The Entire Kitchen Sink Reloaded

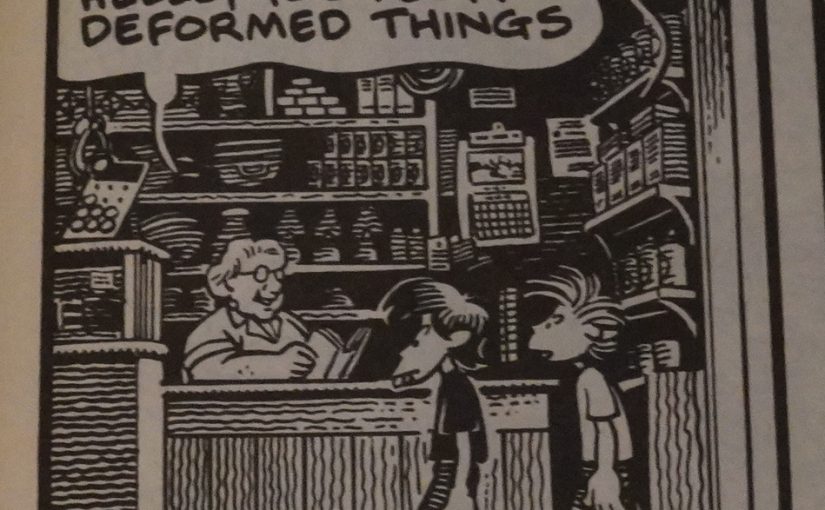

I started a complete (re-)reading of all Kitchen Sink comics in late 2021, and kept at it until August 2022, when I took a little break that turned into a half year break.

I’d gotten up until 1991 in the Kitchen chronology, and there wasn’t anything really in the comics themselves that made me give up the project — I think it was because I’d already conceded defeat, so it just made things less vital.

That is, when I’m doing these comics blog projects, I’m (stupidly enough) challenging myself to read everything relevant that’s published. But I started cheating pretty soon, because I just couldn’t face reading the entirety of the Spirit comics, or the collected Steve Canyon. So once the stupid challenge thing was gone, then it’s just less… fun.

Yes, I know — it’s a pretty odd project anyway, but that’s probably why I stopped, half a year ago.

But now I’m raring to go again, and I’ll try to keep to a schedule — one post a day. There’s about 100 posts to go, so I should be done in three months. And I’ll be covering a pretty interesting part of the Kitchen Sink saga — the Tundra takeover etc.

So join me over at (the now slightly misnamed) The Entire Kitchen Sink blog for a thrilling finish. We’re starting off with Grateful Dead Comix.

Improv Music Festival

The Best Albums of 2002

Let’s pick another year at random… 2002. Here’s a mixtape I made at the time:

And here’s list of the best albums of that year, as decided by how much I’ve listened to them:

| DJ Rupture | Gold Teeth Thief |

DJ /rupture - Gold Teeth Thief | ||

| The Notwist | Neon Golden |

The Notwist - Consequence | ||

| Pet Shop Boys | Disco 3 |

Sexy Northerner (Superchumbo Remix) | ||

| DJ Rupture | Minesweeper Suite |

DJ /rupture - 20 - Bloody Nora / Rough & Rugged | ||

| Arto Lindsay | Invoke |

Arto Lindsay - Ultra Privileged | ||

| Juana Molina | Tres Cosas |

Juana Molina - Ay, No Se Ofendan (Live on KEXP) | ||

| Various | Disco Not Disco 2 |

Lex ''Fourteen Days'' | ||

| Moloko | Statues |

Moloko - Forever more (extended) | ||

| Propaganda | Outside World |

Propaganda - Dr. Mabuse | ||

) | Various | Secondhand Sounds: Herbert Remixes |

Merciful (Herbert's We Mix) | ||

| Max Tundra | Mastered By Guy At The Exchange |

Max Tundra - Lysine | ||

| Jan Jelinek | Computer Soup |

Straight Life | ||

) | Tuxedomoon | Concert In St. Petersburg |

| Nobukazu Takemura | 10th |

Cons | ||

| ESG | Step Off |

Be Good To Me | ||

| Sidsel Endresen & Bugge Wesseltoft | Out Here. In There. |

Sidsel Endresen and Bugge Wesseltoft Try | ||

| The Breeders | Title TK |

The Breeders - Huffer (Official Video) | ||

And… 2002 was a great year! It’s all bangers. We get both of the bootleg remix epics from DJ\Rupture, and we get folktronica classics from The Notwist, as well as glitchy pop from Nobukazu Takemura, Jan Jelinek and Max Tundra.

