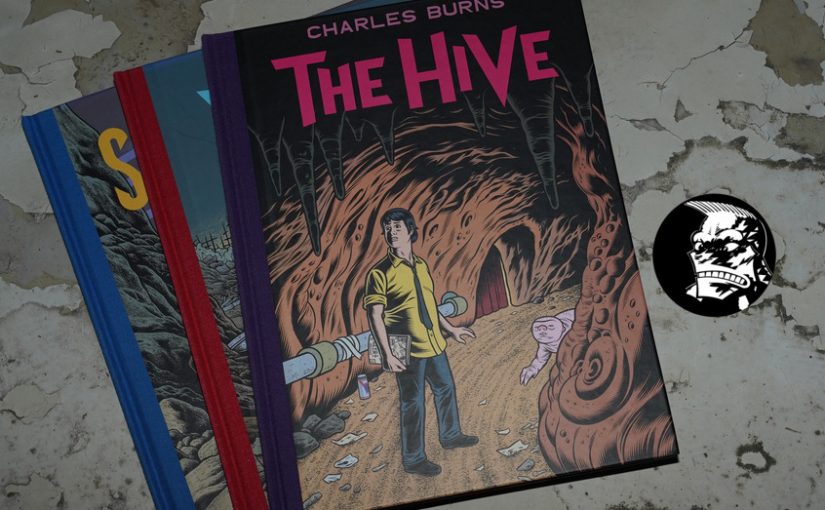

X’ed Out/The Hive/Sugar Skull by Charles Burns (230x303mm)

