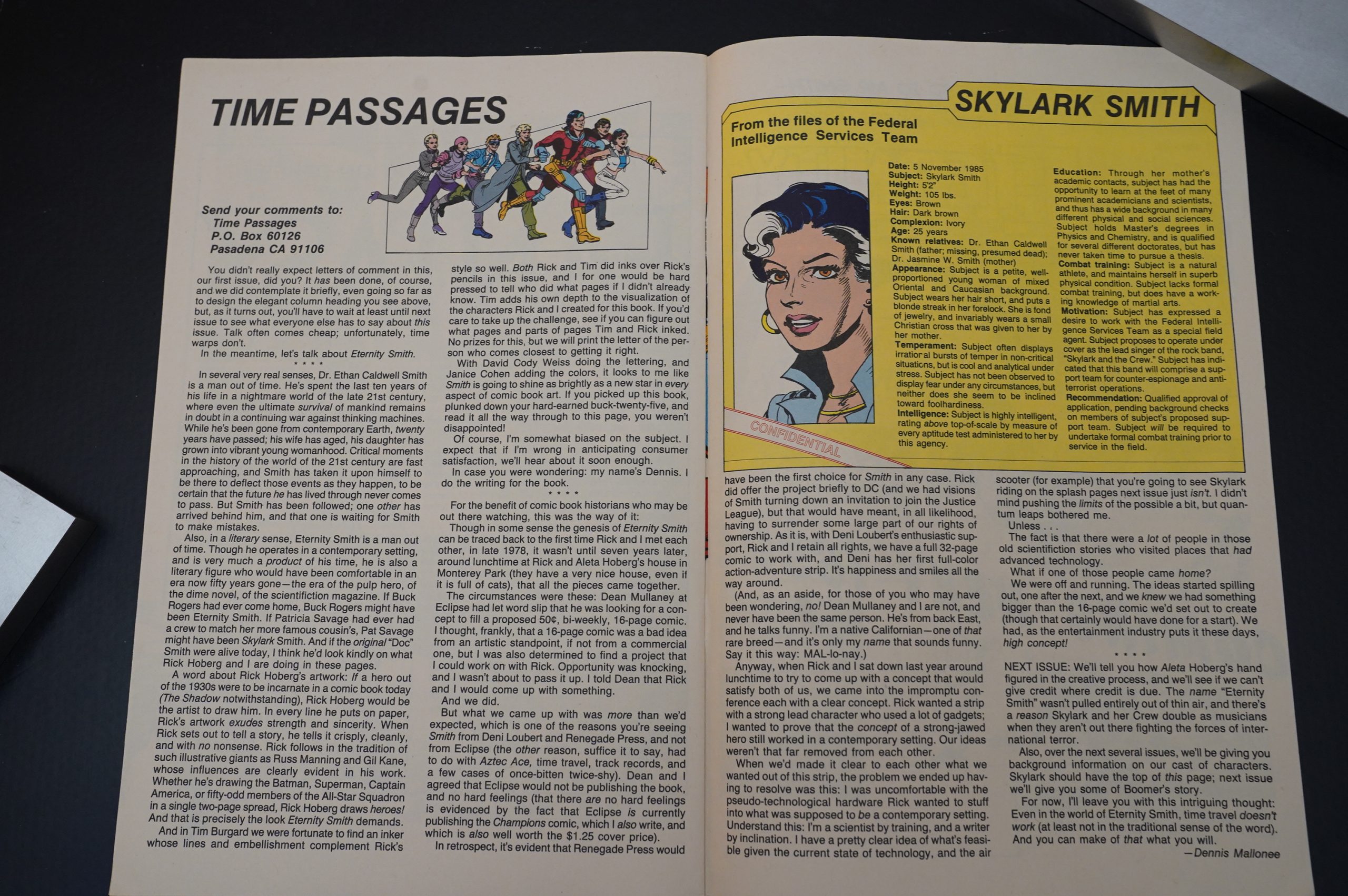

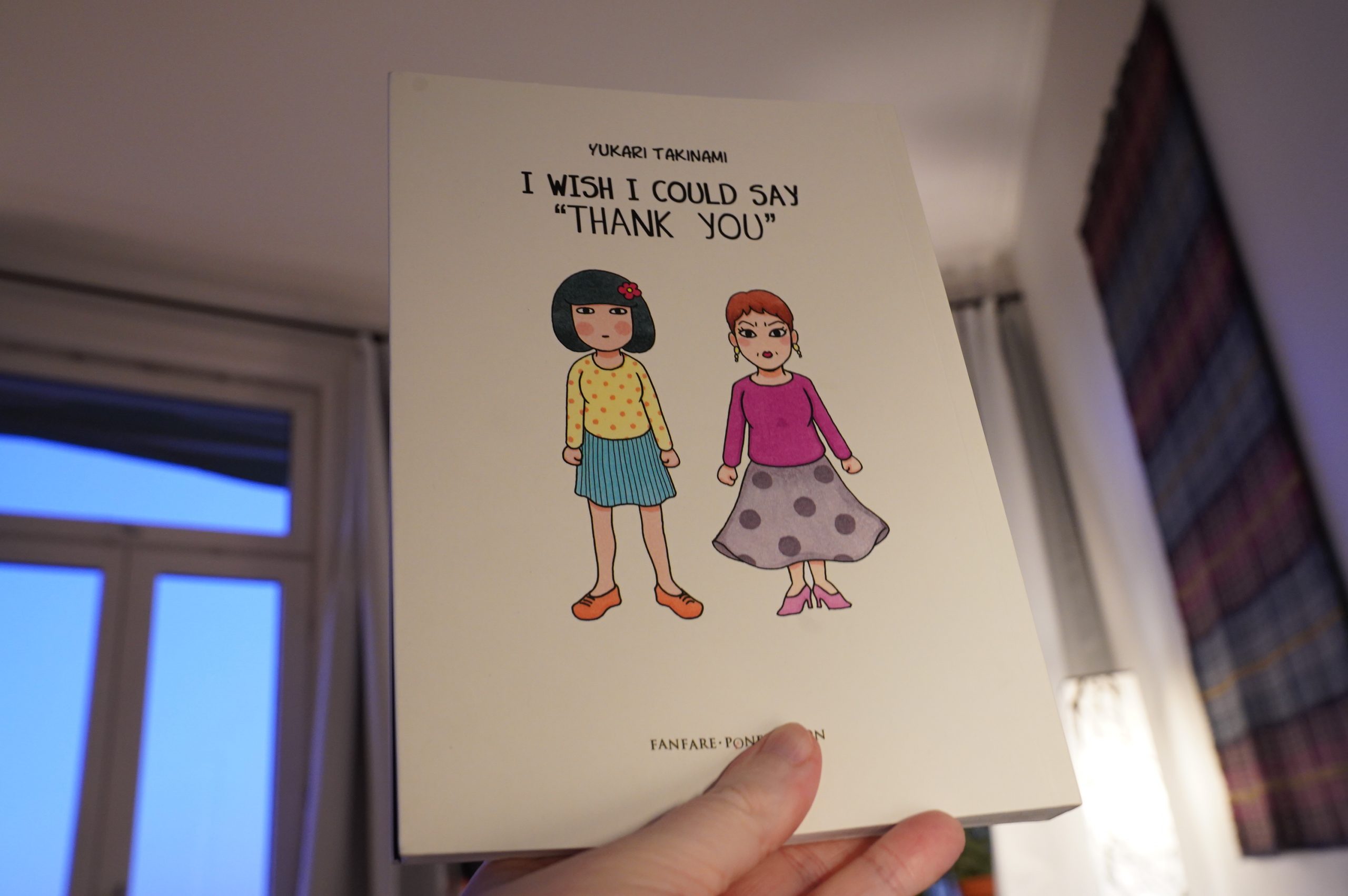

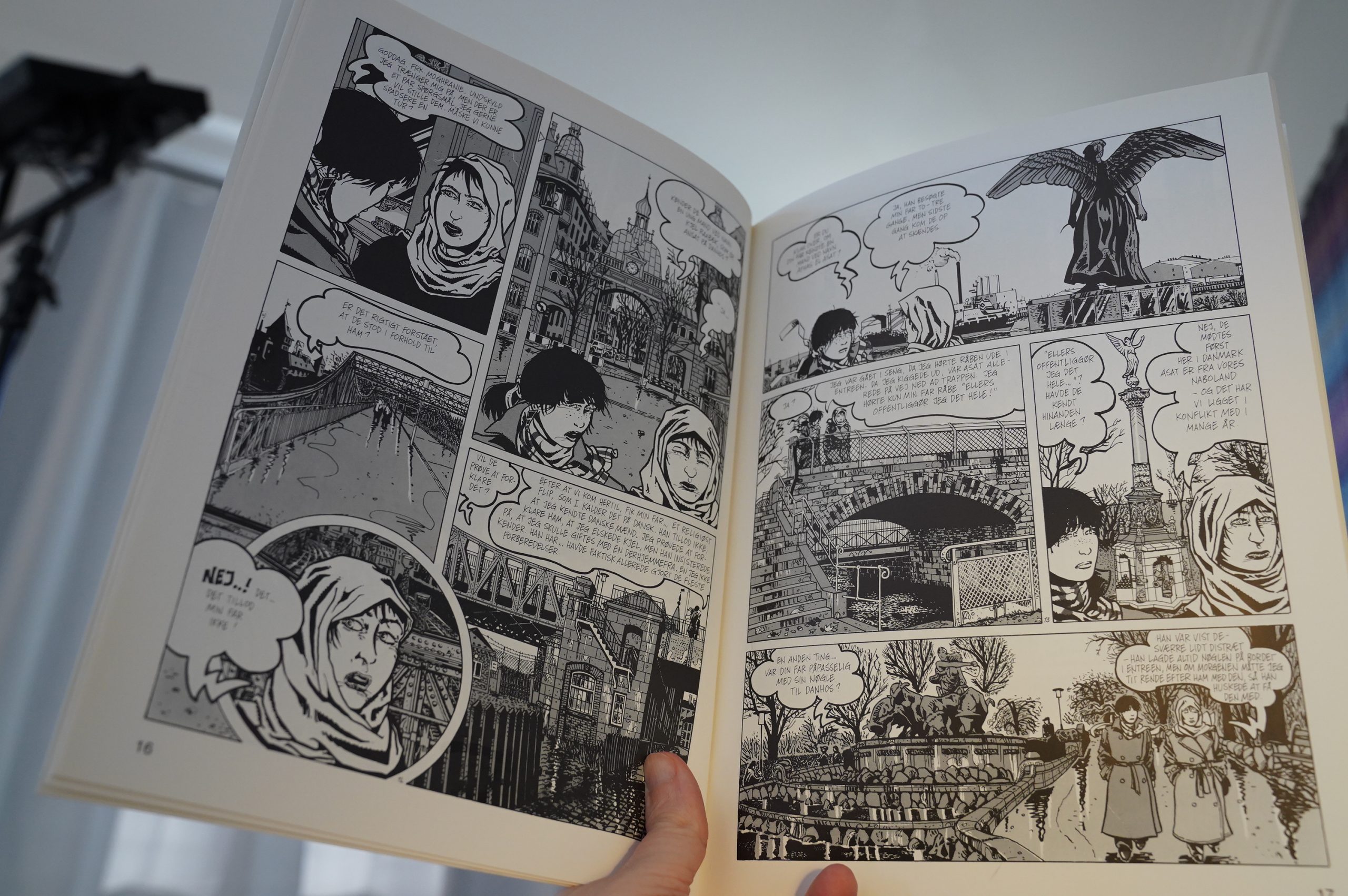

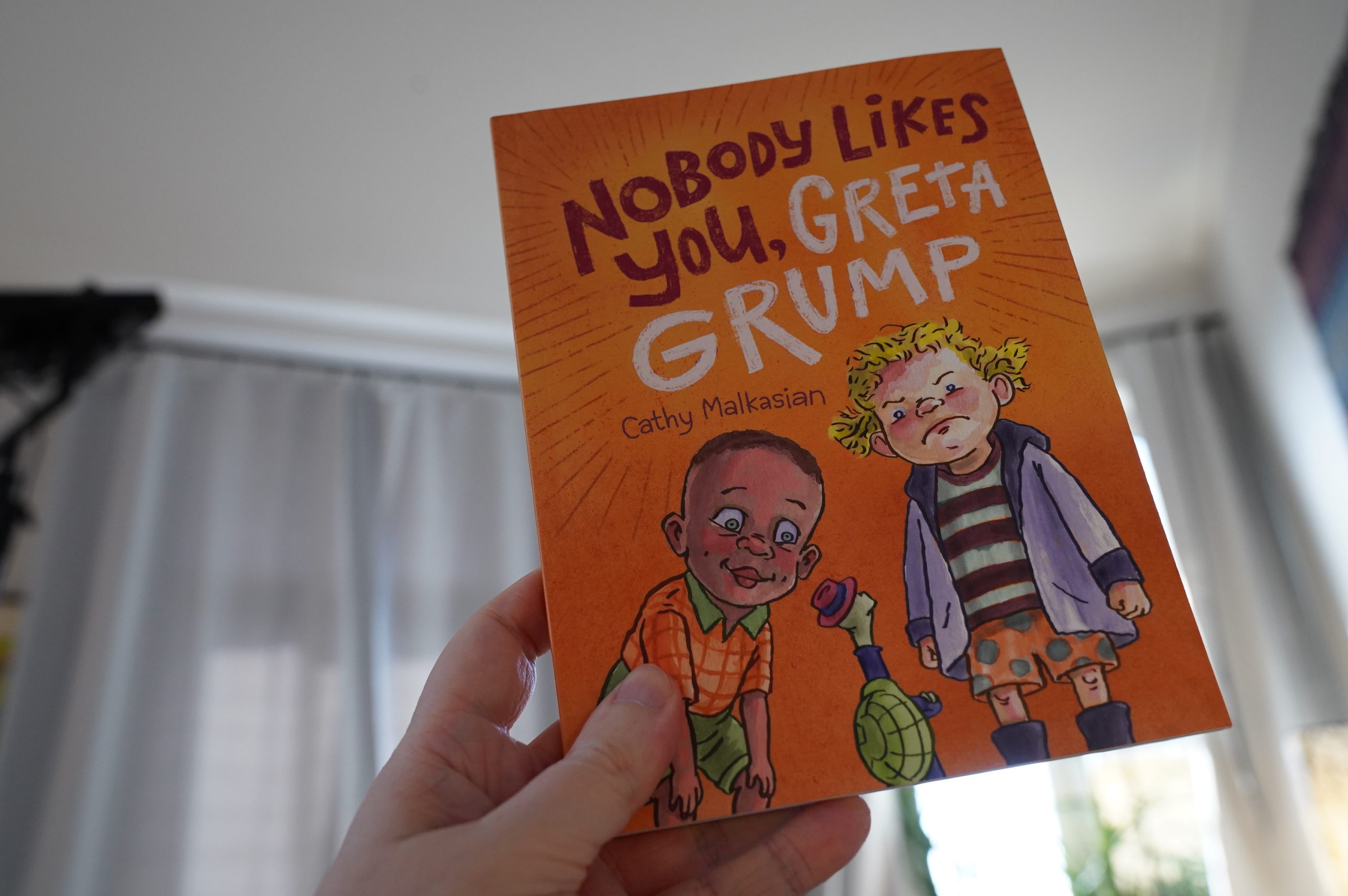

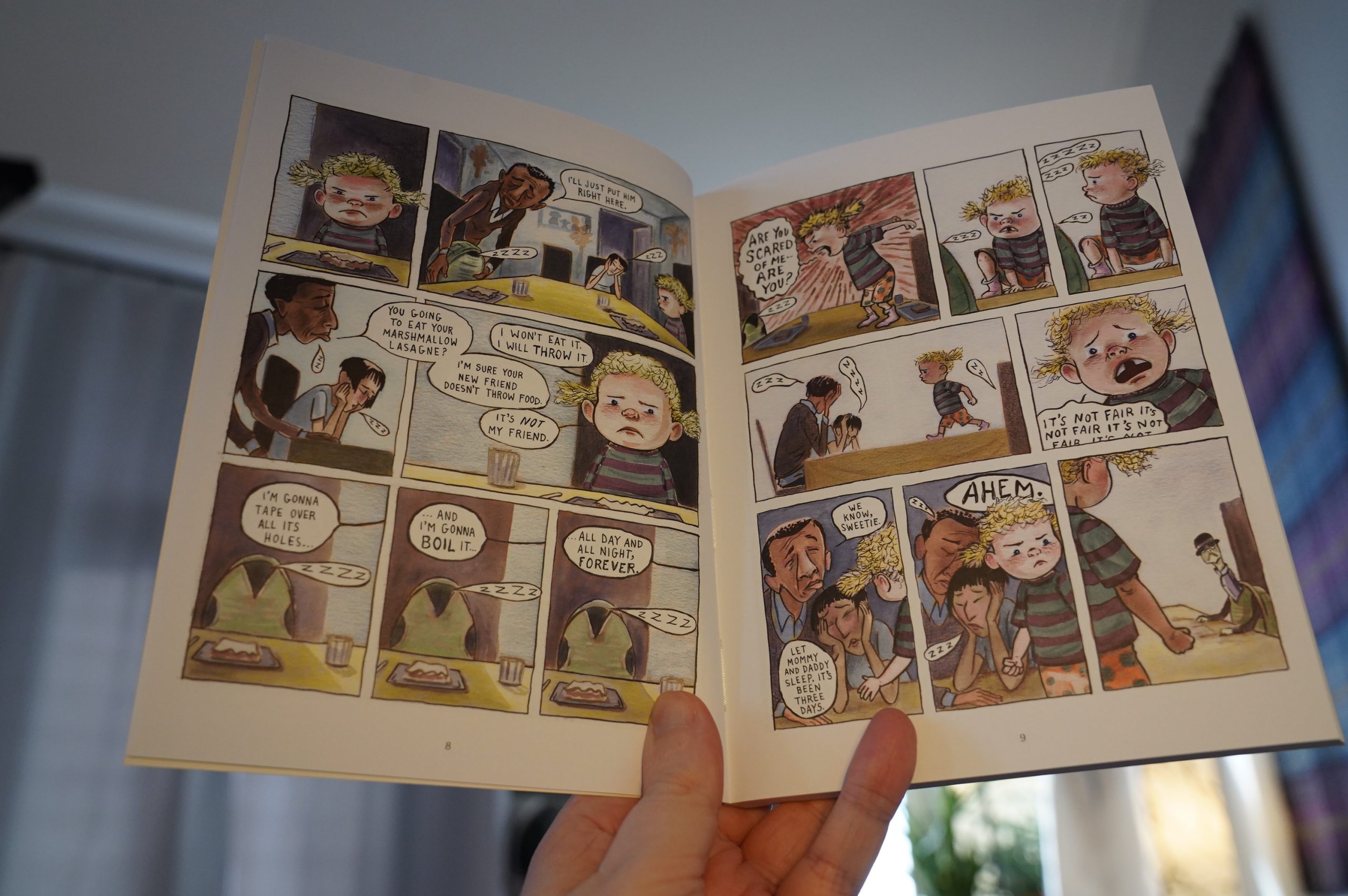

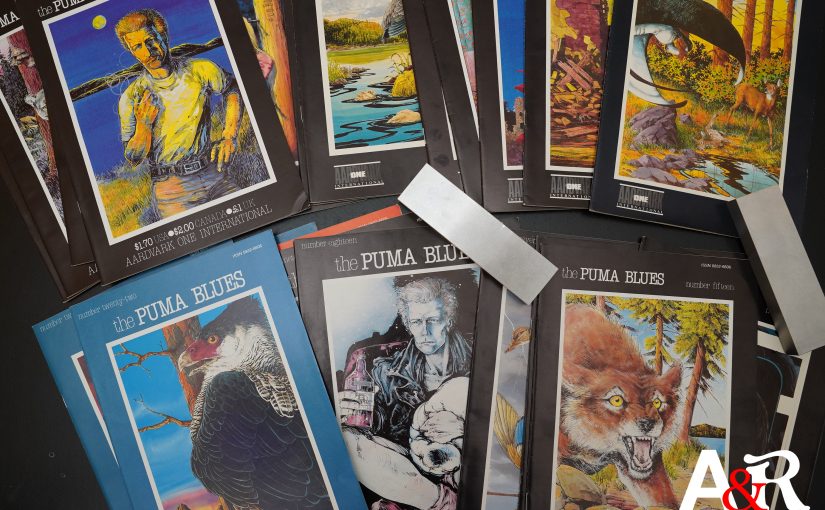

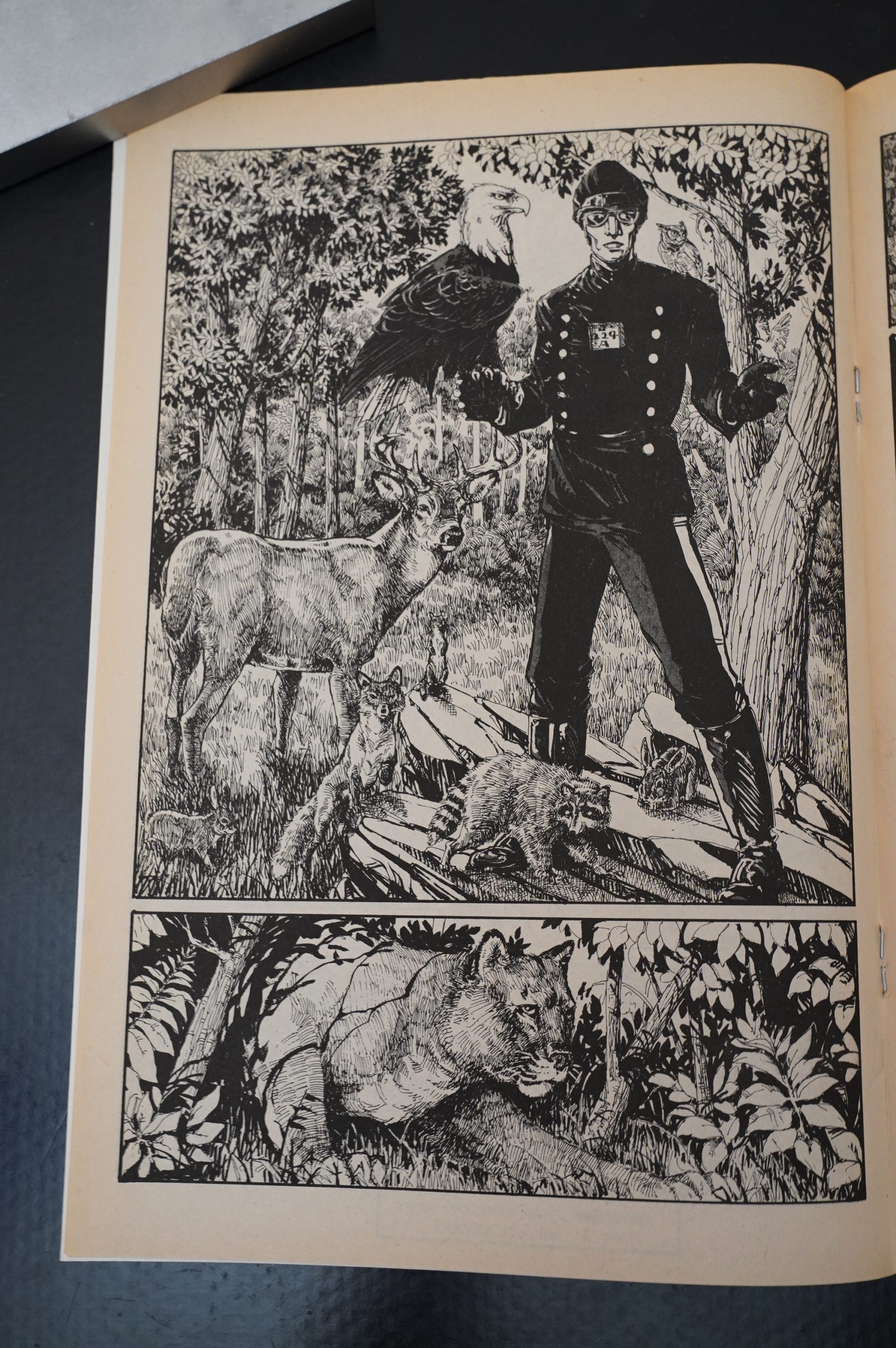

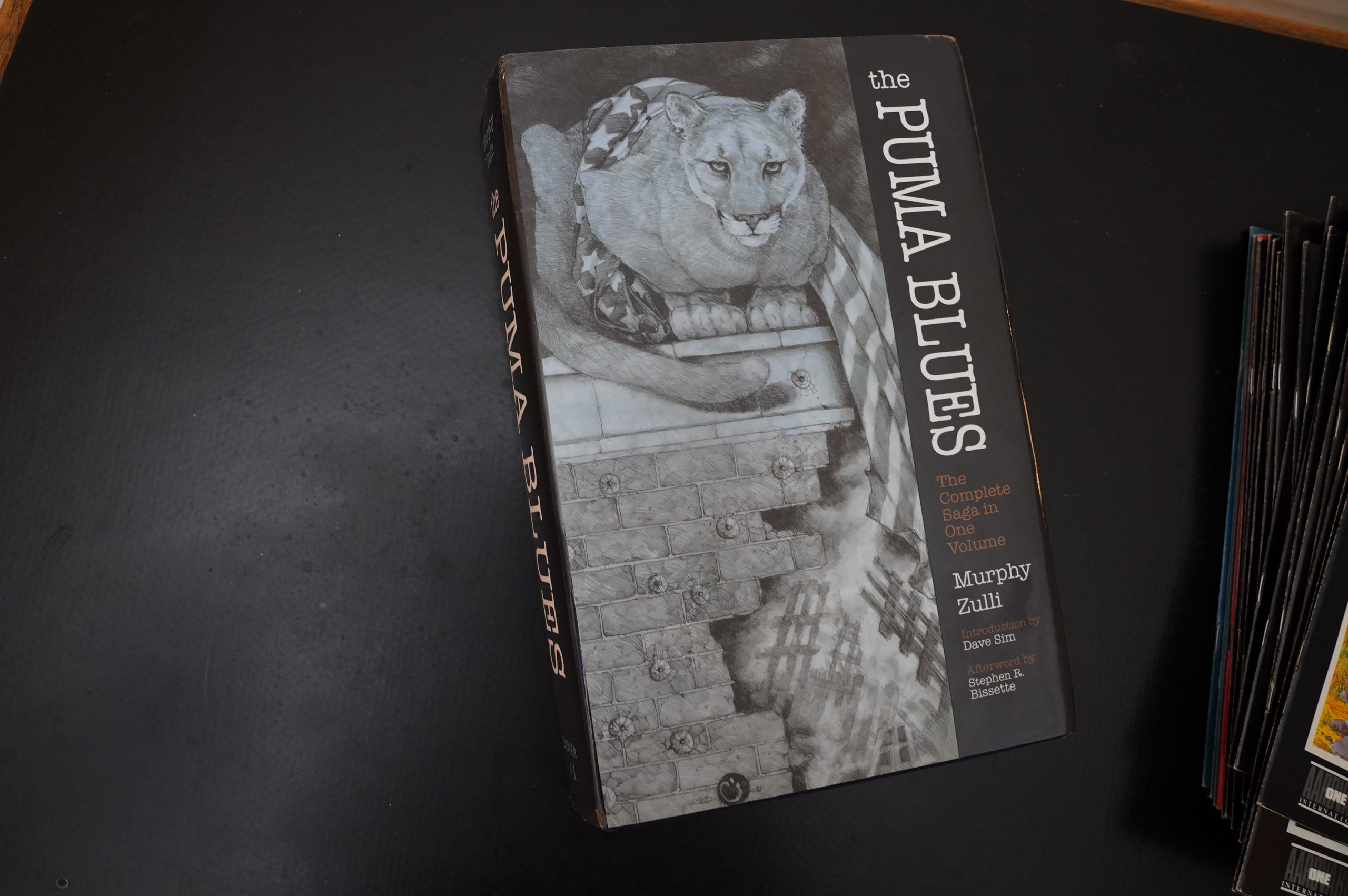

The Puma Blues (1986) #1-23 by Stephen Murphy and Michael Zulli

Oh! This is a series I remember well from when I was a teenager. That is, I don’t remember much of the specifics, but I remember the pensive atmosphere and the sight of those manta rays floating in the sky.

It used to be you could ask anybody “which unfinished comic series do you wish they’d pick up again and finish?” and everybody would answer “Puma Blues”. (For some value of “everybody”.) It’s one of those comics where the publishing history really kinda has to be discussed as well, otherwise nothing much would make sense…

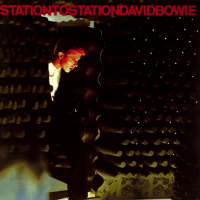

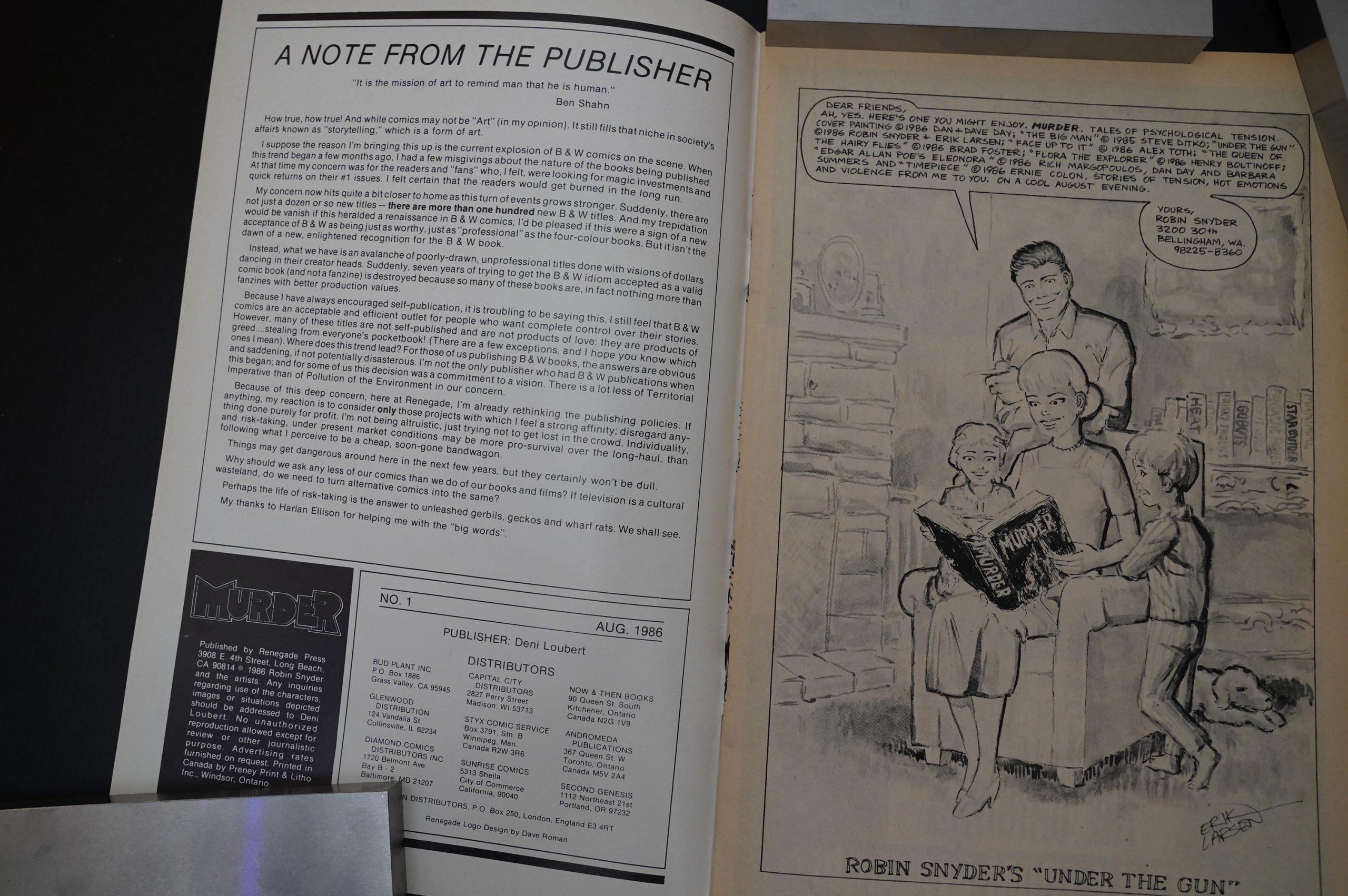

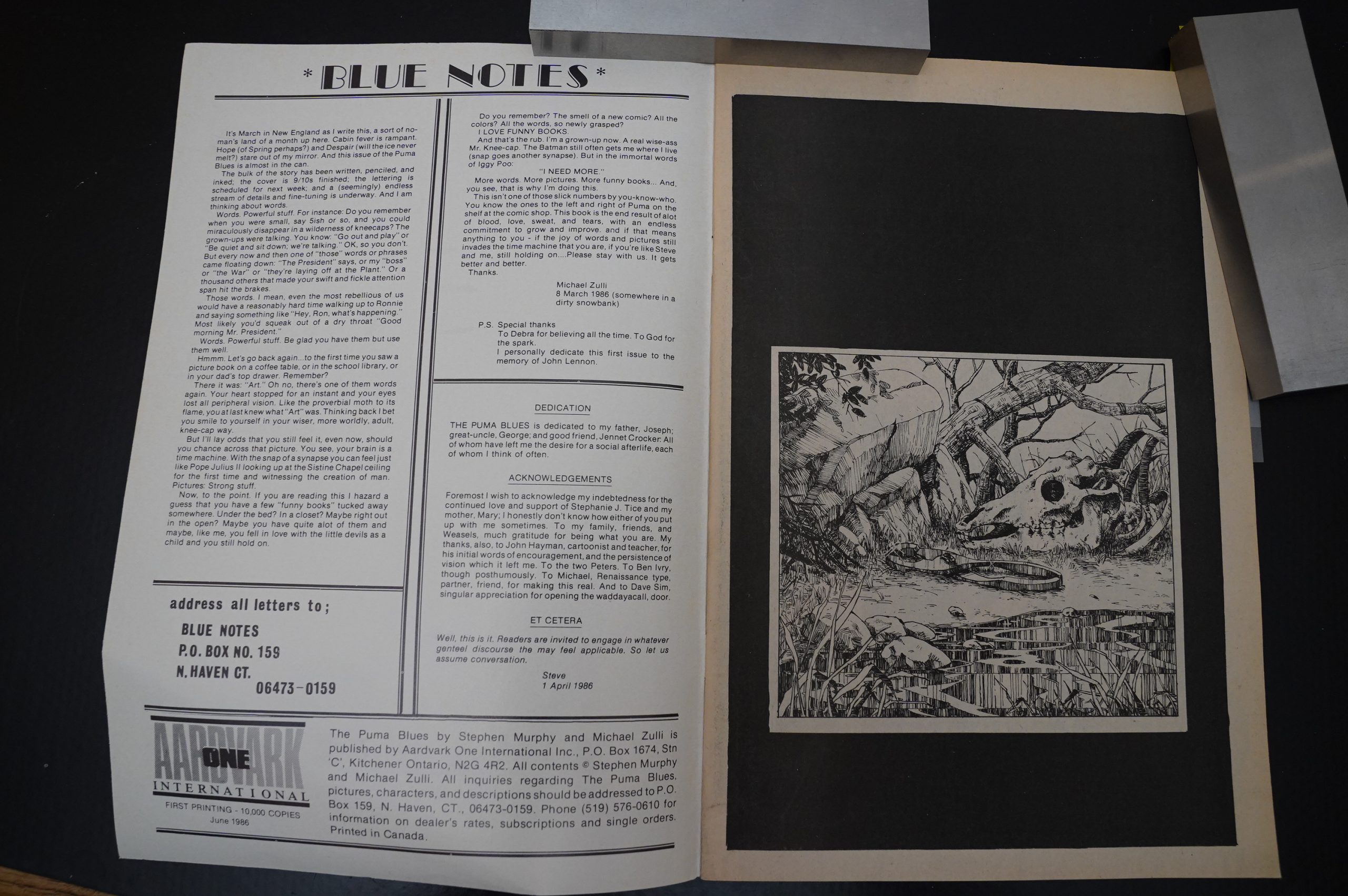

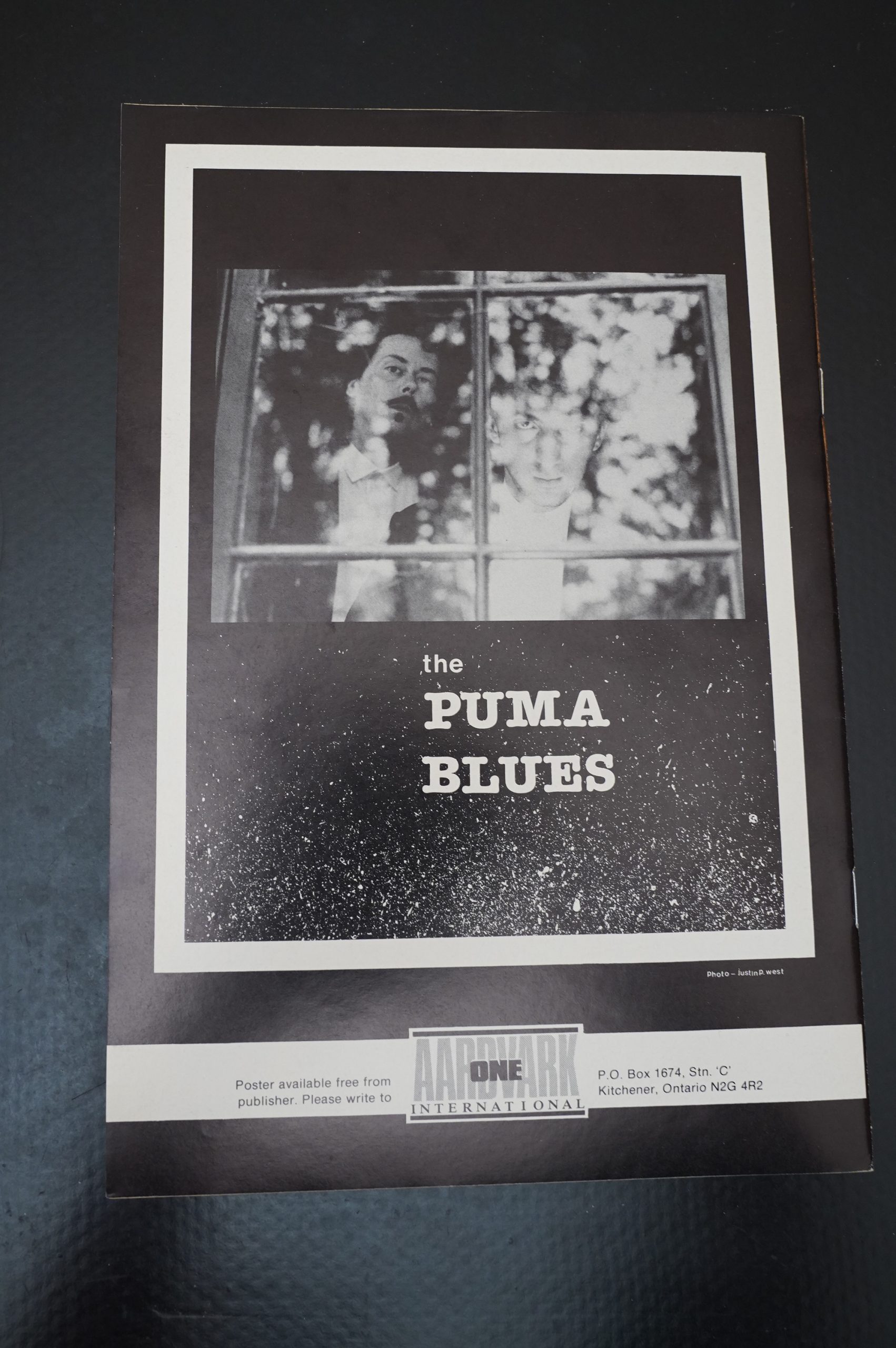

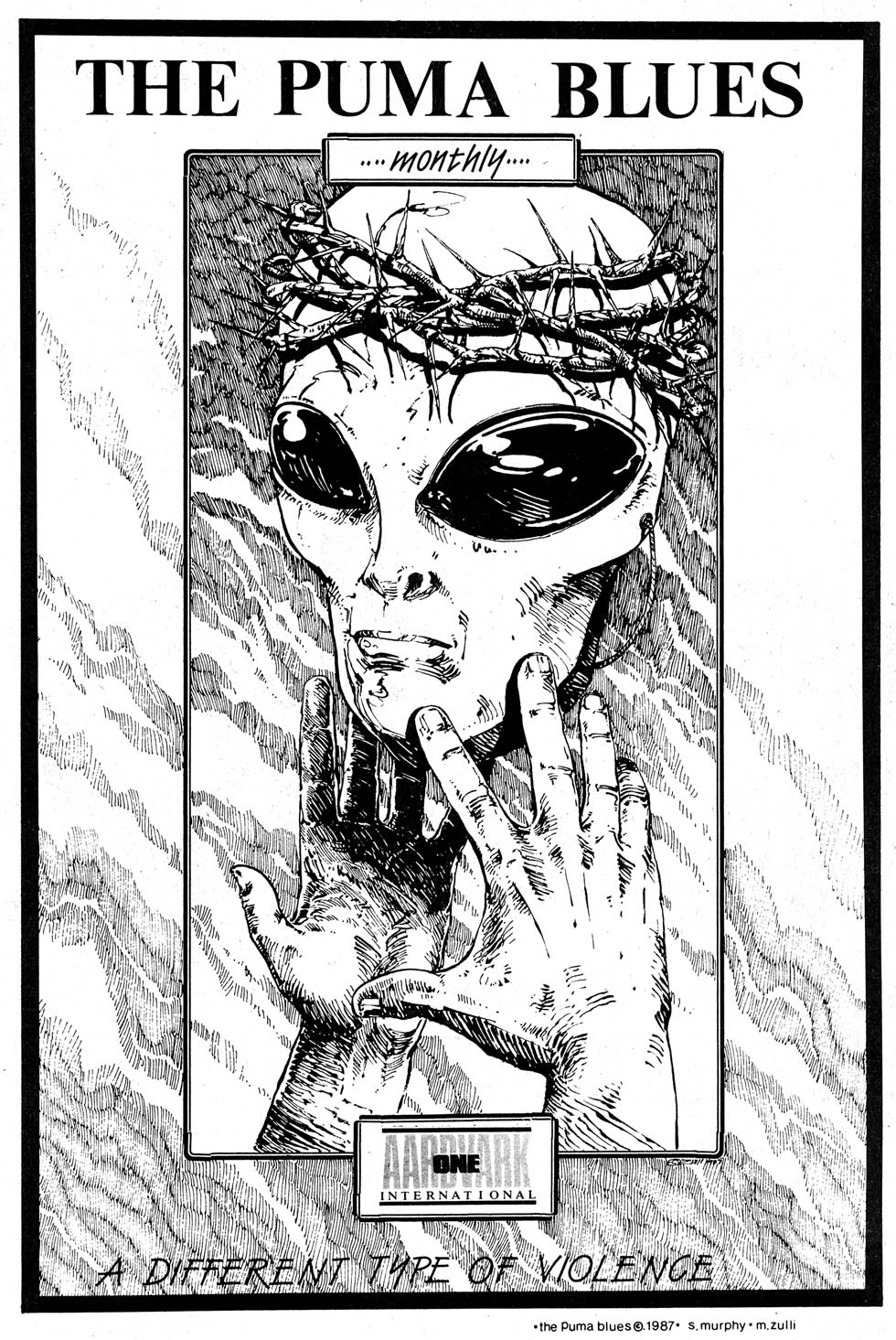

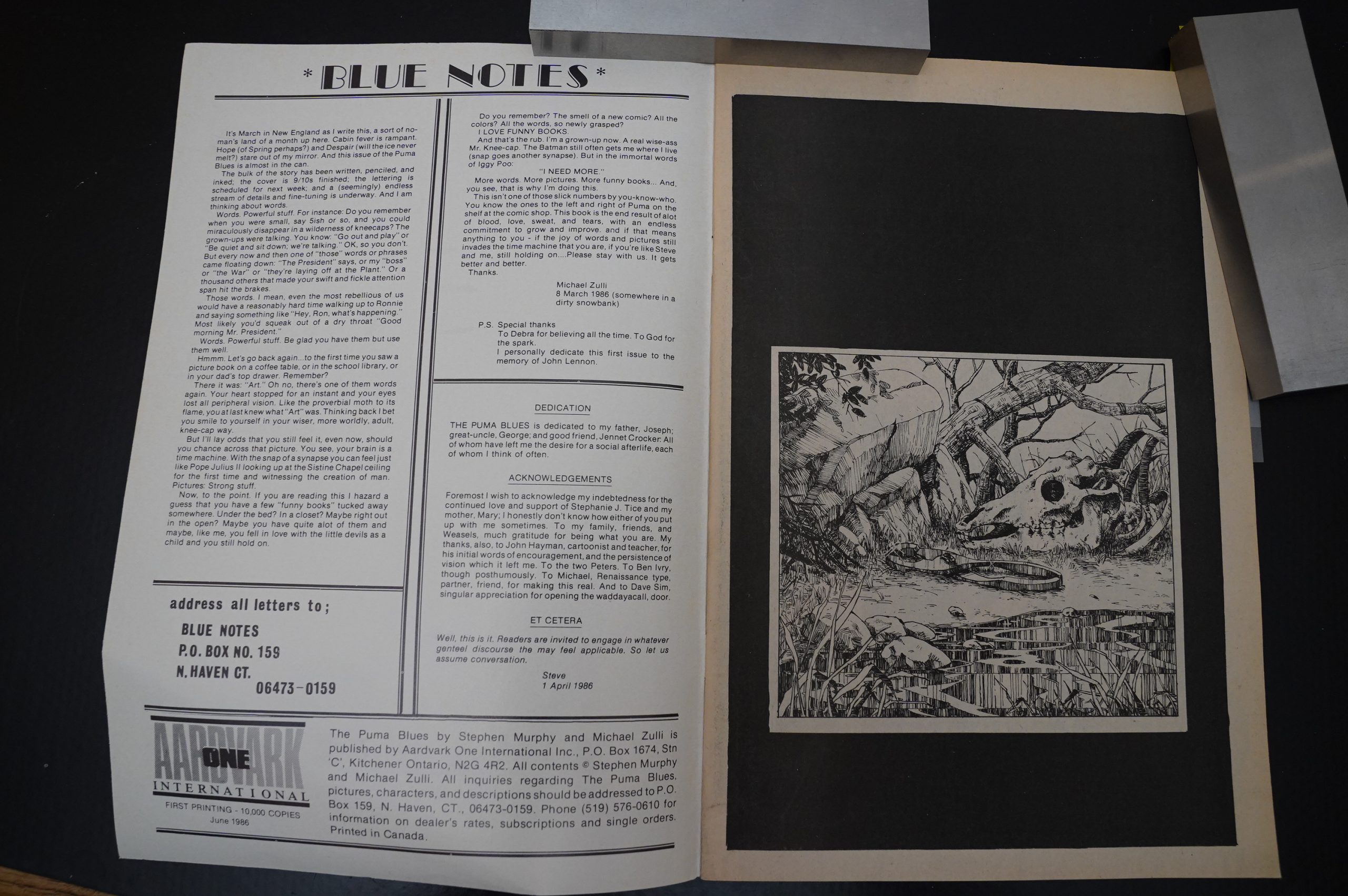

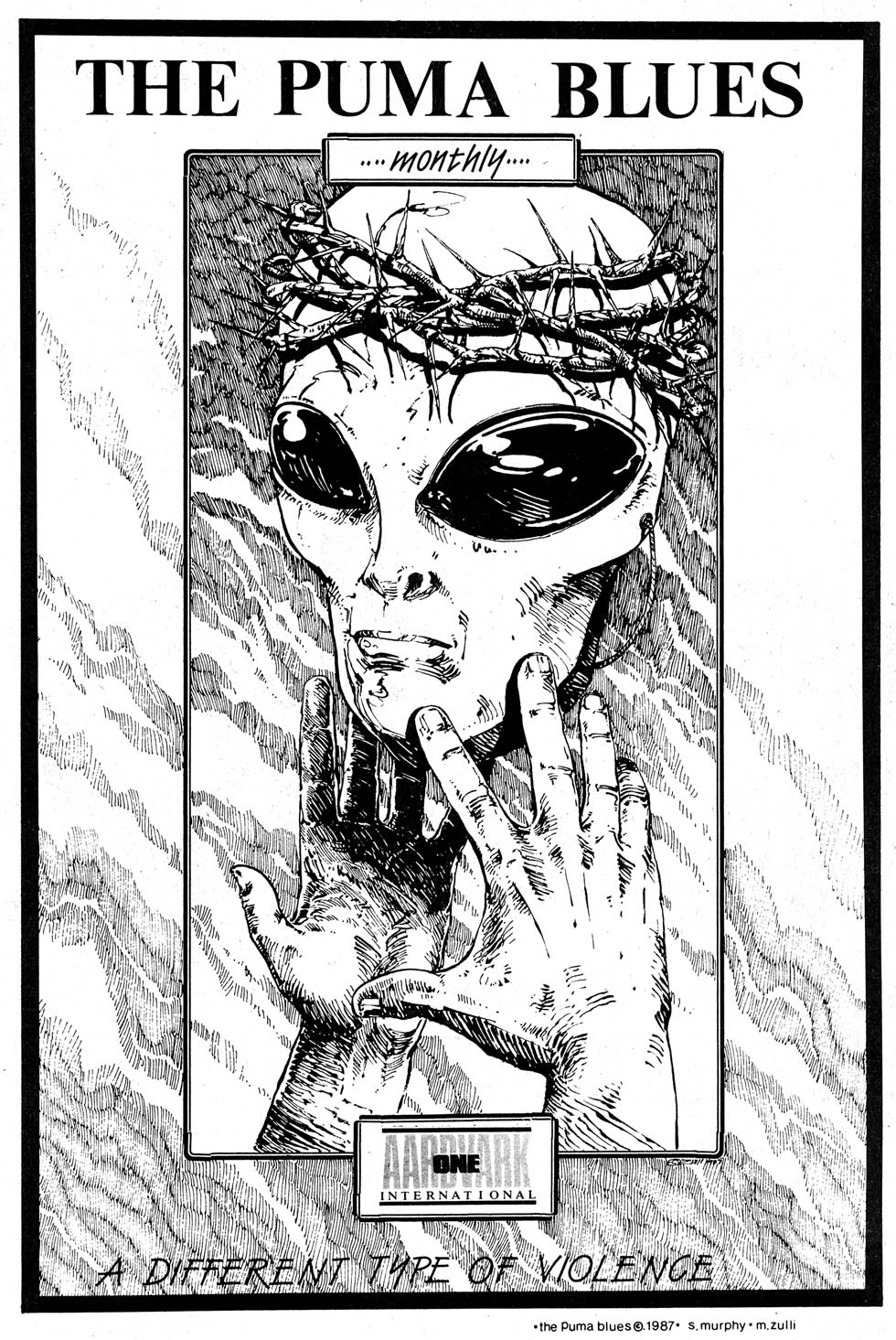

So! This is the first (and as it turned out, only) comic published by Aardvark One International. Dave Sim set up the company because he wanted to provide a venue for creators to publish stuff free from all editorial interference and stuff… and this was in the middle of the Imperial Years of Cerebus, where Sim was starting to become rather flush with money, so my guess is that he wanted to spread some of that around…

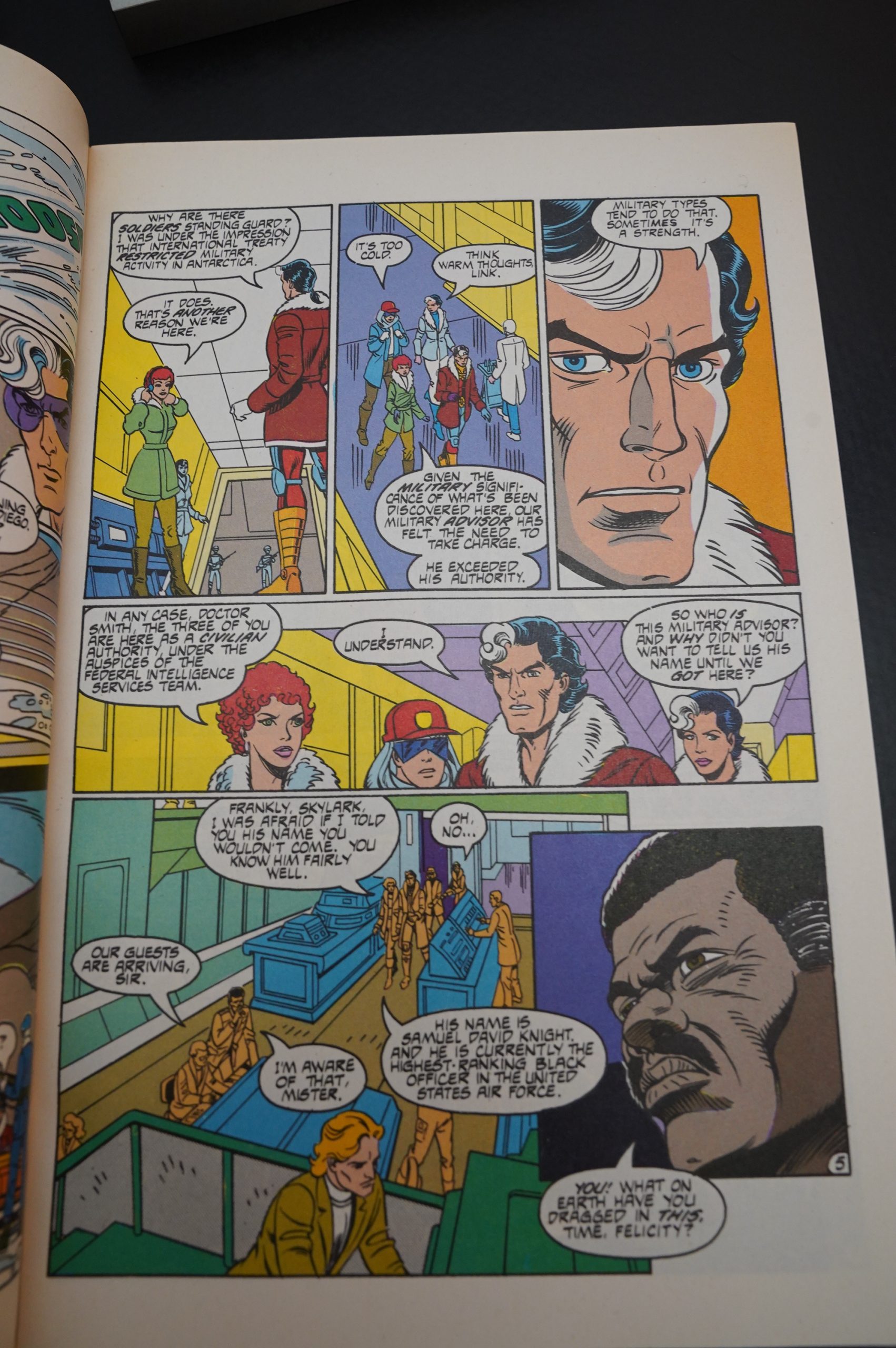

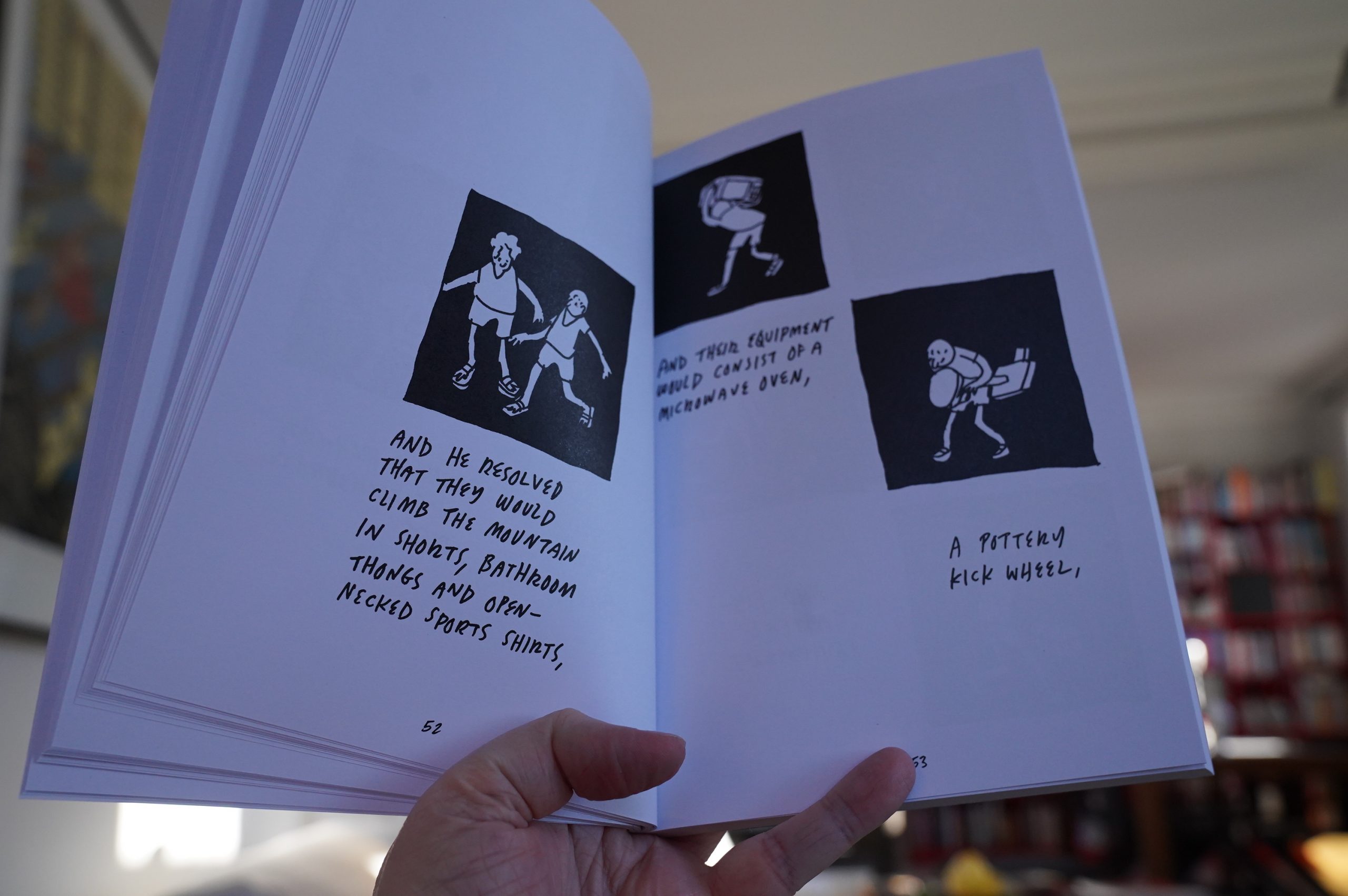

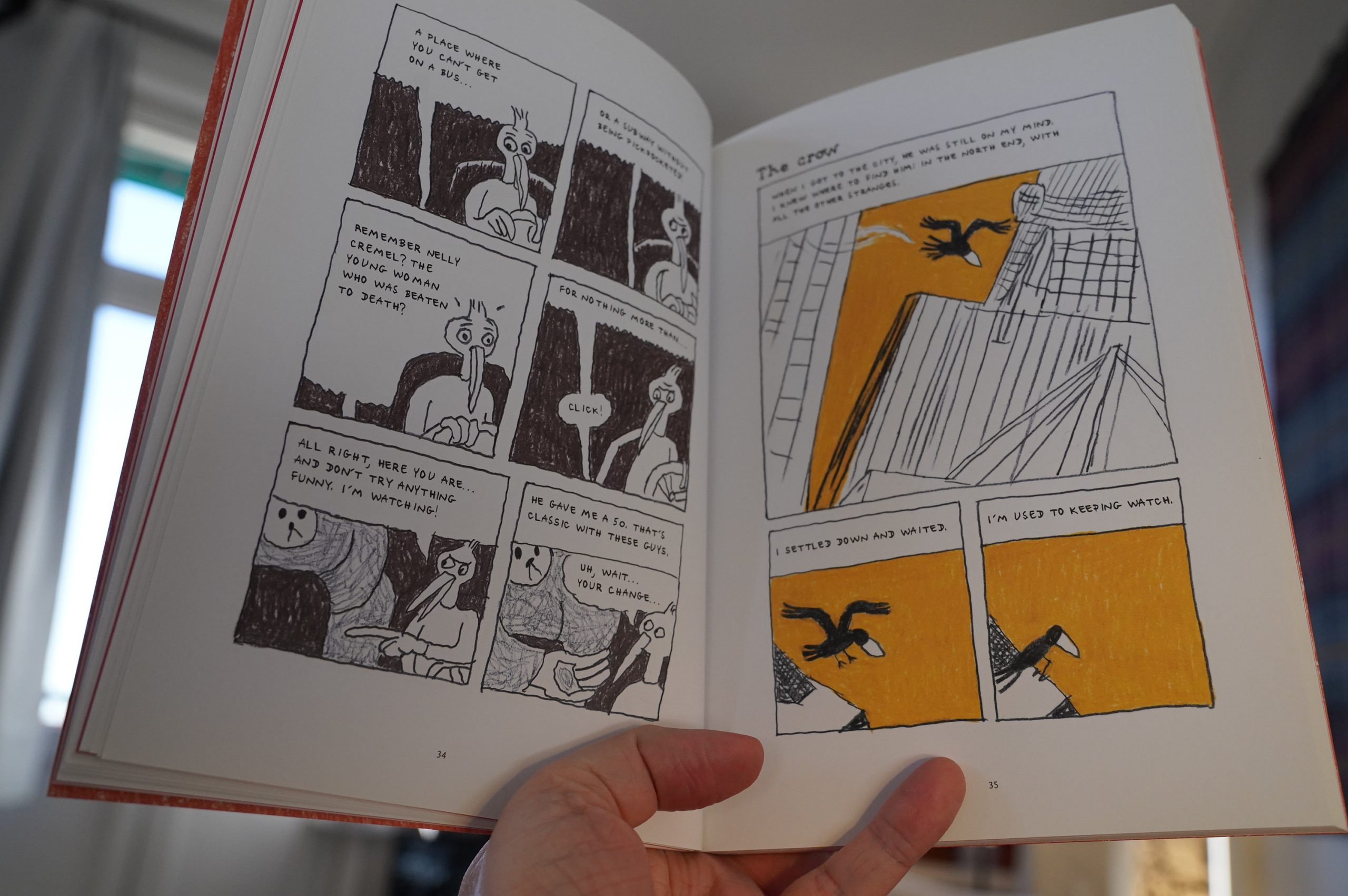

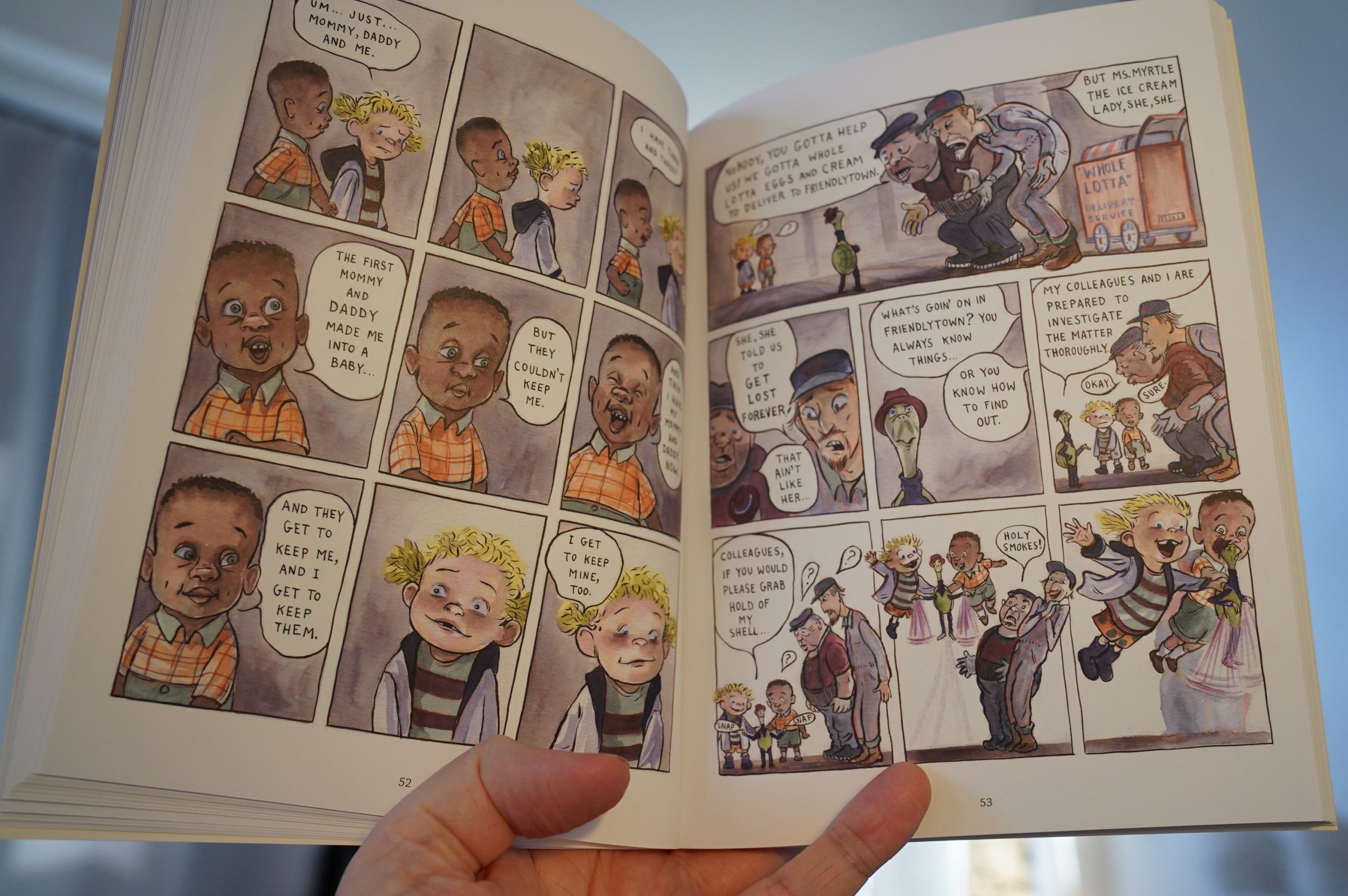

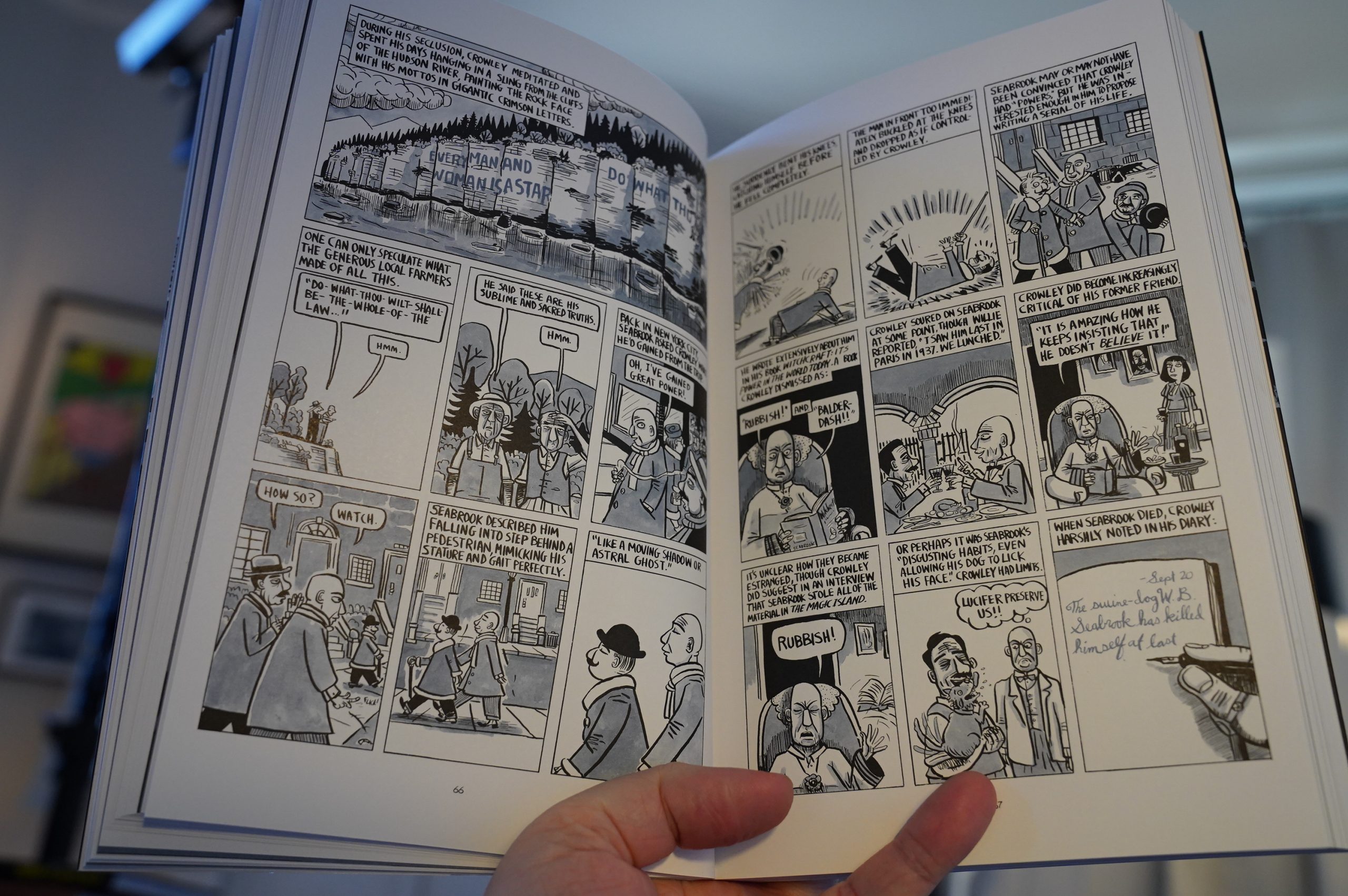

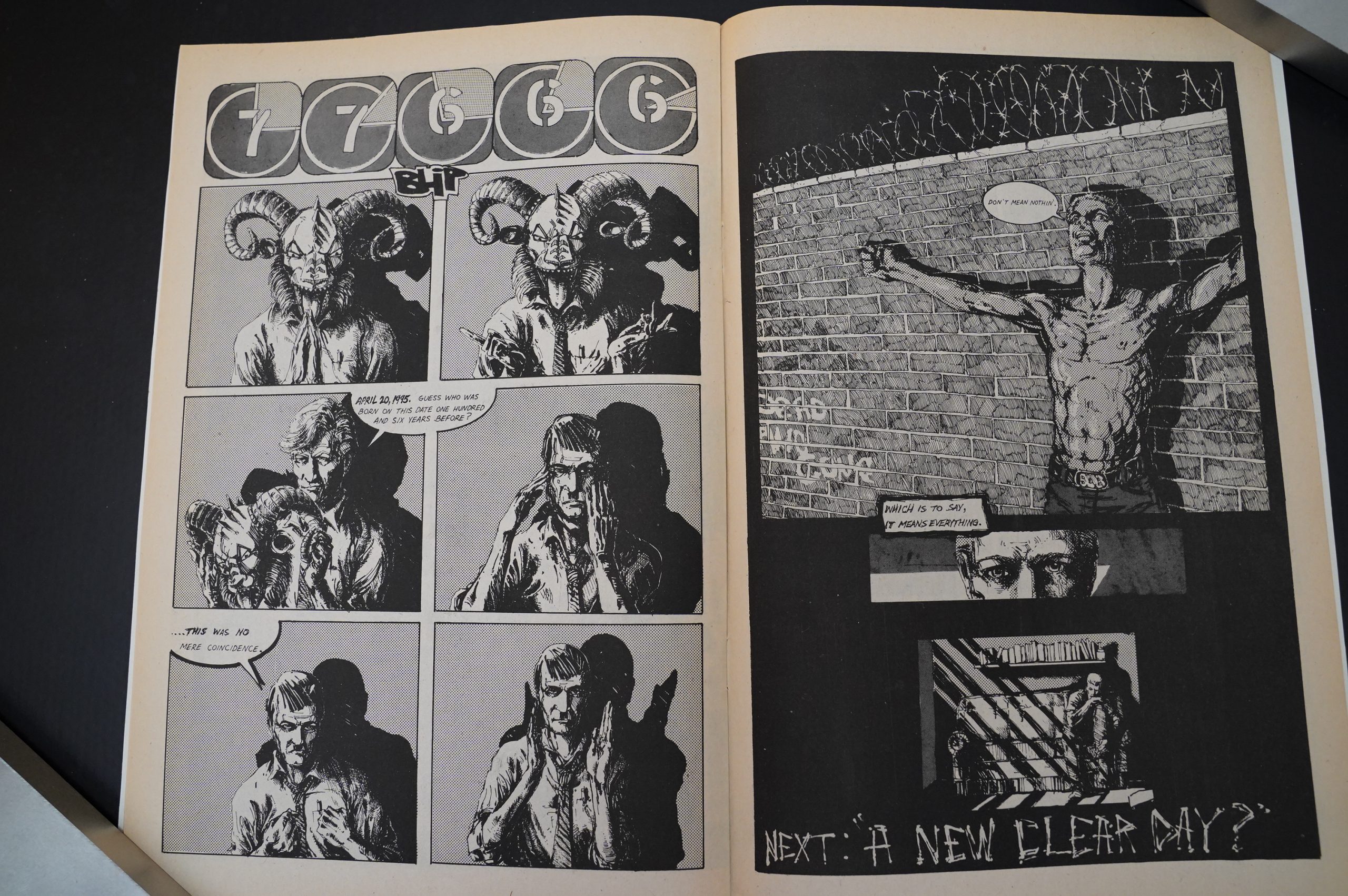

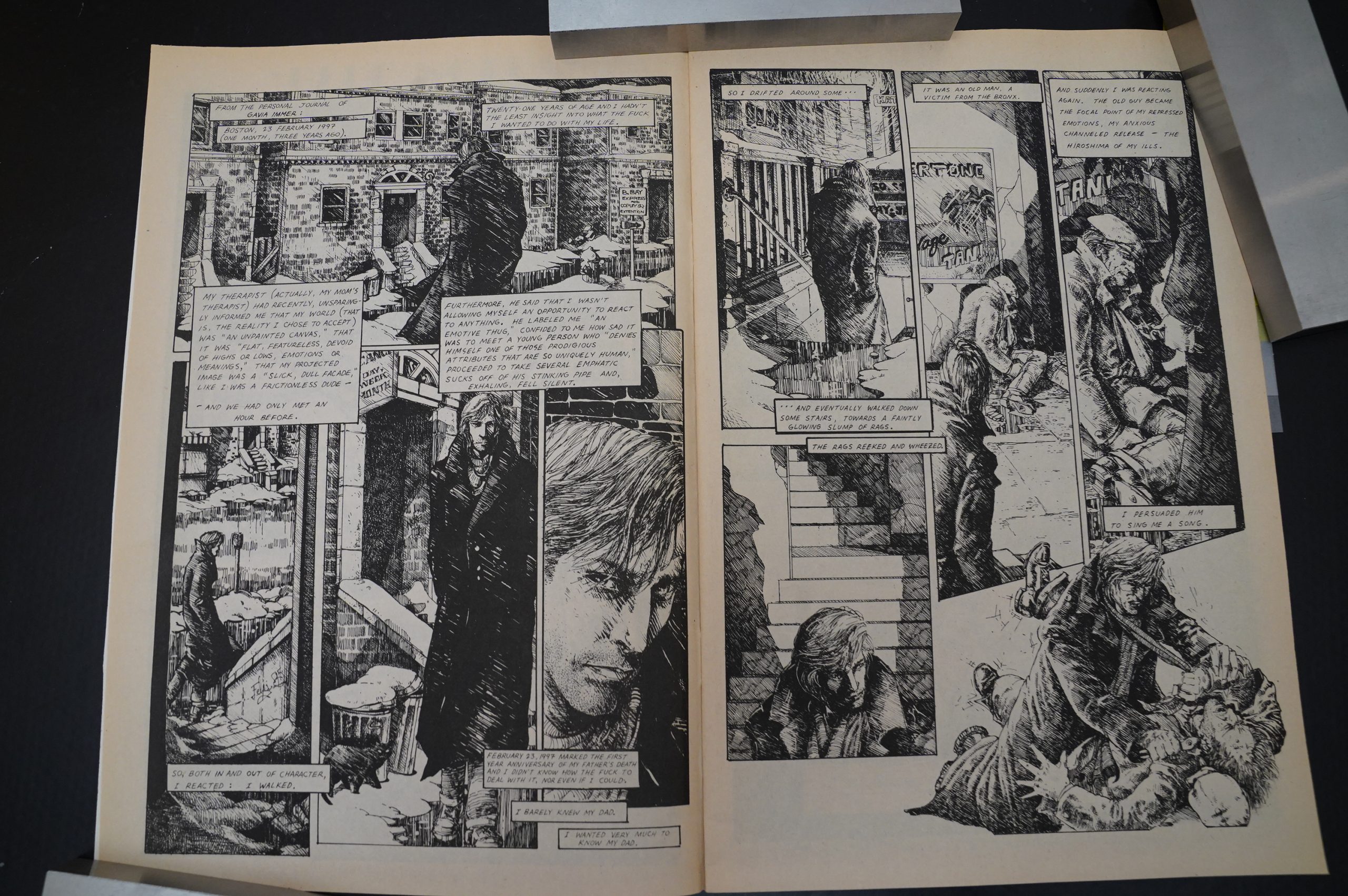

But let’s read the first six pages (because we really have to):

