And finally: The Comic Reader, Hero Illustrated and… FOOM!?

OK, I said the previous post about the kwakk.info search engine for magazines about comics was going to be the last one, but then…

I’ve added The Comic Reader, Hero Illustrated and FOOM. Yes, FOOM — Friends Of Ol’ Marvel.

🤷

And this is the final blog post on this matter, and I mean it this time for sure.

An Excerpt from Comics Interview Presented Without Comment

Comics Magazine Search Engine Tweaks

Sorry about all these posts about kwakk.info in a row — but as usual, after releasing a project, I find myself poking at it way more than before I released it, and I keep finding things to tweak. It’s classic — I always think something is feature complete, every day, and then the next day I find something else to fix/add/etc.

But I thought I should mention this one, because it’s a slightly breaking change.

Before:

After:

See? Some of the magazines I’ve added recently had double page scans, and they don’t really fit into the kwakk.info template: They get shrunken too much (even when clicking on the page to magnify)… and it’s even worse on cell phones. So I scripted something to split double pages into single pages, and re-ran it through the OCR and indexer and gah.

Anyway, the slightly breaking change is that if you have an explicit link like https://kwakk.info/ci/?search=spiegelman&index=CI-070-082, then that link will now probably point to a different page than before. Affected magazines are Comics Interview and Comics Feature, and to some degrees also Marvel Age and Wizard; the rest haven’t been touched.

The URLs should be stable from now on, though. *cough*

Anyway, I was wondering whether there are any further mags that are worth adding… There’s the Comics Buyer’s Guide, of course, with over 1000 issues, but that doesn’t seem to be available anyway. But it would be a valuable resource, just because it was around for so long. Anybody got a collection?