It’s all good stuff.

Home Improvements

Welcome to my new Home Improvements Blog.

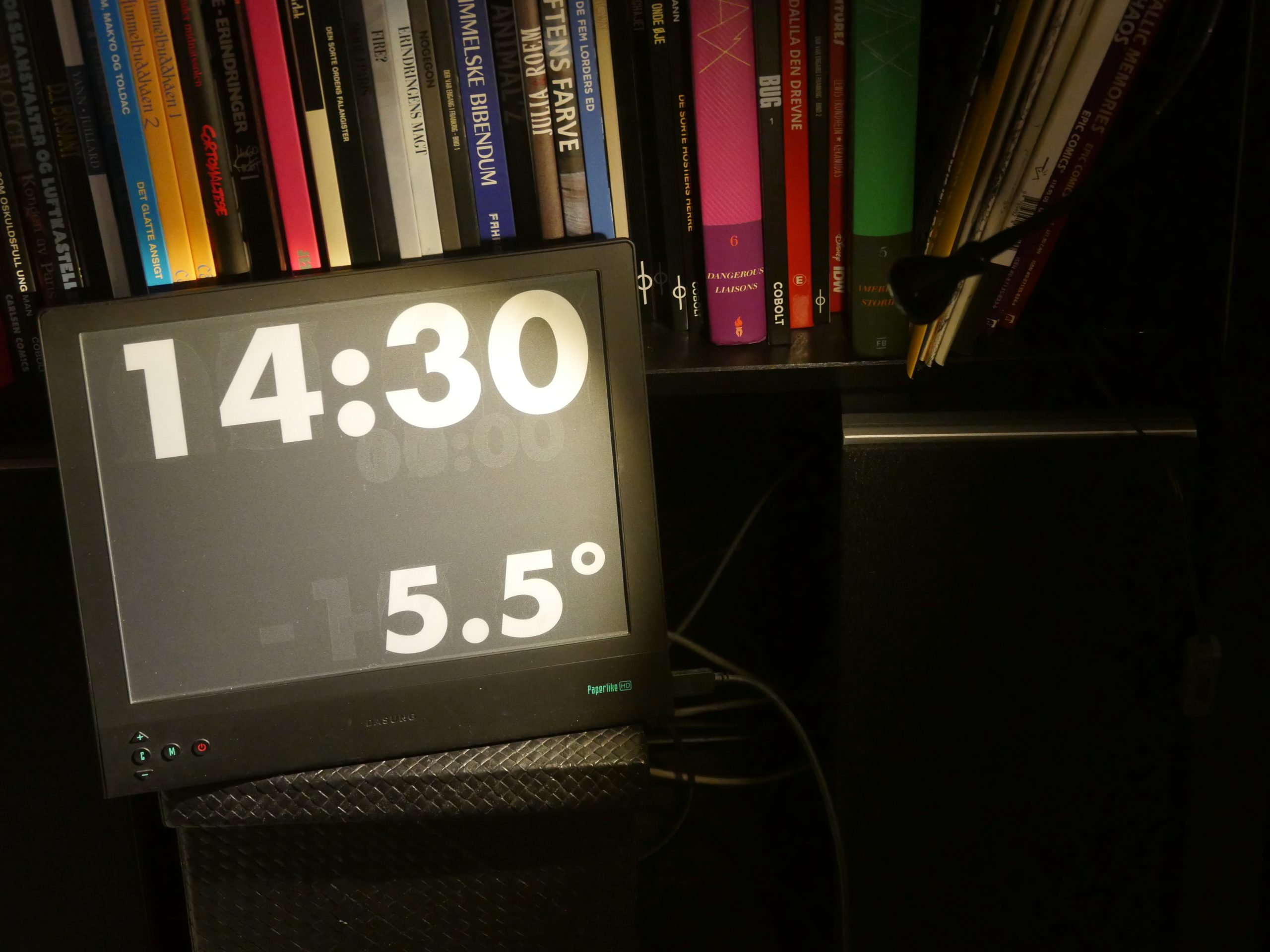

As I’m sure you remember from just four years ago, in my quest to create an Emacs-controlled alarm clock that doesn’t emit any light, I set up a Dasung Paperlike HD screen to use as an alarm clock in my bedroom:

