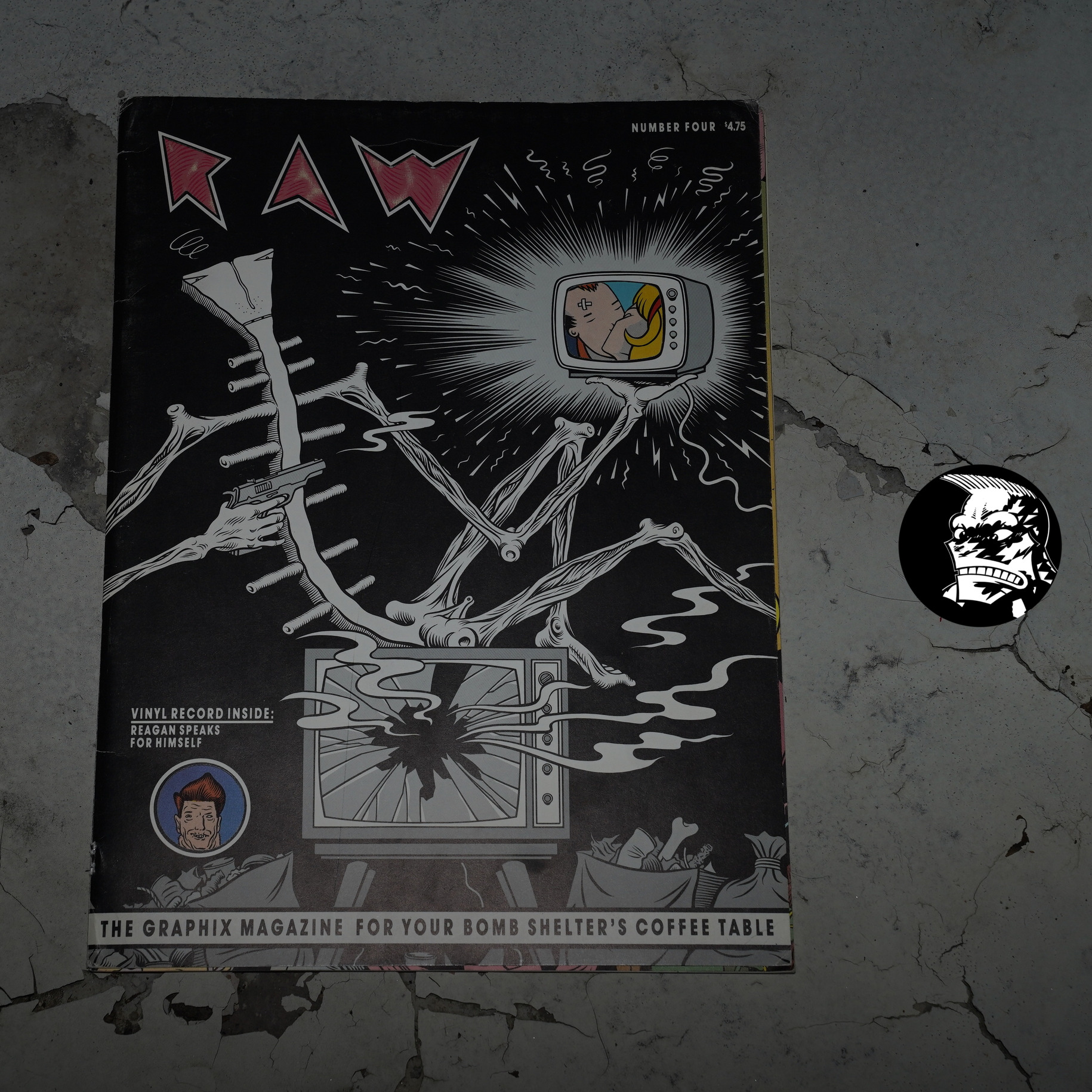

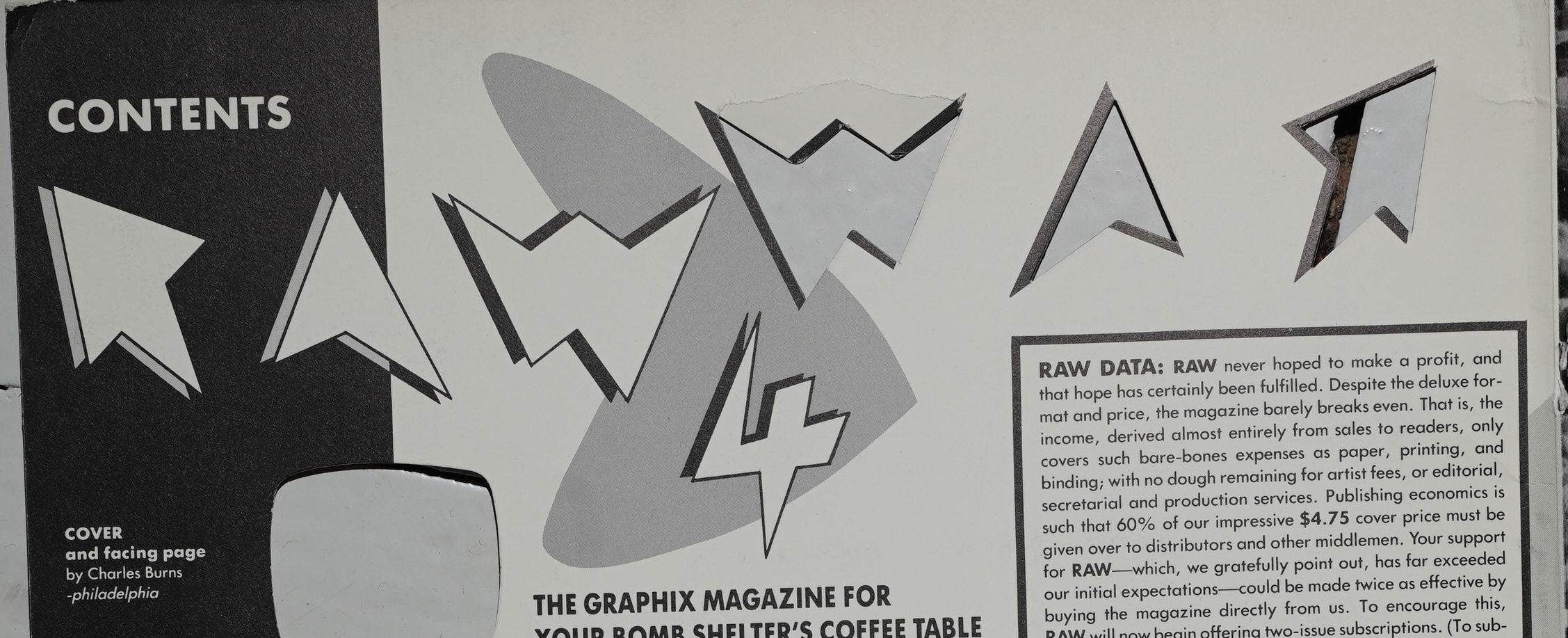

Raw #4: The Graphix Magazine For Your Bomb Shelter’s Coffee Table edited by Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman (265x360mm)

This was the earliest issue of Raw I had as a teenager — but it wasn’t the first issue I laid my hands on. I think I started buying them with the next issue? And then bought this one from Raw Books later.