I had a peek in my shortbox of “non comics mags”, and I found…

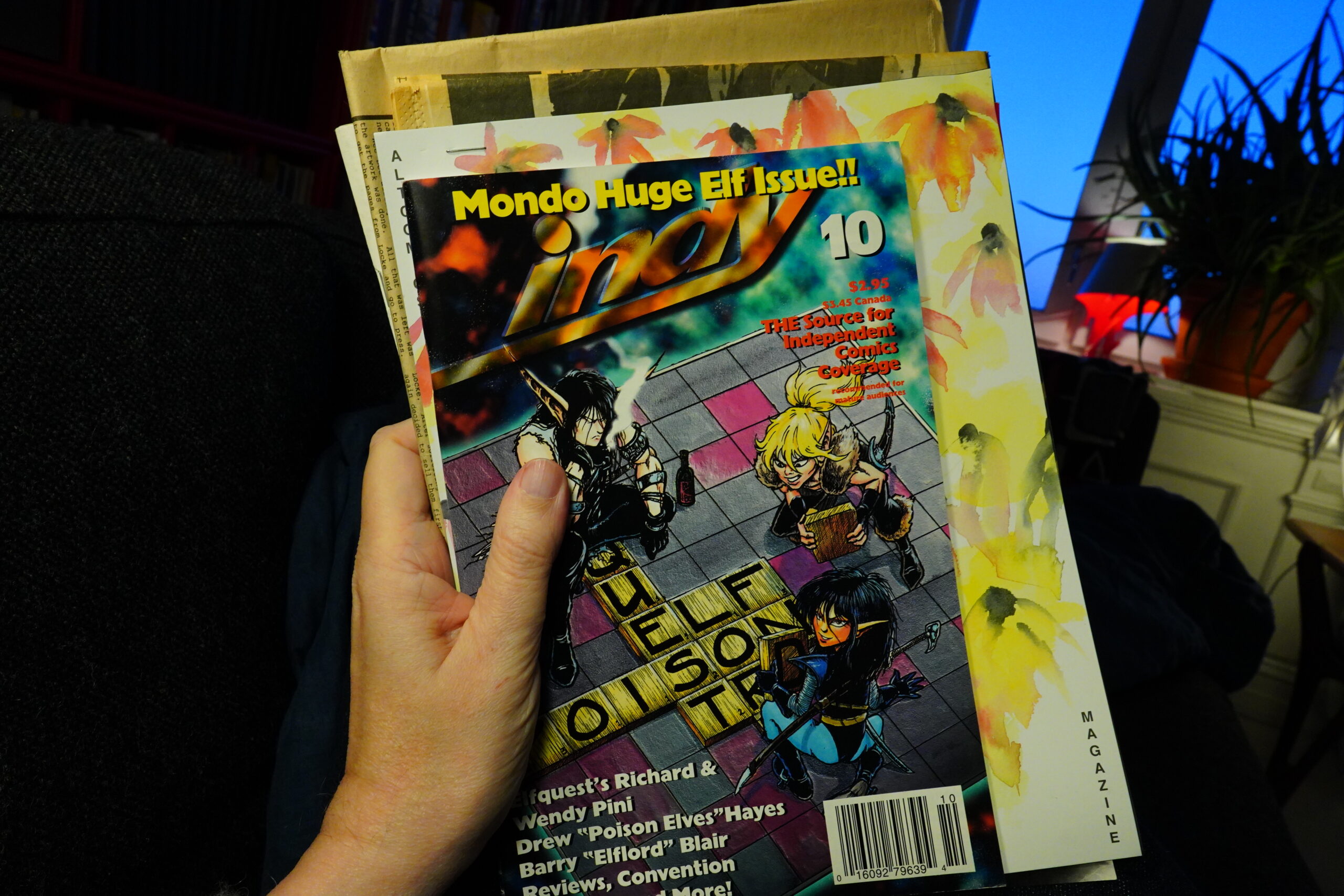

There’s apparently 17 issues of this magazine — Indy: The Source For Independent Comics Coverage. I’ve only got a couple of issues, and there doesn’t seem to be any collections up for grabs at ebay.

