An Anthology of Graphic Fiction, Cartoons, & True Stories Vols. 1 & 2 edited by Ivan Brunetti (200x260mm)

I wanted to have a quick look at these due to their sheer heft, both physically and metaphorically. Altogether they weigh 2.6 kgs, collect over seven hundred pages of comics (or “graphic fiction” as the title portentously tries to convince us that this is), and it’s from the Yale University press.

What are they going to focus on? Is it going to be all Stan Lee superheroes, or just 700 pages of Gary Panter, or what?

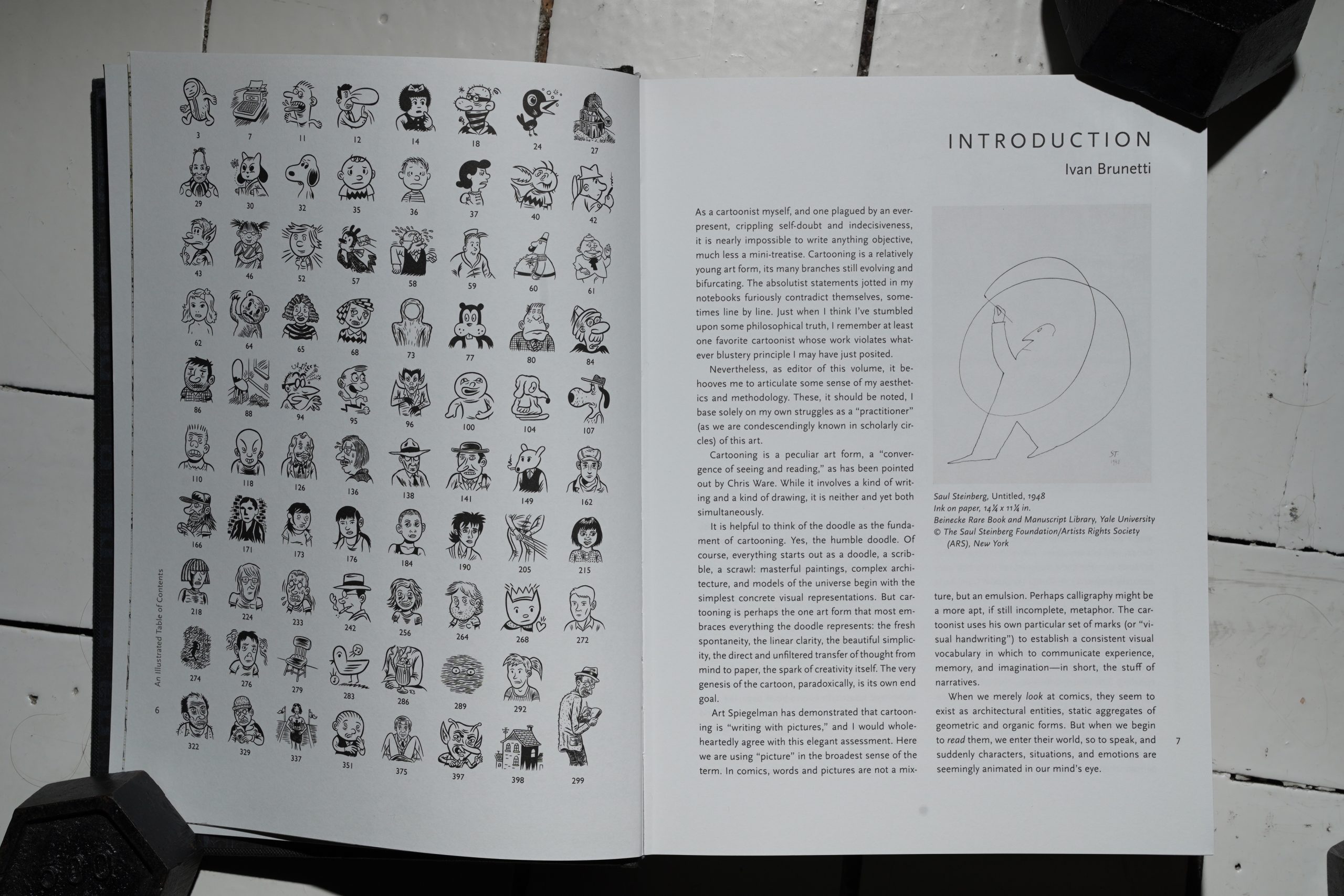

These books are edited by Ivan Brunetti, and I guess that these are meant to be used in college courses about comics? If that’s the case, there’s a surprising dearth of text about the artists and pieces — there’s just a short introduction by Brunetti, and then it’s onto the comics.

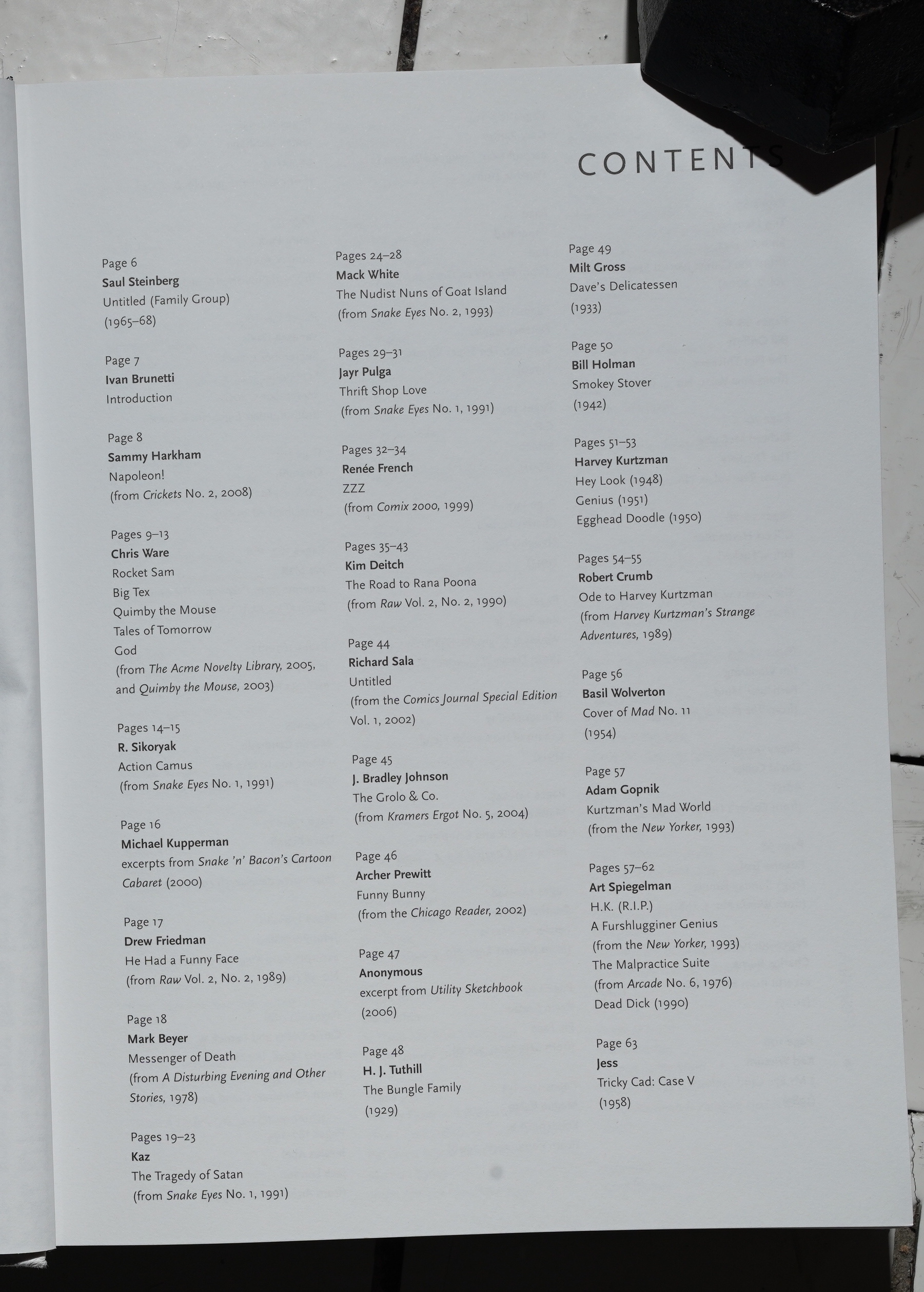

(And, yes, that’s the contents page to the left there. Utterly useless, but… er… fun?)

