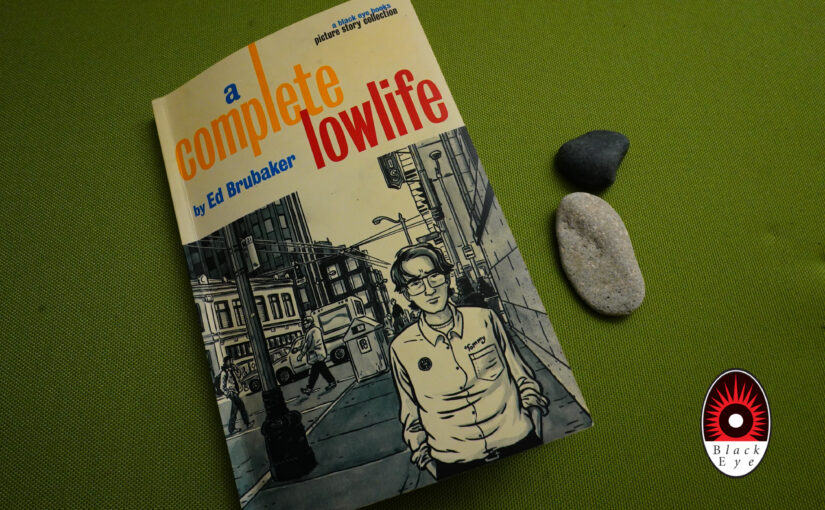

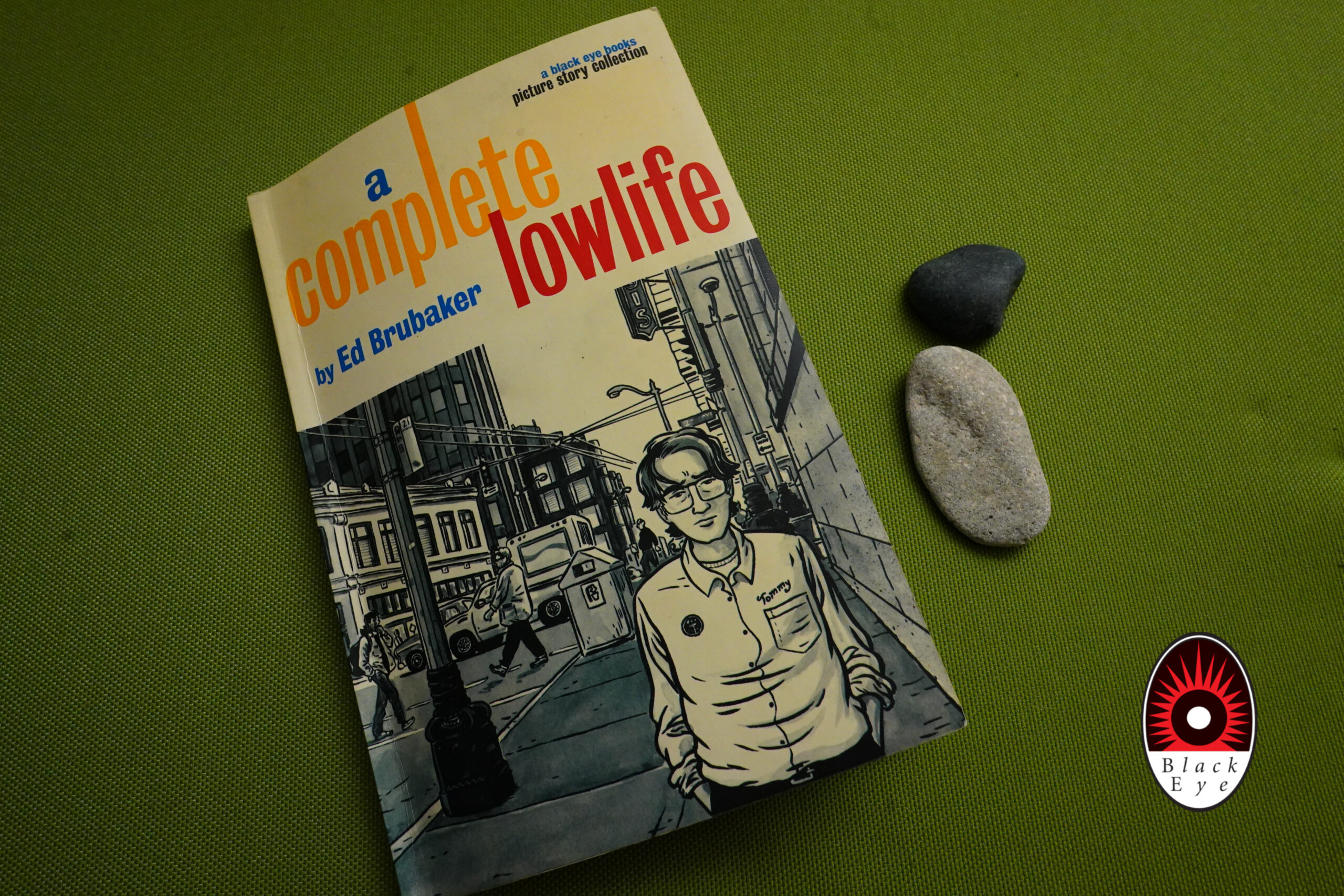

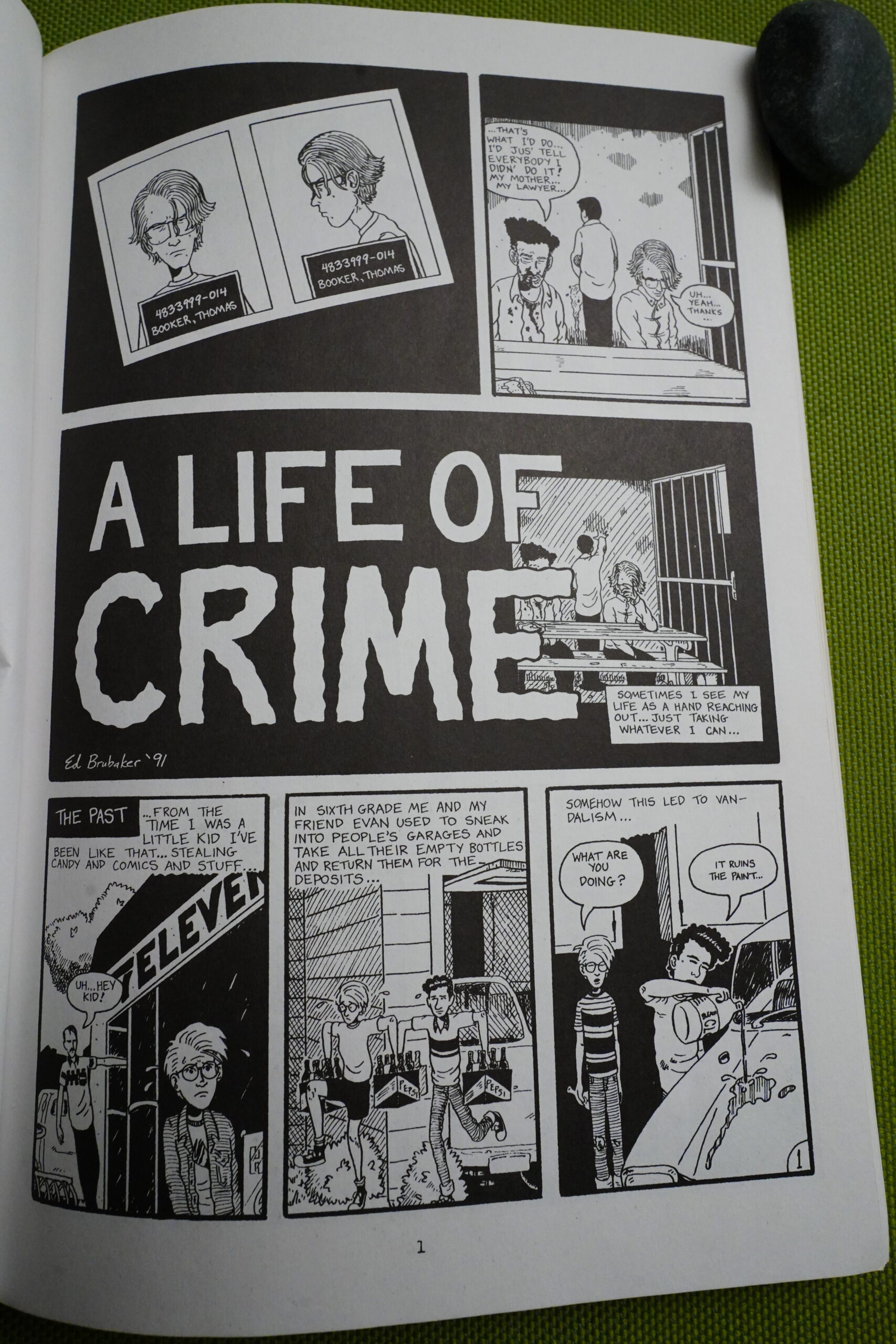

A Complete Lowlife (1997) by Ed Brubaker

This is an odd book for Black Eye to be publishing. First of all, it a (partial?) reprint of a series published by Mu and Caliber, which isn’t something Black Eye used to do. But more importantly, this is autobio comics, which Black Eye had shied away from doing.

Ed Brubaker, though, had gotten pretty famous since these comics were originally published — he was now a writer at DC Comics, and presumably had a larger following. So perhaps that explains it?

I haven’t read this collection before, but I had the Mu issues at the time, and I remember enjoying them quite a bit? But they didn’t exactly revolutionise the comics world, either.

