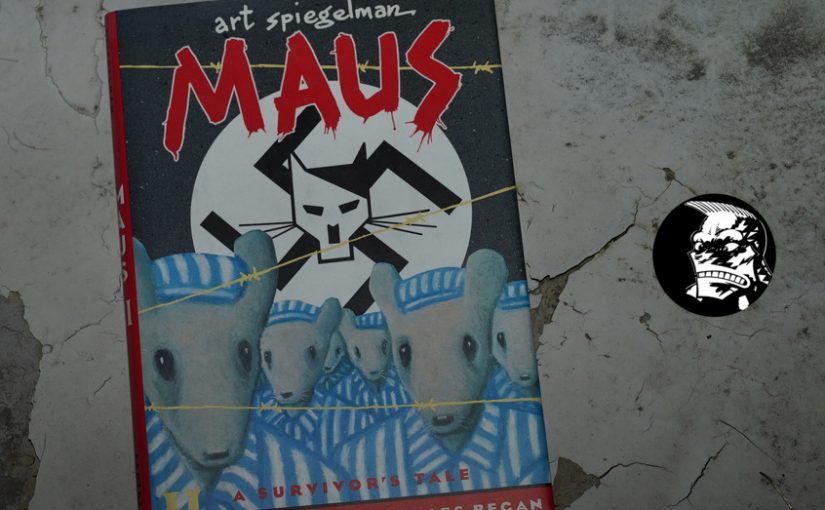

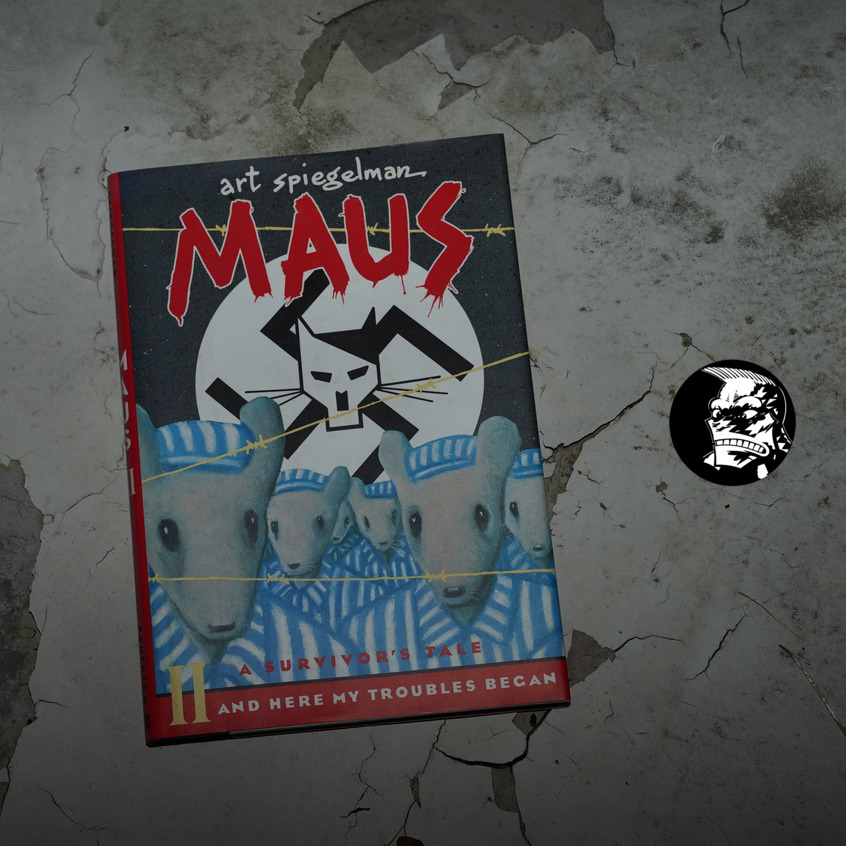

Maus II: And Here My Troubles Began by Art Spiegelman (168x243mm)

This book collects the four chapters of Maus that were published in Raw #8 and Raw Vol 2 #1-3, and adds a fifth and final chapter. While I’ve read the chapters that made up the first book many times (as inserts in the Raw books as a teenager) and know them by heart, I think I may have read the final chapter here only once before? When I bought this book thirty years ago? And forgotten all about it.

So I have absolutely no idea how Maus ends, and I’m kinda excited to find out.

Now, I’ve already talked about the first four chapters in previous blog posts in this series, so I’m not going to go over those again, I think, but let’s look at the book itself.