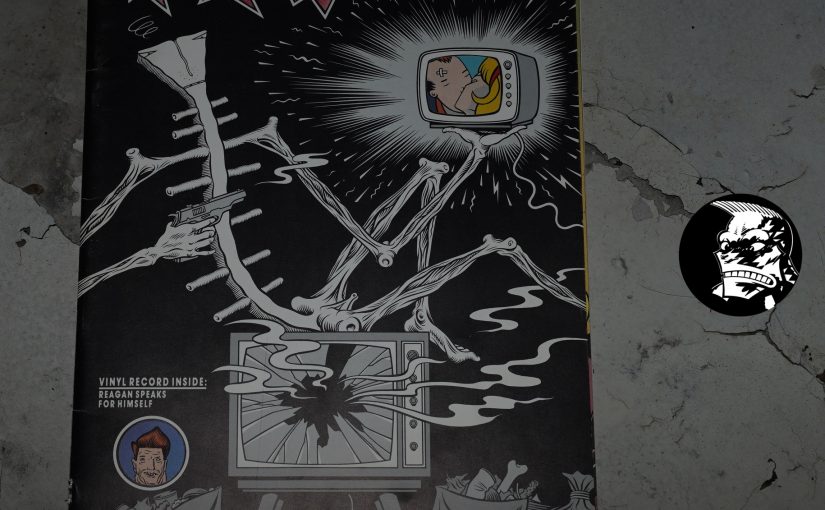

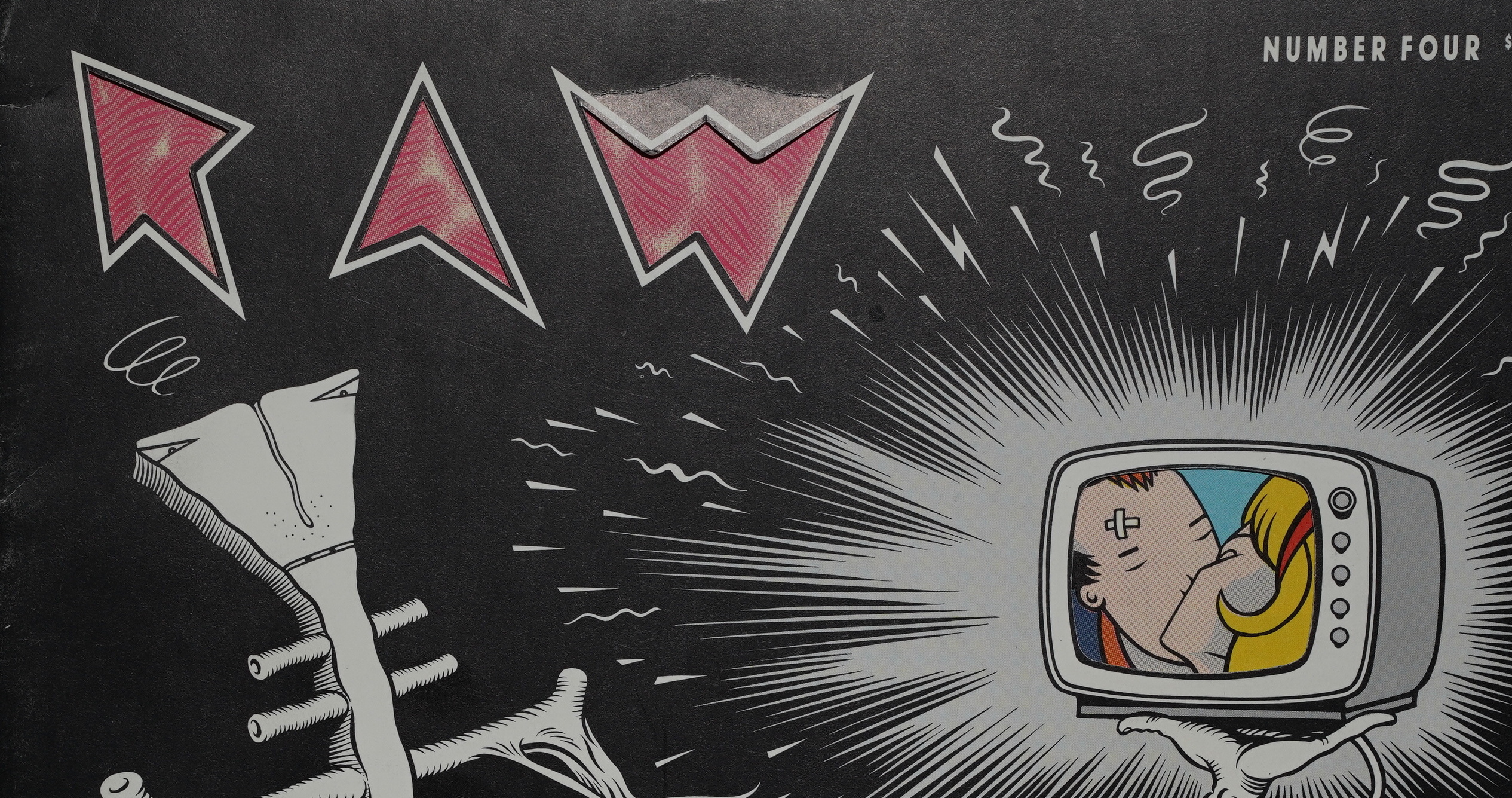

It’s something of a Charles Burns-themed issue: He’s got the cover — printed in black and white, but with die cuts to the first inner page:

… which I (at fifteen) thought was a swell gimmick indeed.

Here’s what the inside front cover looks like — and I think that’s pretty cool, too? We’re talking precision printing and die cutting here.