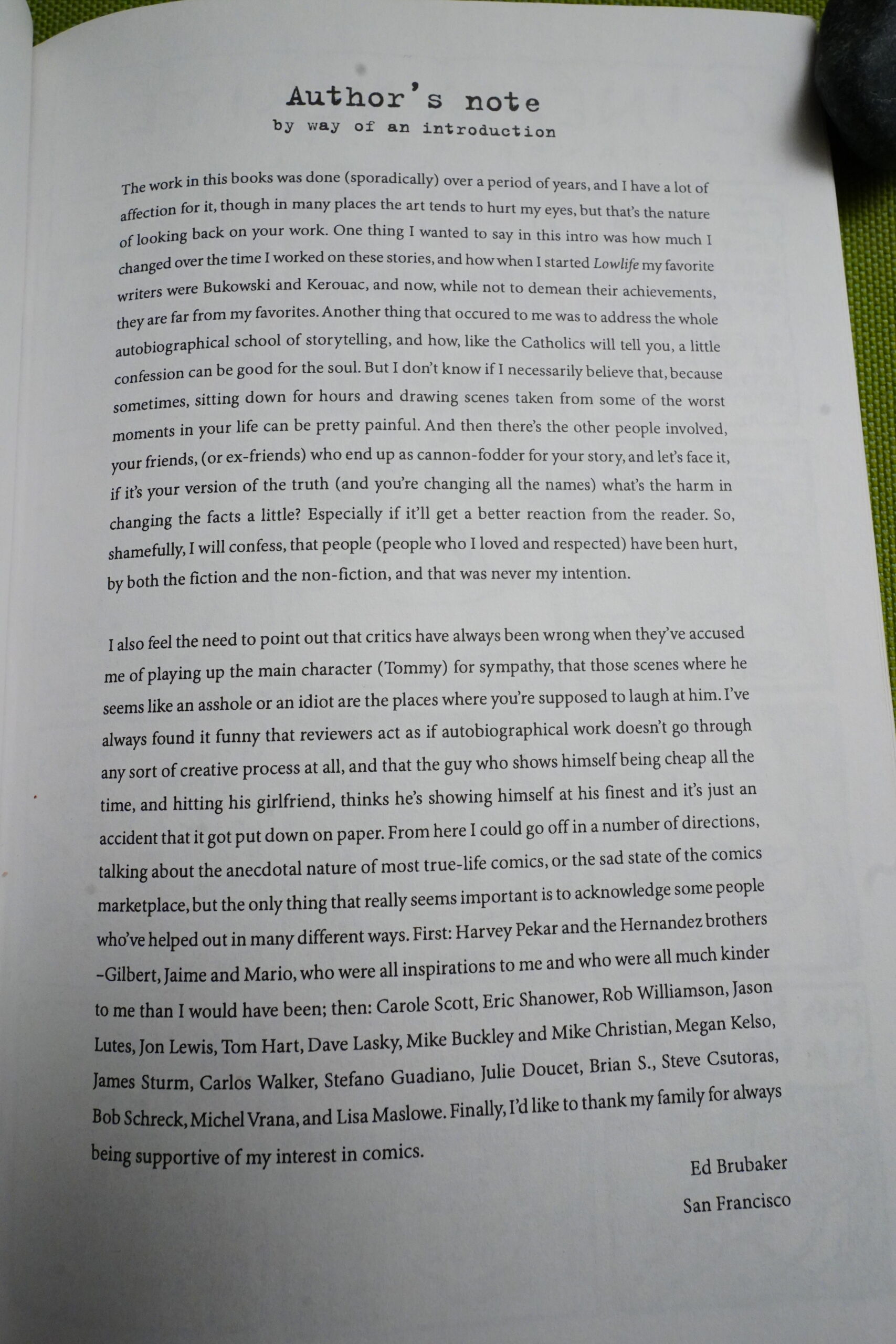

We start with a note that’s both aggressive and defensive — he sort of apologises to the people he depicted here who were hurt, and then he lashes out at stupid, moronic readers who can’t seem to fathom that when he depicted himself (i.e., “Tommy”) as an asshole, that was a deliberate artistic choice.

So… I’m guessing there had been some push back on these comics?

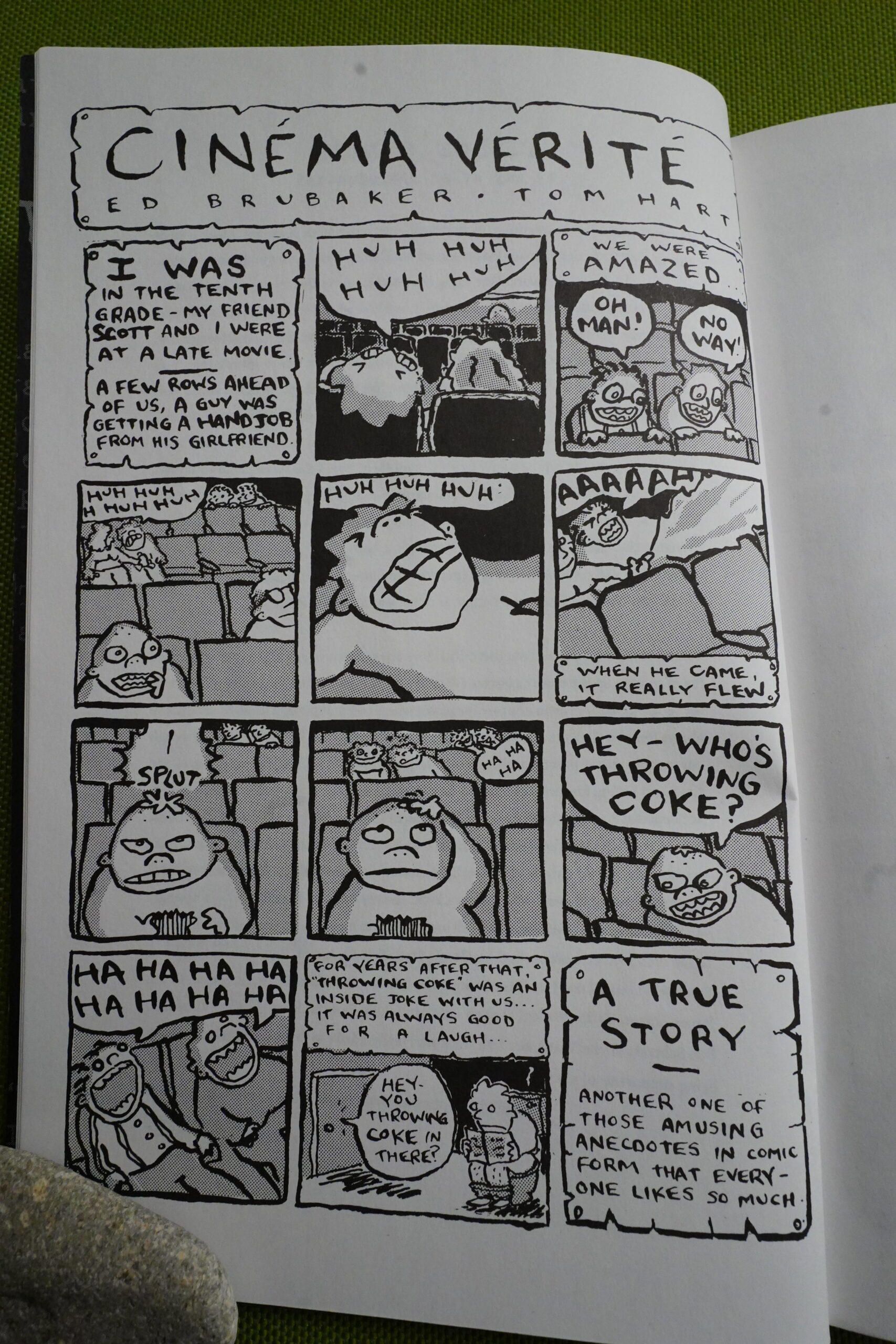

Tom Hart illustrates an anecdote as another introduction, sort of.

