I bought a GPU! A big one! This blog post is about that.

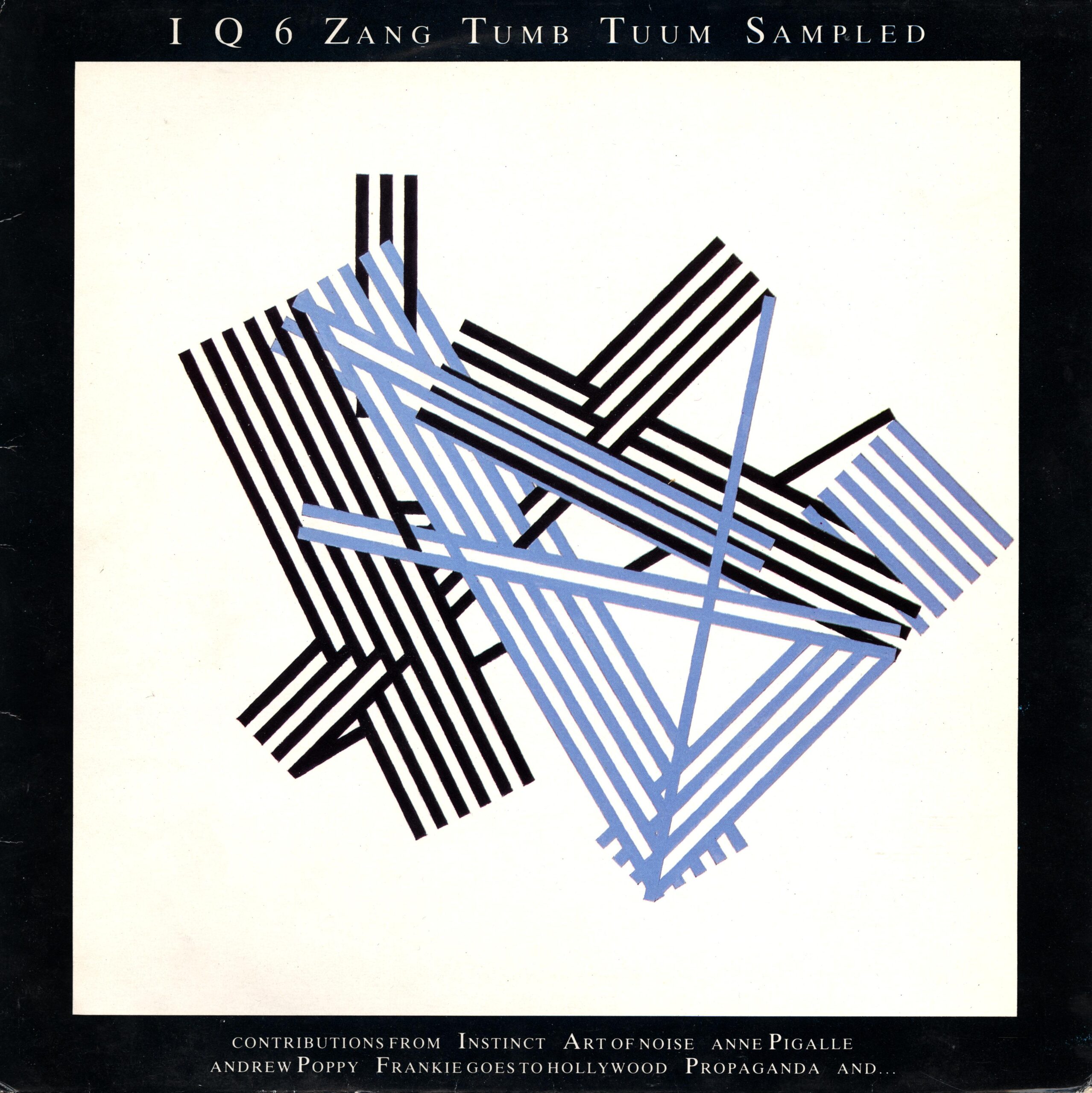

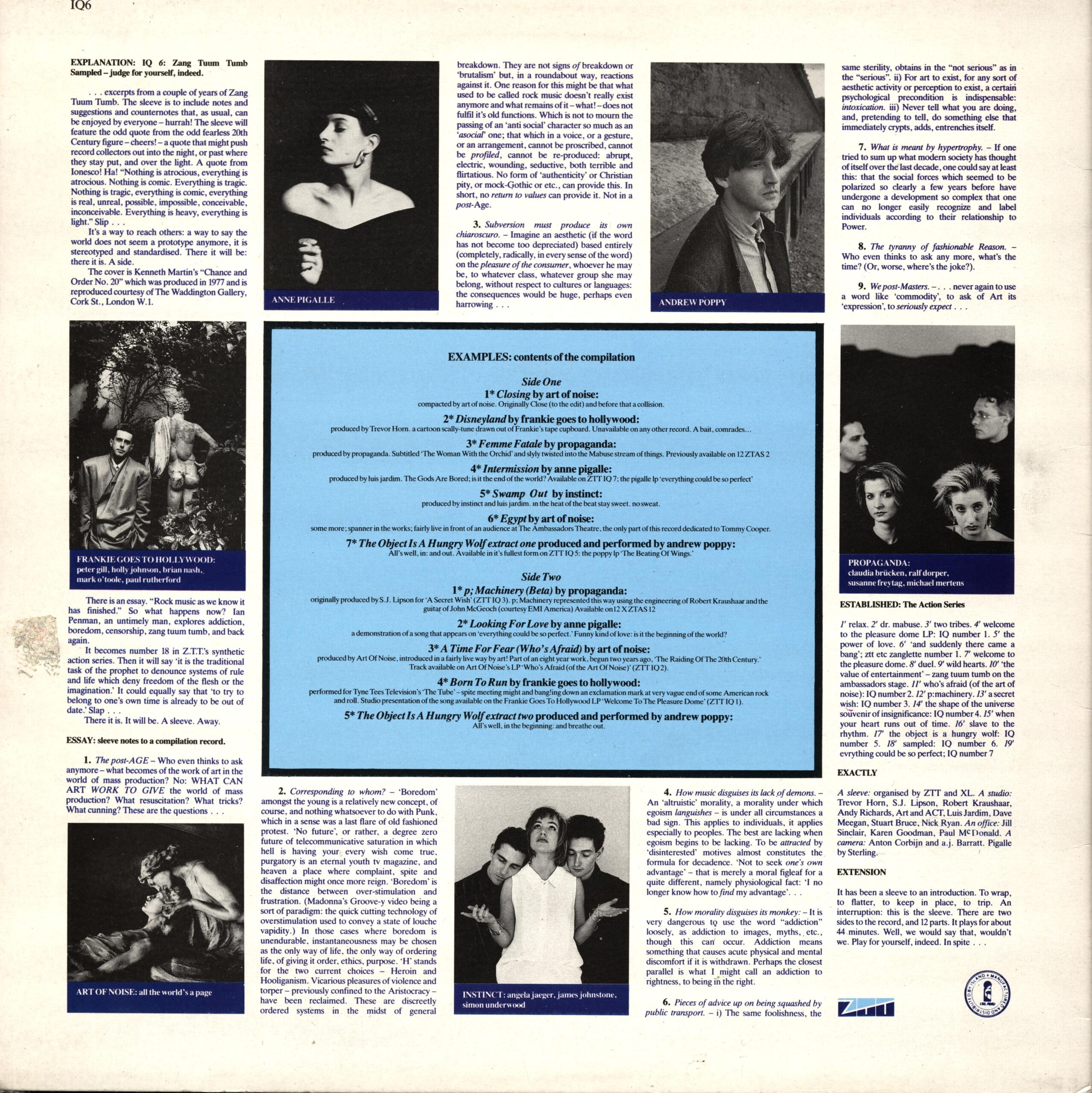

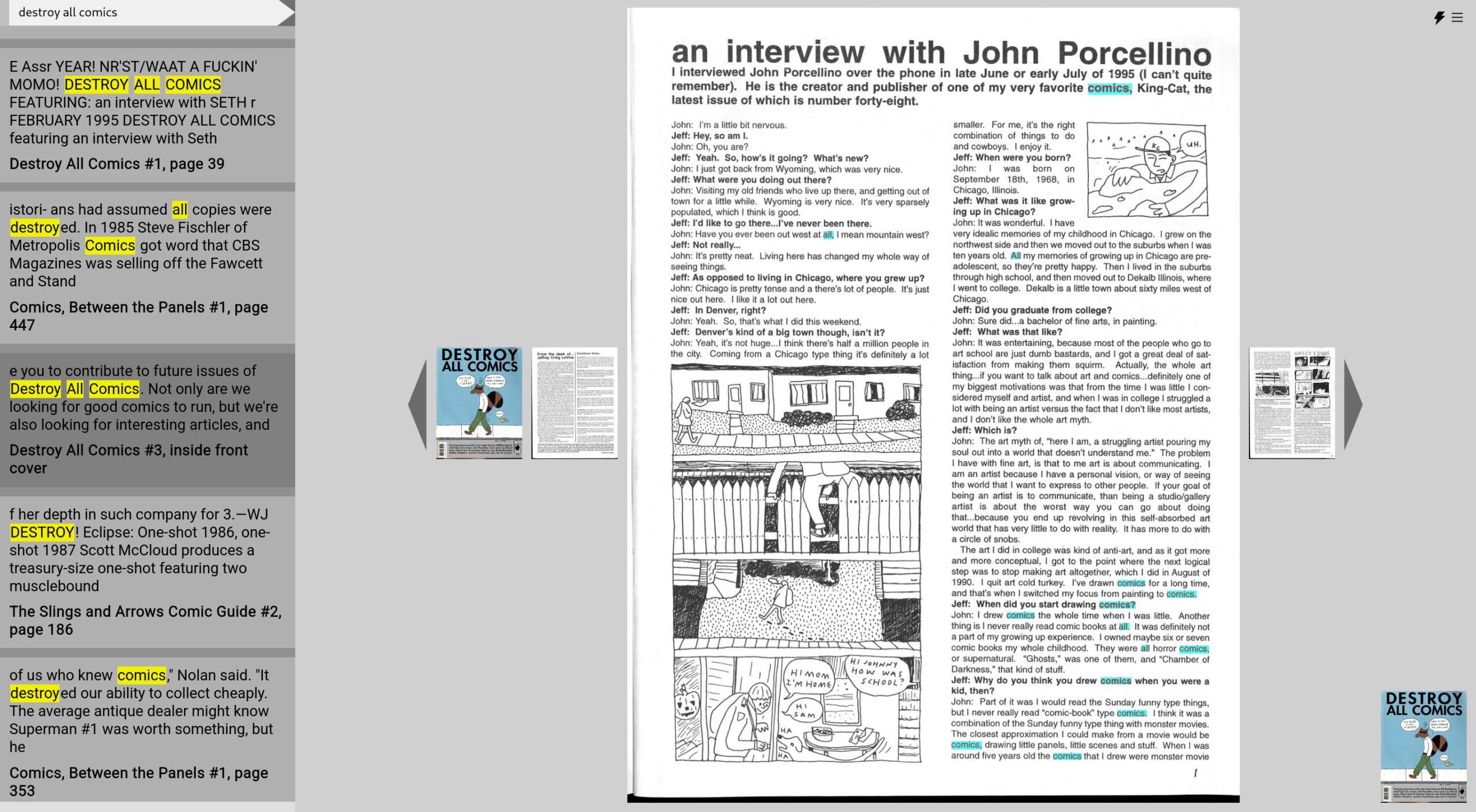

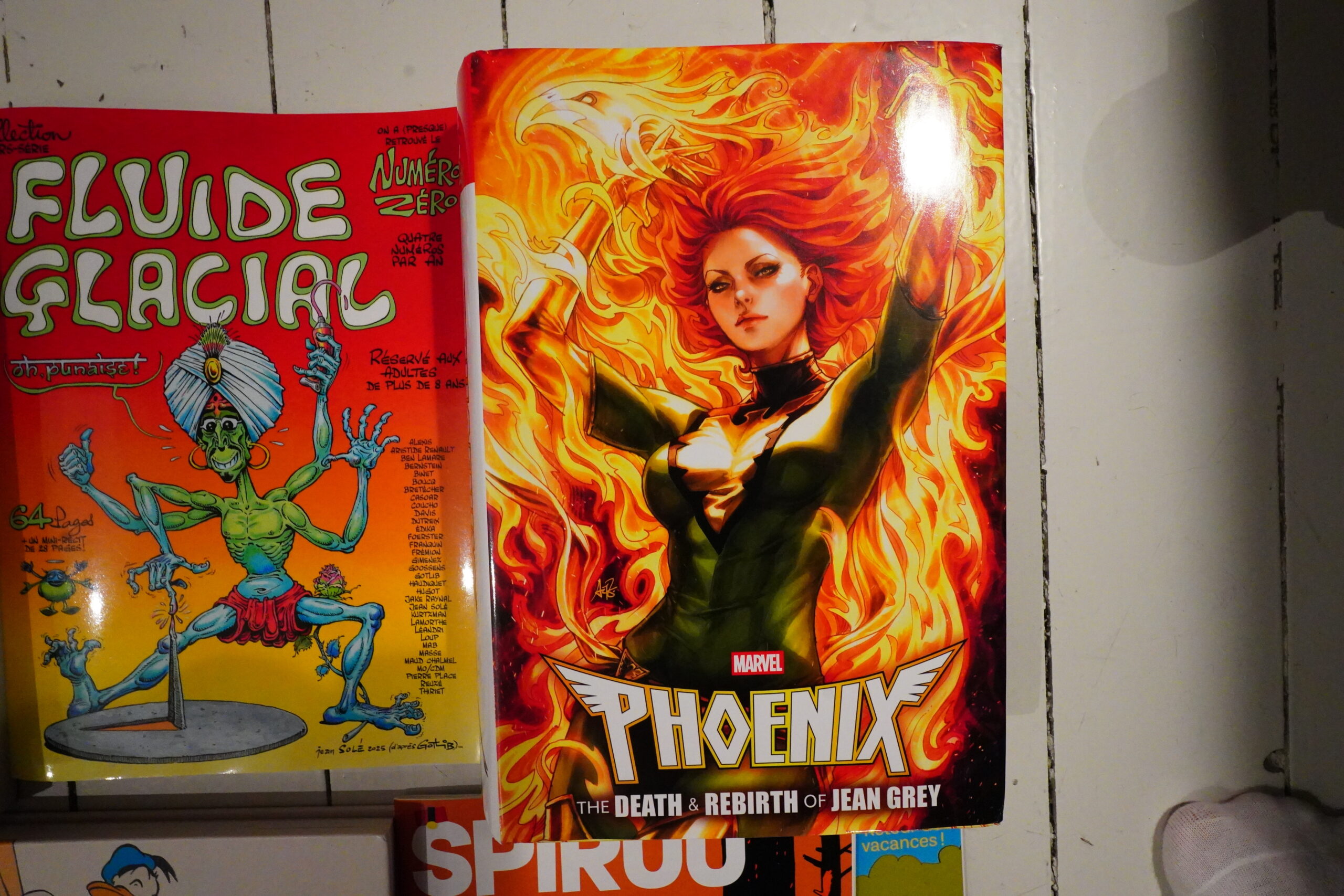

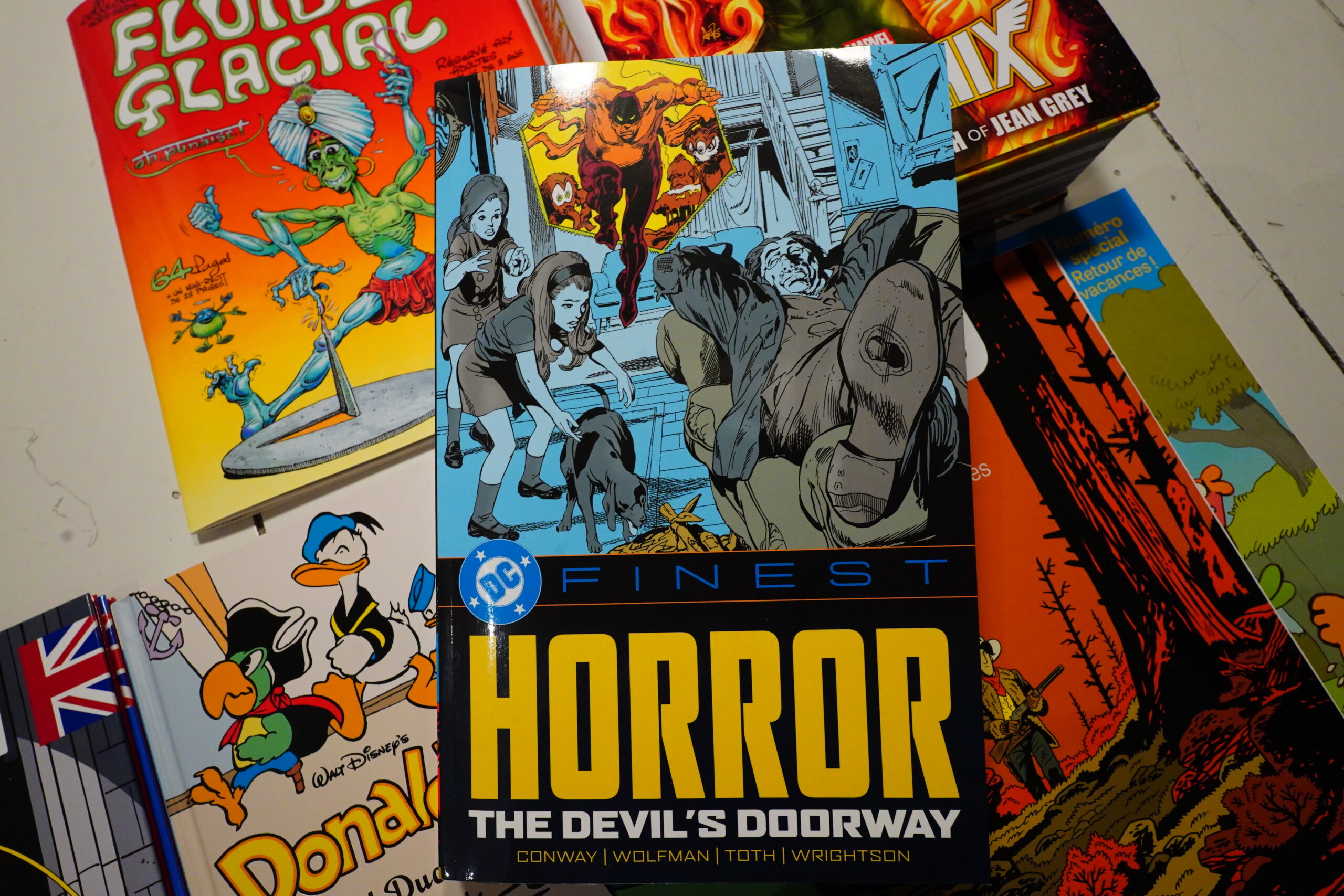

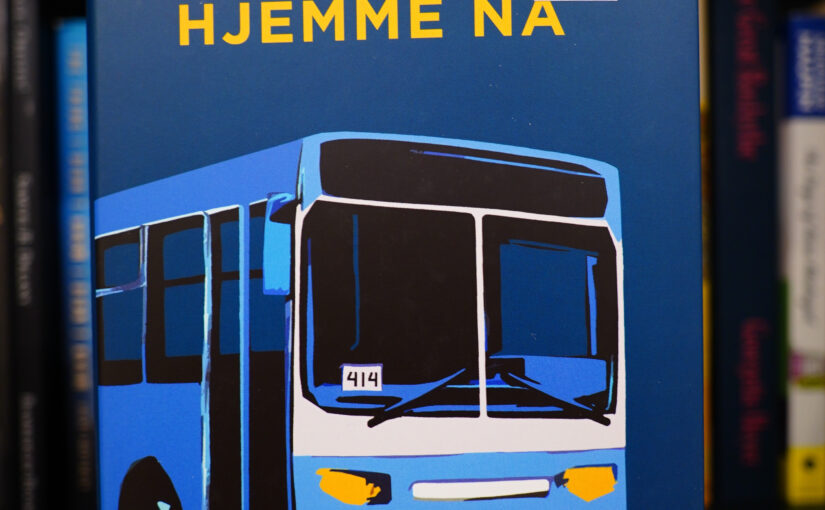

So… like, a few years ago (oh, 2018; time flies) I wanted to put together a thing to do research into comics, and since the comics I was most interested in were from the 80s, all articles/interviews/etc were nowhere to be found on the Internet. So I realised that I should just put together a web site of scanned magazines about comics (note: not comics magazines — magazines and fanzines about comics), and viola: kwakk.info.

