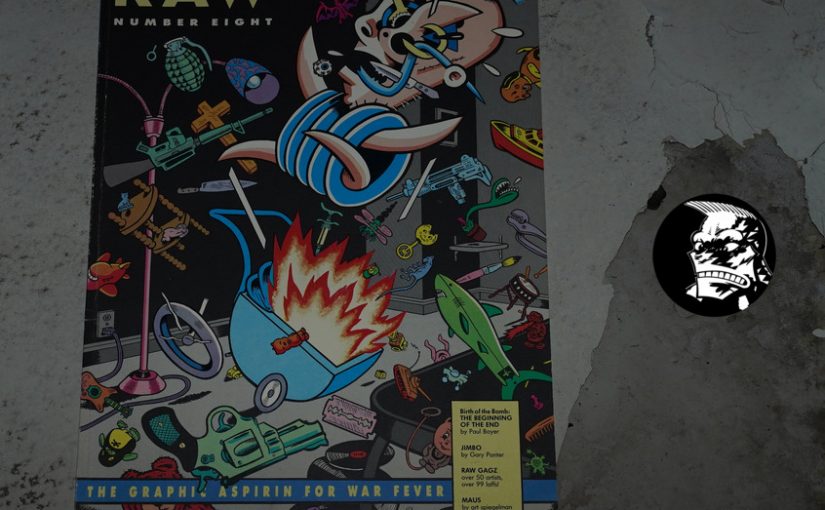

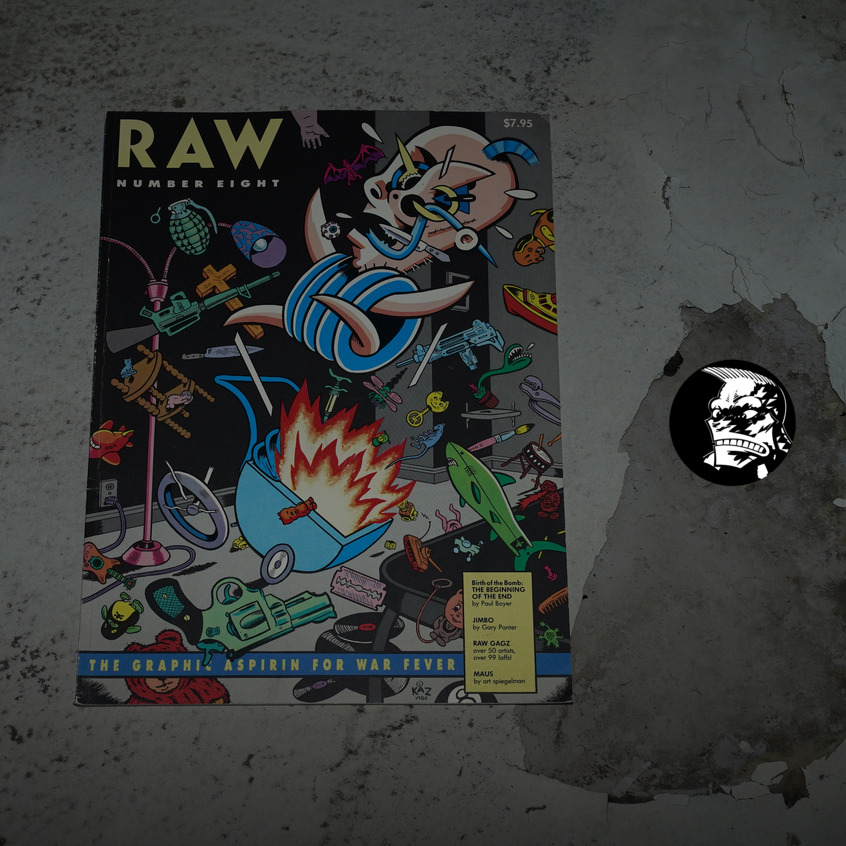

Raw #8: The Graphic Aspirin for War Fever edited by Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman (266x360mm)

I remember being disappointed when I got this in the mail as a teenager… I don’t really remember why now, but looking at the book now, it’s a less … special … object than the previous Raw issues. For one, it’s squarebound, while all the previous issues had been stapled. So this book looks a lot more normal; more professional; more portentous.

But I haven’t actually re-read it yet as I’m typing this; perhaps I totally misremember.

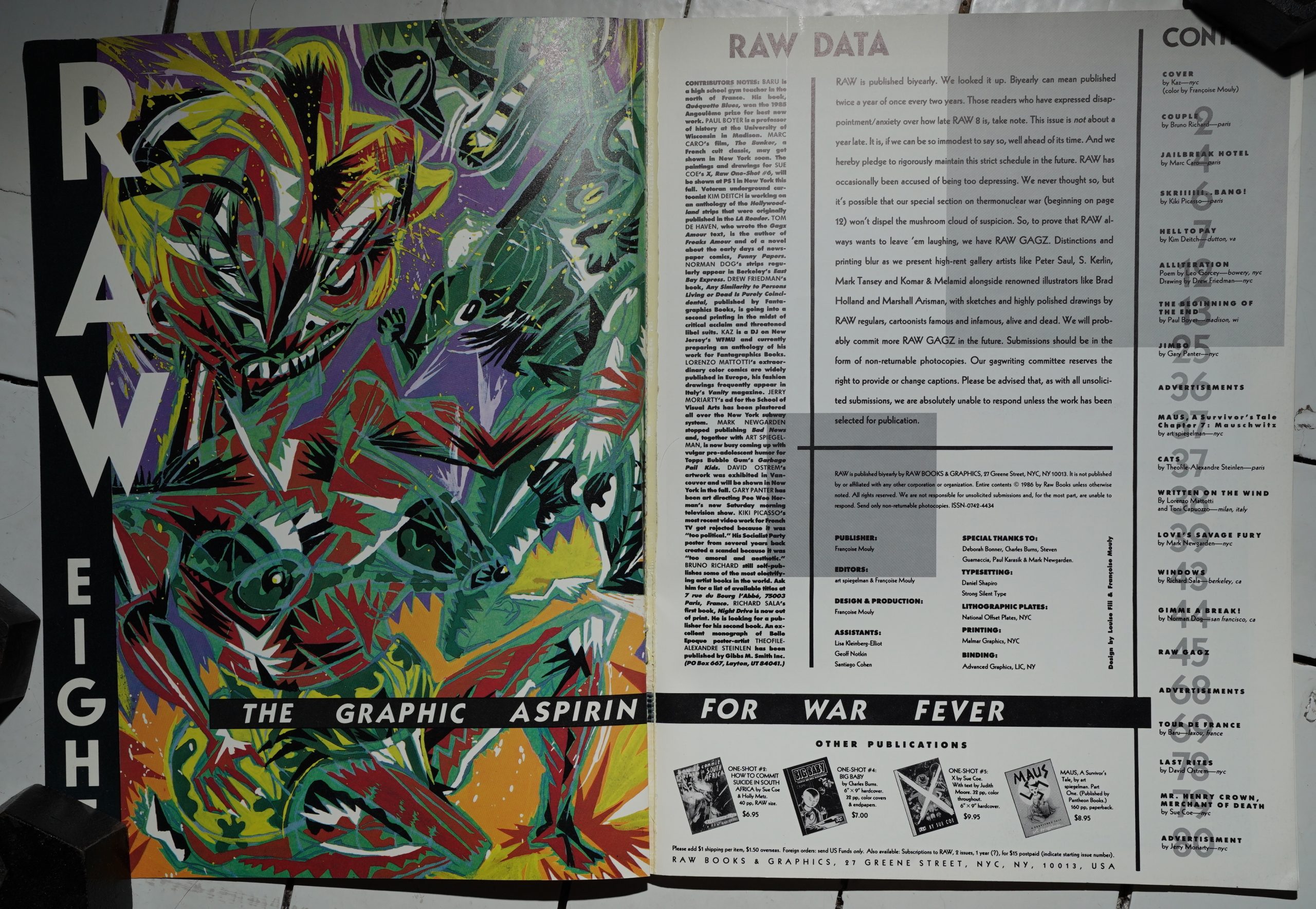

Oh, right — this is also the first time they don’t use the word “graphix” in the subtitle. Perhaps another signifier that they’re all grown-up and respectable now? It’s also noteworthy that the introduction is really chatty and kinda… er… well, it’s amusing, but not very charming?

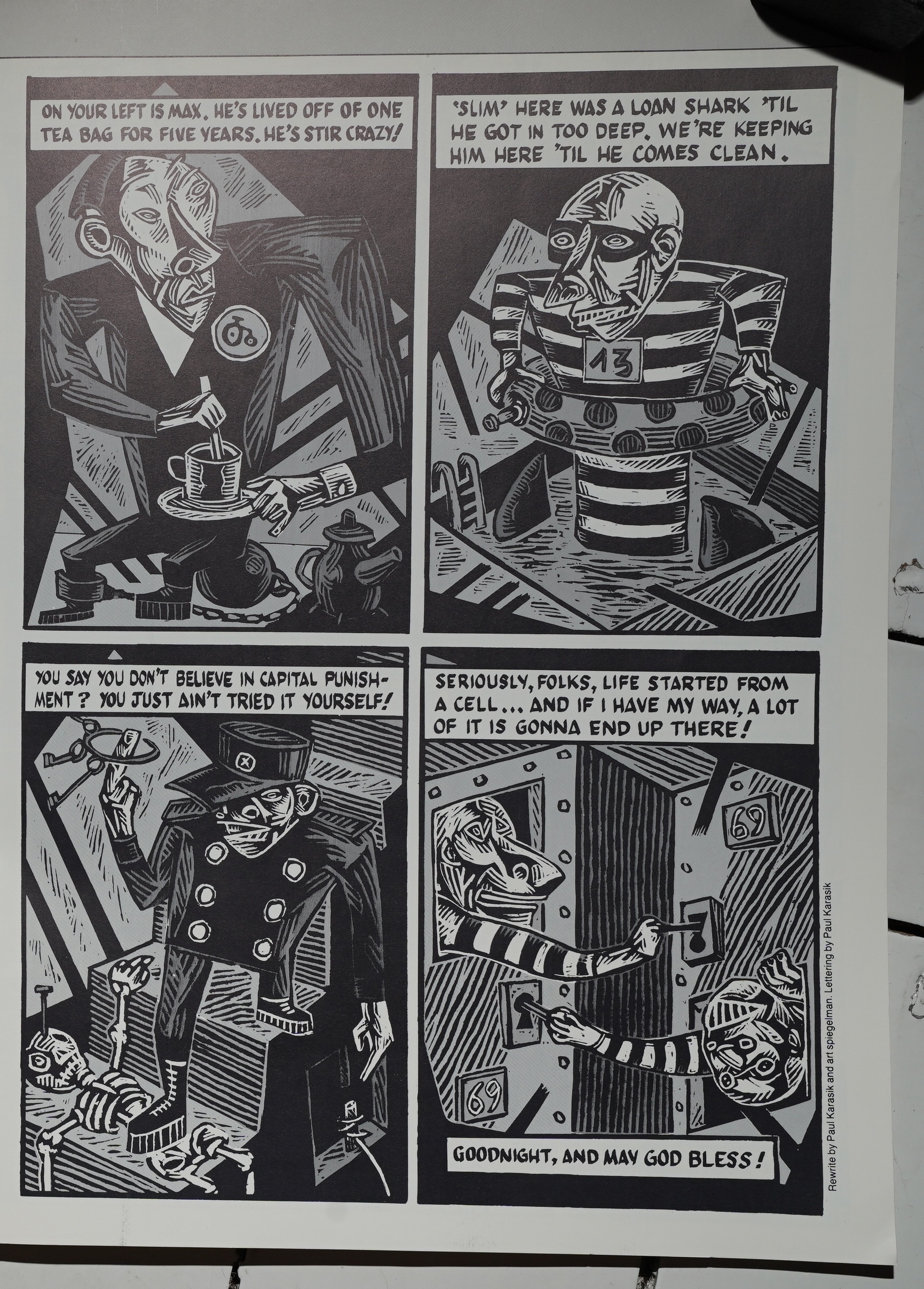

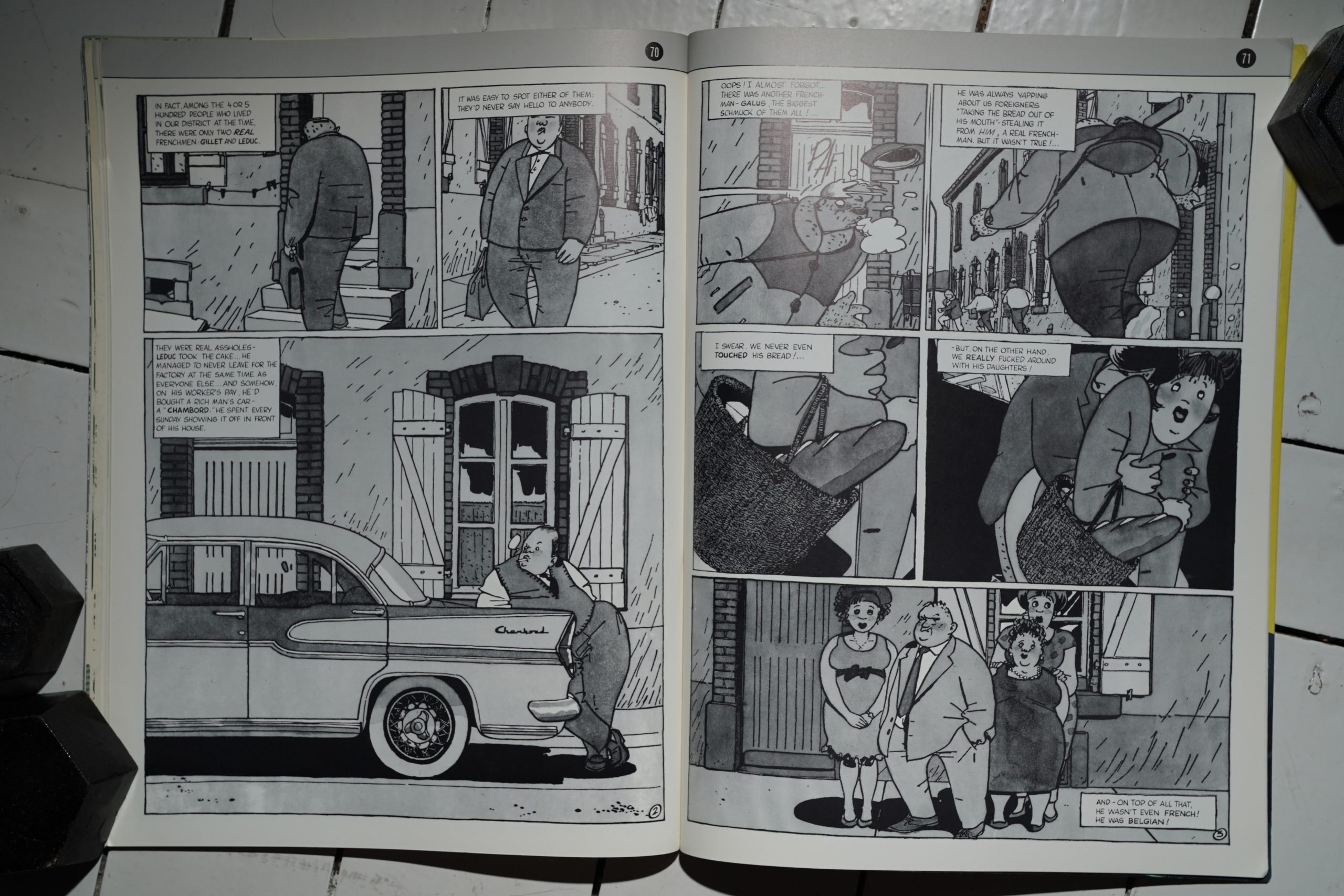

In the introduction, they solicit more gags for future issues, but say that they may rewrite and/or add captions. Did that spread to the rest of the issue, too? Here the Caro strip has a credits line saying it’s been rewritten… and that text does seem very, very American.

How utterly odd. And an obnoxious thing to do?

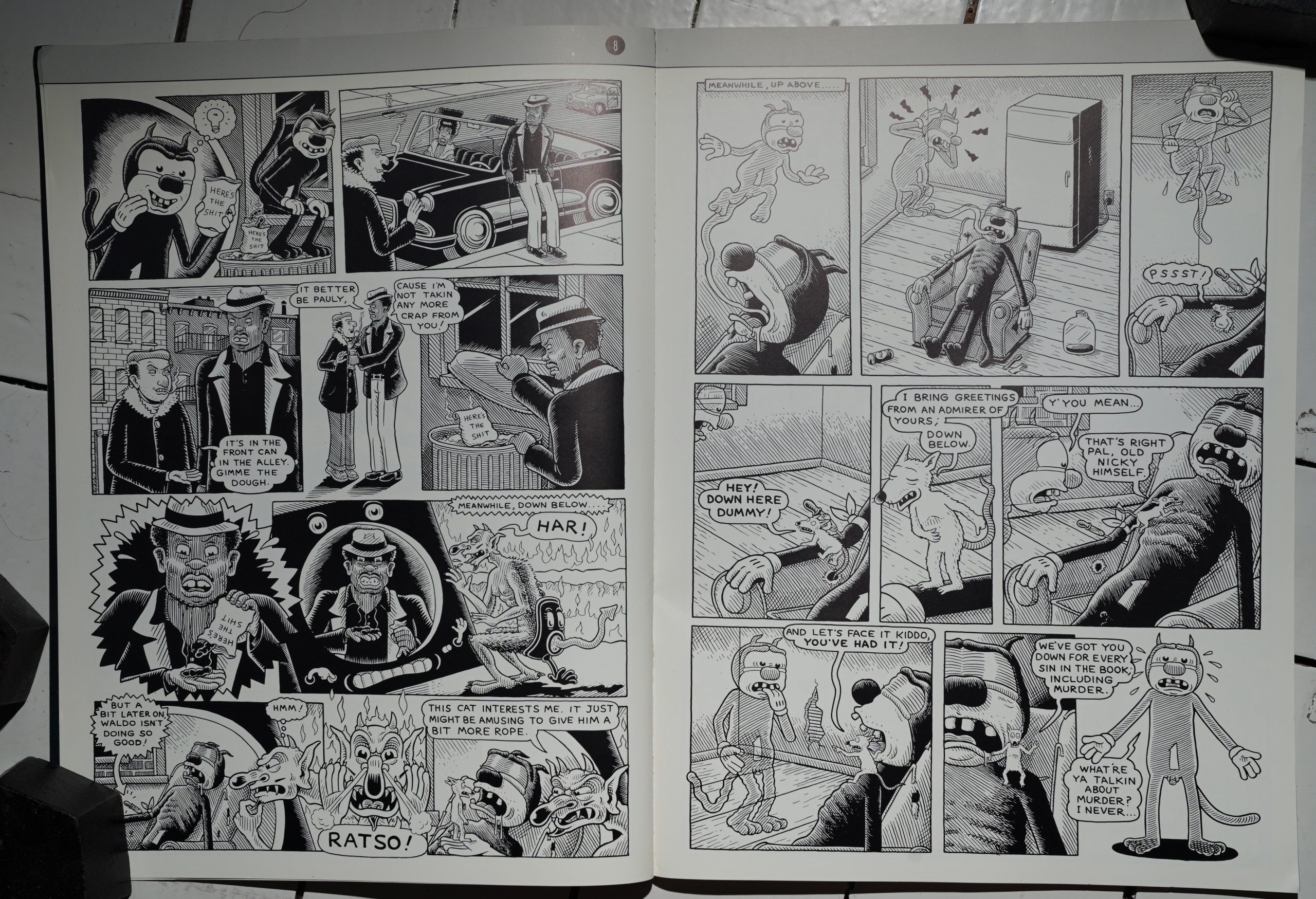

I like Kim Deitch a lot, but the five page thing he contributes here doesn’t really go anywhere.

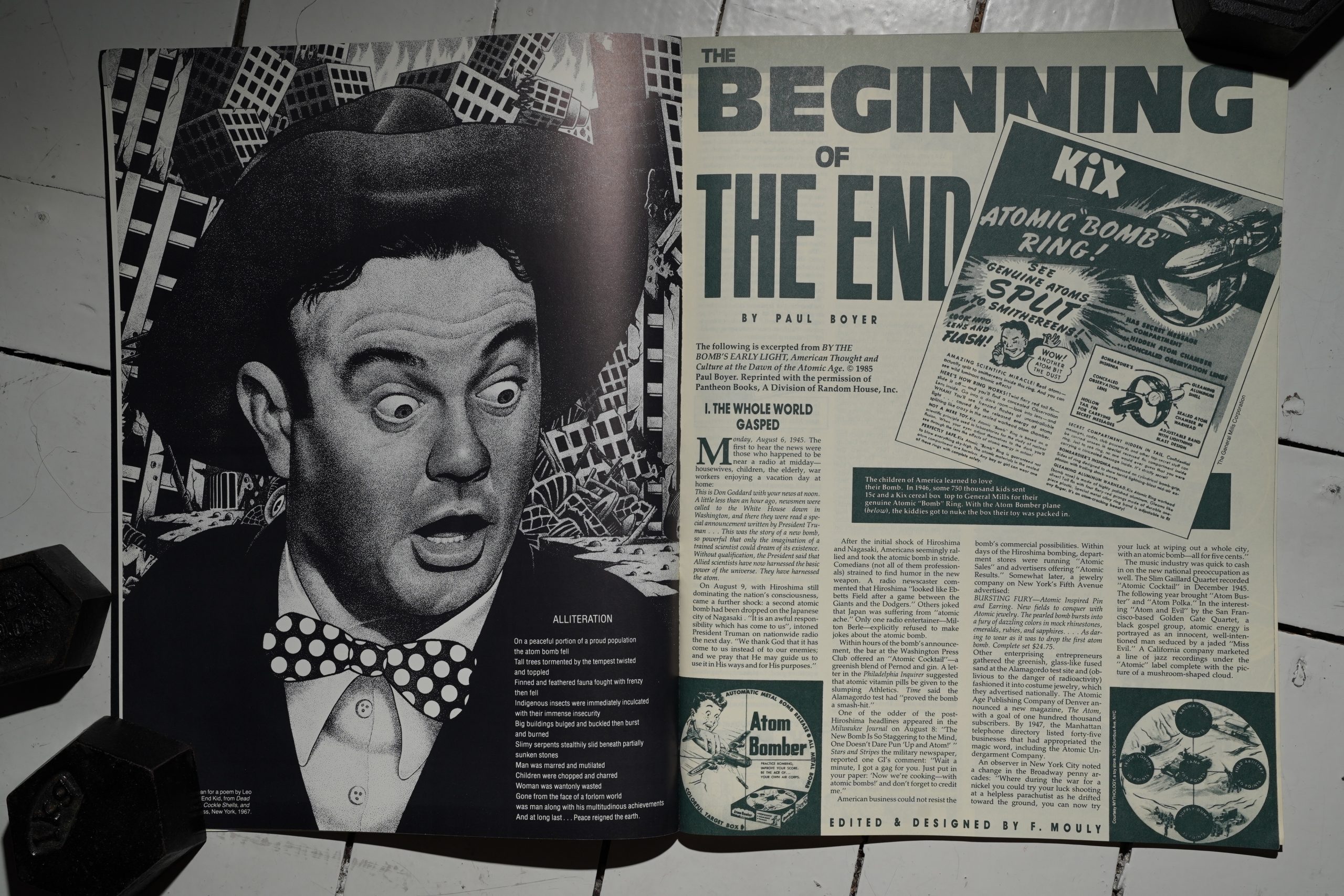

The longest piece here is a twelve page essay excerpted from a book by Paul Boyer (published by Pantheon, who had just published Maus I). Some kind of synergy going on? The design on these pages is by Mouly, and it does look good, but…

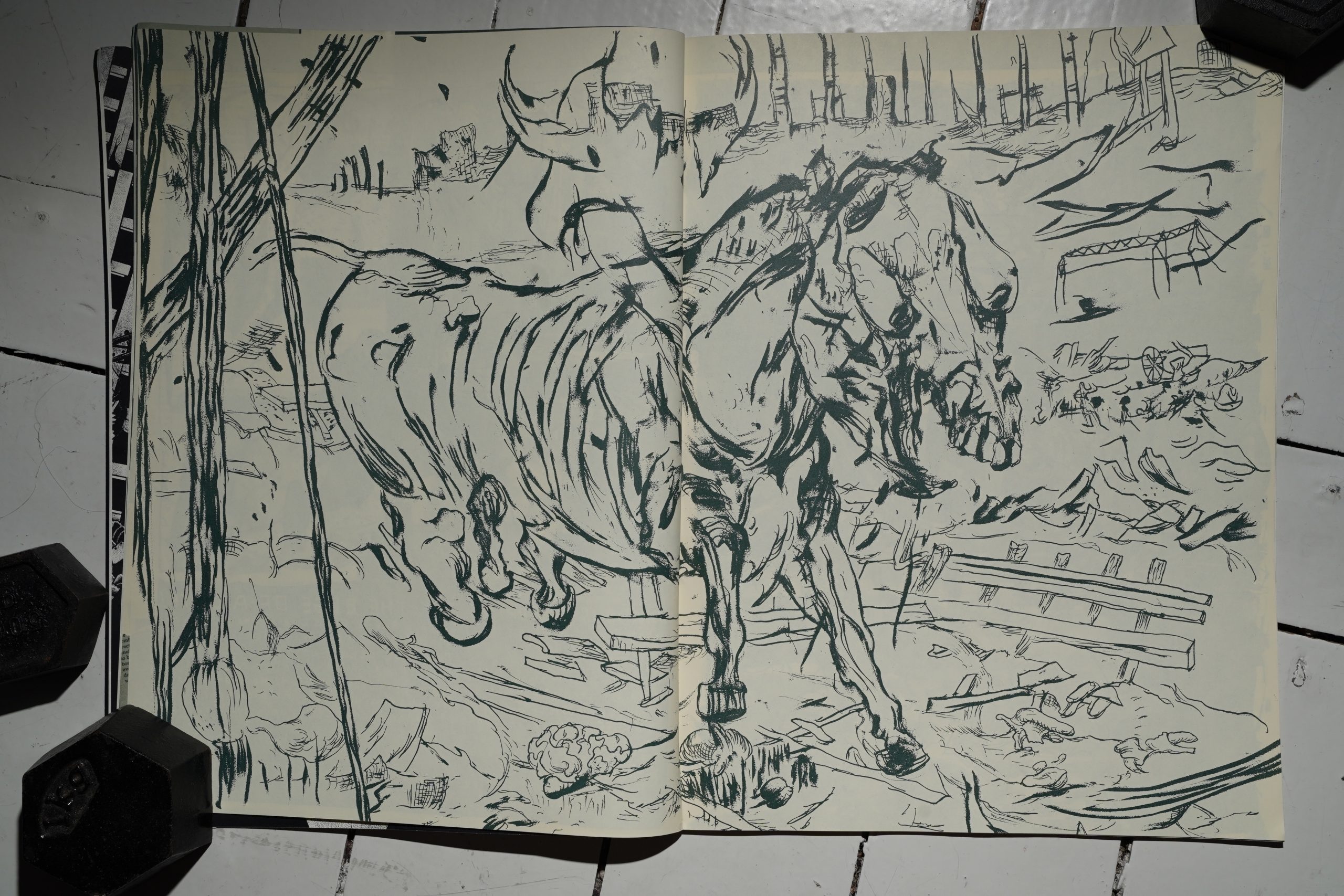

Gary Panter brings the Jimbo story to an end, sort of — it’s a nuclear holocaust. It’s brilliant and packs a real punch.

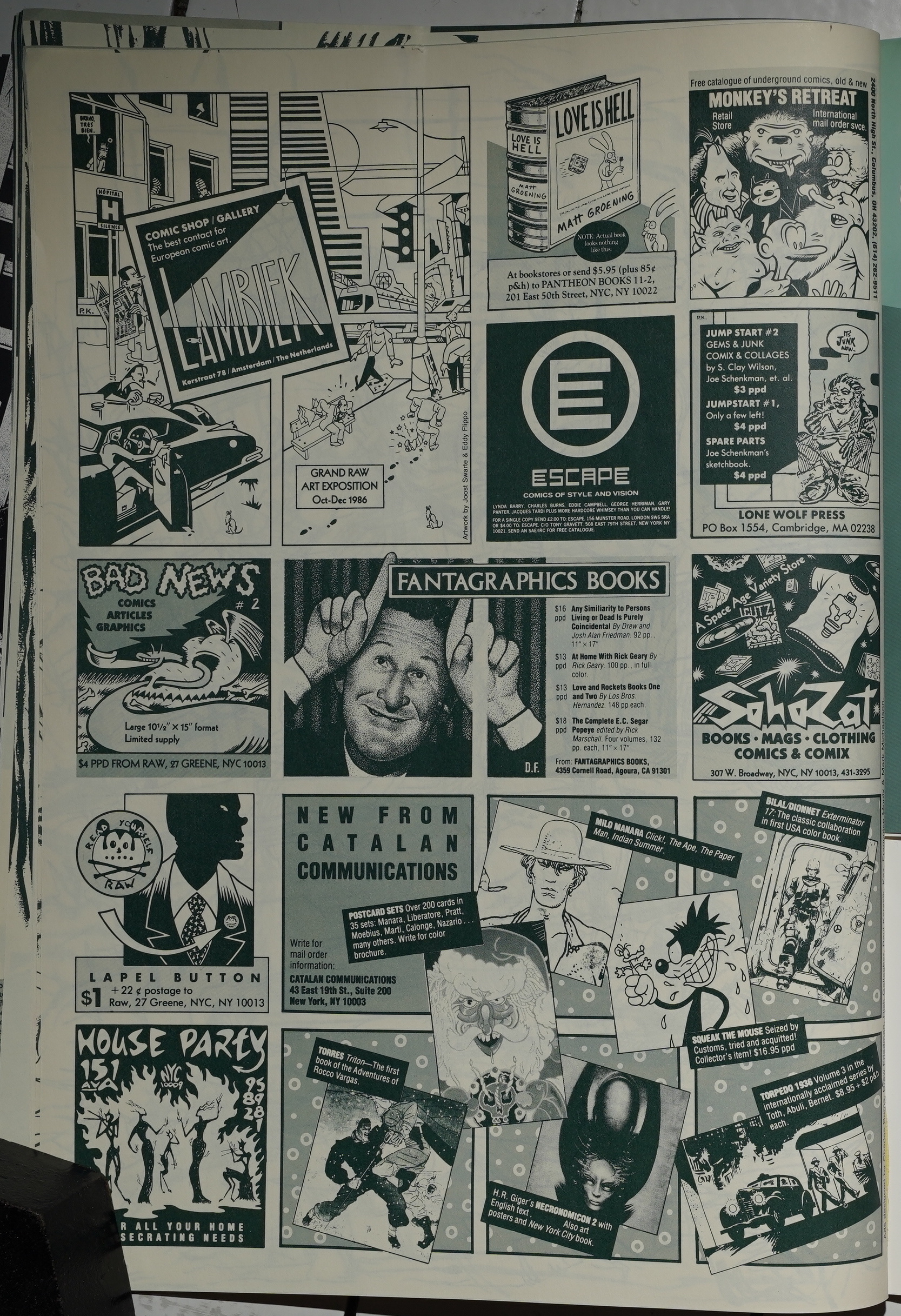

Heh, an ad for Love is Hell, also from Pantheon…

Oh! Yes! I had that lapel button! The Read Yourself Raw one! I remember wearing it on my really cool jacket in high school… but I haven’t seen it in decades.

*pout*

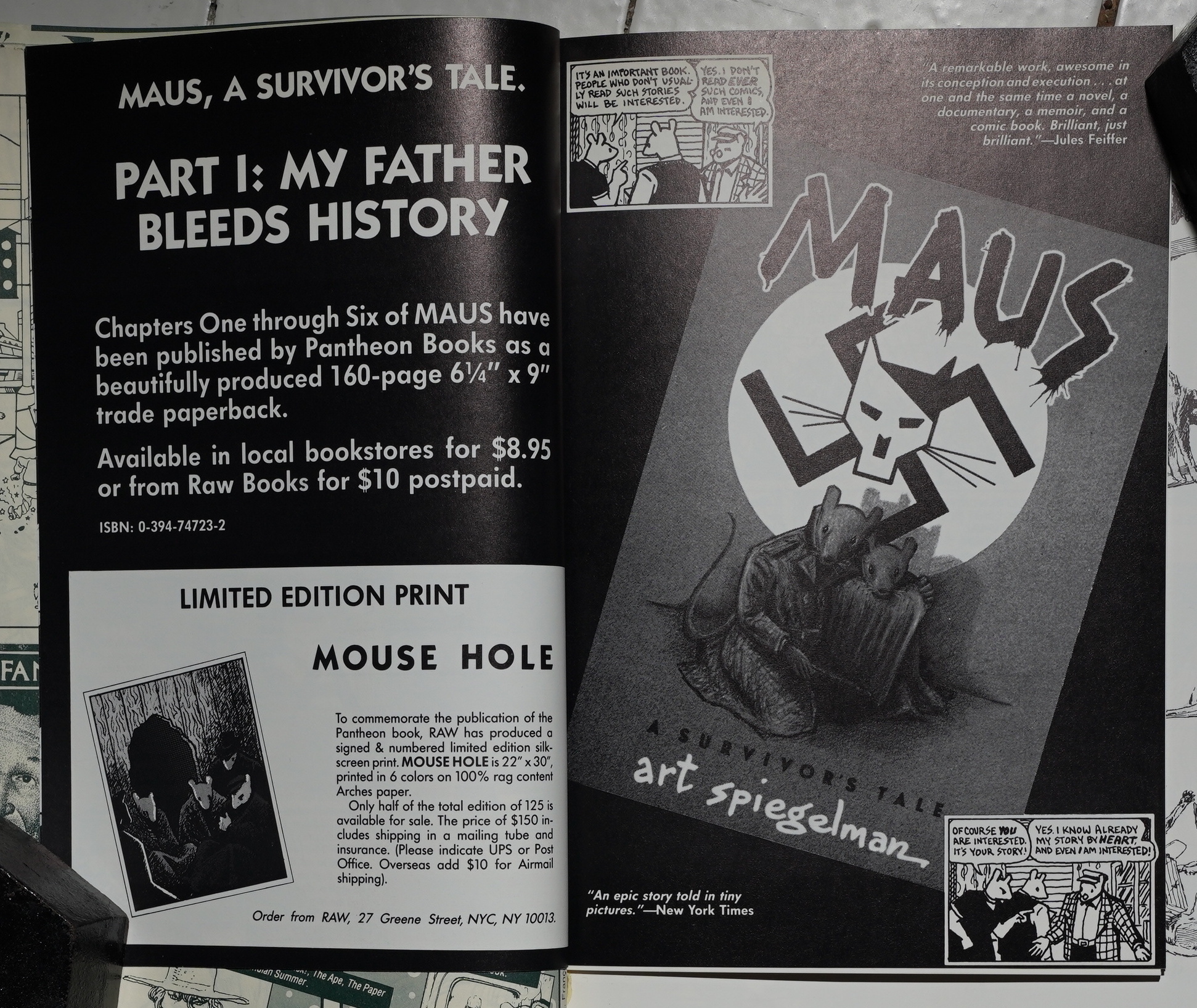

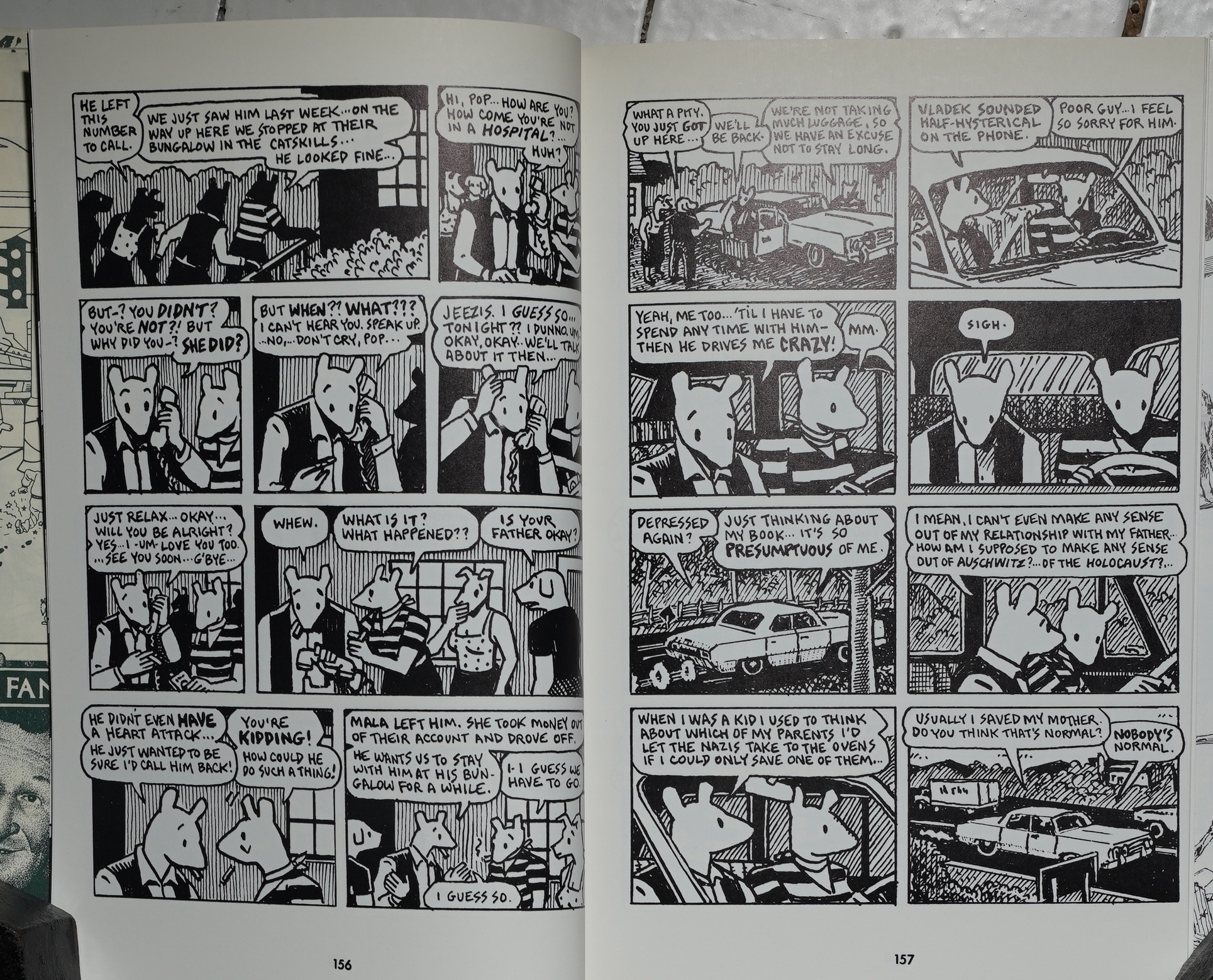

The only insert in this issue is another chapter of Maus. And… it starts with an ad for the Pantheon-published first volume, replete with a quote by Feiffer that says how brilliant it is.

I’m guessing most of this was done before the astounding commercial success of the book… it’s a really strong chapter, but then aren’t they all.

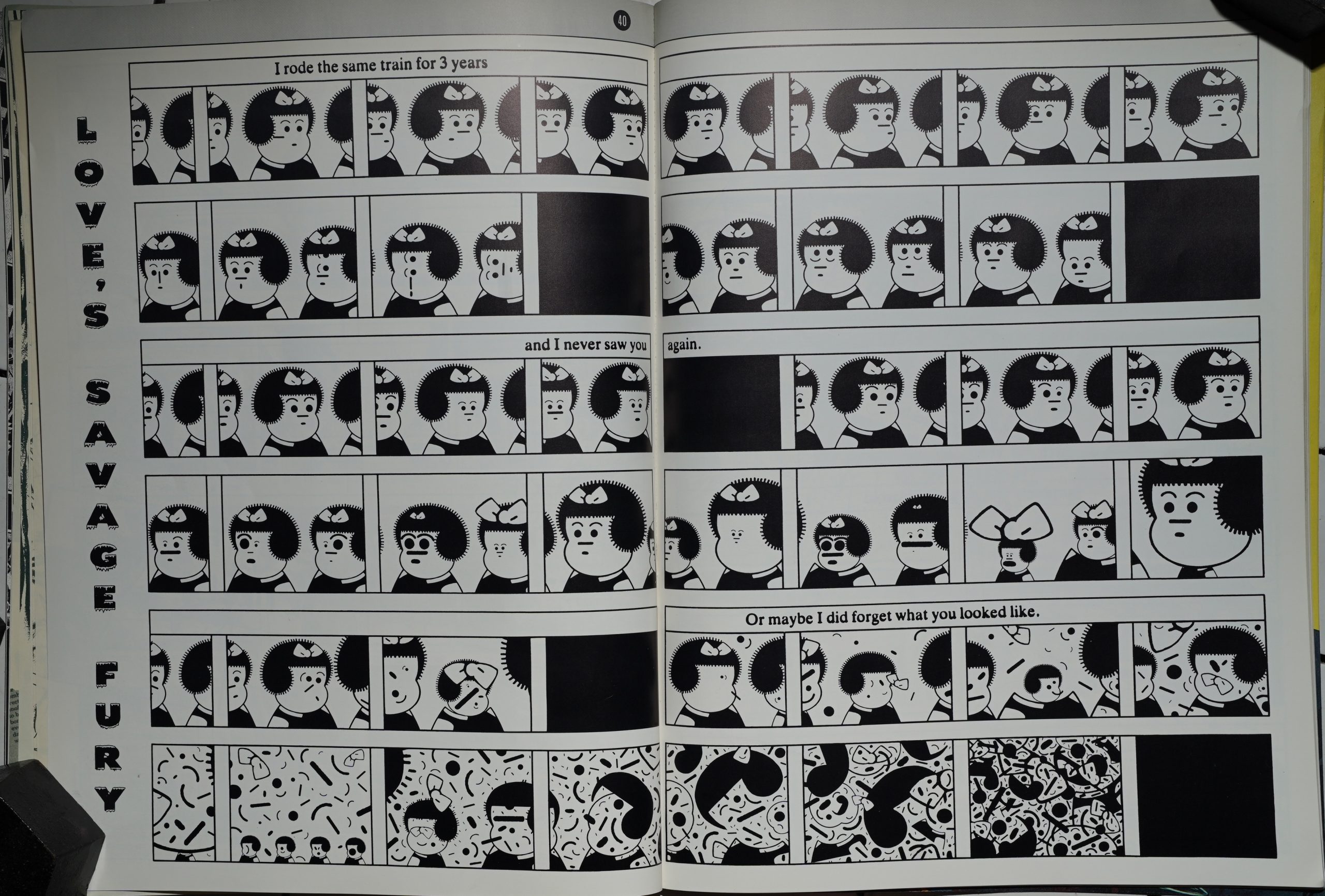

Oh! This one! Love’s Savage Fury by Mark Newgarden. I was so fascinated by this as a teenager — I attempted to make it into a computer demo of sorts, but it never got very far. I had lots of ideas, but they were kinda abstract.

This piece was originally meant for Bad News, but (according to Newgarden), Spiegelman pressured them into putting it in Raw instead. Newgarden is interviewed in The Comics Journal #161, page 84:

Also RAW was kind of instrumental in killing Bad

News. When we were doing the second one, about to go

into a third one, suddenly Spiegelman got all paranoid

about our little comic book. Like we were muscling in on

his turf. I got into this big fight with him. At a certain point

he said, “I’m gonna bury you.” Just like Kruschev! And a

lot of stuffthat ended up in the very next RA Wwas actually

intended for a third issue of Bad News. My Nancy strip,

“Love’ s Savage Fury” was done for Bad News and Drew ‘ s

great illustrated piece using Leo Gorcey’ s poetry and that

strip that Richard McGuire did, “Here,” were all projects

initially done for Bad News. We kind of got muscled out

of business for a while. Eventually [Spiegelmanl I guess

got over it, but he saw it as some kind of threat to RA W’,

which was pretty ridiculous.

KELLY: Now you and Spiegelman haven ‘t talkedfor what ?

More than nvo years now?

NEWGARDEN: Yeah. At least since my Blab! interview on

GarbagePailKids. I did a GarbagePail Kidinterview, and

I guess basically didn’t mention his name often enough so

he called me up and just went berserk — beyond normal

berserk for Art —and I yelled back at him and we really

haven’t talked since then. So that’s what happened.

KELLY: So you ‘re not going to be in any more RAWs.

NEWGARDEN: No, I’ve definitely been blacklisted. He’s

been vindictive. I could tell stories that would curl your

hair.

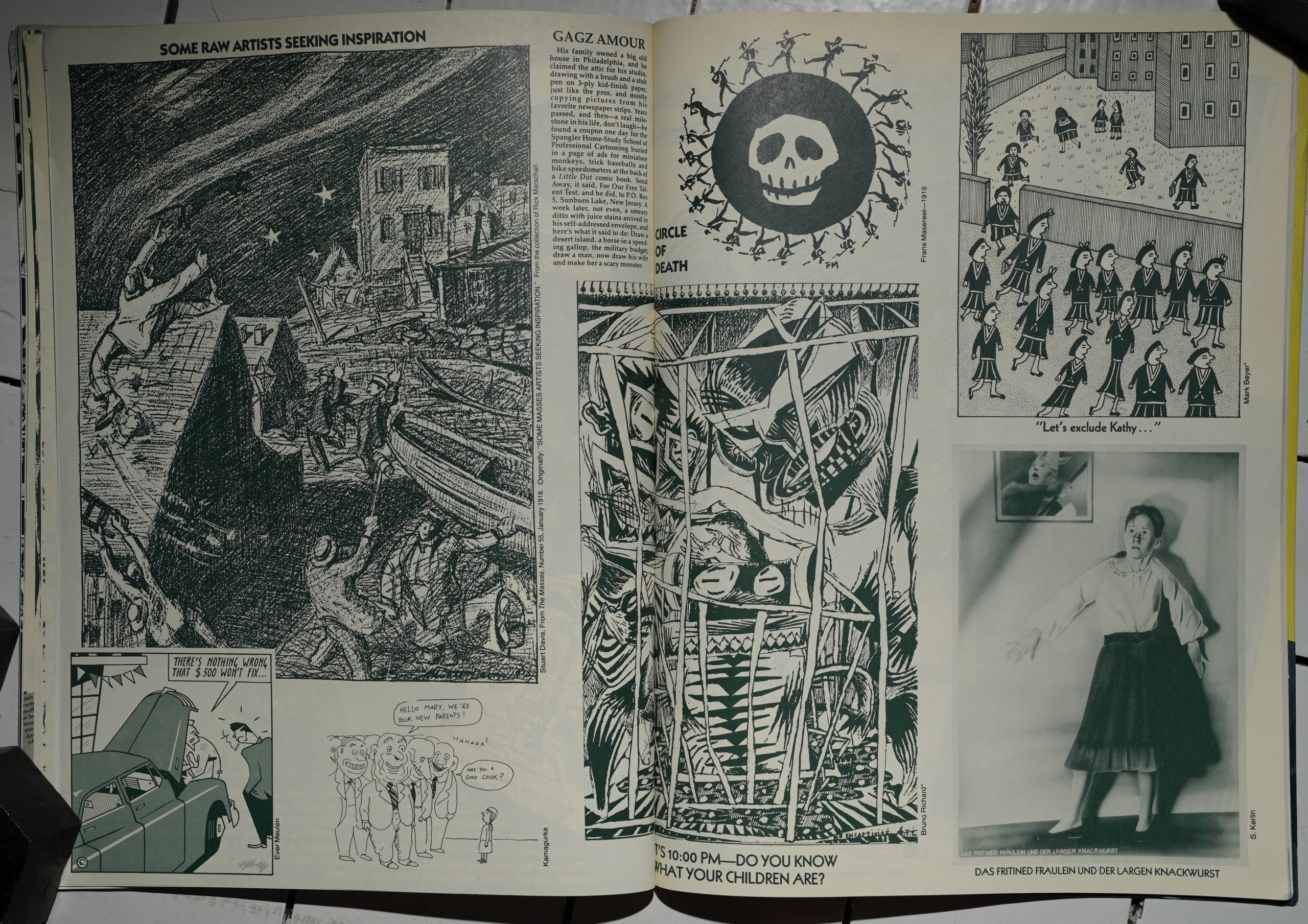

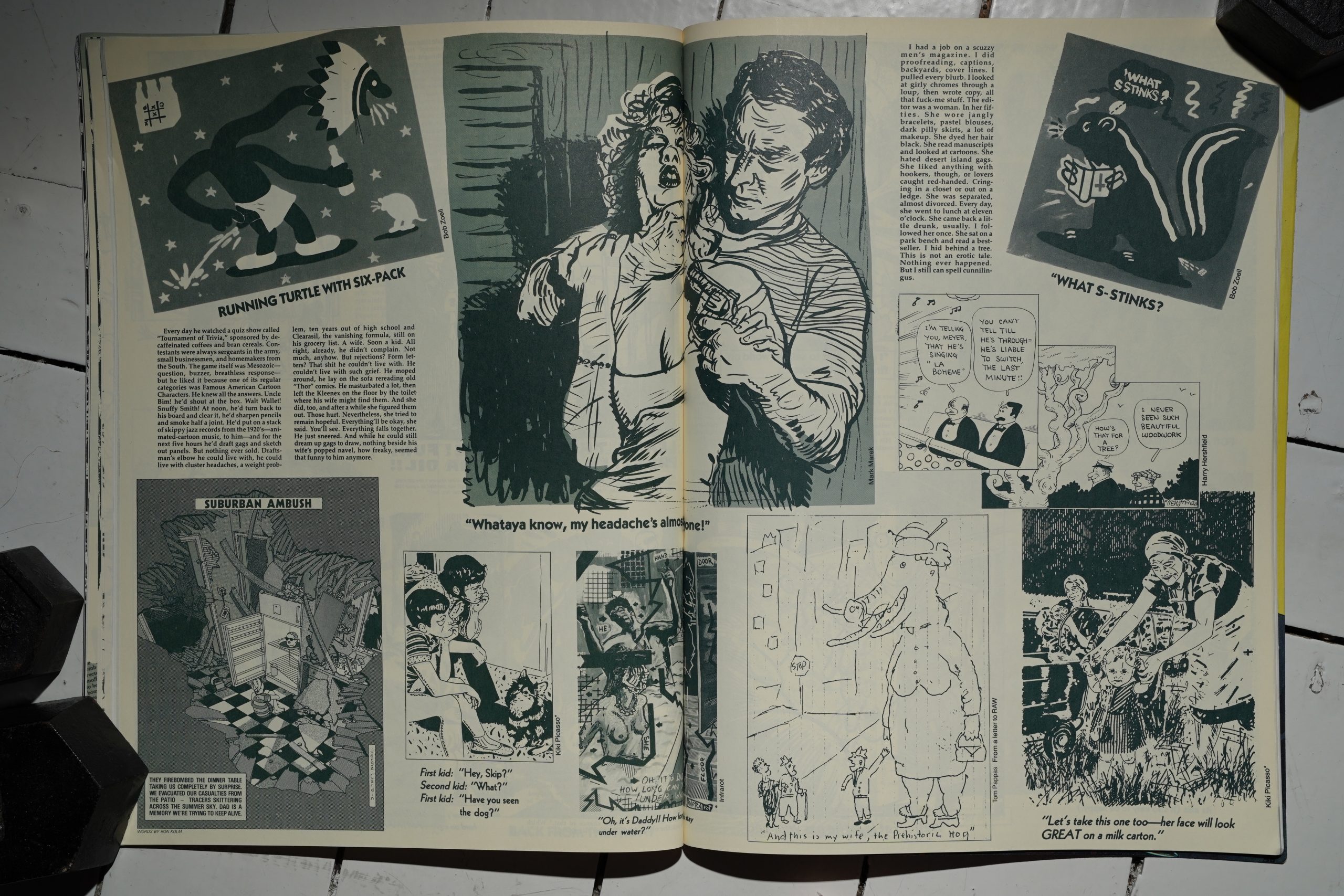

And then the longest section in the book: 22 pages of “gagz”. I guess it was an excuse to plonk a lot of unused illustrations into the book?

Not many of these pieces are, you know, actually funny.

And I’m guessing the section was put together during a drunk party or something?

Finally we round out with a pretty slight story by Baru.

I can totally see why I was disappointed by this as a teenager. There’s basically three things of note in here: The Maus chapter and the devastating Jimbo thing (but neither of which were surprising), and then the mind-boggling Newgarden thing. The rest barely register — and that’s such a huge change from where Raw was a couple years earlier, when there was basically nothing in a Raw issue that’s not flabbergastingly good.

This is just… OK? It’s got a handful of good stuff and a lot of filler?

I guess it’s a sign of the times, too: We’re at the height of the Reaganite era, where people had finally accepted that their 70s ideals were for nought.

This blog post is part of the Punk Comix series.