Emacs is moving away from ImageMagick support, and is instead handling all the major image formats (PNG, JPEG, etc) natively. The reason for this is that the ImageMagick libraries have a pretty bad track record: Over the years, a large number of Emacs crashes have turned out to stem from ImageMagick crashing. While things have been getting better, this is still a problem, especially as Emacs is being used as a web browser and a buffer overflow can lead to code execution.

But ImageMagick provides features that the native libraries do not, like image scaling and rotation, and without image scaling, everything’s sad. Have you tried looking at a web page in Emacs with all images being ENORMOUSxGINORMOUS pixels large?

Sad.

Fortunately, Emacs 27, while deprecating ImageMagick, has gained native image transforms at the same time, so we’re all set, I think. The only thing that’s missing is a way for image-mode and the like to suss out what the rotation of images should be, and that data is stored in the Exif portion of JPEG images.

So this weekend I finally got started with writing an Emacs Lisp package to parse Exif data (in JPEG images)… and I finished, too, because the format is way simple. Which shouldn’t come as a surprise, because it’s meant to be implemented by camera manufacturers, and they er well you know.

But it’s an interesting format. It has the smell of being cobbled together from whatever formats people had lying around, and it’s not… er… smart. I don’t think I’m being controversial when I’m saying that.

I’m not an Exif expert: All I know what was I googled while writing exif.el yesterday. If I say anything horribly wrong here, I’m er horribly wrong:

Basically, the Exif format is a TIFF file plonked into the APP1 field of a JPEG. The TIFF format is the weirdness: It’s based on four-byte (32 bit) offsets instead of something sensible like length specifications. And the offsets are always from the start of the TIFF file, so they’re absolute. (Well. Relative to the start. Relatively absolute.)

This means that there’s no way to say “just extend this string”: You have to recompute (or regenerate) the entire TIFF file, because everything that points to something after the string will have their offsets changed. One person writing one of the many web pages that try to explain the format laconically commented that no Exif editors do so correctly, or without corrupting at least some part of the data.

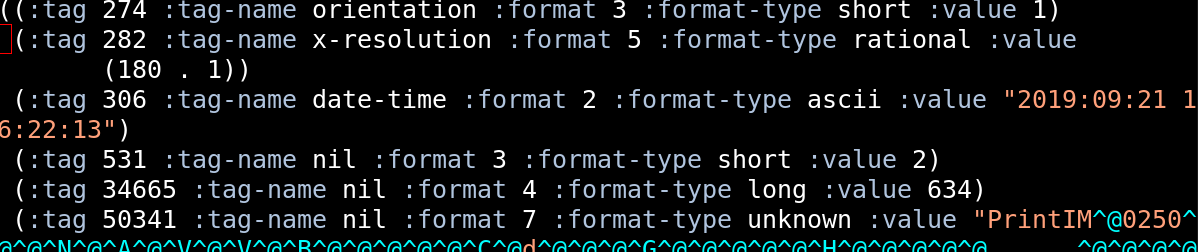

The main part of the TIFF is the IDF: The Image File Directory. It looks like this:

LL TT|FF|LLLL|VVVV TT|FF|LLLL|VVVV TT|FF|LLLL|VVVV ... NNNN

LL (two bytes; a 16 bit number) say how many entries there are, and then each entry is 12 bytes long. In each entry TT is the tag, FF says what “format” the data is, LLLL says how long the data is (a 32 bit number), and VVVV is the value of the data.

Simple, eh? Hah!

The format is stuff like “ascii”, “short” and “long”. A “short” is 2 bytes and s “long” is 4 bytes. To find the actual length of the data, you have to multiply LLLL with this number of bytes, so if you introduce a new format (with a different byte length), there’s no way for older parsers to know how long the data is! No wonder it’s common for Exif editors to mangle the data.

Besides not making sense, it’s not even any kind of optimisation, because no part in a TIFF file can be longer than what can be described by a 32-bit number, so having LLLL just specify the length directly would have been just as fine.

*sigh*

And then the real fun: If LLLL (times the format length) is shorter than 4, then VVVV is the value. If it’s longer than 4, then obviously it can’t fit into VVVV, so… VVVV (a 32 bit number) holds an offset value that points to a place in the TIFF file where the data really is.

But there’s nice things about the TIFF format. I mean, it has fractions. (They’re represented by eight bytes, the numerator is the four first and the denominator is the last four.) Ideal for parsing with Common Lisp, but unfortunately Emacs Lisp doesn’t have rational numbers.

Oh, I didn’t mention what NNNN is: It’s a pointer to the next directory section, which is er useful if er you have more than 65536 directory entries, I guess.

I think the funniest part of the Exif format is that the numbers embedded in it can be either little-endian and big-endian. Fortunately this is called out explicitly with a bit that says either “II” (Intel) or “MM” (Motorola), so it’s no biggie, but it’s just weird that they couldn’t decide on one or the other.

But isn’t it nice that all this archaeological technology lives inside our modern devices and programs? Just think of that the next time you see an image that’s correctly rotated for sure.

One thought on “Parsing Exif Data”