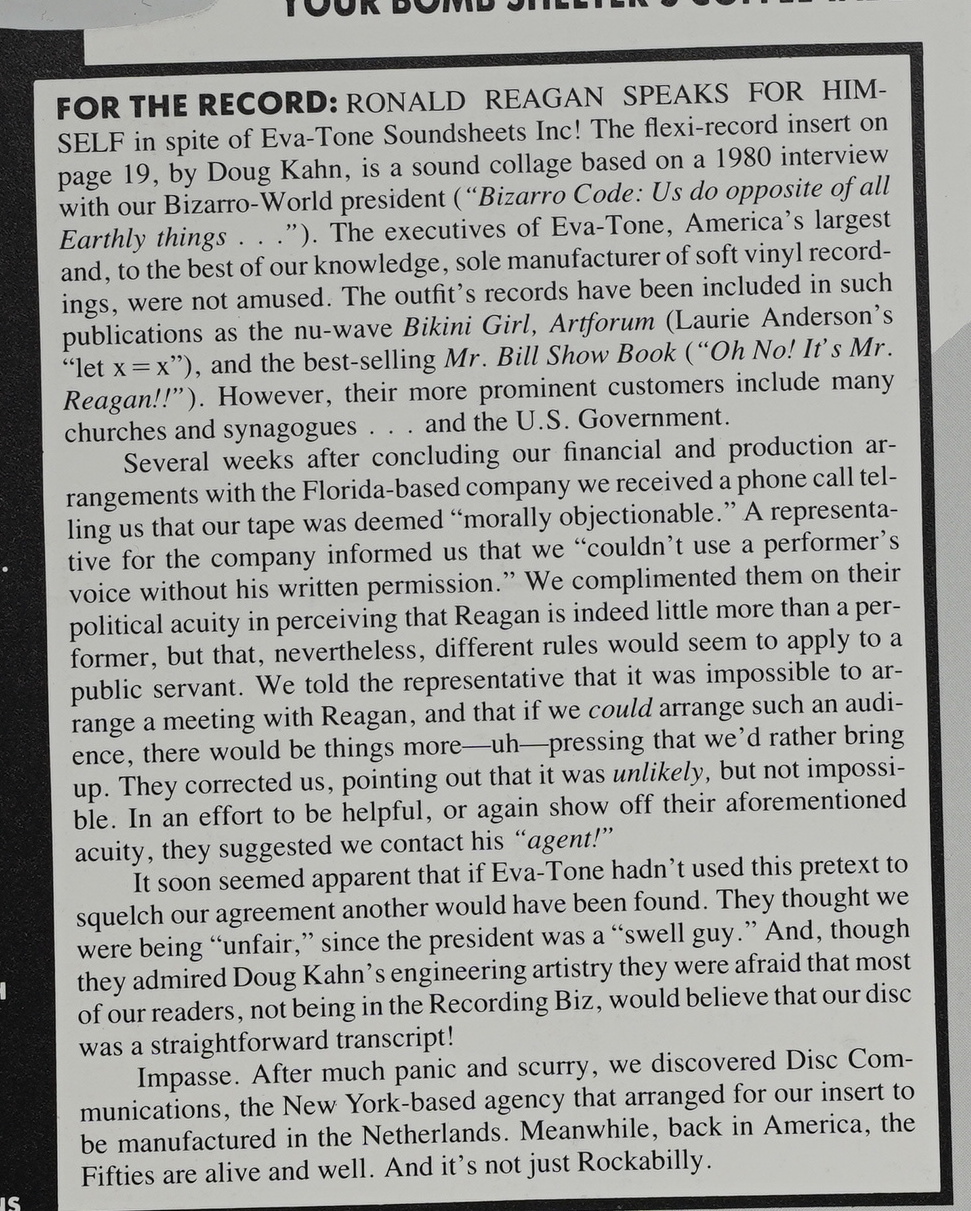

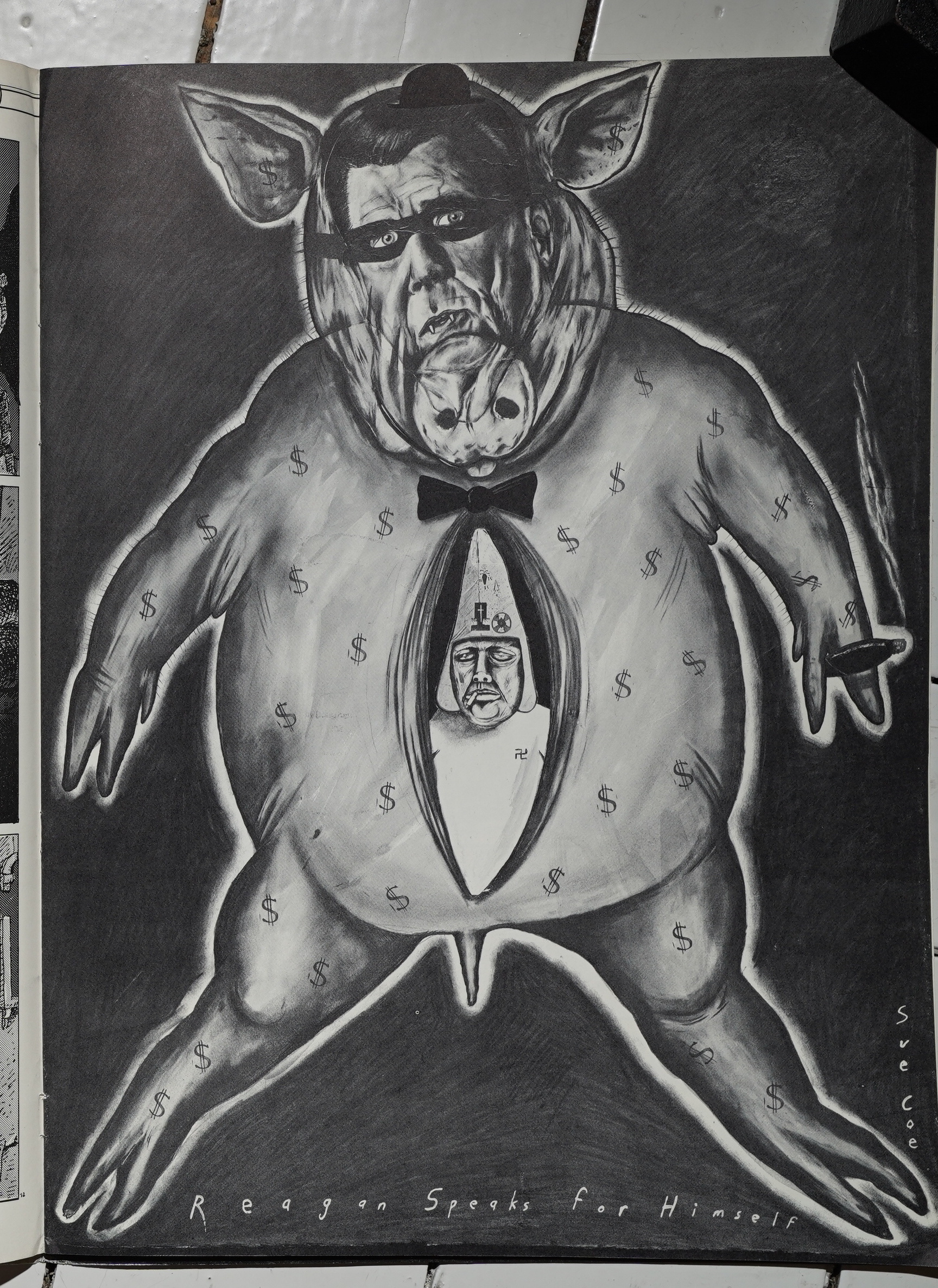

The editors tells the tale of how they struggled to get a Florida-based company to print the Ronald Reagan-themed flexi included with this issue. “Contact his agent.” Heh heh.

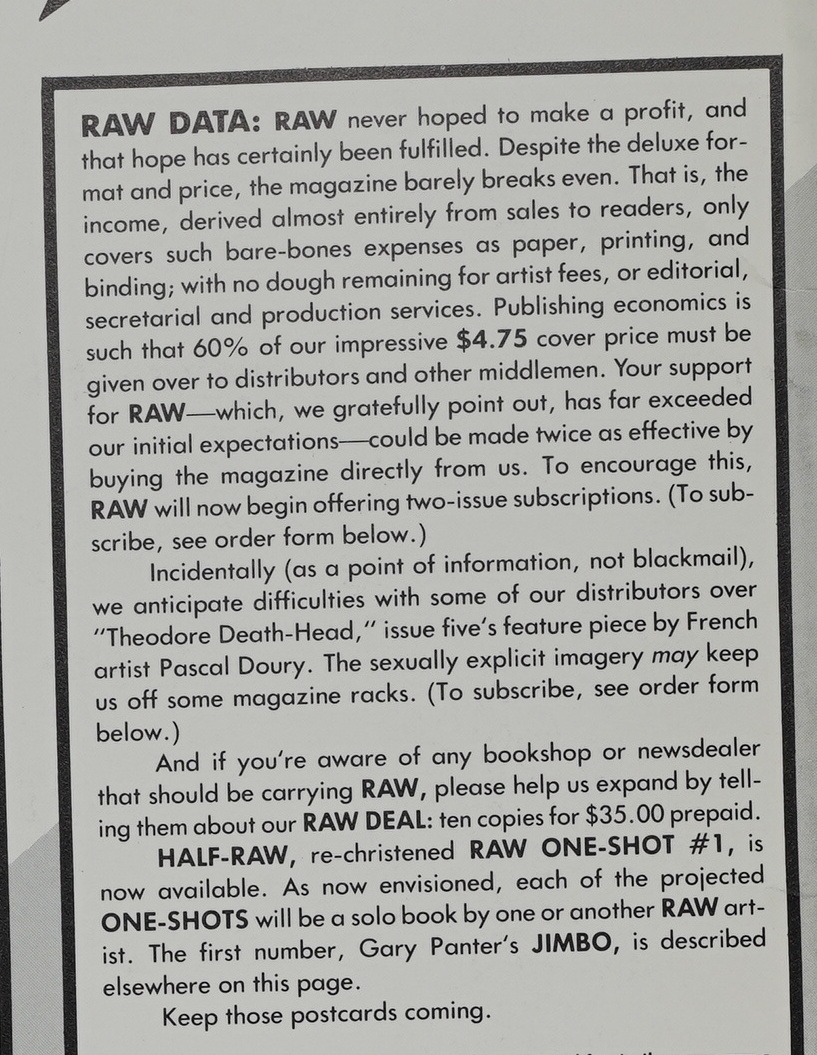

They also tell us that they’d really like to start selling stuff directly to the readers now, because that’s more economically sound. And “Half-Raw” has wisely been renamed to “Raw One-Shot”. Oh, and the next issue will have stuff by Pascal Doury that perhaps not all shops will want to carry.

Exciting times. I mean it — all this stuff was so thrilling to me at the time…

And then we come to the innards, and it’s just flabbergastingly good. I hadn’t read the first three issues when I read this one, so it’s all so surprising. Reading this now, in context, I can see that they’d pretty much established this format in the third issue, and this is… er… is there a positive word for “coasting”? They’re publishing a consistently brilliant magazine.

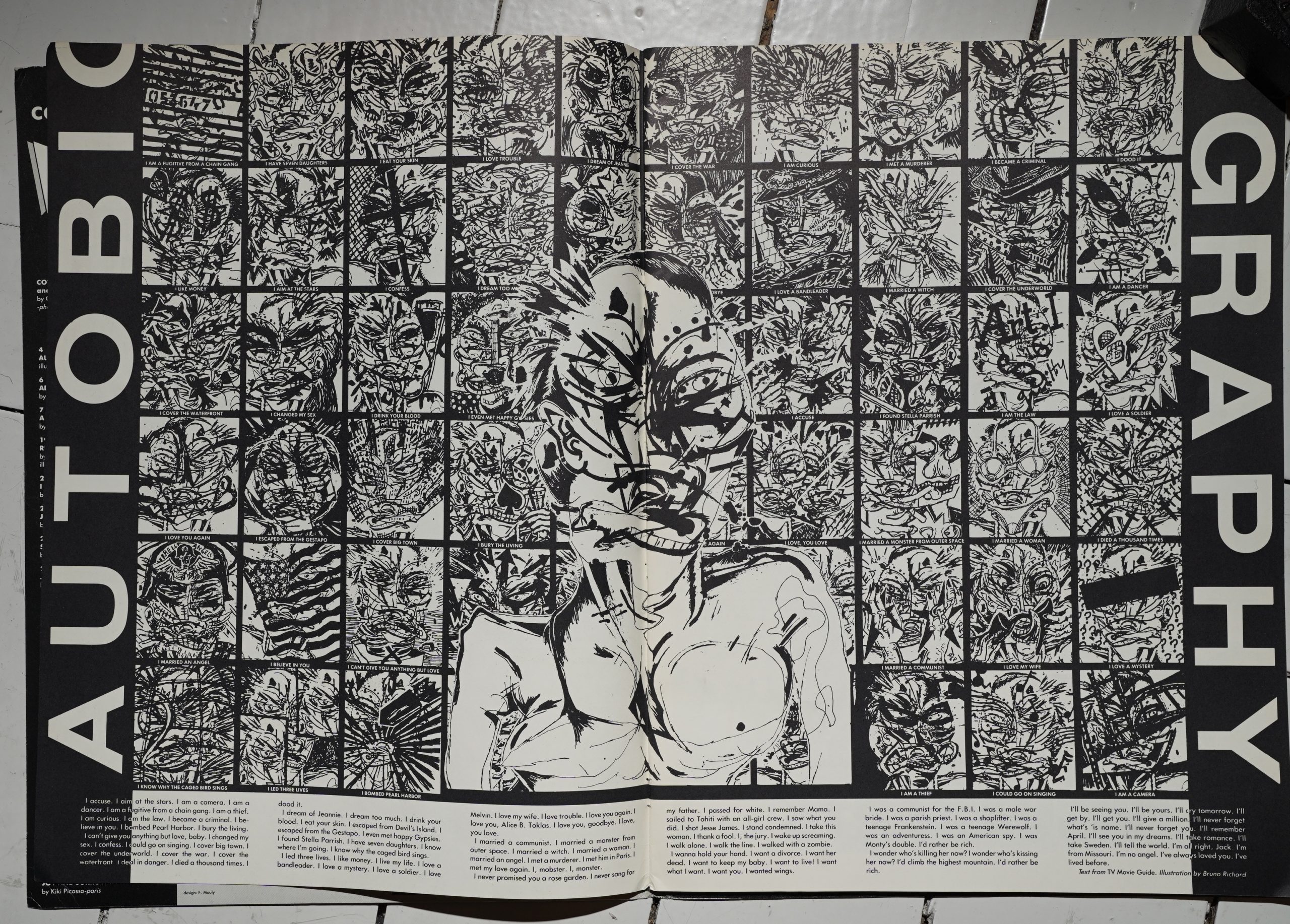

This one seems to have a theme of sort — it’s more dadaish than the previous issues. So here we have Bruno Richard illustrating found sentences from the TV Guide (allegedly): They’re all film titles? Or most of them?