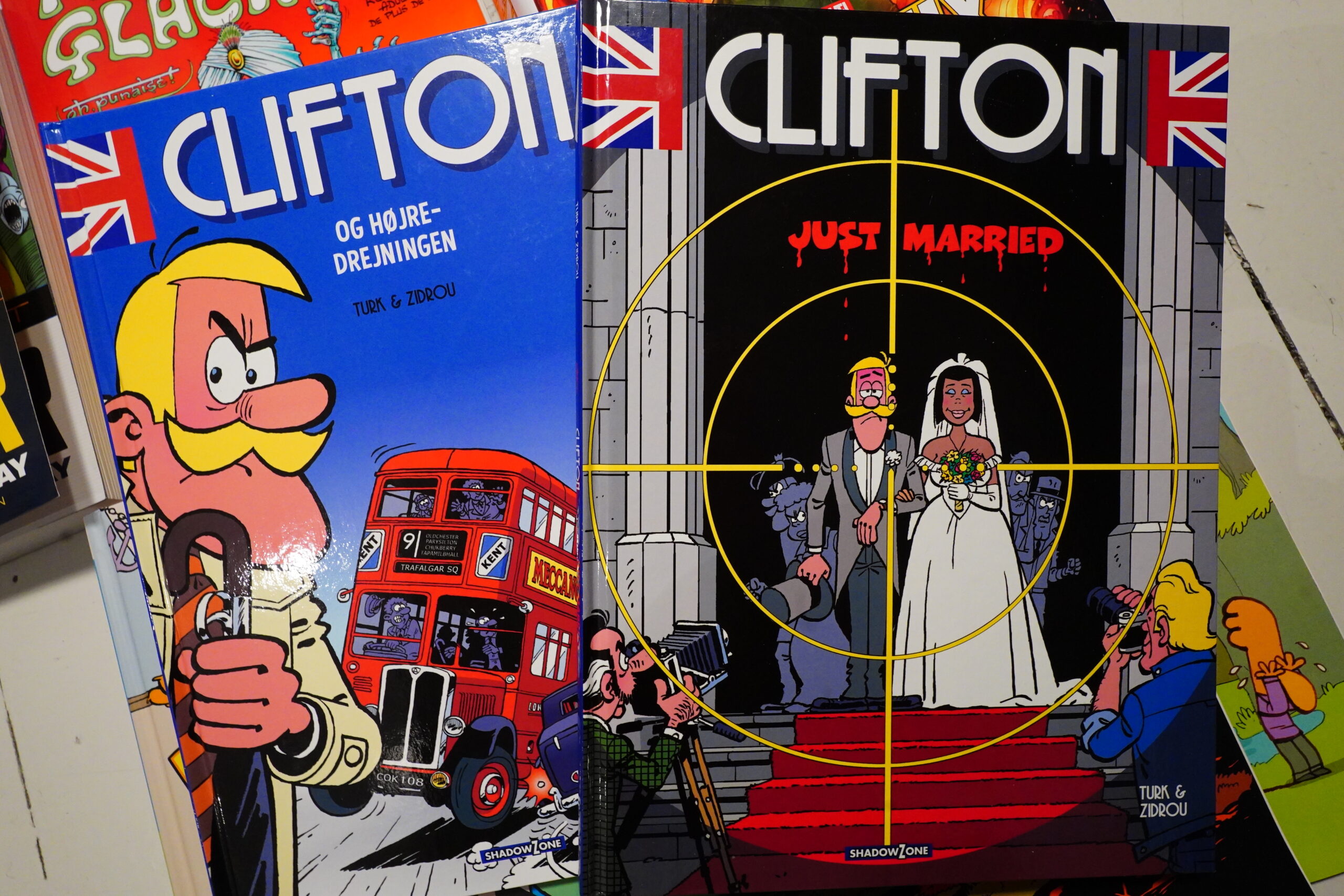

Which now has 11K issues, which is… probably most of what’s been written about comics and published in papery form?

Er, I mean, 9600 issues, because I’ve only made publicly available magazines that aren’t commercially available any more; wouldn’t want to be all rude and stuff. So 1500 issues just for me mua ha ha.

