I know. I know.

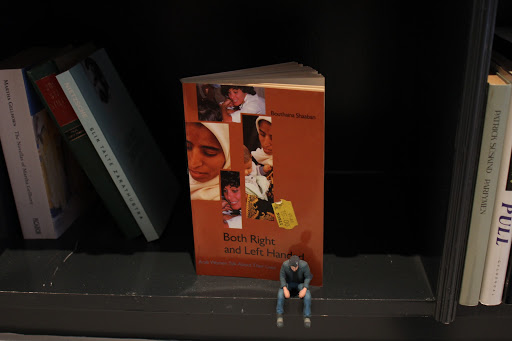

Anyway. Shaaban writes with a quite bracing sense of quiet fury about what had happened to herself, and what’s happening to women in Arab countries. This book was published in 1988, and is mainly a series of interviews with women, where they, er, talk about their lives.

So we get stories about forced marriages at the age of 12; fathers who kill their daughters who have disobeyed them; brothers who sneak into houses where their sisters have sought refuge (after “shaming” the family in some way) and stabbing their sisters to death; husbands who beat and rape their 13-year old wives. And so on.

But also stories from women who have participated in revolutions and fighting. Who have gone to universities and gotten PhDs, and who have made some progress. At least they feel they have. The author frequently becomes rather exasperated with the women she interviews, but she mainly presents what they have to say without arguing against them explicitly.

Instead she allows the stories themselves to carry out all the eye-rolling she was probably doing while doing the interviews. For instance, when she interviews this older woman who complains bitterly about her husband, and how awful he was, and how she was forced to marry him. Then she interviews the daughter of this mother, who says that she herself was forced by her mother to marry at 12. And that her father was the nice one.

It’s a recurring theme in the book. As awful as the Arab men are (and they are very awful indeed in this book), the Arab women are complicit, and can wait to take up the veil. As one tiresome woman puts it: “For another thing, men no longer follow me in the streets uttering obscene words and dirty jokes. All Arab men respects women who wear Al Shari. This is why I feel this dress strengthens my characters and confirms my independence.” You can hear Shabaan gnashing her teeth.

So it’s an interesting book, but I’m not quite sure about the fact checking. For instance:

Er, what? Ok, in 1988 Wikipedia didn’t exist, but 1) the bits about Sweden and Japan are kinda absurd, and the bit where she compares laws in one country to the statistical reality in another are kinda risible.

This genre has to include one uplifting section, so in the final section she visits the southern bits of Algeria, where she interviews people from the Al Tawariqu tribes. Apparently in this matrilinial society, men wear the veils, rape and violence upon women are unheard of, and both men and women marry and divorce as they see fit. It’s a kind of paradise:

See? It’s great. But it’s failing, because it’s coming into further contact with the northern, patriarchal parts of Algeria.

So it’s an interesting book, but it has its problems. And all the women she interviews speak in exactly the same voice. I had started to suspect that she had recreated these interviews from notes, but then she mentions that she has a tape recorder (“After talking in a monologue for a long time he pretended to have just noticed my tape recorder and asked me to switch it off because he was not well prepared. ‘I’ve already done that, I’m sorry to say,’ I answered. ‘Because my books is devoted to what women think; it is not about what men think of women.'”), so I don’t know why she has edited all these voices into sameyness. But it doesn’t make the text particularly vibrant.

At the time this book was written, the Muslim Brotherhood were rattling their swords, but most of the women interviewed in this book seem to regard them as a pretty minor nuisance, and the book ends on a hopeful note:

Yes, that would have been nice.

Rating: Muslimacious