I then realised that er there’s no way to actually see what time it is in the middle of the night, because it’s an e-ink display, so I put a lamp (controlled via Nexa from a button next to my bed) on the shelf above it and said “there. I did it!”:

This worked fine, of course, but the light is too bright and it looks wonky, so after just procrastinating for four years (i.e., a quick process for me), I decided to do something about it. So what about one of those lamps people use for paintings, eh? It’s 150lm, so it shouldn’t be too bright…

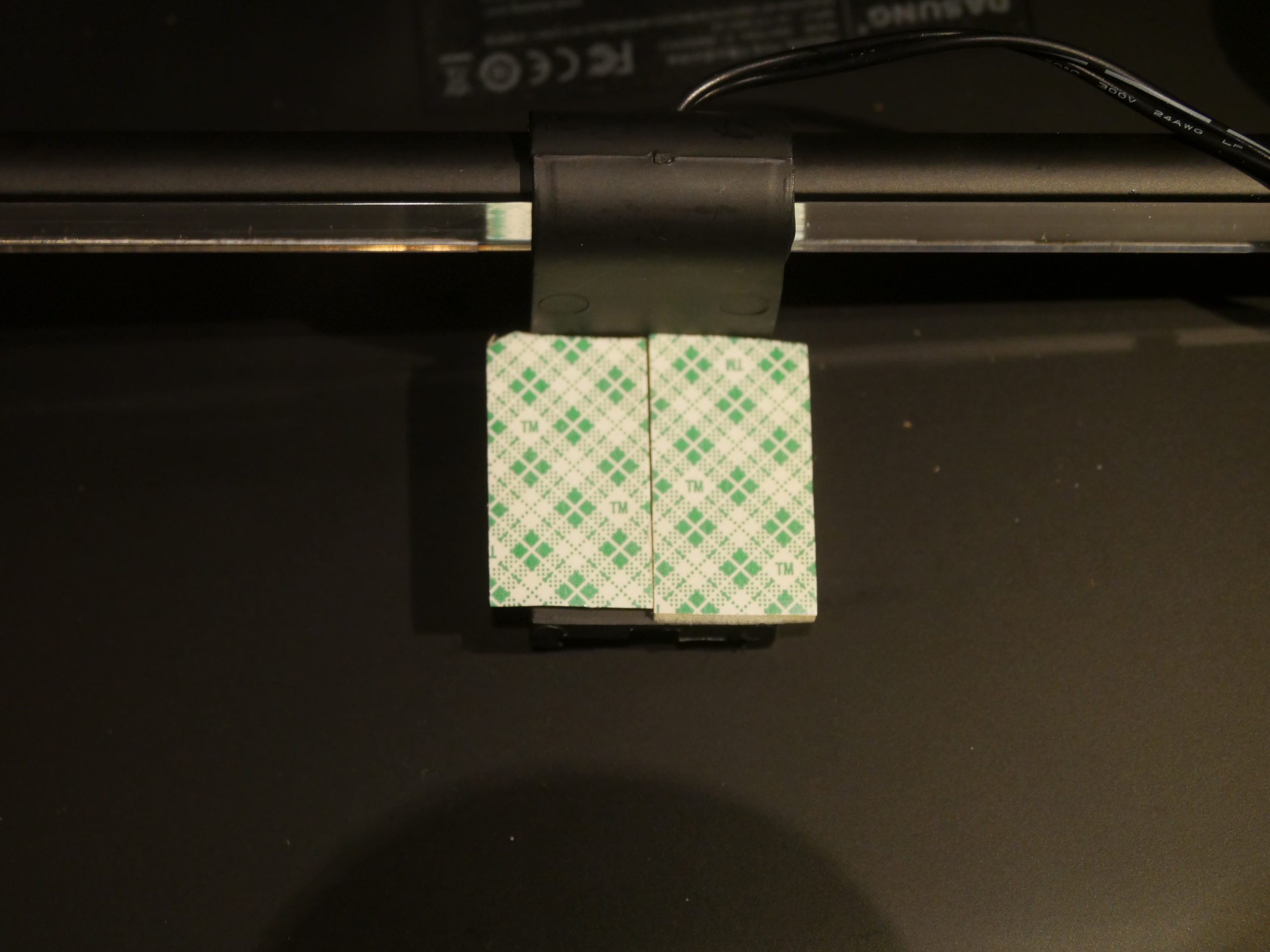

But how to fasten it?

