Lighting Out for the Territories

PX08: Gary Panter

Gary Panter by Gary Panter (242x309mm)

This massive box was published by Picturebox in 2008, and I think I got it at the time? Or pretty soon afterwards? When I got it, I was amazed at the… er… weight… of the box. It’s the most paper for the least amount of money ever. (I think they sold these boxes for $60?)

But… I’ve never actually looked at the books before now. I know! So weird. But I have this thing about boxed sets — I’ll buy them with great enthusiasm, but then they sort of languish on the shelves, because they never seem that urgent? I can always read them later? *points to shelves with beaucoup de box sets* When is later gonna happen? Must happen at some point.

But, OK, I’m finally gonna pop these books out of the box.

Man, the box set is so heavy. Let’s see… it’s 4.4 kgs. That’s a lot of paper.

It feels like a real artefact — I like touches like printing even the innards of the box.

Oh! I didn’t notice before — it’s got a little sketch on the bottom (!) of the box. It’s King Kong and some airplanes.

There’s two books — they’re the same dimensions (so they fit into the box nicely), but one is horizontal and the other one is vertical. Let’s look at the horizontal one first.

Those are nice end papers.

We start off the book with two introductions — the first one, by Mike Kelley, is both funny and oddly informative (if you have a decoder ring, which I think I do).

And then there’s an interview with Panter. This makes the book feel a bit front-loaded with text, and I was wondering why they didn’t put some of this further in the book; at this point I just wanted to look at some art and not read any more. But it turns out that every section has a text piece to introduce it, so it makes sense.

