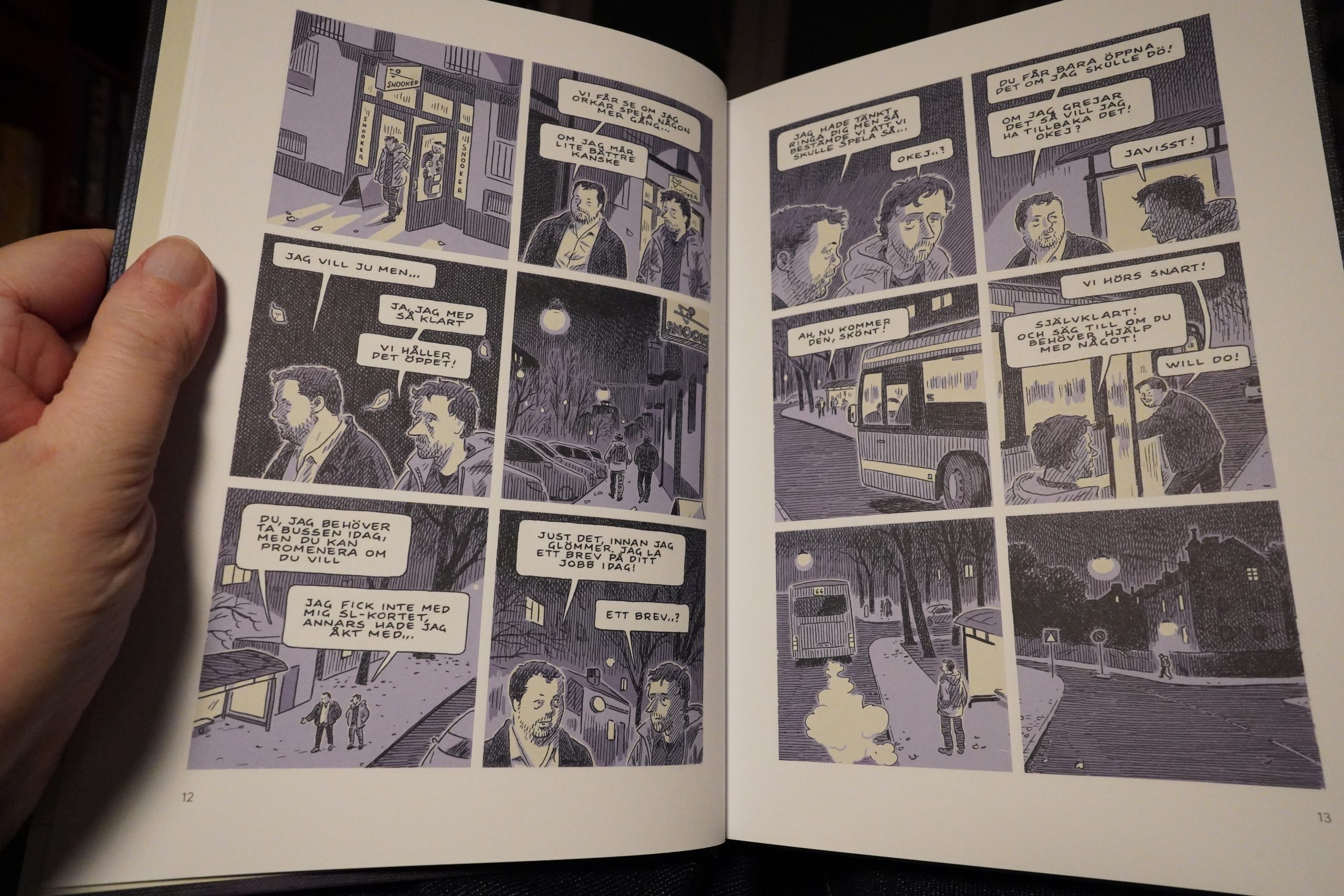

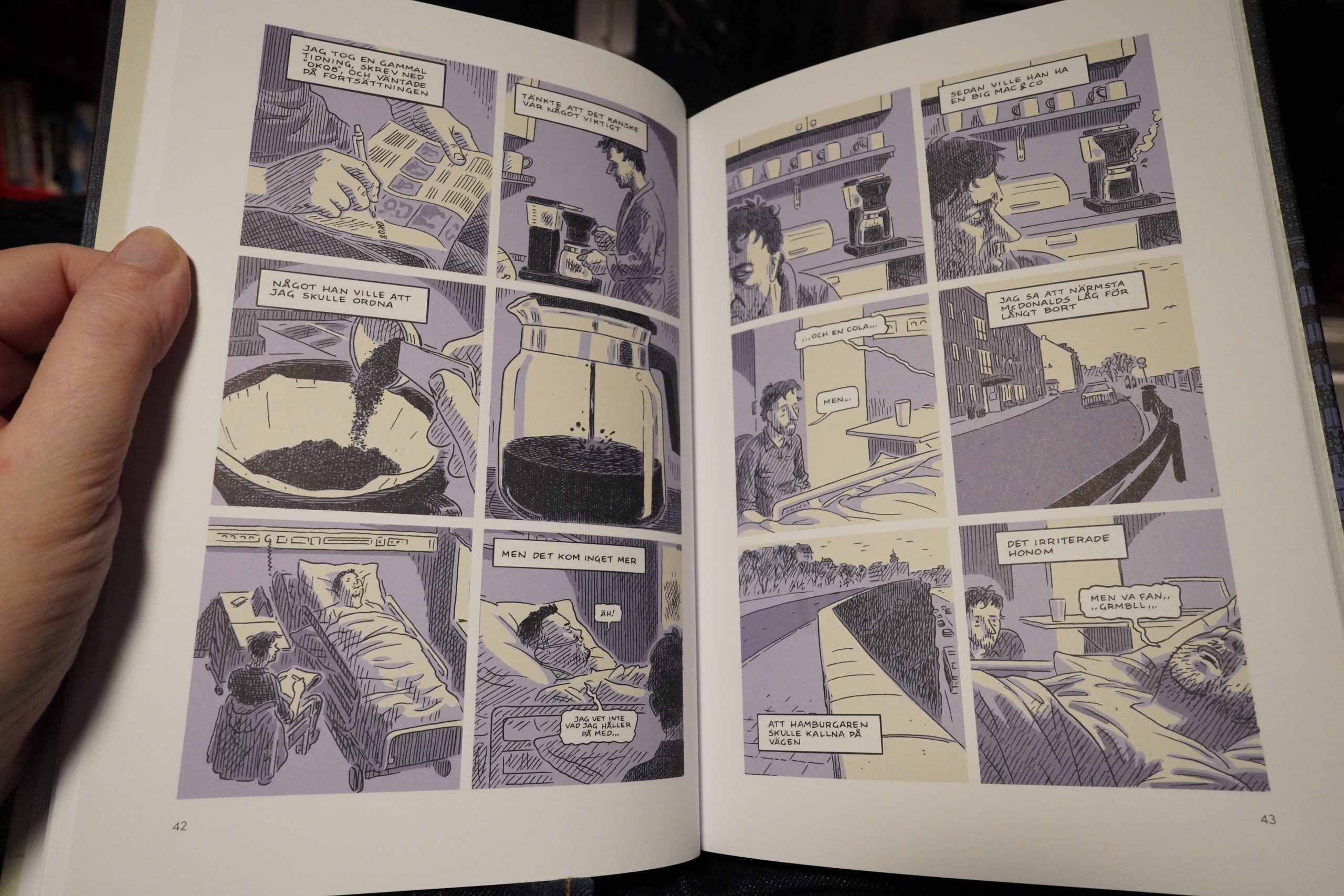

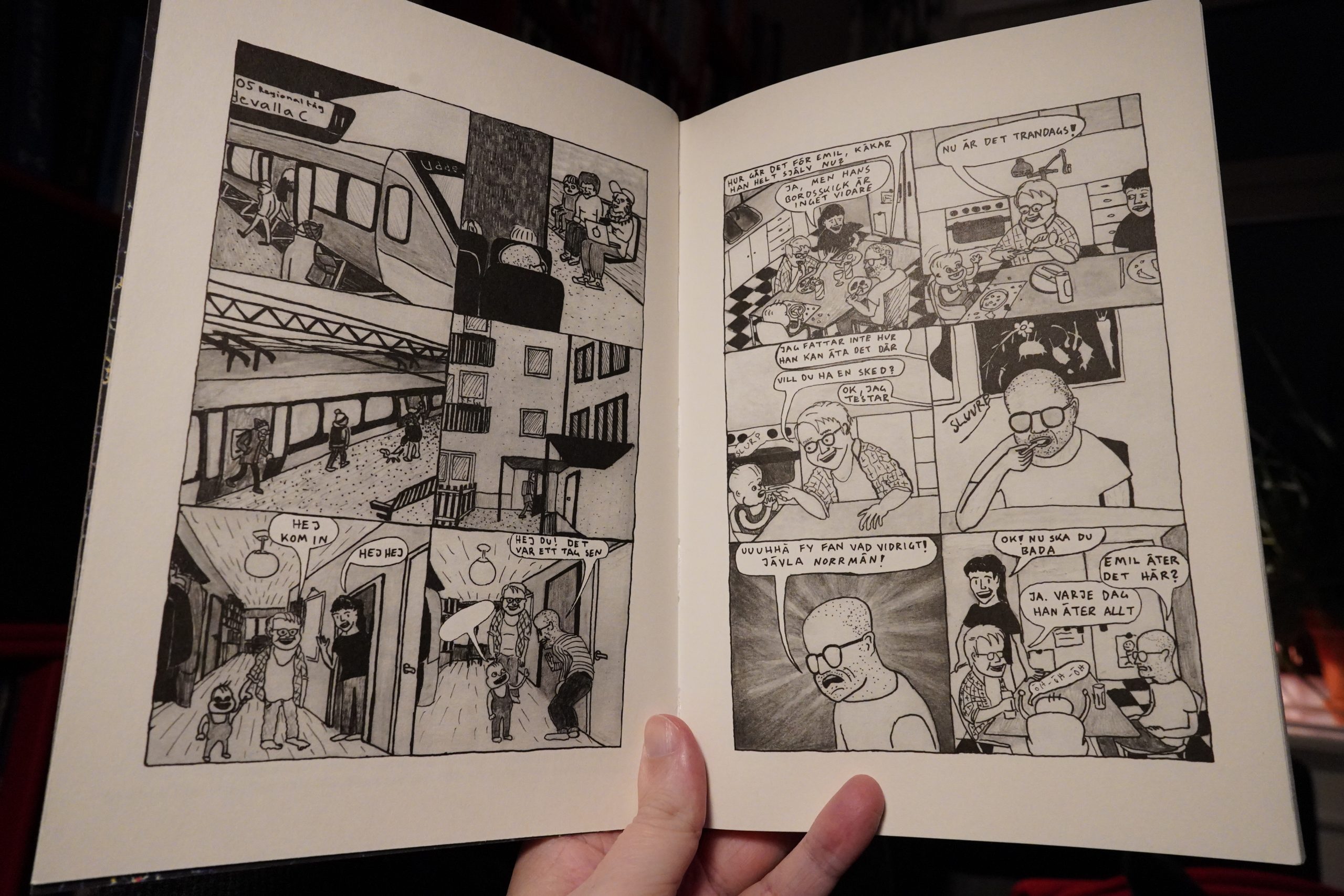

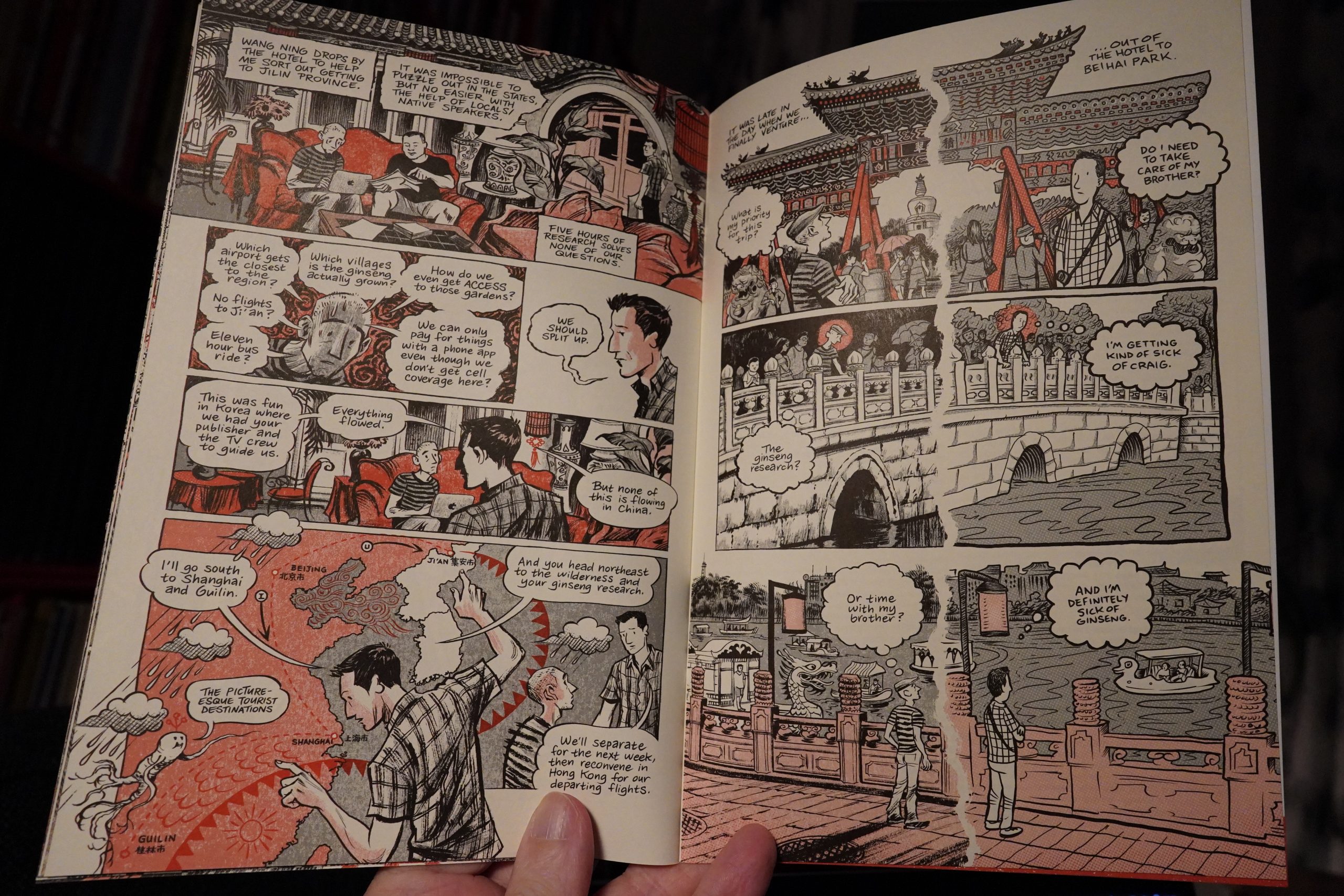

19:31: Måste ringa brorsan by Magnus Jonason (Kartago)

This is apparently autobiographical, but I haven’t checked? It presents itself as being so, but you never know. It’s about the author’s older brother dying, or rather — mostly about the aftermath of him dying, and cleaning out the apartment, and then ruminating about their relationship.

And the reason I’m wondering whether this is fictional or not is because the author portrays himself as resenting his brother a lot, and presents the dead brother as being a fuck-up, not very bright, and something of an asshole. Which seems harsh for a thing like this! Of course he loves his sibling, but he doesn’t portray his brother as being lovable, or having, well, any interesting qualities at all. (Until the eulogy where he realises that there’s stuff he didn’t know about him.)

So it seems… oddly undigested? … even as he portrays himself talking to a shrink a lot about his family, too. It’s just “hmm”.

But misunderstand me correctly! It’s a really good book! Quite moving. But odd.

