Wut! Another day of reading comics just a couple of days after the last one? Indeed. And for music today: Kate Bush Only.

| Kate Bush: Remastered (1): The Kick Inside |  |

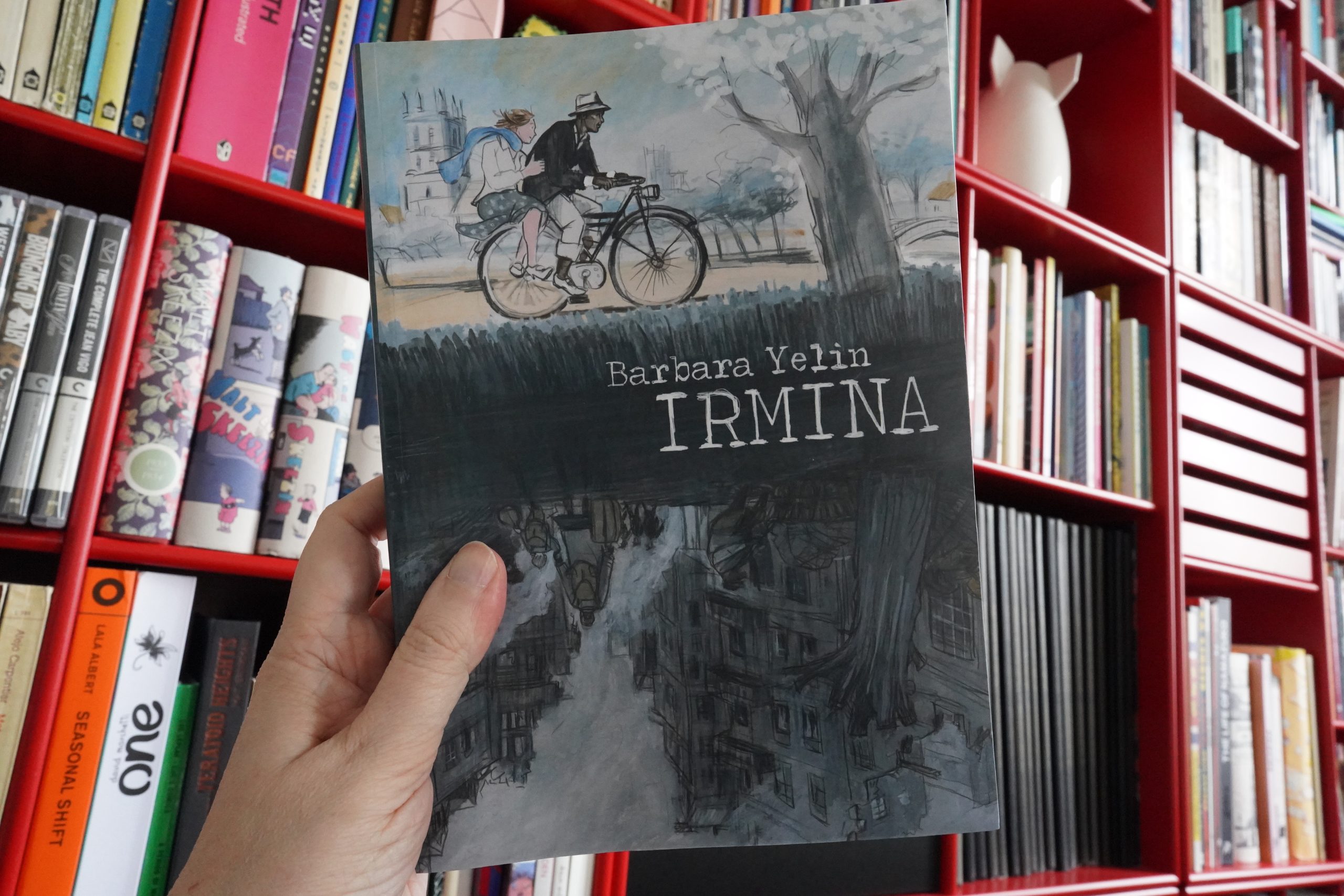

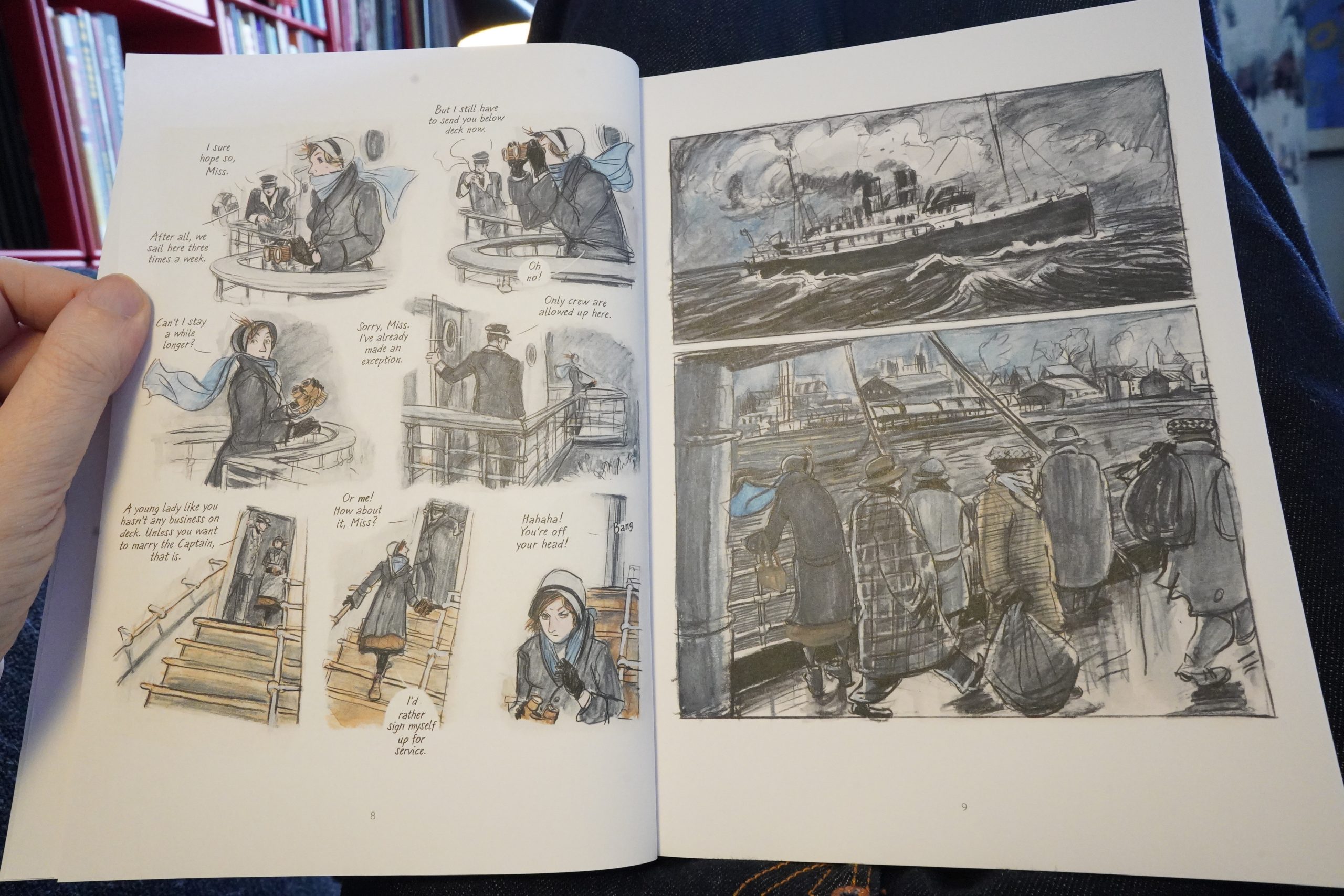

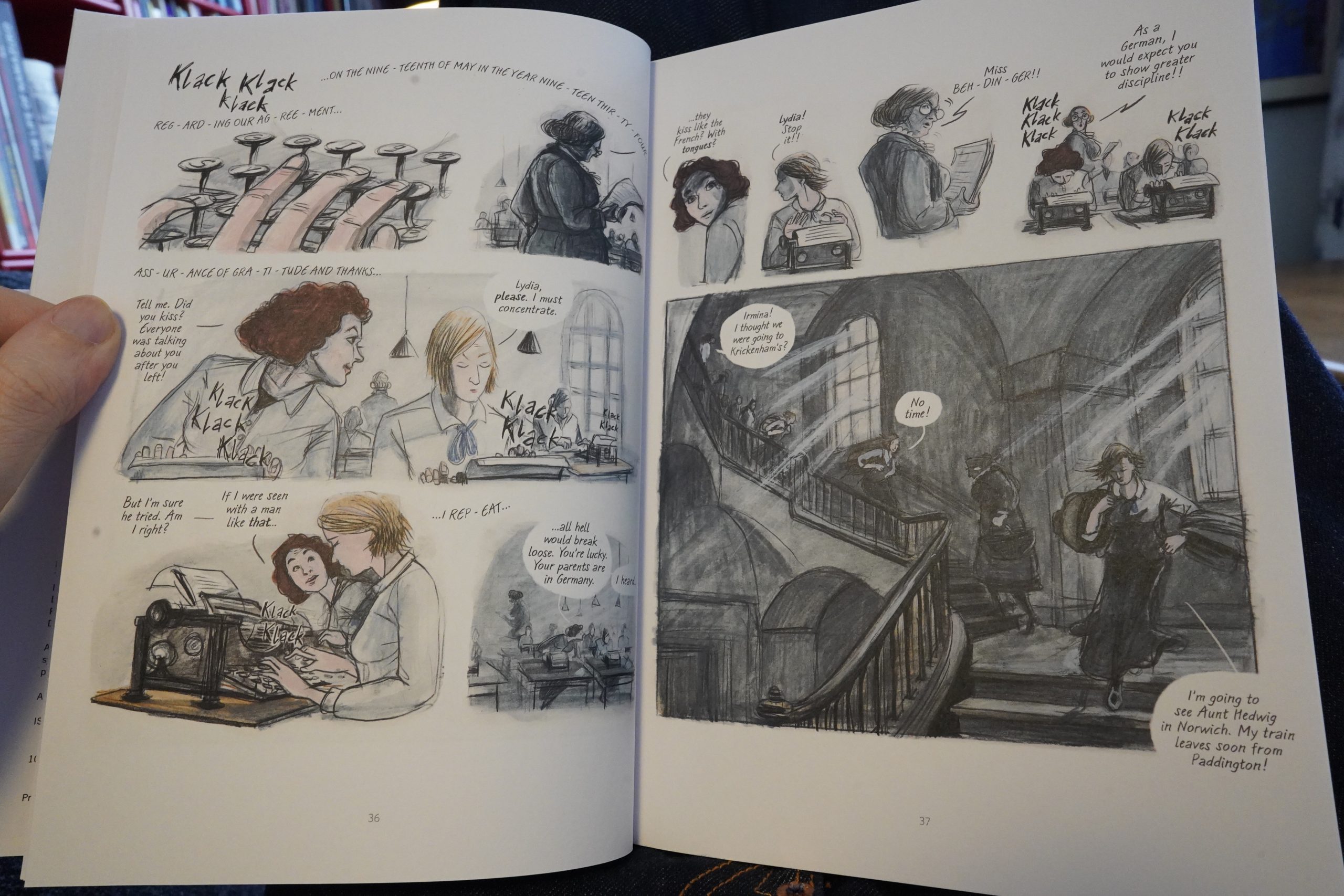

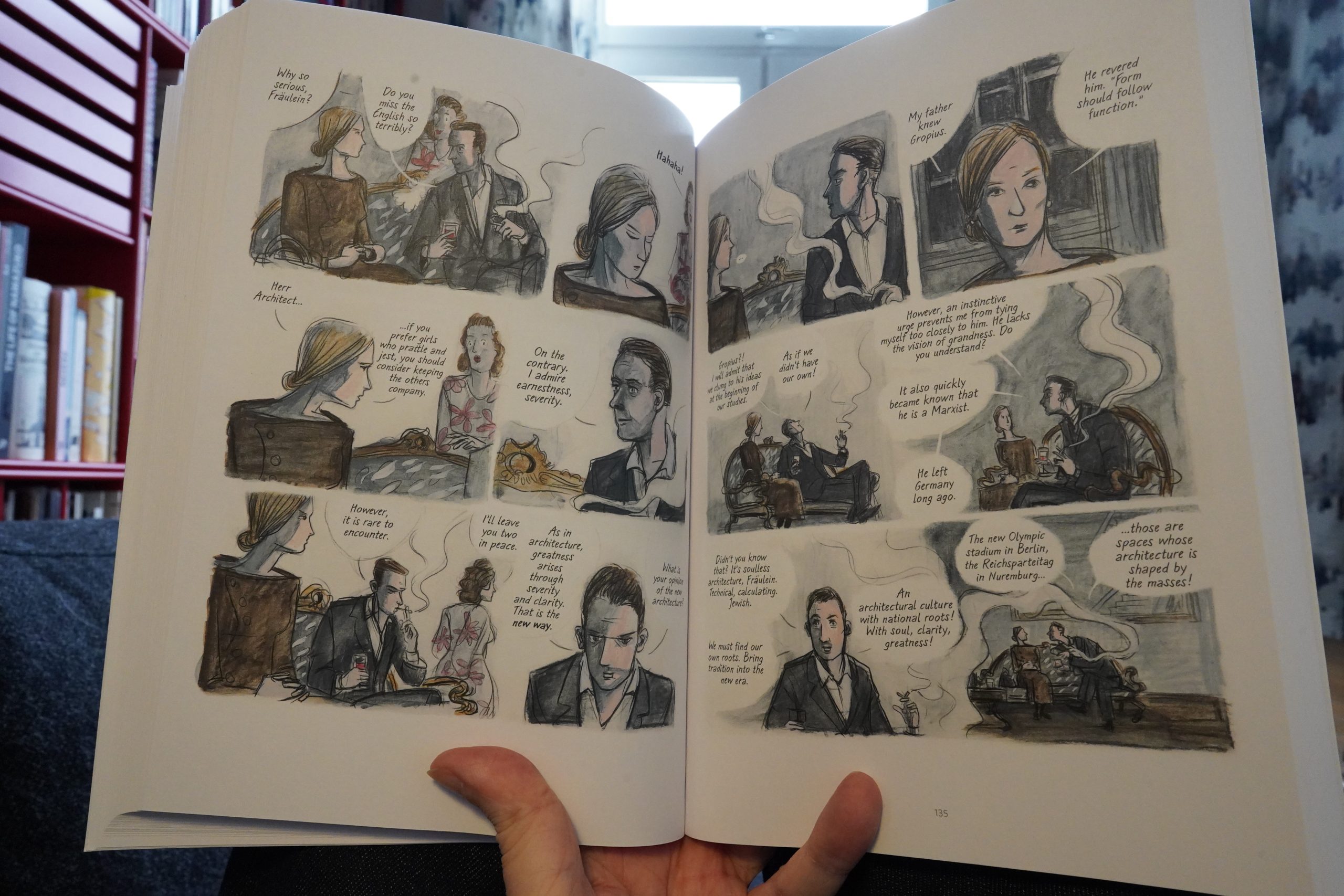

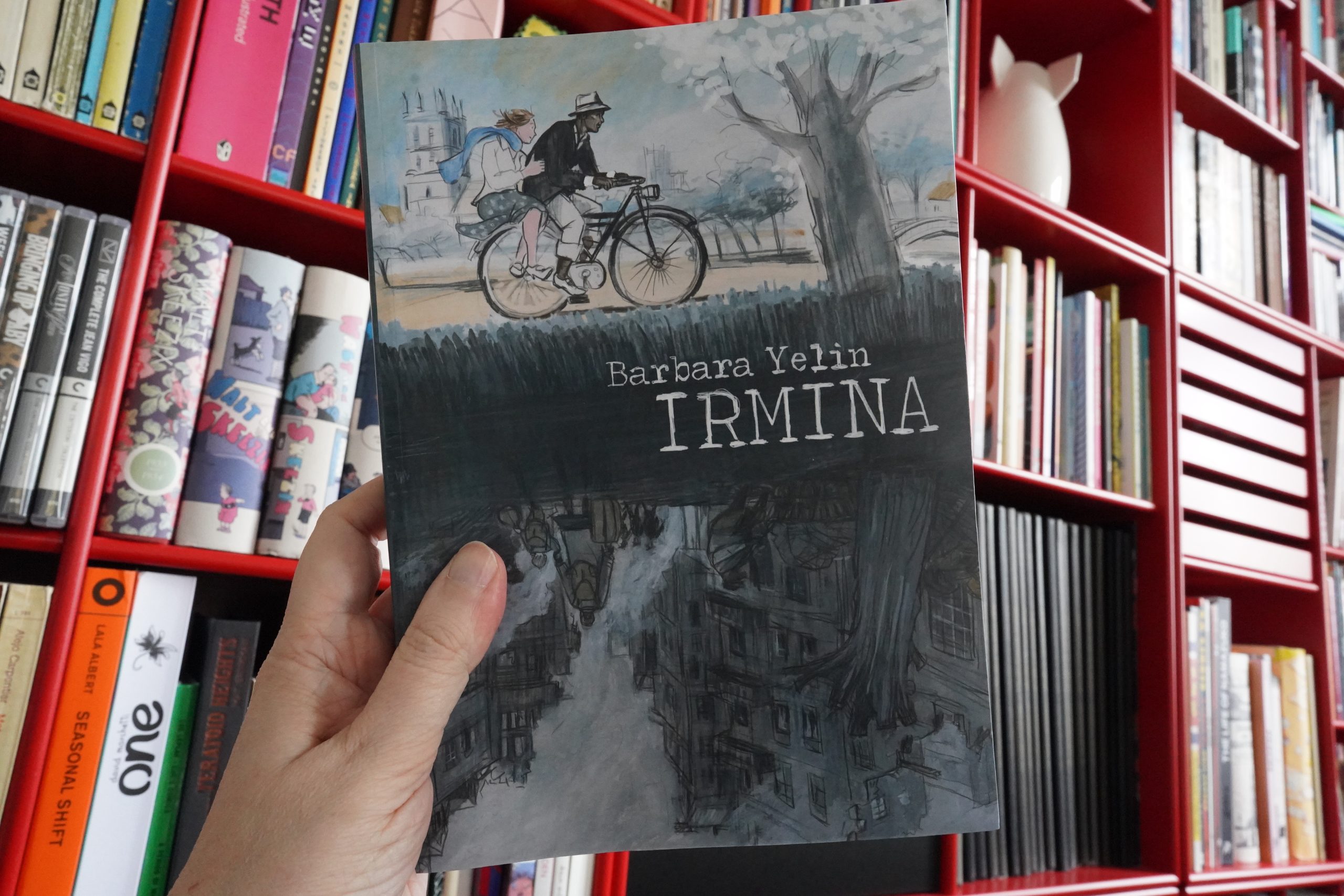

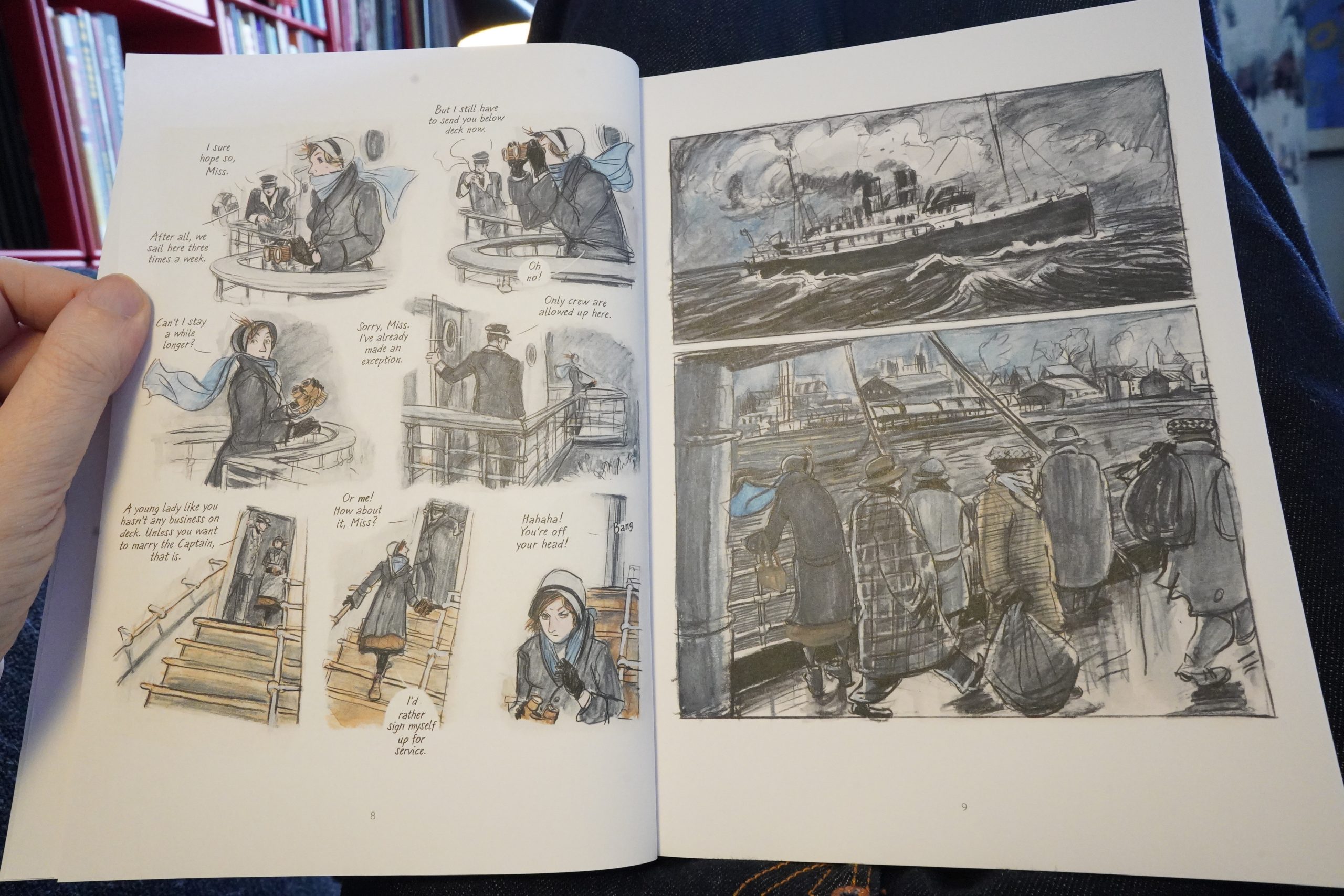

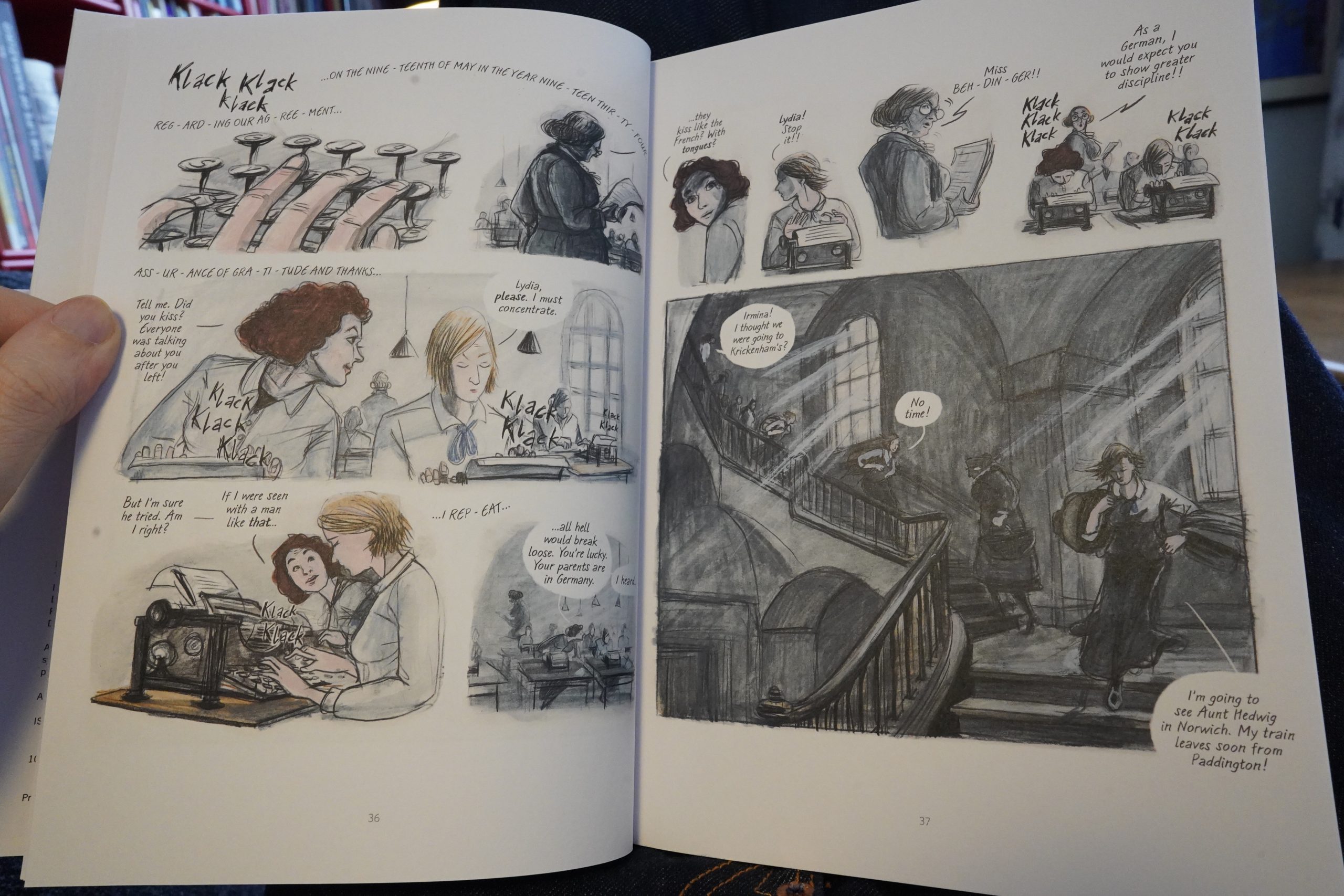

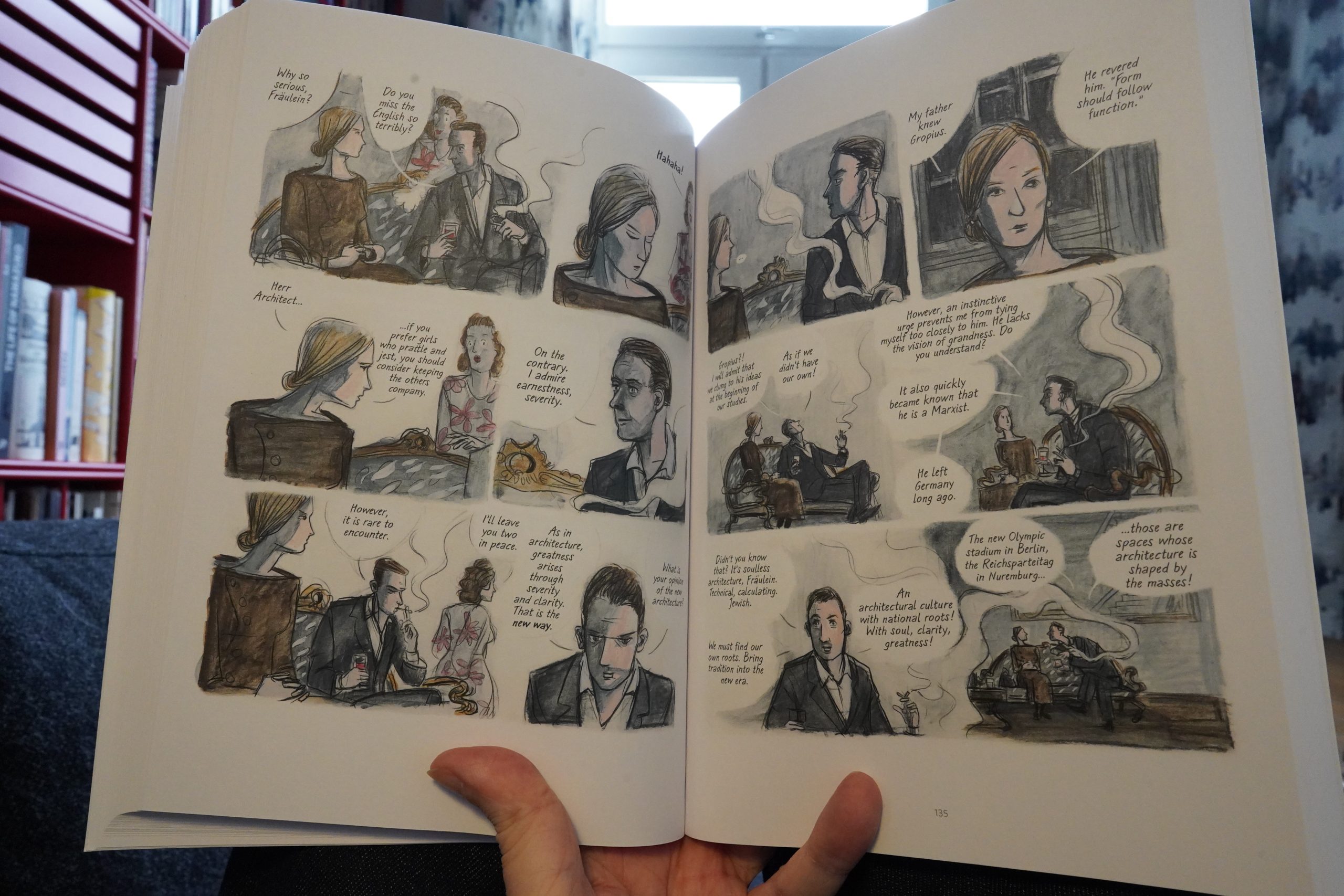

13:32: Irmina by Barbara Yelin (Selfmadehero)

The artwork here is nice, and the storytelling has a good flow.

But god, this is tedious. It’s about the author’s grandmother, and it’s just unbelievably humourless. Just about everybody she meets is an asshole, and she’s not that much better herself (as she’s portrayed here).

| Kate Bush: Remastered (2): Lionheart |  |

And it gets even more boring when we return to the Germany.

If I had to sum up the plot of this book it would be “my grandfather was in the SS, and my grandmother didn’t really suffer a lot during the war, but here’s a whole book about how sad she was because of reasons”. It’s borderline offensive — a “well, OK, my grandmother was a Nazi, but look — it could have happened to anybody!” narrative. But just incredibly boring, with plodding, unconvincing dialogue, characters with little character and a frankly unbelievable storyline. (It claims that it’s based on a true story, but has anybody checked?)

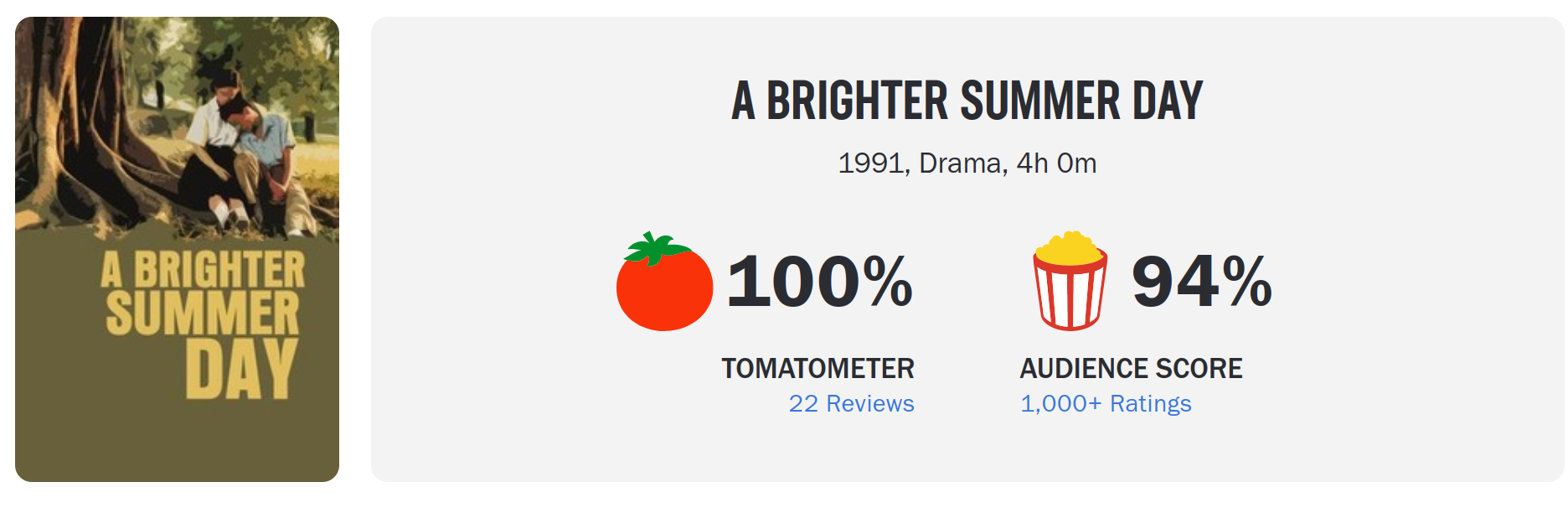

I googled a bit to see what the reception was, and it looks like all the

reviews are rapturous:

Anyone who takes the comic medium seriously should read Irmina as soon as they possibly can. Much like Art Spiegelman’s Maus, I can see it becoming a classic that fans of the form and scholars alike will return to time and again.

It won’t.

| Kate Bush: Remastered (3): Never For Ever |  |

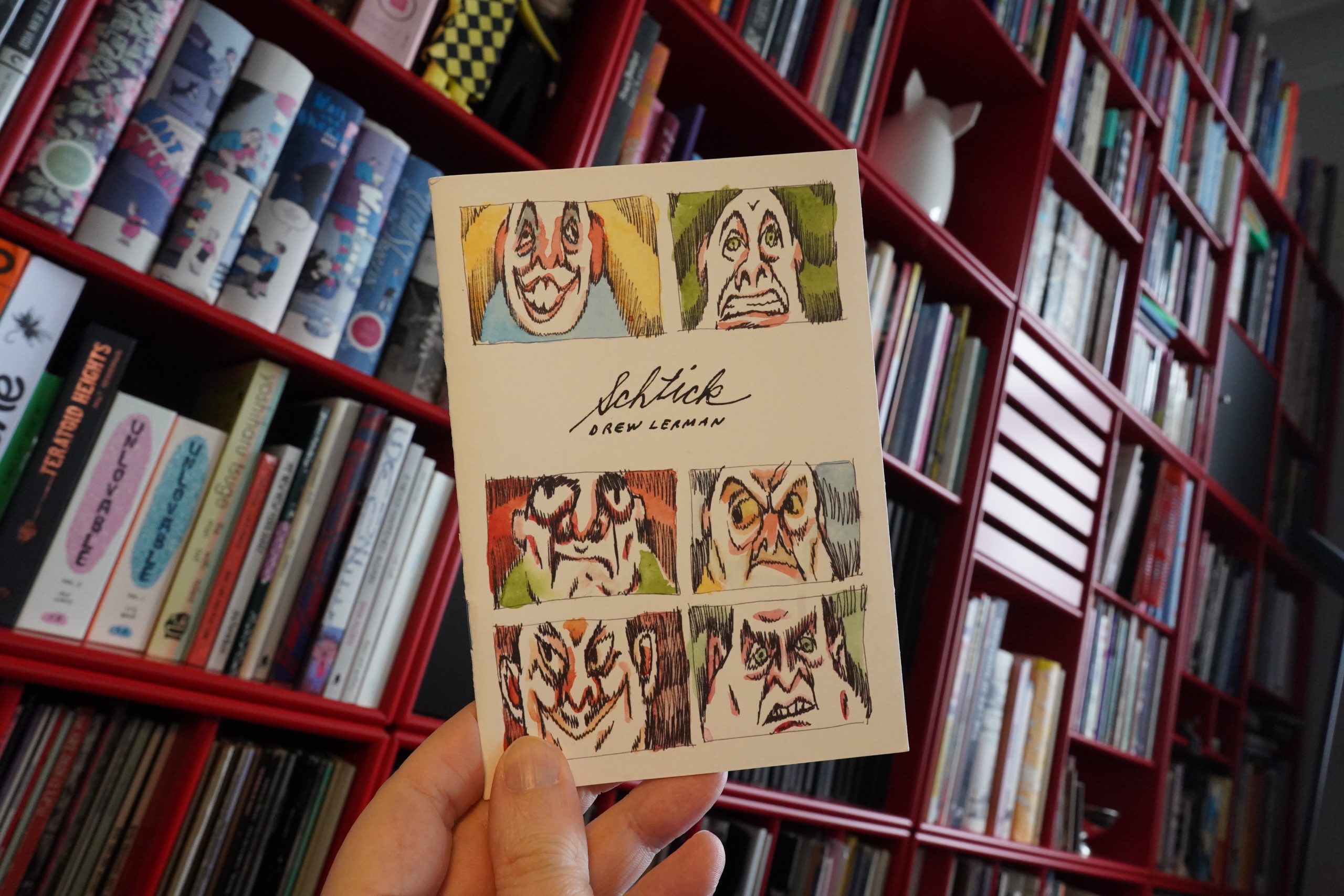

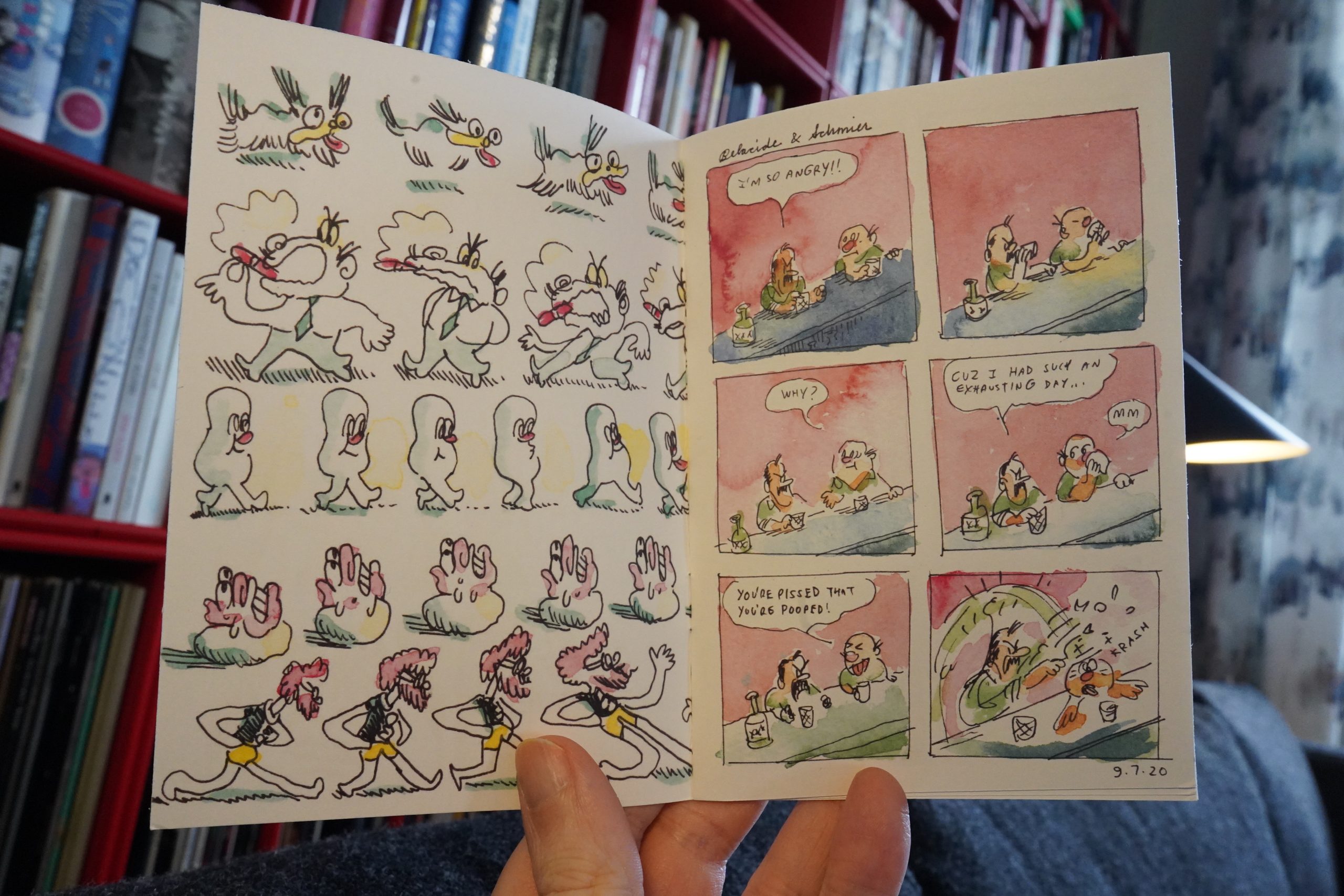

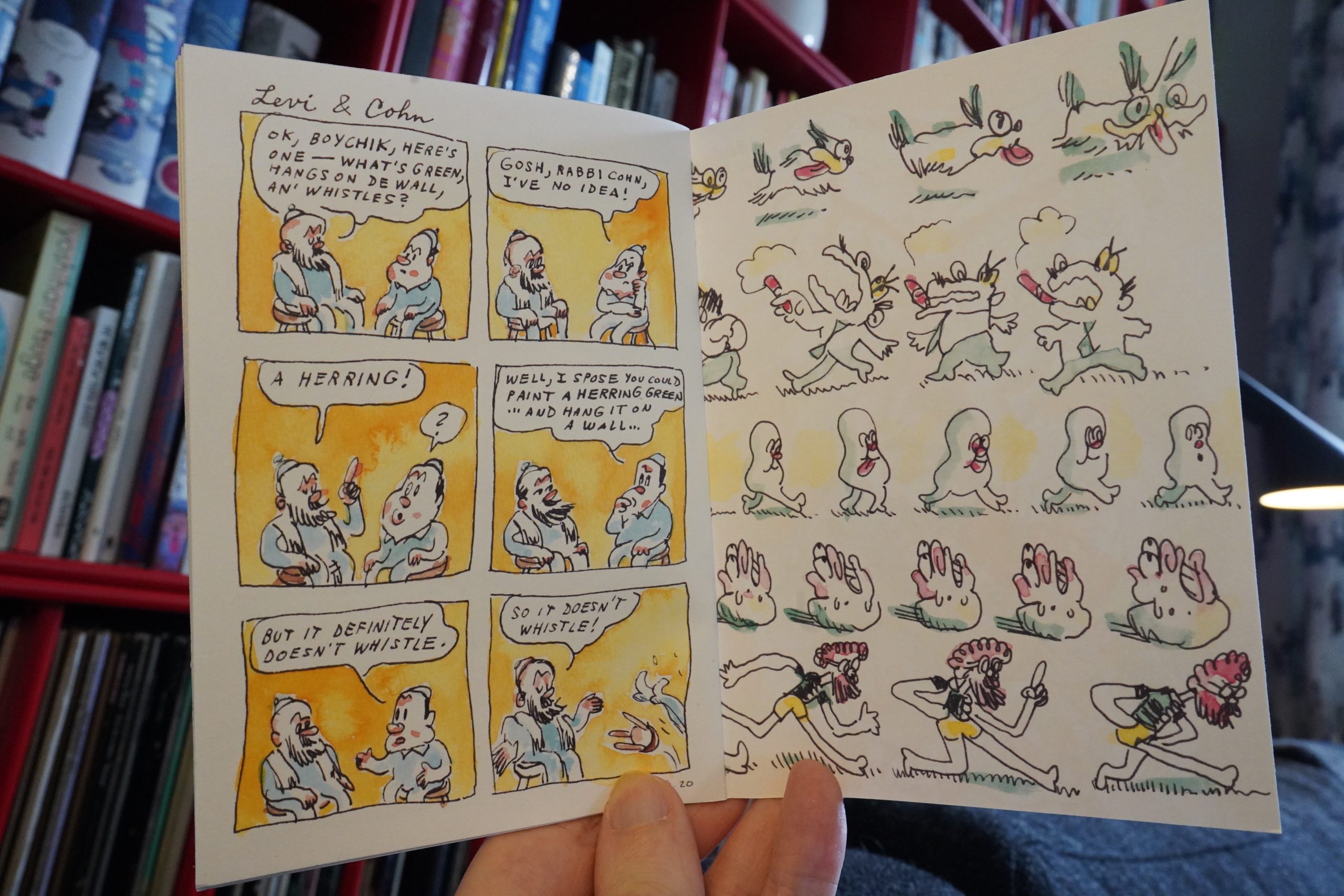

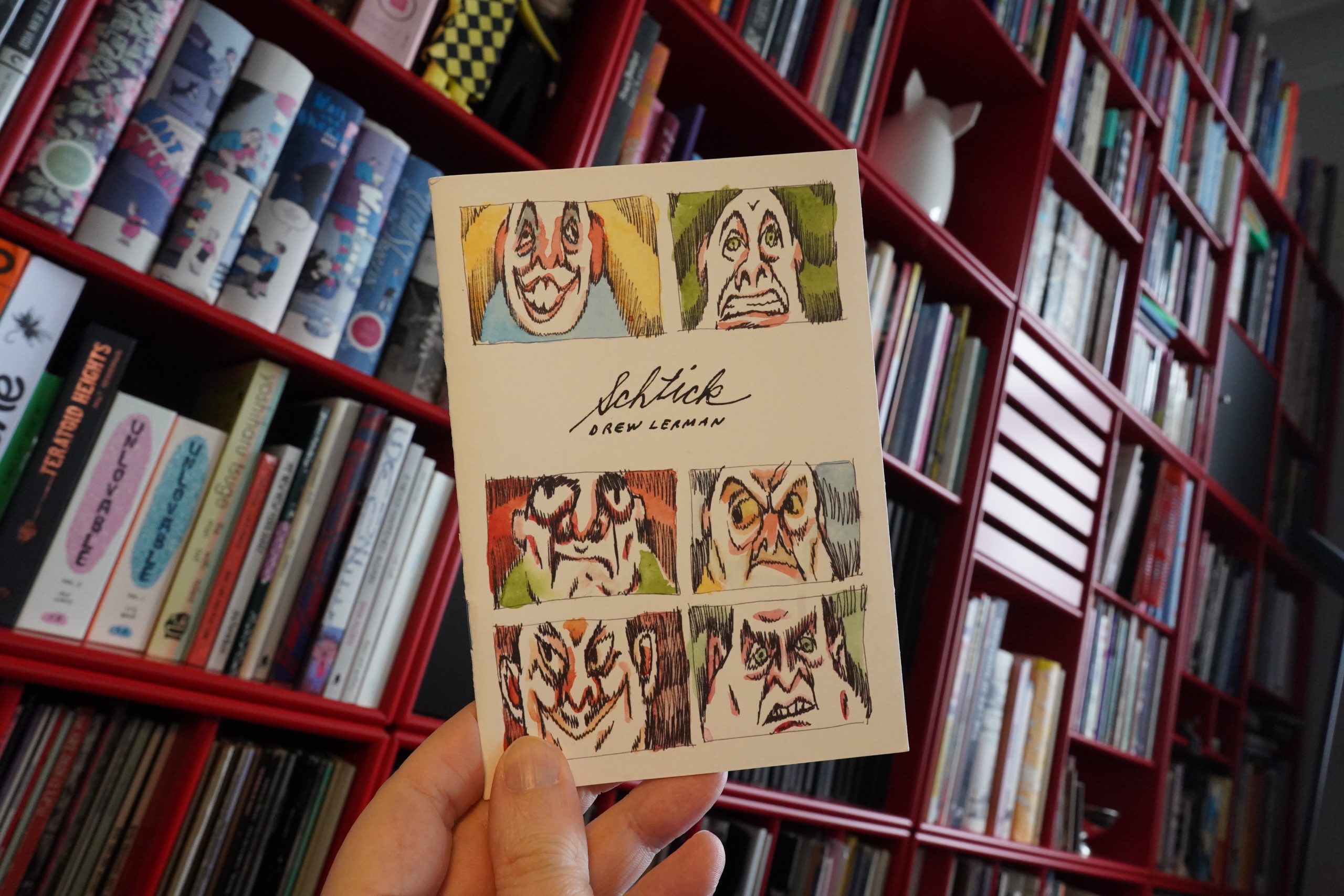

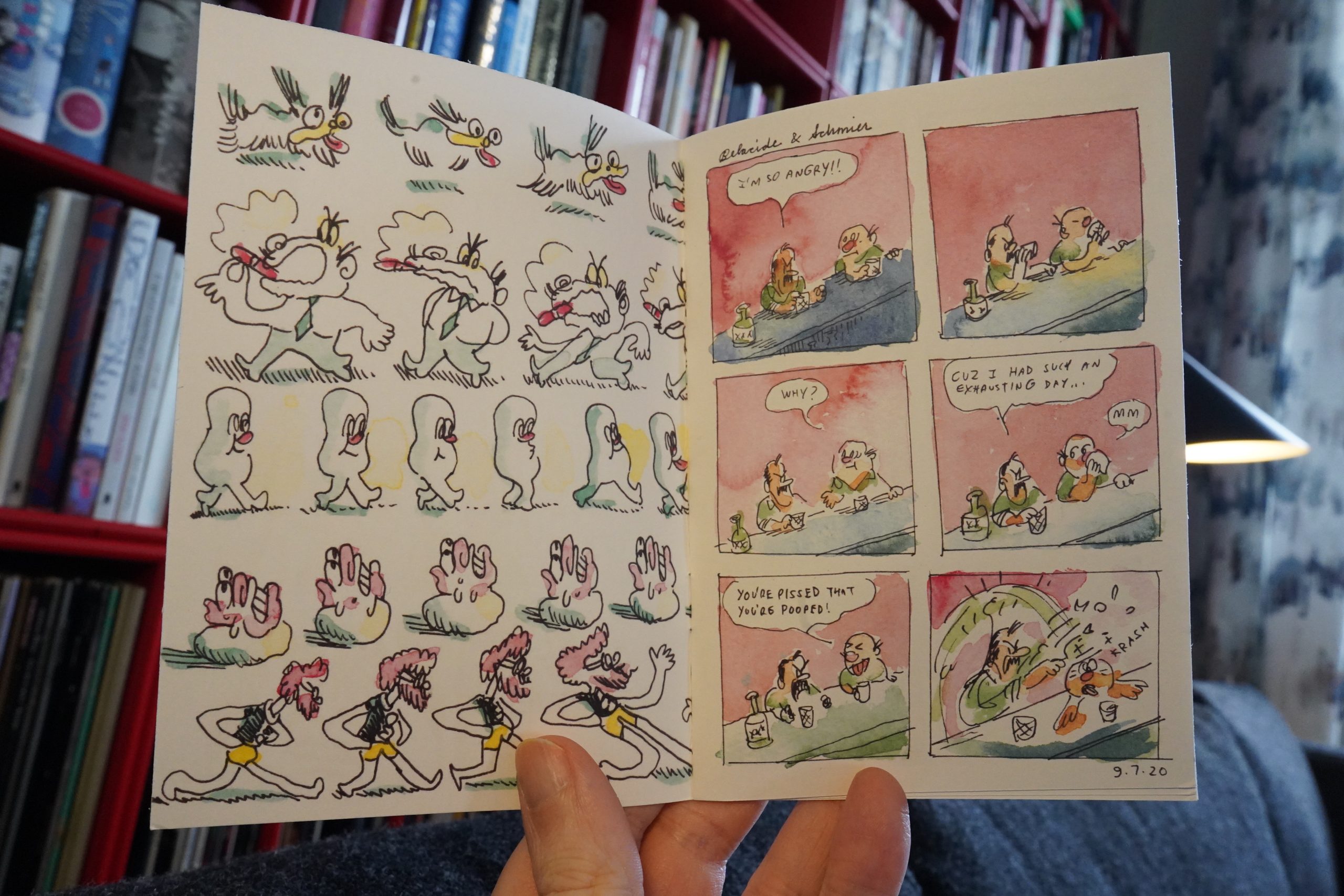

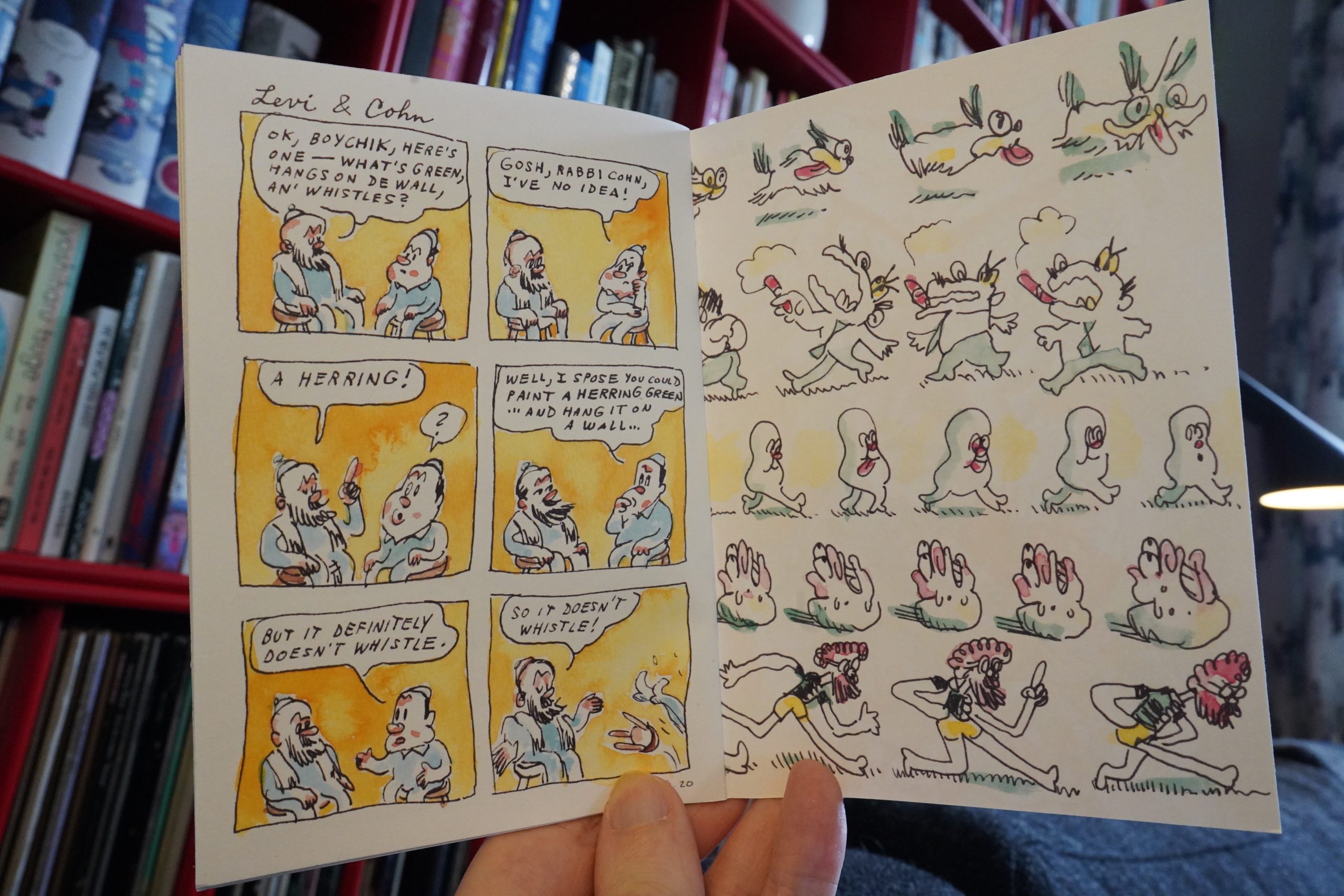

14:57: Schtick by Drew Lerman

Love the cartooning here.

And I laughed out loud a couple times. Class mini.