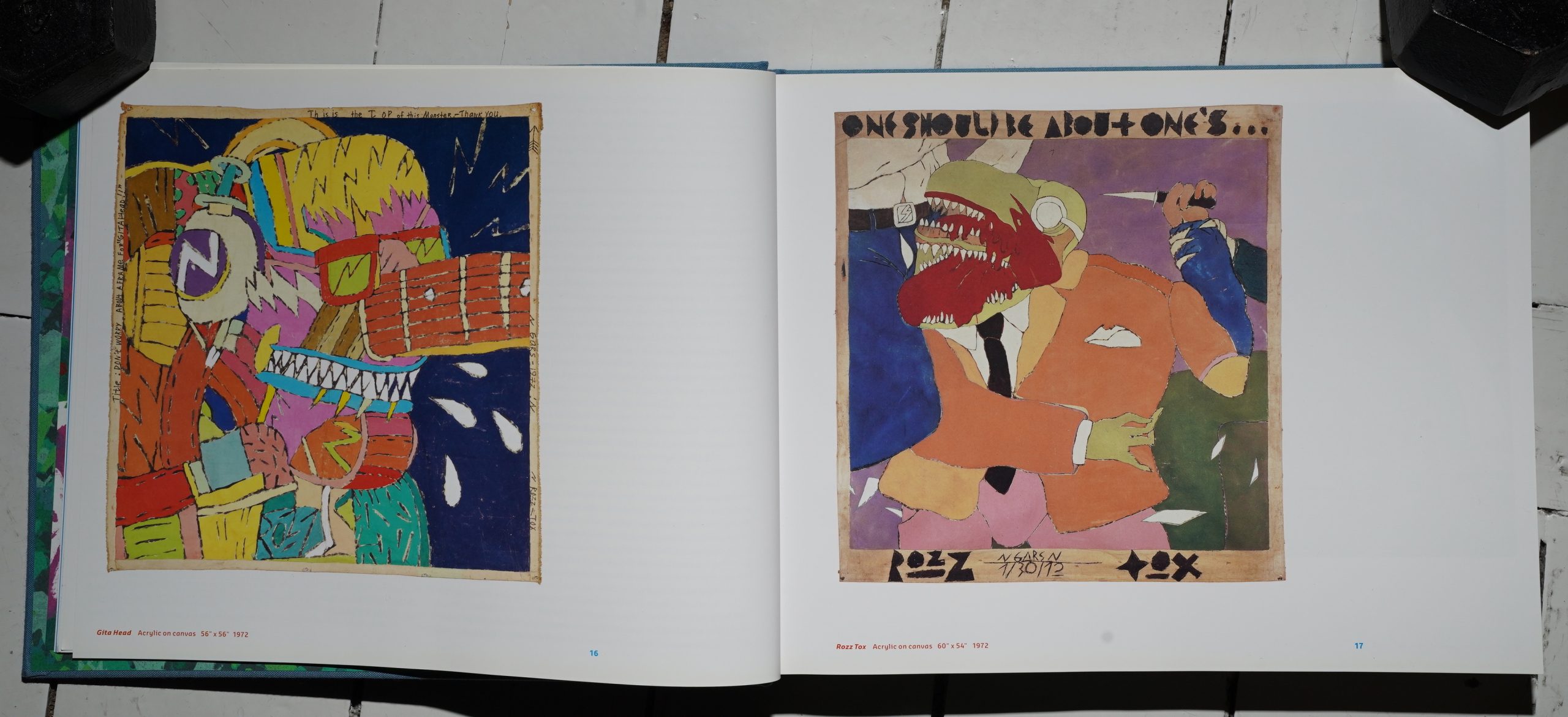

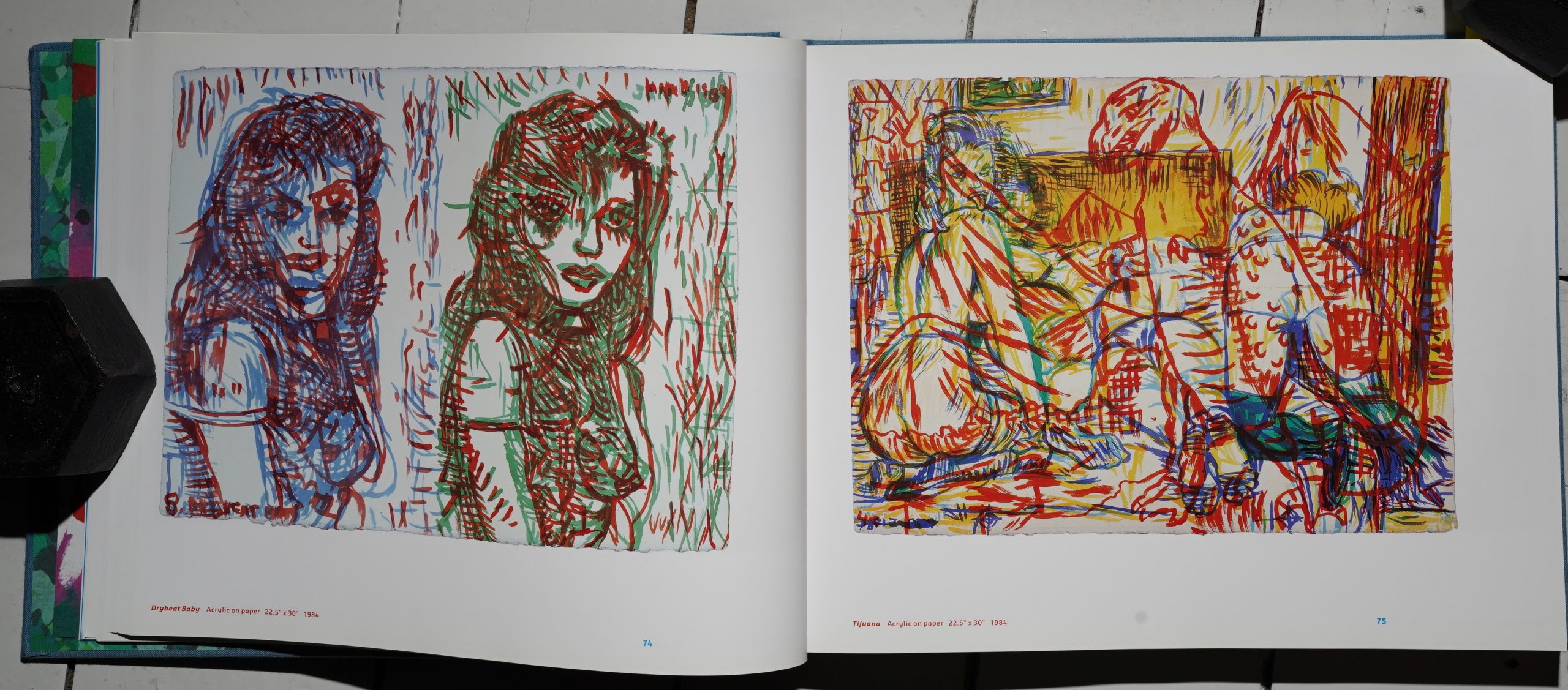

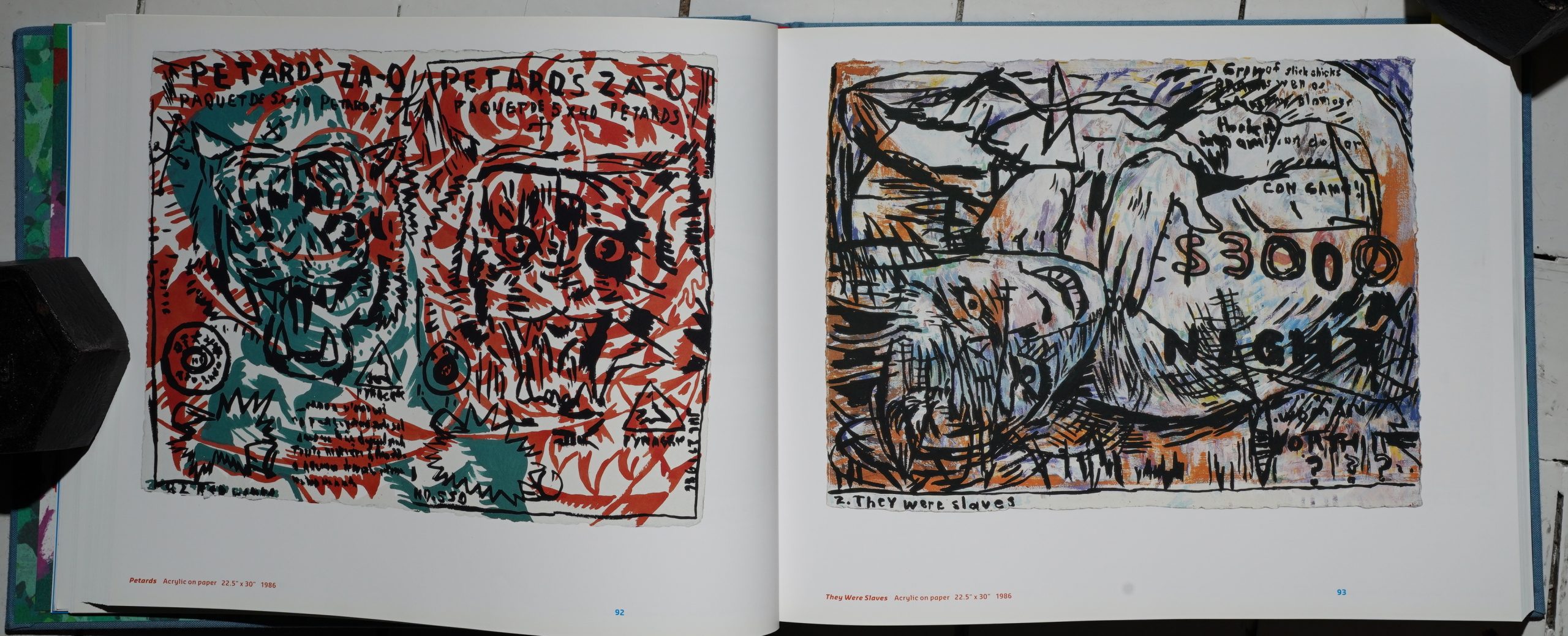

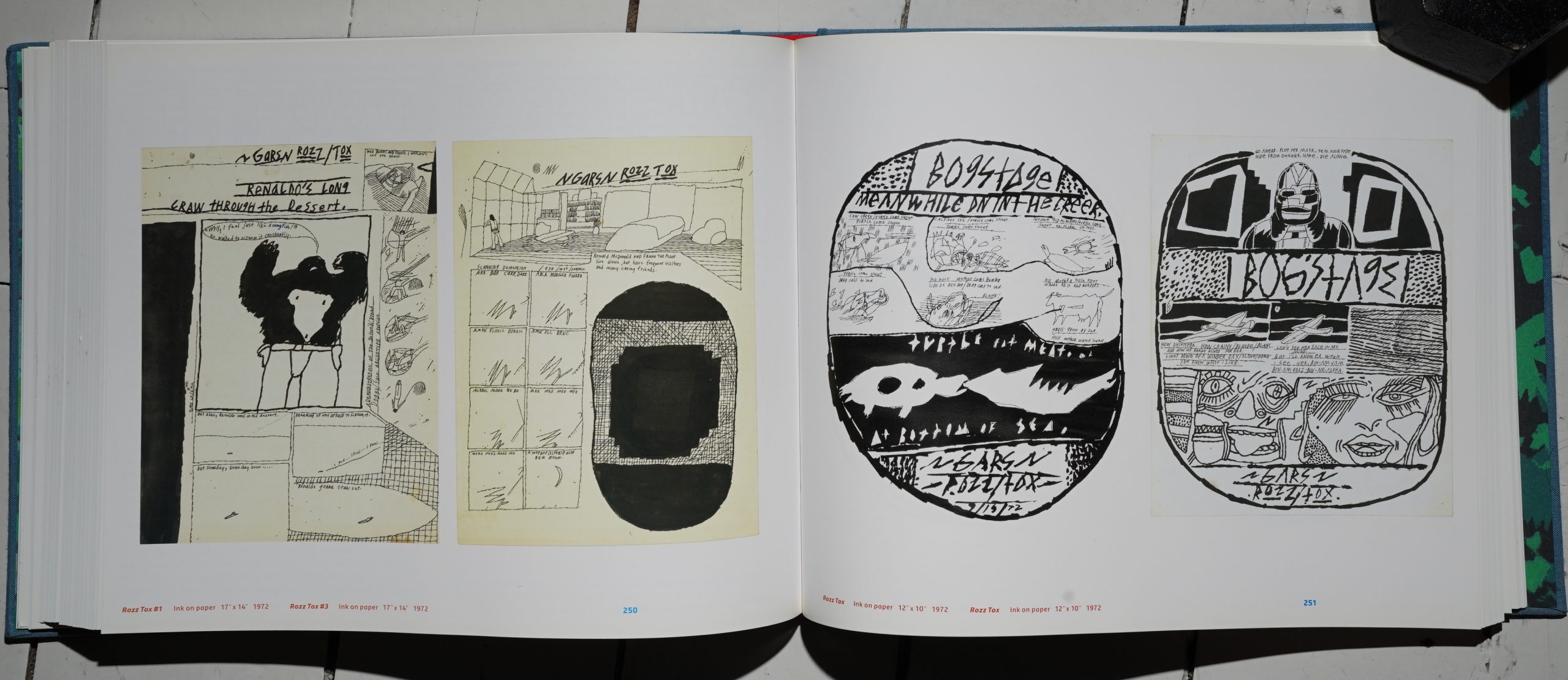

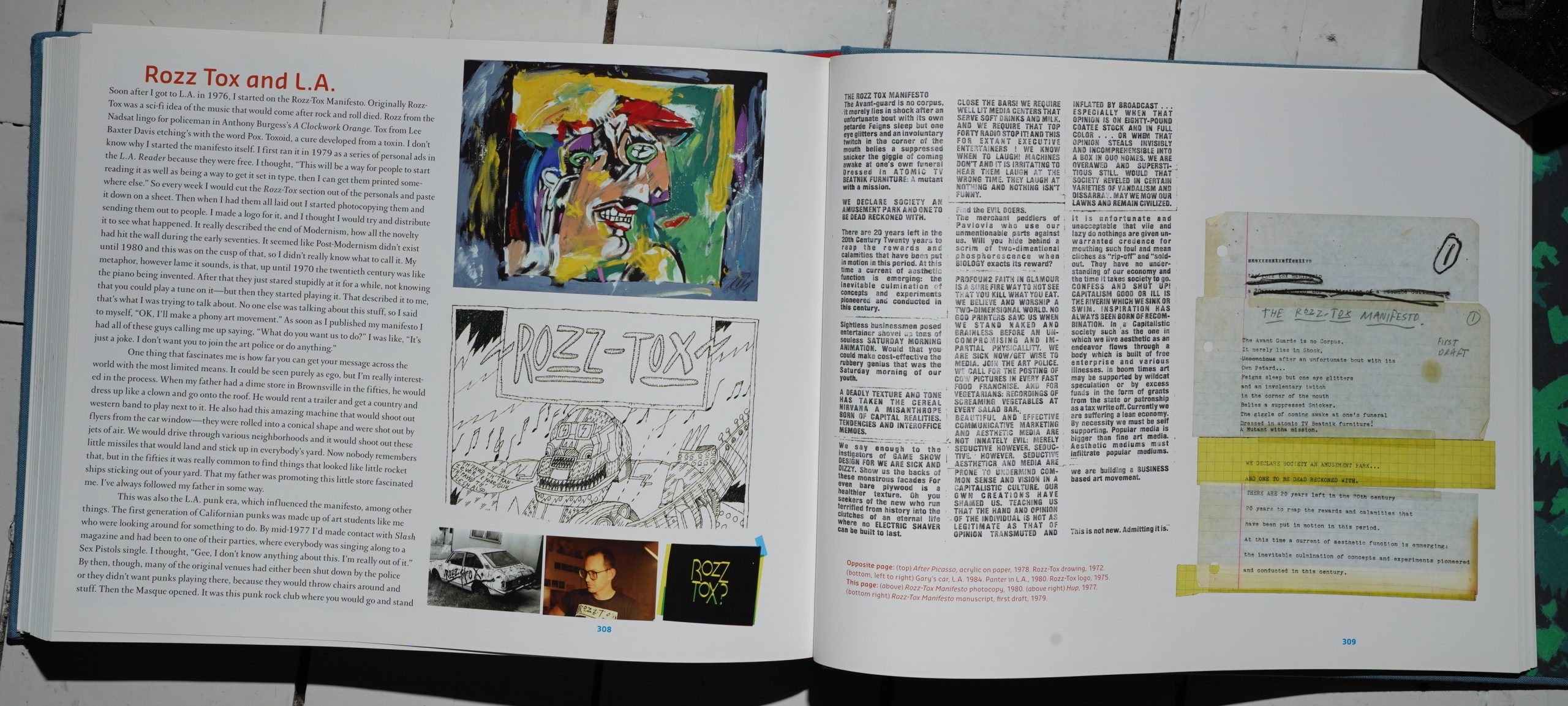

The bulk of the first book (the landscape one) is Panter’s paintings. I’d say about two thirds are paintings? We start off in the very early 70s, where Panter is still kinda hippyish in his choices (but already has that Rozz Tox thing)….

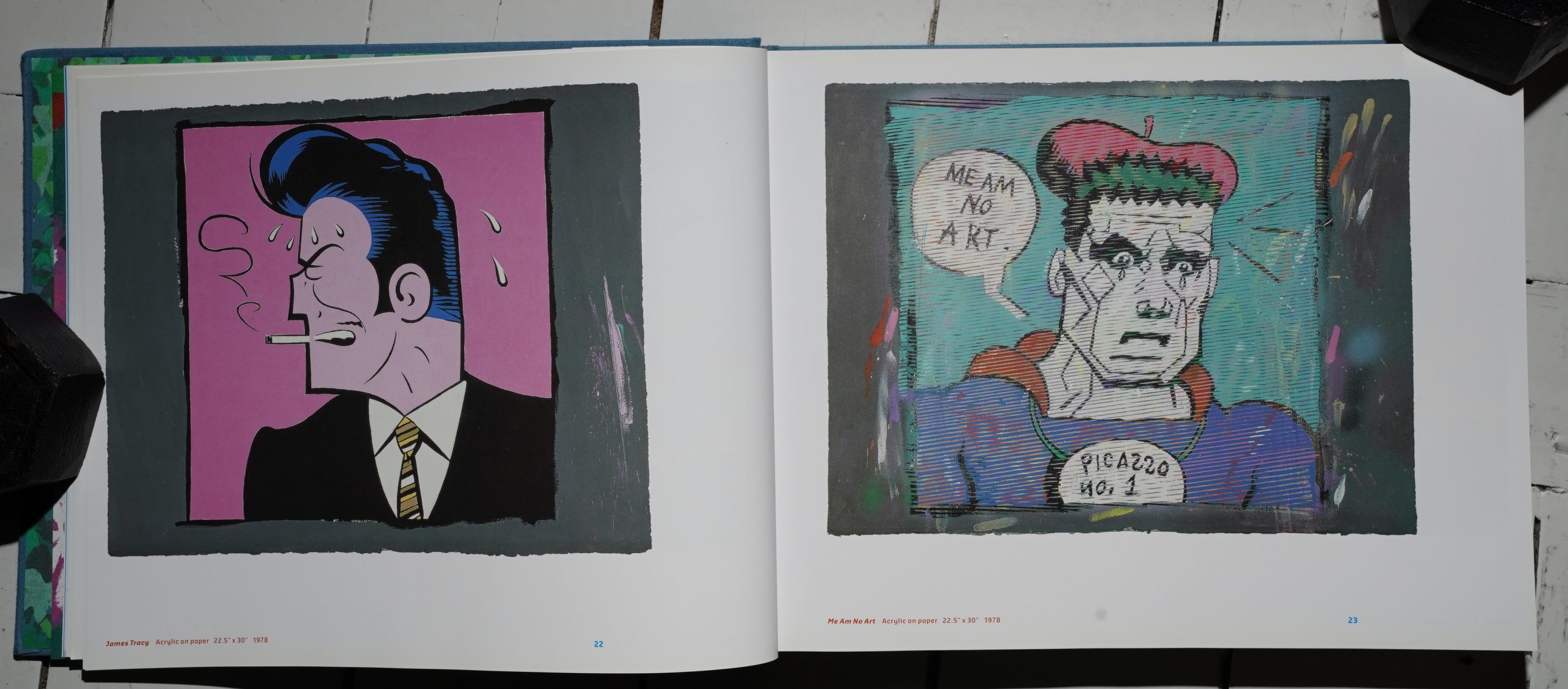

… and skip to the late 70s, where he’s gone all punk.