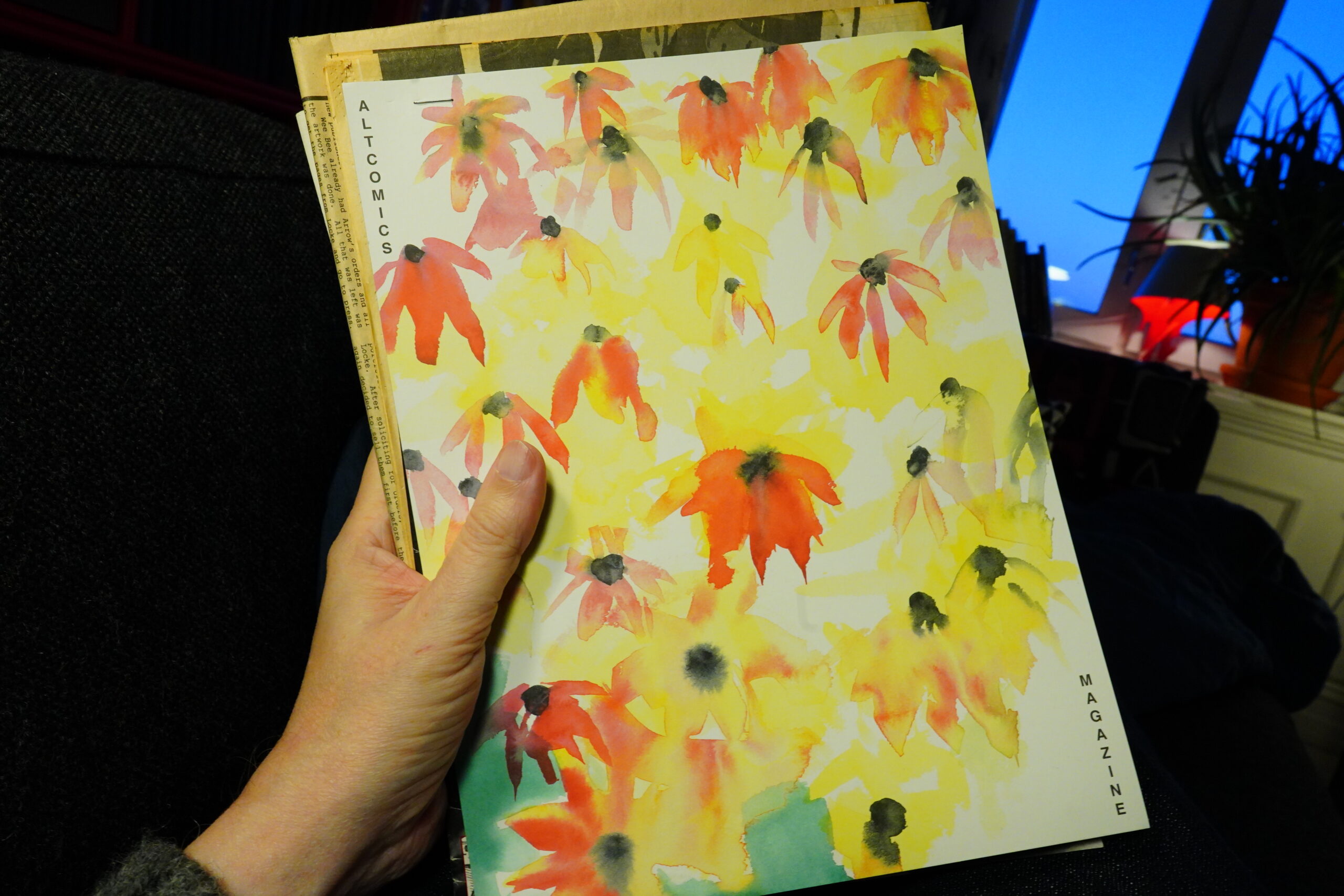

I’ve got all issues of Altcomics Magazine, but I think that’s too recent to add to something like kwakk.info — and you can still get all issues from 2d cloud.