I was so taken with this that I used a few of the little images as a basis for some t-shirts I printed while teaching myself screenprinting a few years back. This one is always a success when wearing it at music festivals.

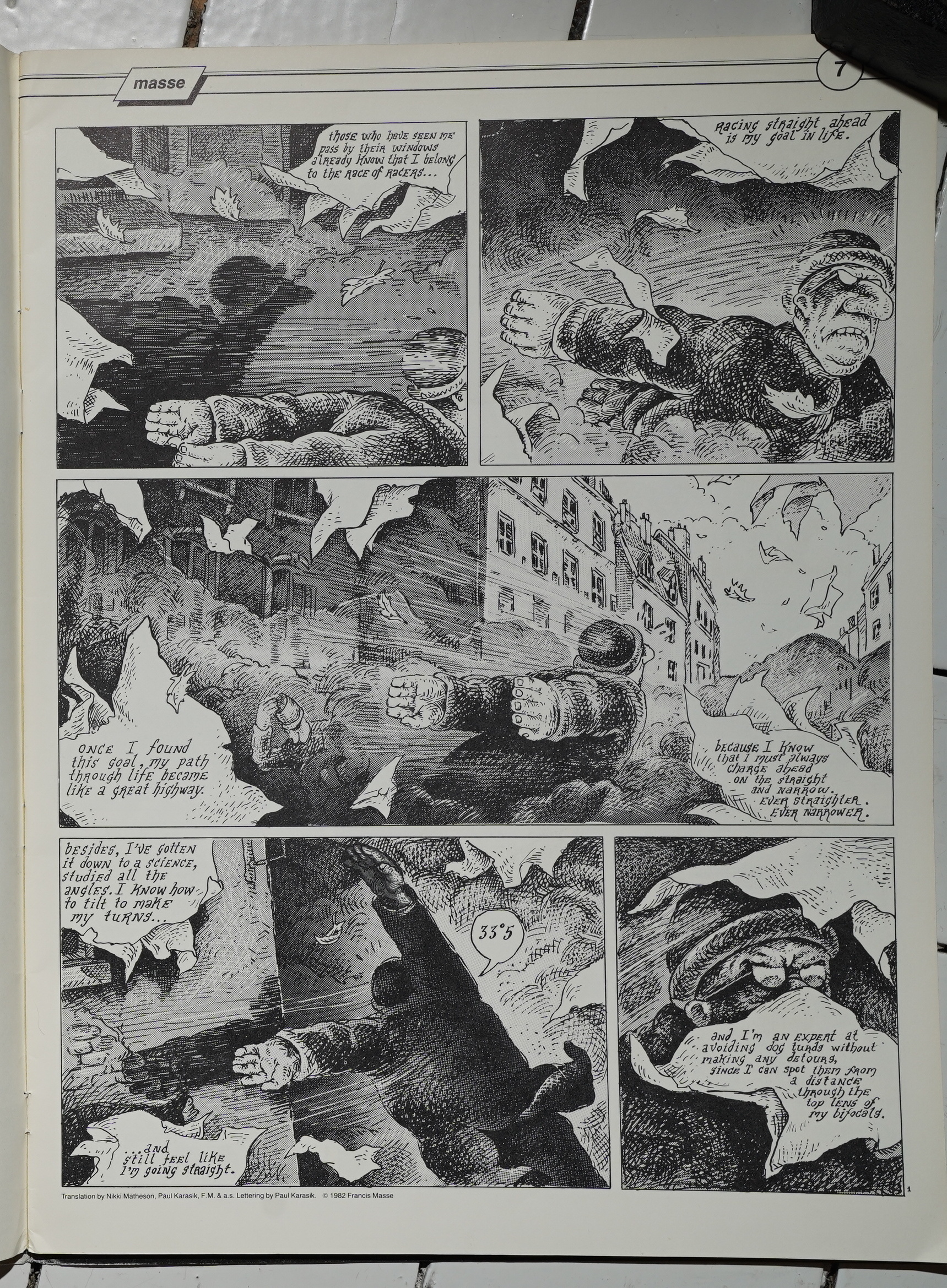

The longest piece here is by Francis Masse, and it’s quite funny, beautifully rendered, and keeps up the dada-ish theme.

Eep! There’s supposed to be a flexidisk here? I know I had it here in 2016, because I digitised it then, but… I can’t find it now? *sigh*

But it’s on youtube, of course. It’s a sort of cut-up piece by Doug Kahn.

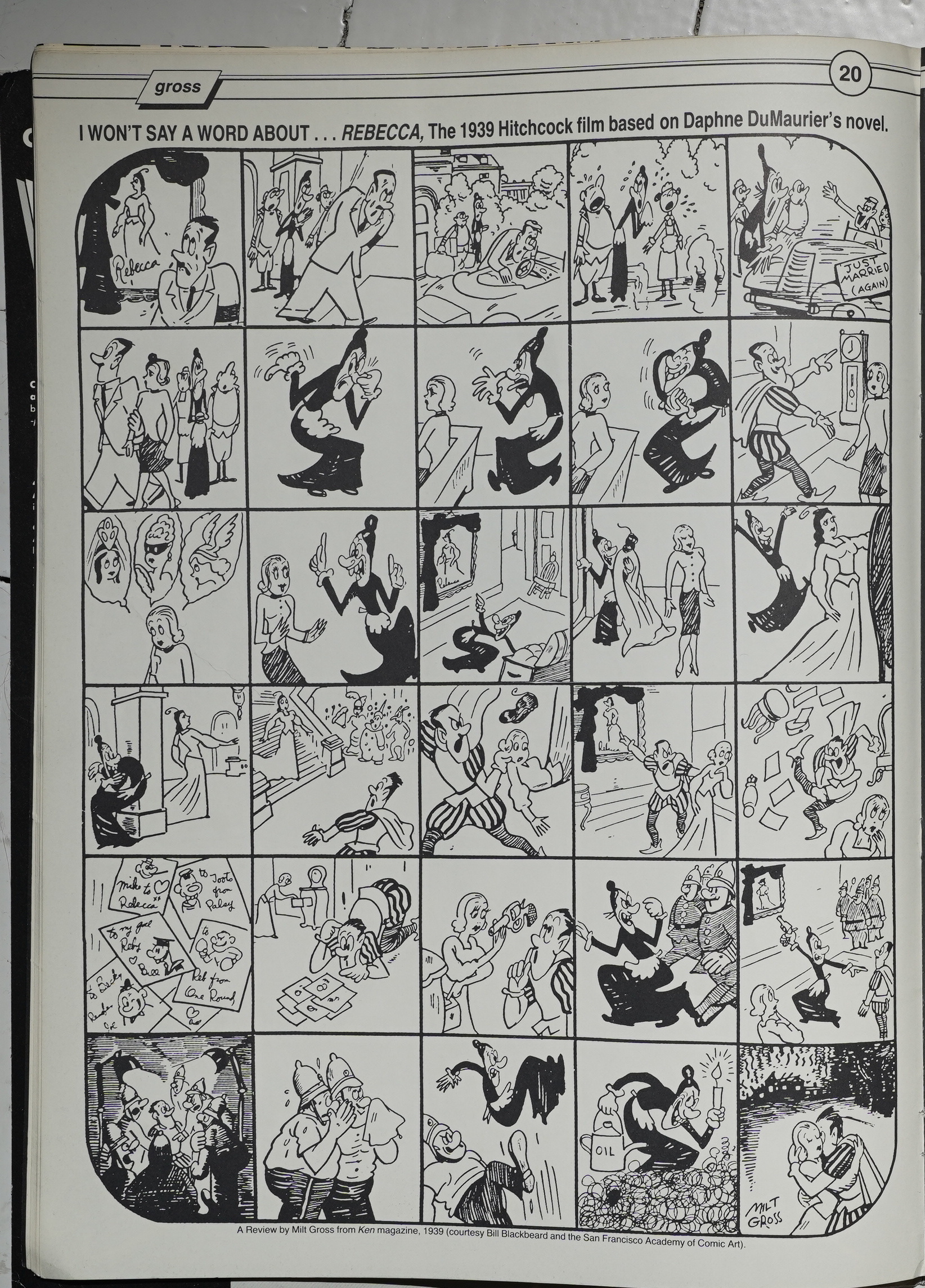

Like basically any Raw issue, there’s some oldee tymey thing in here, too. This time it’s Milt Gross, who’s also in Bad News #2.

