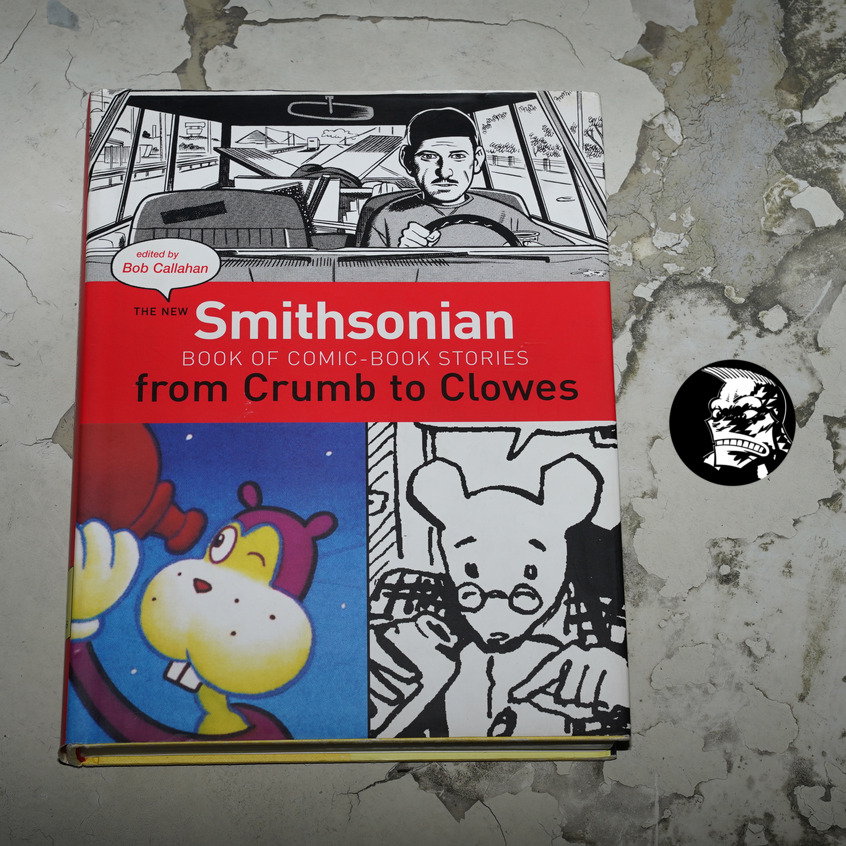

The New Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Stories: From Crumb to Clowes edited by Bob Callahan (220x284mm)

Callahan had previously had a go at creating a book like this in 1991: The New Comics Anthology. It wasn’t entirely successful — it read more like a catalogue than an anthology (and the artists had difficulties getting paid, the reproduction was pretty bad, and it sank without a trace in the marketplace).

But now he’s back — and the Smithsonian is probably more supportive than his previous publisher, Macmillan (who needed a lot of persuasion to include the more avant garde artists, apparently).

The main problem with the previous book was that there were so many contributors that the median story length was two pages. It doesn’t look like that’s going to be a problem here…

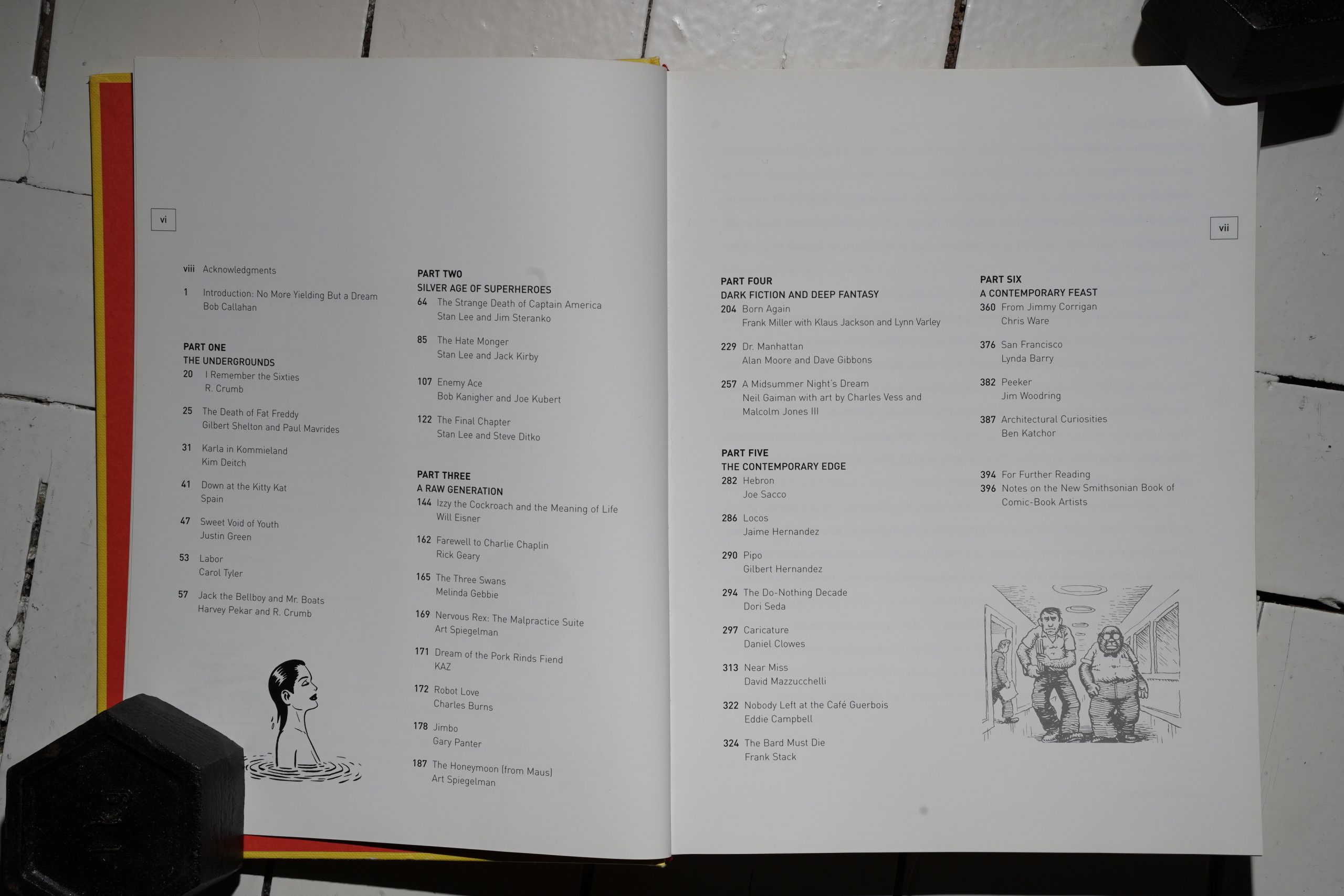

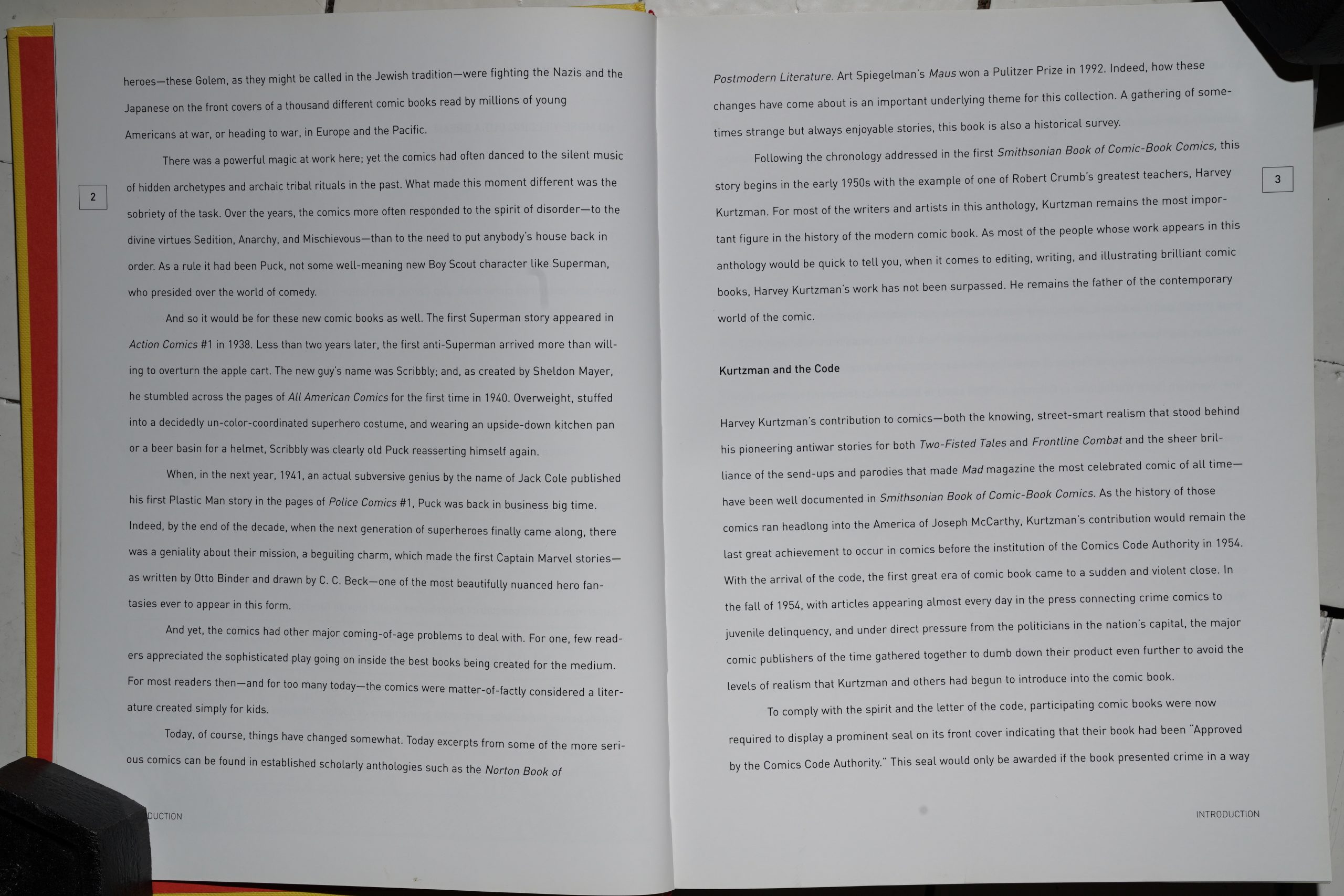

We begin with an overview of comics history, and it’s OK, I guess.

Ooh! The Upper West Side! Swanky!