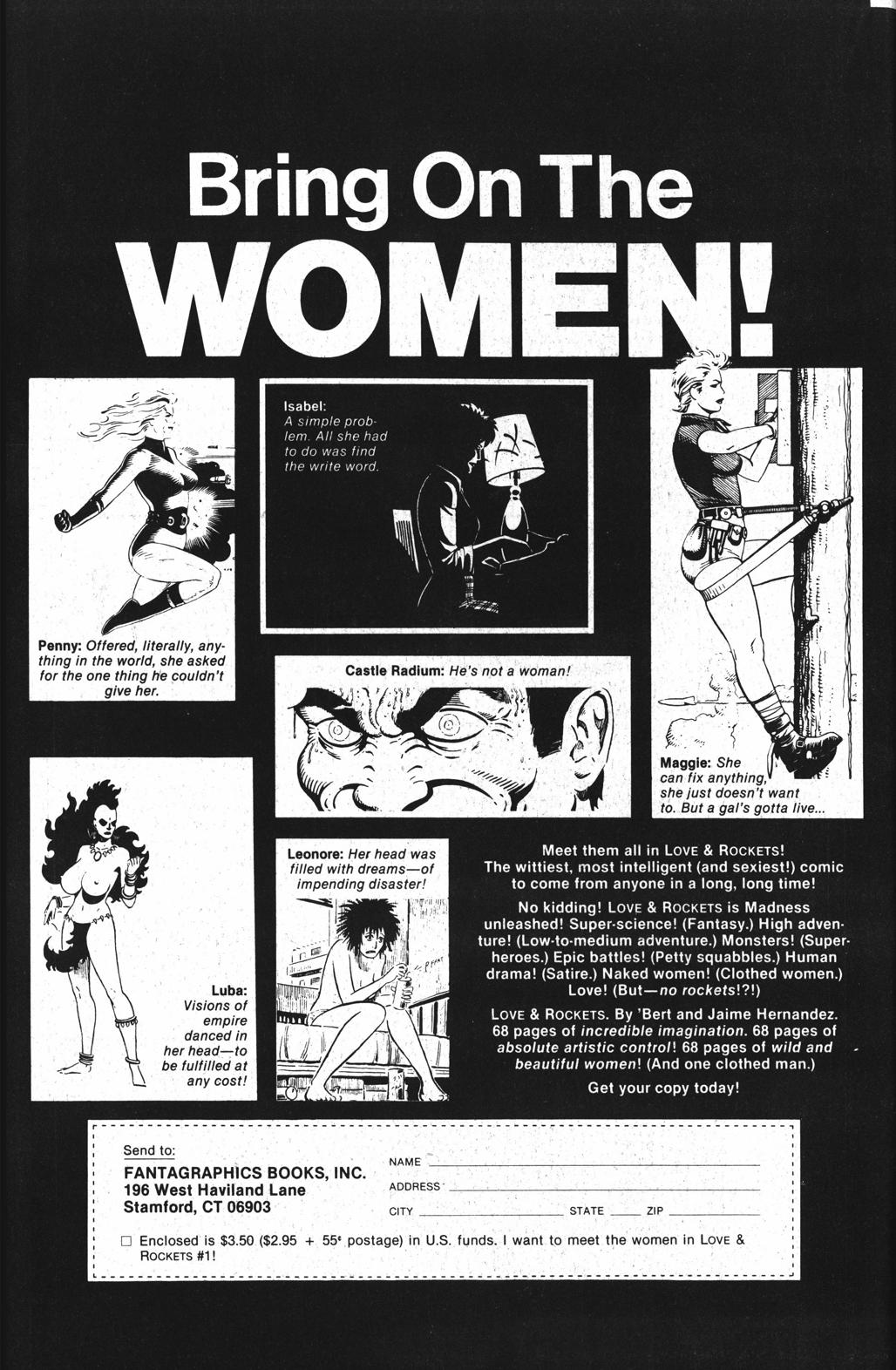

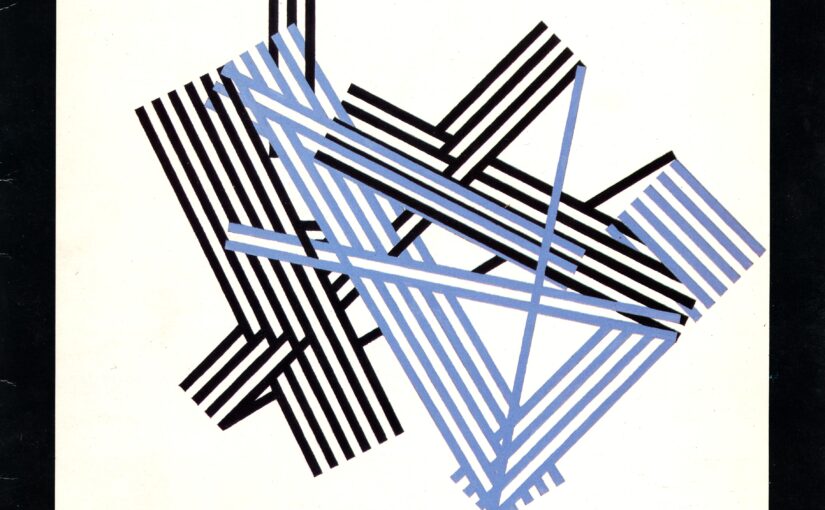

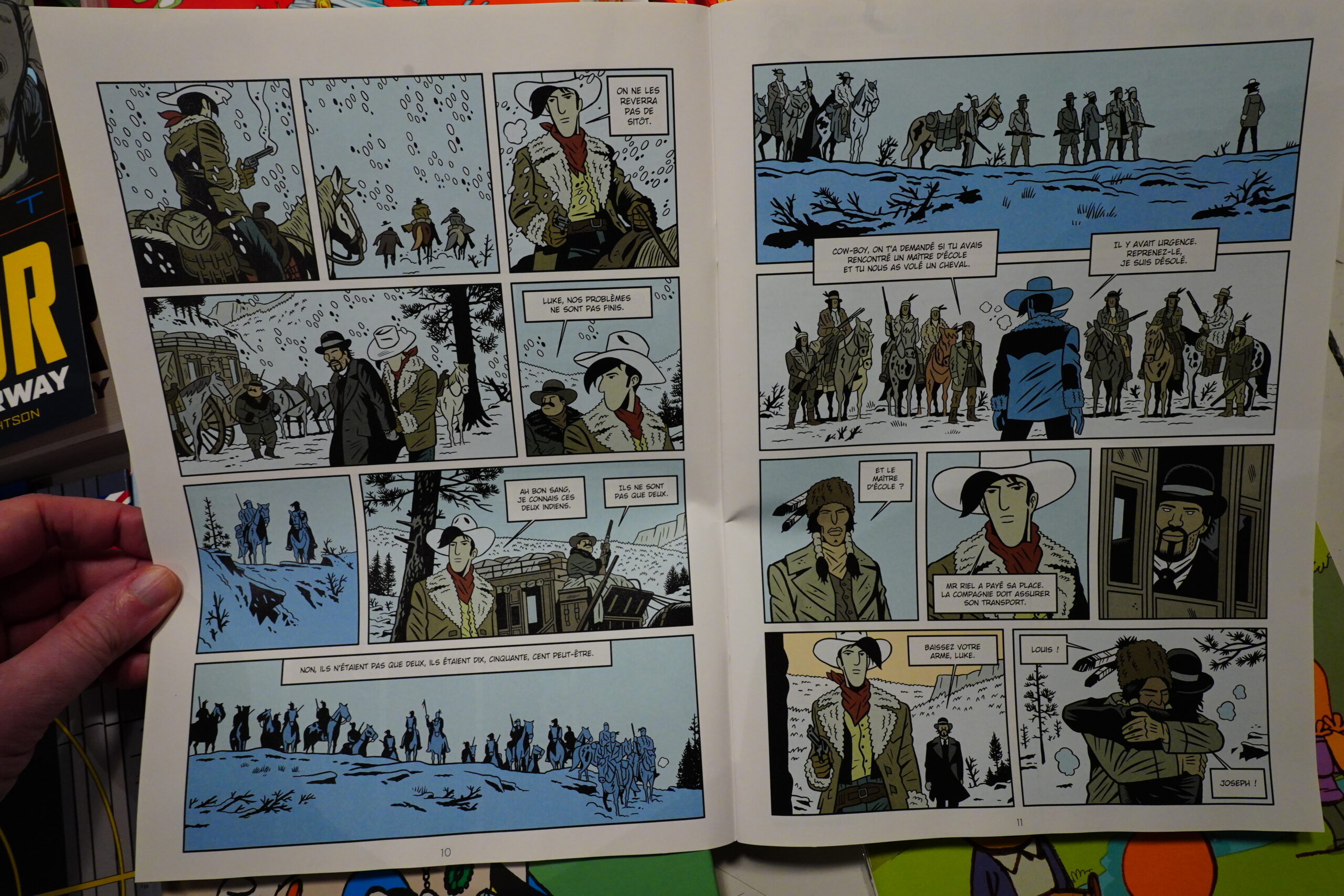

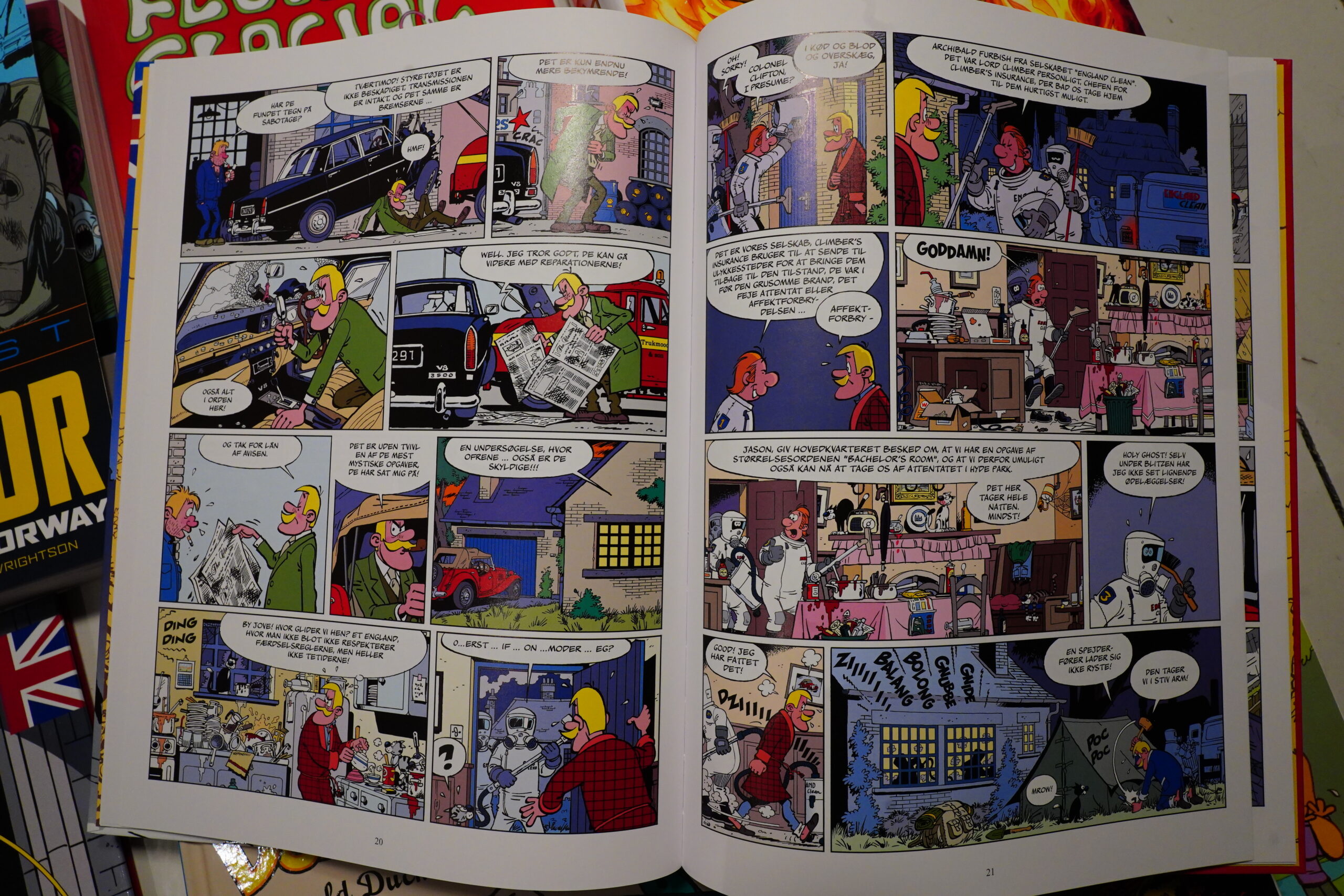

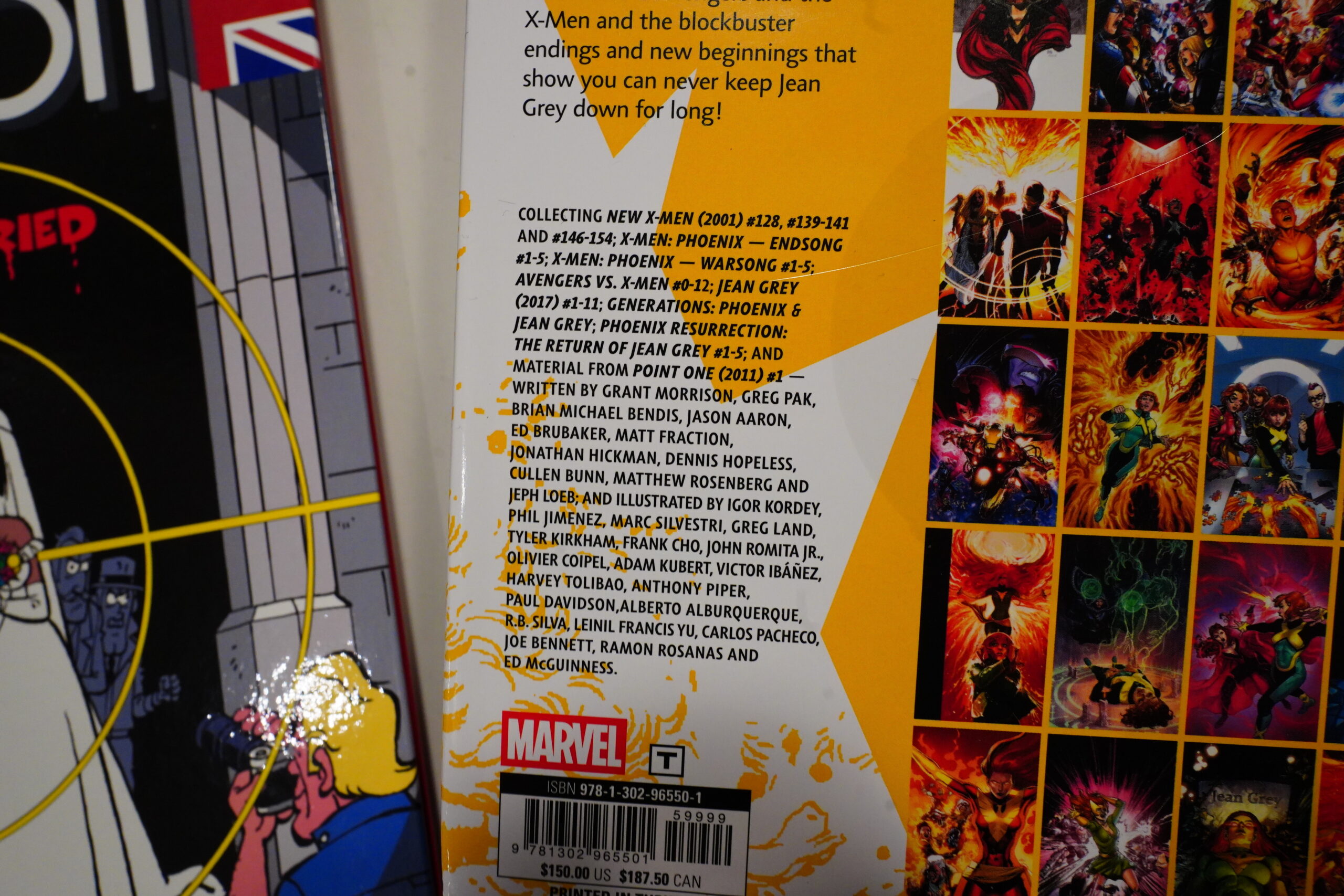

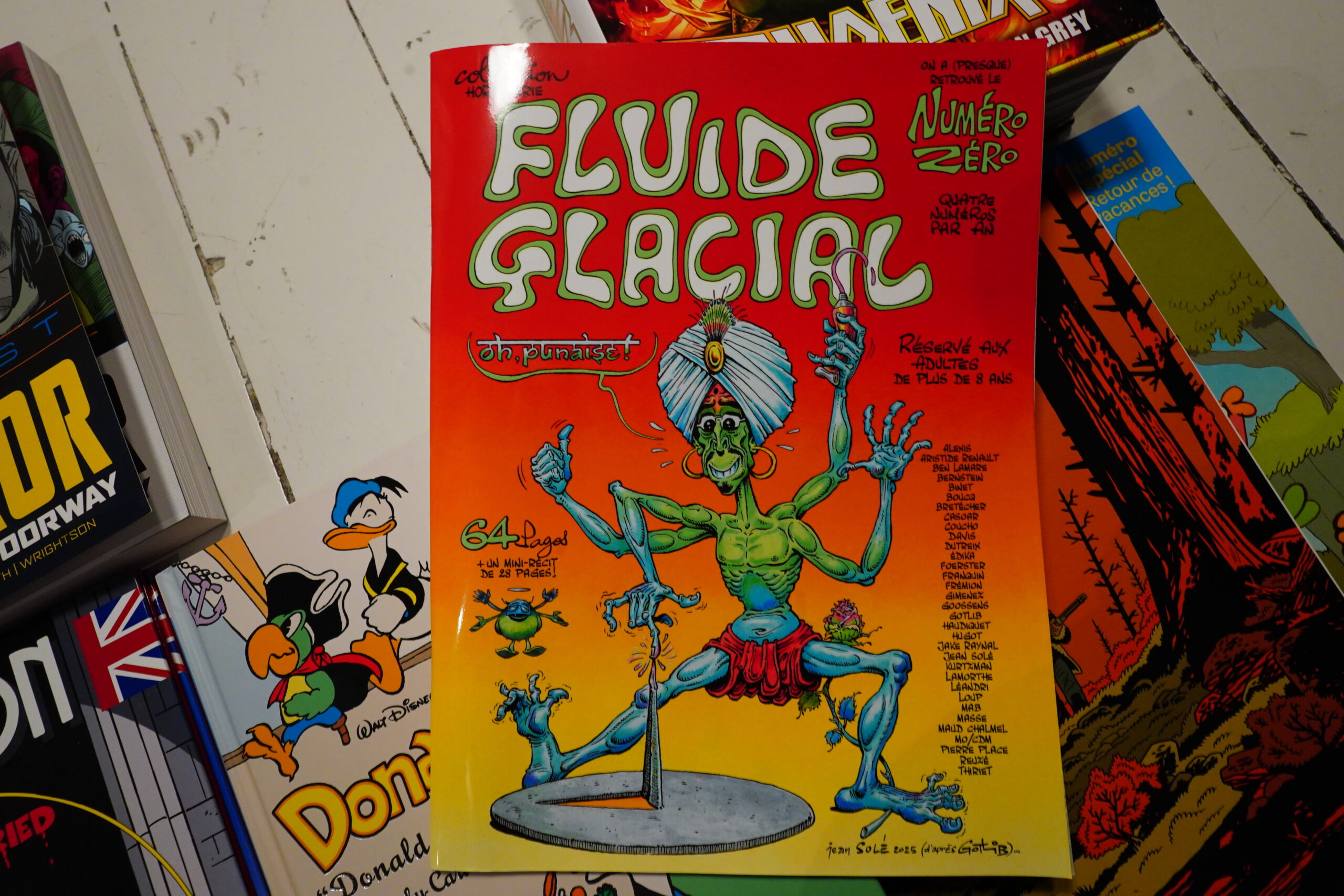

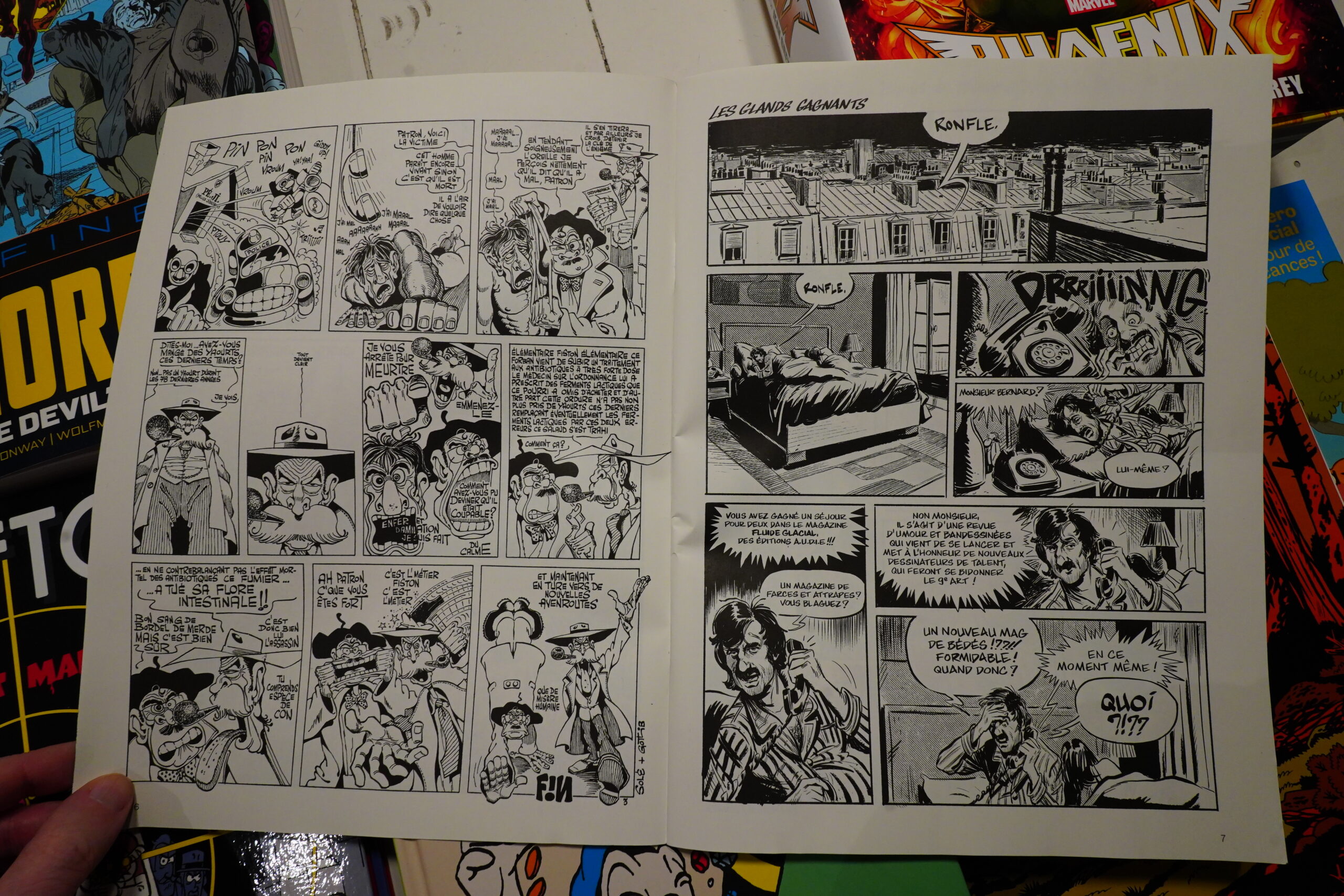

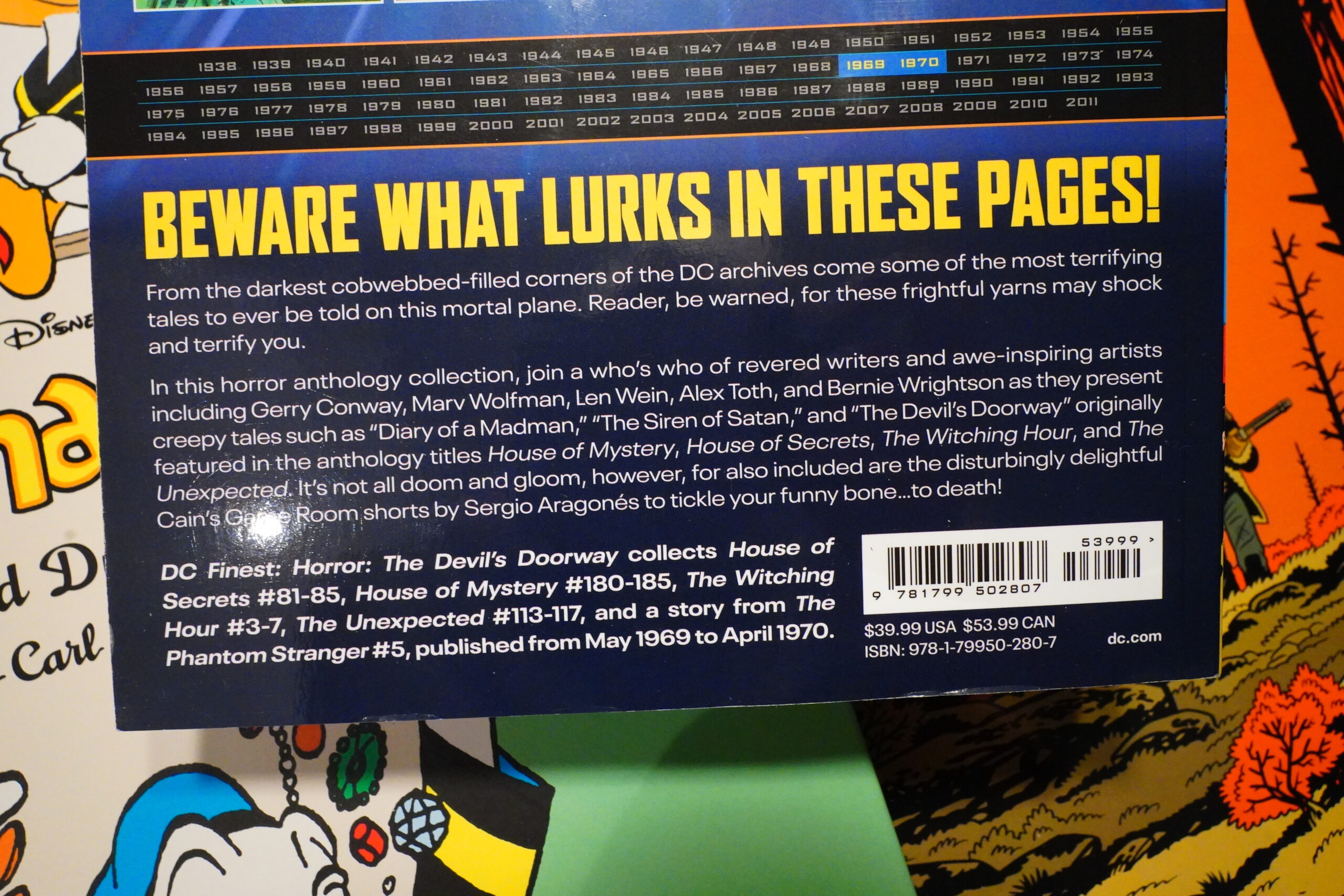

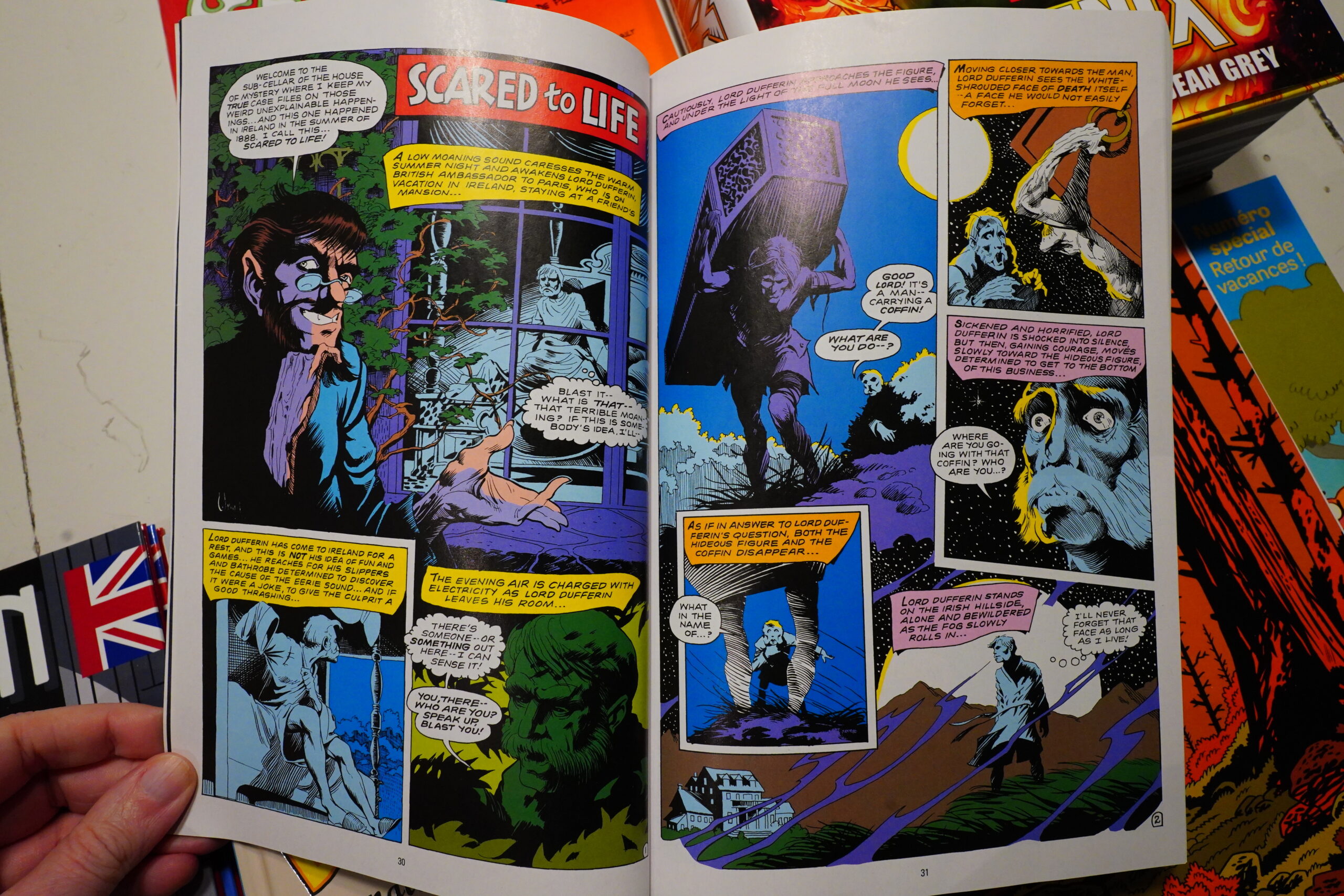

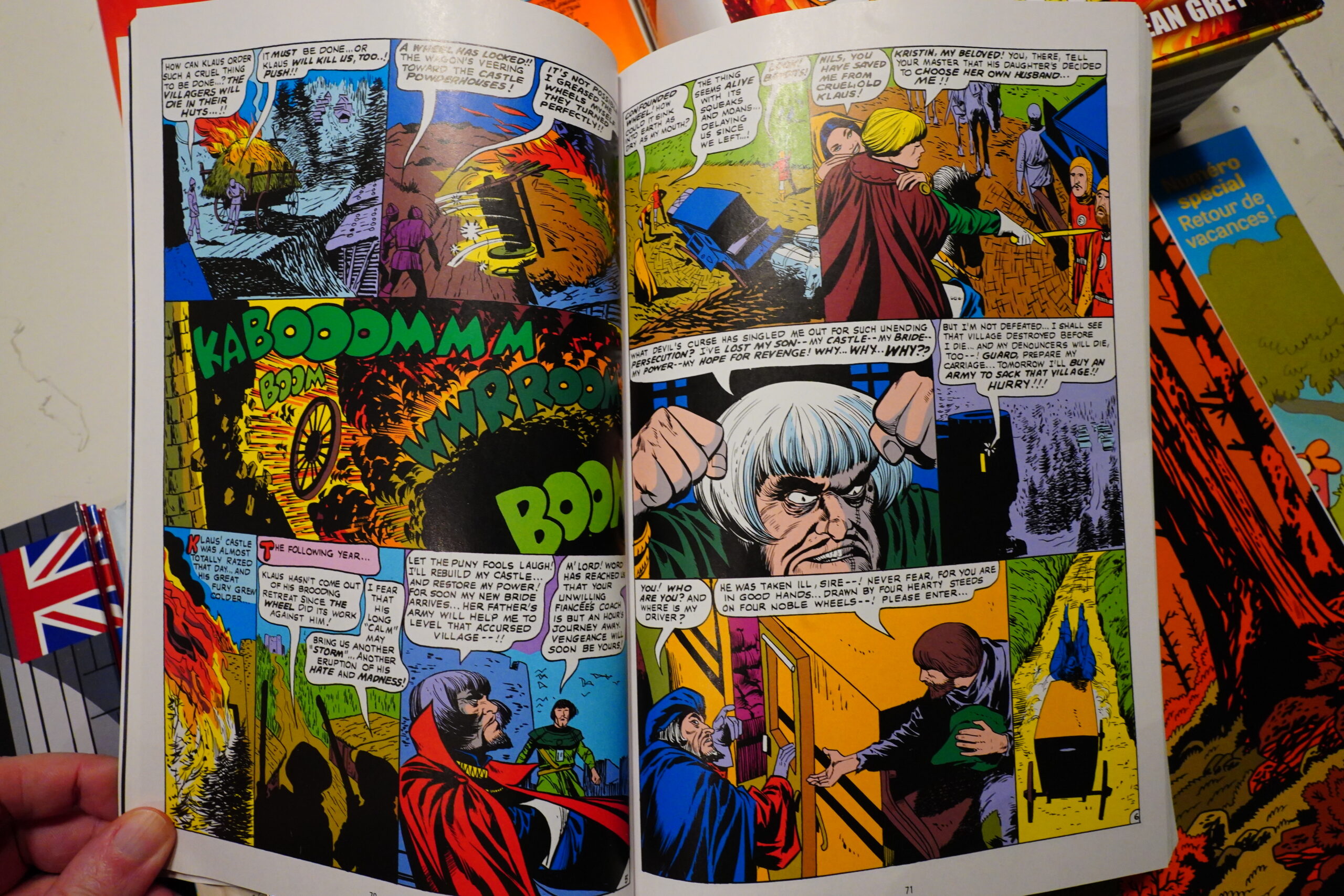

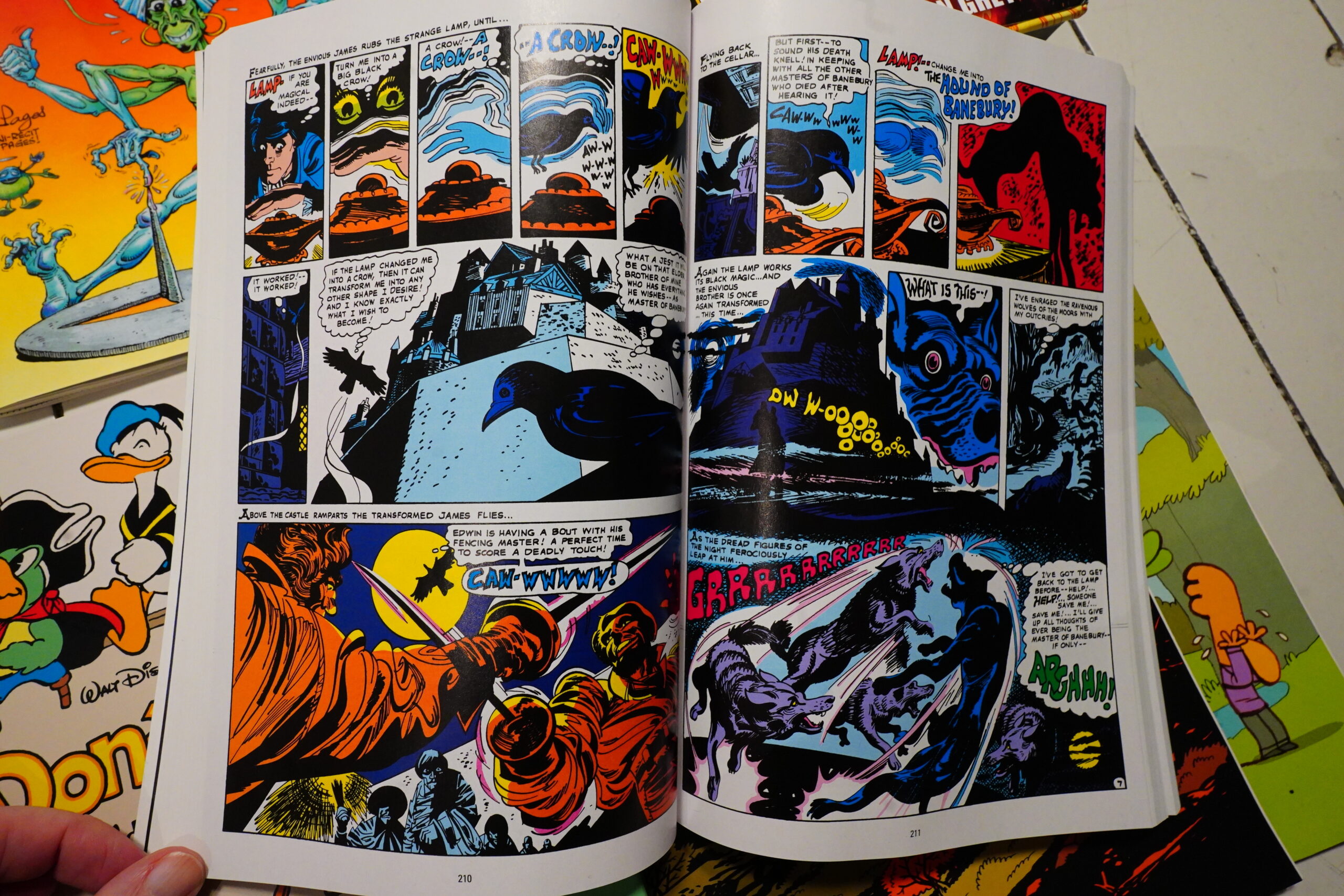

Anyway! I’ve been using ocr.space for the actual OCR. It’s pretty good, but it’s far from perfect. It’s much better than (for instance) Tesseract — Tesseract doesn’t even get white-on-black text right (which is important for pages like the above). But there’s still a persistent problem about accuracy. I assumed that ocr.space would get better over the years, but nope — it’s the same as when I started, which is just annoying.

I can hear people muttering out there… “OCR! Pah! That’s a solved problem!” They’ve been saying that since the 90s, really. And you’d think so, but only if you haven’t had experience with using OCR over a wide variety of documents. If you have a small set with consistent typesetting/fonts, cleanly scanned, then yes, you can train the OCR for that set.

But I have around 600 different magazines, all using different… everything. Text over pictures, mimeographed typewritten fanzines, weird fonts, handwritten snippets of text… I’ve tried a lot of different solutions over the year, and nothing can be said to actually, like, “work”. ocr.space is the best I’ve found — it can take basically everything, and the results aren’t stellar, but they’re what you may call almost good enough.