Joe Schwind does a pretty amusing, absurd text/photo thing…

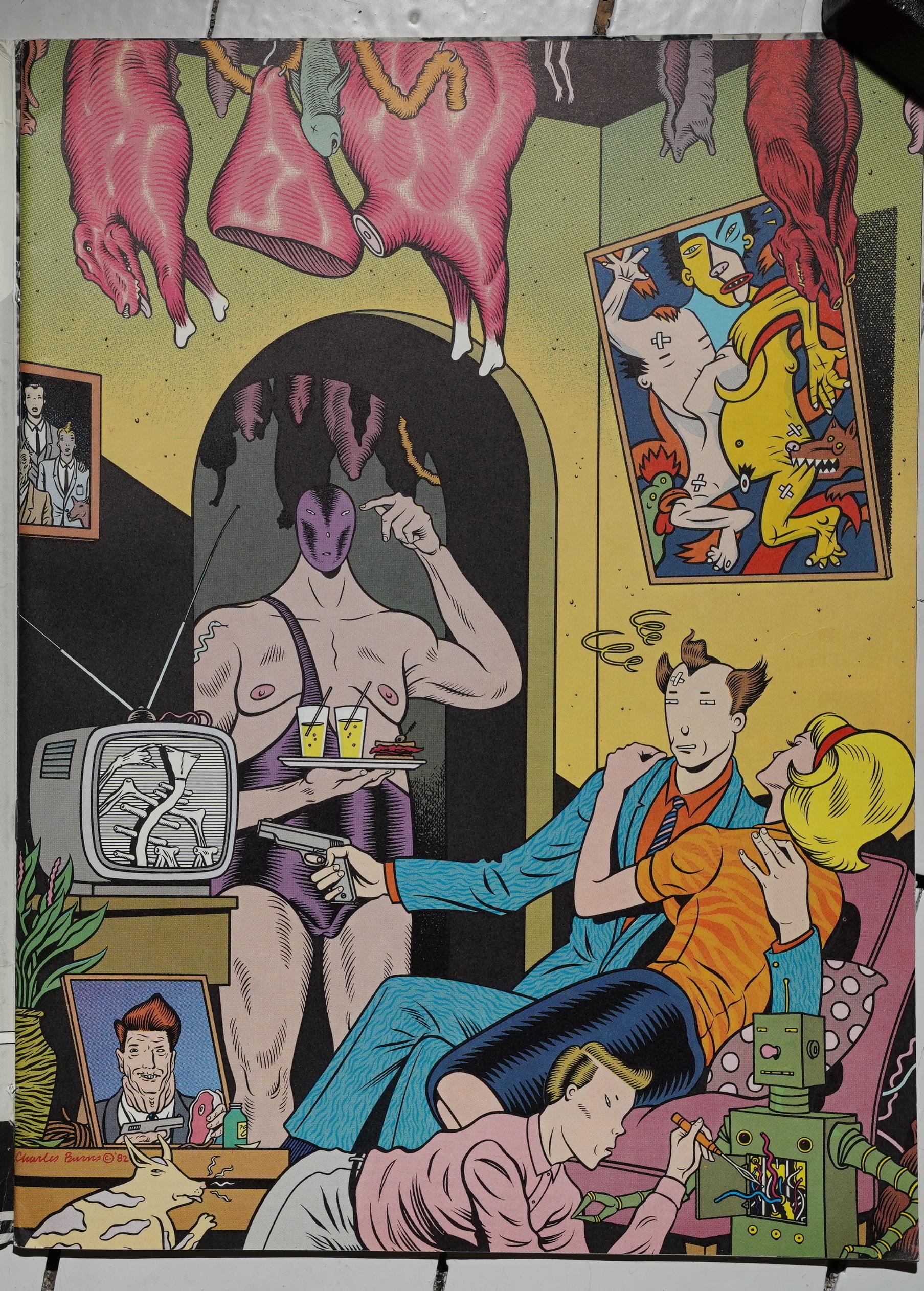

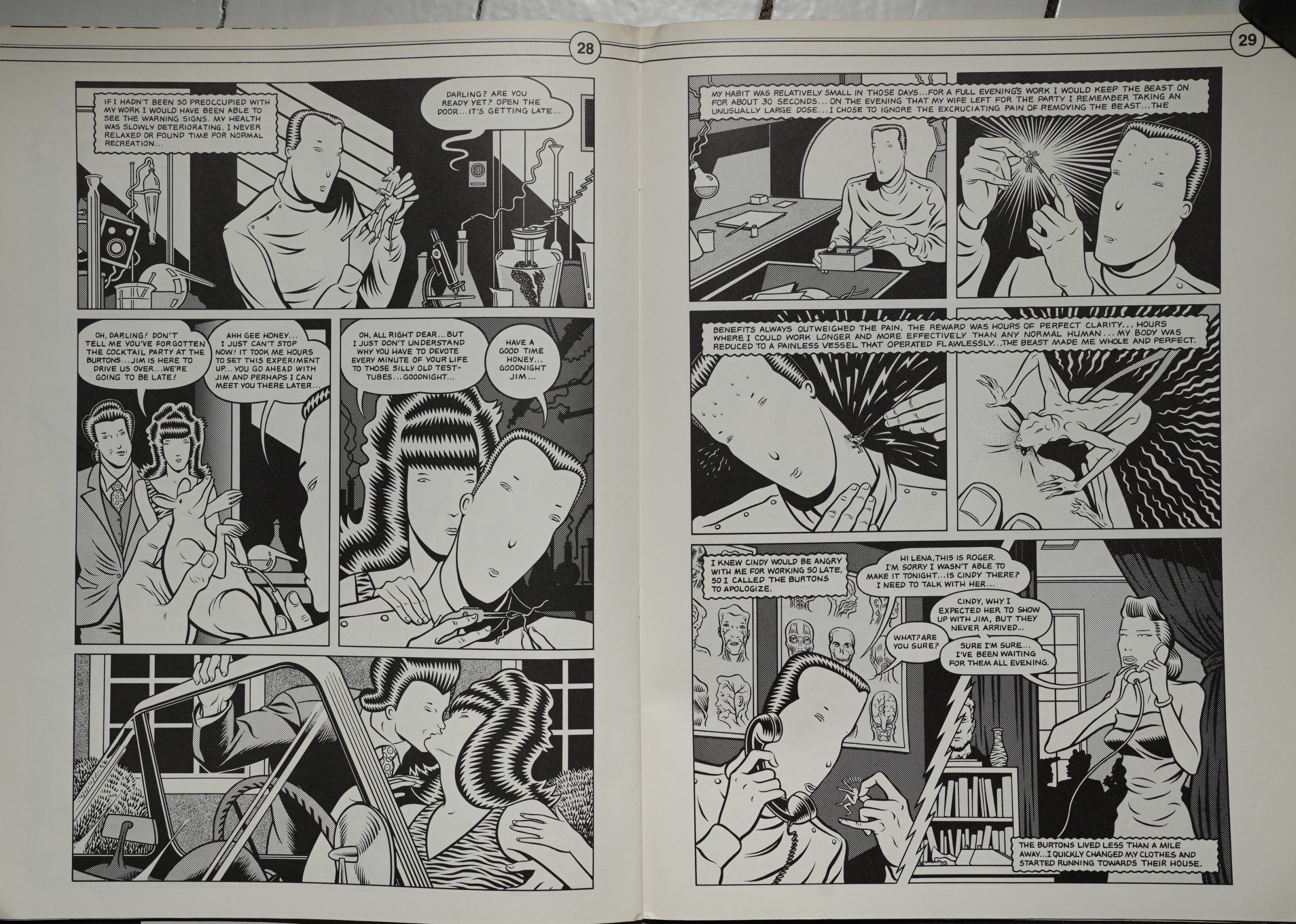

… and Charles Burns does a longer story. Is this his first longish published thing? It’s so striking: The line work is absolutely inhumanly precise, and those faces are so insectile. It’s makes your flesh crawl while also attracting you with that inking technique. It’s not Burns’ most accomplished story, though — it veers into O. Henry territory, but is too oddly paced for that to really work.