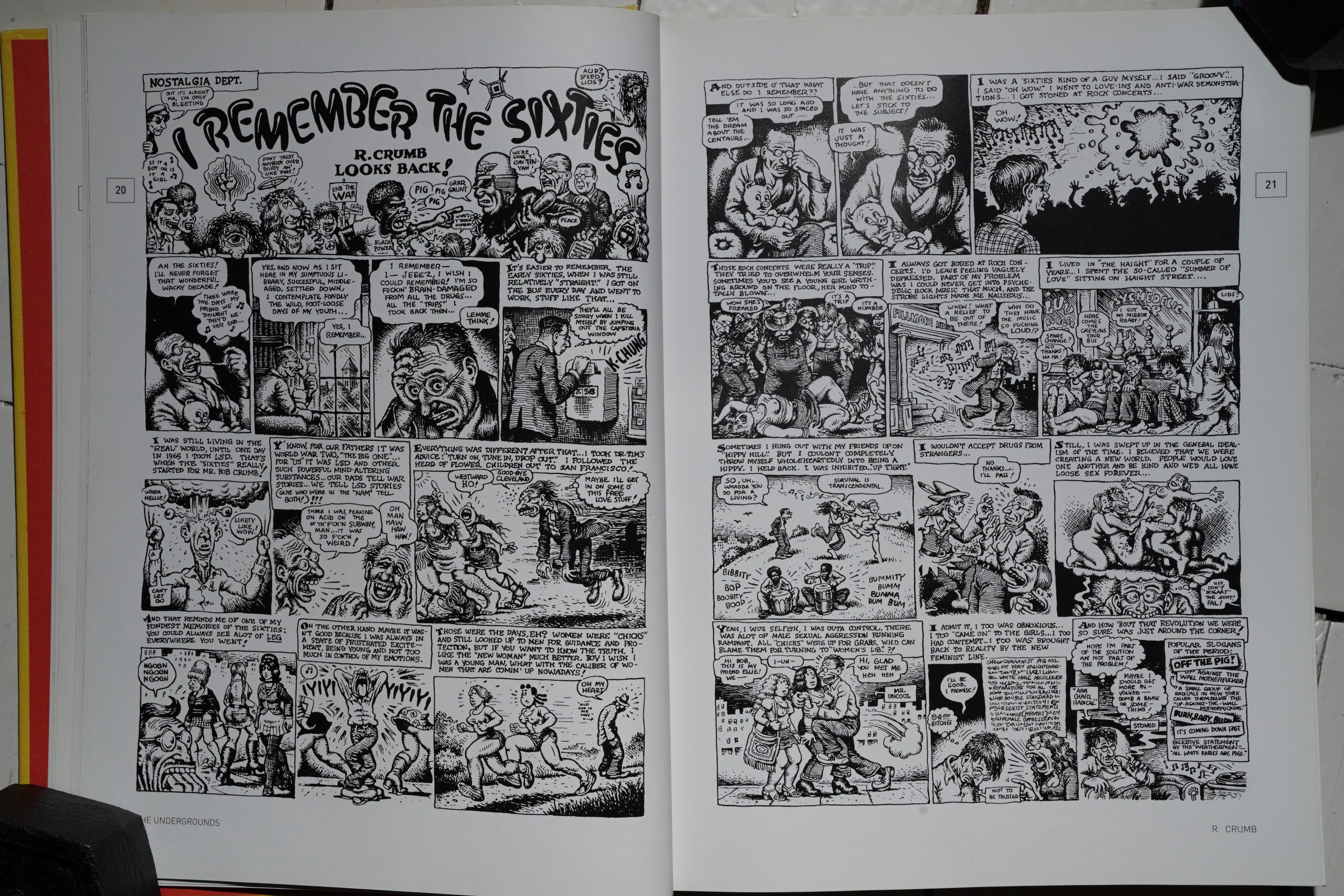

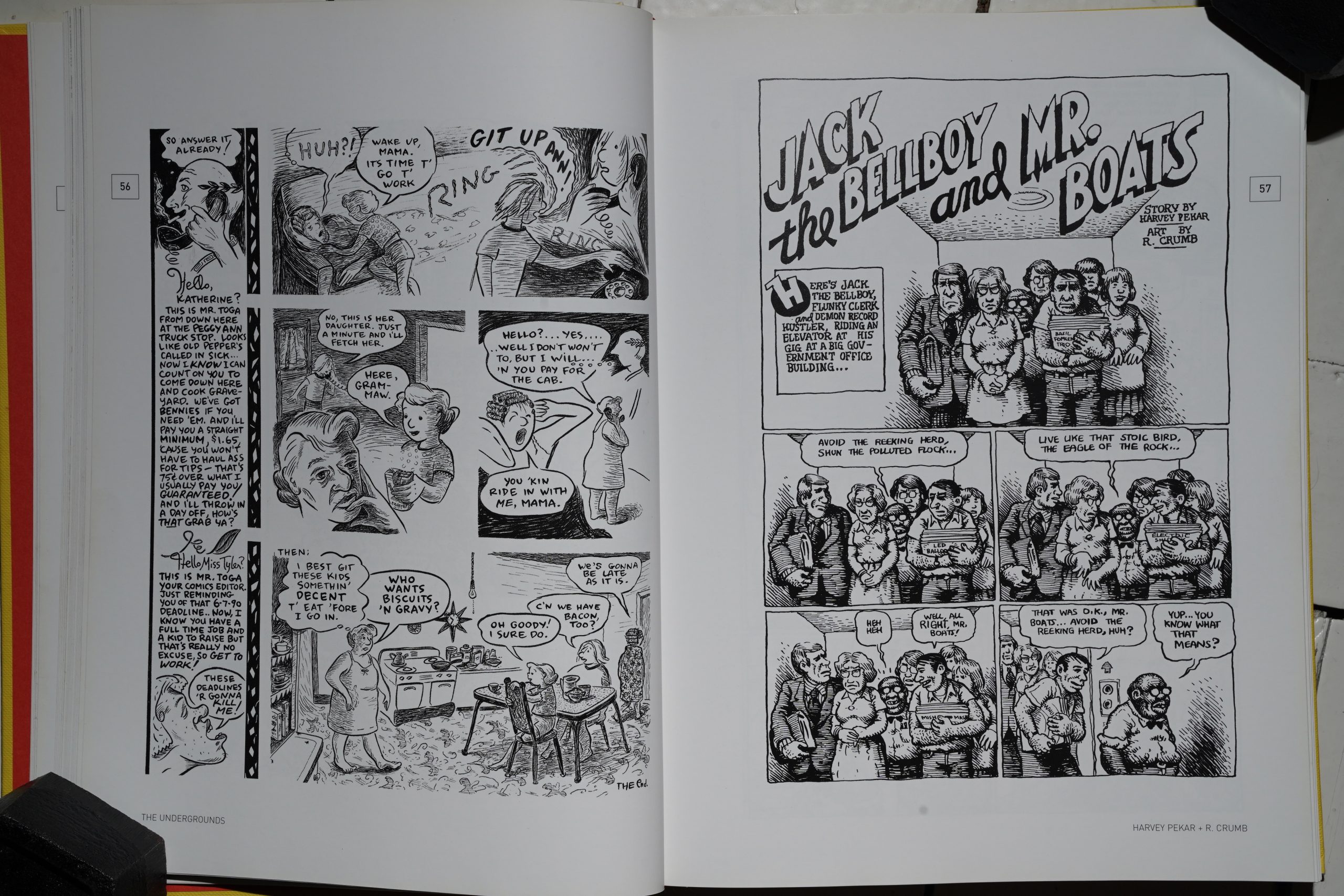

The comics start off with a section about the Undergrounds, so R. Crumb leads the pack. The reproduction’s OK — shiny paper and very black ink, so it looks nice. But it’s just a tad too small, innit?

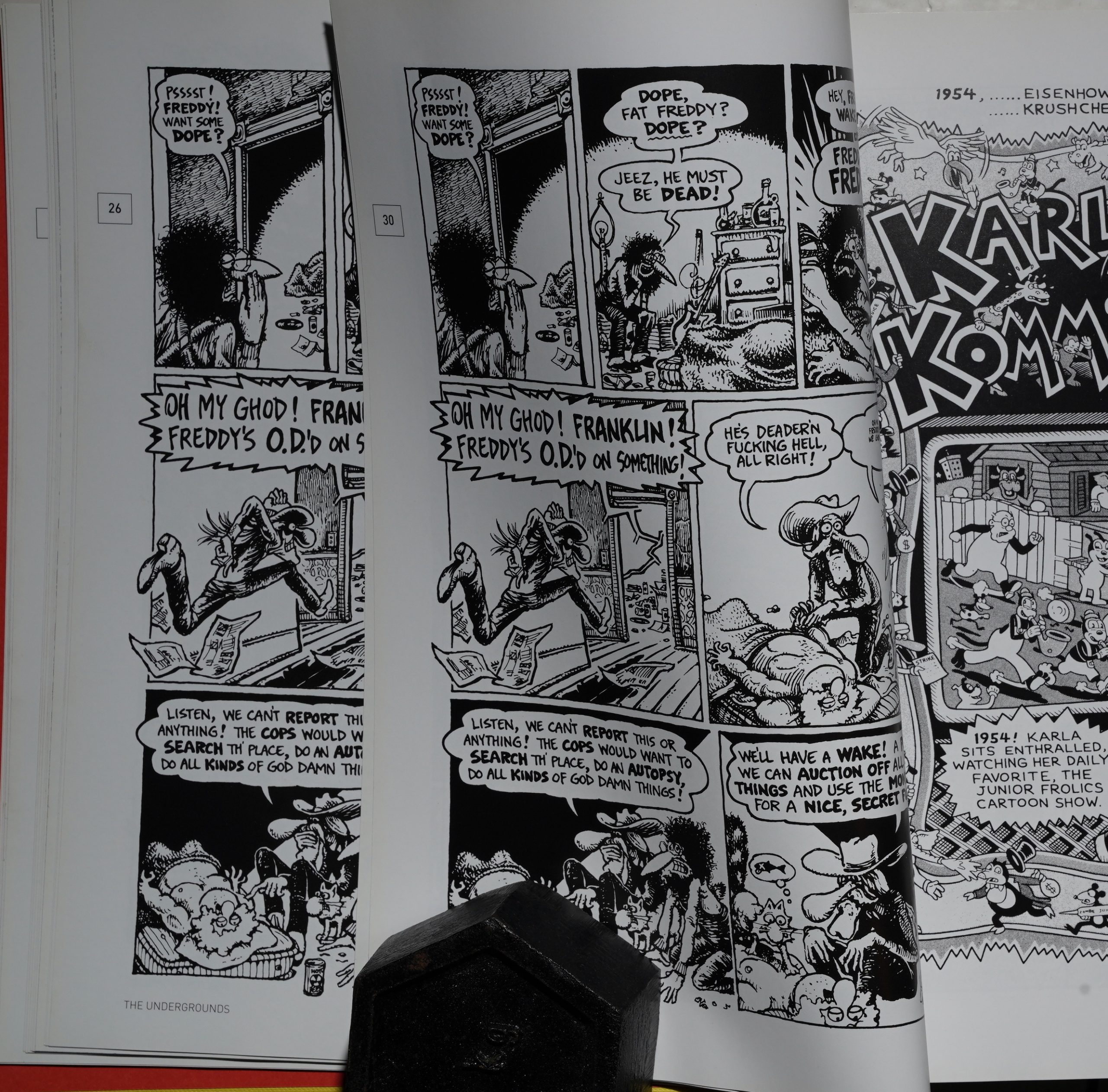

The previous book was plagued by production issues, like running pages out of order… and it looks like this has a similar lack of quality control: The Freak Bros. story repeats a page and neglects to include the final page of the story.

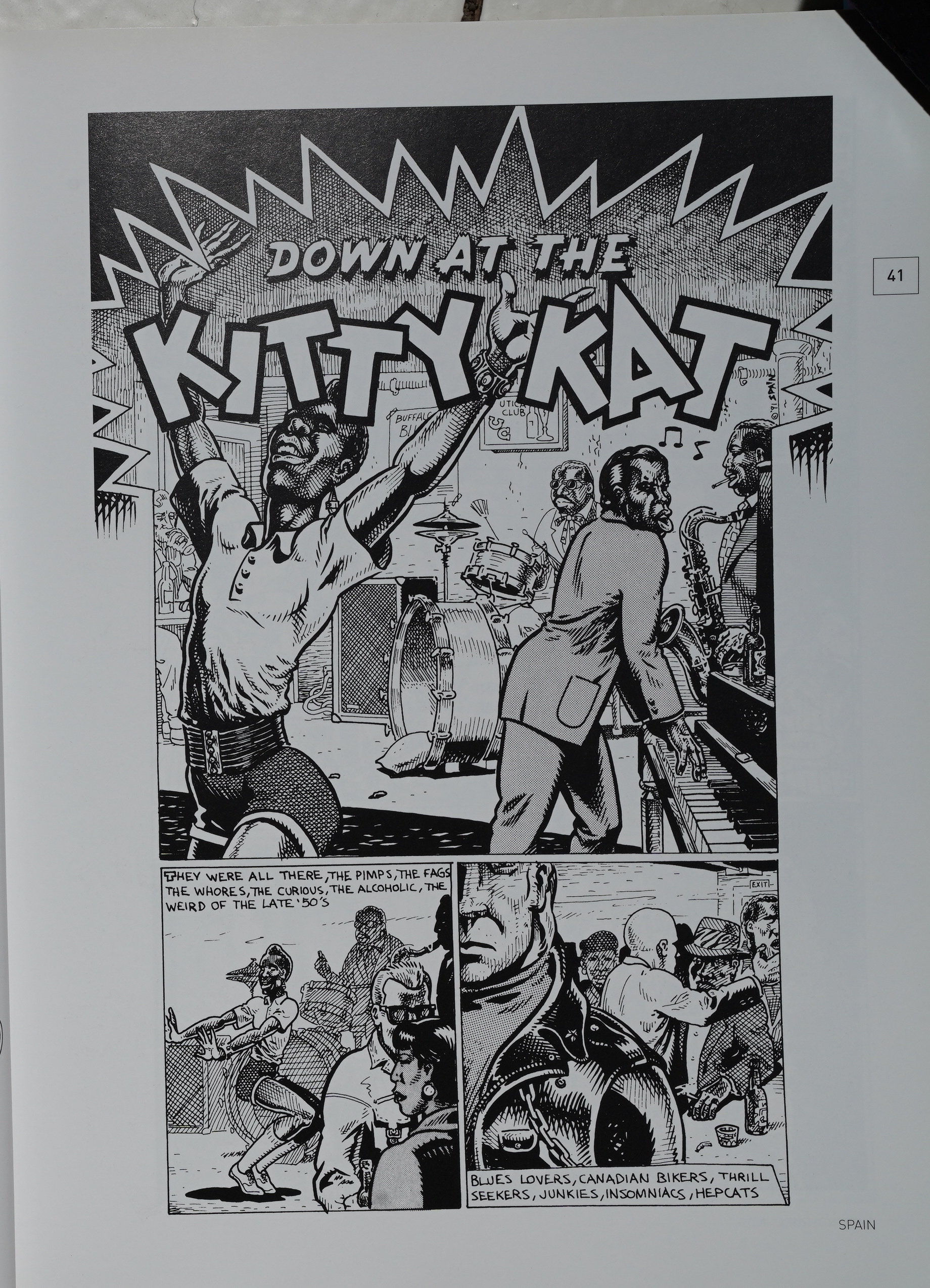

The selection of Undergrounds is reasonable, I guess, if you’re only including a handful of people. Callahan seems to be building a somewhat idiosyncratic gallery of people: We don’t get any of the “out there” artists, but only the extremely narrative-heavy people. But, you know, can’t complain about Spain… it’s a good story to include, too, if you’re only doing one Spain story.

And then… Carol Tyler!? As an Underground artist? Well… I guess she works in that idiom… And, again, it’s a good strip. (It was also included in the New Comics anthology).

And then Crumb again, but with Harvey Pekar.

So: The Undergrounds were just about doing autobio. Check!