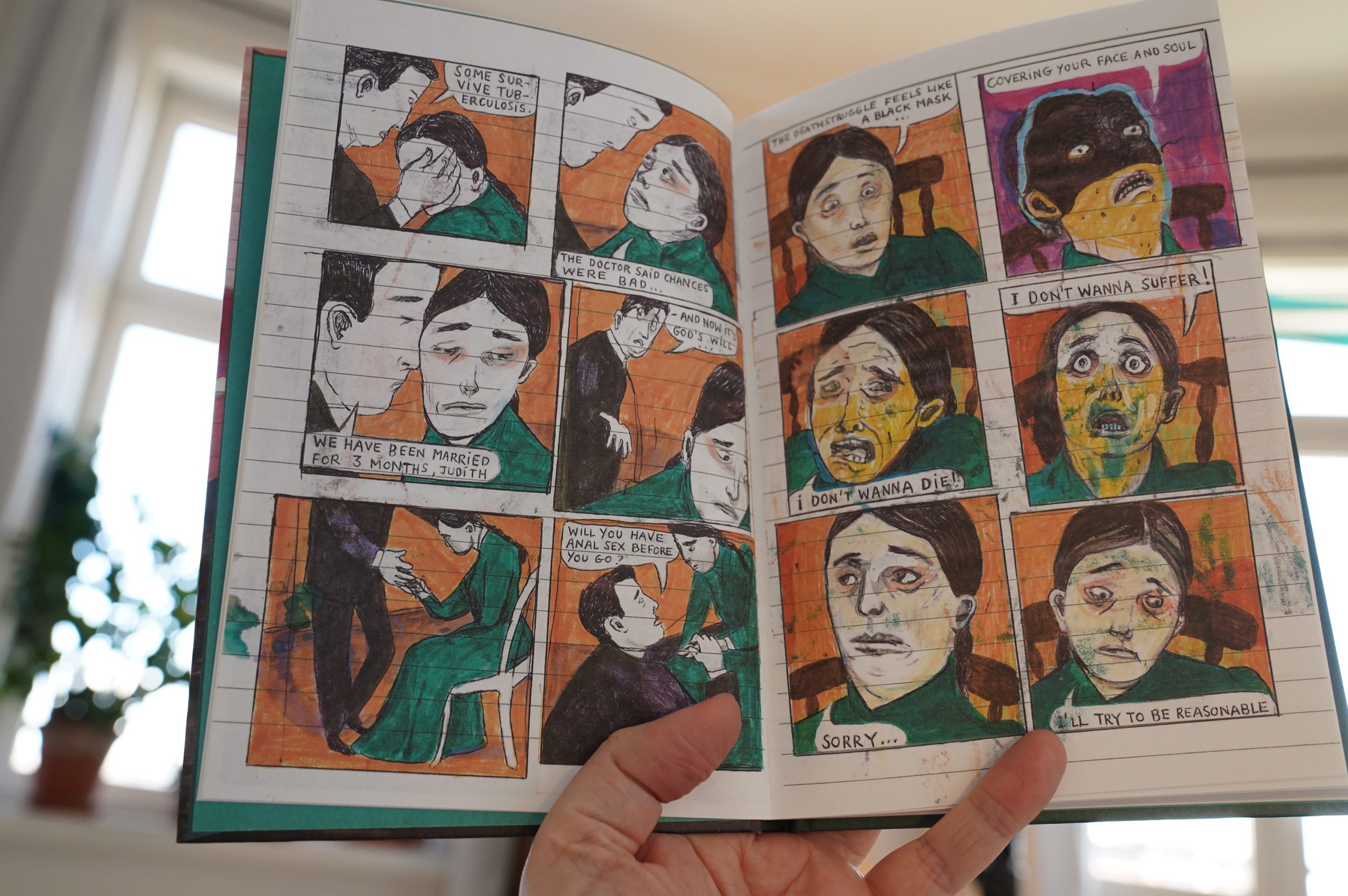

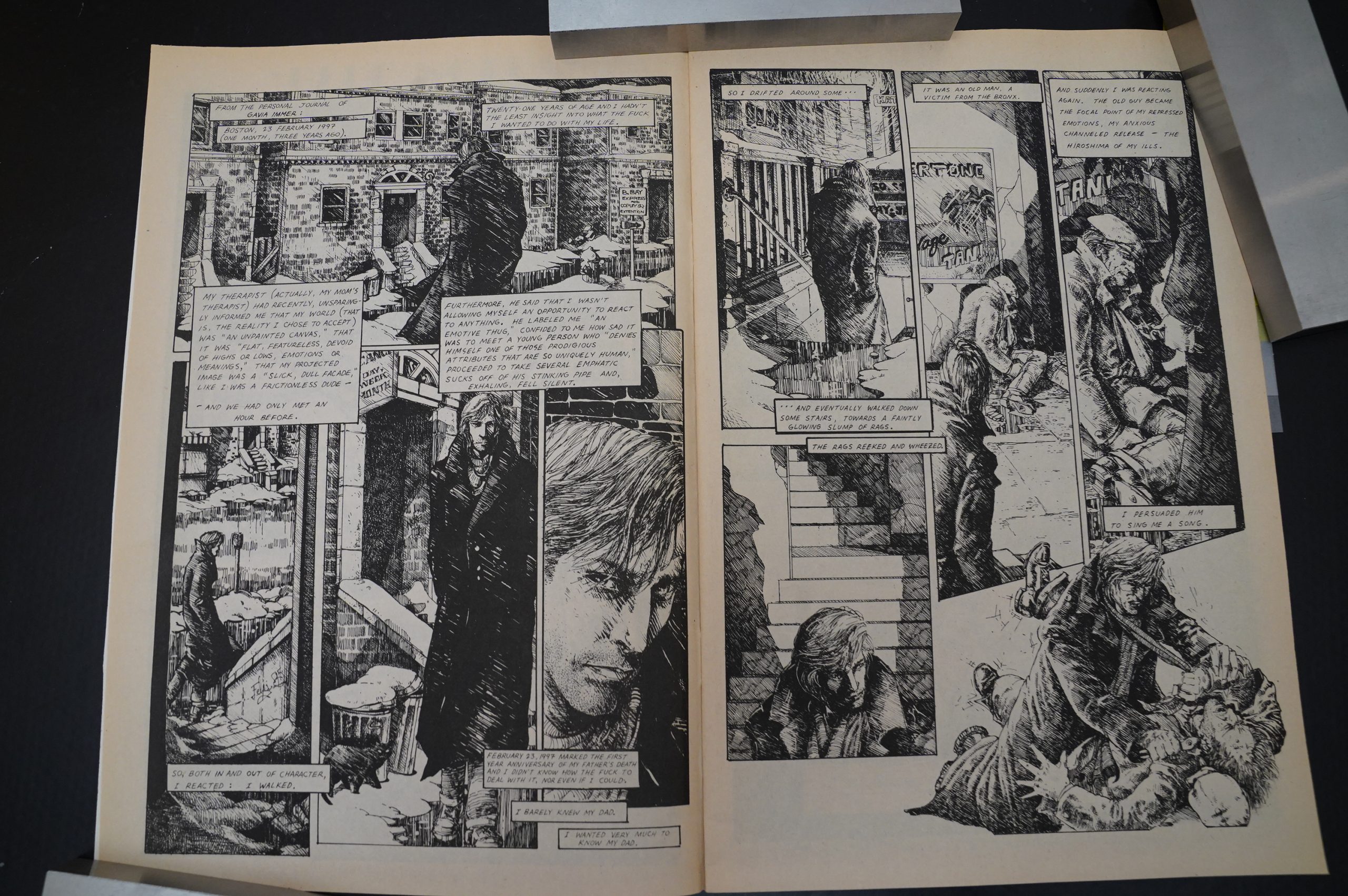

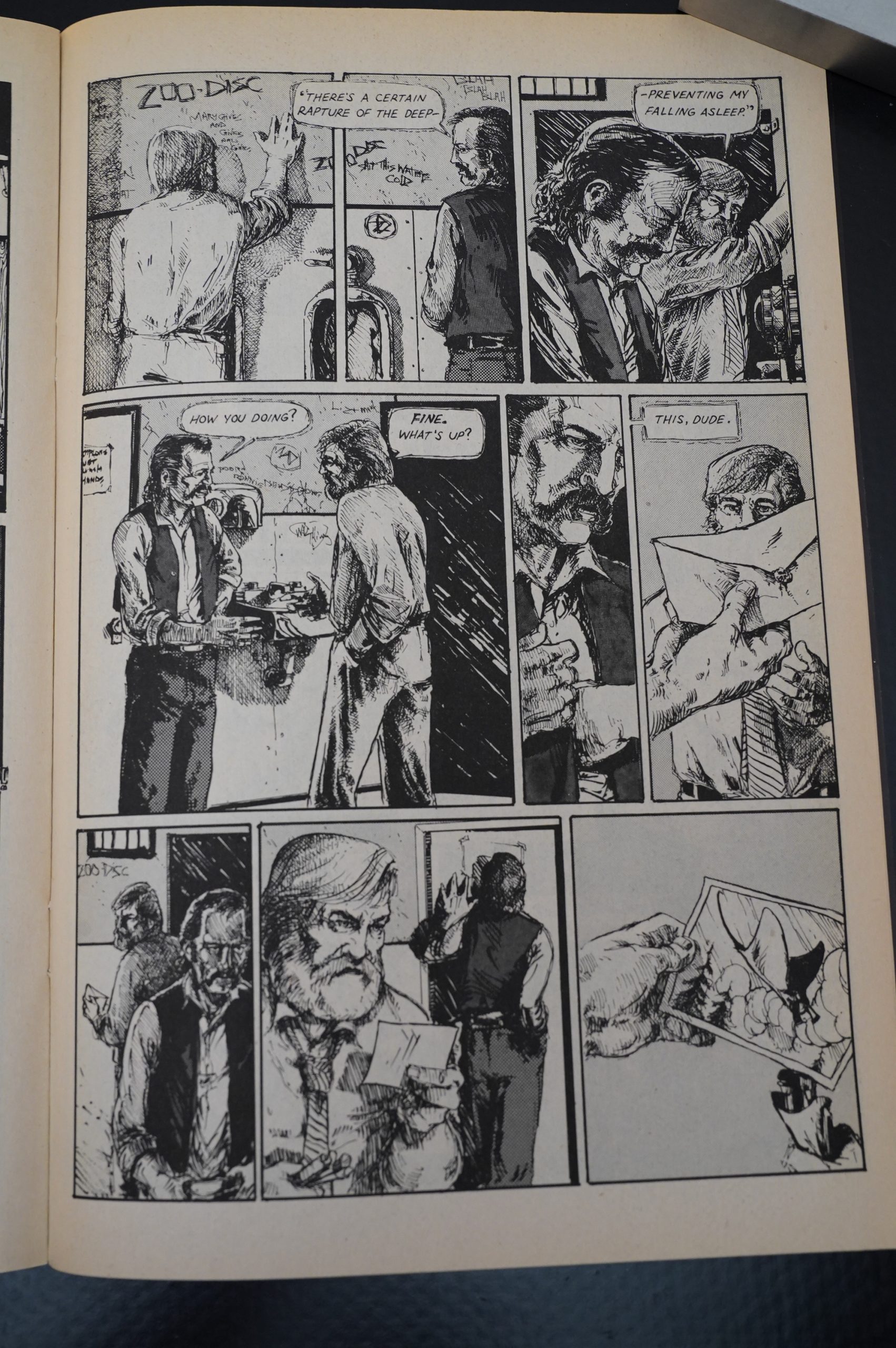

First of all… That’s the worst lettering ever! Second of all…

Whoa.