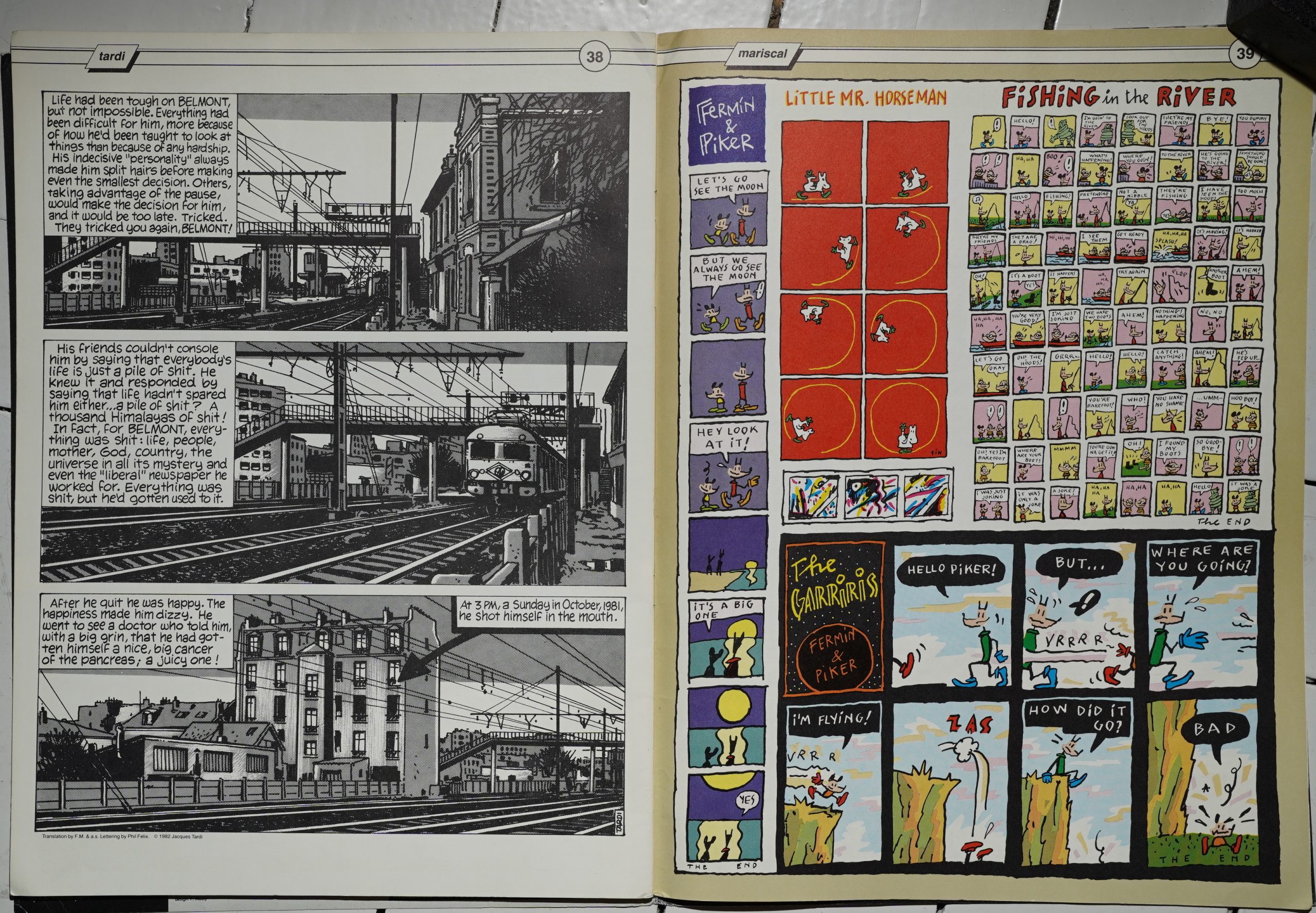

We get a one-page callback to the long Tardi story in the first issue — is it the same guy who kills himself? Is it another guy? It seems so random to include this, but it also gives me the shivers a bit: It’s an unexpected connection.

And everybody loves Mariscal.

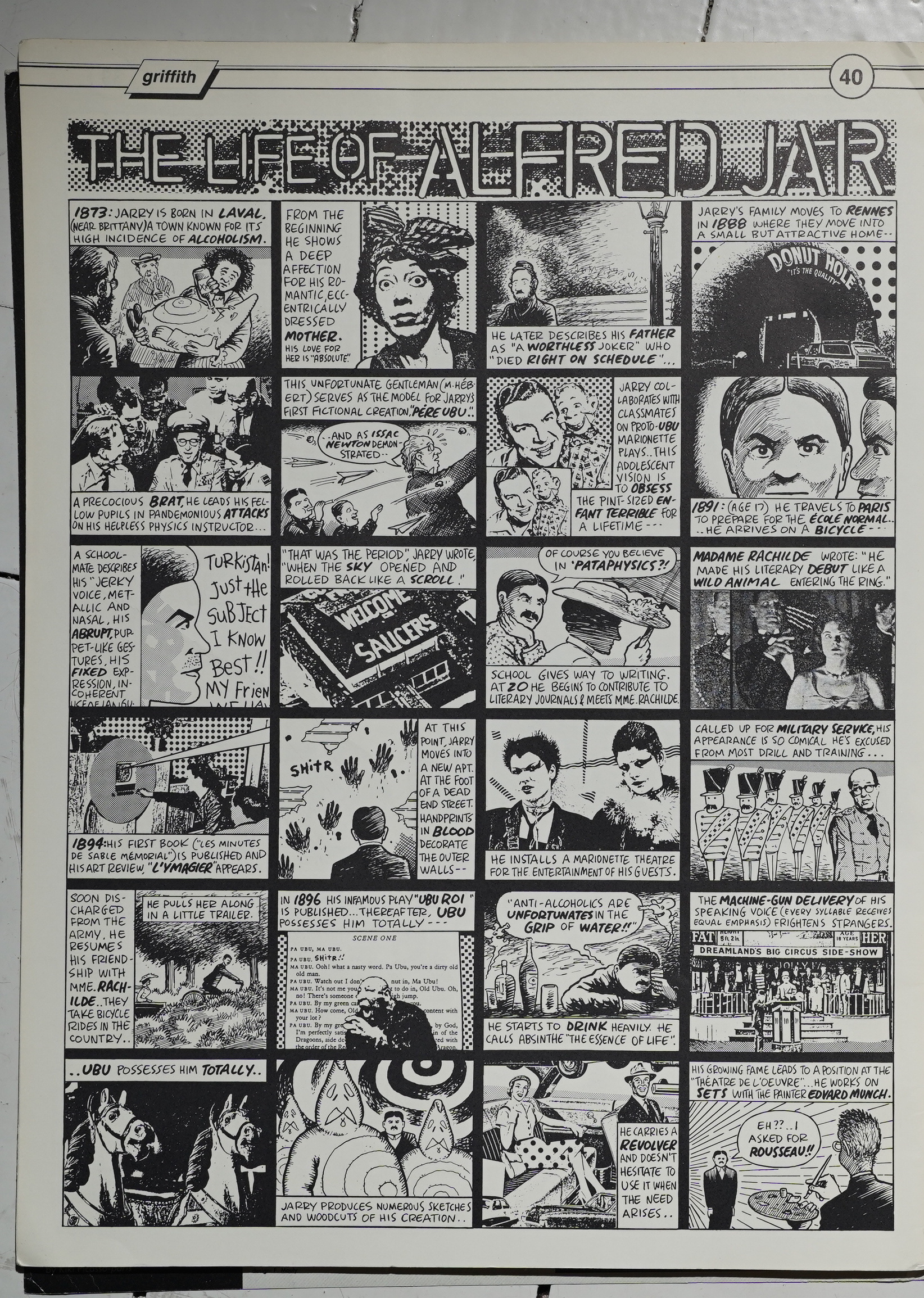

Continuing with the dada thing, Bill Griffith distills Alfred Jarry’s biography down into two pages, illustrated by somewhat random found images that are traced. It’s great!

