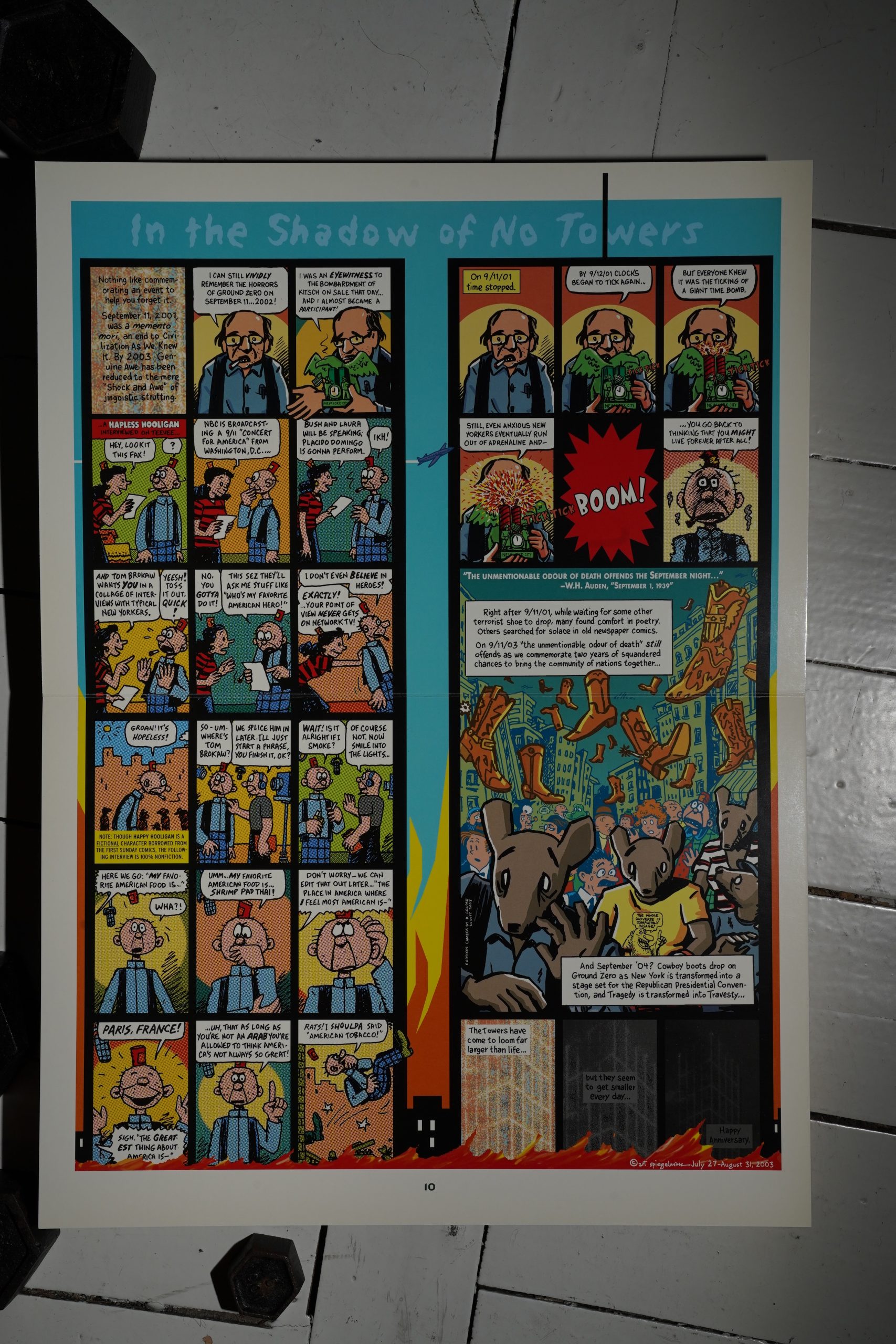

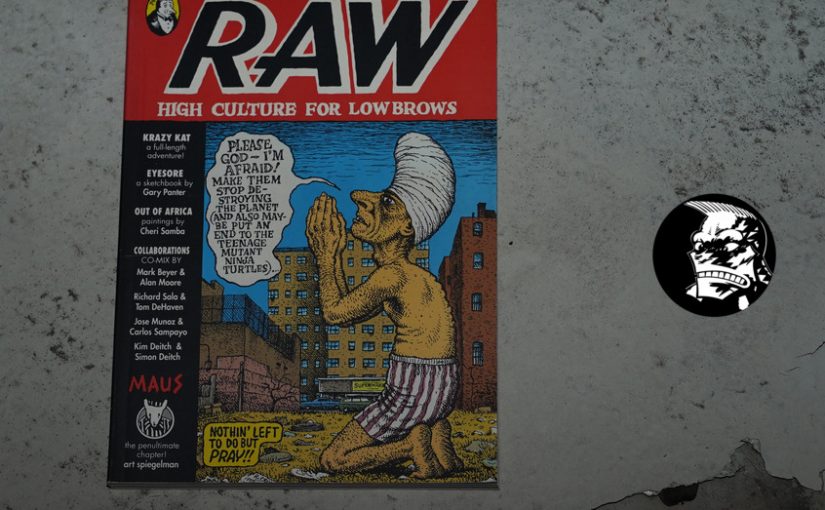

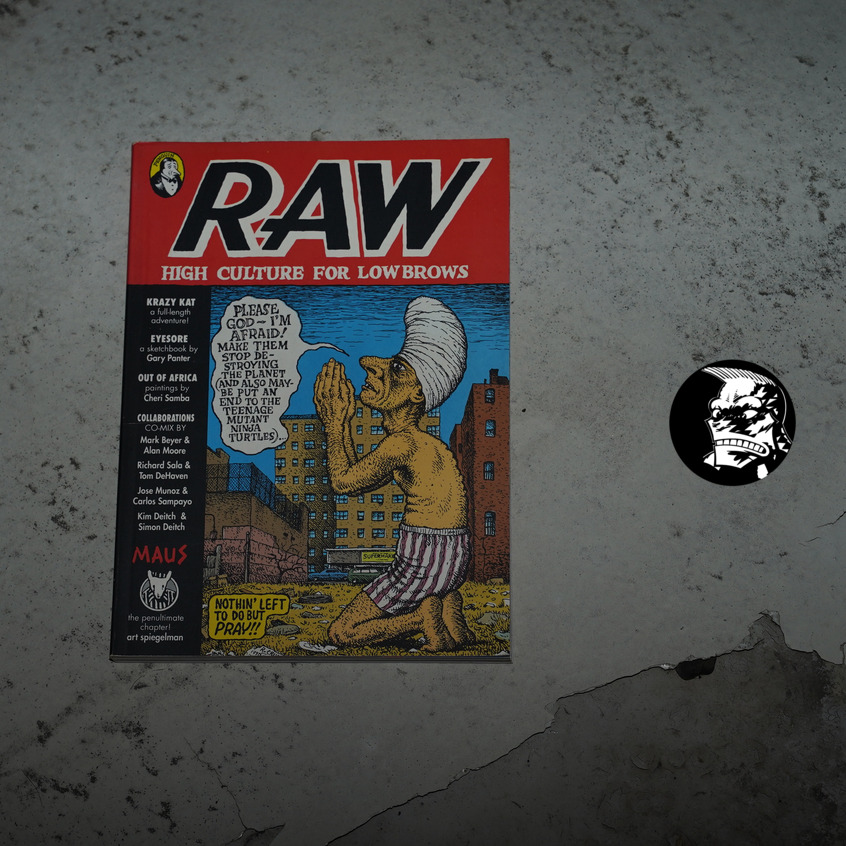

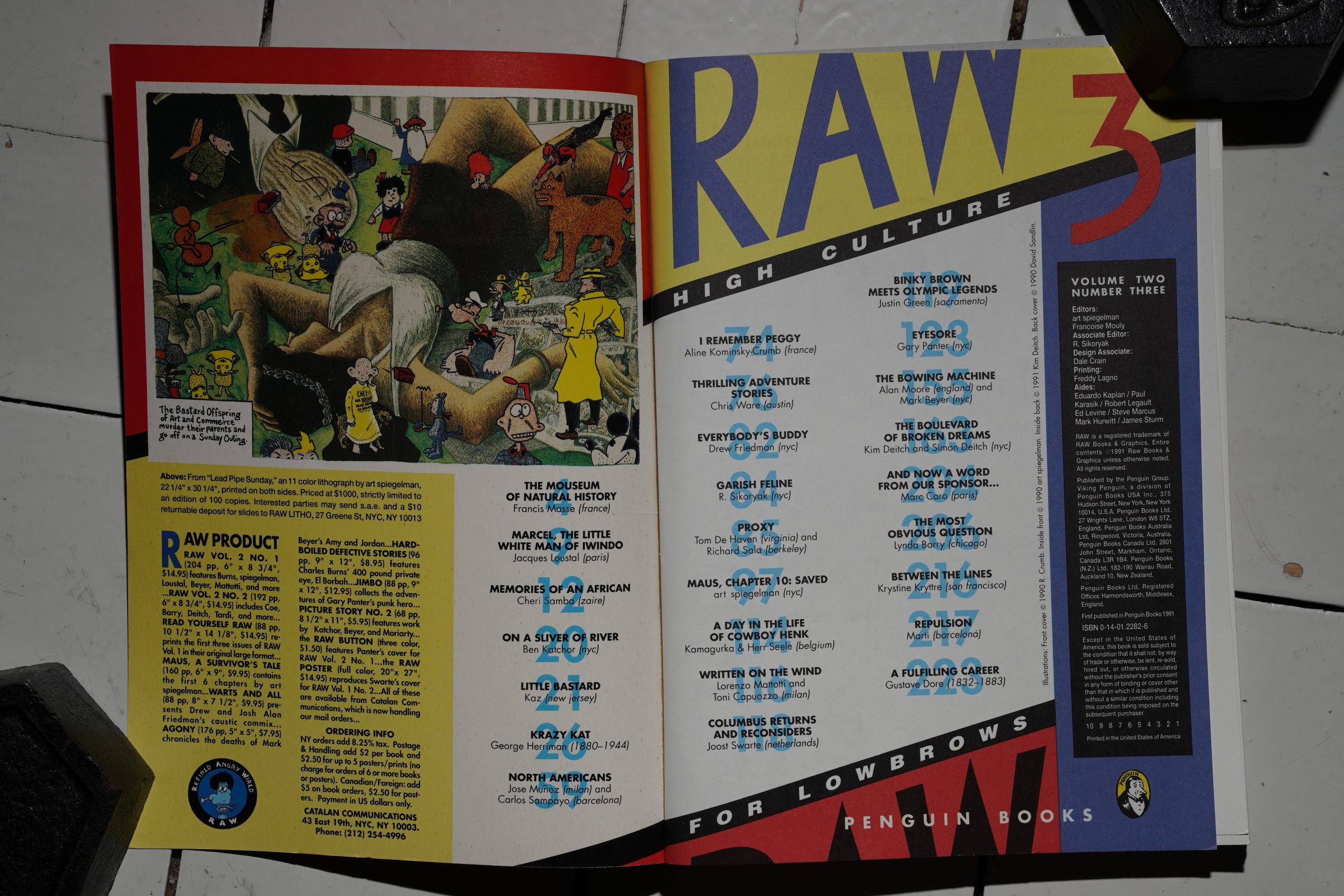

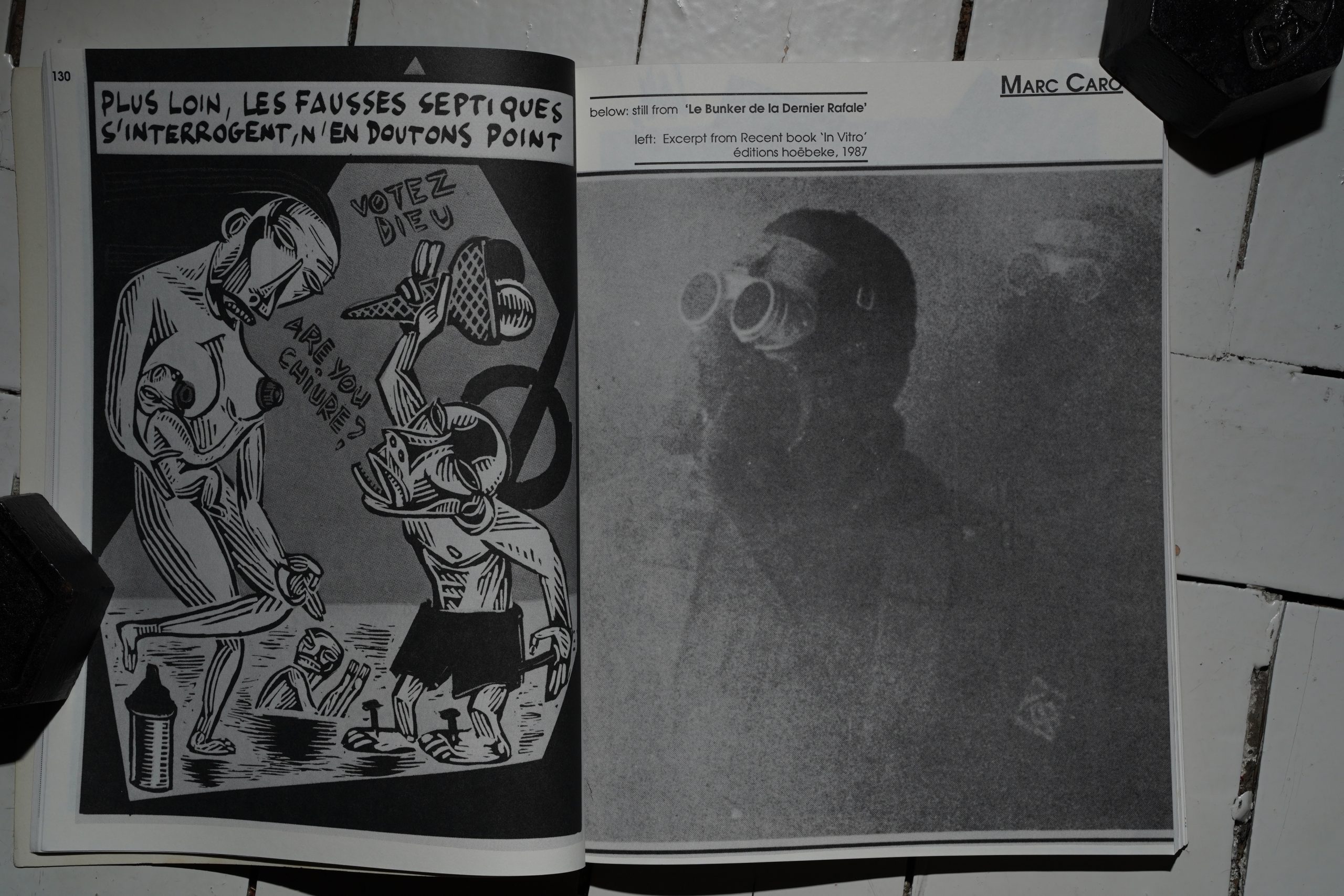

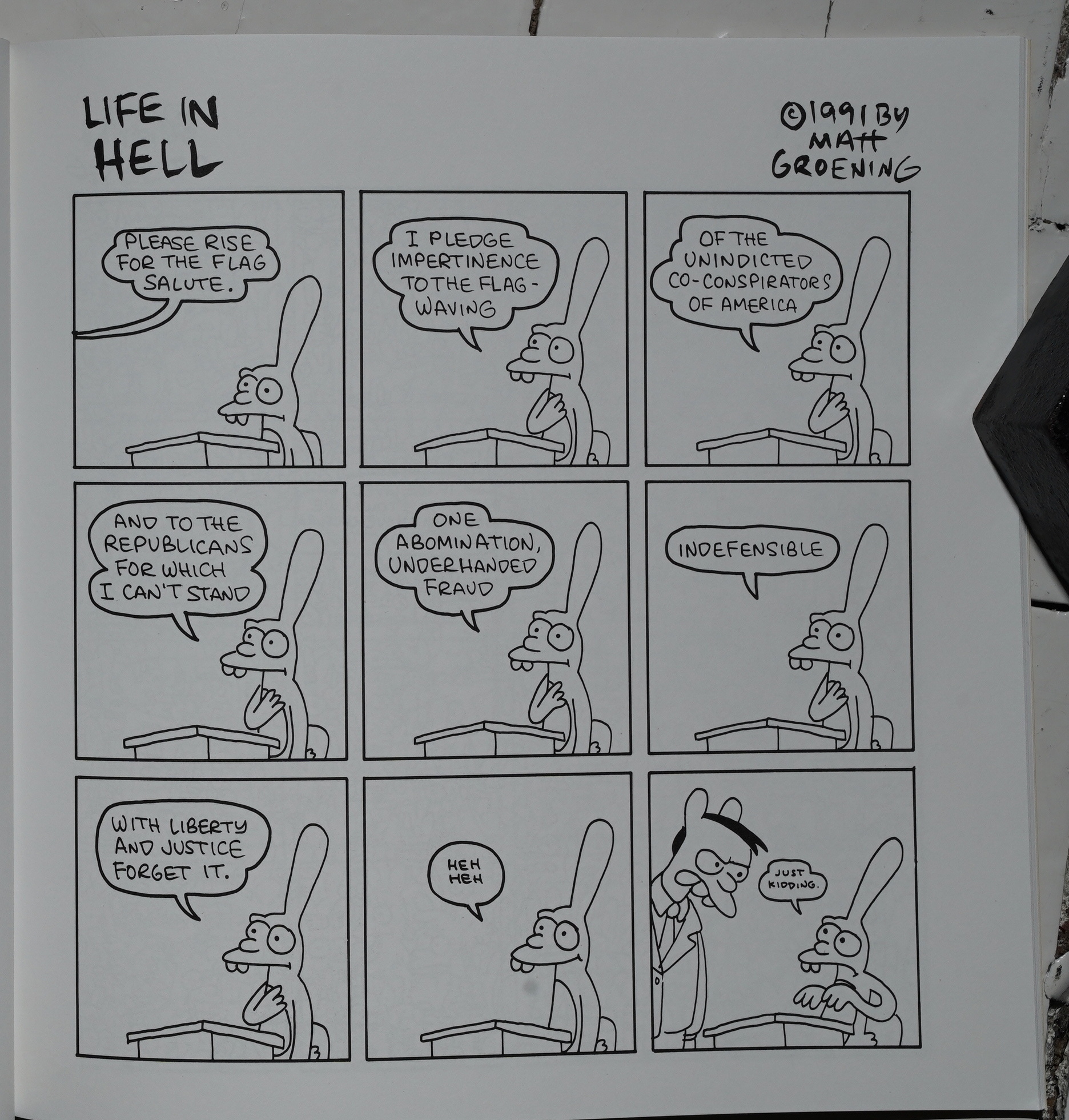

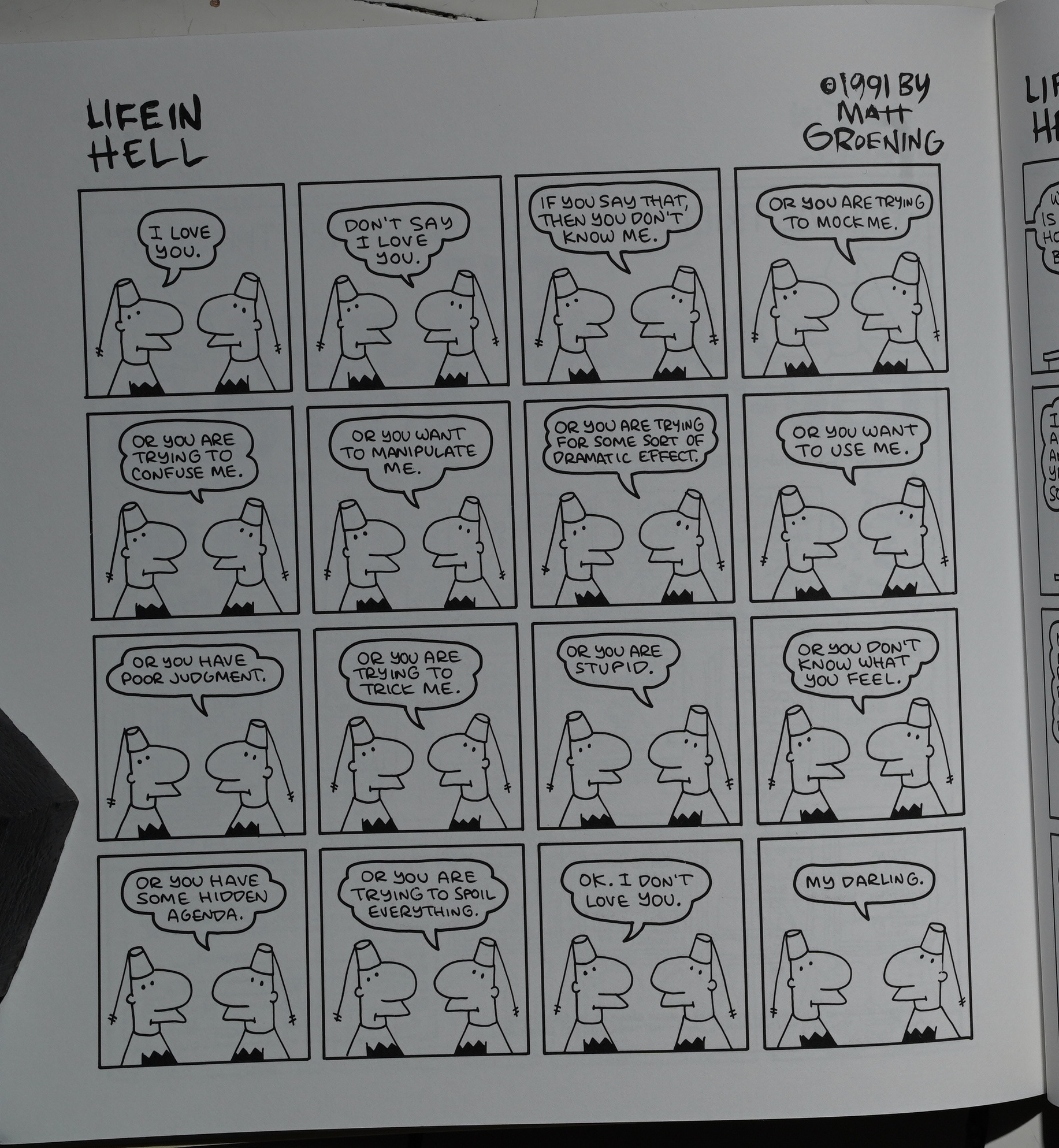

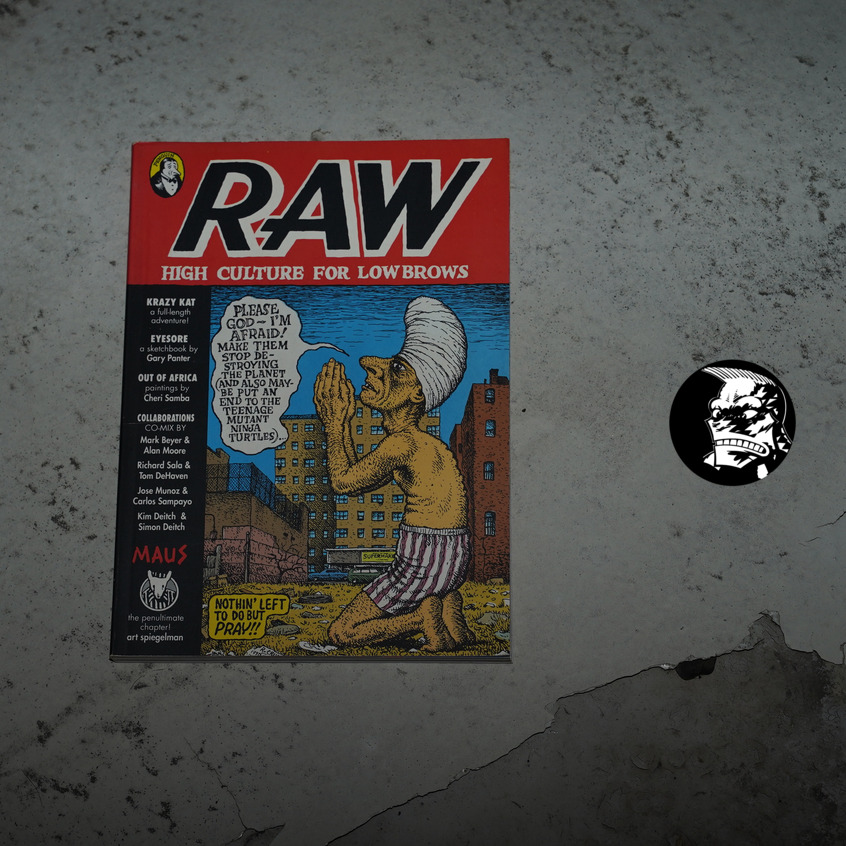

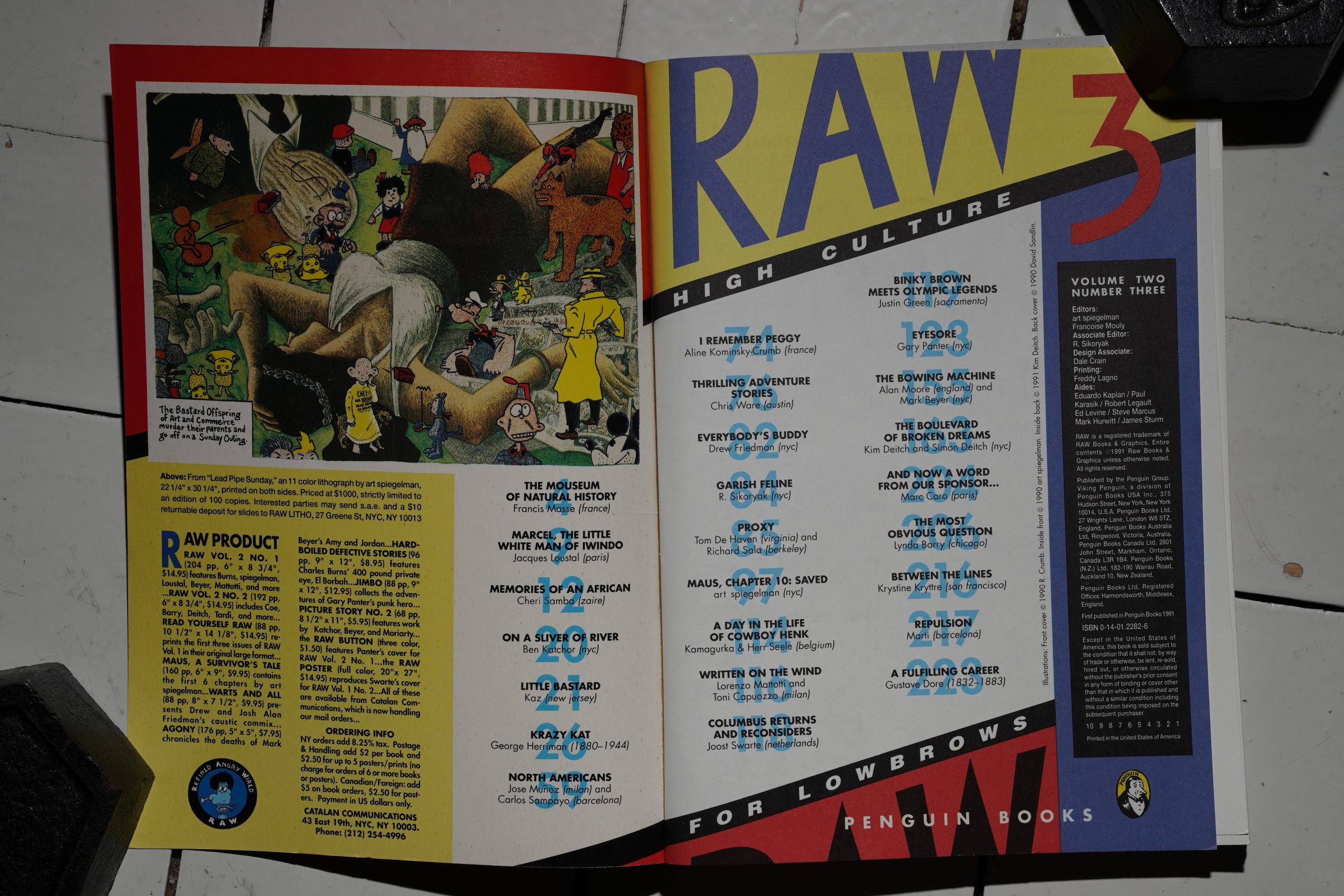

Raw Vol 2 #3: High Culture for Lowbrows edited by Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman (165x229mm)

