My blog series about “punk comix”/”the Raw generation”/whatchamacallit is finally over. I had originally planned on about eighty posts — but it ended up being one hundred and seventy posts.

Good Lord! *choke*

I had meant to focus on just Raw and the artists surrounding Raw — in the 80s. But then things got away from me.

Let me ramble on a bit here…

The subject matter is somewhat nebulous. The comics I was talking about here were never a genre, and never even really got a “name”. But it’s not as if people weren’t discussing these artists as a group at the time.

Bhob Stewart writes in The Comics Journal #89, page 14:

Boredom With Mainstream Spawns “As-yet-Unnamed” Cartoon Movement

A Cover story in the Washington

D.C. weekly City paper finds

underground comics

“practically dead,” recent

independent companies such as

Pacific “mean-spirited retreads

Of 1950s EC,” and mainstream

comics a situation of “boys

drawing for other boys (the

same old story).” The three-

page article, in the January 6

1984 issue, concludes that

“enough kids are bored by the

space barbarians and skintight

suits to make a small market for

some more adventurous maga-

zines” and spur an “as-yet-

unnamed cartoon/art movement

that will have increasing

repercussions in the hip graphics

that we will all pore over in the

next five years.

Author Matt Groening, artist

of “Life In Hell,” sums up the

current mainstream/ independent

company titles: “Death, blood

and decapitation are back in

style, along with an

unprecedented preoccupation

with impossibly huge breasts

and male muscles bulging

everywhere except in the crotch.

The comic book industry may

someday redeem itself with a

well written book, but right now

things are in as pulpy a State as

ever... ” In contrast, writes

Groening, “The new cartoons

say: All that technique by the

big guys doesn’t matter if you

don’t have anything to say.”

This reactionary cartoon/art

movement, which embraces

“punk, new wave, newave,

artoons, scratch art, messy art,

ugly comics,” is dated by

Groening as beginning in 1977.

‘ •The new cartoonists,” states

Groening, “offer a humanistic

reaction to media slickness and

an almost technophobic disdain

for the future, portraying in

their crude markings the

clumsinesses of everyday life

and all its little lumps.” They

• ‘work to please themselves

first,” and their output is

sometimes characterized by an

“unashamed amateurishness.”According to Groening,

“dozens, perhaps hundreds” Of

artists “began drawing Oddly

for the first time in the

mid-’70s, some of them aware

of each other and others

creating in isolation. ” He cites

Pennsylvania artist Mark Beyer

(Dead Stories), Lynda J. Barry

(Girls & Boys, “Ernie pook’s

Comeek”), Flick Ford (cartoon

editor Of the East Village Eye),

NYC artist Mark Marek (New

Wave Comics), “the Harvey

Kurtzman-intluenced cartoons

of J.D. King and John

Holmstrom” (Punk, Stop!) and

LA artist Gary Panter (Jimbo).Titled “Why Cartoonists

Can’t Draw Nice Or Think

Clear Or Write Good

Anymore,” the article is

illustrated with front covers

from the French comics

magazine Viper, Beyer’s Dead

Stories, Japanese cartoonist

Yoshikzau Ebisu’s My Man Is

punk, Lynda Barry’s Big Ideas,

the Spanish comics magazine

Makoki, and Stop!, plus

Eraserhead director David

Lynch’s “Angriest Dog In the

World” comic strip (L4

Reader) and a drawing by

Raymond Pettibon from

Capricious Missives. The color

cover art is a 1982 panel,

Mutantis, by Charles Burns

(Raw, Heavy Metal). A sidebar

lists ten alternative weekly

papers around the U.S. which

carry strips discussed by

Groening.As GroeninÅ sees it, since

“taboos have crumbled” and

“audiences are more

sophisticated,” a change is

happening on all levels, even

syndicated strips which “have

loosened up considerably.” He

cites Norman Fagan’s Drabble

(“the only strip more poorly

drawn than my own”),

Guindon’s Guindon, Nicole

Hollander’s Sylvia (“the oddest

looking strip in the dailies”),

Jim Unger’s Herman (“which

would have been rejected in the

past for the ugliness of its

eyeless characters alone”) and

Gary Larson’s The Far Side

(“the funniest offering in the so-

called funny pages today”).

Changes are also happening in

mainstream comics, says

Groening, but “as yet these

changes have not amounted to

much artistically.”

