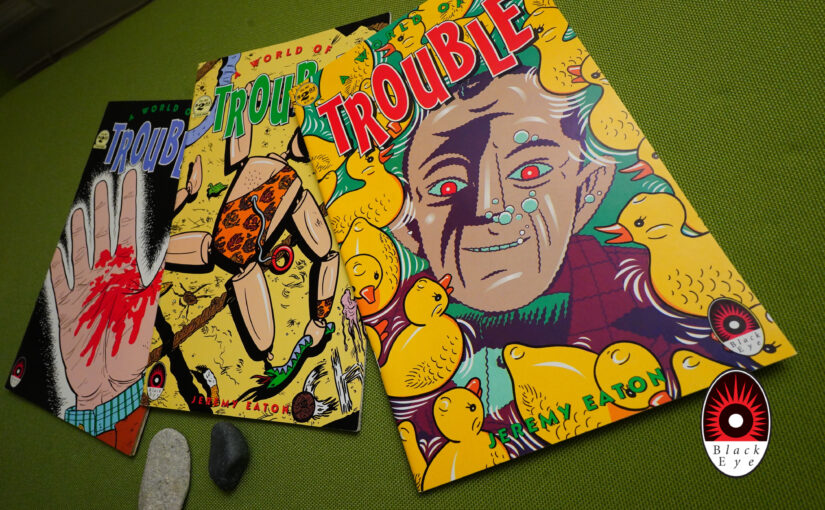

A World of Trouble (1995) #1-3 by Jeremy Eaton

Oops! I claimed in a previous entry in this blog series that Black Eye (after a certain date) didn’t publish anything in the standard US comics format, but I’d forgotten about this series. Sorry for the fake news!

Anyway, I’ve read quite a few books by Jeremy Eaton over the years, like Whotnot and what not, and he’s certainly a talented artist, but I’ve never really connected with his comics.

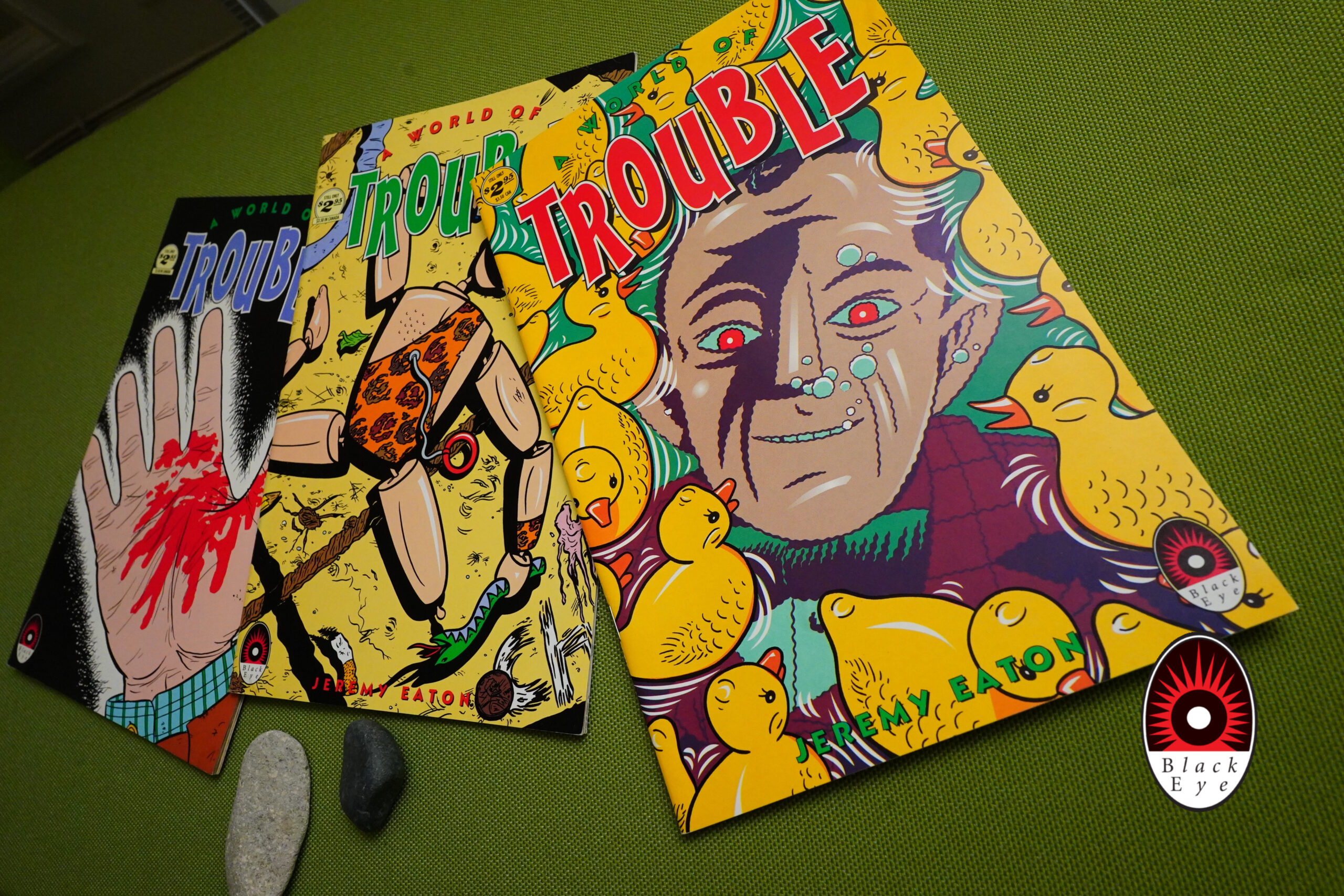

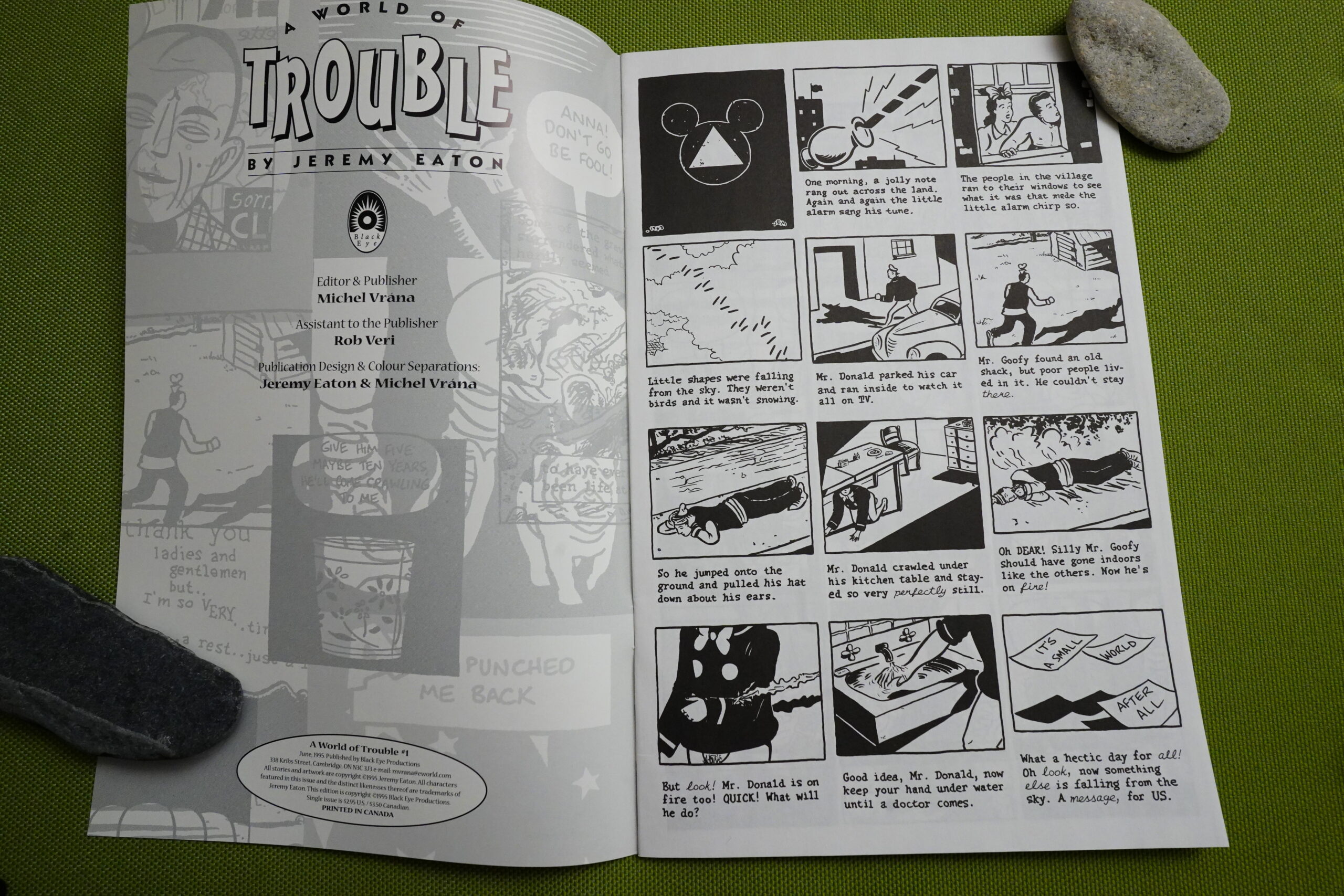

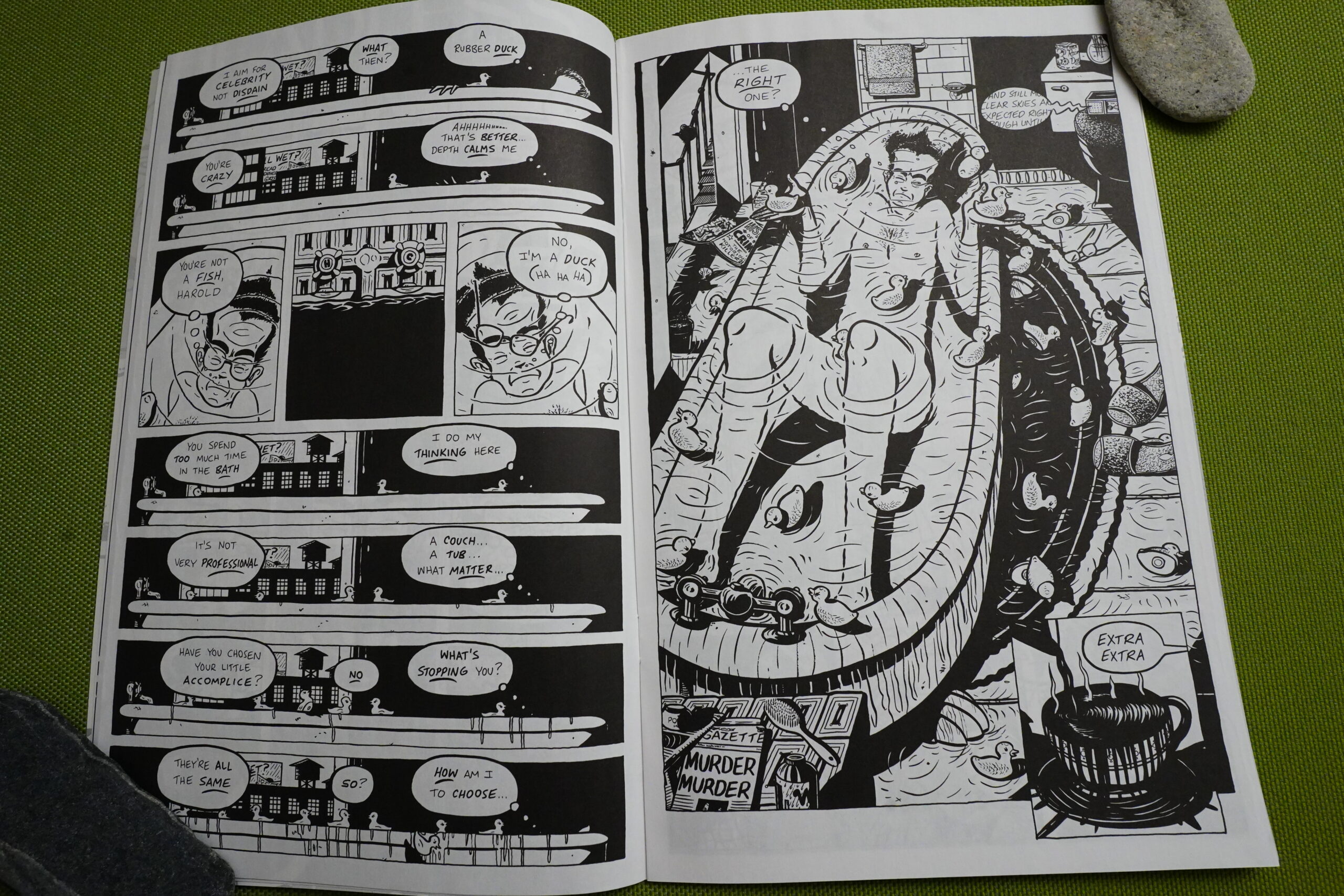

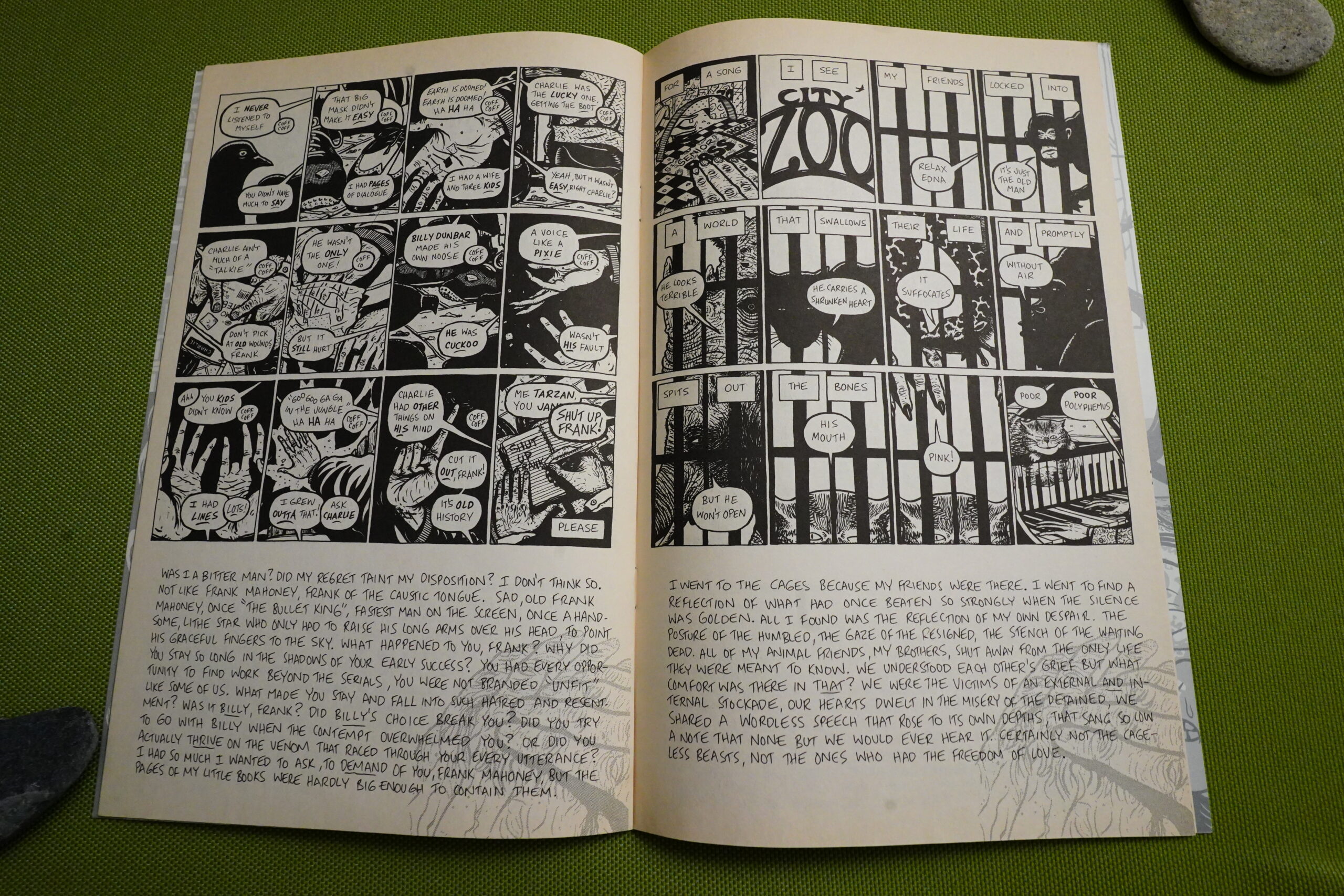

This starts off with a series of unrelated one page strips, so I assumed it was going to continue like that. And they’re pretty successful — like the change between black and white background on the left hand page (but a kinda bad joke), and the pensive mood on the right hand page.

But then all that stops, and most of the rest of the issue is one long story…

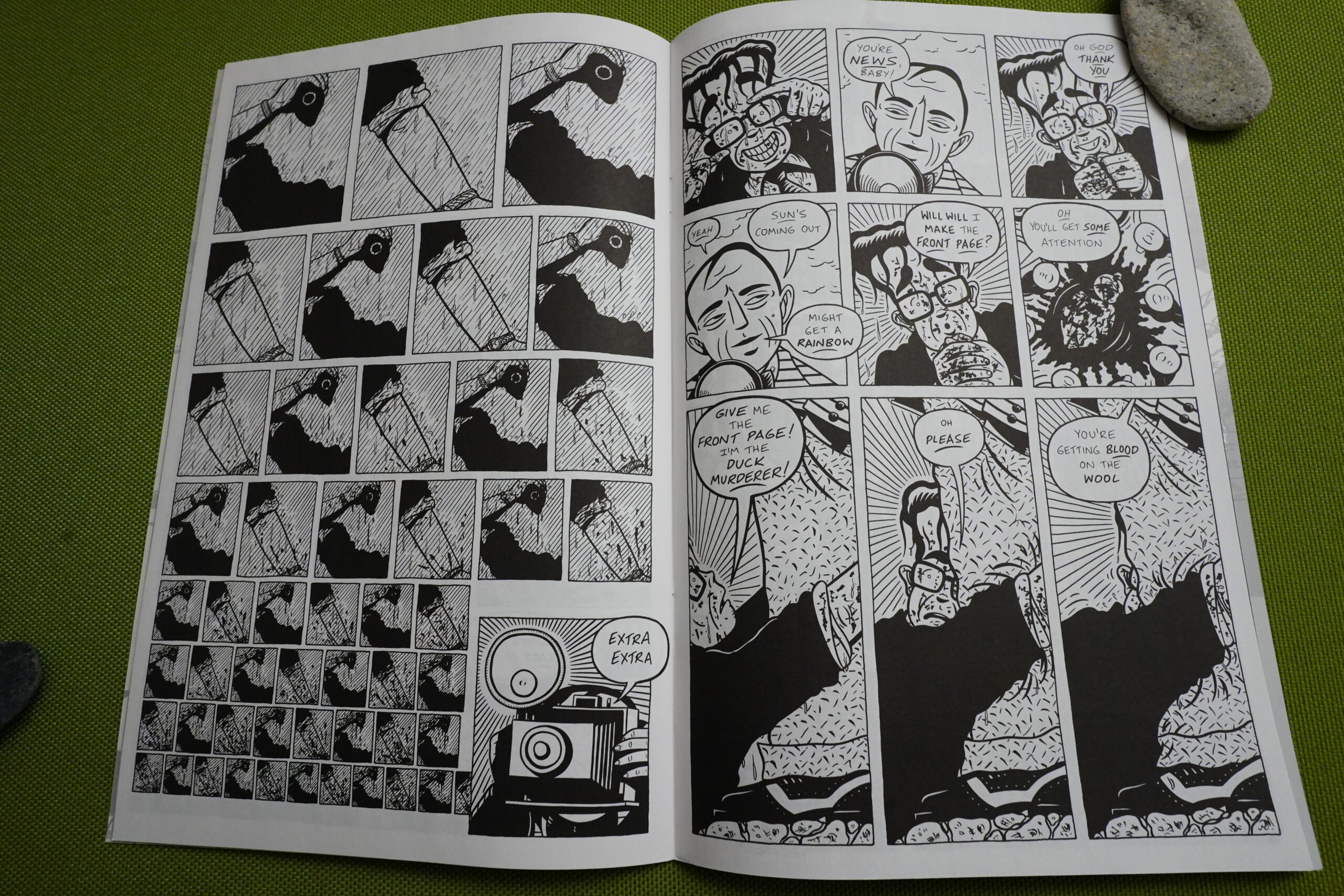

… about a guy who comes up with the idea of bludgeoning people to death using rubber ducks, because that’s such an original thing to do that he finally ends up in the newspaper.

So it’s a pretty trite media critique, but it’s told in an interesting way.

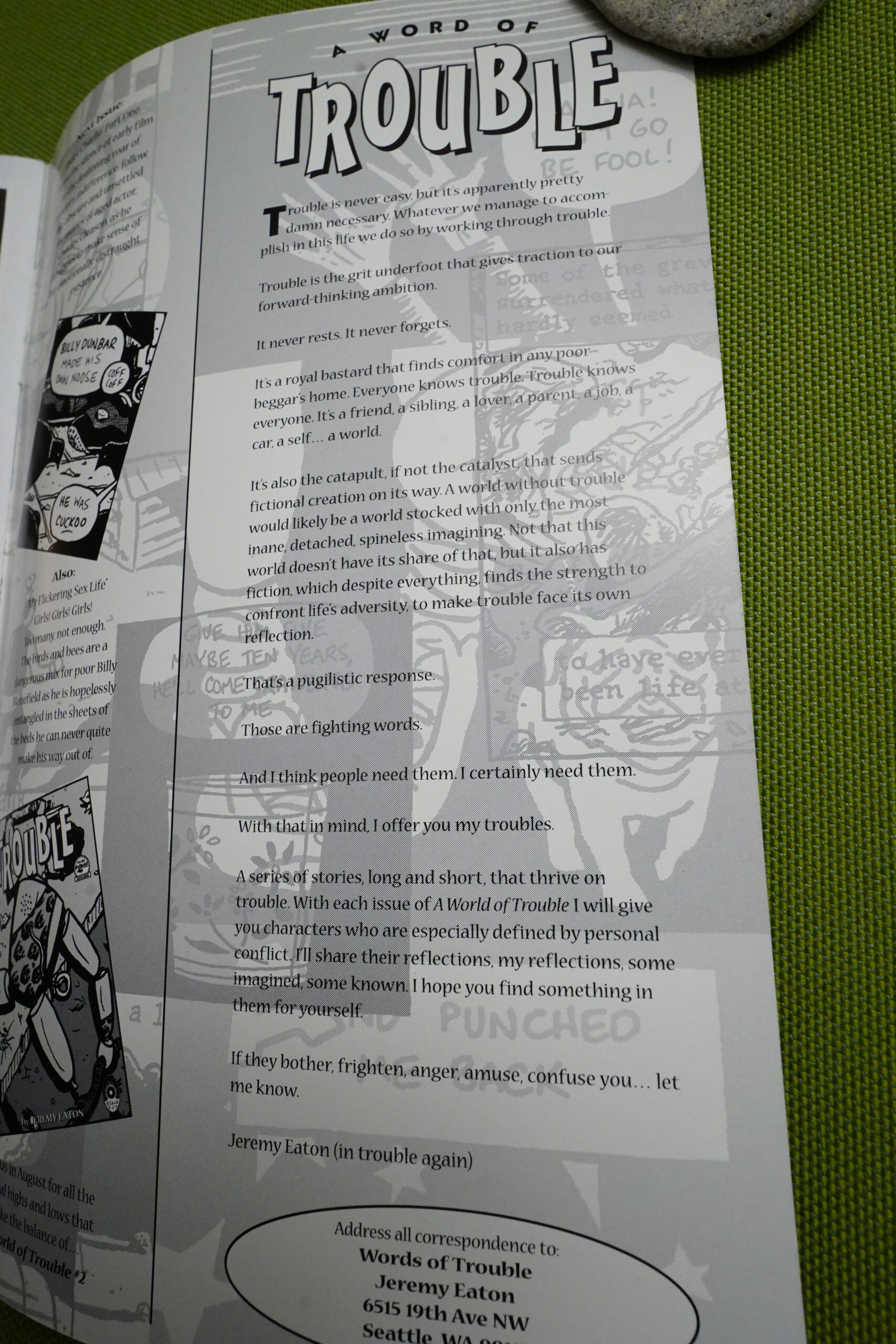

And we get an er manifesto.

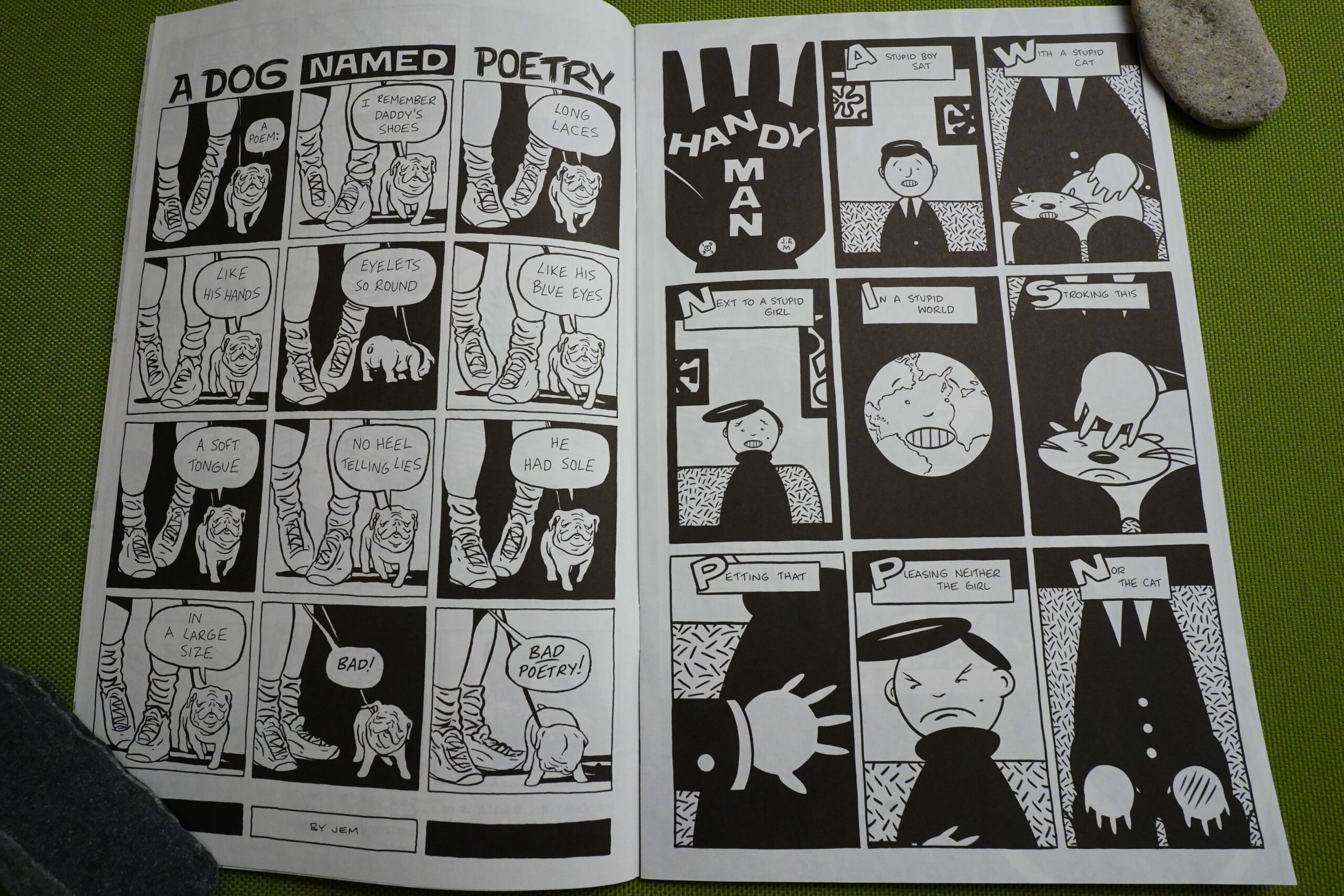

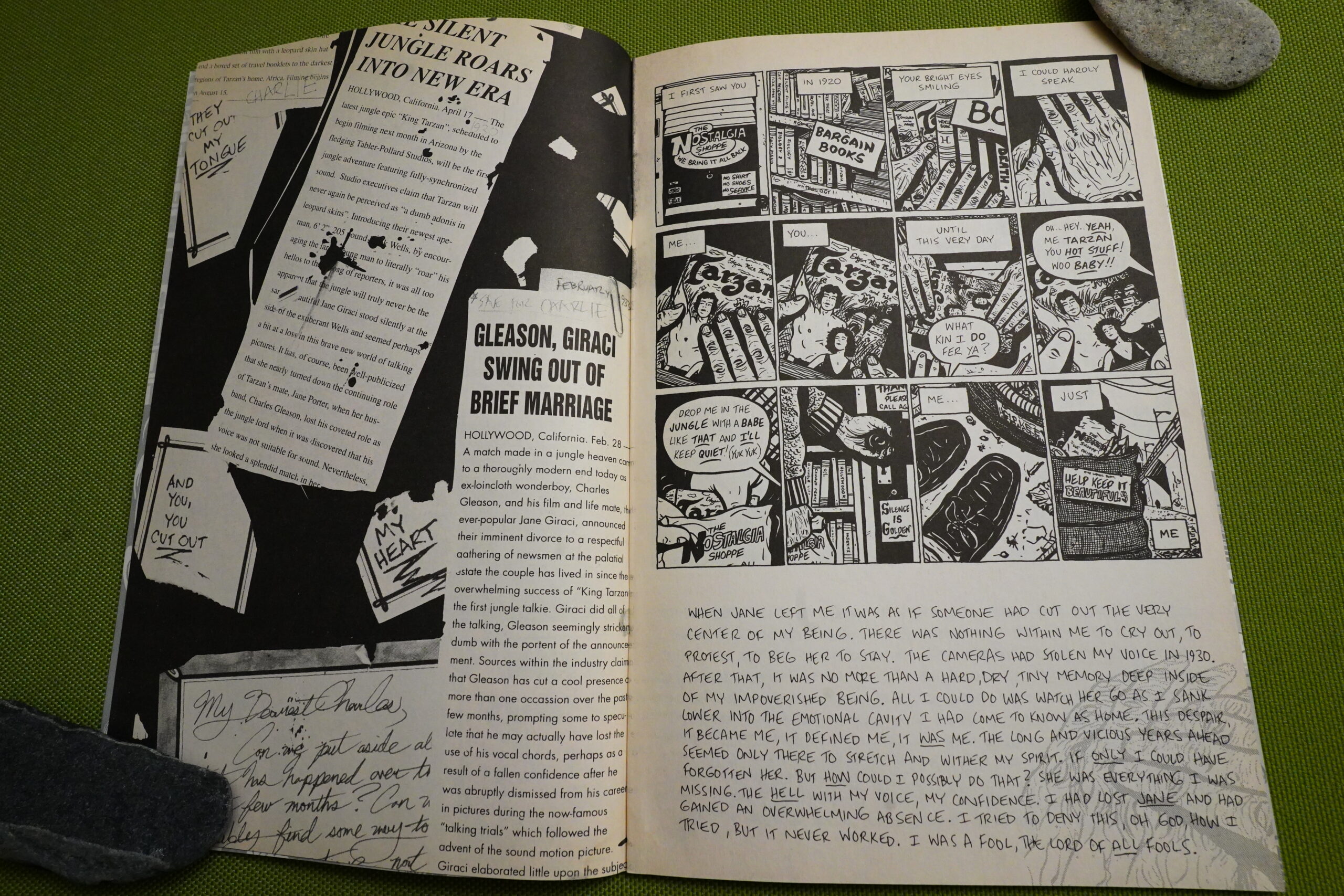

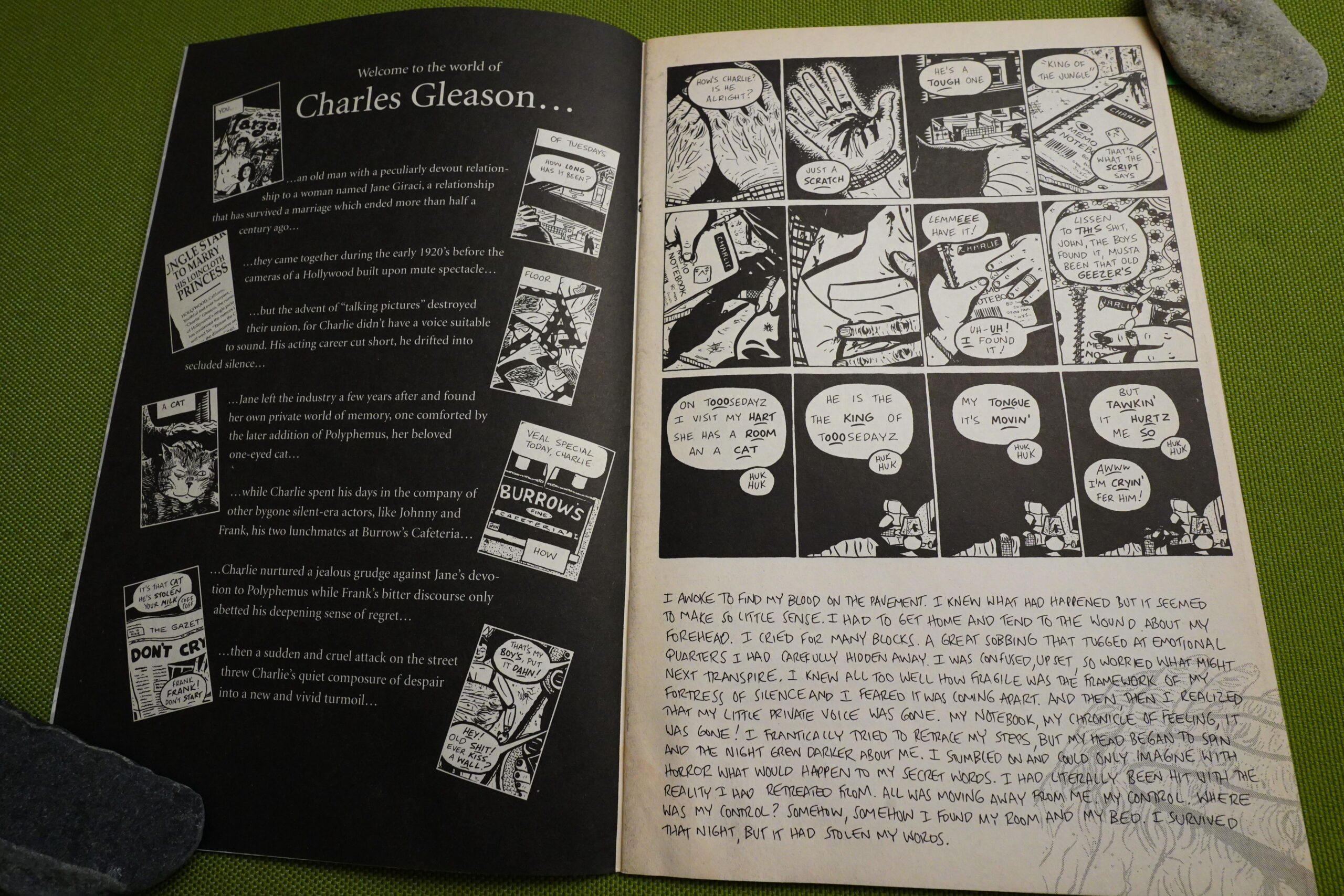

The two remaining issues are dominated by this story — about a guy who used to play Tarzan in the movies who’s in love with a woman called Jane. (Such irony.)

And most of the pages are like this — with some intriguing, but often vague, panels above, and a text below. The combined effect is something that’s perhaps meant to be Raw adjacent, but for me, it didn’t really work: The text just didn’t hold my interest.

And if you’re asking the reader to work at it like this, you have to convince the reader that it’ll be worth it, and I rapidly lost confidence.

The final issue helpfully has a recap of what happened in the second issue.

