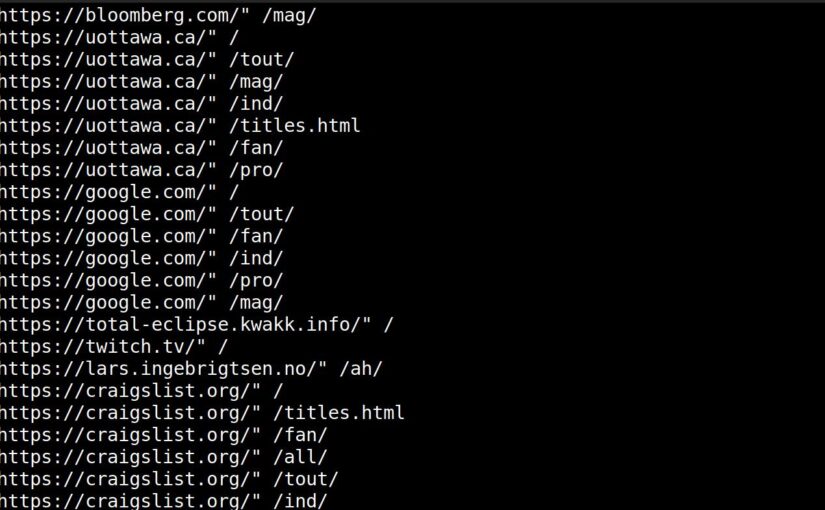

While looking through some log files, I noticed that I had a whole bunch of referrers from sites like kfc.com and expedia.com in the Apache log file (for my non-blog server that hosts oodles of static content and “content” like eyesore and stuff).

I naturally assumed that I’d gone totally viral on a global scale!

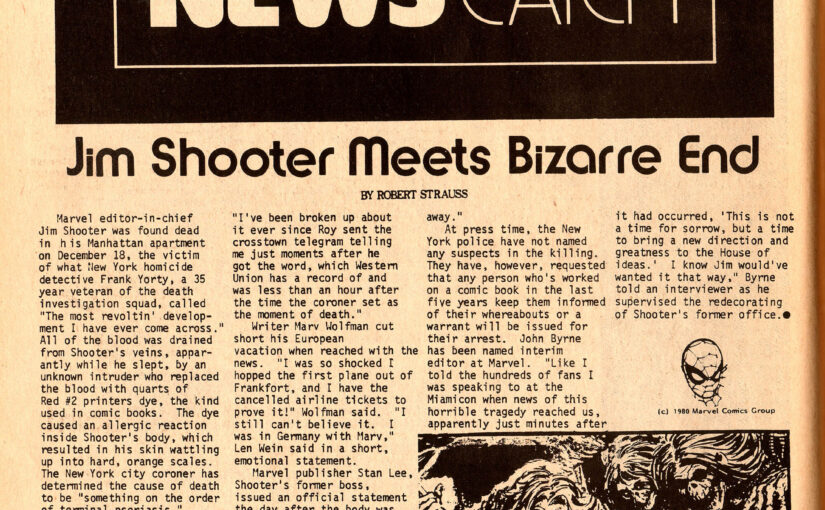

Just kidding! “Referrer Spam” isn’t a new thing — back in the 90s, people used to display referrers on their web sites, so of course scum started faking the referrers to get more traffic to their scam sites.

But this is something I haven’t seen before — they’re stuffing well-known domains into the Referrer, and surely KFC isn’t paying for spam like this (especially not in 2025).

So what’s going on?

Well, the obvious guess is that some genius has invented a new AI scraper, and decided that it’s less suspicious if the visits have a referrer. But it’s not, of course — it’s much more suspicious, which is why I’m leaning even harder towards this being AI related, because there’s just so much natural stupidity going on in that camp.

