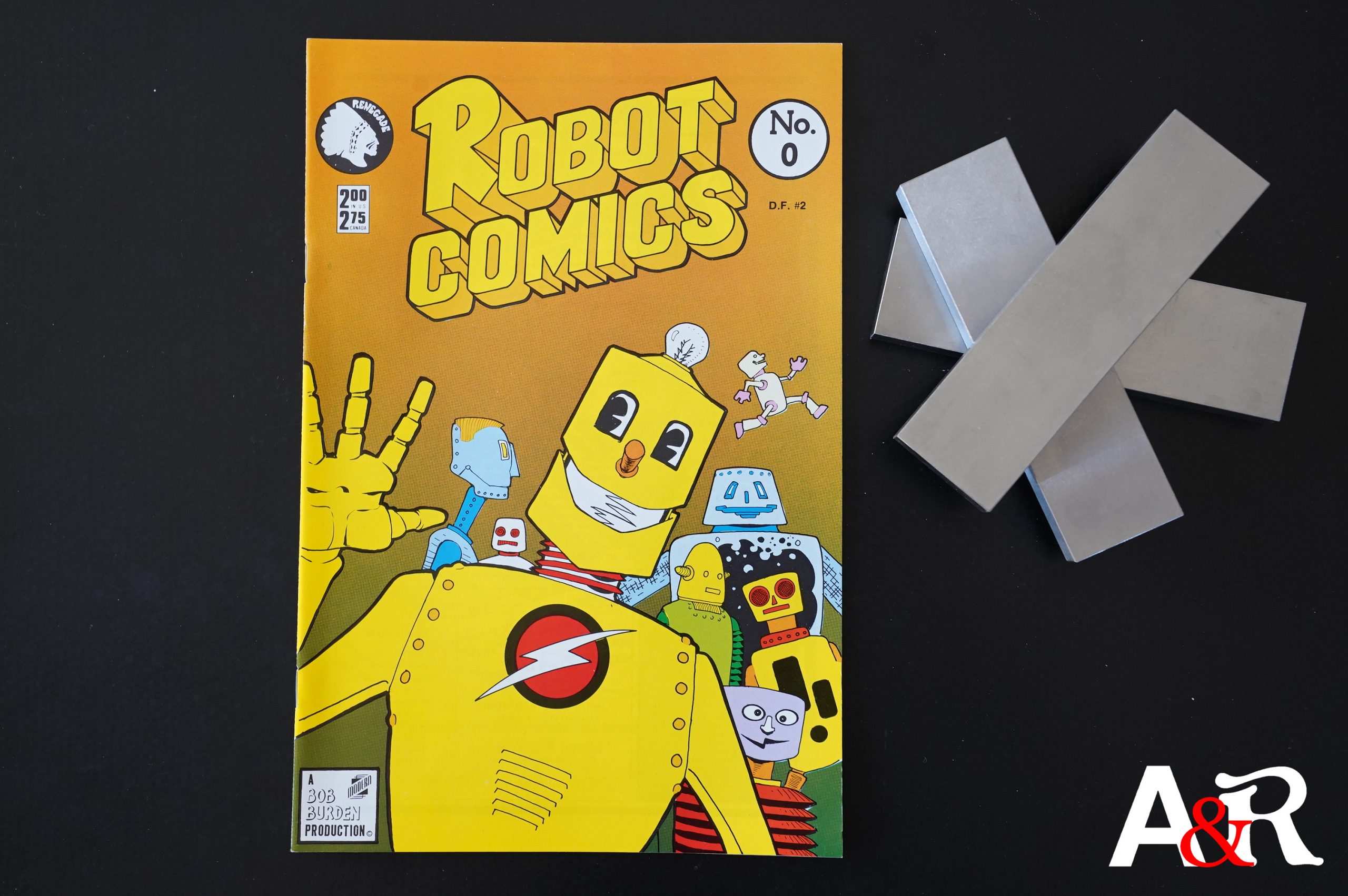

Robot Comics (1987) #0 by Bob Burden

Burden is, of course, most famous for the Flaming Carrot series, also published by Renegade.

This is apparently a reprinting of a comic Burden had done in 1981. “Elecra-Fiction” is the name of the genre. Let’s read the opening spread:

OK, so it’s prime Burden lunacy. The entire issue is just one big fight scene in this bar, which gives Burden room to come up with a joke in just about every panel.

That one made me laugh out loud, for some reason.

It’s very funny! I also like how the general lunacy is also reflected in the layouts… and Burden’s unique rendering has probably never looked as good as here?

