I moved to a self-hosted WordPress last week, and importing the images failed, so I had to do that manually. (That is, with rsync.)

Everything seemed to work fine, but then I noticed that loading the images of some of the older pages seemed to take a long time. Like, downloading megabytes and megabytes of data.

Time to do some debuggin’.

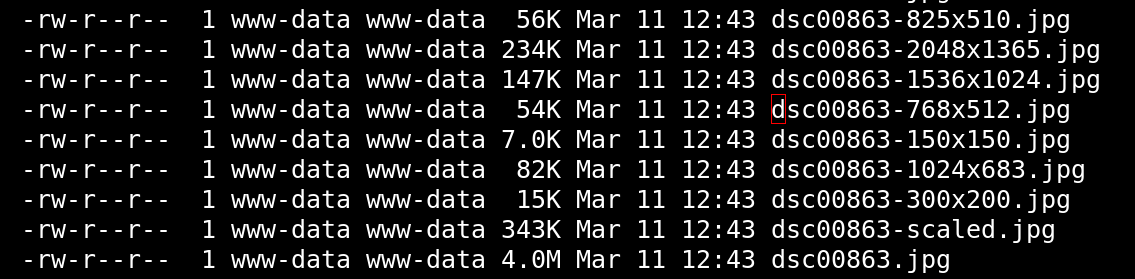

I’ve been a WordPress.com user for almost a decade, and I have avoided actually looking at the WordPress mechanisms as much as I can. But I did know that WordPress rescales images when you add them to the media library:

So uploading that dsc00863.jpg file results in all those different files being made, and since that hadn’t happened during my migration, I tried the Media Sync plugin, which is apparently designed just for my use case. I let it loose on one of the directories, and all the scaled images were dutifully made, but… loading the page was just as slow.

*sigh*

I guess there’s really no avoiding it: I have to read some WordPress code, which I have never done, ever, in my life. And my initial reaction to reading looking at the code can best be described as:

AAAAARGH!!!! IT”S THE MOST HORRIBLE THING EVER IN THE HISTORY OF EVER!

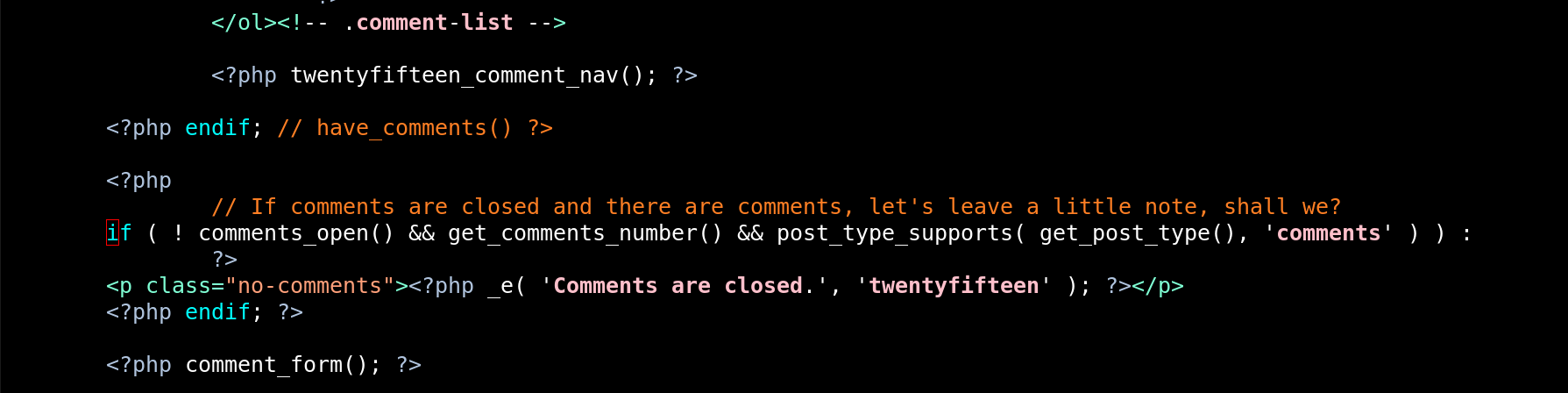

It’s old-old-style PHP, which is an unholy mix of bad HTML and intermixed PHP, with 200-column-wide lines. I had imagined that WordPress was … you know, clever, or something. I mean, it’s what the internet is built on, and then it’s just… this?

Anyway, I started putting some debugging statements here and there, and after a surprisingly short time, I had narrowed down what adds srcset (with the scaled images) to the img elements:

And I started to appreciate the WordPress code: Sure, it’s old-fashioned and really rubs me the wrong way with its whitespace choices, but it’s really readable. I mean, everything is just there: There’s no mysterious framework or redirection or abstract factories.

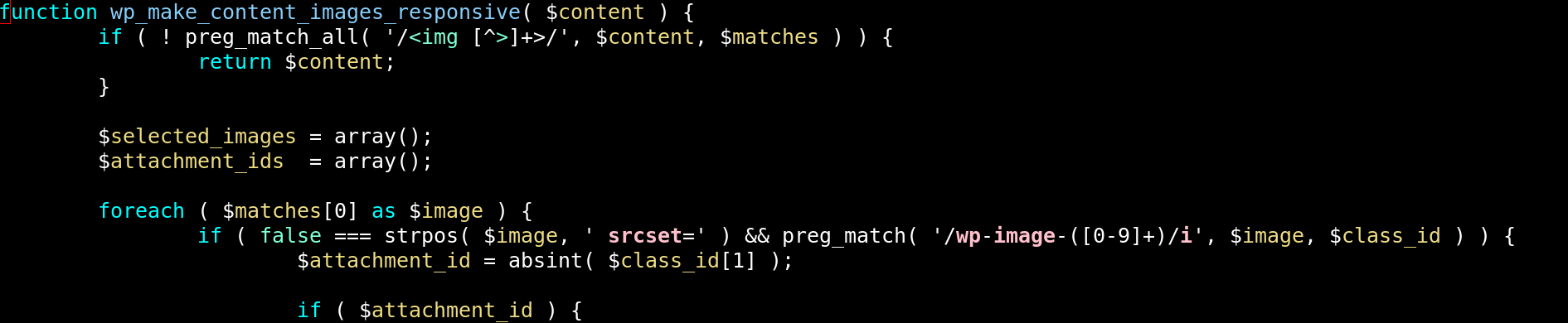

The code above looks at the HTML of an img tag, and if the class (!) of the img contains the string “wp-image-