The User-Agents say nothing about being a bot. Typical example:

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/137.0.0.0 Safari/537.36

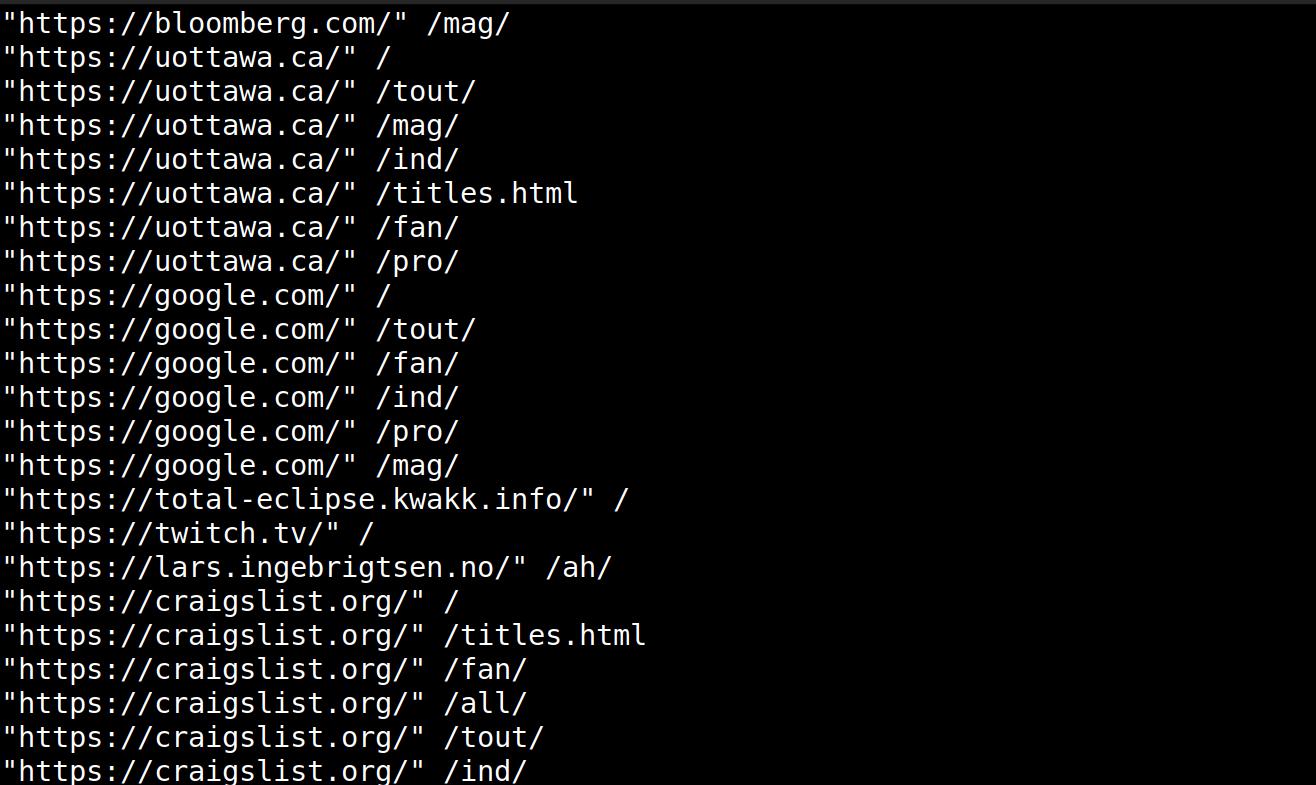

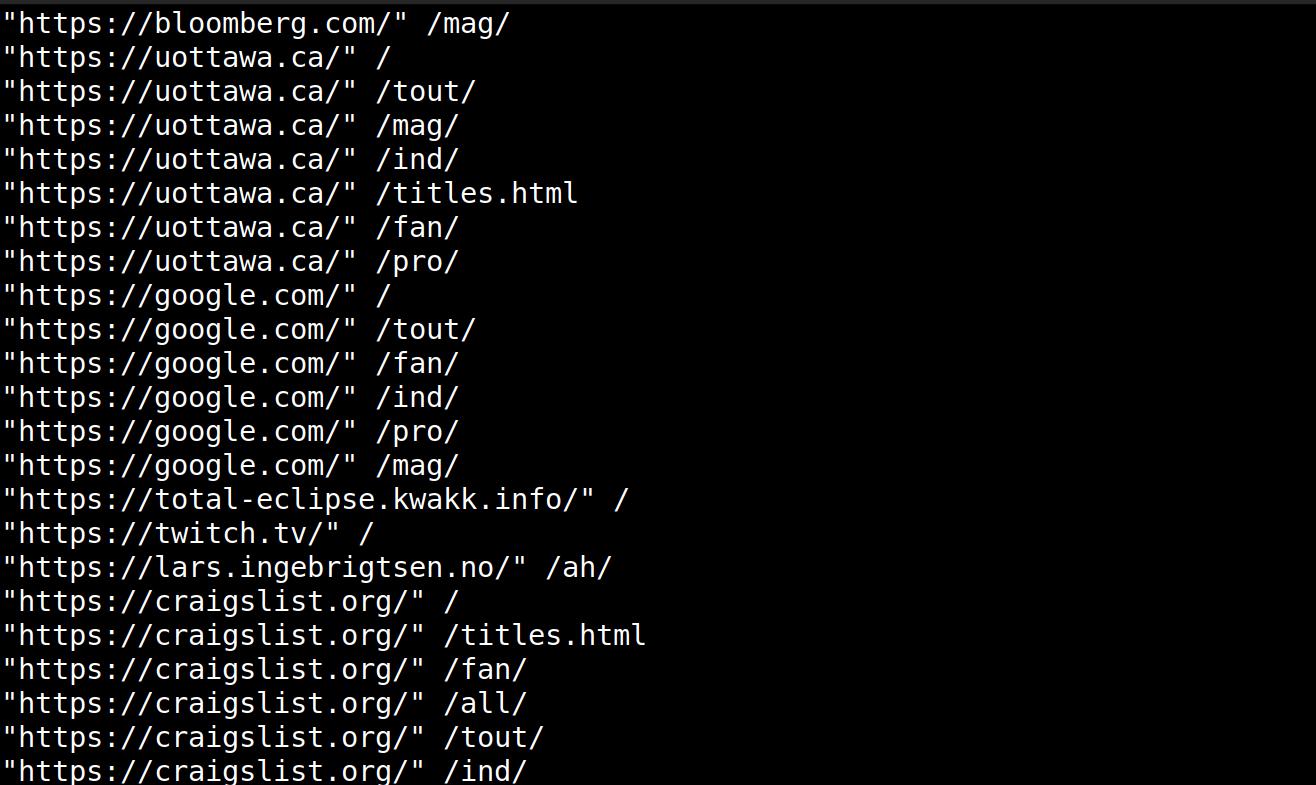

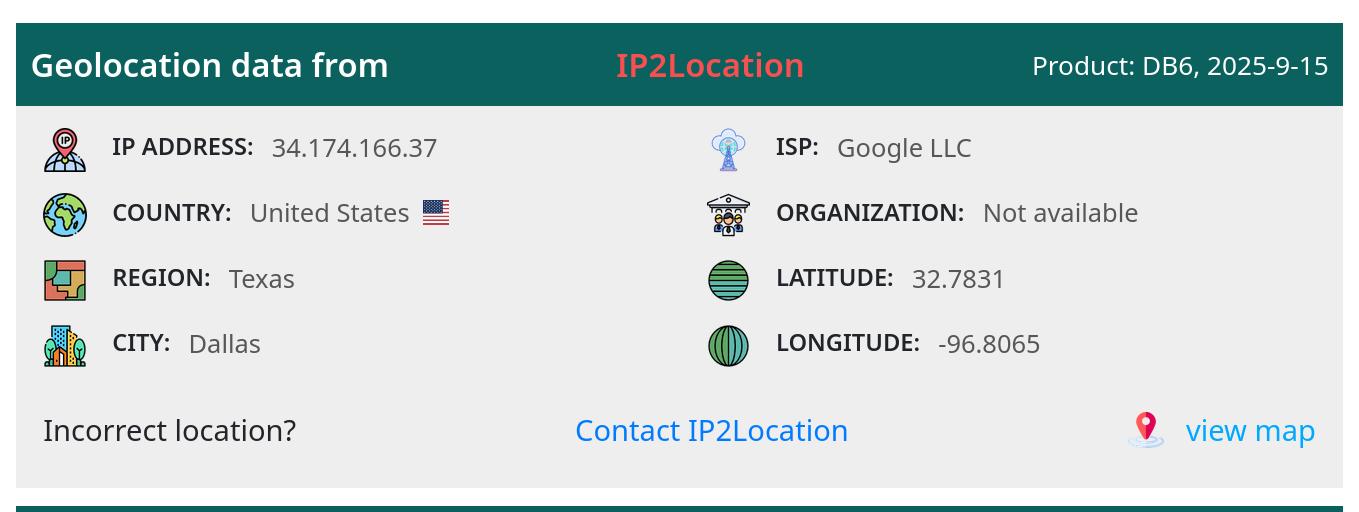

But where’s the traffic coming from?

Well, much of it is from Google Cloud, so it’s people renting CPU from Google, presumably. (And not Google itself.)

How much of the traffic towards this server comes from data centres, anyway? I copied over the access.log file from the last two days, and:

(with-temp-buffer