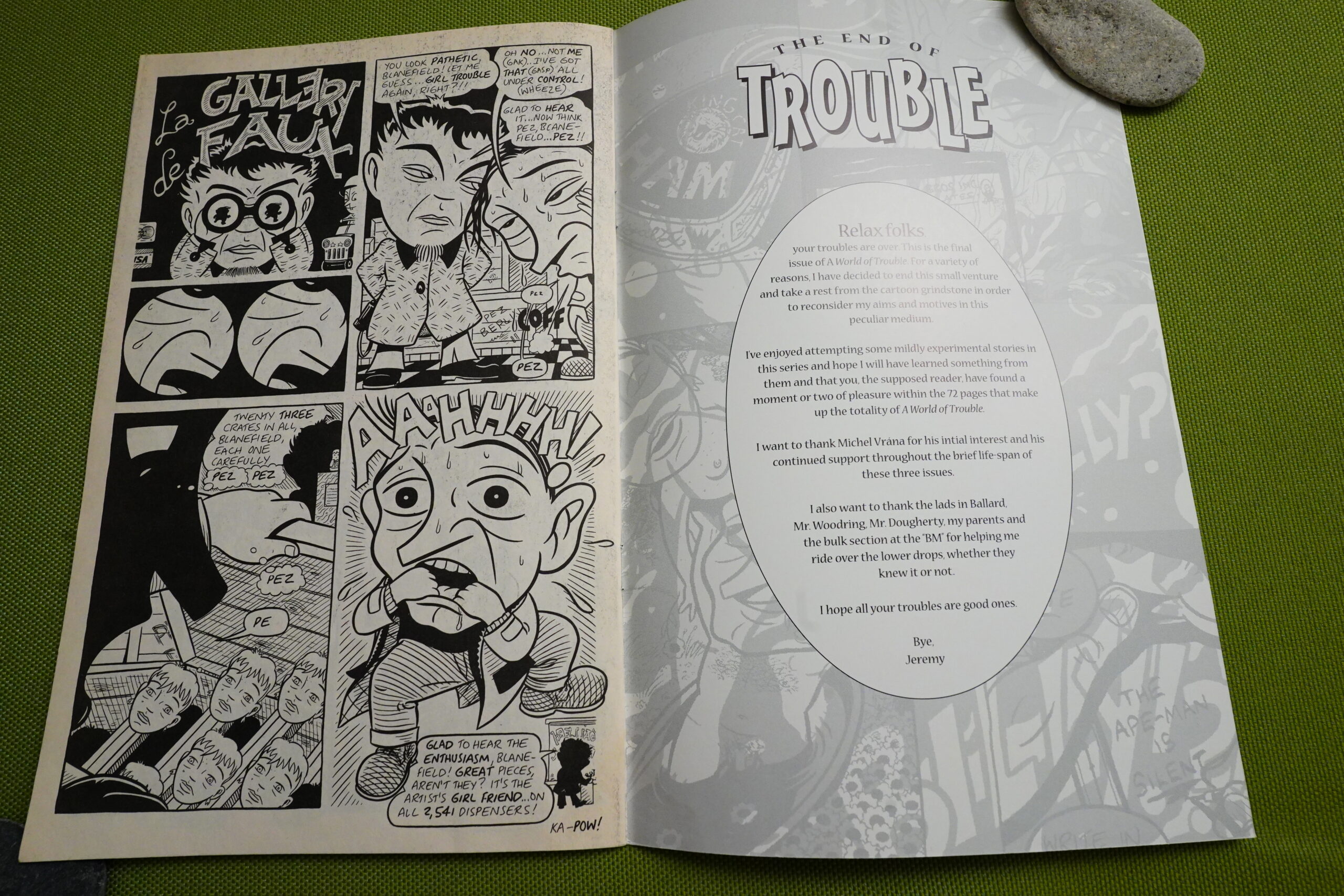

And then it’s over — I’m guessing they lost money on this book?

Whit Spurgeon writes in The Comics Journal #180, page #88:

BEFORE READING the material ass-

embled for this review, my only exposure to

Jeremy Eaton was A Sleepyhead Tale,

Fantagraphics’ 1992 collection of one-page

strips originally published for the most part in

alternative newspapers in 1990-92. Having read

that cover’s rave reviews from people like Jim

Woodring, I purchased Sleepyhead expecting

Eaton’s strips to bowl me over.

They didn’t.

Don’t get me wrong. Eaton’s art made an

impression. His clean, stylized work perfectly

conveyed his sense Of humor, while his atten-

tion to tiny details provided visual entertain-

menton every page in much the same manner as

Will Elder. In addition, Eaton’s dialogue was

very clever and choice of subject matter amus-

ing, if somewhat pedestrian.

What was stifling about Sleepyhead Tale

was the format. As individual one-pagers,

Eaton’s strips made their points quickly and

clearly. Collected in book form, what was amus-

ing and incisive became decidedly less so. Be-

cause Eaton’ s work engaged a select number Of

topics, reading Sleepyhead en masse felt like

getting hit repeatedly in the head with an anti-

establishment frying pan (“Government bad.”

Clang! “Police cormpt.” Clang! “People stu-

pid.” Clang! Clang! Clang!) Still the verbal and

visual talent on display in these strips was

impressive. and made me wonder how the car-

toonist would approach lengthier, more com-

plex material.

In A World of Trouble #2, the latest issue Of

Eaton’s new series from Black Eye, I got my

answer. Unlike the backlog of material which

saw print in , A World of Trouble #2 contains

two new stories. What is remarkable is that

given the freedom of the larger comic book

format, Eaton makes severely limiting formal,

structural choices. Unlike his earliest work,

however, Eaton uses these limitations to set the

tone and aid the narrative force of his comics.[…]

If this sounds a bit overwhelming and some-

what confusing. well, occasionally it is. There’ s

so much to process, both visually and textually,

that one runs the risk of t*ing bogged down in

the story. The prose also has a tendency to turn

a bit purple, as in “His flippancy had less effect

than a fly in the gears of all fate’ s machinery,”

or “I was a fool, the lord of all fools.” But most

of this works, and works well. And the art is

hauntingly beautiful, using simple, spare lines

to communicate minute details.

Wizard Magazine #58, page #85:

A World of Trouble Jeremy Eaton is breaking new ground with recent stories in his comic A Worldof Trouble. Most notable of these is DQUiet Charlie/’

where he tells the tale of Charles Gleason, an actorwho played Tarzan in silent films and was forced out of his job with the advent of movies with synchro-

nized sound. Gleason’s silent world istold through o series of fake newspaper clippings, and a comic story supplemented by a text storye With itsinteresting

combination of different techniques, -“Quiet Charlie” is one of the few stories that can only be told effectively in comics.

It doesn’t look like these issues have been collected.

This blog post is part of the Total Black Eye series.