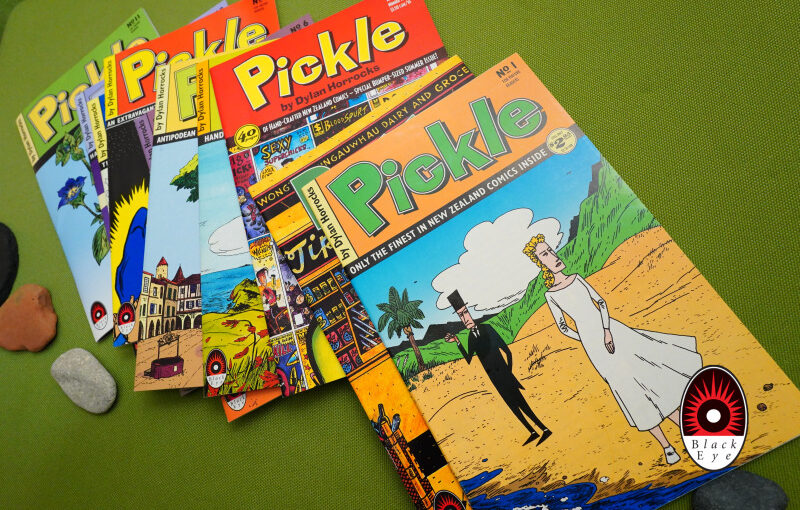

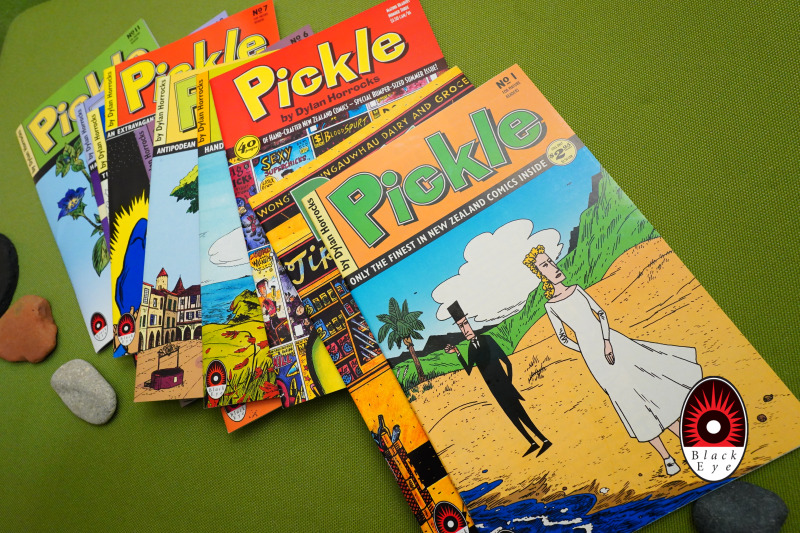

Pickle (1992) #1,

Pickle (1993) #1-11 by Dylan Horrocks

With this blog post, we get to the first actual Black Eye book, and Black Eye is the subject of this blog series, so it’s about time.

The first issue of Pickle was published by Tragedy Strikes Press, and then moved to Black Eye when Michel Vrána left Tragedy Strikes and started Black Eye. I don’t actually have that first issue here — instead I’ve got the second edition (published by Black Eye), but I think the contents are basically the same? Hm, looking at the comics.org, it seems like some bits were dropped and some are new, but nothing major…

In any case, before going on to the comic book itself, let’s have a look at what happened to Tragedy Strikes:

Because back in those days, there was a thing called “journalism” in comics. I know! It sounds incredible! But instead of having “web sites” that are all either 1) press releases or 2) somebody yammering on about how much they like something (ahem), there were people calling up other people! On the phone! And asking “hey, what’s up with that thing that happened”… And you can still read these things, thirty three years later!

Anyway:

The Comics Journal #161, page #022:

SIN, PICKLE, WAY OUT STRIPS PICKED UP BY OTHER PUBLISHERS

Tragedy Strikes Press Founders Split

The three men responsible for

publishingcomic books under

the Tragedy Strikes Press im-

print of Guelph, Ontario, have

parted ways. Michel Vråna —

Managing Editor and creator

of the title character in the an-

thology Reactor Girl — has re-

signed; he was not a partner in

the company. Nick Craine —

Art Director, creator Of The

Cheese Heads , and co-pub-

lisher — has sent a letter rec-

ommending the company’s dissolution to part-

ner Shane Kenny. Kenny — owner of the Col-

lage chai n ofretai I sports card and comics shops,

co-publisher, and self-described financier of

Tragedy Strikes Press — has refused to dissolve

the company, despite the departure of the car-

toonists who had previously guided it.

Drama!

According to Vråna, he and Craine told

Kenny in January that their partnership was not

working, due to “irreconcilable creative differ-

ences.” According to Craine, “ifTragedy Strikes

continued [without Craine and Vråna], and I was

walking into a store, and I saw Tragedy Strikes

Press Presents: Hockey Comics Monthly — to

tell you the truth, I would not be surprised.” Both

cartoonists claim that Kenny wished to take the

company in that direction.

Kenny denies the desire to publish sports

comics under Tragedy Strikes, but instead sug-

gested that Craine and Vråna did not want to

make necessary changes in the comics they

publish, changes that wou ld have made Tragedy

Strikes profitable — such as color printing and

taking on otherprojects, like Richard Comeley’s

Captain Canuck. Kenny told the Journhl hehad

approached Craine and Vråna with the idea, but

that “anything commercial was dirty” to them,

and they refused. “Tragedy Strikes introduced

some excellent artists to the marketplace,” says

Kenny. *’Michel is an excellent editor… [But]

the boys have to learn the world of finance.”[…]

Michel Vråna has formed his own publish-

ing company, Black Eye Productions. It will

publish a new anthology magazine: Sputnik,

which will appear in stores this November. Black

Eye will also pick up two ofthe former Tragedy

Strikes comics.[…]

Kenny says Vråna signed Tragedy Strikes

Creators immediately after resigning, without

consulting him. “I’m not real happy about how

that went down,” Kenny says. Nevertheless, he

also says Michel “has been given the opportu-

nity” to sell Tragedy Strikes back issues through

his new company, which will be solicited through

Diamond and Capitol. Some of the potential

profits are slated for the Tragedy Strikes debt,

says Kenny, and some for Vråna himself, al-

though Kenny did not elaborate on the specifics

of this arrangement.

So opinions differ on what went down, but the main thing was that Shane Kenny (the person who was financing the thing) thought that it was time that Tragedy Strikes make some money, but the other two (Vrána and Craine) didn’t want to compromise on quality.

Which must have made what happened next feel rather ironic for Kenny (as a certain singer would say) — because Pickle was that book he was looking to publish, anyway.

Or as least I assume so! I know nothing! I’m not a journalist! But from my recollection at that time, Tragedy Strikes was well-reviewed, but hadn’t made a real splash yet. With Pickle, they made a splash: It soon became one of those “staple” series, where if you ask people “well, aren’t there any good comics being published?” they’d answer, “sure, there’s Love & Rockets, Dirty Plotte, Pickle and Eightball” or some variation of that list.

I haven’t re-read this series since it was published, and I picked up the issues in random order (I was a poor student at the time), so I’m totally excited to finally read the series in the proper order for the first time! Which I will now do, and I’ll type the rest of this blog post after I’ve done that.

[time passes]

Wow, that was a pretty nice way to spend the afternoon.

And now I’ve gotta do more typing.

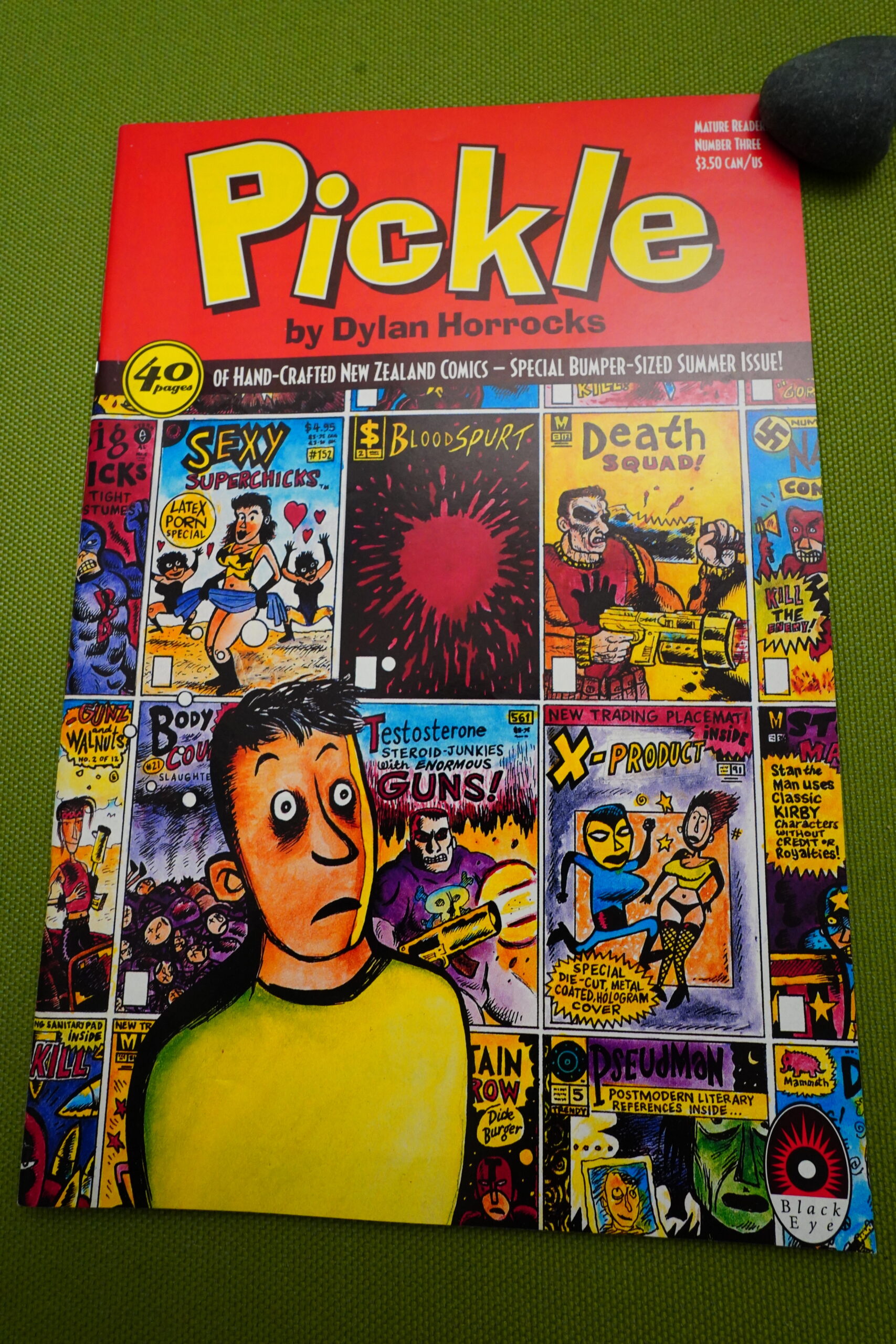

The physical format varies slightly over the issues. I’m guessing this was originally on newsprint, but the 2nd edition is on extremely white paper, and the series would vacillate on that point. And it varies between 32 and 24 pages, with one 40 page special.