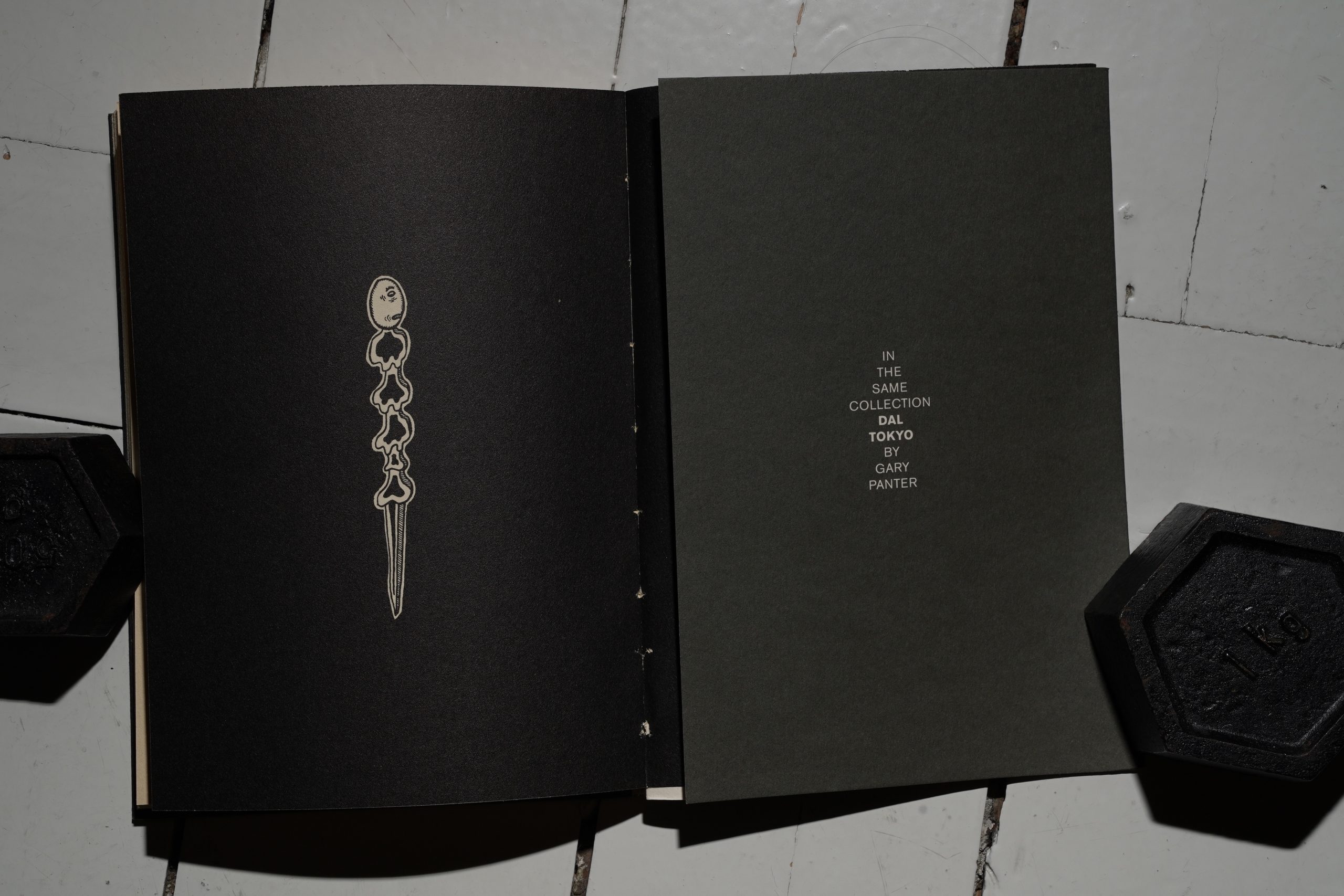

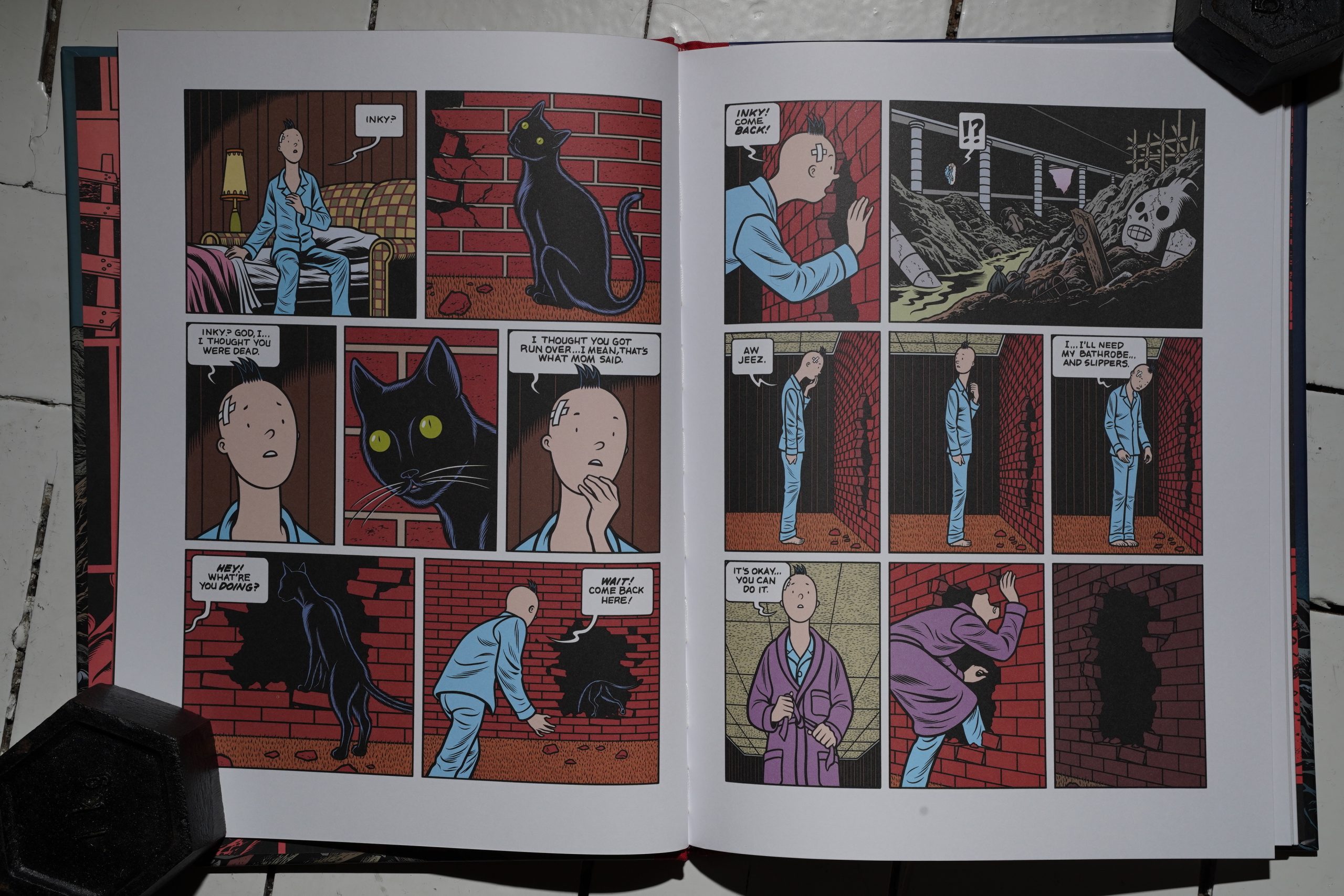

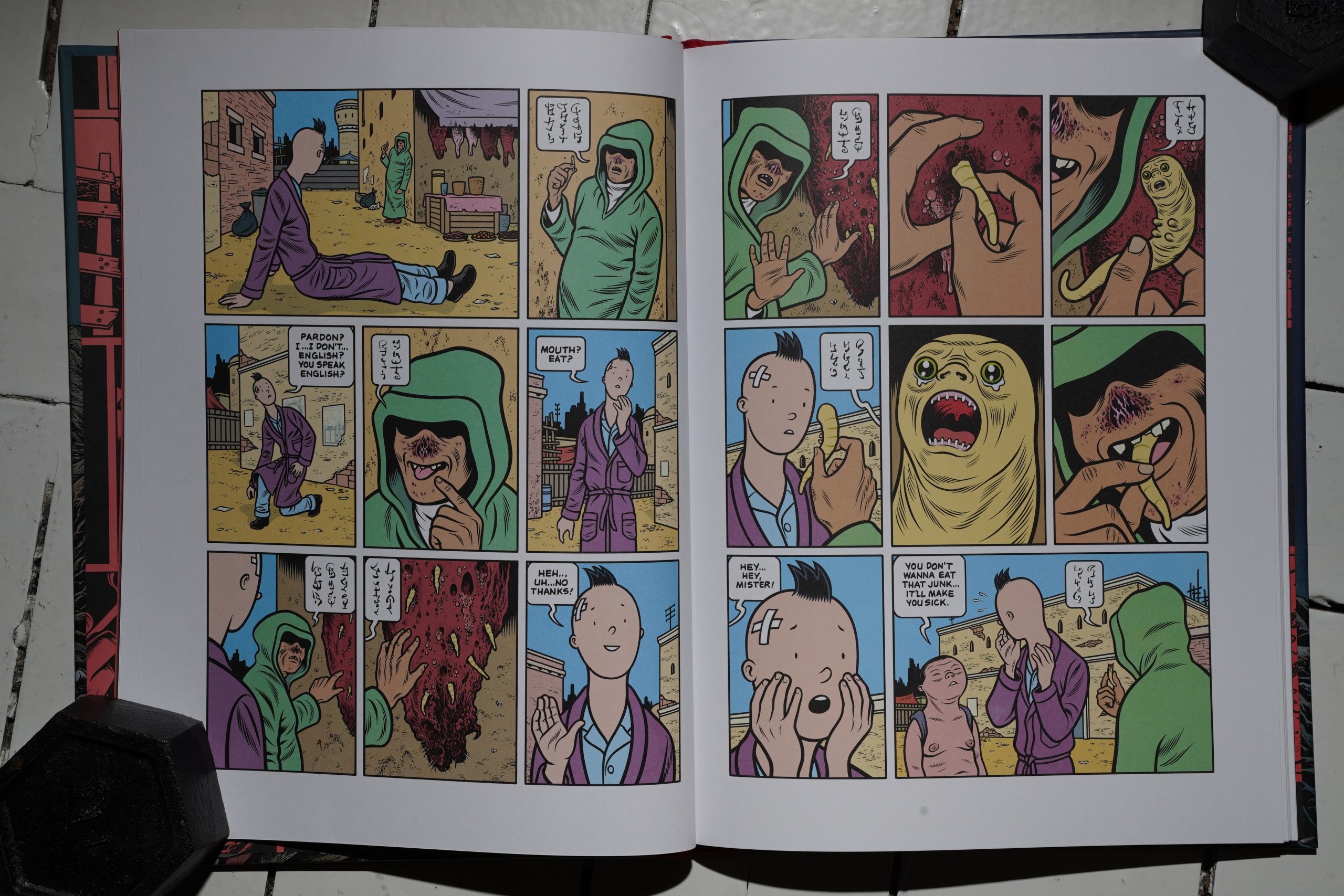

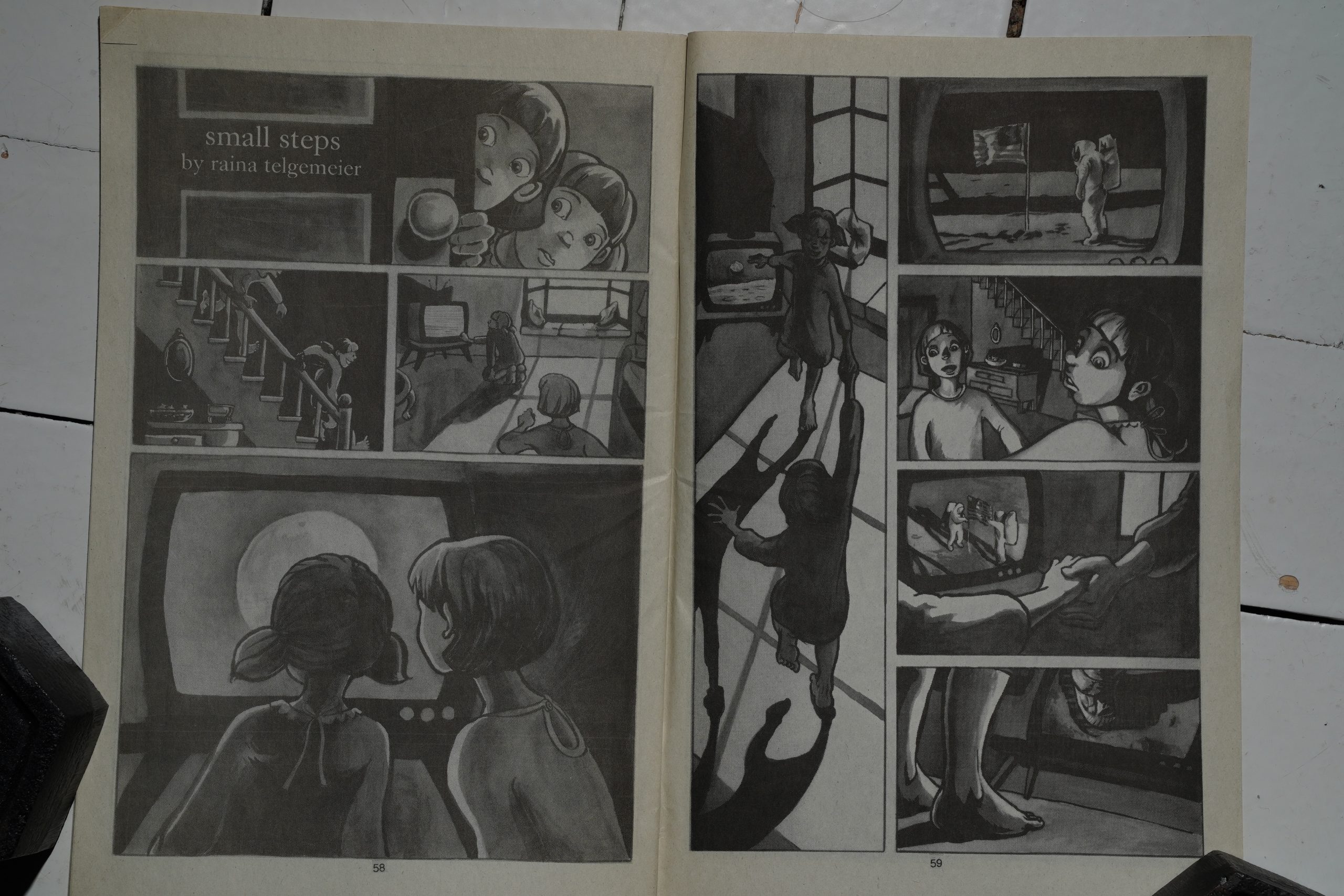

After Burns had been doing comics about diseased teenagers for a few decades, X’ed Out arrived out of the blue. I certainly wasn’t expecting a kinda surreal Tintin-referencing book from Charles Burns: It’s in the classic European hardback album format, looking very classy.

I remember being really excited about X’ed Out, but… I remember nothing about the subsequent volumes (that arrived with a two year gap between).

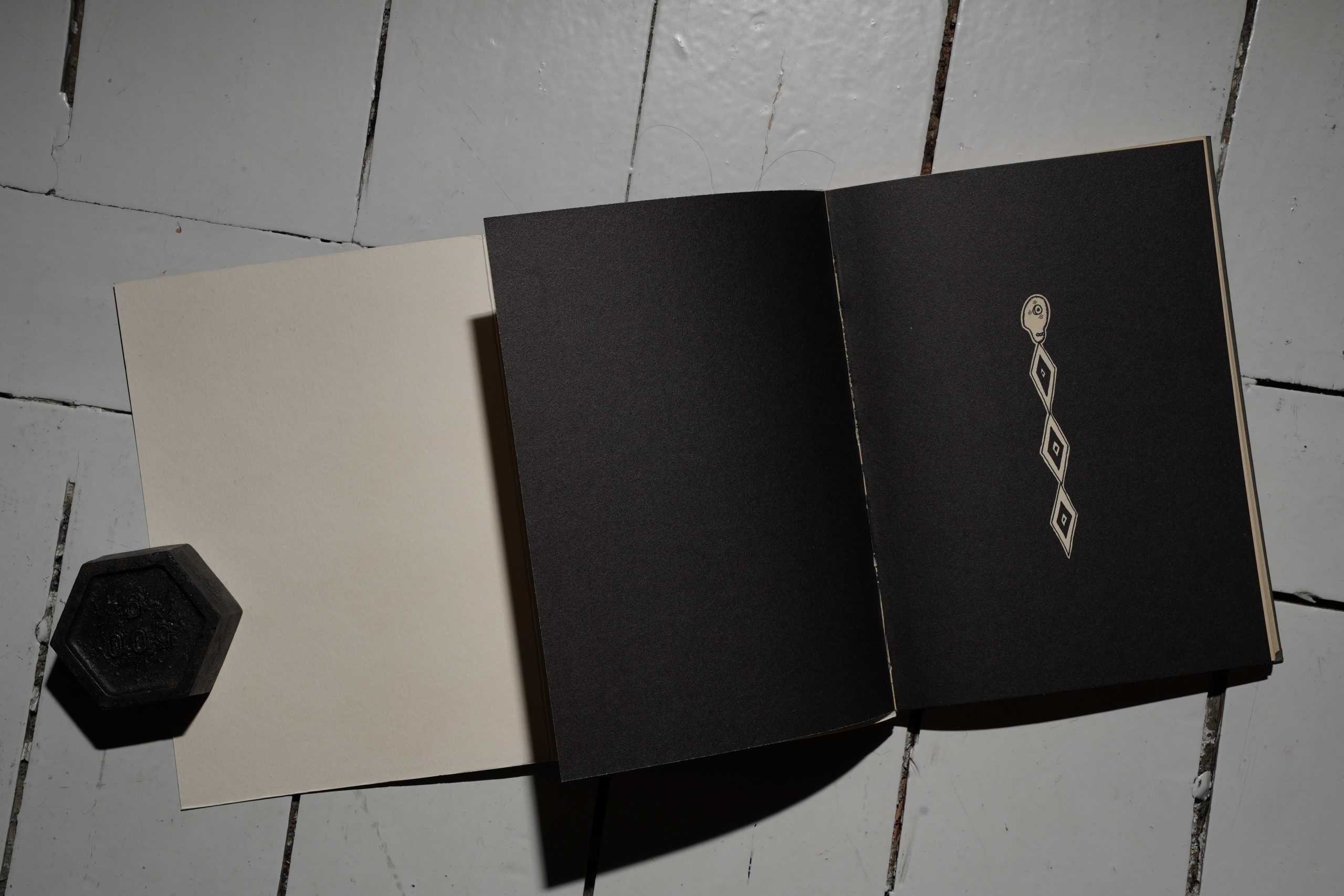

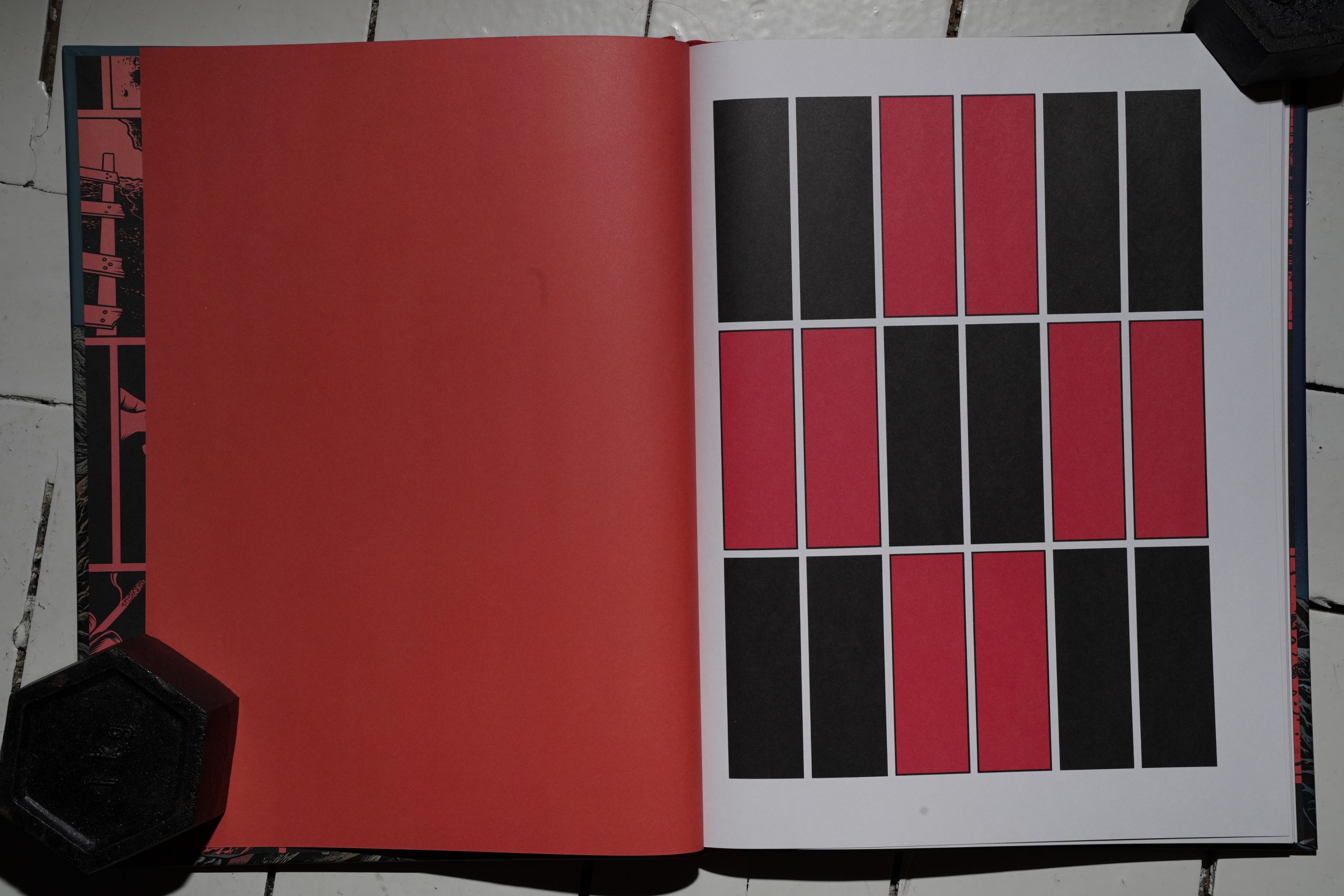

But let’s open the first volume.