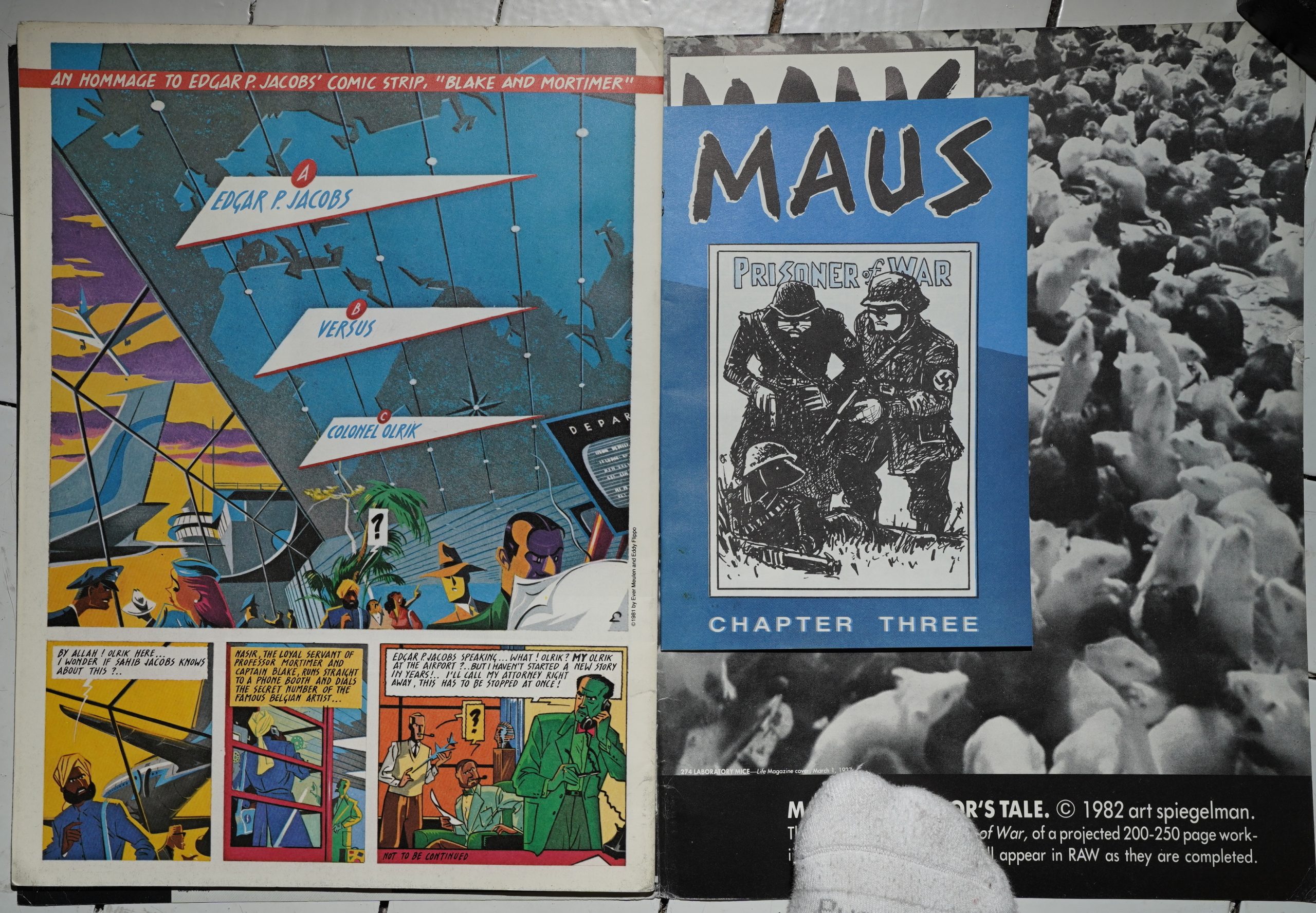

Ever Meulen does a better Edgar P. Jacobs than Edgar P. Jacobs. If only every Blake and Mortimer strip had been this much to the point.

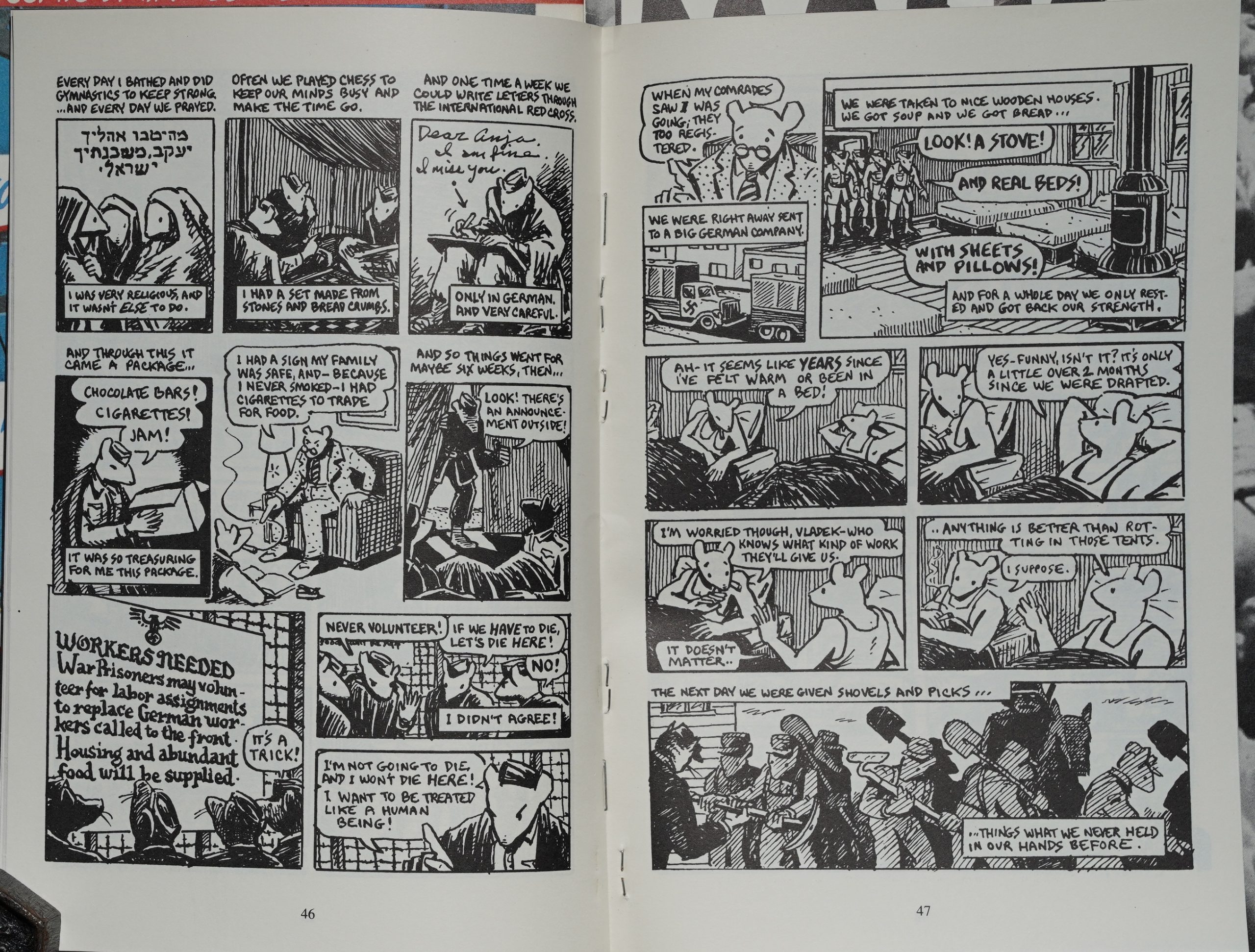

And then a Maus insert that’s stapled to the back cover — not bound into the book itself, so I’m guessing that Mouly and Spiegelman (no doubt assisted by a large number of people) stapled the booklet into the issue themselves (while the rest was printed by a professional printer).

And… I like that picture of rats? Mice?

