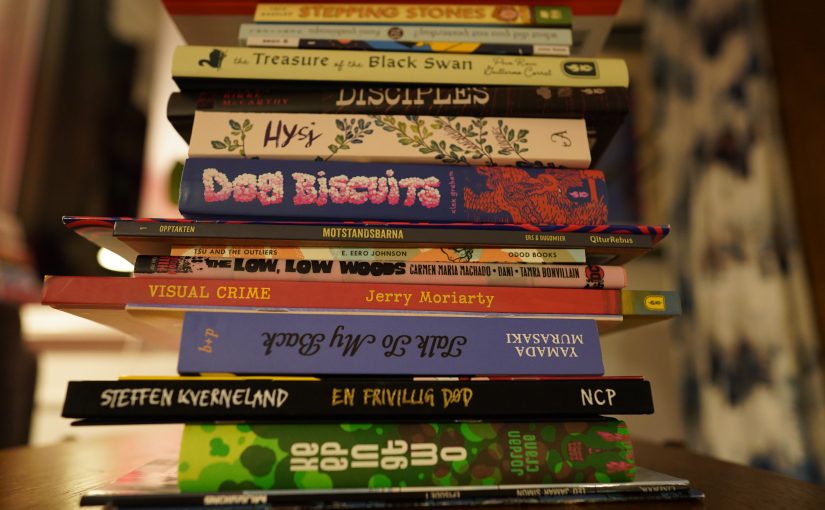

Somehow I’ve managed to buy a whole lot more comics the last few weeks, so I guess it’s time to take time out and spend a day reading. It’s a hard knock life.

See, it’s such an… awful day… that I just can’t go outside.

Oh, whatever.

| Stephen Mallinder: tick tick tick |  |

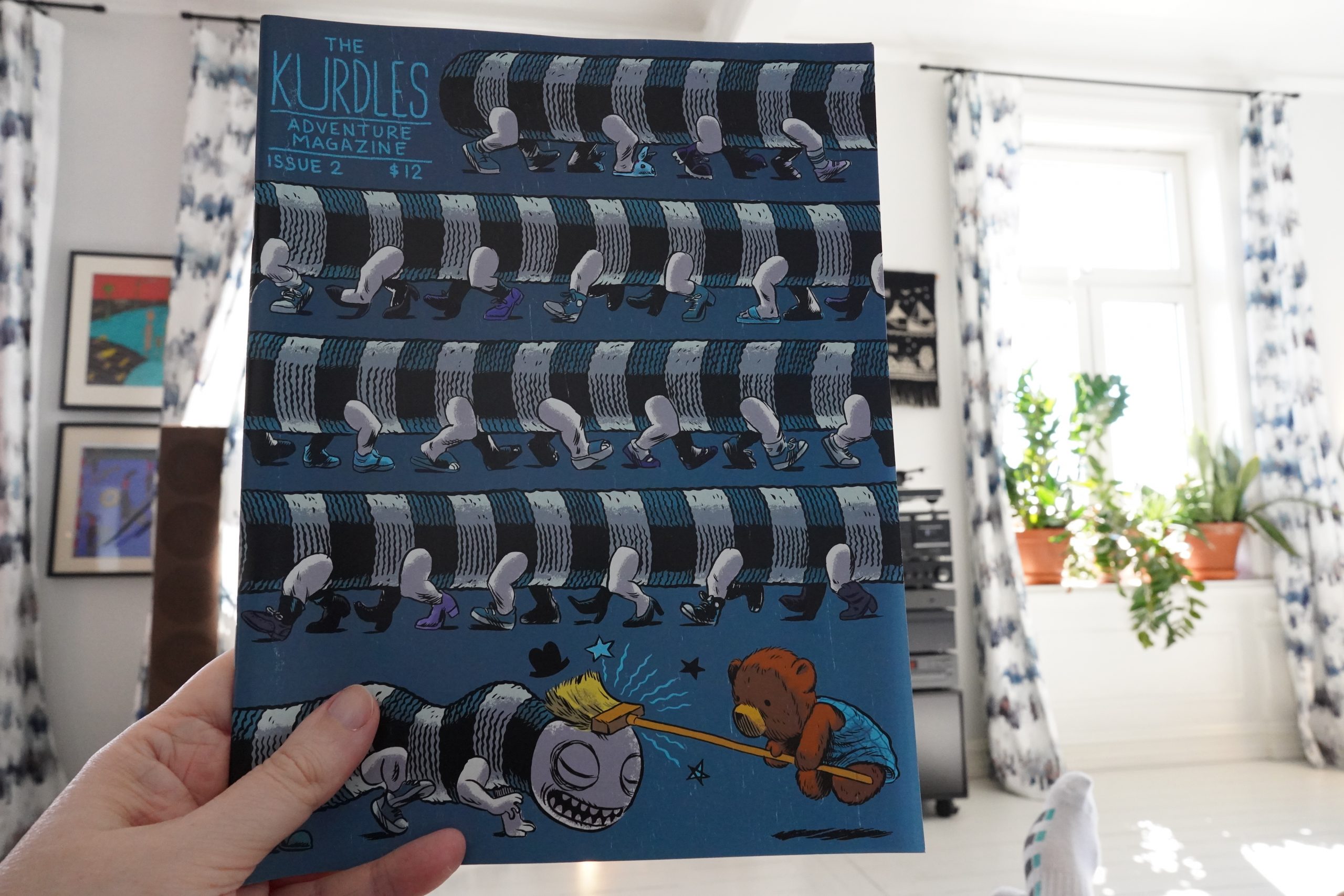

12:15: The Kurdles #2 by Robert Goodin (Fantagraphics)

I love this magazine. I mean, I really enjoyed the Kurdles book, but it’s really finding itself in magazine format, because it makes it such a natural place to be a bit meta…

… before going into the main story. (Which is delightful.)

And then — more bizarre fun. With fake bleed-through done perfectly.

This is such a perfect single author anthology, and is a perfect example of what’s been lost when most comics people ditched the format and went straight for huge graphic novels. (But there’s advantages to that, too.)

| Stephen Mallinder: tick tick tick |  |

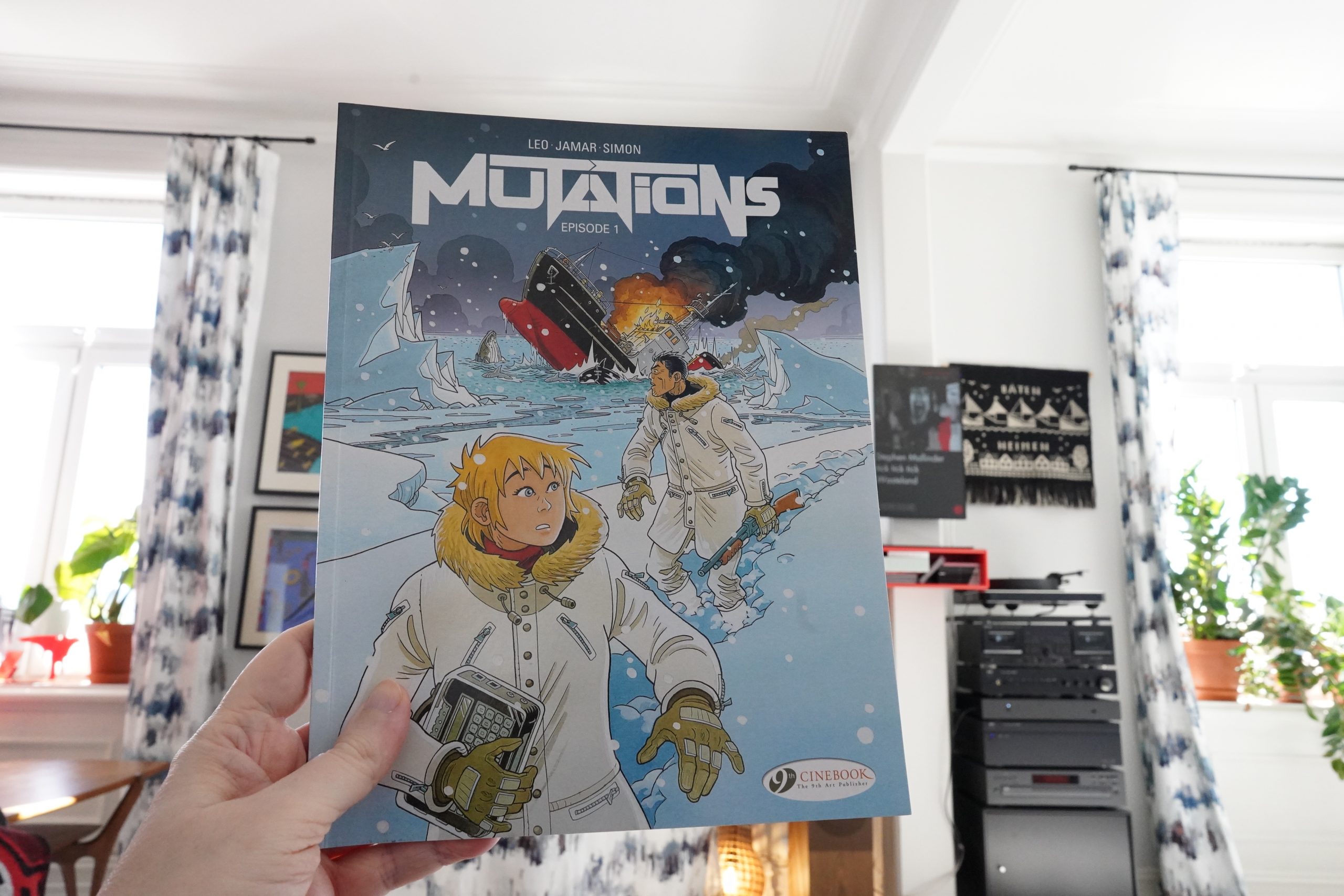

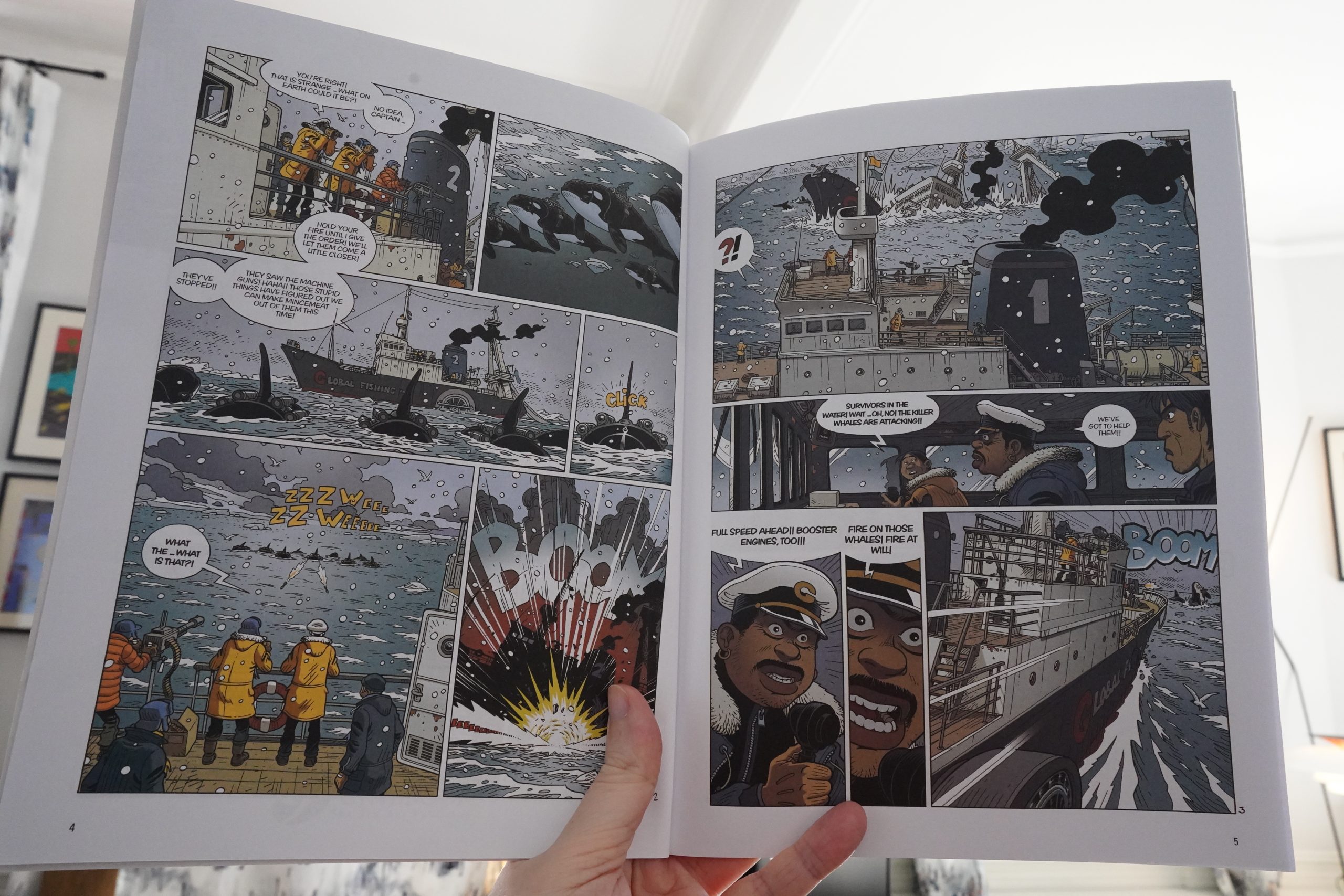

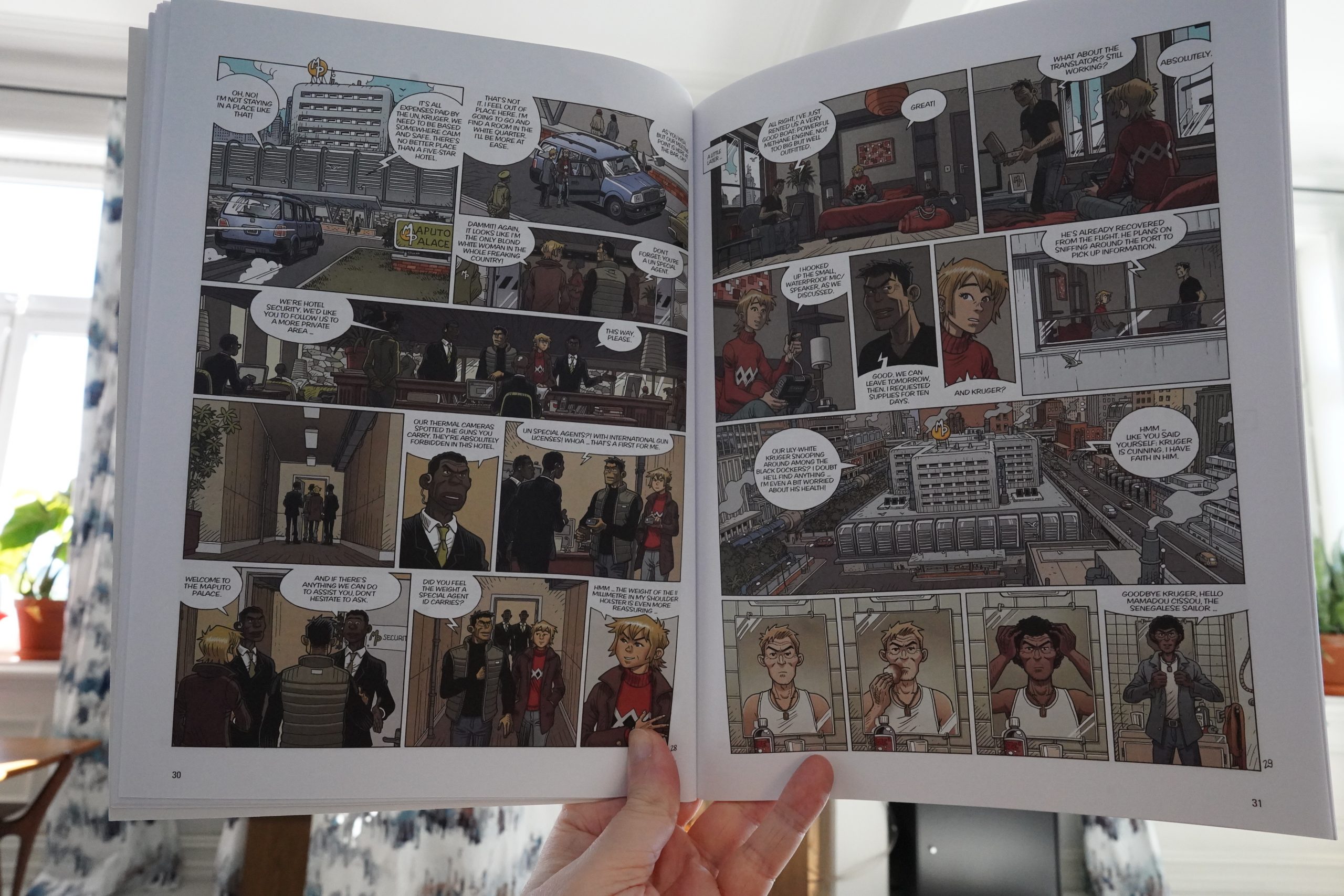

12:32: Mutations episode 1 by Leo/Jamar/Simon (Cinebook)

Ah, right — this is a direct continuation of The Mermaid Project, which was fine…

This is better — it’s full of oddball ideas that add up to a pretty compelling alternate reality. The racial politics are er uhm er something — white people are now discriminated against brutally etc. I’m not sure whether Leo is being an edgelord here or not, but.

| A. G. Cook: 7G (3): Supersaw |  |

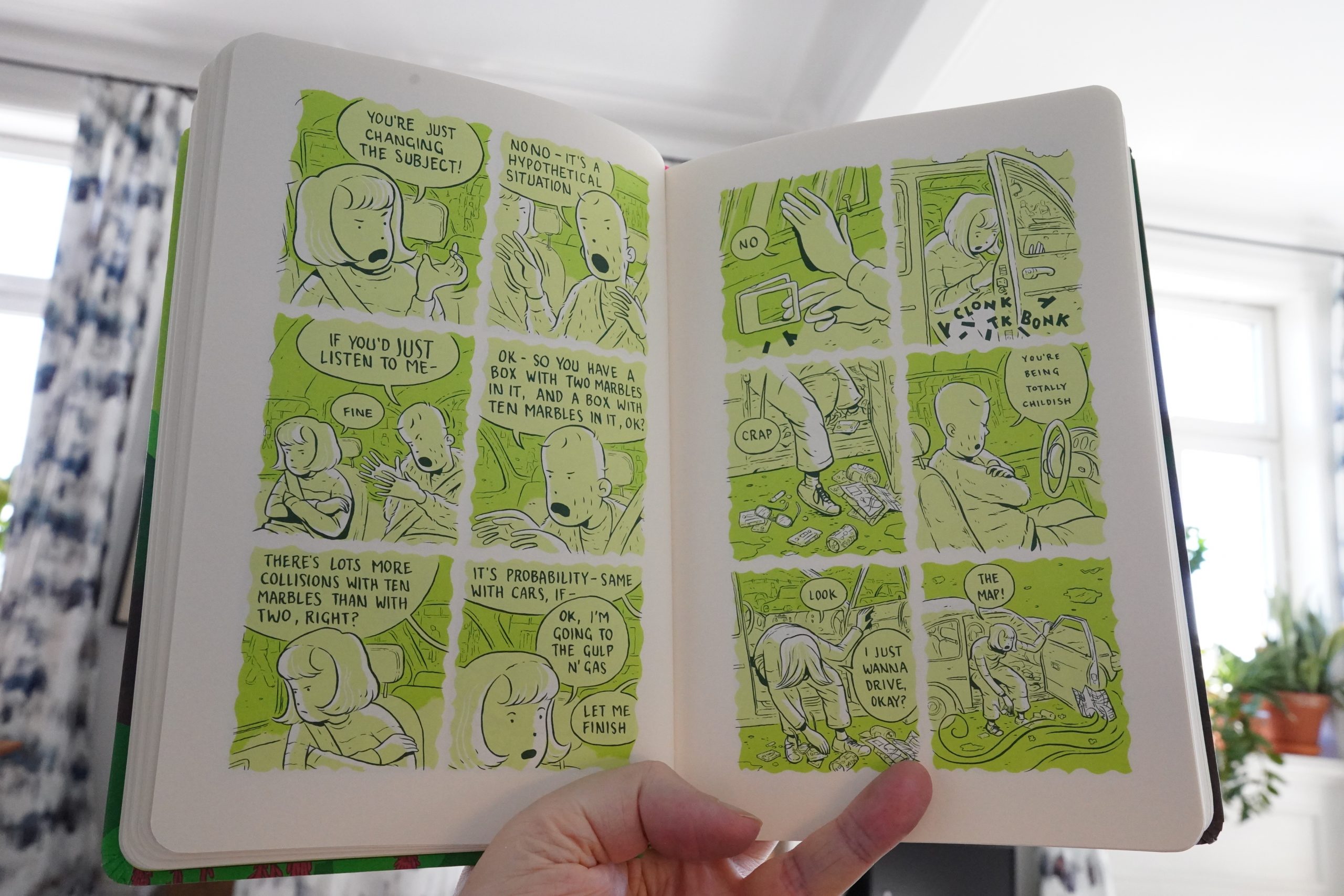

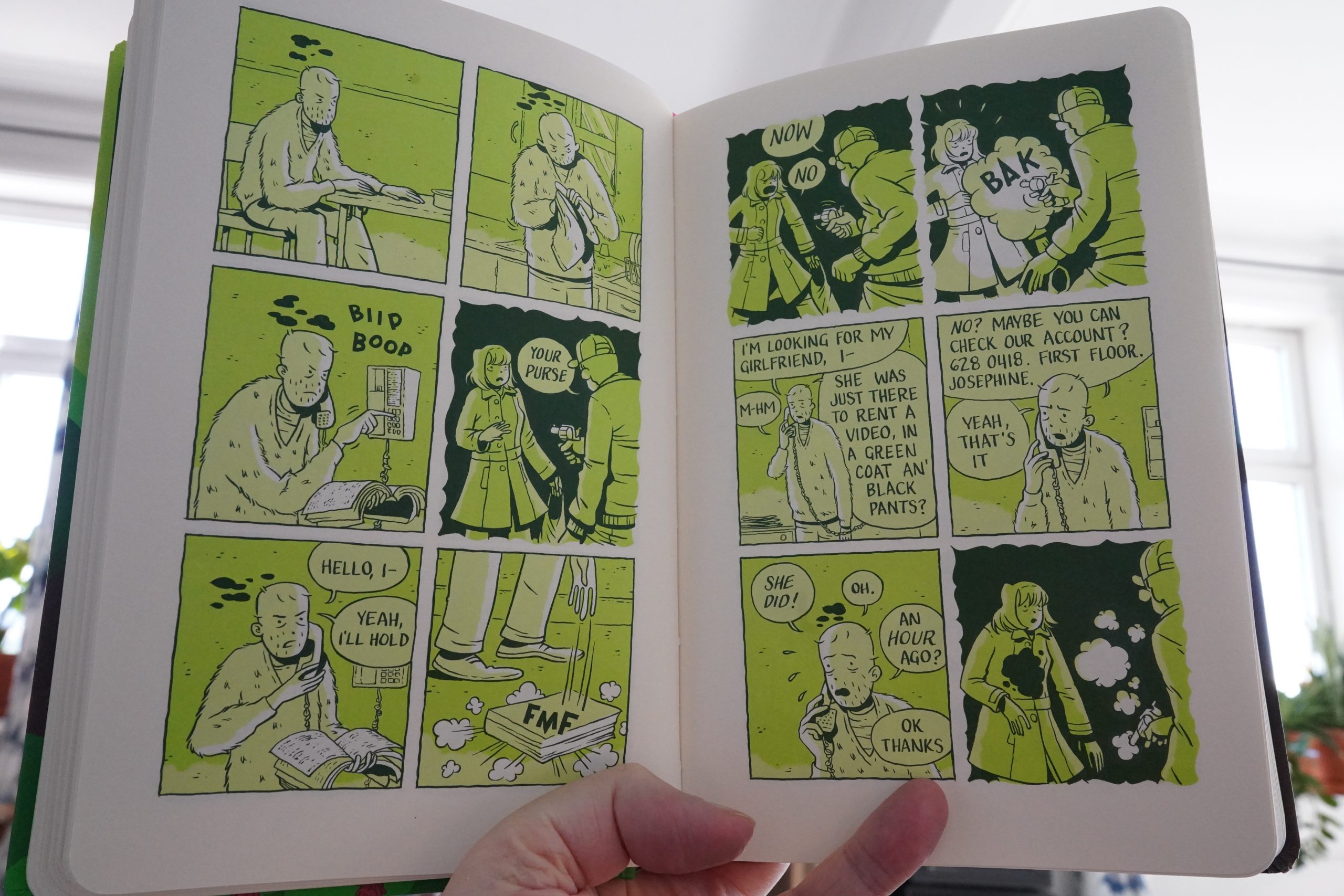

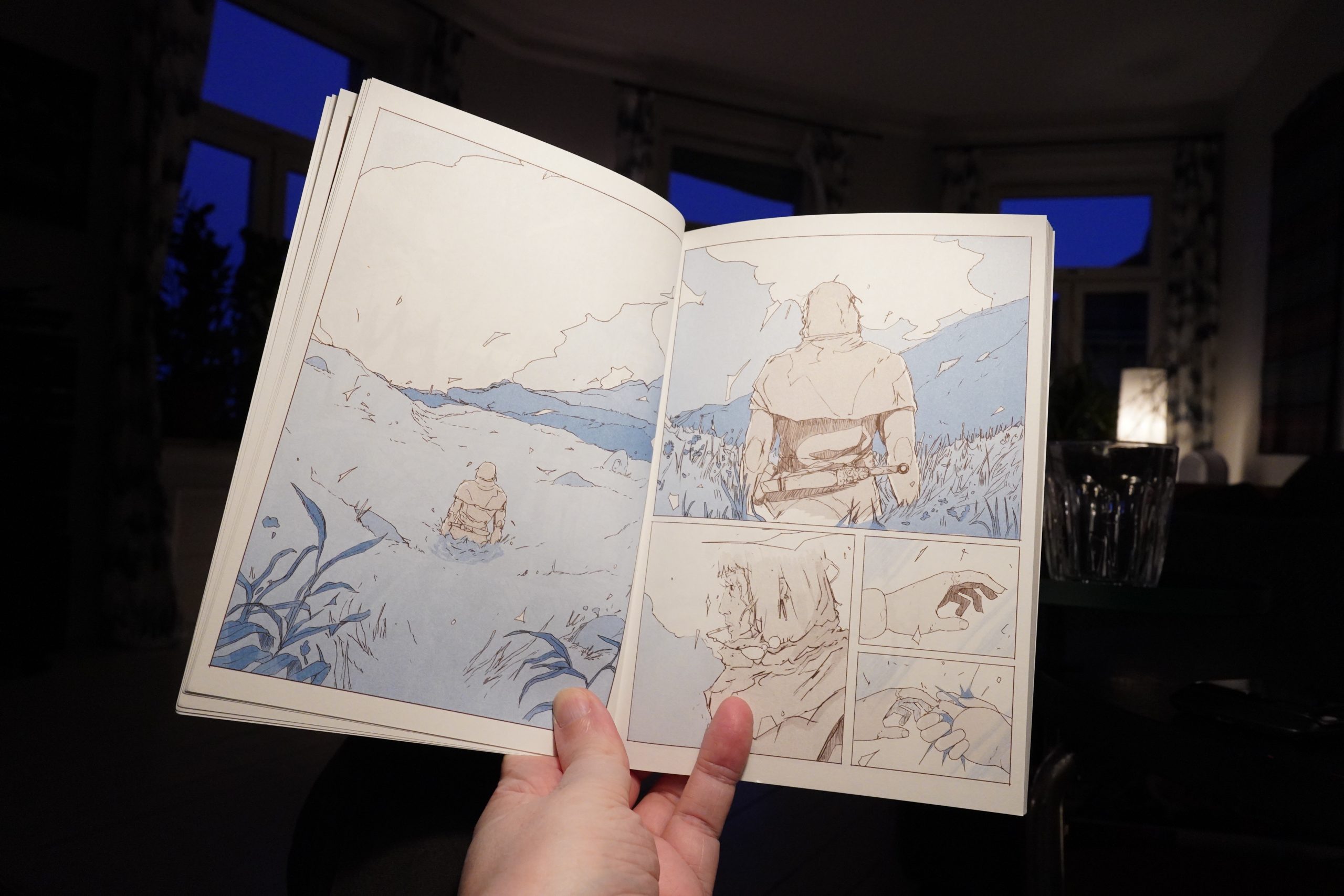

13:10: Keeping Two by Jordan Crane (Fantagraphics)

I’ve read all but the final chapter of this as mini-comics published by Crane over… what… a decade? Two decades? But here’s the collection.

Every mini was a great stab of paranoia and love and stuff, and I love Crane’s cartooning and sense of colour. And perhaps it’s because my expectations were just really high, since I loved reading the minis.

But I find myself being really impatient with this book. It’s all about imagining catastrophe, but when the protagonist starts calling around to the video shop and grocery stores one hour after she leaves, it reads pretty psycho here in this book. It didn’t feel that way reading the minis, of course, since it took years there, but in this book? Hm…

It’s structurally intriguing, though — he’s remembering things, and imagining things, and he’s also reading a book where people are doing the same, so it’s not immediately clear what’s memory, what’s imagination and what’s him reading, or remembering reading, or remembering reading about the characters in the book imagining er er I think I’ll stop that sentence there.

I feel like an asshole and a schmuck for writing this, because it is (and this is going to sound even stupider than usual) perfectly executed. It’s flawless in a way, and it will deservedly end up on everybody’s Best Comics Of 2022 lists, and I’m sitting here going “but… but…” incoherently.

Typing this, I realise that some of my impatience with the plot may just stem from its out-of-time-ness. When the book was started, the plot made some sense: It was possibly to be out of communications range at the time. These days, people are more likely to forget to put on their pants than forgetting their phones.

