Everything in the World by Lynda Barry (230x149mm)

“Love the hurly ding-dong.”!?

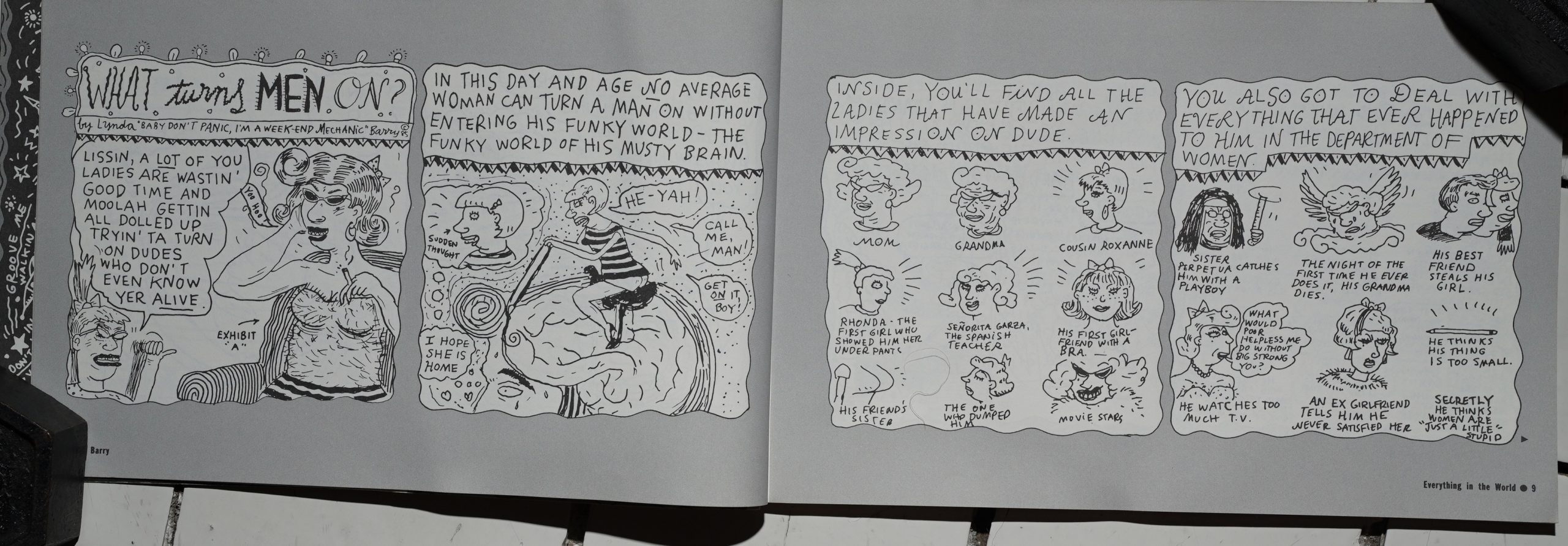

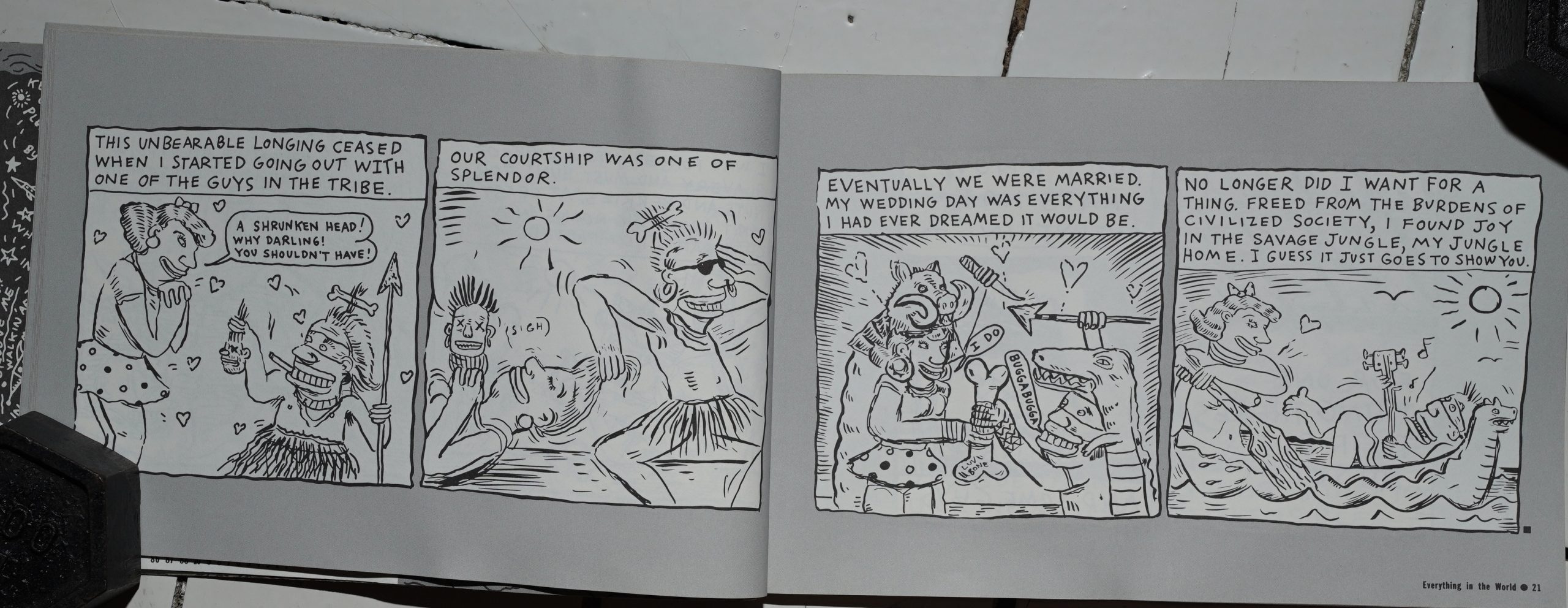

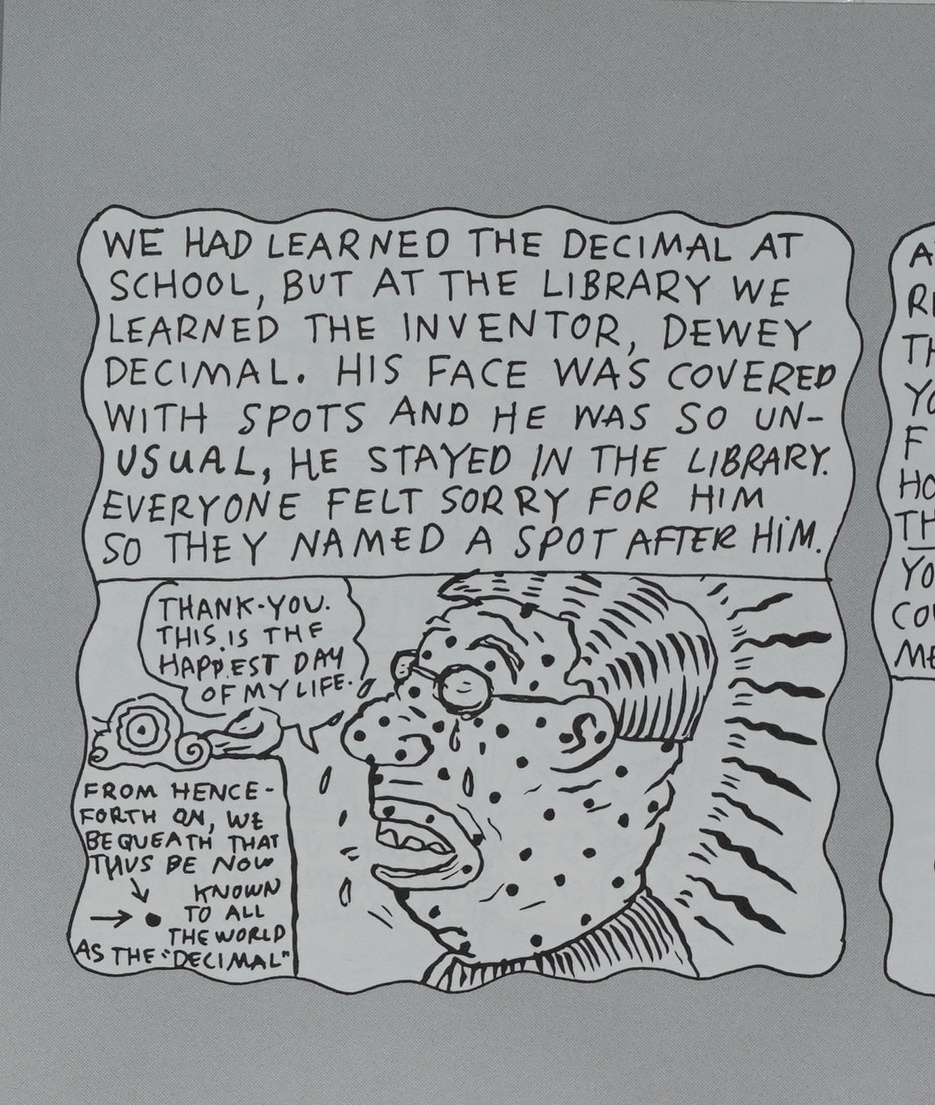

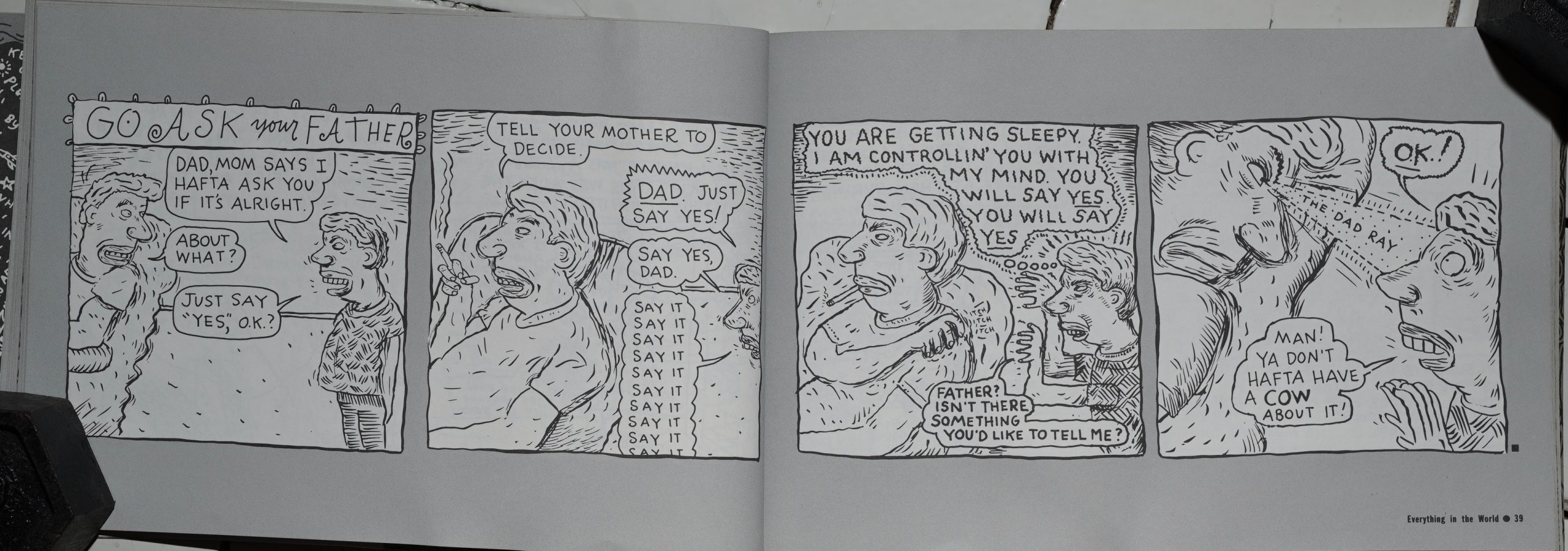