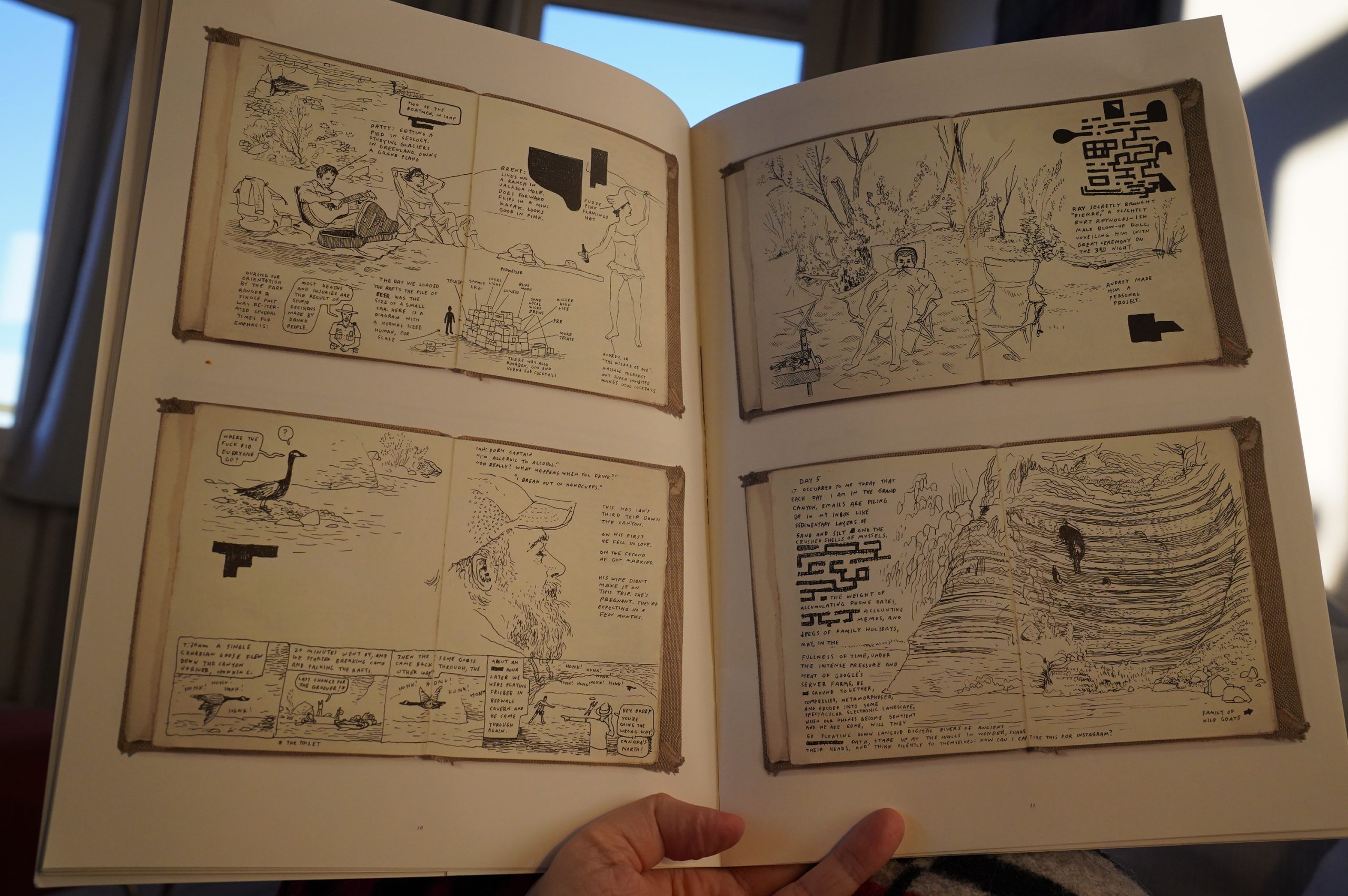

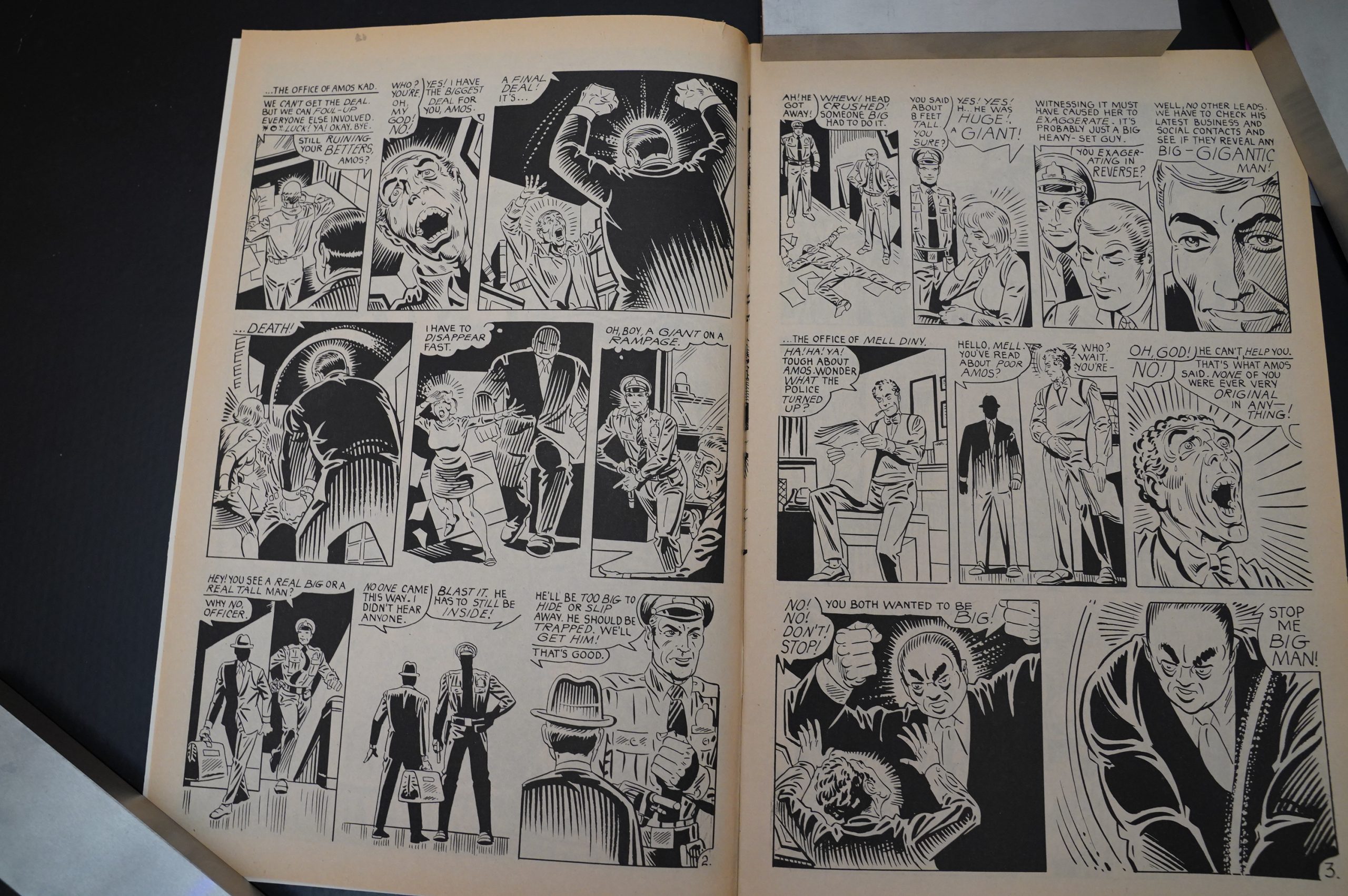

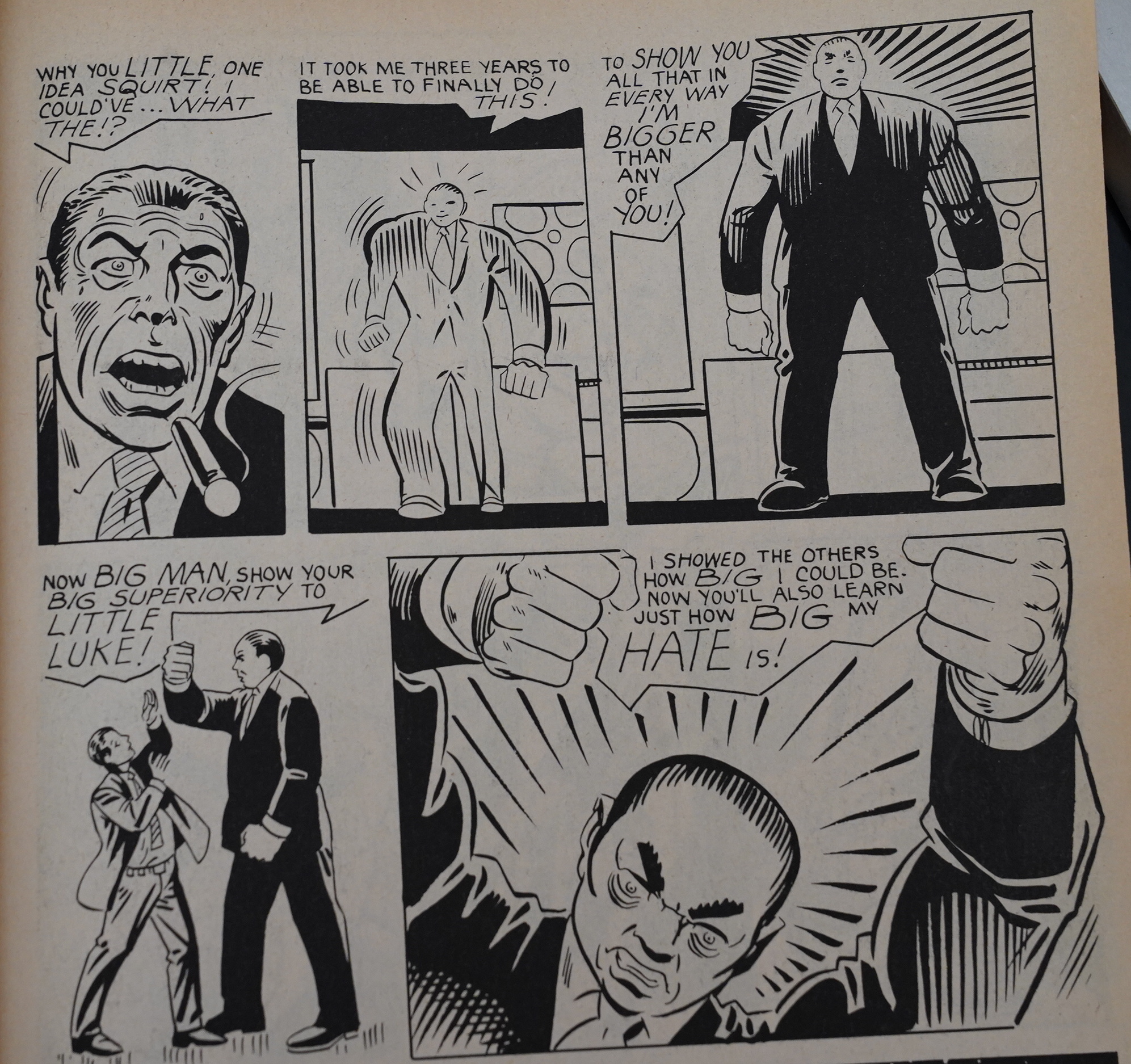

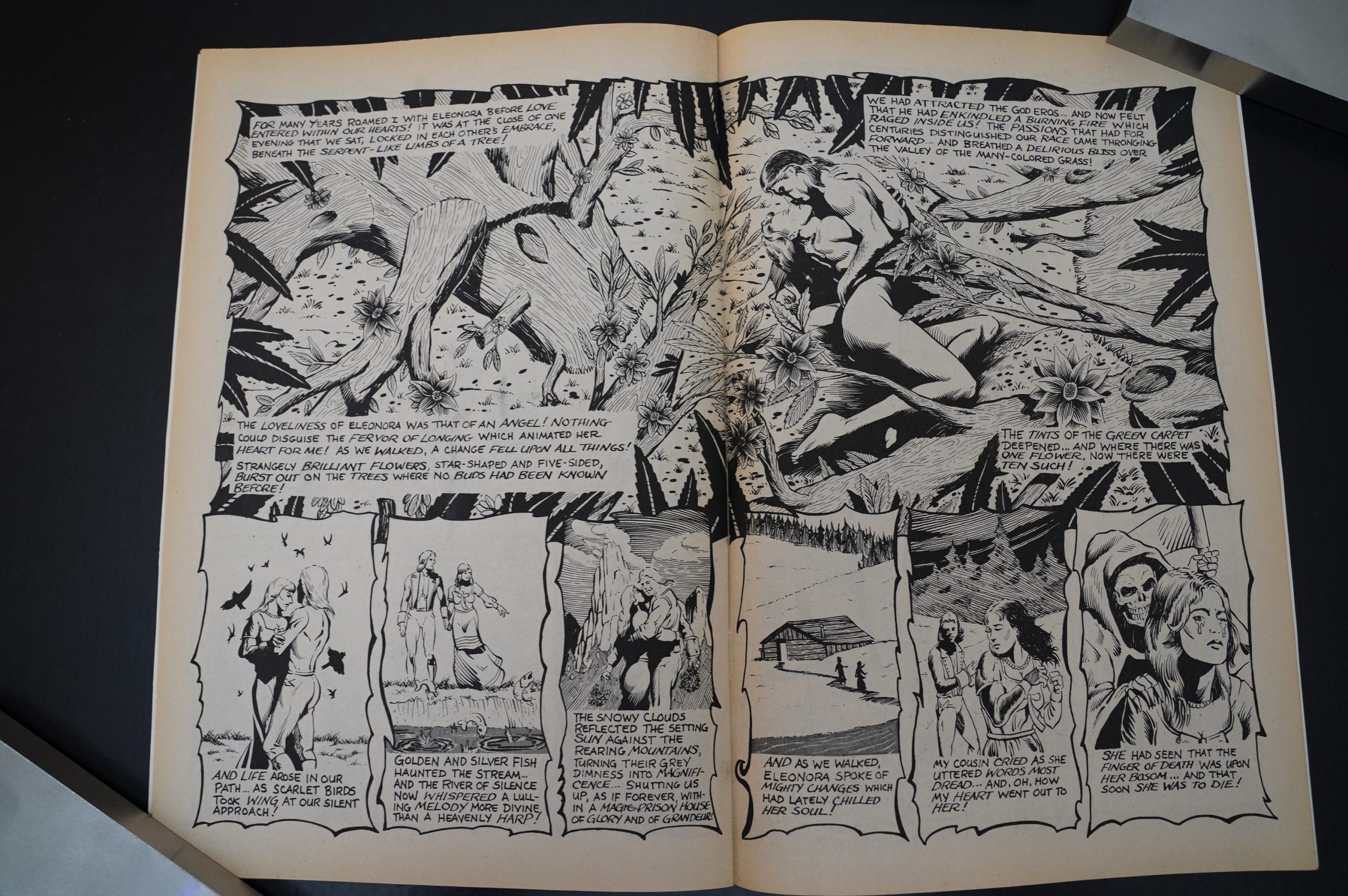

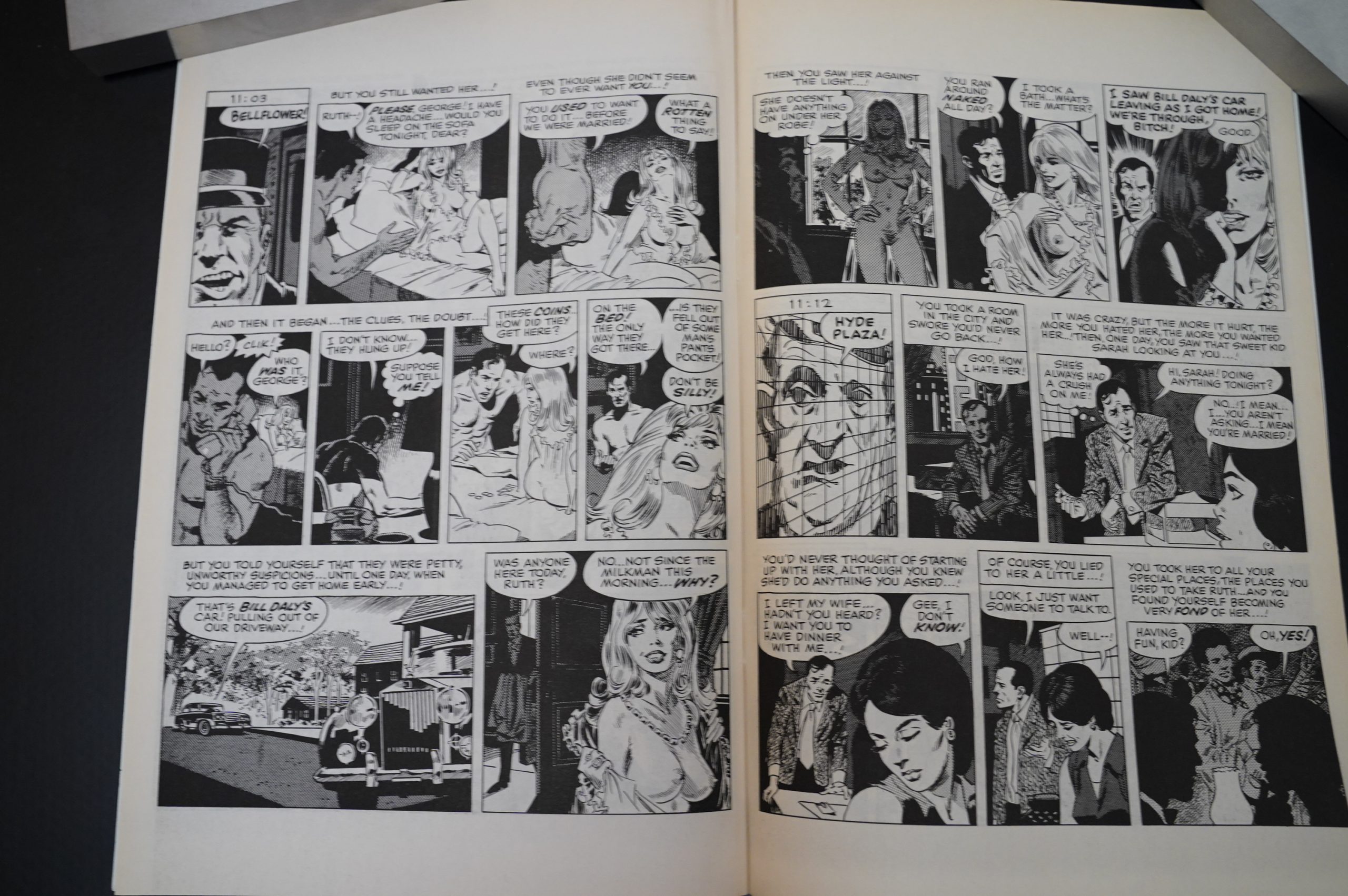

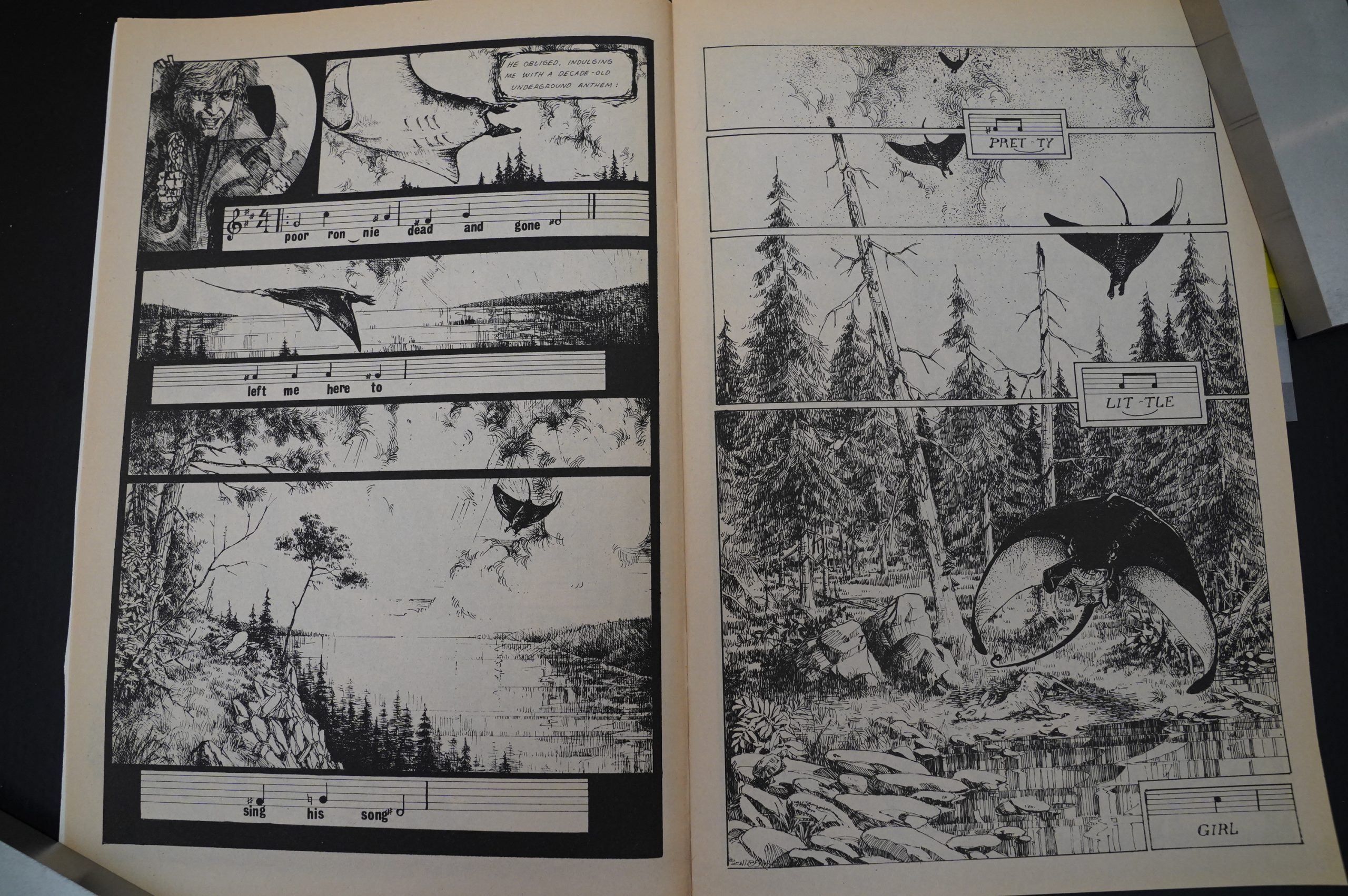

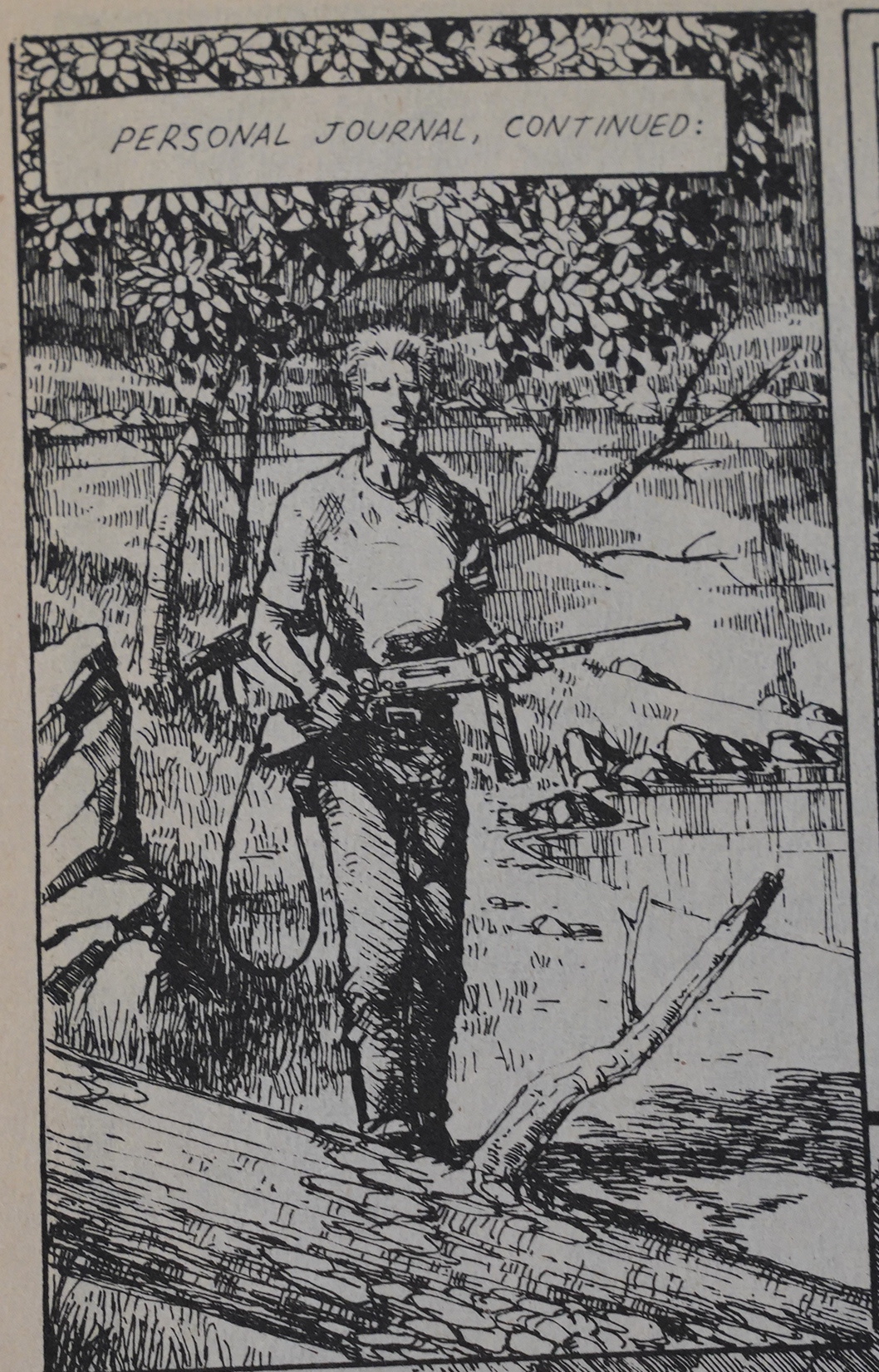

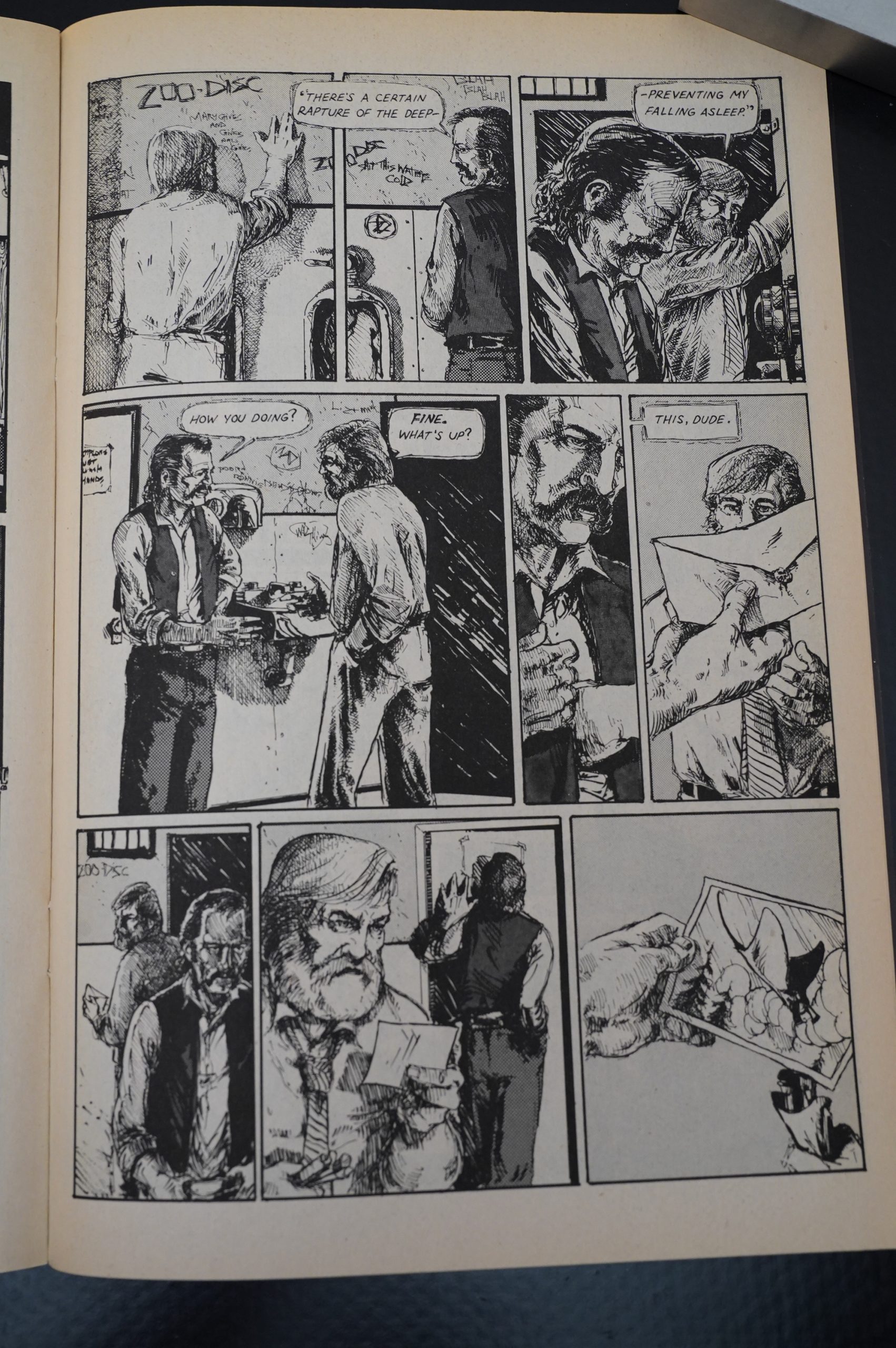

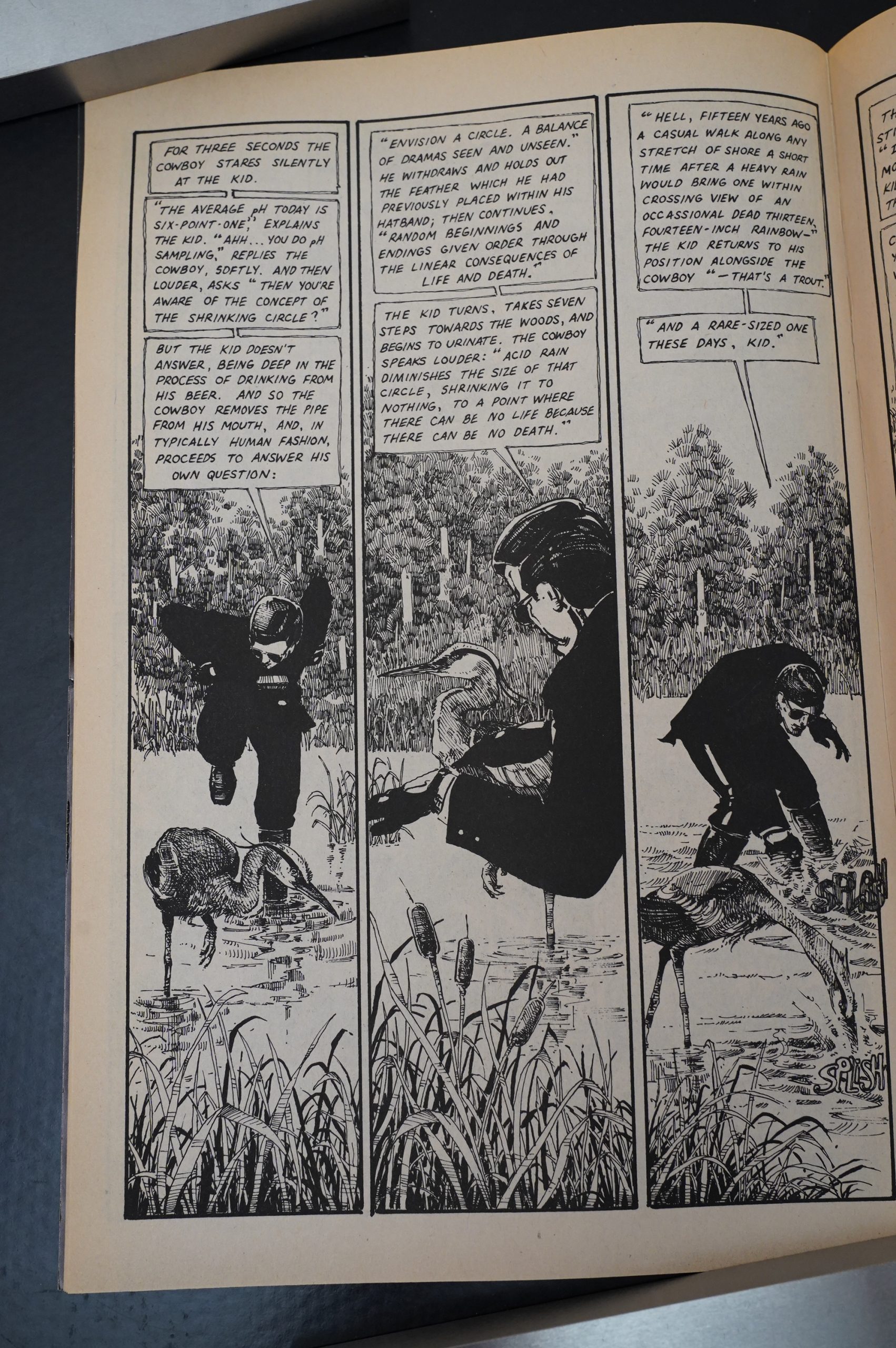

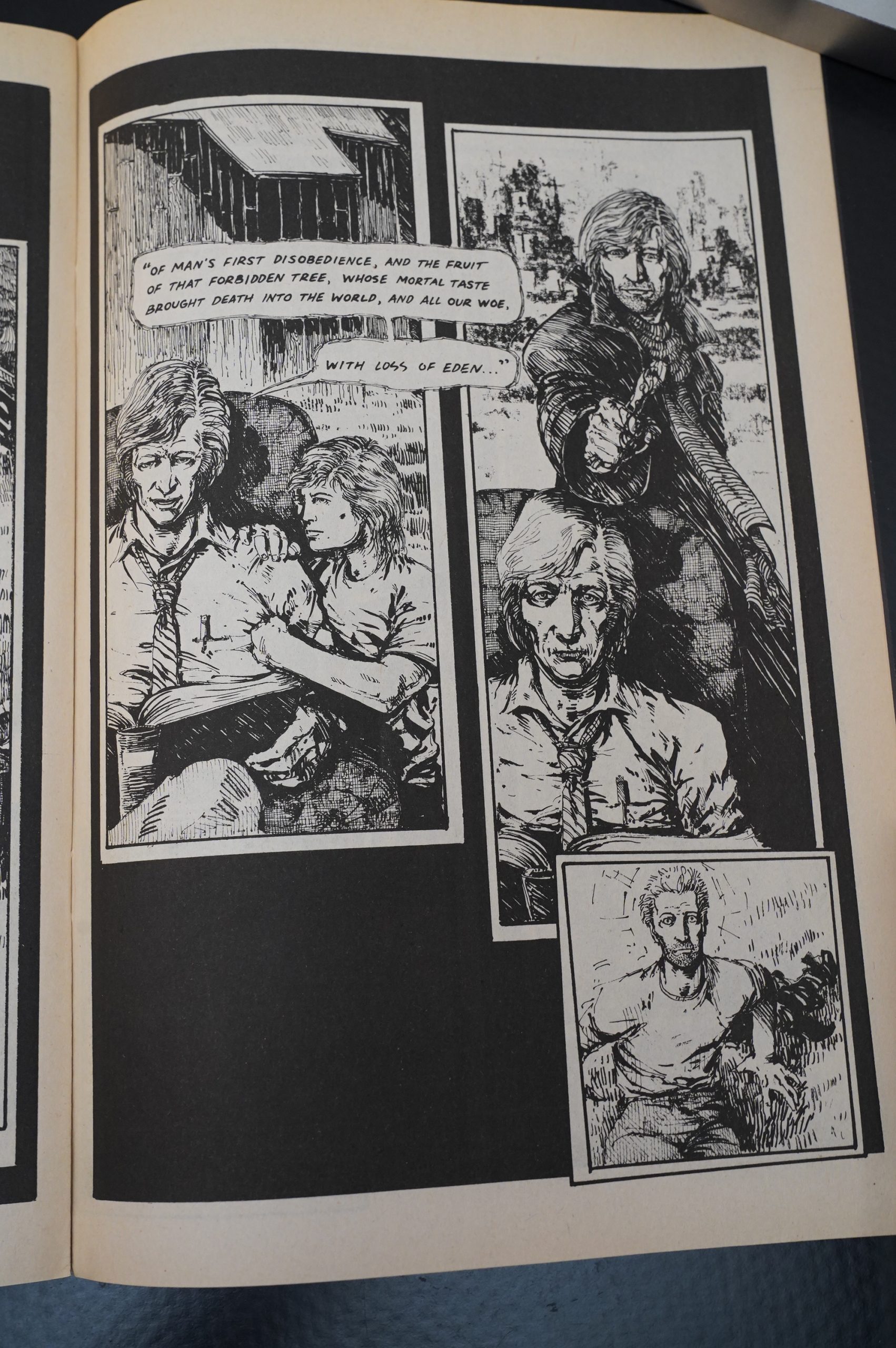

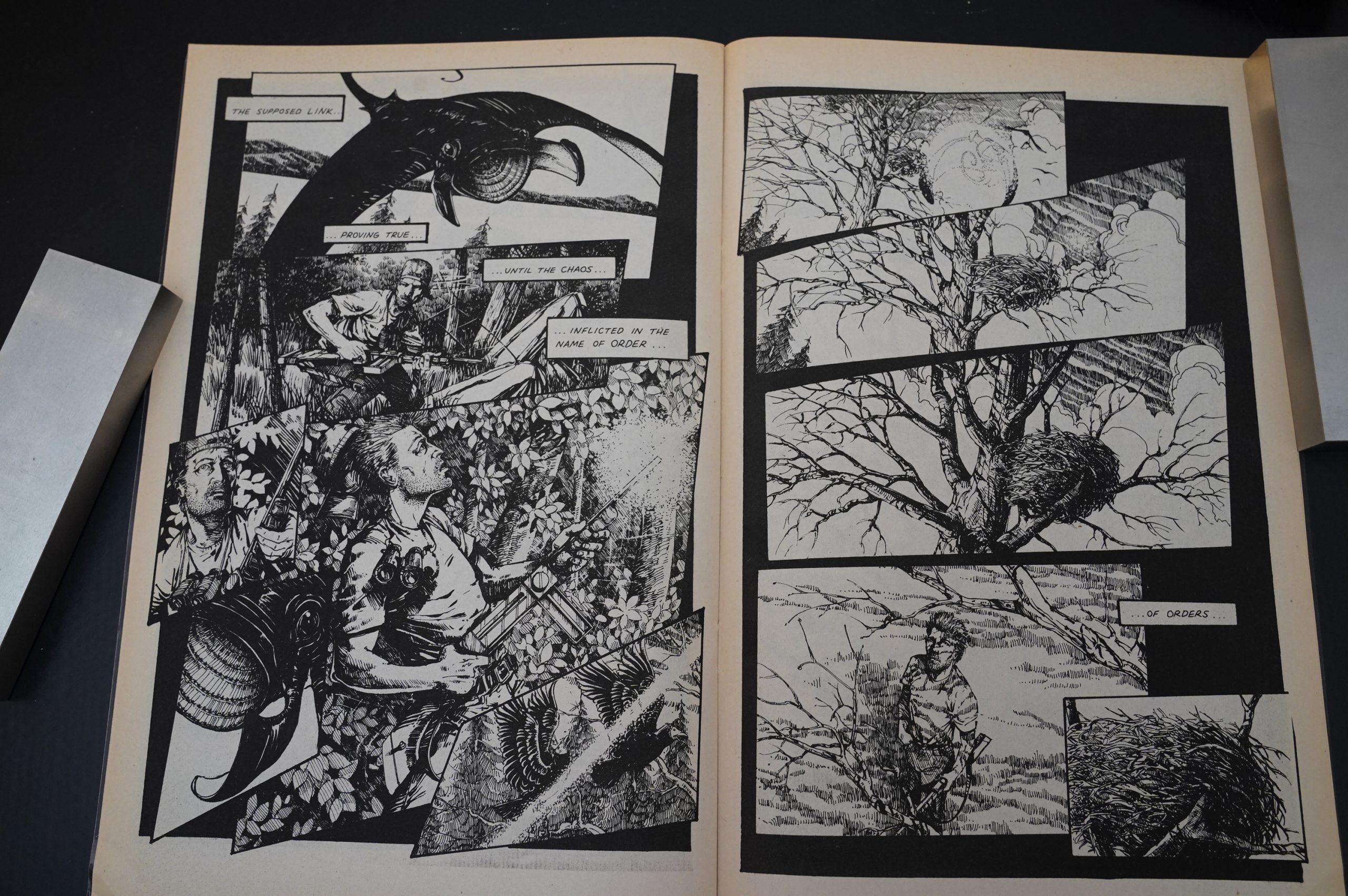

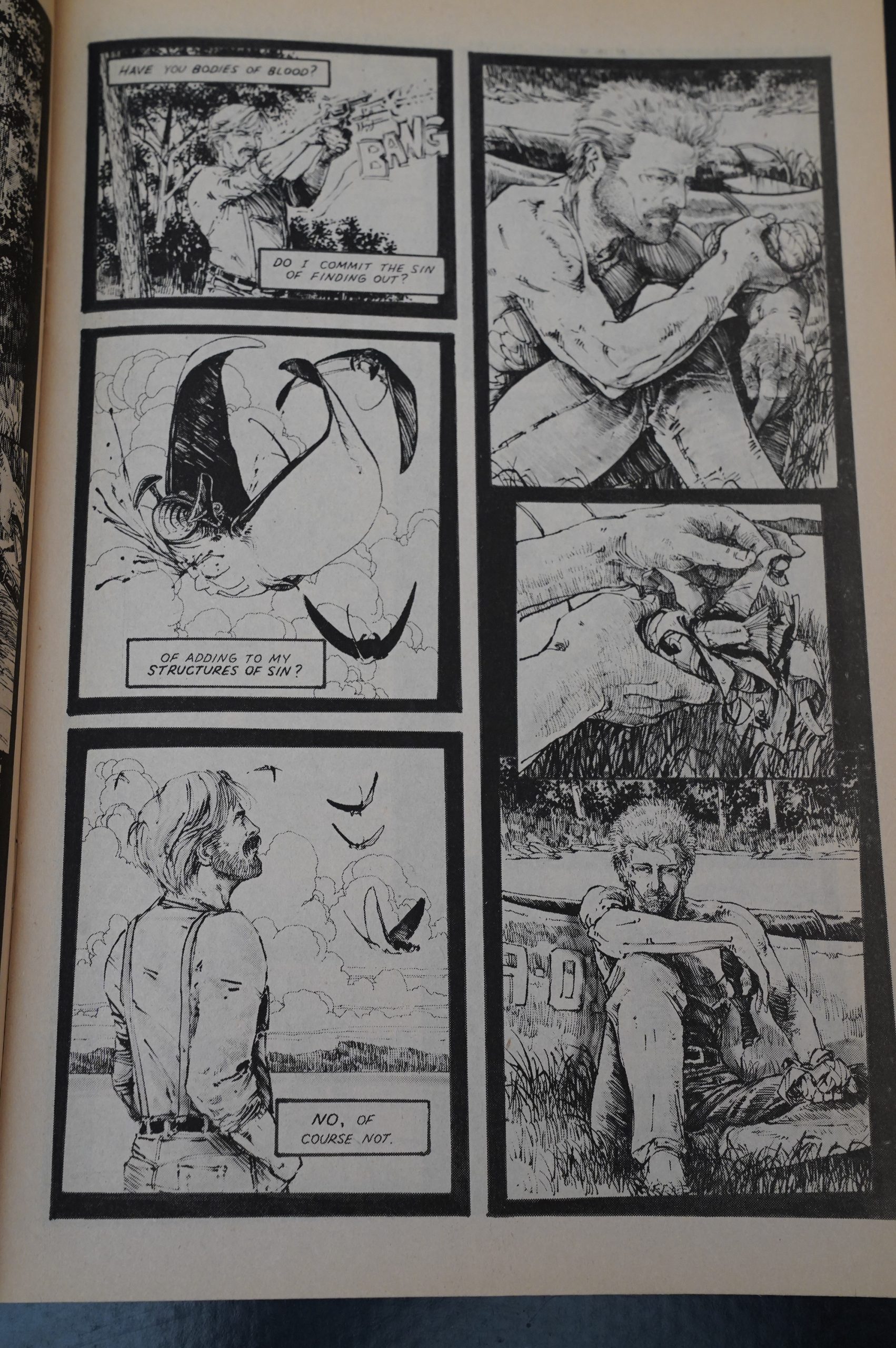

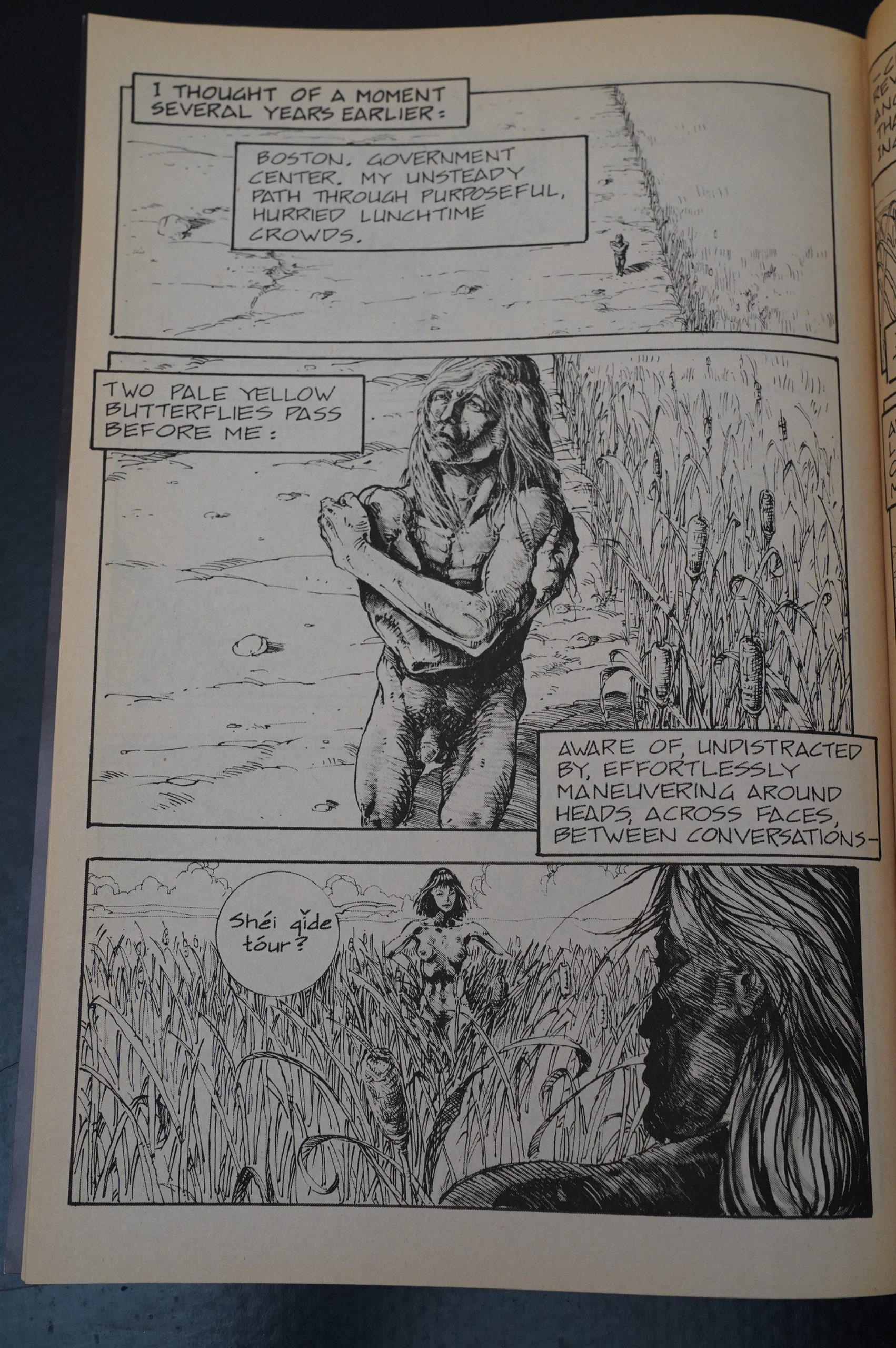

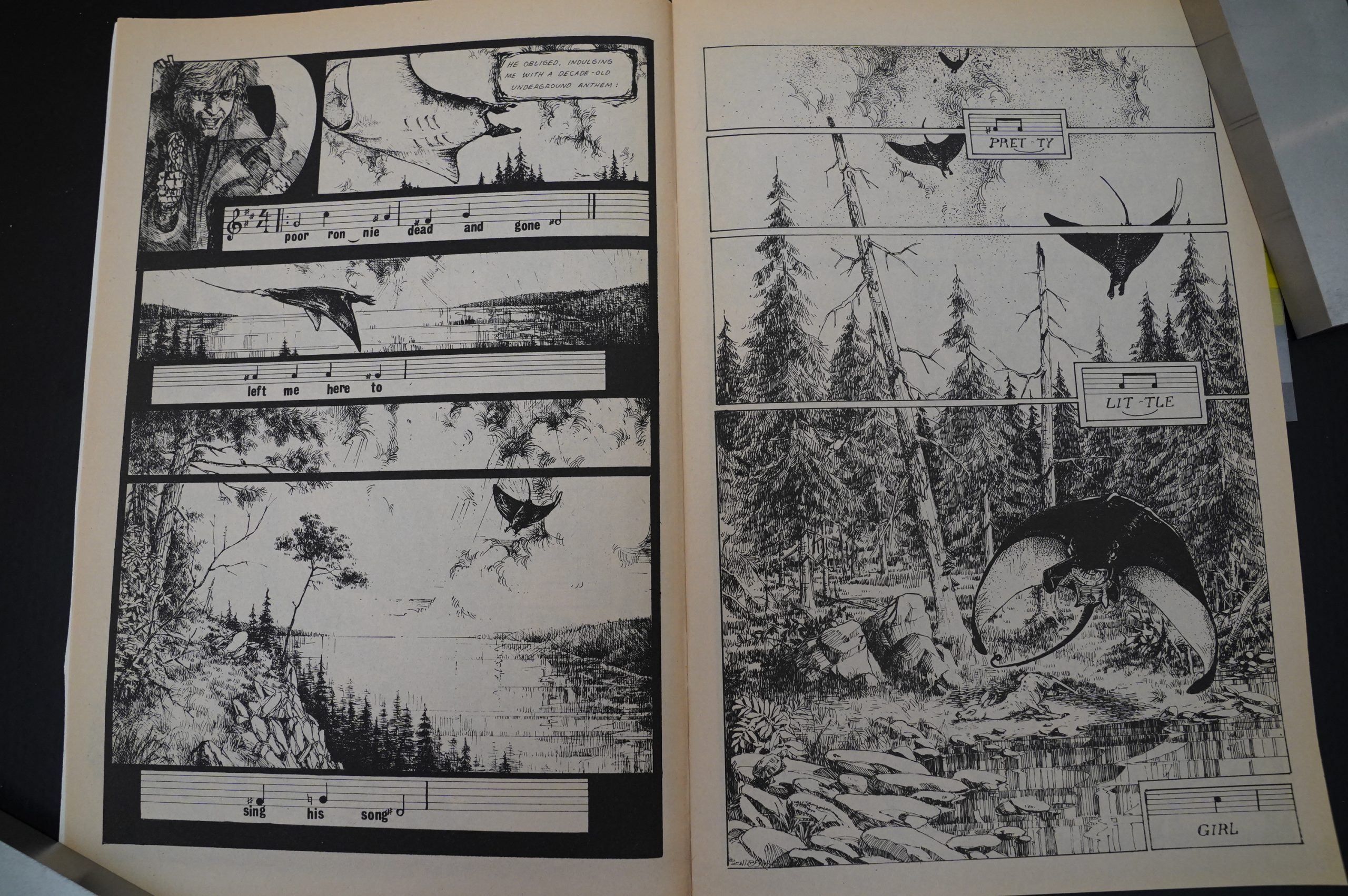

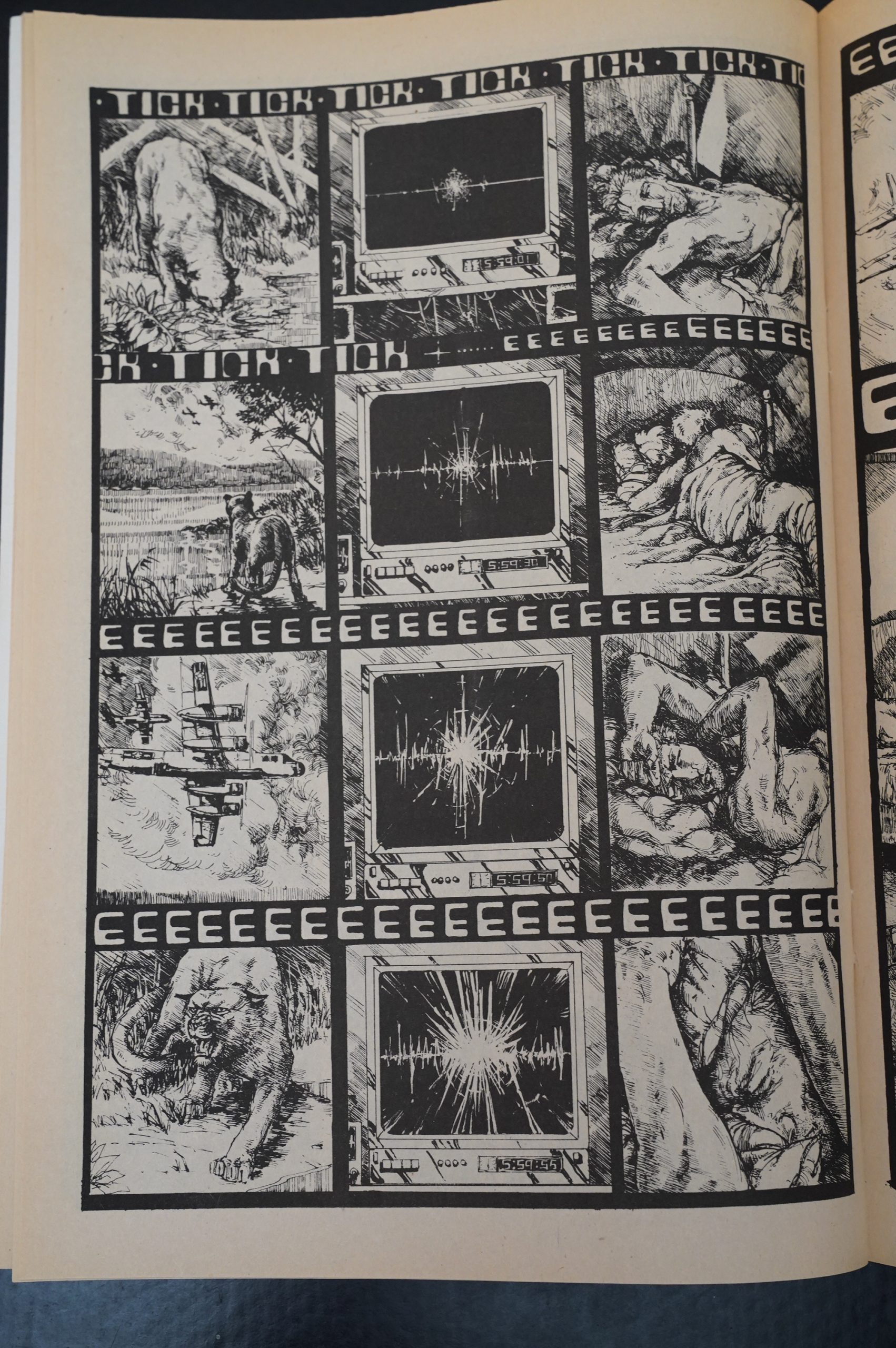

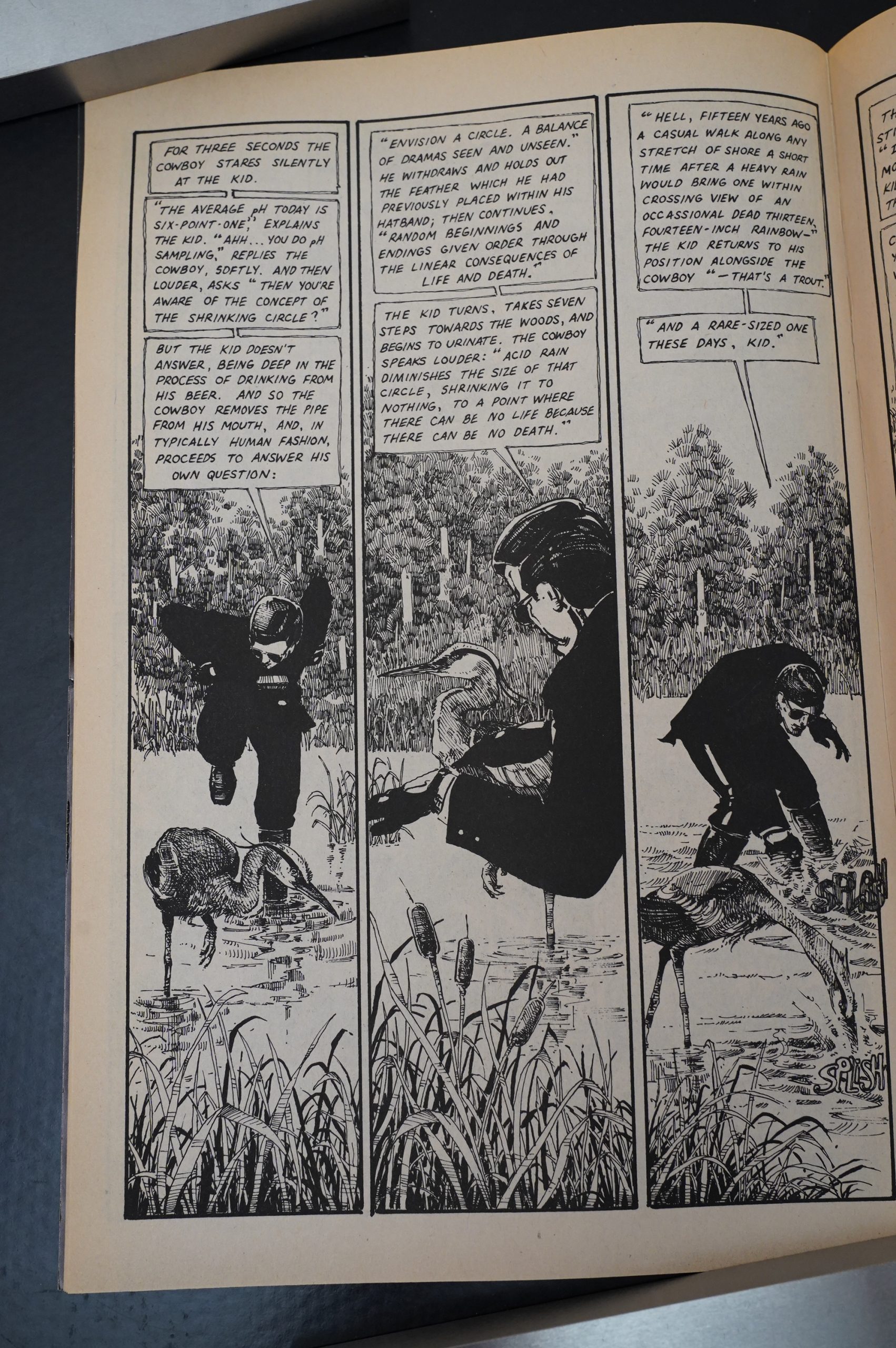

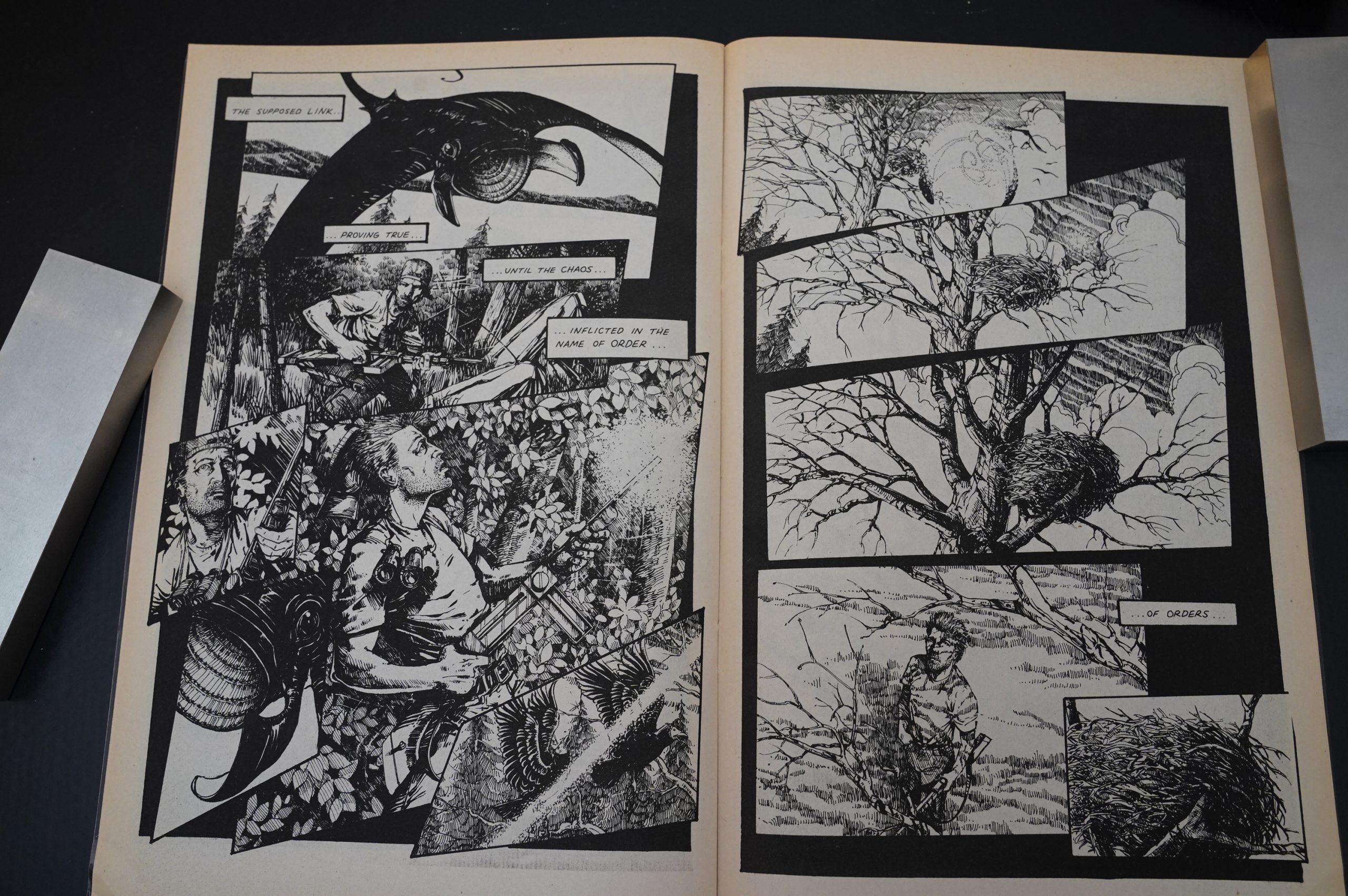

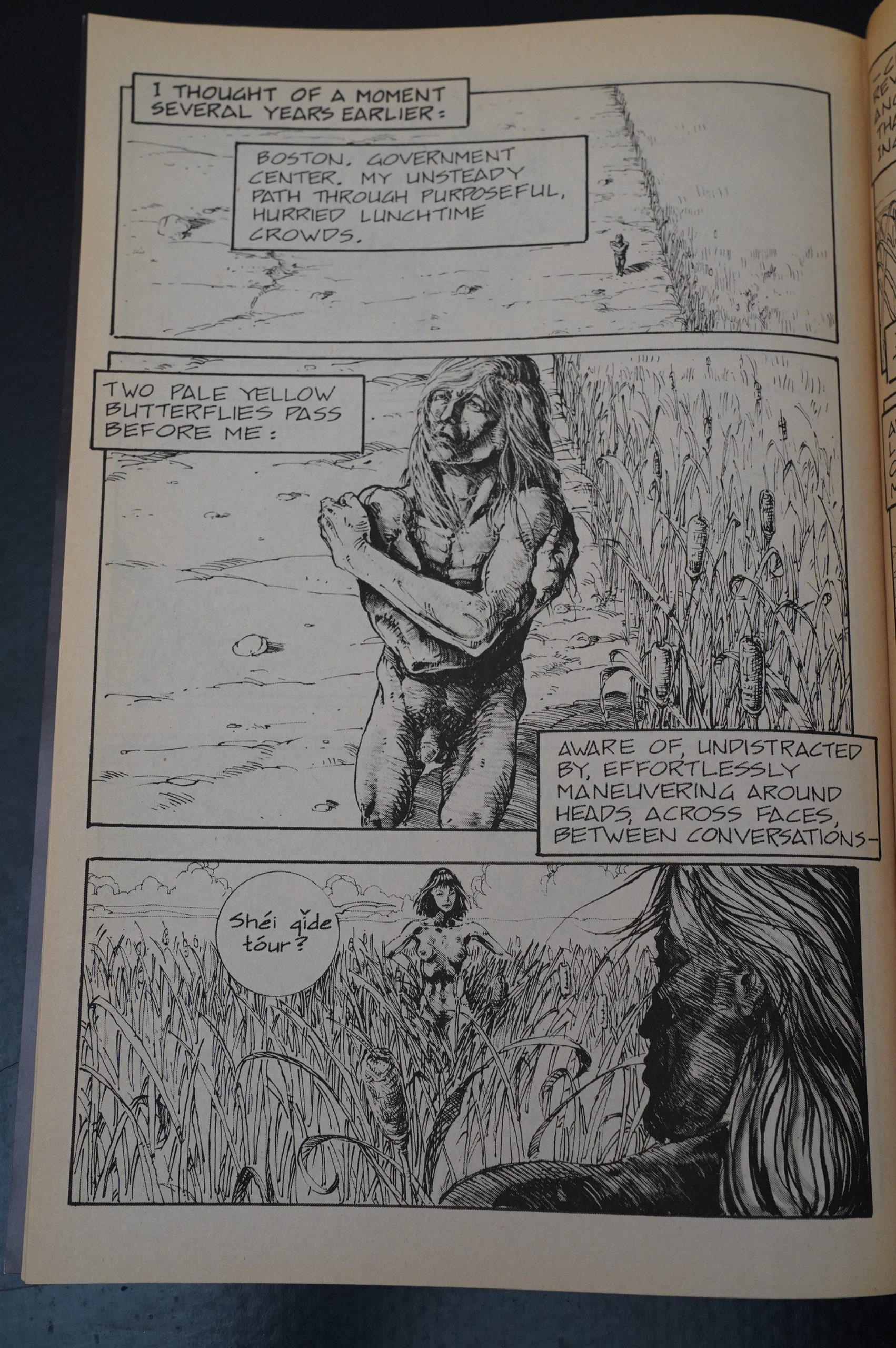

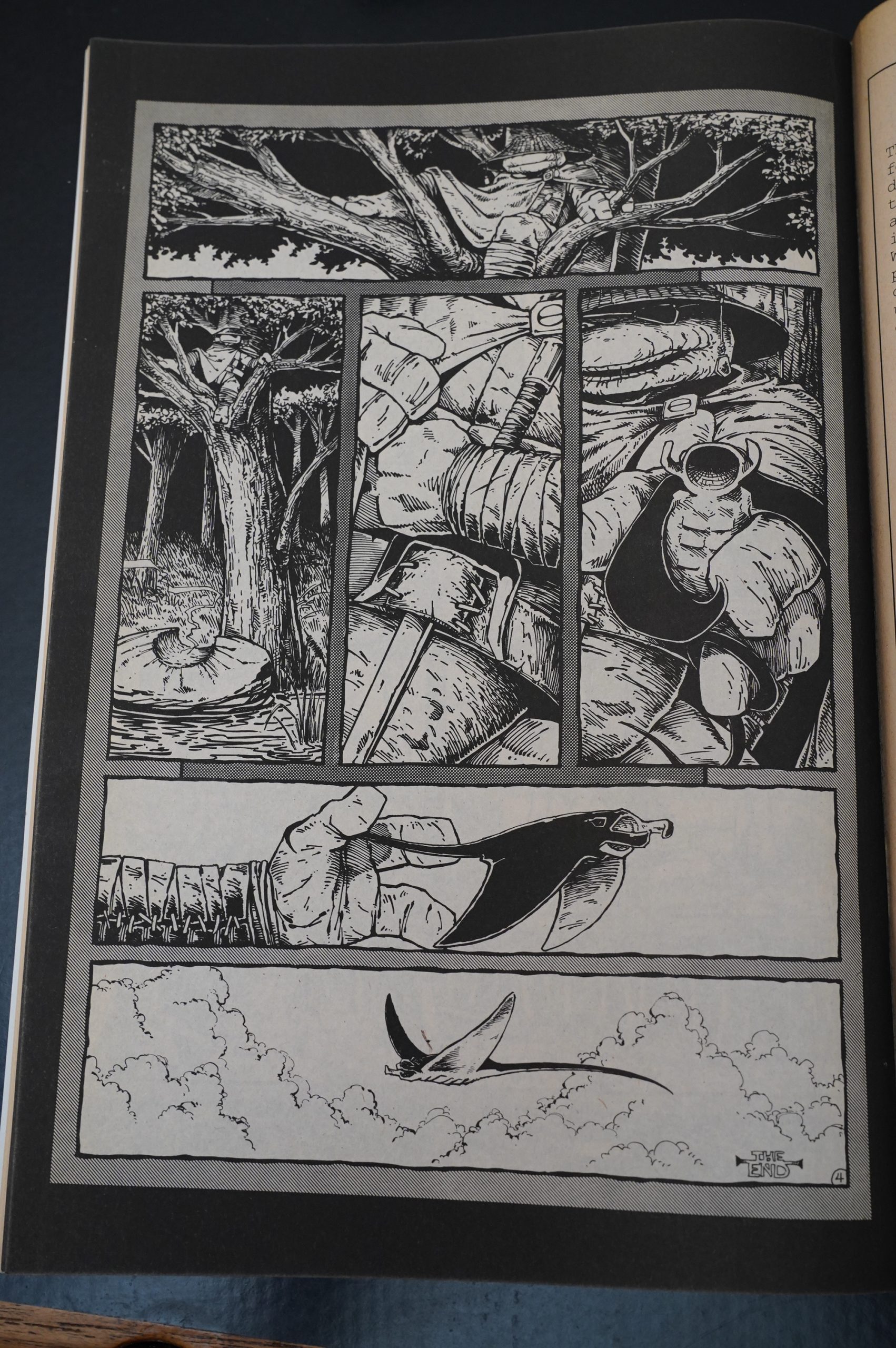

There’s so much going on here — we start off with a pretty oblique introduction from the creators, then an opening page with a scull out in a forest. Then we’re in the head of some hippie who seems to be all sensitive and stuff… who then gets out some pliers!? And … cuts off the ear lobe of some drunk? And then a smash cut to manta rays flying in the sky?

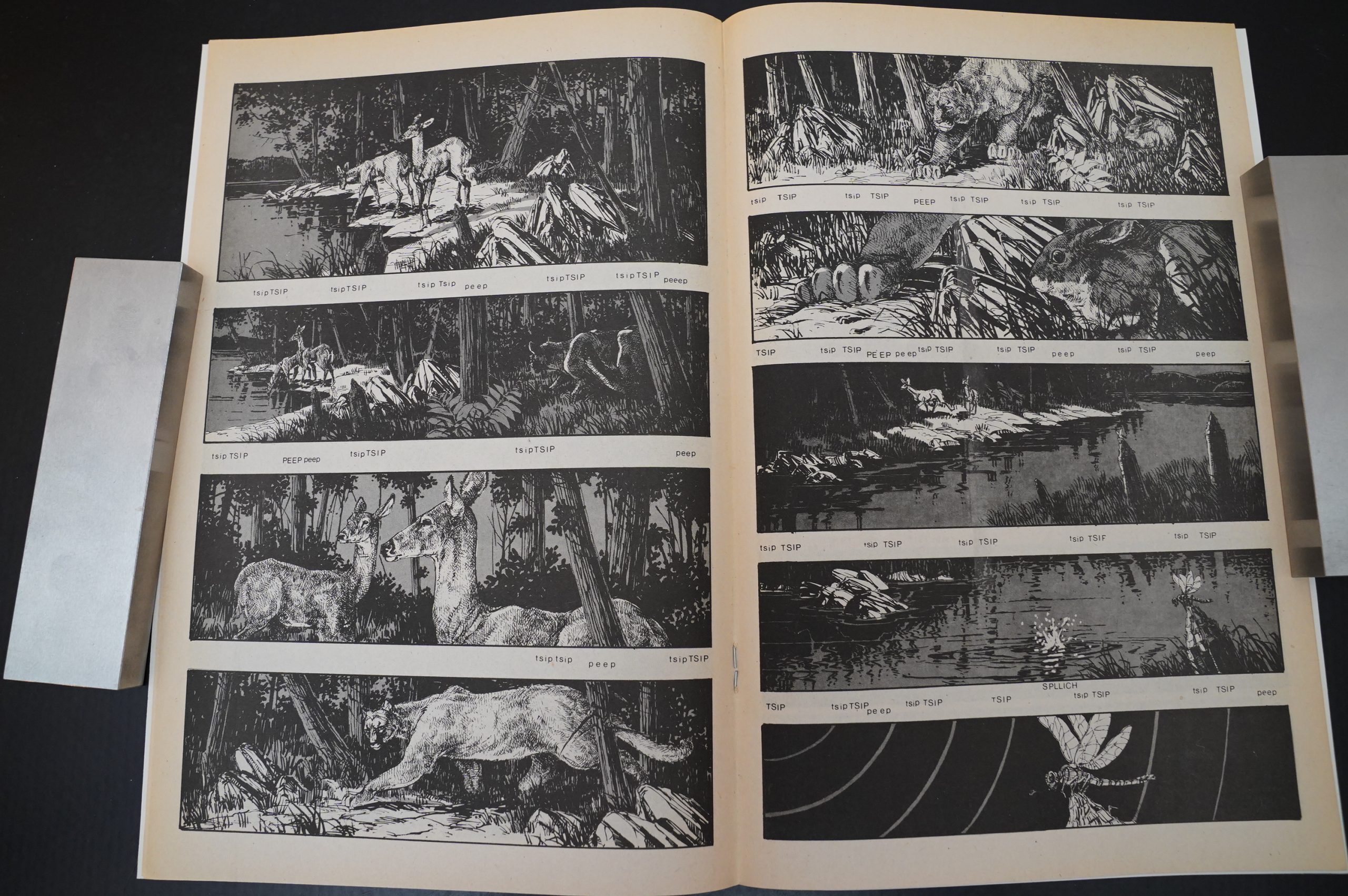

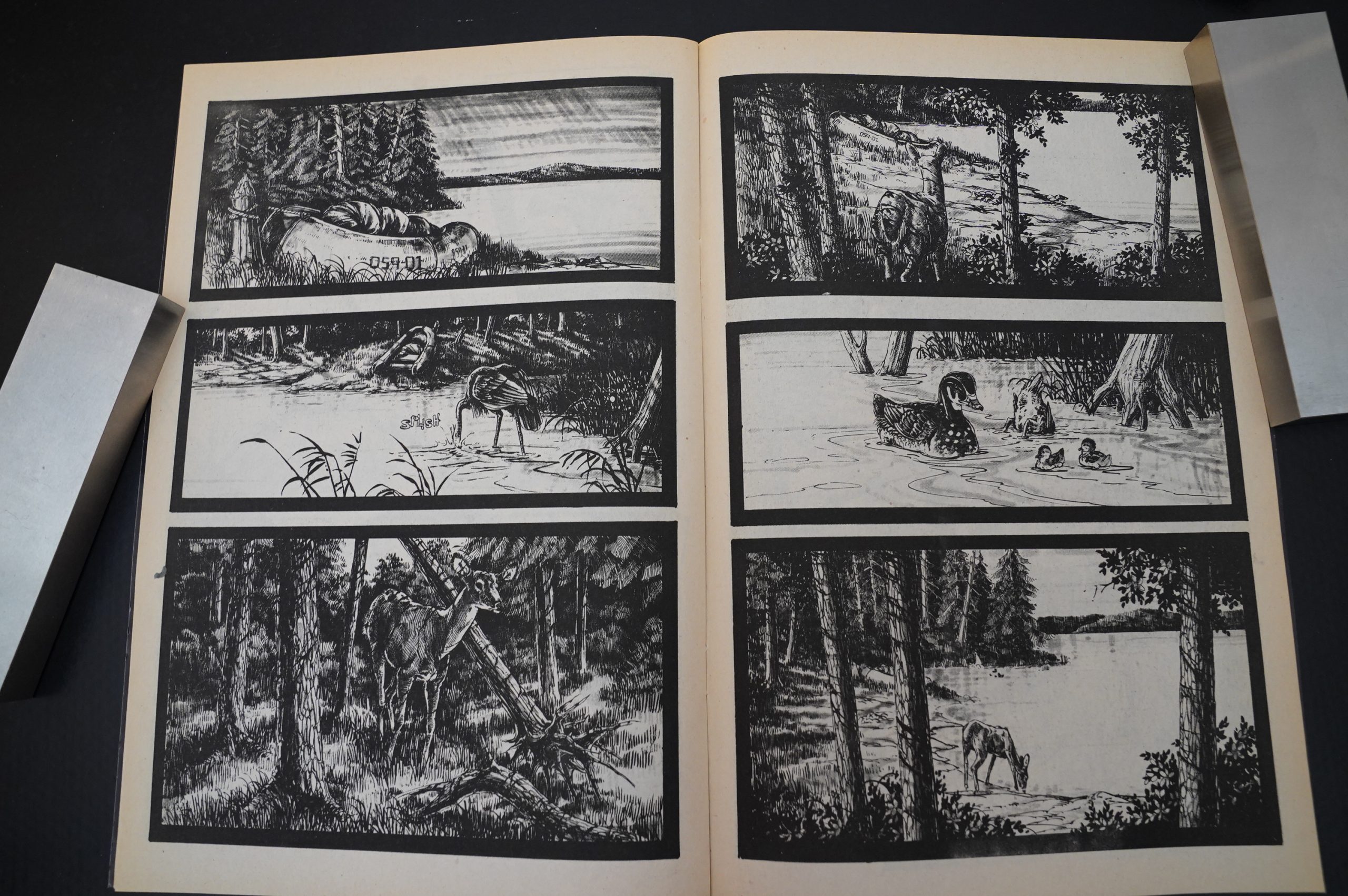

And the nature bits are exquisitely drawn, while the figure work is a bit dodgy, and…

If this isn’t the most intriguing way to start a comics series, I think it’s in the top ten? I guess you could quibble with the sensitive guy/ultraviolence schtick which has been done to death, but the pliers are just such an insane choice that it’s all kinda flabbergasting.

If there’s one immediate problem, it’s Zulli’s inconsistent rendering of people. We surmise from the caption that this is the same guy as in the opening pages, but there’s really nothing from the drawing that would even hint at that (beyond it being a thin, blond(e) guy, but then we don’t know if that’s just how Zulli draws people (spoilers: sure)).

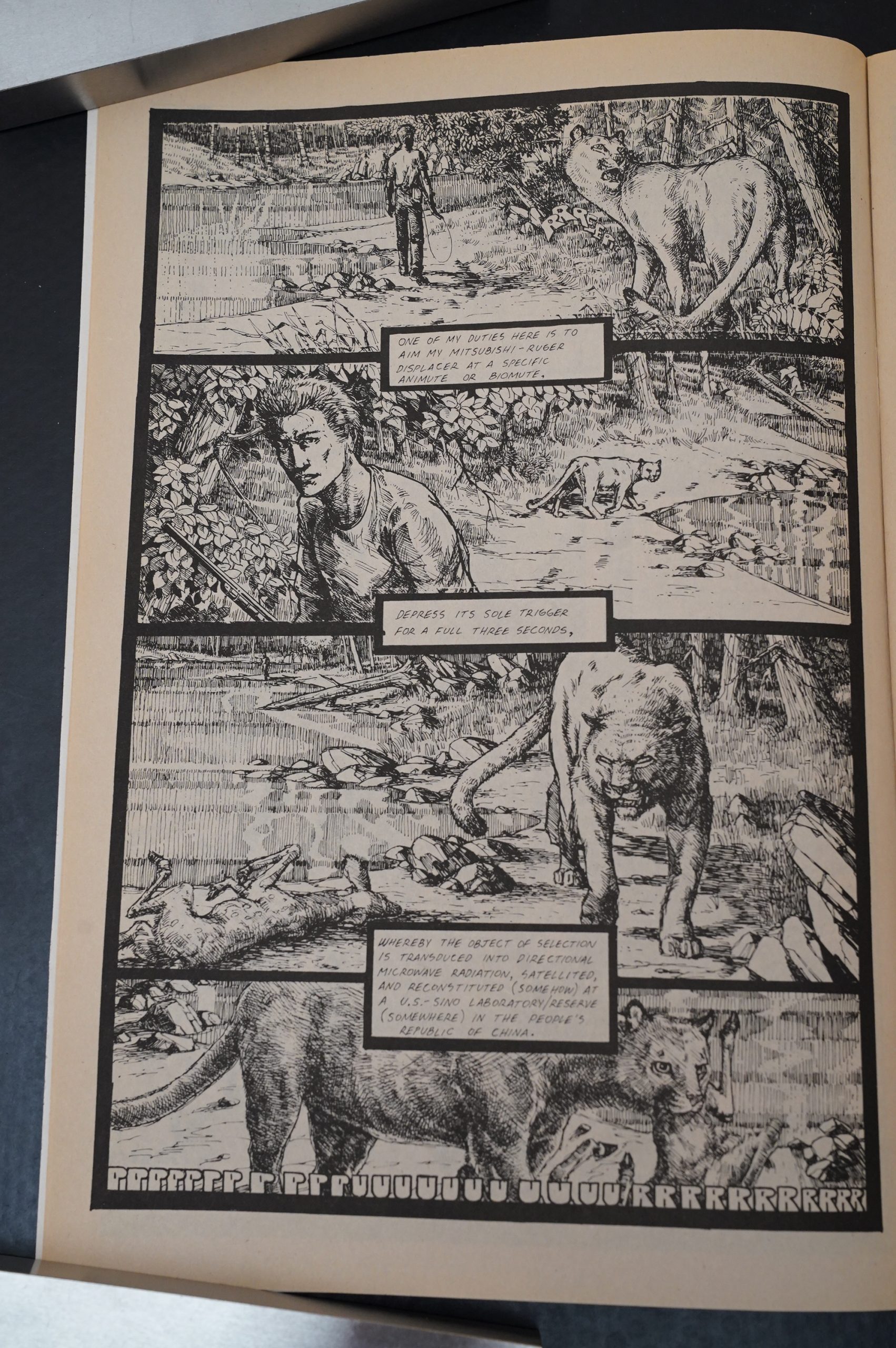

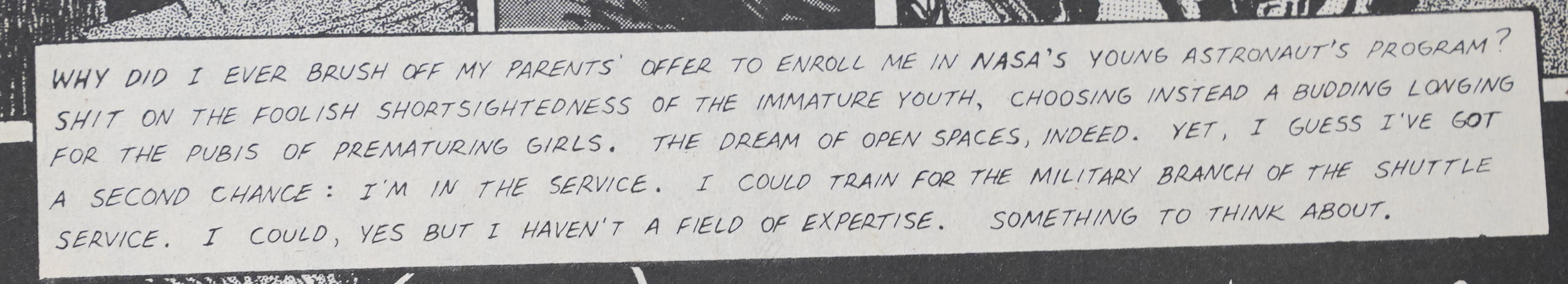

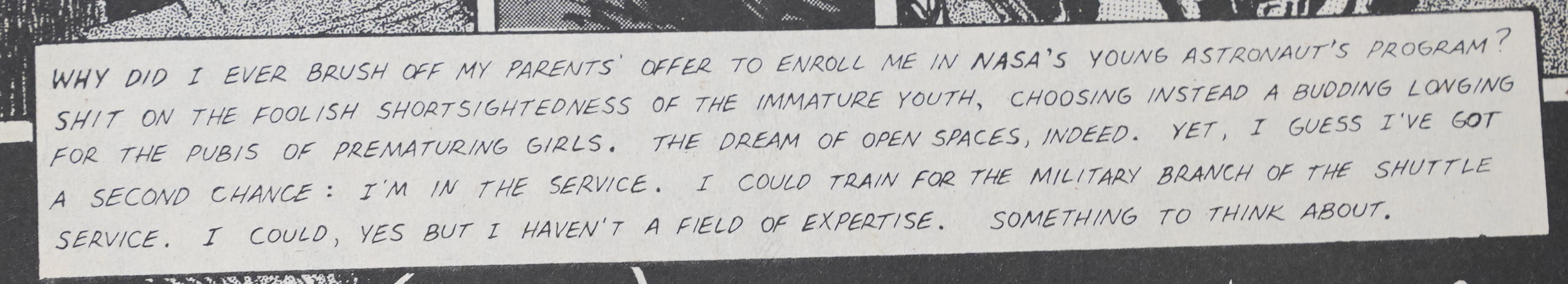

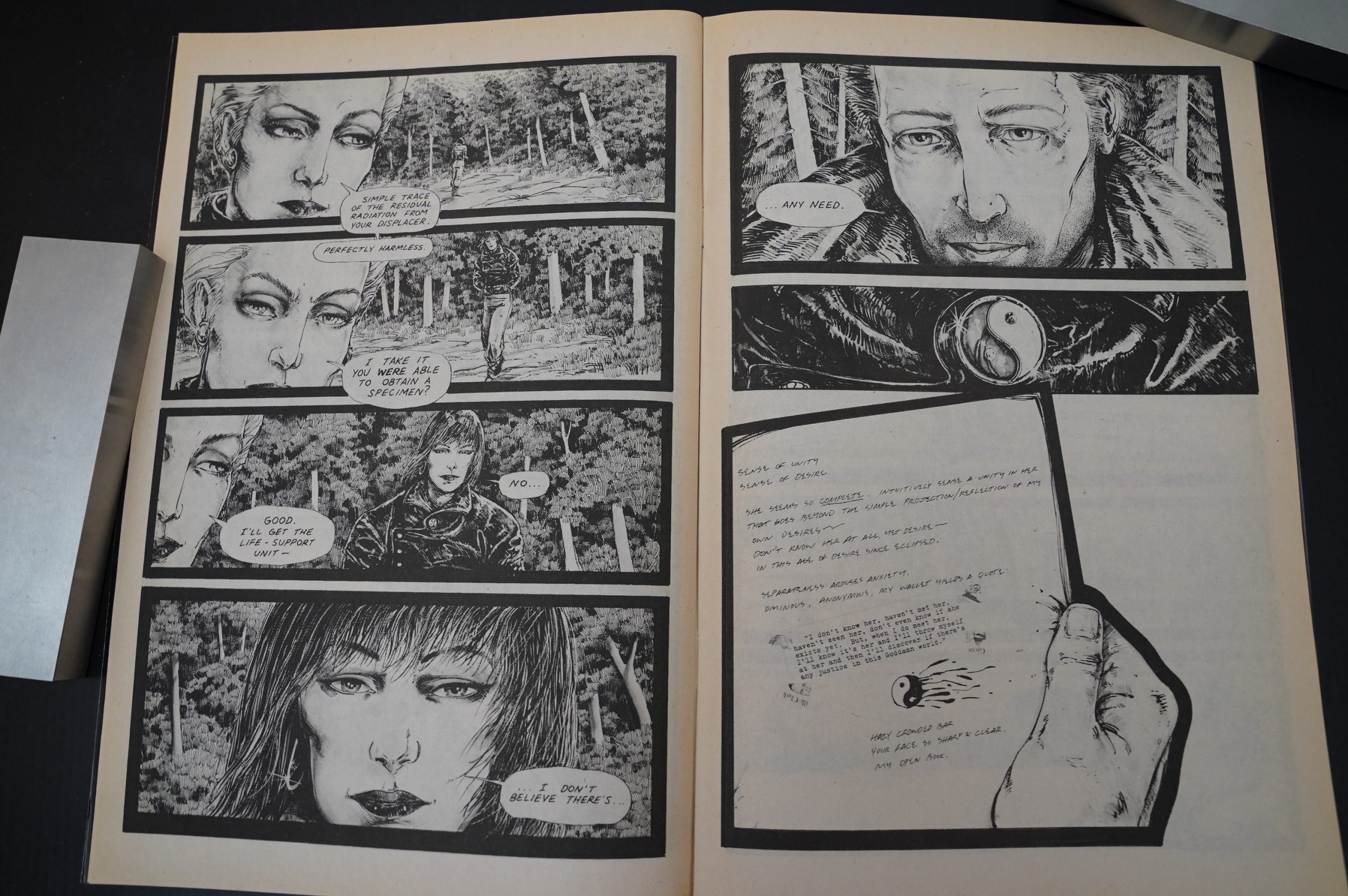

I think you could also quibble with some of the storytelling choices: They withhold a lot of information (which is always fun), but when they give us information, it’s often in the form of internal monologues (or as here, a journal excerpt) that tells us about stuff… and in the context of the storytelling style, it feels a bit like cheating.

And the prose goes purple all the time.

But it’s mostly just absolutely on point: Ripping off storytelling ticks from the best of them (Chaykin/Miller/Lee).

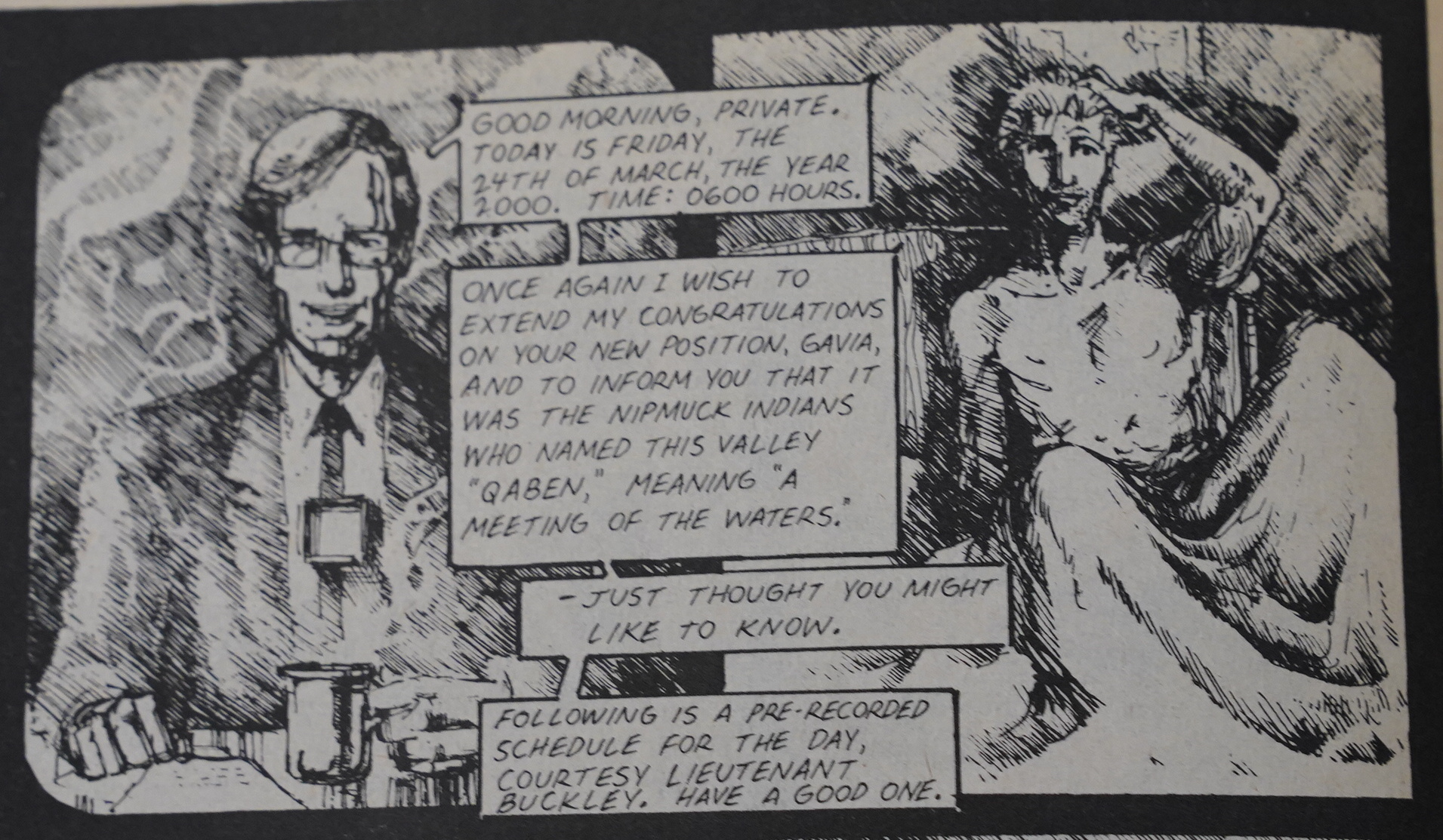

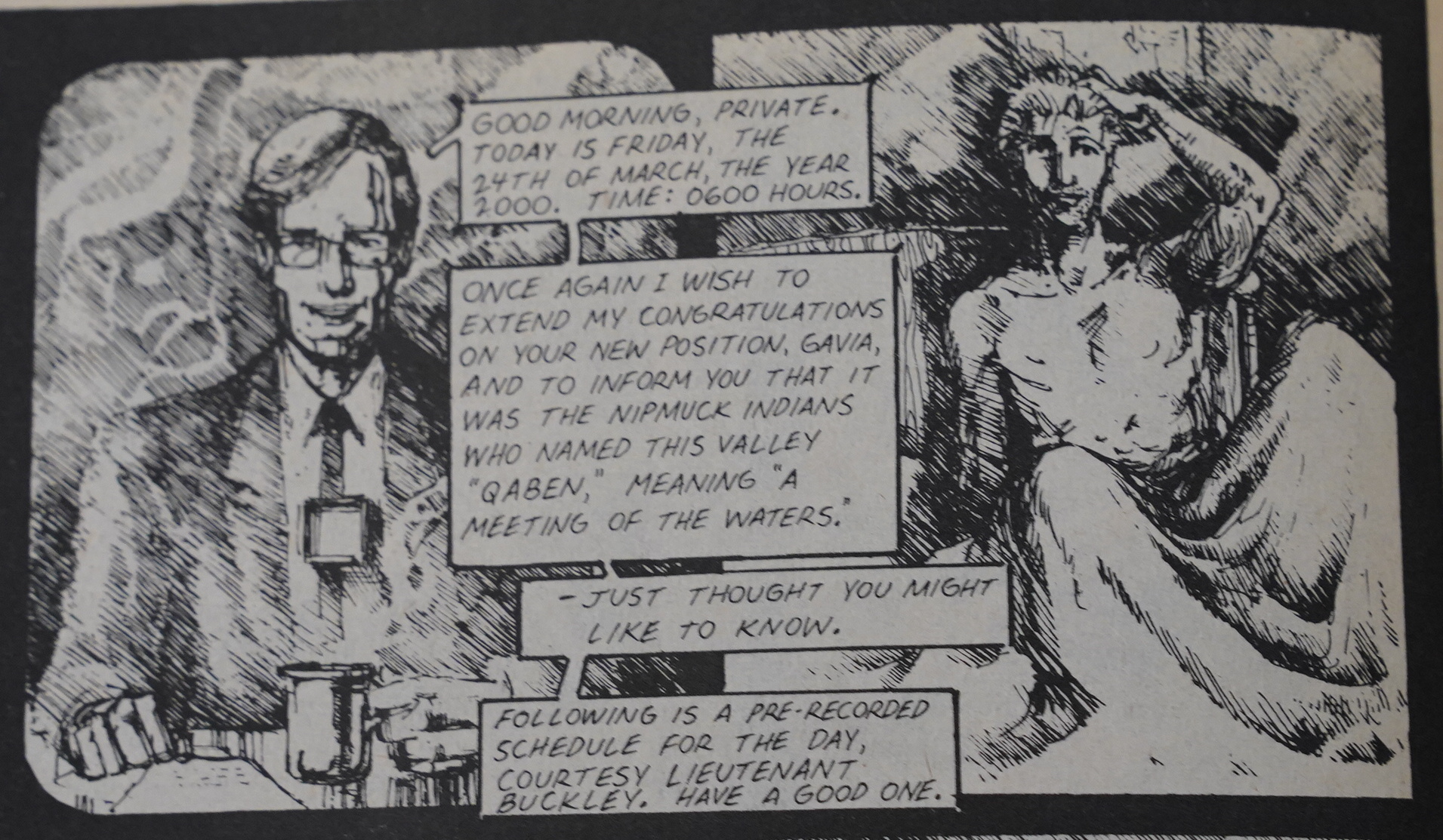

“As you know, you’re a soldier and your name is Gavia” the robot helpfully tells the reader. I mean, that guy.

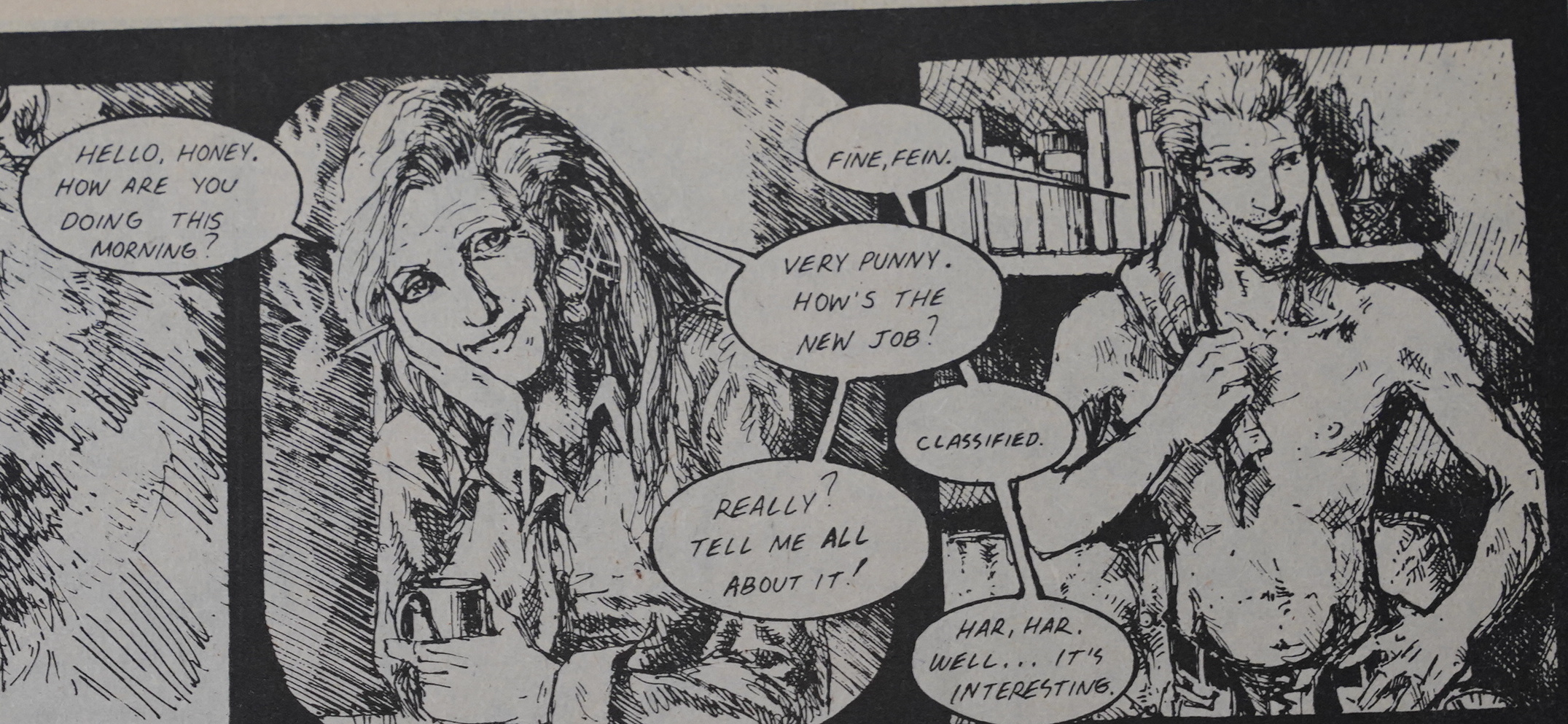

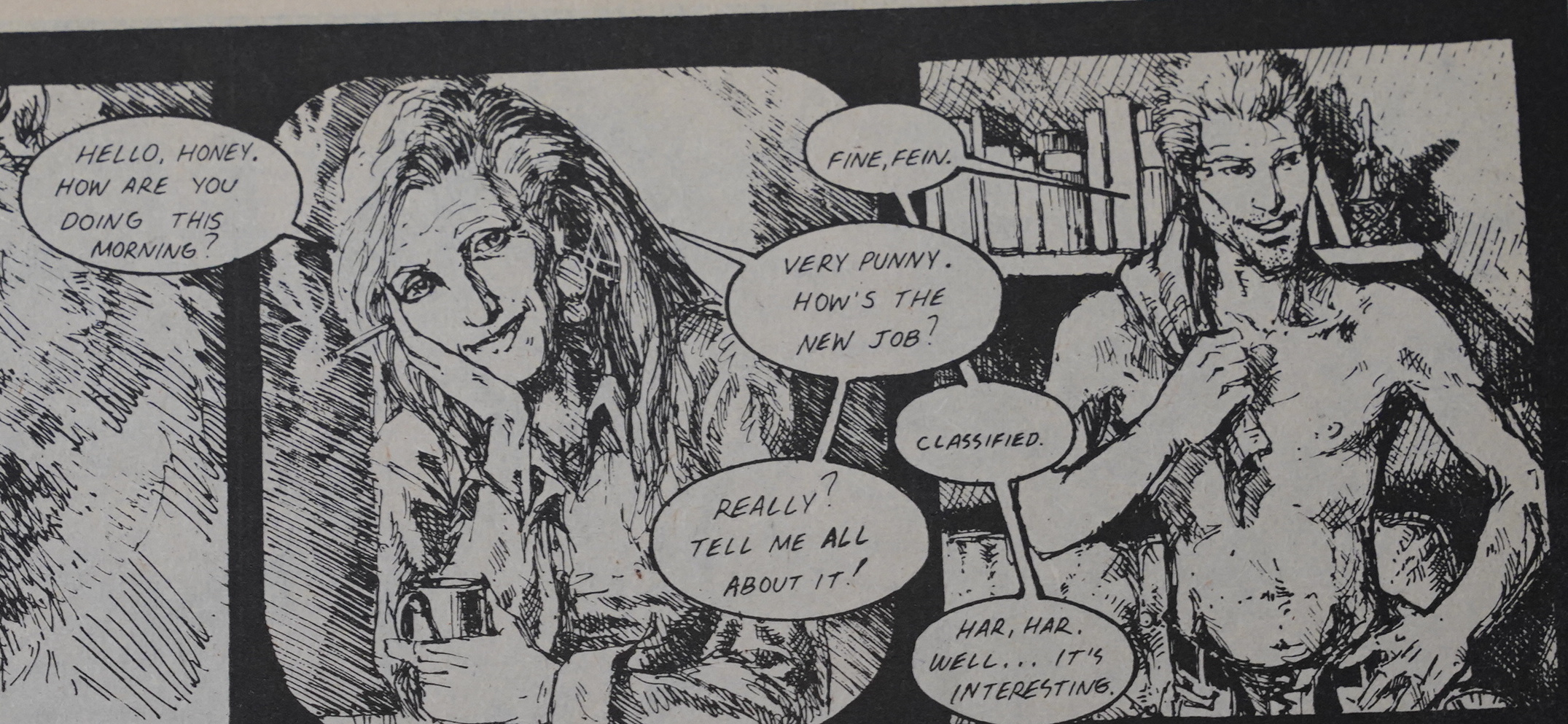

You can totally tell that he said “Fein” instead of “Fine” to her (her name is Fein).

Oops. That turned out very blurry. But it’s a shout out to Sue Coe, which is pretty cool.

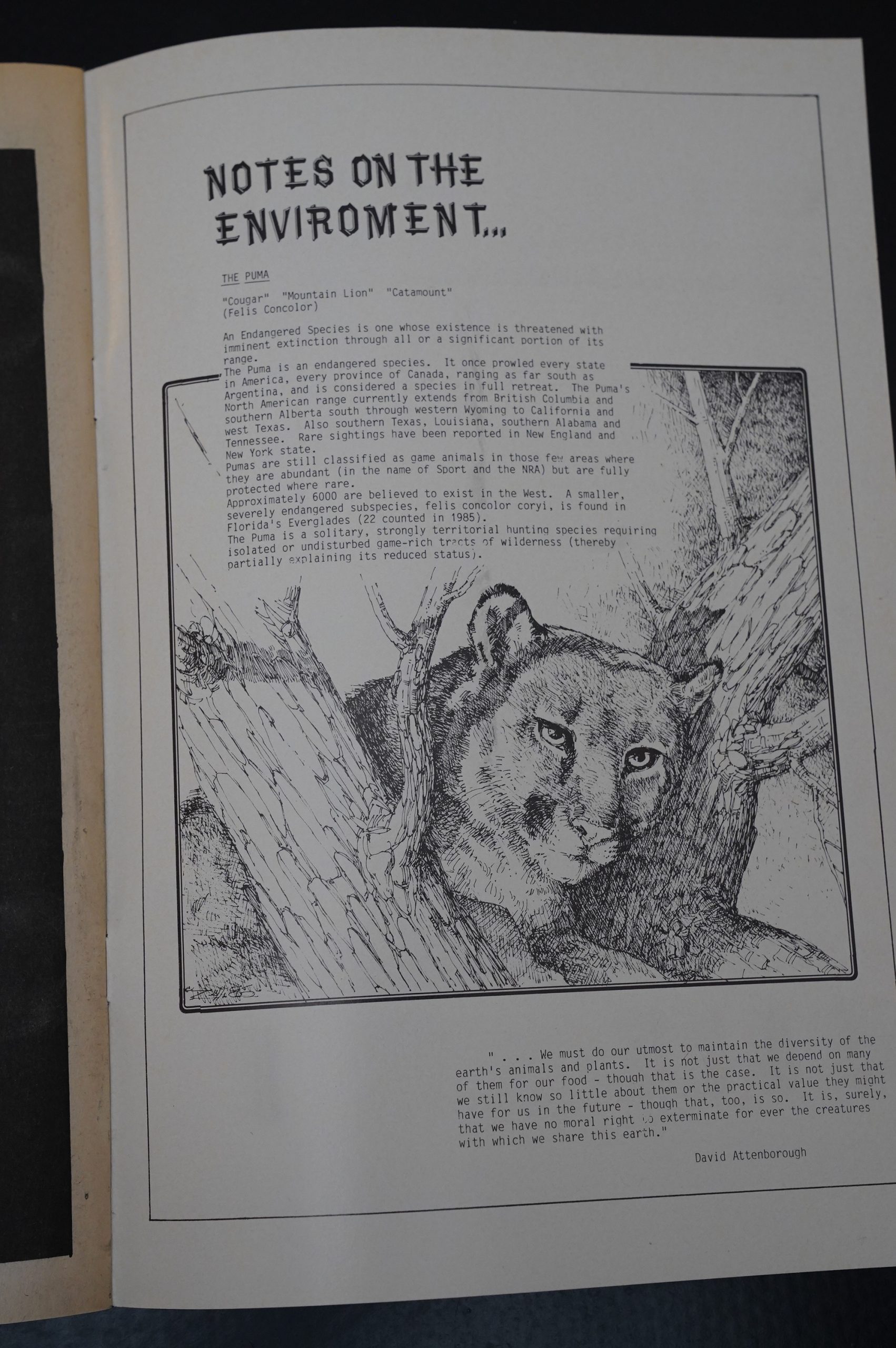

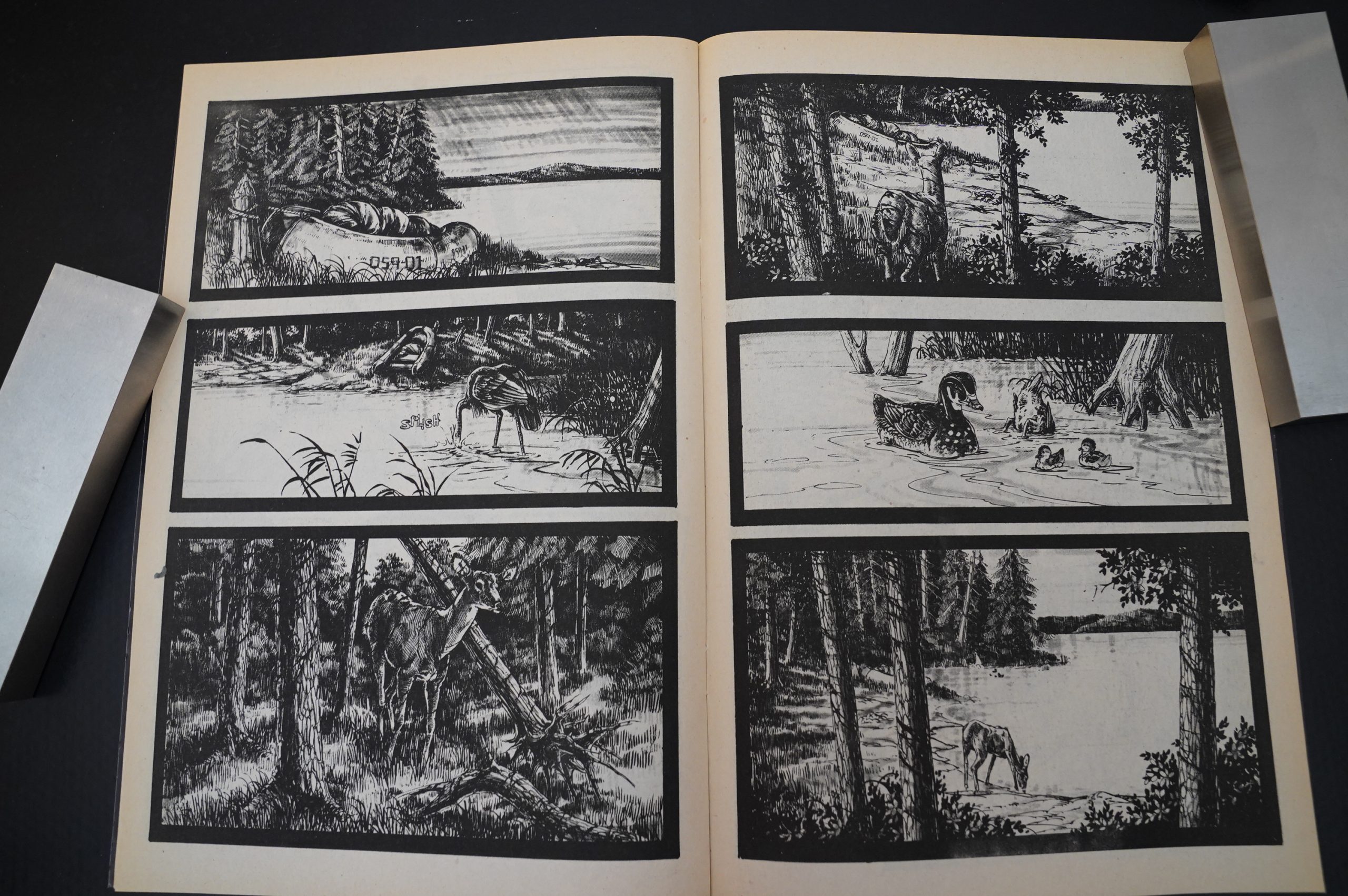

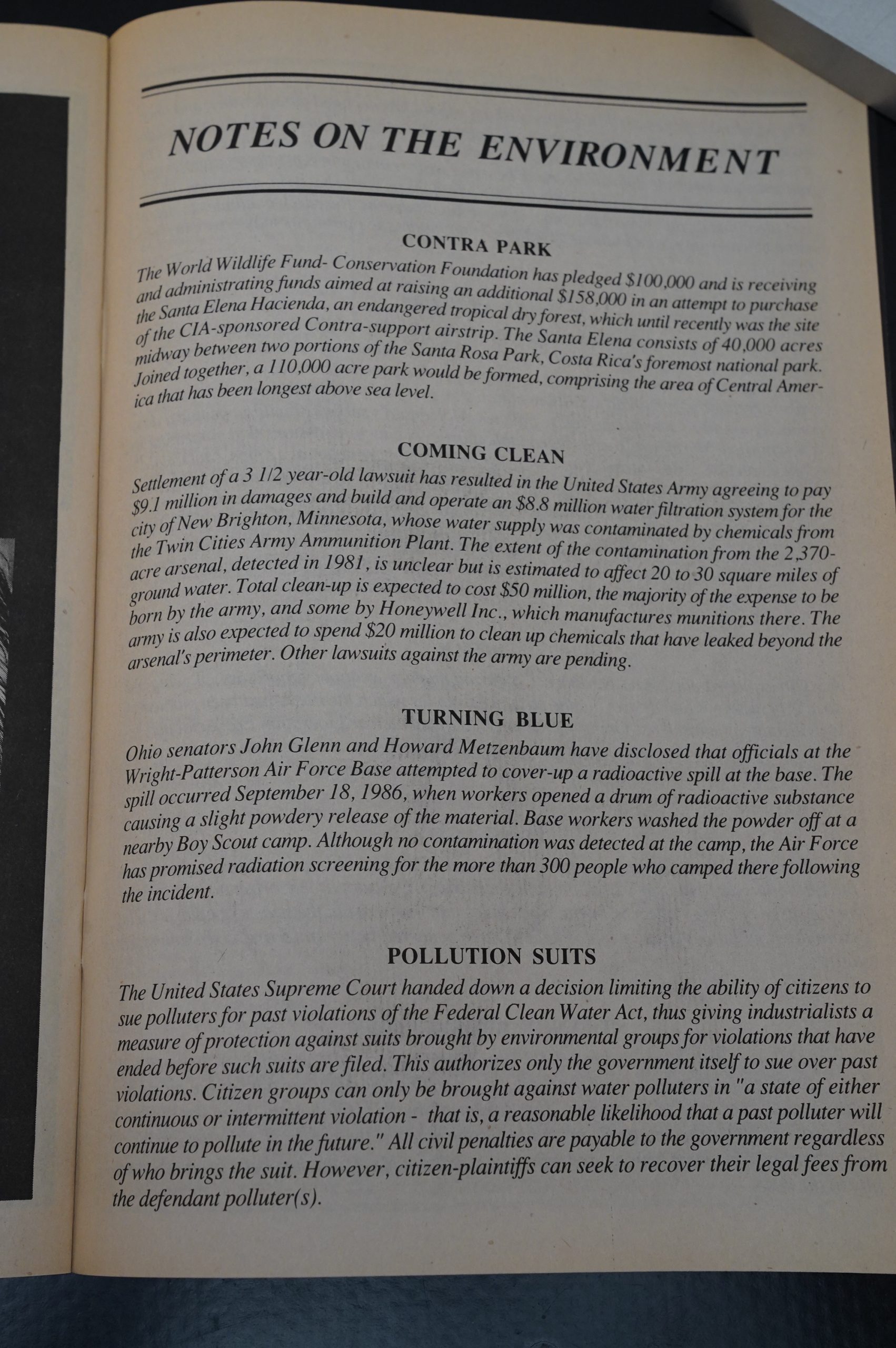

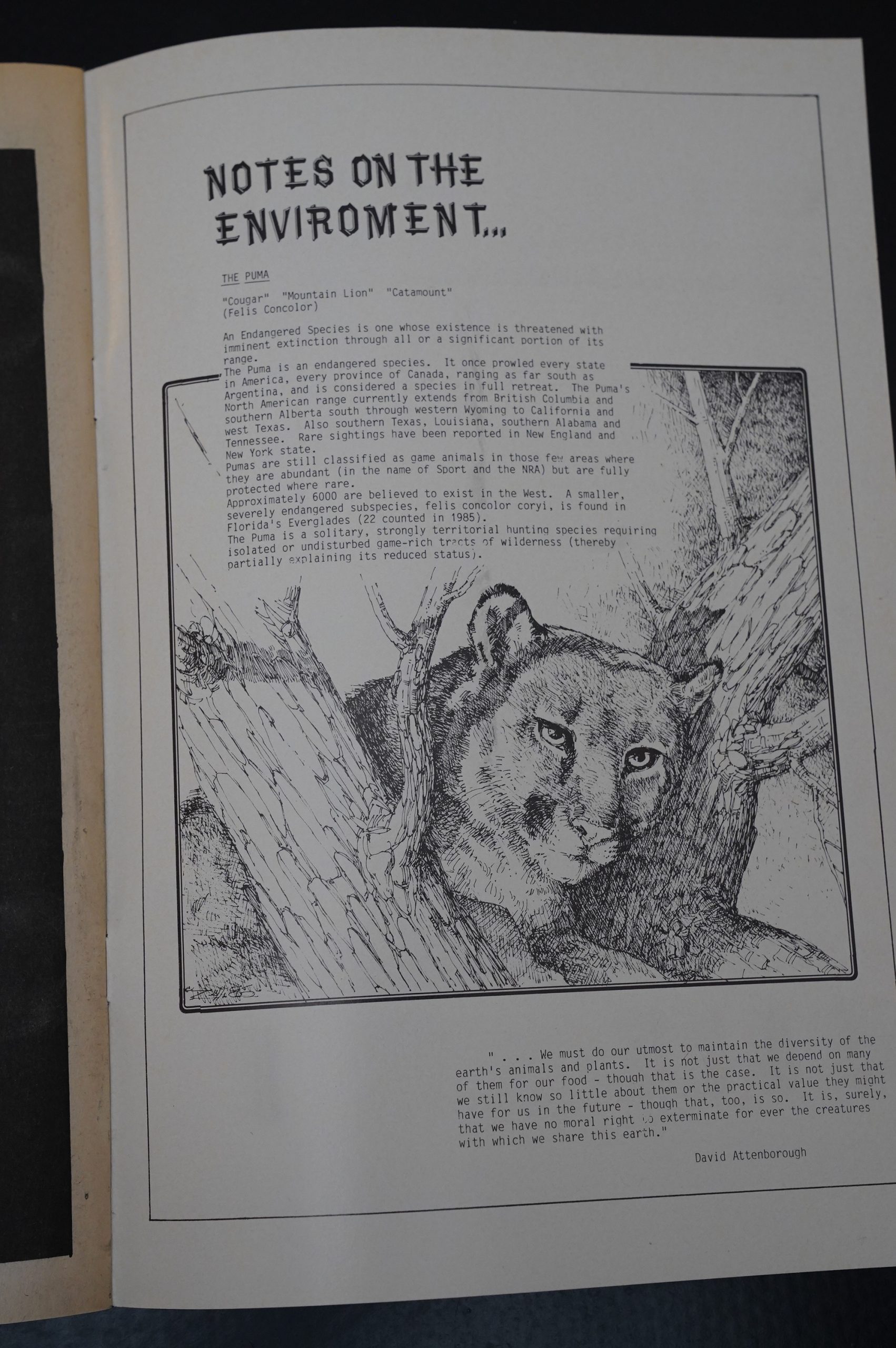

Every issue has fun nature facts. I mean, depressing nature facts.

The first handful of issues are jam packed. The introductions don’t really talk about the comic itself much, and we then get 24 pages of storytelling. The way the narrative stands on its own feels really fresh and intriguing — it’s impossible to even guess at what they’re up to or where this is going.

And note the circulation numbers: 10K copies printed. Not bad, but not awesome, either.

I wondered whether they would re-letter these pages before doing the collected edition(s), but nope. It’s really quite horrible lettering in these early issues…

But the storytelling is on point: It just flows so naturally, pulling you into the milieu.

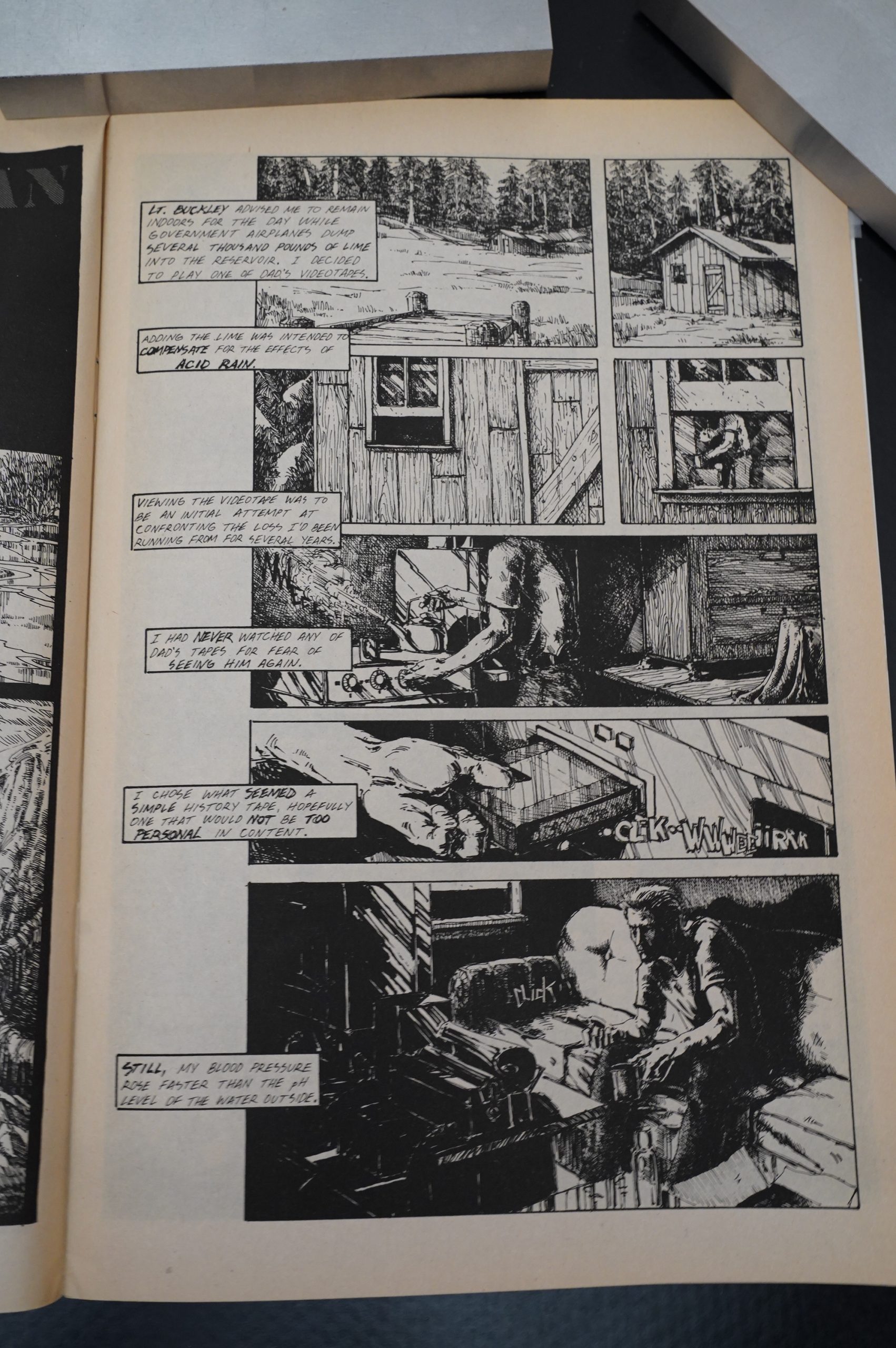

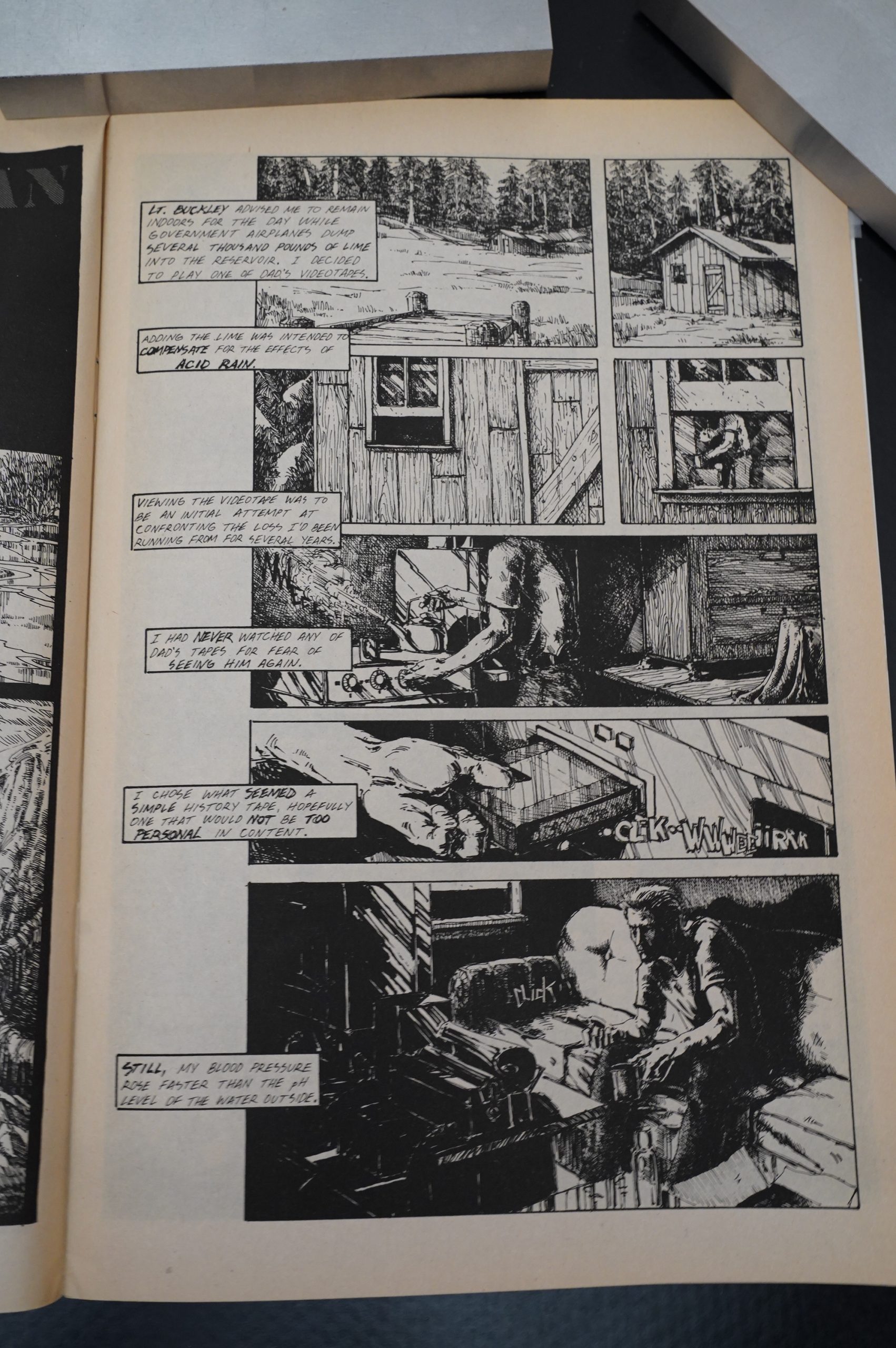

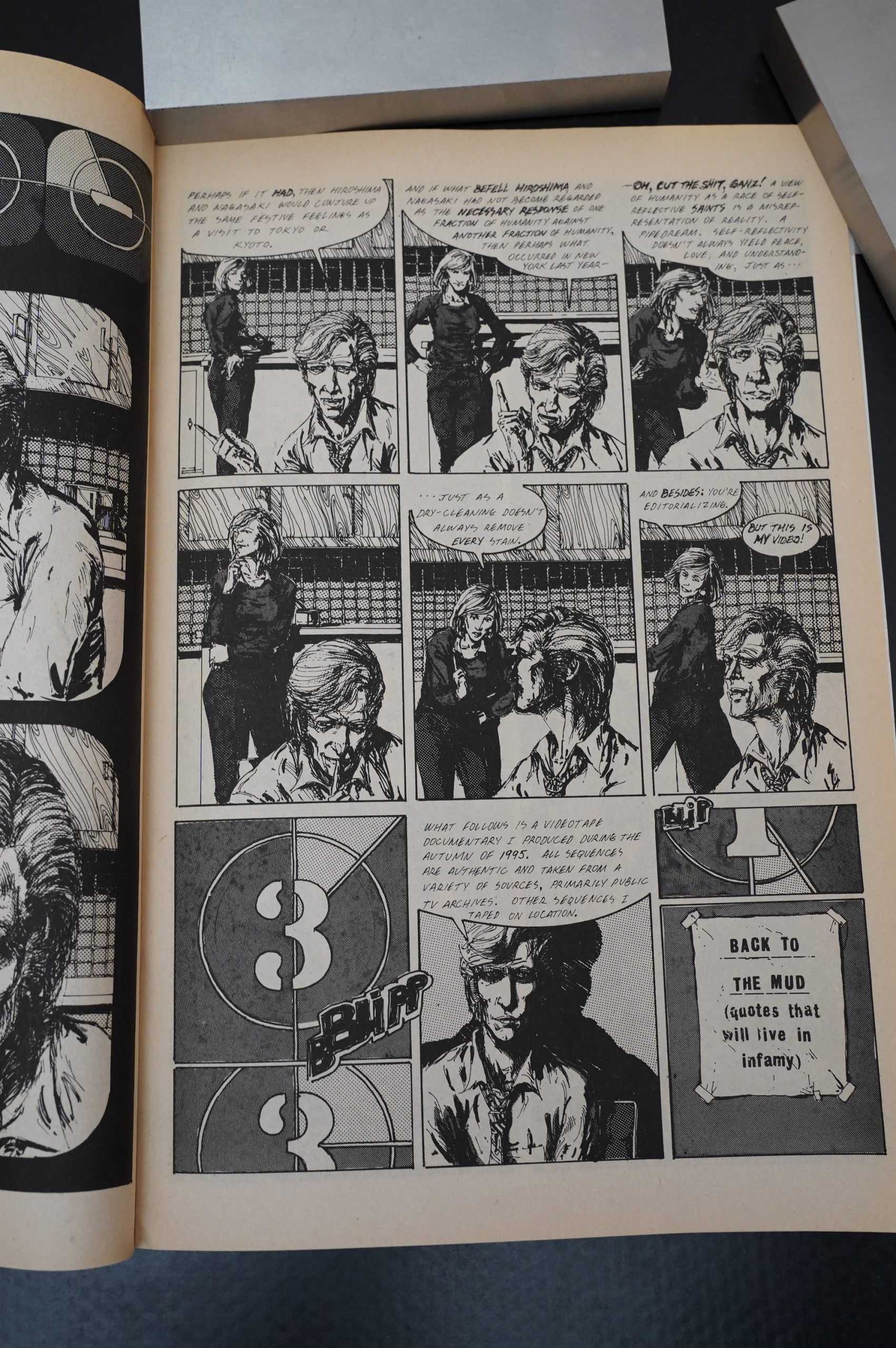

However, they make some a pretty odd choices, like having the protagonist watch a lot of VHS tapes made by his now-dead father.

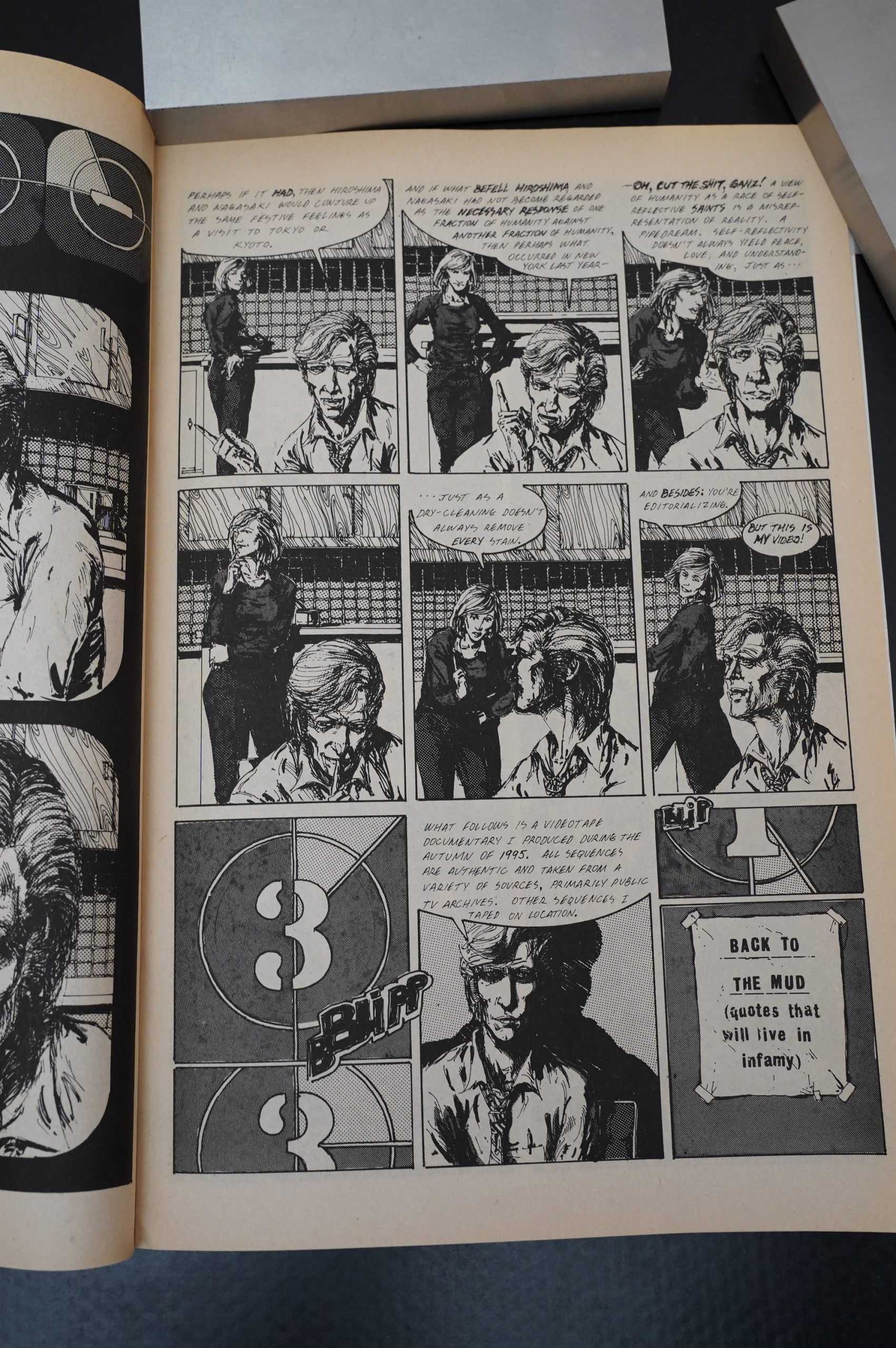

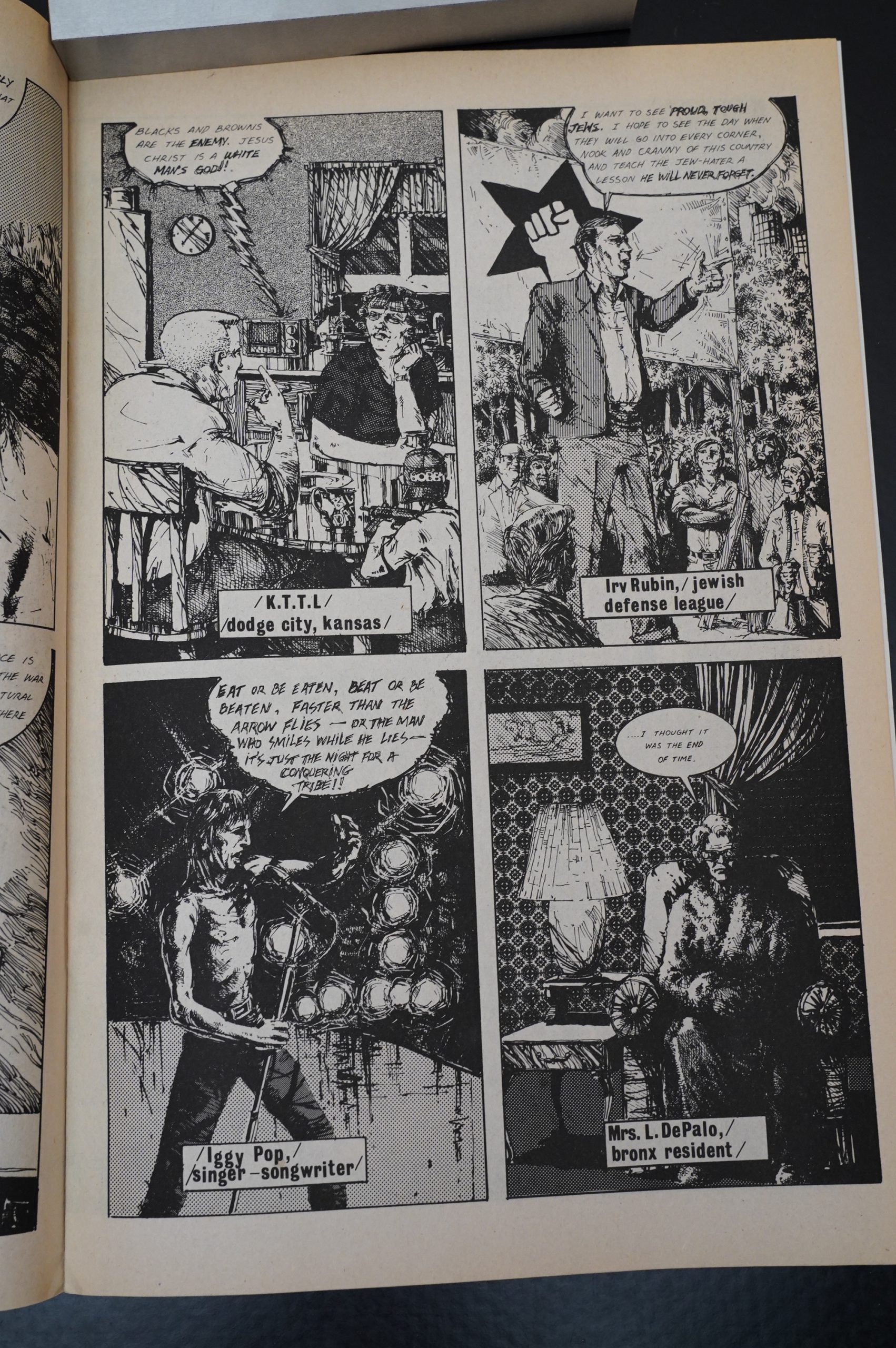

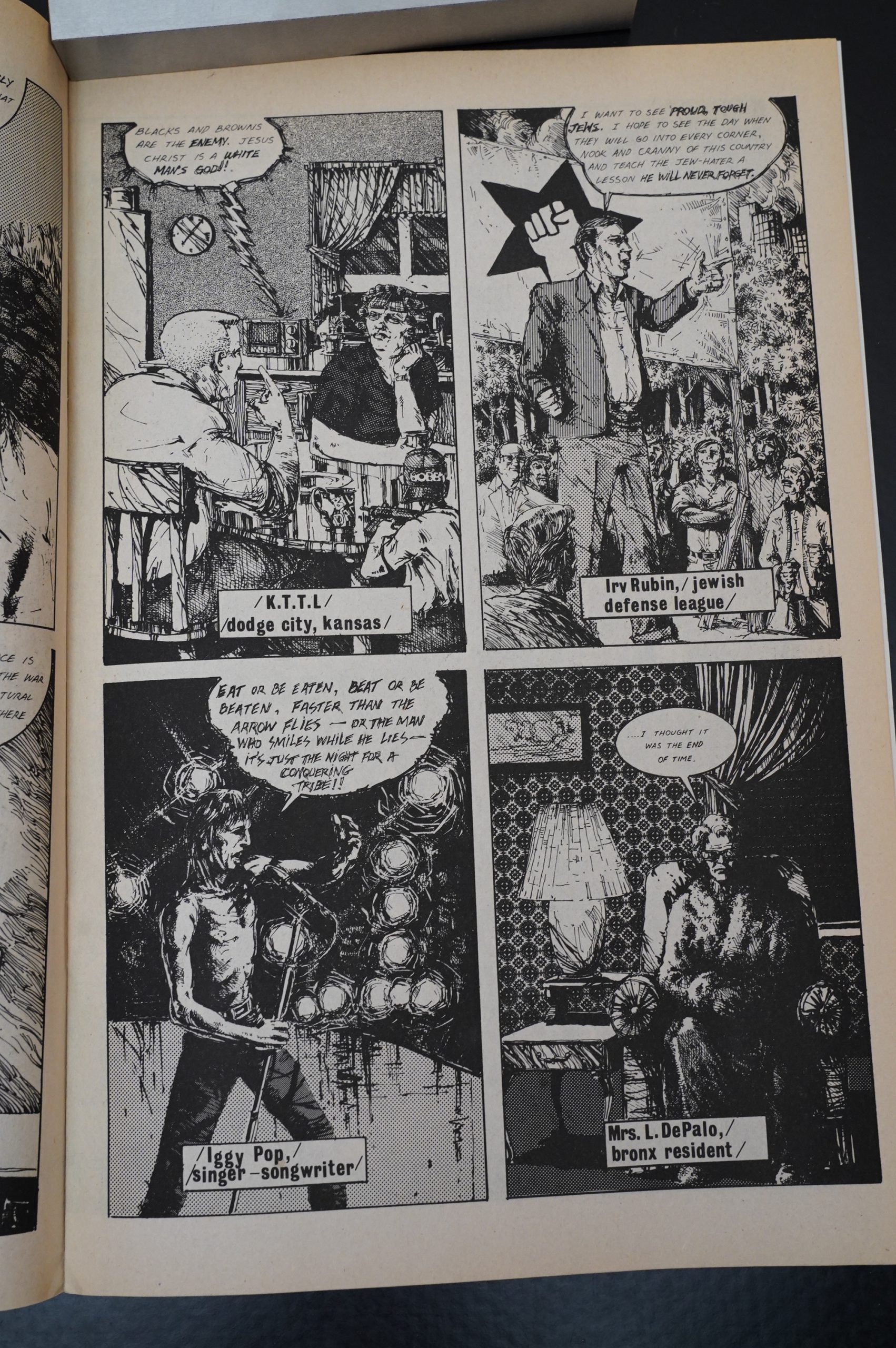

The tapes are meant to be really heavy and interesting, but they seem to me to be the worst of all genres: American sound byte documentaries.

I hates it so much. I hates it!

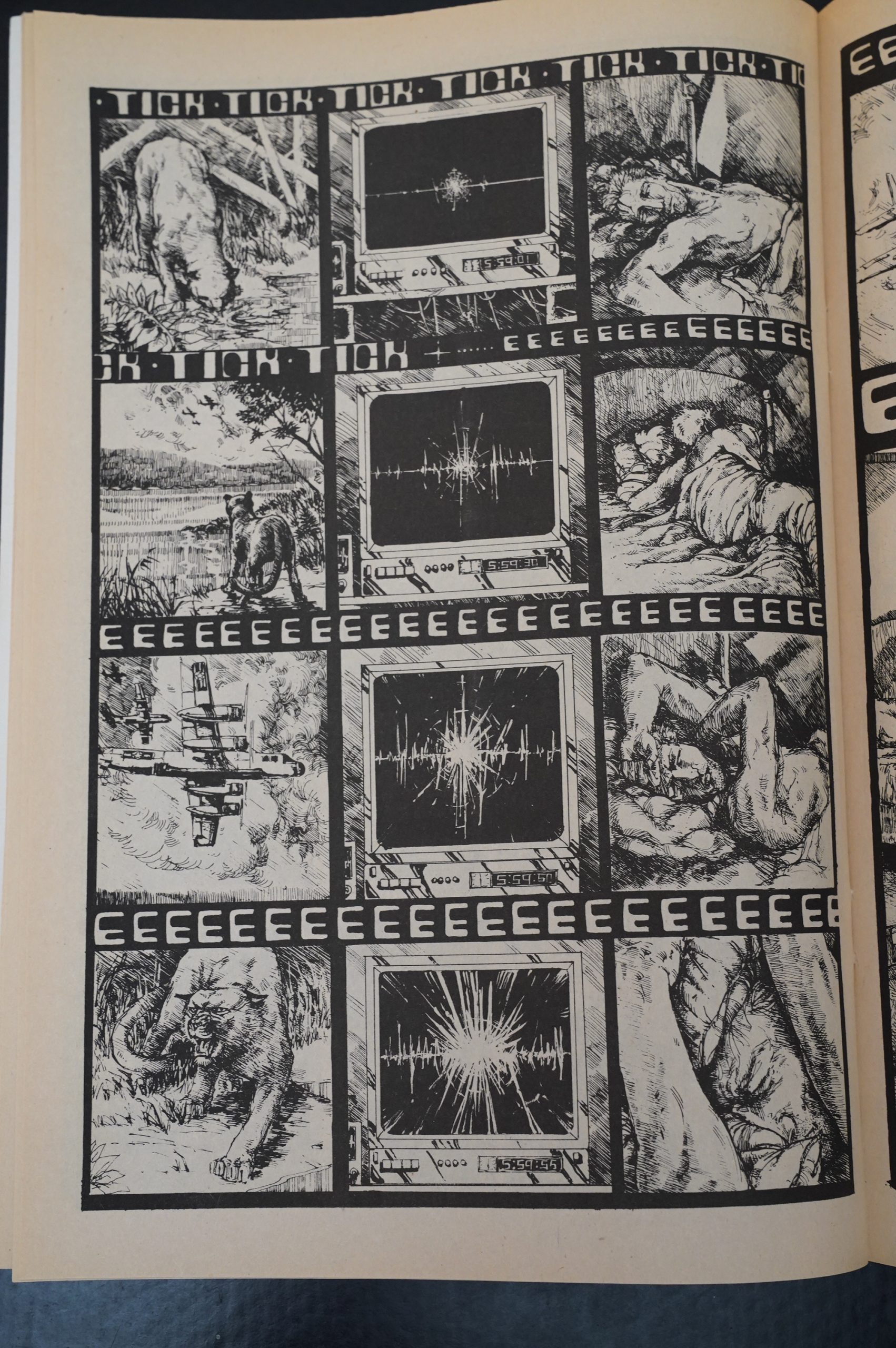

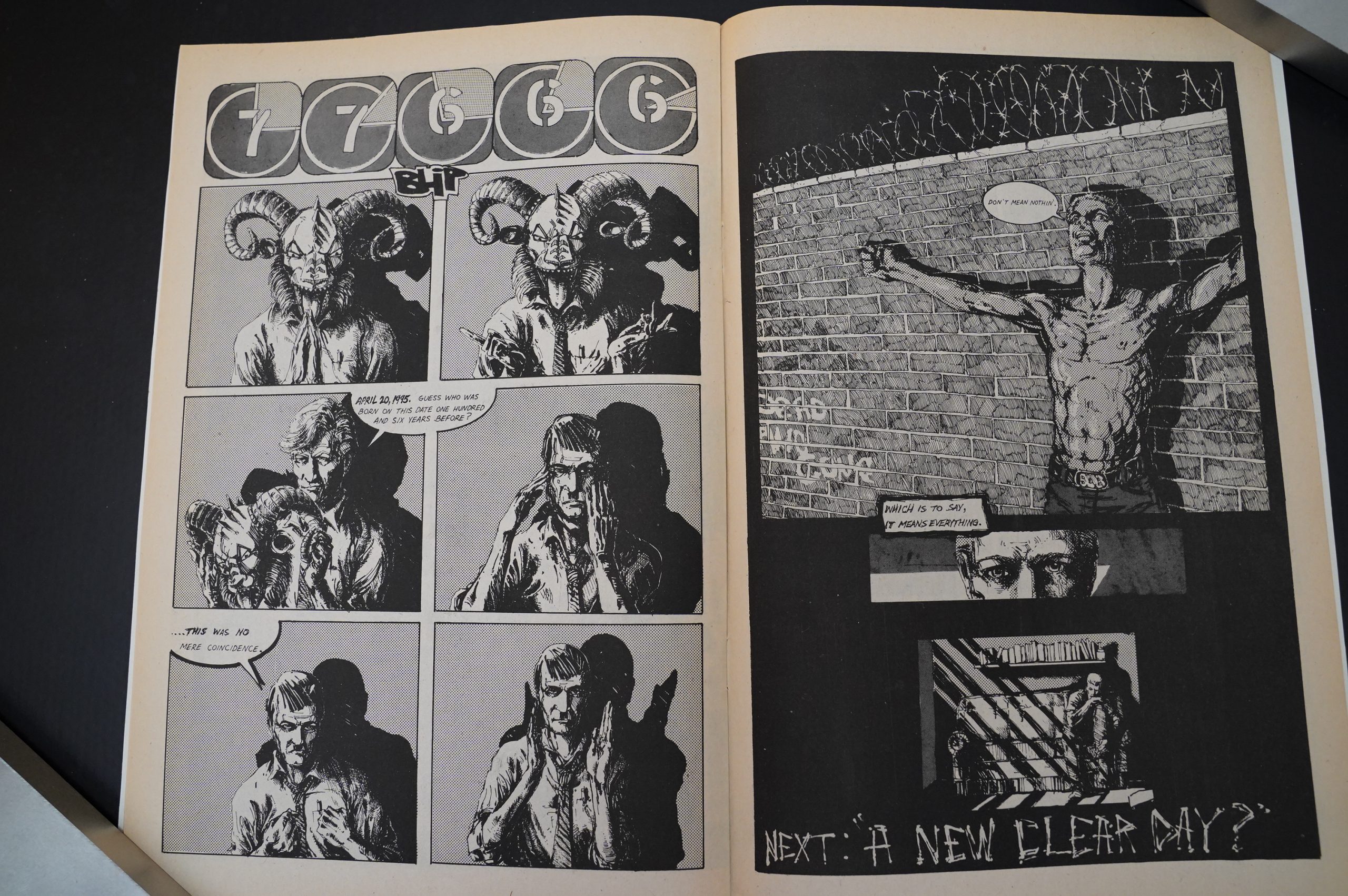

And already here the first warning lights go off: It’s becoming clear that Murphy and Zulli are fans of “synchronicity”, or as normal people call it “random stuff happening”. It adds of so much depth and resonance when actions are somehow connected via various … things… Yes sir indeed.

But here it gets to be kinda moronic, because in this story, some Nazis set off a nuclear bomb in the Bronx in 1997… and as the father (here in a mask) explains… IT HAPPENED ON HITLER”S BIRTHDAY!!!1!!ONE!

Now, if you’re pointing out synchronicity in the real world, that’s fun, but here it’s… just… kinda silly.

For one bright issue, the circulation goes up to 19K… but this is during the height of the black and white boom, so my guess would be that a few stores had decided to “invest” heavily into the issue?

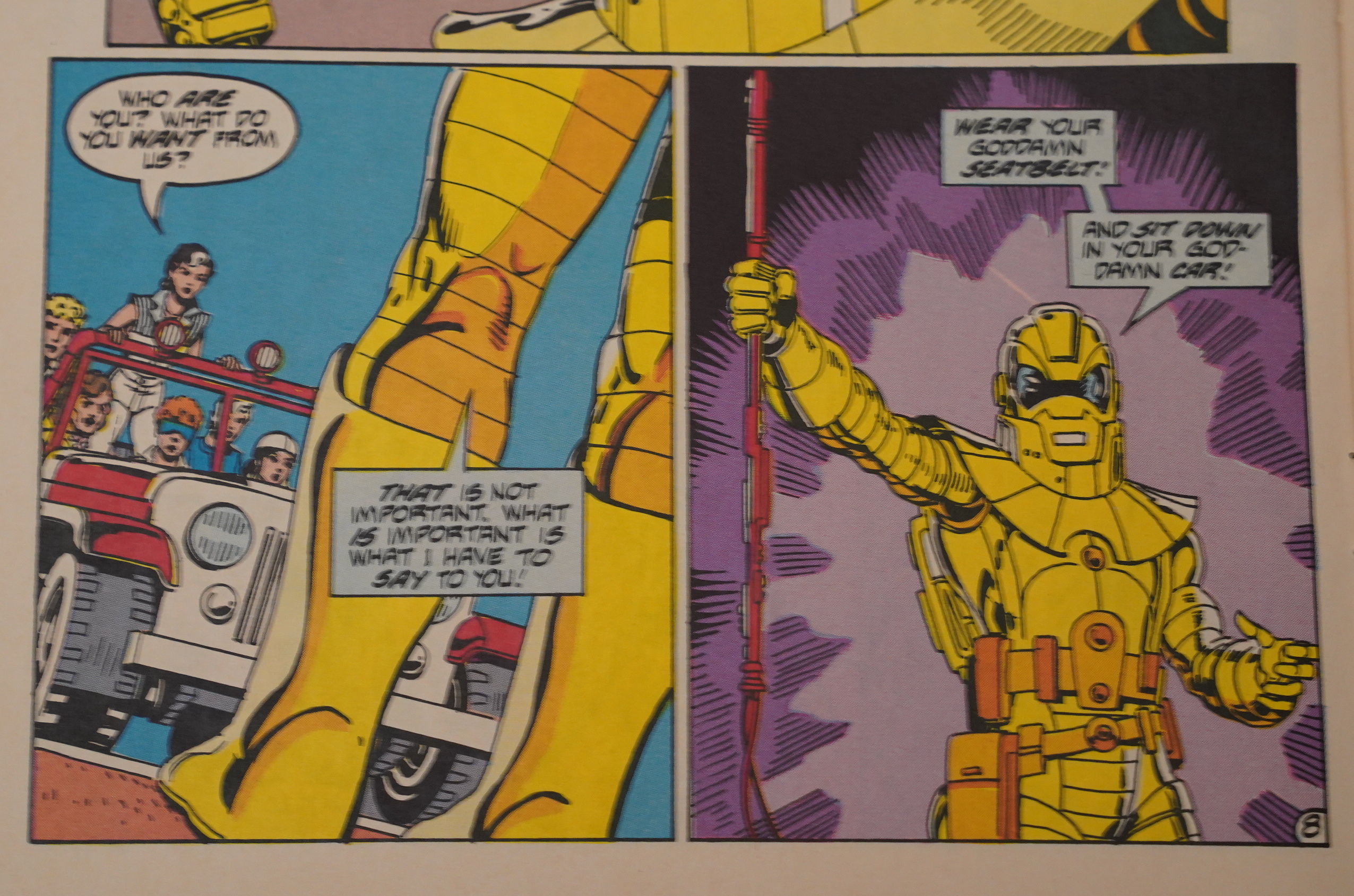

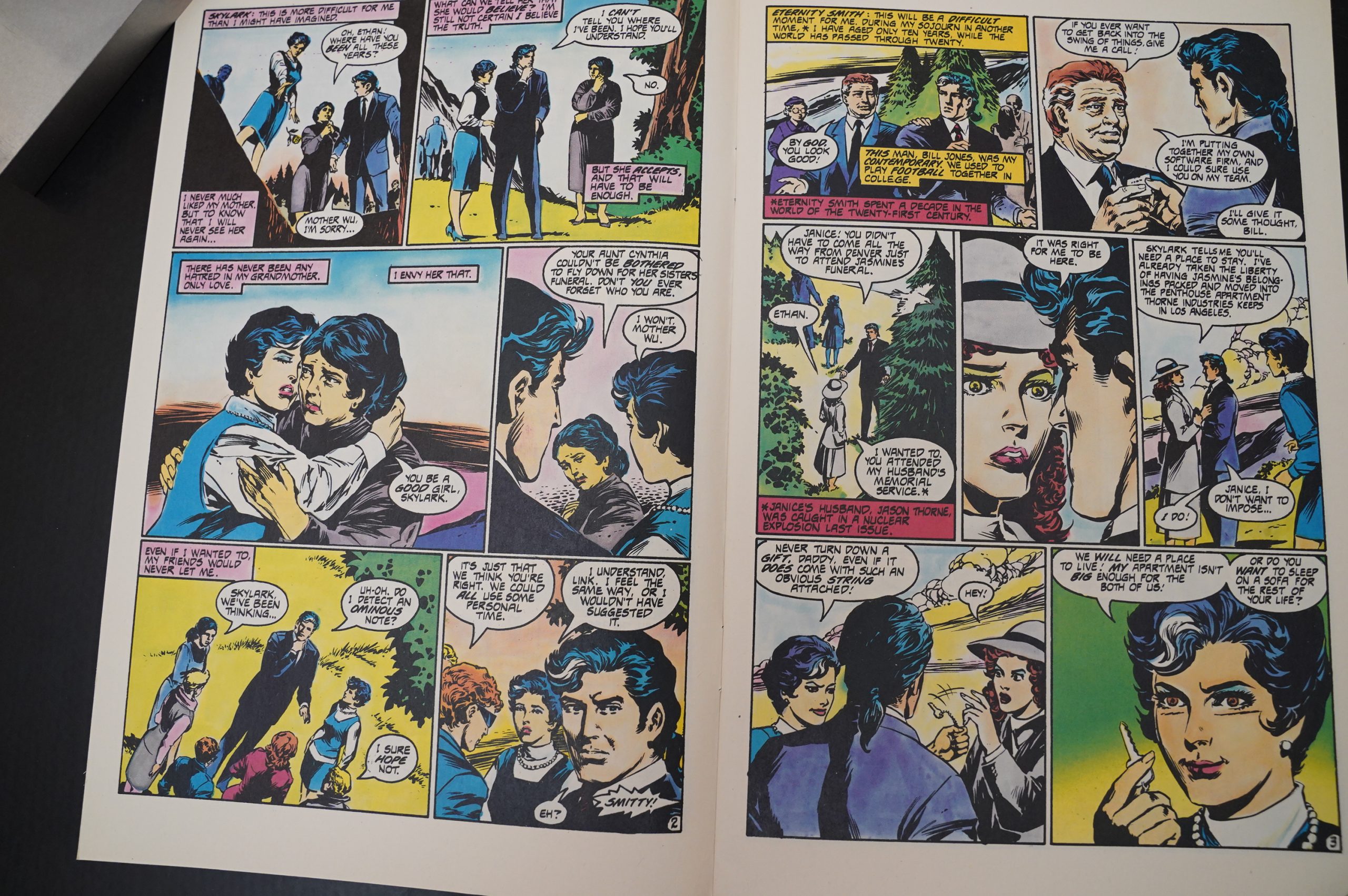

There’s so much here! This robot guy was the chauffeur to a rich older woman… but he felt like he had to run off into the woods, so he did. I don’t think we ever learnt what happened to the woman? Did she die in that car?

This is a harbinger of things to come.

These issues are quite brisk reading — there’s a lot of philosophy and nature scenes, and the amount of plotting isn’t overwhelming. But we get hints at greater conspiracies and stuff happening around the edges. It’s fun and intriguing.

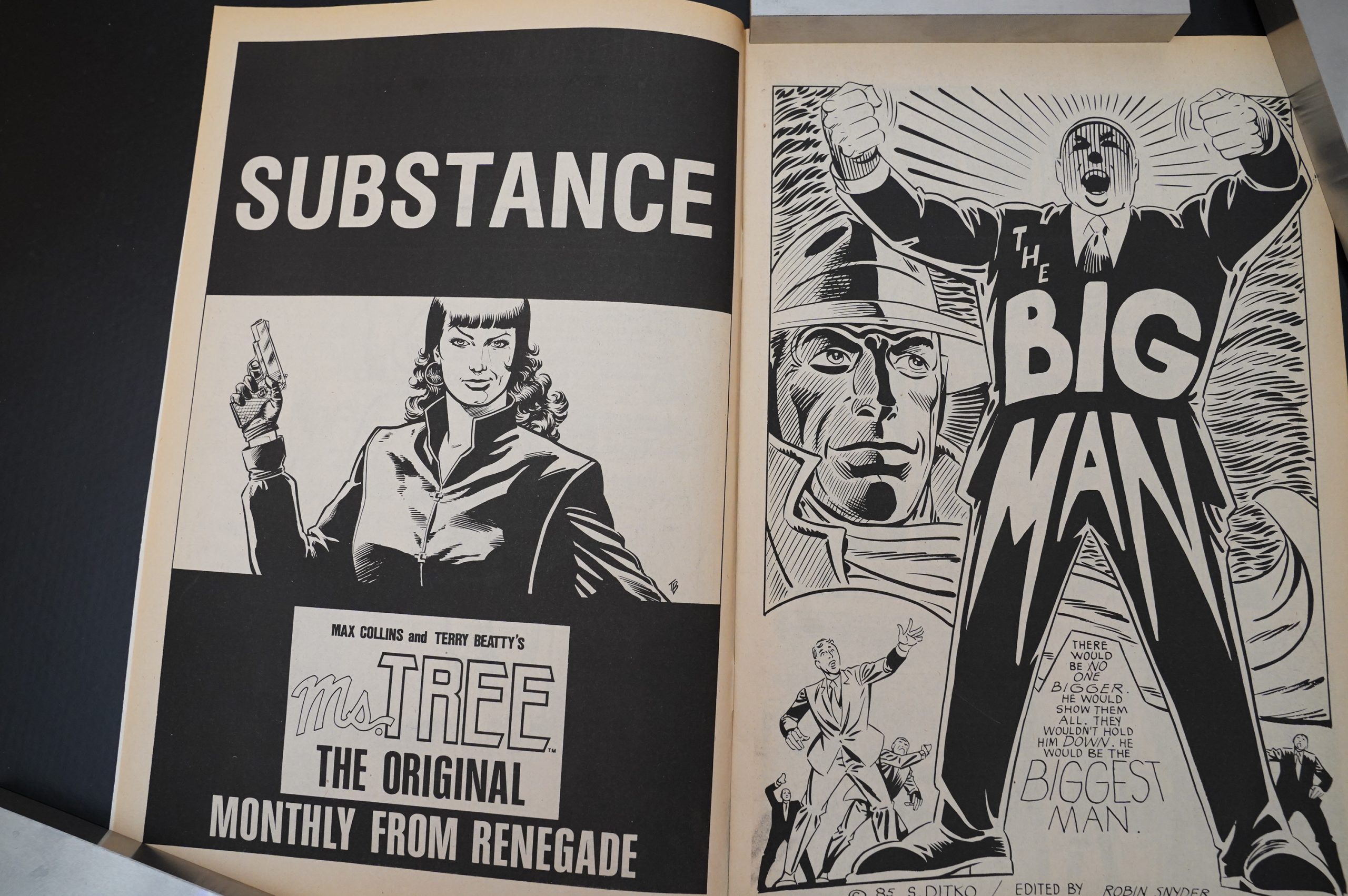

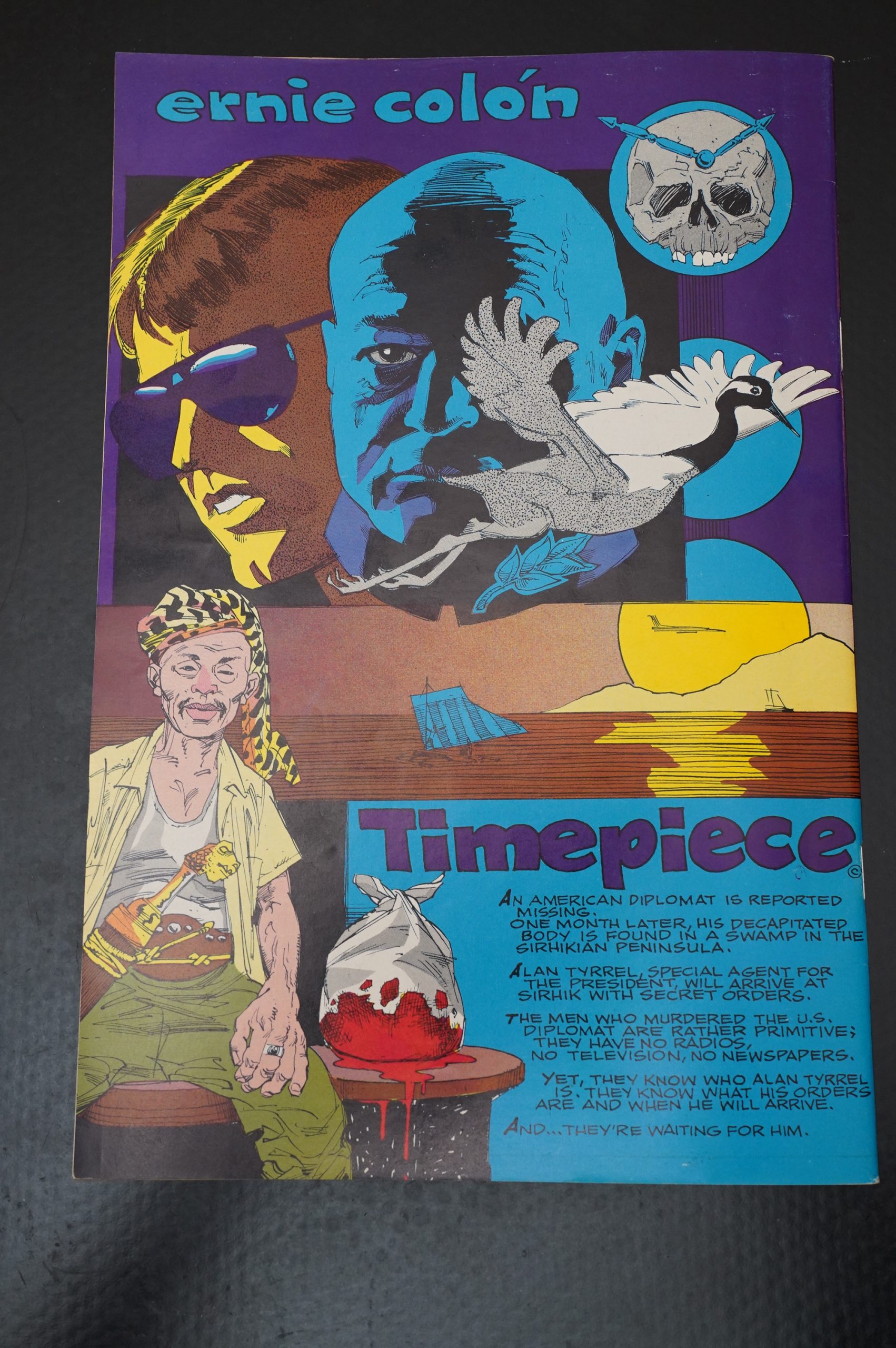

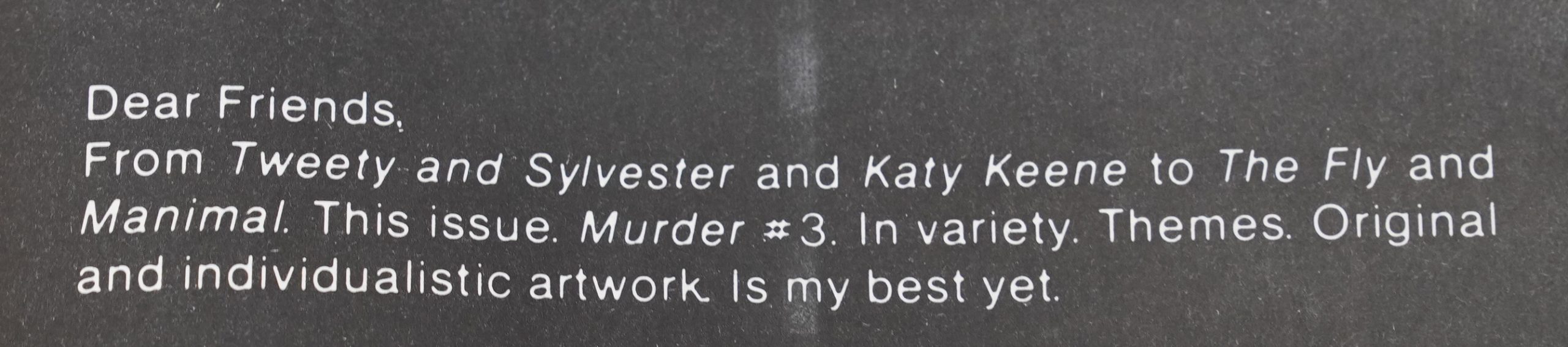

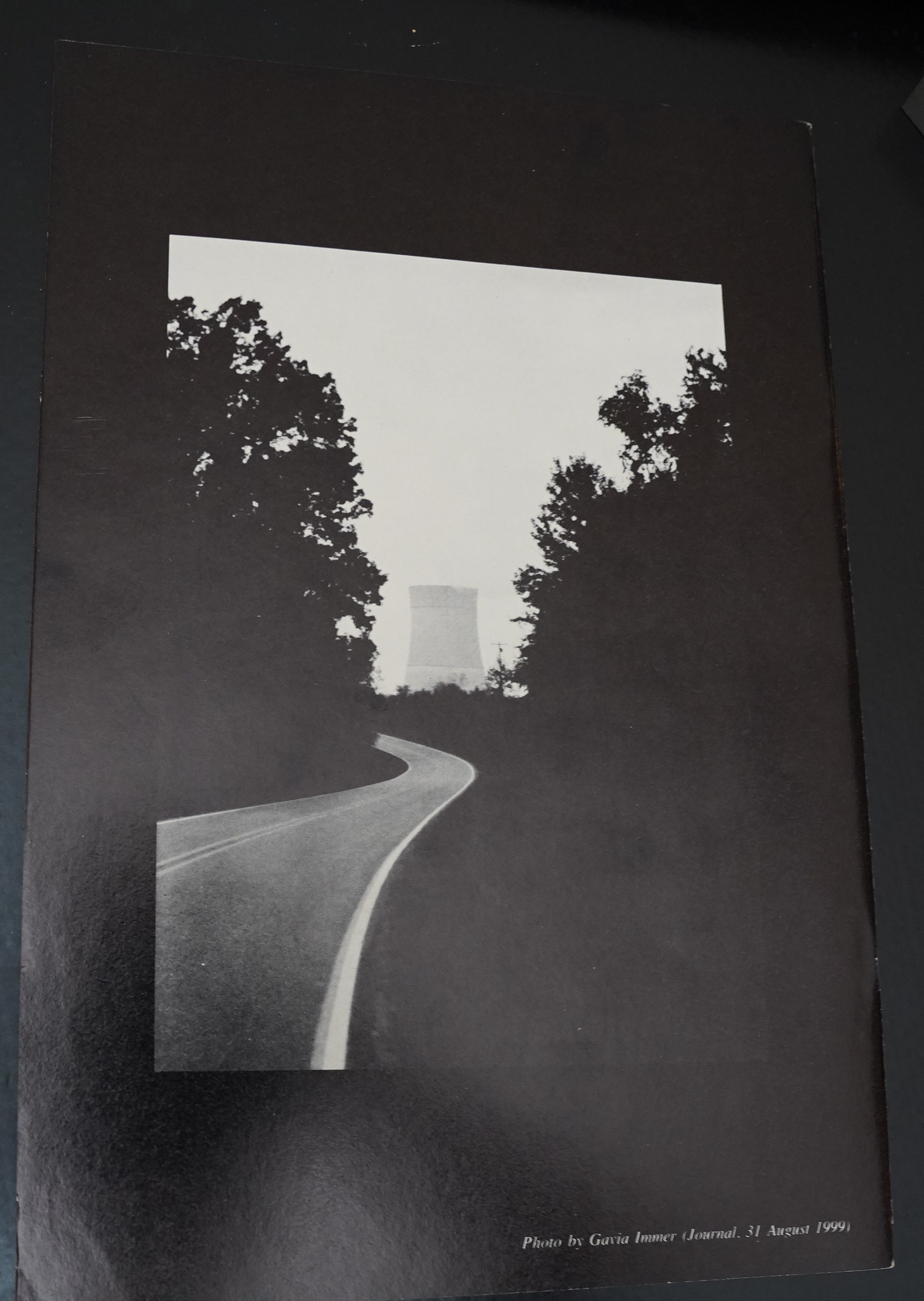

Hm… is that the best promotional poster they could come up with?

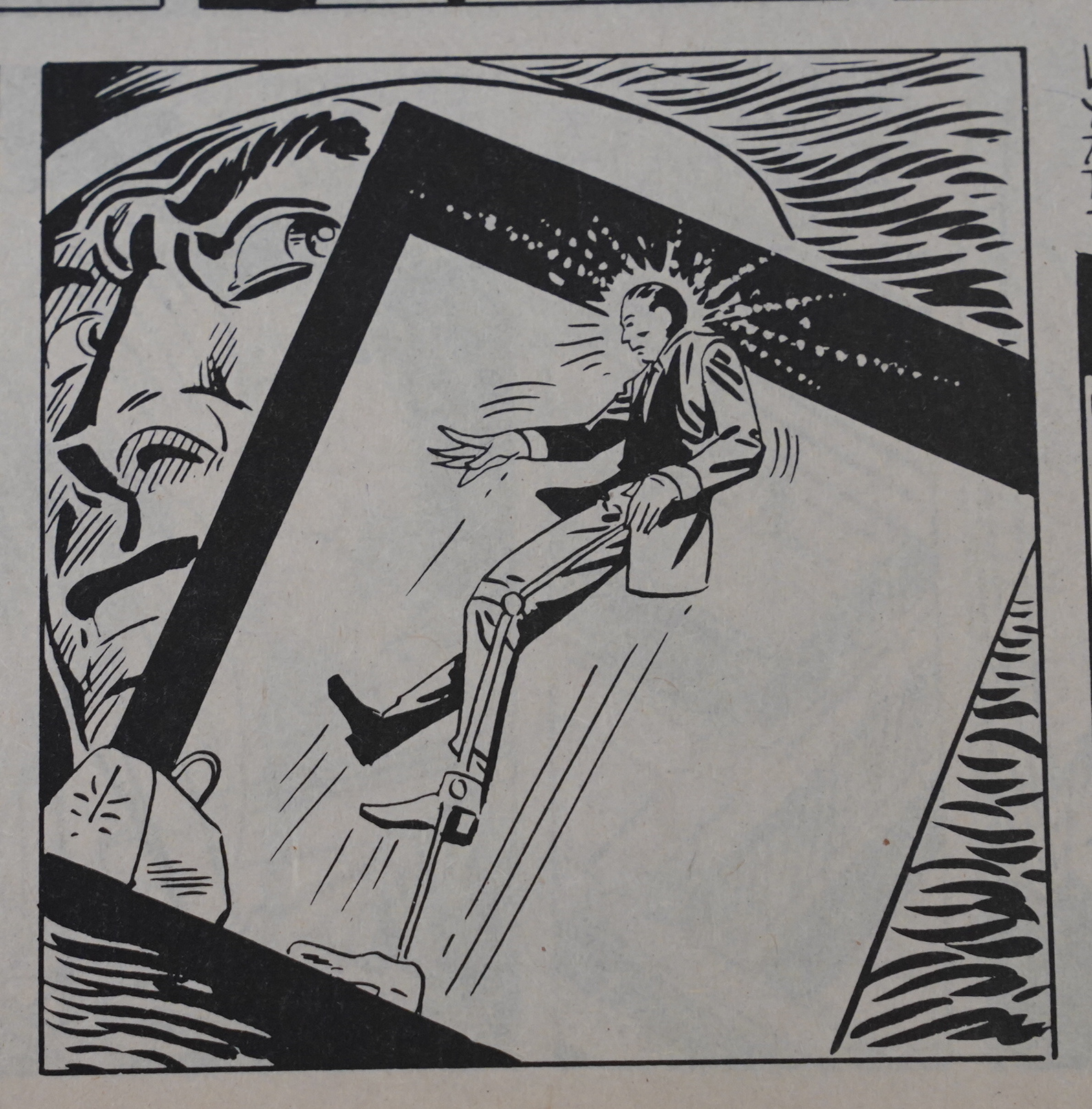

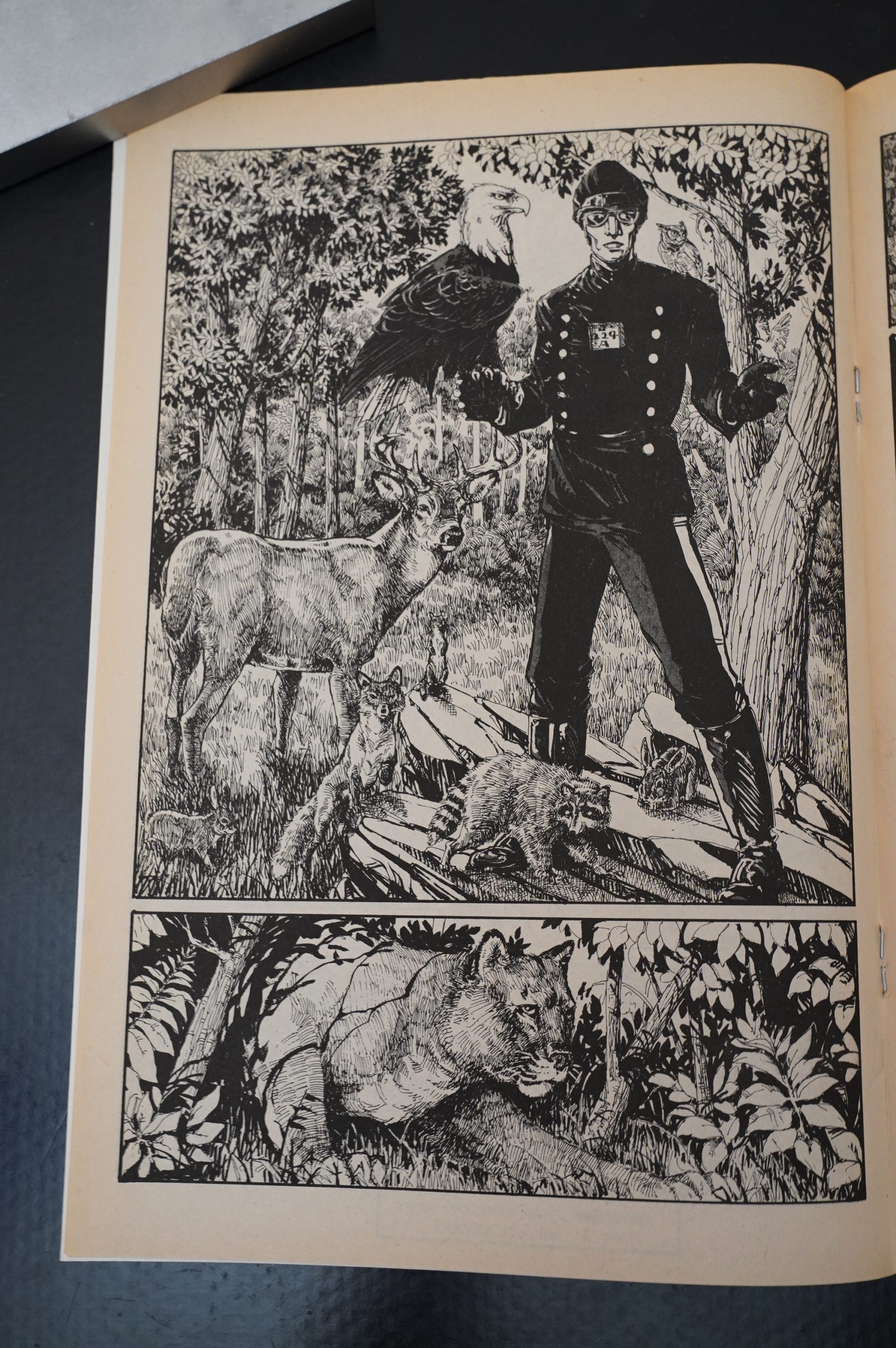

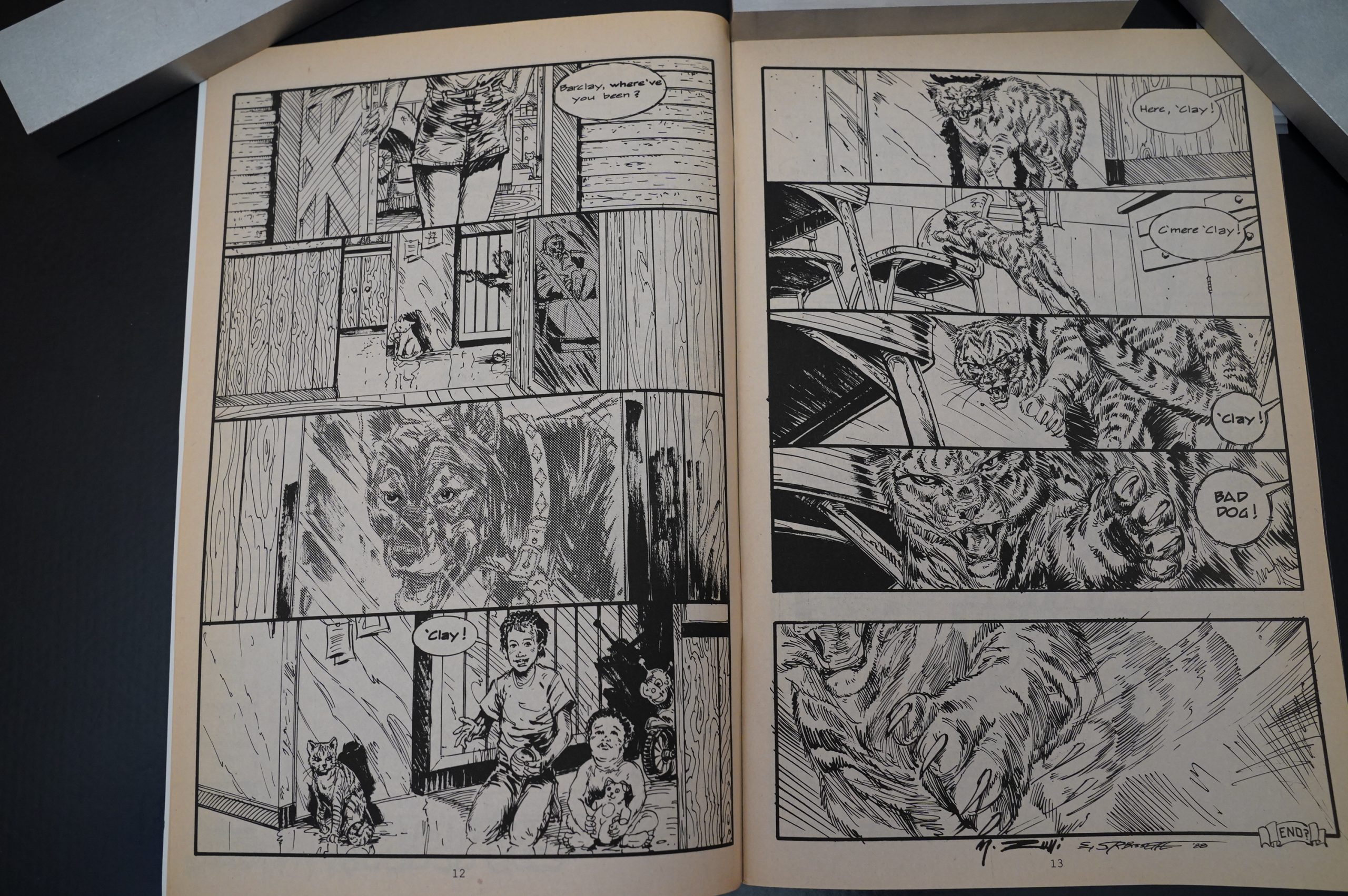

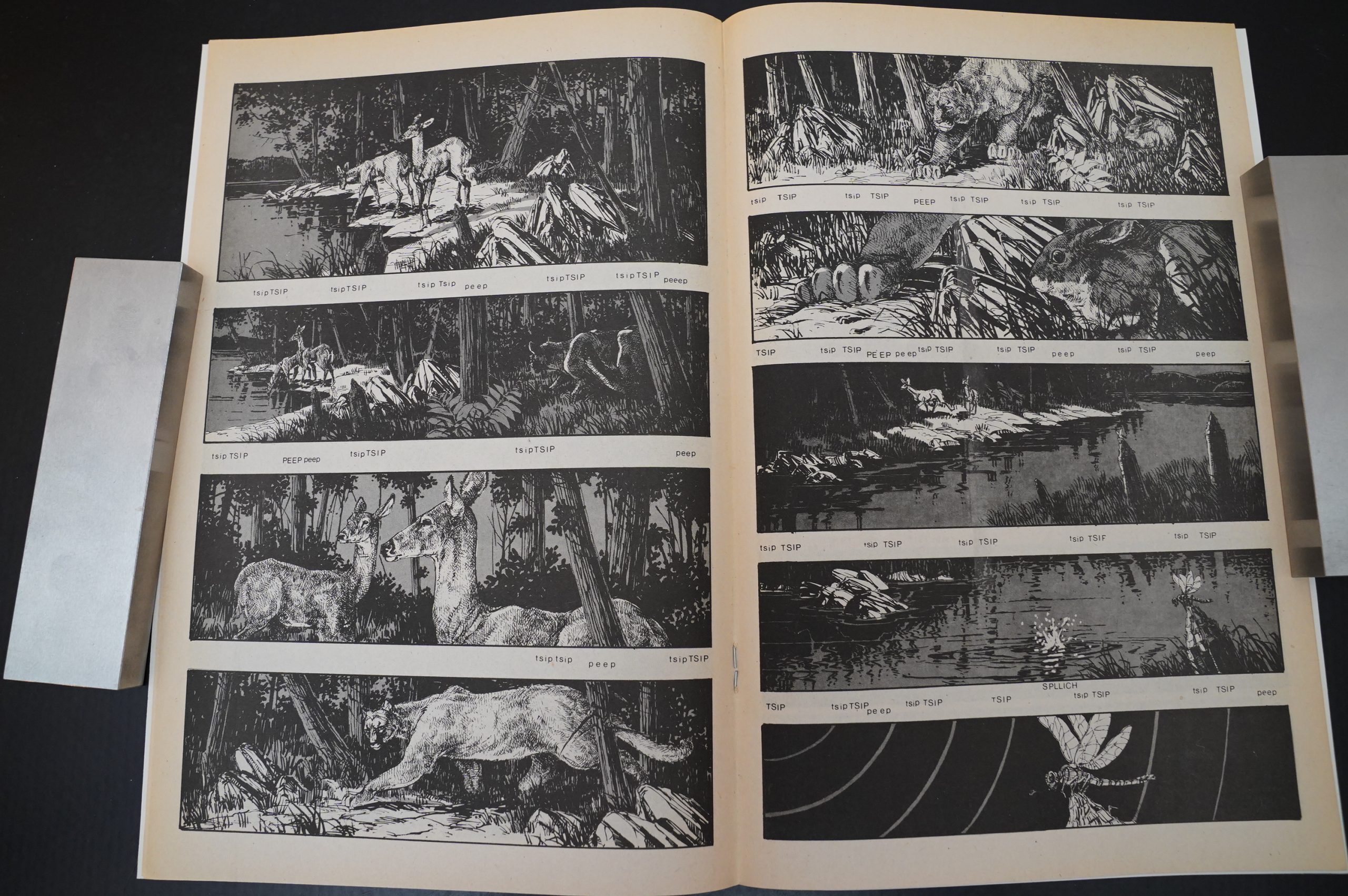

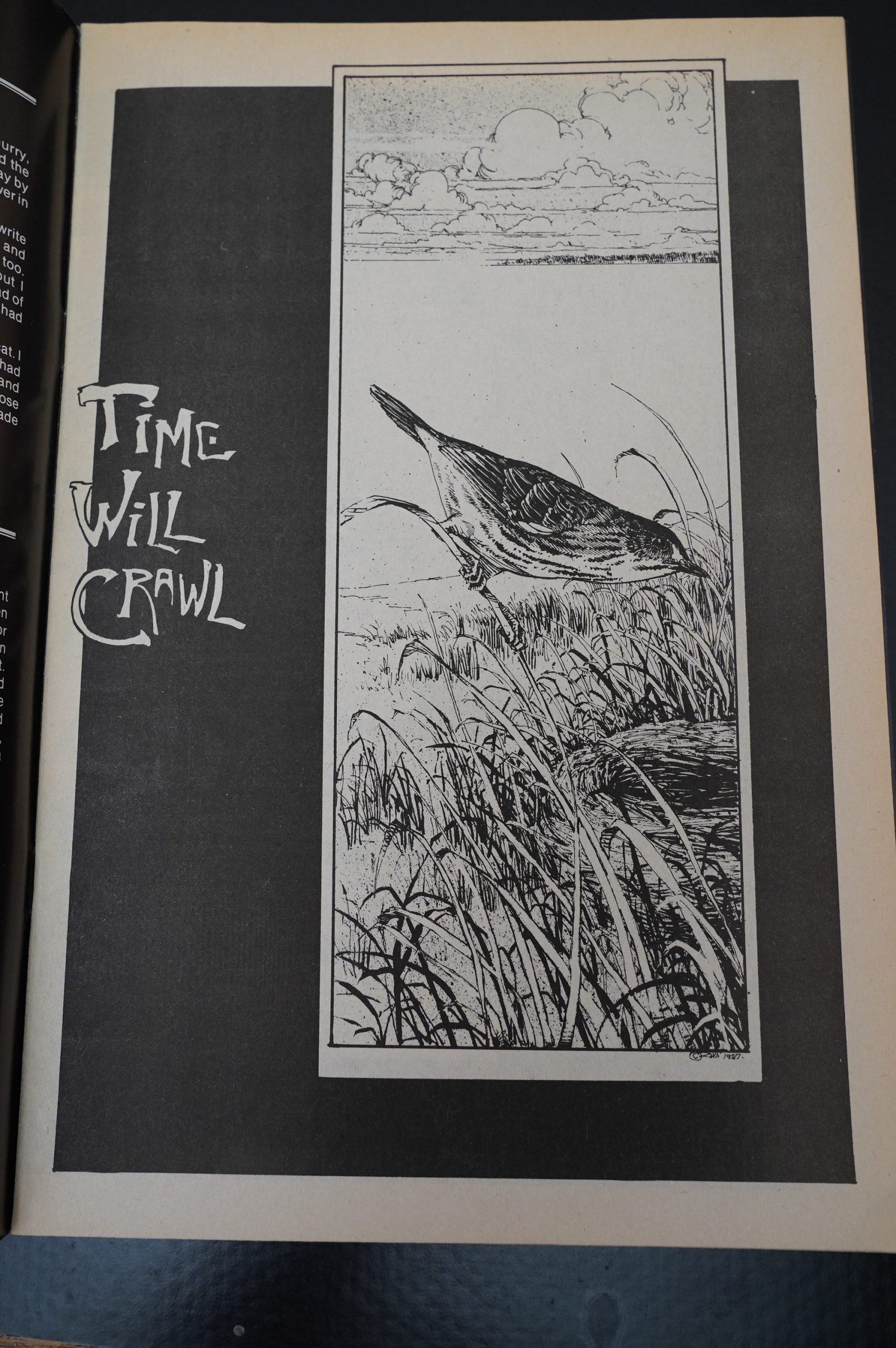

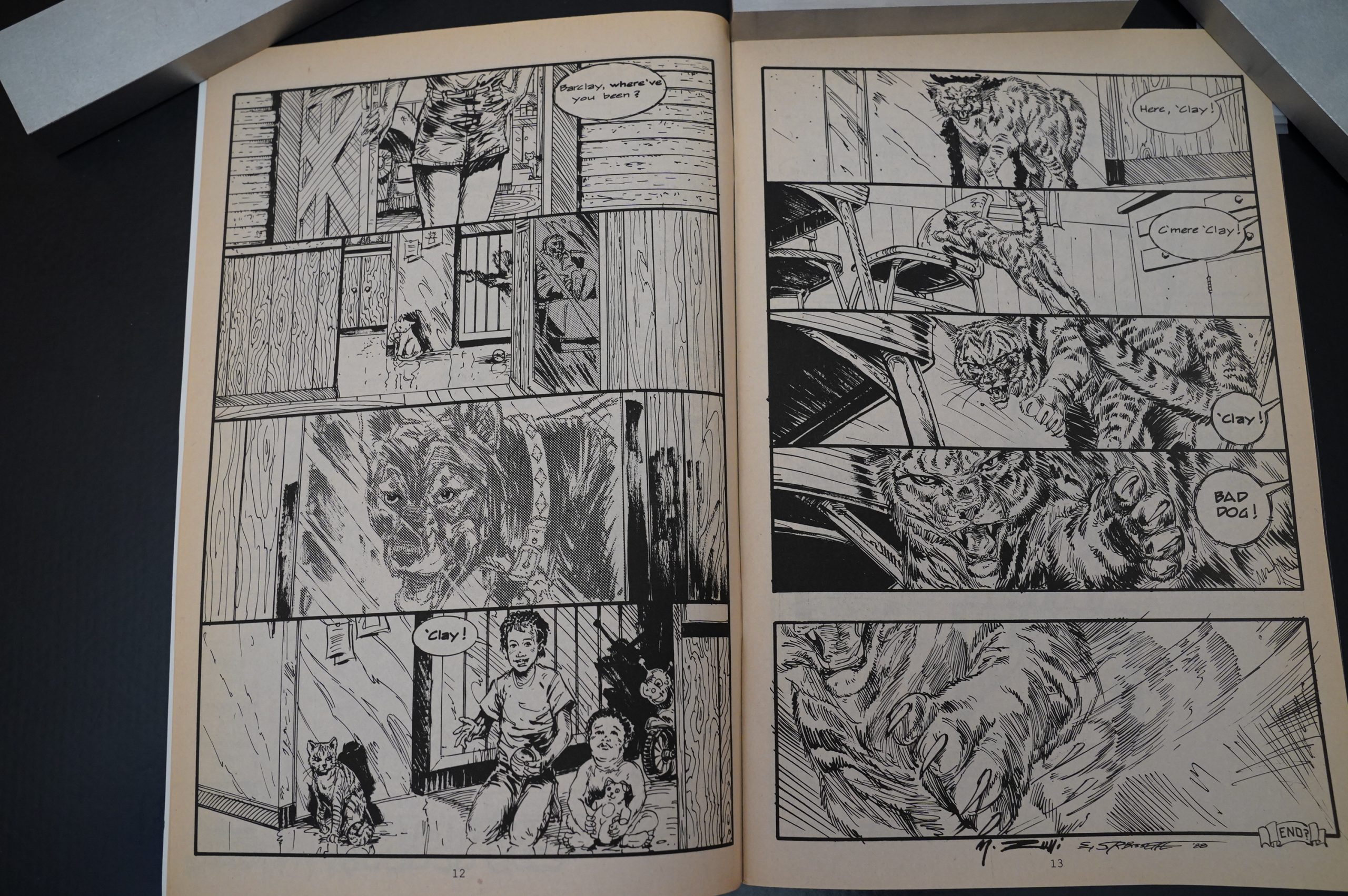

This was a lovely issue — it’s almost all like this: We follow this puma around for a night. Zulli’s nature scenes are amazeballs.

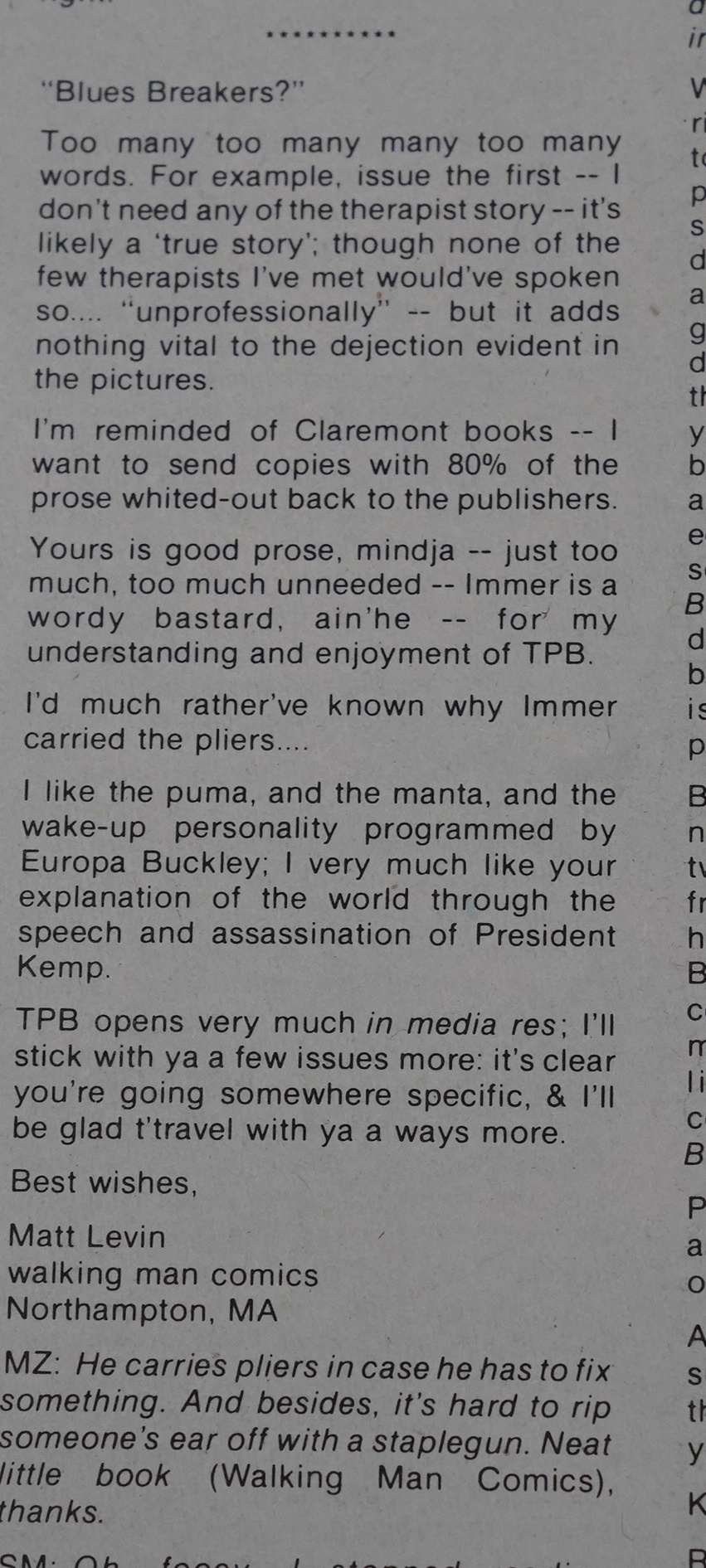

Somebody asks the real questions, and they don’t really have an explanation.

Some of the storytelling ticks seem to make little sense, but they work in context, I think? For instance, the chauffeur robot had overheard a conversation between two guys, and now he’s repeating it to these birds (while moving around like a bird).

That’s more fun than watching those guys talk, right?

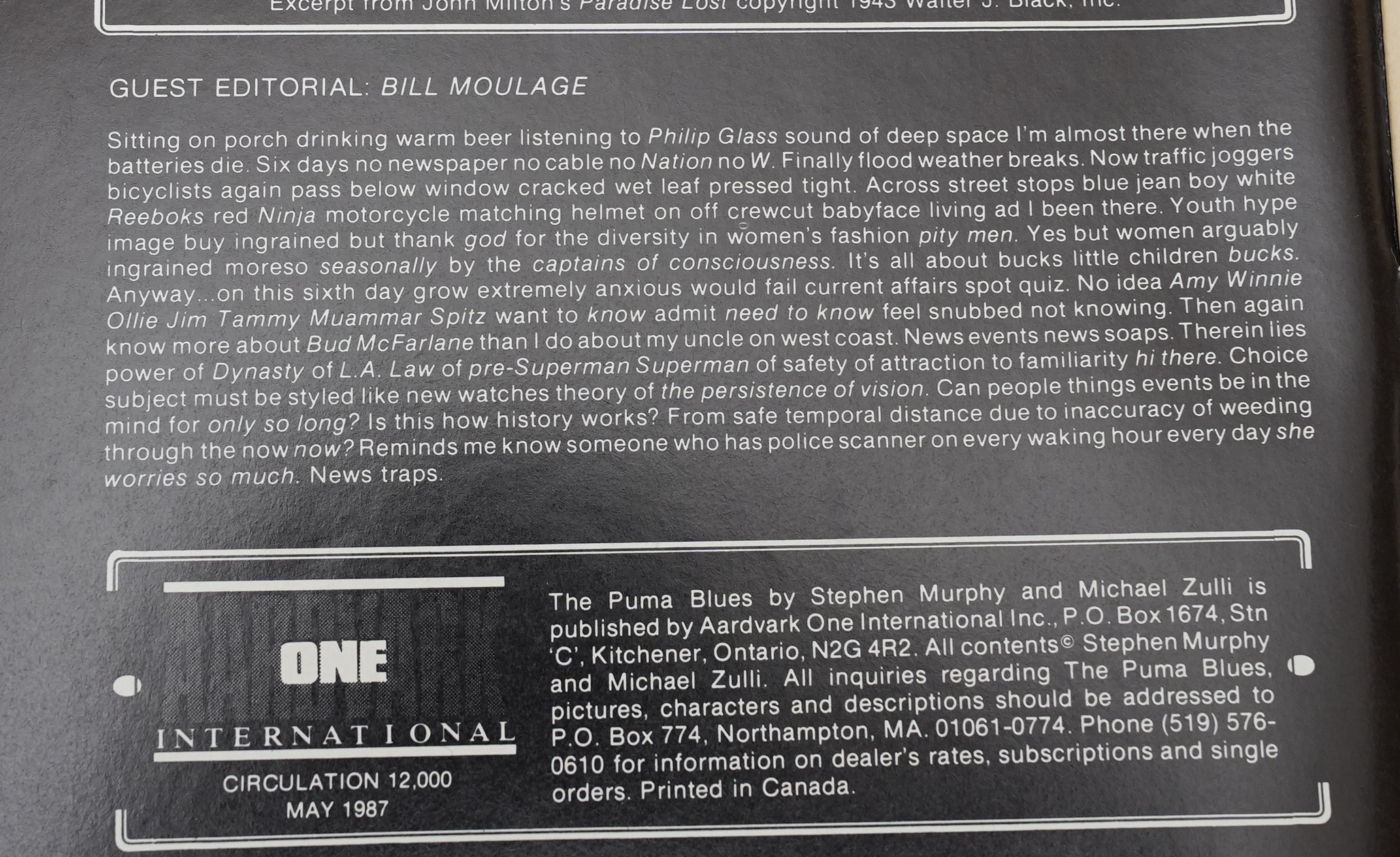

The circulation went down to 13K the issue after the 19K top, and then 12K, and then they stopped saying what the circulation is. Which I interpret as “it’s depressing; don’t ask”.

I assumed that “Bill Moulage” was an acronym for Murphy (doing a kinda-sorta William Burroughs thing), but he apparently exists?

Finally! The pliers are back! In a dream! Unfortunately that’s the last we see of them… ever… but it turns out that the protagonist used to wear ear rings (back in his hippie days), so perhaps there’s some sort of connection? As with most things in Puma Blues, it’s never resolved.