The ending is lovely, though — reminds me of Ron Rege Jr.

| Hercules & Love Affair: In Amber |  |

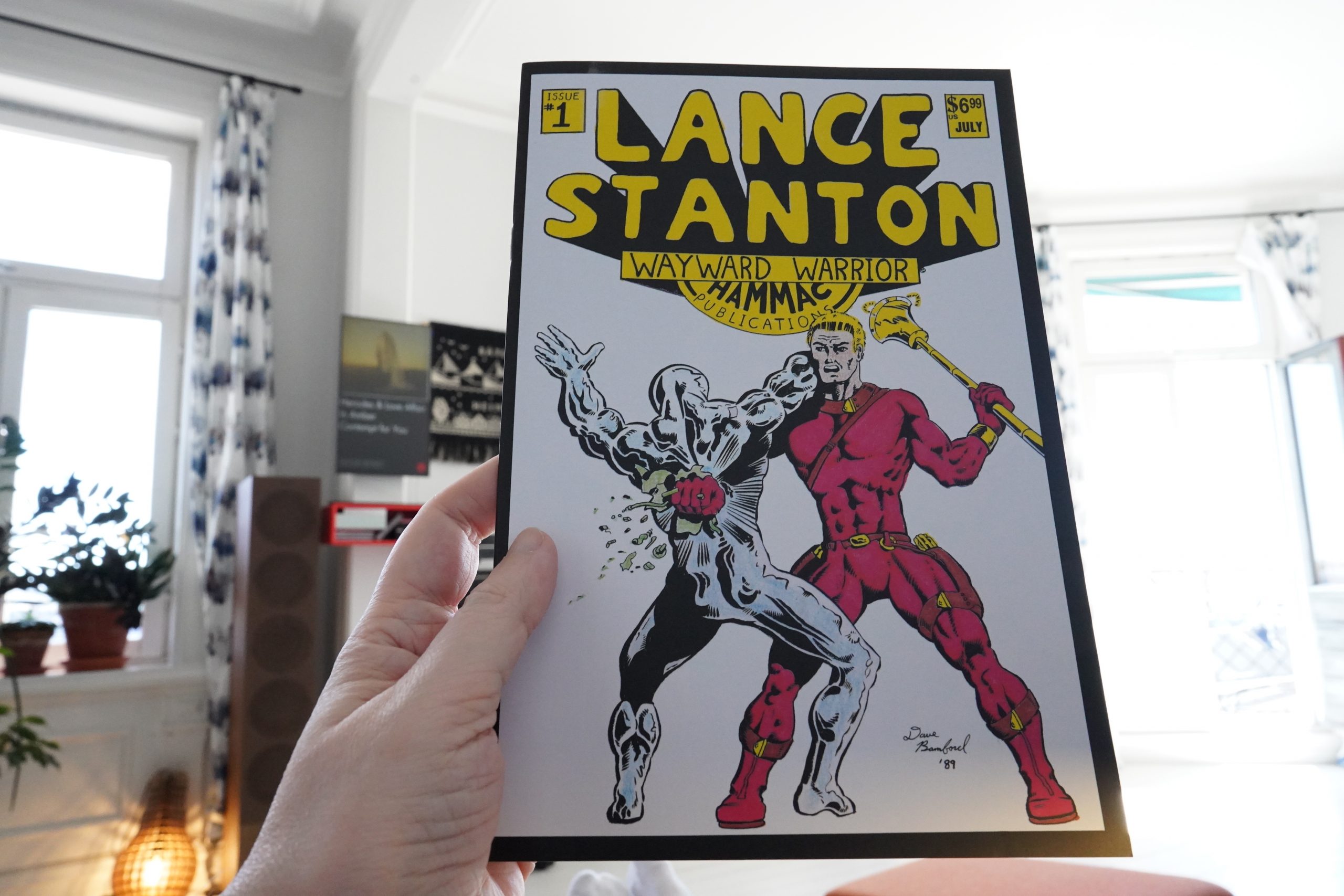

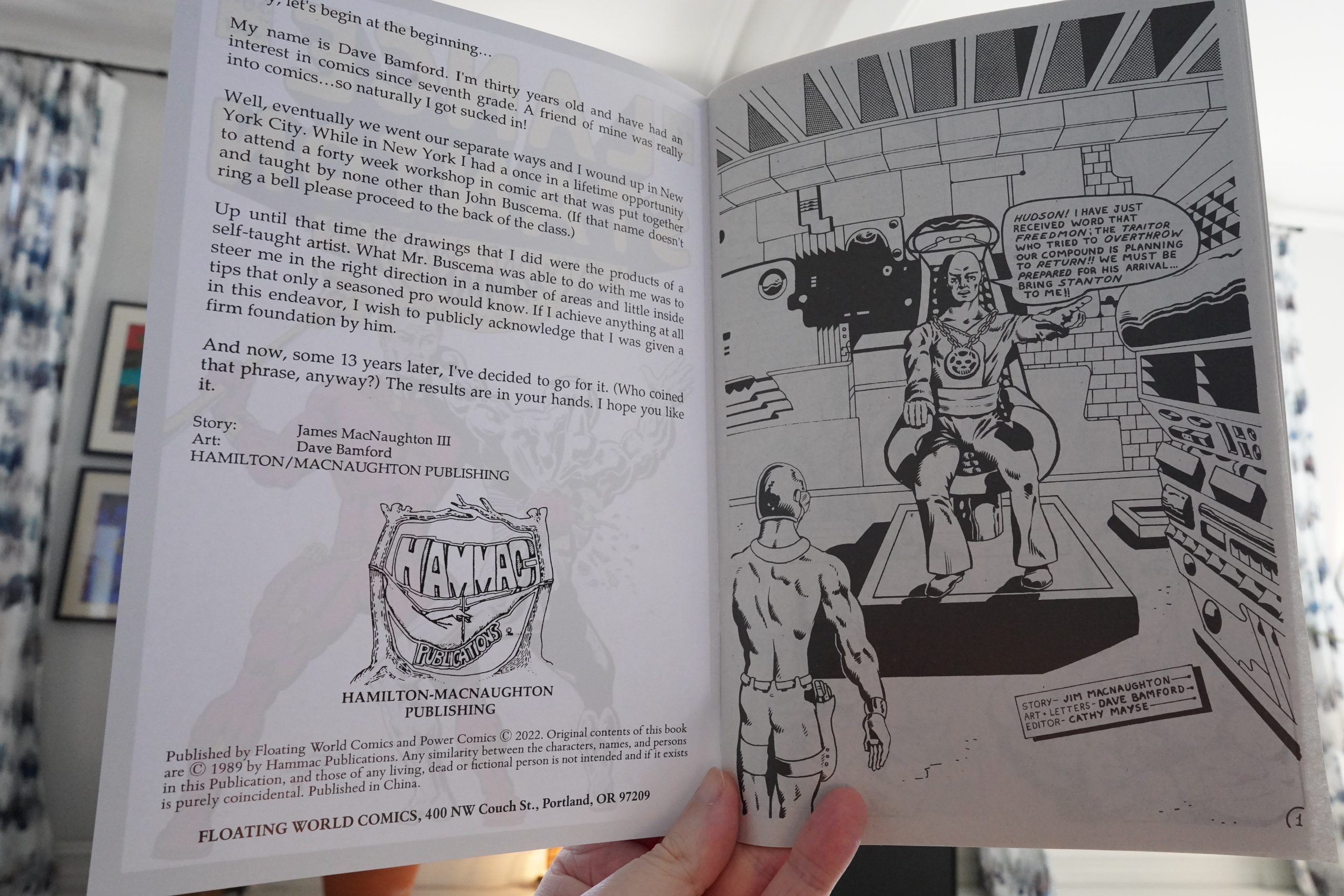

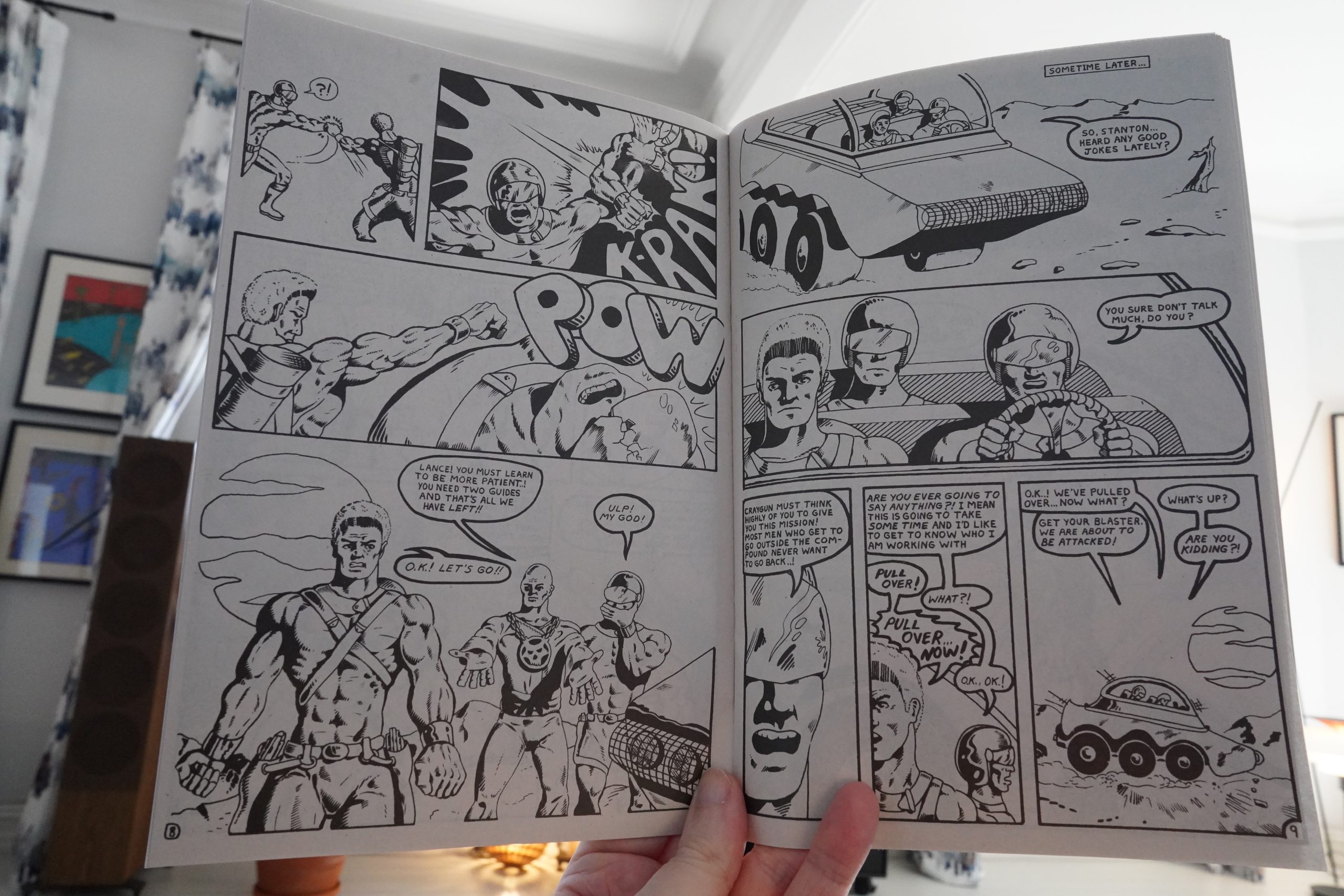

14:02: Lance Stanton Wayward Warrior by James MacNaughton III/Dave Baumford (Floating World Comics)

This book presents itself as being a reprint of a comic from 1989. I have no idea whether that’s true or not, but it’s a fun conceit, anyway.

It reminds me a bit of those All-Time Comics, but is 1000x better. Does that make it actually good, though?

| Hercules & Love Affair: In Amber |  |

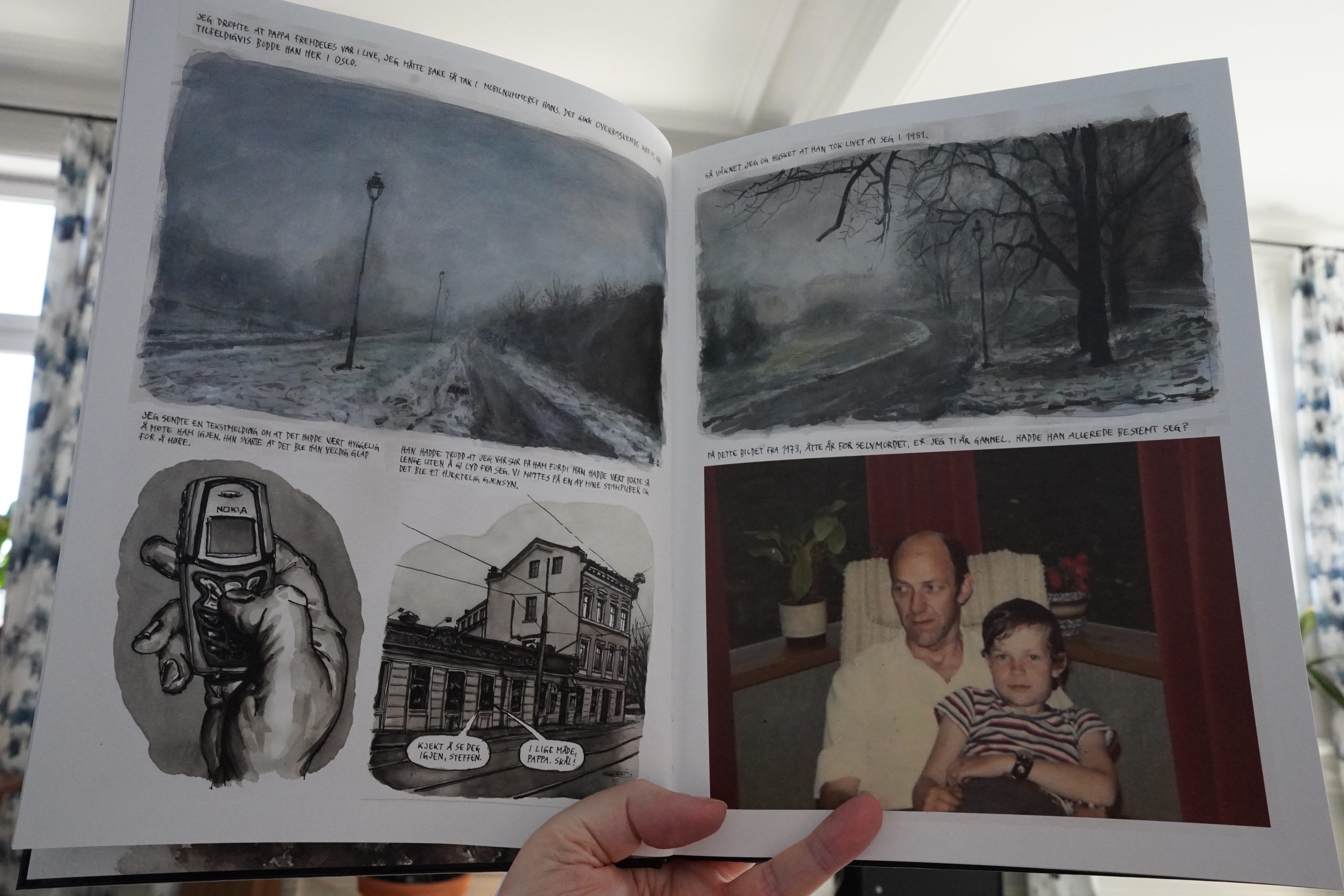

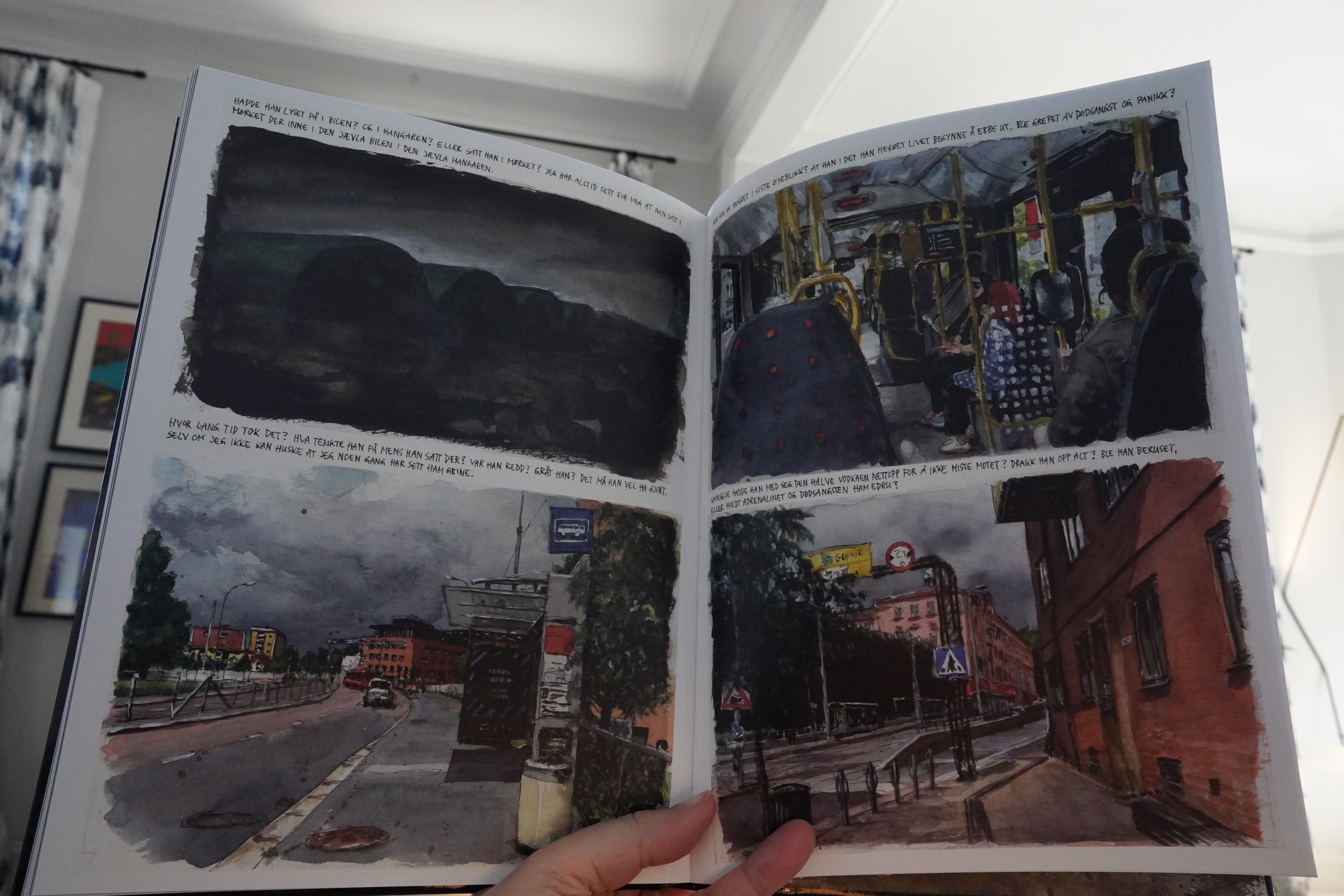

14:13: En frivillig død by Steffen Kverneland (No Comprendo Press)

Oh, right, this is that book about the author’s father’s suicide. I forgot to buy this when it was published four years ago.

This book is great! I don’t know quite what I expected, but Kverneland ruminates honestly on his father’s life, resisting any impulse to reduce him into something easily understood, but instead presents him like a real human being. Impressive.

And the artwork’s lovely, too. It’s a moving book that’s not maudlin for one microsecond.

| Neneh Cherry: The Versions |  |

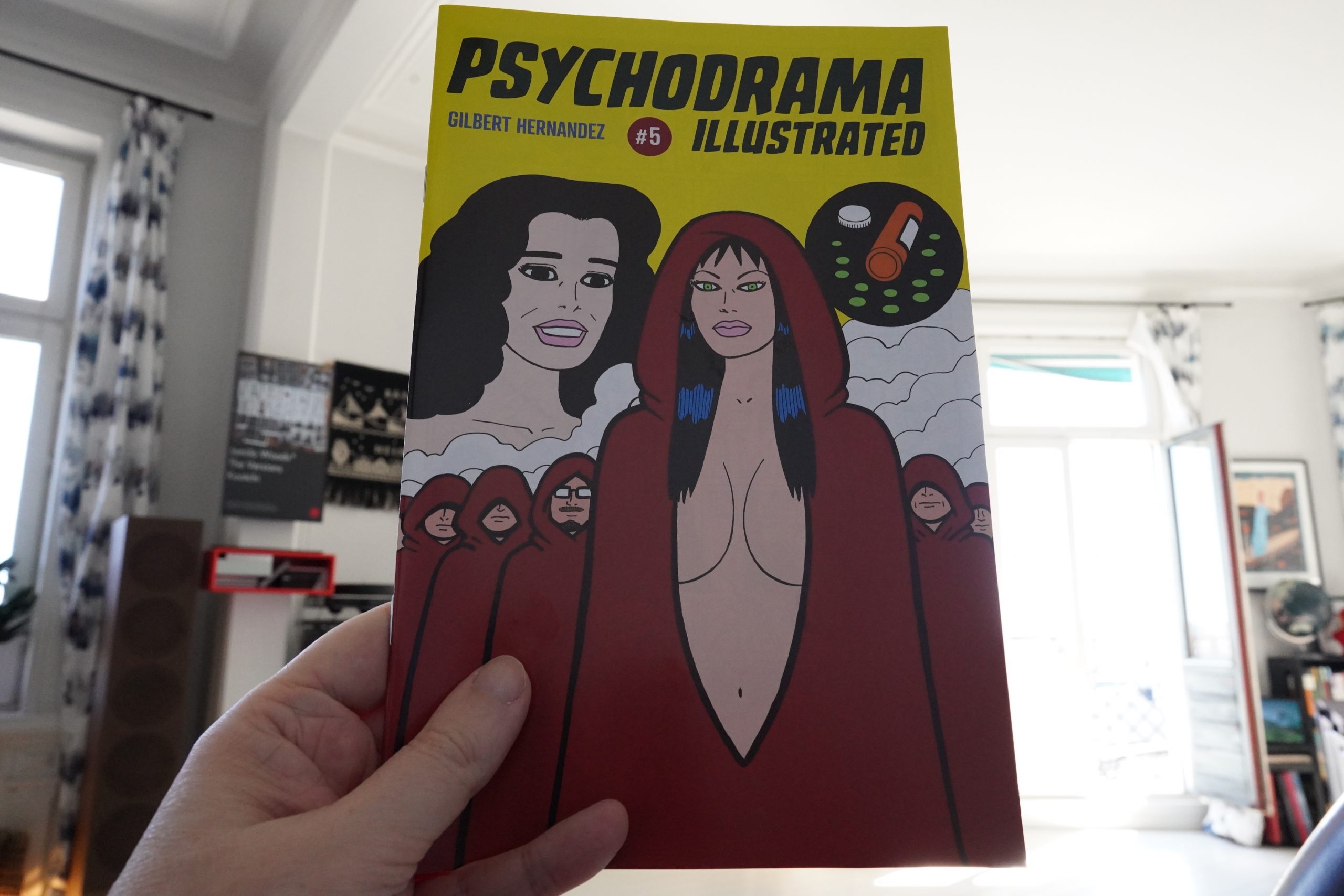

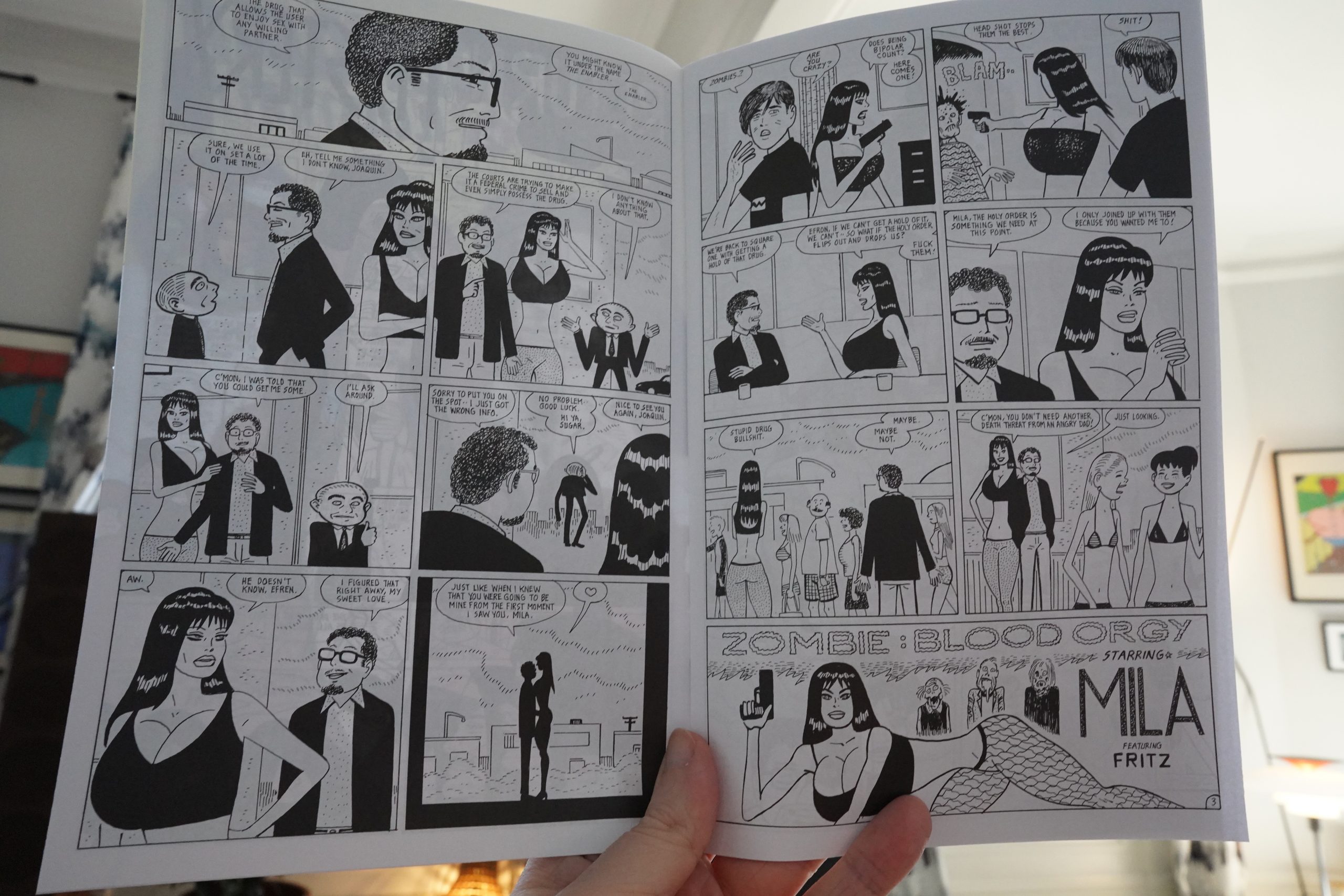

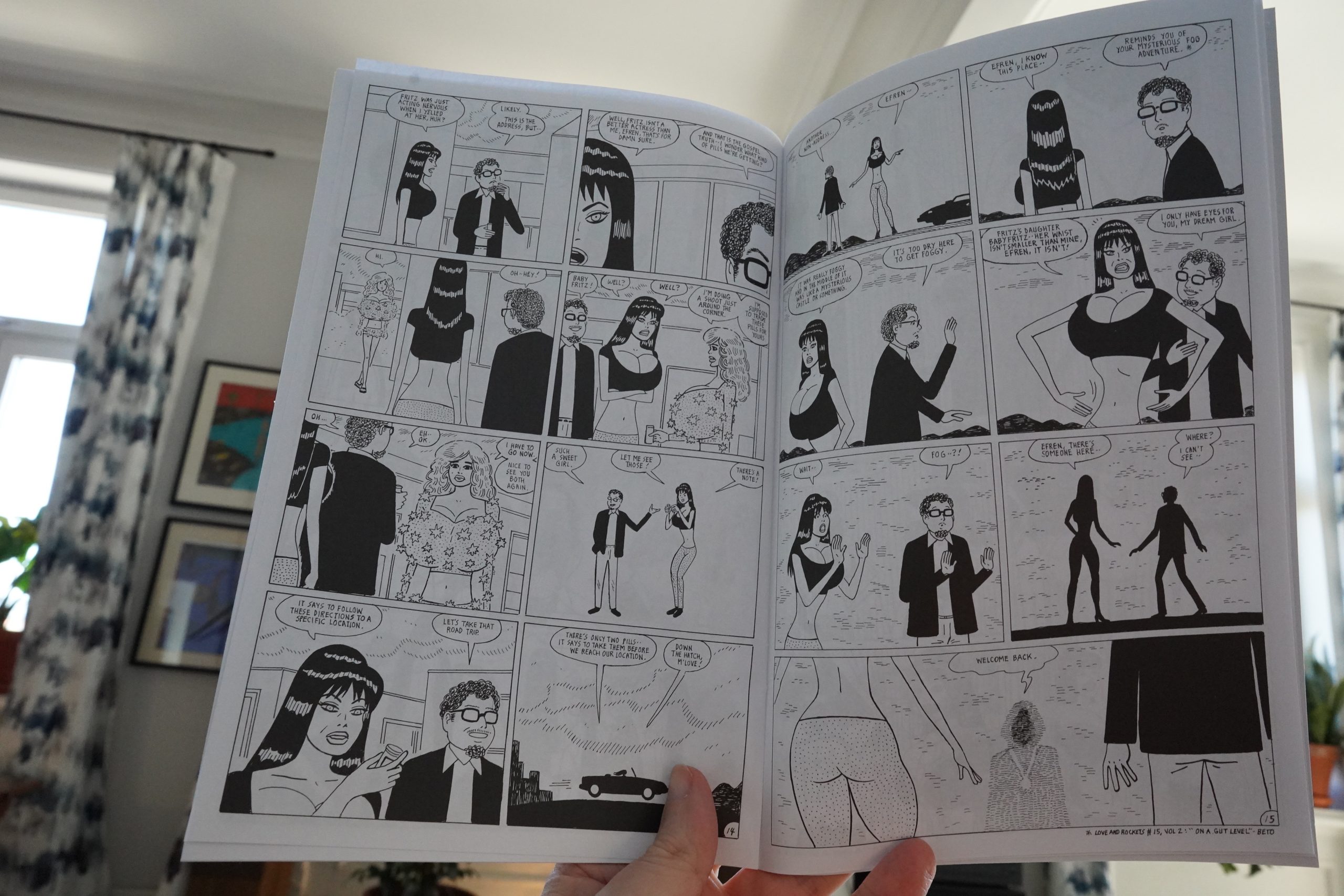

14:49: Psychodrama Illustrated #5 by Gilbert Hernandez (Fantagraphics)

It’s been a while since the previous issue, hasn’t it?

