Listen to 4AD 1987 on Spotify.

This isn’t complete, unfortunately. The Fat Skier mini-album by Throwing Muses doesn’t exist on Spotify. Three of the tracks appear on various compilations, and I’ve included them on the playlist, but you’re missing some wonderful songs like And A She-Wolf After The War, Pools in Eyes and Soap and Water.

Hey, 4AD people! Get the rights for this thing and get it on Spotify already!

The songs from the Frazier Chorus EP Sloppy Hearts are included in the playlist, but they are the re-recorded versions from their debut album, and not the versions from the EP. The differences aren’t huge, though.

4AD didn’t release that many releases in 1987, but it was a momentous year, anyway. The three major releases:

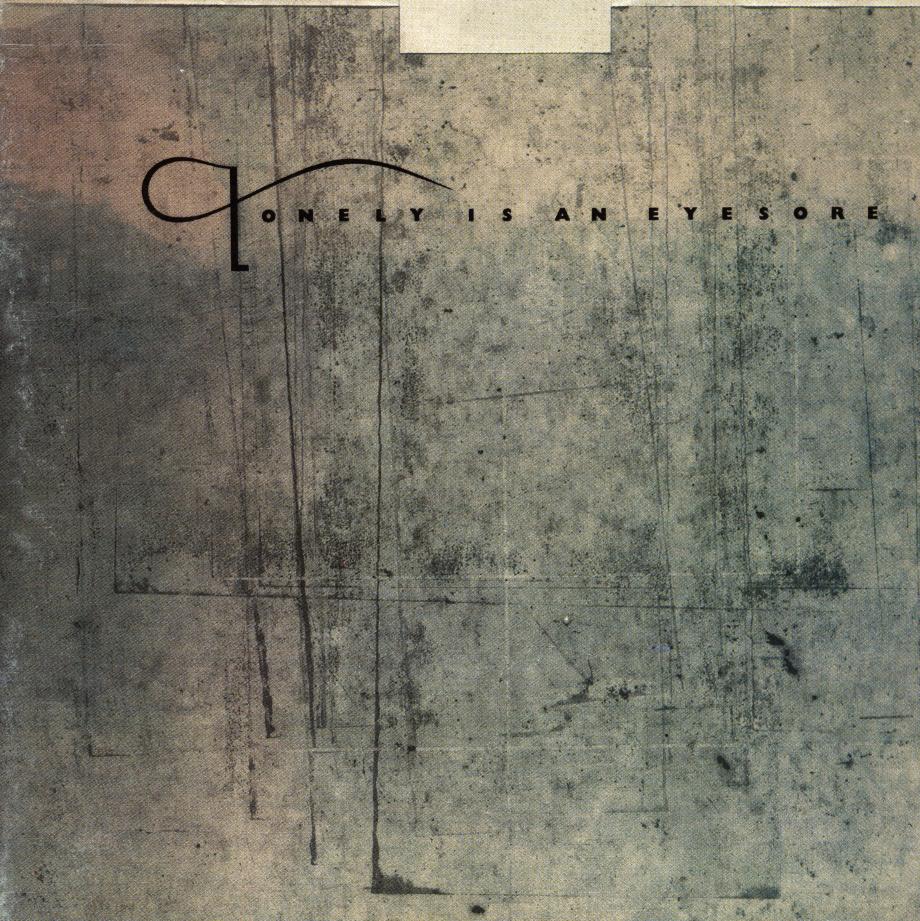

Lonely is an Eyesore is a label sampler, but it’s the best one ever. All the bands contribute new songs, not featured anywhere else, and they contribute top shelf items. Almost any of these tracks would have been standouts on their respective bands’ albums, so you have to wonder how label head Ivo Watts-Russell managed to wrangle those tracks out of them. And it’s such a striking, excessive release (it was done in several formats, one of which was in a wooden box in an edition of 100) that it further cemented 4AD as being a “thing” more important than the individual artists (in many people’s eyes).

And while there are ten tracks on the album, two are from Dead Can Dance, and three of the tracks (by Clan of Xymox, Dif Juz and Colourbox) are from groups that would release barely nothing after this release. So in a way it’s an (unplanned?) epitaph of an era of 4AD instead of a celebration of it.

The second thing of particular import is the first album (well, mini-album) by Pixies. Not only was it a shock to the system: It’s such a wild, ferocious thing, but a whole genre was spawned based on somebody in Seattle getting a copy of it and the subsequent album. (I’m talking about grunge.)

And then there’s Pump Up The Volume by M|A|R|R|S, which is basically one of the guys from Colourbox trapped in a studio with the guys from A. R. Kane. Who didn’t do much except bitch, apparently, until Martyn Young made the song (recollections differ greatly), which was Ivo’s basic plan to prod Young into making something. It was a huge, huge worldwide hit and 4AD’s best-selling release. I remember visiting my sister in Portugal during the summer of 1987, and we were walking around the old part of Lisboa and hearing that song streaming out of somebody’s window and everything was perfect.

The commercial success of the song had all kinds of negative repercussions, though. A. R. Kane sued 4AD and or Colourbox because they wanted more money, and some of the people sampled on the song did likewise. Martyn Young basically dropped out and didn’t write a single track afterwards, and the process was a time and energy drain on 4AD and Watts-Russell.

Less distressing was Sleeps With The Fishes by Pieter Nooten and Michael Brook: It’s an album I never grow tired of listening to.

1987

|   BAD701 BAD701Throwing Muses — Chains Changed Finished, Reel, Snail Head, Cry Baby Cry |

|   BAD702 BAD702The Wolfgang Press — Big Sex The Wedding, The Great Leveller, That Heat, God’s Number |

|      CAD703 CAD703Various — Lonely Is An Eyesore Crushed, The Protagonist, Cut The Tree, Frontier, Hot Doggie, Acid Bitter And Sad, Muscoviet Musquito, Fish, No Motion |

|  BAD704 BAD704A. R. Kane — Lollita Lollita, Sado-Masochism Is A Must, Butterfly Collector |

|    CAD705 CAD705Dead Can Dance — Within The Realm Of A Dying Sun Anywhere Out Of The World, Windfall, In The Wake Of Adversity, Xavier, Dawn Of The Iconoclast, Cantara, Summoning Of The Muse, Persephone (The Gathering Of Flowers) |

| MAD706 Throwing Muses — The Fat Skier Garoux Des Larmes, Pools In Eyes, A Feeling, Soap And Water, And A She-Wolf After The War, You Cage, Soul Soldier |

|      BAD707 BAD707M/A/R/R/S — Pump Up The Volume Pump Up The Volume, Anitina |

|      BADR707 BADR707M/A/R/R/S — Pump Up The Volume (Remix) Pump Up The Volume (Remix), Anitina (Remix) |

|   BAD708 BAD708Frazier Chorus — Sloppy Heart Sloppy Heart, Typical, Storm |

| MAD709 Pixies — Come On Pilgrim Caribou, Vamos, Isla de Encanta, Ed Is Dead, The Holiday Song, Nimrod’s Son, I’ve Been Tired, Leviate Me |

|   CAD710 CAD710Pieter Nooten / Michael Brook — Sleeps With The Fishes Several Times I, Searching, The Choice, After The Call, Finally II, Instrumental, Suddenly II, Suddenly I, Clouds, Finally I, Several Times II, Equal Ways, These Waves, Several Times III |

|  BAD711 BAD711Xymox — Blind Hearts Blind Hearts, A Million Things, Scum |

This post is part of the chronological look at all 4AD releases, year by year.