Ooh, cool.

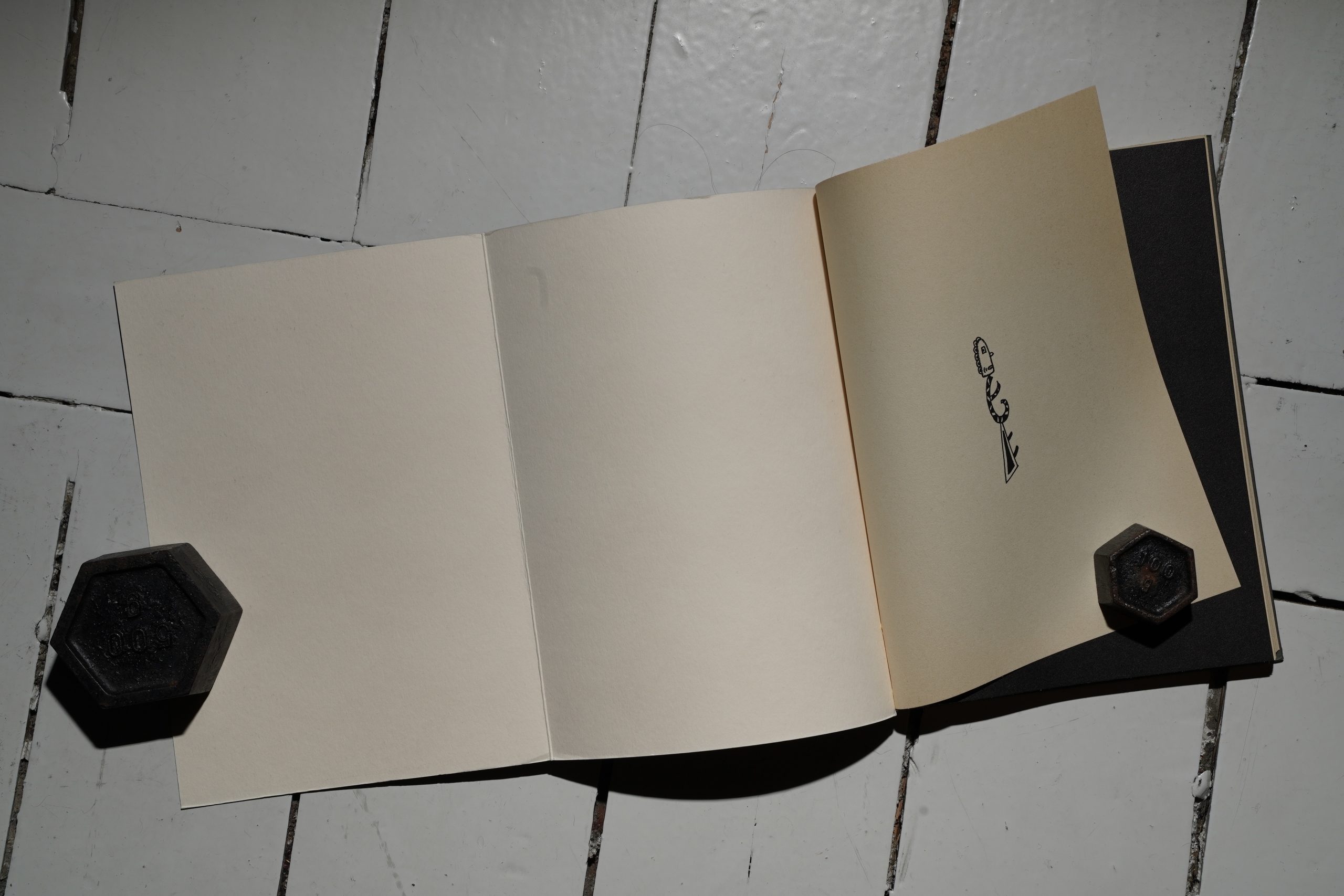

Ooh, nice!

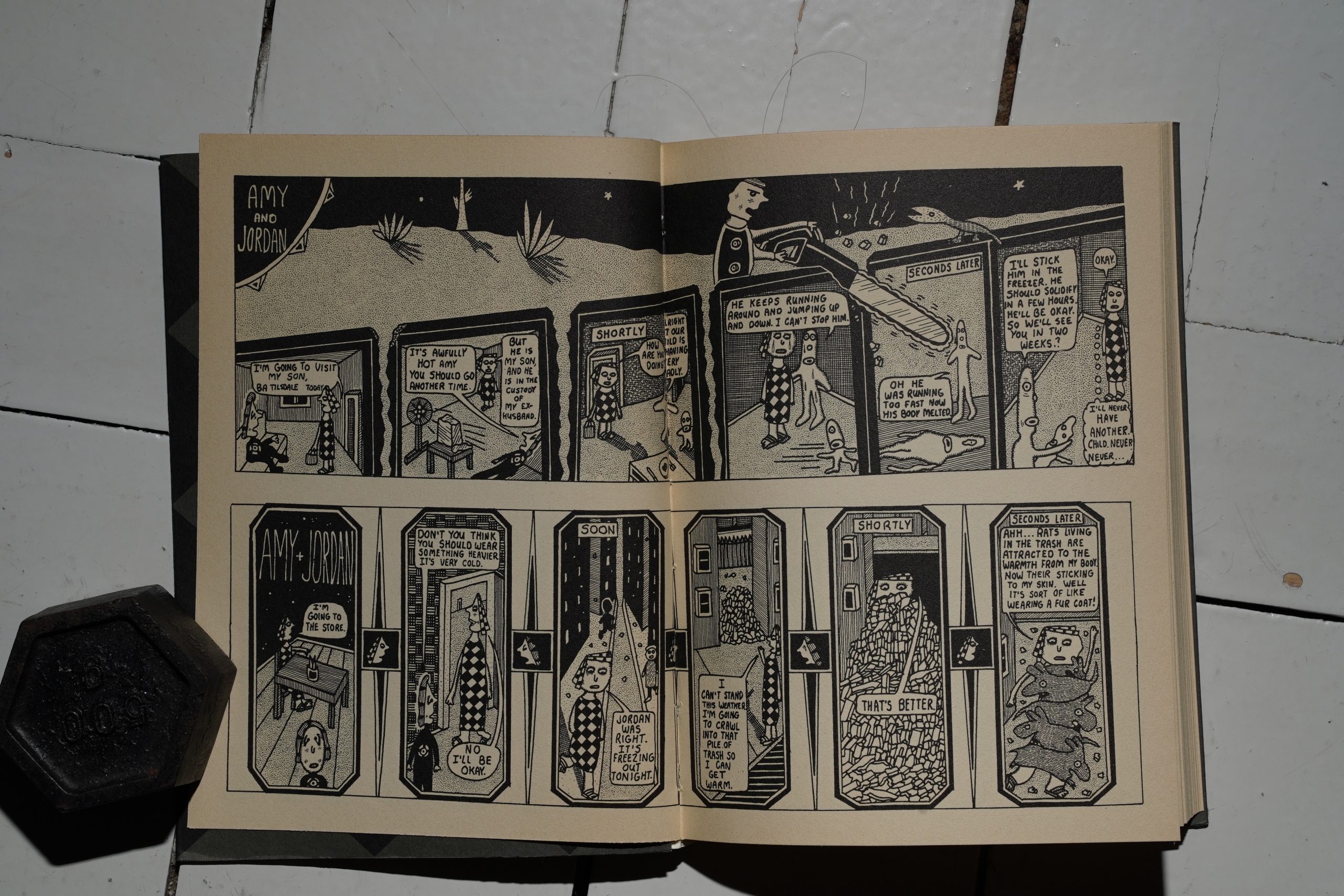

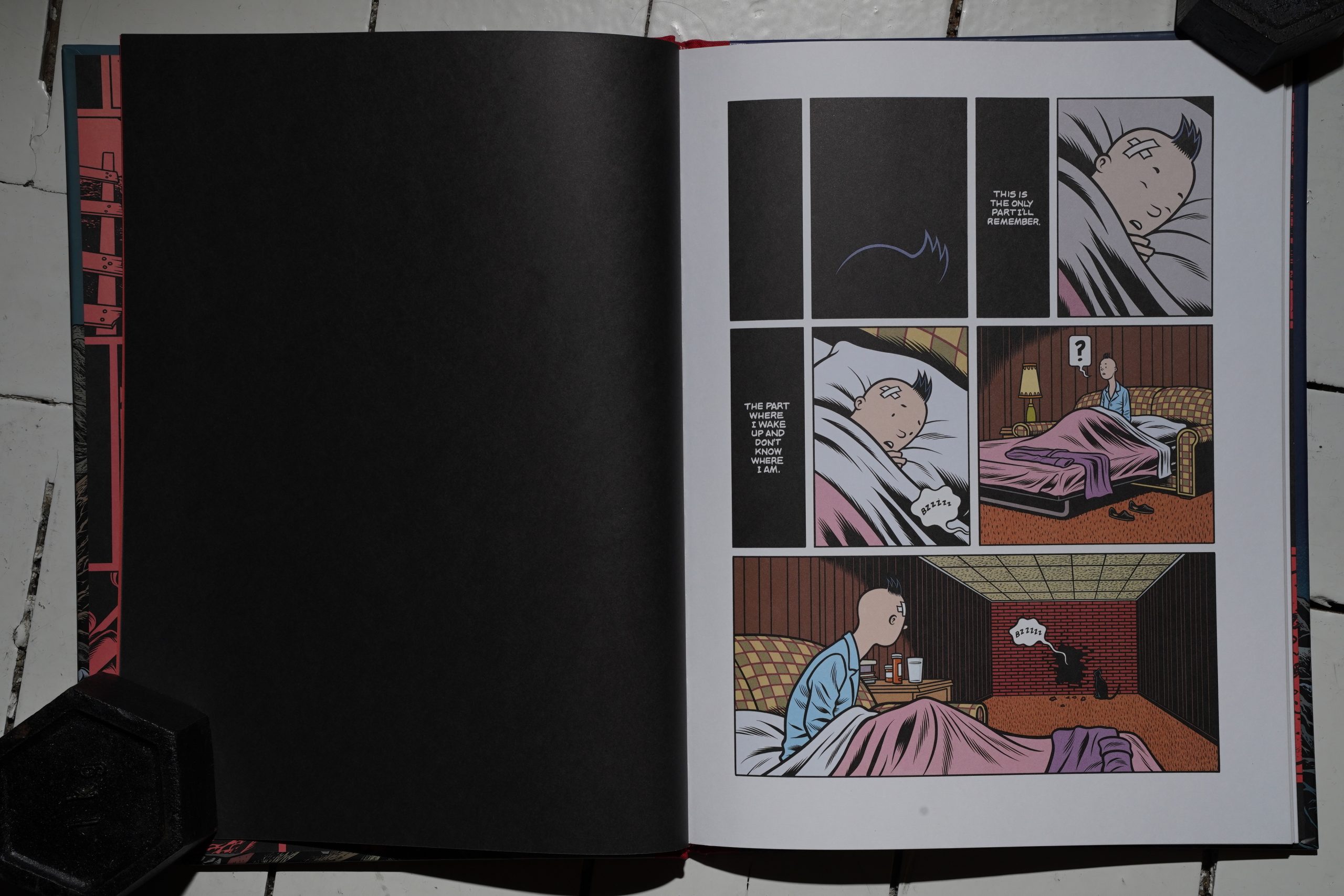

Oooh!

