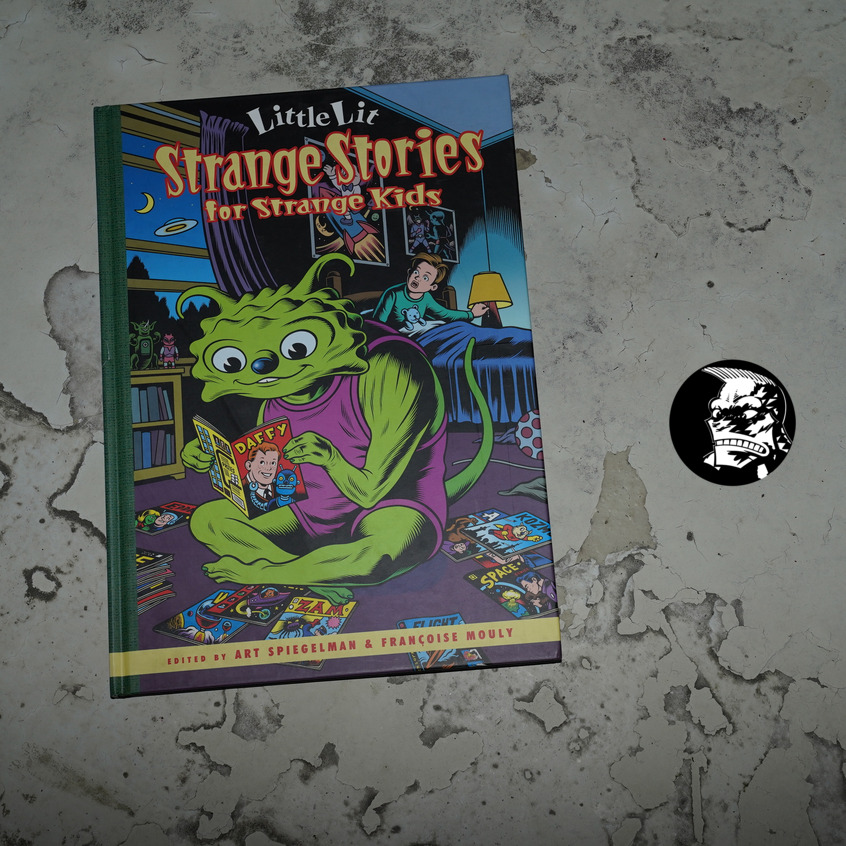

Little Lit: Strange Stories for Strange Kids edited by Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly (242x340mm)

The first Little Lit book wasn’t… very good, and this one doesn’t even have Chip Kidd as a co-designer. So let’s have a look.

Heh, that’s pretty good… (Kaz.)

That’s not bad, either. (Art Spiegelman.)

There were quite a few of these activities pages in the first book, but only one here. (Martin Handford.)

OK, this is much better than the first book. (Ian Falconer and David Sedaris.) The pieces here are generally longer, more inventive, and things that I can see actual kids would actually enjoy. And that makes for a better experience for us childish adults, too.

Perhaps it was the fairy tale theme that messed up the first book?

It was difficult to find anything in the first book that actually worked well, but basically everything here’s either fine or very good indeed. (Claude Ponti.) There’s a great variety in the approaches, from the formal play here…

… to the straightforward storytelling in Posy Simmond’s story.

The book reprints a bunch of oldee things from famous illustrators, like Jules Feiffer here, as well as Maurice Sendak and Crockett Johnson. I guess these are just things Spiegelman really enjoyed… but they’re not the strongest pieces in the book.

Nice. (Kim Deitch.)

The Crocket Johnson thing is pretty cool. Gotta love the Futura.

Lewis Trondheim does a very playful thing where you have to choose your way among branches.

And finally, Loustal and Paul Auster does… er… uhm… Well, it’s a good story, but it feels very out of place in this book.

So! That was a really good book, which I didn’t expect after suffering through the first one.

Ng Suat Tong writes in The Comics Journal #244, page 38:

With the success of the first Little Lit

volume, immaculate reputations, money,

a good publisher and a sizeable contact

list, Spiegelman and Mouly had one

potential stumbling block when it came

to editing the second volume of their

children’s comics anthology. The ability

to truly “edit,” to chop and to cut and to

refuse without severely offending. In

essence, do you ask Paul Auster and

Jacques de [nustal to contribute some-

thing and proceed to tell them that their

story is average and really not a very good

children’s story? Do you ask an old

friend, a distant contact or an artist

whose merits equal or exceed your own

to remove, redraw or otherwise com-

pletely alter a story which he has worked

long and hard on? Was it within the abil-

ities of Spiegelman and Mouly to edit,

strongly direct and advise on their con-

tributor’s works? Did they even the

chance to exercise this ability? I

know. If they have had this opportunity,

then their collective “taste” is wholly cul-

pable in the debacle that is L;ttle Lit:

Strange Stories for Strange Kids. If not,

they have knowingly succumbed to the

pitfalls of the “strong” contributor list.

The latter is the lesser of the two evils but

the editors remain guilty of producing a

very mediocre book in what can only be

described as the optimum conditions.

Let us begin with Spiegelman’s story,

“The Several Selves of Shelby Sheldrake, ”

a clear indicator that he is ill-suited to the

production of children’s comics.[…]

Any semblance Of an engaging plot is

suffocated by Spiegelman’s rough, unfin-

ished line and flat, frigid narration. His

desire to amuse his young readers With a

repetitive, claustrophobic explosion Of

imagery is both ill-judged and tedious.