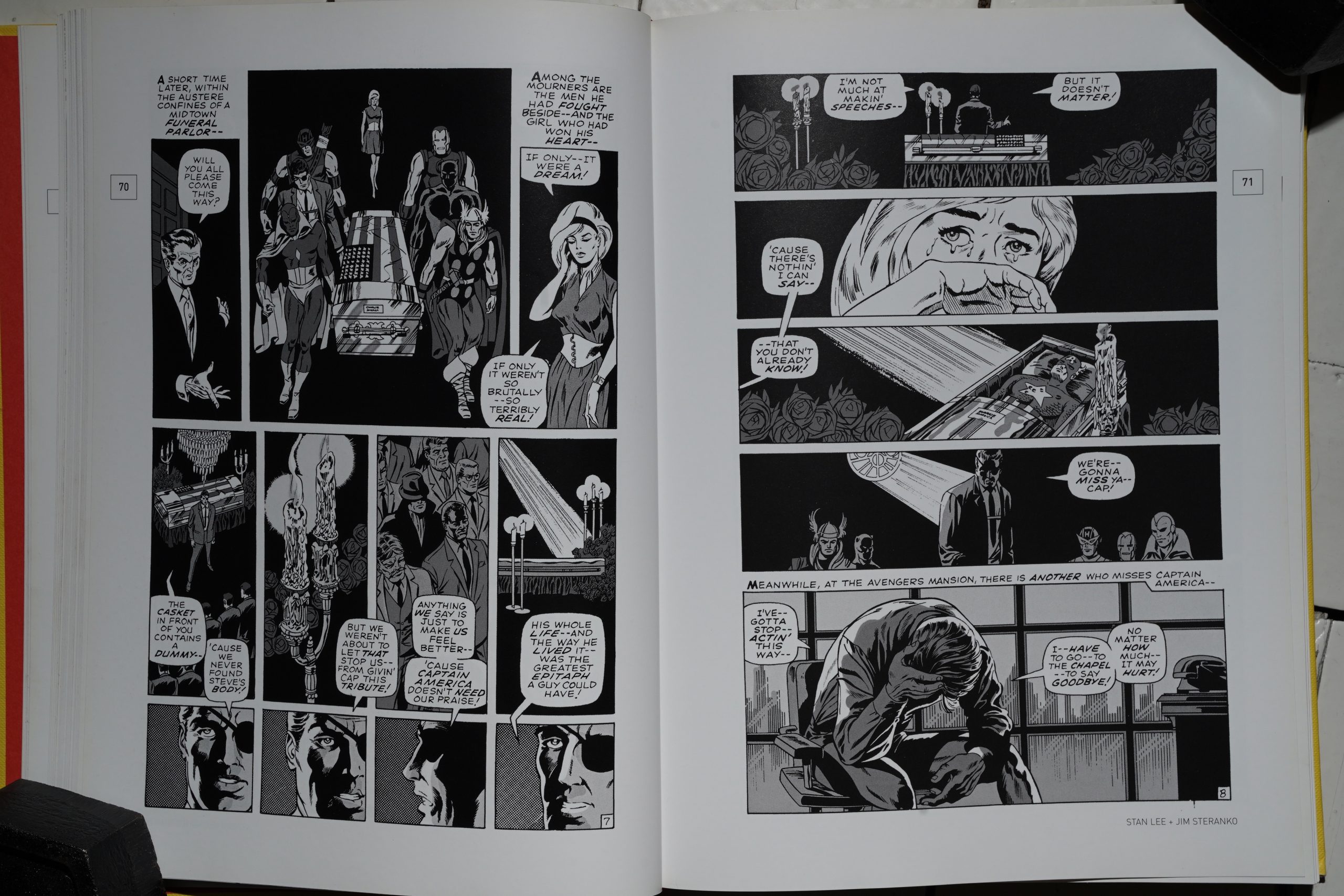

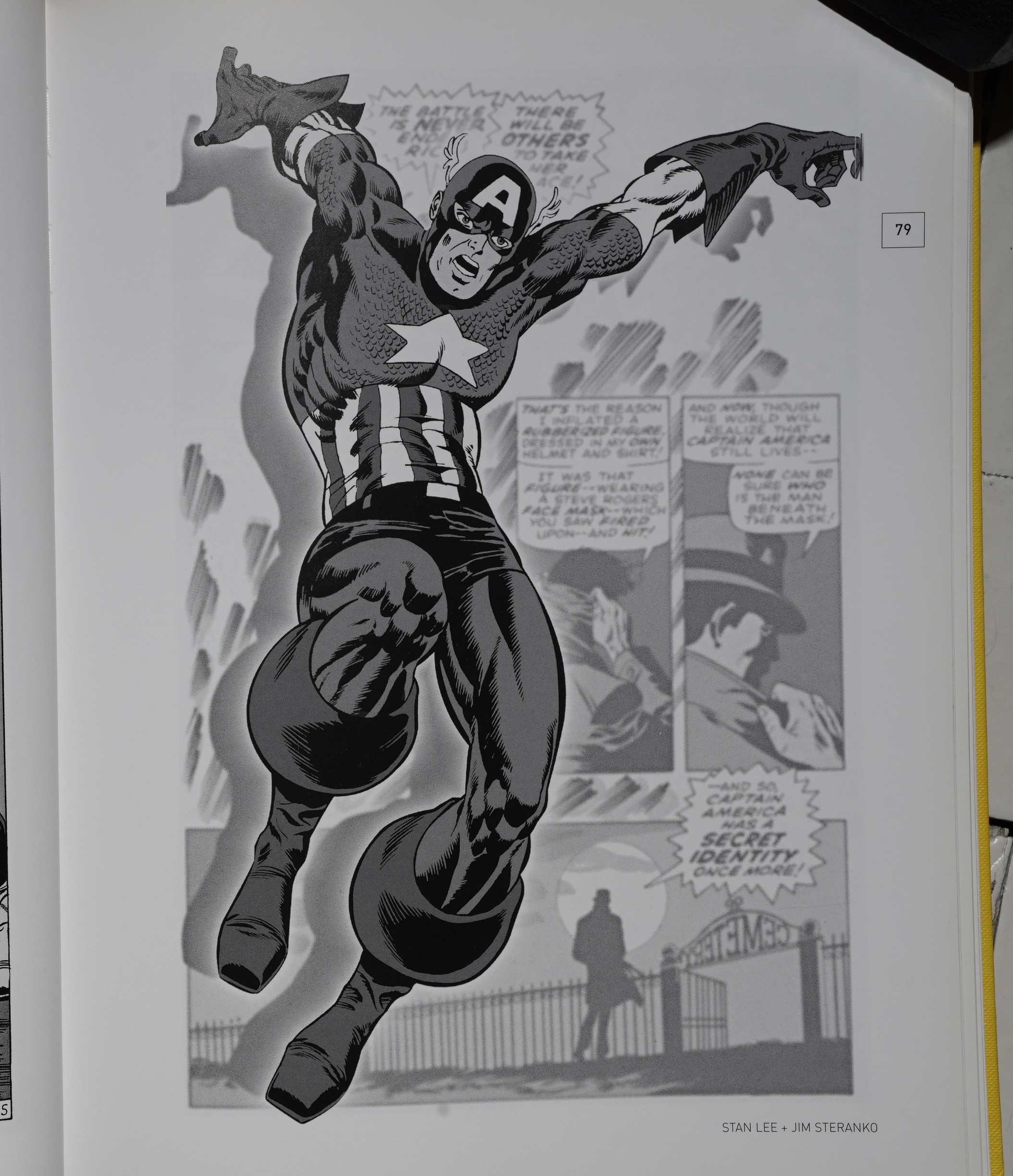

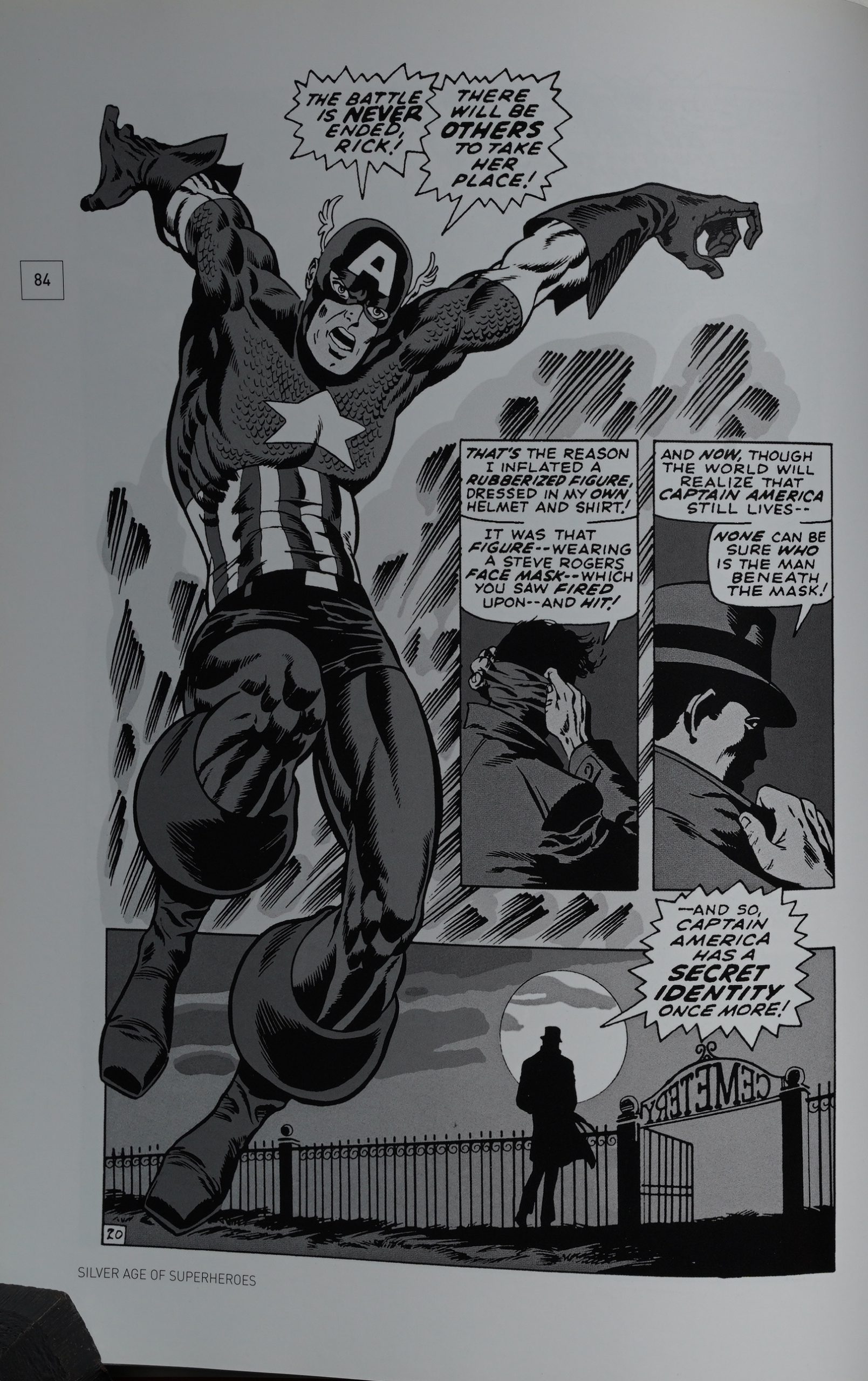

Then we go to the super-hero section, and we get three Stan Lee things, taking up more than 60 pages. First out is a Captain America story with artwork by Jim Steranko (and probably an inker? Callahan doesn’t mention the inkers on any of the super-hero stories anywhere). It’s a sappy story about Captain America faking his death and fighting the Nazi Hydra org.

I got very confused, because in the middle of the story, there was this page? Was it inserted to get the correct left/right-hand page thing going for the subsequent pages?

Then we get it again at the end of the story. I’m guessing this was meant to be this way, but it’s … weird.

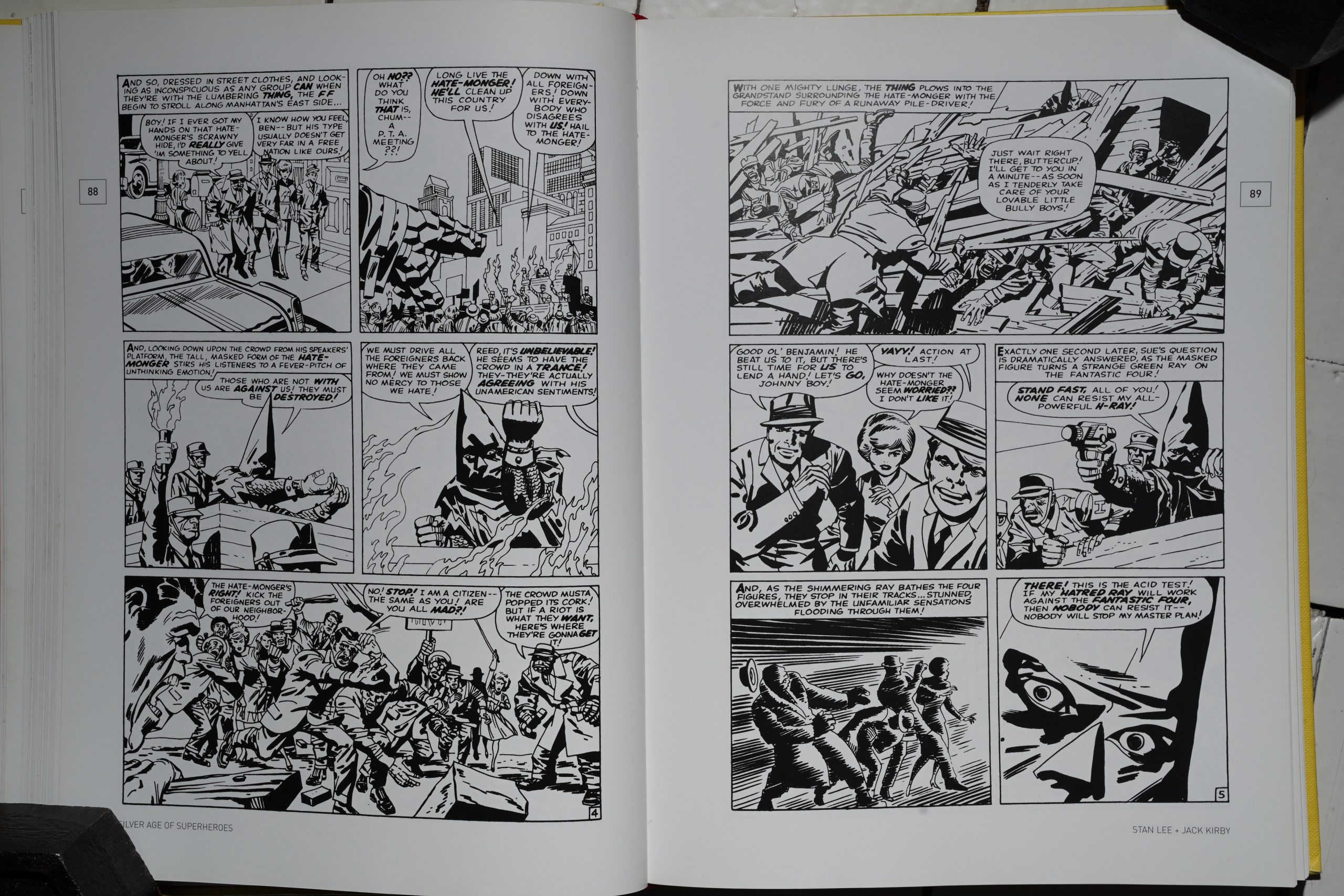

The third Lee story is the one where Spider-Man saves his aunt (by doing a blood transfusion), and it’s very soap-operaish. (When I say “Lee story” here I take it as read that the artists really created the story. At ease! No need to comment!) But we get this Fantastic Four story which has a lot of fighting indeed, and Kirby has them fight the Hate Monger (who is really Adolf Hitler (or a clone (oops spoilers))).

It’s, again, a very lop-sided view of super-heroes, but the selections aren’t bad? Callahan is definitely building some kind of narrative through his selections: Comics are all about auto-bio and fighting Nazis. Check!