This is it: The third and final edition of the Penguin-published Raw, and the final Raw book. (Sort of.)

And… we’re getting pretty high in the instep, aren’t we? Spiegelman is selling a $1K print. Tsk tsk.

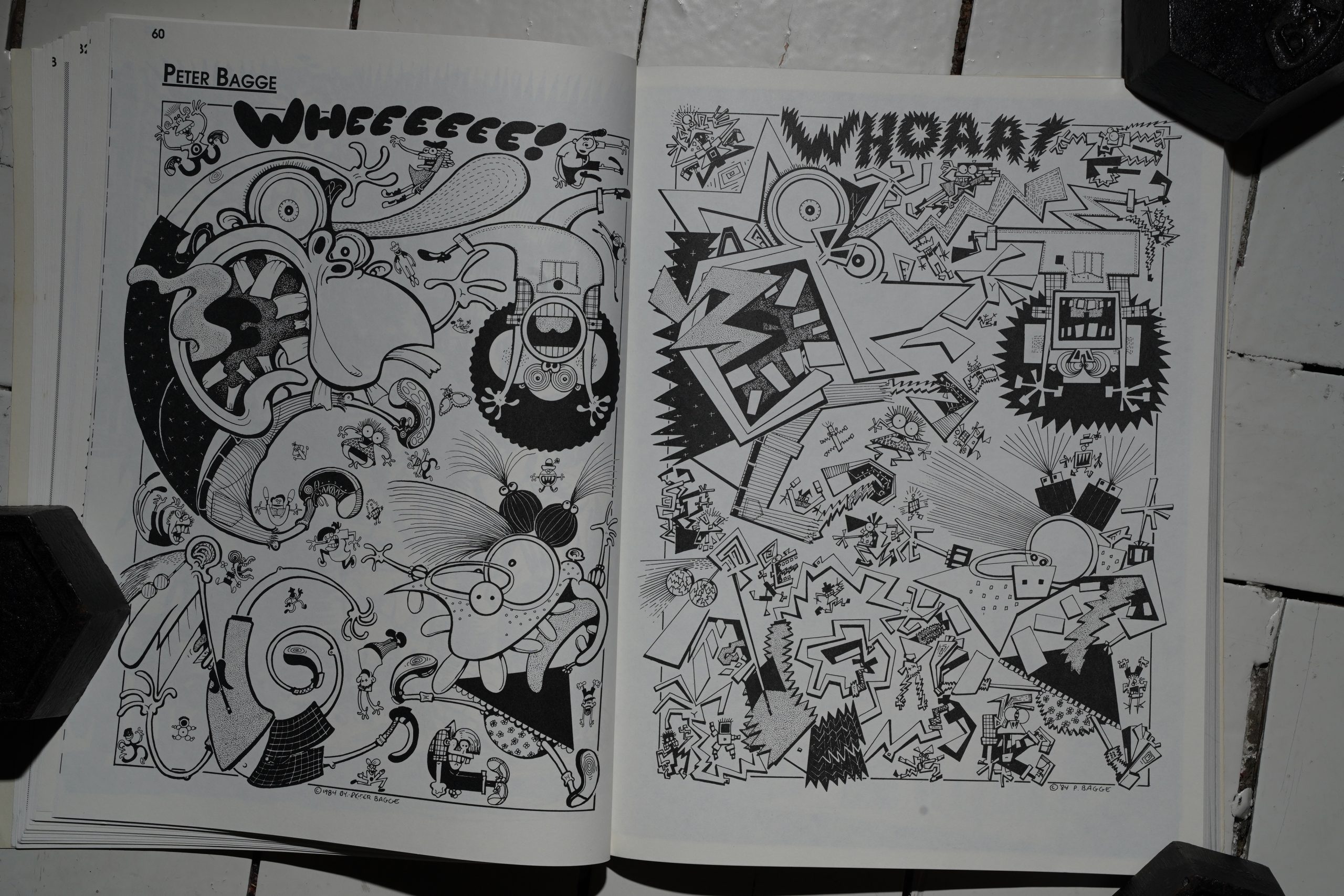

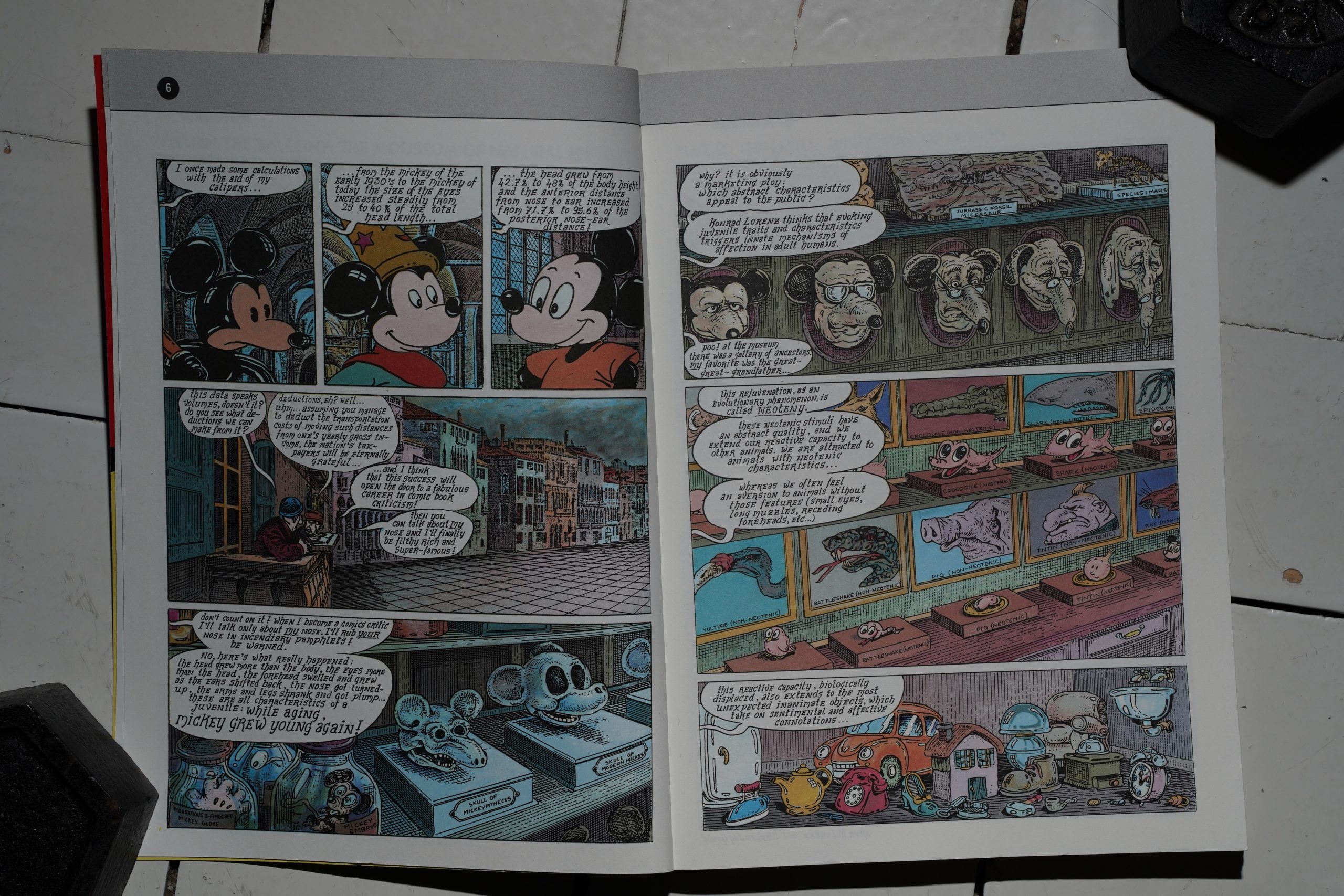

The book starts off with some vignettes from old acquaintances — here’s Francis Masse, and you can’t really escape the thought that his artwork looked so much better in the old, larger Raw format.

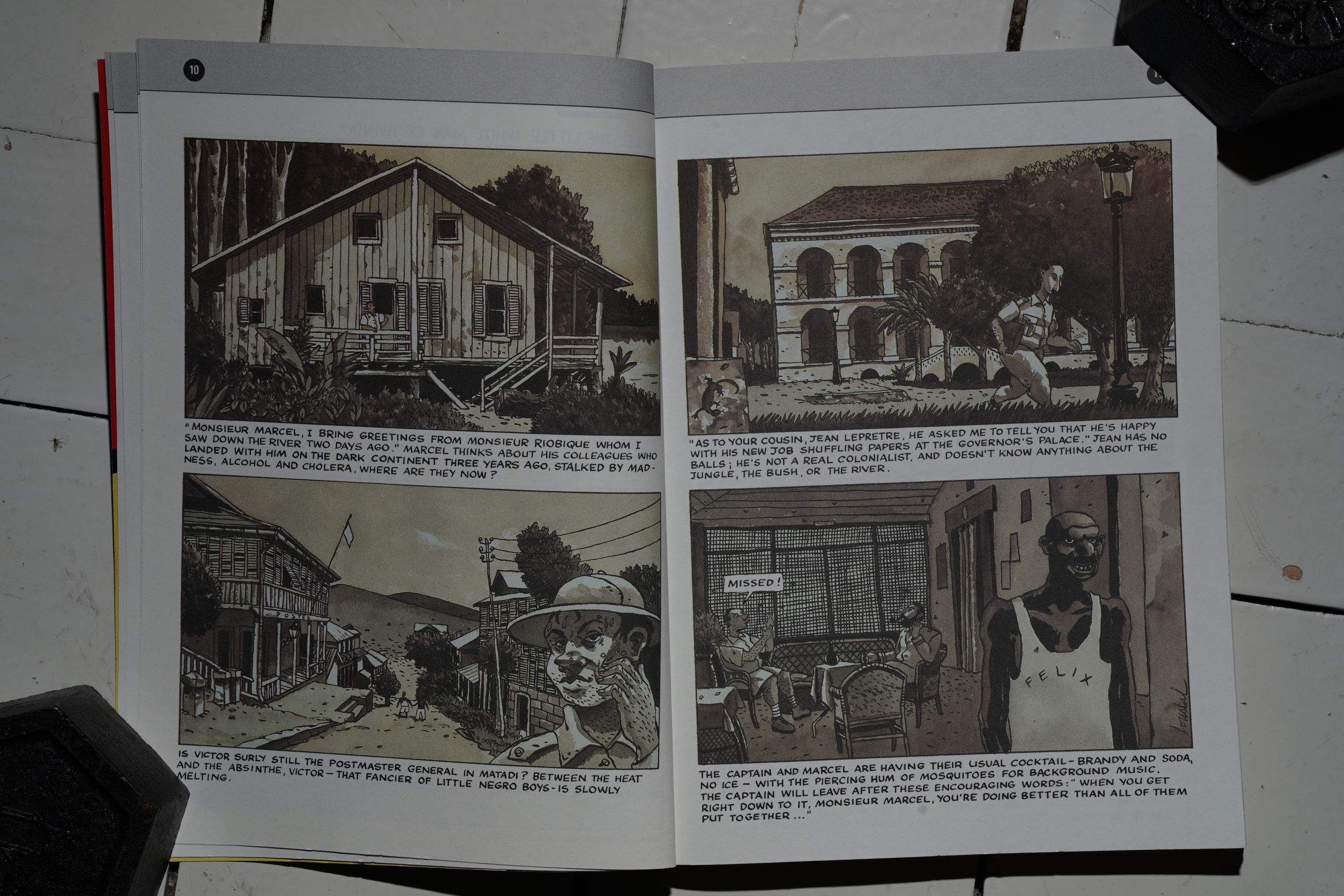

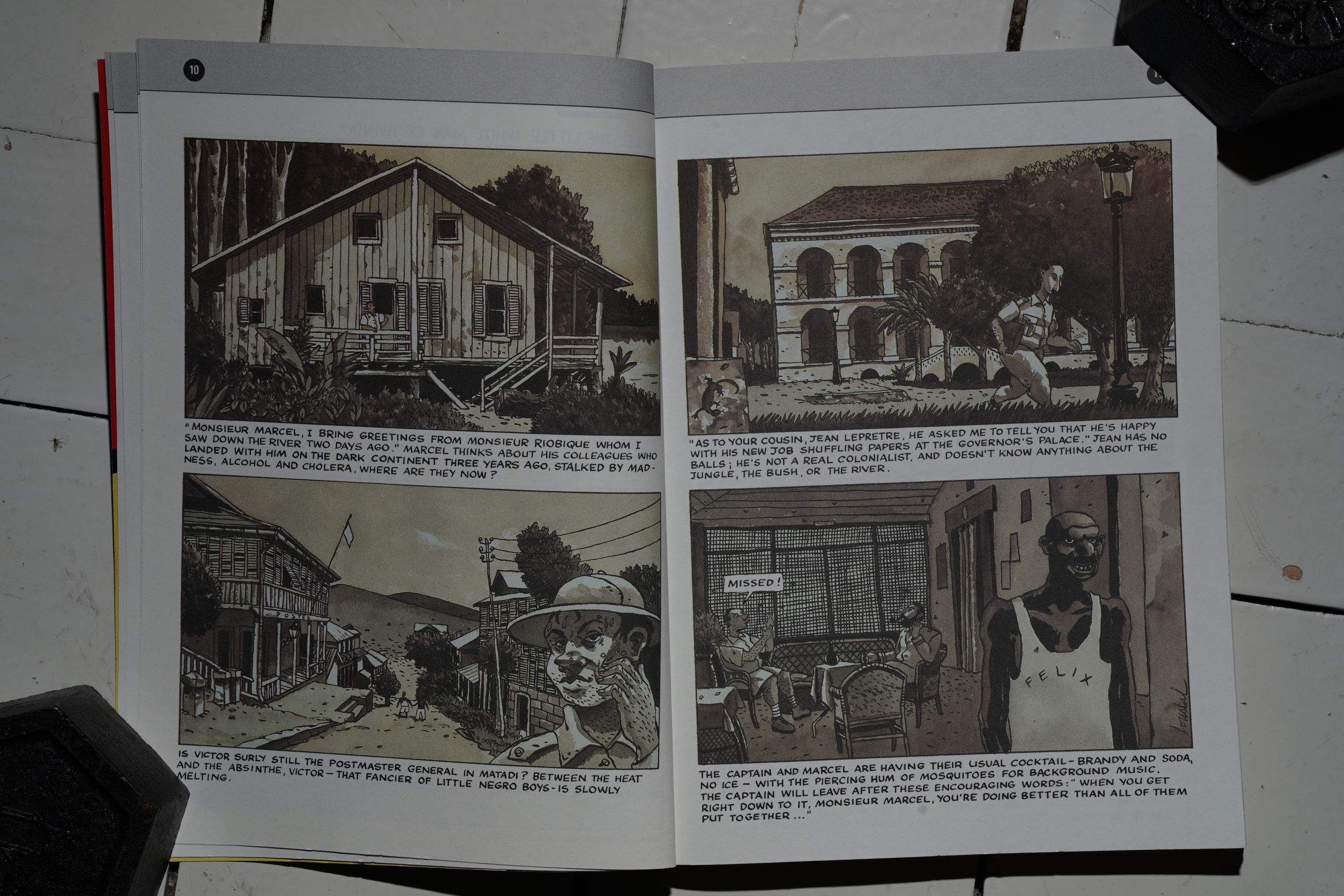

Then a three pager by Loustal, and I’m thinking — are the editors making the same mistake here they did in the first Penguin edition? That is, just jamming a lot of shorter pieces into the book, without any thought for rhythm or how things fit together?