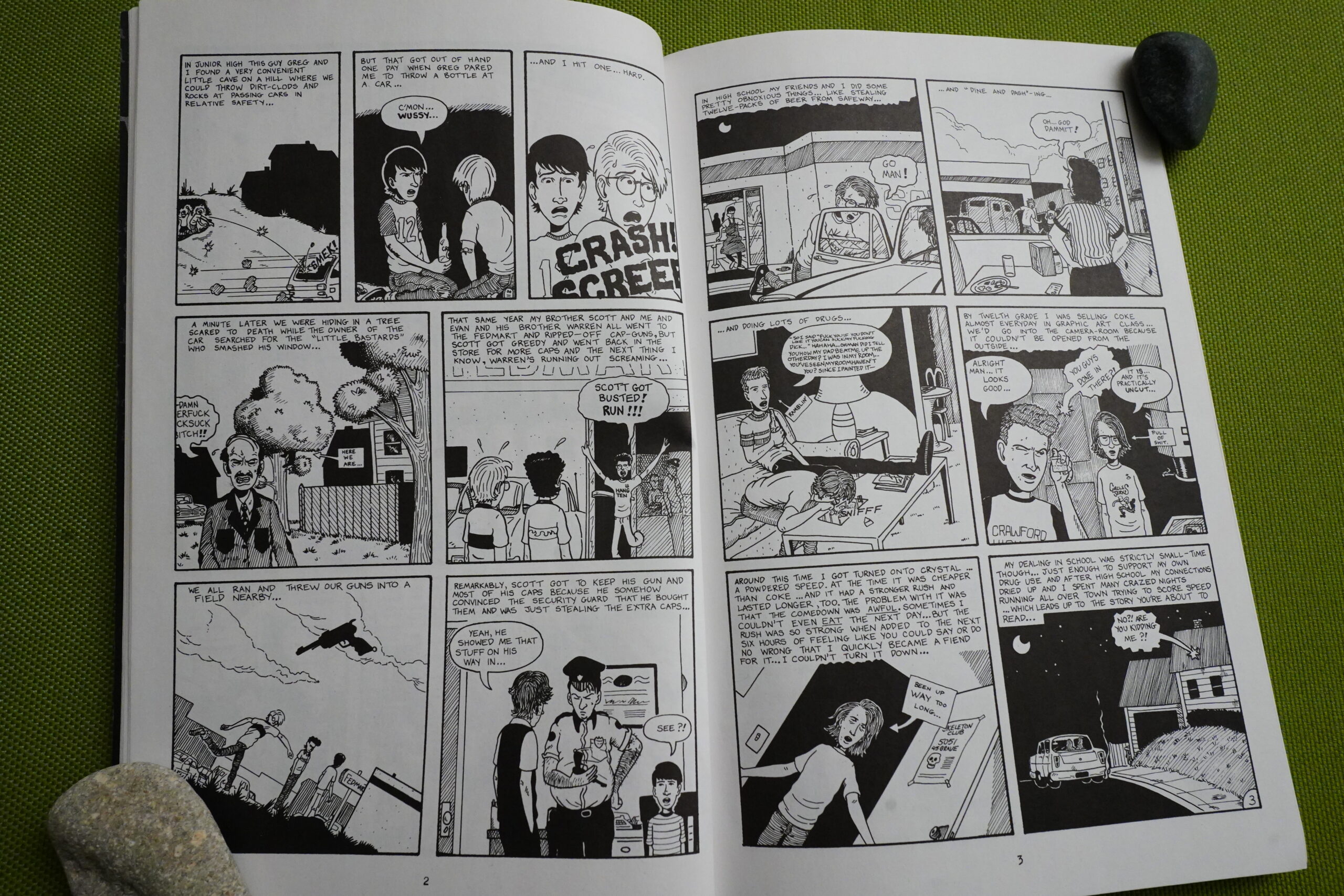

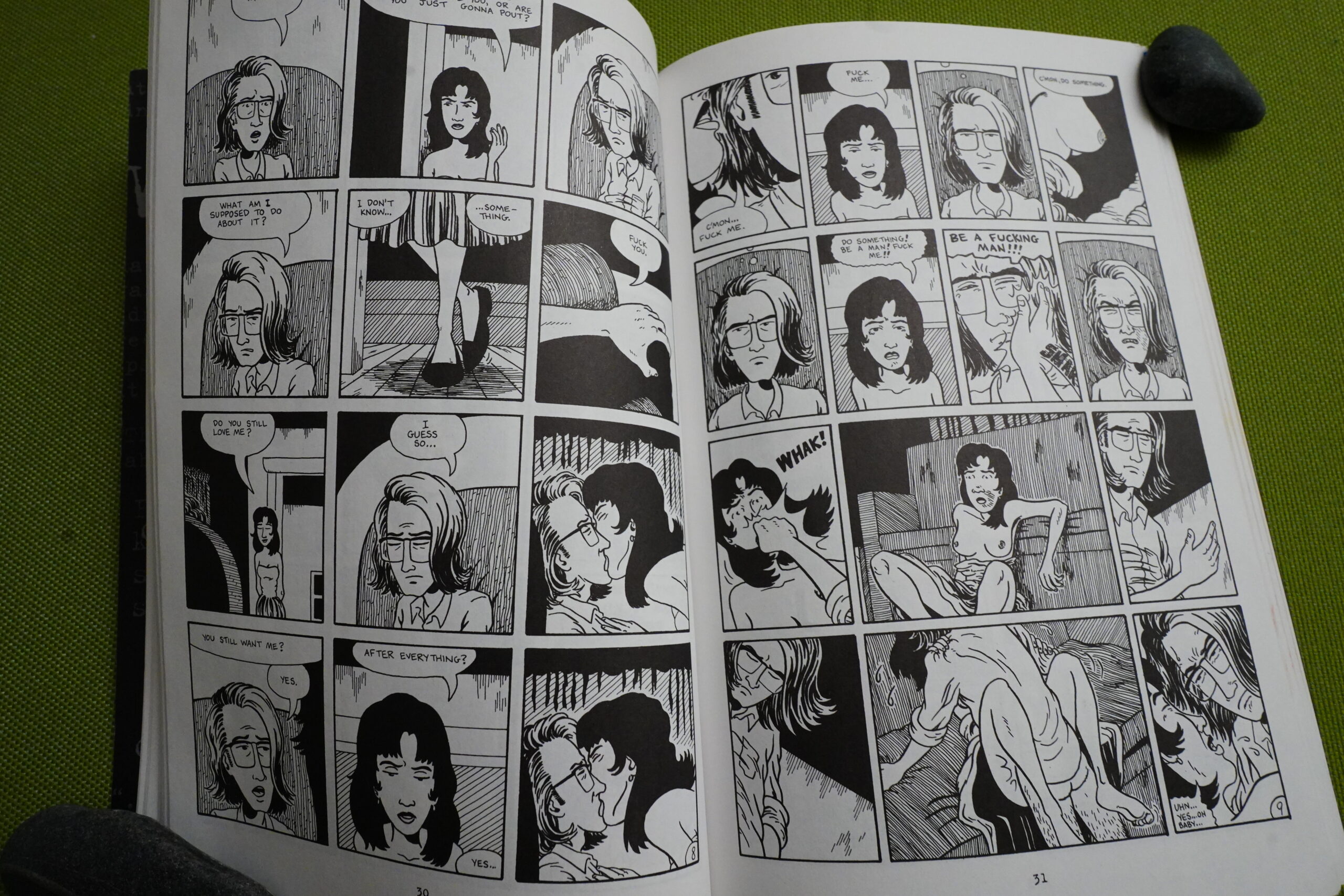

All the other stories are about this guy called Tommy, who’s apparently the author’s stand in. We start off with some youthful hi-jinx…