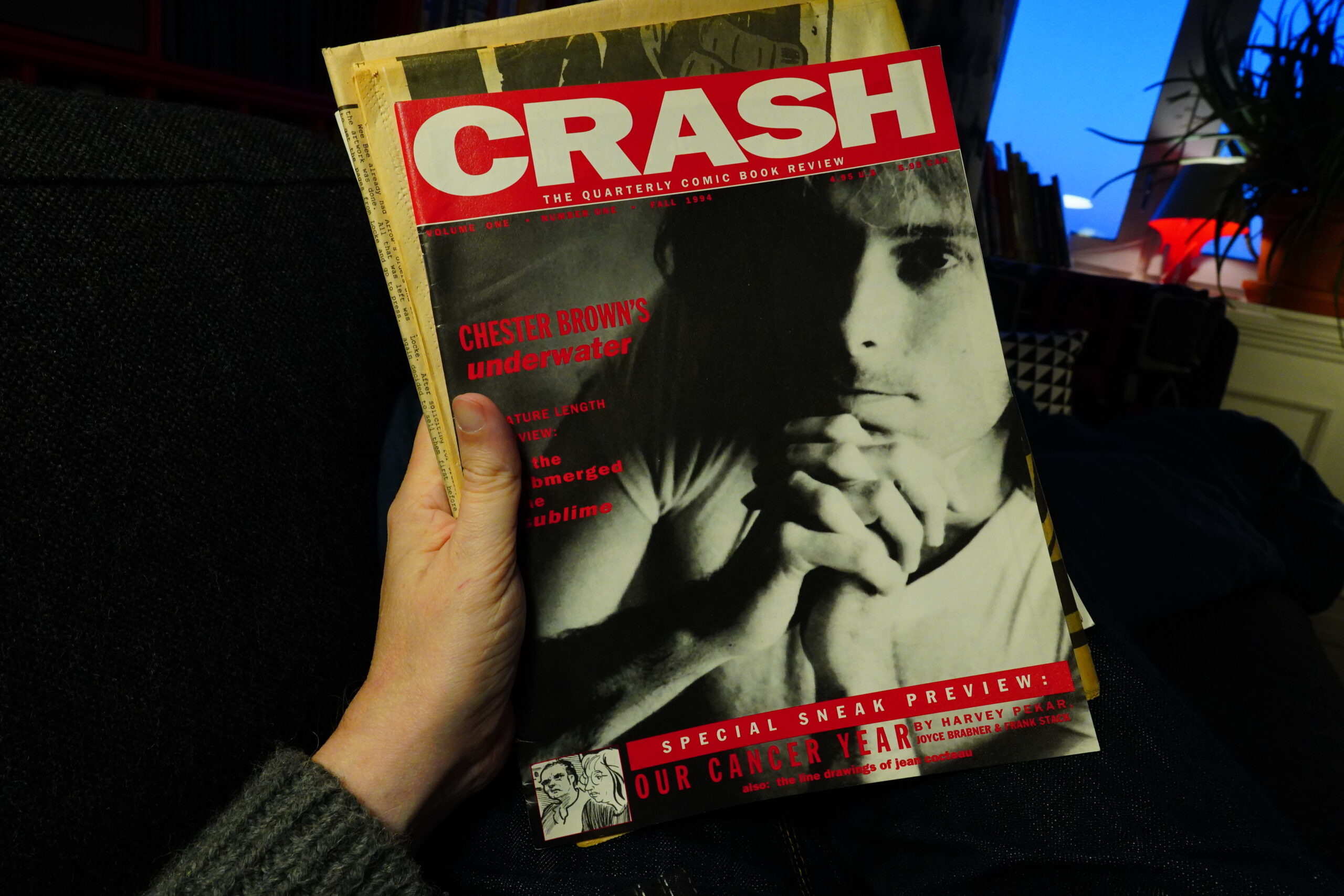

Crash: The Quarterly Comic Book Review was something that Drawn & Quarterly tried to get running, but they apparently only got two issues out. (Apparently Chris Ware was to do the cover of the third issue.) I’ve only got the first issue.