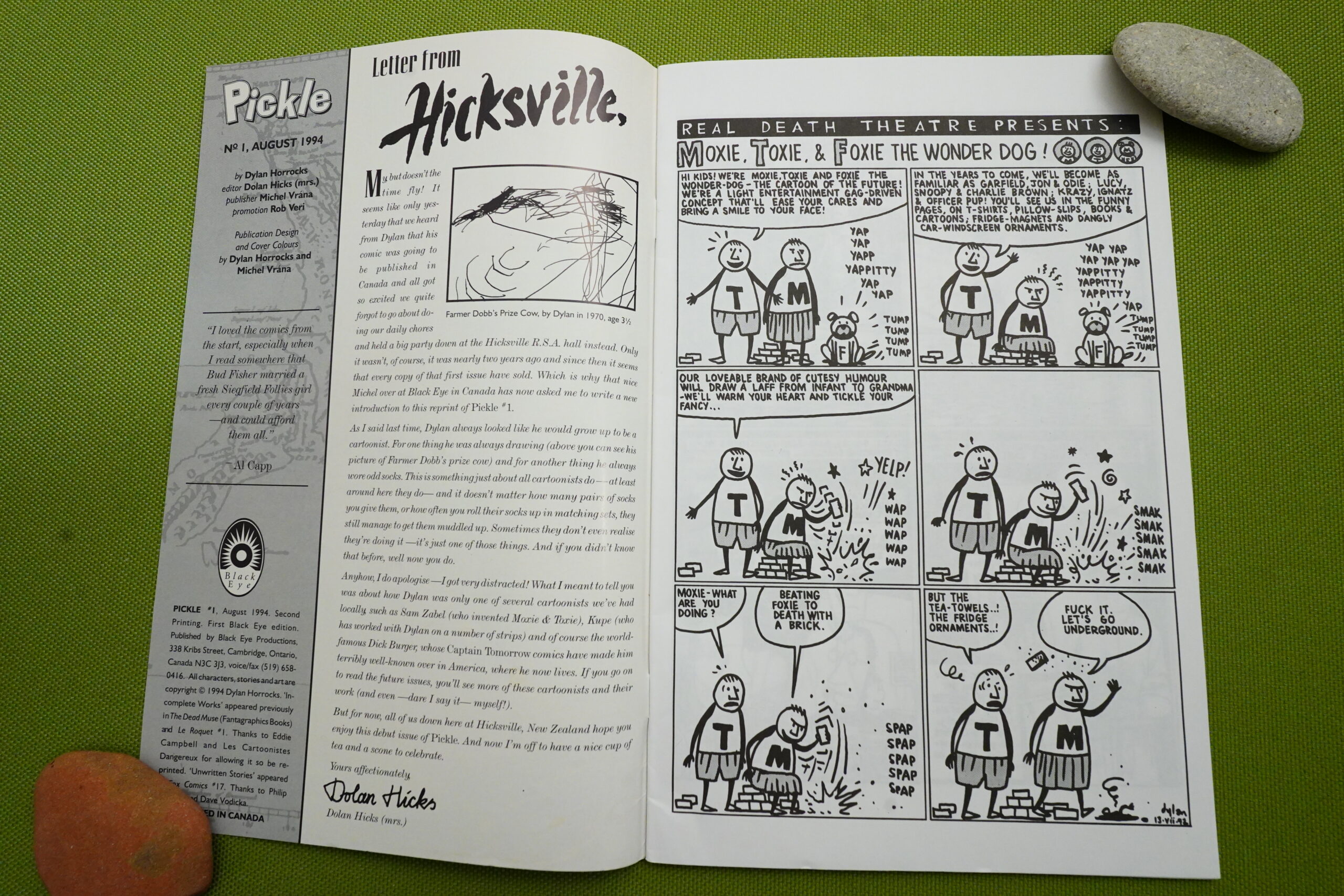

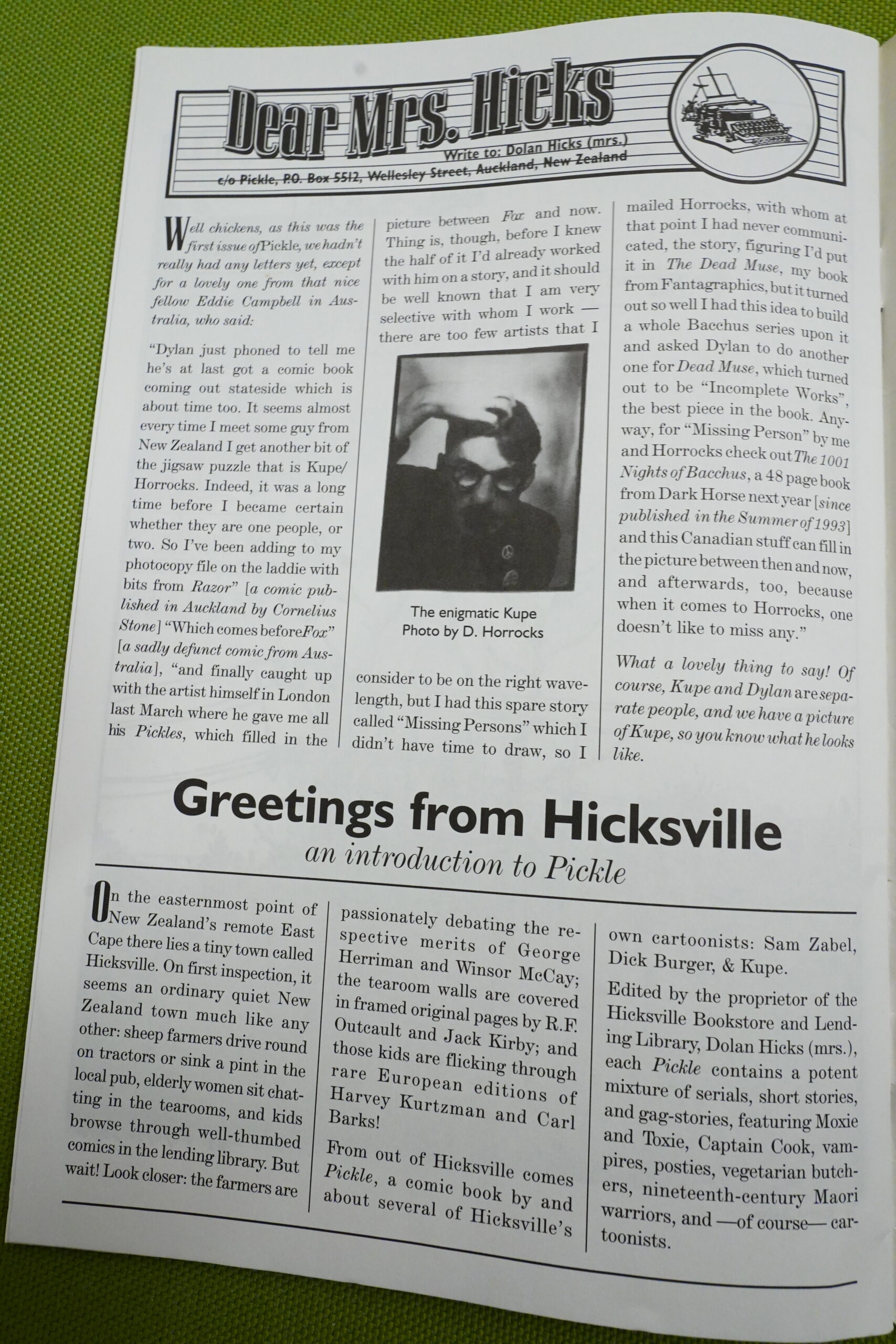

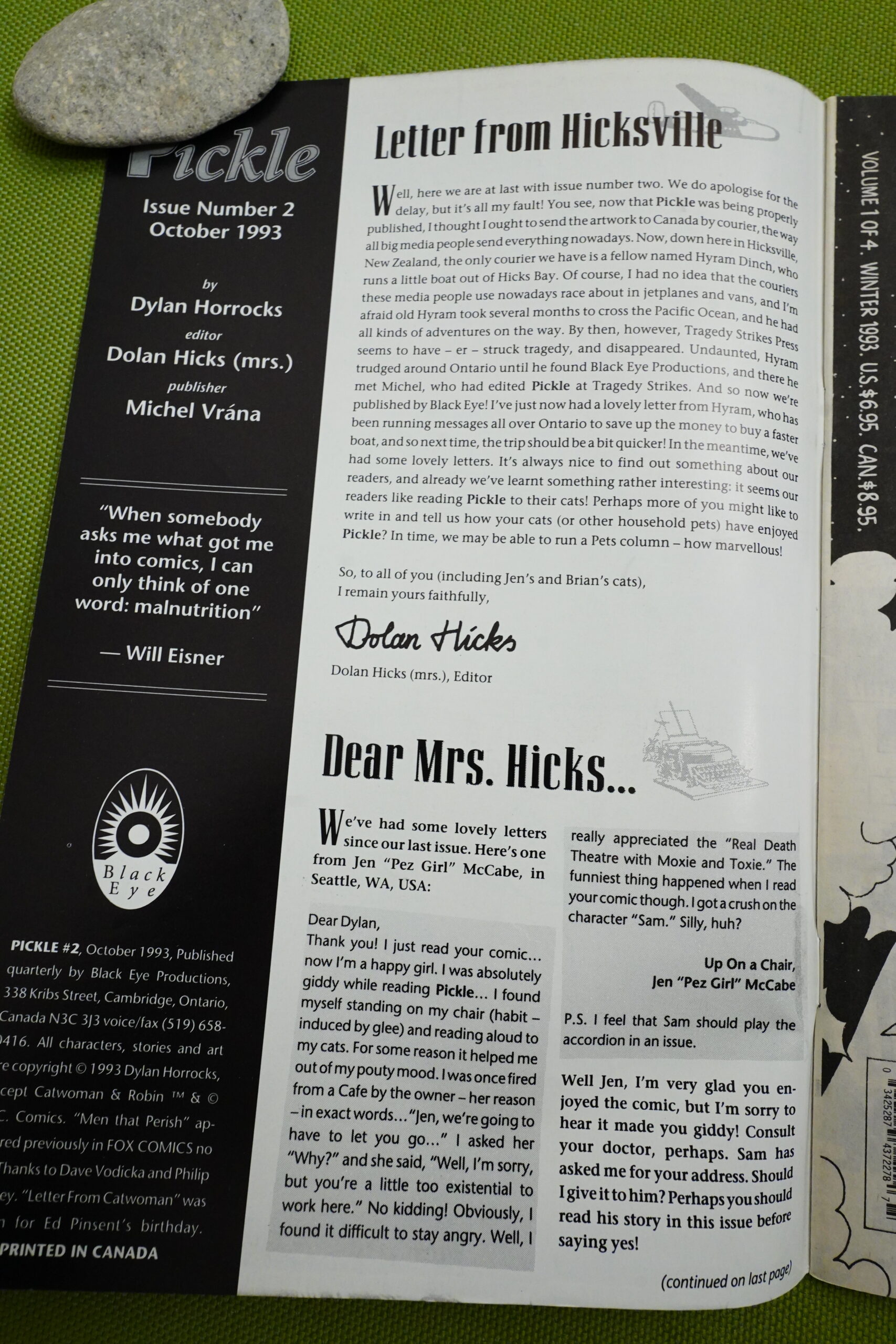

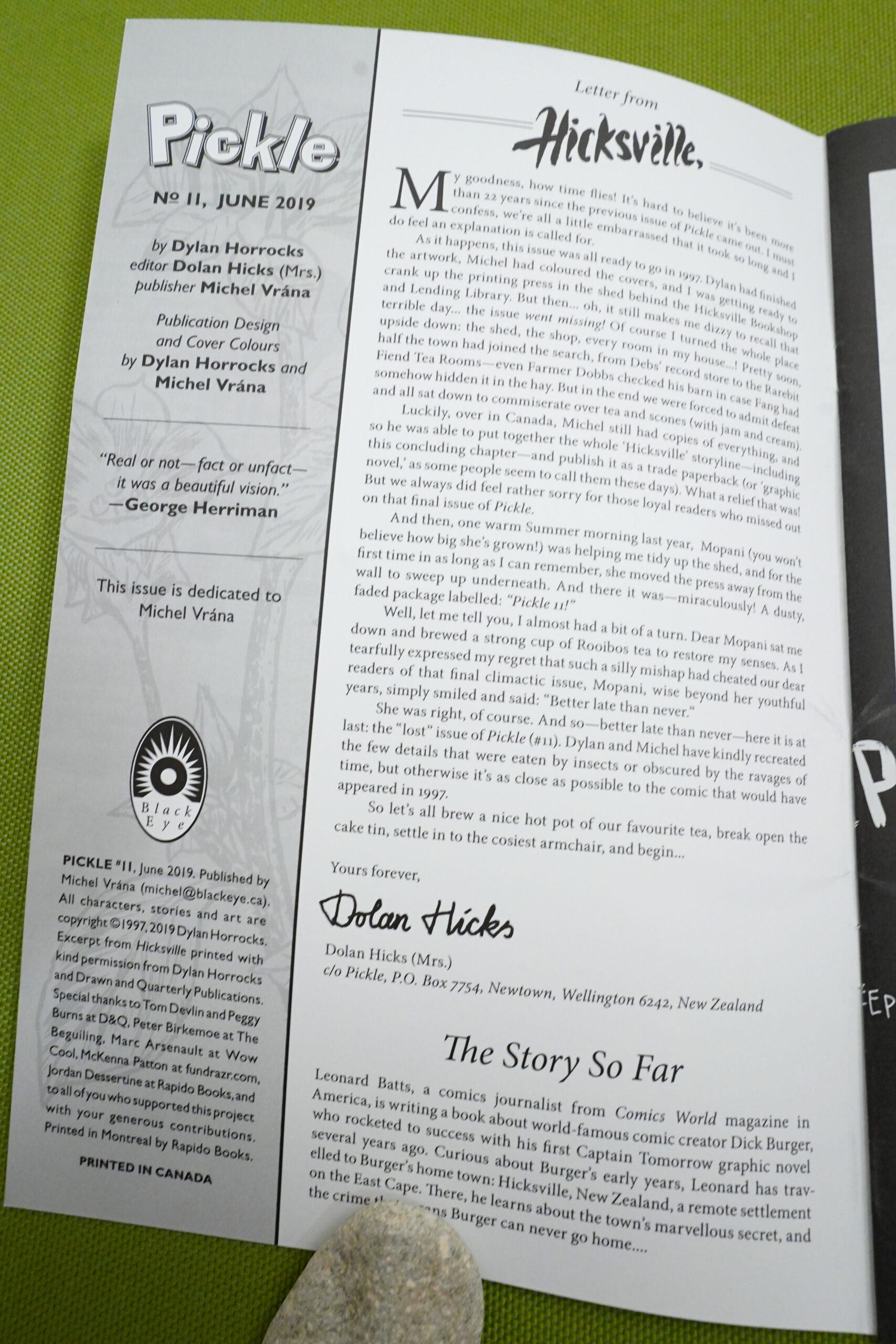

The contents are pretty regular, though: We start with an editorial from the (fictional) Dolan Hicks (mrs.), and we also get a depressing quote from somebody in the comics business on the left-hand page of the inside front cover.

