The next poultry disk in the Bistro Cooking book is a chicken-in-vinegar thing, and I’m not all that fond of vinegar, so I’m slightly sceptical. But let’s see.

The ingredients are simple enough: A chicken, tarragon, wine and vinegar (and some veggies).

So to get the show started, the chicken has to be butcherized. I’ve done this only a couple times before, and, boy, is it easier with a really sharp knife. And I’ve gotten a bit less squeamish, which also helps.

Doesn’t that look tasty? Huh? DOESN”T IT!?

A bucket of parts. (Whenever I’m doing stuff like this, I’m always singing Meat Is Murder to myself.)

So basically, the chicken is just cooked in a pan, and given a good sear. I don’t have a pan big enough to do all the chicken parts at once, so this takes a while…

So I started doing the sauteed potatoes while waiting.

Which sounds fancy, but is basically that you first cook the potatoes until they’re almost done, and then you fry them up some in a pan.

Then back to the chicken: Debone the tomatoes.

And I added a little salad, too.

And then it’s done, and I forgot to take more pictures.

The recipe called for half a cup of tarragon vinegar, but I thought that sounded way, way, way too much, so I scaled that back to a fraction of that. (A small fraction, nerds.) And the result was plenty vinegary, and the tarragon flavours came through well.

It was pretty good! Almost everything got eaten, which left just one breast left over for lunch the next, and it was very nice indeed.