It’s yet another expansion of the Fritzverse…

But the more Hernandez fills inn all the crooks and nooks of Fritz’s life, the more cluttered and inconsequential it all feels.

I mean, it’s a good issue, but it feels like a random walk through plot elements.

| Mark Stewart: Vs |  |

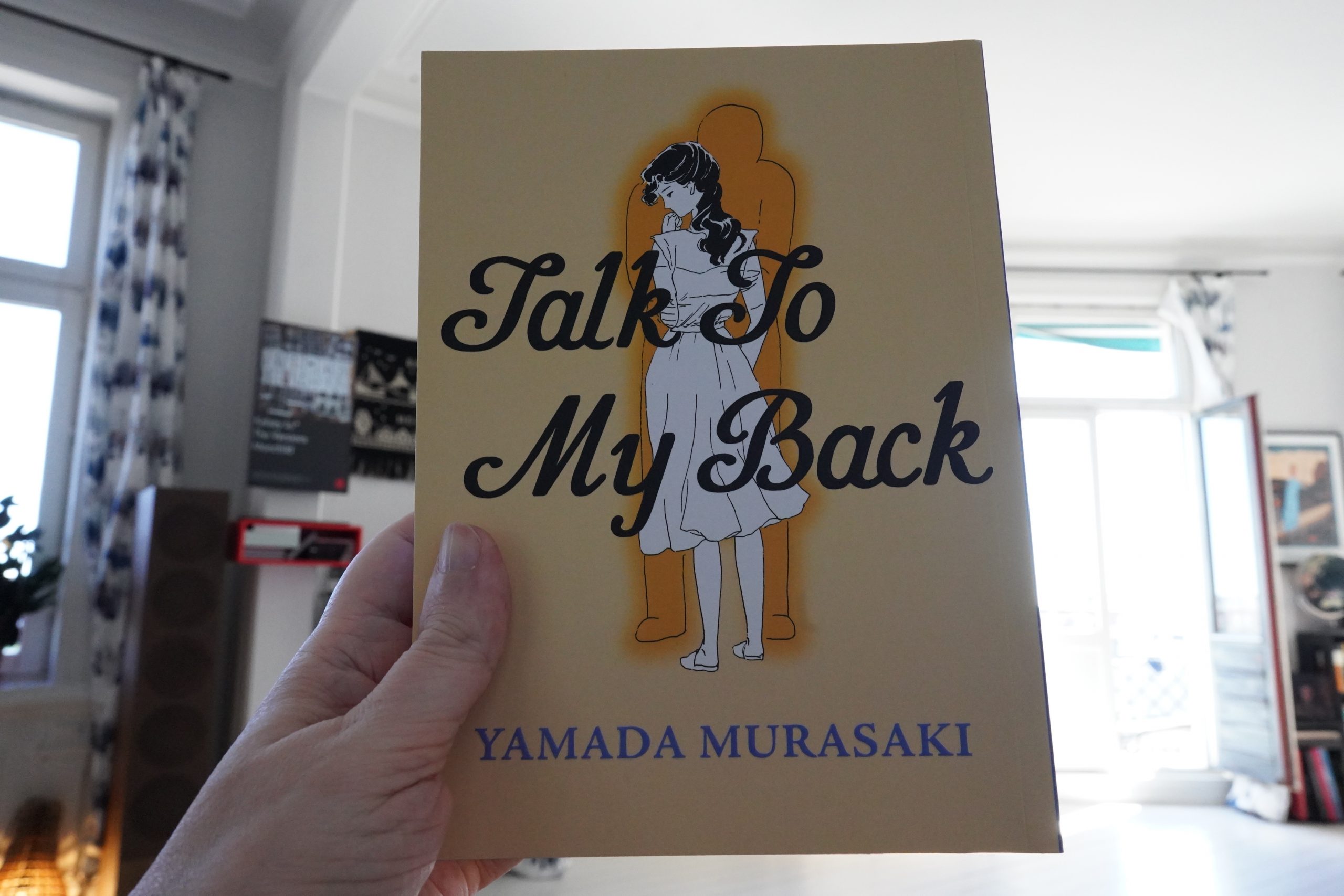

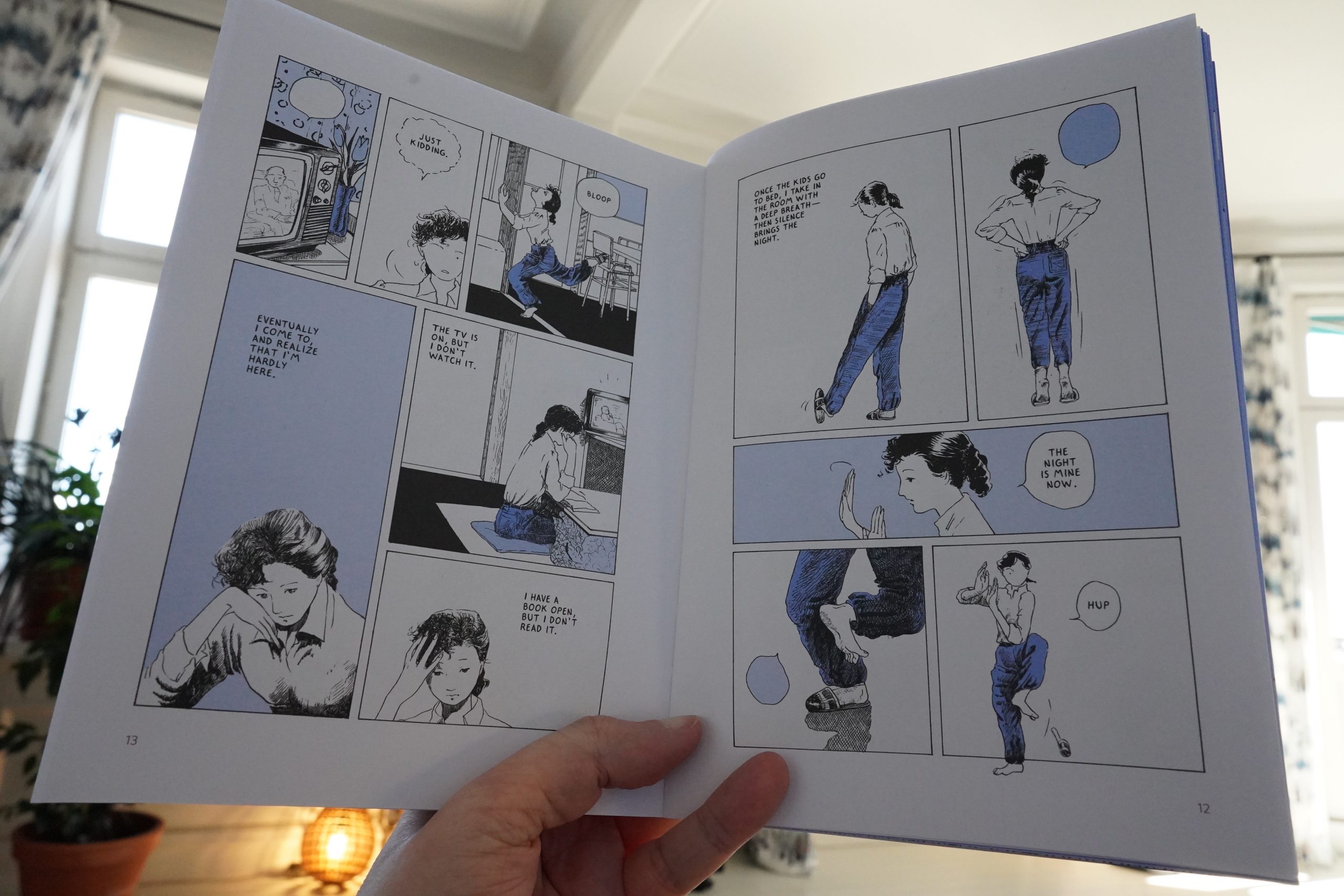

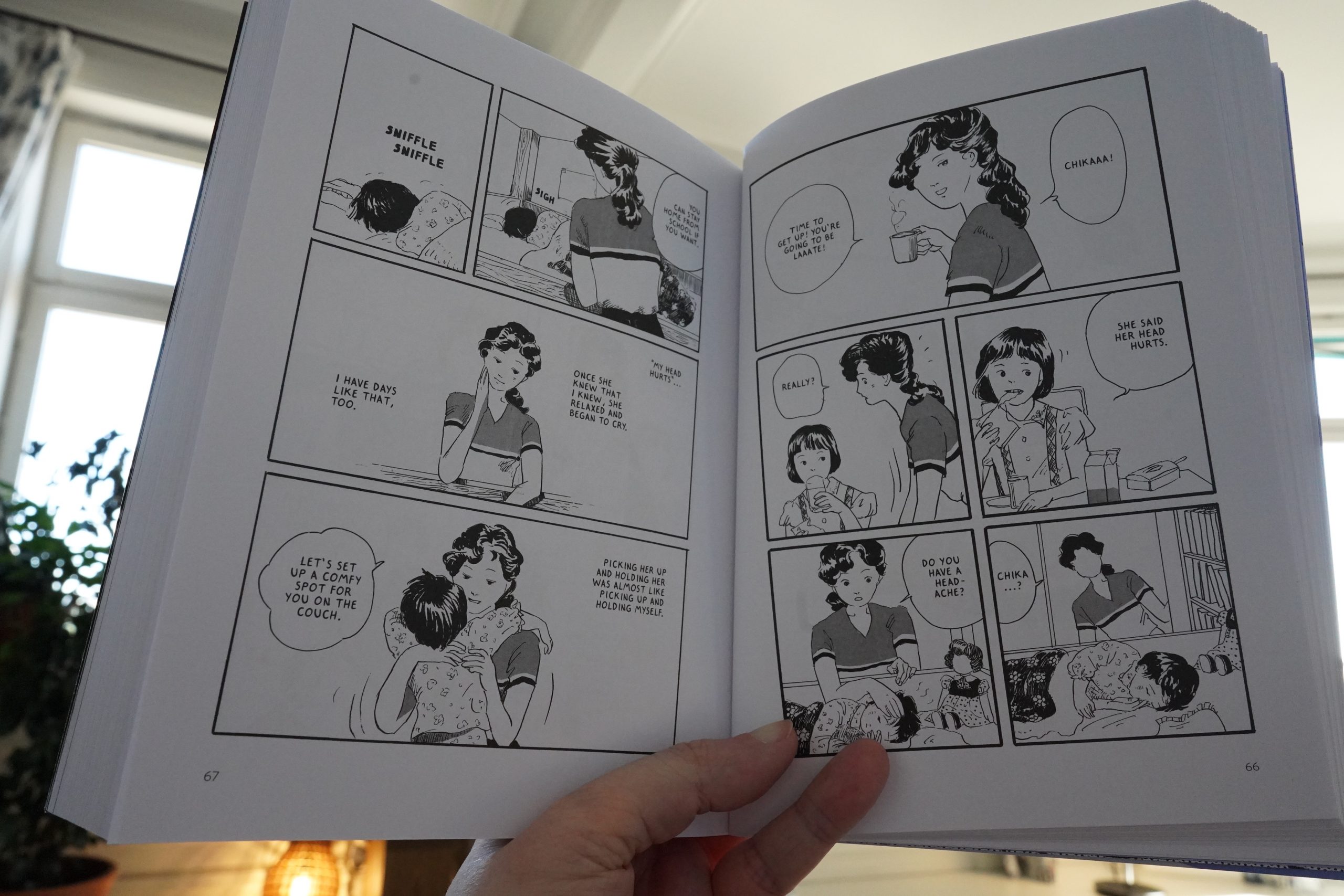

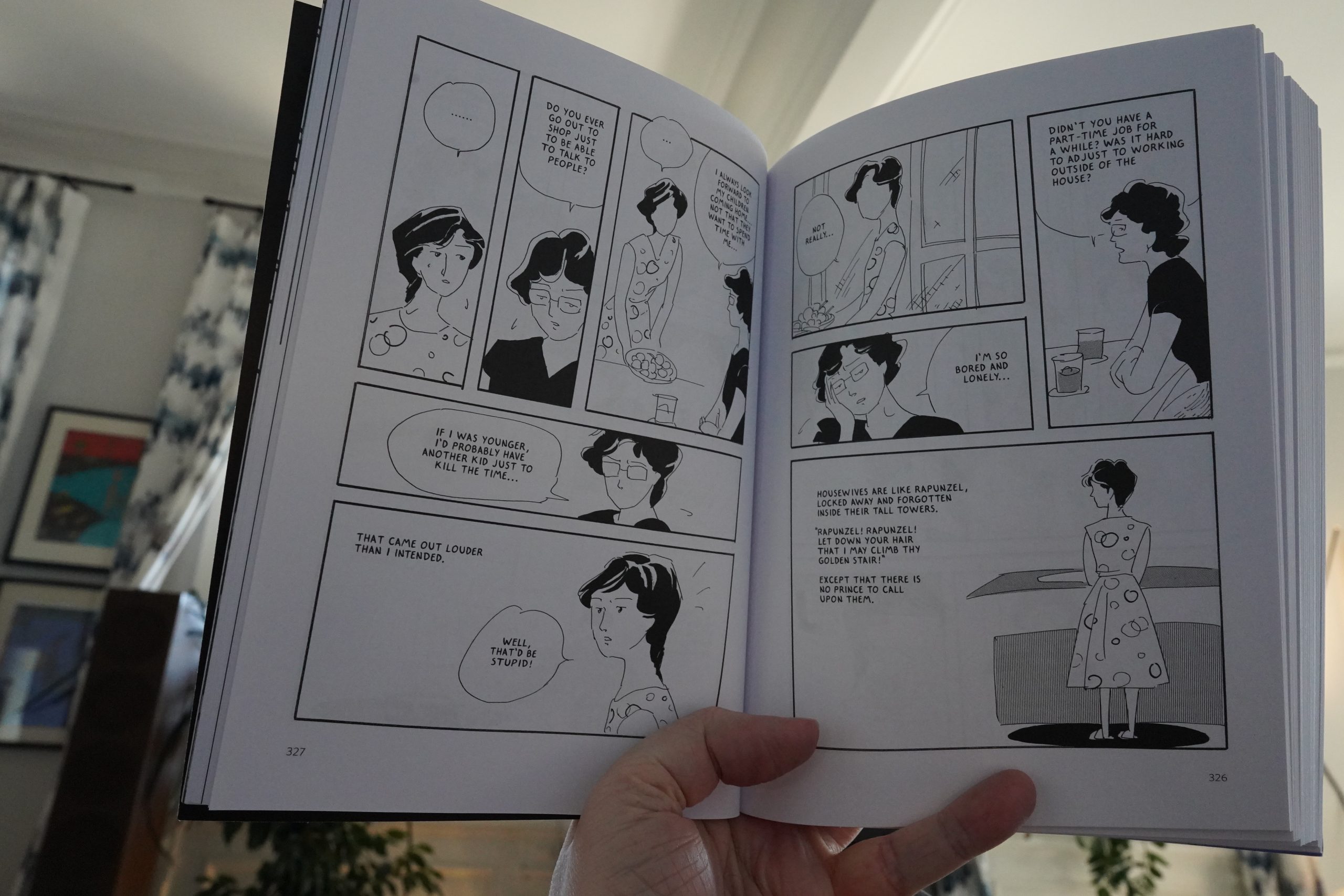

15:07: Talk To My Back by Yamada Murasaki (Drawn & Quarterly)

So here’s the new Ryan Holmberg essay vehicle… er, I mean, the latest collection of stories from Garo. Why don’t somebody just translate the entire anthology series already?

This book is a number of brief tableaux, sometimes extremely brief, but it does add up to a complete narrative of sorts, even if it’s very episodic.

I was interested throughout in that “what’s going to happen next?” kind of way, but I found the philosophical ruminations pretty boring. I wonder how these read in the anthology? A few moments of stillness between the more noisy contributions?

It’s sometimes really hard telling the characters apart, but I enjoy the airy qualities of the art.

| Mark Stewart: Vs |  |

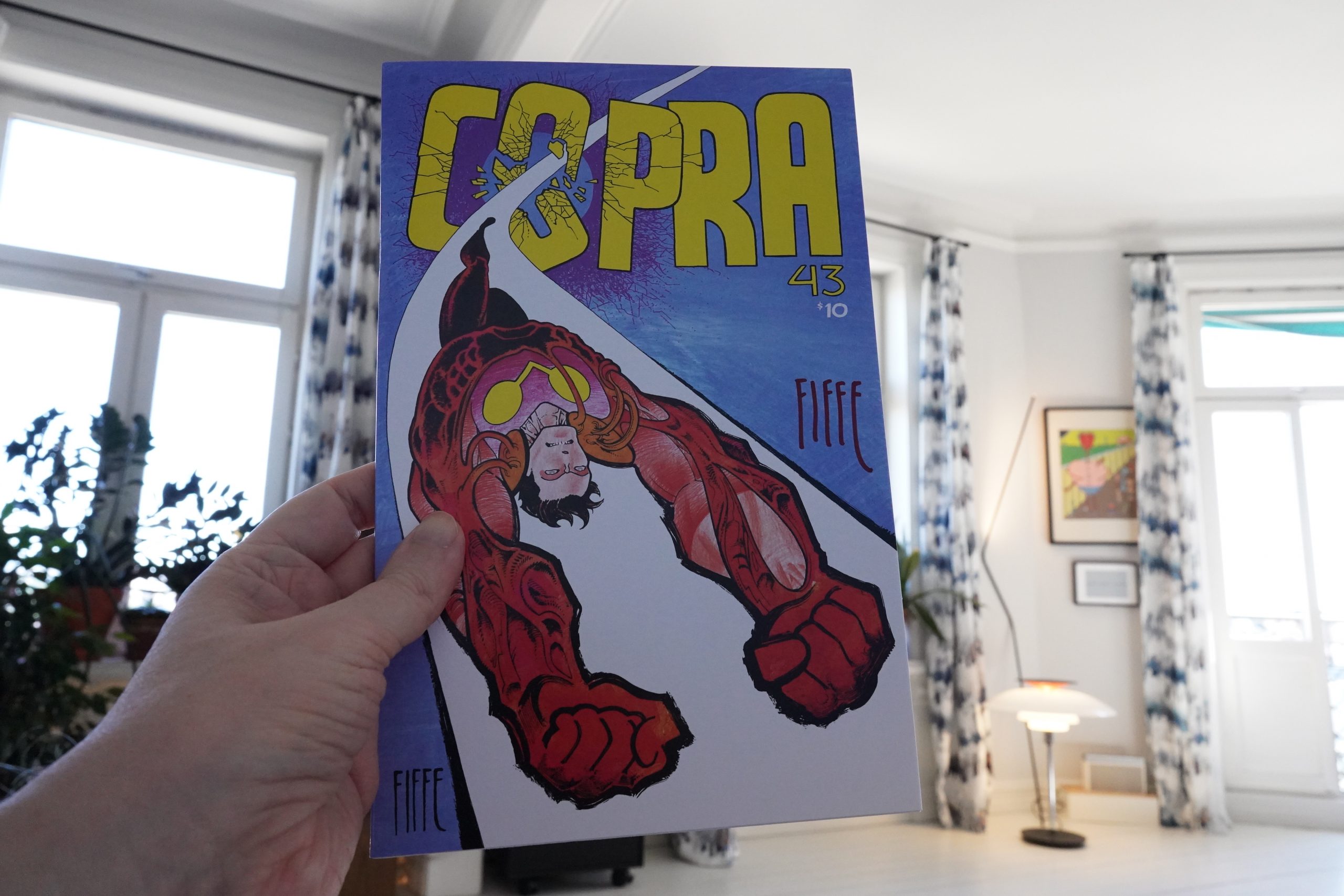

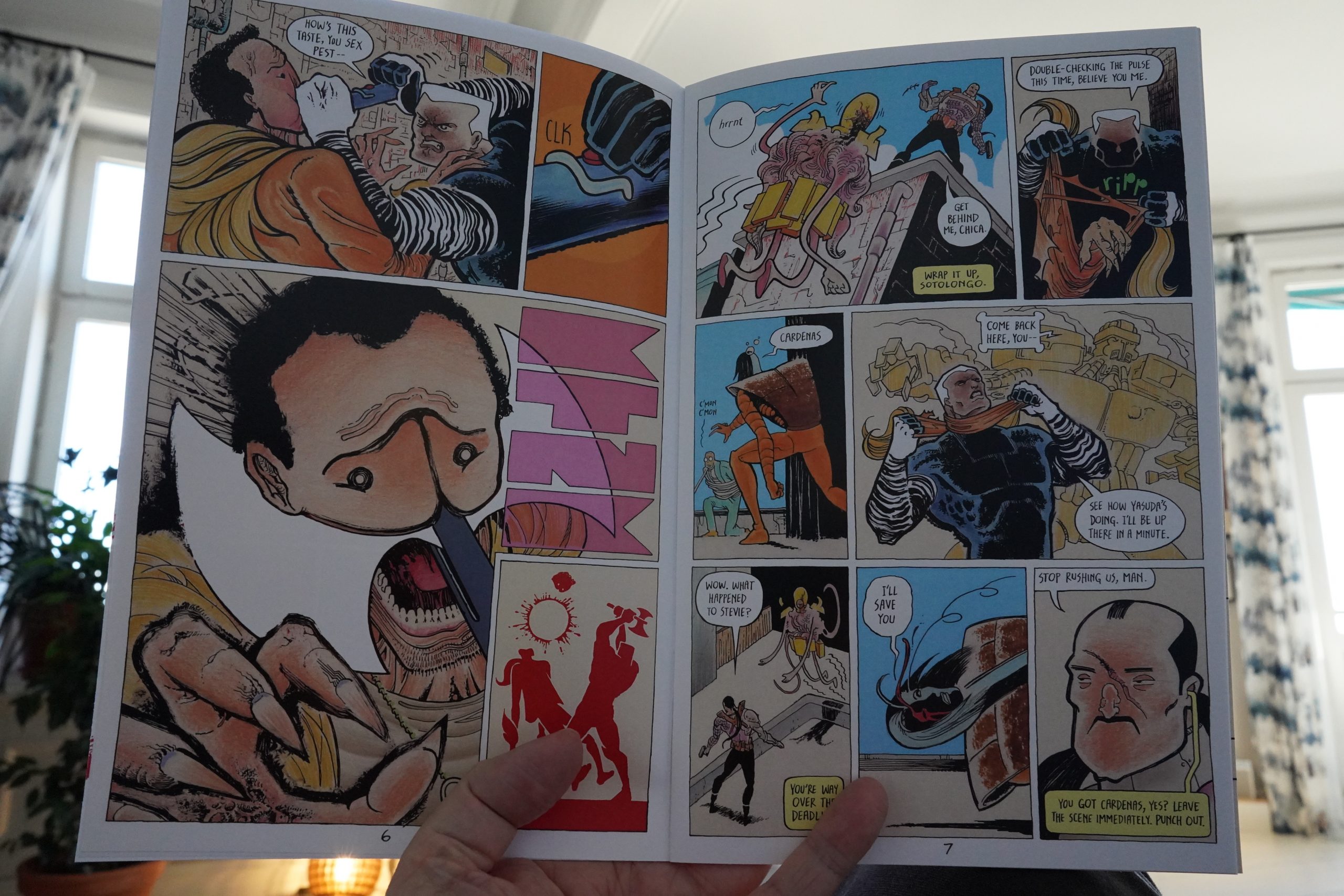

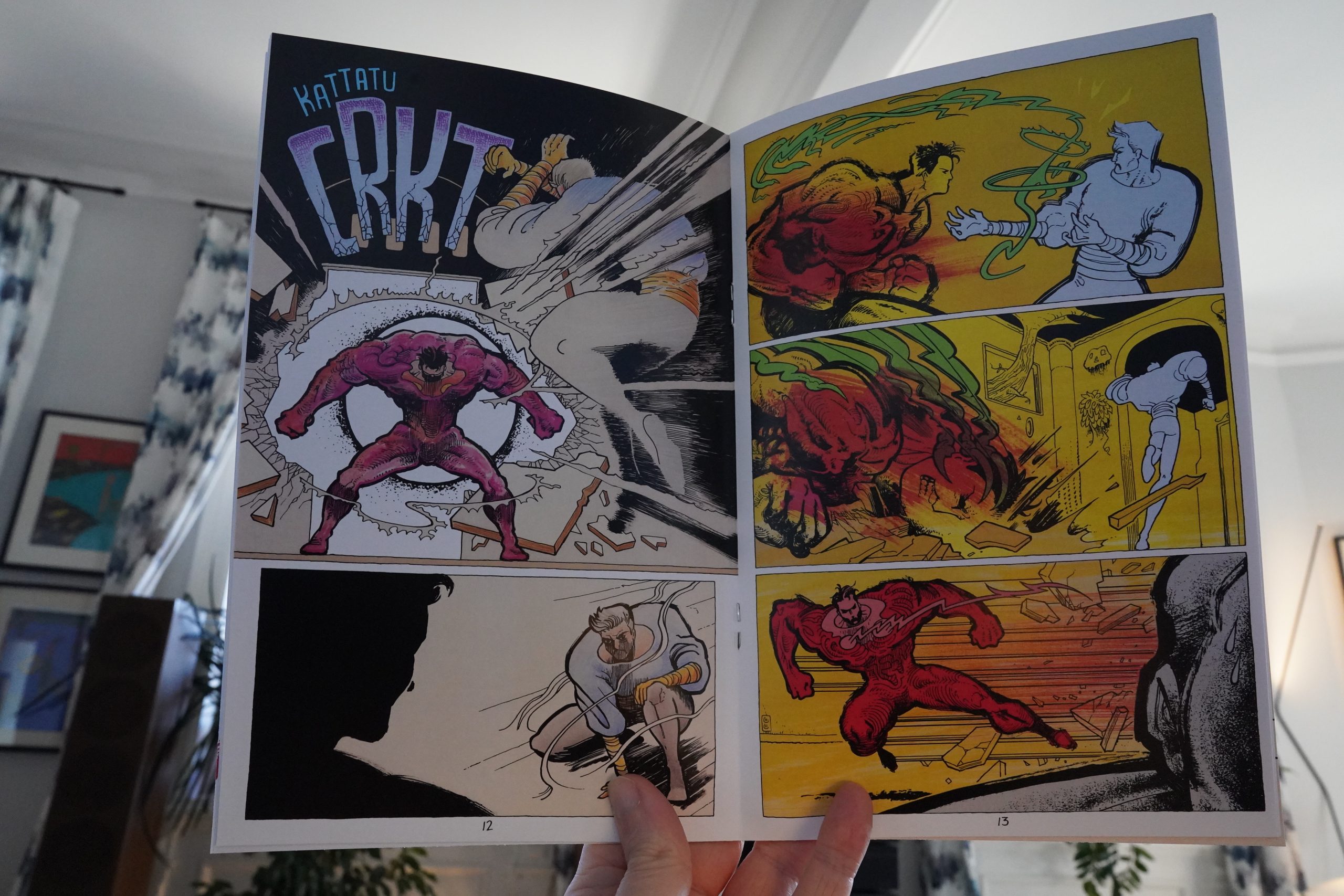

16:03: Copra #43 by Michael Fiffe

As usual with Copra, I have no idea what’s going on, because I’ve forgotten who all these people are, and what they’re going on about.