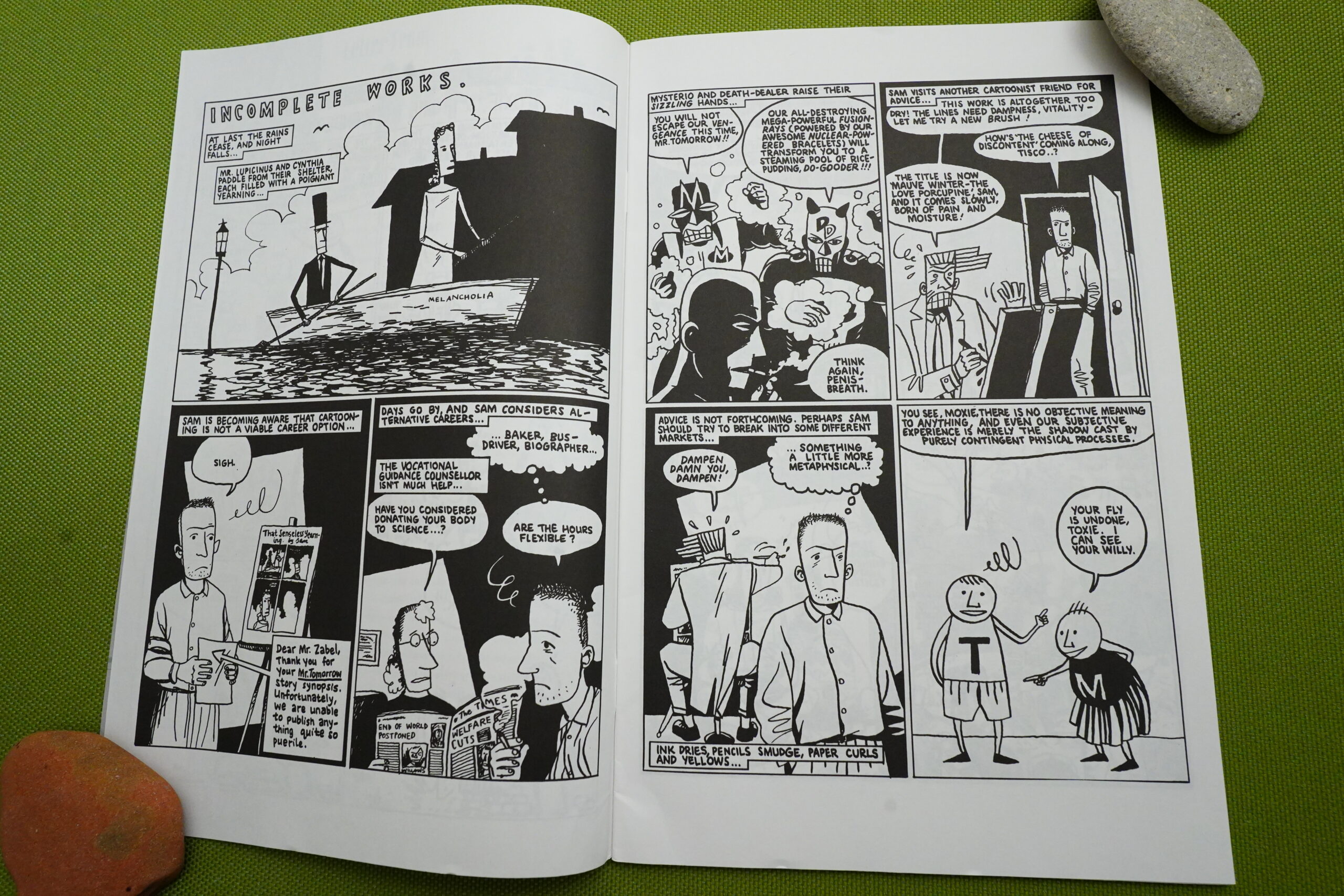

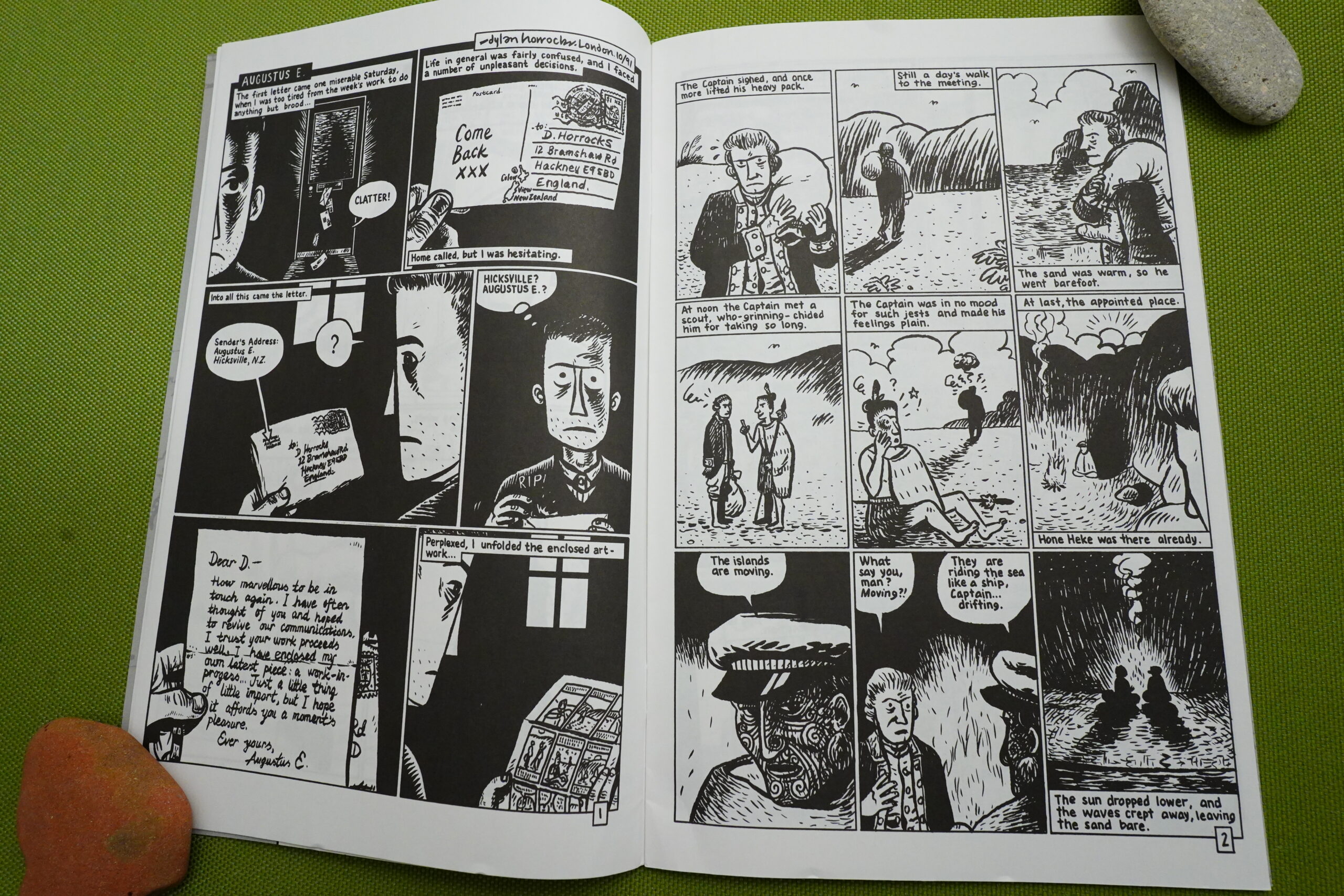

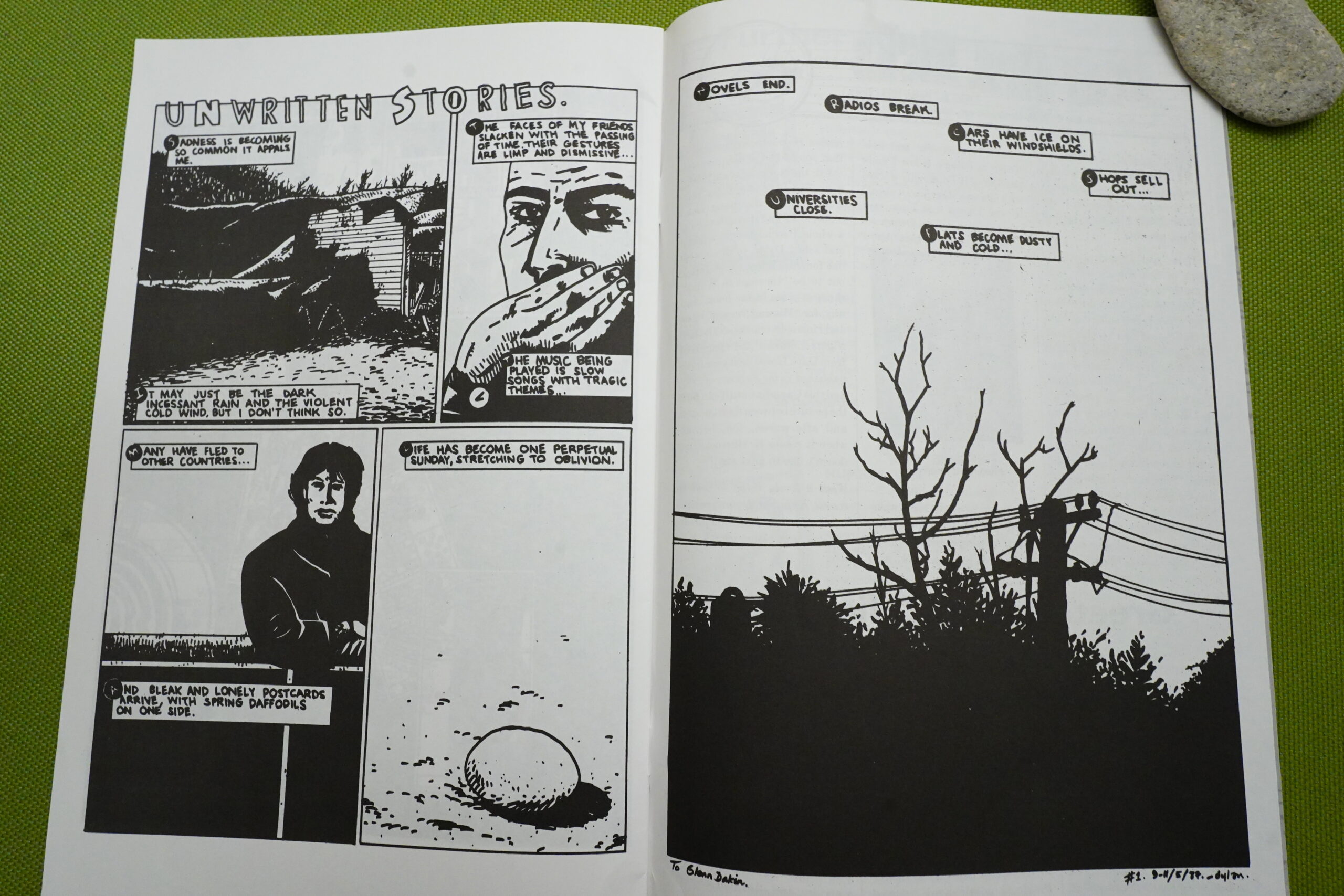

The first few issues are superficially like a traditional one person anthology: Lots of random shorter bits and some continuing stories… but here all the pieces seem to somehow speak with each other, even if the connection isn’t quite clear.

One of the reasons things cohere in this way is because Horrocks is pretty consistently playful with identity. He runs a letter from Eddie Campbell questioning whether frequent Horrocks collaborator Kupe is really Horrocks himself, before saying “nope”. Horrocks appears as a character in the book (briefly), and then Kupe appears more extensively… and what with the fictional editor Dolan Hicks (mrs.), we’re firmly in that Auster/Borges/Calvino area where everything potentially has meaning.

Which is the best place to be… if you can pull it off. That is, if what you’re doing is sufficiently interesting that the reader doesn’t just go “whatever”, but gets involved.

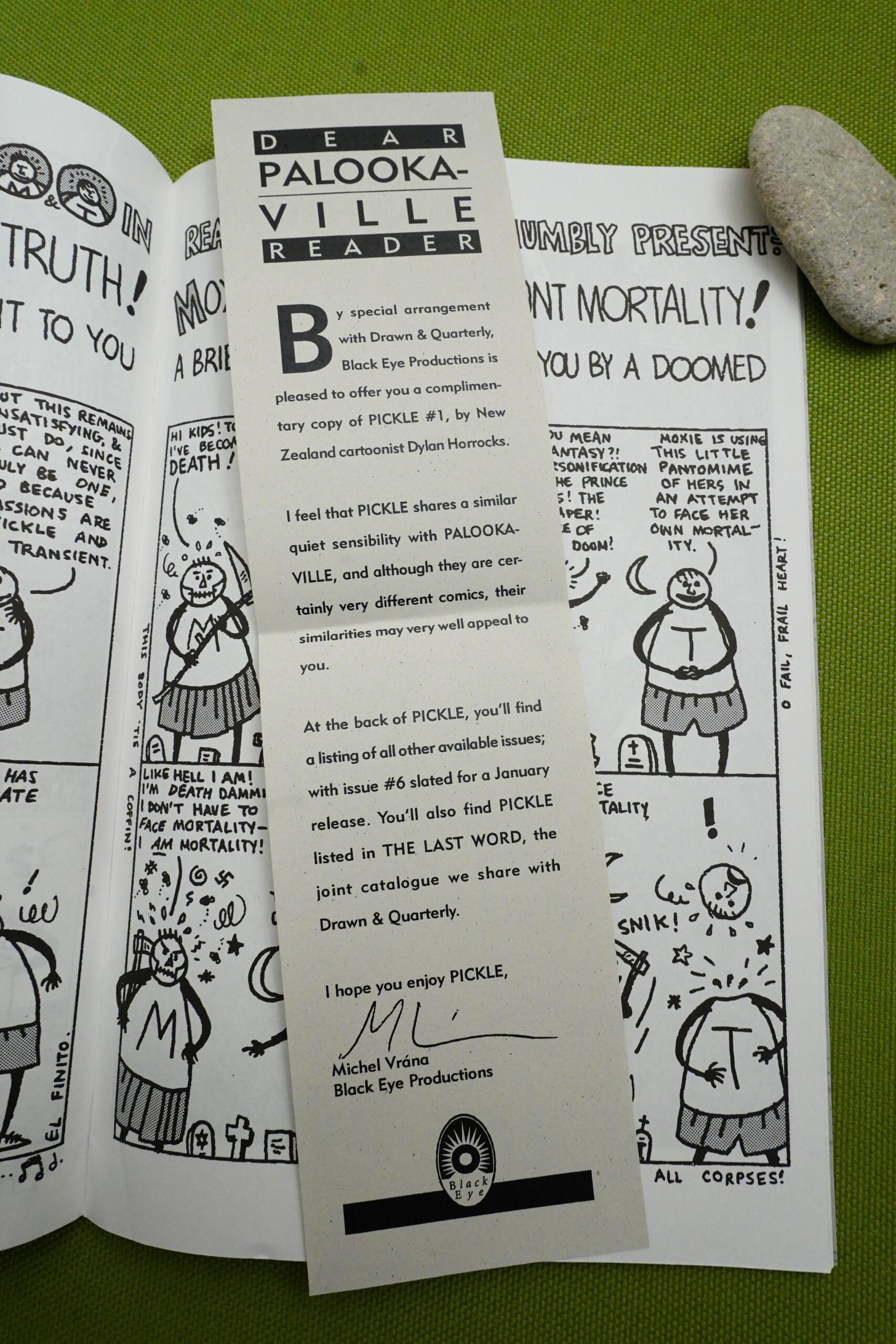

Oh, they gave away copies of this along with issues of Palookaville as a way to attract new readers? Sounds like a good idea to me.