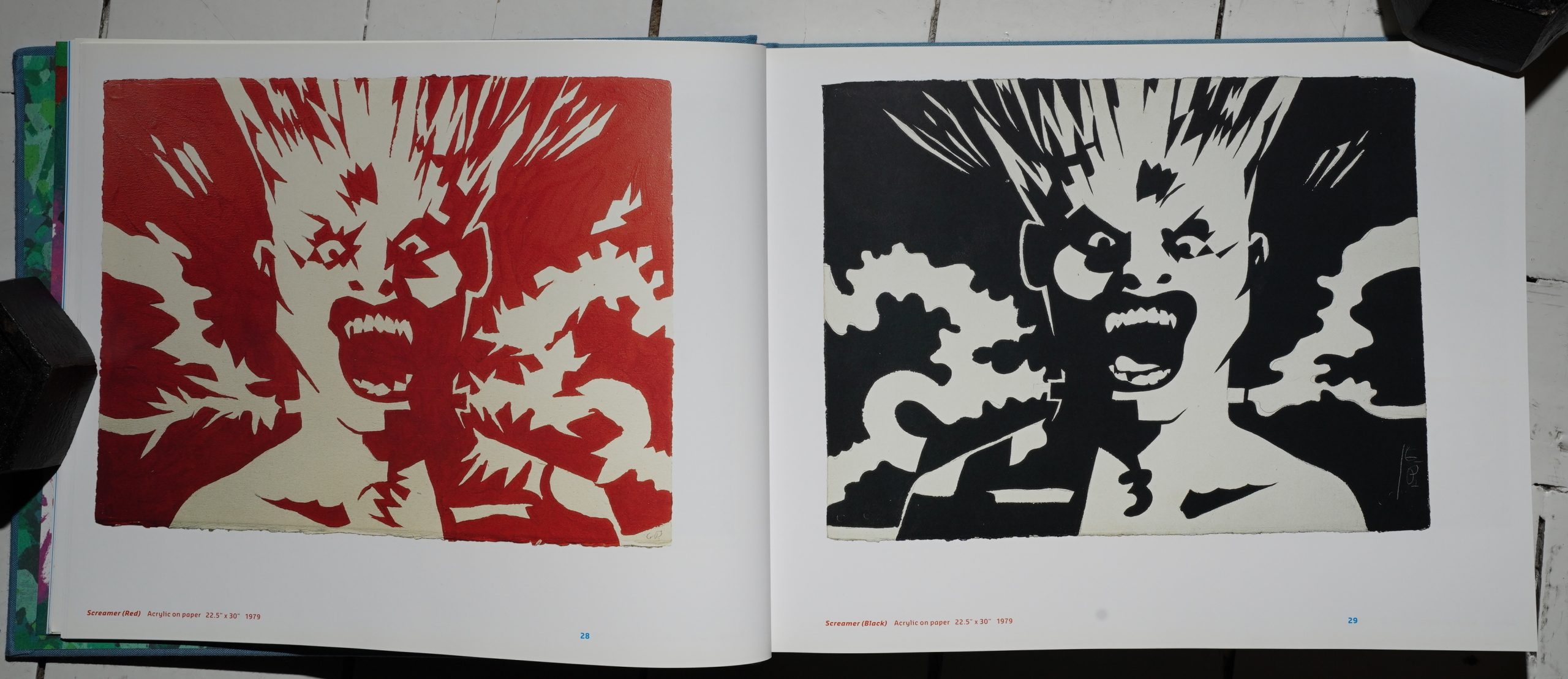

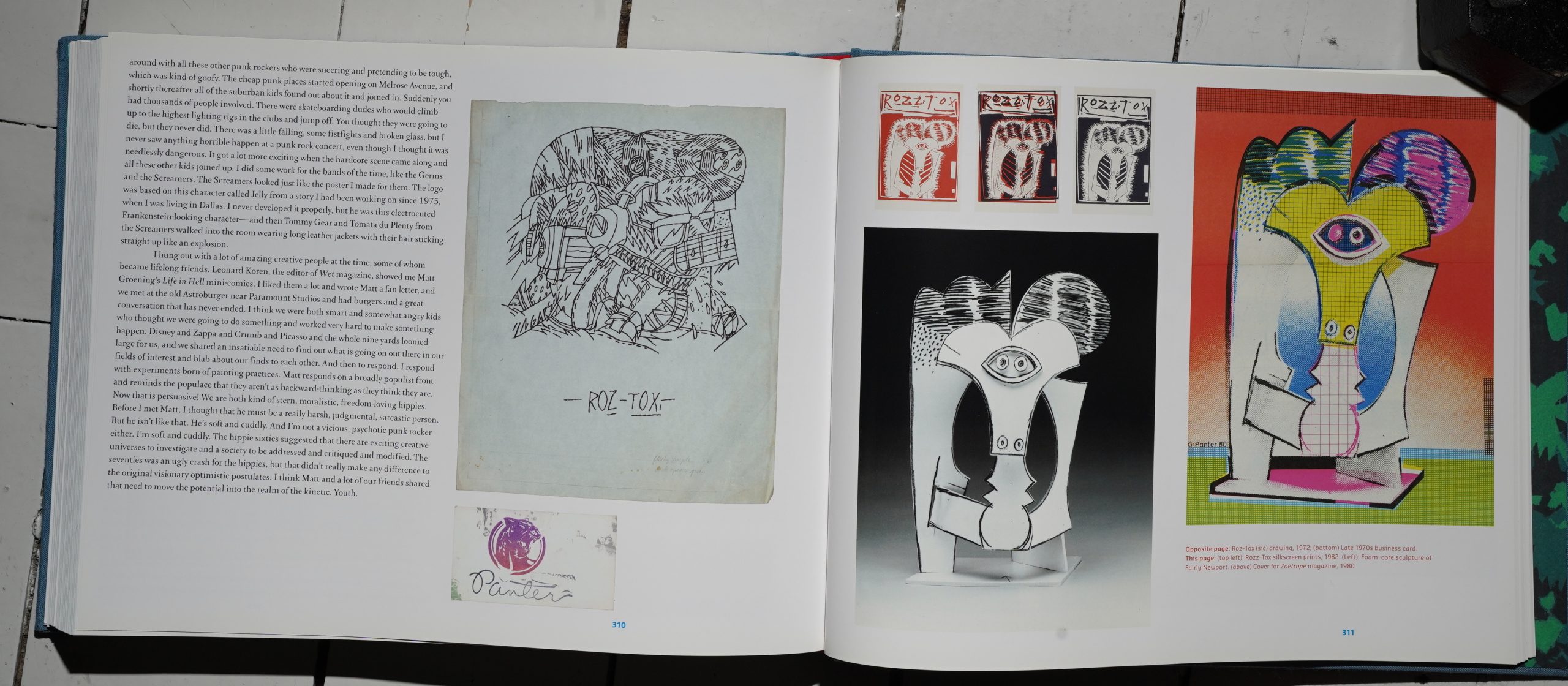

Most of the stuff is unfamiliar to me, but we also get the hits, like variations on the Screamers poster that probably was Panter’s major claim to fame for a few minutes.

Panter’s method seems to involve working through variations on a single theme or technique — we get groups of paintings, like a dozen, that’s are variations in theme…

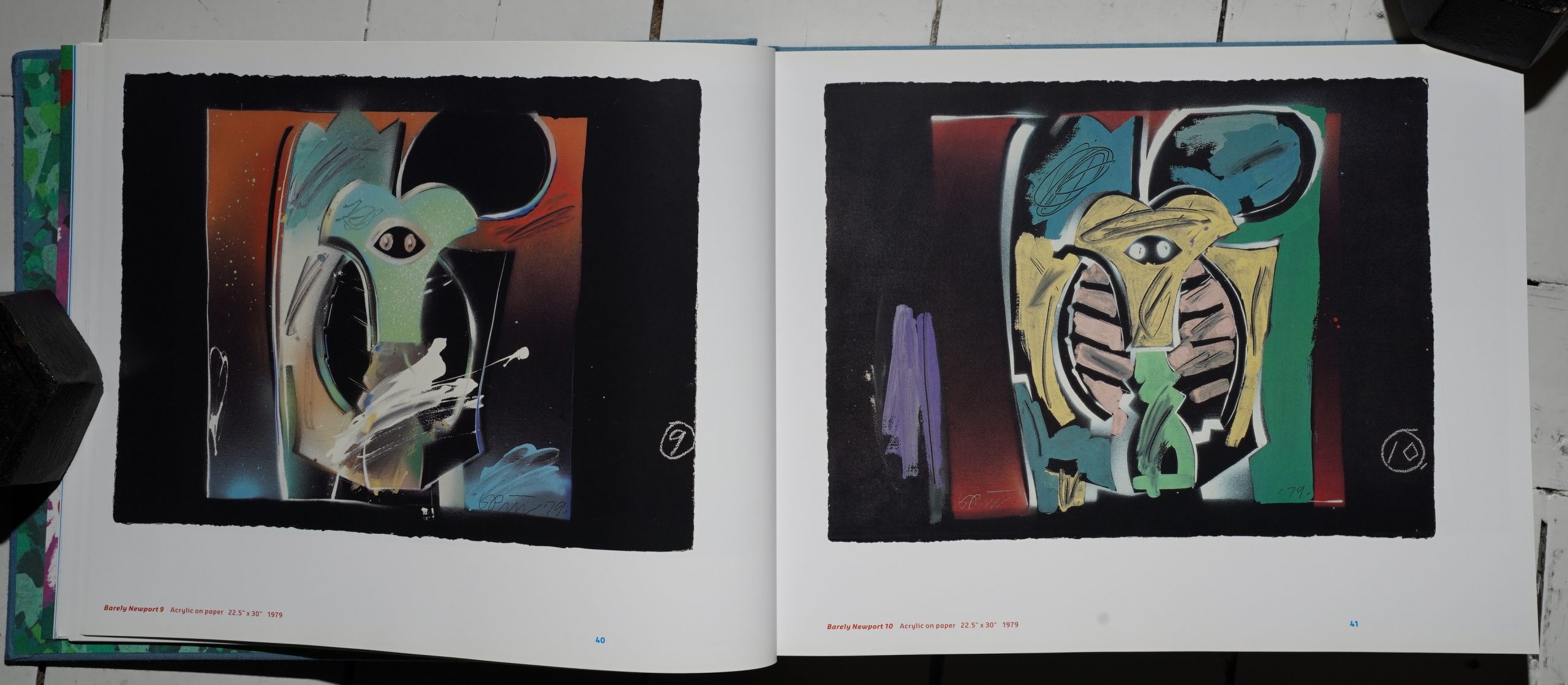

… or technique. I love this period, with the “off-register” painting technique.

Trey gorge, right?

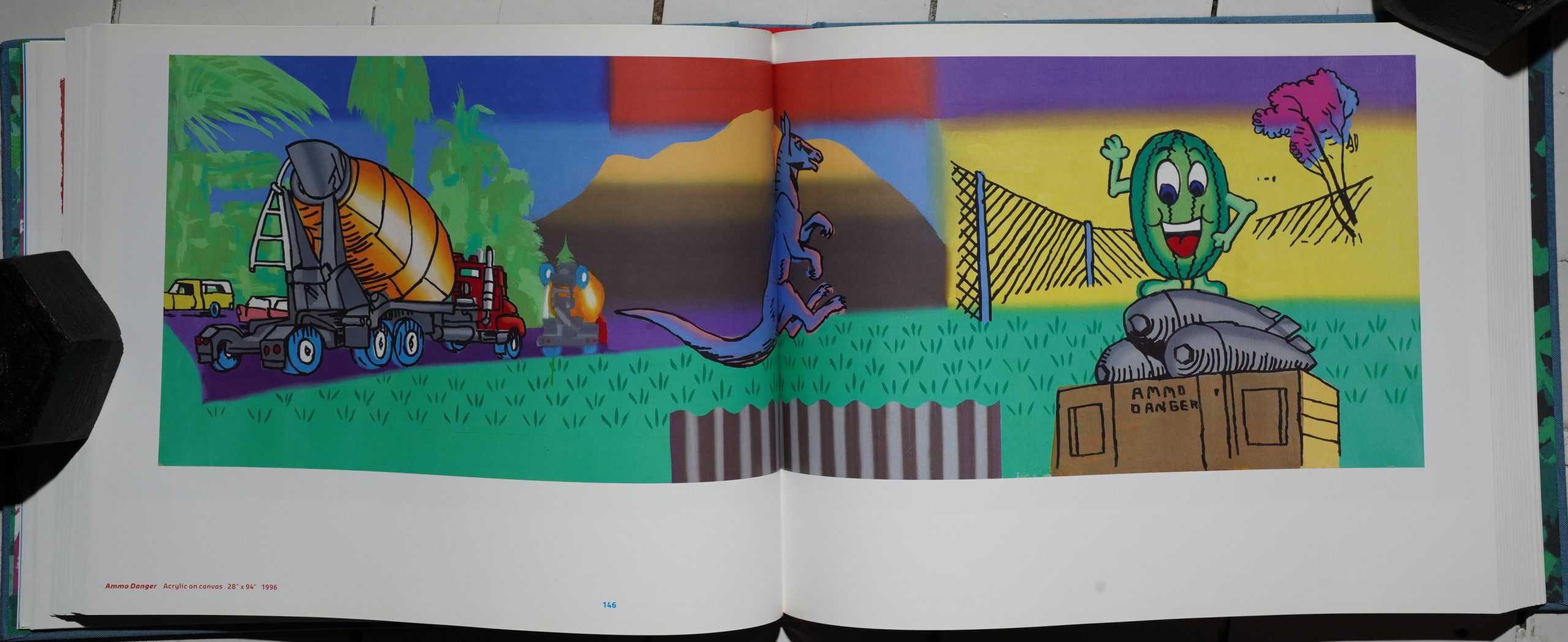

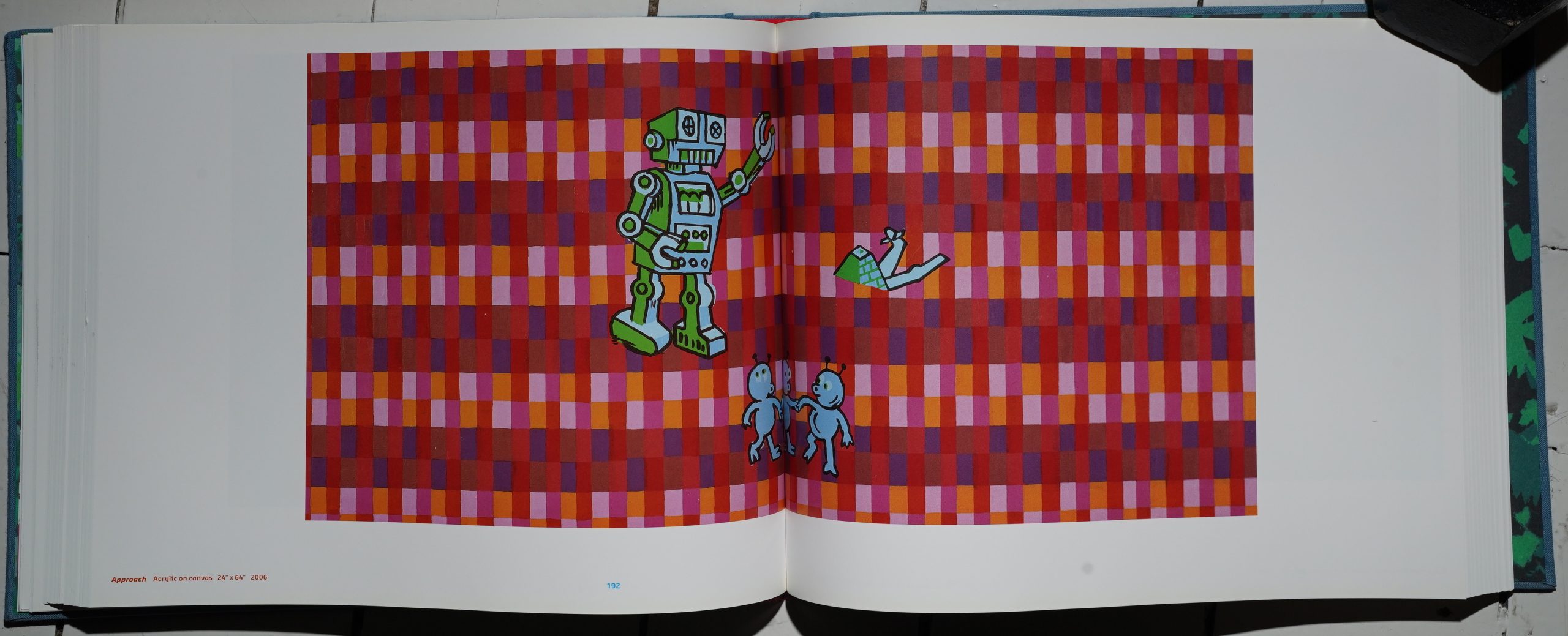

When we get to the 90s, the paintings become larger and a whole lot less aggressive. And while this book is pretty much impeccable in all other ways (the design, the printing, the binding, the smell), these two-page spreads aren’t the ideal way to print these large horizontal paintings.