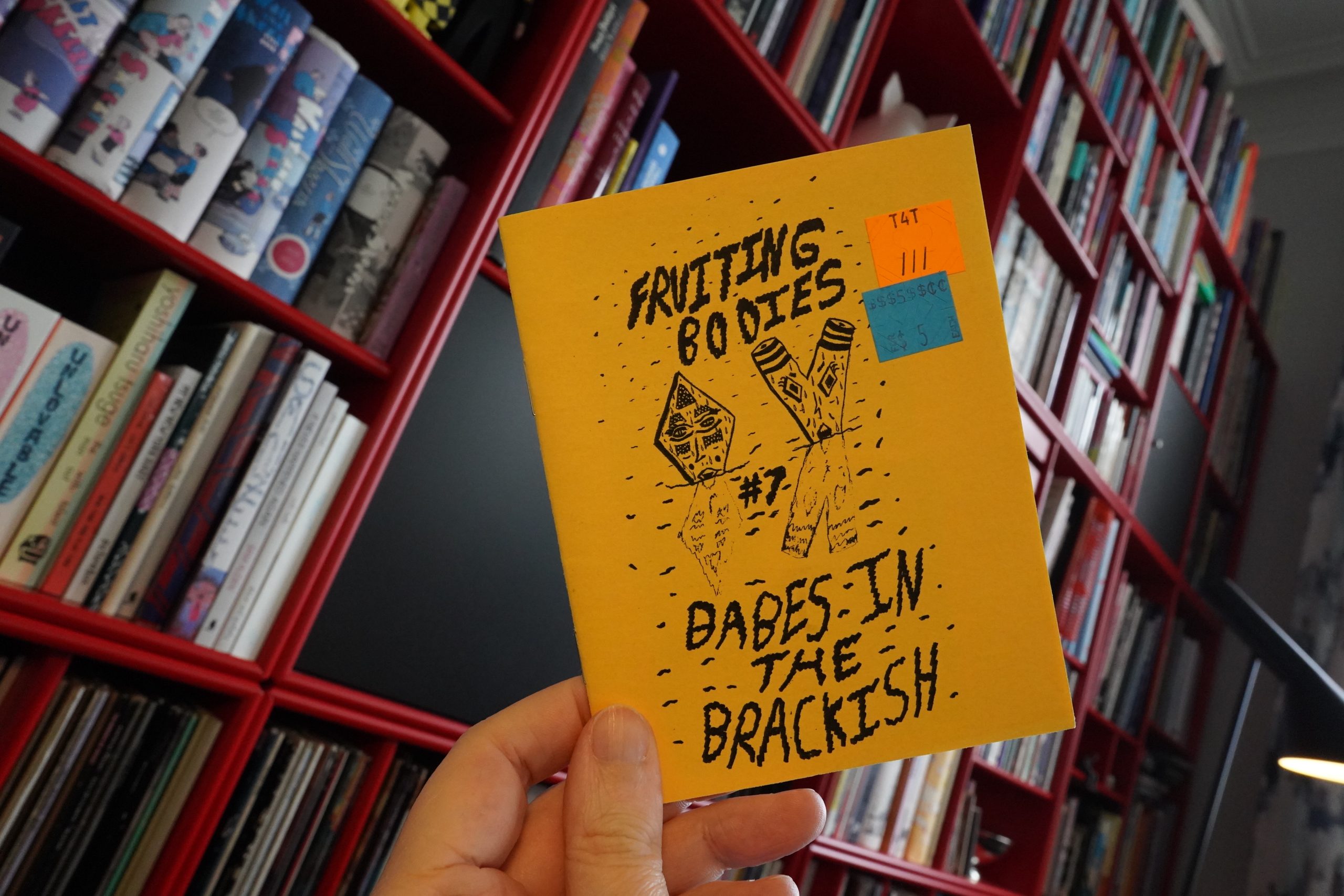

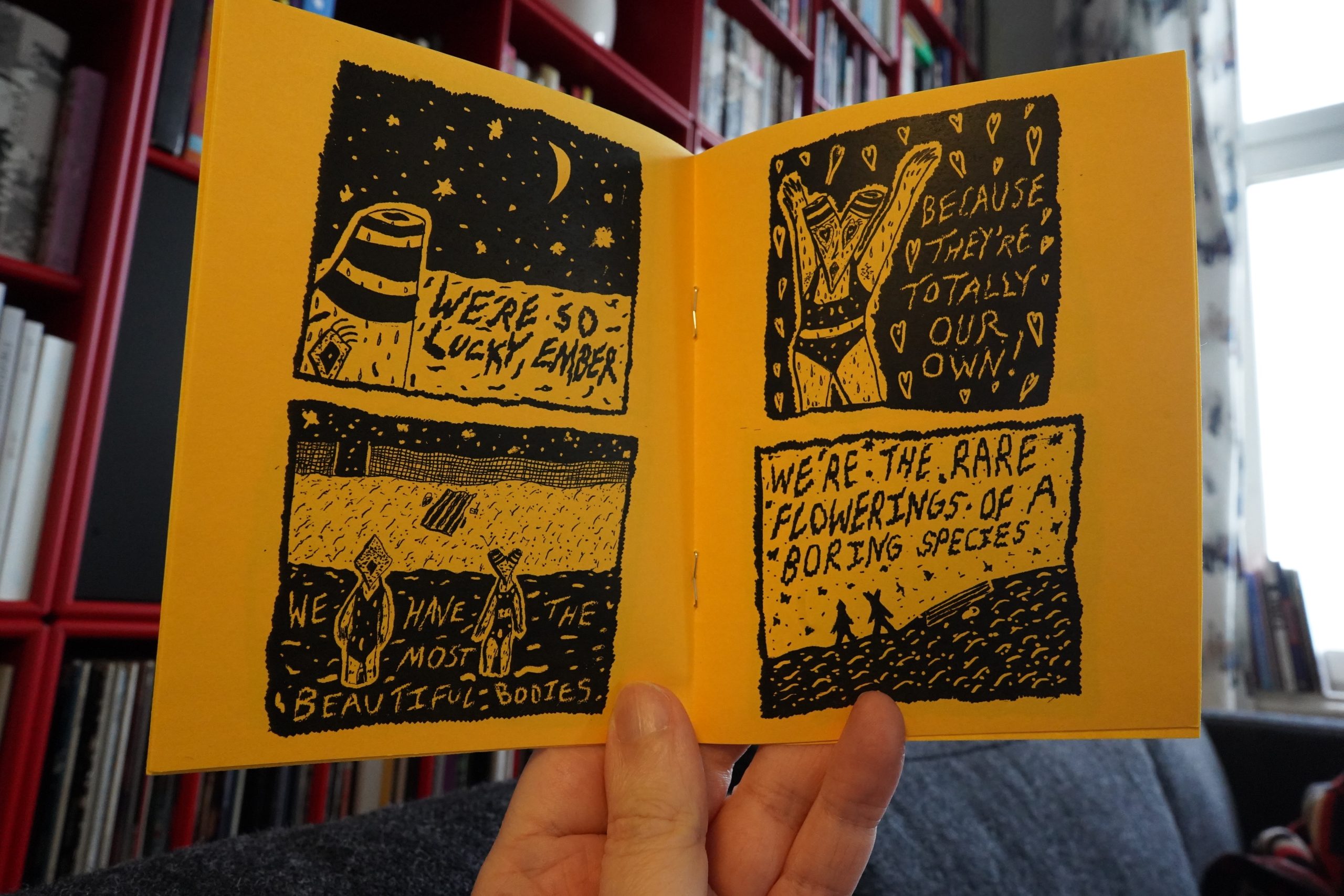

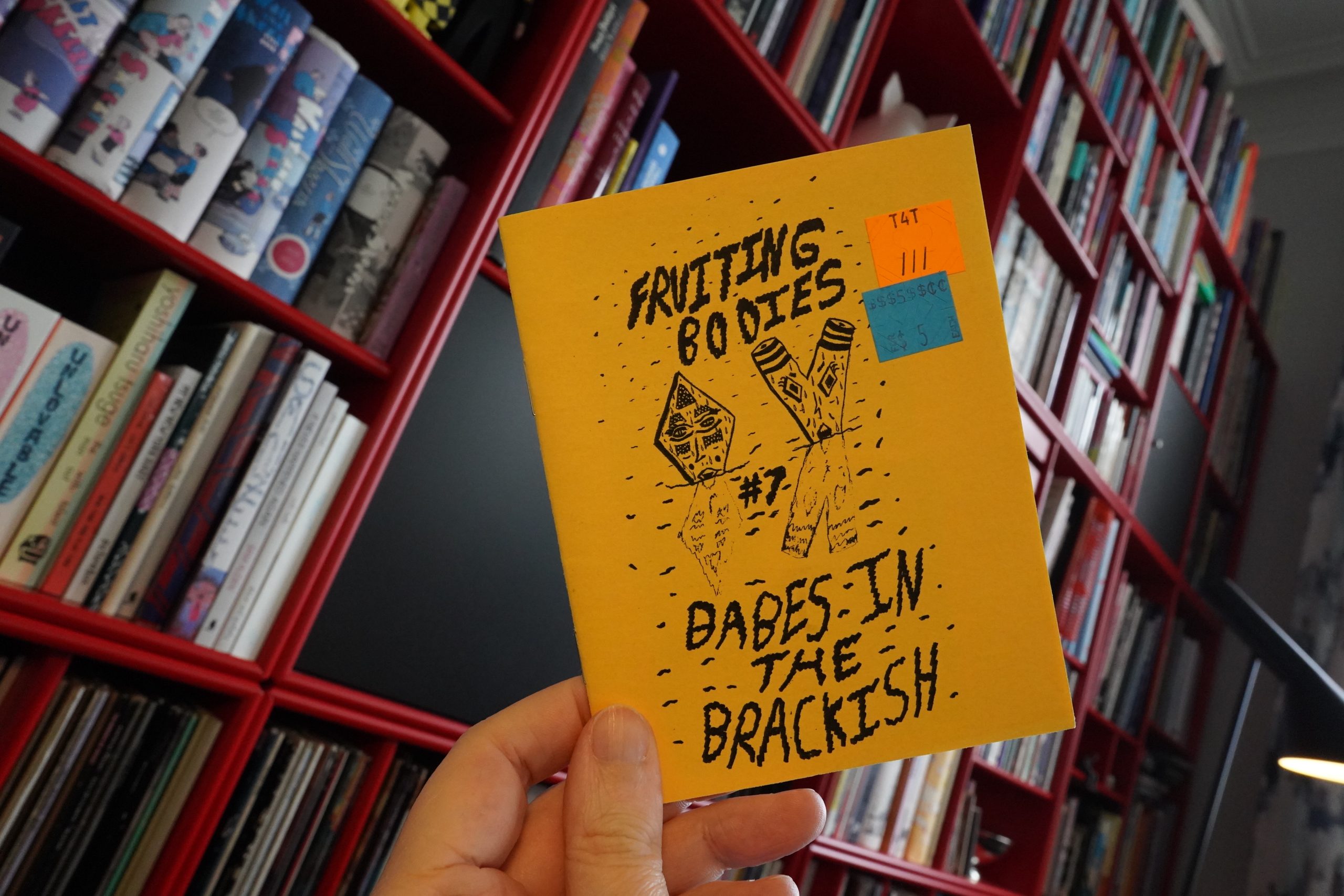

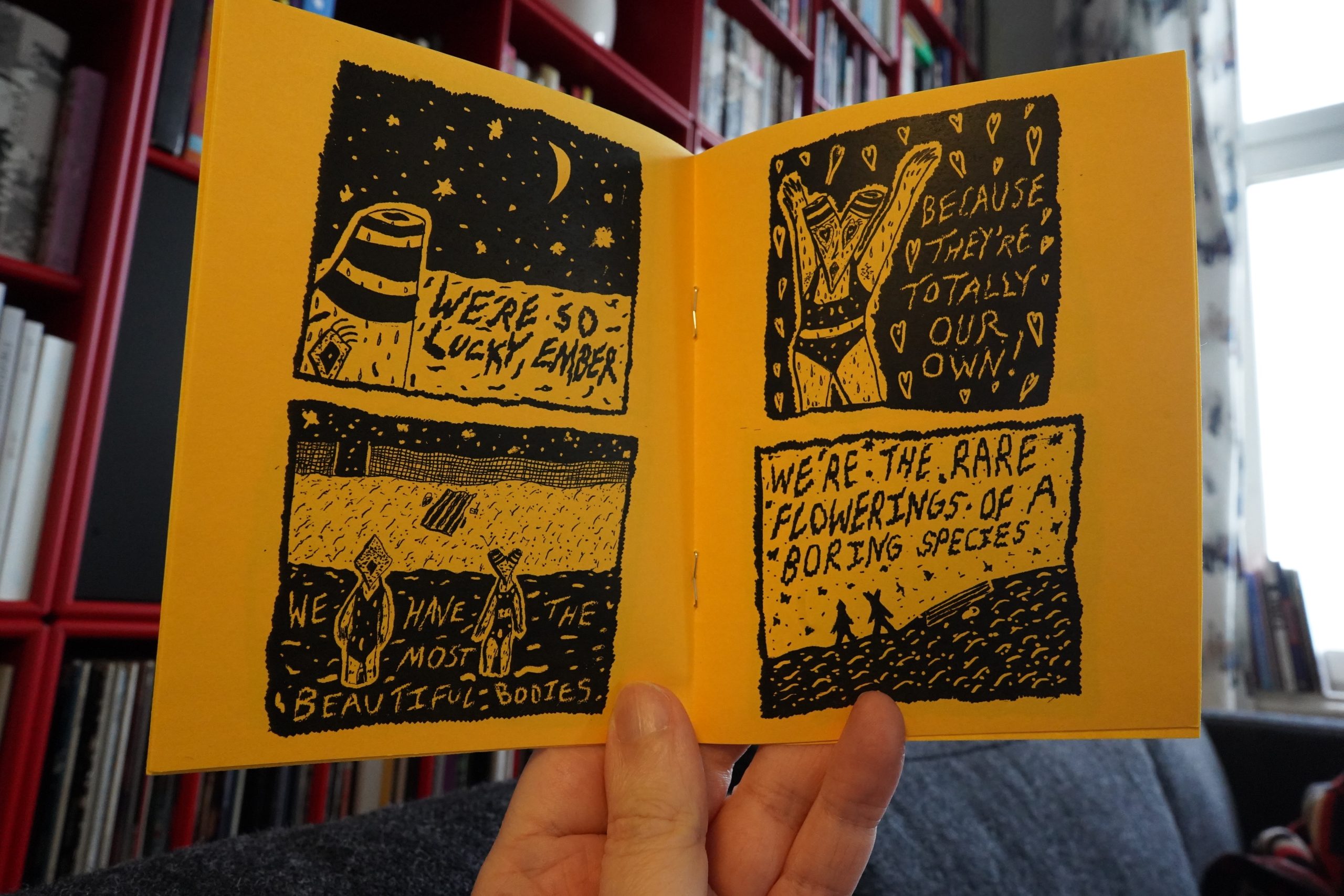

15:01: Fruting Bodies: Babes in the Brackish by Ana Woulfe

It’s very short, but it’s nice.

| Kate Bush: Remastered (4): The Dreaming |  |

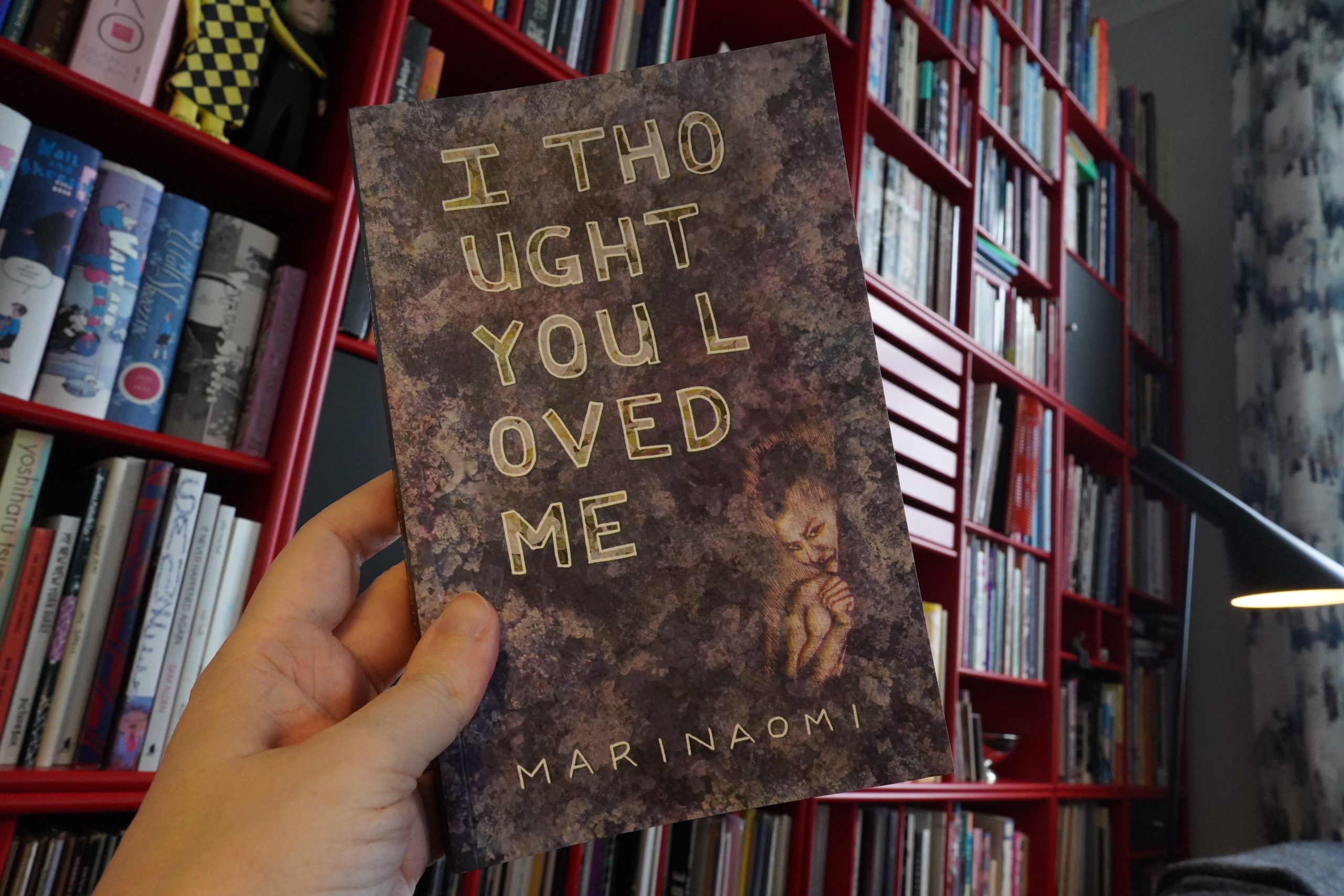

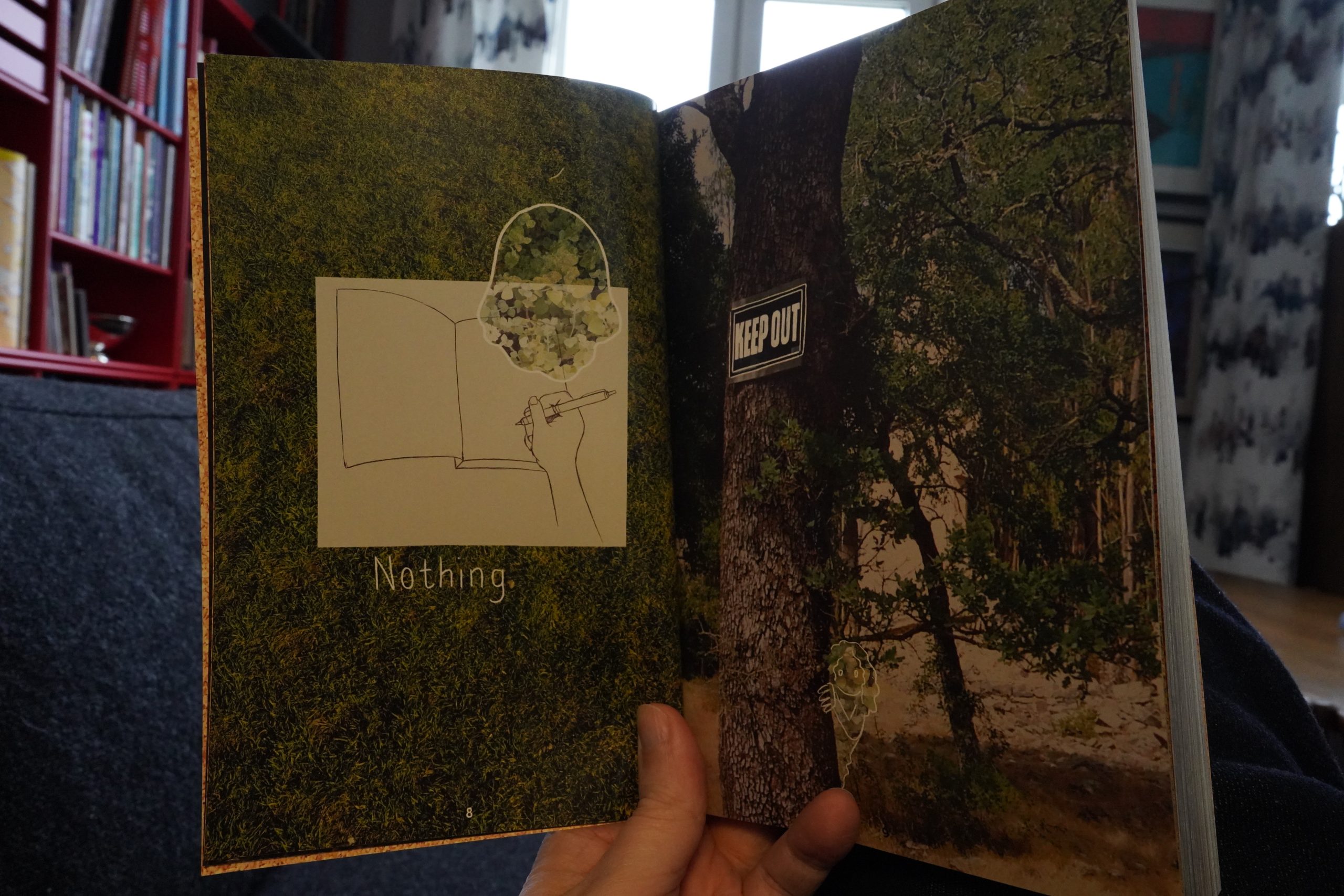

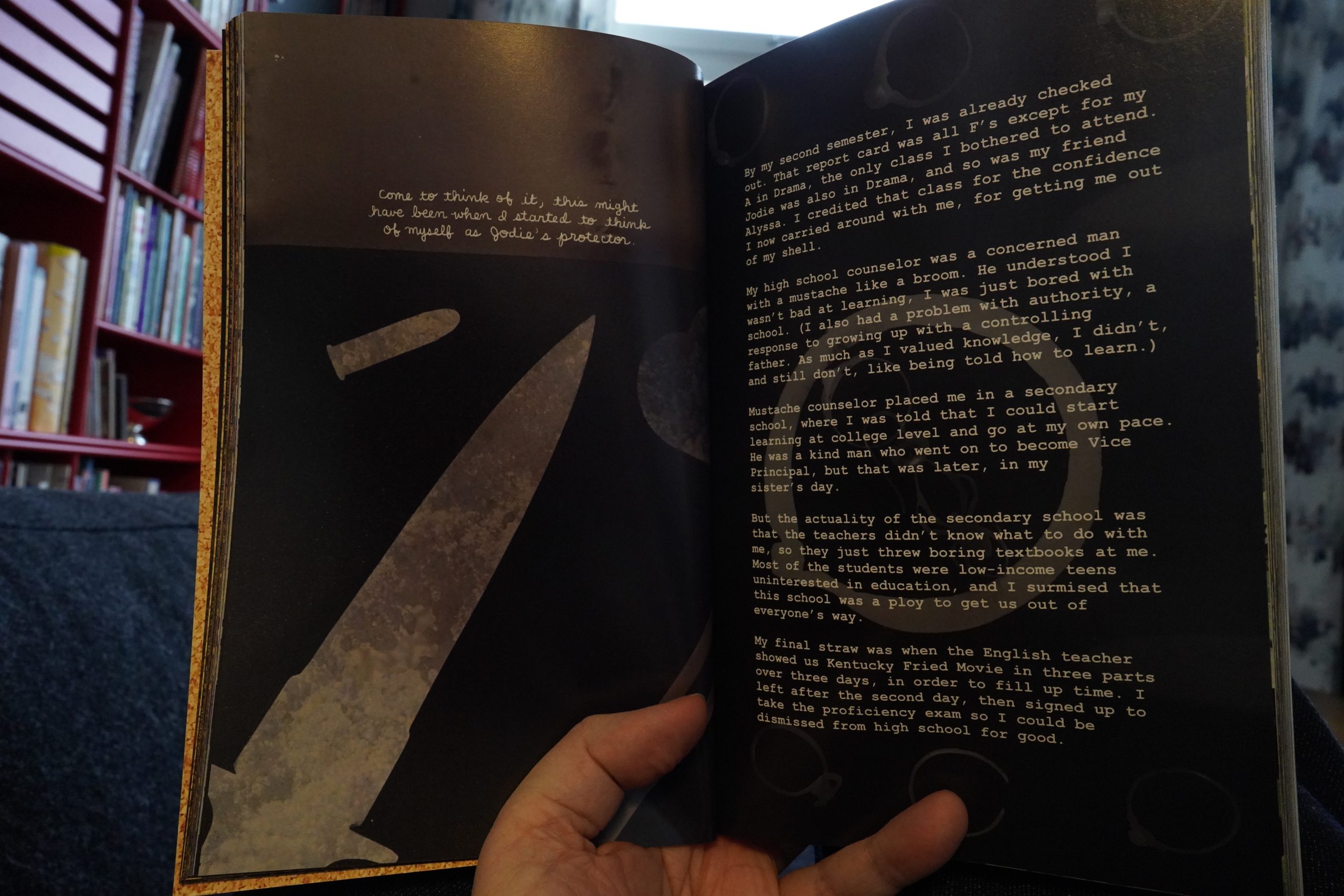

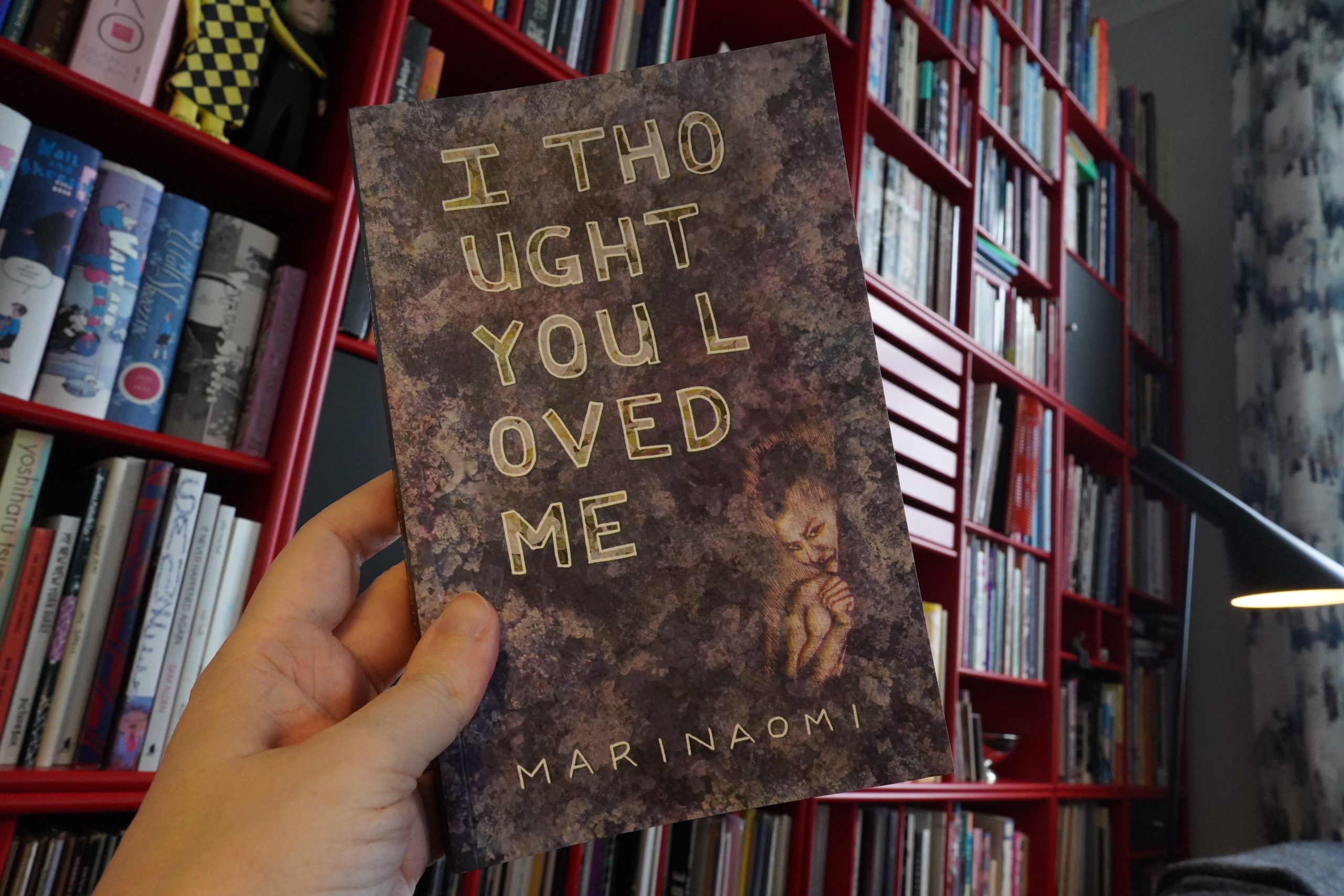

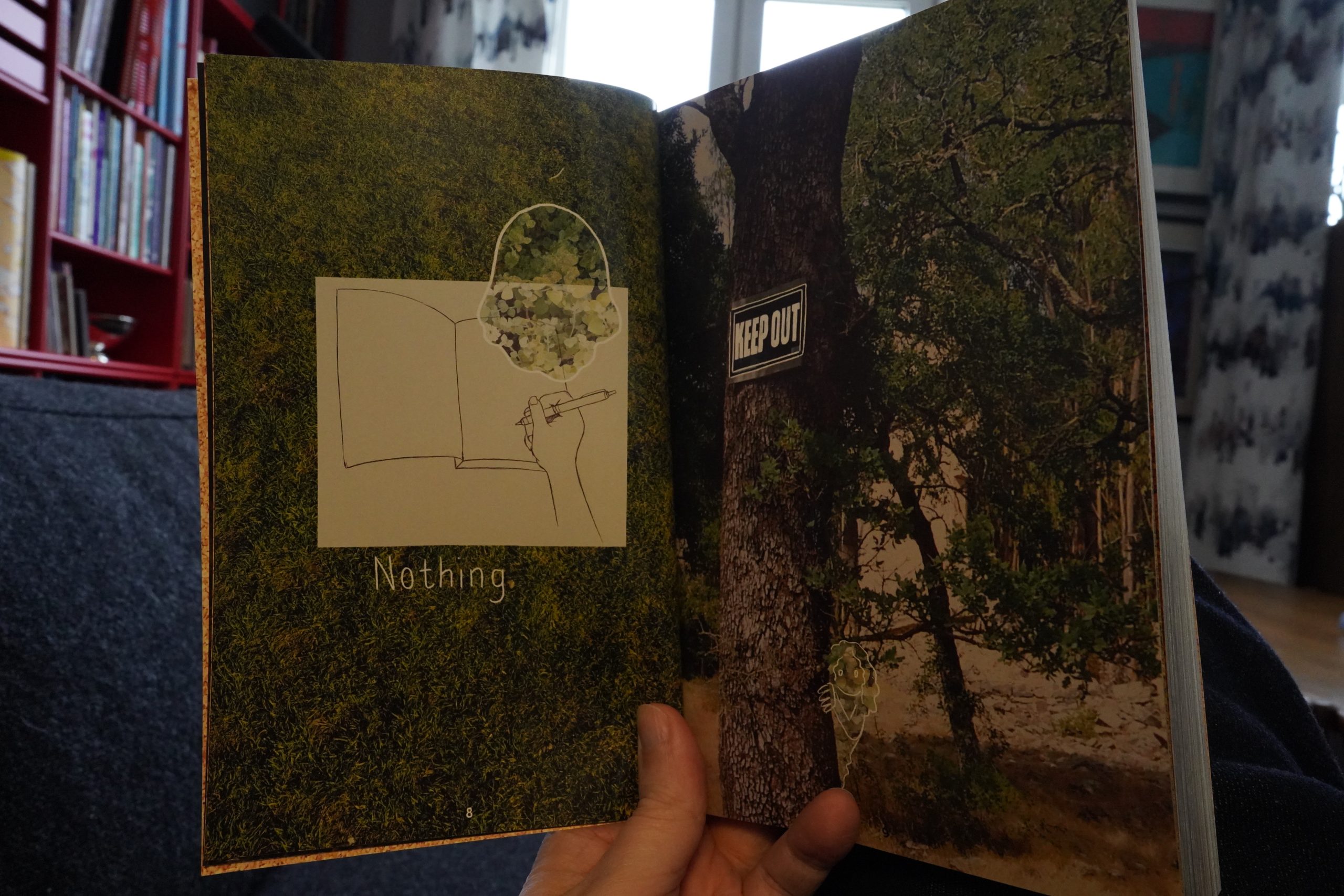

15:05: I Thought You Loved Me by MariNaomi (Fieldmouse Press)

Oh, this isn’t a comic book? Boo! I really like MariNaomi’s comics…

I guess you’d call it “a text” or something.

Anyway, I was sitting here reading it, sort of going “yes, but why should I be interested in this” — it’s a story about a friendship that fell apart, and memory, and then getting more input from others that change what you knew etc etc.

And the thing is, by the time I was halfway through the book, I was completely engrossed, sitting at the edge of the sofa, like this was the most thrilling thriller ever or something. That is, the book really works. And the graphics are pretty interesting, too.

It’s really good.

But I wouldn’t be surprised if Netflix wants to adapt it into a TV series.

| Kate Bush: Remastered (5): Hounds of Love |  |

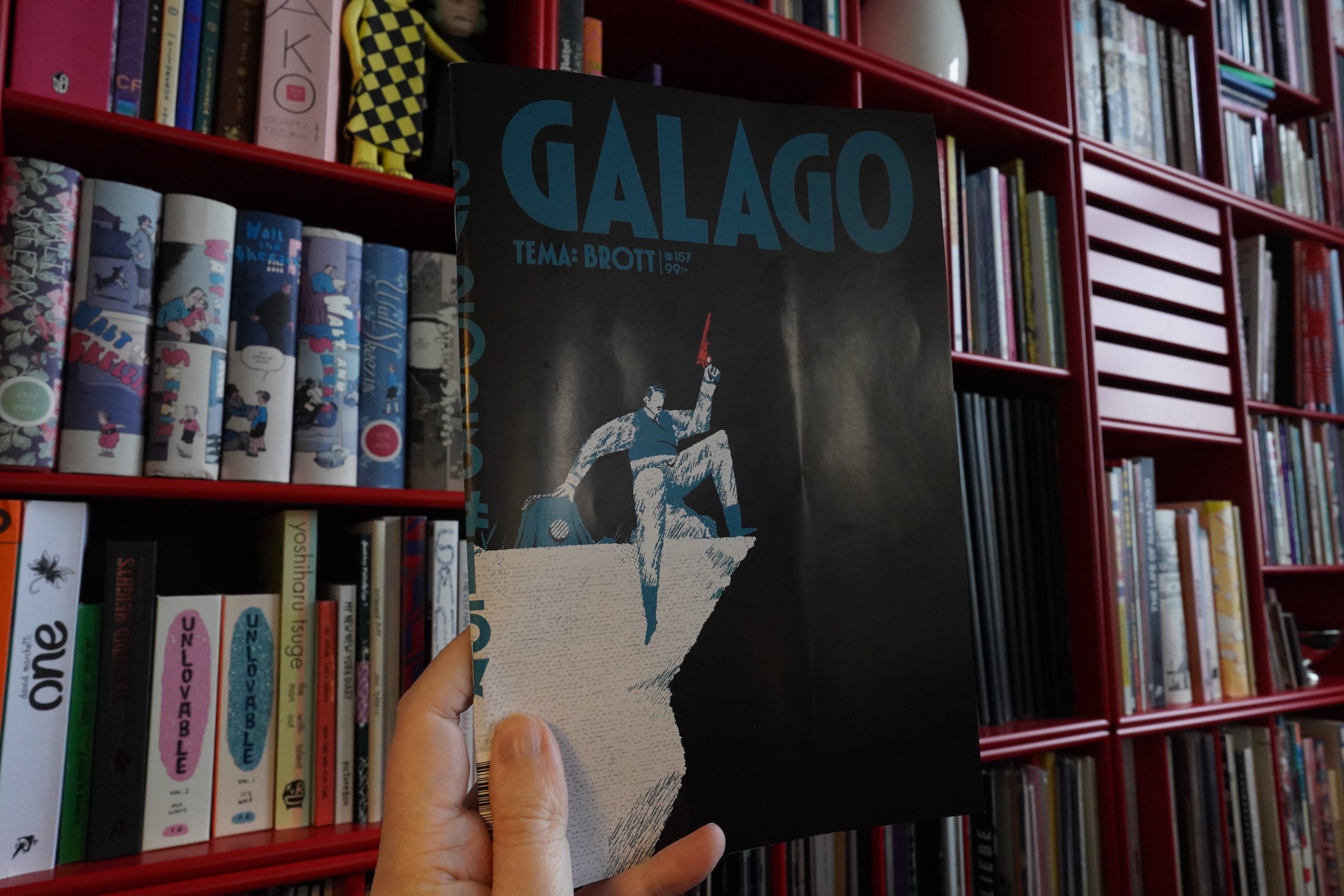

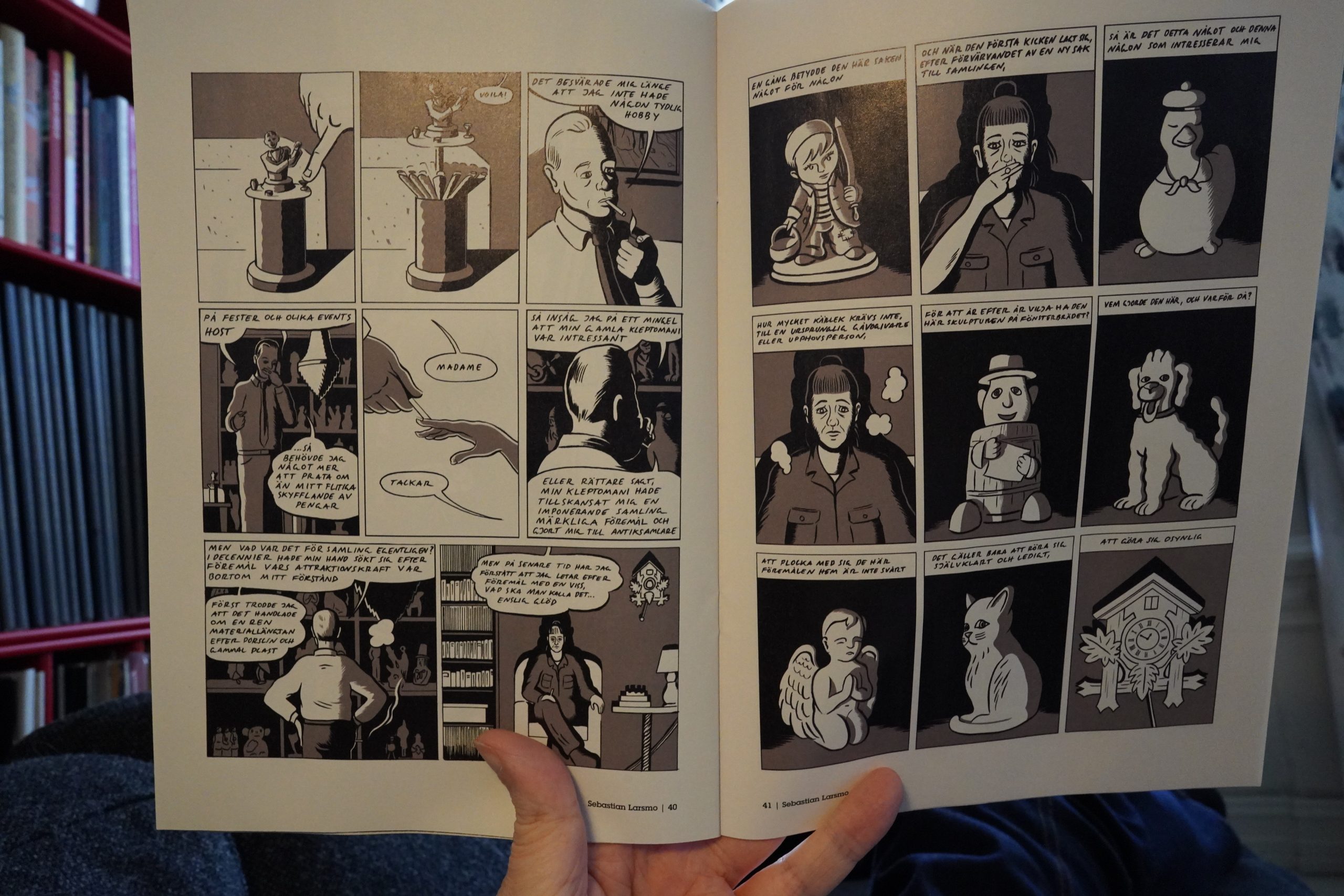

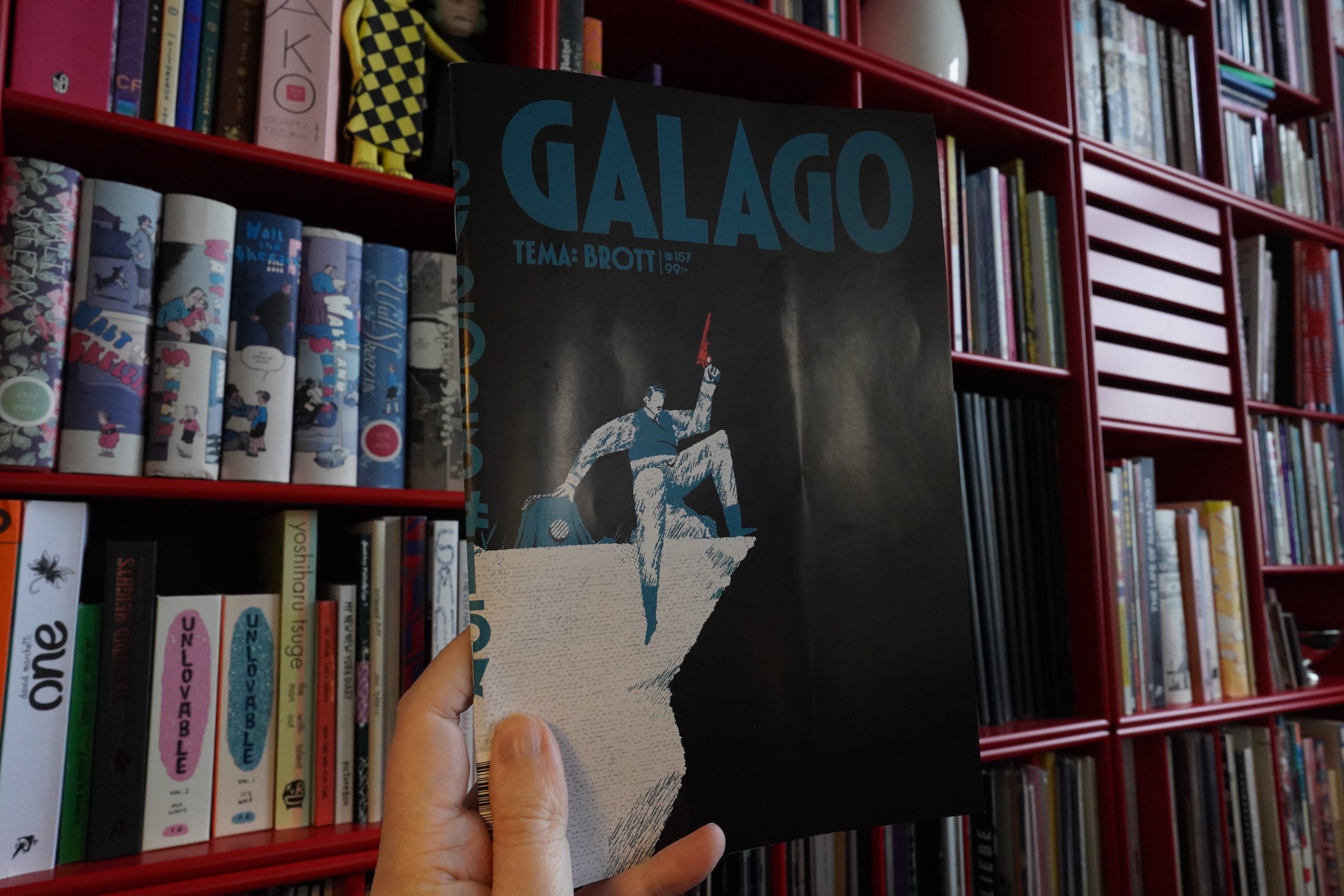

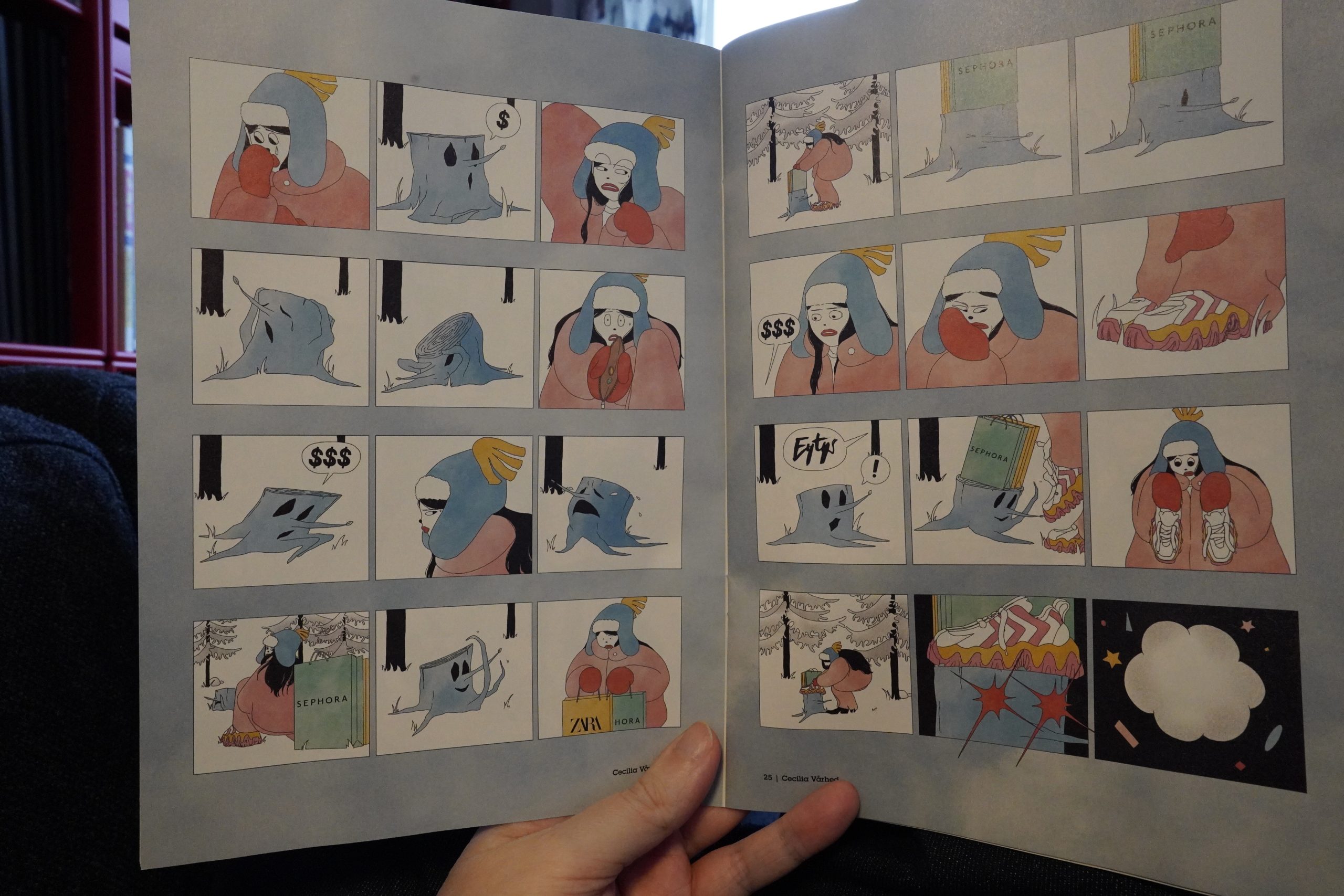

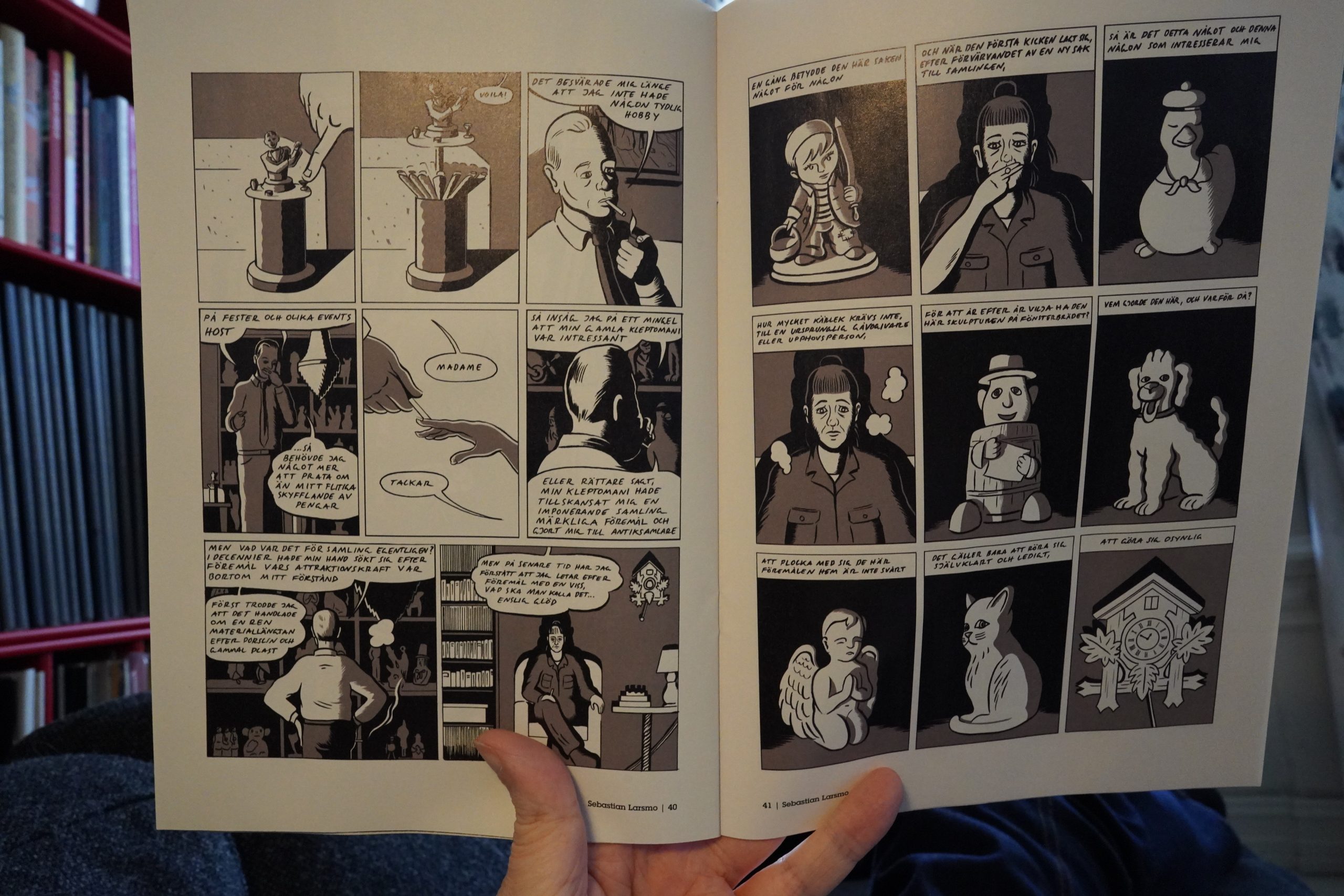

16:46: Galago #157 edited by Rojin Pertow (Galago)

This is a long-running Swedish anthology, but it’s somehow never occurred to me to get a subscription until now. (Or perhaps it’s because it’s not been available abroad before — Swedish companies and shops are the most reluctant to export things in the world: I can easily buy stuff from, say, Spain, but Sweden? Usually a big “Nope”.)

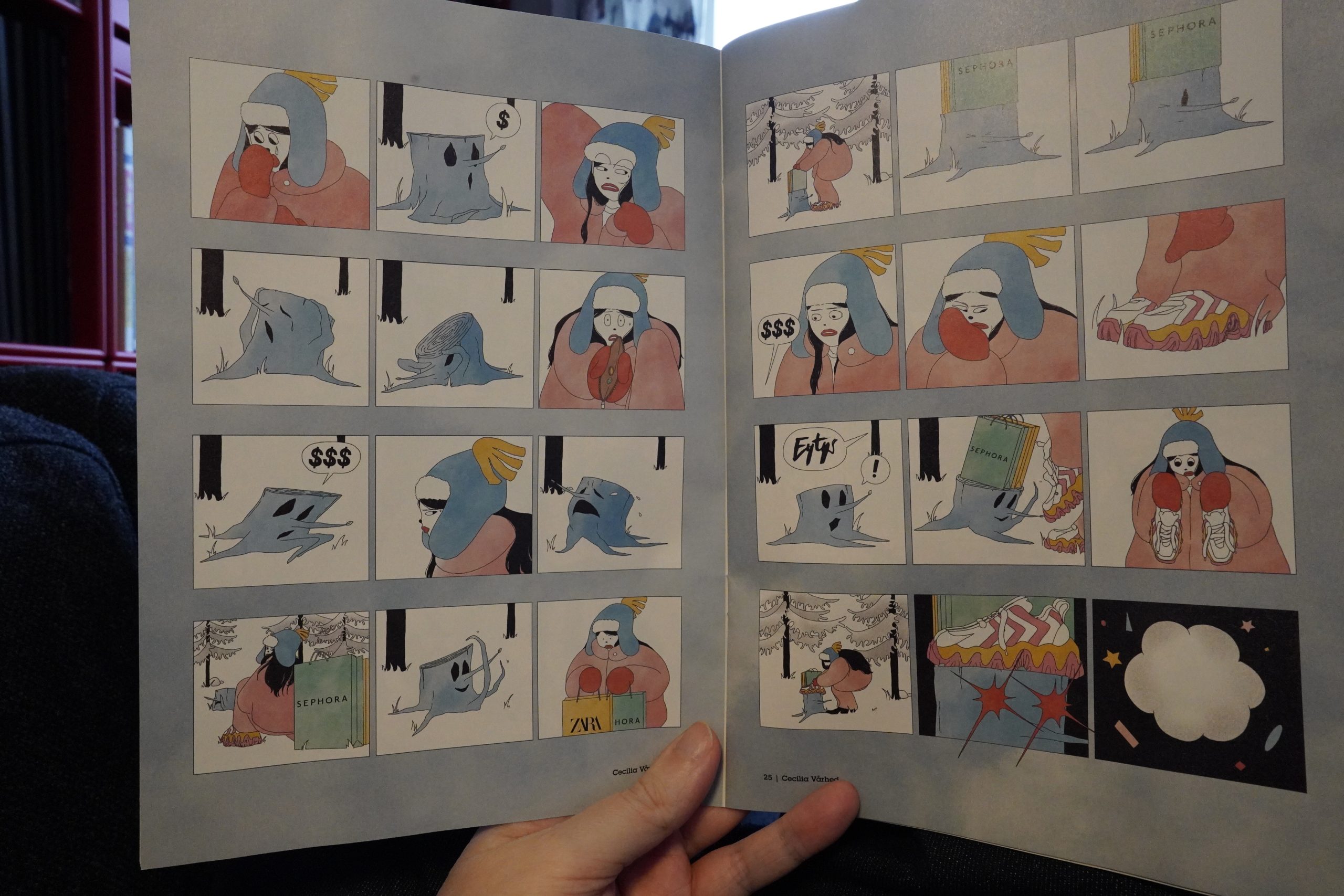

It’s a pretty good anthology — it’s all Swedish contributors, I guess?

It’s not as arty as, say, Kuš.

The magnum opus is this, which is a Daniel Clowes-like vague story. It’s good.

And this was the funniest bit. I feel seen!