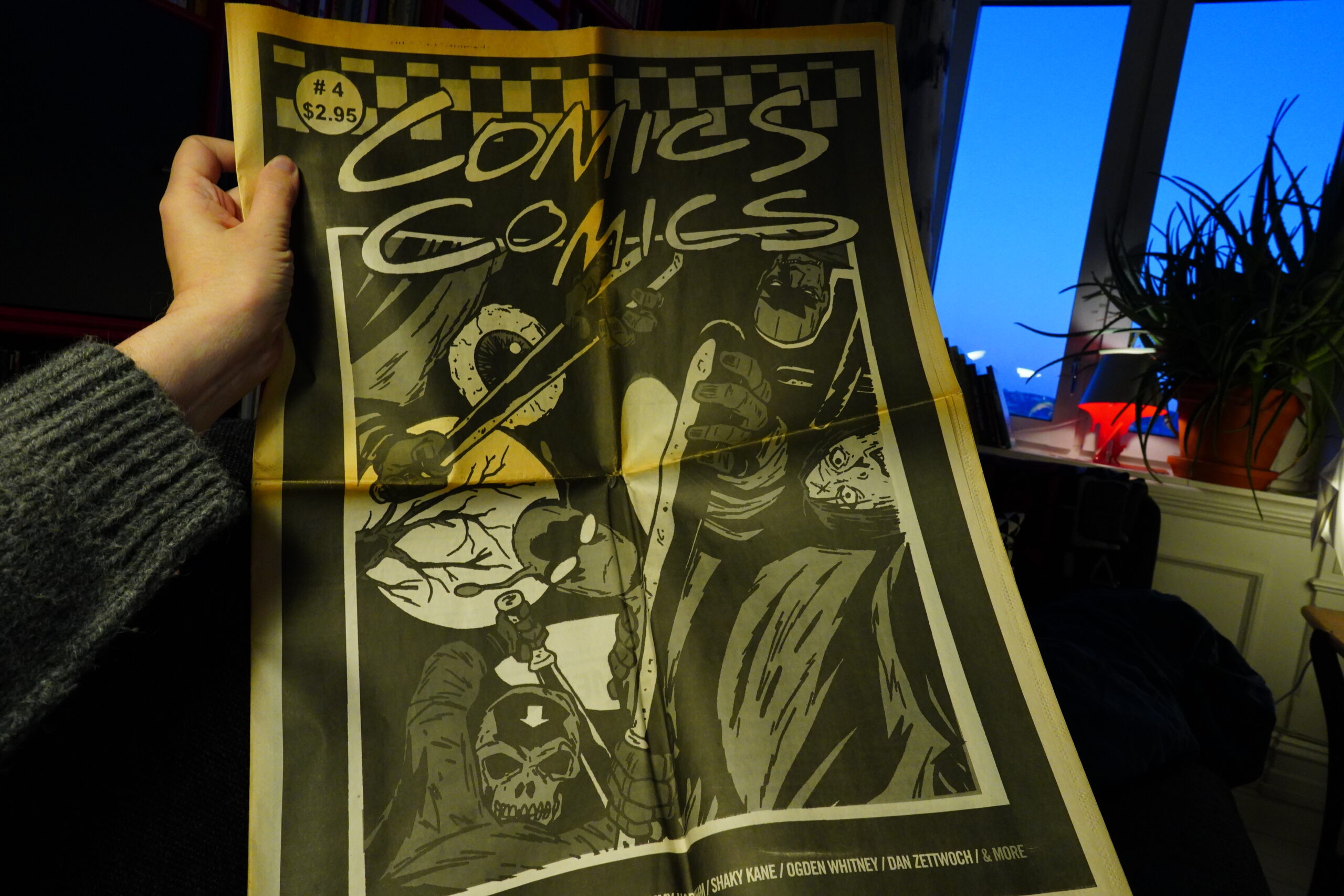

I’m guessing the Comics Comics material is up at their web site? So probably not worth adding.

