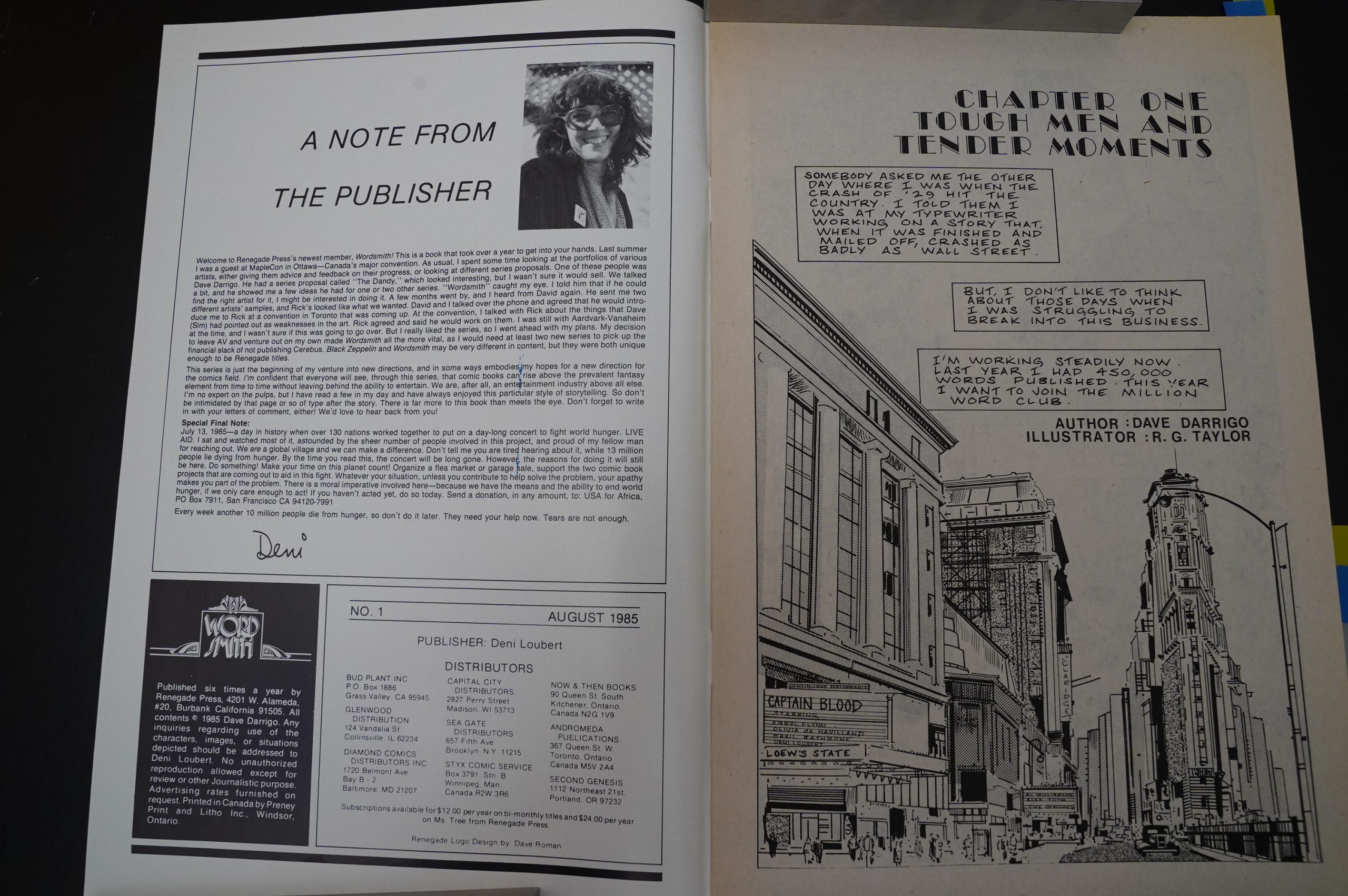

Wordsmith (1985) #1-12

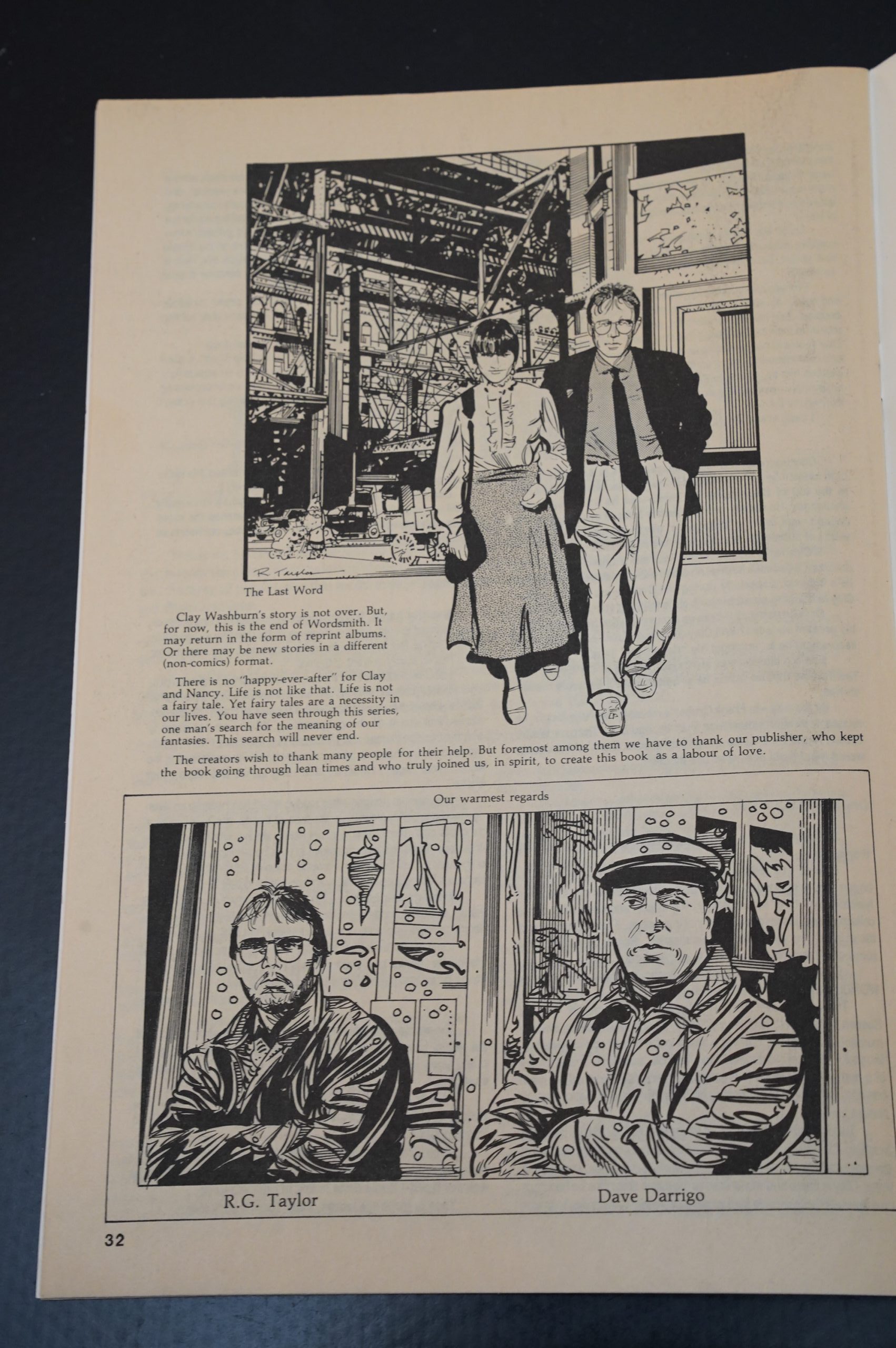

by Dave Darrigo and Richard G. Taylor

I liked Renegade a lot back in the 80s, and comics like this were a major part of that: Comics that just seem… out of whack with what anybody else was publishing.

This comic is about a pulp writer… in the mid-to-late 30s… and… that’s it: The writer isn’t a detective by night, and there’s no alien invasion, and there’s not a spy sub plot. It’s about a pulp writer.

It’s so low concept that only Renegade would have thought this was something commercially viable to publish.