In attempting to define the

Nu Mutant art sensibility,

Groening often achieves a tone

highly reminiscent of Susan

Sontag’s famed 1964 Partisan

Review essay, “Notes on

•Camp’. Sontag prefaced her

notes with the comment, “Taste

has no system and no proofs.But there is something like a

logic of taste: the consistent

sensibility which underlies and

gives rise to a certain taste. A

sensibility is almost, but not

quite, ineffable. Any sensibility

which can be crammed into the

mold of a System, Or handled

with the rough tools Of proof, is

no longer a sensibility at all. It

has hardened into an idea… To

snare a sensibility in words,

especially one that is alive and

powerful, one must be tentative

and nimble.” Groening nimbly

nails down the roots Of the

movement—a generation that

“lapped up the lousiest,

cheesiest junk in kid culture

right along with the best,

cheesiest stuff.. ”

AS usually seems to be the

case these days, the Japanese are

several Steps ahead. In Japan it

has hardened into an idea, been

given a name—the “Bad-nice”

style—and is packaged for a

mass audience through ads,

postcards, calendars, animation,

book jackets, and magazine

covers. Leader Of the ‘ ‘Bad-

nice” style is the much-imitated

Flamingo Terry (Teruhiko

Yumura), a cartoonist who

often draws Bad-nice scenes of

America. The highly popular

Yumura, who became

disenchanted with his studies in

graphic design at Tama Art

School, found more latitude for

personal expression in Bad-nice,

which he describes as

s’ something that doesn’t 100k

like it was the work Of a

professional, or somebody who

went to the art academy. It

looks like something that any

kid could draw.”

Groening is onto something, but is (I think) trying to frame this “Nu Mutant art” thing in a too populist way.

I think it’s basically much simpler: It’s comics by people who either went to art school, or ended up teaching at art school.

(Plus Mark Beyer.)

There’d been plenty of comics by people who drew “primitive” before (the early Underground movement) or had an expressive, wild style (Aline Kominsky, for instance). But these were artists that had an… shall we say… uneasy? relationship with the art world. Well, let’s face it — a significant number of them were downright hostile towards it. I feel you could create many anthologies just consisting of comics artists hissing at the art world. And to this day, there’s this “woe is poor widdle me” thing about how unfair the world is to hard-working comics people. Here’s Chris Ware:

When you don’t understand a painting, you assume you’re stupid. When you don’t understand a comic strip, you assume the cartoonist is stupid.

This is moronic on so many levels that I don’t even know where to start. Most people assume that art you don’t understand is stupid art, and would rather have something nice that matches the drapes instead. Most people want their art (and comics) to come nicely digested and easy to understand.

This is what made the comics I’m talking about here so thrilling: In issue after issue of Raw, we could see comics artists that didn’t give a fuck whether you understood what they were doing or not. They present works of astounding emotional impact, but do not didactically explain to you how it’s supposed to make you feel. Doing vignettes that hint at something much larger, and then stop. It’s art comics, pure and simple, doing the same in comics that’s been going on in art cinema, contemporary literature and, yes, fine art.

(To see how awful comics that insist on telling you how to feel about what you’re reading can get, look no further than Seth’s Clyde Fans.)

The undergrounds were cool, but they were mostly about making jokes or being gross. Or both at the same time. Being really heartfelt was looked at askance, most of the time: Underground were mostly just working in the EC tradition with O. Henry endings, but with more sex. The Raw generation didn’t work in opposition to this, per se, but as if that lineage of comics didn’t even exist. Instead we got intensely personal expression, satire and art. (And less sex, because punks don’t really find sex that intriguing.)