In addition to the quality issues, ocr.space isn’t exactly free either. So I was wondering whether LLM OCR had finally become viable.

I’m going to spoil the answer now: “Yes, it has”.

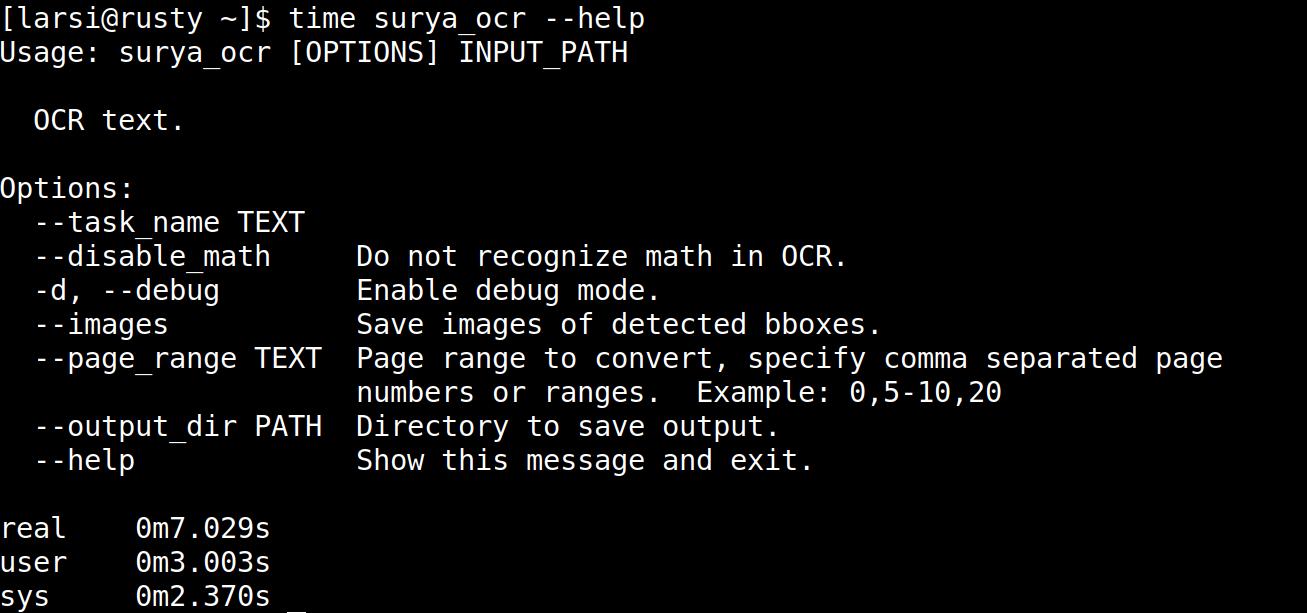

I’ve tried this stuff before last year, and it definitely wasn’t ready then, but since I’m going to be using LLMs anyway, I asked ChatGPT which LLM OCR was the spiffiest now, and it confidently said “surya ocr”, which I assumed was a hallucination. But it’s not!

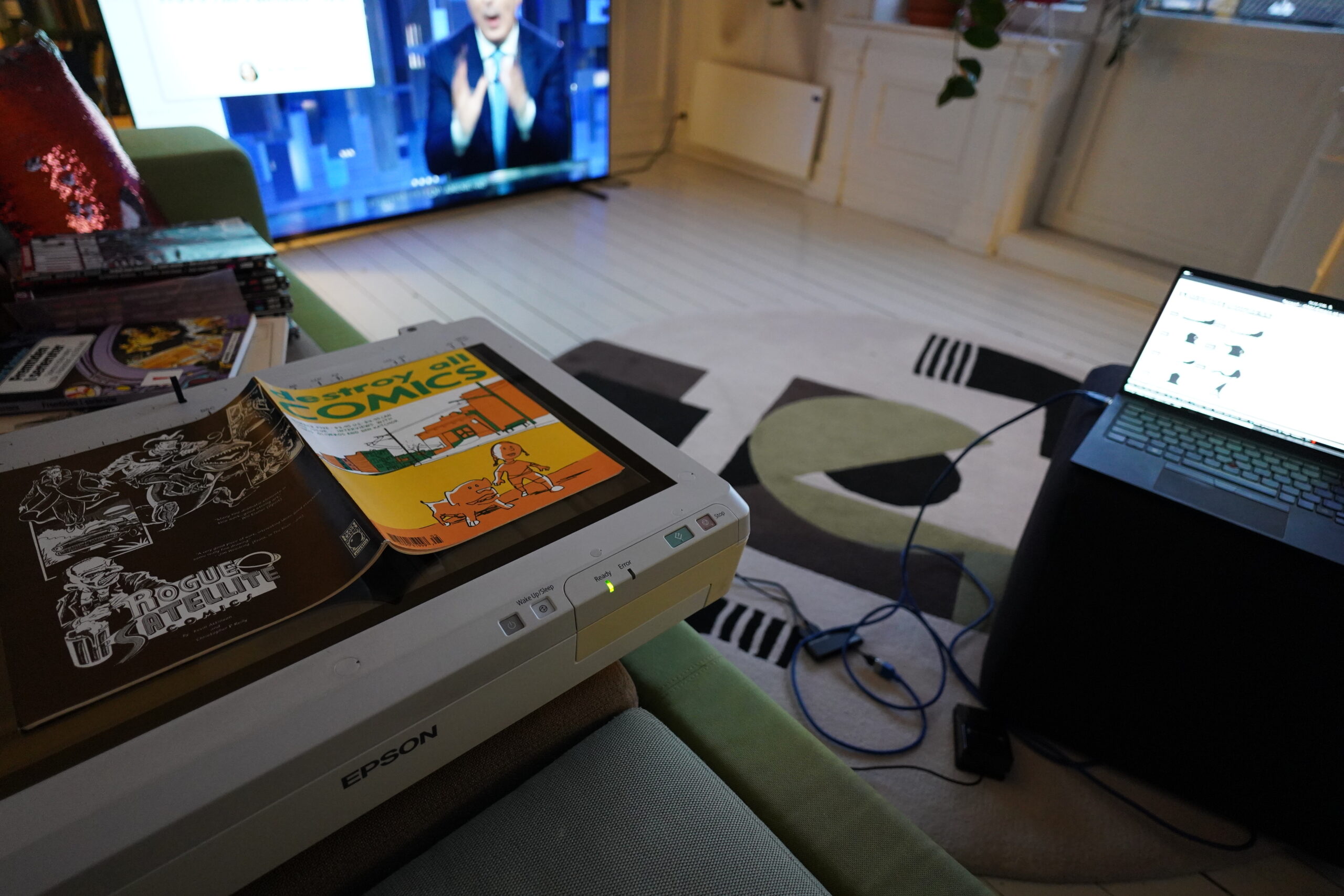

So just for giggles, I tried it on my laptop (which doesn’t have any GPU-ness to speak of; just built-in Intel), and doing one page took three and a half minutes.

But! The results look good! So I asked ChatGPT which GPU was the spiffiest (from among the ones the local gadget emporium had in store), and it said “Nvidia RTX 5000 Ada Generation”, so I bought that. I think it may be the single most expensive component I’ve ever bought? I mean, I’ve bought plenty more expensive servers and even laptops, but no single component… I see how Nvidia came to be swimming in cash.

[Edit next day: Heh heh, I checked, and that was bad advice: An RTX 5090 costs 40% less and is 60% more powerful than the RTX 5000 Ada. Oh, LLMs; you never fail to be mediocre. But I guess I would have had to have a more powerful PSU for the 5090; I dunno.]

