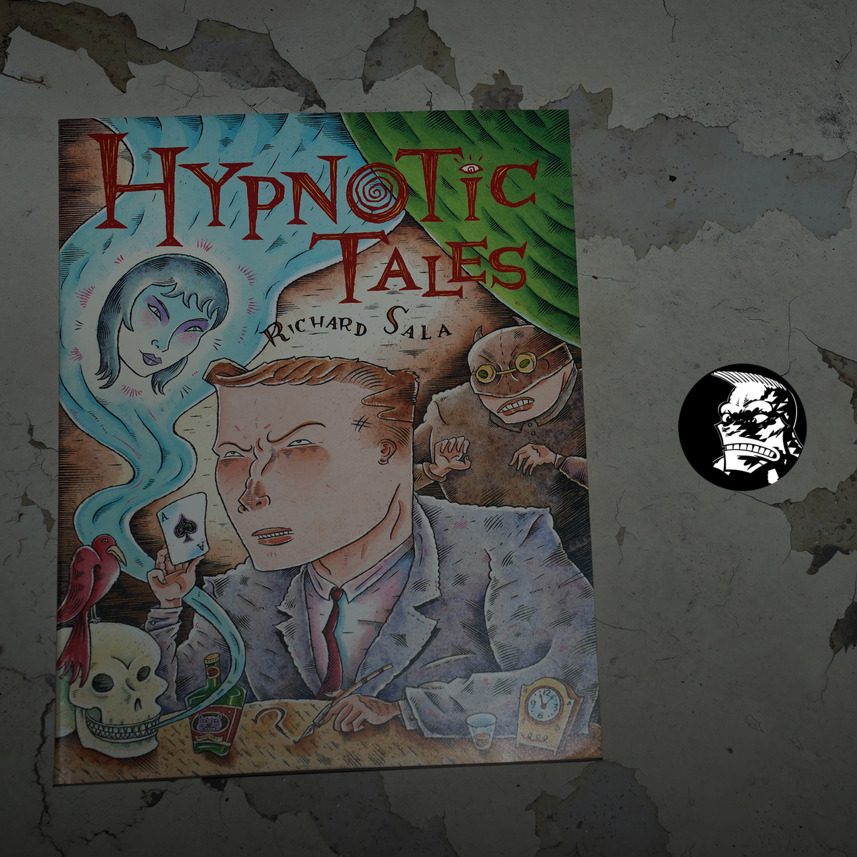

Hypnotic Tales by Richard Sala (213x276mm)

OK, I seem to be digressing from the putative subject matter of this blog series more and more… I originally planned on focusing hard on the Raw period of comics (so, 1978-89… ish), and the artists around Raw, really. I wasn’t going to do anything newer than 1990, and avoid artists more aligned with Underground/”alternative” comics.

But the time period thing is blown now, of course, and here I’m reading a Richard Sala book.

But! Sala was obviously influenced by people like Mark Beyer and Charles Burns, and he did appear in two Raw books, so while more aligned with the Blab/Fantagraphics crowds, it’s not that much of a stretch.

These are stories produced over the previous half dozen years for $ALL_THE_ANTHOLOGIES. Sala’s style was basically established before this, and he just refines it over the years.

Stumbling over one of Sala’s stories in an anthology was always a delight: The artwork’s super stylish, and the stories are short and punchy. (And usually pretty amusing.)

There’s so many … weird things in the stories. Here we have a guy obsessed with a woman, so he paints her into lots of famous paintings, and then he has to kill all the art critics so they can’t blab about the alterations. Isn’t that just amazing? I mean, coming up with a plot that convoluted?

However, many of these stories come off as if Sala just doodling away without any plan, so he gets to draw all this cool stuff, but it doesn’t really add up to much (except a vague feeling of unease).

Right, this is the story from Raw #8… I wonder how it was printed there?

Reading this collection, there isn’t really much of a cumulative effect… except slight boredom. Because every story is basically the same. Reading one of these is amazing; reading a dozen in a row is less so.

I think Sala is mainly going for a dreamline effect (plot wise), but they feel less like real dreams and more like Freudian examples of dreams.

There’s helpfully a bibliography at the end. I’ve tried getting hold of Sala’s self-published Night Drive book, but it’s impossible to find.

Darcy Sullivan interviews Sala in The Comics Journal #208, page 67:

SULLIVAN: When did you do the stories that appeared

in Night Dream.

SALA: Night Drive.

SULLIVAN: Night Drive.

SALA: You’re not the first person to make that mistake.

The guy at Bud Plant who rejected carrying it said,

“Four dollars is a little expensive for Night

Dreams, don’t you think?”

SULLIVAN: When didyou do those stories?

SALA: I did those stories when I was 29 years

old, believe it or not. Right now to me it look

like juvenalia. I was a really late starter. Night

Drive was the start ofa certain period and The

Chuckling Whatsit is the start ofa new period. I

look at my work from that first period and all I

see is the struggle. If people like the work I’ve

done, I’m glad. But I think the best is yet to

come. You know, Chester Gould was in his

prime in his 40s. Thads when he created Flattop

and some of his best characters

But as far as Night Drive, I wasn’t sure ifl

was doing art or popular culture. I think I

thought I was making art. There is a clue in

there as to the direction I would eventually go.

At the very end, there’s a story that I almost left

out, called “Invisible Hands,” which was my

take-offon my love ofpulps. It was non-linear,

it was broken up, and I didn’t really bother to

end it. I thought it didn’t need an ending. ltwas

supposed to be a chapter from a non-existent

serial — i€s like Andre Breton and the surreal-

ists. They loved stuff liked Fantamo$. Andre

Breton did this famous thing where he’d walk

into the middle ofa movie and watch a part Of it, and

get up and go into another theater and watch part of

another movie, and would never see the entire movie.

So I did this thing, “Invisible Hands,” which was

not meant to be taken seriously. The rest of Night

Drive has more to do with the world offine art than the

world of comics.

I had never stopped writing. I would take the

BART train to work every day, writing, then at home,

rd draw pictures to go with the stories. The main

influence on me was not so much or Weirdo, but

Mark Beyeds Dead Stories; when I saw that, it was a

revelation. I really related to his feeling of negativity

and his primitive art style. I looked through it to see

who the publisher was. I couldn’t find the name ofa

publisher, and it dawned on me that this guy did this

himself. I followed Mark Beyer’s format with the card

stock cover, magazine-size, for Night Drive.

If I haven’t said it before, I should say that I never

thought I would make it to 30. One of the reasons I

couldn’t really imagine becoming a successful artist in

my 20s was that I had been thinking about suicide

every day since the time I was a teenager.

This blog post is part of the Punk Comix series.