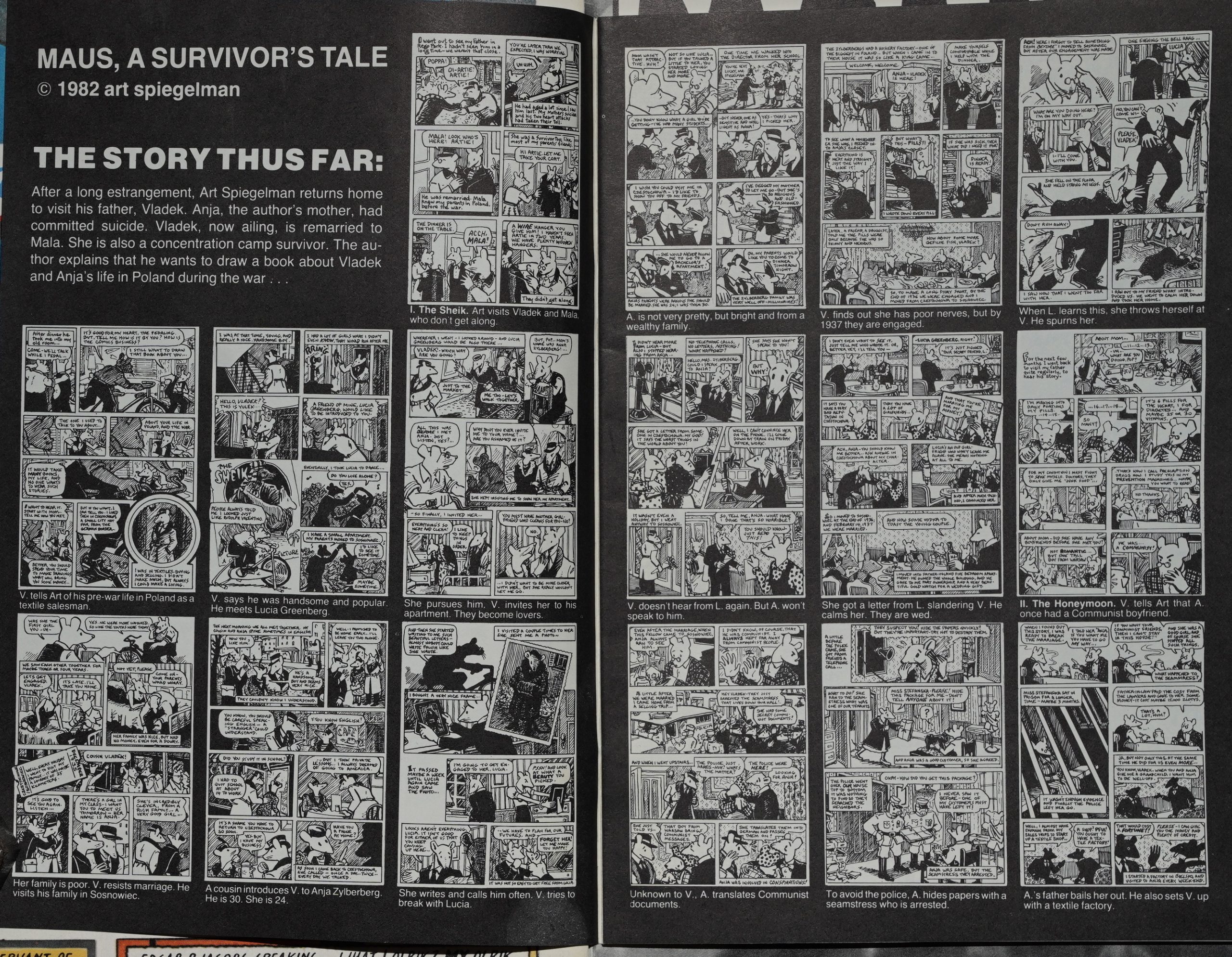

Like I said earlier, I didn’t have the first three Raw issues — and the first two were out of print by this time. Spiegelman helpfully reprints the first two chapters in this itsy bitsy format, and I remember reading this as a teenager. Man, it was nice to have sharp eyes.

As you can see, the stapling here is… er… enthusiastic…

It’s the longest Maus chapter so far, and Spiegelman is really getting into the swing of things — mixing his ambivalent feelings towards his father with the sheer horror going on in Vladek’s tale in an incredibly affecting way.

Kiki Picasso rounds of the issue with this amazing drawing.

So there you go: Another perfect magazine, with a mixture of funny and serious, longer stories and shorter pieces, text and graphics, European and American. Mouly and Spiegelman are on a roll.

Charles Burns is interviewed in The Comics Journal #148, page 60:

BURNS: The first issue said, “We’re interested in sub-

missions,” and that’s what I did. One of the few cases

where someone was “found” through submissions. I set

up an interview, and Art Spiegelman looked through all

my stuff and said, *’This is pretty good.”

SULLIVAN: Did yu like RAW when you saw it?

BURNS: Yeah. My initial reaction was that I really liked

the size. I liked looking at comics that weren’t necessar-

ily narrative, but that you could just enjoy looking at, like

ink on paper, and I liked the large format. I didn’t like

everything that was in there, but I liked what it was.

SULLIVAN: After you had the interview and he was en-

coumging, how did il proceed from there?

BURNS: I went ahead and made a piece specifically for

the magazine, more nan-narrative stuff. And one of the

strips I was sending to this place in California was the

first Dog Boy strip. I was about to send it out, and Art

said. “I want this.” I said, “0K. you’ve got it.”

SULLIVAN: What kind Of direction or encouragement did

you get from Art?

BURNS: It was from both Art and Francoise Mouly. In

those days Francoise was much more involved directly with

the editing. It was just having someone who could cri-

tique your work well. Someone whose opinion I would

trust. Not big editorial comments: ‘ ‘l don’t like this guy’s

forehead” or “I dorü like the way this hand is drawn,”

but more how the stories were structured. That was very

beneficial for me, that very constructive criticism.

The best kind of criticism is stuff that you know sub-

consciously already, and then someone that you trust

reconfirms your worst fears. Occasionally I’ll draw some-

thing and I’ll show it to my wife or somebody, and say,

“This is 0K, isn’t it?” “Nah, it’s not really 0K.” “Aw

shit.” I already knew it wasn’t working, but I had to have

that confirmed by someone else.

SULLIVAN: Did you go into the RAW office and meet the

other artists?

BURNS: At that point, it was just Art and Francoise’s liv-

ing area — one sprawling room with a few dividers, a big

cavelike structure. Somebody was always there working,

it seemed like, or somebody was coming over. When I

was going to go up to New York, maybe Gary hinter would

be in town, and I’d meet him, and Mark Beyer, whoever

was around. It seemed like there was always a flow of FEO-

pie. tempers flaring, on edge. There was always this flurry

of activity.

SULLIVAN: Did you get involved in projects, like the rear-

ing of the covers?

BURNS: Not very much. I was involved with the die-cut

cover [#41, trying to figure out how to do it. No, I never

bagged any bubble gum. I was not a New Yorker and

wasn’t there on call.

Dale Luciano writes in The Comics Journal #75, page 22:

Raw arrives with cover billing as ‘ ‘the

graphix magazine for your bomb shelter’s

coffee table.” Damned if this issue doesn’t

truthfully live up to that self-description.

For the most part, this issue is a revelling in

distortion and the grotesque that, on the

whole, summarizes a mood of contempo-

rary despair.

I believe in Mikel Dufrenne’s definition

Of beauty as the integrity Of an art object’s

completeness, its commitment to the fulfill-

ment of its own selfness. Undeniably, most

of the work appearing in Raw has an un-

usually pure beauty. Still, I’m beginning to

wish there were more room in Raw for

work that exhibited less absorption in the

uniqueness of its own formal properties or

preoccupation with the grotesque—or fail-

ing that, work like Art Spiegelman’s own

Maus that has a little human resonance in

it. Now that I’ve gotten that Out of my

system, let me hasten to add that on its

Own terms, Raw certainly fulfills its own

aspirations to present new and startling

work. It remains a lively and sorely needed

assemblage of material that is anything but

dull Or predictable.

The centerpiece of this issue, the 12-page

epic Race Of Racers” by the Swiss car-

toonist Francis Masse, is an imaginative

but gloomy vision of incoherence.[…]

Though the

work is visually remarkable—there are

some hauting images of this ersatz

apocalypse—it’s a pretentious imposture.

Worse yet, none of it is very funny. I found

it a disappointing entry.

Charles Burns’s “The Voice of Walking

Flesh” is a slice of grotesquerie, a sort of

stylized parody of horror with a nightmar-

ish plot that leaps past logic into irra-

tionality.[…]

In truth, Burns gives us a highly stylized,

creepy vision of things—the people have

elongated faces and almost irrelevant

distinguishing features, like mannekins in a

department store window—and the whole

is a peculiarly unsettling variety of surreal

nightmare-horror. The effort is shot

through with a macabre sense of humor.

The plot situations are intentionally

ludicrous, and there are apropos absurdist

touches—the caretakers at the Institute, for

example, are clean-cut, freckle-faced

McDonald’s waiters. Taken On its own

merits, it’s a masterwork of the bizarre.

Some of Burns’s work appeared in Raw 3,

but “The Voice of Walking Flesh” is a full-

blown, major example of the Philadelphia.

based artist’s work.

It’s growing more evident with each issue

of Raw that Spiegelman’s artistic sensibility

as manifested in Maus stands almost mys-

teriously apart from the editorial sensibil-

ity, along with Francoise Mouly’s, that

selects the material in Raw. In vivid con-

trast to the portentousness that tends to

characterize this issue Of is the careful.

ly observed, human-scale pathos of his

mice characters. This is the third install-

ment of Spiegelman’s work-in-progress,

and it is no disappointment. The writing

continues on a level of uncommon intelli-

gence.[…]

This is a remarkably unmanipulative ap-

proach to writing. Spiegelman doesn’t take

advantage of the material by wringing it

dry of life in hope of soliciting a conven-

tional emotional response. He’s content to

allow ambiguities of situation and char-

acter to arise without comment or resolu-

tion. Maus is based on actual events as

communicated to Spiegelman by his

father. This quality in Maus, a kind of

clearheaded purity in the plotting and

drawing of the action and dialogue, may

grow out of Spiegelman’s responsibility to

the material as lived family biography; still,

this should in no way diminish the artist’s

achievement in transforming recollection

Into art.[…]

In truth, I found much of the remaining

material in Raw disappointing. There’s a

highly concentrated, one-page dose of

Mariscal antics that is entertaining but

minor. Josef Schwind’s “Slug Alley

Gazette,” is all of an excruciating, dull

piece with Schwind’s dada-collage work,

“Growing Pain,” that appeared in Raw

This issue contains a special record insert,

of all things….what they call a “flexi-disc,”

I believe.

This blog post is part of the Punk Comix series.