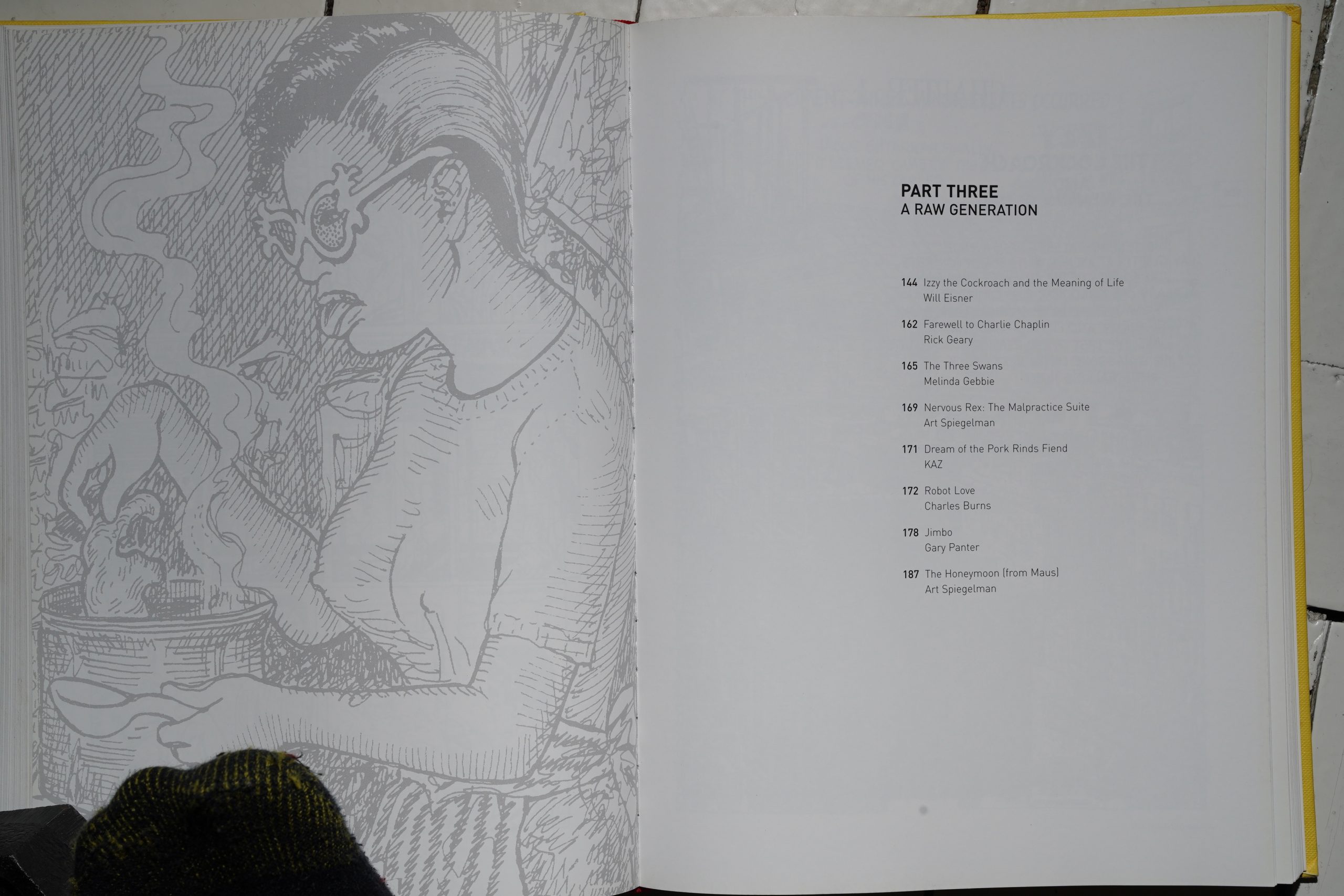

And here we come to the reason I’m doing this book in this blog series: “A Raw Generation”. In the New Comics book, he called the sorta-kinda equivalent section “Punk Comics”, but by 2004, it was getting pretty obvious that this kinda-sorta approach to comics had changed name.

And… the first artist here is…

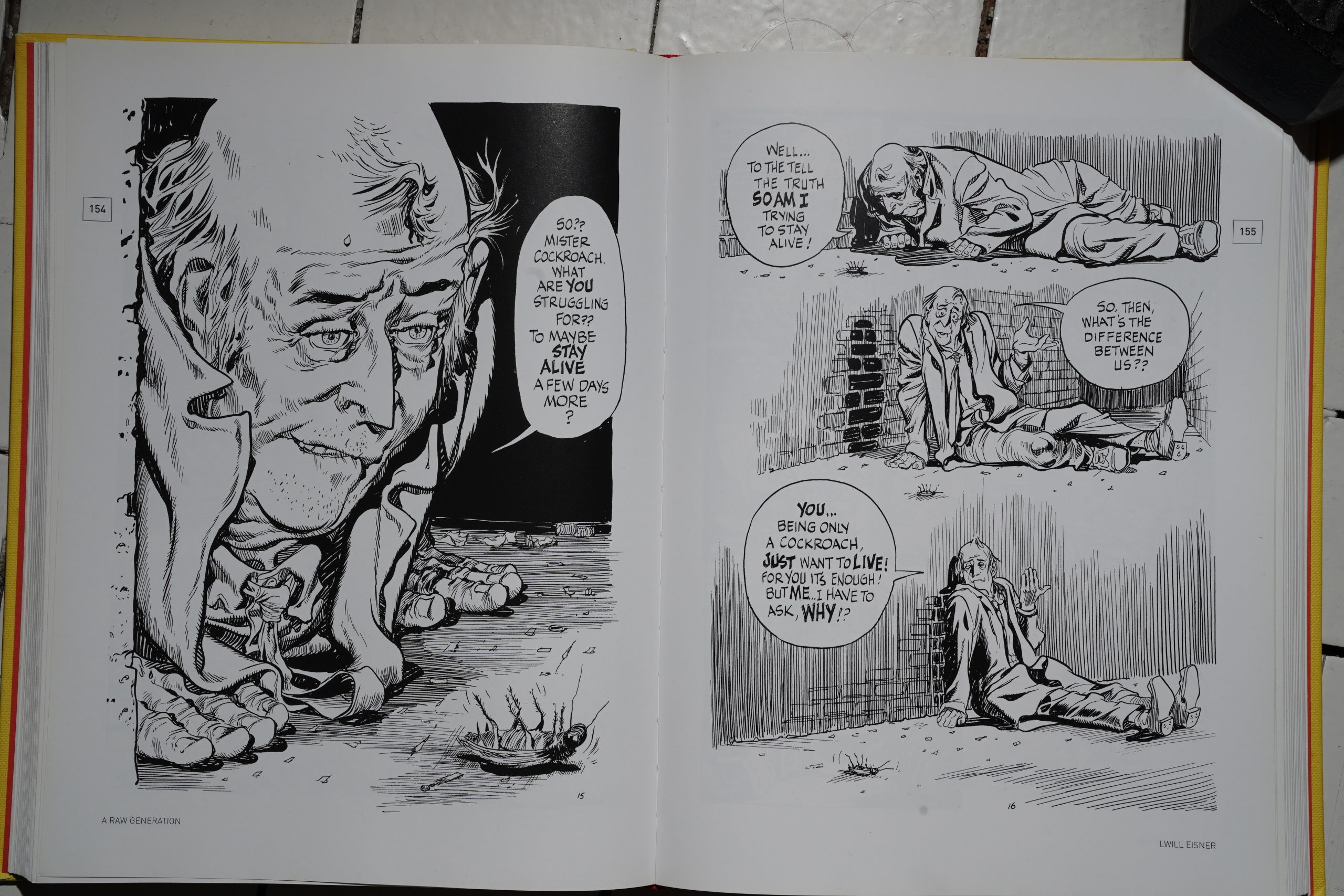

Will Eisner.

I think it’s one of the stories from Dropsie Avenue? Uhm…

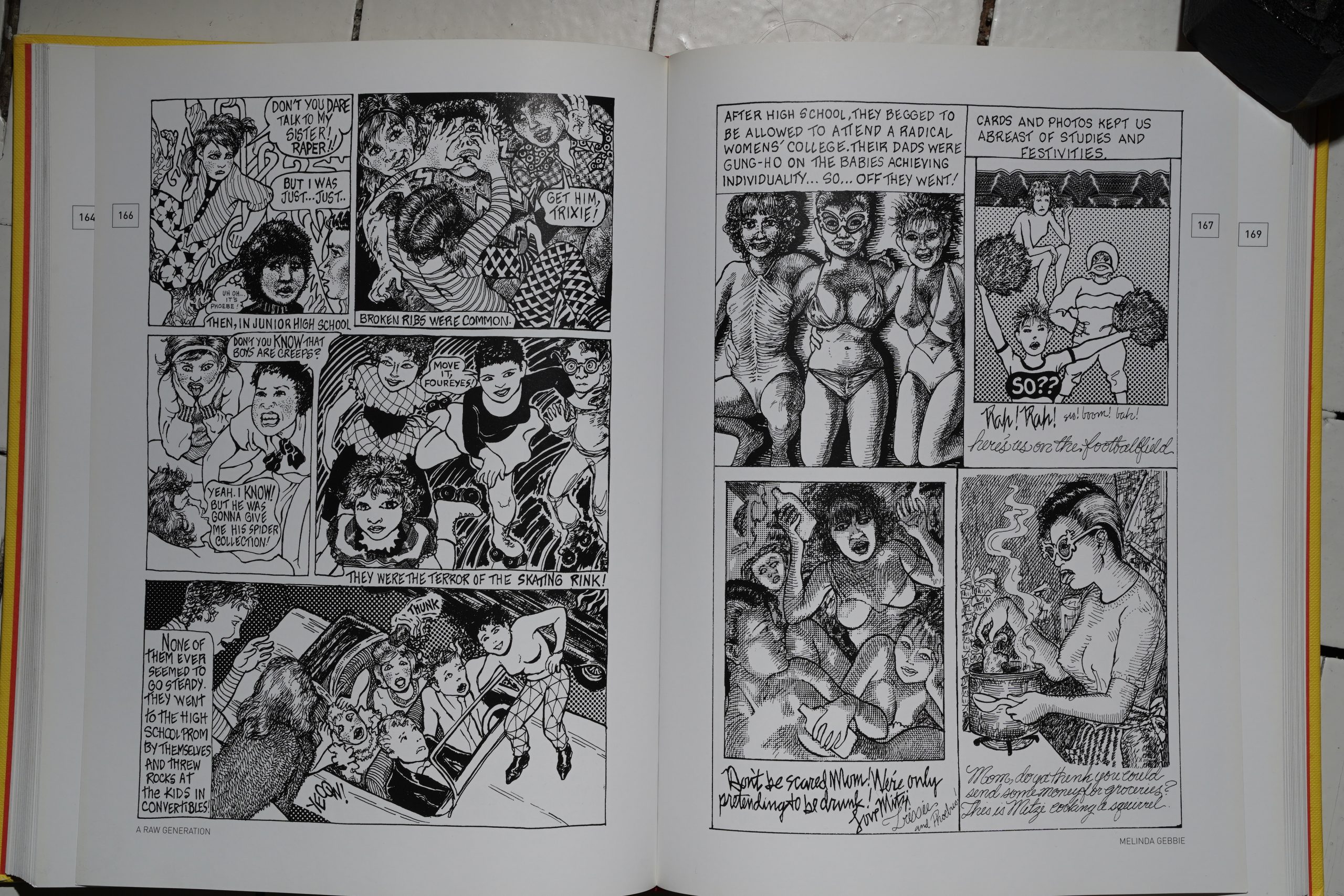

Hey, Melinda Gebbie! She’s awesome, and it’s a really smart choice, but is Callahan pointing to her as being part of the Raw Generation? She seems more like a second-wave Underground artist to me.

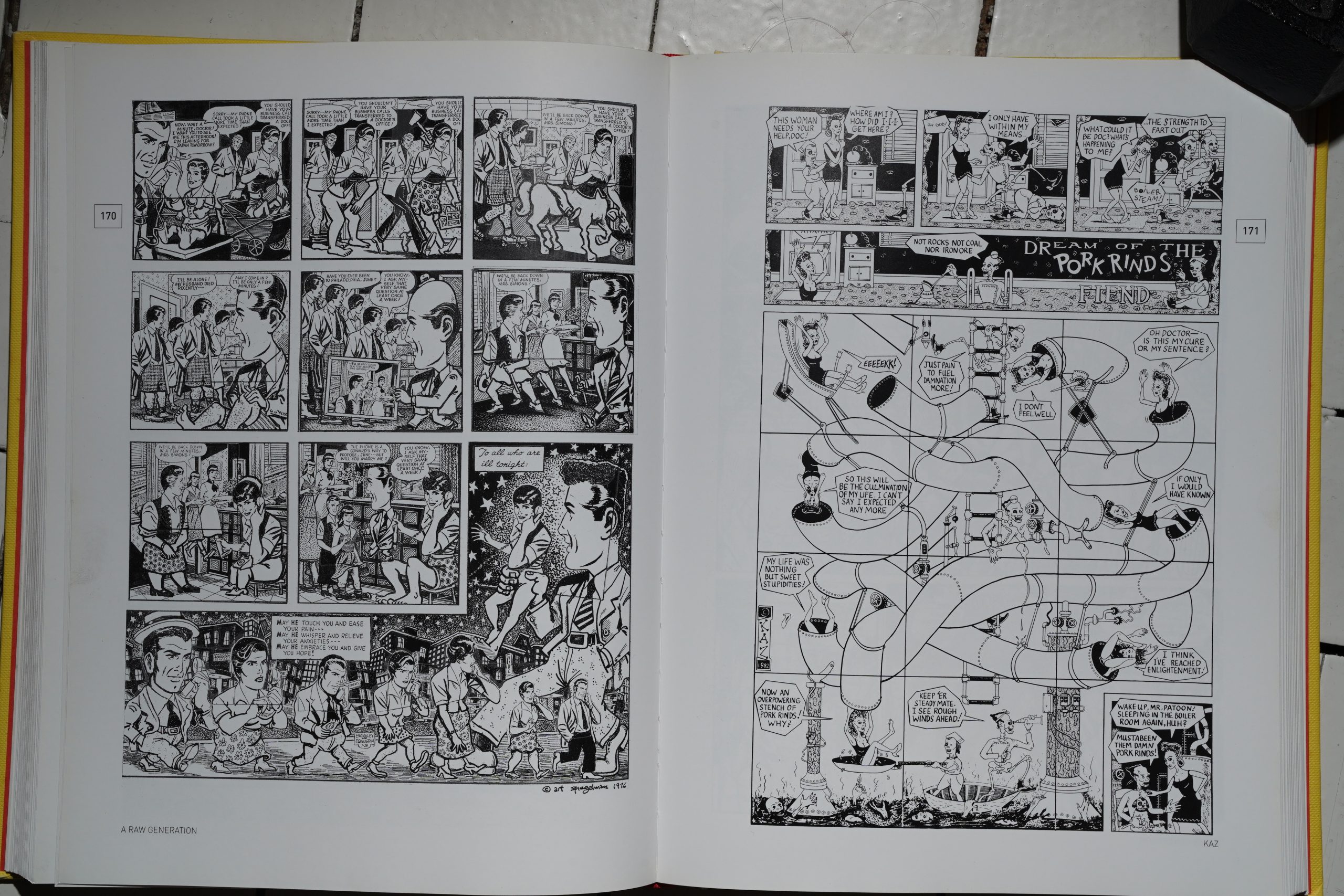

The pieces in this section are a lot shorter than in the other sections. In the New Comics book, Callahan had problems convincing the editors that it’s smart to put some avant garde stuff in the book (so that section was mostly single-page items), and perhaps that was the case here, too? We get, for instance, a badly reproduced Malpractice Suite from Spiegelman and a one-page thing from Kaz. Both are good choices, but…

An why not do the two-page Spiegelman strip as a spread?