Burden saw his early comics as being part of a series: Draconian Features, and Flaming Carrot was the first one, Robot Comics was #2, and there was supposed to be a Sponge Boy Comics and a Disco Detective. According to comics.org, these comics never happened.

Robot Comics #0 is a new one-shot

written and drawn by BOB BUR-

DEN, featuring a single story,

“Robot Nite,” in which robots swing

and bop, among other things.

Premiering in June, it’s part’ of

Burden’s new “Draconian Features

Zero” series, each issue of which

will have a different title and be

numbered A). The original naming

Carrot #1 published by Burden’s

Killian Barracks Press is now retrcy

actively being considered as the first

“DFZ” issue, and should therefore

technically be considered as Ham-

ing Carrot #0 ‘even though, as

“it says #1 on the

Burden notes,

cover.” Robot Comics is thus

Draconian Features Zero #2, etc.

Asked to explain why “Draconian

Features,” Burden explained: “The

whole concept of draconianism is

this: out of a draconian measure is

born a society. Out of harsh laws is

where civilations and peach comes

from.”

Right.

The Comics Journal #268, page 137:

DEPPEY: There was a manic weirdness to Robot Comics, which you did

With Renegade —

BURDEN: — which was almost kind of like a rock video. I did that

thing, and that was a big turning point with me. It was experimental.

I wanted to see how far I could go without a story, just making it up

as I went along. I had just done Flaming Carrot #1, which was an

attempt to carry a full issue and a longer storywith the character. The

first three episodes of Flaming Carrot were little eight-page vignettes,

hit-and-run.

With the oversized No. 1 1 did in 1981, it was a full-fledged sto-

ry. and it turned out pretty well — it had a wrap-up at the ending and

everything like that. But there were some problems with it. When we

premiered it at the Atlanta convention, I didn’t get the bang I expect-

ed. So I said, “l can do something better than this.” So, I sat down

and I started really going nuts with Robot Comics. I knocked that

thing out the very night I got home from the convention — that very

Sundaynightand I started working on the “Robot Nite” story. I just

went to town with it. The issue just started flying out of my mind and

I just started puttingdown on the page. This was like 1981. It didn’t

getpublished till years later. The original artis now dog-eared and

worn. I used to carry the art around in my car and show it to people

and go, “Isn’t this weird? Look at this crazy thing I did. I mean this is

the craziest thing.”

DEPPEY: It does read as though you were making up the Story panel-by-

panel as you went.

BURDEN: And it has sort of a faux-ending; it’s got an ending, but it’s

more ofan epilogue more than a real ending.

The Comics Journal #119, page 48:

I was pleased to discover that

Renegade had published Robot Com-

ics K). Burden’s Flaming Carrol Com-

ics has developed a following during

its run as a Renegade comic—and

many issues have presented Burden’s

zonked•out sensibility in its purest

form. Burden is an adventurous talent,

though it’s never been exactly clear

how he would use and develop his

talent within the parameter Of the

comic book industry. Robot Comics

reveals the early Burden at his most

audacious and experimental—an un-

bridled anarchist generating his own

brand of dad havoc—while Comico’s

Gumby •s Summer Fun Special shows

Burden adapting and using his skills

to engineer a pleasant return to the

dream world of childhood fantasy.

writes in The Comics Journal #119, page 47:

Robot Comics is a surrealist vi-

Sion of barroom Americana. a succes-

Sion of bizarre, unrelated images that

flow with the internal illogic ofa dada

poet’s dream. Item: during the height

of the festivities, one panel features

Orson Welles in his Harry Lime get-

up from The Third Man passing a tat-

tered package to the “banjo mummy.”

while the next has “Uncle Billy”—

who, moments earlier, put a pie crust

on his head and declared himself “The

Ghost of Christmas presents”—now

playing “meatloaf football” with the

robots who have invaded the premises.

The anti-story reaches a climax

when, among Other things, a “space

monster/super cancer” invades the

body of a robot and electrocutes itself

and a probate lawyer is “hung from

the rafters following an ad hoc

plebiscite.” This comic book}dada

poem concludes with an image that is

a fittingly macabre apotheosis of all

that precedes it. At sunrise, figures

“bury the dead (and some of the

wounded)” on the grounds of the

Dixie Twi-Life drive-in movie. It’s an

eerie, apt, funny, nonsense conclu-

sion: America’s lowbrow pop culture

dreams begin and end at the drive-in.

It’s the 722nd item on Tom Spurgeon’s list of things to like about comics:

722. Robot Comics

This blog post is part of the Renegades and Aardvarks series.