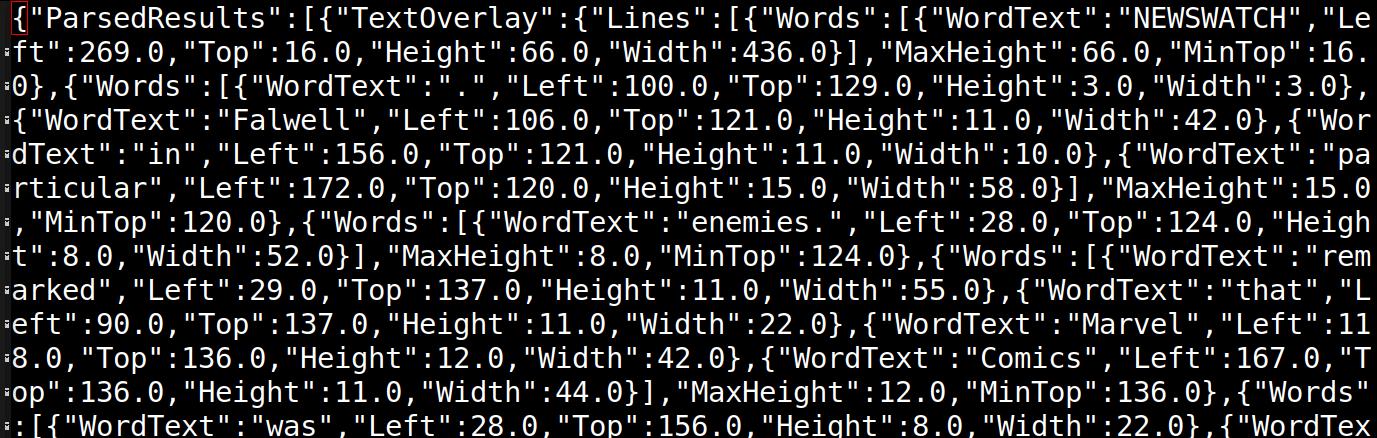

Anyway, while waiting for the card to arrive, I took a look at the output from surya, and it’s JSON. But of course not on the same format as ocr.space, so I took this as a sign to stop using the raw output from ocr.space on the web site and instead post-process it a bit.

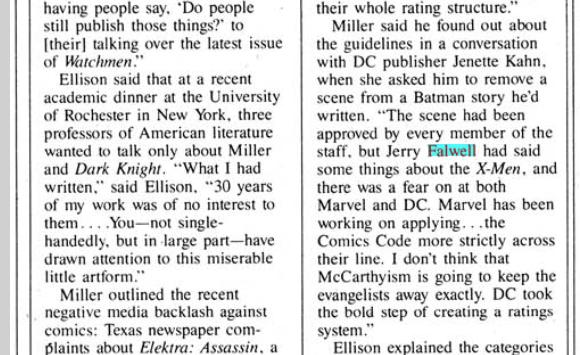

Because the ocr.space output looks like this:

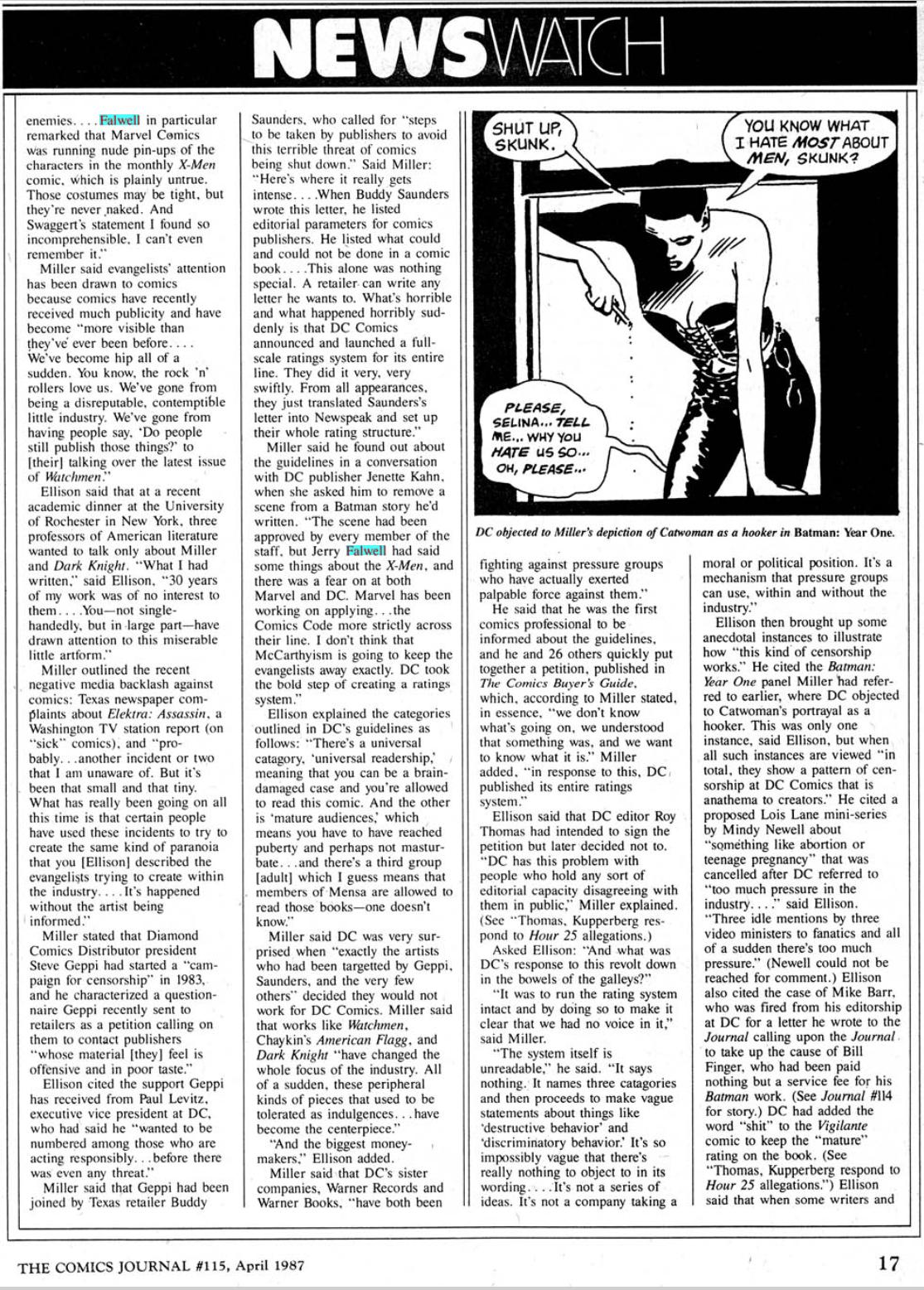

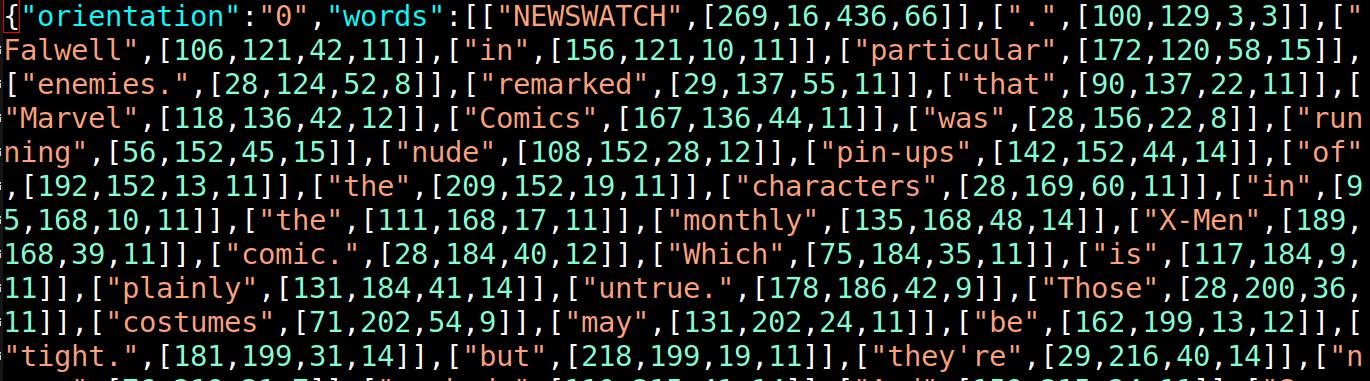

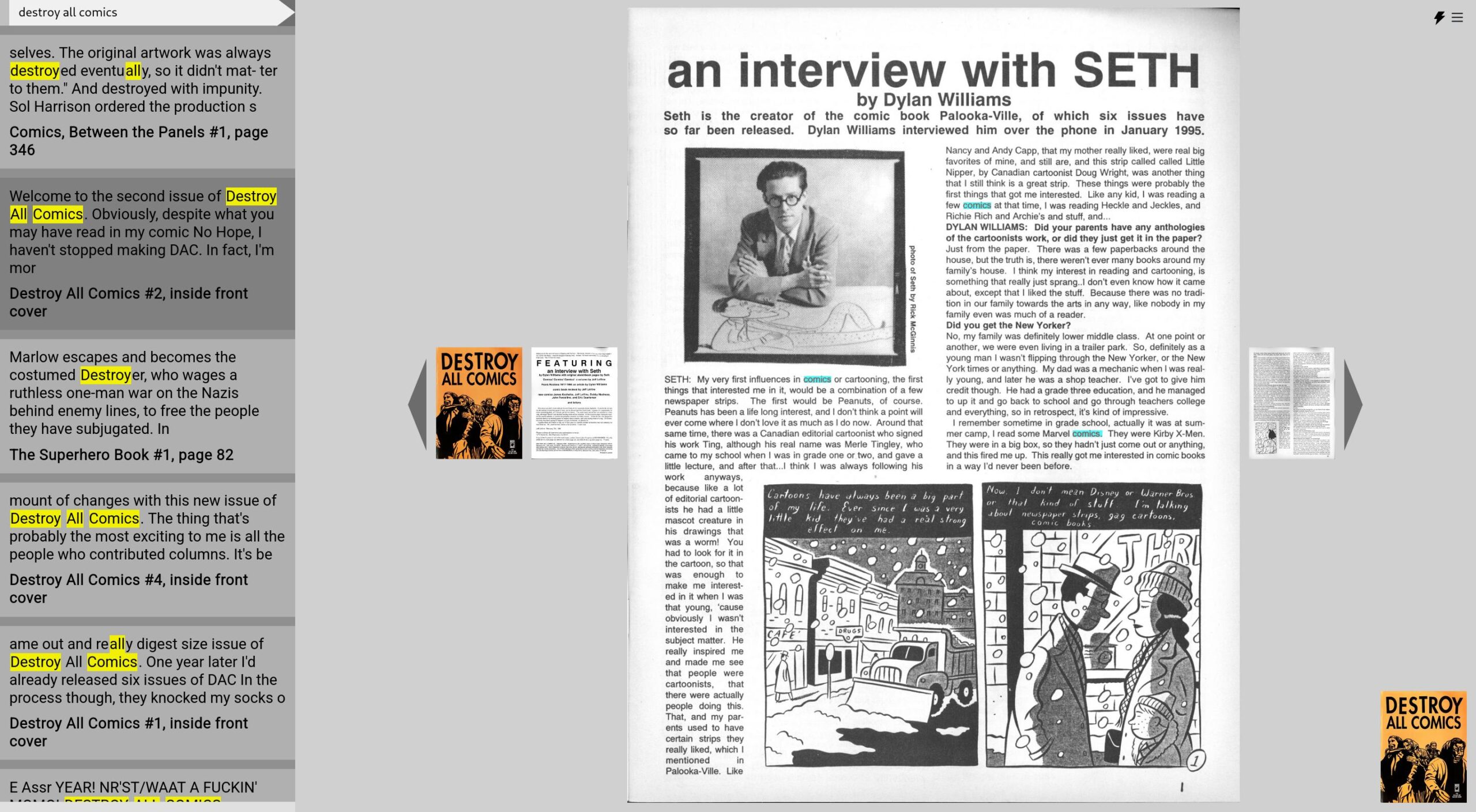

So we get a bounding box per word, which allows me to highlight matches. Here I’m searching for Falwell singlehandedly, and we see how nicely it’s highlighting everything:

Oops! Just “Falwell”!

Yes, because “singlehandedly” is split across two lines, so I took the opportunity to change the format completely:

In the new format, each word can have multiple bounding boxes. Tada:

There; I fixed it. So even if you have

supercalli- fragilistic- expialidocious

broken over an arbitrary number of lines, it’ll highlight things correctly. (Searching pages manually, looking for words, is just such a drag.)

So, problem solved!

But…

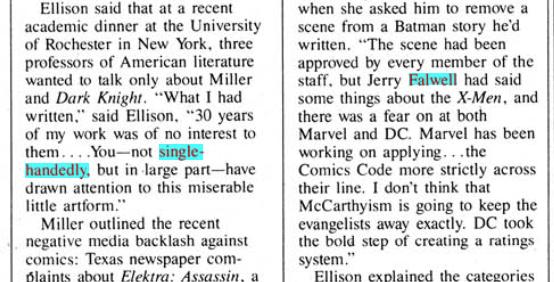

That’s the output from surya. Surely that can’t be correct? The bounding box for the line is 167,237-945,275, which seems likely, but then the bounding box for the “B” (surya gives me coordinates for each individual letter, and I have to put them together into words) is 446,241-516,265? That’s in the middle of the line; that can’t be correct. And then the “u” in “Buyer’s” comes before the “B”? OK, all the X coordinates for the letters are nonsense.

Time to bug report! But nope; it’s a known issue:

We’ve identified the issue, which is a regression from our latest model. We’re working on updating the model ASAP to rectify. In the meantime, please use the older version of surya. I’ll keep you updated when we release a fix.

*sigh* But the version of surya from July works well, too, and doesn’t have this problem, so I guess I’ll just use that until they fix the problem.

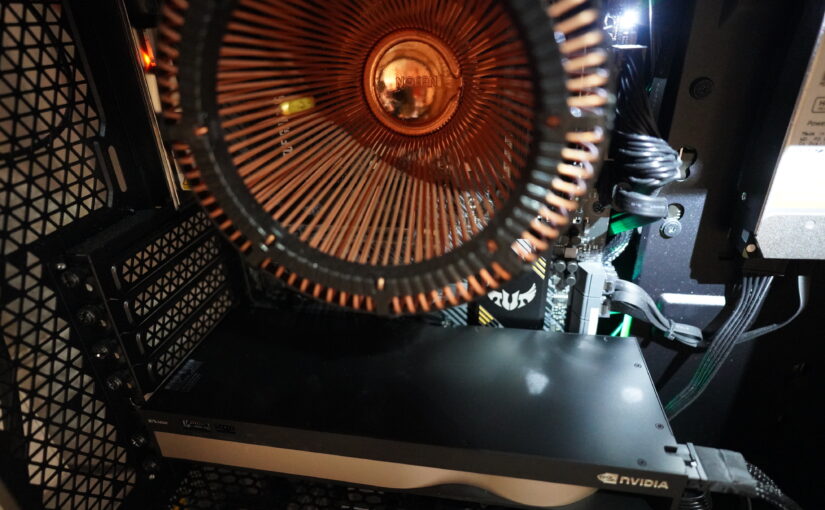

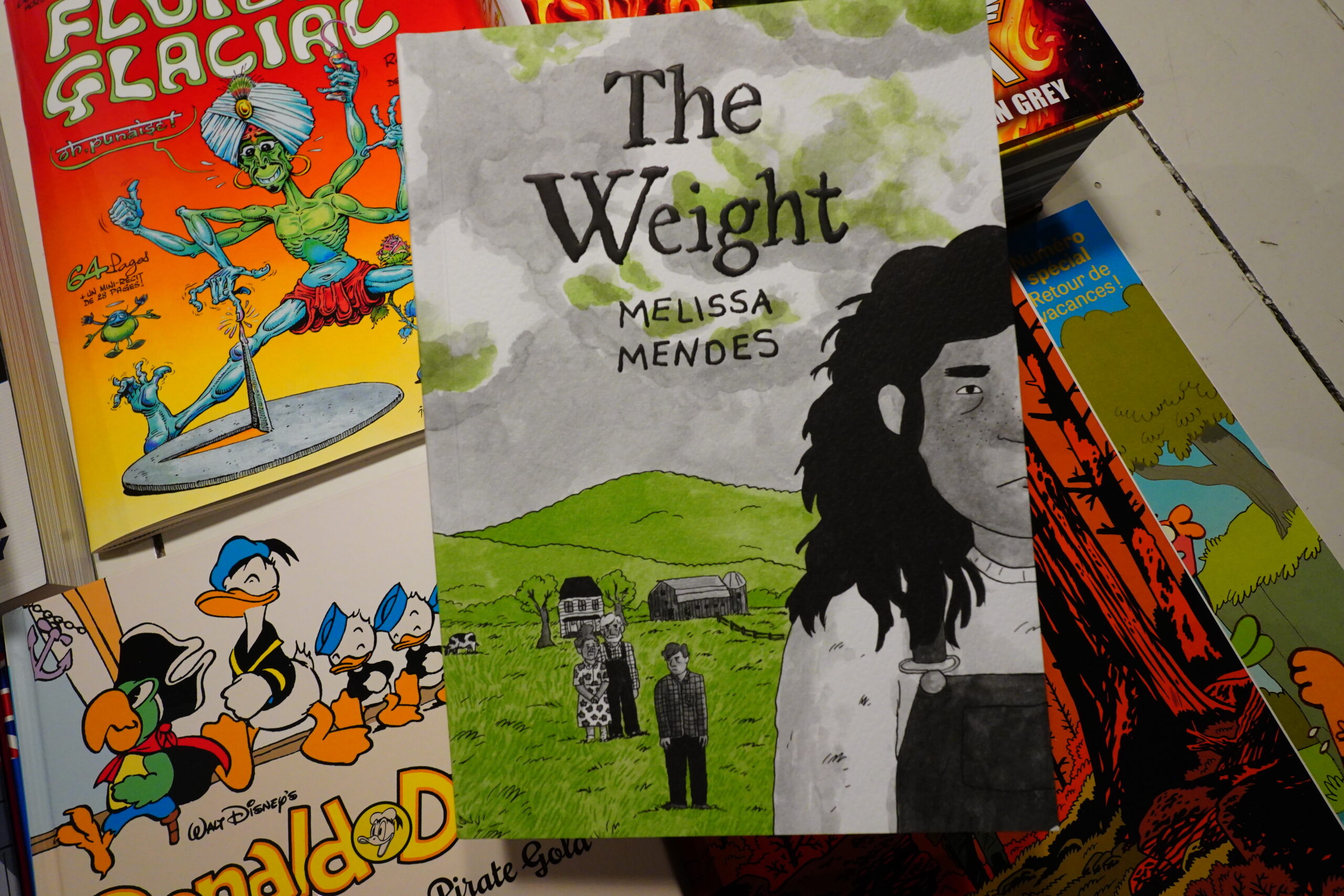

And then it’s the next day, and look what I got!