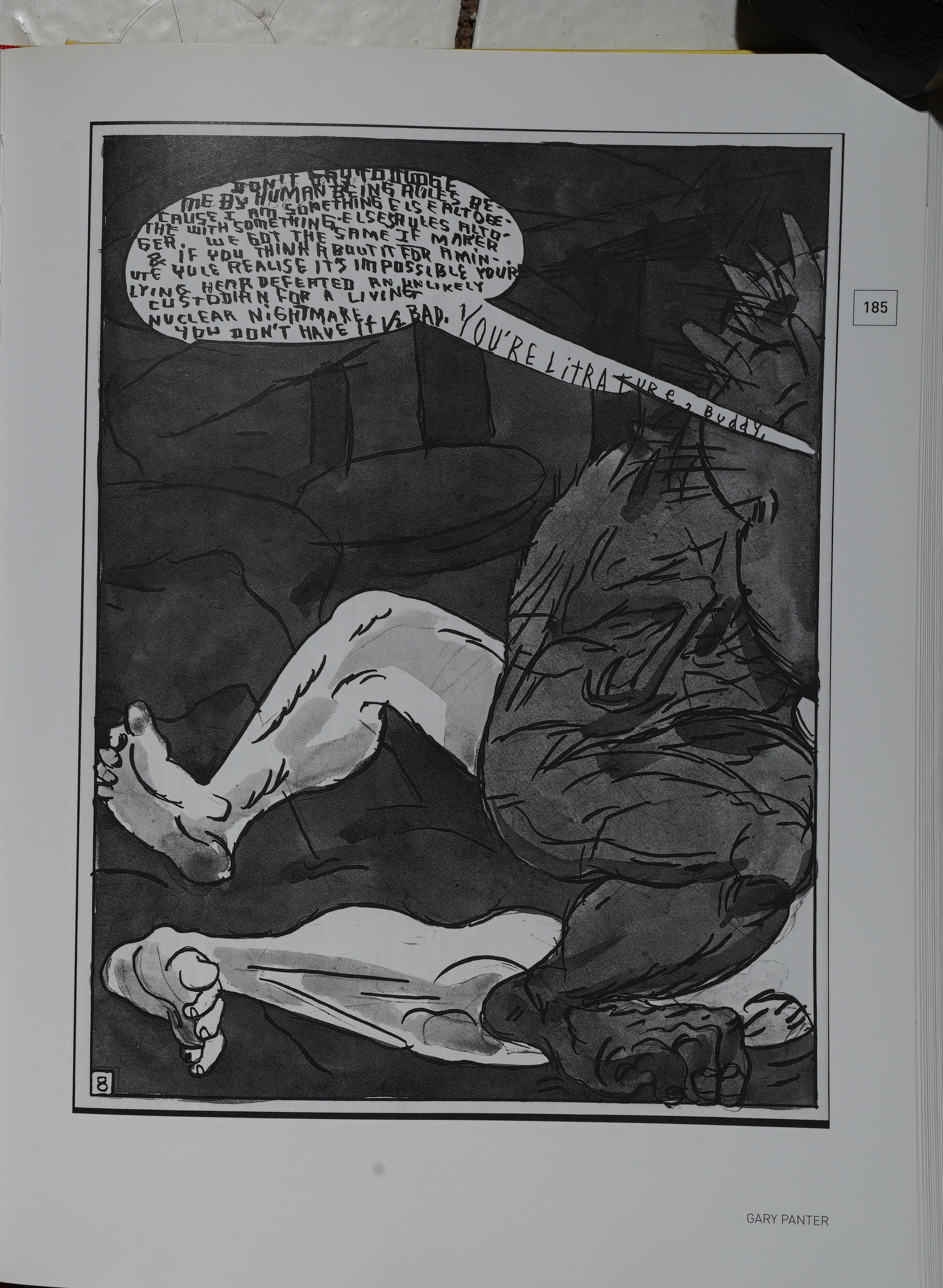

Callahan includes the final chapter of the original Jimbo sequence (by Gary Panter), and it’s a great choice: It’s absolutely awesome. But again — we get the two final pages as a right-hand-page…

… and then a left-hand page. It’s bizarre! Didn’t the people doing the layouts look at the comics at all?

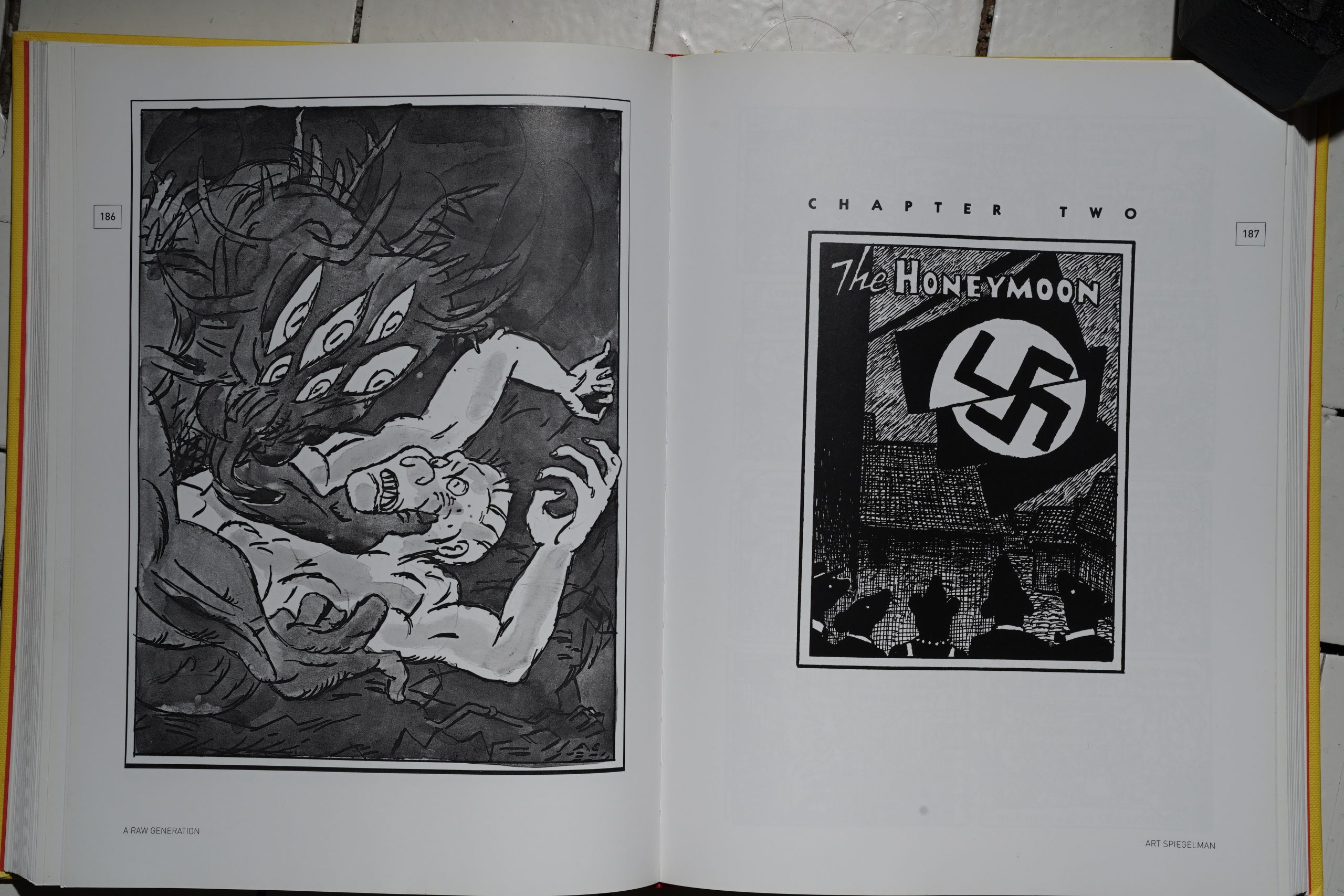

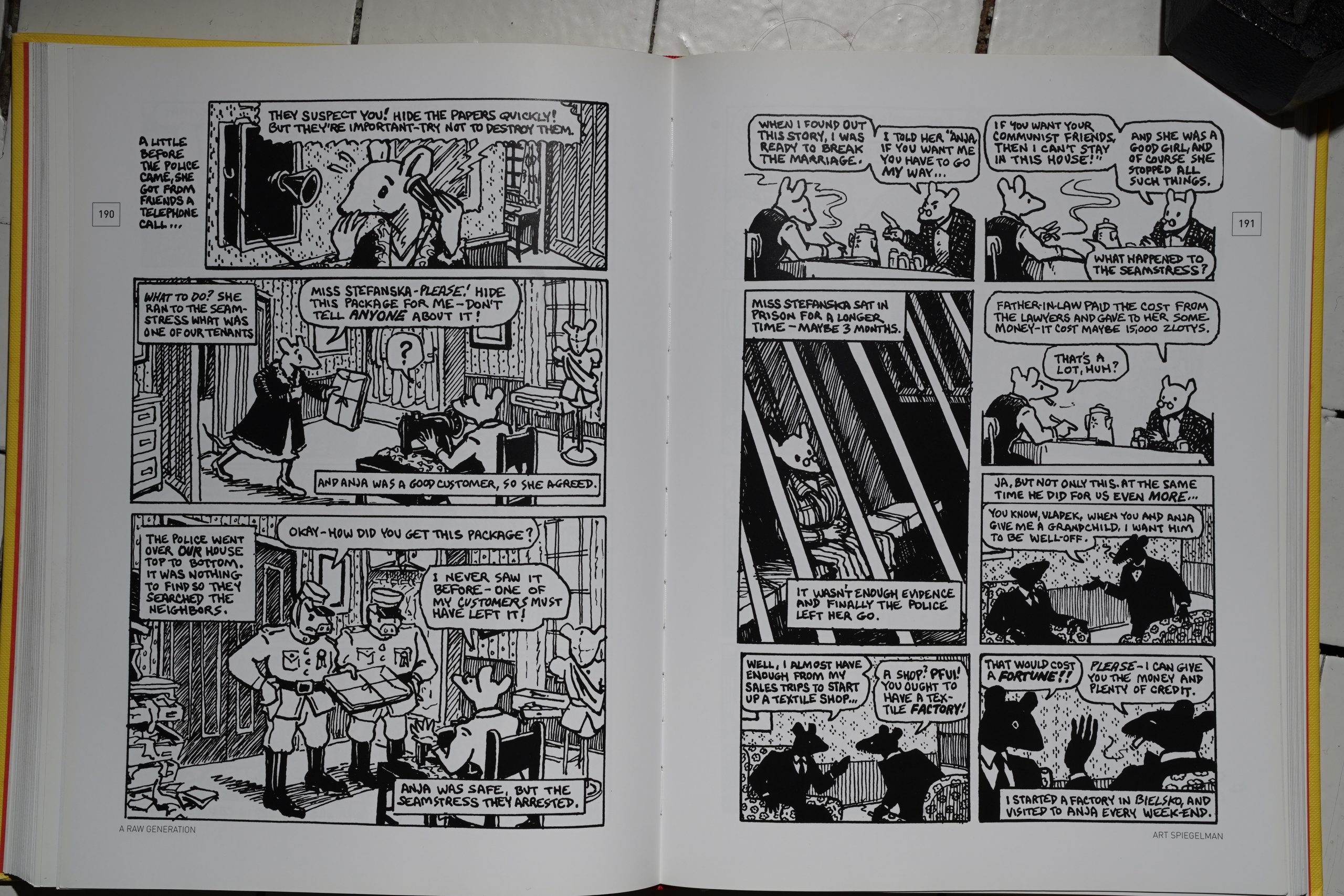

And speaking of weird — it’s jarring to see Maus printed this large.

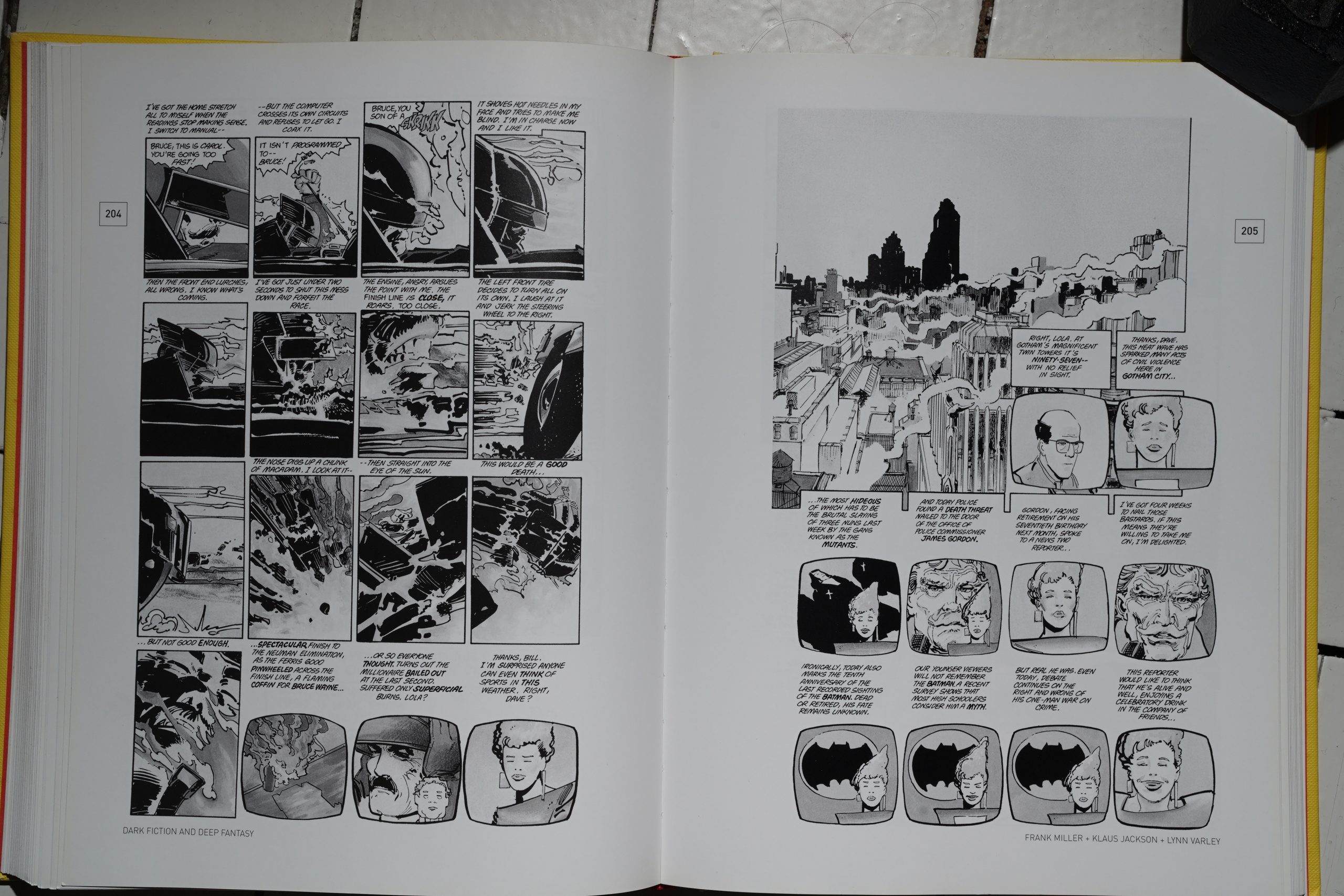

And… then we get more lengthy reprints of super-hero comics. But the “modern” ones (i.e., made 20 years before this book was made). So here’s Frank Miller (et al) with a Dark Knight excerpt…