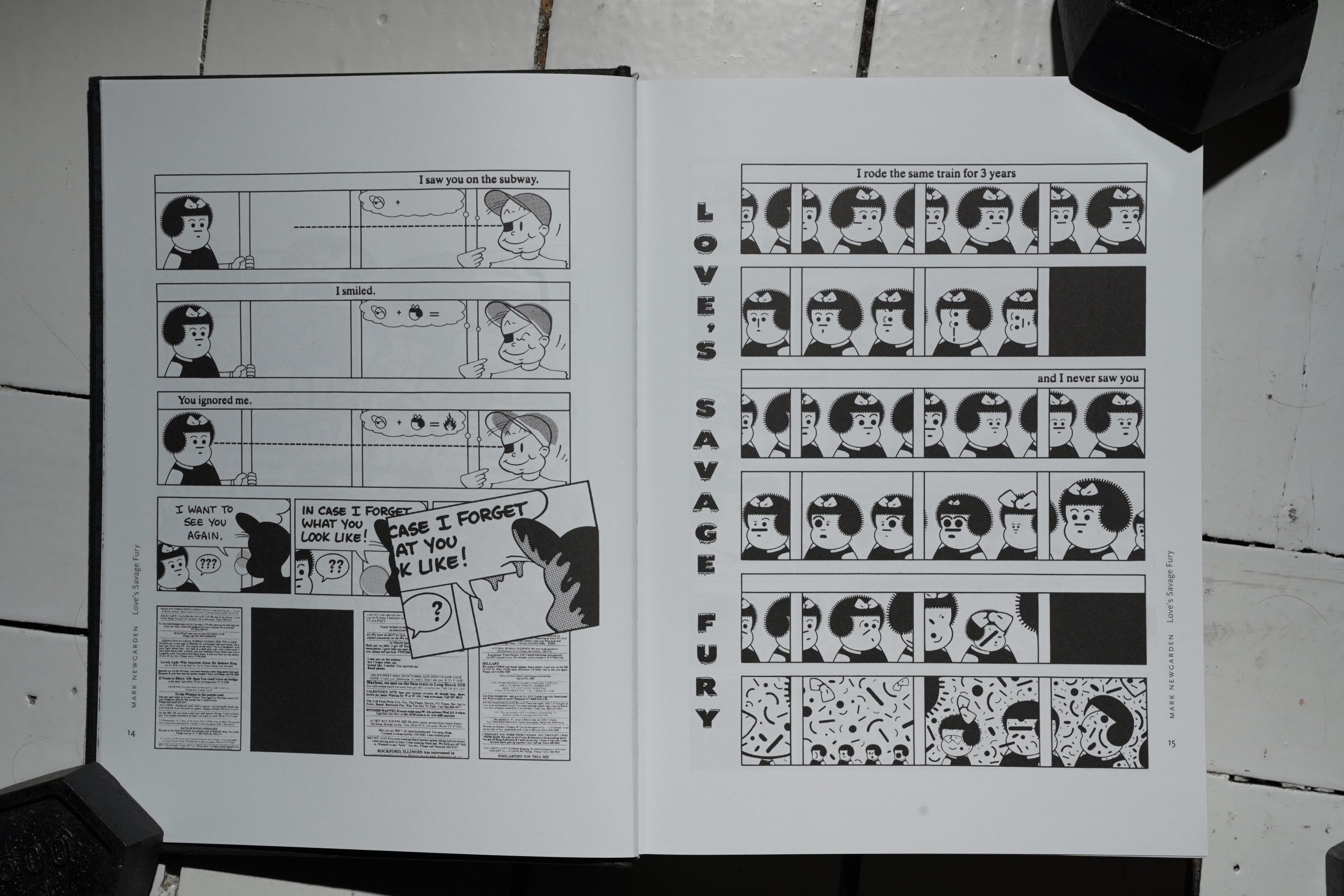

I’m not re-reading these books now — I read them last year, I think, so I’m just flipping through them for this blog post. I wanted basically to see whether the 80s “punk comics” generation was going to be represented here or not, and in that case, by which pieces. And, indeed, it seems like all the more famous people from Raw are here, and with… er… sometimes obvious (but understandable) choices, like Love’s Savage Fury by Mark Newgarden.

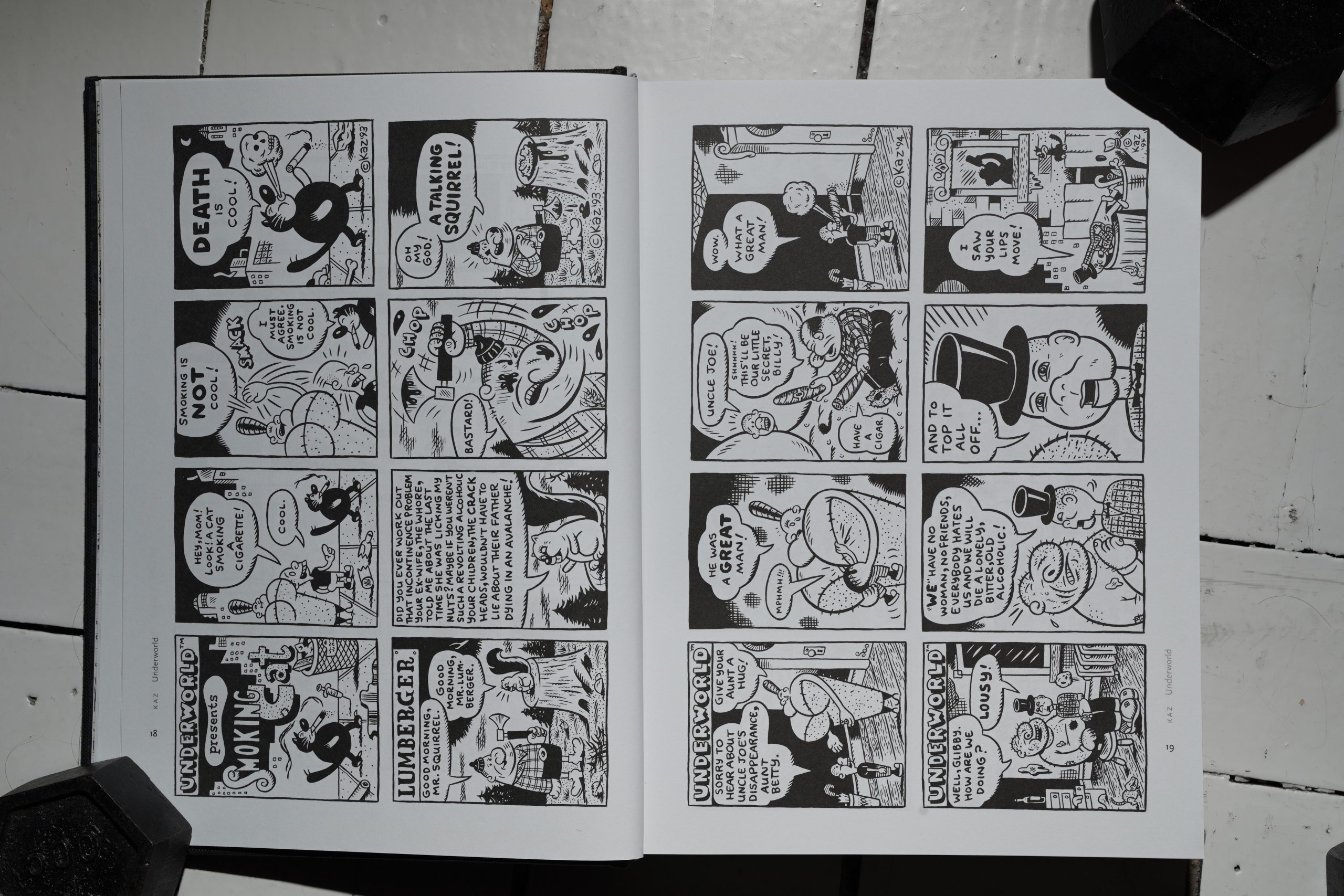

The most annoying thing about these books (especially the first volume) is how many strips are printed sideways. That’s fun in pamphlets, but it’s a chore with these heavy books. But I guess students can handle it and get a work-out at the same time. (Kaz.)

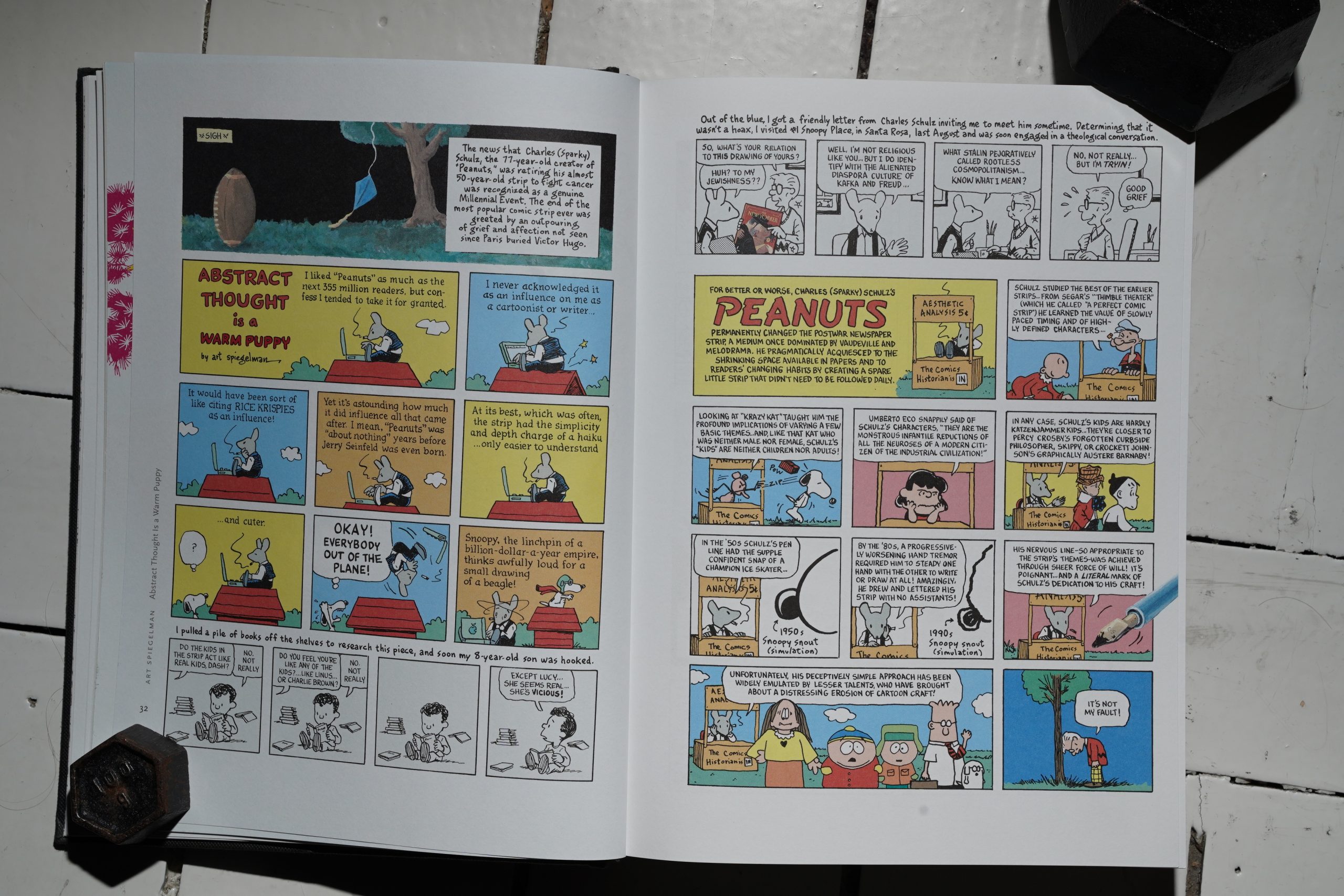

The book has a few sections (not marked as such) dealing with the same subject, like a handful of different cartoonists doing Charles Schulz. (Art Spiegelman.)