Unpacking sequence commence.

It’s not a very … extravagant package. GPUs in the olden days used to have at least a tiger jumping out of fire, riding a motorbike and being shot at by lasers on the box. I mean, as a bare minimum.

How demure.

The card doesn’t even have any multicoloured LEDs!!! Not a single LED of any kind! What has happened to our culture!

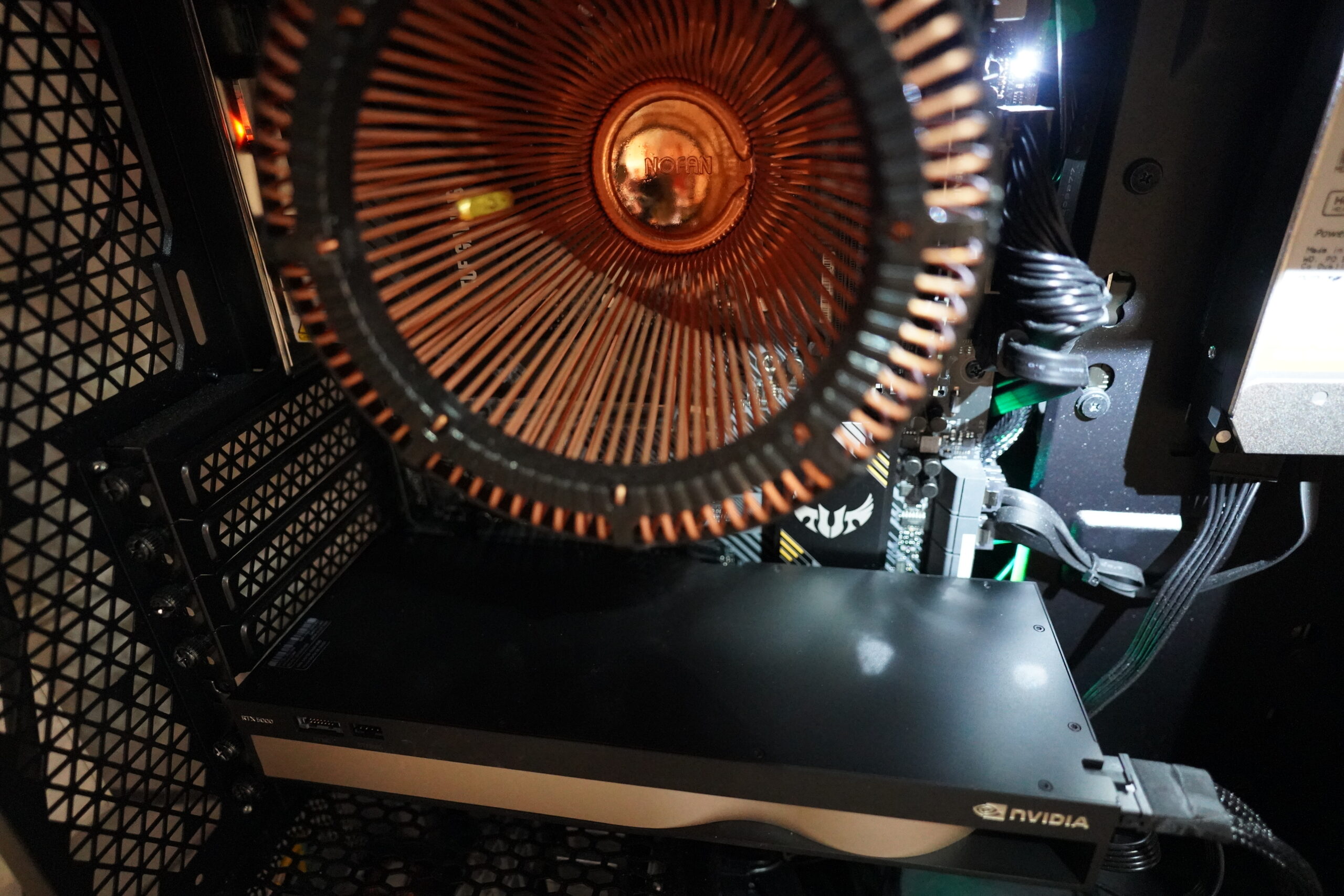

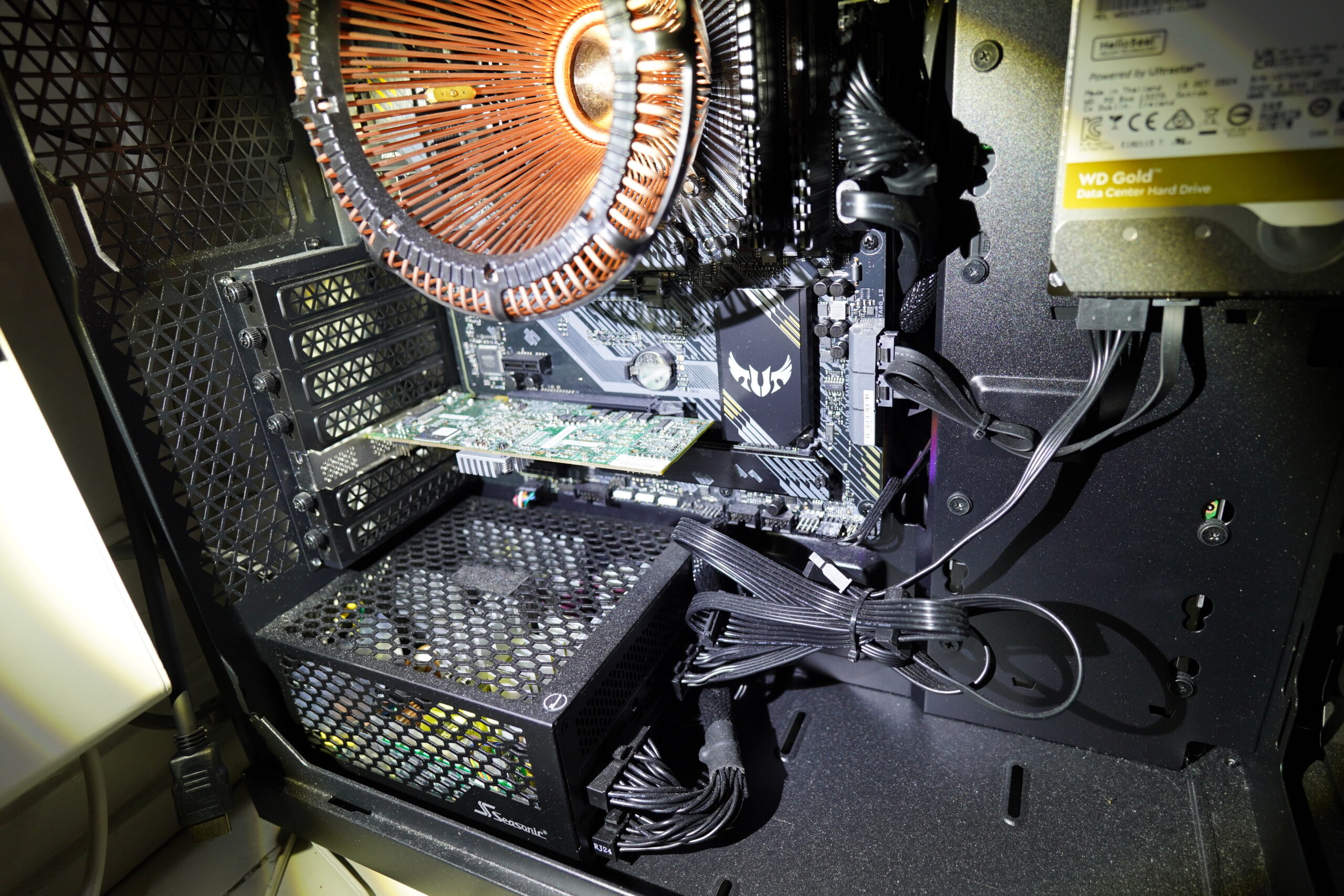

Ah, yes, this takes up two PCIe slots, but it’s got a blower that blows the air out back. Which is ideal for me, because the machine I’m putting this into doesn’t have any fans.

Is that one of those Nvidia connectors that melt and catch fire?

And then there’s PCIe power in the other end. Two of them. I guess it uses a lot of power…

Where did all that dust come from? Anyway, the PSU is 700W, which should be more than enough. *crosses fingers*

Slot it right in there.

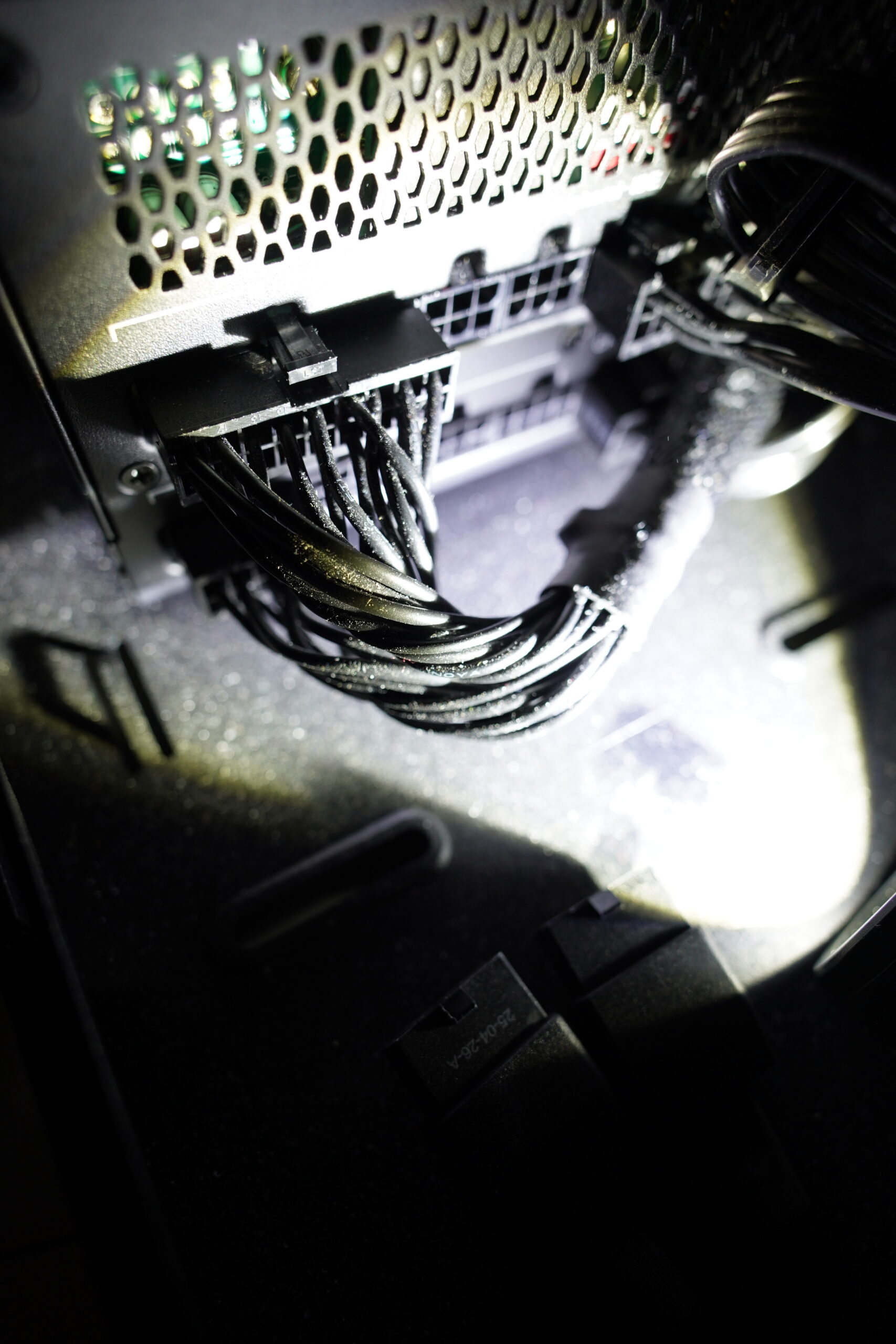

And… Oh, the PSU is one of those modular ones? That doesn’t have all the unused cables dangling? EEK! Where did I put those, then?

Yeah, I’d thrown those in the electronics recycling box, because I thought I’d never have to use them for anything… But I’m so lazy I haven’t actually recycled them yet.

Procrastination wins, yet again.

So many cables…

So those go into the PSU…

And then the other thing goes into the GPU. I have to say that this connector isn’t very satisfying. No click, like you want to have when connecting things.

NVIDIA has determined that the main culprit behind the overheating connectors was user error. If the connector is not fully engaged, it will overheat and, in extreme cases, melt the connector itself.

Yeah, and if you’d designed the connector to give a little “click”, then people would know when it’s been seated fully, right? God, these nerds.

There. Ironically, I’m running this machine headless, so while the video card has got four ports, none of them are connected.

Don’t you think? It’s like a OK I’ll stop there.

Yes! It’s alive!

Er… that’s very slow? Oh, I forgot to install the Nvidia drivers.

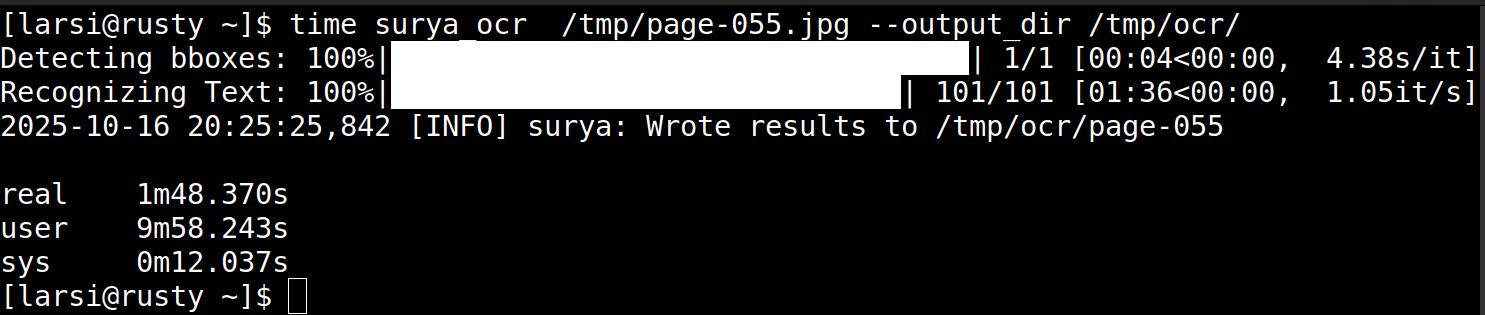

That’s better.

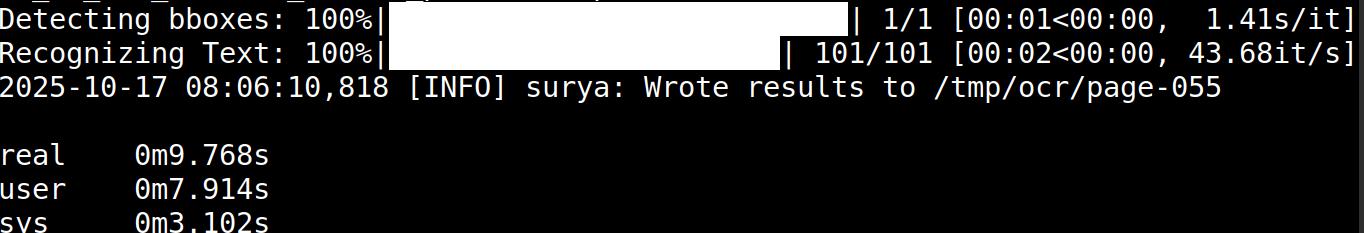

But 10 it’s still seconds for a page? That’s certainly better than a couple minutes, but it’s still slow. But the reason is this:

surya uses seven seconds just to start up. So the OCR part took just three seconds. And it can batch — just point it at a directory, and it’ll do the entire directory, and indeed, the throughput is between 1s to 3s per page when batching. Which is acceptable, because:

(/ (* 750000 1.7) 60 60 24) => 14.75

It’ll take about two weeks to re-OCR all the magazine pages.