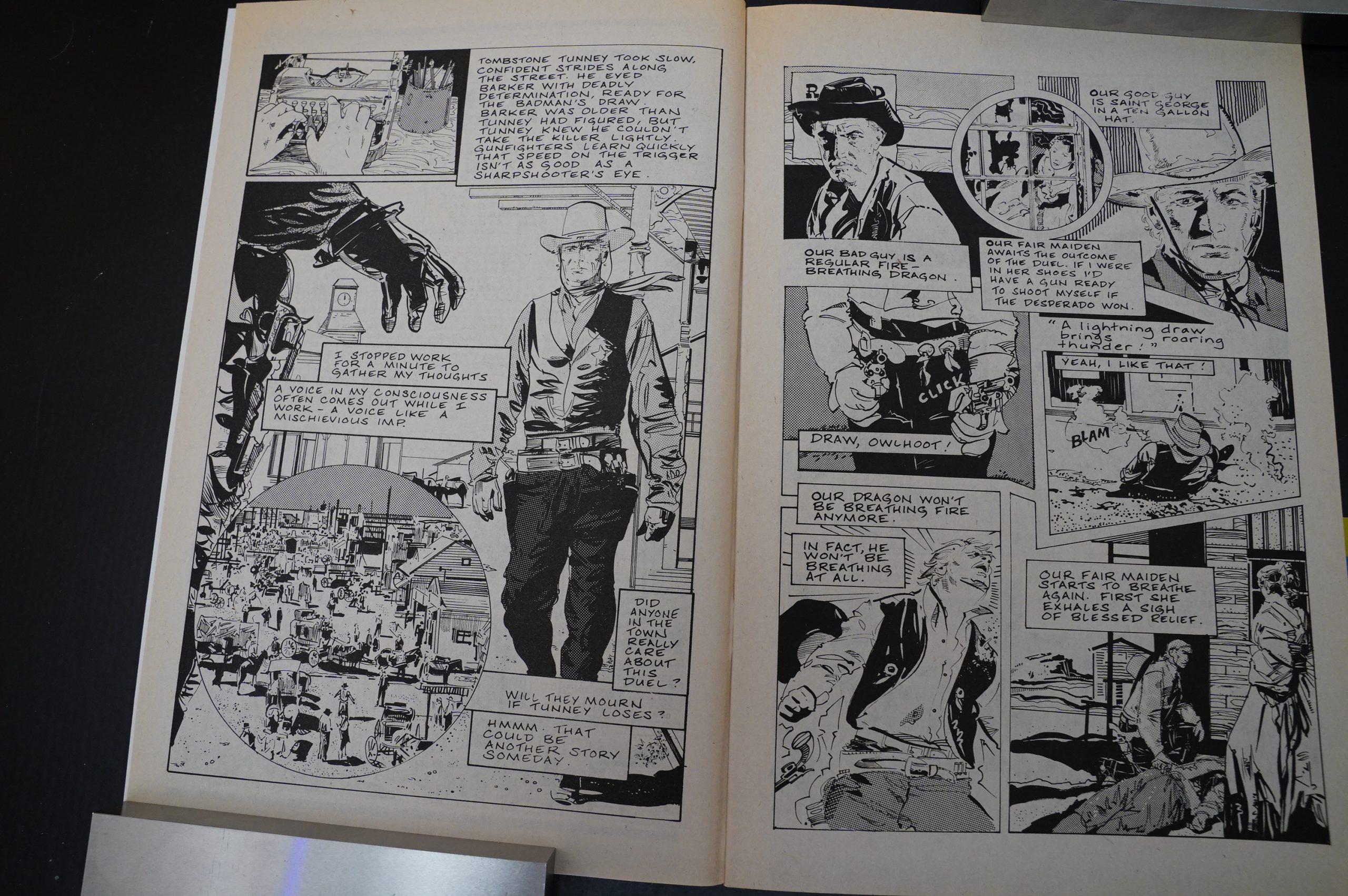

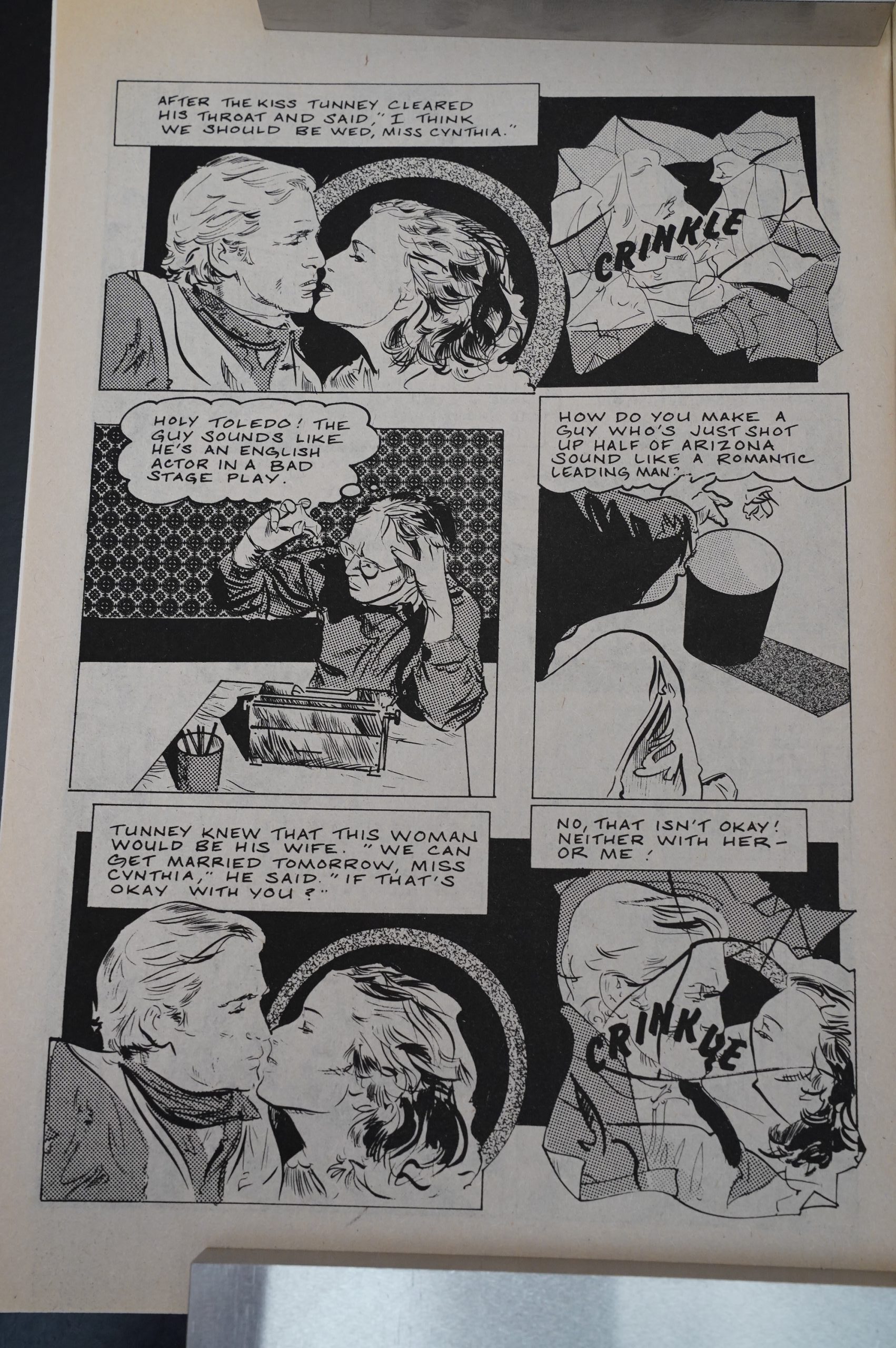

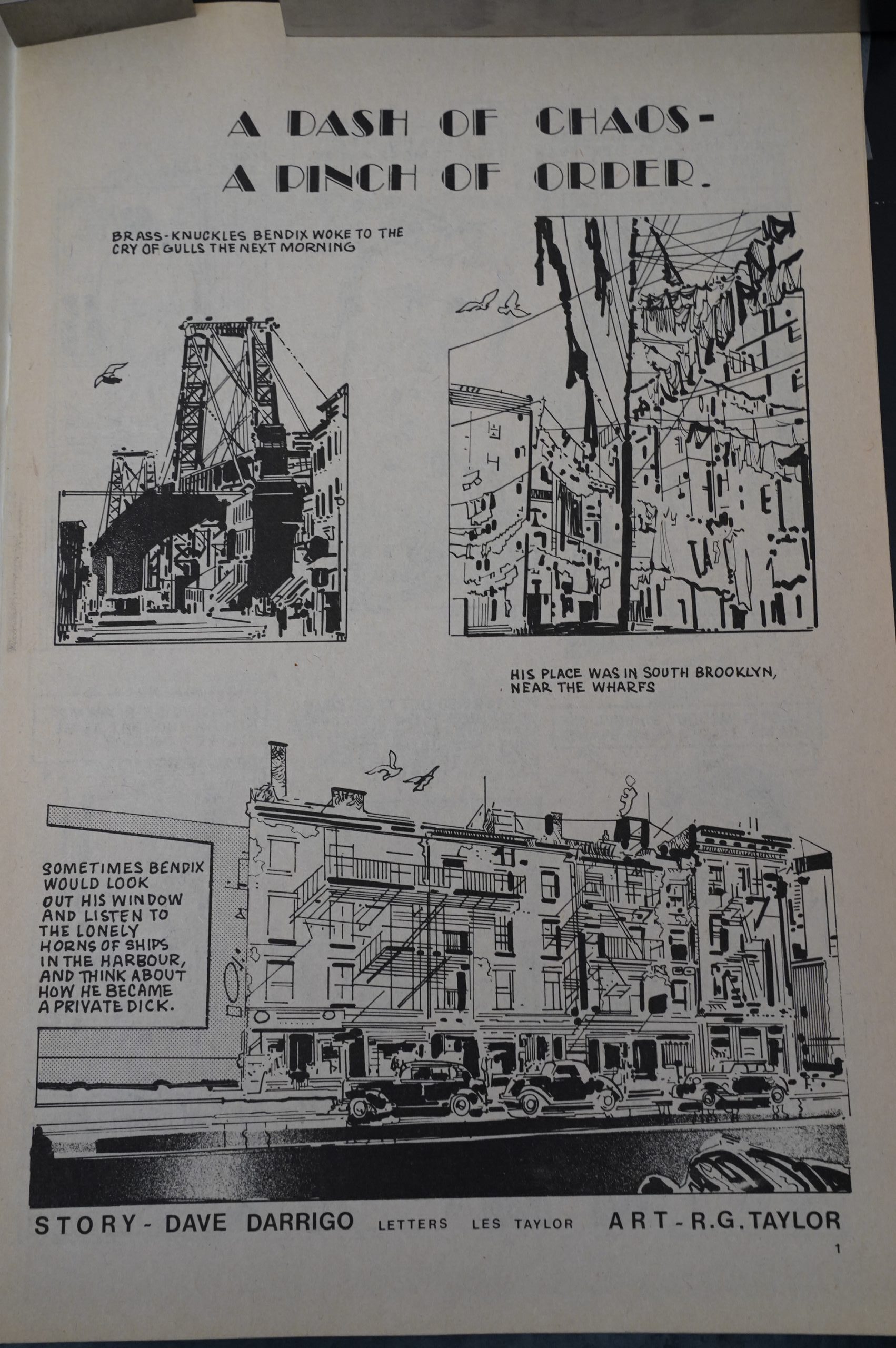

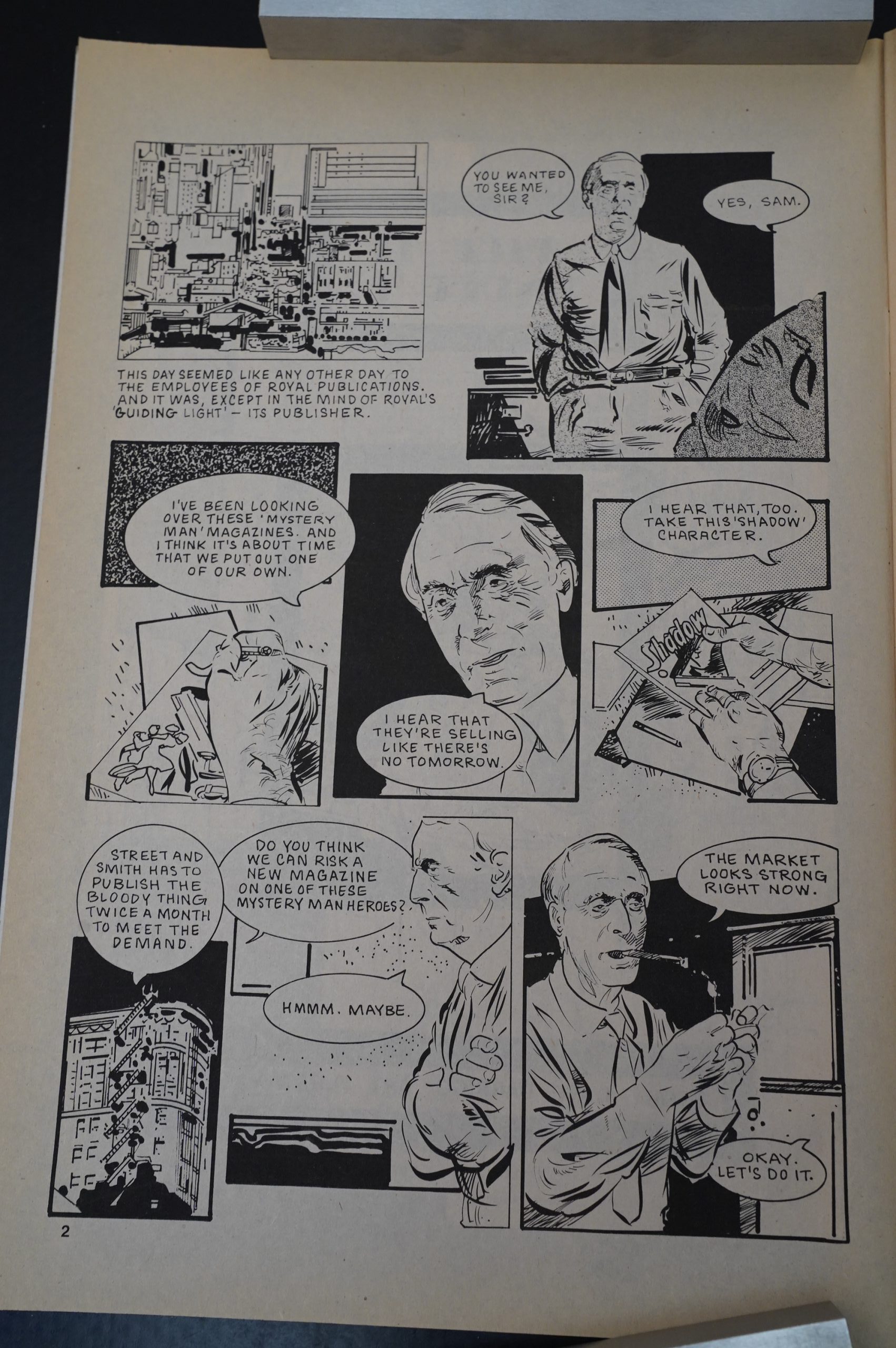

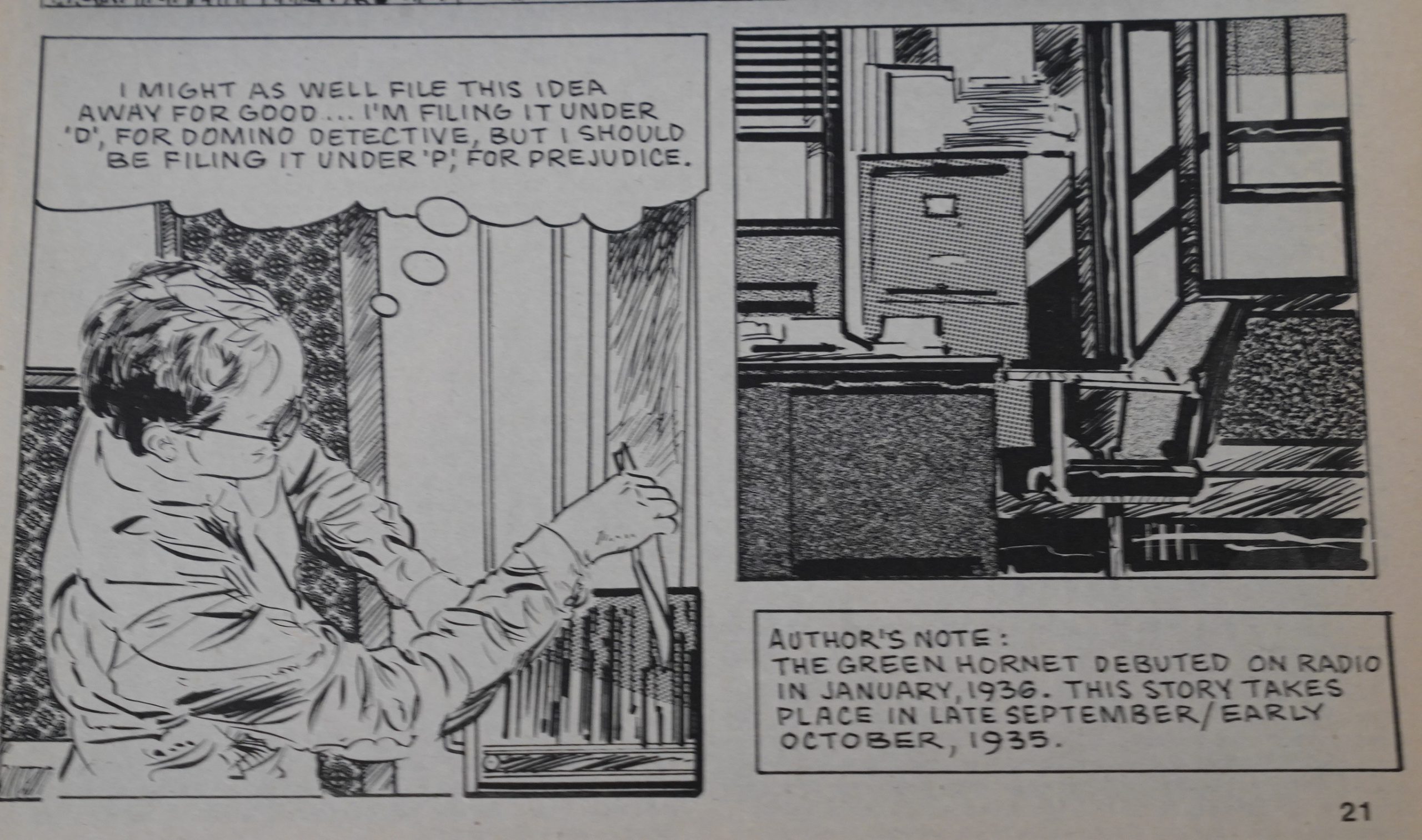

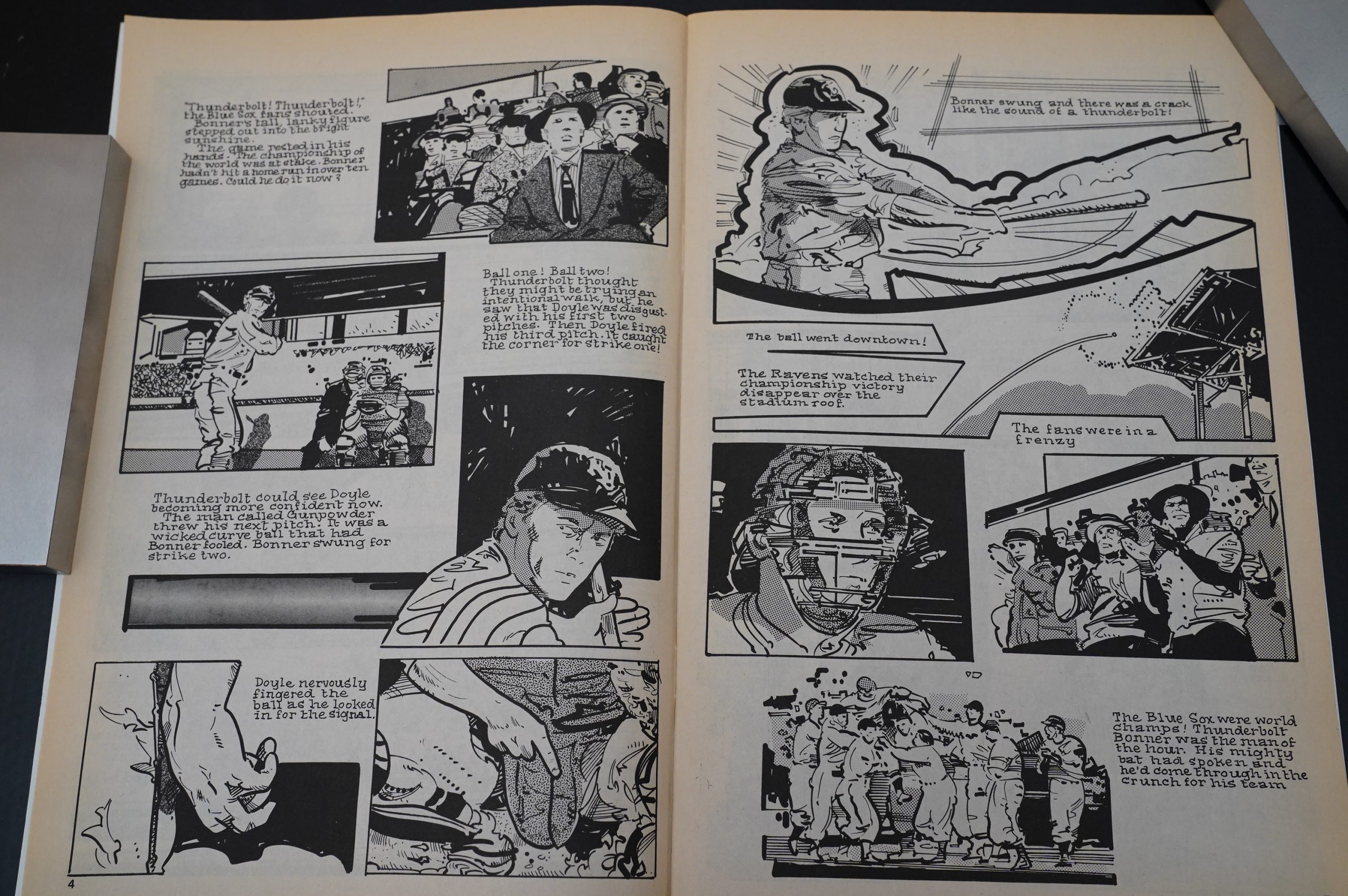

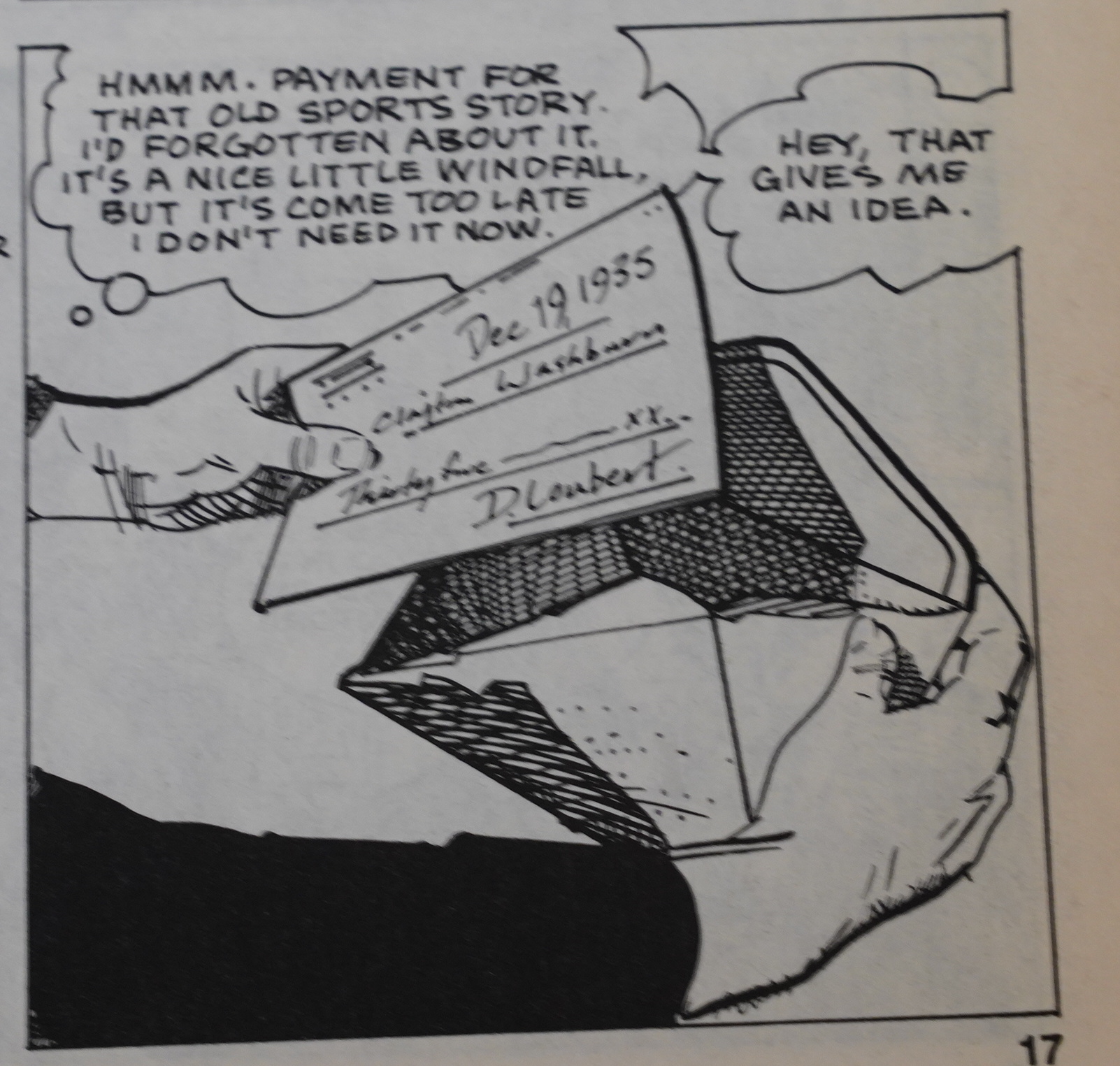

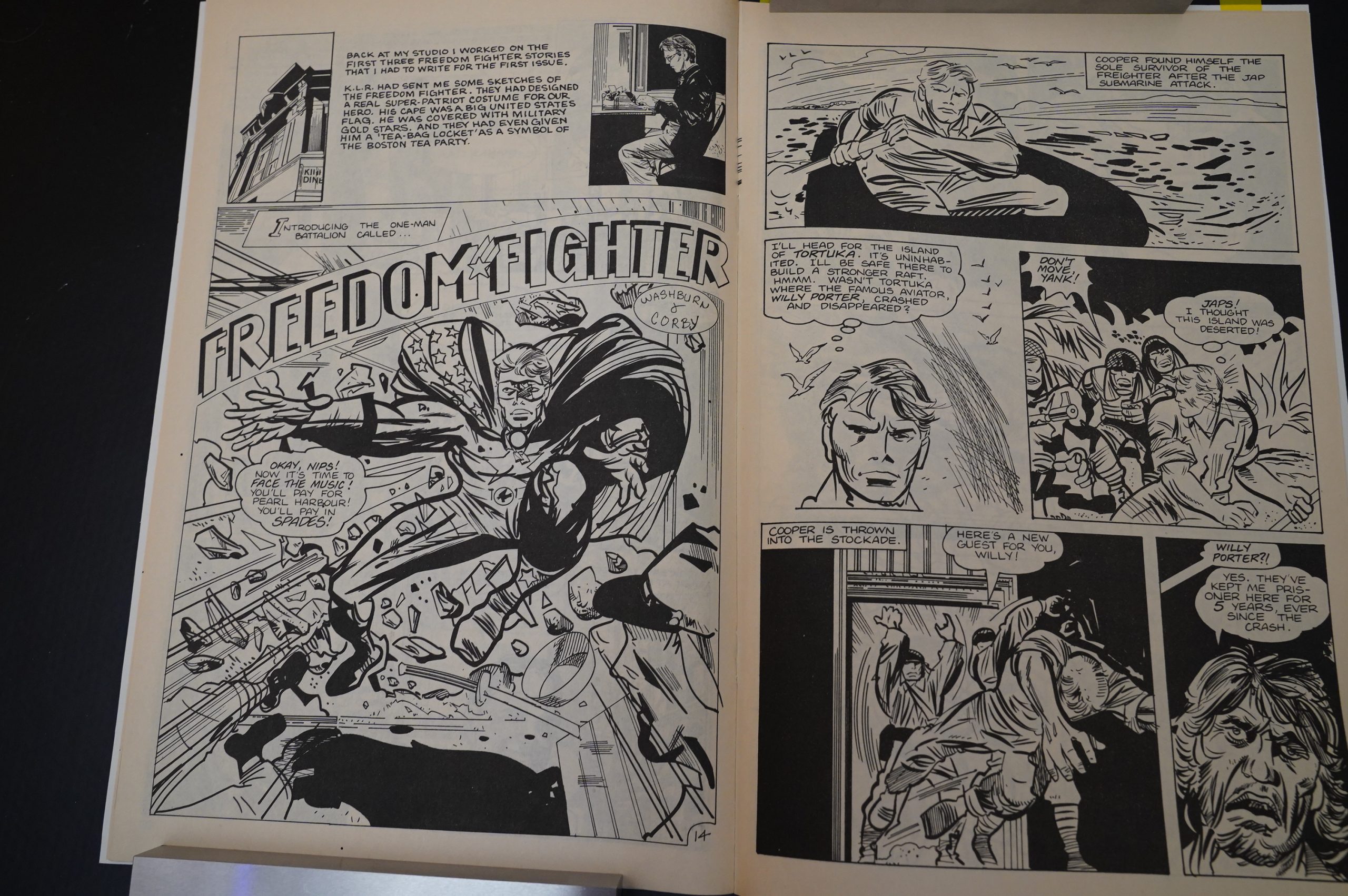