… that grow progressively less fun…

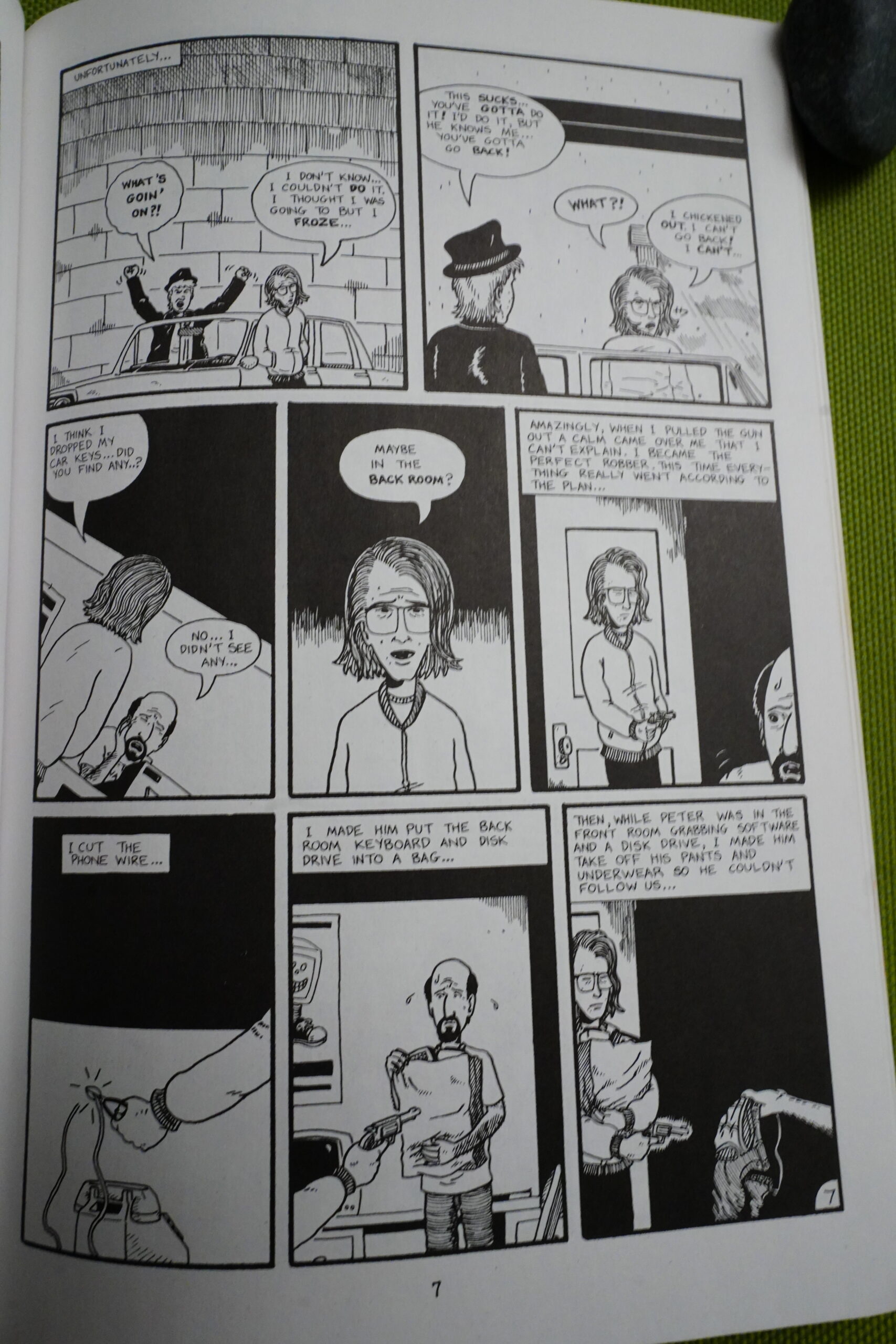

… and then Tommy holds a guy up a gun point? And then later his buddy shoots a redneck.

So what are we to make of this? My guess at the time was that Brubaker had punched up a duller story, and none of the “serious” stuff had happened. I mean, he’s saying he robbed a guy. Using a gun. So that’s still my guess — that this didn’t happen.

As for the artwork, it seems like he’s taken quite a bit from Chester Brown, doesn’t it? I think he’s also been looking at the Hernandez brothers, but he doesn’t really have the talent of either of those people, so everything looks pretty unappealing.

And this is just a personal quirk: I loathe bobble heads. But that’s just me! Most people love them!

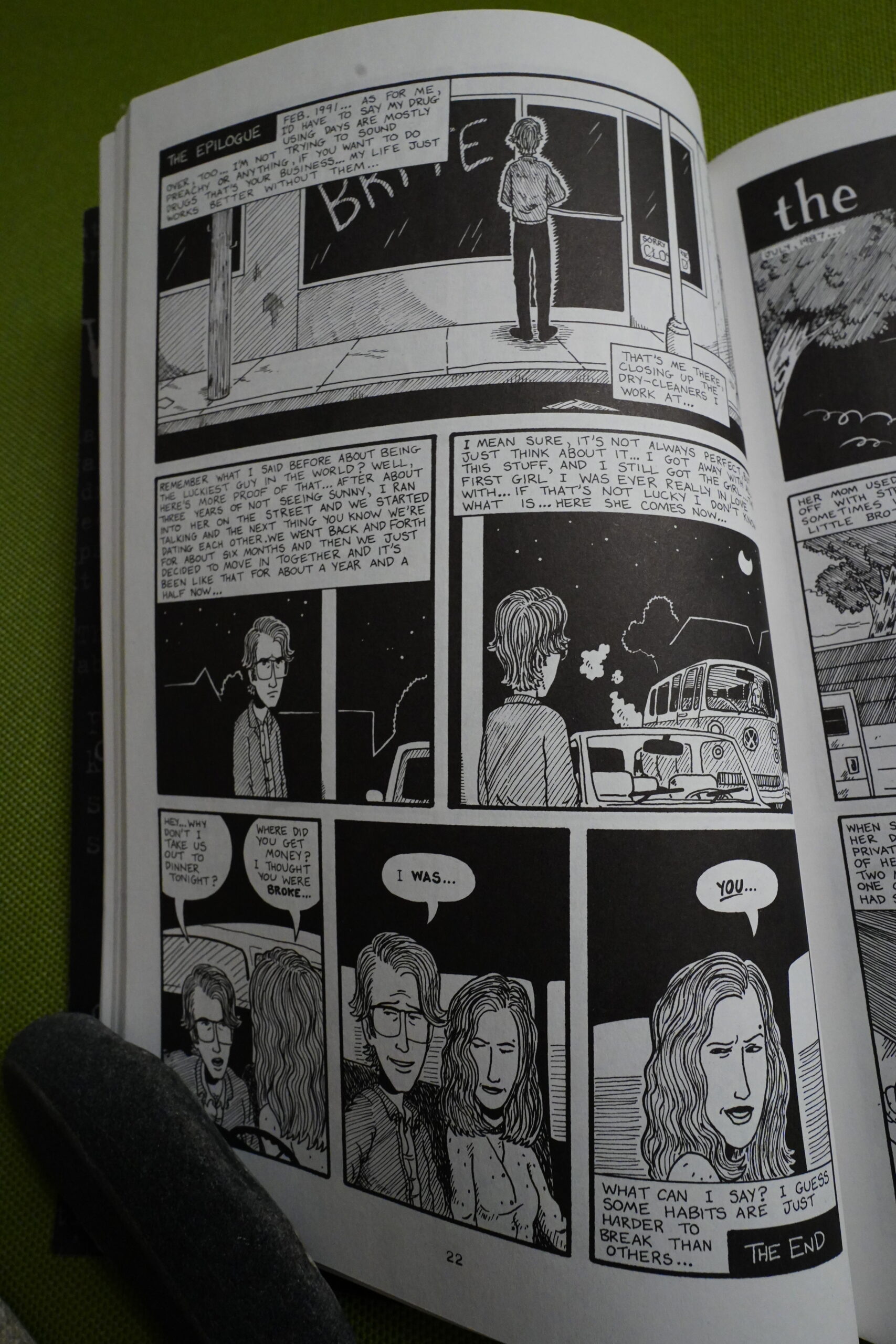

But what about his defence in his opening notes? Is he depicting Tommy as an asshole, or does wink at us an want us to understand that he’s really a swell guy, despite everything? Well, the opening story ends with him getting the girl of his dreams, and a wink. So…

And this is him hitting his girlfriend — but it’s apparently because she really wanted him to.

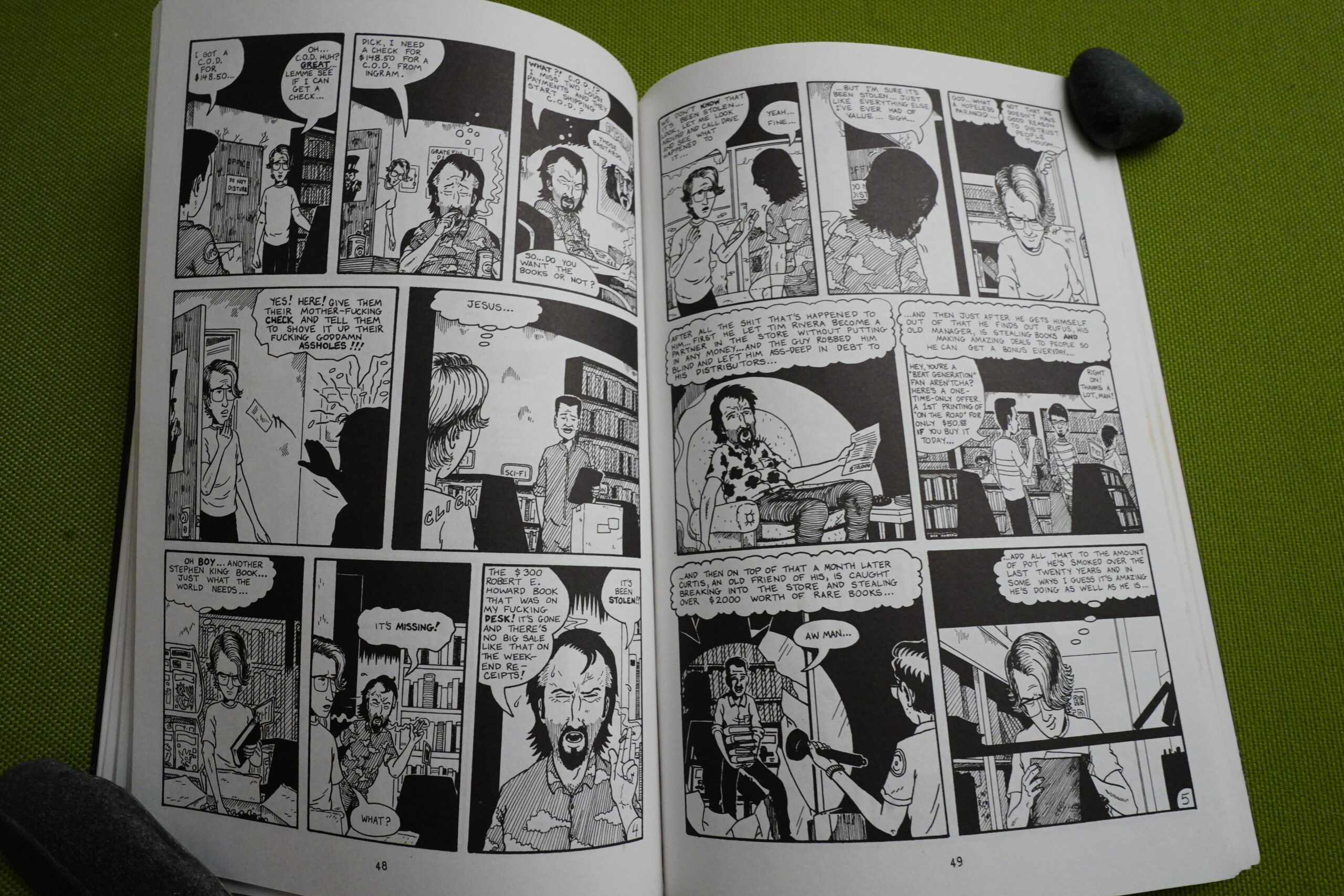

As for how he depicts people around him — I hope he made up most of them, because they’re mostly morons and sleazeballs. (Although this story has a nice ironic twist.)

Black Eye chose to print this at a smaller size than the original comic books. And it’s a cute format, but it makes some of these pages an absolute chore to read. If there had been anything interesting in those speech balloons, it would have been better, of course, but having to strain to read this twaddle is like *chef’s kiss*.

It was a chore to get through this book. As individual comics, it’s probably fine, but page after page after page of this guy you’d like to strangle… it’s a lot.

The Comics Journal #263, page #73:

laughs.] Were you happy the later auto-

biographical stuff Dissatisfied? Because pret-

soon stopped.

BRUBAKER: I think I was happy with it.

That last issue of Lowlife was the best One.

But I knew when I finished it that I was

done with autobiography for a while. I was

just tired Of writing about myself. I was

getting more into different kinds of fic-

tion, and starting to write more for other

artists, so it was kind of a natural slide.

Then I had this year where I started to

get more writing work and able to

focus on drawing at all, and I had this ter-

rible personal stuff going On at the same

time. so I went on this break where I trav-

eled around the country on the train and

visited people. When I settled back down

I had a bunch writing deadlines, and just

started writing and suddenly I was making

a good living as a writer.

I think I was always a frustrated car-

toonist, in that I was never good enough

for my own standards. And I started to

enjoy writing about stuff outside of

myself, Started to actually look at it as a

craft, and think Of myself more as a writer

and less as an artist. But I still think very

visually, and when I write comics I still see

the pictures in my head most Of the time,

the panel compositions.

Changes

Darcy Sullivan writes in The Comics Journal #144, page #48:

As revealed in Lowlife, Brubaker lives like

a pig, hates his job, spats with his roommates,

and is unlucky in love. All of these read more

like boasts than complaints. Without a Story to

tell, Brubaker can only parade his afflictions,

which wear thin fast — he just carft be as much

of a stereotype as he makes himself sound.

For audacity alone, “You’re a Good Man,

Chester Brown” stands apart from the rest of

lowlife #1. Brubaker argues that his work isn’t

a copy of Chester Brown’s, as Fanta-graphics’

Kim Thompson apparently suggested. Brubaker

reproduces bits of Brown art to prove his point,

delineates long conversations he’s had with

Brown about how different their styles are, and

even draws himself standing next to Brmvn, say-

ing “Do I look like Chester Brown to you?”

This is a one-sided invective, and it doesrft

really advance Brubaker’s “am not!” protest

much — he’s way, way too defensive. But the

story is perversely captivating, because

Brubaker doesn’t rein himself in. He’s pissed

Off enough to rail in an unflattering, embarrass-

ing, and thoroughly honest way. He’s showing

off with his “here’s what Chester said” argu-

ments, but the very lack of artistry and delicacy

gives this Story the primitive appeal of a train

wreck.

