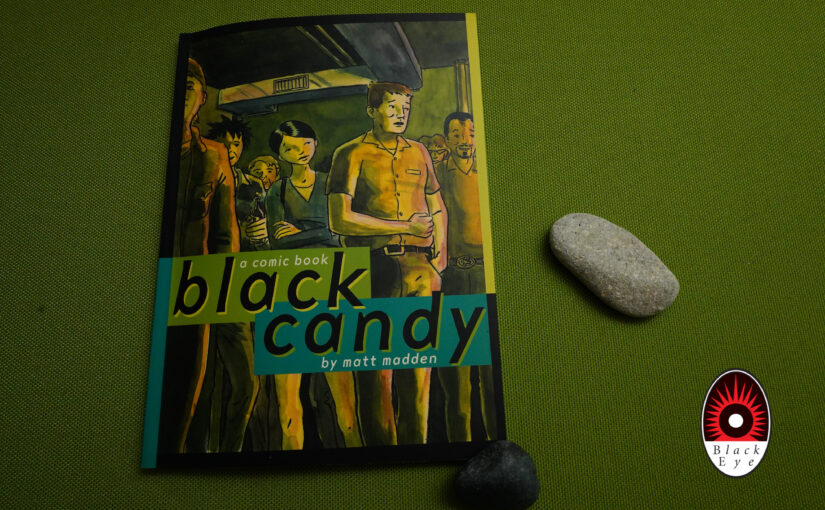

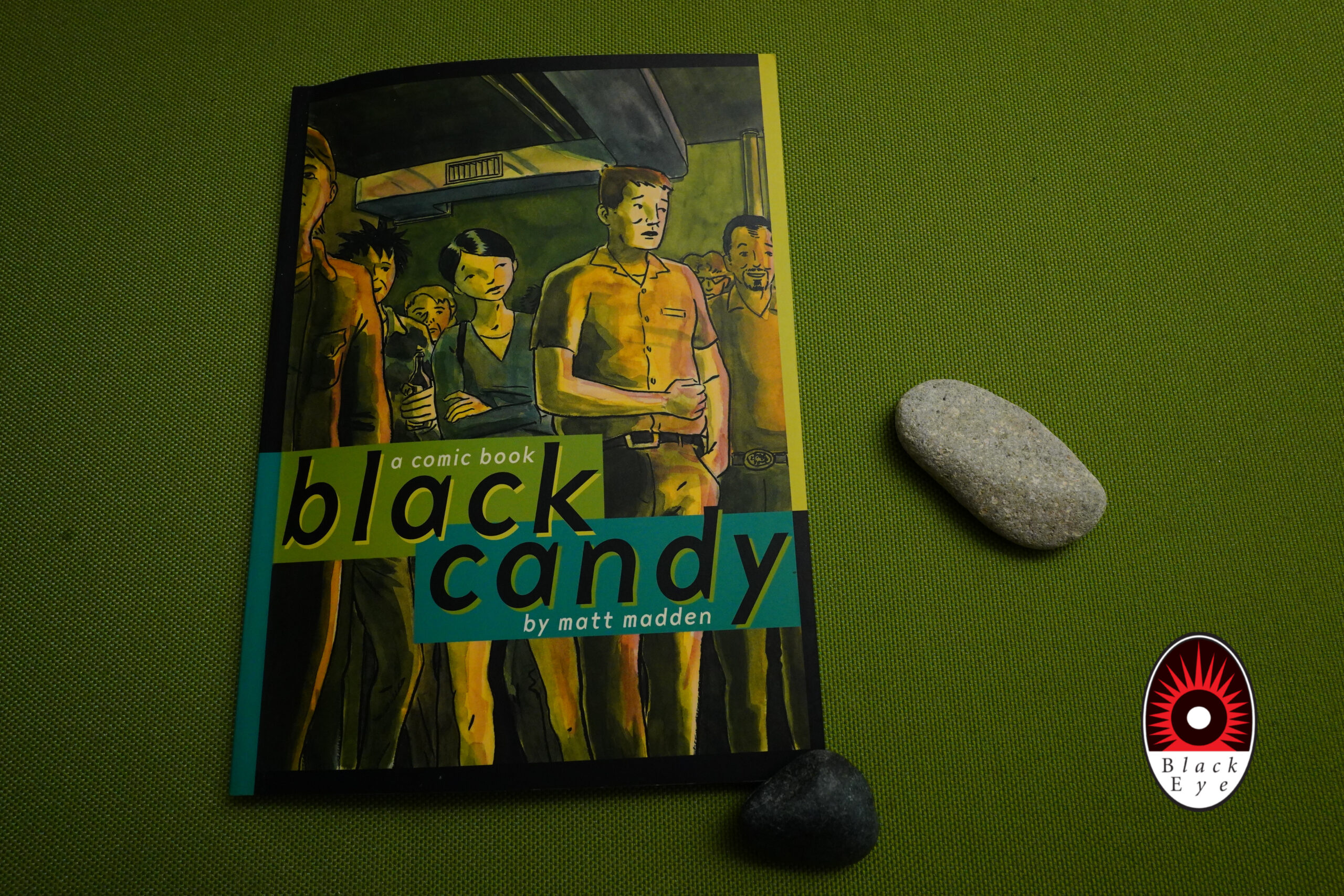

Black Candy (1998) by Matt Madden

Matt Madden! That’s a name I sort of vaguely remember, but have extremely positive vibes about… I don’t remember this book at all, though.

Oops! Do I remember how to censor things on this blog… This blog was censored from linking from Facebook for over a decade, and that’s presumably because of some of the comics I’ve posted snaps from over the years…

Yeah, it’s ‘class=”redact”‘. There we go — you have to hover over the pictures to see them, because they will surely destroy civilisation otherwise.