And it starts off pretty sweet, with pages like this that illustrate the creative process. I like the crumpled-up panels. And if it was all like this, this would have been a fun series.

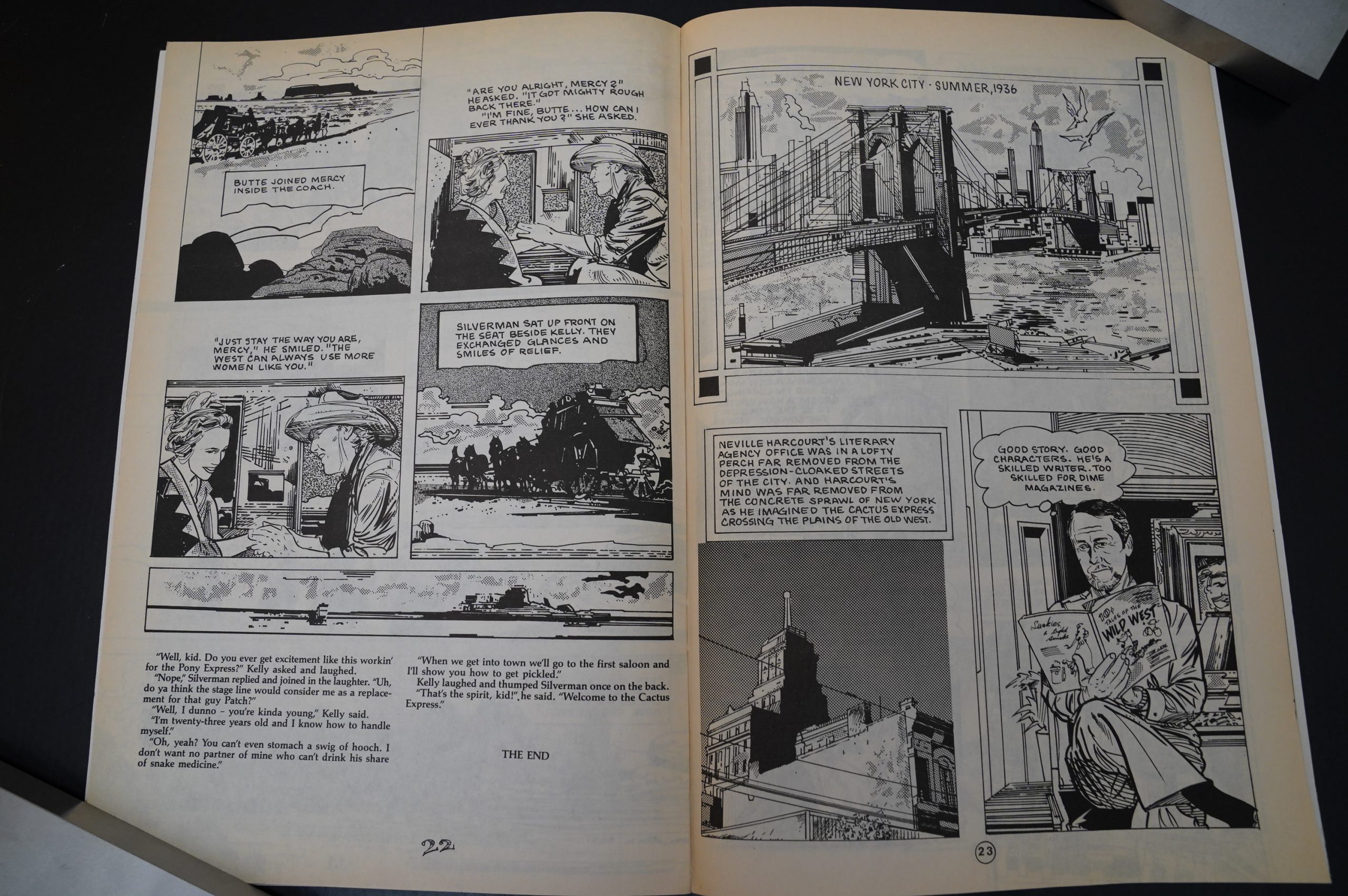

Taylor’s artwork is pretty attractive, even if it’s slavishly drawn from photo reference. It’s got an attractive stiffness to it, and the usage of different zip-a-tones and patterns works really well.