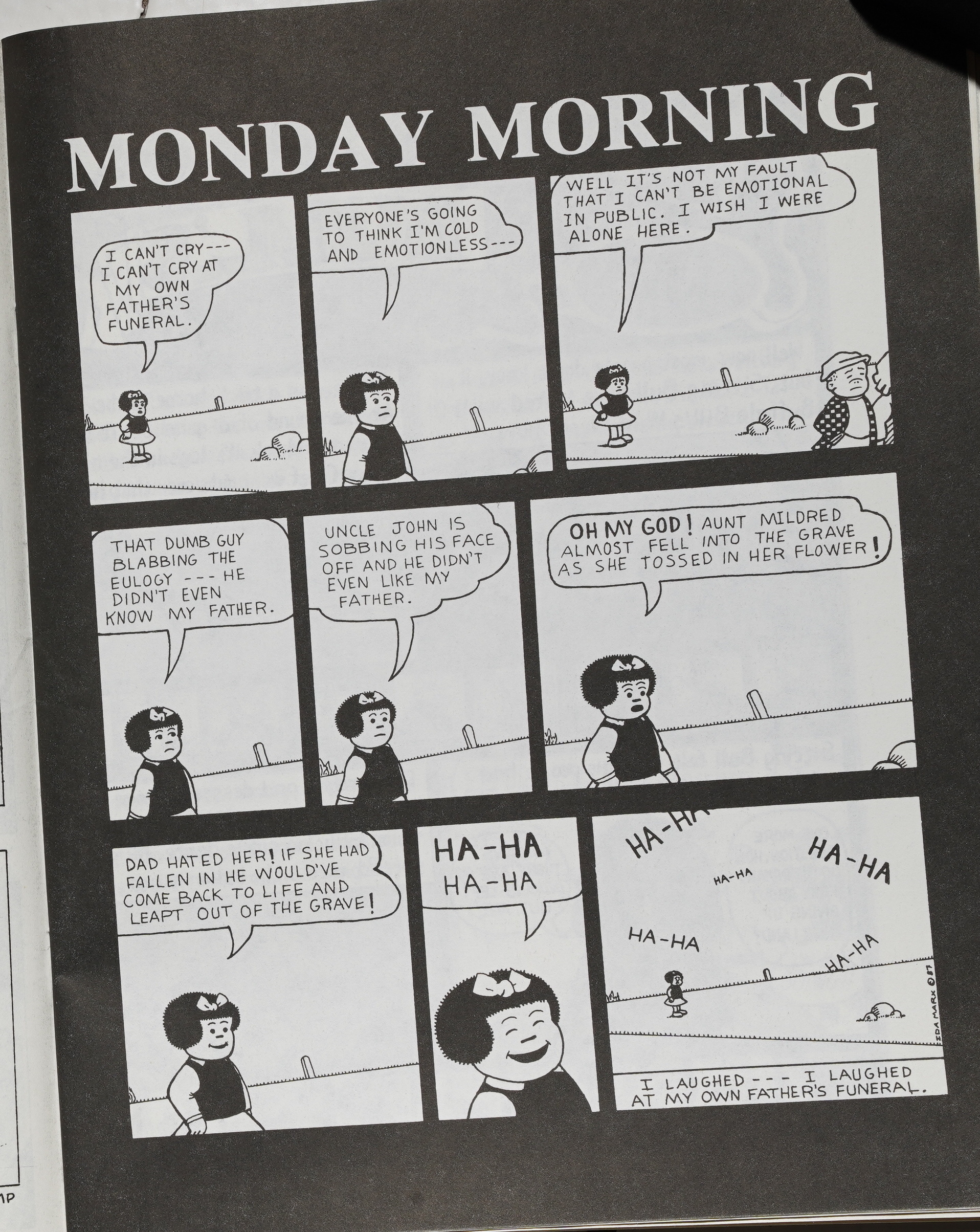

The wonderful This Isn’t Happiness blog has been linking to a few of the images I’ve been posting in this blog series, and they excerpted this page by Ida Marx (from Bad News #3), and it made me realise that this single page sums up many of the qualities I find interesting about this non-genre.

The page apparently had its origin in a class assignments at the School of Visual Arts: The assignment was to do a strip detailing a personal experience using Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy character.

So we get this story of Marx laughing at her father’s funeral, as told by Nancy. It seems like this distancing device should turn the story into a joke or something, but the result is a chilling, heartbreaking piece.

Imagine this story coming out of a different comics culture… for instance as a 70s underground comic. It’s not that hard to imagine — but instead of being a retelling, we’d see Aunt Mildred almost falling into the grave, and it’d basically be a gag strip, meant to elicit laughter. (And it probably would have been funny.) The eerie distancing here means that Marx can really lean into the abject without becoming mawkish or sentimental, and without having to lessen the effect by adding a punchline.

Or imagine this story coming appearing in a late-90s autobio anthology. You’d likely have drawings of the “I” character tearfully talking at the reader, and also explaining the relationship she had with her father and Aunt Mildred… and I’d be sitting there, reading, thinking “well, that sucked for her… but… why should I be interested?” That is, instead of being intensely personal, it’d tip into being private. (See the horrible Stitches memoir for an example of the genre.)

The artwork on this page is very straightforward, but combines two things many of the people in “Nu Mutant” comics were interested in: Formal comics play, and the history of comics. It’s definitely on the Herriman side on the Herriman/Caniff scale.

So to sum up what I think makes this page so good: It’s not afraid to use the whole range of emotions, without making excuses. It’s doesn’t feel the need for contextualisation or closure. It’s pure comics — this isn’t a storyboard for a short indie film. It’s playful — it has fun with comics conventions and history. It’s got a striking visual quality as a page.

Vagueness is an underappreciated element in comics. Recently there was a survey of comics artists that had been/are working in animation, and they were asked things like “how has working in animation changed your work?” and I was waiting for somebody to say “well, of course working for commercial machinery breaks your soul, but I hope I have retained some personality”, but no: They were all “my comic are so much better, because they’re so clear and structured now”.