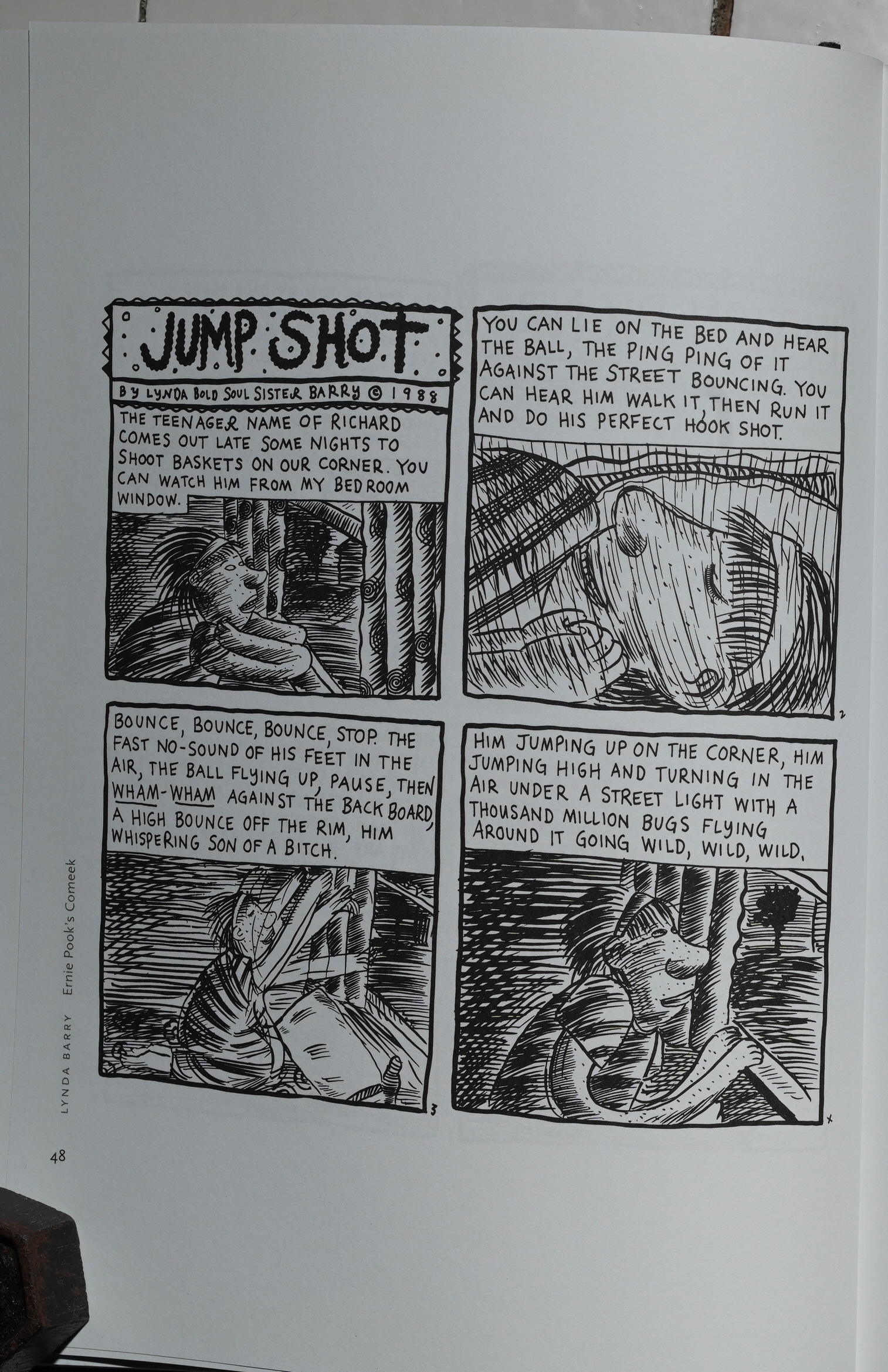

Most of the people are represented with less than a handful of pages: A bunch of people only get a single page, and Lynda Barry gets three. It makes for a choppy reading experience, but I guess that’s not really the point of these books?

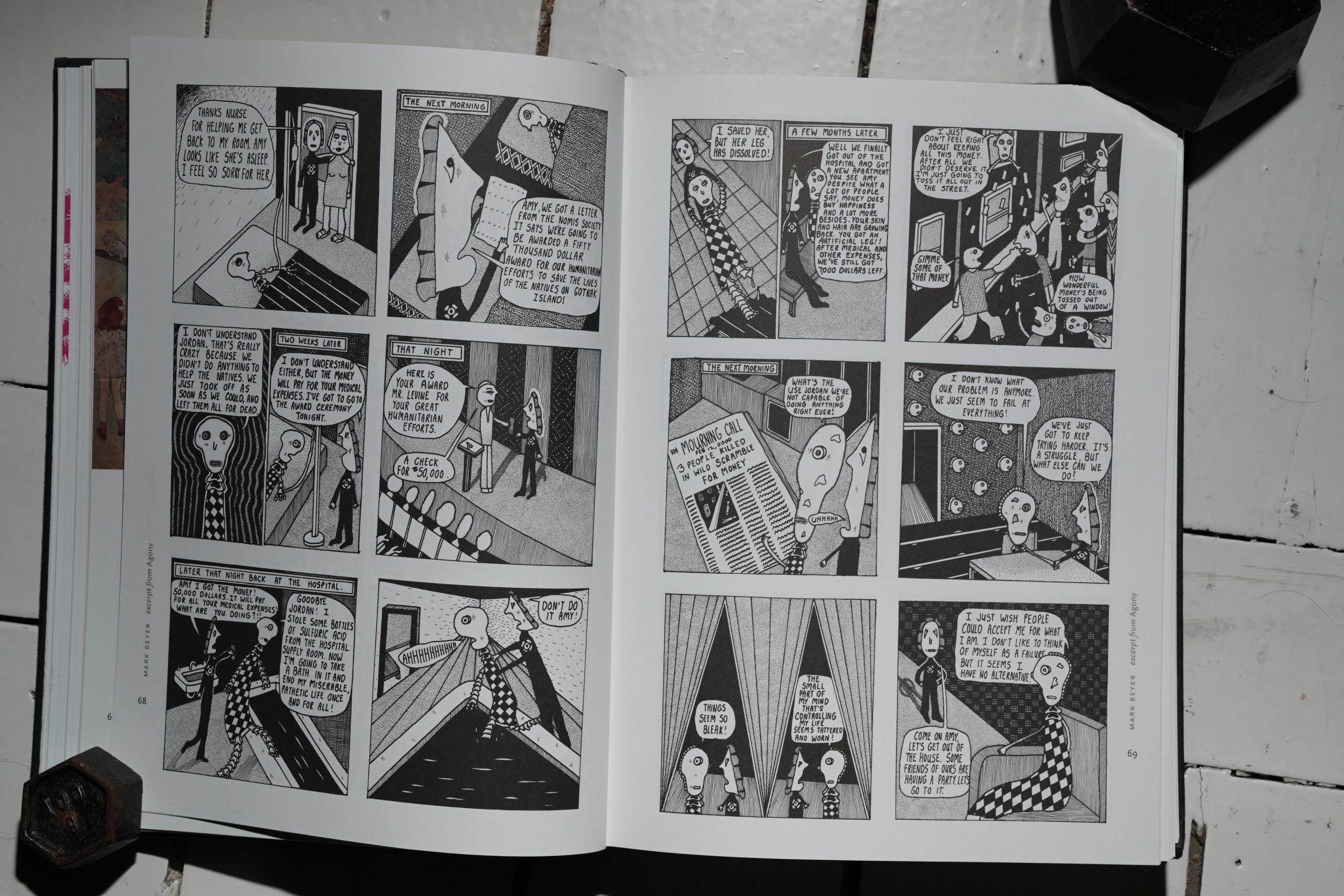

All the Raw people are here (except Sue Coe). Here’s Mark Beyer…

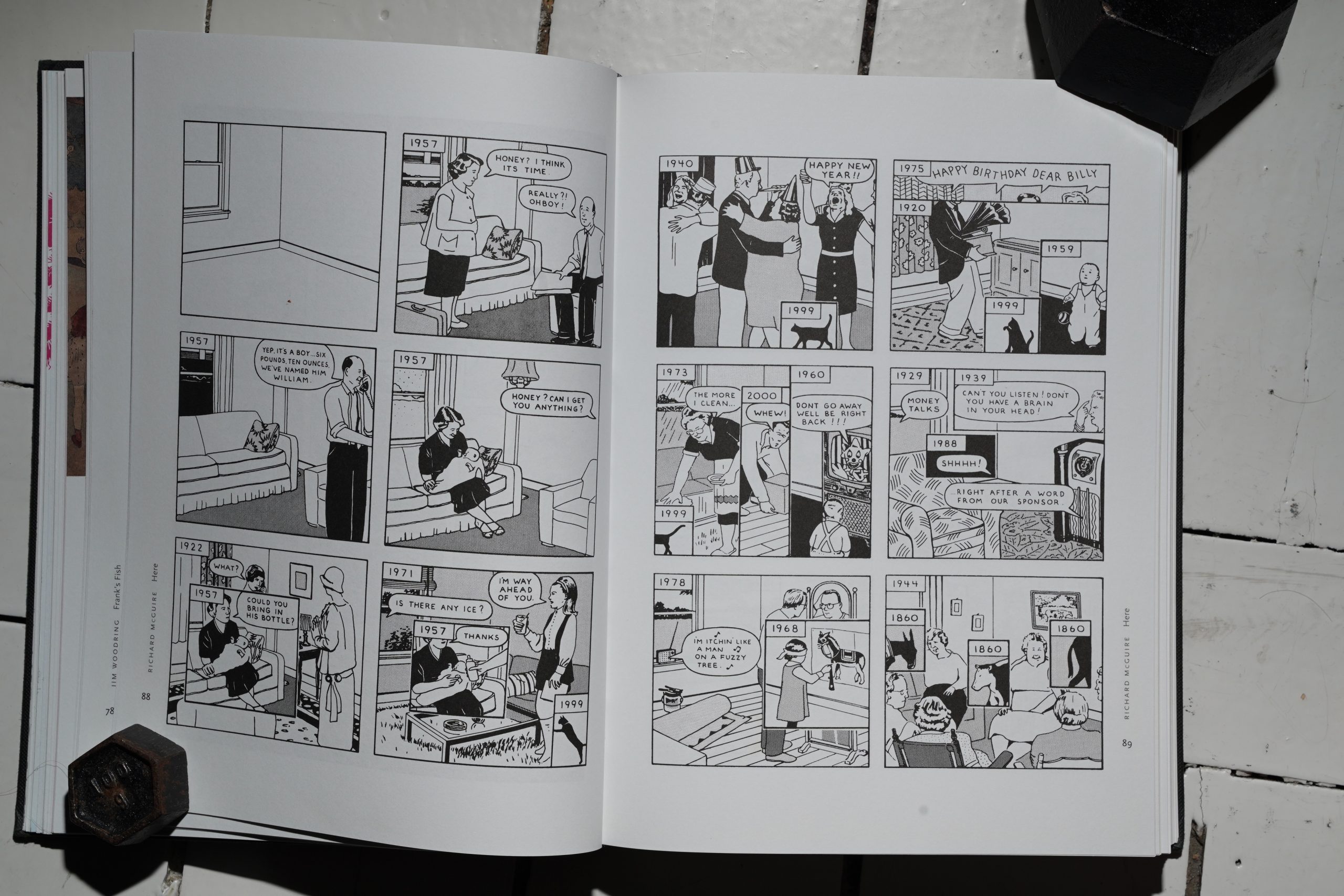

Can’t do a book like this without Richard McGuire’s Here.