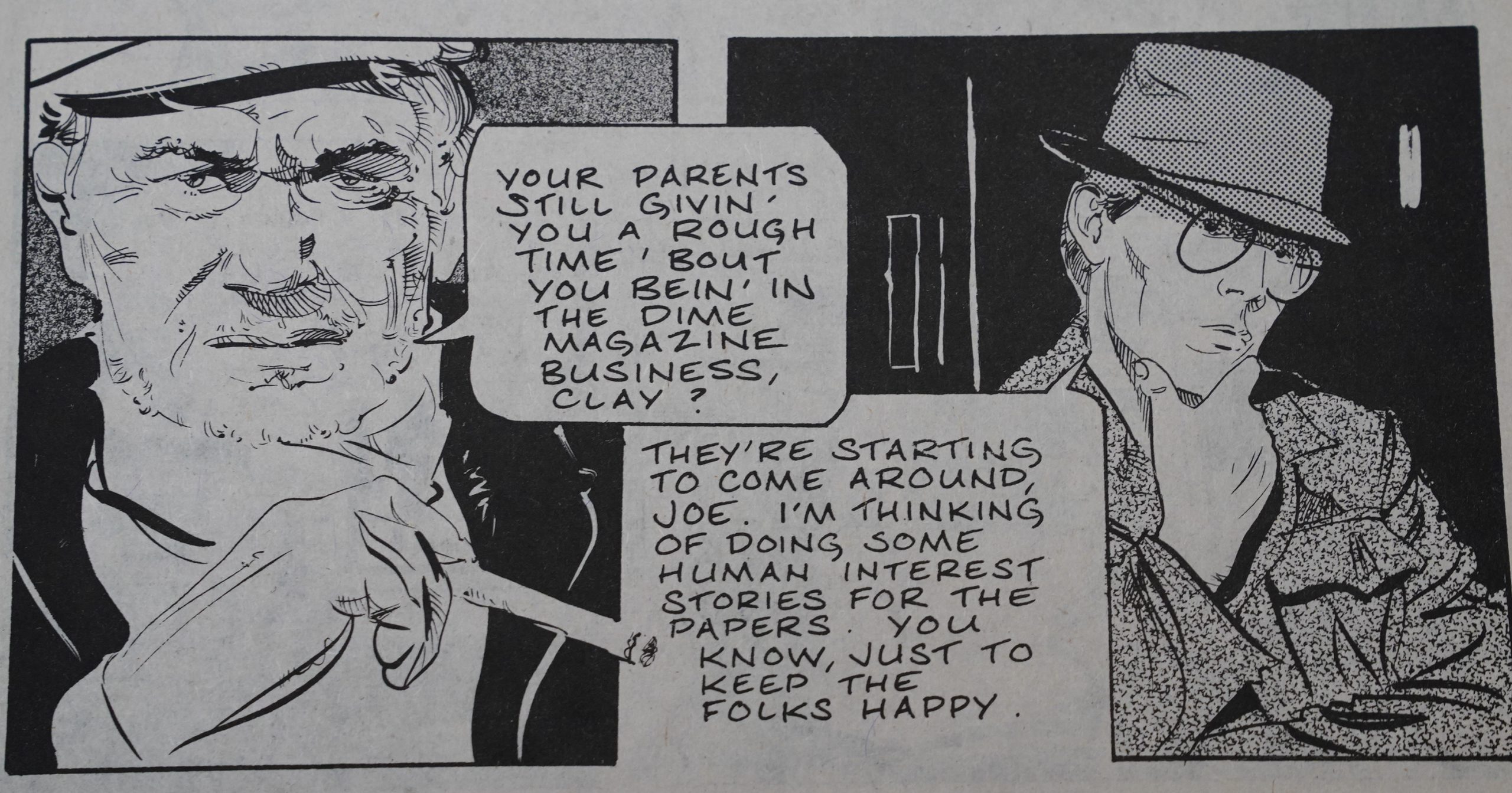

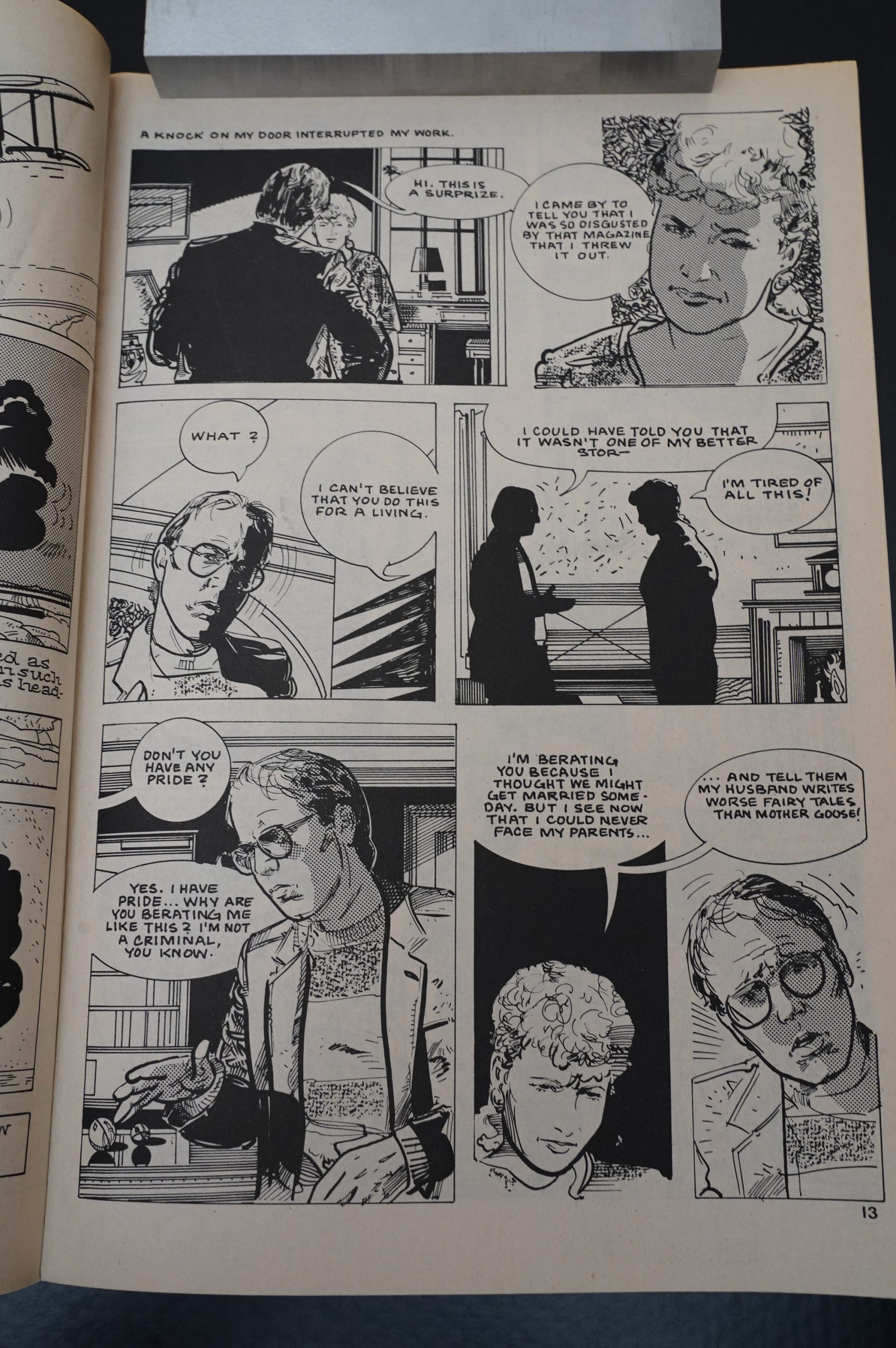

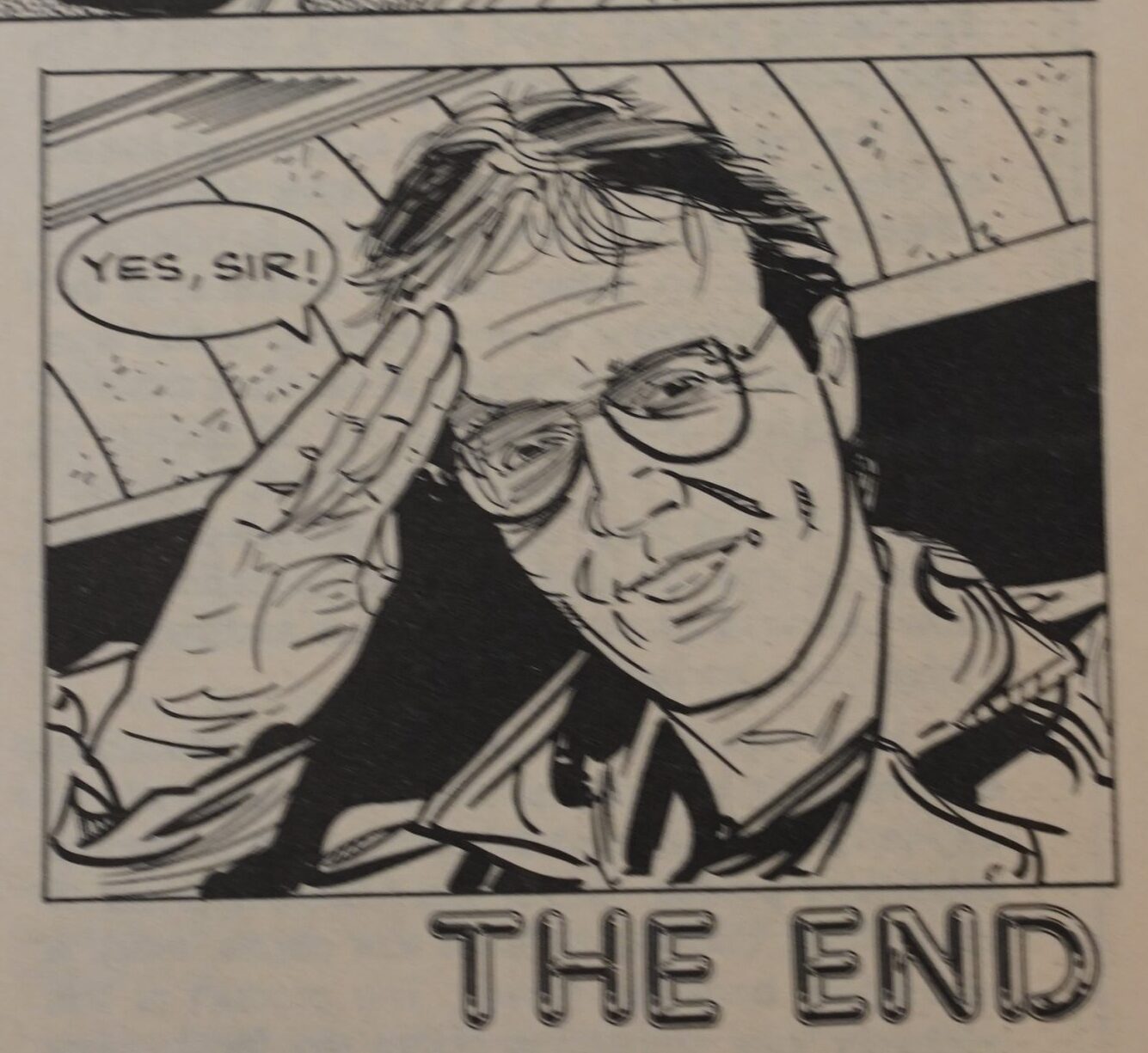

Unfortunately, when the people acting out the parts look unconvincing, then it all just looks wonky. The worst “actor” here is really the guy who’s doing the lead, unfortunately: He’s always looking down or away and holding his chin. I’m going to go out on a limb and guess that Taylor used himself as the model. Especially since those glasses look really 70s and not very 30s.