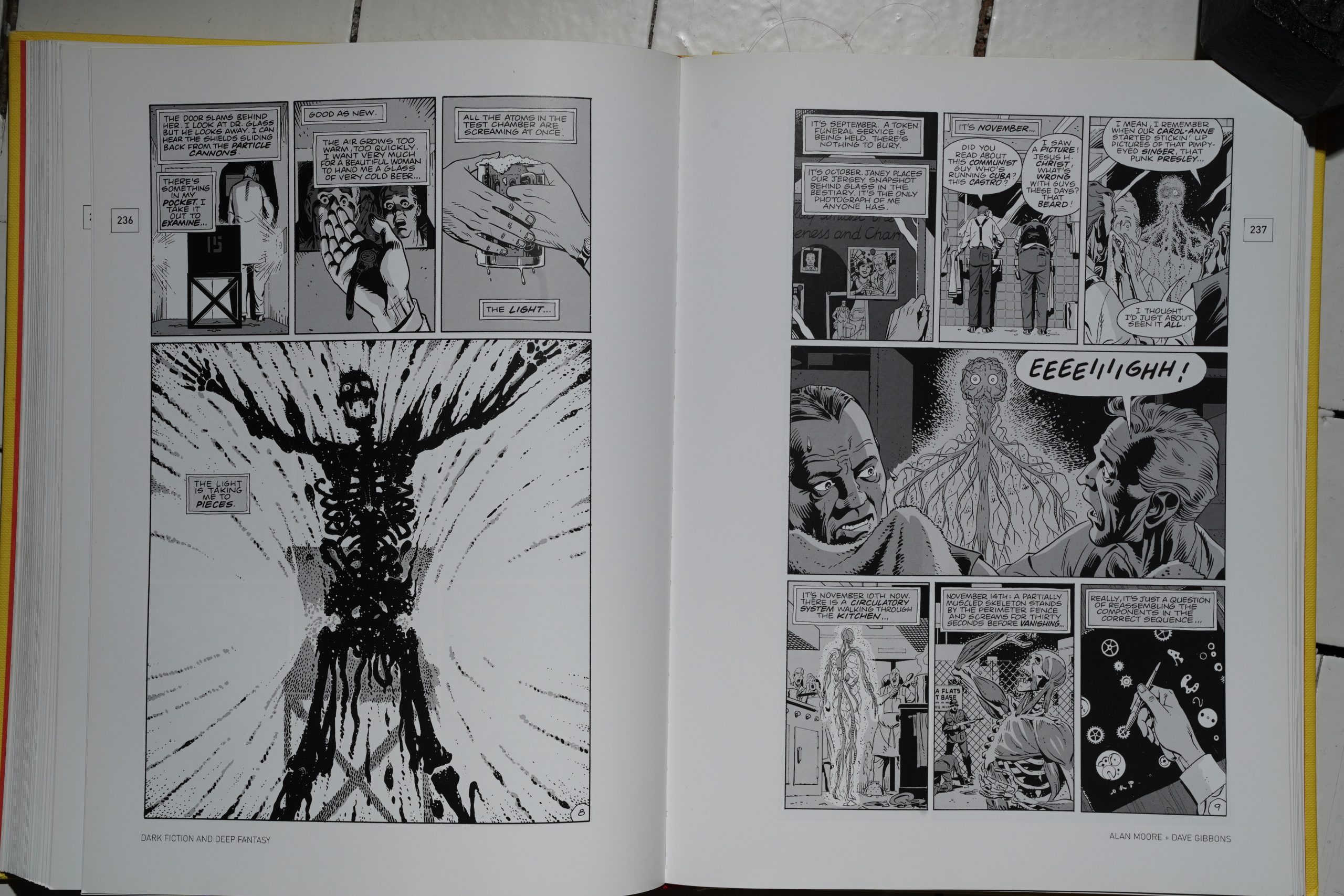

… and we get an entire issue of Watchmen? I mean, it’s a nice issue, but…

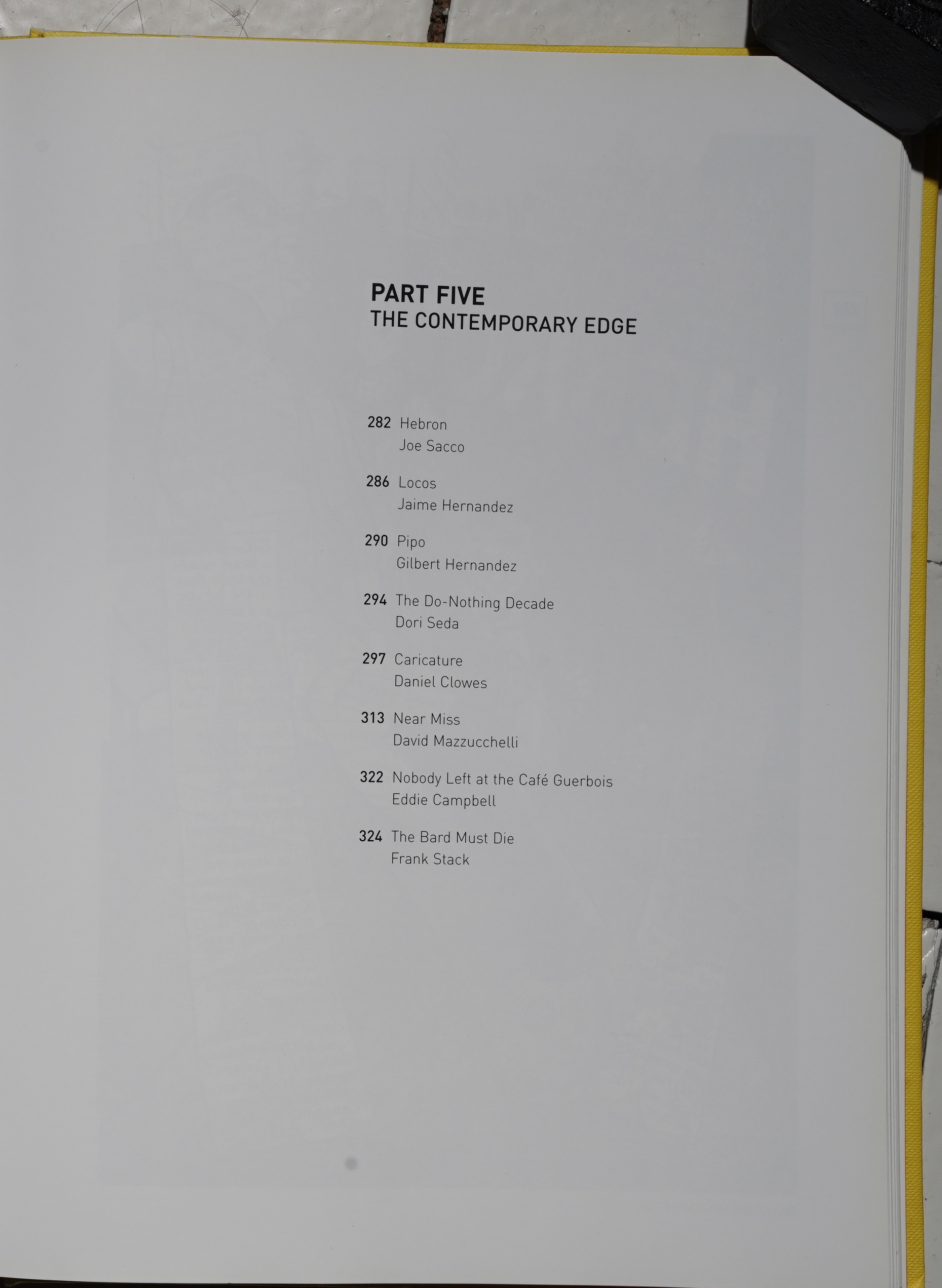

Finally, we get more… er… edgy? work. The Contemporary Edge.

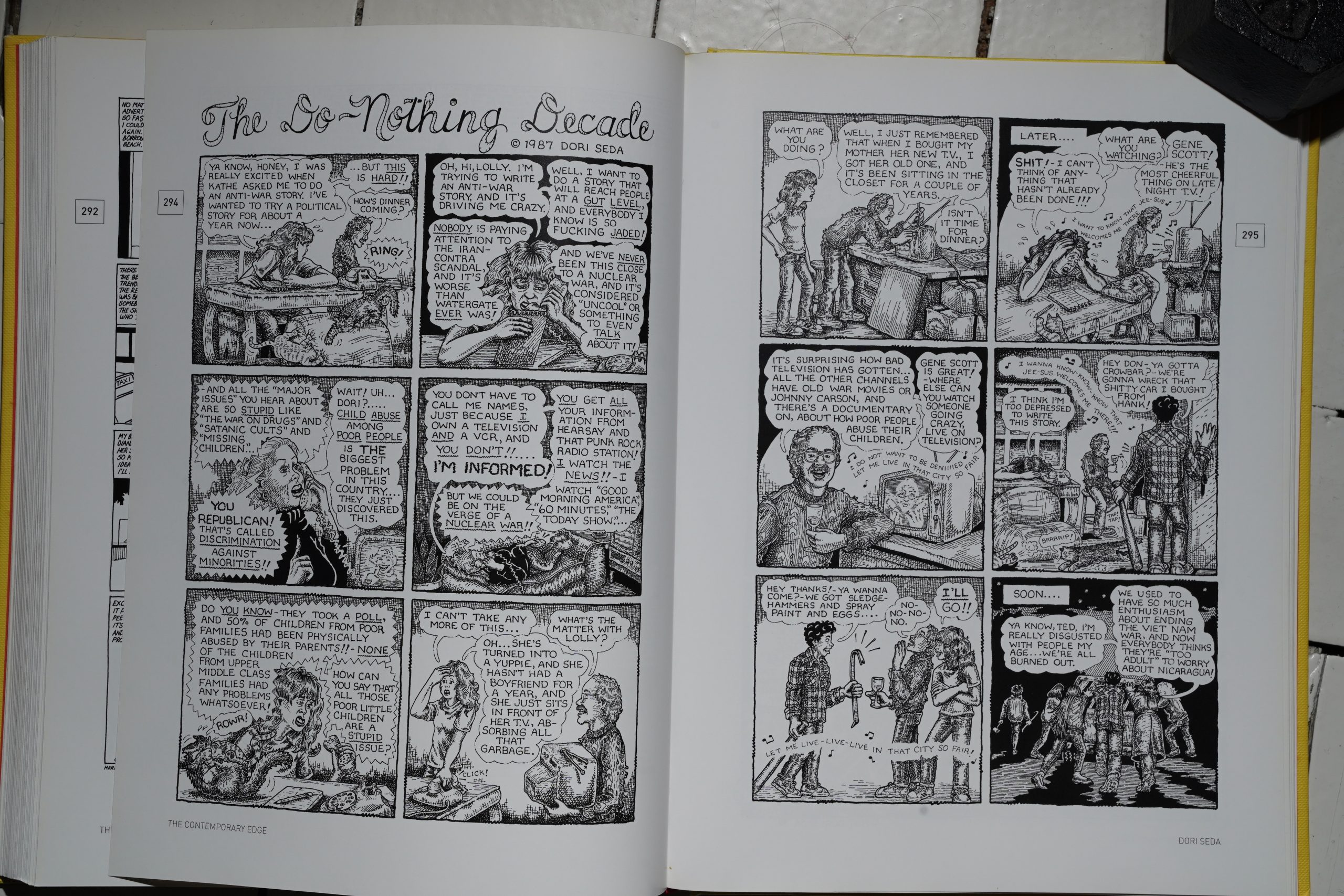

Which includes an almost 20 year old Dori Seda story. Again, it’s a great piece — I’ve said this a lot, but Callahan has good taste — but it feels like he’s given up on coherence.

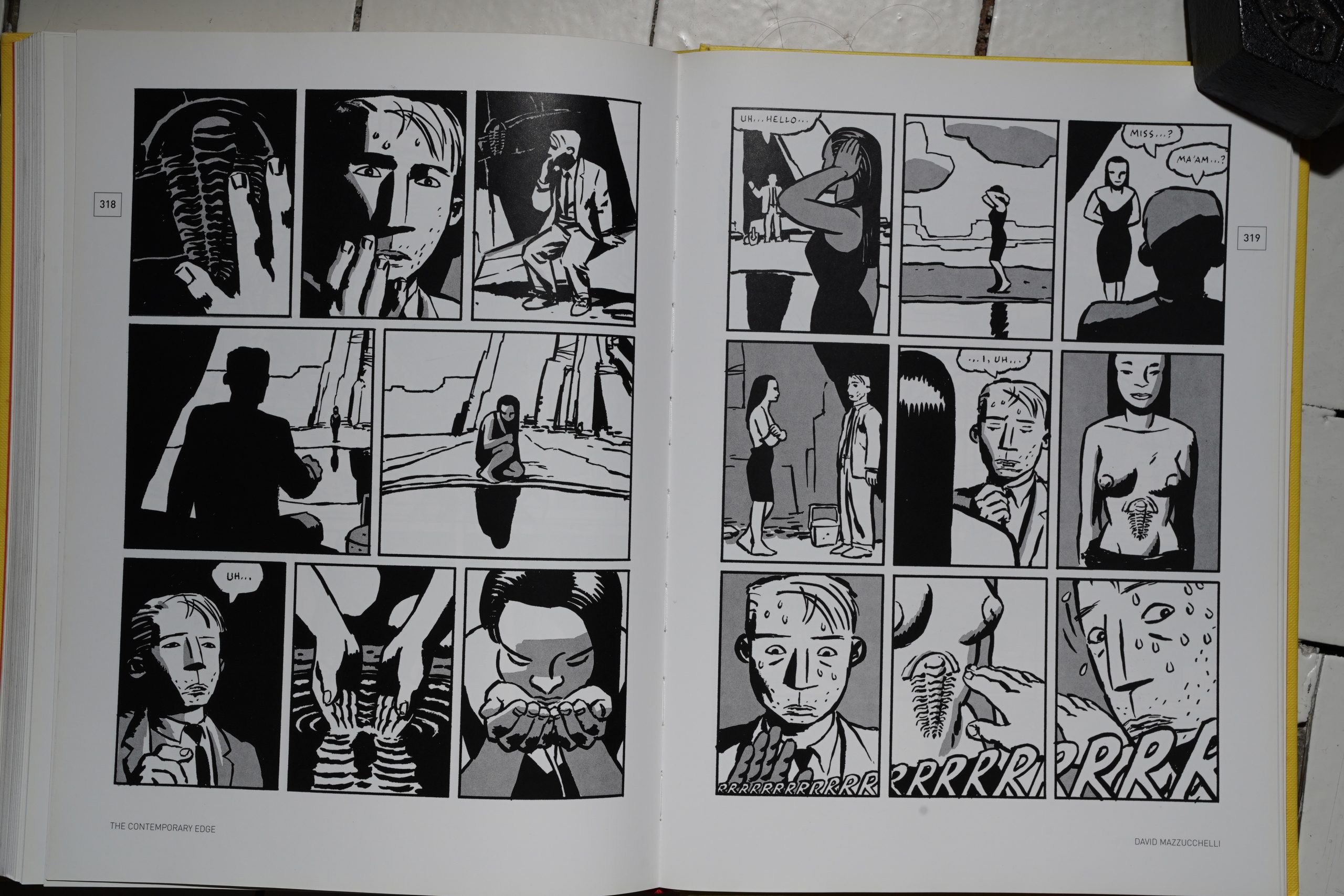

The David Mazzucchelli piece here is more like it. I mean, it’s from 1991.