Anyway, it’s been fun reading these early Lynda Barry books chronologically — I sorta knew that her style had changed a lot during her first (say) five years… but now we’re kinda getting near to the style she was going to use when her strip had the major mainstream breakthrough (which happened a couple years later). Gone are most of the angular, aggressive lines, and everything’s kinda rounded and busy…

In some of these strips, she does seem to be casting about for something new to write about — sometimes more successfully than others…

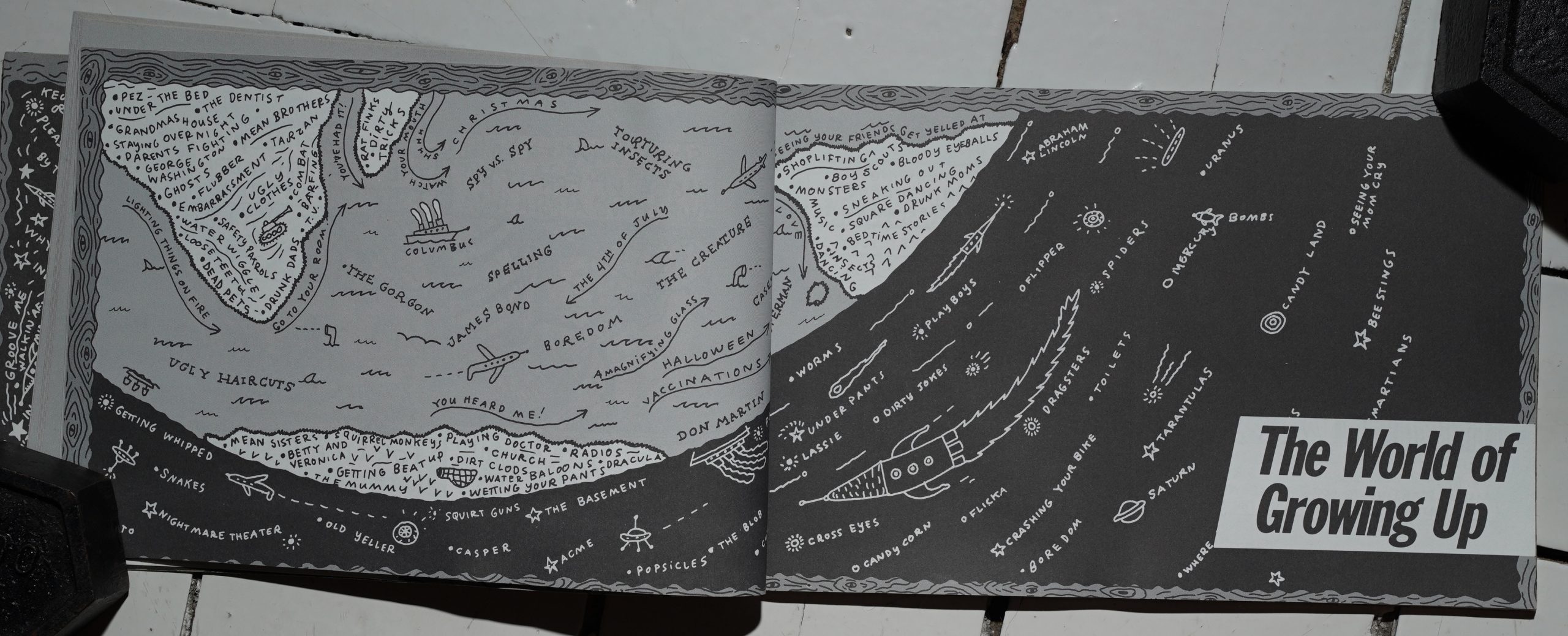

This book is divided into themed chapters and I think it’s pretty obvious what her prime subject matter was going to be:

Childhood.