OOoh whaaaa!

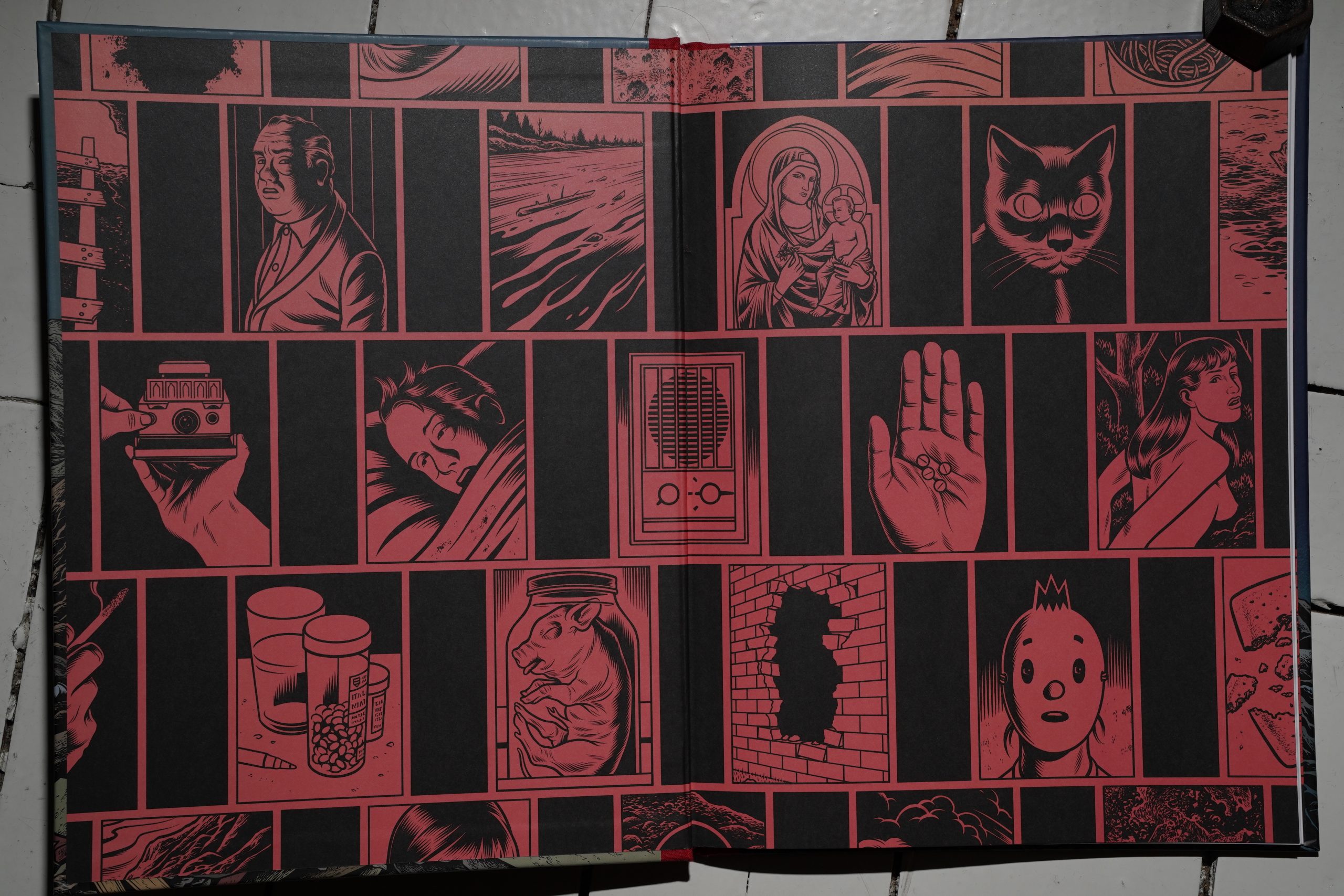

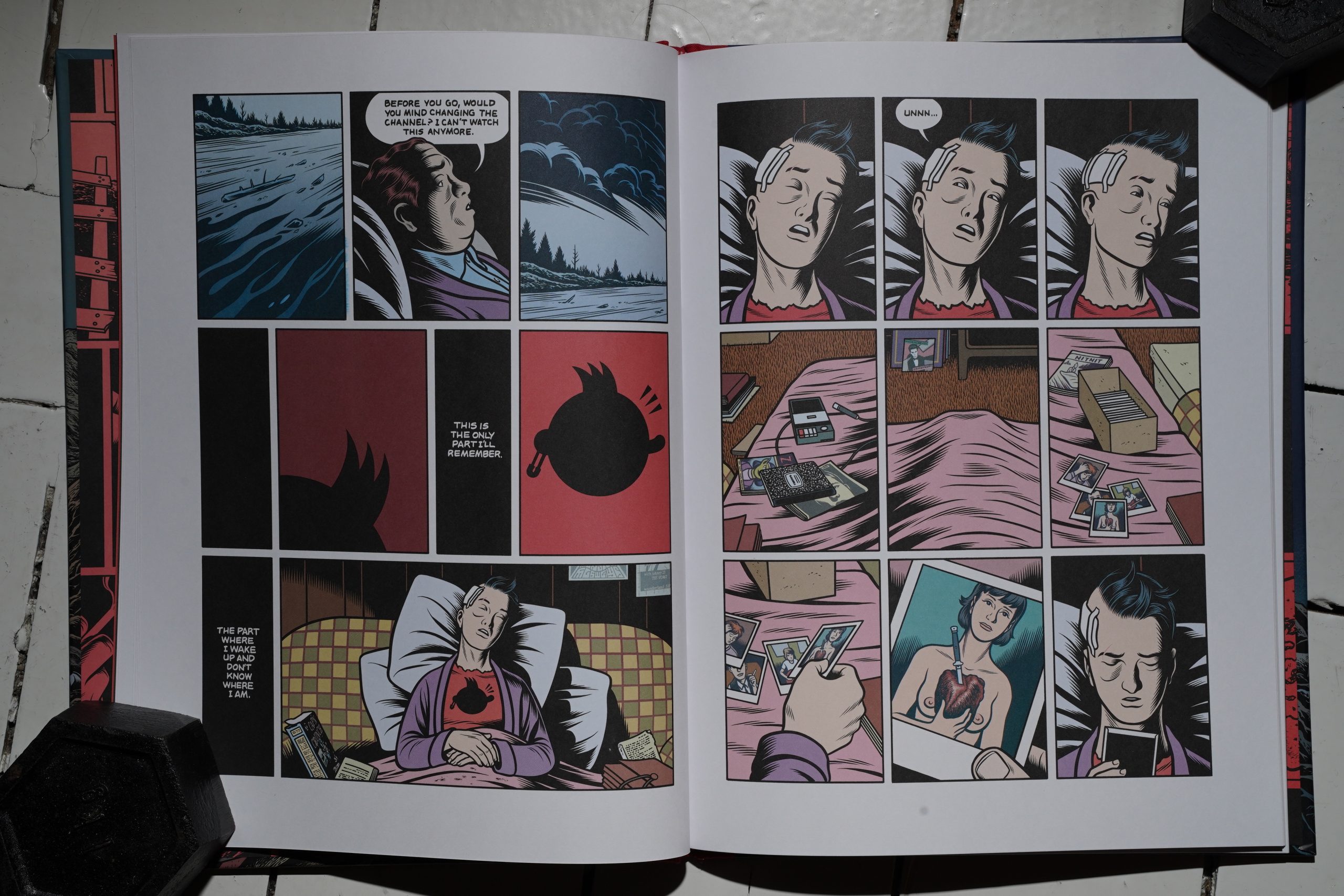

Now that’s the way to do a book. Burns sets the tone from the moment you flip open the cover: The endpapers are perfect, then there’s some mysterious squares, and then we’re dropped right into some very mysterious action indeed.