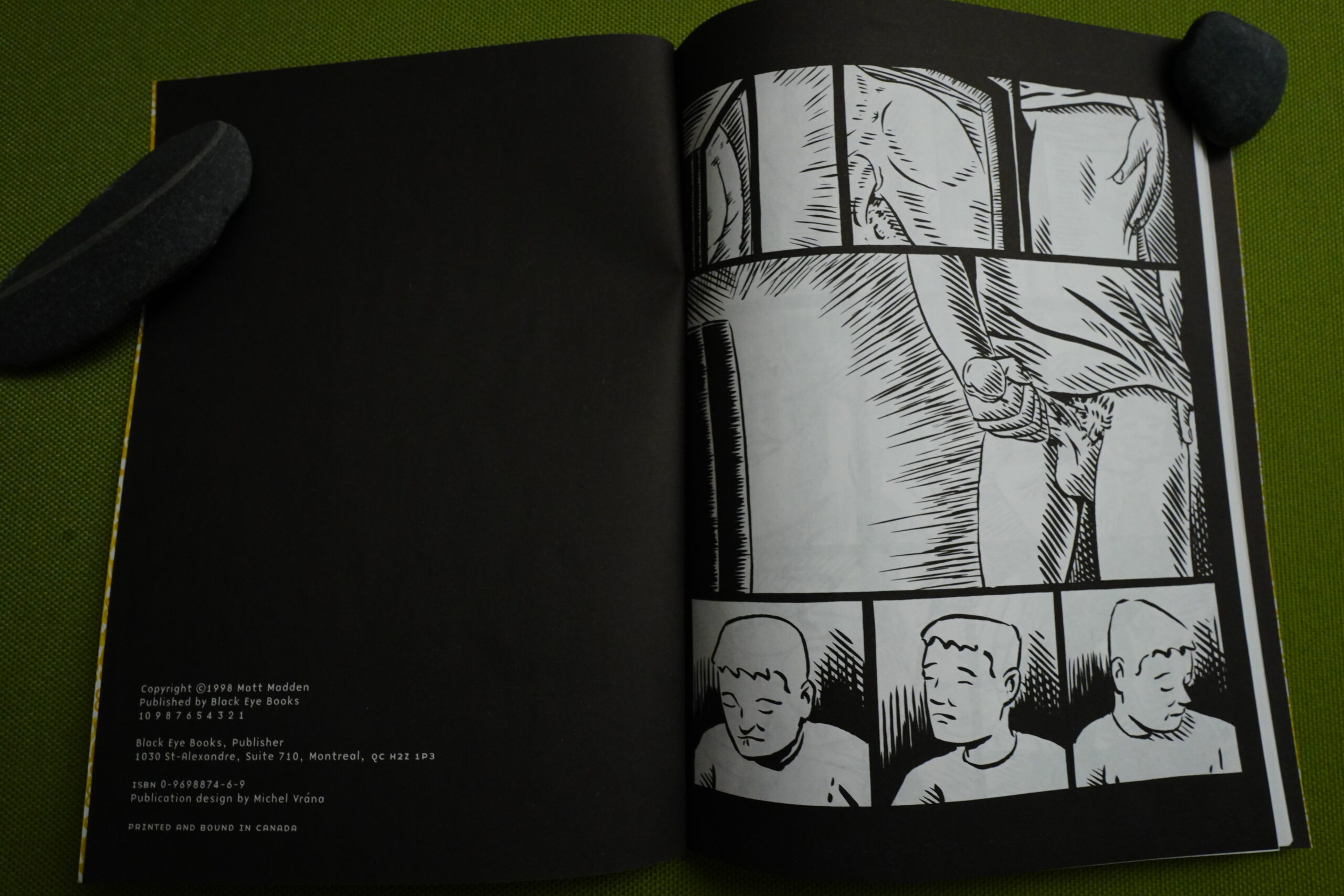

But that’s certainly a way to start a comic! Very in your face, so to speak.