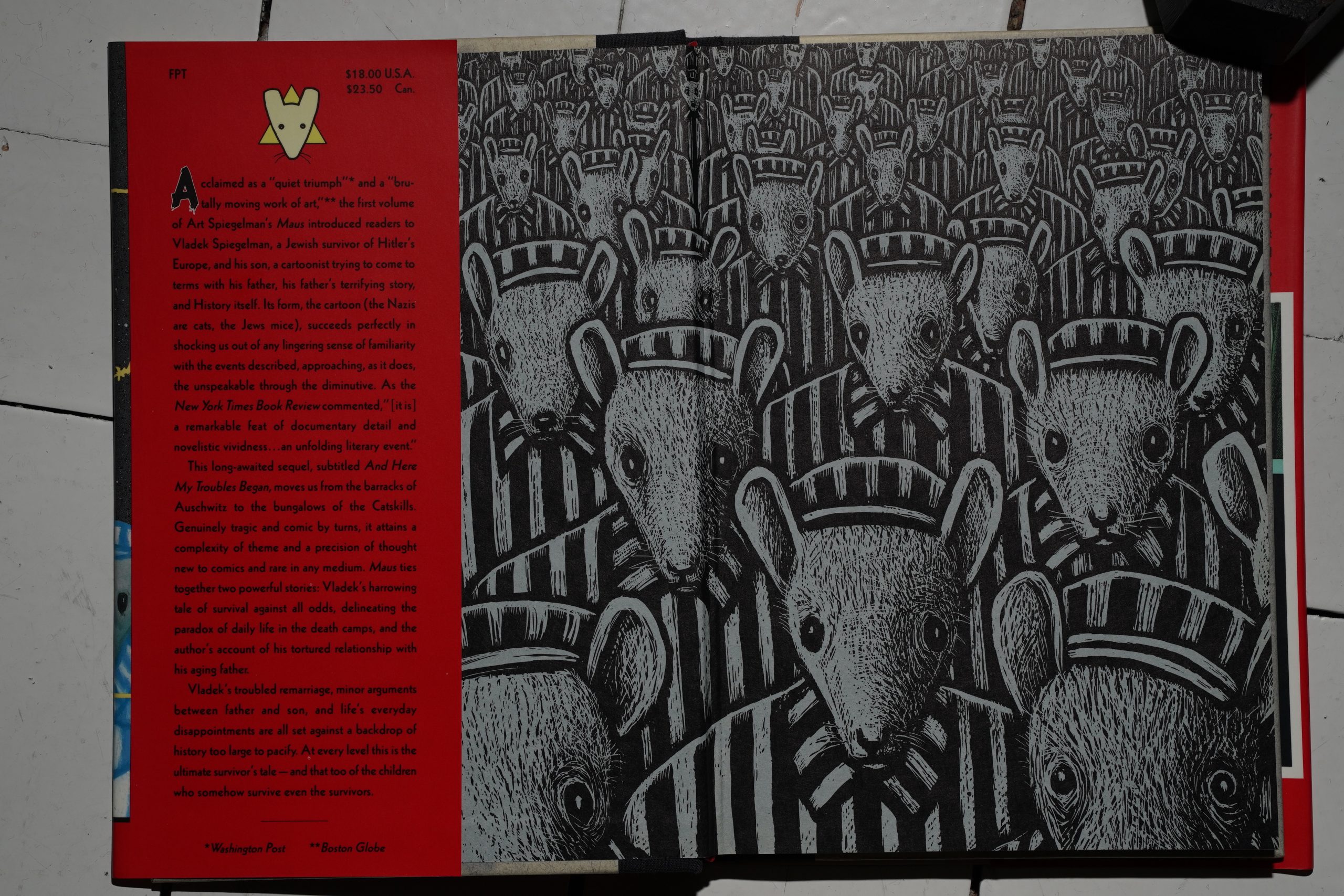

We get the customary hard sell on the inside flap, which sits really uncomfortably next to the end papers…

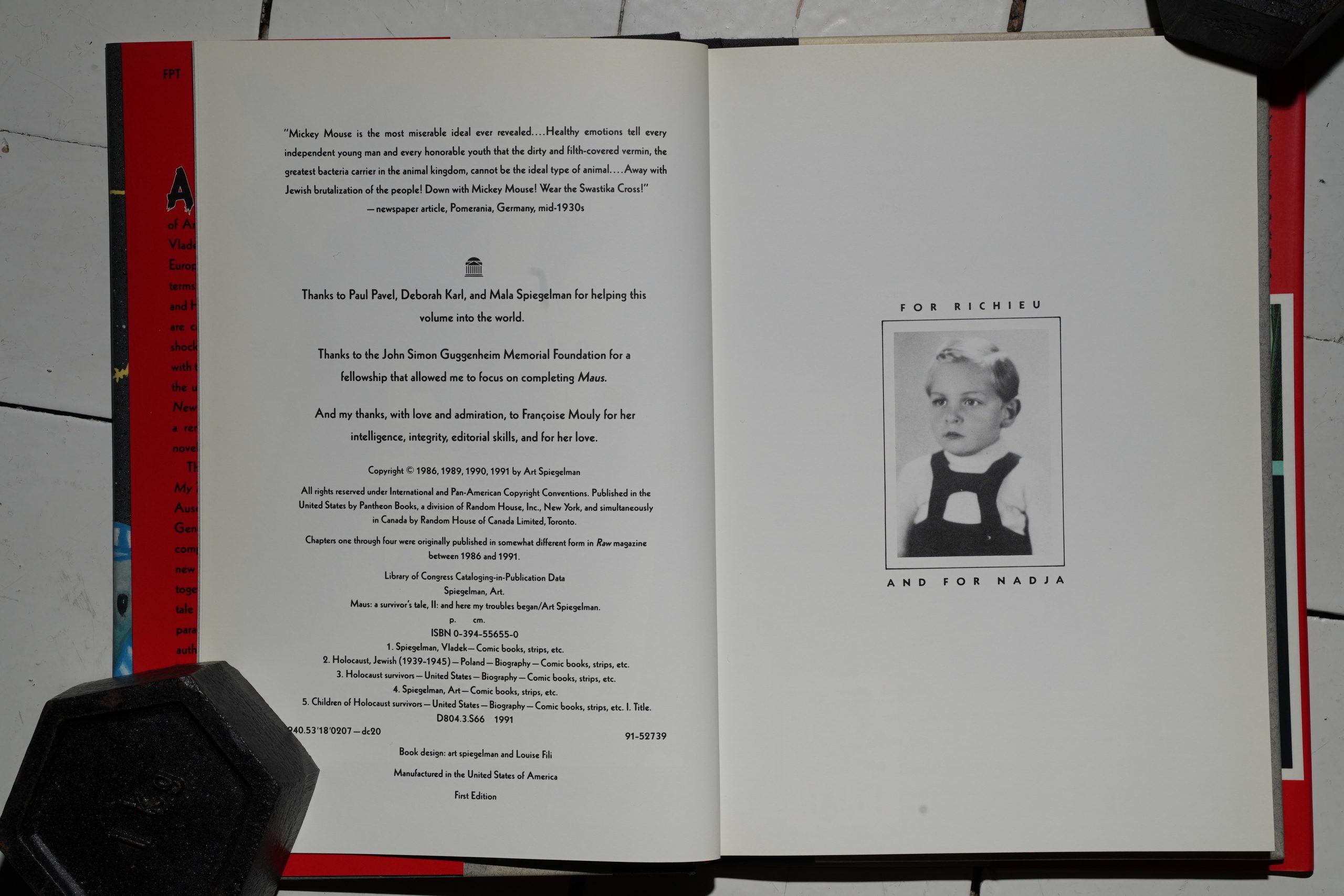

Spiegelman’s brother Richieu, and a quotation from some Nazi that explains the visual metaphor.