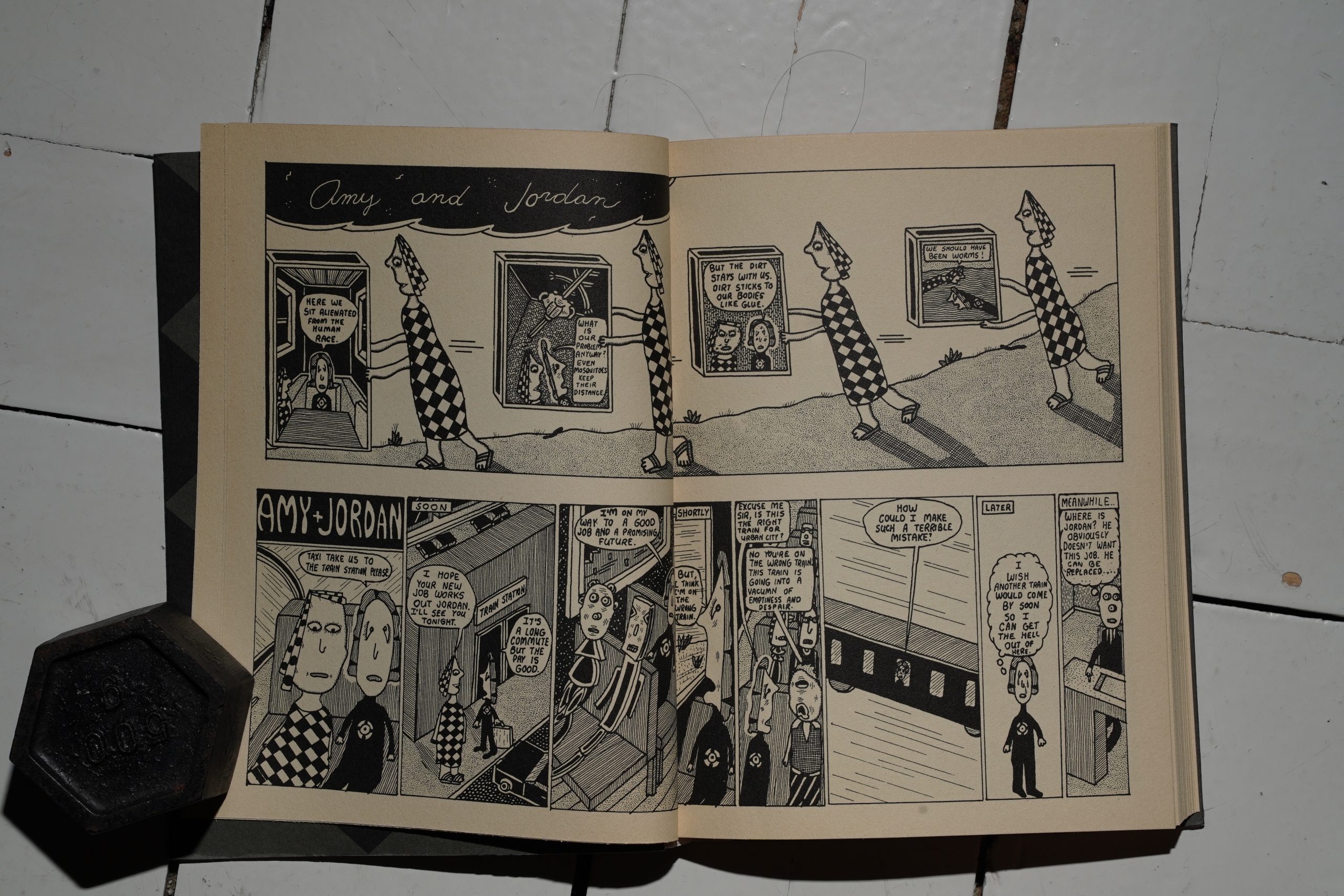

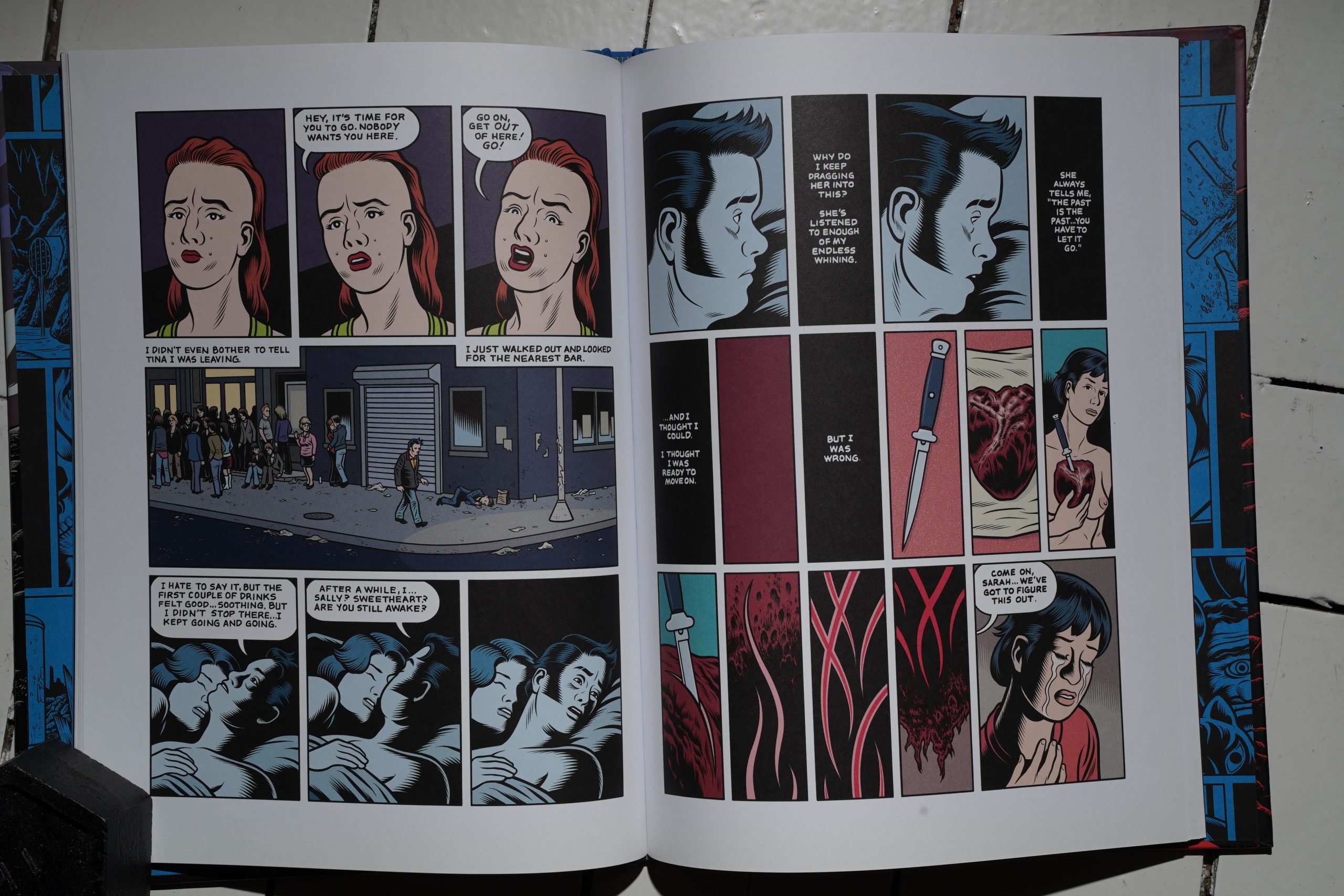

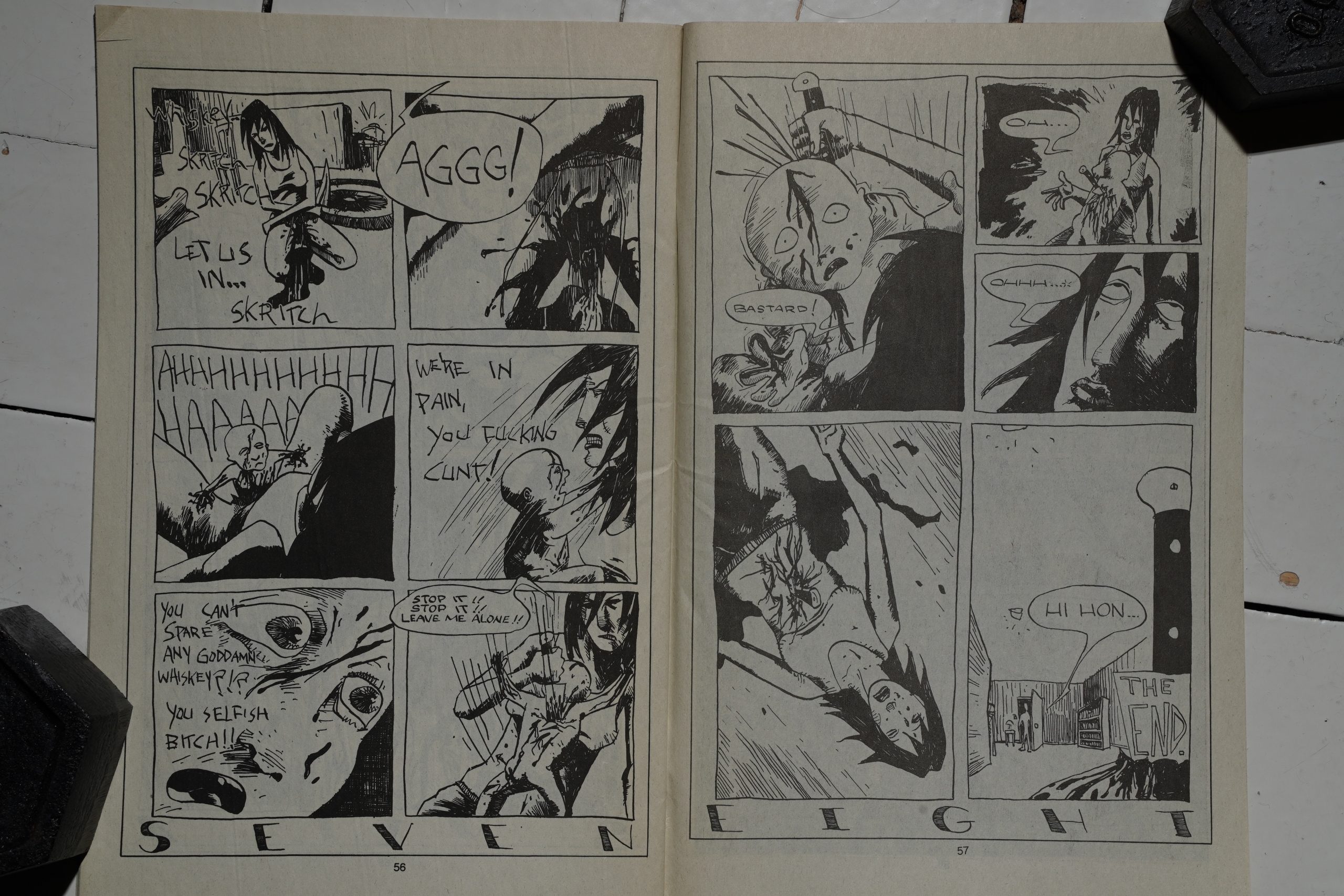

It wouldn’t be Burns without plenty of body horror.

And then… we’re out of that universe and into the “real world”, and everything seems to reference everything else. It’s great! It’s gripping!

Those squares at the start? They’re used to mark shifts between time periods or worlds, and we slowly but surely are given more and more information about what’s really going on here.

Perfect first volume, and shows a lot of growth from Burns.

