Have you noticed how crowd-sourced “genre” tags are kinda…. a thing that exists?

That is, I got some feedback on my Emacs package for keeping track of your books, and the suggestions were eminently reasonable, so now there’s more usage instructions on Microsoft Github and stuff.

But it was also suggested that it’d be useful to add support for genres, and I was doubtful. I mean, people don’t have hundreds of thousands of books (except the ones that do), so what would the actual utility be? And besides, adding genre markers yourself would be actual work, and that’s ewwww. Work! Yuck.

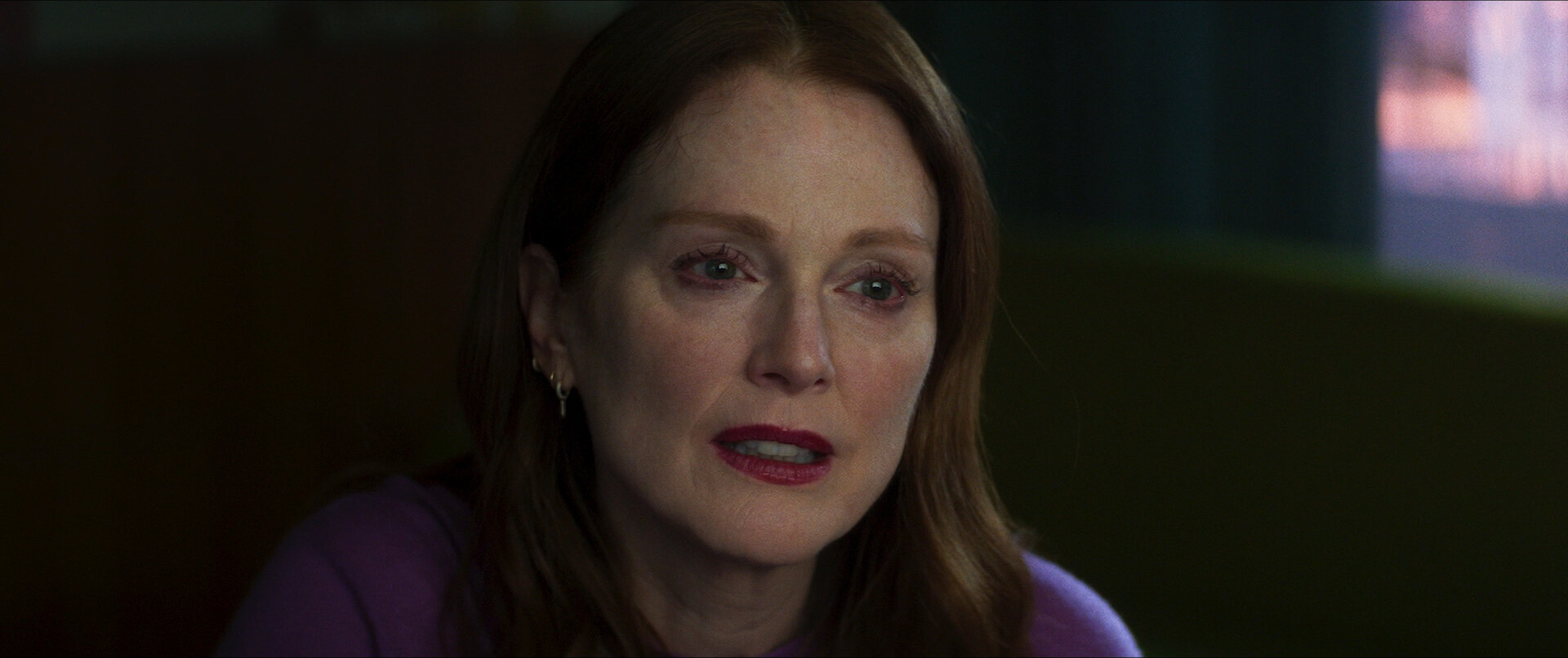

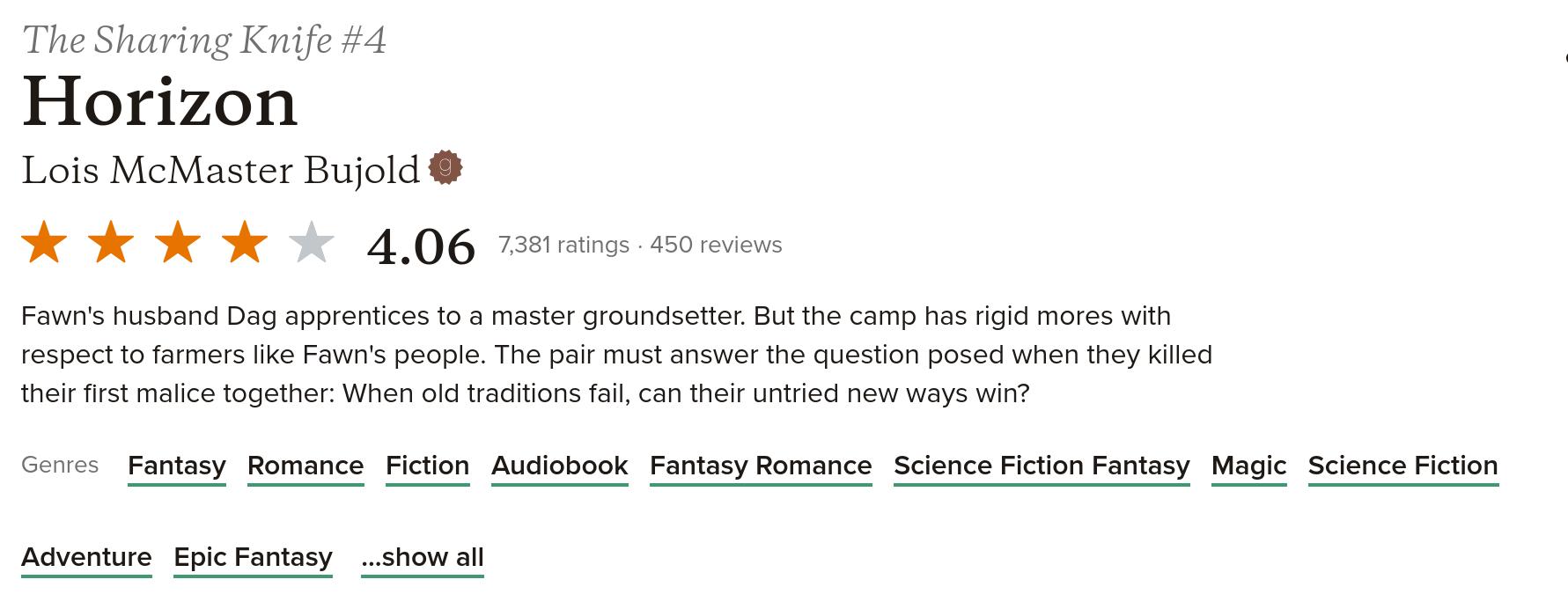

Alors, I remembered that Goodreads has crowdsourced genre tags, so I could just query them? So:

And I don’t know whether that’s useful, but it’s kinda fun, eh?

However, these are crowdsourced, so:

Eh. Yeah, “Autistic Spectrum Disorder” is definitely a genre that exists.