Which explains why I run away, screaming, from works of so many of that cohort in this generation. Most of it’s pure shit.

I loved reading this interview:

It’s Unfortunate That So Many Cartoonists Talk About Structure As If It Were Something Desirable

Yeah! Fuck structure!

Well, OK, perhaps not, but there’s something that’s just deadly about the structures many younger animation-influenced cartoonists apply to their work these days.

But… death to the three act structure! Fuck that shit! In any art form: Comics, movies, whatever.

Er… where was I… oh yeah, punk comix.

Groening’s “Nu Mutant” label is pretty much on point, although you can’t really use the word “mutant” about comics without everybody jumping to the wrong, Marvellian, conclusions. The Ze record label (also from New York, also from the late 70s/early 80s) called their retrospective releases “Mutant Disco: A Subtle Dislocation of the Norm”. There was something mutating in New York at the time, and Raw was part of that.

And then, as all movements do, it fizzled. In this case, it’s easy to pinpoint when it did: It ended when Penguin published the first Maus collection in 86.

Not because that was a bad book. No, the opposite — it was such a fantastic book that it seemed like everything had to change. Suddenly mainstream publishers, all over the world, had their first break-through comics hit, and it came from this milieu, so they tried publishing all the other artists from the Raw generation in bookstores…

And they all failed dismally. I mean, commercially.

What the mainstream audience wanted to read, to put it coarsely indeed, was a book about daddy issues, because that’s the only worthwhile subject that exists, apparently. (OK: “The uneasy relationship between children and their fathers.” OK?) It took a couple decades for the next mainstream breakthrough comic to arrive — which was Fun Home, which is about, yes, you guessed it…

Daddy issues didn’t much interest the rest of the Nu Mutant generation, so of course they didn’t sell. And it’s one thing to be a successful artist in relative obscurity (the Nu Mutant comics artists before 86) — it’s quite another thing to be a commercially unsuccessful artist in the mainstream. The former is awesome, the latter is disheartening.

So most of the people involved went into fine art or into illustration and never really looked back. Even the ones that didn’t leave comics behind (Beyer and Panter, for instance) reduced their comics output radically, which is why I’ve got a gazillion Beyer prints on my walls instead of twenty Beyer books on my shelves.

Gary Panter published the Rozz Tox manifesto, which was about infecting the mainstream with their weirdness. And that was certainly a successful strategy — selected people from this generation of comics artists are among the most successful (critically and popularly) ever (i.e., Matt Groening and Art Spiegelman). But you have to ask to what extent the infection went the other way — I don’t think many people are claiming that anybody involved here did their most interesting work after their successes.

There’s always a next generation of artists, but the 90s was pretty slim pickings for someone who was into this sort of thing. In the 90s, most of the leading art comics proponents used a more Underground aesthetic. Things didn’t really change, I’d say, until we got to the Paper Rad people, which led to PictureBox, and then things really got swinging again, with art for art’s sake.

And, of course, then came 2d cloud, the most important publisher of this century: Maggie Umber, Blaise Larmee, Austin English, Gina Wynbrandt, etc, etc, but things seem to be in the doldrums now. FU Press and Domino are trying to pick up the slack, but are too lacking in… volume… to be a real movement, I think.

I’m waiting for the next quixotic publisher to step up and lose a whole bunch of dollars.

Is that enough kvetching and bloviating? OK?

Thank you for attending my TED talk.

This is finally the final blog post in this series… except for a bunch of index-type posts that will follow over the next few days.

Meanwhile, here’s my setup for this blog series. I wanted to get a kind of stark, sharp look to the snaps of the pages (trey punk, you know), so I got a big flash and some arms and stuff for my camera rig:

Expert set-up for snapping pics of comics, eh? Eh? EH!!!

I’m not sure actual photographers would recommend using a tote bag filled with steel blocks as a counterweight, but what the hey.

Wow, that tidbit about animation really does explain so much. That’s gonna stick with me.

Thanks for the series. I read every entry and found it fascinating.

Chris ware is spot on. Americans are culturally conditioned to see painting as art and comic books as trash. Not sure what you disagree with in his statement.

Slightly avant garde comics (like Ware’s) sell a lot better than slightly avant garde novels or poetry. Ware has a nice mansion while poets are lucky of their collections sell in the double digits. And the same goes for avant garde artists: The Koons (etc.) who make easily digestible works are really popular, but the ones that make artwork that’s hard to “get” are way out in the margins.

Or to put it another way: Normal people despise smarty-pants art, no matter whether it’s a painting, a poem or a comic book.