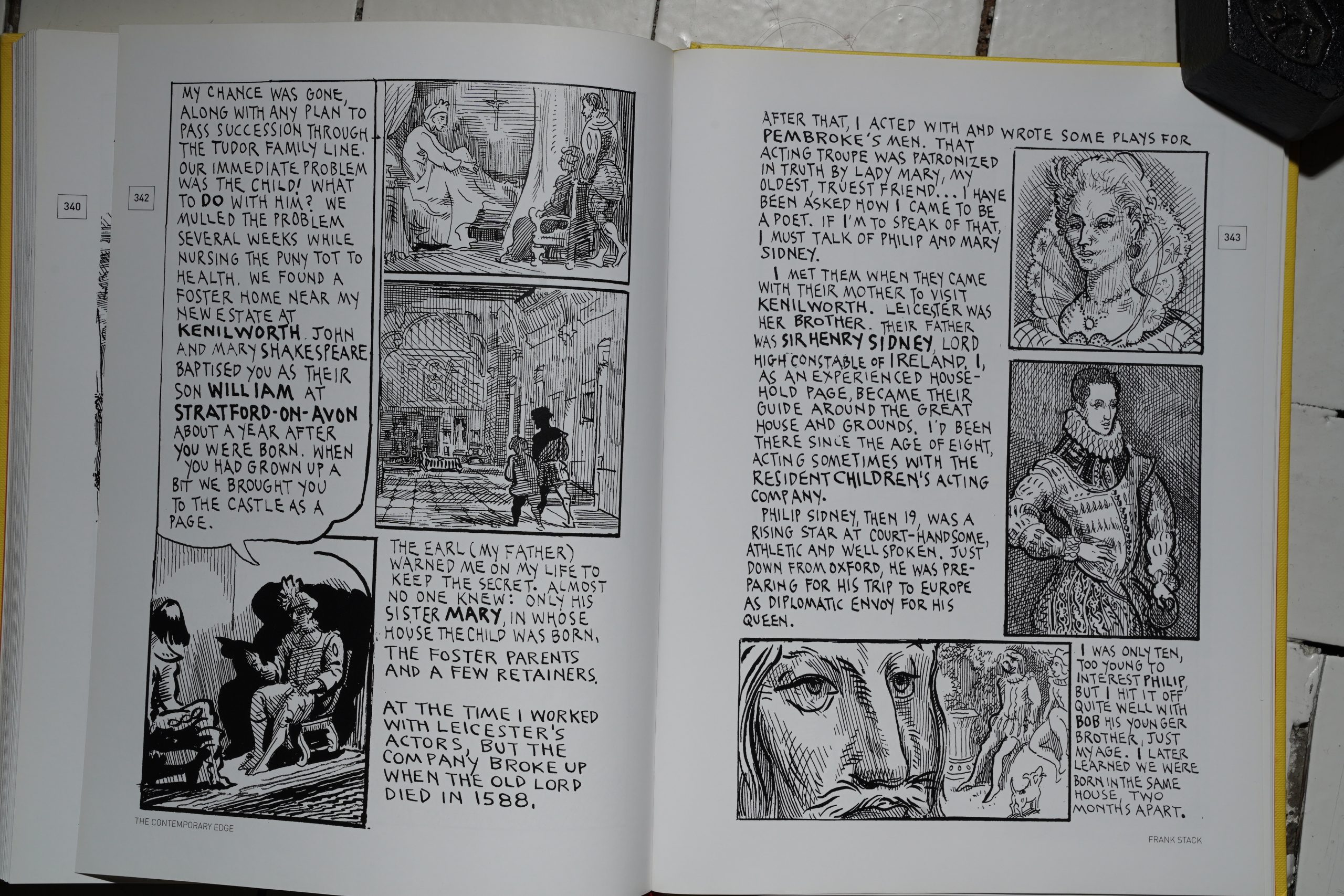

The most puzzling piece of all here is a 35 page story by Frank Stack. I love Stack’s work, but this basically sums up all the most moronic ideas about Shakespeare, and adds some illustration. It’s almost not a comic at all, and it’s totally tedious. (Did I mention that it’s also stupid? I did? OK.) I started wondering whether Stack was going to go “and if you believed anything of that, you should check yourself” at the end, but no.

And then… A Contemporary Feast? Eh?

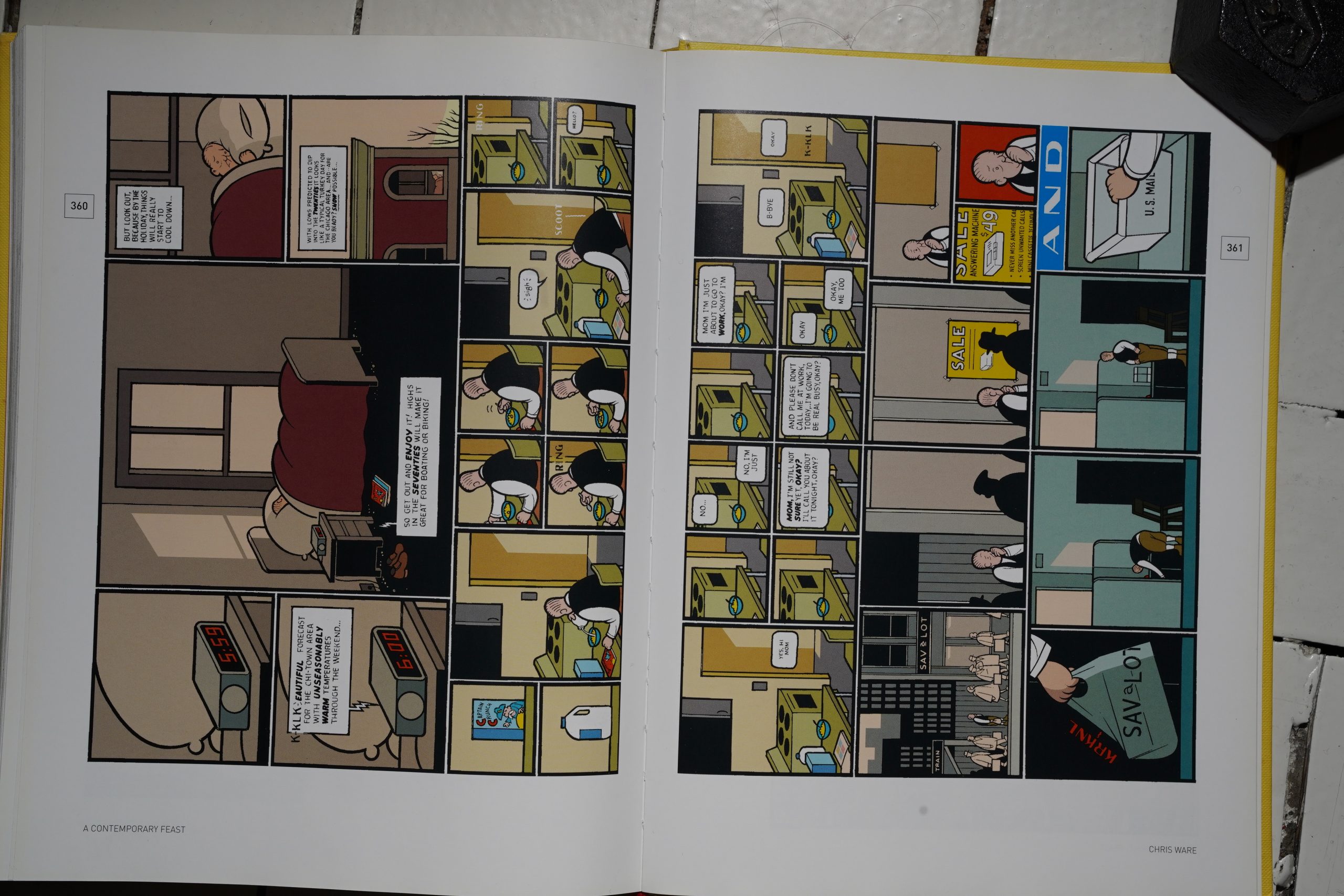

Oh, it’s the colour section. Well… OK. We start of with a pretty random selection of Chris Ware pages, but these have been selected by Ware himself, apparently? It’s an utterly baffling selection, which leaves me wondering whether they messed up somehow in production. (And printing stuff sideways in such a large and heavy book is less than amusing.)

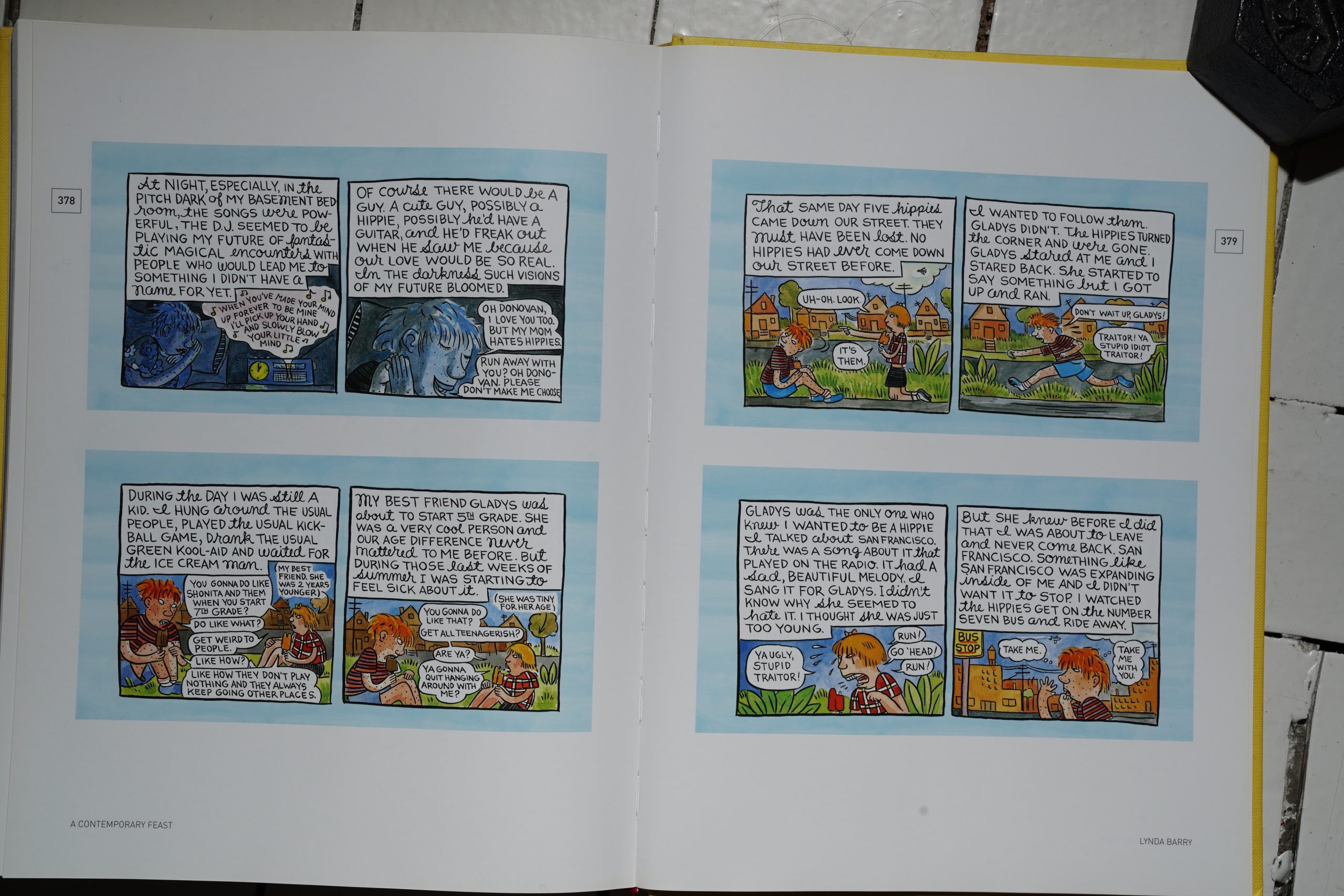

Lynda Barry, with some strips from One! Hundred! Demons!, which is cool.