| Kate Bush: Remastered (6): The Sensual World |  |

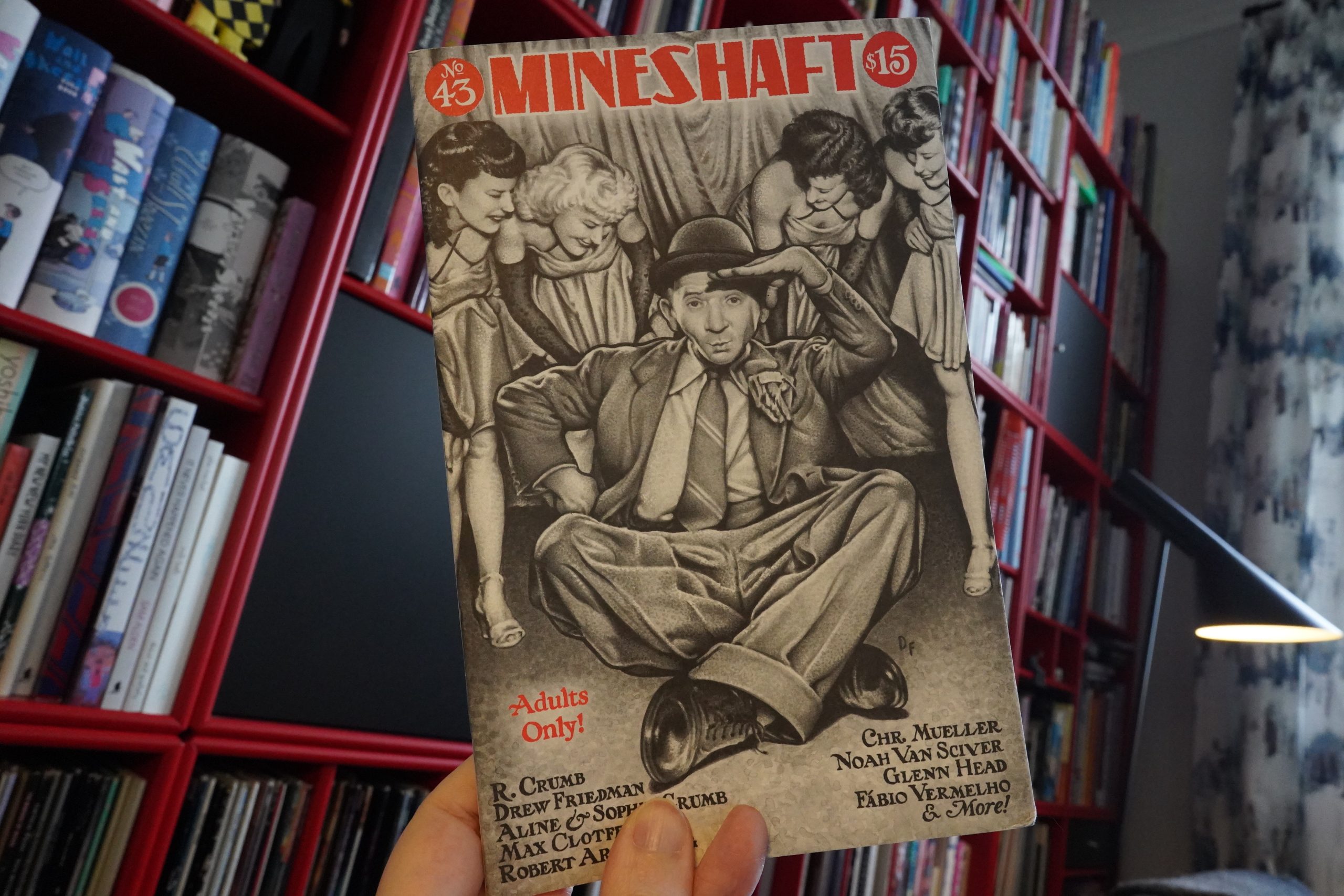

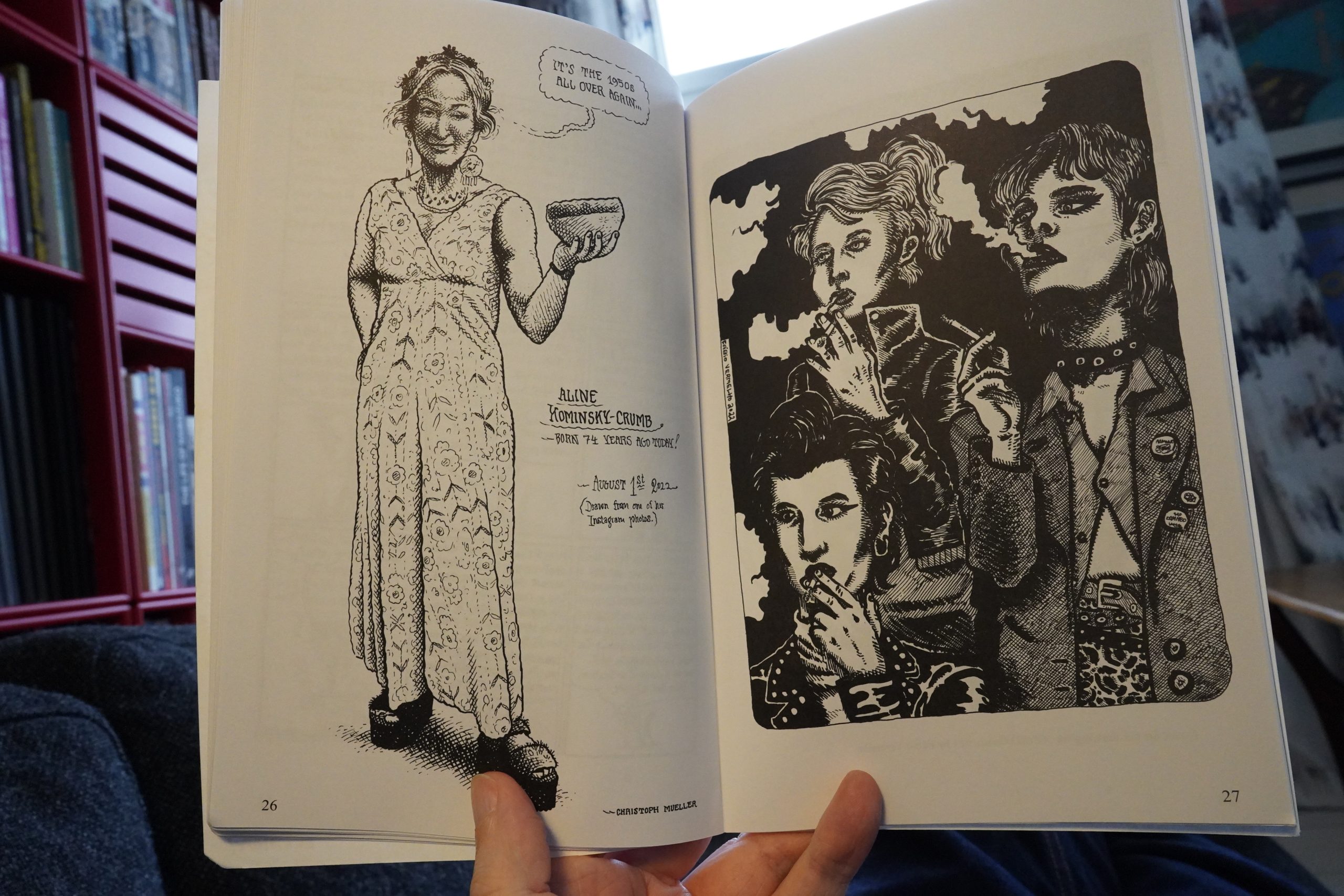

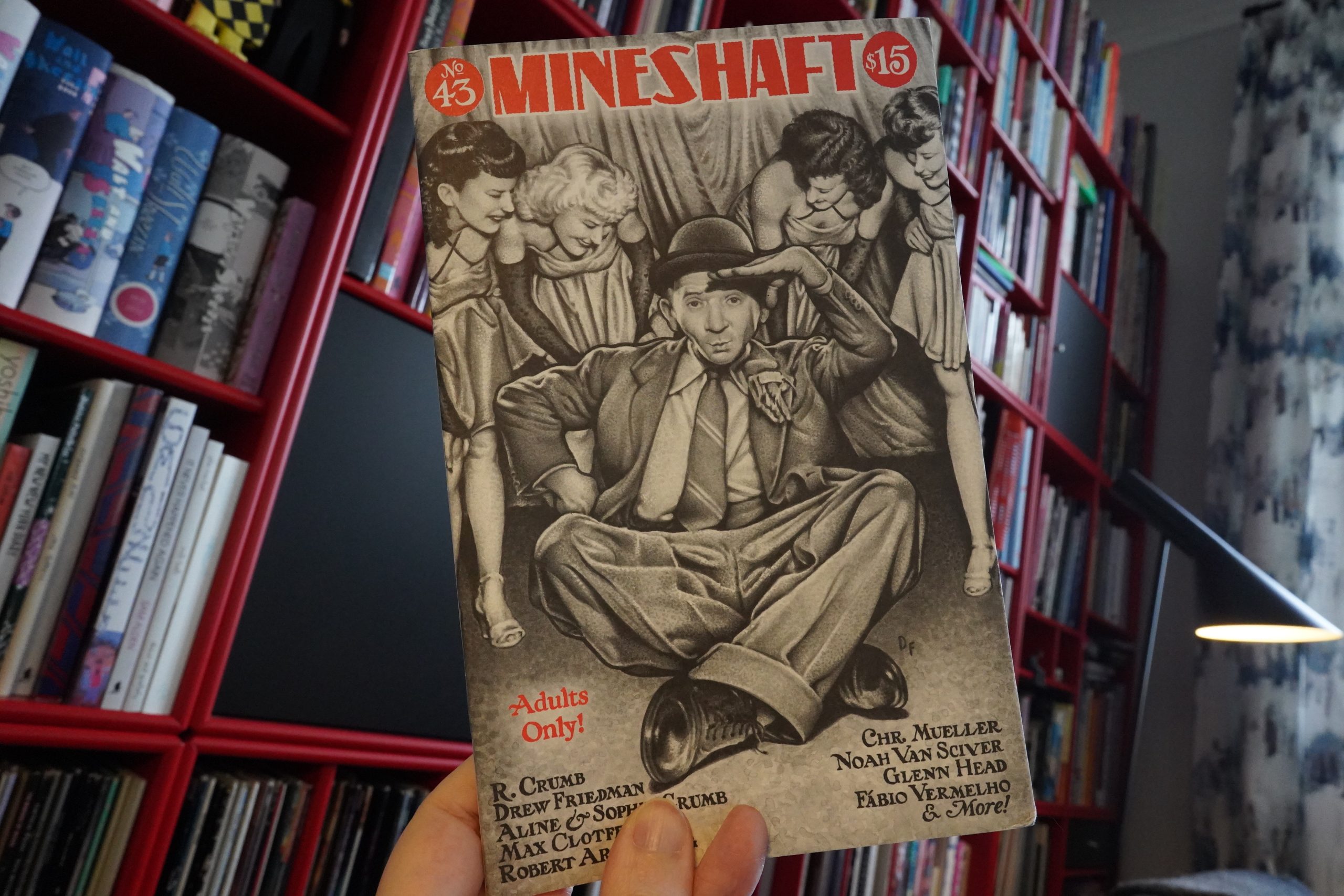

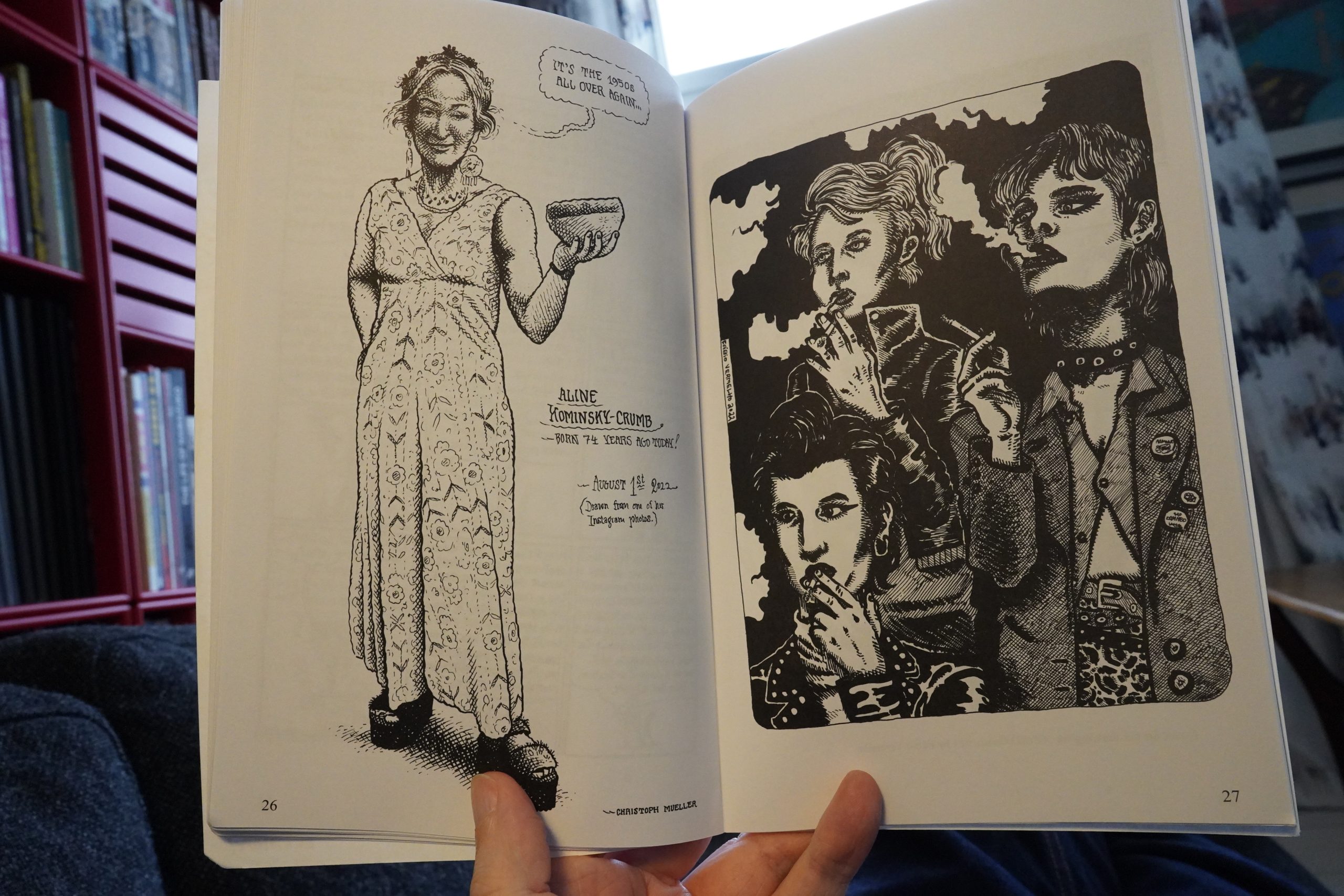

17:14: Mineshaft #45 edited by Everett Rand

And speaking of long-running anthologies…

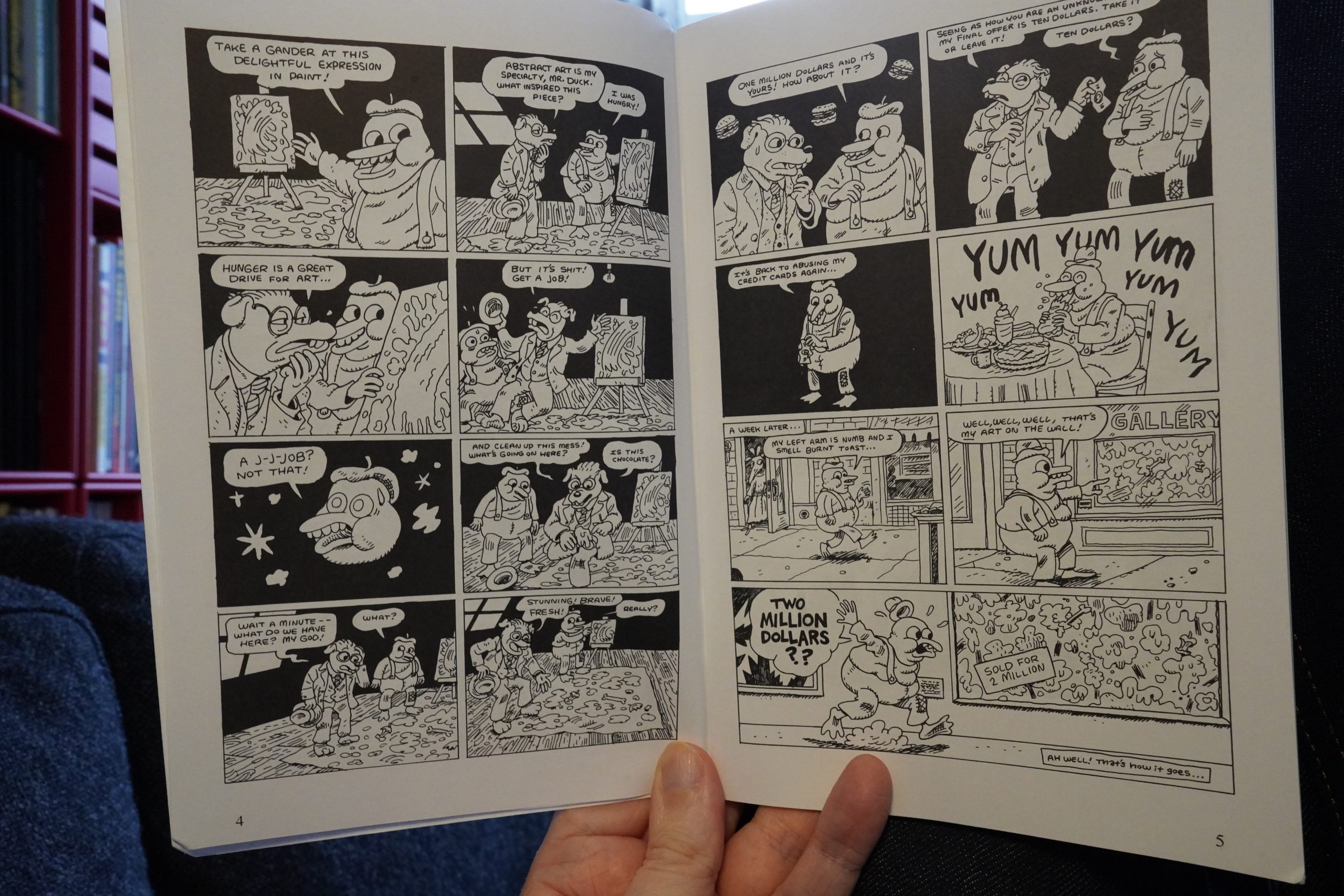

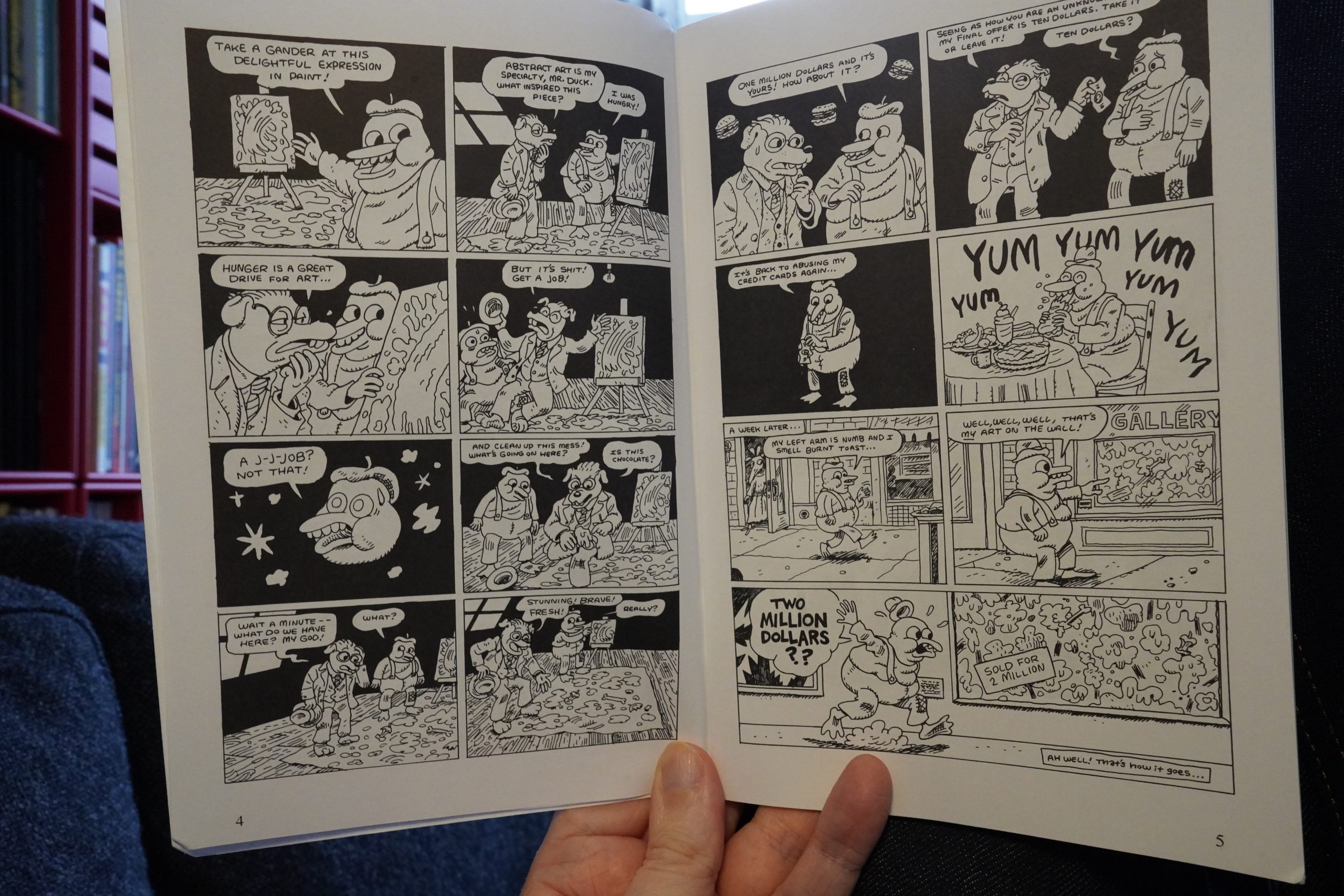

Noah Van Sciver delivers a perceptive, incisive look at the fine arts industry. I mean, he does that bog-standard whining and moaning about fine arts that comics artists always do, and which is really very unattractive.

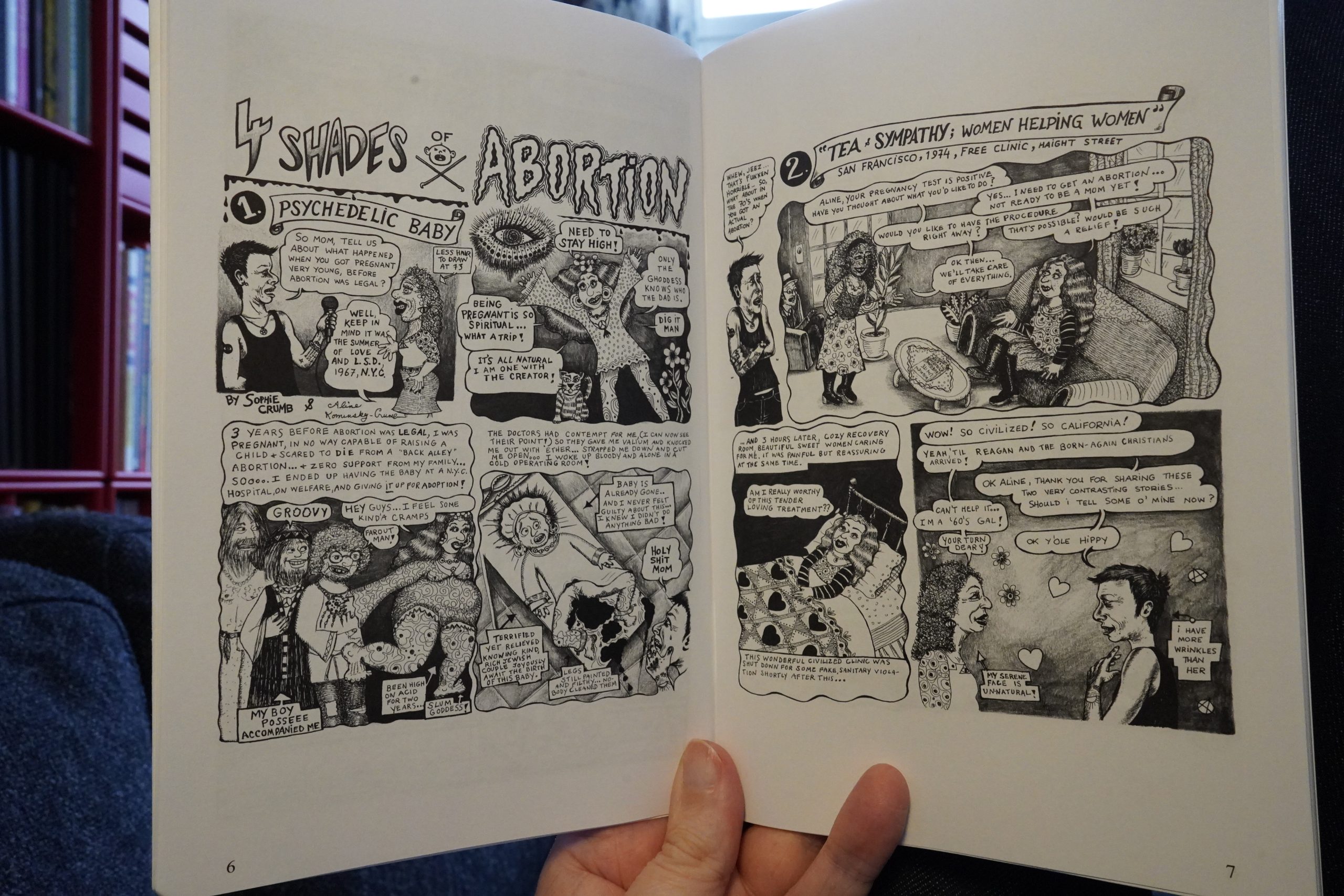

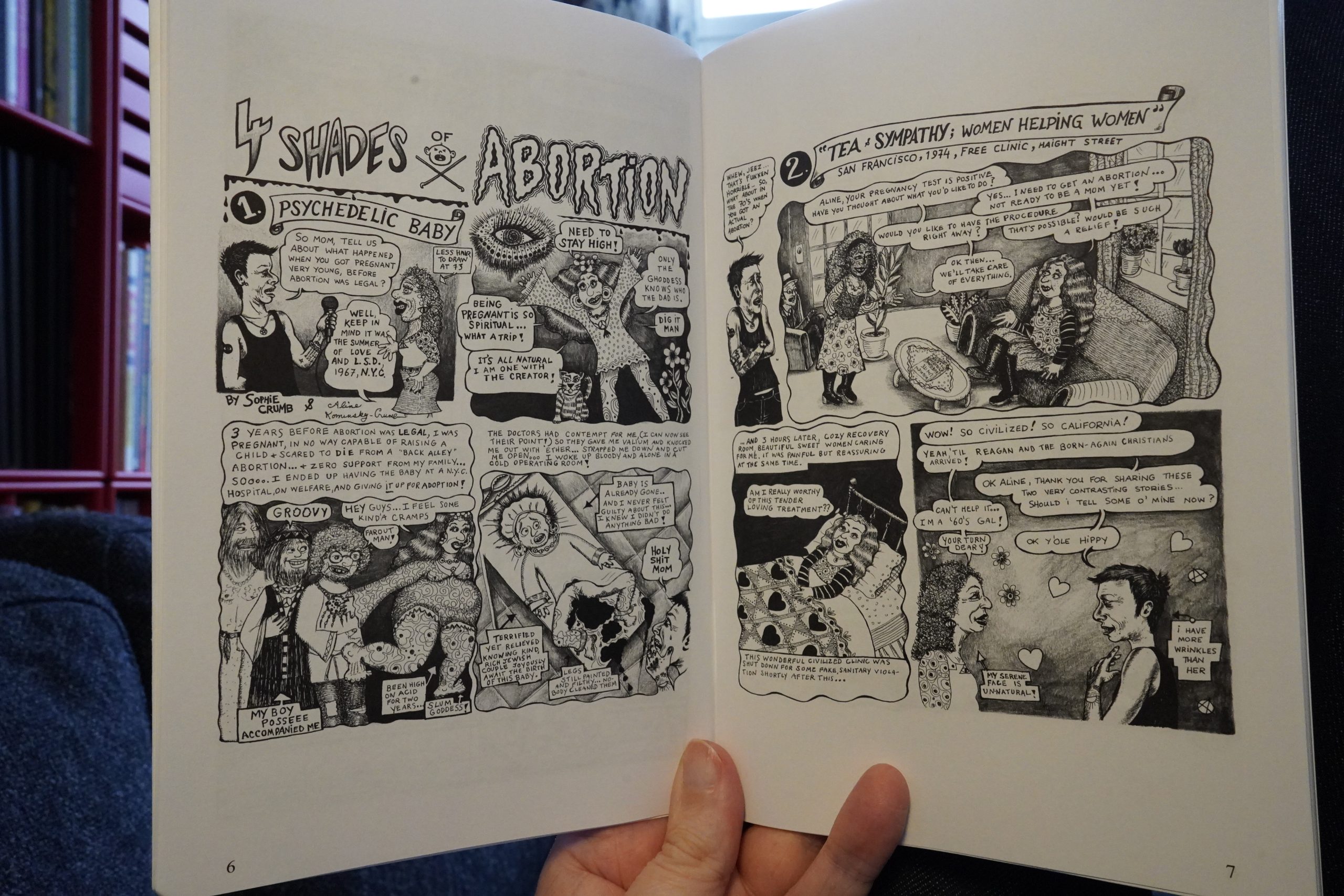

Aline Kominsky-Crumb and Sophie Crumb does a four pager about abortion which is great, but which I’ve already read somewhere… uhm… oh, that book published by that gallery? Yeah.

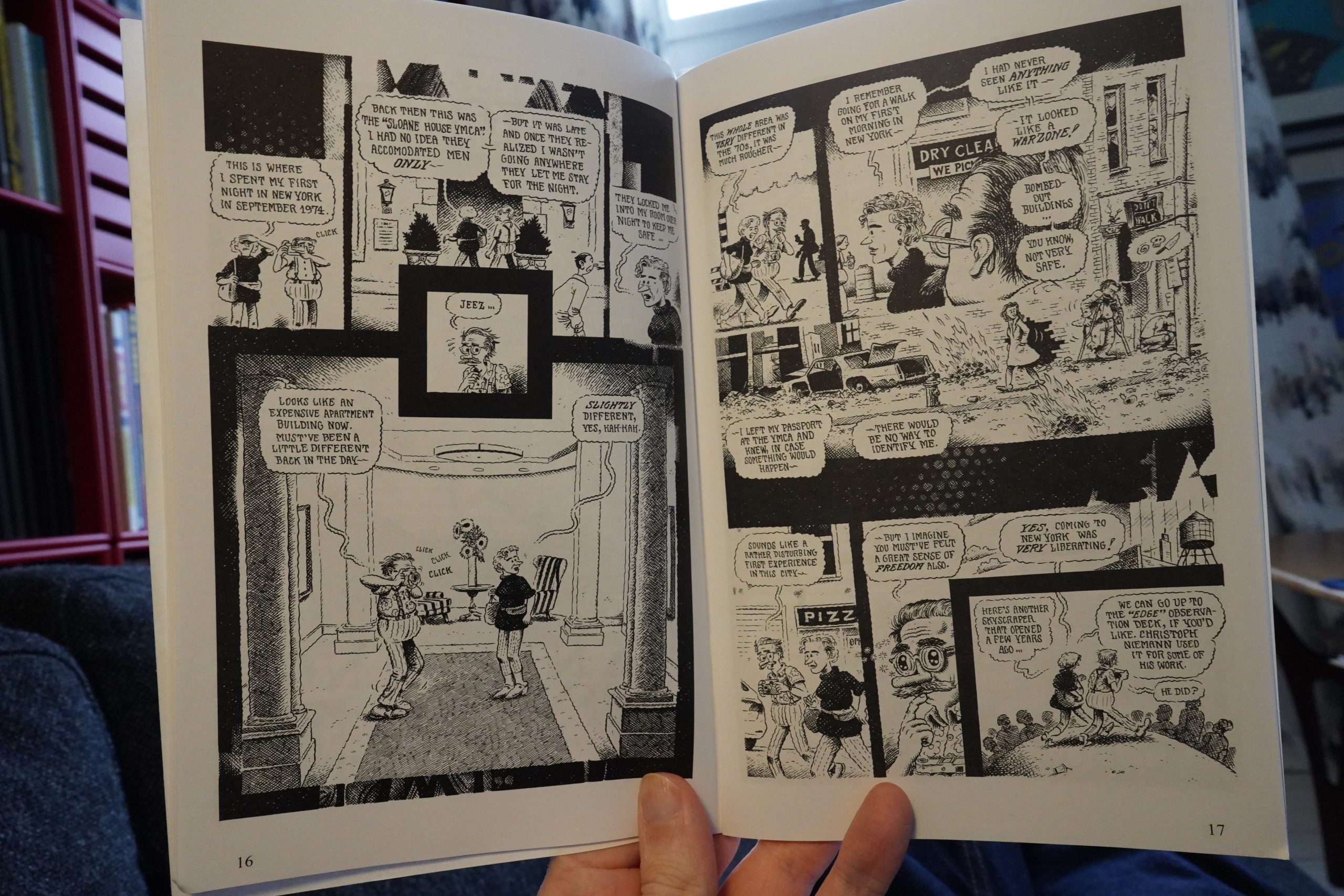

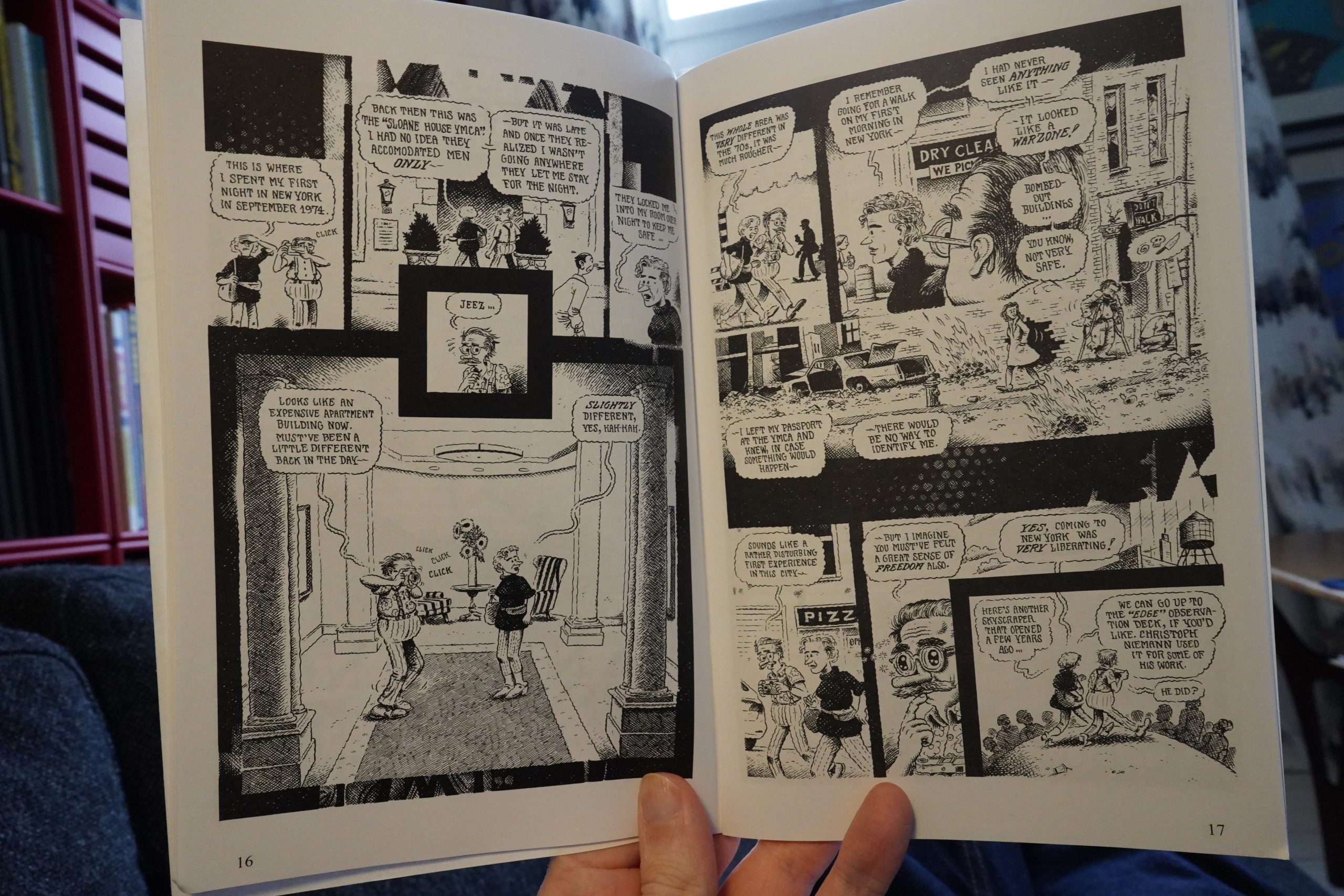

Christoph Mueller does a thing about Françoise Mouly — love the art; the dialogue is a bit dominated by Mueller, so it’s kinda lopsided.

And… I wish this anthology just printed the names of the artists on every page, like Galago does. It’s just annoying ferreting out who did what — some people label their pages, but most don’t.

But kvetching aside, it’s pretty good. And the back pages point out that David Collier has books out which that I didn’t know about. *gasp* *shopping mode engage!*

| Kate Bush: Remastered (7): The Red Shoes |  |

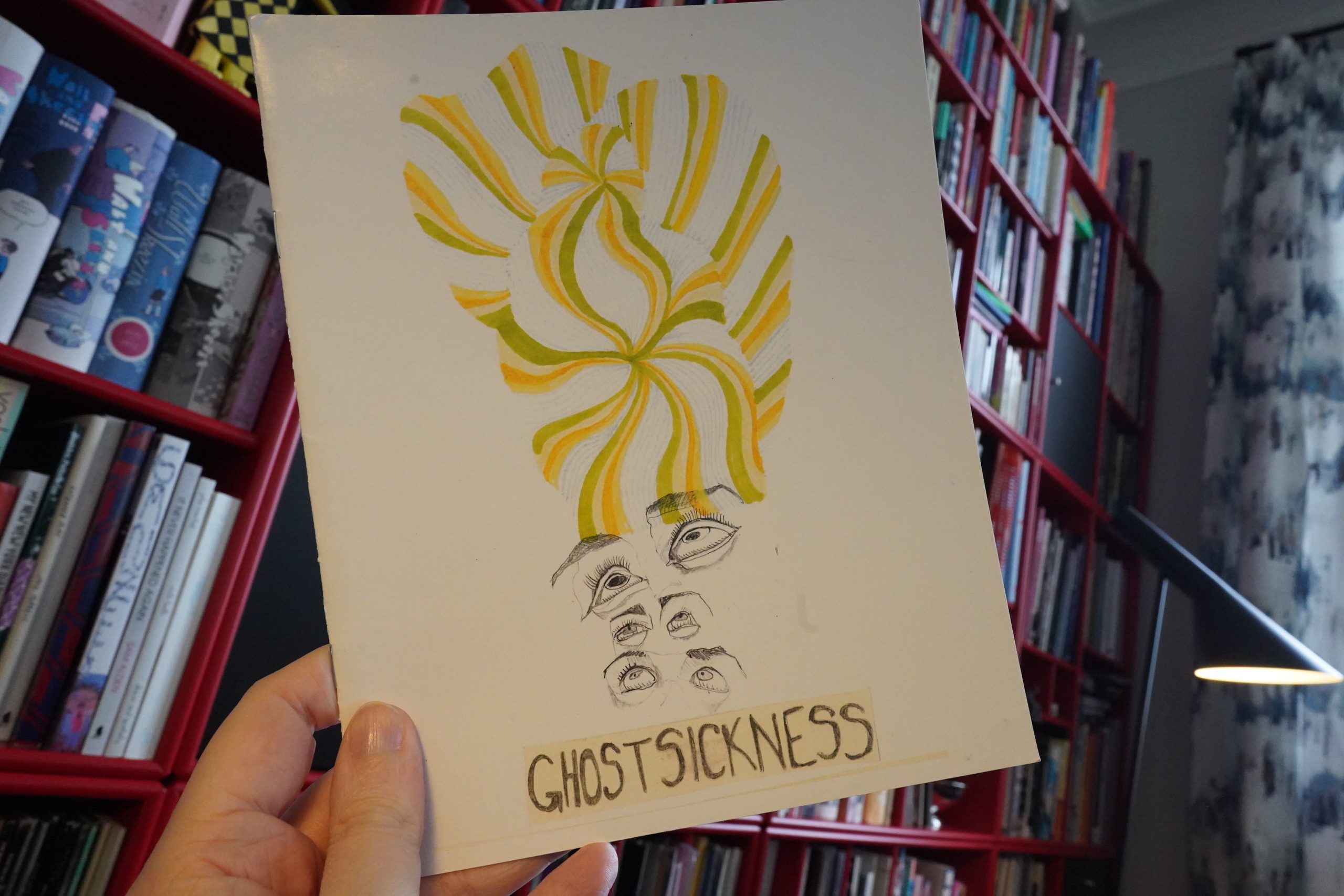

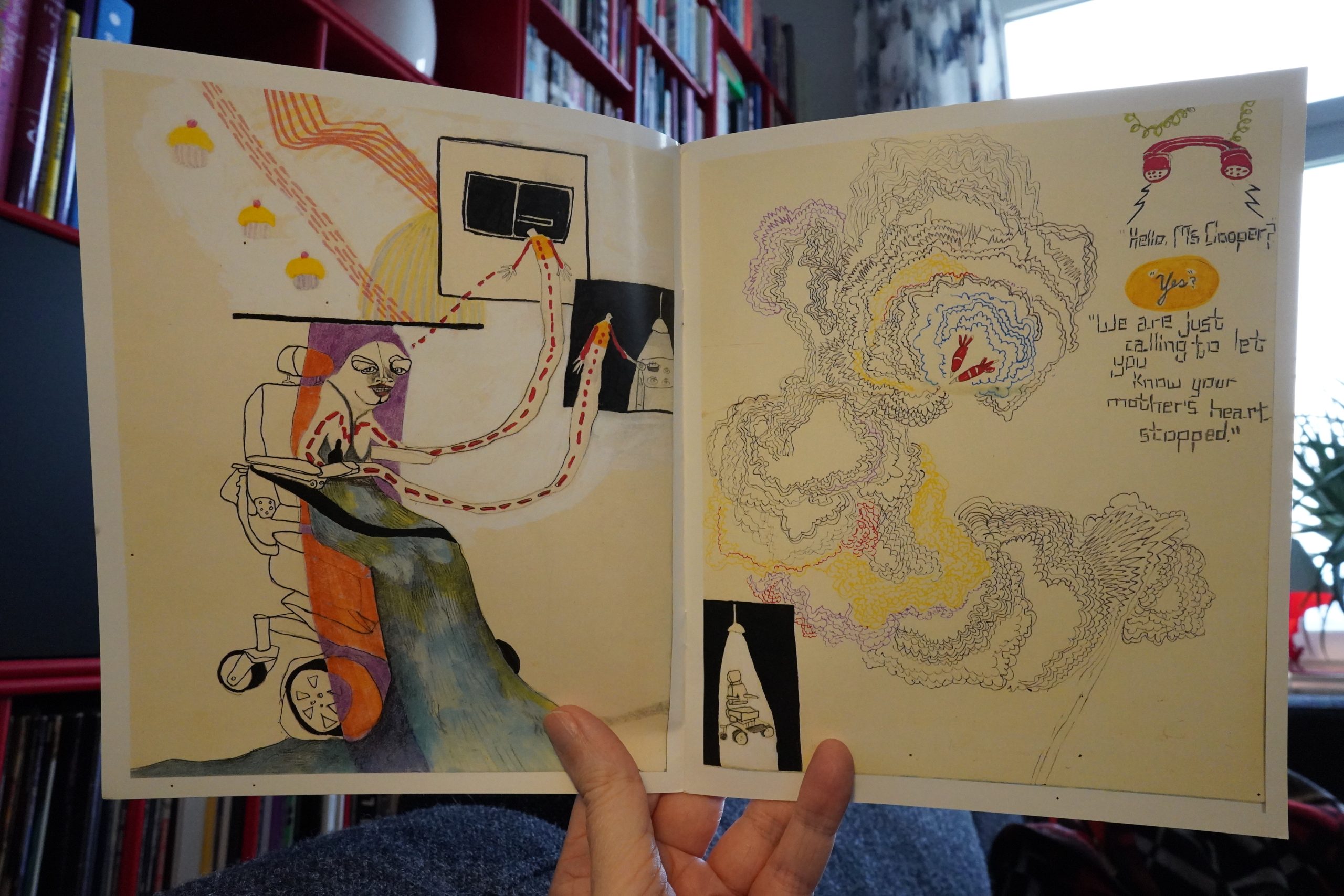

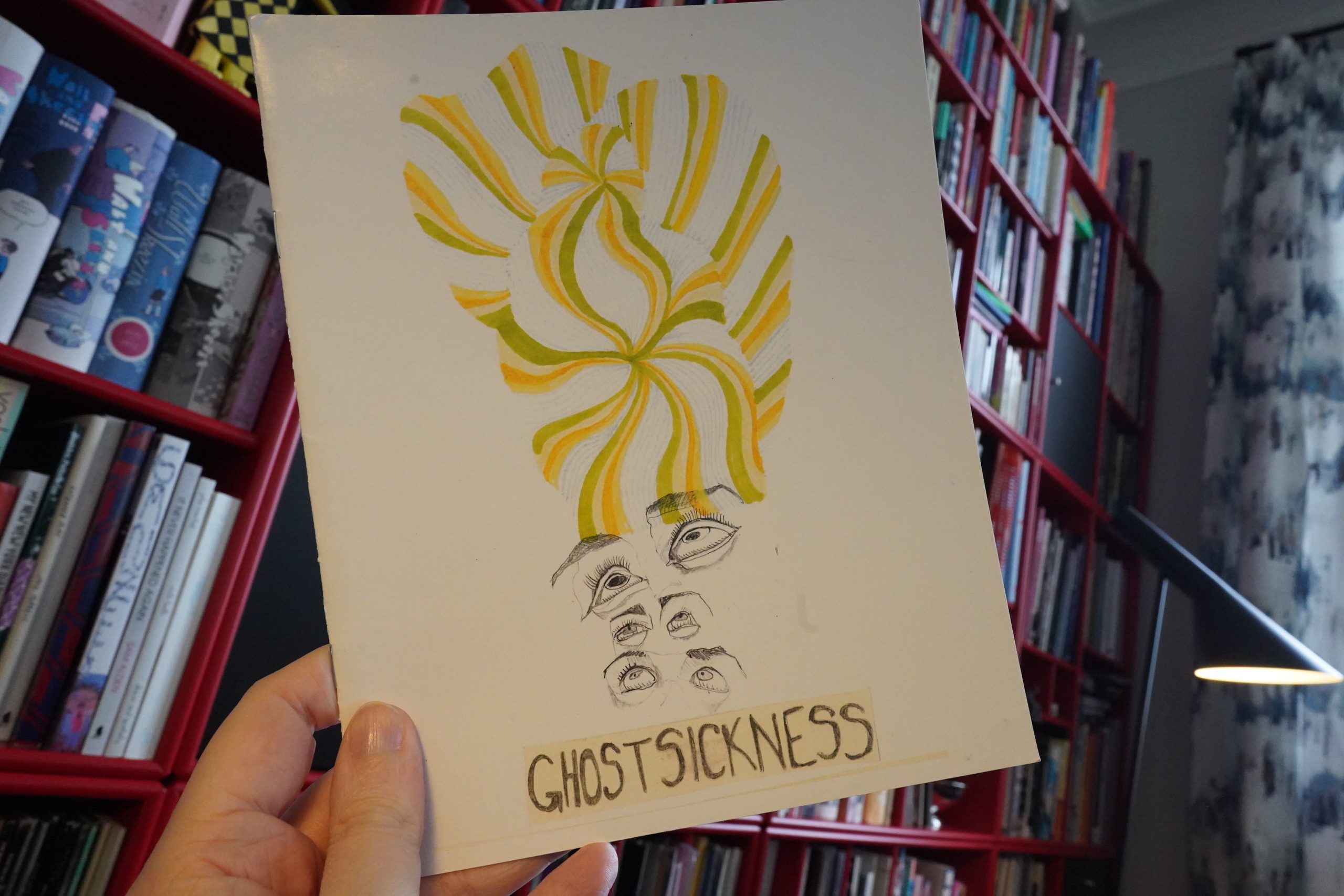

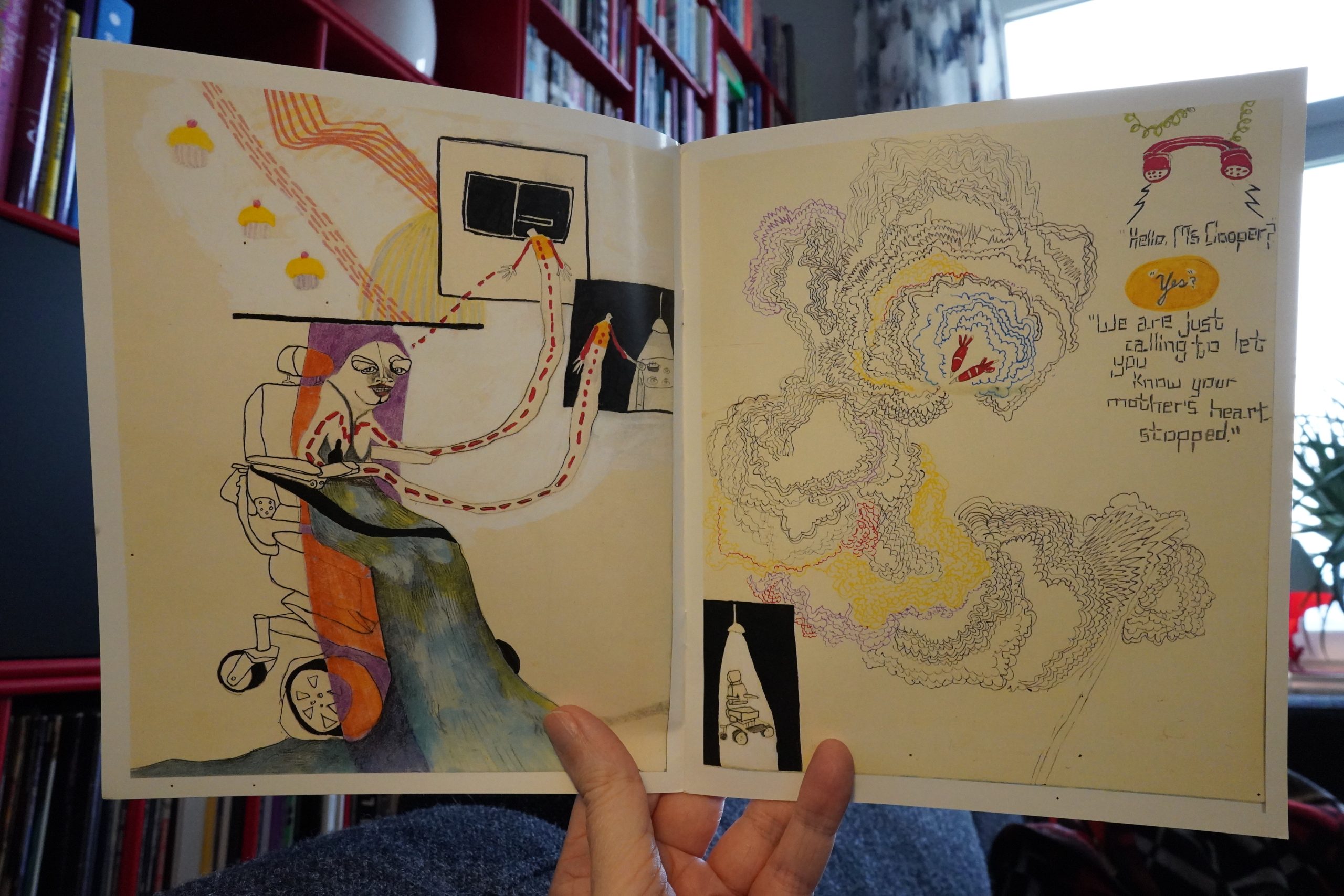

17:44: Ghost Sickness by Ariel Cooper

Horrifying, but in a good way.

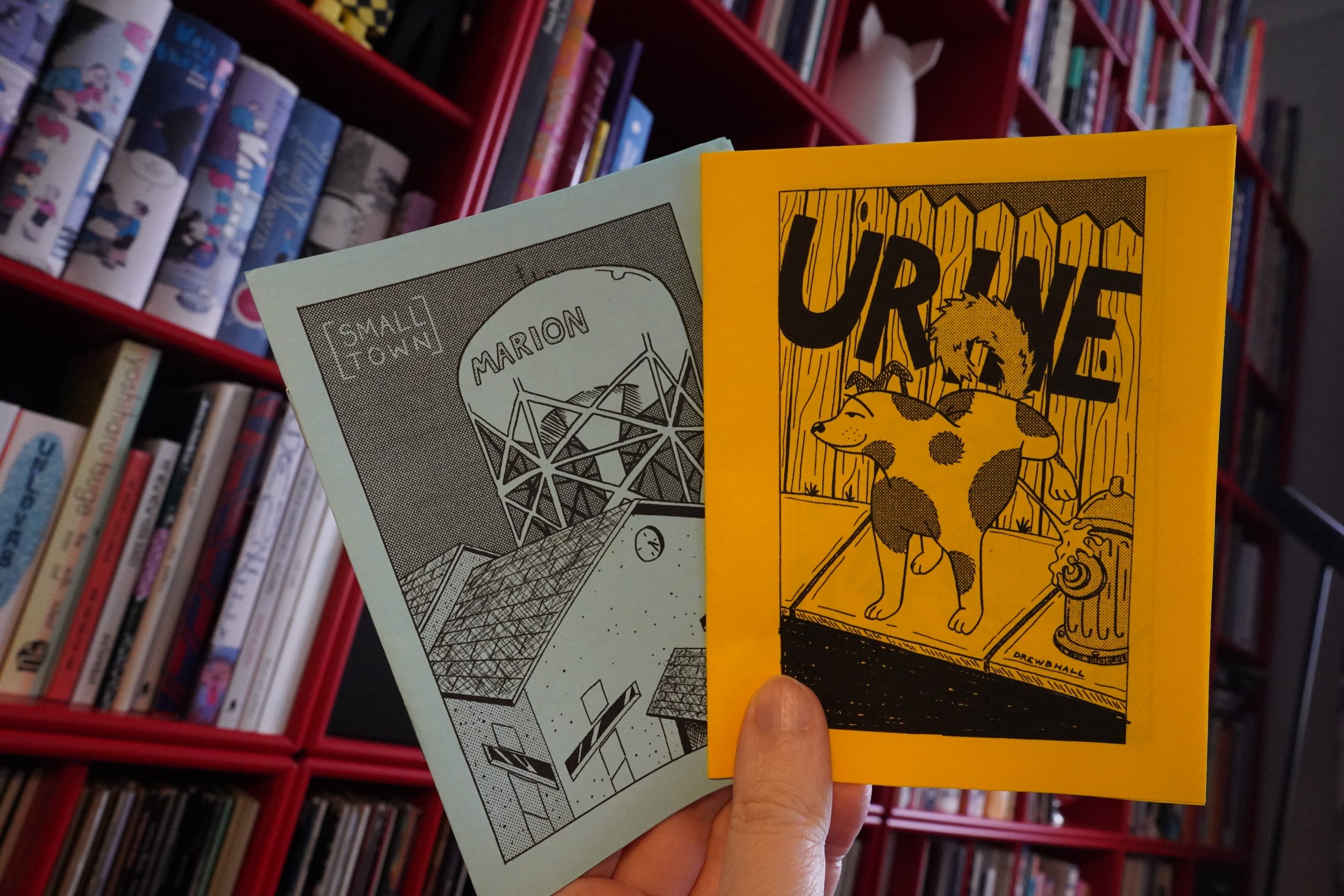

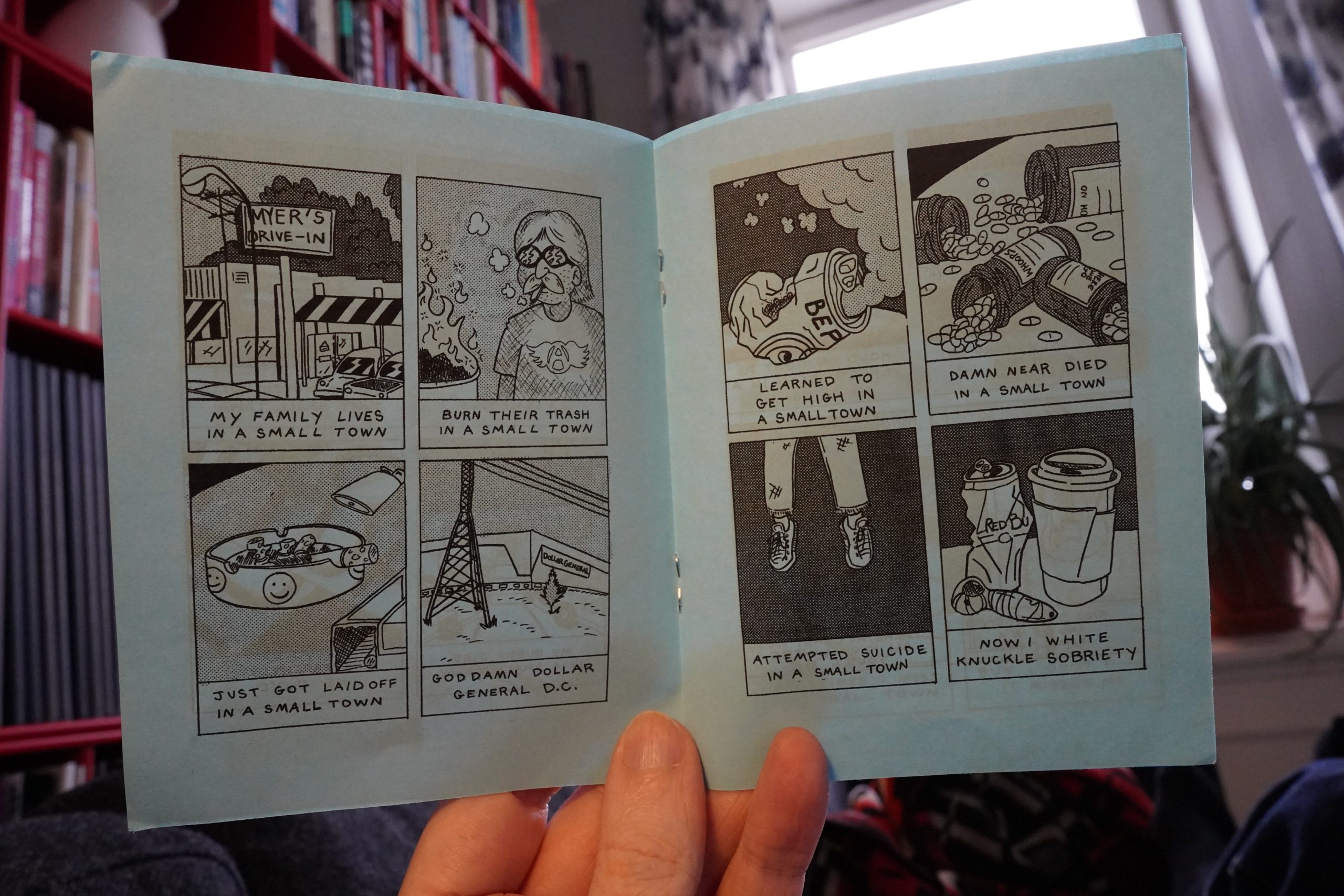

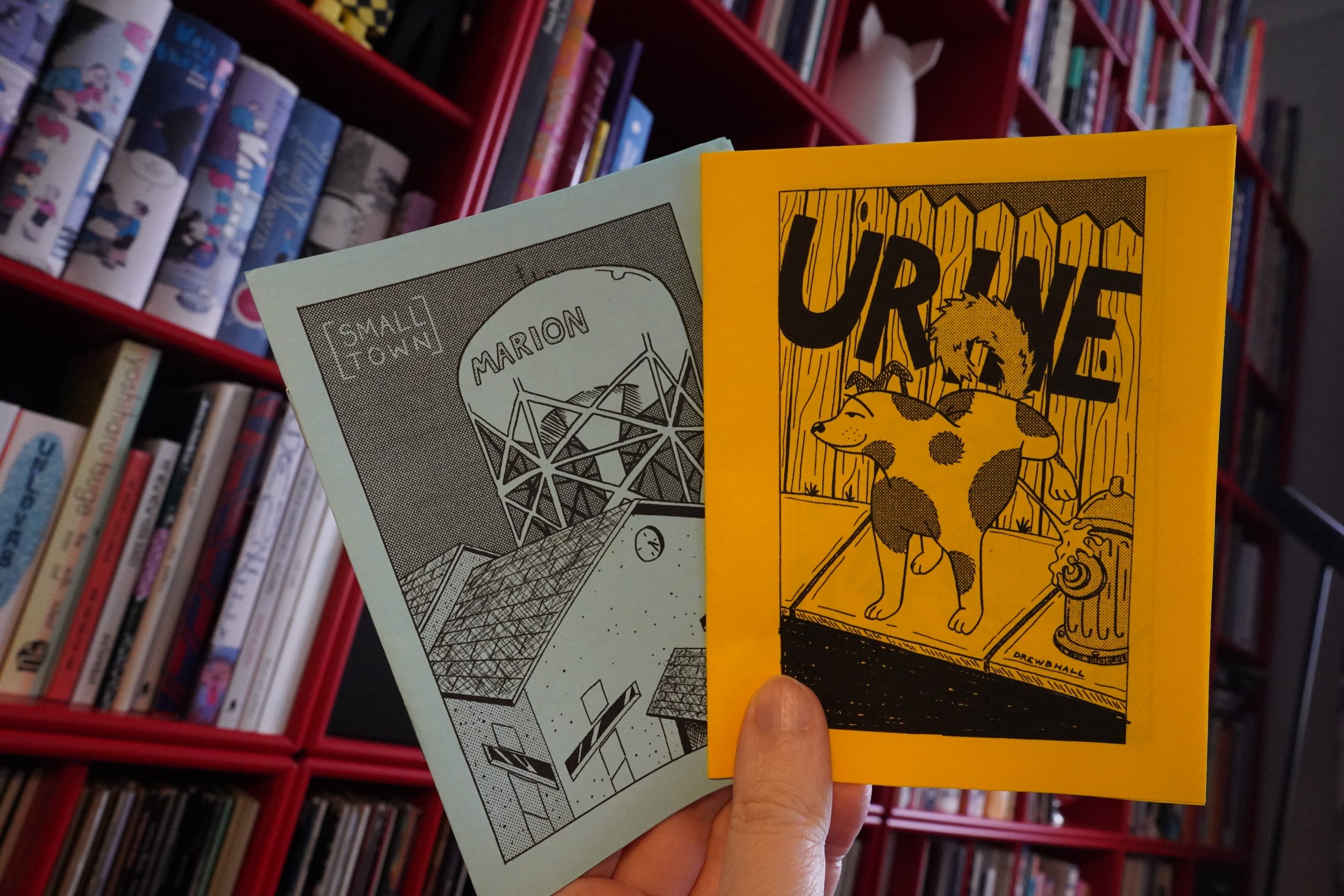

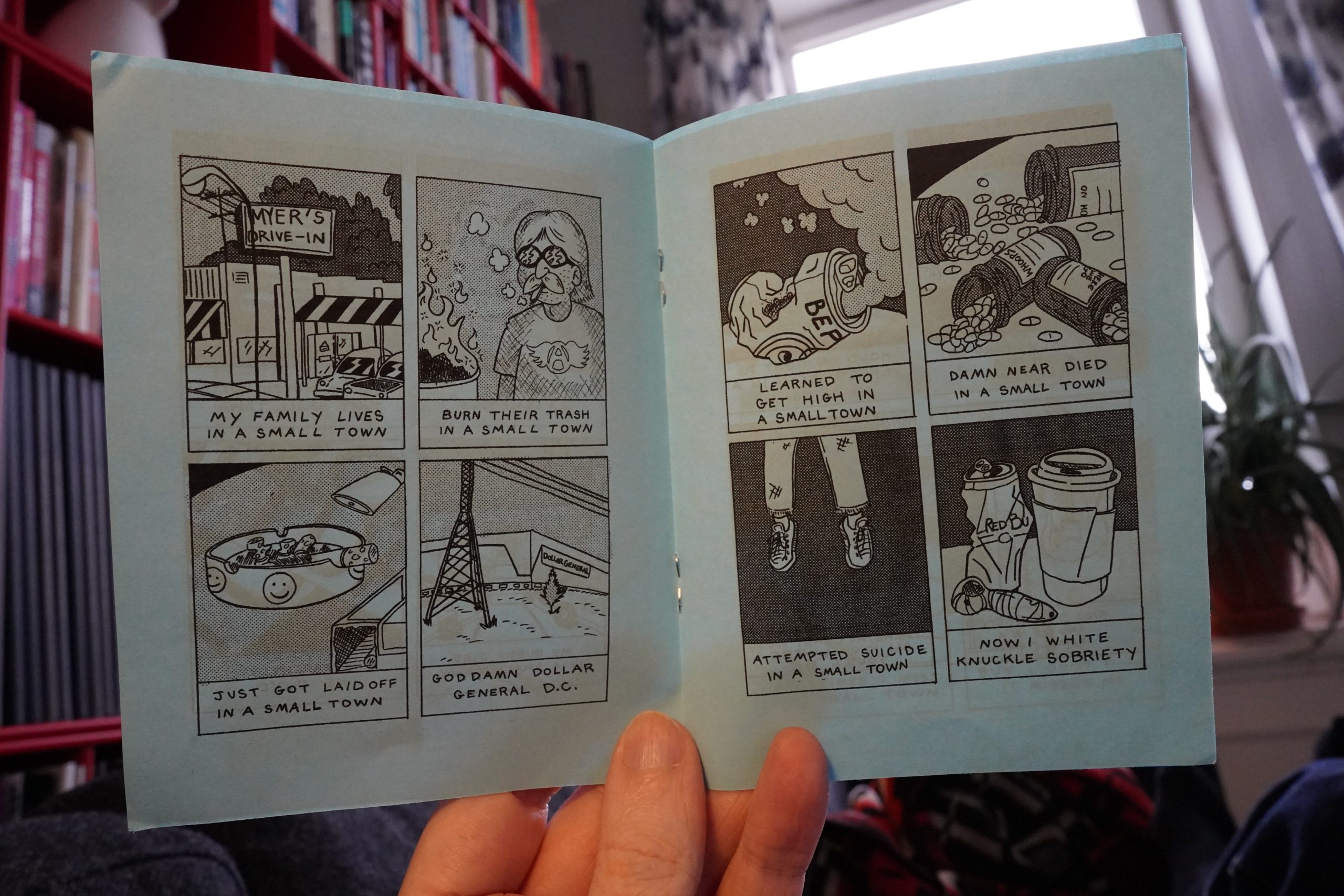

17:48: Urine & Small Town by Drew B. Hall

Is this based on a song or something?

It’s the circle of urine. I mean life.

Two fun little minis.