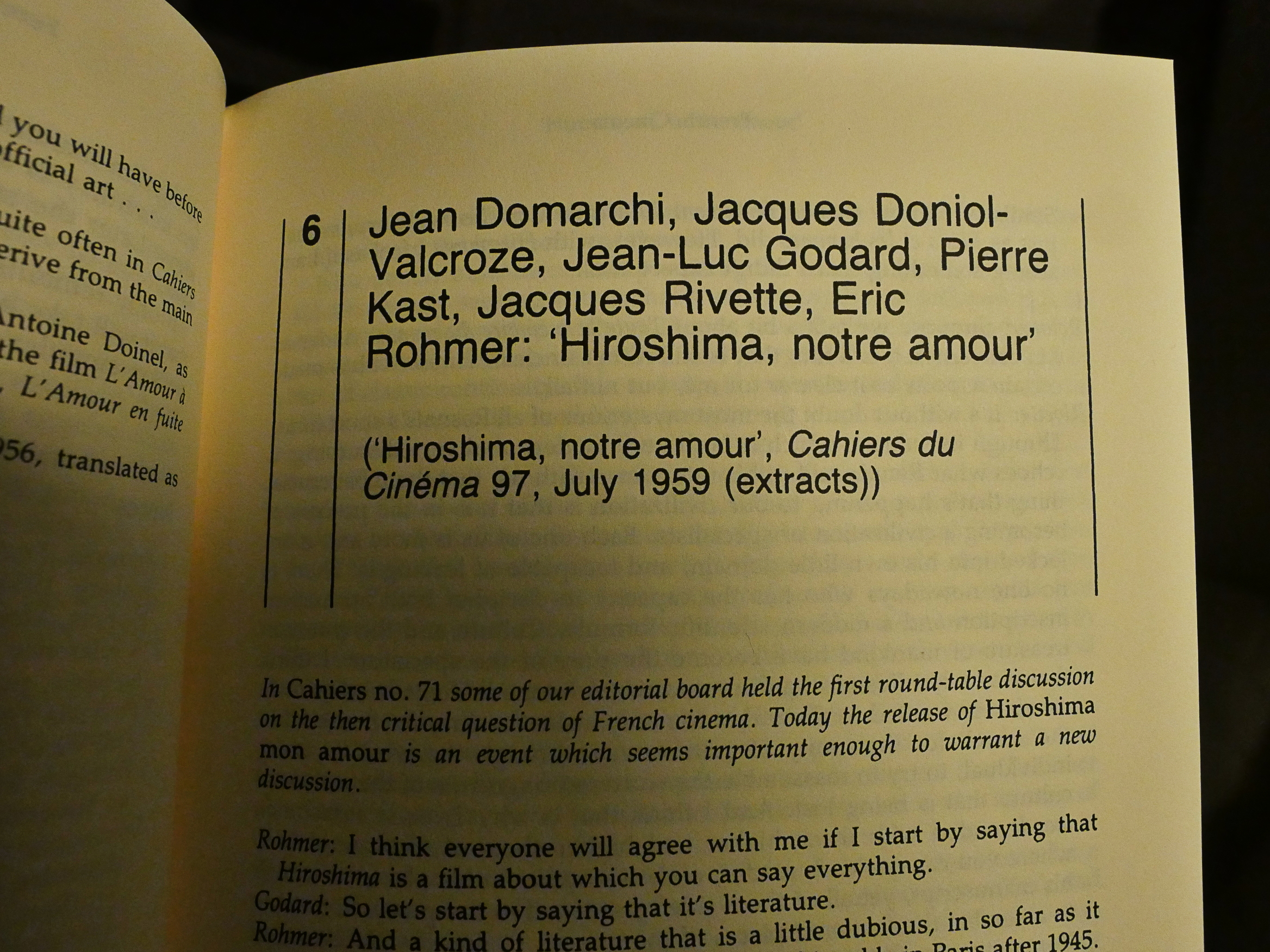

I quite like nouvelle vague movies, but I’ve never read the magazine all the directors (Goddard, Truffout, Rivette, Rohmer etc) were writing for before they started their careers in film: Cahiers du Cinéma. I was sure that surely somebody had published translated editions of these magazines by now, but nope. A couple of books doing a “best of” thing exists, though, so I got this one from the mid-80s, published by the British Film Institute, god bless them. Especially since the only thing these people have to say about British film is that is sucks.

So we get an introduction fist, giving an overview of Cahiers and the historical background.

And we also get a precis of what came out of Cahiers in the 50s: The mise en scene/auteur theory of filmmaking, which is very much a reaction against “French quality cinema”, which was dominated by literary sources and politics. Instead they wanted to herald film where the interesting thing is what’s on the screen: The way people talk, the framing, the pace, the lighting; in other words, what American filmmakers like Howard Hawks had been doing. That is, any Hawks movie has a plot that’s mostly piffle, but his movies are still fascinating because what’s on the screen is fascinating.

OK, that’s just my moronic summation of the thing.

The introduction uses the reception of a Howards Hawks movie in the UK as an example of their rapid influence: When Rio Bravo was first shown in the UK in 1959, it was dismissed as pure tripe. There was a revival of the movie four years later, and then a critic in the same newspaper gushes over it.

But, you know, I think perhaps the influence didn’t really have a very long reach. To this day, whenever you read a movie review, nine tenths of it is the reviewer recapping the plot, and then there’s a paragraph about whether the actors are any good, and then it’s “I like it/I hate it”.

It’s still all about the plot. For most people. I mean, I don’t mind plot, but I don’t care that much.

And after the introduction, most of the rest of the book consists of translations of articles from Cahiers. The most surprising thing to me is how short each article is – three to five pages. These mostly aren’t in-depth explorations of whatever, but are pretty normal, magazine-length reviews, mostly.

Oh! But we need more food. Foood. Beefy food.

(OK, I’ll give away a secret about how this blog article series is made: I’m not always making both the dishes I’m talking about on the same day. Hah! You never guessed, right?)

So this is a beef stew, and what’s fun about the recipe is that it takes that “oh, the stew is better the next day” thing and does the logical thing: This is to be eaten the day after it’s been cooked. I’m excited.

So the recipe called for “stewing beef”, and suggested having the butcher cut the meat into (large) pieces, but I’ve got a new knife and I wanna use it.

I used two different cuts of beef, just because. But both are supposed to be stew compatible.

There. Chopped.

And then you chop a lot of veggies (onions, garlic, carrots, celery (well, that’s supposed to be minced, and I’m a specialist)) and dump it into the pot. The recipe specified an enameled pot, but I don’t have one, so I just used a stainless steel one. Hopefully that’s OK…

The recipe also called for a Provençal wine, but I just had a Burgundy. Are those places anywhere near each other?