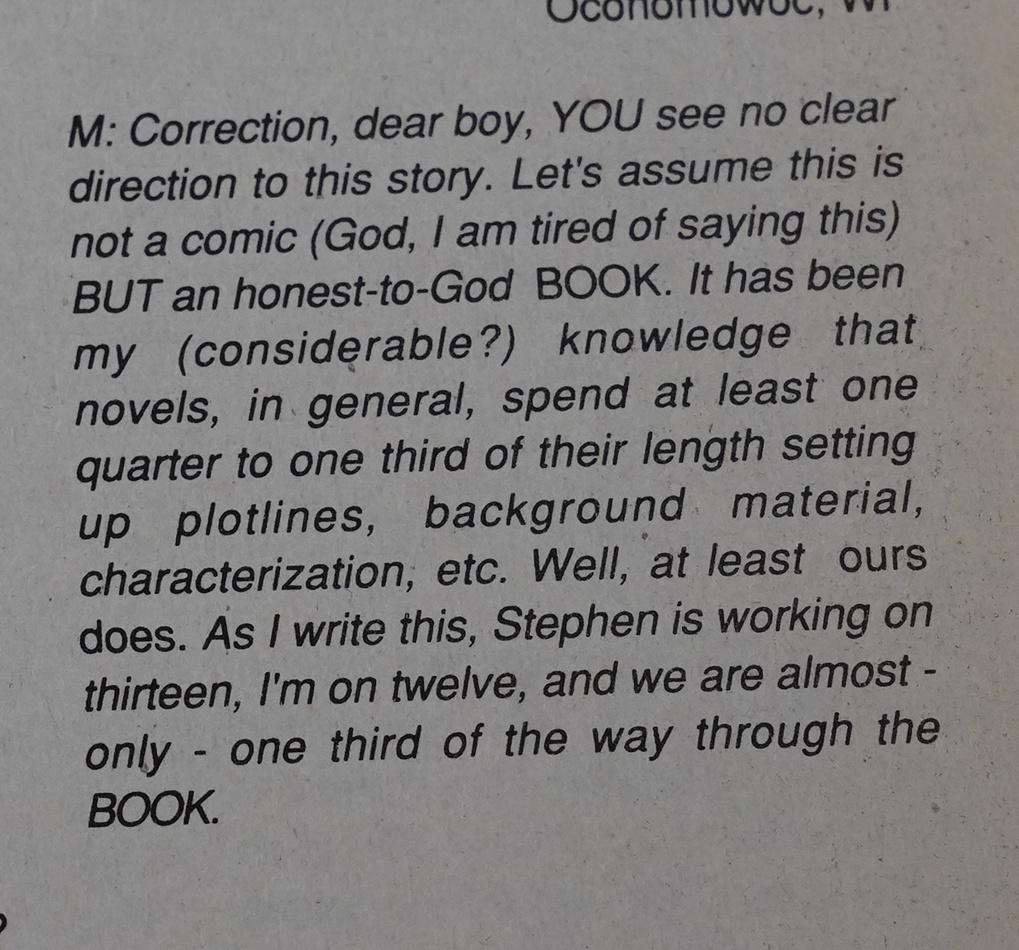

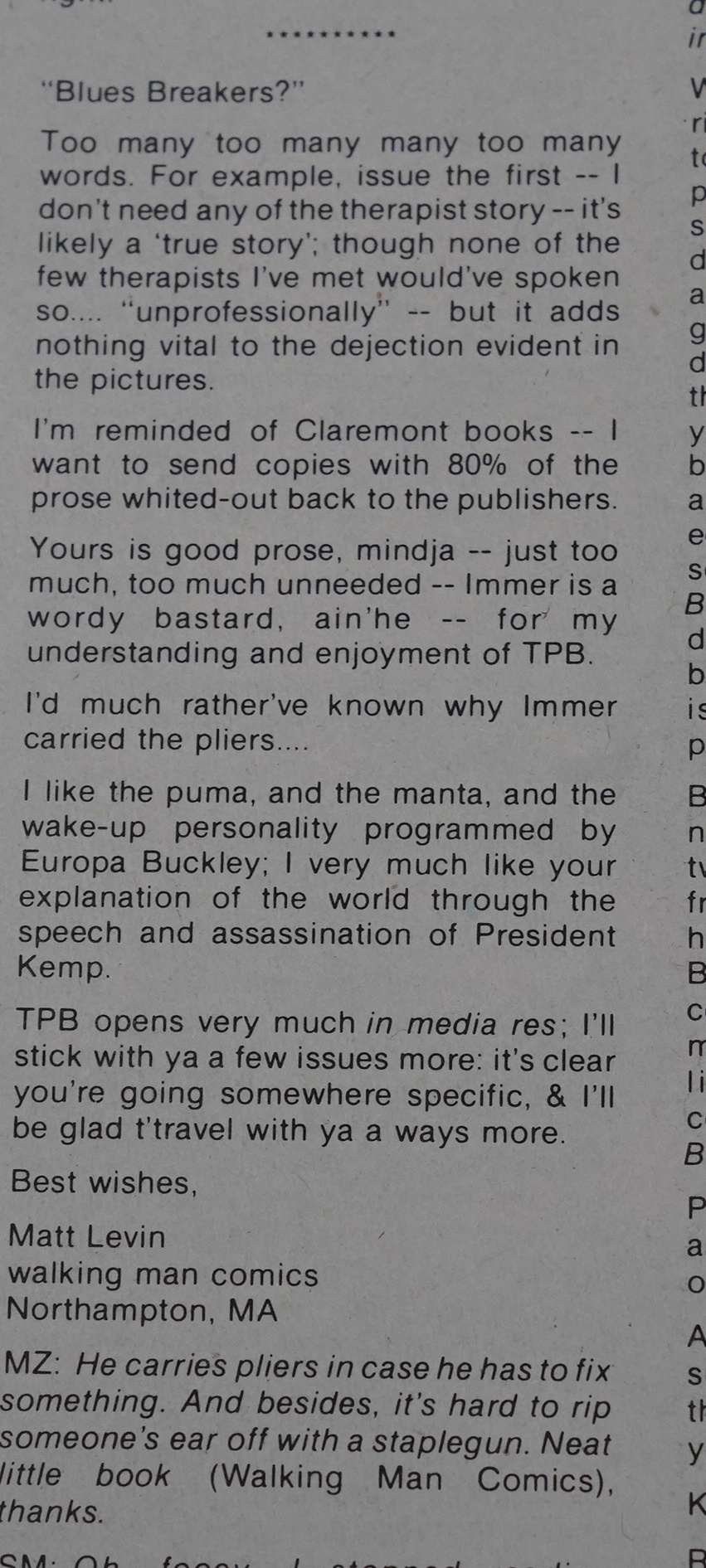

A reader expresses the common take on Puma Blues, I think.

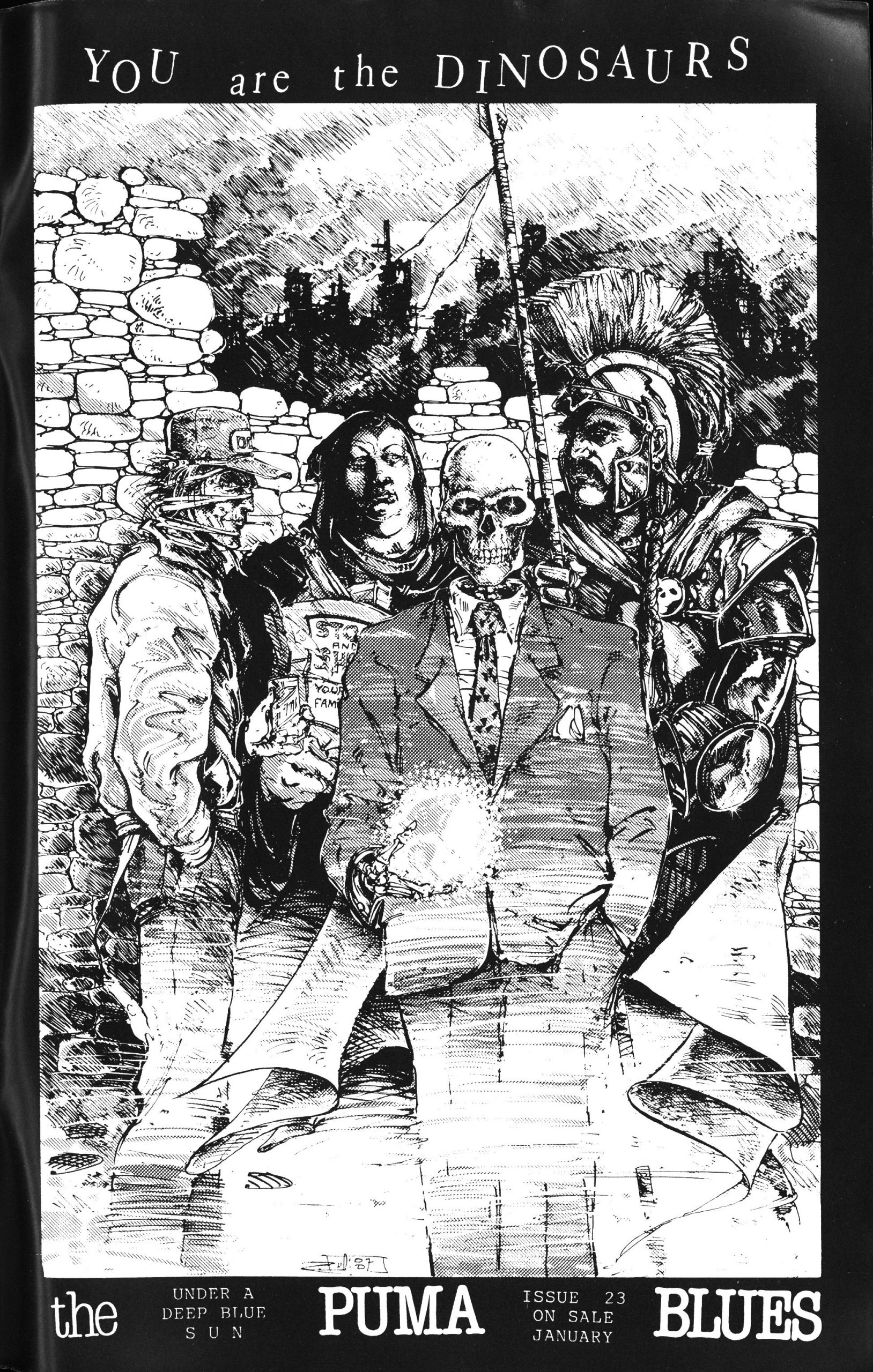

They got a better promo poster.

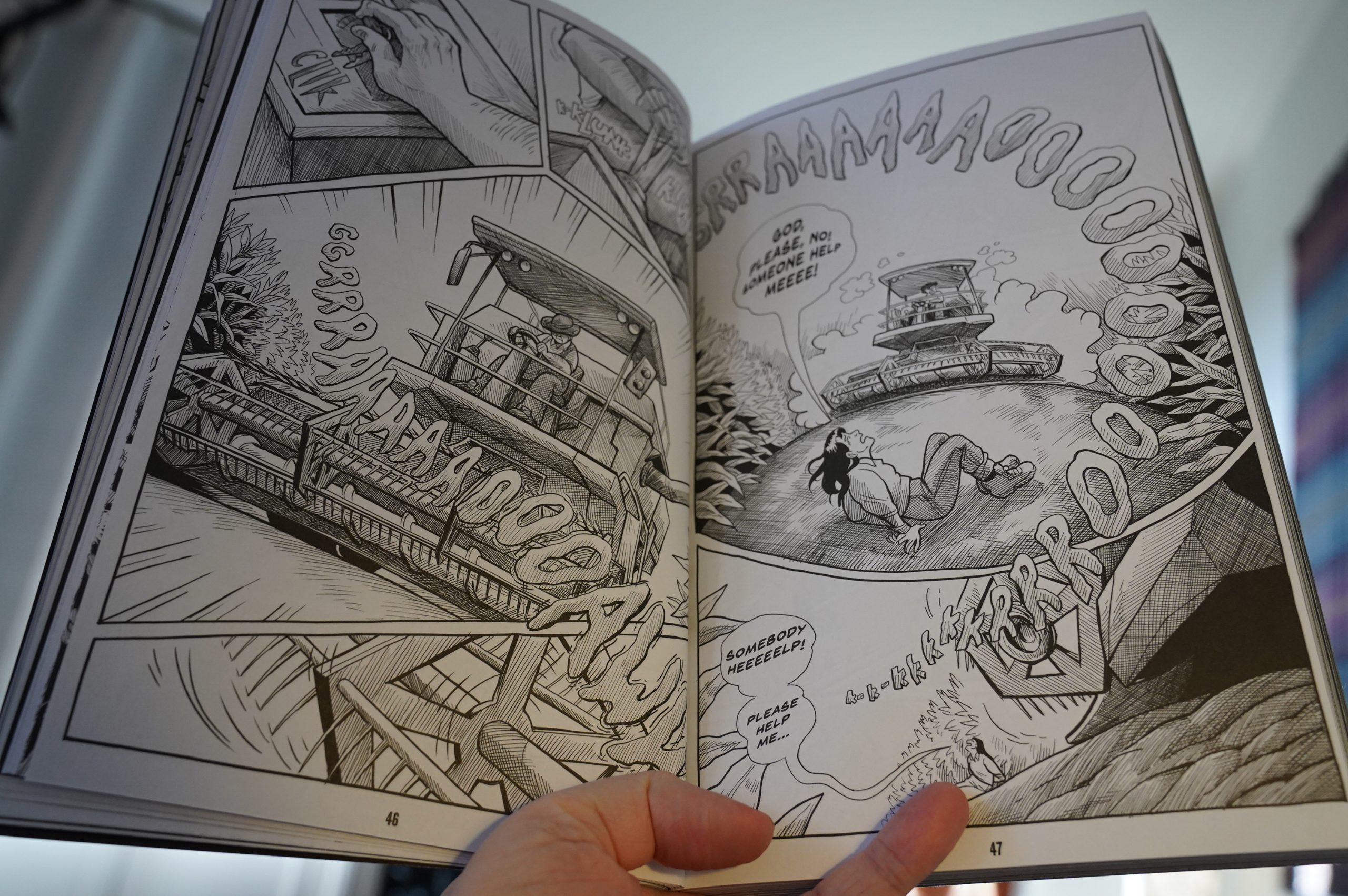

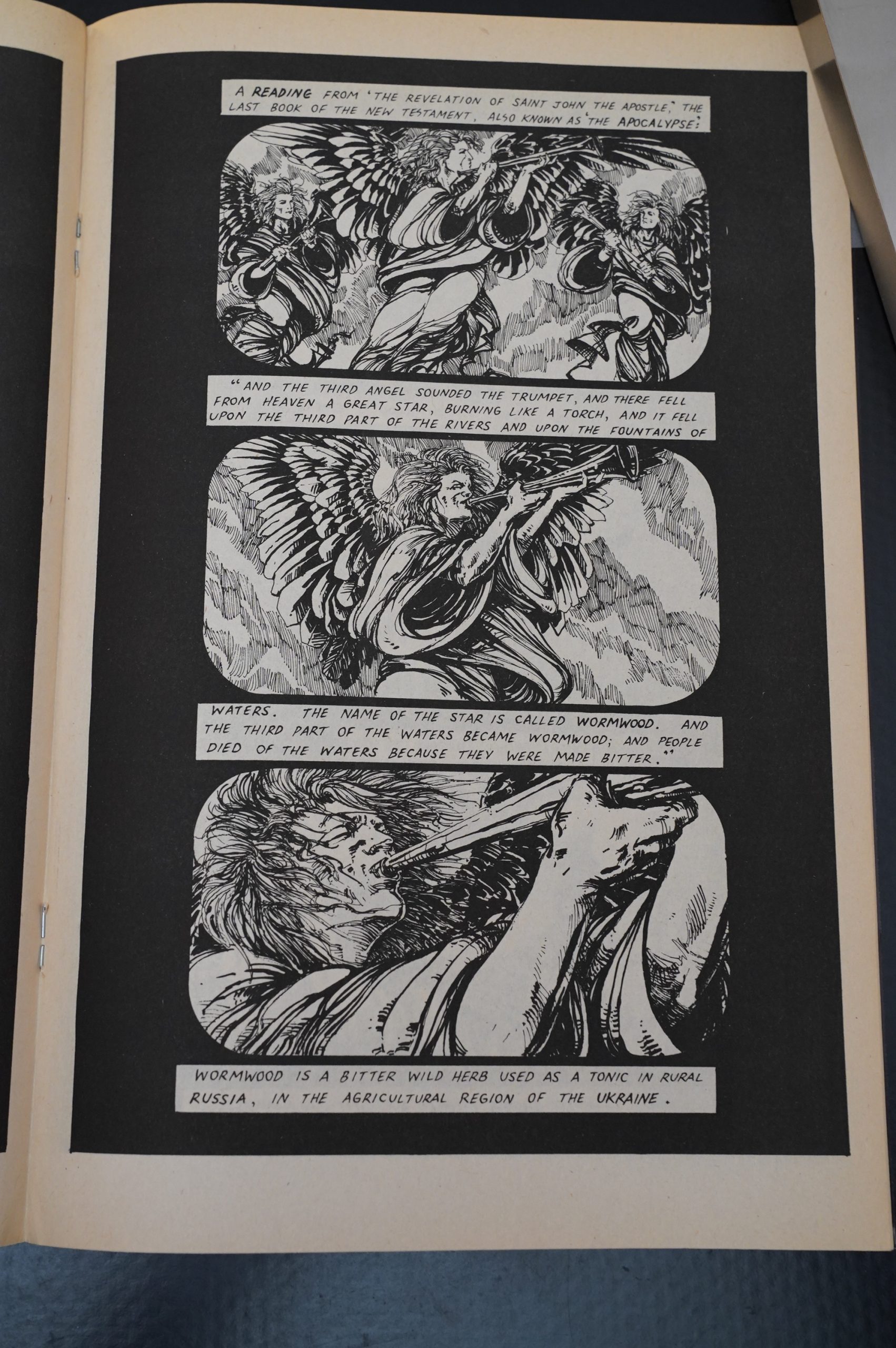

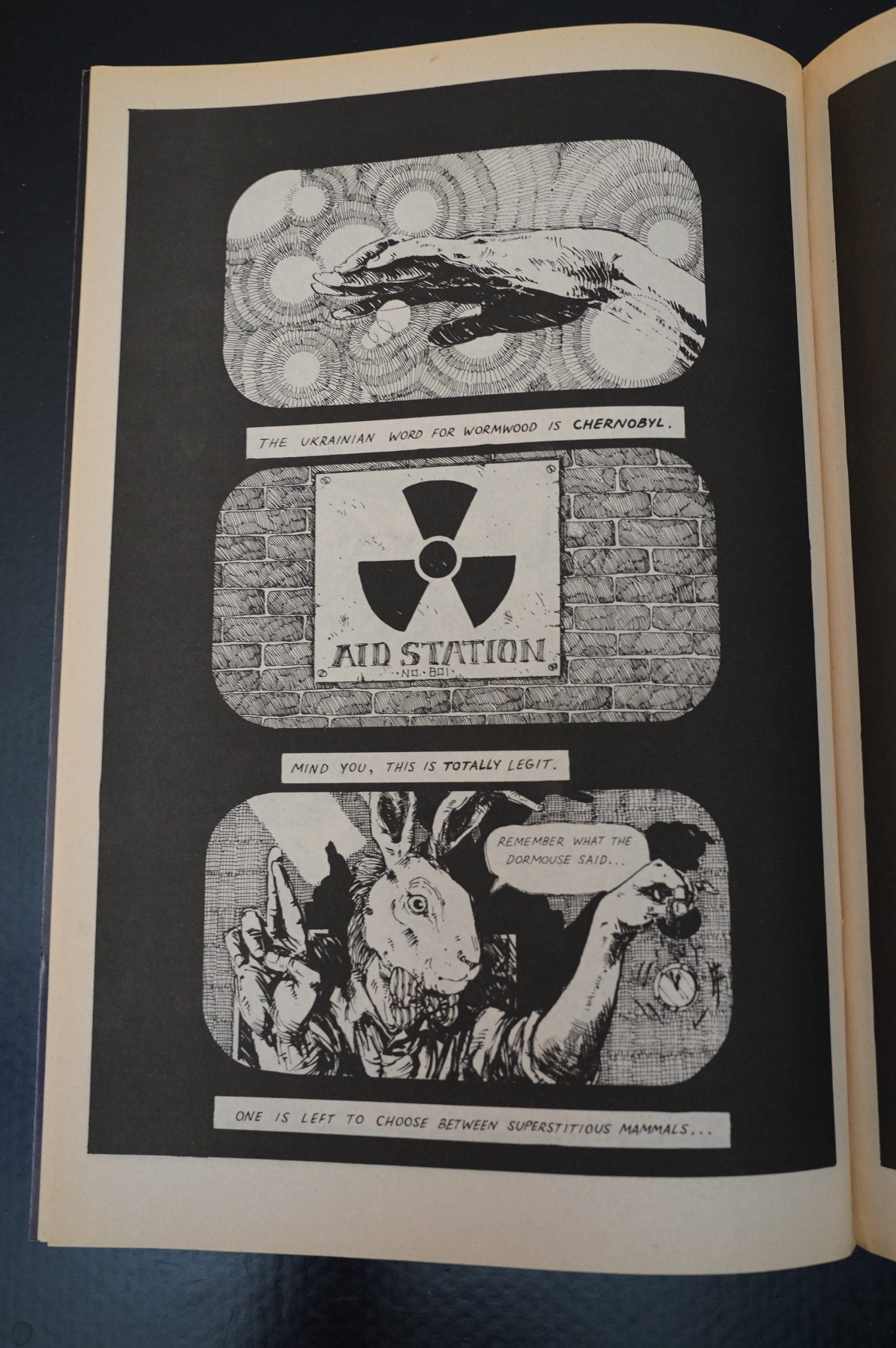

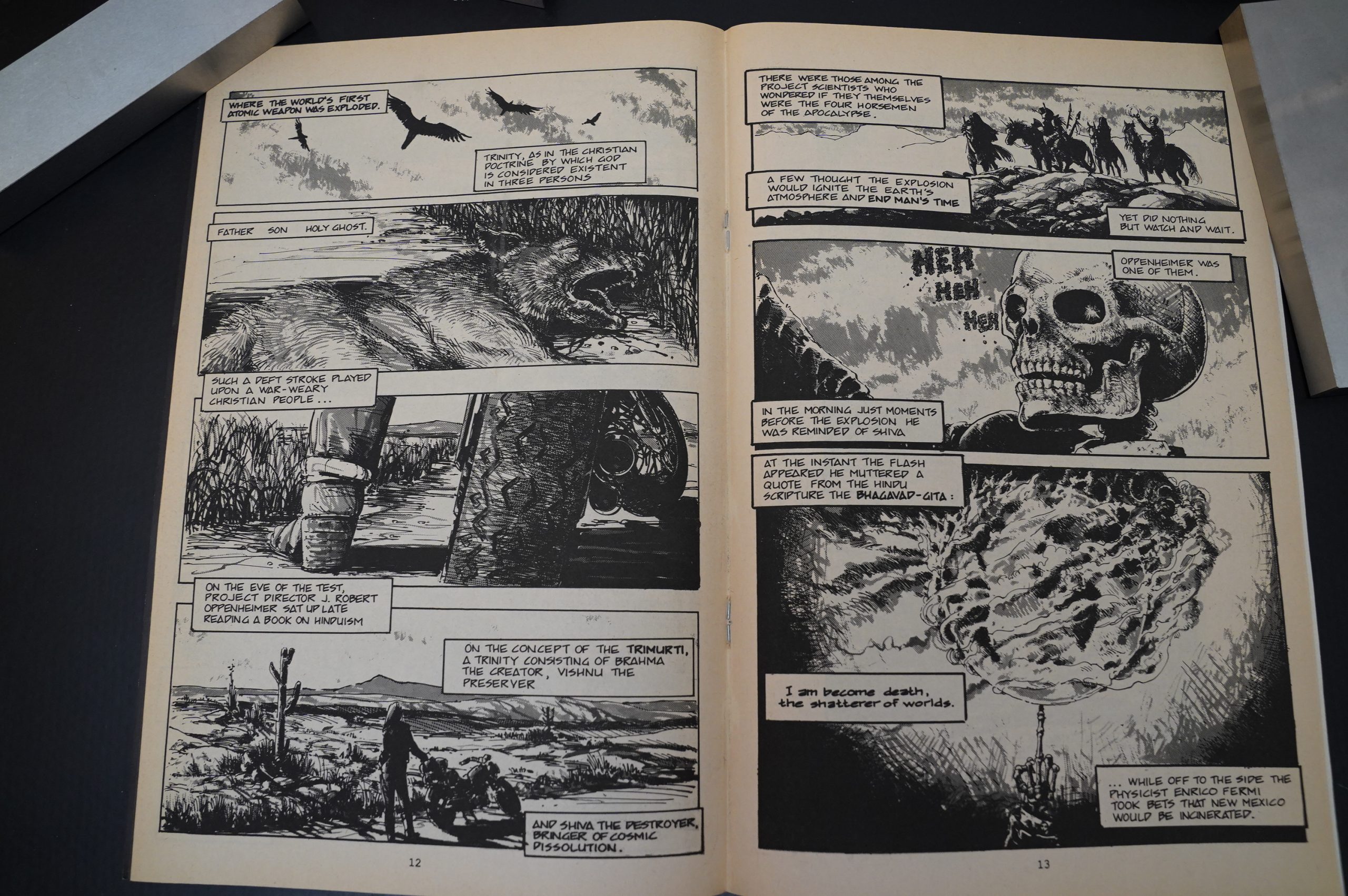

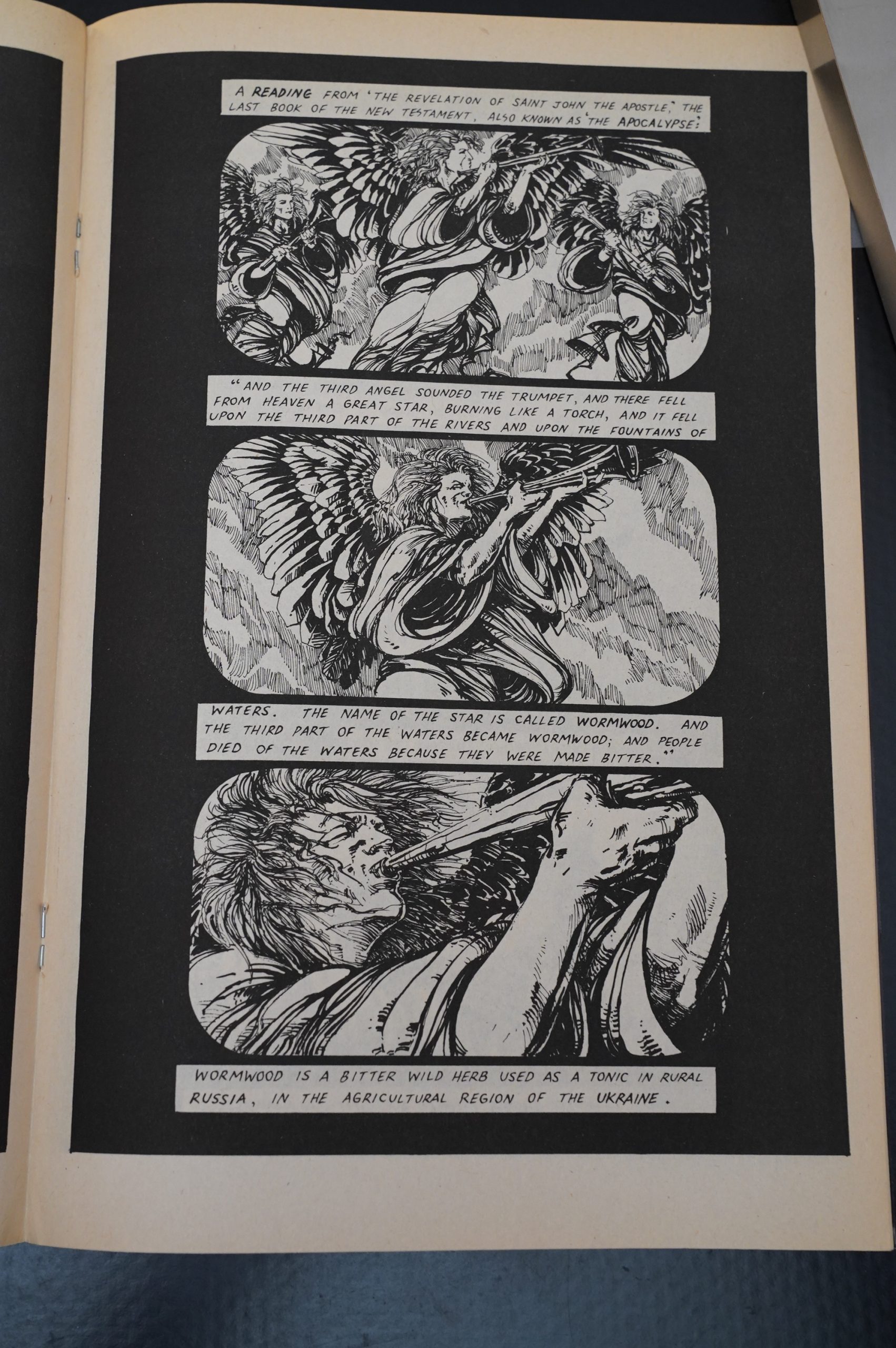

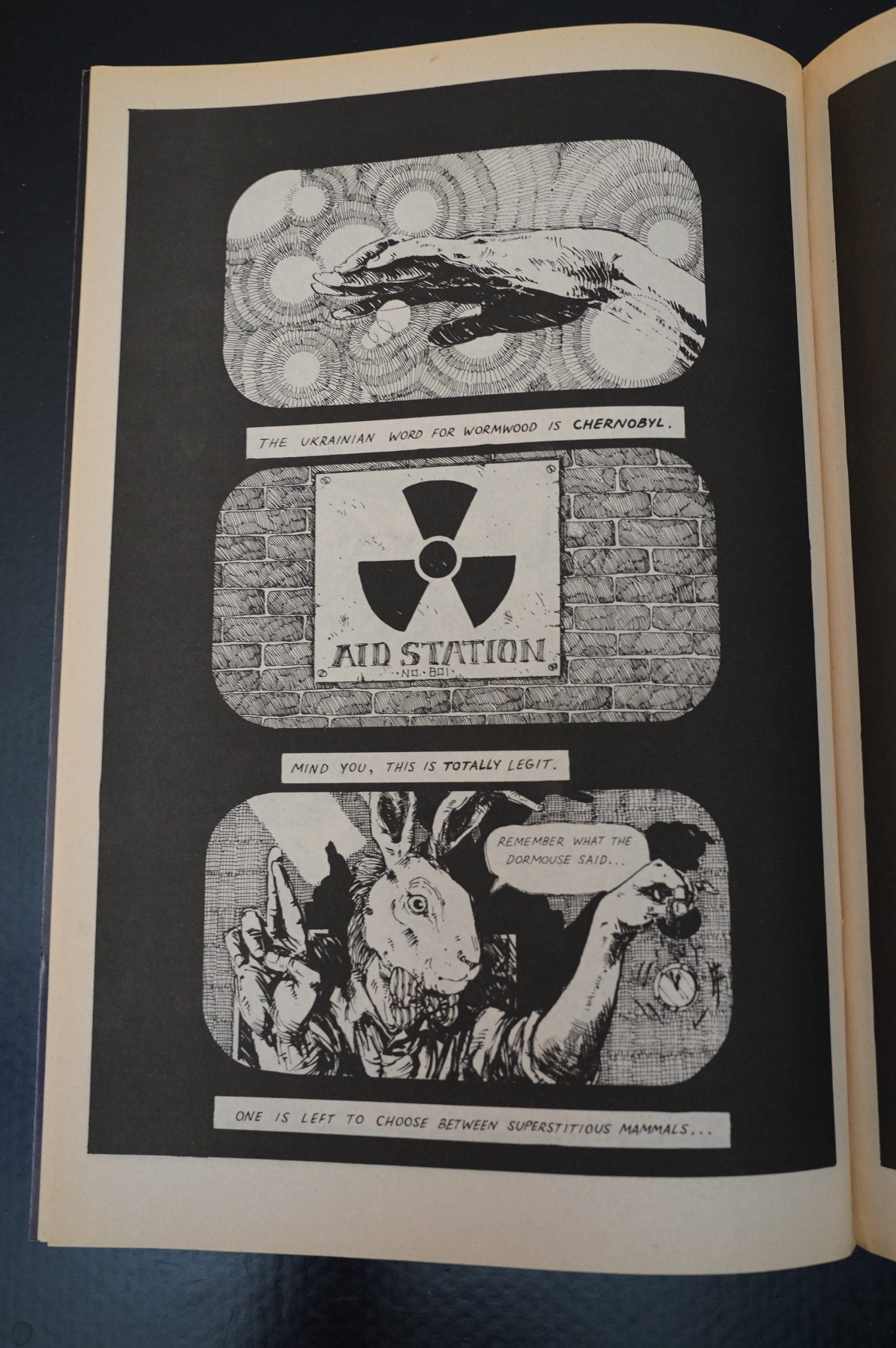

OK, remember that “woo woo synchronicity” thing? Read these two pages:

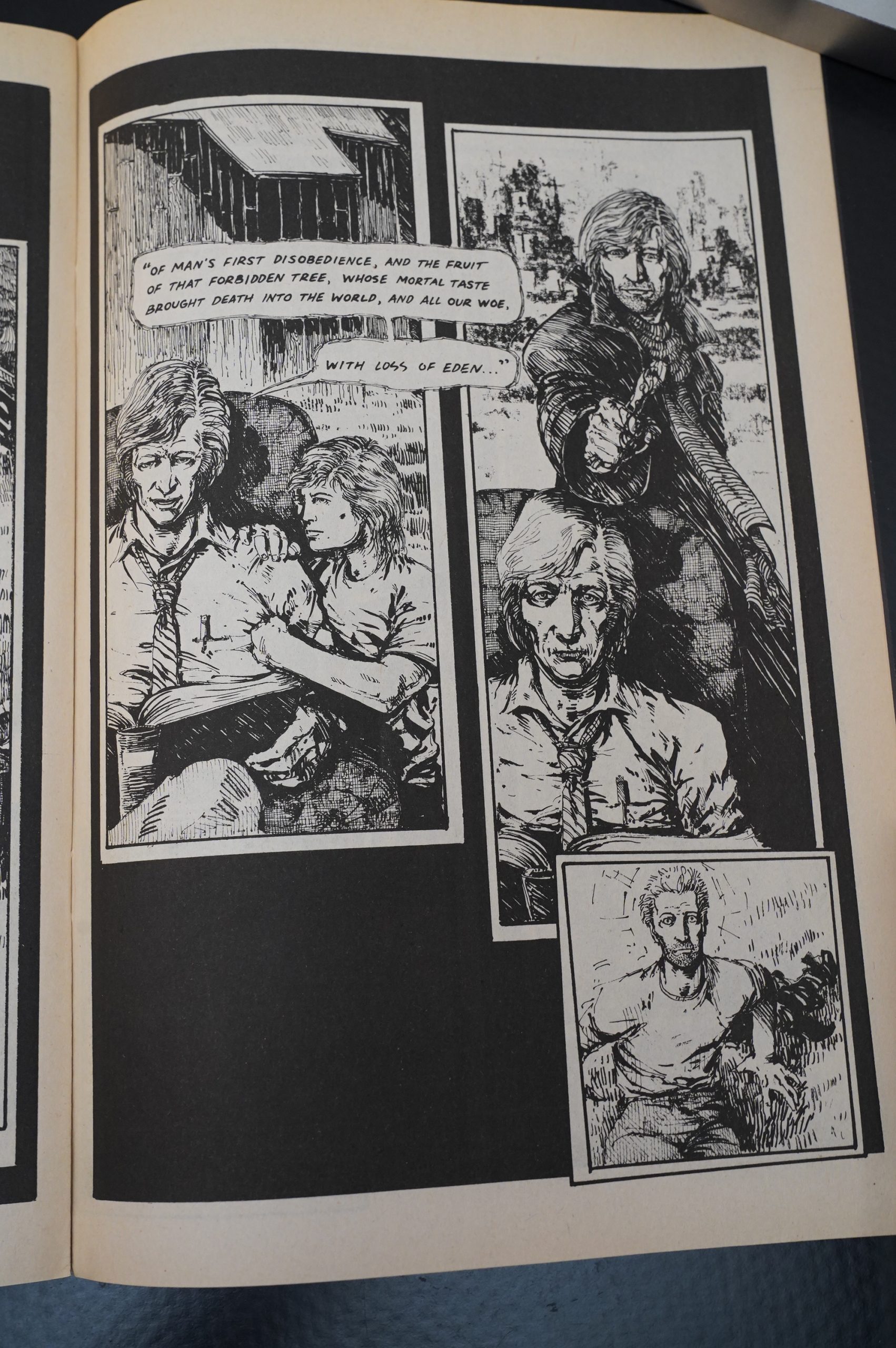

CHERNOBYL MEANS WORMWOOD! LIKE FROM THE BIBLE! WELL I HAVE NEVER!

I mean… it’s fun, but like the protagonist says later: “Rosebud”.

Murphy/Zulli really likes this kind of stuff, while making fun of it, too, I think? Slightly? But you can see why Dave Sim would publish Puma Blues, because he’s all about these paranoid connections that shows that there’s “meaning” and “connection” in the world.

There isn’t much overt environmentalism in the storyline itself, but every issue has a lot of sad nature facts, and they sort of set up a clearing house for information about these issues…

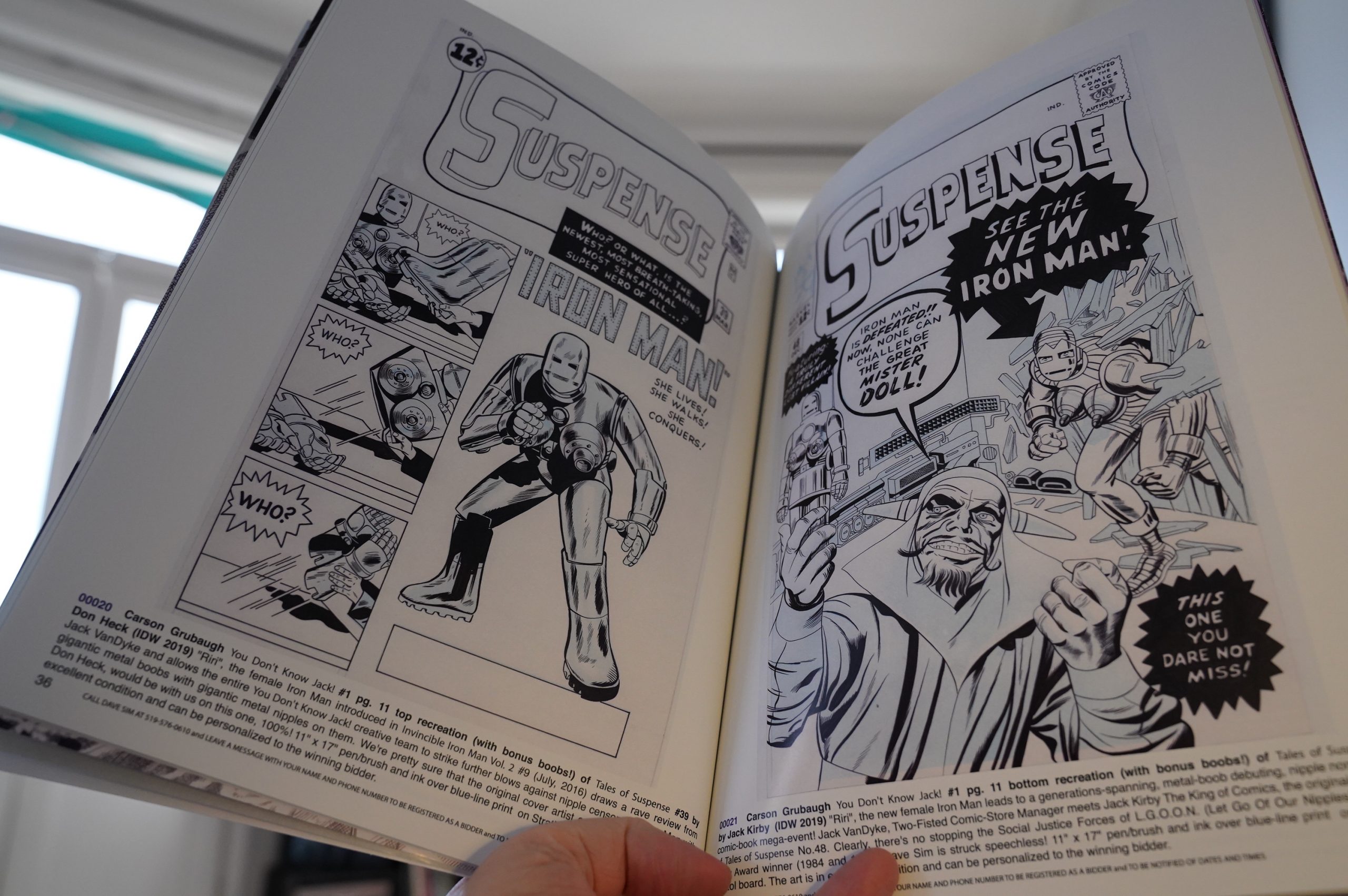

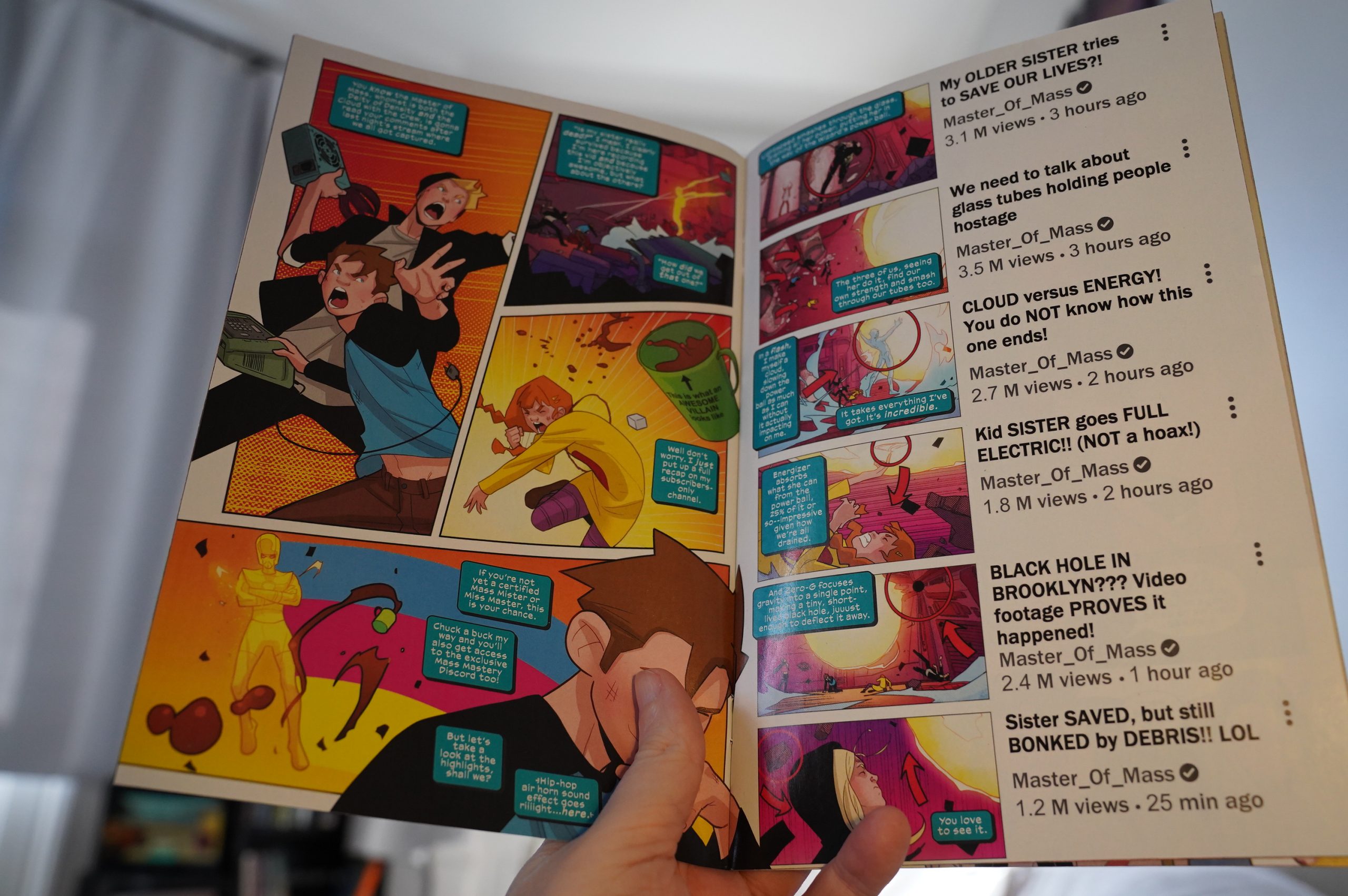

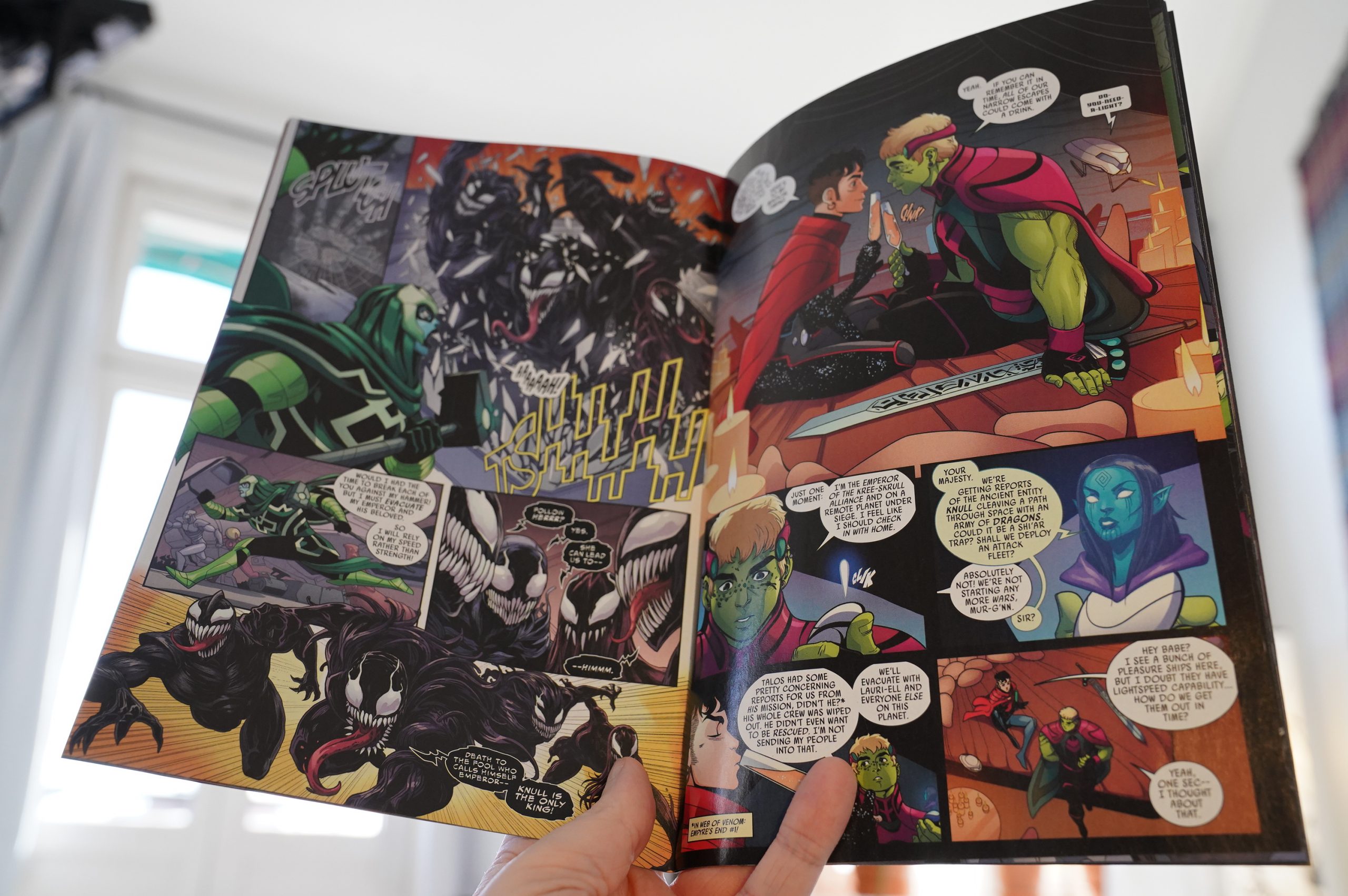

Well now they’ve gone too far! They use a lot of quotes from pop music (mostly Talking Heads, David Bowie and Iggy Pop), and here they do Bowie again: But from his then-current album, which is his worst album ever. Tsk tsk.

I think this is the first time they’ve mentioned that Puma Blues is supposed to run for three years? At least that’s what I get from this…

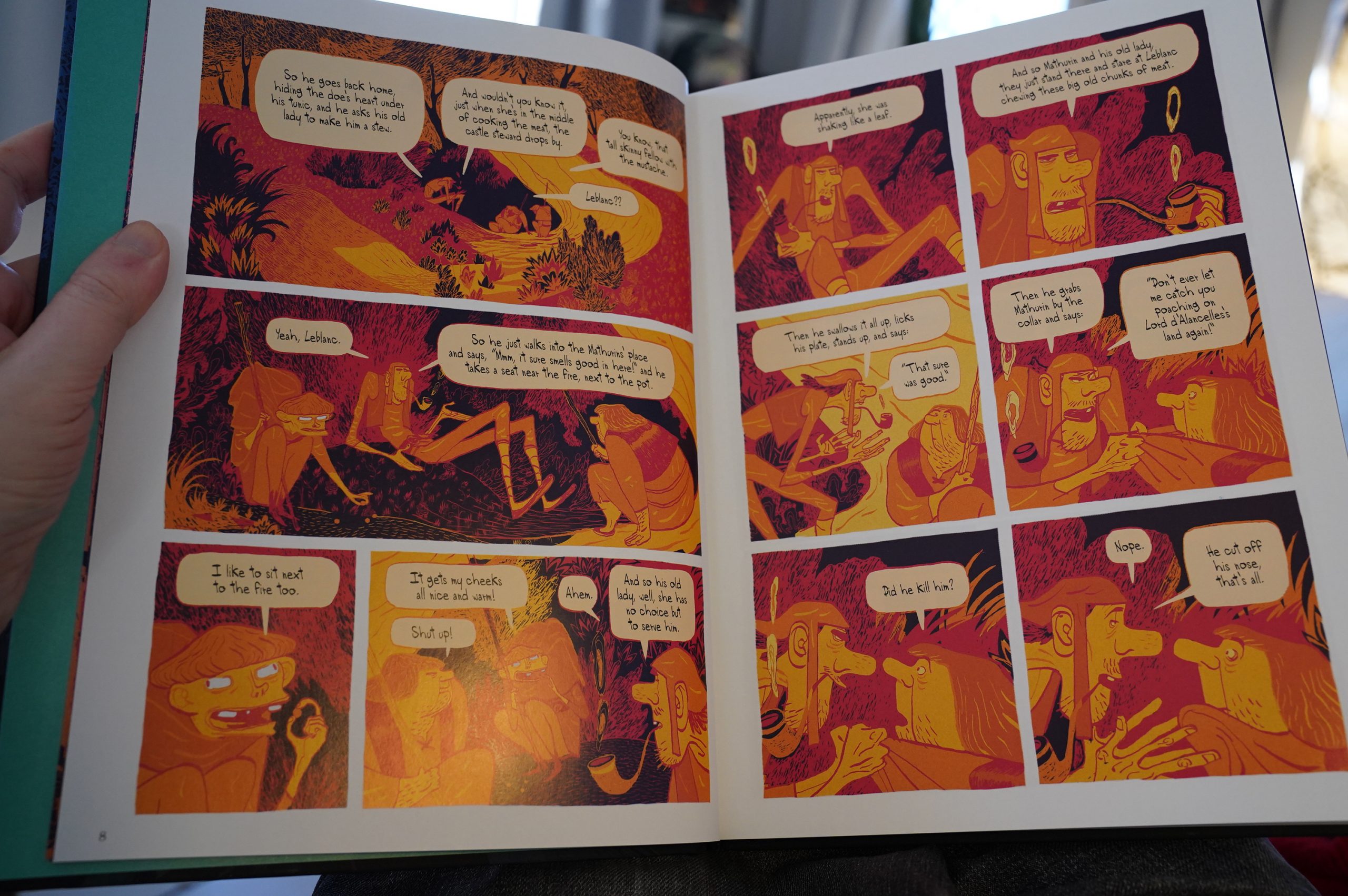

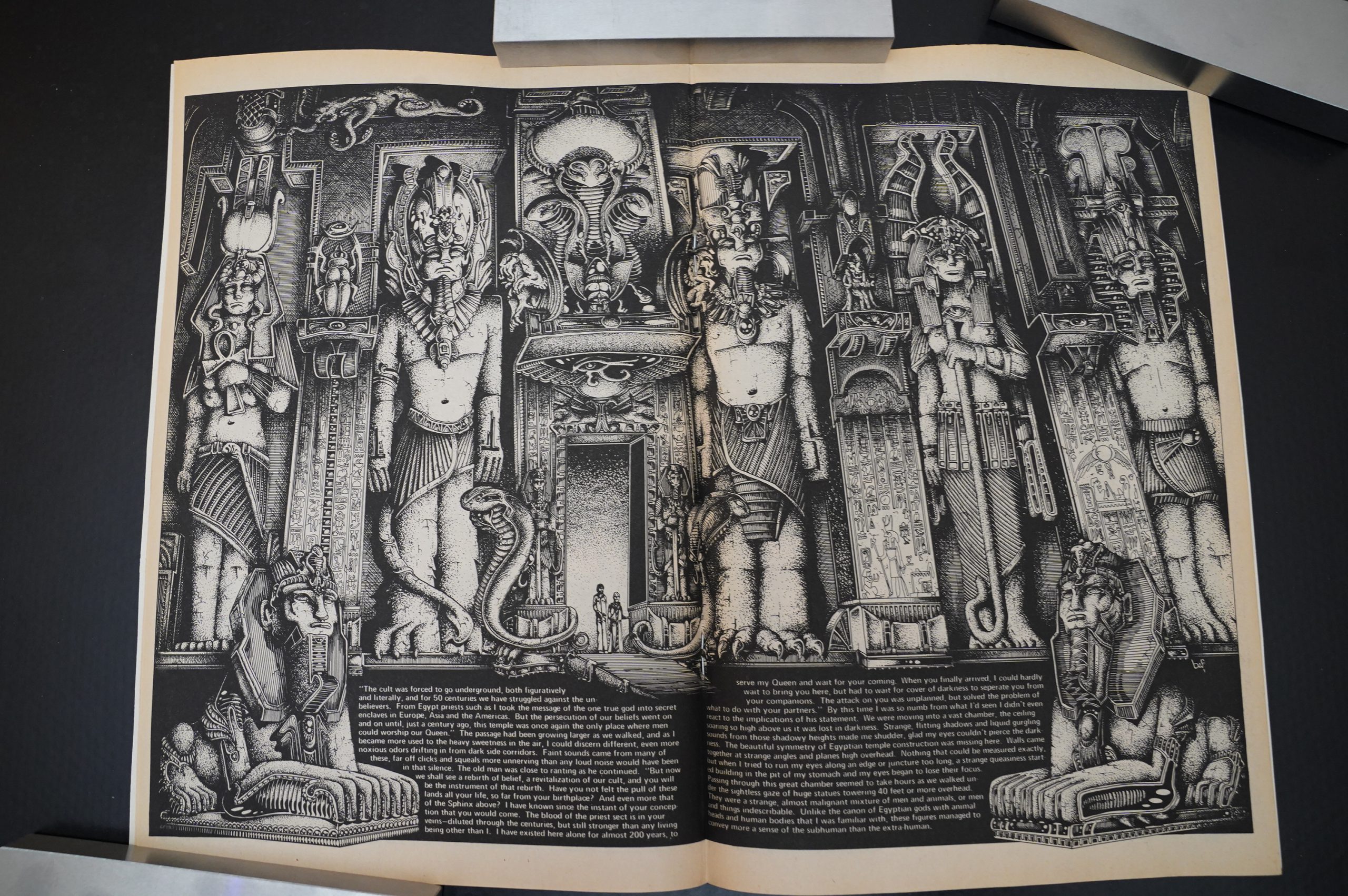

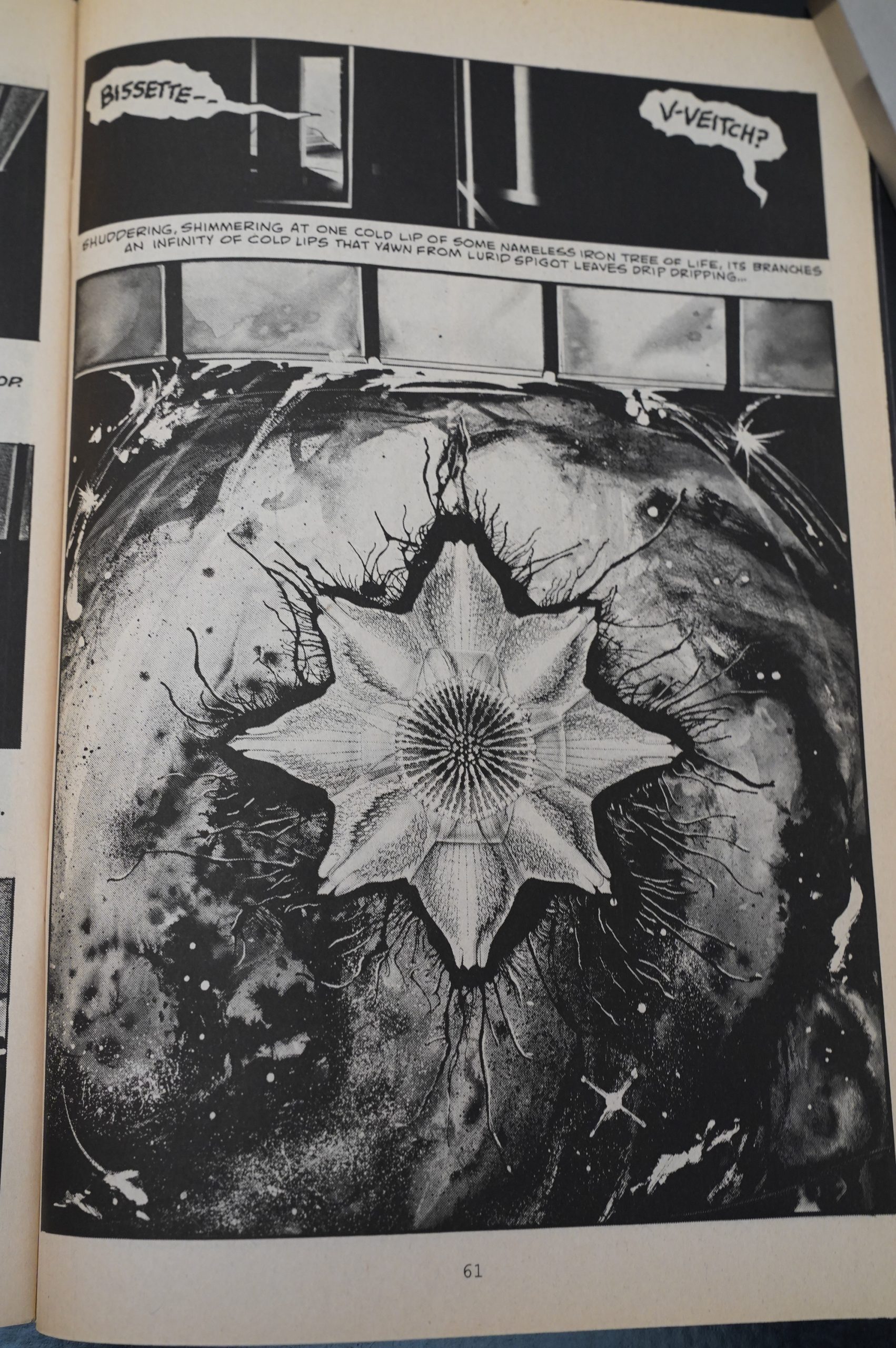

Whoa. Gorgeous.

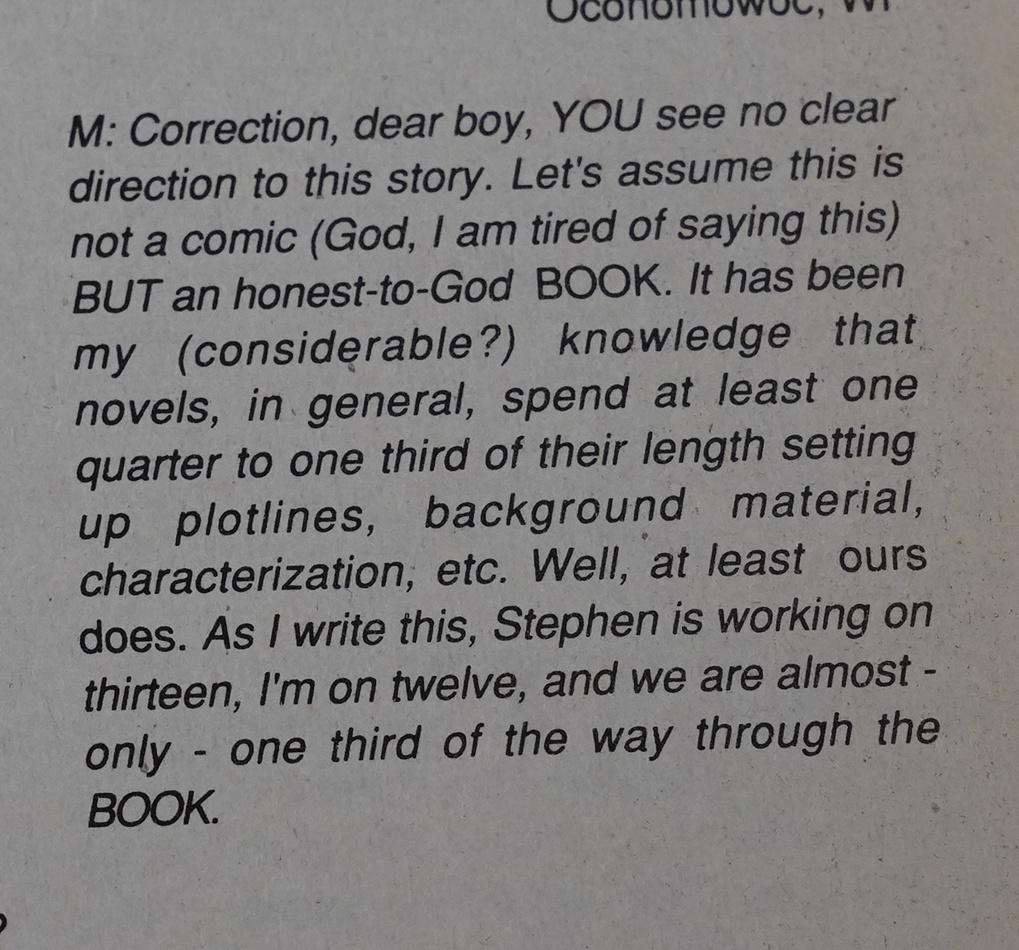

Zulli confirms it: They’re now one third through the narrative, and they’re done setting up plotlines and stuff.

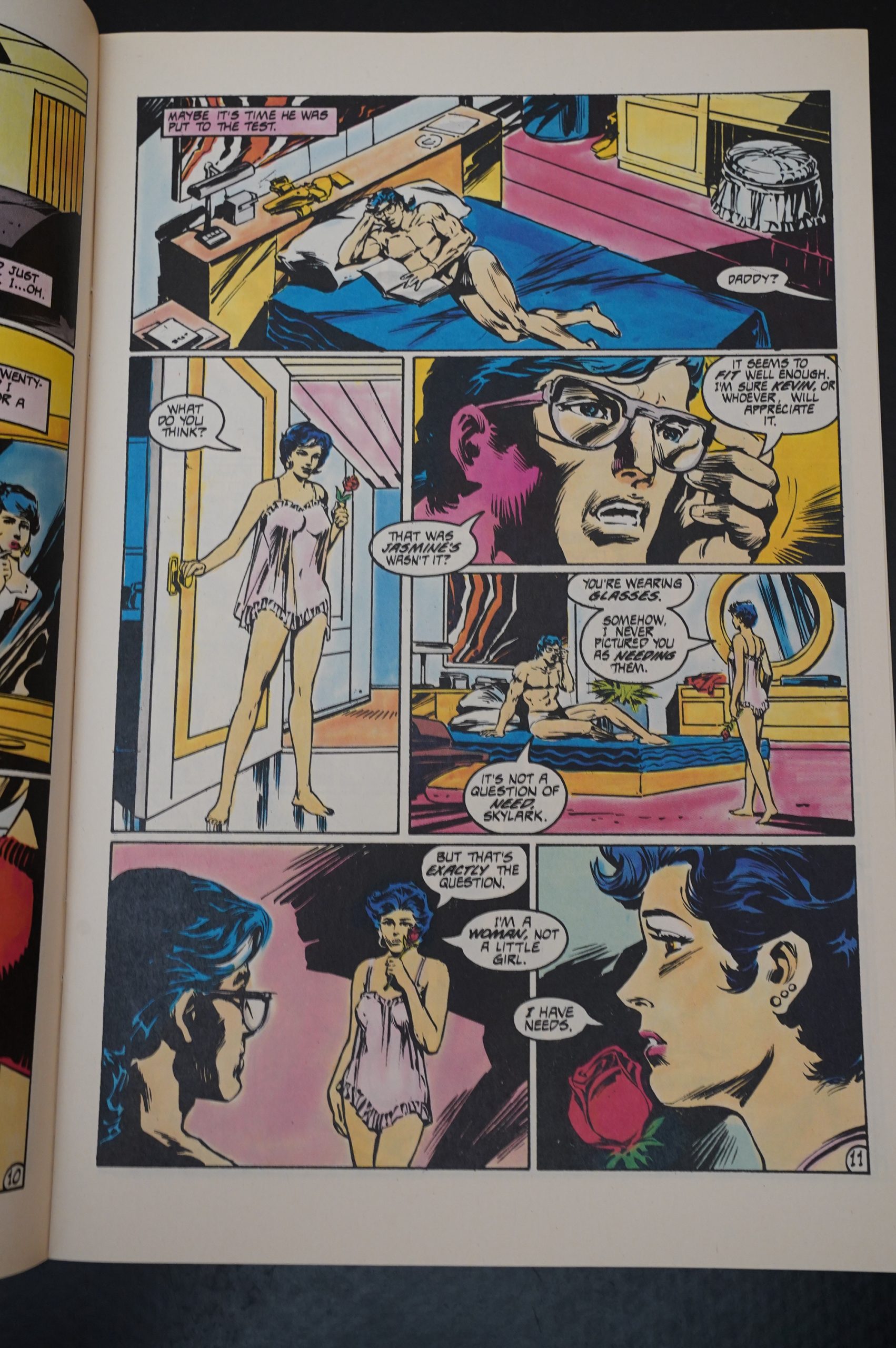

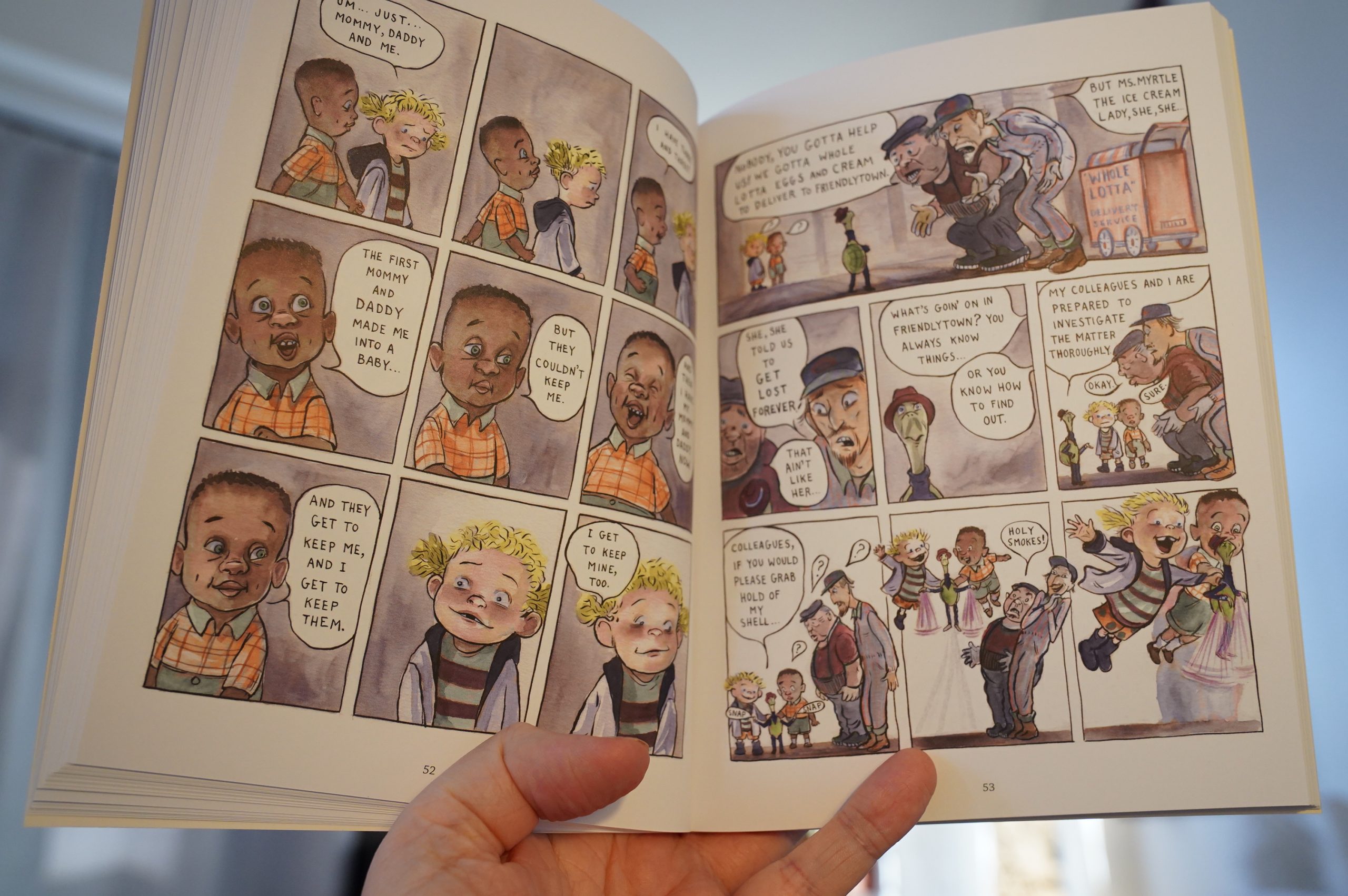

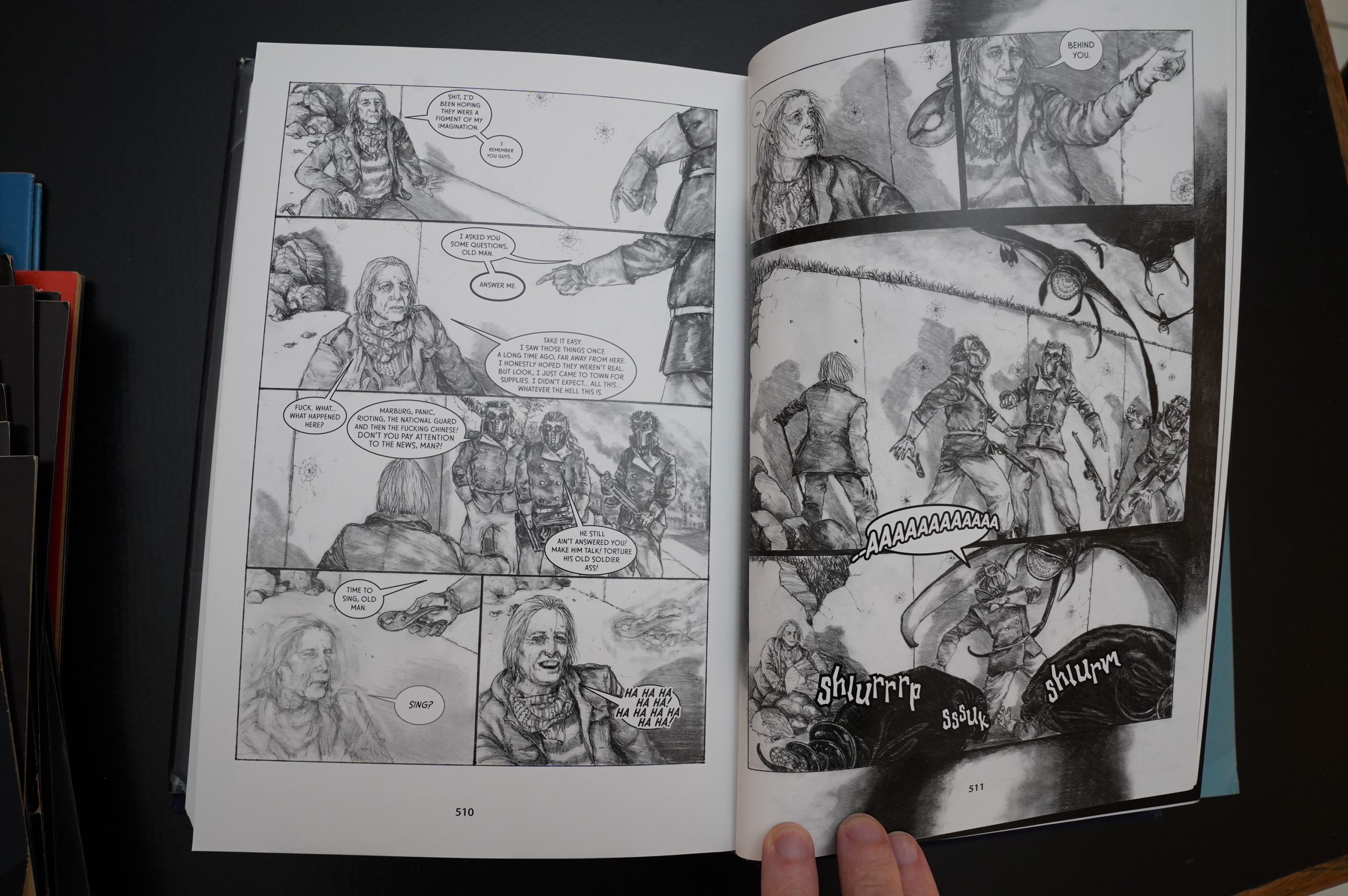

So does things change with the 13th issue? Well… yes and no. Zulli’s artwork changes: He start using graytones. But we don’t really get any acceleration in the plot development…

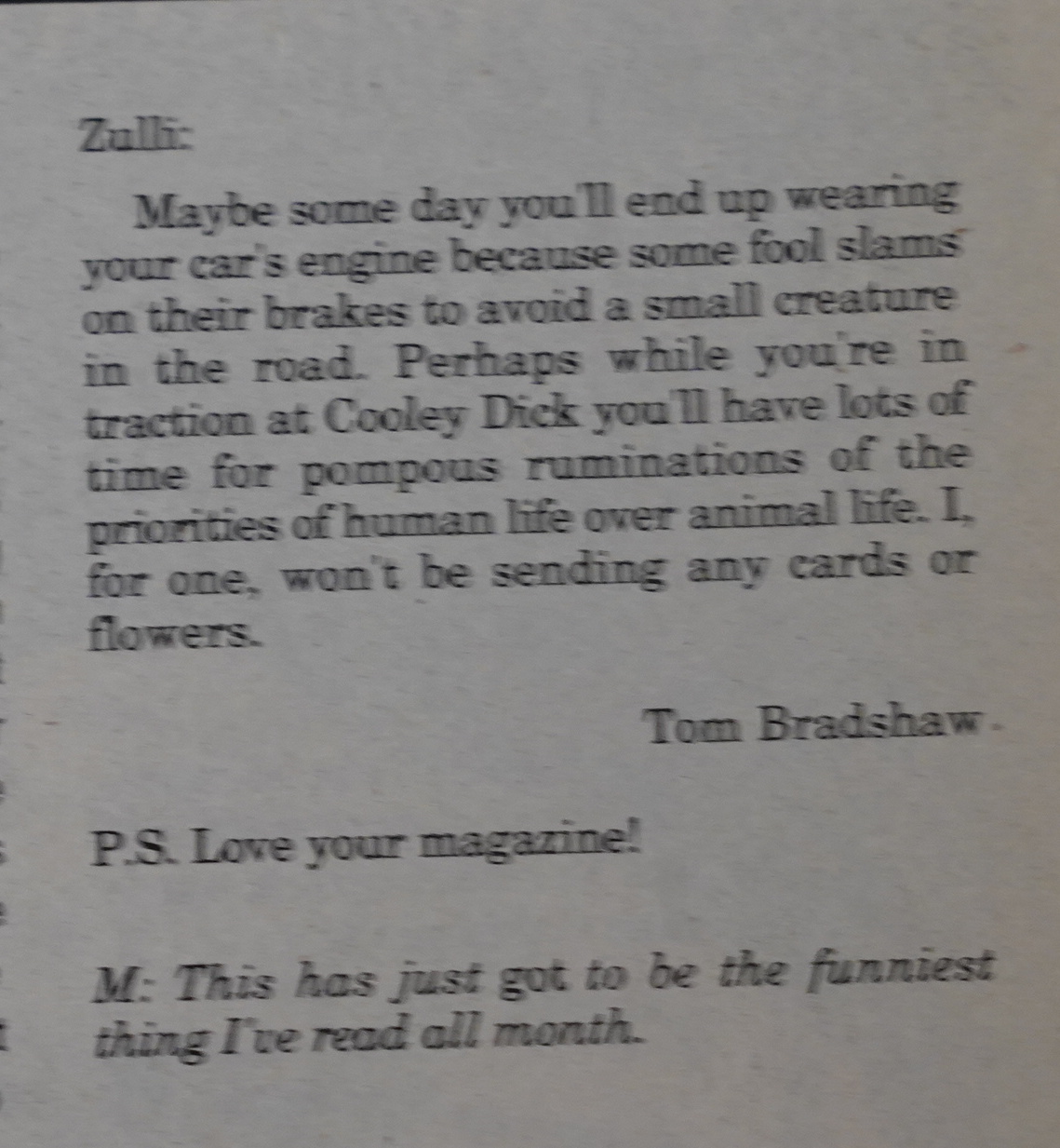

Some people hate animals?

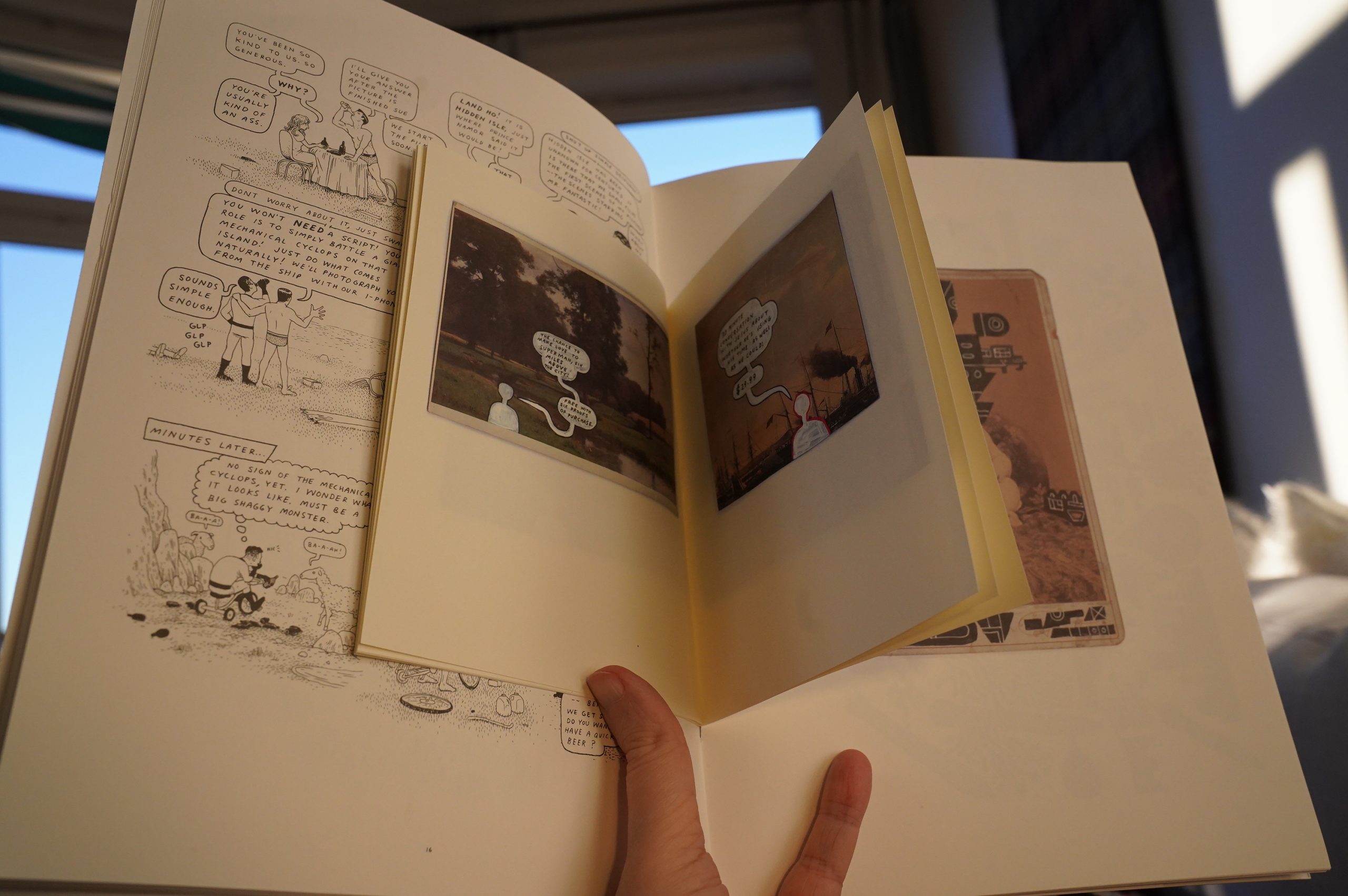

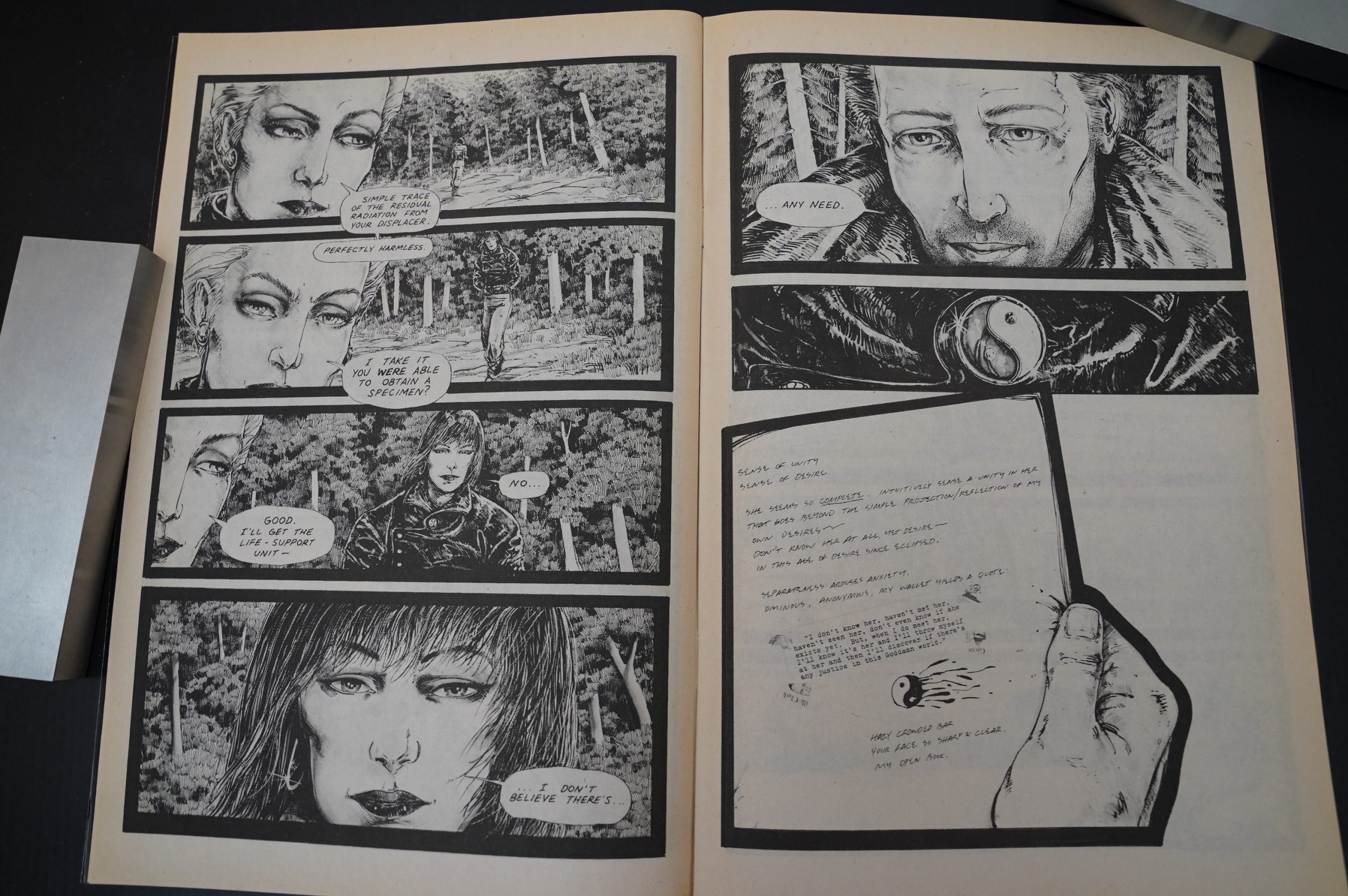

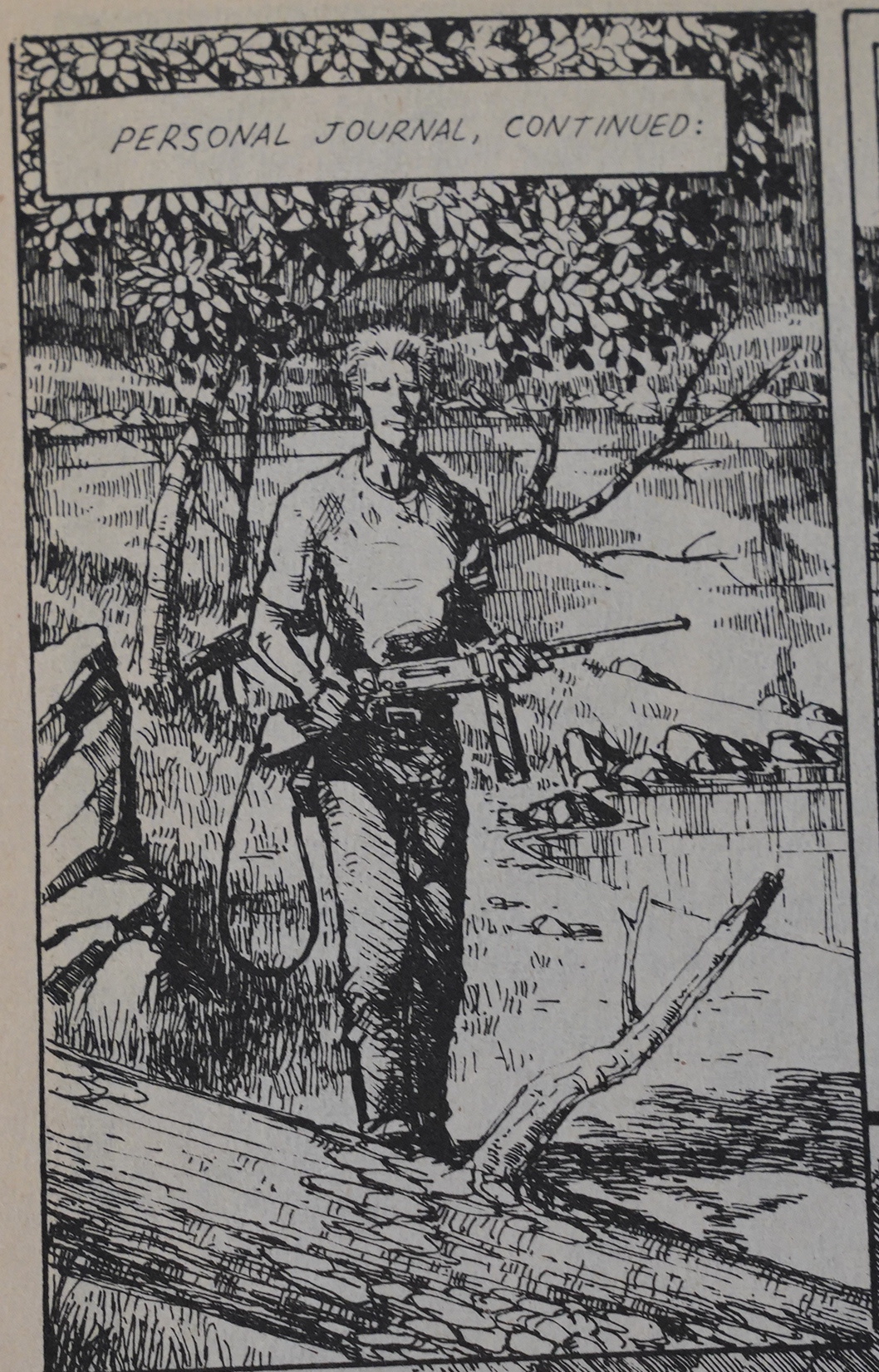

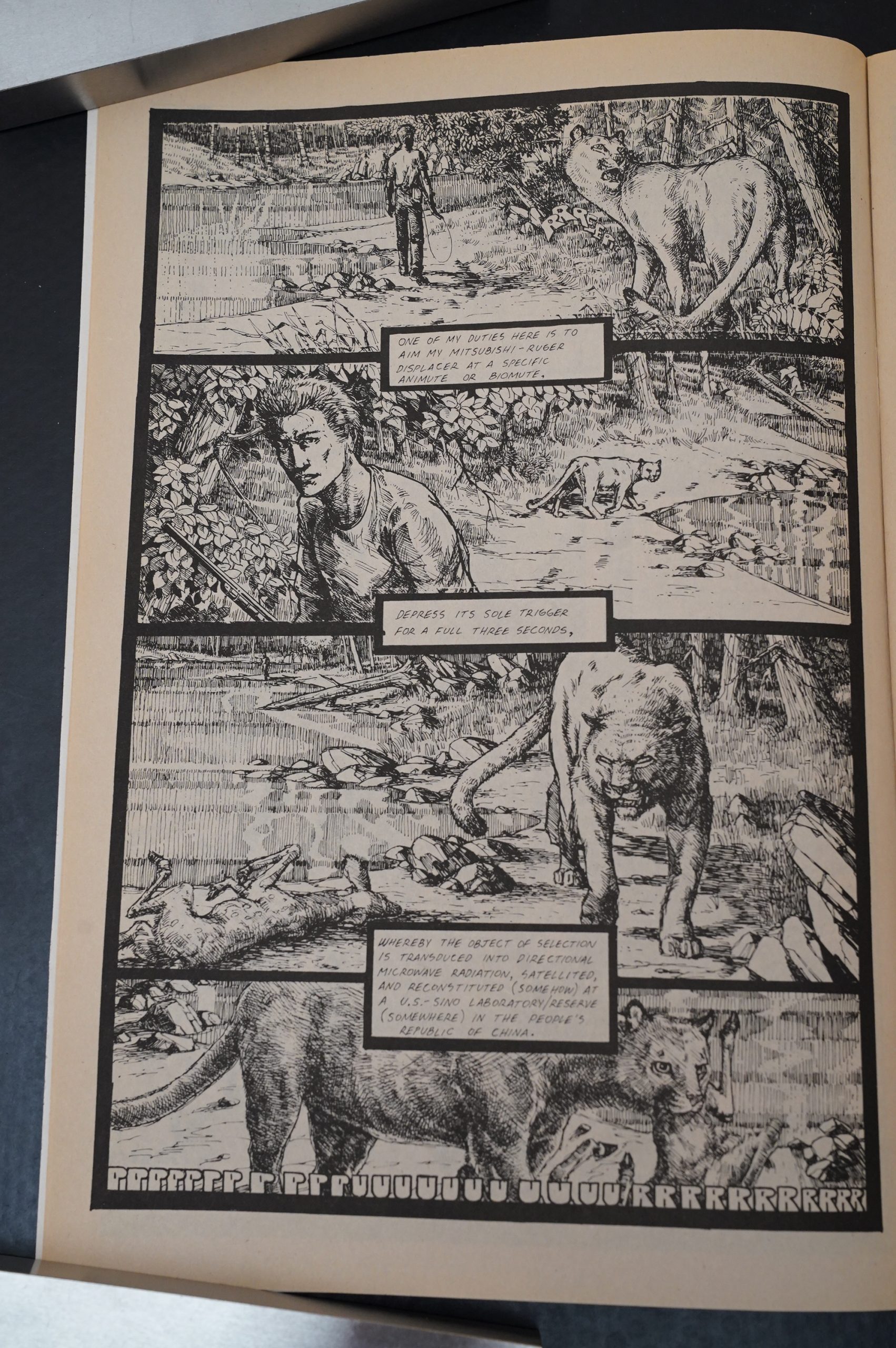

Then! Plot development! For one issue! It turns out that the displacement gun he’s using on the mantas is sending them to… China…? So this (Chinese?) woman, wearing a yin/yang symbol, which has resonance for the protagonist (we now see, but this hasn’t really been set up before, I think? or has it?), gets a baby manta ray from him, and… er…

I like it, but I guess we’re not meant to understand things too quickly.

The issues are now down to 20 pages of story and then four pages of letters and lots of news items.

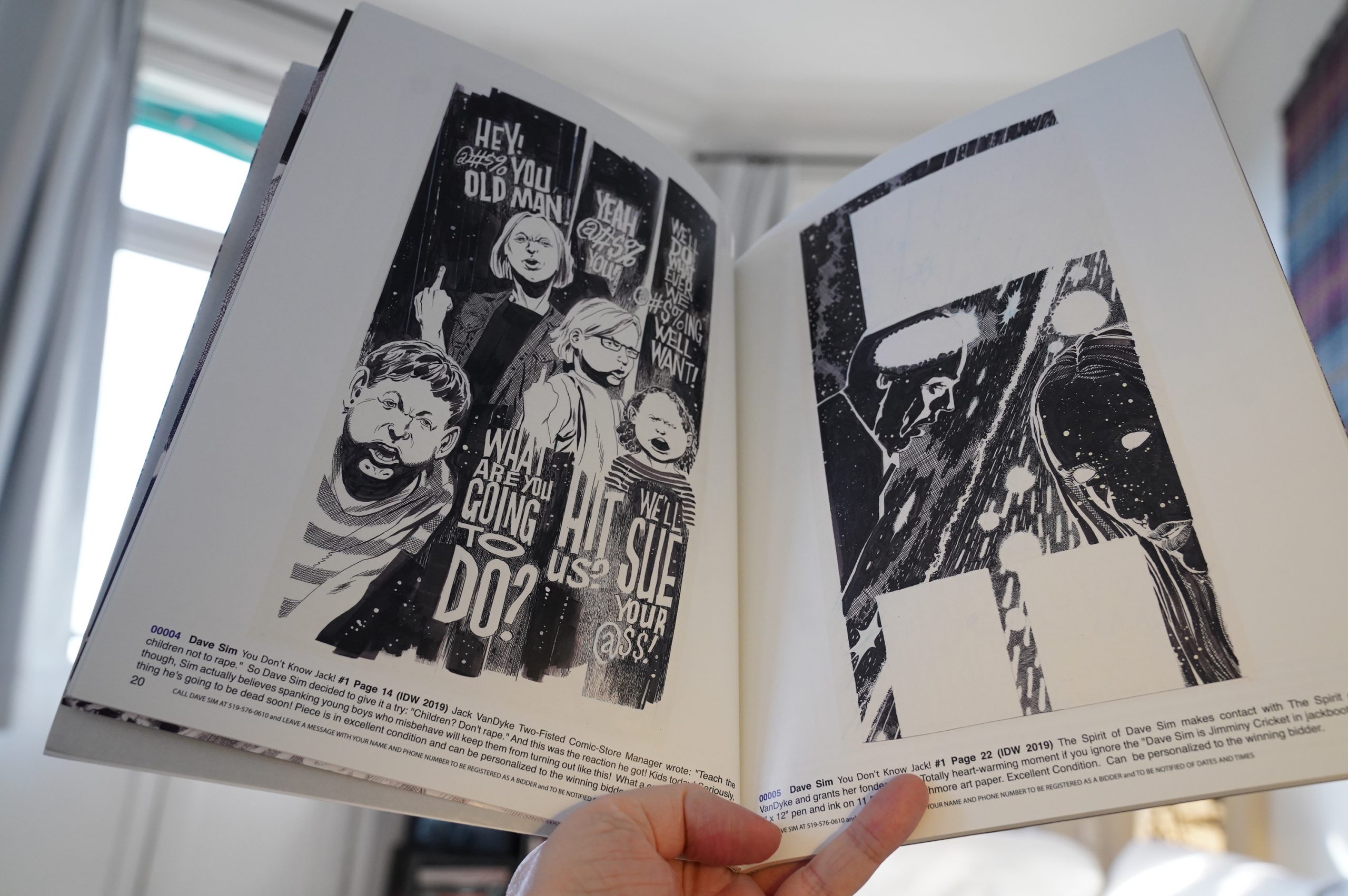

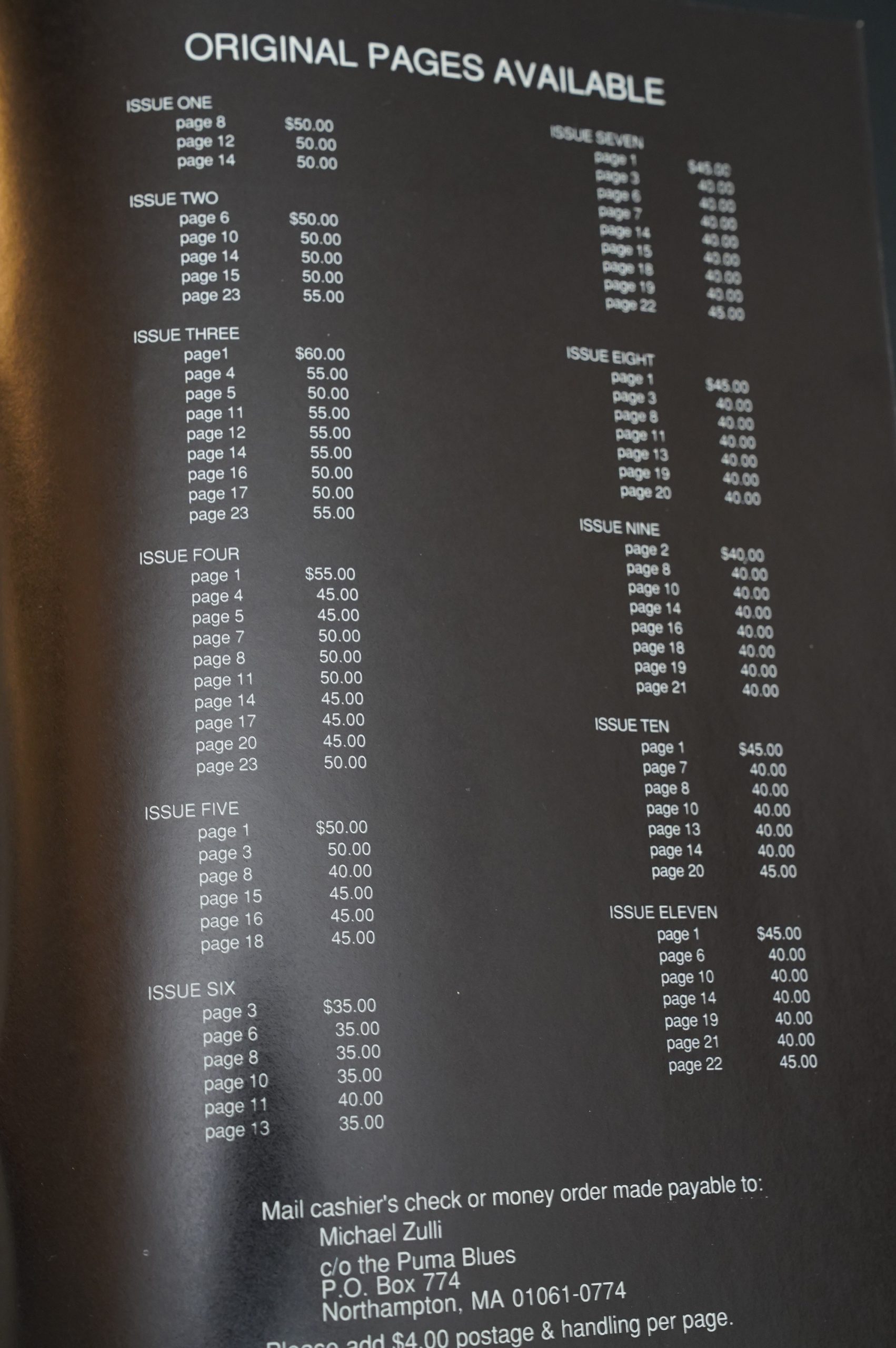

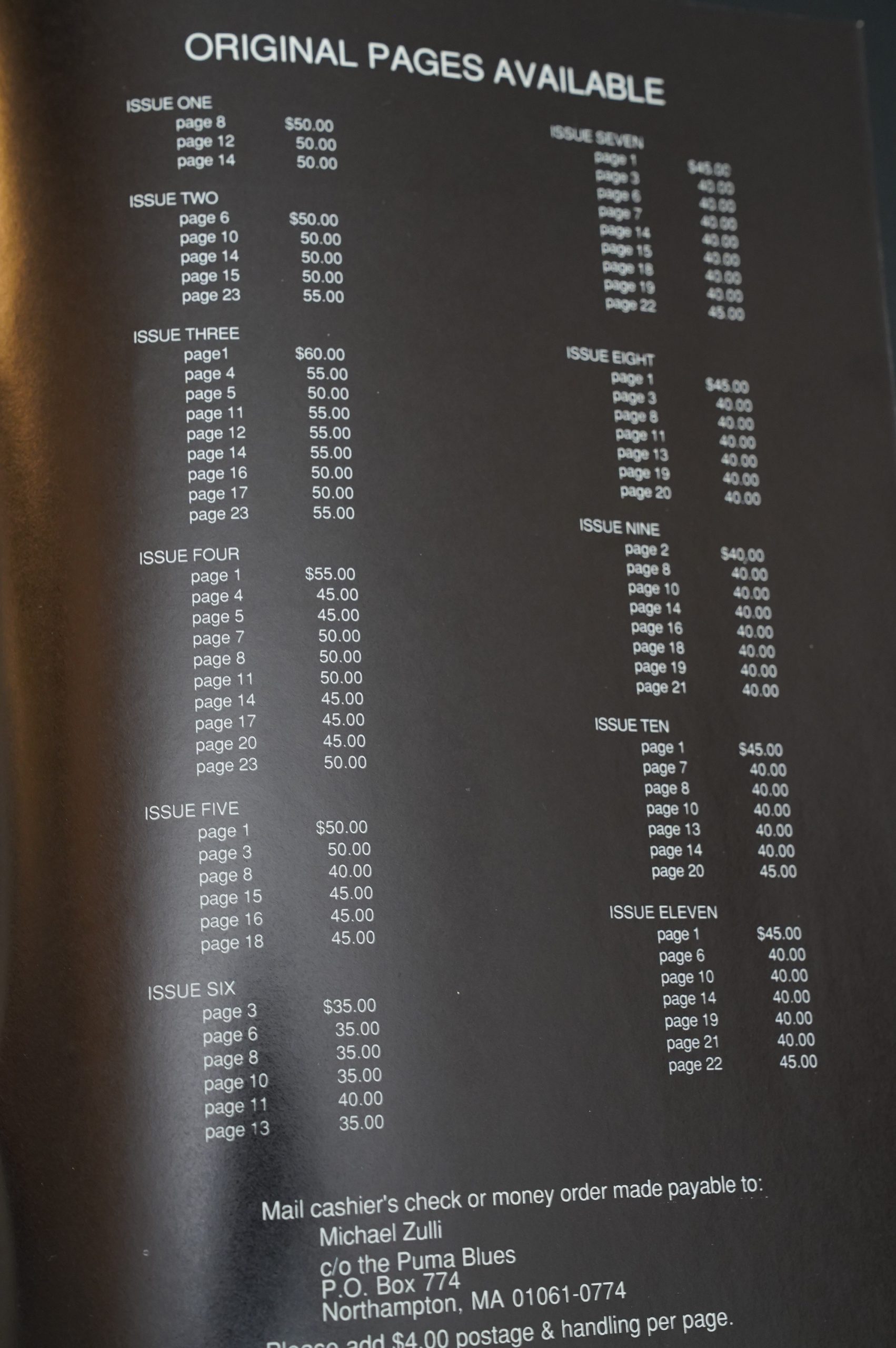

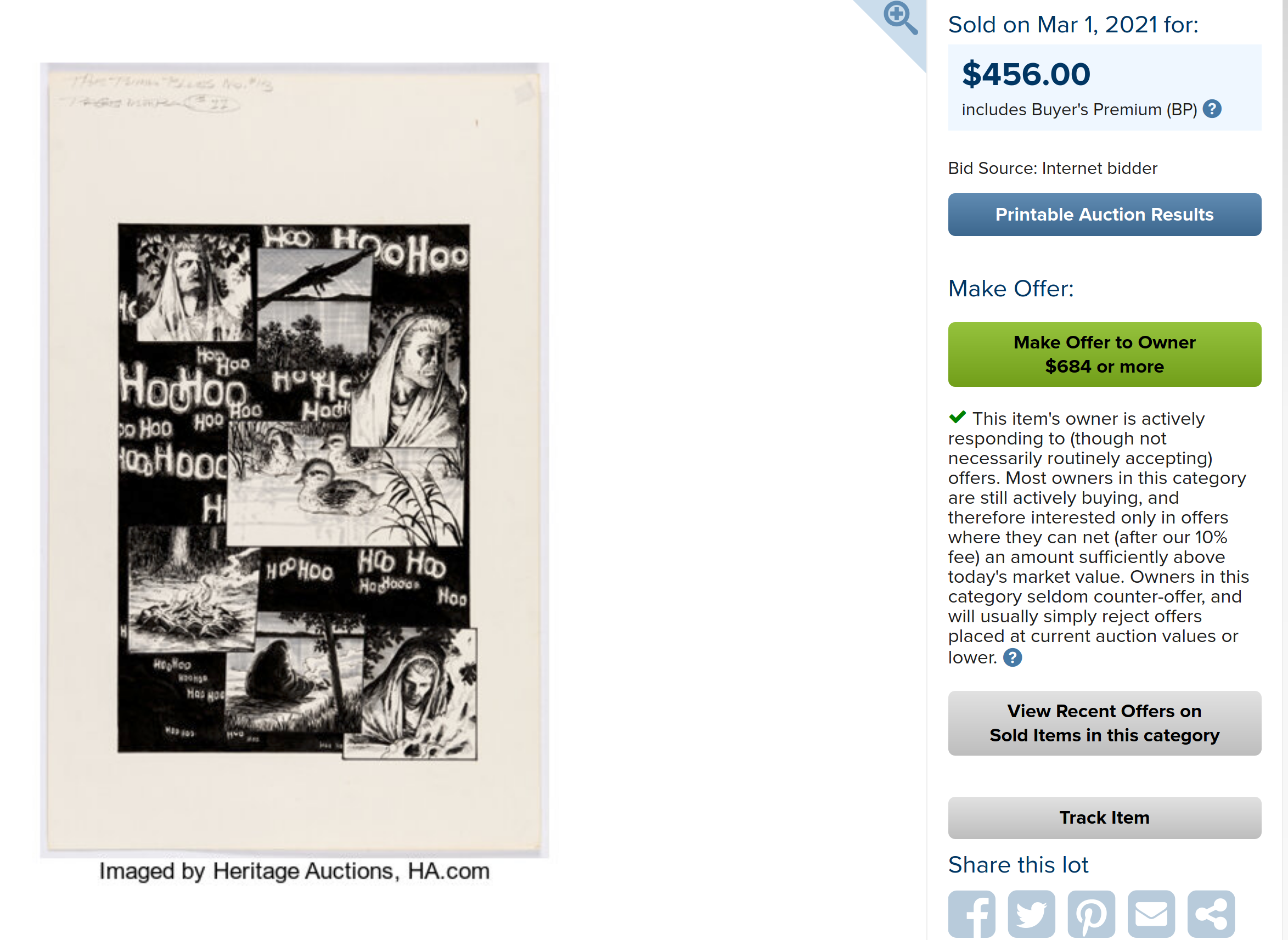

*gasp* You could buy a page of Zulli artwork for $40. I wonder what they go for now…

Oh, well. That’s not too expensive.

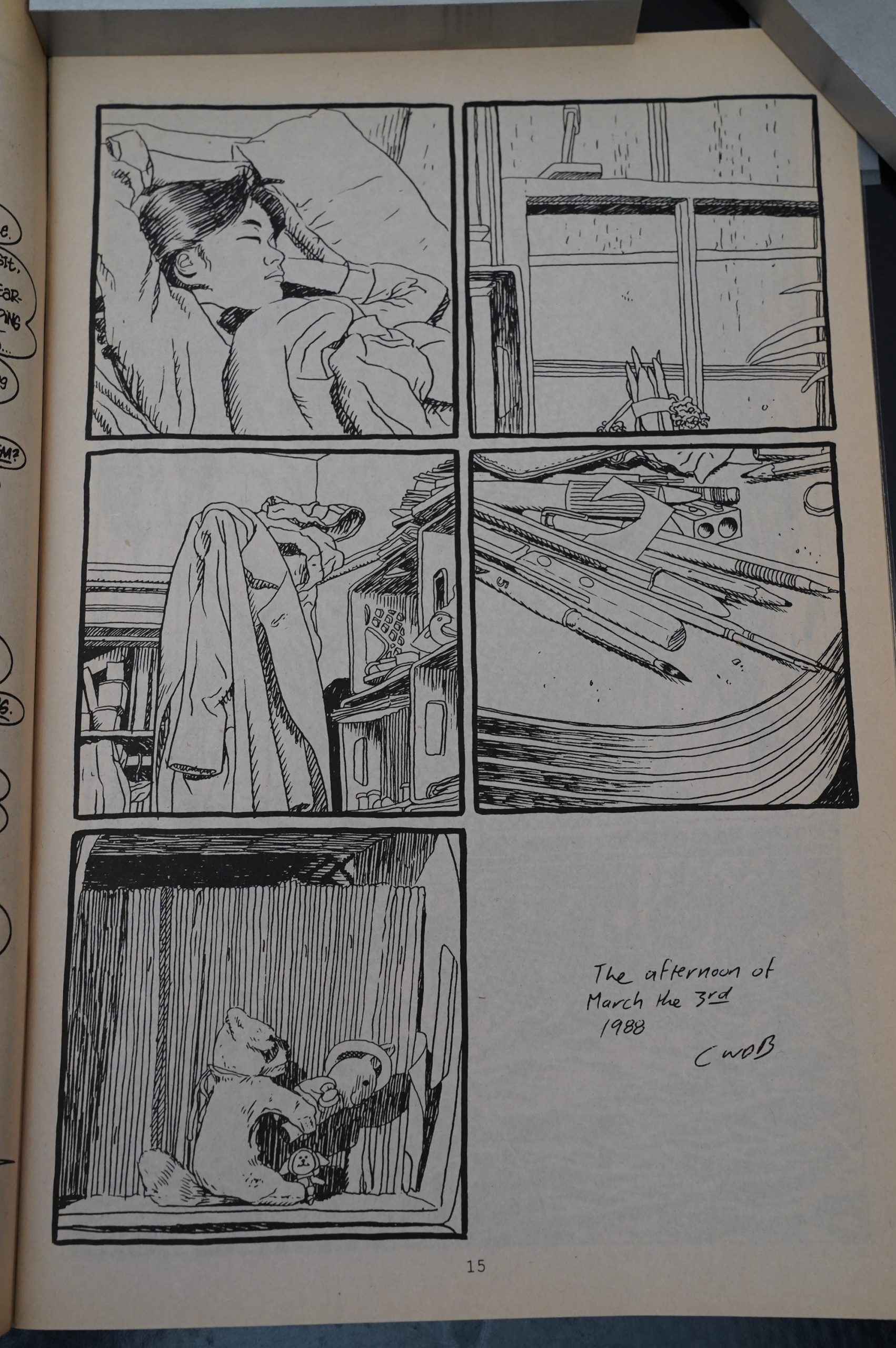

The protagonist takes pictures, too.

So I think The Puma Blues was on a nice trajectory at this point… They’d set up the characters, introduced a lot of intriguing plot strands, established a fantastic milieu, and Zulli’s lettering is getting better… and then:

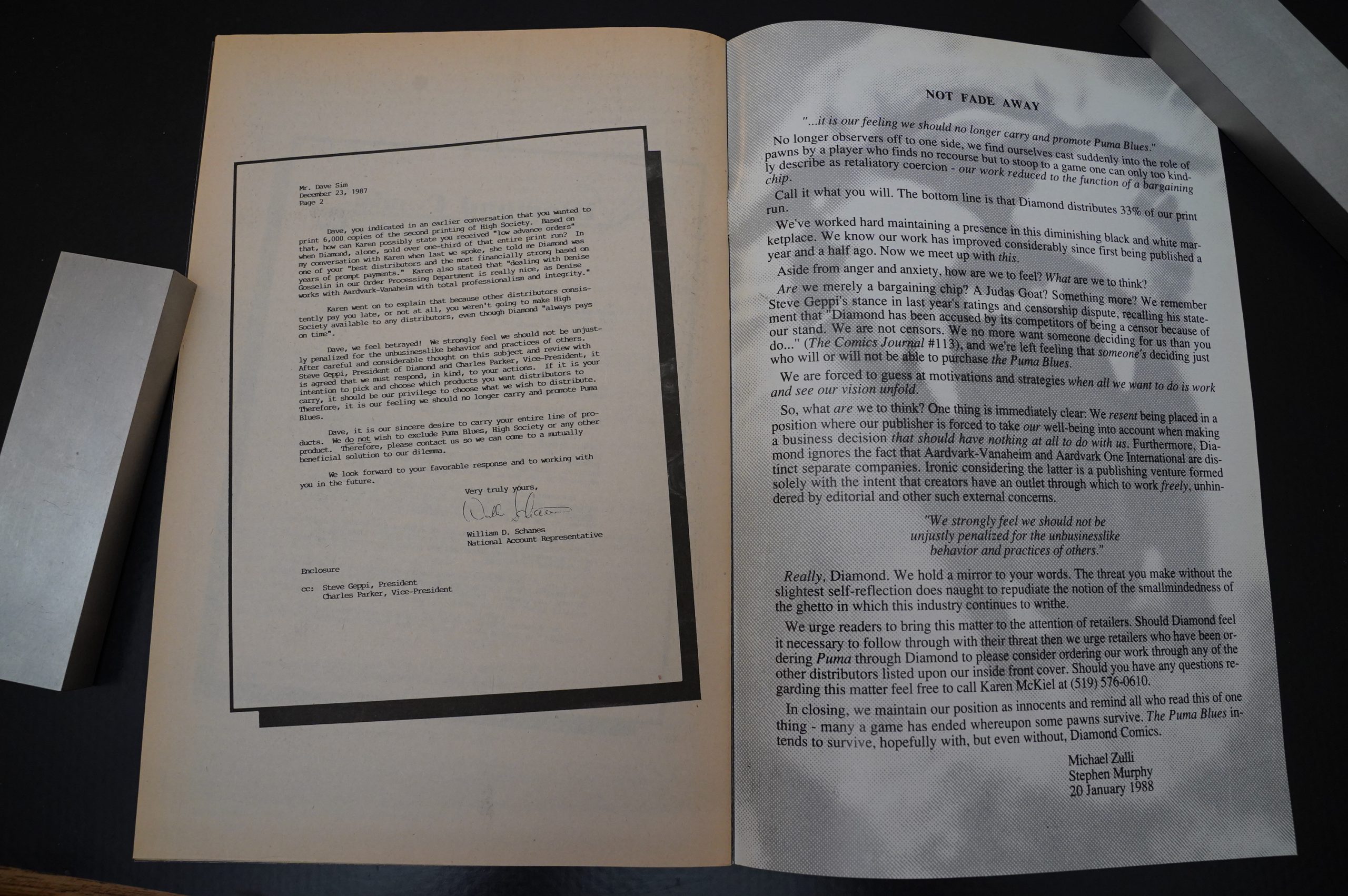

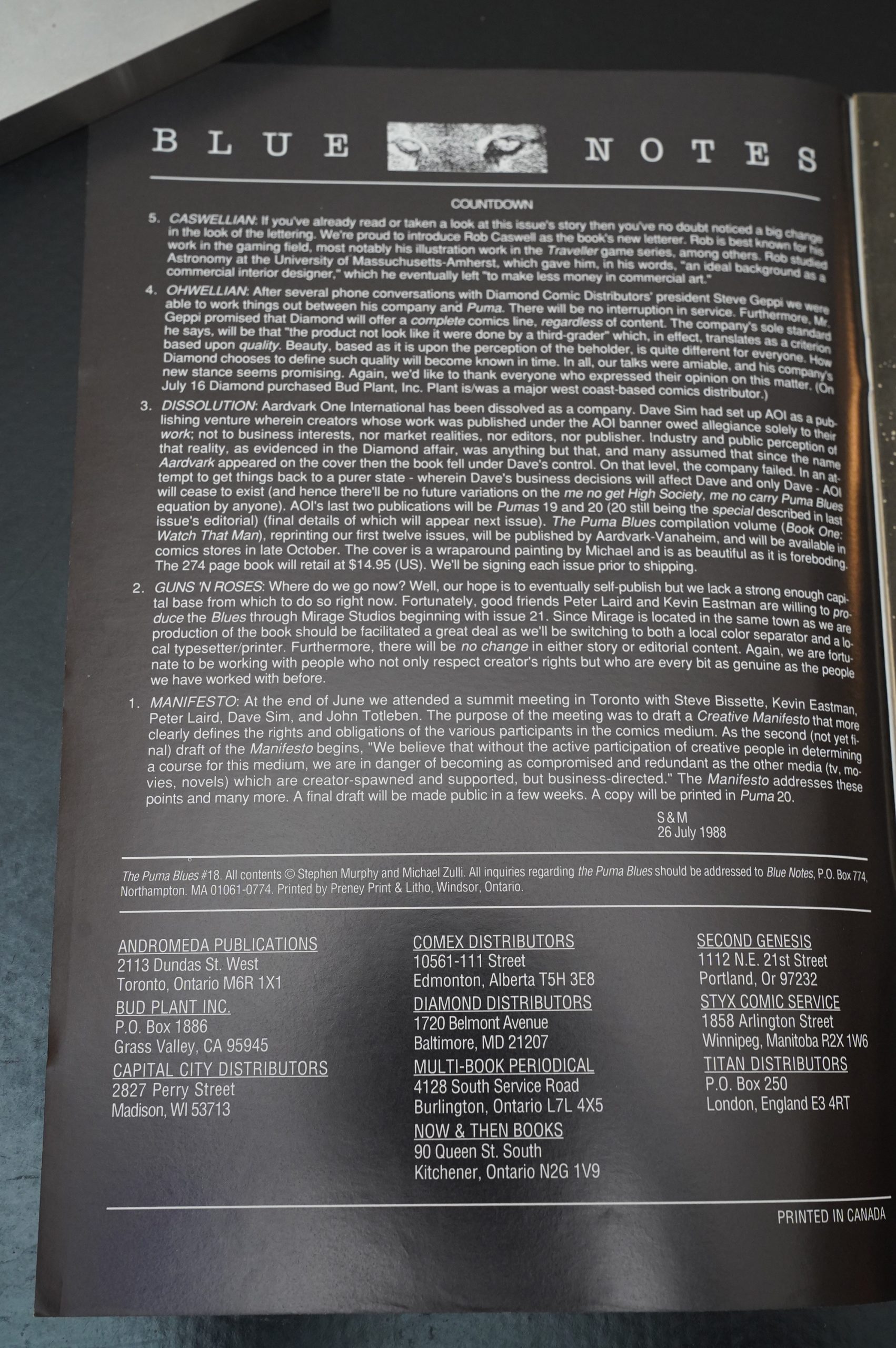

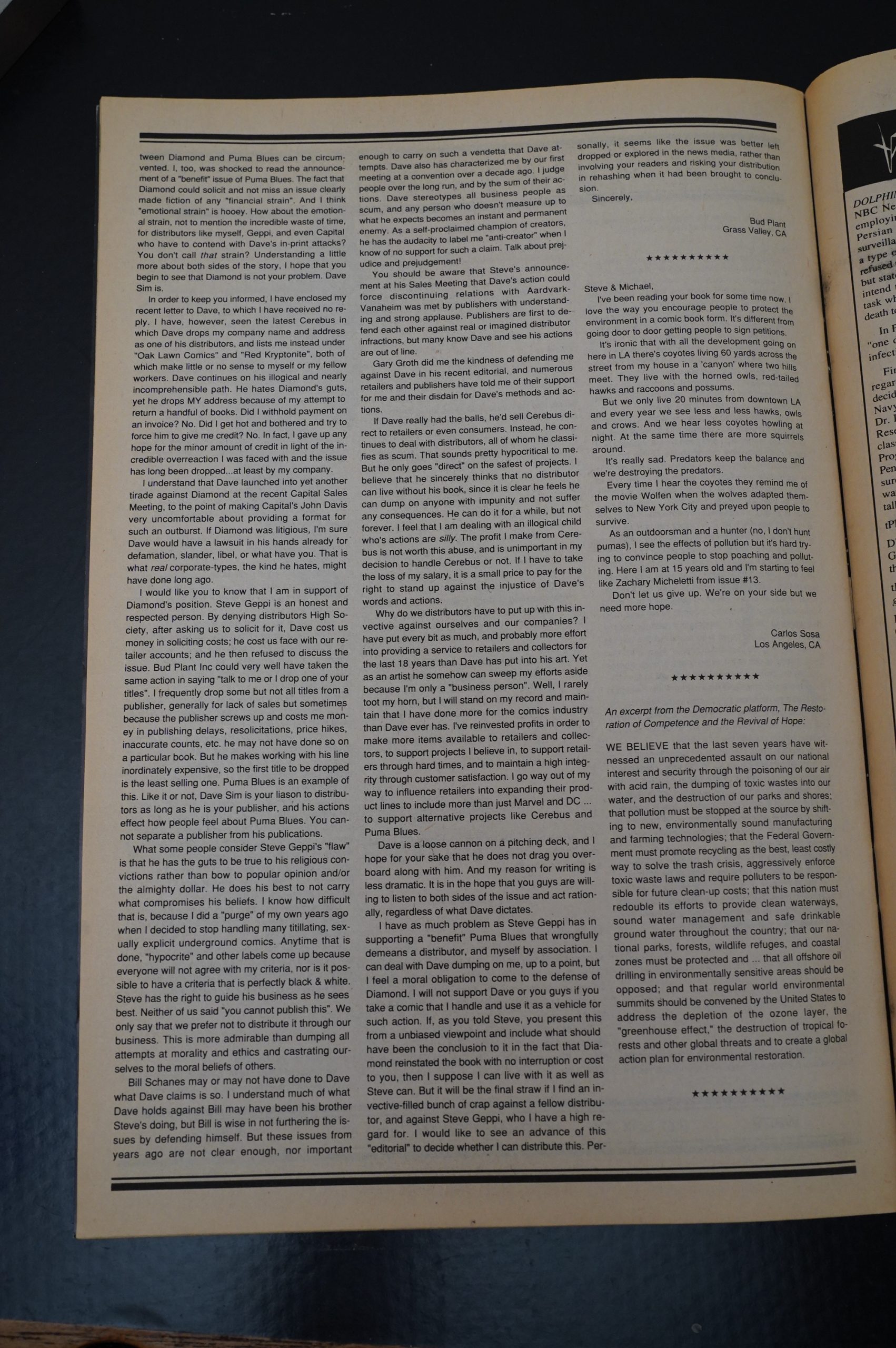

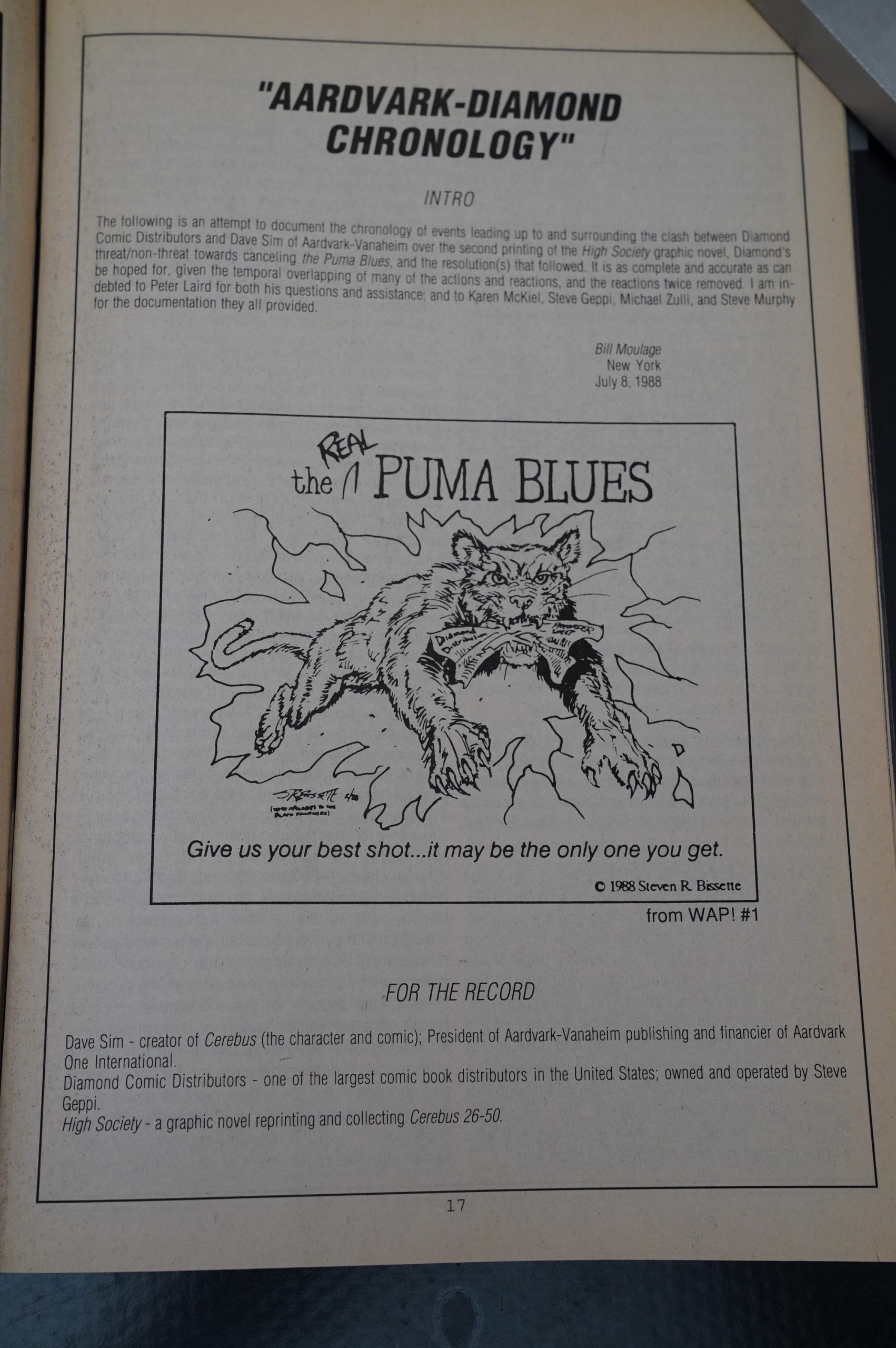

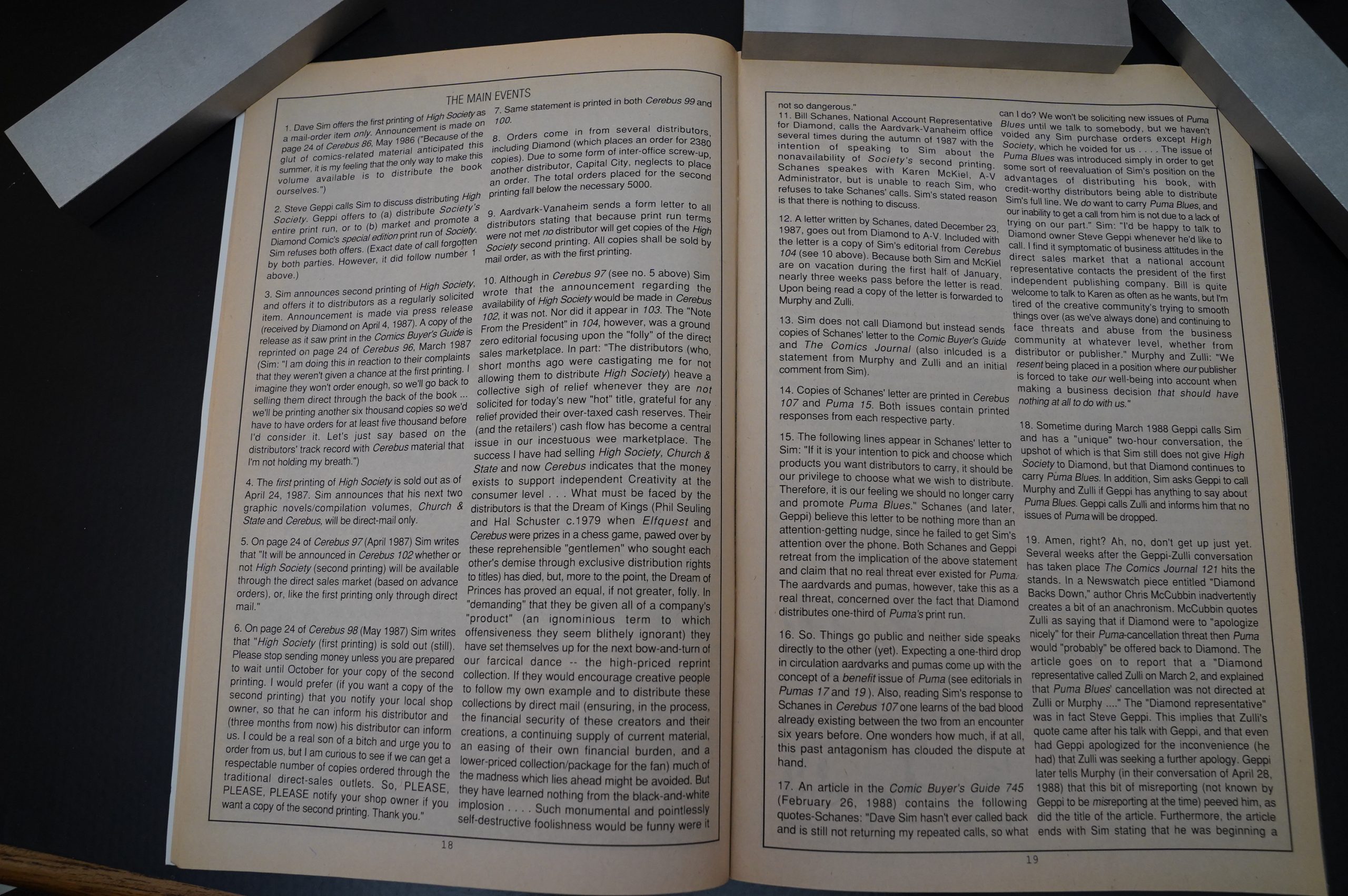

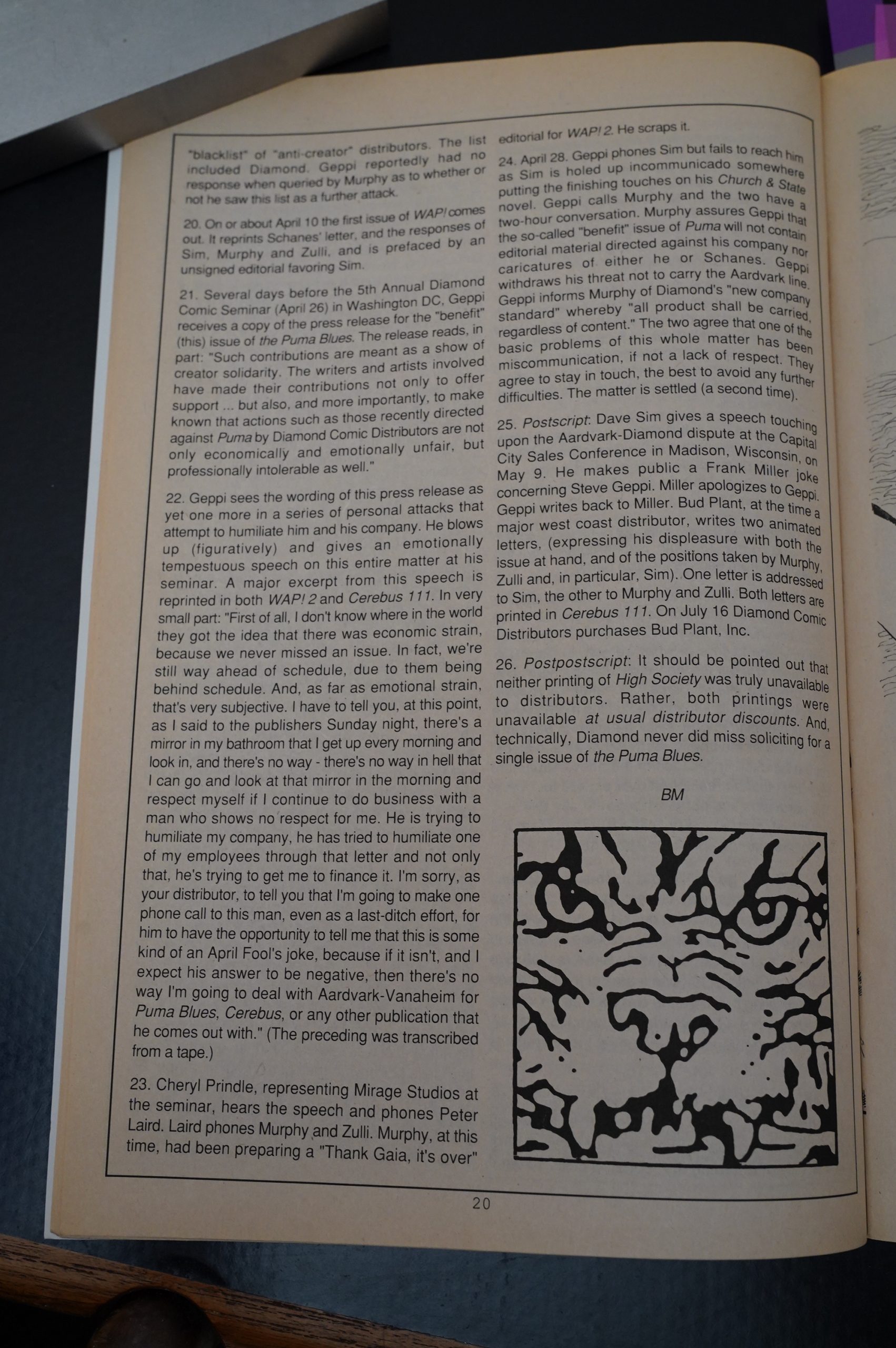

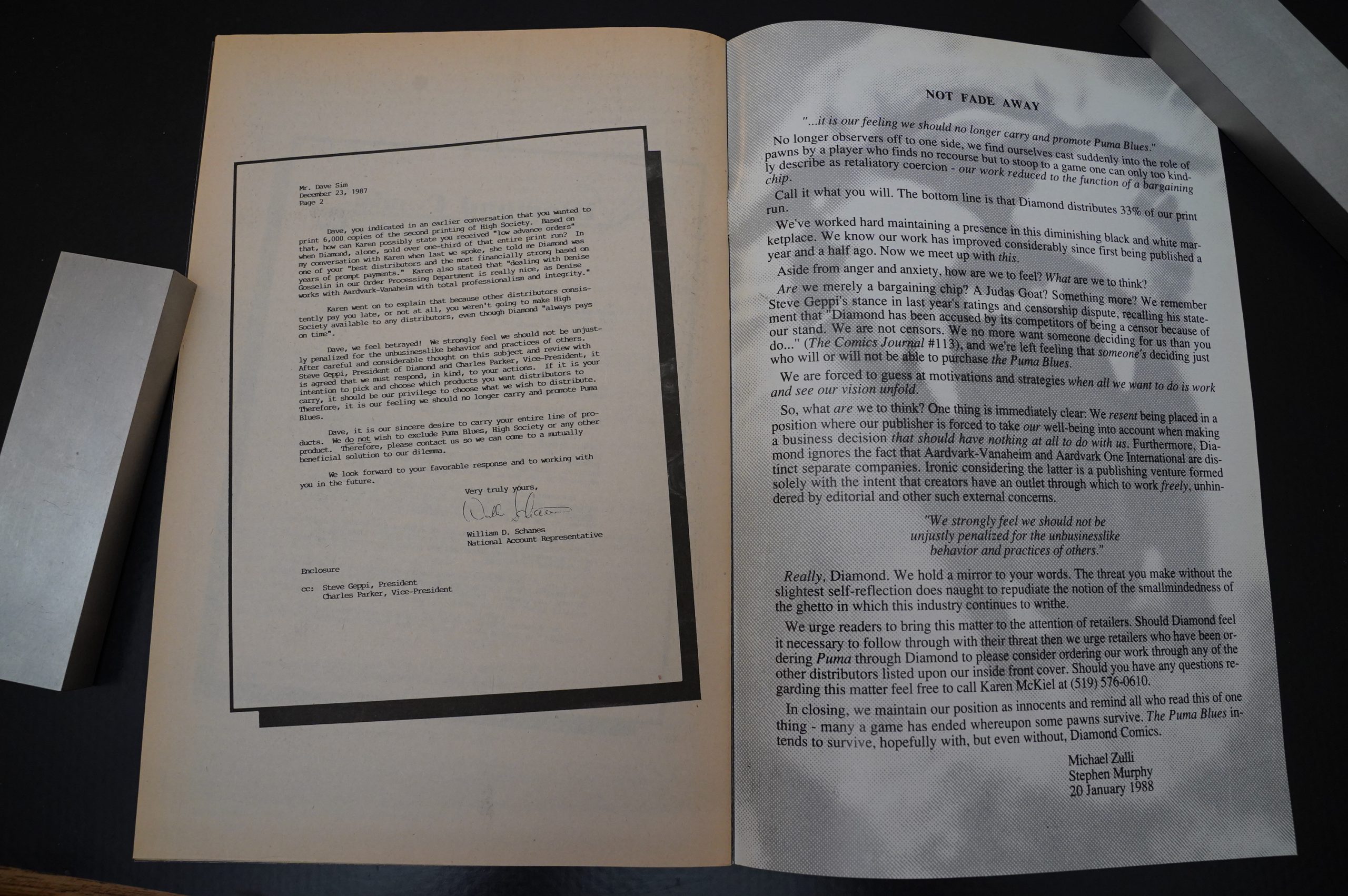

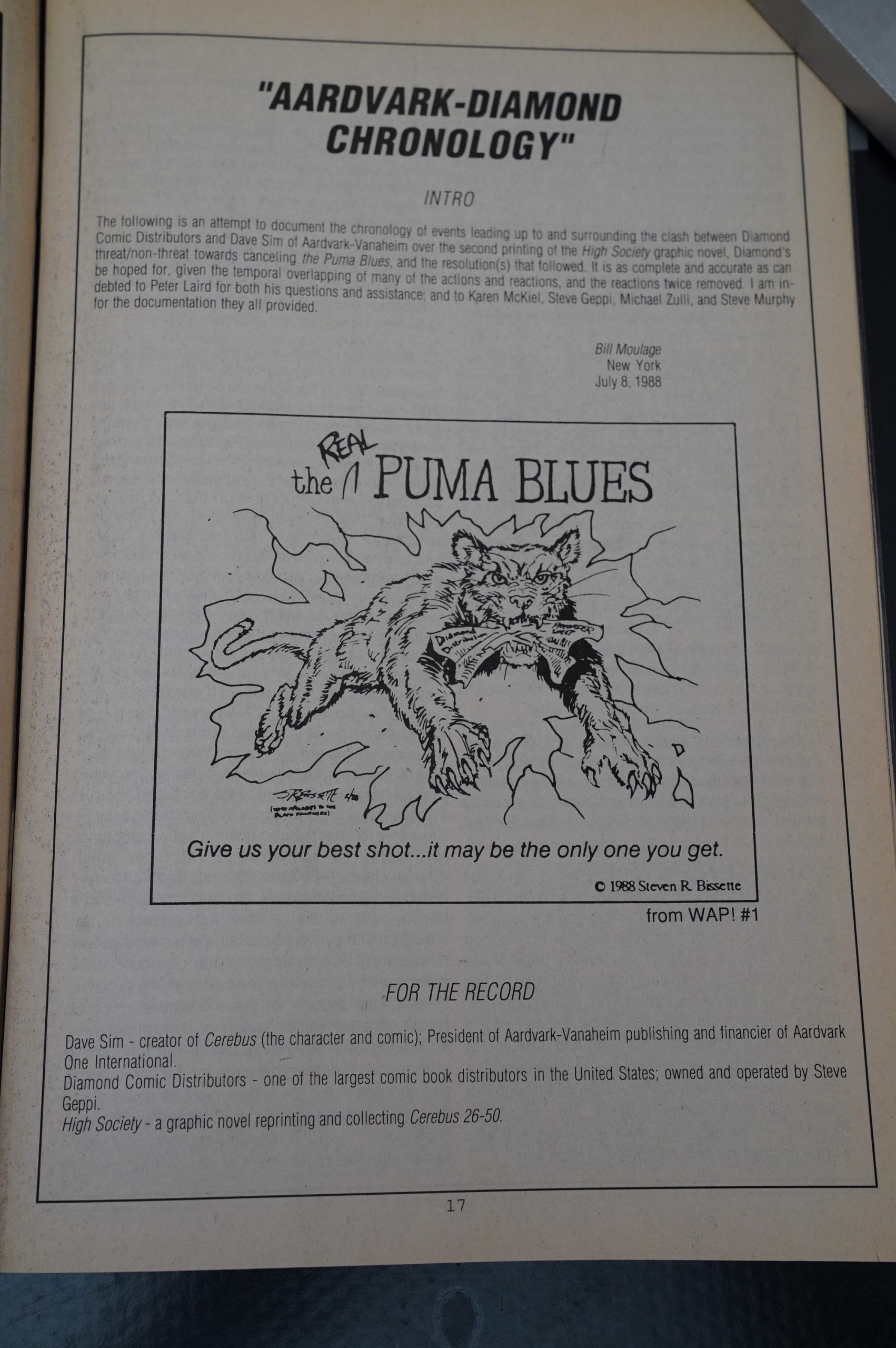

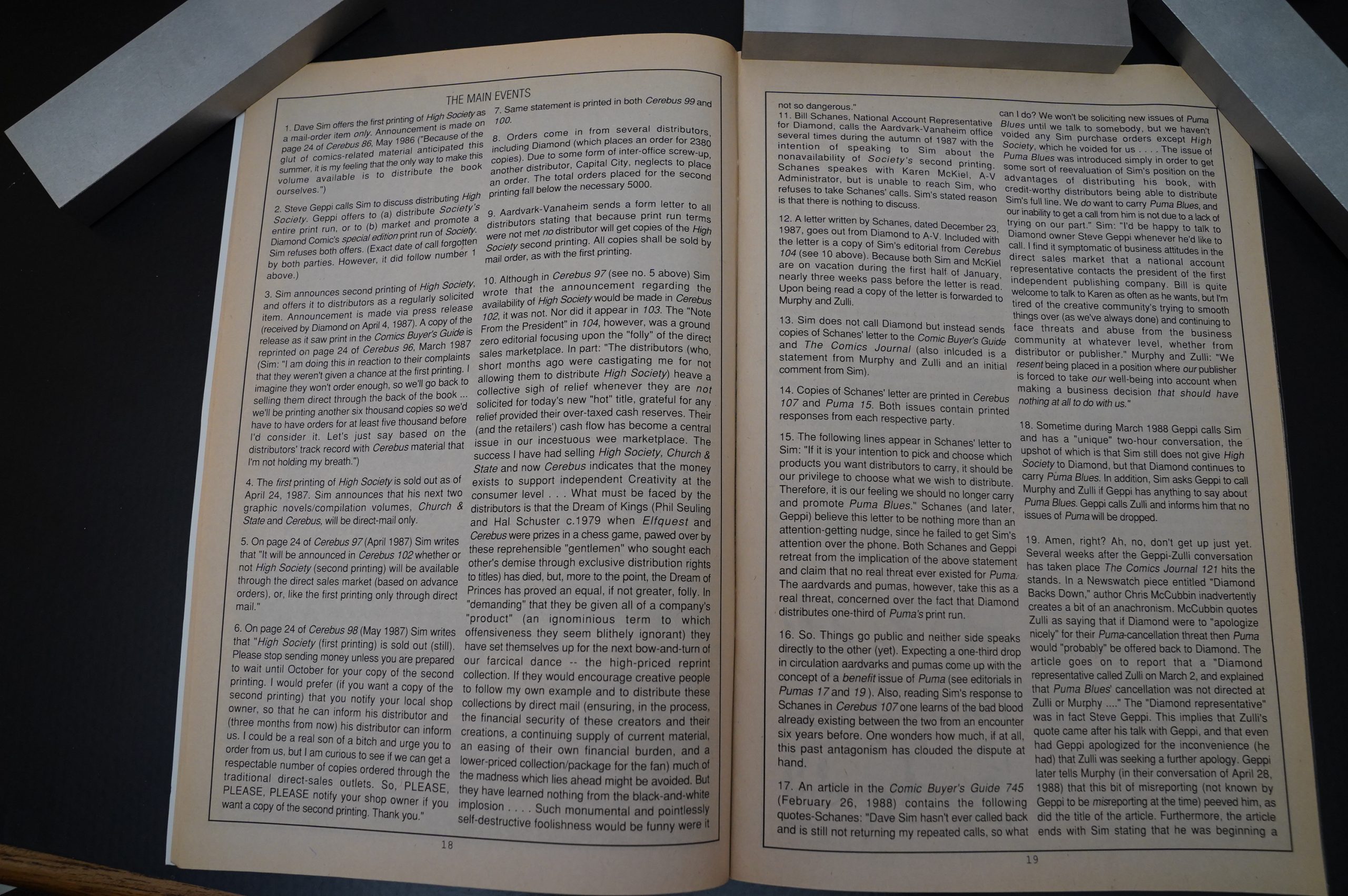

Dave Sim wanted to sell the trade paperback reprints of Cerebus via mail order only. Diamond Comics, the largest distributor, was mad about this (because they wanted in on the action). So Diamond, in “retaliation”, said that they were going to stop carrying Puma Blues.

This despicable move by Steve Geppi and William Schanes (basically “so you don’t wanna give us money? how about we break the legs of your friends, who have otherwise done nothing to offend us?”) naturally perturbed Murphy and Zulli. If Diamond went through with this extortion, they’d lose one third of their sales, and that means that Puma Blues would no longer be viable.