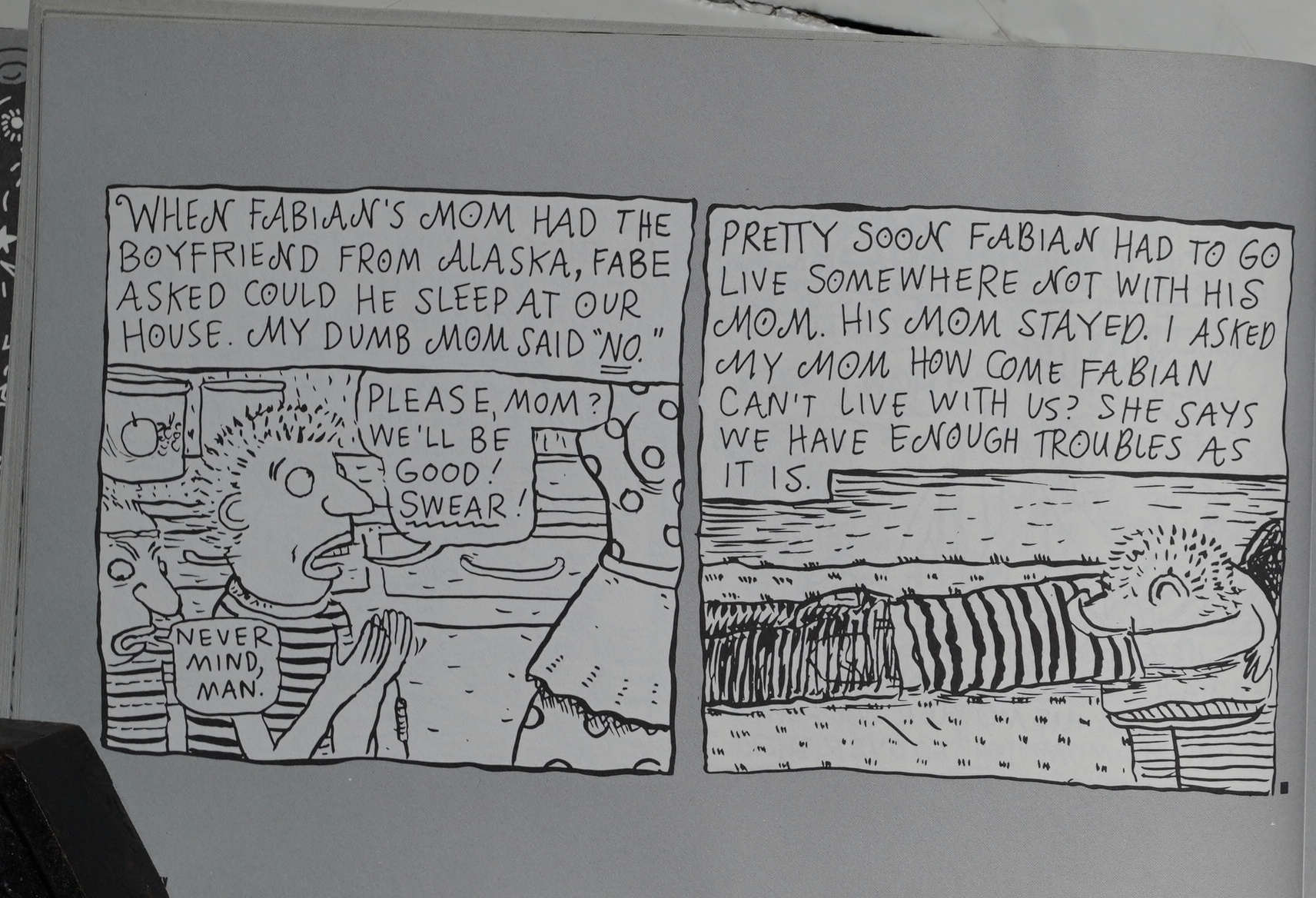

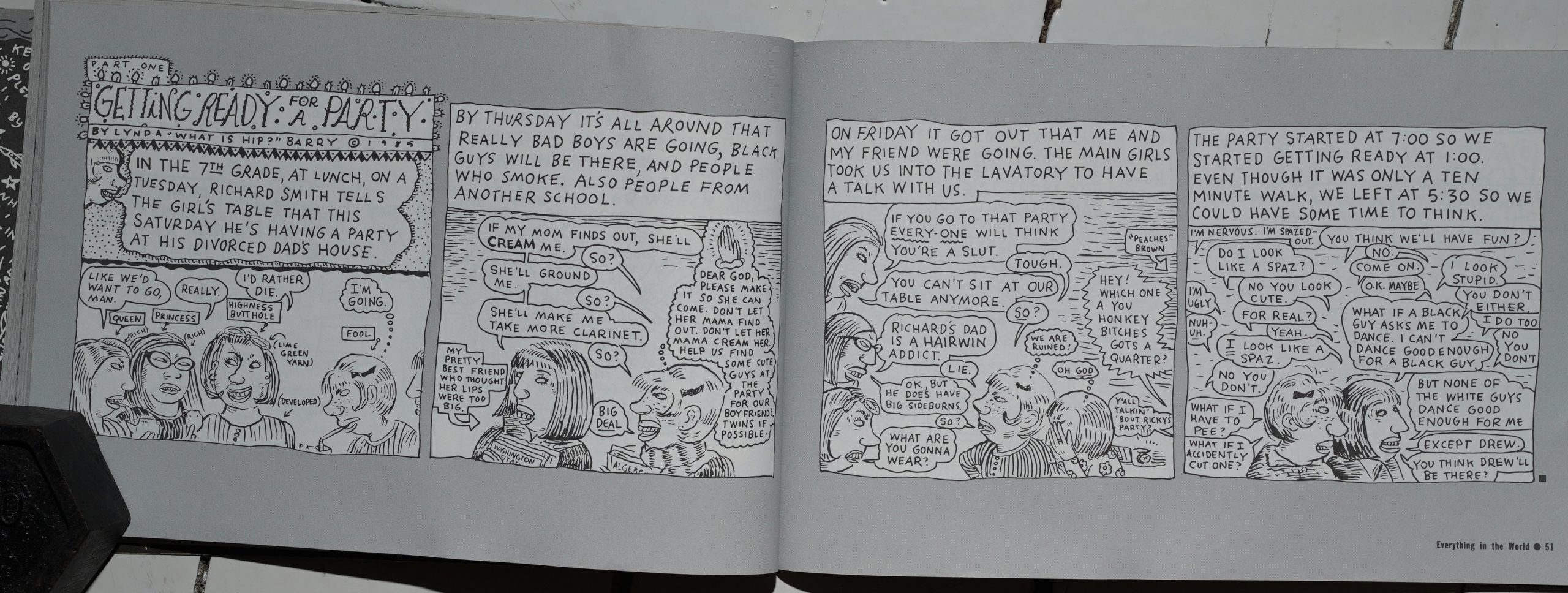

The strips that focus on childhood and teen-age stuff are both funnier and sadder than the rest of the book. Not that the rest of the book is bad or anything, but this stuff positively sparkles.

I don’t think anybody else does this thing with their linework — you have the figures and faces outlined in a pretty solid, thick line, but then there’s a plethora of thinner, more tentative lines inked on either side of the more solid line.

Barry wouldn’t really become a megastar until she hit upon writing about the Maybonne/Marlys/Freddie family (i.e., using continuing characters), but in this book we see some tentative steps taken towards slightly longer continuities… and she uses herself (as a teenager) as the focal character. It’s kinda thrilling to read these, because you can just tell that she knows that she’s uncovering a seam of material here that she’ll be mining for years to come…

Anyway, it’s another fabulous collection. I don’t plan on covering her entire career in this blog series: She’s moving away from the “punk comix” thing I’m vaguely nattering on about here, so I think I’ll just be doing a couple more and that’s it.