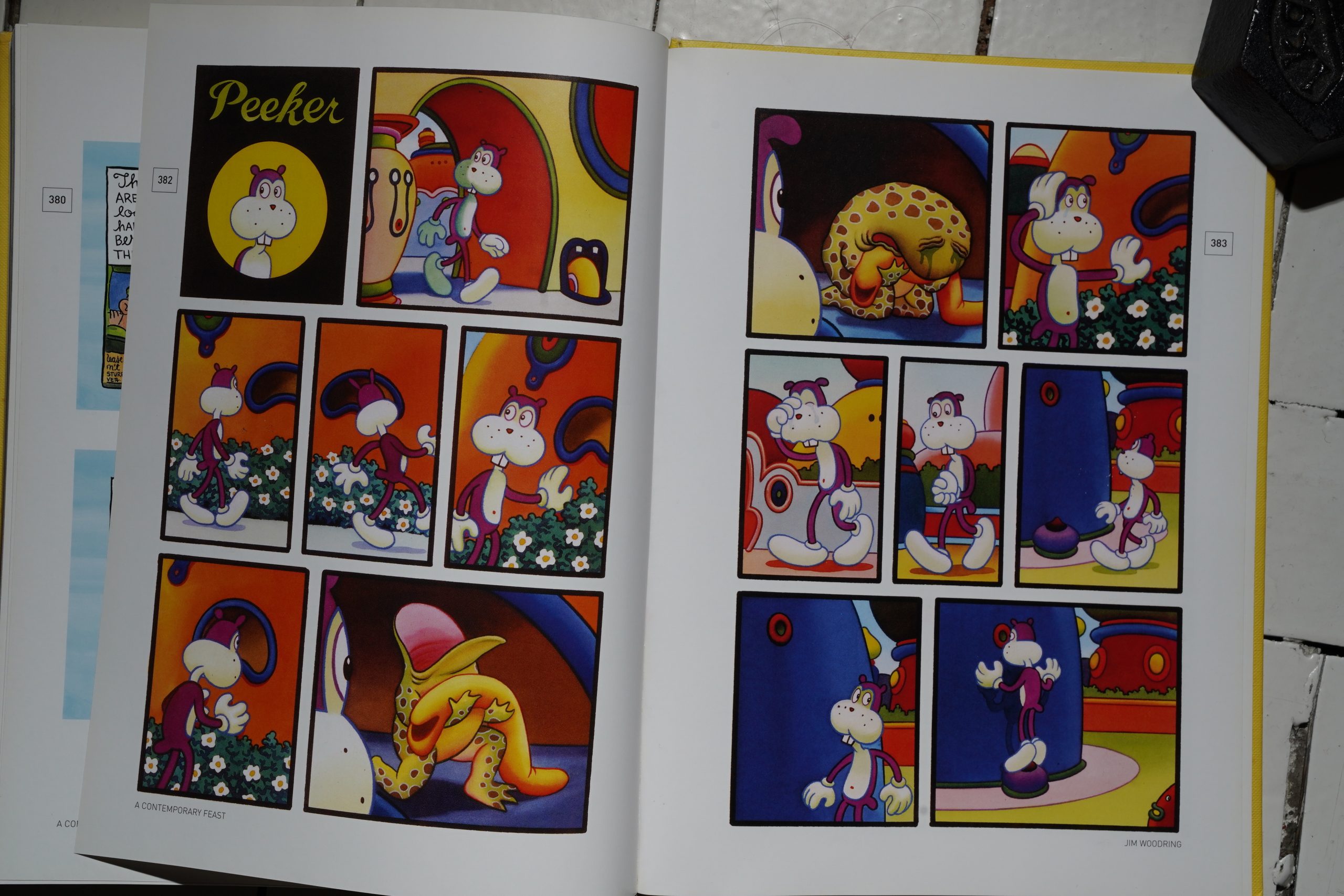

So is the Jim Woodring piece.

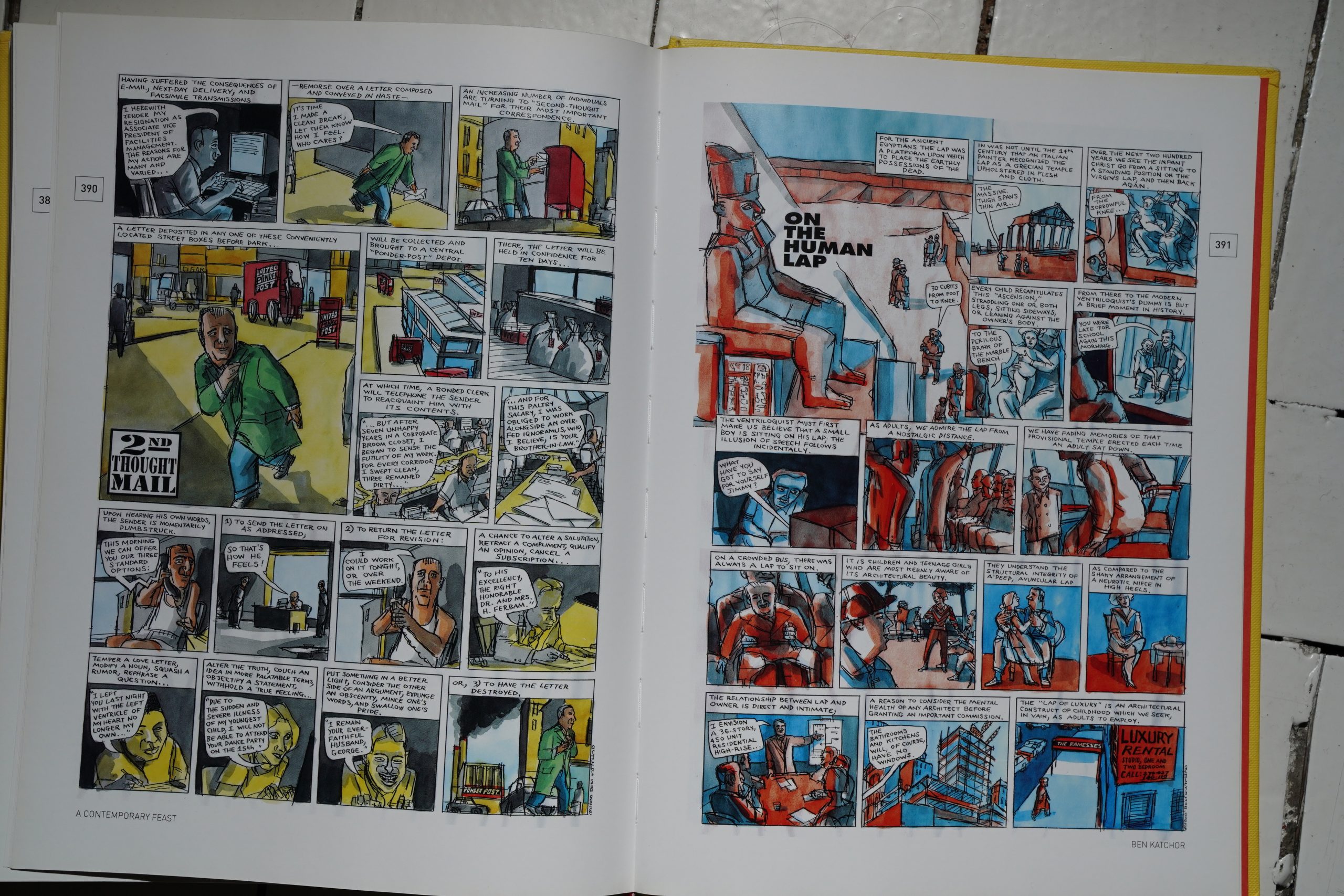

And… whoa… Ben Katchor? These are apparently pages from Metropolis magazine, and… I’m not sure I’ve read them before? The one of the left feels familiar, but I don’t think I’ve seen the one on the right? And such gorgeous colours! I had no idea! I mean, Katchor mostly works in grey washes, but I guess these are watercolours? Fabulous.

And that’s the book.

It’s a bit difficult to say who this book is for? I guess it’s a good overall introduction to comics — it’s a good mixture of stuff, with shorter and longer pieces: it reads well. It just feels a bit under cooked, like a bit more work could have gone into the selection of pieces, the sequencing, and the production work.

Mark Campos writes in The Comics Journal #267, page 51:

The Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book

Comics, 24 years after its publication,

still throws a long shadow. Before it, there

were dozens of books that promised 10 tell

the history Of comics, but most were either

stuffed with camp (the Batman TV show

still exerts its lunar pull to this day) or were

held together carelessly, With slack schol-

arship and crappy art reproduction. The

Smithsonian book’s editors, Michael Barrier

and Martin Williams, conducted themselves

With dignity, writing lucid historical essays

and selecting top-rate examples of the com-

ics art form. Between its pages were some

of the first rediscoveries of then-forgotten

old masters Will Eisner, Jack Cole and Shel-

don Moldoff; until recently, it was the Only

Widely available sampling Of the dada glories

of George Carlson’s “Pie-Faced Prince of

Pretzelburg.” Its presence in the of

almost every library in the United States

gave thousands of kids their first taste of the

glories Of comics’ Golden Age.

[…]A follovFup to the Smithsonian book

seemed like a good idea. Crumb is in The

New Yorker, Ware is in the Whitney, Speigel-

man Wins a Pulitzer, Spider-Man is Tobey

Maguire — it’s time to recap what happened

there, right? When plans to publish The New

Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Comics, to

be edited by Bob Callahan, were announced,

fans and readers anticipated another deeply

satisfying collection Of stories and history,

like the first book. It’s probable that even the

best effort would have a hard time following

that classy first volume. Hank Williams Jr. is

great, but

people still

compare him un-

favorably to his Old

man. (In the song “Liv-

ing proof”, Hank Jr. sang:

Why just the other night after the

show an Old drunk came up to me / He says

you ain’t as good as your daddy, boy, and

you never Will be.”) Even without comparing

to its predecessor. though, The New Smith-

sonian Book Book Comics (l call it

Smithsonian Jr.) would be disappointing.

First off, there are

serious production flaws

with this volume. The last page of Gil-

bert Shelton’s “The Death of Fat Freddy”

story is missing, replaced with a repeat of

the second page. There is a mysterious page

in the middle of “The Death of Captain

America,” which is a later page reprinted but

blurred weirdly — it’s a space-saver page

from an earlier reprint, originally used to

keep the spreads in sequence (but its inclu-

Sion throws them out of whack here). Two

pages of “Caricature” by Dan Clowes

are printed Out of sequence, exception-

ally galling since the art has page

numbers written at the bottom.[…]

Is this book a history? A hagiography?

Choices veer between historically important

and personally representative. The Crumb

Story isn’t from his innovative period, it’s a

Weirdo-era piece, though it deals with the

•60s era. If the goal is to Show how influ-

ential Crumb has been, Why not use a page

or two Of the influential work? As often as

they’ve been reprinted, as familiar as the

characters are, and as obvious a choice it

might have seemed, perhaps one Of his well-

loved Zap stories might have been a better

selection. Anything before Fritz the Cat had

his meeting With the fatal icepick Would

suffice. My choice would have been the

“Cheesus K. Rcist” Story from Zap #1 —

the

perfect cocktail of bigfoot Americans, danc-

ing ketchup bottles, and metaphysics, the

Story that launched a thousand ripoff Com-

mercial designs. And yet “The Death Of Fat

Freddy” strikes me as the perfect representa-

tion Of Gilbert Shelton’s comedic brilliance,

which was always Offset in the best way by

Paul Mavrides’ art. Mavrides perfectly Cap-

tured the way gentle San Francisco had, by

1978, become dangerous and reptilian, and

the sight Of Shelton’s amiable Freaks Wan-

dering those mean streets always made me

chuckle. Shame the last page is missing.[…]

The Silver Age superhero stories are

by Lee/Ditko, Lee/ Kirby, Lee/Steranko, and

Kanigher/Kubert. Fuzzy black-and-white

reproduction nearly ruins the Spider-Man

and Fantastic Four stories here, but even

thick lettering and furry outlines can’t ne-

gate the primal power of Ditko’s character

design, or dim the wackiness of Kirby’s

baroque machines and faces. The Fantastic

Four story contains my new favorite single

panel: “Hey, What’s With the mad scientist

bit?” “I’m just shutting down some nuclear

activators so I can hear you better.” The

Captain America Story looks less innovative

than it must’ve, once; half the Enemy Ace

tale could have been left on the cutting room

floor, but it seems more influential than it

probably — wasn’t making a sympa-

thetic character out of an enemy combatant

against the Code? Speaking of the Code: As

regards the mainstream we go straight from

Code-era to post-Code without making any

stops, and it’s unclear what historical forces

led to those changes. More background info

here, please.

There are only three women repre-

sented: Dori Seda, Carol Tyler, and Melinda

Gebbie. At least one web commentator has

speculated that the only reason Melinda

is included is because she’s partnered with

Alan Moore. That’s hard cheese — her work

was out and around long before she hooked

up with Moore — but if we’re picking to-

kens, why her instead ofTrina Robbins or

Shari Flenniken or Roberta Gregory or Aline

Kominski-Crumb or Julie Doucet or Megan

Kelso? The Carol Tyler Story is nice, and

appreciate that Callahan didn’t select “The

Hannah Story,” which would have looked

awful if the lavish and emotional colors had

been changed to grey tones. Seda’s Story is

uncharacteristically free Of dog-fucking, and

Will shock nobody, so is not really represen-

tative Of her best work.

“Uncharacteristic” describes many Of

the selections found in the later part Of the

book. A chapter Of is a fine excerpt

from that work, and “Caricature” is one Of

the strongest Clowes stories there are (shame

about the pages being scrambled); but both

Hernandez brothers are represented by weak

choices. I’m guessing that Callahan saw this

as an opportunity to entice new readers into

the Hernandez’s mythos, since both the Jai-

me and Beto stories mention but don’t really

show their major characters, quietly asking

“Don’t they seem interesting? Wouldn’t you

like to learn more about them The Beto

Story is less than successful at that: Four

pages Of yattering about Luba and

Khamo and Gato and Carmen is too insular

to intrigue a newbie.[…]

As for the Bard, Frank Stack’s “Shake-

speare Must Die!” is a gabfest Of incredible

proportions. The pages turn to text blocks

as the chatter builds up — not that it’s un-

interesting. And just When you’re ready to

give up on the verbiage and go ogle the girl

in the Chris Ware Story again, Stack throws

in a couple panels Of his accomplished figure

study work, which will keep this book off

the Wal-Mart shelves for sure now (except

that the W M good-taste police Will crap out

on the Story after page two).[…]

That’s a serious amount of omission.

You can’t really tell the story of mod-

ern comics without mentioning how the fan

press, which gave the underground its first

and best, mutated into the small-press scene

— and continues to introduce new talents to

the comics world. You have to mention the

black-and-white boom, the Teenage Mutant

Ninja Turtles and their imitators, and once

there you might as well go into the Tundra

debacle. The success Of the Turtles enabled

the Xeric Foundation to fund a load of bril-

Kant work by new creators (and some dross,

true). And there’s direct causality between

the Turtles’ and the Pokemon merchandis-

ing phenomena, Which greased the skids for

the manga boom in the United States. Then

there’s the French influence (Moebius, Tin-

tin, et al); the Canadian renaissance (Sim,

Seth, Chester Brown, Julie Doucet); the Jap-

anese (Tezuka, Rumiko Takashi, CLAMP);

the gay and lesbian creators (Howard Cruse,

Alison Bechdel), the New Zealanders .

See? In the end, one winds up making

lists of the omissions in this book. Maybe

it isn’t supposed to be a strict history of

modern comics, but as an overview, it’s shal-

low — McSweeney’s #13 beats this volume

all hollow. Odd selection, shaky scholar-

ship, bad printing, low budget: The New

Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Comics is

a fumbled opportunity. You ain’t as good

as your daddy, boy, and you never Will be.

I think he didn’t like it.

Callahan purports to cover the scope of comics from the last 40 or so years, but leaves out hugely influential figures in contemporary comics, including Mark Beyer, Aline Kominsky, Julie Doucet, Phoebe Gloeckner (there’s a severe dearth of female cartoonists), Howard Chaykin, Chester Brown, Todd McFarlane, S. Clay Wilson, Dave Sim and many, many others. Instead, there are minor works by minor cartoonists like Rick Geary, Melinda Gebbie and Frank Stack, and jumbled or inconsequential work from great cartoonists like Gilbert Hernandez, Kaz, Joe Sacco, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko. Neither a definitive anthology nor a helpful resource, this is a haphazard grab bag of some good comics, numerous dubious achievements and some downright mysteries.

This blog post is part of the Punk Comix series.