You may quibble and say that stashing that data in the class of the img is a hacky choice, but I just admire how the Automattic programmers didn’t do a standup where that went:

“well, what if we, in the future, change ‘wp-image-‘ to be something else? And then the regexp here will have to be updated in addition to the code that generates the data, so we need to encapsulate this in a factory factory that makes an object that can output both the regexp and the function to generate the string, otherwise we’re repeating ourselves; and then we need a configuration language to allow changing this on a per-site basis, and then we need a configuration language generator factory in case some people want to store the ‘wp-image-‘ conf in XML and some in YAML, and then”

No. They put this in the code:

preg_match( '/wp-image-([0-9]+)/i', $image, $class_id )

Which means that somebody like me, who’s never seen any WordPress code before, immediately knows what had to be changed: The HTML of the blog posts has to be changed when doing the media import, so that everything’s in sync. Using the Media Sync plugin is somewhat meaningless for my use case: It adds the images to the library, but doesn’t update the HTML that refers to the media.

So, what to do… I could write a WordPress plugin to do this the right way… but I don’t want to do that, because, well, I know nothing about WordPress internals, so I’d like to mess that up as little as possible.

But! I’ve got an Emacs library for editing WordPress articles. I could just extend that slightly to download the images, reupload them, and then alter the HTML? Hey? Simple!

And that bit was indeed trivial, but then I thought… “it would be nice if the URLs of the images didn’t change”. I mean, just for giggles.

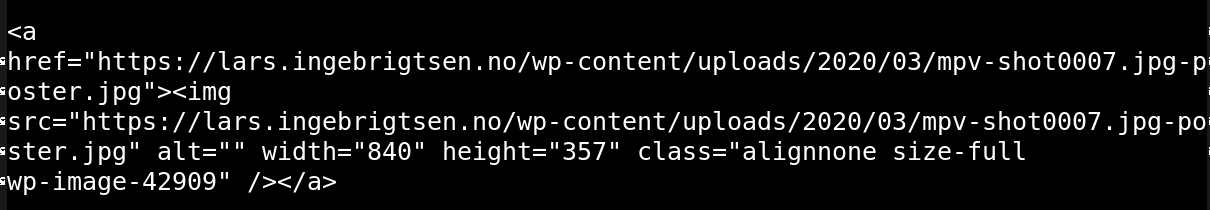

This is basically what the image HTML in a WordPress source looks like. The images are in “wp-content/uploads/” and then a year/month thing. When uploading, your image lands in the current month’s directory. How difficult would it be to convince WordPress to make it save it to the original date via the API?

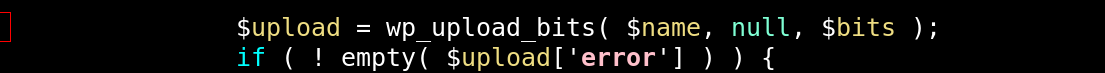

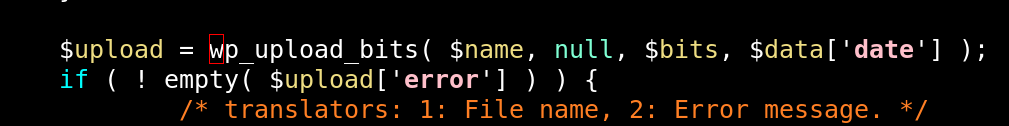

I grepped a bit, and landed on mw_newMediaObject() in class-wp-xmlrpc-server.php, and changed the above to:

And that’s it! Now the images go to whatever directory I specified in the API call, so I can control this from Emacs.

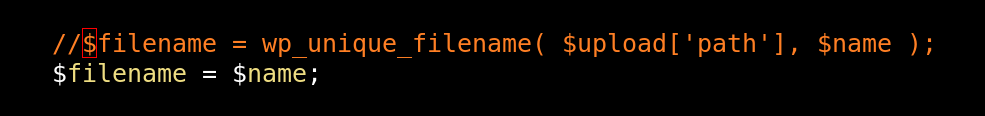

WordPress doesn’t like overwriting files, of course, so if asked to write 2017/06/foo.jpg, and that already exists, it writes to 2017/06/foo-1.jpg instead. Would it be difficult to convince WordPress otherwise?

No! A trivial substitution in wp_upload_bits() in functions.php was all that it took.

With those in place, and running an Emacs on the same server that WordPress was running (for lower latency), Emacs reuploaded (and edited) all the 2K posts and 30-40K images in a matter of hours. And all the old posts now have nice srcsets, which means that loading an old message doesn’t take 50MB, but instead, like… less than that…

It’s environmentally sound!

(Note: I’m not recommending anybody doing these alterations “for real”, because there’s probably all kinds of security implications. I just did them, ran the reupload script, and then backed them out again toot sweet.)

Anyway, my point is that I really appreciate the simplicity and clarity of the WordPress code. It’s unusual to sit down with a project you’ve never seen before, and it turns out to be this trivial to whack it into doing your nefarious bidding.