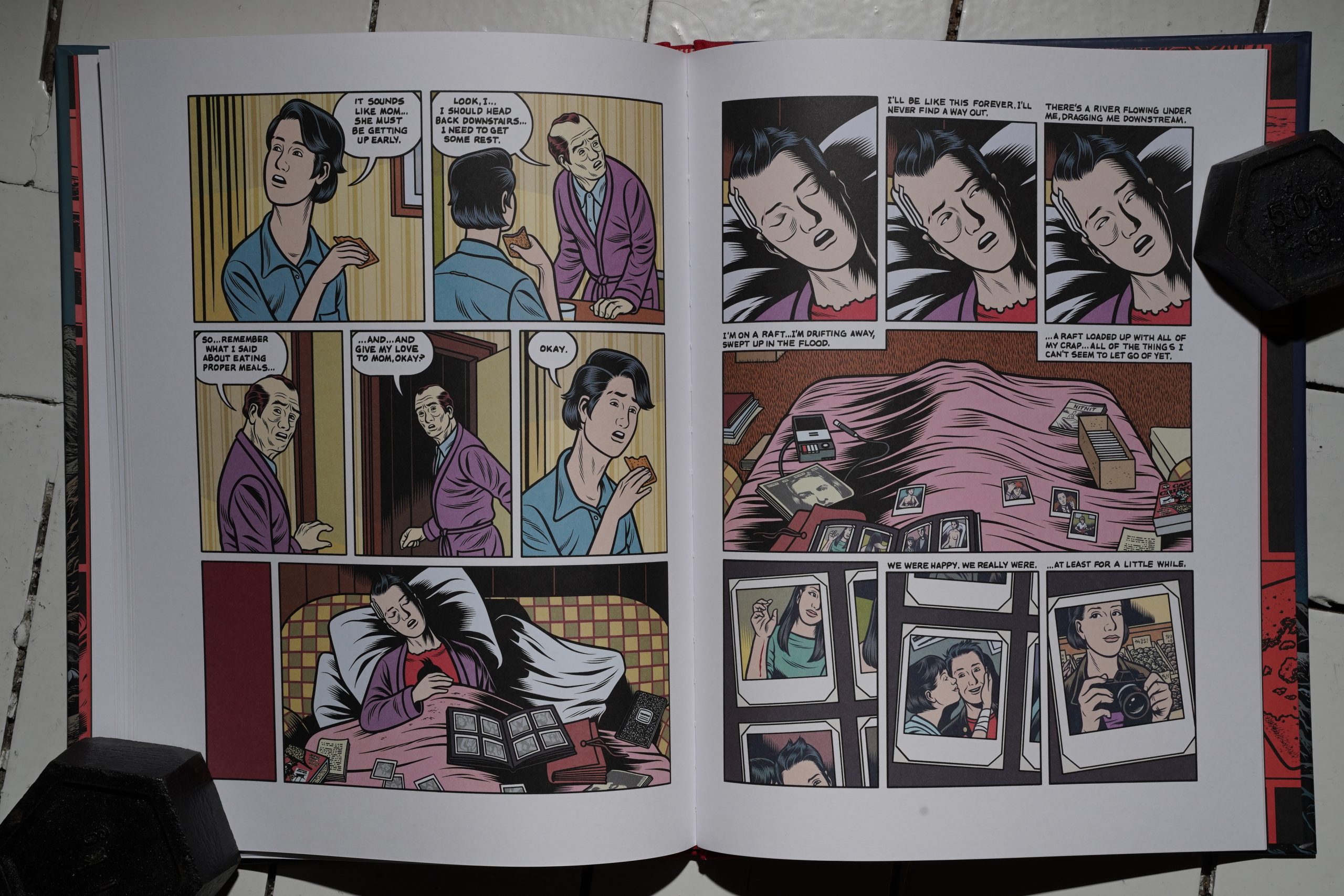

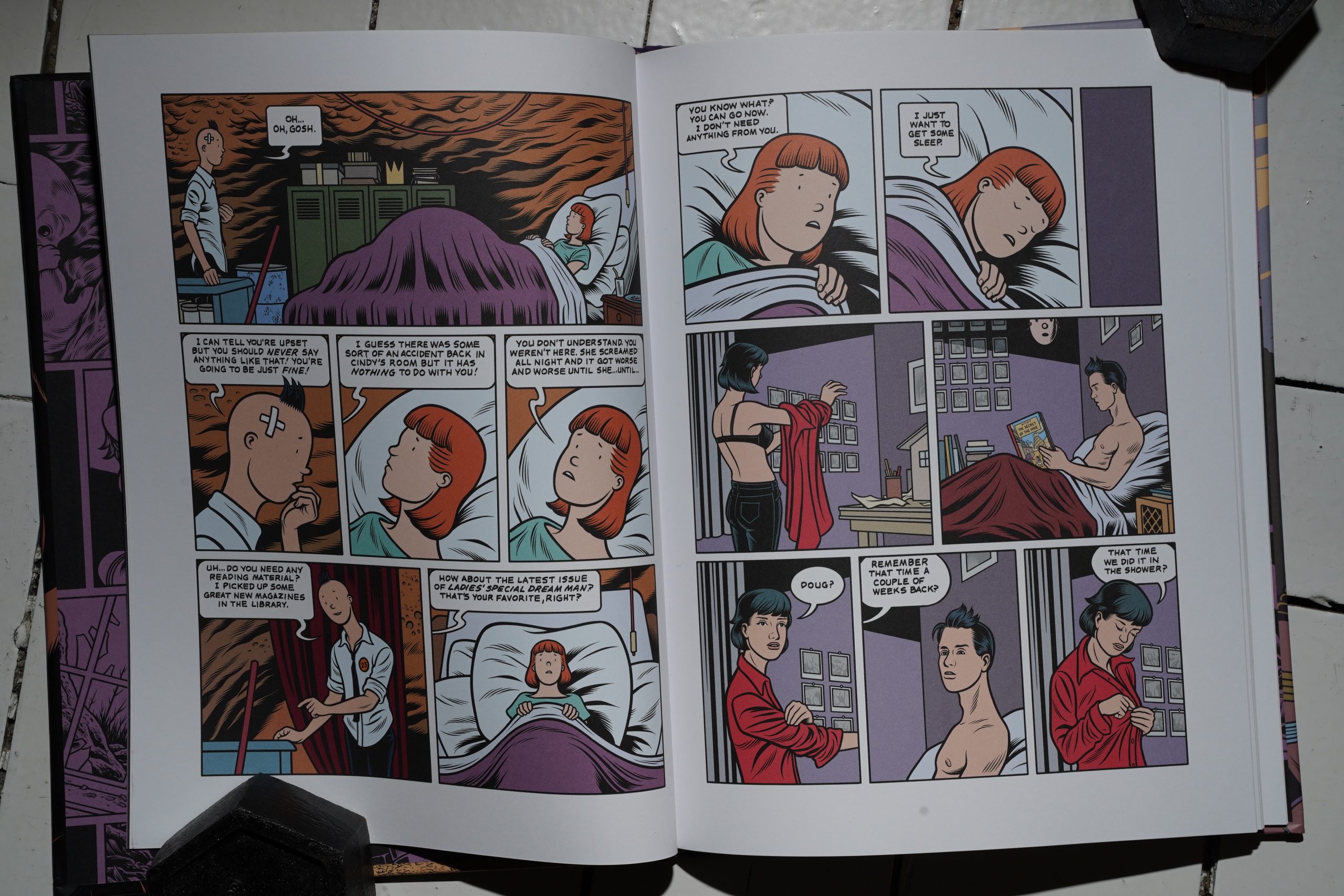

And then… the second volume. Burns adds more time levels, and adds more body horror in the Tintin-verse… but… we get more melodrama, and things start seeming less like a kick ass comic than the storyboards to a post-Lynch indie movie.

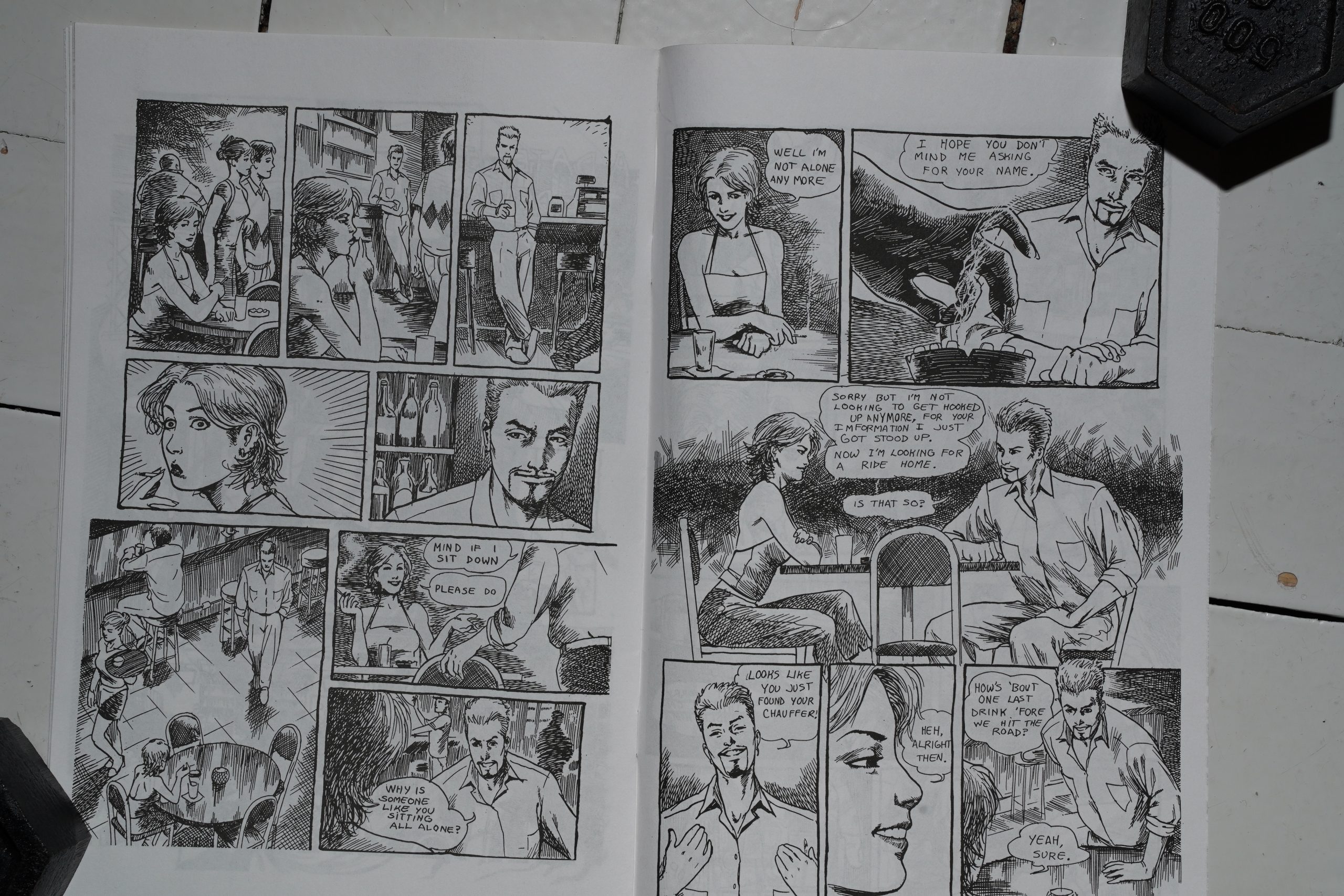

Burns does have a lot of fun with bringing romance comics into the proceedings — while the “real world” gets progressively more like an indie drama movie.