I wonder whether Panter still has most of these paintings? I mean, the reproduction’s so good that presumably PictureBox had to have access to the originals… and none of the pages say “from the collection of Rich McBastard”…

Anyway, the paintings section of the book is strictly chronological…

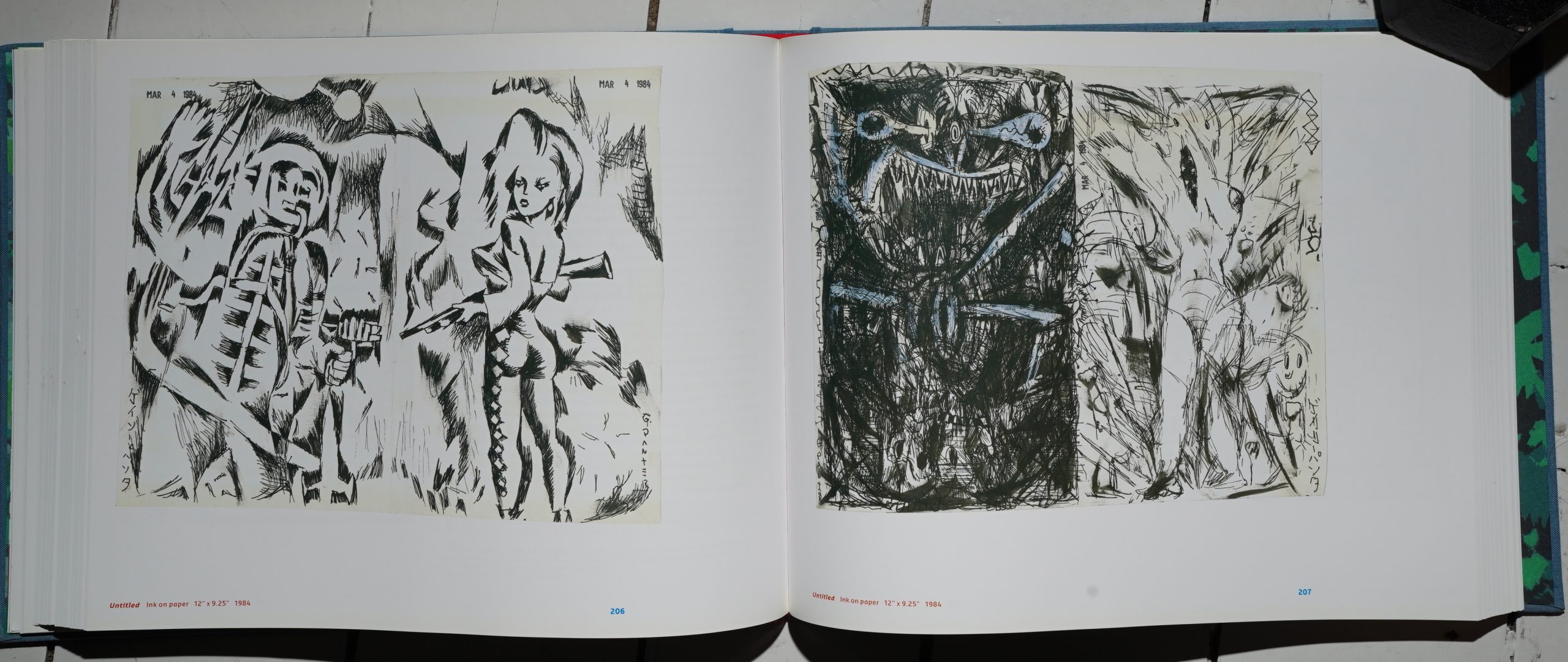

… and then the last third of the book is a bunch of shorter sections, which are also mostly chronological, but it means that we skip back, time-wise. So we get a section of pen-and-ink illustrations, for instance.

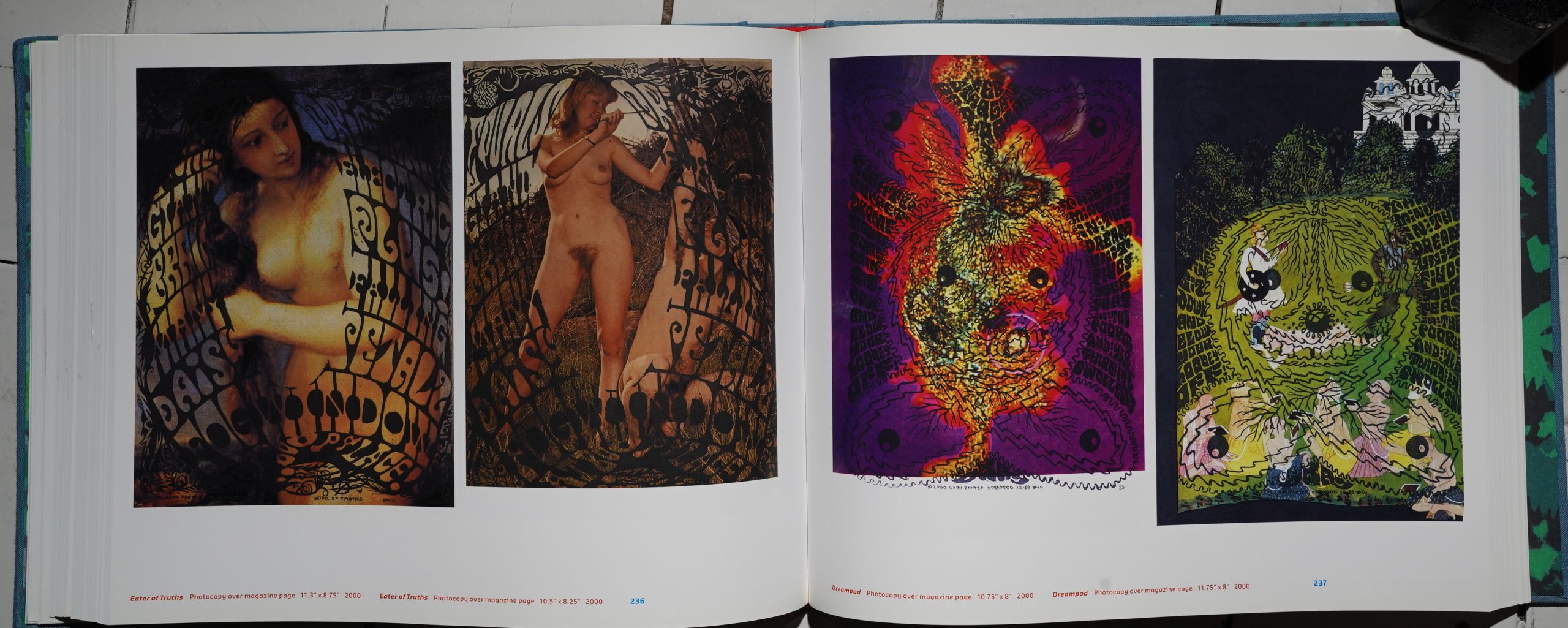

And the seldom-seen photocopy-over-magazine-pages medium. Trippy!

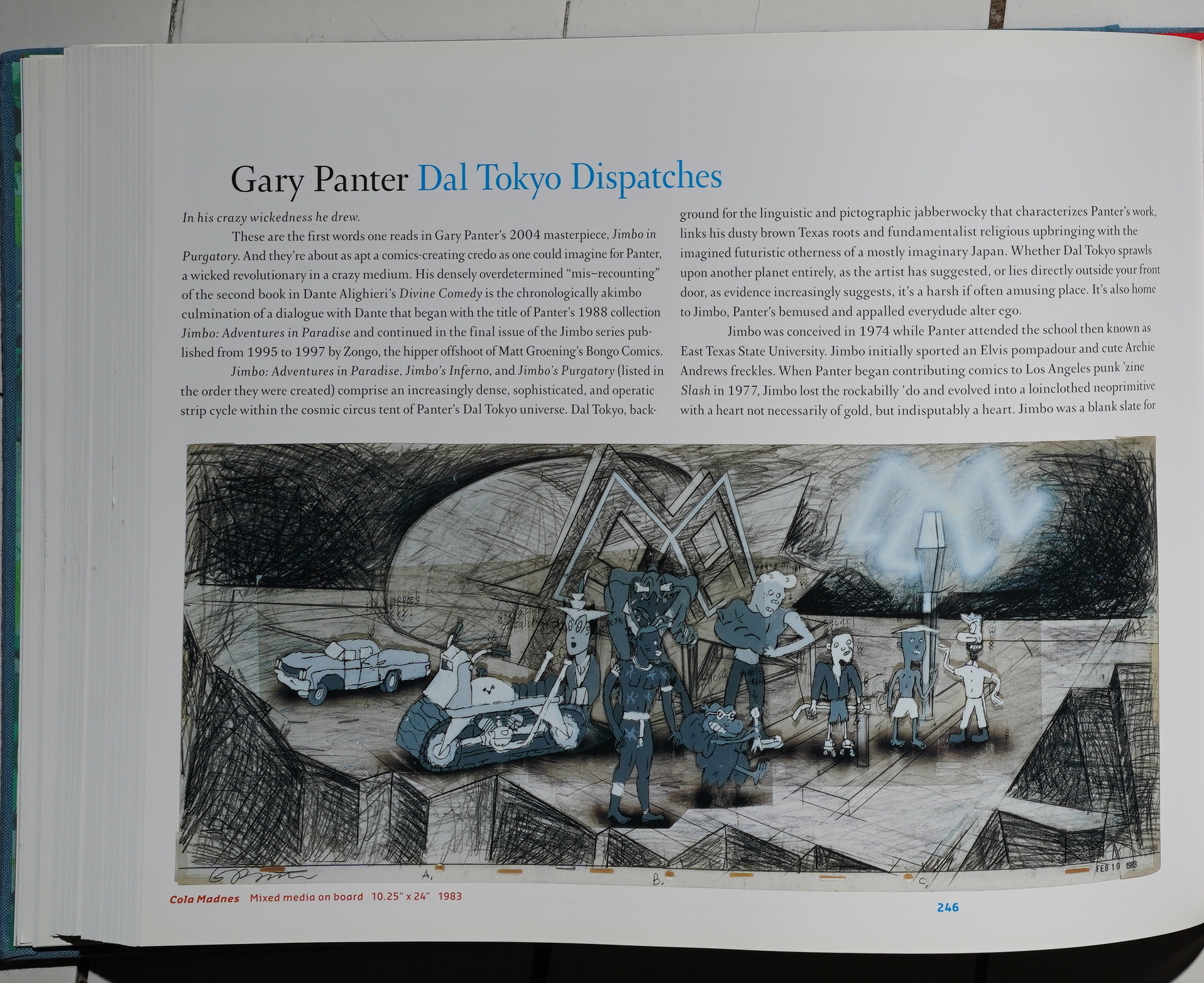

As I said earlier, each section has an introduction, and these are informative and interesting. Dan Nadel (the publisher) has made some good choices.