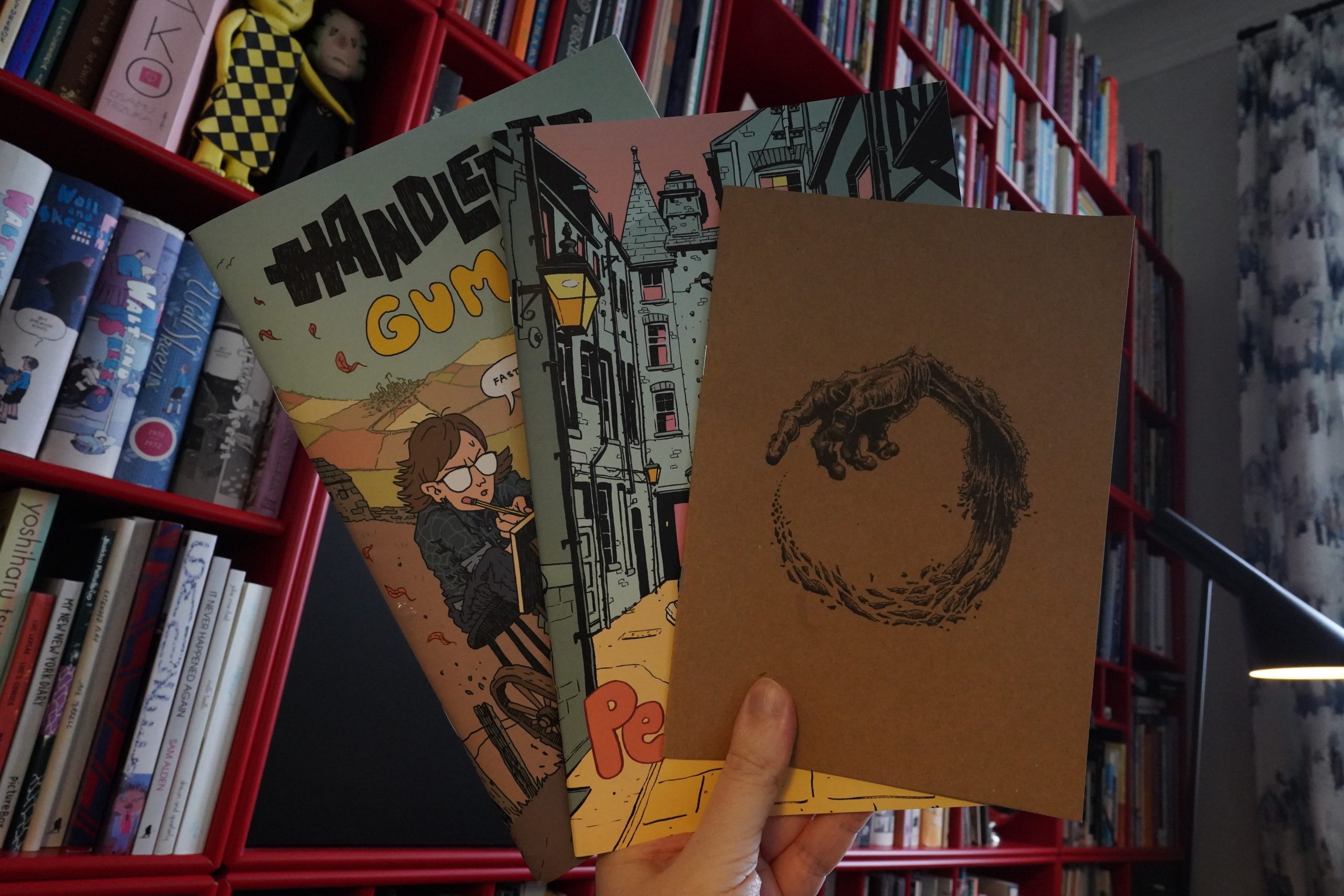

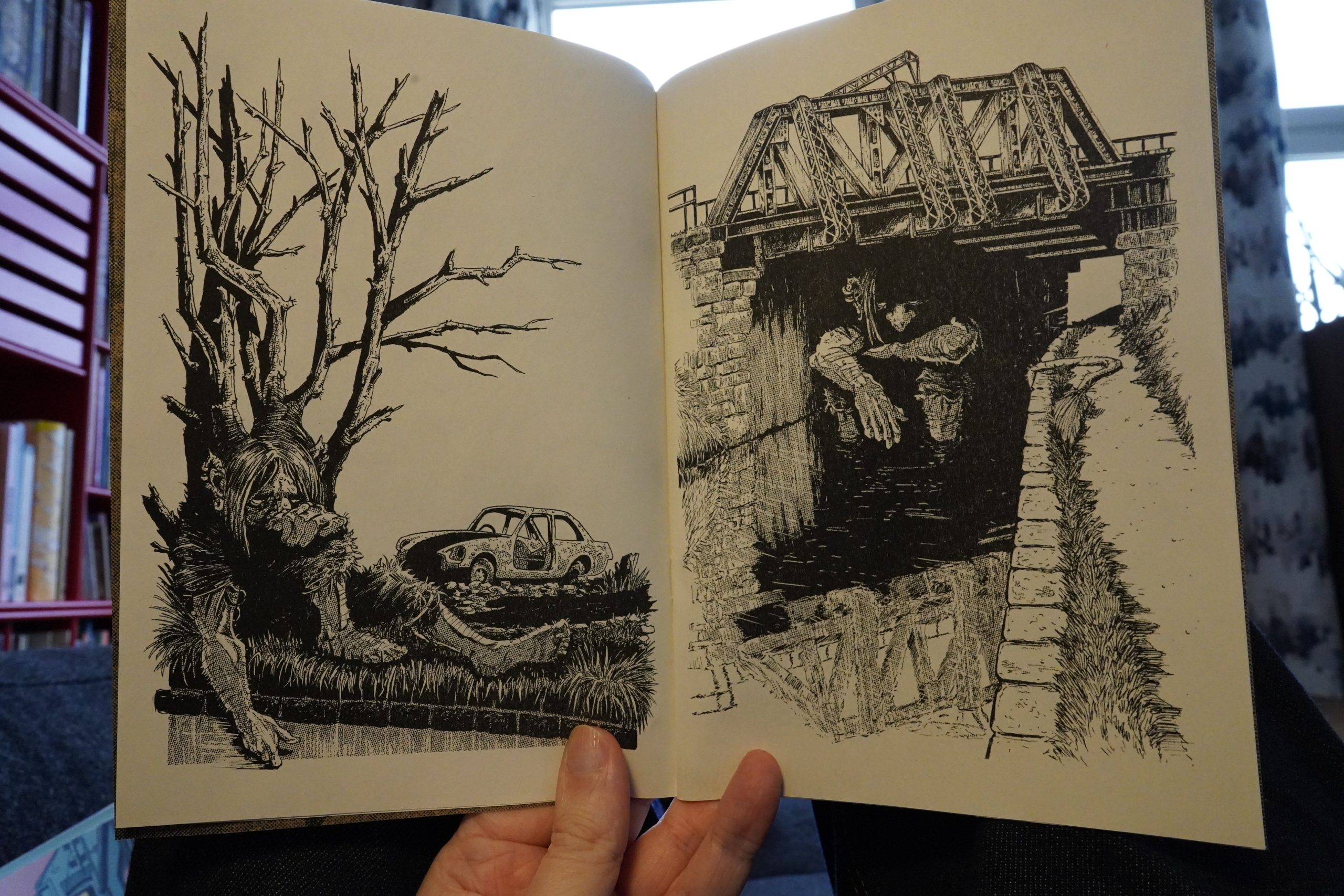

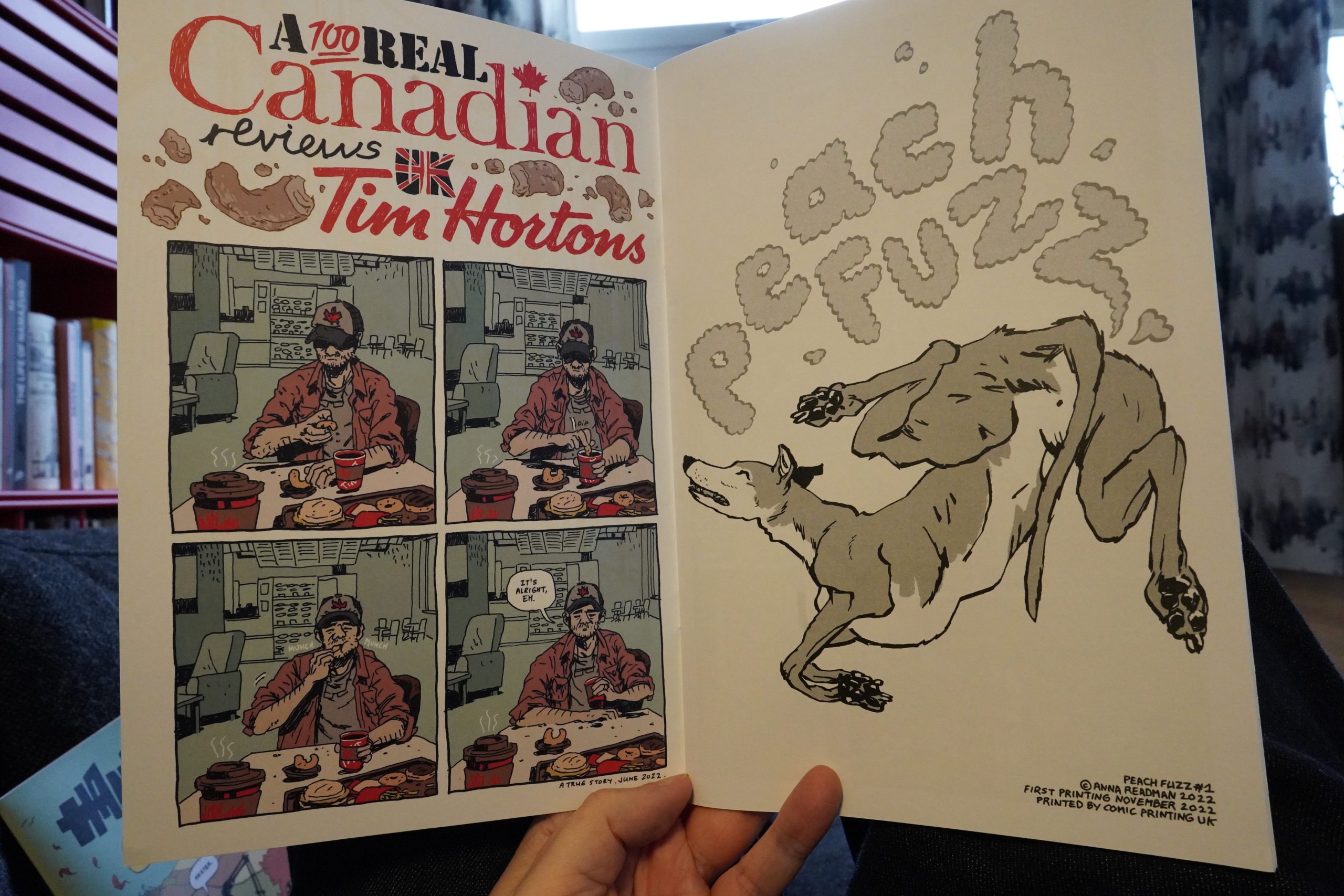

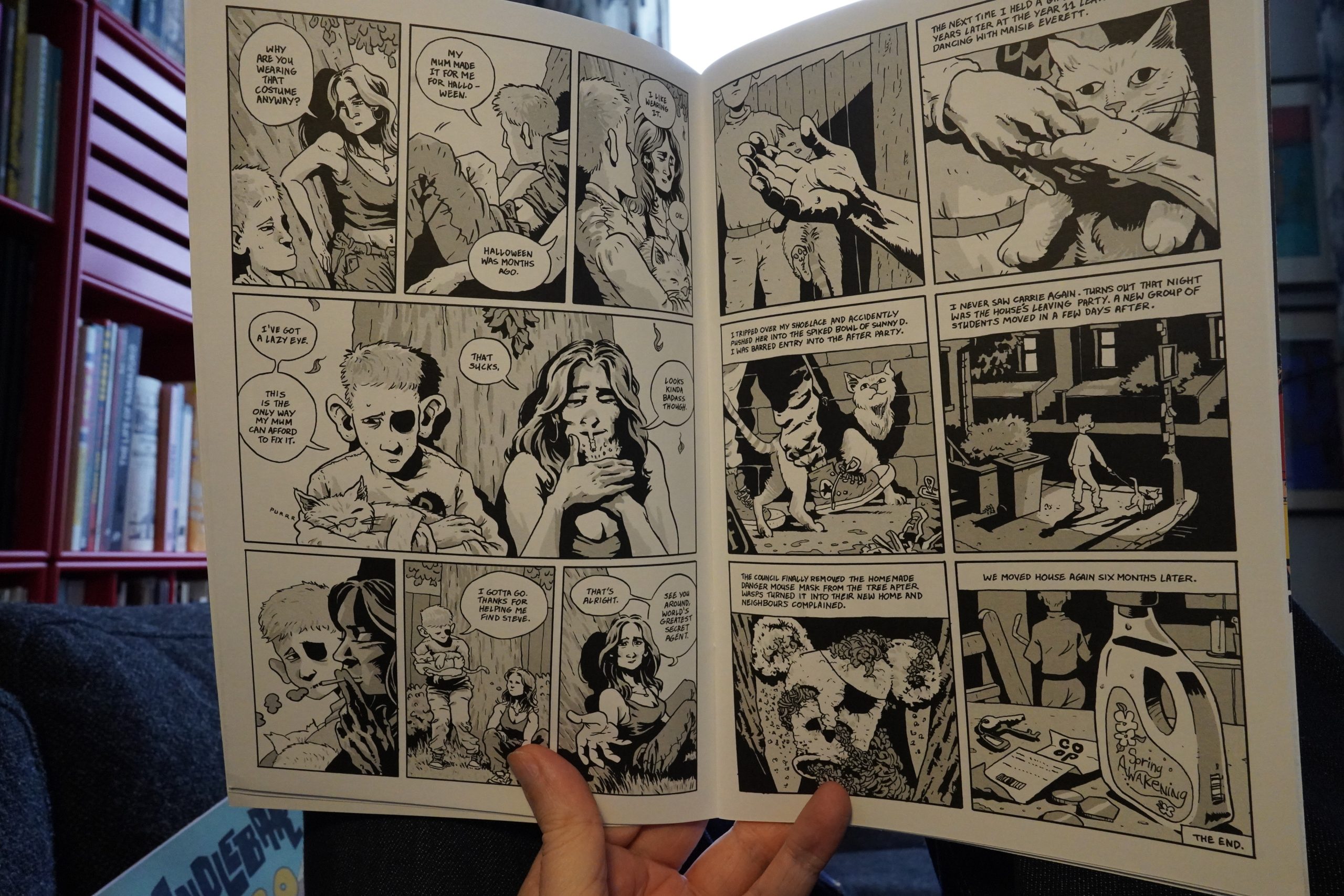

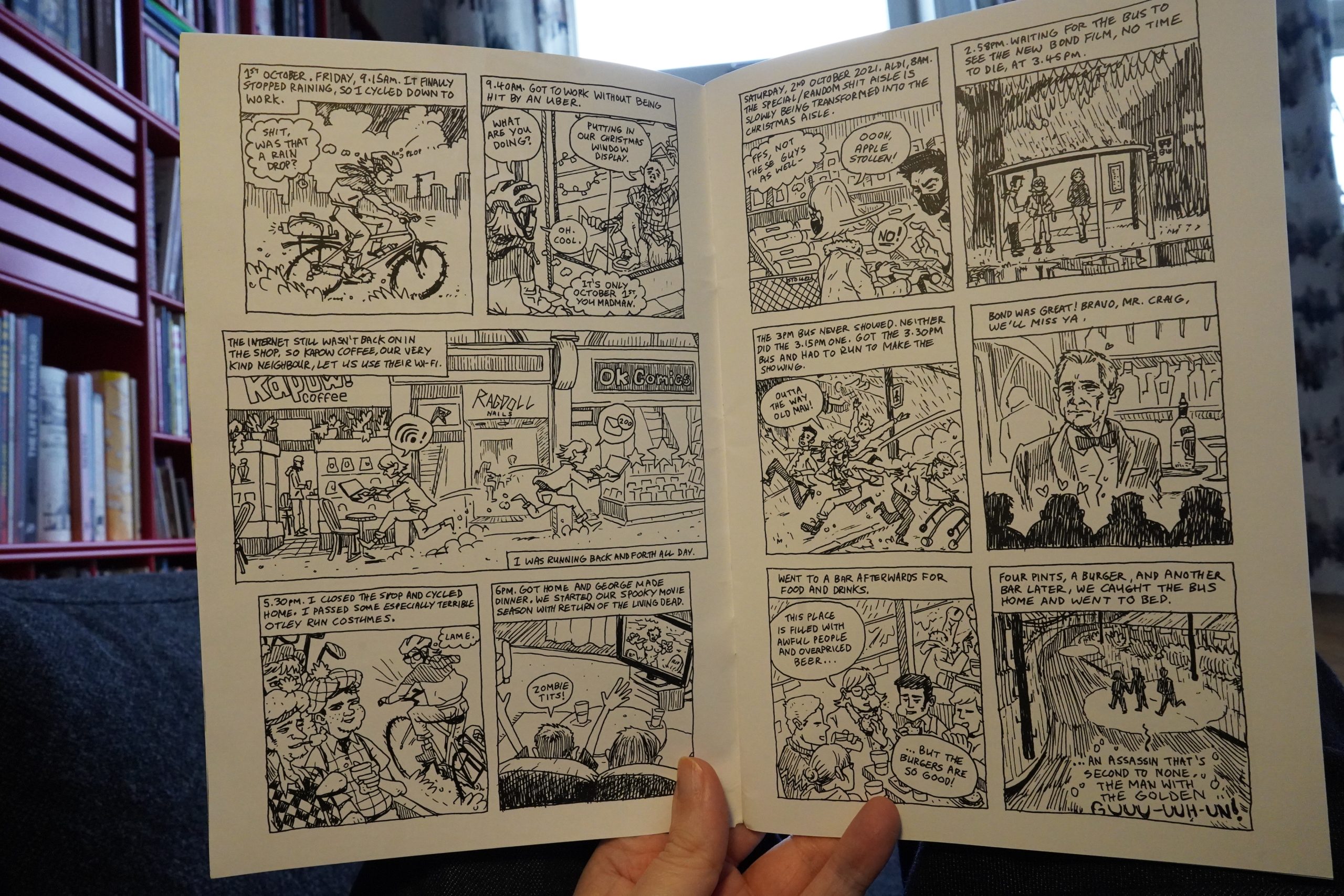

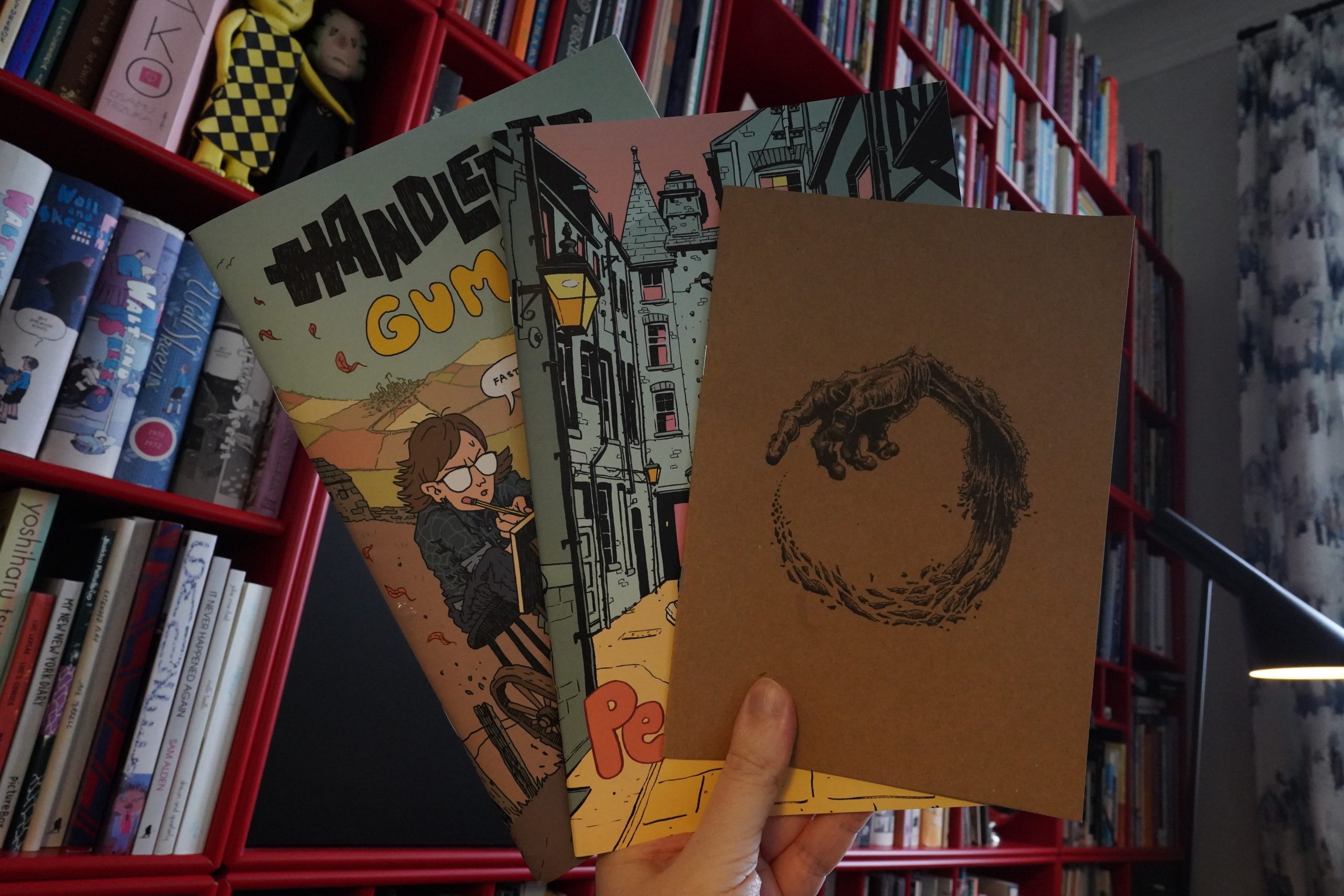

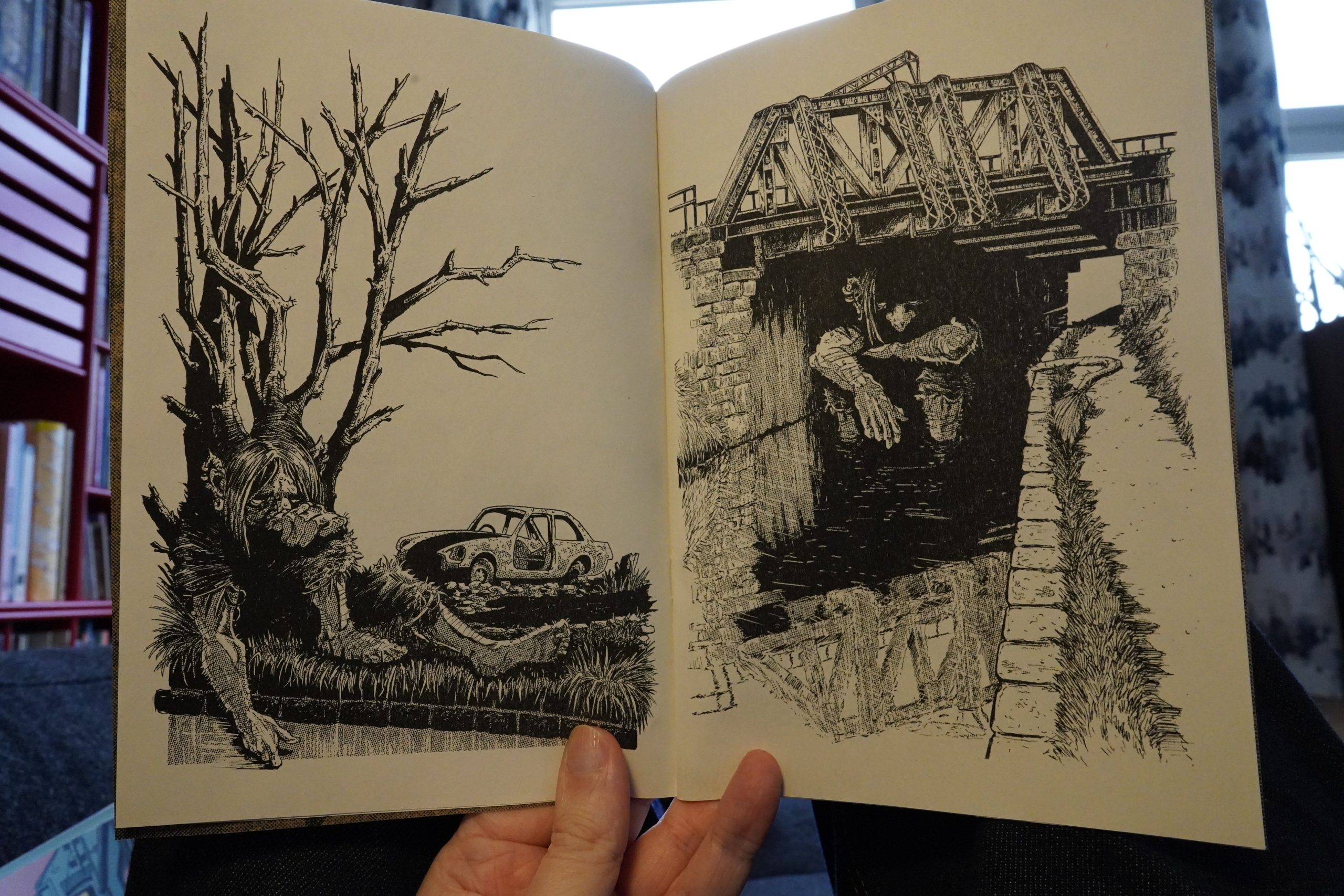

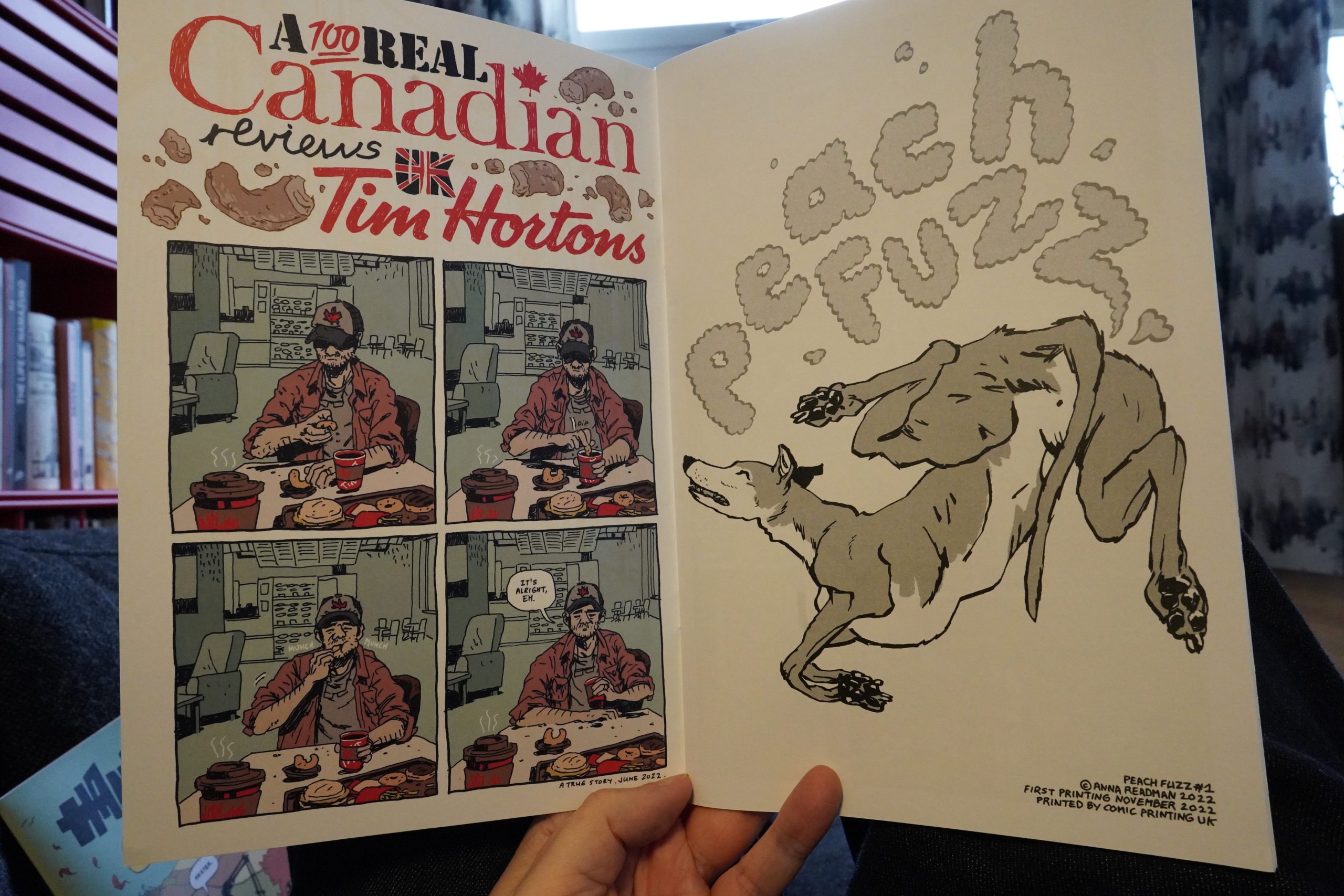

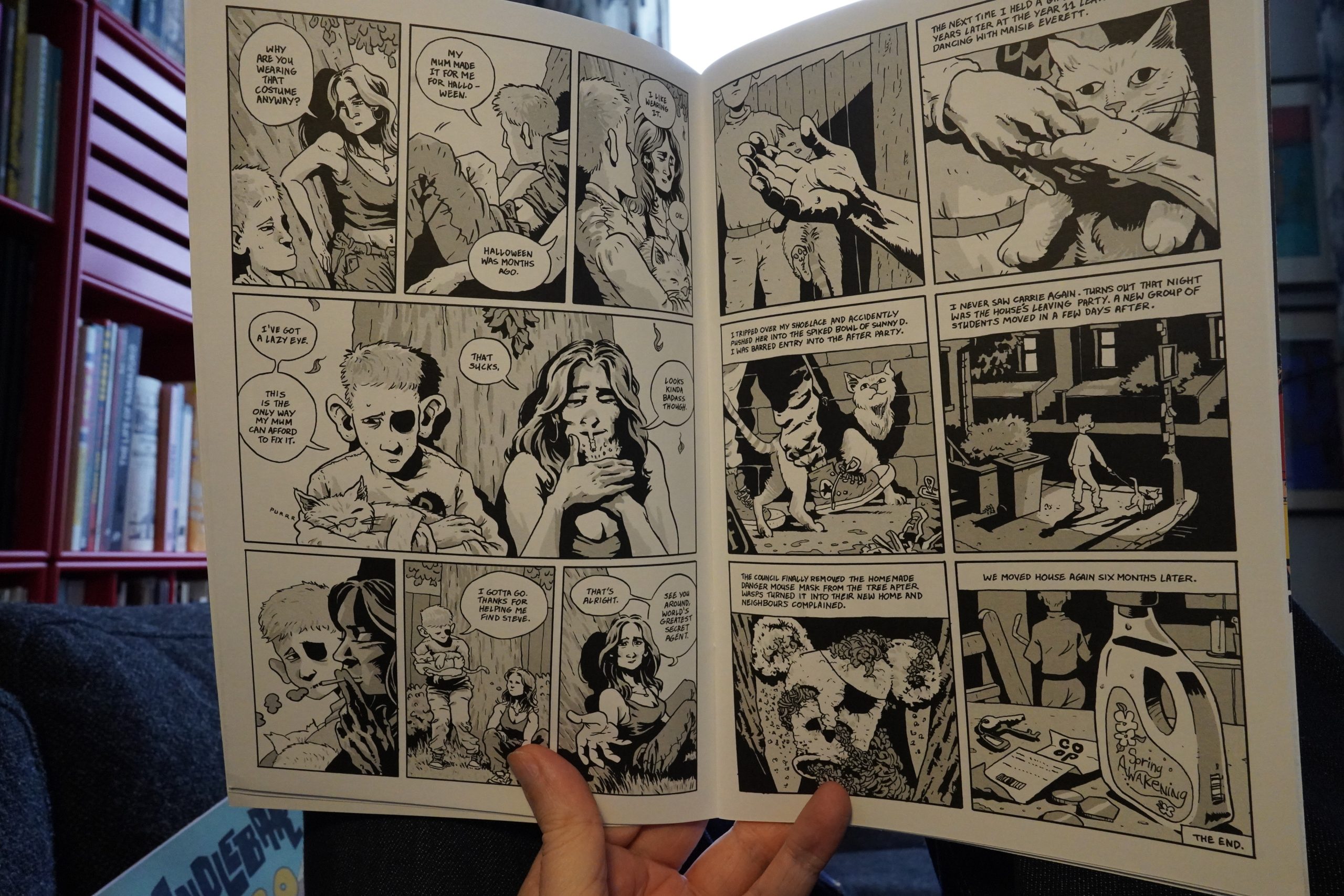

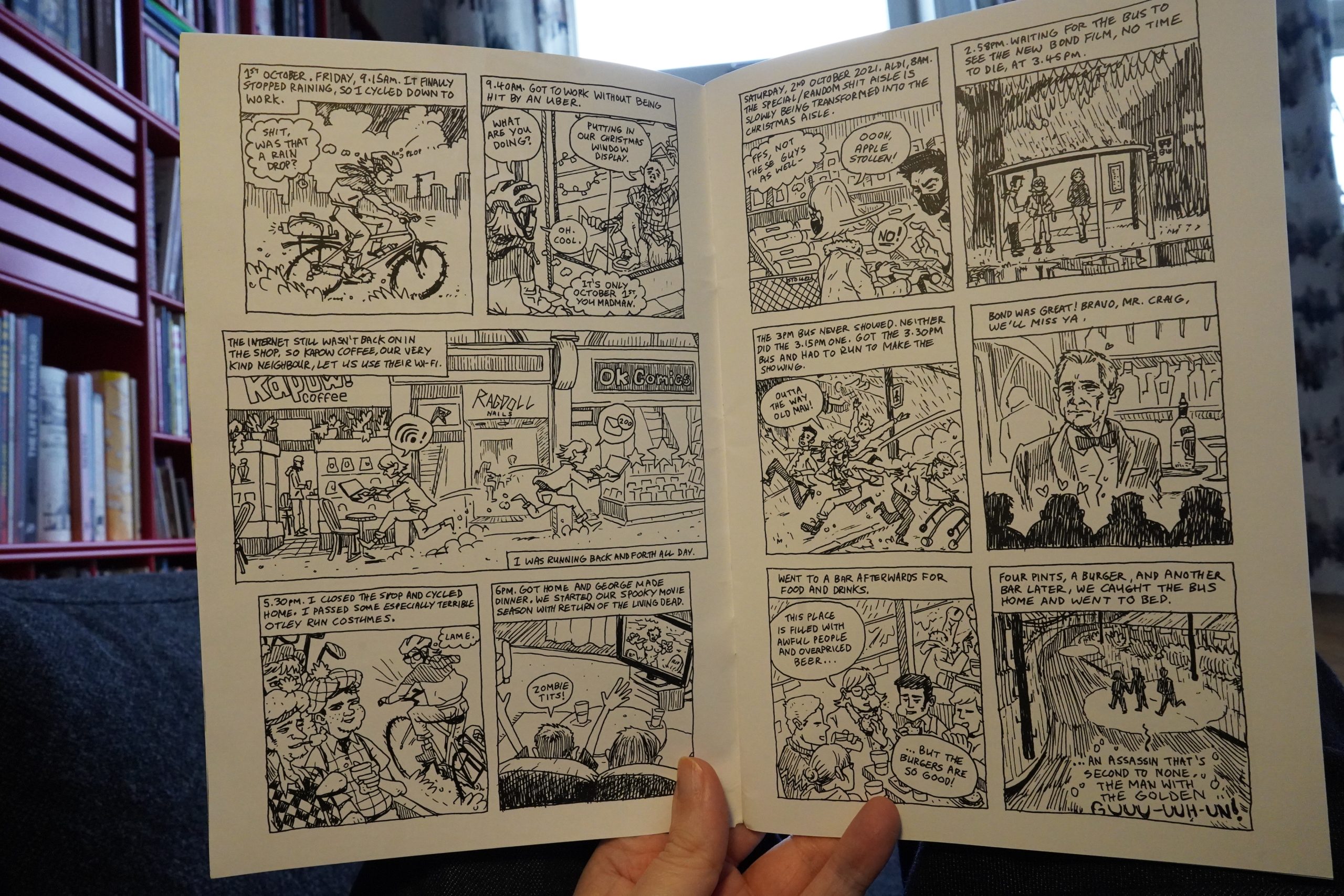

17:51: Peach Fuzz #1, Handlebar Gumbo & The Lost Loiners by Anna Readman

Last first — this is a collection of gnarly, dissatisfied trolls mostly under bridges.

Very Canadian.

Peach Fuzz has several shorter stories, and I love the art style — it’s like proper 90s alternative cartooning. The stories feel really fresh and have impact — great stuff.

Finally, a book of diary comics, and it’s very amusing. And very young — it’s about working in a comics shop, watching horror movies and biking. Very refreshing.

Buy these comics from Readman’s web site.