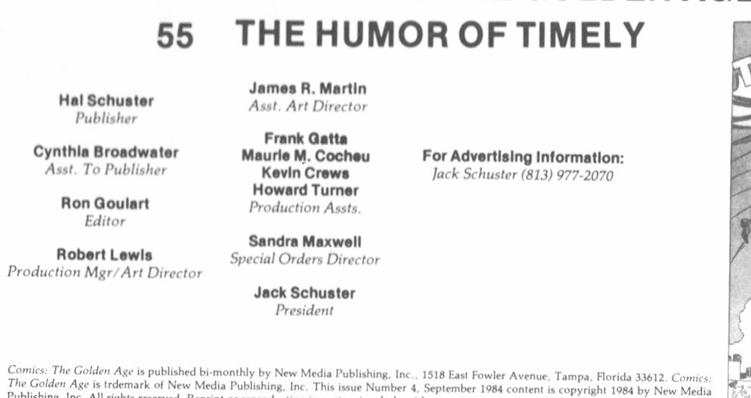

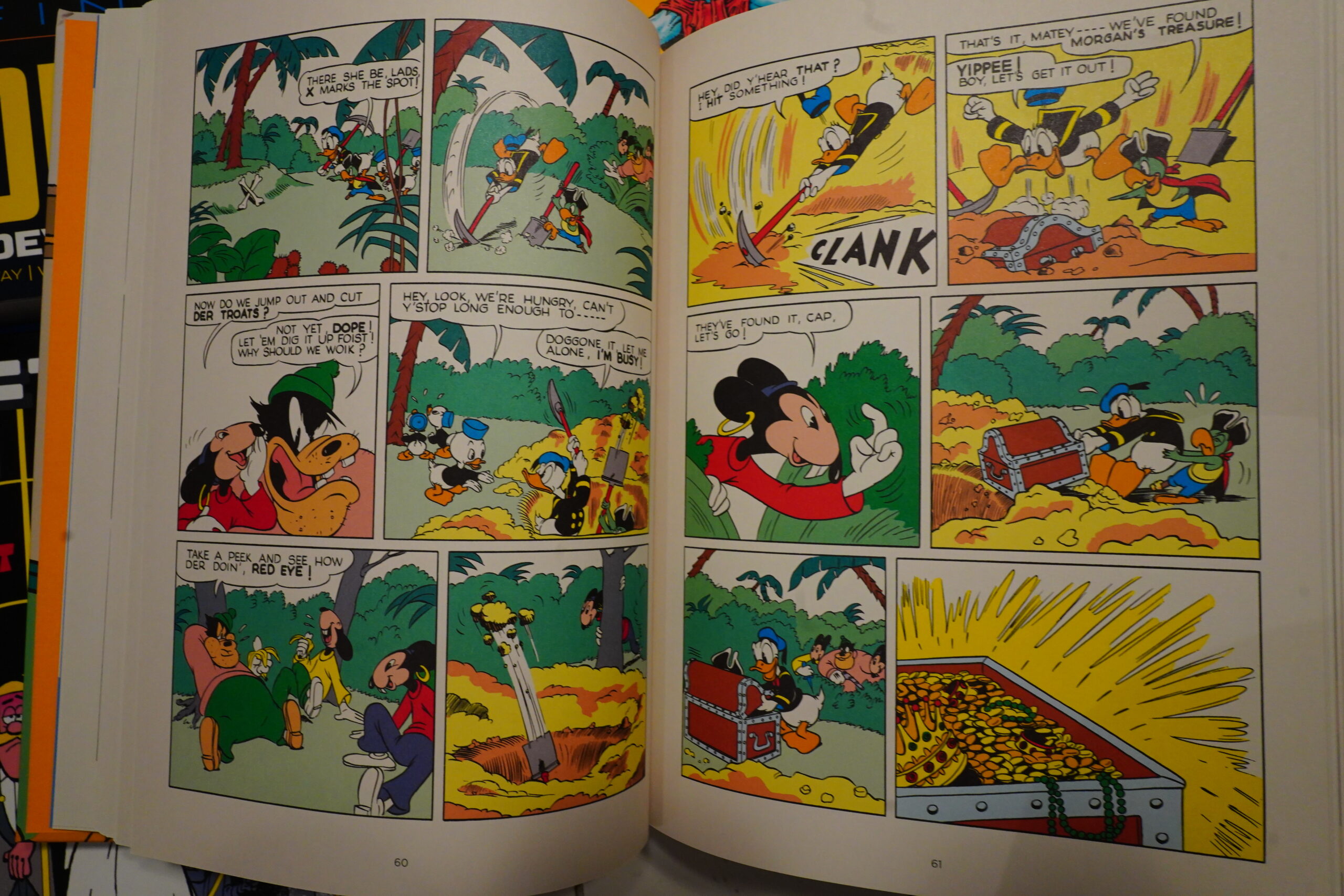

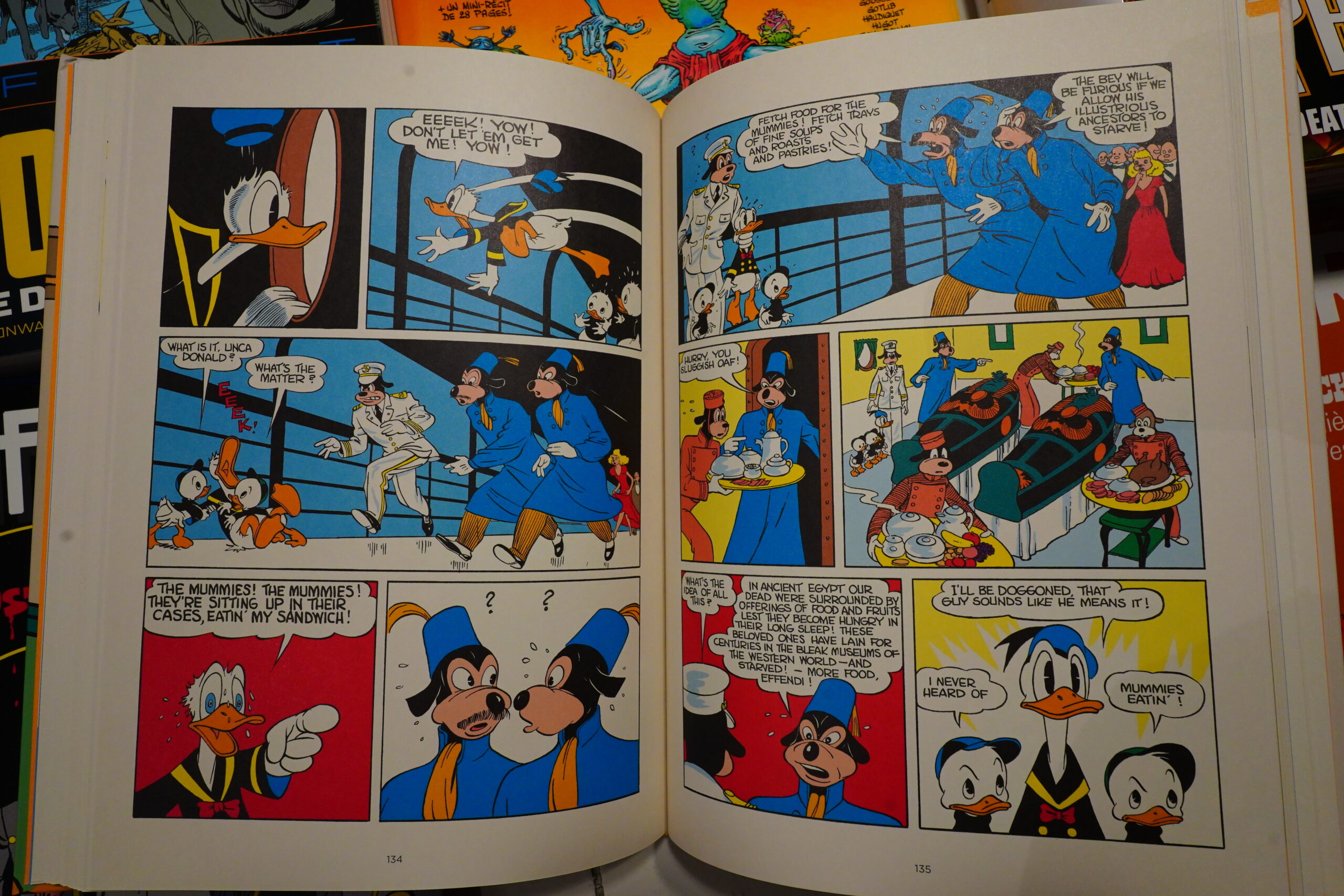

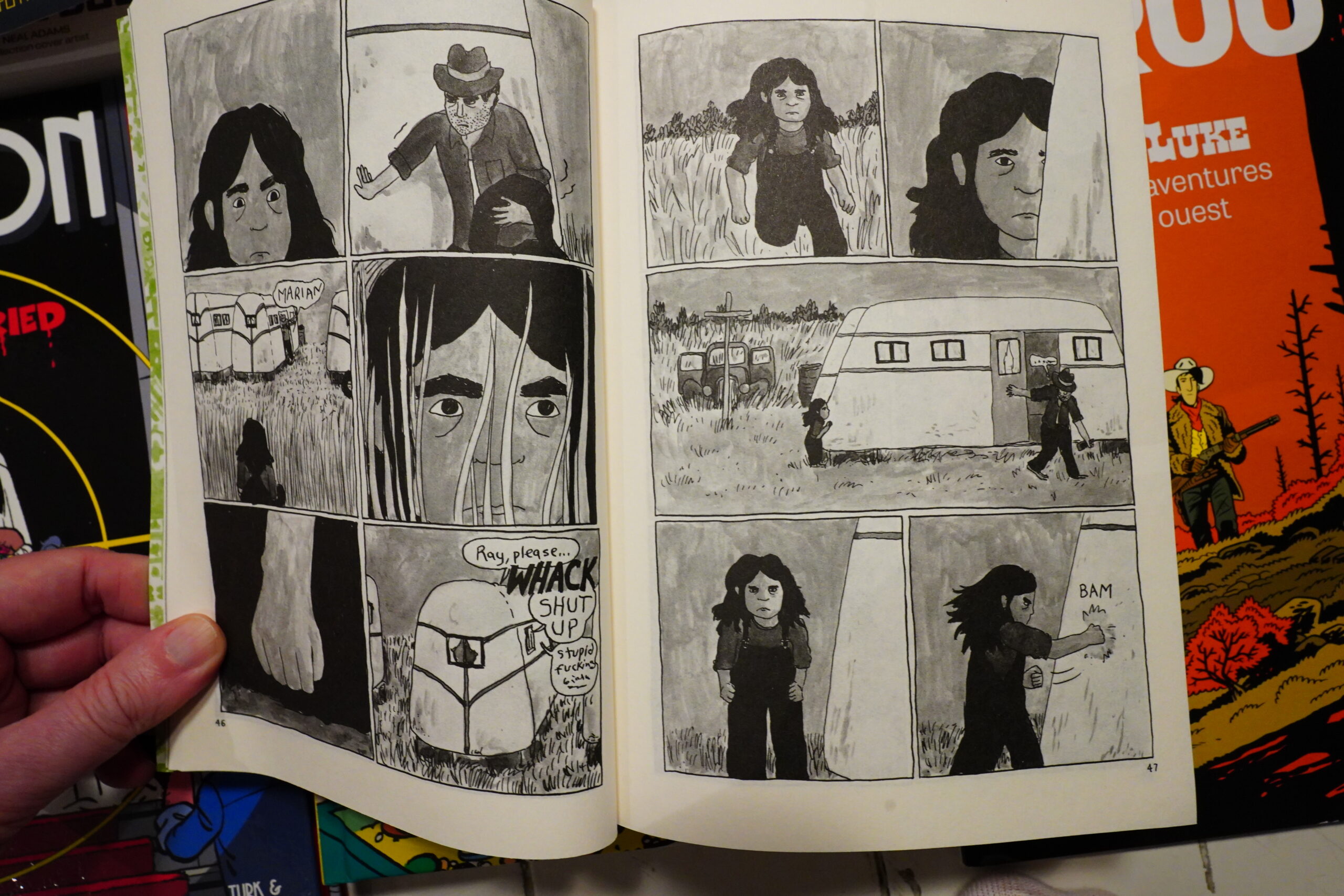

But what’s the quality like? Well, ocr.space does well with things that have been scanned well, but let’s look at some bad scans. Like this:

ocr.space gives us this:

James R. Martin Asst. Art Director Frank Gatt. Maurie M. Coch•u Kovln Crews Howard Turner Production Assts. Sandra Maxwell Special Orders Director Jack Schuster President For Advert181ng Information: Jack Schuster (813) 977-2070

Which isn’t very good. And here’s surya:

James R. Martin Asst. Art Director Frank Gatta Maurie M. Cocheu Kevin Crews Howard Turner Production Assts. Sandra Maxwell Special Orders Director Jack Schuster President For Advertising Information: Jack Schuster (813) 977-2070

I think that’s basically perfect?