| Alasdair Roberts og Völvur: The Old Fabled River |  |

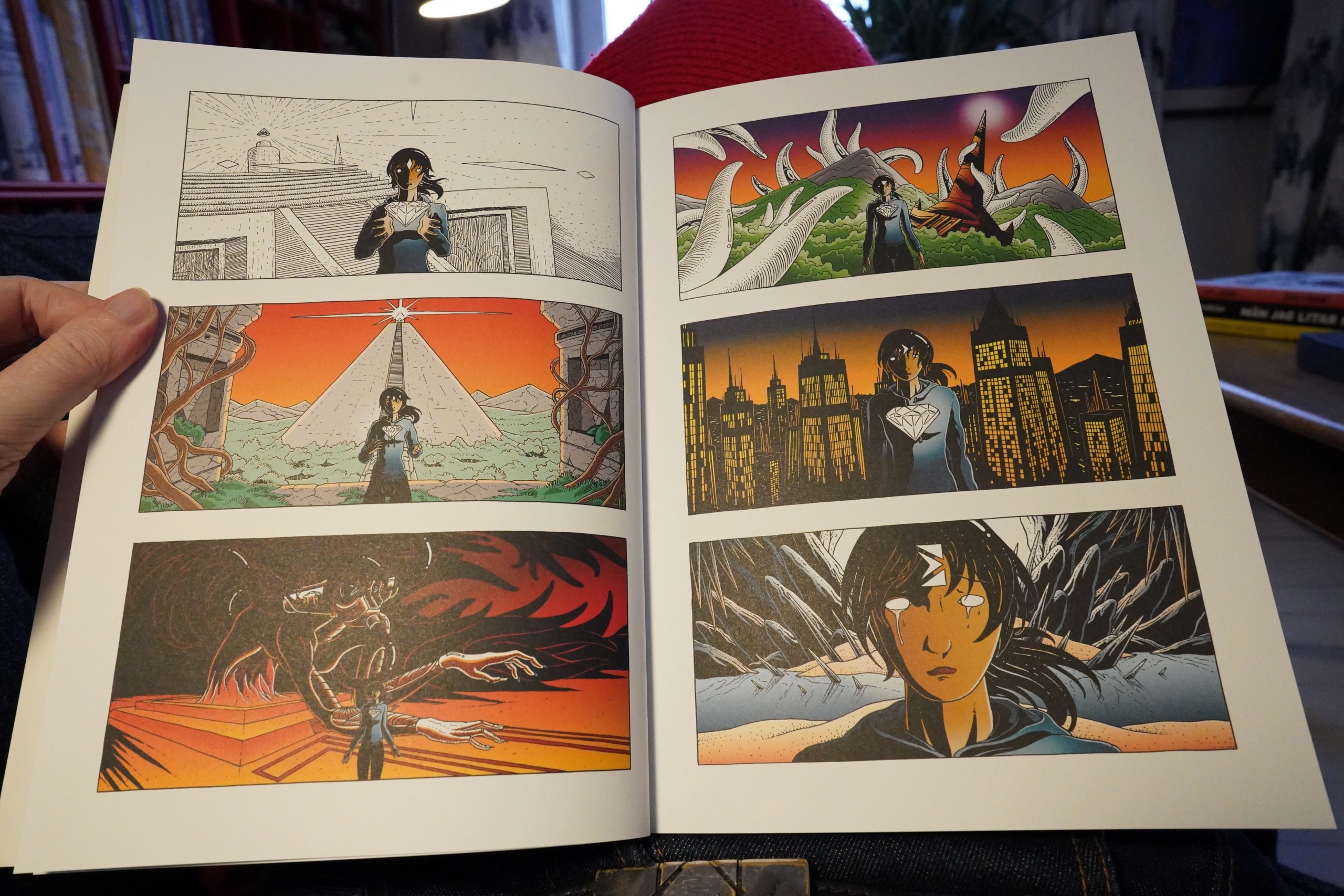

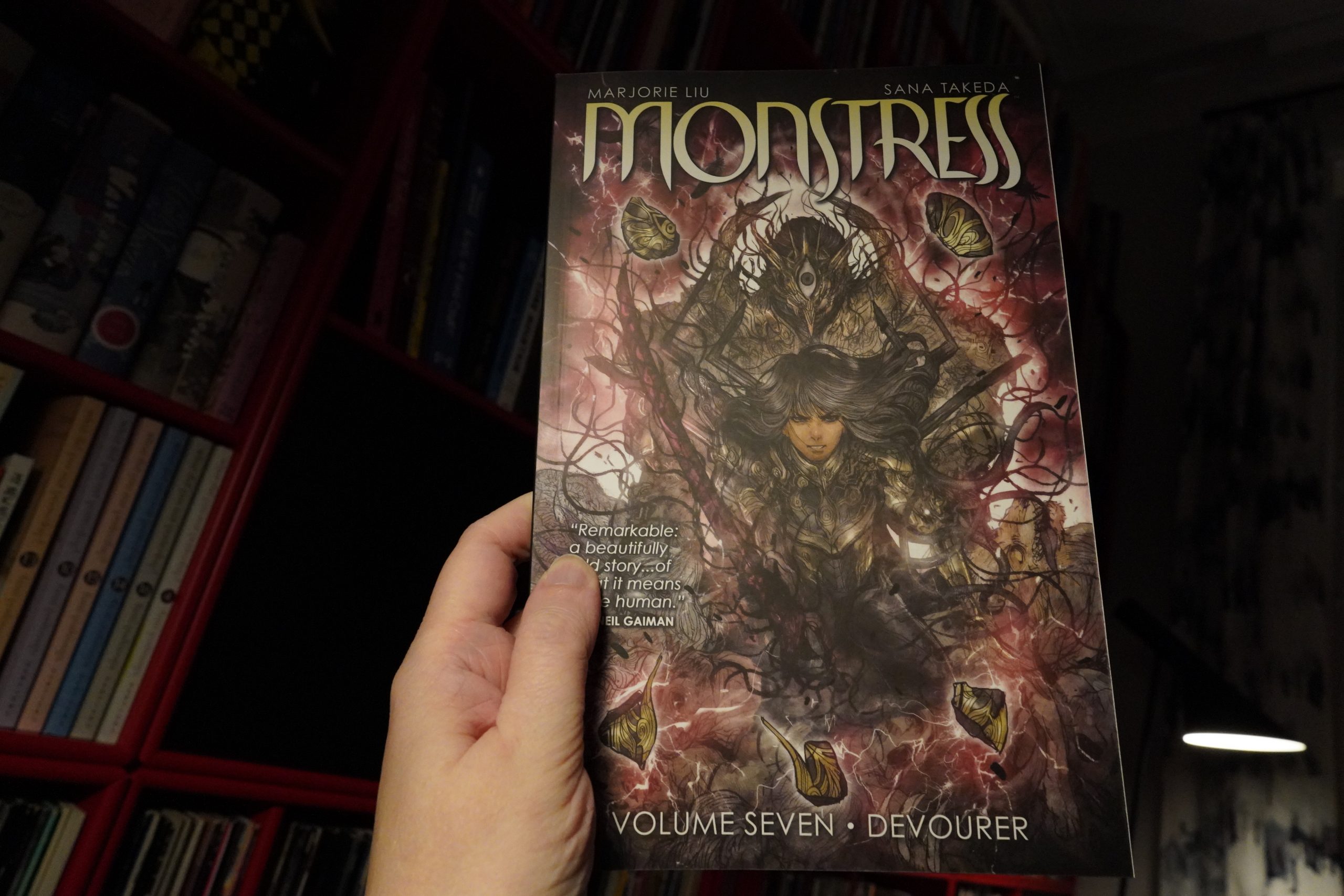

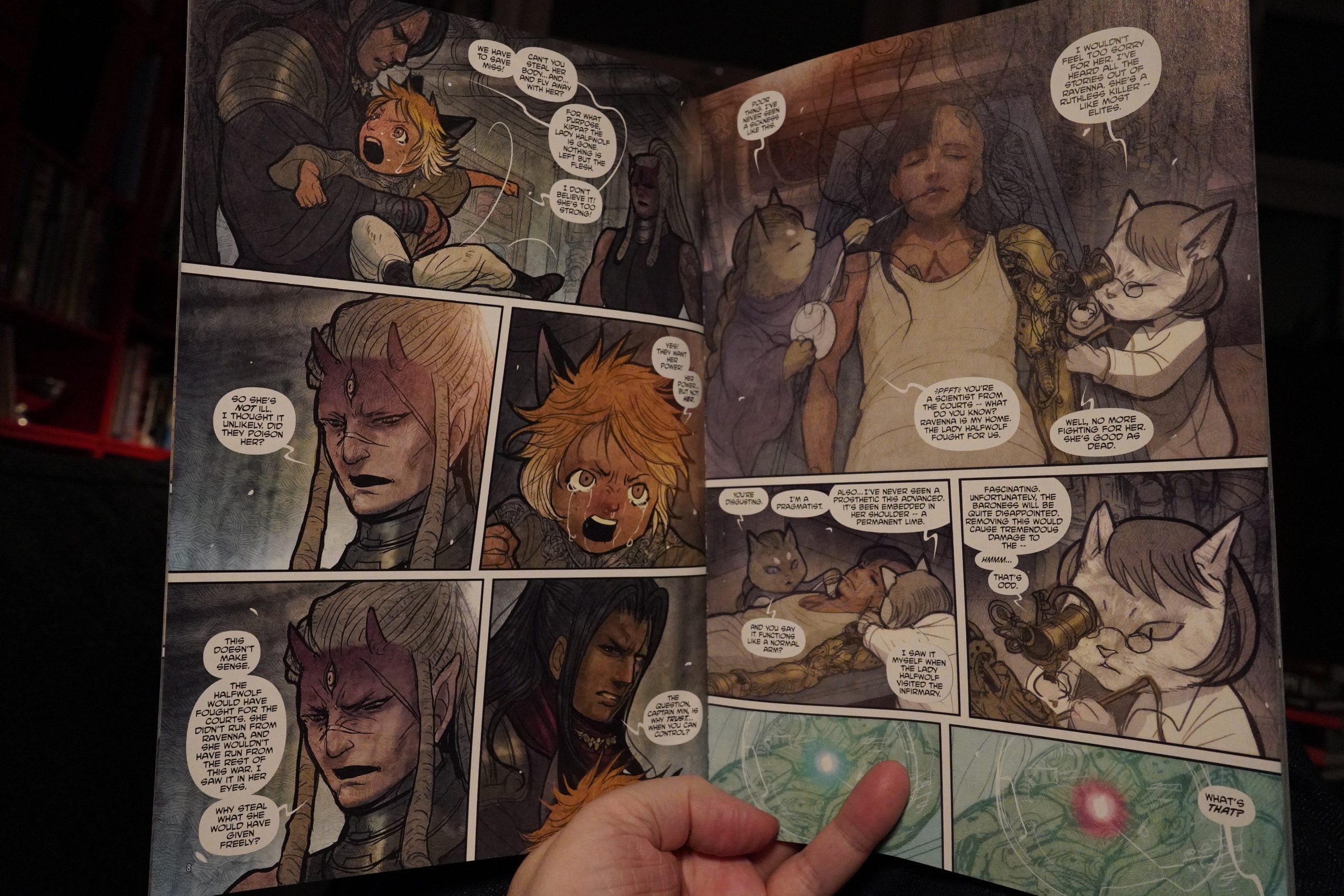

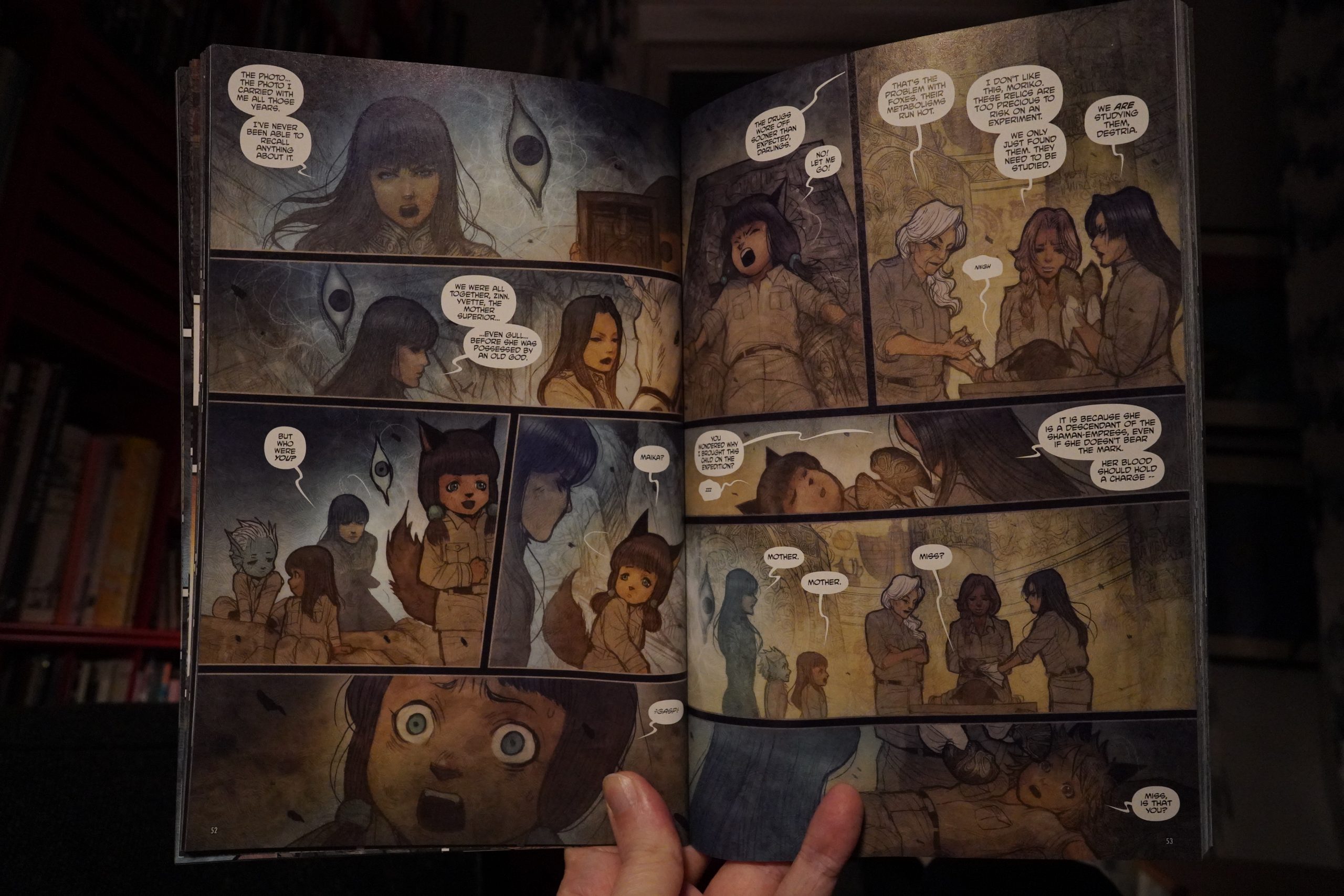

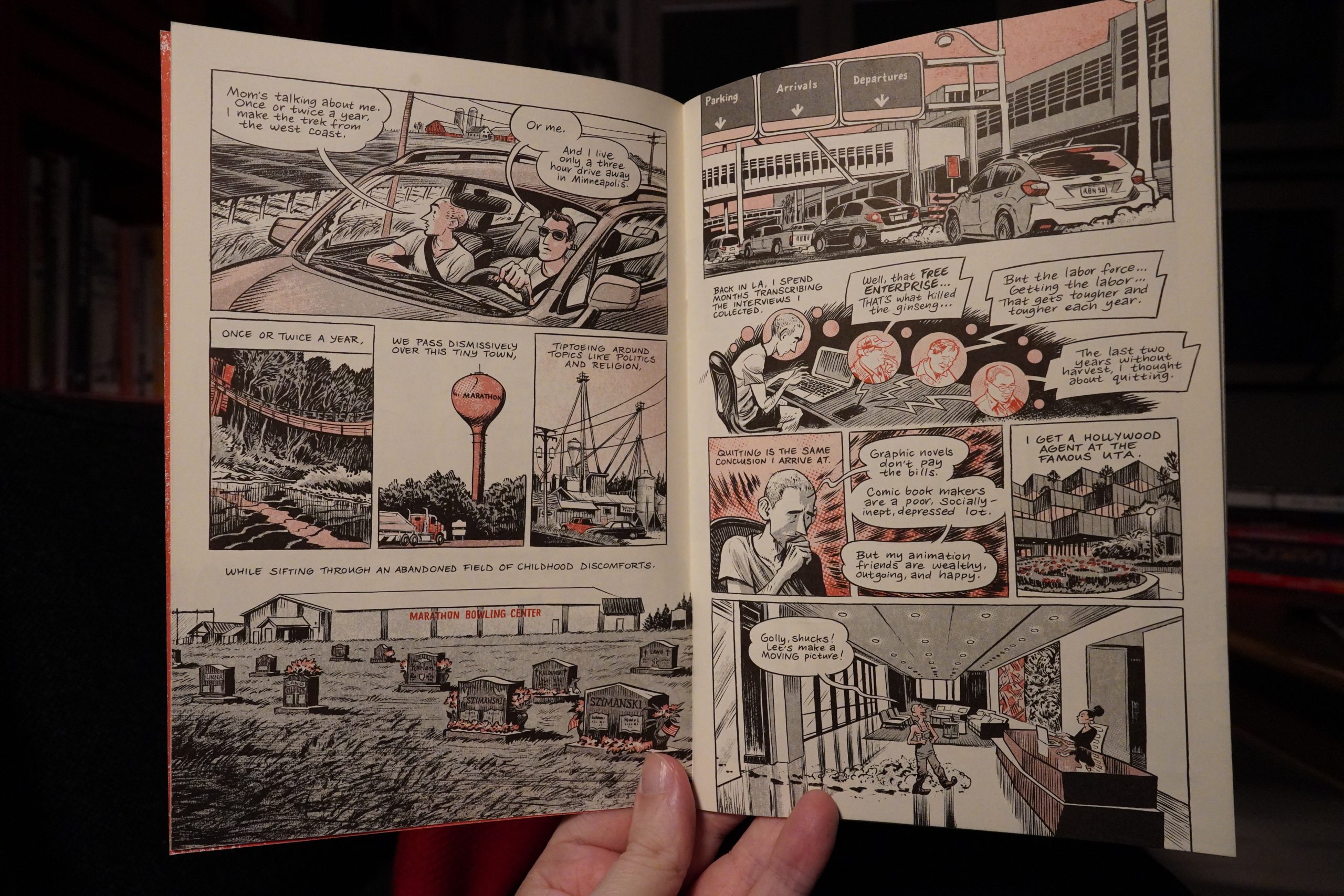

20:21: Monstress Volume Seven by Marjorie Liu / Sana Takeda (Image Comics)

As usual, I don’t really remember what’s going on here, since it’s so long between volumes, and there are no “as you know, Maika, you have a bionic arm and an alien entity called Zinn” lines. I keep meaning to go back and read the entire thing…

… but I find that I’m fine with reading these books in a state of befuddlement. Confusion is fun! And some of the storytelling seems very subtle, and I’d hate to be disappointed by finding out that it’s all 100% straightforward by re-reading it all. (That’s happened more than once before — I’m reading something serialised over years, thinking that it’s all very complex and satisfying, and then sitting down to re-read it all in one go, and find that it’s all pretty trivial.)

The artwork is lovely as usual, but it would be nice if there was more than one template for faces — but she gives almost everybody distinctive hair-dos, so you can tell them apart by looking at the hair.