| Kate Bush: Remastered (8): Aerial: A Sea Of Honey |  |

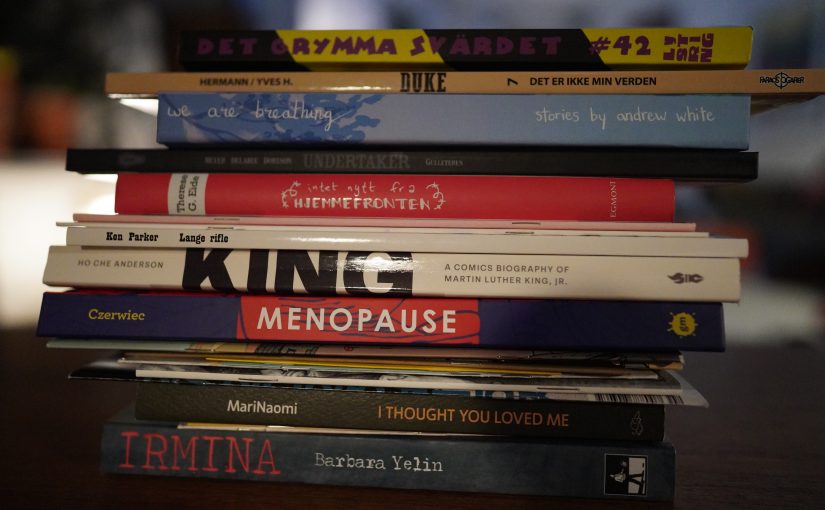

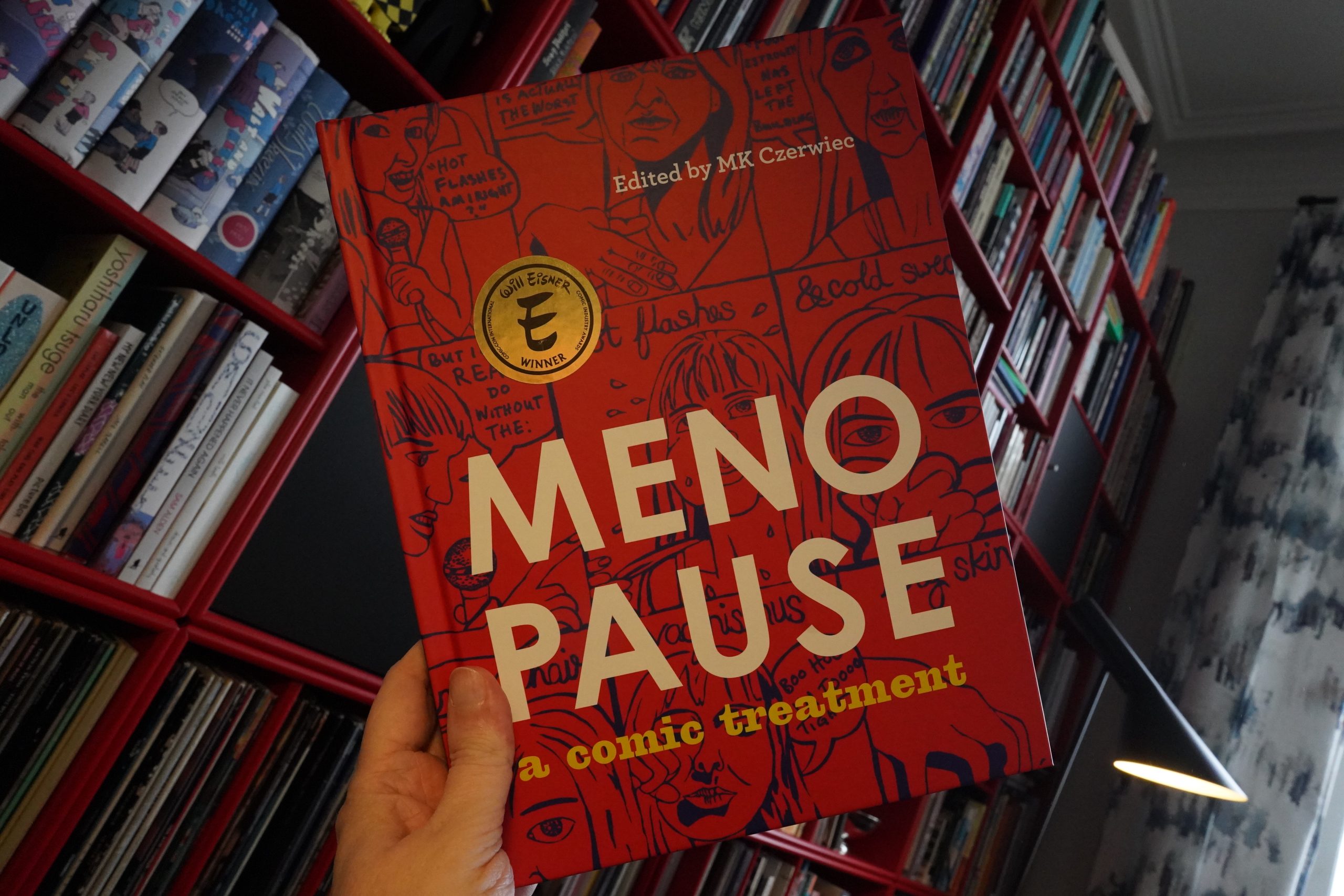

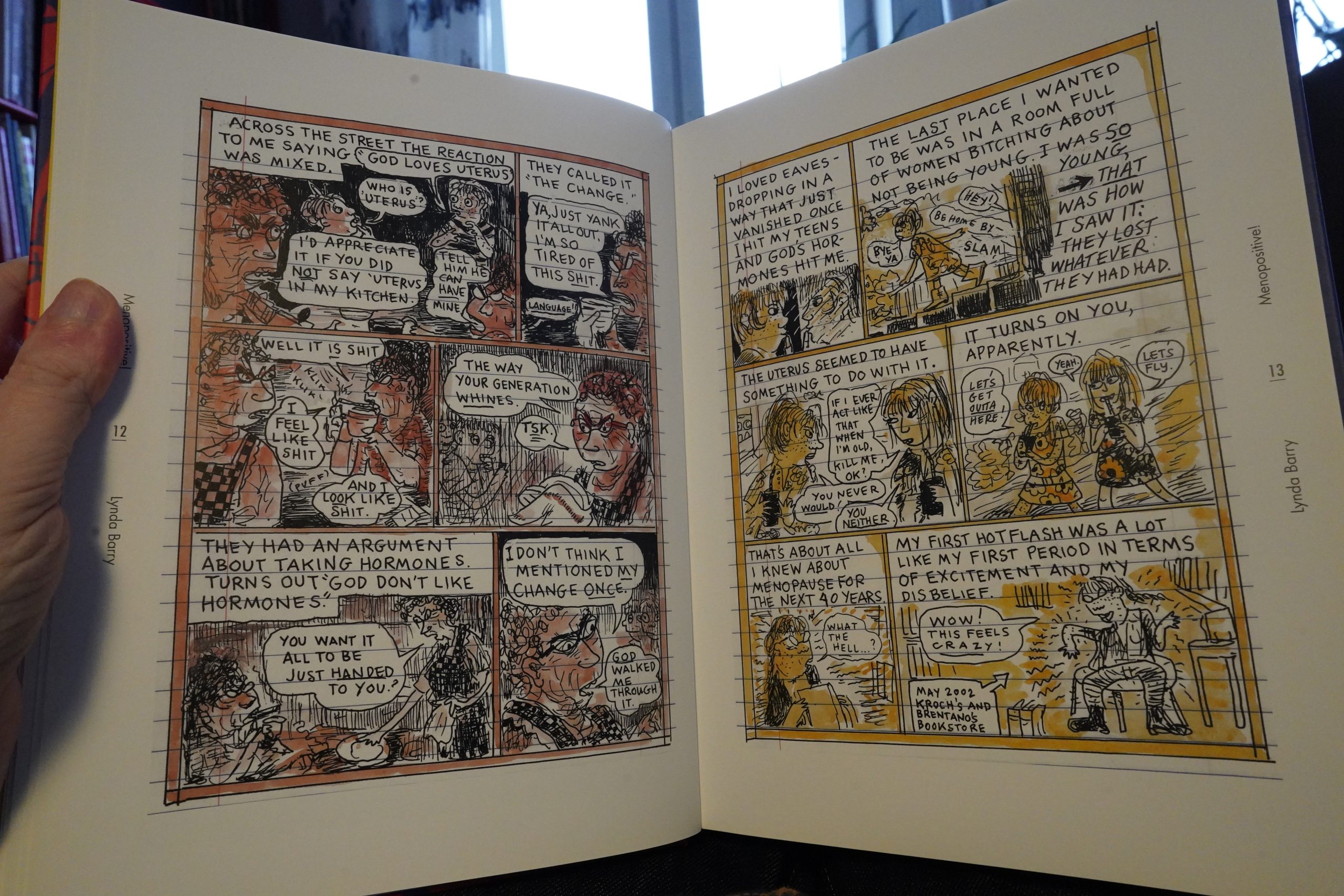

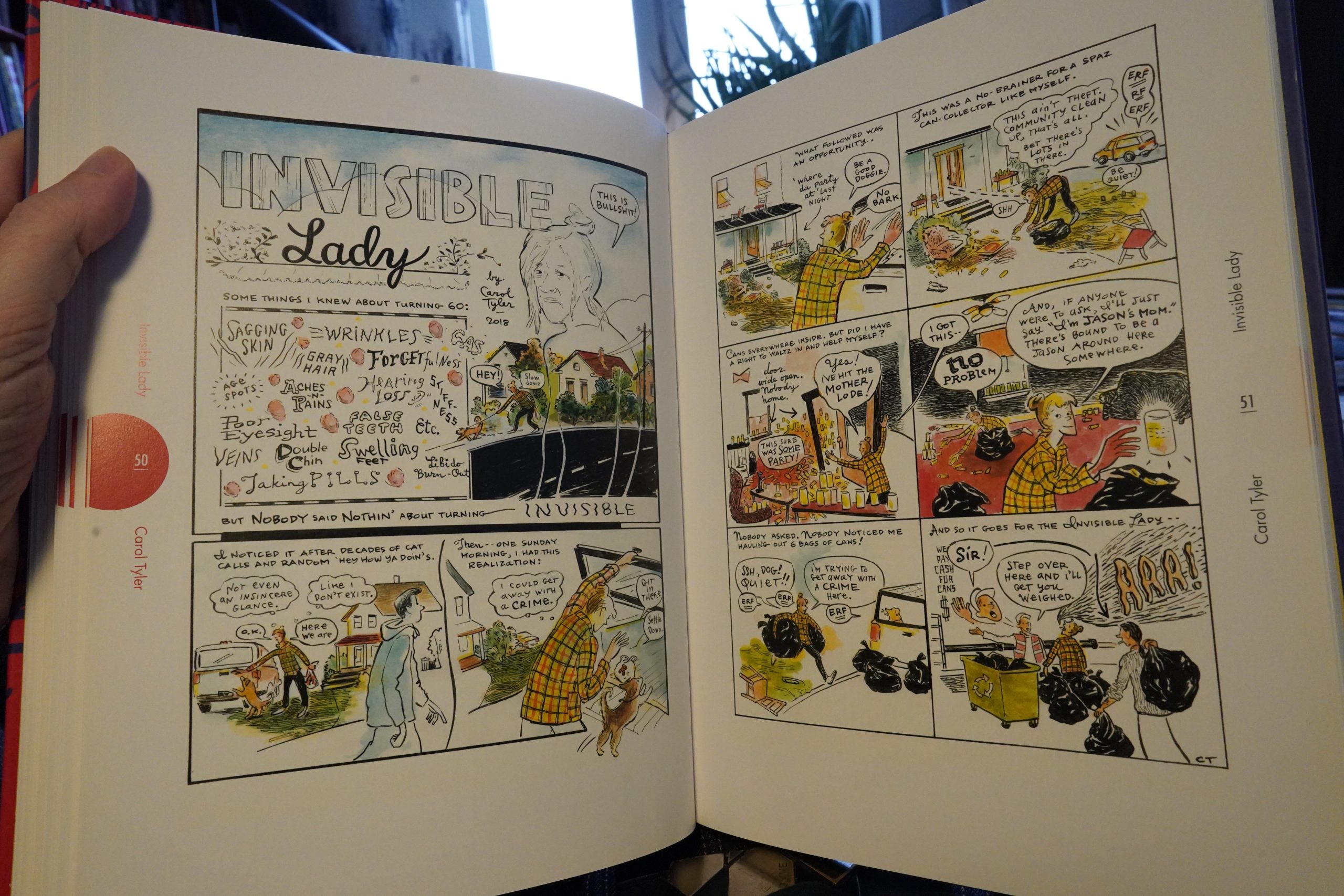

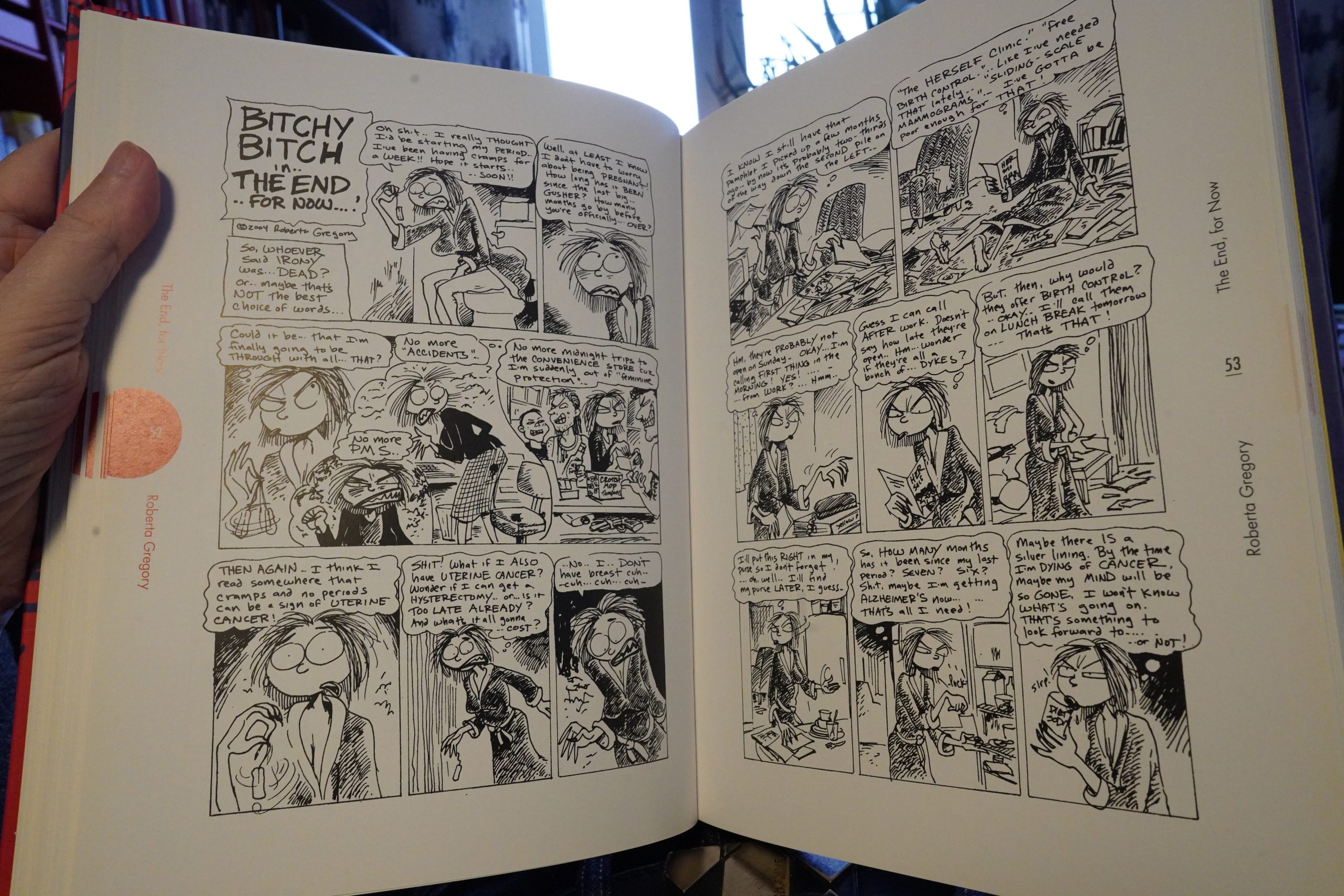

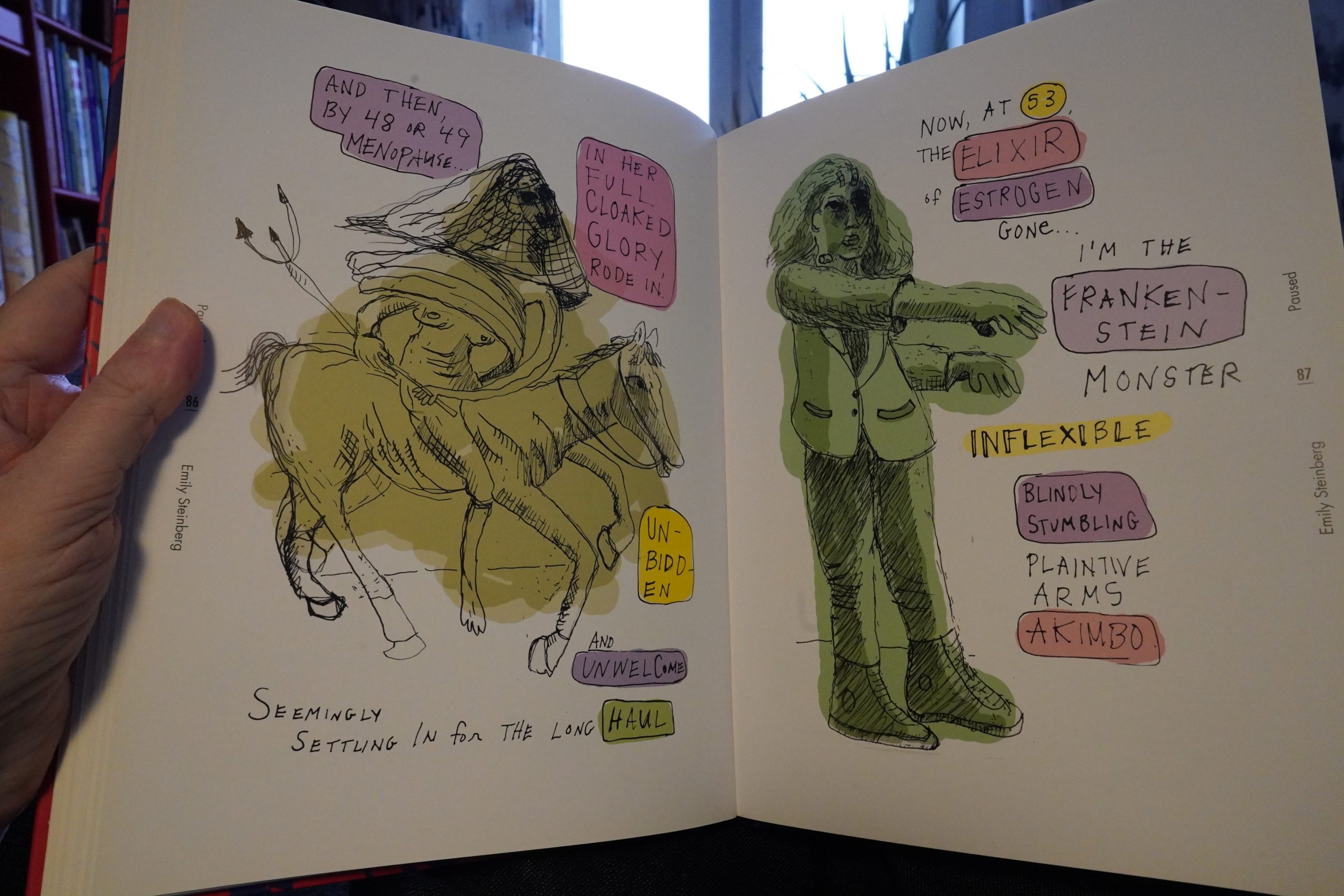

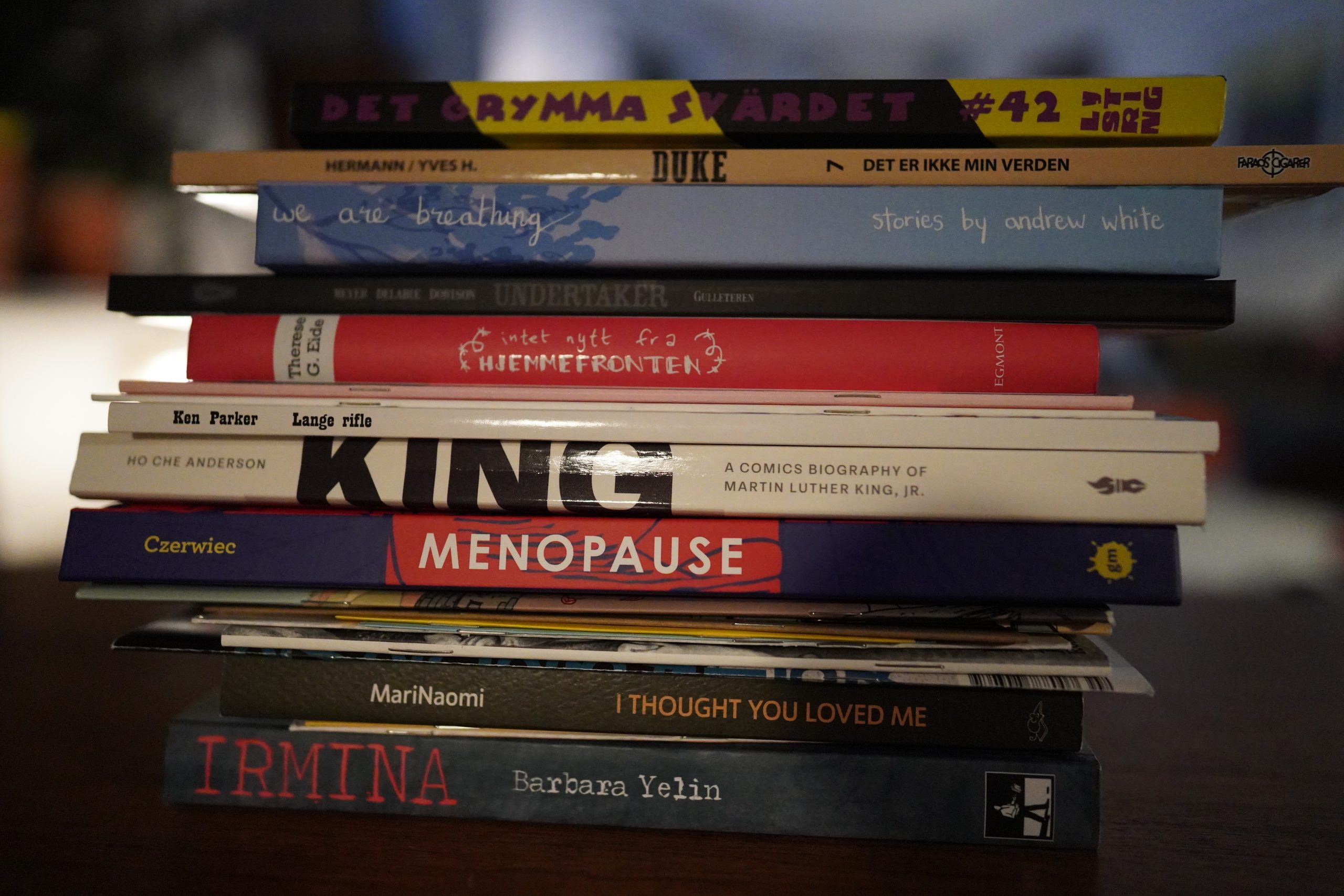

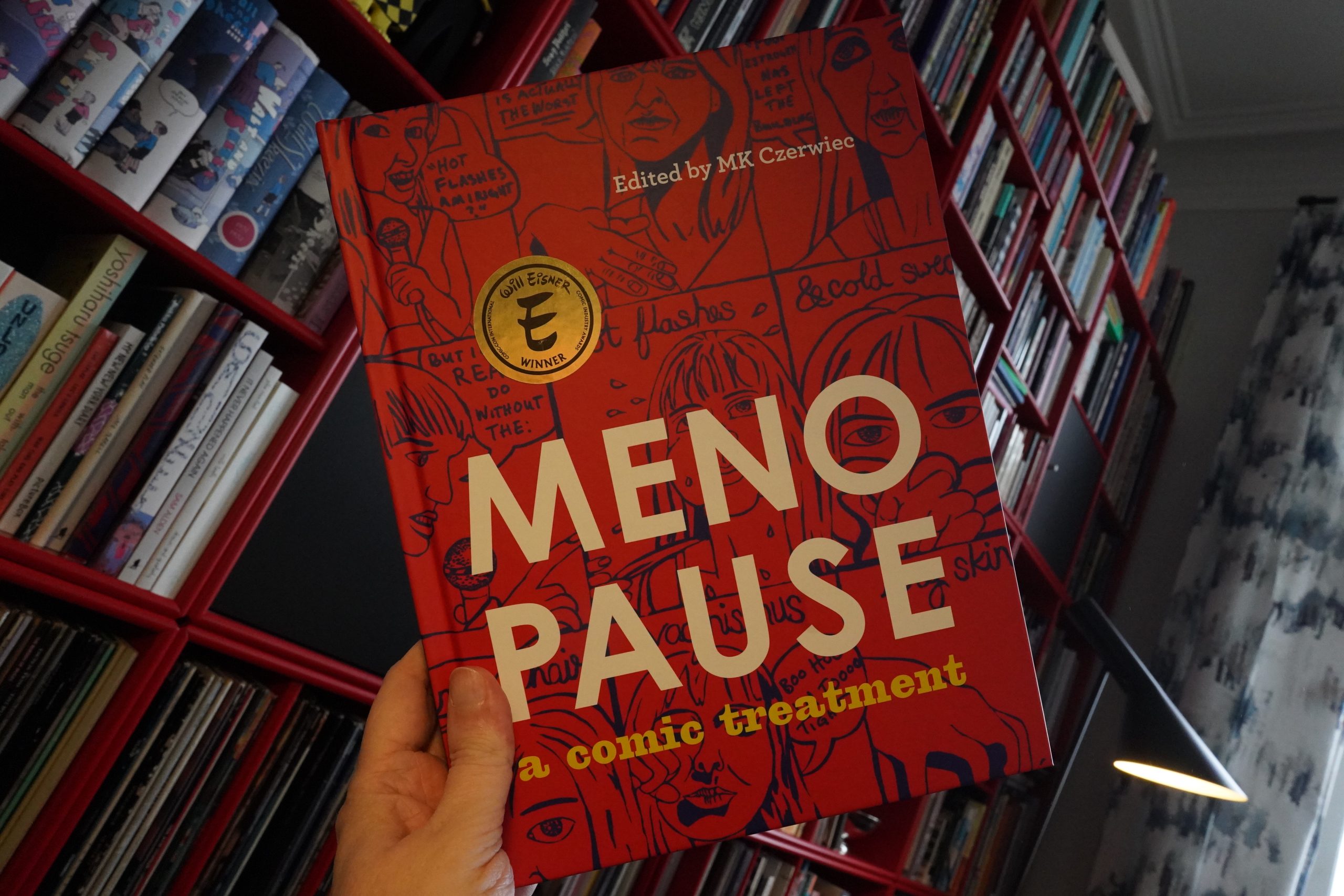

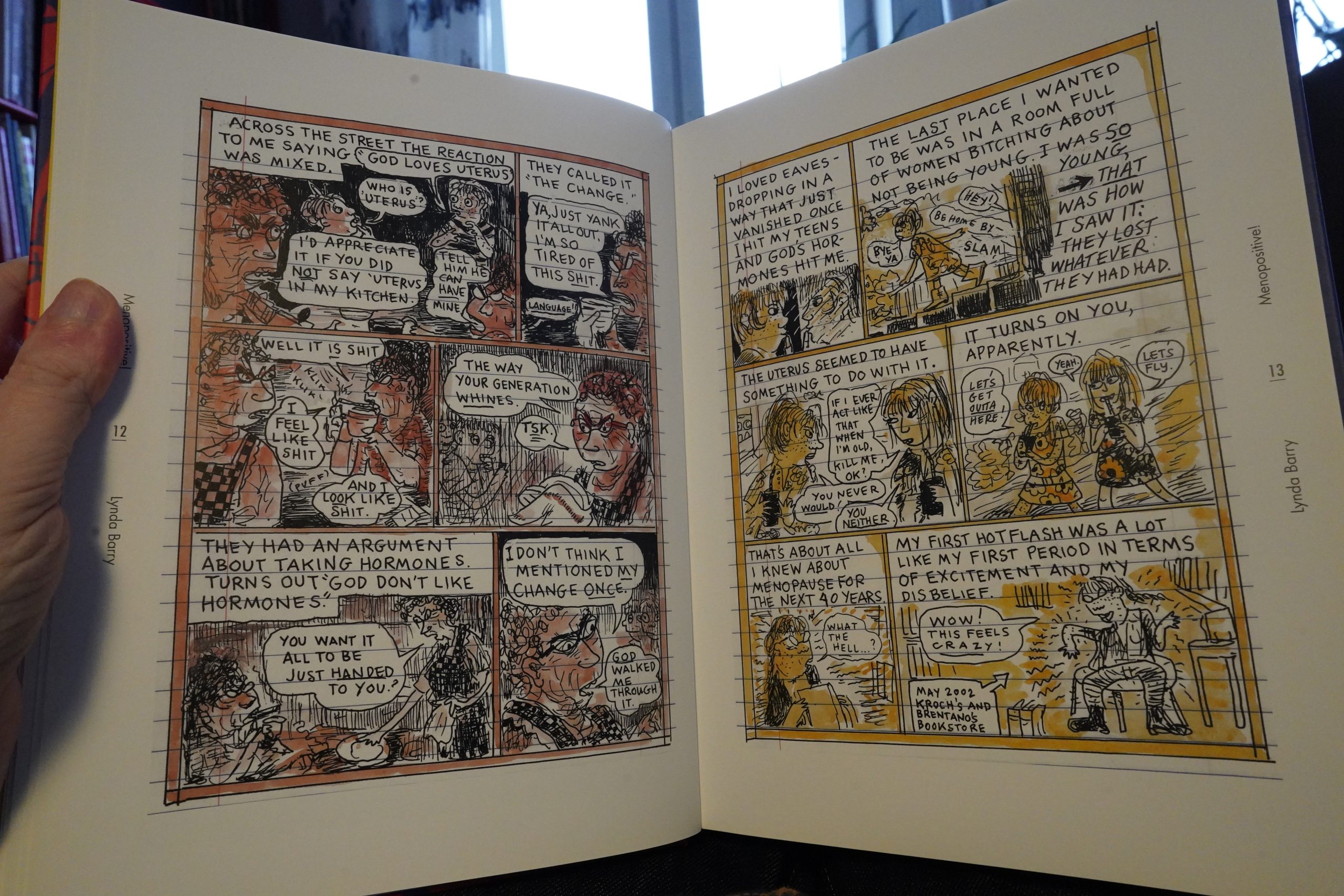

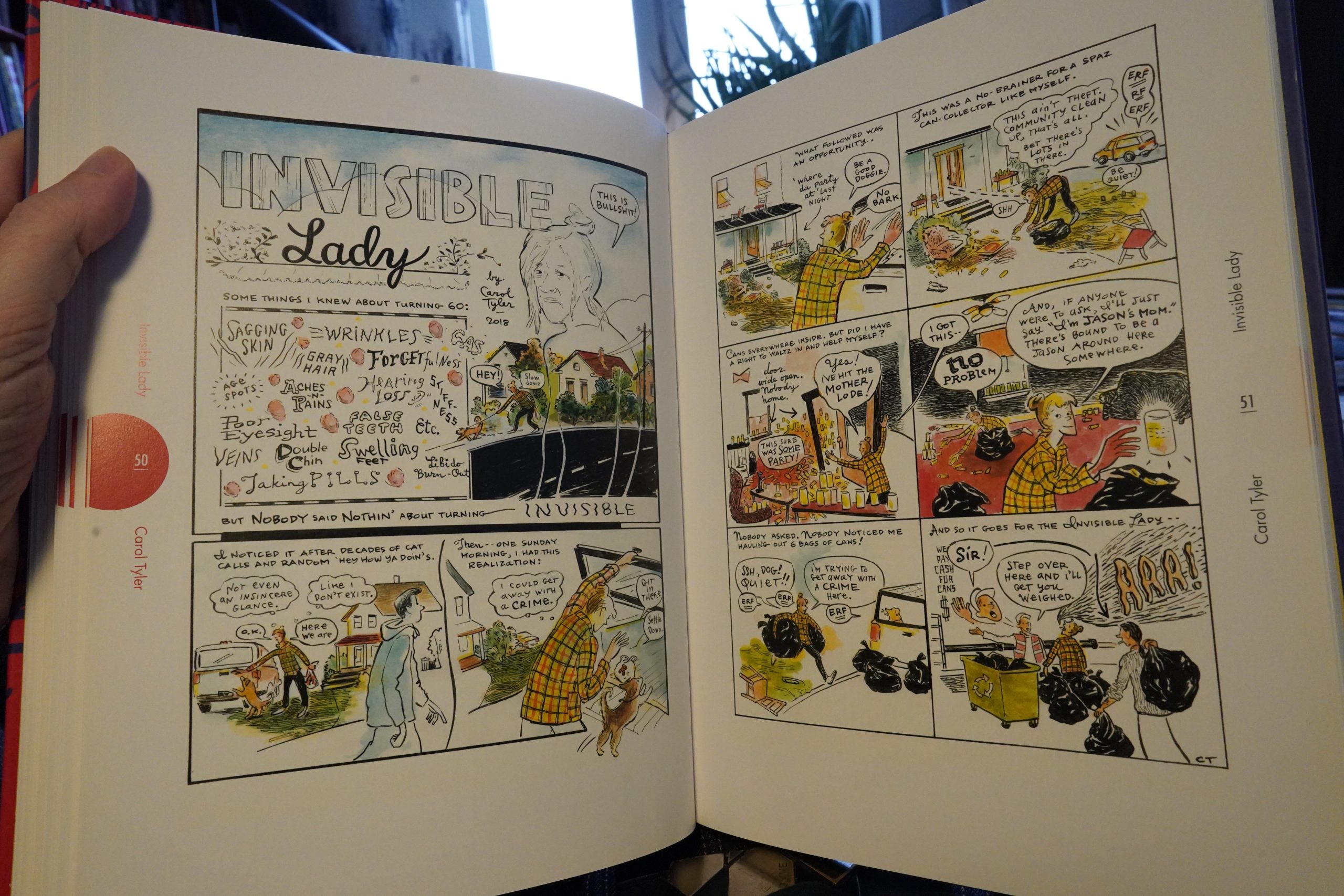

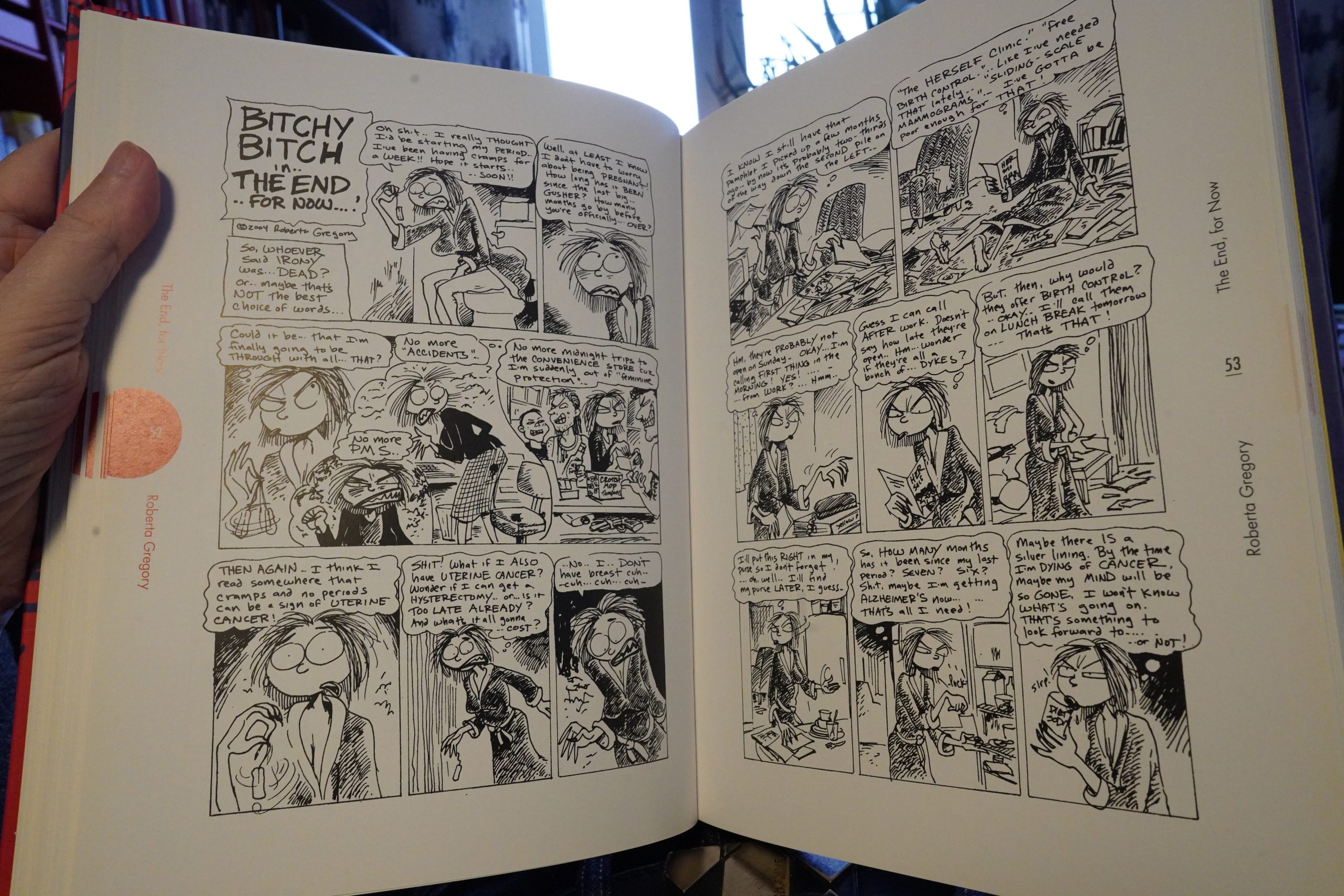

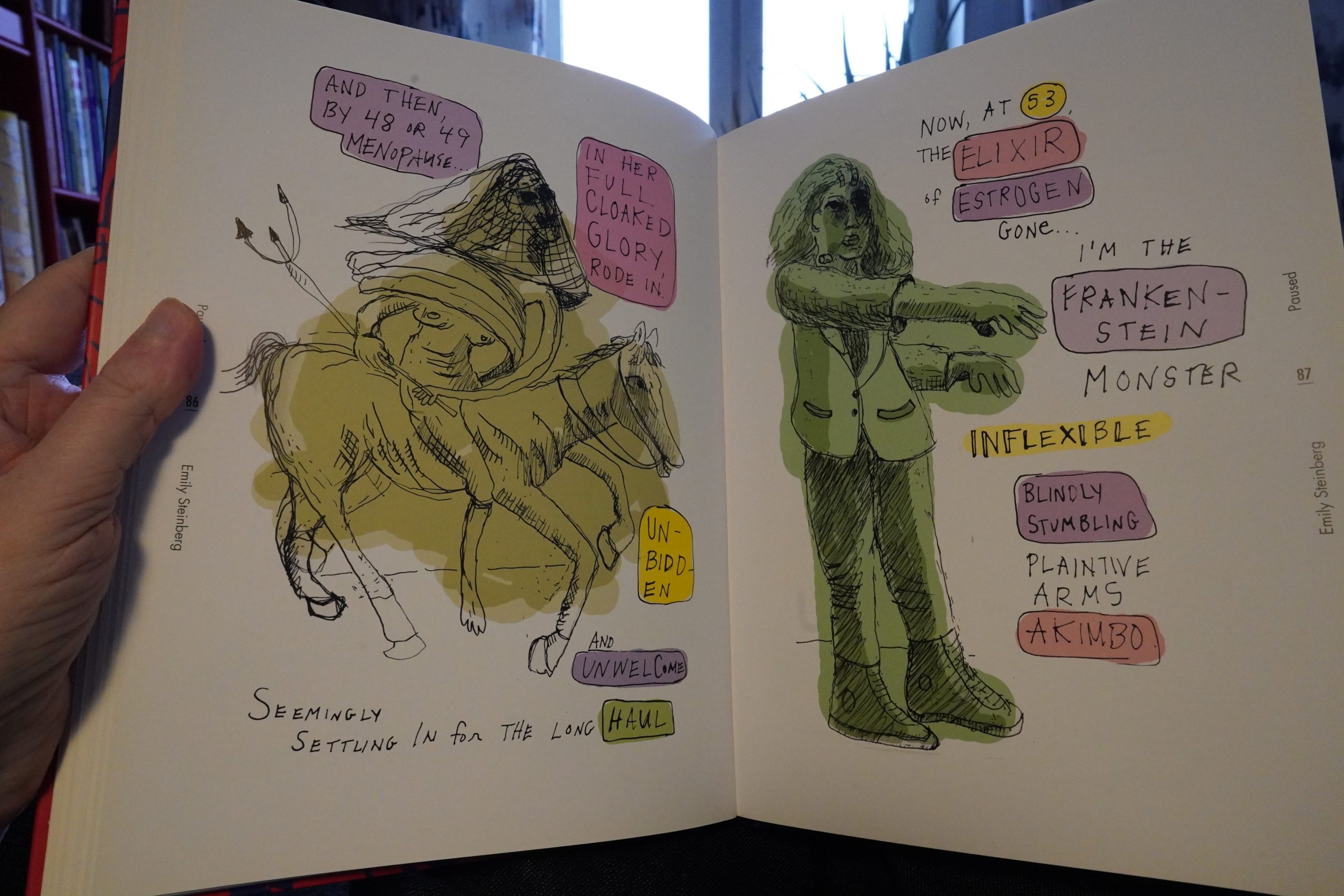

18:33: Menopause by MK Czerwiec (Graphic Mundi)

This book is chock full of short pieces about menopause. Some big names (like Lynda Barry above), but also a lot of less well known people (and I’m guessing it’s the first comic for many people).

There’s a lot of great stuff (Carol Tyler above), but there’s also a many pieces that are just “rah rah menopause”, which isn’t that exciting.

Most of the pieces seem to be made in 2018, but I’ve read at least two of them before, so there’s also some older reprints here (like this Roberta Gregory Bitchy Bitch thing).

Well, OK, there’s one piece that refreshingly non-rah rah (by Emily Steinberg).

It’s a pretty solid anthology.

| Kate Bush: Remastered (9): Aerial: A Sky of Honey |  |

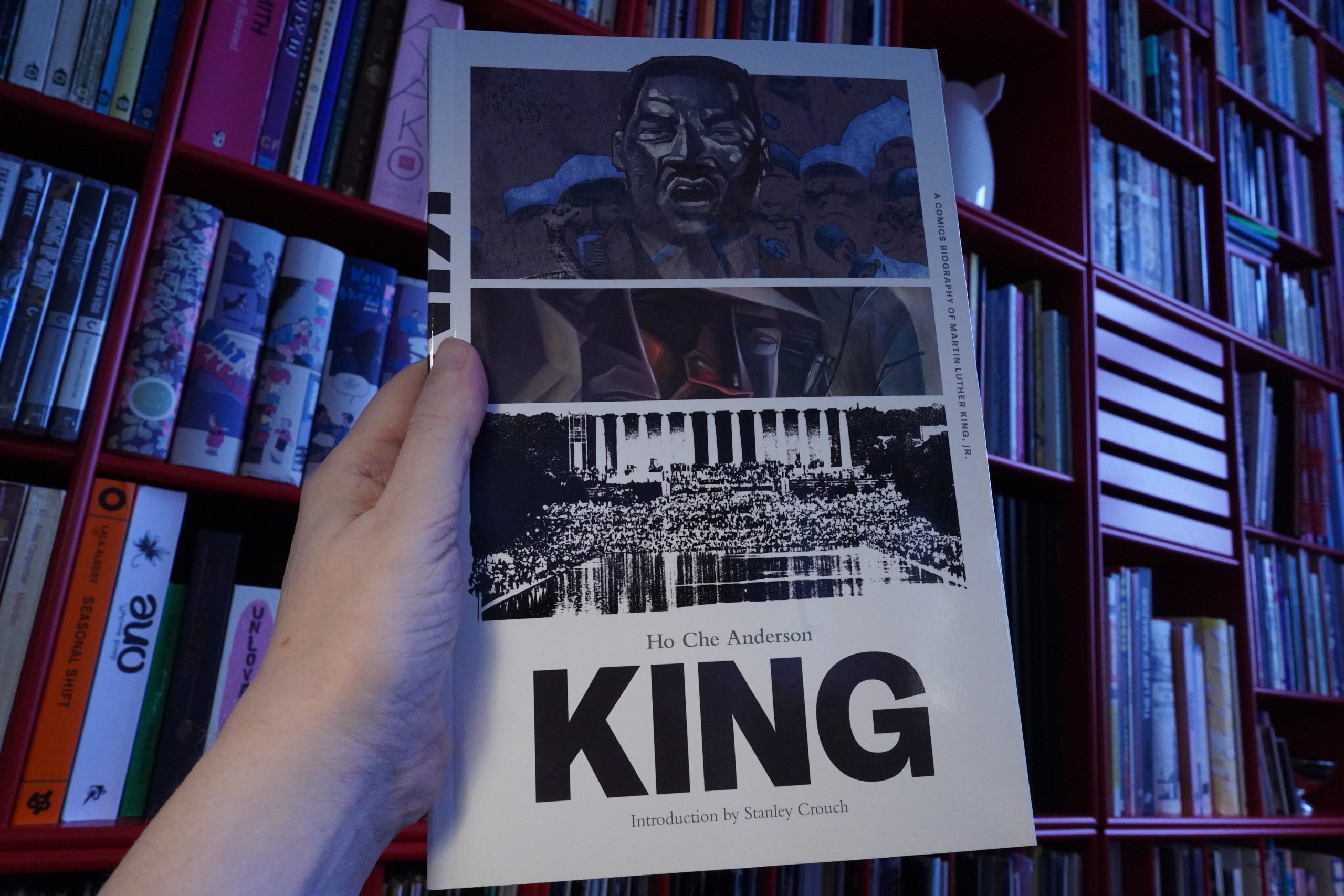

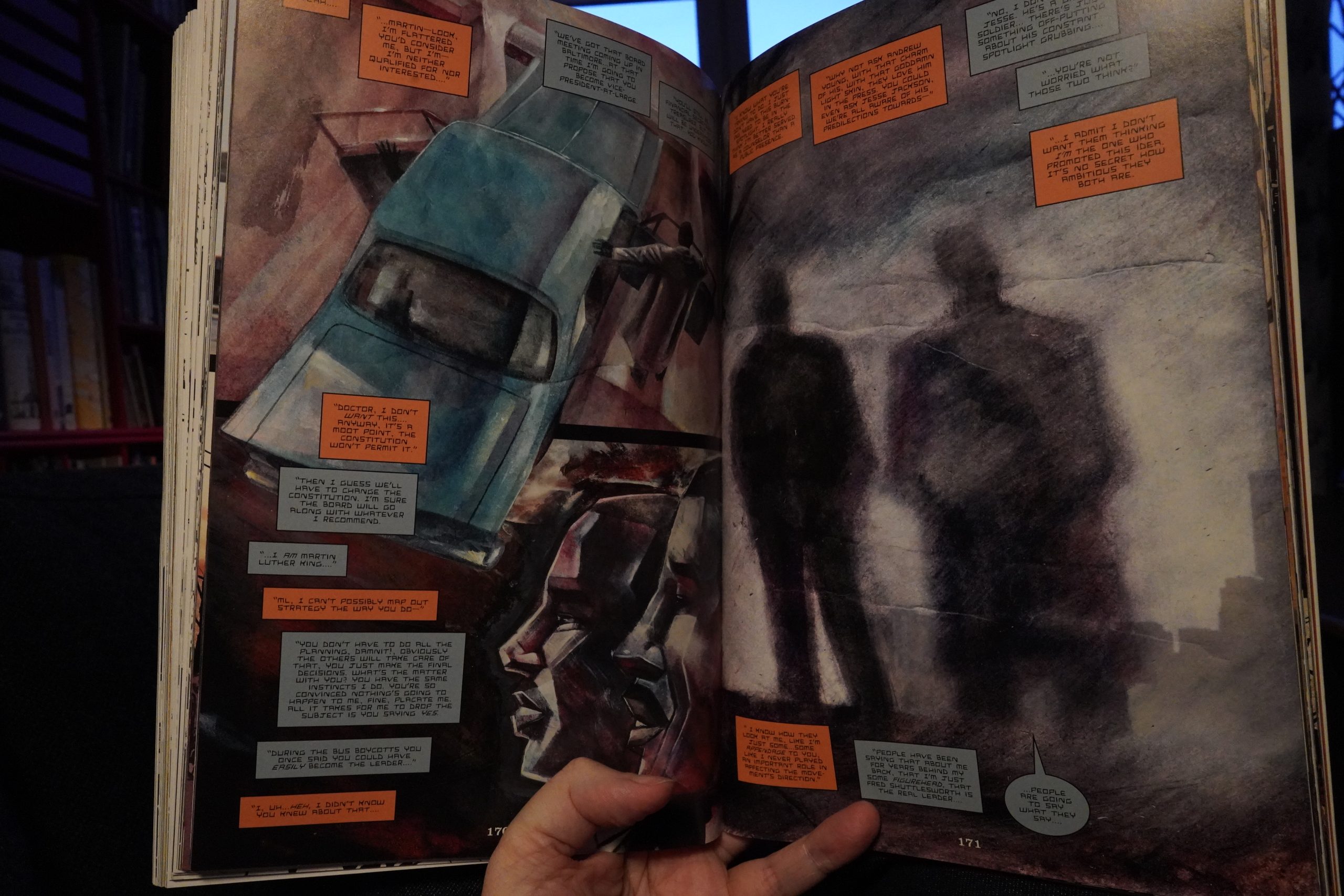

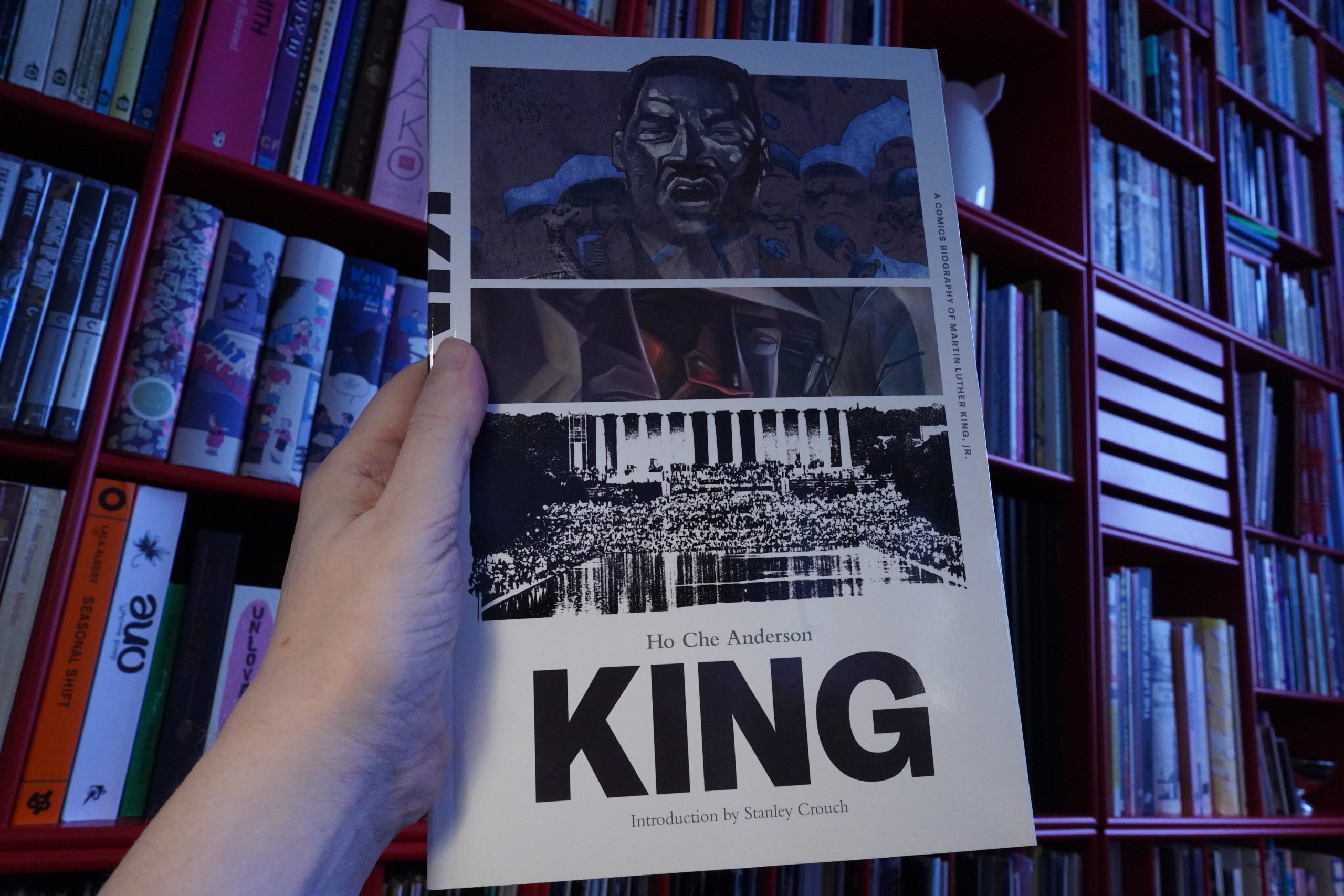

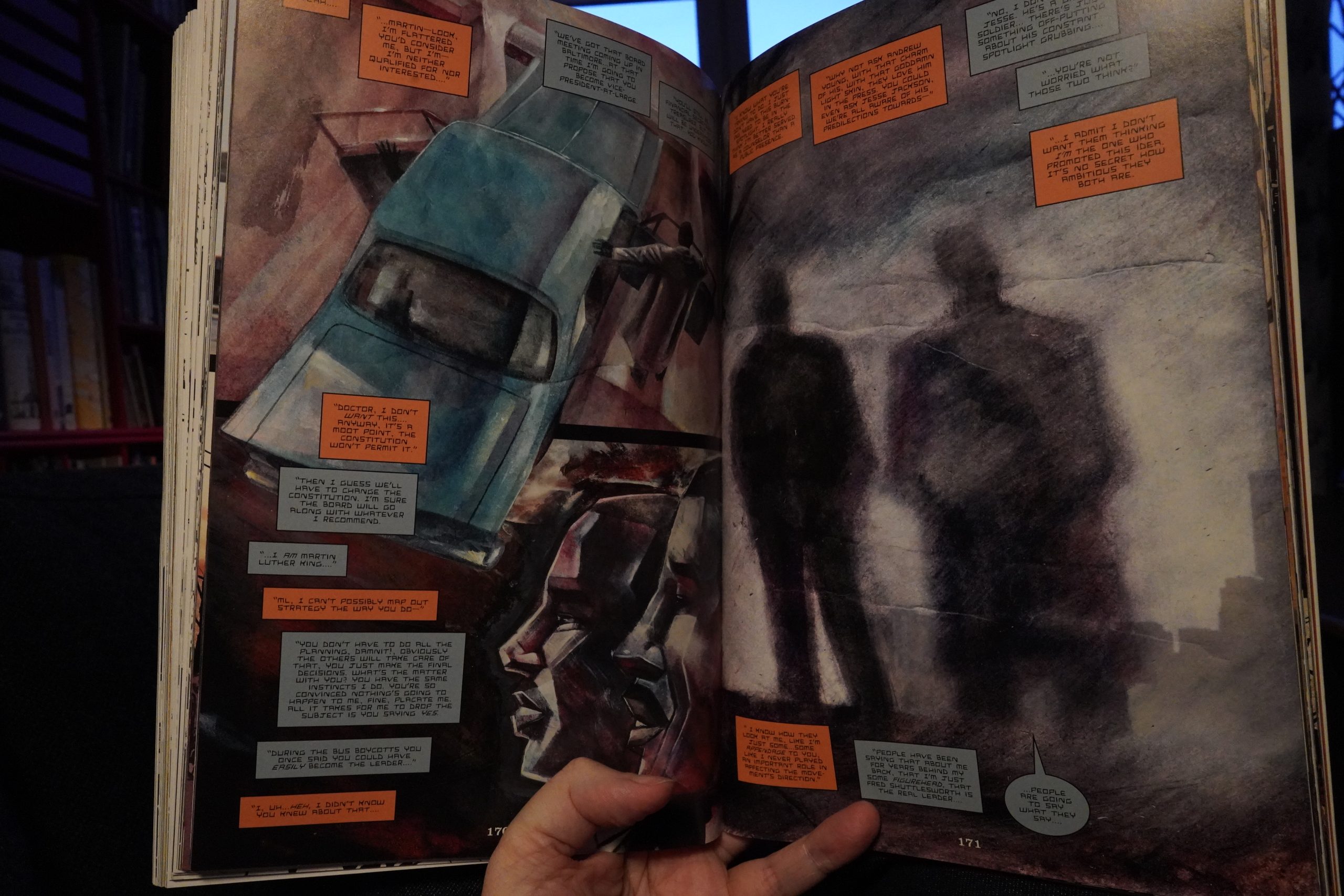

19:19: King by Ho Che Anderson (Fantagraphics)

Was this serialised like 15 years ago? I feel like I’ve read at least some of this before, but I may be mistaken.

Well, this sure isn’t March (Nate Powell/John Lewis), but that shouldn’t come as a surprise to Ho Che Anderson fans. But this was published at a weird time for comics, I think? Maus had been a mainstream break-through comic, but nothing else had the same impact until Persepolis/Fun Home, and that seemed to finally clue people in to what makes crossover successes: Clear, simple auto-bio storytelling that non-comics readers can understand.

| Kate Bush: Remastered (10): Director’s Cut |  |

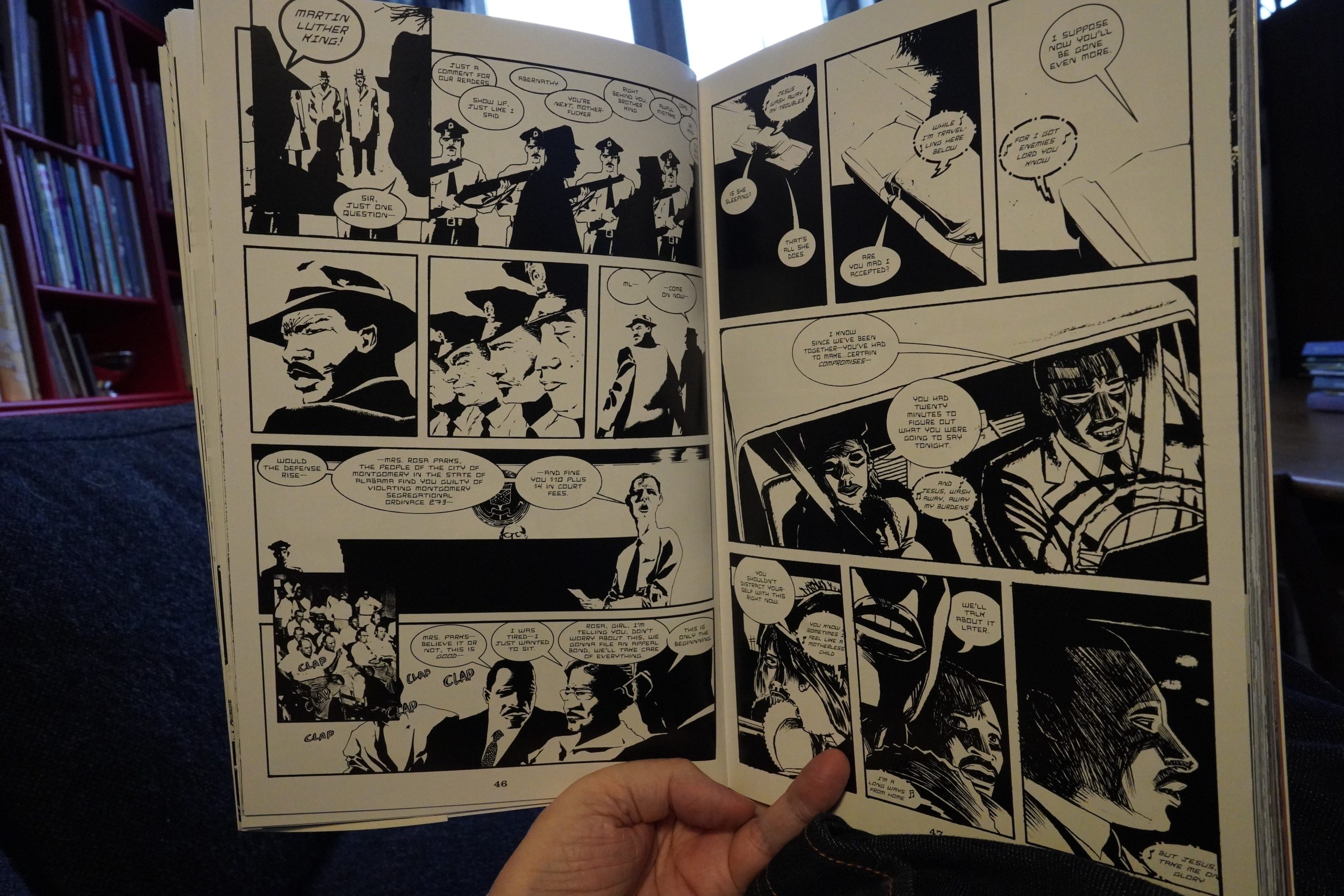

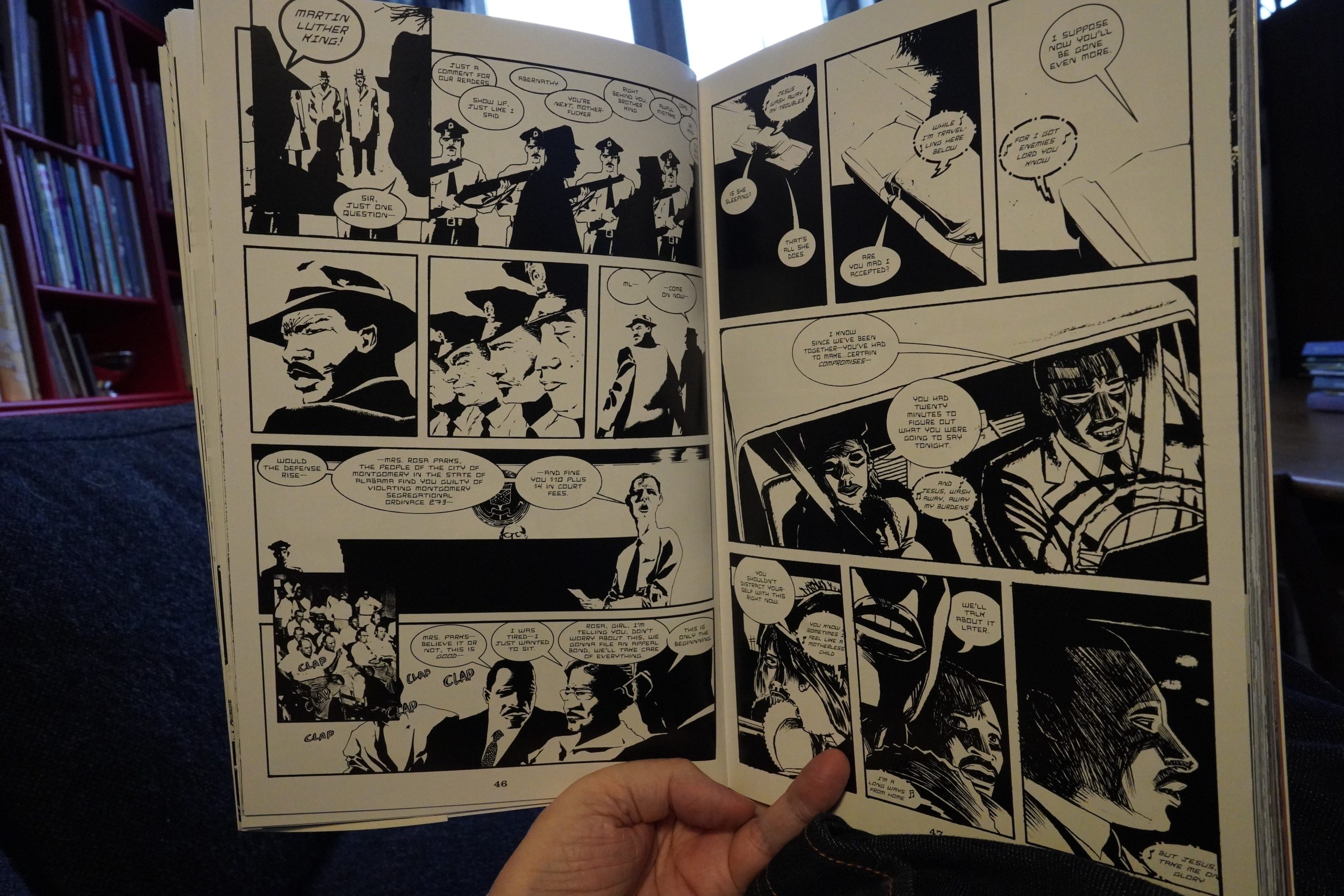

(Huh, Anderson made Rosa Parks have basically no agency? Well, that’s a choice.)

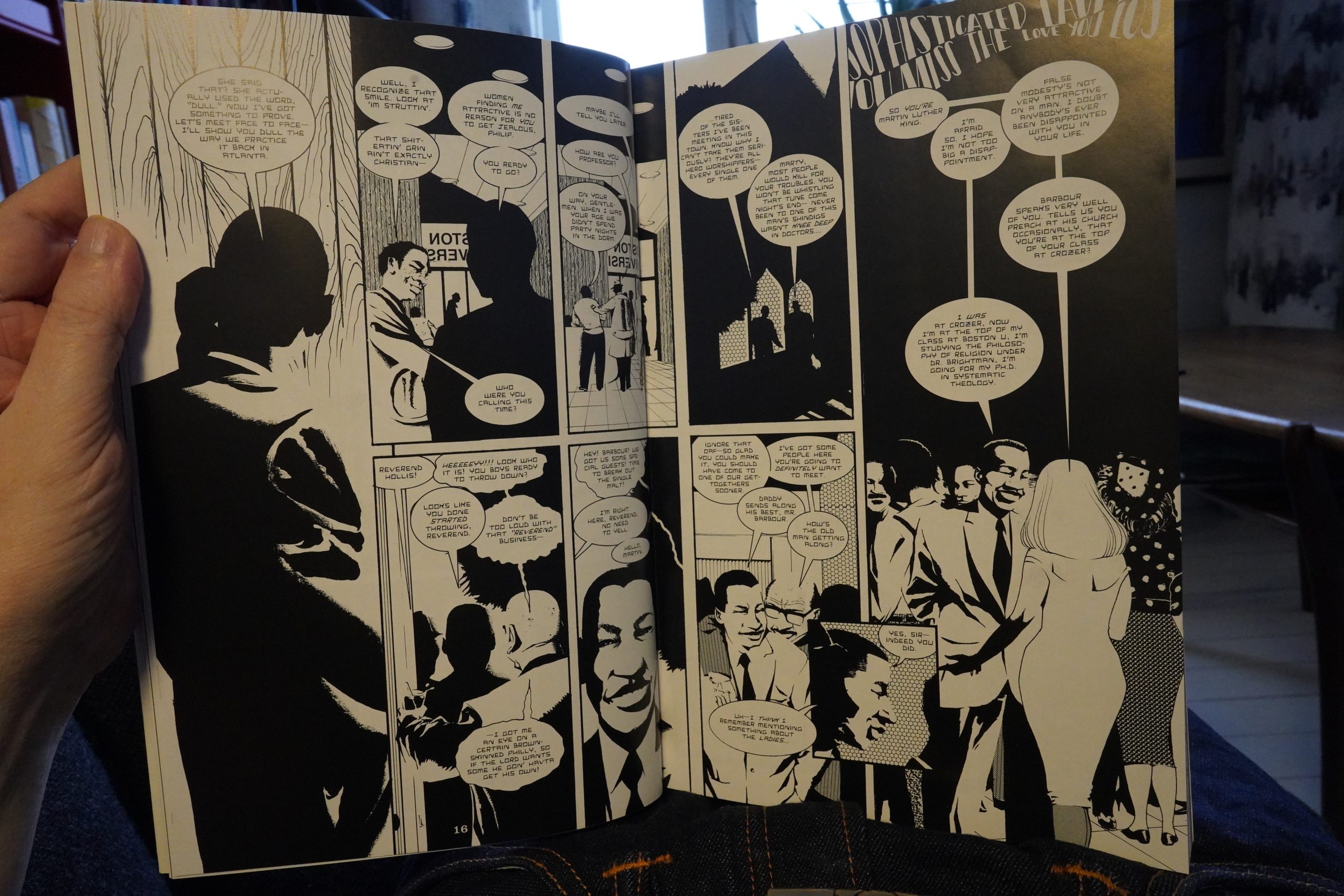

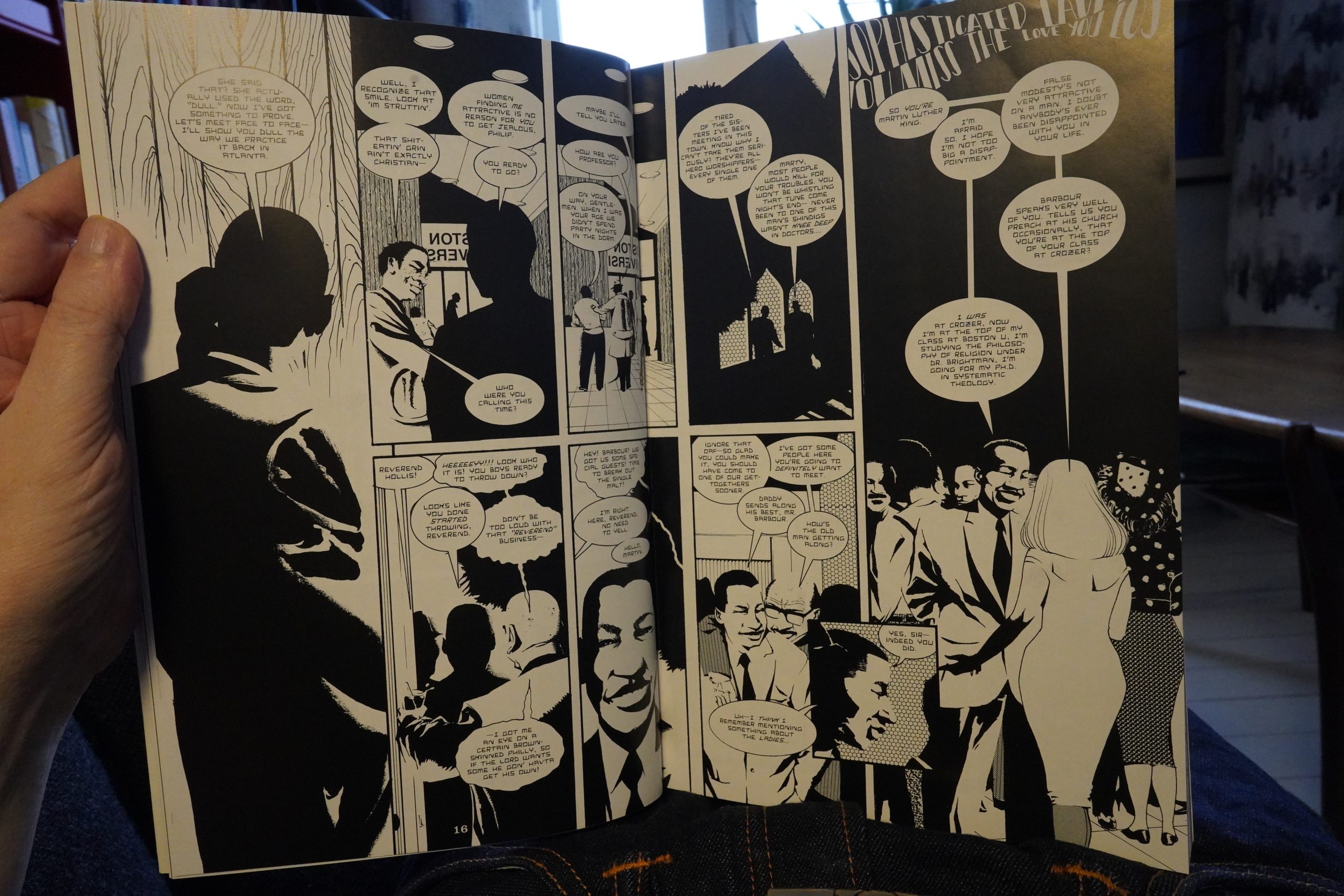

That is not at all what Anderson is doing (and probably not interested in doing). Instead we have layouts that shift wildly, from traditional panel layouts to things that aren’t trivial to tell what order you’re supposed to read them in, and with gazillions of characters that are barely introduced, and with little to no use of captions to tell us what’s going on. (And the way he draws them, he doesn’t really help the reader much — there’s panels where MLK is talking to Kennedy, and I can’t tell who is who.)

But on the other hand, this doesn’t really seem to be an intensely personal book, either.

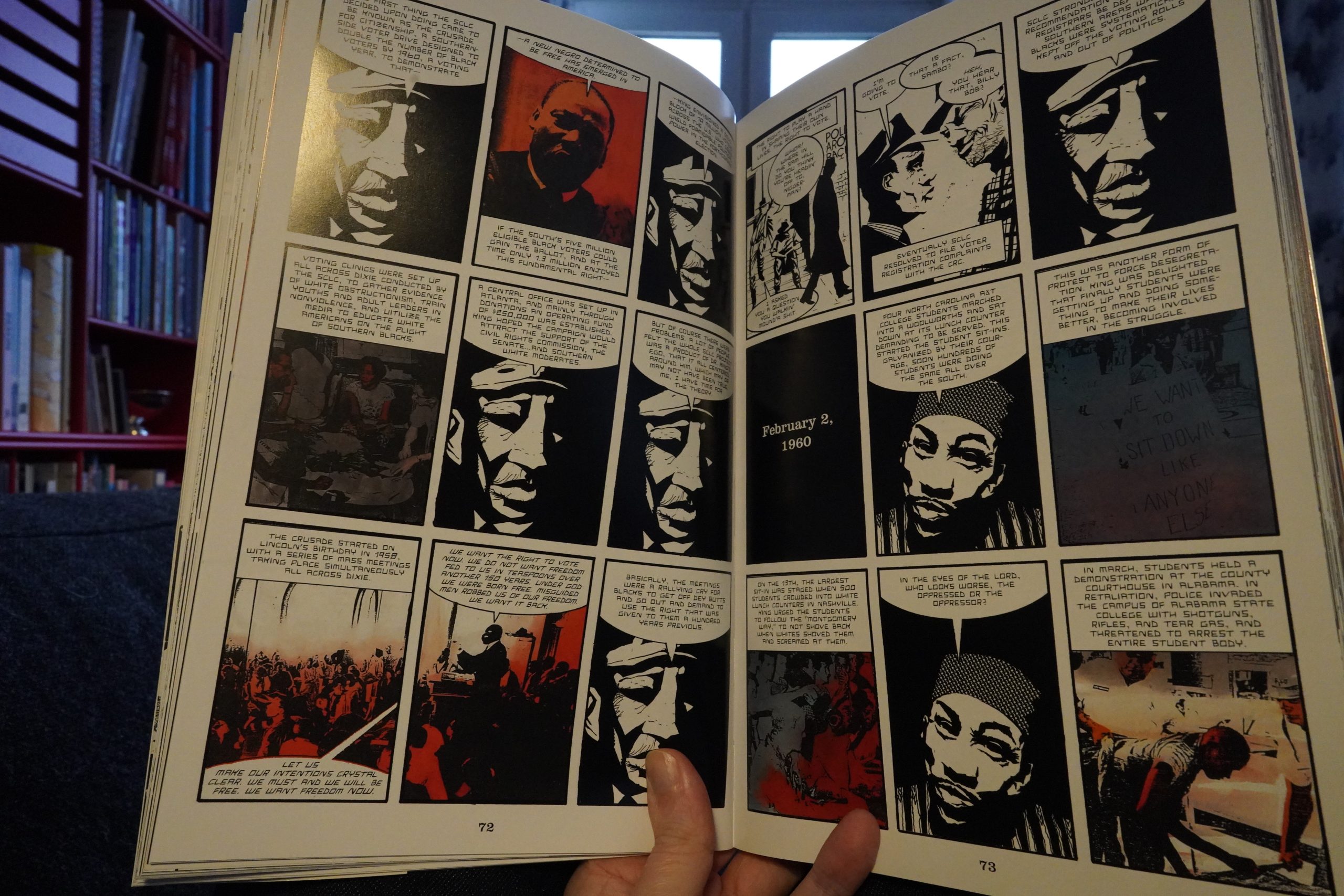

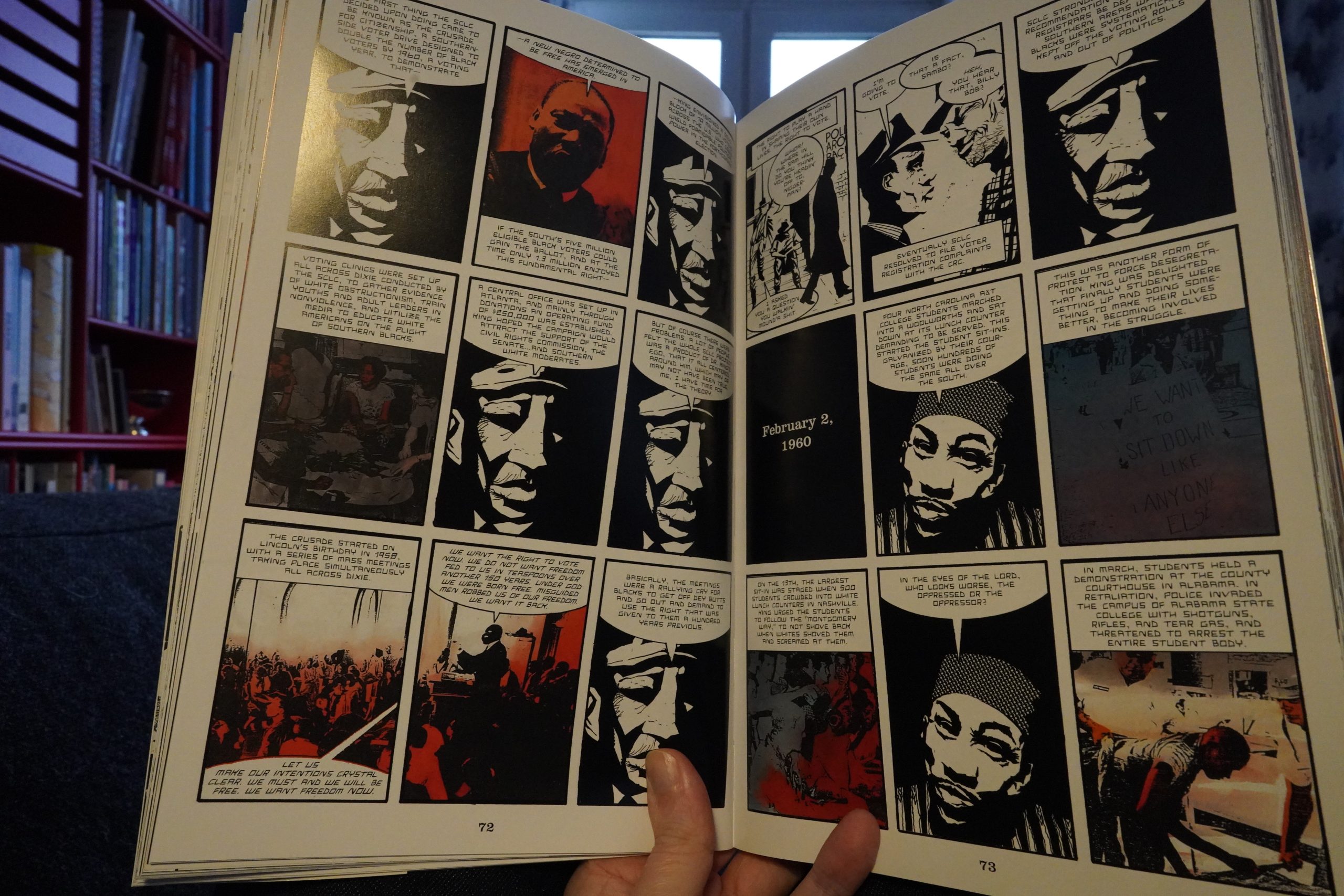

That is, Anderson crams as much text as possible (presumably taken from various history books) into these pages — and he seems to be really half-assing the artwork a lot of the time. Look, I love his style, but the incessant photo-copying is just disturbing: When you have totally identical panels going on like this, the eyes just snap to them immediately, because it just sticks out. (And the rest of the panels here look to be traced newspaper photos.)

So… The book just doesn’t work very well. It seems to live in a no man’s land between Extruded Biographical Comic Book (which we are plagued these days by the metric ton) and Expressionist Artee Book.

And then towards the end, Anderson apparently grows tired of drawing all the little panels.

The ending of the book is really good, though.