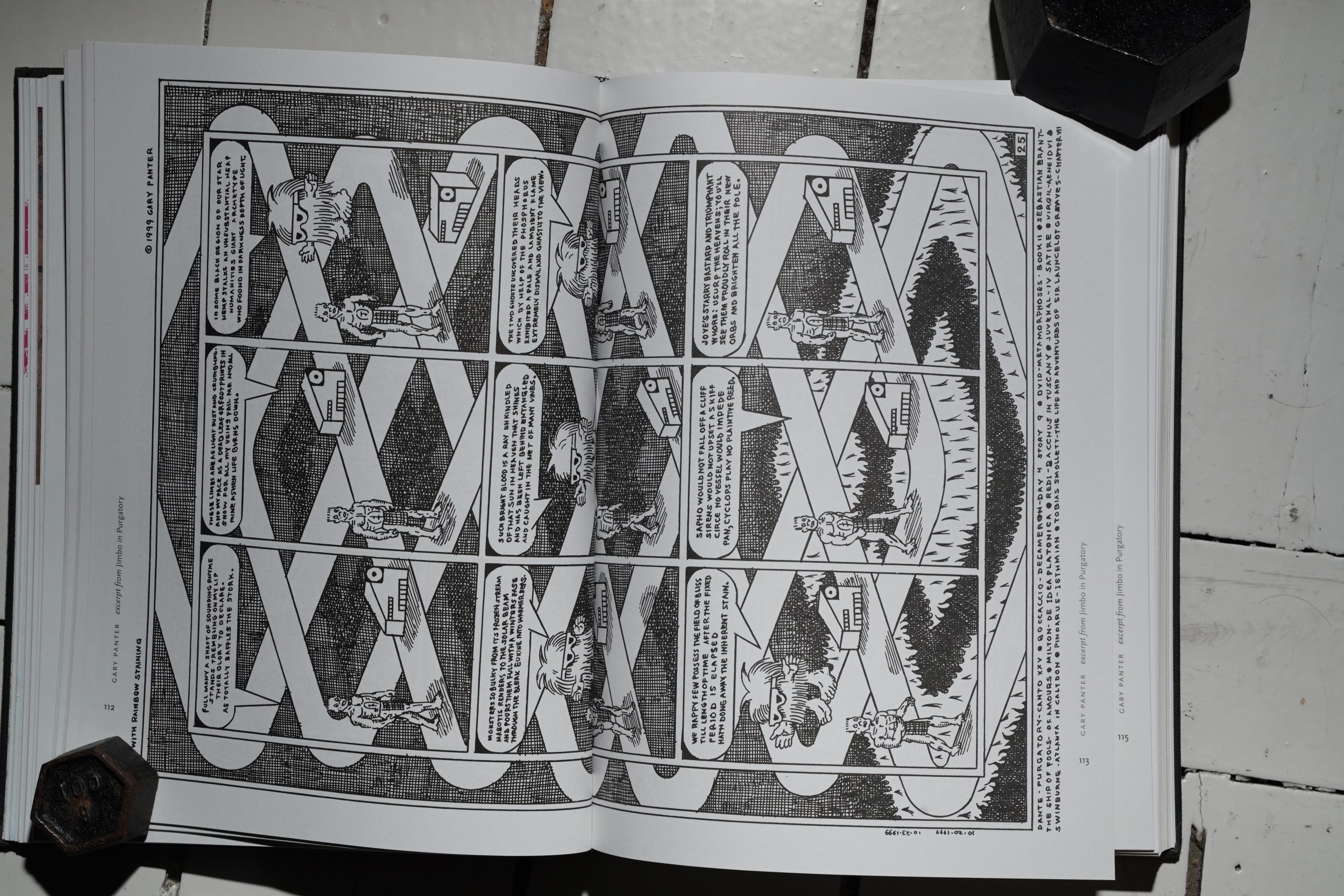

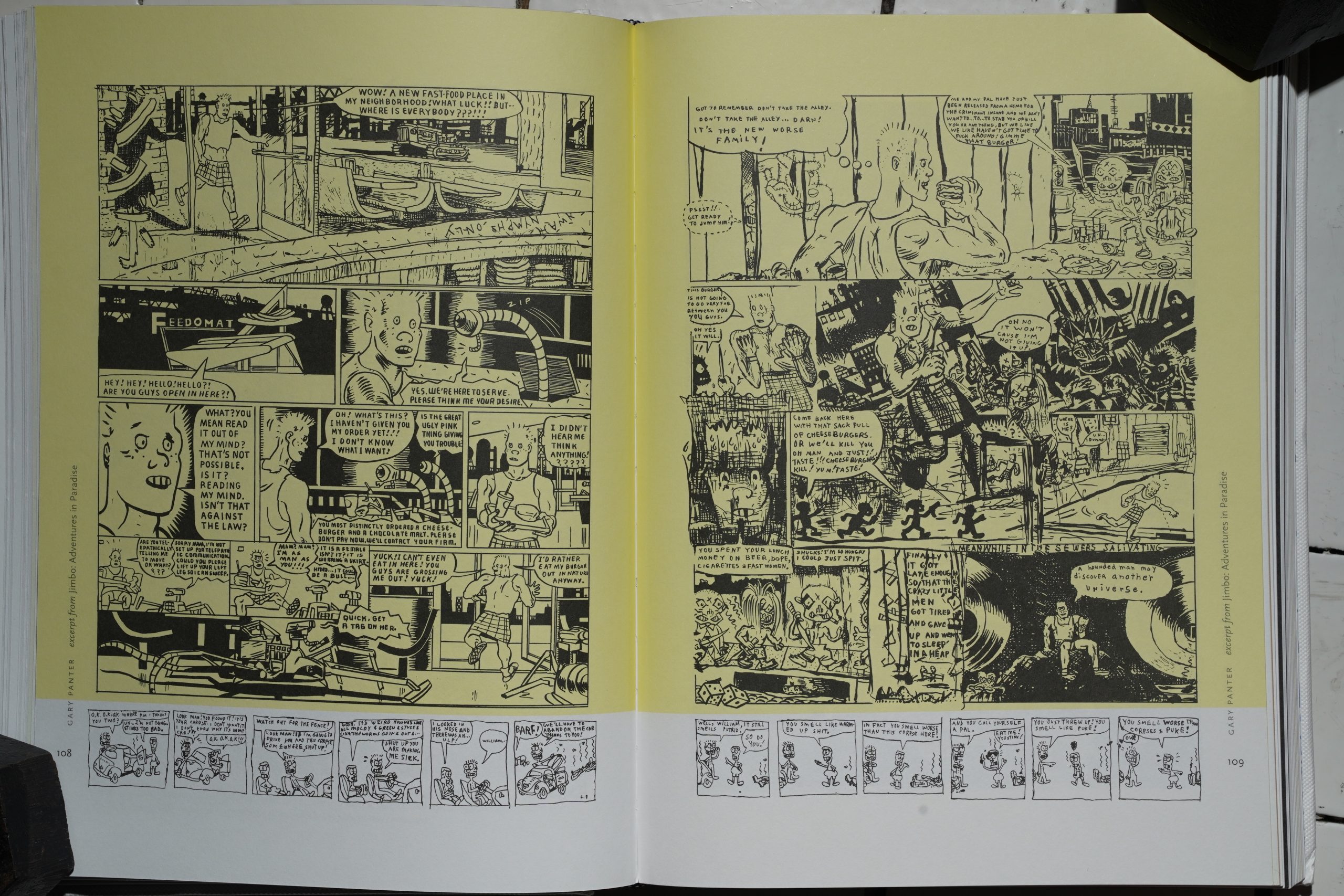

Oddball choice for Gary Panter: A Jimbo in Purgatory (I think) excerpt.

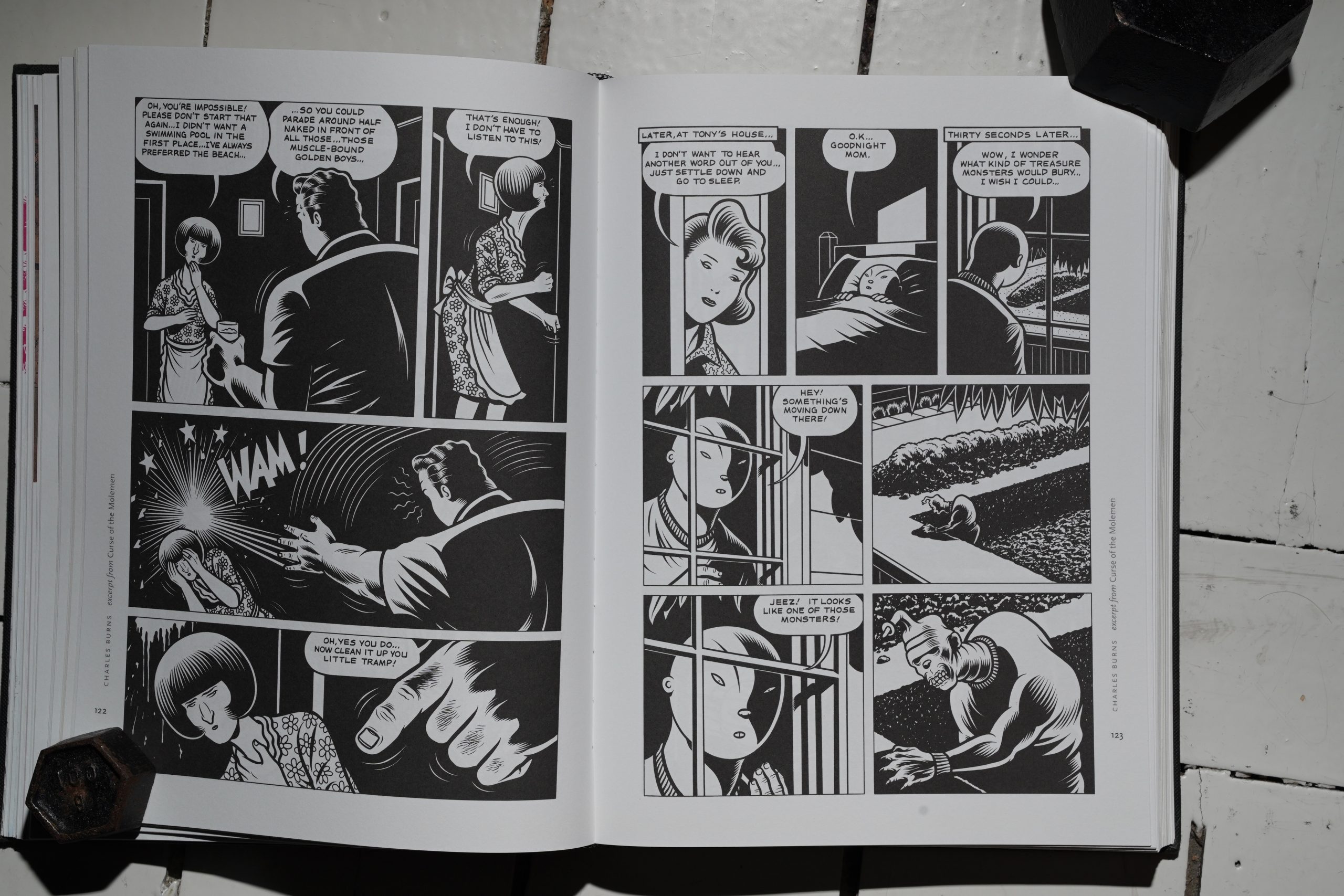

Charles Burns, of course.