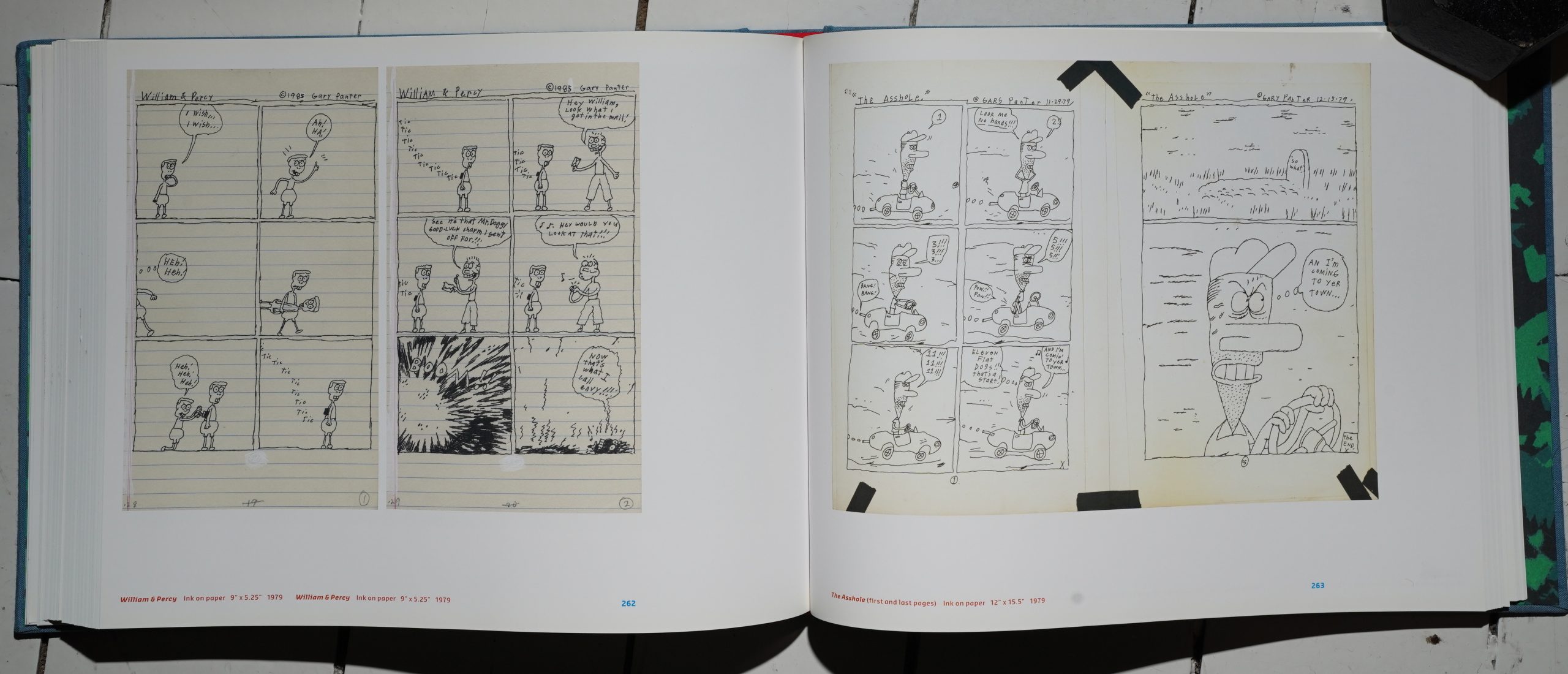

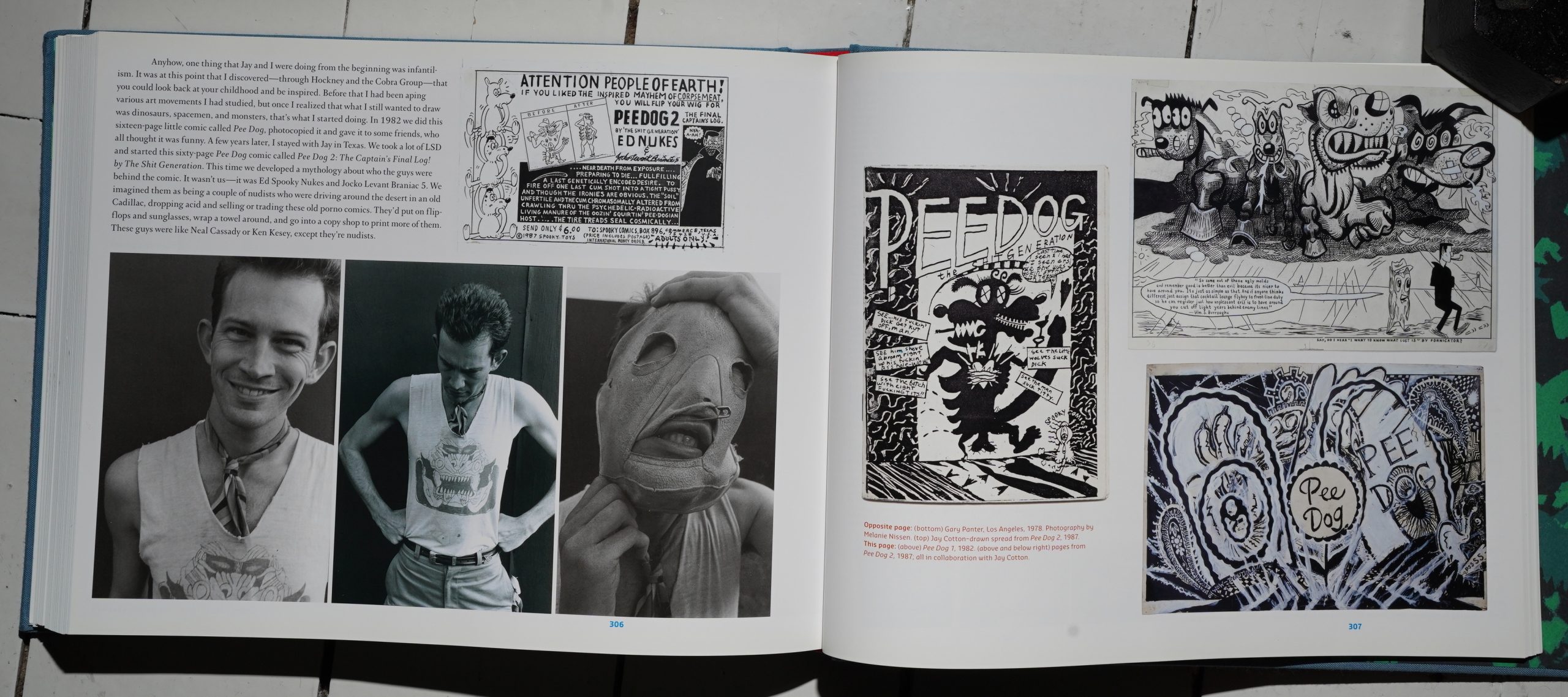

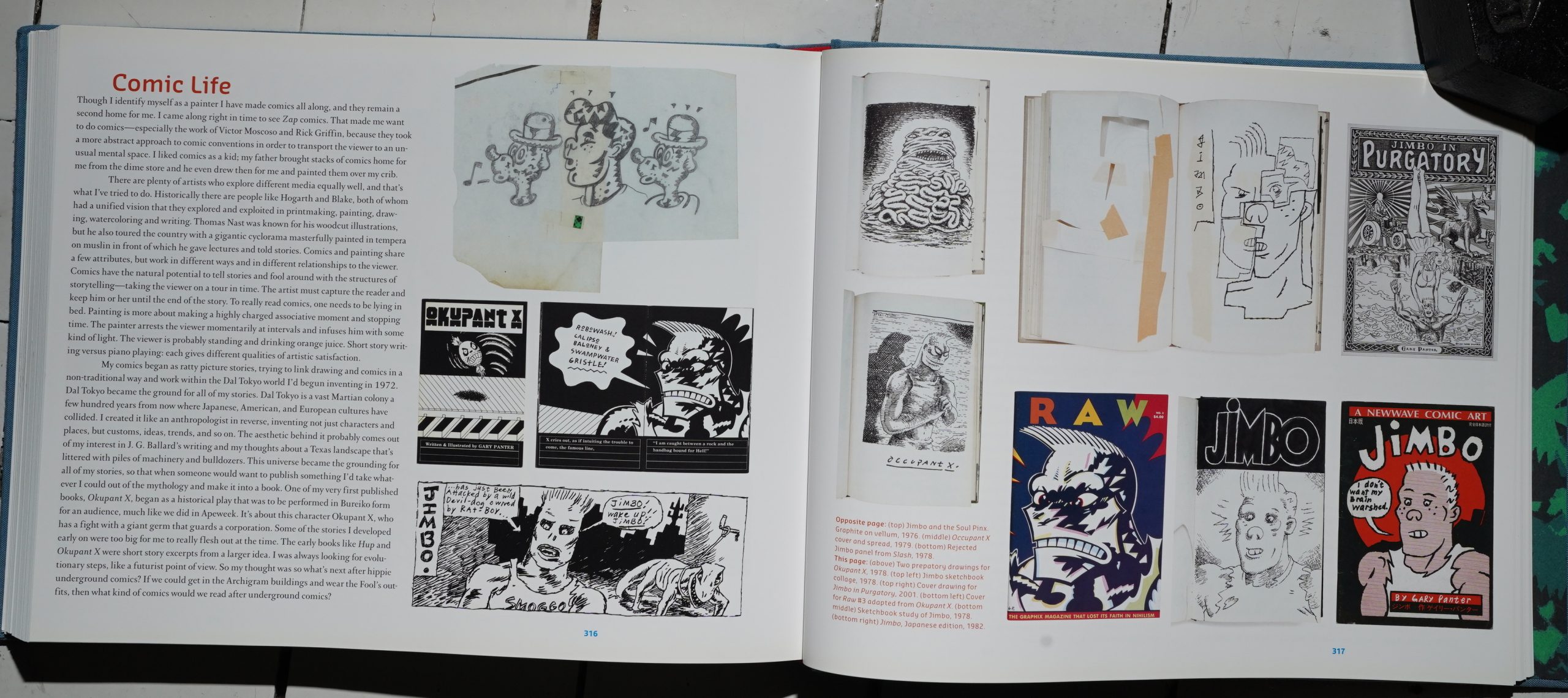

I assumed that this was going to be a book only about the paintings and illustrations, but we get examples of everything that Panter has done, like these very early comics things.

And various bits and bobs.

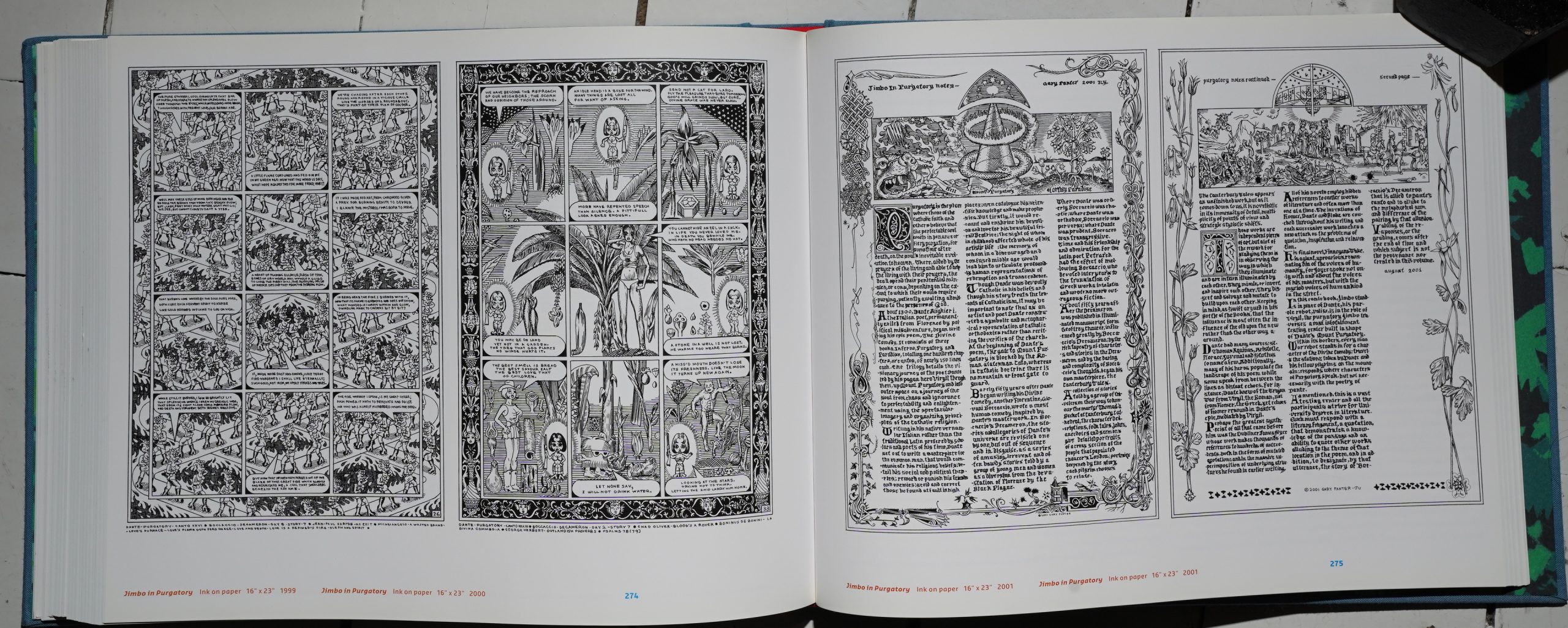

And even an excerpt from Jimbo in Purgatory. It’s a completist impulse, I guess, but these pages aren’t very readable here. But you get an impression of their insanely intricate look, at least.

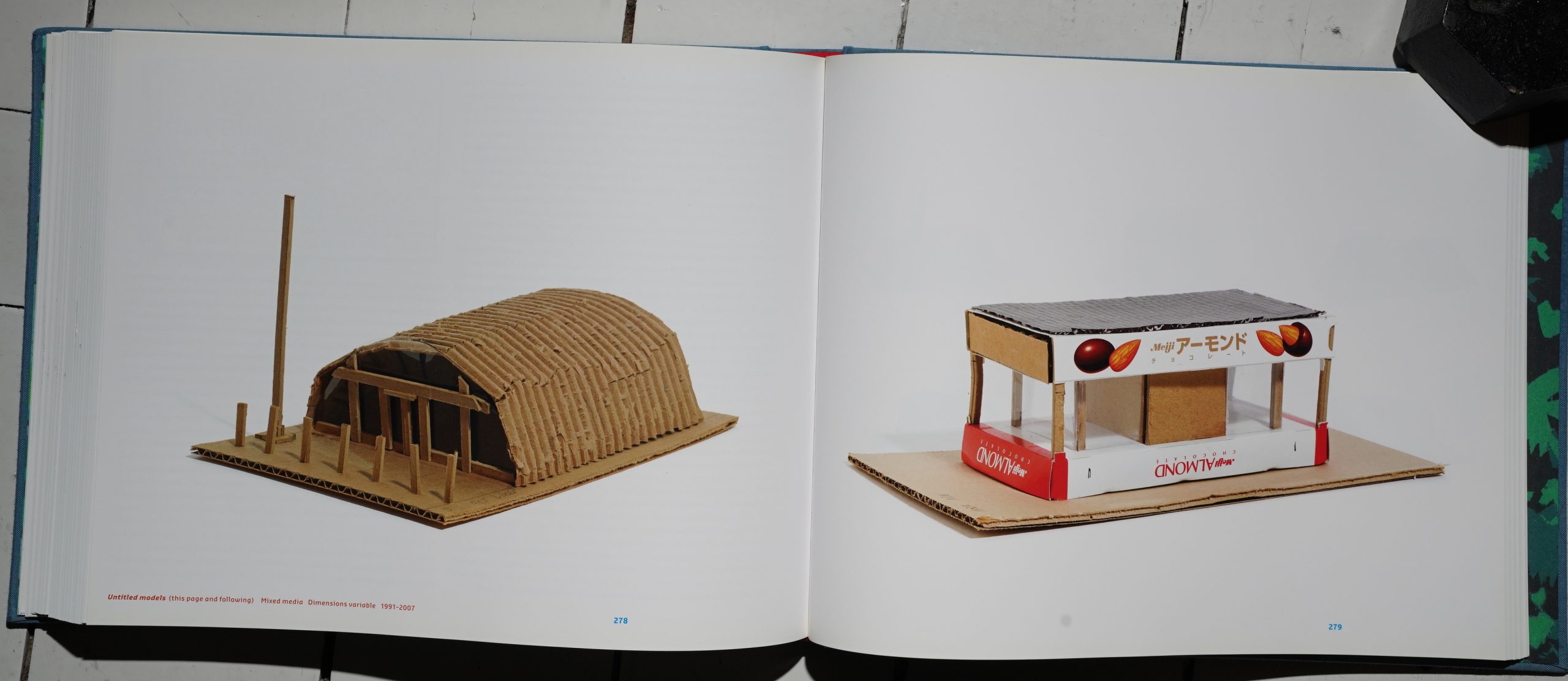

I did not know that Panter did little model houses, but we get a section dedicated to these, too…