Rob Rodi writes in The Comics Journal #114, page 59:

As with Groening, two trade-paperback

collections of these early strips are available

at bookstores. But her newest collection,

Everything in the World, also incorporates

some Of her strips on a new theme: the

tribulations of growing up. Like Groening,

Barry has moved on (or moved back) from

the sexual frontline to the realm of

childhood, (That Groening and Barry are

friends and occasional collaborators may ex-

plain this simultaneous shift in focus.)

She •seems to have little to say about

romance any more, and looking over her

phenomenal coverage Of that sphere you

don’t wonder—there may be in fict, nothing

left to say. Ever. But she has plenty to say

akX)ut her juvenile days, and the remarkable

thing about that is how her style mellowed

so abruptly; astonishingly, she writes about

the terrors and humiliations of childhood

without bitterness, without rancor, almost

without judgment. Despite the unpleasant-

ness of some of her memories, despite the

fact that again, there is pain here, and she

must feel it, she’s utterly honest about grow-

ing up. She seems to want to record exactly

what happened, exactly what she felt, ex-

actly what shaped her. This isn’t situation

comedy, as is the case with John Stanley,

or even at times with Groening; the humor

in her reminiscences is never that forced.

Everything has a natural ambience; it’s her

juxtapostion of events and feelings, her time

ing, and above all her uncanny gift for the

vernacular that make them funny. “Bit-

tersweet” is a debased word, having been

lent too Often to phony romance movies,

but it applies, in its original sense, to Barry”s

current work.

Her art style, too, has softened, has

become distinctive. It’s rounder and more

careful, still earmarked by the appealing

crudity, but with a real cartoonist’s eye for

faces and body language. When she relates

how the boys in her neighborhood fell in-

to an obsession with “pimp walking” (“Boy’s

Life”), the slack jive of their bodies is

hilariously realized; despite the crudity of

the rendering, you can, after you’ve read it,

get up and do the “pimp walk” yourself; it’s

that complete a picture. •And when Barry

gets down to faces, her prejudices can’t be

hidden. If there is a villain in this series of

strips, it’s her cousin, Marlys, who figures’

as a spoiler in just about every scheme

Barry’s gang devises; Marlys’ face iS like a

mass of boils with pigtails. Ugly is as ugly

does—as just about any kid knows

instinctively.

The strips themselves run the gamut of

childhood experiences, to a much greater

extent than Groening’s; Barry relates her

adventures from her earliest childhood

through her teen years, and occasionally

does a strip with a child protagonist Other

than herself (including boys.) As such, she

has a much broader scope than does

Groening, whose Bongo is more-or-less fixed

in the fifth grade.

And whereas Groening is interested in

youthful alienation, Barry is much more in-

terested in the entire social Structure that

surrounded her. She was part of her world

in a way that Groening perhaps was not.

One Of her most telling strips in this respect

is “How Things Turn Out,” where she deals

with social class. “In school,” she tells us,

“there were the queen girls and then there

were the rest and at the bottom of the rest

were the ones, whatever you want to call

them, the ones you Would be ashamed to

have to touch.” Okay, nothing we all didn’t

know already; we’ve live it. But she goes on

to examine this particulai-ly hierarchical

phenomenon inadetail, discussing the fixi-

ty of social position (“Occasionally someone

could get lowered for, say, wetting their

pants on a field trip, but it was almost im-

possible to move up”) and concluding with

an analysis of the origins of class assignment

that is nothing short of brilliant, and which

would have shaken Karl Marx to his very

bootstraps: It had nothing to do with how

smart you were. And even if you weren’t that

cute’, if you were a queen, people would copy

you. It was just something decided between us,

even though it wasn’t us who decided it. It was

something we all knew about. It was Our main

rule of life.

This blog post is part of the Punk Comix series.

One thought on “PX86: Everything in the World”