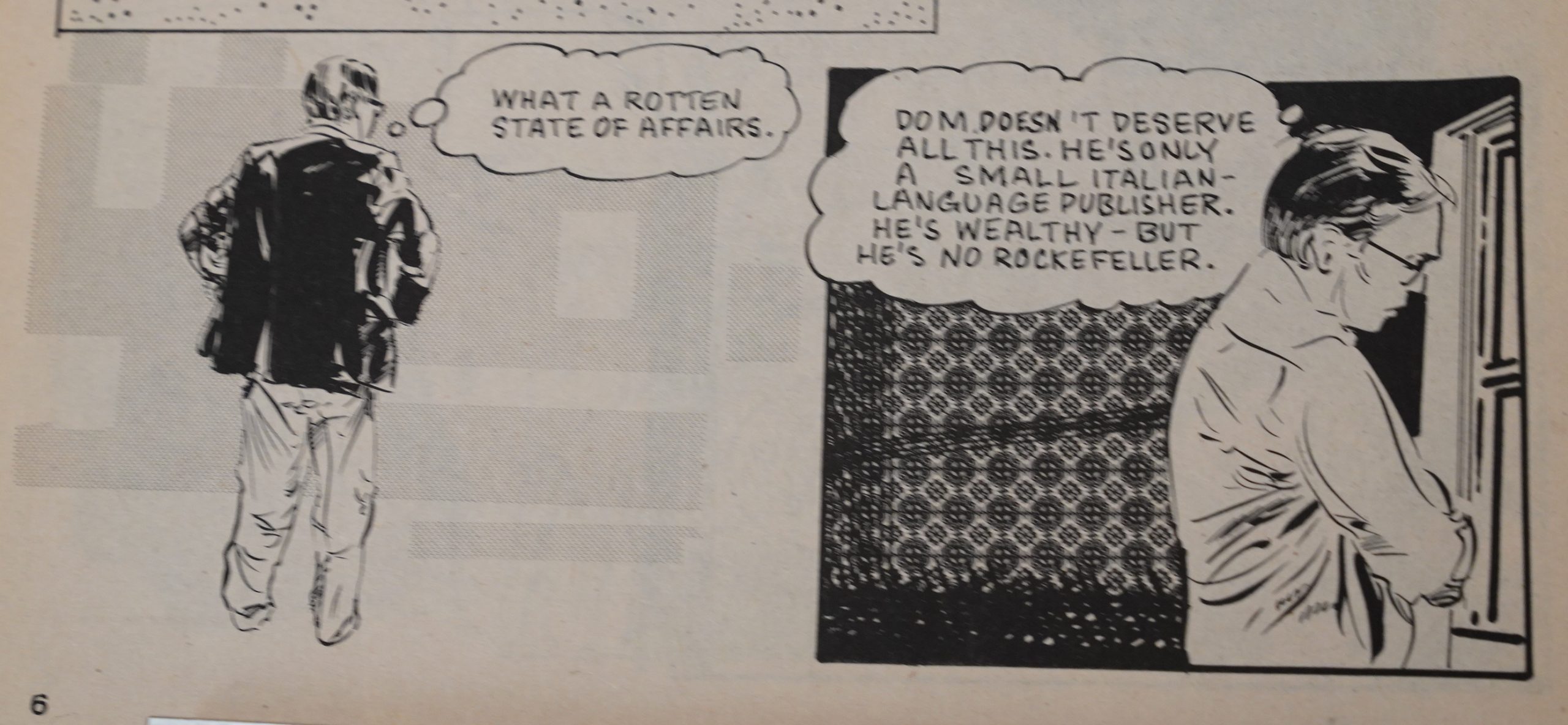

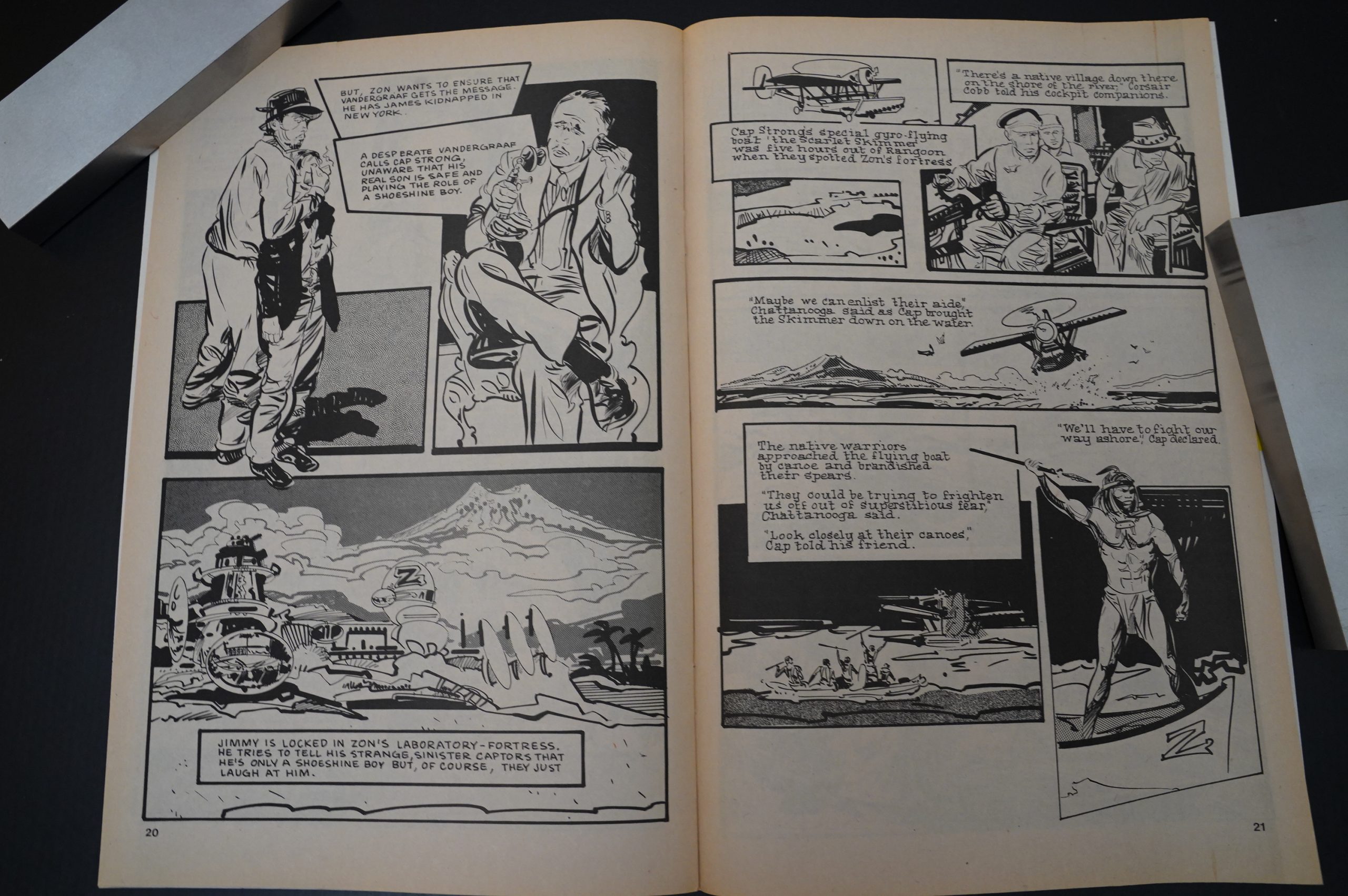

(Ooops, blurry pic.) It’s also got the same problem Scott McCloud’s The Sculptor has: It’s talking a lot about making art, and coming up with really good stuff. (The writer protagonist here is really successful and everybody loves his stories.) McCloud had an artist who was supposed to be awesome, but whenever his artwork was shown on the page, it was the worst god-awful crap ever, which kinda undermined the story. The problem isn’t as severe here: But that line up there took a lot of work (in-story) to be created, and it’s supposed to be fantastically good… and… well, you can probably read yourself, even if it’s blurry.

Darrigo really loves the pulps, I think is what he’s saying here. I have read very little, and the little I’ve read has bored me silly.

So — in every issue, we get a couple scenes from whatever the protagonist is writing, but the bulk of each issue is about his life, moving around in New York and talking to people.

The protagonist feels pressure to write serious literature instead of violent pulp stories, but the wise editor sets him straight with some tired platitudes.

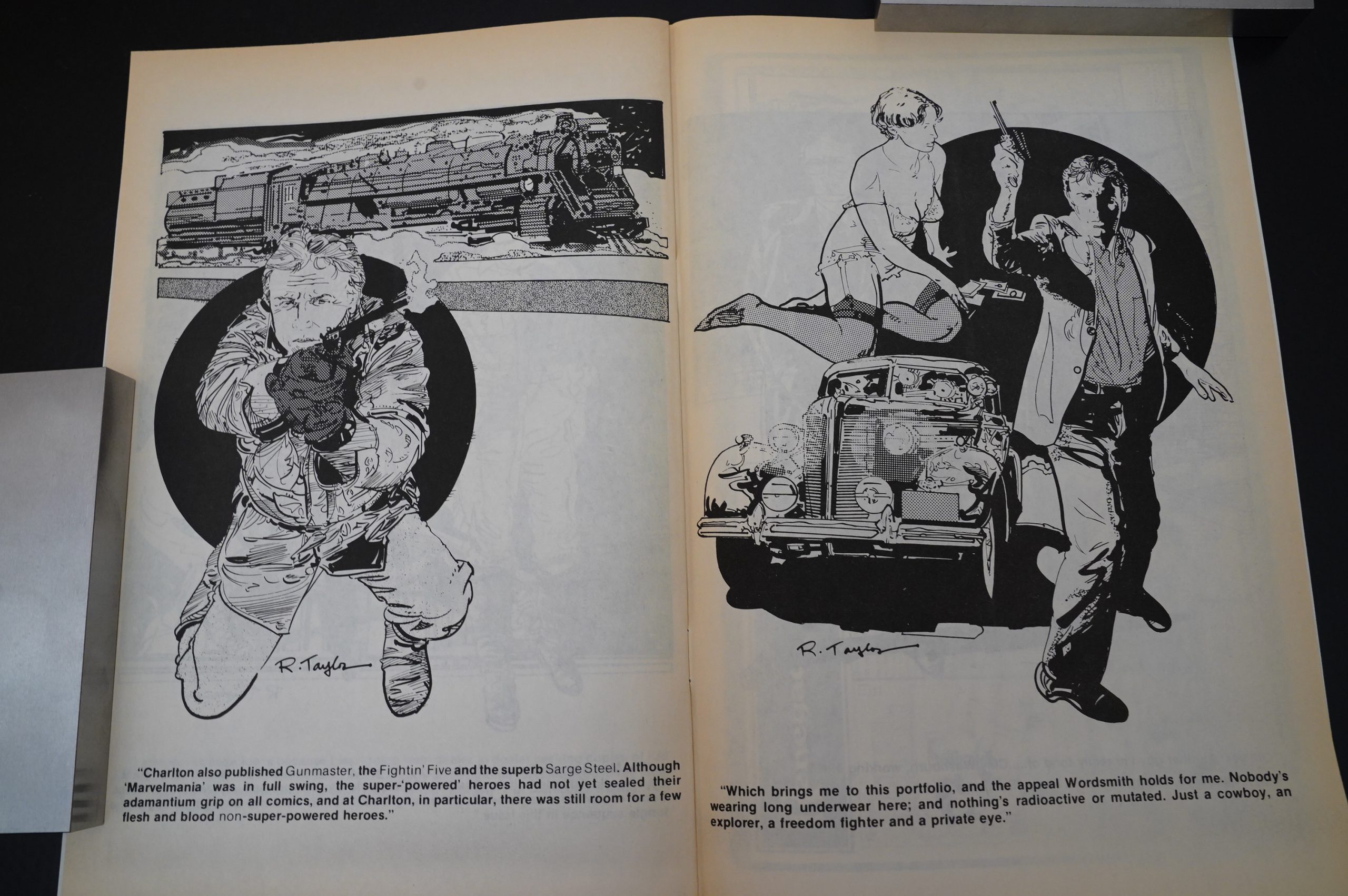

Oh, yeah, there’s a pin-up in most issues… and … they’re not particularly good?

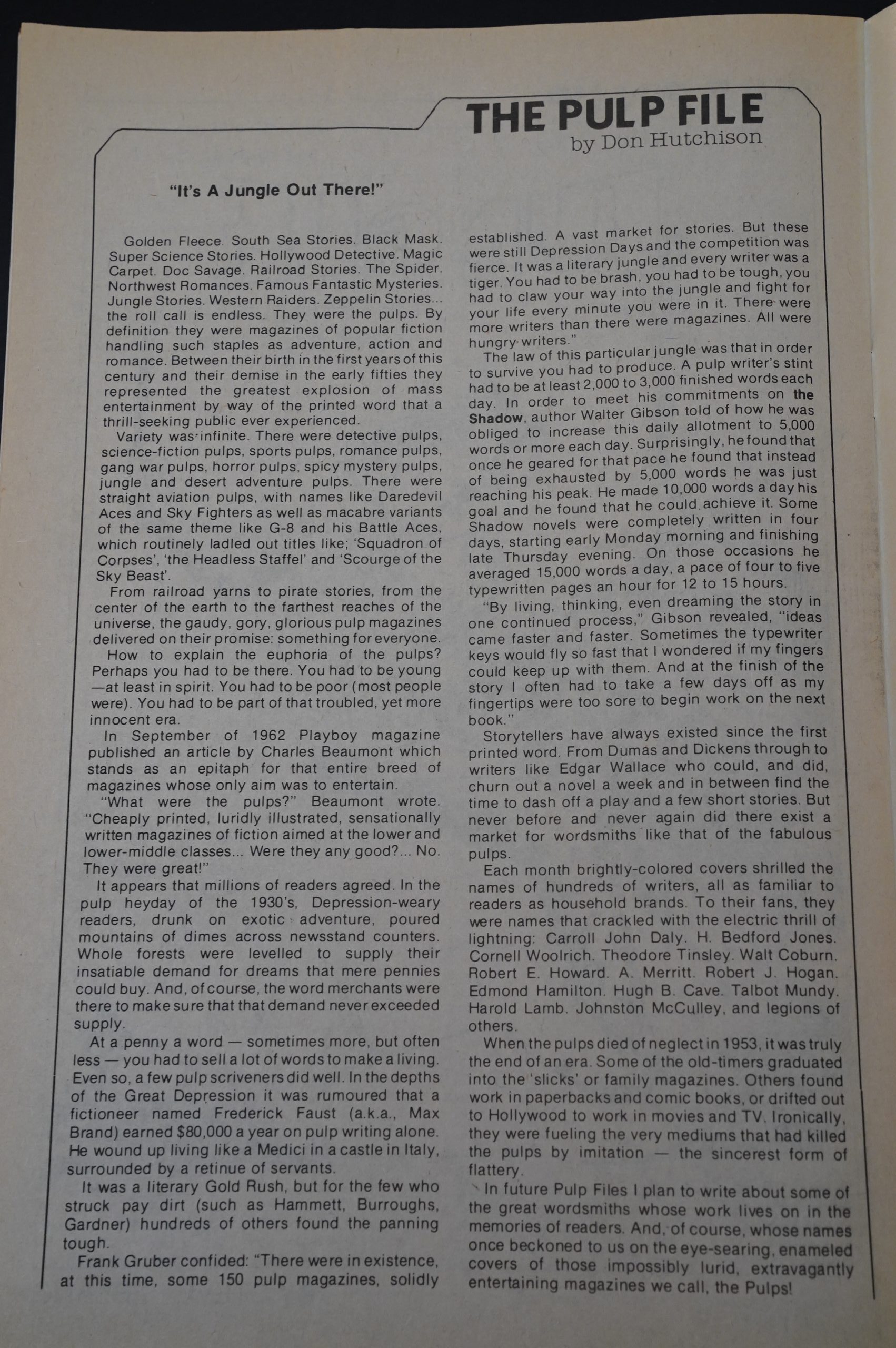

Don Hutchinson also has a recurring column about the pulps. It’s very rah rah pulps.