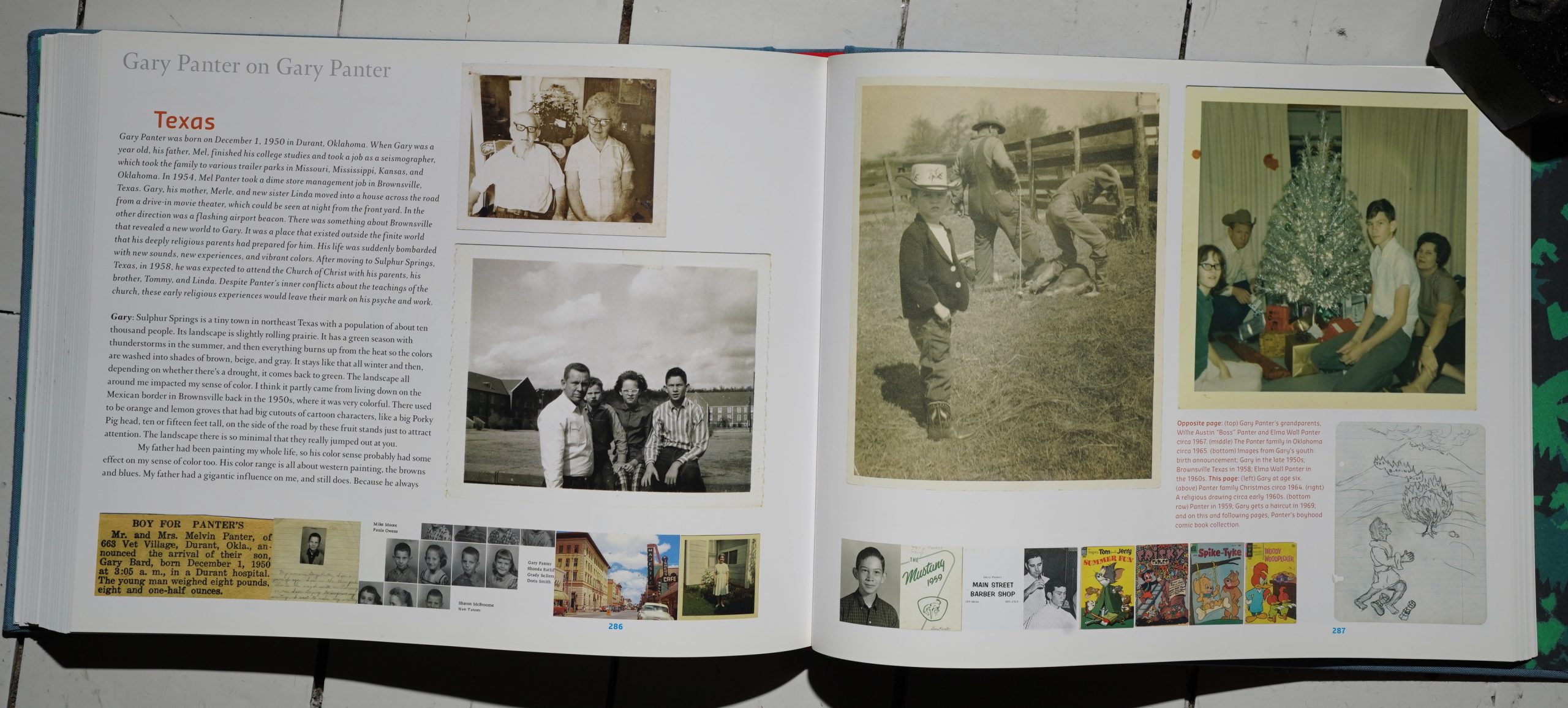

And then, towards the end, we get his biography.

What a punk!

The entire book is very interesting (and entertaining), but this section is of particular relevance to this blog series. Panter goes over the story behind Rozz-Tox, and how he published it in the classifieds section to get it typeset for free.

And then photocopied it and mailed it out to a bunch of people (and it sounds like everybody were pretty nonplussed about it all). It’s great.

Panter explains that all his comics takes place in Dal Tokyo, and they’re all interconnected, but in… er… somewhat vague ways. He also explains that one of his problems is that he doesn’t want to put any of his characters through anything bad, really, which limits his storytelling options. (But he created the character The Asshole specifically to allow himself to have a character that bad things could happen to.)

There’s a huge amount more here in this book — it covers the Pee-Wee Herman connection, the Japanese connection, etc etc. It’s really jam packed with interesting things, beautifully presented.

So if that’s the first book, what’s in the other book? It seems like we’ve covered everything possible…