Double sided adhesive tape, of course. I’m no amateur!

(The lamp is all plastic and weighs next to nothing.)

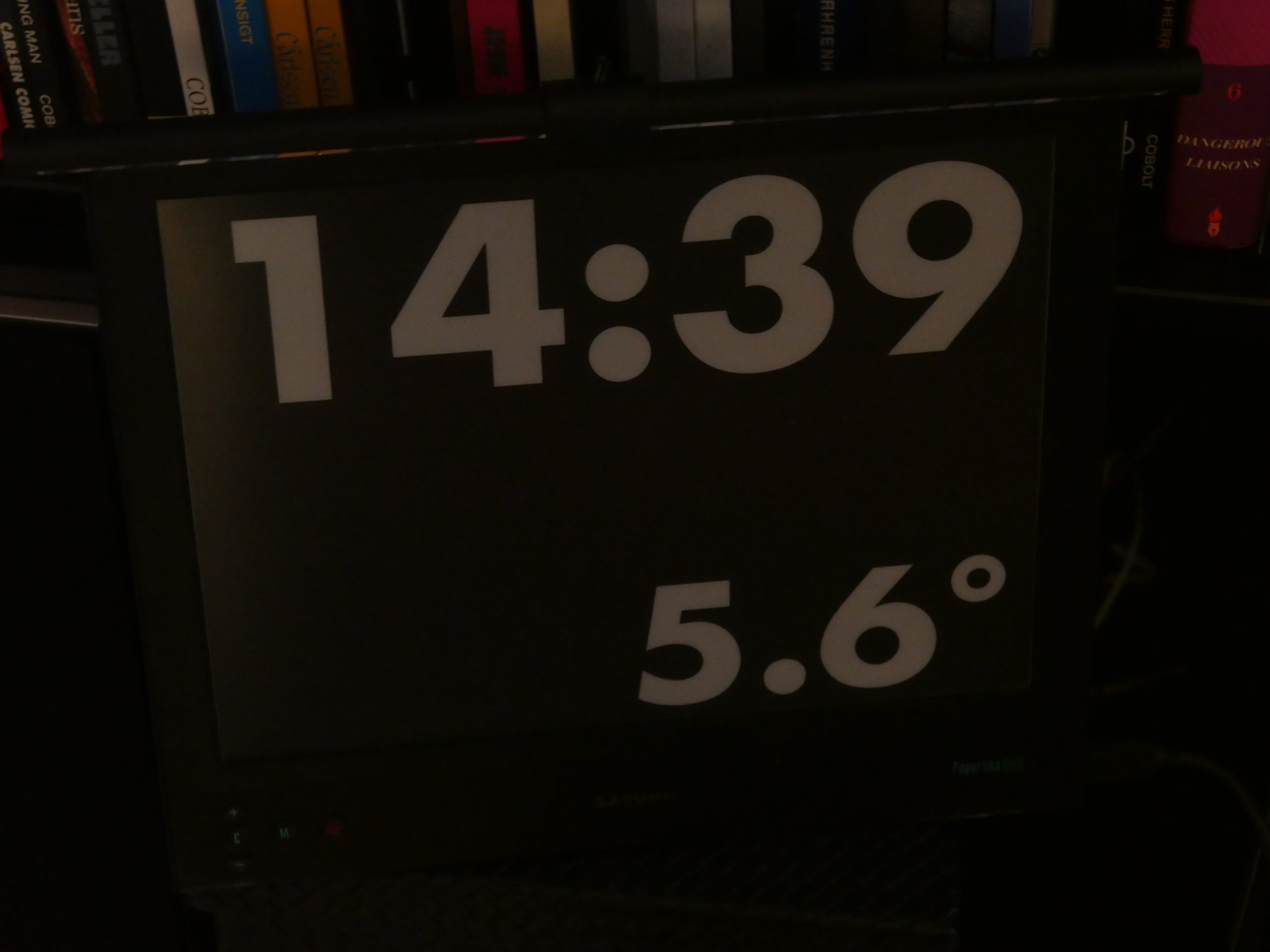

So here it’s mounted…

And here’s what it looks like in the middle of the night from my bed. (Note: Emulated time.)

So… I guess that worked? It’d be nice if the LED lights weren’t visible at all, and perhaps it should stick out more from the screen… Unfortunately, it doesn’t allow adjusting the angle, and it can’t really stick out more than it does.

Mission accomplished!