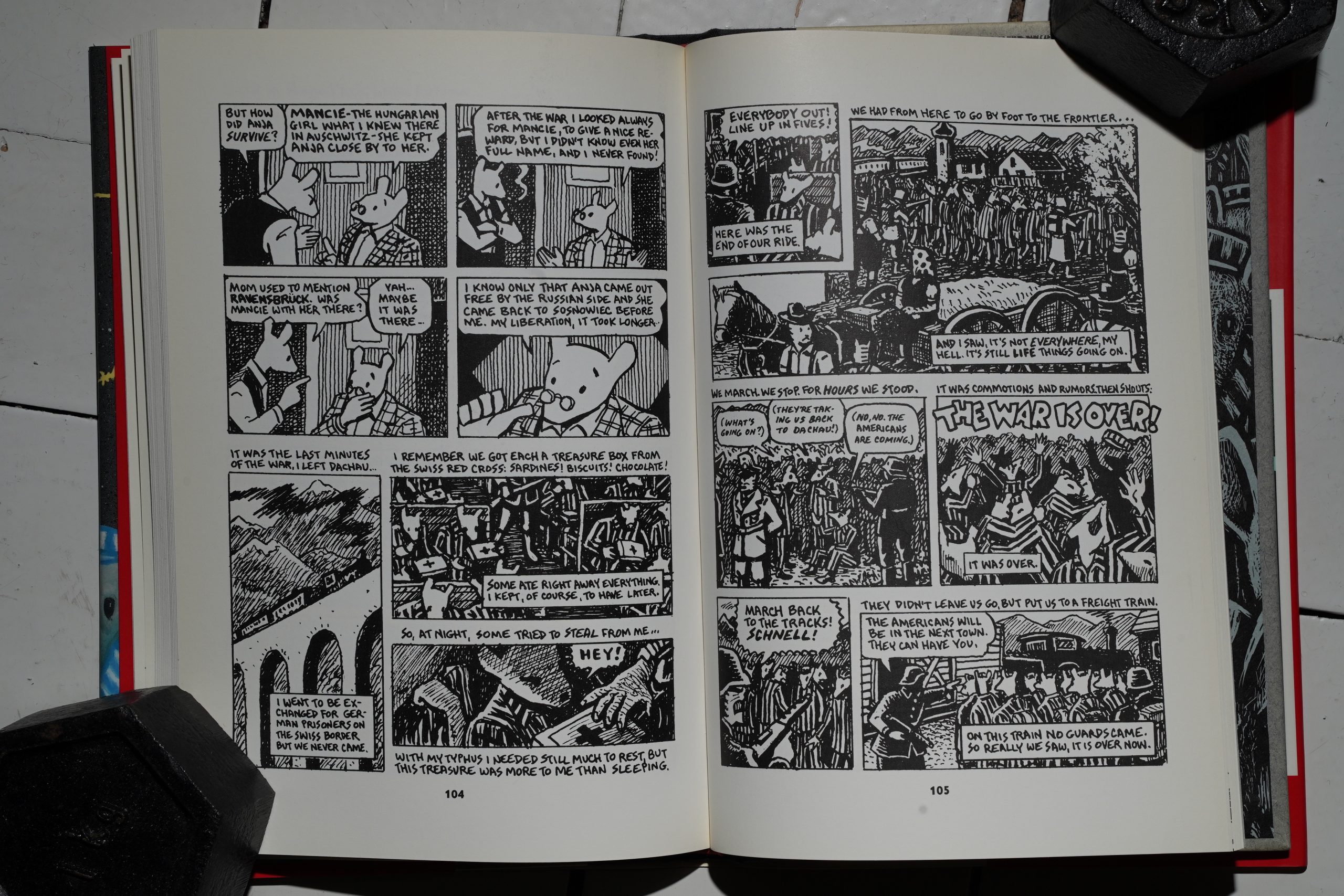

As promised, I’m not talking about the first four chapters, but reading them now was pretty hard going: The German and Polish atrocities keep on coming with just momentary relief brought by unexpected kindness and mind-boggling heroism from people like Marcie. (I wonder whether they perhaps managed to find out her full name and who she was after this was published — perhaps there’s stuff about that in Metamaus (which I haven’t read yet).)