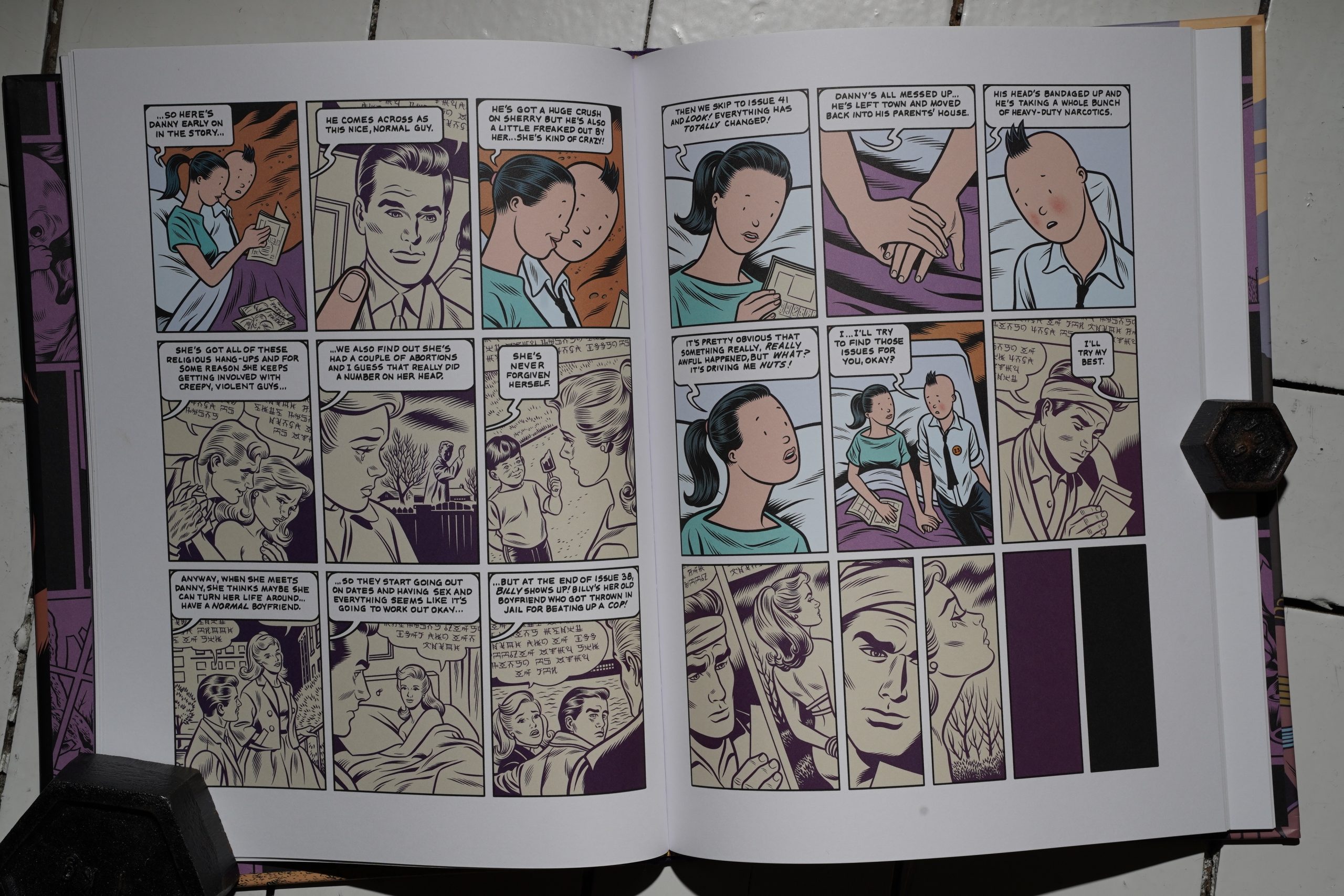

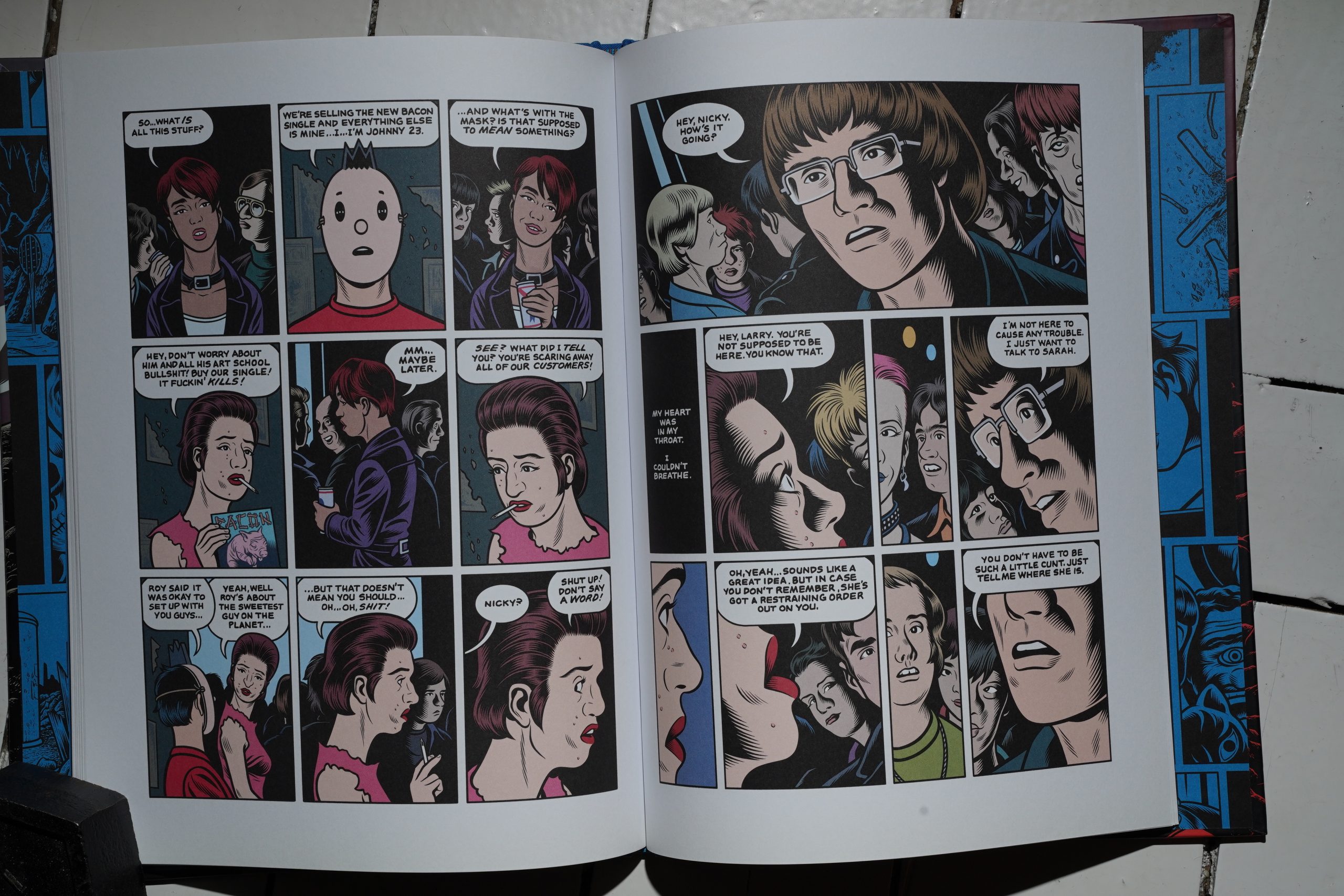

Finally, in the third book, he lost me. Everything ties together so neatly — we started with nothing but mystery, and we end with everything being made exceedingly clear. And it turns out that what we’ve been reading wasn’t that interesting, really.

Even Burn’s inhumanly fabulous artwork starts looking trite.

Burns is usually such a consummate perfectionist and amazing storyteller that pages like these are a real disappointment.

The post-ending (after the plot ends and everything is resolved) is pretty nice, though.

Sugar Skull was an immensely disappointing let-down to what has otherwise been a fascinating series. Charles Burns explains everything in this final volume of his X’ed Out Trilogy, which is something you’ll either appreciate, because you hate any ambiguity at the end of a story, or dislike because that’s not consistent with the way this has been written thus far.

But worse – far worse – is the disproportionate balance between the apocalyptic, messed-up, heightened tragedy of Doug and Sarah’s story, that has been built up now over two volumes, and the bafflingly banal and truly uninspired reveal of the secret at the heart of this series.