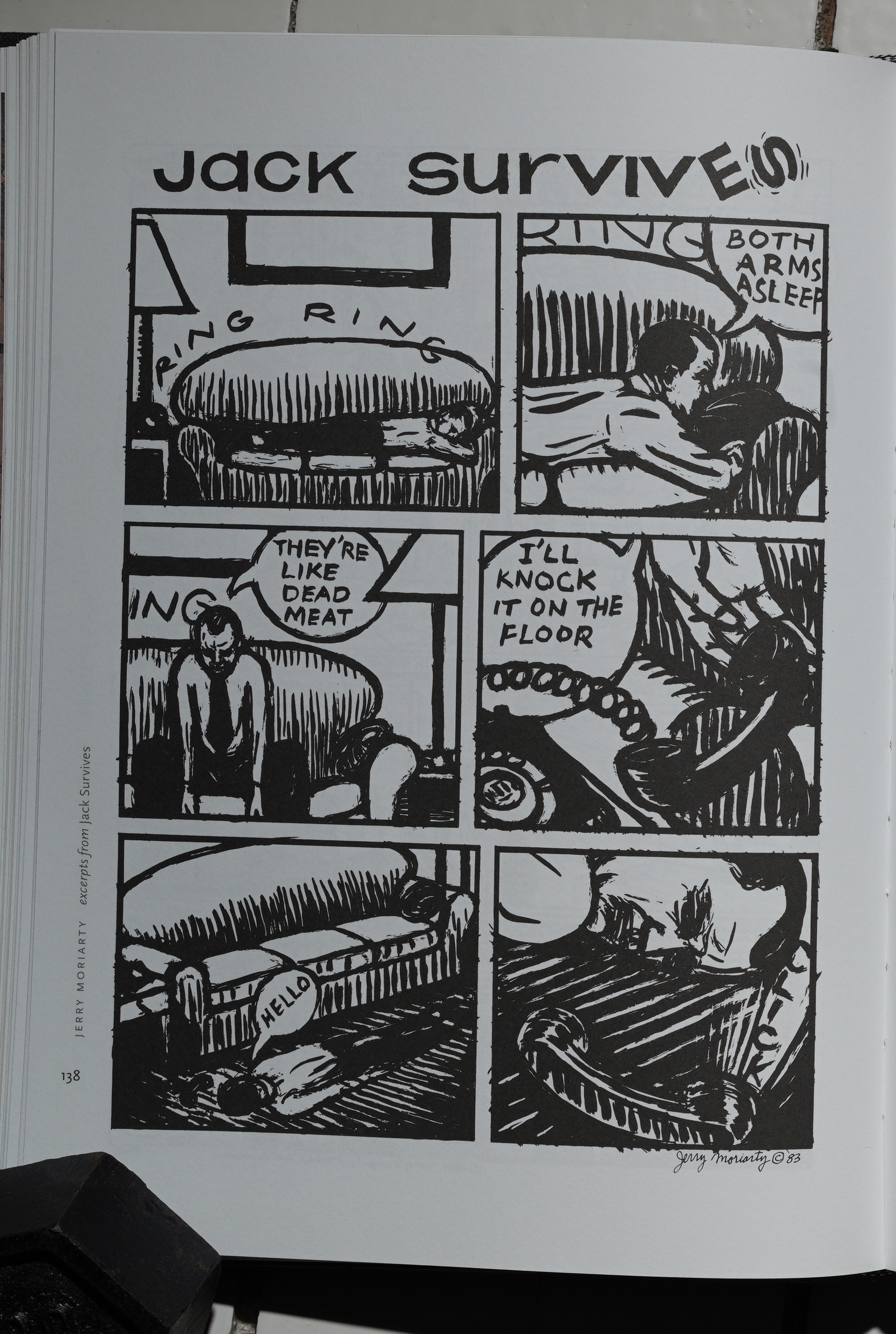

Jerry Moriarty.

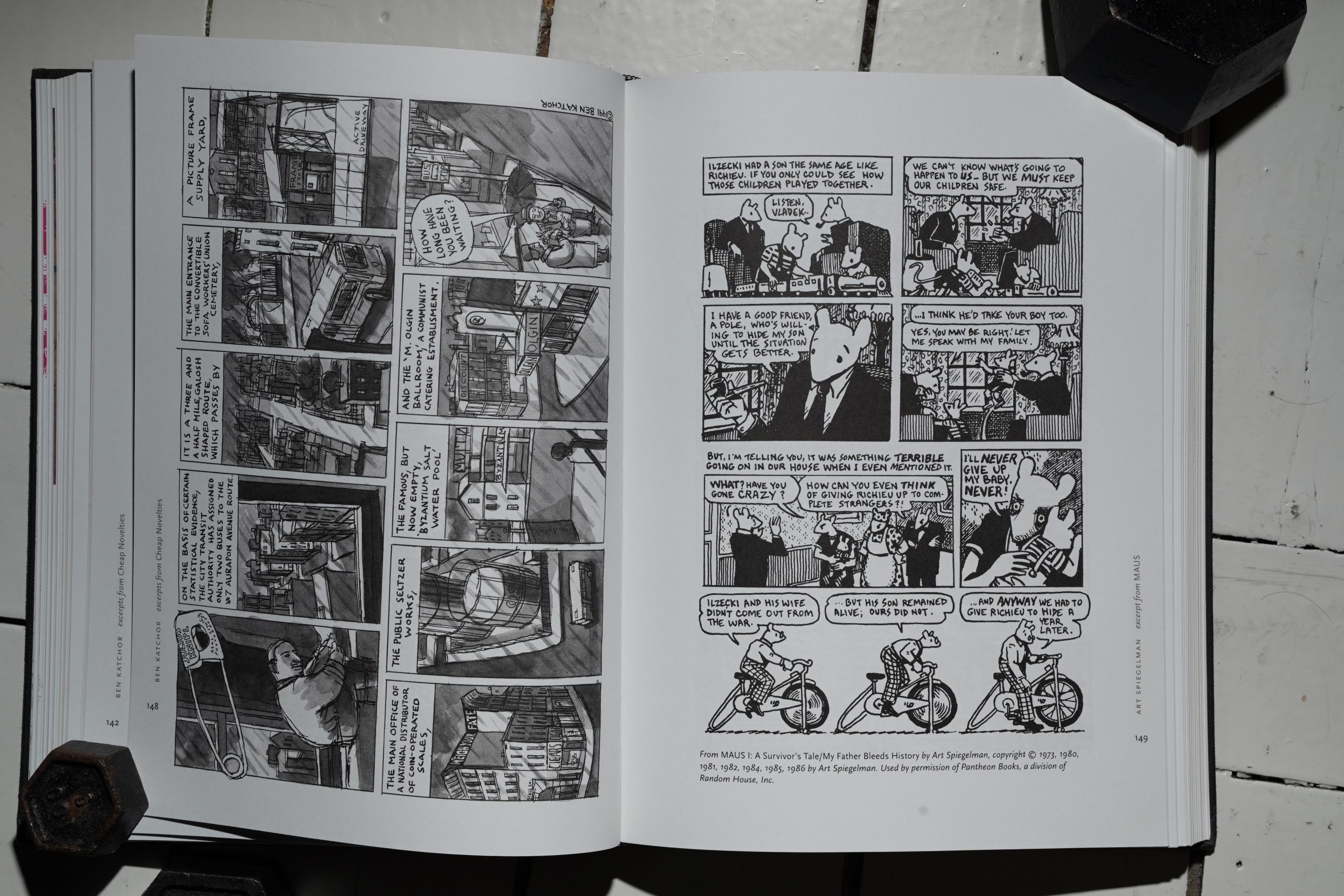

Ben Katchor and Art Spiegelman again. They’re all here.