Our eyes glaze over with disinterest upon

encountering each monotonous page of

this four-page offering.

Where Open Me — A Dog suc-

ceeded to a certain extent as an amusing

novelty book, Spiegelman’s children’s

comics are hampered by overportentous-

ness and his unwillingness or inability to

change his drawing style to suit his pur-

pose. His story in the first Little Lit

(“Prince Rooster”), for example, replaced

fun and excitement With unleavened les-

sons for the day. One does not question

the right of an editor to include his own

stories in his own book, but I do wonder

what hidden forces compelled him to

place his middling stories at the forefront

Of his collections not once but twice. The

utter lack of insight in this respect from

someone so experienced is astonishing.

More importantly, Spiegelman

should eradicate his delusions of

grandeur about producing comics for

children in a day and age when no one is

producing comics for children.

Spiegelman and Mouly appear to have so

distanced themselves from comics in the

intervening years since the publications

Of Raw and Maus that they no longer

have a feeling for or knowledge of the

various delightful children’s comics that

have surfaced in recent years.

As if to prove my point, the pair of

tales that bookend Little Lit II are an

example of the worst kind of children’s

comics. The calamitous closing tale

(“The Day Disappeared”) is by two

otherwise exceptional talents, Paul

Auster and Jacques de Loustal. It is a

metaphorical tale of how a man loses and

then finds and saves himself in the course

of a day. Auster stubbornly refuses to

abandon his roots in existentialism and

adult fables for the sake Of a “mere” chil-

dren’s comic and Loustal, for his part,

struggles gamely along, creating art per-

fectly compatible with Auster’s very dour

purpose. In truth, Loustal cannot be

blamed for his writer’s ultimately disas-

trous foray into the realm Of the gravity

laden children’s Story. As a fairy tale for

adults, “The Day I Disappeared” is

remarkably shallow compared to any of

Auster’s existentialist tales in The New

York Trilogy and yet almost certainly

beyond the comprehension of young

children. It lacks the swift movement of

plot requisite of childretfi stories and fails

at every turn to produce the careful and

uncluttered delineation of emotions,

replacing this with drawn out, silent,

morose exposition.

In truth, the distinguished contribu-

tor list of Little Lit II is nothing more than

a mirage; a whispered hope and a ceaseless

dirge that masks the tepid quality of the

book. Jules Feiffer, a wonderful writer and

artist, produces a story that I would not

put beyond the worst Of Mantel hacks.

One does not suspect some sudden emas-

culation of his artistic prowess but a fail-

ure to undertake a proper and recent

review of children’s comics and literature.

“Trapped in a Comic Book” is about a

child who encounters and annoys a car-

toonist only to be sucked into the very

comic the cartoonist is drawing. Feiffer

adopts a tonal dot pattern to indicate that

we are deep within a comic page, blowing

up the printing deficiencies of the four-

color world of comics. It is a deadly com-

mon trick — which is not a criticism in

itself, since it •would be too much to ask

every artist to create elements of daring

innovation every time they produce a

new comic. Yet Feiffer’s art is inadequate

to the job Of conveying the fantasy he

means to communicate. His harried

linework (so essential to the meter Of his

cartoon strips) has a severe distancing

effect here in view Of its lack Of clarity

both narratively and figuratively. It is a

defect further exacerbated by the flavor-

less narration ofa trite plot.[…]

Some of the other editorial choices

also help to lift Little Lit II beyond the

zone Of death. Richard Maguire produces

a technically interesting “Can You find”

activity page filled with twisted shapes

and unusual perspectives. Lewis

Trondheimk amusing cartoon maze is a

few minutes of harmless entertainment

Which is bound to generate more neural

connections in the minds Of young chil-

dren, and Roca makes a good, if

somewhat traditional, account Of himself

With a surreal “Can you Spot the

Mistakes” page. Claude ponti also deliv-

ers the goods in his pleasantly related

story of “The Little House That Ran

Away From Home,” a tale filled with

touching pictures ofa house weeping and

other worldly Dr. Seuss-like creatures

collecting “happy sounds” and “smoke-

plumes-that-rise-in-the-distance. ” To cap

all this Off there is a well known intro-

ductory tale from Barnaby which appears

to be slightly edited When compared to

the first Barnaby collection published by

Henry Holt and Company.

Only time will tell if the series has

sufficient weight to generate the clouds

of nostalgia that inform an appreciation

of a Barks Duck story, a Stanley Little

Lulu or a Lee and Kirby story from the

Silver Age. I would suggest, however,

that one hardly needs to journey to the

island Of Patmos to discern that Little Lit

Will not be looked upon (if at all) With

kindness in ten years’ time.

Children are not a very demanding

audience but they are terribly exacting in

their requirements. In the case Of Little Lit,

Spiegelman and Mouly have subscribed to

the ultimately false and Kitile values of

choosing the most “name” artists they

could muster in order to produce a chil-

drenk book Which is, simply put, merely

lukewarm water meant to be spat out.

They have declined to look beyond an

artises past laurels and hence blinded

themselves to those with less prestige but

proven abilities in a combination of both

comics narrative and the childrer* story.

This is ultimately the path of safety. There

is a sense of security inherent in such a

position; a feeling of warmth and comfort

in the nebulous cloud of quality inherent

in the flock of “names” surrounding your

project. But it is not necessarily the path

to artistic success. With all the resources

eminently at Spiegelmank and Moulis

disposal, no excuses are sufficient to justi-

6′ such a failure.

I think he didn’t like it? But he did like the first book?

Well, OK!

This blog post is part of the Punk Comix series.