The last Daze of the year, I think. But I may have to take a nap in the middle.

| Girls: Reunion |  |

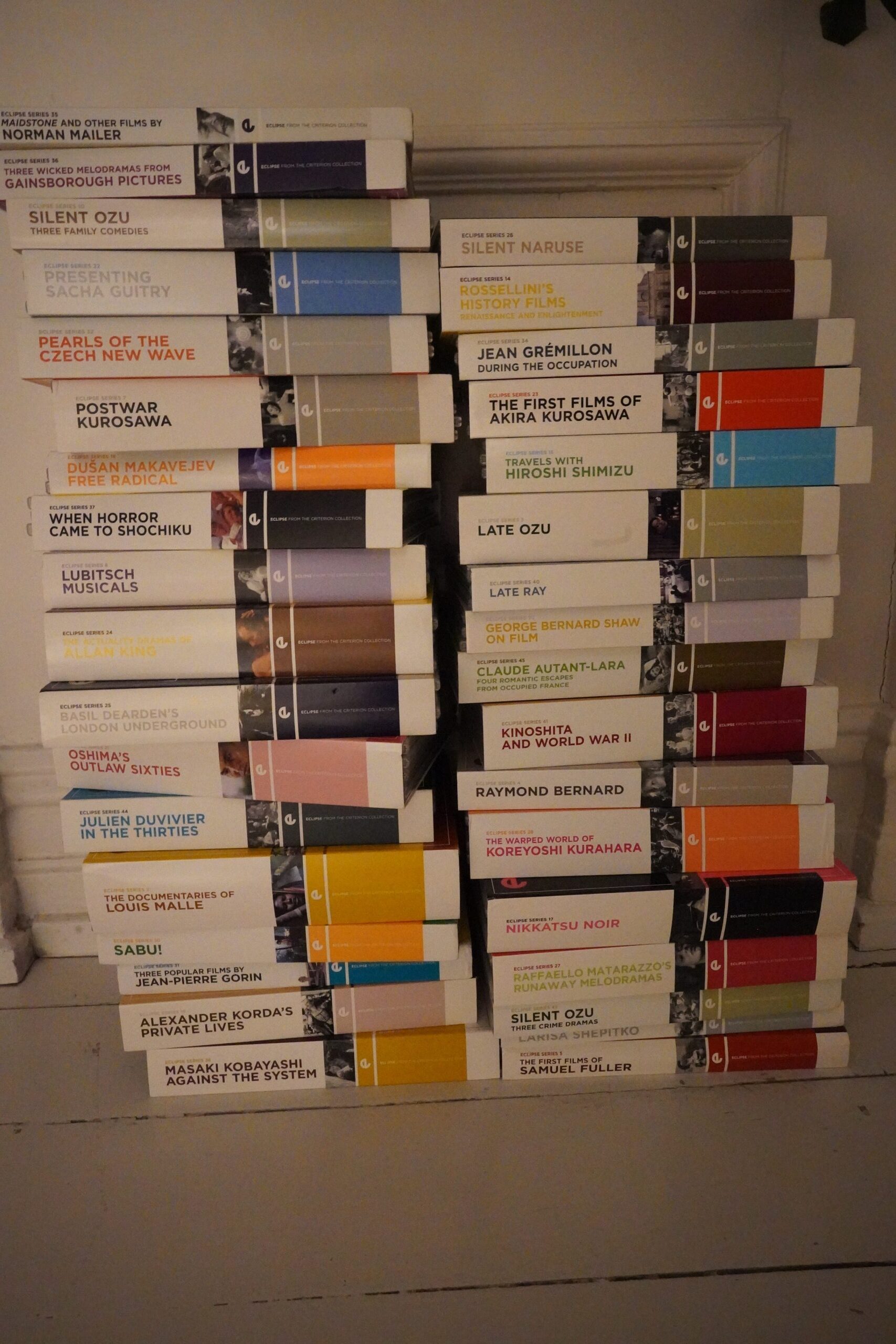

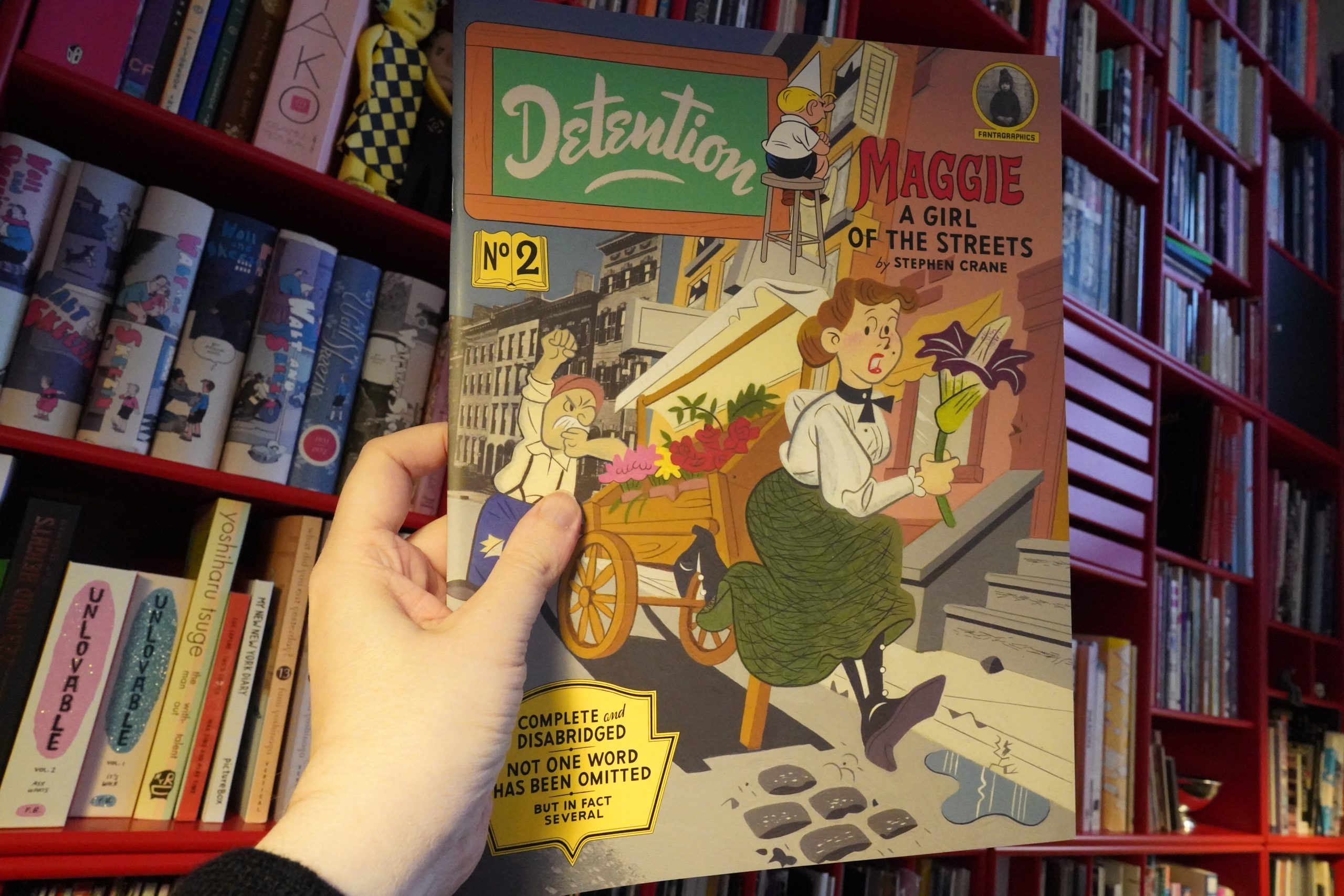

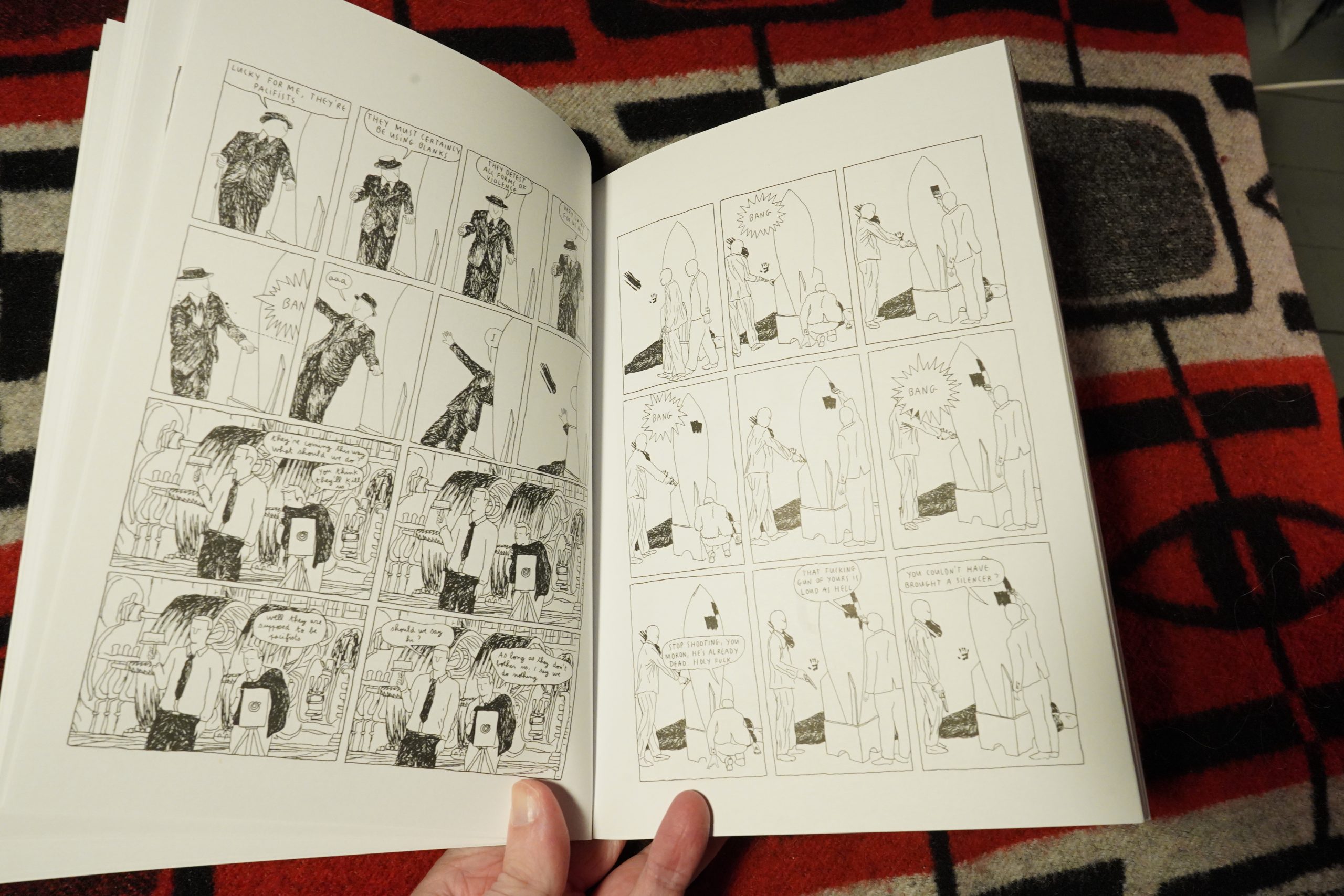

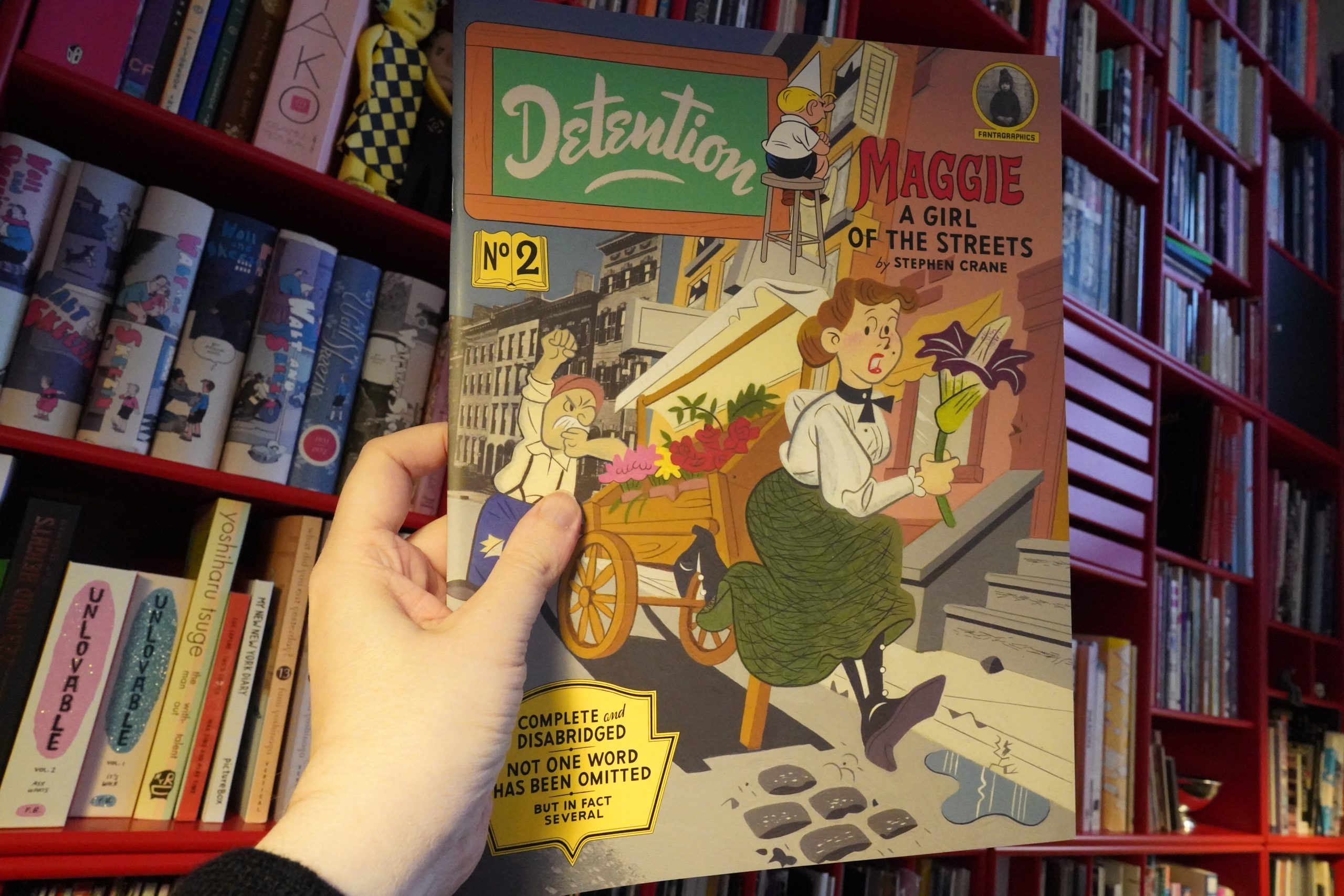

12:47: Detention no. 2 by Tim Hensley (Fantagraphics)

Will Hensley ever release a #1 of anything?

As someone who’s suffered through American lit., I never understood the fetishisation of Stephen Crane — it seemed to me (back then, 30 years ago) that it was part of some American mythology building: There had to be Great American Literature in the 1800s, so Crane was it. (And it didn’t hurt that he died young, I guess.)

That said, I don’t remember reading this novella at all, and I wonder whether Hensley is being faithful to the story or not… let’s see…

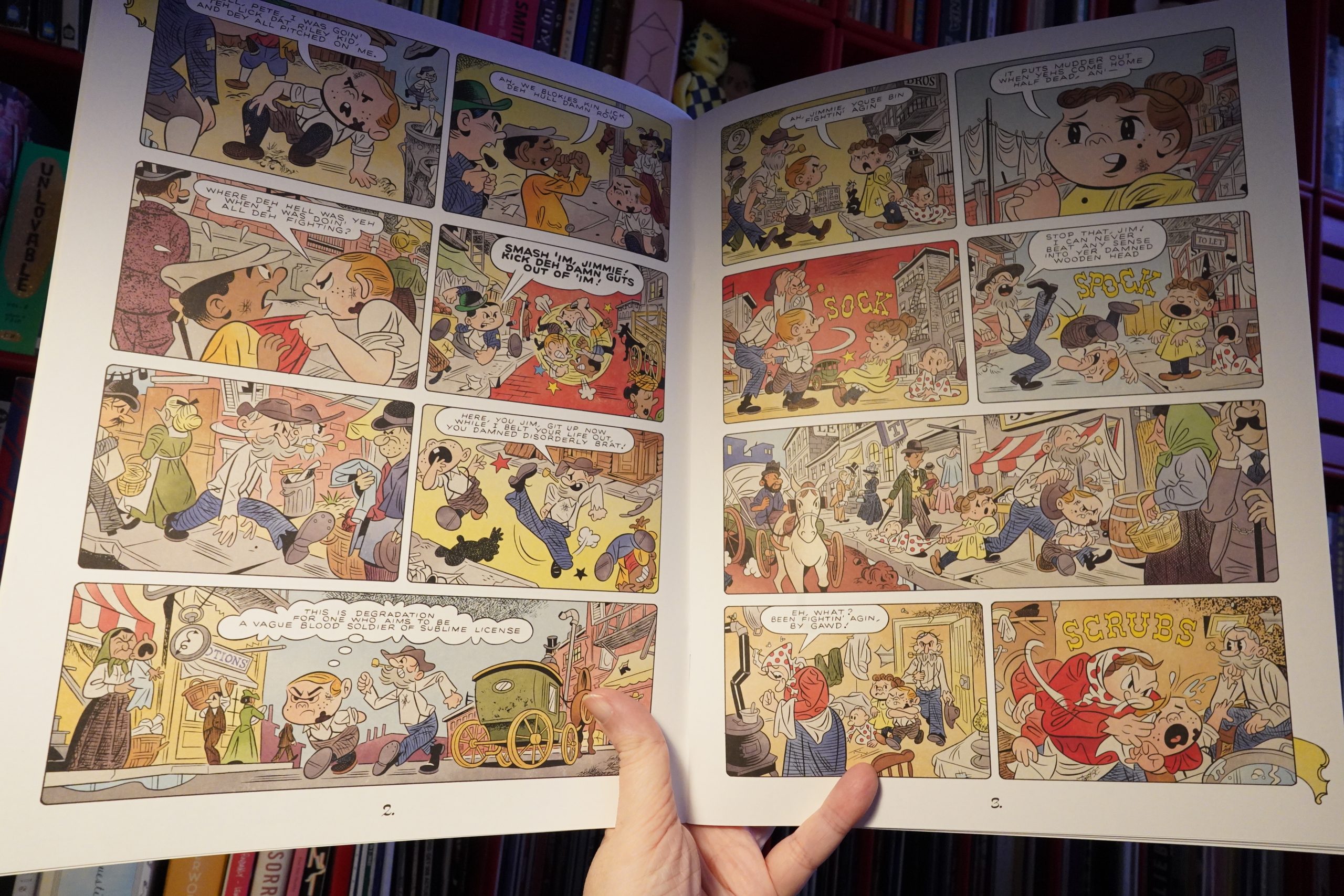

Yes indeed:

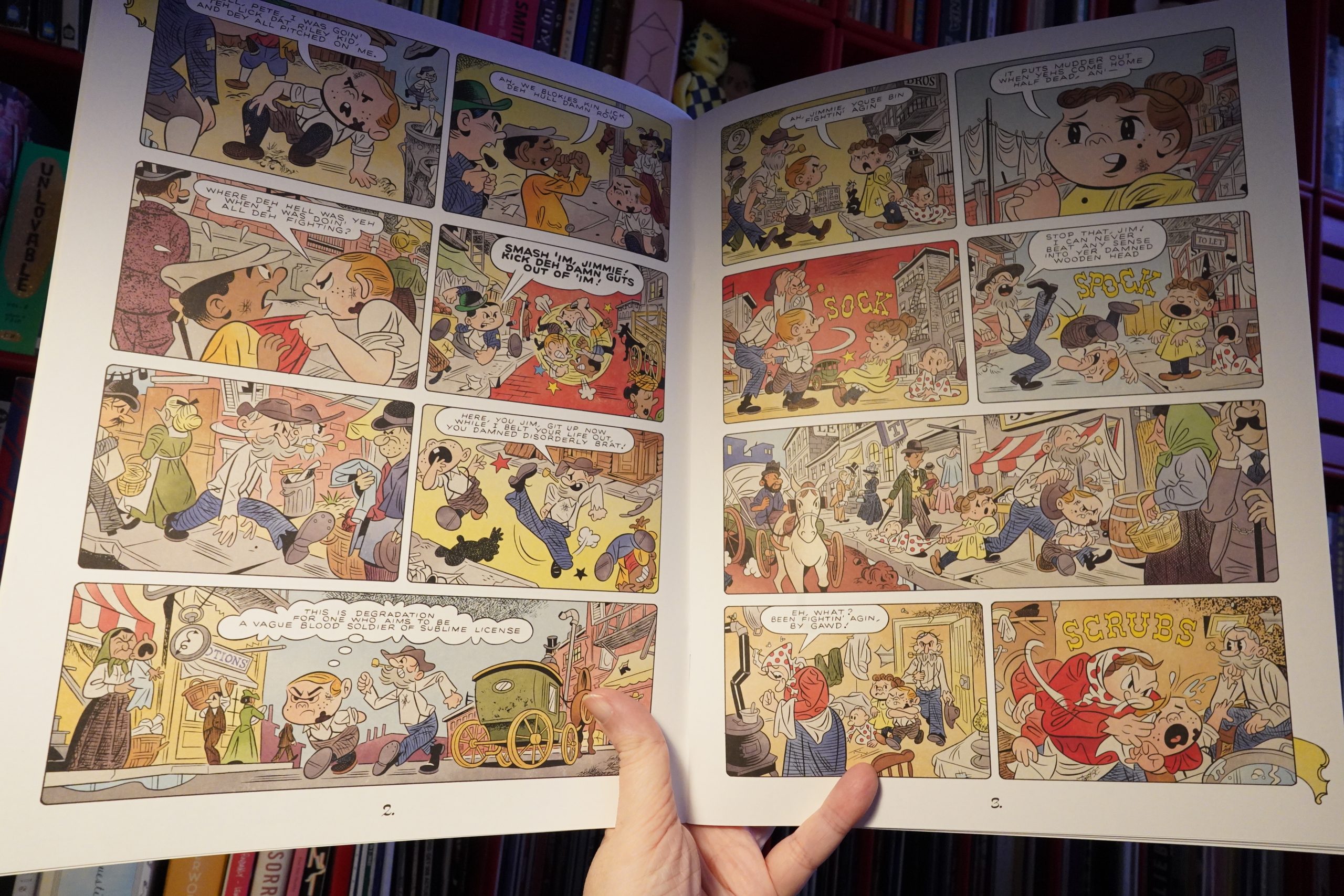

The mother raised lamenting eyes to the ceiling.

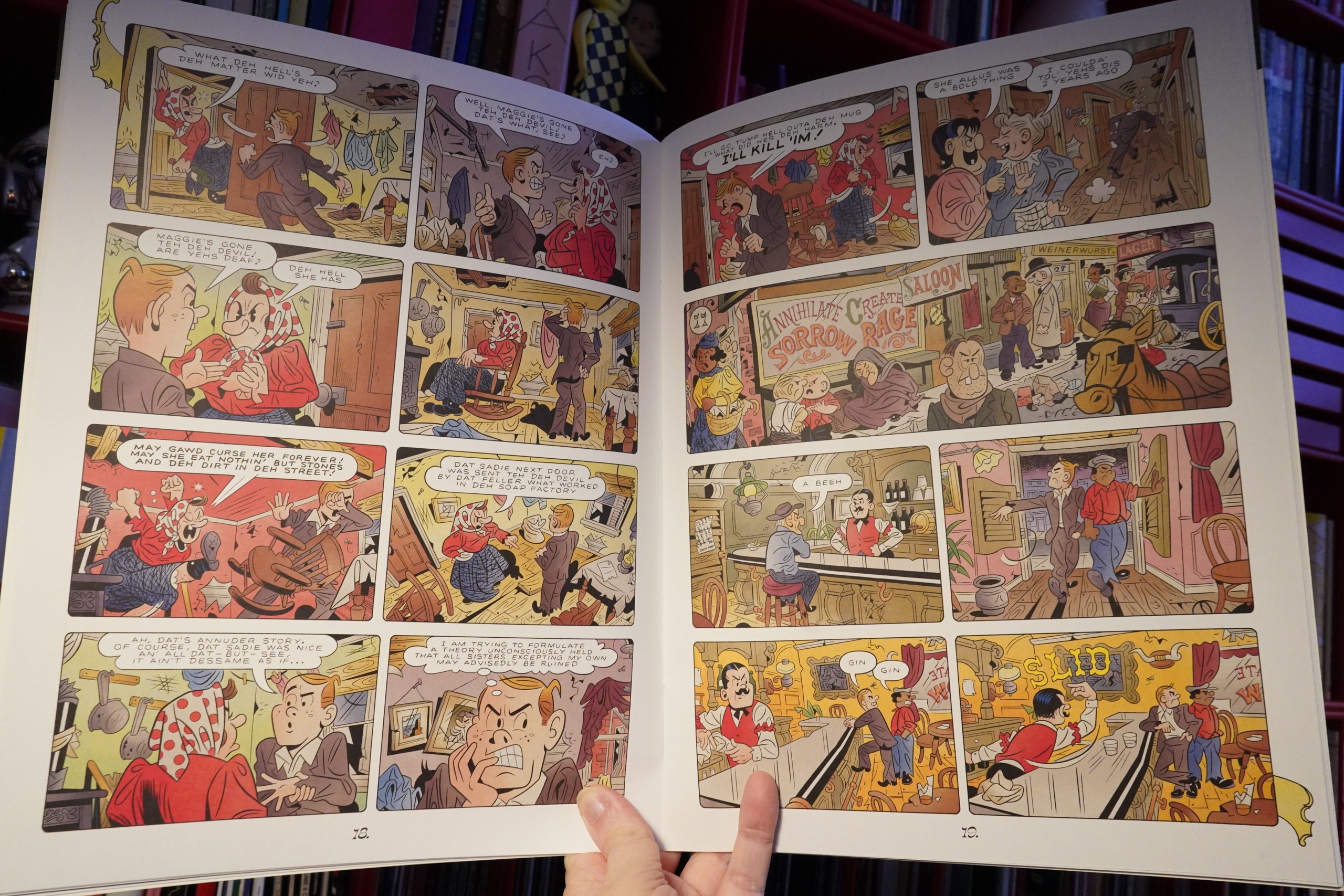

“She’s deh devil’s own chil’, Jimmie,” she whispered. “Ah, who would t’ink such a bad girl could grow up in our fambly, Jimmie, me son. Many deh hour I’ve spent in talk wid dat girl an’ tol’ her if she ever went on deh streets I’d see her damned. An’ after all her bringin’ up an’ what I tol’ her and talked wid her, she goes teh deh bad, like a duck teh water.”

The tears rolled down her furrowed face. Her hands trembled.

“An’ den when dat Sadie MacMallister next door to us was sent teh deh devil by dat feller what worked in deh soap-factory, didn’t I tell our Mag dat if she—”

“Ah, dat’s annuder story,” interrupted the brother. “Of course, dat Sadie was nice an’ all dat—but—see—it ain’t dessame as if—well, Maggie was diff’ent—see—she was diff’ent.”

He was trying to formulate a theory that he had always unconsciously held, that all sisters, excepting his own, could advisedly be ruined.

He suddenly broke out again. “I’ll go t’ump hell outa deh mug what did her deh harm. I’ll kill ‘im! He t’inks he kin scrap, but when he gits me a-chasin’ ‘im he’ll fin’ out where he’s wrong, deh damned duffer. I’ll wipe up deh street wid ‘im.”

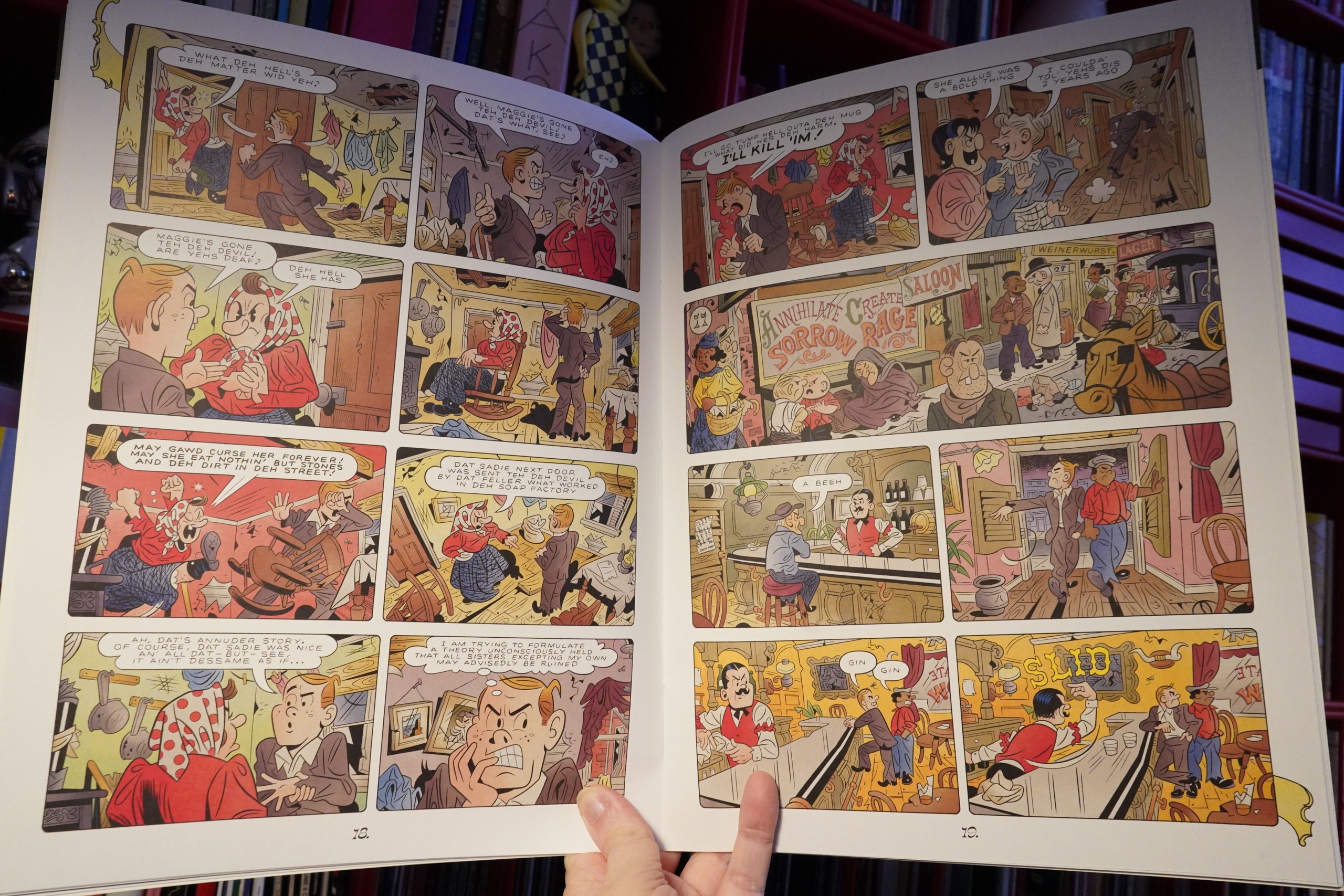

I kinda assumed that Hensley was exaggerating the “dialect” to contrast with the omnipotent authorial point of view, but nope. But he puts things like “He was trying to formulate a theory…” into thought bubbles as “I was trying to formulate a theory…” which makes the contrast even more stark.

I don’t think Hensley’s book quite works — I mean, the Archie/Don Martin artwork’s nice, but what’s the point of the book? To make fun of the novella he’s presumably been forced to read once upon a time? Is it a heart-felt adaptation?

| Brigid Mae Power: Head Above the Water |  |

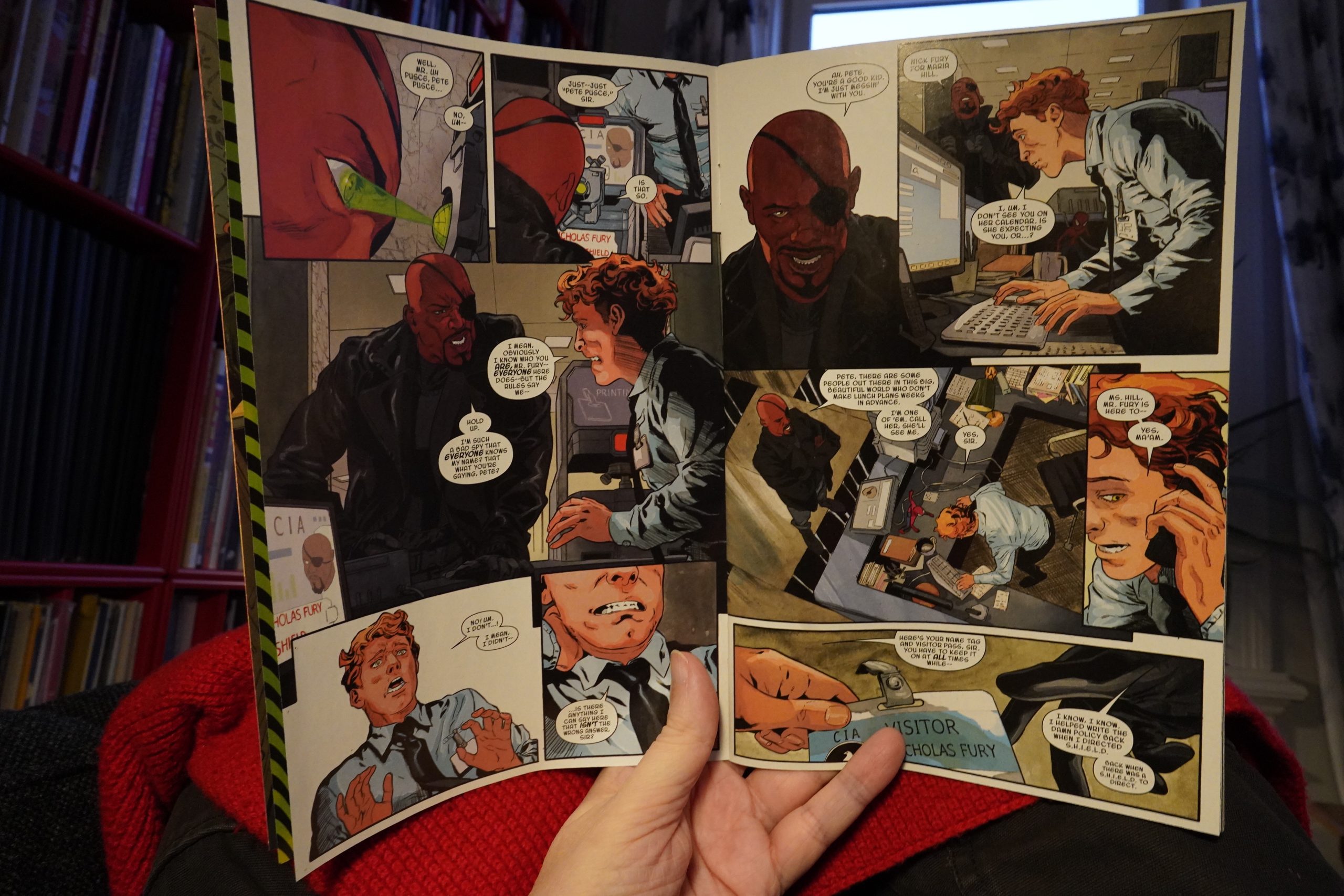

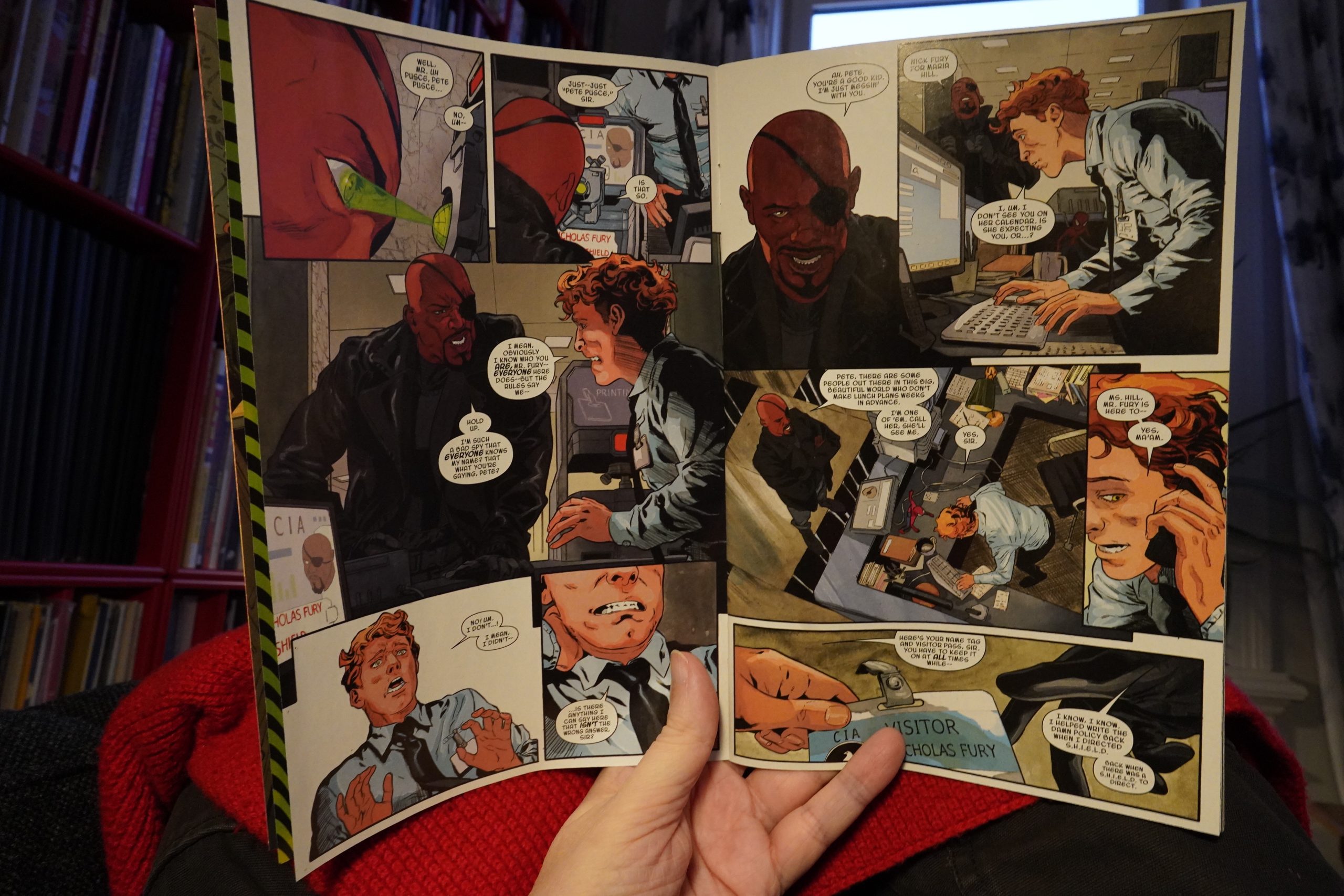

13:27: Fantastic Four #1 & Secret Invasion #1 by Ryan North and others (Marvel Comics)

Ryan North has two new series at Marvel!? And they look like they’re “serious” (i.e., actual super-hero) books?

I didn’t see this coming.

Well, perhaps not totally normal — it’s a Groundhog Day issue, and it’s pretty sweet. Not that many jokes, though.

Secret Invasion #1 is even more traditional — like the FF book, there’s not much fighting, but there’s even fewer jokes.

It’s not bad, though.

| Cabaret Voltaire: Easy Life |  |

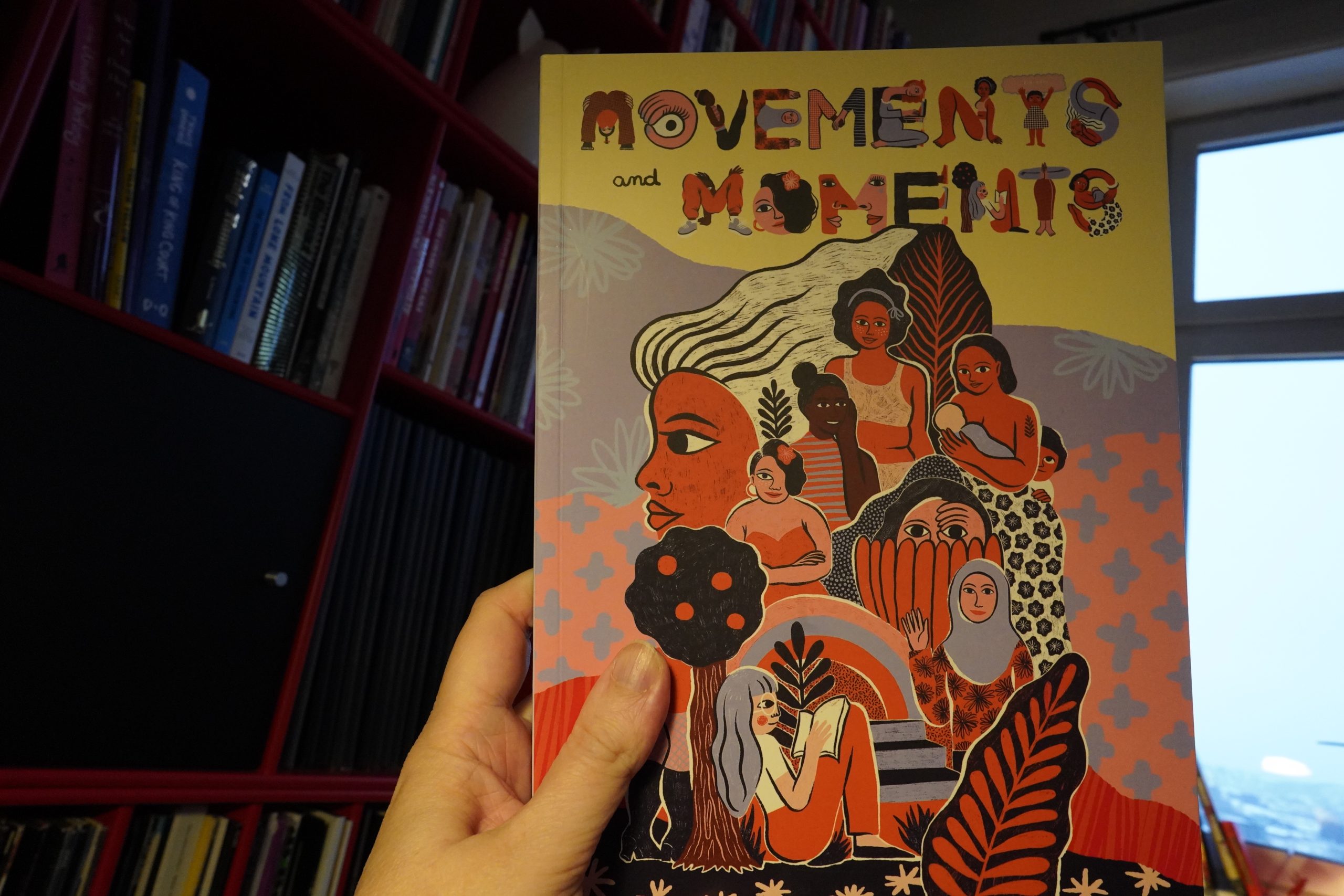

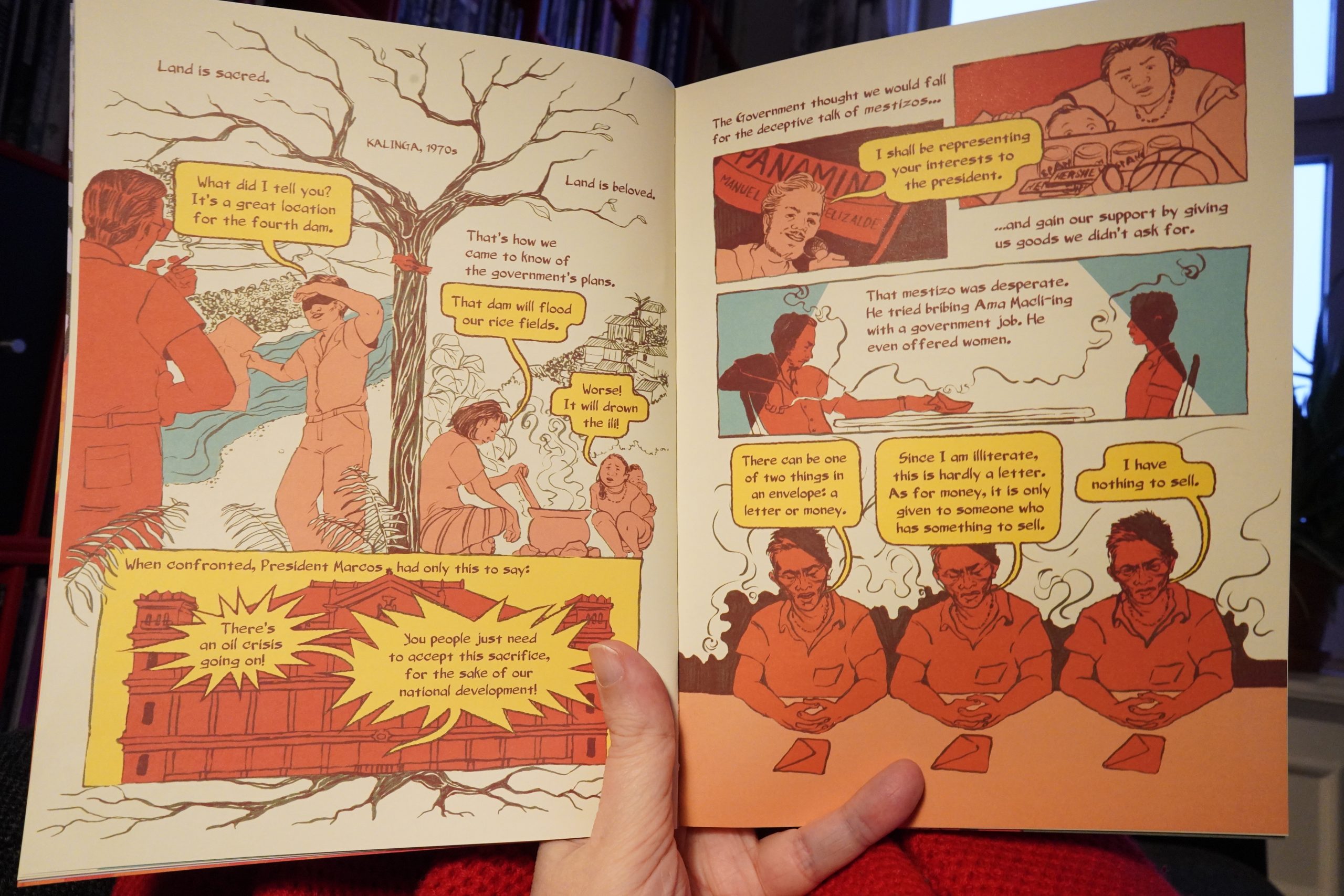

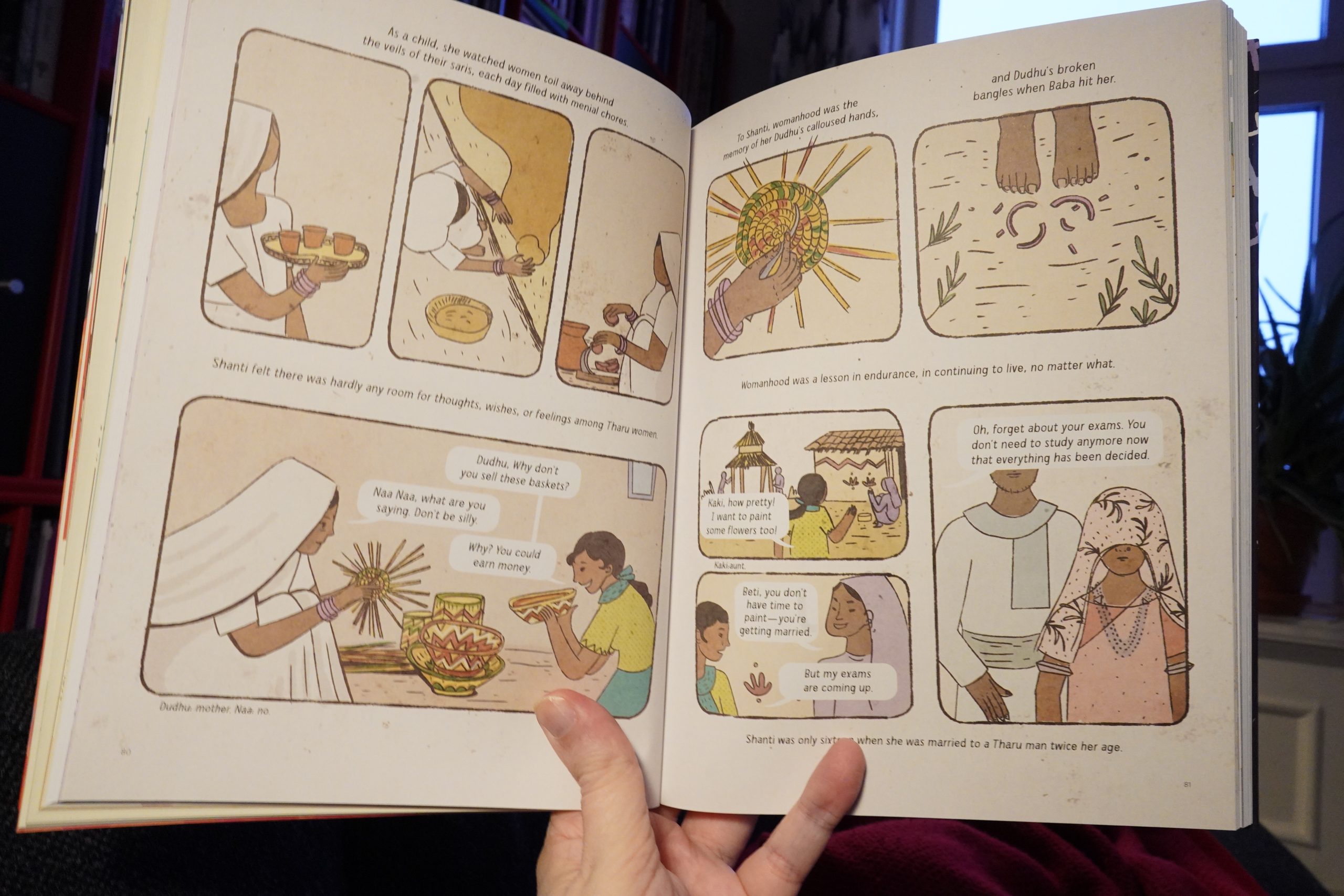

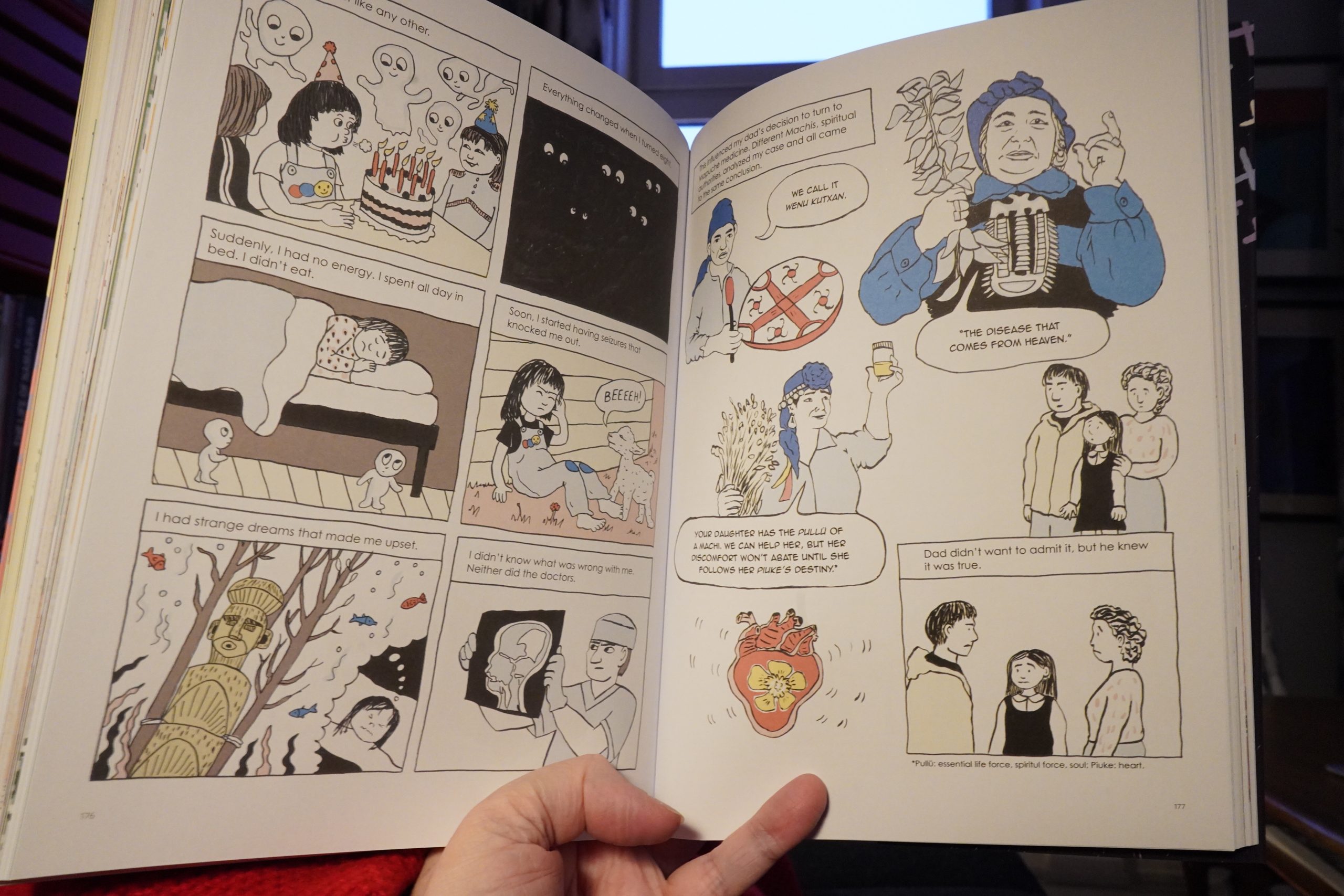

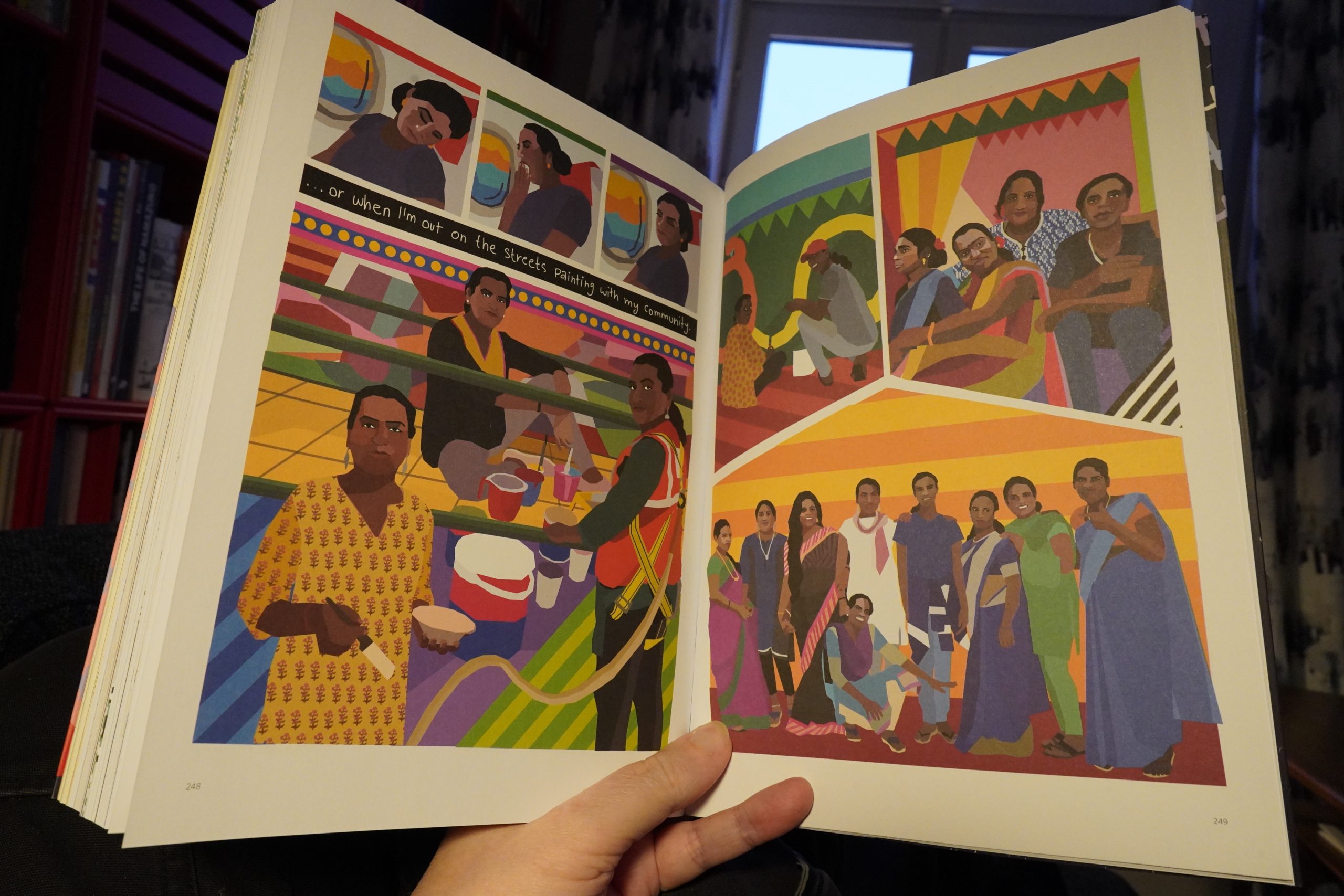

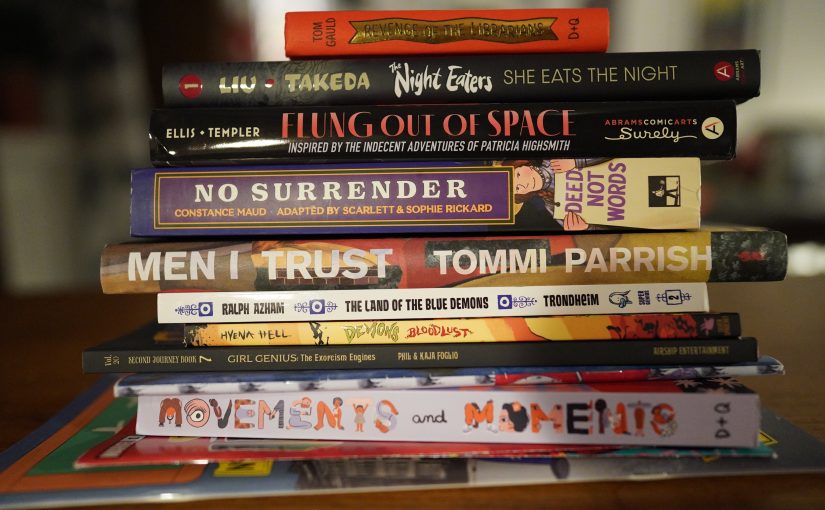

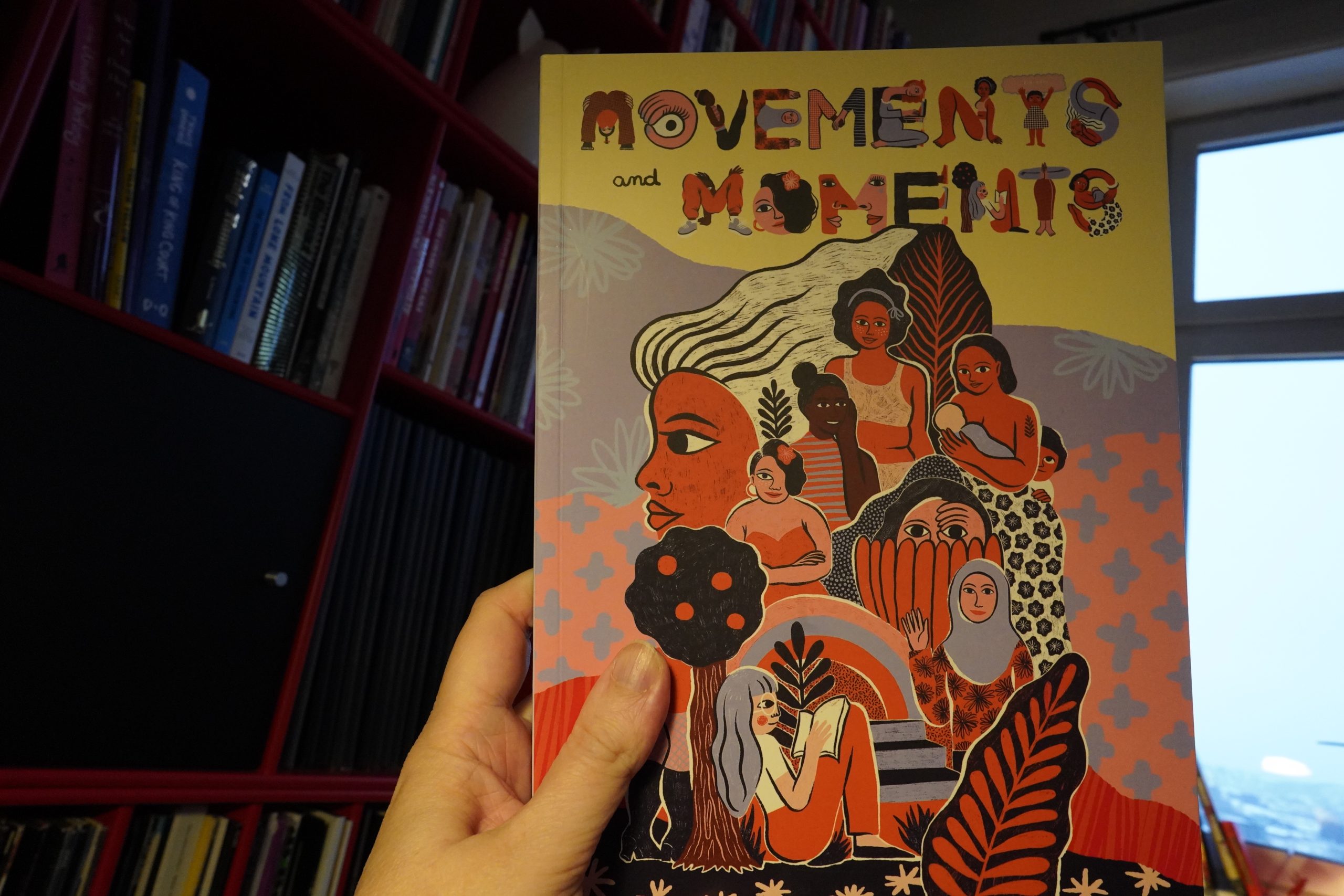

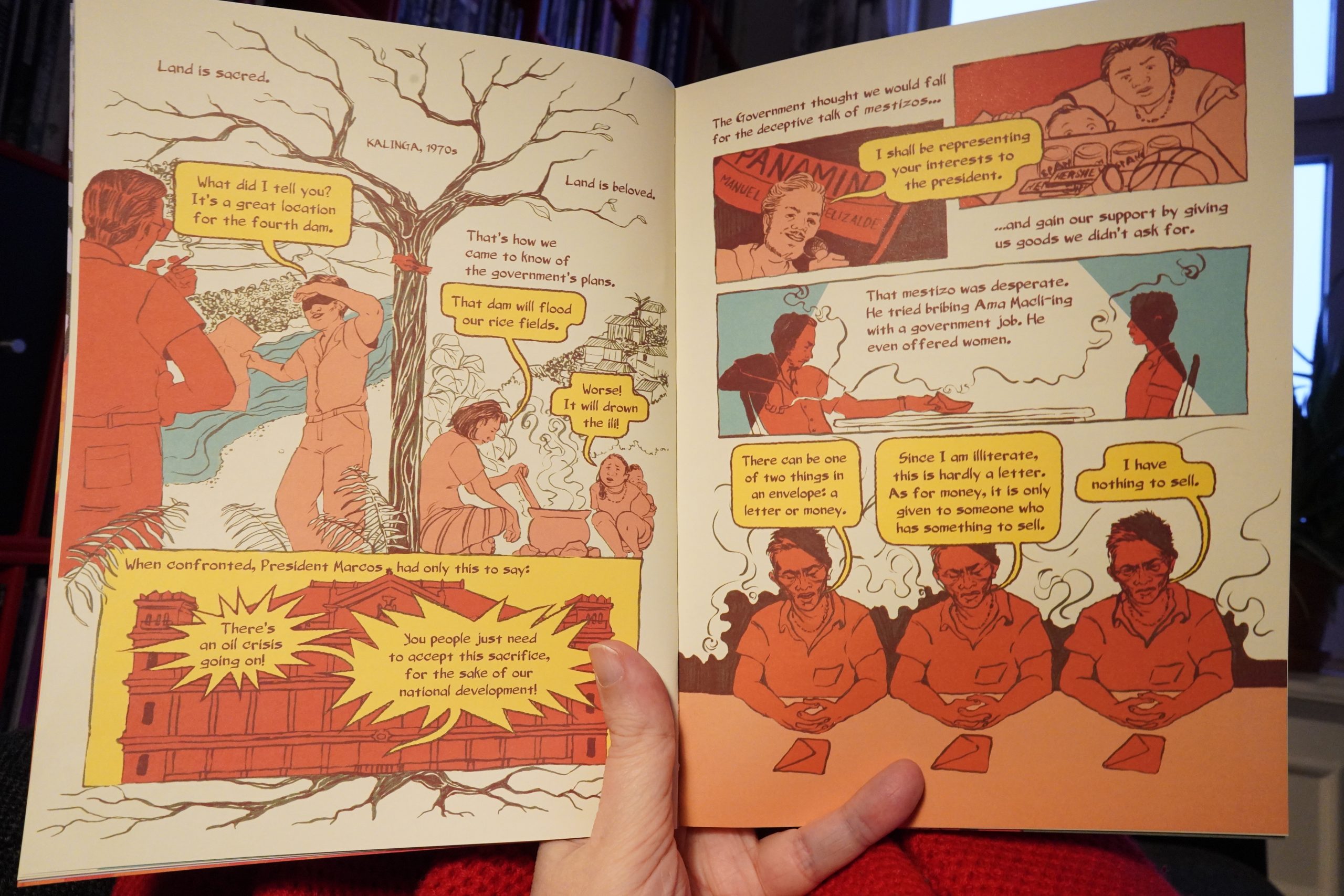

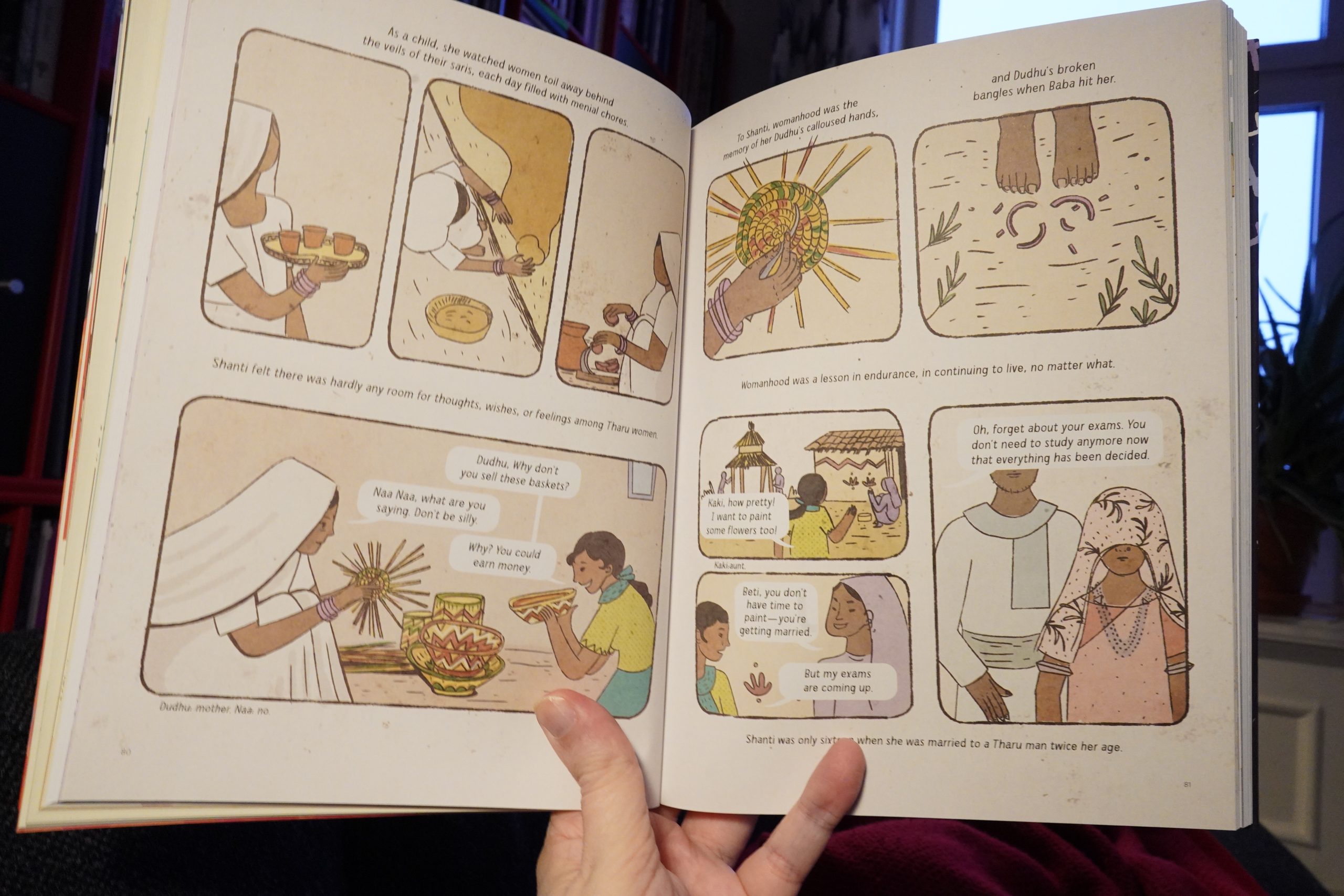

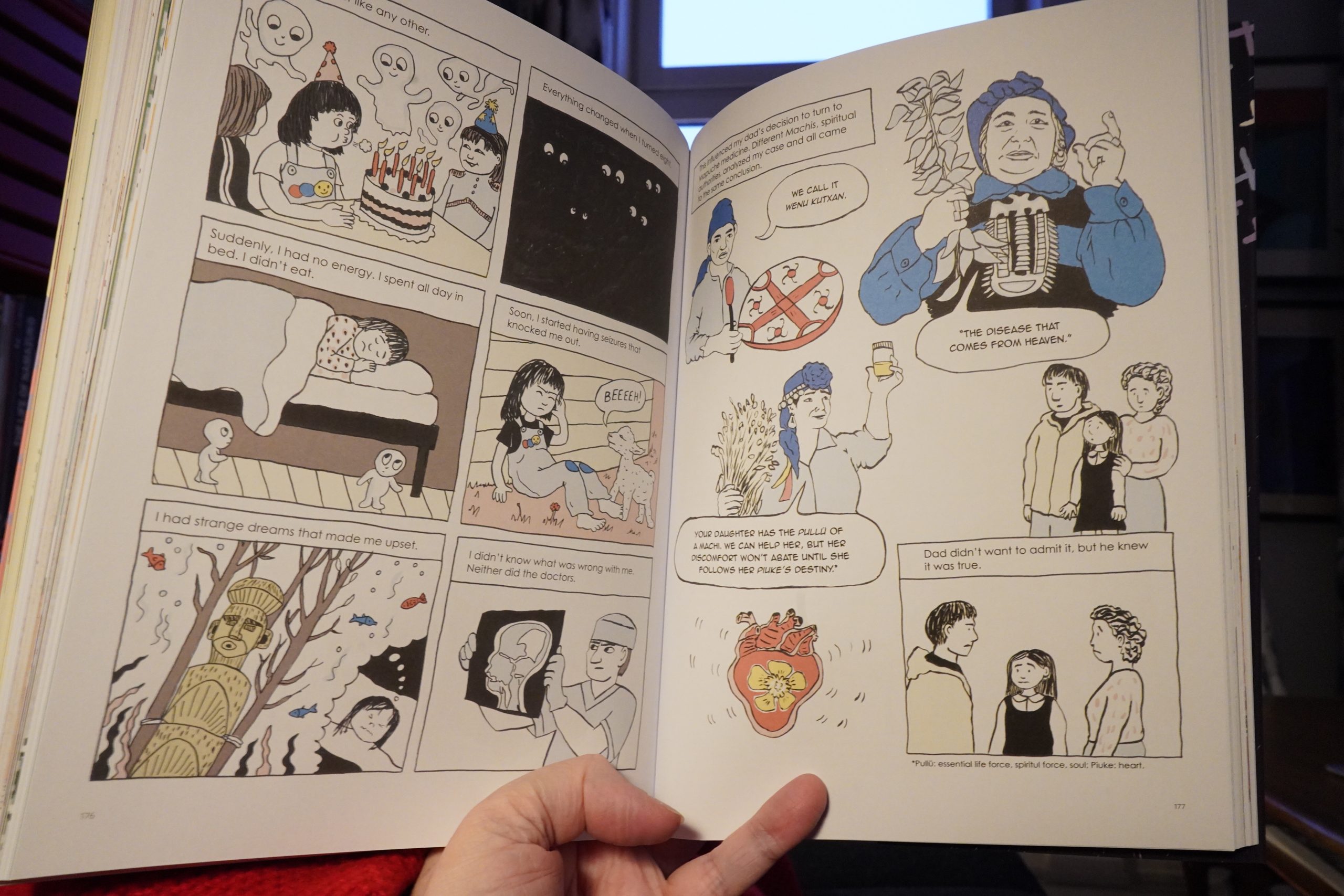

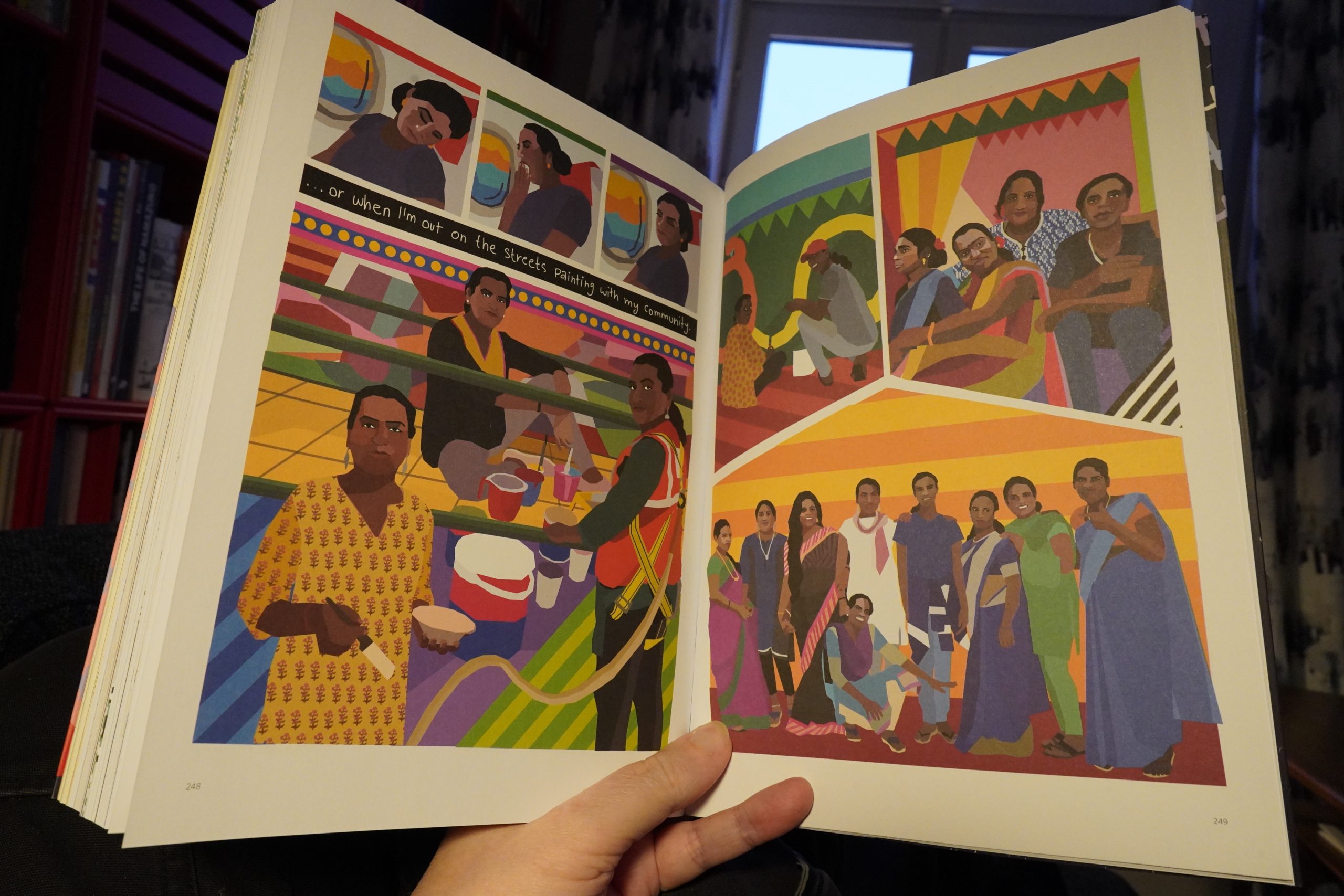

13:51: Movements and Moments (Drawn & Quarterly)

This is an anthology about struggle and rebellion and stuff.

I guess the obvious point of comparison here would be with World War 3 Illustrated, but more upscale, less anarchic and 100% serious all the time. The main problem, though, is that many of these stories are barely comics at all. They read like simplified excerpts from the Wikipedia articles about their subjects, with the text sprinkled across panels.

It makes for really choppy reading. Is the idea here to sell this as a book to be taught in, say, sixth grade?

Wat.

Yes, there’s also a lot of… spirituality… here.

There’s one piece that works, though: Sadhna Prasad’s illustrations for this brief, simple story are great, and the story has a good flow.

And now I need a nap.

| Anna B Savage: A Common Turn |  |

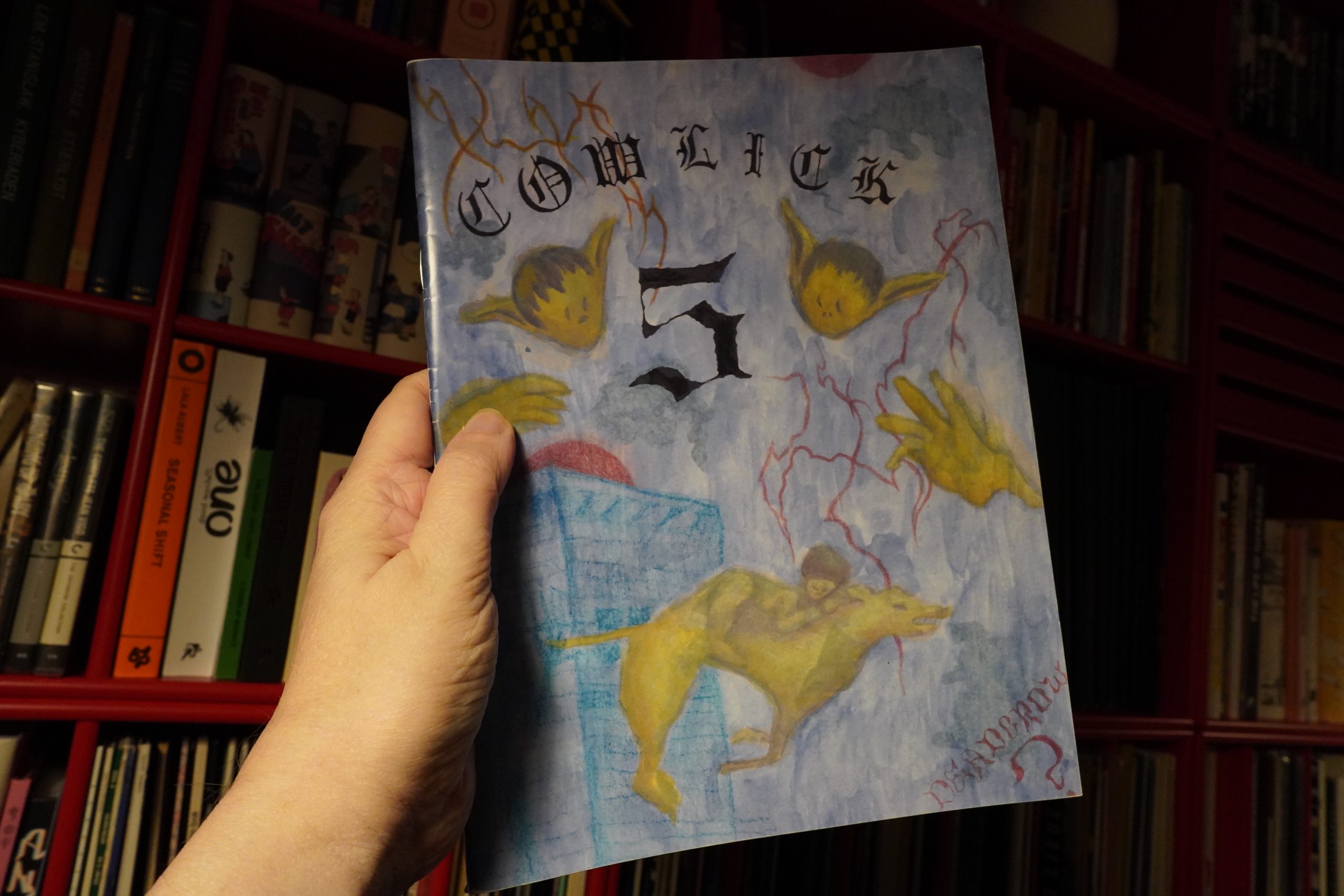

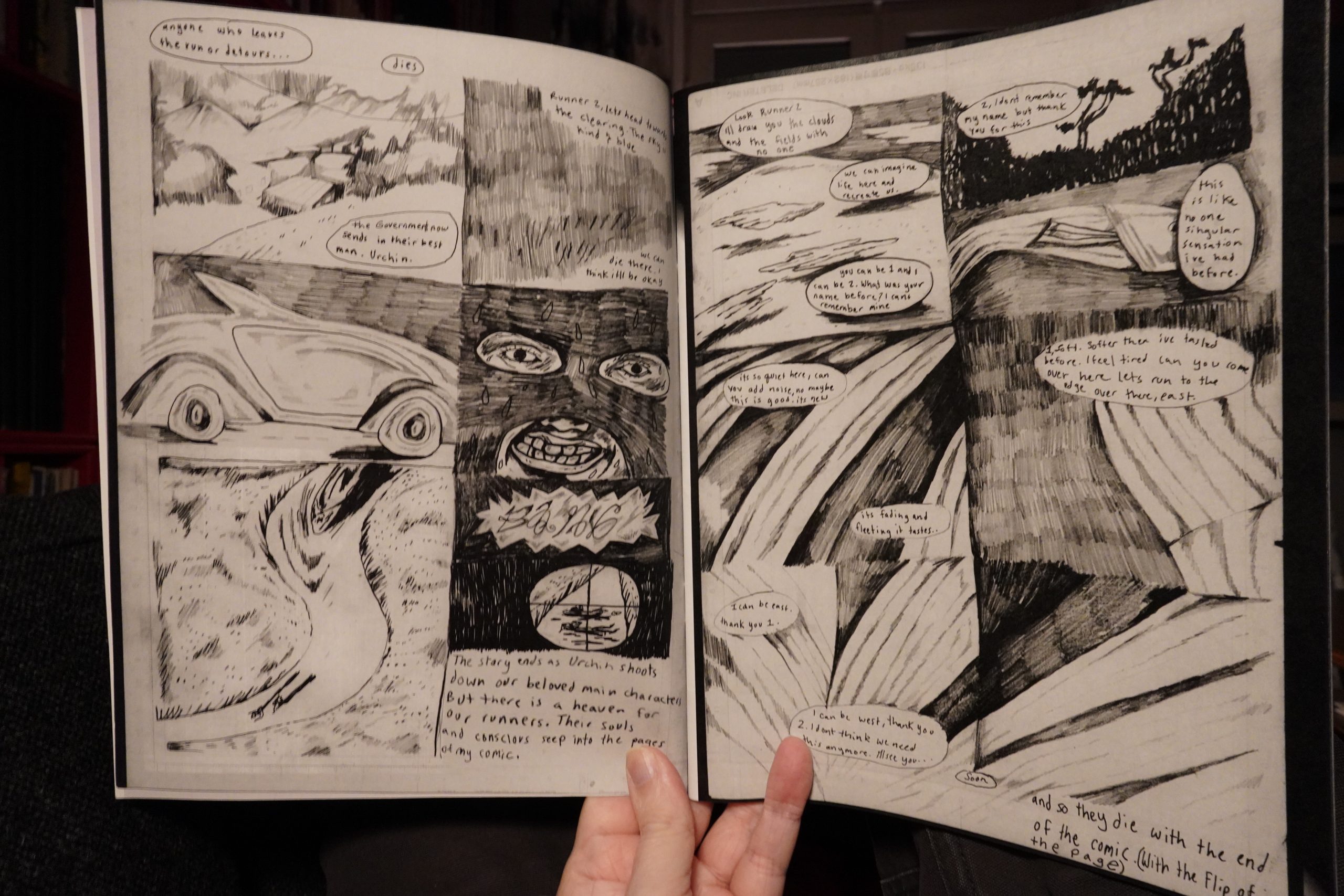

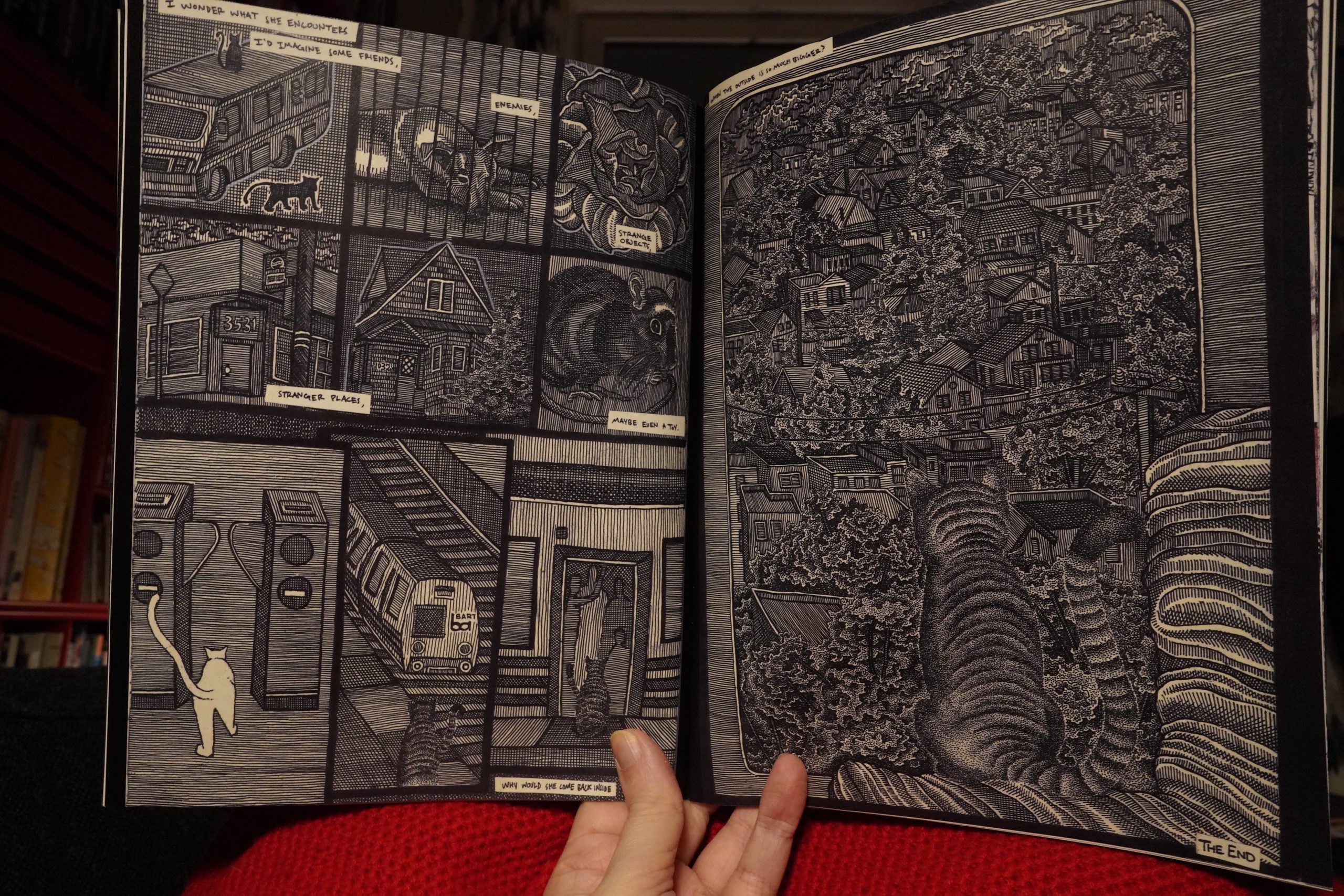

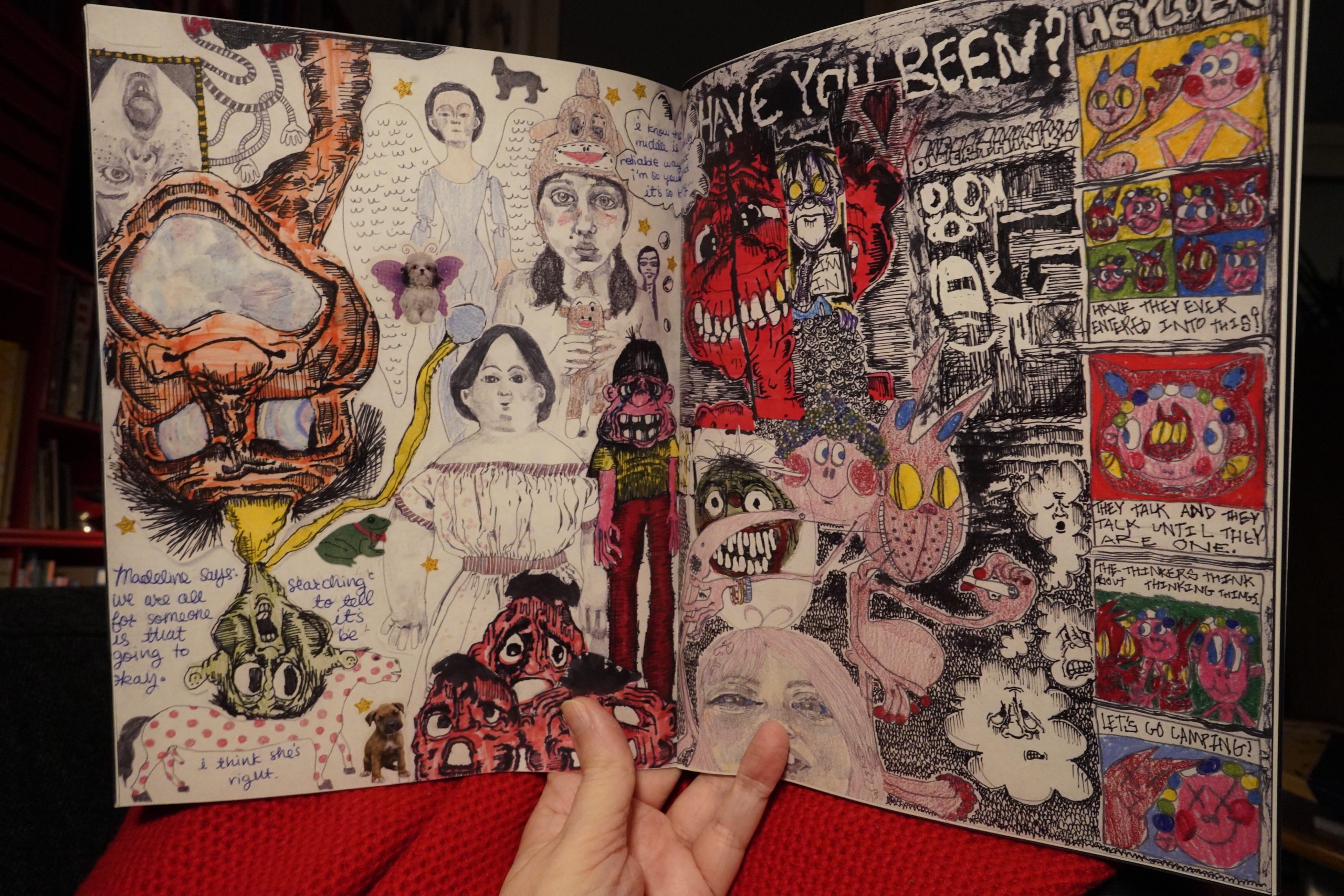

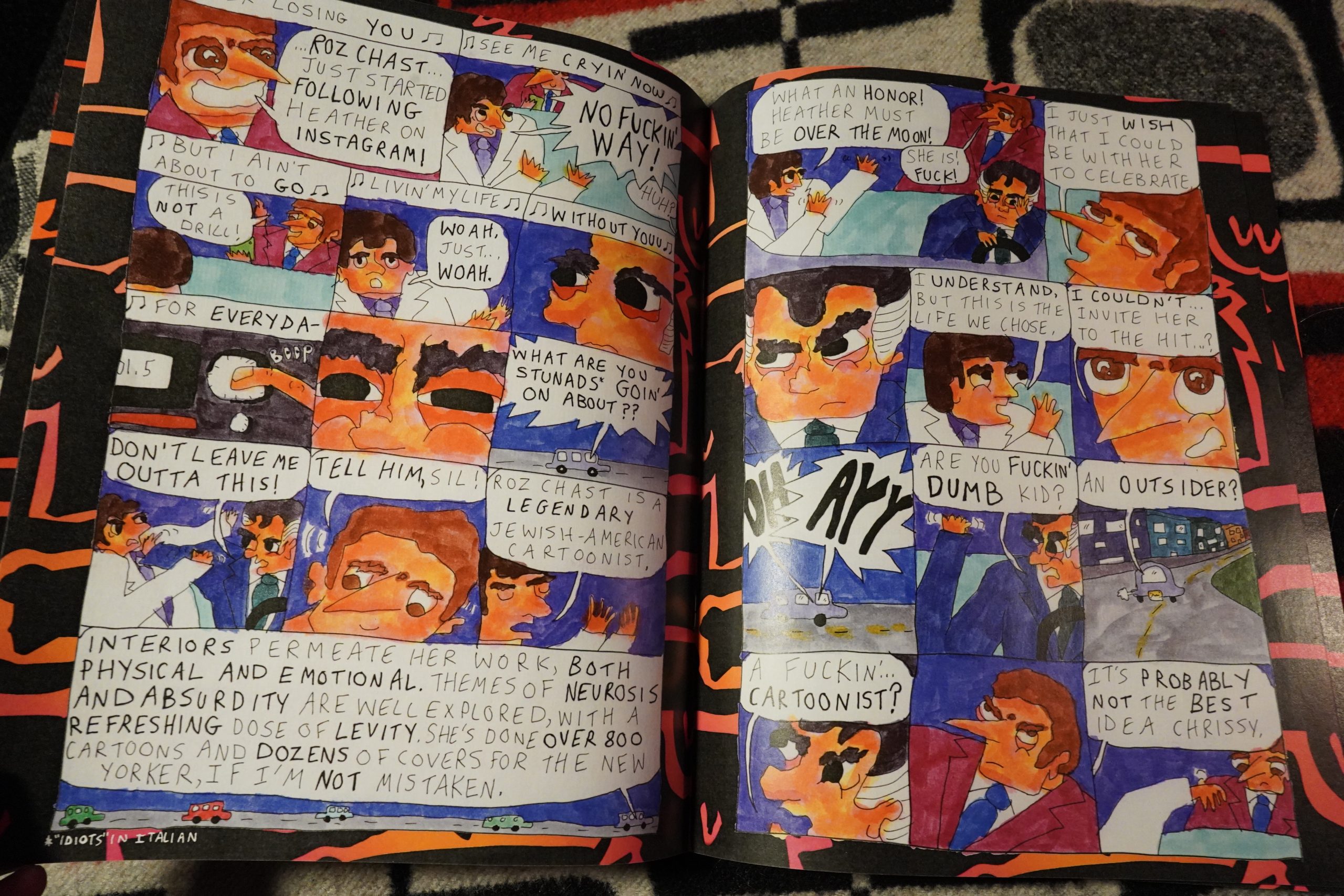

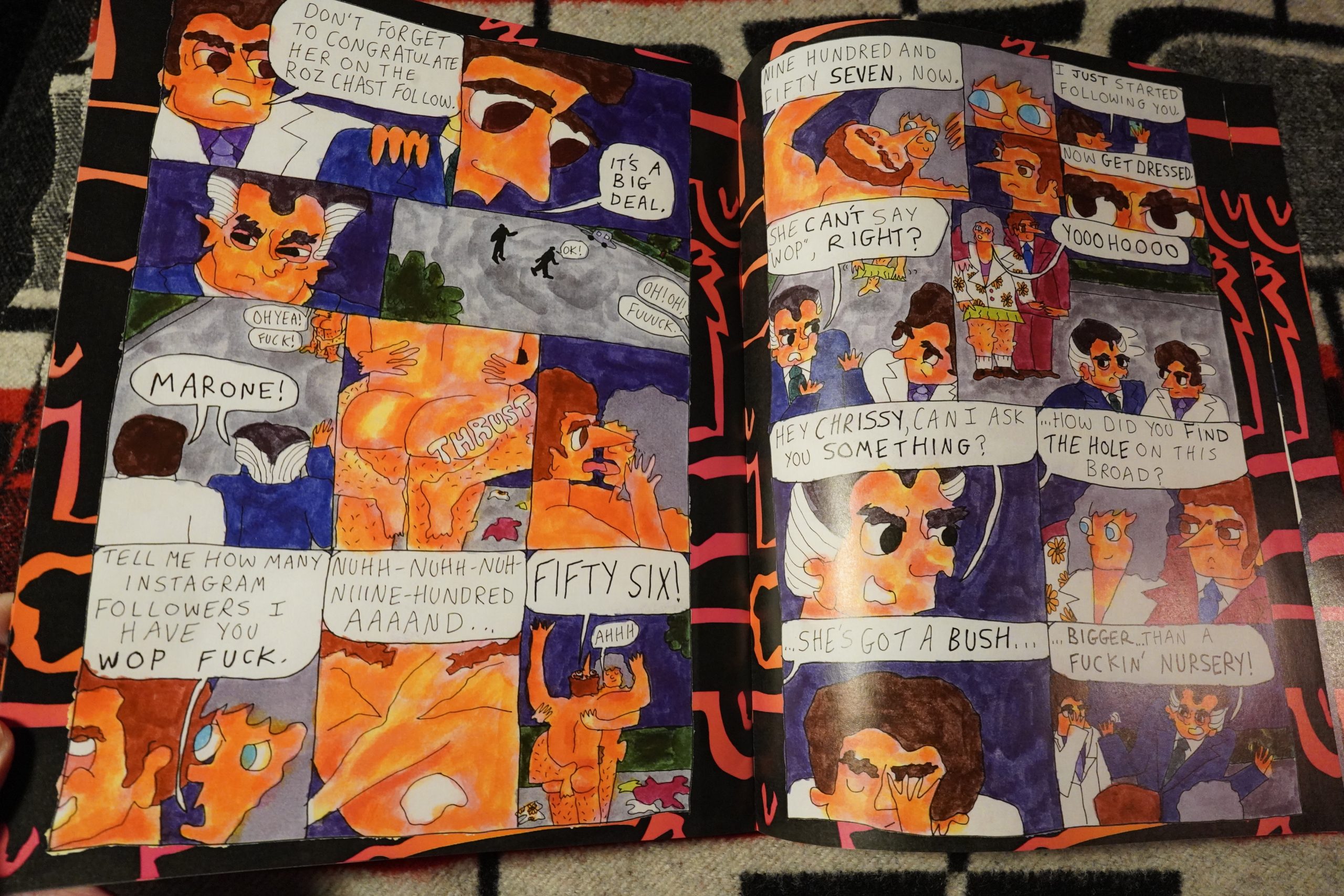

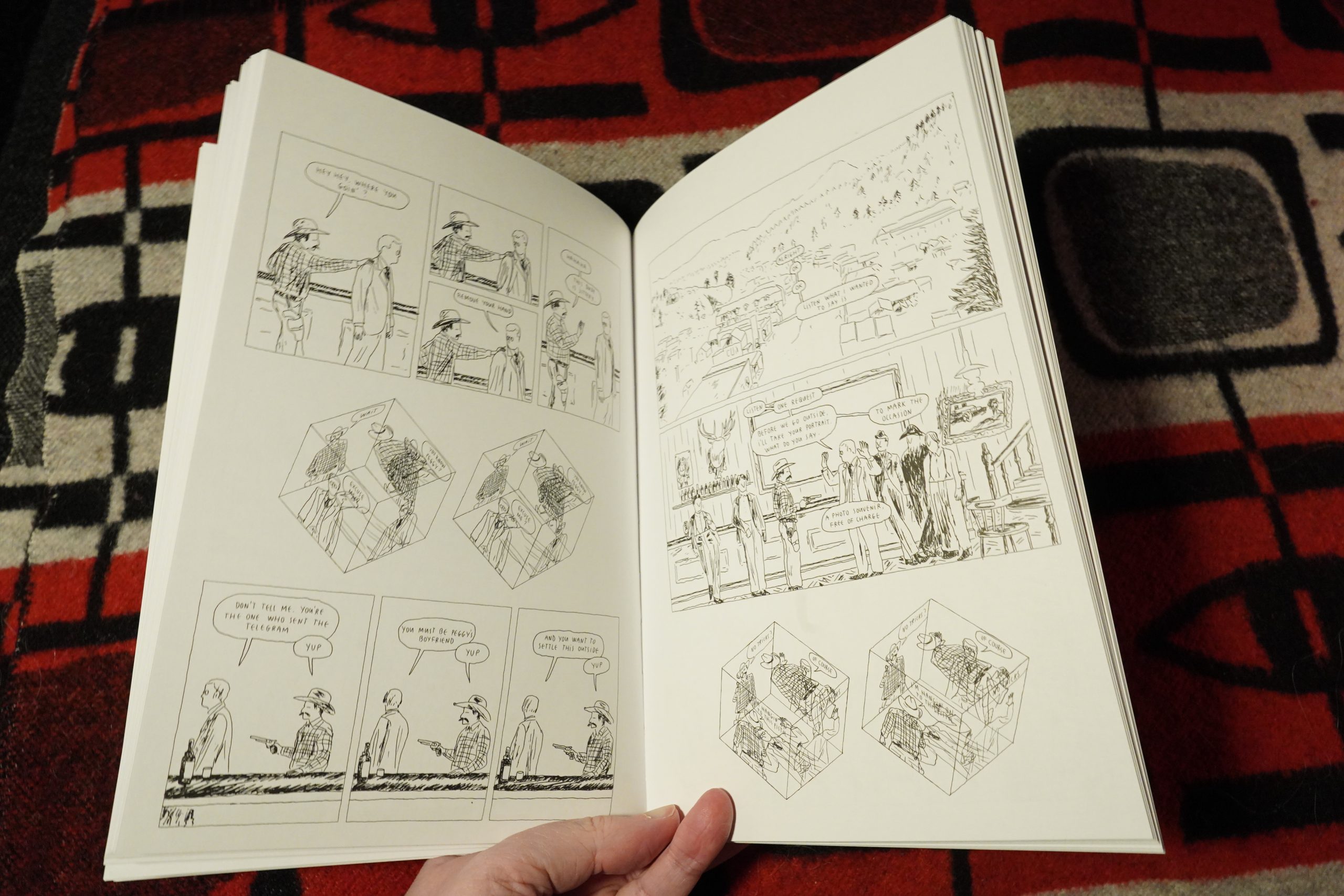

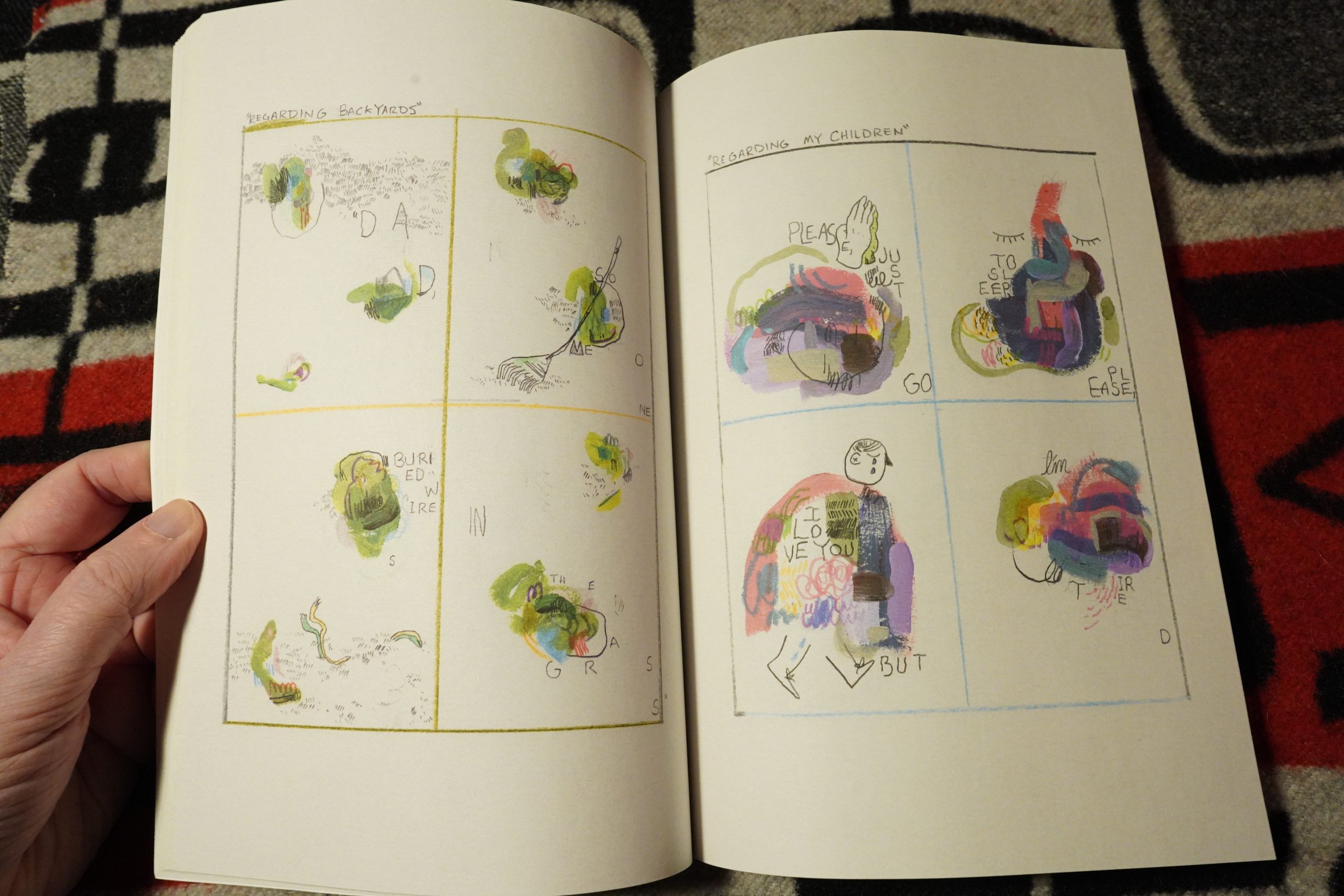

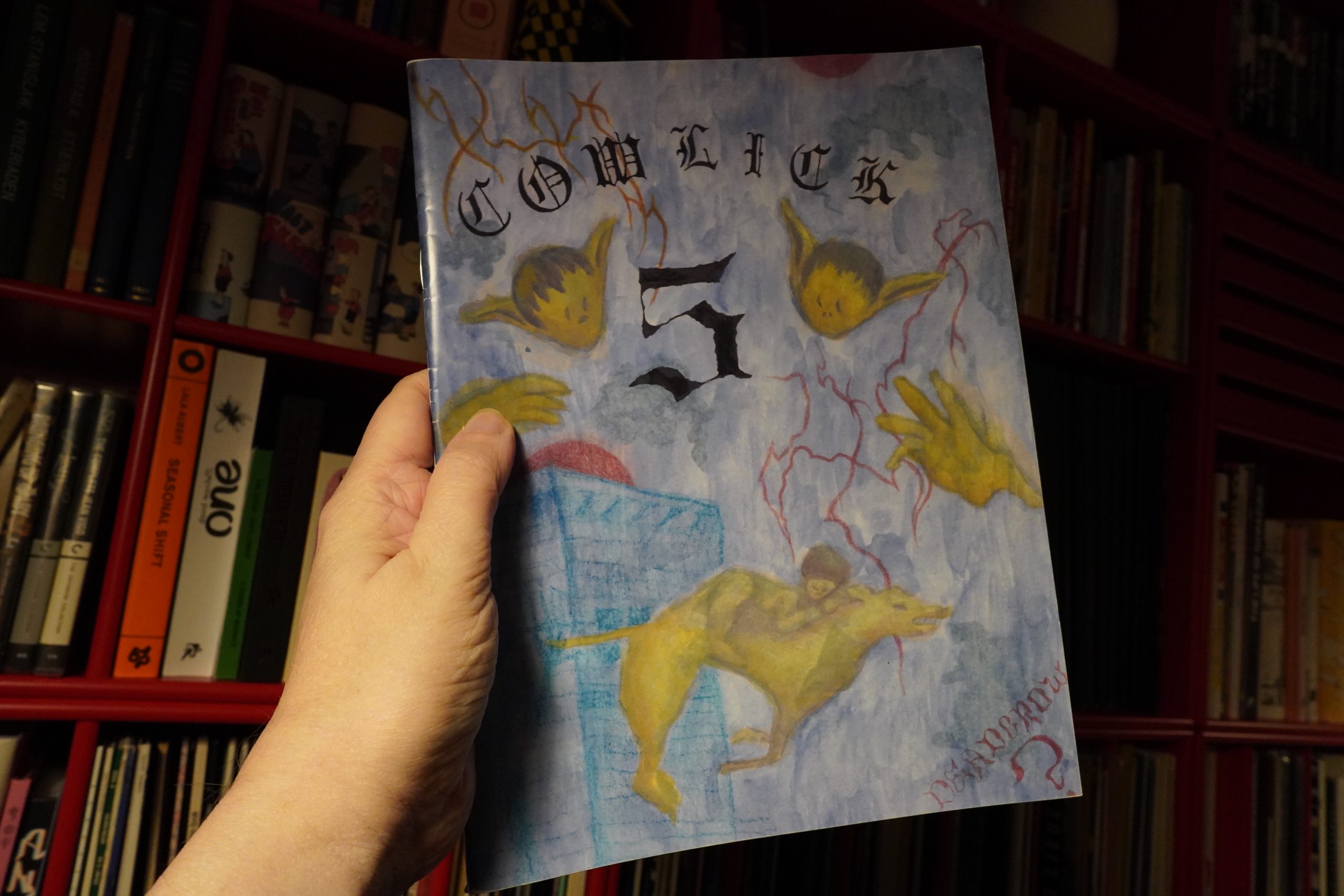

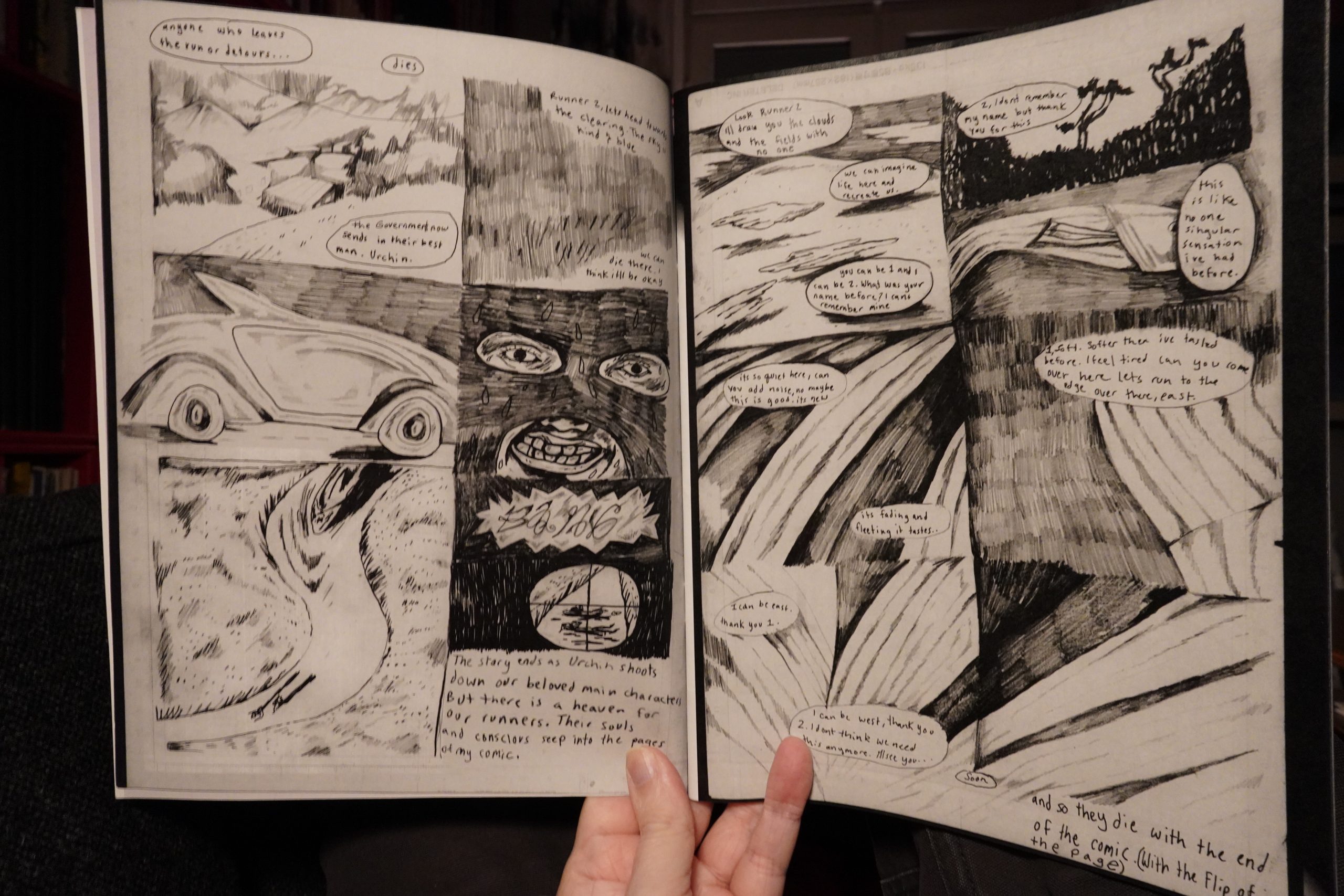

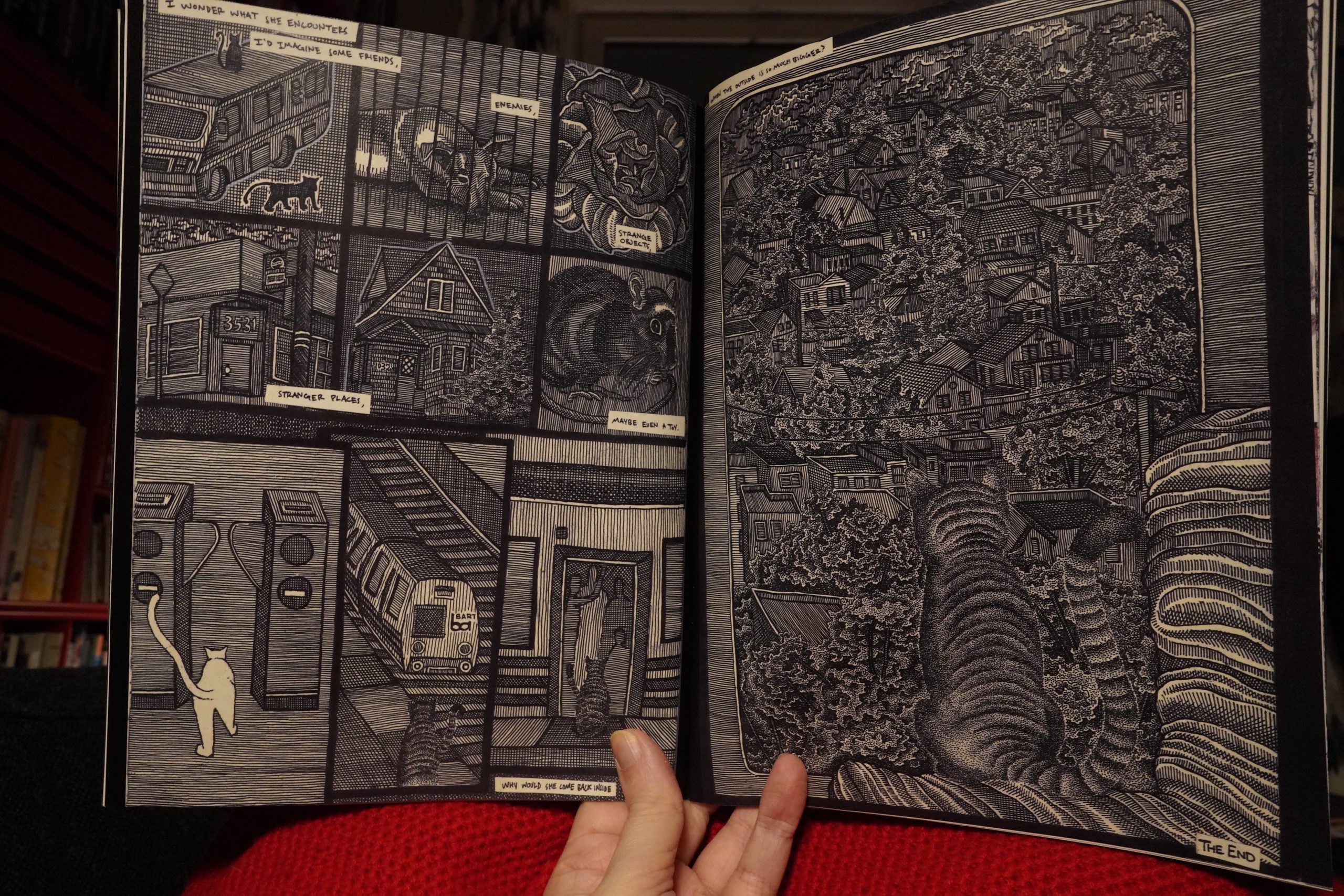

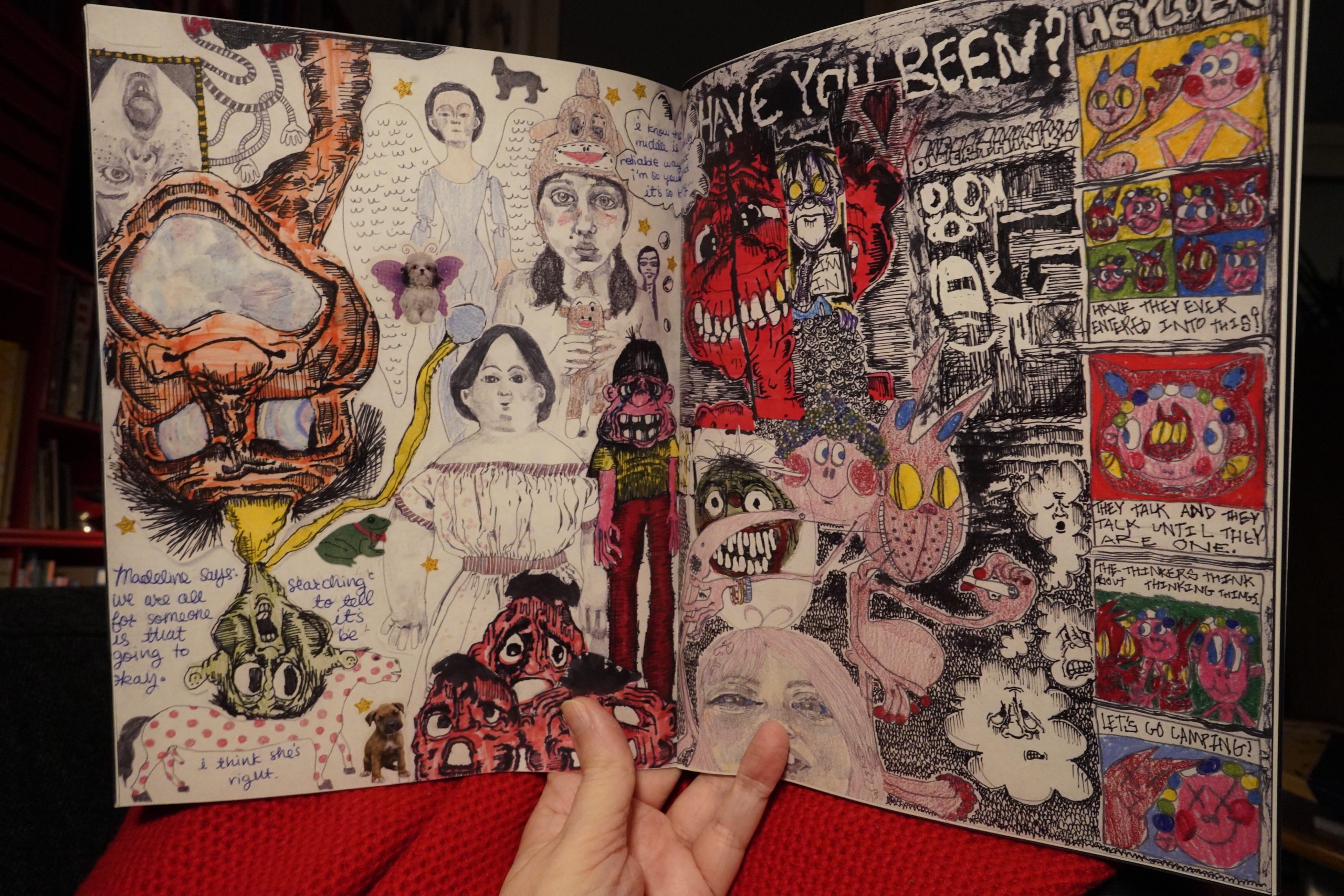

17:35: Cowlick 5 edited by Floyd Tangeman (Deadcrow)

That was a bit too much napping, but I combined it with a post-nap dinner, so now I’m all set.

Tangeman anthologies are always a nice surprise… this issue has mostly longer pieces (5+ pages), and most of them are straightforwardly narrative.

It’s lovely as ever. I liked everything in here, but especially this kitty thing by Wyatt Warren — the cartooning is overwhelming.

There’s also more abstract stuff in here, which I also love.

In short, another great anthology from Deadcrow.

| The Body: I’ve Seen All I Need To See |  |

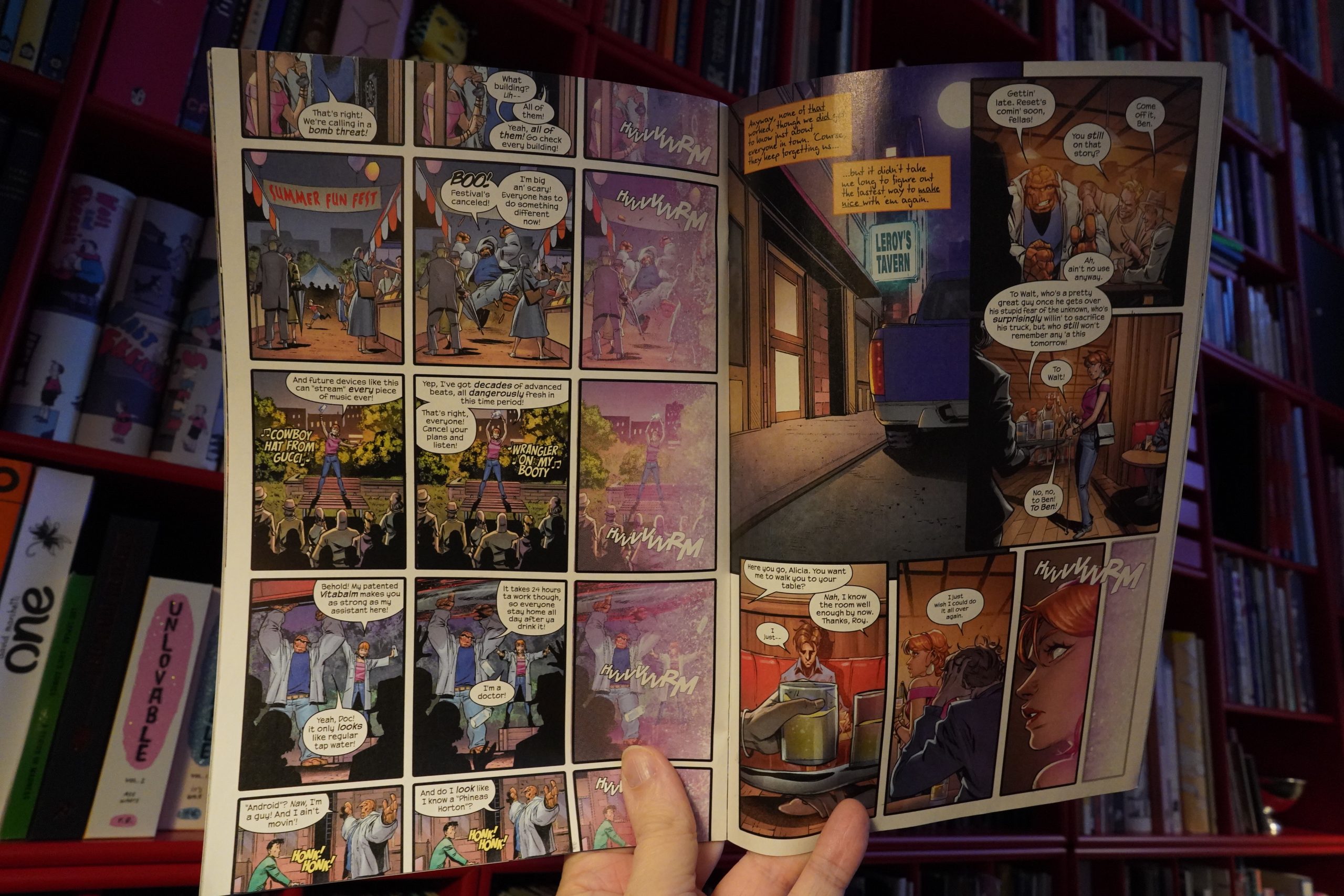

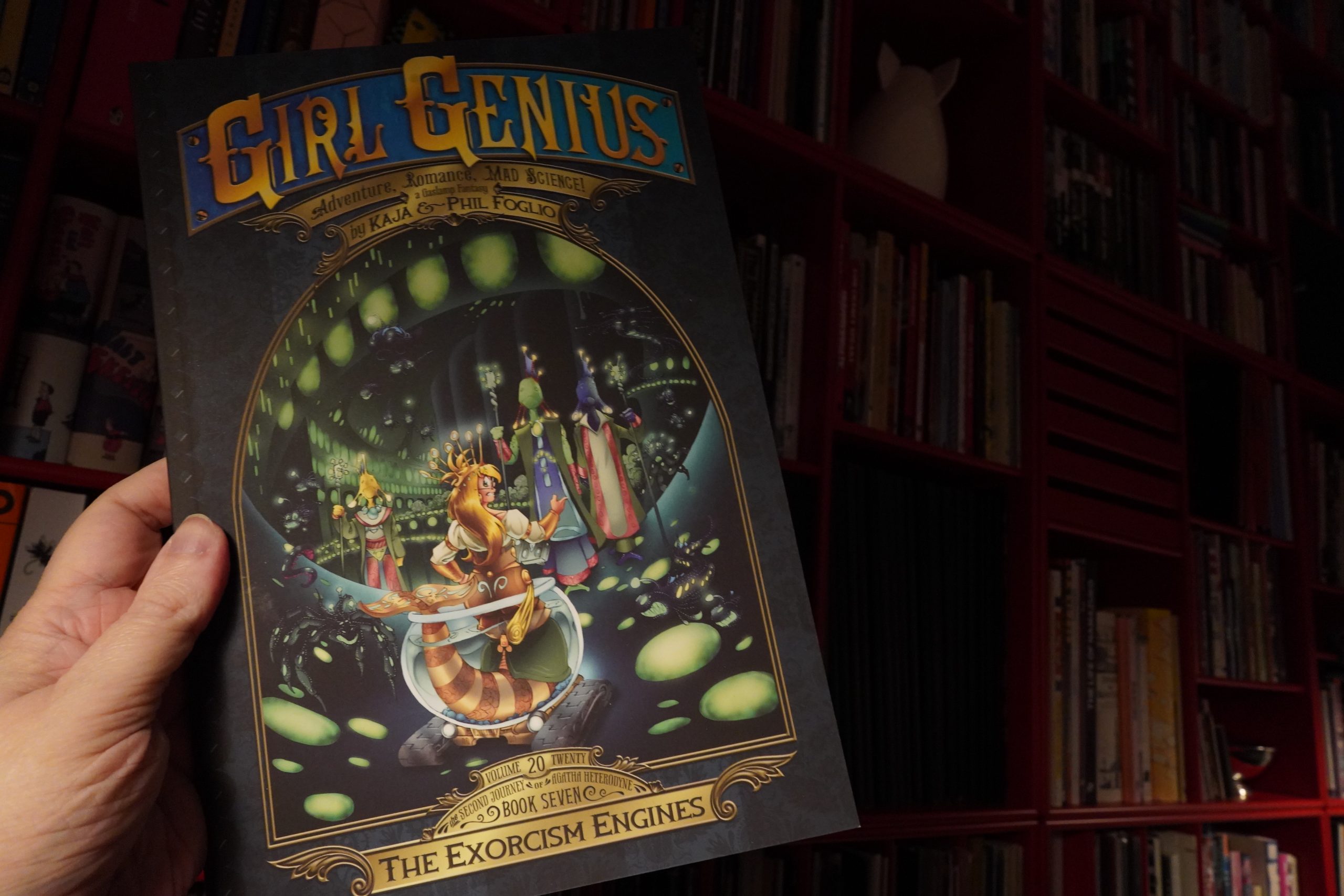

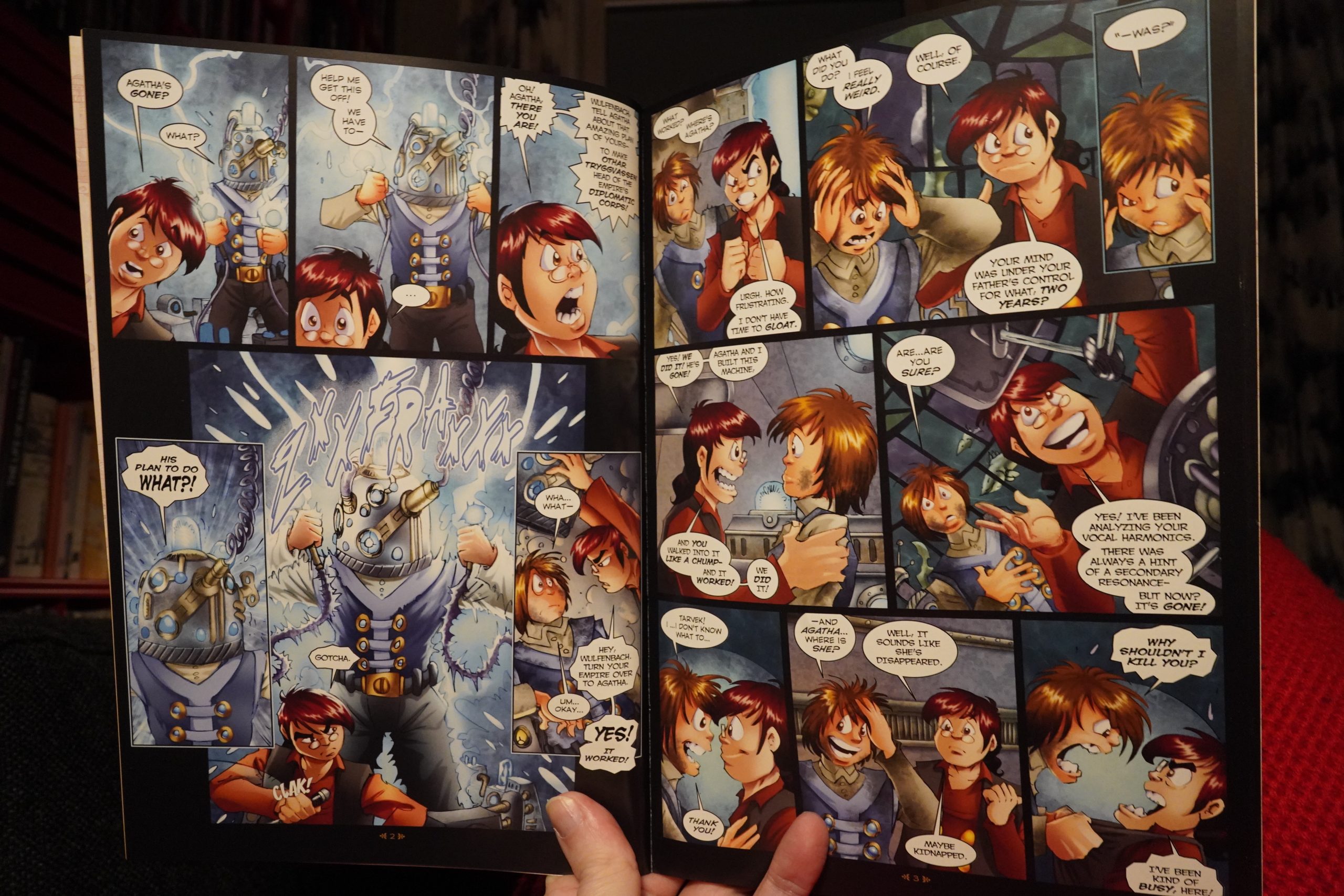

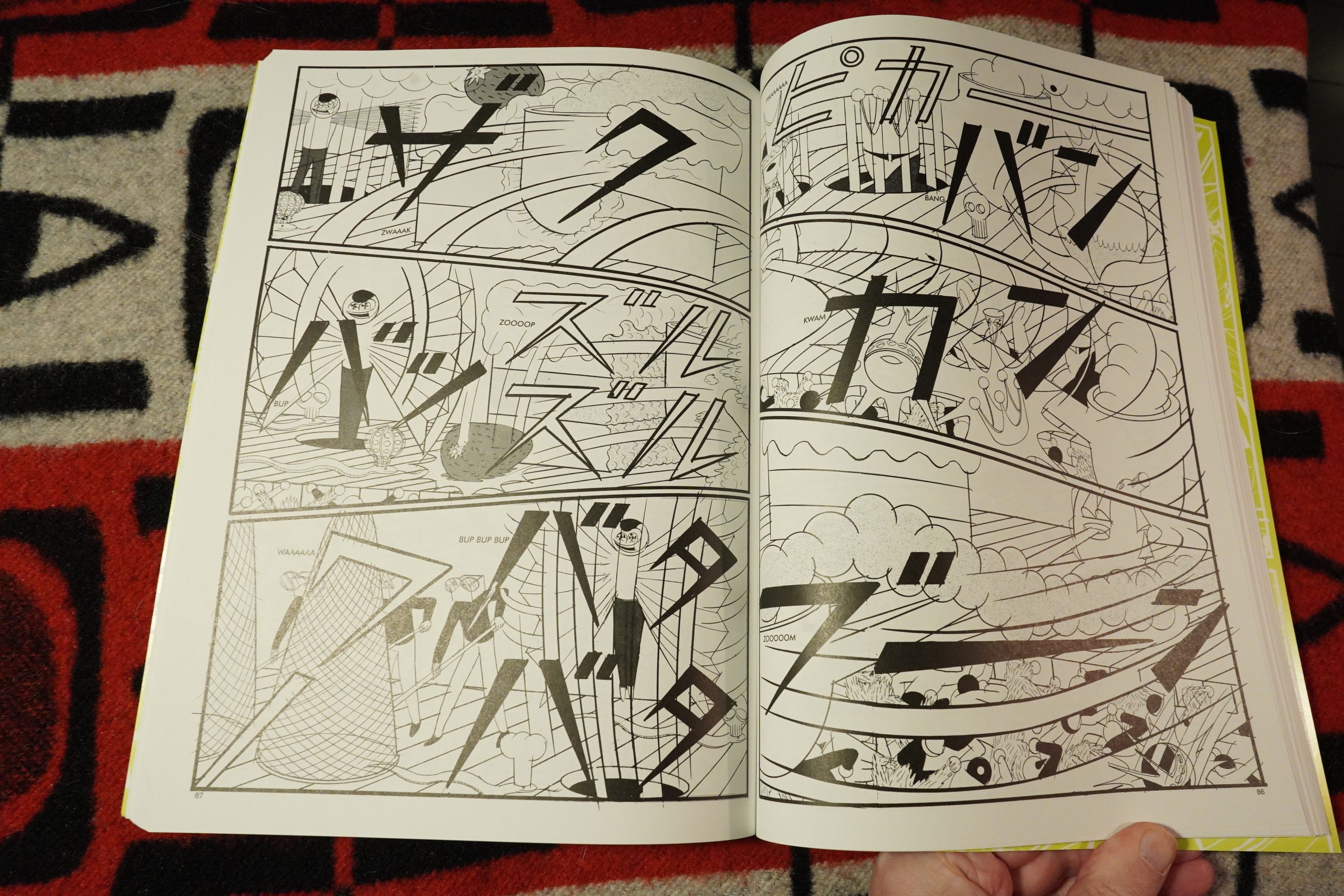

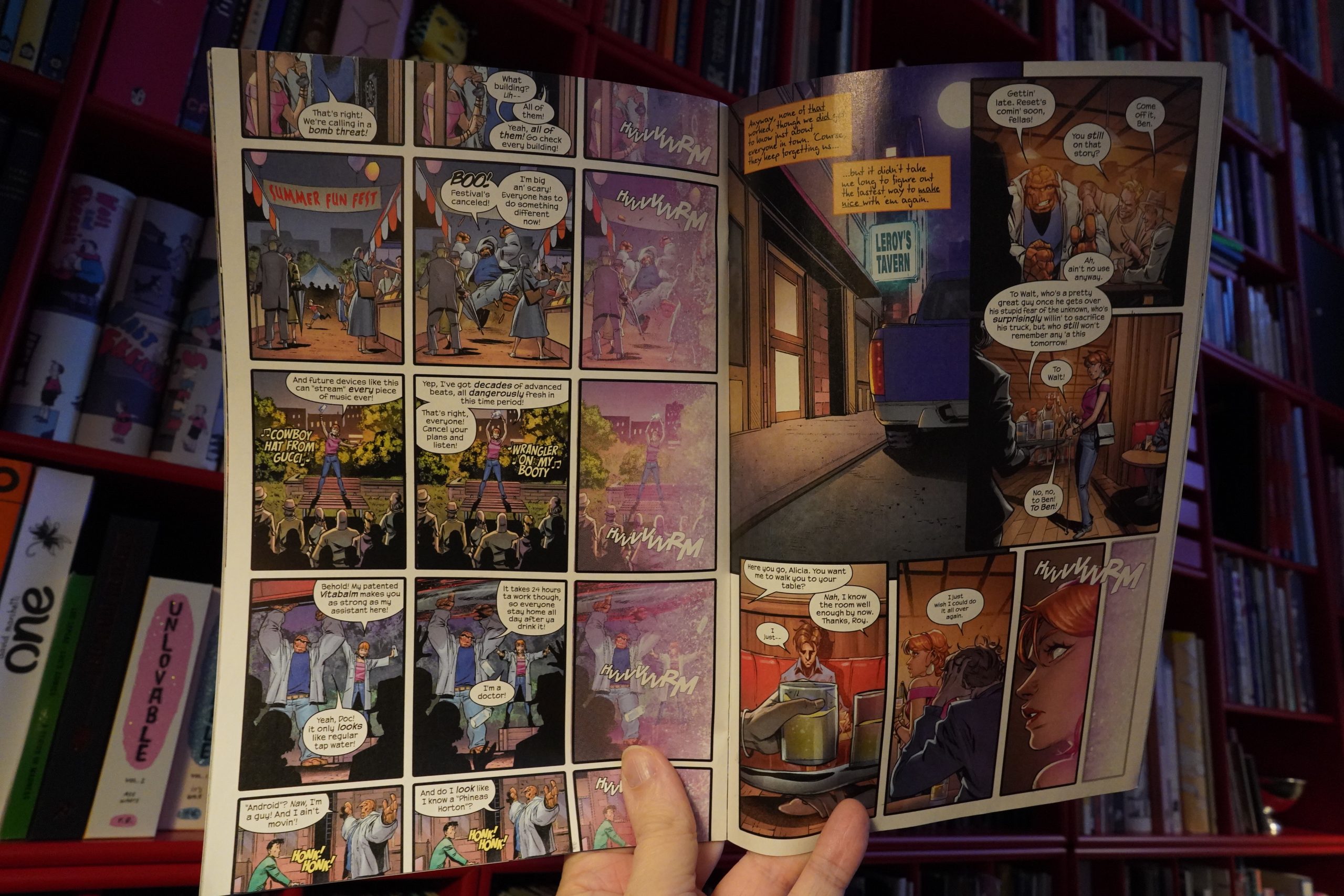

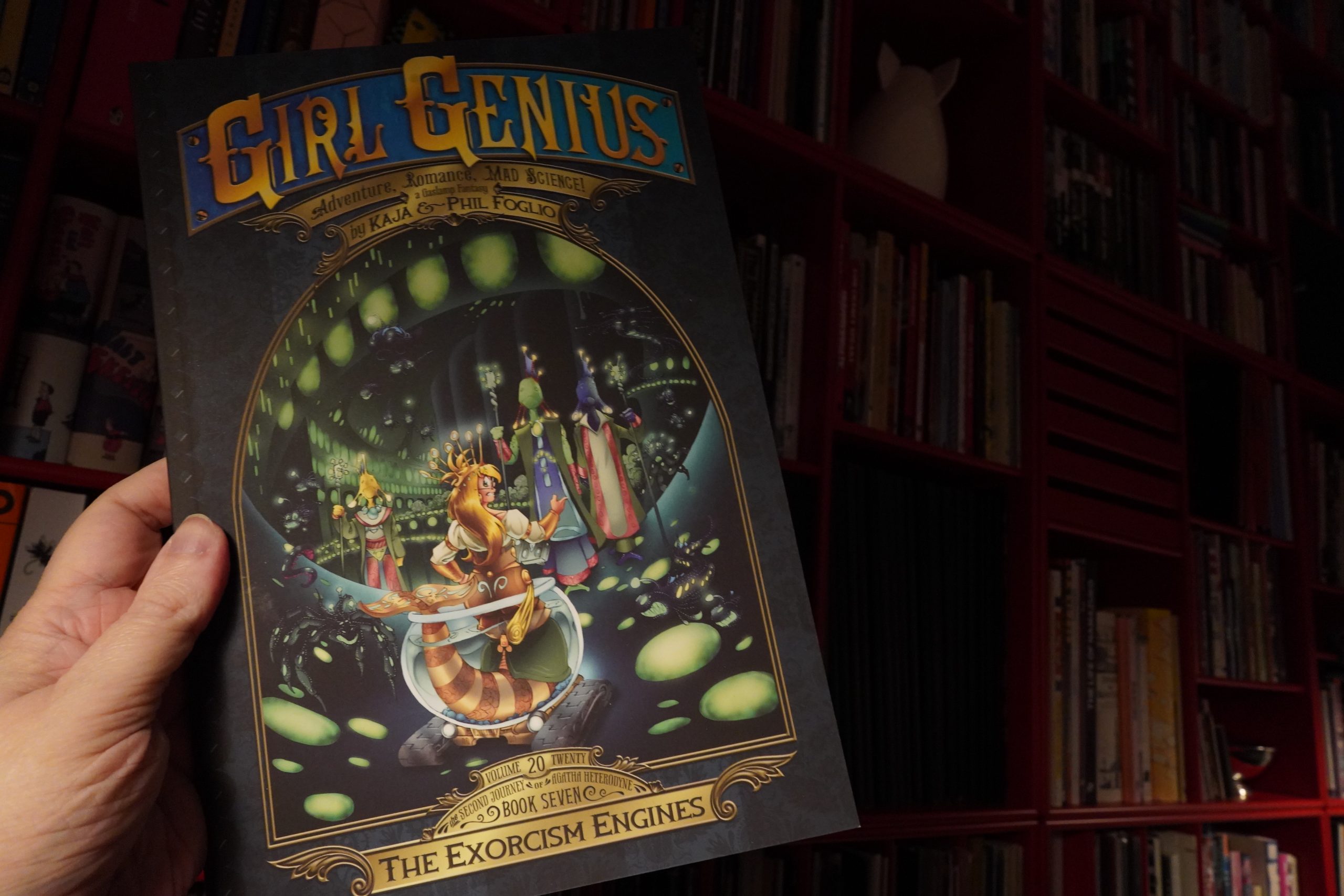

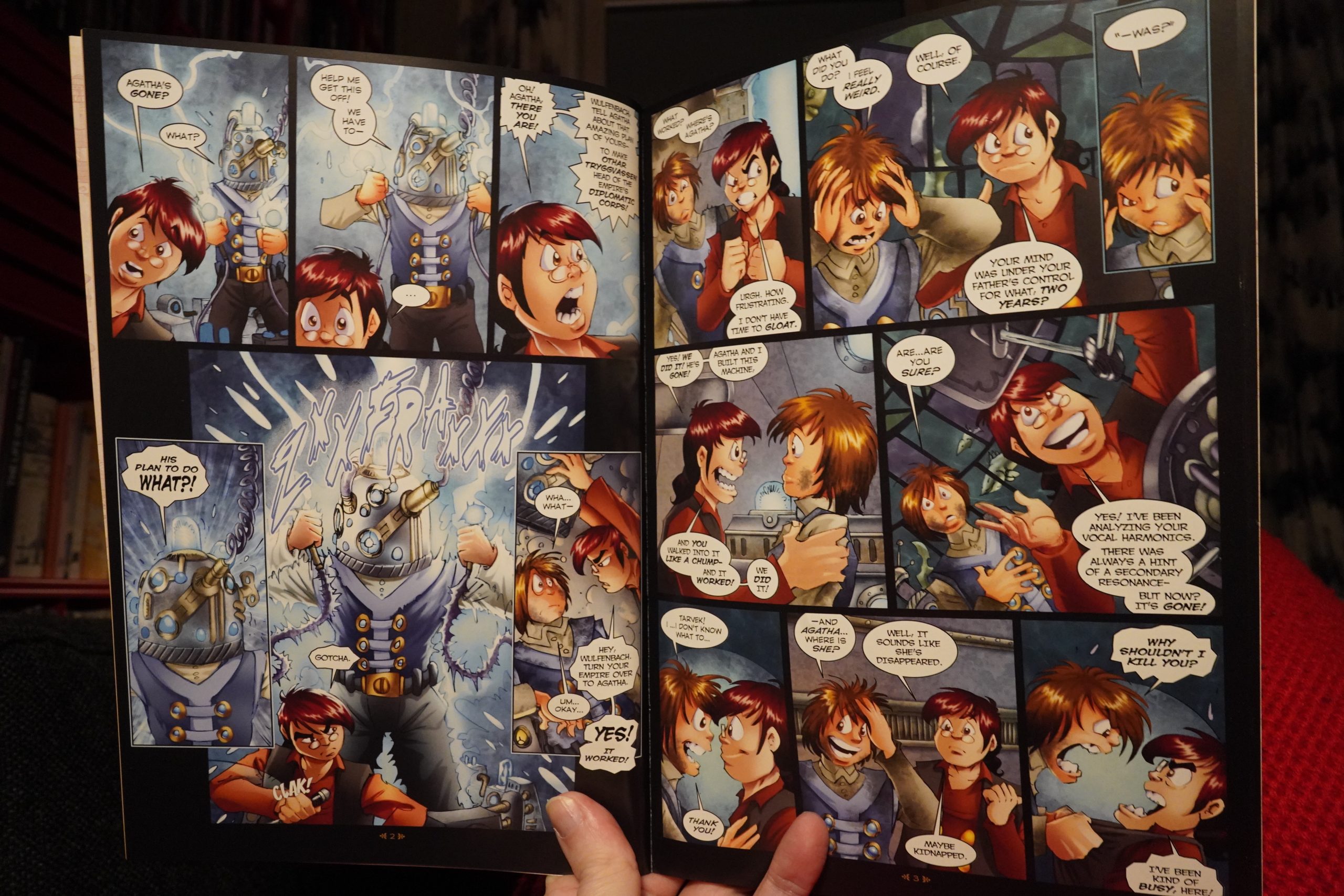

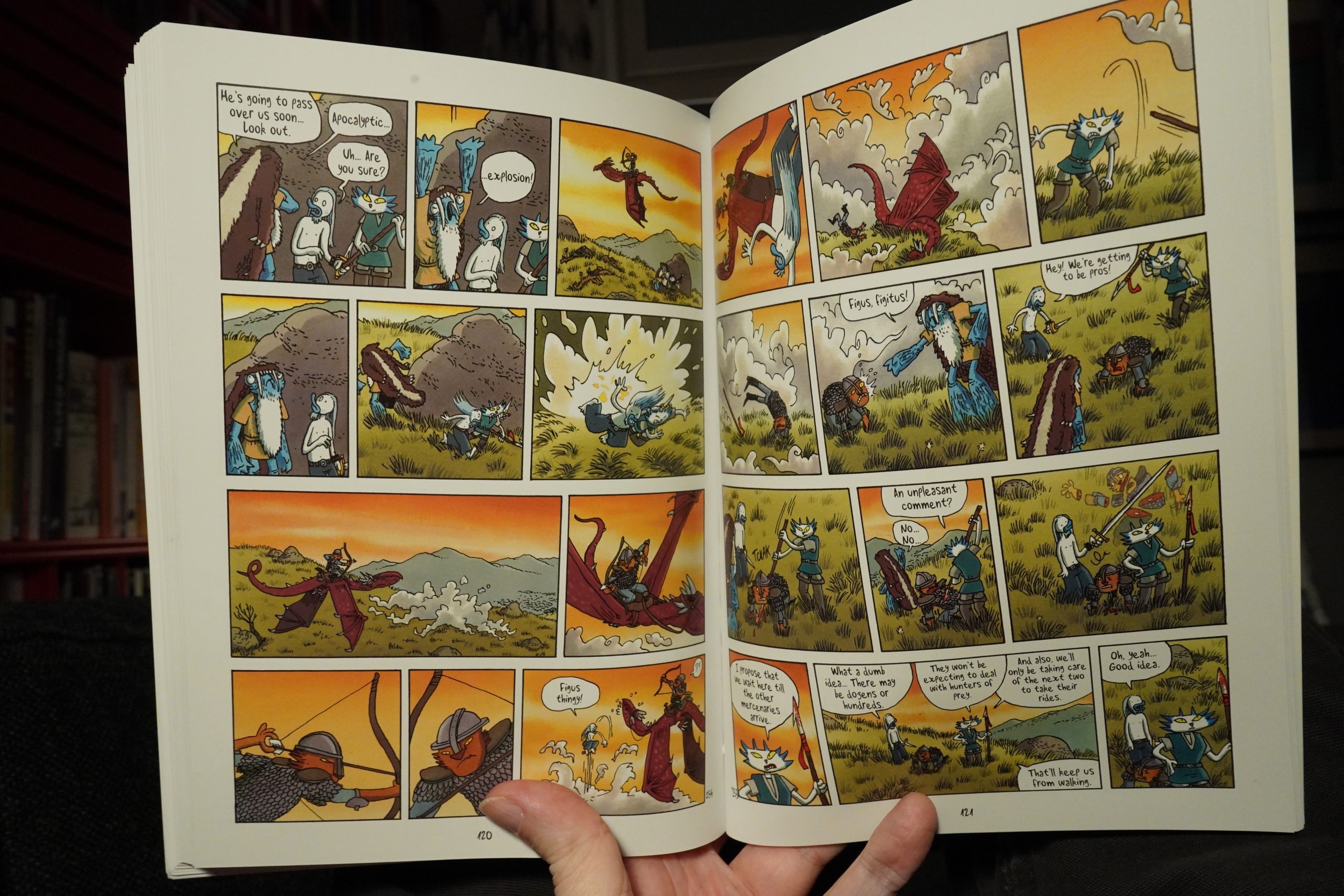

17:59: Girl Genius Volume 20 by Kaja & Phil Foglio (Airship Entertainment)

Wow, book 20… One day, I have to gather up all my Girl Genius issues and collections and re-read the whole epic — I’ve never re-read any of this, I think, and it’s been going a couple decades now?

Girl Genius is so full on — it’s always 110% intense with everybody jabbering at each other, mostly saying sarcastic things, which gets extra confusing as half the characters always seem to be possessed by other characters, so any given utterance is either 1) what the character means, 2) sarcastic, 3) what the possessed character means, or 7) the possessed character being sarcastic.

It’s fun, but it’s very dense.

| The Raincoats: Moving |  |

It’s an odd volume, though. Midway through the book, we get the climax and resolution to the storyline that’s been going for at least a decade (I think), and then… we segue into an entirely new storyline, with a bunch of new characters and species we’ve never seen before. It’s just weird: We’re all revved up on page 60, and it would have been the perfect ending to a volume, but then there’s 60 pages more of a low-key start to another sure-to-be amusing adventure.

I guess they don’t do the plotting and pacing with the collected volumes in mind — this is serialised on the web, after all.

| My Brightest Diamond: Bring Me The Workhorse |  |

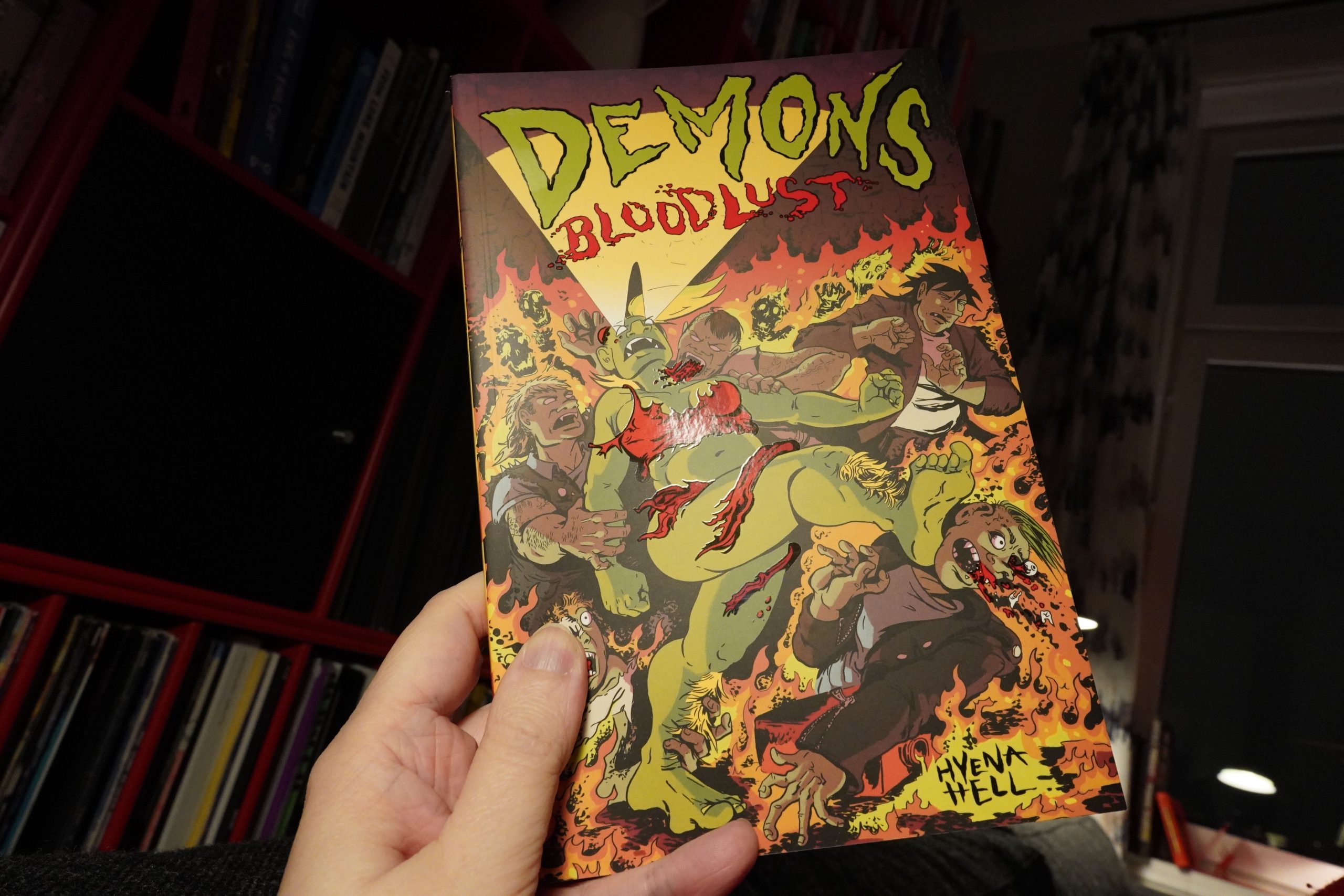

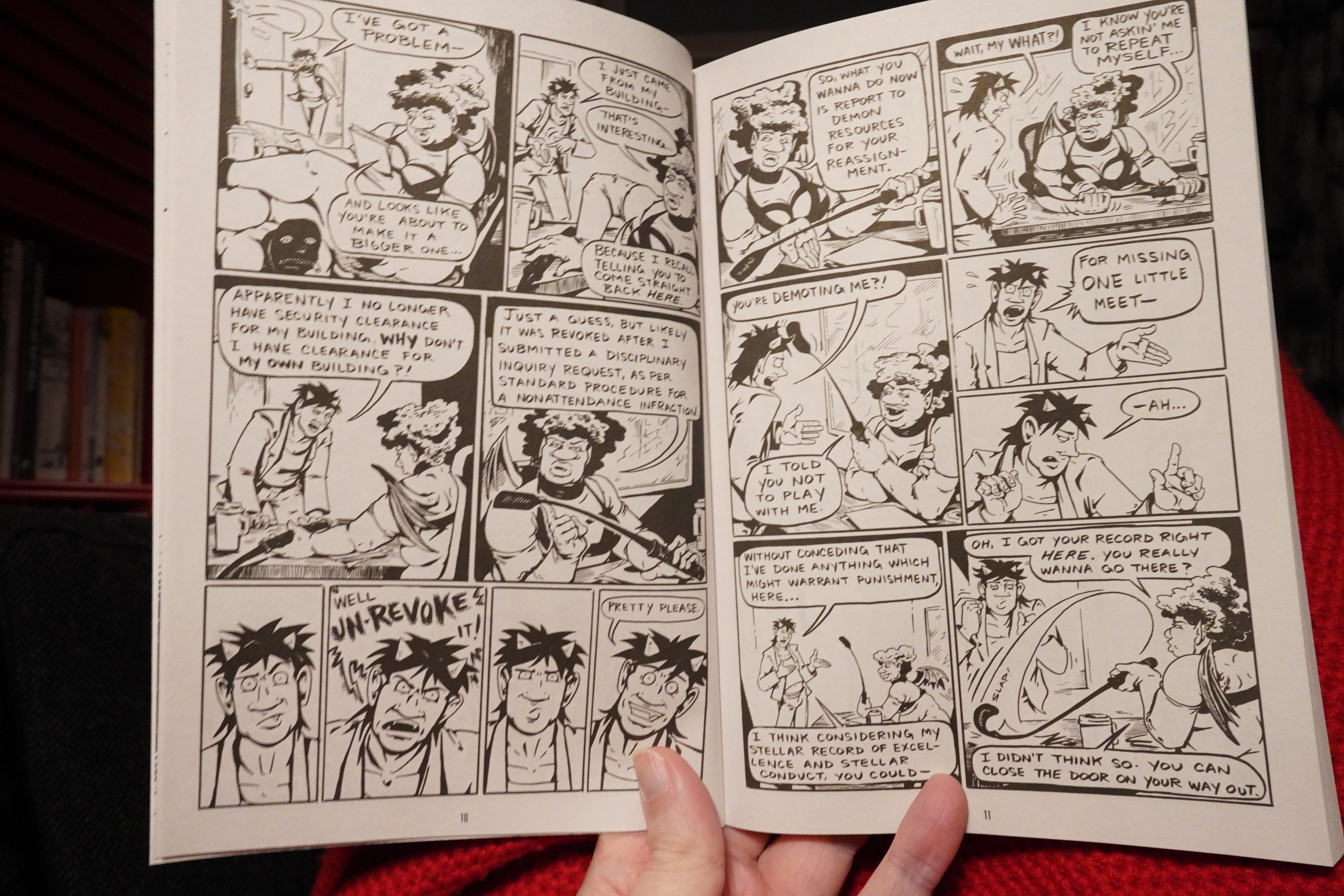

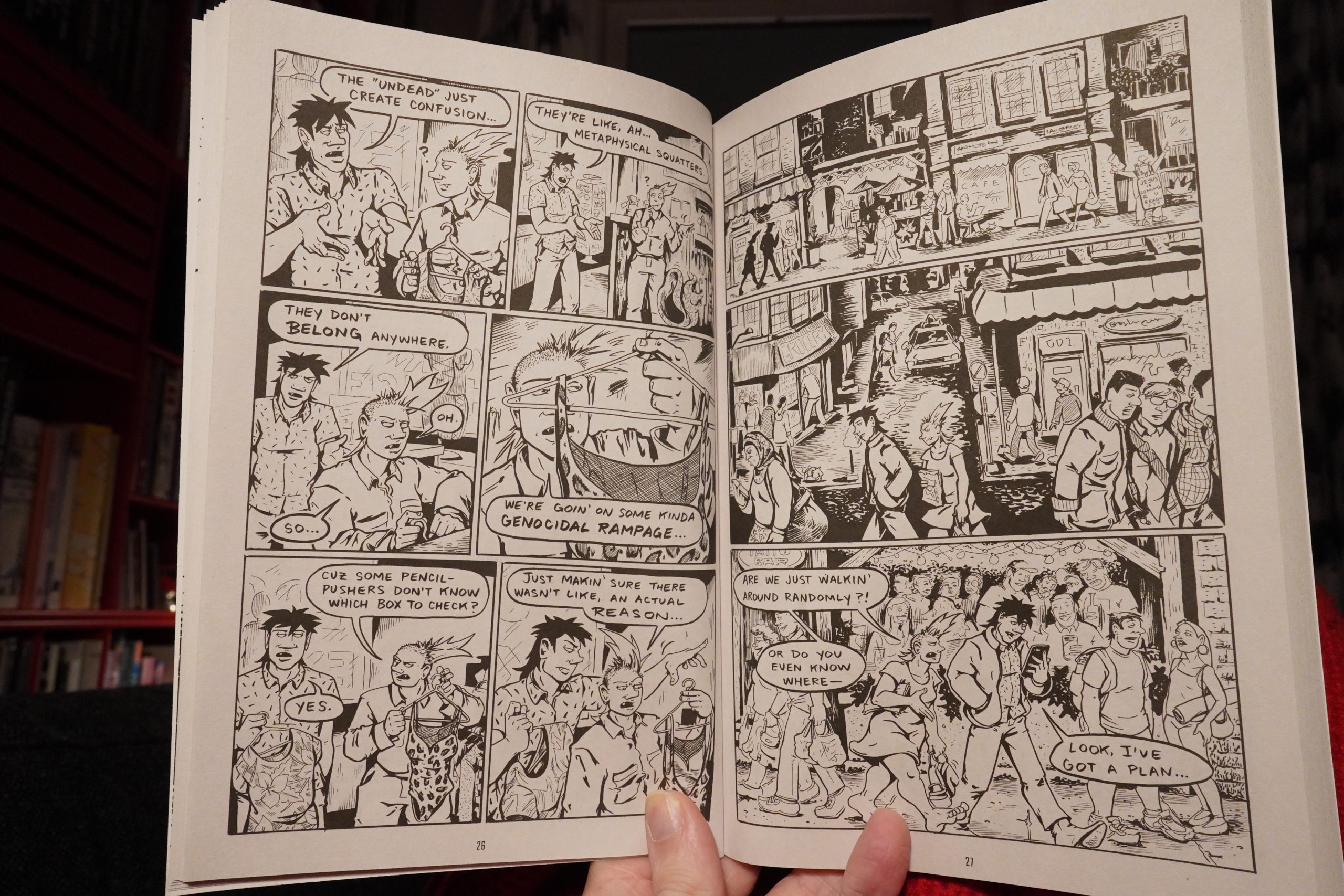

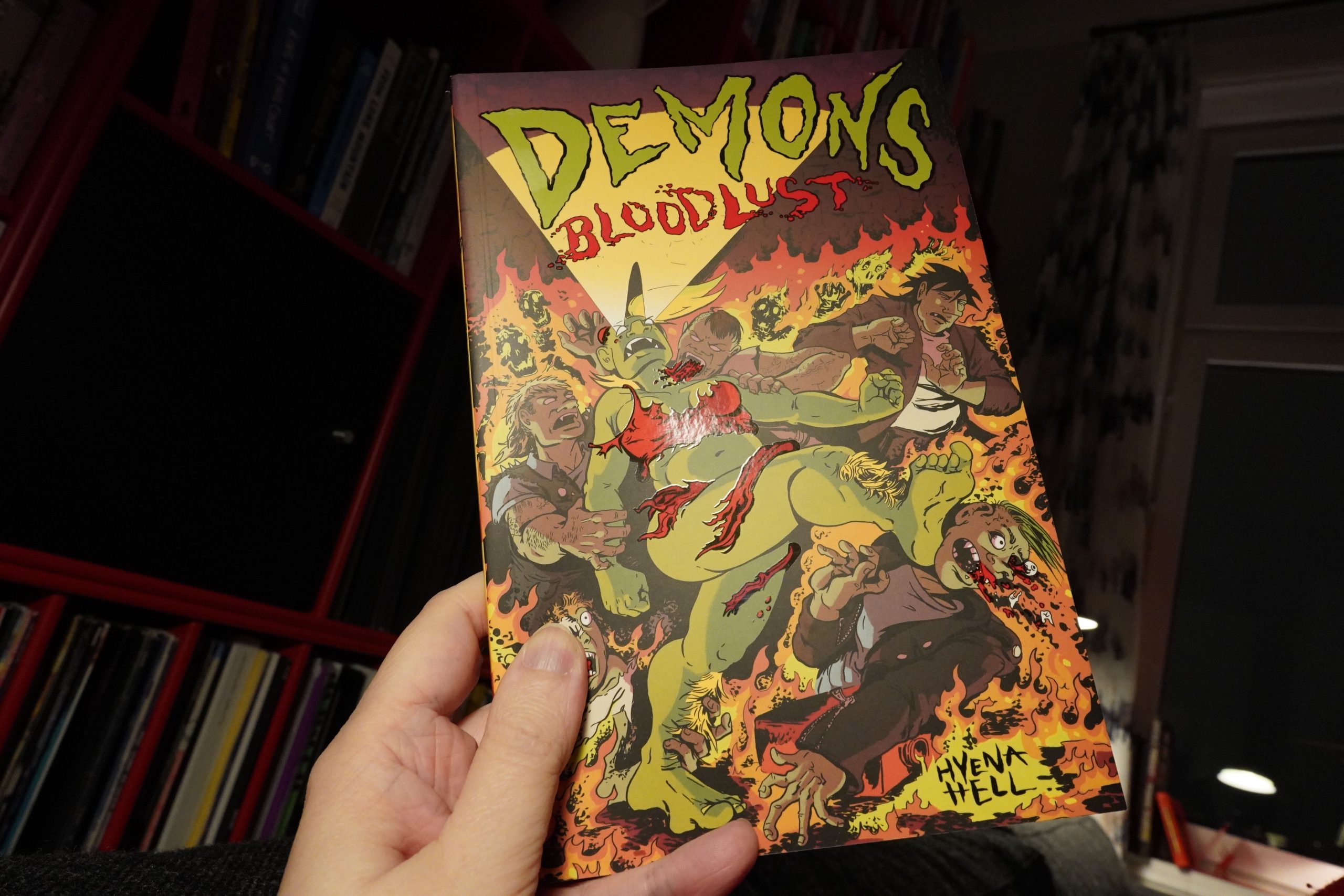

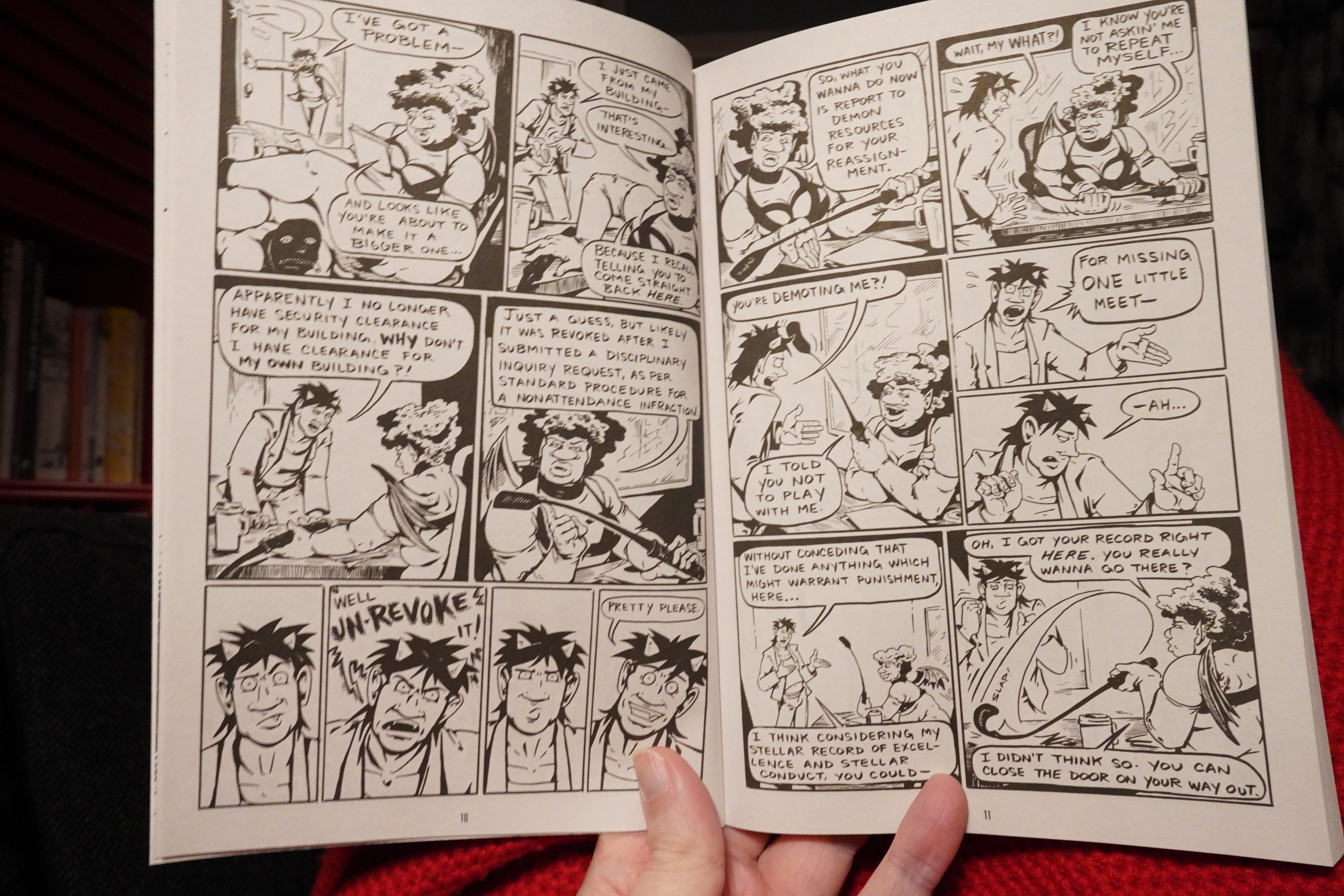

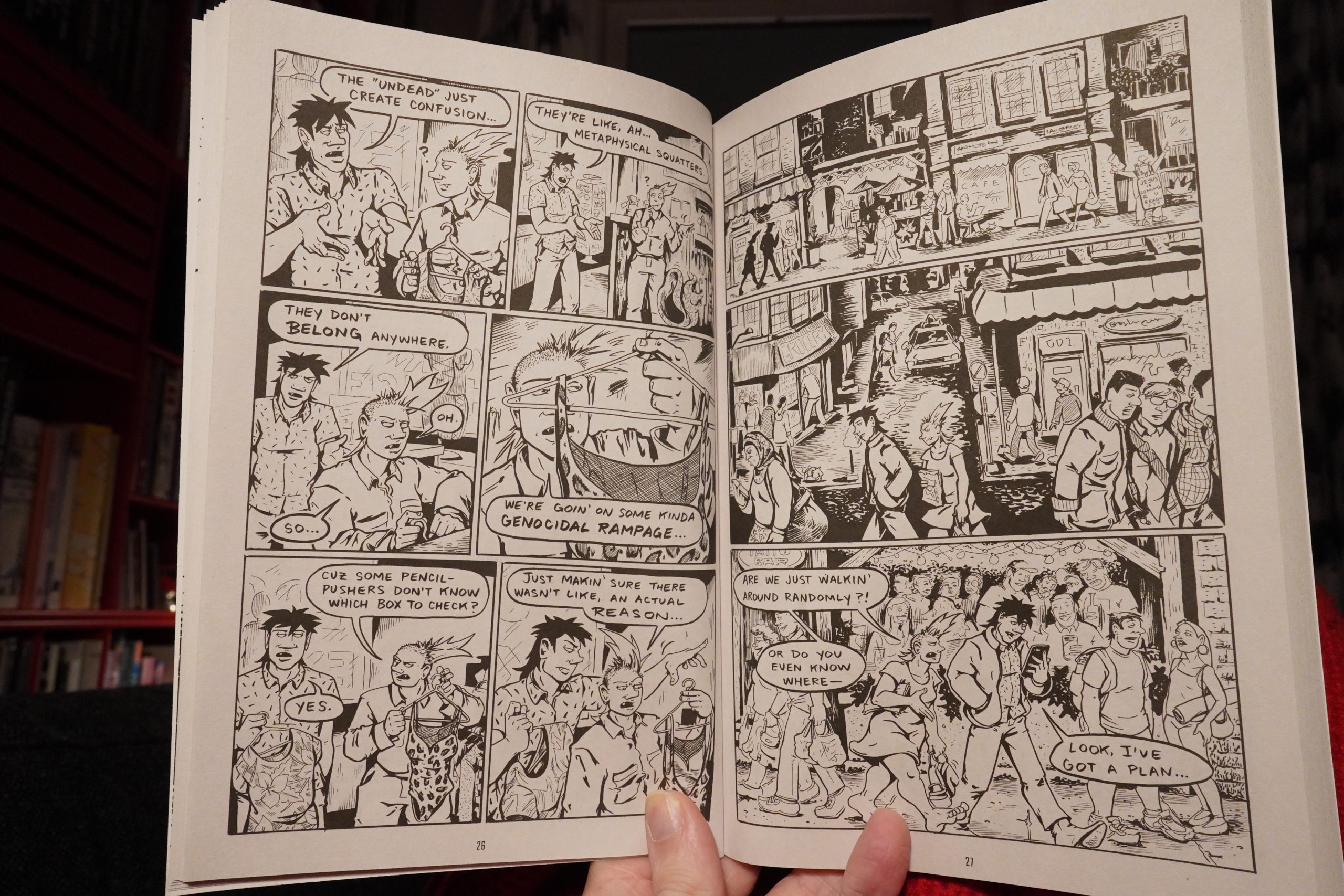

19:37: Demons Bloodlust by Hyena Hell (Silver Sprocket)

It’s kind of high concept — demons killing vampires, but as a workplace sitcom. Sort of.

It’s a lot of fun. It’s very straightforward and reminds me of 90s alternative comics quite a bit. It’s got a distinct world-view and atmosphere, and it’s just… downright wholesome.

| My Brightest Diamond: Bring Me The Workhorse |  |

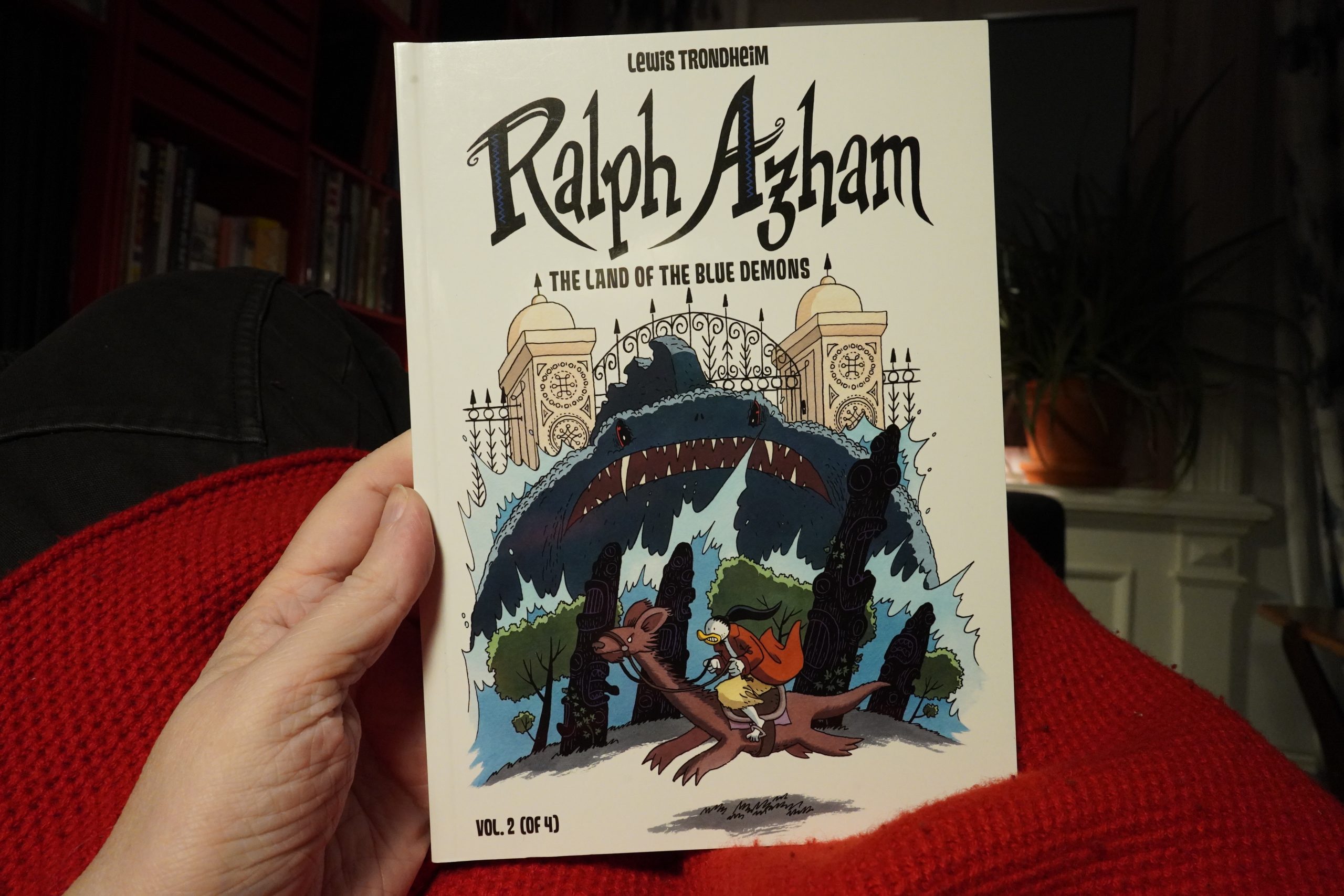

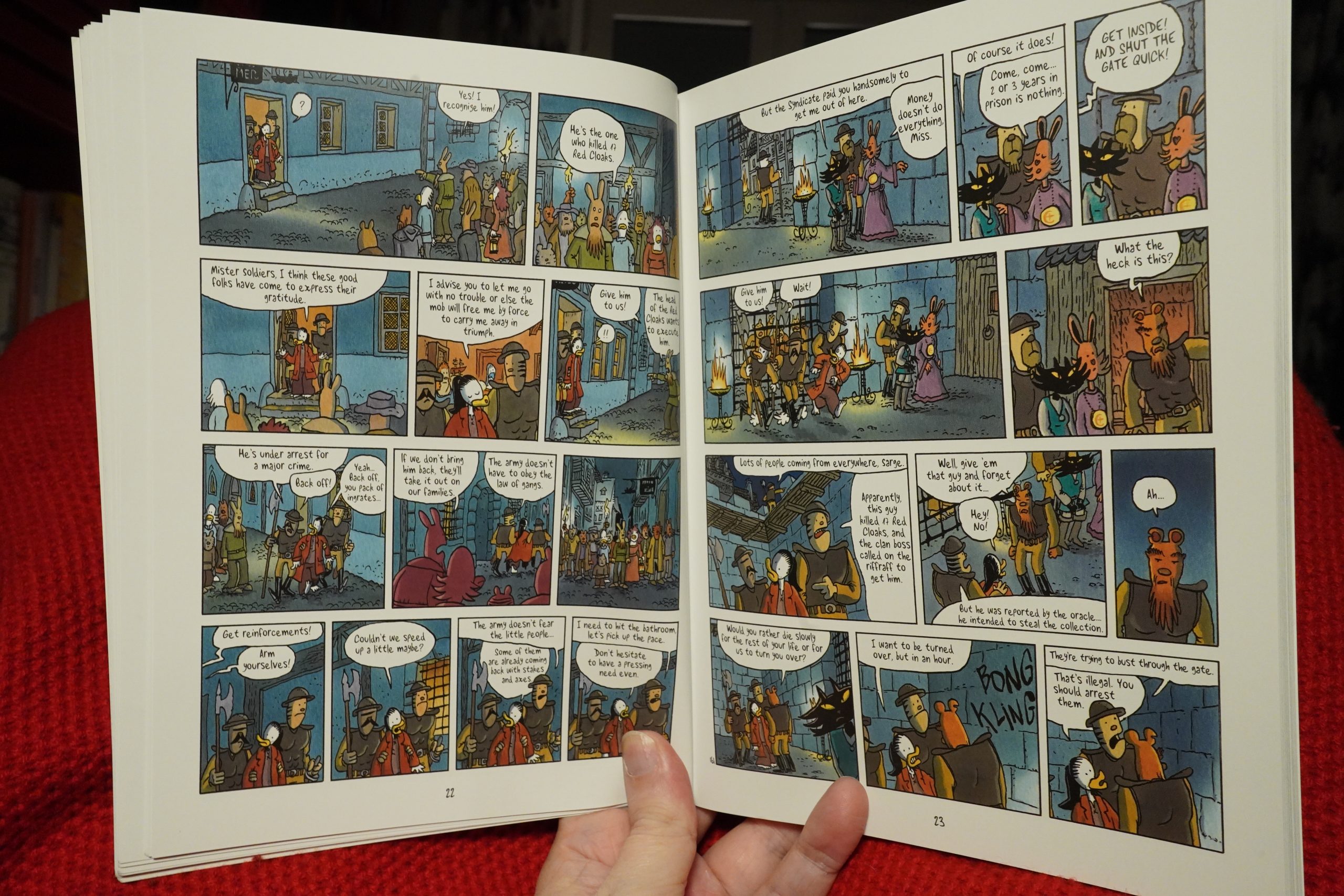

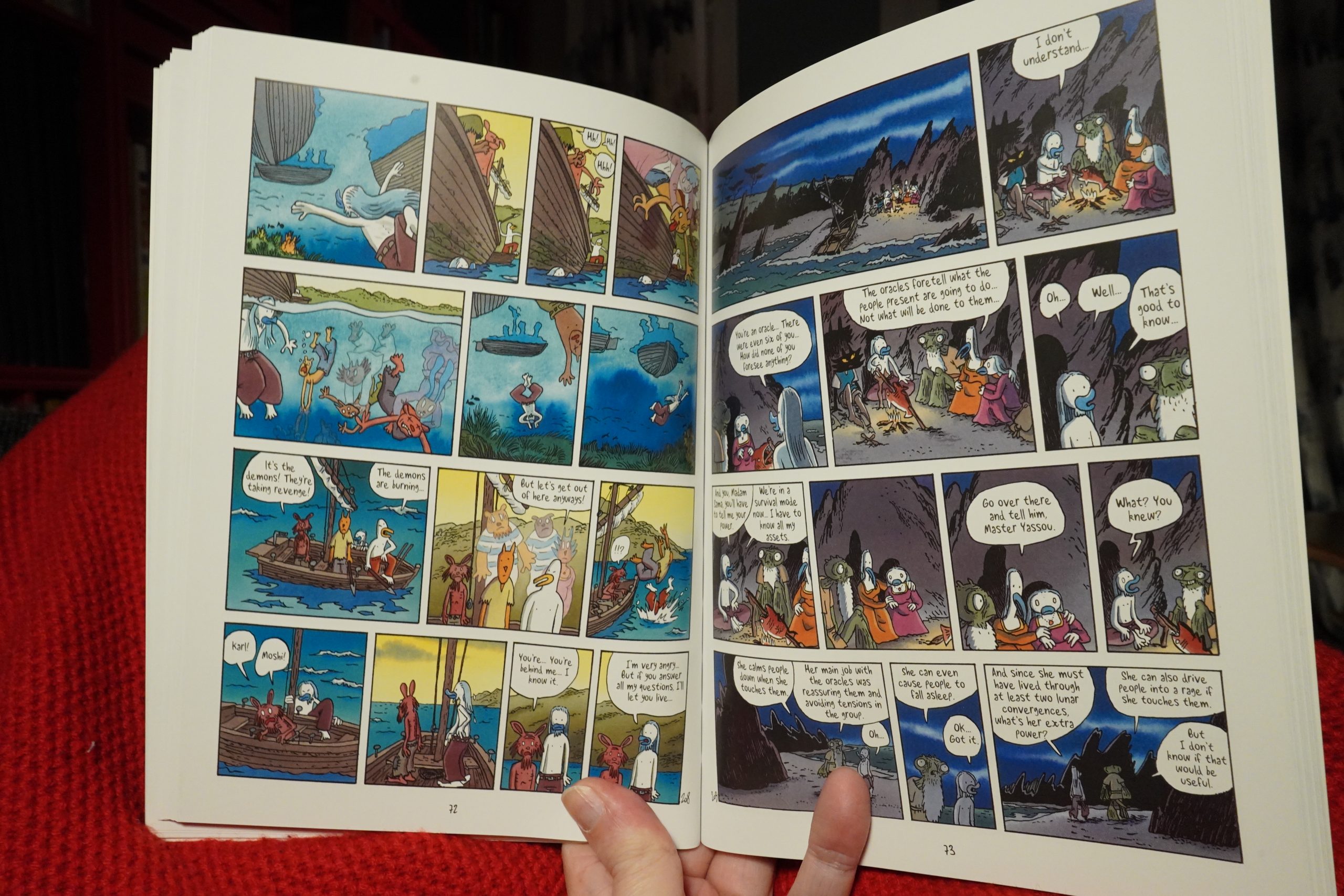

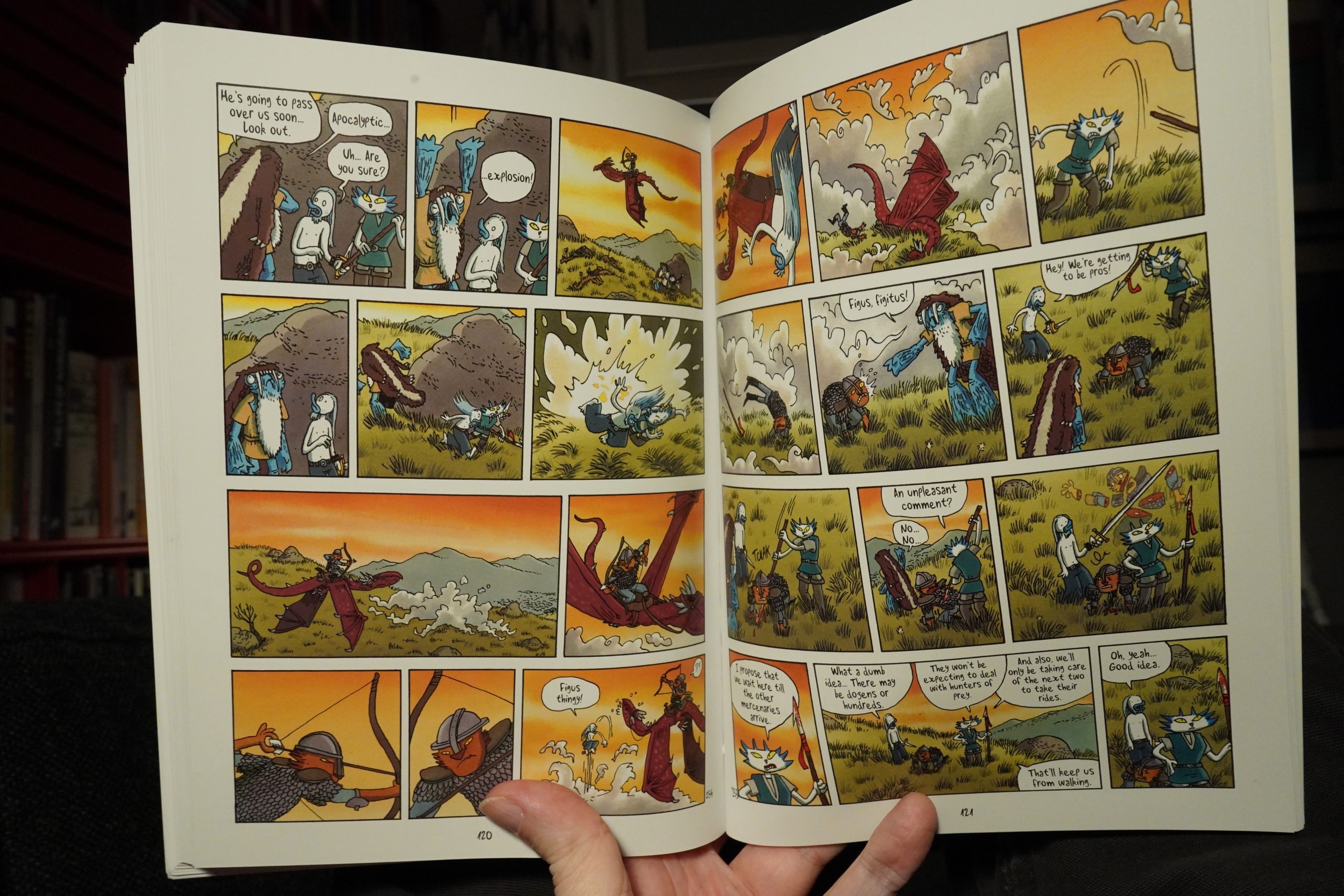

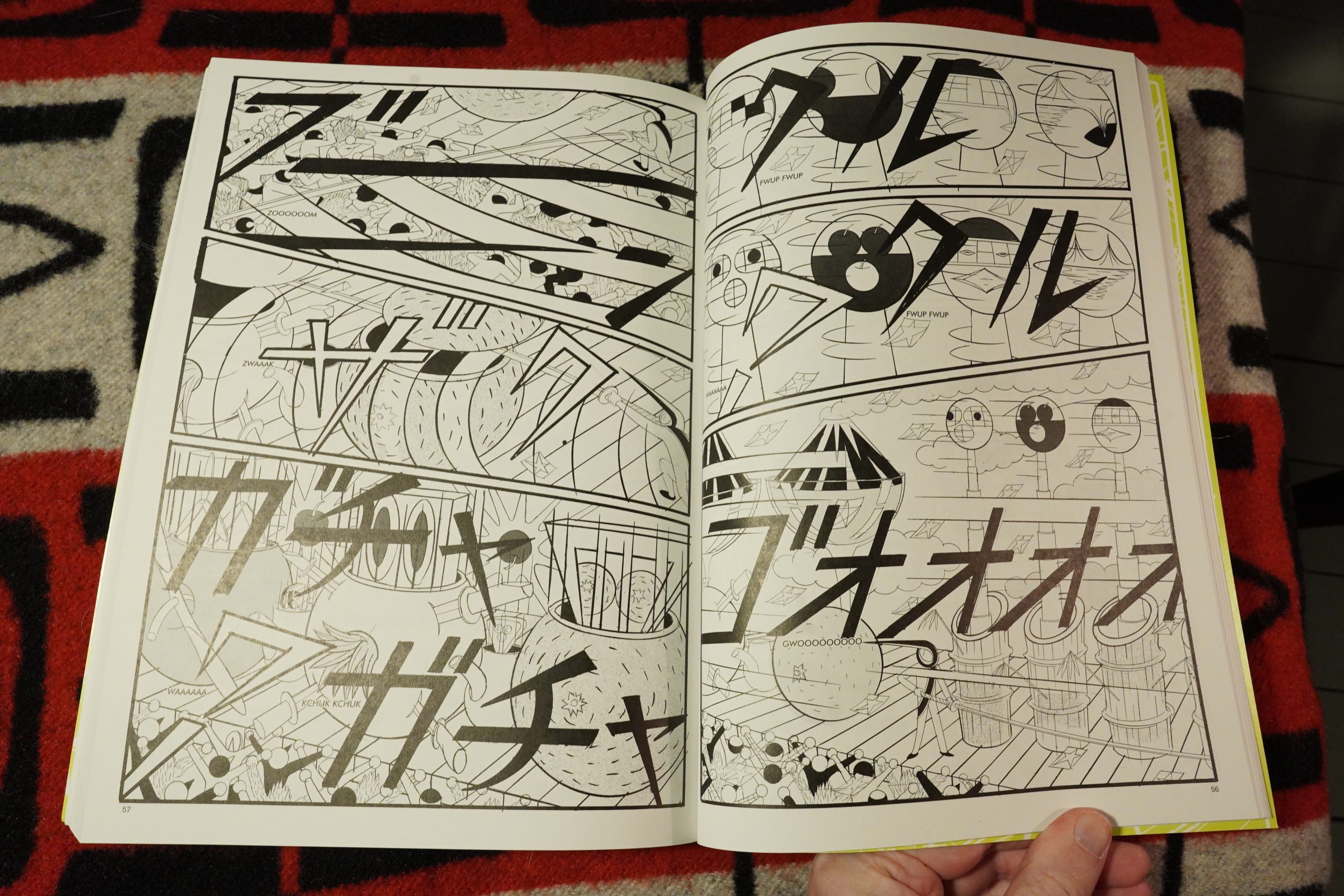

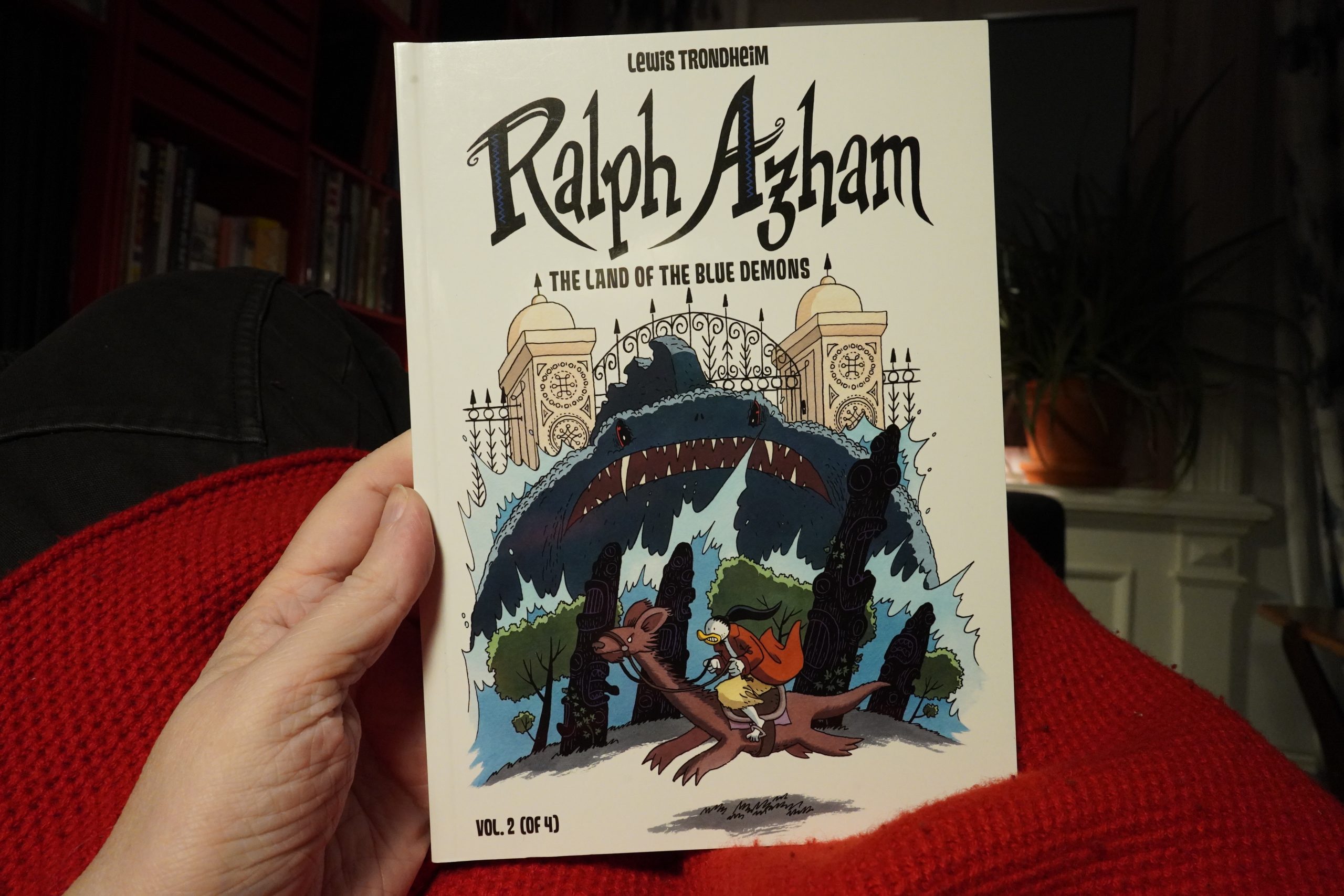

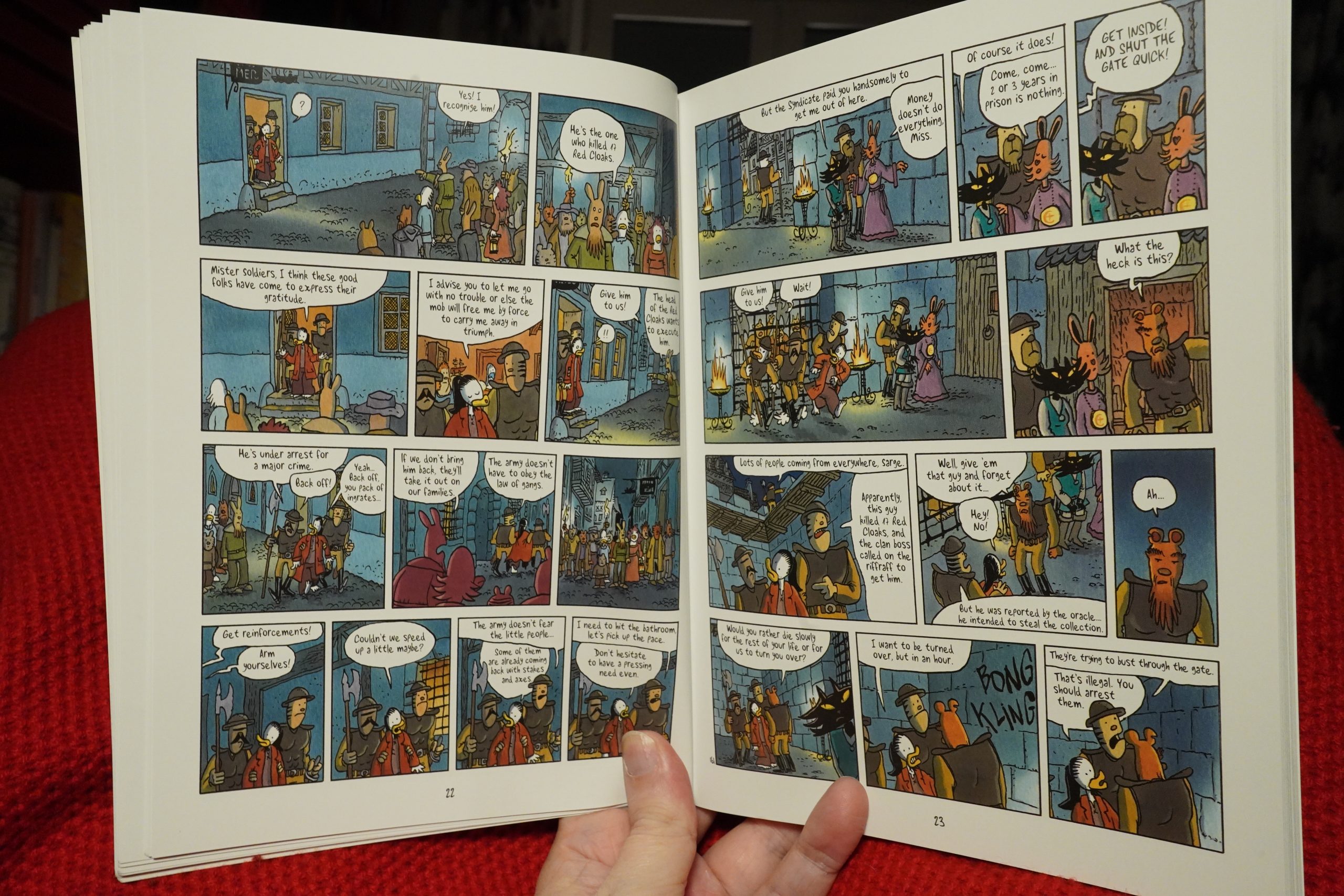

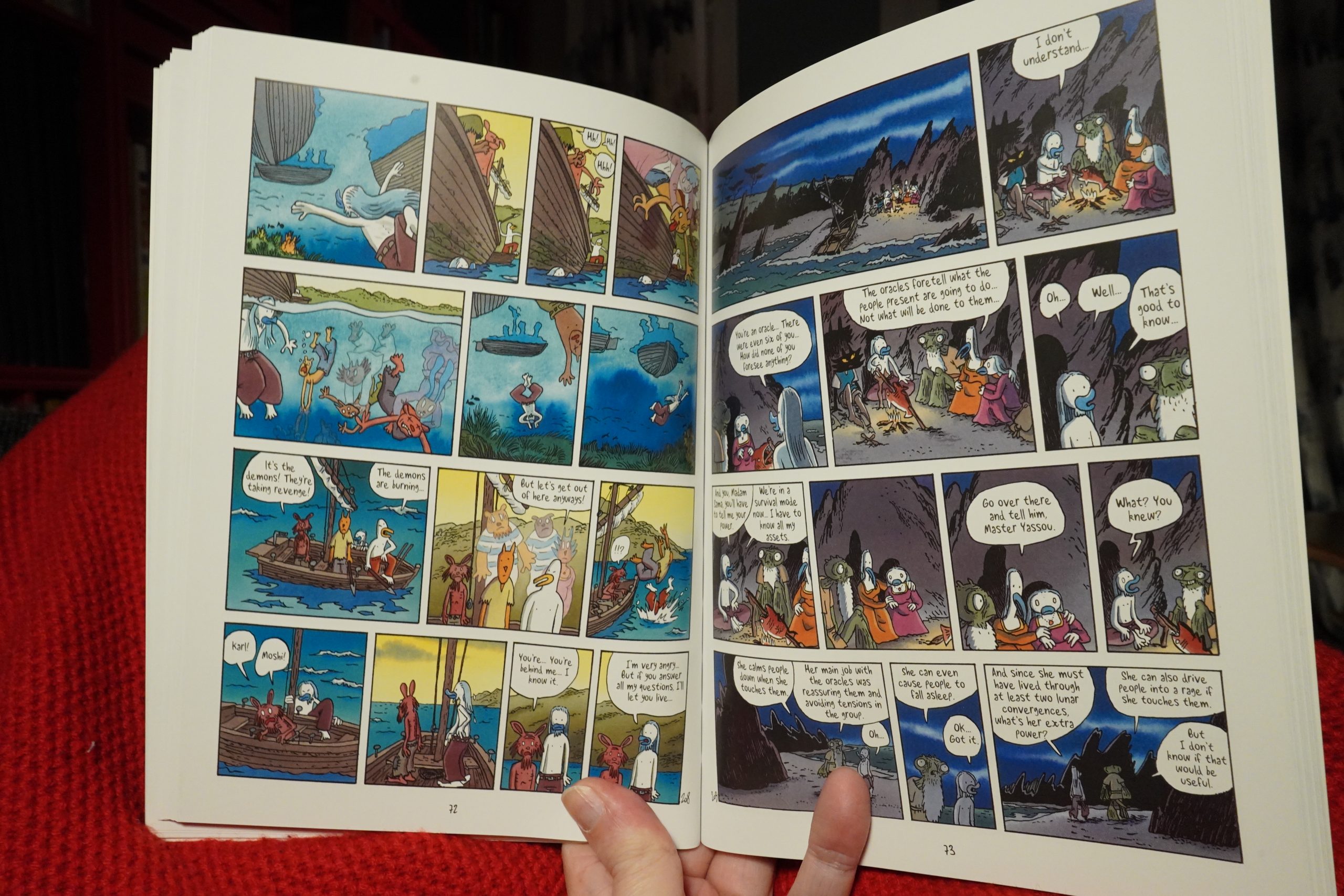

20:31: Ralph Azham 2: The Land of the Blue Demons by Lewis Trondheim (Super Genius)

This was presumably printed in normal album size, because it looks pretty shrunken here… but it’s still legible. I would really have preferred in in larger size, but these stories are so engrossing anyway — kinda magical. They’re not quite like classic French(ey) children’s comics (Spirou, Tintin, etc) but evoke the same wonder. It’s a fully realised world with great characters and interesting storylines that don’t go where you’d expect.

| Shearwater: The Dissolving Room |  |

This book reprints three albums — each tell a pretty complete story, but it’s all part of a larger epic.

I hope they manage to do the entire series (four books, reprinting all twelve albums), because it’s excellent.

| Shearwater: Shearwater plays Bowie’s Berlin Trilogy: Part 1: Low |  |

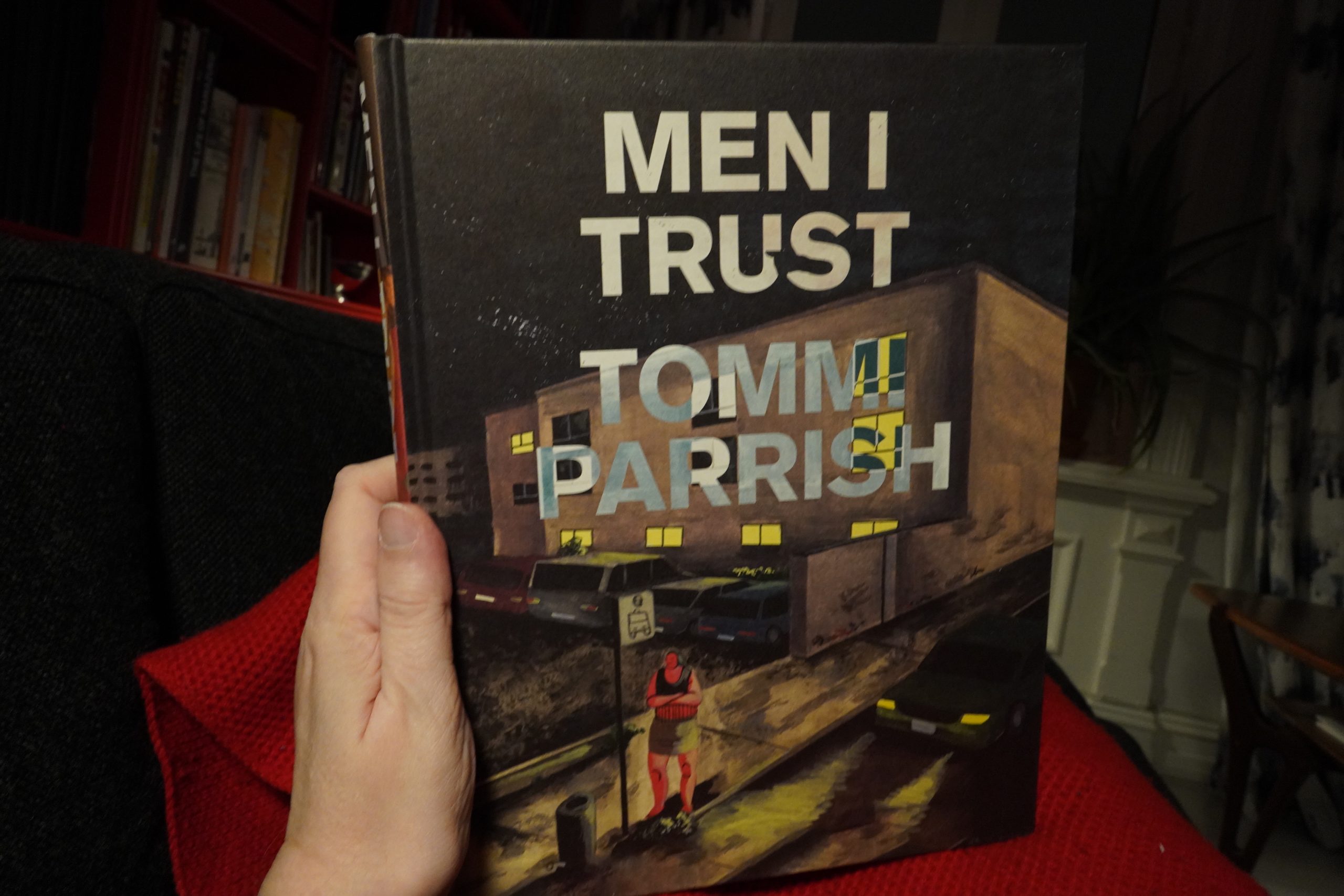

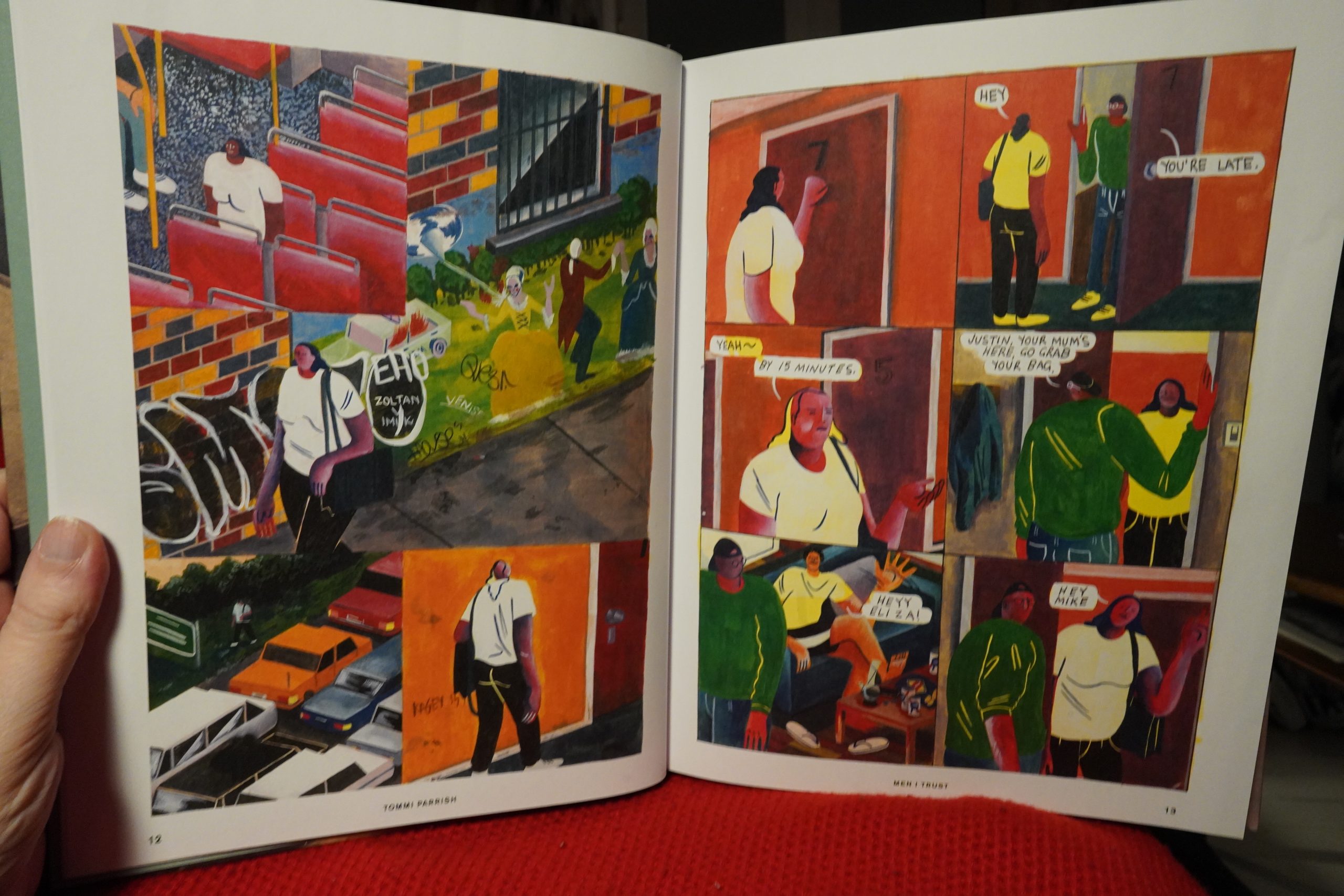

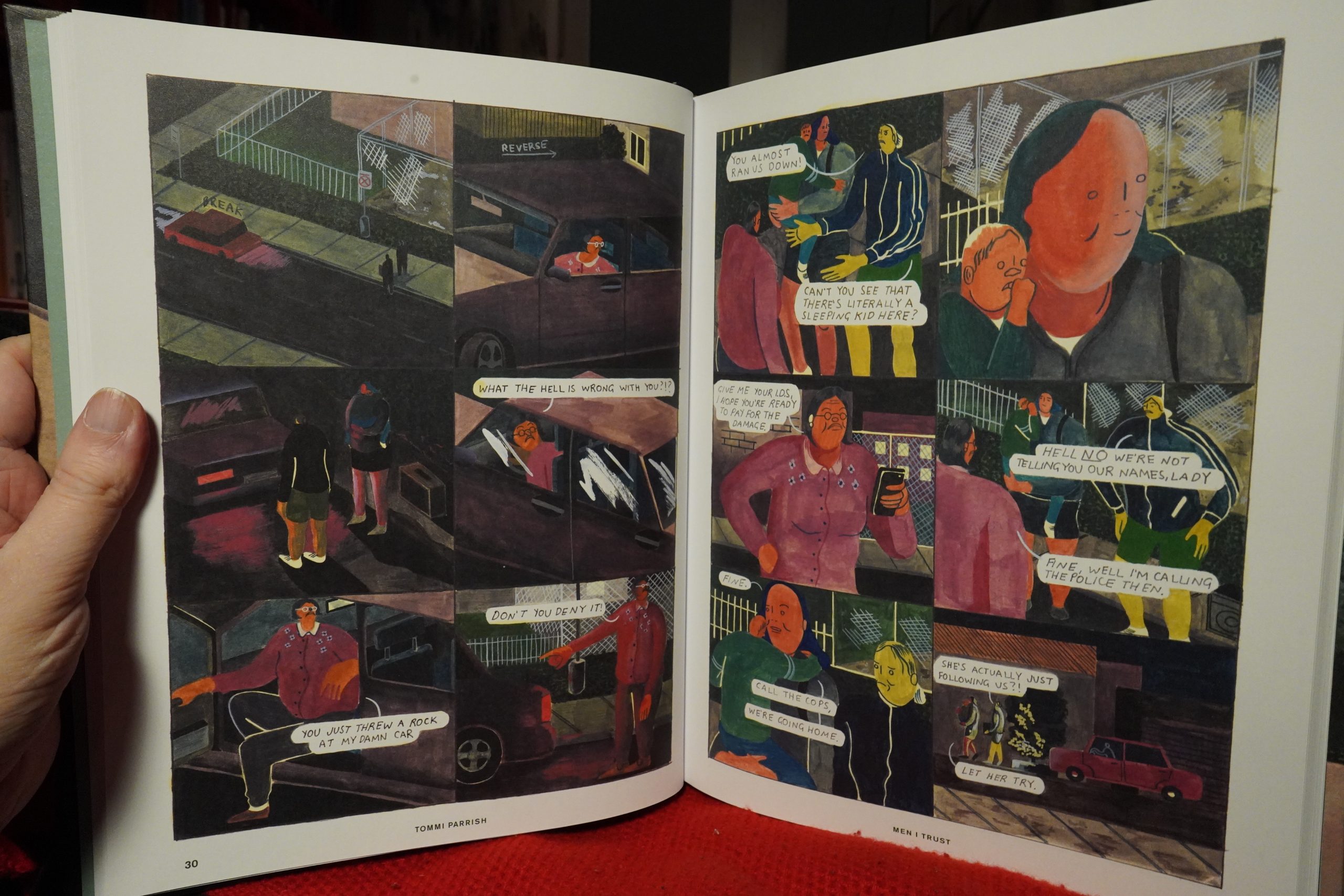

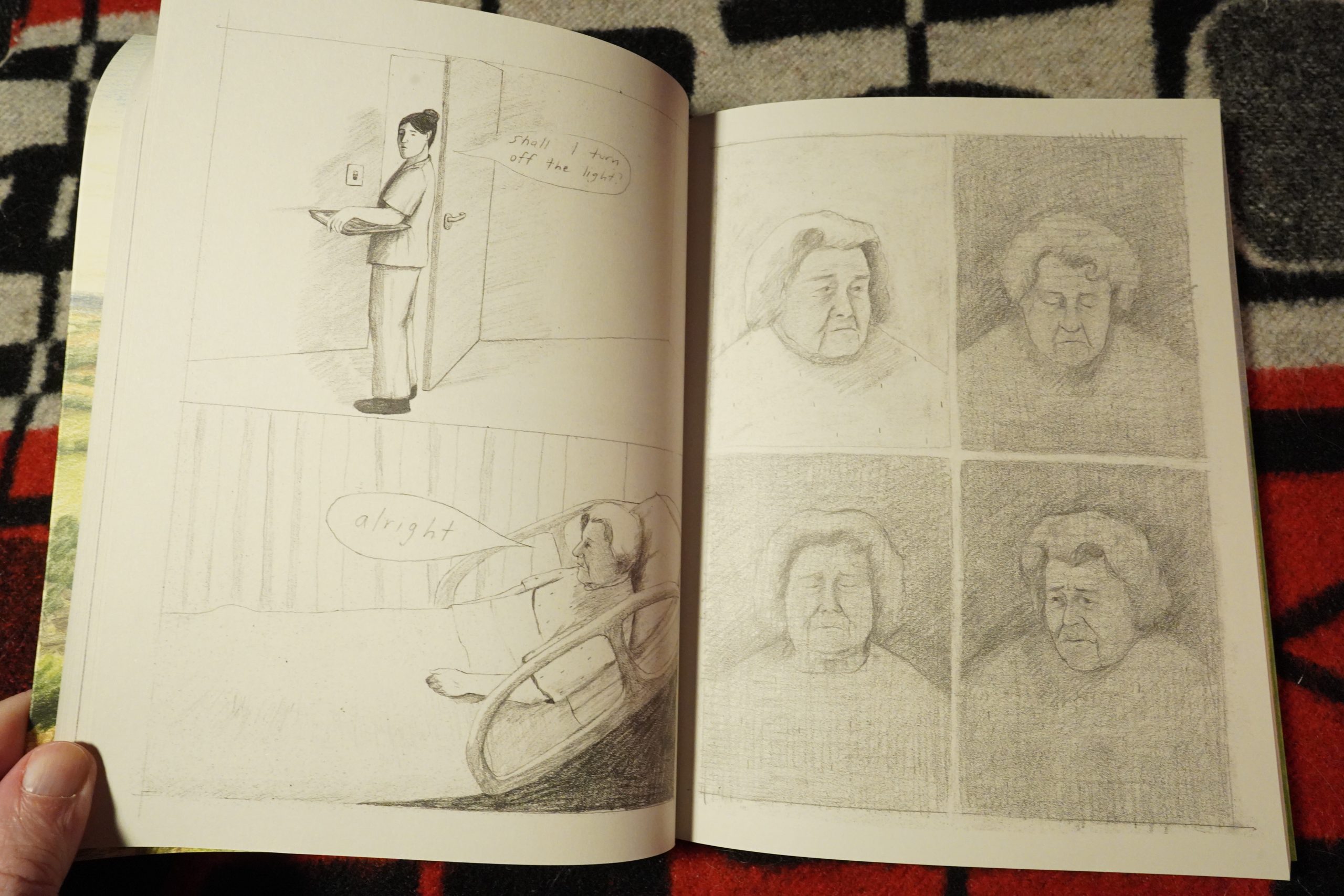

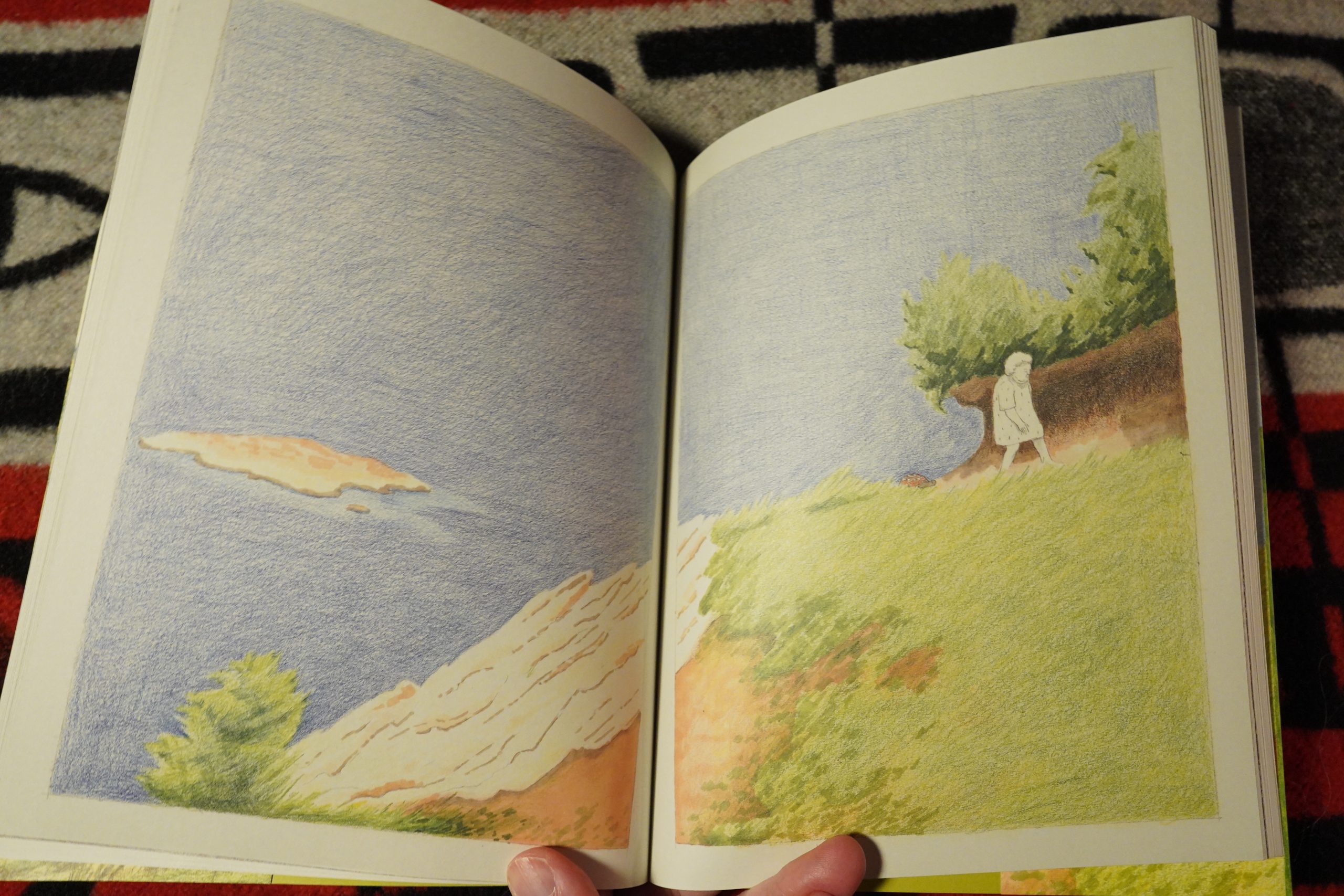

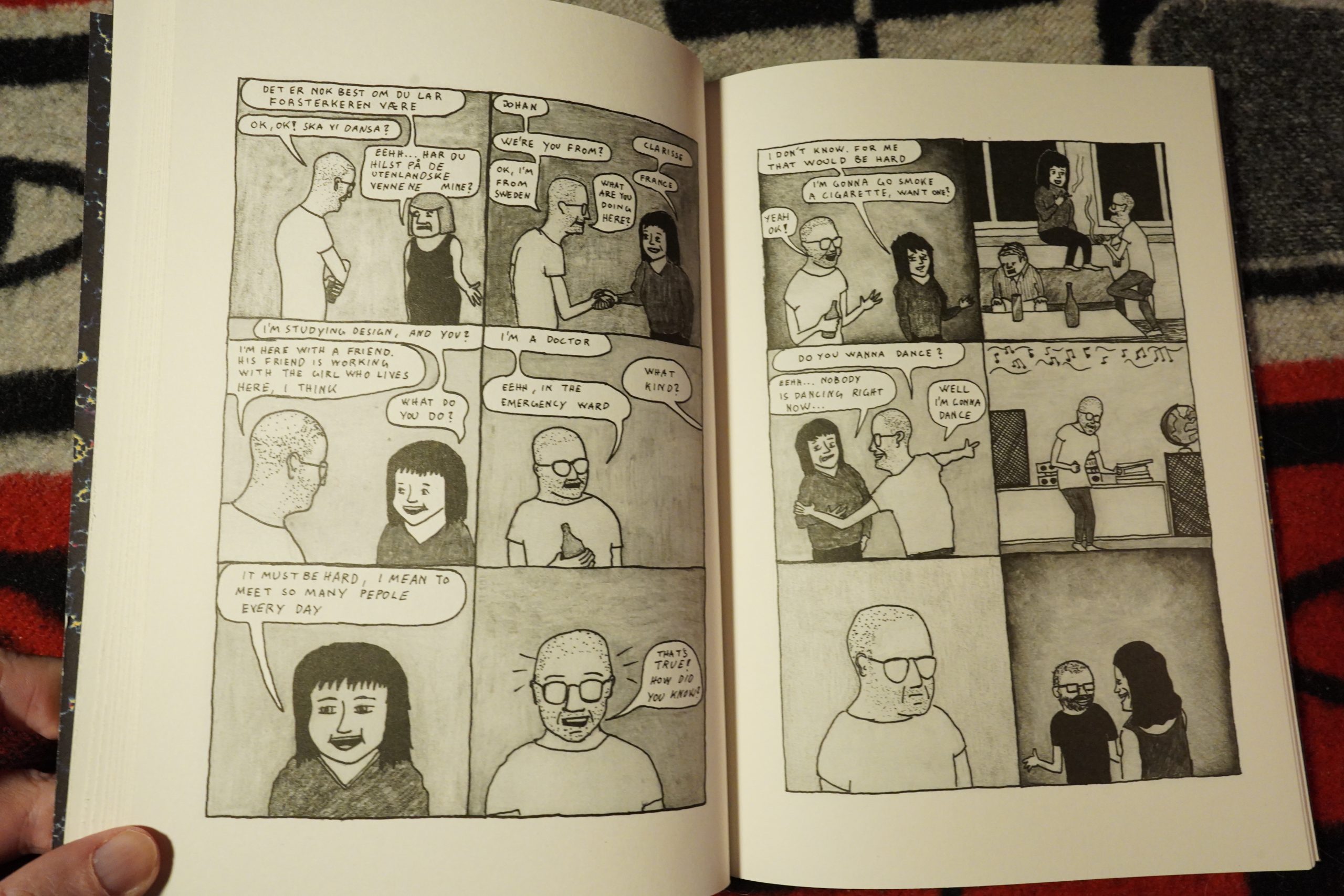

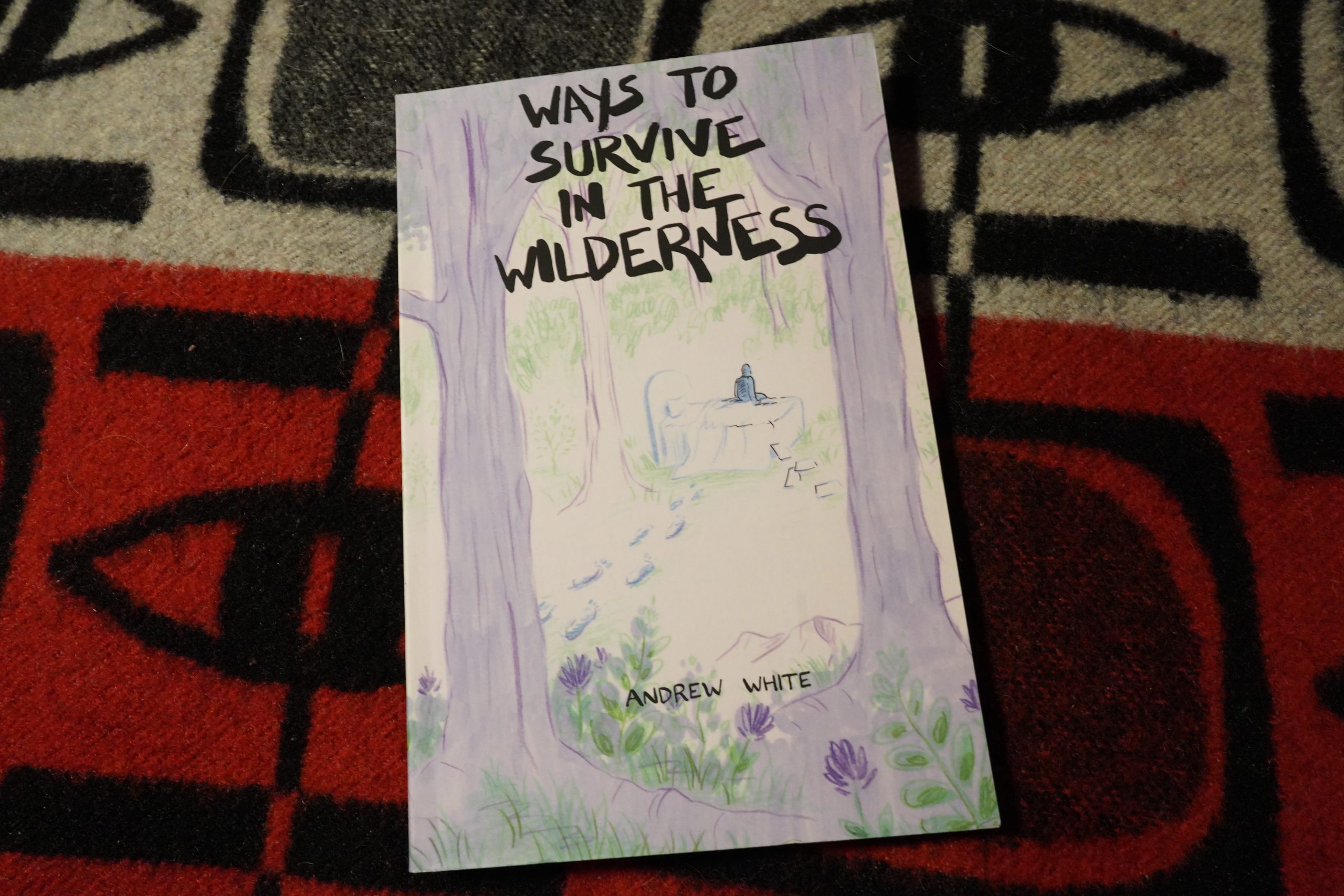

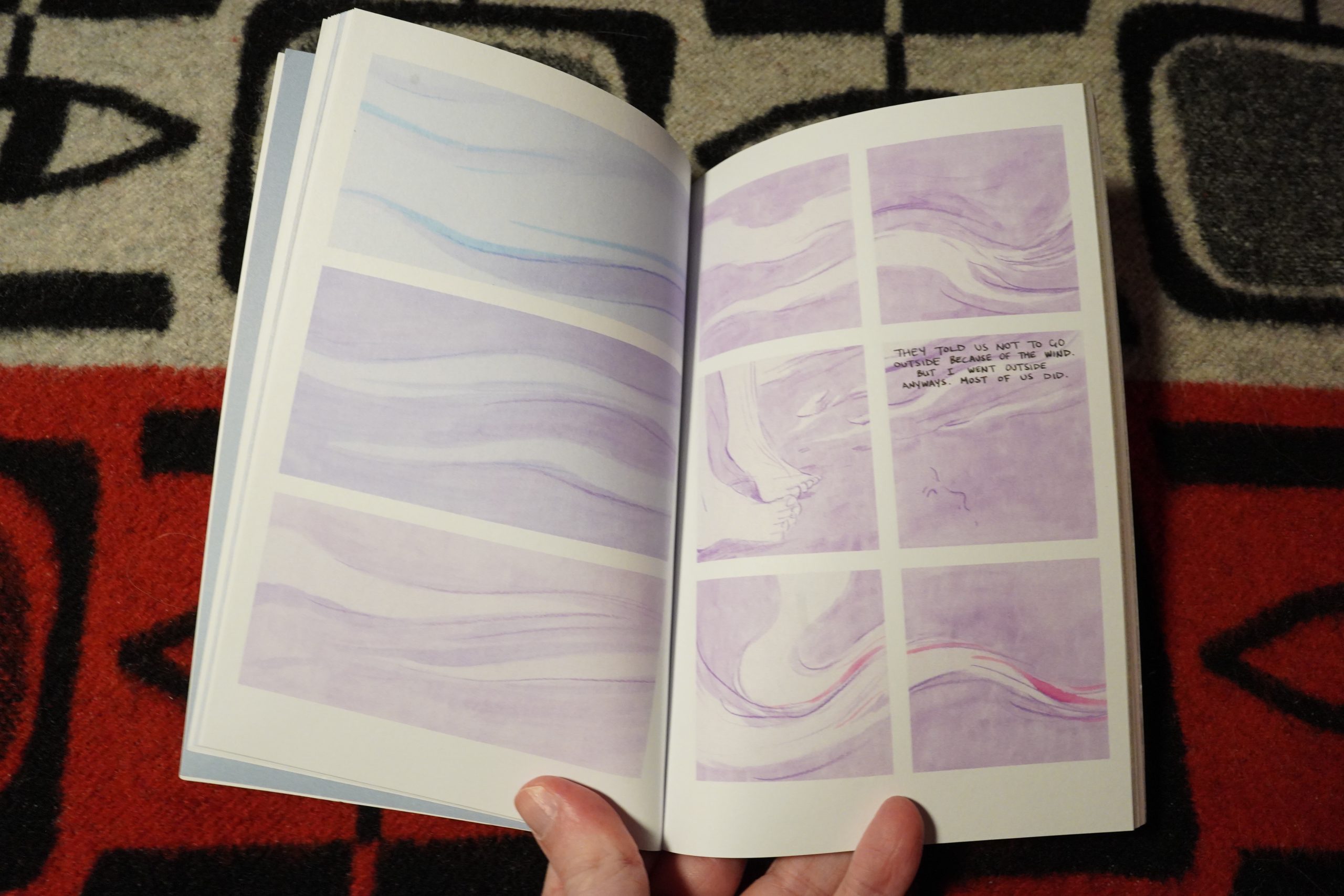

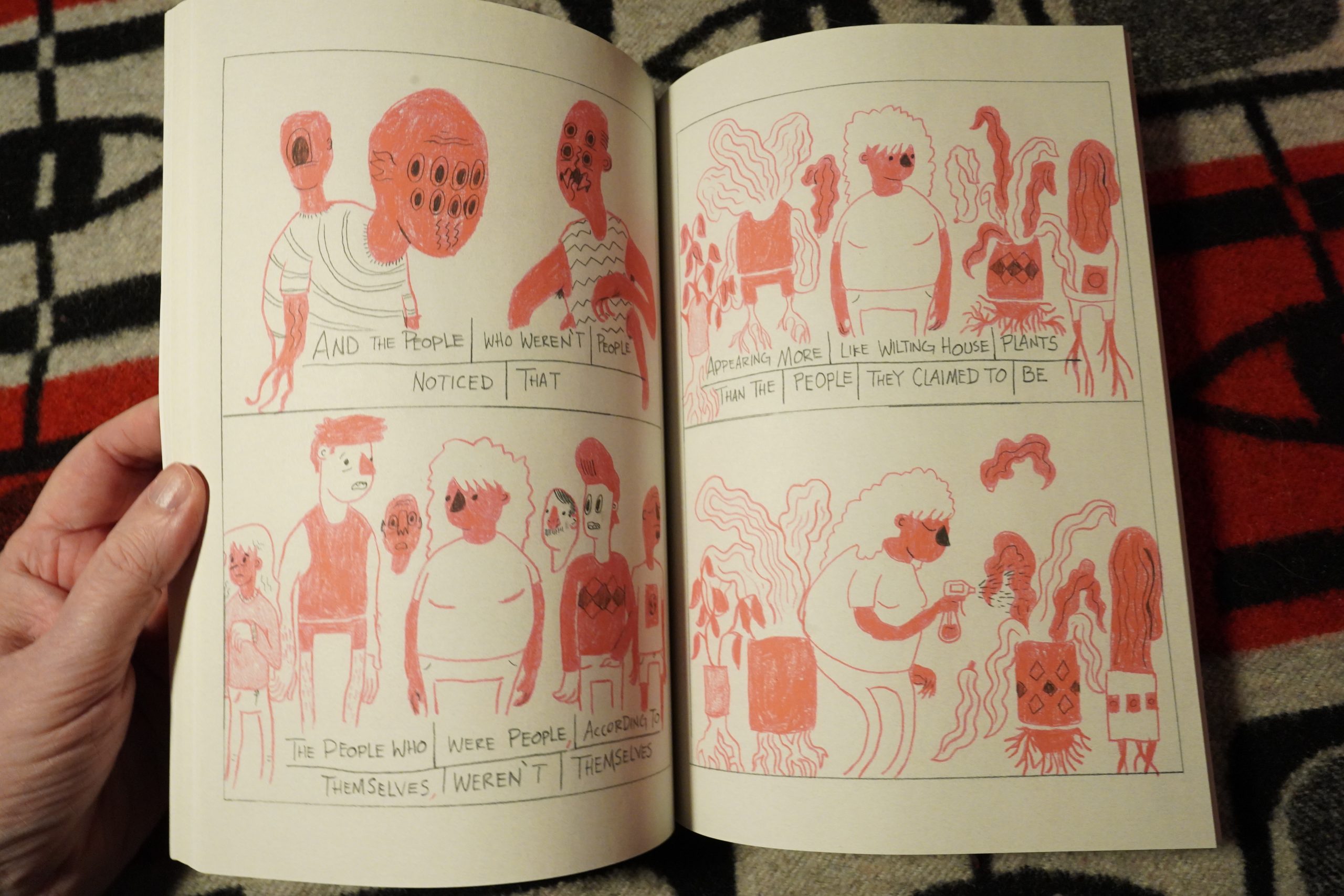

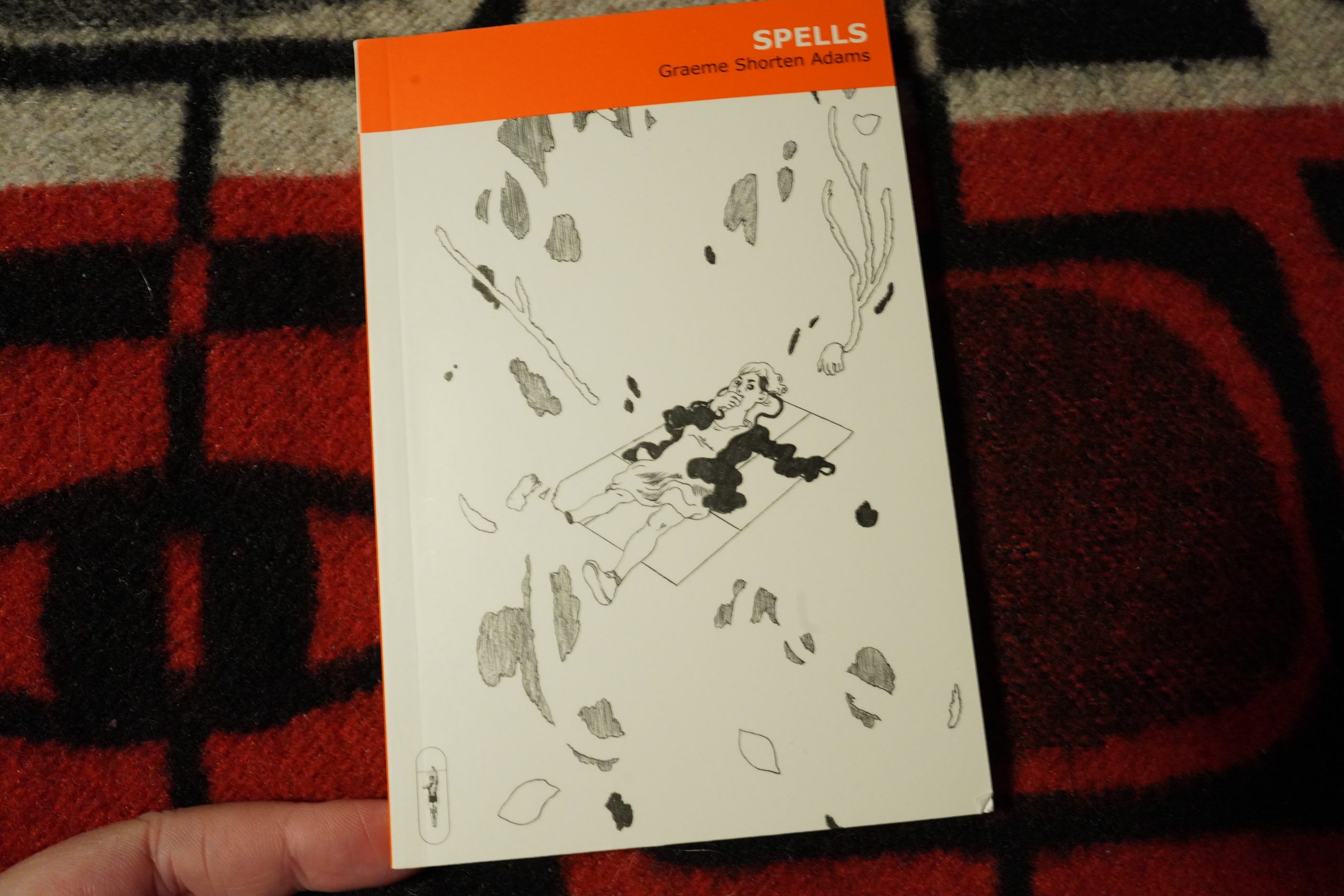

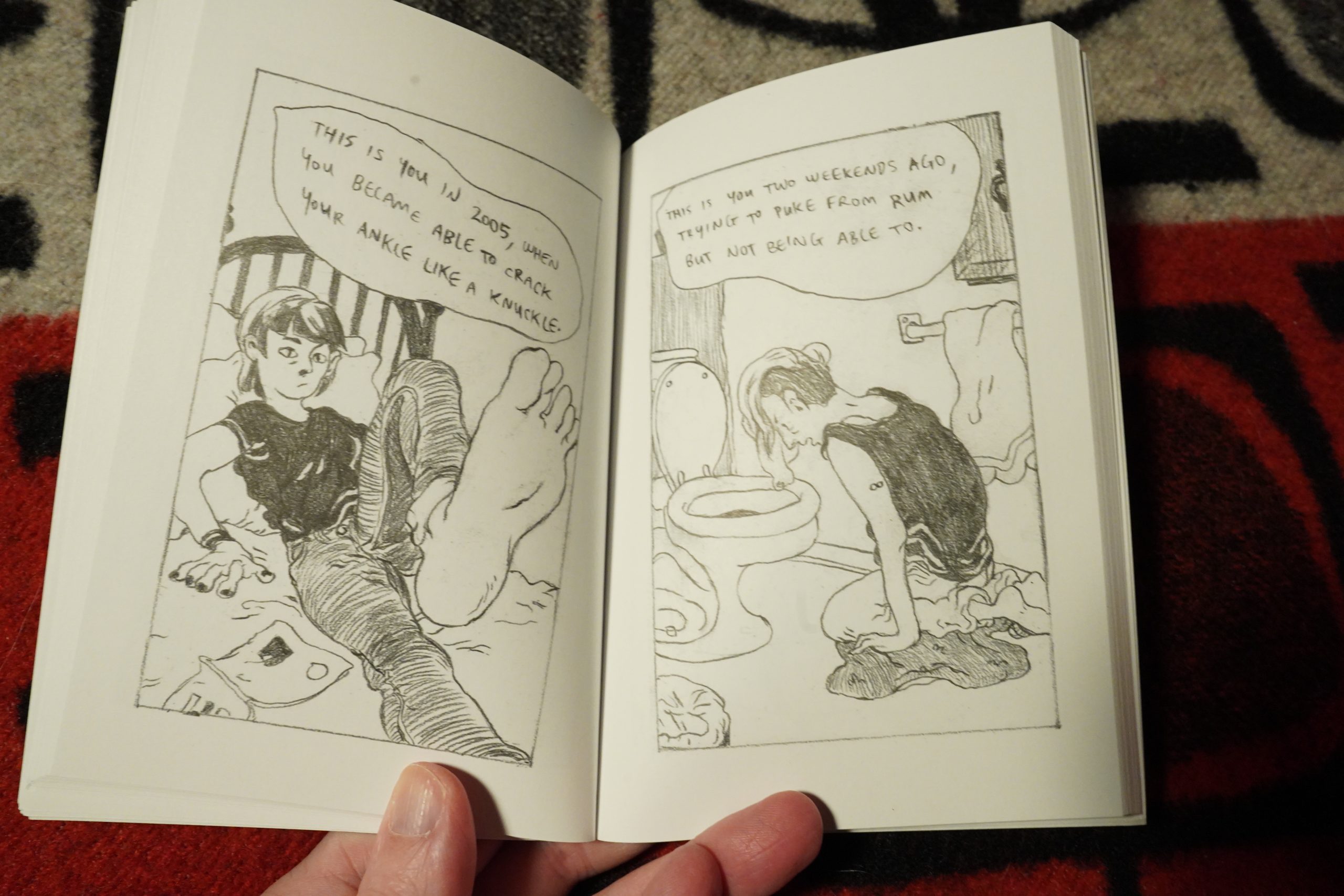

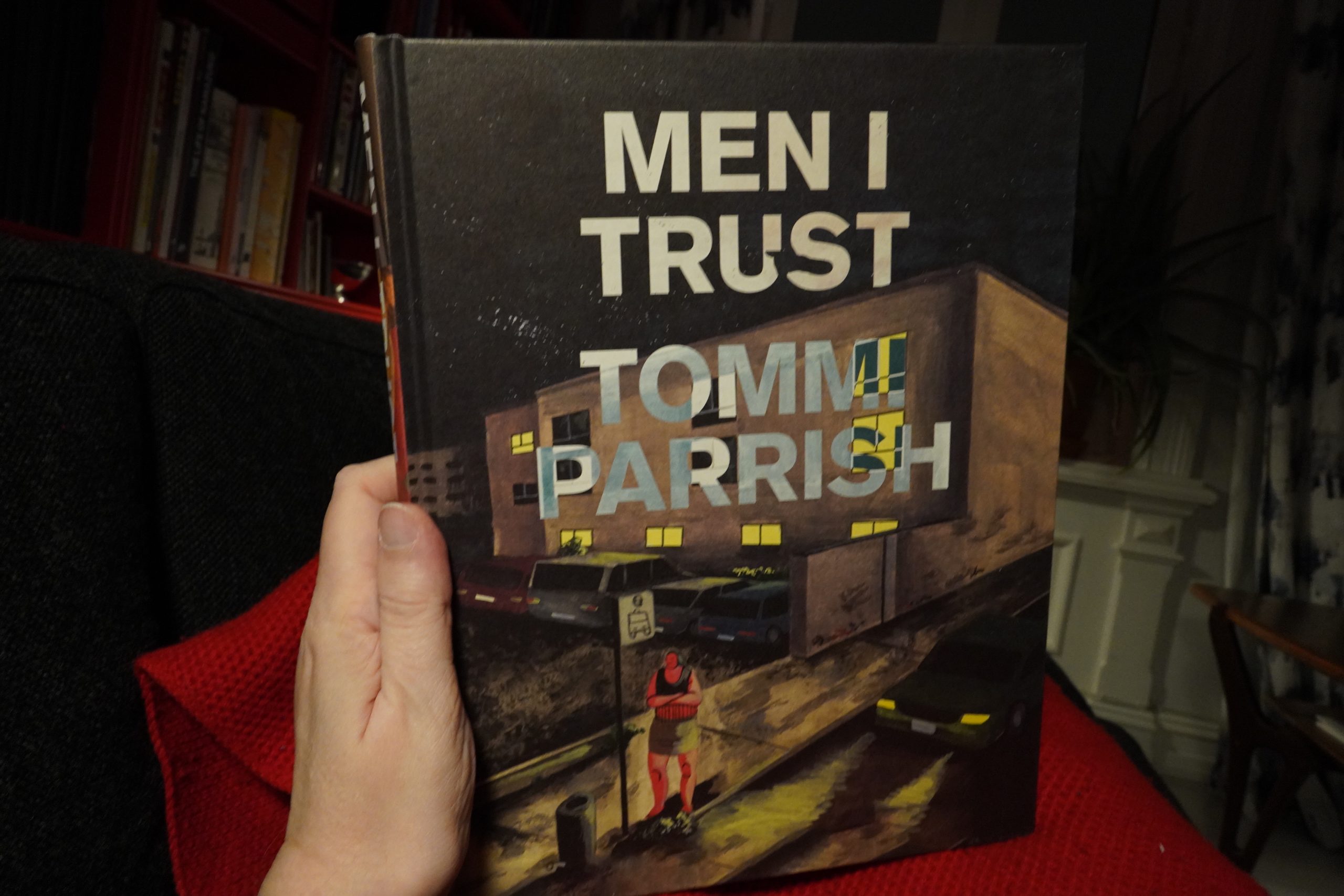

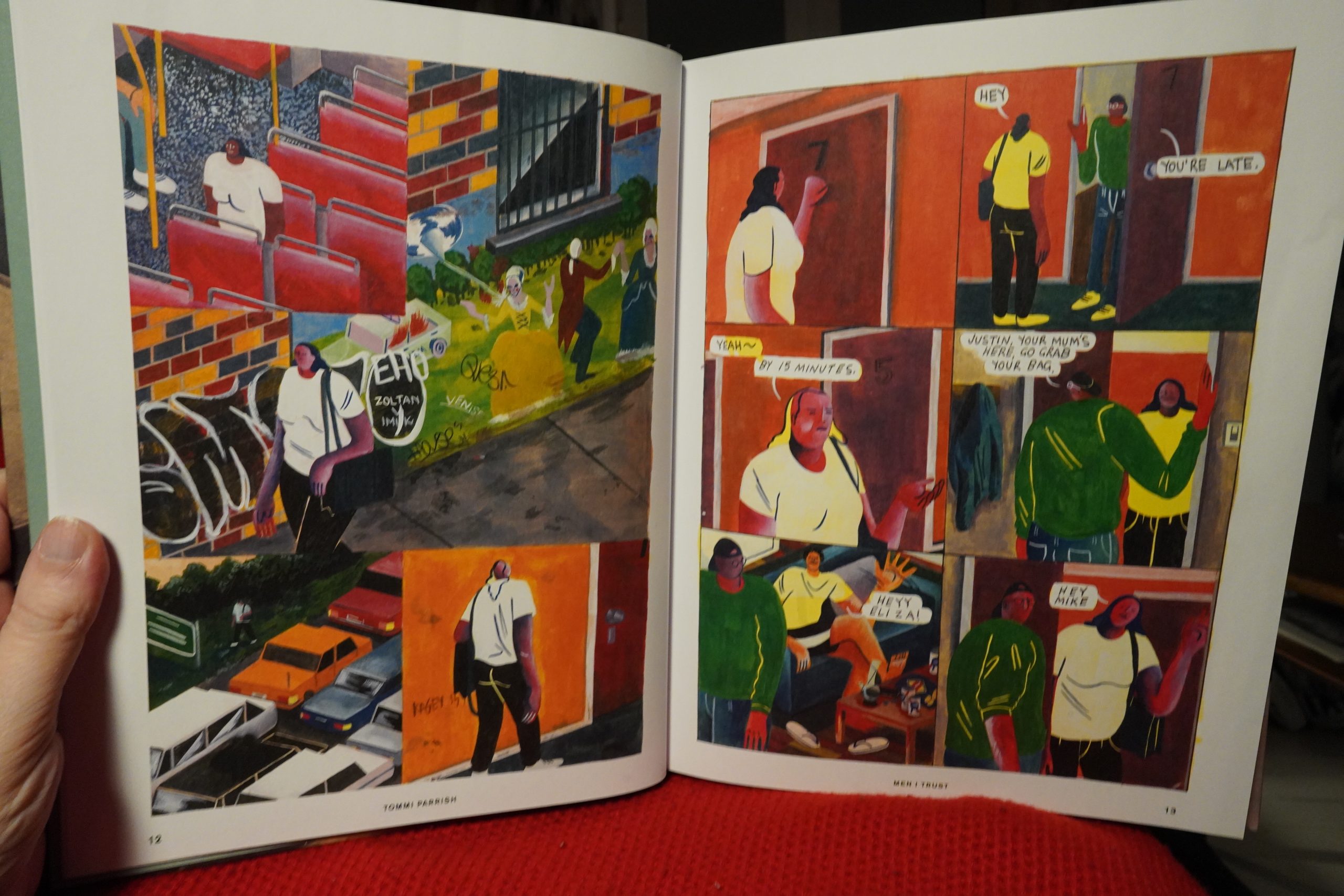

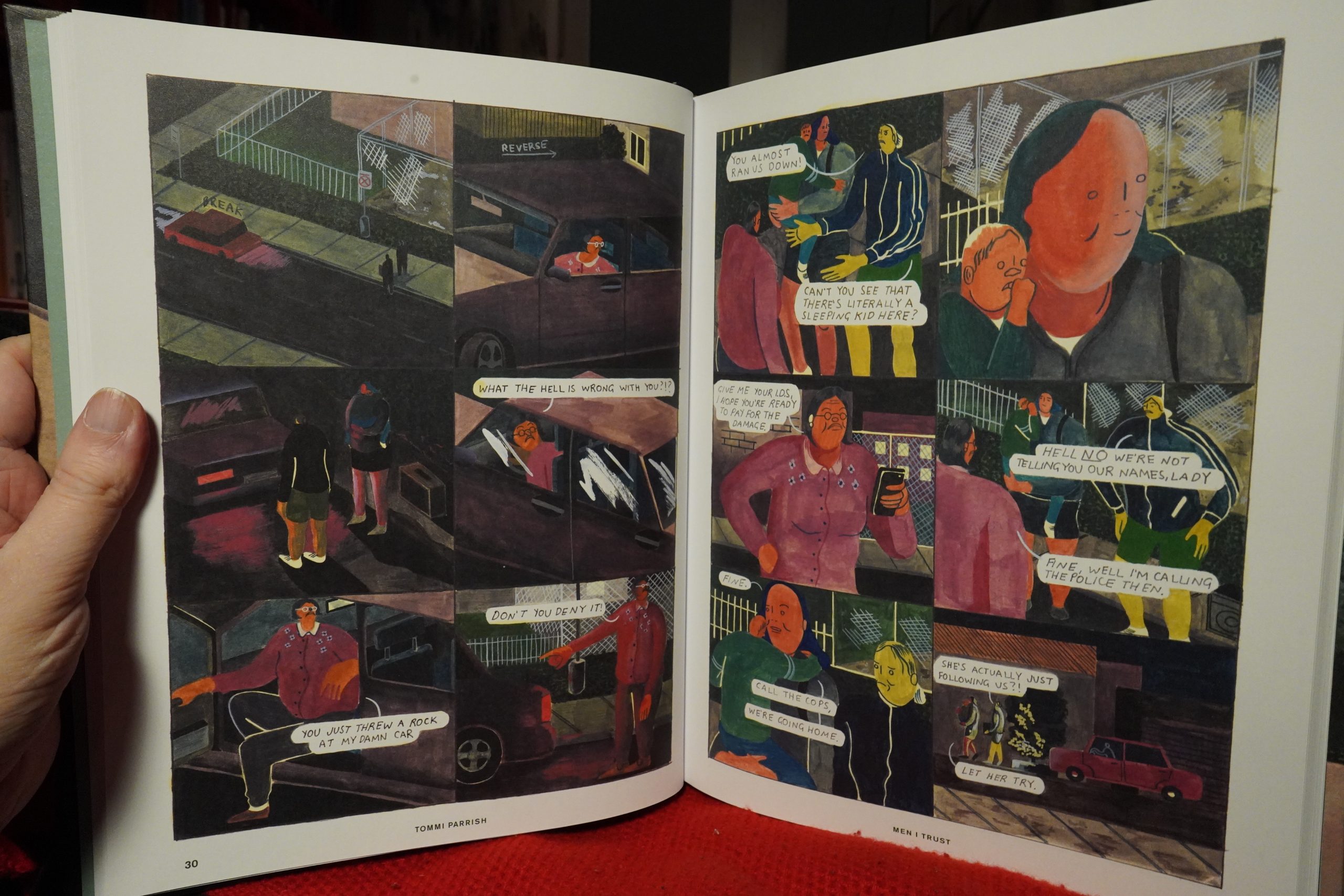

22:25: Men I Trust by Tommi Parrish (Fantagraphics)

I read the Swedish translation of this some months ago, but I accidentally also bought it in English, so I thought I’d re-read it. It just seemed kinda choppy in Swedish, as if the text wasn’t quite… right…

It’s much better in English — it flows better, and there’s no “eh? what?” bits. And the artwork is just a gorgeous… the beautiful colours, the perfect characters…

But I’m still having a lot of problem with the general AA/therapy stuff in here, which is just inherently tedious. The bits that aren’t about that (which is, I guess, about two thirds) are quite exciting and fresh, but…

| Lost Girls: Menneskekollektivet |  |

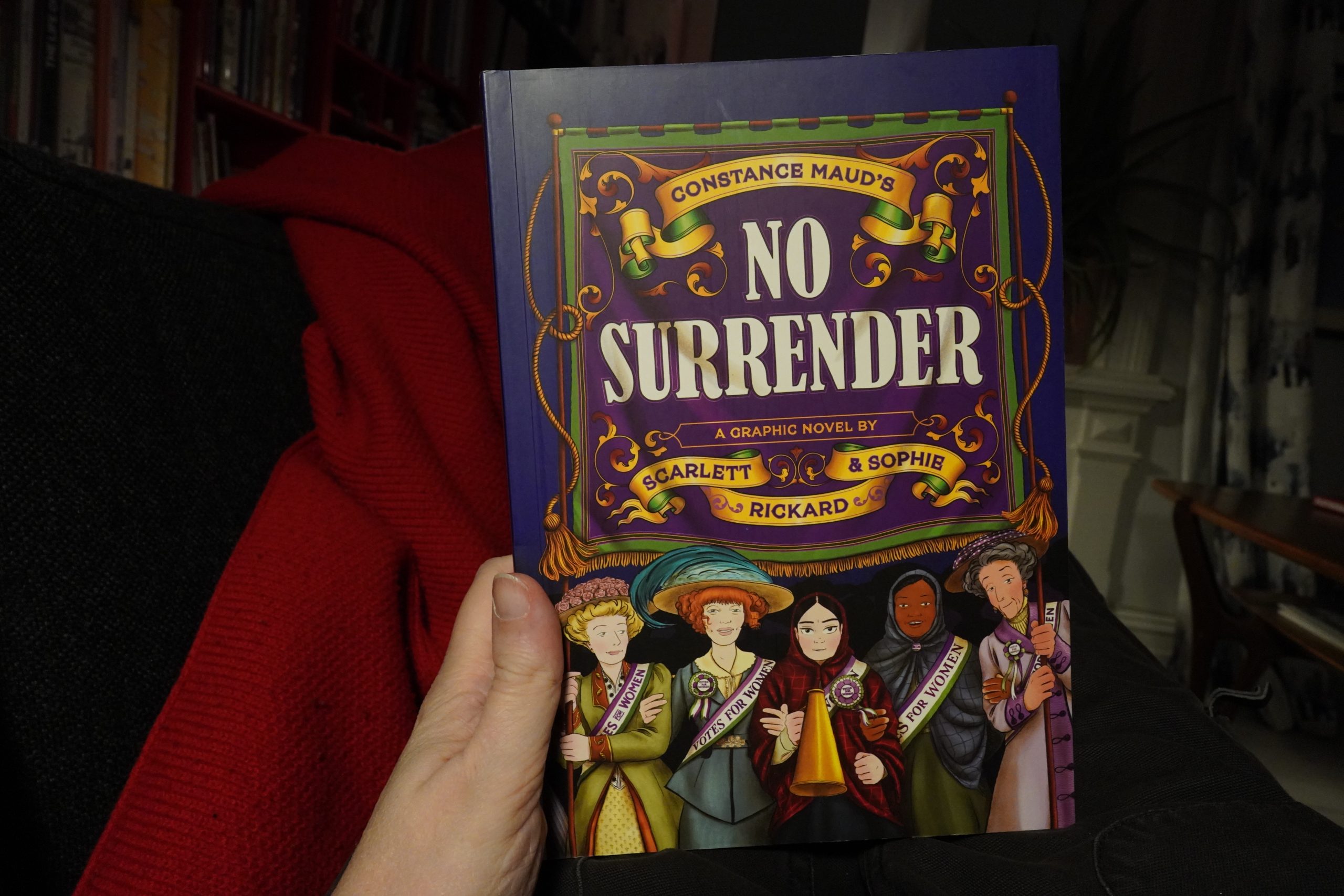

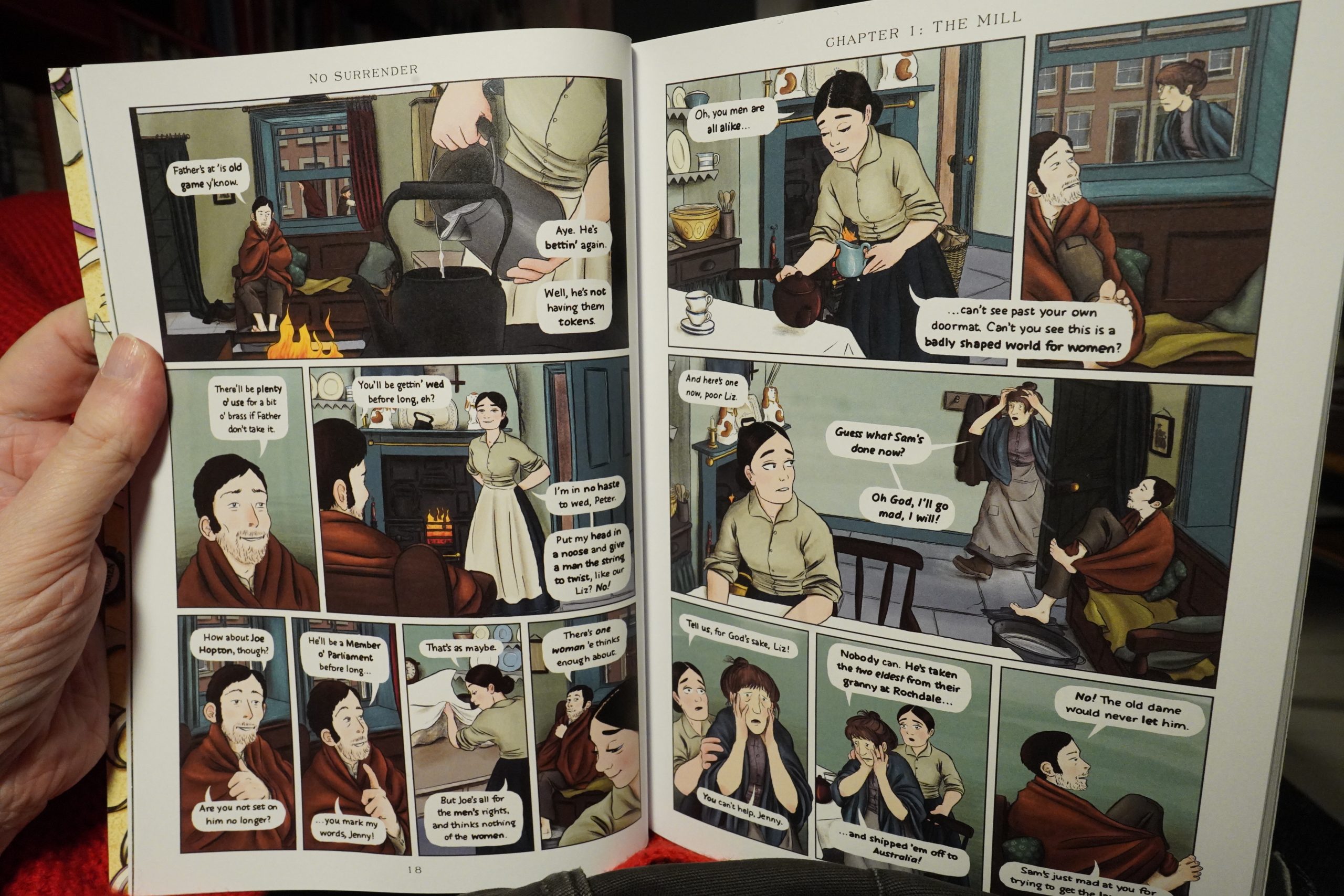

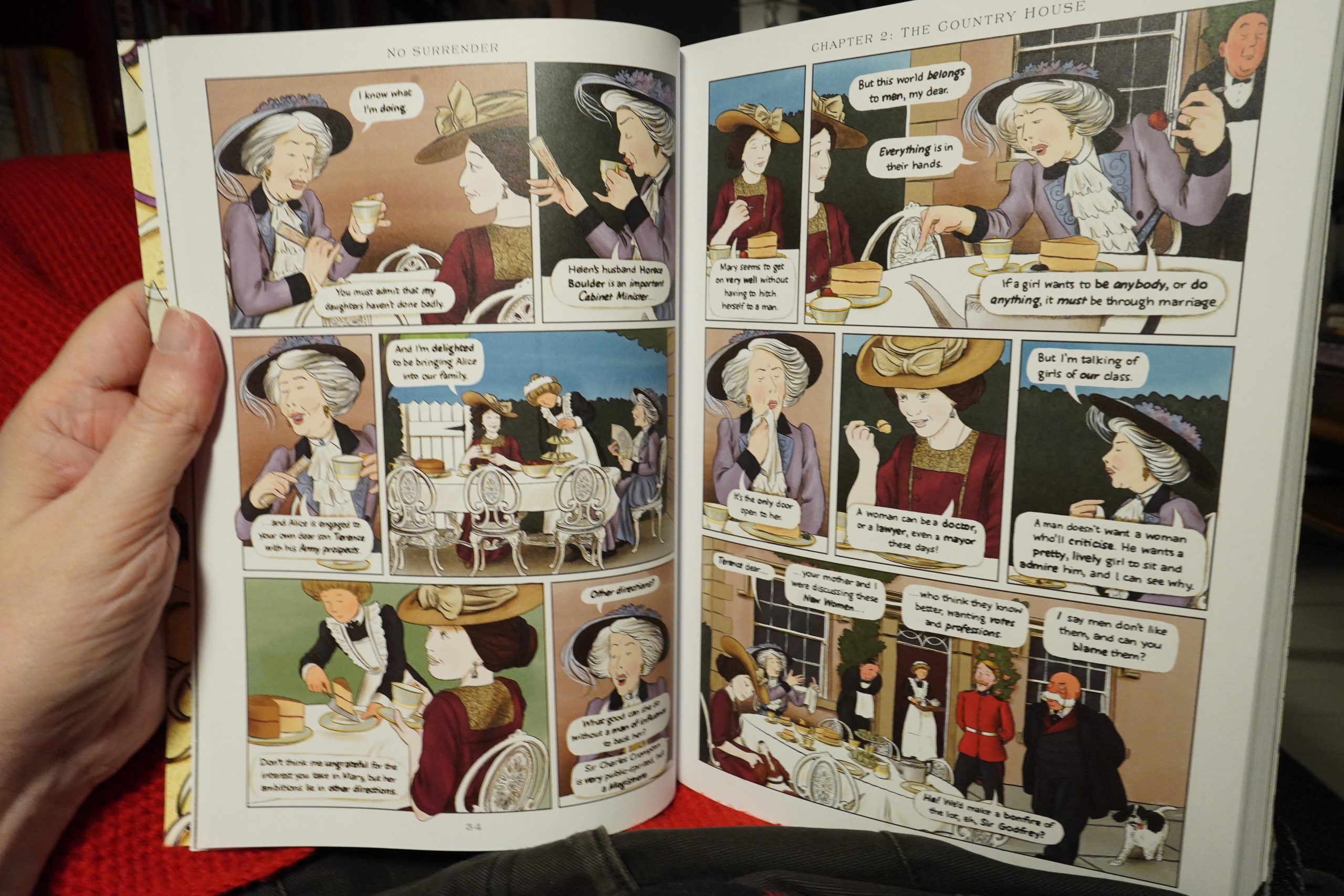

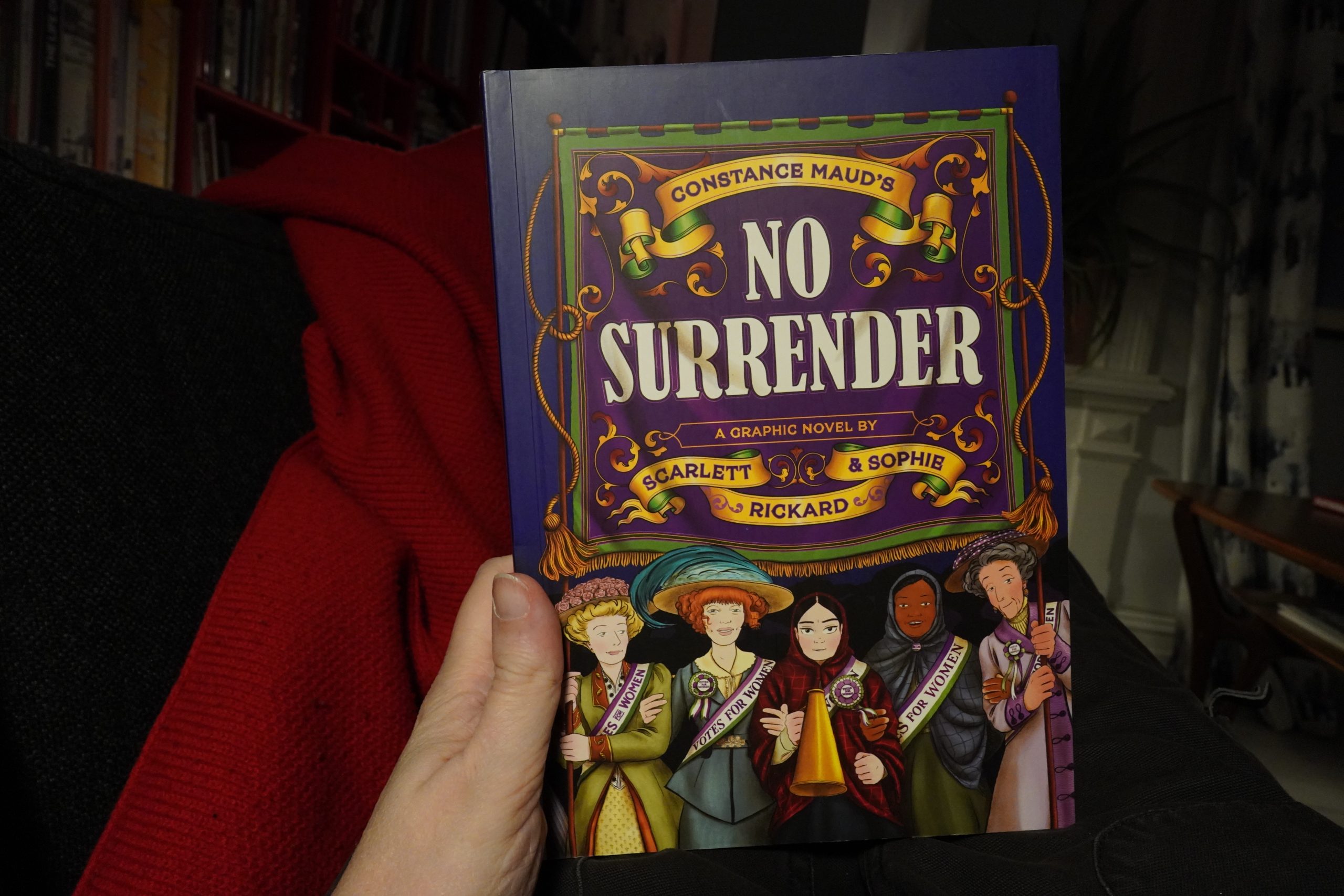

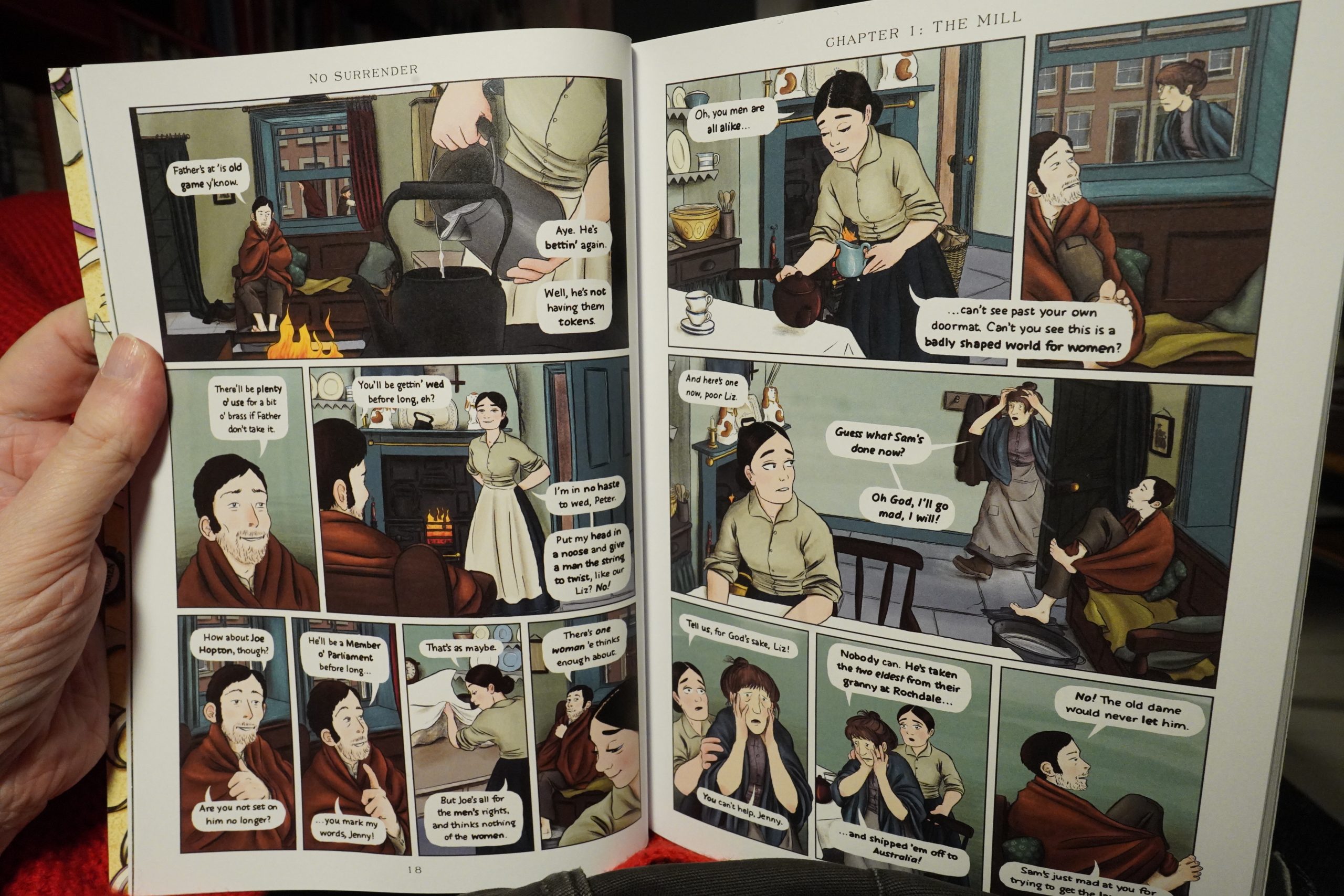

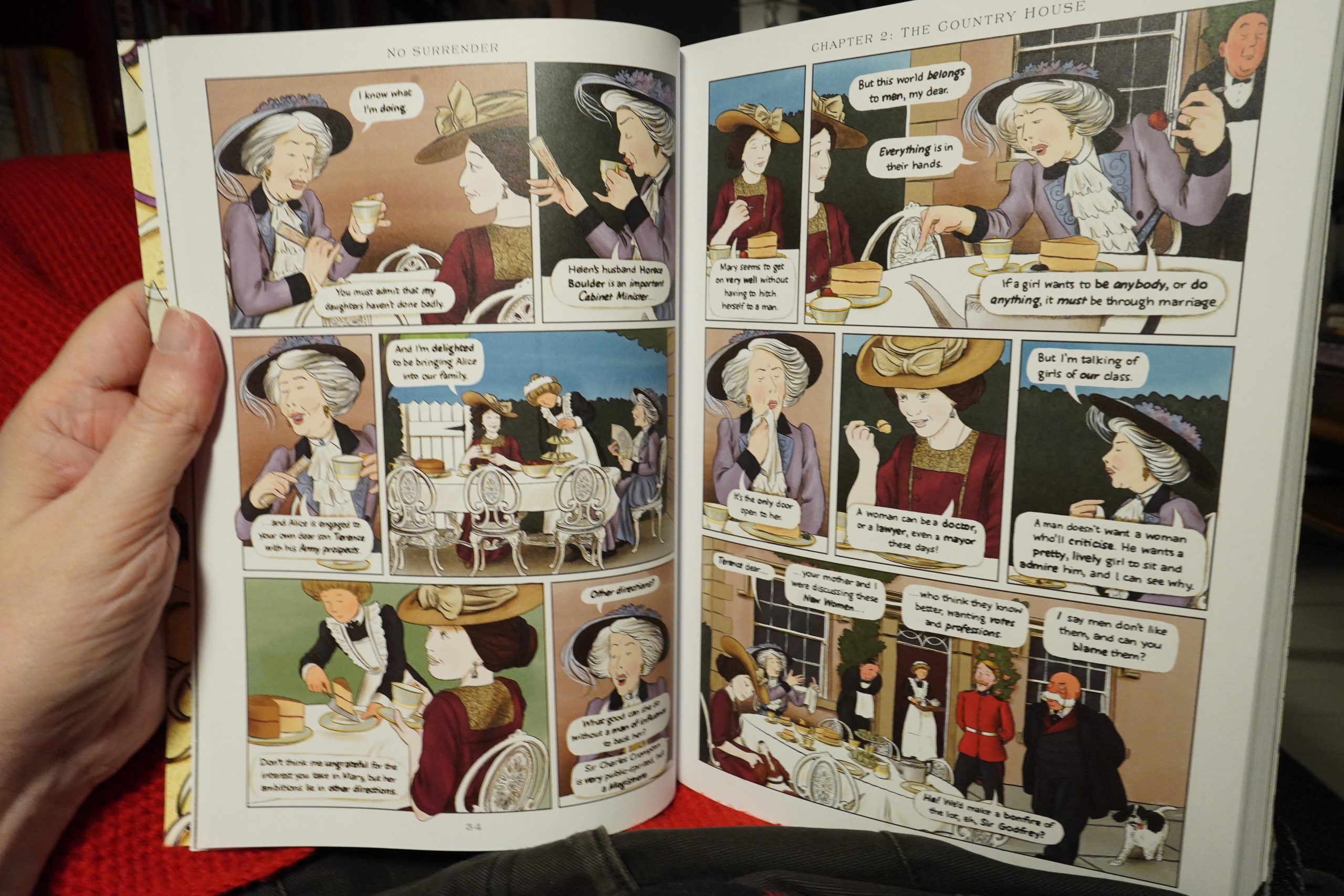

23:26: No Surrender by Constance Maud, Scarlett & Sophie Rickard (Selfmadehero)

This is an adaptation of a 1911 novel, and it seems like an admirable project. There’s obviously gone a lot of work into this, but the results are unfortunately not very compelling.

It’s a very, very talkative book, but the characters seem less like characters than examples of their types. It’s like the author wanted to present the issues from all sides, so you have all the stock characters delivering their lines, making their arguments.

It’s just kinda deadly, and I ditched this book 70 pages in.

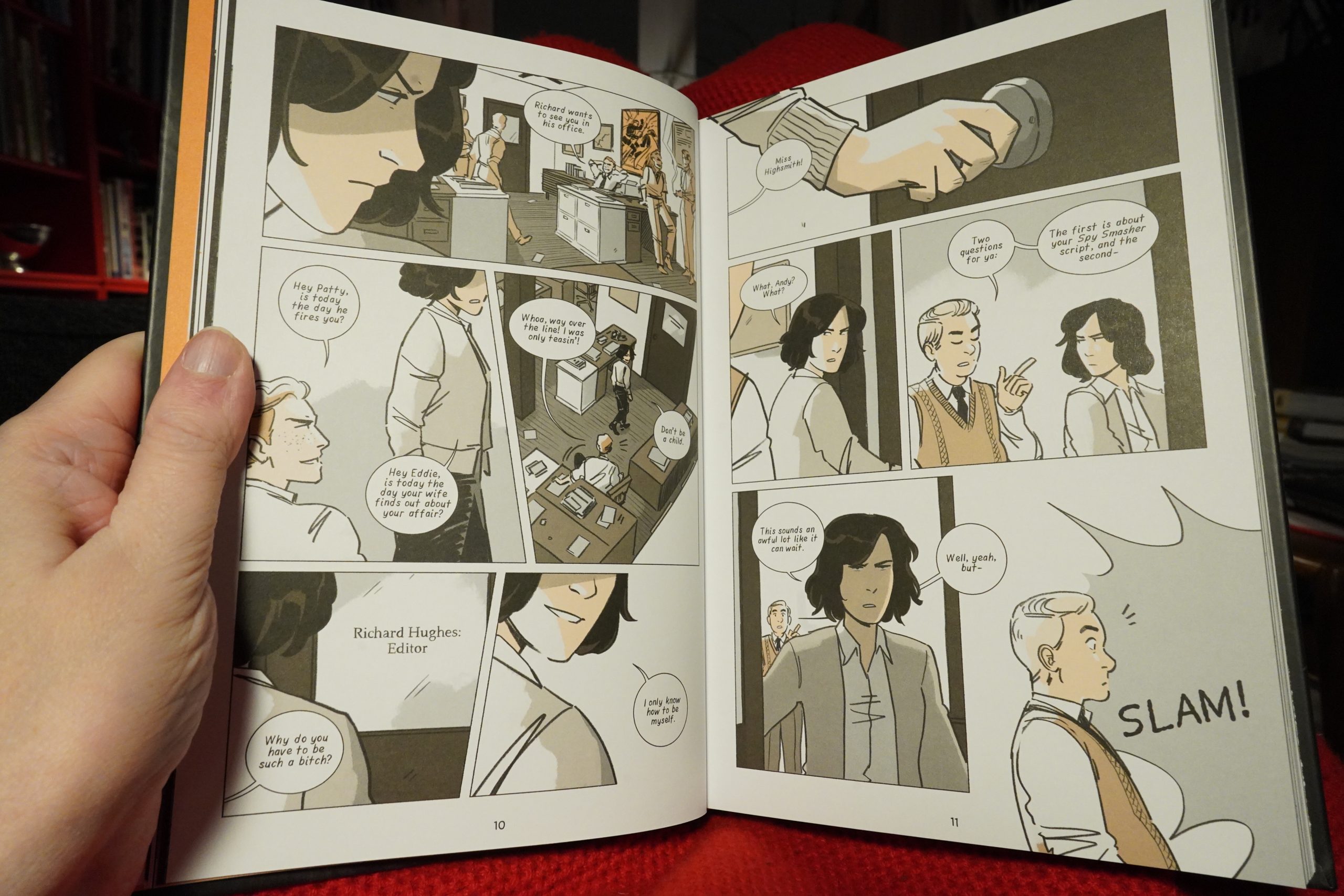

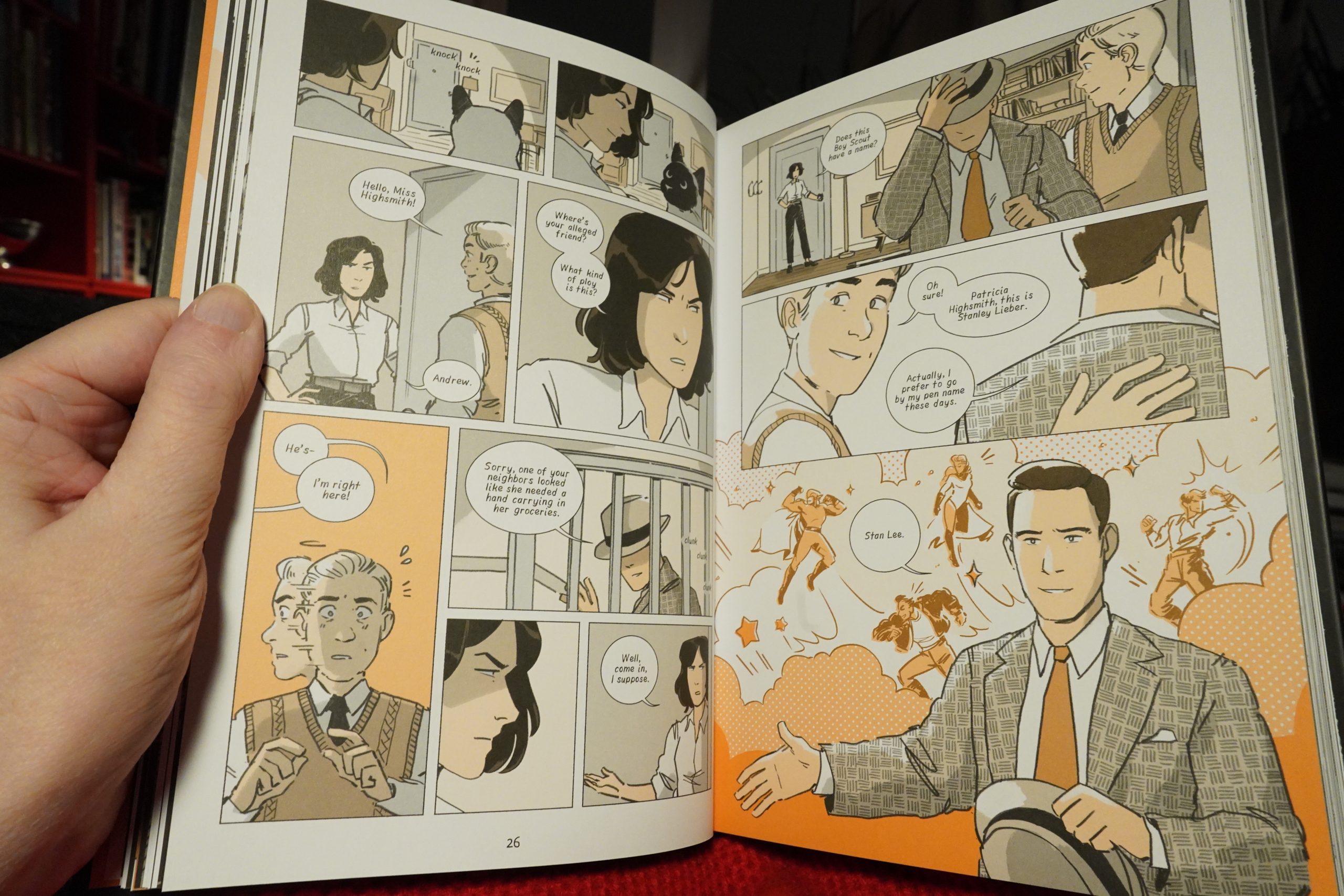

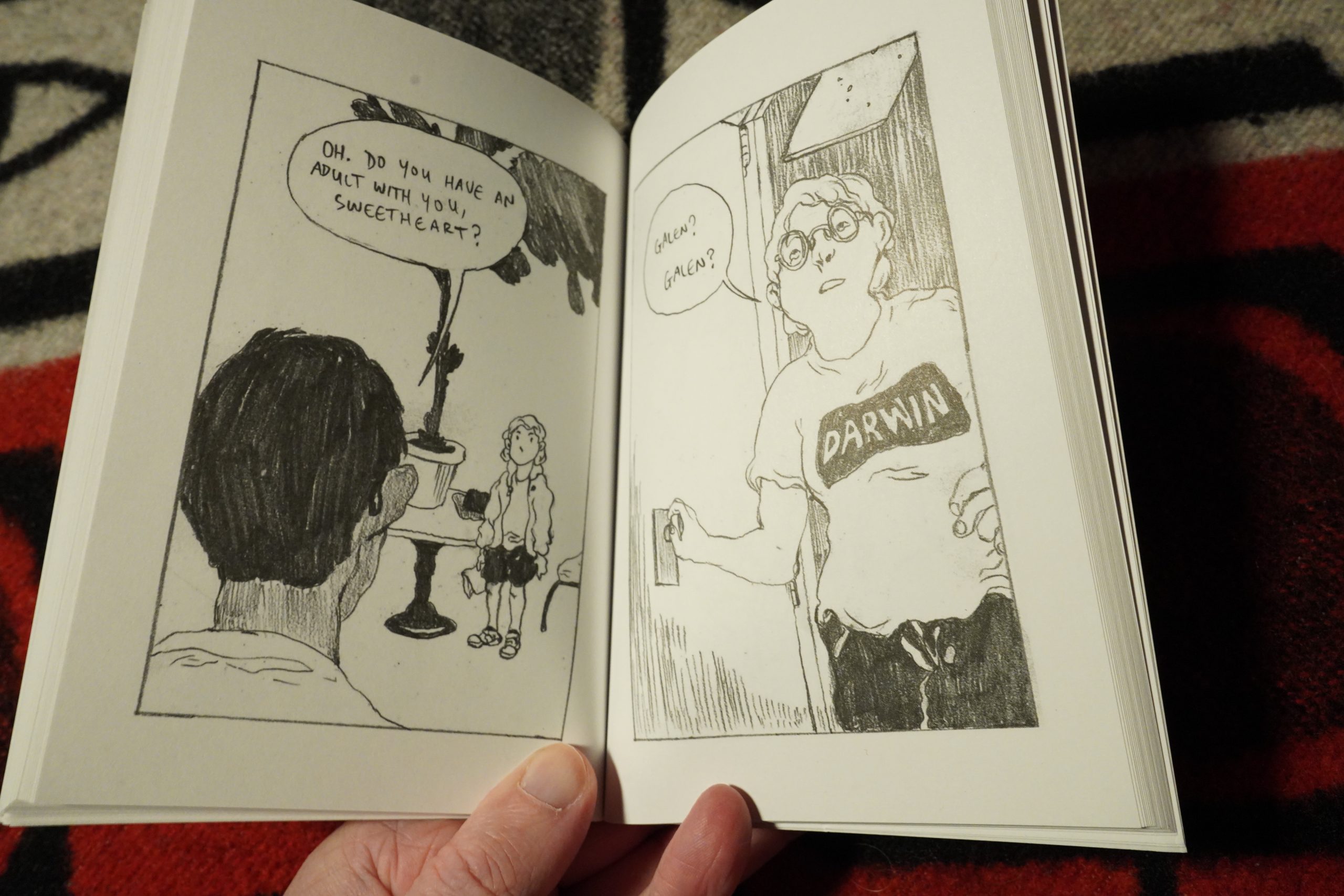

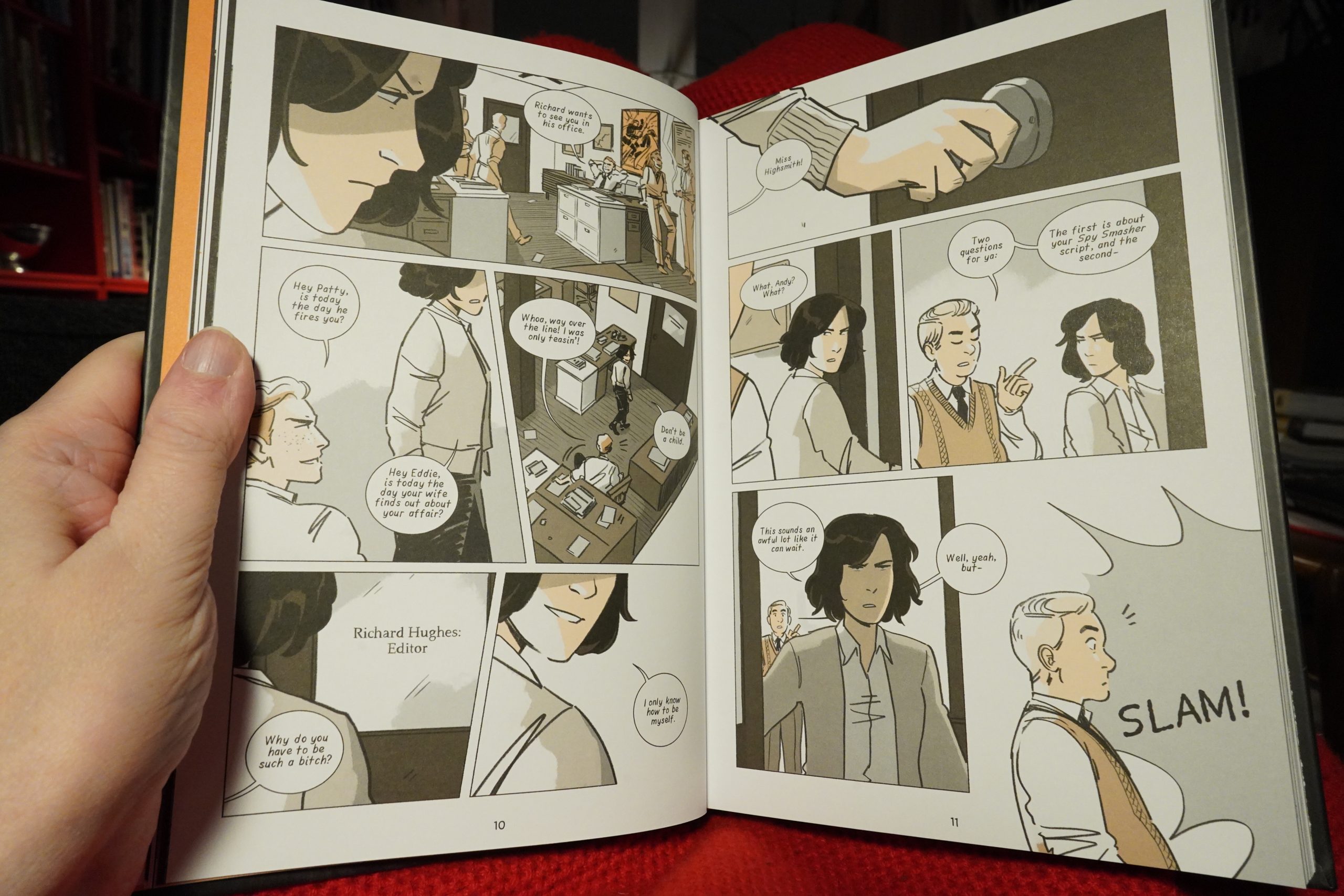

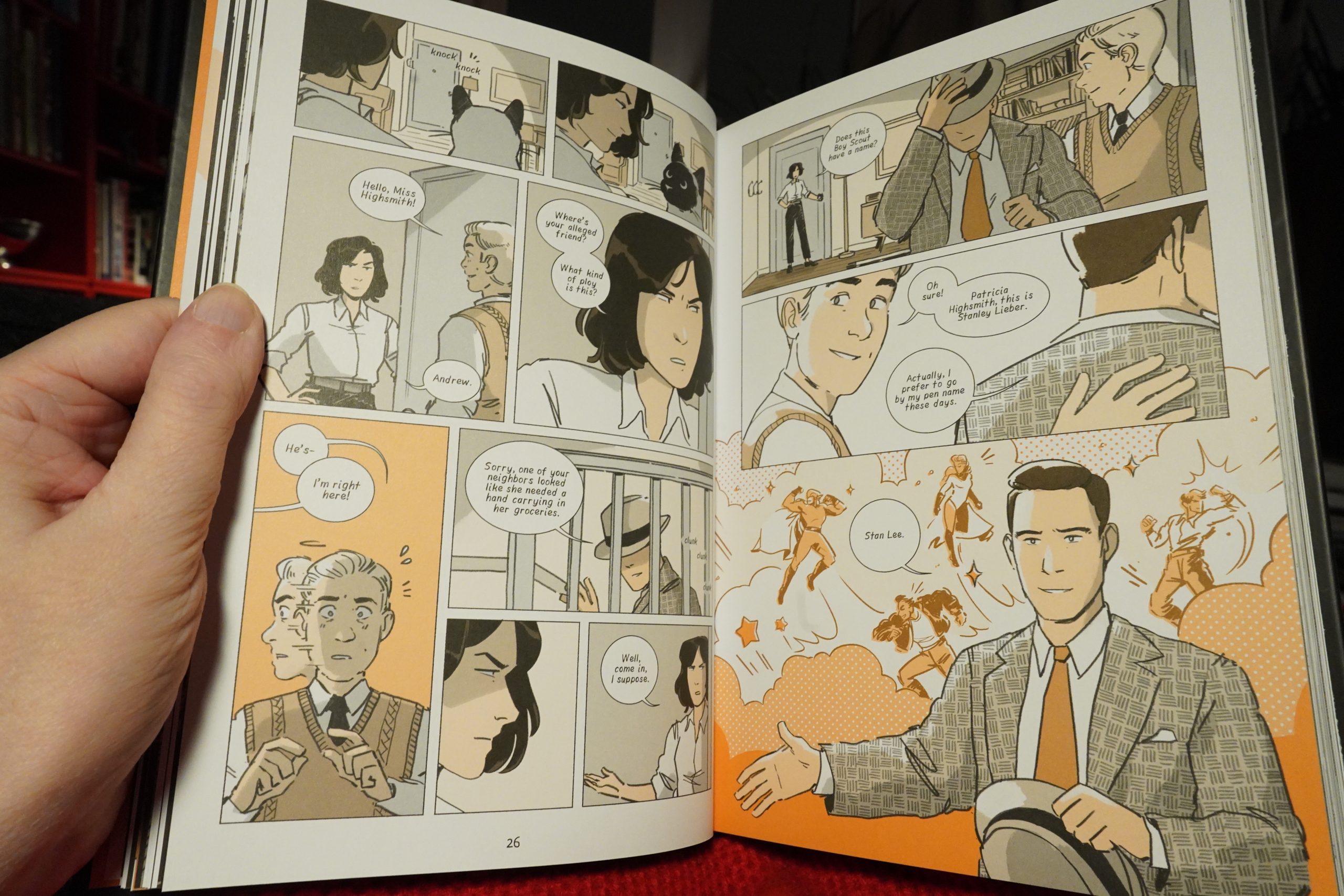

23:46: Flung Out of Space by Grace Ellis & Hannah Templer (Abrams)

This book is kind of Patricia Highsmith biography. The positive bits first: The storytelling is really excellent. The panels flow well, and it’s all propulsive. The influences from Japanese comics are evident here, but it doesn’t overwhelm the book or turn it into pastiche.

But it’s just a really lopsided book. Most of it’s about something most books about Highsmith skips over fast — her career as a comic book writer. So that’s a fun thing to feature in a comic book about her… but it’s got these… beats… where we’re supposed to gasp at her meeting Stan Lee, for instance, which is just kinda nauseating. The other problem is that the book spends a lot of time detailing her sessions with various shrinks, and (again) that rarely makes for compelling reading.

So the book is… OK? It’s OK.

| Benjamin Lew: Le personnage principal est un peuple isolé |  |

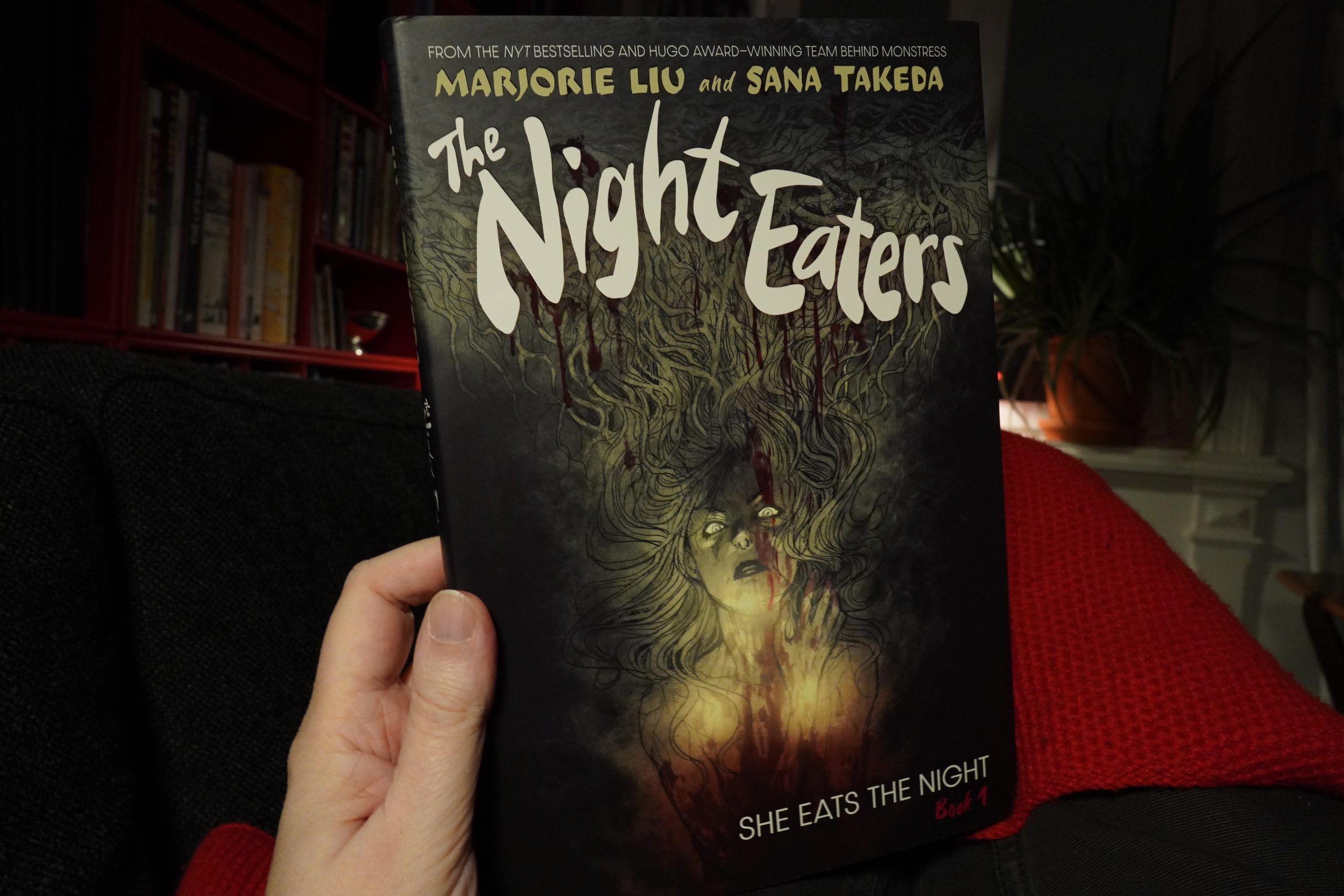

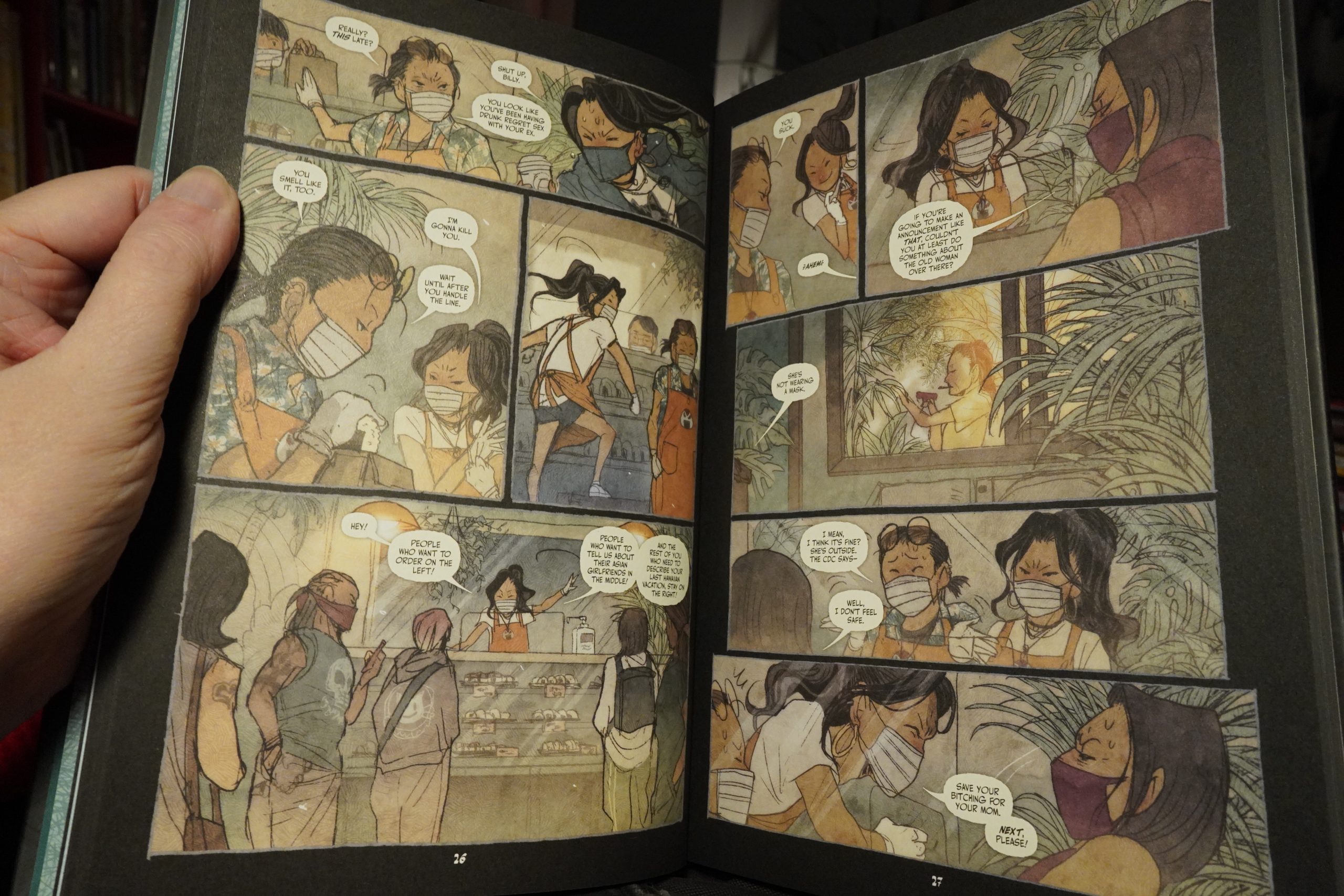

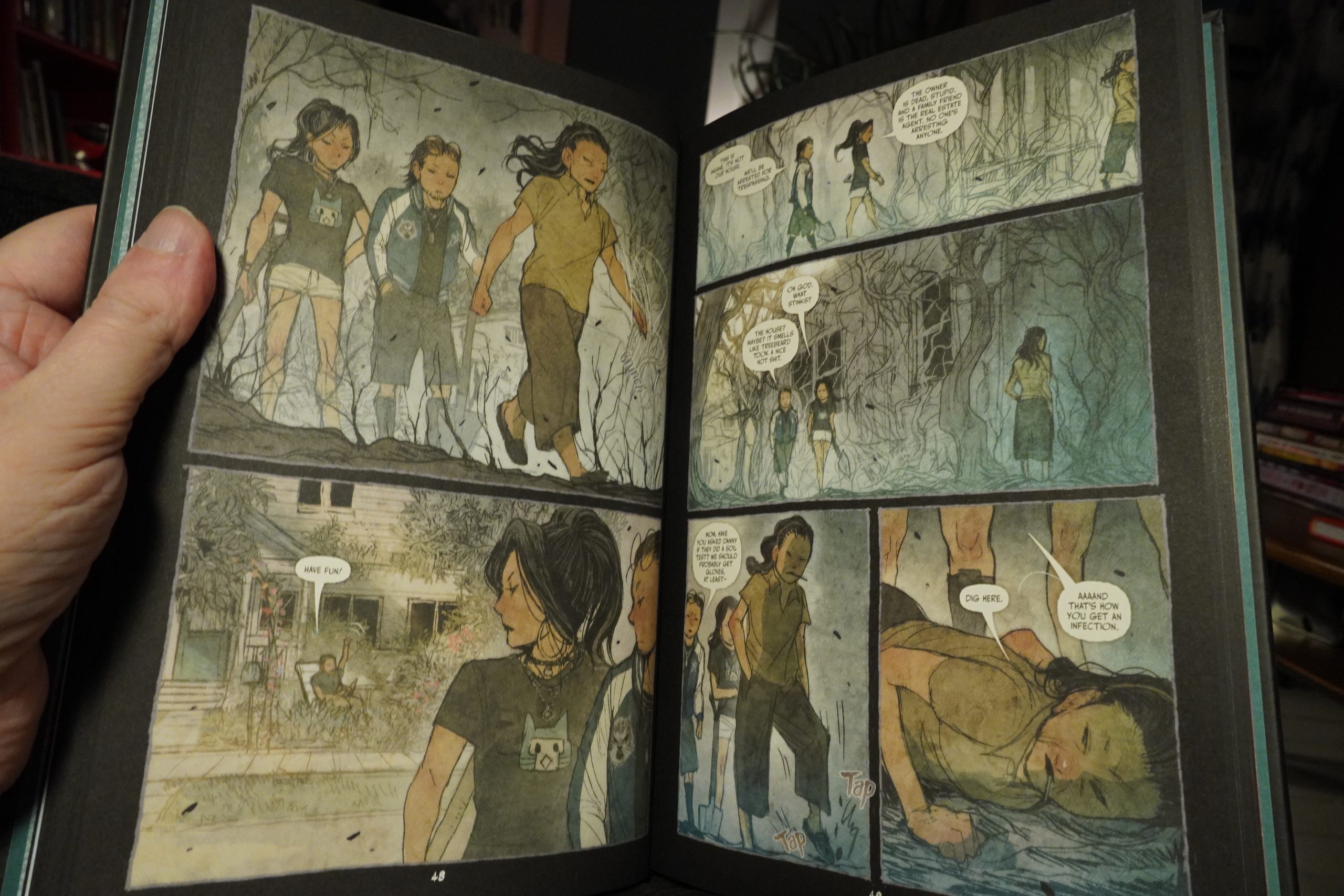

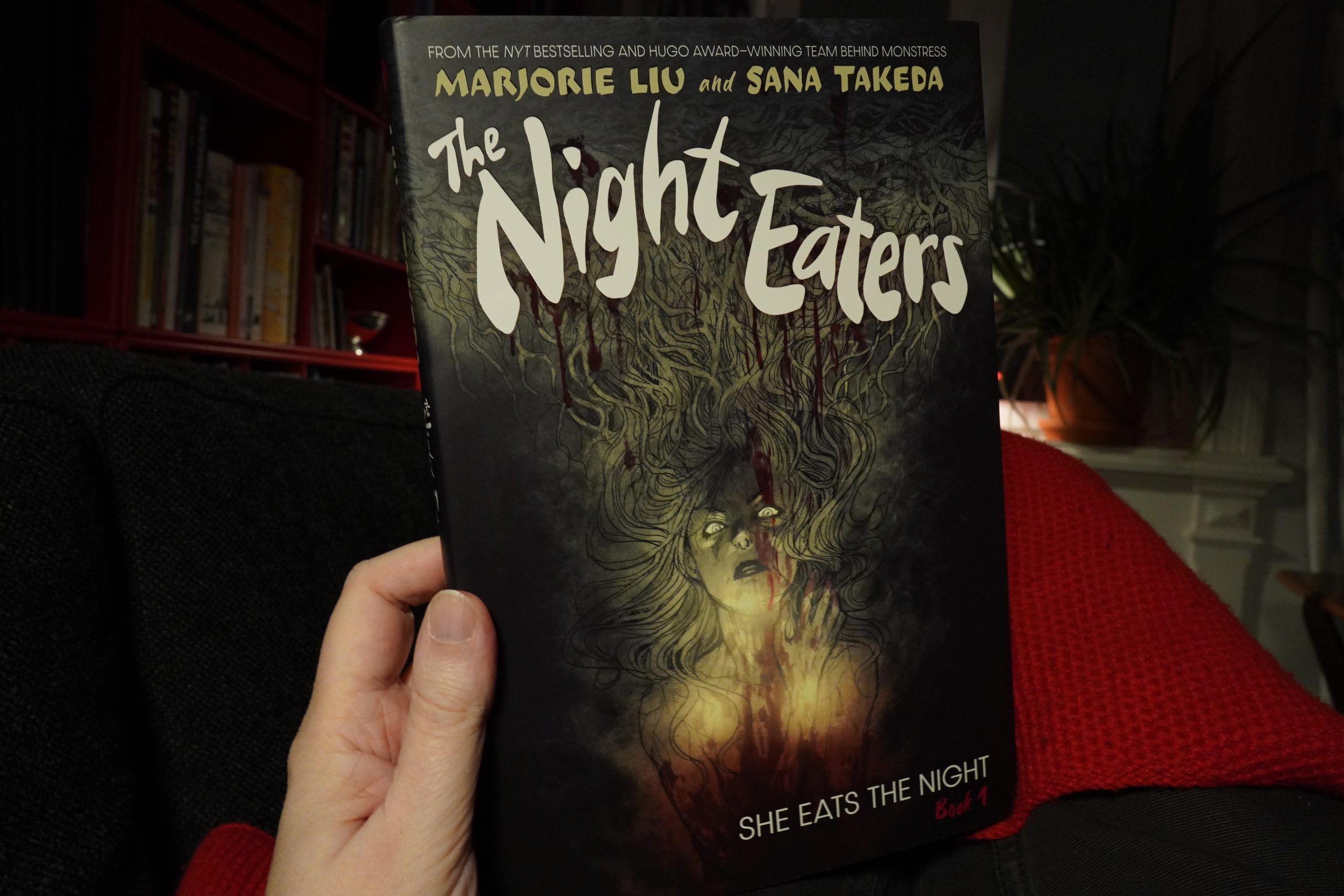

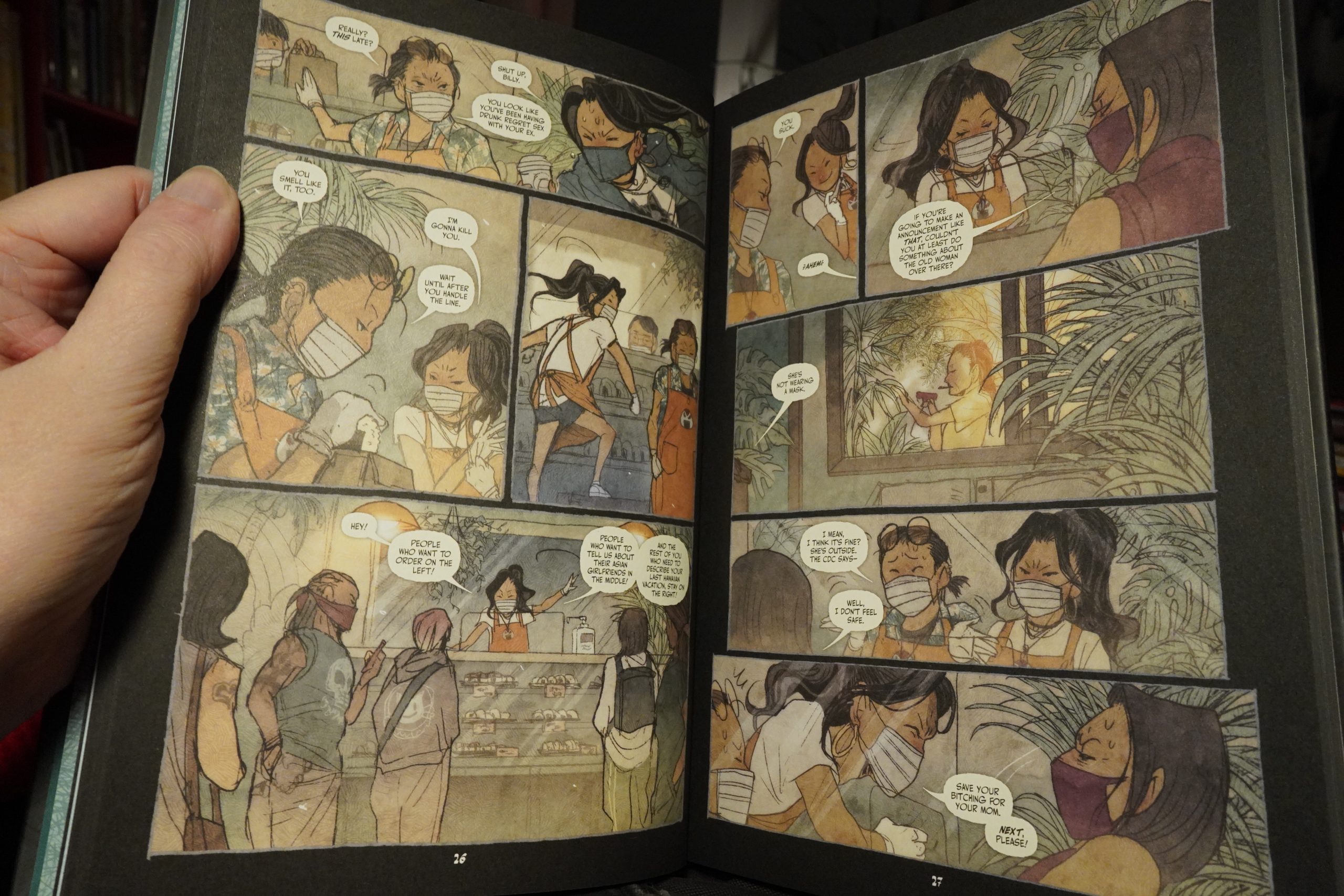

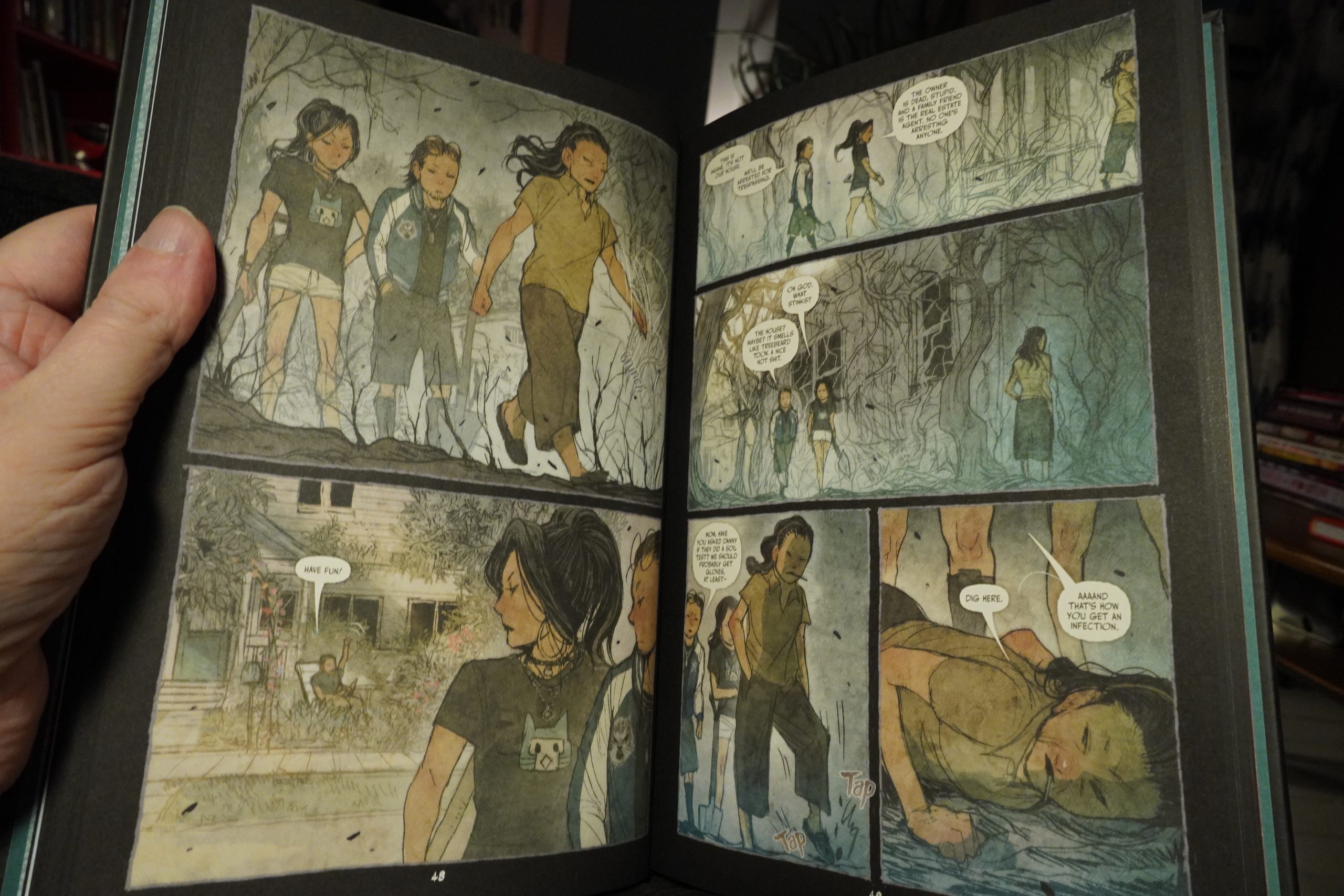

00:23: The Night Eaters Book 1 by Marjorie Liu & Sana Takeda (Abrams)

I first assumed that this was taking place in some post-apocalyptic world where there was heavy fog/smog everywhere, but not — it’s just drawn this way. It’s a choice, I guess…

It’s a nice little horror story, but parts of it seems written with a TV series adaptation in mind. The patter, the TV friendly bite sized scenes, and the general form of the story.

It’s basically American Horror Story: Inscrutable Chinese Mother, and like any AHS season, it starts off in an intriguing way before becoming really boring and nonsensical.

One this I love about Tommi Parrish’ artwork is that it’s like an anti bobble head manifesto. Sana Takeda, unfortunately, seems to be drawing the heads two up from the size they should have, leaving us with these unpleasant visions of monstrous child-sized adults. It’s horrifying.

| Hexting: Post Post Rock Rock |  |

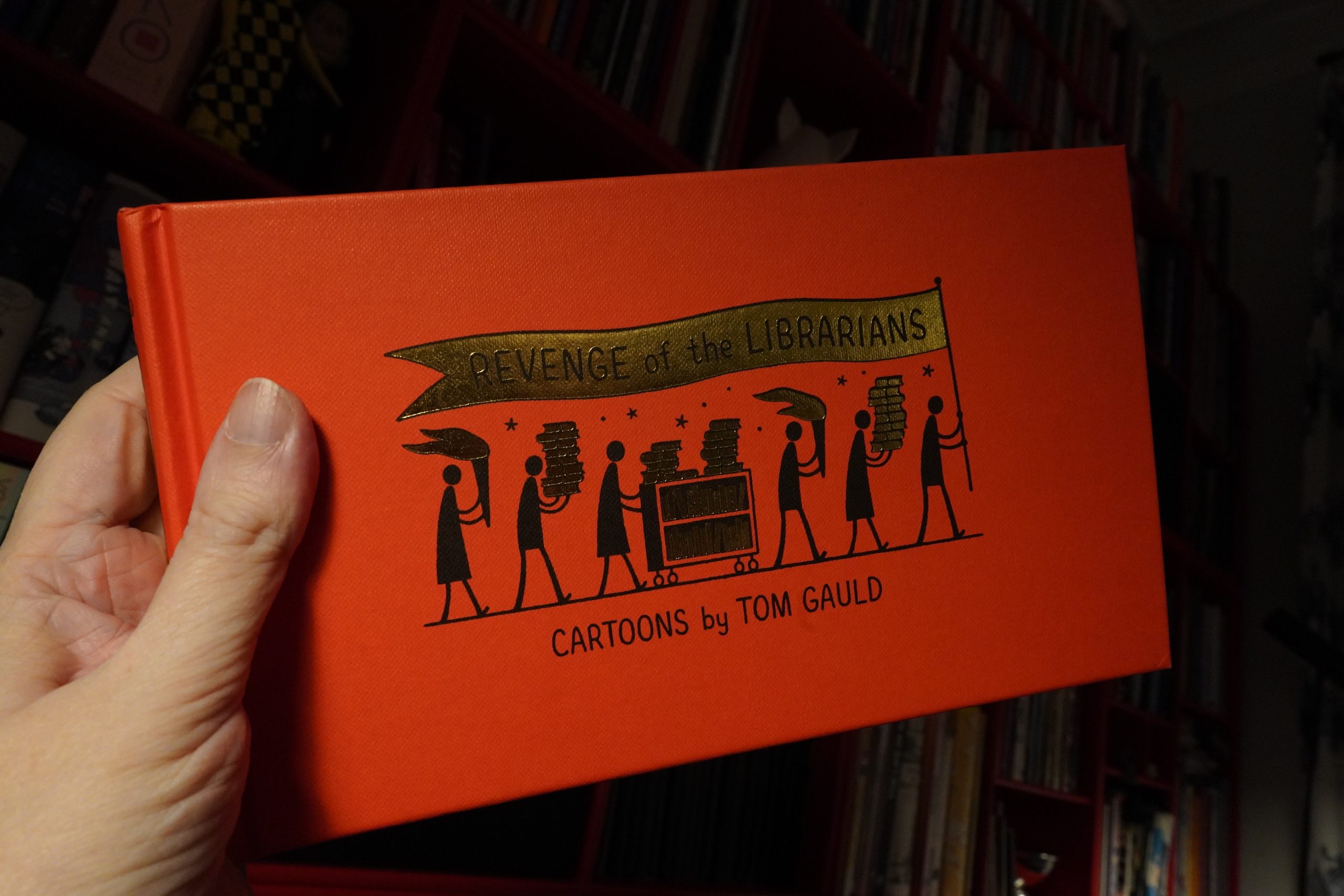

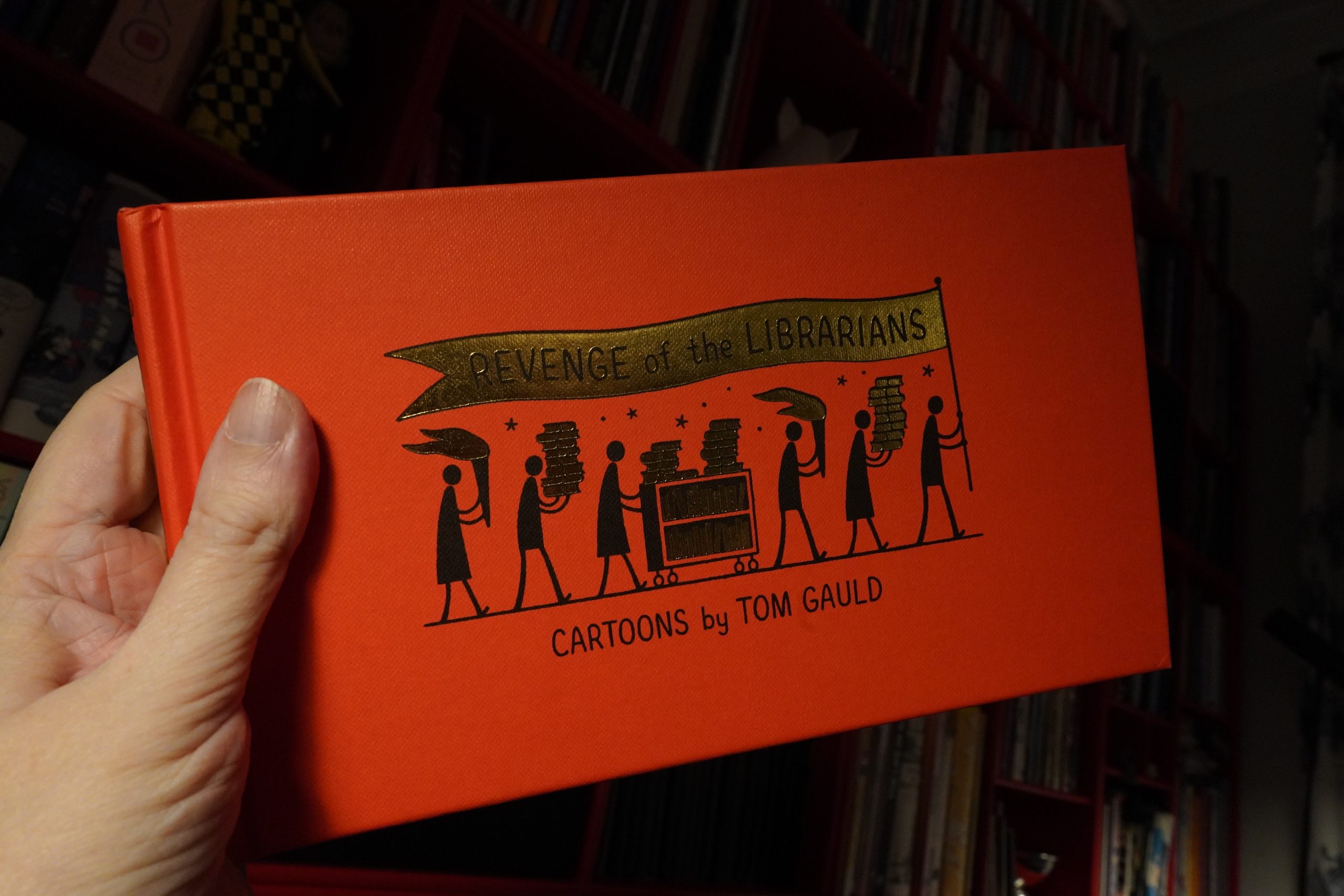

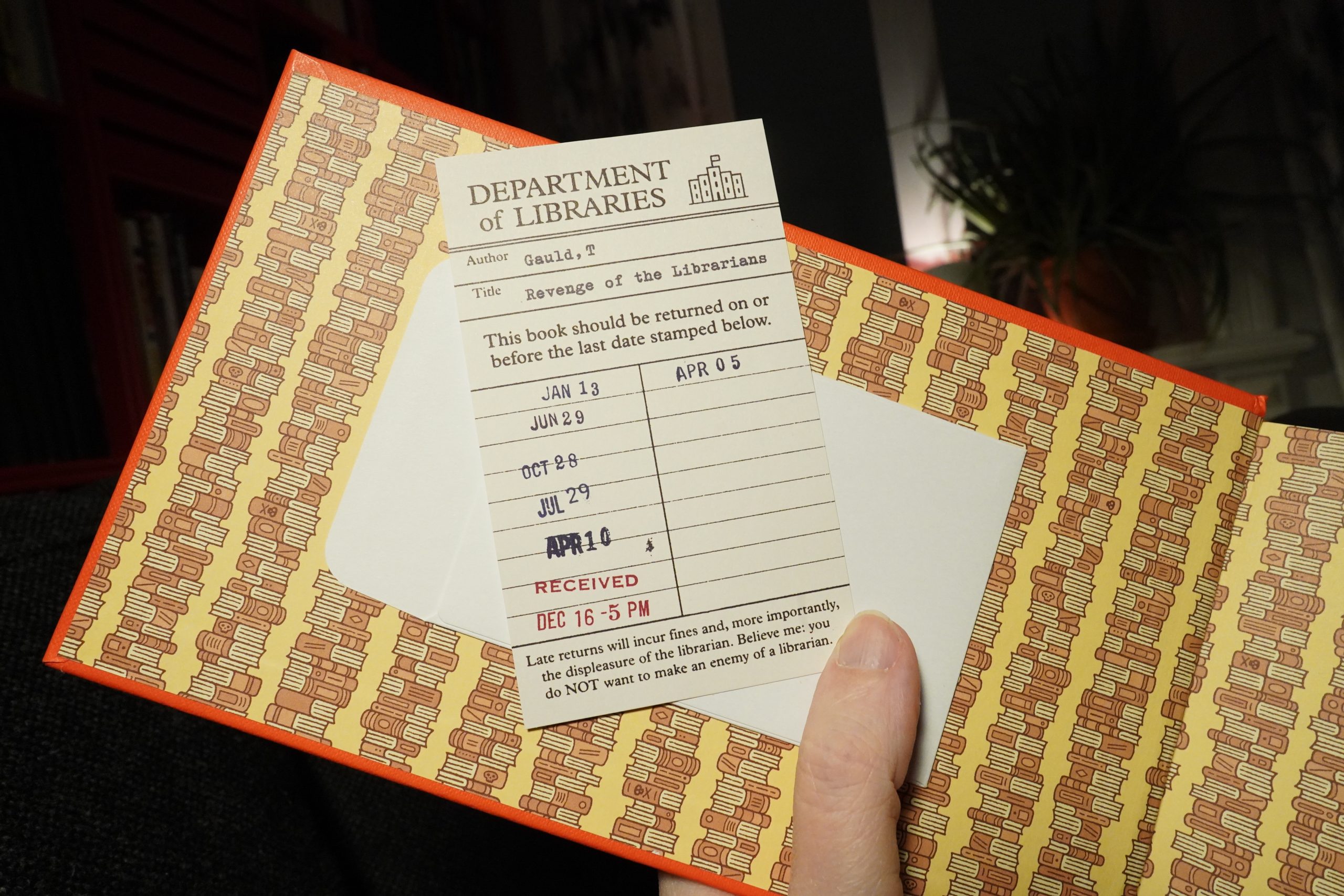

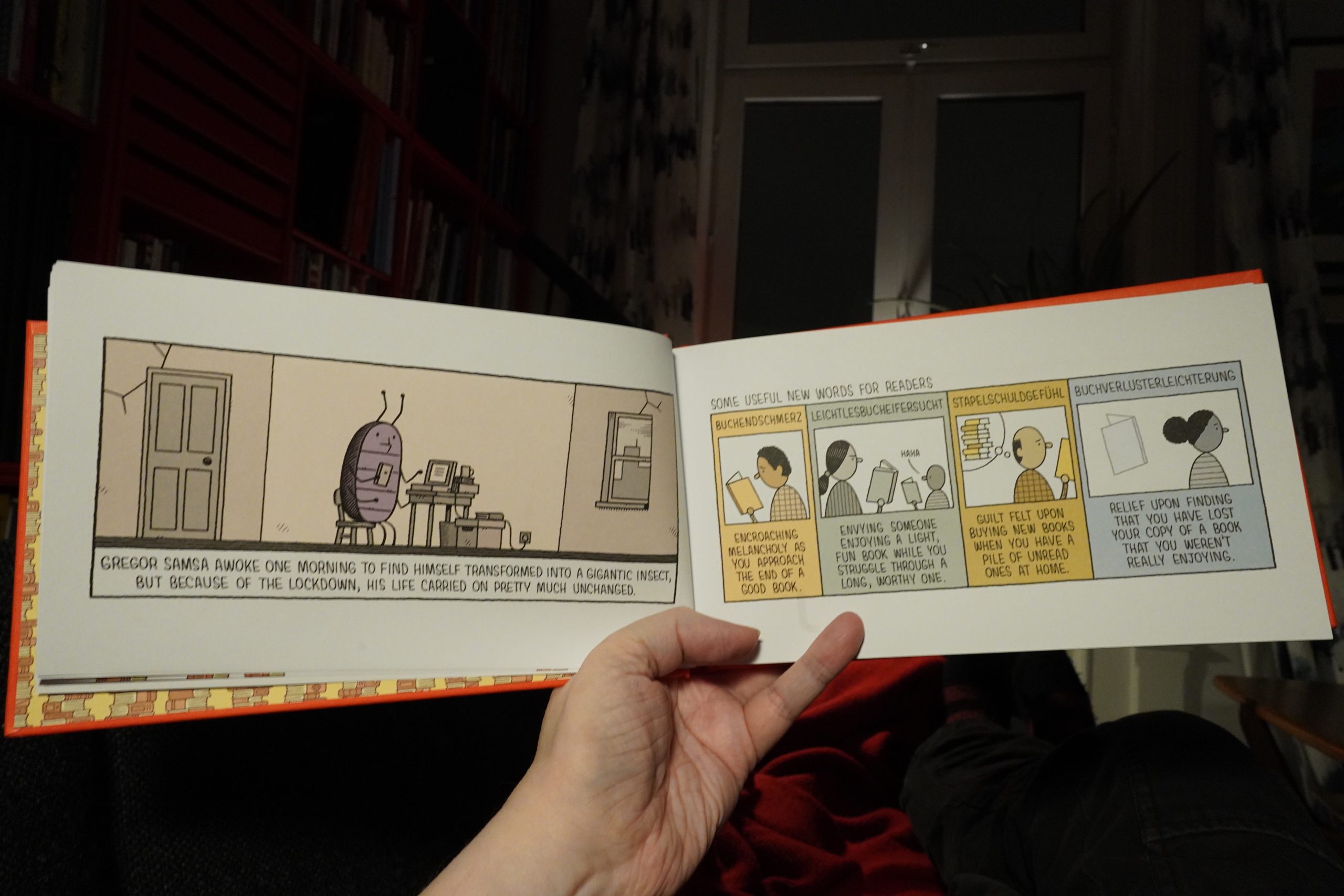

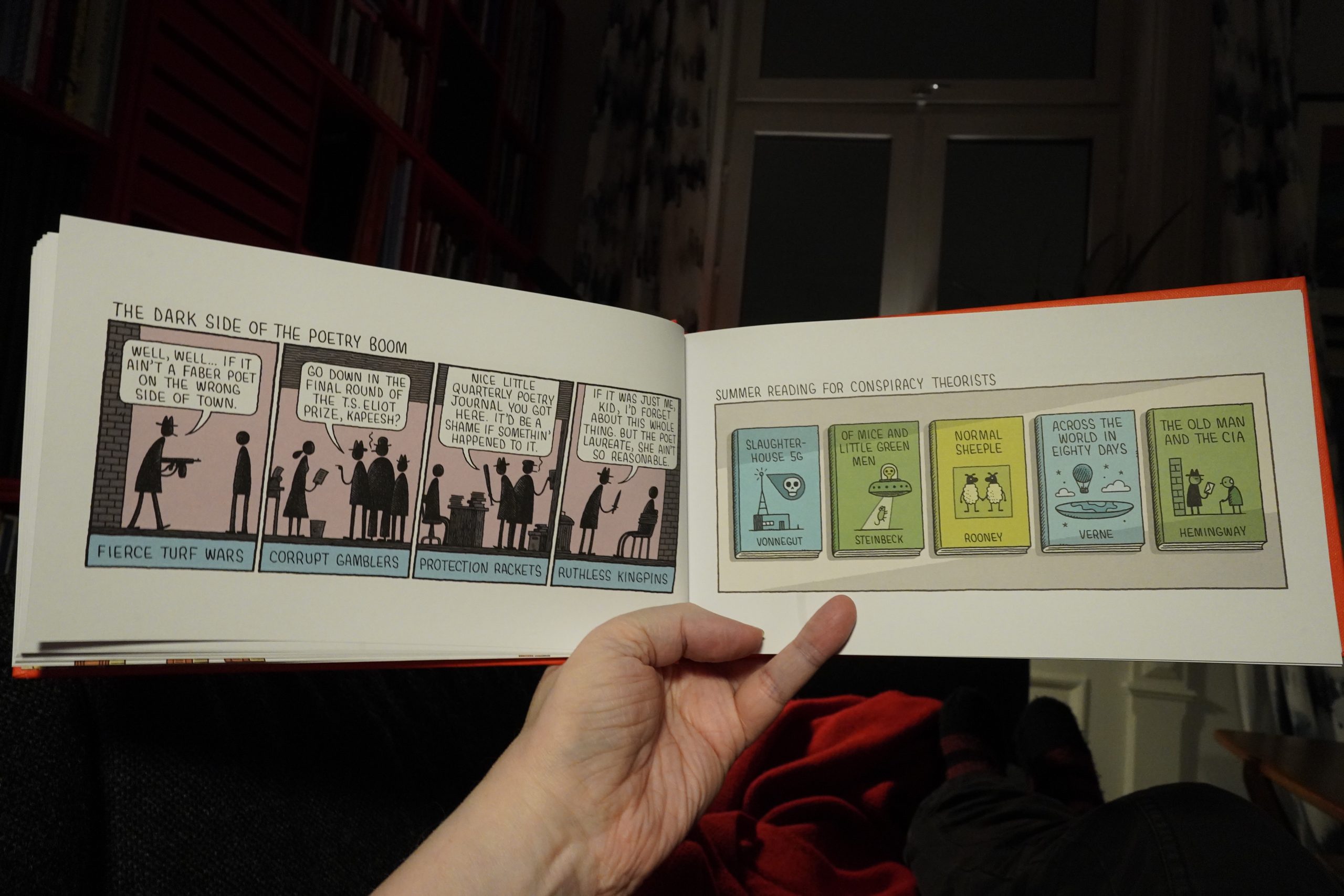

01:01: Revenge of the Librarians by Tom Gauld (Drawn & Quarterly)

I’ve only got a couple of Gauld collections, because I’m not really into gag strip collections, and Gauld’s can veer into the smarmy a lot. But I thought I’d check in for once…

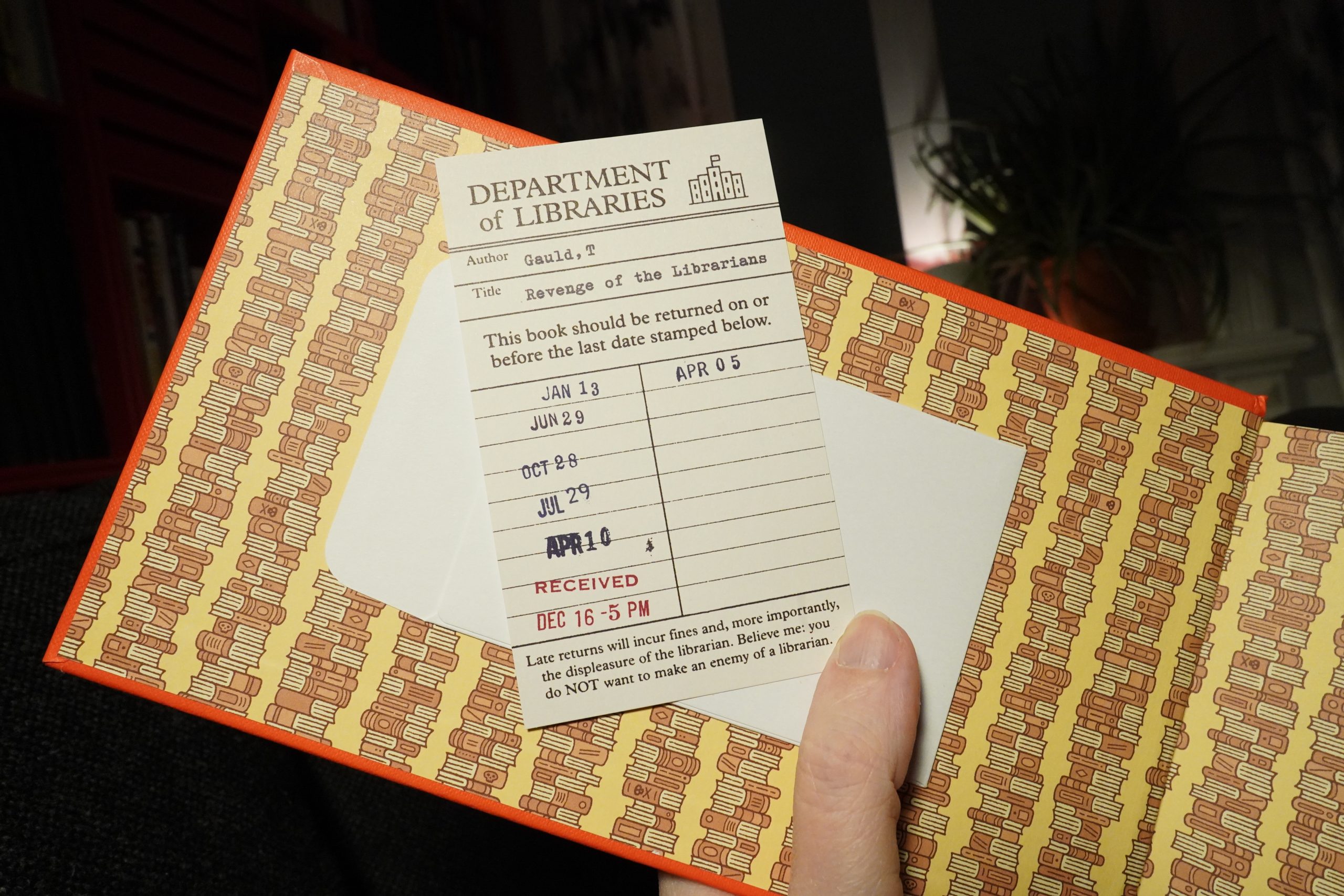

Heh, there’s a fake library card in here… nice.

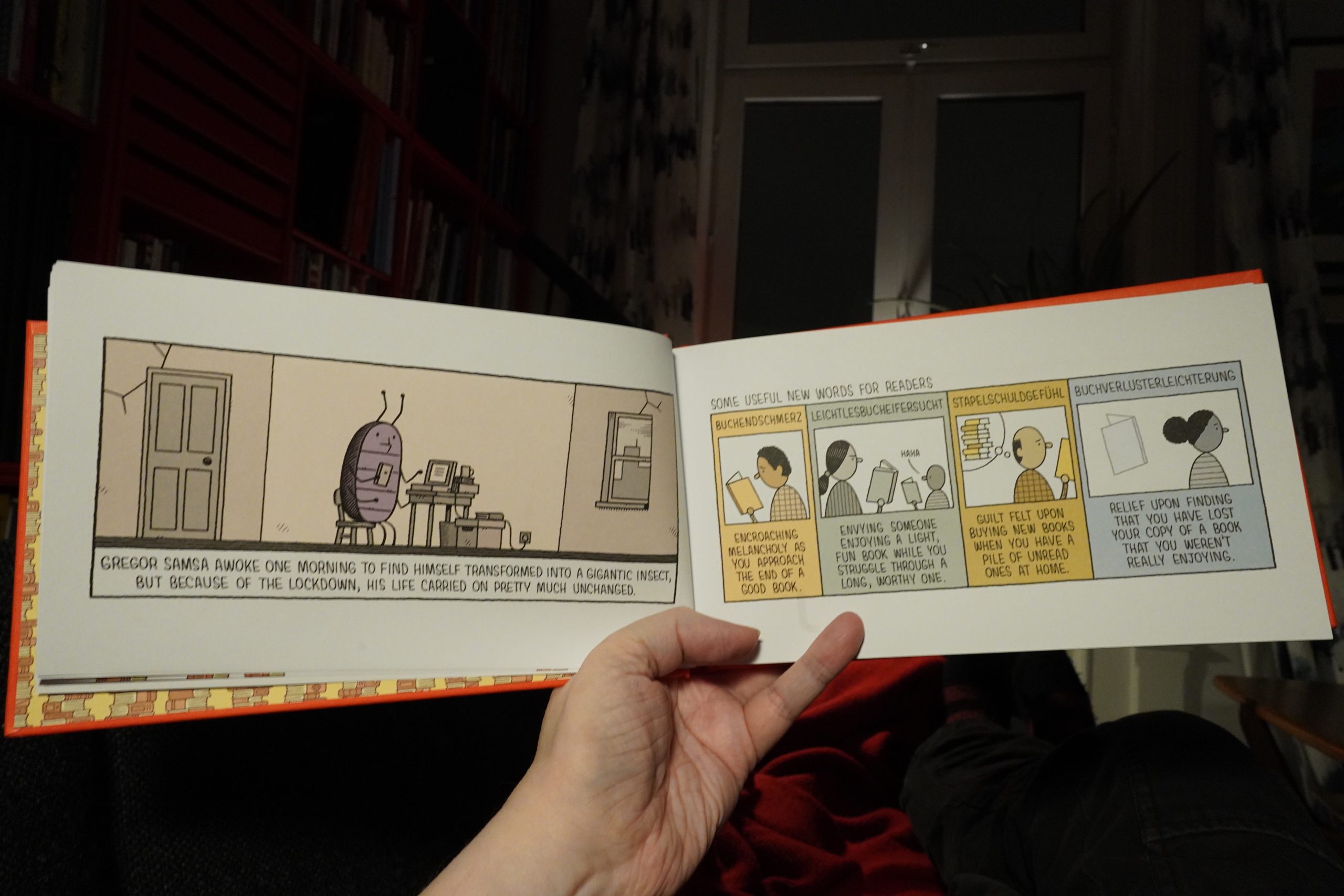

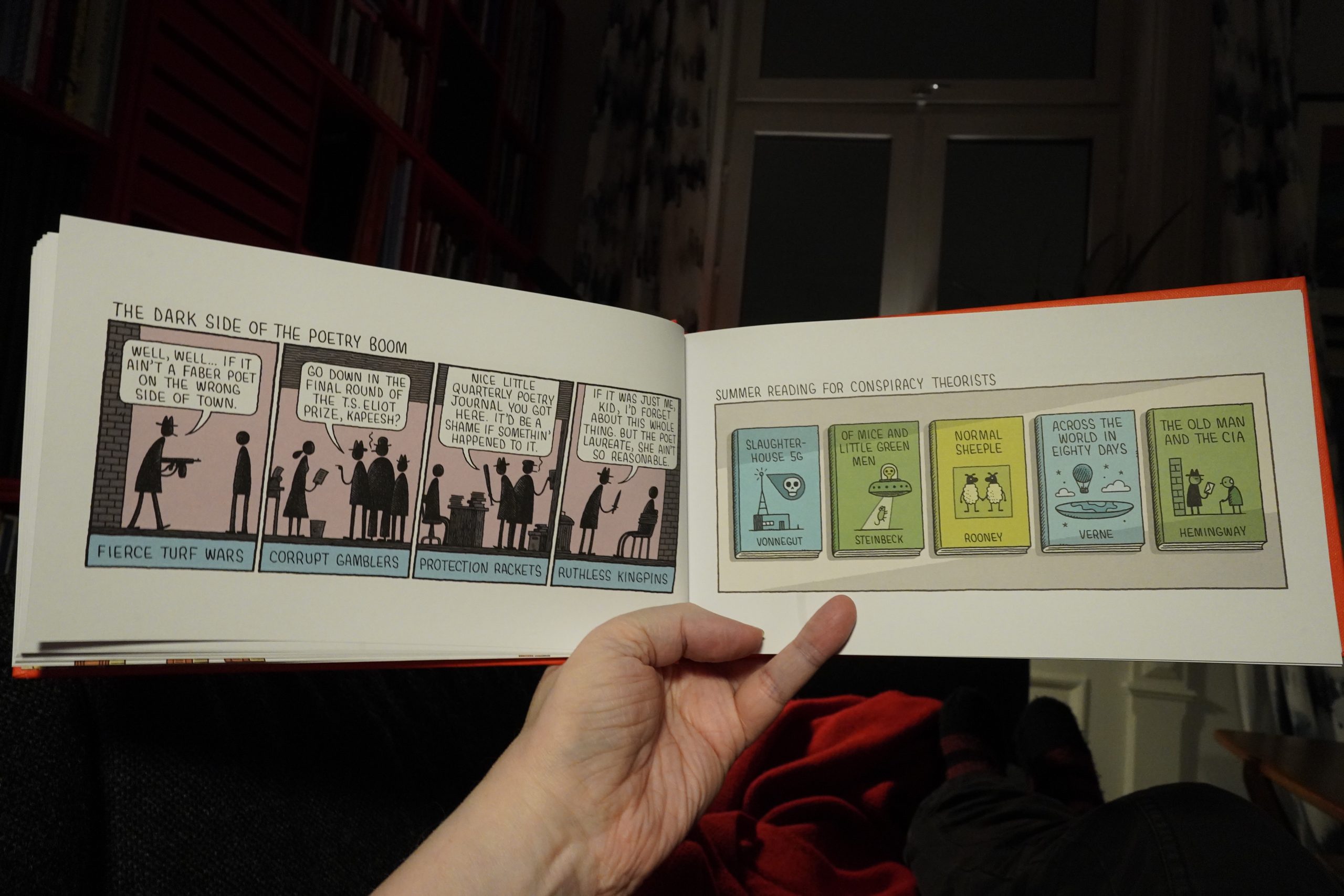

But indeed, it’s like I remembered. It’s not that these are bad jokes on a gag strip scale, but they’re still not actually funny.

Half the strips seem to be designed to make people go “that’s a reference I recognise” (and I do, but I don’t find that automatically to be hilarious), and the other half are basically “you must be a smart person who likes books. Yes you are! You’re so smart! Yes you are!”

And I don’t mind a book pandering to me as a reader, really, but it’s grating coming one after another in this way. So I ditched the book one quarter in.

01:14: The End

And now it’s time to go to sleep, perchance to rub.

)

&album=Wheel+Me+Out+(Long+Version))

)

)