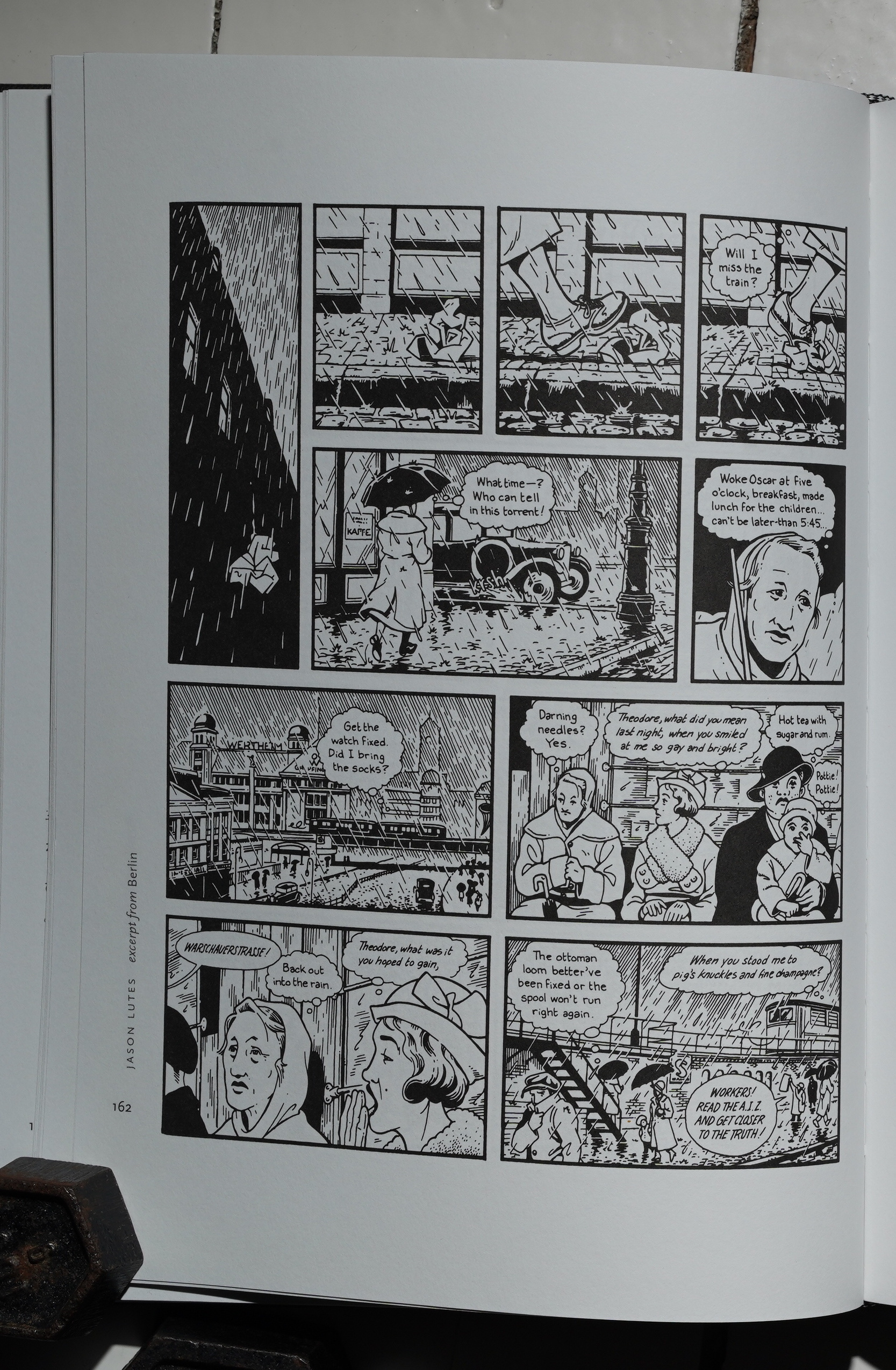

The book does have a certain flow. After Maus, we get Jason Lutes’ Berlin — things are arranged according to themes, but pretty loosely.

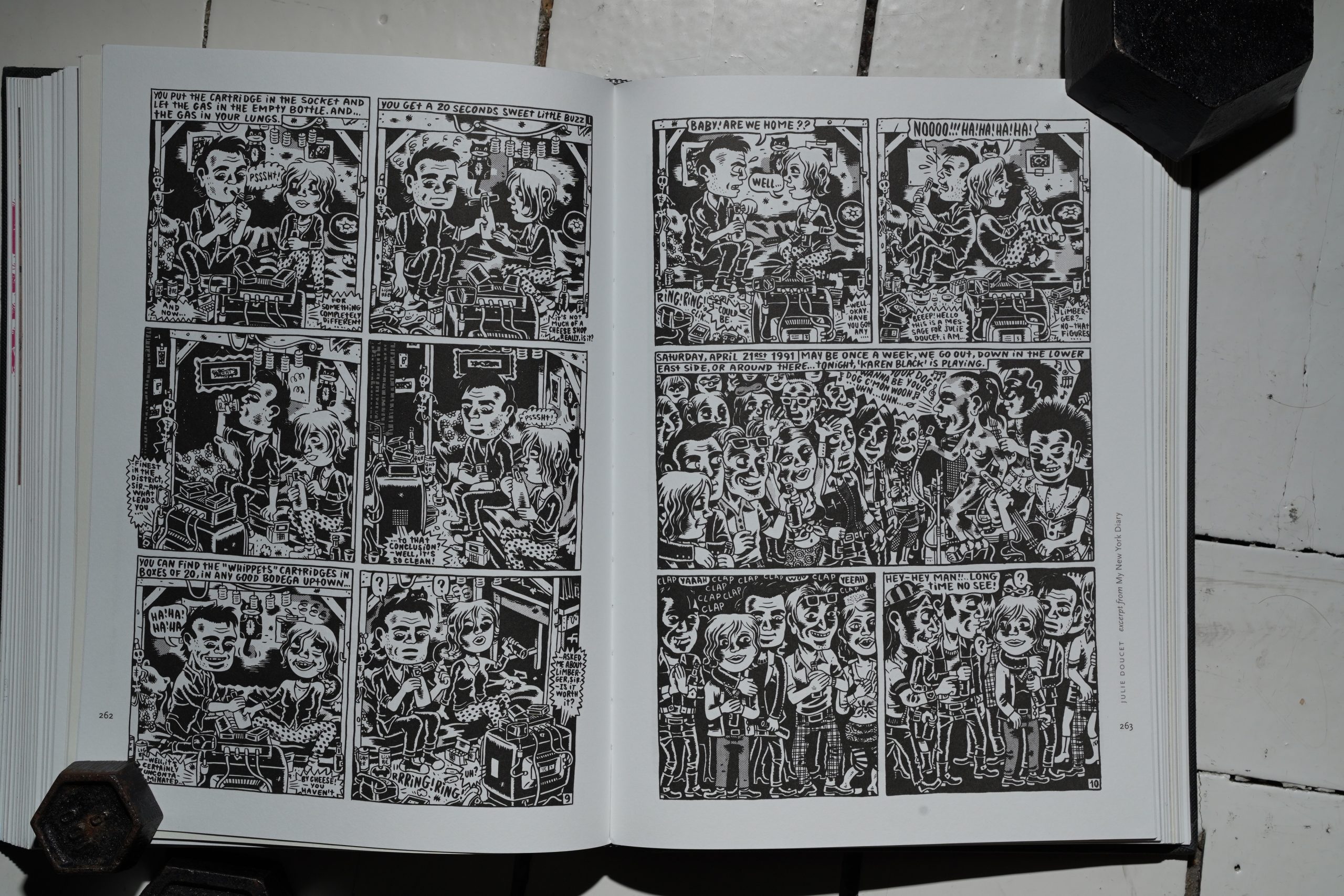

Or according to other connections — we get all the 90s Drawn & Quarterly people in a row: Seth, Chester Brown, Joe Matt, and here Julie Doucet.

The reproduction’s pretty good, too.

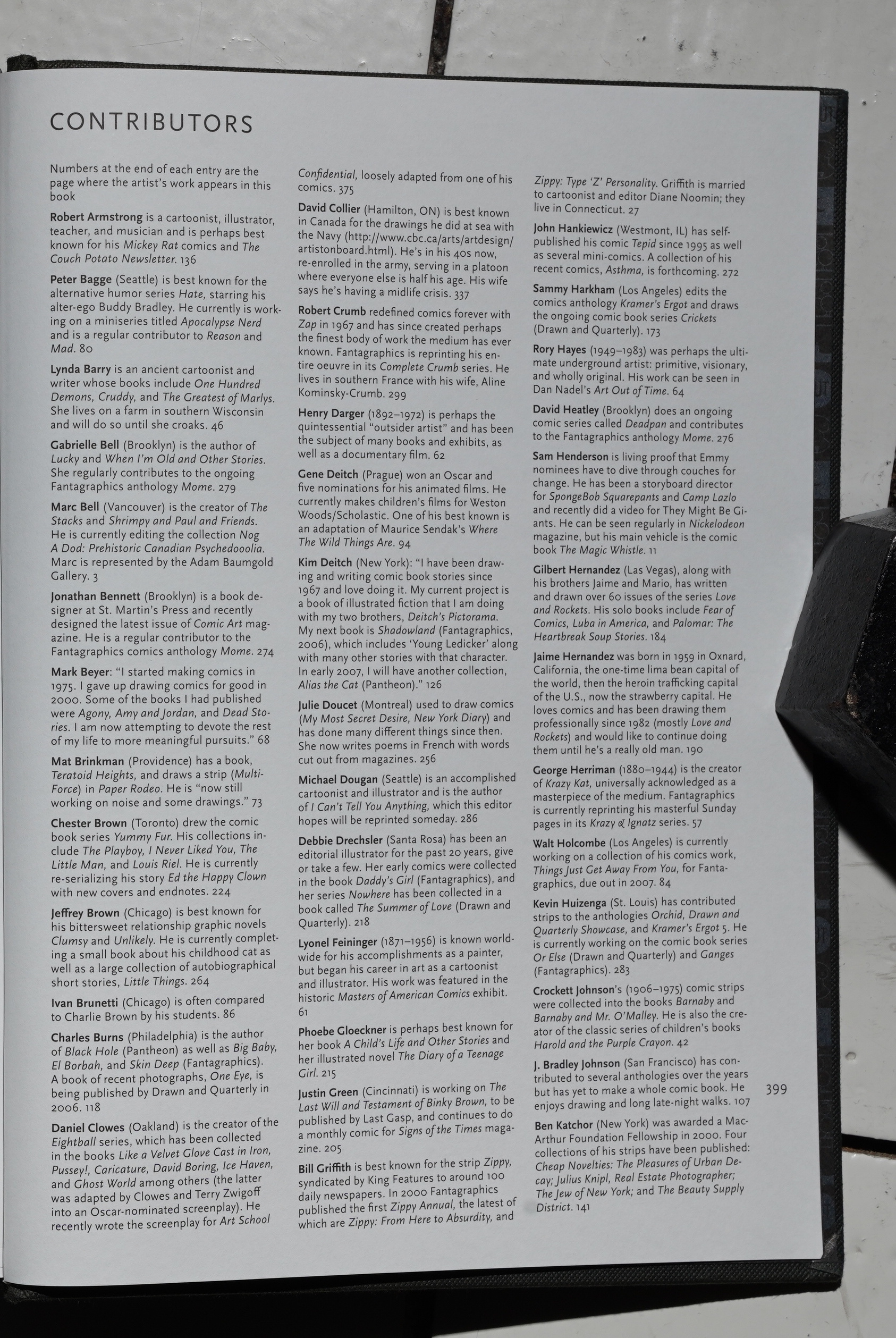

And this is how much we get about each contributor.

Pretty odd.