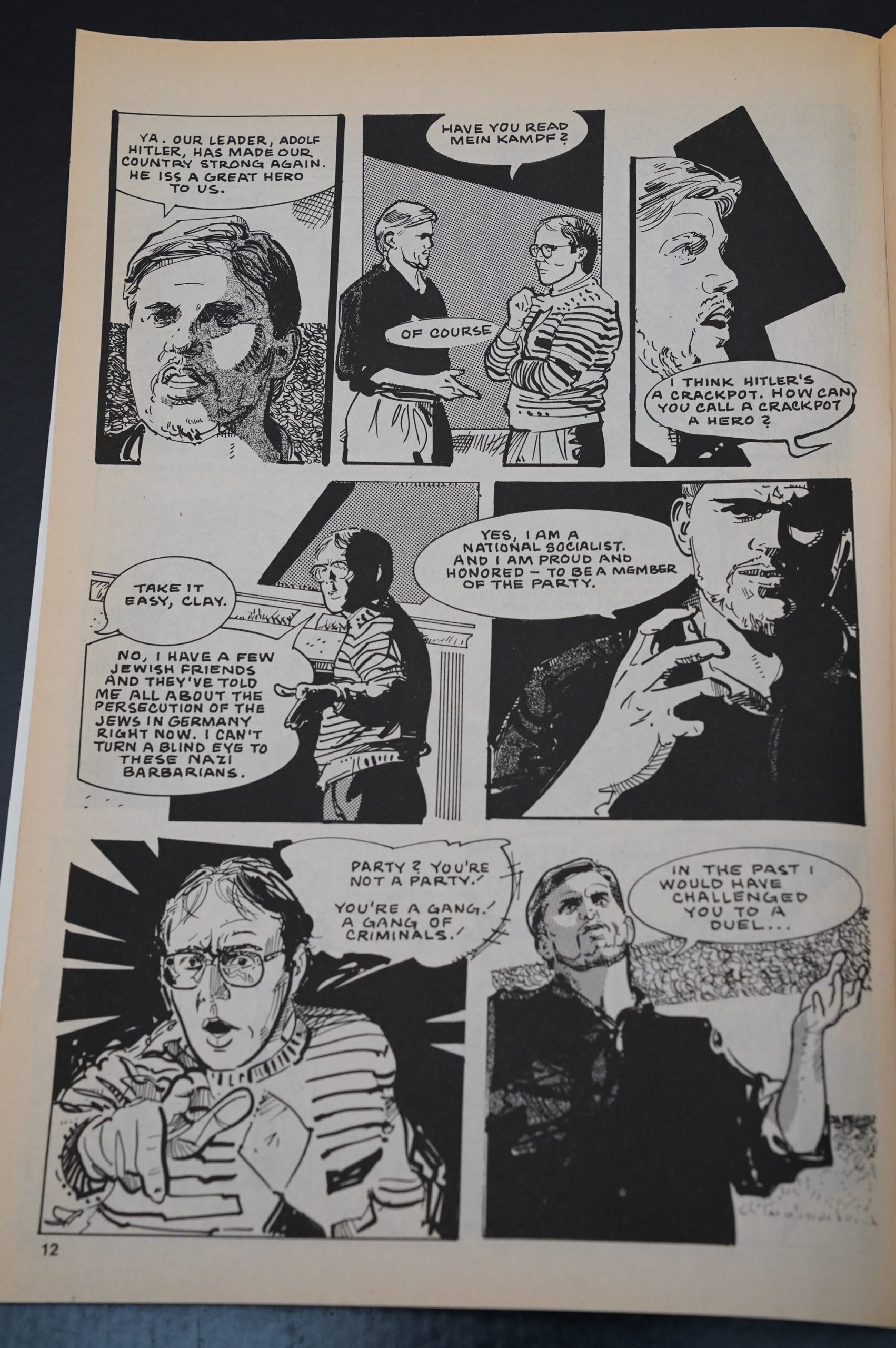

The dialogue is unbelievably stilted. It’s not just that nobody talks like this, but it’s just … I know, I’m so eloquent tonight.

Taylor uses the tones in many interesting ways, like the abstract block shapes to the left, and perhaps less successfully as the wallpaper to the right. But I do like all his schlumpy (that’s a word) pants.

Er, uhm, OK, thanks for letting us know…

It’s a family affair — Taylor’s dad is doing the lettering, and somebody else named Taylor is doing the photo references.

I soon came to dread reading the pulp excerpts: If there’s anything I hate more than reading plot recaps, I don’t know what that is, but reading these telegraphed scenes is also tedious.

OK, re-reading these comics, I have to say that I’m really disappointed. I only had a handful of issues as a teenager, and I remembered them as being more interesting than they are. So now I’m slipping into “angry old man shouts at old comics” mode, which isn’t what I was going for, and isn’t very interesting to read, so I’ll try to not kvetch so much….

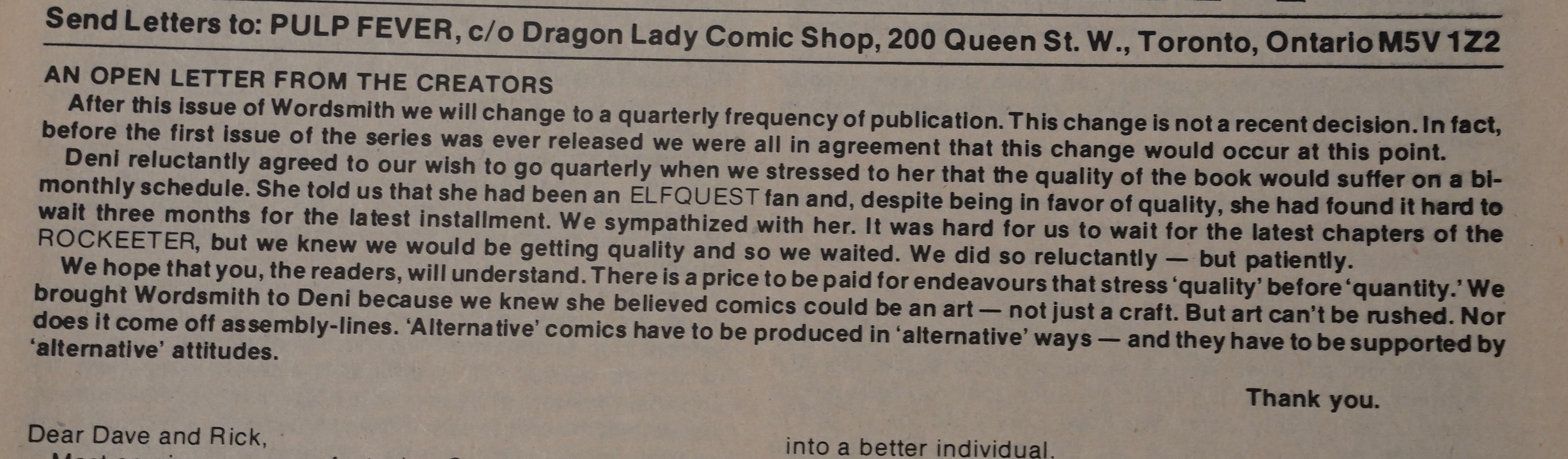

Darrigo announces that they’re going to a quarterly schedule. Strangely enough, they also go to a 32 page format (up from 24), so the number of pages pr. year doesn’t change that much. Perhaps they had planned on adding more letters pages and columns, but most of the issues are wall-to-wall Wordsmith…

OH GOD A BASEBALL STORY LARD HAVE MERCY

The main story is a lot more interesting than the pulp stories, but… er… OK, here, the protagonist meets a Nazi writer. And that’s as dramatic as things get.

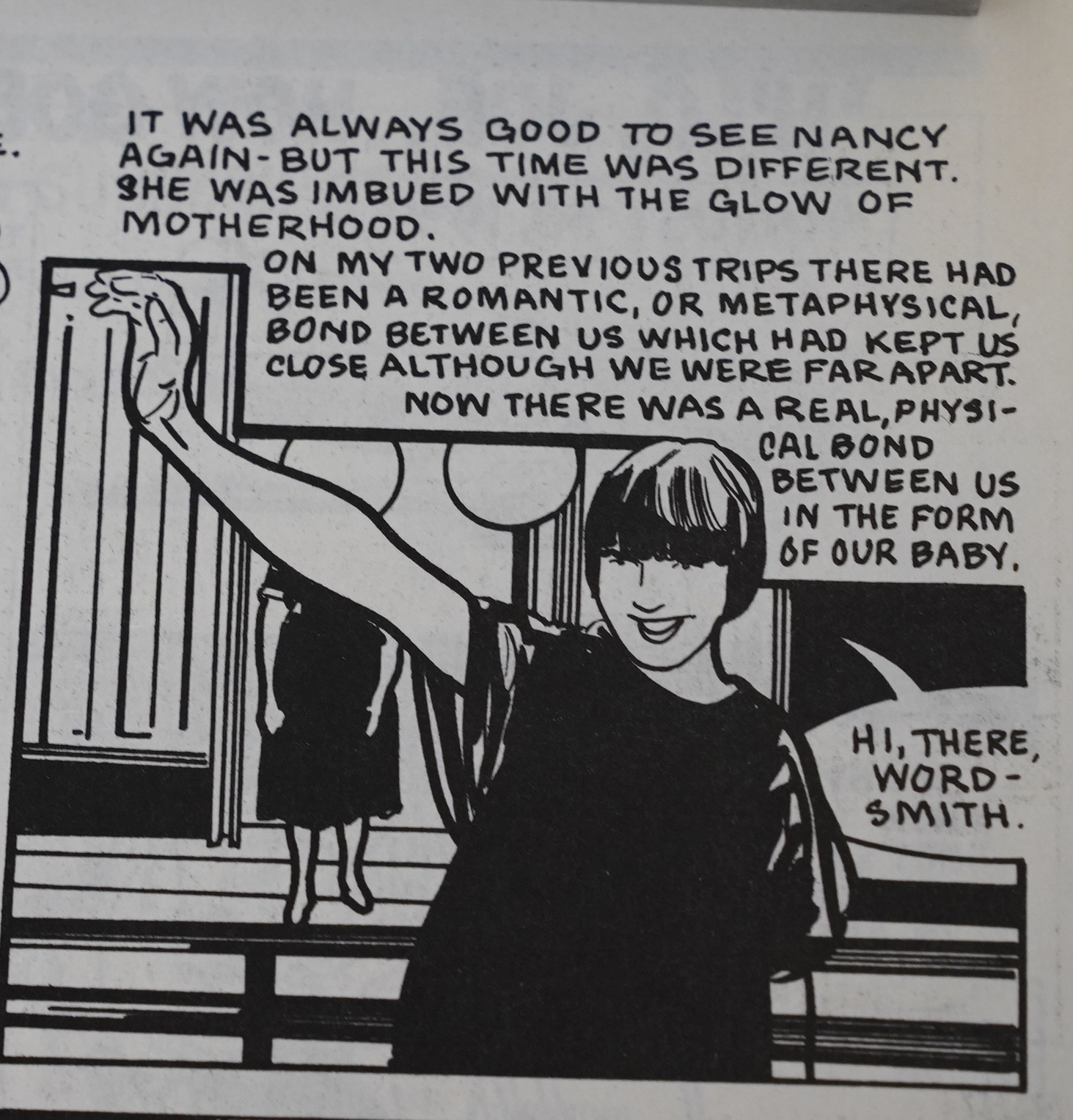

The main problem, I think, is that the protagonist is just kinda vaguely a nice guy, and has no character traits beyond that (and being really into pulps). For instance, for some reason this socialite beauty is his girlfriend… but why? He looks like a slob, he’s not witty or particularly smart, he has no interest beyond writing his pulps… so this millionaire’s daughter hooks up with him? Because he said he was a writer and she assumed he meant of literature?

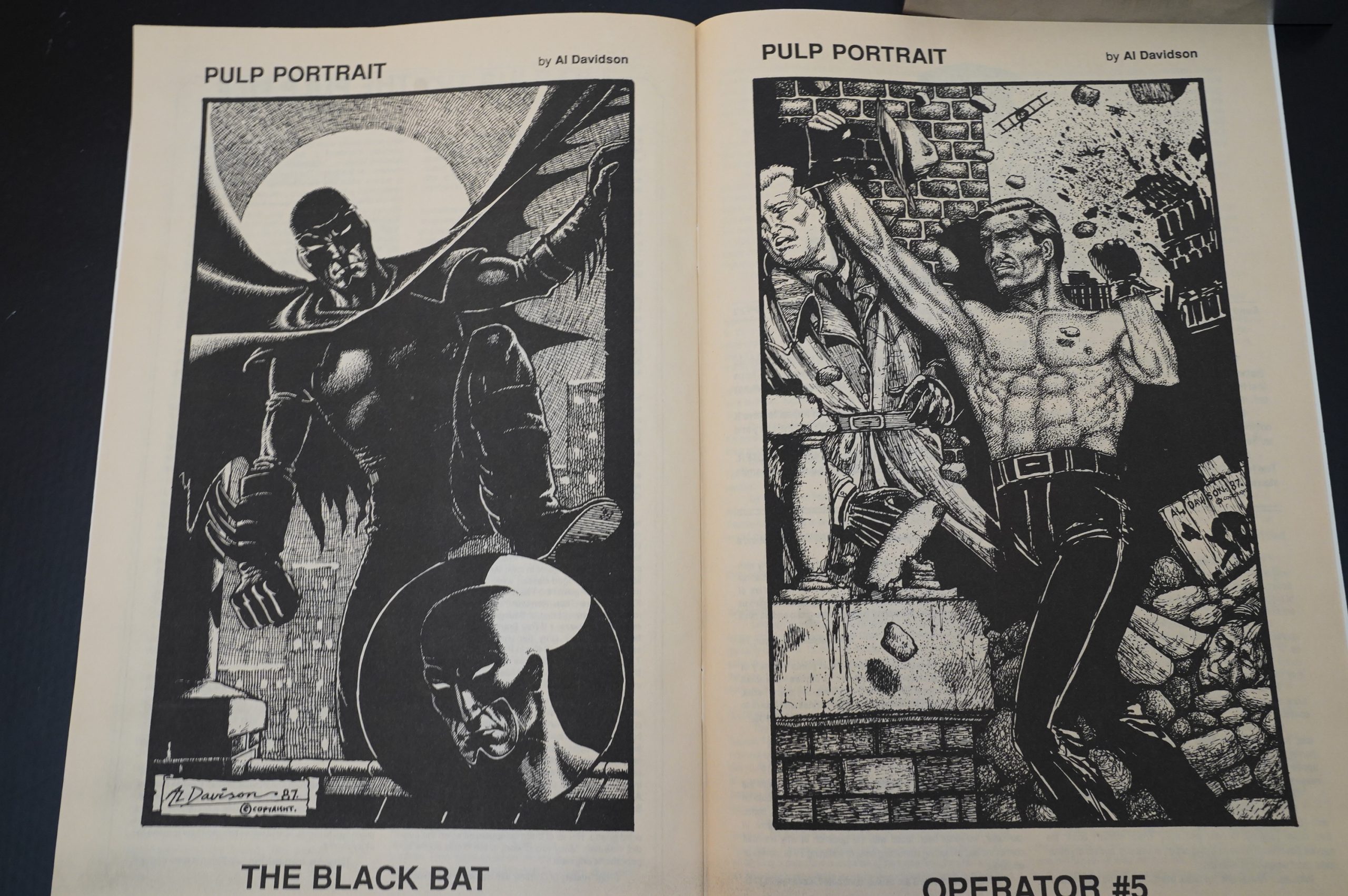

Taylor does some pinups himself.