But that’s OK; it’s still a good read. I love Fiffe’s line work and the colouring.

| This Heat: Deceit |  |

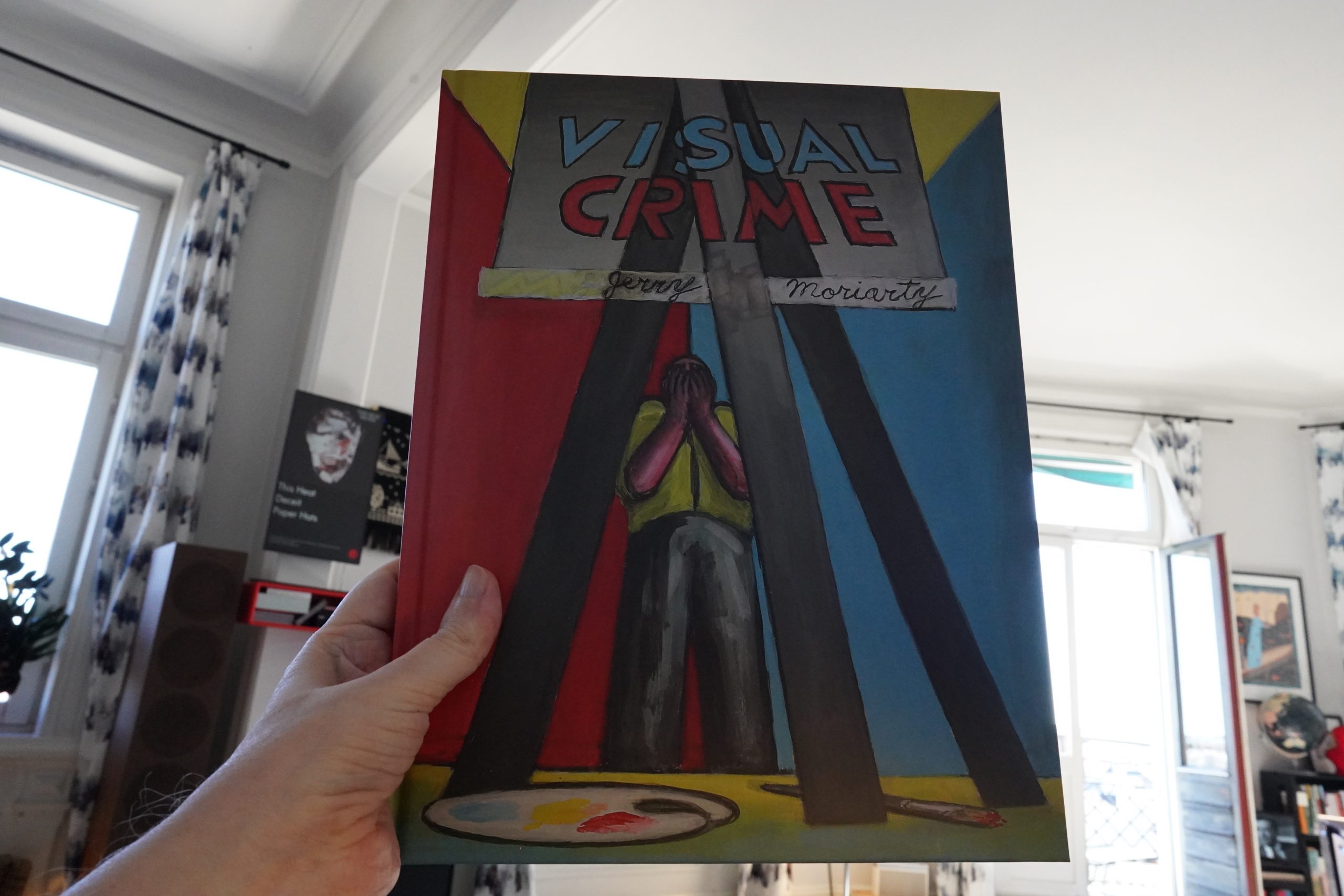

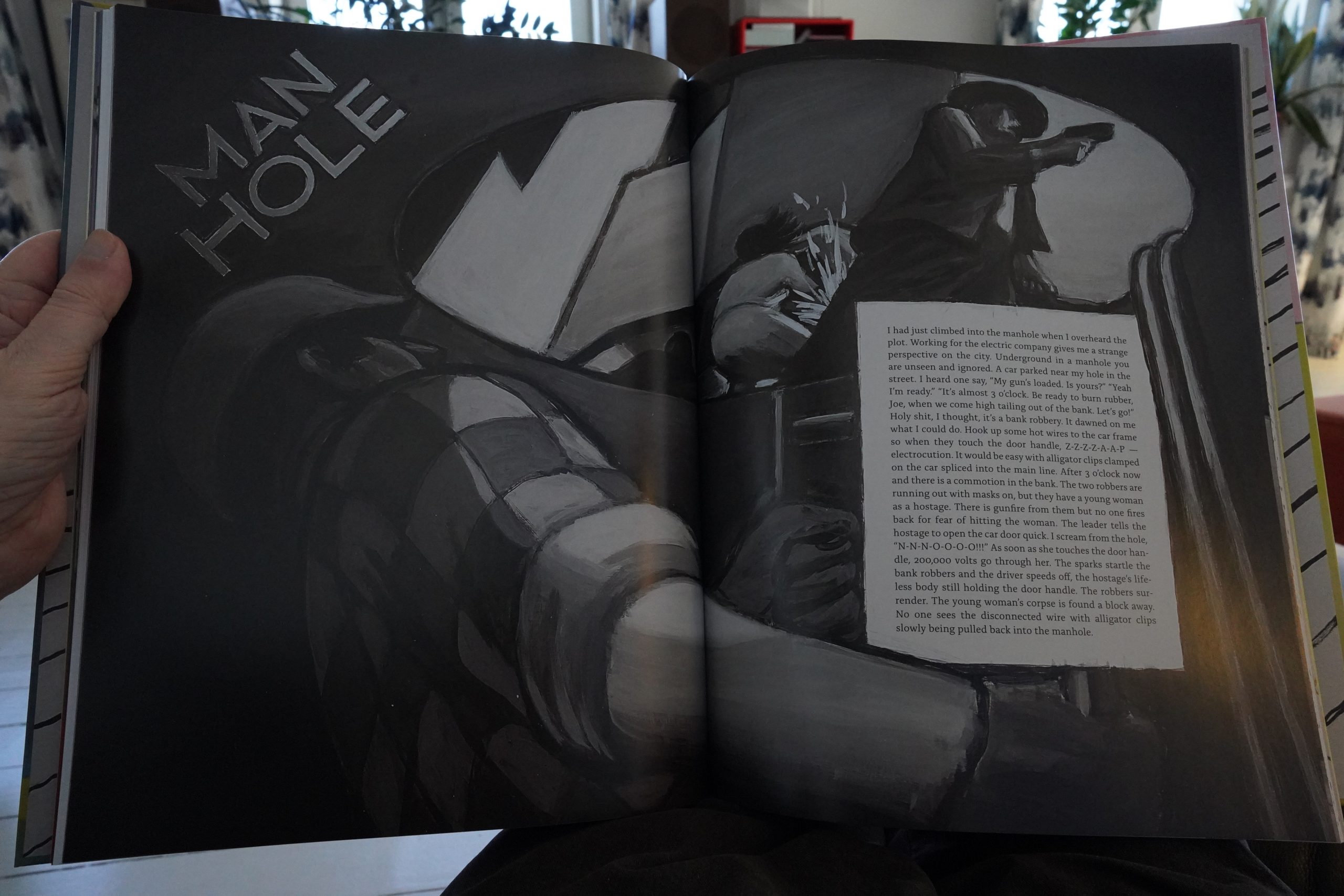

16:14: Visual Crime by Jerry Moriarty (Fantagraphics)

I happened upon this in the comics store the other day and I was confused — I thought I had everything by Moriarty already? But here’s a book published by Fantagraphics last year that I somehow completely missed?

We get a framing story…

… and then a few of Moriarty’s Visual Crime stories that were originally published in the 80s in anthologies like Gin & Comix. But not all of them? I think?

It’s great. Gorgeous paintings and a fun story.

| Various: Pop Psychédélique |  |

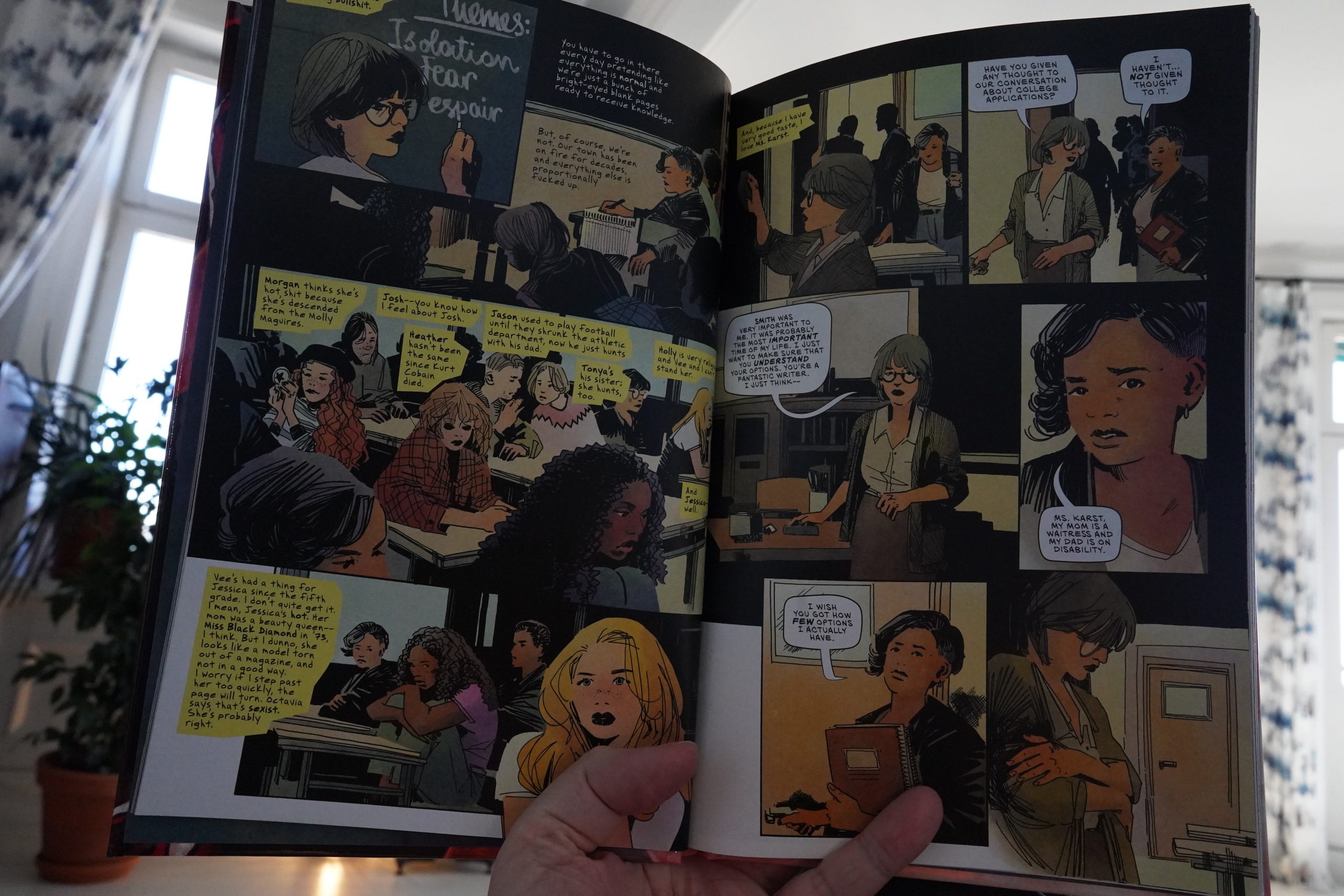

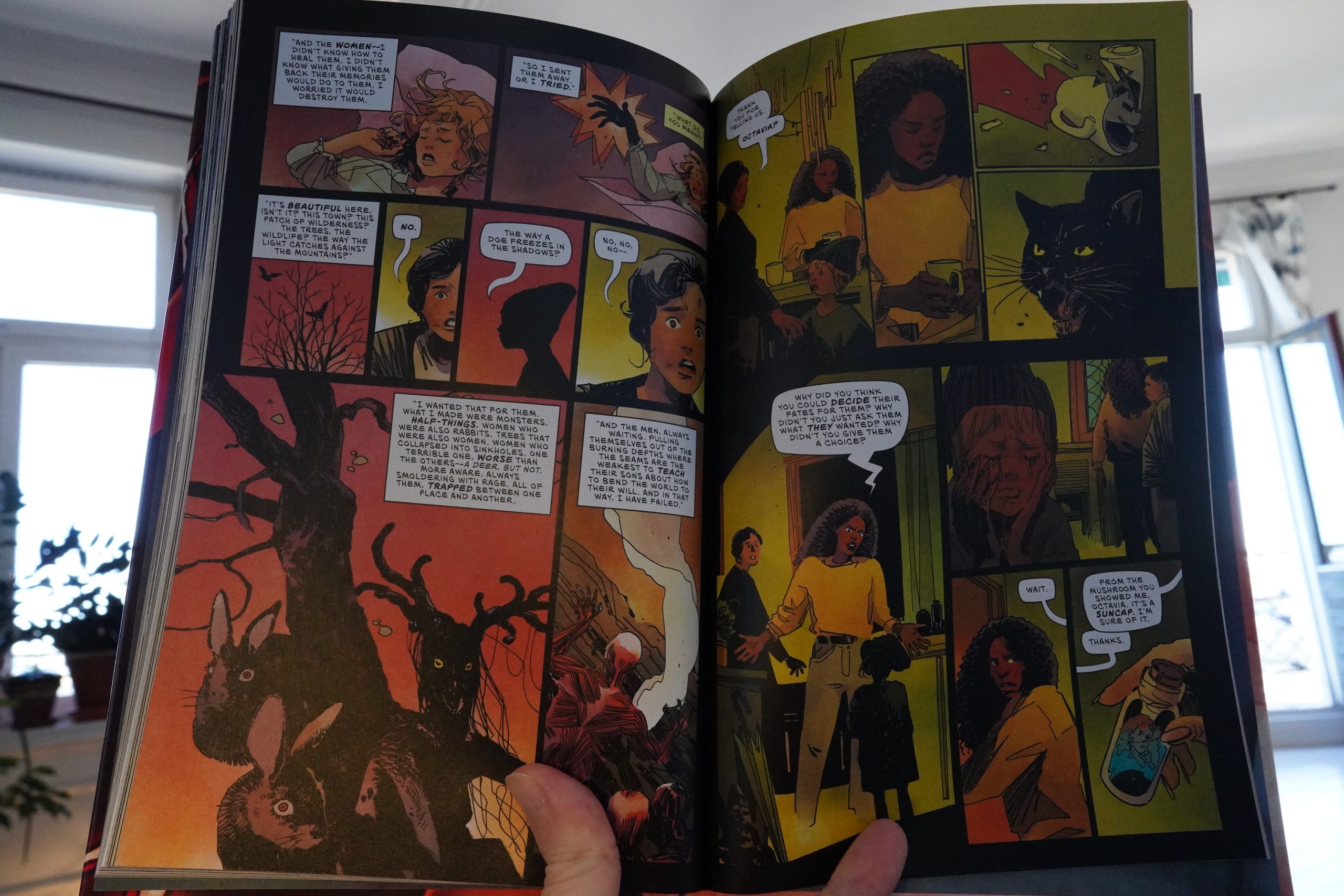

16:37: The Low, Low Woods by Carmen Maria Machado / Dani / Tamra Bonvillain (DC Comics)

I’m not sure how I ended up with this… perhaps I saw somebody recommending it somewhere?

This is a very frustrating horror book. I like the artwork, but the plot — two girls growing up in a little town they know is frequented by actual monsters, but still poo-poo any suggestion that they’re in a horror story — is just dull.

I should eat something… wait here a bit while I fix some food.

*time passes*

Back!

The plot follows the Netflix Plot Structure perfectly, though: They tool around for a while, being mostly ineffective, and then in the fifth issue, somebody spills all the beans on all of the mysteries, just like that. So is a Netflix adaptation coming up soon?

| Low: Hey What |  |

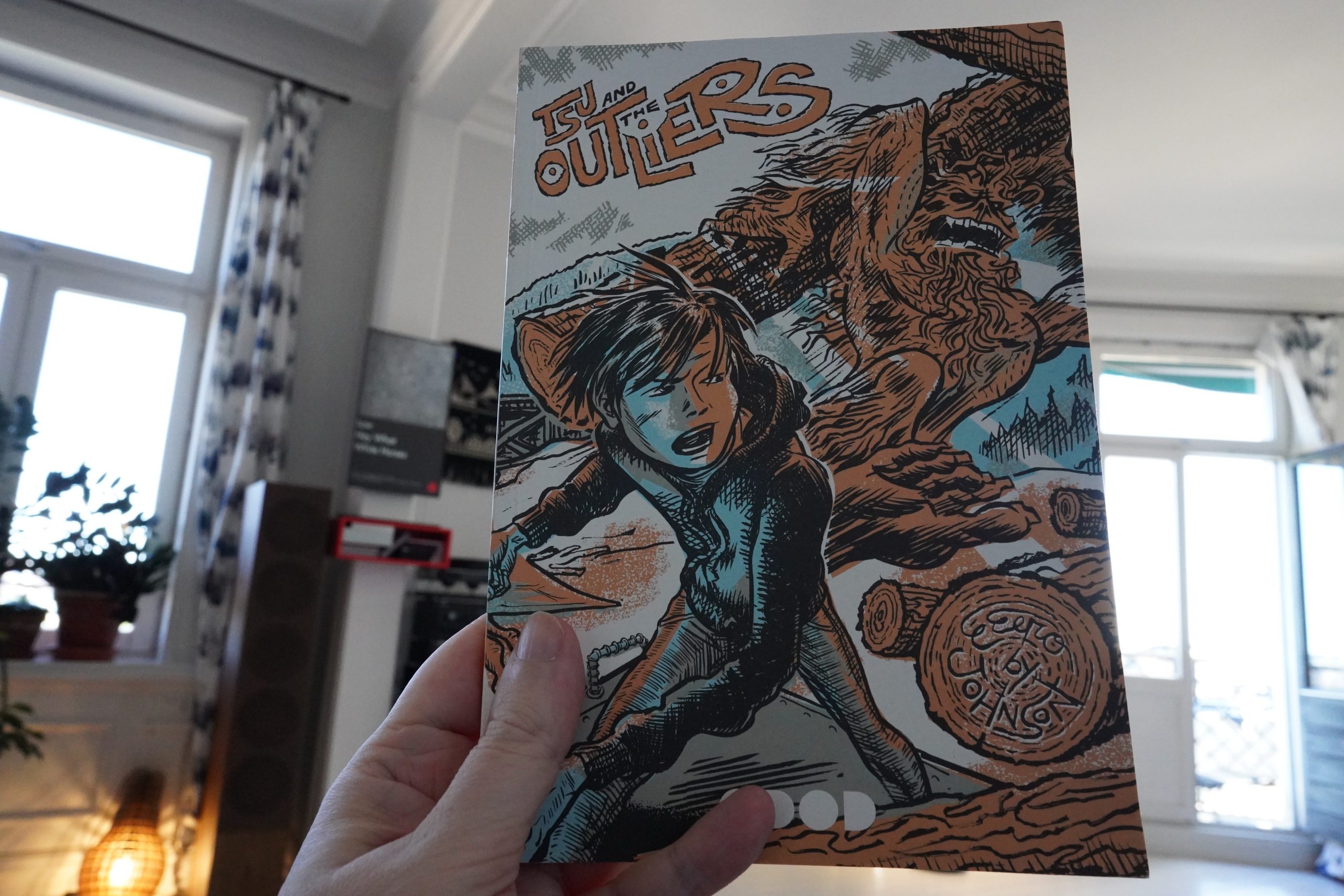

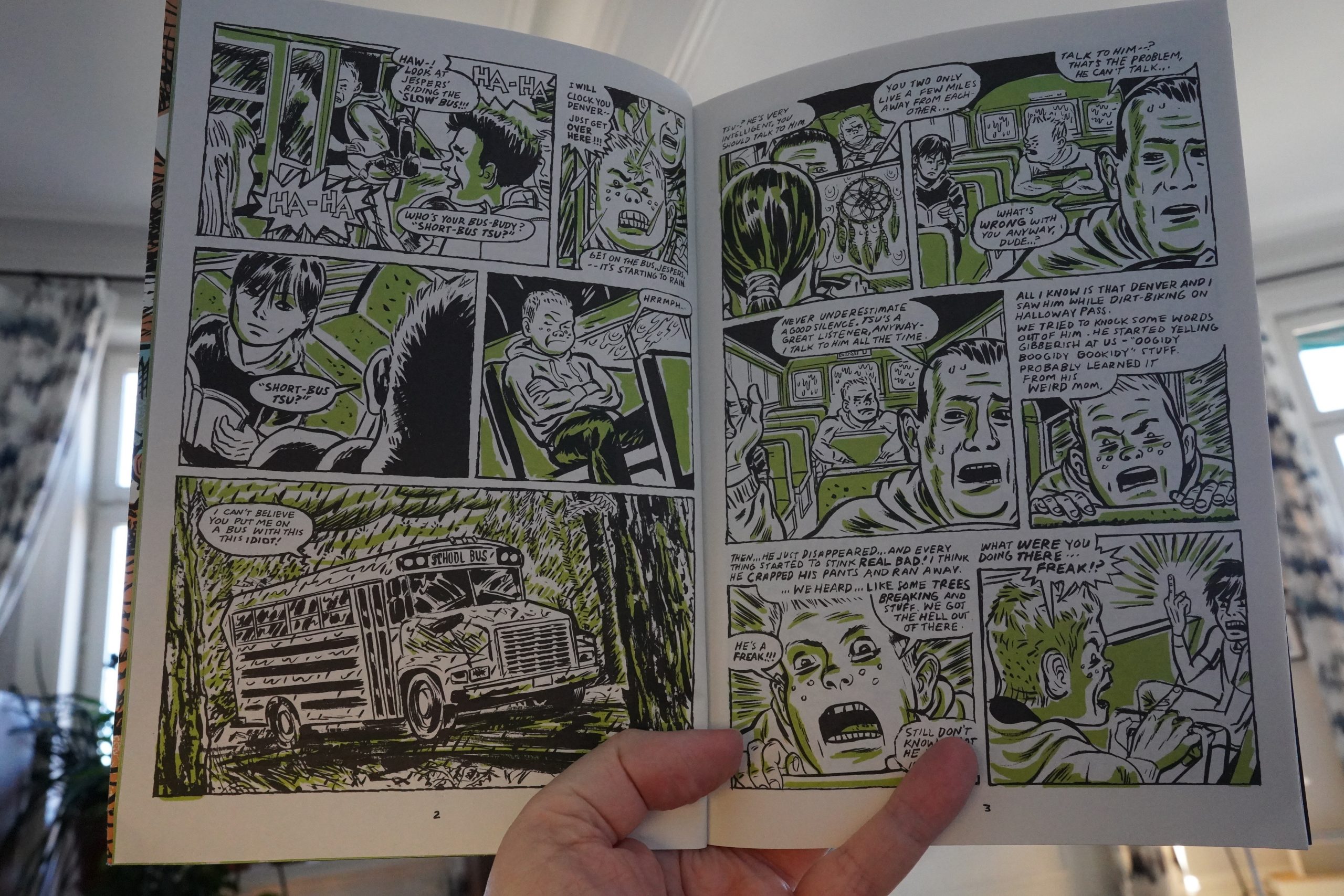

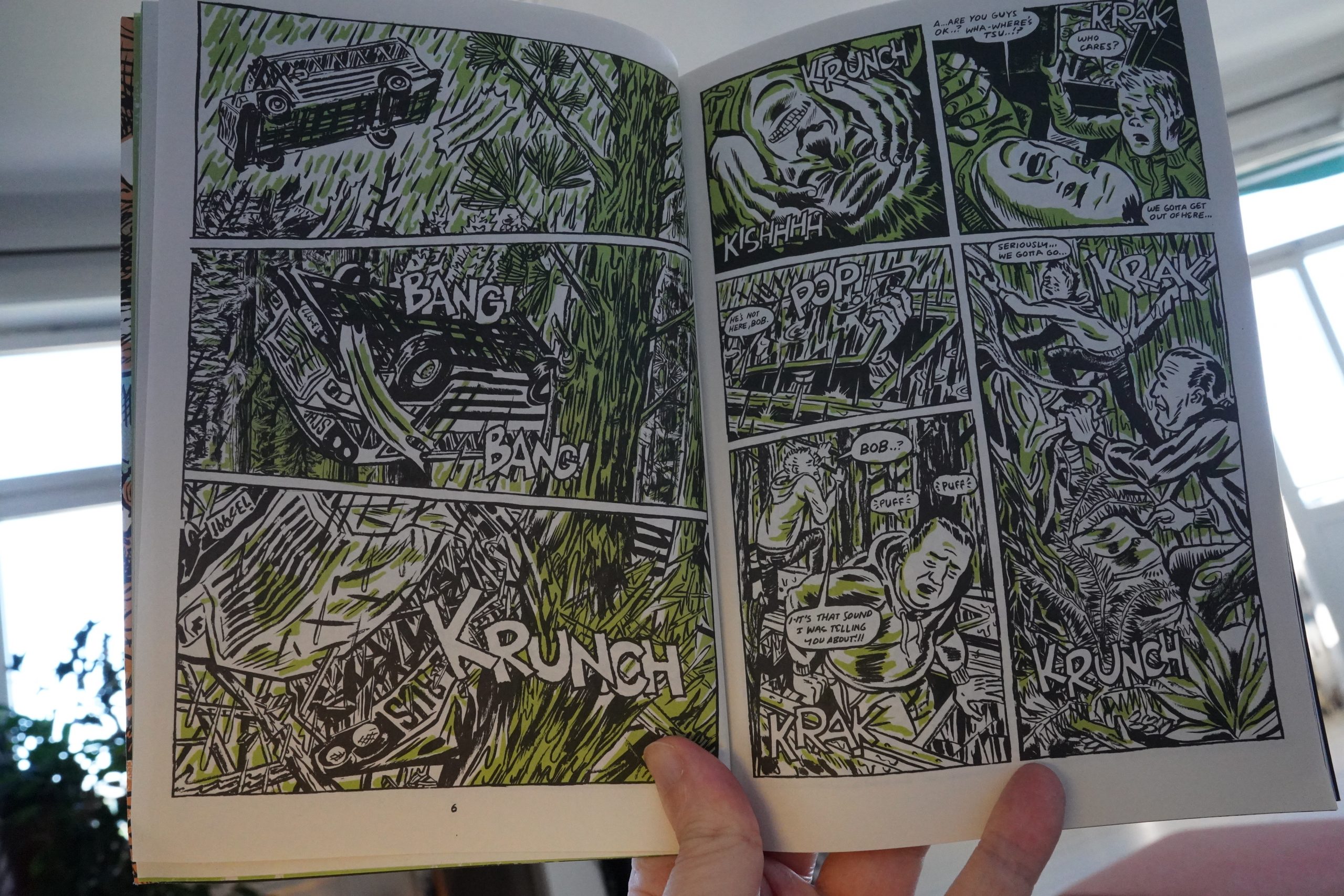

17:59: Tsu and the Outliers by E. Eero Johnson (Uncivilized)

Wow, this is wild. It’s drawn in a style that’s not really used that much any more — a kind of mix between underground style and 90s alternative comics?

It’s a propulsive read, and kinda insane, which I like. However, the ending is a let-down.