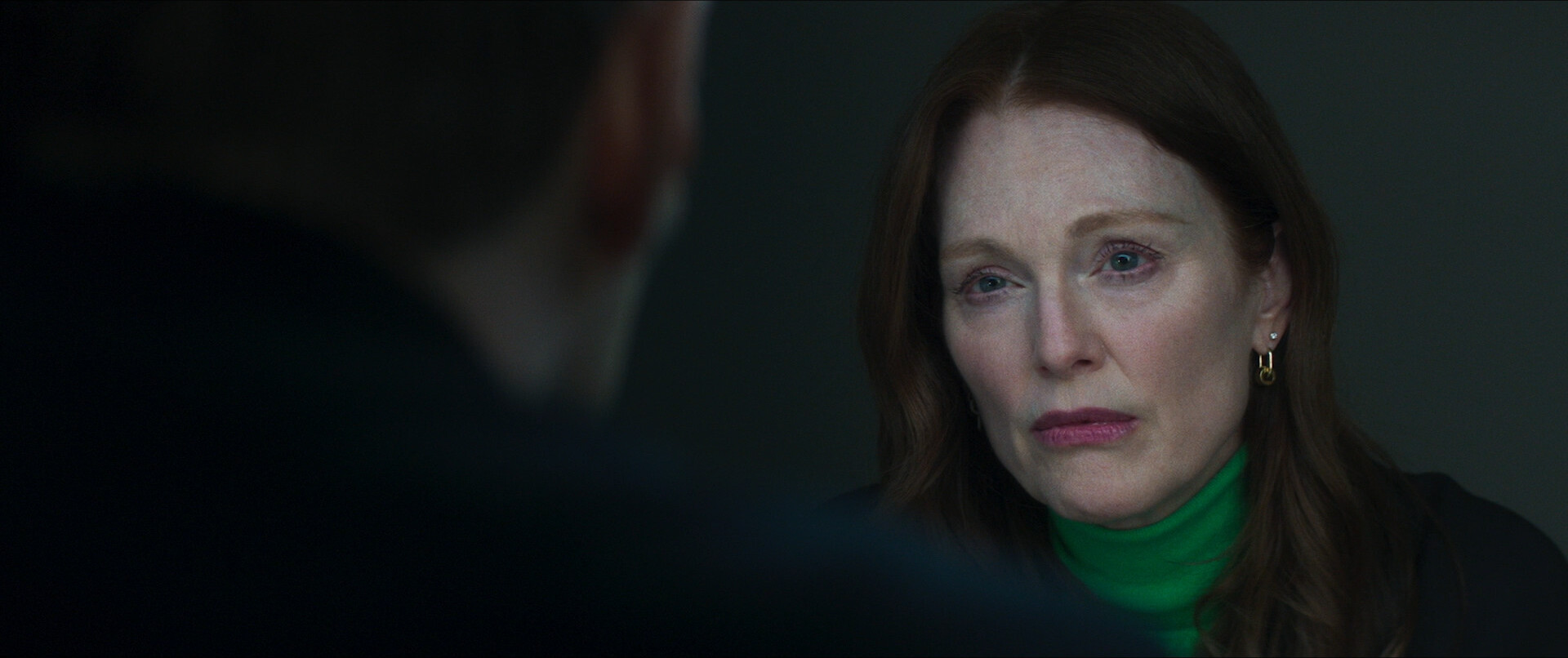

I’ve tried to filter out most of the junk by just using the two first genre tags per book — and that helps a lot, but still…

In any case, you can edit the genres manually if it bothers you. Or just ignore the genres, really.