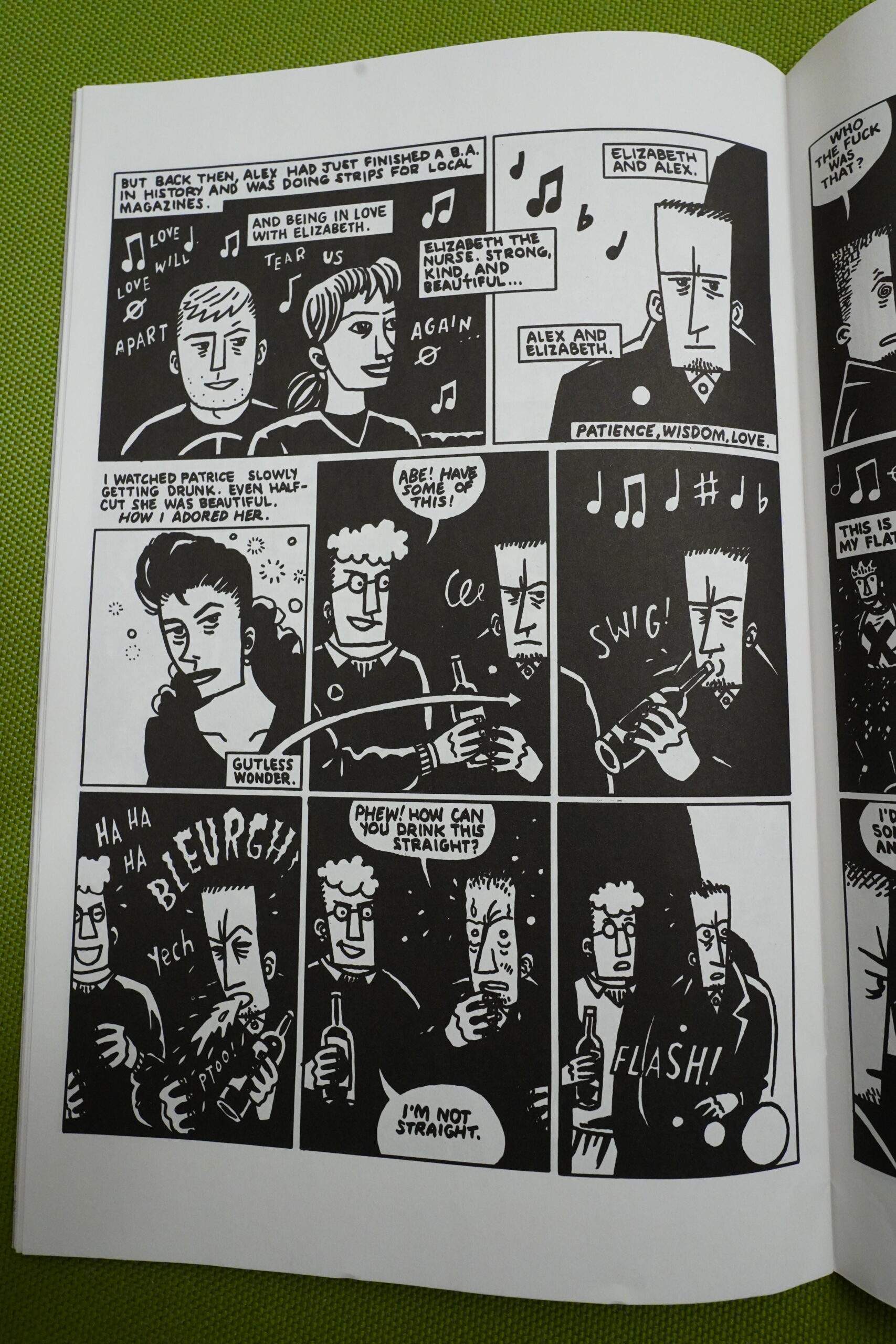

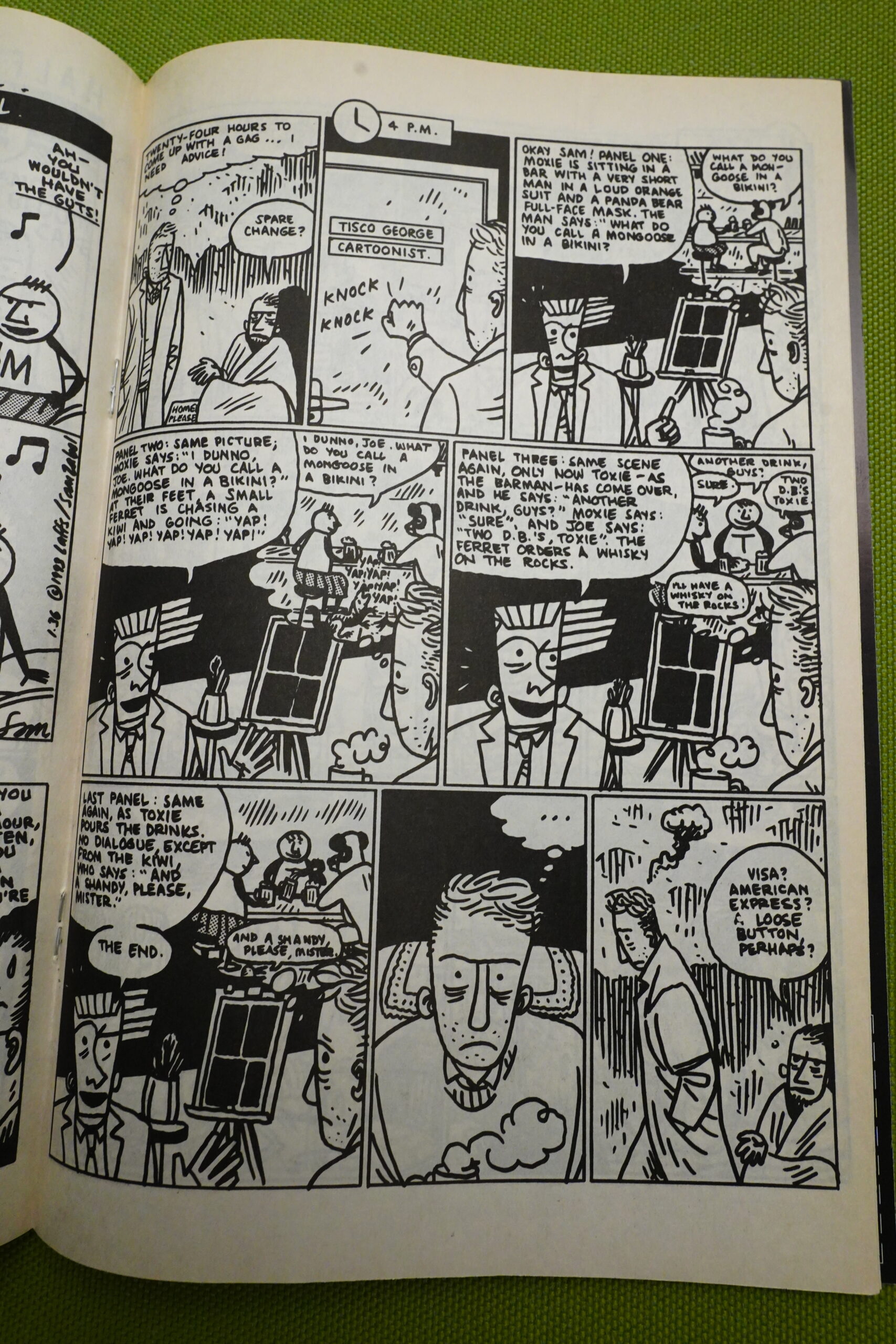

The one thing here that does seem disconnected from the rest is this serial that ran for half a dozen issues — it starts off as a riff on British mid 80s comics: It’s all about hanging out at the pub and then things happen. The serial isn’t credited to Horrocks at all, but you know.

The serial starts off really strong, but then it sort of peters out when it turns out that the (possible) “villain” is a vampire or something. Ooops spoilers. OK, there’s gonna be more spoilers here, but I’m assuming everybody who’s reading this already has a doctorate in Hicksville…

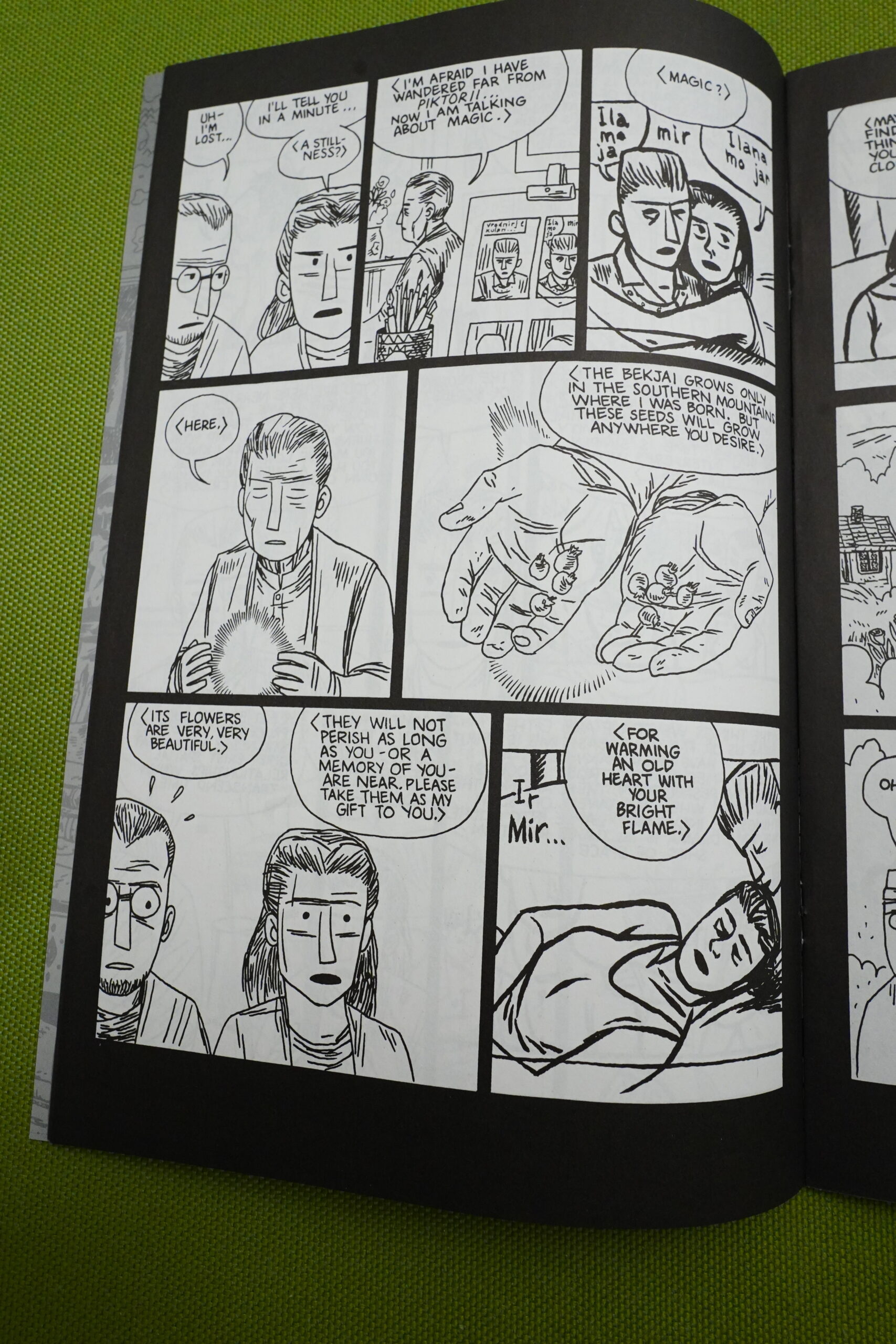

Even lovely short pieces like this seem to somehow tie in with the rest? Many of these pieces have dates that span 86-92, I think, but it’s hard to say whether that’s true or not.

