But not well!

Vincent Price!

I would never have guessed that this was a Sam Fuller movie. It’s so… staid? At least so far. We’ve got a cumbersome framing device where one of these guys is telling the story, and he also provides a voiceover.

Neither seems necessary?

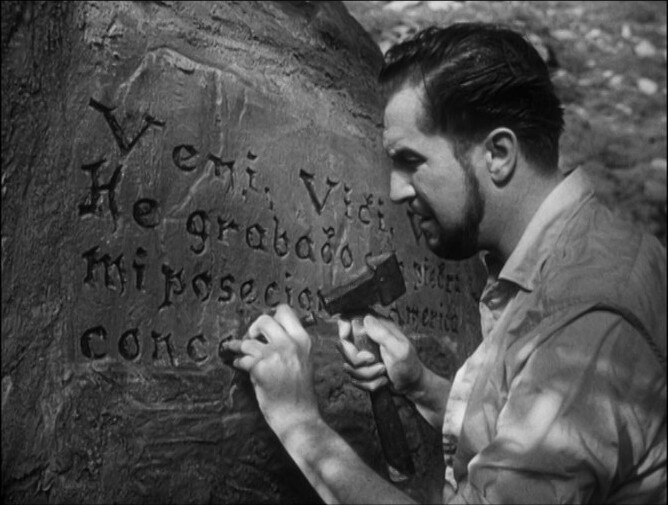

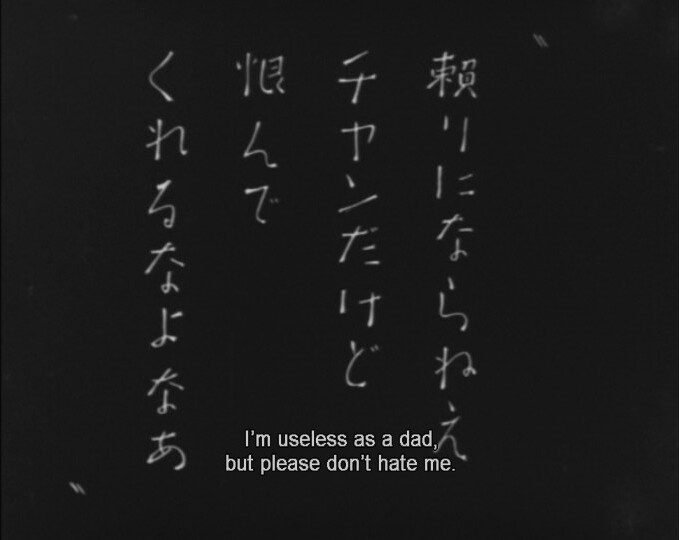

Such subtle.

So passion.

I’m finding this movie to be a bit tedious? Price is fine, but the rest of the actors are playing it for laughs.

The heist plot (i.e., getting Arizona) should be so much more fun than this. It’s just … molasses.