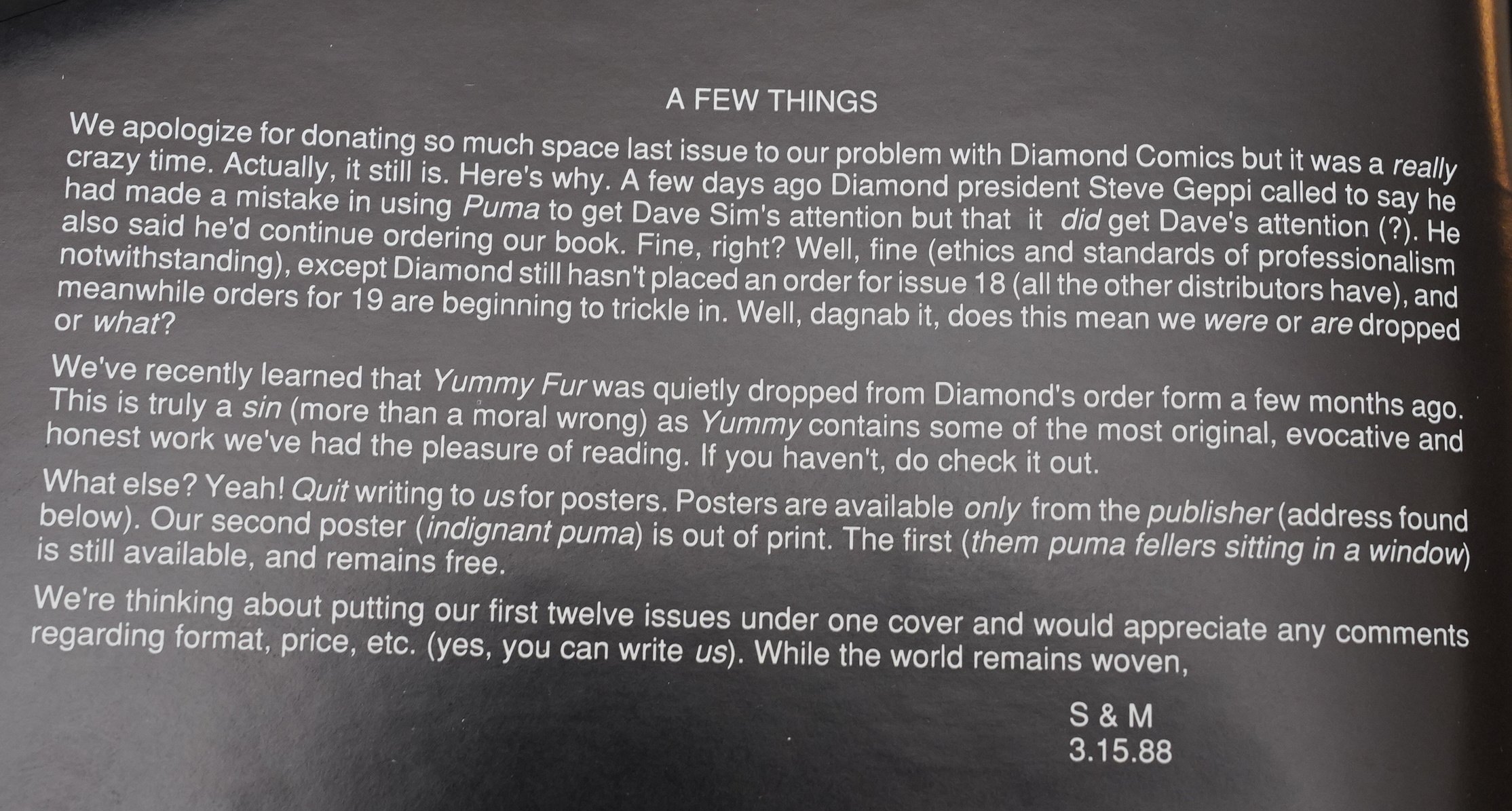

Diamond backed down after The Comics Journal got involved… but then… changed their minds again… until the Journal got involved again… but it meant that for months Murphy and Zulli had no idea whether Puma Blues was basically dead or not.

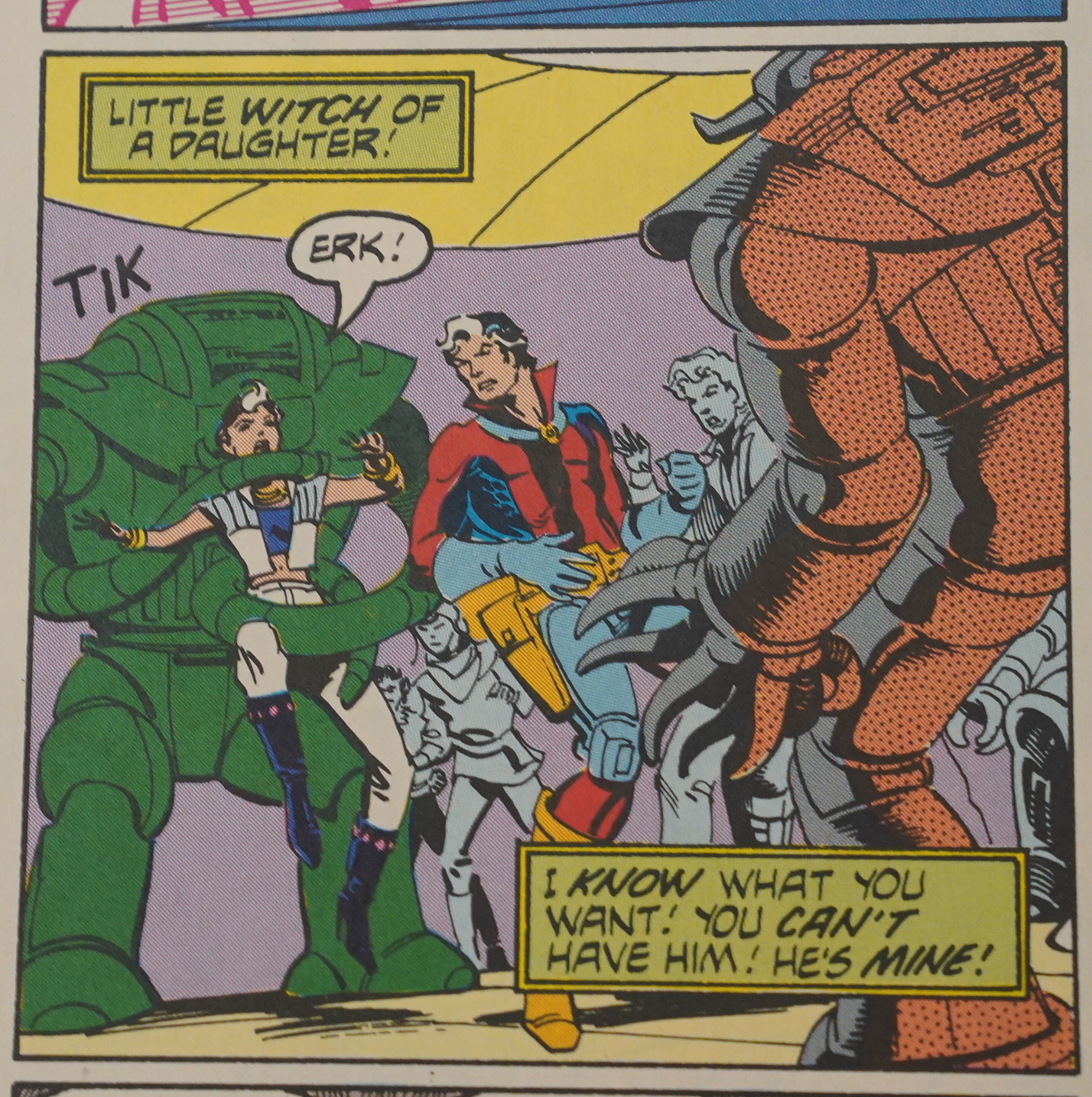

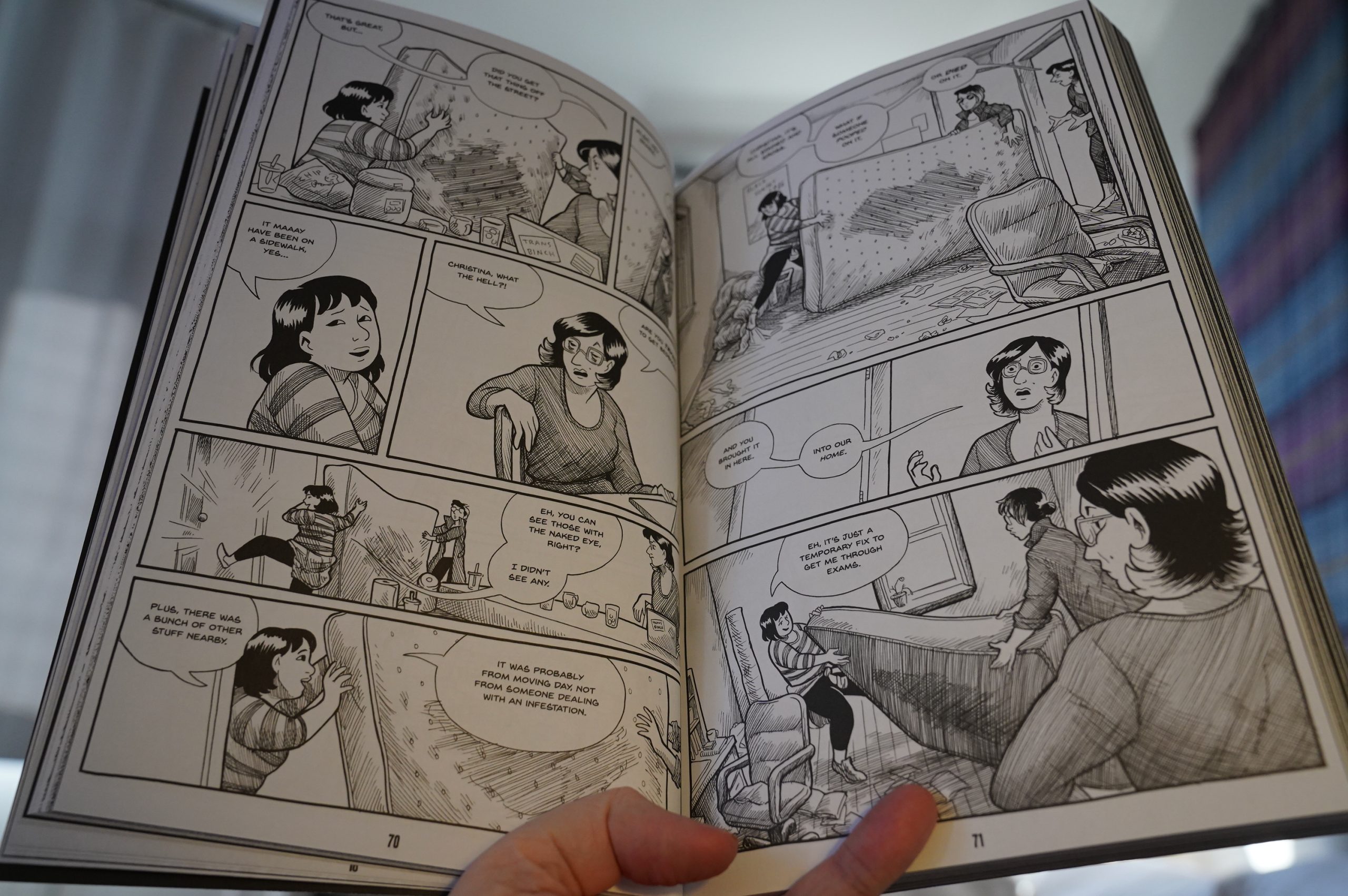

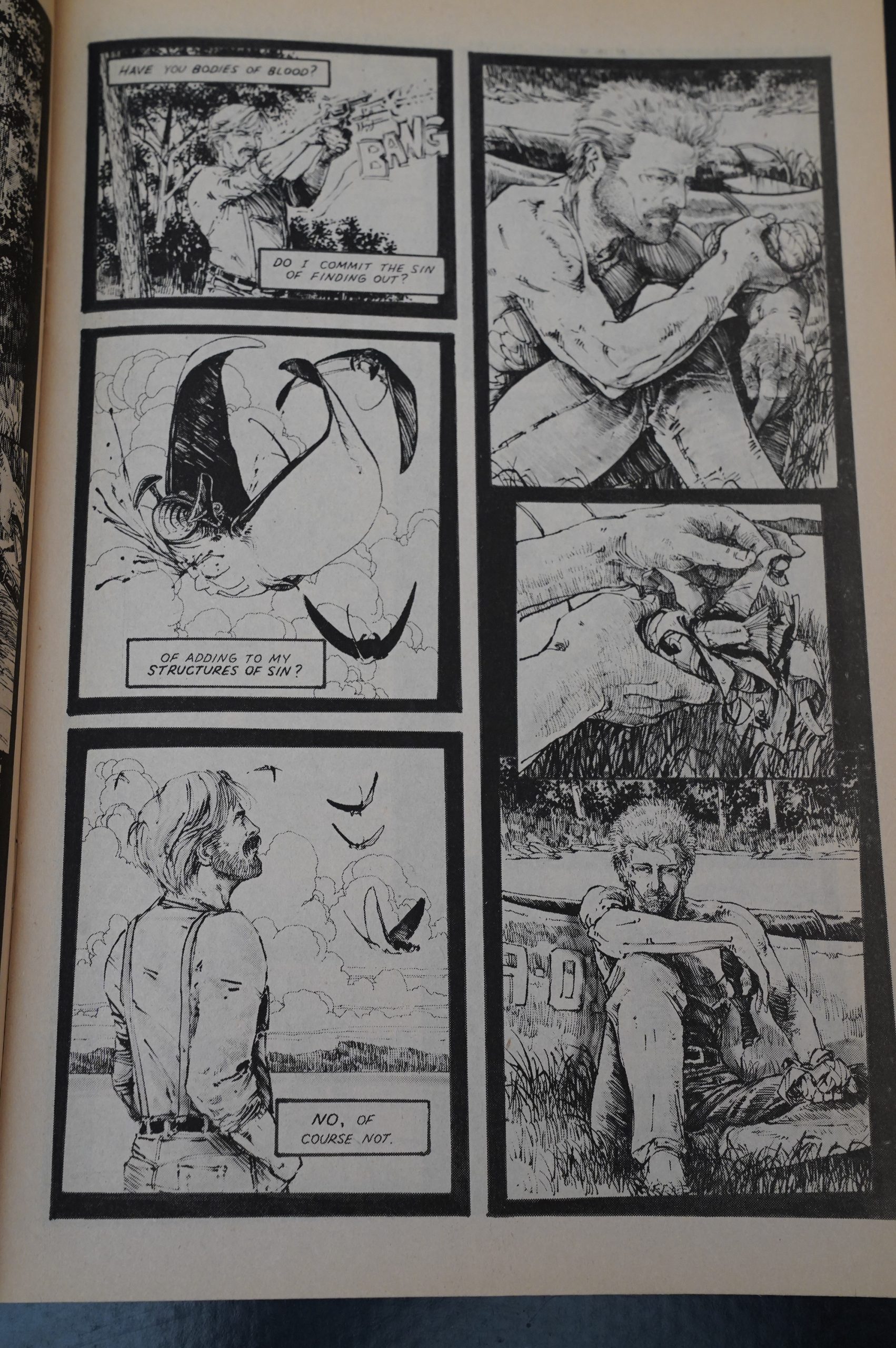

Did this affect their enthusiasm for the book or not? I think it’s pretty easy to tell: Things start unravelling. We do get a couple of issues that seem to advance the plot, but it’s somewhat confused (I don’t get why that guy with the stache (who’s a militant environmentalist, I think?) shot that poor manta ray. Just to find out if they were real or not? (He doesn’t go and collect the corpse.)

Zulli’s artwork improves every issue, though, so that’s nice. Perhaps because he uses more time per issue. Up until the Diamond nuclear threat, they’d done issues regular as clockwork: One per month. The schedule starts slipping now.

Diamond had also threatened to stop carrying all Vortex comics because Geppi was offended by Yummy Fur. So Bill Marks was going to set up a separate publishing company just for Yummy Fur, Fab Comics, and this is the only ad I’ve seen for that. (Diamond backed down here, too, and Marks continued publishing Yummy Fur under the Vortex banner.)

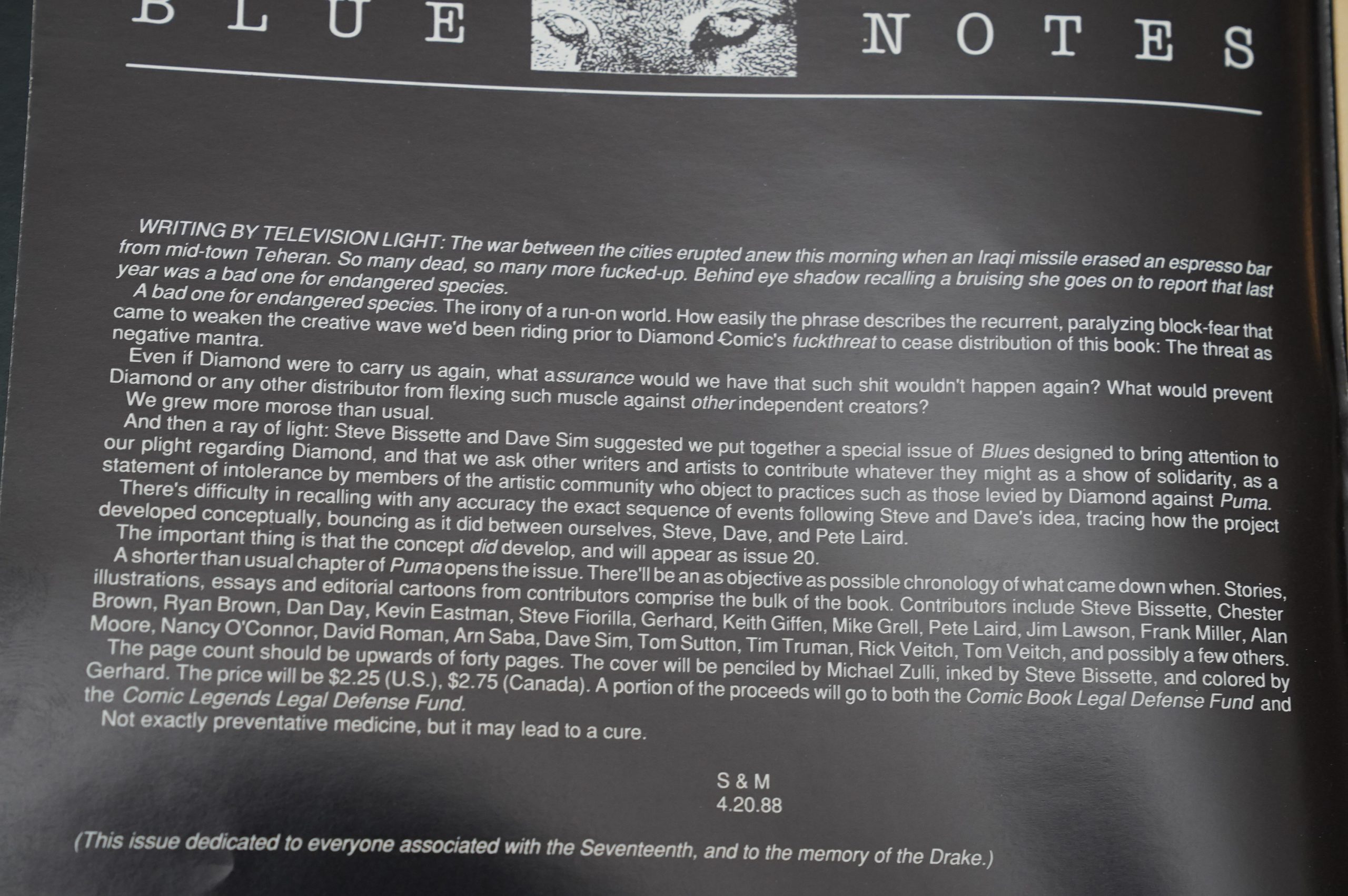

Murphy and Zulli are seem to be growing despondent, even if Diamond had backed down. But there’s gonna be a benefit issue.

Issues 18-20 do not mention “Aardvark One International” at all. Murphy would later write that those three issues were self-published, but apparently Sim did publish them as before.

Bud Plant writes in to say that he totally supports Diamond and Geppi, which surprised many at the time. Because people thought that Bud Plant was an upstanding, non-nutty guy. But then it turned out that Diamond bought Bud Plant’s distribution company some months later, which explains a lot.

Aardvark-Vanaheim was going to publish the Puma Blues collection, because Dave Sim wanted to divest himself of all responsibility as fast as possible (and to avoid having Puma Blues being used as a hostage against him again, perhaps?)

They bring aboard a professional letterer, Rob Caswell… and it’s odd how disturbing that looks. Sure, Zulli wasn’t the best letterer in the world, but this just looks … wrong!

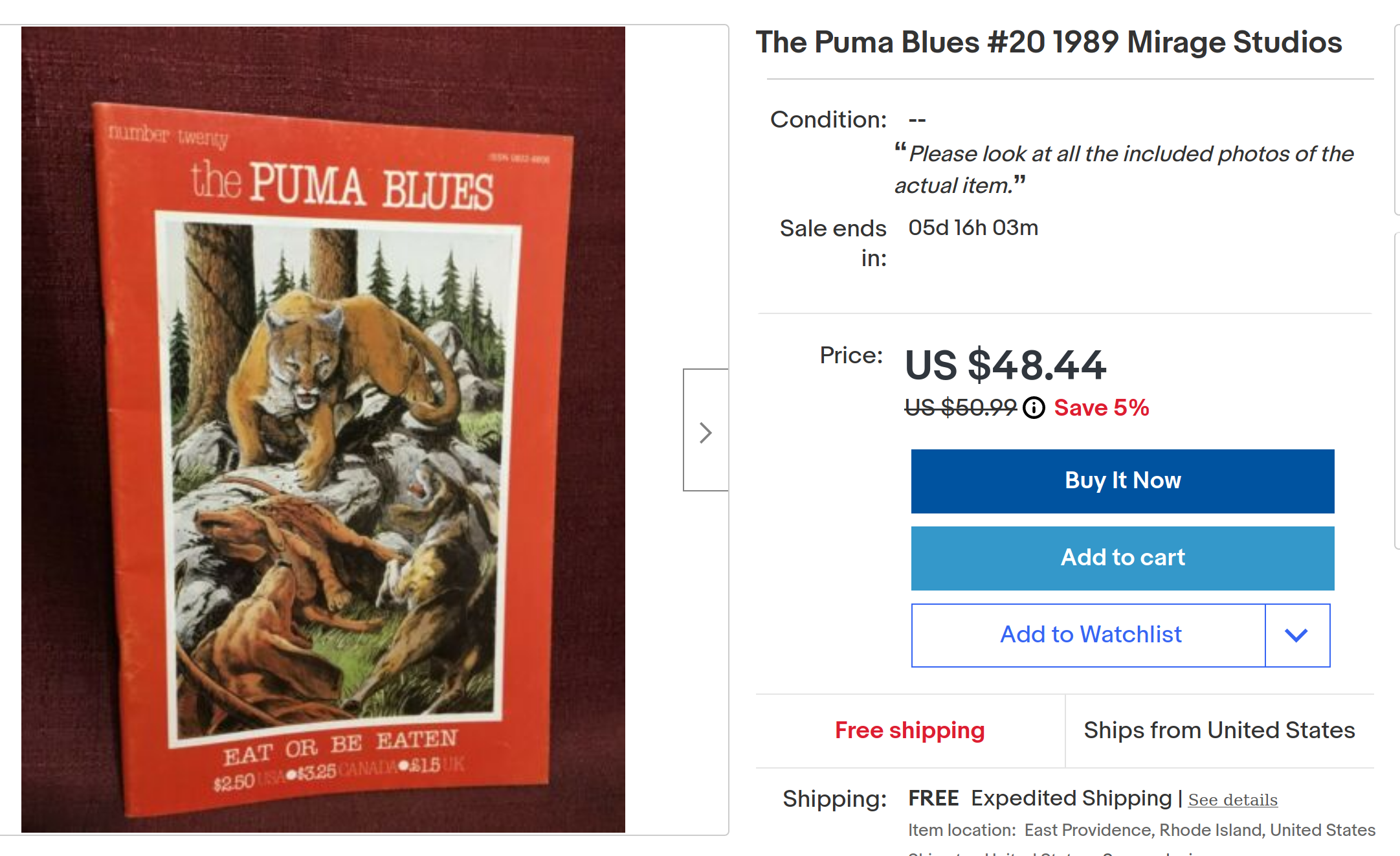

Then there’s issue 20, which is the benefit issue. It’s 64 pages long, and the same price as all the previous issues (i.e., USD 1.70). Which makes me wonder who it benefits, exactly — surely this can’t be earning anybody any money? We get a couple of Puma Blues stories, like this one inked by Steve Bissette. It’s good!

Cool. A page by Chester Brown.

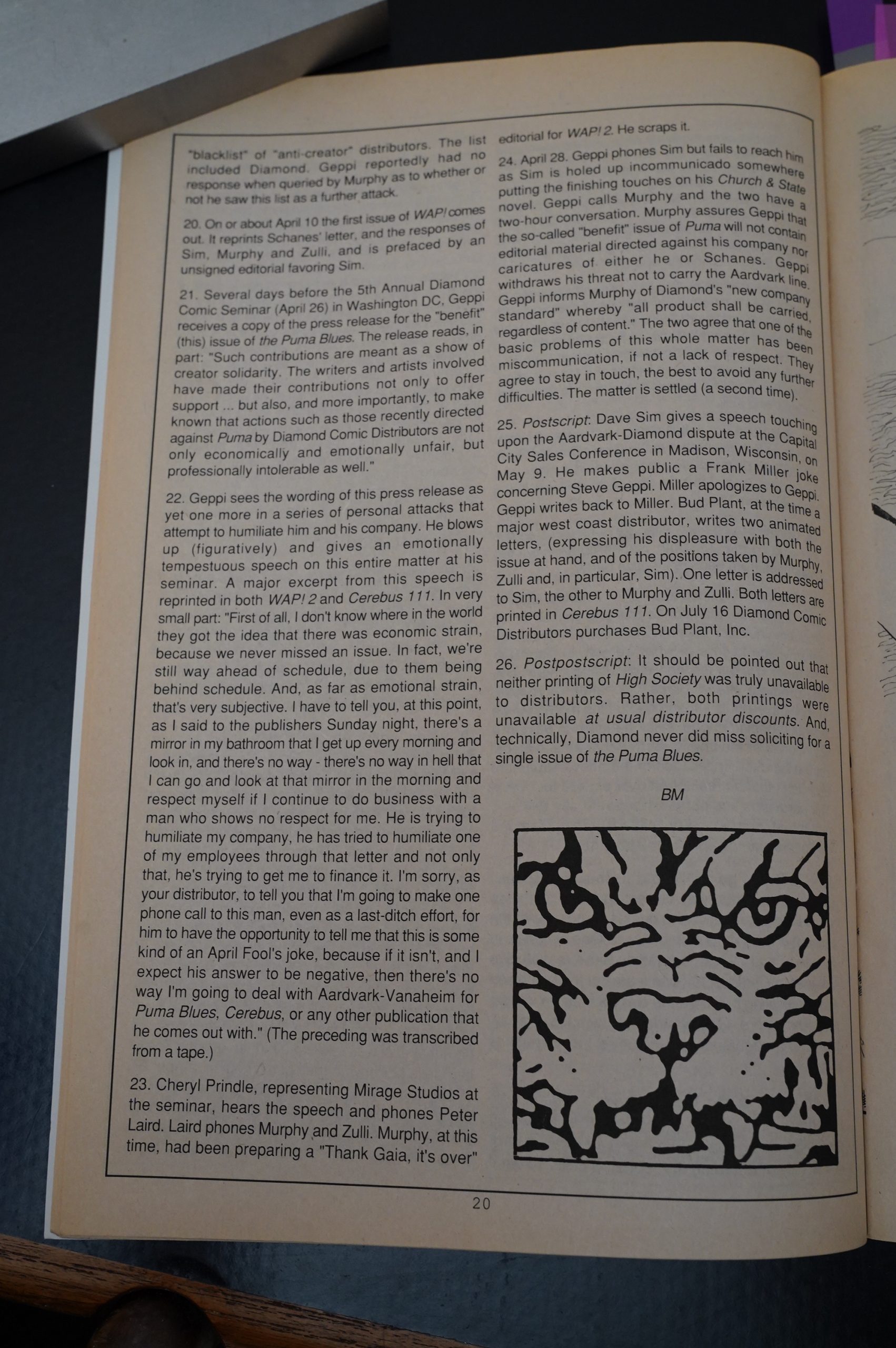

And then we get a retelling of the entire Aardvark/Diamond feud. It’s amazingly even-handed. If it were me, there would have been a lot more rancour… but on the other hand, Diamond would be distributing this issue, too, so… I’ll give you all for pages of it:

Geppi sounds like a total loon.

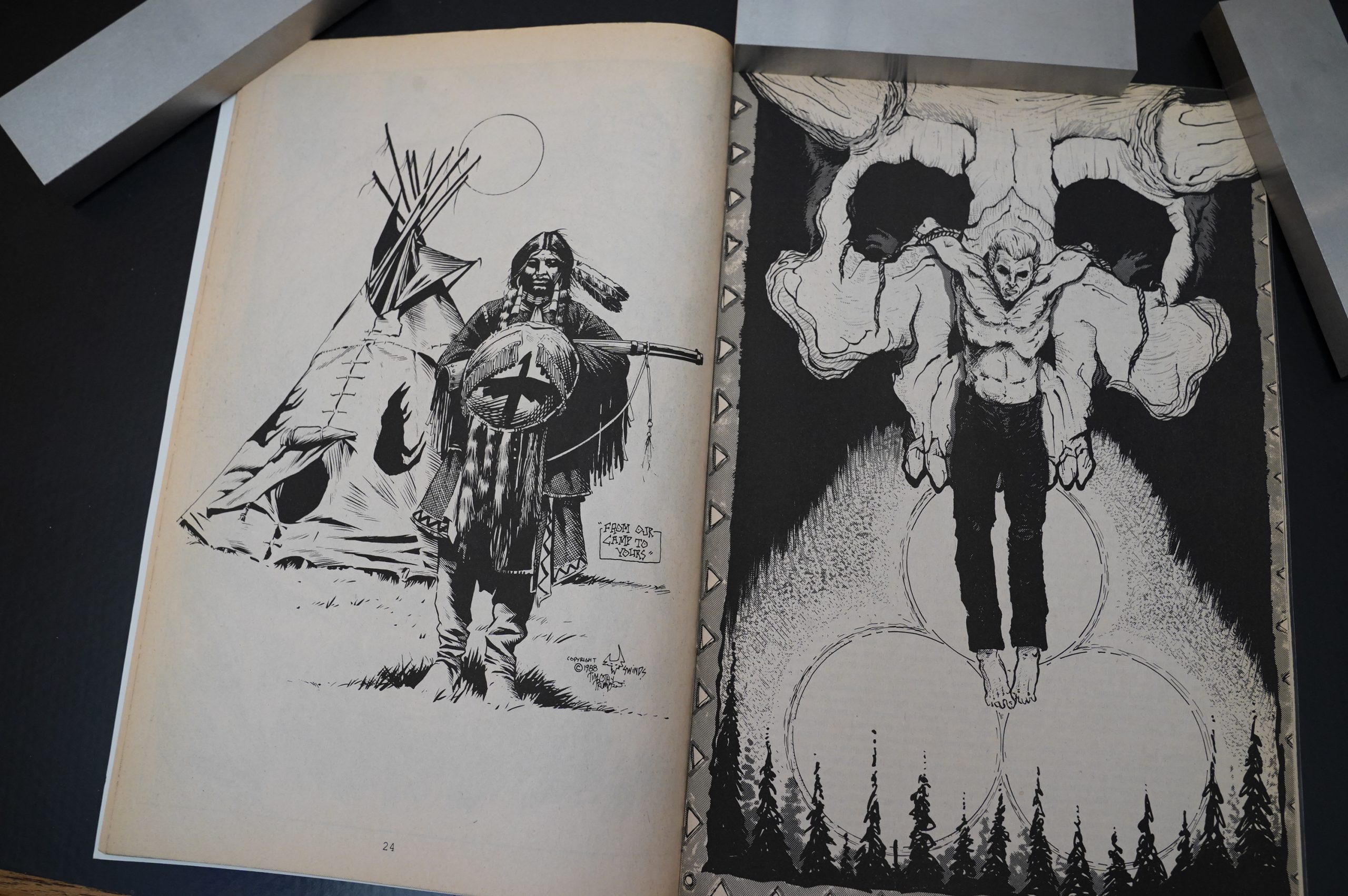

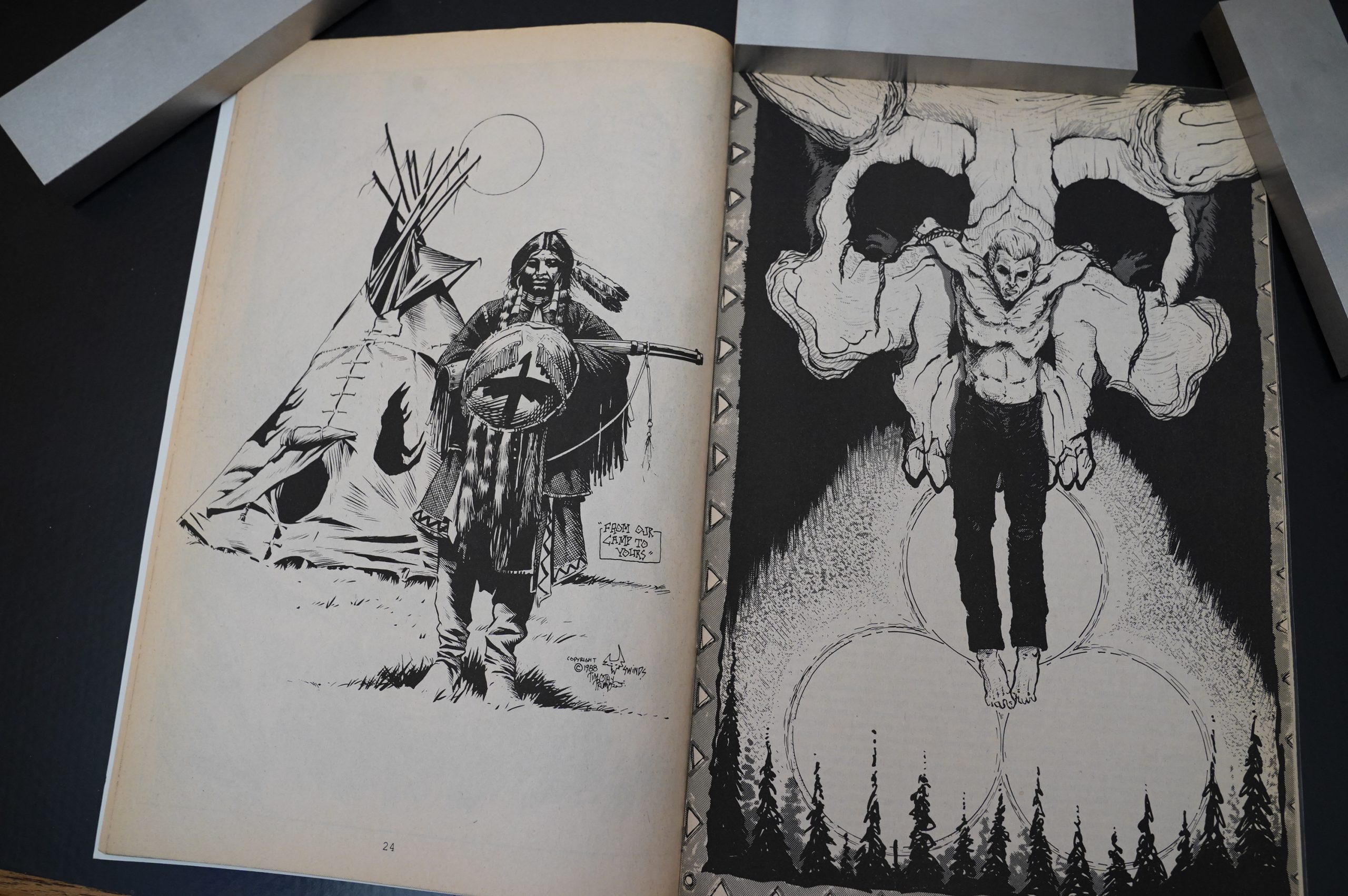

We get a whole bunch of pin-ups — here’s Timothy Truman and Dan Berger.

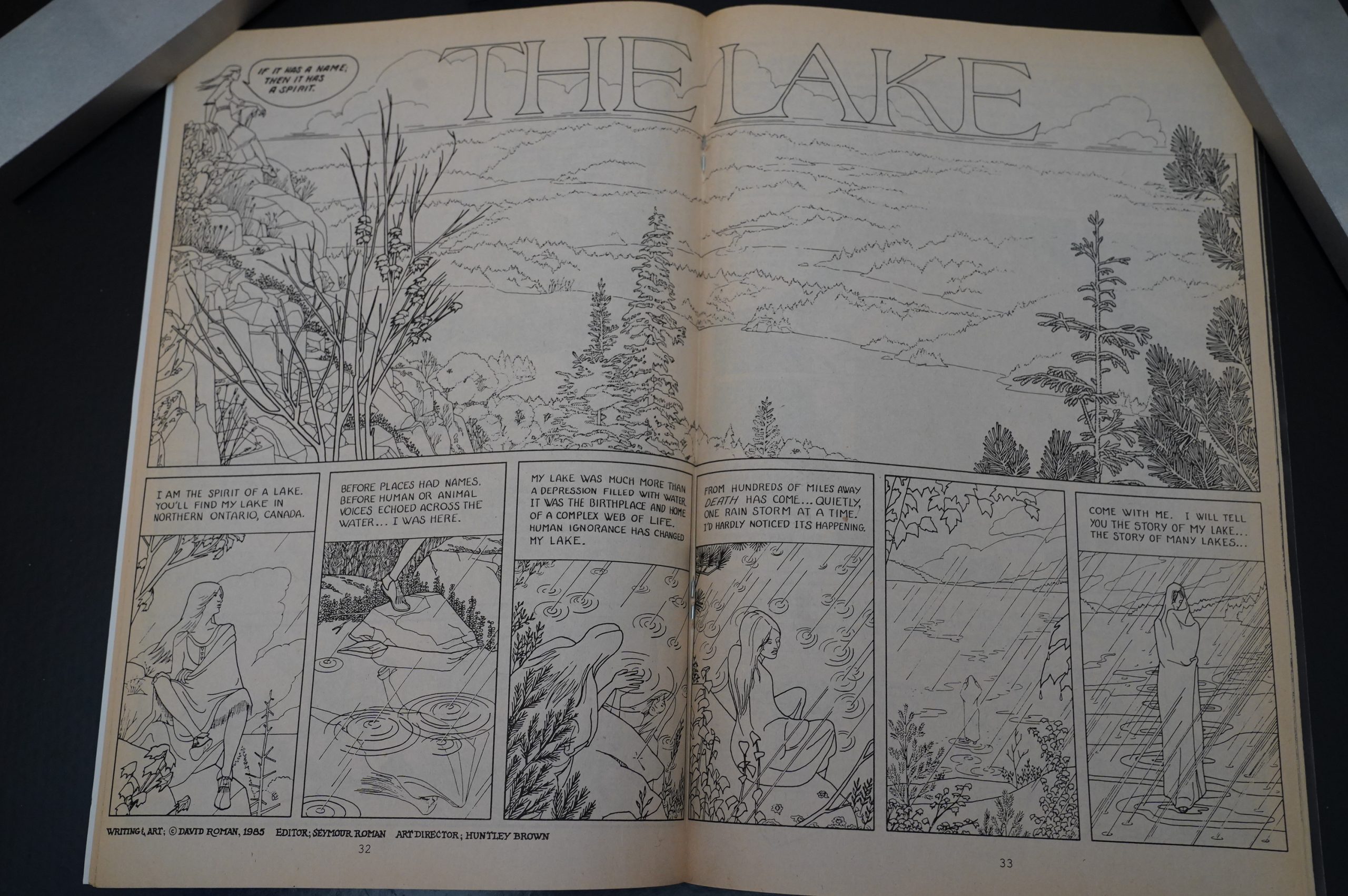

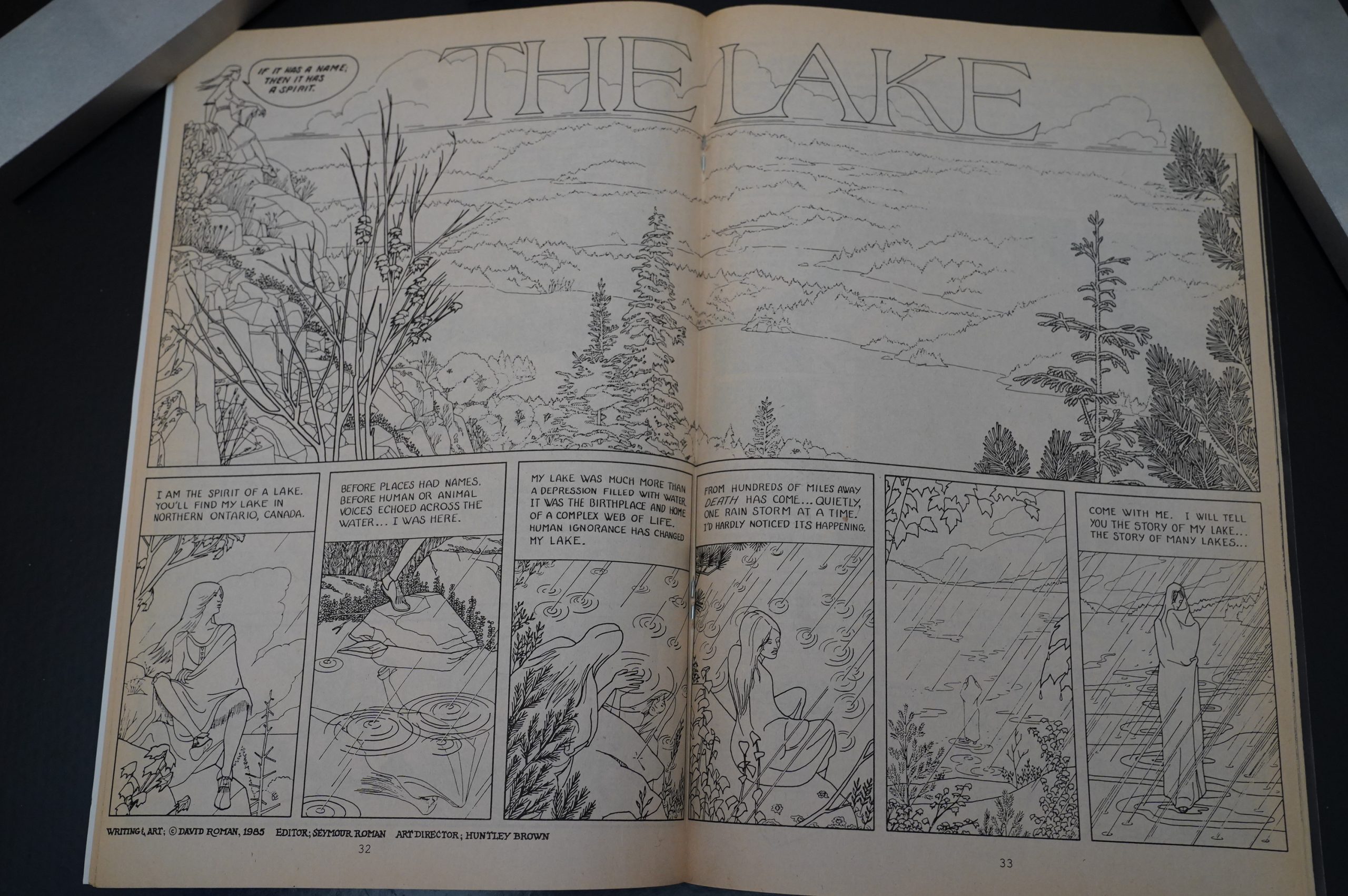

We get a longer story by David Roman, which looks like it was meant for something else, but is pretty apposite for Puma Blues.

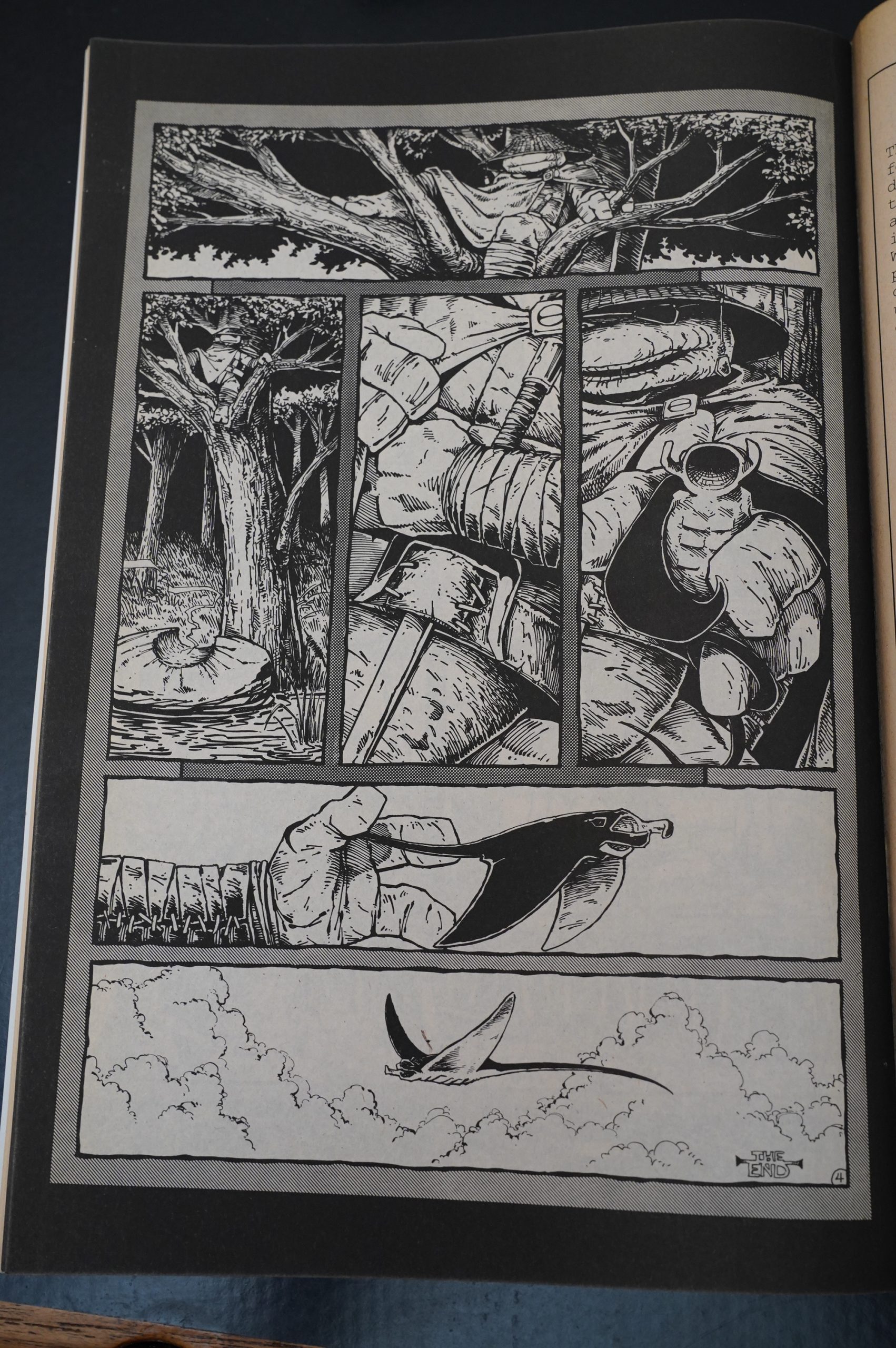

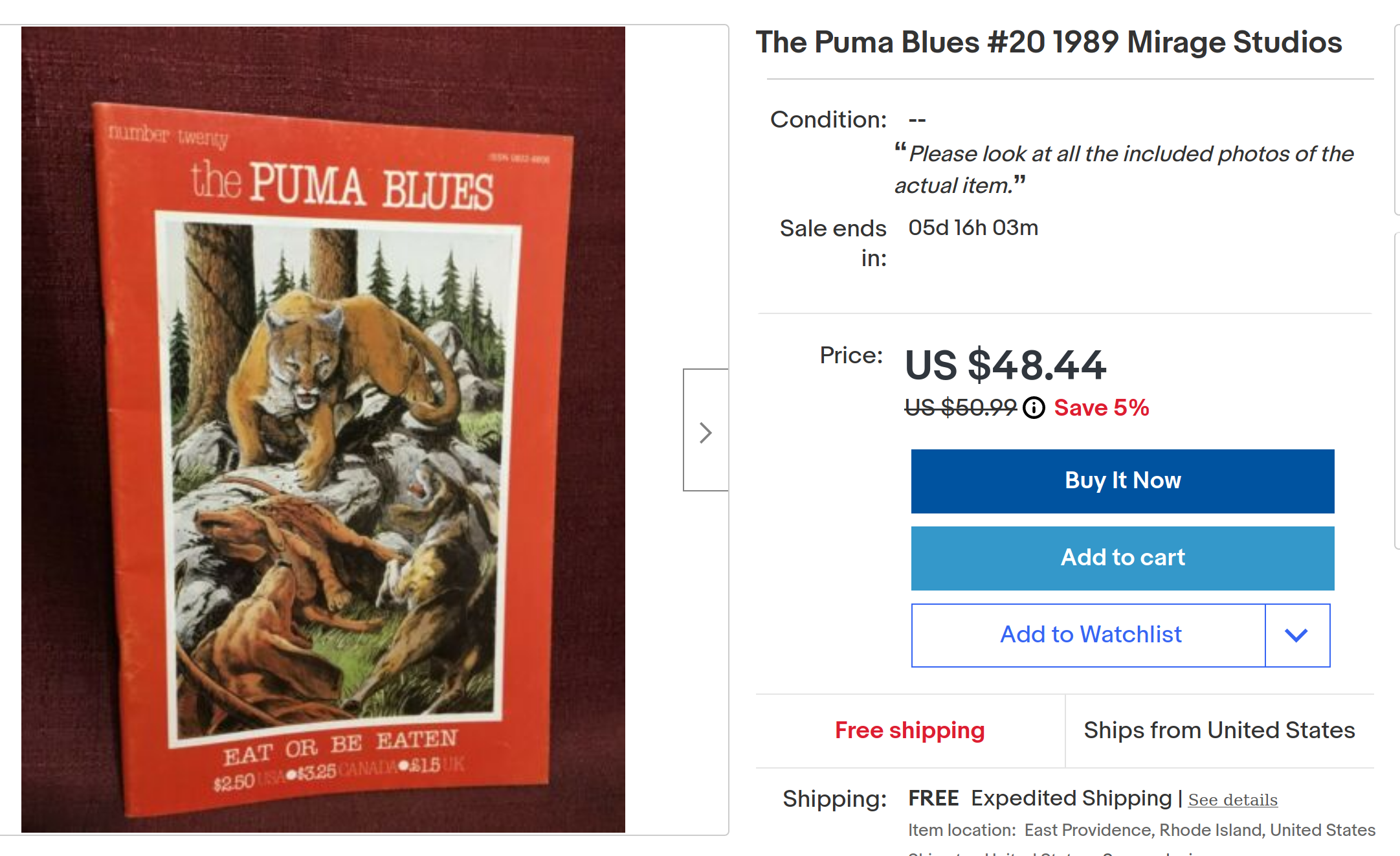

Peter Laird and Kevin Eastman do a Ninja Turtles thing (sort of). Which makes me wonder whether this is a something that people pay a lot of money for now…

I guess?

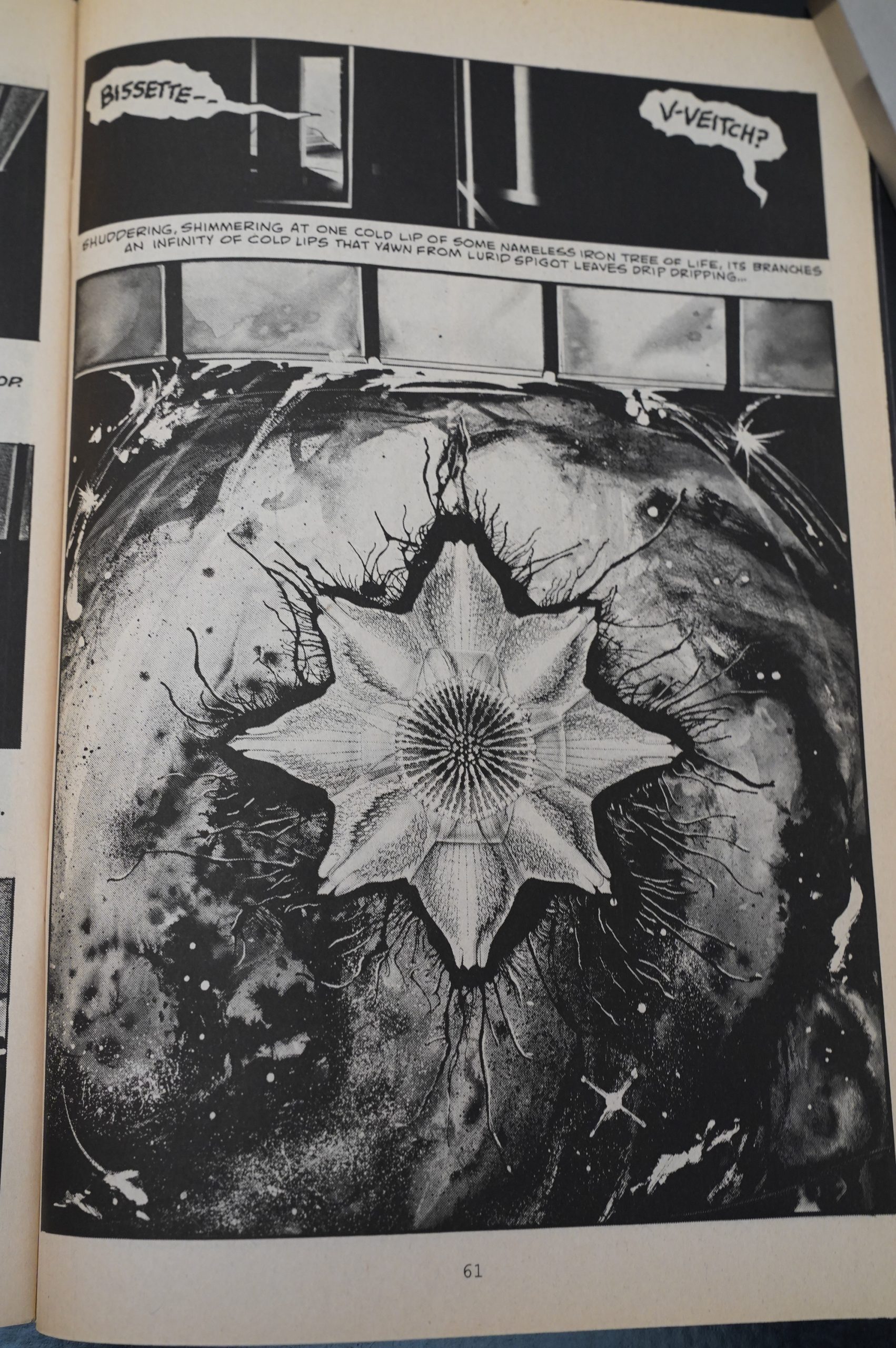

Rick Veitch and Steve Bissette do a kinda cosmic jam thing.

All in all, it’s not a bad issue, as these things go. There’s even an Alan Moore-scripted thing in here.

So now surely the drama is over?

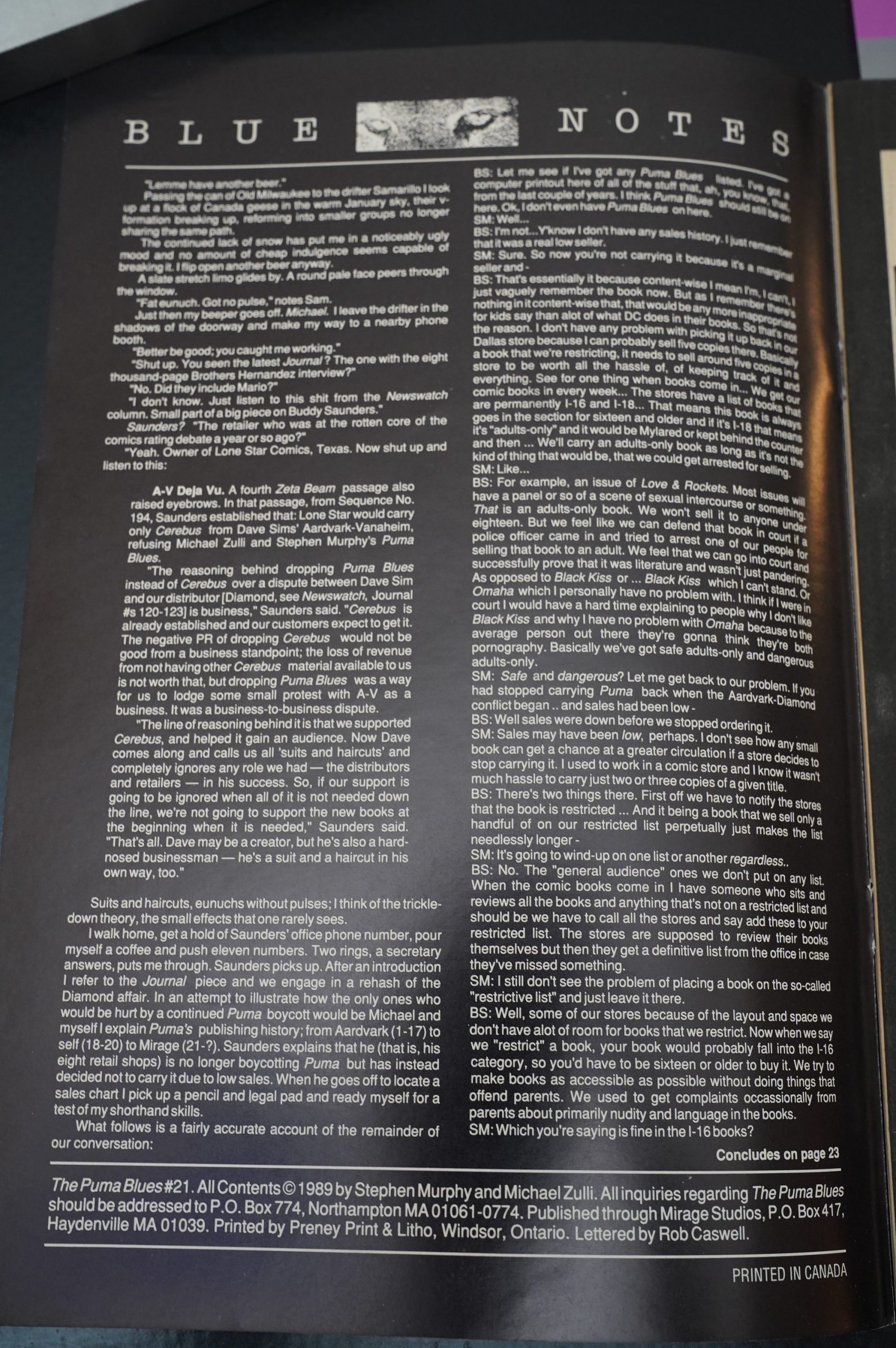

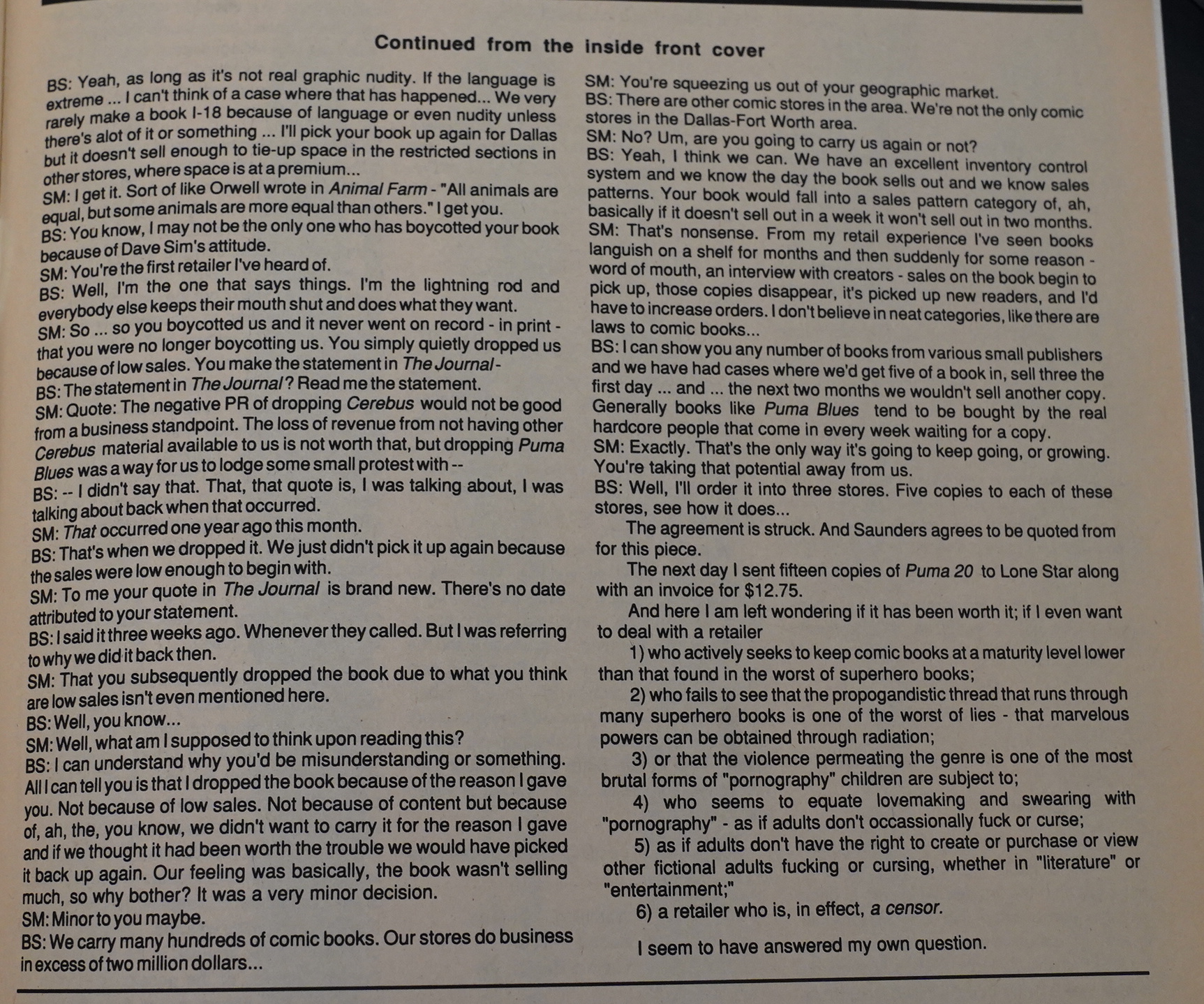

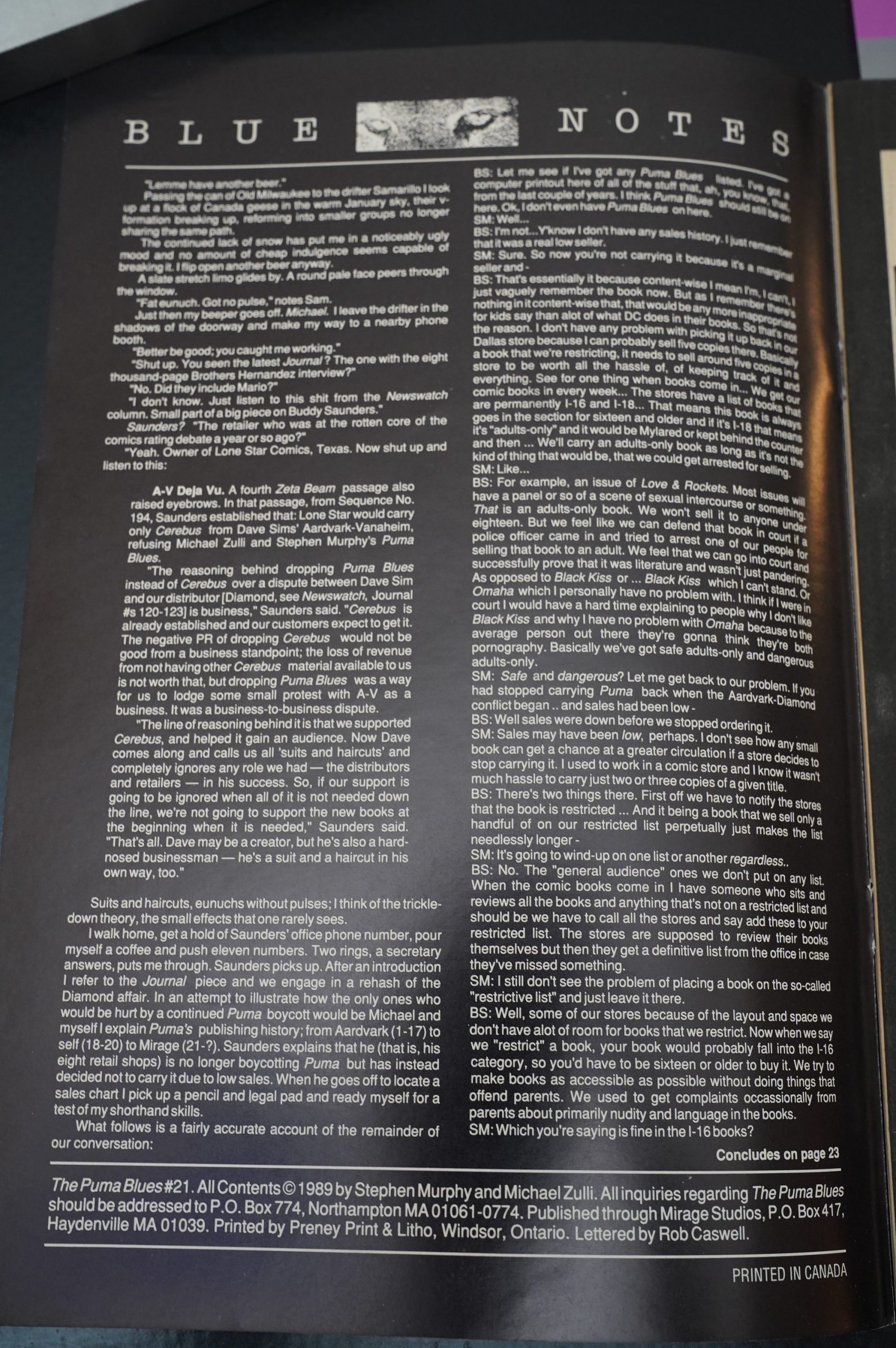

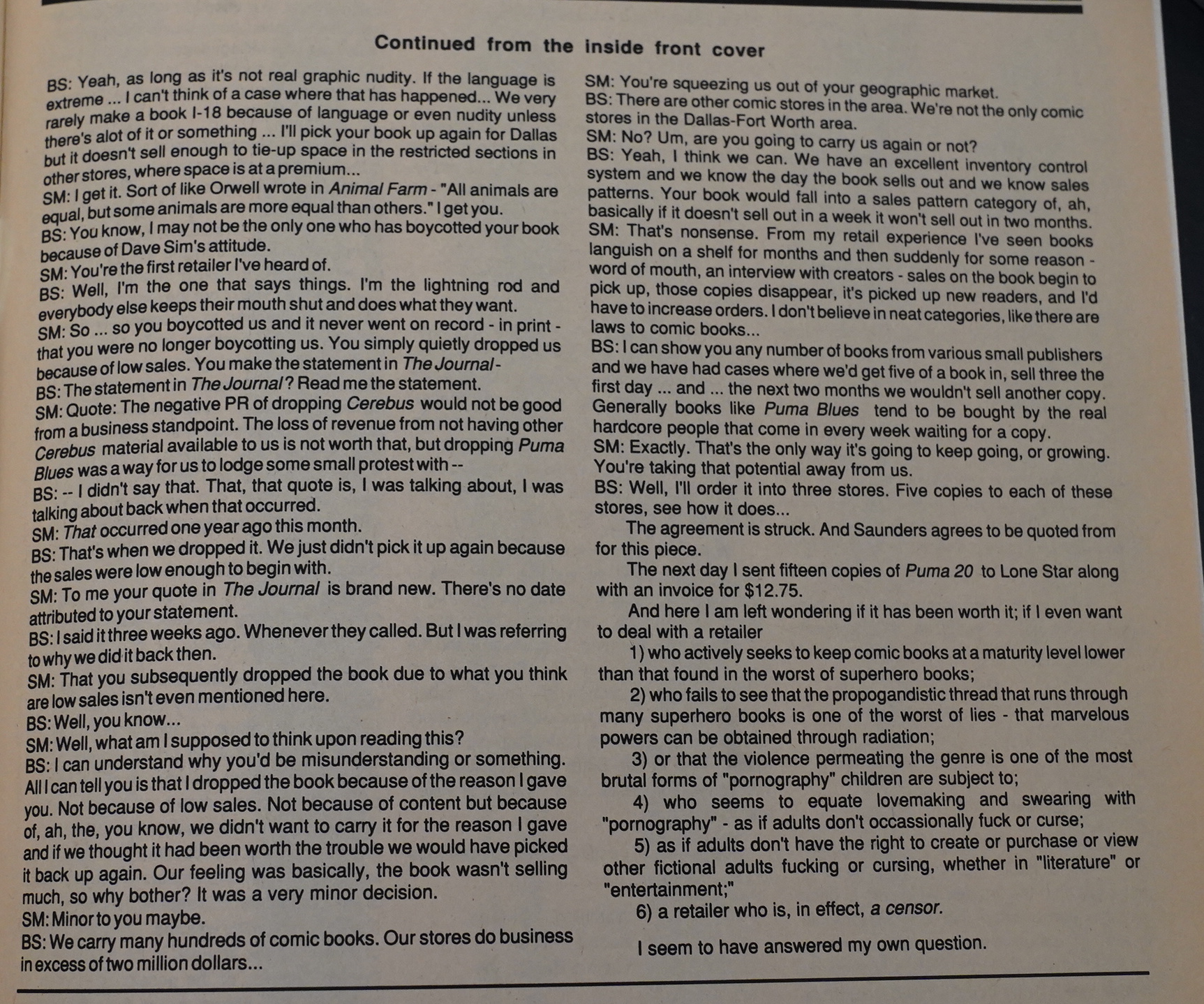

#21 is the first issue published by Mirage (the Turtle people), and more drama is happening. This time, Buddy Saunders, a Texas retailer, had dropped Puma Blues because he wanted to punish Dave Sim. And then he changed his mind, and then he continued to not carry Puma Blues because it just didn’t sell very much.

After talking to this asshole for hours, Murphy hand-sold him $12.75 worth of Puma Blues, and then decided that he was totally fed up with the entire fucking thing, it sounds like.