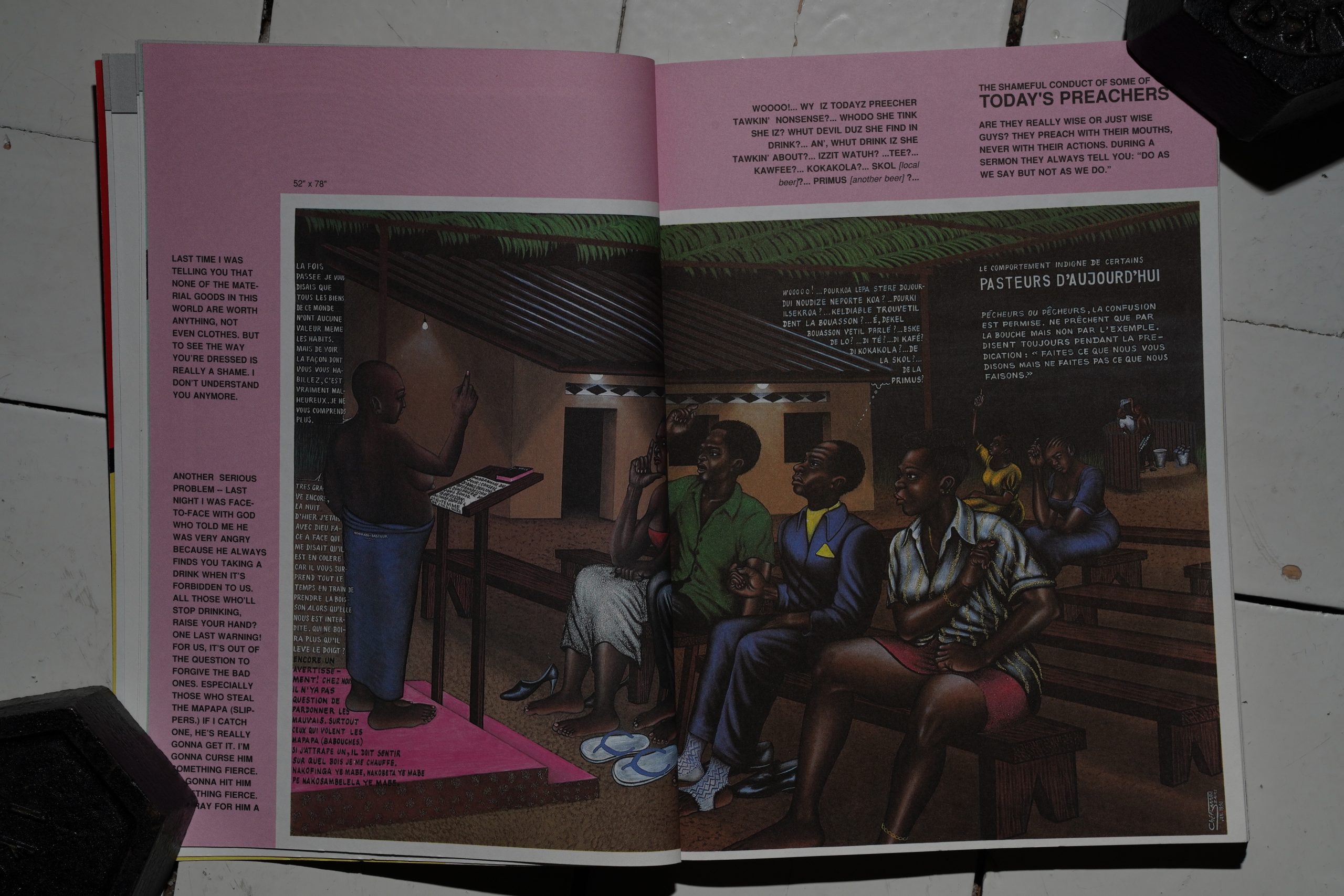

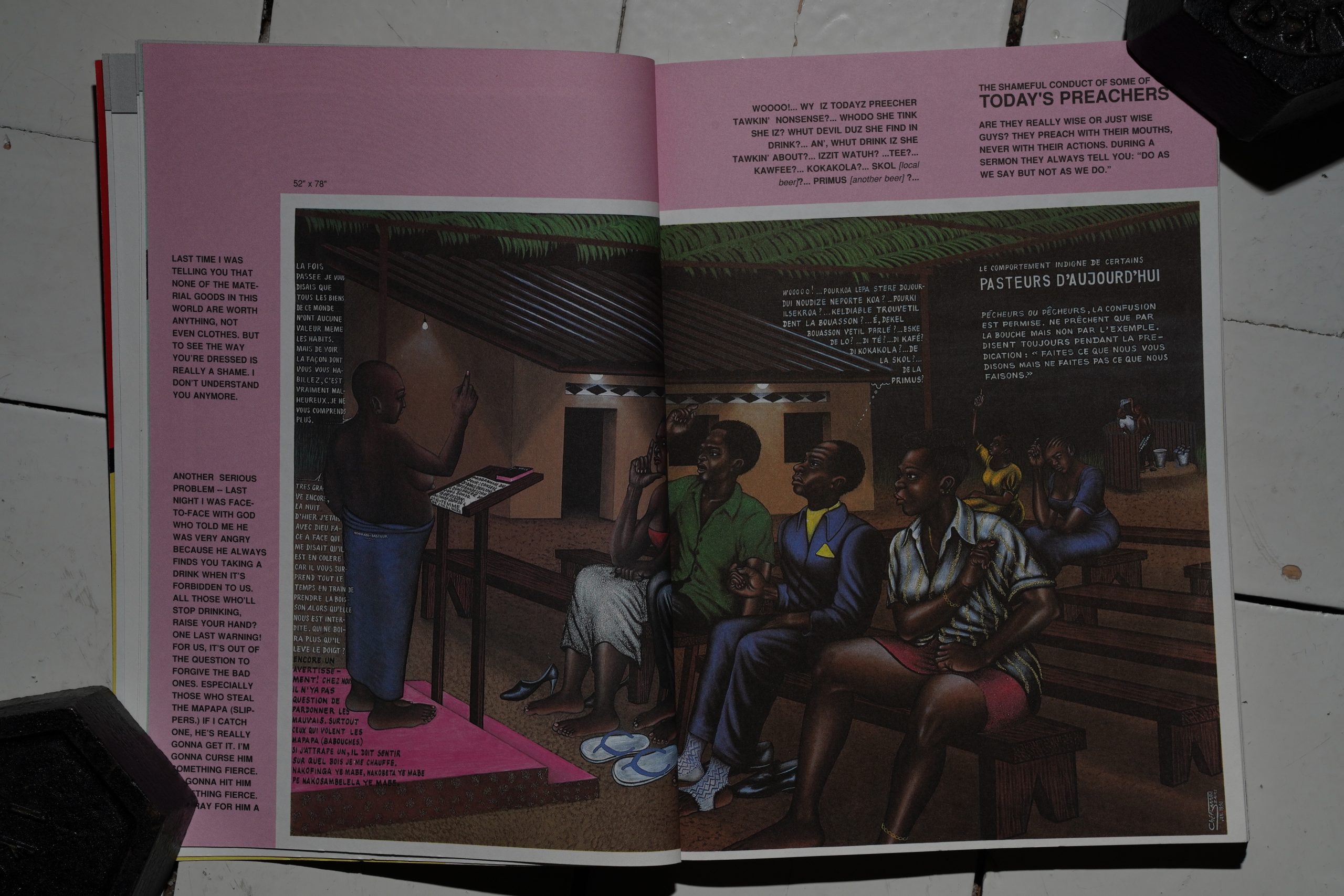

But then we get a longer, intriguing portfolio by Cheri Samba…

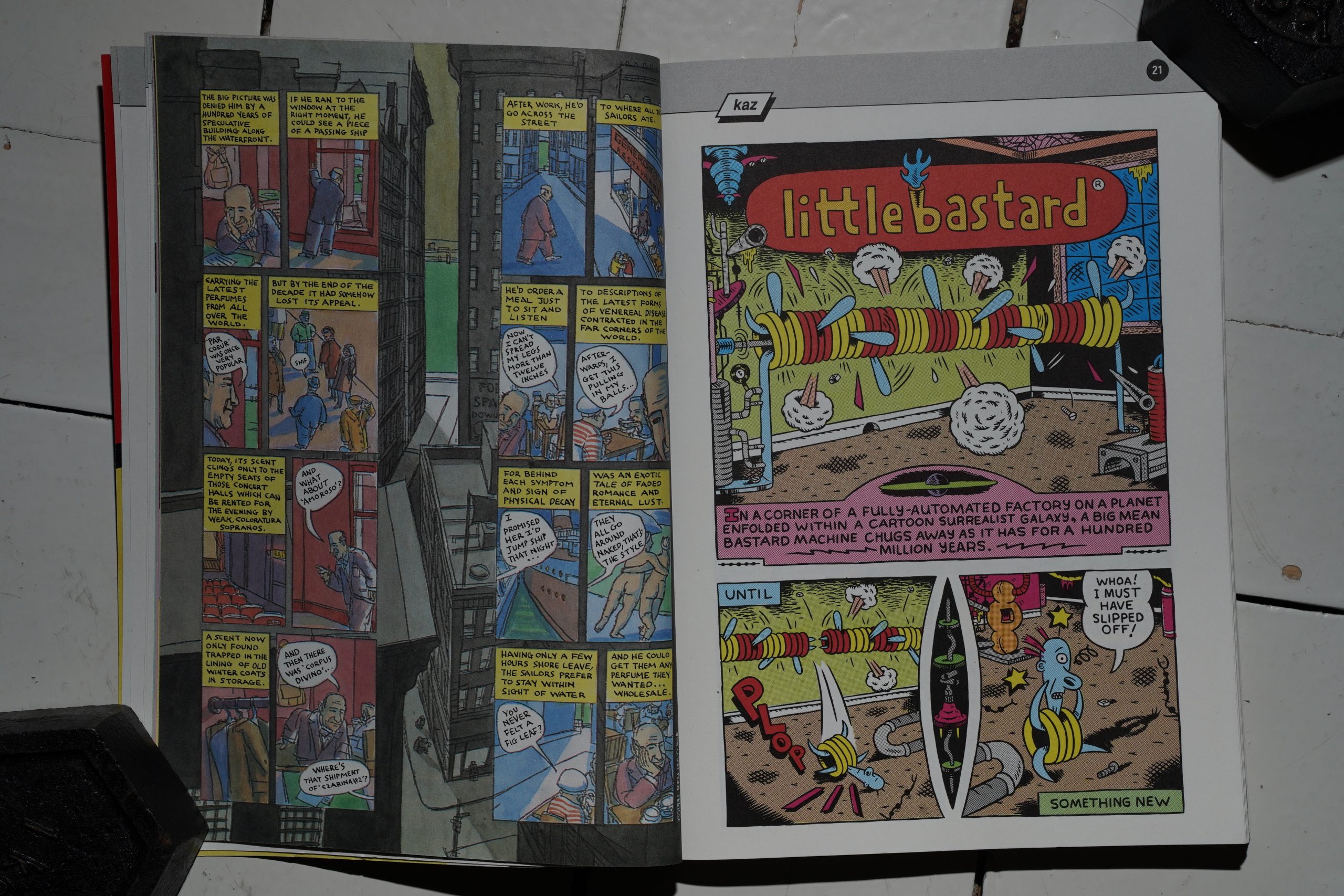

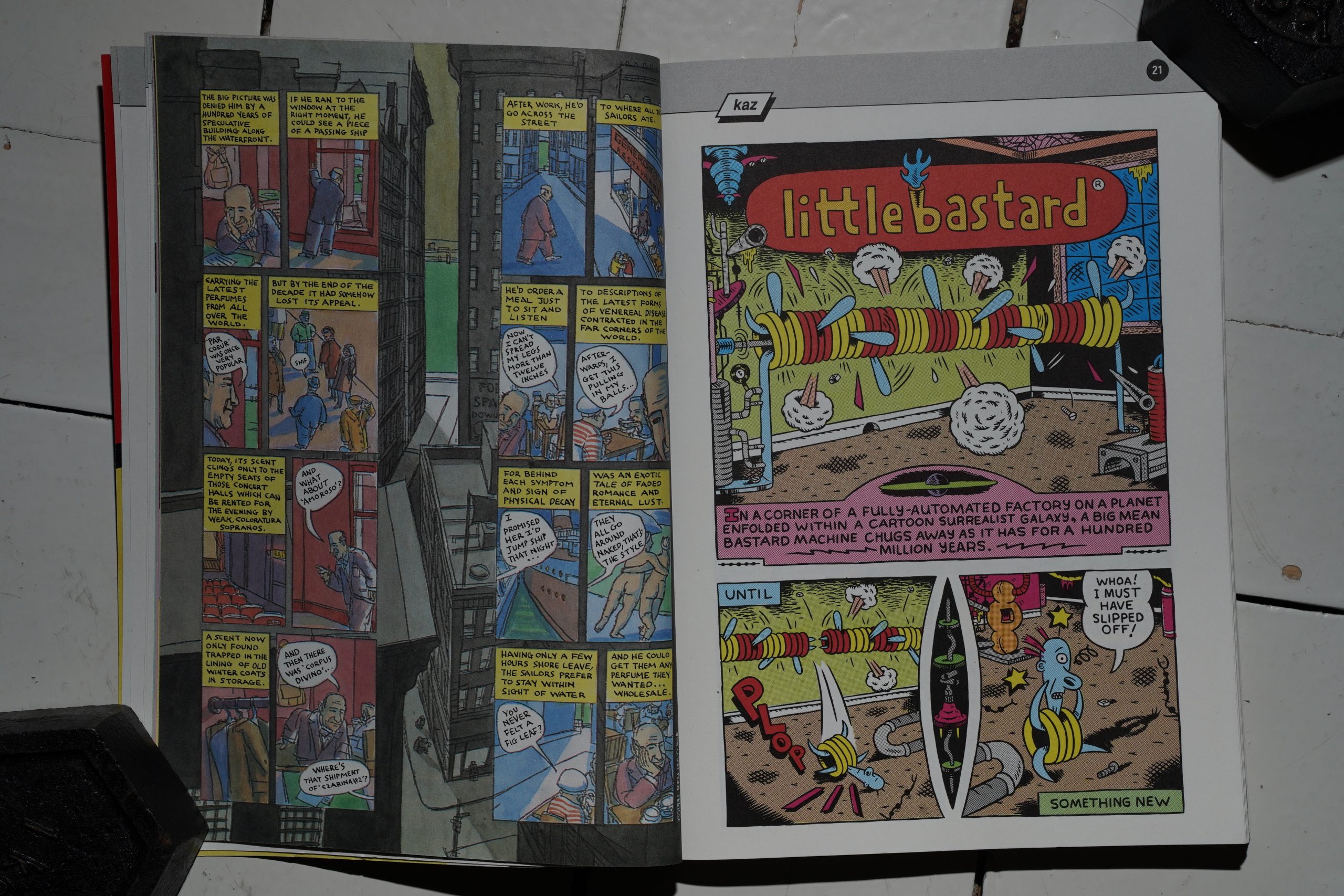

… and then a one-pager (!) from Ben Katchor, and then a wistful/amusing thing from Kaz.

I still wasn’t sure whether this was really working at this point, but then…

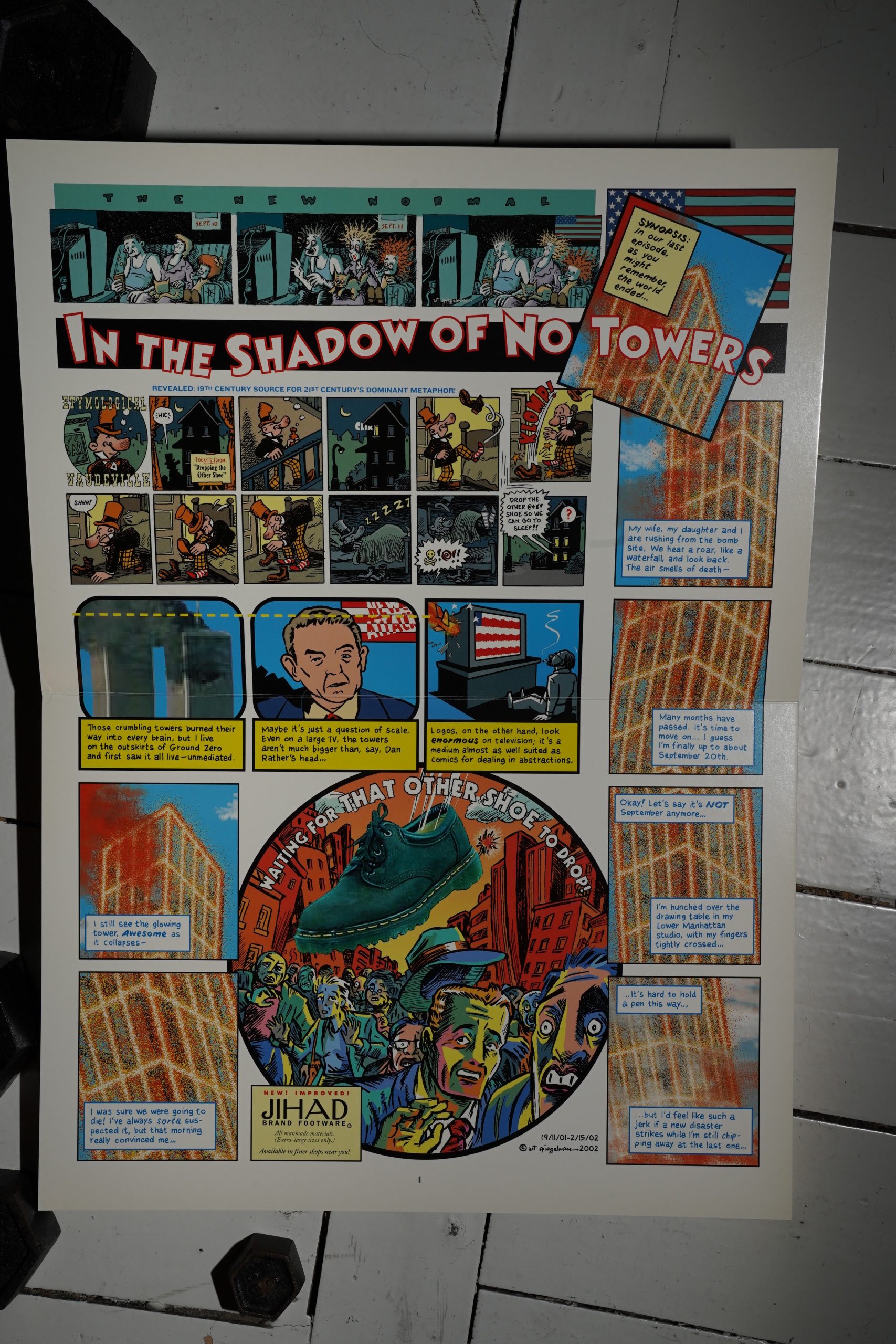

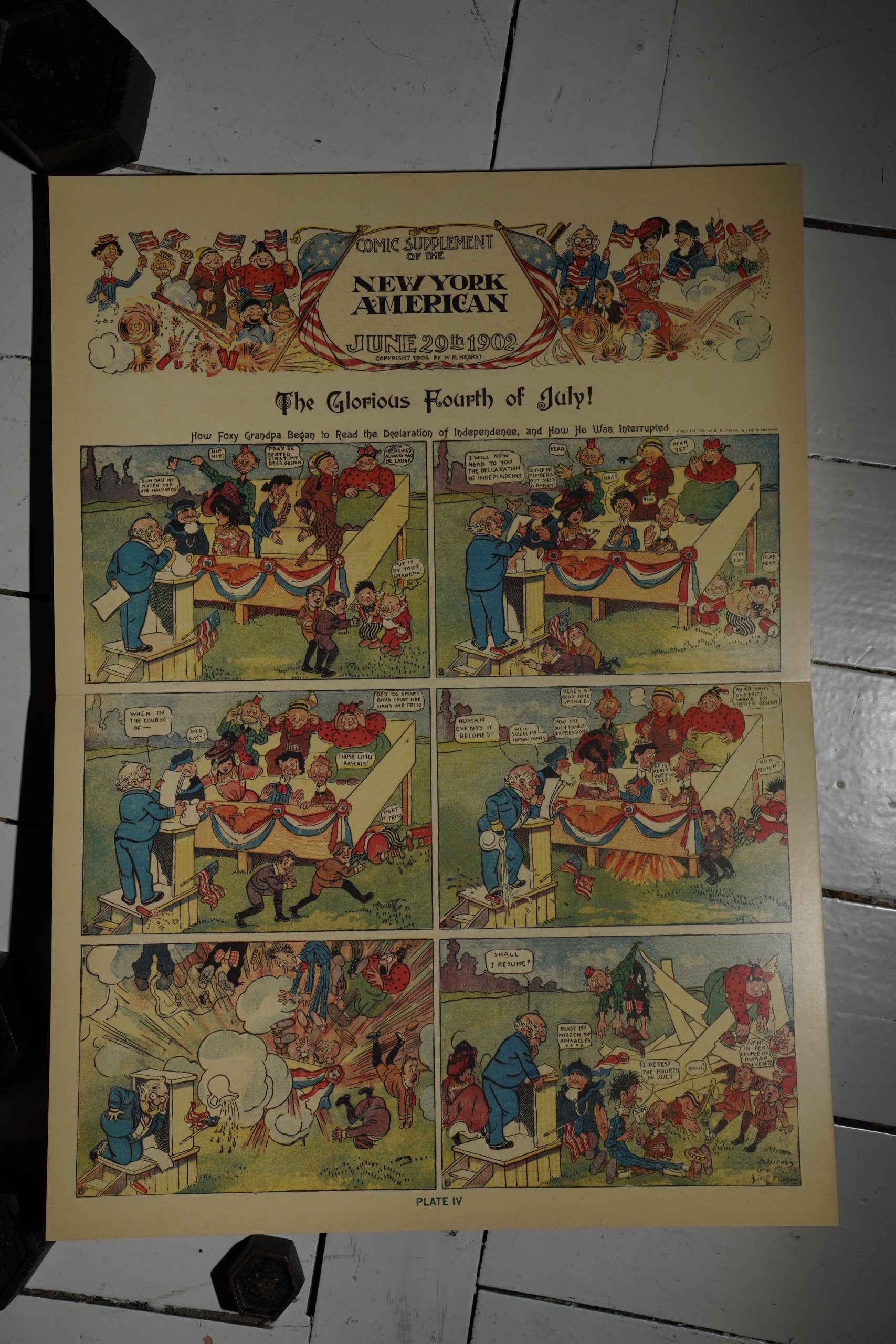

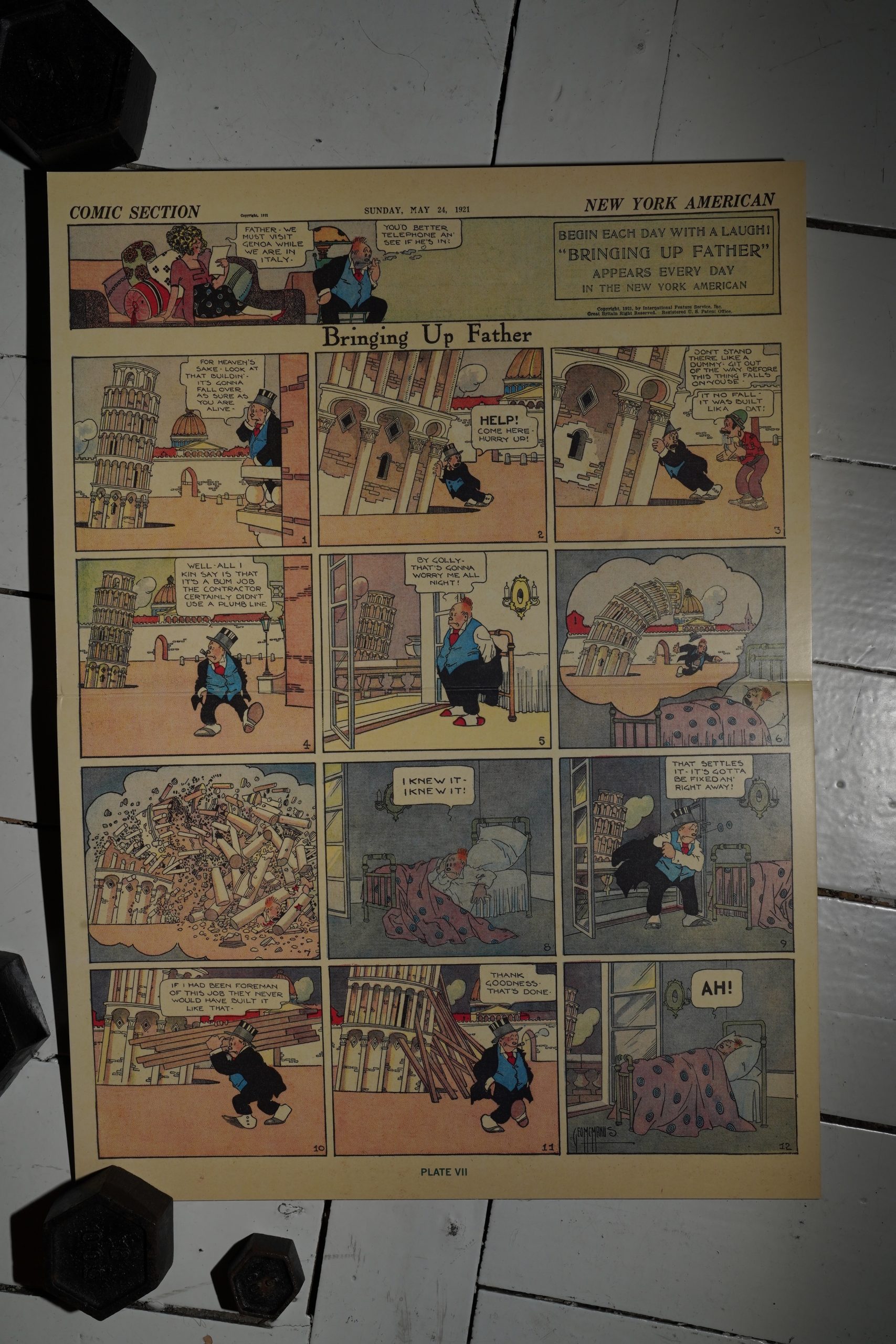

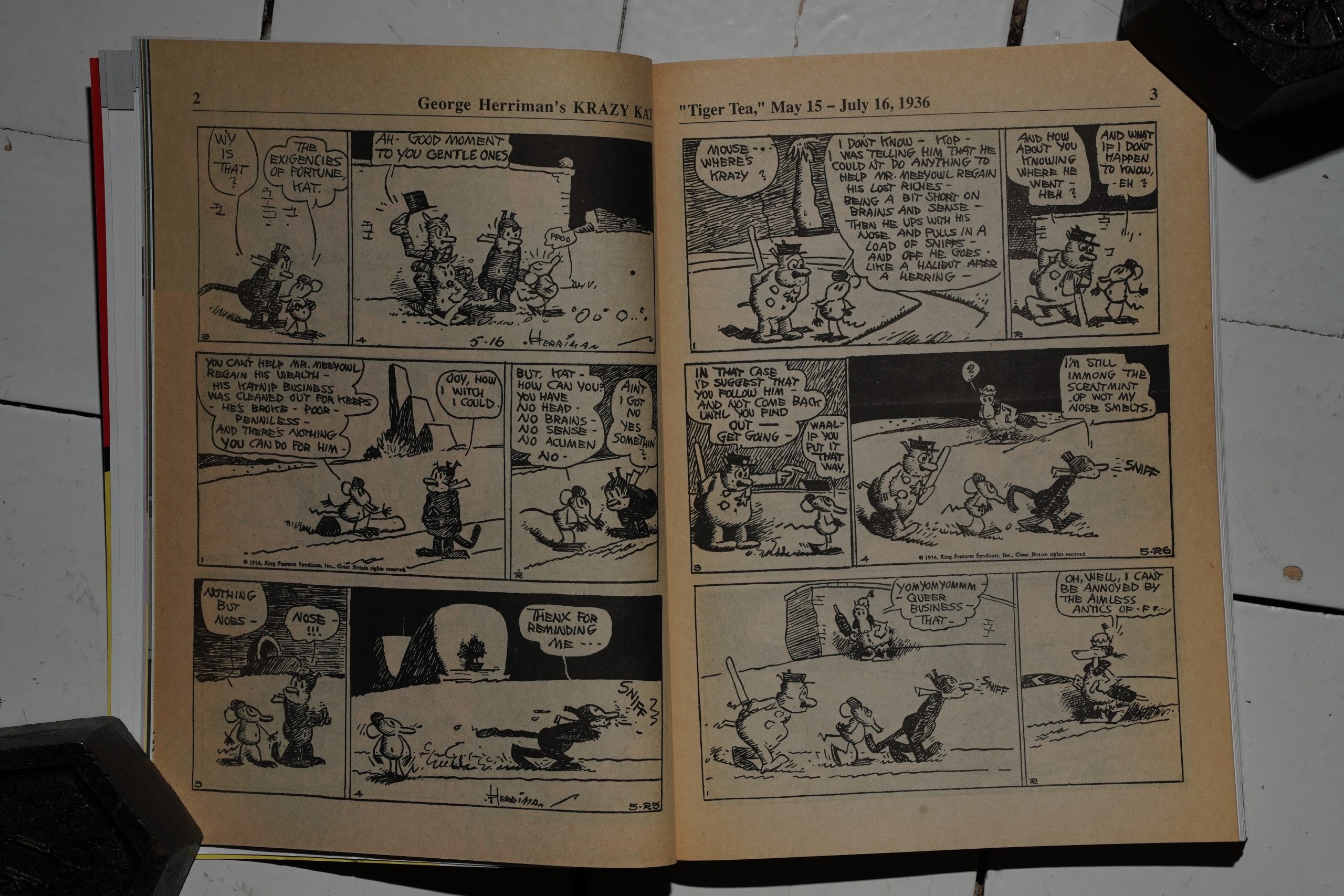

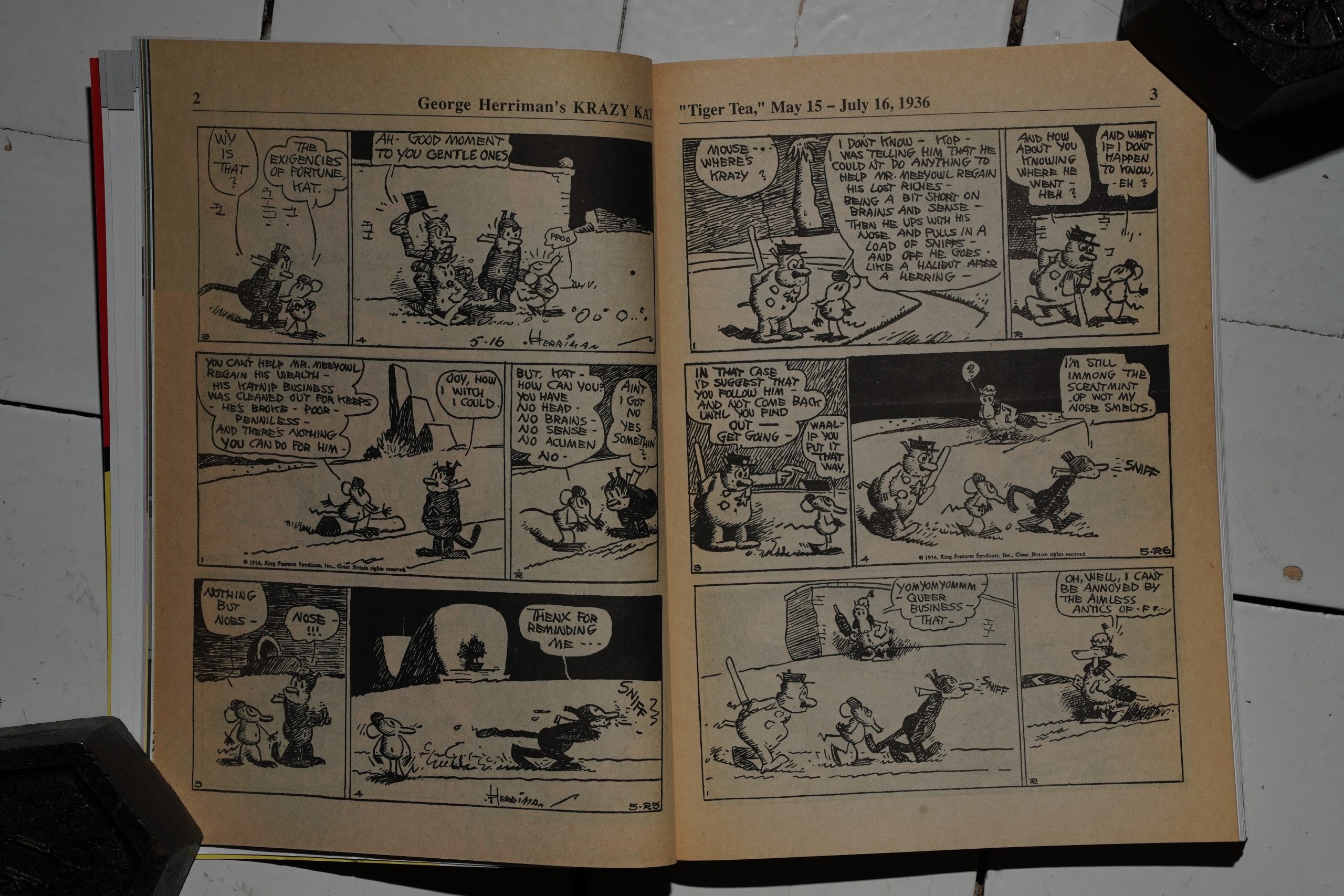

32 pages of Krazy Kat! On newsprint! OK, now I’m aboard.