Let’s say… yes?

Oops.

Anyway, it’s in the pot now, along with a “bunch of thyme”. I consulted the interwebs to determine how much a “bunch” is, and I didn’t chop it, because the recipe didn’t say anything about chopping. So I guess I’ll just have to take it out of the pot before serving… It’ll probably dissolve some, anyway?

And then into the fridge to marinate until the next day.

So I can read some more Cahiers… one of the pieces is a conversation between a few of the Cahiers people, and for some reason or other the translation has been abbreviated? So it’s unfortunately somewhat incoherent, but they still say some pretty eyebrow-raising things. Like Rohmer claiming that nothing has changed in France since 1930. Which is pretty weird, considering WWII and everything in the middle of that time period.

Rivette, of course, thinks the claim is absurd, and rightly so.

And then, the next day, I forgot to put the stew on until three in the morning. So I guess I’ll just have to stay awake until morning.

So the next day I pull the pot out of the fridge, and it looks delicious! I mean, horrible! But I guess that’s to be expected, what with the fat floating to the top and coagulating.

As directed by the recipe, and got rid of the layer of fat…

… and heated the stuff with some orange peel.

I naughtily added a simple salad and some taters.

It’s… quite good? But kinda… I wished it tasted more. The sauce is really thin and watery, which makes it look rather disgusting since the scum of the meat hadn’t been skimmed off. (Because the recipe didn’t say to do so.) A thicker sauce hides many naughtinesses, but there’s no thickening in the sauce, either.

So it looks unpleasant, and the flavour is weak. Perhaps I used the wrong type of wine in the sauce? Should it have reduced more? I don’t know.

But it was OK. The meat was very tender indeed.

The reviews in Cahiers do a lot more plot recapping than I had imagined from the introduction, but there’s also interesting sections where they talk about actual movie stuff.

This is a British book, and I think the assumption here is that everybody has a basic familiarity with French. The book consistently talks about the “scenario” for a movie, and they’re not talking about the scenario, but the script. I THINK. That’s a particularly odd thing not to translate (since it’s ambiguous), but more common is to just leave titles untranslated. Even titles of articles, and I had to dig deep into my brainses to recollect (I mean, at least one whole second) to remember that “notre” is “our”.

But more than that, reading these reviews, I totally understand why there hasn’t been a complete translated collection of them published: It’d be pointless. Godard makes so many reference to movies and people that are completely unknown these days that it’s hard to know just what point he’s trying to make. There’s translators notes for some of the stuff, but even that doesn’t help much.

But back to the food: The day after the day after, there’s a ton of estouffade left, of course, so I heated some more up, but this time I added some sambal oelek and more herbs, and let it cook some more. Then I thickened up the sauce with some Maizena, and by golly: It’s delicious. It’s got a deep and complex flavour and a pleasant texture.

I gotta start using more common sense while doing the recipes in this book. The recipes are perhaps meant as basic scaffolding, and you’re supposed to add any goodies you need to make them into actual courses?

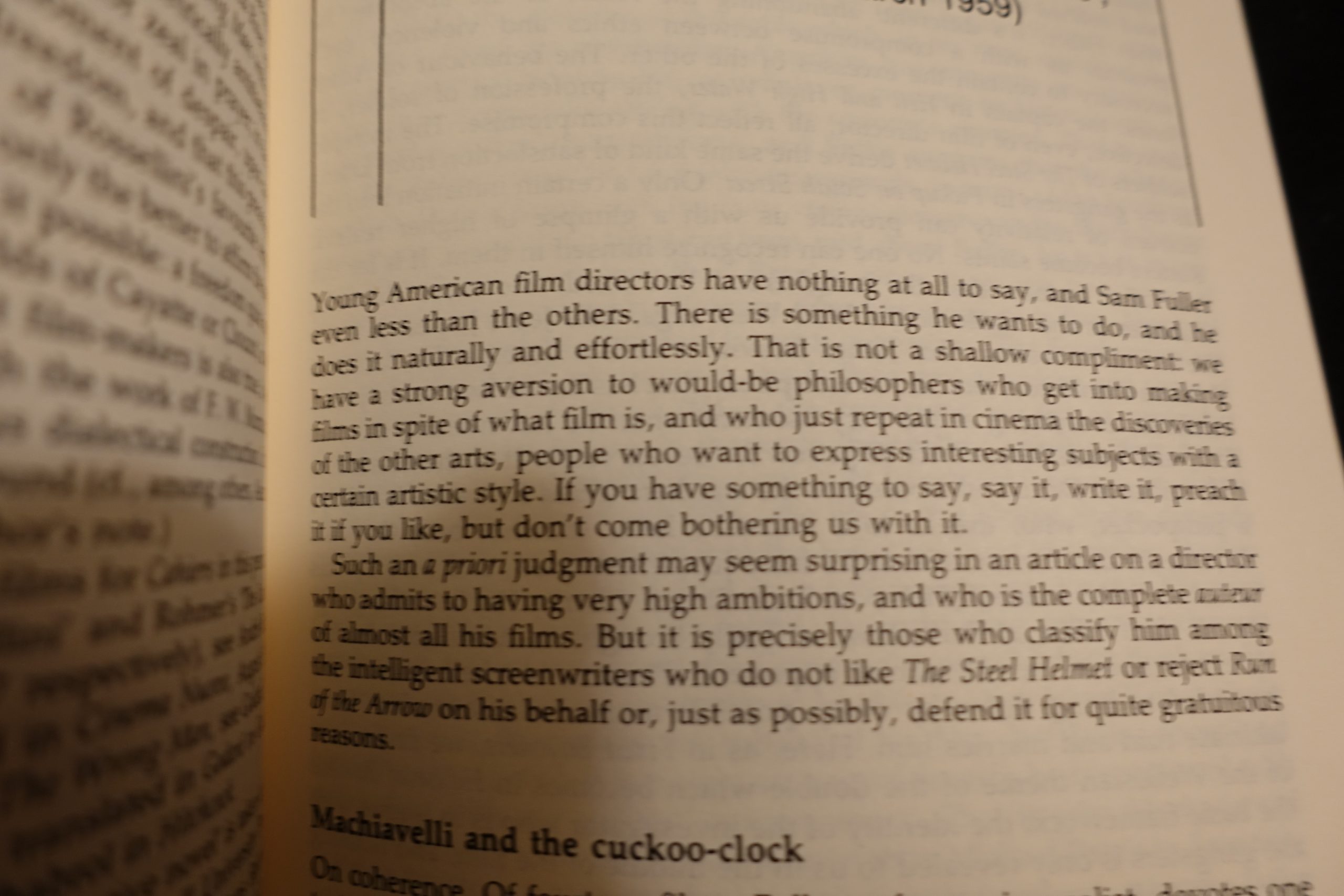

“Don’t come bothering us with it.” Most of the Cahiers writers are staunchly anti-political, and, I guess, somewhat right wing? I think that mostly changed in the 60s, when several of the people involved (like Godard) became very left-wing indeed.

