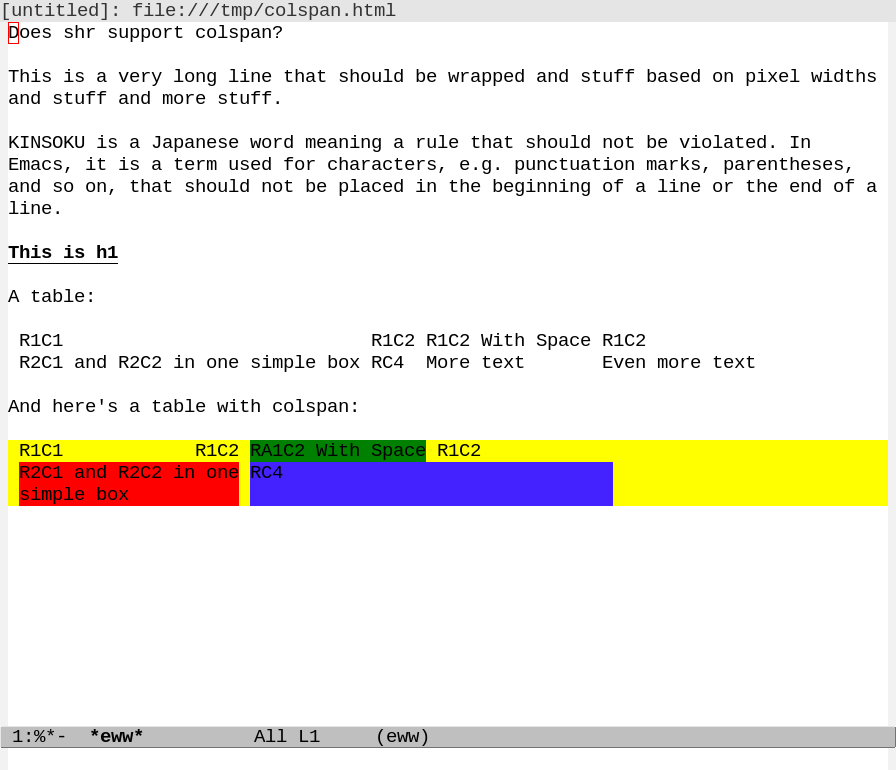

After some help from Eli, I now have a proof of concept of rendering HTML with proportional fonts in Emacs. The main difficulty is, of course, doing line folding on a pixel basis instead of a word basis, and lining stuff up in tables.

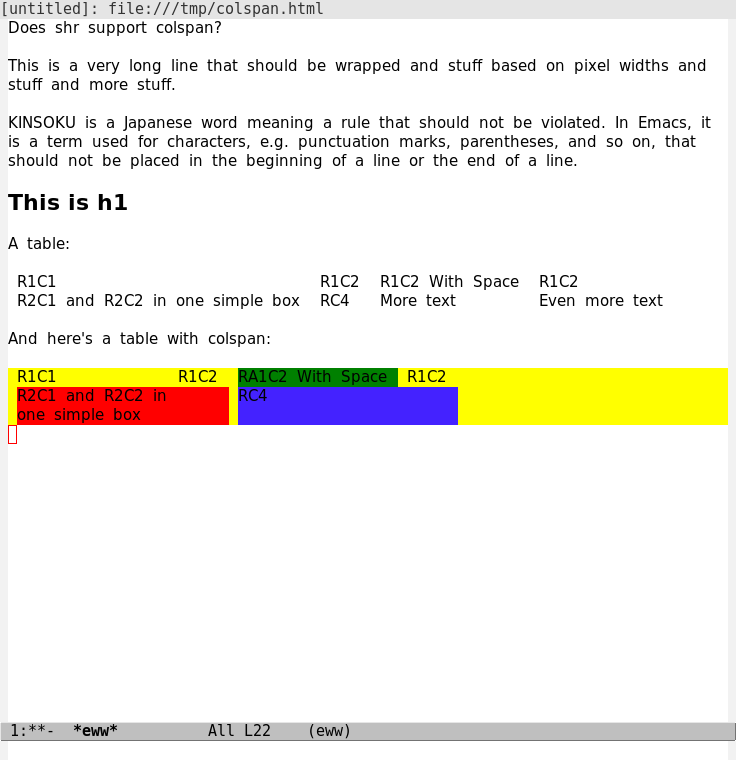

Here’s how my test page looked before these changes:

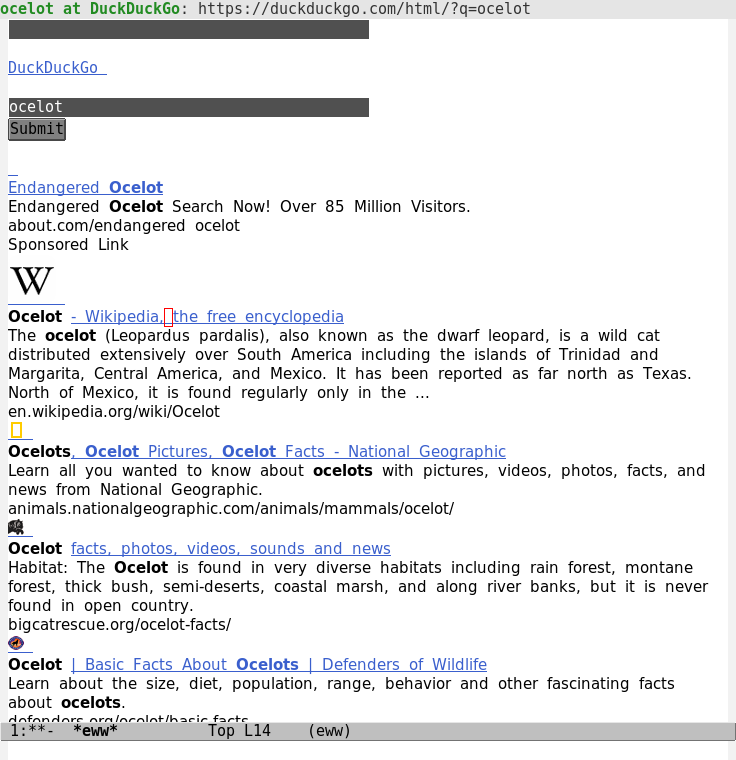

And now with a variable-width font:

And now with a variable-width font:

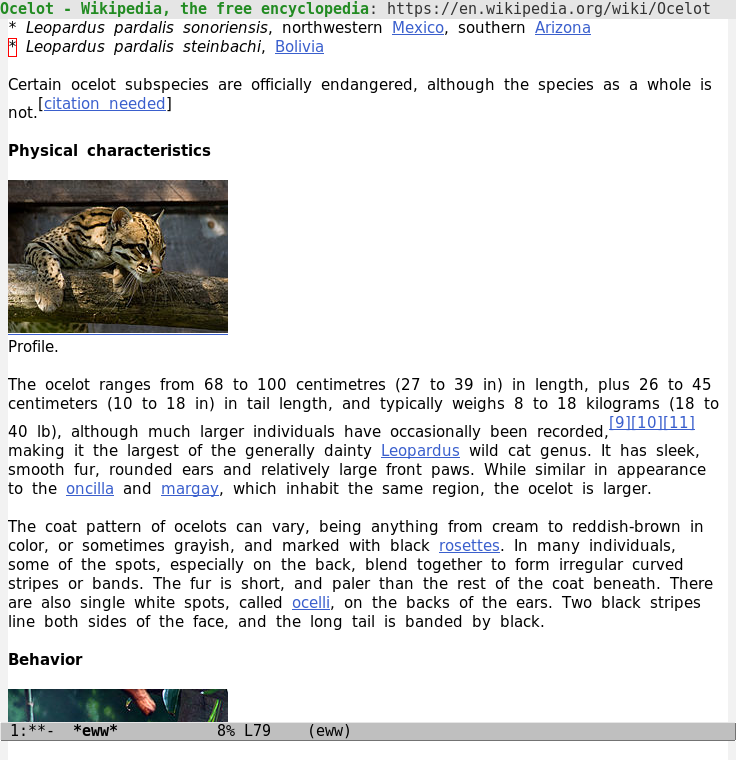

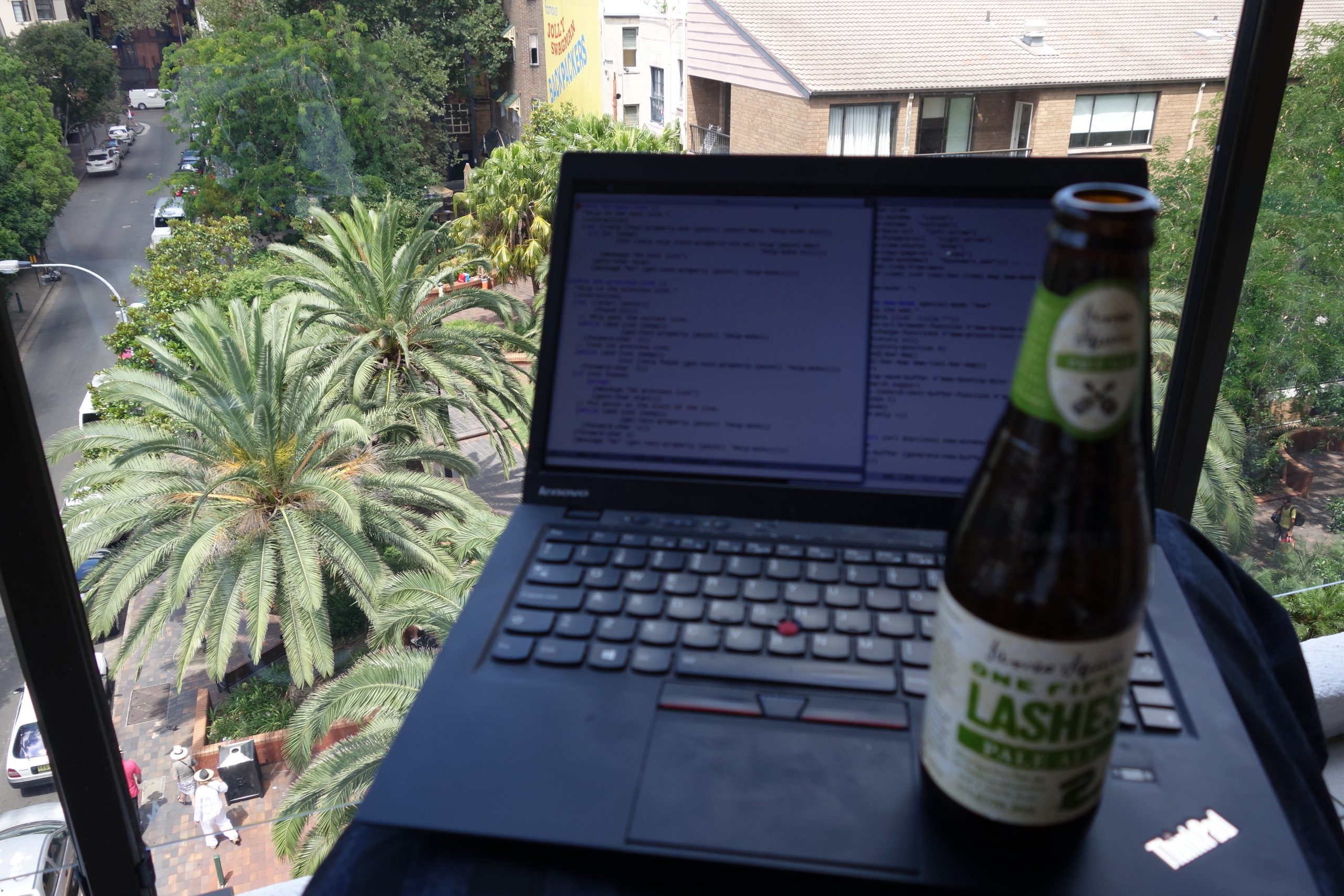

Let’s have a look at a couple of real-life pages. Duck Duck Go:

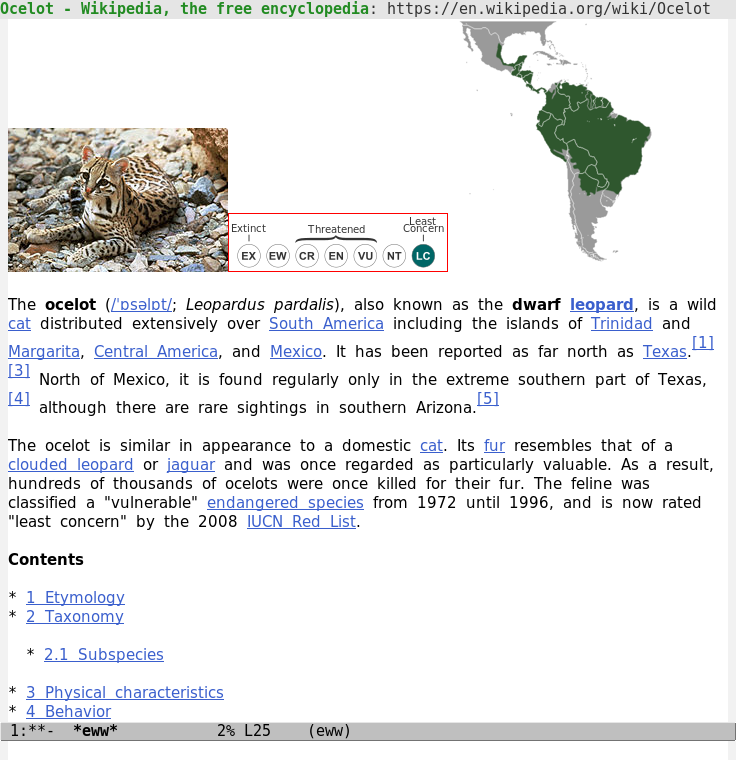

And Wikipedia:

It’s kinda starting to resemble a real browser, if you squint at it. After more than a couple of beers.

It’s just a proof of concept, so far. There is, of course, lots of twiddling to be done with <pre>, font style sheets and stuff, but the main issue that has to be addressed is speed. At the moment, it’s quite slow. I suspect we’ll have to add a C-level function that can say “what pixel column am I at now”, because the Emacs Lisp version I’ve cobbled together isn’t effective enough.