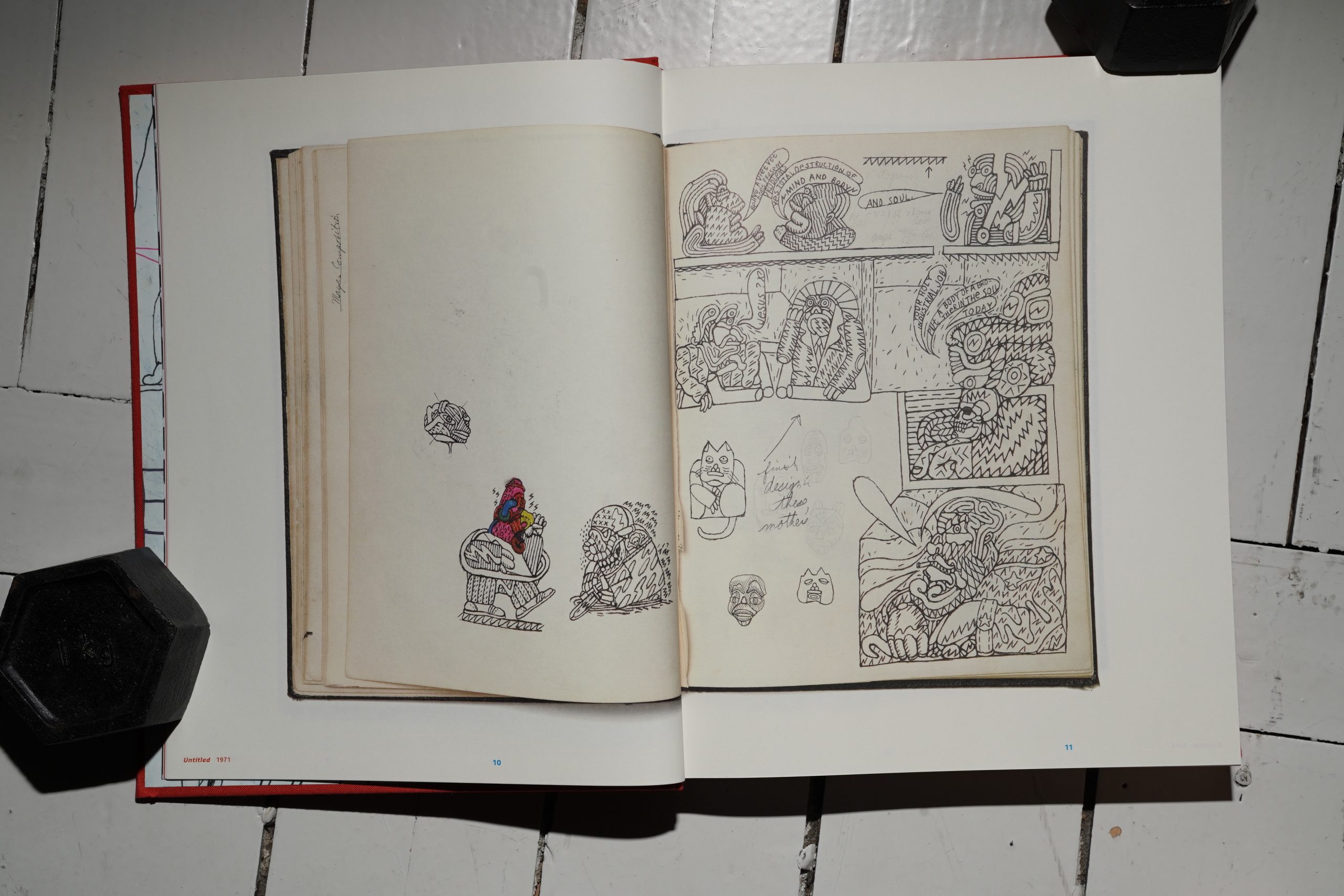

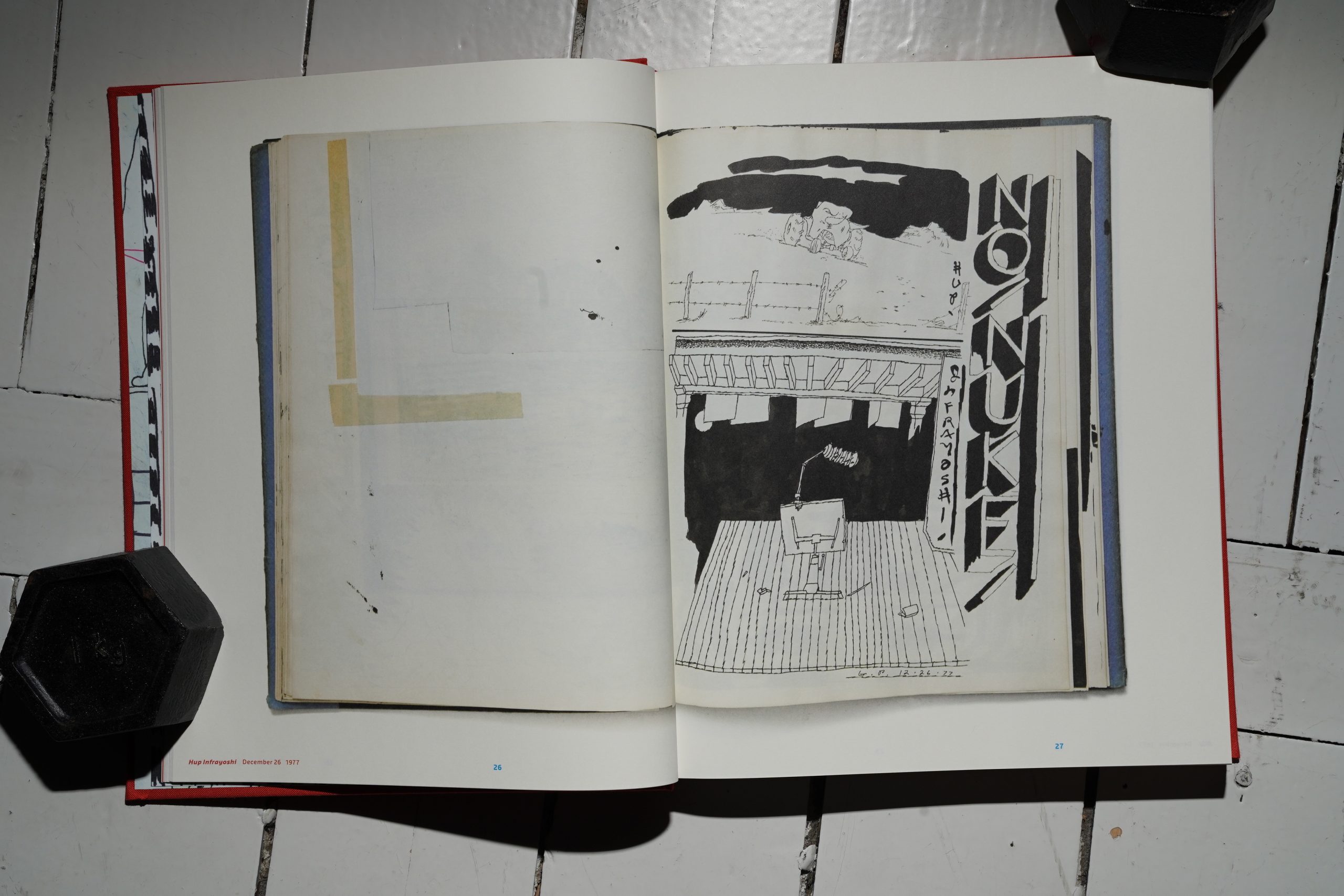

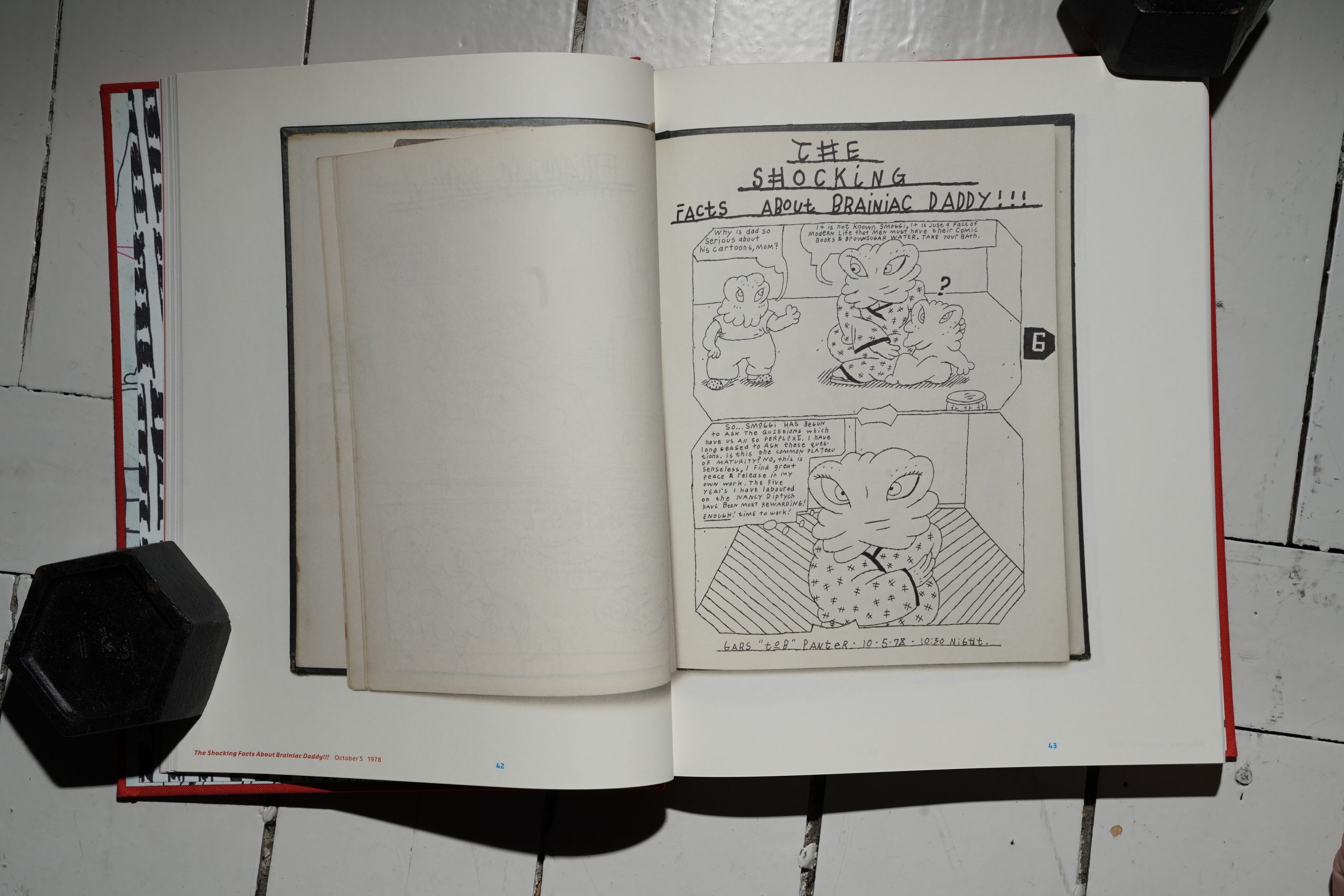

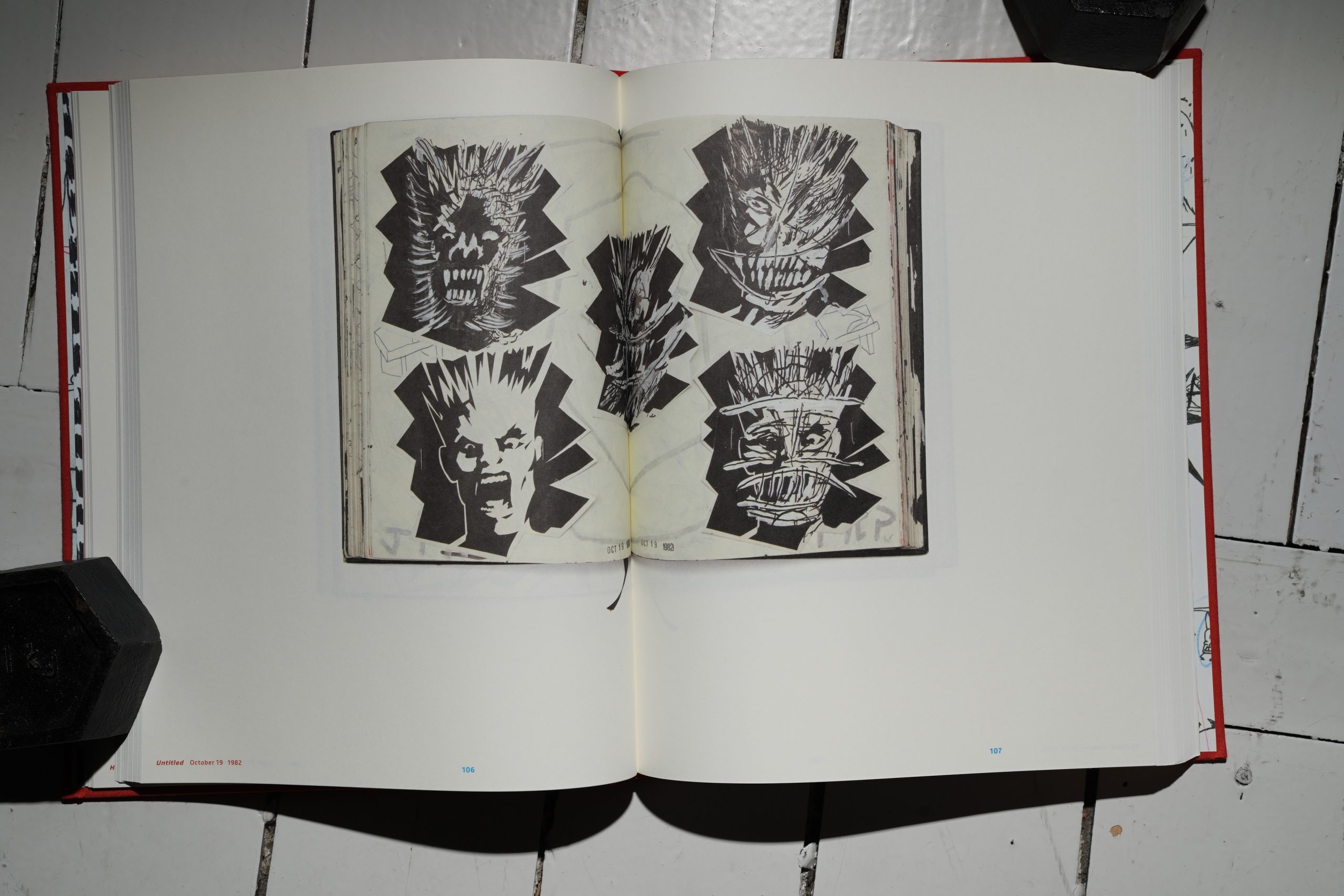

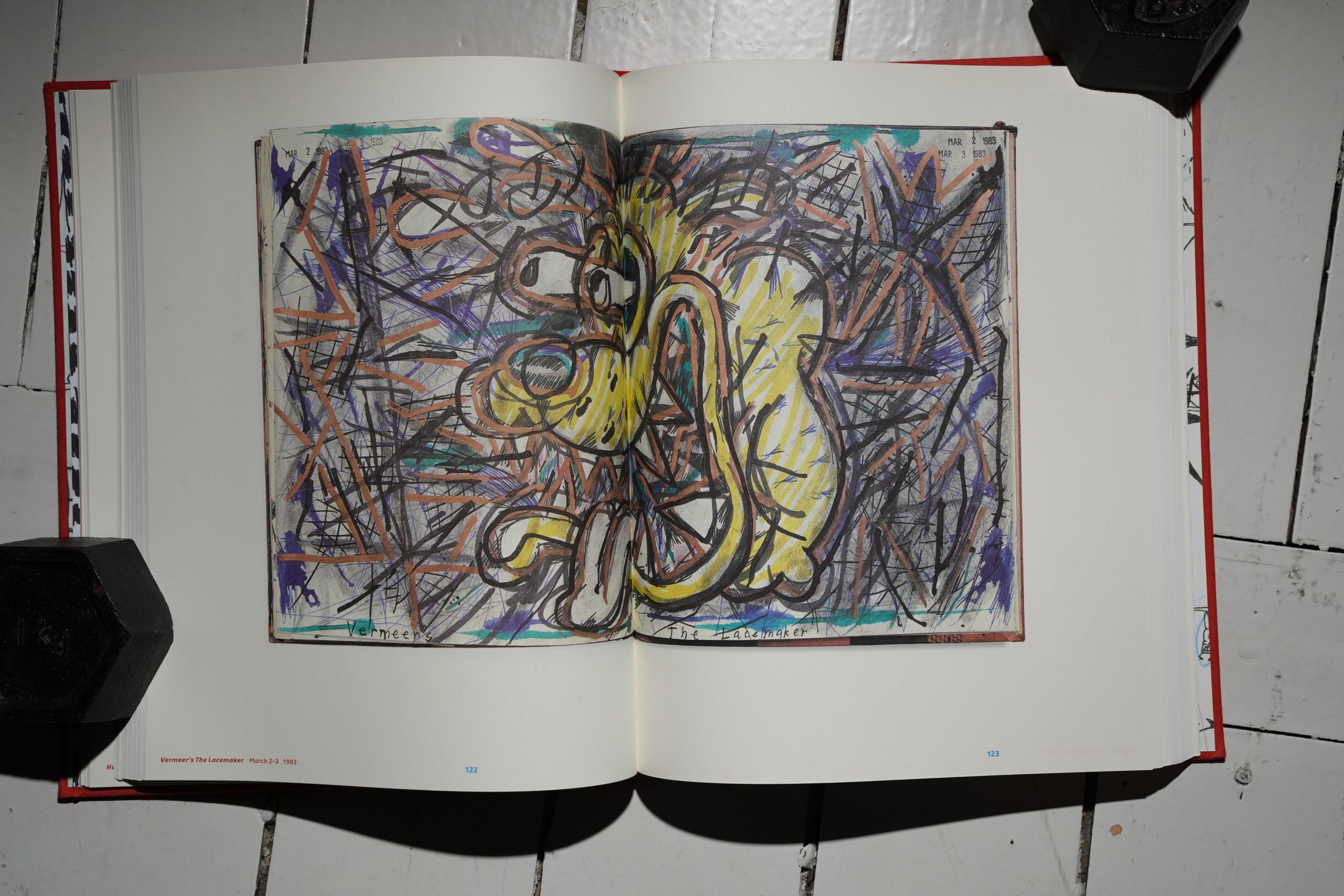

The second book is all pages from Panter’s sketchbooks — he’s got more than a hundred of them.

I love this oddball way of presenting them: It’s not explicitly stated, but I guess we’re getting a 1:1 reproduction of the pages, and some notebooks are smaller than others, so they take up less space on the pages in this book. I don’t think I’ve seen notebooks reproduced this way? It feels intimate, in a way.

There’s not a lot of comics reproduced here, but there’s a few pages.

Sketches of the Screamers guy! Cool.

Cool.