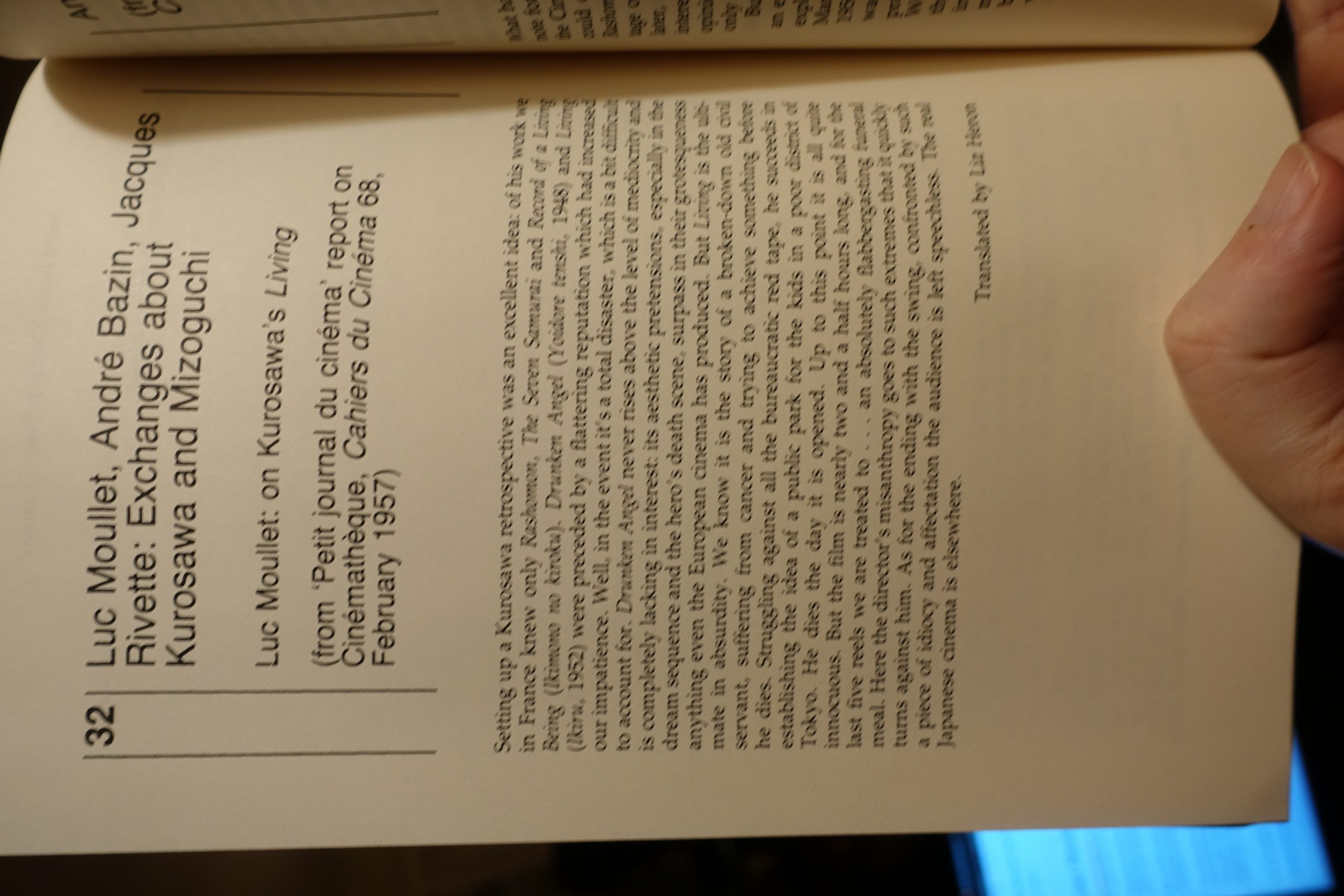

I love this total dismissal of Kurosawa’s Living (Ikiru).

Especially since it’s the 113th most highly-rated movie on imdb.

But many of these reviews and articles are super vague. “Morality is a question of tracking shots” may be a witty saying, but what does it mean, really? Page after page of this sort of stuff makes me feel very smart indeed for reading it, but I’m not sure how much there there is.

The book is having one specific effect on me, though: I’m definitely going to be buying all the movies by Nicholas Ray (of Johnny Guitar fame). He’s the Cahiersienne cause celebre (sort of): He’s a youngish director dismissed by most reviewers, but these people are totally convinced that he’s the bees’ knees, and is going to be The Director people will remember from the 50s.

That bit didn’t quite come true: While three of his movies have been restored by Criterion, and a couple more have apparently survived well (like Rebels Without Causality), most seem to be available unrestored on DVD.

Anyway, I’m buying them all. A dozen French people can’t be wrong.

This blog post is part of the Bistro

Cooking & Books series.