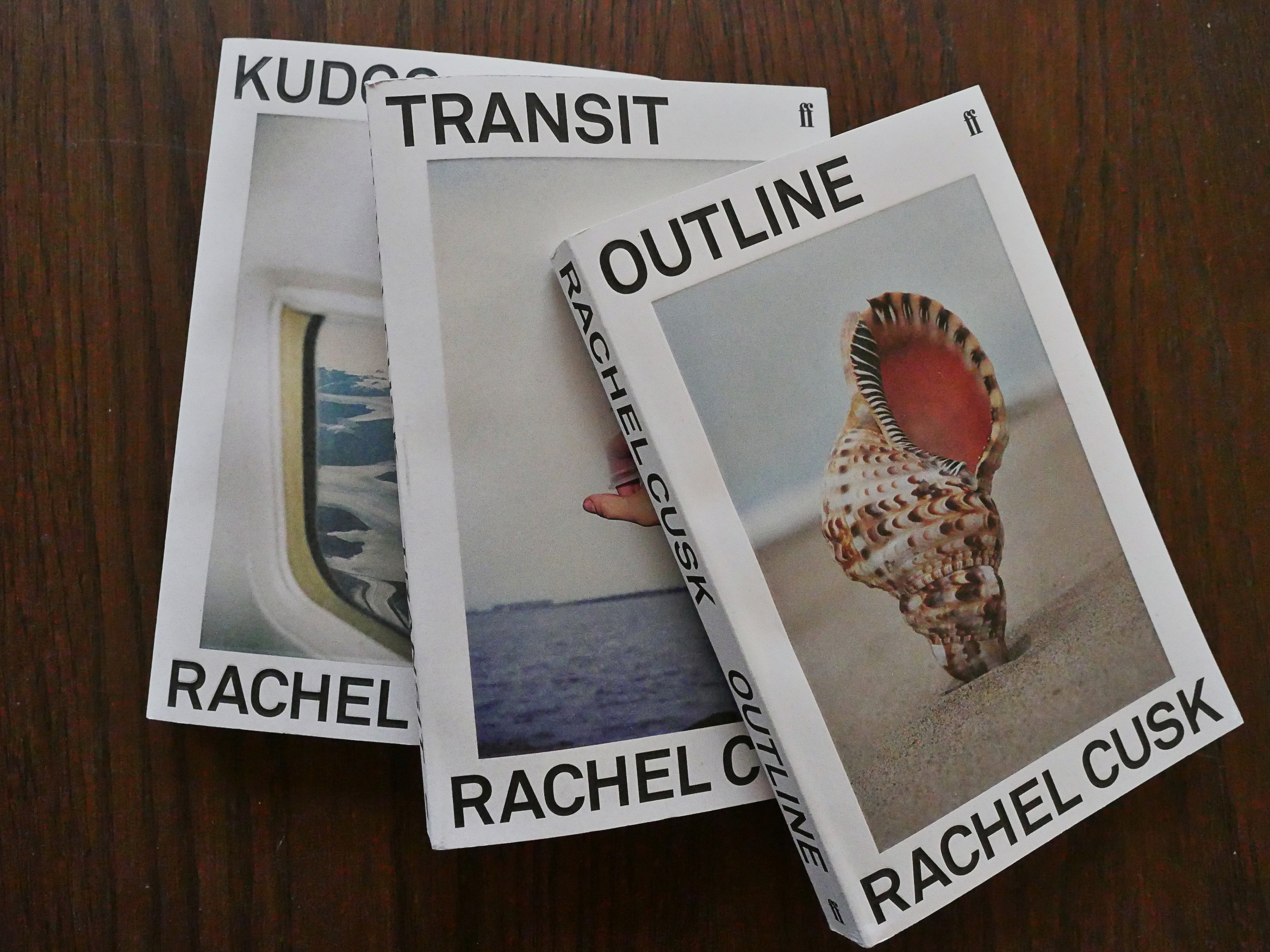

I’ve just read the second book in Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy, and it’s fabulous — perhaps even better than the first?

Anyway, it reminded me that I read a shattering and hilarious parody of Cusk in a Norwegian newspaper a few months back.

So I translated it into English; I hope nobody minds? I think it’s too funny (and accurate) not to be translated. Hey, author, if you want this removed, just leave a comment and I’ll do so.

Here it is:

Rachel Cusk (abbreviated)

KNUT NÆRUM

A monthly column that saves you time by giving you the essence of stuff you think you ought to have read. This time: Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy.

Because it was the last night of the festival for literary realism, and the other participants had apparently decided to call it a night early, I chose to have a walk on the beach in this unspecified country. The fishing boats were beached on the shore, with the painted eyes on the bows angled toward the beach promenade’s many restaurants and bars. I stopped by the restaurants that looked most promising; that is those that had guests, but weren’t too busy and therefore too loud. After visiting five places where nobody had entrusted themselves to me, I needed, to my surprise, to visit a restroom and went into a sixth establishment. When I left the bathroom, a women in a dress with vertical stripes asked me to join her at her table — she was alone with a bottle of wine — and listen to her talk, which I naturally agreed to.

At eight years old, she had had her tonsils removed. When she was leaving the hospital, she told me, the surgeon had approached her with a screw-top mason jar, wherein her tonsils were preserved in alcohol, and asked her if she wanted to keep them. At home she placed the jar on a bookshelf in her room, where everybody could admire them. One day, however, the jar was gone, and when she asked her parents if they knew where her tonsils had disappeared to, her father had immediately admitted that he’d thrown them out, since they were gross and infectious. The girl had never forgiven her father his transgression, and eleven years later she left home.

Maybe, I thought, saving your tonsils in a mason jar on a shelf isn’t that different from writing. It’s something you cut from your own life and then store in a way that can be observed by others, and that some people consider that in poor taste and unhygienic. At the same time I couldn’t help thinking that if you look long enough, you find somebody that tells a story that sheds light on your own life.

On the way back I chose a different route, through the centre of town. On a cobbled street in the old town I heard commotion and gay noises from a cafe decorated with coloured light bulbs and windows open to the street. Inside were all the other authors, who had apparently gone to this place to celebrate the end of the festival.

I entered, and as my colleagues caught sight of me, they grew noticeably quieter. I asked one of them, a man with a grey beard, if they had forgotten to tell me where they were going. He told me the didn’t think I’d be interested, but I could see in his eyes that this was about them being afraid that I was going to repeat everything everybody said in a book. Hang on, I said, let me write this down.

One thought on “Outline”