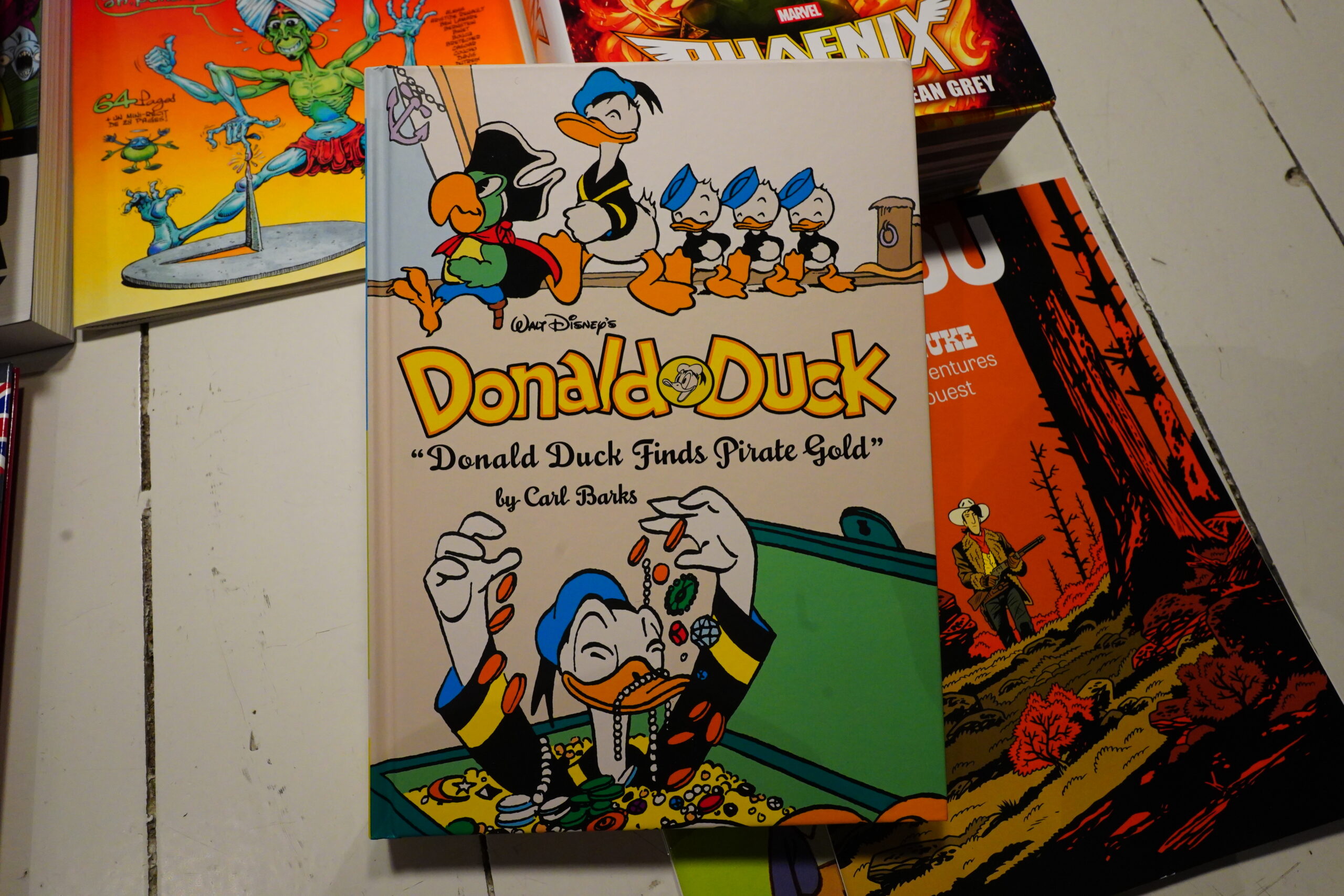

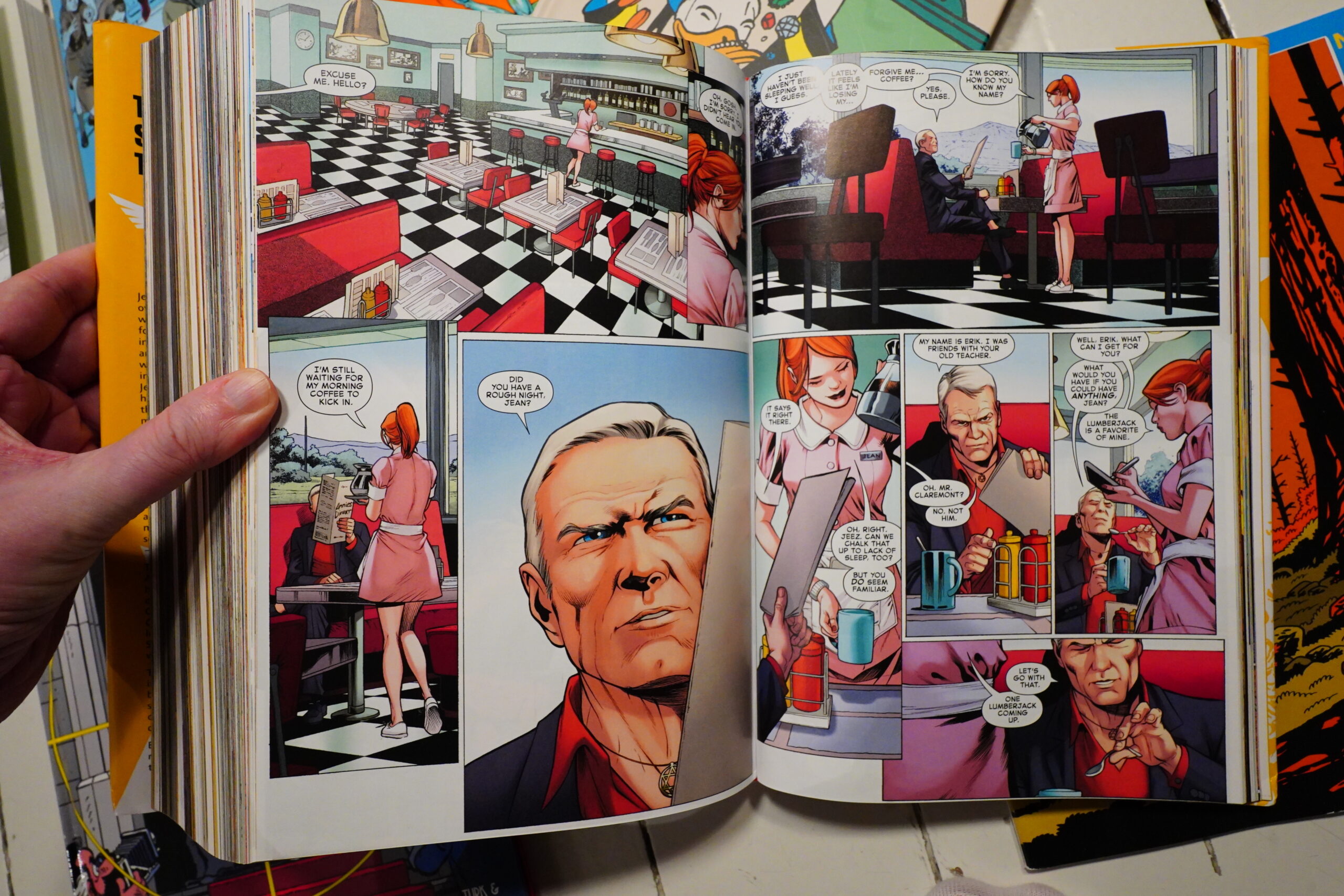

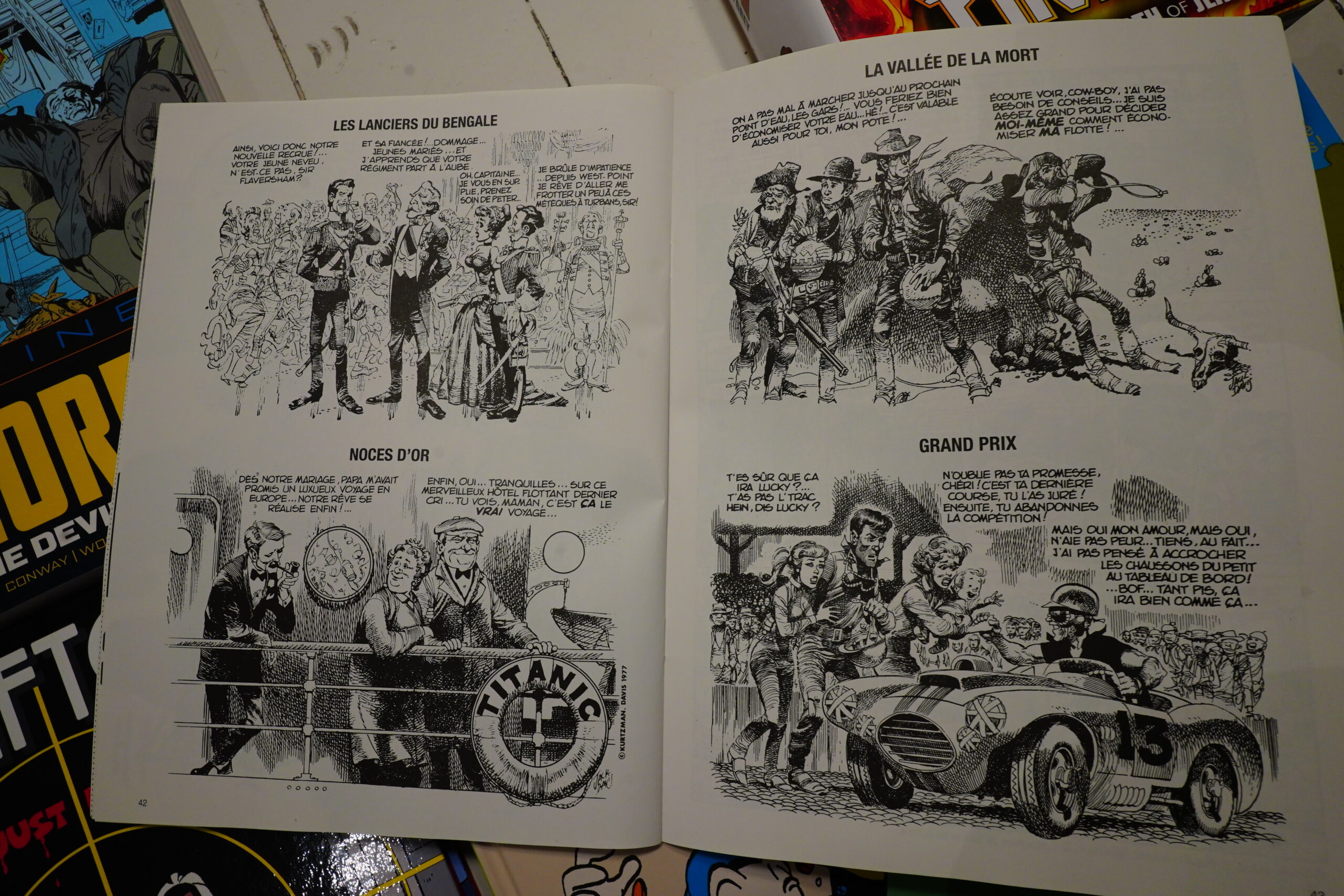

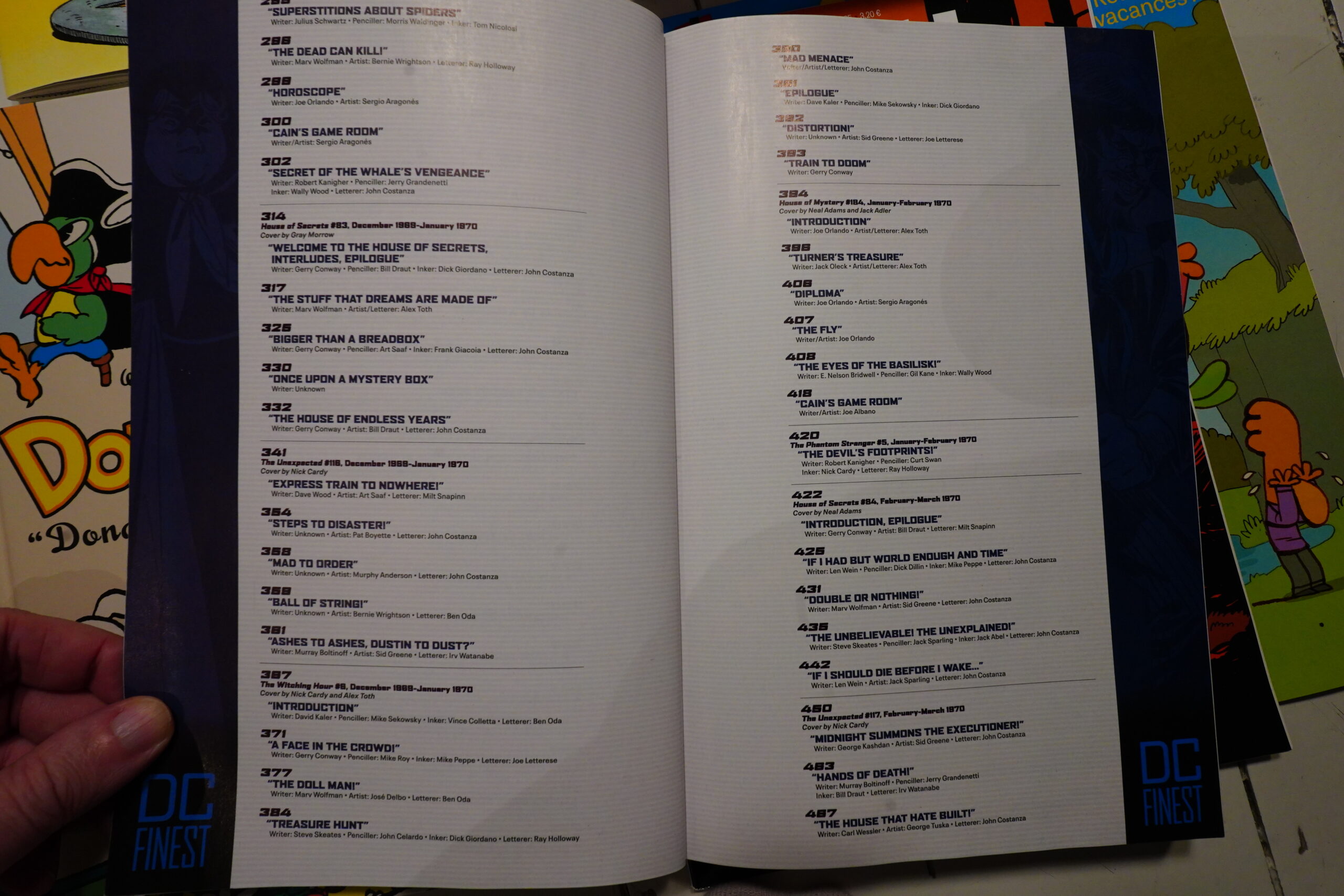

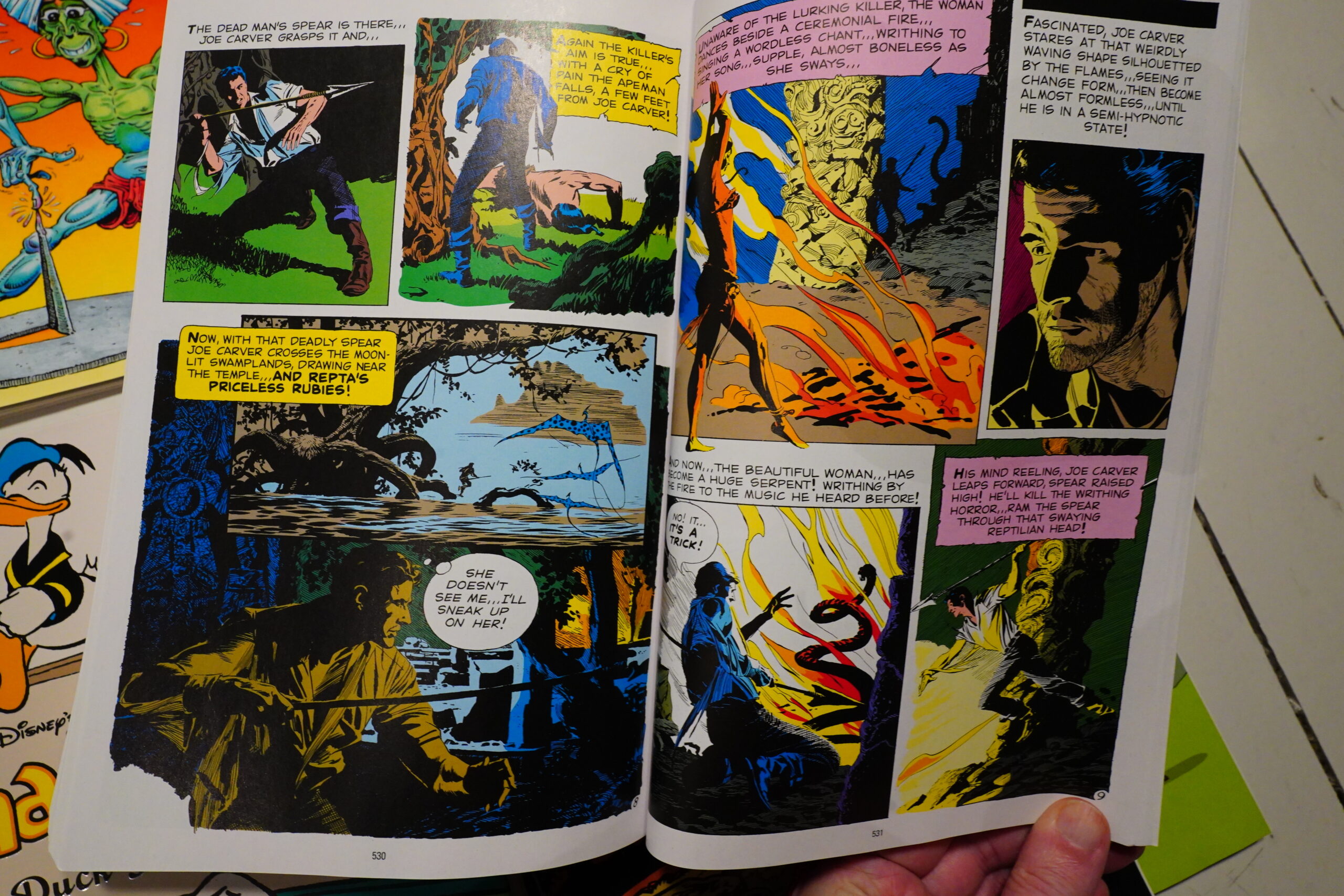

Let’s look at something else where I’ve noticed that ocr.space often struggle — catalogues.

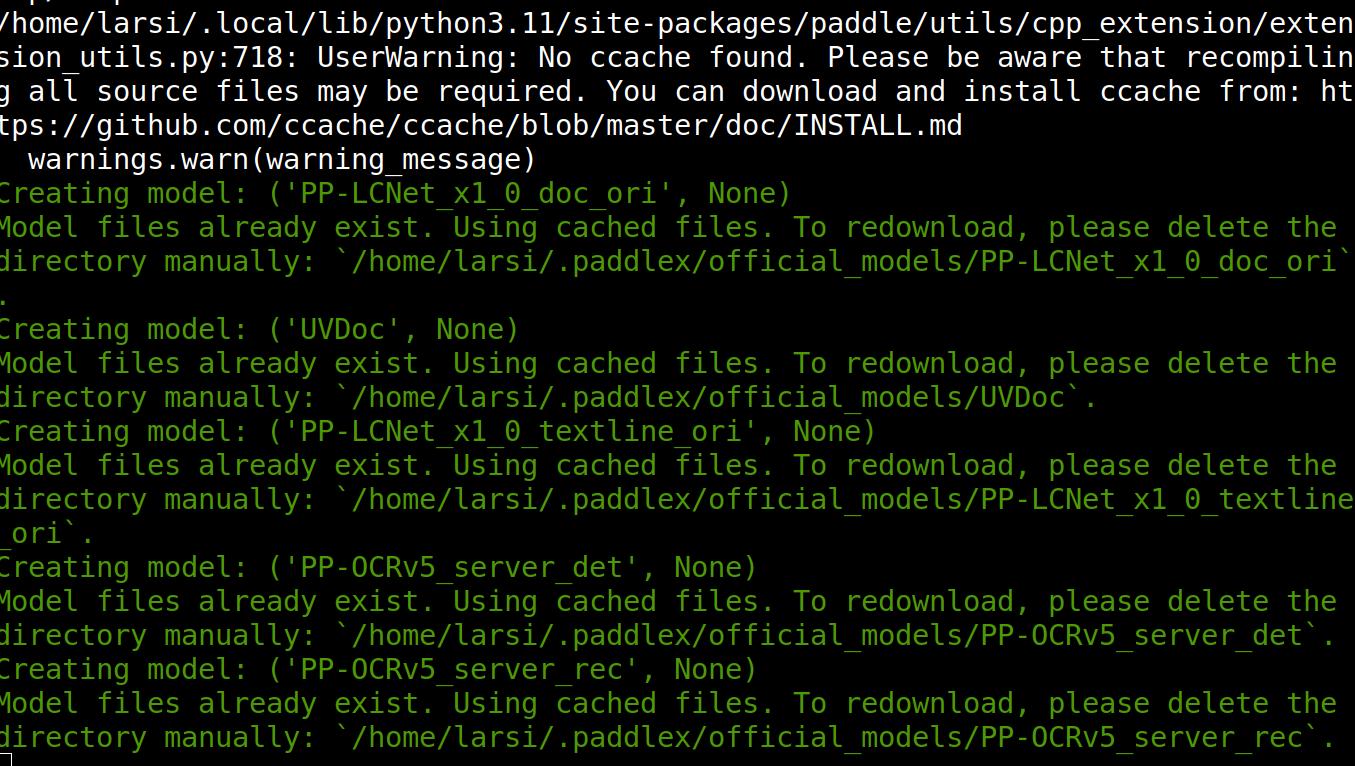

So let’s check that first entry…

It was originally set in a very small point size, and letters have a tendency to grow into each other. Here’s what ocr.space makes of it all:

Look in the Comicooaks section for two Cerebus trade paperback collec- Vons, and the Comics/W811 Art section for a new Cerebus poster. CEREBUS #155 $2.25 B&W. SinyGemard Mohen & continues. Confusion reigns over wtwther Pope Cerebus hu re- turnd to redeem the dty if it is just agwtler illusion. More unexplaitwi phenomena per- plex les?s population. Grin coninues b plan for her asænsion. CEREBOS CHURCH &STATE $2.00

Yeah, that’s not good. “Sim/Gerhard” is “Sinygemard”, and “Cirin” is “Grin”, because keming is hard.

AARDVARK-VANAHEIM CHOINING Look in the Comics/Books section for two Cerebus trade paperback collec- tions, and the Comics/Wall Art section for a new Cerebus poster. CEREBUS #155 $2.25 B&W. Dave Sim/Gerhard Mothers & Daughters continues. Confusion reigns over whether Pope Cerebus has re- turned to redeem the city or if it is just another illusion. More unexplained phenomena per- plex lest's population. Cirin continues to plan for her ascension. CEREBUS CHURCH & STATE #26 $2.00

I think everything there is correct, except that “Iest” has become “lest”. (“Iest” is a city name in Cerebus, but I don’t think you can really blame surya here for getting that wrong, since they two things are identical in this font.)

So — it’s pretty good? And much better than it was — ocr.space is basically useless on a catalogue like this.

(Misunderstand me correctly — I don’t want to dump on ocr.space here. It’s pretty good — it has (I’m guesstimating) a correctness rate of over 90% usually; it’s just that catalogues like this are hard.)

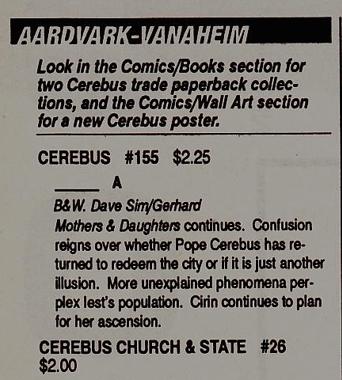

I wondered how warm the card was going to get. Here’s after it’s been OCR-ing a whole bunch of magazines. That’s not bad.

I’m a bit surprised at how quiet the GPU fan is. That is, it’s not “quiet”, but instead of the high-pitched noise I was expecting, it’s more of a pleasant “whoosh” sound. Fans have gotten better, I guess…

And the cable isn’t melting! Which is a pretty important detail.

Anyway, surya is chugging away, and will be working for two or three weeks, but I wondered whether there were any other good LLM-powered OCR things out there, and Google points me to PaddleOCR.

Let’s test:

Eh… doesn’t anybody look at console output anymore? Anyway, paddleocr takes 35 seconds on my test page, which is 10x (or more) than surya, so that seems like a no go.

So there you go — in a couple weeks time, the search results on kwakk.info will be somewhat more accurate, I think.

Was it worth it? Well… what I’ve paid to ocr.space for using their API over the years is probably about half of what I paid for this graphics card. So, er, no. But it feels better, eh? One less API subscription is one less API subscription, and it’s fun to have this in-house. It would have made more sense just to rent some VMs with GPUs, especially since my use case is so bursty, but meh. I just can’t be bothered.

Perhaps I can use the GPU for something else, too, although I have no idea what.