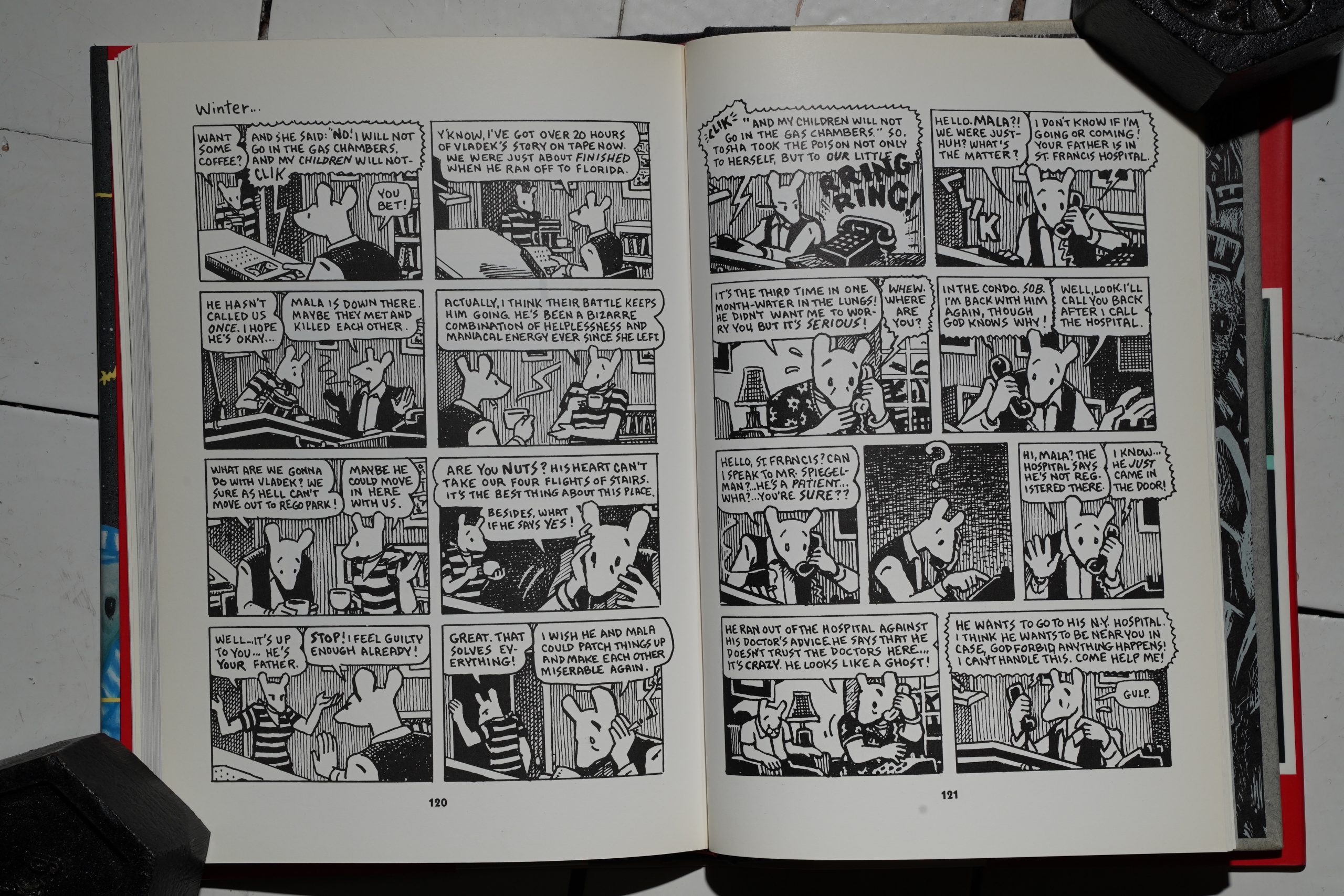

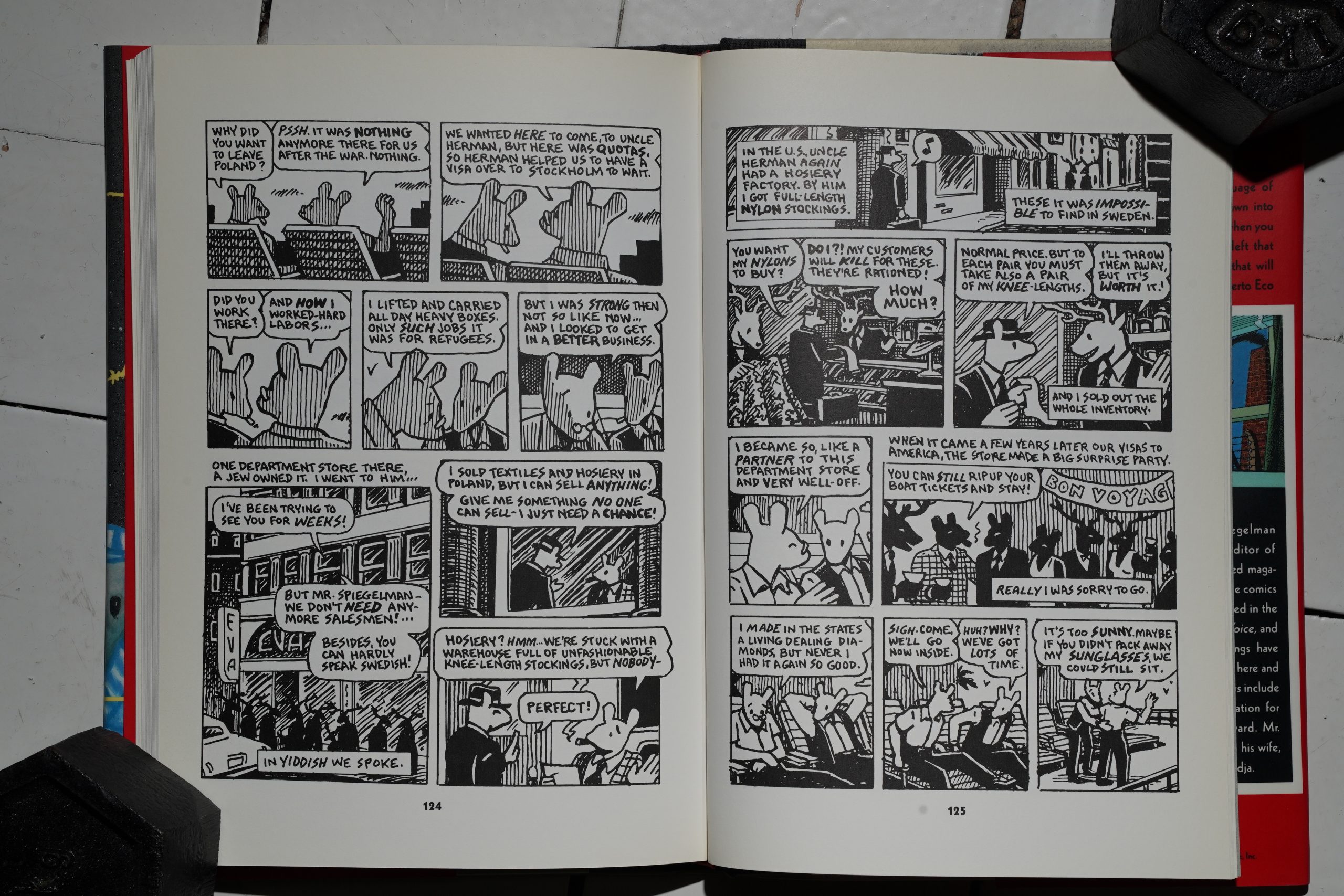

And then the final chapter — it’s mostly about Vladek being even more exasperating than usual (if that’s even possible), and his health problems (and the rest of them dealing with that).

Heh. Swedes are moose. Mooses. Meece?