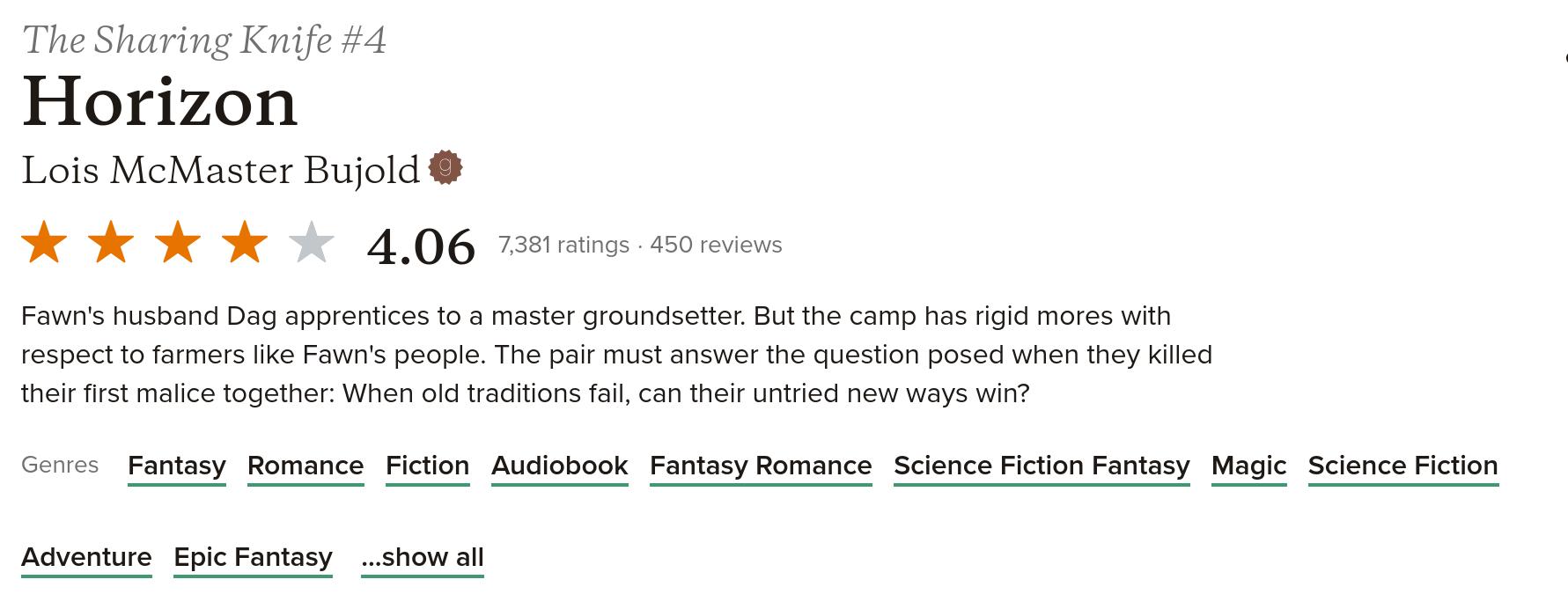

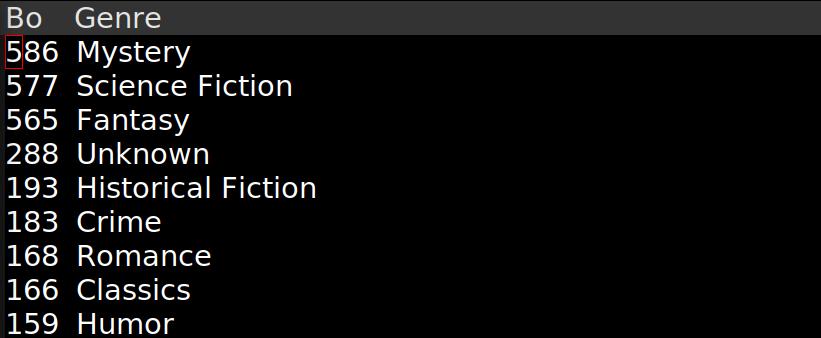

Anyway, you can now list books based on genre, and…

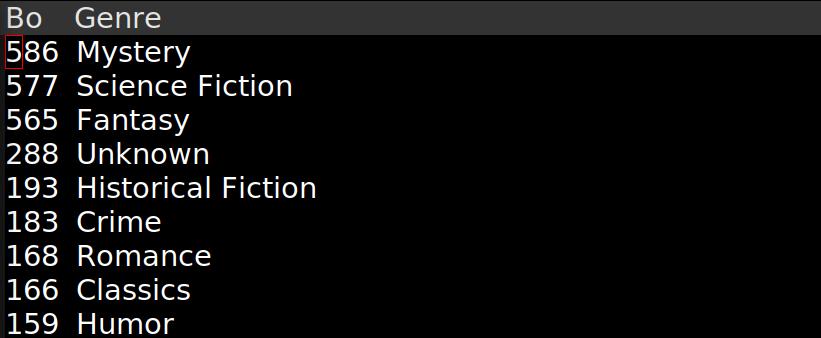

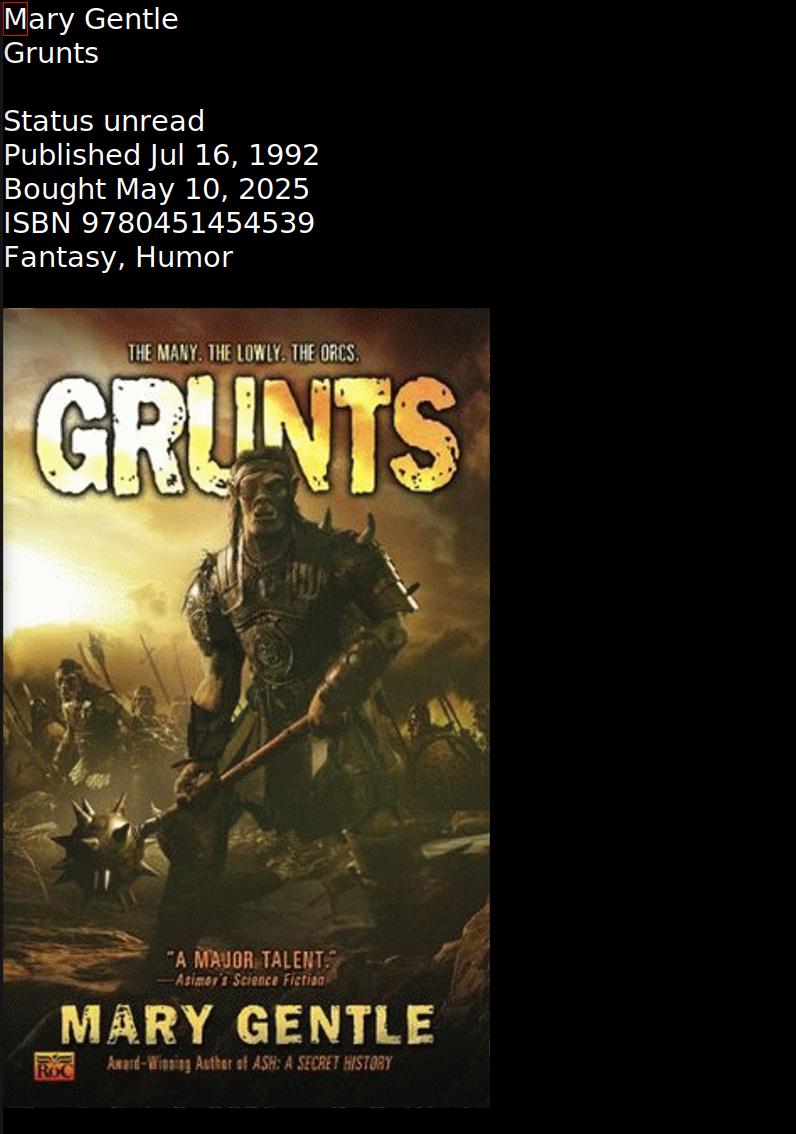

… I’ve also fixed up how book details are displayed.