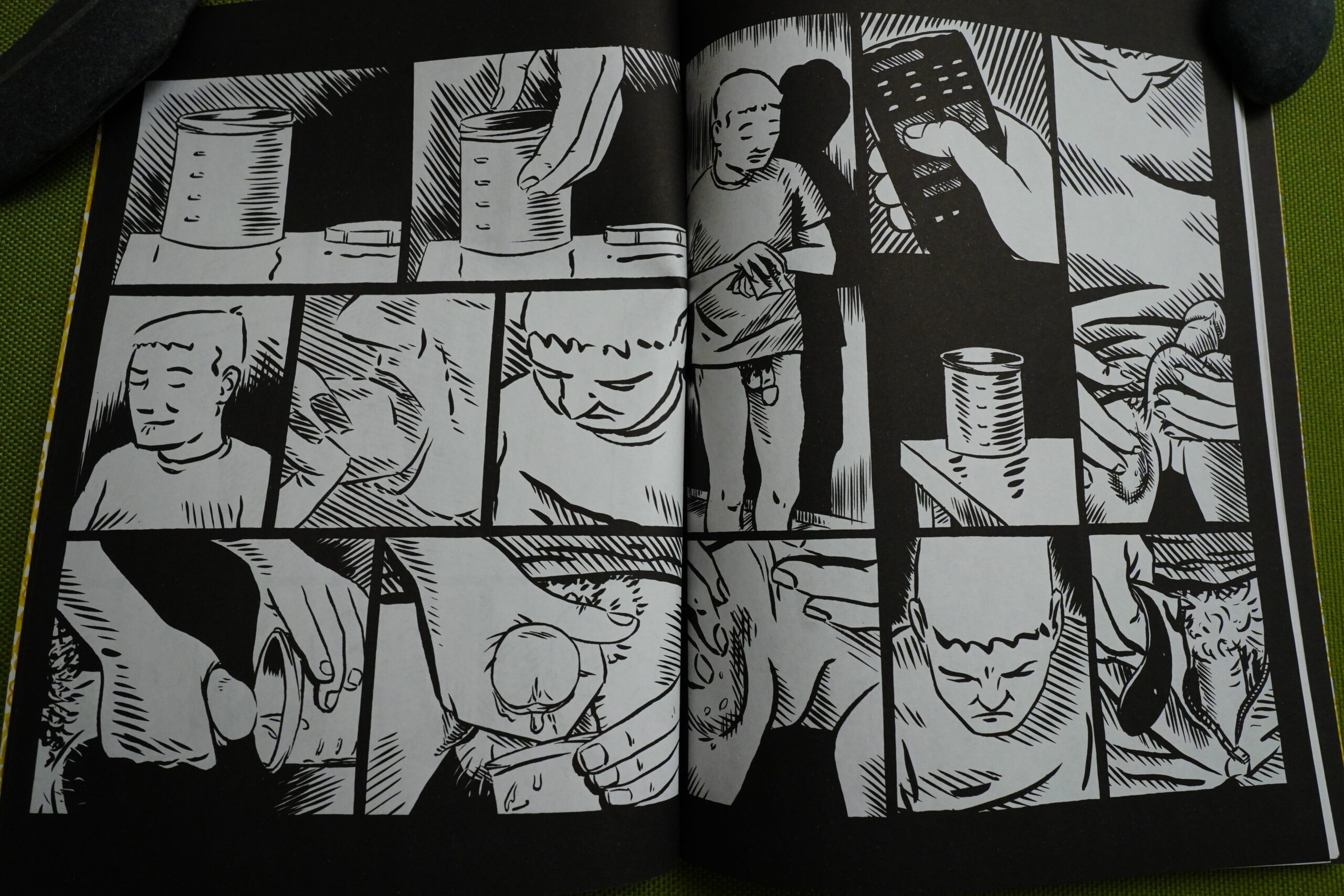

There’s some superficial similarities to some of Charles Burns’ work, I guess — a sort of sex/body horror thing going on, but it’s a lot less mystifying than Burns is. And the artwork rather reminds me of David Mazzucchelli, especially in his City of Glass period.

It’s really good! It doesn’t fall into the trap of trying to explain things too much, but instead goes for, like, confusion and despair.

And it feels like exactly the perfect length, too.

Unfortunately, it hasn’t been reprinted? That’s a shame.

Tom Spurgeon writes in The Comics Journal #199, page #8:

“This is my first attempt to create a

sustained narrative, so a lot of it is

sort of stretching my wings.” says

Madden. “I’d say I was more con-

cerned With pace and mood than

anything else. I was trying to

ture some sense Of daily life (as my

friends and I experience it) being

ruptured by the absurd and

tesque.” Madden, known in his

previous work for a “slice •f life”

approach, isn•tstrayingtoo farfrom

those roots with this latest work

Black Candy draws from real life

situations — the story was initially inspired by a “sperm donors needed” ad in a newspaper — and from there touches on themes including, according

to Madden. “reproduction, parenting, sexuality and the male body flow.” Madden warns that potential readers don’t have to worry about being lectured.

saying he actually followed a very casual artistic approach in working with the material. “I let the themes [in Black Candyl develop at a pretty organic or

unconscious level. I was more interested in just writing the story. then going back and looking at the issues it raises.” Additionally. Black Candy may have

specific resonance for readers in college towns, as Madden drew on Stays in Austin and Ann Arbor, Michigan in completing the work.[…]

Madden hopes that Black Candy will be the first in a series of larger, self-contained works. “l prefer to do longer stories and publish them as

complete books after the European model,” says Madden. The cartoonists notes that a lot of what is in his current offering may set a tone in other

ways. also think that a lot of the concerns in Black Candy— e.g. , formal playfulness, quasi-naturalistic dialogue, episodic structure — will continue

to be present in my future work.”

For now, however, fans will content themselves with Black Candys studied. masterful pace and deeply disturbing subtexts. Like any other “rookie”

with 10 years of experience. Matt Madden will almost certainly take a significant percentage of the comics-reading public by surprise.

Charles Hatfield writes in The Comics Journal #206, page #40:

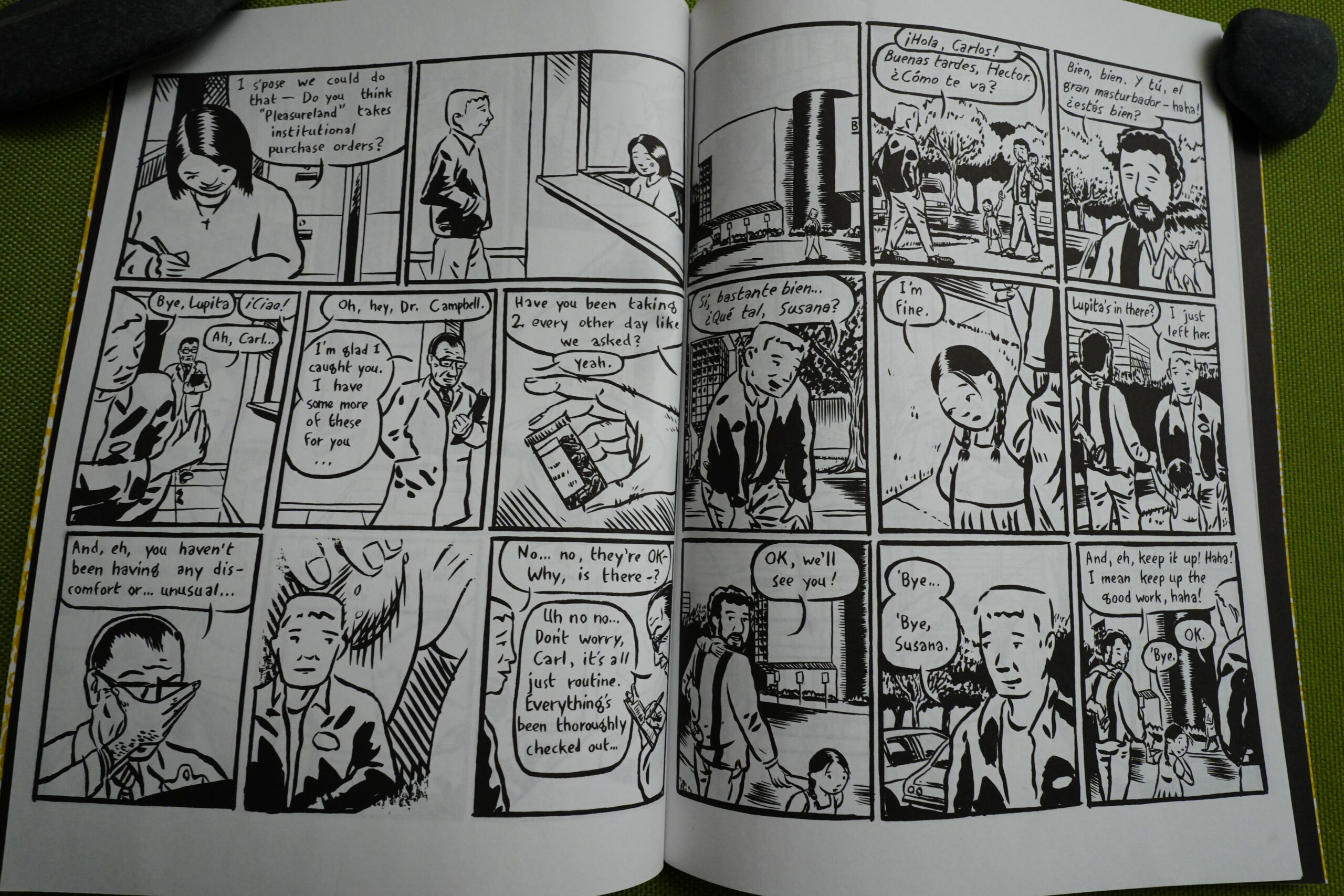

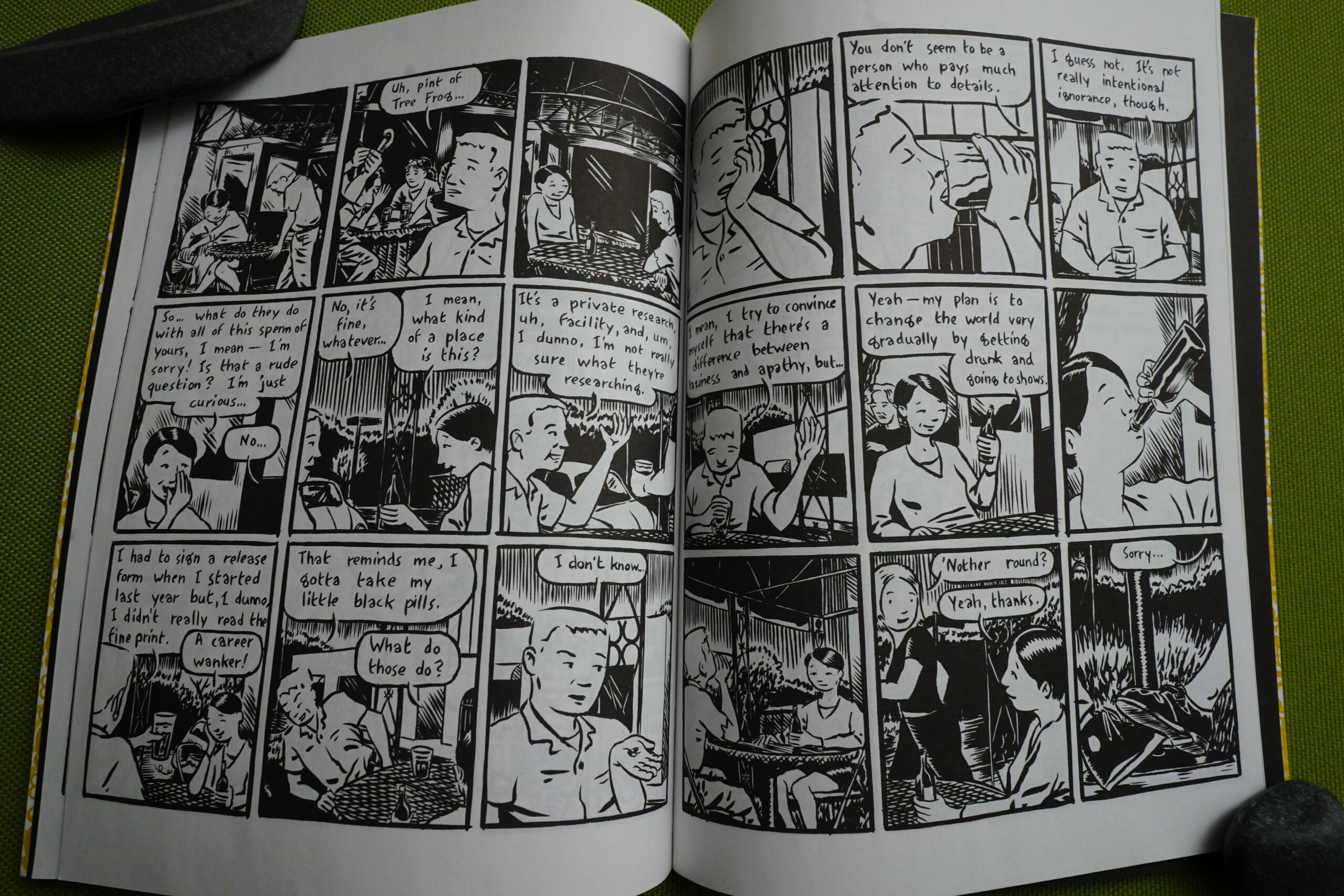

Matt Madden’s Black Candy begins with

masturbation and ends with cremation.

The end follows logically from the begin-

ning, a direct result. In between, the pro-

tagonist “Carl” (i.e., man) endures betrayal

by his own body, hinted at in small, dark

lumps sprouting in his armpit and groin.

“Some kind Of VD,” he reasons, but we

know better: the lumps must have some-

thing to do with the little black pills he’s

been swallowing.

If this sounds disturbing, it should.[…]

Lyrically, Black Candy succeeds in con-

juring mistrust and horror of the body;

narratively, however, it cheats. Plot-wise,

the story yawns wide open and never

closes: Madden ends up relying on a gnaw-

ing suggestiveness rather than full, fair

disclosure. Though the ending earns

grudging admiration for symbolic fit —

the metaphorical significance of the physi-

cal body is played out with an awful final-

ity — it is not motivated logically. If only

it were more carefully anchored.

In sum, Black Candy is a provokingly

evasive story, anchored in realism, au-

thenticated by sharp observations of the

everyday world, and compromised by grim

fantasy. Kudos is due for Black CandYs

looming sense of foreboding and stark

technique; and criticism for an ending

stacked with too many unfulfilled prom-

ises. The novella begins in a dark room,

and ends by taking a walk on the wild side

of speculation. Though Madden excels at

queasy suggestion and quietly modulated

menace, he fumbles the close, as if unwill-

ing to shoulder the expository burden

demanded by his fantastic premise. For all

its advances in craft, Black Candydoes not

pack the same punch as the less elaborate

(and, to be fair, less ambitious) Fair Warn-

ing, in which the disturbing elements are

more in sync with Madden’s low-key real-

ism.

Or so I would argue. Let the debate

commence, confident of Madden’s prom-

ise — Black Candy is worth arguing about,

and Madden’s name should register deeply

with readers. He demands, and delivers,

much. On the strength of this book, I await

his next.

Well, OK.

Anyway, this is the last comic I’ll be covering in the series that was published by Black Eye’s 90s incarnation. I don’t think this was the final thing they published — that might have been The Sands? But the chronology is a bit uncertain here. But in any case, that means that I have to cover Black Eye’s original demise now, so:

The Comics Journal #203, page #20:

The financial and production prob-

lems that forced Black Eye to cease

publishing for several months have

led two of its artists to seek homes at

other publishing houses and have

caused Black Eye publisher Michel

Vrana to rethink his future publishing

strategy by focusing almost exclu-

sively on collections and graphic

novels. From October Of last year to

this spring, Black Eye, which is run

solely by Vrana, was unable to print

its scheduled books (save for one issue

ofJason Lutes’ Berlin); the dormancy

stemmed in part from financial

troubles that began plaguing Black

Eye when Capital City Distribution

went out of business in July 1996, as

well ai time constraints placed on

Vrana when he took a full-timejob as

a graphic designer. The instability at

the company led bothJames Kochalka

and Megan Kelso to pull their books

from the Black Eye line, and reports

surfaced that some stores and dis-

tributors attempting to order books

from the company were getting no

response. In the wake of frustrations

voiced by some of the artists pub-

lished by Black Eye, Vrana has stated

that he is committed to continuing

publishing but is unlikely to publish

be

comics in serial form for the moment,

With the exception Of Berlin.Vrana conceded that he had over-

extended himselfat times by trying to

juggle the duties of operating a one-

man publishing house while taking

on a fill-time job designing maga-

zines. When he began publishing,

Vrana said he was able to devote the

majority of time to Black Eye while

receiving additional money from

freelance design work. By the end Of

1997, he said, “things were difficult

financially” and his fill-time day job

“put a lot ofstrain on things.”

“Being young and overconfident,

I didn’t see any problem with taking

on a full-time job,” Vrana said.

found myself at times unable to do

production on books that had to get

out… I owed lots of money to lots of

people” and had to hold off on pub-

lishinguntil debts to places like printers

could be paid off.For some ofthe artists associated

with Black Eye, the Small press Expo

in Bethesda, Mary. , last September

was something of a watershed for

their frustrations with the company,

in part because ofa lack ofcommu-

nication on the part Of Vrana.

According to James Kochalka, his

book Quit Your Job was first slated to

come out from Black Eye in August,

and was then was pushed back to

come Out in September for SPX.

Unfortunately, the Black Eye artists

found out when they arrived there

that the Black Eye books slated to

debut at the event had not gone to

press, and the rest of the Black Eye

books had also failed to arrive.

“All [the Black Eye] artists were

there, and they were all grumbling,

and [Vrana] wasn’t there” — which

gave them plenty of time to voice

their frustrations, Kochalka said. For

Ed Brubaker, whose Lowlife was seri-

alized by Aeon and collected in the

Black Eye book Complete

“SPX was kind of like the really big

deal… (Sands creator] Tom [Hart]

andJason [Lutes] basically killed them-

selves to get their books out for SPX

and the books just didn’t come out.”

Brubaker added that because Vrana

(who told the Journal that he couldn’t

afford to fly outto SPX) “waited until

the last minute” to have the Black

Eye backlist books shipped overnight

to SPX from a warehouse, a subse—

quent shipping error delayed the

arrival of the books until the second

day of the convention. Brubaker said

that he had to personally call the

holding area in Baltimore, Where the

books were incorrectly scheduled for

delivery two days after SPX, in order

to get someone to drive the Black Eye

books to SPX. “Michel knew about

all this at least a week or two before

the convention and waited until if

they fucked up, it would be too to

fix it,” Brubaker said.