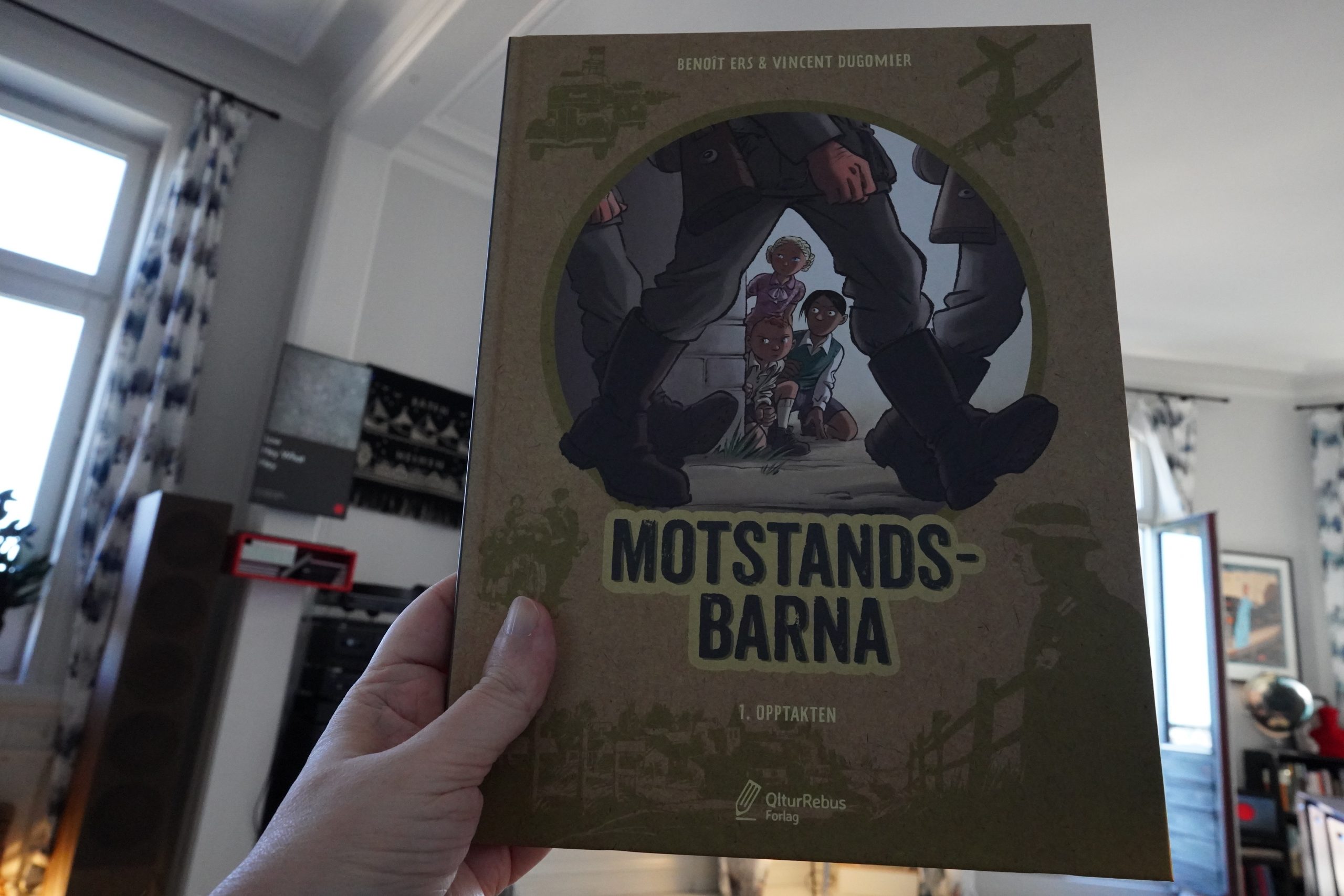

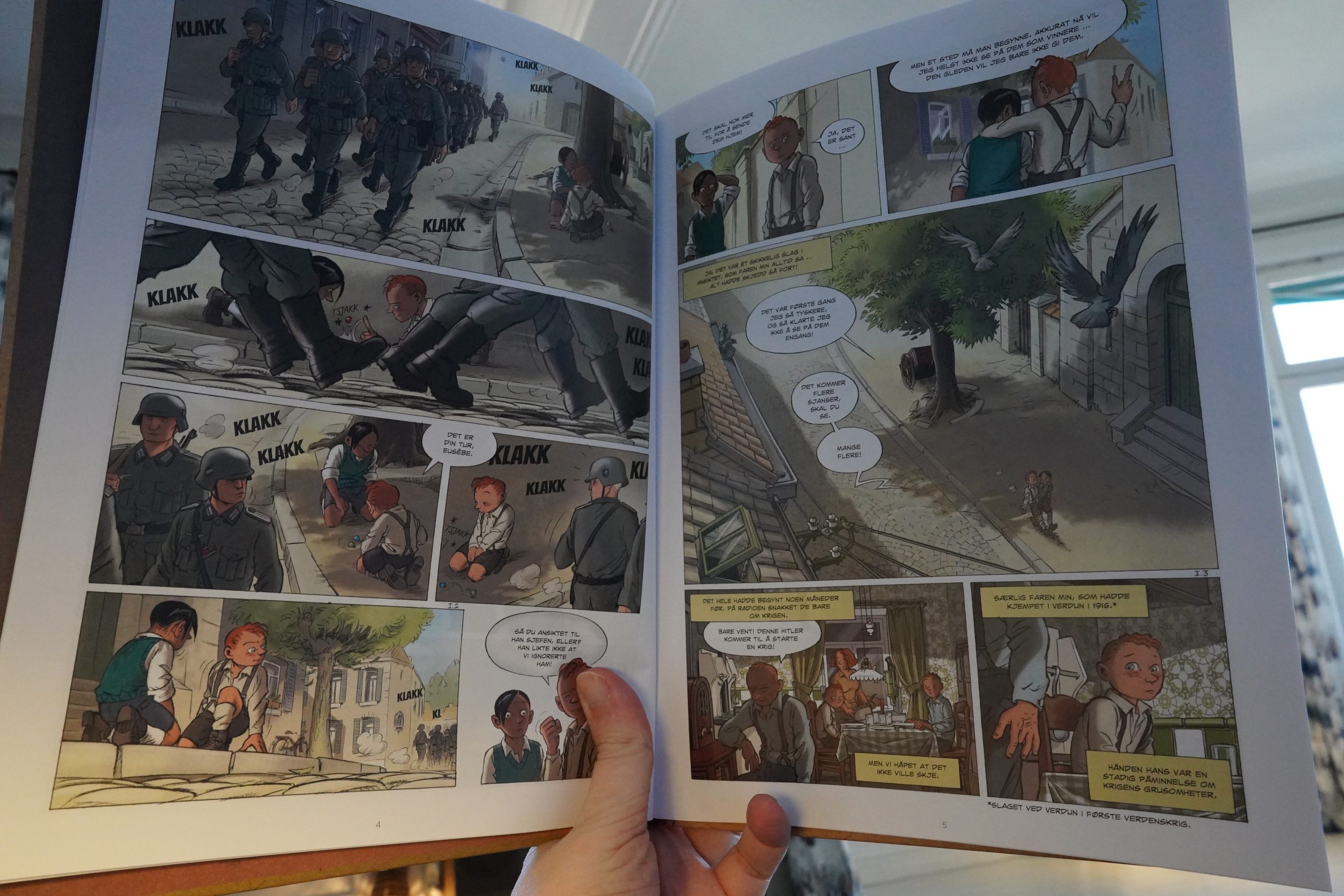

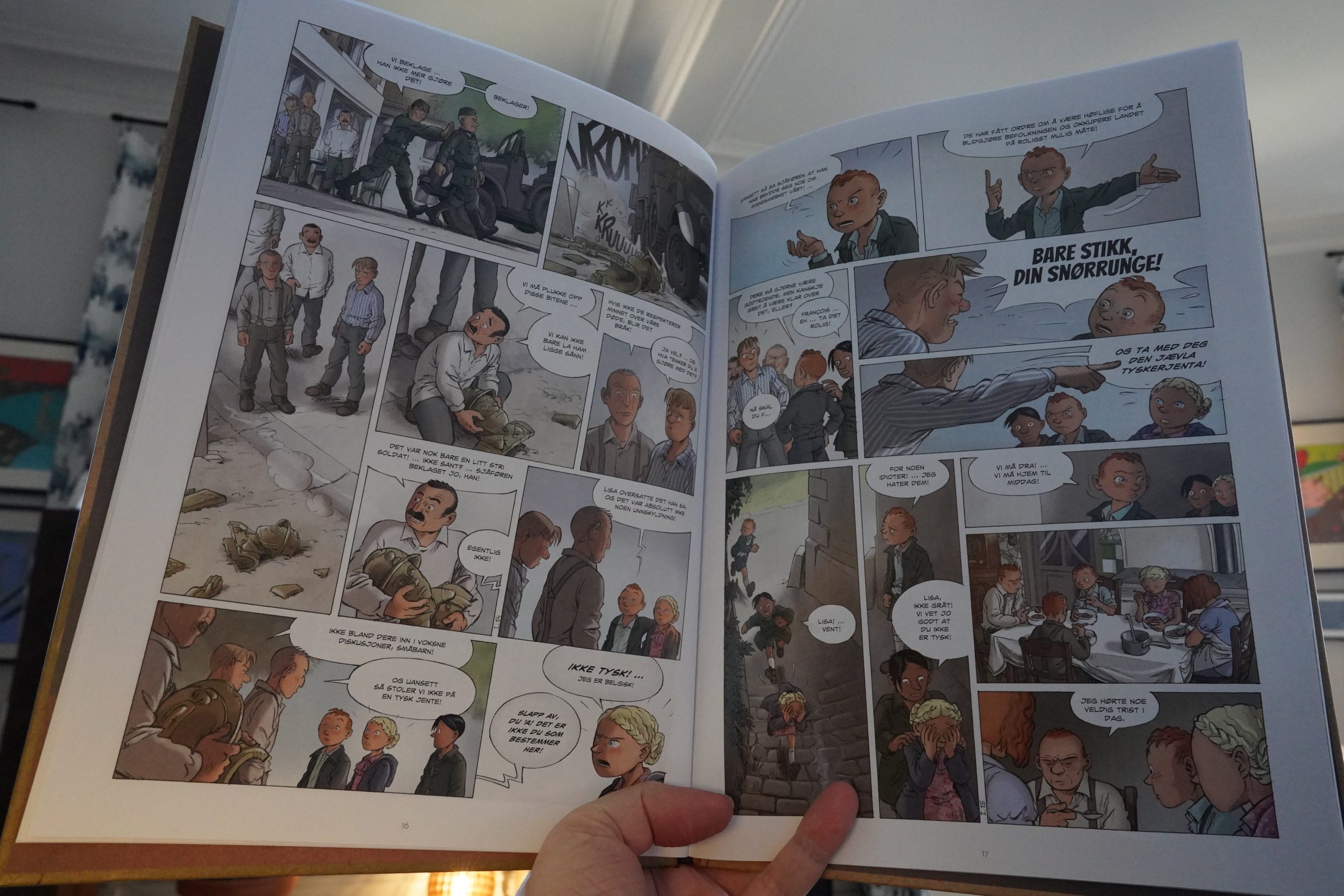

18:14: Les enfants de la Résistance 1 by Benoît Ers & Vincent Dugomier (QlturRebus Forlag)

I assume this edition now (from a company I’ve never heard of before) is because of the Russian war against and occupation of Ukraine. So it’s a timely parallel. But seven albums have been published in France — perhaps there’s more story in the following chapters.

It’s pretty good? I think it’s basically aimed at ten-year-olds — a gentle introduction into the realities of being an occupied country: When to sabotage; who’s the real enemy; how not to be duped by apparent kindnesses; how to successfully get people to resist. Very didactic, and that doesn’t really leave much room for a story.

| Snd: 4, 5, 6 |  |

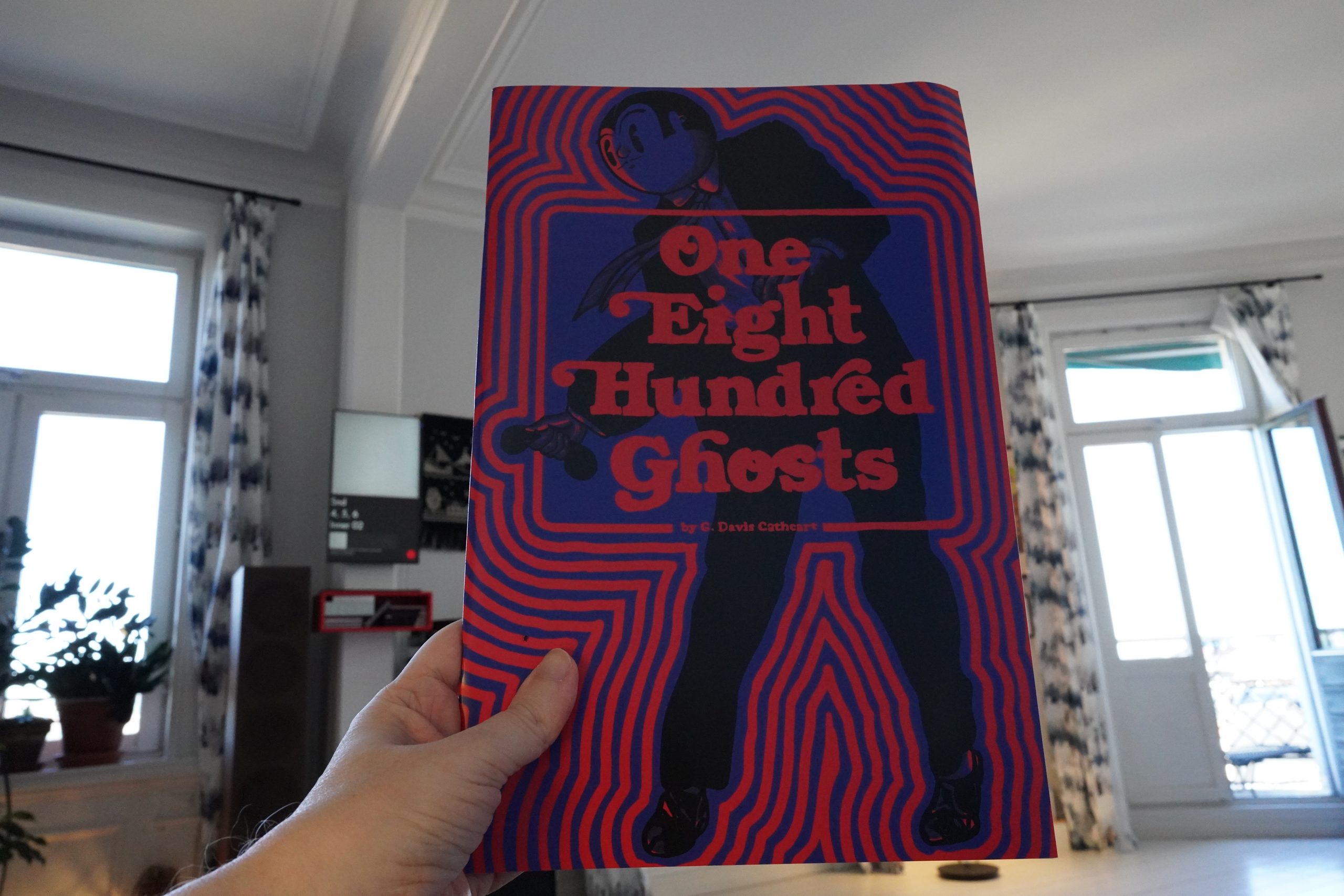

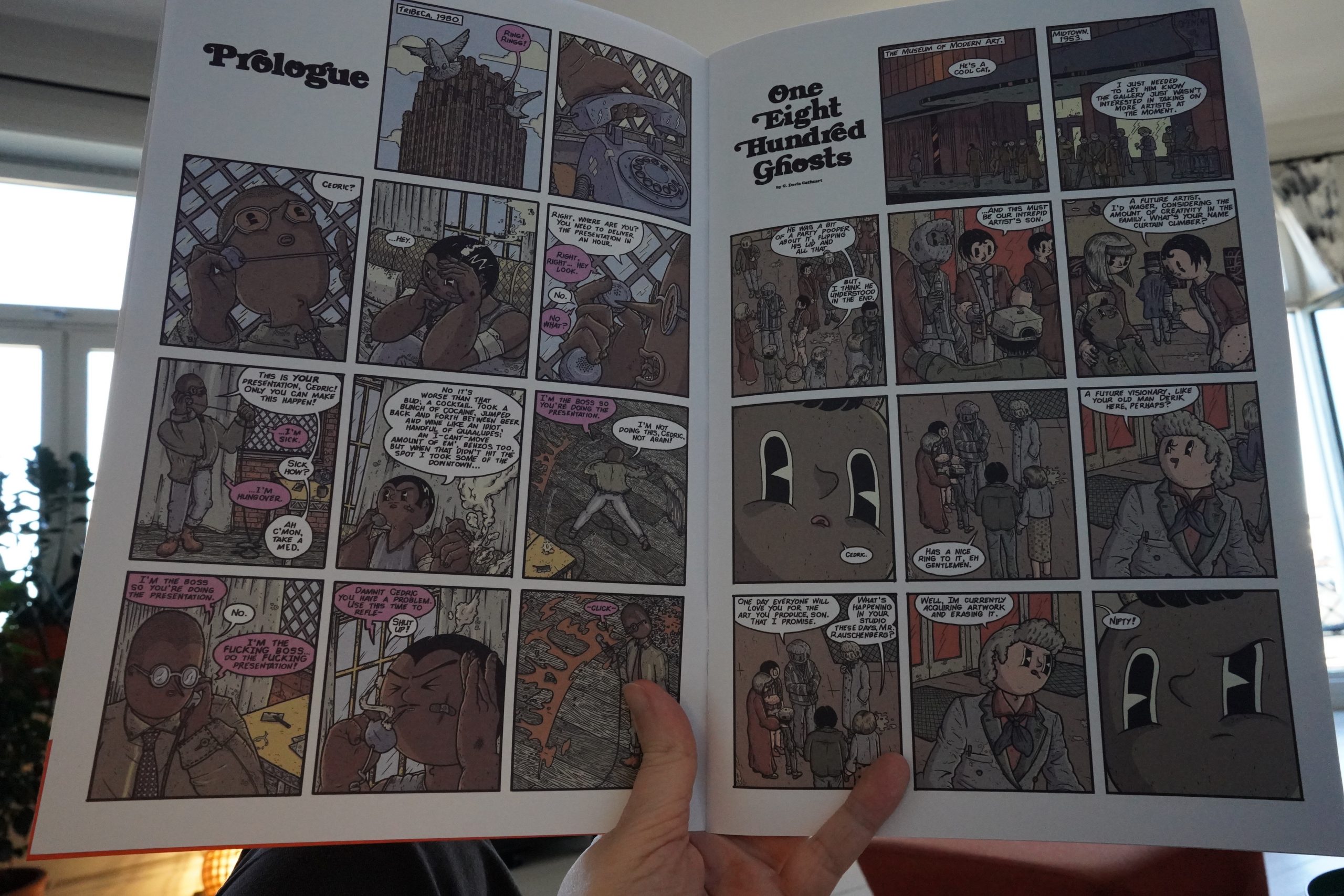

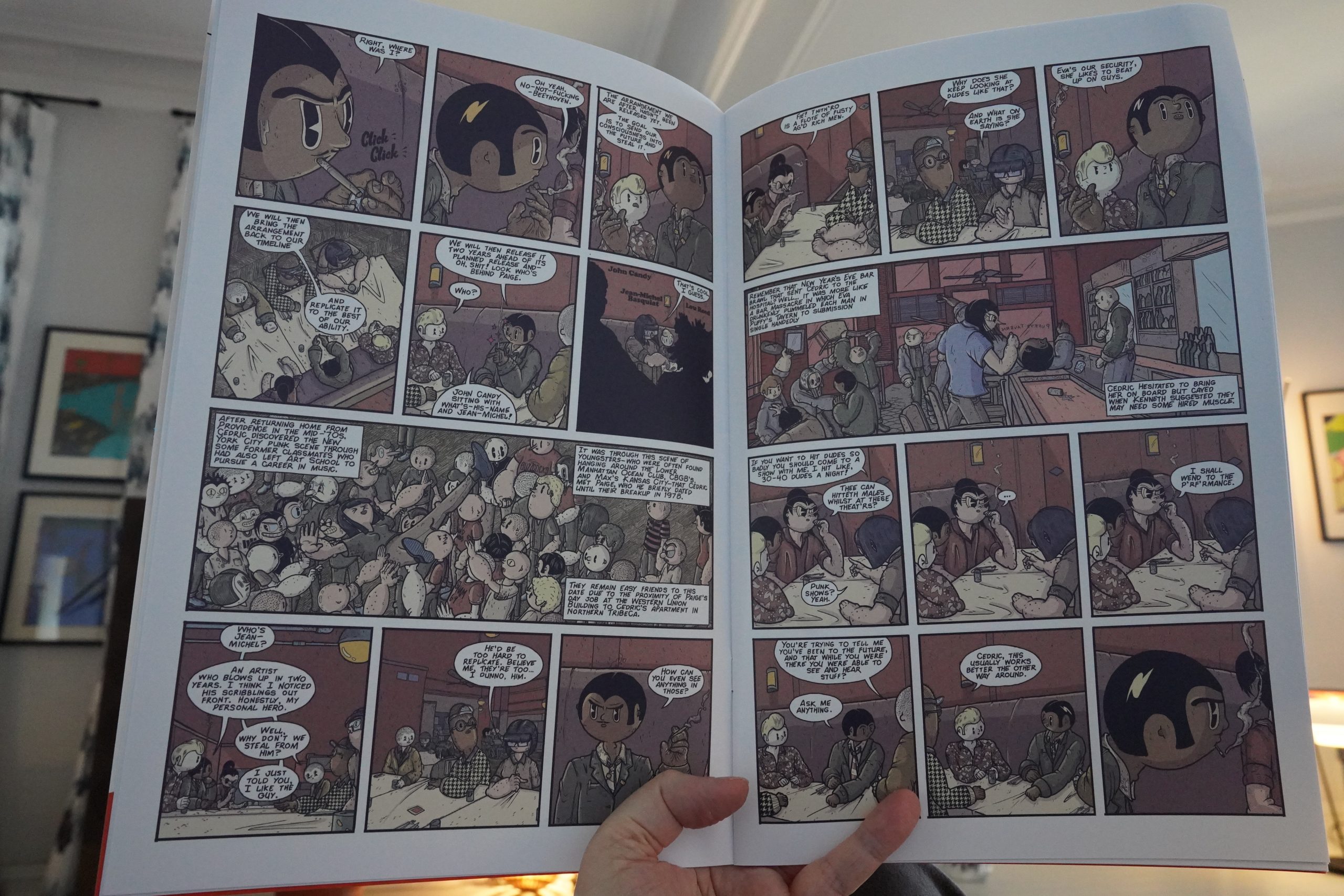

18:52: One Eight Hundred Ghosts by G. Davis Cathcart (Fantagraphics)

On a scale of wha to huh this is way beyond wha.

It’s a time travel heist thing where the main purpose is to sabotage the release of Michael Jackson’s Thriller album. That sounds like it should be a lot of fun, but it more… like… a little bit of fun?

But it’s fine.

| Snd: 4, 5, 6 |  |

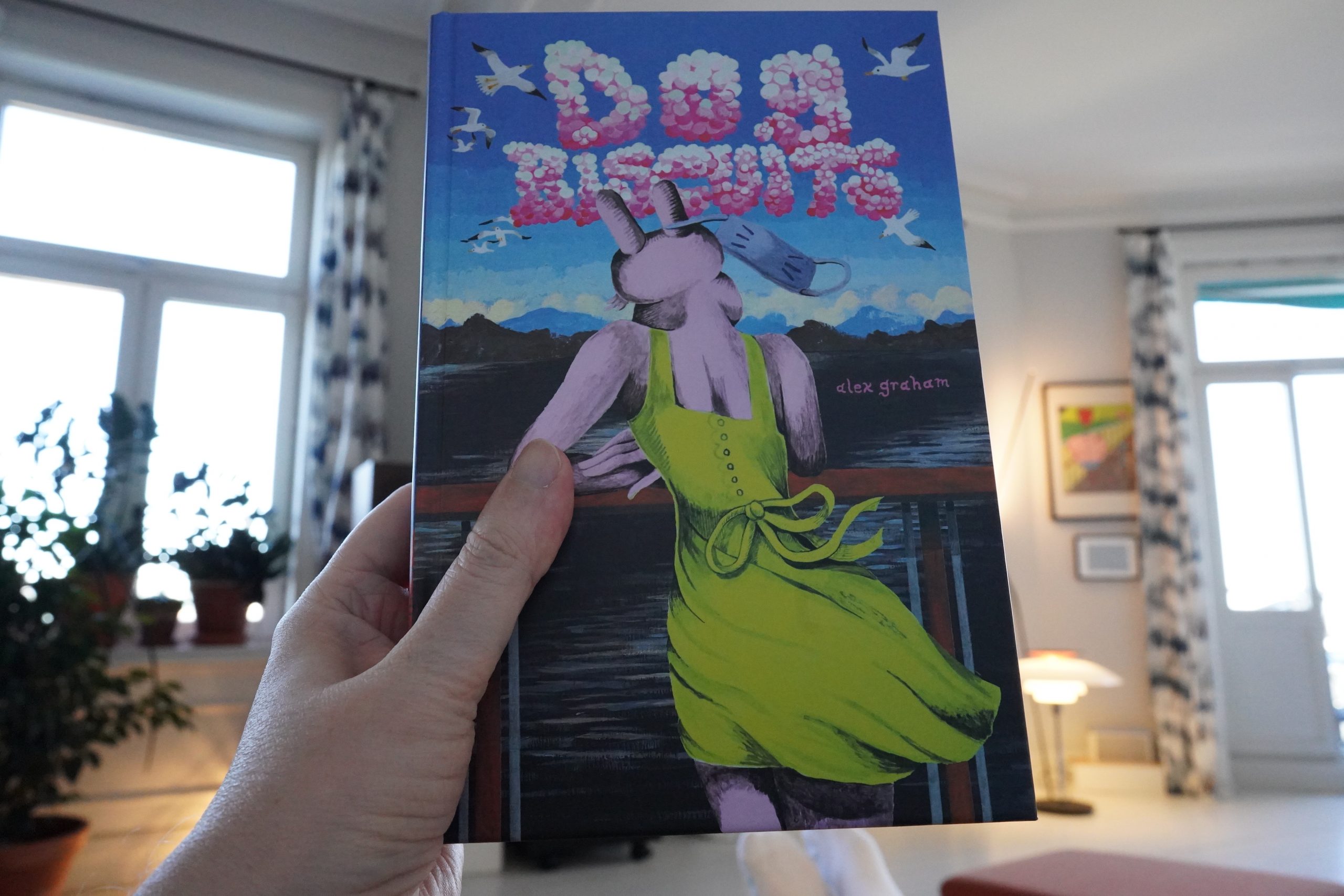

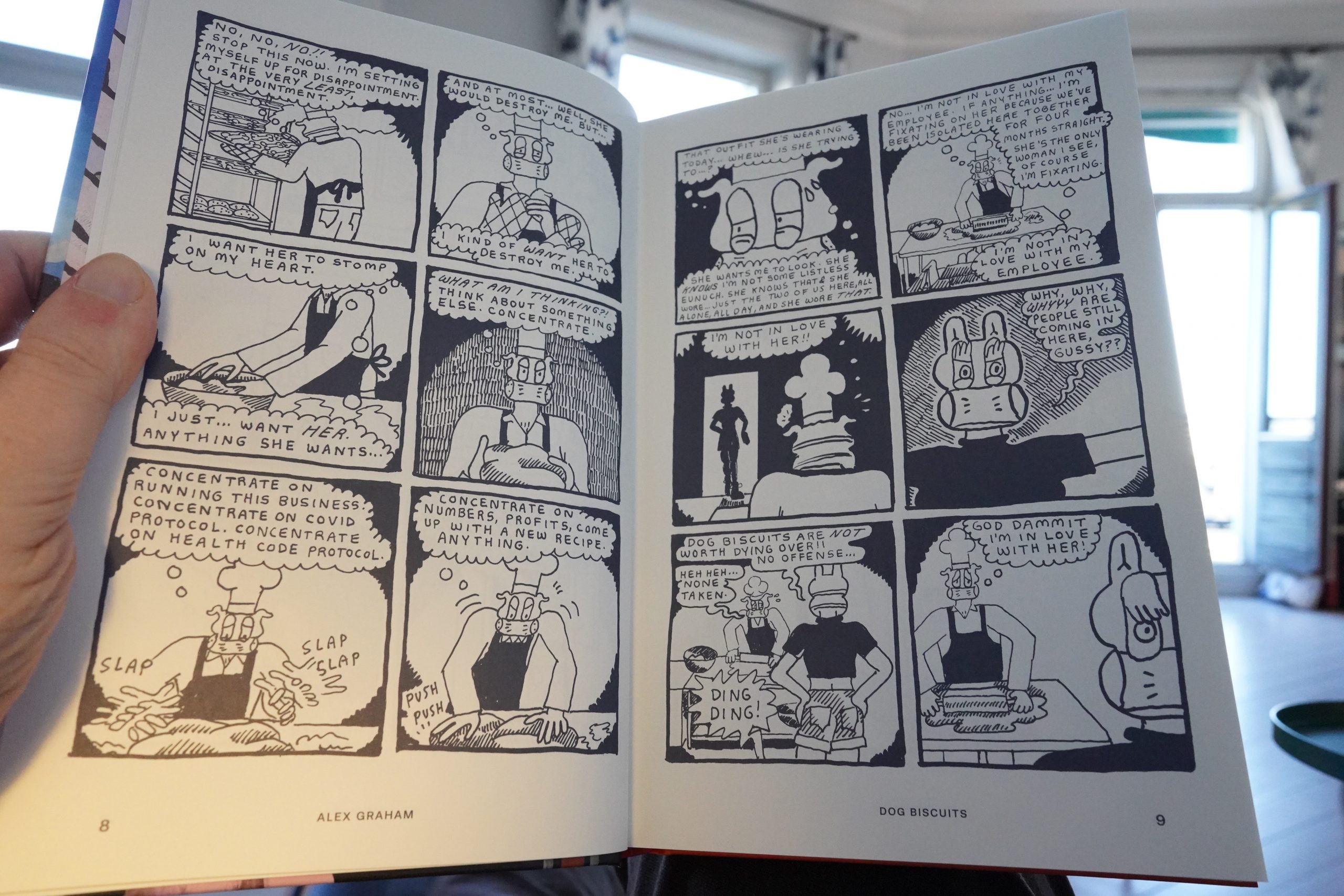

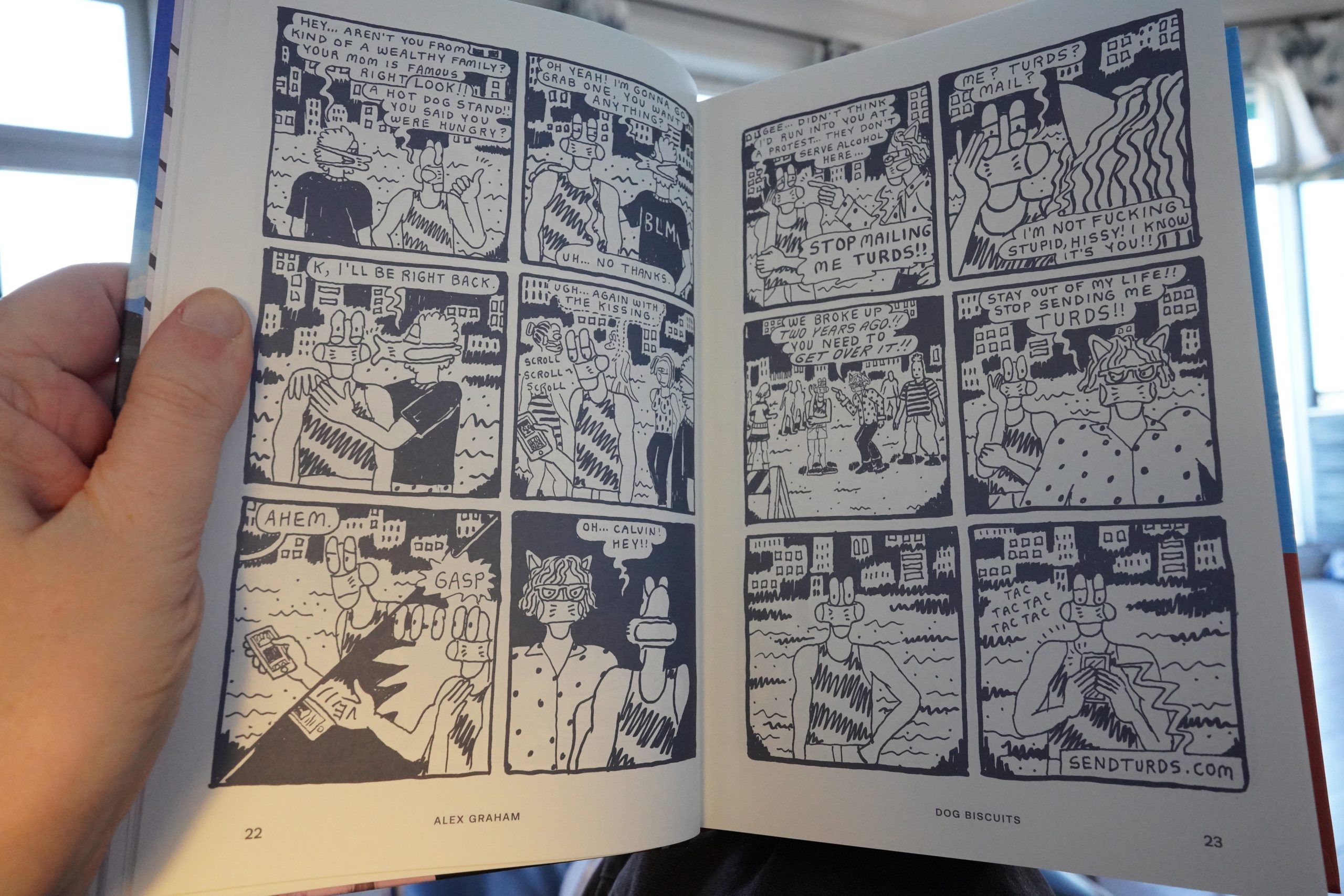

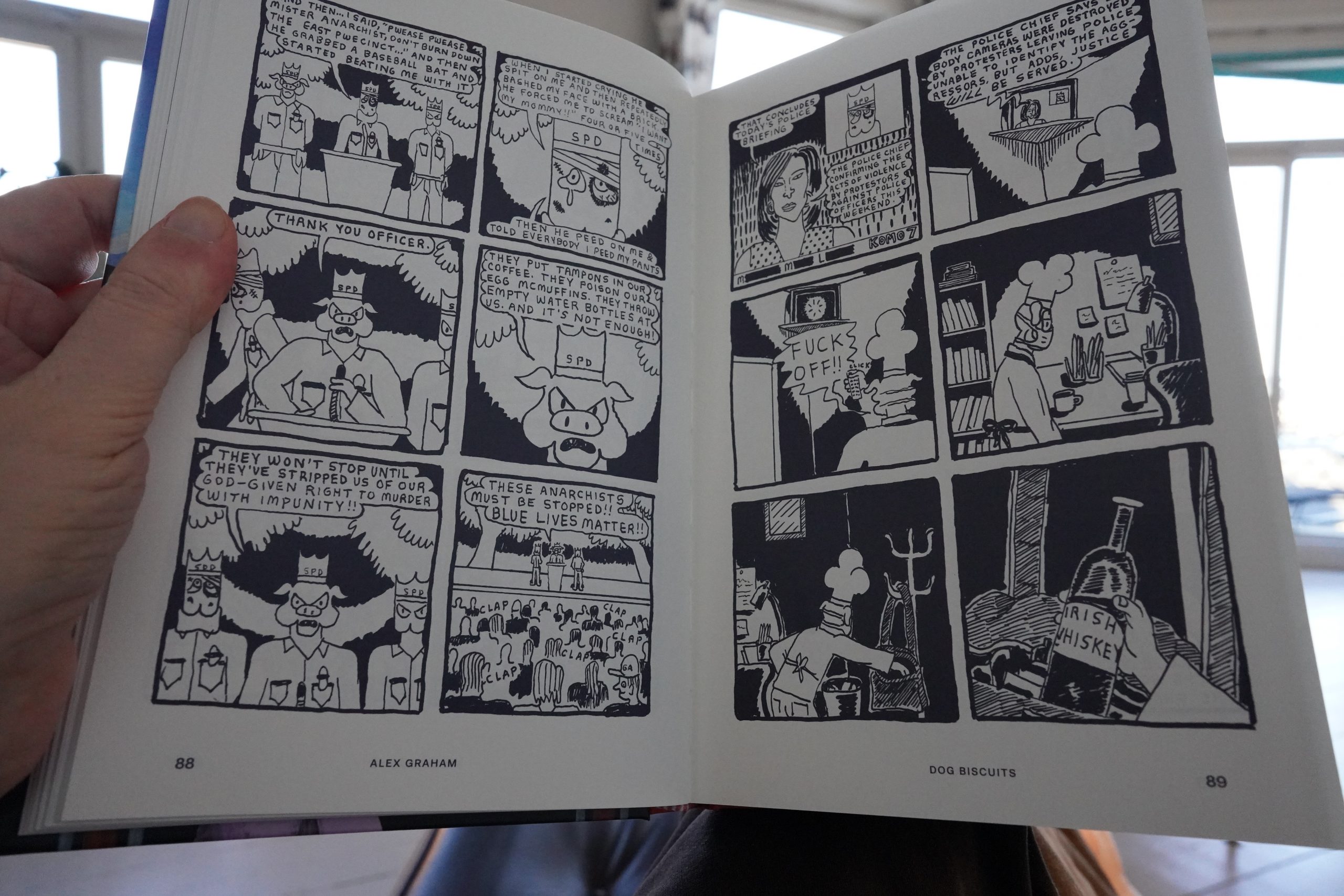

19:17: Dog Biscuits by Alex Graham (Fantagraphics)

Sure is a lot of Fantagraphics in this batch…

This was originally serialised on Instagram, and you can tell — it has that dashed-off quality to it.