| Kate Bush: Remastered (11): 50 Words for Snow |  |

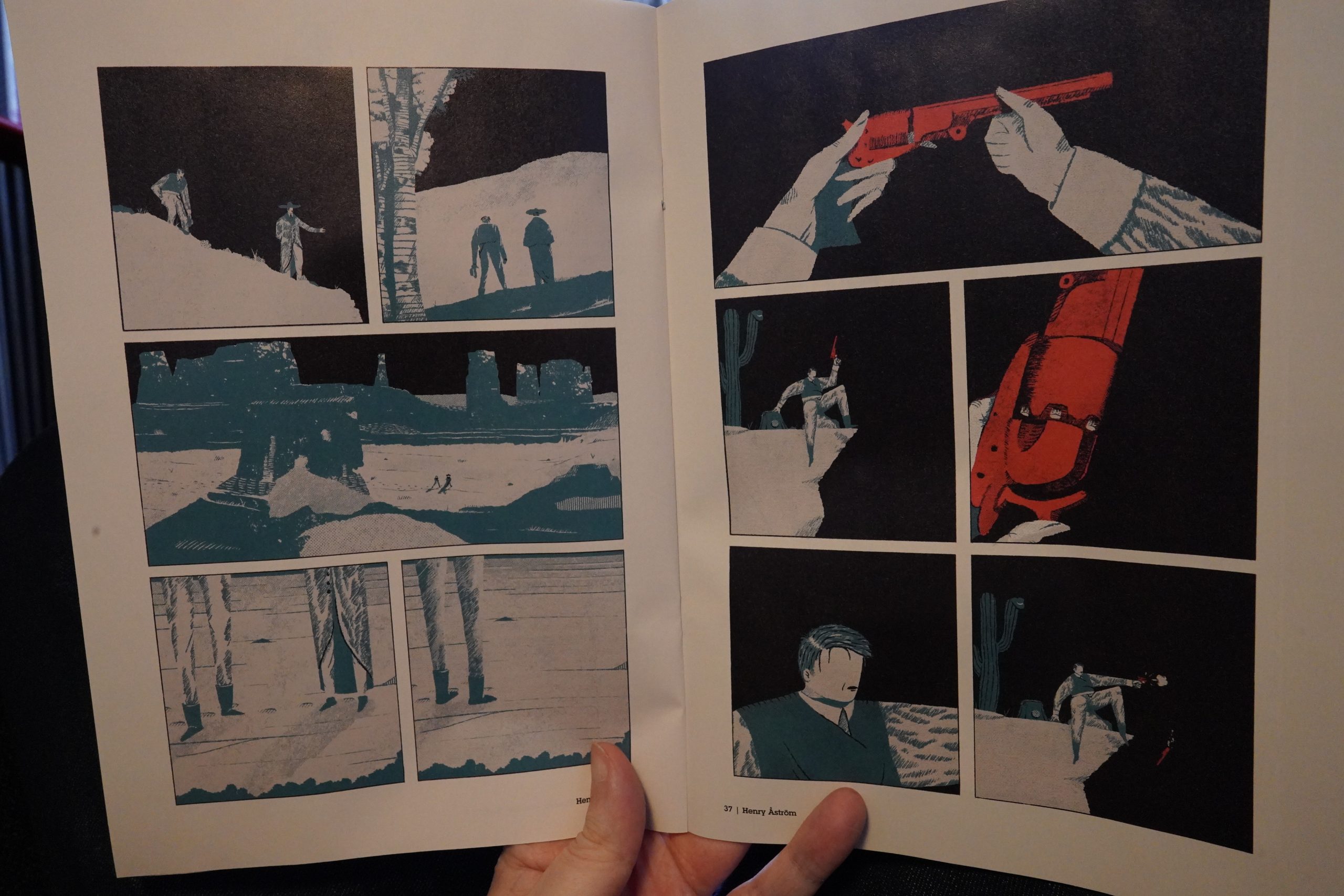

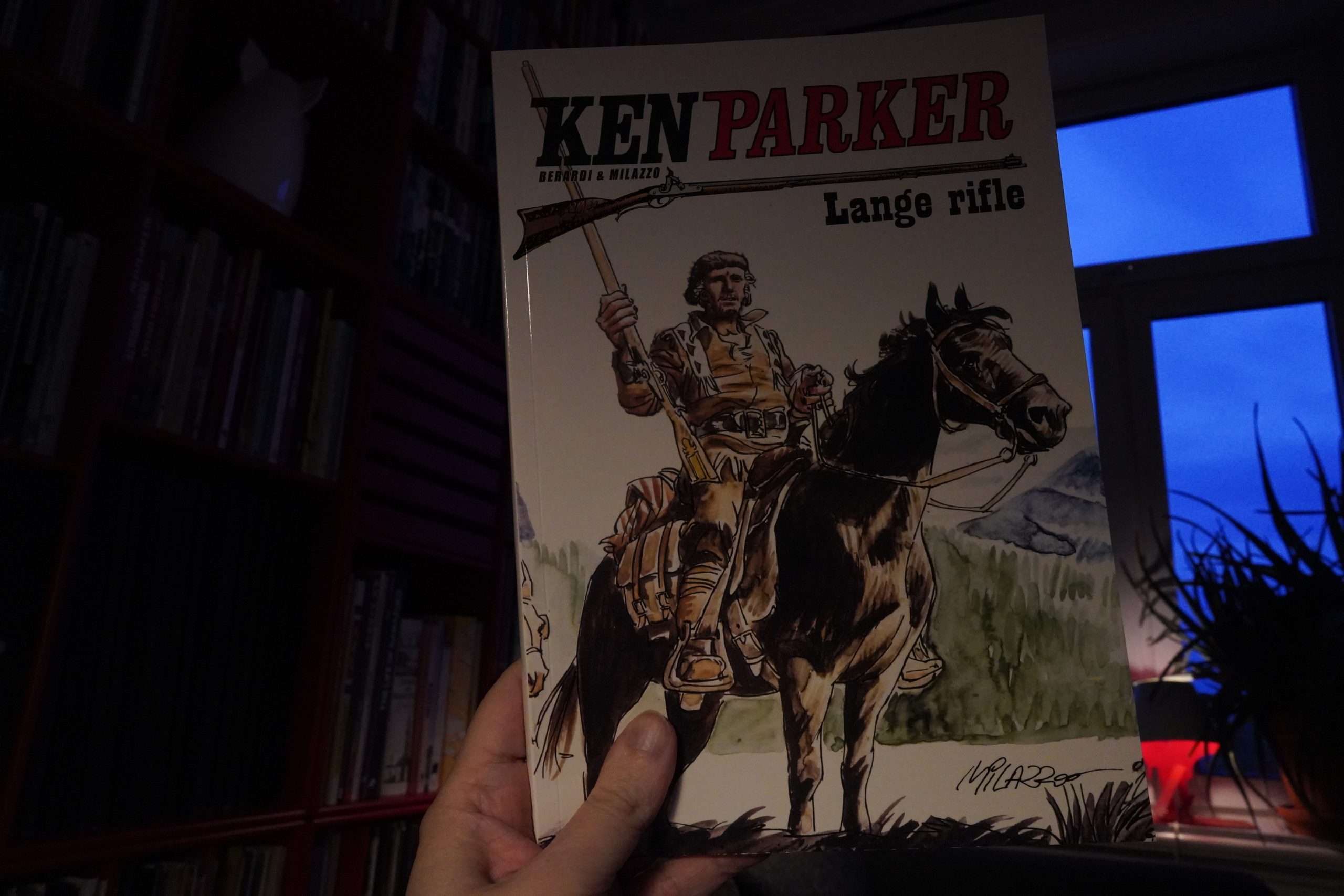

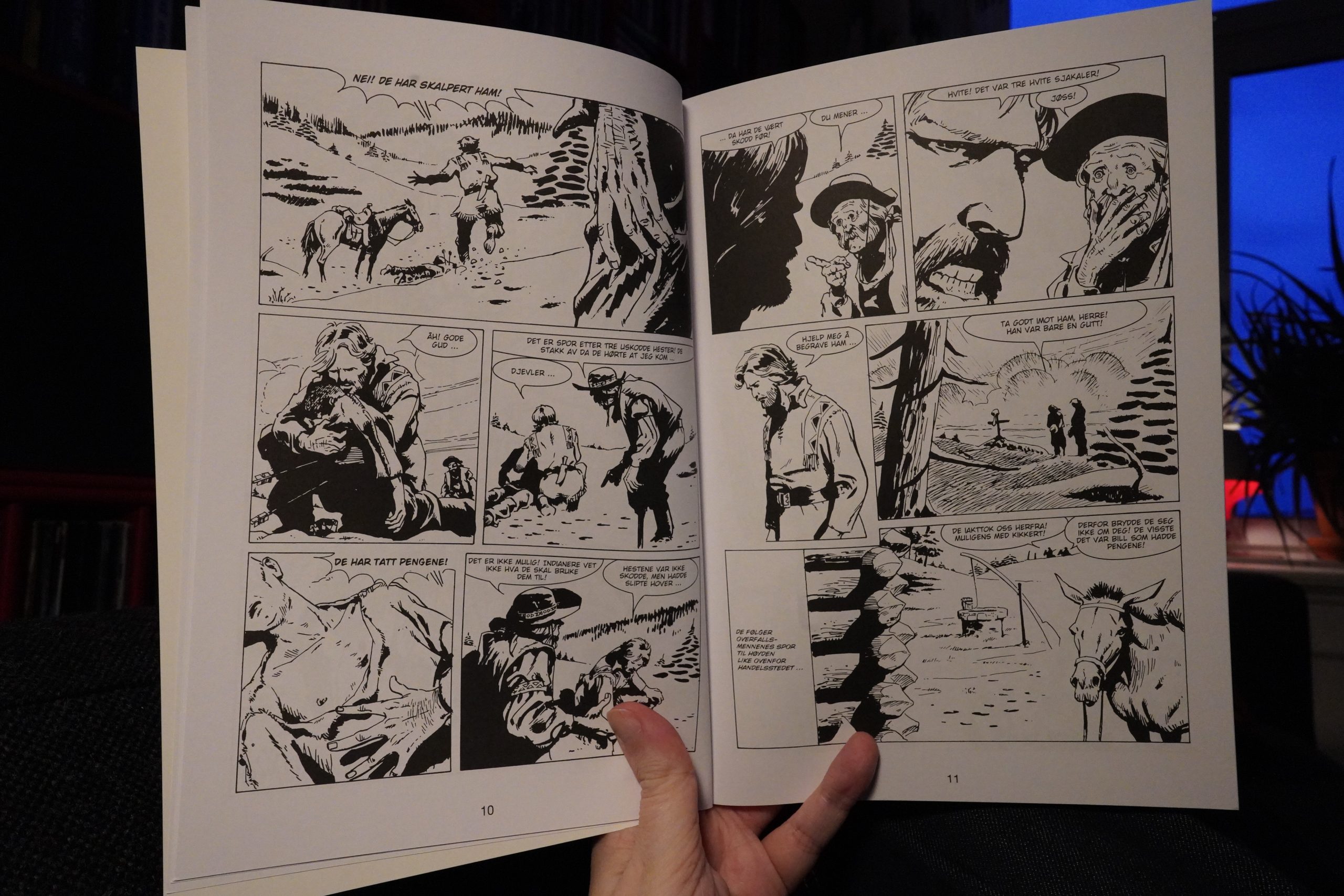

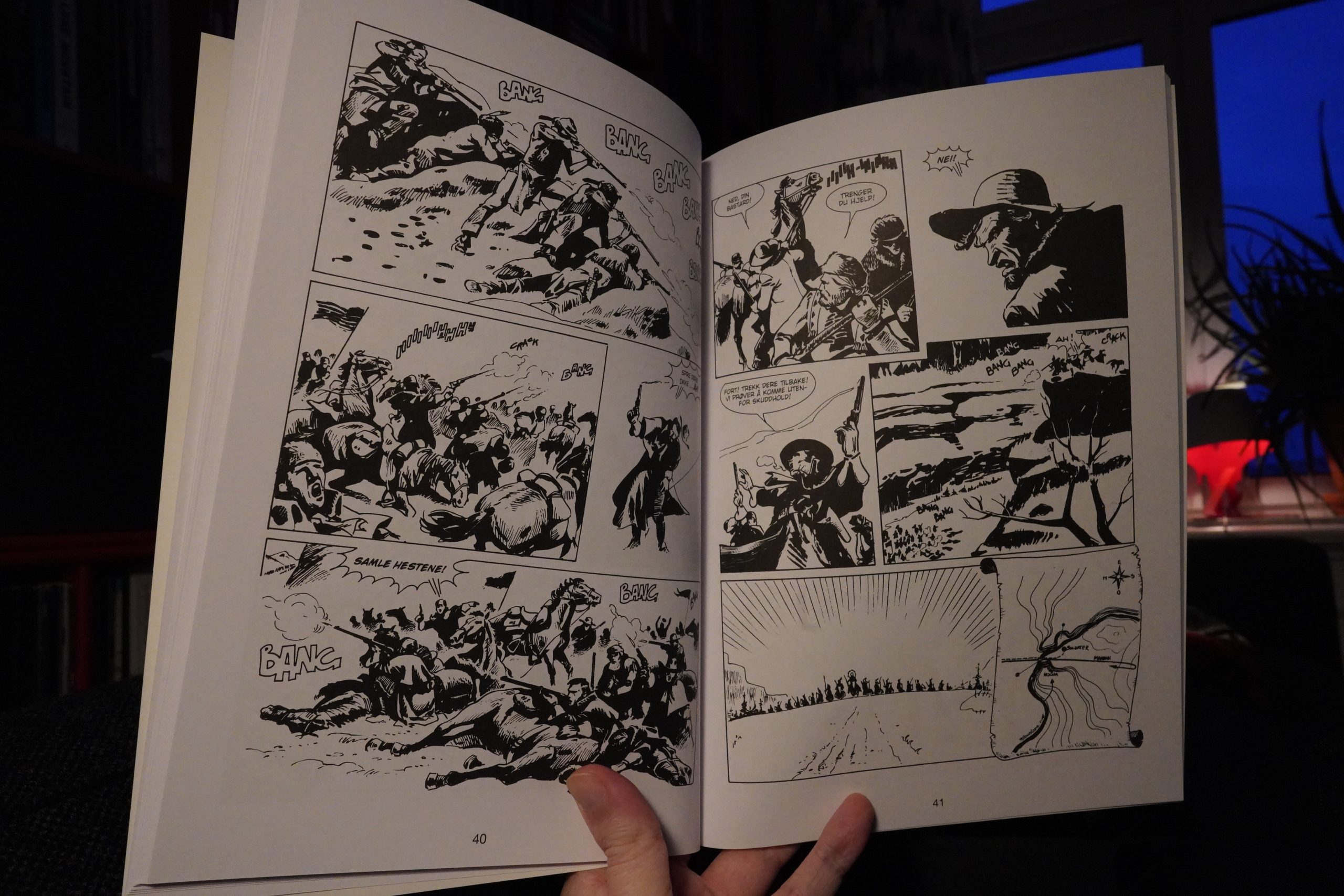

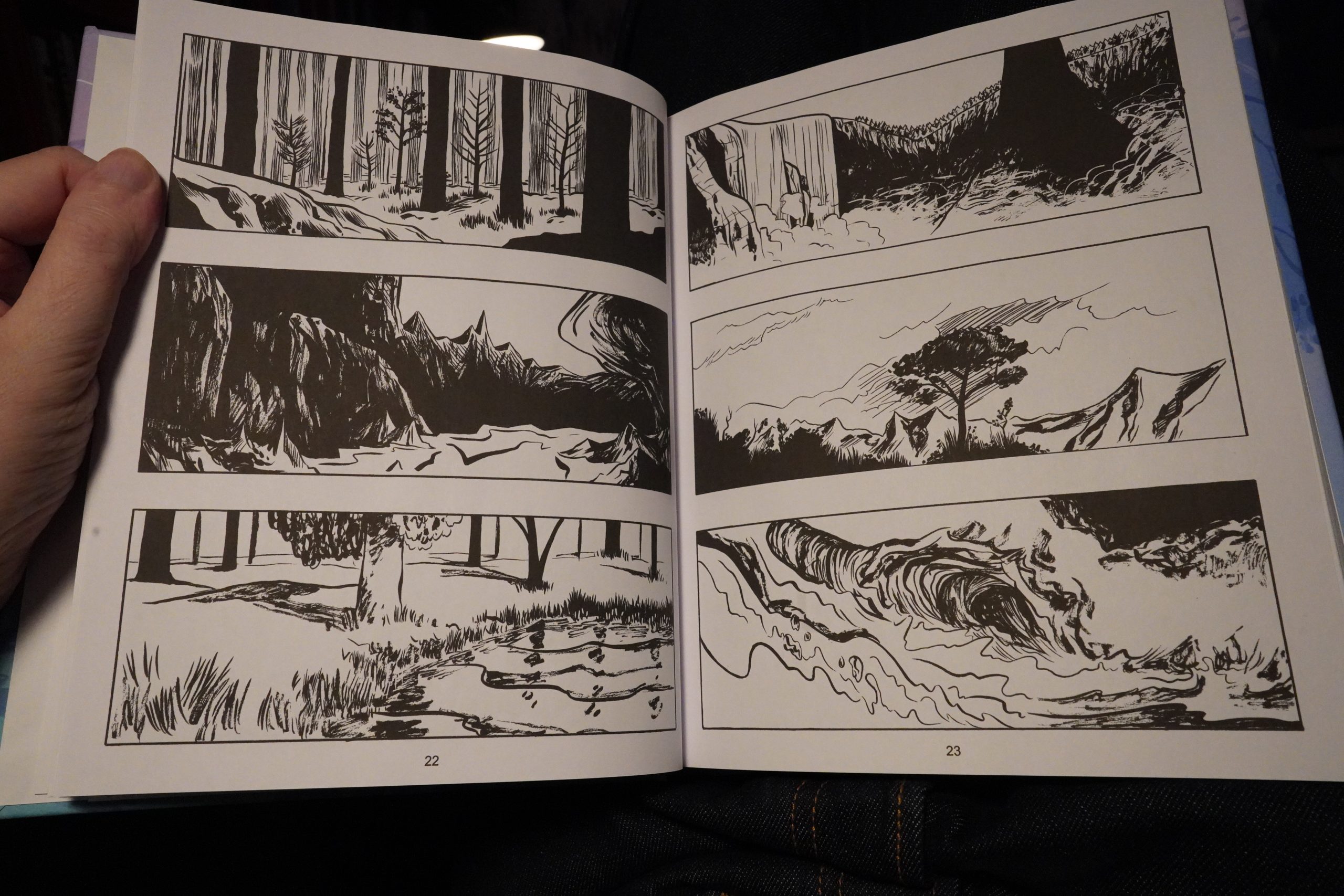

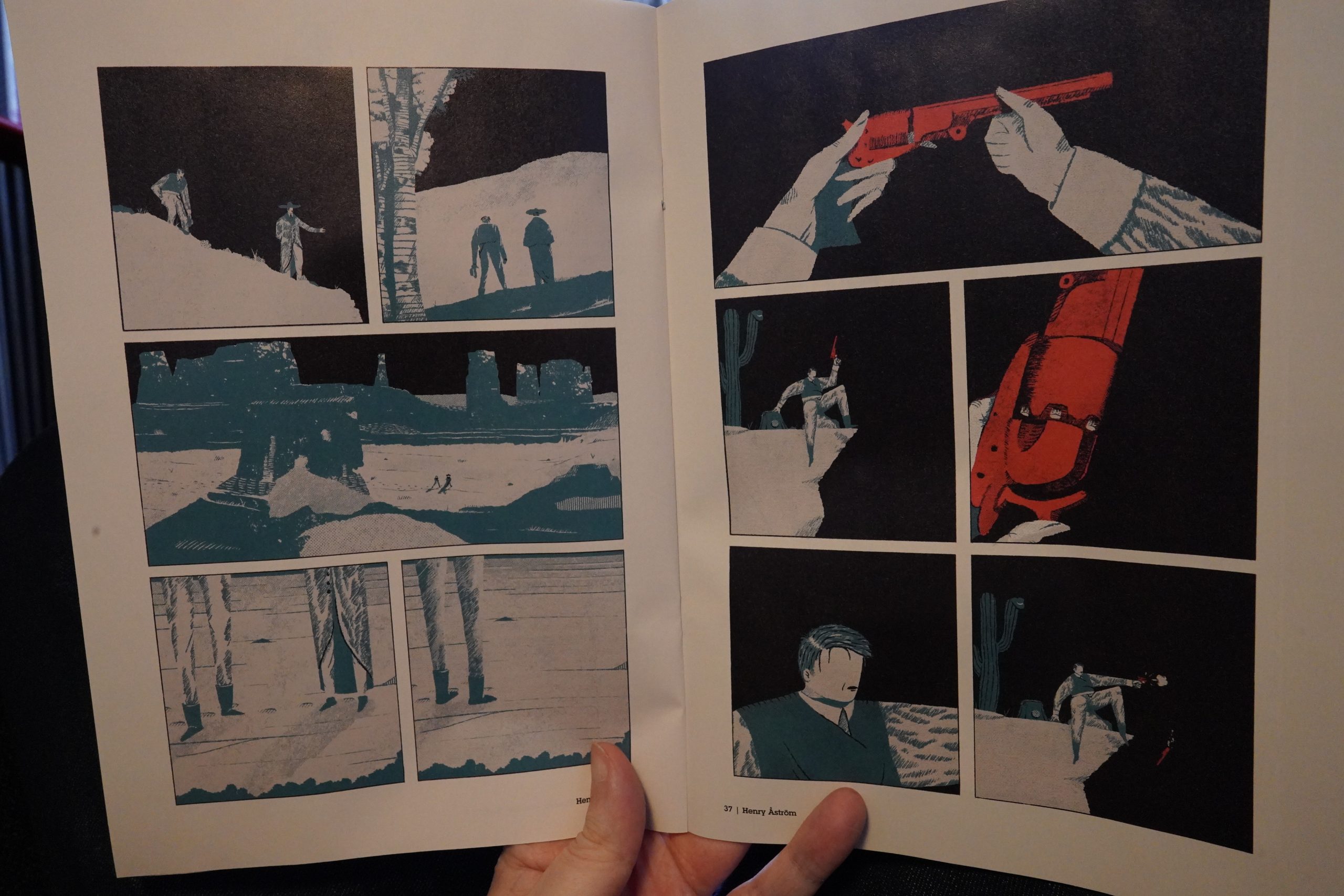

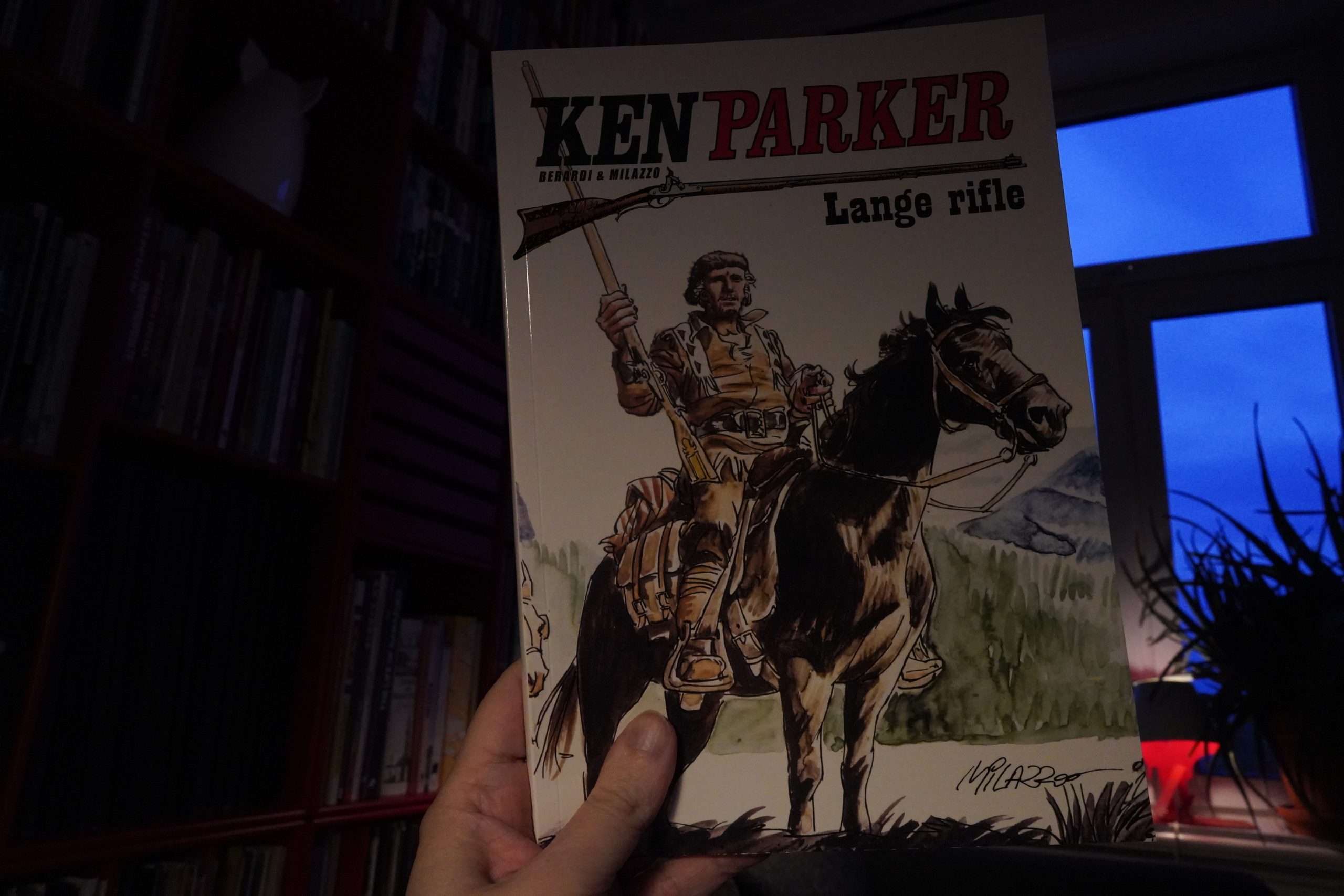

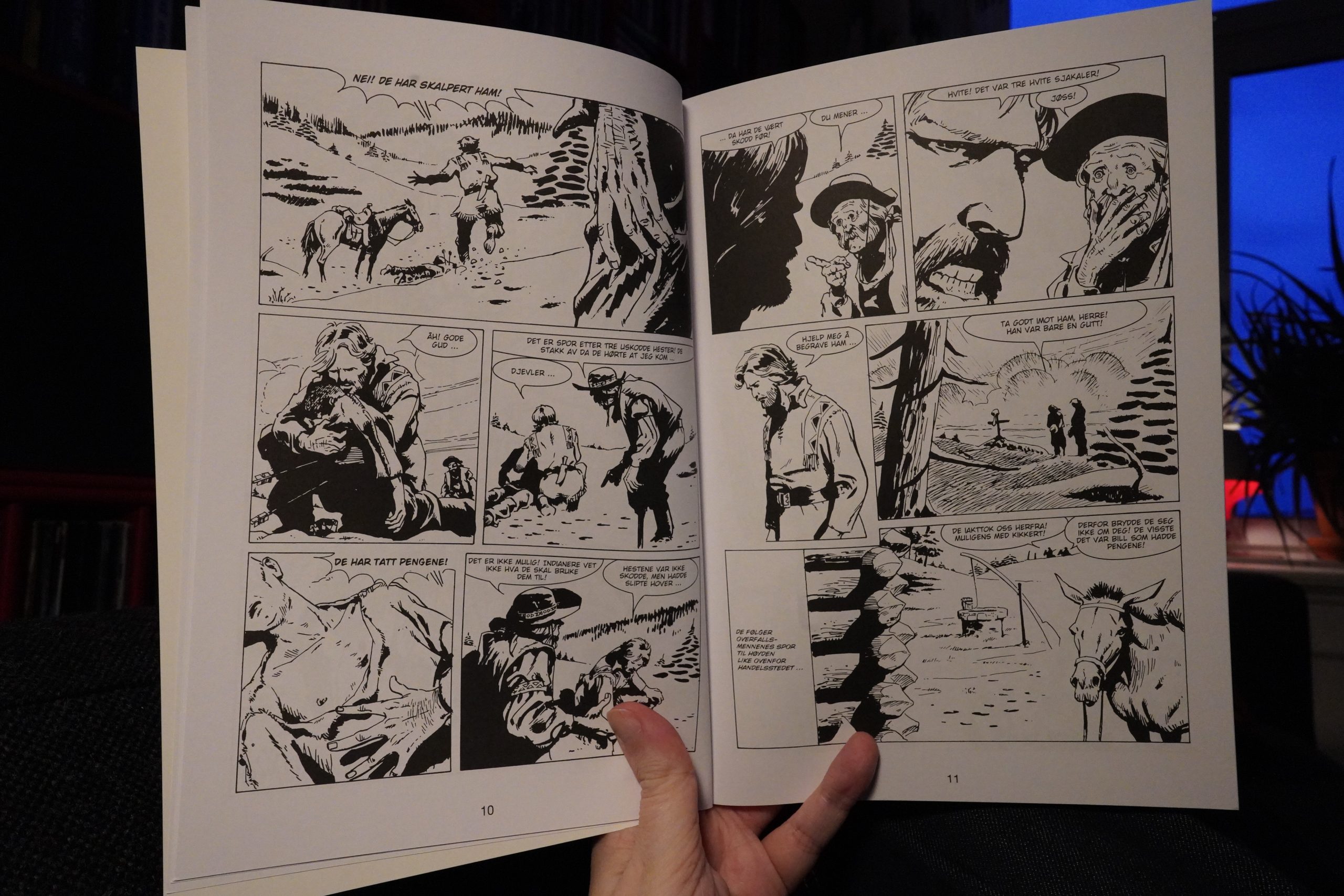

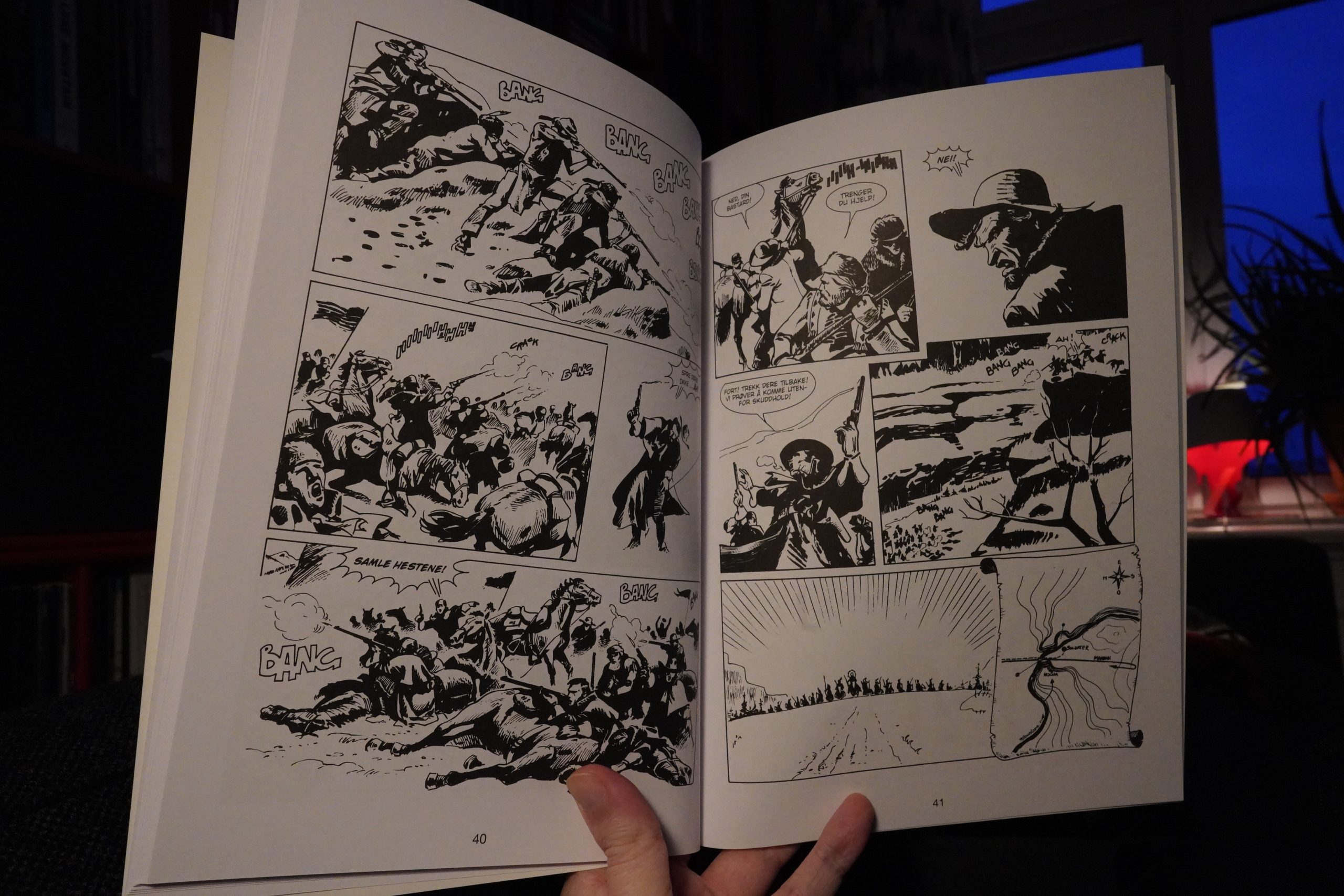

21:42: Ken Parker: Lungu fucile by Berardi & Milazzo (Egmont)

I’ve seen these Italian-produced Western comics around (all over Scandinavia) as far back as I can remember, but apart from reading a couple as a child, I’ve ignored them. But they had a sale, so I picked one up at random.

I’m expecting it to suck, but let’s see…

The reproduction here isn’t very good — it looks like it’s been shot from published copies?

But… this is a lot better than I expected. It moves really fast, there’s a pretty good plot, and the artwork is attractive. And it seems to be “revisionist”; i.e., we’re on the side of the Native Americans, and the hero (Ken Parker) is kinda against violence and stuff.

I wouldn’t mind reading a few more of these to see how it develops (I googled, and it turns out that this was the first album, published in 1977).

| Kate Bush: Remastered (12): Before The Dawn (1) |  |

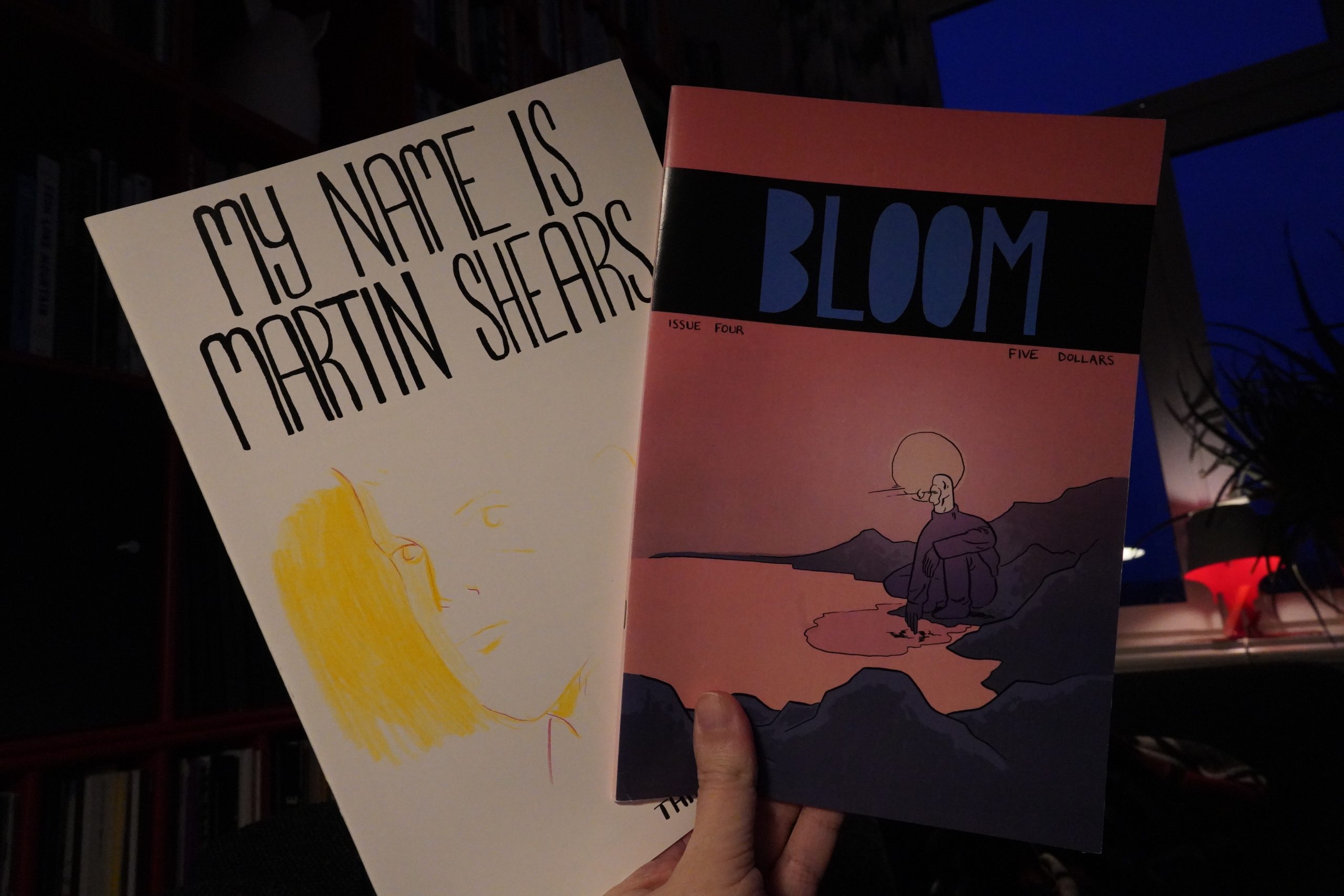

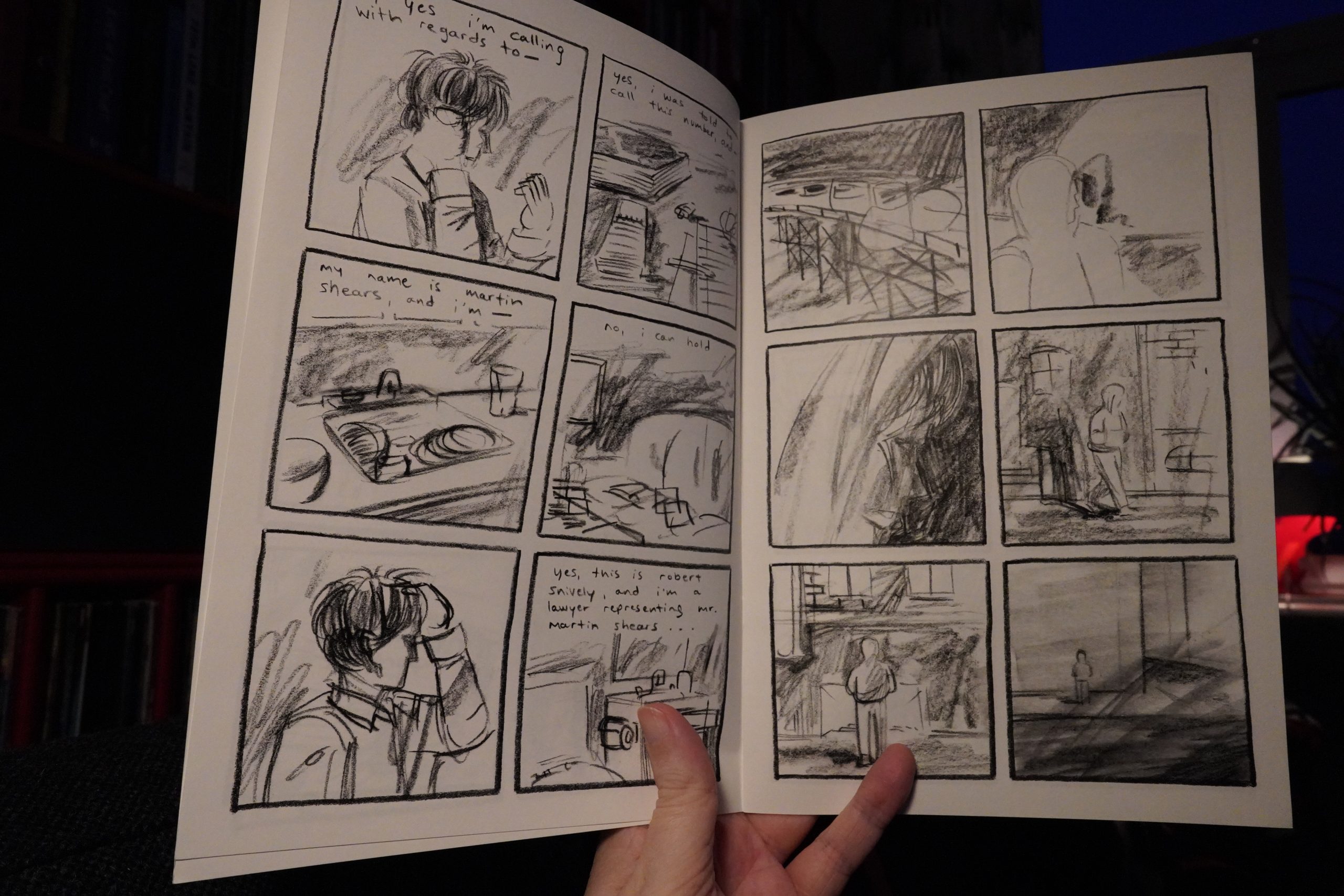

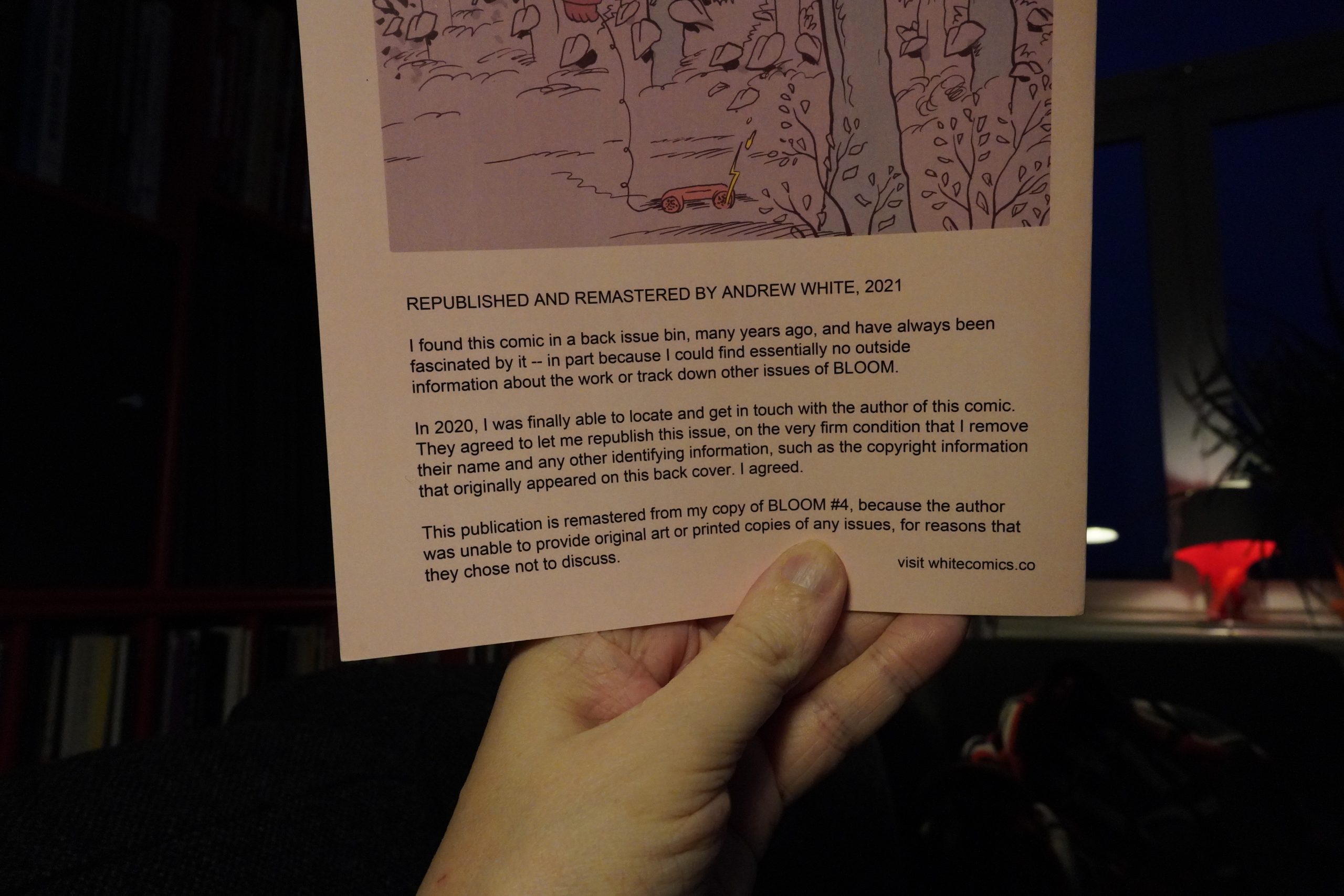

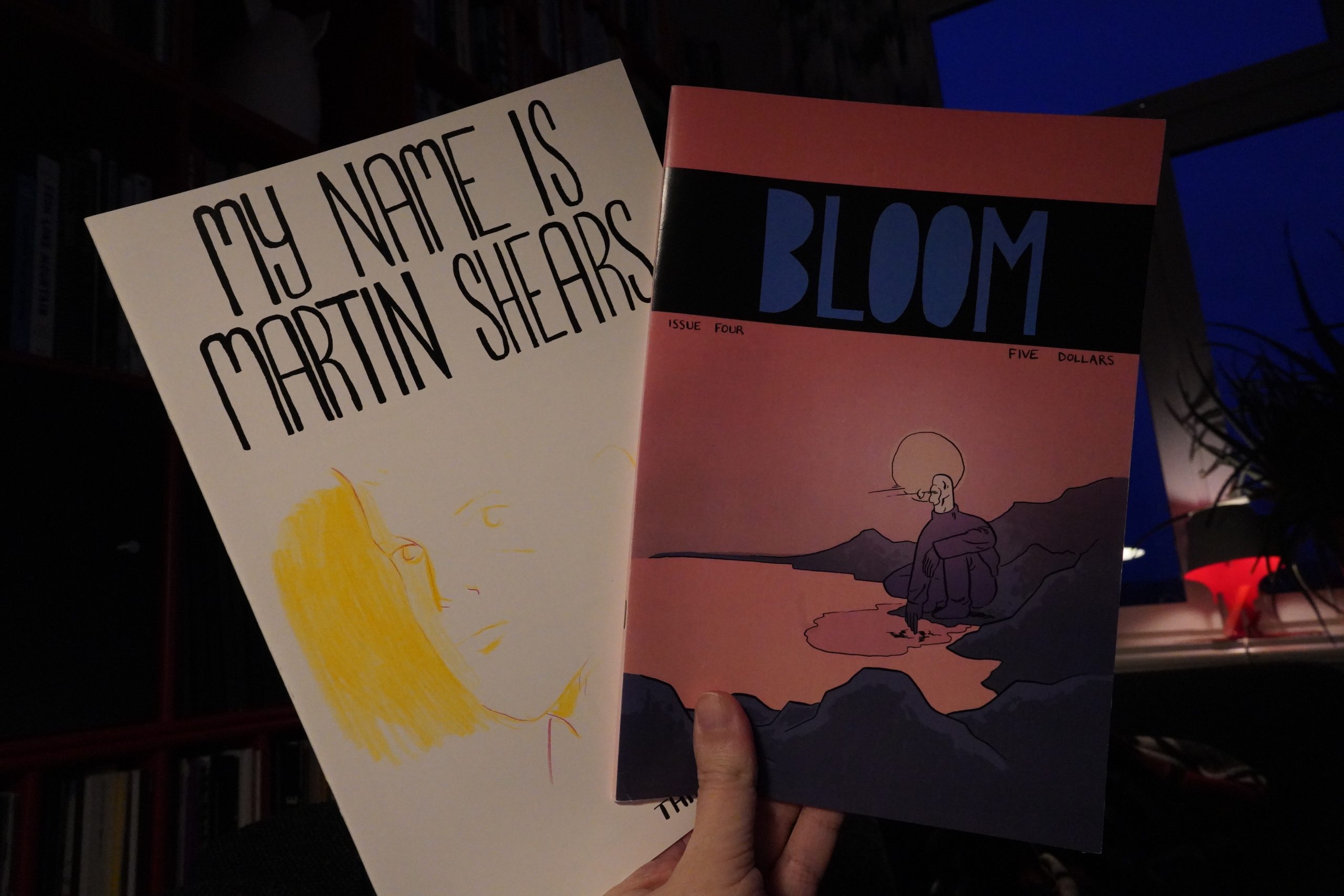

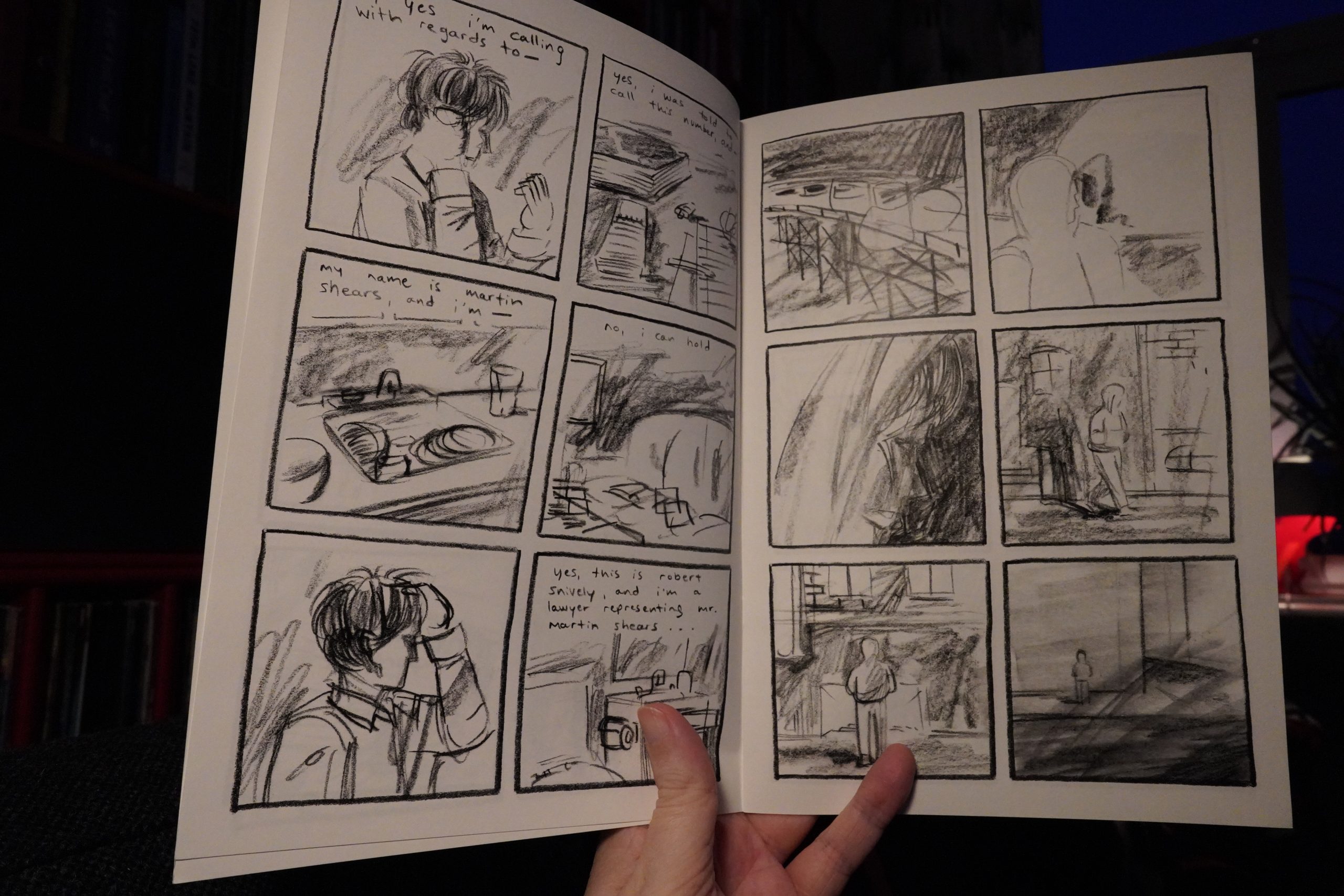

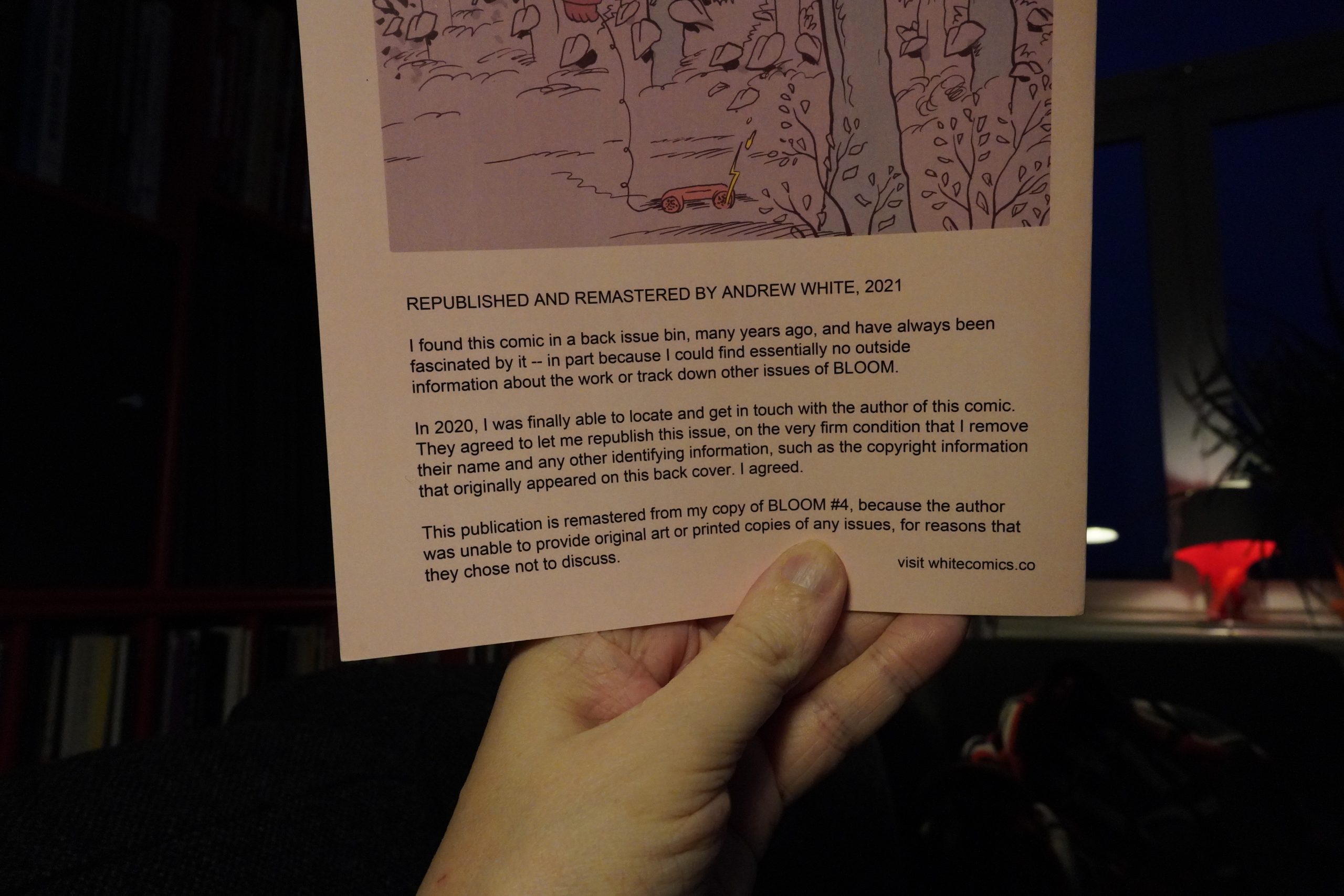

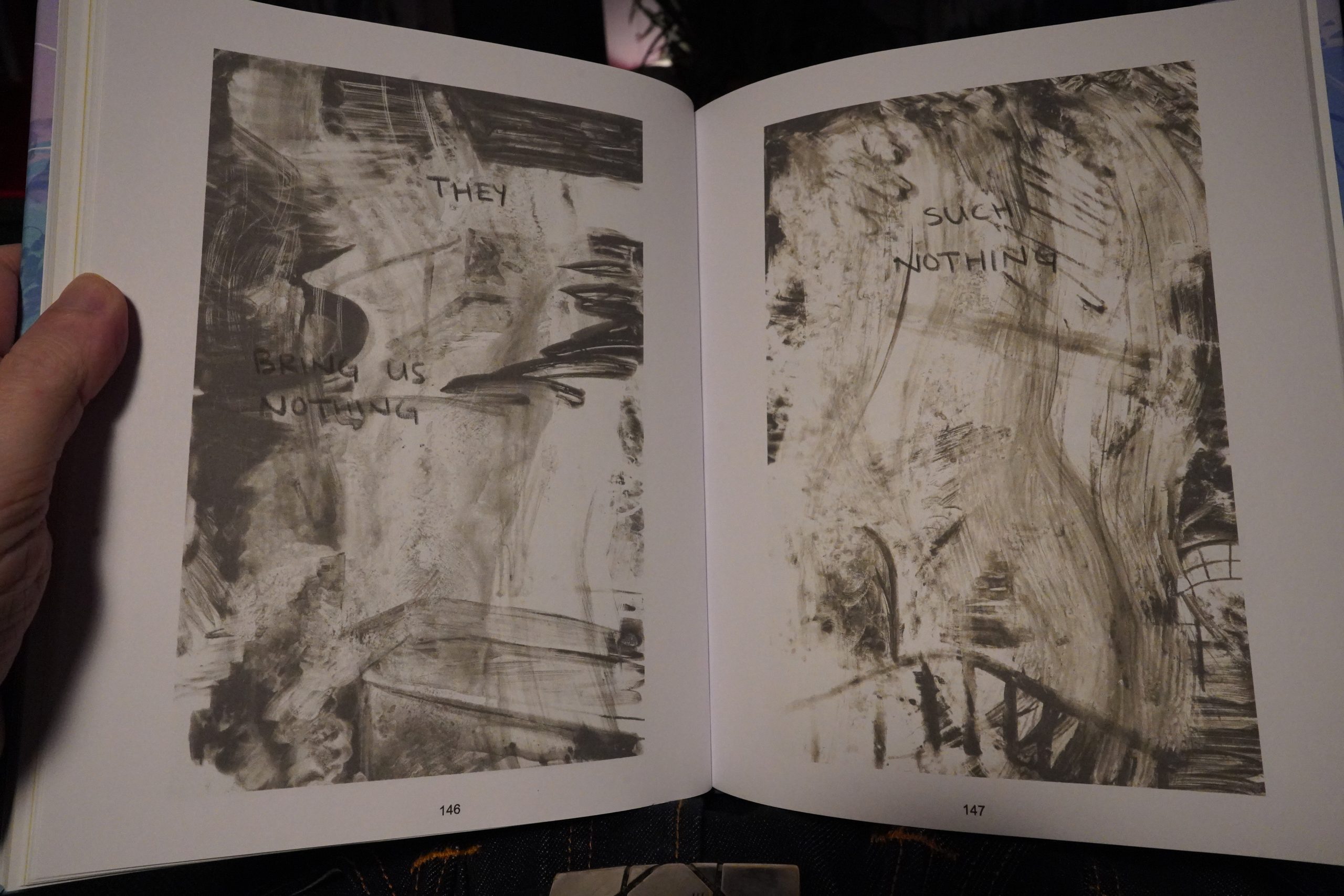

22:11: My Name is Martin Shears / Bloom #4 by Andrew White

“Martin Shears” (from 2014) seems to be dealing with identity in several different ways… it’s intriguing.

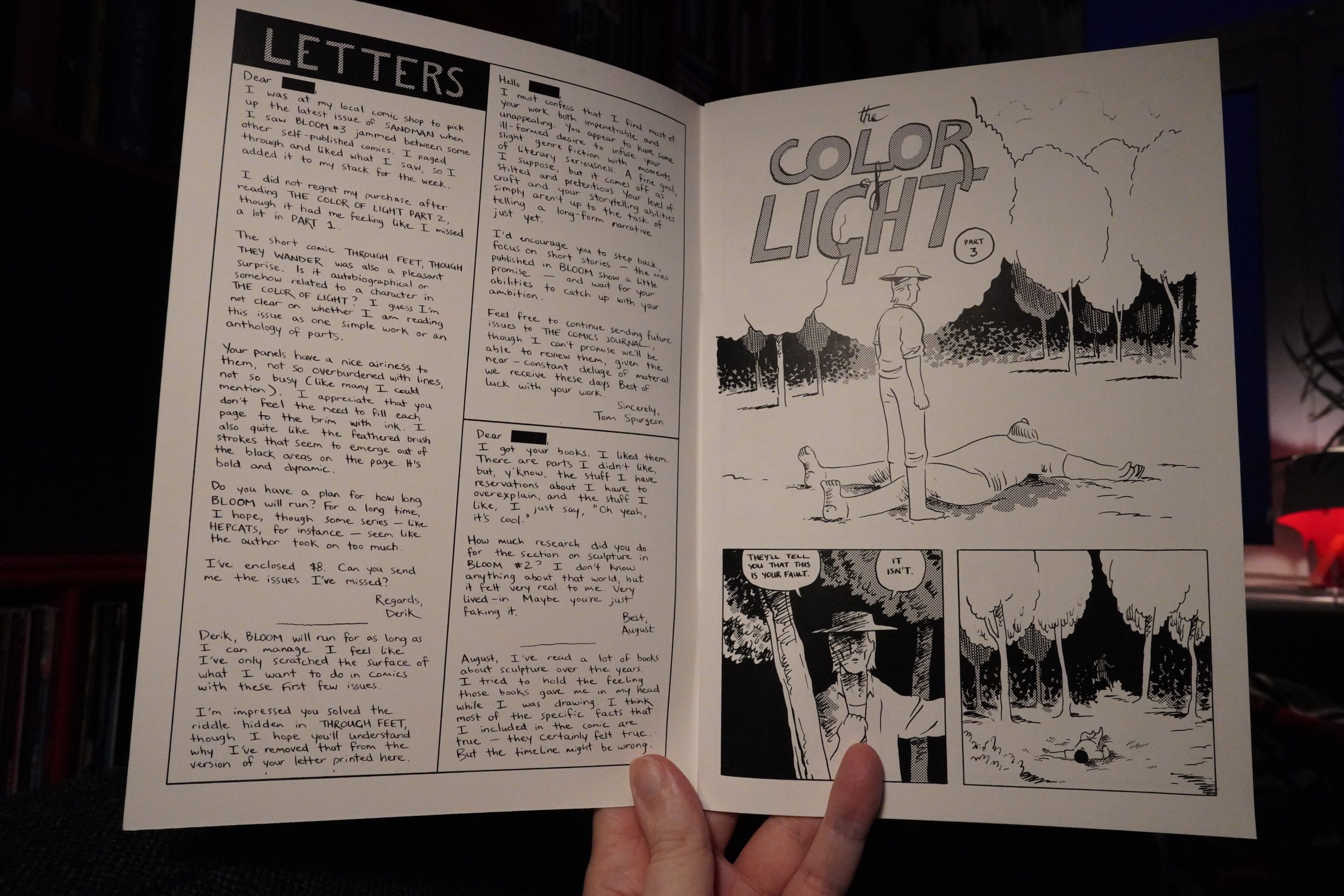

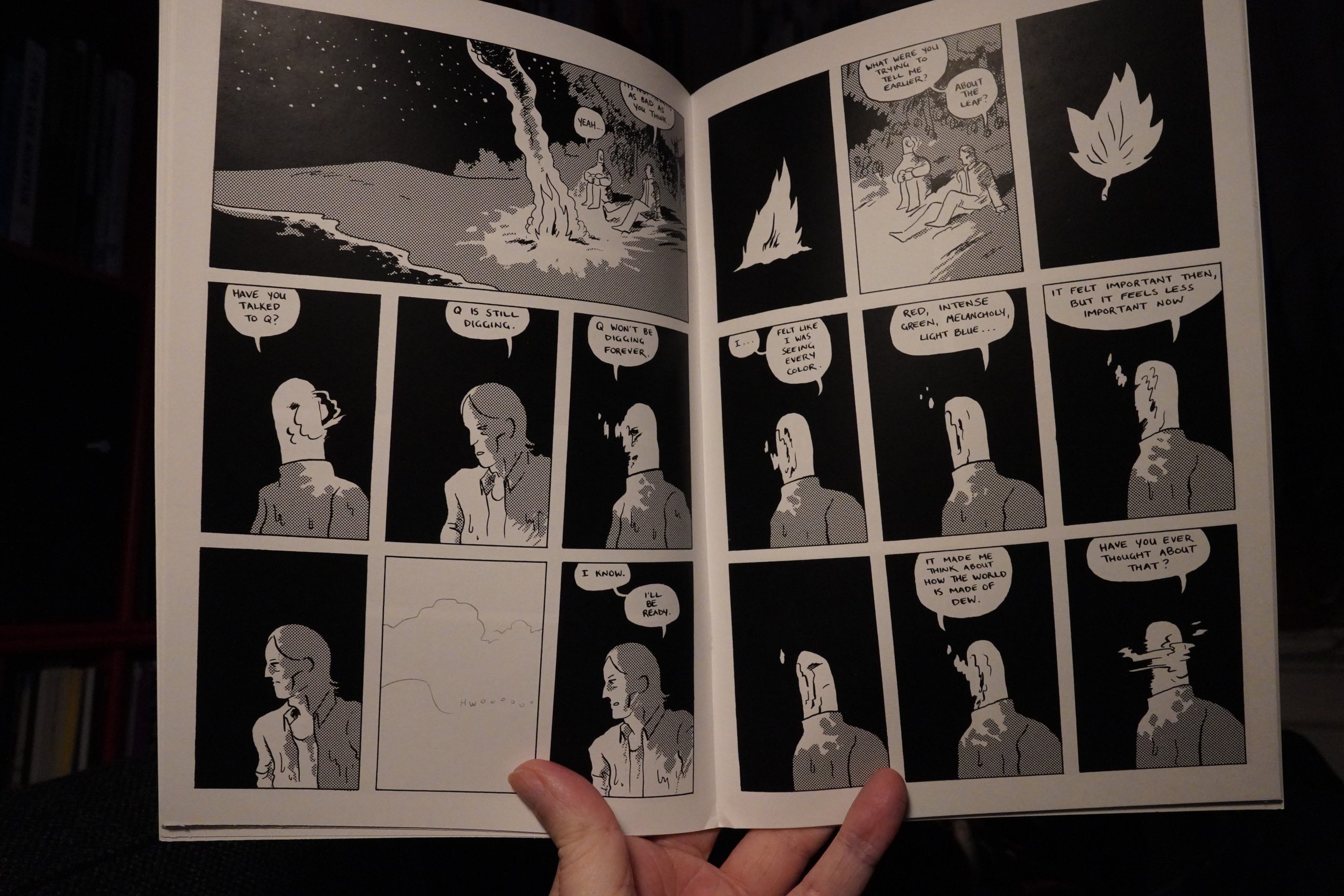

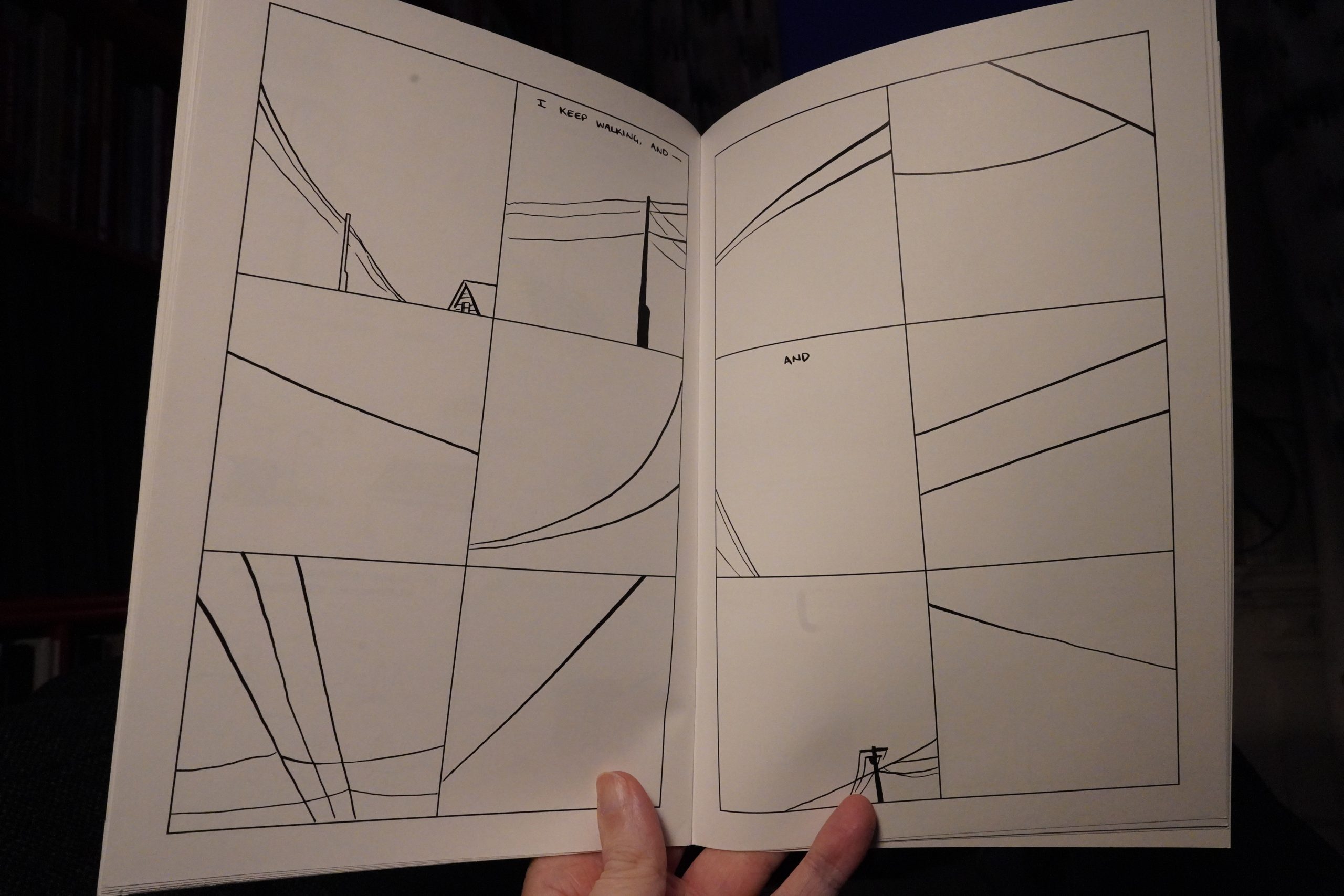

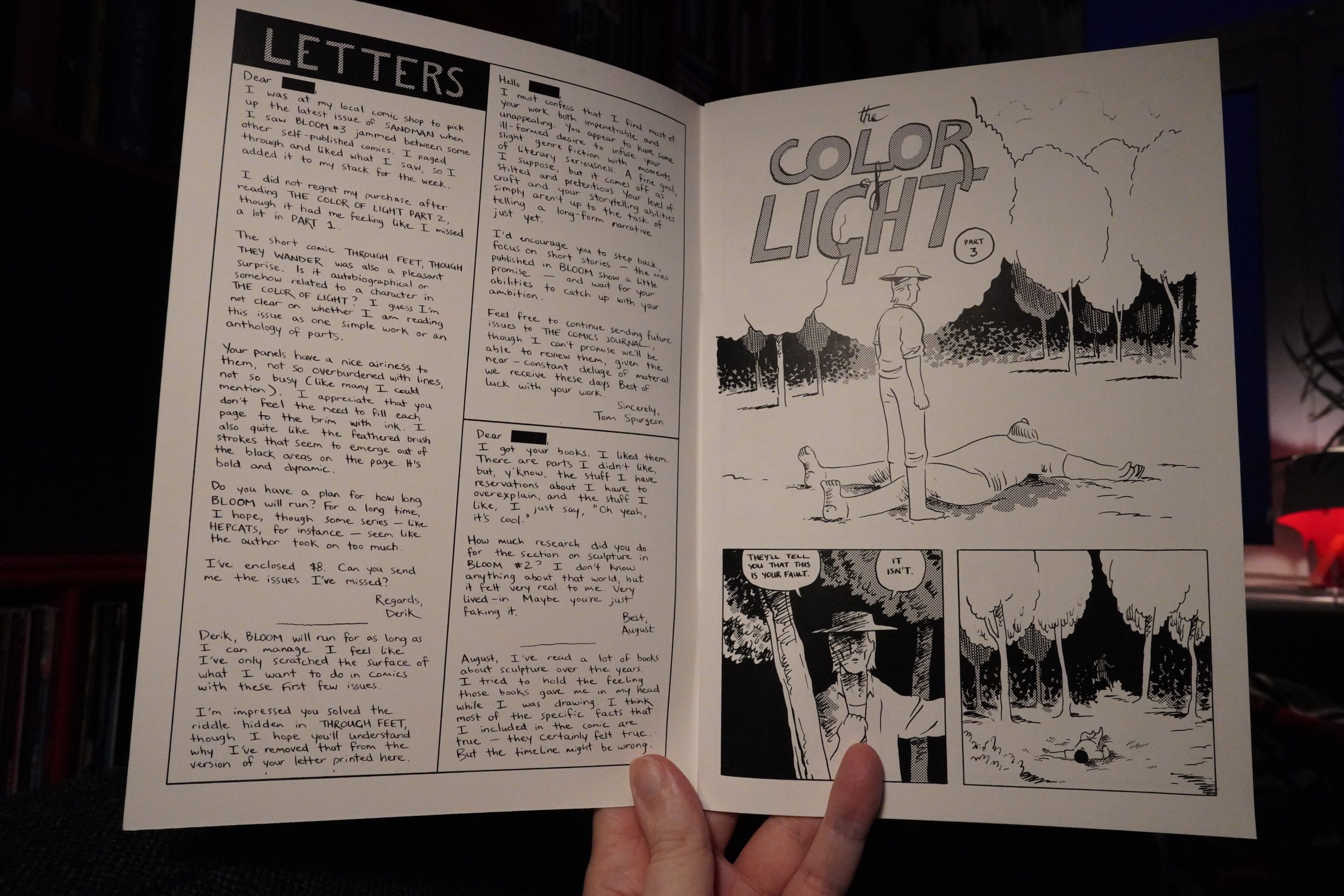

And so does Bloom #4 — even more explicitly. It’s supposedly a reprint of a (90s?) comic book from an unnamed author.

Heh. A rejection letter from Tom Spurgeon (then-editor of the Comics Journal)? I wonder whether that’s just totally made up or whether it’s a real one that’s been repurposed… Mysteries within mysteries, as Dave Sim would (and does) say.

The book itself, though, is pretty slight — it’s not as compelling as White’s books usually are.