If there’s anything that’s the moral predecessor of the Raw generation, it’s George Herriman, with his tendency to avoid making work that can be pinned down easily. So in one way it’s slightly odd that they chose these strips to reprint: The Tiger Tea sequence is the longest narrative that Herriman did (according to the introduction), and it’s perhaps his most straightforward work; his least Avant Garde. So picking it for Raw is odd?

On the other hand, it’s pure and utter brilliance, so why quibble.

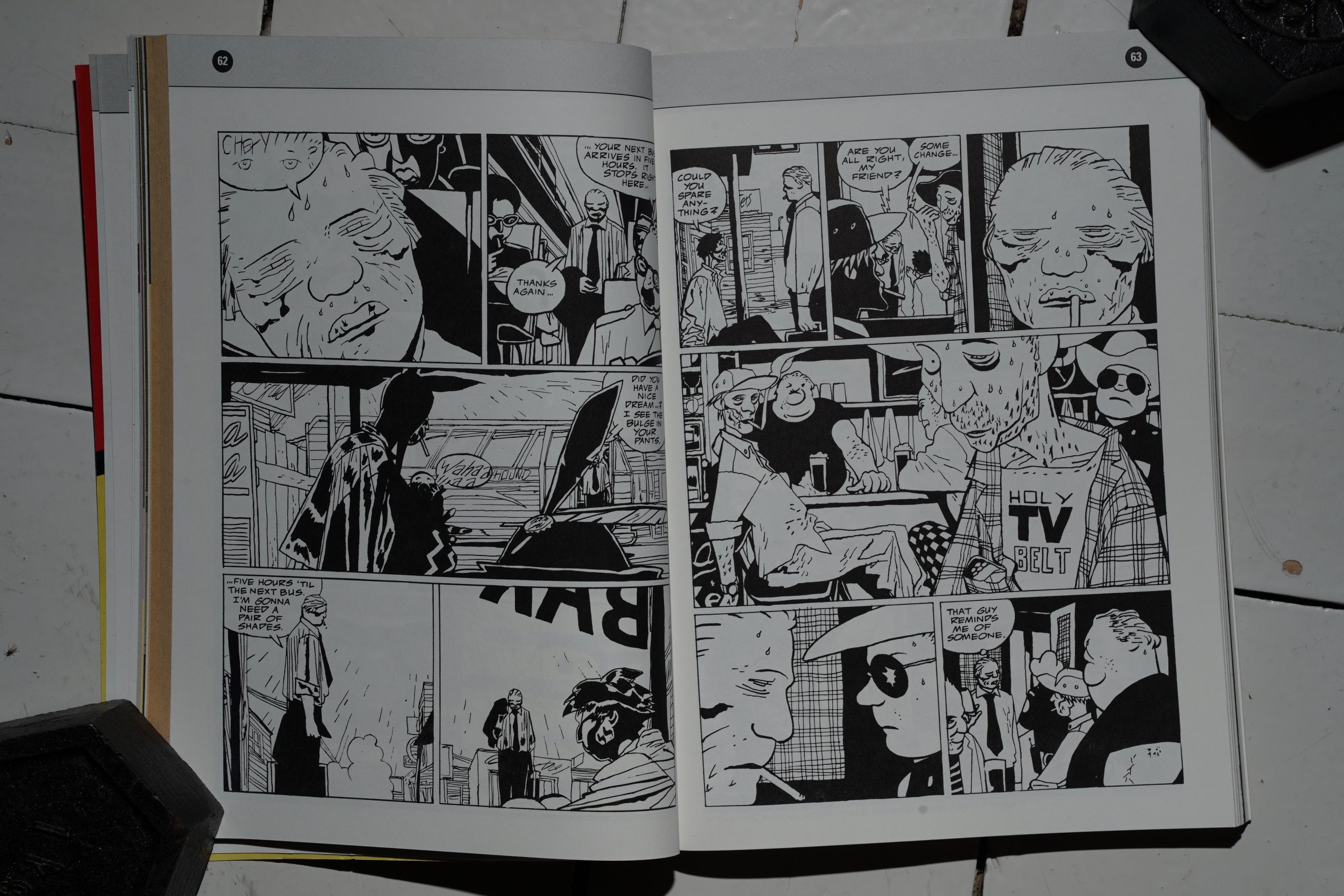

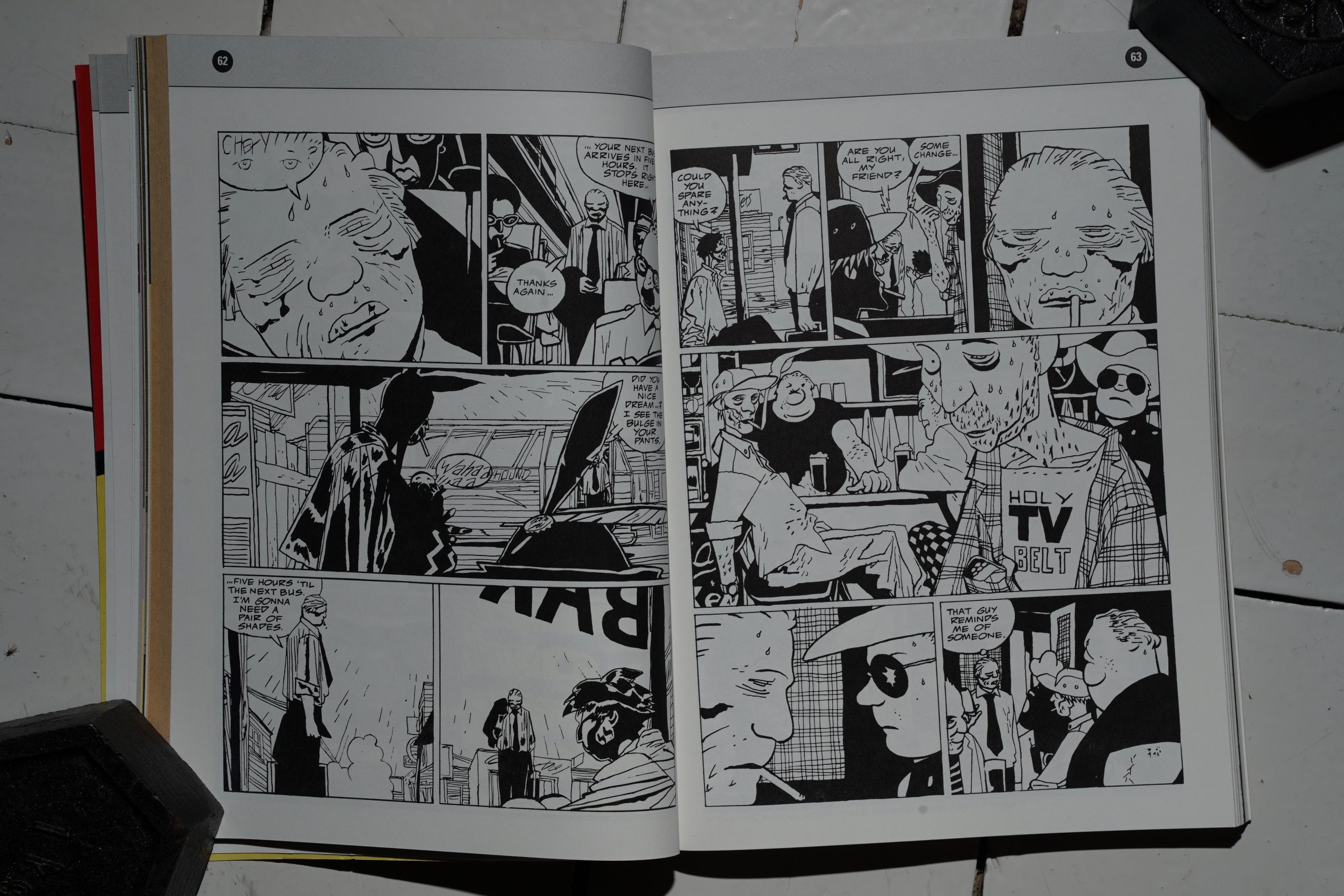

After the Krazy Kat, we’re on a roll here, and it feels like everything coheres in a way: There’s longer pieces, shorter pieces, funny bits, wistful bits and harrowing stuff. This Muñoz/Sampayo strip works well in this format.

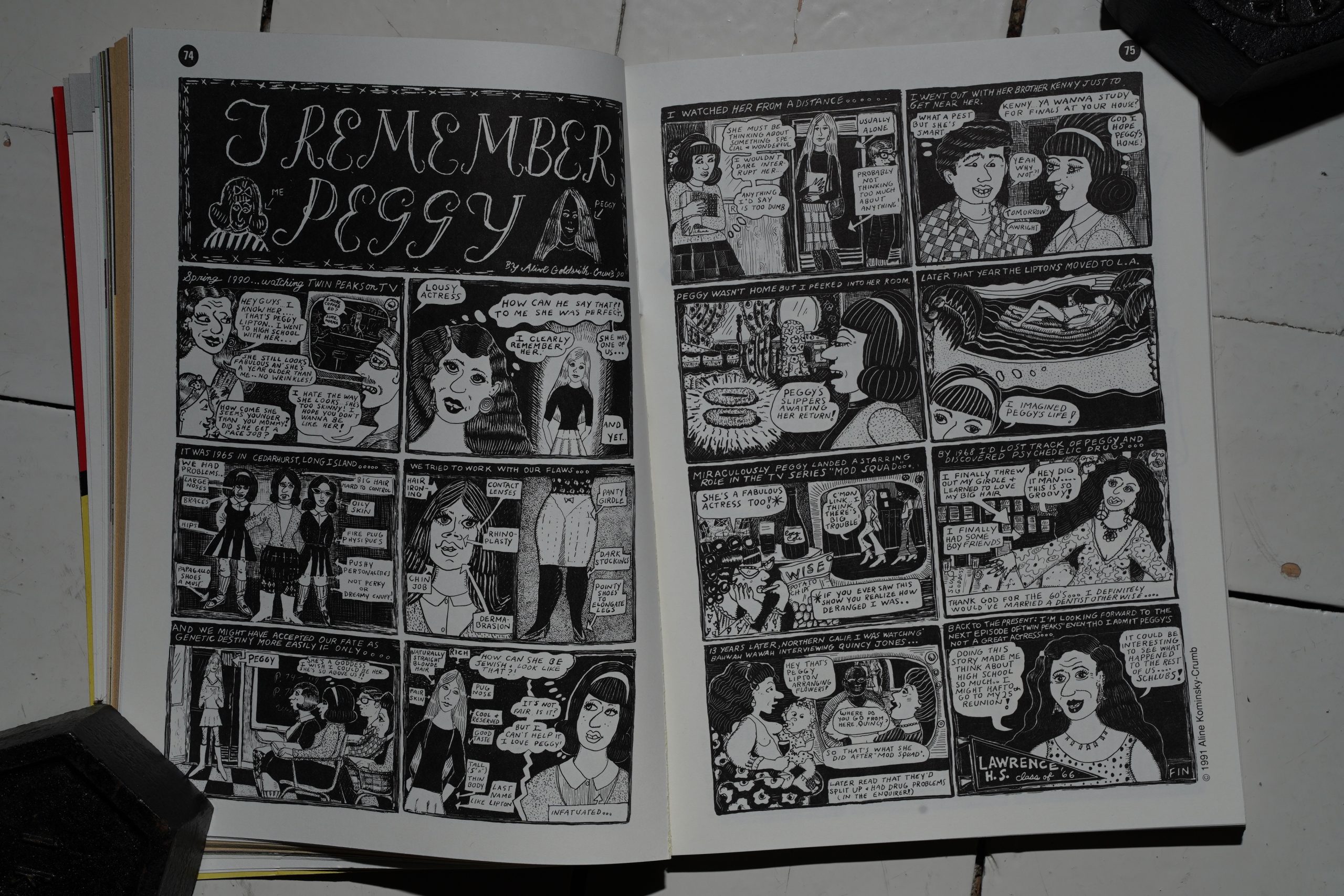

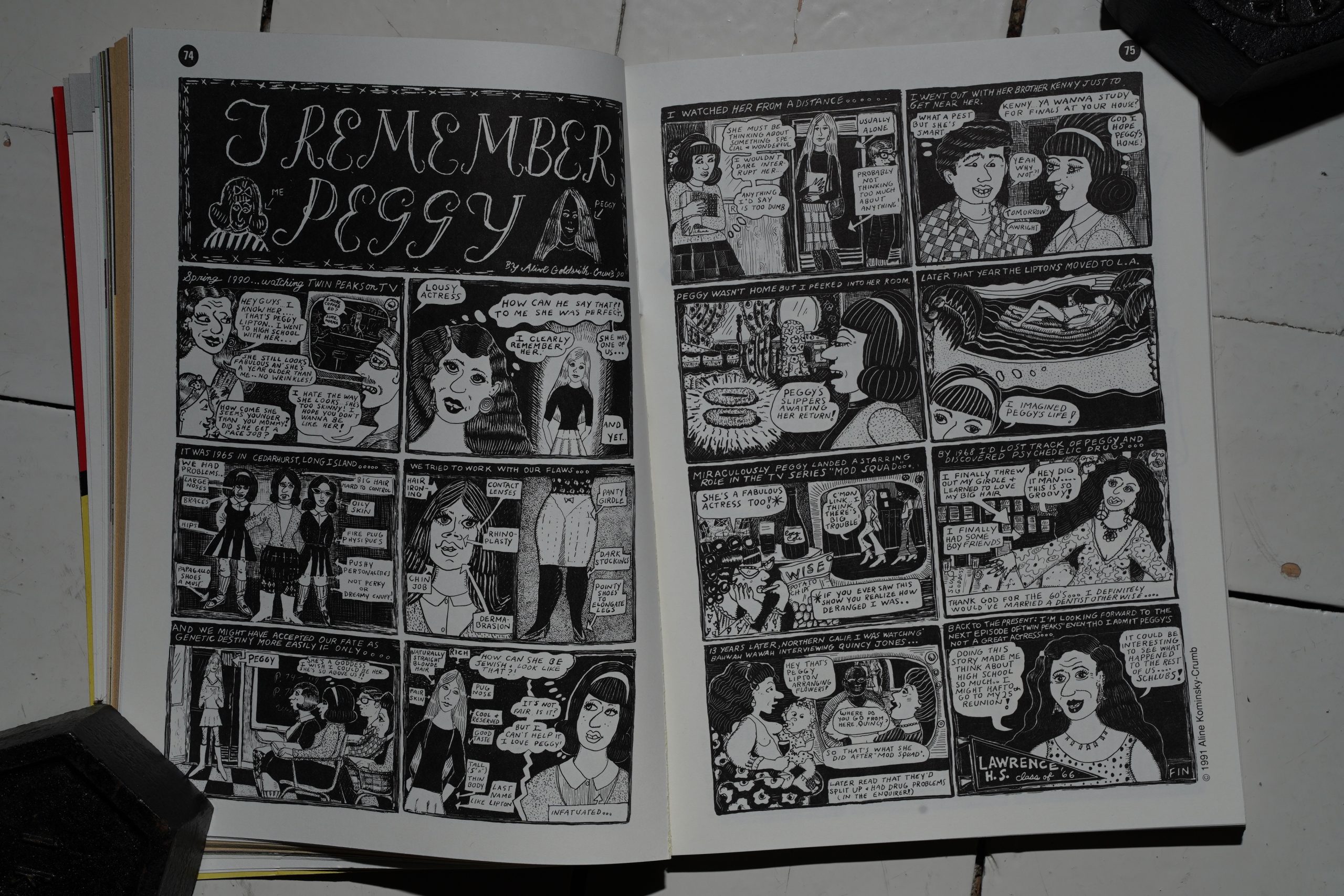

A two-page ditty from Aline Kominsky. Finally.