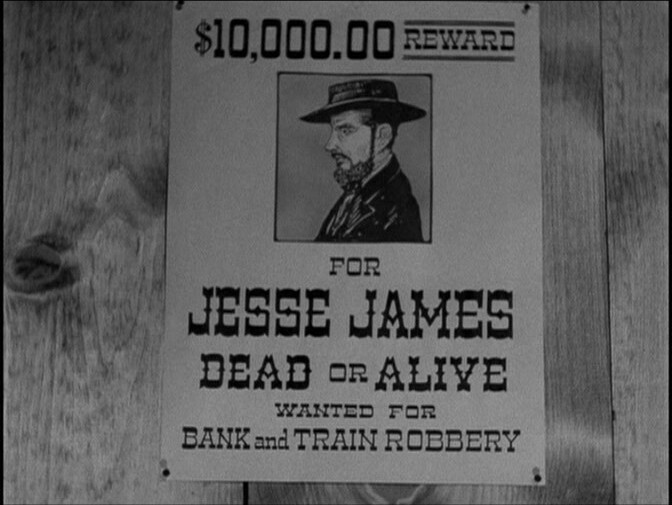

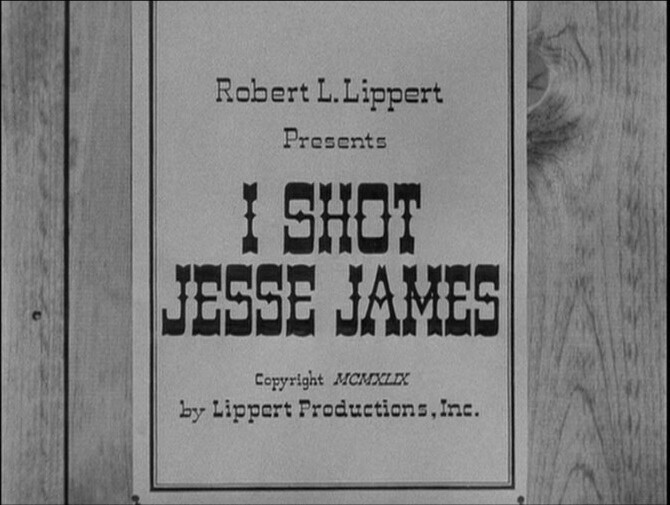

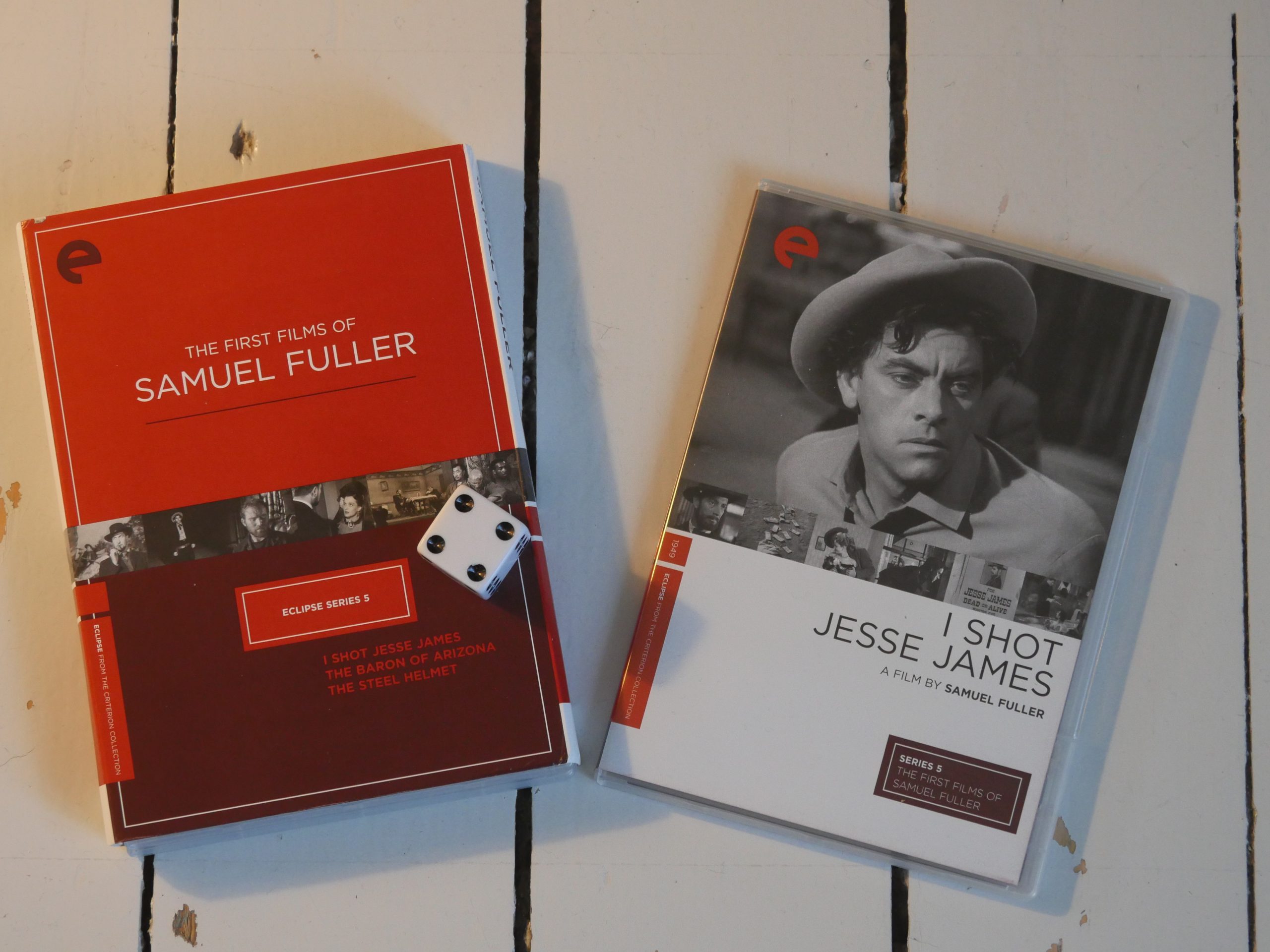

A minor low-budget Sam Fuller (“I Shot Jesse James”) bizarre western, his second feature, tells a fabulous story loosely based on true events that are inefficiently worked out thereby making it seem unlikely. It’s at first appealing but soon becomes tiresome