. If you’re

going to be the publisher, you can’t

rely on everyone else to do every-

thing at the last minute.”

After SPX, Kochalka found his

book delayed yet again when Quit

Your Job was sent to the printer in

N ovember but was not printed due to

Vrana’s outstanding debt. “That was

pretty much the cue for me,” said

Kochalka, who submitted the book

to another publisher, Alternative Press,

which is scheduled to ship it in June.

“I was absolutely sure that I did not

want to give him another book and

then not have it come out,” he said.

Kochalka also rescinded another book

which he had offered to Black Eye

(Tiny Bubbles) and is now publishing

the project with Highwater Books.

“My only problem [with Black Eye],

Kochlaka stated, was having his book

“constantly delayed through no fault

of mine… I really like

Michel and Black Eye as

a company.”

Kelso, who decided

not to publish her Girlhero

comic with Black Eye,

also emphasized that she

did not harbor any “ill

will” towards Vrana. “l

just sort of looked at the

situation [with Vrana’s

new job] and I saw what

everybody else saw —

that everything was

coming outlate, ifatall…

and it just seemed like

[Vranal was really busy,

that he didn’t have time

to put my book out… I

just told him that it

seem like a good time

[for Black Eye to publish

Girlherol.

While Brubaker

echoed Kelso and

Kochalka’s personal as-

sessment of Vrana, he cited

additional frustrations about reports

that stores who were attempting to

order his Lowlife collection found

Black Eye unresponsive. Brubaker

told the Journal that a few retailers

had complained to him personally

about the situation while he was in

their stores or attending conven-

tions. According to Kristine Anstein,

who works for the Bay Area dis-

tributorLast Gasp, Black Eye orders

have recently come in, but she “had

trouble at various points… We got

in a reorder now, so I’m happy; if

you had talked to me a month or

two ago when I was tearing my hair

out trying to get Berlin, I would

have been unhappy.” And Kevin

Halstead, who works as a manager

at the Seattle comics shop Zanadu,

told the Journal that he “pretty much

gave up on trying to place orders

directly [with Black Eye) about six

months ago” when Vrana did not

respond to multiple e-mail mes-

sages he had sent regarding orders.

He added that he had placed reor-

ders with Diamond for Black Eye

Books without receiving anything.

“We used to order directly from

(the publisher] all the time,” said

Halstead. “Then all Of the sudden,

we couldn’t… which is too bad,

because we probably could have

sold a lot more books.

It sounds like an absolute nightmare for Vrána — it sounds like things just got gradually more out of hand until he started withdrawing. I can totally sympathise.

For Vrana’s part, he acknowledged

many of the concerns voiced by the

creators, although he noted that he

wasn’t aware of having failed to re-

spond to requests for reorders. Any

communication problems, while ” Cer-

tainly unintentional,” admittedly

“caused a lot of resentment on the

part Ofthe creators… I was so wrapped

up in trying to reduce my debt that a

lot ofthin5 fell by the wayside… this

is one of the dangers when you have

a company that is run by only one

person.” As for the problems at SPX:

“Some people worked very hard to

have their books come out, it’s true,”

he stated. “It was personal problems

on my side. I should have realized my

financial and time Situation much ear-

lier to be able to say, ‘This isn’t going

to happen. ‘ All Ofthis frustration was

vented in this little vacuum and I

didn’t find out about it until much

later.”

Still, Vrana stated that he was

committed to publishing, that he had

erased most of the debts that stalled

production, and that he would be

able to manage his design work along

with Black Eye as long as he adheres

to a reasonable schedule and shifts

towards a different focus, “from a lot

of periodicals to a few trade

paperbacks… something along the

European model, where you release

three to five trade paperbacks [per

yearl and then slowly build a backlist.[…]

“If it turns out at the end of 1998

that I was unable to do things prop-

erly it may be the best thing for

everybody if I was just to pack it in. I

don’t have a desire to, but ift find out

I’m being both a detriment to myself

and other people, it would be selfish

to do otherwise. [Butl I’ve stuck it

out this far, and you don’t give away

five years of your life on a whim.””

But that was basically it… until 2019.

This blog post is part of the Total Black Eye series.