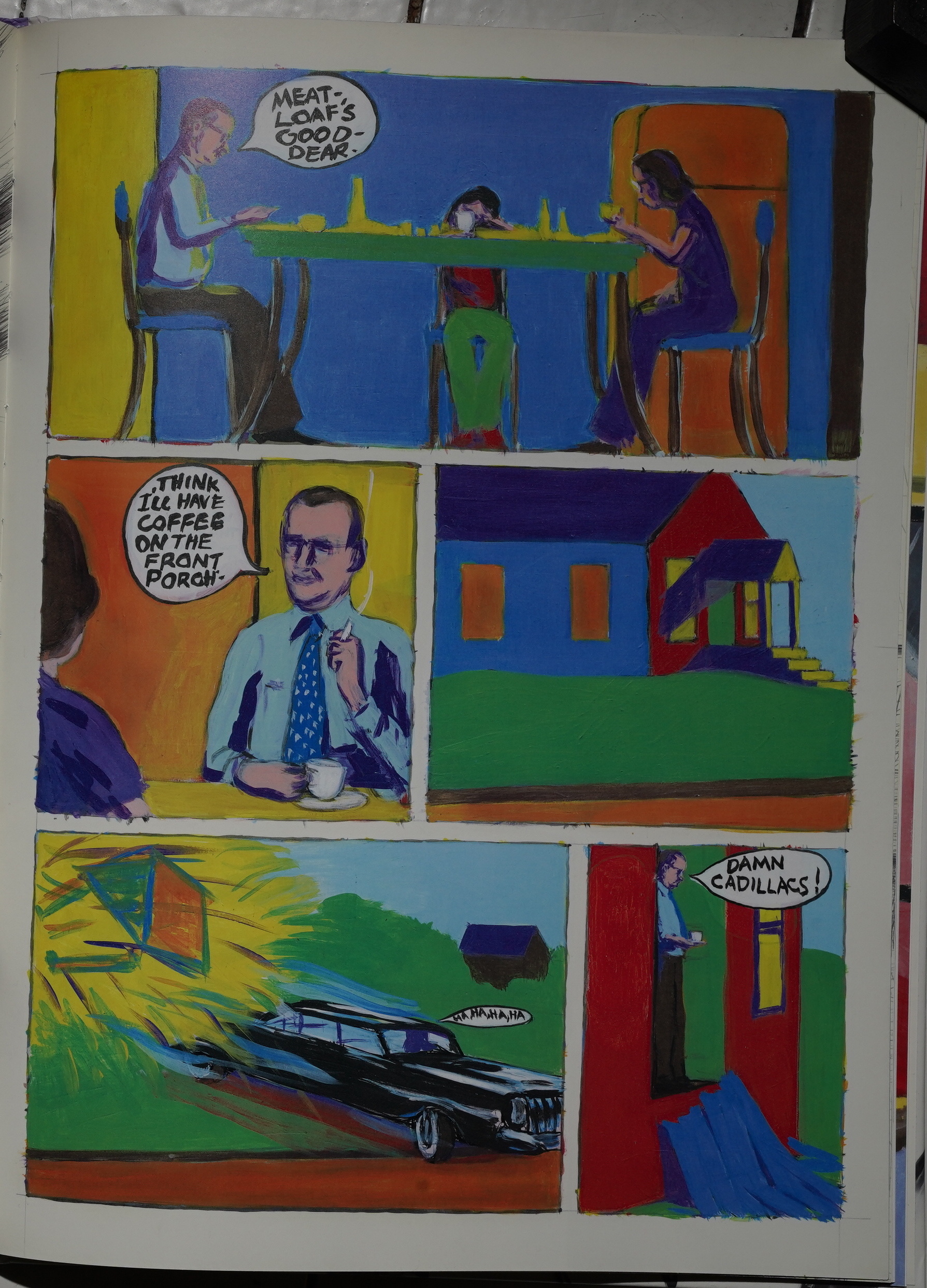

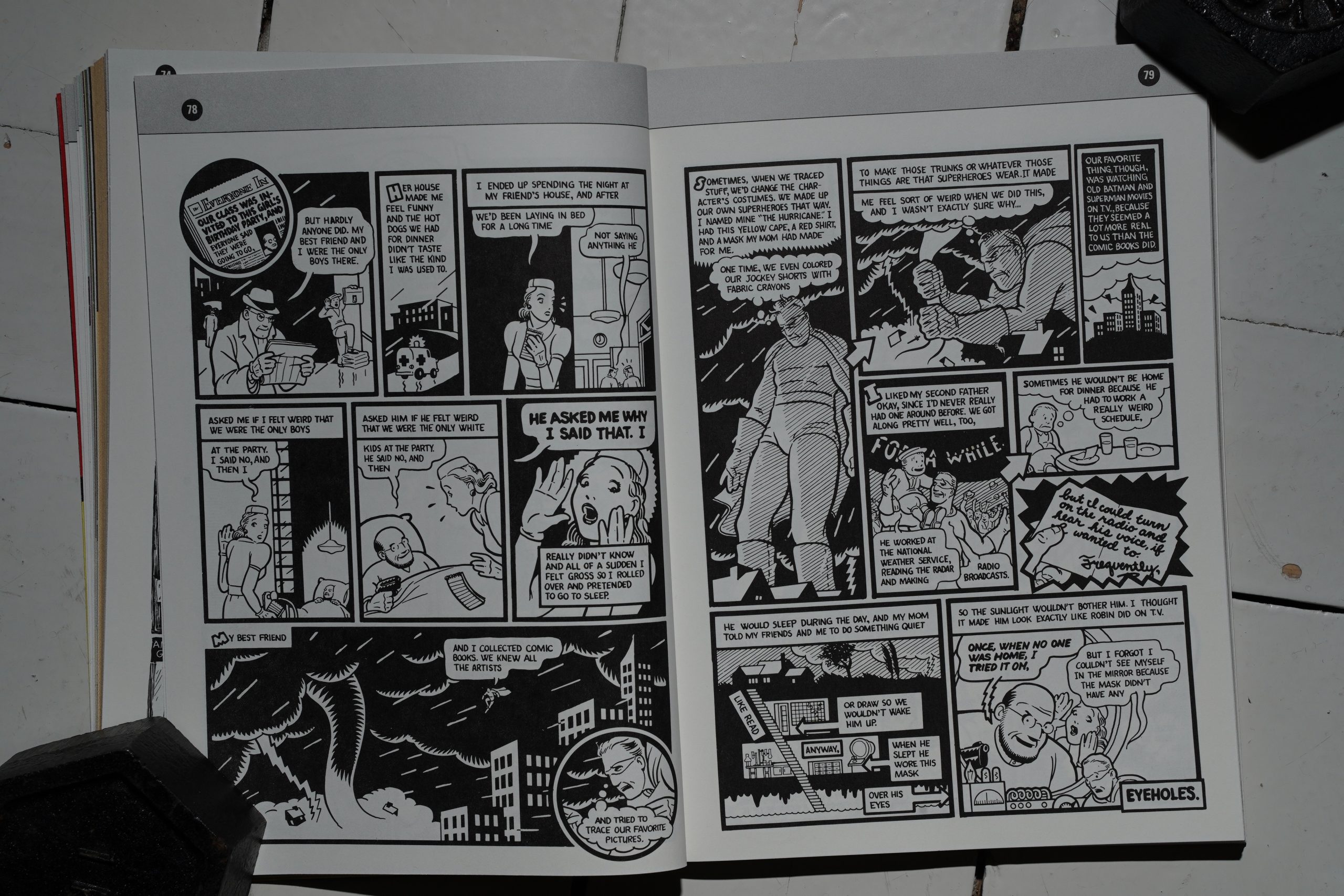

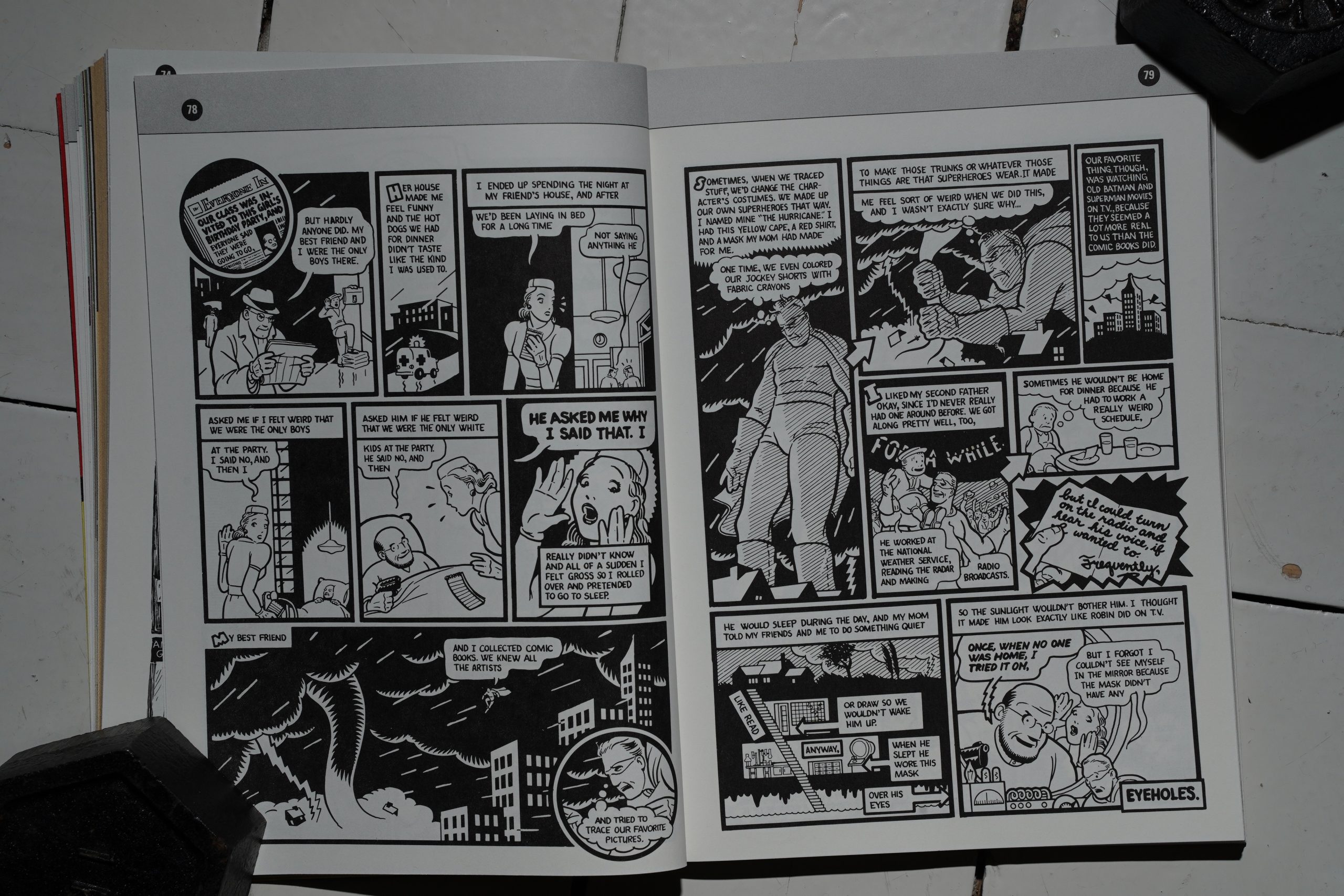

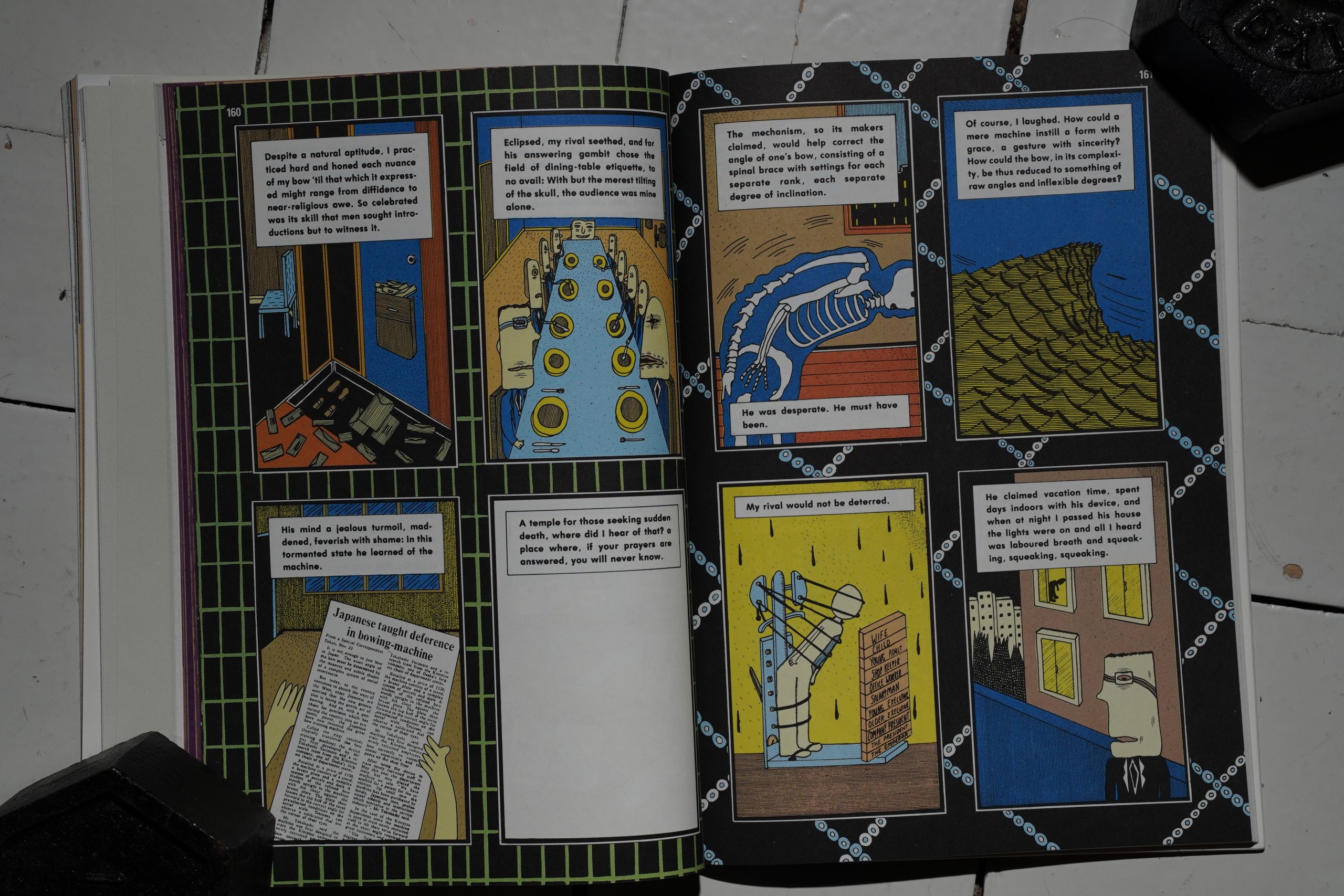

Chris Ware plays with the form, and tells one story in the text and a completely different one in the artwork. It’s a fun schtick, of course, but it really works. It’s an unnerving and affecting piece.

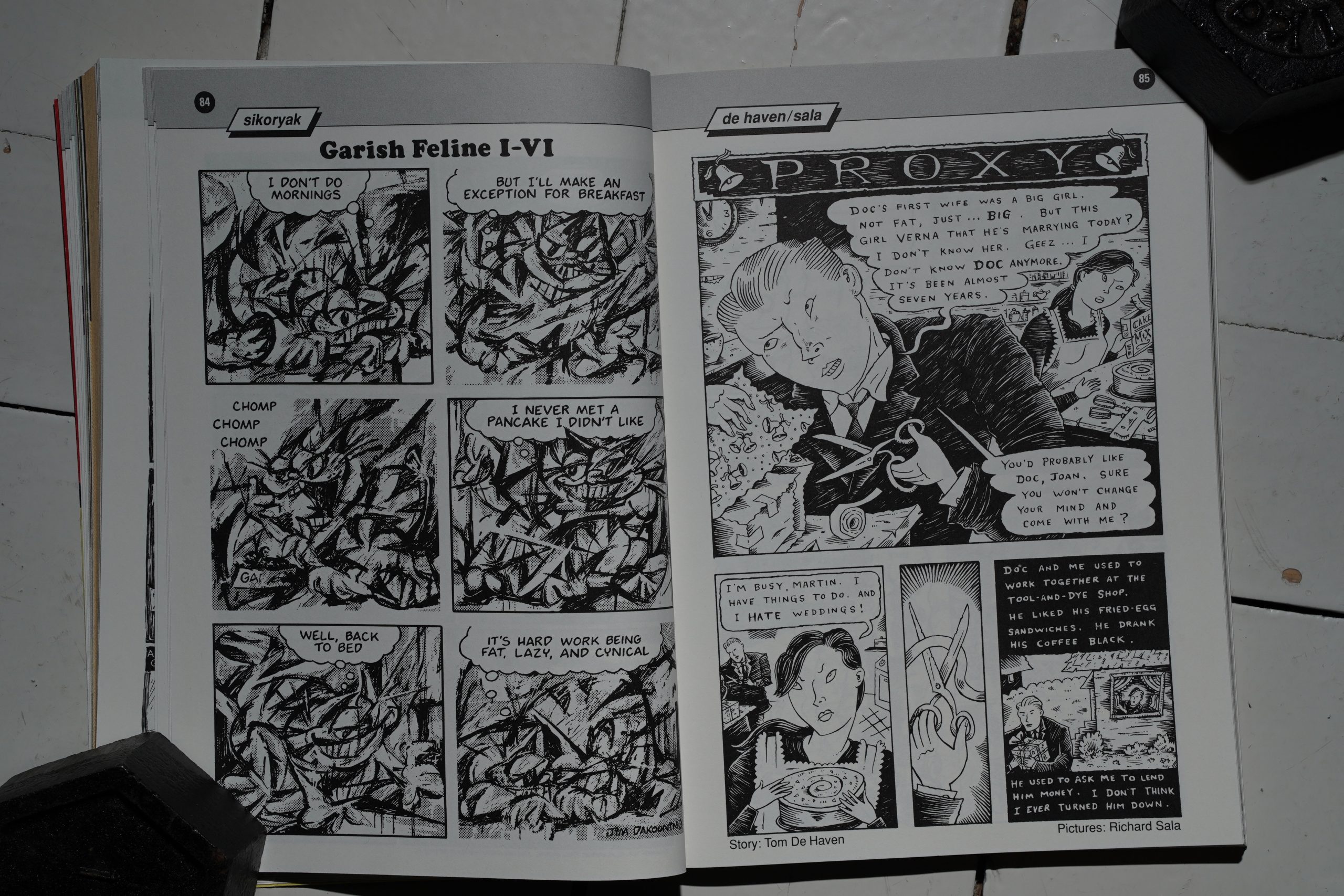

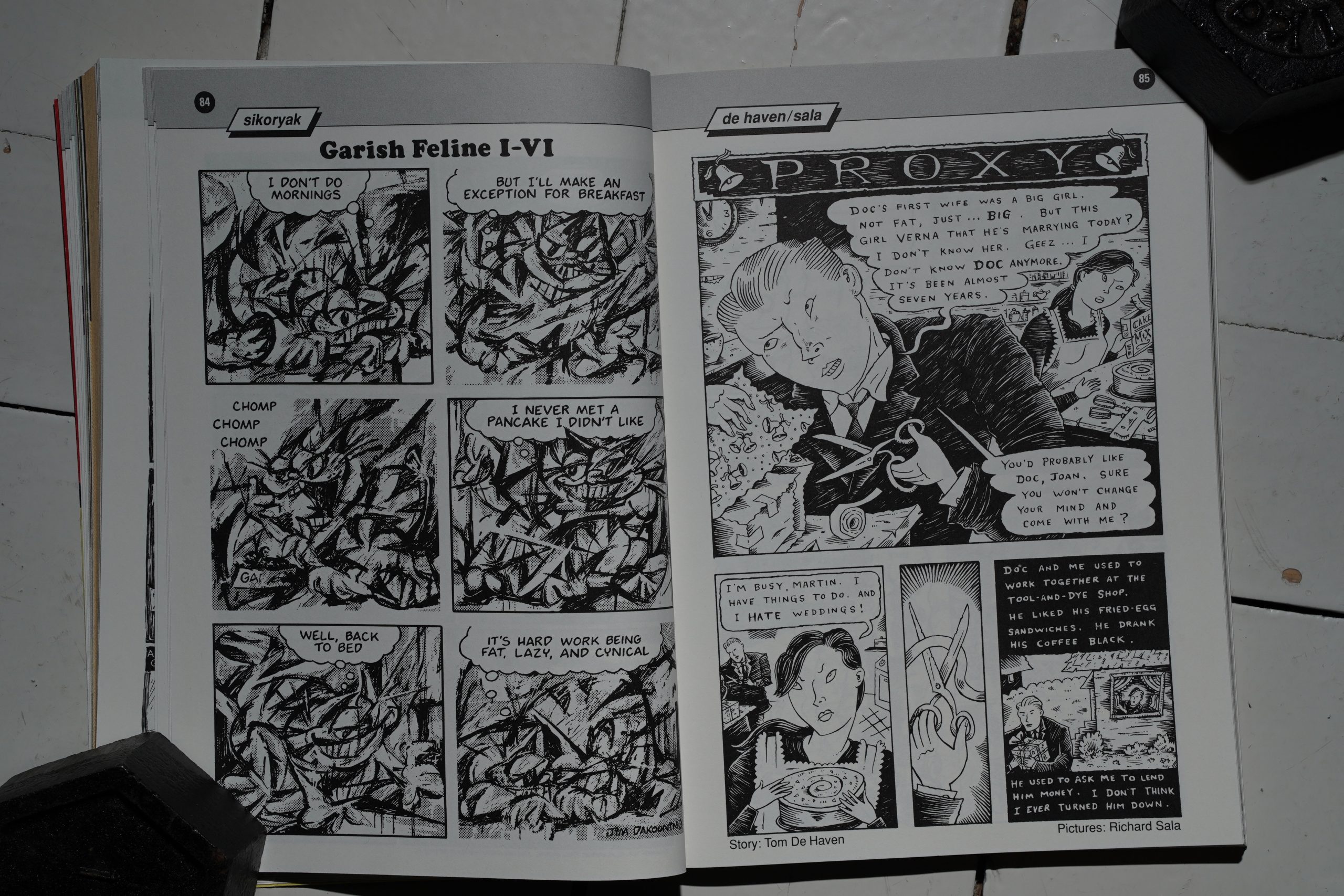

R. Sikoryak deconstructs Garfield, and… Tom de Haven writes a story for Richard Sala to illustrate.

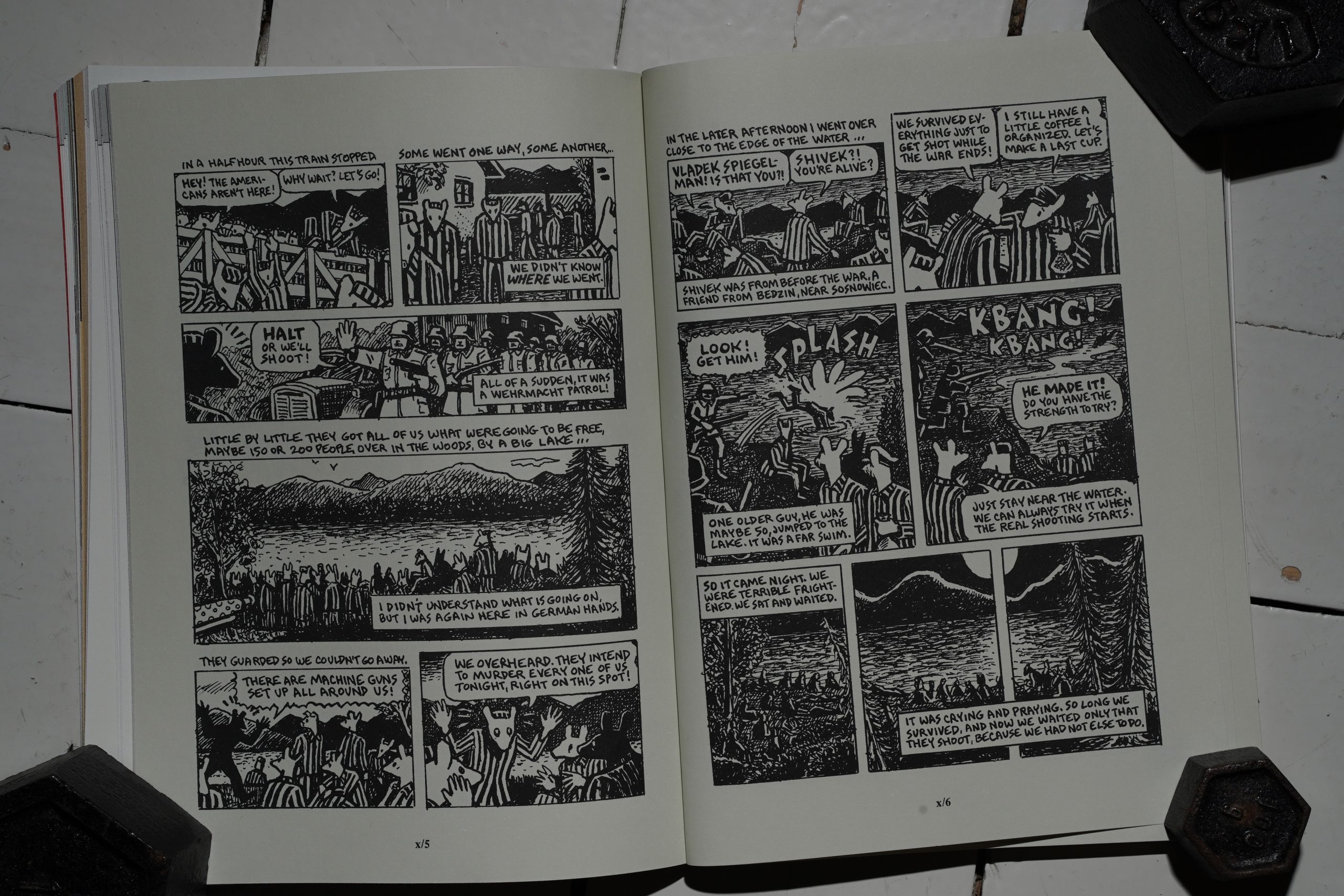

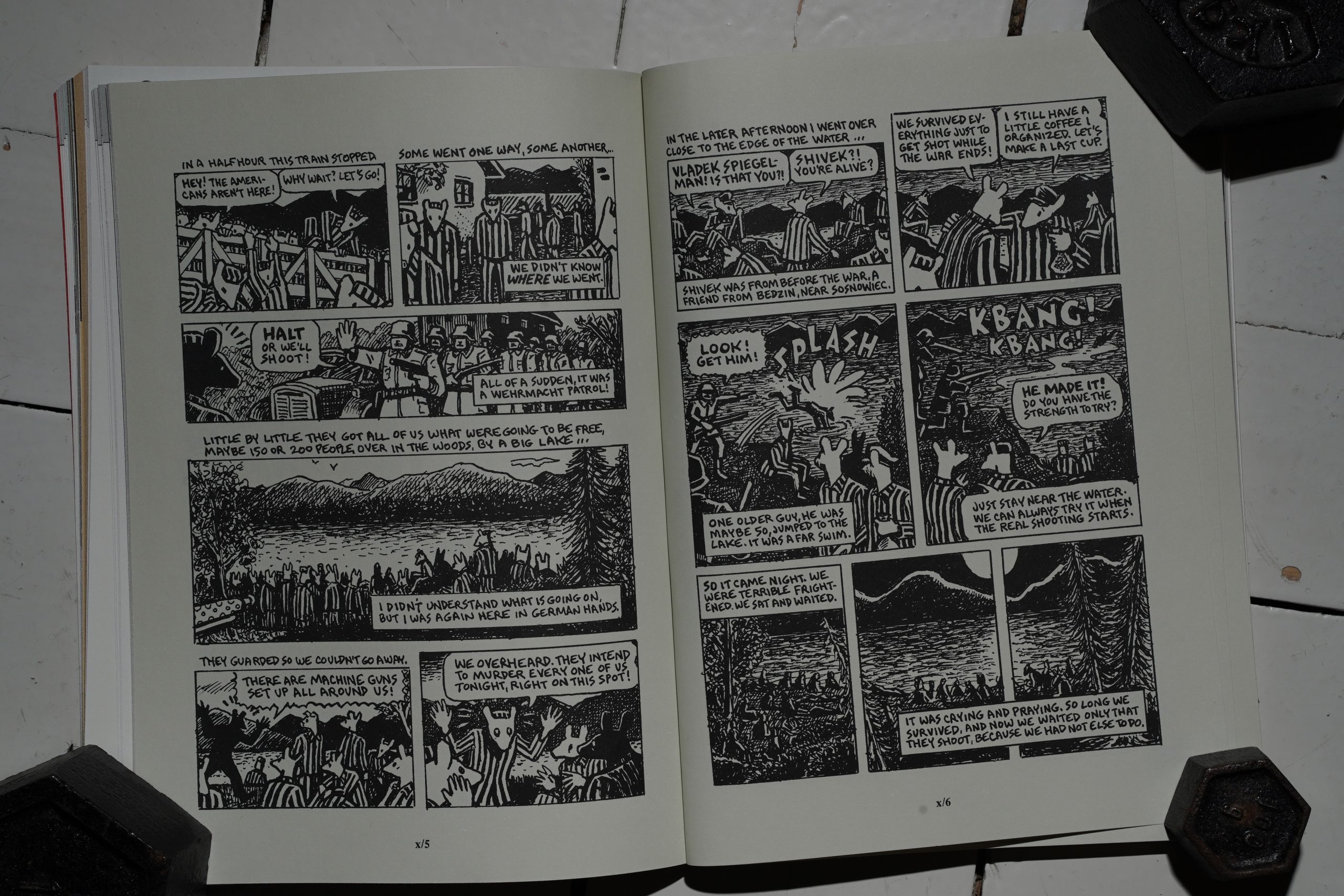

They finally hit on the correct paper stock for the penultimate Maus chapter. It’s a pity Penguin shut down their comics line before Maus was finished… or did the editors shut it down?

We’re on the home stretch in the Maus storyline, but it’s still gripping even as things aren’t as horrific as earlier in Vladek’s story.