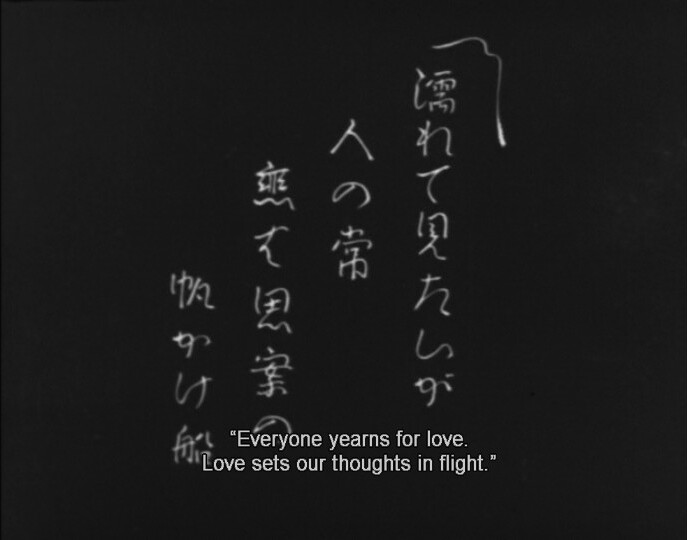

It has no zip — it just trudges along for what seems like hours. I mean, this should be more fun:

During the course of the fraud, Reavis collected an estimated US$5.3 million in cash and promissory notes ($173 million in present-day terms) through the sale of quitclaims and proposed investment plans.

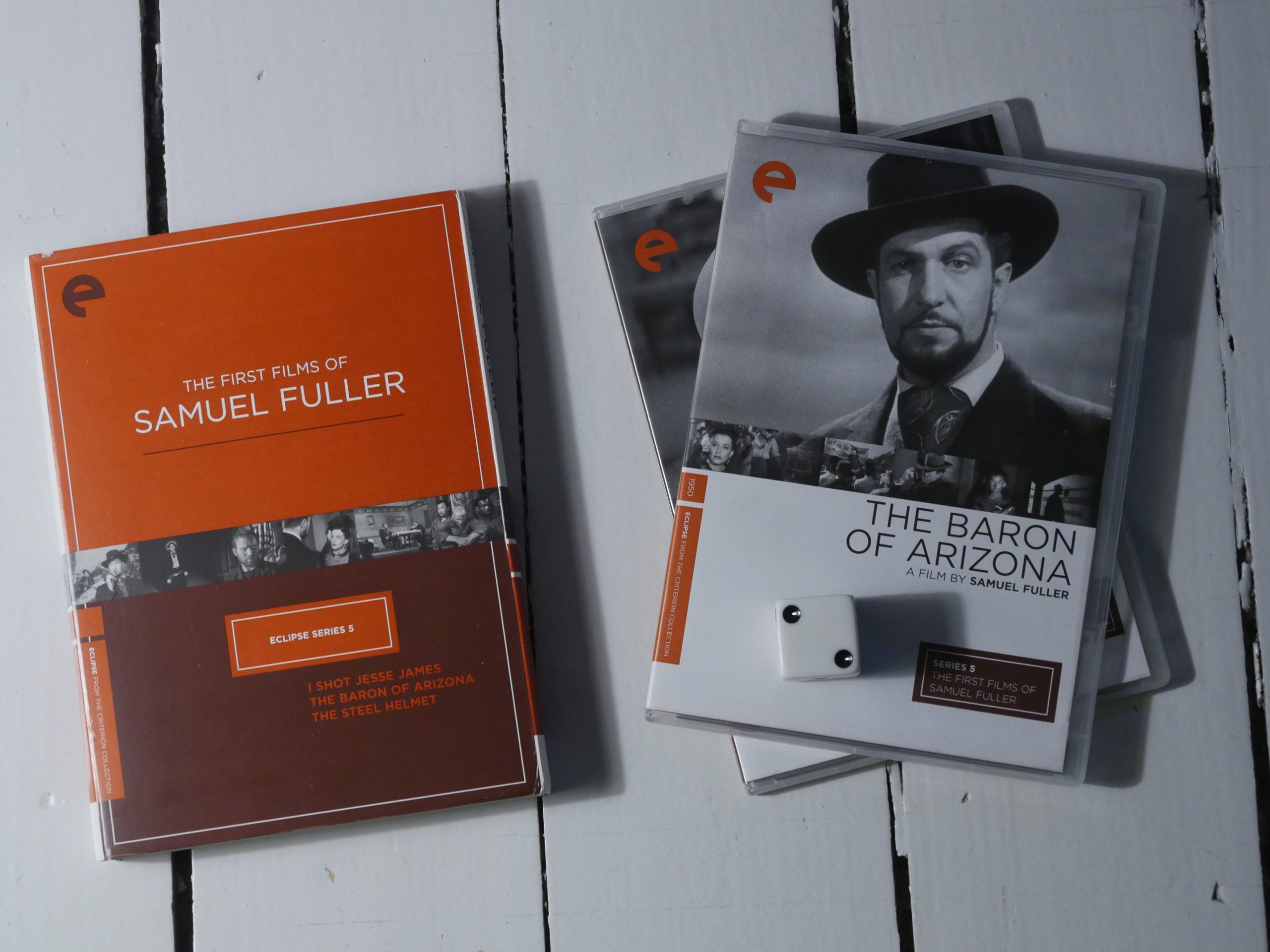

The Baron of Arizona. Samuel Fuller. 1950.

This blog post is part of the Eclipse series.