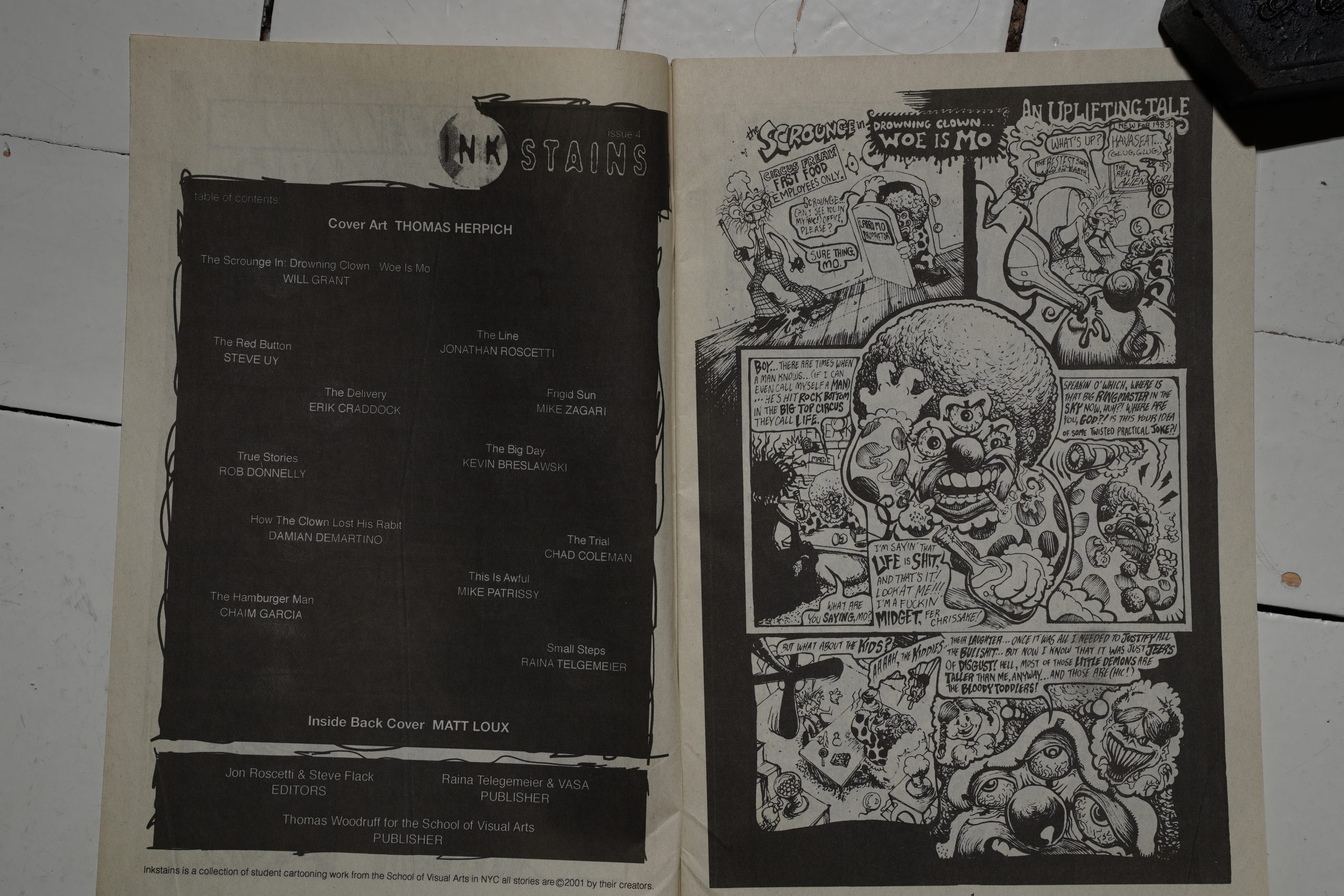

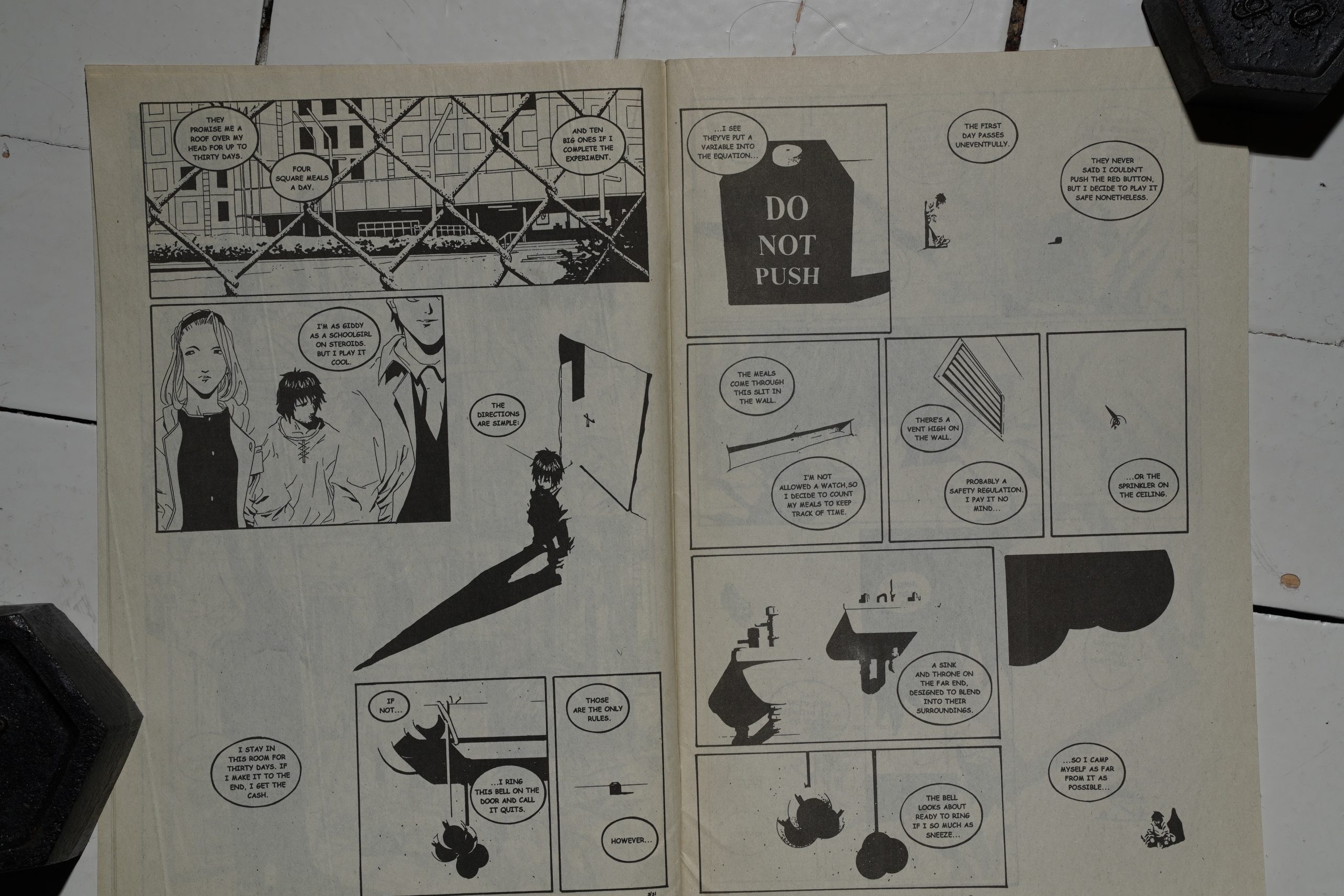

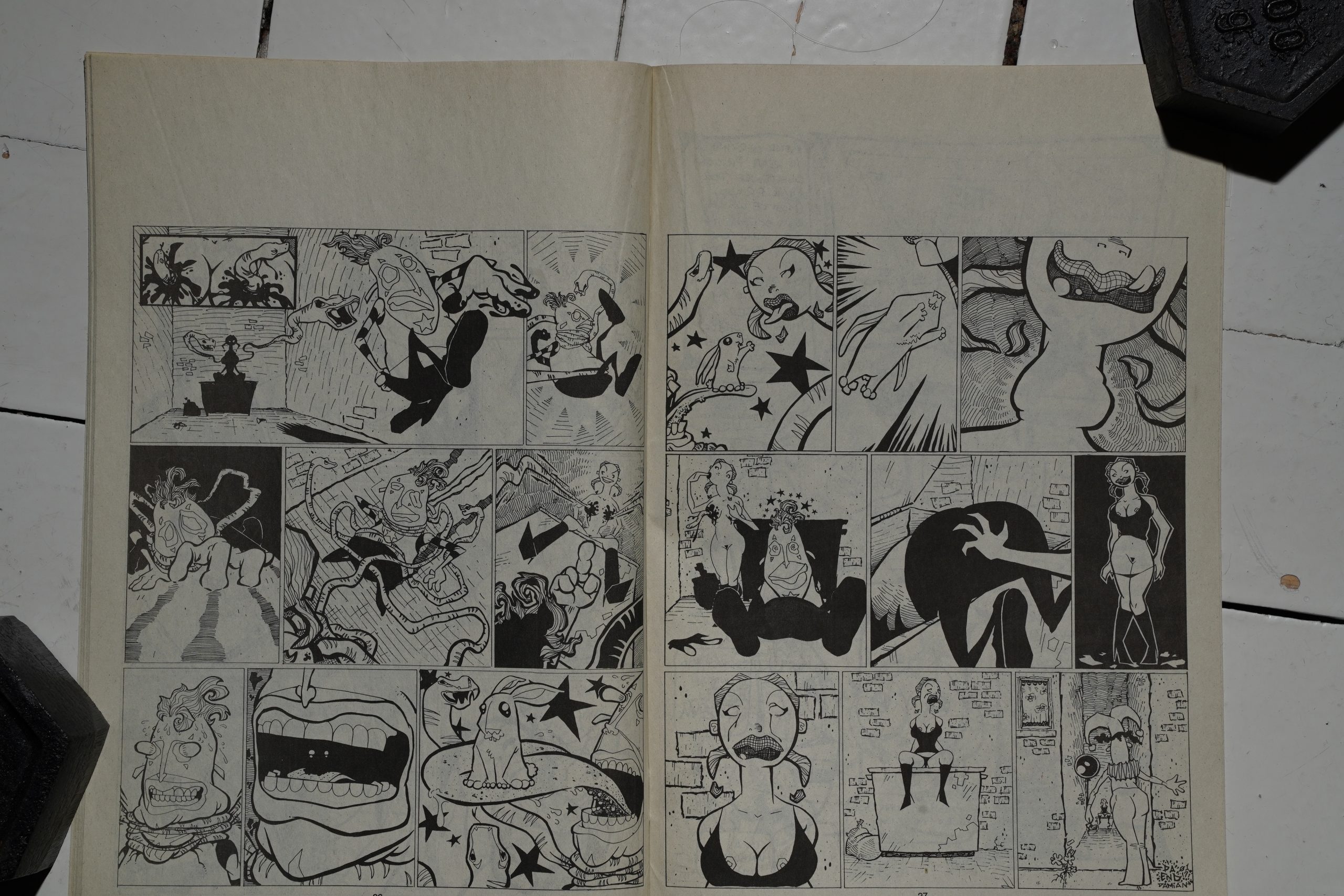

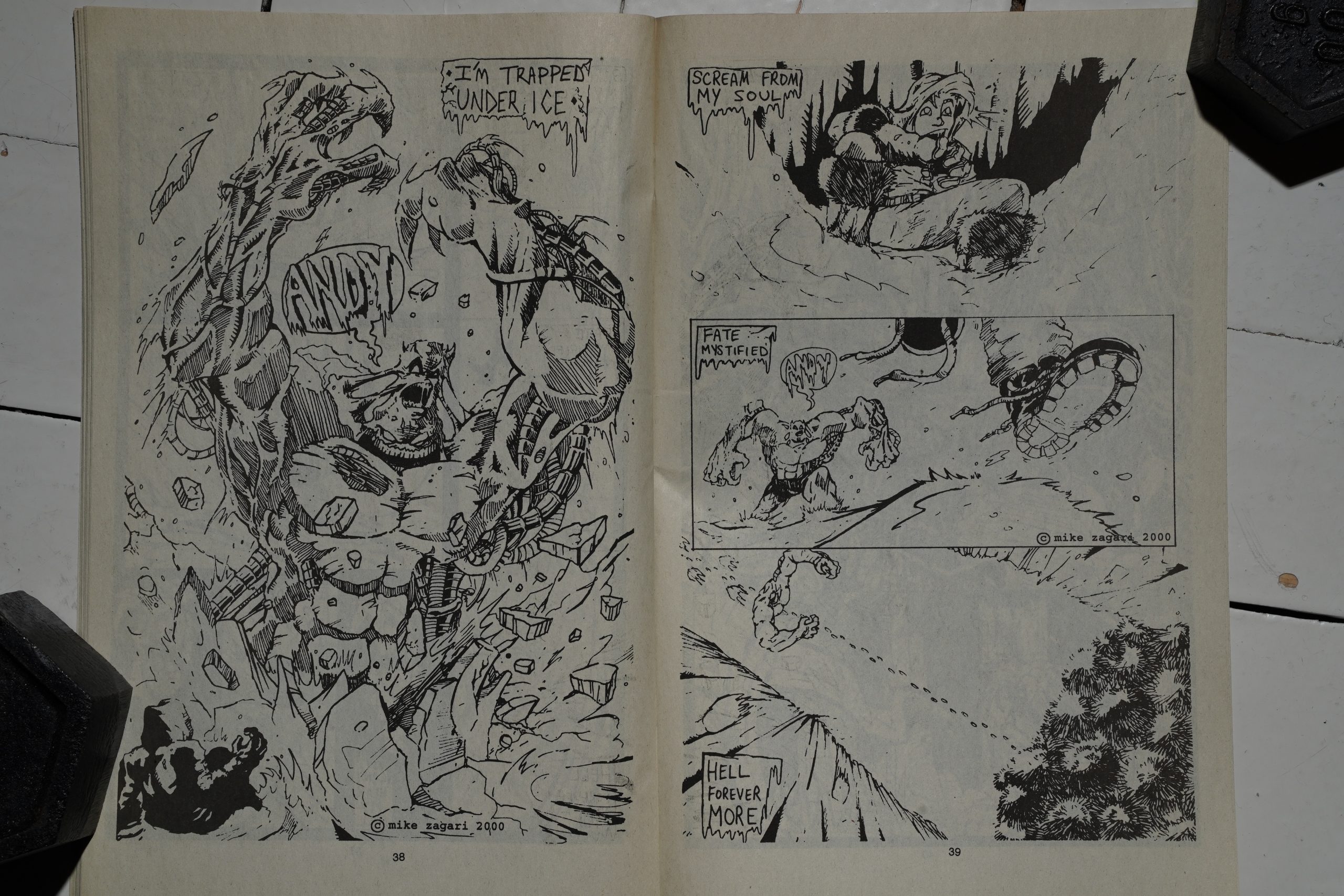

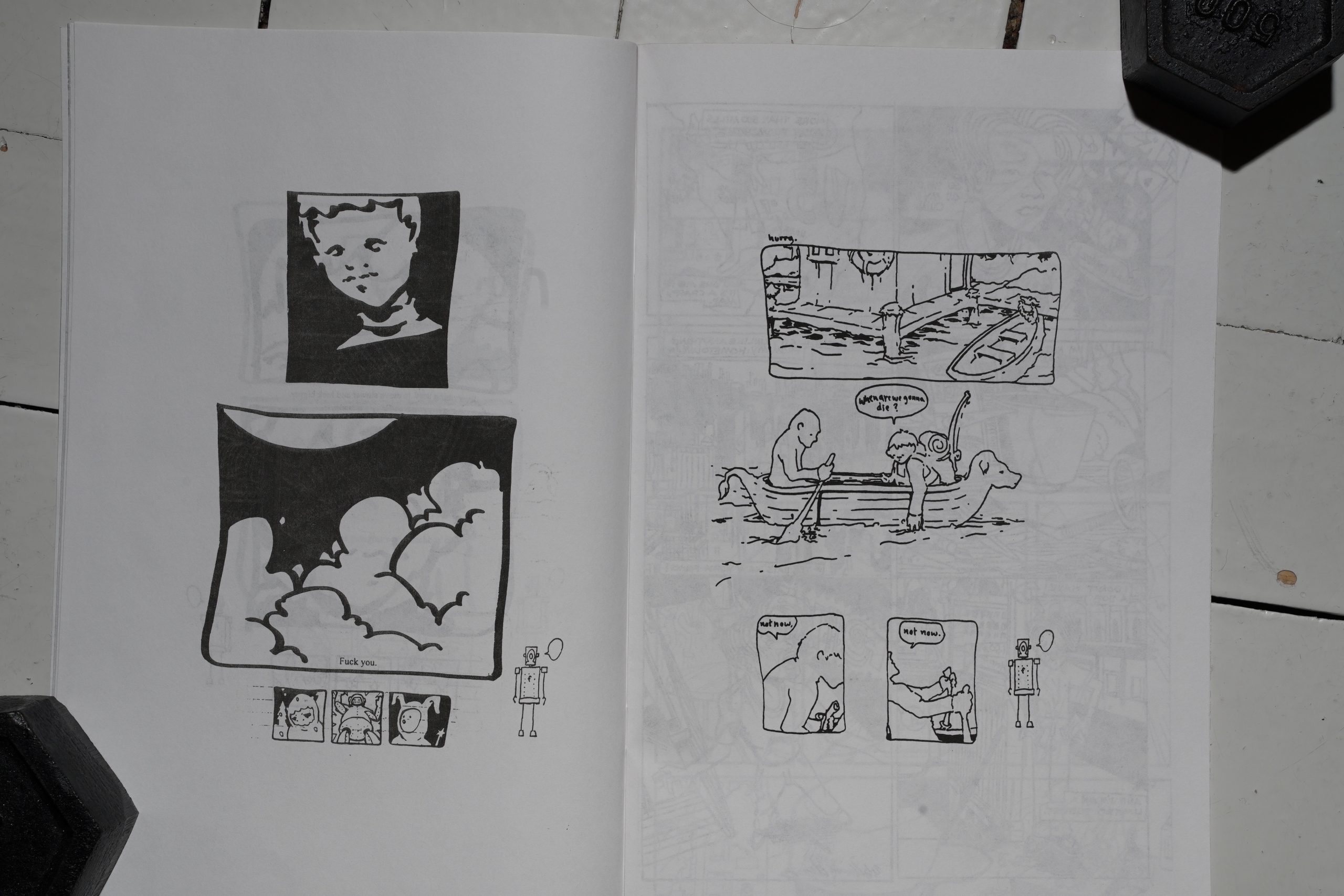

This blog post is part of the Punk Comix series.

+(Mixed+by+Second+Storey))

)

%3A+Live+At+The+Budokan+1980)

%3A+Life+In+Tokyo)

%3A+Music+with+Magnetic+Strings)

)

)

%3A+In+the+Court+Of+The+Crimson+King+(2009+Stereo+Mix))

%3A+Patchwork)