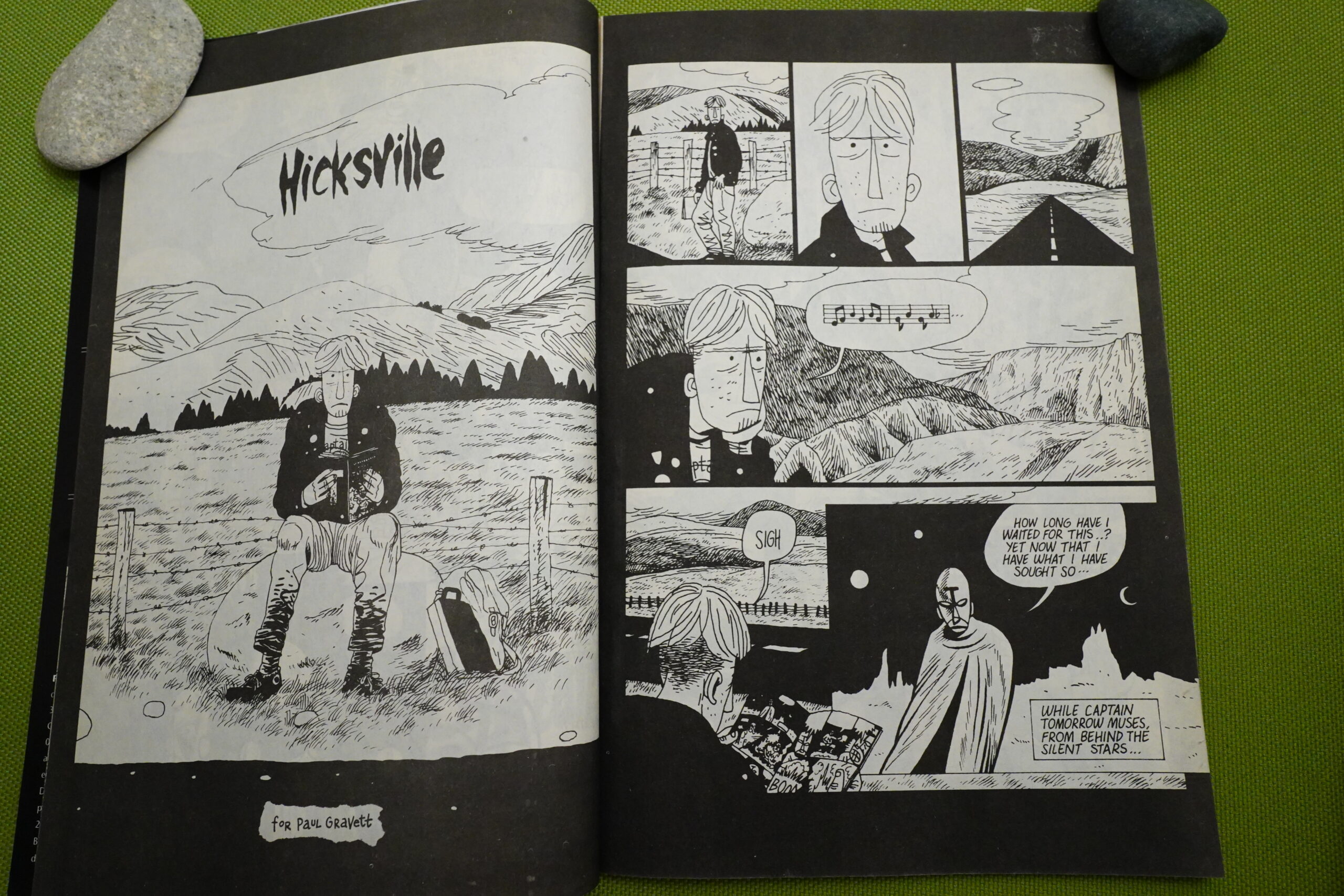

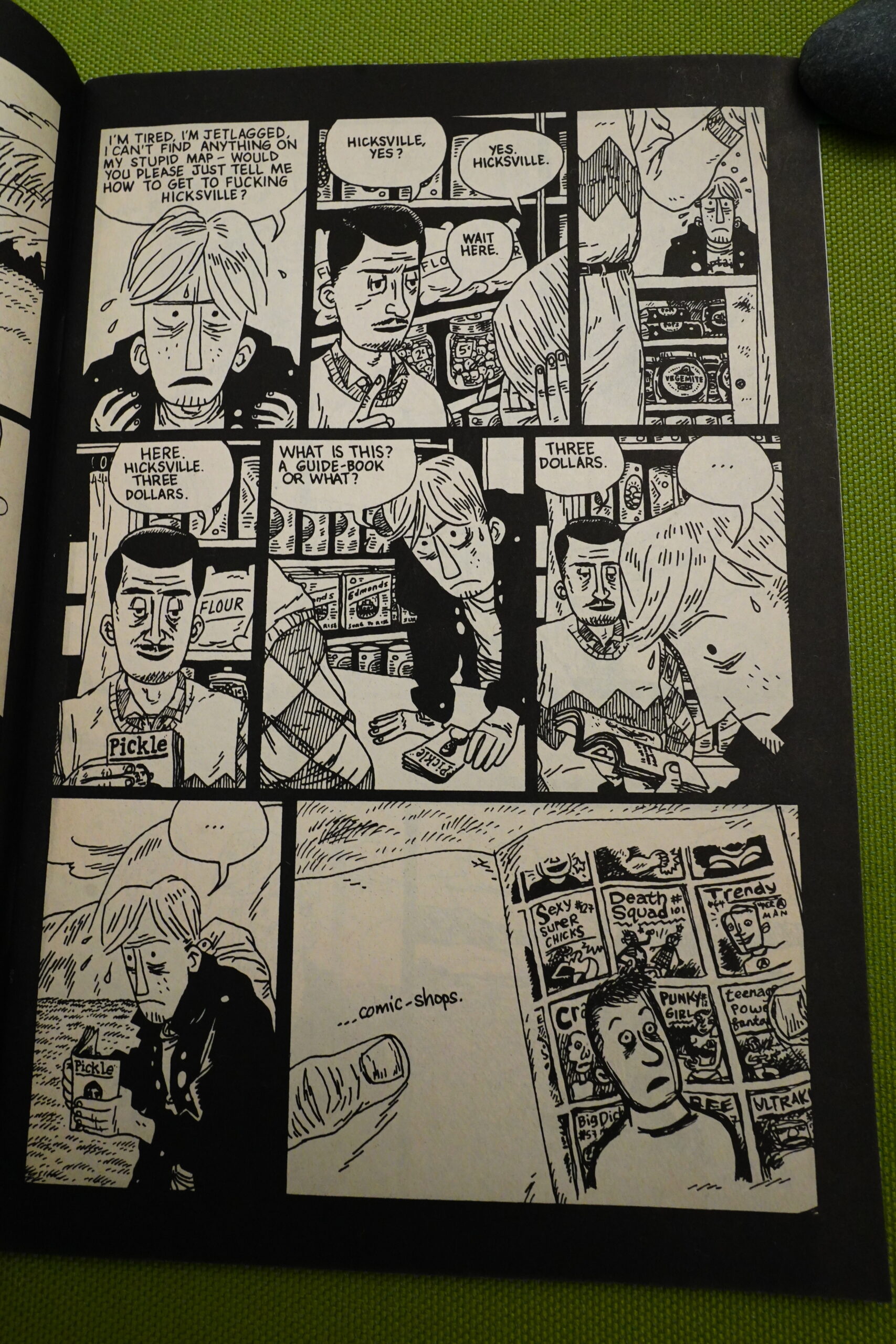

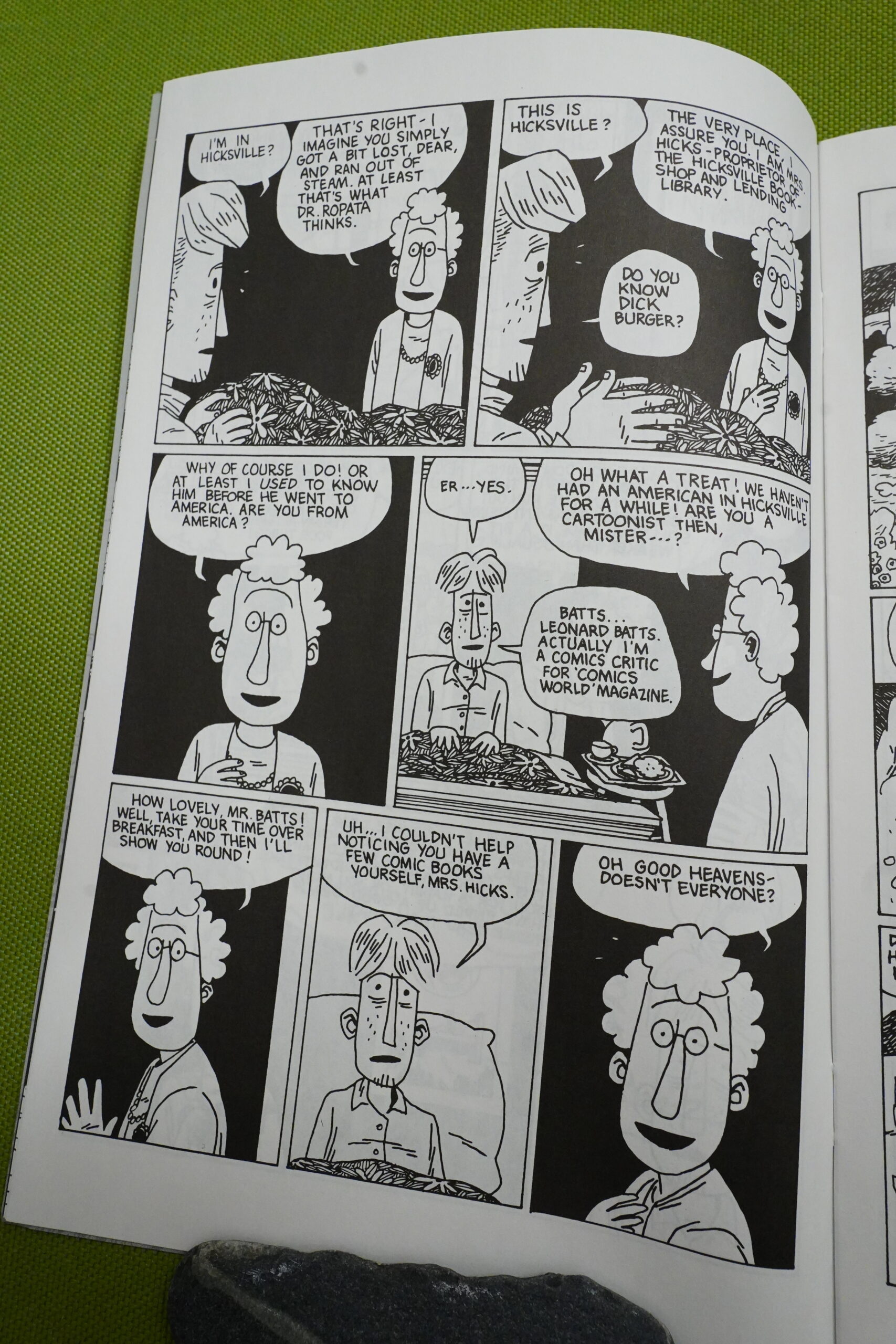

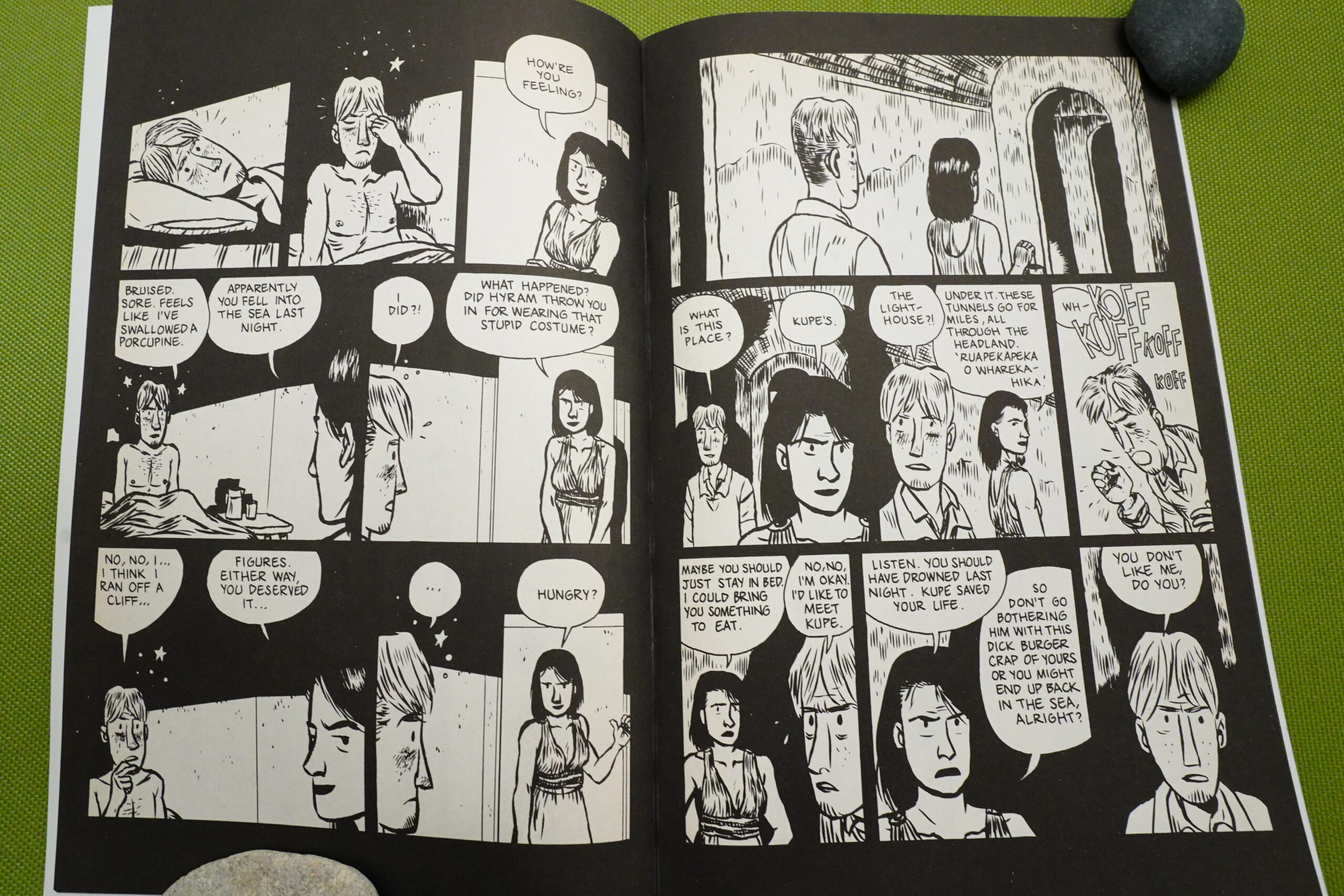

Here we get proof that Kupe is an actual separate person and not Dylan Horrocks. And we get an introduction to Hicksville — the town in Aotearoa where most of the characters come from, and it’s a place where the entire population is really into comics.

Dolan Hicks (mrs.) explains why the second issue is late.

And in the second issue, the Hicksville serial starts properly (but we had hints of it in the first issue).

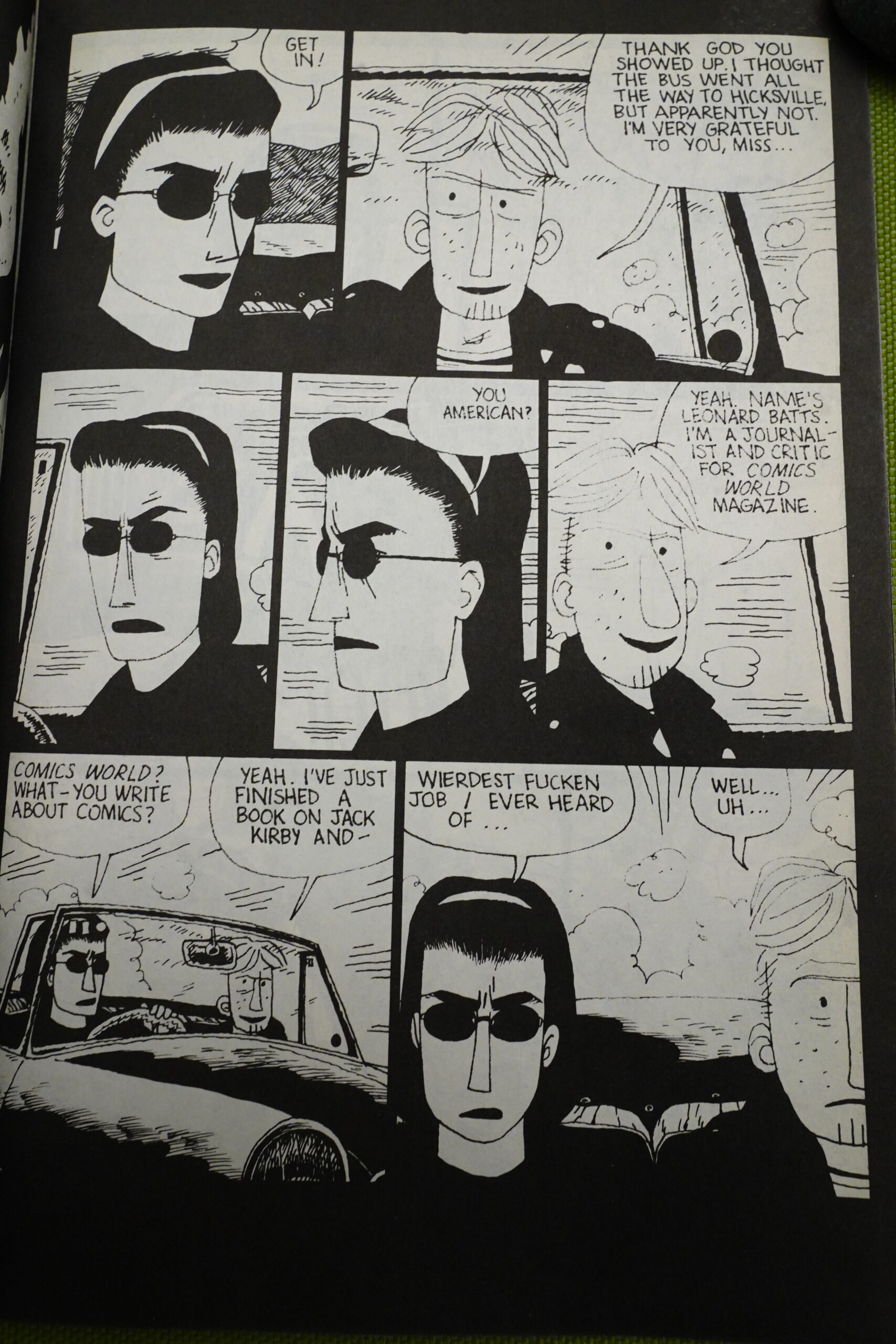

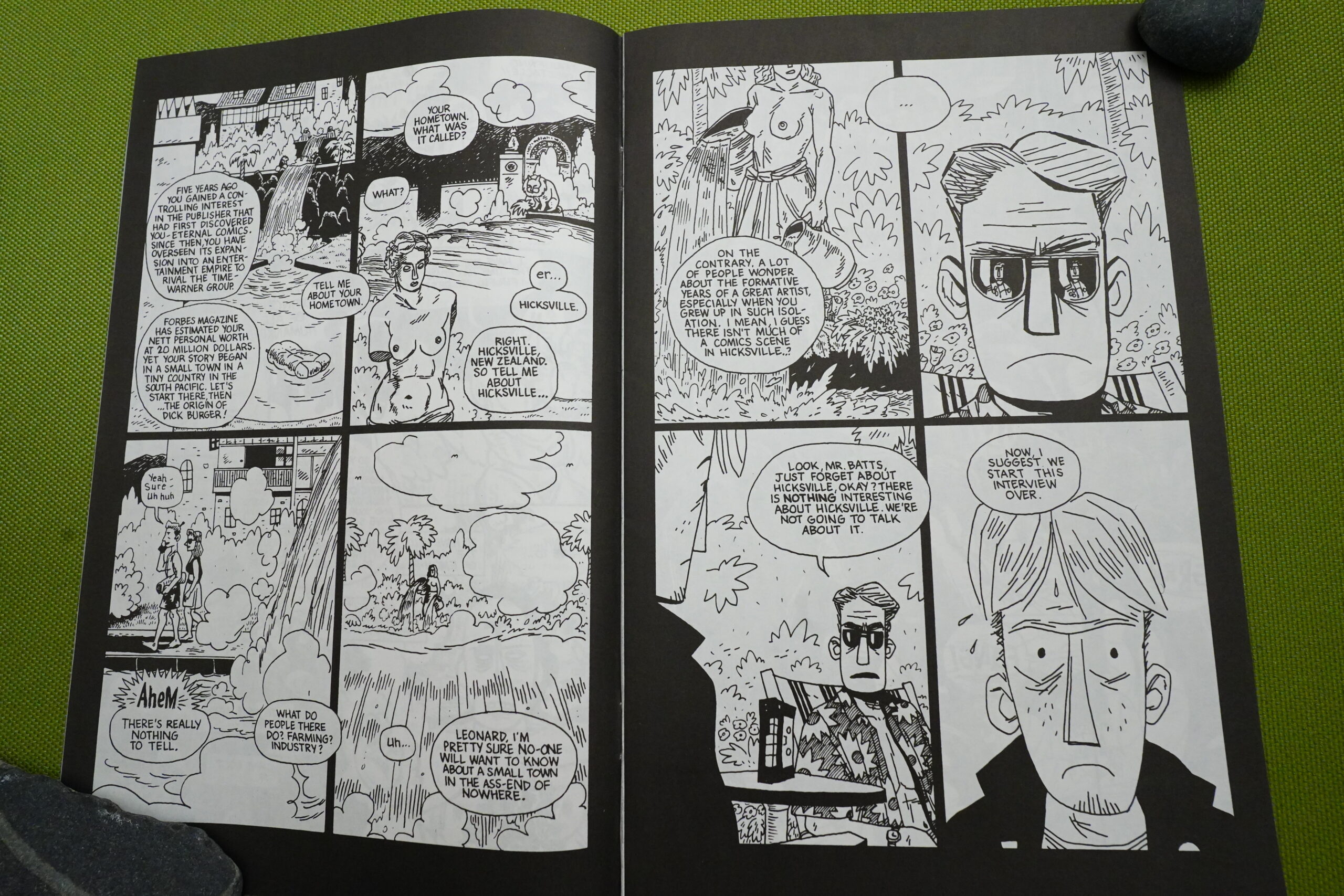

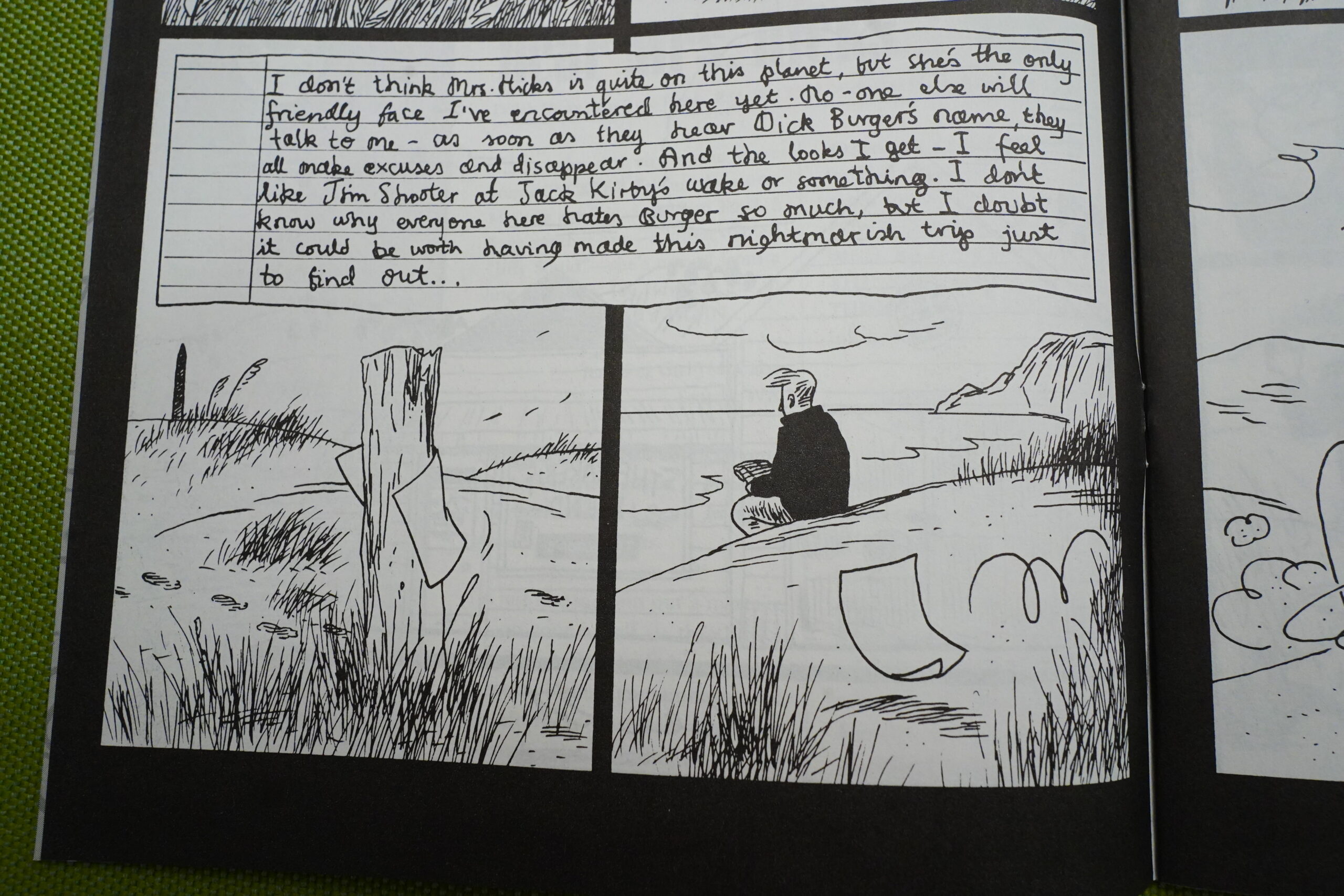

The story is very straightforward, really: It’s about a journalist that’s looking into the background of a very successful comics creator. So he’s gone to Hicksville, but whenever he asks anybody about him (Dick Burger; nice name) people either get angry or refuse to answer. See? Mystery! Intrigue!

Now that’s a good joke.

The third issue is the most impressive and gripping issue. Everything seems to come together here.

We have that journalist in Hicksville… and he’s handed the issue of Pickle (printed in Hicksville) that we’re reading.

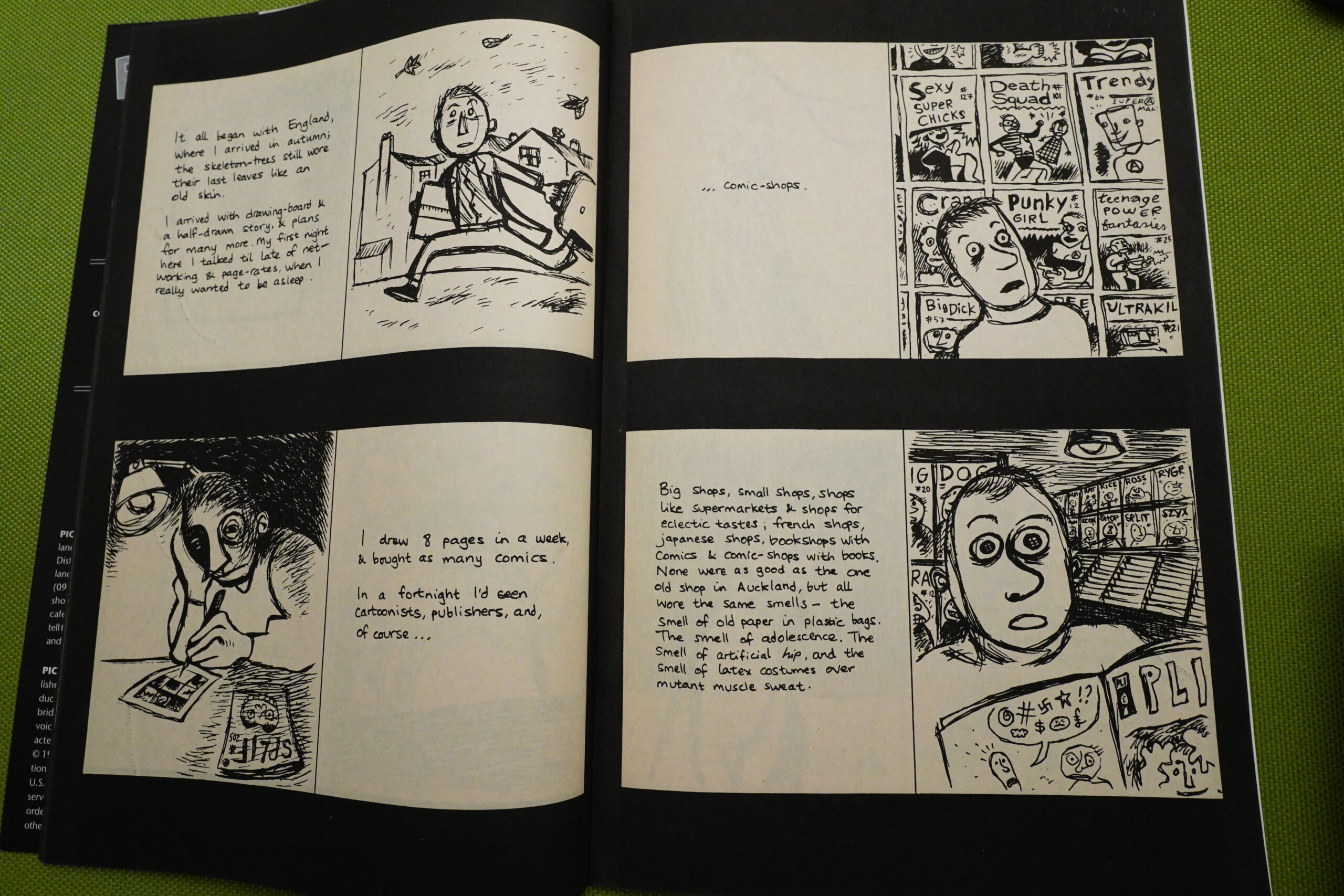

In it, we get the history of somebody trying to write a comic book, failing, and becoming allergic to comics.

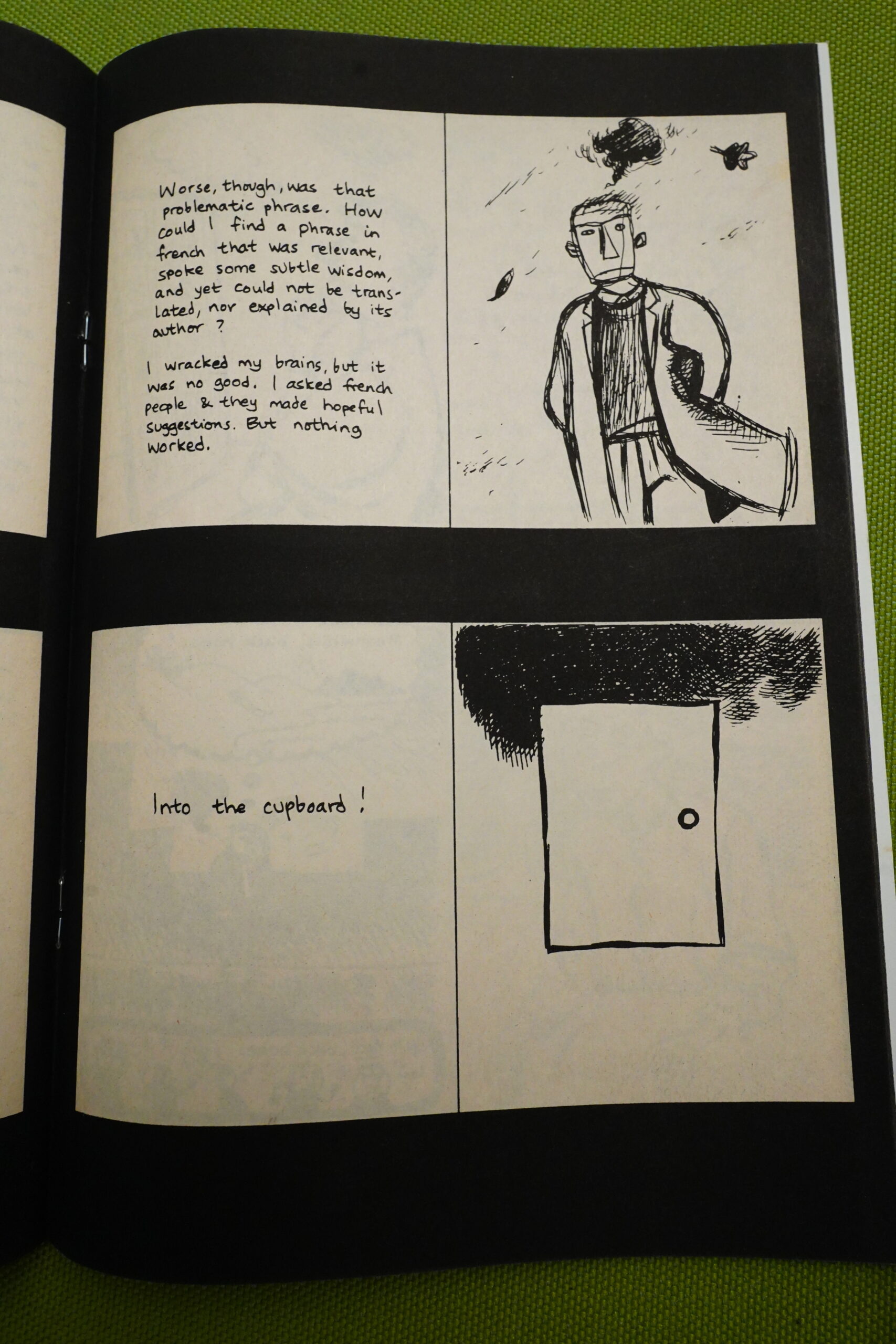

The story he’s trying to write involves a translator that’s having difficulty translating a mysterious paragraphs from French… but then the author realises that he’ll never be able to come up with that mysterious phrase, because really, what would be that mysterious? The story worked perfectly until then — readers accept readily mysteries like that, but we feel cheated if the resolution doesn’t make sense.

So the author has to abandon writing that book.

Which I have to say, after having re-read Pickle now, just seems really portentous for the entire series. Didn’t Horrocks know at this point what the Dick Burger mystery was going to turn out to have been?

Because all we’re getting is people (including Burger) refusing to say anything about the mystery, without any hints as to what it may be.

And perhaps that’s part of what makes these issues so wonderful? You can palpably feel the possibilities bubbling…

Dolan Hicks (mrs.) shows up in the story, too, because of course.

Horrock’s approach to the artwork is sometimes a bit bewildering. He’s generally very influenced by 80s British indies, but seems to change just who he’s doing a lot. It works, but it’s a bit haphazard.

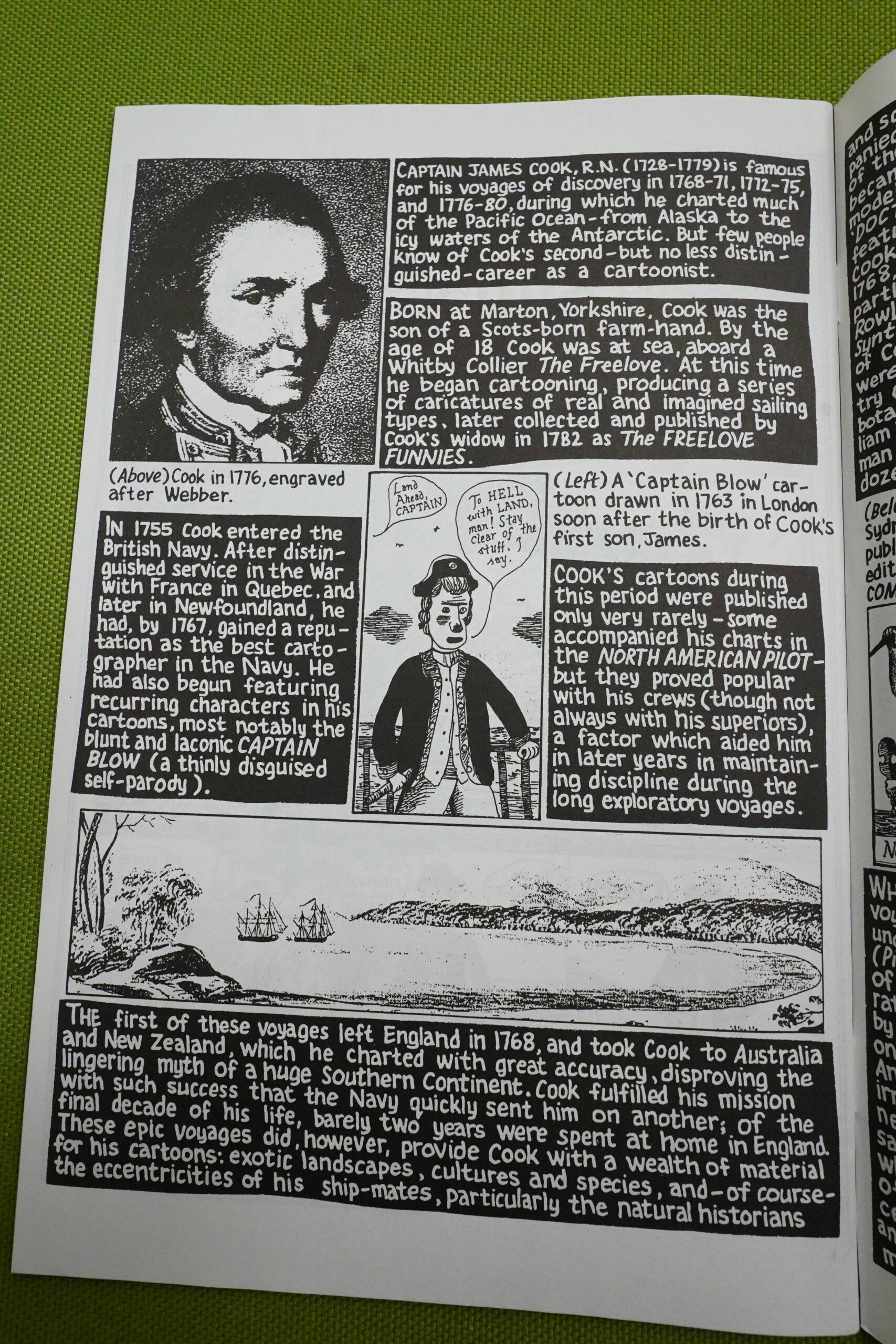

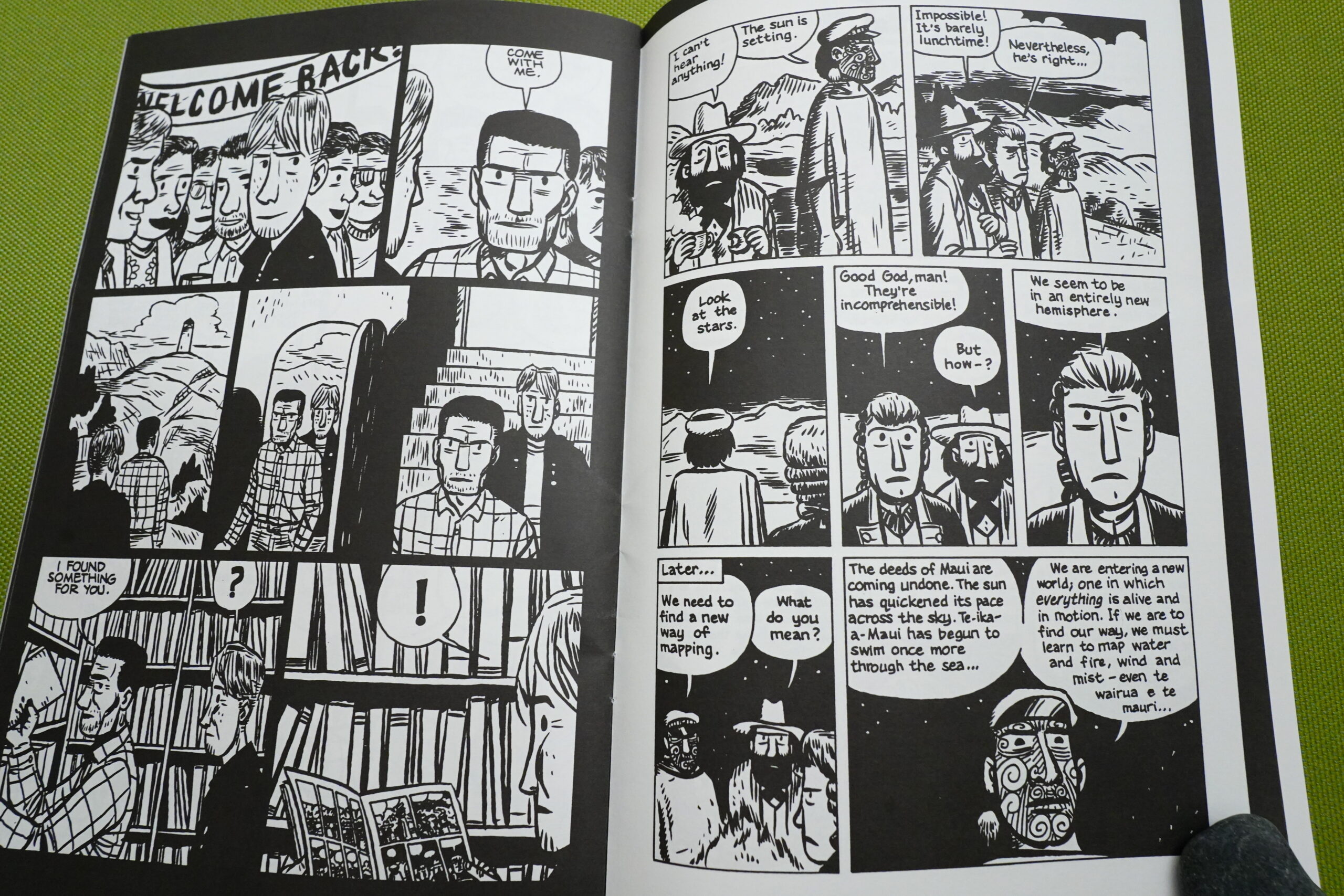

Did you know that Captain James Cook was also a comics creator? Very few people do.

The Hicksville serial isn’t just about Dick Burger — we also follow some other characters and their encounters with people like this, a magician/comics creator from the land of Cornucopia. And even if we don’t spend all that many pages with each character, they still feel like vital characters.

“I feel like Jim Shooter at Jack Kirby’s wake”. There’s quite a lot of insider references here, and I’m guessing not all that many people would get them these days. I mean, anybody under 40.

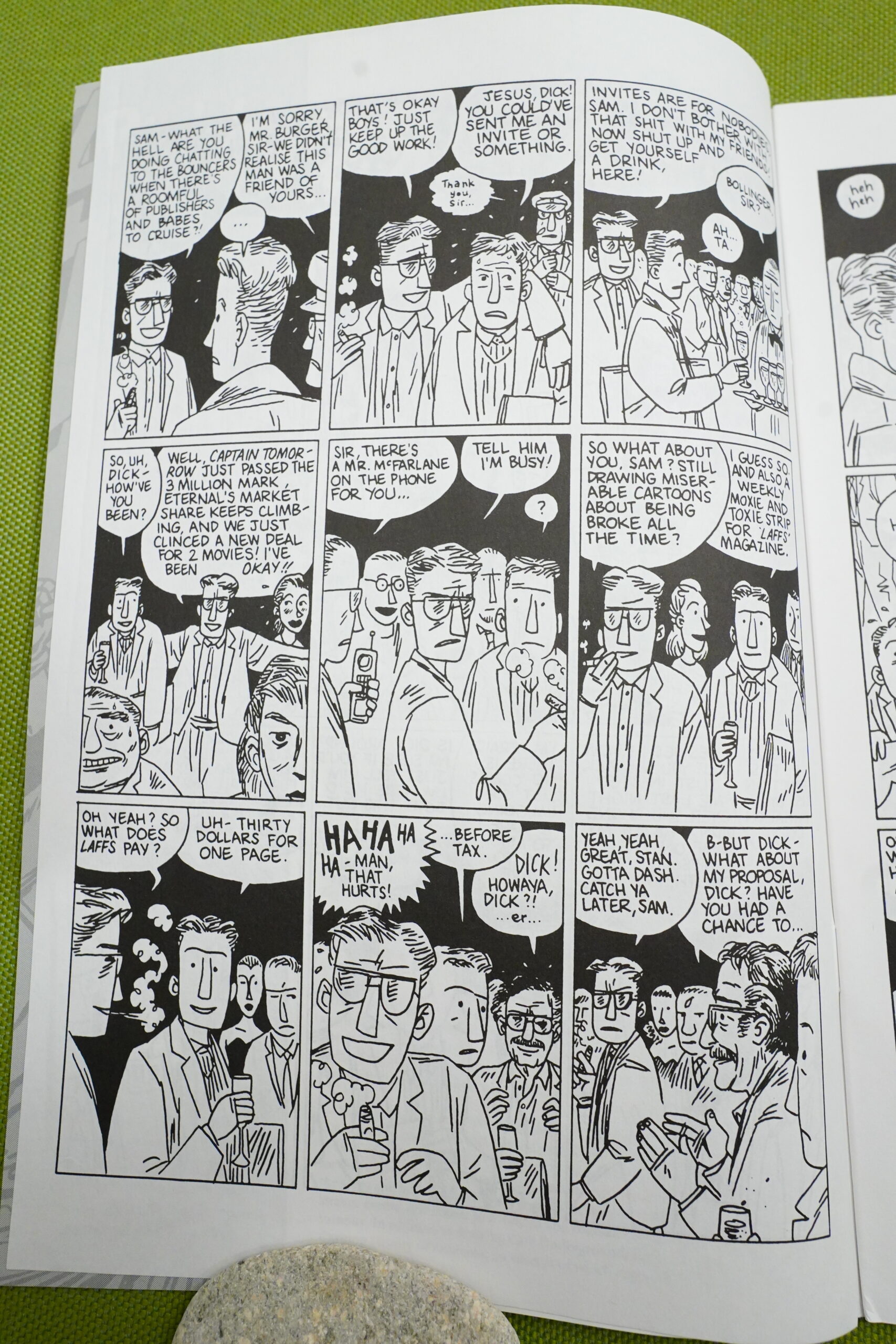

Dick Burger is portrayed as a Todd McFarlane like mogul (Spawn was very big for a couple week), which makes it even more fun that he’s apparently hired somebody called Todd to do pencils.

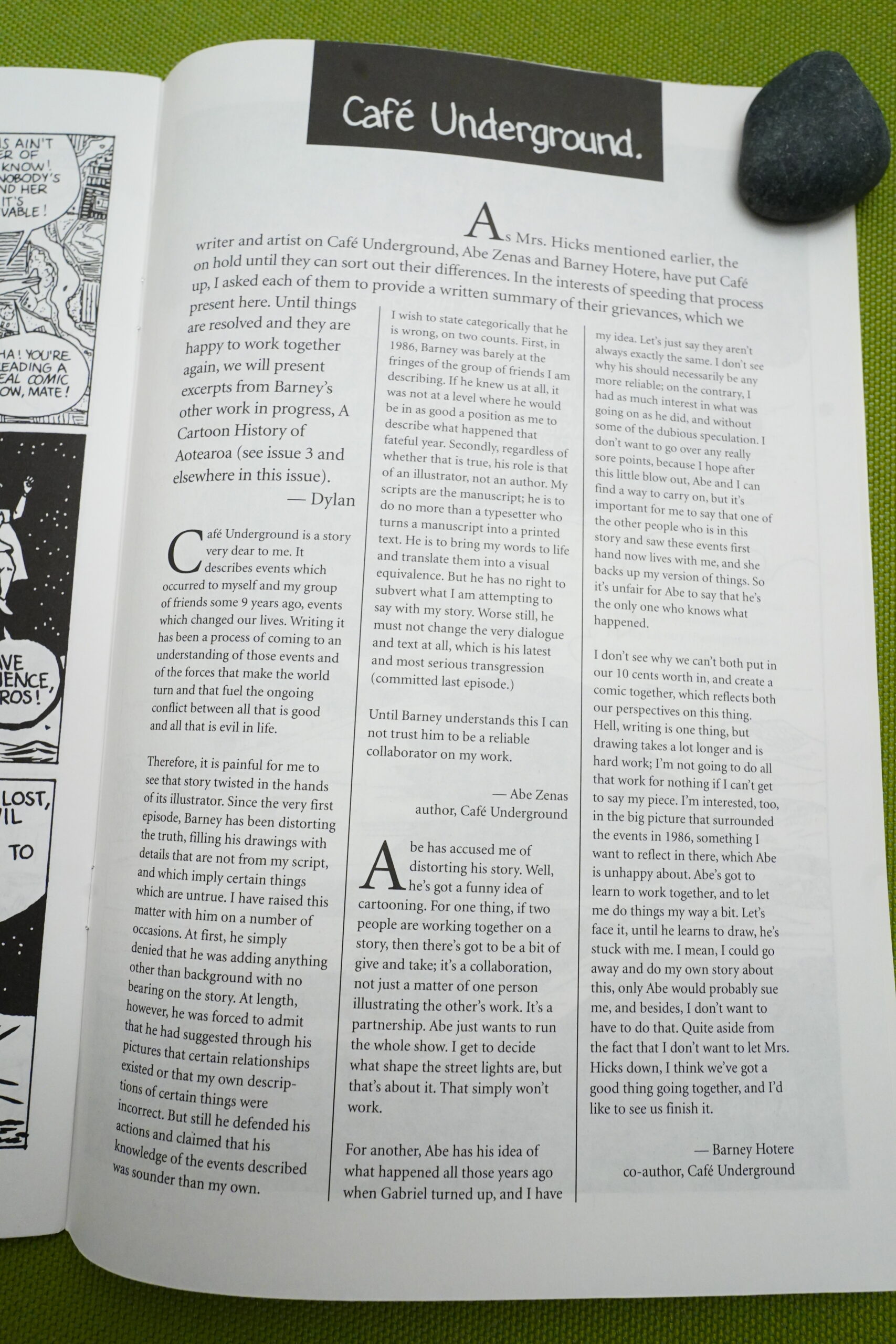

The pub/vampire serial ran out of steam, I think, and Horrocks decided to concentrate on Hicksville. Which was a sound decision, but also kinda sad. It’s here presented as if the two creators involved disagreed with each other too much, which I like.

But it seems obvious that Horrocks had decided what the solution to the Dick Burger mystery should be, because the last five-ish issues are totally straightforward: Gone are (almost) all the side series, and gone are the most of the mysterious things that keep happening.