Ah, perhaps that’s why I remember Lowlife as being better than this book — this book only collects the “Tommy” stuff, but leaves out the more entertaining material. So “A Complete Lowlife” isn’t really an accurate title (in one sense of the word “complete”).

Chris McCubbin writes in Amazing Heroes #196, page #80:

Next up, Ed Brubaker’s I.nwlife. All

of the protagonists in these books are,

to some extent, slackers, but Brubaker

is the only one who revels in it. He’s

also the artist who gives us the most

unflattering portrait of himself. Is he

really that callous and obnoxious, or

is he just trying to make credibility

points by being more confessional

than thou? I suspect the latter.

Two stories in Lowlife are pretty

standard urban descents into hell, both

several years old (the issue seems to

be sort of a clearing house for

Brubaker stories that hadn’t seen

mass-distribution before). In the first,

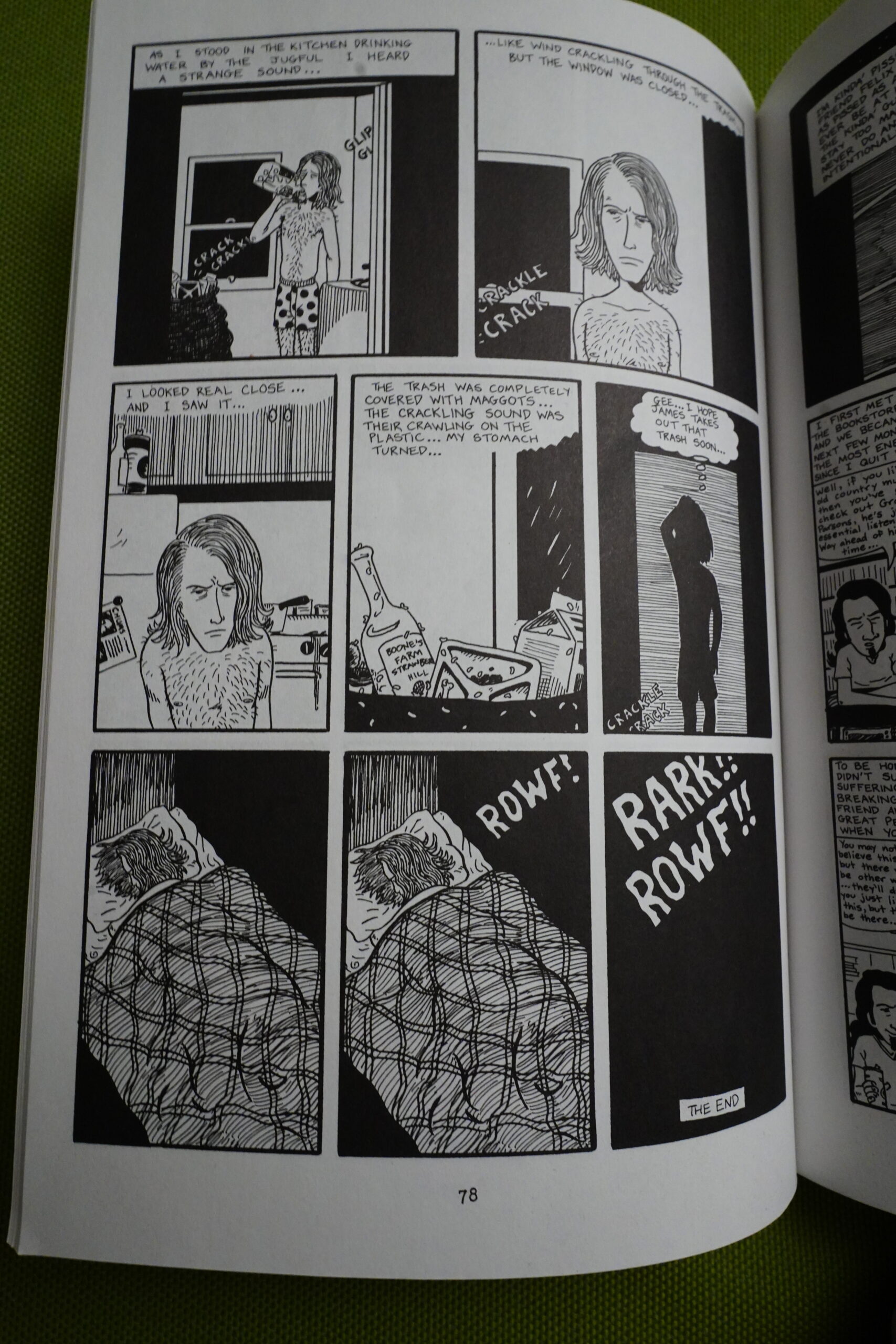

Brubaker’s job gets threatened, and he

gets menaced by a large neighborhood

dog that he fantasizes about killing.

Finally, he gets into an argument with

his roommate and discovers the gar-

bage is breeding maggots. In the other,

he gets thrown out of a trendy

nightclub and beat up after being

excessively drunk and obnoxious.

The middle story is newer and more

interesting. It’s about Fantagraphics

Books’ rejection of Brubaker because

his work is too much like Chester

Brown’s, and Brubaker’s bewilder-

ment and anger over this comparison,

which he can’t see at all. (For the

record, Brubaker is to Brown, both

physically and artistically, approx-

imately as Steve Tyler is to Mick

Jagger: the resemblance is certainly

coincidental, but it’s definitely there.)

In addition to Brown and Brubaker,

the issue features Kim Thompson in

an unflattering, but not unsympathetic

role as the publisher who has to be

painfully honest because no one else

will.

This blog post is part of the Total Black Eye series.