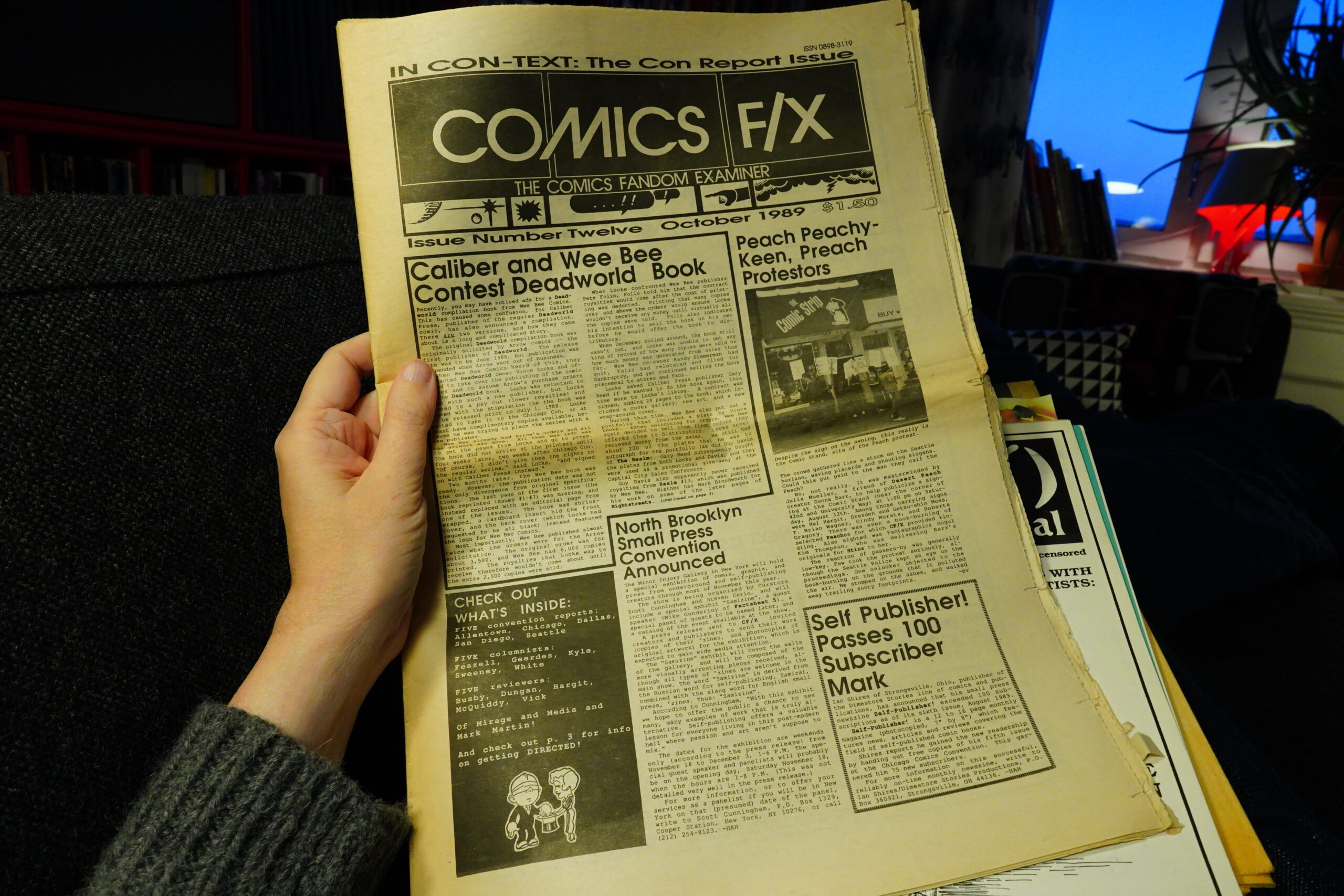

Comics F/X: The Comics Fandom Examiner was apparently published by Mu Press? I’ve only got one issue, which is tabloid size, but it seems to have fluctuated in size, and there were apparently 20 issues. Might be worth adding if somebody has a collection and a scanner.

And… that’s all I’ve got. I’m probably forgetting some mags, but googling for “magazines about comics” is pretty futile. Oh, I should have realised that there’d be a Wikipedia page about this. Hm… Rocket’s Blast Comicollector sounds interesting…

Oh, and The Comics Reader seems even more interesting, and that’s been scanned already… and looks like it’s downloadable? Yup! Coming To A Web Site Mentioned Here Soon!

But now kwakk.info is feature complete for sure!

Comics Interview, Comics Feature and… Marvel Age!?

Like I said the other week, I was wondering whether there were other collections of scans of magazines about comics, like, “out there”. And… it turns out that there are — so I’ve spent the day downloading from pirate sites, massaging/organising the scans to fit into the required layout for the search engine, and… presto.

So there’s now Comics Interview (which I know nothing about), Comics Feature, which seems to be an 80s kind of fanzine (?), and last and definitely least, Marvel Age. Yes! Marvel Age! Because why not.

So there’s now seven magazines indexed and available for searching at kwakk.info.

Now, I previously said that the search interface on kwakk.info is geared towards research, and not reading, so it deliberately makes it difficult to download full magazines, and only gives you five pages at a time to read (for each search result). I still thinks that makes sense for The Comics Journal (where Fantagraphics is selling access) and Amazing Heroes (news possibly upcoming), but for the rest of these long-out-of-print magazines, that doesn’t seem to make much sense: The only way you can read these magazines is by shopping on ebay.

So I’ve now added buttons to allow you to page through an issue (starting at where your search landed you, of course) for all of the non-Fanta mags.

(This only works on the desktop version of the site — the mobile phone version is still the way it was before.)