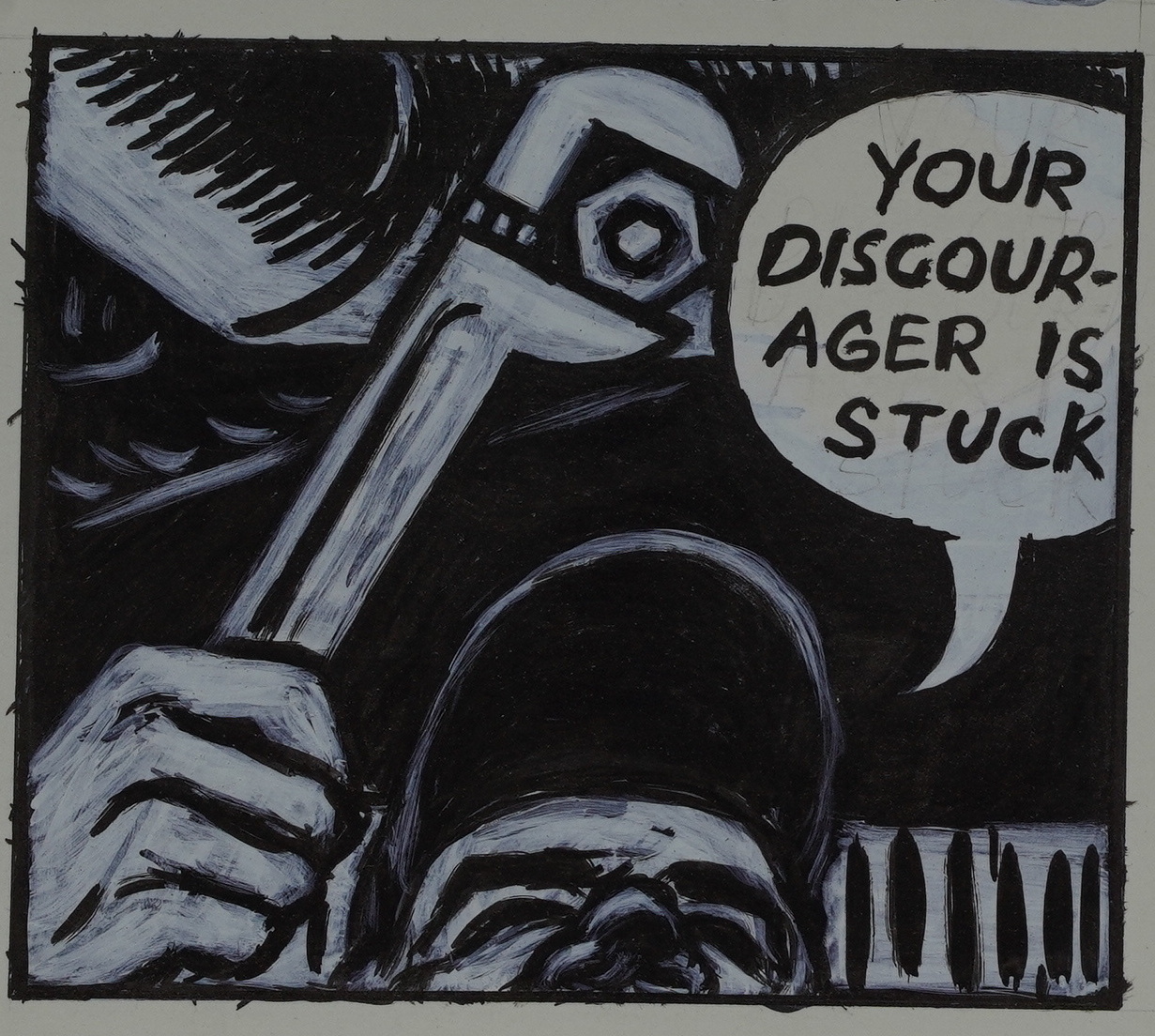

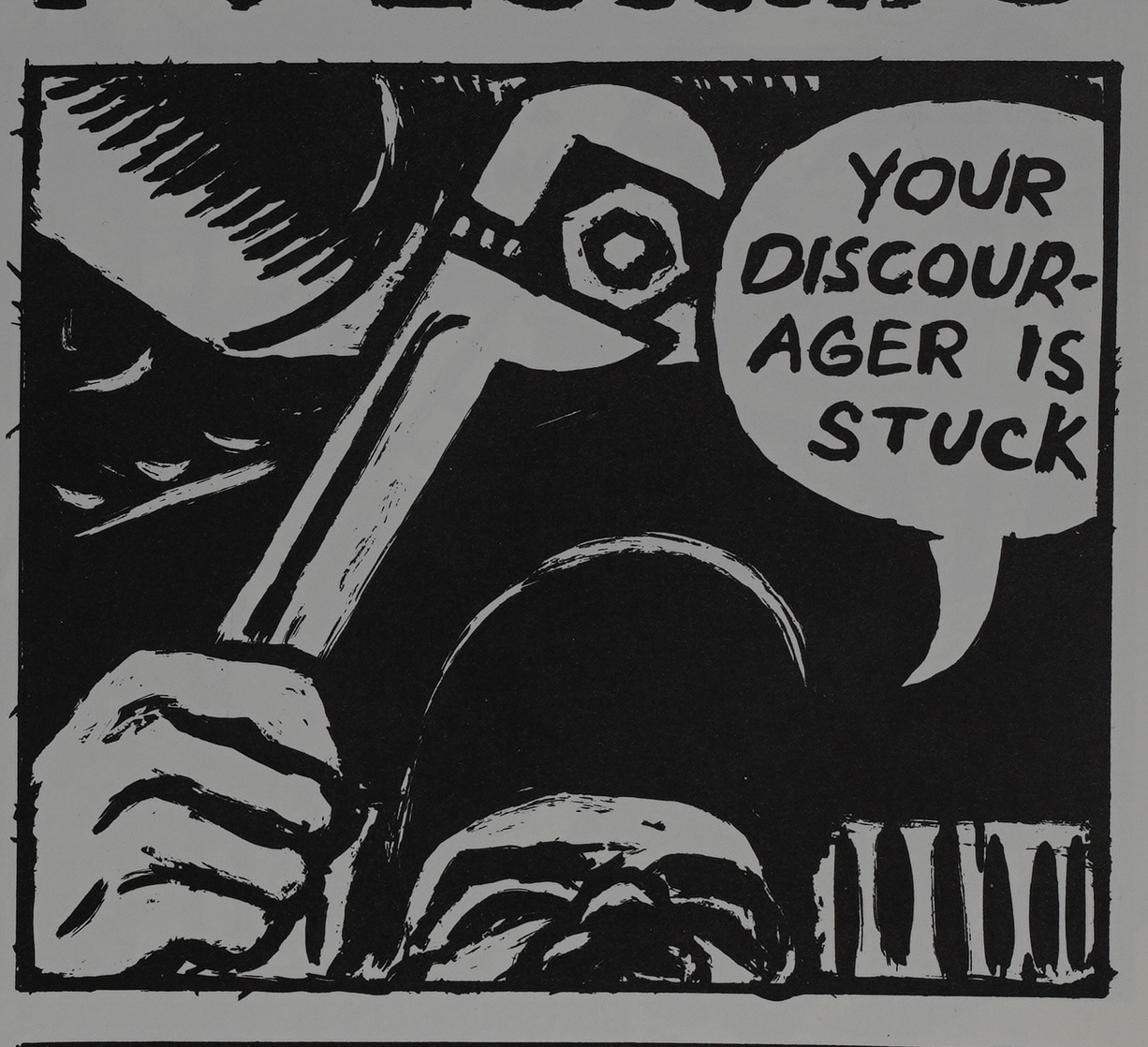

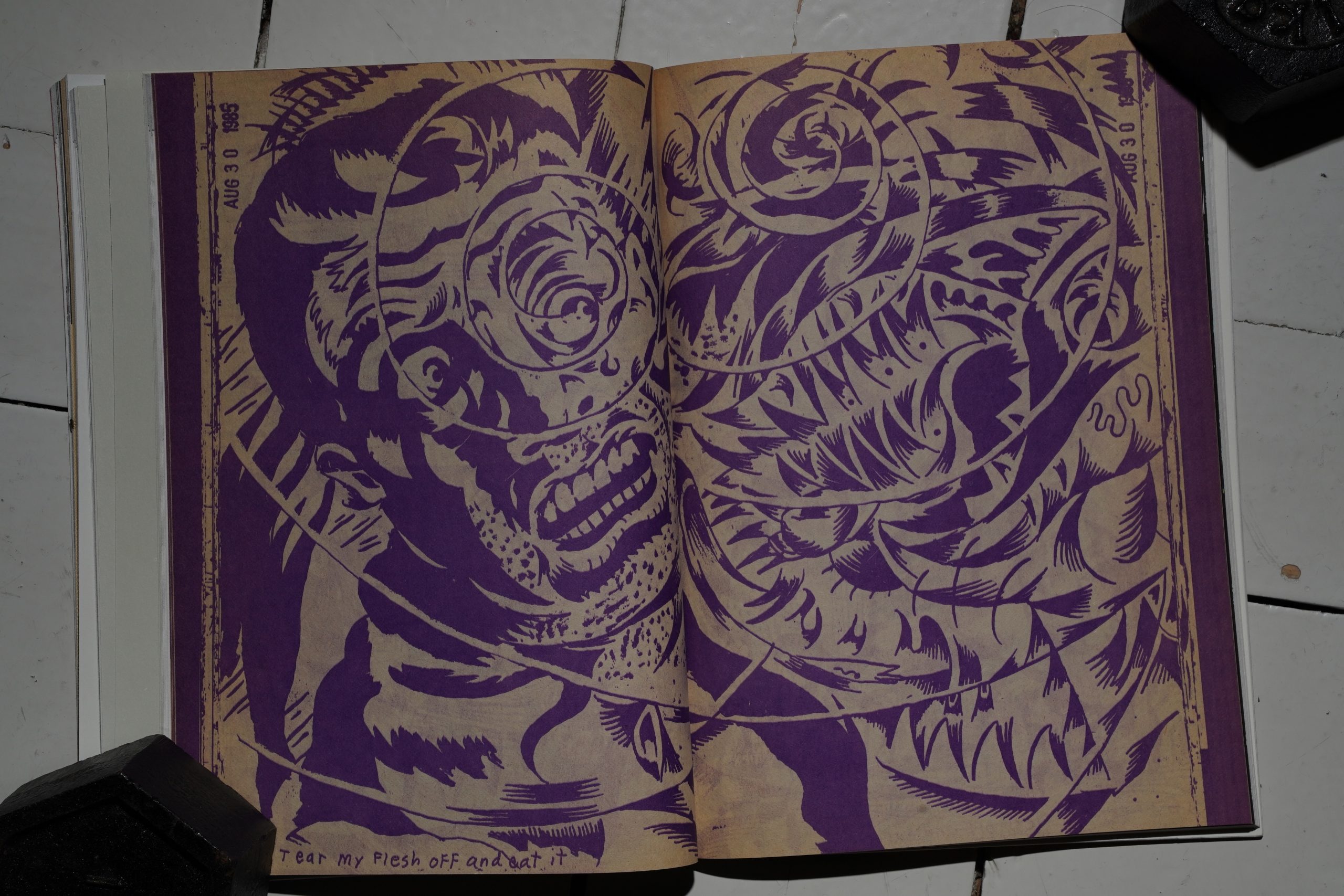

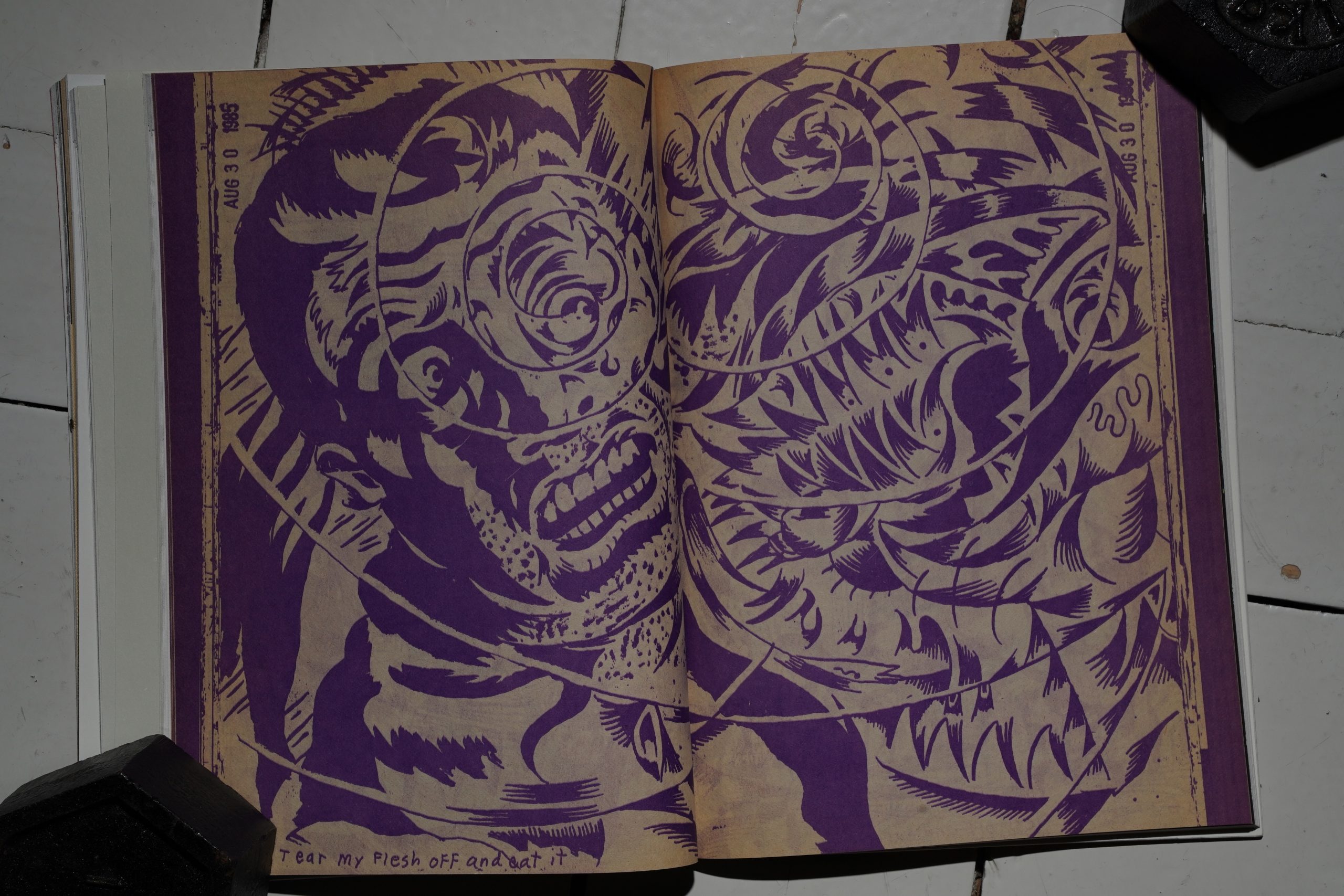

Then… 32 pages of Gary Panter sketchbooks! On newsprint! In purple ink!

Awesome.

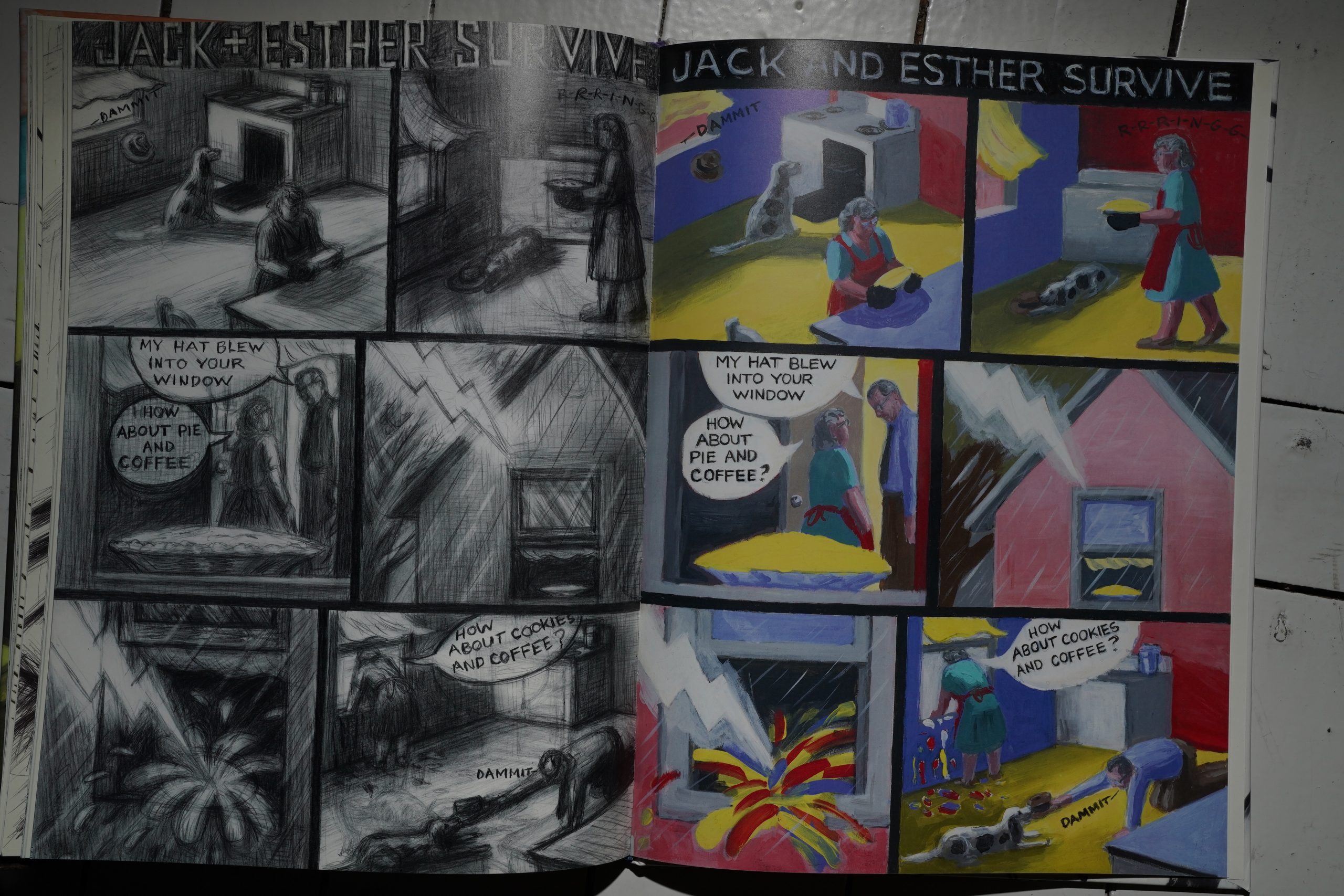

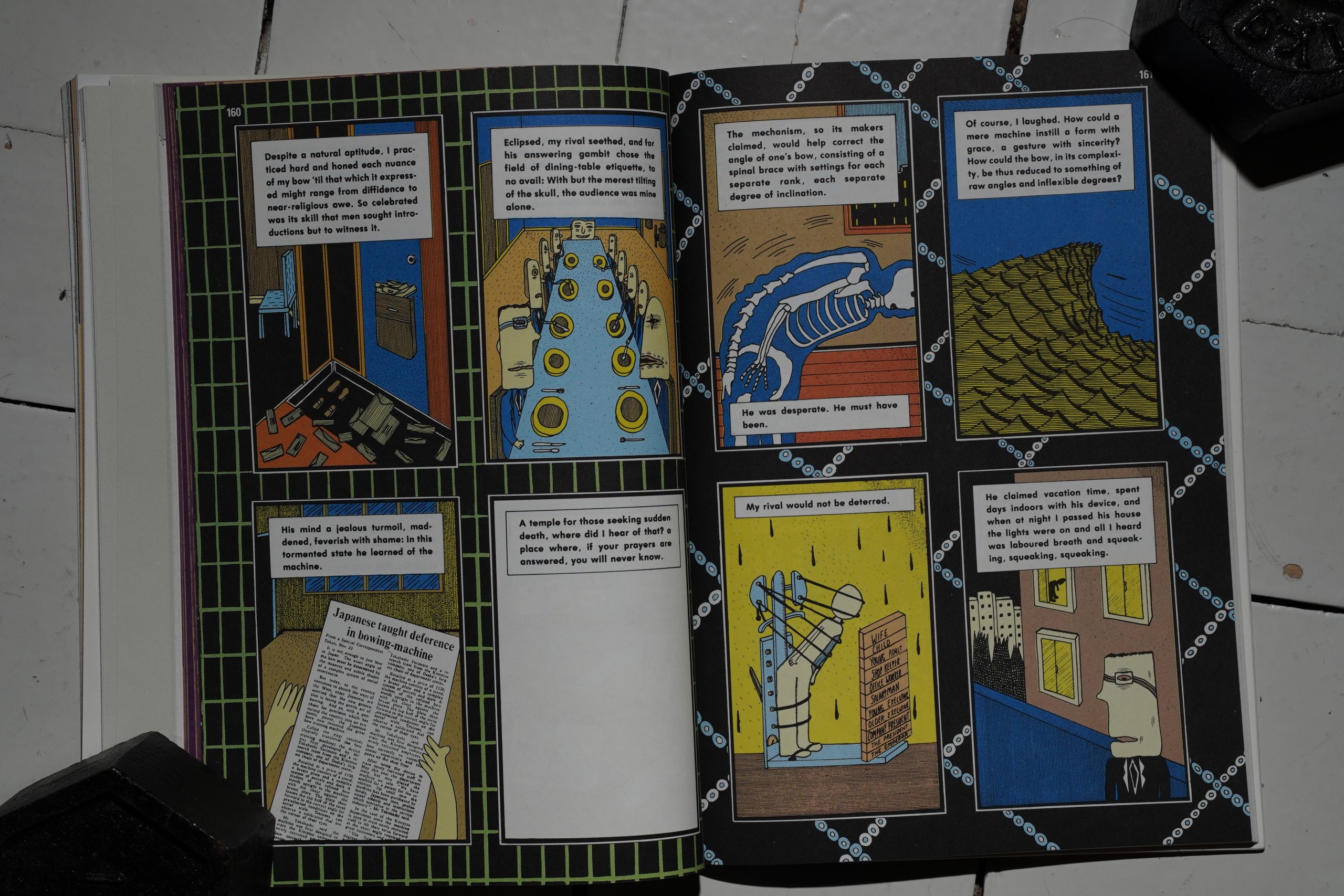

So first de Haven wrote for Sala, and then Alan Moore (yes that one) writes for Mark Beyer?! What’s going on? Did the editors have an idea of pairing iconic artists with writers or something? But then only these two pairs came through?

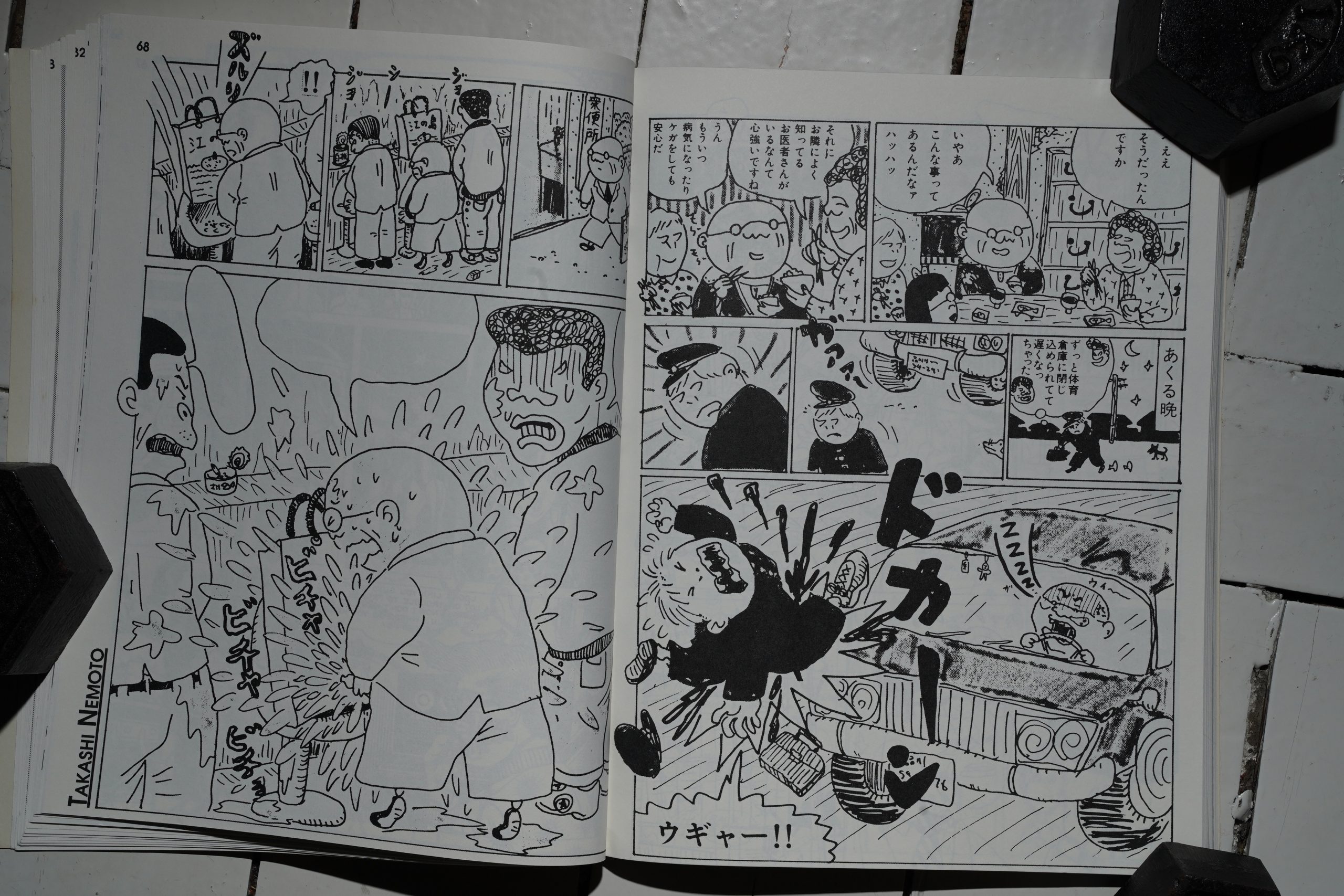

The pairing works — it’s both gripping and amusing. But this “ooh, aren’t the Japanese exotic! So exotic!” schtick was tired already back then.

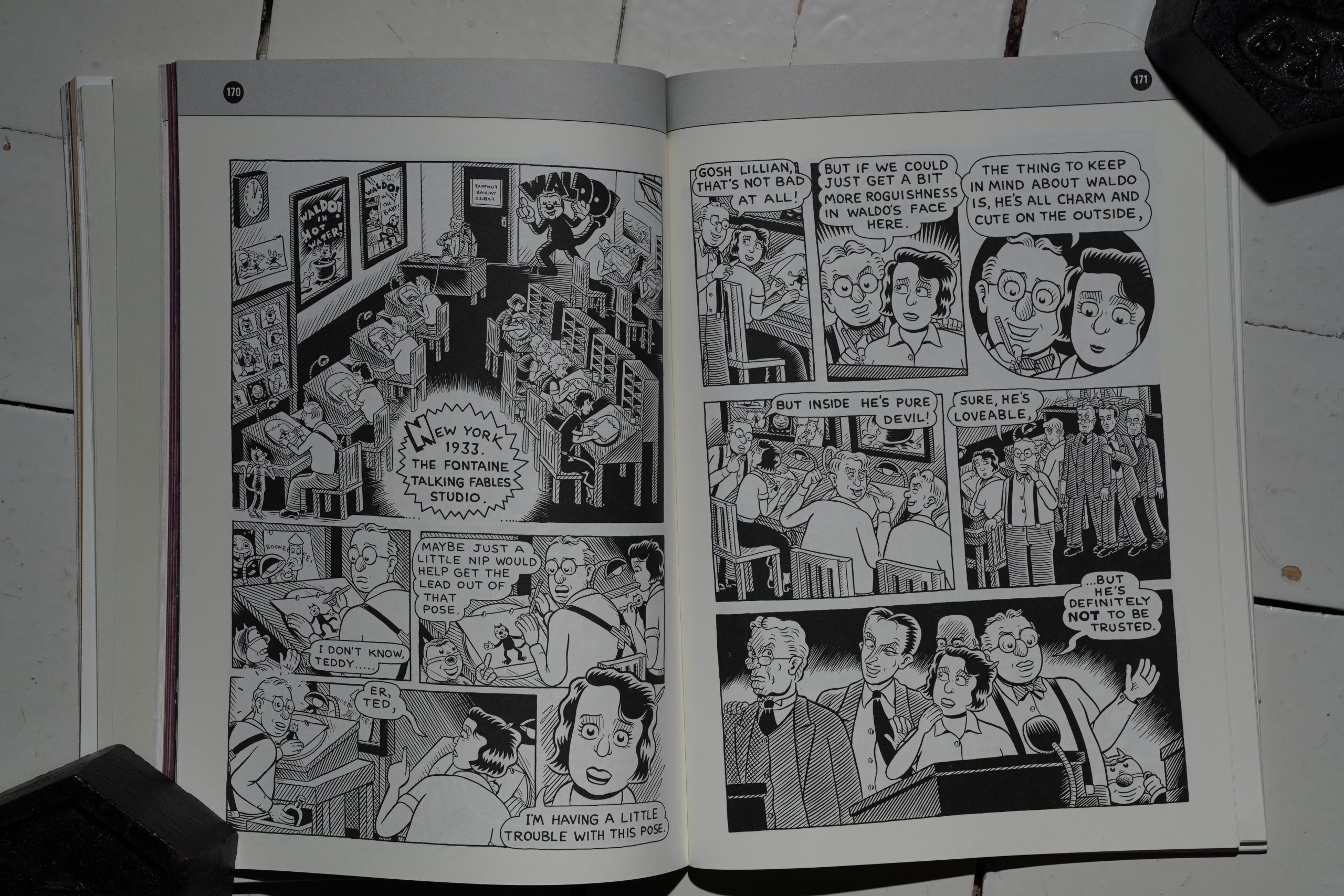

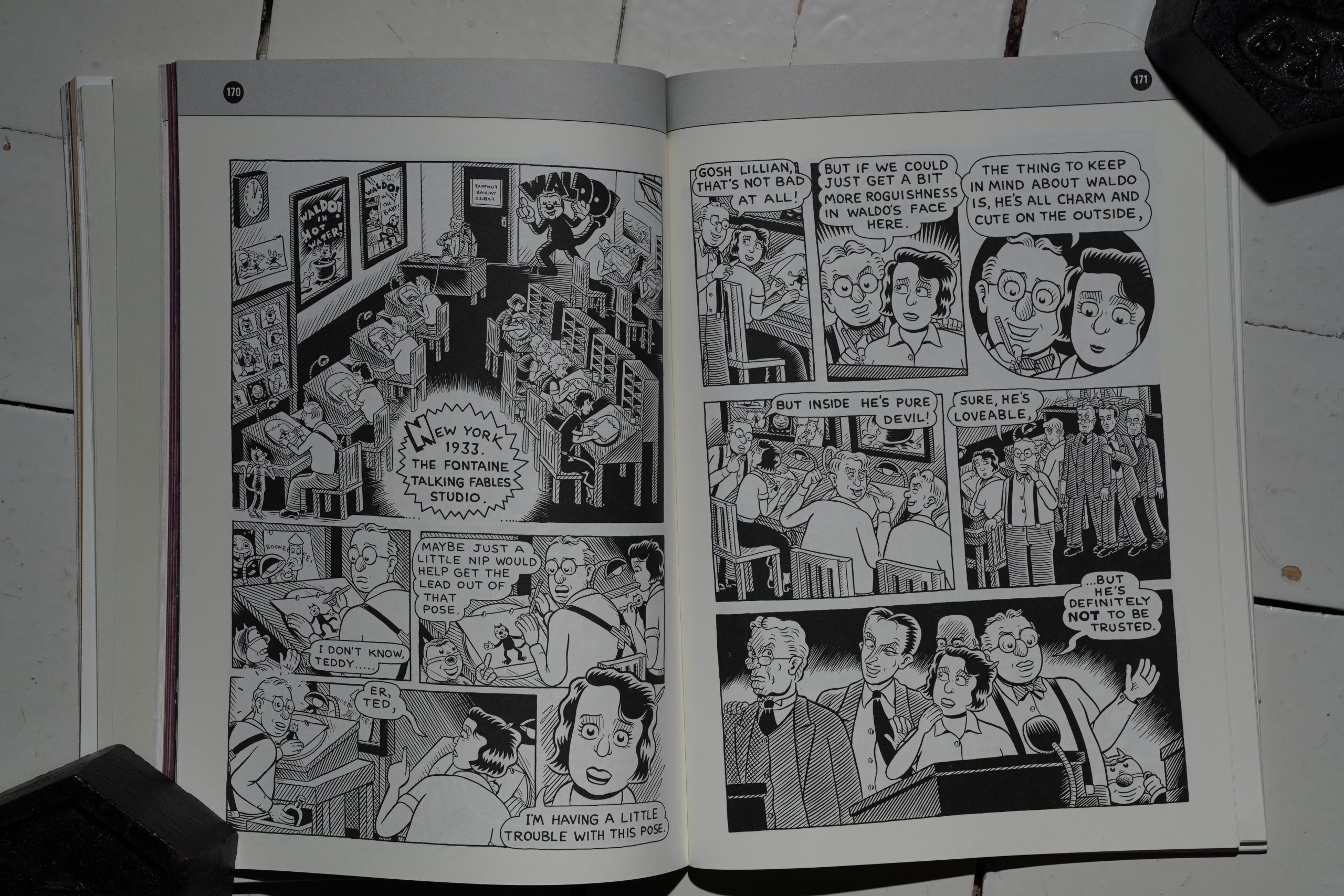

Kim Deitch had had a few shorter pieces in Raw before, but none of them really gelled for me. Here he gets 40 (!) pages, and it’s brilliant: We get the world he’s presenting 100%.

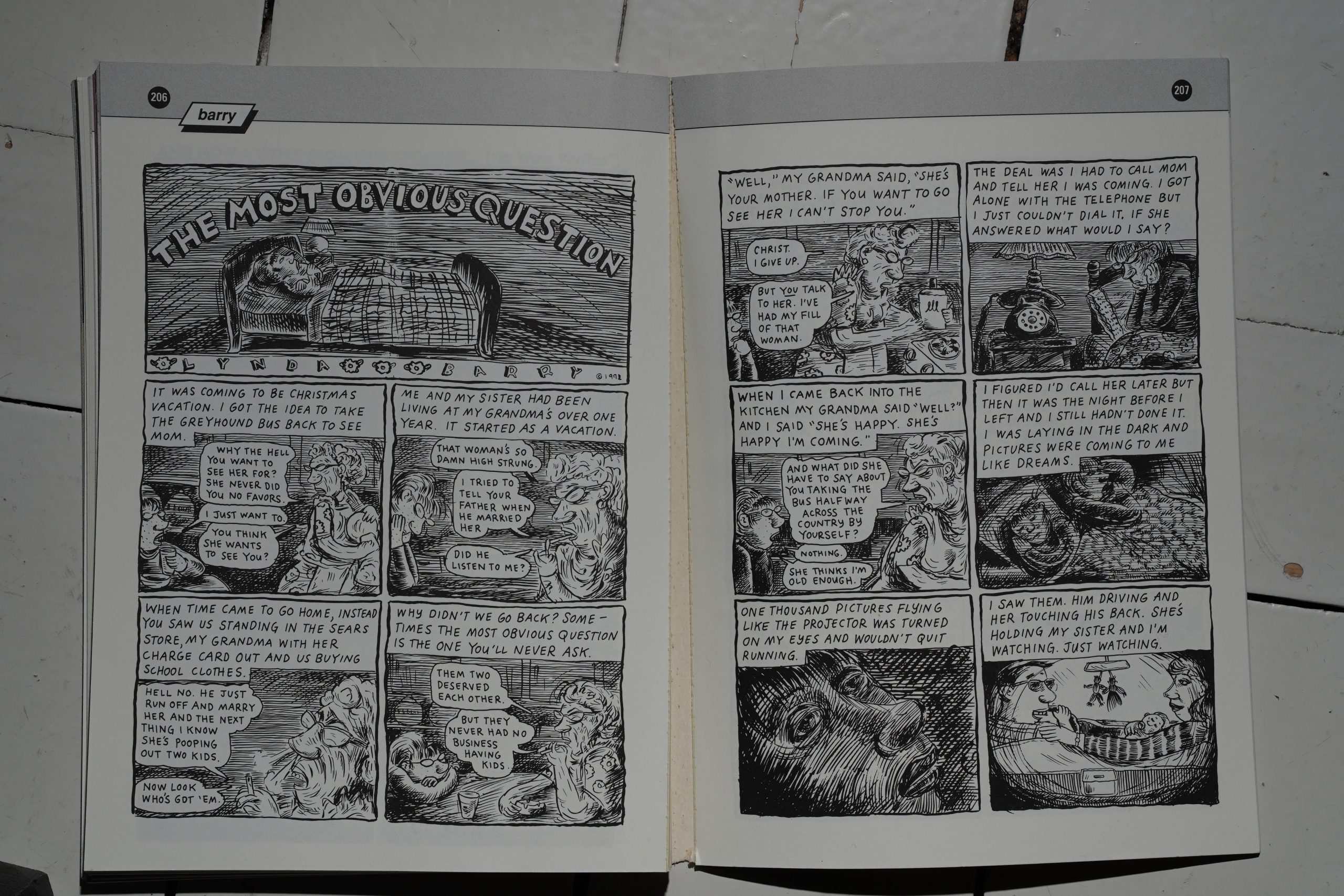

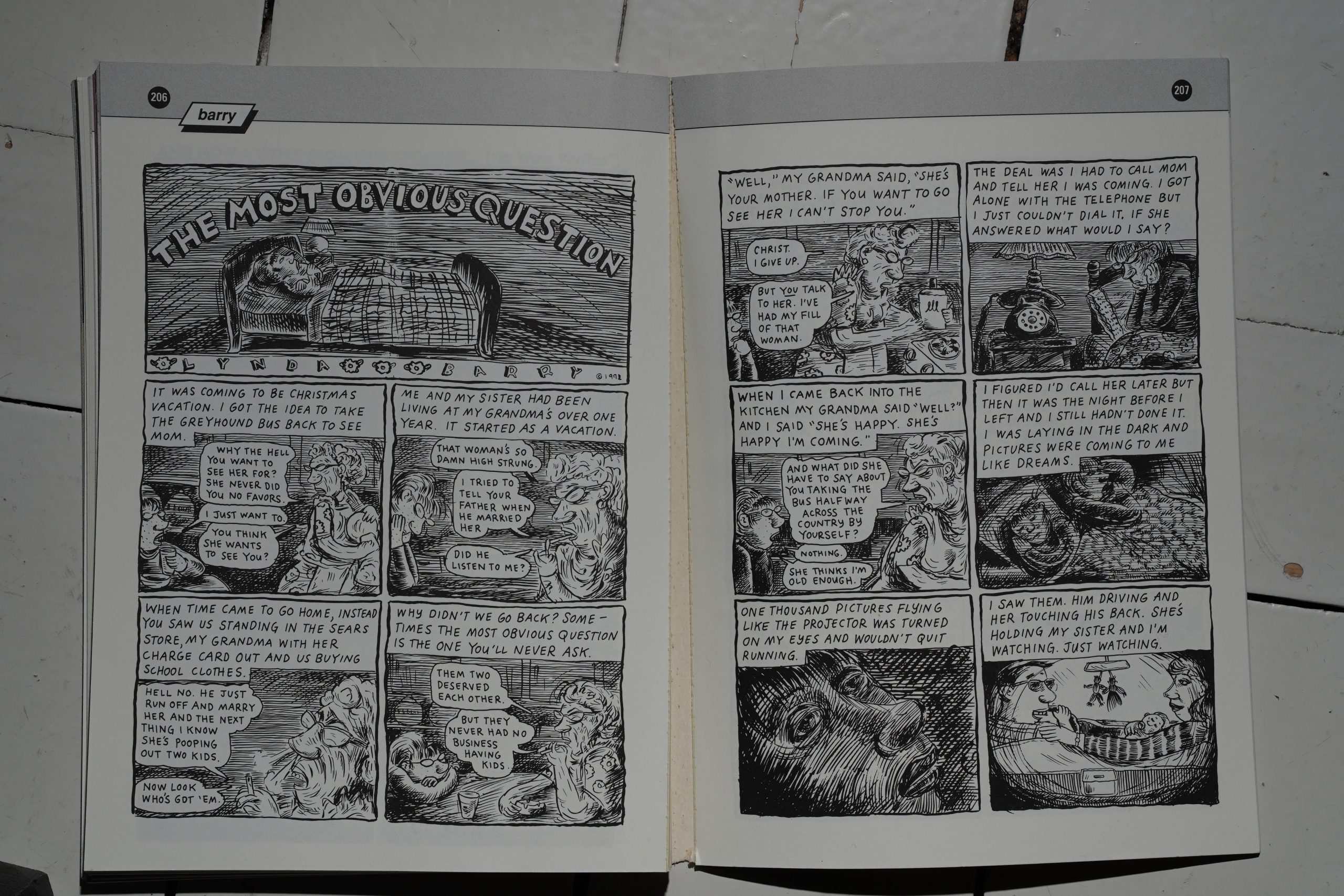

Finally, Lynda Barry returns with her most heart-breaking story ever. It’s amazing, and the artwork’s gorgeous.

So!

I hadn’t read this book since it was published, so that’s 30 years. I remembered nothing about it, except the Moore/Beyer thing, so I wasn’t prepared for just how good it is! It’s the best of the Penguin issues by far: It has that magical flow that some great anthologies sometimes achieve, where it seems like the pieces somehow communicate with each other and create something bigger in sum.

It’s a magical reading experience.

So, of course, it’s the final issue.

Gene Kannenberg, Jr writes in The Comics Journal #200, page 39:

I BEGAN TO REDISCOVER COMICS IN 1991,

after several years of willful disregard.

During my undergraduate years, I had

decided to no longer waste my time or

money on superhero stories — at that

point I didn’t realize that there could be

other kinds of comics — so I just quit cold

turkey. Well, not exactly; somewhere along

the line I picked up Watchmen and The

Dark Knight Returns and the first volume

of Maus, succumbing to the trendy mar-

keting hype of the time. But good as I

thought they were, those all struck me as

anomalies … not that I knew any better.

Then one day on vacation, I saw RAW

Vol. 2 #3 in a bookstore. The cover by

R.Crumb (who?) was a bit different, but

the familiar little Maus icon made me pick

up the book. I flipped through it and saw

styles, subjects —even paper! —that were

unfamiliar to me. On a whim, I bought it

for a little “light reading” on the flight

home. That impulse purchase went a long

way toward changing how I looked at

comics and, ultimately, my Ph.D. disserta-

tion topic. Not bad for a simple little

funnybook.

On the plane my reading was haphaz-

ard, skipping from piece to piece as one

would catch my eye. I read the Mauschapter

first, and as good as it was (and I knew it

would be), it wasn’t my favorite piece in the

book. I grew fascinated by the book’s sheer

variety: of art styles, of narrative techniques,

of historical richness, of subject matter, of

contributors. Though I’ve read a lotof com-

icssince 1991, I continue

to seek out the work Of

Jacques Loustal, Ben

Katchor, Kaz, Munoz &

Aline

Sampayo,

Kominsky-Crumb,

Drew Friedman, R.

Sikoryak, Kamagura &

Seele, Lorenzo Mattotti,

Joost Swarte, Justin

Green, Gary Panter, Mark

Beyer, Kim Deitch, Lynda

Barry, and Kristine

Kryttre, all featured in

RAW vol. 2#3. This is-

sue was also my first

adultexposure to George

Herriman’s Krazy Kat,

with its inclusion of the

extended “Tiger Tea” se-

quence of daily strips

from May 15-July 16,

1936. Talk about variety!

I started with the shorter strips.

Krystine Kryttre’s “Between the Lines” was

my first exposure to the scratchboard

technique in comics, and I was amazed at

the expressiveness of the art — plus the

story’s movement from tragedy to com-

edy (only amplifying the tragedy) was

engaging, especially over only ten, word•

less panels. Kamgura & Seele’s “A Day in

the Life of Cowboy Henk” was delightfully

absurd, while Kaz’s “Little Bastard” — an

orgy of shape, color, and minimalist dia-

logue — was just plain weird (although I

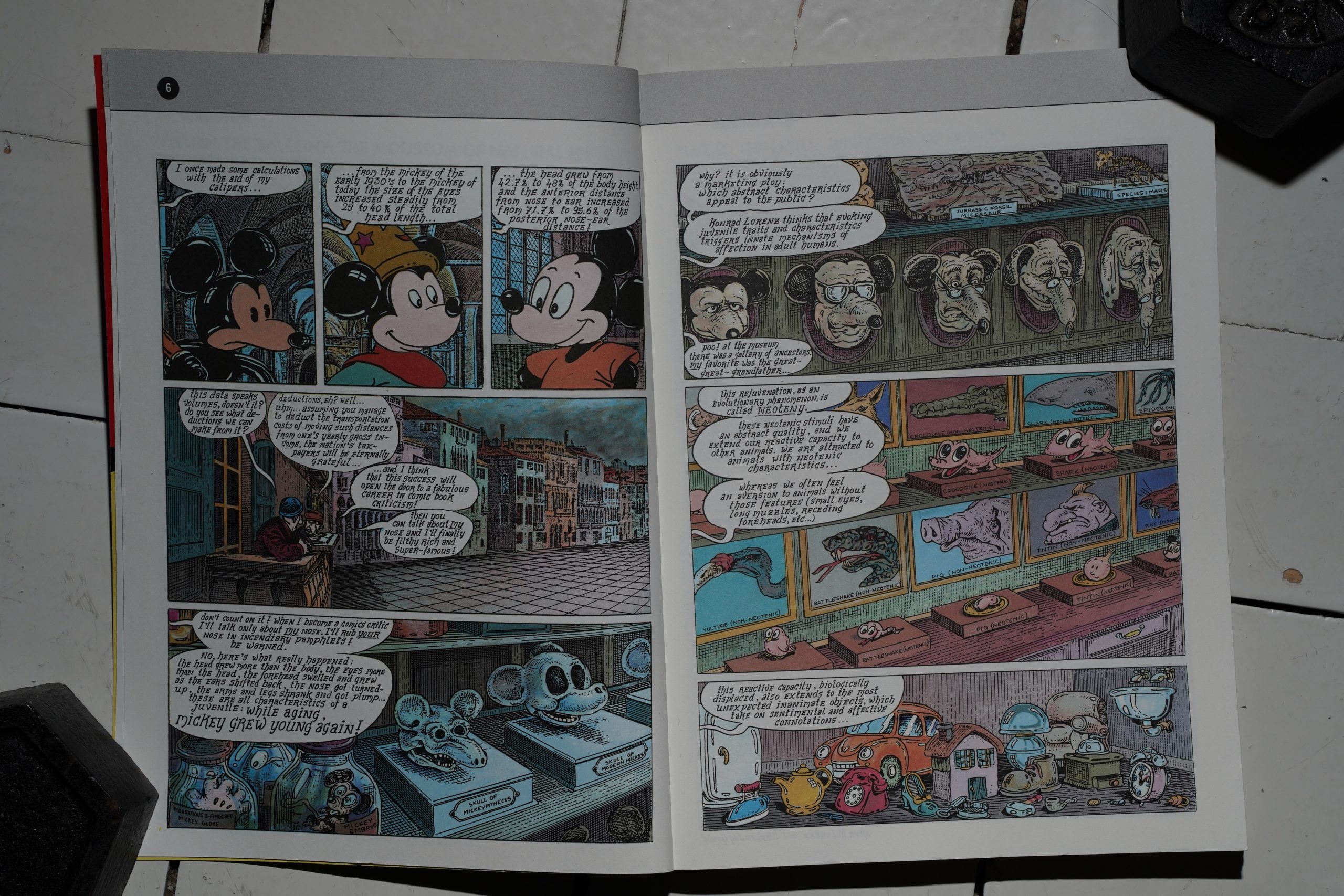

was fascinated all the same). Francis

Masse’s essay on Mickey Mouse and the

appeal Of the neotonic, “The Mouseum of

Natural History,” made me chuckle and

think. For all their humor, these strips

were carefully crafted in ways that my

superhero-trained mind hadn’t before con-

sidered.

The longer stories were even more

affecting. Alan Moore’s script for “The

Bowing Machine” appeared to flow effort-

lessly from history to philosophy to psy-

chology, while Mark Beyer’s primitivist art

was at once elusive and disturbingly con-

crete. Kim & Simon Deitch’s epic “Boule-

vard of Broken Dreams” was, quite simply,

a revelation: its mixture of Fleischer ani-

mation-style art and exploded page de-

signs, along with meditations on anima-

tion, imagination, and ego, brought a dis-

turbingly accurate humanness to its char-

acters. This issue was also my first expo-

sure to the work of Lynda Barry; “The Most

Obvious Question” introduced me to

Barry’s gift for narrative voice, a prose

style at once beautifully lyrical and pain-

fully honest. From this story I observed

how important it is in comics to choose

which moments to illustrate, and which to

not. Barry’s spare use of dialogue in favor

of heavy narration gave the moments of

“action” a distinct life of their own. Here

were “comics” which revealed just how

inadequate that term truly is.

Most significant for me, however, was

Chris Ware’s “Thrilling Adventure Sto•

ries,” a six-page “superhero story that

wasn’t.” Even now it stands up as one of

the strongest pieces he’s ever done. The

visual narrative is a fairly clichéd super-

hero vs. mad scientist story, but the text

— while fitting into traditional caption

boxes, word balloons, sound effects, etc.

— tells a very different story, of a young

boy’s exposure to, and inability to com-

prehend, racism and other family faults.

“TAS” was the first comic I’d ever read

which aggressively challenged my notions

about what comics as an art form were all

about, which made me consider just how

fraught with potential this combination of

words and pictures could truly be if taken

seriously. If I had read Will Eisner’s Comics

and Sequential Art I would have known

that already, but discovering it “on my

own” thanks to Ware’s work made the

realization all the more powerful.

I’ve heard more than one person com-

plain that they simply skipped over “TAS,”

that they’d seen superhero parodies before

and certainly didn’t want to see them in

RAW. Given Ware’s subsequent acclaim, I’d

like to think that those naysayers have

since gone back, actually read the piece,

and discovered how wrong they were. Su-

perhero parodies generally attempt to

deconstruct the superhero genre, expos-

ing its inherent absurdities; “TAS,” how-

ever, deconstructs the comics form itself

to expose its strengths. I’ve since used “TAS’

in the classroom to introduce students to the

complexities of comics. Reading it is an exer-

cise in itself, one which initially leaves stu-

dents more than a bit baffled; but through

discussion they become acutely aware of

the possibilities and potentials of comics

due to the form’s synergistic combination

Of words and pictures.

Even without Ware’s contribution, RAW

Vol. 2 #3 would be perhaps the most

influential comic I’ve ever read; like every

other issue in the series, it served up a

bountiful selection of comics delicacies,

and I hungrily devoured them all. RAW

was my introduction to alternative Ameri-

can comics, European comics, and comics

as a unique artform. When I was younger,

I used to think that I loved comics, but I

can see now that what I’d really enjoyed

then were simply superhero stories. RAW

Vol. 2 #3 taught me how to appreciate

comics. •k

I didn’t mean to quote so much here, but it’s all so correct that I can’t find anything to edit out here. Sorry!

Alan Moore is interviewed in The Comics Journal #138, page 87:

Who else do I like? This is the problem when you’re

talking like this, you end up neglecting so many people,

and you think, “Shit, why didn’t I mention that?” Of

course there’s what Art Spiegelman’s doing at RAW The

new pocketbook-sized editions of RAW; if anything, are

better than the large-scale RAW of old. The last two issues

that I’ve seen are brilliant. It’s accessible without losing

any Of its fervor and experimentation. In fact, as soon as

I finish this episode Of Big Numbers that I’m writing, the

very next project that I’ve got tostart on is writing a strip

for Mark Beyer of RAW which will be very interesting.

I don’t know how the fuck I’m supposed to do that. I spoke

to Mark on the phone, and he sounds like a really great

bloke, undaunted by his brilliance. Mark Beyer’s style is

so personal that the big problem… I think I’ve got a story

that will work, that won’t just pointlessly pastiche Mark’s

own style, but will work with his style Of drawing.

GROTH: You might want to write something really cheer-

ful and upbeat.

MOORE: Yeah, well, I thought of that, but.

GROTH: Filled with people pleased with their lot in life

and just thrilled to be alive.

MOORE: I don’t know, I couldn’t see it somehow, Gary,

you know what I mean? [laughter. I He does have a lot

Of humor in his work, but… You could be right. The

Story I’ve got is a little more downbeat. I don’t know, we’ll

see how it turns out.

GROTH: Frolicking on the beach.

MOORE: I can see Amy and Jordan at the beach, that’d

be good.

Frank Young writes in The Comics Journal #145, page 50:

Since its inception a decade ago,

Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly’s R4W has

been the standard-bearer for progressive com-

ics. RAW has provided a necessary and solid

bridge between the farthest reaches of the avant-

garde and more conventional (but equally val-

uable) work.

The newest RAW, third Of the smaller, thicker

volumes published with Penguin Books, is the

finest to date. Within its 228 pages is inspiring,

challenging and relevant work that spans the en-

tire slrctnam of comics’ barely tapERd potential

Early RAW issues introduced many Amer-

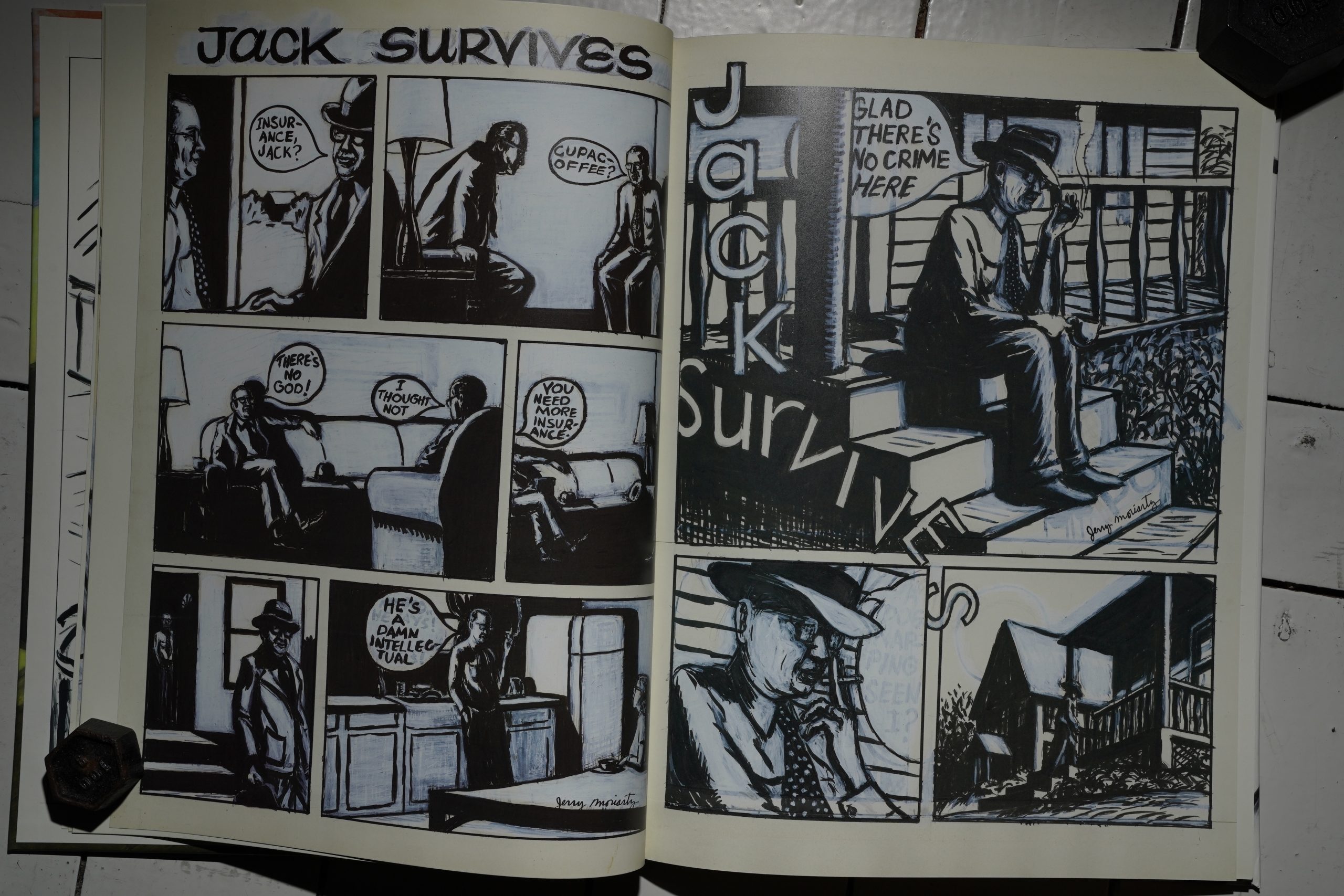

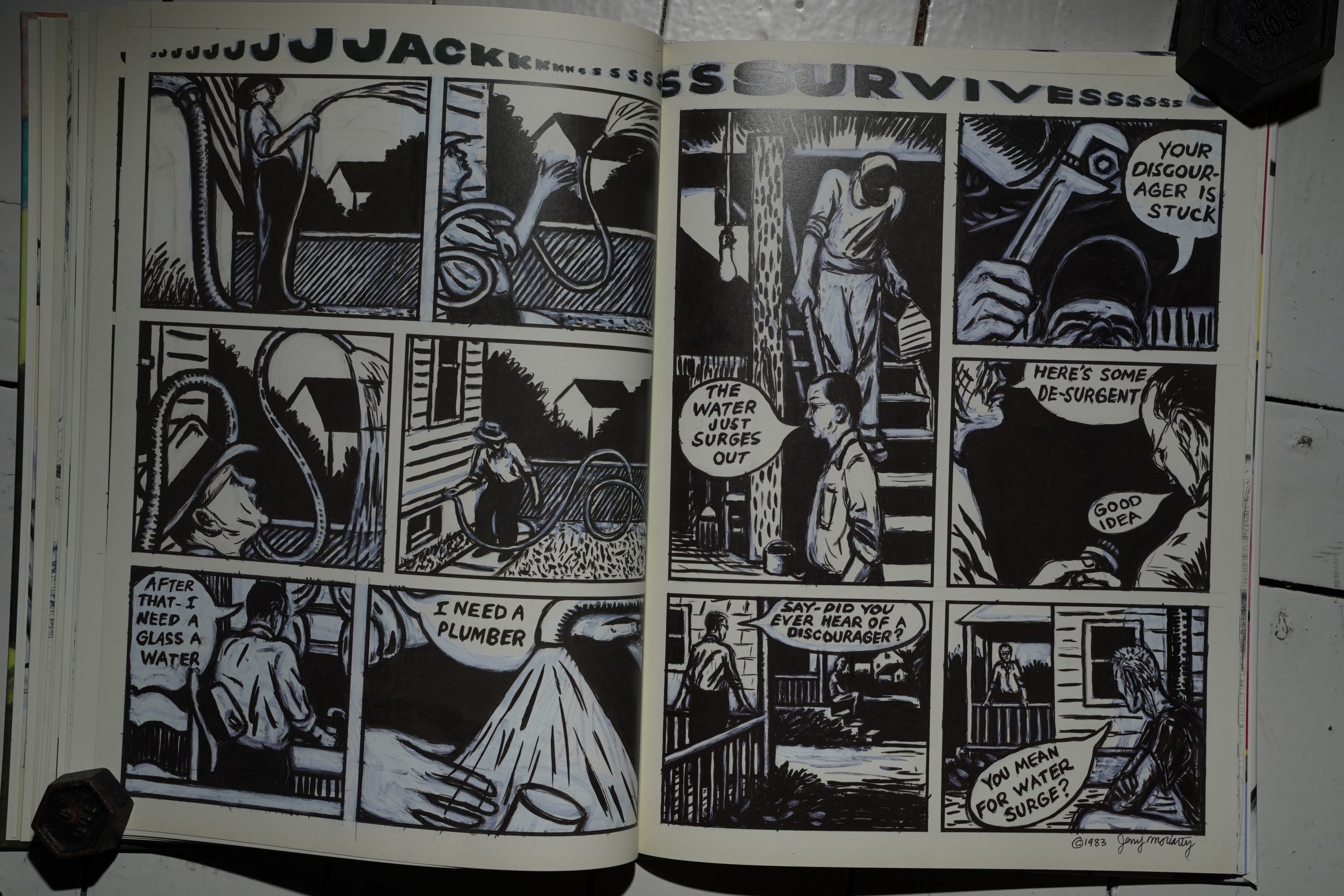

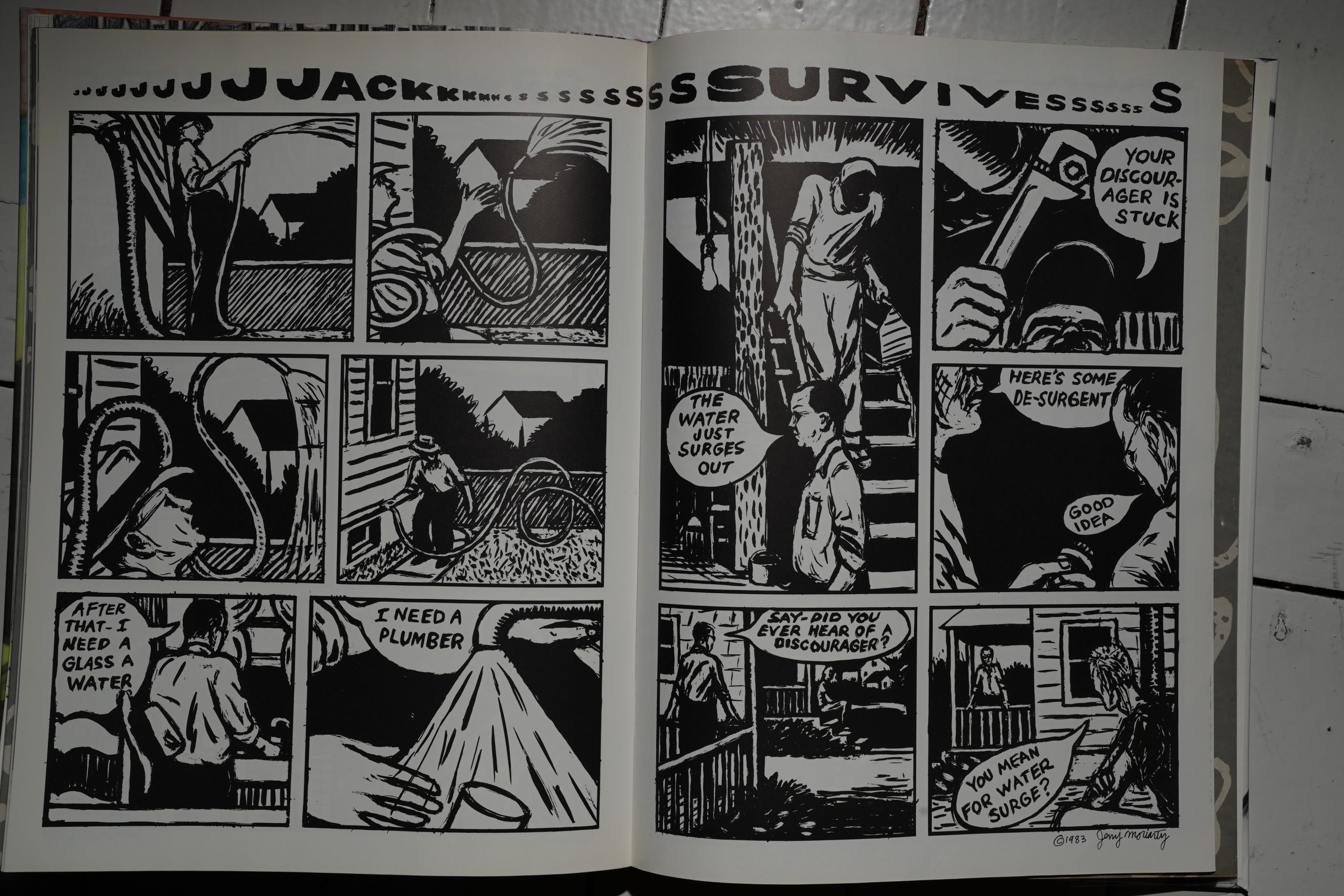

ican readers to such idiosyncratic cartoonists as

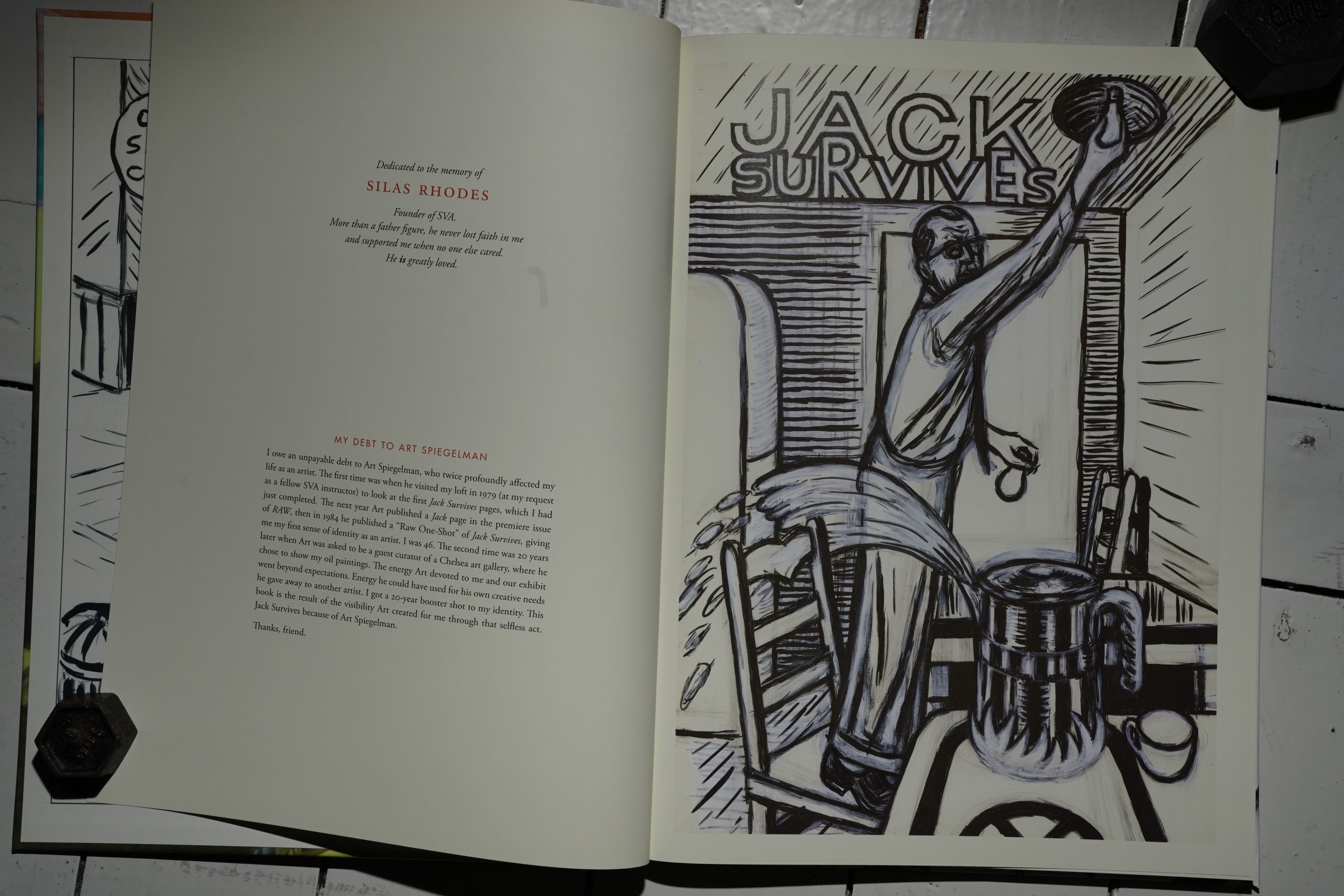

Jacques Tardi, Drew Friedman, Jack Moriarty,

Joost Swarte, Charles Bums, Gary Panter, Mark

Beyer and Francis Masse. But to their detriment,

they sometimes smacked of a detached, ascetic

and ultimately frustrating ambivalence towards

the artform of comics. Many of the RAW crea-

tors seemed to like the idea of comics, but

denied themselves emotional involvement with

their medium.

At its best, this dichotomy — which might

pair the intense drama Of Spiegelman’s Maus

with the supremely inaccessible work of Beyer

has created a fascinating tension. But com-

ics is an artform that innately welcomes pas-

sion, and its greatest creators are those who’ve

arrived at a personal point between sheer emo-

tion and art-for-art’s-sake.

That delicate balance is a constant in this

RAW Almost none of the work is distanced, and

little of it is frivolous. This is strong, signifi-

cant comics, with the pleasant bonus of two

pieces by past masters of cartooning.

The weakest piece here, Chris Ware’s “I

Guess,” hews closest to the “detached” cliche

of RAWS past. Ware uses a clever gimmick: he’s

drawn a perfect simulation of an early ’40s

super-hero story, but replaced its dialogue, nar-

ration and sound-effects with a serious personal

narrative. Mild irony results, and the invasion

Of his incompatible story into the stereotypical

“funny book” images is often humorous. Yet

the story seems more an exercise than a genuine,

vital work. It simply lacks the resonance of the

other pieces in the book.

[…]

As RAW’s cover states, collaborative ‘ ‘co-

mix” dominate the issue. The most valuable and

unusual of these is “The Bowing Machine,”

written by Alan Moore and drawn by Mark

Beyer. The piece casts a fascinated yet reserved

eye toward the social customs and formalities

of a culture equally fascinated with us — Japan.

Beyer’s aformal art is weirdly right for this

piece: it’s hard to think of another artist better

suited for the alienating effect of Moore’s text.

Moore, who has an innate ability to tailor his

writing to an artist’s strengths, is pushed into

new territory in working with Beyer. The story,

written in fractured English (perhaps as if

translated from Japanese) has genuine irony —

even a sort-of punch line — and shows an acute

comprehension of Japanese social conven-

ions. “The Bowing Machine” is Moore’s farth-

est step away from his mainstream roots: it

would be good to see him work with other non-

representational artists.

[…]

This RAWs highlight is Kim and Simon

Deitch’s epic “The Boulevard of Broken

Dreams.” The first segment of a longer work-

in-progress, “Boulevard” may Kim Deitch’s

greatest work to date.

[…]

Kaz’s offhanded surrealism suitably in-

to the first of RAW’s two historical sections —

a 32-page reprint of one of George Herriman’s

most celebrated sequences from his classic Km-

zy Kat. Herriman maintained little continuity in

his comics, and this daily segment, titled ‘Tiger

Tea,” is among his few out-and-out major

narratives.

One of the highlights of Krazy Kars long

run, the 1936 “Tiger Tea” sequence is an Out-

standing example Of Herriman’s unique comic

timing, logic and linguistics. Without compro-

mising his sense of humor, Herriman, with this

story, created his own highly personal take on

the continuity strip.

The “Tiger Tea” sequence is appropriately

printed on cheap newspaper, as in its original

’30s apl_rarance. But it seems a pity that, time

grs by, these wonderful pages will grmv brmvn

and brittle while other paper stocks in this book

remain stable. “Tiger Tea,” along with an exten-

Sive selection of Herriman’s largely neglected

weekday Krazy Kat strips, begs for a permanent

collection.

[…]

In contrast, Lynda Barry’s “The Most Obvi-

ous Question” takes a leisurely 10 pages to relate

its bittersweet tale. Barry has a novelistic sense

of detail, characterization and atmosphere, and

even in her four-panel weekly Ernie Pook’s

Comeek she far surpasses the traditional amount

Of narrative- and character-content in comics.

Here, Barry lingers over a variety of richly

described, familiar settings — the interiors of

homes, bus stations and vehicles — and barren,

wintry landscapes. She tells a deeply emotional

(and admirably unromanticized) coming-of-age

story, underlined with the palpable tension of

a painful family situation.

[…]

Rumor has it that the next issue of RAW —

which will conclude Spiegelman’s Maus — may

also be the last. If this is true, let’s hope that

Spiegelman and Mouly — or someone — can

devise an adequate replacement. Though there •

are other fine comics anthologies, there is

nothing else like RAW, its absence will leave an

unfillable void.

Spiegelman is intereviewed in The Comics Journal #145, page 99:

BOLHAFNER: I thought the last issue of RAW’ was one of

the best yet.

SPIEGELMAN: Yeah, we’ve been hearing a lot of that…

mostly indirectly. We don’t get that many people writing

us. But it’s been well-received compared to the first two

Penguin issues. RAW was originally a large format publica-

tion, like life magazine, and when the Penguin books came

out it was a shock to a lot of people, and they thought

it was a commercial decision on Penguin’s part. But actu-

ally, we had decided to change format in 1988.

The Comics Journal #156, page 17:

Penguin Ceases Publication of Comics Albums

Penguin Books, one Of the few mainstream

American book publishers to print comics al-

bums. has decided to temporarily stop pub-

lishing them, according to Senior Editor David

Stanford. Penguin, which published such books

as From A to Zippy by Bill Griffith, Skin Deep

by Charles Burns, “tarts and All by Drew and

Josh Alan Friedman, Cheap Novelties by Ben

Katchor, and the anthologies Thisted Sisters and

RAW, will publish only tuo more comics col-

lections in 1993. Twisted Sisters II, originally

intended for publication by Penguin, will now

be published elsewhere.

Stanford, who has been with Penguin for

four-and-one-half years, edited the company’s

more avant garde comics projects (previously,

he worked at Henry Holt and Company, where

he edited books by Garry Trudeau, Charles

Schulz, Jeff MacNelly, Skip Morrow and Other

cartoonists). He cited a energy crisis”

as one of the main reasons Penguin is discon-

tinuing the publication Of comics collections,

although modest sales was also a factor.

So Penguin didn’t shut down their comics business until two years after Raw Vol 2 #3, and there was apparently a rumour going round already in 91 that #4 would be the final issue.

Gary Groth writes in The Comics Journal #199, page 77:

After the success of

Maus, Pantheon smelled money and launched a

series of graphic novels; none of them matched

Pantheon’s expectations and the graphic novel

line was canceled. Later, Penguin published RA W,

smelled money, and launched a series of graphic

novels; QED.

But I can’t find anything definite about why there never was any #4 (which would have had the final installment of Maus). Maus II was published in 1992, so it wasn’t because Spiegelman just could get himself to finish it, either.

Oh well. So an era ends. But on an up note.

This blog post is part of the Punk Comix series.