Heh, a check from D. Loubert.

In one issue, we get an entire pulp western for 22 pages, and it’s so tedious that I couldn’t make myself read it all. Sorry! Blog concept failure! I promised to read all the Renegade comics, but I failed.

Then, preposterously enough, the remaining ten pages is about how everybody is so impressed by that turd of a story that they start offering him jobs left and right.

OK, OK, OK…

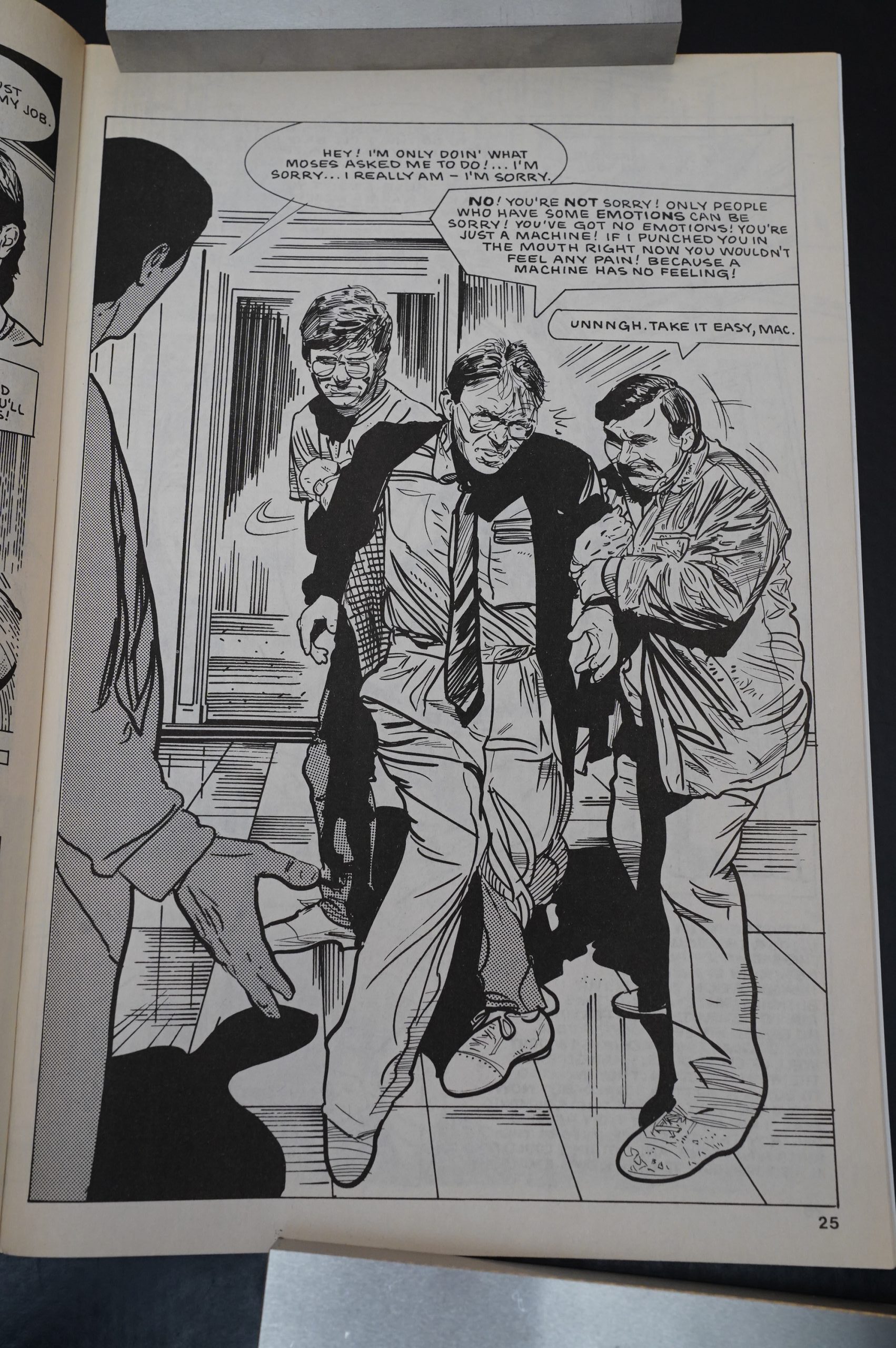

Finally! Dramatic fight scene!

Love that pose.

What a wordsmith.

In the final issue, the pulps meet super-hero comics, and the protagonist teams up with “Jake Corby” for an issue of Freedom Fighter.

Taylor does a pretty amusing pastiche of Kirby, eh?

The series does get a proper ending of sorts, which is nice.

Heh. Pin-ups from Al Davidson…

And I guess I was right that Taylor used himself as the model? Even the glasses? It’s like I’ve got ESPN or something.

But what did the critics think?

Somebody writes in Amazing Heroes #112, page 64:

And, yes, I have one major com-

plaint. The pulp stories written by

the protagonist, Clay Washburn

(which Darrigo cleverly weaves into

the comics as a sort of alternative

storyline), are just too god-awful to

be believed. I guess Darrigo’s play-

ing campily with the overwriting

and corniness that afflicted many of

the pulps, but these are so mon-

strously cliched and lousily written

that it’s impssible to imagine them

being published by even the crassest

pulp house. This issue’s story—in

which Congo Carson saves the shite

women from the savages through the

old predict-the-eclipse routine—

would have been laughed out the

door even in 1935. It’s downright

painful to pound thmugh four pages

of this self-conscious garbage at the

beginning of a story.

This purposely bad writing is par-

ticularly odd considering Darrigo’s

espoused fondness for the pulps; he

seems to be deriding them rather

than paying them tribute. If nothing

else, he owes it to Frank Gruber to

capture some of the genuine fun and

freshness of the actual pulps. Hav-

ing drawn so much from the man’s

remarkably similar pieces of work

from two very different sources.

Both are stories of young dreamers

trying to make it in the pulp pub-

lishing world of New York during

the Depression; one a pulp novelist,

the other a comic book artist. The

first is put together by a couple of

youngsters from secondary sources.

The other is pulled from memory by

a man who lived it all, a pioneer of

comics and one of the medium’s few

true masters. Both are quiet, bit-

tersweet, ultimately very optimistic

tales, low on plot and sensation but

rich in detail. Each is a fond tribute

to a lost phase of America’s growth,

an era of great tribulation but

astonishingly high hopes.

Eisner’s work, of course, is the

better of the two. Wordsmith has

some fine content, but it’s a rather

shapeless and imbalanced work,

never quite able to pack as much

drama as it should into its scenes.

The Dreamer has a similarly loose

storyline, but it’s given form and

strength by Eisner’s mastery of

visual storytelling. He has invented

and assimilated so many subtle

tricks over the decades that he can

draw more feeling from a tiny inci-

dent in his Dreamer’s career than

young storytellers like Darrigo and

Taylor can give to the great traumas

of their Wordsmith’s life.

Will Murray writes in Comics Scene Volume #2, page 14:

Time Out for

“Wordsmith”

ordsmith, Renegade’s ex-

perimental novelistic

story of 1935 pulp magazine writer

Clay Washburn, will undergo

dramatic changes beginning this

summer in an effort to resolve the

characteris fate before being

suspended with issue #12.

“The series’ time frame is going

to be telescoped radically,”

according to creator/writer Dave

Darrigo, beginning with issue #10.

“It’s a story involving the Spanish

Civil War. Clay tries to stop a

friend of his from going to fight in

the Spanish Civil war.

“Issue #11 jumps to the first

week of September in 1939,”

Darigo continues. “Clay is married

and his wife is expecting, and ac-

tually gives birth on the same day

the war breaks out in Europe,

when the Germans invaded

Poland. By this time, Clay is work-

ing in Hollywood and has broken

into the slick magazines. His

good friend at the newsstand, Joe,

dies. And that emphasizes the

passing of the era.

“Issue #12 should be of interest

to most comic fans. Clay’s editor,

Sam Kaiser, is released from the

pulp house he’s working at and

signs on with a comic book

publisher. He recruits Clay to do

his own version of Captain

America, basing it on one of his

old pulp characters. Then, Clay

gets recruited into the Army. Not

as a soldier. He’s a paper shuffler.

He heads off to Washington at the

story’s end. That’s where Word-

smith ends, for now.”

Darrigo says that while

-E Renegade Press would like to con-

tinue Wordsmith, low royalties

caused by slowing sales have

made it difficult for artist Rick

Taylor to continue the series.

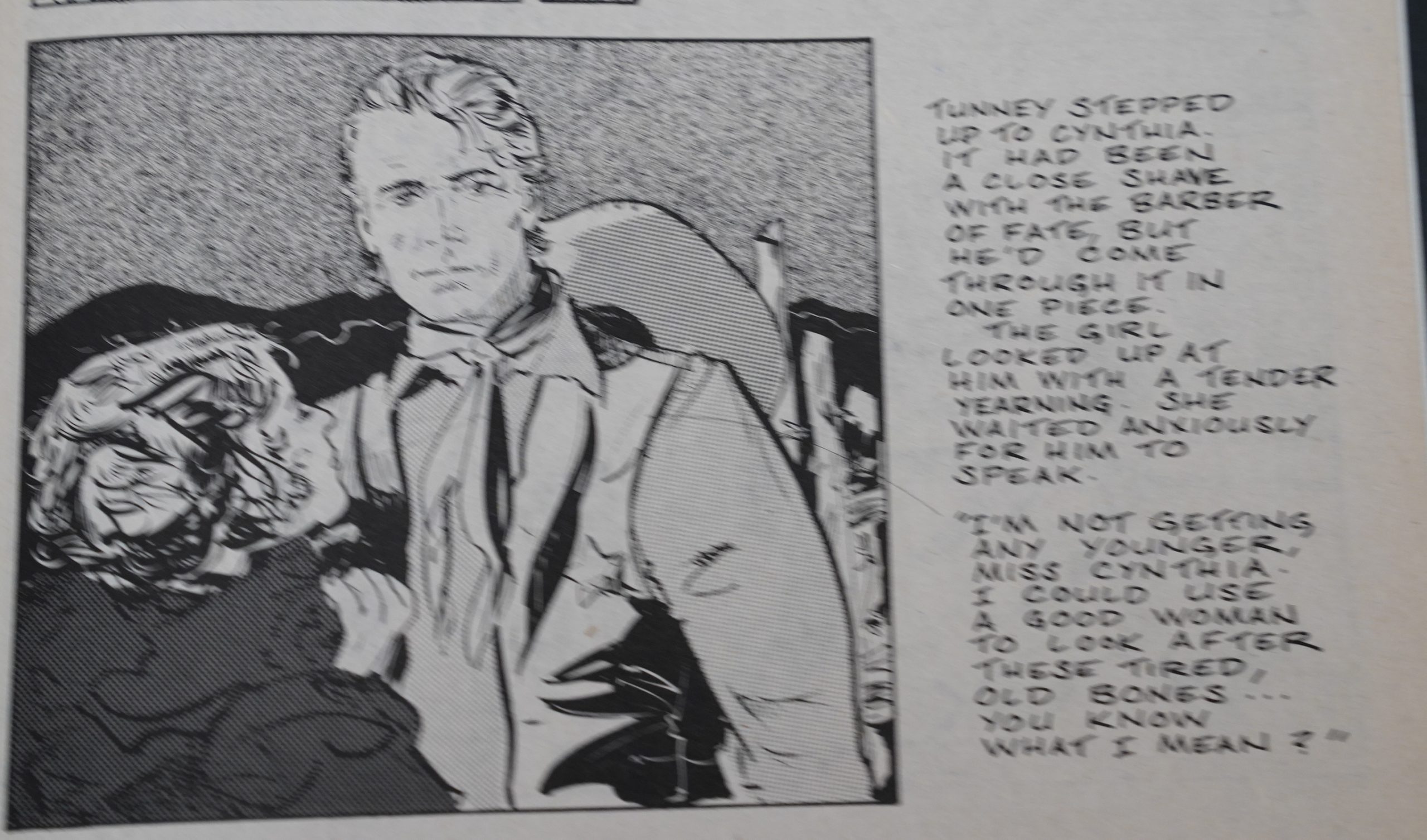

Somebody writes in The Comics Journal #107, page 54:

As it turns out, though, Washburn

needn’t worry about literary pretensions.

Here’s how he marries Off a gunslinger and

a schoolmarm stand-in: ‘Tunney stepped up

to Cynthia. It had been a close shave with

the barber of fate, but he’d come through

it in One piece. The girl looked up at him

with a teqder yearning. She waited anxious-

ly for him to speak. ‘I’m not getting any

younger, Miss Cynthia. I could use a good

woman to look after these tired, old bones

you know what I mean?'”

Real-life interlude: can you hear the girl

slam the door in his face? I thought you

could.

For a supposed professional, Washburn is

a poor writer. • ‘Congo Carson,” the latest

of his literary pretensions, is dropped out

of a cage suspended over a man-eating tiger.

How does he survive? Washburn doesn’t

know either—he has written himself into a

corner. One Can imagine Fitzergerald kill-

ing off Gatsby only to realize four chapters

later that he still needs him.

But, here is where the initial gimmick of

Wordsmith comes into play. As with DC

Challenge readers are given the Opportuni-

ty to solve the writer’s problem. Washburn

falls asleep at the typewriter, then takes a

shower—two whole pages Of diversion (do

the readers have their thinking caps on?).

Finally, Washburn concocts a way out: Car-

son fends Off the tiger with a torch, then

throws the torch into the air, where it ignites

the rope holding the cage over him. The

cage falls over him and he is safe.

Except… the rope would have to be

• soaked liberally with gasoline to catch that

quickly. Also, though it was initially held

at bay, did the tiger just hang back and

watch the rest of this? And, once the cage

was “protecting” Carson, why didn’t the

tiger just leap at it as cats are wont to and

knock it over?