| Sylvester: Sylvester-Step II |  |

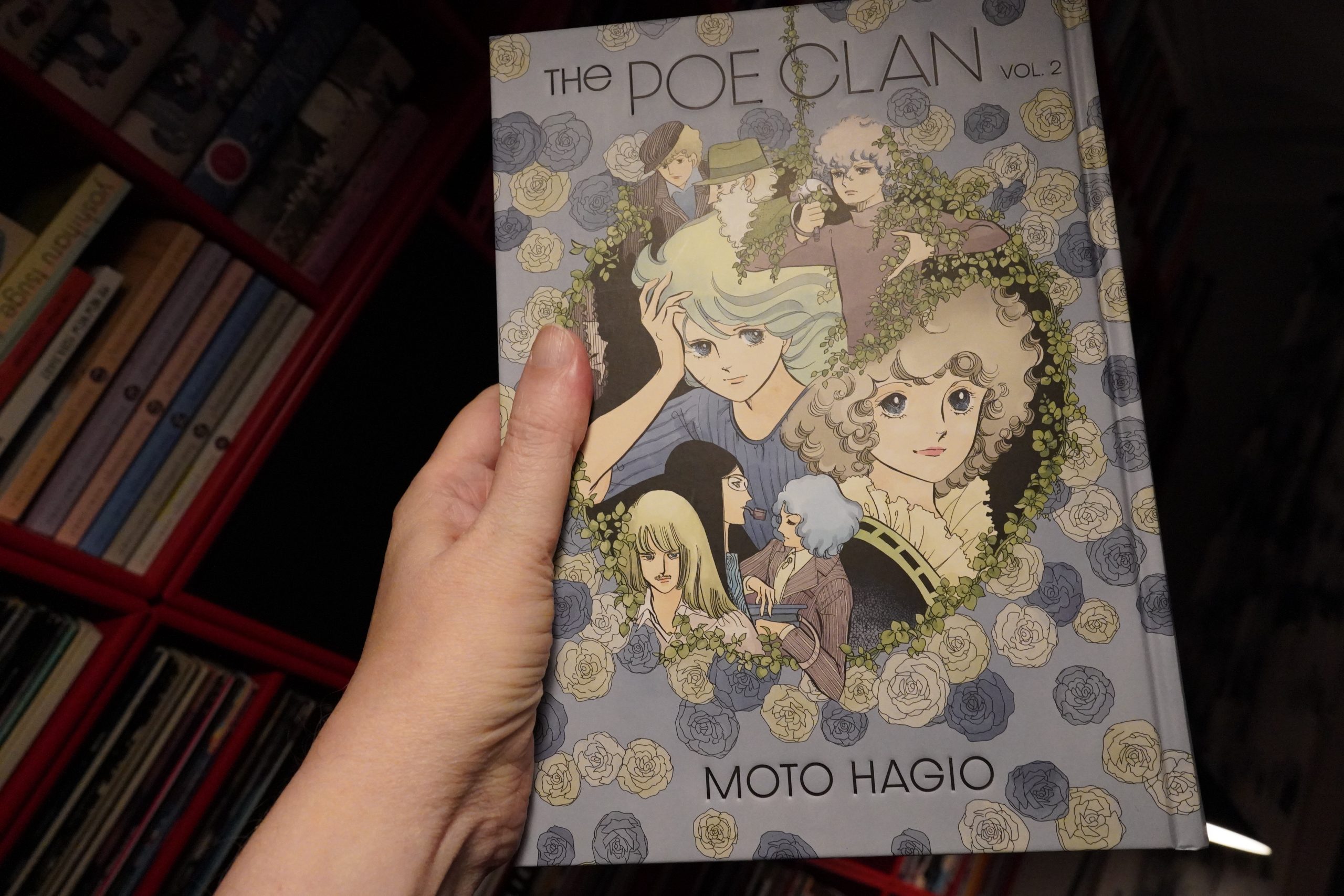

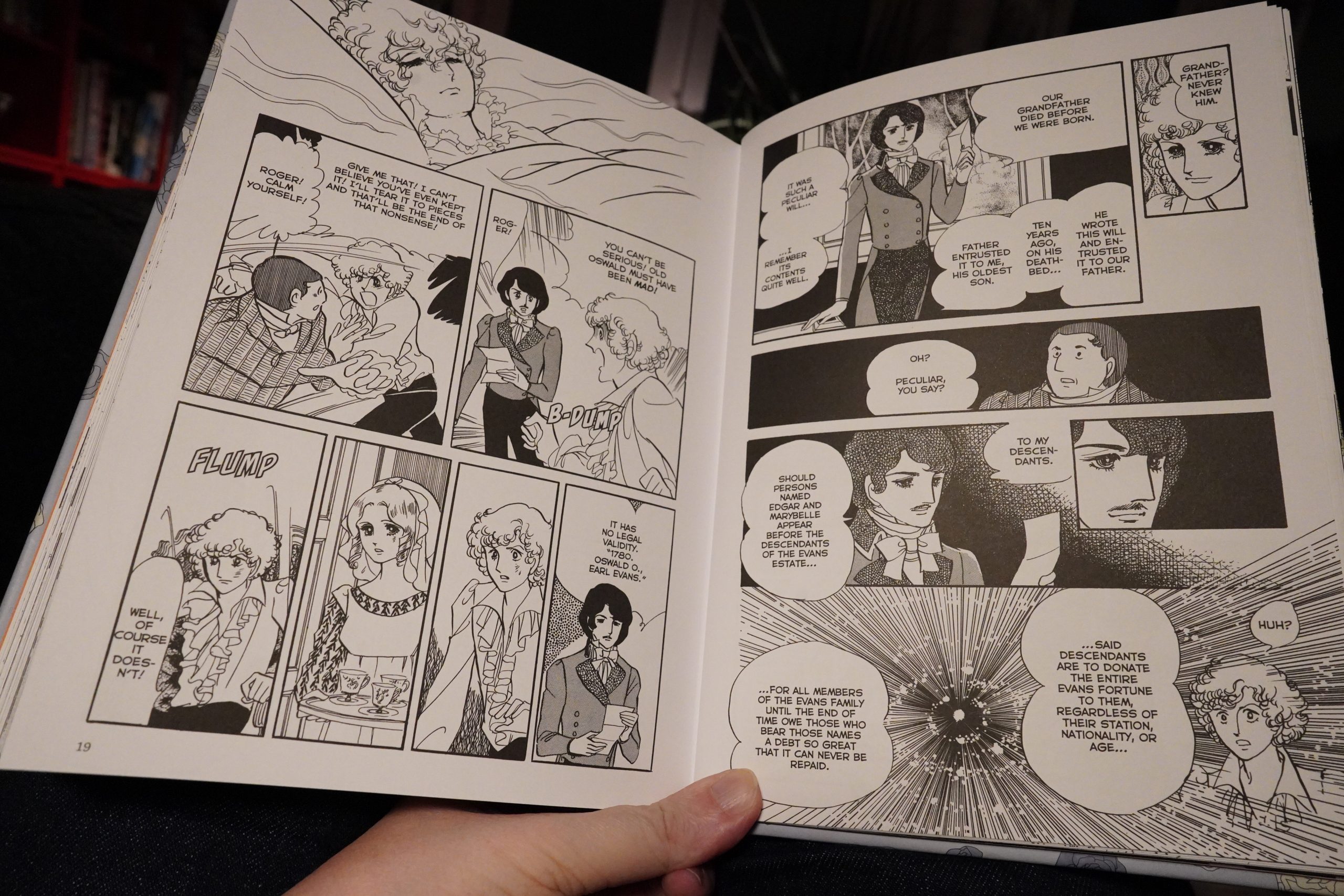

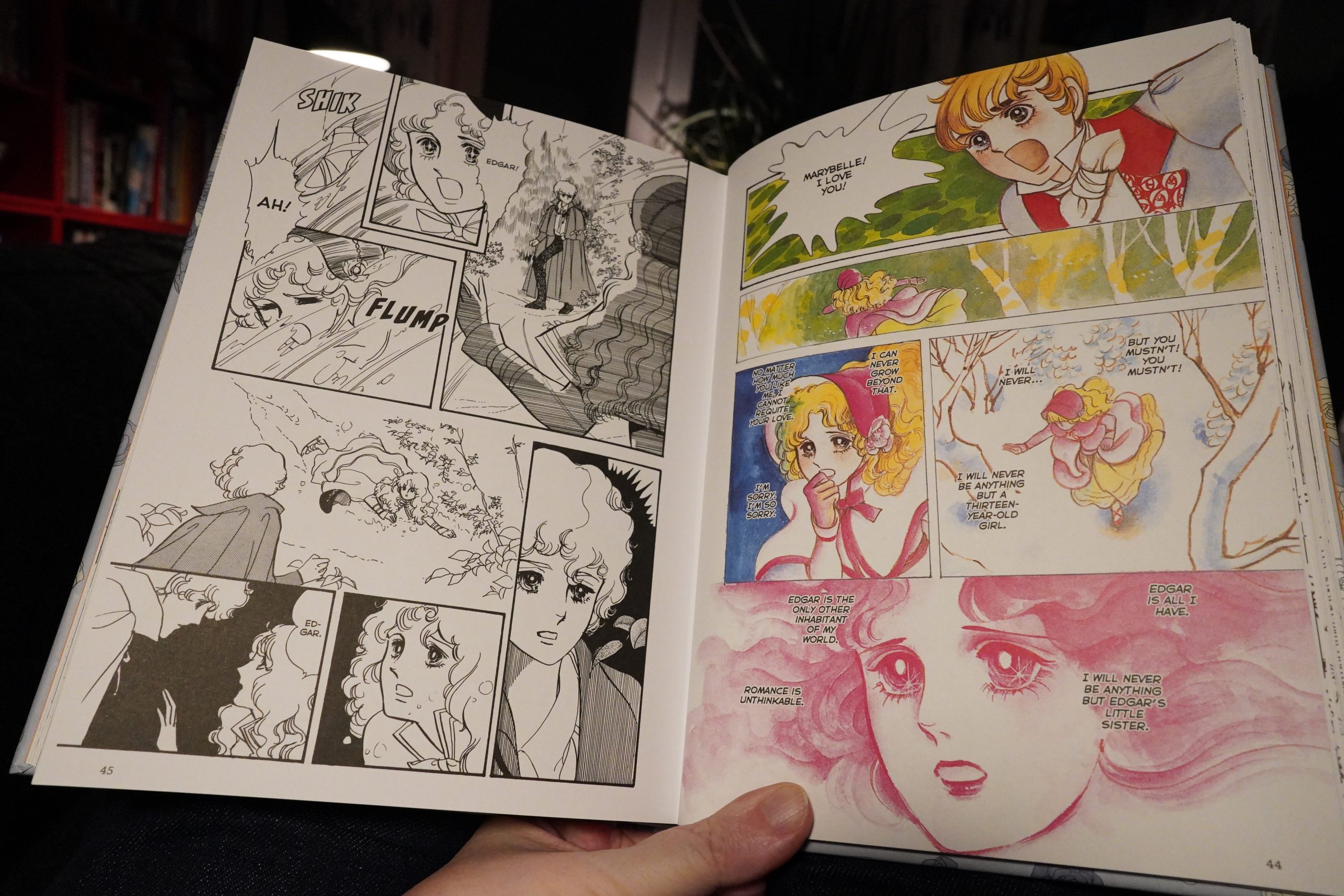

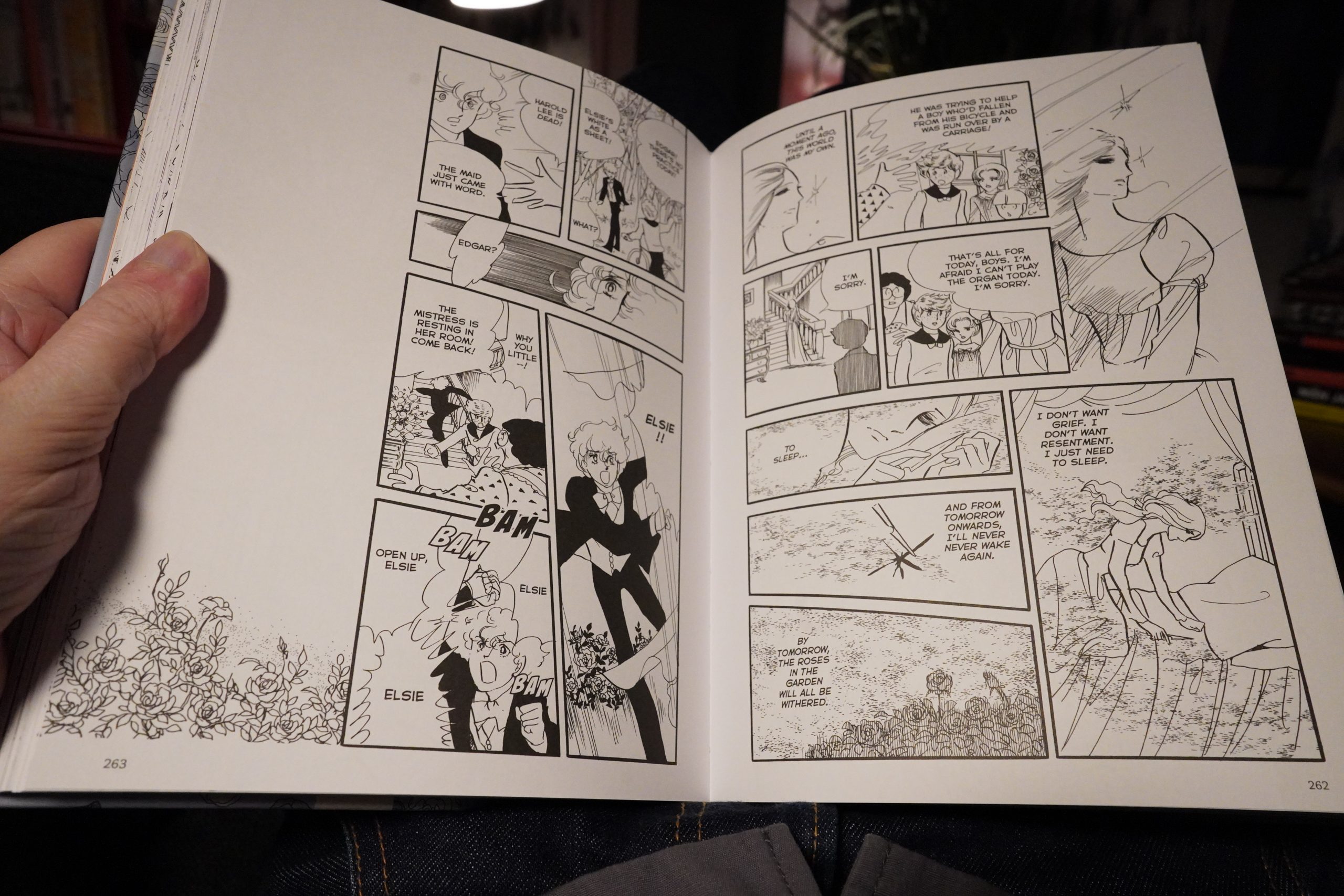

21:21: The Poe Clan vol 2 by Moto Hagio (Fantagraphics)

I found the first volume of this to be underwhelming, so I wasn’t going to buy any further volumes, but apparently I had already ordered this one. Oops.

It’s not that these comics are bad or anything — they were influential and trend-setting. While stories about teenage vampires could become repetetive, she varies the storylines admirably.

| Various: Cold Wave Volume 2 |  |

(Even if the plots are kinda clichés in themselves — in this one Edgar gets amnesia and they futz around for 70 pages until he gets his memory back.)

| Melvin Gibbs: 4 + 1 equals 5 for May 25 |  |

I was thinking I’d ditch this book, but after the first story, it really picked up. Every story seemed fresh and intriguing.

| Body Meπa: The Work Is Slow |  |

23:49: The End

But now it’s sleepy time.