Instead we race to the end, which happens in the worst way possible (spoilers in the next snap; close your eyes):

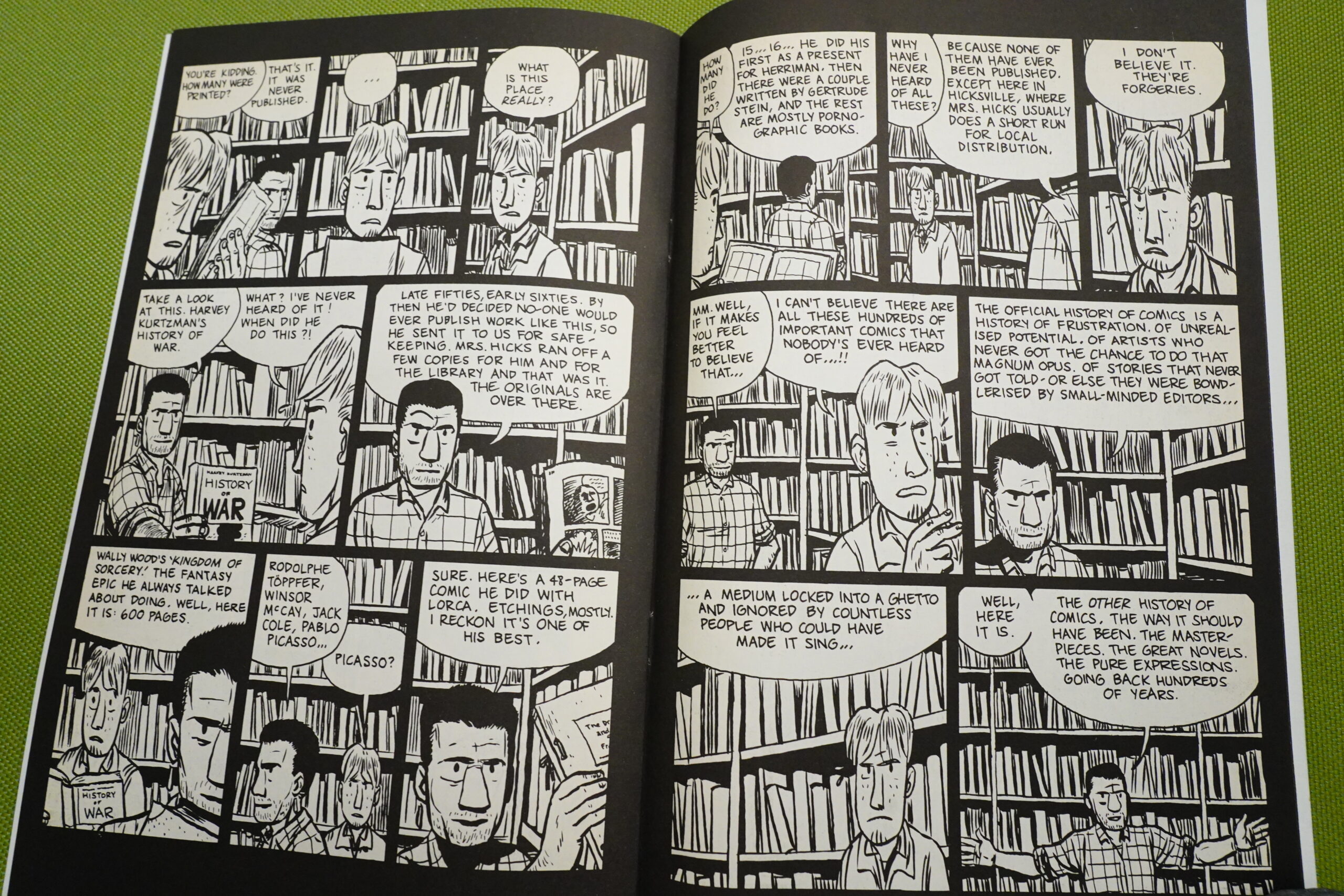

The Kupe character just tells us that Hicksville has a Borgesian library filled with all the wonderful comics that were never published, and Burger plagiarised one of them. And that’s taboo! For reasons never explained! Or even hinted at! And that means that … er … the reason that all the villagers insisted on Kupe being the one to tell the journalist is… er… uhm… er…

What I’m saying is that 1) I love the idea of this library, and 2) it’s a bad ending. It doesn’t really make much sense, even in a poetical way. I mean, the poetry is basically gone.

So we’re back to that story of the mysterious untranslatable French sentence that the author just couldn’t come up with, but this time as the actual plot of the story.

The final issue of Pickle, #10, was published in 1996, and it had almost wrapped up the storyline. In 1998 Black Eye published the Hicksville collection, which added more pages at the end.

Isn’t it annoying when people are serialising something, but then they decide to stop serialising just a few pages before they reach the end. There may be excellent reasons for doing so — perhaps sales had been dropping and they just couldn’t afford to publish the final issue(s). Or perhaps some of the more mercenary ones were thinking “haha, we’ll get the fans to buy it all again!”

I don’t mind the latter, really, but it’s a shame, because reading something in a serialised format is something different than reading the collection. I’ve many a time been super into the serialised version of something, and then when I read the collection it’s “eh, it’s OK I guess”: The context changes things. On the other hand, there’s things where that’s not the case at all. I loved reading Maus serialised in Raw, but Raw was cancelled one issue before the final chapter was published. One issue! (And that issue was the best, by far, of Raw v2, but I guess Penguin had gotten tired of losing money… Or perhaps Mouly/Spiegelman were fed up.)

Anyway:

Just 23 years later, Vrána published #11! Wowza!

It’s been a long time since I read the Hicksville collection, and I can’t find it now, but I think we basically get all the “missing” pages?

So how’s Pickle? I was totally into the first half of the series, reading it now. I mean, I was shocked at how into it I was. It has real magic; it feels so vital and interesting. The po-mo tomfoolery really works. And then the last half of the series is very… efficient? … at telling the Hicksville story, and that wasn’t as interesting to me.

As I said Hicksville was published in a collected edition by Black Eye, and then Drawn & Quarterly picked it up and reprinted it. And it’s been translated into multiple languages, and it generally is huge success.

The Comics Journal #165, page #017:

Dylan Horrocks Explores New Zealand

and Comics in PickleNew Zealand’s recent cultural revival, which

has brought us Keri Hulme’s Bone People in

literature, and Jane Campion’s Piano in film,

now has a new ambassador in comics, Dylan

Horrocks. Although only two issues of

Horrocks’ comic Pickle have been published

so far (with third one due in February) and its

creator is virtually unknown, there are already

signs that this is an ambitious work.

“Hicksville,” a story which began in Pickle #2,

is nothing less than Horrocks’ attempt to si-

multaneously examine the history of comics

and “an alternative history” of his country

New Zealand.

The principal character in “Hicksville” is

Leonard Batts, an American comics critic

who’s just written a biography of Jack Kirby

and is now traveling to New Zealand to re-

search a biography on Dick Burger, a contem-

porary comics superstar who left his home in

Hicksville, New Zealand to become a multi-

billionaire cartoonist in the United States.

Leonard won’t actually reach Hicksville

until chapter three, but when he does he’ll dis-

cover that it’s a town obsessed with comics.

“Everyone there knows comics back to front,”

Horrocks explained in an interview. “Just

about every comic ever published is in

somebody’s library. It’s always been like that

[in Hicksville]. In the 19th century everyone

subscribed to Punch Comic Cuts and the Will-

iam Randolph Hearst newspapers. All the

dairy farmers sit around having learned con-

versations about whether R.F. Outcault was

better than Winsor McCay. There’s an expert

on Greek comics, and a Finnish comics fan,

and the man who runs the Rarebit Fiend Tea

Room only reads comics from the 1950s. The

town is supposed to be a mysterious place and

the reason it’s not on any maps is that there’s

some doubt as to whether or not it really

exists.”

But that’s only half the story. The other half

will be told in a comic within the comic. In

chapter one of “Hicksville,” Leonard comes

across a comic book page featuring Captain

Cook, the first English discoverer of New

Zealand, and Hone Heke, a native Maori

leader as the two main characters. Similar

pages of this mysterious comic showed up in

Pickle #1 where Horrocks depicted himself

living in England and receiving the pages from

a stranger who signed his name “Augustus E.”

Further pages by Augustus E (which is the

name of 19th century painter from New

Zealand) will continue to show up in “Hicks-

Ville.”

Rich Kreiner writes in The Comics Journal #211, page #015:

Prime Location;

Unlimited View;

Must See to BelieveIn most American cities of any size — except

maybe New York —

the artistic community

periodically and publicly considers the influ-

ence of locale and local heritage on the contem-

porary art scene. Usually participants tilt in

one of two major directions. At one side propo-

nents maintain that any sense of regionalism in

art has been all but extinguished by globalism,

media saturation, and/or the Internet; art here

and now is world art. At the opposing pole,

others hold that a specific environ can con-

tinue to exert its own unique influence on art,

even if these adherents are unable to nail down

what the influence may be with any specificity.

They hold art can avail itself of an indigenous

tang.

Dylan Horrocks’ Hicksville would be cited

as tangible support for both sides. The book

comes by way of assembled segments from

Horrocks’ serial comic Pickle. As its cover states,

this volume incorporates “some 40 or so page

of new or revised material,” including the tale’s

concluding chapter, unpublished when Pickle

ended after ten issues. The added material,

coupled with a bit of reshuffling and slight, if

significant, alterations, smooths out some nar-

rative passages, expands atmospheric and

meditative stretches, and makes explicit cer-

tain of the narrative’s marvels. (The volume

does not, however. include the epic mini•comic

The Last Fox Story” which had been so neatly

tucked into a Hicksville chapter in Pickle.)

Hicksville is an evocatively realized (if

imaginary) town, presumably on Hicks Bay Of

the North Island of New Zealand. This alone

carries implications — with varying levels of

dissociation — of a degree of distance, some

provincial insulation, the whiff of cloistered

sensibilities in a cultural backwash, a banish-

ment. When Pickle’s first issue made it into the

Journals “Hit List,” the uncredited reviewer

found the book exhibited the •formal oblique

anxiety known as ‘cultural cringe’ that comes

from beingsofar from the cultural center of the

world” and presented “one of the best evoca-

tion of being a ‘provincial’ artist you’ll ever

read.”[…]

The book winds down in a progression of

satisfying climactic codas and denouements

which increasingly fit lives, ideas, and tales

into an accordant whole. Cook, Heke, and

Heaphy make one last effort at divining their

place, readers now having come to understand

the greater gestalt of such a fix. Heke’s devel-

oped native wisdom challenges Western pre-

sumptions and intellectual questing. Horrocks,

however, avoids political posturing. He refuses

to allow a facile dismissal of Euro-yearnings

and lets the white guys make their rebuttals. In

this flurry of traditional intelligence. scientific

procedure, aesthetic principles, and poetic

truths, Heke has the final say and, more impor•

tantly, hatches the mutually accepted plan. It

concerns seeking the path by which mortals

pass into the land of spirits by leaping from one

life to another. a fitting issue for these histori-

cal figures contemplating passage into poster-

ity (Heke’s scheme, in turn, doubles back to an

earlier map rendered by two Maori of New

Zealand’s Northern Island which includes the

route taken by the dead to the very “leaping off

place” where they depart for the world Of their

ancestors). Heke notes, •We need to find a new

way of mapping,” a way capable of charting

•water and fire, wind and mist,” and even •te

wairua e te mauri,” the spirit and the force that

binds spirit and body together. Even before the

touching epilogue, jaded comic readers will

have an enhanced sense of just what medium,

what sort of mapped stories, might very well

fill the bill. When you thought the book’s sepa-

rate segments could not possibly be more

tightly nested, the final page brings our collec-

tive visits to a lovely, bittersweet close.

That’s a pretty enterprising travelogue for

the place on character calls the •ass-end of the

universe,” depicted in a marginalized art form,

and realized so far from the center of the

cultural world. Shangri-la should be so lucky as

to have a tour guide like Dylan Horrocks. +

Matt Madden writes in The Comics Journal #175, page #045:

In “The Last Fox Story,” from #3,

the leaps of imagination Horrocks

asks for are a bit more problem-

atic. This story about a story about

the translation of a story posits a

French comic about the sorrows

of a knight’s ghost during the

crusades. The translations offered

are somewhat stilted and overwrought— “And

then, so heavy is that stillness; so heavy and so

terribly sad”— yet we are assured that ‘fit reads

much better in French. ” The translator encoun-

ters a phrase which he cannot translate — “I

understand the phrase, but not the meaning?’

The problem posed by this phrase then transfers

to the author of the framing story, the primary

narrator: he cannot think of a phrase poignant

enough to stand for the one his character cannot

translate. In the end he realizes that this artistic

crisis — the failure of the imagination in the

face Of some posited greater work Of art — has

itself become the object of the story he is trying

to write. While the creative crisis is certainly a

valid subject for art — 8 1/2 comes to mind as

just one example — and while the translation—

between languages, between media— is also

worth exploring, in this case, the gaps left by the

artist for the reader to fill are dangerously large.

Given the sketchiness Of the story, too much

weight is placed on the faith Of the readers that

there is indeed something deep going on here,

as if just the suggestion were enough to bring it

into being. In the case of ‘The Last Fox Story,”

this reader was left with the feeling of being

slightly cheated. Still, though he may falter on

occasions, Horrocks’ successes make the ex-

periments more than worthwhile — which

brings us back once again to Cornucopia, and

the rural studio Of Emil K6pen.[…]

The biggest problem with Pickle is the second

story line, “Café Underground.” In very brief

installments, Horrocks has so far outlined noth-

ing more than a hip, gothic soap opera, gar-

nished with black coffee and tarot cards. The

Tragedy Strikes Press edition of Pickle #1

claimed that this was projected to be a 120-page

story, so I assume Horrocks has some tricks up

his sleeve, and this story will eventually kick

into gear. As it stands, the characters are unde-

veloped and the ominous tone of the narration

seems out of proportion with the mundanity of

the events — a slick European disrupting a

group of friends by sleeping with everyone in

sight. Perhaps there is meant to be an element of

parody, butitisunclearatthispoint. “Hicksville”

stands up to — even thrives upon — its mean-

dering, slow pace, but the result is nothing more

than indifference in the case of “Café Under-

ground.” Of course, I suppose it is too much to

expect Horrocks to be given the time and the

funding to produce this story as one complete

volume. ideal though that would be.

Minor criticisms aside, Pickle is certainly one

of the most interesting and engaging comics

around. It creates a world of people and places

who grow more familiar and more complex

with every issue, while consistently testing the

boundaries Of comics’ capabilities.

The Slings and Arrows Comic Guide #2, page #503:

The guest-appearance by Stan Lee in 7’s

episode is hilarious.

And its drawing is the least

pretentious that can be seen in the kiosks. Simple, effective and direct, although

it is not at all attractive and

it is directed to those who

know that the drawing of a comic is only a vehicle

to tell a story. And

this story is beautiful, suggestive, unforgettable. So much so that

cartoonist Dylan Horrocks was publishing

the comics he made in his spare time, and

where he did not even finish the Hicksville serial, leaving the end for the

book. And Horrocks, who at that time

earned his living making illustrations and

political strips for the press, was slowly building his story

without hurrying and

without aspiring to do something great.

You initially pre-published Hicksville in your comic series Pickle. For the book, you eventually re-drew about forty pages.

Atlas is now also appearing in comic form for the first time.

Do you plan to revise the book version of Atlas so extensively?

“Well, I have the whole story planned out in broad outline, but I deliberately do not use a complete script. I write each episode separately. I do that mainly to avoid a problem that I experienced with the creation of Café Underground. I wrote that between 1985 and 1989 with the aim of making it the main strip in

Pickle. I worked very detailed; even the layout was mostly done. By the time I

was drawing chapter four or five, it had become very boring and slavish work —

without any surprise or sense of freedom. That was the reason

why I started with Hicksville from Pickle 2 onwards with a small idea and

saw where it went as I went. It was only when I was well on my way that I

worked out the answers to the big questions in the story, such as why

everyone hates Dick Hamburger and what is in the lighthouse. I

valued the fact that I could give the whole story a different twist if I wanted to,

as I did with chapter four when the storyline suddenly changed.

Oh my god — I guessed right! About both Café Underground and why Horrocks ditched it (boredom) and why Hicksville’s approach changed (Horrocks decided what the secret was).

*pats self on back*

This blog post is part of the Total Black Eye series.