The answer to all this is simple. What is

at play here is pålp logic. Comic-book logic

The sort of logic that has torches instantly

incinerating thick hemp ana that holds

tigers at bay. The sort of logic that makes

me stop reading and start throwing.

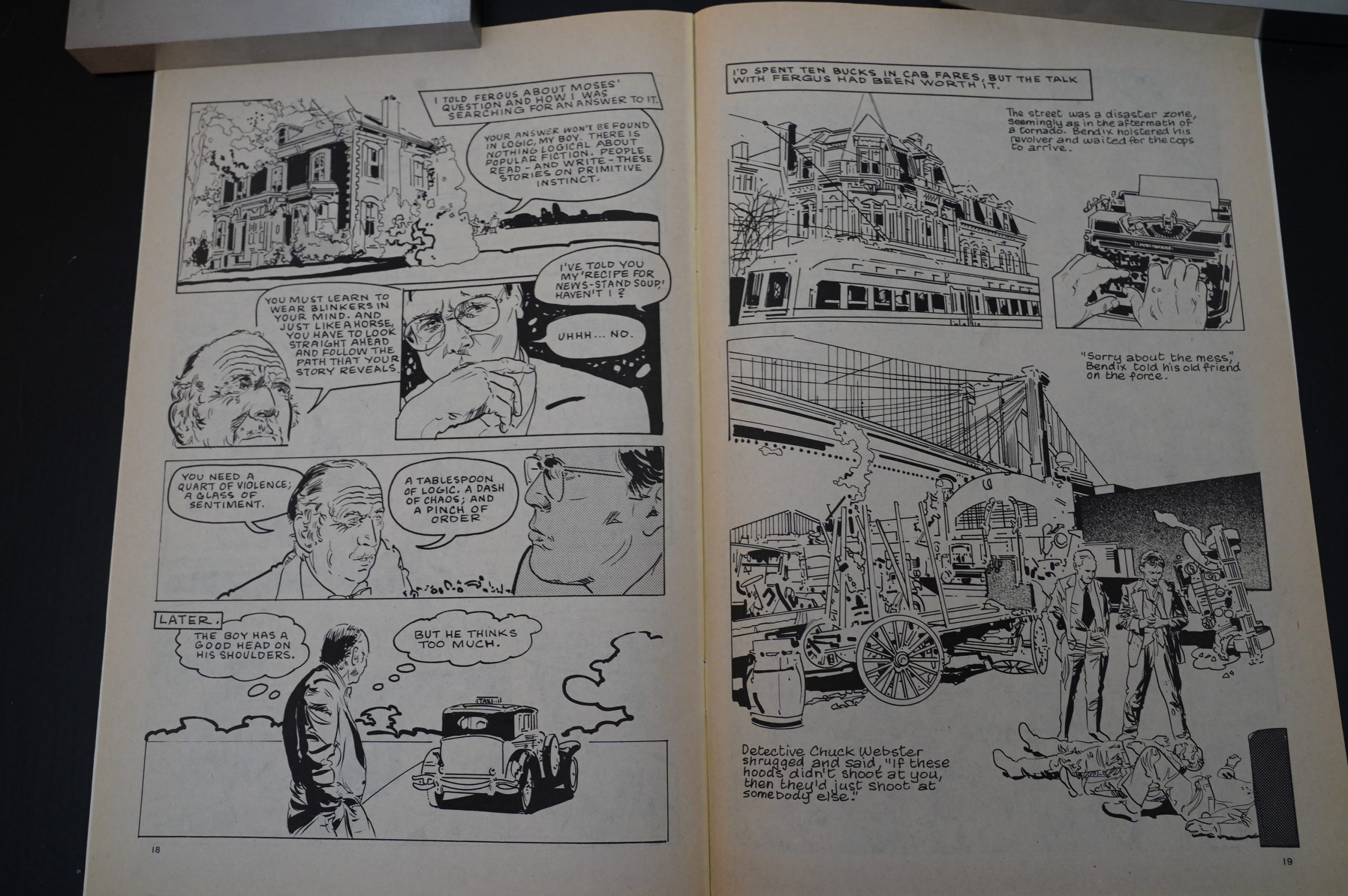

Issue #2 was, in a way, worse. Suddenly

Washburn finds himself faced with an

ethical question: are his stories too violent

and is he, therefore, a violent person by

nature? To find out, he visits a wealthy

writer friend Of his, a murder-mystery

author who assures Washburn that writing

murder mysteries is only slightly more

prestigious than pulp fiction. When Wash.

burn poses his question, Fergus, the presti-

gious friend, tells him to lose his literary

pretensions (of course! what else?). “Ethical

doubts?” Fergus asks, “I don’t understand.”

This character then goes into a monologue

that surely sums up writer Dave Darrigo’s

frame of mind: “Your answer won’t be found

in logic, my boy. There is nothing logical

about popular fiction. people read—and

write—these stories on primitive instinct.”

Voila. Man-eating tigers sitting calmly on

the sideliens. Hemp incinerated,

The monologue goes on: “You must learn

to wear blinkers to your mit)d. And just like

a horse, you have to 100k straight ahead and

follow the path that your story reveals. I’ve

told you my ‘recipe for news-stand soup;

haven’t l? You need a quart Of violence; a

glass of sentiment.”

This great literpry figure wraps up the

meeting with these thoughts about Wash-

burn: “The boy has a good head on his

shoulders. But he thinks too much.”

Now, one could interpret this as Darrigo

winking at us; he knows that this is hooey,

and he’s going to expose how wrong the old

man’s thinking is. However, how does Wash-

burn rationalize his lead character’s

violence?

‘”Sorry about the mess,’ Bendix told his

old friend on the force. Detective Chuck

Webster shrugged and said, ‘If these hoods

didn’t shoot at you, then they’d just shoot

at somebody else.'”

Actually, they would not have shooting

at anyone had not Washburn created them.

And so, whether or not he and Darrigo like

to think so, his ethical problem remains.

Somebody writes in Amazing Heroes #83, page 56:

VVhen you hdve a lead character

who is as as lifeless as old laundry

and about as interesting as bread

mold, ‘you’d bettor put him in a story

that packs a punch if you want to

hold ‘your audience. Having him

struggle to find the right words to put

in a fictional character’s mouth does

not qualify as compelling drama.

The art, though made up of excel-

lent cornponents, owrall adds to the

feeling of listlessness. Rick Taylor has

d very fine illustrative style,

an influence by the terrific Doug

Wildey. Unfortundtely, that’s all he

presents here—illustrations. It looks

more fike a series of static photo-

graphs than the story of genuine

people. Everyone tooks posed and,

in his effort to draw realistic faces

Taylor has forgotten to give any of

them expressions. With a little more

emotion, Rick could become an out-

standing talent.

Russell Freund writes in The Comics Journal #112, page 44:

The sixth issue Of Wordsmith has a few

interesing panels near the beginning where

Clay, the hero, is walking down the street

having an internal monologue, and I swear

it’s like something out of Harvey Pekar and

Gerry Shamray. I compliment Darrigo and

Taylor on their choice of inspiration here,

although this book is still nowhere near in

American Splendor’s league. This issue Clav

settles down to write some “serious litera-

ture,” a turgid W WI novel he intends to call

“The Dirt of Heaven.” The problem with

this series remains that Clay is a no-talent

meatball. and Dave Darrigo insists on

treating him as a sensitive. creative artist.

It’s frustrating to watch this promising book

continue ro miss its mark, the same way,

issue after issue. Still, it ends with a decent

scene where Clay meets a vain, drunken

novelist, and the man’s arrogance is plaved

for a kind of sour comedy. (l think so, any-

way. It cracked me up.) If Wordsmith were

about sodden, chiseling Virgil Grant, the

contumelious man of the letters, I would

probably be an ardent fan.

So this book got plenty of attention at the time — and all of it negative? I guess I wasn’t the only one who was intrigued by the concept, and then disappointed when actually reading it.

Jim Wilson writes in The Comics Journal #105, page 46:

Darrigo’s script flows well, avoids ungram-

matical and clumsy lapses so common in

comics, and combines a surprisingly un-

pretentious and convincing portrait of a’

struggling writer with elegant ’30s flavor

thgat seems very natural end not at all

forced or tacked on. The same natural

formality is evident in the brief moments

Of Washburn with his friends.

A few comments on Taylor’s art. His

detailed style is far superior to a lot of what

passes for art in comics. His work suggests

a more classical, illustrative approach; clearly

his artistic references are far broader than

just other comic books. He gives us an

acceptable and accurate potrayal of the New

York City Of the period; obviously he did

his homework and researched the architec-

ture and style of the 1930s (even including

a background showing the famous “NO Way

Like the American Way” billboard framing

a there is more nuance and

expressiveness in the faces of these charac-

ters than there are in a whole year’s worth

Of mainstream comics (Terry Beatty would

do well to study the way this man draws

faces. )

The biggest flaw in the art is Taylor’s diffi-

culty in spotting blacks, which gives the art

a cluttered, flat, and two-dimensional

appearance. It reminds me Of the comment

that the first half of an artist’s career is learn.

ing what to put in; the second is spent learn-

ing what to leave out. This “less is more”

theory is put to good use in the work of

Eisner and Toth, and—if may be so bold—

I’d suggest that Taylor spend a bit of time

studying the style of those two masters.

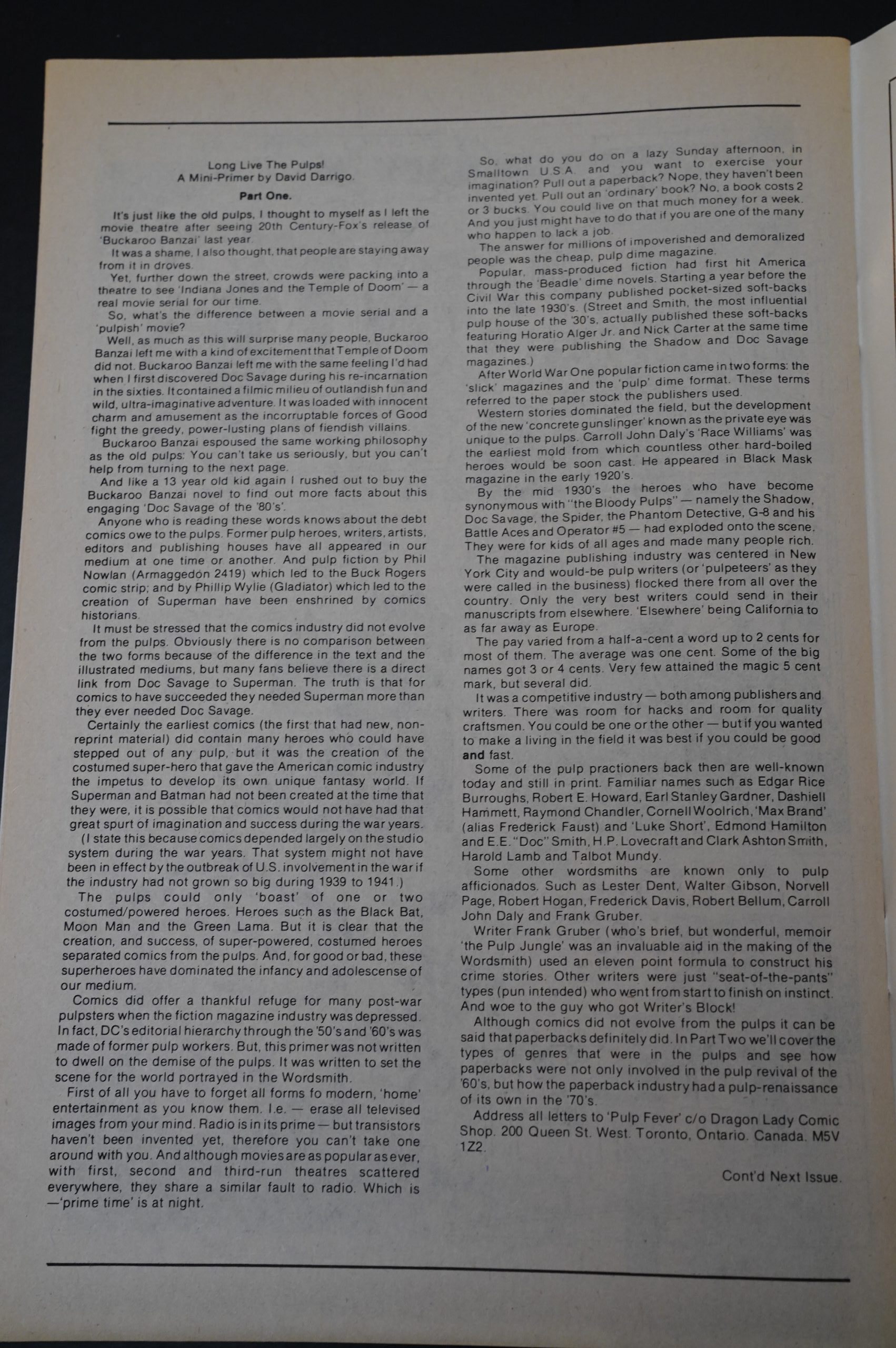

The book concludes with a prose after-

word, “Long Live the Pulps,” which is

author Darrigo’s paean to the magazines

that are his hero’s bread and butter, and an

attempt to give readers a background in the

“dime novels” from which the comics

evolved. It should be interesting to those

unfamiliar With the form (and for those

really interested, Steranko’s comprehensive

chapter on the pulps in his History of Comics

I is a good source).

I urge everyone to follow and support this

book. It is potentially solid gold, and proves

once and for all that comics don’t have to

be pointlesSly violent or display bare.

breasted pin-ups girls to be maéure.

Well, that one was positive.

The series continued with nine issues from Caliber Press. They also reprinted all the Renegade issues in two volumes.

Neither series seems to have been reprinted since.

This person seems to like the one issue they found:

What the hell is going on? That’s two weeks in a row now that I’ve come across these comic books that are fantastic, but are now languishing unwanted, unnoticed, unloved, there in the bargain bin. What the hell happens? How do we lose track of these books? What does it say about a culture that spawns these artistic moments and then disposes of them without a second thought?

And that’s all I could find on dar intertubes.

This blog post is part of the Renegades and Aardvarks series.

As a small note to the article, the nine Wordsmith books from Caliber appear to be a reprint of the Renegade series, rather than a continuation of it.

There was, however, a one-shot titled Heroes from Wordsmith, published by Darrigo’s own self-publishing imprint Special Studio in 1990 and starring the pulp characters from Wordmisth.