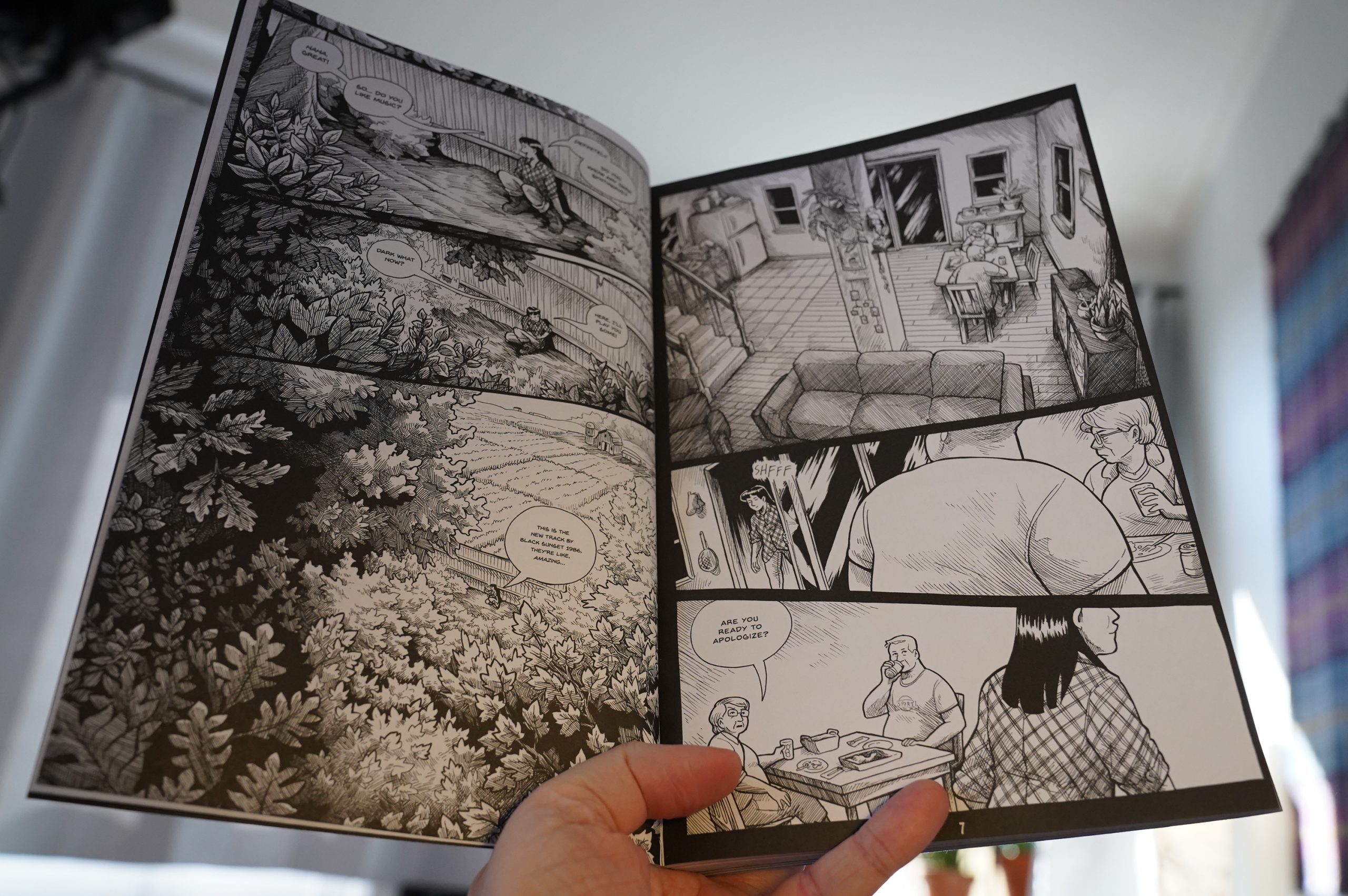

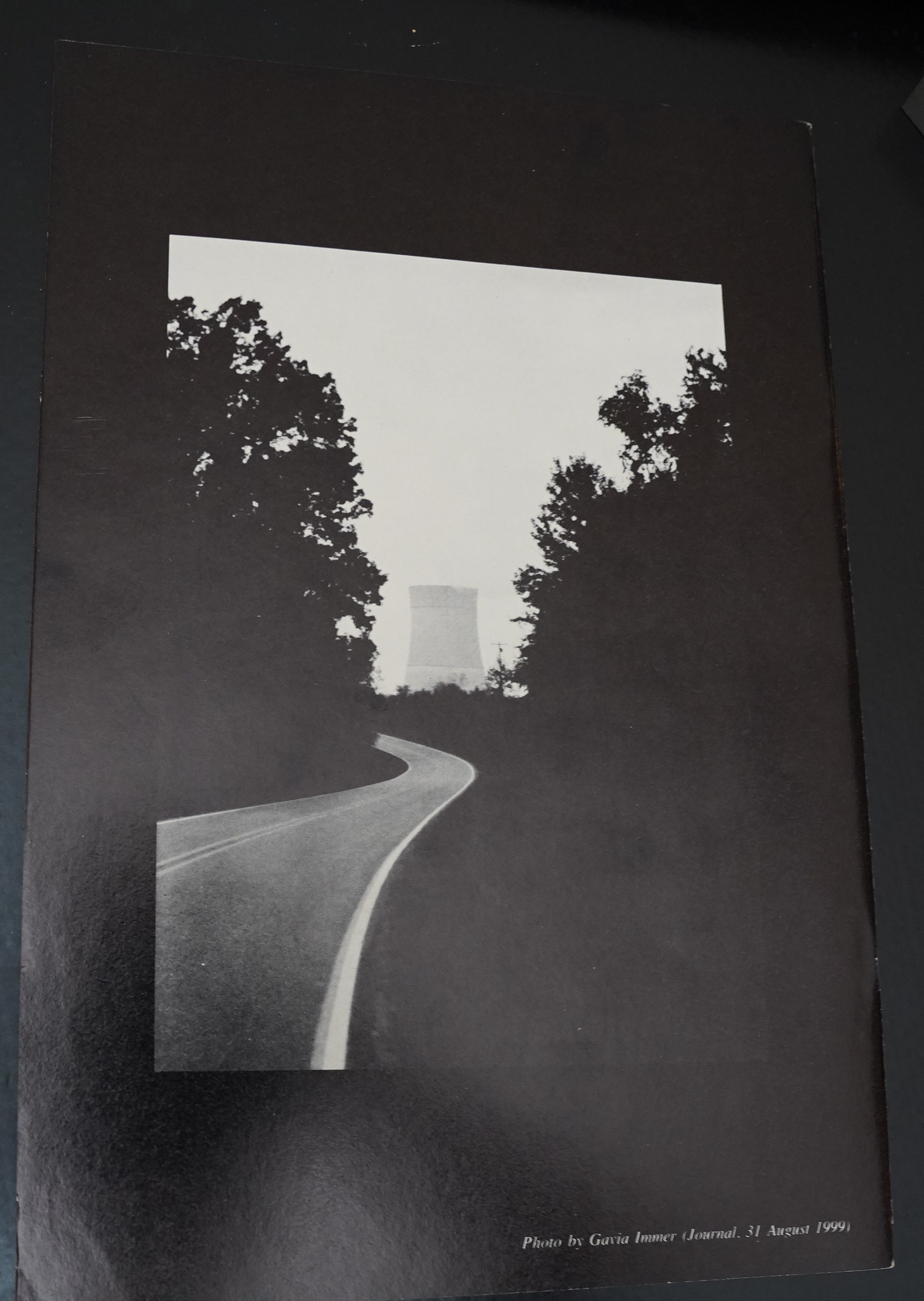

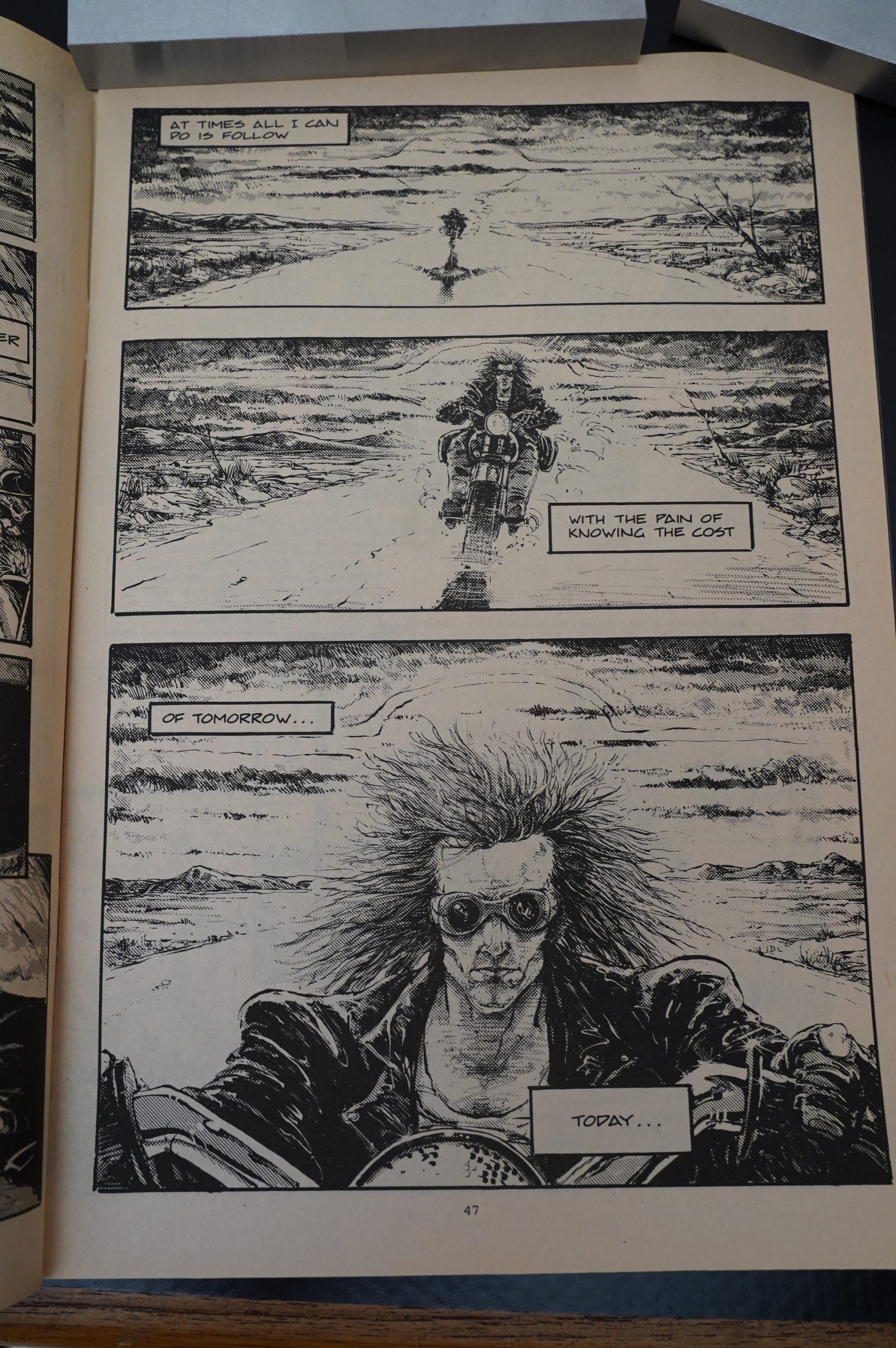

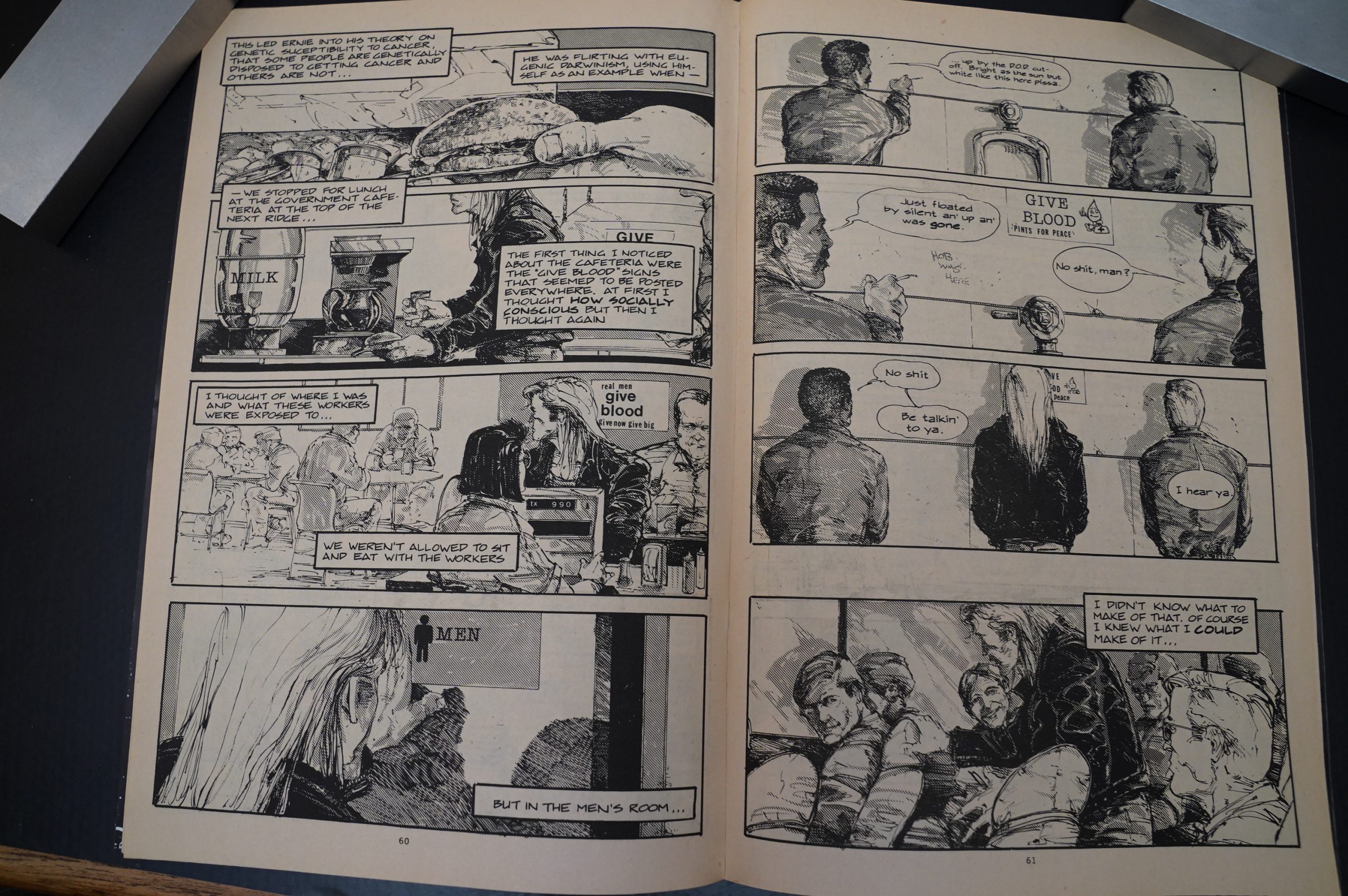

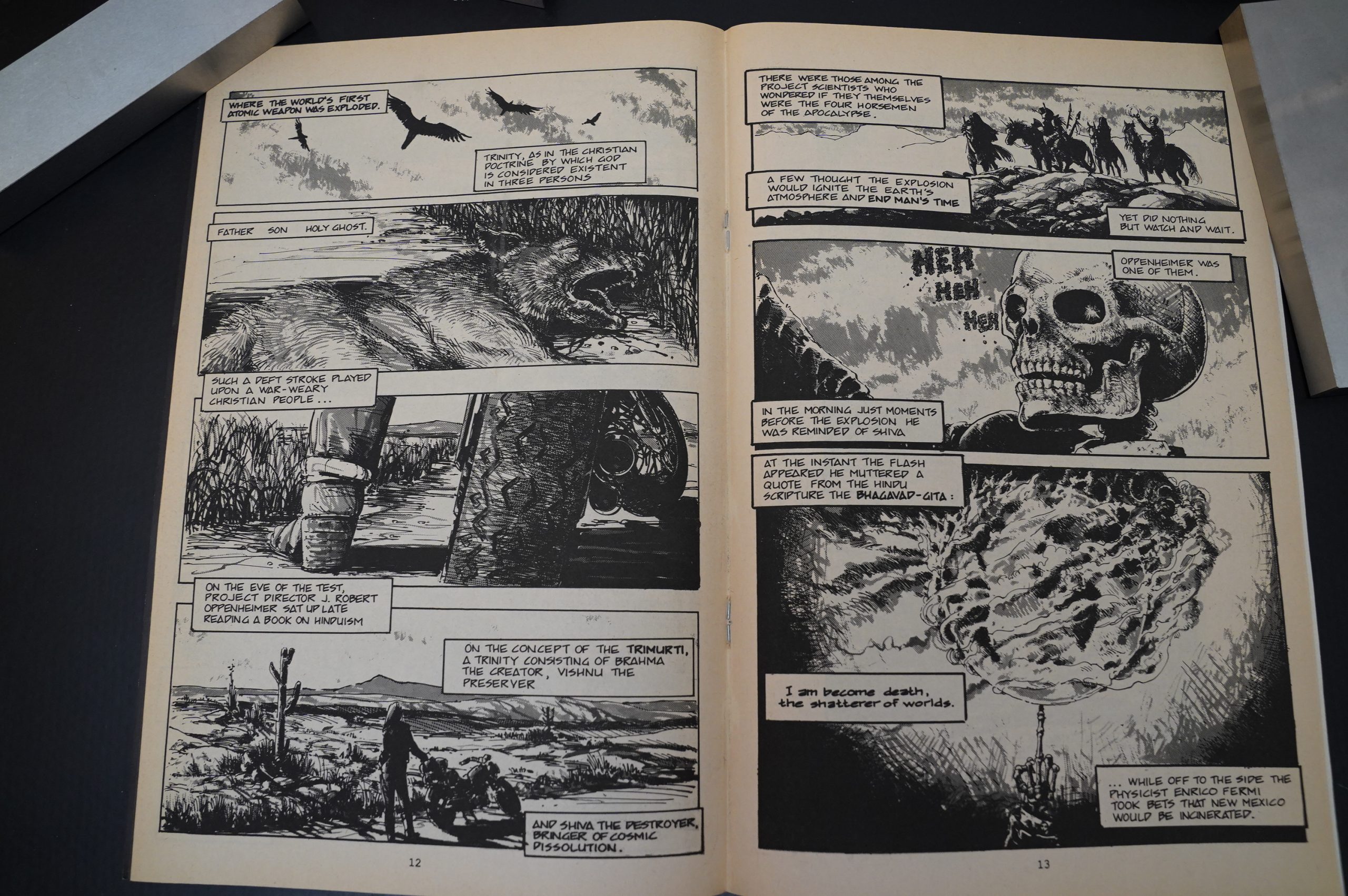

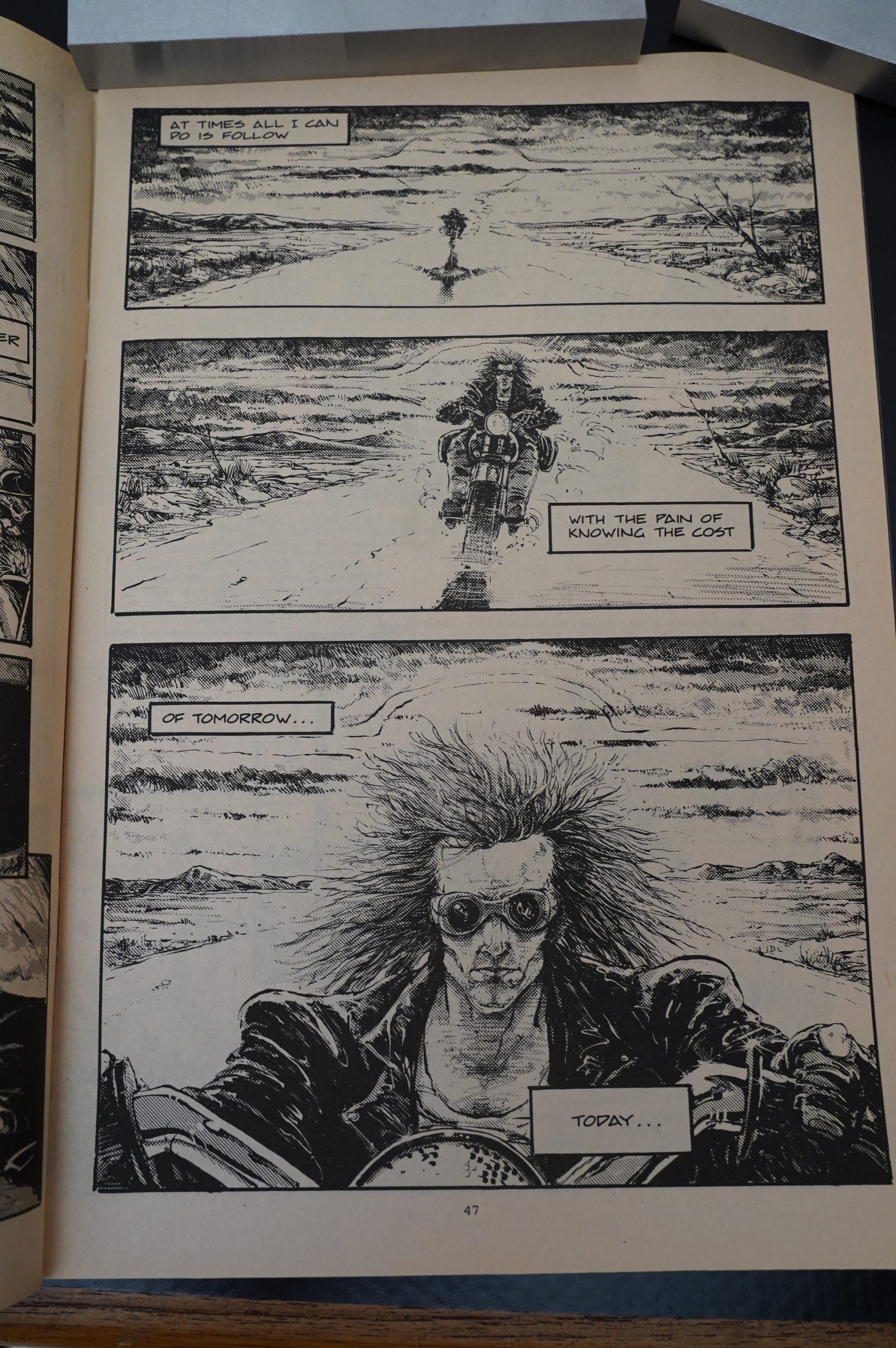

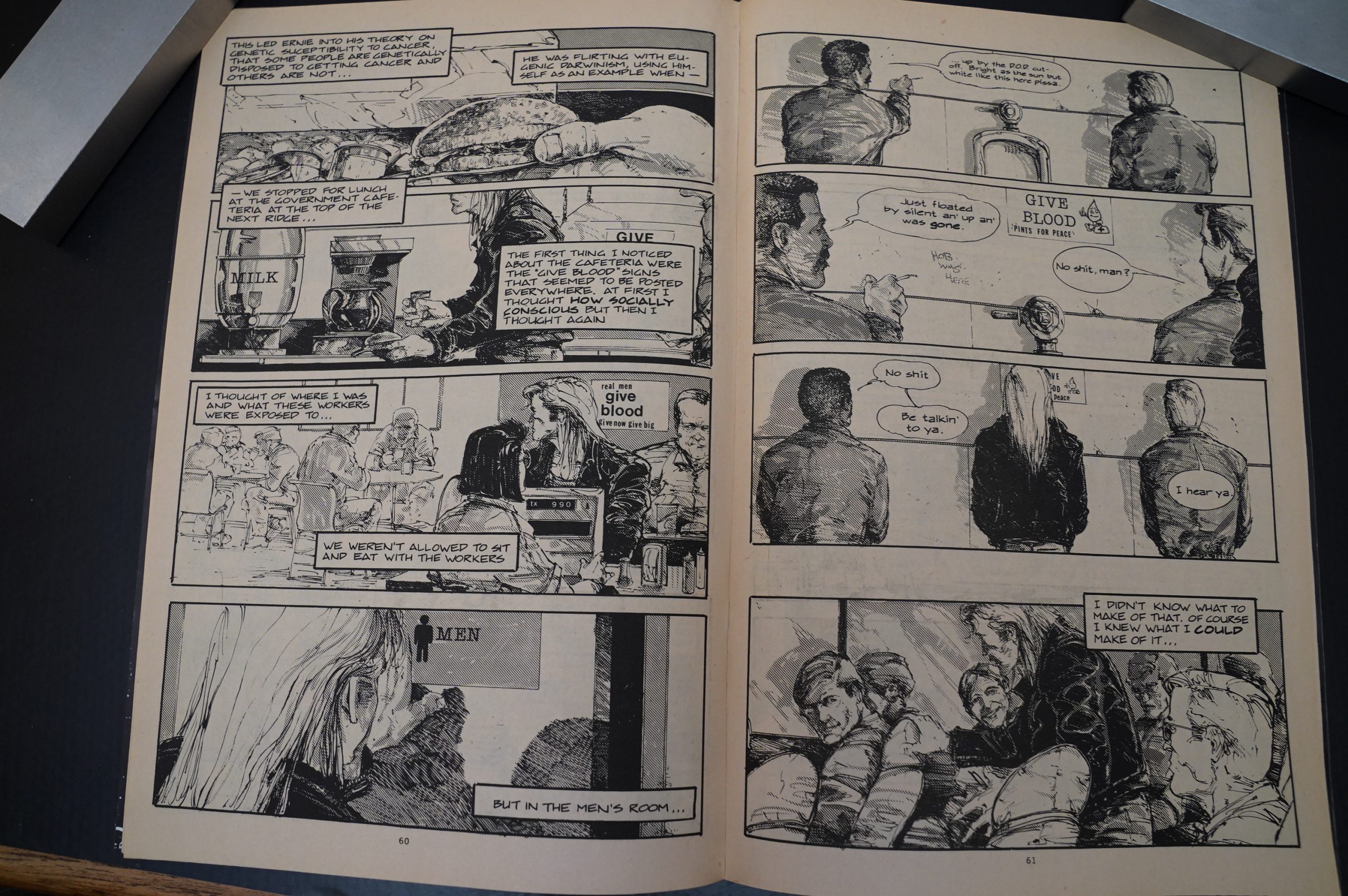

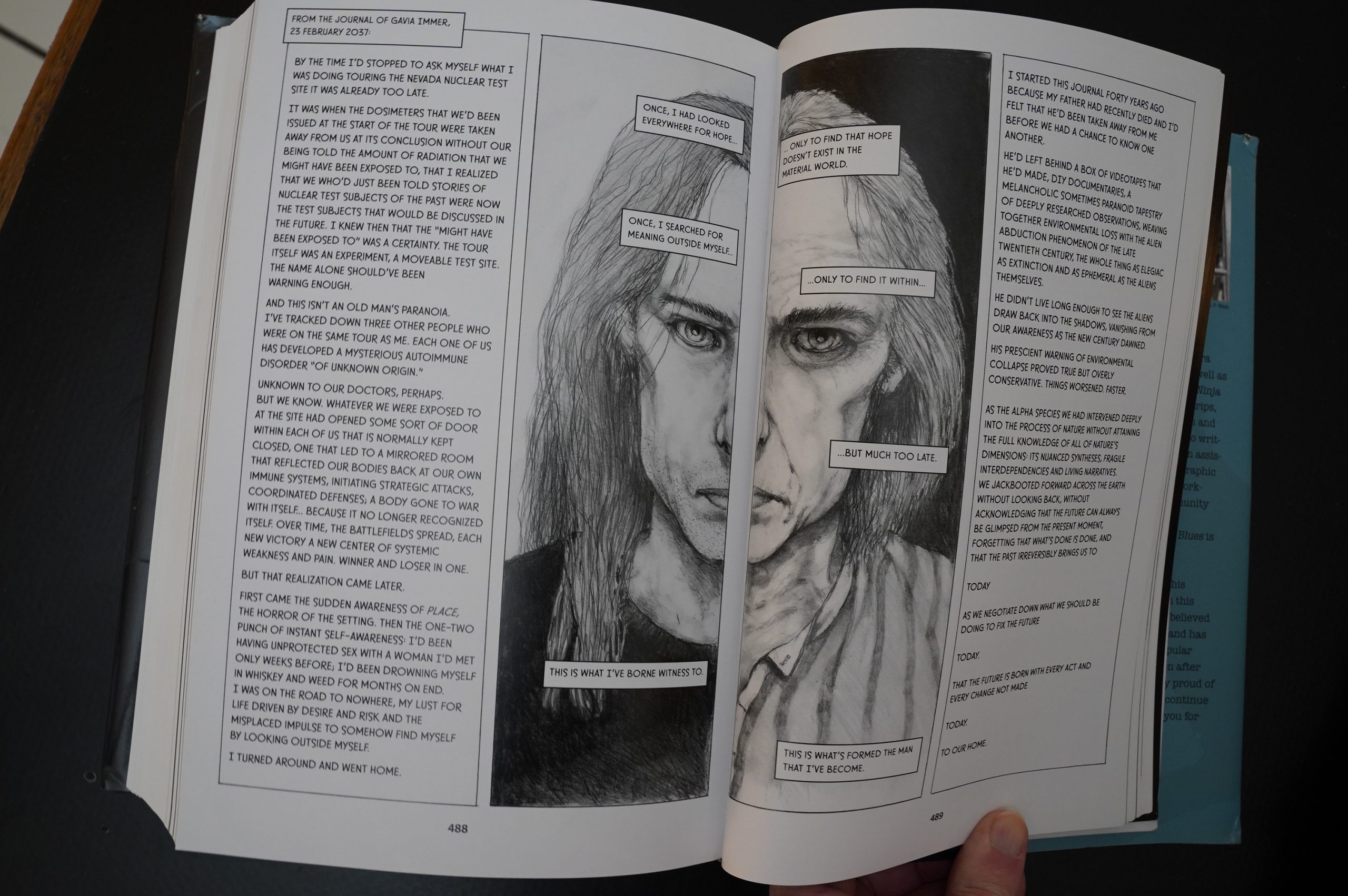

But what’s going on in the storyline, then? We apparently skip back in time to when the protagonist is a hippie again, and he goes on a trip around various sites where there’s been nuclear tests. It’s a slog to get through, and doesn’t seem to have anything at all to do with what’s gone before. I.e., it reads like if they were totally fed up with Puma Blues (and who can blame them after what’s happened the last year?) and wanted to do something else, but didn’t quite know what…

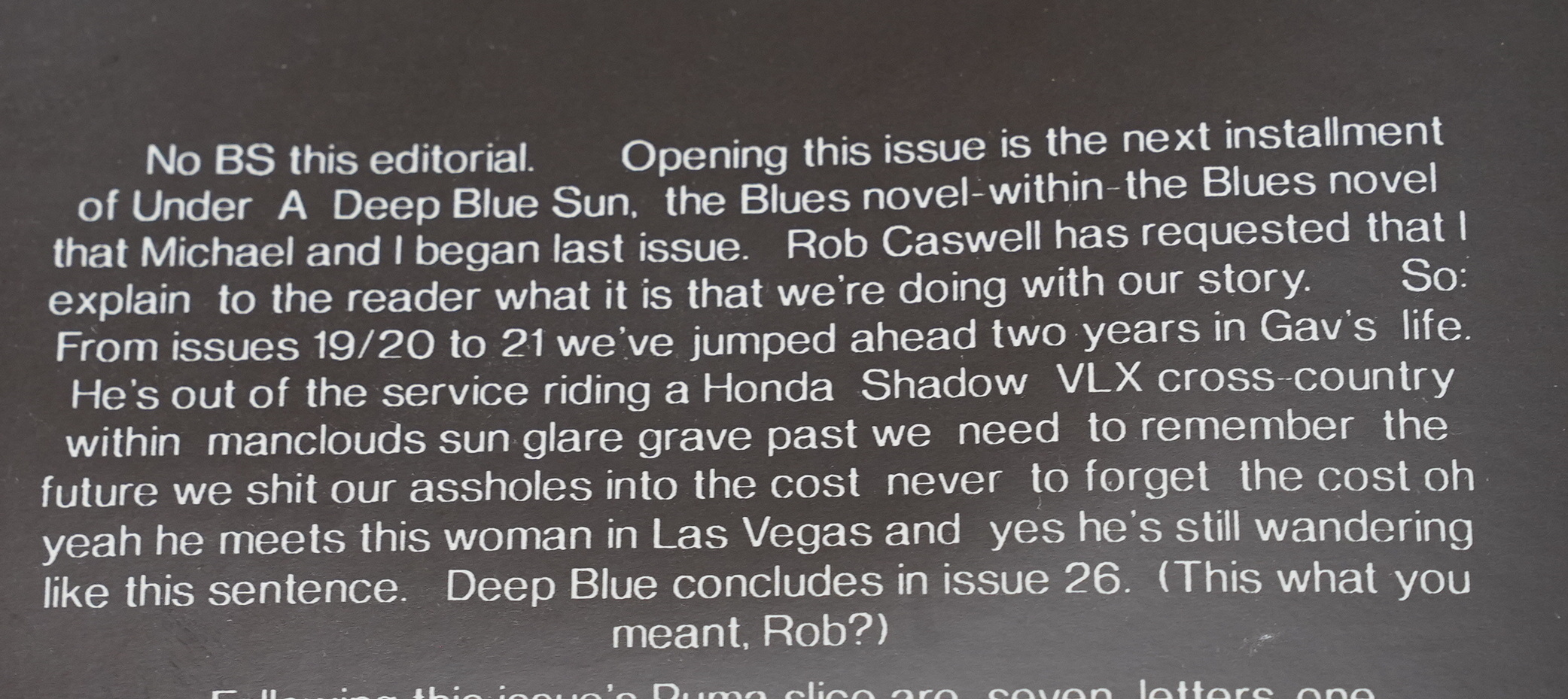

In the next issue, Murphy explains that this isn’t in the past, but in the future. Thank you, Caswell, for asking for an explanation.

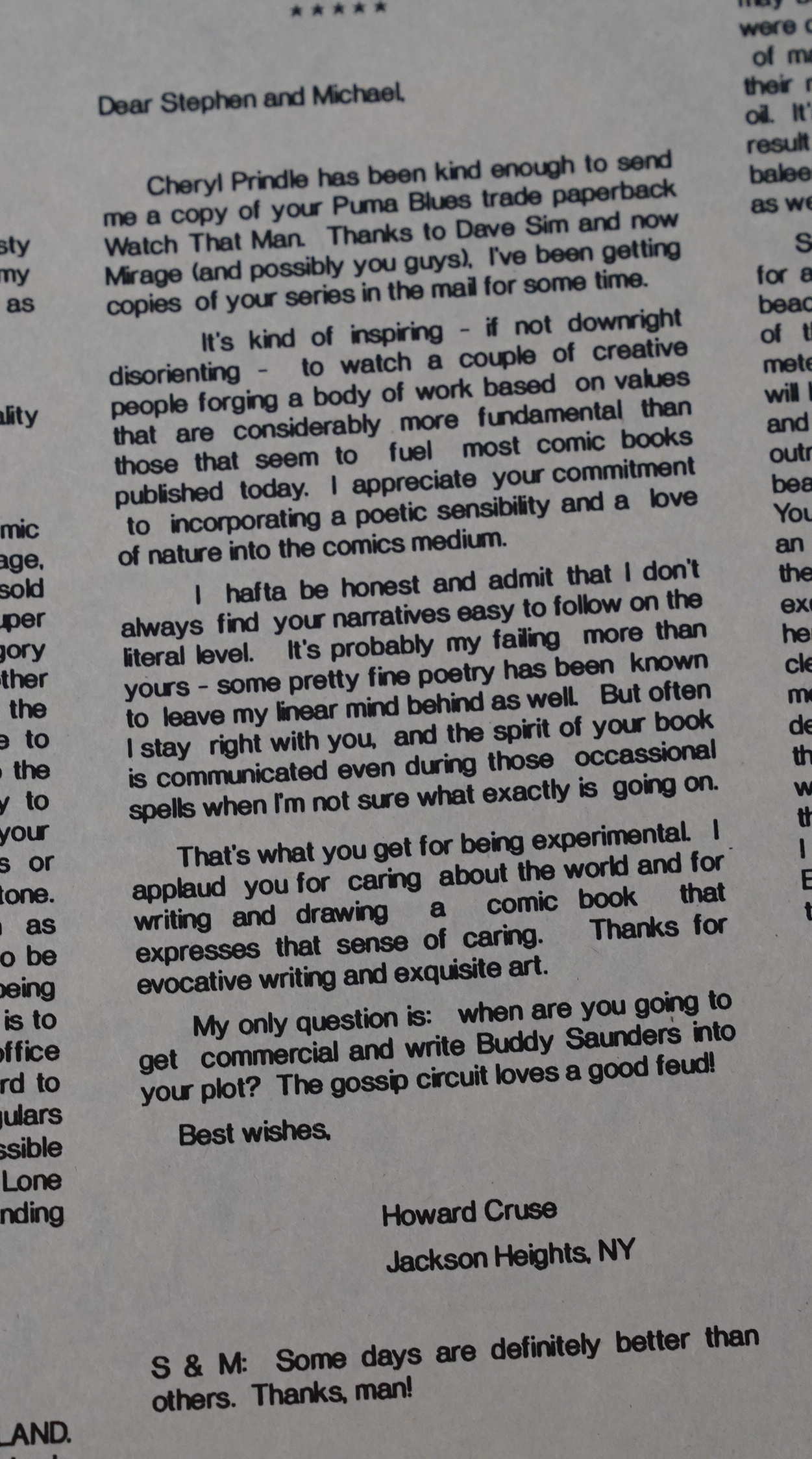

Howard Cruse writes in and asks the real questions.

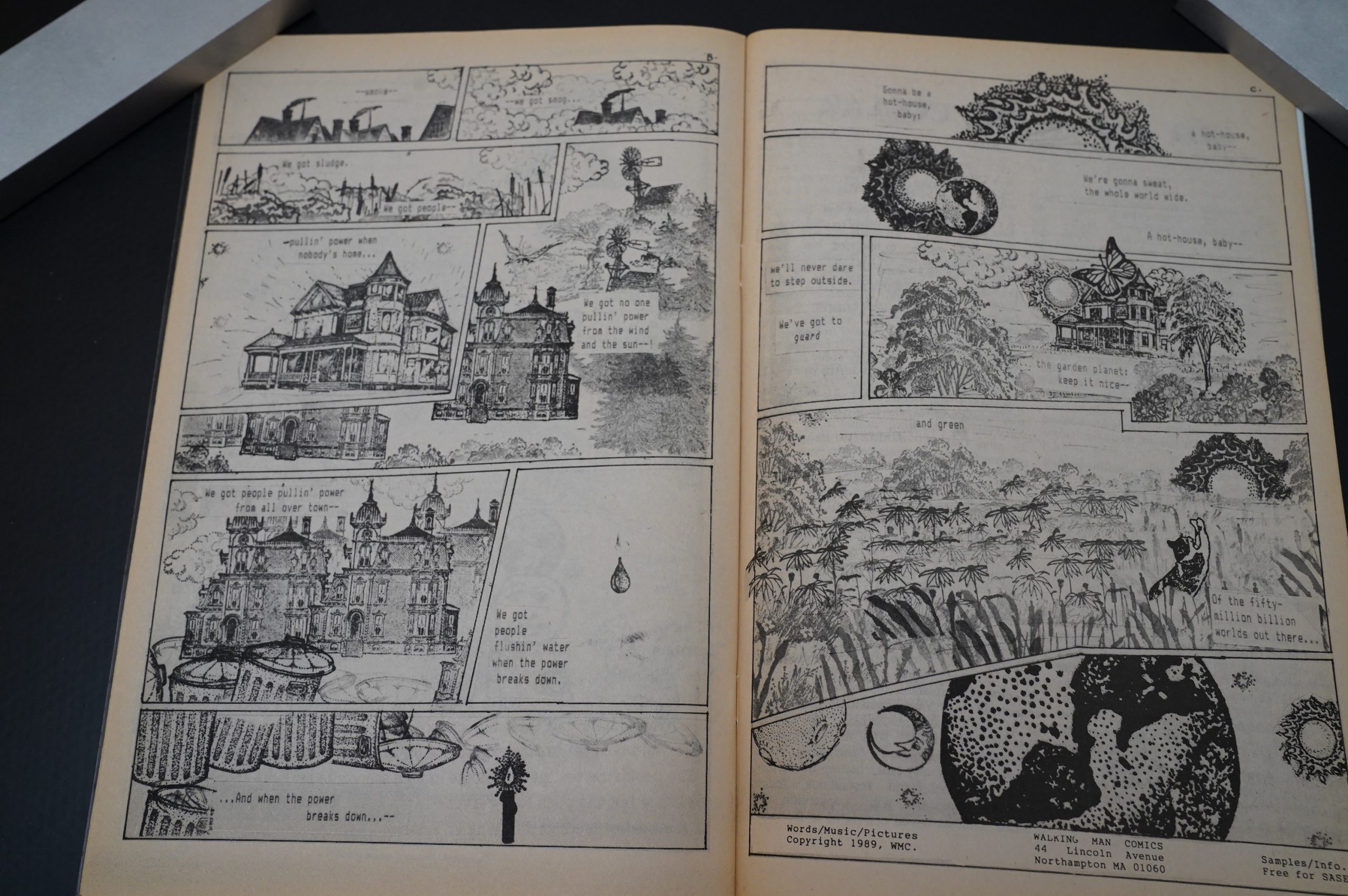

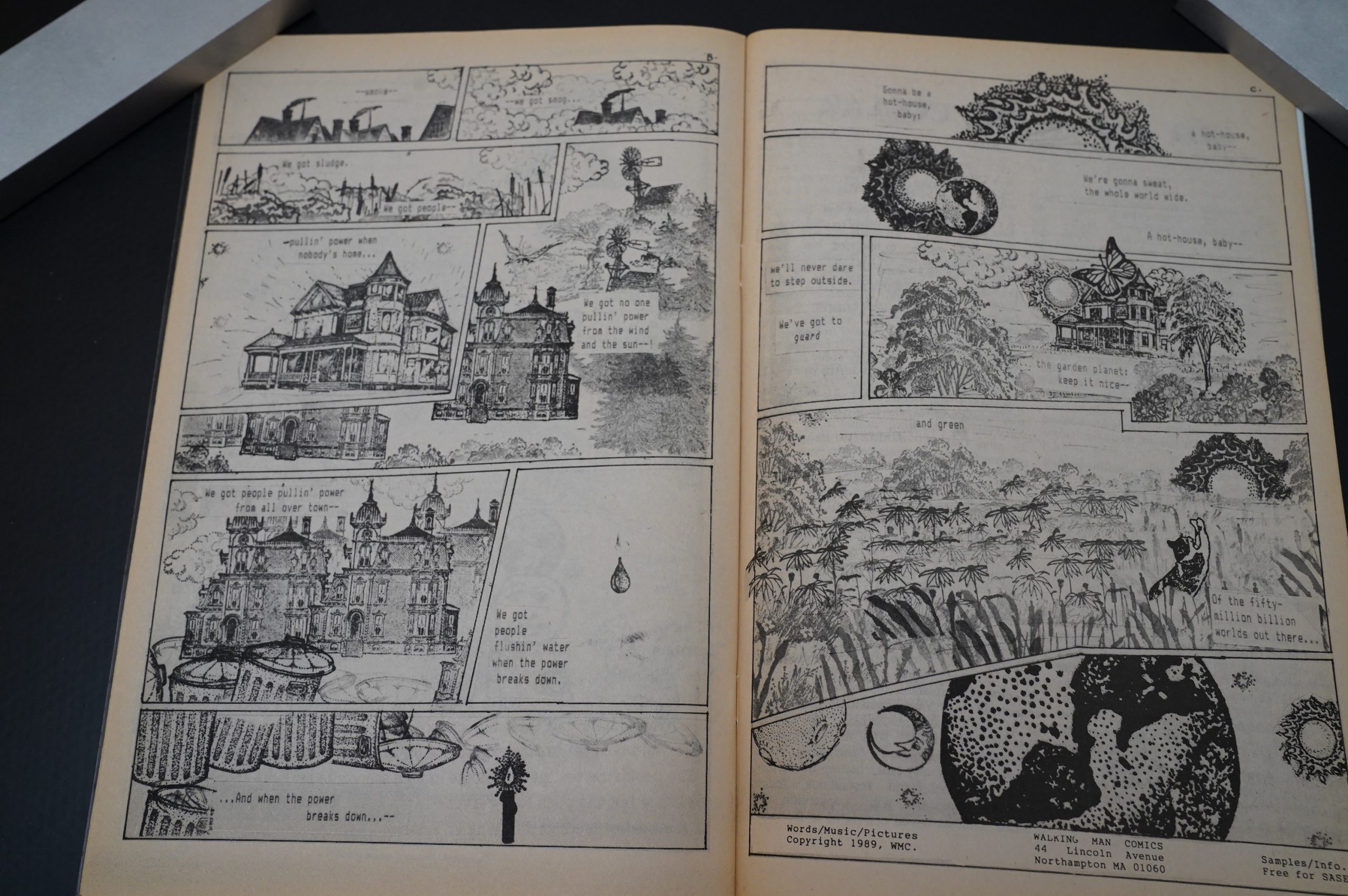

We even get a backup feature (by Walking Man Comics).

Is that still the same guy?

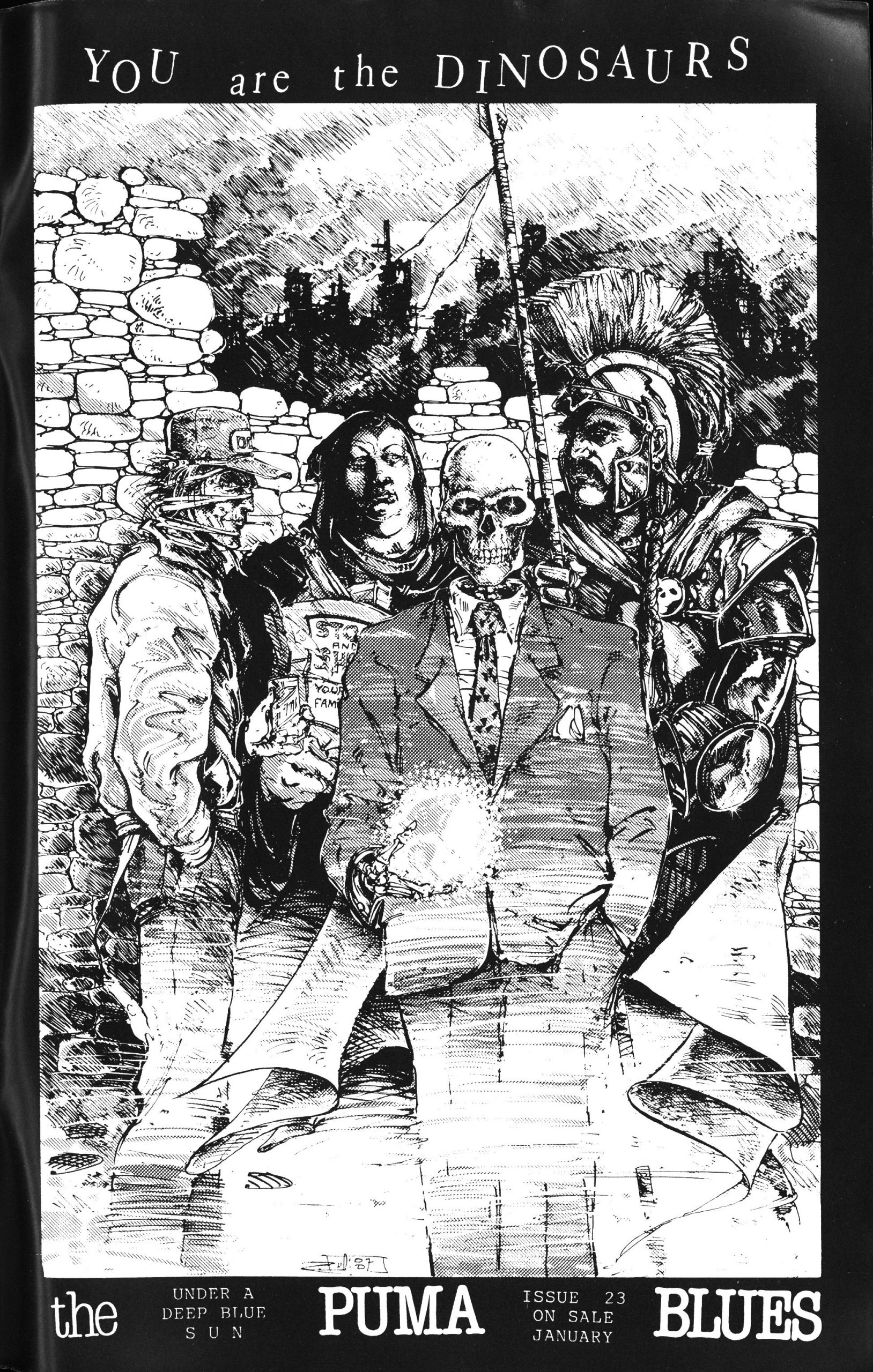

The final issue, #23, reads as if Murphy had gone on a tourist trip to a test site, and then just retells it (but layers Deep Philosophy and paranoia on top). It’s… it’s not very good.

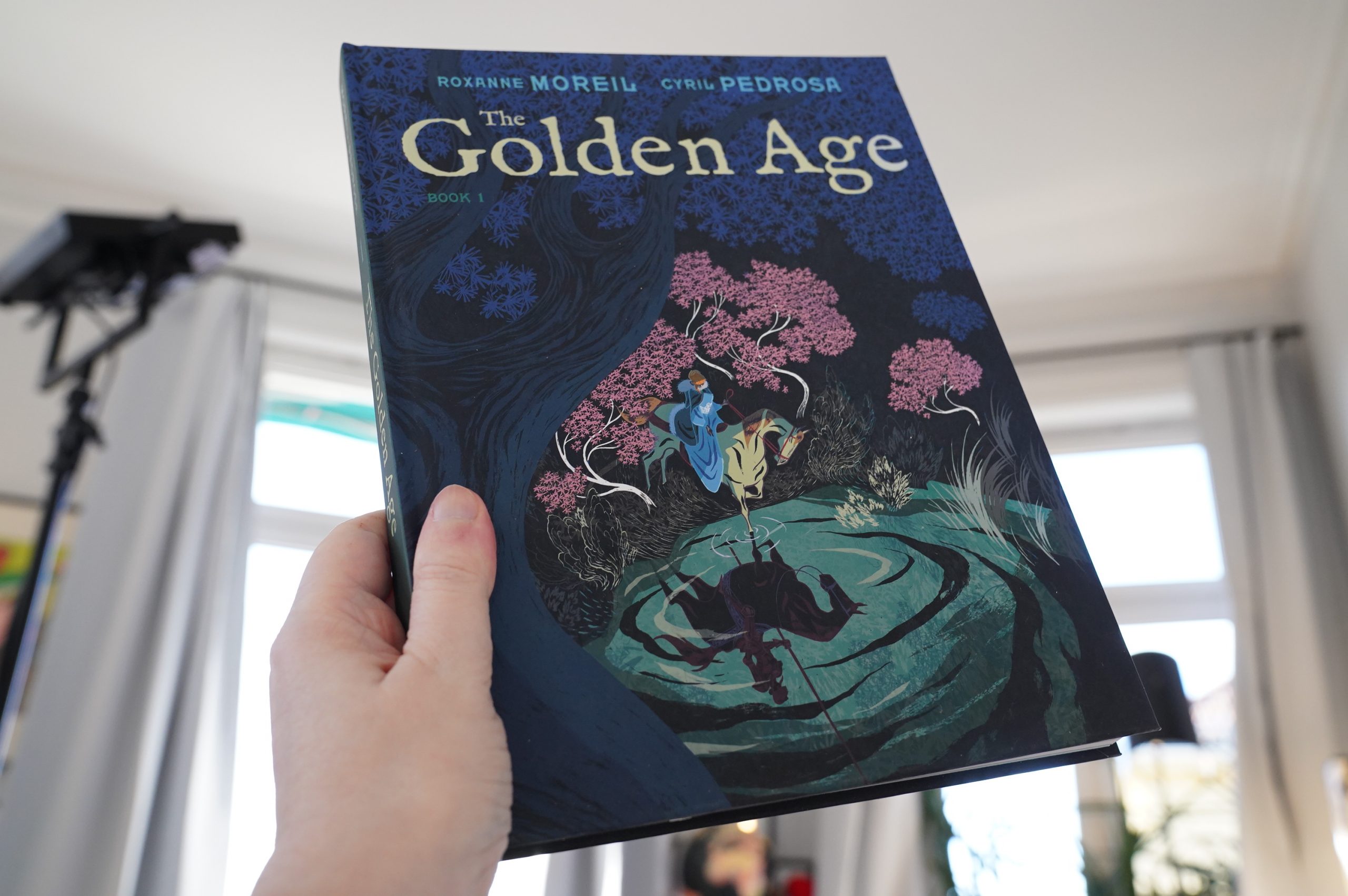

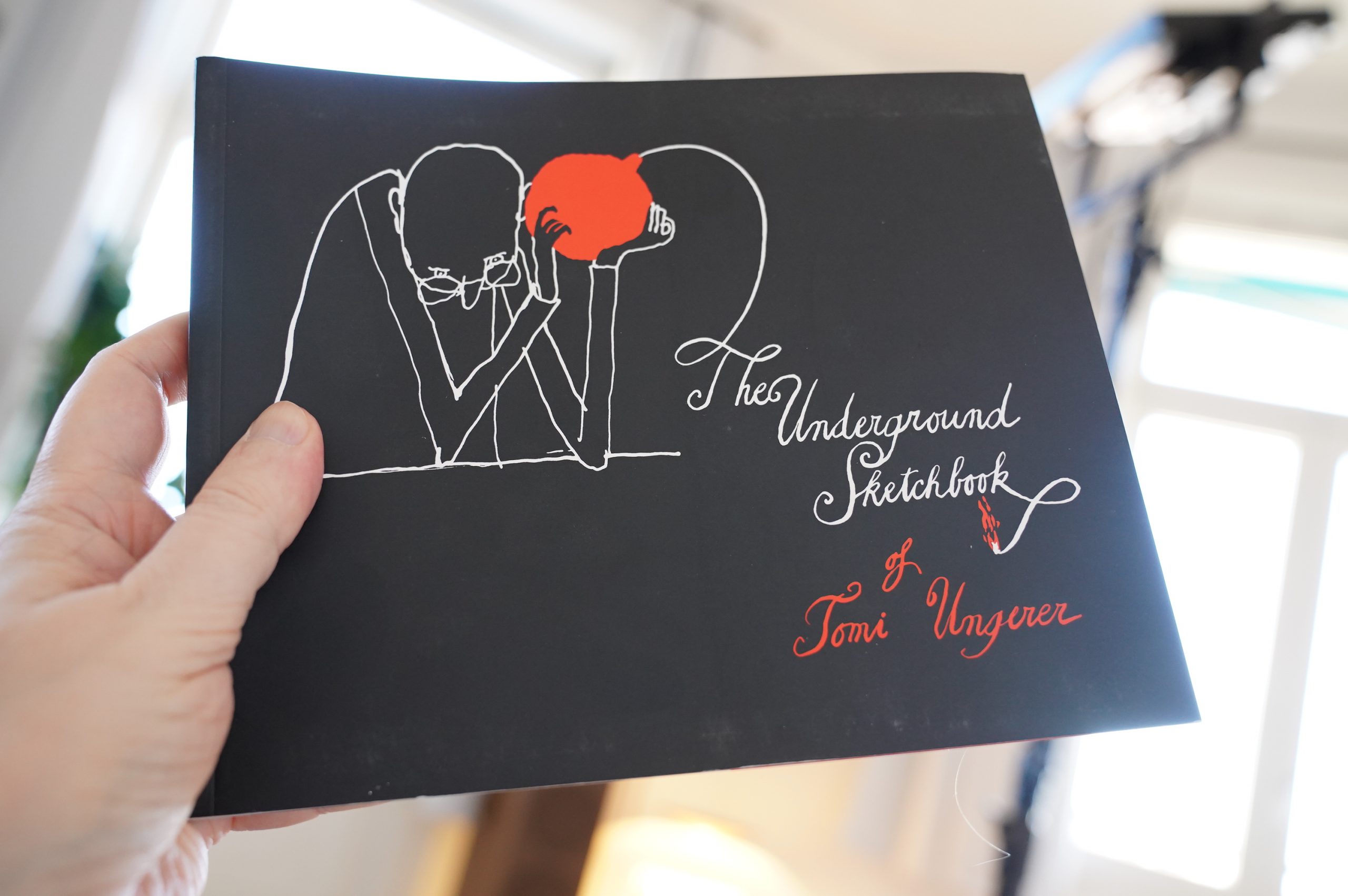

Mirage published two collections of Puma Blues. The first is the first third, 1-12, and the second is just… the other issues? 13-19 doesn’t make much sense as a book.

Issue #24 was solicited, but was never published. A #24 1/2 is mentioned here and there…

But then:

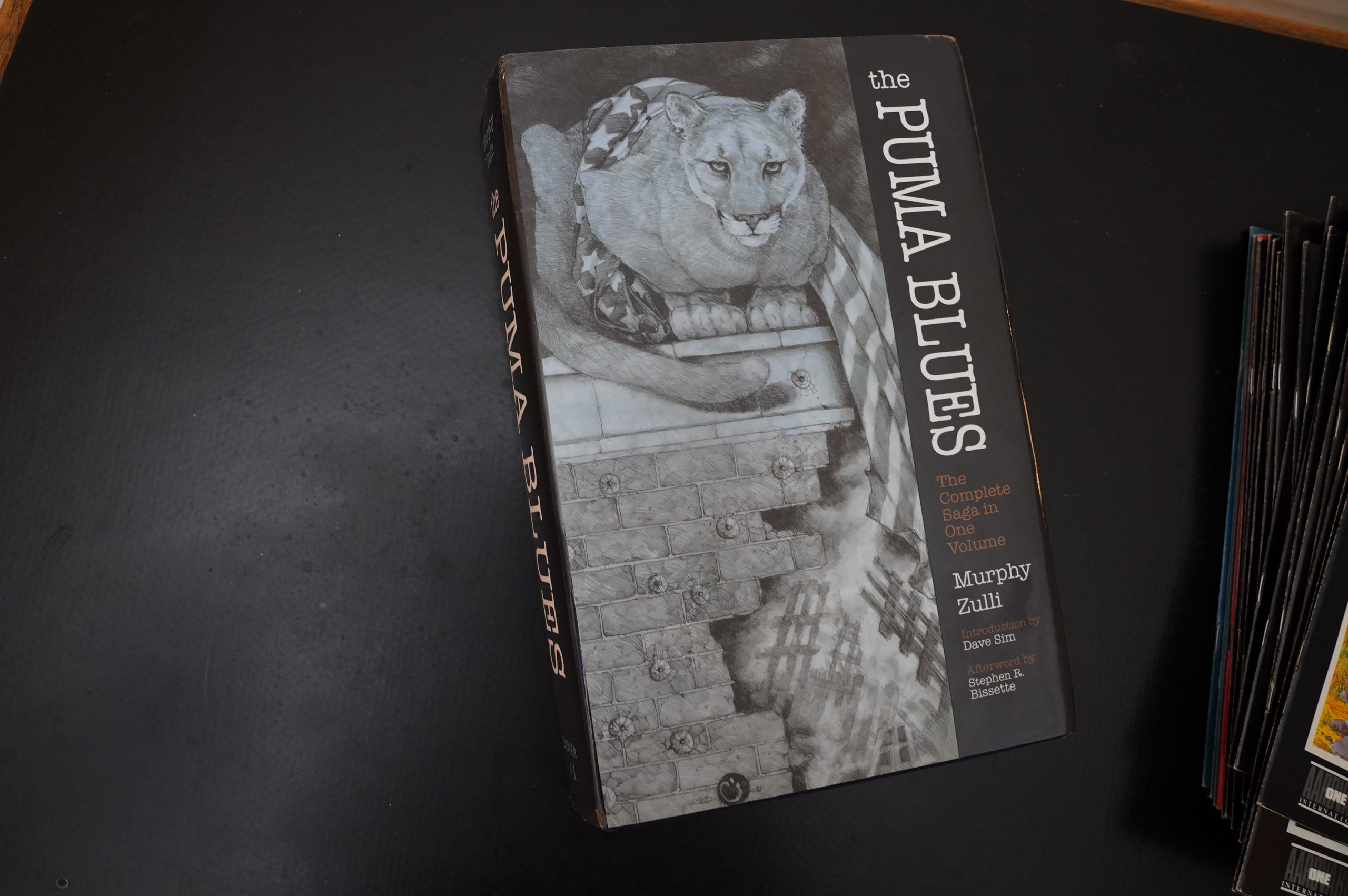

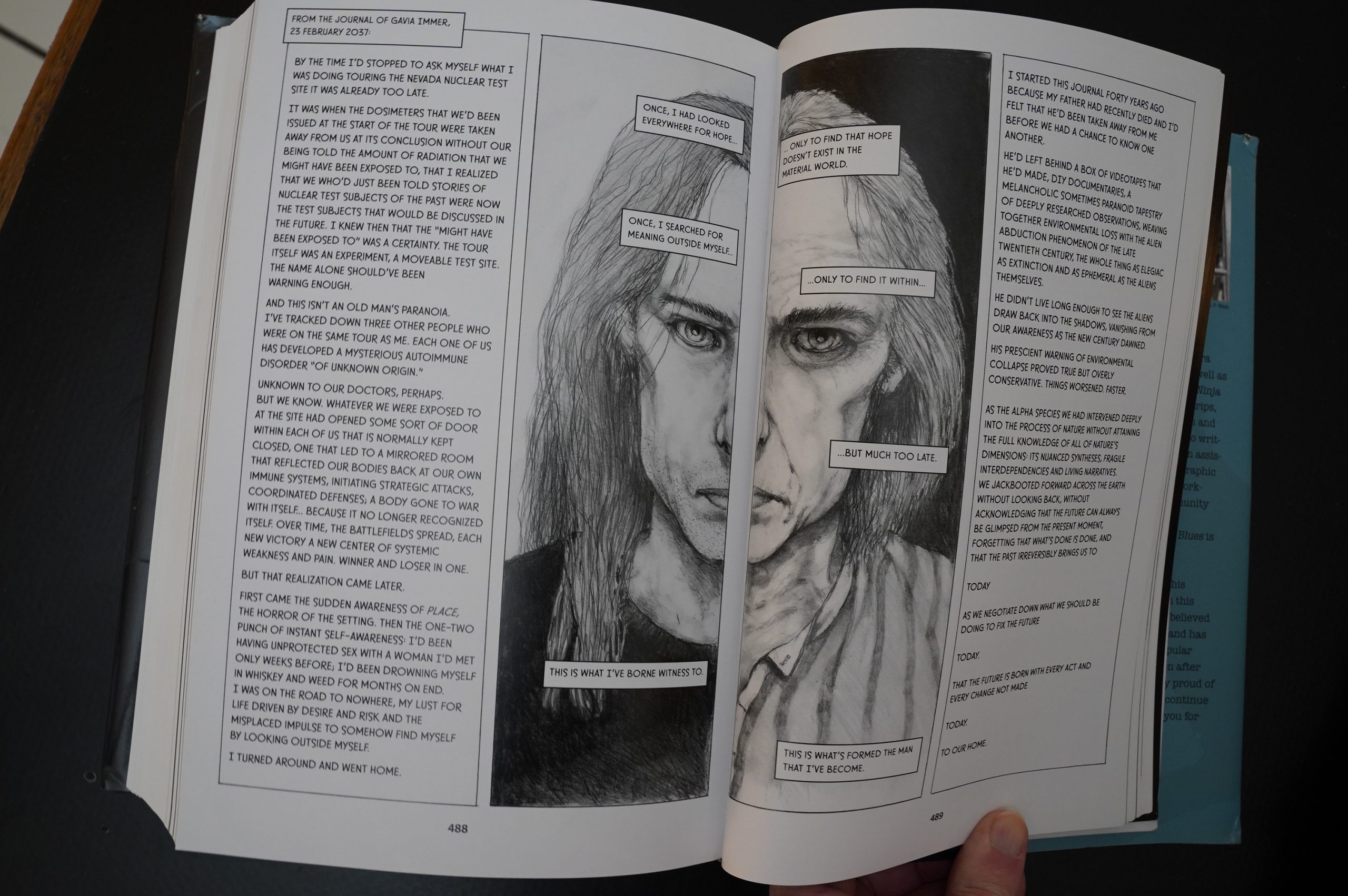

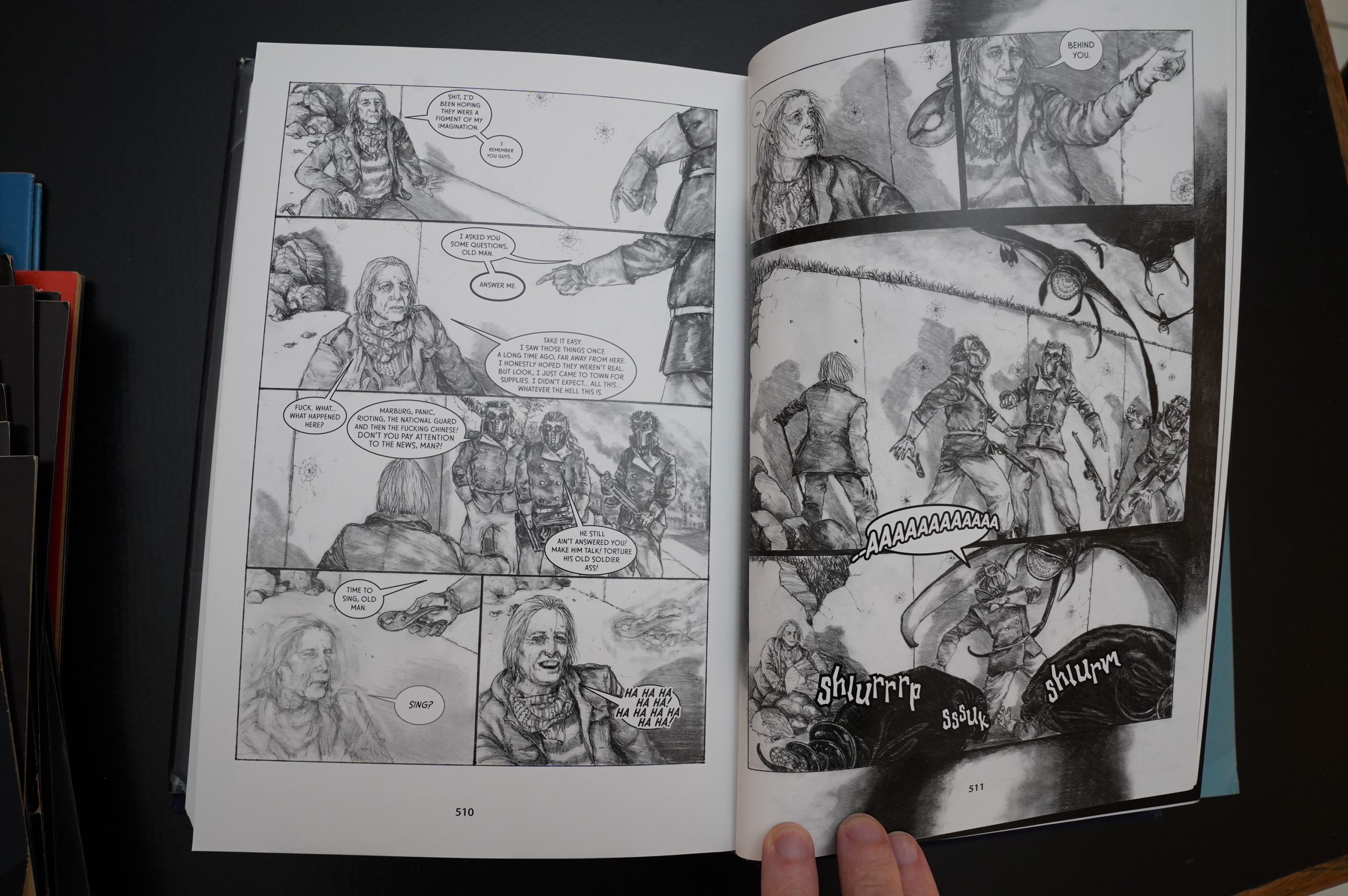

In 2015, Dover published a complete collection, and got the creators to wrap up the series:

Unfortunately, the 36 added pages were all like this, and didn’t wrap up anything much.

None of the interesting, fun bits from the first dozen issues were touched upon at all, I think? Instead it’s just a … rant about … stuff that needs ranting about, but it’s kinda a “fuck you” to the readers. I mean, it’s not meant like that, I’m sure, but that it what it felt like reading the new ending.

Well, OK, there’s this: Two pages of pliers and manta rays, and that connects thing… sorta? But only in the vaguest way, symbolic way… And instead of going “ooo, it all connects”, these pages make me go “well, at least they tried?”

But I’m sure it was painful for the creators to return to this and try to resolve it somehow — the original run of ~19 issues was about at the halfway point, and they certainly couldn’t carry on from these. So it’s understandable, but that doesn’t make the collected edition any more readable.

So there you go: It’s a series that has some absolutely fabulous sequences here and there, and seemed to be going somewhere interesting, but we’ll never know. But those fabulous sequences are still stunning.

CM writes in The Comics Journal #122, page 23:

JUST IN.

As the Journal went to press a EX)ten-

tially new conflict arose between AV

and Diamond. Dave Sim, speaking to

an assembly of retailers at the Capital

City conference held in Madison,

Wisconson, May 8-10, Stated that he;

along with II other self-publishing

creators, are considering a boycott of

Diamorxi Distributors. The matter will

v be voted upon amongst the 12 in

Toronto, OntariO in early July. Sim

identified the roster of self-publishing

creators along with himself as: his

assistant on Cerebus Gerhard; the

creators of the Teenage Mutant Ninja

Tartlés Kevin Eastman and Peter

Laird; Puma Blues creators Michael

Zulli and Stephen Murphy; the editors

of AV’s uExoming Taboo Steve Bissette

and John Totleben; Bill Sienkiewicz

and Alan Moore, who are publishing

through Moore’s new imprint Mad

Love; and Dave Gibbons and Frank

Miller who are rumored to be

collaborating On a. project for self-

publication.

Sim said that when he took an in;

formal poll amongst the 12 asking if

‘they uOuld boycott Diamond given the

decision that day, only a minority said

they would not.

The Journal will have full details of

the reaction to this announcement next?

-issue.

I don’t think that ever happened.

Heidi MacDonald writes in Amazing Heroes #145, page 182:

You know you’re in the ’80s when: a

comic book that’s militantly pro-

environment and which loudly questions

the political status quo becomes the

center of a storm of contrwersy—but not

because of its contents, but rather

because of an arcane dispute over

magazine distribution.

Although Puma Blues creators have

made peace with Steve Geppi, and the

book was technically never dropped by

Diamond, there are still some hard

feelings around (mainly from AV-I •I

publisher Dave Sim).• Writer Steven

Murphy felt somewhat more at peace,

however. He reports that he and Geppi

have spoken at length, and Murphy has

accepted Geppi’s Still, it’s no

fun being a pawn in a larger game,

Murphy points out.

“It felt like shit for months,” he says.

He explains that if Diamond had

Puma Blues it would have meant

a third reduction in the creator’s income

on the “From mid-January to mid-

March was horrible. I couldn’t live with

a third cut in pay. We were really

sweating it out. I just speak for myself

not Michael, but I’ve always been one

who never gave a crap about what was

going on in the industry. I mean, I got

mad about injustice, but I wasn’t really

part of it. But this thrust me into the

middle of it all. It cost a tremendous

amount of creativity. All we did was talk

about it.”

But at present, everything is “cool

between Diamond and Puma Blues. It’s

no longer a controversy [andJ • I’m not

very emotional about it at this point. A

few months were hell, they were awful,

now we’re getting into working on it

again, we don’t have to worry about

phone calls in the middle of the night.”

However, #20 will be double-sized

“benefit book” of sorts, with contribu-

tions by Steve Bissette, Chester Brown,

Dan Day, Gerhard, Keith Giffen, Mike

Grell, Peter Laird, Frank Miller, Alan

Moore, David Roman, Arn Saba, Dave

Sim, Rick Veitch, Steve Fiorilla, Tom

Sutton, and many others, as well as a

story by the regular team. Veitch, Miller,

and Moore all contribute stories of one

sort or another. “Gerhard does some-

thing—I’m not sure what,” Murphy

quips.

Meanwhile, in the regular story line,

starting in #21, Gavia goes on leave for

a weekend, so “he’s in town, on the

town.” This four-issue story will reveal

a lot more about the world of Puma

Blues. “He’s away from the resevoir, but

a lot happens that will affect him when

he returns to the reservoir. He comes

back from leave to a real mess.”

All of the subplots are building to

reach a climax in the early 30s. The

series will be wrapping up with issue

#36.

Although it’s meant a lot of stress for

him personally, Murphy feels that there

may be a worthwhile result to all of the

controversy, in that the creative com-

munity is banding together. “It’s amazing

the support we’ve gotten,” he says of the

benefit book. “If creators can get

together it would be worthwhile. That’s

the good thing that’s going to come out

of this. [We’re] going through a pro-

longed period of redefining people’s

roles.”

Gary Groth interviews Dave Sim in The Comics Journal #130, page 101:

GROVH: Before Iforget, Bhy wus a benefit book publish-

ed when there was no loss?

SIM: Because it was already set in motion for one thing,

and cellainly everybody appreciated that a book like Puma

Blues was probably worth supporting from the ecological

standpoint. I think, “Look at the list of contributors; we’re

all the classic liberals of the field. We want to seea book

like Puma Blues prosper.” It ended up costing quite a lot

of money because the wrong price went on the cover.

GRUI’H: Oh, Jesus. A lower price?

SIM: It was priced like a regular issue and it was sup-

posed to be twice that. So basically everybody got a real

deal on it.

GROTH: Who’s fault was that, the publisher’s or the

creators ‘ ?

SIM: That’s one Of those real funny areas I created by

giving complete autonomous control to the creators. They

didn’t tell Preney to change the price on the cover, and

Karen didn’t either. It’s up to me whichever one I want

to blame.

GRMH: [laughs] O.K.

SIM: So, consequently, I didn’t blame anybody and I Of-

fered to pay them the royalties they would have gotten if

the right price had gotten on the cover, which they declined

and then wanted to use a certain amount of revenues they

would have gotten on it to Offset the losses that I incur-

red, so we’ve got a real Alphonse and Gaston act going

on here with the bowing back and forth. I’ve ended up

deferring to them because they’re the creators, but it still

feels to me that they’re out. I think it worked out to about

S2000 that they lost, and they figure I’m out about

$1500

Geez!

Heidi MacDonald writes in The Comics Journal #112, page 35:

Jesus, the year 2000 is only 14 years away,

although such mathematical platitudes

usually strike mc as being overlay disin-

genuous. This book is plenty odd and

plenty interesting. Murphy’s scripting runs

into the self-indulgent (but what else would

one expect of an A1 International book?),

and it’s as uneven as all first issues are (the

conversation between Immer and his

mother near the end really strains to be

strained, if you know what mean). Zulli

shows the signs of coming from a fine arts

background—too much rendering, not

enough white space—but it’s really quite

lovely in many spots, and the puma of the

title is beautiful enough to break your heart.

Zulli and Murphy need to loosen up a bit,

but allowing for first issue jitters and all, this

is definitely a book to watch.

Somebody writes in The Comics Journal #113, page 52:

Stephen

Murphy’s script for the first issue doesn’t

take us too far into whatever plot may

emerge—the focus is essentially on exposi-

tion, though more questions are raised than

answered—but his storytelling skills may

prove to be considerable. (He certainly

doesn’t pander to the reader: there are tan-

talizing bits and pieces of the future intro-

duced, and it’s up to the reader to assemble

some sort of meaning.) Murphy and artist

Michael Zulli have worked out some beauti•

fully visual passages in this first issue of the

series, which promises to deal with the

ecological balance Of looking for-

ward to the second issue…

Heidi MacDonald writes in The Comics Journal #116, page 54:

And speaking of self-indulgent,

we come to Puma Blues. Writer

Steve Murphy and artist Michael

Zulli are -still decidedly feeling

their way here. (And everyone

knows the lettering in early issues

was… urn, very bad, but certainly

not deserving of Don Thompson’s

screed in CBG.) Zulli’s wildlife art

is utterly breathtaking—the all-

animal story in #5 is probably the

best single issue to date. Zulli

manages to show animal expres-

sions without anthropomorphizing

them—no mean feat. And

Murphy’s concern for the environ-

ment is clearly genuine. There’s all

sorts of intriguing concepts and

situations floating around here.

And yet they’re still casting

about for a story. As of this writing

we’ve had six issues Of mood and

next to nothing to put in it. Still,

in an interview, Murphy was quite

aware of the problems the book is

having with plotlessness and prom-

ised to get things back into focus.

If they do get things under control’

Puma Blues could very well live up

to its potential. If not.. .well, you

know I’m a big softy for noble

experiments that fail.

This person doesn’t seem to have actually read the collection:

Plus, of course, the brand new 40-page conclusion by Murphy and Zulli. Now that it’s done The Puma Blues can take its rightful place alongside the period’s other great monuments, such as Moore and Campbell’s From Hell and Gaiman’s Sandman. Without it, any well-stocked comics library should be considered incomplete.

I’m guessing “nothing”:

I don’t want to say too much about the ending just yet, until more people have had a chance to read it, but I will say that it’s mostly satisfying. Not completely, but a 40 page story to complete what would probably have been 260 or more pages was never going to be, and Murphy and Zulli are obviously in a completely different place now. There are a lot of elements in the new pages which couldn’t have been in the original plans, references to real-world events of the last quarter century, and I’d be fascinated to know how much of the overall arc of the finale was in the original plans.

Most reviewers of the new edition doesn’t seem to have read it:

What I don’t remember in enough detail is the series itself so I confess that this is more of a dim recollection than a review. I don’t have time to re-read five hundred and fifty pages at this time of year.

I know, it’ll take several hours to read…

Anyway!

This blog post is part of the Renegades and Aardvarks series.