Enjoy reading in-depth articles about Art Spiegelman:

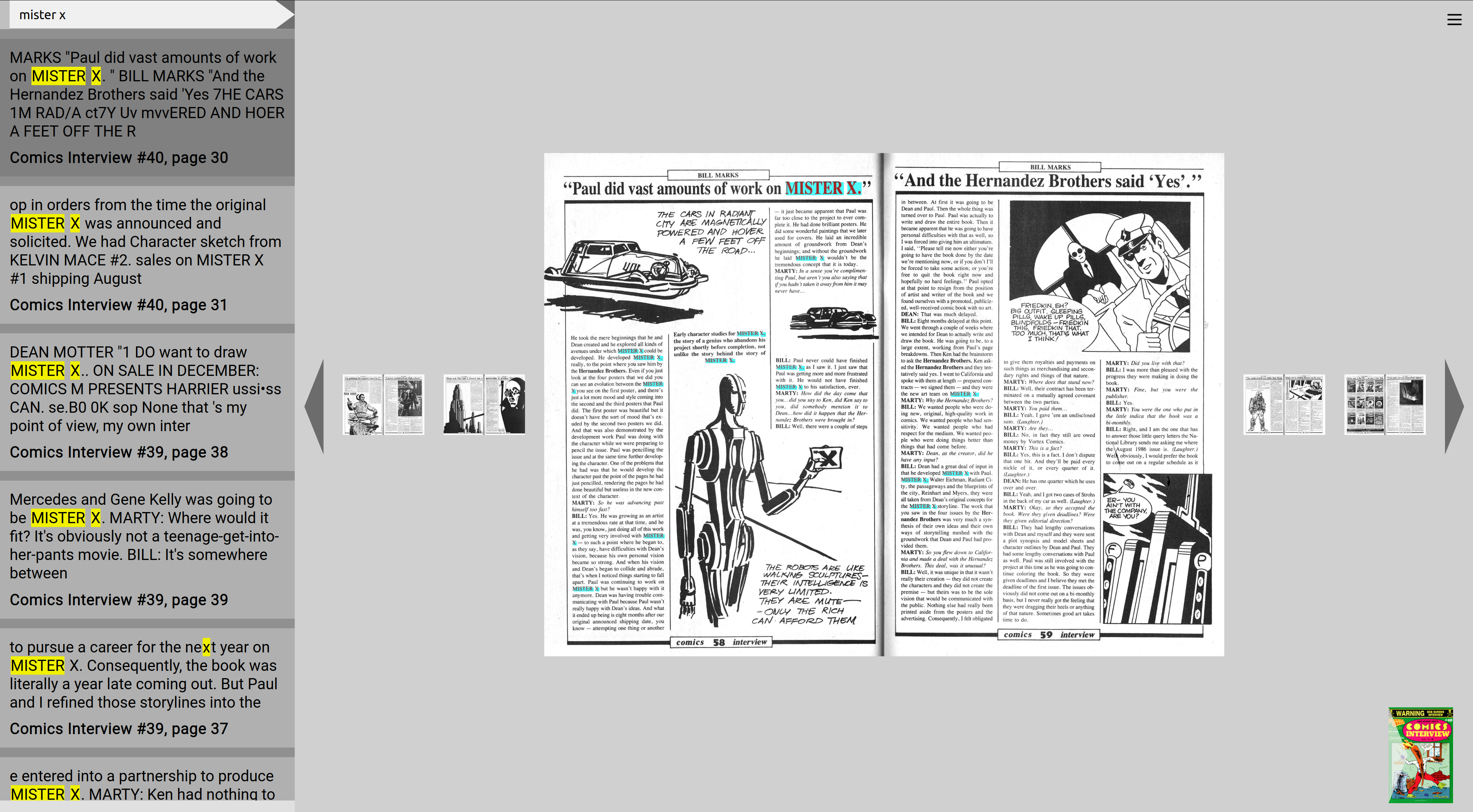

Mister X:

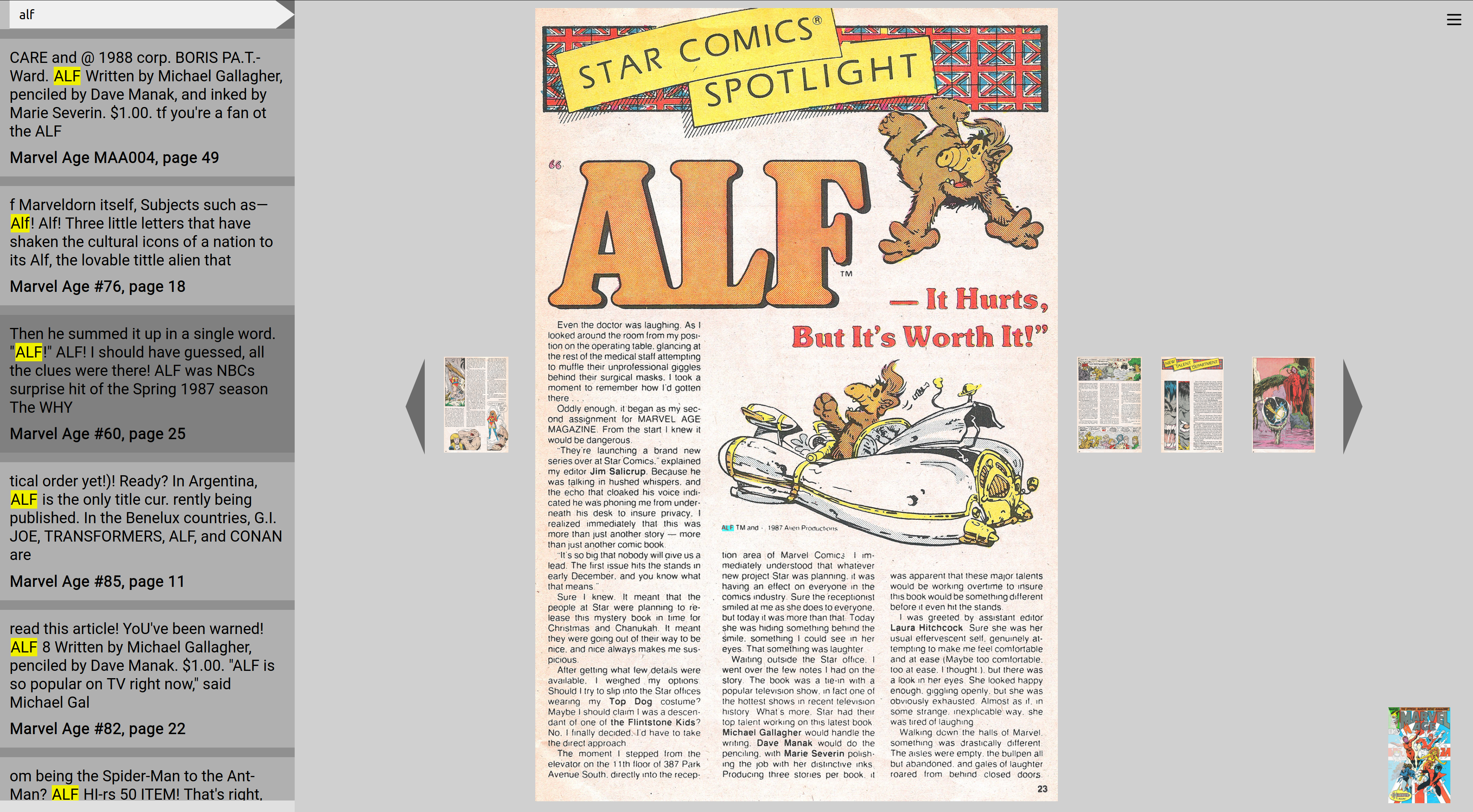

And Alf: