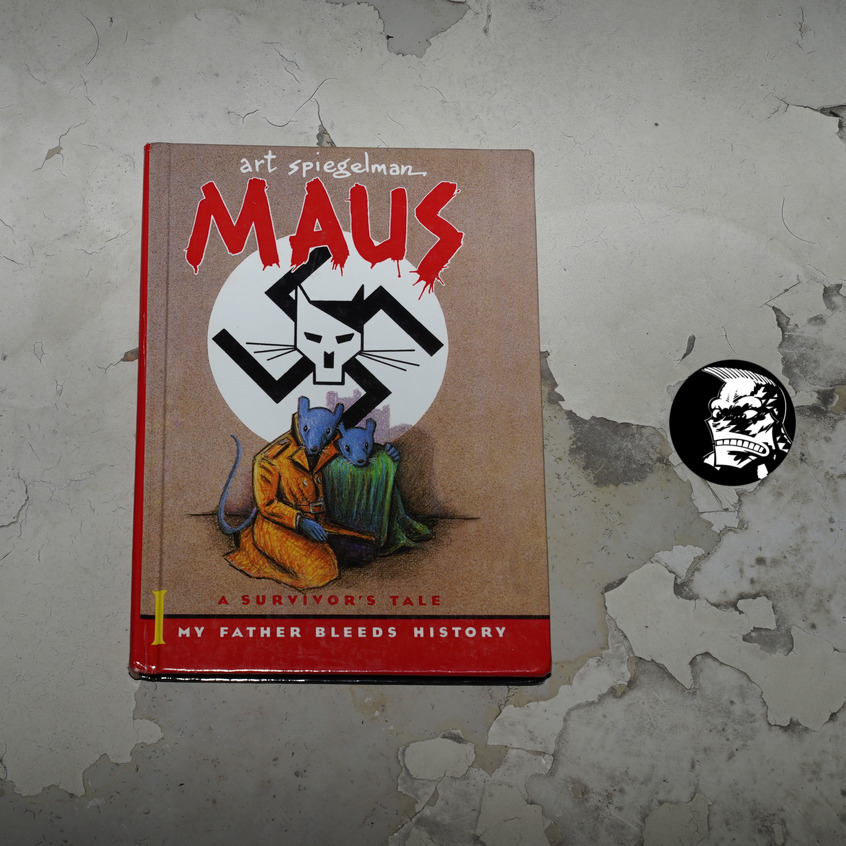

Maus I: My Father Bleeds History by Art Spiegelman (mm)

This is it: The pivot point in this blog series. You may not have thought so (if you’ve been reading a few of these blog posts), but there’s a kind of loose structure going on here. I wanted to divide the series into a “before” and an “after” part, and Maus I is where things change. (That I’m buying more stuff from ebay confuses the picture even more, so er sorry?)

Anyway! This is the most important single comic book in the history of comic books.

I don’t mean that as an aesthetic judgement or anything, but just an impartial observation.

This was the first comic that showed the normal, non-comics-reading audience that there existed some comics worth reading. (And for two decades, it showed that audience that there was exactly two comics worth reading: Maus I, and Maus II, and that didn’t change until Fun Home was published in 2006, and after that, the floodgates opened.)

This is when art comics went from being a punk, underground thing to being something that normal, well-adjusted, educated and/or rich people would buy (and read). In principle.

I remember visiting a couple in Manhattan a few years ago that owned an entire house on the lower east side — it was totally gorgeous; smart and interesting people. And in their bookcase, filled with Pulitzer prize novels (think Philip Roth and John Updike) and art books, there were the two red spines of Maus I & II, and absolutely no other comics: Among a certain class of people, these are still the only two comic books that are worth reading.

Maus I led to all the major publishers, all over the world, going “there’s a market here”, and for a couple of years, they all published “comics for adults”… and nothing else sold to a general audience other than Maus, and they all shut down that thing fast.

But, I think, it made the world aware that reading a comic was, like, possible, and I don’t think the post-2006 comics history would have been possible without Maus I opening some doors. These days, the New York Review are publishing comics, and The Paris Review are interviewing comics creators.

Before this blog post, most of the comics covered were either self-published or published by various oddball art publishers. The rest of this blog post will be dominated by comics published by the big, mainstream book publishers. (I mean, modulo what I’m finding on ebay…)

I didn’t actually own this book back in the 80s: I had read the booklets included in Raw, and I got a collected edition decades later, so this is the first time I’m reading the Actual Book.

This turns out to not actually be The Actual Book — this is (re)bound by Turtleback Books, and was published after Maus II had been published… so… sometimes in the mid-90s? Darn those ebay peeps.

Does this mean that I have to find an actual early edition… My CDO is acting up… let’s see what happens…

And does that line of 75 … 71 mean what it usually does? That this is the 71st printing of Maus I? It sounds in-credible, but… I tried googling how many copies of this has been published (by Pantheon), but I’m unable to find any numbers. So…

There’s been a buttload of translations, though — that page lists more than a 100 different editions.

The first few chapters here have been redrawn from the original booklets in Raw, making the artwork more consistent.

The lower left hand corner panel now seems more than a bit funny.

You may find this mixture of telling the reader about the making of the book they’re reading kinda cutesy? I think it works brilliantly — it’s not just a gag; it gives us some breathing space between the pages of heartbreak from Vladek’s story.

His incredible daring and intelligence…

… and at the same time being the most exasperating parent ever.

But you’ve all read Maus, so I’m not going to natter on about it. And I’ve read this already once over the previous months in serialised form, and I was wondering how it read in book form… You read some serialised works and it’s WOW and then it’s collected and it’s “eh?” Loses some of the magic in book form?

That’s not the case with Maus. It was really flabbergasting reading it as inserts in Raw, and it’s still a punch to the stomach to read it in book form.

I love reading take-downs of books that I love, so let’s look at the only negative article I can remember seeing about Maus, and this is from 1986. Harvey Pekar writes in The Comics Journal #113, page 54:

Spiegelman diminishes his book’s inten-

sity and immediacy by representing humans

as rather simply and inexpressively drawn

animals—Jews as mice, Germans as cats,

Poles as However, the animal metaphor

is ineffective because this single element of

fantasy is contradicted by Spiegelman’s

detailed realism. For instance, he uses the

real names Of people and places; i.e., a mouse

named Vladek Spiegelman lives in the

Polish town of Sosnowiec, wears human

clothing, and walks on two feet.

The animal metaphor also perpetuates

ethnic stereotypes. Spiegelman generally

portrays Jews as prey (mice) for the Germans

(cats). However, he shows some Poles tak-

ing risks for Jews, yet insultingly pictures all

of them as pigs.

Art’s narrative sometimes rambles and

bous down, partly because he is preoccupied

with making Vladek look bad. Using a sub-

plot involving contemporary sequences is

good idea, but in them Art denounces his

father as a petty cheapskate and tyrant far

more Often and predictably than is neces-

sary. This distracts attention from the Holo-

caust story, clamorously interfering with the

elevated tone of Vladek’s reminiscences.

One might think Spiegelman dwells on

his father’s faults to illustrate the terrible

mark the Holocaust left on people. How

ever, he quotes Mala, who also ‘ ‘went

through the camps” as saying that no Holo-

caust survivor she kne.v was a heartless

miser like Vladek. A complex person With

contradictory characteristics, Vladek isn’t

portrayed clearly in Maus, but perhaps the

next volume will allow us to understand

him better.

Spiegelman’s prose is sometimes stiff, but

this problem is largely overcome by the rich

material he presents. He does not attempt

to sensationalize information already so evo-

cative, but lets his father speak of his

Holocaust experiences simply and With dig-

niry, creating a work historically significant

and often moving.[…]

I hold to the opinion that Maus is overall

good and a significant work, primarily,

because of Vladek Spiegelman’s moving and

informative narrative. That seems obvious.

It seems equally obvious to me that Art

Spiegelman has done some things in Maus

that are less than admirable, and I have

heard some criticism of the book expressed

privately but for some reason people seem

reluctant to go on record in print about its

defects. Perhaps the serious tone of Mates

and its subject matter cows them. Howard

Chaykin, who has a reputation for being

outspoken, seemed on the verge of saying

something “pejorative” about Spiegelman

during a recent Comics Joumal interview but

asked that the tape recorder be turned off

at the crucial moment. A gentile comic

book fan suggested to me that some people

might be reluctant to criticize Maus for fear

of being called anti-Semitic—that’s under-

standable these days when right-wing Jews

accuse left-wing Jews Of being “self•hating

Jews,” their definition of a self-hating Jew

apparently being any Je.v more liberal than

Ariel Sharon.[…]

Questions occur to me in this regard, such

as why, if Spiegelman is so offended by

brutality, he prints such violent, ewen

sadistic, stories in RAW as am a Cliche,”

“Tenochtitlan,” “Theodore Death Head.”

and “It Was the War Of the Trenches.” I don’t

criticize him for doing this; I merely point

out that it seems inconsistent with his state-

ment abhorring inhumanity in the Louis-

Ville Times. (These stories, incidentally, con•

tain human characters, not cats and mice.)

The major defect in Maus, one that is far

more disturbing than the use Of “animal

metaphors,” is Spiegelman’s biased,

sided portrayals of his father, himself, and

their relationship. Some reviewers of Maus

have come away with the impression that

Art is the hero of the book and Vladek the

villain. Let me, for example, quote from

Laurie Stone’s Village Voice review. “Spieg-

elman’s finest, subtlest achievement is mak-

ing Art’s survival of life in his family as

important as Vladek and Anja’s survival of

the war… It doesn’t dawn on Vladek that

his tyrannies are a mouse-play of Nazi ter-

rorism; nor does he question why Anja

lived through Auschwitz but not her mar-

riage to him… The irony that the Holo-

caust alone gave Vladek a chance to be

brave and generous—to rise above his small-

mindedness—isn’t lost on Art… Spiegel-

man understands that Hitler isn’t to blame

for Vladek’s and Anja’s personalities. Long

before the war Vladek was wary of other

people and Anja nervous, overly compliant

and clinging—she had her first nervous

breakdown after the birth of Richieu.

Vladek and Anja don’t recover from their

lives, but their son does. He lets his parents

live inside him in order to let them go. And

detachment has served this brave artist

ceptionally well.”

I disagree with Stone’s interpretation,

especially assuming it is based solely on

evidence presented in Maus. For one thing,

there is very little meaningful material about

Anja, always a subsidiary character in the

book. To blame her suicide on Vladek, or

Art, for that matter, as One of the family

friends does is to jump to conclusions with-

out sufficient evidence. Perhaps Art can give

us more facts in Maus’s second volume to

clear things up, but until then there’s n0

point in jumping to conclusions, especially

as Anja’s mental breakdown in the 1930s

occurred at a time when she was seemingly

getting along with Vladek.

I also would question whether Art is as

noble and Vladek as base as Art apparent-

ly would have us believe. I see Art in Mates

as a guy going after a big scoop who cares

less about his father than his father does

about him. Why is Art finally visiting

Vladek after two years, though both live in

the same city? Is it because Vladek has had

two heart attacks, lost vision in one eye, and

Art wants to comfort him? No. it’s because

Art wants a story from him. That is clearly

demonstrated in the book. Art shows

Vladek asking him to leave information

about his bachelor lovelife out of Maus, say-

ing that it has nothing to do with the Holo-

causti Art protests but Vladek holds firm

so Art promises he won’t use it. But, Sur-

prise, it shows up in the book anyway.

Did Stone notice this occurrence involv-

ing her “brave” artist! The reason I men-

tion it is not to question Art’s ethics, which

are of no concern to me, but to point out

that it and other things make me doubt

whether Art’s portrayal of his father is

accurate.

It’s easy for American Jewish writers to

parody their European-born parents,

especially if they’re old and sick like Vladek.

I’ve done it and it is often justifiable because

someof them have less than admirable char-

acteristics. However, in a parody, readers

recognize that distortion and exaggeration

are involved in order to draw attention to

these characteristics. people are So holy

that they can’t be parodied or kidded. Mat’S,

howe.’er, is presented as a “serious,” realistic

work that attempts to portray characters in

a multidimensional manner. Why then is

Vladek routinely shown to be a crazy, pet-

ty, tyrannical miser at both the beginning

and end of two-thirds of Maus’s chapters

(the third, fourth, fifth and sixth)! At the

beginning of the second chapter Vladek

isn’t counting his money but he is counting

his pills—there’s another metaphor for you.

What’s the reason for this overkill? Is

Spiegelman afraid we’ll miss the point about

his feeble old father, that we might overlook

two or three incidents of Vladek’s cheapness

so that ten must be cited? The malice in

Spiegelman’s portrayal of his father is so

obvious to me, despite the fact that Spieg-

elman tries to veil it, that I question his

ability to portray Vladek accurately. Is

cheapness Vladek’s only qualityd

I am a Jew with a background similar to

Spiegelman’s. Many of my relatives died in

the Holocaust. My parents, uncles, aunts,

and some Of my cousins were born in

Poland. Furthermore they came from small

towns and probably would seem unsophis-

ticated and puritanical to most Americans

ewen by comparison with Spiegelman’s pap

ents. Spiegelman’s father owned a factory;

my father was literally a teamster, driving

a horse and wagon for a living, picking up

grain from farmers and taking it to mills to

be ground into flour. My folks were tight

with me about mone,•; it seemed that I had

fewer toys than everyone else, that my

clothes were older, if not hand-me-downs.

I resented my parents; they were trying to

raise me as their parents had raised them.

They didn’t realize treating urban American

children as if they were living in a Polish

shtetl could result in serious problems. They

didn’t understand and I didn’t realize that

they didn’t until a lot Of damage was done.

But if Eastern European Jews like my

parents didn’t provide their kids with a lot

of toys that seemed worthless to them, they

good about other things. If possible

they made sure thgir kids had good health

care and ate well and they sacrificed so that

their children could go to college. They tried

to be good parents but often didn’t know

all that being a good parent in America

involved.

I have the feeling based on the informa-

tion in Maus, which is all we readers have

to go on, that Art deliberately tried to make

Vladek look bad, yet there are scenes in the

book where Vladek does show concern for

his son, despite Art’s intentions. For ex-

ample, once befuddled Vladek throws out

an old coat that Art’s been wearing, cone

sidering it shabby, and offers him another

one which he believes is better. Art has a

fit, accusing the old man of treating him like

a kid. L imagine most people sympathize

with Art during this scene, especially the

way it’s presented, but is what the old man

did really so terrible? Yes, he misjudged his

kid, something parents commonly do, but

Vladek was trying to help him by giving

him what he thought was a better coat.

What’s the big deal? Don’t gentile parents

throw out their children’s stuff too—even

their valuable baseball card and comic book

collections? Some mildly unpleasant things

have to be taken in stride because they’re

so common. It’s silly for a 35-year-old man

to blow up athis sick Old father an Old

coat.

Heh heh heh. I love Pekar.

There was much backlash.

The Comics Journal #116, page 78:

Further into the review, Pekar

says that he feels “that Art delib-

erately tried to make [his fatherl

look bad.” Here, especially, Pekar

presumes too much. First of all,

both father and son are shown to

be alternately compassionate and

reactionary; in other words,

human. Secondly, in reading

Maus, I gave the benefit of the

doubt to both Spiegelman and his

father. insofar as the passages they

share are personal reflections that

can scarcely be considered per-

fectly factual or entirely objective.

I have to doubt that the various

situations between them happened

as depicted. but to expect such

scenes to be anything but subjec-

tive is to miss the point entirely.

Pekar justifies his presumptions

by saying that lots of kids have

problems with their parents, so

what’s the big deal? When citing

a sequence in which Spiegelman’s

father throws out his son’s coat and

gives him one he thinks is better,

Pekar writes,’ “It’s silly for a

35-year-old man to blow up at his

SICK old ratner over an old coat:

It’s equally silly to presume that it

was simply the loss of a coat that

was the basis of Spiegelman’s out-

burst. I would venture to say that

it was more a matter of personal

respect, as well as the likelihood

that Spiegelman and his father

simply did not get along, and that

this was just another in a lifelong

series of mounting frustrations.

Edward Shannon writes in The Comics Journal #116, page 78:

Throughout his piece, Mr. Pekar refers to the

character Of Art Spiegelman as if he were One and

the same with Spiegelman the artist. Not only is this

impossible for us to know (as Pekar does admit), it

is completely beside the point! Although Spiegelman

uses his own name, he gives his readers a clue as

to just how closely he is identified with his character:

Spiegelman isn’t a mouse!

Indeed, the quality Mr. Pekar despises is the very

quality that makes the character Of Art, and the rest

of Maus. work. This quality is pettiness. Art, in the

story, is a selfish brat who cares little about what

his father has experienced except that it is useful

in his own work. In the same way, Mala and Vladek

do not try to understand each other and grab what

they can get out of their own lives—just as the Nazis

feared and hated the Jews for being different and ex-

ploited them for what they could supply.

Pekar and R. Fiore went into an endless discussion…

It started like this in The Comics Journal #132, page 43:

Now that you’ve all had time to digest

Harvey Pekar’s article in Journal #130

— and what a great, big, fiber-laden

chunk it was — it’s as good a time as

any to examine the stool. What it

demonstrates primarily is that, other

accomplishments notwithstanding, Pe-

kar is a lousy critic: slipshod in his

methods, weak on facts, given to shod-

dy reasoning even when he’s correct,

and largely motivated by envy of any-

one in comics he perceives to have a

higher reputation than his.

But what did Fiore really mean?

It went on for years.

Did somebody ever collect the entire discussion?

Anyway: Maus I: The comic book that changed everything forever.

This blog post is part of the Punk Comix series.