Some of the pages are printed in a sort of bluish hue? Are they supposed to be?

But… While there’s some amusing bits here, and the political analysis is on point, I’m just so turned off by the art style that I can’t be bothered with this. Sorry! I ditched it after 100 pages.

I’m sure it’s appealing to millions of people.

| ESP Summer: Kingdom of Heaven |  |

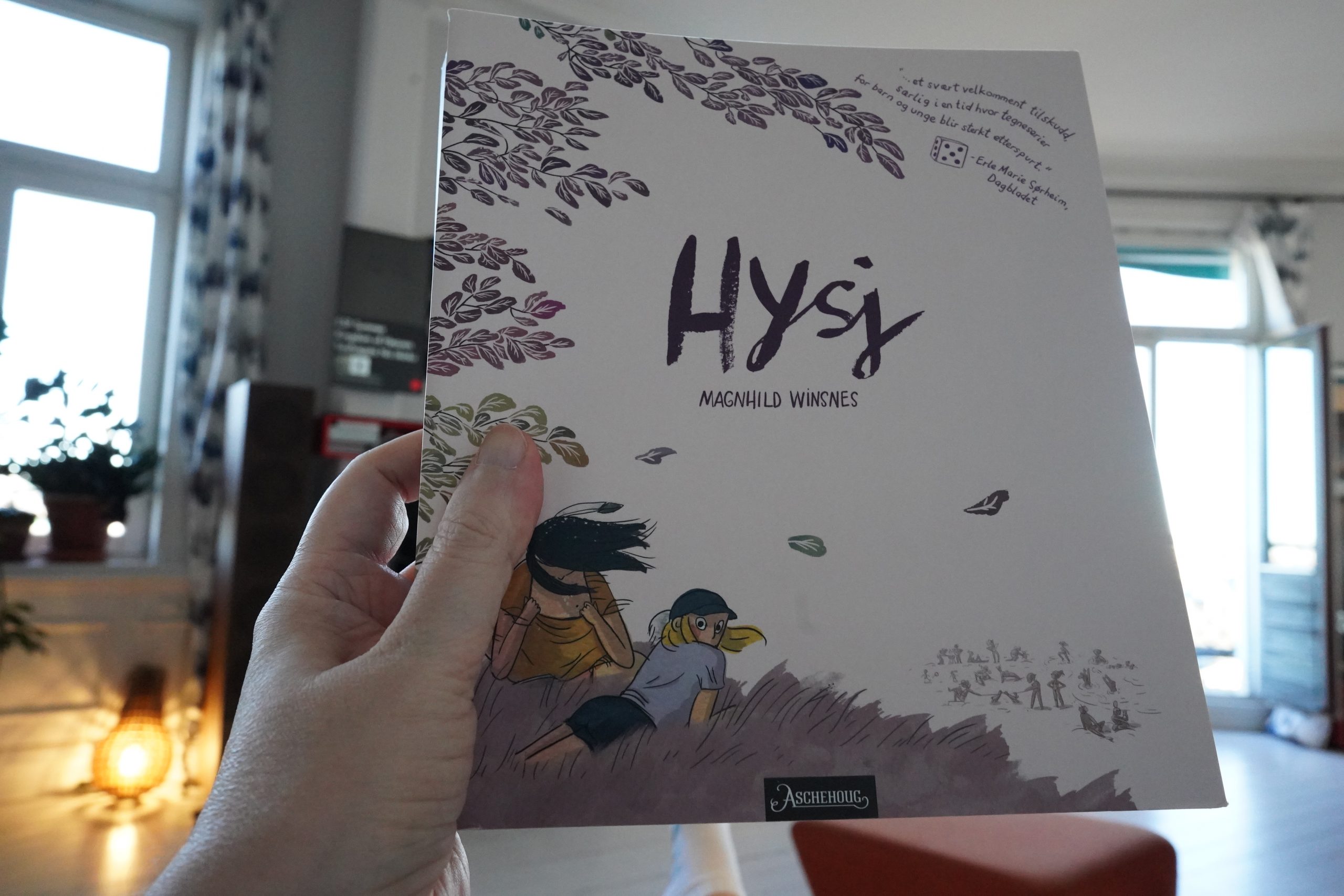

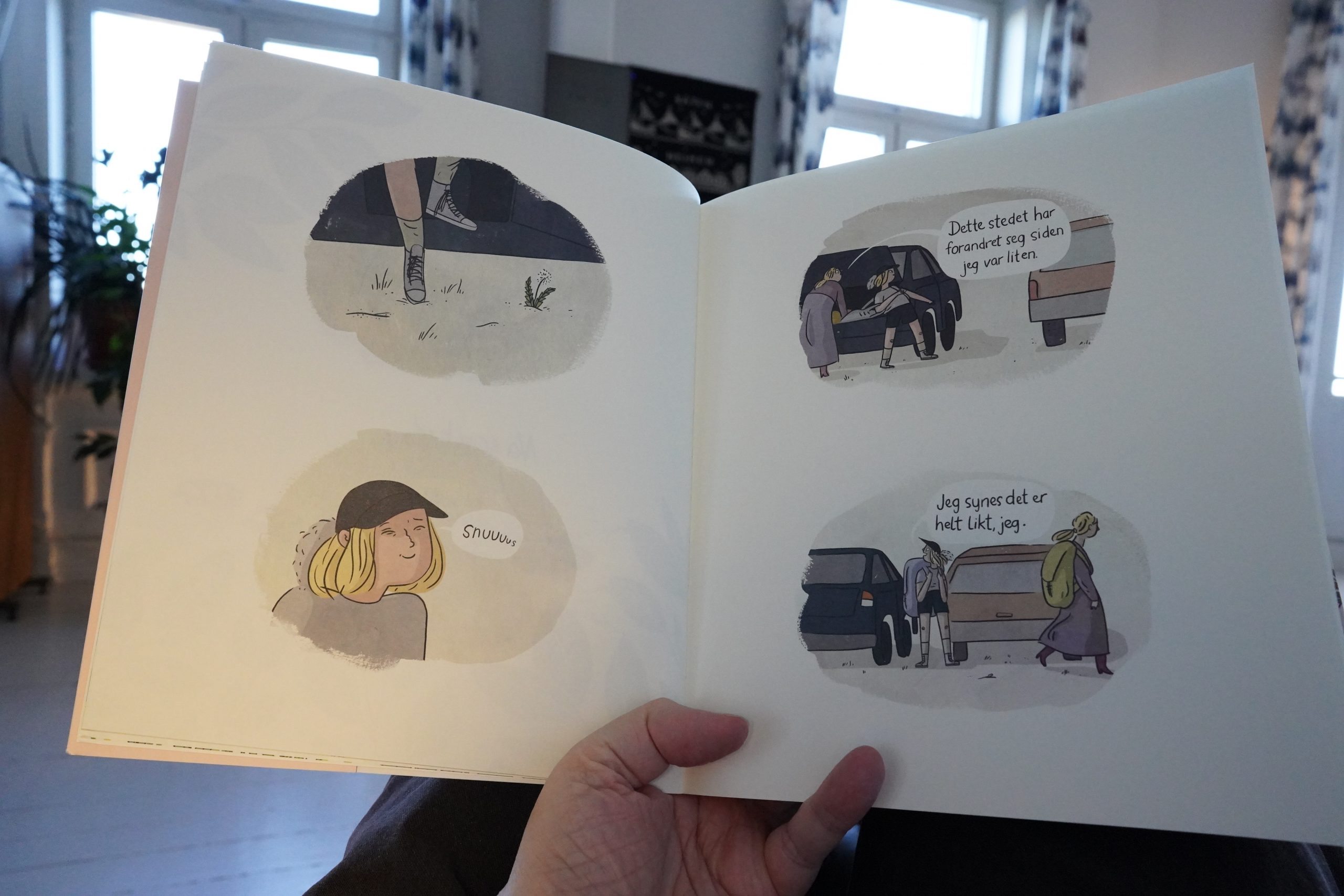

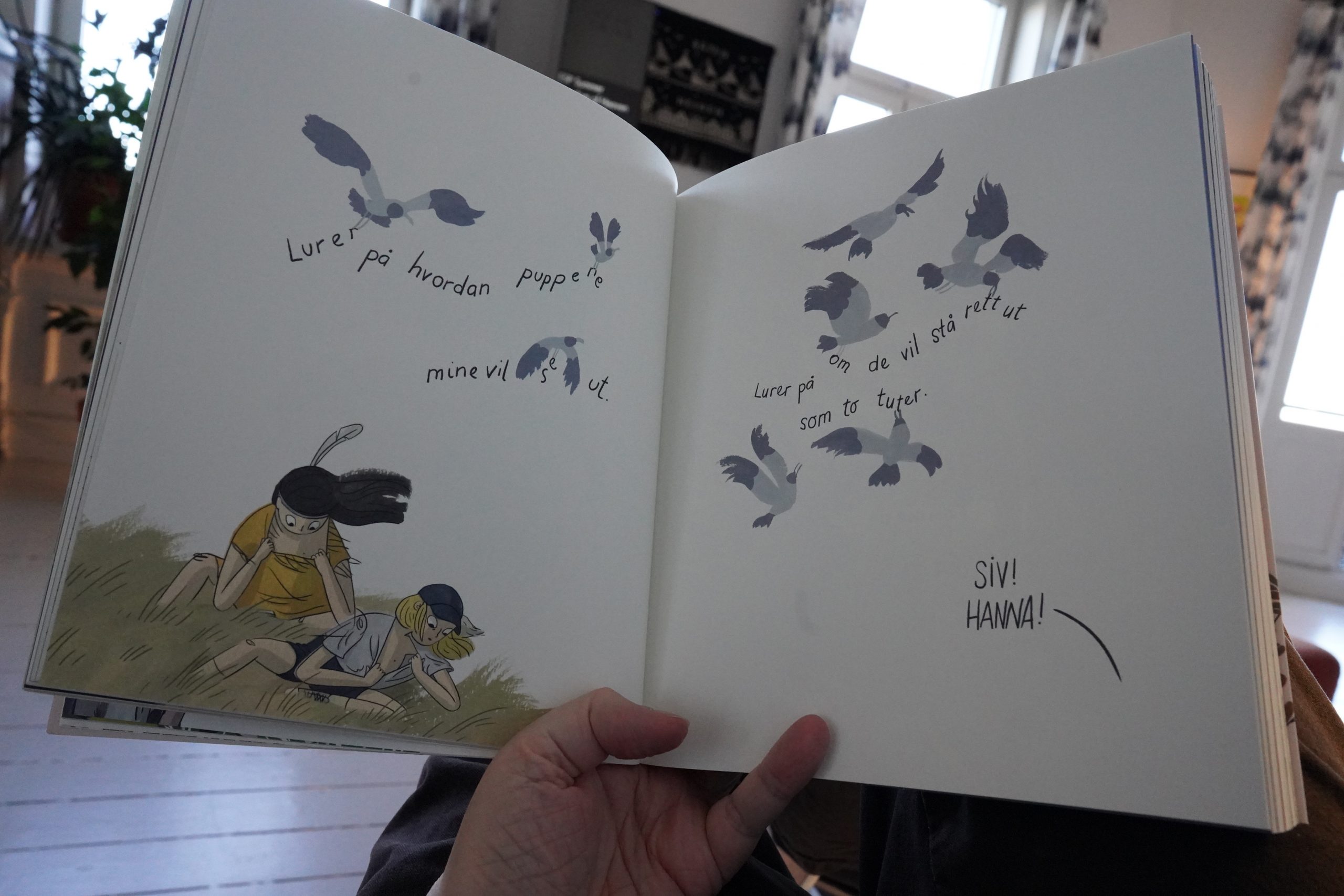

19:50: Hysj by Magnhild Winsnes (Aschehoug)

Heh heh. I like the blurb on the cover — “… comics for kids are most welcome these days”. Urk! Gasp! Choke! Comics aren’t just for old people any more.

This is a really, really brisk read — I’m sure I’ve gotten RSI just from flipping the hundreds of pages of this book now.

But it’s really good? It’s a typical coming-of-age wistful story, and the author covers all the expected plot points. But it’s done with such aplomb that it’s hard to resist. It’s just… sweet? And such lovely artwork.

Low time per mass, though

| Yves Tumor: The Asymptotical World (EP) |  |

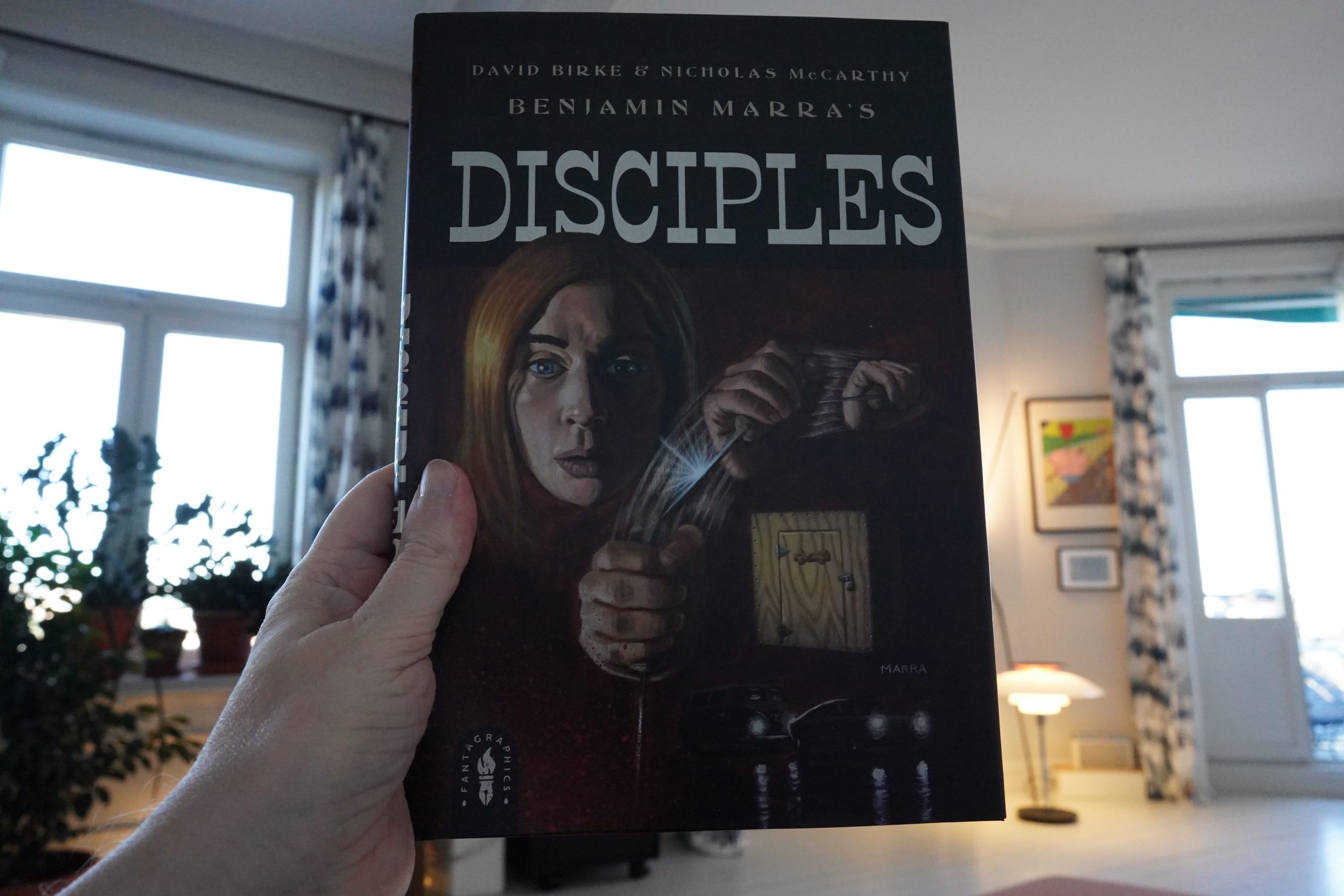

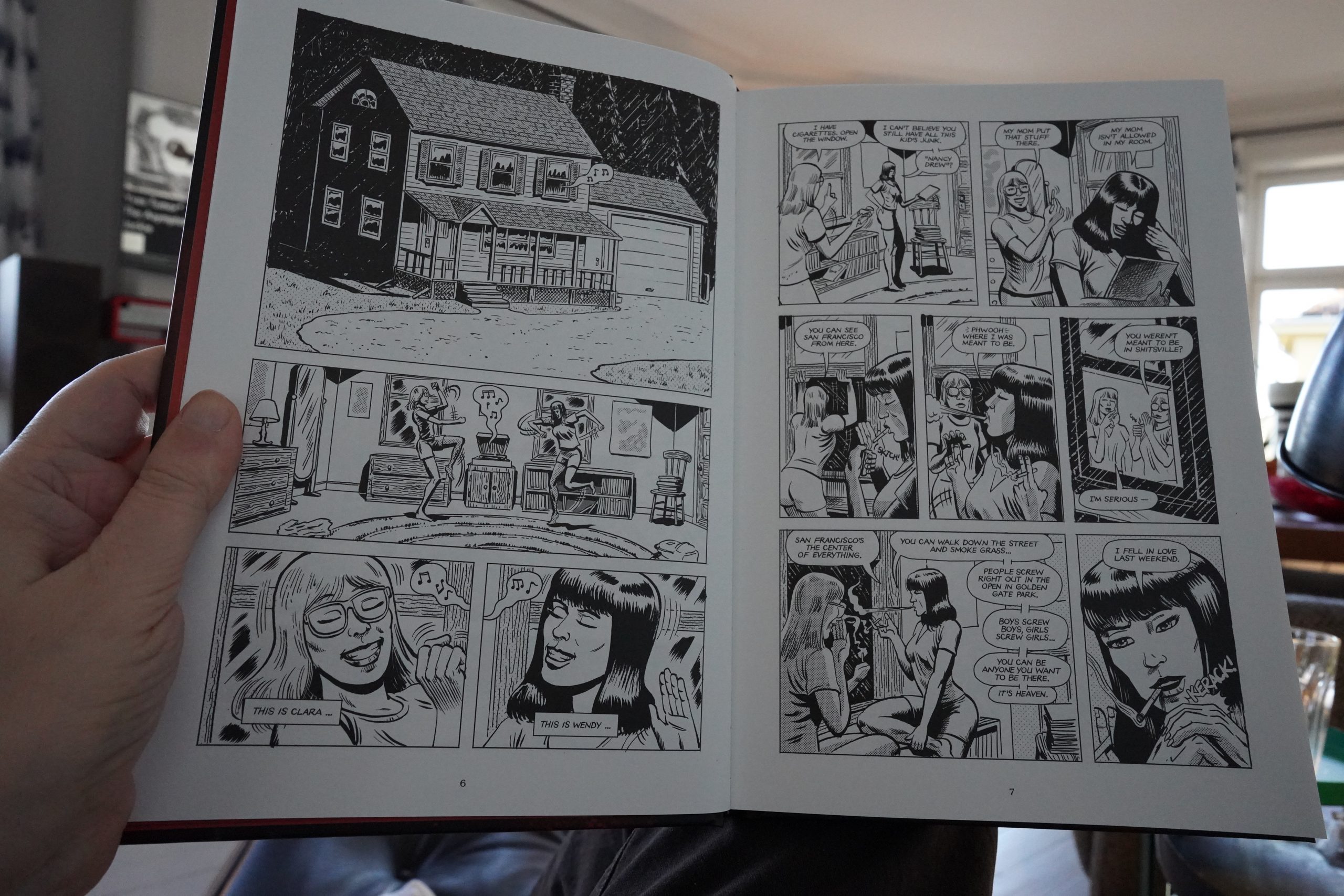

20:05: Disciples by David Birke, Nicholas McCarthy and Benjamin Marra (Fantagraphics)

More Fantagraphics!

This is very different from Marra’s other comics — it’s a perfectly normal, well-told vampire movie in comic book form. Which makes it so incongruous, because it seems so impersonal. Why do this book? I suspect the reason might be “because he got a page rate” or something, but I’m just guessing.

Or perhaps they’re going to pitch this as a movie, and want to have a comic book to show investors. I have no idea.

It’s fine?

| Matmos: The Consuming Flame: Open Exercises in Group Form (3): Extraterrestrial Masters |  |