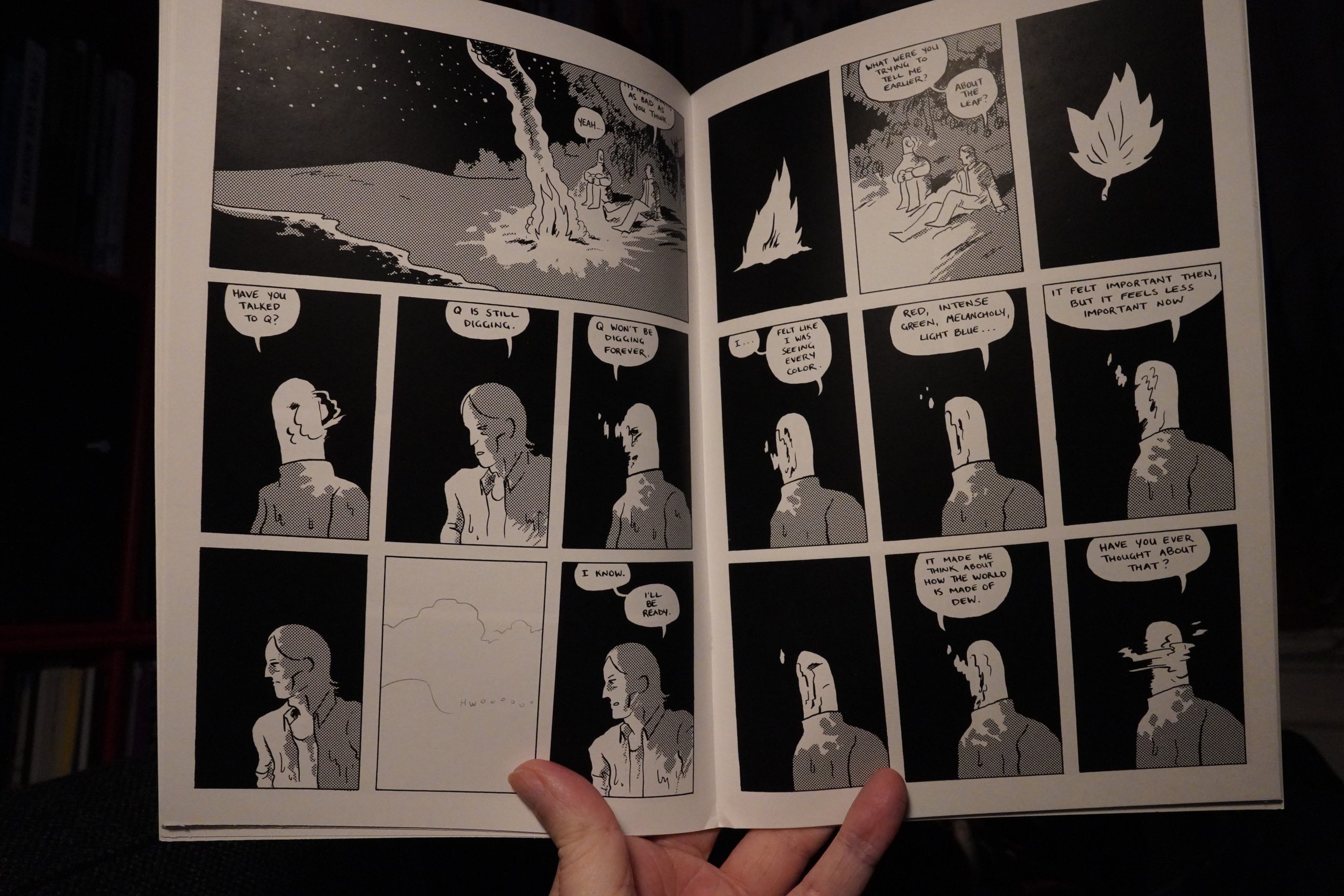

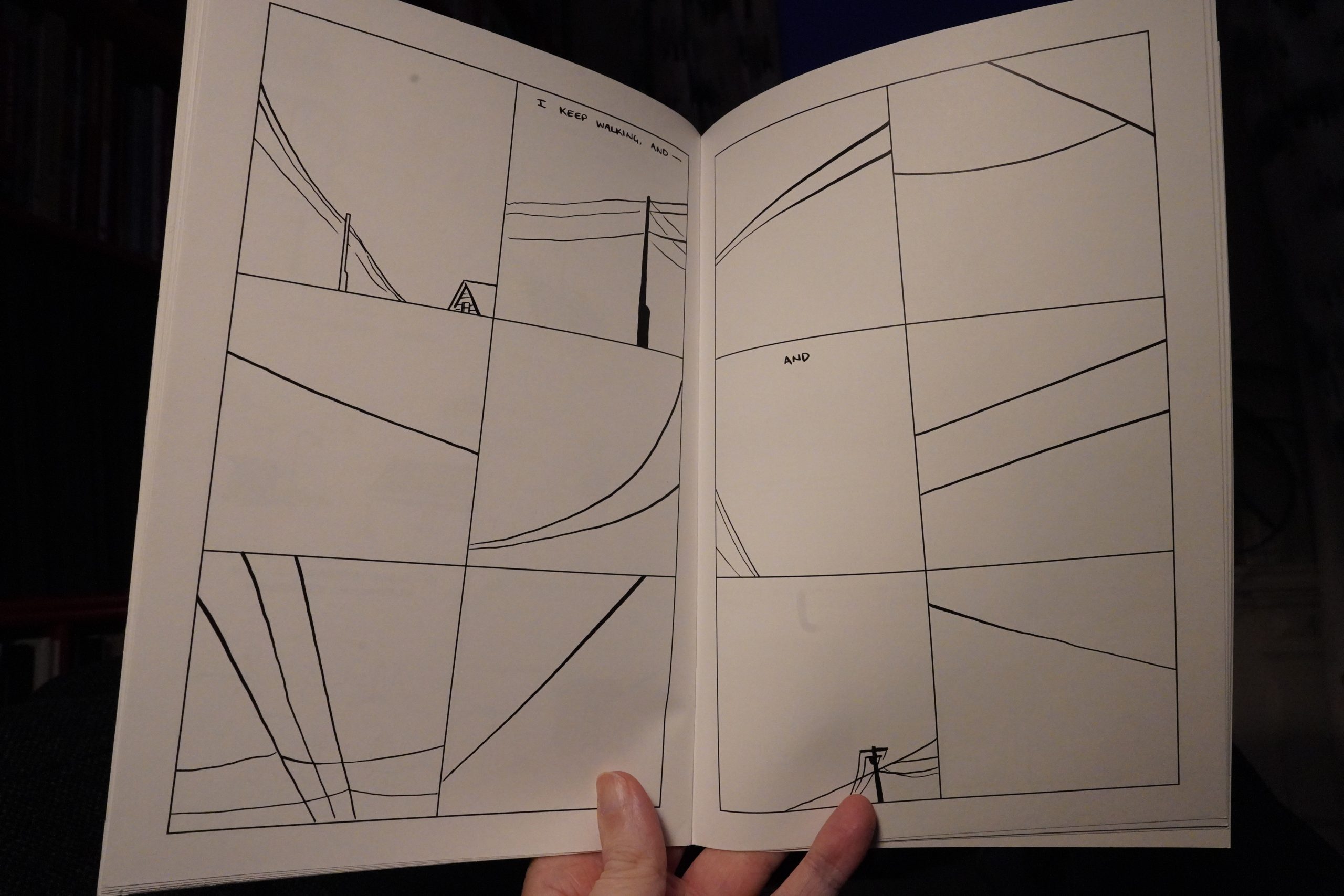

But this spread was pretty neat.

| Kate Bush: Remastered (13): Before The Dawn (2) |  |

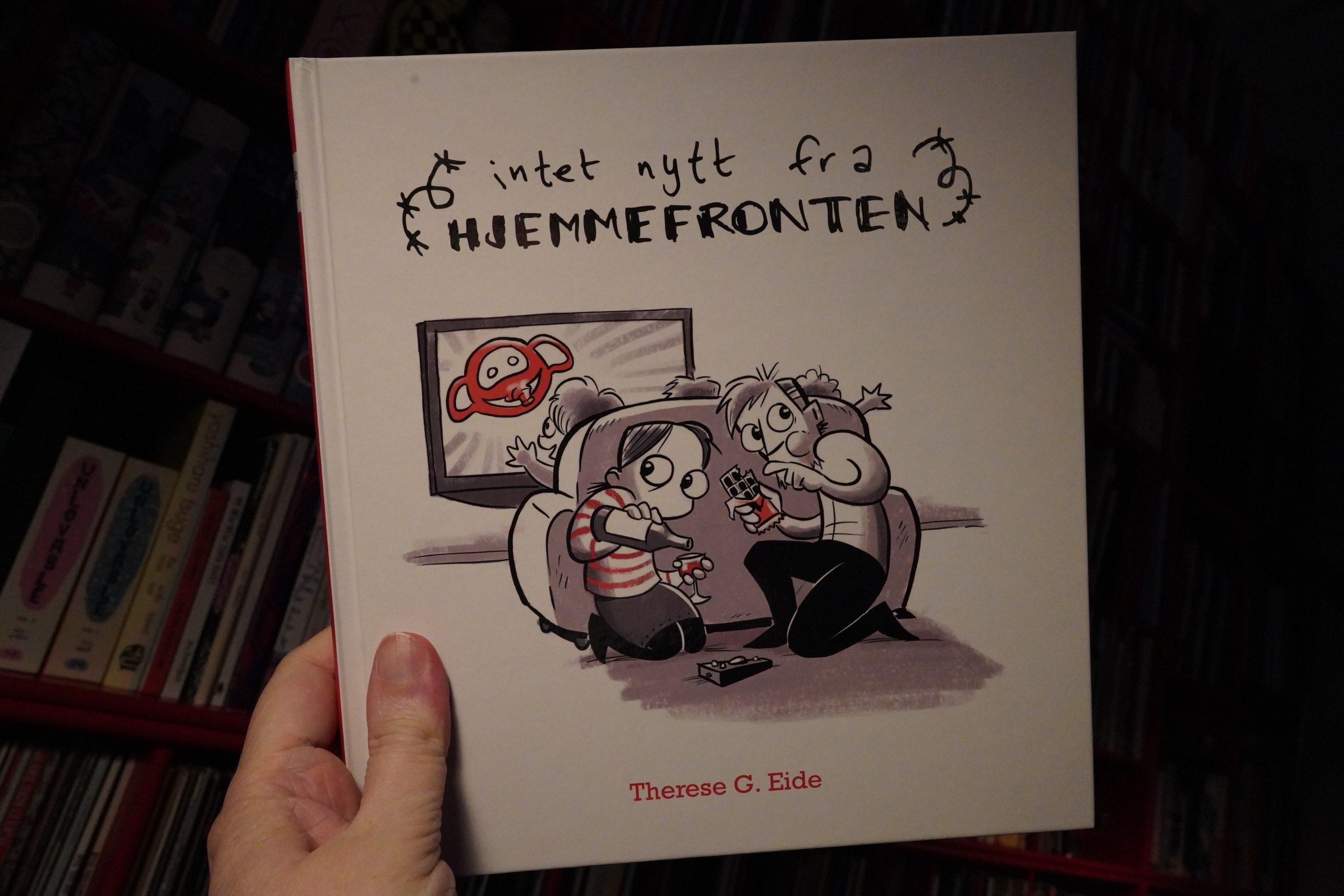

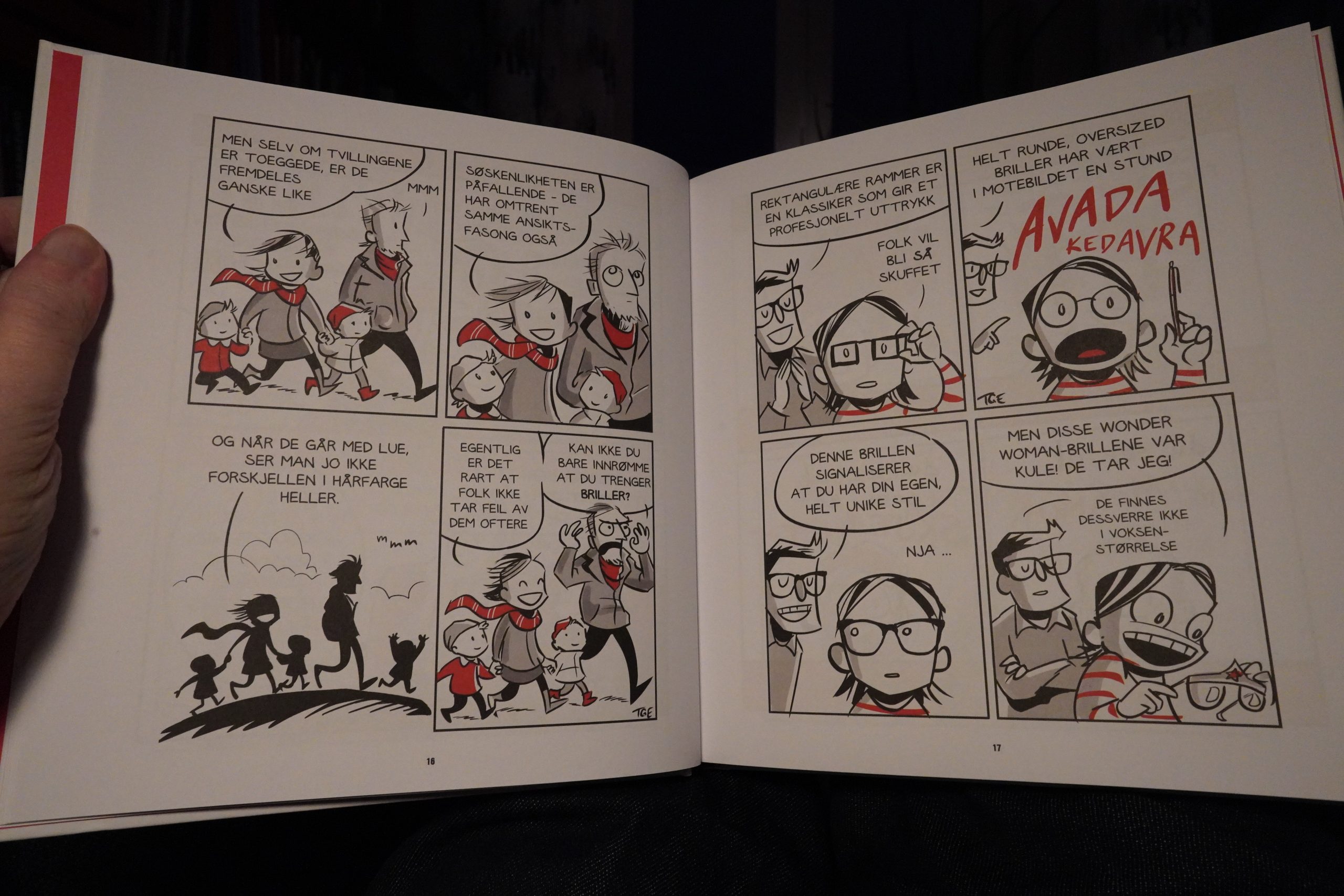

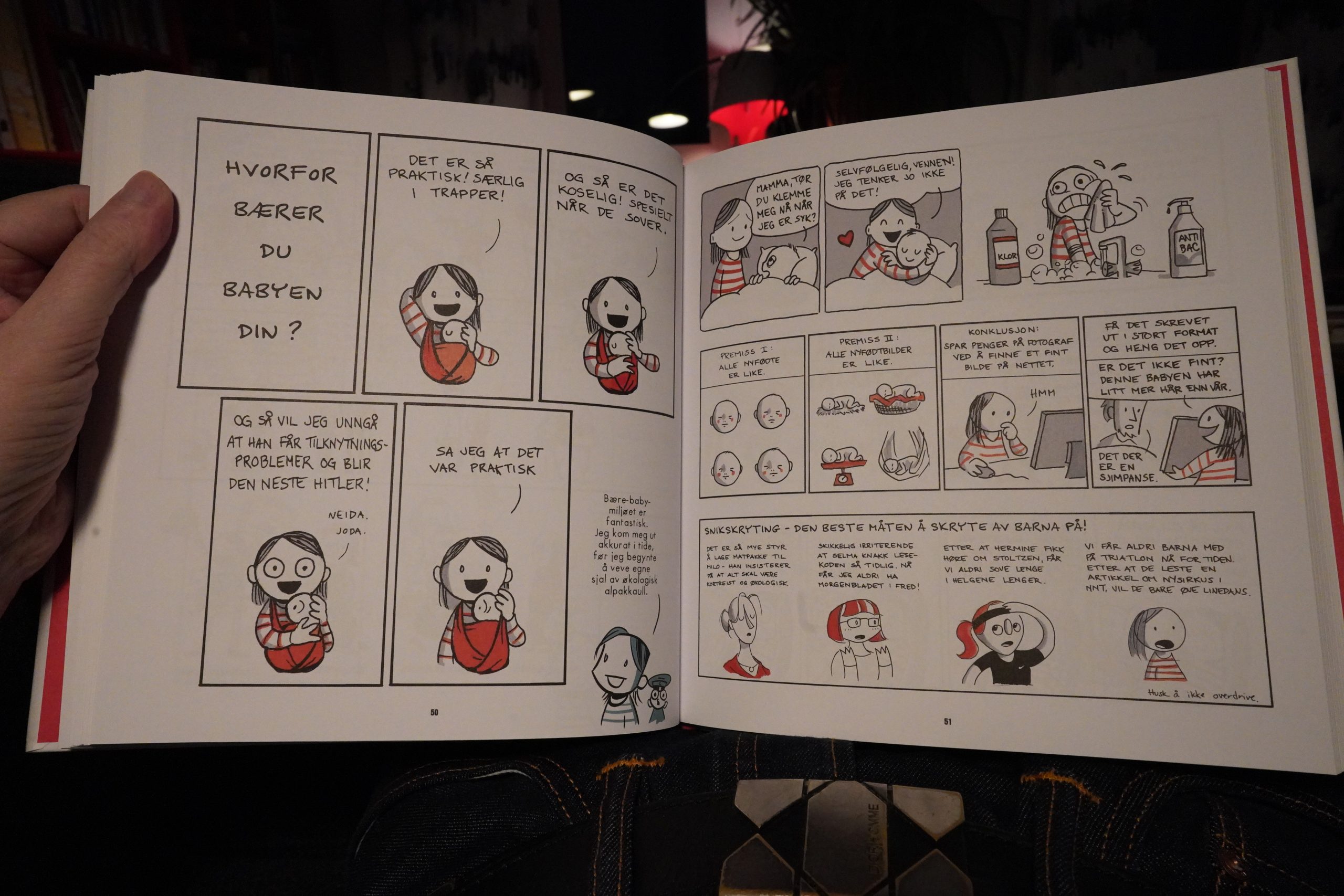

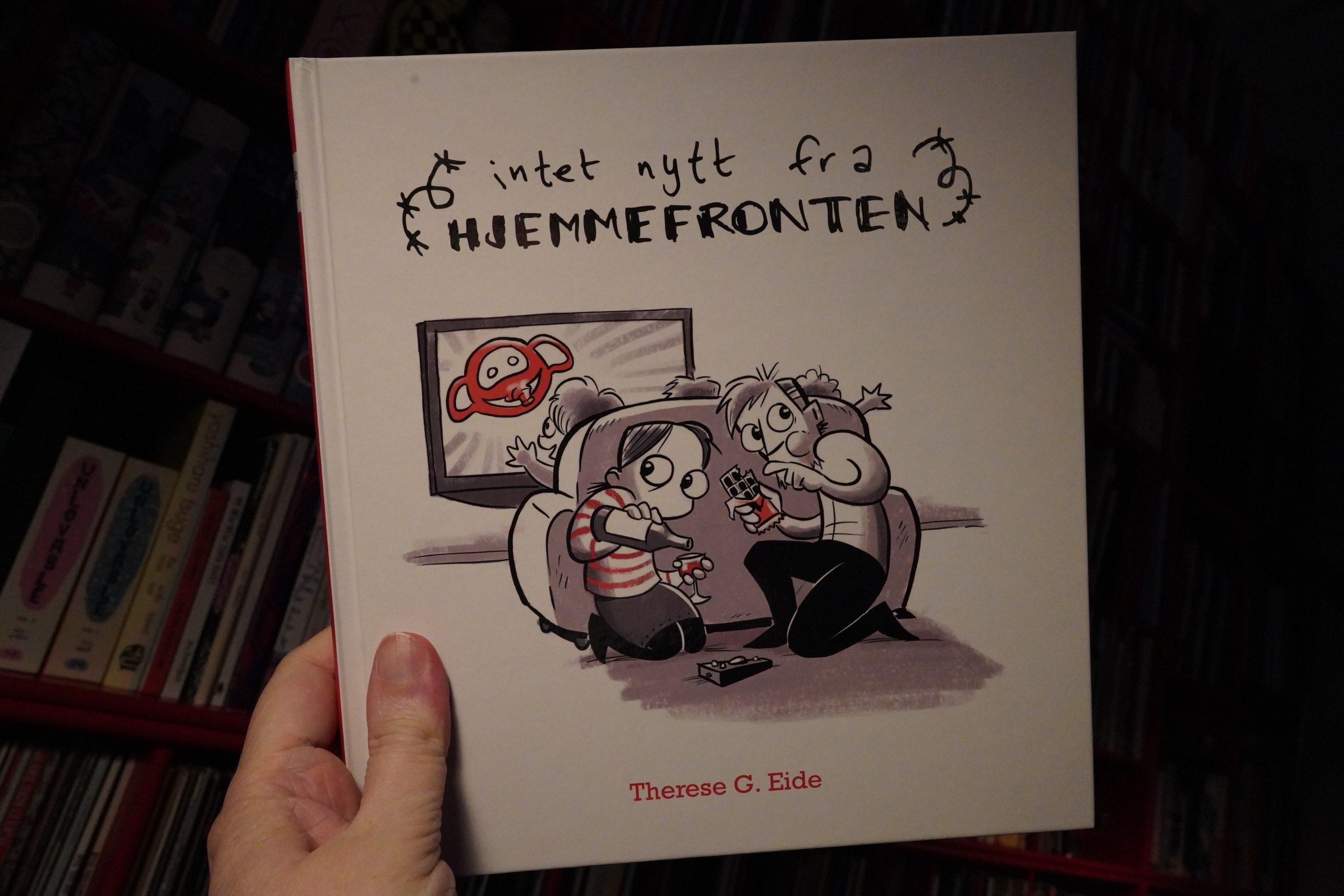

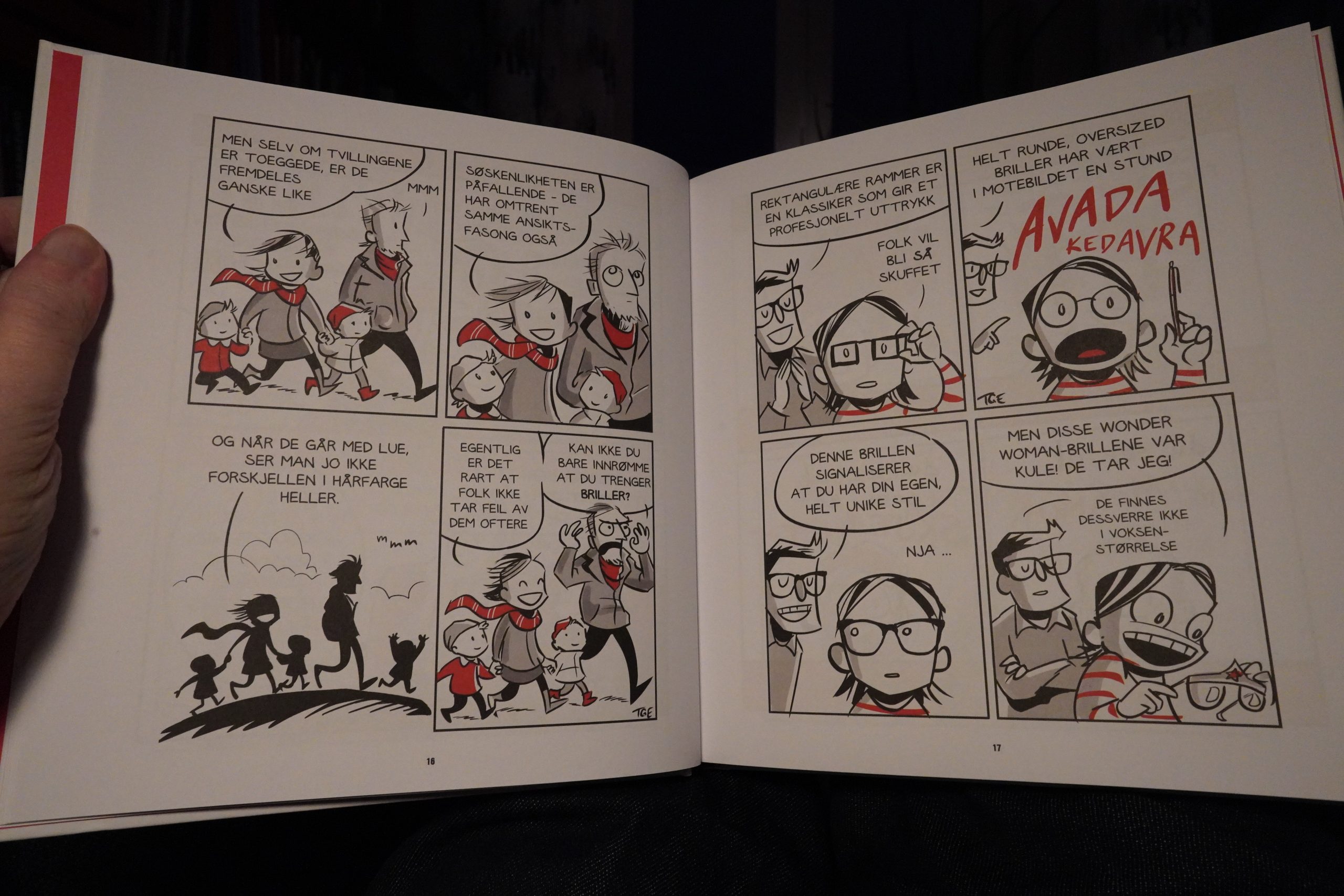

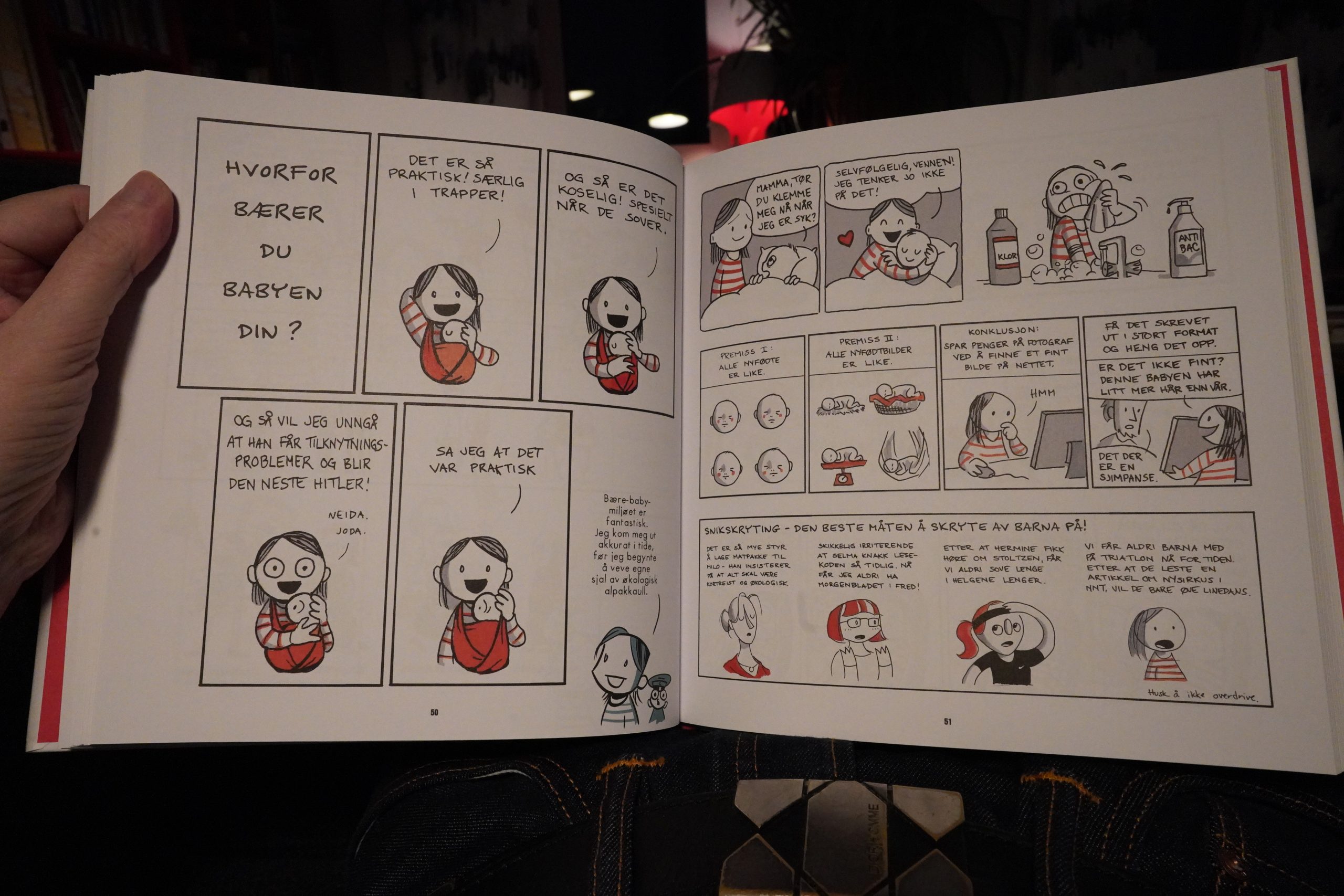

22:27: Intet nytt fra hjemmefronten by Therese G. Eide (Egmont)

This is a Norwegian comic strip collection, and the strip is really funny and pretty original.

It’s perfect as a daily strip, but it would have been nice if there had been more longer sequences in the book to mix things up a bit.

| Kate Bush: Remastered (14): Before The Dawn (3) |  |

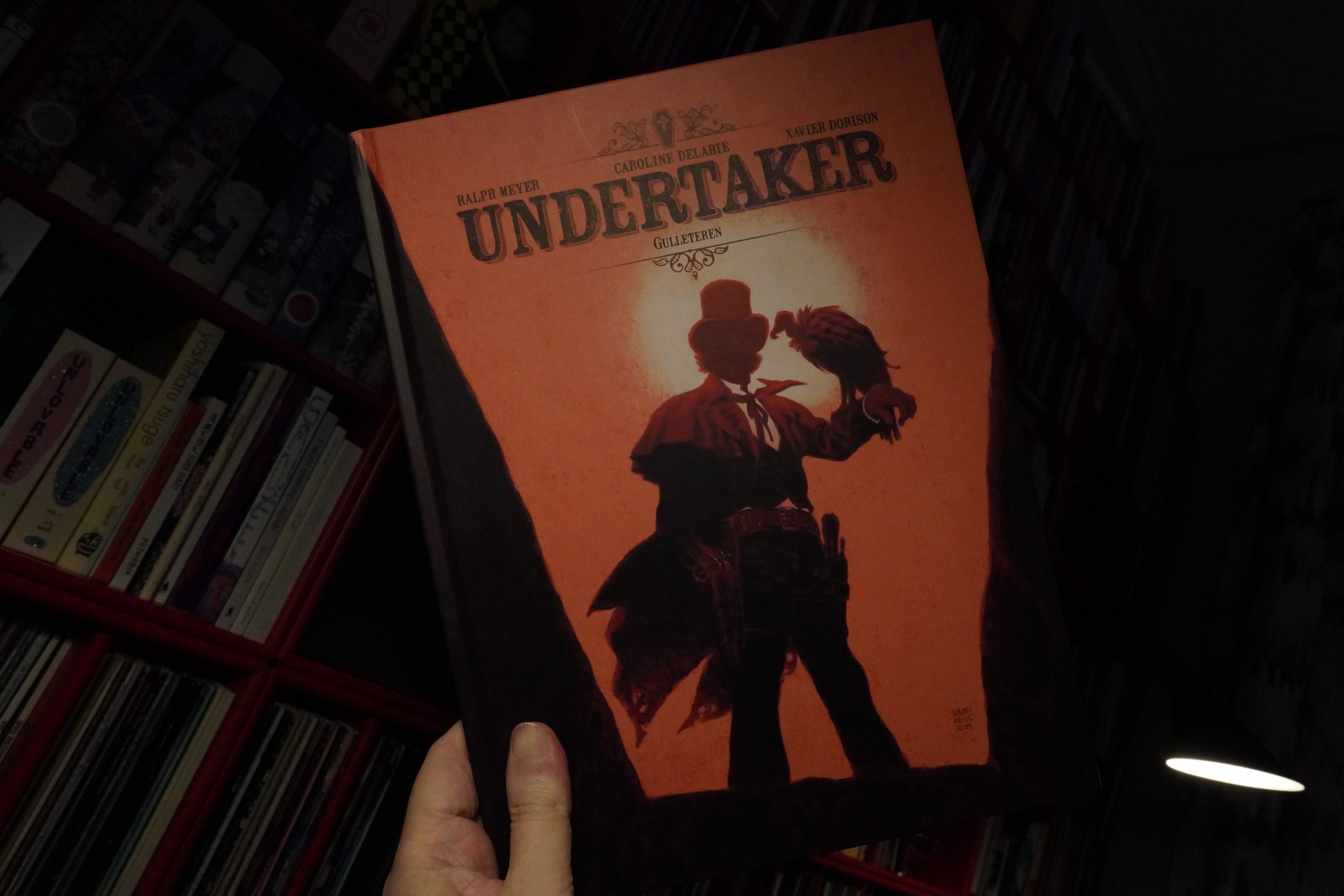

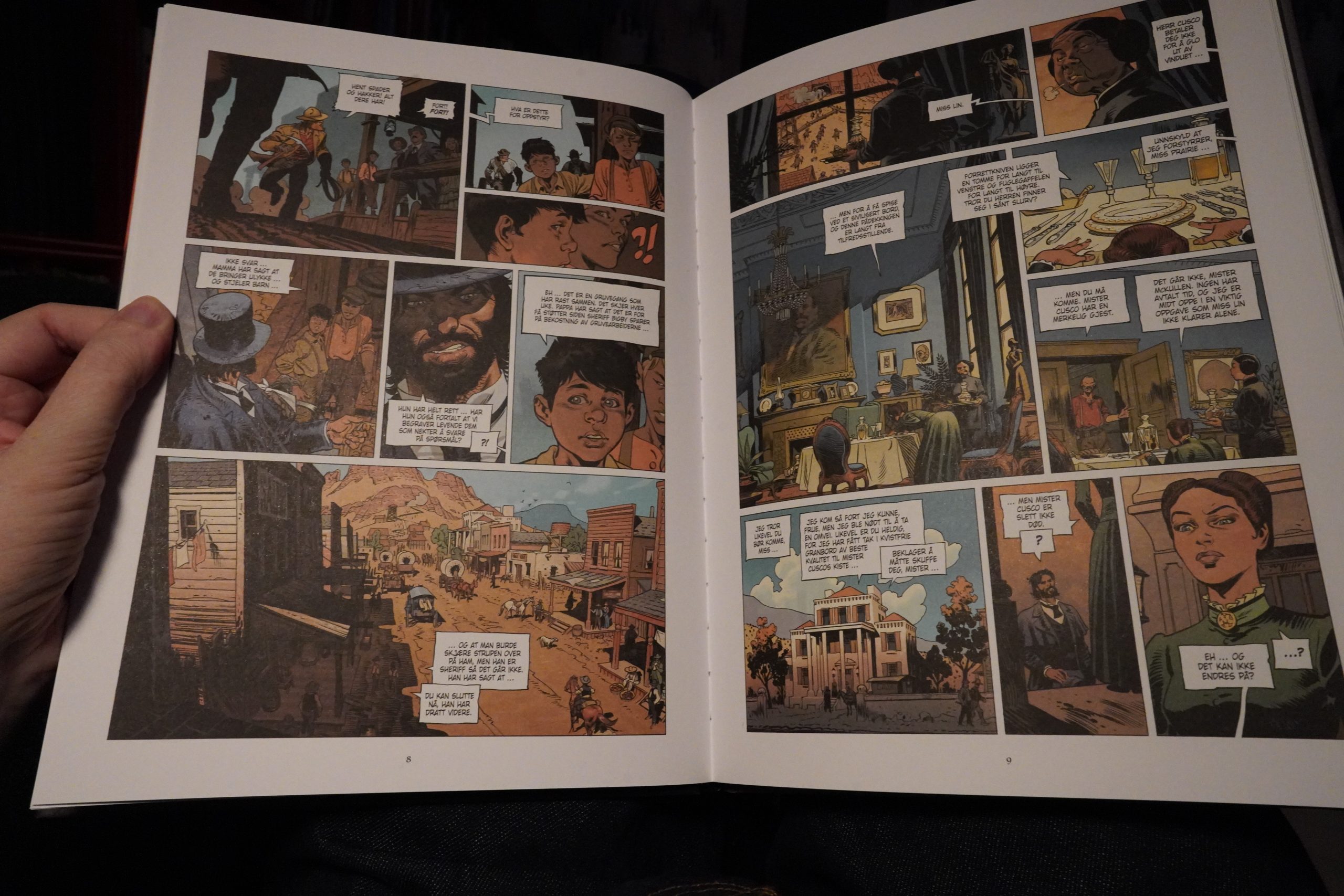

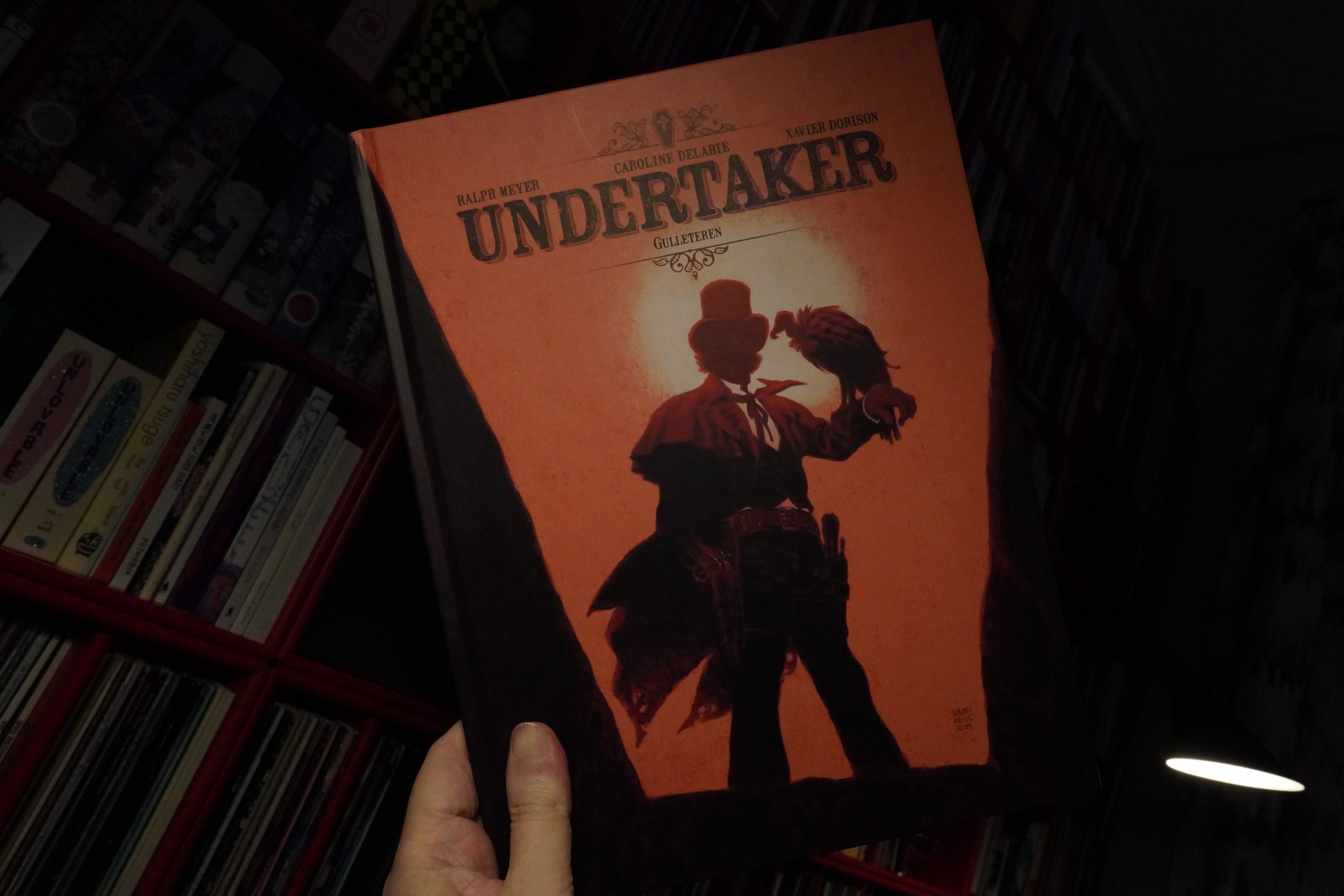

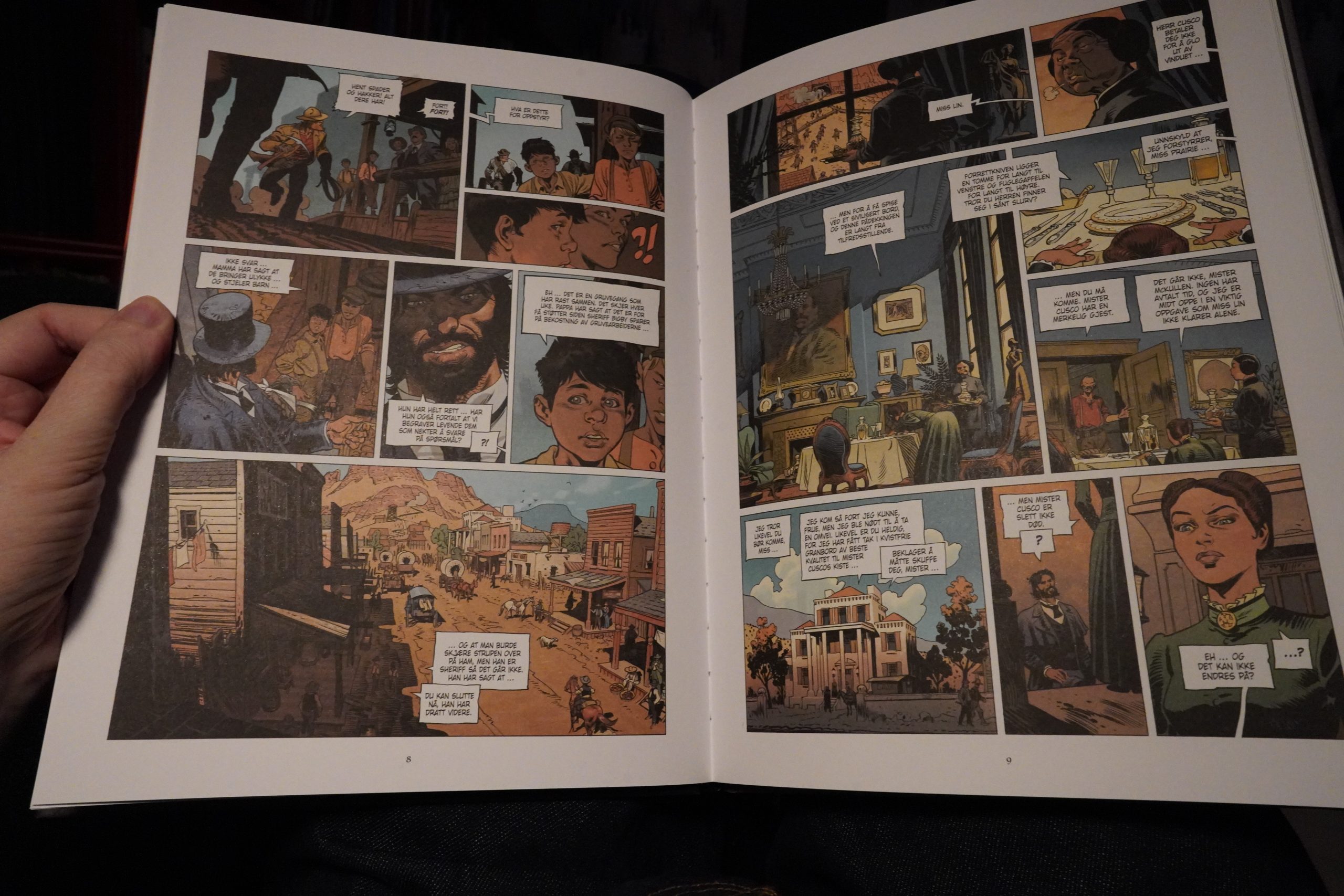

23:24: Undertaker 1 by Meyer / Delabie / Dorison (Egmont)

All these Egmont books are from the same sale, I think…

Oh, I assumed that this was an old series, but this is from 2015. The artwork is slightly generic in the French(ey) Western tradition, but is oddly cartooney here and there.

I found the pacing odd, but it turns out that it’s not a complete story — it’s more like the first chapter, I guess. It’s a pretty original book; doesn’t go anywhere I expected, really. It’s entertaining enough.

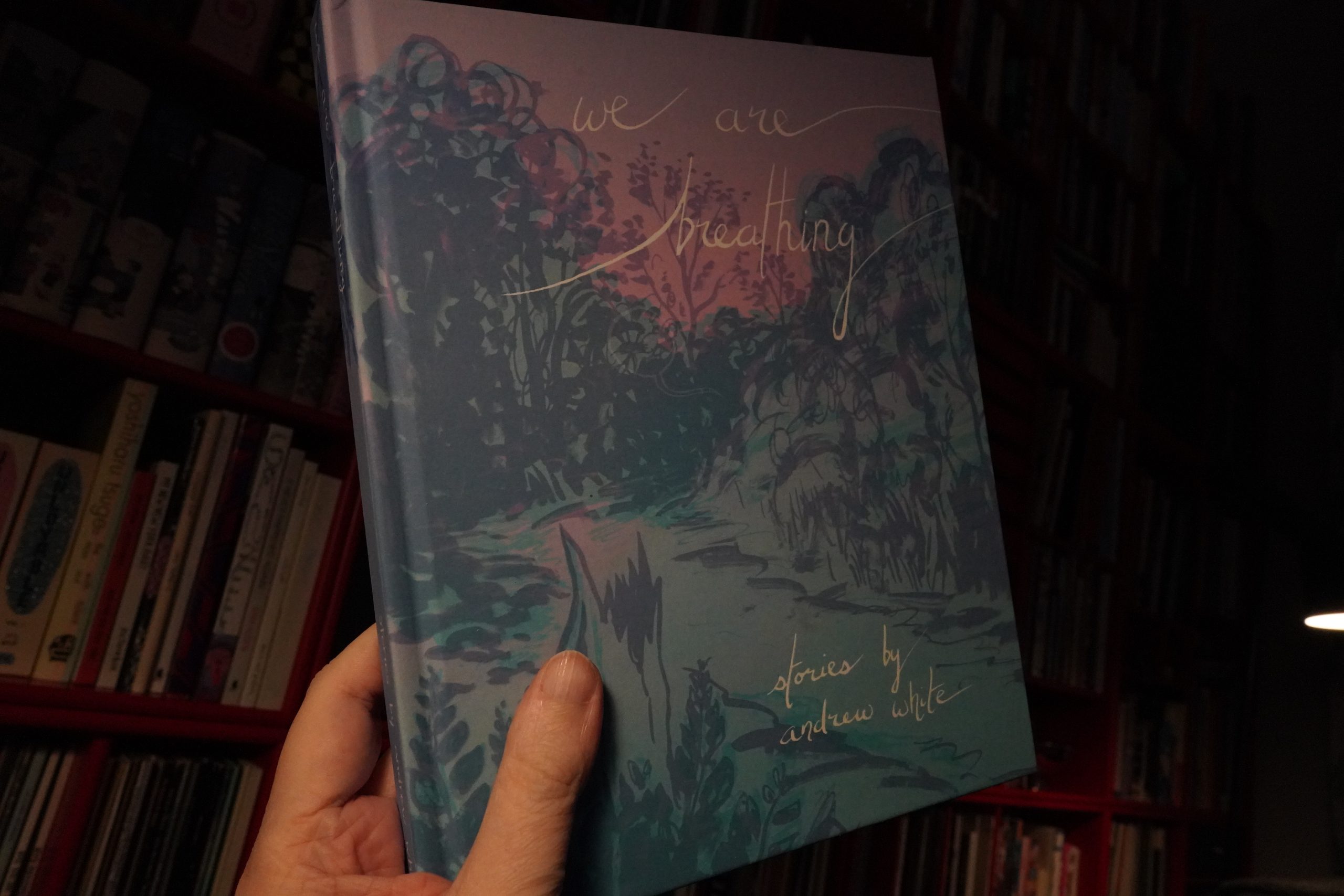

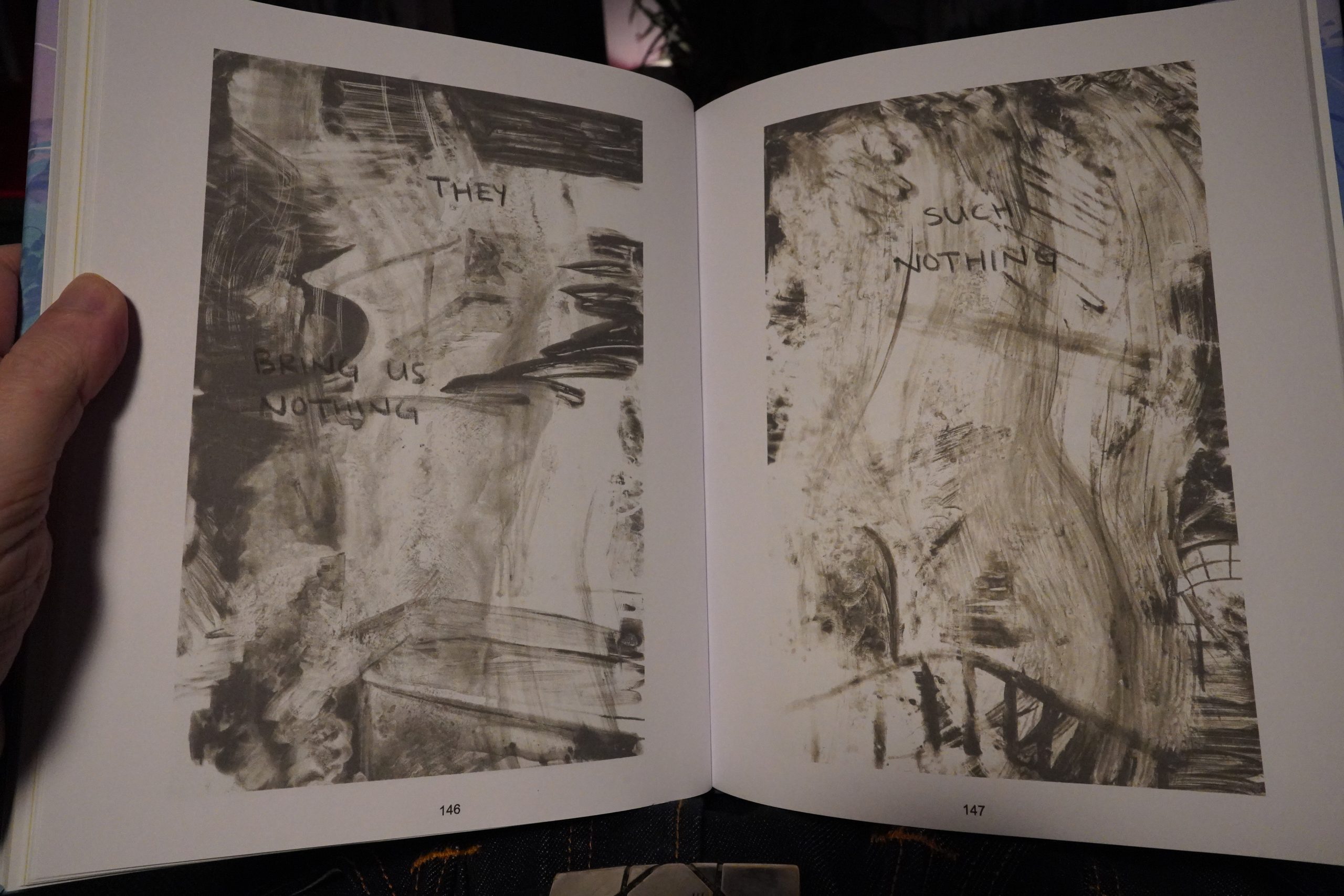

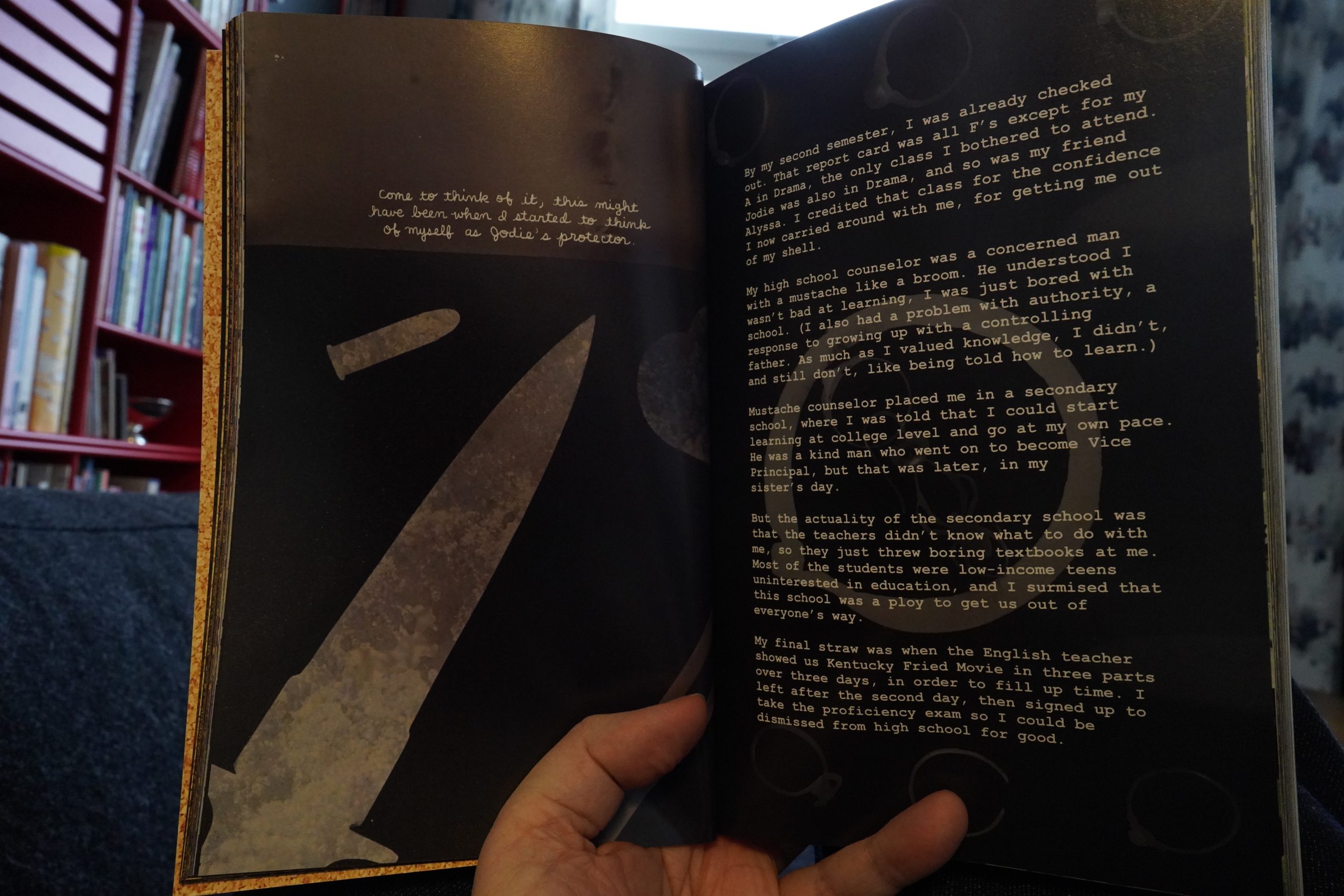

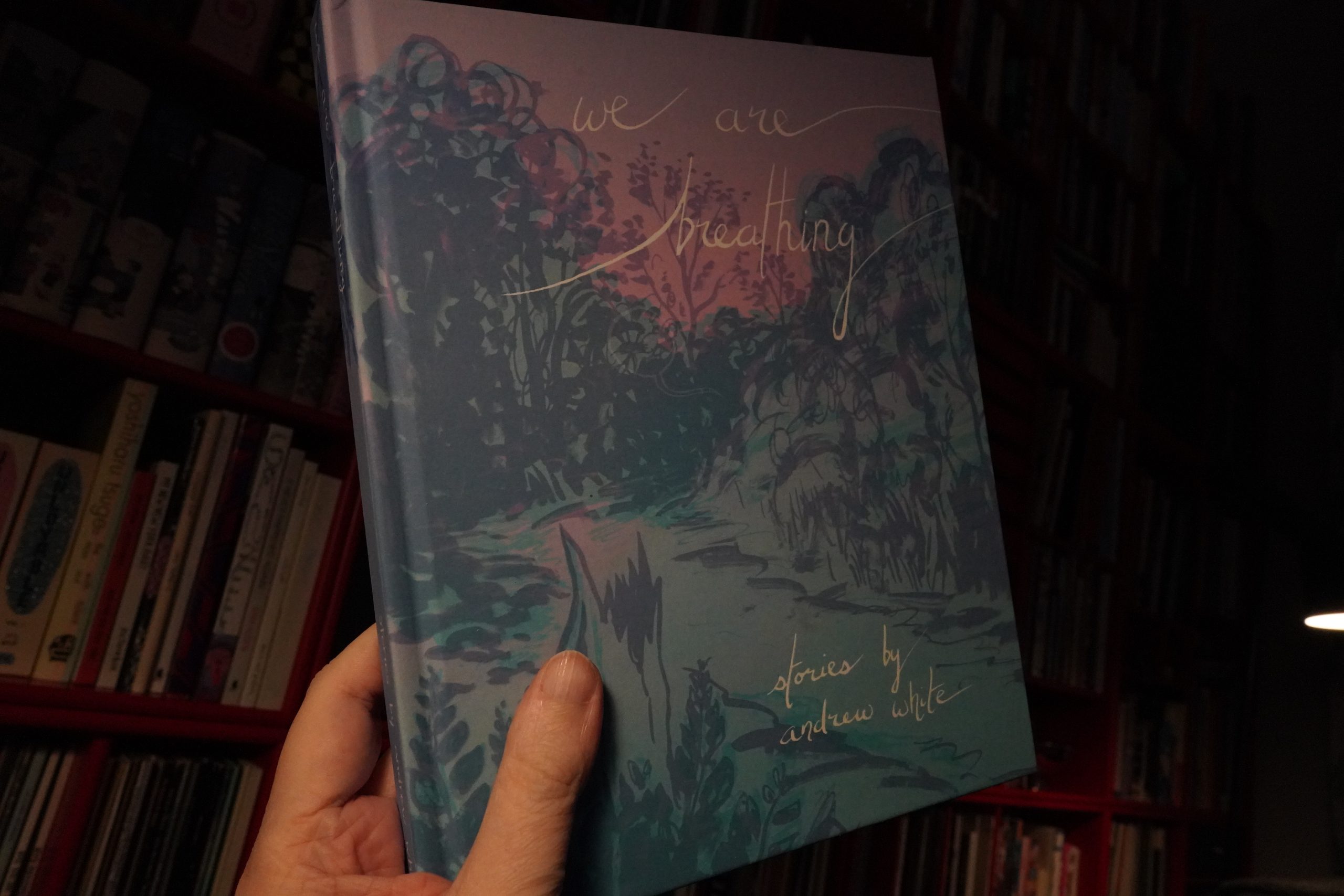

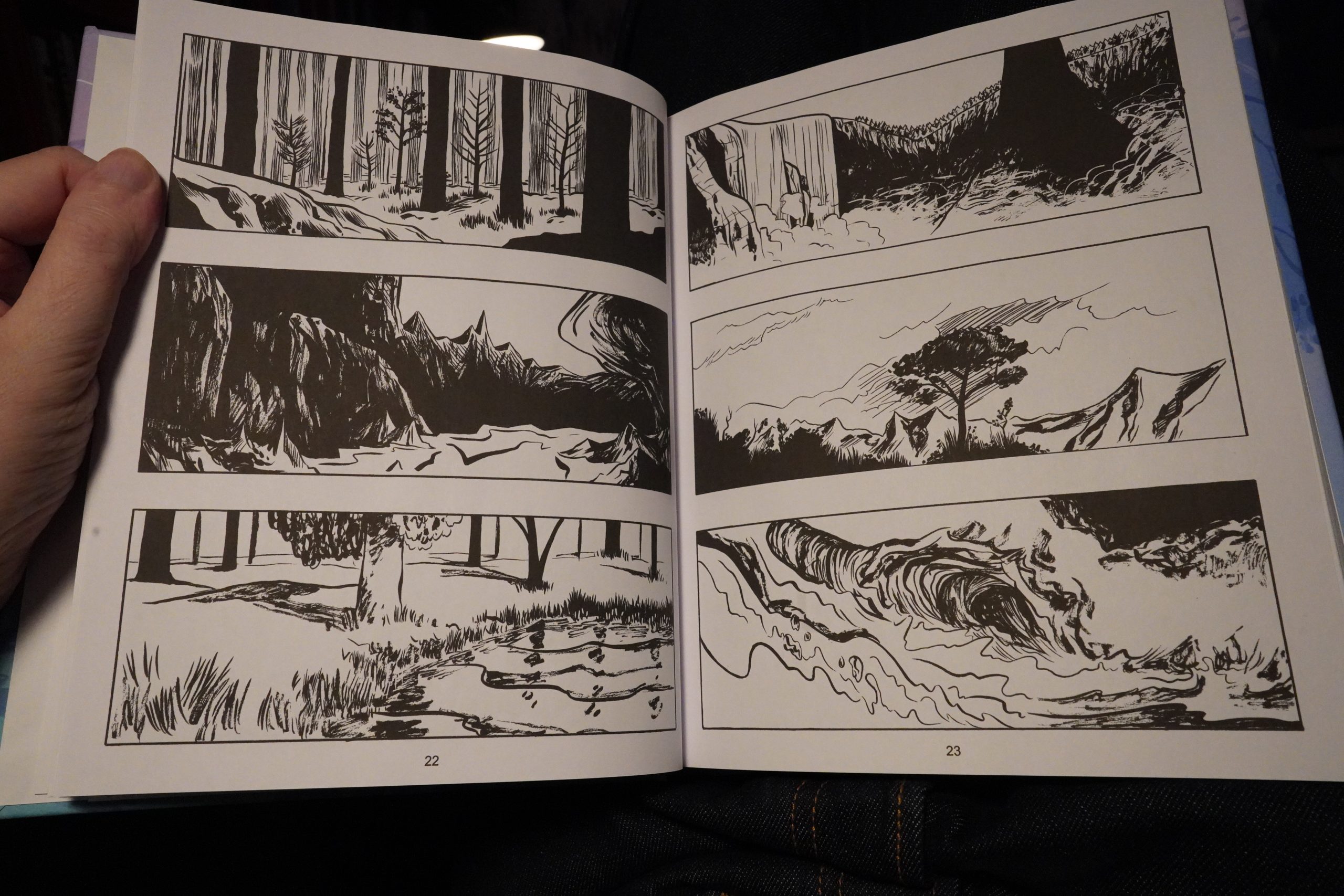

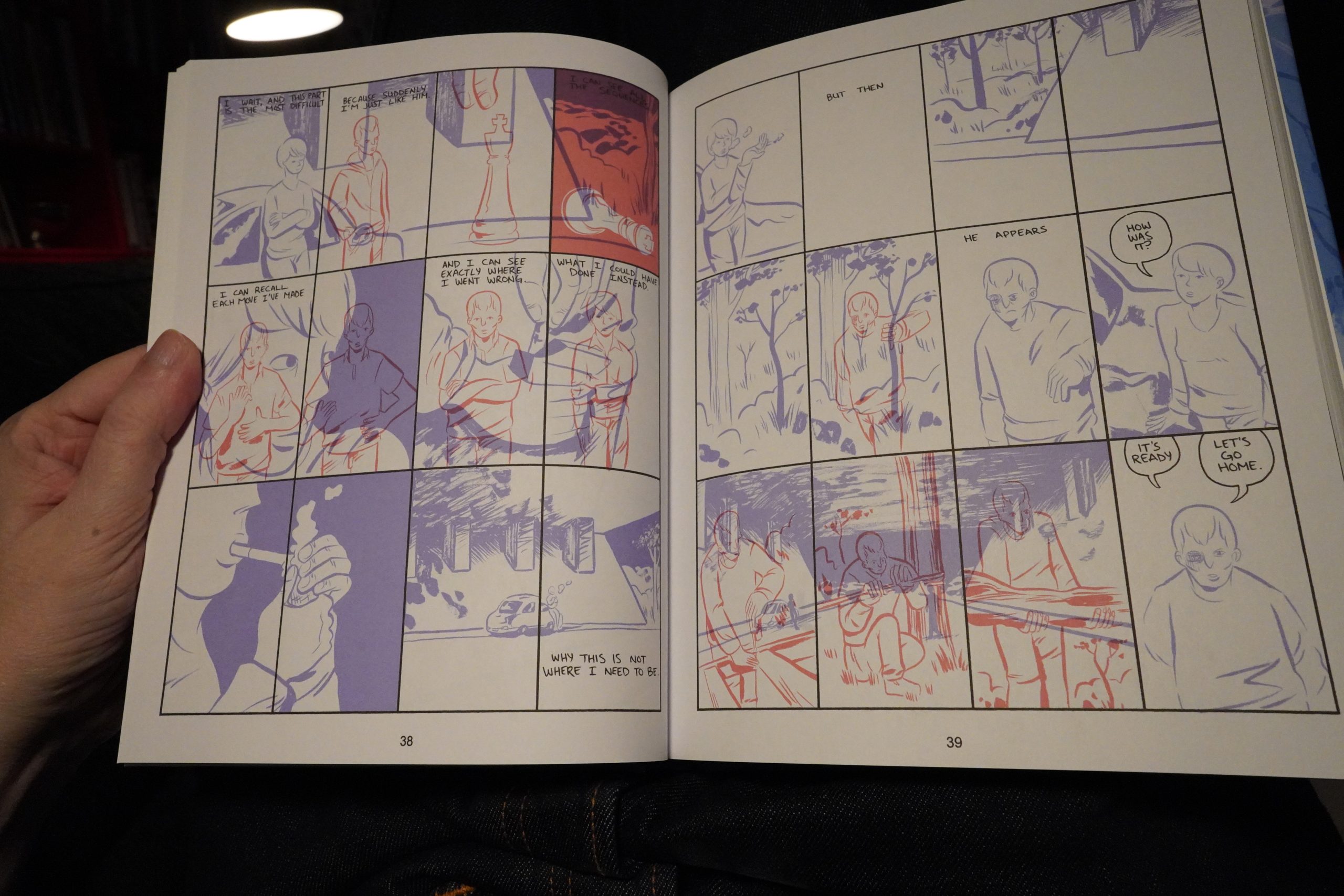

23:54: We Are Breathing by Andrew White

This is the final book I got from Andrew White’s web store, and it’s a pretty hefty tome.