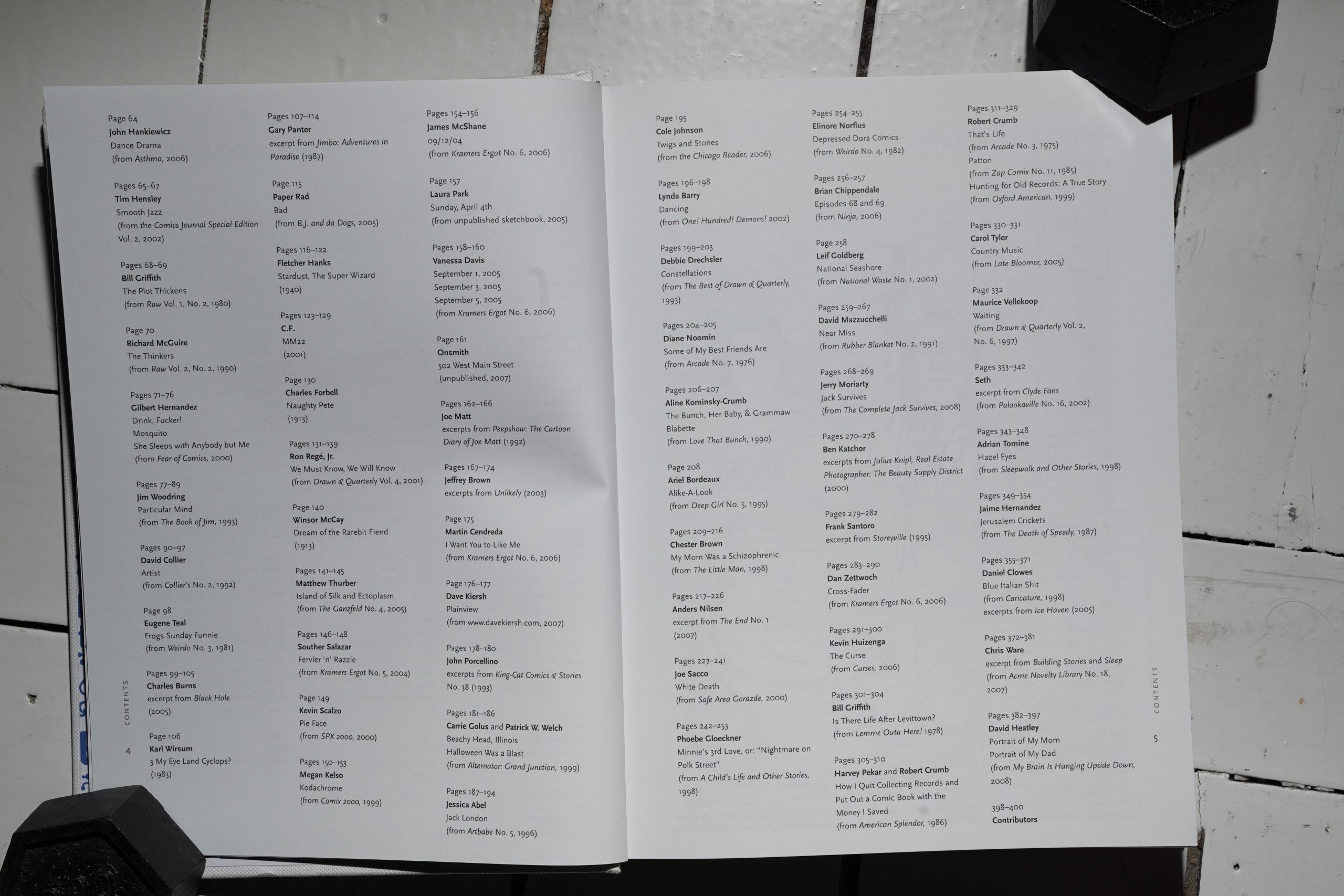

The first volume must have been a success for Yale, because we get a second volume two years later. This one has real contents pages!

And as you can see, it’s basically all of the people from the first volume all over again. But with some new additions. If these books were meant for reading in class, you’d think the next volume would be all-new artists? Brunetti says in the introduction that he’s just gathered people he loves to read, so it’s a singular vision.

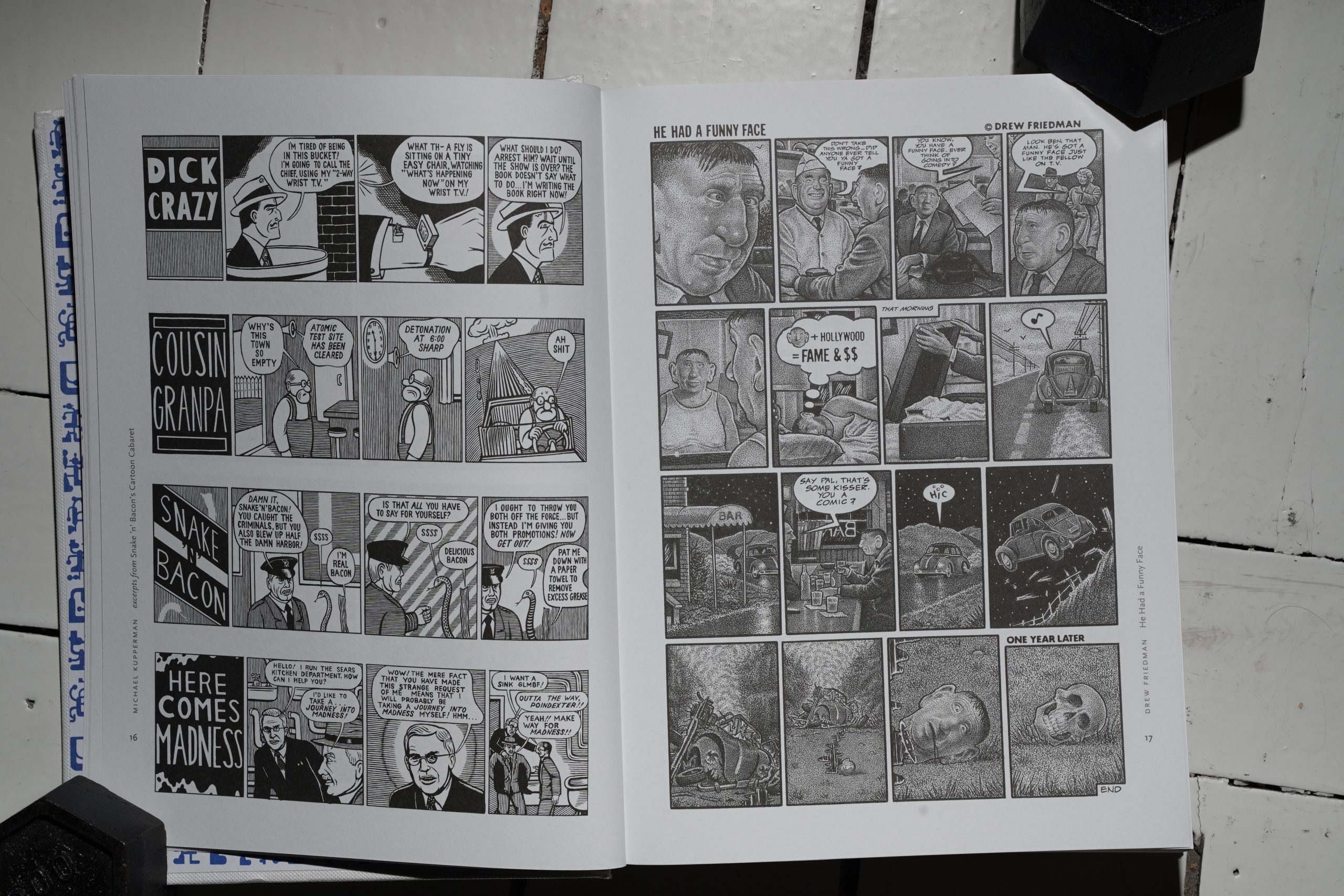

Some of the juxtapositions are pretty good, like Mike Kupperman and Drew Friedman.

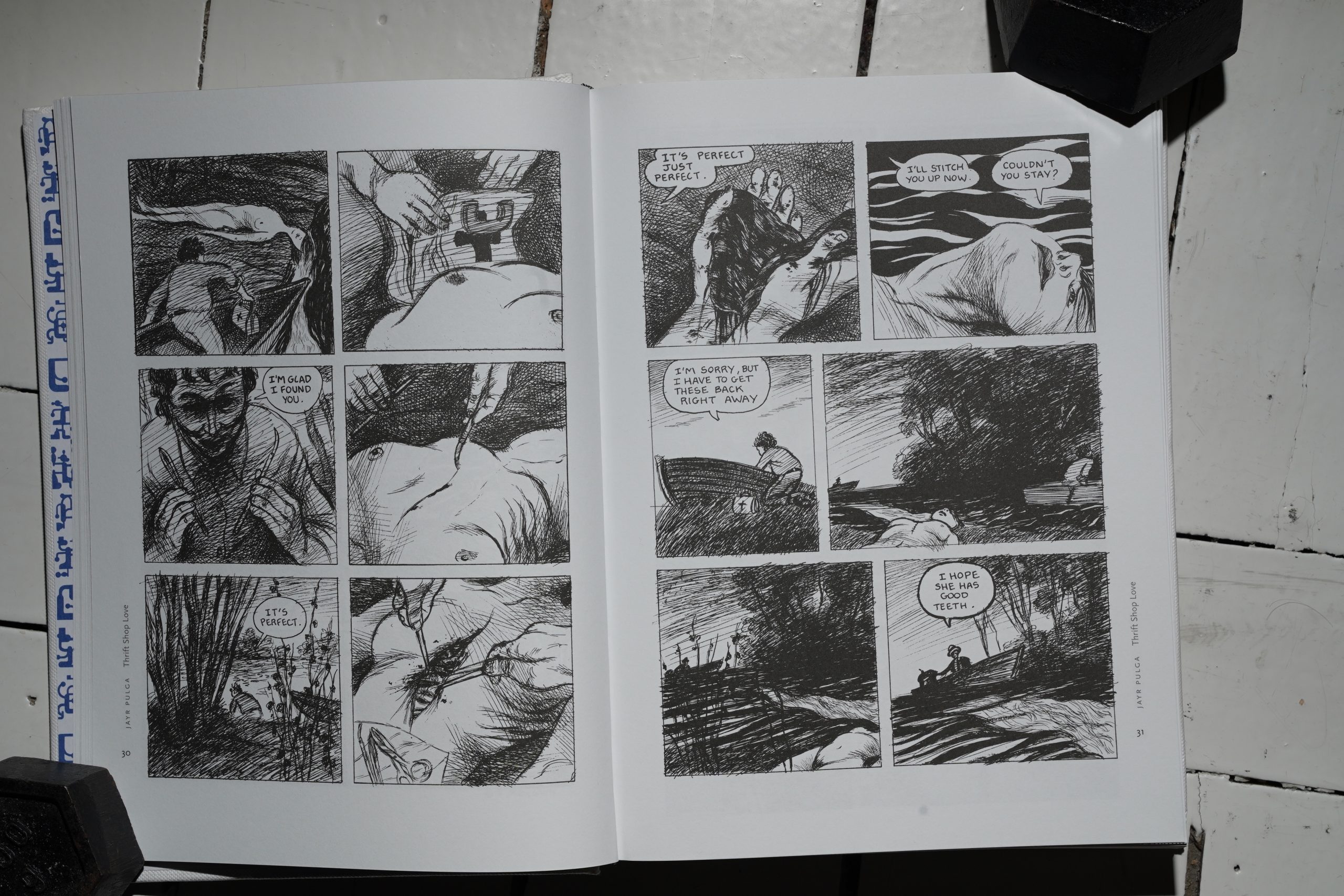

We also get a few of the Raw people that weren’t included the first time around, like Jayr Pulga.