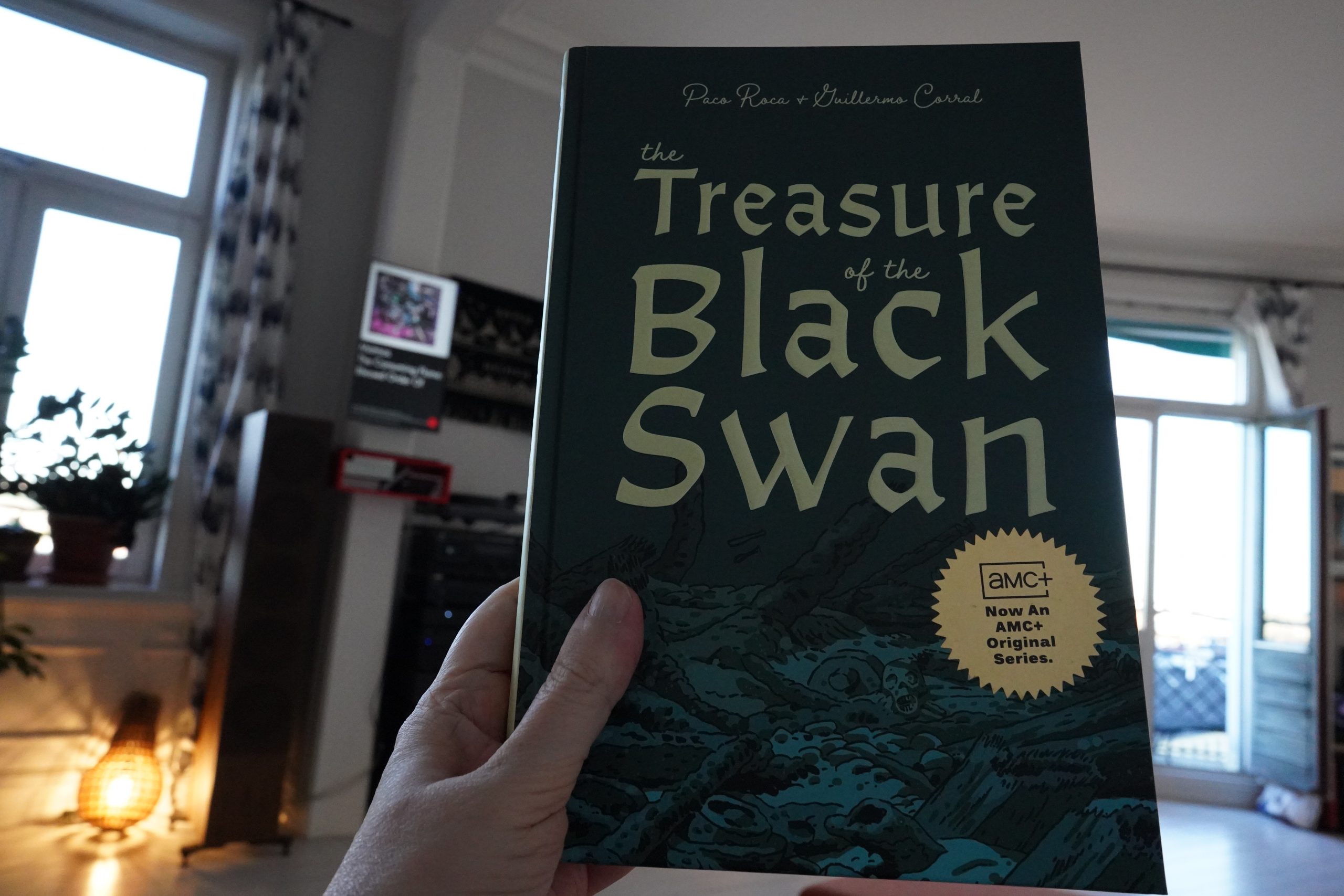

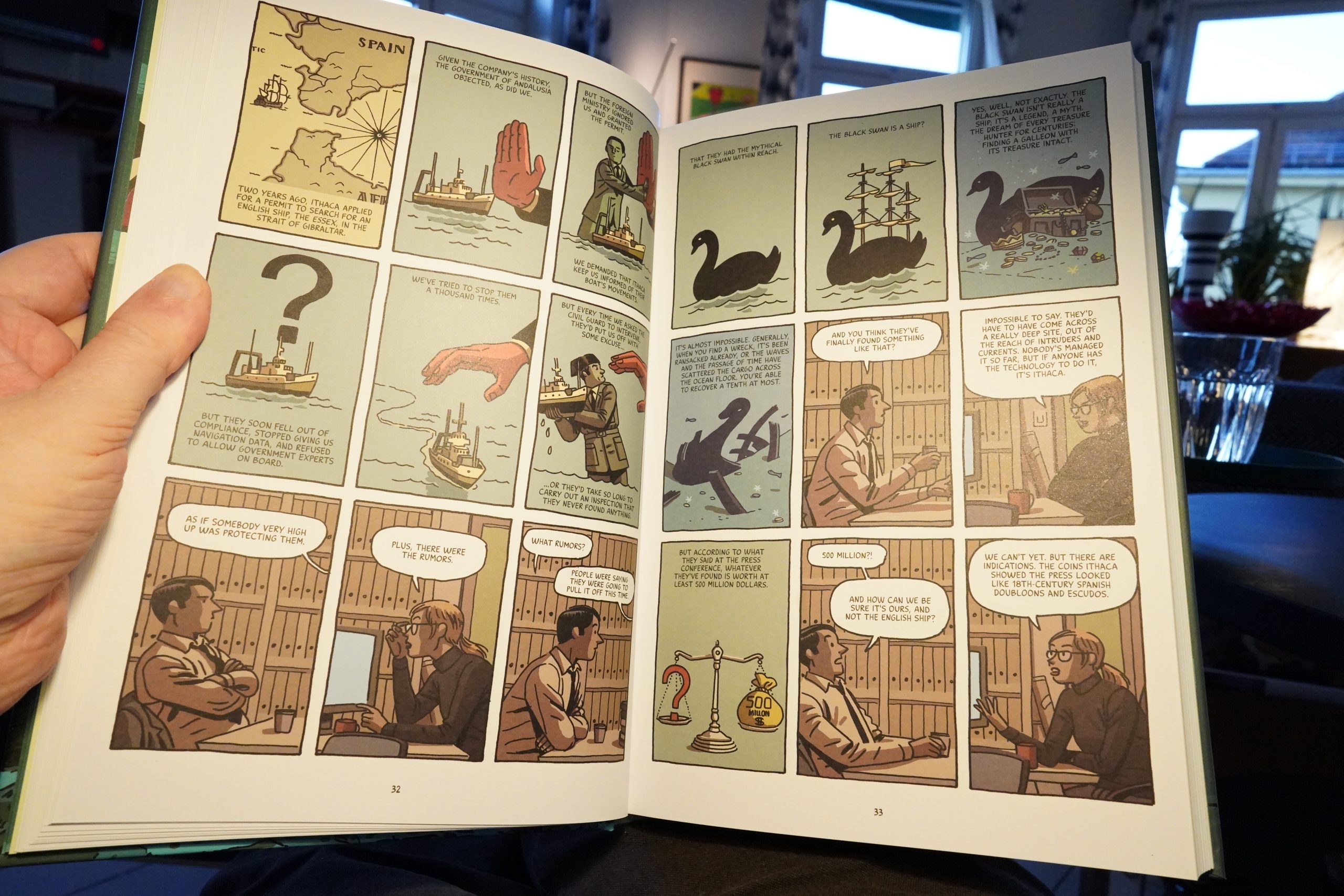

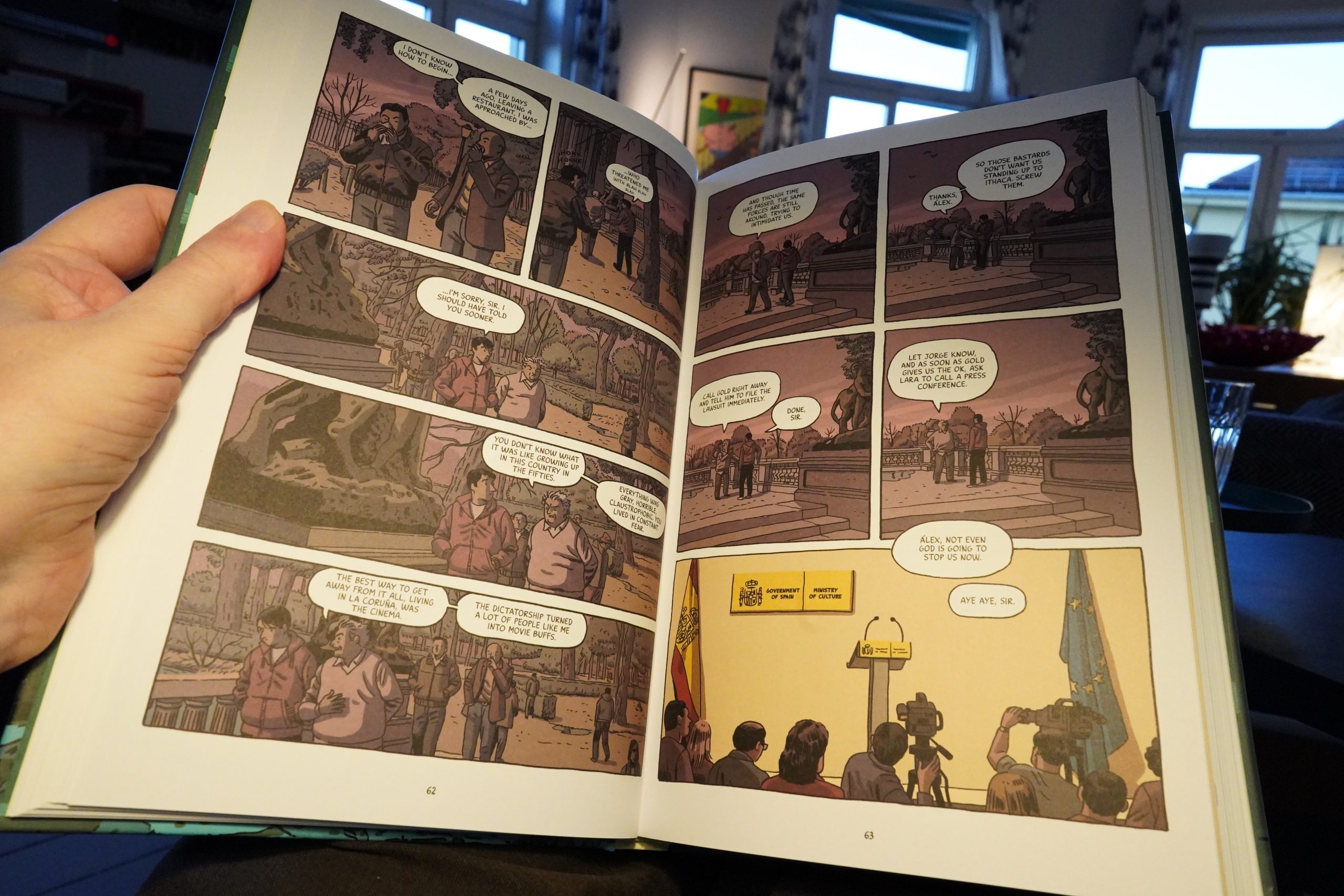

20:57: The Treasure of the Black Swan by Paco Roca & Guillermo Carral (Fantagraphics)

The Fantagraphicness never ends…

Hey, this is a lot of fun. It’s a bit like watching a procedural TV series — there’s a lot of back and forth and twists, and the obligatory romance B plot, but it somehow works?

So I’m not the least surprised to see the “Now an AMC+ Original Series” sticker on the front, because they can just film this as is. They probably won’t, though — I’m guessing they’ll pad it out to eight times its length, but not add anything of interest. Hm… No, they kept it down to a snappy six hours. Perhaps I’ll give it a go.

The protagonists are Spanish bureaucrats who spend all day lecturing people about their ideals until they find out about the find and embark on a quest to use legal technicalities to appropriate the treasure they didn’t find or even look for from the man who committed everything to finding it. It’s a socialist morality play in which the State destroys the capitalist, so if that’s your thing, you’ll like La Fortuna.

OK, now I’ll watch it for sure.

| Lush: Chorus (1): Gala |  |

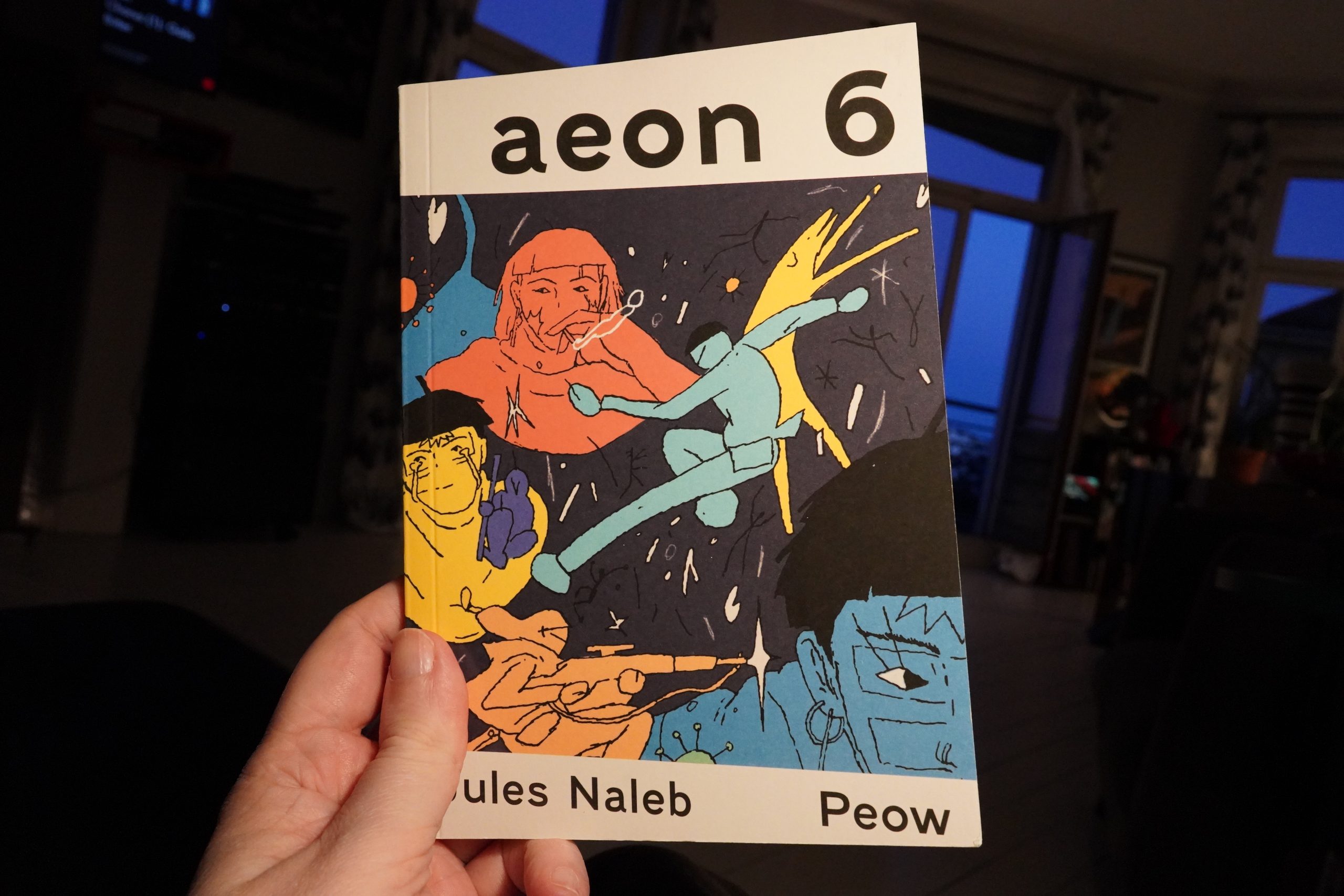

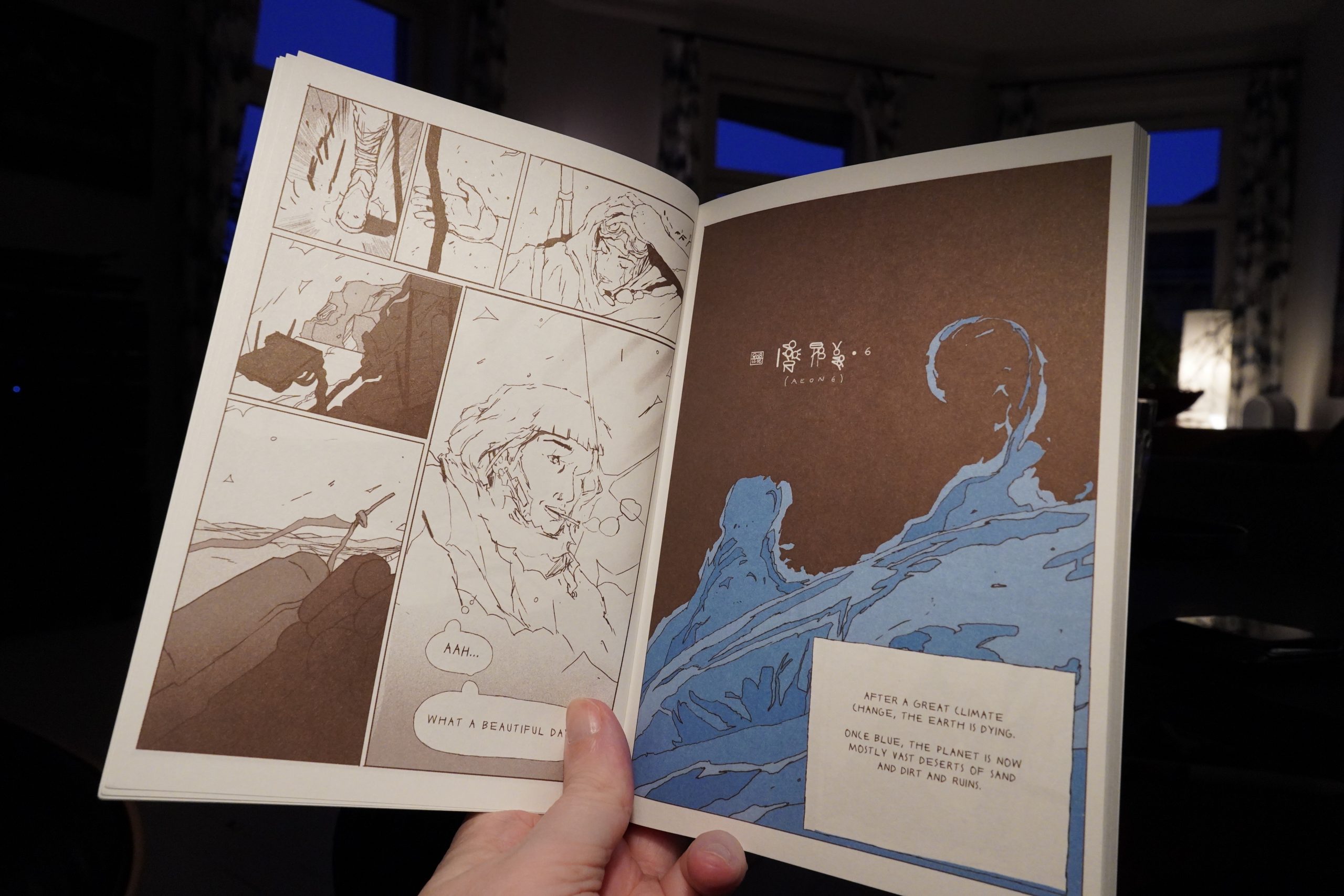

22:25: Aeon 6 by Jules Naleb (Peow)

This is kinda special… it’s full of action, but kinda gentle at the same time?

I like it a lot.

OK, I’m fading, but perhaps one more comic book?

| Lush: Chorus (1): Gala |  |

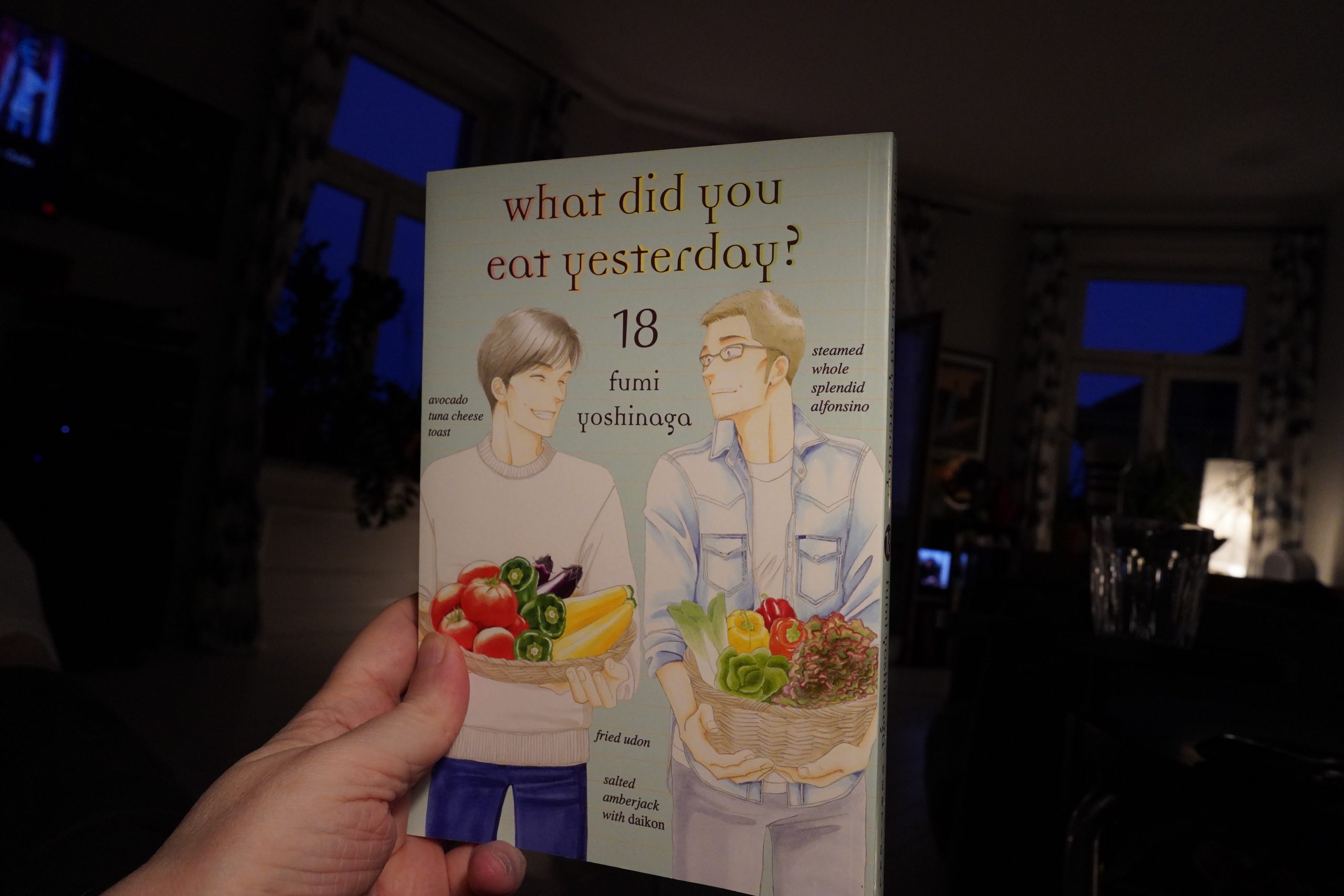

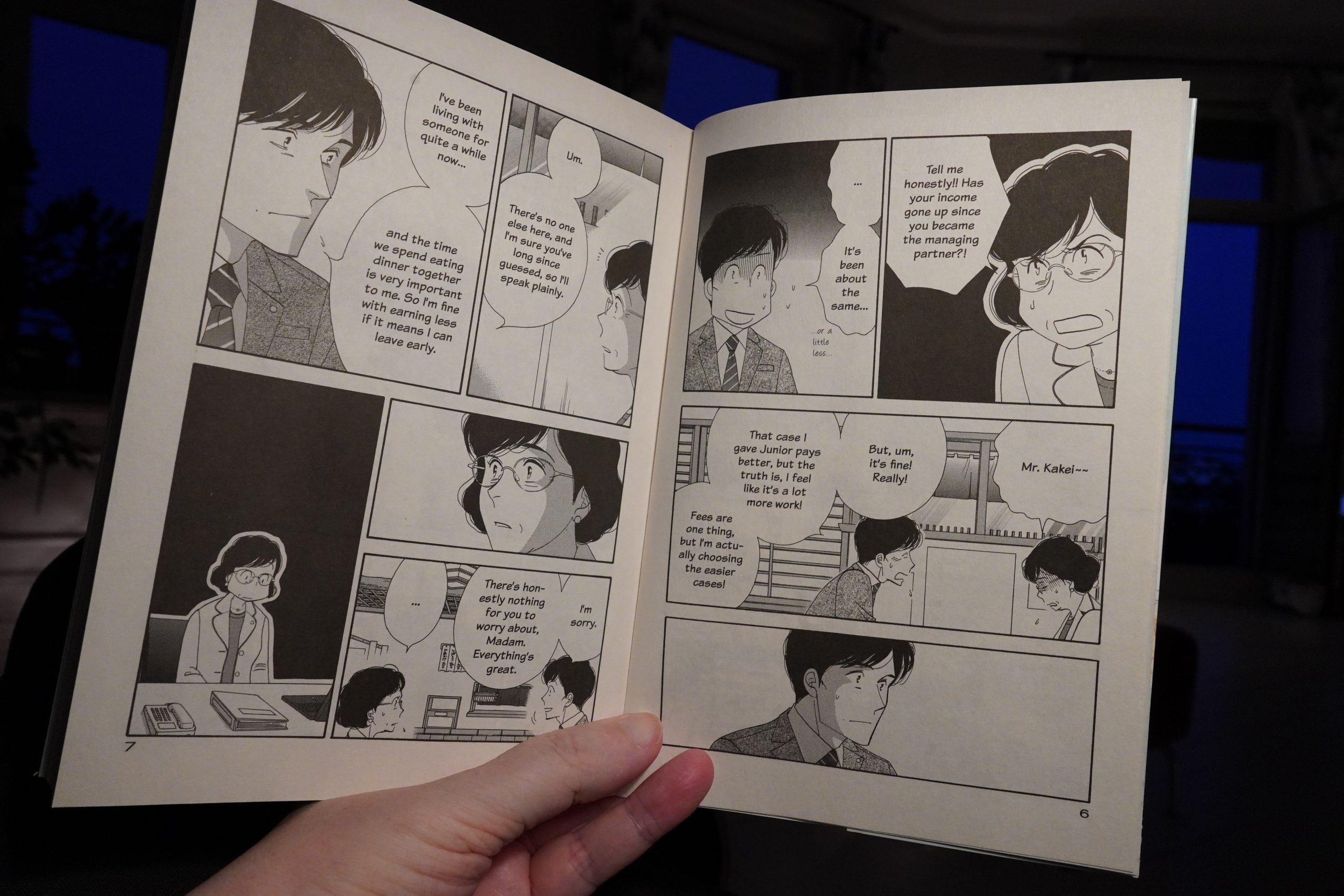

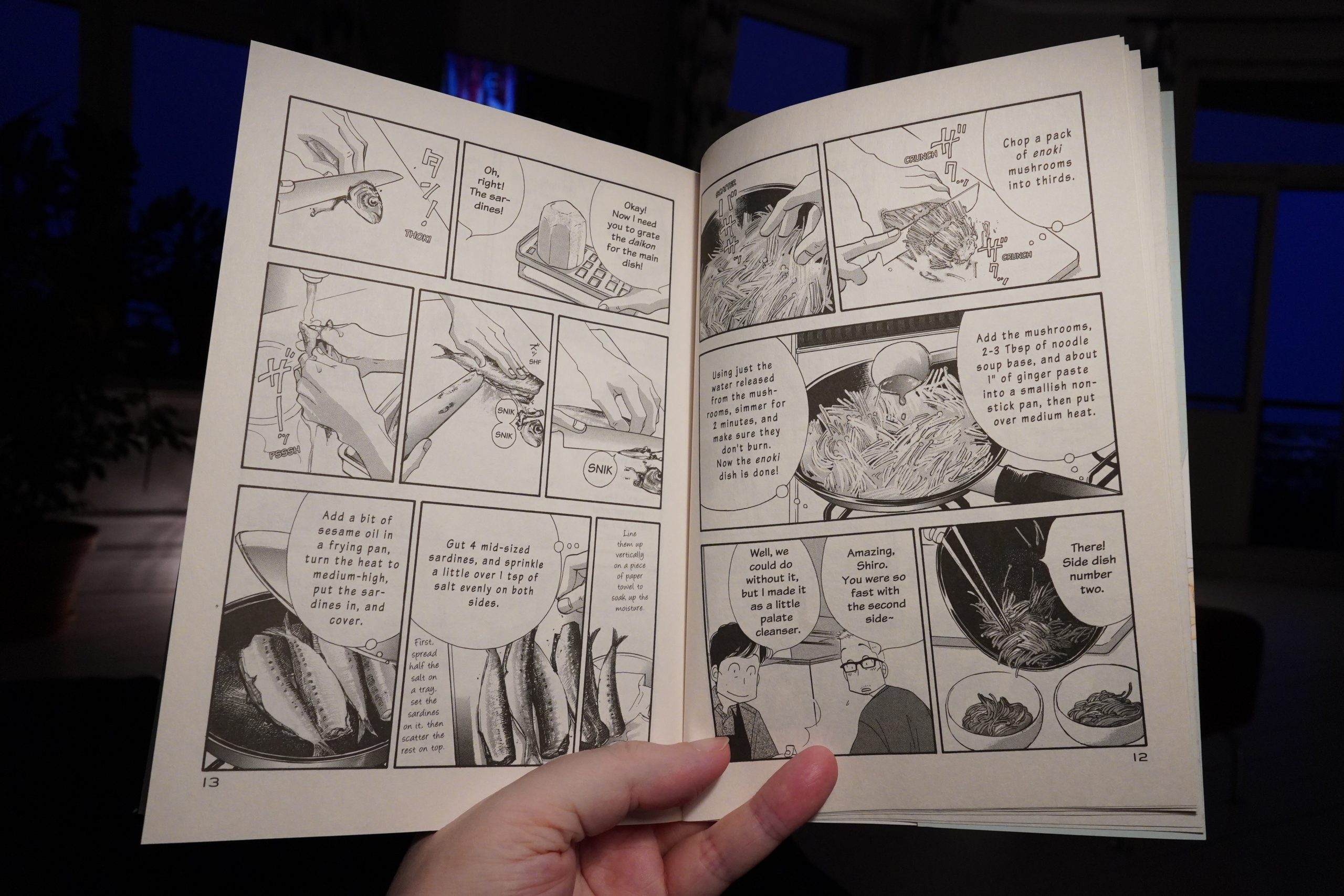

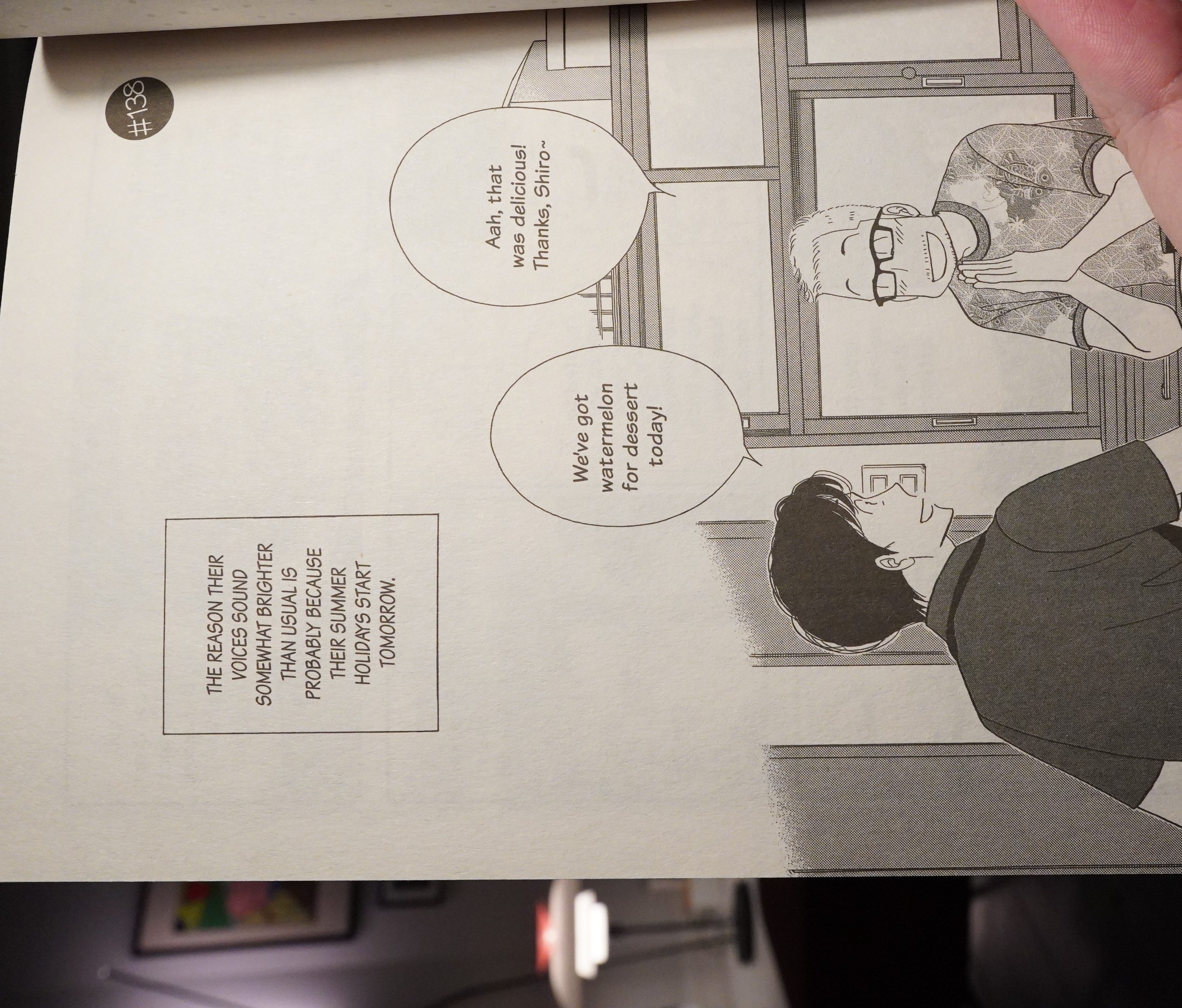

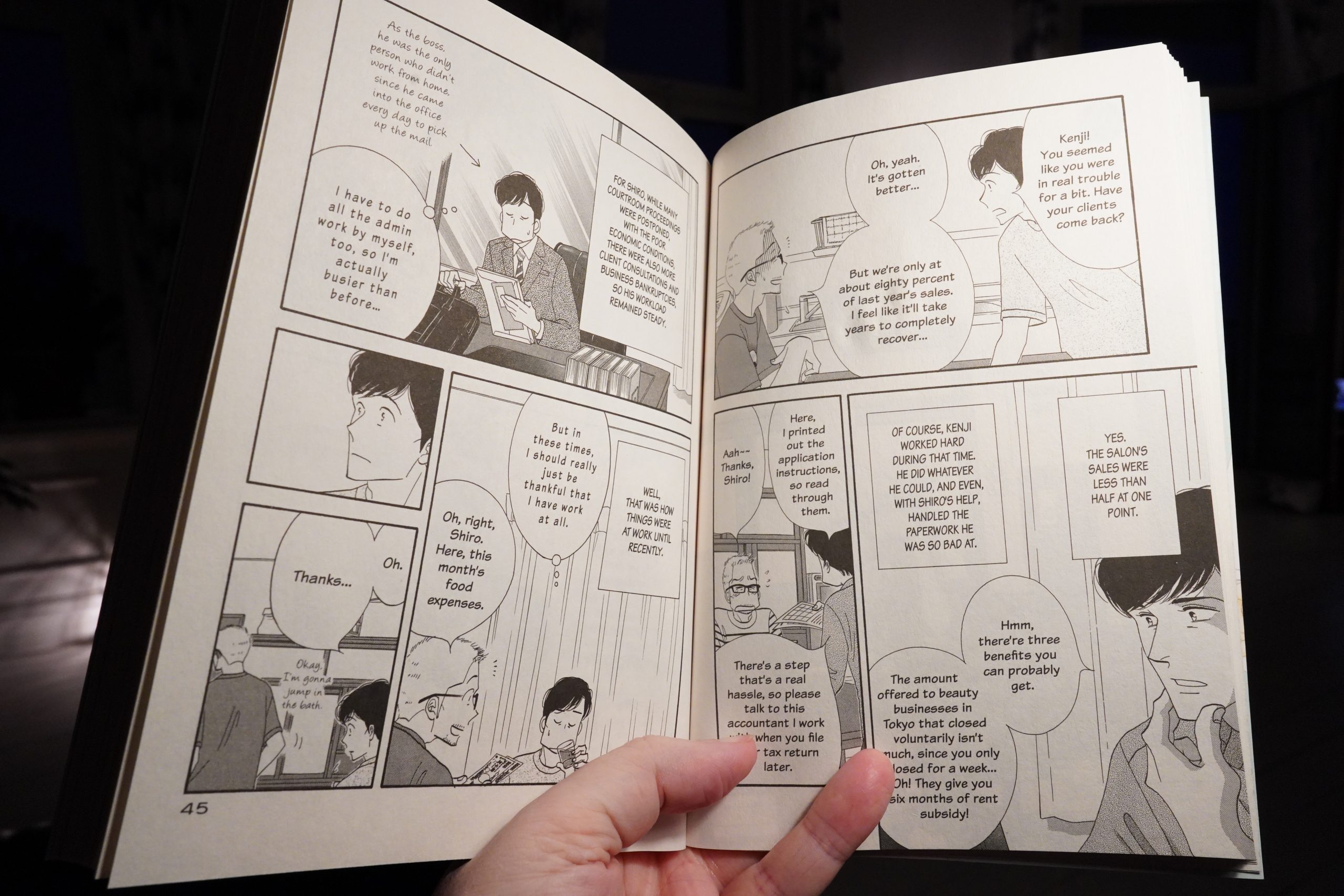

22:34: What Did You Eat Yesterday? 18 by Fumi Yoshinaga (Vertical)

It’s not all cooking — there’s a veeeery slowly developing soap opera plot.