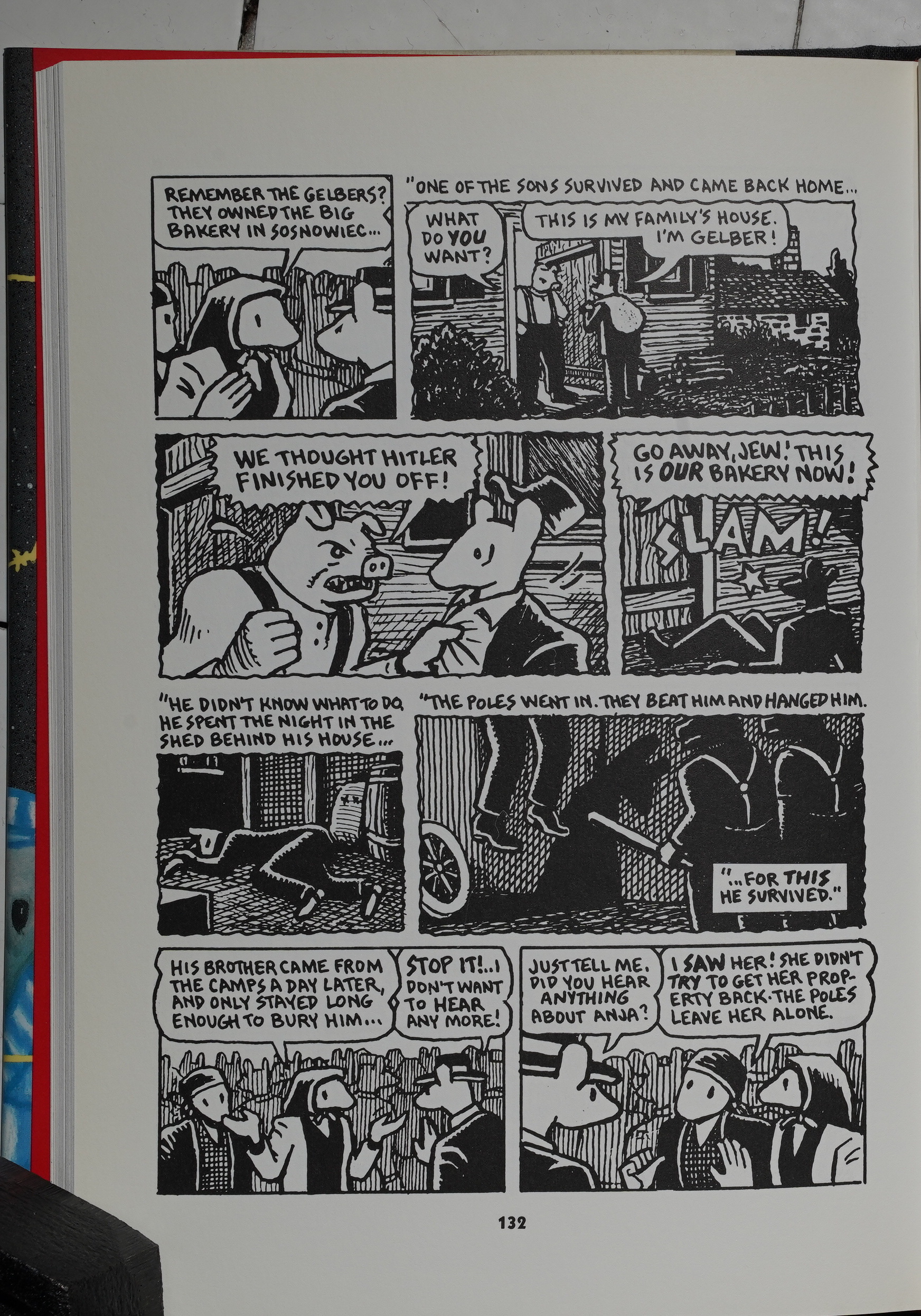

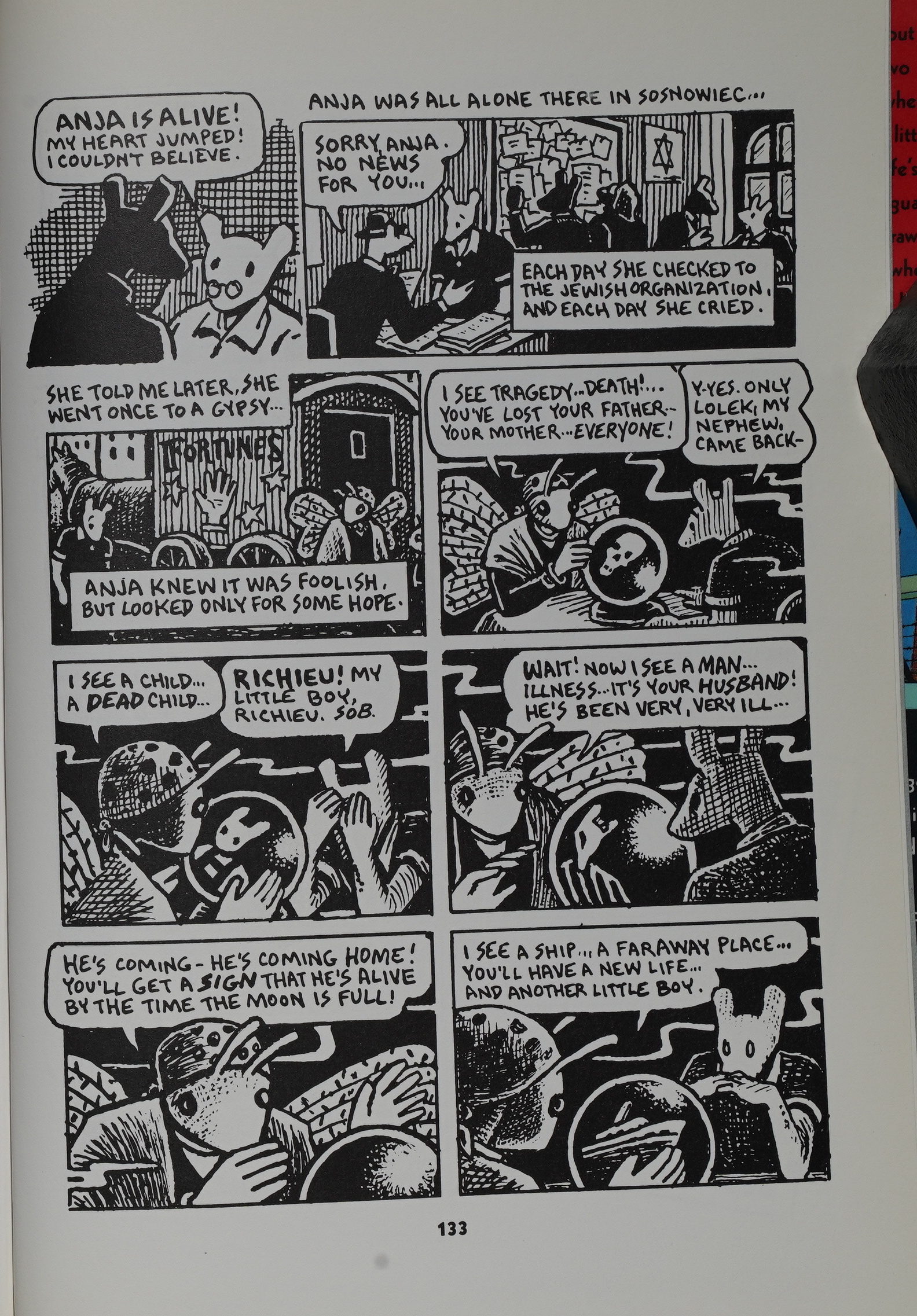

The chapter ends with Vladek telling the final part of his story: About going back to Poland to find Anja. And meeting… er… well, murdering Polish assholes. Is Maus banned in Poland, I wonder? I think the current regime’s policy is that there have never been any anti-Semitic feeling in any person from Poland ever? And certainly nobody has ever participated in any crime against any Jewish person; that was all the Germans…

(I probably shouldn’t say anything more, or this blog will get banned in Poland.)

OK, now Spiegelman’s just fucking with us: Gypsies as moths? Is he undermining the metaphor on purpose, saying that it’s time to stop using it (by going to these extreme lengths)?

The first Maus book ended with a scene of Speigelman’s anger towards his father… This book ends with two pages of Vladek talking from his bed, bringing closure to the story by finally reuniting him with Anja. And gives Vladek the final word: There’s only silence after he stops talking.

It’s an amazingly powerful end.

*sniff*

Maus is an incredible achievement. It was created over more than a decade, but manages to be impeccably readable. It could have gone wrong at any point, but Spiegelman stuck with it, and succeeded.

But what did people think about it at the time?

Bruce Canwell writes in Amazing Heroes #198, page 70:

Forget your American Flaggs. Forget

your Dark Knights and your Watch-

tnen. I assert that comics has produced

only one true work of literature—and

Maus is it.

I have nothing against the three

aforementioned series. I read them all

and enjoyed the dickens out of them—-

each is a wonderful example of comics

with an adult sensibility, but each is

ultimately limited by the traditional

comic book conventions: gaudy cos-

tumes, conflicts of almost mythic

proportions, and a pervasive feeling

of people and events that are larger

than life. For comics creators to prove

they can produce work of true literary

merit, they have to put aside the

medium’s familiar trappings and tell

“little” stories. tales with a tight focus

that deal with the subtle interplay of

idea and emotion among mundane

characters, and they must tell them

with a skill that will compare favor-

ably to a Joyce Carol Oates, a John

Cheever, or a Raymond Chandler.

Y,/hat comics artists and writers

working today are up to that chal-

lenge? Will Eisner had come close,

bless him, with The Dreamer and To

The Heart of the Storm, but only Art

Spiegelman has hit the bullseye.

And he hit it again with Maus II:

And Here Mv Troubles Began, the

conclusion of the two ‘ stories so

skillfully interwoven in the first Maus

volume. Maus II chronicles the atroci-

ties of the Holocaust from a survivor•s

view within the Nazi concentration

camps of Auschwitz, Birkenau, and

Dachau, interwoven with the modern-

day tale of an emotionally complex

relationship of the type that can only

exist between a father and a son. The

connection between these two narra-

tives is that the survivor from the first

story—a resourceful, admirable cha-

racter—is also the miserly, flint-heart-

ed father of the second. His name is

Vladek Spiegeltnan. Art Spiegelman

is his son, an artist who has found the

best way to tell these intense and

personal stories is through comics (he

makes all his Jewish characters mice,

all his Germans cats, all his Poles pigs,

all his Americans dogs, and so on).

By using anthropornorphism, Spie-

gelman makes pålatable both the harsh

reality of the death camps and the

ternpe

The Comics Journal #147, page 24:

SPIEGELMAN BOOK RECEIVES UNPRECEDENTED CRITICAL PRAISE

Mad About the Maus

Art Spiegelman’s Maus, a Survivor’s Tale II:

And Here My Troubles Began was published by

Random House in late October to a level of cri-

tical acclaim seldom, if ever, before afforded

to a cartoon book. Some critics refused to call

it a comic, claiming that nothing this good

deserved the name.

“Art Spiegelman doesn’t draw comics,”

wrote Holocaust scholar Lawrence L. Langer

in the New York Times Book Review (in the first

front-page review it ever gave to a comic pub-

lication). “It might be clever to say that he draws

tragics, but that would be inaccurate too…

Maus II is a serious form of pictorial literature,

sustaining and even intensifying the power Of

the first volume. It resists defining labels.”

A less condescending reference to the com-

ics medium was given in a daily Times review

by Michiko Kakutani, who wrote that when the

first Maus collection appeared in 1986 it created

a sensation for daring to tell a serious story

“through the form ofa comic book, a form asso-

ciated in most readers’ minds with the Sunday

funny papers. That Mr. Spiegelman portrayed

Jews as mice and Nazis as cats, however, did

not end up trivializing the event, as one might

fear; rather, it served to goad the reader into

looking at the event anew.” Kakutani said of the

second book, “Mr. Spiegelman has stretched the

boundaries of the comic book form and in do-

ing so has created one of the most powerful and

original memoirs to come along in recent years.”

Robert Wilson wrote in USA Today that the

first book “turned out to be anything but the

bad joke it might at first appear. Maus in fact

reinvigorated a story so familiar that, in spite

(or because) of its encompassing horror, it

threatened to inspire only a numb acceptance,

or even indifference. This is how the past, no

matter how grotesque, becomes the past. But

Spiegelman, whose parents Vladek and Anja’s

Story Maus was, made that painfully present

once again… The illustrations themselves,

which had the graphic simplicity of the comic

strip, were also wonderfully effective at convey-

ing mood… But the words, floating in their car-

toon balloons, were also effective and even mov-

ing, even within the forced economy of the form.

Vladek’s broken English was especially so.”

Maus II entered the New York Times and

Publisher’s Weekly bestseller lists in December.

According to a Times article, “The Times lists

it under fiction, reasoning that the events,

though real, did not happen to animals. Pub-

lisher’s Héekly has it under nonfiction.”

An exhibit of Spiegelman’s original draw-

ings, Project: Art Spiegelman, opened Dec. 17

at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

All but the last chapter of Maus II was

originally published in Spiegelman and Fran-

coise Mouly’s RAW anthology. It is unclear

whether the last chapter will get such treatment.

Penguin USA’s contract to publish RAW has run

out with the third trade-paperback volume, and

Spiegelman says he hasn’t decided whether to

accept Penguin’s Offer for another series. “Every

time we finish an issue, I tell myself it’s going

to be the last one. With this most recent issue,

I was telling myself that back when it was just

getting started.”

Yeah, it was pretty much universally hailed as the best thing ever.

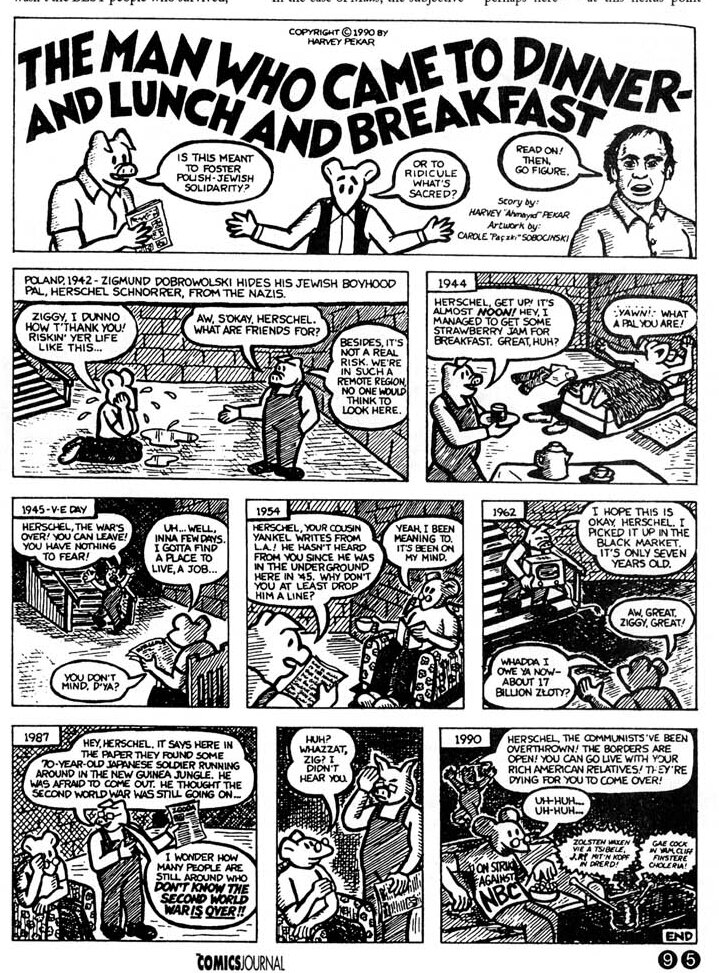

Harvey Pekar and Carole Sobocinski respond bizarrely.

The Comics Journal #149, page 96:

HIT LIST

Unless you’ve been vacationing somewhere in the

Himalayas for the last eight months, you’ve certainly

heard about Maus II. And, for once, something more

than lives up 10 the praise accorded it by the media.

The completion of Spiegelman3 Maus gives the art-

form of comics one Of its true epics, and it’s un-

mistakably one Ofthe most emotionally resonant and

compelling uorks in any medium. In this volume,

which compiles Maus chapters that have appeared in

the last several issues of RAW, Spiegelman continues

his moving document of the strength Of human will,

contrasting the truly existential drama of Vladek

Spiegelman’s experiences in a German concentration

camp with the equally moving and finely comical at-

tempts of son Art to capture his father•s memories Of

the most horrible human experience in history. Maus

ITS latter-day sequences are as absorbing and precise

as the camp memories — Vladek Spiegelman is among

the most complex, whole characters in the artform’s

history. Spiegelman’s artwork continually impresses

with its economy and expression, and the hardcover

book is beautifully packaged and printed. Maus II is

a testament to the sheer potential Of comics, and a

walloping refutation of the artform’s “inferior” status.

In comics, people were definitely using it as a “See? Comics are good! Now stop giving me wedgies!” thing.

Gary Groth is a party pooper in The Comics Journal #147, page 5:

The Maus Fallacy

An Editorial By GARY GROrHArt Spiegelman’s Maus II was re-

eased in November and was an immediate

critical and commercial success. By the time you

read this, some 100,000 copies should have been

sold. In a nation that consumes troughs-full of

mediocre cultural slop and ignores work of keen

insight and intelligence, Maus’s success looks

like nothing less than a miracle, and leads us

to the inevitable question: How in the name of

God is this possible? And secondly, what does

the success Of Maus mean for comics in general?

Beginning with the second question first, the

answer, unfortunately, is not much. Contrary to

what you will soon begin hearing in the pop-

ular media and especially from the comics in-

dustry’s flacks and cheerleaders, the commercial

success of Maus will not usher in widespread

recognition of comics as an art form, the ac-

ceptance of the graphic novel in mainstream

bookstores, or any other wildly optimistic, ex-

trapolated surmise.

But the public breast-beating has already be-

gun. Capital City Distributors has jumped on

the Maus bandwagon in the December issue of

their retailer newsletter, Internal Correspon-

dence. They spend a column Of copy drooling

Over the recent New York Times coverage of

Maus. The tone is one of collective triumph,

as if by its efforts Of the fraternity of the com-

ics profession has should all share the achieve-

ment of Art Spiegelman. It revels in the “greatly

increased sales” it hopes to reap because of said

coverage and ends with this: “The ‘golden age’

Of the graphic novel, originally forecast to begin

in 1989, may finally be underway now.”

It takes a certain amount Of chutzpah for a

distributor who spends at least 99 percent of its

resources promoting illiterate junk to bask in

the glory of Maus’s success. Capital’s cover

feature that month, just to give you one exam-

ple of their typical high-mindedness, is of DC’s

forthcoming Star Trek comic. (Nor have they

ever featured a cover of any work even remotely

aesthetically comparable to Maus.) But, get used

to this sort of thing: schlockmeisters and mar-

keting professionals who otherwise preoccupy

themselves with finding ways to make the lowest

common denominator just a bit lower pointing

to Maus with a wholly undeserved pride.[…]

Why won’t Maus spur the success of other

literary efforts within the comics form? Though

Maus deserves all the success it gets, the book’s

popularity derives from circumstances unique

to it and that cannot be easily duplicated by any

other graphic novel or comics collection. For-

tuitously, Maus plays into the prejudices of lit-

erary snobs as well as the vulgar requirements

of the mass media (through no fault of its own,

mind you).

First and foremost, its subject matter just

happens to be one of the three greatest human

tragedies of this century (and the most well

known and sympathetic); the Holocaust has

practically been appropriated by literature, be-

coming a literary subject known by critics who

know nothing about comics; and the work itself

demonstrates a sensitivity toward its historical

subject that makes it defensible among conser-

vative literary circles. The holocaust is intellec-

tually “current” in a way that stories of an

analogous literary quality about young women

in an LA punk milieu or a graphic novel Of de-

pression-era hoboes are not.

The one thing establishment media demand,

whether it’s the highbrow New York Times Book

Review or the cretinous USA Today, is respec-

tability of the kind Maus radiates and that talk-

ing penises or Mexican barrios, for example,

do not.

One of the many myths the mass media pro-

pagate about themselves is their love of diver-

sit)’. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

The mass media hate diversity and love same-

ness. The mass media are not devoted to help-

ing individuals become well-rounded human

beings; rather, they are devoted to turning indi-

viduals into like-minded consumer drones. The

Age of Information is actually The Age of the

Hard-Sell. The goal is to sell and this is done

most effiaciously by repeating the same image

over and over and over again — until it has

achieved its maximum sales saturation at which

point another image takes over. Since culture

only exists to stimulate economic transactions,

it is in nearly everyone’s best economic interest

to sell as many units of as few products as possi-

ble, thereby taking full advantage of the tech-

niques of mass production.[…]

The review of Maus in The New York Times

Book Re.’iew by Lawrence L. Langer does not

bode well, either. Langer reveals his prejudice

in his first line: “Art Spiegelman doesn’t draw

comics.” This means that anyone who draws

comics of literary value does not draw comics.

(What did George Herriman draw, anyway?)

This is the stuffy cant of the dilettante who

knows nothing of comics, doesn’t respect the

form, and must therefore immediately divorce

a work from its own medium. The message is

clear: only comics that aren’t comics will be re-

viewed in The New York Times Book Review.

A few good books always benefit from The

Age of the Hard-Sell, and Maus is one of them.

We should, I suppose, count our blessings. (We

being those of us fighting for a humane culture.)

But, while we may celebrate the deserved suc-

cess of this fine book, let’s not delude ourselves

into believing that this is a turning point and that

the public — and the mass media — is going

to suddenly rise from its stupor and reward

excellence.

Heh heh. I mean, he’s totally right — none of the comics he alluded to would go on to break through to the mainstream. But Groth didn’t see Fun Home coming.

This blog post is part of the Punk Comix series.