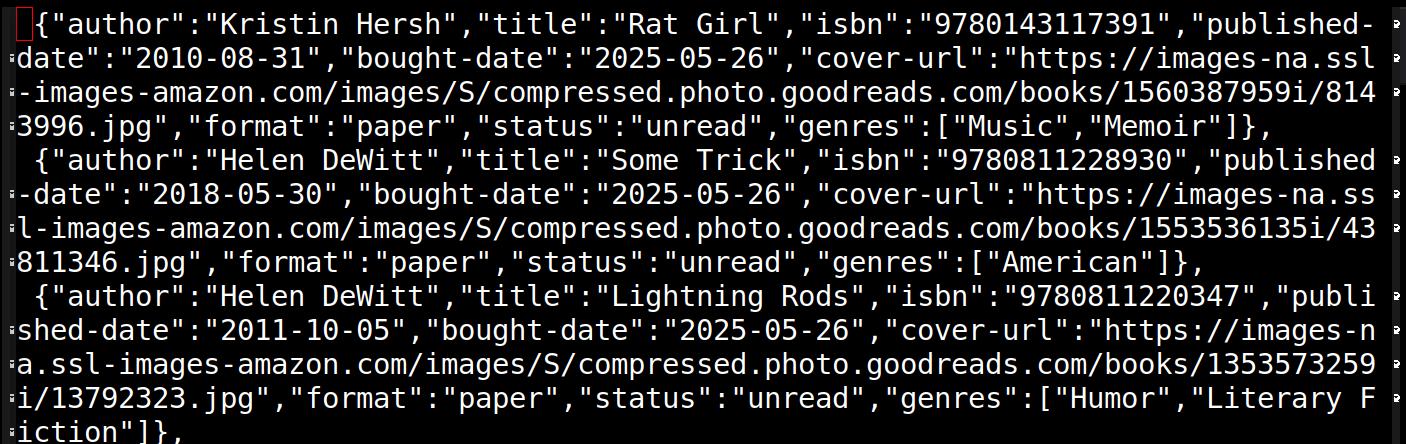

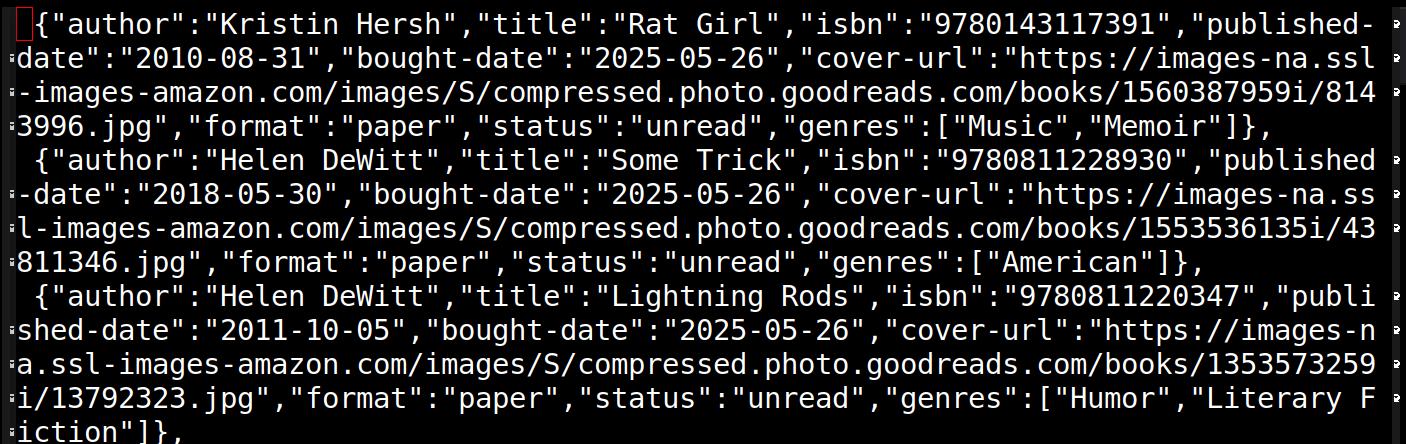

And I’ve also changed the data format from a very, er, “ad hoc format” is perhaps putting it too gently… to JSON:

So that should make it easier to import into other programmes, and also allow extending the format gracefully.

And there’s, of course, support for using barcode scanners, but I’ve extended that with a kinda “serverish” mode, so that you don’t have to select Emacs (or a bookiez mode) before scanning. Just pick up the scanner and *beep*.

So there you go. I think bookiez might actually be usable now… perhaps.