Oh, this comes with a drawing. Lovely.

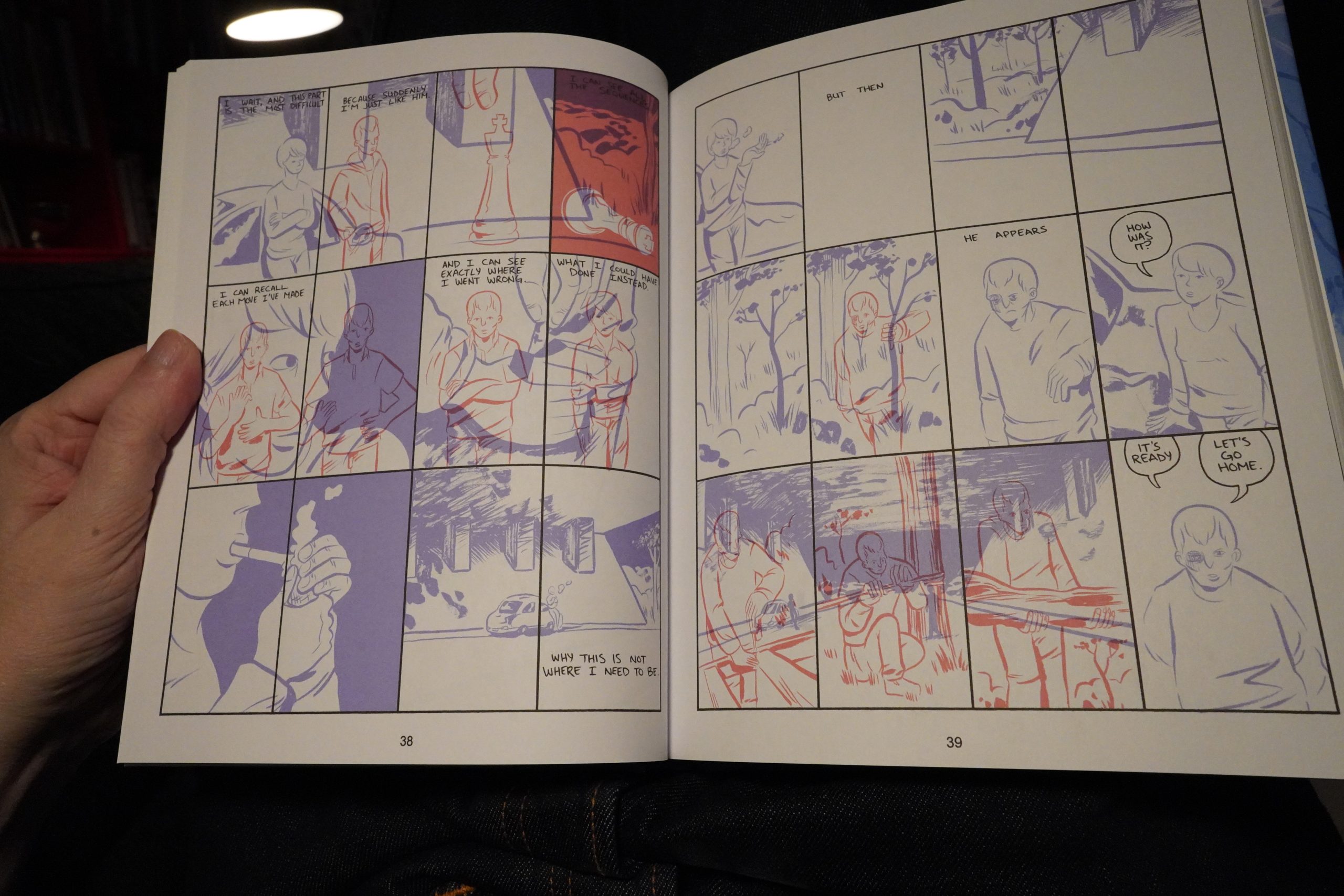

So, this collects twelve different pieces, and it’s striking how different the approaches are here.

This one is absolutely flabbergastingly good.

But it’s all good, really. Fantastic book.

And I should stop reading here to go out on a high point, but I’ve got just two more unread comics and then my Windowsill Of Unread Comics is empty! So let’s press on.

| repository: Kate Bush |  |

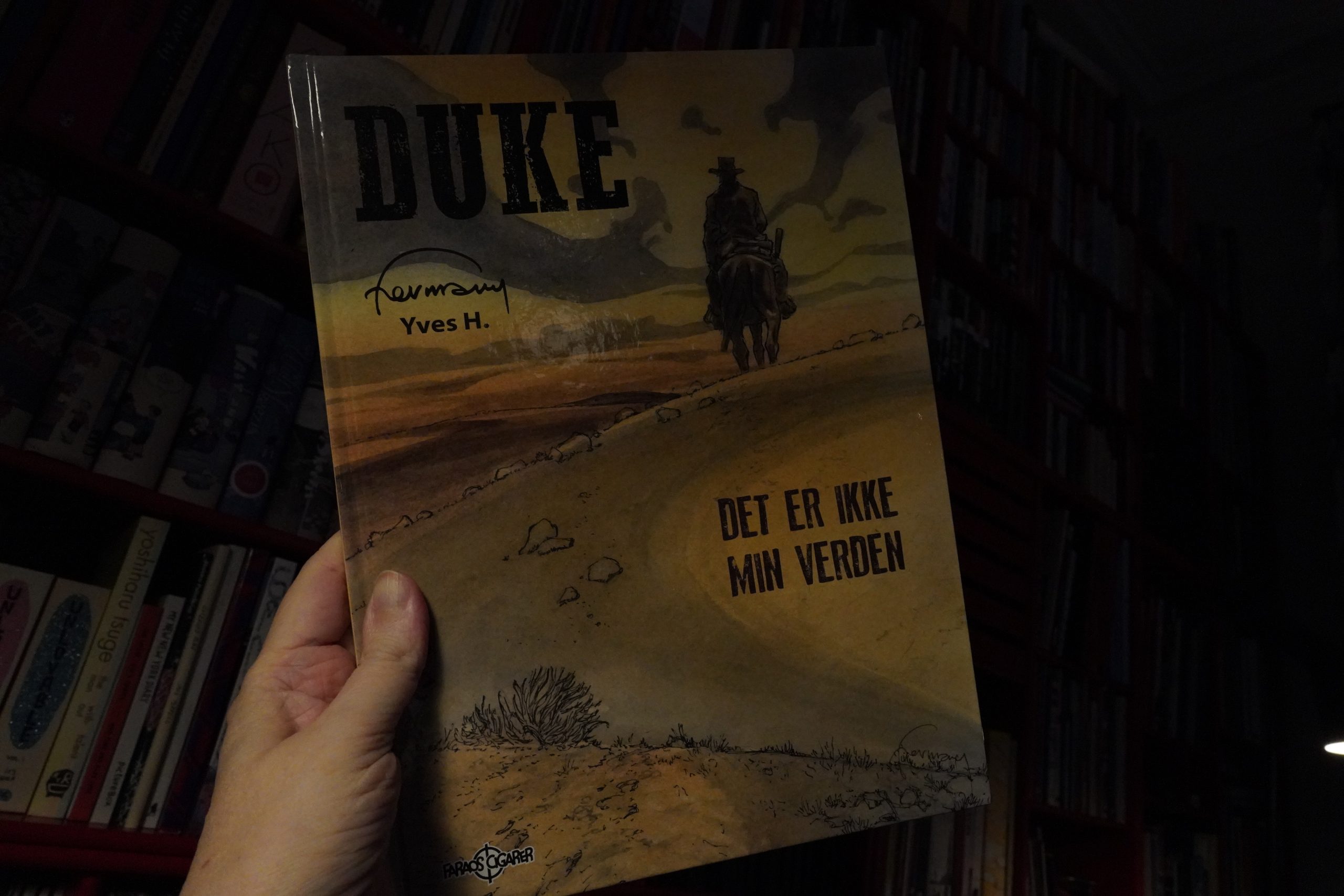

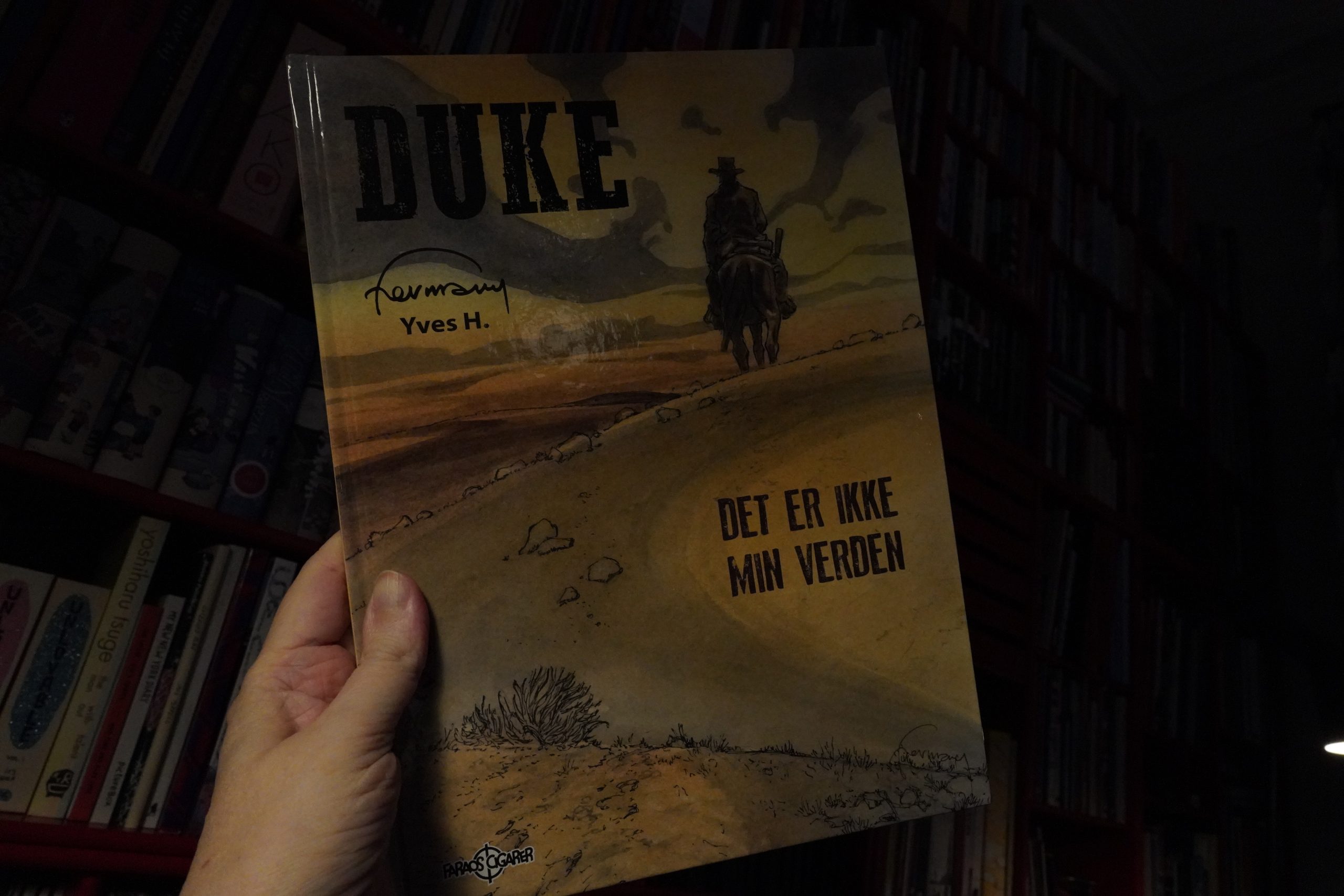

00:26: Duke 7: Ce monde n’est pas le mien by Hermann / Yves H. (Faraos Cigarer)

I’ve only read one other Duke album, I think, and it was pretty bad. I basically bought this by mistake, but I might as well read it.

Yves H. is Hermann’s son, and after reading a few reviews of the pair’s books on Bedetheque, it seems like everybody’s blaming Yves H. for how bad these books are. (He started doing scripts for his father about 20 years ago…)

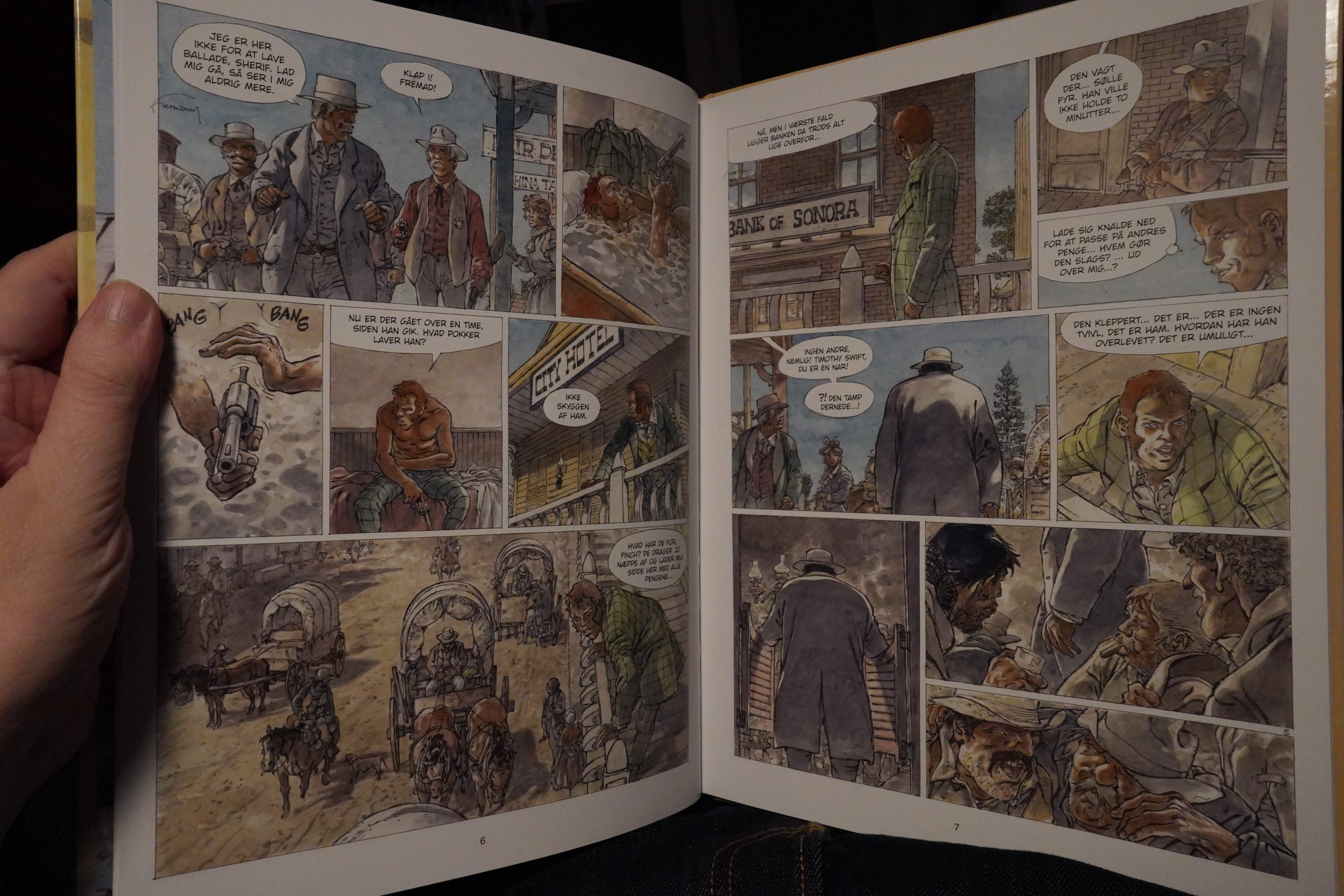

Well, this looks pretty good, at least.

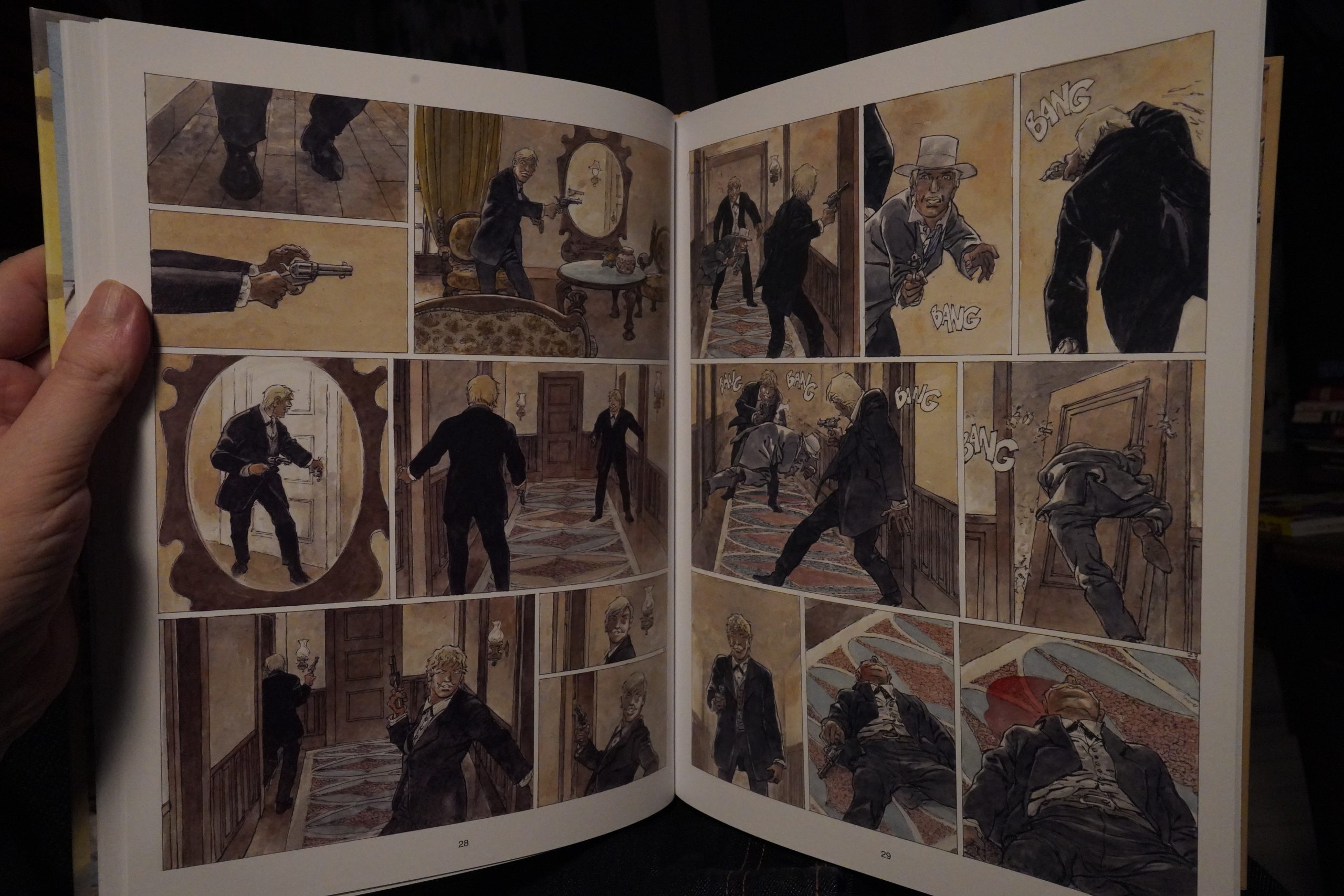

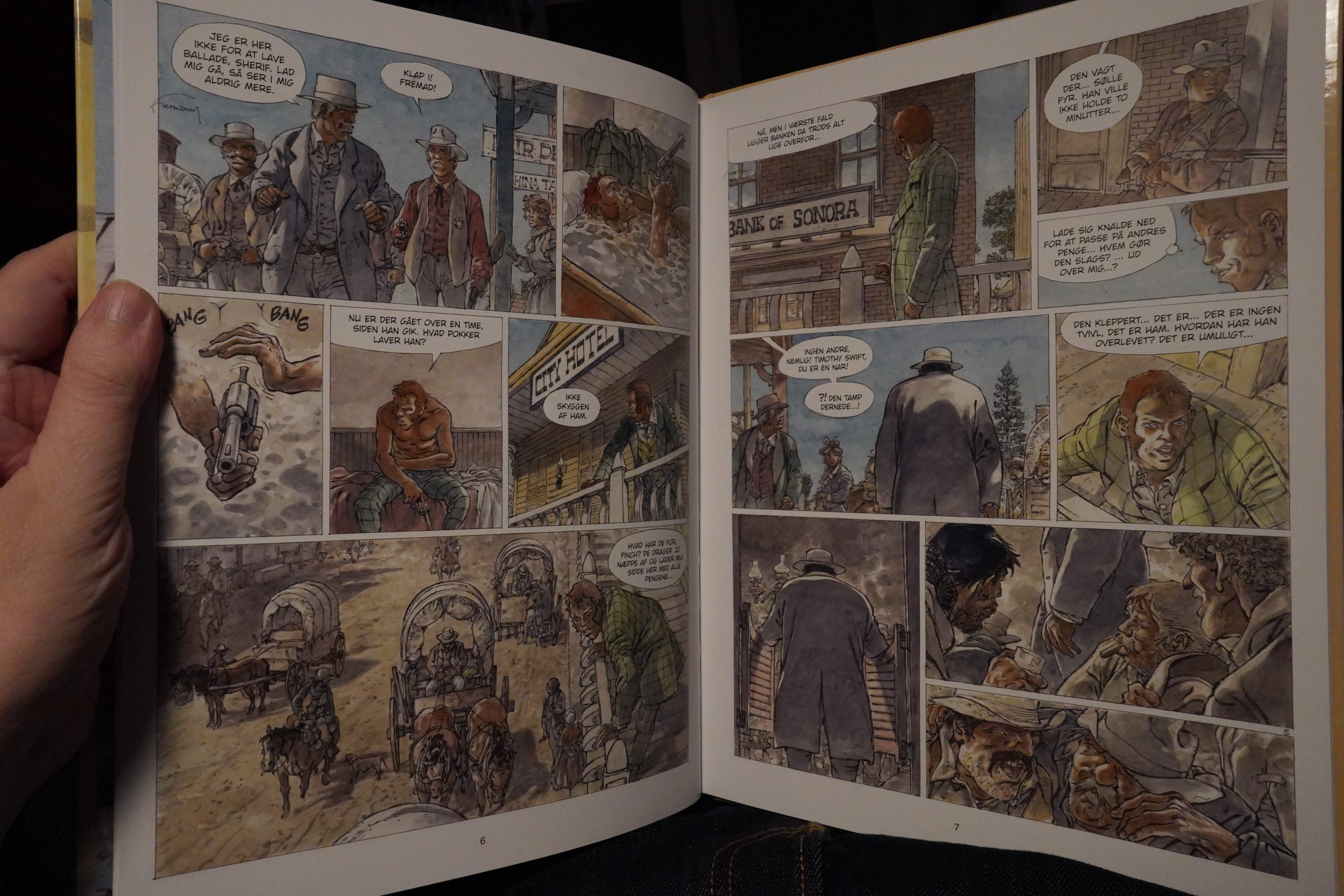

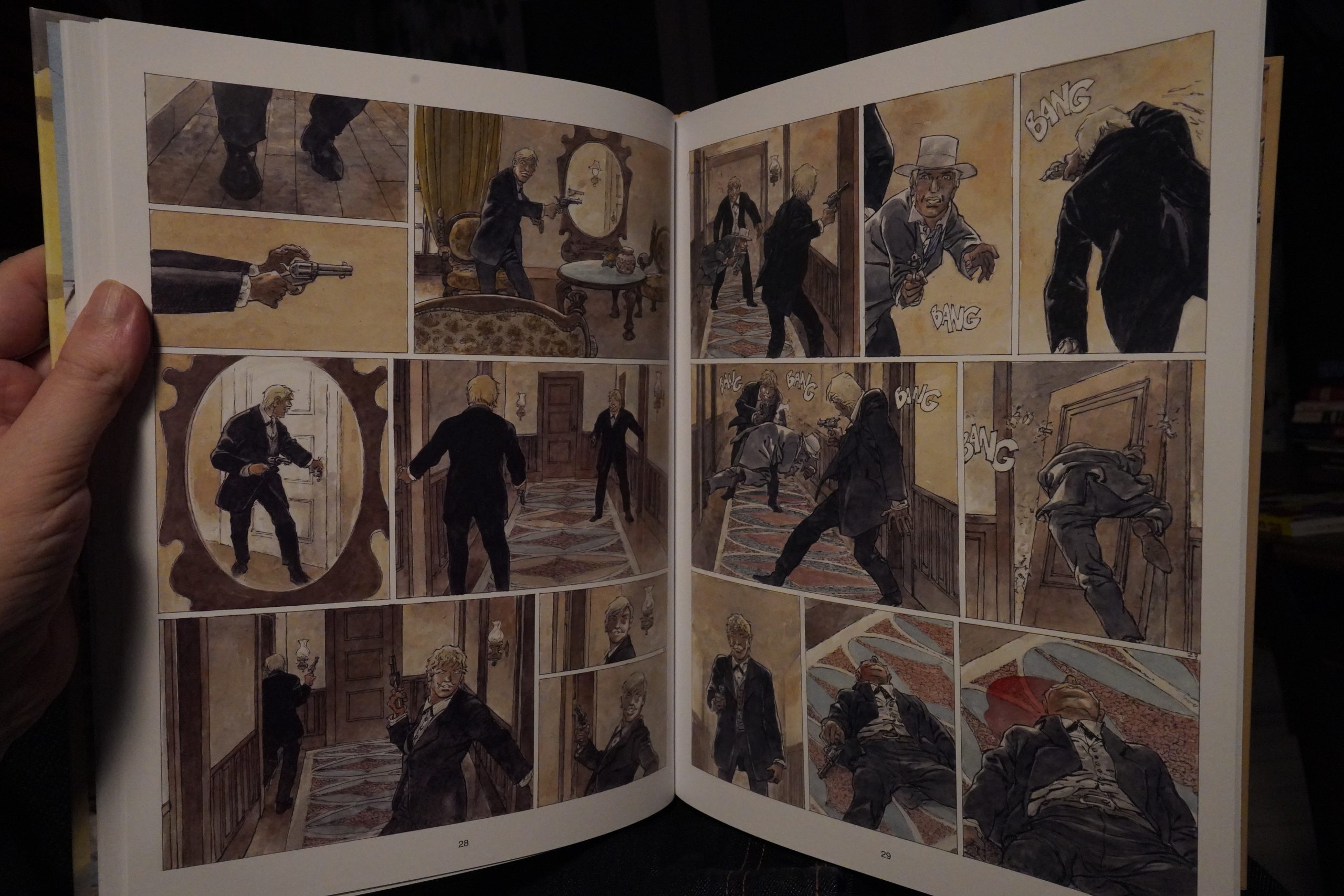

Unfortunately, it seems like it’s a direct continuation of an apparently long story, and I have no idea what it’s all about. So it all seems rather loopy. Perhaps it all makes perfect sense? It’s also apparently the last Duke album, but it ends on what seems like a non sequitur?

The reader will have to reread the six previous books to find their way around.

[…]

the cycle ends a little curiously .

[…]

This opus is the end of the trail for Duke who leads his last stand to deliver Peg from the hands of the sinister Mr. King and his henchmen.

All the characters will have either suffered, been injured, or been executed, or all three at the same time. Too bad to eliminate almost all the characters from the story just to drive home the point, we understood the message well: black is black, as a certain singer said.

I guess the French nerds weren’t much impressed, either.

| Kate Bush: Remastered (16): The Other Sides (2): The Other Side 1 |  |

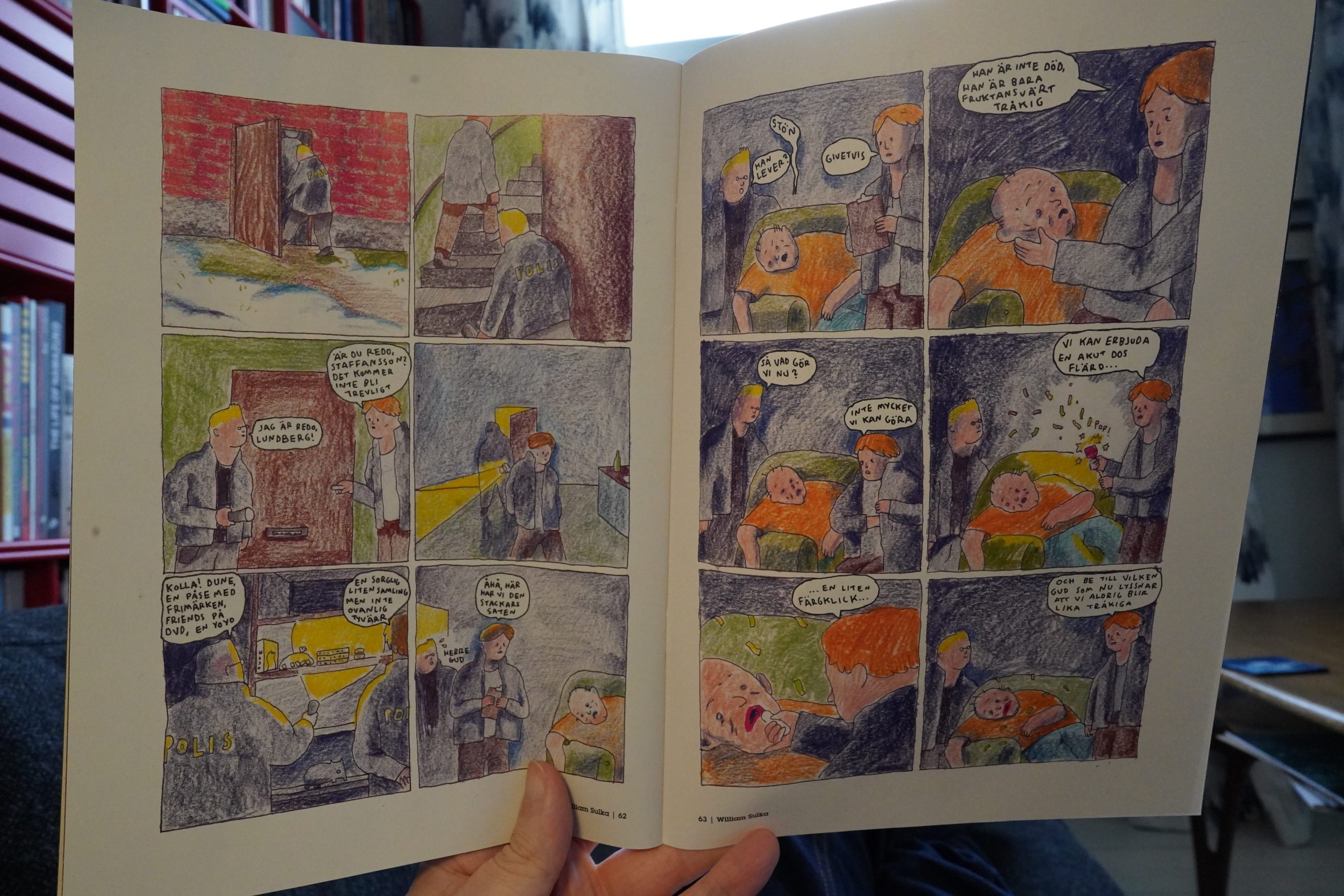

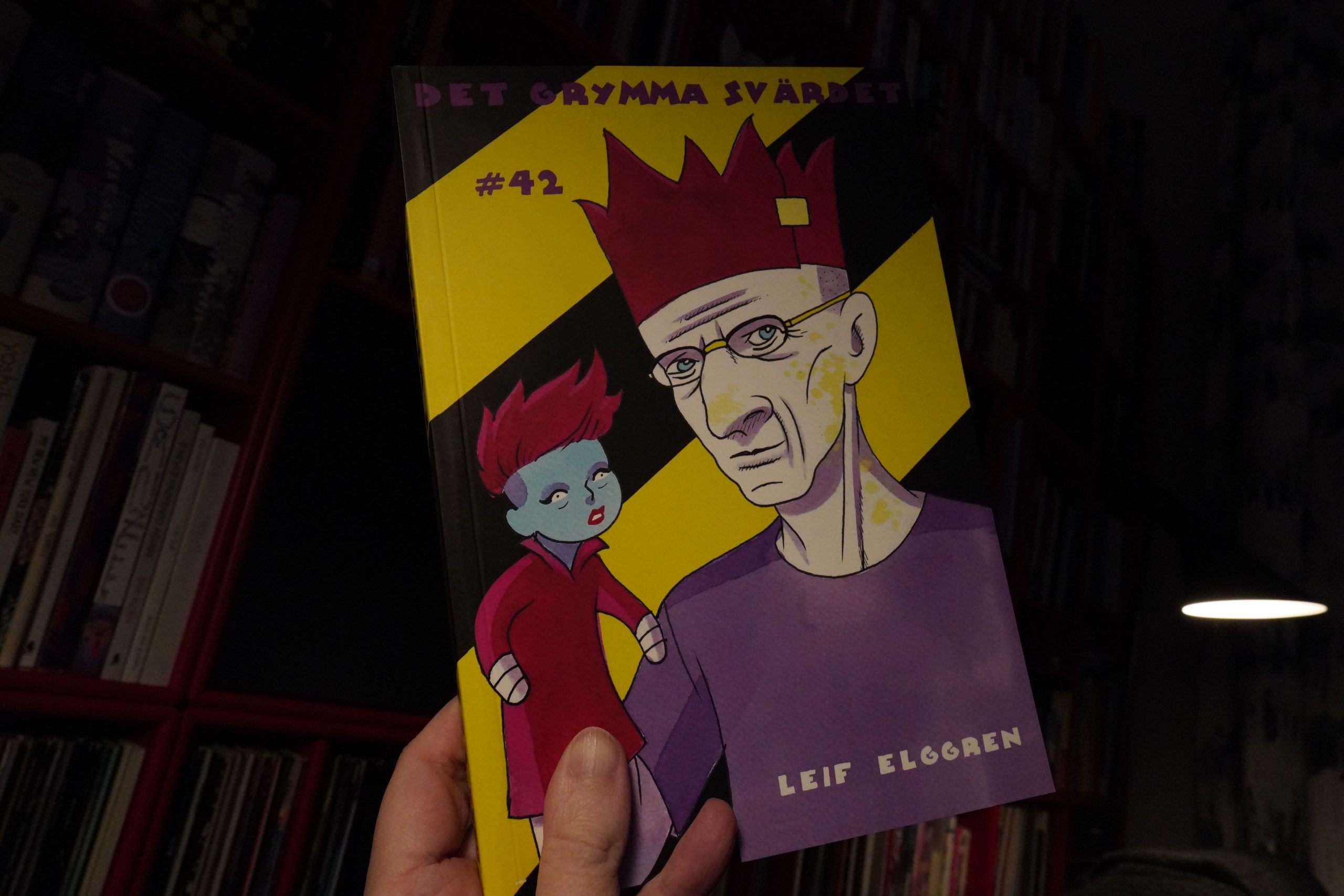

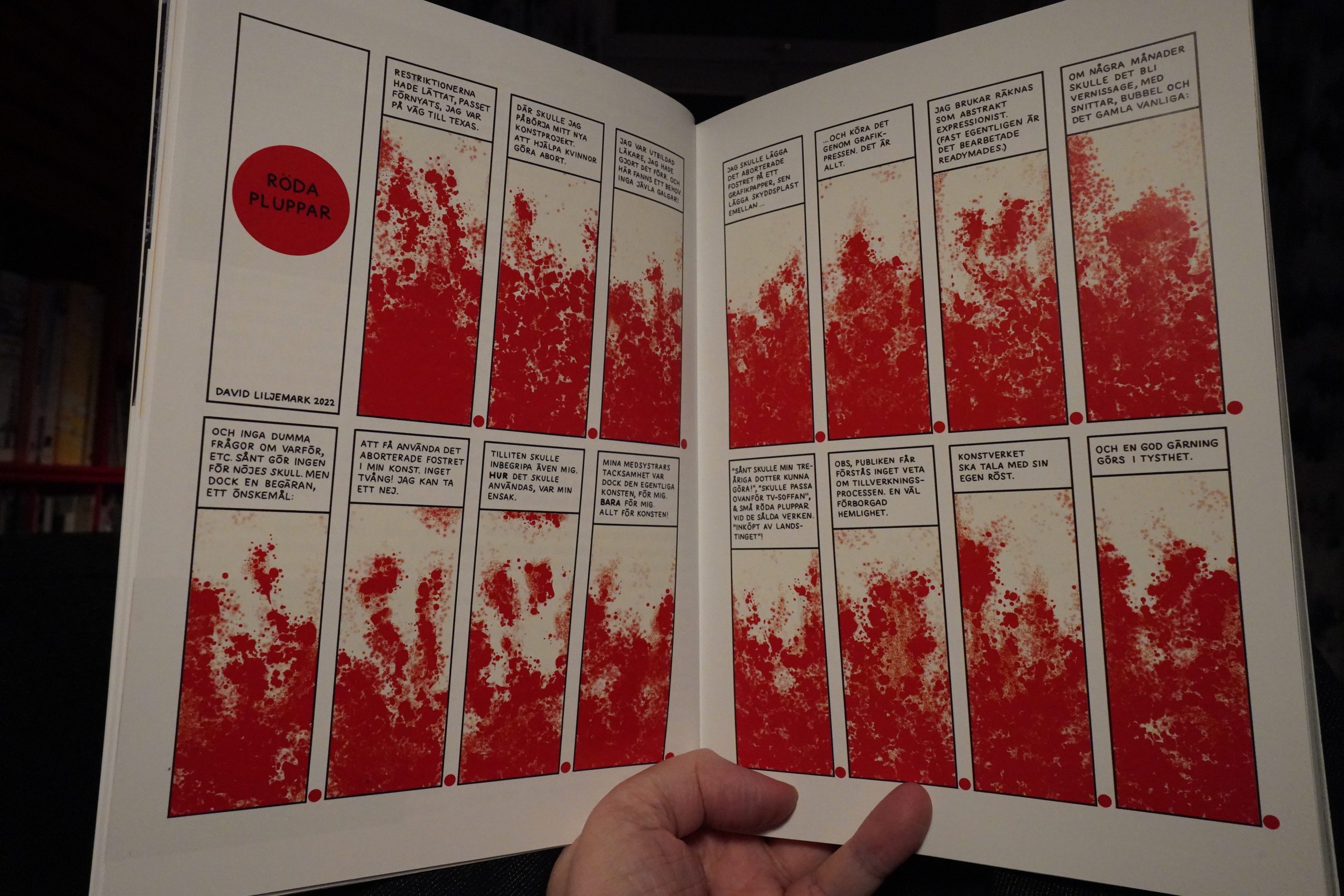

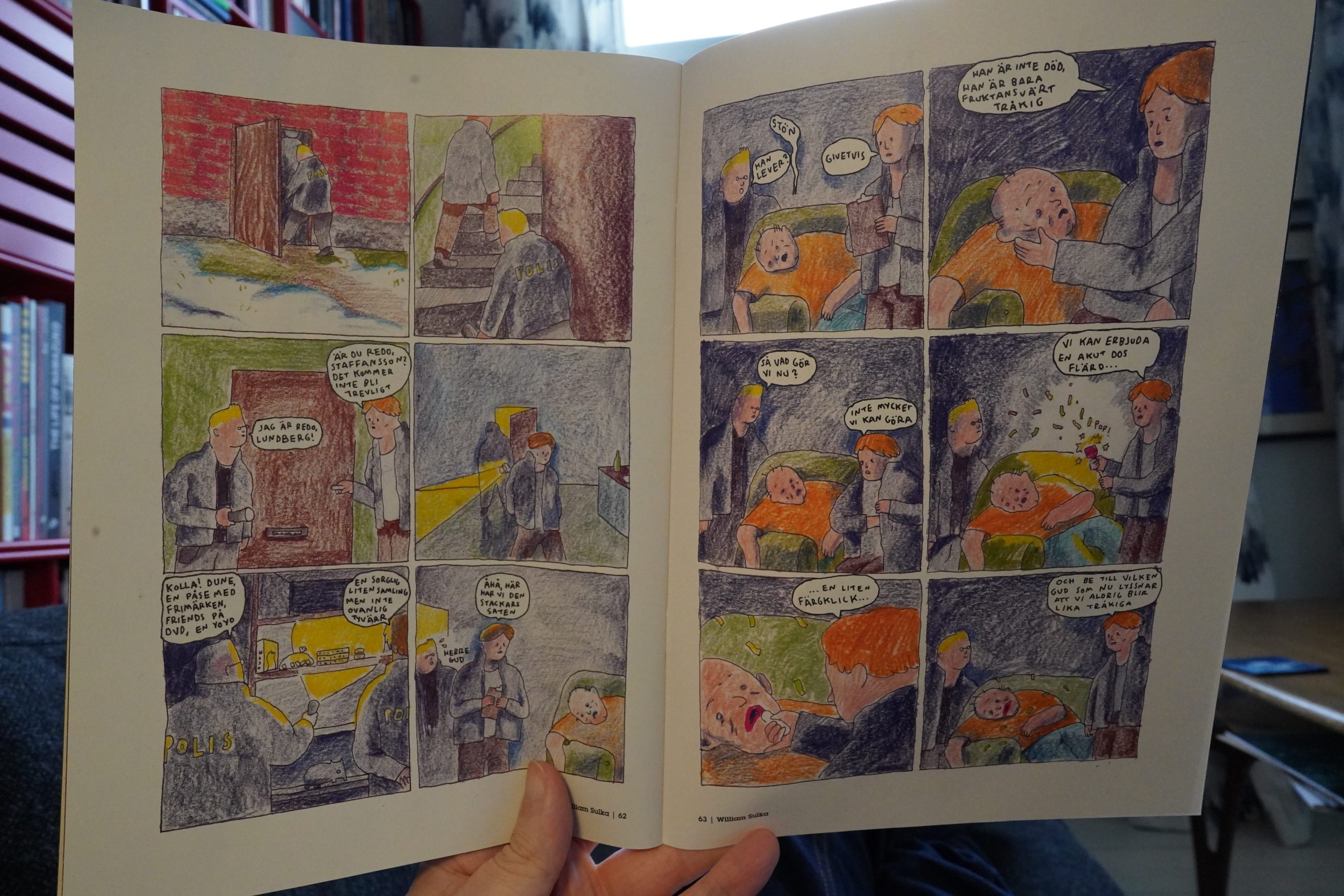

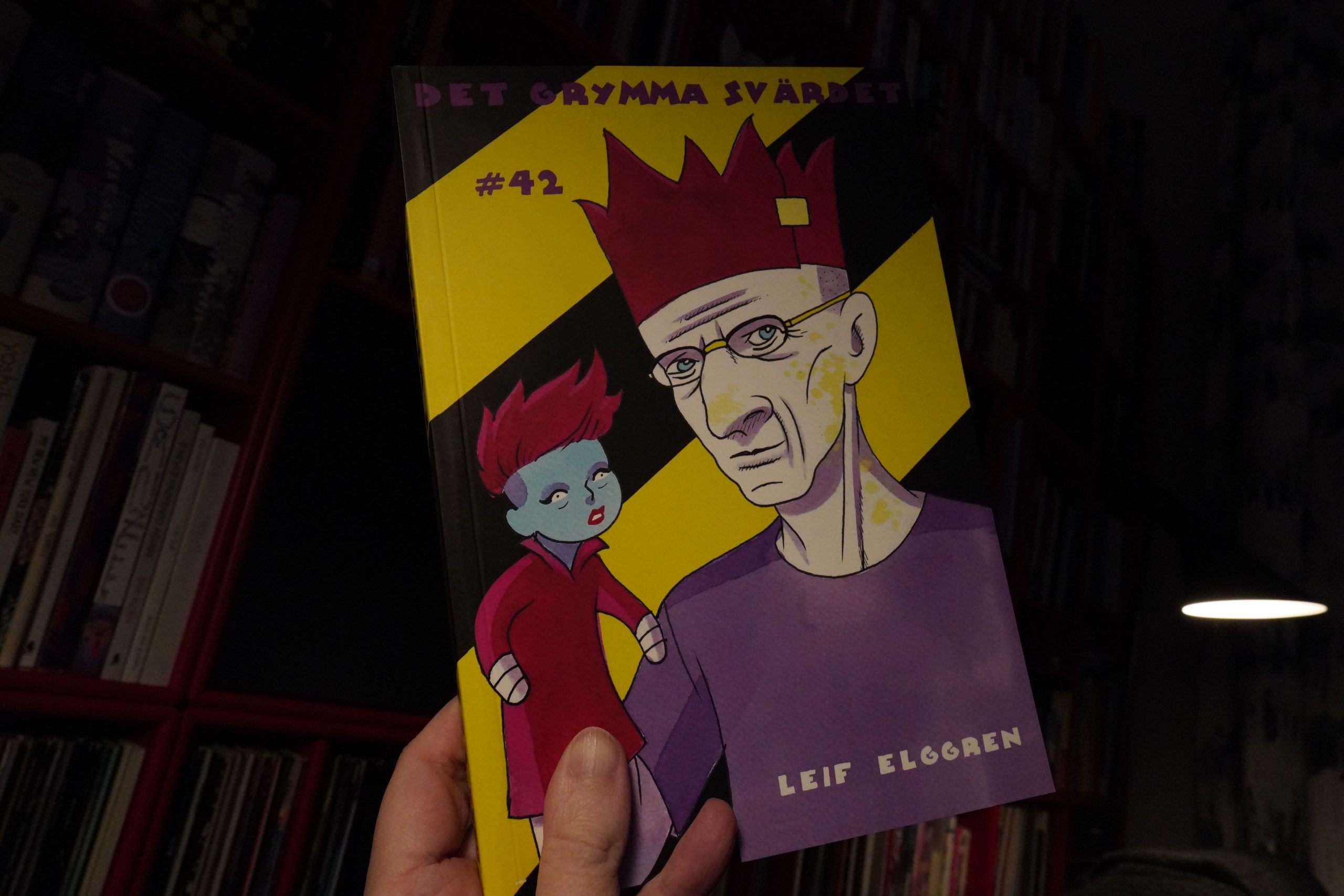

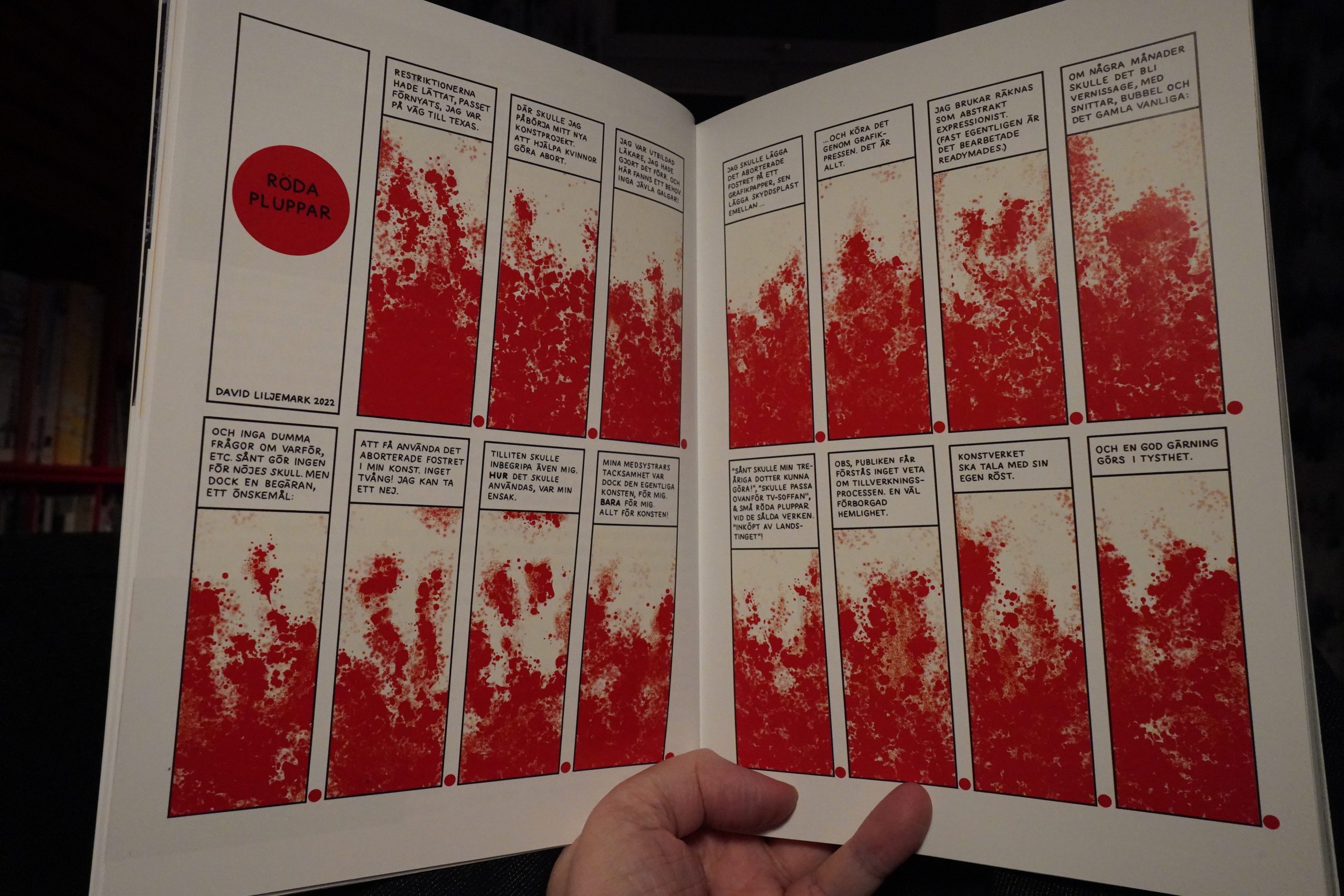

00:50: Det grymma svärdet #42 edited by Fredrik Jonsson (Lystring)

Heh heh. This strip is probably illegal in Texas. DON”T USE GOOGLE TRANSLATE ON IT

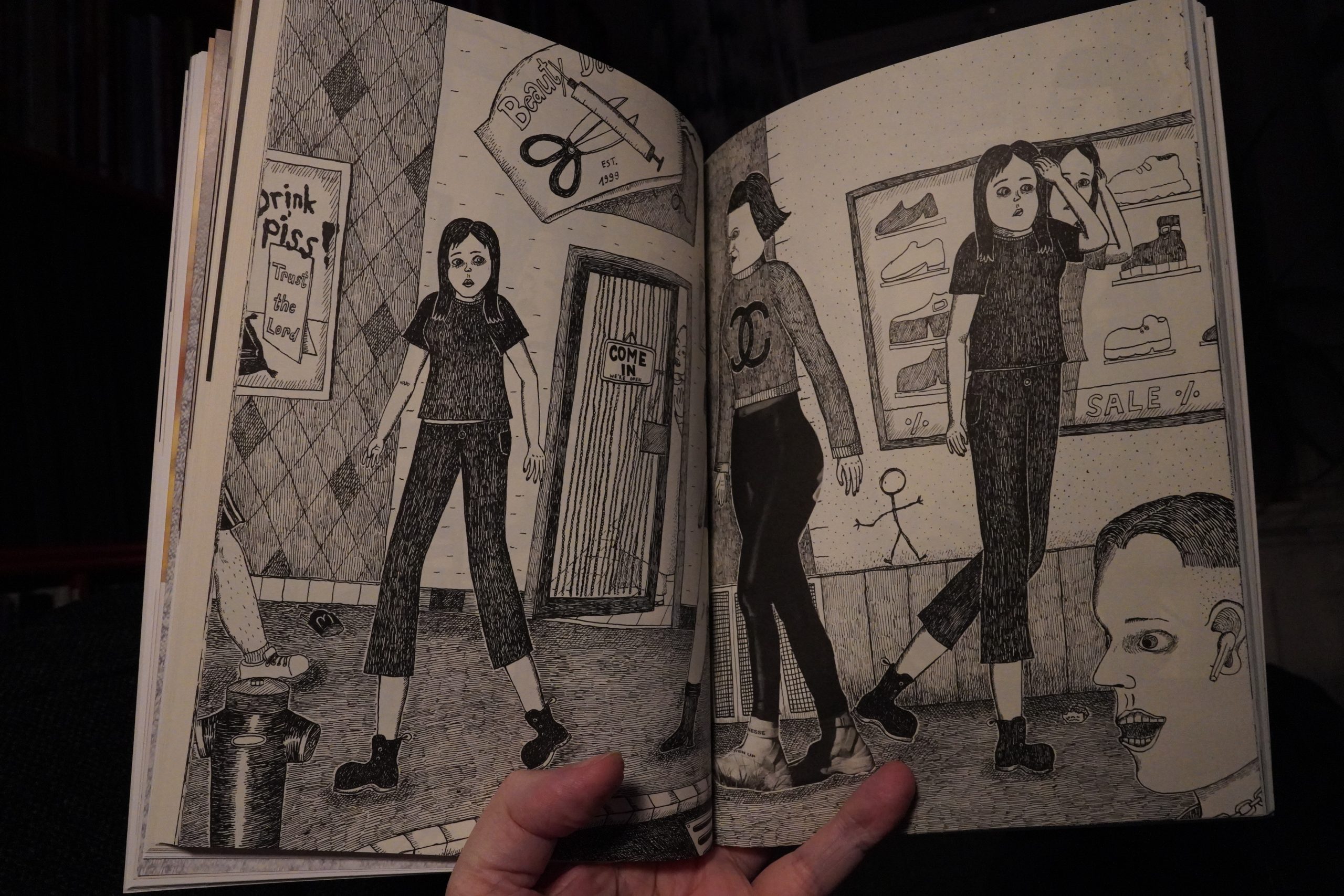

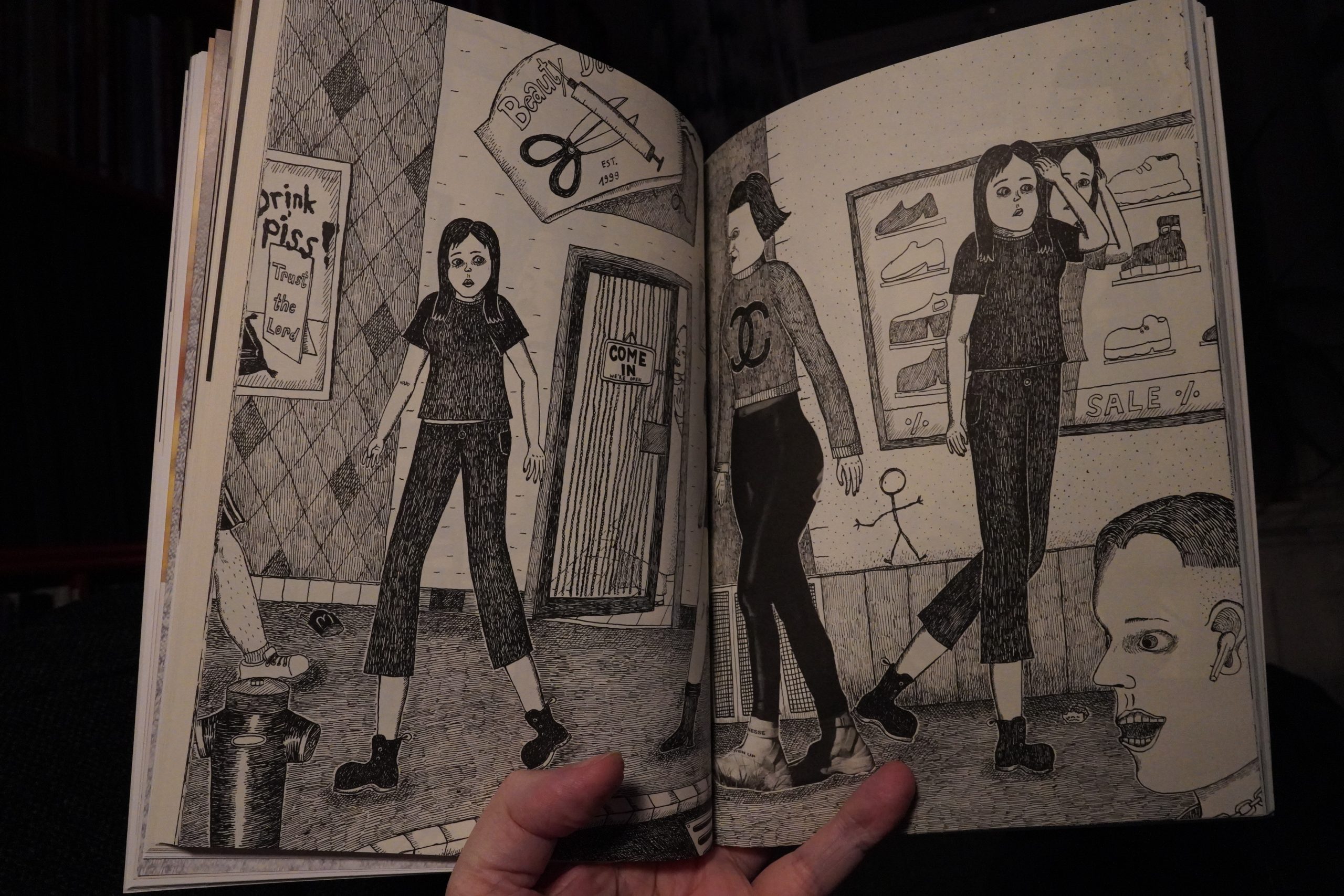

There’s a whole bunch of Simon Hanselmann strips in this on (that I hadn’t read yet, so perhaps they’re from a forthcoming book in the US?), and otherwise a pretty good mix of stuff? OK, I’m too exhausted to be typing, so:

01:22: The End

Time to go to bed.