(insert-file-contents "/tmp/access.log")

(cl-loop with gcp = 0

with lines = 0

for line = (wse--read-apache)

while line

do

(when (and (not (wse--bot-p (plist-get line :user-agent)))

(not (equal (plist-get line :host) "kwakk.info")))

(cl-incf lines)

(when (wse--data-center-ip-p (plist-get line :ip))

(cl-incf gcp)))

finally (return (list (/ (float gcp) lines) lines gcp))))

=> (0.3933 350403 137815)

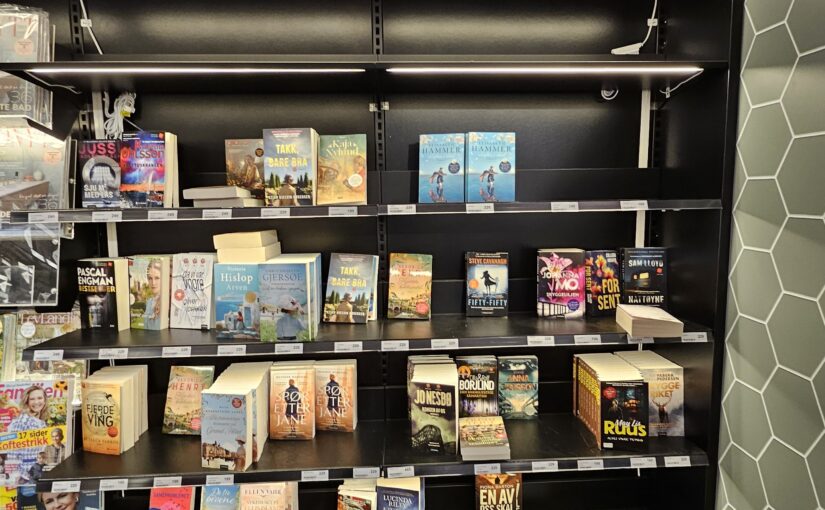

So 39%. If I filter out the traffic that announces that it’s a bot, that decreases to 29%. Filtering on specific providers, 9% of the traffic I get is from GCP, 5% is from Azure, 0.4% from AWS… and 15% from Cloudflare! Geez. It’s those edge workers? Or Cloudflare tunnels from China? I have no idea.

(Note that I’m filtering out traffic to kwakk.info, which uses Cloudflare itself, so I don’t know where the traffic to that site really comes from.)

OK, back to the original subject here — what percentage of hits come from data centres, and have non-bot User-Agent, and have a (presumably fake) Referrer header?

7%!

So there you have it — just when you thought AI scrapers couldn’t get more annoying, they found a way.