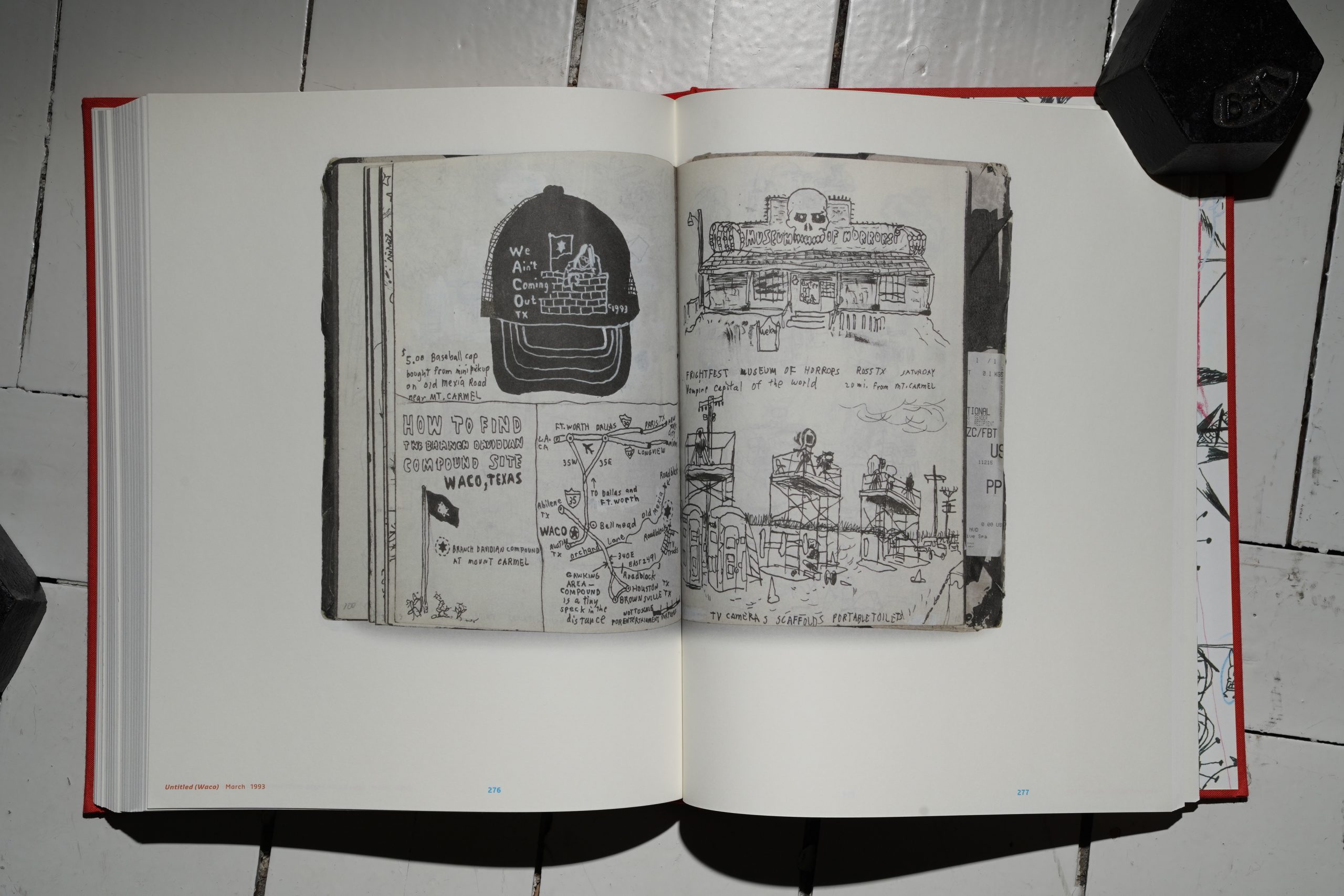

There’s a whole lot of sketches about the Waco thing, for some reason…

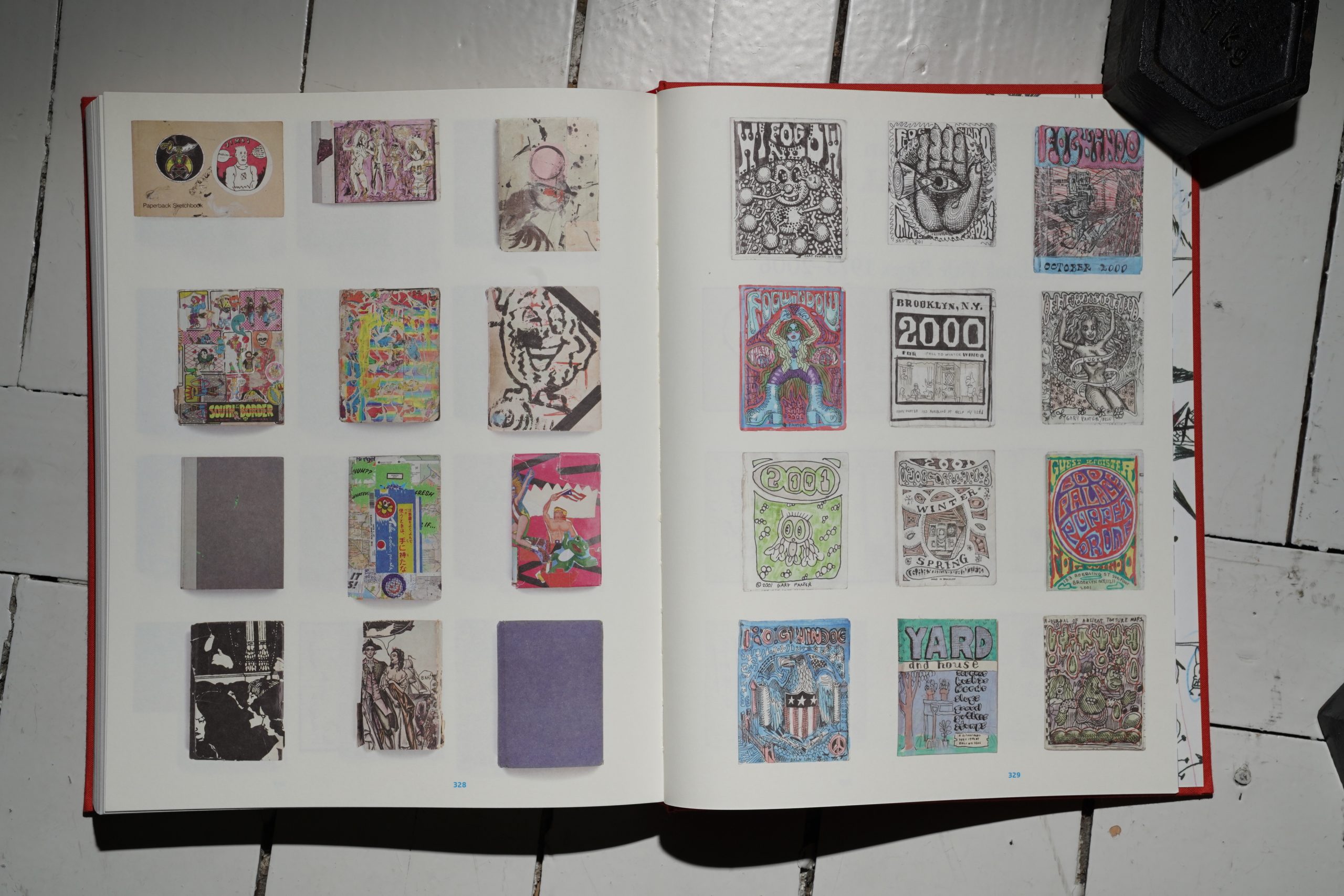

Finally, we get a selection of the covers of the notebooks.

Paul Karasik has the book on his “best of 2008” list in The Comics Journal #296, page 34:

Gary Panter, Gary Panter (PictureBox)

Wake up, America.

A terrific bargain for so much terrific work. This is one

art book that I keep pulling off my shelf to bathe in. Do

yourself a favor and splurge. Buy this two-volume set now

and a towel.

It’s also featured on a bunch of other people’s lists.

PictureBox created a web site for the book (and a tour), but it’s gone now. But the Wayback Machine has a copy. Looks like fun was had by all.

Aha! The book originally retailed for $95, but it looks like it was actually sold for $60 for a couple of years… So I guess PictureBox printed quite a lot of these? My copies of the books has a little paper thing saying “14571”, but I have no idea whether that’s supposed to be the copy number or just some technical printing thingie. It seems to be a really huge number if it’s they printed that many copies. It’d be tons and tons of cellulose.

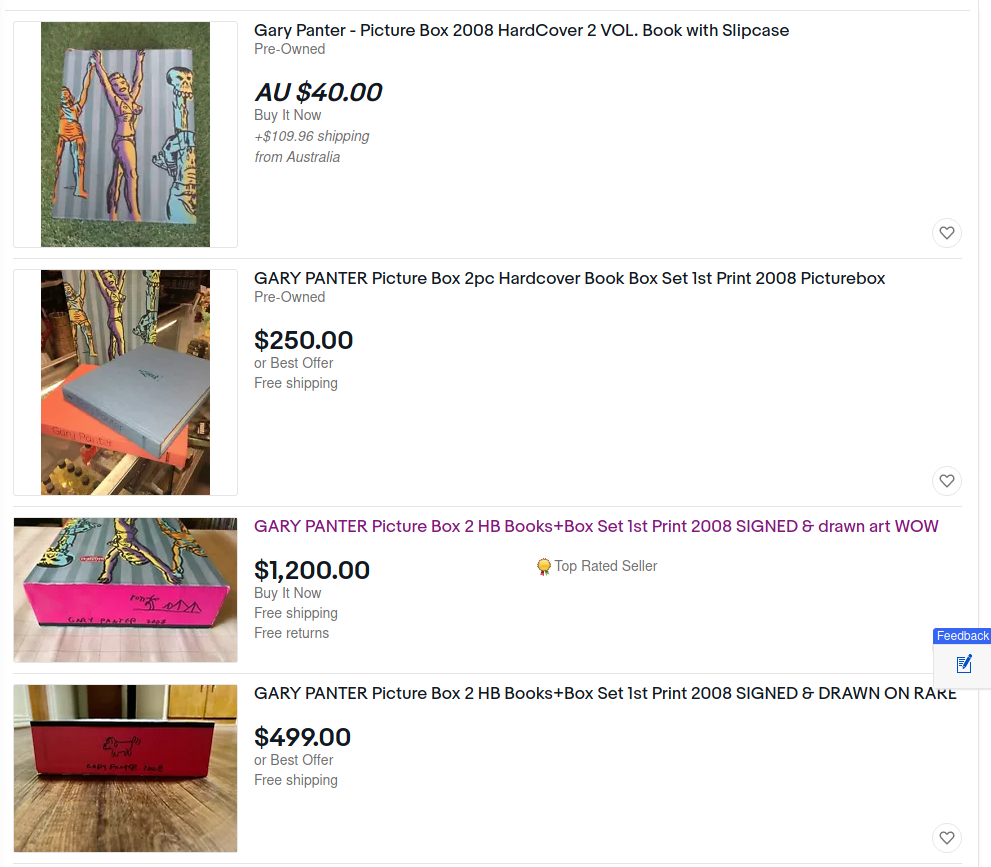

Which makes me curious to see what they’re going for these days.

Er… a wide variety of prices… And it seems like a lot (or all of them?) are signed on the top (or bottom).

There’s a lot of these floating around, almost a decade and a half after it was published, so perhaps PictureBox really did print 15K copies? It seems incredible.

Ooh:

This is an interesting interview with Panter:

BLVR: I noticed in that series that sometimes you’ll kill a character off only to have him reappear a few pages later, having survived due to miraculous circumstances.

GP: Well, you never actually see them die. You see them about to die. I love lying to the reader and making it look like something’s happened when it hasn’t. I do feel bad about killing characters, but I don’t feel bad about them doing bad things. Maybe that makes my stories more boring.

BLVR: What happened to the Zongo series?

GP: Nobody was buying them at all.

BLVR: Do you think that was because they were only available in comic-book stores?

GP: Maybe. That’s not where the audience is. Also I included some earlier stuff in the fifth issue that I’d done when I was really young and it was kind of dirty. It makes comic-book stores nervous when they might get arrested if the wrong kid picks up the comic, and they stop ordering them, so then they weren’t in comic-book stores, either. At the time I thought I should stand by my old stuff, but when it was published I was a little like, Maybe I have grown up and shouldn’t be standing behind this. Matt wasn’t happy about publishing some of that, either.

Which explains some of the questions I had about the Zongo series.

As you’ve probably understood already, I’m just typing away at this while I’m googling for reviews of the book… and I can’t find a single one. There’s apparently one in Printmag, but that’s off the webs now.

Panter has staked out especially productive territory, which can be detected in the relationship between his paintings and his comics (which are excerpted in this monograph and available in full elsewhere). Panter literally made his mark in comics by bringing the values of painting into the medium with a bold gestural approach and an aggressive style-mixing that were, at the time, still rare for a visual genre that traditionally favored relatively smooth continuity. He accomplished this, moreover, without undermining his cartoon language or narrative flow. Equally remarkable is his ability to simultaneously import cartoon imagery into his paintings without mummifying or ironizing his visual subject. The resulting work in each medium addresses separate formal concerns but clearly belongs to an artistic sensibility, identifying Panter as an artist to be reckoned with.

Still, it doesn’t seem like this publication got the attention it deserved. Perhaps PictureBox just didn’t have a persuasive enough PR division (heh heh) to get it placed in the relevant publications.

This blog post is part of the Punk Comix series.

Is this the greatest tune ever?

Well it might be this:

But it’s not as existential.

PX Stuff

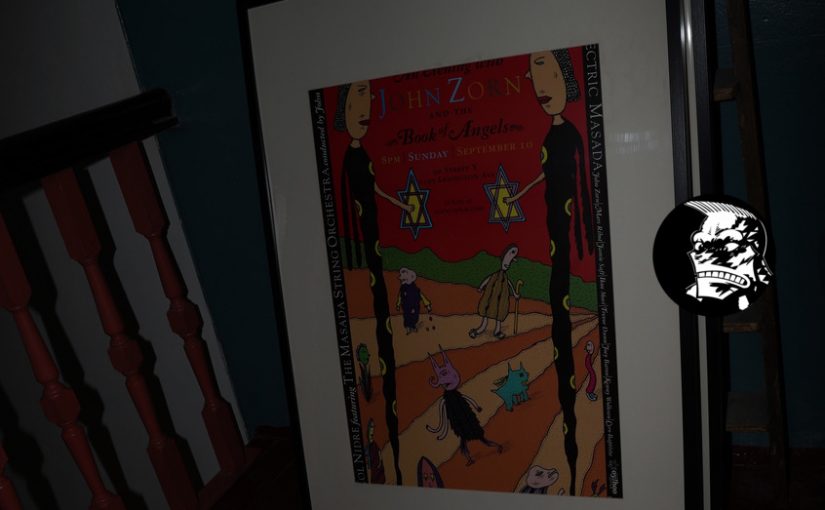

A Mark Beyer poster from John Zorn’s Book of Angels.

This blog post is part of the Punk Comix series.