And yet another strange Gary Panter choice — this is from the first part of the collection Jimbo edition.

Brunetti’s aesthetic is pretty congruent with mine, so there’s only a handful of things in these books that I don’t already have. But… it’s like a small subset of the comics I like: Brunetti leans hard into harsh, stark, shocking comics, and nothing else, basically.

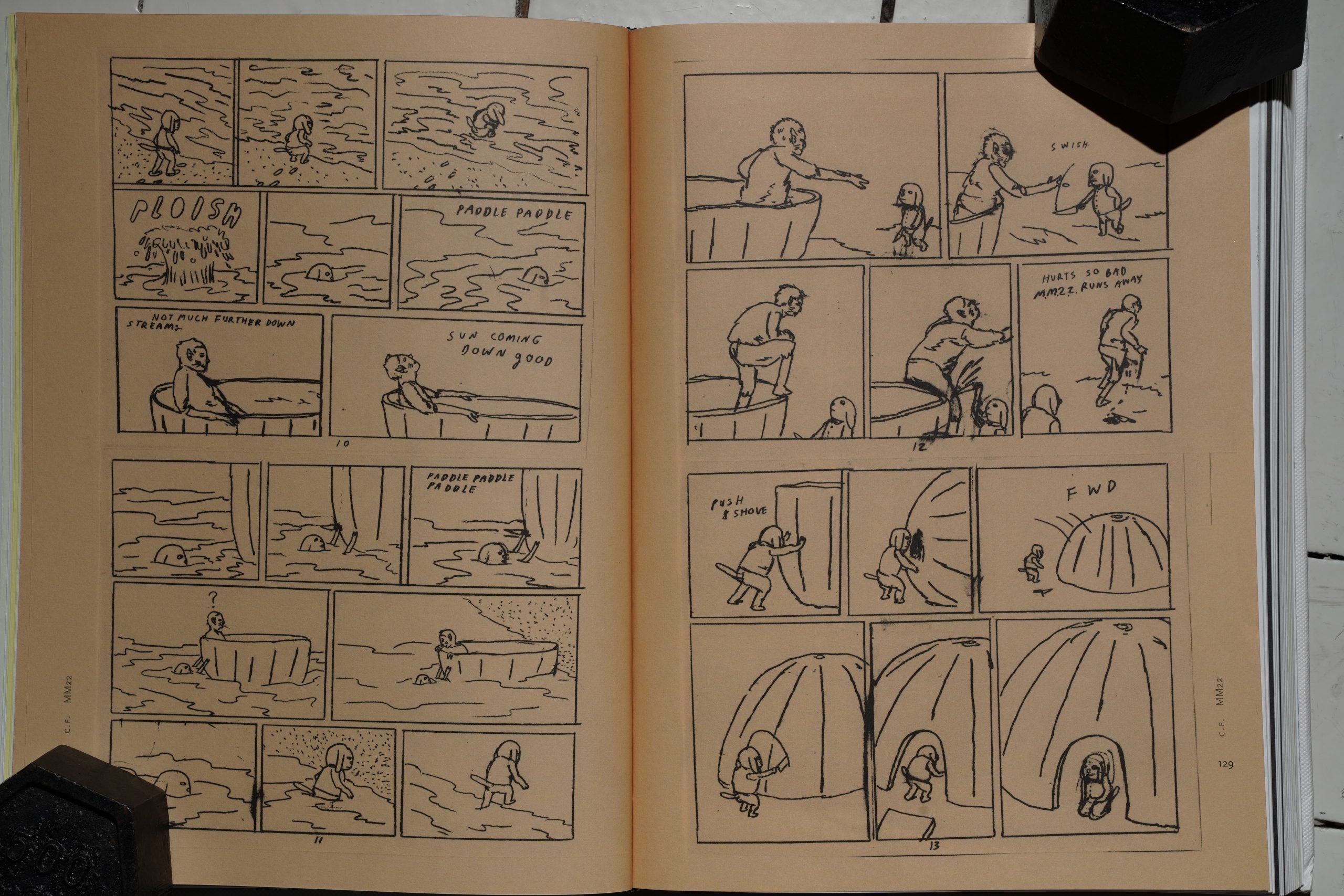

One new development in this development is the inclusion of a few up-and-coming people, like C. F….

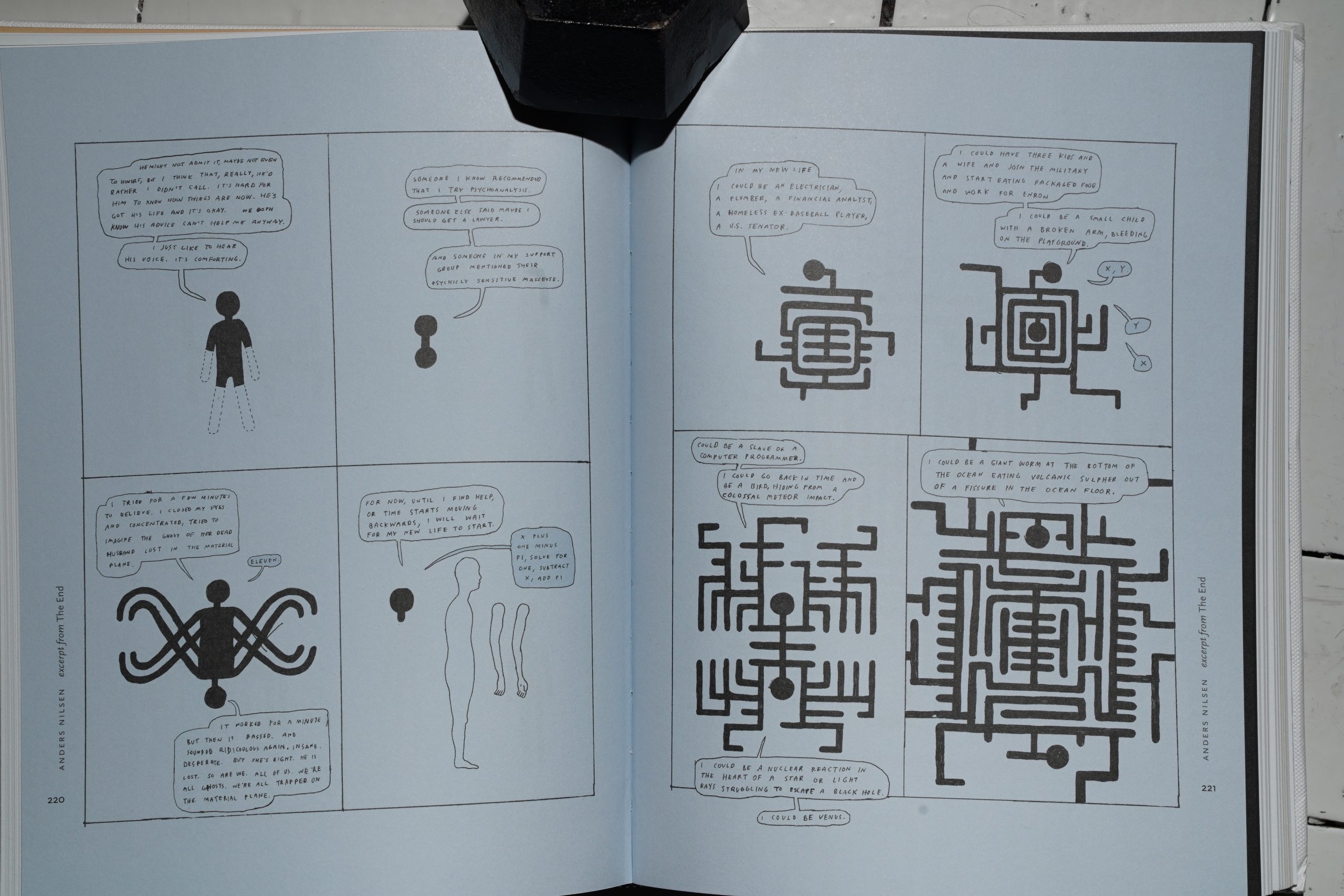

… and Anders Nilssen. So it’s not all heavily narrative comics, like the first volume was.

I’ve only included snaps of a handful of people in this blog post — this isn’t an ahem in-depth look at these books. There’s oodles of fantastic stuff in here, and if you don’t already have all these comics, it’s a great way to get several kilos of fabulous comics.

And you can pick them up cheaply. Perhaps students are flogging them after finishing whatever comics course they’re being used in? Or perhaps people just hate the books?

But perhaps it wasn’t made for students?

Aain unlike past anthologies of comics — indeed, unlike many anthologies of most kinds — this one is conceived not as a reference book but as an episodic narrative. “After much deliberation,” Brunetti explains, “I have chosen to arrange the work so that it flows smoothly, unobstructed by strict chronology.” The stories connect, one to another, with threads sewn deep: A tale of quiet despair, by Jerry Moriarty, leads to another of genteel solitude by Ben Katchor; a memoir of childlike sexless love by Chester Brown leads us to one of frantic carnal yearning by Joe Matt. This design works — so well that despite the mad variety of visual styles in the book, one comes away with an appreciation for the commonalty of serious comics today.

Yup:

Brunetti’s second collection of his favorite cartoonists’ work is even better than the first—more far-ranging, more personal and eccentric. Clearly a tour of one person’s singular tastes, it’s arranged in a stream-of-consciousness “oh, and you have to see this one” sort of way

There are, however, some less successful moments. Both the overly iconic table of contents and the reductive contributors section are unhelpful, especially to readers not familiar with the material. Equally baffling is the decision to lavish attention exclusively on Charles Schulz, who receives several graphic tributes yet, curiously, is himself represented by a written essay rather than his comics.

And why include an extended excerpt from Daniel Raeburn’s (poorly proofread) article about graphic artist Daniel Clowes and not do the same for other contributors? And what rationale underlies an explanatory caption for Crockett Johnson and introductory notes for Frans Masereel and Henry Darger and no one else?

Awkward and uneven, such formal eccentricities undermine the spirit of the anthology, as does erratic editing that sometimes turns a selection into a banal half-thought.

This blog post is part of the Punk Comix series.