But it’s mainly cooking.

Oh! Didn’t I buy some watermelon today?

I did!

Huh. I’ve been used to this being such a timeless series — difficult to place time-wise, but here it’s quite topical. So I guess this must have been drawn in early-to-mid 2020, after the Covid restrictions set in.

It’s delightful as always.

Oh, I should go to bed, but I’m drunk on good comics, so one more? Something relaxing.

| Lush: Chorus (2): Spooky |  |

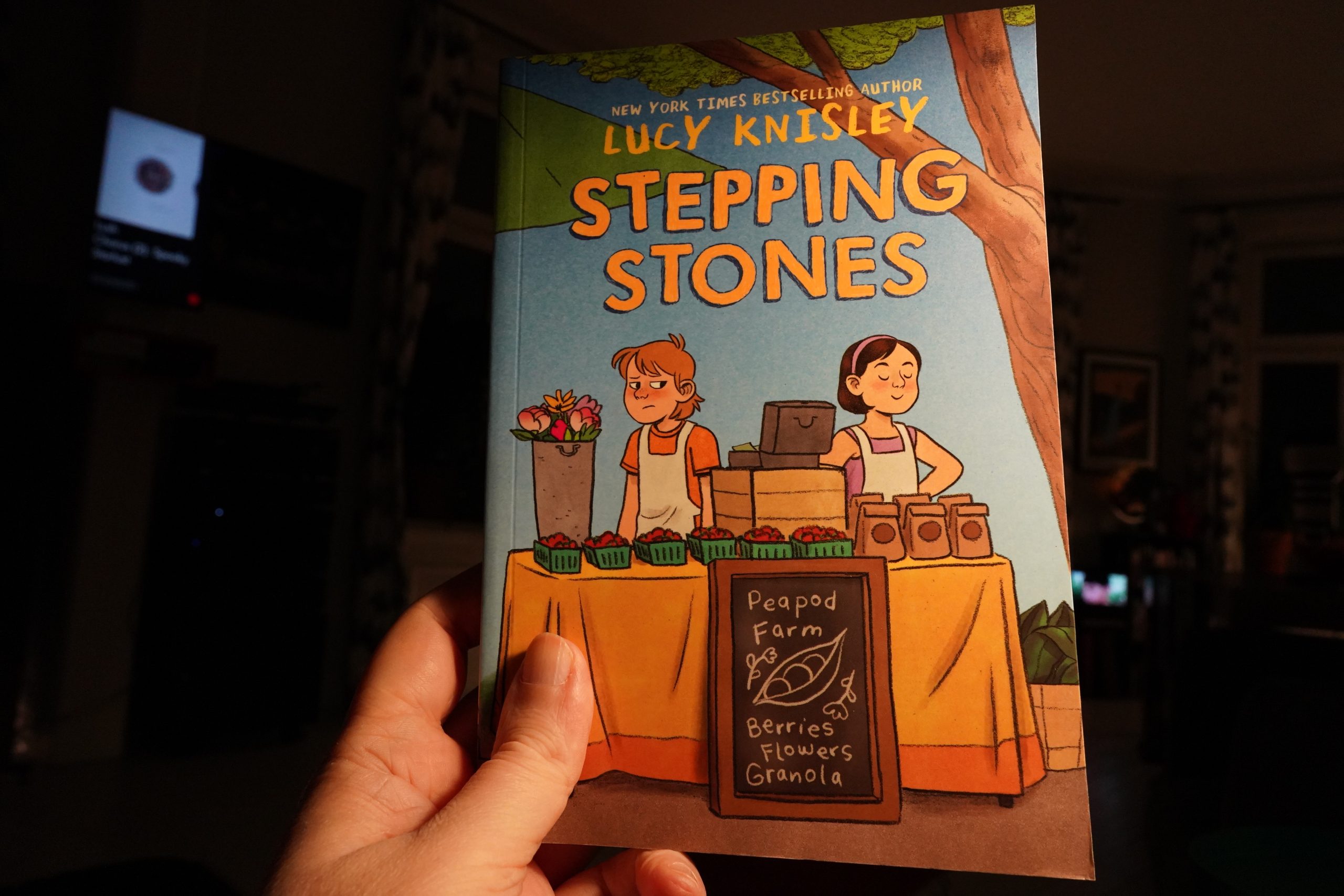

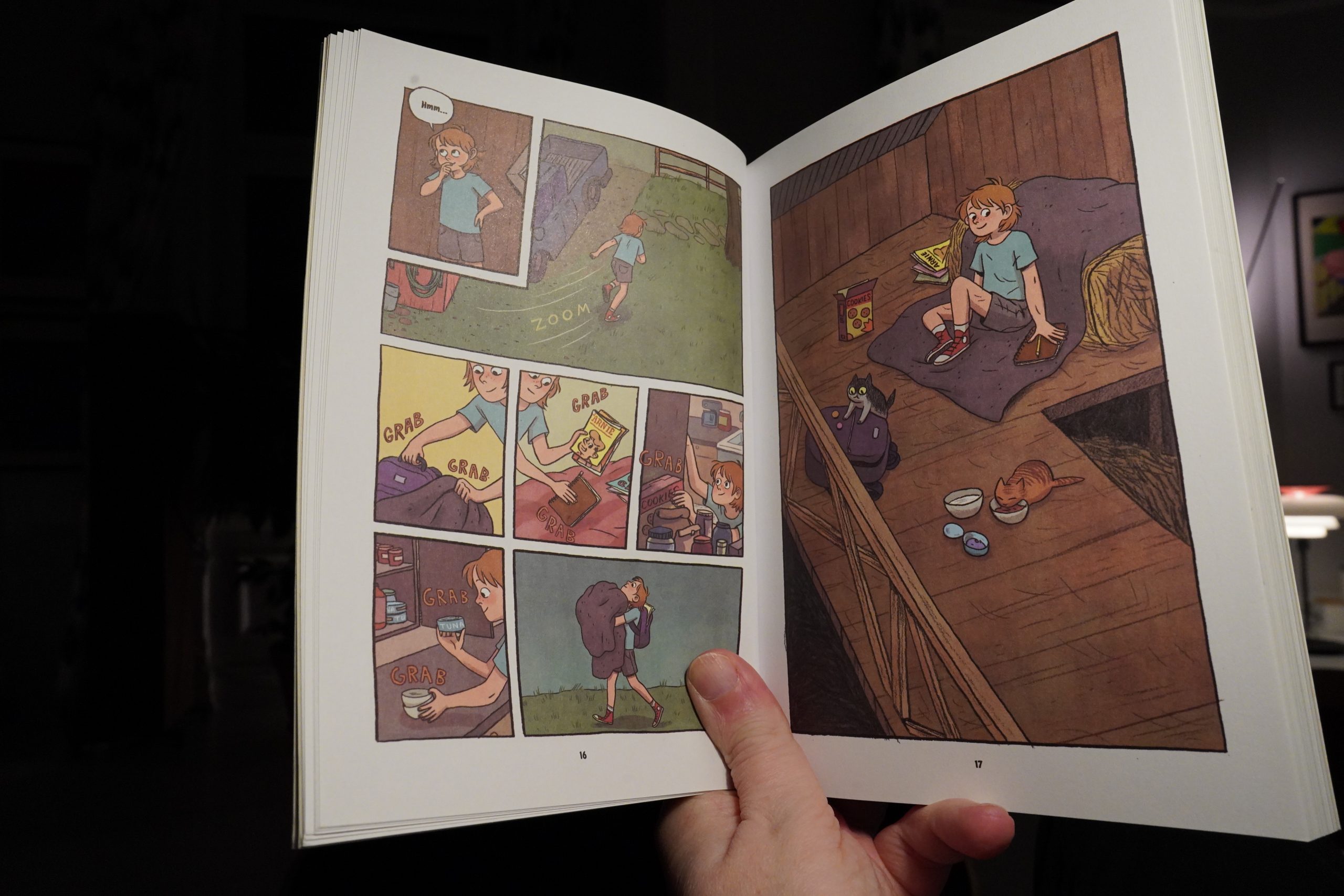

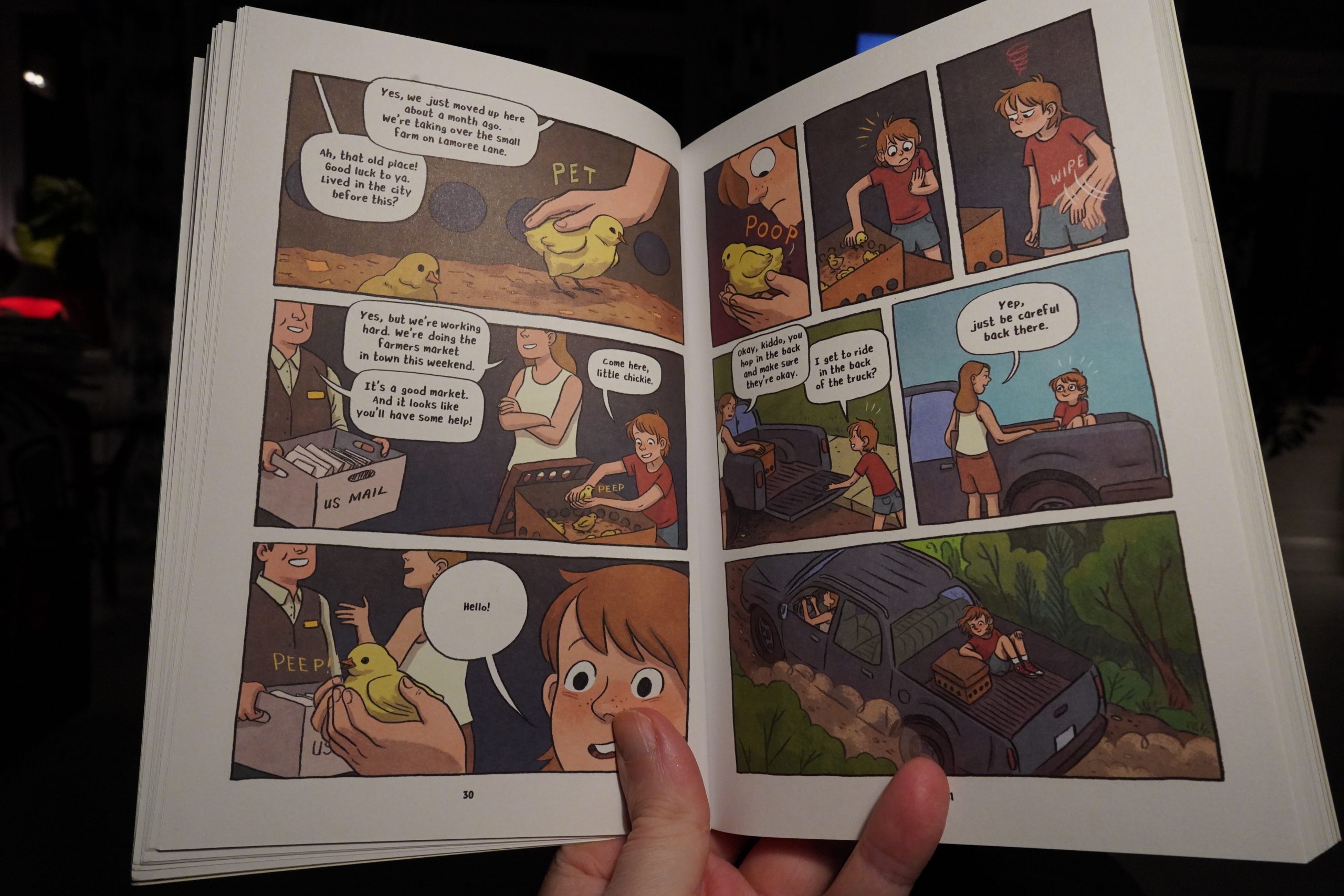

23:40: Stepping Stones by Lucy Knisley (RH Graphic)

This is really sweet.

It’s got some drama, but it’s not super-dramatic drama — and it’s gently didactic, while also being amusing throughout. It’s the kind of book you smile the entire time you read it?

Err… one more?

| Lush: Chorus (3): Split |  |

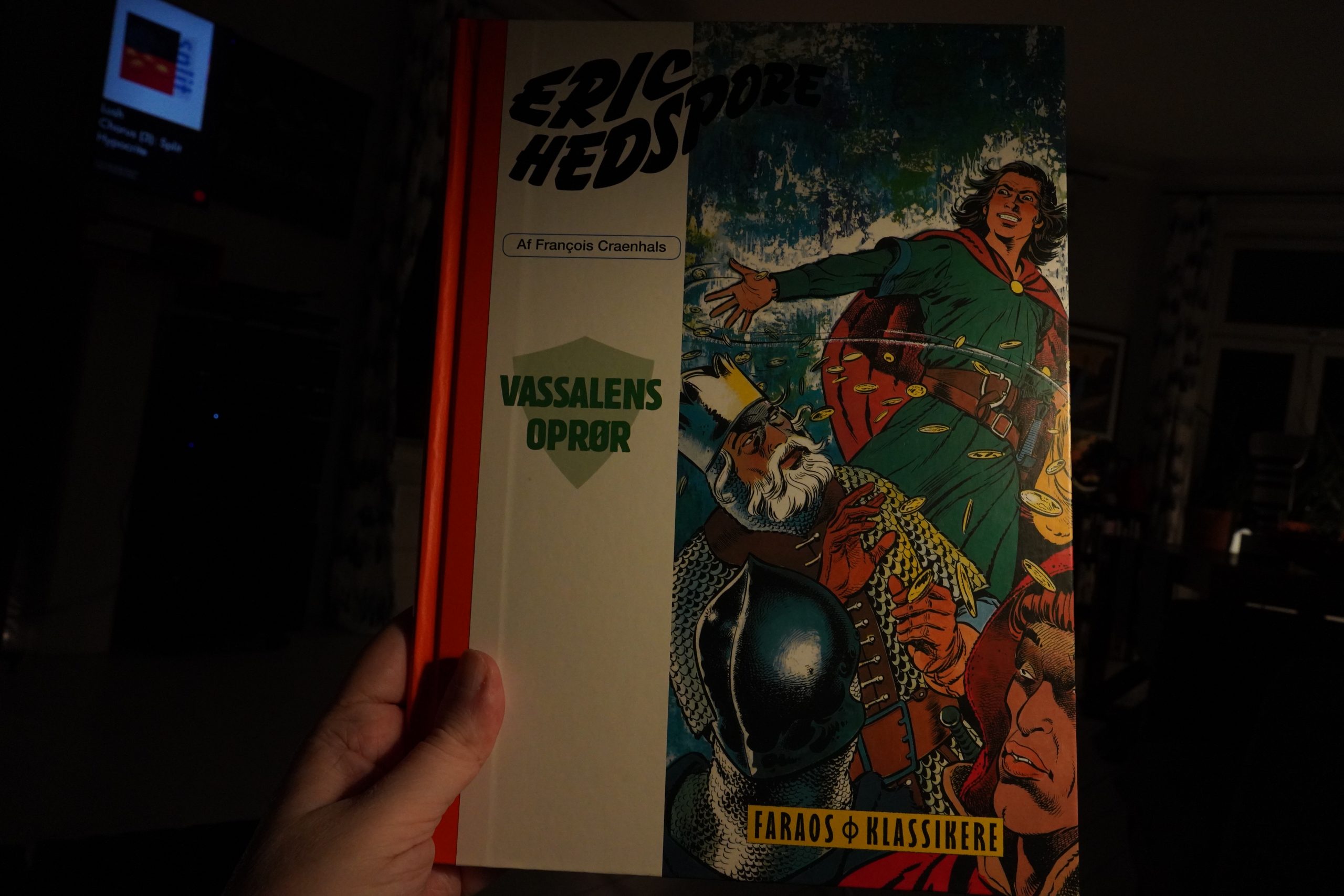

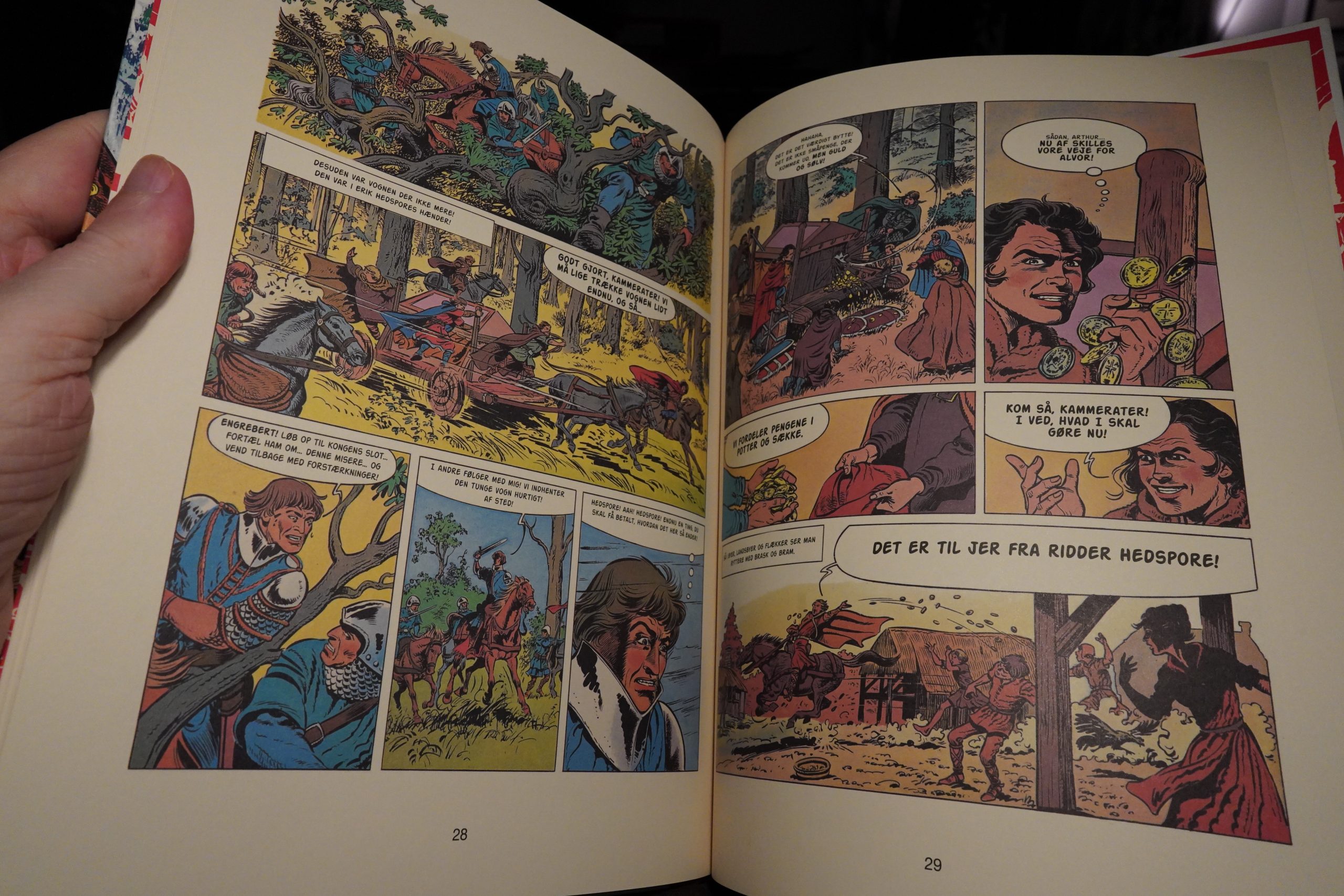

00:12: Chevalier Ardent 11: Le révolte du vassal by François Craenhals (Faraos Cigarer)

There’s so many of these French series, and the Danes are publishing stuff I’ve never heard of before. This apparently ran regularly from 1970 to the mid-80s and then petered out slowly. The Danes are selling this as a “classic”, but…

Well, let’s see? Perhaps it’s awesome.

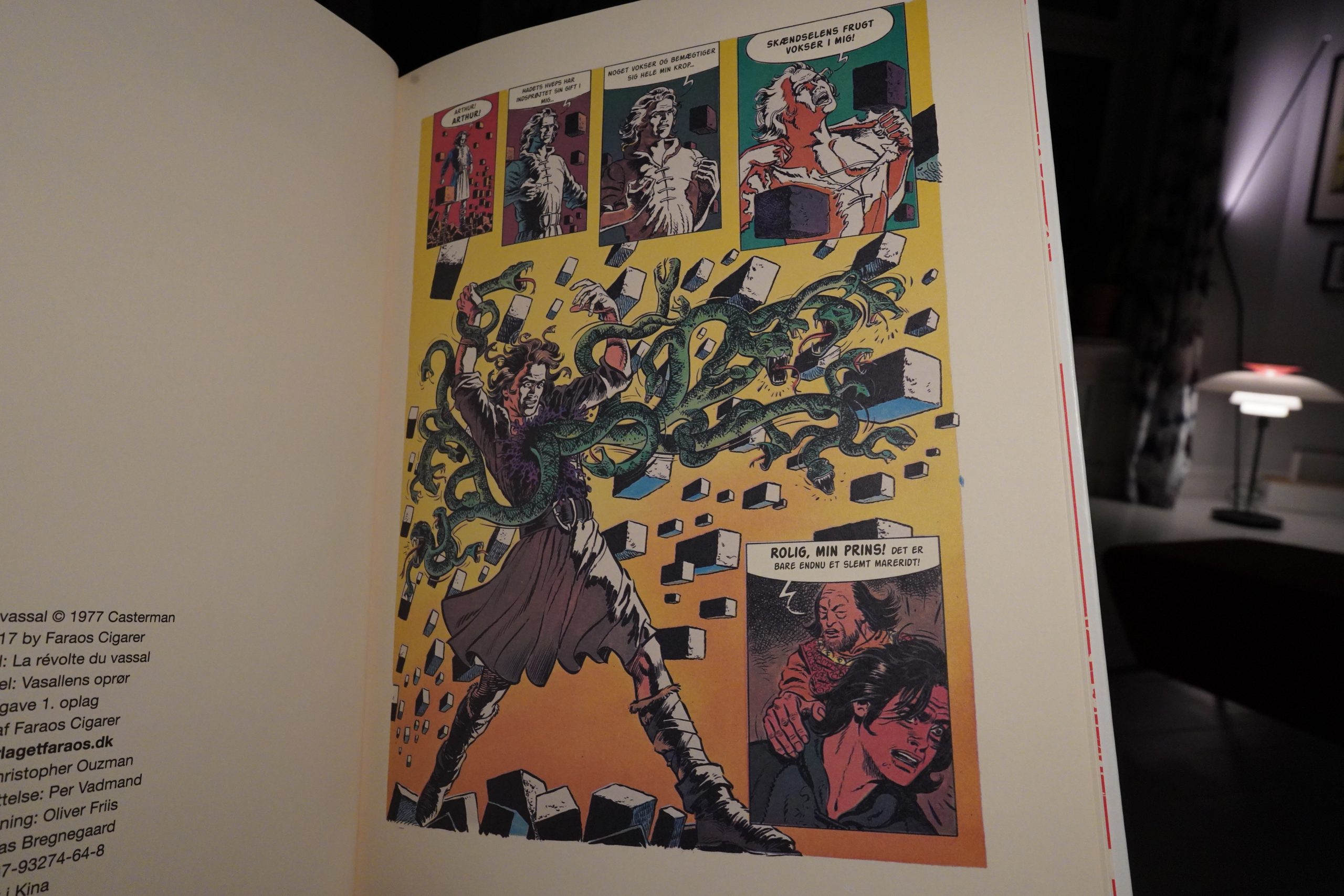

Well, this starts off in a very 70s cosmic way…

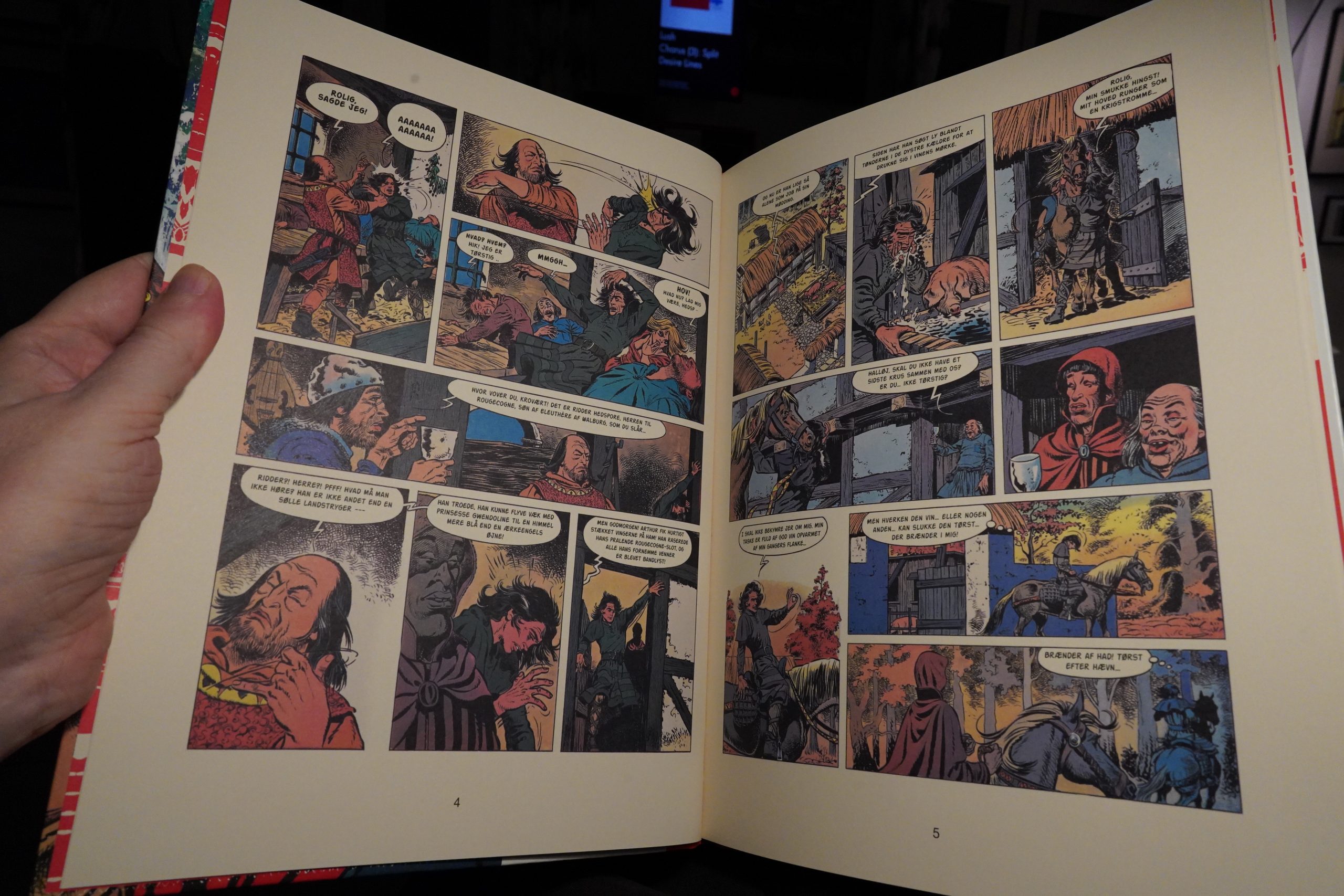

… but it turns out that is was just a dream. I like the way that nothing’s explained — not even whether the protagonist is a villain or a hero.

Or just totally insane, because everything he does here seems pretty loopy, until we get the explanation halfway through. But I guess people that have read the preceding ten tomes know everything already, but still — pretty unusual for a French(ey) series to have albums that are so much part of a series.

It’s not that bad? I don’t think I’ll be reading the rest of the series (unless I stumble over the albums for sale, I guess), but it’s fine.

00:38: The End

OK, now I’m zonked for real.